Title: Aliens or Americans?

Author: Howard B. Grose

Release date: September 7, 2006 [eBook #19198]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Dave Kline, Janet Blenkinship and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

NEW YORK: EATON & MAINS

CINCINNATI: JENNINGS & GRAHAM

Copyright, 1906, by

Young People's Missionary Movement

New

York

| Wide open and unguarded stand our gates, |

| And through them presses a wild, motley throng— |

| Men from the Volga and the Tartar steppes, |

| Featureless figures of the Hoang-Ho, |

| Malayan, Scythian, Teuton, Celt, and Slav, |

| Flying the old world's poverty and scorn; |

| These bringing with them unknown gods and rites, |

| Those, tiger passions, here to stretch their claws. |

| In street and alley what strange tongues are these, |

| Accents of menace alien to our air, |

| Voices that once the Tower of Babel knew! |

| O Liberty, White Goddess! is it well |

| To leave the gates unguarded? On thy breast |

| Fold Sorrow's children, soothe the hurts of fate, |

| Lift the downtrodden, but with the hand of steel |

| Stay those who to thy sacred portals come |

| To waste the gifts of freedom. Have a care |

| Lest from thy brow the clustered stars be torn |

| And trampled in the dust. For so of old |

| The thronging Goth and Vandal trampled Rome. |

| And where the temples of the Cæsars stood |

| The lean wolf unmolested made her lair. |

—Thomas Bailey Aldrich.

| Preface | 9 | |

| Introduction, by Josiah Strong | 13 | |

| I. | The Alien Advance | 15 |

| II. | Alien Admission and Restriction | 51 |

| III. | Problems of Legislation and Distribution | 87 |

| IV. | The New Immigration | 121 |

| V. | The Eastern Invasion | 157 |

| VI. | The Foreign Peril of the City | 193 |

| VII. | Immigration and the National Character | 231 |

| VIII. | The Home Mission Opportunity | 267 |

| APPENDIXES | ||

|---|---|---|

| A. | Tables of Immigrants Admitted and Debarred | 305 |

| B. | The Immigration Laws | 309 |

| C. | Work of Leading Denominations for the Foreign Population | 314 |

| D. | Bibliography | 321 |

| INDEX | 326 | |

| Coming Americans | Frontispiece |

| The Inflowing Tide | 18 |

| Ellis Island Immigration Station | 34 |

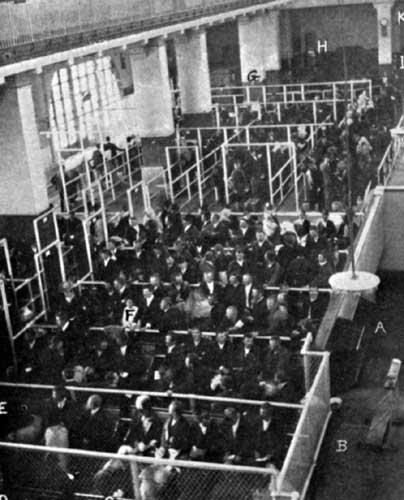

| Receiving Room at Ellis Island | 59 |

| Detained for Special Examination | 74 |

| An Appeal from the Special Inquiry Board to Commissioner Watchorn | 94 |

| The Landing at the Battery in New York | 102 |

| A German Family | 128 |

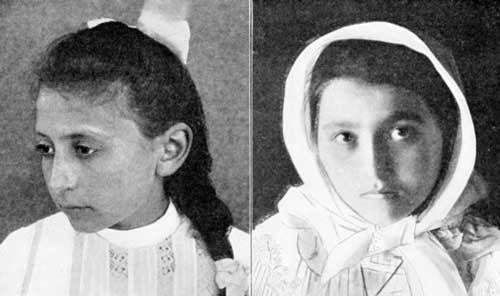

| Italian and Swiss Girls | 144 |

| A Group of Twelve Different Nationalities | 166 |

| Three Types of Immigrants | 180 |

| A Group of Immigrants Just Arrived at Ellis Island | 198 |

| An Italian Family Crowded in a New York Tenement | 210 |

| Four Nationalities | 236 |

| Portuguese and Spanish Children | 256 |

| An Italian Sunday School in New England | 283 |

| Sketch Maps and Charts | |

|---|---|

| Immigration at the Port of New York for 1906 | 32 |

| Immigrant Distribution by States for 1905 | 106 |

| Immigrant Distribution by Races: | |

| Scandinavian | 108 |

| Canadian and British | 109 |

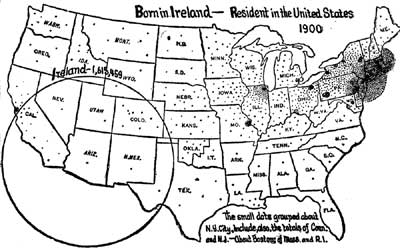

| Irish | 114 |

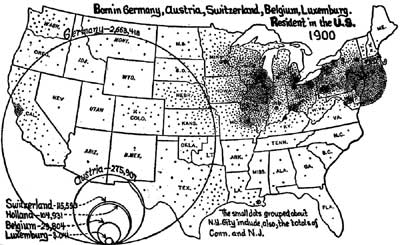

| Germanic | 115 |

| French and Iberic | 146 |

| Slavic | 171 |

| Changes in Sources of Immigration Causing Increase of Illiteracy | 125 |

| Countries from which the Slavs Come | 161 |

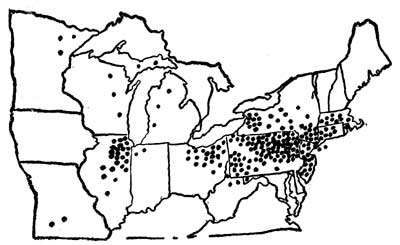

| Distribution of Slavs in the United States | 163 |

| Wave of Immigration for Eighty-seven Years | 308 |

| Colored Chart of Races of Immigrants for 1905 | End |

It is not a question as to whether the aliens will come. They have come, millions of them; they are now coming, at the rate of a million a year. They come from every clime, country, and condition; and they are of every sort: good, bad, and indifferent, literate and illiterate, virtuous and vicious, ambitious and aimless, strong and weak, skilled and unskilled, married and single, old and young, Christian and infidel, Jew and pagan. They form to-day the raw material of the American citizenship of to-morrow. What they will be and do then depends largely upon what our American Protestant Christianity does for them now.

Immigration—the foreign peoples in America, who and where they are, whence they come, and what under our laws and liberties and influences they are likely to become—this is the subject of our study. The subject is as fascinating as it is vital. Its problems are by far the most pressing, serious, and perplexing with which the American people have to do. It is high time that our young people were familiarizing themselves with the facts, for this is preëminently the question of to-day. Patriotism and religion—love of country[Pg 10] and love of Christ—unite to urge thoughtful consideration of this great question: Aliens or Americans? One aim of this book is to show our individual responsibility for the answer, and how we can discharge it.

Immigration may be regarded as a peril or a providence, an ogre or an obligation—according to the point of view. The Christian ought to see in it the unmistakable hand of God opening wide the door of evangelistic opportunity. Through foreign missions we are sending the gospel to the ends of the earth. As a home mission God is sending the ends of the earth to our shores and very doors. The author is a Christian optimist who believes God has a unique mission for Christian America, and that it will ultimately be fulfilled. While the facts are in many ways appalling, the result of his study of the foreign peoples in our country has made him hopeful concerning their Americanization and evangelization, if only American Christians are awake and faithful to their duty. The Christian young people, brought to realize that immigration is another way of spelling obligation, must do their part to remove that tremendous IF.

These newcomers are in reality a challenge to American Christianity. The challenge is clear and imperative. Will we give the gospel to the heathen in America? Will we extend the hand of Christian brotherhood and helpfulness to the[Pg 11] stranger within our gates? Will we Christianize, which is the only real way to Americanize, the Aliens? May this book help to inspire the truly Christian answer that shall mean much for the future of our country, and hence of the world.

The author makes grateful acknowledgment to all who have assisted by suggestion or otherwise. He has tried to give credit to the authors whose works he has used. He is under special obligation for counsel and many courtesies to Josiah Strong, one of the modern patriot-prophets who has sought to awaken Americans to their Christian duty and privilege.

Briarcliff Manor, June, 1906.[Pg 13][Pg 12]

A million immigrants!

A million opportunities!

A million obligations!

This in brief is the message of Aliens or Americans?

A young man who came to this country young enough to get the benefit of our public schools, and who then took a course in Columbia University, writes: "Now, at twenty-one, I am a free American, with only one strong desire; and that is to do something for my fellow-men, so that when my time comes to leave the world, I may leave it a bit the better." These are the words of a Russian Jew; and that Russian is a better American, that Jew is a better Christian, than many a descendant of the Pilgrim Fathers.

In this country every man is an American who has American ideals, the American spirit, American conceptions of life, American habits. A man is foreign not because he was born in a foreign land, but because he clings to foreign customs and ideas.

I do not fear foreigners half so much as I fear Americans who impose on them and brutally abuse them. Such Americans are the most dan[Pg 14]gerous enemies to our institutions, utterly foreign to their true spirit. Such Americans are the real foreigners.

Most of those who come to us are predisposed in favor of our institutions. They are generally unacquainted with the true character of those institutions, but they all know that America is the land of freedom and of plenty, and they are favorably inclined toward the ideas and the obligations which are bound up with these blessings. They are open to American influence, and quickly respond to a new and a better environment.

They naturally look up to us, and if with fair and friendly treatment we win their confidence, they are easily transformed into enthusiastic Americans. But if by terms of opprobrium, such as "sheeny" and "dago," we convince them that they are held in contempt, and if by oppression and fraud we render them suspicious of us, we can easily compact them into masses, hostile to us and dangerous to our institutions and organized for the express purpose of resisting all Americanizing influences.

Whether immigrants remain Aliens or become Americans depends less on them than on ourselves.

New York, June 26, 1906.[Pg 15]

We may well ask whether this insweeping immigration is to foreignize us, or we are to Americanize it. Our safety demands the assimilation of these strange populations, and the process of assimilation becomes slower and more difficult as the proportion of foreigners increases.

"And Elisha prayed, and said, Jehovah, I pray thee, open his eyes, that he may see. And Jehovah opened the eyes of the young man: and he saw" (2 Kings vi. 17). Elisha's prayer is peculiarly fitting now. The first need of American Protestantism is for clear vision, to discern the supreme issues involved in immigration, recognize the spiritual significance and divine providence in and behind this marvelous migration of peoples, and so see Christian obligation as to rise to the mission of evangelizing these representatives of all nations gathered on American soil.—The Author.

Out of the remote and little-known regions of northern, eastern, and southern Europe forever marches a vast and endless army. Nondescript and ever-changing in personnel, without leaders or organization, this great force, moving at the rate of nearly 1,500,000 each year, is invading the civilized world.—J. D. Whelpley.

Political optimism is one of the vices of the American people. There is a popular faith that "God takes care of children, fools, and the United States." Until within a few years probably not one in a hundred of our population has ever questioned the security of our future. Such optimism is as senseless as pessimism is faithless. The one is as foolish as the other is wicked.—Josiah Strong[Pg 17].

What does a million of immigrants a year mean? Possibly something of more significance to us if we put it this way, that at present one in every eighty persons in the entire United States has arrived from foreign shores within twelve months. Of this inpouring human tide one of the latest writers on immigration says, in a striking passage:

"Like a mighty stream, it finds its source in a hundred rivulets. The huts of the mountains and the hovels of the plains are the springs which feed; the fecundity of the races of the old world the inexhaustible source. It is a march the like of which the world has never seen, and the moving columns are animated by but one idea—that of escaping from evils which have made existence intolerable, and of reaching the free air of countries where conditions are better shaped to the welfare of the masses of the people.

"It is a vast procession of varied humanity. In tongue it is polyglot; in dress all climes from[Pg 18] pole to equator are indicated, and all religions and beliefs enlist their followers. There is no age limit, for young and old travel side by side. There is no sex limitation, for the women are as keen as, if not more so than, the men; and babes in arms are here in no mean numbers. The army carries its equipment on its back, but in no prescribed form. The allowance is meager, it is true, but the household gods of a family sprung from the same soil as a hundred previous generations may possibly be contained in shapeless bags or bundles. Forever moving, always in the same direction, this marching army comes out of the shadow, converges to natural points of distribution, masses along the international highways, and its vanguard disappears, absorbed where it finds a resting-place."[1]

See the living stream pour into America through the raceway of Ellis Island.[2] There is no such sight to be seen elsewhere on the planet. Suppose for the moment that all the immigrants of 1905 came in by that wide open way, as eight tenths of them actually did. If your station had been by that gateway, where you could watch the human tide flowing through, and if the stream had been steady, on every day of the 365 you would have seen more than 2,800 living beings—men, women, and children, of almost every con[Pg 19]ceivable condition except that of wealth or eminence—pass from the examination "pens" into the liberty of American opportunity. Since the stream was spasmodic, its numbers did reach as high in a single day as 11,343.

Imagine an army of nearly 20,000 a week marching in upon an unprotected country. At the head come the motley and strange-looking migrants—largely refugee Jews—from the far Russian Empire and the regions of Hungary and Roumania. At the daily rate of 2,800 it would take this indescribable assortment more than 166 days to pass in single file. Then the Italians would consume about eighty days more. For over eight months you would have watched so large a proportion of illiteracy, incompetency, and insensibility to American ideals, that you would be tempted to despair of the Republic. Nor would you lose the sense of nightmare when the English and Irish were consuming forty-two days in passing, for the "green" of the Emerald Isle is vivid at Ellis Island, and the best class of the English stay at home. The flaxen-haired and open-faced Scandinavians would lighten the picture, but with the equally sturdy Germans they would get by in only a month and four days.

This much is certain, whatever may be thought of the fanciful procession. No American who spends a single day at Ellis Island, when the loaded steamships have come in, will afterward[Pg 20] require awakening on the subject of immigration and the necessity of doing something effective in the way of Americanization. A good view of the steerage is the best possible enlightener.

A million a year and more is the rate at which immigrants are now coming into the United States.[3] It is not easy to grasp the significance of such numbers: yet we must try to do so if we are to realize the problem to be solved. To get this mass of varied humanity within the mind's eye, let us divide and group it. First, recall some small city or town with which you are familiar, of about 10,000 inhabitants; say Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where the treaty of peace between Japan and Russia was agreed upon; or Saratoga Springs, New York; or Vincennes, Indiana; or Ottawa, Illinois; or Sioux Falls, South Dakota; or Lawrence, Kansas. Settle one hundred towns of this size with immigrants, mostly of the peasant class, with their un-American languages, customs, religion, dress, and ideas, and you would locate merely those who came from Europe and Asia in the year ending June 30, 1905. Those who came from other parts of the world would make two and a half towns more, or a city the size of Poughkeepsie in New York, seat of Vassar College, or Burlington in Iowa, of about 25,000 each.[Pg 21]

Gather these immigrants by nationality, and you would have in round numbers twenty-two Italian cities of 10,000 people, or massed together, a purely Italian city as large as Minneapolis with its 220,000. The various peoples of Austria-Hungary—Bohemians, Magyars, Jews, and Slavs—would fill twenty-seven and one half towns; or a single city nearly as large as Detroit. The Jews, Poles, and other races fleeing from persecution in Russia, would people eighteen and one half towns, or a city the size of Providence. For the remainder we should have four German cities of 10,000 people, six of Scandinavians, one of French, one of Greeks, one of Japanese, six and a half of English, five of Irish, and nearly two of Scotch and Welsh. Then we should have six towns of between 4,000 and 5,000 each, peopled respectively by Belgians, Dutch, Portuguese, Roumanians, Swiss, and European Turks; while Asian Turks would fill another town of 6,000.Queer Towns these would be We should have a Servian, Bulgarian, and Montenegrin village of 2,000; a Spanish village of 2,600; a Chinese village of 2,100; and the other Asiatics would fill up a town of 5,000 with as motley an assortment as could be found under the sky. Nor are we done with the settling as yet, for the West Indian immigrants would make a city of 16,600, the South Americans and Mexicans a place of 5,000, the Canadians a 2,000 village, and[Pg 22] the Australians another; leaving a colony of stragglers and strays, the ends of creation, to the number of 2,000 more. Place yourself in any one of these hundred odd cities or villages thus peopled, without a single American inhabitant, with everything foreign, including religion; then realize that just such a foreign population as is represented by all these places has actually been put somewhere in this country within a twelvemonth, and the immigration problem may assume a new aspect and take on a new concern.

But let us carry our imagination a little further. Suppose we bring together into one place the illiterates of 1905—the immigrants of all nationalities, over fourteen years of age, who could neither read nor write. They would make a city as large as Jersey City or Kansas City, and 15,000 larger than Indianapolis. Think of a population of 230,000 with no use for book, paper, ink, pen, or printing press. This mass of dense ignorance was distributed some way within a year, and more illiterates are coming in by every steamer. Divide this city of ignorance by nationalities into wards, and there would be an Italian ward of 100,000, far outnumbering all others; in other words, the Italian illiterates landed in America in a year equal the population of Albany, capital of the Empire State. The other leading wards would be: Polish, 33,000;[Pg 23] Hebrew, 22,000, indicating the low conditions whence they came; Slav, 36,000; Magyar and Lithuanian, 12,000; Syrian and Turkish, 3,000. These regiments of non-readers and writers come almost exclusively from the south and east of Europe. Of the large total of illiterates, 230,882 to be exact—it is noteworthy that only seventy-five were Scotch; and only 157 were Scandinavian, out of the more than 60,000 from Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. That almost one quarter of a total million of newcomers should be unable to read or write is certainly a fact to be taken into account, and one that throws a calcium light on the general quality of present-day immigration and the educational status of the countries from which they come. Illiteracy is a worse reflection upon the foreign government than upon the foreign immigrant.

To complete this grouping, we should go one step further, and make up a number of divisions according to occupation and no-occupation, skilled and unskilled labor. To begin with, the unskilled laborers would fill a city of 430,000, or about the size of Cincinnati. Those classified as servants, with a fair question mark as to the amount of skill possessed, numbered 125,000 more, equal to the population of New Haven. Those classified as without occupation, including the children under fourteen, numbered 232,000, equal to the population of Louisville. Gathering[Pg 24] into one great body, then, what may fairly be called unskilled labor, the total is not far from 780,000 out of the 1,026,499 who came. This mass would fill a city the size of Boston, Cambridge, and Lynn combined, or of Cleveland and Washington. Imagine, if you can, what kind of a city it would be, and contrast that with these centers of civilization as they now are.

To put all the emphasis possible upon these facts, consider that the immigration of a single year exceeded by 26,000 the population of Connecticut, which has been settled and growing ever since early colonial days. It exceeded by 37,000 the combined population of Alaska, Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah. These immigrants would have repopulated whole commonwealths, but they would hardly be called commonwealths in that case. If such immigrant distribution could be made, how quickly would the imperative necessity of Americanization be realized. The Italians who came during the year would exceed the combined population of Alaska and Wyoming. The Hungarians and Slavs would replace the present population of New Hampshire, or of North Dakota, and equal that of Vermont and Wyoming together. The Russian Jews and Finlanders would replace the people of Arizona. The army of illiterates would repeople Delaware and Nevada. And the much larger army of the unskilled would exceed by[Pg 25] 50,000 the population of Maine, that of Colorado by about 80,000, and twice that of the District of Columbia.

The diagram at the end of the book, taken from the Report of the Commissioner-General of Immigration for 1905, will help us to fix in mind the race proportions of the present immigration. The increase of 1905 over 1904 was 213,629. Almost one half of this was from Austria-Hungary, and all of it was from four countries, the other three being Russia, Italy, and the United Kingdom. There was a decrease from Germany, Sweden, and Norway.

We have been considering thus far the immigration of a single year. To make the effect of this survey cumulative, let us include the totals of immigration from the first.[4] The official records begin with 1820. It is estimated that prior to that date the total number of alien arrivals was 250,000. In 1820 there were 8,385 newcomers, less than sometimes land at Ellis Island in a single day now, and they came chiefly from three nations—Great Britain, Germany, and Sweden. The stream gradually increased, but with many fluctuations, governed largely by the economic conditions. The highest immigration prior to the potato famine in Ireland in[Pg 26] 1847 was in the year 1842, when the total for the first time passed the 100,000 mark, being 104,565. In 1849 the number leaped to 297,024, with a large proportion of the whole from Ireland; in 1850 it was 310,000; while 1854 was the high year of that period, with 427,833. Then came the panic and financial depression in America, and after that the civil war, which sent the immigration figures down. It was not until 1866, after the war was over, that the total again rose to 300,000. In 1872 it was 404,806; in 1873, 459,803; falling back then until 1880, when a high period set in. The totals of 1881 (669,431) and of 1882 (788,992) were not again equaled until 1903, when for the first time the 800,000 mark was passed.

Taking the figures by decades, we have this enlightening table:

| 1821 to 1830 | 143,439 |

| 1831 to 1840 | 599,125 |

| 1841 to 1850 | 1,713,251 |

| 1851 to 1860 | 2,598,214 |

| 1861 to 1870 | 2,314,824 |

| 1871 to 1880 | 2,812,191 |

| 1881 to 1890 | 5,246,613 |

| 1891 to 1900 | 3,687,564 |

| 1901 to 1905 | 3,833,076 |

| ————— | |

| Total, 1821 to 1905, | 22,948,297 |

From this it appears that more aliens landed in the single decade from 1880 to 1890 than in[Pg 27] the period of forty-five years from 1820 to 1865. Indeed, the immigration of the past six years more than outnumbers that of the forty years from 1820 to 1860.

Thus, from colonial days above twenty-three millions of aliens have been received upon these hospitable shores. And more than thirteen millions of them have come since 1880, or in the last quarter century. No wonder it is said that the invasion of Attila and his Huns was but a side incident compared to this modern migration of the millions.

Canada, our northern neighbor, is a prosperous colony of 5,371,315, according to her latest census. We could almost have peopled Canada entire with as large a population out of the immigration of the decade 1880-1890. More than that, the whole population of Scotland, or that of Ireland, above four and a quarter millions, could have moved over to America, and it would only have equaled the actual immigration since 1900. If the whole of Wales were to come over, the 1,700,000 odd of them would not have equaled by 100,000 the total immigration of the two years 1904-05. If all Sweden and Norway packed up and left the question of one or two kingdoms to settle itself, the 7,300,000 sturdy Scandinavians would fall short of the immigrant host that has come in from everywhither since 1891. More people than the entire population of Switzerland[Pg 28] (3,315,000) have landed in America within four years. If only the majority of these aliens had possessed the love of liberty and the characteristic virtues of the Protestant Swiss, our problem would be very different. These comparisons strongly impress the responsibility and burden imposed upon America by practically free and wide-open gates.

Here are the totals which we have now reached. Of the 23,000,000 aliens who have come into America since the Revolution, the last census (1900) gave the number then living at 10,256,664. A census taken to-day would doubtless show about 14,000,000. Add the children of foreign parentage and it would bring the total up to between 35,000,000 and 40,000,000. Mr. Sargent estimates this total at forty-six per cent. of our entire population. The immigration problem presents nothing less than the assimilation of this vast mass of humanity. No wonder thoughtful Americans stand aghast before it. At the same time, the only thing to fear is failure to understand the situation and meet it. As Professor Boyesen says: "The amazing thing in Americans is their utter indifference or supine optimism. 'Don't you worry, old fellow,' said a very intelligent professional man to me recently, when I told him of my observations during a visit to Castle Garden.[5] 'What does it matter whether[Pg 29] a hundred thousand more or less arrive? Even if a million arrived annually, or two millions, I guess we could take care of them. Why, this country is capable of supporting a population of two hundred millions without being half so densely populated as Belgium. Only let them come—the more the merrier!' I believe this state of mind is fairly typical. It is the sublime but dangerous optimism of a race which has never been confronted with serious problems." But we believe it is the optimism of a race which, when fairly brought face to face with crises, will not fail to meet them in the same spirit that has won the victories of civil and religious liberty and established a free government of, by, and for the people in America.

The causes of immigration are variously stated, but compressed into three words they are: Attraction, Expulsion, Solicitation. The attraction comes from the United States, the expulsion from the Old World, and the solicitation from the great transportation lines and their emissaries. Sometimes one cause is more potent, sometimes another. Of late, racial and religious persecution has been active in Europe, and America gets the results. "In Russia there is an outbreak, hideous and savage, against the Jew, and an impulse is started whose end is not[Pg 30] Expulsionreached until you strike Rivington Street in the ghetto of New York. The work begun in Russia ends in the seventeenth ward of New York." Cause and effect are manifest. Military service is enforced in Italy; taxes rise, overpopulation crowds, poverty pinches. As a result, the stream flows toward America, where there is no military service and no tax, and where steady work and high wages seem assured.Attraction The mighty magnet is the attractiveness of America, real or pictured. America is the magic word throughout all Europe. No hamlet so remote that the name has not penetrated its peasant obscurity. America means two things—money and liberty—the two things which the European peasant (and often prince as well) lacks and wants. Necessity at home pushes; opportunity in America pulls. Commissioner Robert Watchorn, of the port of New York, packs the explanation into an epigram: "American wages are the honey-pot that brings the alien flies." He says further: "If a steel mill were to start in a Mississippi swamp paying wages of $2 a day, the news would hum through foreign lands in a month, and that swamp would become a beehive of humanity and industry in an incredibly short space of time." Dr. A. F. Schauffler says, with equal pith, that "the great cause of immigration is, after all, that the immigrants propose to better themselves in this country. They come here not because they[Pg 31] love us, or because we love them. They come here because they can do themselves good, not because they can do us good."[6] That is natural and true; and it furnishes excellent reason why we must do them good in order that they may not do us evil. To make their good ours and our good theirs is both Christian and safe.

Three ClassesThe three causes produce three classes of immigrants: 1. Natural; 2. Assisted; and 3. Solicited.

The prosperity of this country has undoubtedly chiefly influenced immigration in the past. This is shown by the marked relationship between industrial and commercial activity in the United States and the volume of immigration.[7] Our prosperity not only induces desire to come but makes coming possible. The testimony before the Industrial Commission showed that from forty to forty-five per cent. of the immigrants have their passage prepaid by friends or relatives in this country, and from ten to twenty-five per cent. more buy their tickets abroad with money sent from the United States. In 1902 between $65,000,000 and $70,000,000 was sent home to Italy alone from the United States, and the stream of earnings flowing out to Ireland and[Pg 32] [Pg 33]Germany and Sweden and Hungary has been not less steady. American prosperity has been feeding and paying taxes for millions of people who owe far more to our government than to their own, and foreign governments have been reaping the benefit. The United States has a small standing army of its own, but through the gold sent abroad by the alien wage earners here we have been helping maintain the vast armaments of Europe. The letters and the money sent by immigrants to the home folks awaken the desires and dreams that mean more immigrants. The United States Post-office is a marvelous immigration agent in Europe. Immigrants are not the only persons induced to migrate through the feeling that where one is not will prove a much better place than where one is. That seems to inhere in human nature.

"Not only the American money and letters, but the American ideas are at work abroad," says the Rev. F. M. Goodchild, D.D.,[8] in a recent address: "The praises of America are told abroad by every person who comes here and gets along. Some things to be sure, these people miss—the blue skies of Italy and the vineyards on the hillside. But they have for them the compensation of such a liberty as they never knew before. The real reason why all southern Europe is in a turmoil to-day, is that American ideas of liberty are[Pg 34] working there like leaven. We get our notions of liberty from the Bible and from the men who forced the Magna Charta from King John at Runnymede, but all other peoples in the world seem to be getting their ideas of liberty from us. That is what is the matter with the Old World to-day.The American Idea The American idea is working like leaven. That is the force at work in France, where absolute divorce has just been proclaimed between Church and State. That is at the bottom of the movements in Russia, where the Stundists have just won religious liberty, and where, let us hope, all classes of people ere long will have won complete civil liberty. These people have felt the uplift of our American free institutions and they want them for themselves. They have heard 'Yankee Doodle,' and the 'Star Spangled Banner,' and 'My Country, 'tis of Thee,' and they cannot get the music of liberty out of their ears and their hearts. Broughton Brandenburg tells us that he heard some Italians who had been in America singing our classic song 'Mr. Dooley' in the vineyards near Naples."

Let the immigrants themselves tell why they come. These testimonies are typical, condensed from a most interesting volume of immigrant autobiography,[9] fresh and illuminating.[Pg 35]

A German nurse girl says: "I heard about how easy it was to make money in America and became very anxious to go there. I was restless in my home; mother seemed so stern and could not understand that I wanted amusement. I sailed from Antwerp, the fare costing $35. My second eldest sister met me with her husband at Ellis Island and they were glad to see me and I went to live with them in their flat in West Thirty-fourth Street, New York. A week later I was an apprentice in a Sixth Avenue millinery store earning four dollars a week. I only paid three for board, and was soon earning extra money by making dresses and hats at home." Friends in Germany would be sure to hear of this new condition.

Why do the Poles come? A Polish sweat-shop girl, telling her life story, answers. The father died, then troubles began in the home in Poland. Little was needed by the widow and her child, but even soup, black bread, and onions they could not always get. At thirteen the girl was handy at housekeeping, but the rent fell behind, and the mother decided to leave Poland for America, where, "we heard, it was much easier to make money. Mother wrote to Aunt Fanny, who lived in New York, and told her how hard it was to live in Poland, and Aunt Fanny advised her to come and bring me." Thousands could tell a similar story to that. "Easier to make money"[Pg 36] has allured multitudes to leave the old home and land.

A Lithuanian (Russian) tells how it was the traveling shoemaker that made him want to come to America. This shoemaker learned all the news, and smuggled newspapers across the German line, and he told the boy's parents how wrong it was to shut him out of education and liberty by keeping him at home. "That boy must go to America," he said one night. "My son is in the stockyards in Chicago." These were some of his reasons for going: "You can read free papers and prayer books; you can have free meetings, and talk out what you think." And more precious far, you can have "life, liberty, and the getting of happiness." When time for military service drew near, these arguments for America prevailed and the boy was smuggled out of his native land. "It is against the law to sell tickets to America, but my father saw the secret agent in the village and he got a ticket from Germany and found us a guide. I had bread and cheese and vodka (liquor) and clothes in my bag. My father gave me $50 besides my ticket." Bribery did the rest, and thus this immigrant obtained his liberty and chance in America. The American idea is leavening Russia surely enough.

An Italian bootblack who already owns several bootblacking establishments in this country, was[Pg 37] trained to a beggar's life in Italy, and ran away. "Now and then I had heard things about America—that it was a far-off country where everybody was rich and that Italians went there and made plenty of money, so that they could return to Italy and live in pleasure ever after." He worked his passage as a coaler, and was passed at Ellis Island through the perjury of one of the bosses who wring money out of the immigrants in the way of commissions, getting control of them by the criminal act at the very entrance into American life.

A Greek peddler, a graduate of the high school at Sparta—think of a modern high school in ancient Sparta!—after two years in the army, was ready for life. "All these later years I had been hearing from America. An elder brother was there who had found it a fine country and was urging me to join him. Fortunes could easily be made, he said. I got a great desire to see it, and in one way and another I raised the money for fare—250 francs—($50) and set sail from the old port of Athens. I got ashore without any trouble in New York, and got work immediately as a push-cart man. Six of us lived together in two rooms down on Washington Street. At the end of our day's work we all divided up our money even; we were all free."

A Swedish farmer says: "A man who had been living in America once came to visit the[Pg 38] little village near our cottage. He wore gold rings set with jewels and had a fine watch. He said that food was cheap in America and that a man could earn nearly ten times as much there as in Sweden. There seemed to be no end to his money." Sickness came, with only black bread and a sort of potato soup or gruel for food, and at last it was decided that the older brother was to go to America. The first letter from him contained this: "I have work with a farmer who pays me sixty-four kroner[10] a month and my board. I send you twenty kroner, and will try to send that every month. This is a good country. All about me are Swedes, who have taken farms and are getting rich. They eat white bread and plenty of meat. One farmer, a Swede, made more than 25,000 kroner on his crop last year. The people here do not work such long hours as in Sweden, but they work much harder, and they have a great deal of machinery, so that the crop one farmer gathers will fill two big barns."

An Irish cook, one of "sivin childher," had a sister Tilly, who emigrated to Philadelphia, started as a greenhorn at $2 a week, learned to cook and bake and wash, all American fashion, and before a year was gone had money enough laid up to send for the teller of the story. The two gradually brought over the whole family,[Pg 39] and Joseph owns a big flour store and Phil is a broker, while his son is in politics and the city council, and his daughter Ann (she calls herself Antoinette now) is engaged to a lawyer in New York. That is America's attractiveness and opportunity and transformation in a nutshell.

A Syrian, born on the Lebanon range, went to an American mission school at fifteen, learned much that his former teacher the friar had warned him against, had his horizon broadened, gave up his idea of becoming a Maronite monk when he learned that there were other great countries beside Syria, and had all his old ideas overthrown by an encyclopedia which said the United States was a larger and richer country than Syria or even Turkey. The friar was angry and said the book told lies, and so did the patriarch, who was scandalized to think such a book should come to Mount Lebanon; but the American teacher said the encyclopedia was written by men who knew, and the Syrian boy finally decided to go to the United States, where "we had heard that poor people were not oppressed." His mother and uncle came, too, and as the boy was a good penman he secured work without difficulty in an Oriental goods store. As for his former religious teaching he says: "The American teacher never talked to me about religion; but I can see that those monks and priests are the curse of our country, keeping the people in[Pg 40] ignorance and grinding the faces of the poor, while pretending to be their friends." In his case it was the foreign mission school that was the magnet to America.

A Japanese says: "The desire to see America was burning in my boyish heart. The land of freedom and civilization of which I had heard so much from missionaries and the wonderful story of America I had heard from those of my race who returned from there made my longing ungovernable." A popular novel among Japanese boys, "The Adventurous Life of Tsurukichi Tanaka, Japanese Robinson Crusoe," made a strong impression upon him, and finally he decided to come to this country to receive an American education.

A representative Chinese business man of New York was taught in childhood that the English and Americans were foreign devils, the latter false, because having made a treaty by which they could freely come to China and Chinese as freely go to America, they had broken the treaty and shut the Chinese out. When he was sixteen, working on a farm, a man of his tribe came back from America "and took ground as large as four city blocks and made a paradise of it." He had gone away a poor boy, now he returned with unlimited wealth, "which he had obtained in the country of the American wizards. He had become a merchant in a city called Mott Street,[Pg 41] so it was said. The wealth of this man filled my mind with the idea that I, too, would go to the country of the wizards and gain some of their wealth." Landing in San Francisco, before the exclusion act, he started in American life as a house servant, but finally became a Mott Street merchant, as he had intended from the first.

Thus we have gone the rounds of immigrants of various races. The two ideas—fortune and freedom—lie at the basis of immigration, although the money comes first in nearly all cases. These testimonies could be multiplied indefinitely. Ask the first immigrant you can talk with what brought him, and find out for yourself. Mr. Brandenburg says a Greek who was being deported told him that all Greece was stirred up over the matter of emigration, and that in five years the number of Greeks coming to the United States would have increased a thousand per cent.[11] The reasons are the too onerous military duties in Greece and prosperity of Greeks in America. The remittances fired the zeal of the home people to follow, and the candymakers' shops were full of apprentices, because the idea had gone abroad that candymakers could easily gain a fortune in America.

From these illustrations, it can readily be seen how widespread is the knowledge of America as[Pg 42] a desirable place. The other side is rarely told and that is the pitiful side of it. The stories that go back are always of the fortunes, not of the misfortunes, of the money and not of the misery.

If immigration were left to the natural causes, there would be little reason for apprehension. It is in the solicited and assisted immigration that the worst element is found. Commercial greed lies at the root of this, as of most of the evils which afflict us as a nation. The great steamship lines have made it cheaper to emigrate than to stay at home, in many cases; and every kind of illegal inducement and deceit and allurement has been employed to secure a full steerage. The ramifications of this transportation system are wonderful. It has a direct bearing, too, upon the character of the immigrants. Easy and cheap transportation involves deterioration in quality. In the days when a journey across the Atlantic was a matter of weeks or months and of considerable outlay, only the most enterprising, thrifty, and venturesome were ready to try an uncertain future in an unknown land. The immigrant of those days was likely, therefore, to be of the sturdiest and best type, and his coming increased the general prosperity without lowering the moral tone. Now that the ocean has become little more than a ferry, and the rates of railway and steam[Pg 43]ship have been so reduced, it is the least thrifty and prosperous members of their communities that fall readiest prey to the emigration agent.

Assisted immigration is the term used to cover cases where a foreign government has eased itself of part of the burden of its paupers, insane, dependents, and delinquents by shipping them to the United States. This was not uncommon in the nineteenth century, especially in the case of local and municipal governments. Our laws were lax, and for a time nearly everybody, sane or insane, sound or diseased, was passed. The financial gain to the exporting government can be seen in the fact that it costs about $150 per head a year to support dependents and delinquents in this country, while it would not cost the foreign authorities more than $50 to transport them hither. This policy seems scarcely credible, but Switzerland, Great Britain, and Ireland followed it thriftily until our laws put a stop to it, in large part, by returning these undesirable persons whence they came, at the expense of the steamship companies bringing them. It was not until 1882, however, that our government passed laws for self-protection, and in 1891 another law made "assisted" immigrants a special class not to be admitted.

Other and incidental causes there are, such as the influence of new machinery, opening the way for more unskilled labor, such as the ordi[Pg 44]nary immigrant has to sell; the protective tariff, which shuts out foreign goods and brings in the foreign producers of the excluded goods; the thorough advertising abroad of American advantages by boards of agriculture and railway companies interested in building up communities; and a fear of restrictive legislation. But undoubtedly, ever back of all other reasons is the conviction that America is the land of plenty and of liberty—a word which each interprets according to his light or his liking.

Having thus considered the remarkable proportions of immigration, and

the causes of it, it will be well at this point to say a cautionary word

as to the attitude of mind and heart in which this subject should be

approached. Impartiality is necessary but difficult. There is a natural

prejudice against the immigrant. A Christian woman, of ordinarily gentle

and sweet temper, was heard to say recently, while this very subject of

Christian duty to the immigrant was under discussion at a missionary

conference: "I hate these disgusting foreigners; they are spoiling our

country." Doubtless many would sympathize with her. This is not uncommon

prejudice or feeling, and argument against it is of little avail.

Nevertheless, as Christians we must endeavor to divest ourselves of it.

We must recognize the brotherhood of man and the value of the individual

soul as taught by Jesus. It may aid us, per[Pg 45]haps, if we remember that we

are all—with the exception of the Indians, who may lay claim to

aboriginal heritage—in a sense descendants of immigrants. At the same

time, it is essential to draw a clear distinction between colonists and

immigrants.Colonists

and

Immigrants Distinguished Colonization, with its attendant hardships and heroisms,

steadily advanced from its beginnings in New England, New Amsterdam, and

Virginia, until there resulted the founding of a free and independent

nation, with popular government and fixed religious principles,

including the vital ones of religious liberty and the right of the

individual conscience. In other words, colonization created a nation;

and there had to be a nation before there could be immigration to it.

"In discussing the immigration question," says Mr. Hall, "this

distinction is important," for it does not follow that, because, as

against the native Indians, all comers might be considered as intruders

and equally without claim of right, those who have built up a

complicated framework of nationality have no rights as against others

who seek to enjoy the benefits of national life without having

contributed to its creation."[12]

It ought clearly to be recognized that the colonists and their descendants have sacred rights, civil and religious, with which aliens should not be permitted to interfere; and that[Pg 46] these rights include all proper and necessary legislation for the preservation of the liberties, laws, institutions, and principles established by the founders of the Republic and those rights of citizenship guaranteed under the constitution. If restriction of immigration becomes necessary in order to safeguard America, the American people have a clear right to pass restrictive or even prohibitory laws. In other words, America does not belong equally to everybody. The American has rights which the alien must become American to acquire.

At the same time, our attitude toward the alien should be sympathetic, and our minds should be open and inquiring as we study the incoming multitudes. We do not wish to raise the Russian cry, "Russia for the Russians," or the Chinese shibboleth, "China for the Chinese." The Christian spirit has been compressed into the epigram, "Not America for Americans, but Americans for America." We must see to it that the immigrants do not remain aliens, but are transformed into Christian Americans. That is the true missionary end for which we are to work; and it is in order that we may work intelligently and effectively that we seek to familiarize ourselves with the facts.

The facts already brought out are surely sufficient to arrest attention. Suppose this million-a-year rate should continue for a decade—and[Pg 47] there is every reason to believe it will, unless unusual and unlikely restrictive measures are taken by our government. That would mean ten millions more added, and probably seventy per cent. of them from southeastern Europe. Add the natural increase, and estimate what the result of these millions would be upon the national digestion. Politically, the foreign element would naturally and inevitably assume the place which a majority can claim in a democracy, and not only claim but maintain, by the use of votes—a use which the immigrant learns full soon from the manipulators of parties. Religiously, unless a great change should come over the spirit of American Protestantism, and the work of evangelization among foreigners be conducted along quite different lines from the present, is it not plain that our country would cease to be Christian America, as we understand the term? There is enough in these questions to set and keep the patriotic American thinking.

The personal inquiry for each one to make is, "As an American and a Christian, have these facts and queries any special message for me, and have I any direct responsibility in relation to them?"[Pg 48]

These questions have been prepared to suggest to the leader and student the most important points in the chapter, and to stimulate further meditation and thought. Those marked * should encourage discussion. The leader is not expected to use all of these questions, and should use his judgment in eliminating or adding others that are in harmony with the aim of the lesson. For helps for conducting each class session, the leader should not fail to write to the Secretary of his Home Missionary Board.

I. To Learn by Comparison the Magnitude of a Million Aliens.

1. At what rate per annum is our population now being increased by immigration?

2. What are the sources of this invasion? Its principal gateway?

3. What comparison helps you most to realize the number of immigrants?

4. What are some of the largest groups in the mass, as classified by nationality? By race? By knowledge or ignorance? By fitness for labor?

5. What states may be compared with last year's arrivals?

II. To Realise the Proportion of Our Population that has Immigrated since 1820.

6. How does the total number of our immigrants compare with the population of Germany? England? Canada?[Pg 49]

7. Has the number of immigrants been increasing steadily? Will it tend to increase?

8. Has the present rate been long continued? What proportion of the population of the United States is derived from immigration subsequent to the American Revolution?

9. * Do you think there is any serious menace in such large numbers of immigrants? Why?

III. Why do Aliens Come?

10. Name the principal causes of immigration. The principal classes.

11. What American ideals have the greatest attractive power? What opportunities?

12. Give some typical instances of immigrants' stories. * Would you have wished to come under the same circumstances?

13. What other forces stimulate immigration to the United States? What agencies?

IV. What Should be our Attitude toward Aliens, and What is our Individual Responsibility for Them?

14. * What is the Christian attitude toward these newcomers? How can we remove prejudice?

15. * What is our personal responsibility as Christians in improving the condition of aliens?

I. Compare modern immigration with the migration of peoples in earlier times; for example, those of the Hebrews, Aryans, Goths, Huns, Saracens, and other races.

Any good Encyclopedia or General History.[Pg 50]

II. What resemblances and what differences between the Colonial settlement of America, and the later immigration, say, during the Nineteenth Century?

III. The Causes of Immigration.

Hall: Immigration, II.

Lord, et al: The Italian in America, III, VIII.

Warne: The Slav Invasion, III, IV; 78, 83.

Holt: Undistinguished Americans, 35, 244-250.

IV. What agencies can you name and describe that are trying to receive the immigrants in a humane and Christian spirit? For example, the United States Government, American Tract Society, New York Bible Society, Society for Italian Immigrants, and other organizations and agencies. Study especially any that work in your own neighborhood.

As for immigrants, we cannot have too many of the right kind, and we should have none of the wrong kind. I will go as far as any in regard to restricting undesirable immigration. I do not think that any immigrant who will lower the standard of life among our people should be admitted.—President Roosevelt.

Unrestricted immigration is doing much to cause deterioration in the quality of American citizenship. Let us resolve that America shall be neither a hermit nation nor a Botany Bay. Let us make our land a home for the oppressed of all nations, but not a dumping-ground for the criminals, the paupers, the cripples, and the illiterate of the world. Let our Republic, in its crowded and hazardous future, adopt these watchwords, to be made good all along our oceanic and continental borders: "Welcome for the worthy, protection to the patriotic, but no shelter in America for those who would destroy the American shelter itself."—Joseph Cook.

It is not the migration of a few thousand or even million human beings from one part of the world to another nor their good or bad fortune that is of interest to us. We are concerned with the effect of such a movement on the community at large and its growth in civilization. Immigration, for instance, means the constant infusion of new blood into the American commonwealth, and the question is: What effect will this new blood have upon the character of the community?—Professor Mayo-Smith.

It is advisable to study the influence of the newcomers on the ethical consciousness of the community—whether there is a gain or a loss to us. In short, we must set up our standard of what we desire this nation to be, and then consider whether the policy we have hitherto pursued in regard to immigration is calculated to maintain that standard or to endanger it.—Idem[Pg 53].

How do immigrants obtain entrance into the United States? New York is the chief port of entry, and if we learn the conditions and methods there we shall know them in general. The great proportion coming through New York is seen by comparison of the total admissions for 1904 and 1905 at the larger ports:

| Port | 1904 | 1905 |

|---|---|---|

| New York | 606,019 | 788,219 |

| Boston | 60,278 | 65,107 |

| Baltimore | 55,940 | 62,314 |

| Philadelphia | 19,467 | 23,824 |

| Honolulu | 9,054 | 11,997 |

| San Francisco | 9,036 | 6,377 |

| Other Ports | 22,702 | 24,447 |

| Through Canada | 30,374 | 44,214 |

The proportion for New York is not far from eight tenths of the whole. Hence it is true, that while the "dirty little ferryboat John G. Carlisle is not an imposing object to the material eye, to the eye of the imagination she is a spectacle to inspire awe, for she is the floating gateway of the[Pg 54] Republic. Over her dingy decks march in endless succession the eager battalions of Europe's peaceful invaders of the West. That single craft, in her hourly trips from Ellis Island to the Battery,[13] carries more immigrants in a year than came over in all the fleets of the nations in the two centuries after John Smith landed at Jamestown."[14]

Reading about the arrivals at Ellis Island, no matter how realistic the description, will not give a vivid idea of what immigration means nor of what sort the immigrants are. For that, you must obtain a permit from the authorities and actually see for yourself the human stream that pours from the steerage of the mighty steamships into the huge human storage reservoirs of Ellis Island.[15] We know that however perfect the system, human nature has to be taken into account, both in officials and immigrants, and human nature is imperfect; much of it at[Pg 55] Ellis Island is exceedingly difficult to deal patiently with. Hence, from the very nature of things and men, the situation is one to develop pathos, humor, comedy, and tragedy, as the great "human sifting machine" works away at separating the wheat from the chaff. The tragedy comes in the case of the excluded, since the blow falls sometimes between parents and children, husband and wife, lover and sweetheart, and the decree of exclusion is as bitter as death.

To make the manner and method of getting into America by the steerage process as real as possible, try to put yourself in an alien's place, and see what you would have to go through. Do not take immigration at its worst, but rather at its best, or at least above the average conditions. Assume that you belong to the more intelligent and desirable class, finding a legitimate reason for leaving your home in Europe, because of hard conditions and poor outlook there and bright visions of fortune in the land of liberty, whither relatives have preceded you. Your steamship ticket is bought in your native town, and you have no care concerning fare or baggage. A number of people of your race and neighborhood are on the way, so that you are not alone.

Before embarking you are made to answer a long list of questions, filling out your "manifest," or official record which the law requires[Pg 56] the vessel-masters to obtain, attest, and deliver to the government officers at the entrance port.[16]

Your answers proving satisfactory to the transportation agents, a card is furnished you, containing your name, the letter of the group of thirty to which you are assigned, and your group number. Thus you become, for the time being, No. 27 of group E. You are cautioned to keep this card in sight, as a ready means of identification.

Partings over, you enter upon the strange and unforgetable experiences of ten days or more in the necessarily cramped quarters of the steerage—experiences of a kind that do not invite repetition. Homesickness and seasickness form a trying combination, to say nothing of the discomforts of a mixed company and enforced companionship.

Your first American experience befalls you when the steamship anchors at quarantine inside[Pg 57] Sandy Hook, and the United States inspection officers come on board to hunt for infectious or contagious diseases—cholera, smallpox, typhus fever, yellow fever, or plague. No outbreak of any of these has marked the voyage, fortunately for you, and there is no long delay. Slowly the great vessel pushes its way up the harbor and the North River, passing the statue of Liberty Enlightening the World, that beacon which all incomers are enjoined to see as the symbol of the new liberty they hope to enjoy.

At last the voyage is done, your steamship lies at her pier, and you are thrust into the midst of distractions. Families are trying to keep together; the din is indescribable; crying babies add to the general confusion of tongues; all sorts of people with all sorts of baggage are making ready for the landing, which seems a long time off as you wait for the customs officers to get through with the first-class passengers. At last word is given to go ashore, and the procession or pushing movement rather begins. You are hurried along, up a companionway, lugging your hand baggage; then down the long gangway on to the pier and the soil of America.

It is not a pleasant landing in the land of light and liberty. You have been sworn at, pushed, punched with a stick for not moving faster when you could not, and have seen others treated much more roughly. Just in front of you[Pg 58] a poor woman is trying to get up the companionway with a child in one arm, a deck chair on the other, and a large bundle besides. She blocks the passage for an instant. A great burly steward reaches up, drags her down, tears the chair off her arm, splitting her sleeve and scraping the skin off her wrist as he does so, and then in his rage breaks the chair to pieces, while the woman passes on sobbing, not daring to remonstrate.[17] This is not the first treatment of this sort you have seen, and you feel powerless to help, though your blood boils at the outrage.

As you pass down the gangway your number is taken by an officer with a mechanical checker, and then you become part of the curious crowd gathered in the great somber building, filled with freight, much of it human. Here there is confusion worse confounded, as separated groups try to get together and dock watchmen try to keep them in place. Many believe their baggage has been stolen, and mothers are sure their children have been kidnaped or lost. The dockmen are violent, not hesitating to use their sticks, and you find yourself more than once in danger, although you strive to obey orders you do not understand very well, since they are shouted out in savage manner. The inspector reaches you finally, and you are hustled along in a throng to the barge that is waiting. You are tired and[Pg 59] hungry, having had no food since early breakfast. Your dreams of America seem far from reality just now. You are almost too weary to care what next.

The next is Ellis Island, whose great building looks inviting. Out of the barge you are swept with the crowd, baggage in hand or on head or shoulder, and on to the grand entrance. As you ascend the broad stairs, an officer familiar with many languages is shouting out, first in one tongue and then another, "Get your health tickets ready." You notice that the only available place many have in which to carry these tickets is in their mouths, since their hands are full of children or baggage.

(A) Entrance stairs; (B) Examination of health ticket; (C) Surgeon's examination; (D) Second surgeon's examination; (E) Group compartments; (F) Waiting for inspection; (G) Passage to the stairway; (H) Detention room; (I) The Inspectors' desks; (K) Outward passage to barge, ferry, or detention room.

At the head of the long pair of stairs you meet a uniformed officer (a doctor in the Marine Hospital Service), who takes your ticket, glances at it, and stamps it with the Ellis Island stamp. Counting the quarantine officer as number one, you have now passed officer number two. At the head of the stairs you find yourself in a great hall, divided into two equal parts, each part filled with curious railed-off compartments. Directed by an officer, you are turned into a narrow alleyway, and here you meet officer number three, in uniform like the second. The keen eyes of this doctor sweep you at a glance, from feet to head. You do not know it, but this is the first medical inspection by a surgeon of the Marine Hospital[Pg 60] Service, and it causes a halt, although only for a moment. When the person immediately in front of you reaches this doctor, you see that he pushes back the shawl worn over her head, gives a nod, and puts a chalk mark upon her. He is on the keen lookout for favus (contagious skin disease), and for signs of disease or deformity. The old man who limps along a little way behind you has a chalk mark put on his coat lapel, and you wonder why they do not chalk you.

You are now about ten or fifteen feet behind your front neighbor, and as you are motioned to follow, about thirty feet further on you confront another uniformed surgeon (officer number four), who has a towel hanging beside him, a small instrument in his hand, and a basin of disinfectants behind him. You have little time for wonder or dread. With a deft motion he applies the instrument to your eye and turns up the lid, quickly shutting it down again, then repeats the operation upon the other eye. He is looking for the dreaded contagious trachoma or for purulent ophthalmia; also for disease of any kind, or any defect that would make it lawful and wise to send you back whence you came. You have now been twice examined, and passed as to soundness of body, freedom from lameness or defect, general healthfulness, and absence of eye disease or pulmonary weakness.

As you move along to the inclosed space of[Pg 61] your group E, you note that the lame man and the woman who were chalk-marked are sent into another railed-off space, known as the "detention pen," where they must await a more rigid medical examination.The Wicket Gate One other inspector you have faced—a woman, whose sharp eyes seem to read the characters of the women as they come up to her "wicket gate;" for it is her duty to stop the suspicious and immoral characters and send them to the detention rooms or special inquiry boards. Thus you have passed five government officers since landing on the Island. They have been courteous and kindly, but impress you as knowing their business so well that they can readily see through fraud and deception.

The entrance ordeal is not quite over, but for a little while you rest on the wooden bench in your E compartment, waiting until the group is assembled, all save those sent away for detention. Suddenly you are told to come on, and in single file E group marches along the narrow railed alley that leads to officer number six, or the inspector who holds E sheet in his hand. When it comes your turn, your manifest is produced and you are asked a lot of questions. A combined interpreter and registry clerk is at hand to assist. The interpreter pleases you greatly by speaking in your own language, which he rightly guesses, and notes whether your answers agree with those on the manifest.[Pg 62]

As you have the good fortune to be honest, and have sufficient money to escape being halted as likely to become a public charge, you are ticketed "O. K." with an "R" which means that you are bound for a railroad station. You see a ticket "S. I." on the lame man, which means that he is to go to a Board of Special Inquiry, with the chances of being debarred, or sent back home. On another, as you pass, you notice a ticket "L. P. C.," which signifies the dreaded decision, "liable to become public charge"—a decision that means deportation.

All this time you have been guided. Now you are directed to a desk where your railroad ticket-order is stamped; next to a banker's desk, where your money is exchanged for American money; and finally you are motioned to the right stairway of three, this leading to the railroad barge room. Here your baggage is checked and your ticket provided, a bag of food is offered you, and then you are taken on board a barge which will convey you to the railroad station. You have left your fellow-voyagers abruptly, all save the railroad-ticketed like yourself. Had you been destined for New York, you would have gone down the left stairway and been free to take the ferryboat for the Battery. If you had expected friends to meet you, the central stairway would have led you to the waiting room for that purpose. Those three stairways are called "The[Pg 63] Stairs of Separation," and there families are sometimes ruthlessly separated without warning, when bound for different destinations.

The officers, who have treated you courteously, in strong contrast to the steamship and dock employees, keep track of you until you are safely on board an immigrant car, bound for the place where your relatives are. Your ideas of great New York are limited, but you have been saved by this official supervision from being swindled by sharpers or enticed into evil. You are practically in charge of the railway company, as you have been of the steamship company, until you are deposited at the station where you expect to make your home. You are ready to believe, by this time, that America is at least a spacious country, with room enough in it for all who want to come. At the same time you will admit, as you recall some of your fellow-passengers in the steerage, that there should not be room in the country for those who ought not to come—not only the diseased and insane, crippled and consumptive, who are shut out by the law, but also the delinquent and depraved, whose presence means added ignorance and crime. You only wish the inspectors could have seen some of those shameless men on shipboard, so that in spite of their smooth answers they might have been sent back whence they came, to prey upon the innocent there instead of here. Now that it is all[Pg 64] over, you shudder for a long time at night as memory recalls the steerage scenes, through which your faith in God and your constant prayers preserved you.[18]

In such manner the alien gains his chance to become an American. What he will make of that chance is a matter of grave importance to the land that has opened to him the doors of opportunity and liberty. Having seen how the immigrants get into the United States, let us now see how they are kept out. When we know what the restrictive laws are, and how they are enforced or evaded, we shall be in a position to judge as to their sufficiency, and the need of further legislation.

The United States has some excellent immigration laws, the best and most extensive of any nation, as one would expect, since this is the nation to which nearly all immigrants come. The trouble is that every attempt is made to evade these laws, and where they cannot be evaded they are violated. The laws are of two[Pg 65] classes: 1. Protective, in favor of the immigrant; and 2. Restrictive, in favor of the country.

There is a law against overcrowding on shipboard, going back as far as 1819, but overcrowding has gone on ever since.[19] There seems to be no doubt that even on the best steamships of the best lines there is ready disregard of the law when it interferes with the profits to be made out of the steerage. Strong evidence to this effect is given by Mr. Brandenburg. Here is a condensed leaf from his own experience which shows how much regard is paid to the comfort and health of the steerage passengers:[20]

"In a compartment from nine to ten feet high and having a space no larger than six ordinary rooms, were beds for 195 persons, and 214 women and children occupied them. The ventilation was merely what was to be had from the companionway that opened into the alleyway and not on the deck, the few ports in the ship's sides, and the scanty ventilating shafts. The beds were double-tiered affairs in blocks of from ten to twenty, constructed of iron framework, with iron slats in checker fashion to support the burlap-covered bag of straw, grass, or waste which served as a mattress. Pillows there were[Pg 66] none, only cork jacket life-preservers stuck under one end of the mattress to give the elevation of a pillow. One blanket served the purpose of all bedclothing; it was a mixture of wool, cotton, and jute, predominantly jute; the length of a man's body and a yard and a half wide. For such quarters and accommodations the emigrant pays half the sum that would buy a first-class passage. A comparison of the two classes shows where the steamship company makes the most money.

"Enrolled in the blanket each person found a fork, spoon, pint tin cup, and a flaring six-inch-wide, two-inch-deep pan out of which to eat. The passengers were instructed to form groups of six and choose a mess-manager, who was supposed to take the big pan and bucket, get the dinner and drinkables, and distribute the portions to his group. After the meal, some member was supposed to collect the tin utensils and wash them ready for next time. But the crowd in the wash-room was so great that about one third of the people chose to rinse off the things with a dash of drinking water, others never washed their cups and pans. Yet the emigrant pays half the first-cabin rate for fighting for his food, serving it himself, and washing his own dishes. The food was in its quality good, but the manner in which it was messed into one heap in the big pan was nothing short of nauseating. After the[Pg 67] first meal the emigrants began throwing the refuse on the deck instead of over the side or into the scuppers. The result can be imagined. It was an extremely hot night, and the air in the crowded compartment was so foul I could not sleep. The men and boys about me lay for the most part like logs, hats, coats, and shoes off, and no more, sleeping the sleep of the tired.

"My wife said the babies in her compartment were crying in relays of six, the women had scattered bits of macaroni, meat, and potatoes all over the beds and on the floor, and added dishwater as a final discomfort. Two thirds of the emigrants were as clean as circumstances would permit, but the other third kept all in a reign of uncleanliness. The worst could not be put into print. The remedy for the whole matter is to pack fewer people in the same ship's space, and a regular service at tables. The big emigrant-carriers should be forced to give up a part of their enormous profits in order that sanitary conditions at least may prevail."

This certainly is not an unreasonable demand, and proper laws with regard to the steerage rigidly enforced would tend to discourage immigration, instead of the reverse, since the rates would doubtless be raised as the numbers were lowered. Cruel treatment of the helpless aliens by the stewards and ship's officers should be stopped. Mr Brandenburg's description, which[Pg 68] by no means tells the whole story of steerage horrors, should serve to institute reform through the creation of a public sentiment that will demand it.Steerage Reforms Needed There is no other way to reach such conditions; and here is where the young people can exert their influence powerfully for good. Money greed should not be allowed to make the steerage a disgrace to Christian civilization and an offense to common decency. Of course it is difficult to detect what goes on in the hold of a great steamship, and when immigrants make complaint they frequently suffer for it. It is possible, however, to provide government inspectors, and inspectors who will inspect and remain proof against bribes. The one essential is a sufficiently strong and insistent public opinion.

The need of some regulation and restriction of immigration was felt early in our national life. The fathers of the Republic did not agree about the matter, and in this their descendants have been like them. Washington questioned the advisability of letting any more immigrants come, except those belonging to certain skilled trades that were needed to develop the new country. Madison favored a policy of liberality and inducement, so that population might increase more rapidly. Jefferson, on the other hand, wished "there were an ocean of fire between this[Pg 69] country and Europe, so that it might be impossible for any more immigrants to come hither." We can only conjecture what his thoughts would be if he were to return and study present conditions. Franklin, certainly one of the wisest and most far-seeing of the earlier statesmen, feared that immigration would tend to destroy the homogeneity essential to a democracy with ideals. Equally great and good men in our history have taken one or the other side of this question, from the extreme of open gates to that of prohibition, while the people generally have gone on about their business with the comfortable feeling that matters come out pretty well if they are not too much interfered with.

While statesmen were theorizing and differing, conditions made the need of some actual regulations and restrictions felt as early as 1824, although the total immigration of that year was only 7,912, or less than that of a single day at present. The first law resulted from abuse of free admission. It was found that some foreign governments were shipping their paupers, diseased persons, and criminals to America as the easiest and most economical way to get rid of them. This it undoubtedly was for them; but the people of New York did not see where the ease and economy came in on their side of the ledger, and in self-defense, therefore, the state passed the first law, with intent to shut out unde[Pg 70]sirables.[21] This state legislation was the genesis of national enactment. The history of federal laws concerning aliens is covered compactly by Mr. Hall, and those interested in the details of this important phase of the subject are referred to his book.[22] A comprehensive table, by means of which all the significant legislation can be seen at a glance, will be found in Appendix B.

In 1882 there came a tremendous wave of immigration, with effects upon the labor market that largely induced the passage in that year of the first general immigration law. The Federal Government now assumed entire control of the ports of entry, as it was manifestly essential to have a national policy and supervision. Since 1862, when the Chinese coolies were excluded, under popular pressure, Congress has passed eight Acts of more or less importance, culminating in the Act of 1903,[23] which is said by Mr. Whelpley, who has collected all the immigration laws of all countries, and is therefore competent[Pg 71] to judge, to be "up to the present time the most far-reaching measure of its kind in force in any country; and the principles underlying it must serve as the foundation for all immigration restriction." Under this law we have practically unrestricted immigration, with the important exceptions that the Chinese laborers are not admitted, and that persons suffering from obvious contagious diseases, insane persons, known anarchists and criminals, and a certain small percentage likely to become public charges are debarred. The law does not fix a property, income, or educational qualification, does not insist upon a knowledge of a trade, nor impose a tax. In other words, we have at present a more or less effective police regulation of immigration, but we are not pursuing a policy of restriction or limitation.