Title: A Practical Physiology: A Text-Book for Higher Schools

Author: Albert F. Blaisdell

Release date: December 1, 2003 [eBook #10453]

Most recently updated: December 19, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Distributed Proofreaders

[Transcriber’s Note: Figures 162-167 have been renumbered. In the original, Figure 162 was labeled as 161; 163 as 162; etc.]

The author has aimed to prepare a text-book on human physiology for use in higher schools. The design of the book is to furnish a practical manual of the more important facts and principles of physiology and hygiene, which will be adapted to the needs of students in high schools, normal schools, and academies.

Teachers know, and students soon learn to recognize the fact, that it is impossible to obtain a clear understanding of the functions of the various parts of the body without first mastering a few elementary facts about their structure. The course adopted, therefore, in this book, is to devote a certain amount of space to the anatomy of the several organs before describing their functions.

A mere knowledge of the facts which can be gained in secondary schools, concerning the anatomy and physiology of the human body, is of little real value or interest in itself. Such facts are important and of practical worth to young students only so far as to enable them to understand the relation of these facts to the great laws of health and to apply them to daily living. Hence, it has been the earnest effort of the author in this book, as in his other physiologies for schools, to lay special emphasis upon such points as bear upon personal health.

Physiology cannot be learned as it should be by mere book study. The result will be meagre in comparison with the capabilities of the subject. The study of the text should always be supplemented by a series of practical experiments. Actual observations and actual experiments are as necessary to illuminate the text and to illustrate important principles in physiology as they are in botany, chemistry, or physics. Hence, as supplementary to the text proper, and throughout the several chapters, a series of carefully arranged and practical experiments has been added. For the most part, they are simple and can be performed with inexpensive and easily obtained apparatus. They are so arranged that some may be omitted and others added as circumstances may allow.

If it becomes necessary to shorten the course in physiology, the various sections printed in smaller type may be omitted or used for home study.

The laws of most of the states now require in our public schools the study of the effects of alcoholic drinks, tobacco, and other narcotics upon the bodily life. This book will be found to comply fully with all such laws.

The author has aimed to embody in simple and concise language the latest and most trustworthy information which can be obtained from the standard authorities on modern physiology, in regard to the several topics.

In the preparation of this text-book the author has had the editorial help of his esteemed friend, Dr. J. E. Sanborn, of Melrose, Mass., and is also indebted to the courtesy of Thomas E. Major, of Boston, for assistance in revising the proofs.

Albert F. Blaisdell.

Boston, August, 1897.

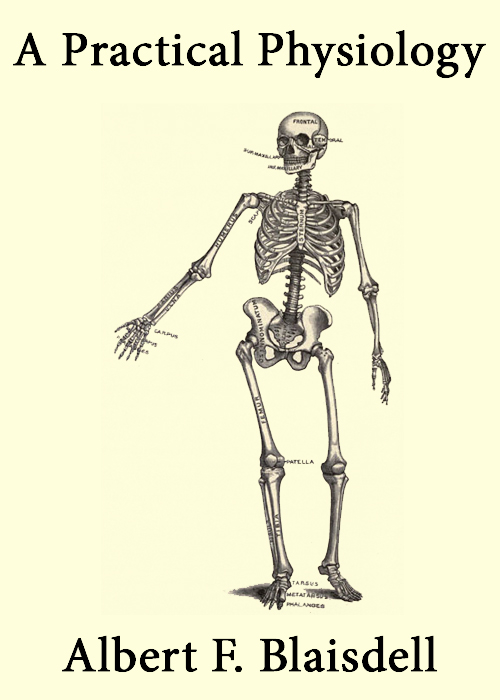

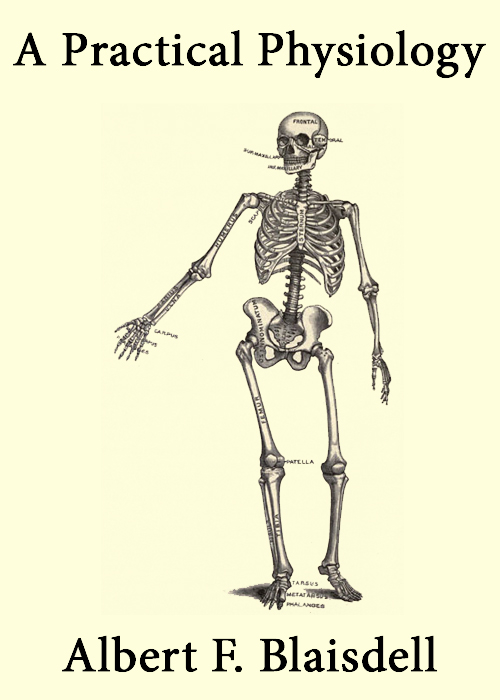

| Chapter I | Introduction |

| Chapter II | The Bones |

| Chapter III | The Muscles |

| Chapter IV | Physical Exercise |

| Chapter V | Food and Drink |

| Chapter VI | Digestion |

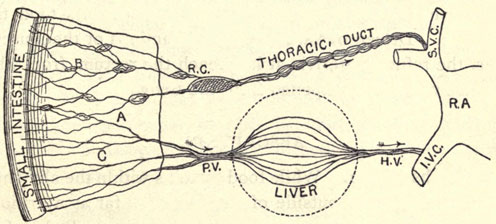

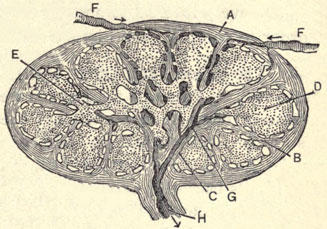

| Chapter VII | The Blood and Its Circulation |

| Chapter VIII | Respiration |

| Chapter IX | The Skin and the Kidneys |

| Chapter X | The Nervous System |

| Chapter XI | The Special Sense |

| Chapter XII | The Throat and the Voice |

| Chapter XIII | Accidents and Emergencies |

| Chapter XIV | In Sickness and in Health |

Care of the Sick-Room; Poisons and their Antidotes; Bacteria; | |

| Chapter XV | Experimental Work in Physiology |

Practical Experiments; Use of the Microscope; Additional Experiments; | |

| Glossary | |

| Index | |

1. The Study of Physiology. We are now to take up a new study, and in a field quite different from any we have thus far entered. Of all our other studies,—mathematics, physics, history, language,—not one comes home to us with such peculiar interest as does physiology, because this is the study of ourselves.

Every thoughtful young person must have asked himself a hundred questions about the problems of human life: how it can be that the few articles of our daily food—milk, bread, meats, and similar things—build up our complex bodies, and by what strange magic they are transformed into hair, skin, teeth, bones, muscles, and blood.

How is it that we can lift these curtains of our eyes and behold all the wonders of the world around us, then drop the lids, and though at noonday, are instantly in total darkness? How does the minute structure of the ear report to us with equal accuracy the thunder of the tempest, and the hum of the passing bee? Why is breathing so essential to our life, and why cannot we stop breathing when we try? Where within us, and how, burns the mysterious fire whose subtle heat warms us from the first breath of infancy till the last hour of life?

These and scores of similar questions it is the province of this deeply interesting study of physiology to answer.

2. What Physiology should Teach us. The study of physiology is not only interesting, but it is also extremely useful. Every reasonable person should not only wish to acquire the knowledge how best to protect and preserve his body, but should feel a certain profound respect for an organism so wonderful and so perfect as his physical frame. For our bodies are indeed not ourselves, but the frames that contain us,—the ships in which we, the real selves, are borne over the sea of life. He must be indeed a poor navigator who is not zealous to adorn and strengthen his ship, that it may escape the rocks of disease and premature decay, and that the voyage of his life may be long, pleasant, and successful.

But above these thoughts there rises another,—that in studying physiology we are tracing the myriad lines of marvelous ingenuity and forethought, as they appear at every glimpse of the work of the Divine Builder. However closely we study our bodily structure, we are, at our best, but imperfect observers of the handiwork of Him who made us as we are.

3. Distinctive Characters of Living Bodies. Even a very meagre knowledge of the structure and action of our bodies is enough to reveal the following distinctive characters: our bodies are continually breathing, that is, they take in oxygen from the surrounding air; they take in certain substances known as food, similar to those composing the body, which are capable through a process called oxidation, or through other chemical changes, of setting free a certain amount of energy.

Again, our bodies are continually making heat and giving it out to surrounding objects, the production and the loss of heat being so adjusted that the whole body is warm, that is, of a temperature higher than that of surrounding objects. Our bodies, also, move themselves, either one part on another, or the whole body from place to place. The motive power is not from the outside world, but the energy of their movements exists in the bodies themselves, influenced by changes in their surroundings. Finally, our bodies are continually getting rid of so-called waste matters, which may be considered products of the oxidation of the material used as food, or of the substances which make up the organism.

4. The Main Problems of Physiology briefly Stated. We shall learn in a subsequent chapter that the living body is continually losing energy, but by means of food is continually restoring its substance and replenishing its stock of energy. A great deal of energy thus stored up is utilized as mechanical work, the result of physical movements. We shall learn later on that much of the energy which at last leaves the body as heat, exists for a time within the organism in other forms than heat, though eventually transformed into heat. Even a slight change in the surroundings of the living body may rapidly, profoundly, and in special ways affect not only the amount, but the kind of energy set free. Thus the mere touch of a hair may lead to such a discharge of energy, that a body previously at rest may be suddenly thrown into violent convulsions. This is especially true in the case of tetanus, or lockjaw.

The main problem we have to solve in the succeeding pages is to ascertain how it is that our bodies can renew their substance and replenish the energy which they are continually losing, and can, according to the nature of their surroundings, vary not only the amount, but the kind of energy which they set free.

5. Technical Terms Defined. All living organisms are studied usually from two points of view: first, as to their form and structure; second, as to the processes which go on within them. The science which treats of all living organisms is called biology. It has naturally two divisions,—morphology, which treats of the form and structure of living beings, and physiology, which investigates their functions, or the special work done in their vital processes.

The word anatomy, however, is usually employed instead of morphology. It is derived from two Greek words, and means the science of dissection. Human anatomy then deals with the form and structure of the human body, and describes how the different parts and organs are arranged, as revealed by observation, by dissection, and by the microscope.

Histology is that part of anatomy which treats of the minute structure of any part of the body, as shown by the microscope.

Human physiology describes the various processes that go on in the human body in health. It treats of the work done by the various parts of the body, and of the results of the harmonious action of the several organs. Broadly speaking, physiology is the science which treats of functions. By the word function is meant the special work which an organ has to do. An organ is a part of the body which does a special work. Thus the eye is the organ of sight, the stomach of digestion, and the lungs of breathing.

It is plain that we cannot understand the physiology of our bodies without a knowledge of their anatomy. An engineer could not understand the working of his engine unless well acquainted with all its parts, and the manner in which they were fitted together. So, if we are to understand the principles of elementary physiology, we must master the main anatomical facts concerning the organs of the body before considering their special functions.

As a branch of study in our schools, physiology aims to make clear certain laws which are necessary to health, so that by a proper knowledge of them, and their practical application, we may hope to spend happier and more useful, because healthier, lives. In brief, the study of hygiene, or the science of health, in the school curriculum, is usually associated with that of physiology.[1]

6. Chemical Elements in the Body. All of the various complex substances found in nature can be reduced by chemical analysis to about 70 elements, which cannot be further divided. By various combinations of these 70 elements all the substances known to exist in the world of nature are built up. When the inanimate body, like any other substance, is submitted to chemical analysis, it is found that the bone, muscle, teeth, blood, etc., may be reduced to a few chemical elements.

In fact, the human body is built up with 13 of the 70 elements, namely: oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, chlorine, fluorine, carbon, phosphorus, sulphur, calcium, potassium, sodium, magnesium, and iron. Besides these, a few of the other elements, as silicon, have been found; but they exist in extremely minute quantities.

The following table gives the proportion in which these various elements are present:

| Oxygen | 62.430 | per cent |

| Carbon | 21.150 | ” ” |

| Hydrogen | 9.865 | ” ” |

| Nitrogen | 3.100 | ” ” |

| Calcium | 1.900 | ” ” |

| Phosphorus | 0.946 | ” ” |

| Potassium | 0.230 | ” ” |

| Sulphur | 0.162 | ” ” |

| Chlorine | 0.081 | ” ” |

| Sodium | 0.081 | ” ” |

| Magnesium | 0.027 | ” ” |

| Iron | 0.014 | ” ” |

| Fluorine | 0.014 | ” ” |

| ——— | ||

| 100.000 |

As will be seen from this table, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen, which are gases in their uncombined form, make up ¾ of the weight of the whole human body. Carbon, which exists in an impure state in charcoal, forms more than ⅕ of the weight of the body. Thus carbon and the three gases named, make up about 96 per cent of the total weight of the body.

7. Chemical Compounds in the Body. We must keep in mind that, with slight exceptions, none of these 13 elements exist in their elementary form in the animal economy. They are combined in various proportions, the results differing widely from the elements of which they consist. Oxygen and hydrogen unite to form water, and water forms more than ⅔ of the weight of the whole body. In all the fluids of the body, water acts as a solvent, and by this means alone the circulation of nutrient material is possible. All the various processes of secretion and nutrition depend on the presence of water for their activities.

8. Inorganic Salts. A large number of the elements of the body unite one with another by chemical affinity and form inorganic salts. Thus sodium and chlorine unite and form chloride of sodium, or common salt. This is found in all the tissues and fluids, and is one of the most important inorganic salts the body contains. It is absolutely necessary for continued existence. By a combination of phosphorus with sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, the various phosphates are formed.

The phosphates of lime and soda are the most abundant of the salts of the body. They form more than half the material of the bones, are found in the teeth and in other solids and in the fluids of the body. The special place of iron is in the coloring matter of the blood. Its various salts are traced in the ash of bones, in muscles, and in many other tissues and fluids. These compounds, forming salts or mineral matters that exist in the body, are estimated to amount to about 6 per cent of the entire weight.

9. Organic Compounds. Besides the inorganic materials, there exists in the human body a series of compound substances formed of the union of the elements just described, but which require the agency of living structures. They are built up from the elements by plants, and are called organic. Human beings and the lower animals take the organized materials they require, and build them up in their own bodies into still more highly organized forms.

The organic compounds found in the body are usually divided into three great classes:

The extent to which these three great classes of organic materials of the body exist in the animal and vegetable kingdoms, and are utilized for the food of man, will be discussed in the chapter on food (Chapter V.). The Proteids, because they contain the element nitrogen and the others do not, are frequently called nitrogenous, and the other two are known as non-nitrogenous substances. The proteids, the type of which is egg albumen, or the white of egg, are found in muscle and nerve, in glands, in blood, and in nearly all the fluids of the body. A human body is estimated to yield on an average about 18 per cent of albuminous substances. In the succeeding chapters we shall have occasion to refer to various and allied forms of proteids as they exist in muscle (myosin), coagulated blood (fibrin), and bones (gelatin).

The Carbohydrates are formed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, the last two in the proportion to form water. Thus we have animal starch, or glycogen, stored up in the liver. Sugar, as grape sugar, is also found in the liver. The body of an average man contains about 10 per cent of Fats. These are formed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, in which the latter two are not in the proportion to form water. The fat of the body consists of a mixture which is liquid at the ordinary temperature.

Now it must not for one moment be supposed that the various chemical elements, as the proteids, the salts, the fats, etc., exist in the body in a condition to be easily separated one from another. Thus a piece of muscle contains all the various organic compounds just mentioned, but they are combined, and in different cases the amount will vary. Again, fat may exist in the muscles even though it is not visible to the naked eye, and a microscope is required to show the minute fat cells.

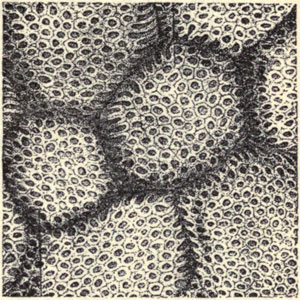

10. Protoplasm. The ultimate elements of which the body is composed consist of “masses of living matter,” microscopic in size, of a material commonly called protoplasm.[2] In its simplest form protoplasm appears to be a homogeneous, structureless material, somewhat resembling the raw white of an egg. It is a mixture of several chemical substances and differs in appearance and composition in different parts of the body.

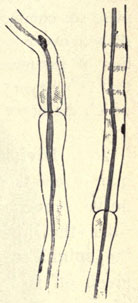

Protoplasm has the power of appropriating nutrient material, of dividing and subdividing, so as to form new masses like itself. When not built into a tissue, it has the power of changing its shape and of moving from place to place, by means of the delicate processes which it puts forth. Now, while there are found in the lowest realm of animal life, organisms like the amœba of stagnant pools, consisting of nothing more than minute masses of protoplasm, there are others like them which possess a small central body called a nucleus. This is known as nucleated protoplasm.

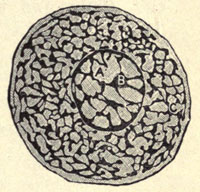

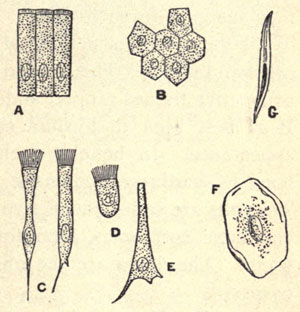

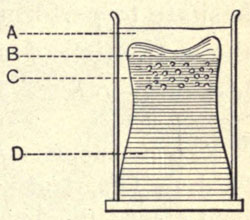

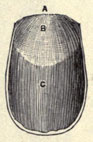

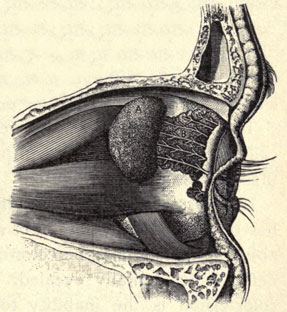

Fig. 1.—Diagram of a Cell.

11. Cells. When we carry back the analysis of an organized body as far as we can, we find every part of it made up of masses of nucleated protoplasm of various sizes and shapes. In all essential features these masses conform to the type of protoplasmic matter just described. Such bodies are called cells. In many cells the nucleus is finely granular or reticulated in appearance, and on the threads of the meshwork may be one or more enlargements, called nucleoli. In some cases the protoplasm at the circumference is so modified as to give the appearance of a limiting membrane called the cell wall. In brief, then, a cell is a mass of nucleated protoplasm; the nucleus may have a nucleolus, and the cell may be limited by a cell wall. Every tissue of the human body is formed through the agency of protoplasmic cells, although in most cases the changes they undergo are so great that little evidence remains of their existence.

There are some organisms lower down in the scale, whose whole activity is confined within the narrow limits of a single cell. Thus, the amœba begins its life as a cell split off from its parent. This divides in its turn, and each half is a complete amœba. When we come a little higher than the amœba, we find organisms which consist of several cells, and a specialization of function begins to appear. As we ascend in the animal scale, specialization of structure and of function is found continually advancing, and the various kinds of cells are grouped together into colonies or organs.

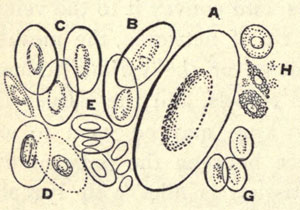

12. Cells and the Human Organism. If the body be studied in its development, it is found to originate from a single mass of nucleated protoplasm, a single cell with a nucleus and nucleolus. From this original cell, by growth and development, the body, with all its various tissues, is built up. Many fully formed organs, like the liver, consist chiefly of cells. Again, the cells are modified to form fibers, such as tendon, muscle, and nerve. Later on, we shall see the white blood corpuscles exhibit all the characters of the amœba (Fig. 2). Even such dense structures as bone, cartilage, and the teeth are formed from cells.

In short, cells may be regarded as the histological units of animal structures; by the combination, association, and modification of these the body is built up. Of the real nature of the changes going on within the living protoplasm, the process of building up lifeless material into living structures, and the process of breaking down by which waste is produced, we know absolutely nothing. Could we learn that, perhaps we should know the secret of life.

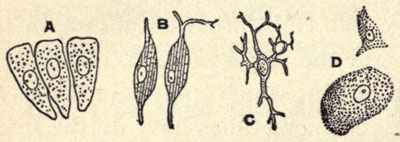

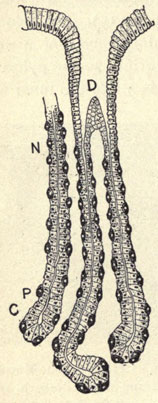

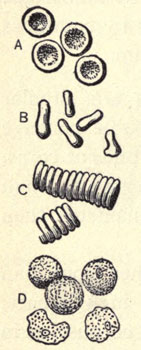

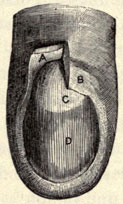

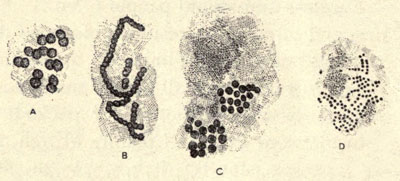

13. Kinds of Cells. Cells vary greatly in size, some of the smallest being only 1/3500 an inch or less in diameter. They also vary greatly in form, as may be seen in Figs. 3 and 5. The typical cell is usually globular in form, other shapes being the result of pressure or of similar modifying influences. The globular, as well as the large, flat cells, are well shown in a drop of saliva. Then there are the columnar cells, found in various parts of the intestines, in which they are closely arranged side by side. These cells sometimes have on the free surface delicate prolongations called cilia. Under the microscope they resemble a wave, as when the wind blows over a field of grain (Fig. 5). There are besides cells known as spindle, stellate, squamous or pavement, and various other names suggested by their shapes. Cells are also described as to their contents. Thus fat and pigment cells are alluded to in succeeding sections. Again, they may be described as to their functions or location or the tissue in which they are found, as epithelial cells, blood cells (corpuscles, Figs. 2 and 66), nerve cells (Fig. 4), and connective-tissue cells.

14. Vital Properties of Cells. Each cell has a life of its own. It manifests its vital properties in that it is born, grows, multiplies, decays, and at last dies.[3] During its life it assimilates food, works, rests, and is capable of spontaneous motion and frequently of locomotion. The cell can secrete and excrete substance, and, in brief, presents nearly all the phenomena of a human being.

Cells are produced only from cells by a process of self-division, consisting of a cleavage of the whole cell into parts, each of which becomes a separate and independent organism. Cells rapidly increase in size up to a certain definite point which they maintain during adult life. A most interesting quality of cell life is motion, a beautiful form of which is found in ciliated epithelium. Cells may move actively and passively. In the blood the cells are swept along by the current, but the white corpuscles, seem able to make their way actively through the tissues, as if guided by some sort of instinct.

Fig. 3.—Various Forms of Cells.

Some cells live a brief life of 12 to 24 hours, as is probably the case with many of the cells lining the alimentary canal; others may live for years, as do the cells of cartilage and bone. In fact each cell goes through the same cycle of changes as the whole organism, though doubtless in a much shorter time. The work of cells is of the most varied kind, and embraces the formation of every tissue and product,—solid, liquid, or gaseous. Thus we shall learn that the cells of the liver form bile, those of the salivary glands and of the glands of the stomach and pancreas form juices which aid in the digestion of food.

15. The Process of Life. All living structures are subject to constant decay. Life is a condition of incessant changes, dependent upon two opposite processes, repair and decay. Thus our bodies are not composed of exactly the same particles from day to day, or even from one moment to another, although to all appearance we remain the same individuals. The change is so gradual, and the renewal of that which is lost may be so exact, that no difference can be noticed except at long intervals of time.[4] (See under “Bacteria,” Chapter XIV.)

The entire series of chemical changes that take place in the living body, beginning with assimilation and ending with excretion, is included in one word, metabolism. The process of building up living material, or the change by which complex substances (including the living matter itself) are built up from simpler materials, is called anabolism. The breaking down of material into simple products, or the changes in which complex materials (including the living substance) are broken down into comparatively simple products, is known as katabolism. This reduction of complex substances to simple, results in the production of animal force and energy. Thus a complex substance, like a piece of beef-steak, is built up of a large number of molecules which required the expenditure of force or energy to store up. Now when this material is reduced by the process of digestion to simpler bodies with fewer molecules, such as carbon dioxid, urea, and water, the force stored up in the meat as potential energy becomes manifest and is used as active life-force known as kinetic energy.

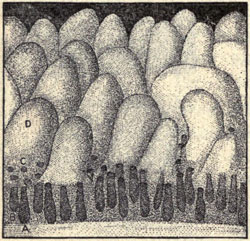

16. Epithelium. Cells are associated and combined in many ways to form a simple tissue. Such a simple tissue is called an epithelium or surface-limiting tissue, and the cells are known as epithelial cells. These are united by a very small amount of a cement substance which belongs to the proteid class of material. The epithelial cells, from their shape, are known as squamous, columnar, glandular, or ciliated. Again, the cells may be arranged in only a single layer, or they may be several layers deep. In the former case the epithelium is said to be simple; in the latter, stratified. No blood-vessels pass into these tissues; the cells derive their nourishment by the imbibition of the plasma of the blood exuded into the subjacent tissue.

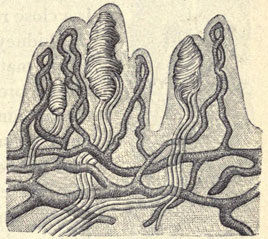

17. Varieties of Epithelium. The squamous or pavement epithelium consists of very thin, flattened scales, usually with a small nucleus in the center. When the nucleus has disappeared, they become mere horny plates, easily detached. Such cells will be described as forming the outer layer of the skin, the lining of the mouth and the lower part of the nostrils.

The columnar epithelium consists of pear-shaped or elongated cells, frequently as a single layer of cells on the surface of a mucous membrane, as on the lining of the stomach and intestines, and the free surface of the windpipe and large air-tubes.

The glandular or spheroidal epithelium is composed of round cells or such as become angular by mutual pressure. This kind forms the lining of glands such as the liver, pancreas, and the glands of the skin.

The ciliated epithelium is marked by the presence of very fine hair-like processes called cilia, which develop from the free end of the cell and exhibit a rapid whip-like movement as long as the cell is alive. This motion is always in the same direction, and serves to carry away mucus and even foreign particles in contact with the membrane on which the cells are placed. This epithelium is especially common in the air passages, where it serves to keep a free passage for the entrance and exit of air. In other canals a similar office is filled by this kind of epithelium.

18. Functions of Epithelial Tissues. The epithelial structures may be divided, as to their functions, into two main divisions. One is chiefly protective in character. Thus the layers of epithelium which form the superficial layer of the skin have little beyond such an office to discharge. The same is to a certain extent true of the epithelial cells covering the mucous membrane of the mouth, and those lining the air passages and air cells of the lungs.

Fig. 5.—Various Kinds of Epithelial Cells

The second great division of the epithelial tissues consists of those whose cells are formed of highly active protoplasm, and are busily engaged in some sort of secretion. Such are the cells of glands,—the cells of the salivary glands, which secrete the saliva, of the gastric glands, which secrete the gastric juice, of the intestinal glands, and the cells of the liver and sweat glands.

19. Connective Tissue. This is the material, made up of fibers and cells, which serves to unite and bind together the different organs and tissues. It forms a sort of flexible framework of the body, and so pervades every portion that if all the other tissues were removed, we should still have a complete representation of the bodily shape in every part. In general, the connective tissues proper act as packing, binding, and supporting structures. This name includes certain tissues which to all outward appearance vary greatly, but which are properly grouped together for the following reasons: first, they all act as supporting structures; second, under certain conditions one may be substituted for another; third, in some places they merge into each other.

All these tissues consist of a ground-substance, or matrix, cells, and fibers. The ground-substance is in small amount in connective tissues proper, and is obscured by a mass of fibers. It is best seen in hyaline cartilage, where it has a glossy appearance. In bone it is infiltrated with salts which give bone its hardness, and make it seem so unlike other tissues. The cells are called connective-tissue corpuscles, cartilage cells, and bone corpuscles, according to the tissues in which they occur. The fibers are the white fibrous and the yellow elastic tissues.

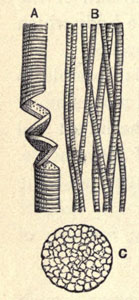

The following varieties are usually described:

20. White Fibrous Tissue. This tissue consists of bundles of very delicate fibrils bound together by a small amount of cement substance. Between the fibrils protoplasmic masses (connective-tissue corpuscles) are found. These fibers may be found so interwoven as to form a sheet, as in the periosteum of the bone, the fasciæ around muscles, and the capsules of organs; or they may be aggregated into bundles and form rope-like bands, as in the ligaments of joints and the tendons of muscles. On boiling, this tissue yields gelatine. In general, where white fibrous tissue abounds, structures are held together, and there is flexibility, but little or no distensibility.

21. Yellow Elastic Tissue. The fibers of yellow elastic tissue are much stronger and coarser than those of the white. They are yellowish, tend to curl up at the ends, and are highly elastic. It is these fibers which give elasticity to the skin and to the coats of the arteries. The typical form of this tissue occurs in the ligaments which bind the vertebræ together (Fig. 26), in the true vocal cords, and in certain ligaments of the larynx. In the skin and fasciæ, the yellow elastic is found mixed with white fibrous and areolar tissues. It does not yield gelatine on boiling, and the cells are, if any, few.

22. Areolar or Cellular Tissue. This consists of bundles of delicate fibers interlacing and crossing one another, forming irregular spaces or meshes. These little spaces, in health, are filled with fluid that has oozed out of the blood-vessels. The areolar tissue forms a protective covering for the tissues of delicate and important organs.

23. Adipose or Fatty Tissue. In almost every part of the body the ordinary areolar tissue contains a variable quantity of adipose or fatty tissue. Examined by the microscope, the fat cells consist of a number of minute sacs of exceedingly delicate, structureless membrane filled with oil. This is liquid in life, but becomes solidified after death. This tissue is plentiful beneath the skin, in the abdominal cavity, on the surface of the heart, around the kidneys, in the marrow of bones, and elsewhere. Fat serves as a soft packing material. Being a poor conductor, it retains the heat, and furnishes a store rich in carbon and hydrogen for use in the body.

24. Adenoid or Retiform Tissue. This is a variety of connective tissue found in the tonsils, spleen, lymphatic glands, and allied structures. It consists of a very fine network of cells of various sizes. The tissue combining them is known as adenoid or gland-like tissue.

25. Cartilage. Cartilage, or gristle, is a tough but highly elastic substance. Under the microscope cartilage is seen to consist of a matrix, or base, in which nucleated cells abound, either singly or in groups. It has sometimes a fine ground-glass appearance, when the cartilage is spoken of as hyaline. In other cases the matrix is almost replaced by white fibrous tissue. This is called white fibro-cartilage, and is found where great strength and a certain amount of rigidity are required.

Again, there is between the cells a meshwork of yellow elastic fibers, and this is called yellow fibro-cartilage (Fig. 8). The hyaline cartilage forms the early state of most of the bones, and is also a permanent coating for the articular ends of long bones. The white fibro-cartilage is found in the disks between the bodies of the vertebræ, in the interior of the knee joint, in the wrist and other joints, filling the cavities of the bones, in socket joints, and in the grooves for tendons. The yellow fibro-cartilage forms the expanded part of the ear, the epiglottis, and other parts of the larynx.

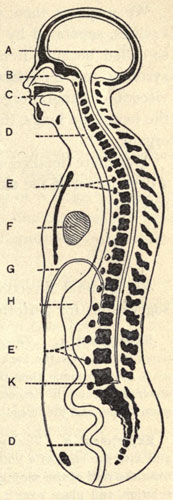

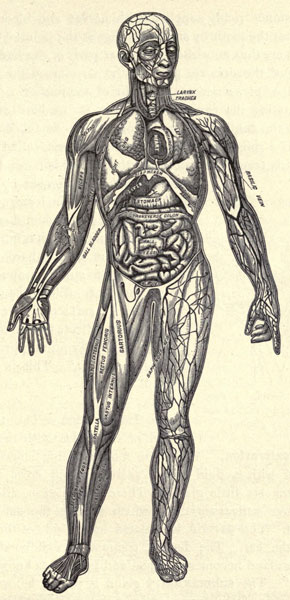

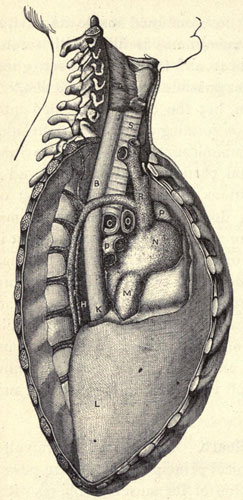

26. General Plan of the Body. To get a clearer idea of the general plan on which the body is constructed, let us imagine its division into perfectly equal parts, one the right and the other the left, by a great knife severing it through the median, or middle line in front, backward through the spinal column, as a butcher divides an ox or a sheep into halves for the market. In a section of the body thus planned the skull and the spine together are shown to have formed a tube, containing the brain and spinal cord. The other parts of the body form a second tube (ventral) in front of the spinal or dorsal tube. The upper part of the second tube begins with the mouth and is formed by the ribs and breastbone. Below the chest in the abdomen, the walls of this tube would be made up of the soft parts.

Fig. 9.—Diagrammatic Longitudinal Section of the Trunk and Head. (Showing the dorsal and the ventral tubes.)

We may say, then, that the body consists of two tubes or cavities, separated by a bony wall, the dorsal or nervous tube, so called because it contains the central parts of the nervous system; and the visceral or ventral tube, as it contains the viscera, or general organs of the body, as the alimentary canal, the heart, the lungs, the sympathetic nervous system, and other organs.

The more detailed study of the body may now be begun by a description of the skeleton or framework which supports the soft parts.

For general directions and explanations and also detailed suggestions for performing experiments, see Chapter XV.

Experiment 1. To examine squamous epithelium. With an ivory paper-knife scrape the back of the tongue or the inside of the lips or cheek; place the substance thus obtained upon a glass slide; cover it with a thin cover-glass, and if necessary add a drop of water. Examine with the microscope, and the irregularly formed epithelial cells will be seen.

Experiment 2. To examine ciliated epithelium. Open a frog’s mouth, and with the back of a knife blade gently scrape a little of the membrane from the roof of the mouth. Transfer to a glass slide, add a drop of salt solution, and place over it a cover-glass with a hair underneath to prevent pressure upon the cells. Examine with a microscope under a high power. The cilia move very rapidly when quite fresh, and are therefore not easily seen.

For additional experiments which pertain to the microscopic examination of the elementary tissues and to other points in practical histology, see Chapter XV.

Note. Inasmuch as most of the experimental work of this chapter depends upon the use of the microscope and also necessarily assumes a knowledge of facts which are discussed later, it would be well to postpone experiments in histology until they can be more satisfactorily handled in connection with kindred topics as they are met with in the succeeding chapters.]

27. The Skeleton. Most animals have some kind of framework to support and protect the soft and fleshy parts of their bodies. This framework consists chiefly of a large number of bones, and is called the skeleton. It is like the keel and ribs of a vessel or the frame of a house, the foundation upon which the bodies are securely built.

There are in the adult human body 200 distinct bones, of many sizes and shapes. This number does not, however, include several small bones found in the tendons of muscles and in the ear. The teeth are not usually reckoned as separate bones, being a part of the structure of the skin.

The number of distinct bones varies at different periods of life. It is greater in childhood than in adults, for many bones which are then separate, to allow growth, afterwards become gradually united. In early adult life, for instance, the skull contains 22 naturally separate bones, but in infancy the number is much greater, and in old age far less.

The bones of the body thus arranged give firmness, strength, and protection to the soft tissues and vital organs, and also form levers for the muscles to act upon.

28. Chemical Composition of Bone. The bones, thus forming the framework of the body, are hard, tough, and elastic. They are twice as strong as oak; one cubic inch of compact bone will support a weight of 5000 pounds. Bone is composed of earthy or mineral matter (chiefly in the form of lime salts), and of animal matter (principally gelatine), in the proportion of two-thirds of the former to one-third of the latter.

The proportion of earthy to animal matter varies with age. In infancy the bones are composed almost wholly of animal matter. Hence, an infant’s bones are rarely broken, but its legs may soon become misshapen if walking is allowed too early. In childhood, the bones still contain a larger percentage of animal matter than in more advanced life, and are therefore more liable to bend than to break; while in old age, they contain a greater percentage of mineral matter, and are brittle and easily broken.

Experiment 3. To show the mineral matter in bone. Weigh a large soup bone; put it on a hot, clear fire until it is at a red heat. At first it becomes black from the carbon of its organic matter, but at last it turns white. Let it cool and weigh again. The animal matter has been burnt out, leaving the mineral or earthy part, a white, brittle substance of exactly the same shape, but weighing only about two-thirds as much as the bone originally weighed.

Experiment 4. To show the animal matter in bone. Add a teaspoonful of muriatic acid to a pint of water, and place the mixture in a shallow earthen dish. Scrape and clean a chicken’s leg bone, part of a sheep’s rib, or any other small, thin bone. Soak the bone in the acid mixture for a few days. The earthy or mineral matter is slowly dissolved, and the bone, although retaining its original form, loses its rigidity, and becomes pliable, and so soft as to be readily cut. If the experiment be carefully performed, a long, thin bone may even be tied into a knot.

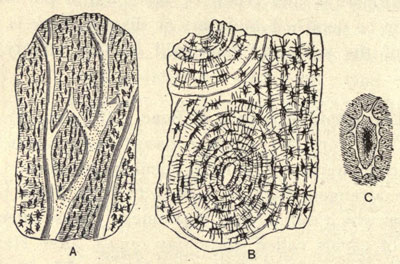

29. Physical Properties of Bone. If we take a leg bone of a sheep, or a large end of beef shin bone, and saw it lengthwise in halves, we see two distinct structures. There is a hard and compact tissue, like ivory, forming the outside shell, and a spongy tissue inside having the appearance of a beautiful lattice work. Hence this is called cancellous tissue, and the gradual transition from one to the other is apparent.

It will also be seen that the shaft is a hollow cylinder, formed of compact tissue, enclosing a cavity called the medullary canal, which is filled with a pulpy, yellow fat called marrow. The marrow is richly supplied with blood-vessels, which enter the cavity through small openings in the compact tissue. In fact, all over the surface of bone are minute canals leading into the substance. One of these, especially constant and large in many bones, is called the nutrient foramen, and transmits an artery to nourish the bone.

At the ends of a long bone, where it expands, there is no medullary canal, and the bony tissue is spongy, with only a thin layer of dense bone around it. In flat bones we find two layers or plates of compact tissue at the surface, and a spongy tissue between. Short and irregular bones have no medullary canal, only a thin shell of dense bone filled with cancellous tissue.

Fig. 12.—The Right femur sawed in two, lengthwise. (Showing arrangement of compact and cancellous tissue.)

Experiment 5. Obtain a part of a beef shin bone, or a portion of a sheep’s or calf’s leg, including if convenient the knee joint. Have the bone sawed in two, lengthwise, keeping the marrow in place. Boil, scrape, and carefully clean one half. Note the compact and spongy parts, shaft, etc.

Experiment 6. Trim off the flesh from the second half. Note the pinkish white appearance of the bone, the marrow, and the tiny specks of blood, etc. Knead a small piece of the marrow in the palm; note the oily appearance. Convert some marrow into a liquid by heating. Contrast this fresh bone with an old dry one, as found in the fields. Fresh bones should be kept in a cool place, carefully wrapped in a damp cloth, while waiting for class use.

A fresh or living bone is covered with a delicate, tough, fibrous membrane, called the periosteum. It adheres very closely to the bone, and covers every part except at the joints and where it is protected with cartilage. The periosteum is richly supplied with blood-vessels, and plays a chief part in the growth, formation, and repair of bone. If a portion of the periosteum be detached by injury or disease, there is risk that a layer of the subjacent bone will lose its vitality and be cast off.[5]

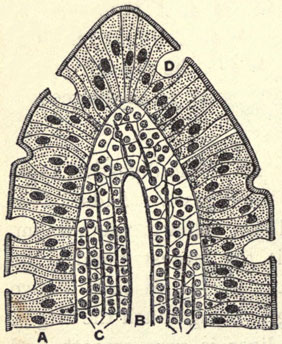

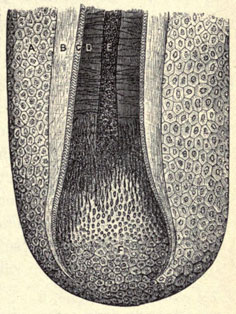

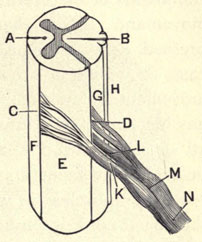

30. Microscopic Structure of Bone. If a very thin slice of bone be cut from the compact tissue and examined under a microscope, numerous minute openings are seen. Around these are arranged rings of bone, with little black bodies in them, from which radiate fine, dark lines. These openings are sections of canals called Haversian canals, after Havers, an English physician, who first discovered them. The black bodies are minute cavities called lacunæ, while the fine lines are very minute canals, canaliculi, which connect the lacunæ and the Haversian canals. These Haversian canals are supplied with tiny blood-vessels, while the lacunæ contain bone cells. Very fine branches from these cells pass into the canaliculi. The Haversian canals run lengthwise of the bone; hence if the bone be divided longitudinally these canals will be opened along their length (Fig. 13).

Thus bones are not dry, lifeless substances, but are the very type of activity and change. In life they are richly supplied with blood from the nutrient artery and from the periosteum, by an endless network of nourishing canals throughout their whole structure. Bone has, therefore, like all other living structures, a self-formative power, and draws from the blood the materials for its own nutrition.

Fig. 13.

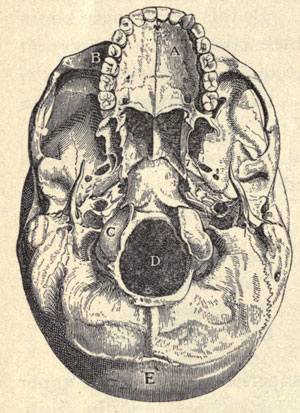

31. The Head, or Skull. The bones of the skeleton, the bony framework of our bodies, may be divided into those of the head, the trunk, and the limbs.

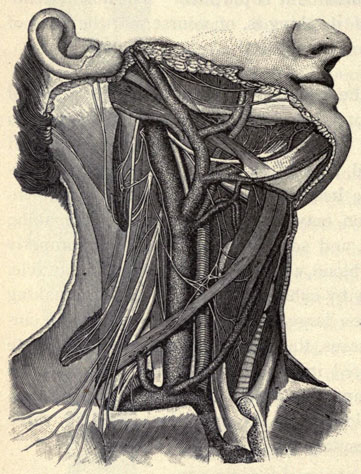

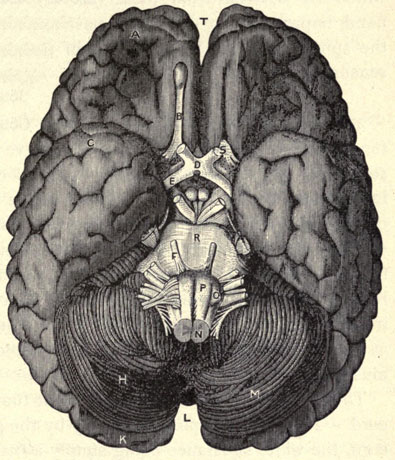

The bones of the head are described in two parts,—those of the cranium, or brain-case, and those of the face. Taken together, they form the skull. The head is usually said to contain 22 bones, of which 8 belong to the cranium and 14 to the face. In early childhood, the bones of the head are separate to allow the brain to expand; but as we grow older they gradually unite, the better to protect the delicate brain tissue.

32. The Cranium. The cranium is a dome-like structure, made up in the adult of 8 distinct bones firmly locked together. These bones are:

The frontal bone forms the forehead and front of the head. It is united with the two parietal bones behind, and extends over the forehead to make the roofs of the sockets of the eyes. It is this bone which, in many races of man, gives a dignity of person and a beauty of form seen in no other animal.

The parietal bones form the sides and roof of the skull. They are bounded anteriorly by the frontal bone, posteriorly by the occipital, and laterally by the temporal and sphenoid bones. The two bones make a beautiful arch to aid in the protection of the brain.

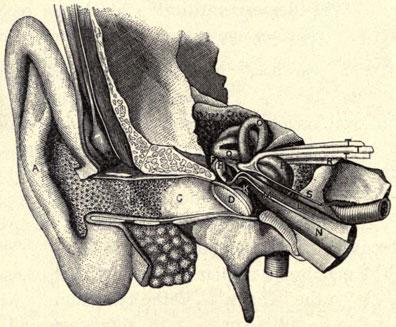

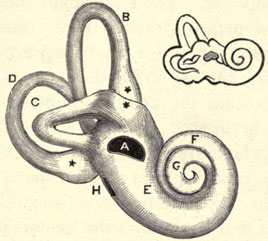

The temporal bones, forming the temples on either side, are attached to the sphenoid bone in front, the parietals above, and the occipital behind. In each temporal bone is the cavity containing the organs of hearing. These bones are so called because the hair usually first turns gray over them.

The occipital bone forms the lower part of the base of the skull, as well as the back of the head. It is a broad, curved bone, and rests on the topmost vertebra (atlas) of the backbone; its lower part is pierced by a large oval opening called the foramen magnum, through which the spinal cord passes from the brain (Fig. 15).

The sphenoid bone is in front of the occipital, forming a part of the base of the skull. It is wedged between the bones of the face and those of the cranium, and locks together fourteen different bones. It bears a remarkable resemblance to a bat with extended wings, and forms a series of girders to the arches of the cranium.

The ethmoid bone is situated between the bones of the cranium and those of the face, just at the root of the nose. It forms a part of the floor of the cranium. It is a delicate, spongy bone, and is so called because it is perforated with numerous holes like a sieve, through which the nerves of smell pass from the brain to the nose.

33. The Face. The bones of the face serve, to a marked extent, in giving form and expression to the human countenance. Upon these bones depend, in a measure, the build of the forehead, the shape of the chin, the size of the eyes, the prominence of the cheeks, the contour of the nose, and other marks which are reflected in the beauty or ugliness of the face.

The face is made up of fourteen bones which, with the exception of the lower jaw, are, like those of the cranium, closely interlocked with each other. By this union these bones help form a number of cavities which contain most important and vital organs. The two deep, cup-like sockets, called the orbits, contain the organs of sight. In the cavities of the nose is located the sense of smell, while the buccal cavity, or mouth, is the site of the sense of taste, and plays besides an important part in the first act of digestion and in the function of speech.

The bones of the face are:

34. Bones of the Face. The superior maxillary or upper jawbones form a part of the roof of the mouth and the entire floor of the orbits. In them is fixed the upper set of teeth.

The malar or cheek bones are joined to the upper jawbones, and help form the sockets of the eyes. They send an arch backwards to join the temporal bones. These bones are remarkably thick and strong, and are specially adapted to resist the injury to which this part of the face is exposed.

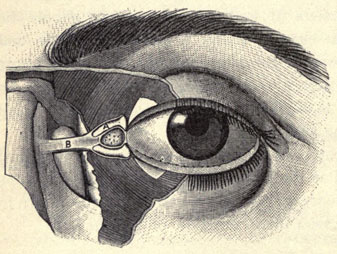

The nasal or nose bones are two very small bones between the eye sockets, which form the bridge of the nose. Very near these bones are the two small lachrymal bones. These are placed in the inner angles of the orbit, and in them are grooves in which lie the ducts through which the tears flow from the eyes to the nose.

The palate bones are behind those of the upper jaw and with them form the bony part of the roof of the mouth. The inferior turbinated are spongy, scroll-like bones, which curve about within the nasal cavities so as to increase the surface of the air passages of the nose.

The vomer serves as a thin and delicate partition between the two cavities of the nose. It is so named from its resemblance to a ploughshare.

Fig. 15.—The Base of the Skull.

The longest bone in the face is the inferior maxillary, or lower jaw. It has a horseshoe shape, and supports the lower set of teeth. It is the only movable bone of the head, having a vertical and lateral motion by means of a hinge joint with a part of the temporal bone.

35. Sutures of the Skull. Before leaving the head we must notice the peculiar and admirable manner in which the edges of the bones of the outer shell of the skull are joined together. These edges of the bones resemble the teeth of a saw. In adult life these tooth-like edges fit into each other and grow together, suggesting the dovetailed joints used by the cabinet-maker. When united these serrated edges look almost as if sewed together; hence their name, sutures. This manner of union gives unity and strength to the skull.

In infants, the corners of the parietal bones do not yet meet, and the throbbing of the brain may be seen and felt under these “soft spots,” or fontanelles, as they are called. Hence a slight blow to a babe’s head may cause serious injury to the brain (Fig. 14).

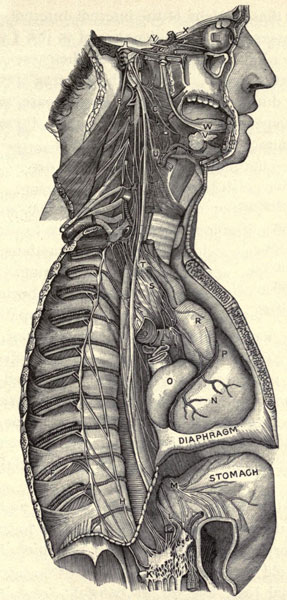

36. The Trunk. The trunk is that central part of the body which supports the head and the upper pair of limbs. It divides itself into an upper cavity, the thorax, or chest; and a lower cavity, the abdomen. These two cavities are separated by a movable, muscular partition called the diaphragm, or midriff (Figs. 9 and 49).

The bones of the trunk are variously related to each other, and some of them become united during adult life into bony masses which at earlier periods are quite distinct. For example, the sacrum is in early life made up of five distinct bones which later unite into one.

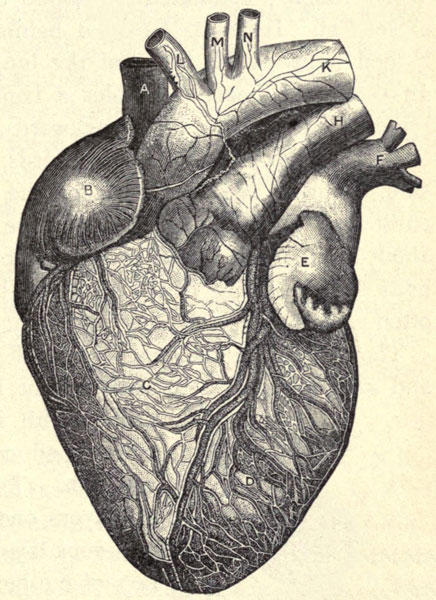

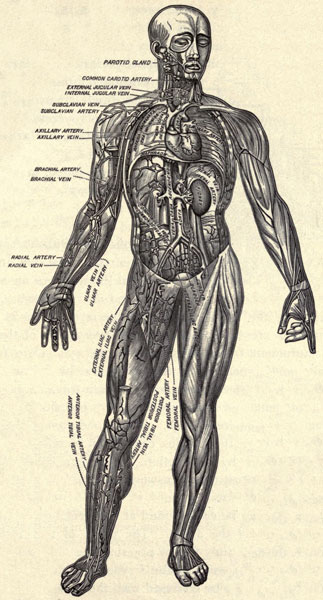

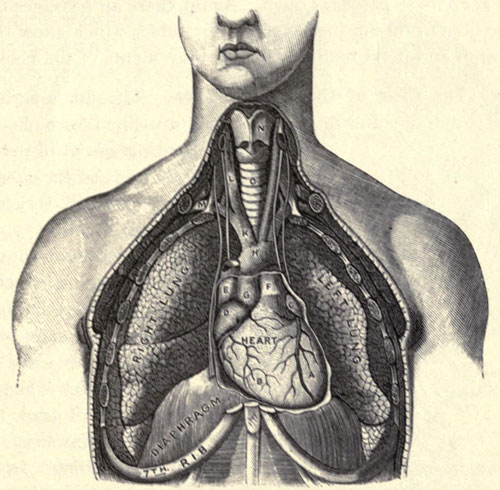

The upper cavity, or chest, is a bony enclosure formed by the breastbone, the ribs, and the spine. It contains the heart and the lungs (Fig. 86).

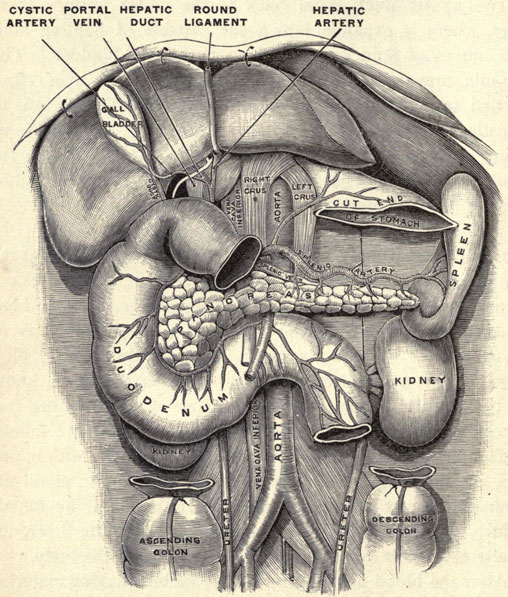

The lower cavity, or abdomen, holds the stomach, liver, intestines, spleen, kidneys, and some other organs (Fig. 59).

The bones of the trunk may be subdivided into those of the spine, the ribs, and the hips.

The trunk includes 54 bones usually thus arranged:

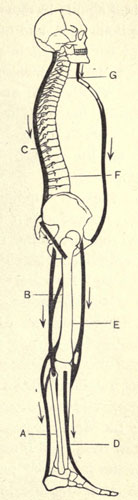

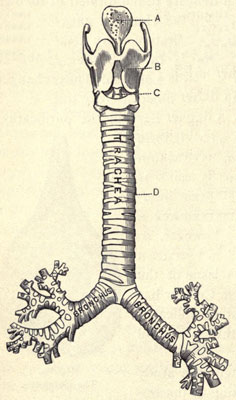

37. The Spinal Column. The spinal column, or backbone, is a marvelous piece of mechanism, combining offices which nothing short of perfection in adaptation and arrangement could enable it to perform. It is the central structure to which all the other parts of the skeleton are adapted. It consists of numerous separate bones, called vertebræ. The seven upper ones belong to the neck, and are called cervical vertebræ. The next twelve are the dorsal vertebræ; these belong to the back and support the ribs. The remaining five belong to the loins, and are called lumbar vertebræ. On looking at the diagram of the backbone (Fig. 9) it will be seen that the vertebræ increase in size and strength downward, because of the greater burden they have to bear, thus clearly indicating that an erect position is the one natural to man.

This column supports the head, encloses and protects the spinal cord, and forms the basis for the attachment of many muscles, especially those which maintain the body in an erect position. Each vertebra has an opening through its center, and the separate bones so rest, one upon another, that these openings form a continuous canal from the head to the lower part of the spine. The great nerve, known as the spinal cord, extends from the cranium through the entire length of this canal. All along the spinal column, and between each two adjoining bones, are openings on each side, through which nerves pass out to be distributed to various parts of the body.

Between the vertebræ are pads or cushions of cartilage. These act as “buffers,” and serve to give the spine strength and elasticity and to prevent friction of one bone on another. Each vertebra consists of a body, the solid central portion, and a number of projections called processes. Those which spring from the posterior of each arch are the spinous processes. In the dorsal region they are plainly seen and felt in thin persons.

The bones of the spinal column are arranged in three slight and graceful curves. These curves not only give beauty and strength to the bony framework of the body, but also assist in the formation of cavities for important internal organs. This arrangement of elastic pads between the vertebræ supplies the spine with so many elastic springs, which serve to break the effect of shock to the brain and the spinal cord from any sudden jar or injury.

The spinal column rests on a strong three-sided bone called the sacrum, or sacred-bone, which is wedged in between the hip bones and forms the keystone of the pelvis. Joined to the lower end of the sacrum is the coccyx, or cuckoo-bone, a tapering series of little bones.

Experiment 7. Run the tips of the fingers briskly down the backbone, and the spines of the vertebræ will be tipped with red so that they can be readily counted. Have the model lean forward with the arms folded across the chest; this will make the spines of the vertebræ more prominent.

Experiment 8. To illustrate the movement of torsion in the spine, or its rotation round its own axis. Sit upright, with the back and shoulders well applied against the back of a chair. Note that the head and neck can be turned as far as 60° or 70°. Now bend forwards, so as to let the dorsal and lumbar vertebræ come into play, and the head can be turned 30° more.

Experiment 9. To show how the spinal vertebræ make a firm but flexible column. Take 24 hard rubber overcoat buttons, or the same number of two-cent pieces, and pile them on top of each other. A thin layer of soft putty may be put between the coins to represent the pads of cartilage between the vertebræ. The most striking features of the spinal column may be illustrated by this simple apparatus.

38. How the Head and Spine are Joined together. The head rests upon the spinal column in a manner worthy of special notice. This consists in the peculiar structure of the first two cervical vertebræ, known as the axis and atlas. The atlas is named after the fabled giant who supported the earth on his shoulders. This vertebra consists of a ring of bone, having two cup-like sockets into which fit two bony projections arising on either side of the great opening (foramen magnum) in the occipital bone. The hinge joint thus formed allows the head to nod forward, while ligaments prevent it from moving too far.

On the upper surface of the axis, the second vertebra, is a peg or process, called the odontoid process from its resemblance to a tooth. This peg forms a pivot upon which the head with the atlas turns. It is held in its place against the front inner surface of the atlas by a band of strong ligaments, which also prevents it from pressing on the delicate spinal cord. Thus, when we turn the head to the right or left, the skull and the atlas move together, both rotating on the odontoid process of the axis.

39. The Ribs and Sternum. The barrel-shaped framework of the chest is in part composed of long, slender, curved bones called ribs. There are twelve ribs on each side, which enclose and strengthen the chest; they somewhat resemble the hoops of a barrel. They are connected in pairs with the dorsal vertebræ behind.

The first seven pairs, counting from the neck, are called the true ribs, and are joined by their own special cartilages directly to the breastbone. The five lower pairs, called the false ribs, are not directly joined to the breastbone, but are connected, with the exception of the last two, with each other and with the last true ribs by cartilages. These elastic cartilages enable the chest to bear great blows with impunity. A blow on the sternum is distributed over fourteen elastic arches. The lowest two pairs of false ribs, are not joined even by cartilages, but are quite free in front, and for this reason are called floating ribs.

The ribs are not horizontal, but slope downwards from the backbone, so that when raised or depressed by the strong intercostal muscles, the size of the chest is alternately increased or diminished. This movement of the ribs is of the utmost importance in breathing (Fig. 91).

The sternum, or breastbone, is a long, flat, narrow bone forming the middle front wall of the chest. It is connected with the ribs and with the collar bones. In shape it somewhat resembles an ancient dagger.

40. The Hip Bones. Four immovable bones are joined together so as to form at the lower extremity of the trunk a basin-like cavity called the pelvis. These four bones are the sacrum and the coccyx, which have been described, and the two hip bones.

The hip bones are large, irregularly shaped bones, very firm and strong, and are sometimes called the haunch bones or ossa innominata (nameless bones). They are united to the sacrum behind and joined to each other in front. On the outer side of each hip bone is a deep cup, or socket, called the acetabulum, resembling an ancient vinegar cup, into which fits the rounded head of the thigh bone. The bones of the pelvis are supported like a bridge on the legs as pillars, and they in turn contain the internal organs in the lower part of the trunk.

41. The Hyoid Bone. Under the lower jaw is a little horseshoe shaped bone called the hyoid bone, because it is shaped like the Greek letter upsilon (Υ). The root of the tongue is fastened to its bend, and the larynx is hung from it as from a hook. When the neck is in its natural position this bone can be plainly felt on a level with the lower jaw and about one inch and a half behind it. It serves to keep open the top of the larynx and for the attachment of the muscles, which move the tongue. (See Fig. 46.) The hyoid bone, like the knee-pan, is not connected with any other bone.

42. The Upper Limbs. Each of the upper limbs consist of the upper arm, the forearm, and the hand. These bones are classified as follows:

making 32 bones in all.

43. The Upper Arm. The two bones of the shoulder, the scapula and the clavicle, serve in man to attach the arm to the trunk. The scapula, or shoulder-blade, is a flat, triangular bone, placed point downwards, and lying on the upper and back part of the chest, over the ribs. It consists of a broad, flat portion and a prominent ridge or spine. At its outer angle it has a shallow cup known as the glenoid cavity. Into this socket fits the rounded head of the humerus. The shoulder-blade is attached to the trunk chiefly by muscles, and is capable of extensive motion.

The clavicle, or collar bone, is a slender bone with a double curve like an italic f, and extends from the outer angle of the shoulder-blade to the top of the breastbone. It thus serves like the keystone of an arch to hold the shoulder-blade firmly in its place, but its chief use is to keep the shoulders wide apart, that the arm may enjoy a freer range of motion. This bone is often broken by falls upon the shoulder or arm.

The humerus is the strongest bone of the upper extremity. As already mentioned, its rounded head fits into the socket of the shoulder-blade, forming a ball-and-socket joint, which permits great freedom of motion. The shoulder joint resembles what mechanics call a universal joint, for there is no part of the body which cannot be touched by the hand.

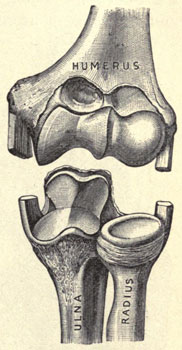

When the shoulder is dislocated the head of the humerus has been forced out of its socket. The lower end of the bone is grooved to help form a hinge joint at the elbow with the bones of the forearm (Fig. 27).

44. The Forearm. The forearm contains two long bones, the ulna and the radius. The ulna, so called because it forms the elbow, is the longer and larger bone of the forearm, and is on the same side as the little finger. It is connected with the humerus by a hinge joint at the elbow. It is prevented from moving too far back by a hook-like projection called the olecranon process, which makes the sharp point of the elbow.

The radius is the shorter of the two bones of the forearm, and is on the same side as the thumb. Its slender, upper end articulates with the ulna and humerus; its lower end is enlarged and gives attachment in part to the bones of the wrist. This bone radiates or turns on the ulna, carrying the hand with it.

Experiment 10. Rest the forearm on a table, with the palm up (an attitude called supination). The radius is on the outer side and parallel with the ulna If now, without moving the elbow, we turn the hand (pronation), as if to pick up something from the table, the radius may be seen and felt crossing over the ulna, while the latter has not moved.

45. The Hand. The hand is the executive or essential part of the upper limb. Without it the arm would be almost useless. It consists of 27 separate bones, and is divided into three parts, the wrist, the palm, and the fingers.

The carpus, or wrist, includes 8 short bones, arranged in two rows of four each, so as to form a broad support for the hand. These bones are closely packed, and tightly bound with ligaments which admit of ample flexibility. Thus the wrist is much less liable to be broken than if it were to consist of a single bone, while the elasticity from having the eight bones movable on each other, neutralizes, to a great extent, a shock caused by falling on the hands. Although each of the wrist bones has a very limited mobility in relation to its neighbors, their combination gives the hand that freedom of action upon the wrist, which is manifest in countless examples of the most accurate and delicate manipulation.

The metacarpal bones are the five long bones of the back of the hand. They are attached to the wrist and to the finger bones, and may be easily felt by pressing the fingers of one hand over the back of the other. The metacarpal bones of the fingers have little freedom of movement, while the thumb, unlike the others, is freely movable. We are thus enabled to bring the thumb in opposition to each of the fingers, a matter of the highest importance in manipulation. For this reason the loss of the thumb disables the hand far more than the loss of either of the fingers. This very significant opposition of the thumb to the fingers, furnishing the complete grasp by the hand, is characteristic of the human race, and is wanting in the hand of the ape, chimpanzee, and ourang-outang.

The phalanges, or finger bones, are the fourteen small bones arranged in three rows to form the fingers. Each finger has three bones; each thumb, two.

The large number of bones in the hand not only affords every variety of movement, but offers great resistance to blows or shocks. These bones are united by strong but flexible ligaments. The hand is thus given strength and flexibility, and enabled to accomplish the countless movements so necessary to our well-being.

In brief, the hand is a marvel of precise and adapted mechanism, capable not only of performing every variety of work and of expressing many emotions of the mind, but of executing its orders with inconceivable rapidity.

46. The Lower Limbs. The general structure and number of the bones of the lower limbs bear a striking similarity to those of the upper limbs. Thus the leg, like the arm, is arranged in three parts, the thigh, the lower leg, and the foot. The thigh bone corresponds to the humerus; the tibia and fibula to the ulna and radius; the ankle to the wrist; and the metatarsus and the phalanges of the foot, to the metacarpus and the phalanges of the hand.

The bones of the lower limbs may be thus arranged:

making 30 bones in all.

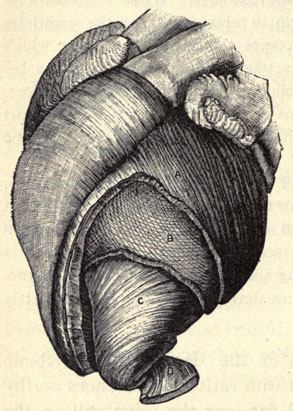

47. The Thigh. The longest and strongest of all the bones is the femur, or thigh bone. Its upper end has a rounded head which fits into the acetabulum, or the deep cup-like cavity of the hip bone, forming a perfect ball-and-socket joint. When covered with cartilage, the ball fits so accurately into its socket that it may be retained by atmospheric pressure alone (sec. 50).

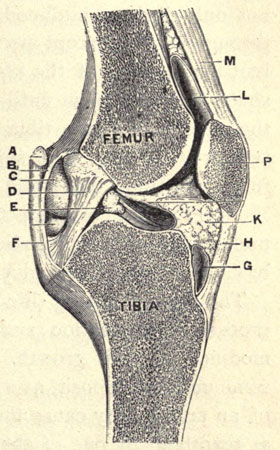

The shaft of the femur is strong, and is ridged and roughened in places for the attachment of the muscles. Its lower end is broad and irregularly shaped, having two prominences called condyles, separated by a groove, the whole fitted for forming a hinge joint with the bones of the lower leg and the knee-cap.

48. The Lower Leg. The lower leg, like the forearm, consists of two bones. The tibia, or shin bone, is the long three-sided bone forming the front of the leg. The sharp edge of the bone is easily felt just under the skin. It articulates with the lower end of the thigh bone, forming with it a hinge joint.

The fibula, the companion bone of the tibia, is the long, slender bone on the outer side of the leg. It is firmly fixed to the tibia at each end, and is commonly spoken of as the small bone of the leg. Its lower end forms the outer projection of the ankle. In front of the knee joint, embedded in a thick, strong tendon, is an irregularly disk-shaped bone, the patella, or knee-cap. It increases the leverage of important muscles, and protects the front of the knee joint, which is, from its position, much exposed to injury.

49. The Foot. The bones of the foot, 26 in number, consist of the tarsal bones, the metatarsal, and the phalanges. The tarsal bones are the seven small, irregular bones which make up the ankle. These bones, like those of the wrist, are compactly arranged, and are held firmly in place by ligaments which allow a considerable amount of motion.

One of the ankle bones, the os calcis, projects prominently backwards, forming the heel. An extensive surface is thus afforded for the attachment of the strong tendon of the calf of the leg, called the tendon of Achilles. The large bone above the heel bone, the astragalus, articulates with the tibia, forming a hinge joint, and receives the weight of the body.

The metatarsal bones, corresponding to the metacarpals of the hand, are five in number, and form the lower instep.

The phalanges are the fourteen bones of the toes,—three in each except the great toe, which, like the thumb, has two. They resemble in number and plan the corresponding bones in the hand. The bones of the foot form a double arch,—an arch from before backwards, and an arch from side to side. The former is supported behind by the os calcis, and in front by the ends of the metatarsal bones. The weight of the body falls perpendicularly on the astragalus, which is the key-bone or crown of the arch. The bones of the foot are kept in place by powerful ligaments, combining great strength with elasticity.

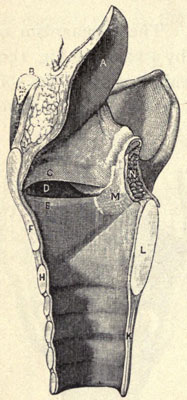

50. Formation of Joints. The various bones of the skeleton are connected together at different parts of their surfaces by joints, or articulations. Many different kinds of joints have been described, but the same general plan obtains for nearly all. They vary according to the kind and the amount of motion.

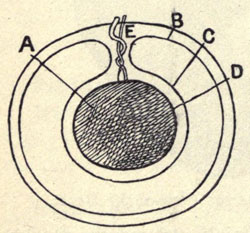

The principal structures which unite in the formation of a joint are: bone, cartilage, synovial membrane, and ligaments. Bones make the chief element of all the joints, and their adjoining surfaces are shaped to meet the special demands of each joint (Fig. 27). The joint-end of bones is coated with a thin layer of tough, elastic cartilage. This is also used at the edge of joint-cavities, forming a ring to deepen them. The rounded heads of bones which move in them are thus more securely held in their sockets.

Besides these structures, the muscles also help to maintain the joint-surfaces in proper relation. Another essential to the action of the joints is the pressure of the outside air. This may be sufficient to keep the articular surfaces in contact even after all the muscles are removed. Thus the hip joint is so completely surrounded by ligaments as to be air-tight; and the union is very strong. But if the ligaments be pierced and air allowed to enter the joint, the union at once becomes much less close, and the head of the thigh bone falls away as far as the ligaments will allow it.

51. Synovial Membrane. A very delicate connective tissue, called the synovial membrane, lines the capsules of the joints, and covers the ligaments connected with them. It secretes the synovia, or joint oil, a thick and glairy fluid, like the white of a raw egg, which thoroughly lubricates the inner surfaces of the joints. Thus the friction and heat developed by movement are reduced, and every part of a joint is enabled to act smoothly.

52. Ligaments. The bones are fastened together, held in place, and their movements controlled, to a certain extent, by bands of various forms, called ligaments. These are composed mainly of bundles of white fibrous tissue placed parallel to, or closely interlaced with, one another, and present a shining, silvery aspect. They extend from one of the articulating bones to another, strongly supporting the joint, which they sometimes completely envelope with a kind of cap (Fig. 28). This prevents the bones from being easily dislocated. It is difficult, for instance, to separate the two bones in a shoulder or leg of mutton, they are so firmly held together by tough ligaments.

While ligaments are pliable and flexible, permitting free movement, they are also wonderfully strong and inextensible. A bone may be broken, or its end torn off, before its ligaments can be ruptured. The wrist end of the radius, for instance, is often torn off by force exerted on its ligaments without their rupture.

The ligaments are so numerous and various and are in some parts so interwoven with each other, that space does not allow even mention of those that are important. At the knee joint, for instance, there are no less than fifteen distinct ligaments.

53. Imperfect Joints. It is only perfect joints that are fully equipped with the structures just mentioned. Some joints lack one or more, and are therefore called imperfect joints. Such joints allow little or no motion and have no smooth cartilages at their edges. Thus, the bones of the skull are dovetailed by joints called sutures, which are immovable. The union between the vertebræ affords a good example of imperfect joints which are partially movable.

54. Perfect Joints. There are various forms of perfect joints, according to the nature and amount of movement permitted. They an divided into hinge joints, ball-and-socket joints and pivot joints.

The hinge joints allow forward and backward movements like a hinge. These joints are the most numerous in the body, as the elbow, the ankle, and the knee joints.

In the ball-and-socket joints—a beautiful contrivance—the rounded head of one bone fits into a socket in the other, as the hip joint and shoulder joint. These joints permit free motion in almost every direction.

In the pivot joint a kind of peg in one bone fits into a notch in another. The best example of this is the joint between the first and second vertebræ (see sec. 38). The radius moves around on the ulna by means of a pivot joint. The radius, as well as the bones of the wrist and hand, turns around, thus enabling us to turn the palm of the hand upwards and downwards. In many joints the extent of motion amounts to only a slight gliding between the ends of the bones.

55. Uses of the Bones. The bones serve many important and useful purposes. The skeleton, a general framework, affords protection, support, and leverage to the bodily tissues. Thus, the bones of the skull and of the chest protect the brain, the lungs, and the heart; the bones of the legs support the weight of the body; and the long bones of the limbs are levers to which muscles are attached.

Owing to the various duties they have to perform, the bones are constructed in many different shapes. Some are broad and flat; others, long and cylindrical; and a large number very irregular in form. Each bone is not only different from all the others, but is also curiously adapted to its particular place and use.

Fig. 27.—Showing how the Ends of the Bones are shaped to form the Elbow Joint. (The cut ends of a few ligaments are seen.)

Nothing could be more admirable than the mechanism by which each one of the bones is enabled to fulfill the manifold purposes for which it was designed. We have seen how the bones of the cranium are united by sutures in a manner the better to allow the delicate brain to grow, and to afford it protection from violence. The arched arrangement of the bones of the foot has several mechanical advantages, the most important being that it gives firmness and elasticity to the foot, which thus serves as a support for the weight of the body, and as the chief instrument of locomotion.

The complicated organ of hearing is protected by a winding series of minute apartments, in the rock-like portion of the temporal bone. The socket for the eye has a jutting ridge of bone all around it, to guard the organ of vision against injury. Grooves and canals, formed in hard bone, lodge and protect minute nerves and tiny blood-vessels. The surfaces of bones are often provided with grooves, sharp edges, and rough projections, for the origin and insertion of muscles.

56. The Bones in Infancy and Childhood. The bones of the infant, consisting almost wholly of cartilage, are not stiff and hard as in after life, but flexible and elastic. As the child grows, the bones become more solid and firmer from a gradually increased deposit of lime salts. In time they become capable of supporting the body and sustaining the action of the muscles. The reason is that well-developed bones would be of no use to a child that had not muscular strength to support its body. Again, the numerous falls and tumbles that the child sustains before it is able to walk, would result in broken bones almost every day of its life. As it is, young children meet with a great variety of falls without serious injury.

But this condition of things has its dangers. The fact that a child’s bones bend easily, also renders them liable to permanent change of shape. Thus, children often become bow-legged when allowed to walk too early. Moderate exercise, however, even in infancy, promotes the health of the bones as well as of the other tissues. Hence a child may be kept too long in its cradle, or wheeled about too much in a carriage, when the full use of its limbs would furnish proper exercise and enable it to walk earlier.

57. Positions at School. Great care must be exercised by teachers that children do not form the habit of taking injurious positions at school. The desks should not be too low, causing a forward stoop; or too high, throwing one shoulder up and giving a twist to the spine. If the seats are too low there will result an undue strain on the shoulder and the backbone; if too high, the feet have no proper support, the thighs may be bent by the weight of the feet and legs, and there is a prolonged strain on the hips and back. Curvature of the spine and round shoulders often result from long-continued positions at school in seats and at desks which are not adapted to the physical build of the occupant.

Fig. 29.—Section of the Knee Joint. (Showing its internal structure)

A few simple rules should guide teachers and school officials in providing proper furniture for pupils. Seats should be regulated according to the size and age of the pupils, and frequent changes of seats should be made. At least three sizes of desks should be used in every schoolroom, and more in ungraded schools. The feet of each pupil should rest firmly on the floor, and the edge of the desk should be about one inch higher than the level of the elbows. A line dropped from the edge of the desk should strike the front edge of the seat. Sliding down into the seat, bending too much over the desk while writing and studying, sitting on one foot or resting on the small of the back, are all ungraceful and unhealthful positions, and are often taken by pupils old enough to know better. This topic is well worth the vigilance of every thoughtful teacher, especially of one in the lower grades.

58. The Bones in After Life. Popular impression attributes a less share of life, or a lower grade of vitality, to the bones than to any other part of the body. But really they have their own circulation and nutrition, and even nervous relations. Thus, bones are the seat of active vital processes, not only during childhood, but also in adult life, and in fact throughout life, except perhaps in extreme old age. The final knitting together of the ends of some of the bones with their shafts does not occur until somewhat late in life. For example, the upper end of the tibia and its shaft do not unite until the twenty-first year. The separate bones of the sacrum do not fully knit into one solid bone until the twenty-fifth year. Hence, the risk of subjecting the bones of young persons to undue violence from injudicious physical exercise as in rowing, baseball, football, and bicycle-riding.

The bones during life are constantly going through the process of absorption and reconstruction. They are easily modified in their growth. Thus the continued pressure of some morbid deposit, as a tumor or cancer, or an enlargement of an artery, may cause the absorption or distortion of bones as readily as of one of the softer tissues. The distortion resulting from tight lacing is a familiar illustration of the facility with which the bones may be modified by prolonged pressure.

Some savage races, not content with the natural shape of the head, take special methods to mould it by continued artificial pressure, so that it may conform in its distortion to the fashion of their tribe or race. This custom is one of the most ancient and widespread with which we are acquainted. In some cases the skull is flattened, as seen in certain Indian tribes on our Pacific coast, while with other tribes on the same coast it is compressed into a sort of conical appearance. In such cases the brain is compelled, of course, to accommodate itself to the change in the shape of the head; and this is done, it is said, without any serious result.

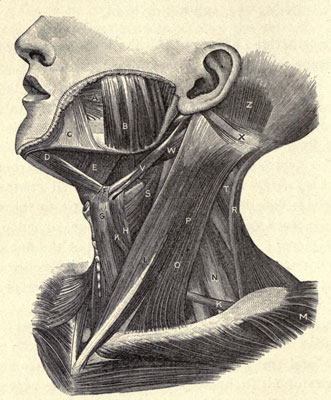

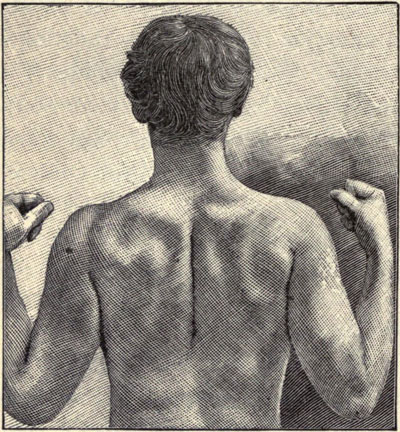

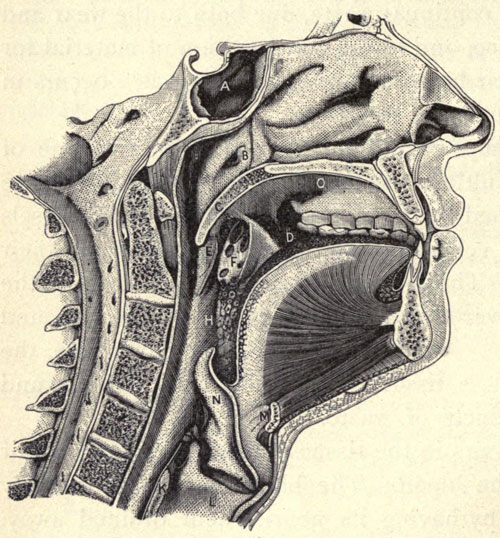

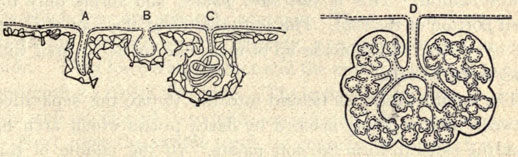

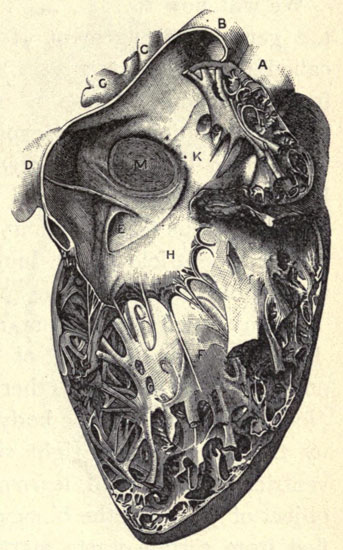

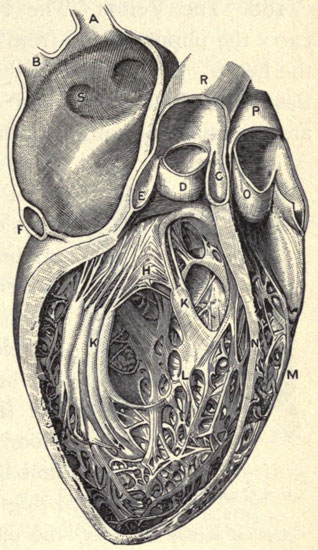

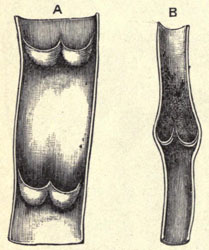

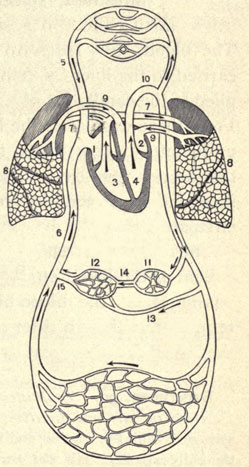

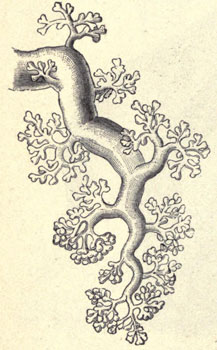

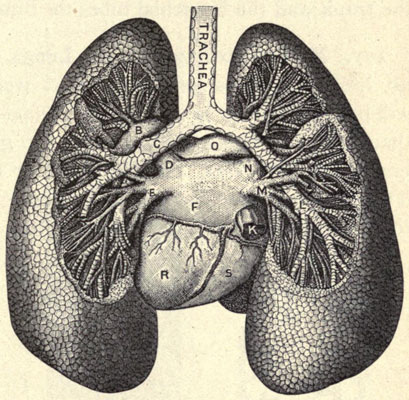

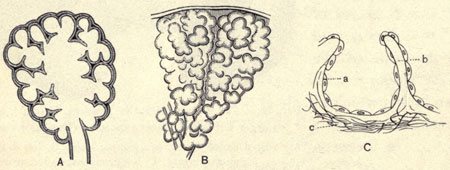

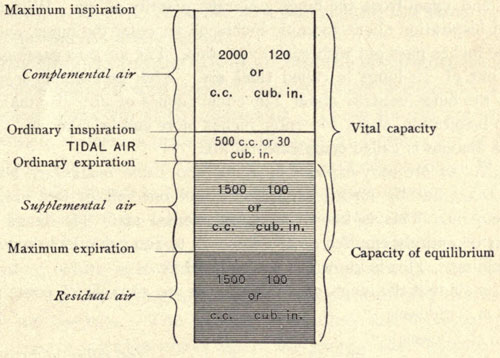

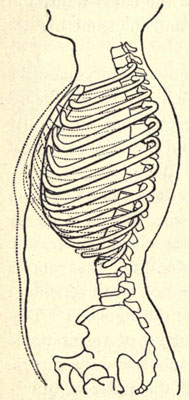

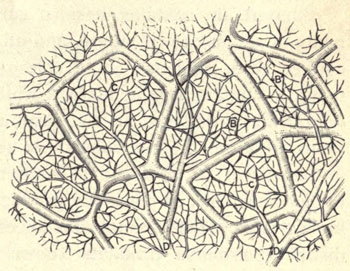

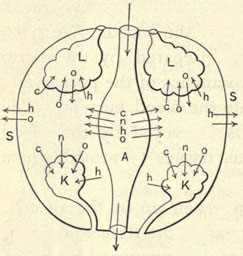

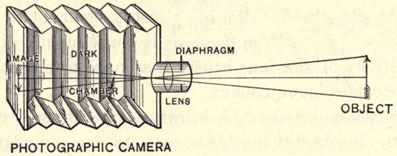

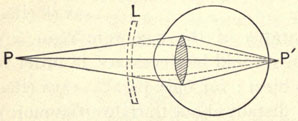

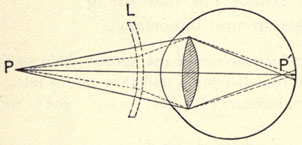

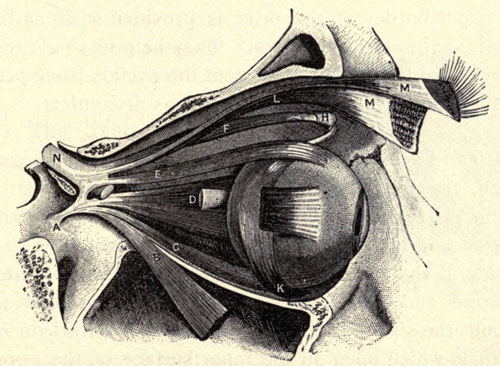

59. Sprains and Dislocations. A twist or strain of the ligaments and soft parts about a joint is known as a sprain, and may result from a great variety of accidents. When a person falls, the foot is frequently caught under him, and the twist comes upon the ligaments and tissues of the ankle. The ligaments cannot stretch, and so have to endure the wrench upon the joint. The result is a sprained ankle. Next to the ankle, a sprain of the wrist is most common. A person tries, by throwing out his hand, to save himself from a fall, and the weight of the body brings the strain upon the firmly fixed wrist. As a result of a sprain, the ligaments may be wrenched or torn, and even a piece of an adjacent bone may be torn off; the soft parts about the injured joint are bruised, and the neighboring muscles put to a severe stretch. A sprain may be a slight affair, needing only a brief rest, or it may be severe and painful enough to call for the most skillful treatment by a surgeon. Lack of proper care in severe sprains often results in permanent lameness.