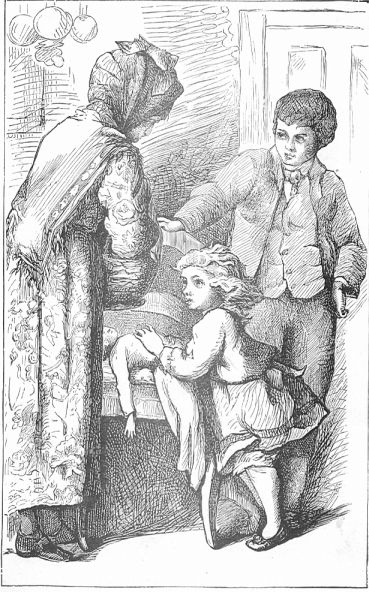

'I Camed Down when I Was a Baby.'

Title: Little Folks Astray

Author: Sophie May

Release date: February 1, 2004 [eBook #11257]

Most recently updated: December 25, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steven desJardins and Distributed Proofreading

Here come the Parlins and Cliffords again. They had been sent to bed and nicely tucked in, but would not stay asleep. They "wanted to see the company down stairs;" so they have dressed themselves, and come back to the parlor. I trust you will pardon them, dear friends. Is it not a common thing, in this degenerate age, for grown people to frown and shake their heads, while little people do exactly as they please?

Well, one thing is certain: if these children insist upon sitting up, they shall listen to lectures on self-will and disrespect to superiors, which will make their ears tingle.

Moreover, they shall hear of other people, and not always of themselves. Fly Clifford, who expects to be in the middle, will be somewhat overwhelmed, like a fly in a cup of milk; for Grandma Read is to talk her down with her Quaker speech, and Aunt Madge with her story of the summer when she was a child. It is but fair that the elders should have a voice. That they may speak words which shall come home to many little hearts, and move them for good, is the earnest wish of

CHAPTER I. — THE LETTER

CHAPTER II. — THE UNDERTAKING

CHAPTER III. — THE FROLIC

CHAPTER IV. — "TAKING OUR AIRS"

CHAPTER V. — DOTTY HAVING HER OWN WAY

CHAPTER VI. — DOTTY REBUKED

CHAPTER VII. — THE LOST FLY

CHAPTER VIII. — "THE FRECKLED DOG"

CHAPTER IX. — MARIA'S MOTHER

CHAPTER X. — FIVE MAKING A CALL

CHAPTER XI. — "THE HEN-HOUSES"

CHAPTER XII. — "GRANNY"

CHAPTER XIII. — THE PUMPKIN HOOD

1. 'I Camed Down when I Was a Baby.'

Katie Clifford sat on the floor, in the sun, feeding her white mice. She had a tea-spoon and a cup of bread and milk in her hands. If she had been their own mother she could not have smiled down on the little creatures more sweetly.

"'Cause I spect they's hungry, and that's why I'm goin' to give 'em sumpin' to eat. Shut your moufs and open your eyes," said she, waving the tea-spoon, and spattering the bread and milk over their backs.

"Quee, quee," squeaked the little mice, very well pleased when a drop happened to go into their mouths.

"What are you doing there, Miss Topknot," said Horace: "O, I see; catching rats."

Flyaway frowned fearfully, and the tuft of hair atop of her head danced like a war-plume.

"I shouldn't think folks would call 'em names, Hollis, when they never did a thing to you. Nothing but clean white mouses!"

"Let's see; now I look at 'em, Topknot, they are white. And what's all this paper?"

"Bed-kilts."

"In-deed?"

"You knew it by-fore!"

"One, two, three; I thought the doctor gave you five. Where are they gone?"

"Well, there hasn't but two died; the rest'll live," said Fly, swinging one of them around by its tail, as if it had been a tame cherry.

Just then Grace came and stood in the parlor doorway.

"O, fie!" said she; "what work! Ma doesn't allow that cage in the parlor. You just carry it out, Fly Clifford."

Miss Thistledown Flyaway looked up at her sister shyly, out of the corners of her eyes. Grace was now a beautiful young lady of sixteen, and almost as tall as her mother. Flyaway adored her, but there was a growing doubt in her mind whether sister Grace had a right to use the tone of command.

"'Cause I spect she isn't my mamma."

"Why, Fly, you haven't started yet!"

"I didn't think 'twas best," responded the child, sulkily, fixing her eyes on the mice, who were dancing whirligigs round the wheel.

"Come here to your best friend, little Topknot," said Horace. "Let's take that cage into the green-house, and ask papa to keep it there, because the mice look like water-lilies on long stems."

Flyaway brightened at once. She knew water-lilies were lovely. Giving Grace a triumphant glance, she danced across the room, and put the cage in Horace's hands, with a smile of trusting love that thrilled his heart.

"Hollis laughs at my mouses, but he don't say, 'Put 'em away,' and, 'Put 'em away;' he says, 'Little gee-urls wants to see things as much as anybody else,'" thought she, gratefully.

"Horace," said Grace, with a curling lip, "that child is growing up just like you—fond of worms, and bugs, and all such disgusting things."

Horace smiled. No matter for the scorn in Grace's tone; it pleased him to be compared in any way with his precious little Flyaway.

"Topknot has a spark of sense," said he, leading her along to the green-house. "I'll bring her up not to scream at a spider."

"Now, young lady," said he, setting the cage on the shelf beside a camellia, and speaking in a low voice, though they were quite alone, "can you keep a secret?"

"Course I can; What is a secrid?"

"Why, it's something you musn't ever tell, Topknot, not to anybody that lives."

"Then I won't, cerdily,—not to mamma, nor papa, nor Gracie."

"Nor anybody else?"

"No; course not. Whobody else could I? O, 'cept Phibby. There, now, what's the name of it."

"The name of it is—a secret, and the secret is this—Sure you won't tell any single body, Topknot?"

"No; I said, whobody could I tell? O, 'cept Tinka! There now!"

"Well, the secret is this," said Horace, laying his forefingers together, and speaking very slowly, in order to prolong the immense delight he felt in watching the little one's eager face. "You know you've got an aunt Madge?"

"Yes; so've you, too."

"And she lives in the city of New York."

"Does she? When'd she go?"

"Why, she has always lived there; ever since she was married."

"O, yes; and uncle Gustus was married, too; they was both married. Is that all?"

"And she thinks you and I are 'cute chicks, and wants us to go and see her."

"Well, course she does; I knew that before," said Fly, turning away with indifference; "I did go with mamma."

"O, but she means now, Topknot; this very Christmas. She said it in a letter."

"Does she truly?" said Fly, beginning to look pleased. "But it can't be a secrid, though," added she, next moment, sadly, "'cause we can't go, Hollis."

"But I really think we shall go, Topknot; that is, if you don't spoil the whole by telling."

"O, I cerdily won't tell!" said Fly, fluttering all over with a sense of importance, like a kitten with its first mouse.

The breakfast bell rang; and, with many a word of warning, Horace led his little sister into the dining-room.

"Papa," said she, the moment she was established in her high chair, "I know sumpin'."

"O, Topknot!" cried Horace.

"I know Hollis has got his elbows on the table. There, now, did I tell?"

"Hu—sh, Topknot!"

There was a quiet moment while Mr. Clifford said grace.

"Hollis," whispered Katie immediately afterwards, "will I take my mouses?"

"'Sh, Topknot!"

"What's going on there between you and Horace?" laughed Grace.

"A secrid," said Fly, nipping her little lips together. "You won't get me to tell."

"Horace," exclaimed Mrs. Clifford, "you haven't—"

"Why, mother, I thought it was all settled, and wouldn't do any harm; and it pleases her so!"

"Well, my son, you've made a hard day's work for me," said Mrs. Clifford, smiling behind her coffee-cup, as eager little Katie swayed back and forth in her high chair.

"You won't get me to tell, Gracie Clifford. She don't want nobody but Hollis and me; she thinks we're very 'cute."

"Who? O, Aunt Louise, probably."

"No, aunt Louise never! It's the auntie that lives to New York."

"Sh, Topknot!"

"Well, I didn't tell, Hollis Clifford!"

"So you didn't," said Grace. "But wouldn't it be nice if somebody should ask you to go somewhere to spend Christmas?"

"Well, there is!"

"O, Topknot," cried Horace, in mock distress, "you said you could keep a secret."

Flyaway looked frightened.

"What'd I do?" cried she; "I didn't tell nuffin 'bout the letter!"

This last speech set everybody to laughing; and the little tell-tale looked around from one to another with a face full of innocent wonder. They couldn't be laughing at her!

"I can keep secrids," said she, with dignity. "It was what I was a-doin'."

"It is your brother Horace who cannot be trusted to keep secrets," said Mrs. Clifford, taking a letter from her pocket. "Hear, now, what your Aunt Madge has written: 'Will you lend me your children for the holidays, Maria? I want all three; at any rate, two.'"

"That's me," cried Flyaway, tipping over her white coffee; "'tenny rate two,' means me."

"Don't interrupt me, dear. 'Brother Edward has promised me Prudy and Dotty Dimple. They may have a Santa Claus, or whatever they like. I shall devote myself to making them happy, and I am sure there are plenty of things in New York to amuse them. Horace must come without fail; for the little girl-cousins always depend so much upon him.'"

A smile rose to Horace's mouth; but he rubbed it off with his napkin. It was his boast that he was above being flattered.

"But why not have Grace go, too, to keep them steady?" said Mr. Clifford, bluntly.

Horace applied himself to his buckwheat cakes in silence, and looked rather gloomy.

"Why, I suppose, Henry, it would hardly be safe to send Grace, on account of her cough."

"I'm so sorry you asked Dr. De Bruler a word about it, mamma; but I suppose I must submit," said Grace, with a face as cloudy as Horace's.

"Horace, my son, do you really feel equal to the task of taking this tuft of feathers to New York?"

"I don't know why not, father; I'm willing to try."

"Horace has good courage," said Grace, shaking her auburn curls like so many exclamation points. "I never could! I never would! I'd as soon have the care of a flying squirrel!"

"Hollis never called me a squirl," said Fly, demurely. "I've got two brothers, and one of 'em is an angel, and the other isn't; but Hollis is 'most as good as the one up in the sky."

"Well, my son," remarked Mr. Clifford, after a pause, "if your mother gives her consent, I suppose I shall give mine; but it does not look clear to me yet. One thing is certain, Horace; if you do undertake this journey, you must live on the watch: you must sleep with both eyes open. Don't trust the child out of your sight—not for a moment. Don't even let go her hand on the street."

"I do believe Horace will be as careful as either you or I, Henry, or I certainly wouldn't trust him with our last little darling," said Mrs. Clifford.

His mother's words dropped like balm upon Horace's wounded spirit. He looked up, and felt himself a man again.

When Flyaway knew she was going to New York, it was about as easy to fit her dresses as to clothe a buzzing blue-bottle fly. With spinning head and dancing feet, she was set down, at last, in the cars.

"Here we are, all by ourselves, darling, starting off for Gotham. Wave your handkerchief to mamma. Don't you see her kissing her hand? There, you needn't spring out of the window! And I declare, Brown-brimmer, if you haven't thrown away your handkerchief! Here, cry into mine!"

"I didn't want to cry, Hollis; I wanted to laugh," said the child, wiping her eyes with her doll's cloak. "When you ride in carriages, you don't get anywhere; but when you ride in the cars, you get there right off."

"Yes; that's so, my dear. You are in the right of it, as you always are. Now I am going to turn the seat over, and sit where I can look at you—just so."

"O, that's just as splendid, Hollis! Now there's only me and Flipperty. There, I put her 'pellent cloak on wrong; but see, now, I've un-wrong-side-outed it! Don't she sit up like a lady?"

Her name was Flipperty Flop. She was a large jointed doll (not a doll with large joints,) had seen a great deal of the world, and didn't think much of it. She came of a high family, and had such blue blood in her veins, that the ground wasn't good enough for her to walk on. She wore a "'pellent cloak" and rubber boots, and had a shopping-bag on her arm full of "choclid" cakes. She was nearly as large as her mother, and all of two years older. A great deal had happened to her before her mother was born, and a great deal more since. Sometimes it was dropsy, and she had to be tapped, when pints of sawdust would run out. Sometimes it was consumption, and she wasted to such a skeleton that she had to be revived with cotton. She had lost her head more than once, but it never affected her brains: she was all the better with a young head now and then on her old shoulders. Her present ailment appeared to be small-pox; she was badly pitted with pins and a penknife. "I declare I forgot to get a ticket for her," said Horace. "What if the conductor shouldn't let her pass?"

"O, Hollis, but he must?" cried Fly, springing to her feet; "I shan't pass athout my Flipperty! Tell the 'ductor 'bout my white mouses died, and I can't go athout sumpin to carry."

"Pshaw! Dotty Dimple don't carry dolls. She don't like 'em: sensible girls never do."

"Well, I like 'em," said Flyaway, nothing daunted. "You knew it byfore; 'n if you didn't want Flipperty, you'd ought to not come!"

Horace laughed, as he always did when his little sister tried her power over him. The conductor was an old acquaintance, and he told him how it stood with Flipperty, how she was needed at New York, and all that; whereupon Mr. Van Dusen gave Fly a little green card, and told her to keep it to show to all the conductors on the road; for it was a free pass, and would take Flipperty all over the United States.

"Yes, sir, if you please," said Fly, with a blush and a smile, and put the "free pass" in Miss Flop's cloak pocket.

After this, she never once failed to show it, whenever Mr. Van Dusen, or any other conductor, came near, but always had to hunt for it, and once brought up a cookie instead, which fearful mistake mortified her to the depths of her soul.

Horace was sure all eyes were fixed on his charming little charge, and was proud of the honor of showing her off; but he paid for it dearly; it cost him more than his Latin, with all the irregular verbs. There was no such thing as her being comfortable. She was full of care about him, herself, and the baggage. Flipperty lost off a rubber boot, which bounced over into the next seat. Horace had to ask a gentleman and his sick daughter to move, and, after all, it was in an old lady's lap.

Then Fly's feet were cold, and Horace took her to the stove; but that made her eyes too hot, and she danced back, to lie with her head on his breast and her feet against the window, till she suddenly whirled straight about, and planted her tiny boots under his chin.

"O, Topknot, Topknot, I pity that woman with the baby, if she feels as lame all over as I do!"

"Where's the baby, Hollis? O, I see."

"What's the matter, now? Why upon earth can't you sit still, child?" said Horace, next minute, catching her as she was darting into the aisle, dragging Miss Flop by the hair of the head.

"O, Hollis, don't you see there's a dolly over there, with two girls and a lady with red clo'es on? 'Haps they'd be willing for her to get 'quainted with Flipperty?"

"Well, Topknot, 'haps they would, but 'haps I wouldn't. I can't have you dancing all over the car, in this style."

Flyaways's lip quivered, and a tear started. Horace was moved. One of Fly's tears weighed a pound with him, even when it only wet her eyelashes, and wasn't heavy enough to drop.

"Well, there, darling, you just sit still,—not still enough, though, to give you a pain (Fly always said it gave her a pain to sit still),—and I'll bring the girls and dollie over here to you. Will that do?"

Fly thought it would.

A dreadful fit of bashfulness came over Horace, when he stood face to face with the black-eyed lady and her daughters, and tried to speak.

"I've got a little girl travelling with me, ma'am; she's so—so uneasy, that I don't know what to do with her. Will you let me take—I mean, are you willing—"

"Bring her over here, and we will try to amuse her," said the black-eyed lady, pleasantly; but Horace was sure he saw the oldest girl laughing at him.

"It's no fun to go and make a fool of yourself," thought he, leading Fly to the new acquaintances, and standing by as she settled herself shyly in the seat.

"How do you do, little one? What is your name?—Flyaway?—Well, you look like it. We saw you were a darling, clear across the aisle. And you have a kind brother, I know."

At these words Fly, for want of some answer to make, sprang forward and kissed Horace on the bridge of the nose.

"There, you've knocked off my cap."

In stooping to pick it up, he awkwardly hit his head against the older girl, who already looked so mischievous that he was rather afraid of her.

"Wish I could get out of the way. She expects me to speak, but I shan't.

"'Needles and pins, needles and pins,

When a man travels his trouble begins.'"

Horace was obliged to stand, very ill at ease, till the black-eyed lady had found out where he lived, who his father was, and what was his mother's name before she was married.

"Tell your father, when you go home, you have seen Mrs. Bonnycastle, formerly Ann Jones, and give him my regards. I knew he married a lady from Maine."

"I know sumpin," struck in Fly; "if ever I marry anybody, I'll marry my own brother Hollis. I mean if I don't be a ole maid!"

"And what is 'a ole maid,' you little witch?"

"I don' know; some folks is," was the wise reply. Flyaway was about to add "Gampa Clifford," but did not feel well enough acquainted to talk of family matters.

When the Bonnycastles left, at Cleveland, Horace thought that was the last of them. Miss Gerty was "decent-looking, looked some like Cassy Hallock; but he couldn't bear to see folks giggle; hoped he never should set eyes on those people again." Whether he ever did, you shall hear one of these days.

"O, Topknot," said he, "your hair looks like a mop. Do you want all creation laughing at you? You'll mortify me to death."

"You ought to water it. If you don't take better care o' your little sister, I won't never ride with you no more, Hollis Clifford!"

"Well, see that you don't, you little scarecrow," said the suffering boy, out of all patience. "If you are going to act in New York as you have on the road, I wish I was well out of this scrape."

Flyaway was really a sight to behold. How she managed to tear her dress off the waist, and loose five boot buttons, and last, but not least, the very hat she wore on her head, would have been a mystery if you hadn't seen her run.

When they reached the city, Horace put the soft, flying locks in as good order as he could, and tied them up in his handkerchief.

"I wisht I hadn't come," whined Fly; "I don't want to wear a hangerfiss; 'tisn't speckerble!"

"Hush right up! I'm not going to have you get cold!—My sorrows! Shan't I be thankful when I get where there's a woman to take care of her?"

On the platform at the depot, aunt Madge, Prudy, and Dotty Dimple, were waiting for them. A hearty laugh went the rounds, which Fly thought was decidedly silly. Aunt Madge took the young travellers right into her arms, and hugged them in her own cordial style, as if her heart had been hungry for them for many a day.

"We're so glad!—for it did seem as if you'd never come," exclaimed Dotty Dimple.

"And I'd like to know," said Horace, "how you happened to get here first."

"O, we came by express—came yesterday."

"By 'spress?" cried Flyaway, pulling away from aunt Madge, who was trying to pin her frock together; "we came by a 'ductor.—Why, where's Flipperty's ticket?"

Horace seized Prudy with one hand, and Dotty Dimple with the other, turning them round and round.

"I don't see anything of the express mark, 'Handle with care.' What has become of it?"

"O, we were done up in brown paper," said Prudy, laughing, "and the express mark was on that; but aunt Madge took it off as soon as she got the packages home."

"Why, what a story, Prudy Parlin! We didn't have a speck of brown paper round us. Just cloaks and hats with feathers in!"

Dotty spoke with some irritation. She had all along been rather sensitive about being sent by express, and could not bear any allusion to the subject.

"There, that's Miss Dimple herself. Let me shake hands with your Dimpleship! Didn't come to New York to take a joke,—did you?"

"No, her Dimpleship came to New York to get warm," said Peacemaker Prudy; "and so did I, too. You don't know how cold it is in Maine."

By this time they were rattling over the stones in their aunt's elegant carriage. It was dusk; the lamps were lighted, the streets crowded with people, the shops blazing with gay colors.

"I didn't come here to get warm, either," said Dotty, determined to have the last word: "I was warm enough in Portland. I s'pose we've got a furnace,—haven't we?—and a coal grate, too."

"I do hope Horace hasnt't got her started in a contrary fit," thought Prudy; "I brought her all the way from home without her saying a cross word."

But aunt Madge had a witch's broom, to sweep cobwebs out of the sky. Putting her arm around Dotty, she said,—

"You all came to bring sunshine into my house; bless your happy hearts."

That cleared Dotty's sky, and she put up her lips for a kiss; while Flyaway, with her "hangerfiss" on, danced about the carriage like a fly in a bottle, kissing everybody, and Horace twice over.

"'Cause I spect we've got there. But, Hollis," said she, with the comical shade of care which so often flitted across her little face, "you never put the trunk in here. Now that 'ductor has gone and carried off my nightie."

If Aunt Madge had dressed in linsey woolsey, with a checked apron on, she would still have been lovely. A white rose is lovely even in a cracked tea-cup. But Colonel Augustus Allen was a rich man, and his wife could afford to dress elegantly. Horace followed her to-night with admiring eyes.

"They say she isn't as handsome as Aunt Louise, but I know better; you needn't tell me! Her eyes have got the real good twinkle, and that's enough said."

Horace was like most boys; he mistook loveliness for beauty. Mrs. Allen's small figure, gentle gray eyes, and fair curls made her seem almost insignificant beside the splendid Louise; but Horace knew better; you needn't tell him!

"Horace," said Aunt Madge, "your Uncle Augustus is gone, and that is one reason, you know, why I begged for company during the holidays. You will be the only gentleman in the house, and we ladies herewith put ourselves under your protection. Will you accept the charge?"

"He needn't pertect ME," spoke up Miss Dimple, from the depths of an easy-chair; "I can pertect myself."

"Don't mind going to the Museum alone, I suppose, and crossing ferries, and riding in the Park, and being out after dark?"

"No; I'm not afraid of things," replied the strong-minded young lady; "ask Prudy if I am. And my father lets me go in the horse-cars all over Portland. That's since I travelled out west."

Here the bell sounded, and the only gentleman of the house gave his arm to Mrs. Allen, to lead her out to what he supposed was supper, though he soon found it went by the name of dinner. Neither he nor his young cousins were accustomed to seeing so much silver and so many servants; but they tried to appear as unconcerned as if it were an every-day affair. Dotty afterwards said to Prudy and Horace, "I was 'stonished when that man came to the back of my chair with the butter; but I said, 'If you please, sir,' just as if I 'spected it. He don't know but my father's rich."

After dinner Fly's eyes drew together, and Prudy said,—

"O, darling, you don't know what's going to happen. Auntie said you might sleep with Dotty and me to-night, right in the middle."

"O, dear!" drawled Flyaway; "when there's two abed, I sleep; but when there's three abed, I open out my eyes, and can't."

"So you don't like to sleep with your cousins," said Dotty, "your dear cousins, that came all the way from Portland to see you."

"Yes, I do," said Fly, quickly; "my eyes'll open out; but that's no matter, 'cause I don't want to go to sleep; I'd ravver not."

They went up stairs, into a beautiful room, which aunt Madge had arranged for them with two beds, to suit a whim of Dotty's.

"Now isn't this just splendid?" said Miss Dimple; "the carpet so soft your boots go in like feathers; and then such pictures! Look, Fly! here are two little girls out in a snow-storm, with an umbrella over 'em. Aren't you glad it isn't you? And here are some squirrels, just as natural as if they were eating grandpa's oilnuts. And see that pretty lady with the kid, or the dog. Any way she is kissing him; and it was all she had left out of the whole family, and she wanted to kiss somebody."

"Yes," said aunt Madge.

"'Her sole companion in a dearth Of love upon a hopeless earth.'

"If that makes you look so sober, children, I'm going to take it down. Here, on this bracket, is the head of our blessed Saviour."

"O, I'm glad," said Fly. "He'll be right there, a-looking on, when we say our prayers."

"Hear that creature talk!" whispered Dotty.

"And these things a-shinin' down over the bed: who's these?" said Flyaway, dancing about the room, with "opened-out" eyes.

"Don't you know? That's Christ blessing little children," said Dotty, gently. "I always know Him by the rainbow round His head."

"Aureole," corrected Aunt Madge.

"But wasn't it just like a rainbow—red, blue and green?"

"O, no; our Saviour did not really have any such crown of light, Dotty. He looked just like other men, only purer and holier. Artists have tried in vain to make his expression heavenly enough; so they paint him with an aureole."

Prudy said nothing; but as she looked at the picture, a happy feeling came over her. She remembered how Christ "called little children like lambs to his fold," and it seemed as if He was very near to-night, and the room was full of peace. Aunt Madge had done well to place such paintings before her young guests; good pictures bring good thoughts.

"All, everywhere, it's so spl-endid!" said Fly; "what's that thing with a glass house over it!"

"A clock."

"What a funny clock! It looks like a little dog wagging its tail."

"That's the penderlum," explained Dotty; "it beats the time. Every clock has a penderlum. Generally hangs down before though, and this hangs behind. I declare, Prudy, it does look like a dog wagging its tail."

"Hark! it strikes eight," said Aunt Madge. "Time little girls were in bed, getting rested for a happy day to-morrow."

"I don't spect that thing knows what time it is," said Fly, gazing at the clock doubtfully, "and my eyes are all opened out; but if you want me to, auntie, I will!"

So Flyaway slipped off her clothes in a twinkling.

"We're going to lie, all three, in this big bed, Fly, just for one night," said Dotty; "and after that we must take turns which shall sleep with you. There, child, you're all undressed, and I haven't got my boots off yet. You're quicker'n a chain o' lightning, and always was."

"Why, how did that kitty get in here?" said auntie, as a loud mewing was heard. "I certainly shut her out before we came up stairs."

Dotty ran round the room, with one boot on, and Prudy in her stockings, helping their aunt in the search. The kitten was not under the bed, or in either of the closets, or inside the curtains.

"Look ahind the pendlum," said Fly, laughing and skipping about in high glee; "look ahind the pendlum; look atween the pillow-case."

Still the mewing went on.

"O, here is the kitty—I've found her," said auntie, suddenly seizing Fly by the shoulders, and stopping her mocking-bird mouth. "Poor pussy, she has turned white—white all over!"

"You don't mean to say that was Fly Clifford?" cried Prudy.

"Shut her up, auntie," said Dotty Dimple; "she's a kitty. I always knew her name was Kitty."

Fly ran and courtesied before the mirror in her nightie.

"O, Kitty Clifford, Kitty Clifford," she cried, "when'll you be a cat?"

"Pretty soon, if you can catch mice as well as you can mew," laughed auntie; "but look you, my dear; are you going to bed to-night? or shall I shut you down cellar?"

"Don't shut me down cellow, auntie," cried the mocking-bird, crowing like a chicken; "shut me in the barn with the banties."

Next moment it occurred to the child that this style of behavior was not very "speckerful;" so she hastily dropped on her knees before her auntie, and began to say her prayers. The change was so sudden, from the shrill crow of a chicken to the gentle voice of a little girl praying, that no one could keep a sober face. Prudy ran into the closet, and Dotty laughed into her handkerchief.

"There, now, that's done," said Flyaway, jumping up as suddenly as she had knelt down. "Now I must pray Flipperty."

And before any one could think what the child meant to do, she had dragged out her dolly, and knelt it on the rug, face downward, over her own lap.

"O, the wicked creature!" whispered Dotty. But Aunt Madge said nothing.

"Pray," said the little one, in a tone of command. Then, in a fine, squeaking voice, Fly repeated a prayer. It was intended to be Flipperty's voice, and Flipperty was too young to talk plain.

"There, that will do," said Aunt Madge, her large gray eyes trying not to twinkle; "did she ever say her prayers before?"

"Yes, um; she's a goody girl—when I 'member to pray her!"

"Well, dear, I wouldn't 'pray her' any more. It makes us laugh to see such a droll sight, and nobody wishes to laugh when you are talking to your Father in heaven."

"No'm," replied Flyaway, winking her eyes solemnly.

But when the "three abed" had been tucked in and kissed, Fly called her auntie back to ask, "How can Flipperty grow up a goody girl athout she says her prayers?"

There was such a mixture of play and earnestness in the child's eyes, that auntie had to turn away her face before she could answer seriously.

"Why, little girls can think and feel you know; but with dollies it is different. Now, good night, pet; you won't have beautiful dreams, if you talk any more."

Flyaway awoke singing, and sprang up in bed, saying,—

"Why, I thought I's a car, and that's why I whissiled."

"But you are not a car," yawned Prudy; "please don't sing again, or dance, either."

"It's the happerness in me, Prudy; and that's what dances; it's the happerness."

"That's the worst part of Fly Clifford," groaned Dotty; "she won't keep still in the morning. Might have known there wouldn't be any peace after she got here."

Dotty always came out of sleep by slow stages, and her affections were the last part of her to wake up. Just now she did not love Katie Clifford one bit, nor her own mother either.

"Won't you light the lamp?" piped Flyaway.

"Please don't, Fly," said Prudy; "don't talk!"

"Won't you light the la-amp?"

"No, we will not," said Dotty, firmly.

"Won't you light the la-amp?"

"Is this what we came to New York for?" moaned Dotty; "to be waked up in the middle of the night by folks singing?"

"Won't you light the la-amp?"

"I'll pack my dresses, and go right home! I'll—I'll have Fly Clifford sleep out o' this room. Why, I—I—"

"Won't you light the la-amp?"

Prudy sprang out of bed, convulsed with laughter, and lighted the gas; whereupon Fly began to dance "Little Zephyrs," on the pillow, and Dotty to declare her eyes were put out.

"Little try-patiences, both of them," thought Prudy; "but then they've always had their own way, and what can you expect? I'm so glad I wasn't born the youngest of the family; it does make children so disagreeable!"

As soon as Dotty was fairly awake, her love for her friends came back again, and her good humor with it. She made Fly bleat like a lamb and spin like a top, and applauded her loudly.

"It's gl-orious to have you here, Fly Clifford. I wouldn't let you go in any other room to sleep for anything."

Which shows that the same thing looked very different to Dotty after she got her eyes open.

When the children went down to breakfast, they found bouquets of flowers by their plates.

"I am delighted to see such happy faces." said Aunt Madge. "How would you all like to go out by and by, and take the air?"

"We'd like it, auntie; and I'll tell you what would be prime," remarked Horace, from his uncle's place at the head of the table; "and that is, to take Fly to Stewart's, and have her go up in an elevator."

"Why couldn't I go up, too?" asked Dotty, with the slightest possible shade of discontent in her voice. She did not mean to be jealous, but she had noticed that Flyaway always came first with Horace, and if there was anything hard for Dotty's patience, it was playing the part of Number Two.

"We'll all go up," said Aunt Madge. "I've an idea of taking you over to Brooklyn; and in that case we shan't come home before night."

"Carry our dinner in a basket?" suggested Dotty.

"O, no; we'll go into a restaurant, somewhere, and order whatever you like."

"Will you, auntie? Well, there, I never went to such a place in my life, only once; and then Percy Eastman, he just cried 'Fire!' and I broke the saucer all to pieces."

"I've been to it a great many times," said Fly, catching part of Dotty's meaning; "my mamma bakes 'em in a freezer."

At nine o'clock the party of five started out to see New York. Aunt Madge and Horace walked first, with Flyaway between them. "We are going out to take our airs," said the little one.

"I don't think you need any more," said Horace, looking fondly at his pretty sister. "You're so airy now, it's as much as we can do to keep your feet on the ground."

Flyaway wore a blue silk bonnet, with white lace around the face, a blue dress and cloak, and pretty furs with a squirrel's head on the muff. She had never been dressed so well before, and she knew it. She remembered hearing "Phibby" say to "Tinka," "Don't that child look like an angel?" Fly was sure she did, for big folks like Tinka must know. But here her thoughts grew misty. All the angels she had ever heard of were brother Harry and "the Charlie boy." How could she look like them?

"Does God dress 'em in a cloak and bonnet, you s'pose?" asked she of her own thoughts.

Prudy and Dotty Dimple wore frocks of black and red plaid, white cloaks, and black hats with scarlet feathers. Horace was satisfied that a finer group of children could not be found in the city.

"Aunt Madge and I have no reason to be ashamed of them, I am sure," thought he, taking out his new watch every few minutes, not because he wished to show it, but for fear it was losing time.

"How I wish we had Grace and Susey here! and then I should have all my nieces," said Aunt Madge. "Is it possible these are the same children I used to see at Willowbrook? Here is my only nephew, that drowned Prudy on a log, grown tall enough to offer me his arm. (Why, Horace, your head is higher than mine!) Here is Prudy, who tried yesterday—didn't she?—to go up to heaven on a ladder, almost a young lady. Why, how old it makes me feel!"

"But you don't look old," said Dotty, consolingly; "you don't look married any more than Aunt Louise?"

Here they took an omnibus, and the children interested themselves in watching the different people who sat near them.

"Aren't you glad to come?" said Dotty. "See that man getting out. What is that little thing he's switching himself with?"

"That's a cane," replied Horace.

"A cane? Why, if Flyaway should lean on it, she'd break it in two.—Prudy, look at that man in the corner; his cane is funnier than the other one."

Horace laughed.

"That is a pipe, Dotty—a meerschaum."

"Well, I don't see much difference," said Miss Dimple; "New York is the queerest place. Such long pipes, and such short canes!"

Fly was too happy to talk, and sat looking out of the window until an elegantly-dressed lady entered the stage, who attracted everybody's attention; and then Flyaway started up, and stood on her tiptoes. The lady's face was painted so brightly that even a child could not help noticing it. It was haggard and wrinkled, all but the cheeks, and those bloomed out like a red, red rose. Flyaway had never seen such a sight before, and thought if the lady only knew how she looked, she would go right home and wash her face.

"What a chee-arming little girl!" said the painted woman, crowding in between Aunt Madge and Flyaway, and patting the child's shoulder with her ungloved hand, which was fairly ablaze with jewels; "bee-youtiful!"

Flyaway turned quickly around to Aunt Madge, and said, in one of her very loud whispers, "What's the matter with her? She's got sumpin on her face."

"Hush," whispered Aunt Madge, pinching the child's hand.

"But there is," spoke up Flyaway, very loud in her earnestness; "O, there is sumpin on her face—sumpin red."

There was "sumpin" now on all the other faces in the omnibus, and it was a smile. The lady must have blushed away down under the paint. She looked at her jewelled fingers, tossed her head proudly, and very soon left the stage.

"Topknot, how could you be so rude?" said Horace, severely; "little girls should be seen, and not heard."

"But she speaked to me first," said Flyaway. "I wasn't goin' to say nuffin, and then she speaked."

A young gentleman and lady opposite seemed very much amused.

"I'm afraid of your bright eyes, little dear. I'll give you some candy if you won't tell me how I look," said the young lady, showering sweetmeats into Flyaway's lap.

"Why, I wasn't goin' to tell her how she looked," whispered Fly, very much surprised, and trying to nestle out of sight behind Horace's shoulder.

When they left the omnibus, the children had a discussion about the painted lady, and could not decide whether they were glad or sorry that Fly had spoken out so plainly.

"Good enough for her," said Dotty.

"But it was such a pity to hurt her feelings!" said Prudy.

"Who hurted 'em?" asked Fly, looking rather sheepish.

"Poh! her feelings can't be worth much," remarked Horace; "a woman that'll go and rig herself up in that style."

"She must be near-sighted," said Aunt Madge. "She certainly can't have the faintest idea how thick that paint is. She ought to let somebody else put it on."

"But, auntie, isn't it wicked to wear paint on your cheeks?"

"No, Dotty, only foolish. That woman was handsome once, but her beauty is gone. She thinks she can make herself young again, and then people will admire her."

"O, but they won't; they'll only laugh."

"Very true, Dotty; but I dare say she never thought of that till this little child told her."

"Fly," said Horace, "You are doing a great deal of good going round hurting folks' feelings."

"Poor woman!" said Aunt Madge, with a pitying smile; "she might comfort herself by trying to make her soul beautiful."

"That would be altogether the best plan," said Horace, aside to Prudy; "she can't do much with her body, that's a fact; it's too dried up."

All this while they were passing elegant shops, and Aunt Madge let the children pause as long as they liked before the windows, to admire the beautiful things.

"Whose little grampa is that?" cried Fly, pointing to a Santa Claus standing on the pavement and holding out his hands with a very pleasant smile; "he's all covered with a snow-storm."

"He isn't alive," said Dotty; "and the snow is only painted on his coat in little dots."

"Well, I didn't spect he was alive, Dotty Dimple, only but he made believe he was. And O, see that hossy! he's dead, too, but he looks as if you could ride on him."

"This other window is the handsomest, Fly; don't I wish I had some of those beautiful dripping, red ear-rings?"

"Why, little sister," said Prudy, "I'd as soon think of wanting a gold nose as those cat-tail ear-rings. What would Grandma Read say?"

"Why, she'd say 'thee' and 'thou,' I s'pose, and ask me if I called 'em the ornaments of meek and quiet spirits," said Dotty, with a slight curl of the lip. "Auntie, is it wicked to wear jewels, if your grandma's a Quaker?"

"I think not; that is, if somebody should give you a pair; but I hope somebody never will. It is a mere matter of taste, however. O, children, now I think of it, I'll give you each a little pin-money to spend, to-day, just as you like. A dollar each to Prudy and Dotty; and, Horace, here is fifty cents for Flyaway."

"O, you darling auntie!" cried the little Parlins, in a breath. Dotty shut this, the largest bill she had ever owned, into her red porte-monnaie, feeling sure she should never want for anything again that money can buy.

"There, now, Hollis," said Fly, drawing her mouth down and her eyebrows up, "where's my skipt? my skipt?"

"What? A little snip like you mustn't have money," answered Horace, carelessly; "auntie gave it to me."

The moment he had spoken the words, he was sorry, for the child was too young and sensitive to be trifled with. She never doubted that her great cruel brother had robbed her. It was too much. Her "dove's eyes" shot fire. Flyaway could be terribly angry, and her anger was "as quick as a chain o' lightning." Before any one had time to think twice, she had turned on her little heel, and was running away. With one impulse the whole party turned and followed.

"Prudy and I haven't breath enough to run," said Aunt Madge. "Here we are at Stewart's. You'll find us in the rotunda, Horace. Come back here with Fly, as soon as you have caught her."

As soon as he had caught her!

They were on Broadway, which was lined with people, moving to and fro. Horace and Dotty had to push their way through the crowd, while little Fly seemed to float like a creature of air.

"Stop, Fly! Stop, Fly!" cried Horace; but that only added speed to her wings.

"She's like a piece of thistle-down," laughed Horace; "when you get near her you blow her away."

"Stop, O, stop," cried Dotty; "Horace was only in fun. Don't run away from us, Fly."

But by this time the child was so far off that the words were lost in the din.

"Why, where is she? I don't see her," exclaimed Horace, as the little blue figure suddenly vanished, like a puff of smoke. "Did she cross the street?"

"I don't know, Horace. O, dear, I don't know."

It was the first time a fear had entered either of their minds. Knowing very little of the danger of large cities, they had not dreamed that the foolish little Fly might get caught in some dreadful spider's web.

Yes, Fly was out of sight; that was certain. Whether she had turned to the right, or to the left, or had merely gone straight on, fallen down, and been trampled on, that was the question. How was one to find out? People enough to inquire of, but nobody to answer.

Horace had as many thoughts as a drowning man. How had he ever dared bring such a will-o'-the-wisp away from home? How had his mother consented to let him? His father had charged him, over and over, not to let go Fly's hand in the street. That did very well to talk about; but what could you do with a child that wasn't made of flesh and blood, but the very lightest kind of gas?

"Dotty, turn down this street, and I'll keep on up Broadway. No—no; you'd get lost. What shall we do? Go just where I do, as hard as you can run, and don't lose sight of me."

Dotty began to pant. She could not keep on at this rate of speed, and Horace saw it.

"You'll have to go back to Stewart's."

"Where's Stewart's?" gasped Dotty, still running.

"Why, that stone building on Tenth Street, with blue curtains, where we left auntie."

"I don't know anything about Tenth Street or blue curtains."

"But you'll know it when you get there. Just cross over—"

"O, Horace Clifford, I can't cross over! There's horses and carriages every minute; and my mother made me almost promise I wouldn't ever cross over."

"There are plenty of policemen, Dotty; they'll take you by the shoulder—"

"O, Horace Clifford, they shan't take me by the shoulder! S'pose I want 'em marching me off to the lockup?" screamed Dotty, who believed the lockup was the chief end and aim of policemen.

"Well, then, I don't know anything what to do with you," said Horace, in despair.

It seemed very hard that he should have the care of this willful little cousin, just when he wanted so much to be free to pursue Flyaway.

"If you won't go back to Stewart's, you won't. Will you go into this shop, then, and wait till I call for you?"

"You'll forget to call."

"I certainly won't forget."

"Well, then, I'll go in; but I won't promise to stay. I want to help hunt for Fly just as much as you do."

"Dotty Dimple, look me right in the eye. I can't stop to coax you. I'm frightened to death about Fly. Do you go into this store, and stay in it till I call for you, if it's six hours. If you stir, you're lost. Do—you—hear?"

"Yes, I hear.—H'm, he thinks my ears are thick as ears o' corn? No holes in 'em to hear with, I s'pose! Horace Clifford hasn't got the say o' me, though. I can go all over town for all o' him!"

"What will you have, my little lady?" said a clerk, bowing to Dotty.

"I don't want anything, if you please, sir. There was a boy, and he asked me to stay here while he went to find something."

"Very well; sit as long as you please."

"Screwed right down into the floor, this piano stool is," thought Dotty; "makes it real hard to sit on, because you can't whirl it. Guess I'll walk 'round a while. Why, if here isn't a window right in the floor! Strong enough to walk on. There's a man going over it with big boots and a cane. I can look right down into the cellar. Only just I can't see any thing, though, the glass is so thick."

Dotty watched the clerks measuring off yards of cloth, tapping on the counter, and calling out, "Cash." It was rather funny, at first, to see the little boys run; but Dotty soon tired of it.

"Horace is gone a long while," thought she, going to the door and looking out.

"He has forgotten to call, or he's forgotten where he left me, or else he hasn't found Fly. Dear, dear! I can't wait. I'll just go out a few steps, and p'rhaps I'll meet 'em."

She walked out a little way, seeing nothing but a multitude of strange faces.

"Well, I should think this was queer! I'll go right back to that store, and sit down on the piano stool. If Horace Clifford can't be more polite! Well, I should think!"

Dotty went back, and entered, as she supposed, the store she had left; but a great change had come over it. It had the same counters, and stools, and goods on lines, marked "Selling off below cost;" but the men looked very different. "I don't see how they could change round so quick," thought Dotty; "I haven't been gone more'n a minute."

"What shall I serve you to, mees," said one of them, with a smile that was all black eyes and white teeth. Dotty thought he looked very much like Lina Rosenbug's brother; and his hair was so shiny and sticky, it must have been dipped in molasses.

She answered him with some confusion. "I don't want anything. I was the girl, you know, that the boy was going somewhere to find something."

The man smiled wickedly, and said, "Yees, mees." In an instant it flashed across Dotty that she had got into the wrong store. Where was the glass window she had walked on? They couldn't have taken that out while she was gone. The floor was whole, and made of nothing but boards.

"Well, it's very queer stores should be twins," thought Dotty.

She entered the next one. It was not a "twin;" it was full of books and pictures.

"Why didn't Horace leave me here, in the first place, it was so much nicer. And they let people read and handle the pictures. O, they have the goldest-looking things!"

How shocked Prudy would have been, if she had seen her little sister reaching up to the counter, and turning over the leaves of books, side by side with grown people! Miss Dimple was never very bashful; and what did she care for the people in New York, who never saw her before? She soon became absorbed in a fairy story. Seconds, minutes, quarters; it was a whole hour before she came to herself enough to remember that Horace was to call for her, and she was not where he had left her.

"But he can't scold; for didn't he keep me waiting, too? Now I'll go back."

The next place she entered was a cigar store.

"I might have known better than to go in; for there's that wooden Indian standing there, a-purpose to keep ladies out!"

"O, here's a 'Sample Room.' Now this must be the place, for it says 'Push,' on the green door, just as the other one did."

What was Dotty's astonishment, when she found she had rushed into a room which held only tables, bottles, and glasses, and men drinking something that smelt like hot brandy!

"I shan't go into any more 'Sample Rooms.' I didn't know a 'Sample' meant whiskey! But, I do declare, it's funny where my store is gone to."

The child was going farther and farther away from it.

"Here is one that looks a little like it Any way, I can see a glass window in there, on the floor."

A lady stood at a counter, folding a piece of green velvet ribbon. Dotty determined to make friends with her; so she went up to her, and said, in a low voice, "Will you please tell me, ma'am, if I'm the same little girl that was in here before? No, I don't mean so. I mean, did I go into the same store, or is this a different one? Because there's a boy going to call for me, and I thought I'd better know."

Of course the lady smiled, and said it might, or might not be the same place; but she did not remember to have seen Dotty before.

"What was the number of the store? The boy ought to have known."

"But I don't believe he did," replied Dotty, indignantly; "he never said a word to me about numbers. I'm almost afraid I'll get lost!"

"I should be quite afraid of it, child. Where do you live?"

"In Portland, in the State of Maine. Prudy and I came to New York: our auntie sent for us—I know the place when I see it; side of a church with ivy; but O, dear! I'm afraid the stage don't stop there. She's at Mr. Stewart's—she and Prudy."

"Do you mean Stewart's store?"

"O, no'm; it's a man she knows," replied Dotty, confidently; "he lives in a blue house."

The lady asked no more questions. If Dotty had said "Stewart's store," and had remembered that the curtains were blue, and not the building, Miss Kopper would have thought she knew what to do; she would have sent the child straight to Stewart's.

"Poor little thing!" said she, twisting the long curl, which hung down the back of her neck like a bell-rope, and looking as if she cared more about her hair than she cared for all the children in Portland. "The best thing you can do is to go right into the druggist's, next door but one, and look in the City Directory. Do you know your aunt's husband's name?"

"O, yes'm. Colonel Augustus Allen, Fiftieth Avenue."

"Well, then, there'll be no difficulty. Just go in and ask to look in the Directory; they'll tell you what stage to take. Now I must attend to these ladies. Hope you'll get home safe."

"A handsome child," said one of the ladies. "Yes, from the country," replied Miss Kopper with a sweet smile; "I have just been showing her the way home."

Ah, Miss Kopper, perhaps you thought you were telling the truth; but instead of relieving the country child's perplexity, you had confused her more than ever. What should Dotty Dimple know about a City Directory? She forgot the name of it before she got to the druggist's.

"Please, sir, there's something in here,—may I see it?—that shows folks where they live."

"A policeman?"

"No; O, no, sir."

After some time, the gentleman, being rather shrewd, surmised what she wanted, and gave her the book.

"Not that, sir," said Dotty, ready to cry.

Perhaps you will be as ready to laugh, when you hear that the child really supposed a City Directory was an instrument that drew out and shut up like a telescope, and, by peeping through it, she could see the distant home of Colonel Allen, on "Fiftieth Avenue."

The apothecary did not laugh at her; but, being a kind man, and, moreover, not having curls hanging down his neck which needed attention, he gave his whole care to Dotty, found an omnibus for her, told the driver just where to let her out, and made her repeat her uncle's street and number till he thought there was no danger of a mistake.

One would have thought that now all Dotty's troubles were over; and so they would have been, if she had not tried so hard to remember the number. She said it over and over so many times, that all of a sudden it went out of her mind. It was like rolling a ball on the ground, backward and forward, till most unexpectedly it pops into a hole. Very much frightened, Dotty bit her lip, twirled her front hair, and pinched her left cheek—all in vain; the number wouldn't come.

"O, dear, what'll I do? I'd open that cellar door, where the driver is; but he's all done up in a blue cape, and don't know anything only how to whip his horses. And there don't anybody know where anybody lives in this city; so it's no use to ask. For what do they care? They'd tell you to look in the Dictionary. There's nobody in Portland ever told me to look in a Dictionary. Here they are, sitting round here, just as happy, all but me. They all live in a number, and they know what it is; but they keep it to themselves,—they don't tell. It always makes people feel better to know where they're going to. When I'm in Portland I know how to get to Park Street, and how to get to Munjoy, and how to get to Back Cove, with my eyes shut. But they don't make things as they ought to in New York. You can't find out what to do."

So the stage rumbled, and Dotty grumbled. Presently a lady in an ermine cloak got out, and Dotty did not know of anything better to do than to follow. She certainly was on Fifth Avenue, and perhaps, if she walked on, she should come to the number.

"There isn't any house along here that looks like auntie's," said she, anxiously; "only they all look like it some. I never saw such a place as this city, So many same things right over, and over; and then, when you go into 'em, its just as different, and not the place you s'posed it was."

Here Dotty ran up some steps, and rang a bell. She thought the damask curtains looked familiar.

"No, no," cried she, running down again, as fast as the mouse ran down the clock; "my auntie don't keep onions in her bay window, I hope!"

It was hyacinth bulbs, in glass vases, which had excited Dotty's disgust.

"O, I guess I'm on the wrong side of the street; no wonder I can't find the house. There, I see a chamber window open; our chamber window was open. I'm going to cross over and get near enough to see if there's a little clock on the shelf that ticks like a dog wagging his tail."

No, there was no clock of any sort, and where the shelf ought to be was a baby's crib.

"Well, any way, here's that beautiful church, with ivy round it; it's ever so near auntie's; so I'll keep walking."

Dotty was right when she said the church was near auntie's—it was within three doors; but she was wrong when she kept walking precisely the wrong way. She crossed over to Sixth Avenue. Now, where were the brown houses? She saw the horse-cars plodding along, and tried to read the words on them.

"'Sixth Ave. and Fifty-Ninth Street.' Why, what's an ave? I never heard of such a thing before; we don't have 'aves' in Portland. There are ever so many people getting out of that car. While it stops, I'll peep in, and see where it's going to. Perhaps there's a name inside that tells."

And, with her usual rashness, Dotty stepped upon the platform of the car, and looked in. What she expected to see she hardly knew,—perhaps "Aunt Madge's House," in gold letters; but what she really saw was, "No Smoking;" those two words, and nothing more.

"Well, who wants to smoke? I'm sure I don't," thought Dotty, disdainfully, and was turning to step off the platform, when Horace Clifford seized her by the shoulder.

"Where did you come from, you runaway?" said he, gruffly.

Close beside him were Aunt Madge and Prudy; all three were getting out of the car.

"Thank Heaven, one of them is found," cried Aunt Madge, her face very pale, her large eyes full of trouble.

Prudy kissed and scolded in the same breath. "O, Dotty Dimple, you'd better believe we're glad to see you?—but what a naughty girl! A pretty race you've led Horace, and he just wild about Fly!"

"H'm! what'd he go off for, then, and leave me there, sitting on a piano stool? S'pose I's going to sit there all day? Didn't I want to go home as much as the rest of you."

"And how did you get home? I'd like to know that," said Horace, walking on with great strides, and then coming back again to the "ladies;" for his anxiety about his little sister would not allow him to behave calmly.

"I rode."

"You weren't in the car we came in."

"N-o; I just happened to be peeking in there you know. But I came in an omnibius."

"It is wonderful," said Aunt Madge, looking puzzled, "that you ever knew what omnibus to take."

Dotty looked down to see if her boot was buttoned, and forgot to look up again. "Well, I shouldn't have known one omnibius, as you call it, from another," said Prudy, lost in admiration. "Why, Dotty, how bright you are! And there we were, so afraid about you, and spoke to a policeman to look you up."

"I wouldn't let a p'liceman catch me," said Dotty, tossing her head. "But haven't you found Fly yet?"

They were at home by this time, and Horace was ringing the bell.

"No, the dear child is still missing; but the police are on her track," said Aunt Madge, looking at her watch. "It is now one o'clock. Keep a good heart, Horace, my boy. John shall go straight to the telegraph office, and wait there for a despatch. Don't you leave us, dear; we can't spare you, and you can do no good."

Horace made no reply, except to tap the heels of his boots together. He looked utterly crushed. A large city was just as strange to him as it was to Dotty, and he could only obey his aunt's orders, and try to hope for the best. Dotty seemed to be the only one who felt like saying a word, and she talked incessantly.

"O, what'd you send the p'lice after her for? To put her in the lockup, and make her cry and think she's been naughty? It's the awfulest city that ever I saw. Folks might send her home, if they were a mind to, but they won't. They don't care what 'comes of you. There's cars and stages going to which ways, and nothing but 'No Smoking,' inside. And I went and peeped in at a window, and there was onions! And how'd I know where to go to? There was a girl with a long curl, and she said, 'Go to the 'pothecary's;' and what would Fly have known where she meant? And he looked in a Dictionary, and put me in a stage,—I was going to tell you about that when I got ready,—and asked me if I had ten cents, and I had; and then I forgot what the number was, and that was the time I saw the onions, or I should have gone right into somebody's else's house. And I knew there was a church with ivy round, but Fly don't know; she's nothing but a baby. And I should have thought, Horace Clifford, you might have given her that money! That was what made her run off; you was real cruel, and that's why I wouldn't mind what you said. And—and—"

"Hush," said Aunt Madge, brushing back a spray of fair curls, which the wind had tossed over her forehead. "I don't allow a word of scolding in my house. If you don't feel pleasant, Dotty, you may go into the back yard and scold into a hole."

Dotty stopped suddenly. She knew her aunt was displeased; she felt it in the tones of her voice.

"Dotty, the wind has been at play with your hair as well as mine. Suppose we both go up stairs a few minutes?"

"There, auntie's going to reason with me," thought Dotty, winding slowly up the staircase; "I didn't suppose she was one of that kind."

"No dear, I'm not one of that kind," said Mrs. Allen, roguishly; for she saw just what the child was thinking. "'I come not here to talk.' All I have to say is this: Disobey again, and I send you home immediately."

"Yes'm," said the little culprit, blushing crimson. "Now, brush your hair, and let us go down." This was the only allusion Mrs. Allen ever made to the subject; but after this, she and Dotty understood each other perfectly. Dotty had learned, once for all, that her aunt was not to be trifled with.

The child really was ashamed—thoroughly ashamed; but do you suppose she admitted it to Horace? Not she. And he, so full of anguish concerning the lost Fly, found not a word of fault; scarcely even thought of his naughty cousin at all.

Now we must go back and see what has become of the little one.

At first her heart had swollen with rage. Anger had set her going, just as a blow from a battledoor sends off a shuttlecock. And, once being started, the poor little shuttlecock couldn't stop.

"Auntie gave me that skipt. Hollis is a very wicked boy; steals skipt from little gee-urls. I don't ever want to see Hollis no more."

What she meant to do, or where to go, she had no more idea than the blue clouds overhead. She had no doubt her brother was close behind, trying to overtake her. Her sole thought was, that she "wouldn't ever see Hollis no more." She knew nothing could make him so unhappy as that. "I'll lose me, and then how'll he feel?"

"Lose me!" A wild thought, gone in a moment; but meanwhile she was already lost.

"I hope auntie won't give Hollis nuffin to eat, 'cause he's took away my skipt; nuffin to eat but meat and vertato, athout any pie."

Flyaway shook her head so hard, that the "war-plume" under her bonnet would have nodded, if the air could have got at it. "Why, where's Hollis?" said she, looking back, and finding, to her surprise, he was not to be seen. "I spected he'd come. I thought I heard him walking ahind me."

Flyaway's anger had died out by this time. It never lasted longer than a Fourth of July torpedo.

"He didn't know I runned off. Guess I'll go back, and he'll give me the skipt; and then I'll forgive him all goody."

A very nice plan; only, instead of going back, she turned a corner, and tripped along towards University Place. She had twisted her head so much in looking for Horace, that it was completely turned round. And, besides, a little farther on was a man playing a harp, and a small boy a violin. Fly paused and listened, till she no longer remembered Horace or the "skipt." She forgot this was New York, and dreamed she had come to fairy-land. Her soul was full of music. Happy thoughts about nothing in particular made her smile and clap her hands. Birds, flowers, Santa Clauses, Flipperties, and "pepnits" seemed to hover near. Something beautiful was just going to happen, she didn't know what.

After the man had played for some time without attracting attention from any body but Flyaway and a poor old beggar woman, he put his harp in a green bag, slung it over his shoulder, and walked off. Flyaway followed without knowing it. Down Sixth Avenue went the music-man, and close at his heels went she. By and by she saw a little girl, no larger than herself, with a great bundle on her shoulders.

"You don't s'pose she's got a music on her back?—No, not a music; it's too soft all swelled out in a bunch."

Fly went nearer the little girl, to see what she was carrying; and as she did so, some gray coals, mixed with ashes, fell out of the bundle upon her nice cloak.

"Why, she's been and carried off her mother's fireplace," thought Fly, shaking her cloak in disgust; "what you s'pose she wanted to do that for?"

But far from carrying off her mother's fireplace, the ragged little girl had only been picking up old coal out of barrels, and was taking it home to burn. It had already been burned once, and picked over and burned again, and thrown away; but perhaps this poor child's mother could coax it into a faint glow, warm enough to fry a few potatoes.

While Flyaway was shaking her cloak, and staring at some old silk dresses and bed-quilts, which were hung before a shop-door, the man with the harp on his back, and the boy with a violin under his arm, had turned a corner, and passed out of sight. Flyaway rubbed her eyes, and looked again. They must have gone down through the brick pavement, but she couldn't see any hole. Far away in the distance she heard their music again, and it did not come from under ground. She ran to overtake it, and turned into Bleecker Street. No music-man there, but a good supply of oranges and apples.

"Needn't folks put their hands in, and take some out the barrels? Then why for did the folks put 'em on' doors?"

While pondering this grave question, she was jostled by a man carrying a rocking-chair, and very nearly fell down stairs into an oyster-saloon. A minute more and she was back on Broadway, the very street, where Aunt Madge and Prudy were waiting for her, but so much lower down that she might as well have been in the State of Maine.

"Now, I'll go find my Hollis," said she turning another corner, and running the wrong way with all her might. Past candy-stalls, past toy-shops, past orange-wagons. Hark, music again! Not the soft strains of a harp, but the stirring notes of bugle, fife, and drum. Fly kept time with her feet.

"Here we go marchin' on," hummed she. But the crowd "marchin' on" with her was a strange one. Carts full of hammers, pincers, and all sorts of iron tools, and men in gray shirts, with black caps on their heads. Some of the men had banners, with great black words, such as "Equal Rights," or something like them, in German; but of course Fly could not tell one letter from another. She only knew it was all very "homebly," in spite of the music. She began to think she had better get away as soon as she could; so she tried to cross the street, but some one held her back; it was a lady, carrying a small dog in her arms, like a baby.

"Don't go there, child; that's a strike, you'll get killed."

Fly knew but one meaning for the word strike; and, tearing herself from the lady, ran screaming down Broadway, with the thought that every man's hand was against her.

On she went, and on went the strike, close behind her. A little while ago she had been following music, and now music was following her. But the fifes and drums were rather slow, and Flyaway's feet were very swift; so it was not long before the gray men, with their white banners and clattering carts, were far behind her. No danger now that any of the wicked creatures would strike her; so she slackened her pace.

She did begin to wonder why she had not found Horace; still, she was not at all alarmed, and there was a dreadful din in the streets, which confused her thoughts. It seemed as if people were making it on purpose. Once, at Willowbrook, she had heard boys banging tin pans, grinding coffee mills, and pounding with mortars. She had liked that,—they called it the "Calathumpian Band,"—and she liked this too; it sounded about as uproarious.

While she sauntered along, spying wonders, her eye was attracted by some balancing-toys, which a man was showing off at one of the corners. What a pleasant man he was, to set them spinning just to amuse little girls! Fly was delighted with one wee soldier, in a blue coat with brass buttons, who kept dancing and bowing with the greatest politeness. "Captain Jinks, of the horse-marines," said the toy-man, introducing him. "Buy him, miss; he'll make a nice little husband for you; only fifteen cents."

Fly felt quite flattered. It was the first time in her life any one had ever asked her to buy anything, and she thought she must have grown tall since she came from Indiana. She put her fingers in her mouth, then took them out, and put them in her pocket.

"Here's my porte-monnaie-ry," said she, dolefully; "but I haven't but two cents—no more. Hollis carried it off."

"Well, well, run along, then. Don't you see you're right in the way?"

Fly was surprised and grieved at the change in the man's tone: she had expected he would pity her for not having any money.

"Come here, you little lump of love," called out a mellow voice; and there, close by, sat a wizened old woman, making flowers into nosegays. She had on a quilted hood as soft as her voice, but everything else about her was as hard as the door-stone she sat on.

"See my beautiful flowers," said the old crone, pointing to the table before her; "who cares for them jumping things over yonder? I don't."

The flowers were tied in bouquets—sweet violets, rosebuds, and heliotrope. Fly, whose head just reached the top of the table, smelt them, and forgot the "little husband, for fifteen cents."

"He's a cross man, dearie," said the old woman, lowering her voice, "or he wouldn't have sent you off so quick, just because you hadn't any money. Now, I love little girls, and I'll warrant we can make some kind of a trade for one of my posies."

Fly smiled, and quickly seized a bouquet with a clove pink in it.

"Not so fast, child! What you got that you can give me for it? I don't mind the money. That old pocket-book will do, though 'tain't wuth much."

It was very surprising to Fly to hear her port-monnaie called old; for it was bought last week, and was still as red as the cheeks of the painted lady.

"I don't dass to give folks my porte-monnaie-ry," said she, clutching it tighter, but holding the flowers to her nose all the while.

"O, fudge! Well, what else you got in your pocket? A handkerchief?"

"No, my hangerfiss is in my muff."

"That? Why, there isn't a speck o' lace on it. Nice little ladies always has lace. Here's a letter in the corner; what is it?"

"Hollis says it's K; stands for Flyaway."

"Well, you're such a pretty little pink, I guess I'll take it; but 'tain't wuth lookin' at," said the crafty old woman, who saw at a glance it was pure linen, and quite fine.

"Now run along, baby; your mummer will be waitin' for you."

Fly walked on slowly. Ought she to have parted with her very best hangerfiss!

"Nice ole lady, loved little gee-urls; but what you s'pose folks was goin' to cry into now?"

Tears started at the thought. One of them dropped into the eye of the squirrel, who sat on the muff, peeping up into her face.

"Nice ole lady, I s'pose; but folks never wanted to buy my hangerfisses byfore!" thought Fly, much puzzled by the state of society in New York. "And I've got some beau-fler flowers to my auntie's house. Wake up—wake up!" added she, blowing open a pink rose-bud; "you's too little for me."

But the bud did not wish to wake up and be a rose; it curled itself together, and went to sleep again.

"I don't see where Hollis stays to all the time," exclaimed the little one, beginning to have a faint curiosity about it.

But just then a gentle-looking blind girl came along led by a dog. The sight was so strange that Flyaway stopped to admire; for whatever else she might be afraid of, she always loved and trusted a dog.

"Doggie, doggie," cried she, patting the little animal's head.

"O, what a sweet voice," said the blind girl, putting out her hand and groping till she touched Fly's shoulder. "I never heard such a voice!"

This was what strangers often said, and Flyaway never doubted the sweetness was caused by eating so much candy; but just now she had had none for two days.

"What makes you shut your eyes up, right in the street, girl? Is the seeingness all gone out of 'em?"

"Yes, you darling. I haven't had any seeingness in my eyes for a year."

"You didn't? Then you's blind-eyed," returned Flyaway, with perfect coolness.

"And don't you feel sorry for me—not a bit?"

"No, 'cause your dog is freckled so pretty."

"But I can't see his freckles."

"Well, he's got 'em. Little yellow ones, spattered out all over him."

"But if I had eyes like you, I shouldn't need any dog. I could go about the streets alone."

"Well, I don't like to go 'bout the streets alone; I want my own brother Hollis."

"I hope you haven't got lost, little dear?"

"No," laughed Fly, gayly; "I didn't get lost! But I don't know where nobody is! And there don't nobody know where I am!"

The blind girl took Fly's little hand tenderly in hers.

"Come, turn down this street with me, and tell me all about it."

Fly trudged along, prattling merrily, for about a minute: then she drew away. "'Tisn't a nice place; I don't want to go there."

A look of pain crossed the blind girl's face.

"No, I dare say you don't. It isn't much of a place for folks with silk bonnets on."

"You can't see my bonnet; you can't see anything, you're blind-eyed; but," said Fly, glancing sharply around, "it isn't pretty here, at all; and there's a dead cat right in the street."

"Yes, I think likely."

"And there's a boy. I spect he frowed the cat out the window; he hasn't nuffin on but dirty cloe's."

"Do you see some steps?" said the blind girl, putting her hand out cautiously. "Don't fall down."

"I shan't fall down; I'm going home."

"O, don't child; you must come with me. My mother will take care of you."

"I don't want nobody's mother to take 'are o' me; I've got a mamma myself!"

"How little you know!" said the blind girl, thinking aloud; "how lucky it is I found you! and O, dear, how I wish I could see! You'll slip away in spite of me."

But Flyaway allowed herself to be drawn along, step by step, partly because she liked the "freckled dog," and partly because she had not ceased being amused by the droll sight of a person walking with closed eyes.

"What's the name of you, girl?"

"Maria."

"Maria? So was my mamma; her name was Maria, when she was a little girl. O, look, there's another boy; don't you see him? Up high, in that house. Got a big box with a string to it."

A very rough-looking boy was standing at a third-story window, lowering a bandbox by a clothes-line. As Fly watched the box slowly coming down, the boy called out,—

"Get in, little un, and I'll give you a free ride."

"O, no—O, no; I don't dass to."

"Yes, yes; go in, lemons," said the boy, choking with laughter, as he saw the child's horror. "If you don't do it, by cracky, I'll come down and fetch you."

At this, Fly was frightened nearly out of her senses, and ran so fast that the dog could scarcely have kept up with her, even if he had not had a blind mistress pulling him back.

"O, where are you?" exclaimed Maria. "Don't run away from me,—don't!"

"He's a-gon to kill me in two," cried Flyaway, stopping for breath.' "he's a-gon to kill me in two-oo!"

"No, he isn't, dear! It's only Izzy Paul He couldn't catch you, if he tried. He's lame, and goes on crutches."

"But he said a swear word,—yes he, did," sobbed the child, never doubting that a boy who could swear was capable of murder, though he had neither hands nor feet.

"Stop, now," said Maria, clutching Fly as if she had been a spinning top. "This is my house. Mother, mother, here's a little girl; catch her—hold her—keep her!"

"Me? What should I catch a little girl for?" said Mrs. Brooks, a faded woman with a tired face, and a nose that moved up and down when she talked. She had been standing at the door of their tumbledown tenement, looking for her daughter, and was surprised to see her bringing a strange child with her. It was not often that well-dressed people wandered into that dirty alley.

"The poor little thing has got lost, mother. Perhaps you can find out where she came from. I didn't ask her any questions; it was as much as I could do to keep up with her."

Maria put her hand on her side. Fast walking always tired her, for she was afraid every moment of falling.

They had to go down a flight of stairs to get into the house; and after they got there Fly looked around in dismay.

"I don't want to stay in the stable," she murmured. Indeed it was not half as nice as the place where her father kept his horse.

"But this is where we have to live," sighed Maria.

"Have things to eat?" asked the little stranger, in a solemn whisper.

There were a few chairs with broken backs, a few shelves with clean dishes, a few children with hungry faces. In one corner was a clumsy bedstead, and in a tidy bed lay a pale man.

"Who've you got there, Maria?" said he. "Bring her along, and stick her up on the bed."

"Don't be afraid," said Mrs. Brooks; "it's only pa; wouldn't the little girl like to talk to him? He's sick."

Flyaway was not at all afraid, for the man smiled pleasantly, and did not look as if he would hurt anybody. Mrs. Brooks set her on the bed, and Maria, afraid of losing her, held her by one foot. The children all crowded around to see the little lady in a silk bonnet holding a button-hole bouquet to her bosom.

"Ain't she a ducky dilver!" said the oldest boy. "Pa'll be pleased, for he don't see things much. Has to keep abed all the time."

Mr. Brooks tried to smile, and Flyaway whispered to Maria, with sudden pity,—

"Sorry he's sick. Has he got to stay sick? Can't you find the camphor bottle?"

"O, father, she thinks if ycu had some camphor to smell of, 'twould cure you."

Then they all laughed, and Fly timidly offered the sick man her flowers.

"What, that pretty posy for me? Bless you, baby, they'll do me a sight more good than camfire!"

"There," said Maria, joyfully, "now pa is pleased; I know by the sound of his voice. Poor pa! only think, little girl, a stick of timber fell on him, and lamed him for life!"

"Yes," said Bennie, "the lower part of him is as limber as a rag."

"She don't sense a word you say," remarked Mrs. Brooks, shaking up a pillow, "See what we can get out of her. What's your name, dear?"

"Katie Clifford."

"Where do you live?"

"I have been borned in Nindiana."

Fly spoke with some pride. She considered her birth an honor to the state.