Title: The Story of Newfoundland

Author: Earl of Frederick Edwin Smith Birkenhead

Release date: June 20, 2006 [eBook #18636]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by a www.PGDP.net volunteer, Jeannie Howse, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Our Roots (http://www.nosracines.ca/e/index.aspx)

E-text prepared by a www.PGDP.net volunteer, Jeannie Howse,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net/)

from page images generously made available by

Our Roots

(http://www.nosracines.ca/e/index.aspx)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Our Roots. See http://www.nosracines.ca/e/toc.aspx?id=1319 |

Transcriber's Note:

Spelling and hyphenation inconsistencies from the original document have been preserved.

A number of obvious typographical errors have been corrected in this text.

For a complete list, please see the end of this document.

Twenty-two years ago the enterprise of Horace Marshall & Son produced a series of small books known as "The Story of the Empire Series." These volumes rendered a great service in bringing home to the citizens of the Empire in a simple and intelligible form their community of interest, and the romantic history of the development of the British Empire.

I was asked more than twenty-one years ago to write the volume which dealt with Newfoundland. I did so. The little book which was the result has been for many years out of print. I have been asked by my friends in Newfoundland and elsewhere to bring it up to date for the purpose of a Second Edition. The publishers assented to this proposal, and this volume is the result.

The book, of course, never pretended to be anything but a slight sketch. An attempt has been made—while errors have been corrected and the [4]subject matter has been brought up to date—to maintain such character as it ever possessed.

I shall be well rewarded for any trouble I have taken if it is recognized by my friends in Newfoundland that the reproduction of this little book places on record an admiration for, and an interest in, our oldest colony which has endured for considerably more than twenty-one years.

BIRKENHEAD.

House of Lords,

May 1920.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Land and its People | 7 |

| II. | The Age of Discovery | 22 |

| III. | Early History | 45 |

| IV. | Early History (continued) | 64 |

| V. | The Struggle for Existence | 81 |

| VI. | The English Colonial System and its Results | 95 |

| VII. | Self-Government | 114 |

| VIII. | Modern Newfoundland | 126 |

| IX. | The Reid Contract—and After | 143 |

| X. | The French Shore Question | 171 |

| Maps— | ||

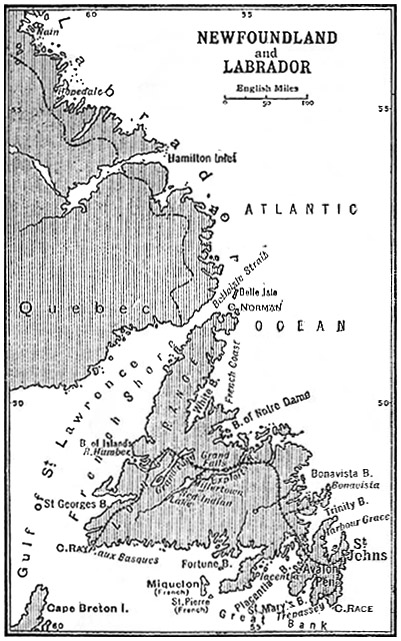

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6 | |

| Newfoundland in Relation to Western Europe | 33 | |

| Index | 188 | |

The island of Newfoundland, which is the tenth largest in the world, is about 1640 miles distant from Ireland, and of all the American coast is the nearest point to the Old World. Its relative position in the northern hemisphere may well be indicated by saying that the most northern point at Belle Isle Strait is in the same latitude as that of Edinburgh, whilst St. John's, near the southern extremity, lies in the same latitude as that of Paris. Strategically it forms the key to British North America. St. John's lies about half-way between Liverpool and New York, so that it offers a haven of refuge for needy craft plying between England and the American metropolis. The adjacent part of the coast is also the landing-place for most of the Transatlantic cables: it was at St. John's, too, that the first wireless ocean signals were received. From the sentimental point of view Newfoundland is the oldest of the English colonies, for our brave fishermen were familiar with its [8]banks at a time when Virginia and New England were given over to solitude and the Redskin. Commercially it is the centre of the most bountiful fishing industry in the world, and the great potential wealth of its mines is now beyond question. On all these grounds the story of the colony is one with which every citizen of Greater Britain should be familiar. The historians of the island have been capable and in the main judicious, and to the works of Reeves, Bonnycastle, Pedley, Hatton, Harvey, and above all Chief Justice Prowse, and more recently to J.D. Rogers,[1] every writer on Newfoundland must owe much. Of such elaborate work a writer in the present series may say with Virgil's shepherd, "Non invideo, miror magis"; for such a one is committed only to a sketch, made lighter by their labours, of the chief stages in the story of Newfoundland.

To understand that story a short account must be given at the outset of the situation and character of the island. But for the north-eastern side of the country, which is indented by deep and wide inlets, its shape might be roughly described as that of an equilateral triangle. Its area is nearly 43,000 square miles, so that it is larger than Scotland and considerably greater than Ireland, the area of which is 31,760 square miles. Compared to some of the smaller states of Europe, it is found to be [9]twice as large as Denmark, and three times as large as Holland. There is only a mile difference between its greatest length, which from Cape Ray, the south-west point, to Cape Norman, the northern point, is 317 miles, and its greatest breadth, from west to east, 316 miles from Cape Spear to Cape Anguille. Its dependency, Labrador, an undefined strip of maritime territory, extends from Cape Chidley, where the Hudson's Straits begin in the north, to Blanc Sablon in the south, and includes the most easterly point of the mainland. The boundaries between Quebec and Labrador have been a matter of keen dispute. The inhabitants are for the most part Eskimos, engaged in fishing and hunting. There are no towns, but there are a few Moravian mission stations.

The ruggedness of the coast of Newfoundland, and the occasional inclemency of the climate in winter, led to unfavourable reports, against which at least one early traveller raised his voice in protest. Captain Hayes, who accompanied Gilbert to Newfoundland in 1583, wrote on his return:

"The common opinion that is had of intemperation and extreme cold that should be in this country, as of some part it may be verified, namely the north, where I grant it is more colde than in countries of Europe, which are under the same elevation; even so it cannot stand with reason, and nature of the clime, that the south parts should be so intemperate as the bruit has gone."

[10]Notwithstanding the chill seas in which it lies, Newfoundland is not in fact a cold country. The Arctic current lowers the temperature of the east coast, but the Gulf Stream, whilst producing fogs, moderates the cold. The thermometer seldom or never sinks below zero in winter, and in summer extreme heat is unknown. Nor is its northerly detachment without compensation, for at times the Aurora borealis illumines the sky with a brilliancy unknown further south. A misconception appears to prevail that the island is in summer wrapped in fog, and its shores in winter engirt by ice. In the interior the climate is very much like that of Canada, but is not so severe as that of western Canada or even of Ontario and Quebec. The sky is bright and the weather clear, and the salubrity is shown by the healthy appearance of the population.

The natural advantages of the country are very great, though for centuries many of them were strangely overlooked. Whitbourne, it is true, wrote with quaint enthusiasm, in the early sixteenth century: "I am loth to weary thee (good reader) in acquainting thee thus to those famous, faire, and profitable rivers, and likewise to those delightful large and inestimable woods, and also with those fruitful and enticing lulls and delightful vallies." In fact, in the interior the valleys are almost as numerous as Whitbourne's adjectives, and their fertility promises a great future for agriculture when the railway has done its work.

[11]The rivers, though "famous, faire, and profitable," are not overpoweringly majestic. The largest are the Exploits River, 200 miles long and navigable for some 30 miles, and the Gander, 100 miles long, which—owing to the contour of the island—flows to the eastern bays. The deficiency, however, if it amounts to one, is little felt, for Newfoundland excels other lands in the splendour of its bays, which not uncommonly pierce the land as far as sixty miles. The length of the coast-line has been calculated at about 6000 miles—one of the longest of all countries of the world relatively to the area. Another noteworthy physical feature is the great number of lakes and ponds; more than a third of the area is occupied by water. The largest lake is Grand Lake, 56 miles long, 5 broad, with an area of nearly 200 square miles. The longest mountain range in the island is about the same length as the longest river, 200 miles; and the highest peaks do not very greatly exceed 2000 feet.

The cliffs, which form a brown, bleak and rugged barrier round the coasts of Newfoundland, varying in height from 300 to 400 feet, must have seemed grim enough to the first discoverers; in fact, they give little indication of the charming natural beauties which lie behind them. The island is exuberantly rich in woodland, and its long penetrating bays, running in some cases eighty to ninety miles inland, and fringed to the water's edge, vividly [12]recall the more familiar attractiveness of Norwegian scenery. Nor has any custom staled its infinite variety, for as a place of resort it has been singularly free from vogue. This is a little hard to understand, for the summer climate is by common consent delightful, and the interior still retains much of the glamour of the imperfectly explored. The cascades of Rocky River, of the Exploits River, and, in particular, the Grand Falls, might in themselves be considered a sufficient excuse for a voyage which barely exceeds a week.

Newfoundland is rich in mineral promise. Its history in this respect goes back only about sixty years: in 1857 a copper deposit was discovered at Tilt Cove, a small fishing village in Notre Dame Bay, where seven years later the Union Mine was opened. It is now clear that copper ore is to be found in quantities almost as inexhaustible as the supply of codfish. There are few better known copper mines in the world than Bett's Cove Mine and Little Bay Mine; and there are copper deposits also at Hare Bay and Tilt Cove. In 1905-6 the copper ore exported from these mines was valued at more than 375,000 dollars, in 1910-11 at over 445,000 dollars. The value of the iron ore produced in the latter period was 3,768,000 dollars. It is claimed that the iron deposits—red hematite ore—are among the richest in the world. In Newfoundland, as elsewhere, geology taught capital where to strike, and when the interior is more [13]perfectly explored it is likely that fresh discoveries will be made. In the meantime gold, lead, zinc, silver, talc, antimony, and coal have also been worked at various places.

A more particular account must be given of the great fish industry, on which Newfoundland so largely depends, and which forms about 80 per cent. of the total exports. For centuries a homely variant of Lord Rosebery's Egyptian epigram would have been substantially true: Newfoundland is the codfish and the codfish is Newfoundland. Many, indeed, are the uses to which this versatile fish may be put. Enormous quantities of dried cod are exported each year for the human larder, a hygienic but disagreeable oil is extracted from the liver to try the endurance of invalids; while the refuse of the carcase is in repute as a stimulating manure. The cod fisheries of Newfoundland are much larger than those of any other country in the world; and the average annual export has been equal to that of Canada and Norway put together. The predominance of the fishing industry, and its ubiquitous influence in the colony are vividly emphasised by Mr Rogers[2] in the following passage, though his first sentence involves an exaggerated restriction so far as modern conditions are concerned:

"Newfoundlanders are men of one idea, and that idea is fish. Their lives are devoted to the sea and [14]its produce, and their language mirrors their lives; thus the chief streets in their chief towns are named Water Street, guides are called pilots, and visits cruises. Conversely, land words have sea meanings, and a 'planter,' which meant in the eighteenth century a fishing settler as opposed to a fishing visitor, meant in the nineteenth century—when fishing visitors ceased to come from England—a shipowner or skipper. The very animals catch the infection, and dogs, cows, and bears eat fish. Fish manures the fields. Fish, too, is the main-spring of the history of Newfoundland, and split and dried fish, or what was called in the fifteenth century stock-fish, has always been its staple, and in Newfoundland fish means cod."

The principal home of the cod is the Grand Newfoundland Bank, an immense submarine island 600 miles in length and 200 in breadth, which in earlier history probably formed part of North America. Year by year the demand for codfish grows greater, and the supply—unaffected by centuries of exaction—continues to satisfy the demand. This happy result is produced by the marvellous fertility of the cod, for naturalists tell us that the roe of a single female—accounting, perhaps, for half the whole weight of the fish—commonly contains as many as five millions of ova. In the year 1912-13 the value of the exported dried codfish alone was 7,987,389 dollars, and in 1917 the total output of the bank and shore cod [15]fishery was valued at 13,680,000 dollars; and at a time when it was incomparably less, Pitt had thundered in his best style that he would not surrender the Newfoundland fisheries though the enemy were masters of the Tower of London. So the great Bacon, at a time when the wealth of the Incas was being revealed to the dazzled eyes of the Old World, declared, with an admirable sense of proportion, that the fishing banks of Newfoundland were richer far than the mines of Mexico and Peru.

Along the coasts of Norfolk and Suffolk the codfish is commonly caught with hook and line, and the same primitive method is still largely used by colonial fishermen. More elaborate contrivances are growing in favour, and will inevitably swell each year's returns. Nor is there cause to apprehend exhaustion in the supply. The ravages of man are as nothing to the ravages and exactions of marine nature, and both count for little in the immense populousness of the ocean. Fishing on a large scale is most effectively carried on by the Baltow system or one of its modifications. Each vessel carries thousands of fathoms of rope, baited and trailed at measured intervals. Thousands of hooks thus distributed over many miles, and the whole suitably moored. After a night's interval the catch is examined.

In 1890 a Fisheries Commission was established for the purpose of conducting the fisheries more [16]efficiently than had been the case before. Modern methods were introduced, and the artificial propagation of cod and also of lobsters was begun. In 1898 a Department of Marine and Fisheries was set up, and with the minister in charge of it an advisory Fisheries Board was associated.

Though the cod-fishery is the largest and the most important of the Newfoundland fisheries, the seal, lobster, herring, whale and salmon fisheries are also considerable, and yield high returns. As to all these fisheries, the right to make regulations has been placed more effectively in the hands of Great Britain by the Hague arbitration award, which was published in September 1910, and which satisfied British claims to a very large extent.

A pathetic chapter in the history of colonization might be written upon the fate of native races. A great English authority on international law (Phillimore) has dealt with their claims to the proprietorship of American soil in a very summary way.

"The North American Indians," he says, "would have been entitled to have excluded the British fur-traders from their hunting-grounds; and not having done so, the latter must be considered as having been admitted to a joint occupation of the territory, and thus to have become invested with a similar right of excluding strangers from such portions of the country as their own industrial operations covered."

[17]It is better to say frankly that the highest good of humanity required the dispossession of savages; and it is permissible to regret that the morals and humanity of the pioneers of civilization have not always been worthy of their errand.

It rarely happens that the native, as in South Africa, has shown sufficient tenacity and stamina to resist the tide of the white aggression: more often the invaders have gradually thinned their numbers. The Spanish adventurers worked to death the soft inhabitants of the American islands. Many perished by the sword, many in a species of national decline, the wonders of civilization, for good and for bad, working an obsession in their childish imaginations which in time reacted upon the physique of the race.

Sebastian Cabot has left a record of his standard of morality in dealing with the natives. When he was Grand Pilot of England it fell to his lot to give instructions to that brave Northern explorer, Sir Hugh Willoughby:

"The natives of strange countries," he advises, "are to be enticed aboard and made drunk with your beer and wine, for then you shall know the secrets of their hearts." A further practice which may have caused resentment in the minds of a sensitive people, was that of kidnapping the natives to be exhibited as specimens in Europe.

The natives of Newfoundland were known distinctively as Boeothics or Beothuks (a name [18]probably meaning red men), who are supposed to have formed a branch of the great Algonquin tribe of North American Indians, a warlike race that occupied the north-eastern portion of the American continent. Cabot saw them dressed in skins like the ancient Britons, but painted with red ochre instead of blue woad. Cartier, the pioneer of Canadian adventure, who visited the island in 1534, speaks of their stature and their feather ornaments. Hayes says in one place: "In the south parts we found no inhabitants, which by all likelihood have abandoned these coasts, the same being so much frequented by Christians. But in the north are savages altogether harmless." Whitbourne, forty years later, gives the natives an equally good character: "These savage people being politikely and gently handled, much good might be wrought upon them: for I have had apparant proofes of their ingenuous and subtle dispositions, and that they are a people full of quicke and lively apprehensions.

"By a plantation" [in Newfoundland] "and by that means only, the poore mis-beleeving inhabitants of that country may be reduced from barbarism to the knowledge of God, and the light of his truth, and to a civill and regular kinde of life and government."

The plantation came, but it must be admitted that the policy of the planters was not, at first sight, of a kind to secure the admirable objects [19]indicated above by King James's correspondent. In fact, for hundreds of years, and with the occasional interruptions of humanity or curiosity, the Boeothics were hunted to extinction and perversely disappeared, without, it must be supposed, having attained to the "civill and regular kinde of life" which was to date from the plantation.

As lately as 1819 a "specimen" was procured in the following way. A party of furriers met three natives—two male, one female—on the frozen Red Indian Lake. It appeared later that one of the males was the husband of the female. The latter was seized; her companions had the assurance to resist, and were both shot. The woman was taken to St. John's, and given the name of May March; next winter she was escorted back to her tribe, but died on the way. These attempts to gain the confidence of the natives were, perhaps, a little brusque, and from this point of view liable to misconstruction by an apprehensive tribe. Ironically enough, the object of the attempt just described was to win a Government reward of £100, offered to any person bringing about a friendly understanding with the Red Indians. Another native woman, Shanandithit, was brought to St. John's in 1823 and lived there till her death in 1829. She is supposed to have been the last survivor. Sir Richard Bonnycastle, who has an interesting chapter on this subject, saw her [20]miniature, which, he says, "without being handsome, shows a pleasing countenance."

Before closing this introductory chapter a few figures may be usefully given for reference to illustrate the present condition of the island.[3] At the end of 1917 the population, including that of Labrador, was 256,500, of whom 81,200 were Roman Catholics and 78,000 members of the Church of England. The estimated public revenue for the year 1917-18 was 5,700,000 dollars; the estimated expenditure was 5,450,000 dollars. In the same year the public debt was about 35,450,000 dollars. The estimated revenue for 1918-19 was 6,500,000 dollars; expenditure, 5,400,000 dollars. In 1898 the imports from the United Kingdom amounted to £466,925, and the exports to the United Kingdom to £524,367. In the year 1917-18 the distribution of trade was mainly as follows: imports from the United Kingdom, 2,248,781 dollars; from Canada, 11,107,642 dollars; from the United States, 12,244,746 dollars; exports to the United Kingdom, 3,822,931 dollars; to Canada, 2,750,990 dollars; to the United States, 7,110,322 dollars. The principal imports in 1916-17 were flour, hardware, textiles, provisions, coal, and machinery; the chief exports were dried cod, [21]pulp and paper, iron and copper ore, cod and seal oil, herrings, sealskins, and tinned lobsters. In 1917 there were 888 miles of railway open, of which 841 were Government-owned; and there are over 4600 miles of telegraph line. The tonnage of vessels entered and cleared at Newfoundland ports in 1916-17 was 2,191,006 tons, of which 1,818,016 tons were British. The number of sailing and steam vessels registered on December 31st, 1917, was 3496.

[1] "A Historical Geography of the British Colonies." Vol. v. Part 4. Newfoundland. (Oxford, 1911.)

[2] Op. cit., p. 192.

[3] In view of the nature and object of the present book, only a few figures can be given here; fuller information can easily be obtained in several of the works referred to herein, and more particularly in the various accessible Year Books.

"If this should be lost," said Sir Walter Raleigh of Newfoundland, "it would be the greatest blow that was ever given to England." The observation was marked by much political insight. Two centuries later, indeed, the countrymen of Raleigh experienced and outlived a shock far more paralyzing than that of which he was considering the possible effects; but when the American colonies were lost the world destiny of England had already been definitely asserted, and the American loyalists were able to resume the allegiance of their birth by merely crossing the Canadian frontier. When Raleigh wrote, Newfoundland was the one outward and visible sign of that Greater England in whose future he was a passionate believer. Therefore, inasmuch as Newfoundland, being the oldest of all the English colonies, stood for the Empire which was to be, the moral effects of its loss in infancy would have been irretrievably grave. How nearly it was lost will appear in the following pages.

Newfoundland, as was fitting for one of the largest islands in the world, and an island, too, [23]drawing strategic importance from its position, was often conspicuous in that titanic struggle between England and France for sea power, and therefore for the mastery of the world, which dwarfs every other feature of the eighteenth century. Nor did she come out of the struggle quite unscathed. Ill-informed or indifferent politicians in the Mother Country neglected to push home the fruits of victory on behalf of the colony which the struggle had convulsed, and the direct consequence of this neglect may be seen in the French fishery claims, which long distracted the occasional leisure of the Colonial Office. Newfoundland has indeed been hardened by centuries of trial. For years its growth was arrested by the interested jealousy of English merchants; and its maturity was vexed by French exactions, against which Canada or Australia would long ago have procured redress. Newfoundland has been the patient Griselda of the Empire, and the story of her triumph over moral and material difficulties—over famine, sword, fire, and internal dissension—fills a striking chapter in the history of British expansion.

That keen zest for geographical discovery, which was one of the most brilliant products of the Renaissance, was slow in making its appearance in England. Nor are the explanations far to seek. The bull (1494) of a notorious Pope (Alexander VI.)—lavish, as befits one who bestows a thing which he cannot enjoy himself, and of [24]which he has no right to dispose—had allocated the shadowy world over the sea to Spain and Portugal, upon a fine bold principle of division; and immediately afterwards these two Powers readjusted their boundaries in the unknown world by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which could not, however, be considered as binding third parties. The line of longitude herein adopted was commonly held to have assigned Newfoundland to Portugal, but the view was incorrect. England was still a Catholic country, and for all its independence of the Pope in matters temporal, the effects of such a bull must have been very considerable. Nor did the personal character of Henry VII. incline him to the path of adventure; and on the few occasions when he was goaded to enterprise, almost in spite of himself, we are able to admire the prudence of a prince who was careful to insert two clauses in his charter of adventure: the first protecting himself against liability for the cost, the second stipulating for a share of the profits. It is to the robust insight of Henry VIII. into the conditions of our national existence that the beginnings of the English Navy are to be ascribed, and it was under this stubborn prince that English trade began to depend upon English bottoms. But the real explanation of Anglo-Saxon backwardness lies somewhat deeper. Foreign adventure and the planting of settlements must proceed, if they are to be successful, from an exuberant [25]State; neither in resources, nor in population, nor, perhaps it must be added, in the spirit of adventure, was the England of King Henry VII. sufficiently equipped. Hence it happened that foreign vessels sailed up the Thames, or anchored by the quays of Bideford in the service of English trade, at a time when the spirit of Prince Henry the Navigator had breathed into the Portuguese service, when Diaz was discovering the Cape, and the tiny vessels of Da Gama were adventuring the immense voyage to Cathay.

It is now clearly established that the earliest adventurers in America were men of Norse stock. More than a thousand years ago Greenland was explored by Vikings from Iceland, and a hundred years later Leif Ericsson discovered a land—Markland, the land of woods—which is plausibly identified with Newfoundland. Still keeping a southern course, the adventurer came to a country where grew vines, and where the climate was strangely mild; it is likely enough that this landfall was in Massachusetts or Virginia. The name Vinland was given to the newly-discovered country. The later voyages of Thorwald Ericsson, of Thorlstein Ericsson—both brothers of Leif—and of Thorfinn Karlsefne, are recounted in the Sagas. The story of these early colonists or "builders," as they called themselves, is weakened by an infusion of fable, such as the tale of the fast-running one-legged people; but with all allowances, the [26]fact of Viking adventure on the American mainland is unquestioned and unquestionable, though we may say of these brave sailors, with Professor Goldwin Smith, that nothing more came of their visit, or in that age could come, than of the visit of a flock of seagulls.

It has been asserted by some writers that Basque navigators discovered the American continent a century before Cabot or Columbus; but evidence in support of such claims is either wanting or unconvincing. "Ingenious and romantic theories," says a critic of these views, "have been propounded concerning discoveries of America by Basque sailors before Columbus. The whale fishery of that period and long afterwards was in the hands of the Basques, and it is asserted that, in following the whales, as they became scarcer, farther and farther out in the western ocean, they came upon the coasts of Newfoundland a hundred years before Columbus and Cabot. No solid foundation can be found for these assertions. The records of the Basque maritime cities contain nothing to confirm them, and these assertions are mixed up with so much that is absurd—such as a statement that the Newfoundland Indians spoke Basque—that the whole hypothesis is incredible."[4]

The question has been much discussed whether [27]Columbus or Cabot in later days rediscovered the American mainland. It does not, perhaps, much matter whether the honour belongs to an Italian employed by Spain or an Italian employed by England; and it is the less necessary to ask whether Cabot explored the mainland before Columbus touched at Paria, that in any event the real credit of the adventure belongs to the great Spanish sailor. It is well known that Columbus thought, as Cabot thought after him, that he was discovering a new and short route to India by the west. Hence was given the name West Indies to the islands which Columbus discovered; hence the company which administered the affairs of Hindostan was distinguished as the East India Company. Hence, too, the spiritual welfare of the Great Khan engaged the attention of both Columbus and Cabot, whereas, in fact, this potentate (if, indeed, he existed) was secluded from their disinterested zeal by a vast continent, and thousands of miles of ocean. These misconceptions were based on a strange underestimate of the circumference of the world, but they add, if possible, to our wonder at the courage of Columbus. Sailing day after day into the unknown, with tiny ships and malcontent crews, he never faltered in his purpose, and never lost faith in his theory. When he landed at Guanahana (Watling's Island) he saw in the Bahamas the Golden Cyclades, and bethought him how he might convey to the Great Khan the letters of his Royal [28]patron. He saw in the west coast of Juana the mainland of Cathay, and in the waters which wash the shores of Cuba he sought patiently, but vainly, for the Golden Chersonese and the storied land of the Ganges.

John Cabot inherited both the truth and the error of Columbus. His career is one of those irritating mysteries which baffle the most patient inquiry. Born at Genoa, and naturalized in 1476 at Venice after fifteen years' residence, he seems to have settled in England eight or nine years before the close of the fifteenth century. Already his life had been an adventurous one. We catch glimpses of him at long intervals: now at Mecca, pushing curious inquiries into the region whence came the spice caravans; now in Spain, under the spell, perhaps, of the novel speculations of Toscanelli and Columbus; now plying his trade as a maker of charts in Bristol or on the Continent. The confusion between John Cabot and his son Sebastian adds to the uncertainty. Those who impute to Sebastian Cabot a cuckoo-like appropriation of his father's glory are able to support their opinion with weighty evidence. The most astounding feature of all is that the main incidents of a voyage which attracted as much attention as the first voyage of John Cabot should so soon have passed into oblivion.

Marking the boundary as clearly as possible between what is certain and what is probable, [29]we find that on March 5th, 1496, Henry VII. granted a charter in the following terms:

"Be it known to all that we have given and granted to our well-beloved John Cabot, citizen of Venice, and to Lewis, Sebastian, and Sanctus, sons of the said John, and to their heirs and deputies ... authority to sail to all parts, countries, and seas of the East, of the West, and of the North, under our banner and ensigns, with five ships, and to set up our banner on any new found land, as our vassals and lieutenants, upon their own proper costs and charges to seek out and discover whatsoever isles ... of the heathen and infidels, which before the time have been unknown to all Christians...."

No sooner was the patent granted than the vigilant Spanish ambassador in London wrote to his master King Ferdinand, that a second Columbus was about to achieve for the English sovereign what Columbus had achieved for the Spanish, but "without prejudice to Spain or Portugal." In reply to this communication Ferdinand directed his informer to warn King Henry that the project was a snare laid by the King of France to divest him from greater and more profitable enterprises, and that in any case the rights of the signatory parties under the Treaty of Tordesillas would thereby be invaded. However, the voyage contemplated in the charter was begun in 1497, in defiance of the Spanish warning and arrogant [30]pretensions. It will be noticed that the charter extends its privileges to the sons of John Cabot. It is better, with Mr Justice Prowse, to see in this circumstance a proof of the prudence of the adventurer, who prolonged the duration of his charter by the inclusion of his infant sons, than to infer in the absence of evidence that any of them was his companion. According to one often quoted authority, Sebastian Cabot claimed in later life not merely to have taken part in the expedition, but to have been its commander,[5] and placed it after his father's death. Against this claim, if it was ever made, we must notice that in the Royal licence for the second voyage the newly found land is said to have been discovered by John Cabotto. It is impossible to say with certainty how many ships took part in Cabot's voyage. An old tradition, depending upon an unreliable manuscript,[6] says that Cabot's own ship was called the Matthew, a vessel of about fifty tons burden, and manned by sixteen Bristol seamen and one Burgundian. It is probable that the voyage began early in May, and it is certain that Cabot was back in England by August 10th, for on that date we find the following entry in the Privy Purse expenses of Henry VII., revealing a particularly stingy [31]recognition of the discoverer's splendid service, which, however, was soon afterwards recognized less unhandsomely:

"1497, Aug. 10th.—To hym that found the New Isle, £10."[7]

The only reliable contemporary authorities on the subject of John Cabot's first voyage are the family letters of Lorenzo Pasqualigo, a Venetian merchant resident in London, to his brother, and the official correspondence of Raimondo di Raimondi, Archpriest of Soncino. The latter's account is somewhat vague. He says, in his letters to Duke Sforza of Milan, August 24th, and December 18th, 1497, that Cabot, "passing Ibernia on the west, and then standing towards the north, began to navigate the eastern ocean, leaving in a few days the north star on the right hand, and having wandered a good deal he came at last to firm land.... This Messor Zoanni Caboto," he proceeds, "has the description of the world in a chart, and also in a solid globe which he has made, and he shows where he landed." Raimondo adds that Cabot discovered two islands, one of which he gave to his barber and the other to a Burgundian friend, who called themselves Counts, whilst the commander assumed the airs of a prince.[8]

[32]We have from the Venetian, Pasqualigo, a letter, dated August 23rd, 1497, which was probably a fortnight or three weeks after the return of Cabot. According to this authority, Cabot discovered land 700 leagues away, the said land being the territory of the Great Khan (the "Gram cham"). He coasted along this land for 300 leagues, and on the homeward voyage sighted two islands, on which, after taking possession of them, he hoisted the Venetian as well as the English flag. "He calls himself the grand admiral, walks abroad in silk attire, and Englishmen run after him like madmen."[9] It is easy to overrate the reliability of such letters as those of Pasqualigo and Raimondo, and Pasqualigo's statement that Cabot sailed from Bristol to this new land, coasted for 300 leagues along it, and returned within a period of three months, is impossible to accept. At the same time, the accounts given by these writers occur, one in the frank intimacy of family correspondence, the other in the official reports of a diplomatic representative to his chief. They are both unquestionably disinterested, and are very much more valuable than the later tittle-tattle of Peter Martyr and Ramusio, which has plainly filtered through what Mr Beazley would call Sebastianized channels.

[35]A keen controversy has raged as to the exact landfall of John Cabot in his 1497 voyage, and it cannot be said that a decisive conclusion has followed. A long tradition (fondly repeated by Mr Justice Prowse) finds the landfall in Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland. It is difficult to say more than that it may have been so; it may too have been in Cape Breton Island, or even some part of the coast of Labrador. In any case, whether or not Cabot found his landfall in Newfoundland, he must have sighted it in the course of his voyage. It may be mentioned here by way of caution that the name Newfoundland was specialized in later times so as to apply to the island alone, and that it was at first used indifferently to describe all the territories discovered by Cabot.

As no true citizen of Newfoundland will surrender the belief that Cape Bonavista was in fact the landfall of Cabot, it seems proper to insert in the story of the island, for what they are worth, the nearest contemporary accounts of Cabot's voyage. They are more fully collected in Mr Beazley's monograph,[10] to which I am indebted for the translations which follow. The first account is contained, as has already been pointed out, in a letter written by Raimondo di Raimondi to the Duke of Milan:

"Most illustrious and excellent my Lord,—Perhaps among your Excellency's many [36]occupations, you may not be displeased to learn how His Majesty here has won a part of Asia without a stroke of the sword. There is in this kingdom a Venetian fellow, Master John Cabot by name, of a fine mind, greatly skilled in navigation, who, seeing that those most serene kings, first he of Portugal, and then the one of Spain, have occupied unknown islands, determined to make a like acquisition for His Majesty aforesaid. And having obtained Royal grants that he should have the usufruct of all that he should discover, provided that the ownership of the same is reserved to the Crown, with a small ship and eighteen persons he committed himself to fortune. And having set out from Bristol, a western port of this kingdom, and passed the western limits of Hibernia, and then standing to the northward, he began to steer eastwards [meaning westwards], leaving, after a few days, the North Star on his right hand. And having wandered about considerably, at last he fell in with terra firma, where, having planted the Royal banner and taken possession in the behalf of this King; and having taken several tokens, he has returned thence. The said Master John, as being foreign-born and poor, would not be believed, if his comrades, who are almost all Englishmen and from Bristol, did not testify that what he says is true.

"This Master John has the description of the world in a chart, and also in a solid globe which [37]he has made, and he [or it] shows where he landed, and that going toward the east [again for west] he passed considerably beyond the country of the Tansis. And they say that it is a very good and temperate country, and they think that Brazil wood and silks grow there; and they affirm that that sea is covered with fishes, which are caught not only with the net but with baskets, a stone being tied to them in order that the baskets may sink in the water. And this I heard the said Master John relate, and the aforesaid Englishmen, his comrades, say that they will bring so many fish, that this kingdom will no longer have need of Iceland, from which country there comes a very great store of fish called stock-fish ('stockfissi'). But Master John has set his mind on something greater; for he expects to go further on towards the east [again for west] from that place already occupied, constantly hugging the shore, until he shall be over against [or on the other side of] an island, by him called Cimpango, situated in the equinoctial region, where he thinks all the spices of the world and also the precious stones originate. And he says that in former times he was at Mecca, whither spices are brought by caravans from distant countries, and these [caravans] again say that they are brought to them from other remote regions. And he argues thus—that if the Orientals affirmed to the Southerners that these things come from a distance from them, and so from hand to hand, [38]presupposing the rotundity of the earth, it must be that the last ones get them at the north, toward the west. And he said it in such a way that, having nothing to gain or lose by it, I too believe it; and, what is more, the King here, who is wise and not lavish, likewise puts some faith in him; for, since his return he has made good provision for him, as the same Master John tells me. And it is said that in the spring His Majesty aforenamed will fit out some ships and will besides give him all the convicts, and they will go to that country to make a colony, by means of which they hope to establish in London a greater storehouse of spices than there is in Alexandria, and the chief men of the enterprise are of Bristol, great sailors, who, now that they know where to go, say that it is not a voyage of more than fifteen days, nor do they ever have storms after they get away from Hibernia. I have also talked with a Burgundian, a comrade of Master John's, who confirms everything, and wishes to return thither because the Admiral (for so Master John already entitles himself) has given him an island; and he has given another one to a barber of his from Castiglione, of Genoa, and both of them regard themselves as Counts, nor does my Lord the Admiral esteem himself anything less than a prince. I think that with this expedition will go several poor Italian monks, who have all been promised bishoprics. And as I have become a friend of the Admiral's, if I wished to [39]go thither, I should get an Archbishopric. But I have thought that the benefices which your Excellency has in store for me are a surer thing."

To those who, in the teeth of contemporary evidence, prefer the claims of Sebastian, the following extracts may be offered; the first from Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, who wrote in the early sixteenth century, the second from Ramusio. Martyr writes:

"These north seas have been searched by one Sebastian Cabot, a Venetian born, whom, being yet but in matter an infant, his parents carried with them into England, having occasion to resort thither for trade of merchandises, as is the manner of the Venetians to leave no part of the world unsearched to obtain riches. He therefore furnished two ships in England at his own charges; and, first, with 300 men, directed his course so far towards the North Pole, that even in the month of July he found monstrous heaps of ice swimming in the sea, and in manner continual daylight, yet saw he the land in that tract free from ice, which had been molten by heat of the sun. Thus, seeing such heaps of ice before him, he was enforced to turn his sails and follow the west, so coasting still by the shore he was thereby brought so far into the south, by reason of the land bending so much southward, that it was there almost equal in latitude with the sea called Fretum Herculeum [Straits of Gibraltar], having [40]the North Pole elevate in manner in the same degree. He sailed likewise in this tract so far toward the west that he had the Island of Cuba [on] his left hand in manner in the same degree of longitude. As he travelled by the coasts of this great land, which he named Baccallaos [cod-fish country], he saith that he found the like course of the water towards the west [i.e. as before described by Martyr], but the same to run more softly and gently than the swift waters which the Spaniards found in their navigation southward.... Sebastian Cabot himself named those lands Baccallaos, because that in the seas thereabout he found so great multitudes of certain big fish much like unto tunnies (which the inhabitants called Baccallaos) that they sometimes stayed his ships. He found also the people of those regions covered with beasts' skins, yet not without the use of reason. He saith also that there is great plenty of bears in those regions, which used to eat fish. For, plunging themselves into the water where they perceive a multitude of those fish to lie, they fasten their claws in their scales, and so draw them to land and eat them. So that, as he saith, the bears being thus satisfied with fish, are not noisome to men."

Ramusio represents Sebastian Cabot as making the following statement:

"When my father departed from Venice many years since to dwell in England, to follow the trade of merchandises, he took me with him to [41]the city of London while I was very young, yet having nevertheless some knowledge of letters, of humanity, and of the sphere. And when my father died, in that time when news were brought that Don Christopher Colombus, the Genoese, had discovered the coasts of India, whereof was great talk in all the Court of King Henry the Seventh, who then reigned; in so much that all men, with great admiration, affirmed it to be a thing more divine than human to sail by the west into the east, where spices grow, by a way that was never known before; by which fame and report there increased in my heart a great flame of desire to attempt some notable thing. And understanding by reason of the sphere that if I should sail by way of the north-west wind I should by a shorter track come to India, I thereupon caused the King to be advertised of my device, who immediately commanded two caravels to be furnished with all things appertaining to the voyage, which was, as far as I remember, in the year 1496 in the beginning of summer. Beginning therefore to sail toward north-west, nor thinking to find any other land than that of Cathay, and from thence to turn towards India, after certain days I found that the land ran toward the north, which was to me a great displeasure. Nevertheless, sailing along by the coast to see if I could find any gulf that turned, I found the land still continent to the 56th degree under our Pole. And seeing [42]that there the coast turned toward the east, despairing to find the passage, I turned back again and sailed down by the coast of that land toward the equinoctial (ever with intent to find the said passage to India) and came to that part of this firm land which is now called Florida; where, my victuals failing, I departed from thence and returned into England, where I found great tumults among the people and preparation for the war to be carried into Scotland; by reason whereof there was no more consideration had to this voyage."[11]

The discoveries of Cabot were appreciated by Henry VII., a prince who rarely indulged in unprovoked benefactions, for on December 13th, 1497, we find a grant of an annual pension to Cabot of £20 a year, worth between £200 and £300 in modern money (a pension that was drawn twice):

"We let you wit that we for certain considerations as specially moving, have given and granted unto our well-beloved John Cabot, of the parts of Venice, an annuity or annual rent of £20 sterling."[12] It is material to notice that Sebastian, so considerable a figure in the later accounts, is not mentioned in this grant. So it has been observed [43]that John Cabot is mentioned alone in the charter for the second voyage; the authority is given explicitly to "our well-beloved John Kabotto, Venetian." Apparently the second voyage was begun in May, 1498, but a cloud of obscurity besets the attempt to determine its results. It is noted in the Records under 1498 that Sebastian Gaboto, "a Genoa's son," obtained from the King a vessel "to search for an island which he knew to be replenished with rich commodities." It is likely enough that Sebastian Cabot took part in this voyage, as indeed he may have done in the earlier one; but it is clear that John Sebastian was present in person, for Raimondo describes an interview in which John unfolds his scheme for proceeding from China (which he imagined himself to have discovered) to Japan.

This brief account of the Cabots, so far as their voyages relate particularly to Newfoundland, may be closed by some further citations from the Privy Purse expenses of Henry VII.:

"1498, March 24th.—To Lanslot Thirkill of London, upon a prest for his shipp going towards the New Ilande, £20.

"April 1st.—To Thomas Bradley and Lanslot Thirkill, going to the New Isle, £30.

"1503, Sept. 30th.—To the merchants of Bristoll that have been in the Newfounde Lande, £20.

"1504, Oct. 17th.—To one that brought hawkes from the Newfounded Island, £1.

[44]"1505. Aug. 25th.—To Clays goying to Richemount, with wylde catts and popynjays of the Newfound Island, for his costs 13s. 4d."[13]

[4] Stanford's "Compendium of Geography and Travel" (New Issue). North America, vol. i. Canada and Newfoundland. Edited by H.M. Ami (London, 1915), p. 1007.

[5] See the excellent contribution of Mr Raymond Beazley to the "Builders of Greater Britain" Series—"John and Sebastian Cabot."

[6] The Fust MSS., Mill Court, Gloucestershire.

[7] S. Bentley, "Excerpts Historica" (1831), p. 113.

[8] These letters, together with other relative documents, are given in the publication of the Italian Columbian Royal Commission: "Reale Commissione Colombiana: Raccolta di Documenti e Studi" (Rome, 1893), Part 3, vol. i., pp. 196-198.

[9] "Reale Commissione Colombiana: Raccolta di Documenti e Studi" (Rome, 1893), Part 3, vol. ii., p. 109: "Calendar of State Papers," Venetian Series, vol. i., p. 262.

[10] The more authoritative Italian source has already been indicated.

[11] The testimony of both Peter Martyr and Ramusio, and of others, like Gomara and Fabyan, who support the claims of Sebastian as against John Cabot, does not now find favour; cf. Rogers, op. cit., p. 14.

[12] Custom's Roll of the Port of Bristol, 1496-9, edited by E. Scott, A.E. Hudd, etc. (1897).

[13] See Hakluyt Society Publications (1850), vol. vii., p. lxii. Bentley, op. cit., pp. 126, 129, 131.

The motives and projects of the early English colonizers are thus aptly described by a recent writer already referred to:[14] "The colonizers were actuated by three different kinds of definite ideas, and definite colonization was threefold in its character. In the first place, there were men who were saturated in the old illusions and ideas, and intended colonization as a means to an end, the end being the gold and silver and spices of Asia. Secondly, there were fishermen, who went to Newfoundland for its own sake, in order to catch fish for the European market, who were without illusions or ideas or any wish to settle, and who belonged to many nations, and thwarted but also paved the way for more serious colonizers. Thirdly, there were idealists who wished to colonize for colonization's sake and to make England great; but in order to make England great they thought it necessary to humble Spain in the dust, and their ideas were destructive as well as creative. All [46]these colonizers had their special projects, and each project, being inspired by imperfect ideals, failed more or less, or changed its character from time to time. The first and third projects were at one time guided by the same hand; but the first project gradually cast off its colonizing slough, and resolved itself once more into discovery for discovery's sake; and the third project ceased to be a plan of campaign, and resolved itself into sober and peaceful schemes for settling in the land. Even the second project, which was unled, uninspired, unnational, and almost unconscious, and which began and continued as though in obedience to some irresistible and unchangeable natural and economic law, assumed different shapes and semblances, as it blended or refused to blend with the patriotic projects of the idealists. These three types of colonization..., though they tended on different directions, ... were hardly distinguishable in the earlier phases of their history. Perhaps a fourth type should be added, but this fourth type was what naturalists call an aberrant type, and only comprised two colonizers, Rut and Hore, whose aims were indistinct, and who had no clear idea where they meant to go, or what they meant to do when they got there."

After the first discovery of Newfoundland and the adjoining coast, English official interest in the island declined, and English traders were occupied for the time being with their intercourse with [47]Iceland, whence they obtained all the codfish they had need of. The new field of exploration and enterprise was thus left for some twenty years to others. At the beginning of the sixteenth century Gaspar Cortereal, a brave Portuguese sailor, having obtained a commission from the King of Portugal, made two voyages (in 1500 and 1501) with the object of discovering a north-west passage to Asia, explored the coasts of Greenland, Labrador, and Newfoundland, and finally lost his life on the coast of Labrador (1501).[15] On the ground of these discoveries, reinforced by the title conferred by the bull of Alexander VI., the Portuguese asserted their claim to Newfoundland. Henceforward Portuguese fishermen began to share the dangers and profits of the cod fishery with the hardy folk of Normandy and Brittany, and with Spaniards and Basques, who had followed fast in the footsteps of the earliest discoverers. Hence we find that many names of places and the east coast of the island are corruptions of Portuguese words, whilst names on the south coast show a French or a Basque origin.[16]

[48]In a sense it is true that Newfoundland has owed everything to its fisheries, but it is unfortunately also true that a sharp dissidence between the interests of alien fisheries and the policy of local development did much to retard the days of permanent settlement. That the more southern races of Europe took a large part in the development of the fisheries was only natural, inasmuch as the principal markets for the dried and salted codfish were in the Catholic countries of Europe. Continuously from the beginning of the sixteenth century the opening of each season brought vessels of many nationalities to a harvest which sufficed for all. We cannot say that at this time any primacy was claimed for English vessels, but there is no reason to doubt that Englishmen soon played a conspicuous part in opening up the trade. By the time of Henry VIII. the Newfoundland industry was sufficiently well known to be included with the Scotch and Irish Fisheries in an exception clause to a statute which forbade the importation of foreign fish.

This statute is sufficiently noteworthy as an economic curiosity to be set forth in extenso.

"Act 33 Henry VIII., c. xi.

"The Bill conceryning bying of fisshe upon the see.

"Whereas many and dyvers townes and portes by the see side have in tymes past bene in great [49]welthe and prosperitie well buylded by using and exercysing the crafts and feate of fisshing by the whiche practise it was not onelie great strengthe to this Realme by reason of bringing up and encreasing of Maryners whensoever the King's Grace had neede of them but also a great welthe to the Realme and habundance of suche wherebie oure sovereigne Lorde the King the Lords Gentilmen and Comons were alwais well served of fisshe in Market townes of a reasonable price and also by reason of the same fisshing many men were made and grewe riche and many poure Men and women had therebie there convenyent lyving—to the strengthe encreasing and welthe of this realme.

"And whereas many and dyvers of the saide fissherman for their singular lucre and advantage doe leve the said crafte of fisshing and be confederate w Pycardes Flemynghes Norman and Frenche-men and sometyme sayle over into the costes of Pycardie and Flaunders and sometyme doo meete the said Pycardes and Flemynghes half the see over.

"Penalty on subjects bying fishe in Flaunders &c., or at sea to be sold in England, £10.

"And be it furder enacted by the auctoritie aforesaide that it shall be lawful to all and every fissher estraunger to come and to sell.

"Provided furthermore that this Act or any thing therein conteyned shall not extende to any person whiche shall bye eny fisshe in any parties of Iseland, [50]Scotlands, Orkeney, Shotlande, Ireland, or Newland [Newfoundland]."

The caution, however, suggested above must be borne in mind in noticing the earliest mention of Newfoundland; the name was indiscriminately applied to the island itself and to the neighbouring coasts, so that it is for some time impossible to be sure whether it is employed in the wide or narrow sense. It is certain, however, that the island was becoming well known. Its position as the nearest point to Europe made it familiar to the band of Northerly explorers. Verrazzano, a Florentine, in the service of France, determined to discover a western way to Cathay, sailed along America northward from North Carolina, and placed the French flag on the territory lying between New Spain and Newfoundland, which newly acquired territory was thenceforth designated Norumbega or New France. All such original annexations, whether pretended or real, were in the circumstances extremely ill-defined; and maps of the time were frequently vague, confusing, and contradictory. Cartier, on his way to sow the seeds of a French Empire in North America, sailed past the coast (1534), and on his second voyage (1535) foregathered with Roberval in the roadstead of St. John's. Still earlier, in 1527, a voyage was made to the island by John Rut, with the countenance of Henry VIII. and encouragement of Cardinal [51]Wolsey, but the authorities for this voyage are late and unreliable. Purchas reproduces a valuable letter from John Rut (who was a better sailor than scholar) to the King, from which it appears that he found in the harbour of St. John's "eleven saile of Normans and one Brittaine, and two Portugall barks, and all a fishing," as well as two English trade-ships.[17]

The later adventure—"voyage of discovery"—of Master Hore, in 1536, which was undertaken "by the King's favour," is inimitably told by Hakluyt. His co-adventurers are described as "many gentlemen of the Inns of Court and of the Chancerie"; there were also a number of east-country merchants. After missing their proper course, and almost starving, they were succoured by a French vessel off the coast of Newfoundland. The gentlemen of the long robe had been out of their element up to this encounter, but Judge Prowse notes with proper professional pride the tribute of Hakluyt: "Such was the policie of the English that they became masters of [the French ship], and changing ships and vittailing them, they set sail to come into England." The extremities to which these adventurers were reduced before their relief is horribly illustrated by the narrative of Hakluyt:

"Whilst they lay there they were in great want of provision and they found small relief, [52]more than that they had from the nest of an osprey (or eagle) that brought hourly to her young great plenty of divers sorts of fishes. But such was the famine amongst them that they were forced to eat raw herbs and roots, which they sought for in the maine. But the relief of herbs being not sufficient to satisfie their craving appetites, when in the deserts in search of herbage, the fellow killed his mate while hee stouped to take up a root, and cutting out pieces of his body whom he had murthered, broyled the same on the coals and greedily devoured them. By this means the company decreased and the officers knew not what was become of them."[18]

For many years we must be content with the knowledge that the fishing resources of Newfoundland were growing in reputation and popularity. Now and then the curtain is lifted, and we catch a glimpse of life on the island. Thus Anthony Parkhurst, a Bristol merchant, who had made the voyage himself four times, notes in 1578, in a letter written to Hakluyt containing a report of the true state and commodities of Newfoundland, that "there were generally more than 100 sail of Spaniards taking cod, and from 20 to 30 killing whales; 50 sail of Portuguese; 150 sail of French and Bretons ... but of English only 50 sail. Nevertheless, the English are commonly lords of the harbours where they fish, and use all strangers' [53]help in fishing, if need require, according to an old custom of the country."[19]

Clearer still is our information when the ill-fated Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the half-brother of Raleigh, visited the island in 1583. Already in 1574 Gilbert, together with Sir Richard Grenville, Sir George Peckham and Christopher Carleill, applied for a patent with a view to colonizing "the northern parts of America"; but, though a sum of money was raised in Bristol for this object, the scheme fell through. Gilbert's perseverance, however, was by no means checked. For in 1577 he submitted a project to Lord Burleigh, asking for authority to discover and colonize strange lands, and incidentally to seize Spanish prizes and establish English supremacy over the seas. The following year he received a patent to discover, colonize, fortify, own and rule territories not in the possession of friendly Christian Powers—subject to the prerogation of the Crown and the claims of the Crown to a fifth part of the gold and silver obtained. His settlements were to be made within a period of six years. Having obtained the support of such men as Sir George Peckham, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Philip Sidney, Richard Hakluyt, Thomas Aldworth, as well as of Sir Francis Walsingham, the anti-Spanish minister, and of Bristol merchants,[20] Gilbert set sail on June 11th, 1583, [54]from Plymouth with five vessels—the Raleigh (200 tons) which was equipped by Sir W. Raleigh, acting as vice-admiral, the Delight (120 tons) on which was Gilbert, as admiral, the Swallow (40 tons) the Golden Hind (40 tons), and the Squirrel (10 tons). Two days later the Raleigh returned on the ground, it seems, that her captain and many of her men had fallen sick. The entire crew consisted of 260 men, including shipwrights, masons, carpenters, smiths, miners, and refiners. They took with them a good variety of music "for solace of our people, and allurement of the savages"; a number of toys, "as morris dancers, hobby horsse, and many like conceits to delight the savage people, whom we intended to winne by all faire meanes possible"; and also a stock of haberdashery wares for the purpose of barter. Gilbert reached St. John's on August 3rd, 1583, with his four vessels, and found in the harbour twenty Spanish and Portuguese ships and sixteen English ships. The latter made ready to give battle to the newcomers; but as soon as the English vessels were informed of the mission, "they caused to be discharged all the great ordnance of their fleet in welcome," and soon afterwards entertained their guests at their "summer garden." The great importance of the errand was recognized, for it had no less an object than to take possession of the island in the name of Queen Elizabeth, by virtue of Cabot's discoveries, and the later acts of [55]occupation. Even then the small town of St. John's was not without pretension to the amenities of social life. One, Edward Haie (or Hayes), who was present—indeed he was the captain and owner of the Golden Hind—and who has left us an account of the expedition,[21] speaks of it as a populous and frequented place. According to the same account, possession was taken of the territory on August 5th: "Munday following, the General had his tent set up, who being accompanied with his own followers, sommoned the marchants and masters, both English and strangers to be present at his taking possession of those countries. Before whom openly was read and interpreted unto the strangers of his commission: by vertue whereof he tooke possession in the same harbour of S. John, and 200 leagues every way, invested the Queenes Majestie with the tith and dignitie thereof, had delivered unto him (after the custome of England) a rod and a turffe of the same soile, entring [56]possession also for him, his heires and assignes for ever: and signified unto al men, that from that time forward, they should take the same land as a territorie appertaining to the Queene of England, and himself authorized under her majestie to possesse and enjoy it. And to ordaine lawes for the government thereof, agreeable (so neere as conveniently might be) unto the lawes of England: under which all people comming thither hereafter, either to inhabite, or by way of traffique, should be subjected and governed." Gilbert's authority was not seriously questioned; by virtue of his commission he "ordained and established three lawes to begin with." They are given by Hayes as follows:

1. Establishment of the Church of England.

2. Any attempt prejudicial to Her Majesty's rights in the territory to be punished as in a case of High Treason.

3. Anyone uttering words of dishonour to Her Majesty should lose his ears and have his goods and ship confiscated.

"To be brief," concludes the same authority, "Gilbert dyd lette, sette, give, and dispose of many things as absolute Governor there by virtue of Her Majesty's letter patent."

The passage in which Captain Hayes describes the Newfoundland of his day must be of such [57]interest to its present inhabitants that it is worth while to set it out in full:

"That which we doe call the Newfoundland, and the Frenchmen Bacalaos, is an island, or rather (after the opinion of some) it consisteth of sundry islands and broken lands, situate in the north regions of America, upon the gulph and entrance of the great river called S. Laurence in Canada. Into the which navigation may be made both on the south and north side of this island. The land lyeth south and north, containing in length betweene three and 400 miles, accounting from Cape Race (which is in 46 degrees 25 minuts) unto the Grand Bay in 52 degrees of septentrionall latitude. The iland round about hath very many goodly bayes and harbors, safe roads for ships, the like not to be found in any part of the knowen world.

"The common opinion that is had of intemperature and extreme cold that should be in this countrey, as of some part it may be verified, namely the north, where I grant it is more colde than in countries of Europe, which are under the same elevation: even so it cannot stand with reason and nature of the clime that the south parts should be so intemperate as the bruit hath gone. For as the same doe lie under the climats of Briton, Aniou, Poictou, in France, between 46 and 49 degrees, so can they not so much differ from the temperature of those countries: unless upon the [58]out coasts lying open unto the ocean and sharpe winds, it must in neede be subject to more colde, then further within the lande, where the mountaines are interposed, as walles and bulwarkes, to defende and to resiste the asperitie and rigor of the sea and weather. Some hold opinion, that the Newfoundland might be the more subject to cold, by how much it lyeth high and neere unto the middle region. I grant that not in Newfoundland alone, but in Germany, Italy, and Afrike, even under the Equinoctiall line, the mountaines are extreme cold, and seeldome uncovred of snow, in their culme and highest tops, which commeth to passe by the same reason that they are extended towards the middle region: yet in the countries lying beneth them, it is found quite contrary. Even so all hils having their discents, the valleis also and low grounds must be likewise hot or temperate, as the clime doeth give in Newfoundland, though I am of opinion that the sunnes reflection is much cooled, and cannot be so forcible in the Newfoundland nor generally throughout America, as in Europe or Afrike: by how much the sunne in his diurnall course from east to west passeth over (for the most part) dry land and sandy countries, before he arriveth at the West of Europe or Afrike, whereby his motion increaseth heate, with little or no qualification by moyst vapours, where on the contraire, he passeth from Europe and Africa unto America over the ocean, from whence it draweth [59]and carrieth with him abundance of moyst vapours, which doe qualifie and infeeble greatly the sunne's reverberation upon this countrey chiefly of Newfoundland, being so much to the northward. Neverthelesse (as I sayd before) the cold cannot be so intollerable under the latitude of 46, 47, and 48, especiall within land, that it should be unhabitable, as some doe suppose, seeing also there are very many people more to the north by a great deale. And in these south partes there be certain beastes, ounces or leopards, and birdes in like manner which in the sommer we have seene, not heard of in countries of extreme and vehement coldnesse. Besides, as in the monethes of June, July, August, and September, the heate is somewhat more than in England at those seasons: so men remaining upon the south parts neere unto Cape Rece, until after Hollandtide, have not found the cold so extreme, nor much differing from the temperature of England. Those which have arrived there after November and December have found the snow exceeding deepe, whereat no marvaile, considering the ground upon the coast is rough and uneven, and the snow is driven into the places most declyning, as the like is to be seen with us. The like depth of snow happily shall not be found within land upon the playner countries, which also are defended by the mountaines, breaking off the violence of the winds and weather. But admitting extraordinary cold in these south [60]parts, above that with us here: it cannot be so great as that in Swedland, much less in Muscovia or Russia; yet are the same countries very populous, and the rigor of cold is dispensed with by the commoditie of stoves, warme clothing, meats and drinkes; all which neede not to be wanting in the Newfoundland, if we had intent there to inhabite.

"In the south parts we found no inhabitants, which by all likelihood have abandoned those coastes, the same being so much frequented by Christians: but in the north are savages altogether harmlesse. Touching the commodities of this countrie, serving either for sustentation of inhabitants, or for maintenance of traffique, there are and may be made; so and it seemeth Nature hath recompensed that only defect and incommoditie of some sharpe cold, by many benefits: viz., with incredible quantitie and no less varietie of kindes of fish in the sea and fresh waters, as trouts, salmons, and other fish to us unknowen: also cod, which alone draweth many nations thither, and is become the most famous fishing of the world. Abundance of whales, for which also is a very great trade in the bayes of Placentia, and the Grand Bay, where is made trane oiles of the whale. Herring, the largest that have been heard of, and exceeding the alstrond herring of Norway: but hitherto was never benefit taken of the herring fishery. There are sundry other fish very delicate, [61]namely the bonits, lobsters, turbut, with others infinite not sought after: oysters having pearle but not orient in colour: I took it by reason they were not gathered in season.

"Concerning the inland commodities as wel to be drawen from this land, as from the exceeding large countries adioyning; there is nothing which our east and northerly countries doe yeelde, but the like also may be made in them as plentifully by time and industrie: namely, rosen, pitch, tarre, sope, ashes, deel boord, mastes for ships, hides, furres, flaxe, hempe, corne, cables, cordage, linnen-cloth, mettals, and many more. All which the countries will aford, and the soyle is apt to yeelde.

"The trees for the most in those south parts, are firre trees, pine and cypresse, all yielding gumme and turpentine. Cherrie trees bearing fruit no bigger than a small pease. Also peare trees, but fruitlesse. Other trees of some sorts to us unknowen.

"The soyle along the coast is not deepe of earth, bringing foorth abundantly peason, small, yet good feeding for cattel. Roses, passing sweet, like unto our mucke roses in forme, raspases, a berry which we call harts, good and holesome to eat. The grasse and herbe doth fat sheepe in very short space, proved by English marchants which have caried sheepe thither for fresh victuall, and had them raised exceeding fat in lesse than three weekes. Peason which our countrey-men have [62]sowen in the time of May, have come up faire, and bene gathered in the beginning of August, of which our generall had a present acceptable for the rarenesse, being the first fruits coming up by art and industrie, in that desolate and dishabited land.

"We could not observe the hundredth part of these creatures in those unhabited lands: but these mentioned may induce us to glorifie the magnificent God, who hath superabundantly replenished the earth with creatures serving for the use of man, though man hath not used the fift part of the same, which the more doth aggravate the fault and foolish slouth in many of our nation, chusing rather to live indirectly, and very miserably to live and die within this realme pestered with inhabitants, then to adventure as becommeth men, to obtaine an habitation in those remote lands, in which Nature very prodigally doth minister unto mens endeavours, and for art to worke upon."

The story of Gilbert's disastrous expedition and voyage home is well known; how some of his men sailed off in a stolen vessel, some ran away into the woods, and others falling sick were sent home in the Swallow; how he set sail on August 20th (that is, after a stay on the island of only a fortnight) with his three remaining vessels, overloaded and under-manned as they were; how his vessels, after the wreck of the Delight off Sabre Island, were reduced to the Golden Hind and the Squirrel; [63]how in a prodigious hurricane he refused to transfer himself from the tiny Squirrel to the larger vessel; and how he died encouraging his ill-fated company—"We are as near heaven by sea as by land." Though the expedition ended in disaster, and the intention to found a settlement failed utterly, the bold enterprise could not but exert a salutary influence on the hearts and souls of other adventurers and promotors of colonization. As has been well said:[22] "a halo of real enthusiasm illumines this foolish founder of the greatest colonial empire in the world, and where a hero leads, even though it be to ruin, others are apt to follow with enthusiasm, for tragedies such as these attract by their dignity more than they deter." More particularly, Gilbert's voyage is of great interest, because we may reasonably associate him with the colonial ideas of his greater half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh. The slow and difficult process was beginning which was to make Newfoundland a permanent settlement instead of the occasional resort of migratory fishermen.

[14] Rogers, op. cit., pp. 18-19.

[15] The name Labrador is derived from the Portuguese word "llavrador," which means a yeoman farmer. The name was at first given to Greenland, and was afterwards transferred to the peninsula on the assumption that it was part of the same territory as Greenland. The origin of the name itself is due to the fact that the first announcement of having seen Greenland was a farmer ("llavrador") from the Azores.

[16] Compare such names of places as Frenchman's Arm, Harbour Breton, Cape Breton, Spaniard's Bay, Biscay Bay, Portugal Cove, Cape Race, Port-aux-Basques, etc.

[17] Cf. Purchas, "Pilgrims," vol. xiv. pp. 304-5.

[18] Hakluyt, "Principal Navigations," vol. viii. p. 3.

[19] Hakluyt, op. cit., vol. iii.

[20] Cf. J. Latimer, "History of the Society of Merchant Venturers of Bristol" (1903).

[21] "A report of the voyage and successe thereof, attempted in the yeere of our Lord 1583 by Sir Humfrey Gilbert Knight, with other gentlemen assisting him in that action, intended to discover and to plant Christian inhabitants in place convenient, upon those large and ample countreys extended Northward from the cape of Florida, lying under very temperate climes, esteemed fertile and rich in minerals, yet not in the actuall possession of any Christian prince, written by M. Edward Haie gentleman, and principall actour in the same voyage, who alone continued unto the end, and by God's speciall assistance returned home with his retinue safe and entire." See Hakluyt (ed. 1904), vol. viii. pp. 34 seq.

[22] Rogers, op. cit., p. 40.

We have seen that many nations shared in the profits of the Newfoundland trade, but the English and French soon distanced all other competitors. The explanation lies in the conflicting interests which these two great and diffusive Powers were gradually establishing on the American mainland. It is worth while anticipating a little in order to gain some landmarks. In 1609 the colonization of Virginia began in earnest; a few years later sailed the Pilgrim Fathers in the Mayflower, to found New England. In 1632 Lord Baltimore founded Maryland, to be a refuge for English Roman Catholics. Meanwhile, France had not been idle in the great northern continent. The intrepid Champlain trod boldly in the perilous footsteps of Cartier, and Port Royal was founded in 1604, Quebec in 1608. Later still came the splendid adventure of La Salle, who forced his way—a seventeenth century Marchand—from the sources of the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico, thus threatening to cut off the English settlers from [65]expansion to the west. A glance at the map will reveal the immense strategic importance of Newfoundland to two Powers with the possessions and claims indicated above. No doubt a consciousness of deeper differences underlay the keenness of commercial rivalry.