Title: The Attempted Assassination of ex-President Theodore Roosevelt

Author: Oliver E. Remey

Wheeler P. Bloodgood

Henry F. Cochems

Release date: April 30, 2007 [eBook #21261]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by V. L. Simpson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

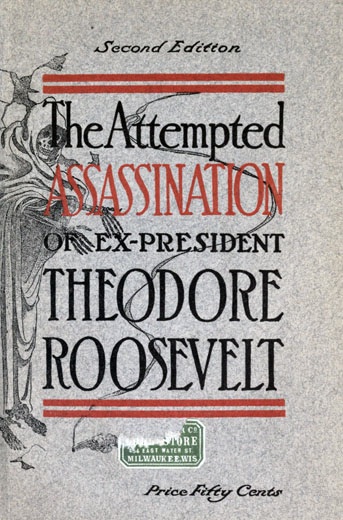

THEODORE ROOSEVELT.

LIBRARY EDITION.

A Library Edition of this book is in the hands of the printers and will be issued shortly.

This edition will be bound in hard cover. The volume will be neatly bound and suitable for public and private libraries.

The Library Edition will be limited in number.

Those who desire a copy will be mailed a copy as soon as the edition is off the press, if they will send one dollar to the Progressive Publishing Company of Milwaukee, Wis., Room 600 Caswell Block, Milwaukee.

The demand for this edition is rapidly exhausting it.

THIS HISTORICAL NARRATIVE

IS DEDICATED TO

EX-PRESIDENT THEODORE ROOSEVELT

THE GREATEST AMERICAN

OF HIS TIME.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| Page. | ||

| Preface | 9 | |

| Chronology | 11 | |

| Chapter I. | The Shot is Fired | 15 |

| Chapter II. | Speaks to Great Audience | 25 |

| Chapter III. | Roosevelt in the Emergency | 51 |

| Chapter IV. | Careful of Collar Buttons | 57 |

| Chapter V. | Arrival at Mercy Hospital | 64 |

| Chapter VI. | Gets Back into Campaign | 74 |

| Chapter VII. | Back at Sagamore Hill | 82 |

| Chapter VIII. | Arrest, Appears in Court | 91 |

| Chapter IX. | Appears in Municipal Court | 99 |

| Chapter X. | Schrank Declared Insane | 105 |

| Chapter XI. | Shows Repentance But Once | 112 |

| Chapter XII. | Schrank Before Chief | 117 |

| Chapter XIII. | Witnesses of the Shooting | 132 |

| Chapter XIV. | A Second Examination | 153 |

| Chapter XV. | Report of the Alienists | 192 |

| Chapter XVI. | Finding of the Alienists | 195 |

| Chapter XVII. | Schrank Describes Shooting | 202 |

| Chapter XVIII. | Conclusion of Commission | 208 |

| Chapter XIX. | Schrank Discusses Visions | 210 |

| Chapter XX. | Schrank's Defense | 213 |

| Chapter XXI. | Schrank's Unwritten Laws | 224 |

| Chapter XXII. | Unusual Court Precedent | 235 |

PREFACE.

At 8:10 o'clock on the night of Oct. 14, 1912, a shot was fired the echo of which swept around the entire world in thirty minutes.

An insane man attempted to end the life of the only living ex-president of the United States and the best known American.

The bullet failed of its mission.

Col. Theodore Roosevelt, carrying the leaden missile intended as a pellet of death in his right side, has recovered. He is spared for many more years of active service for his country.

John Flammang Schrank, the mad man who fired the shot, is in the Northern Hospital for the Insane at Oshkosh, Wis., pronounced by a commission of five alienists a paranoiac. If he recovers he will face trial for assault with intent to kill.

This little book presents an accurate story of the attempt upon the life of the ex-president. The aim of those who present it is that, being an accurate narrative, it shall be a contribution to the history of the United States.

This book is written, compiled and edited by Henry F. Cochems, Chairman of the national speakers' bureau of the Progressive party during the 1912 campaign, and who was with Col. Roosevelt in the automobile when the ex-president was shot, Wheeler P. Bloodgood, Wisconsin representative of the National Progressive committee, and Oliver E. Remey, city editor of the Milwaukee Free Press, who necessarily followed all incidents of the shooting closely.

The story told is an historical narrative in the preparation of which accuracy never has been lost sight of.

CHRONOLOGY.

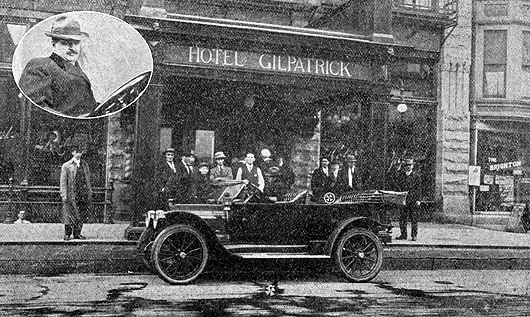

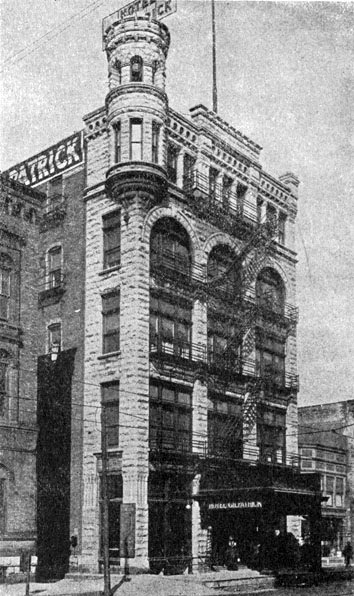

October 14, 1912—At 8:10 o'clock P.M., John Flammang Schrank, of New York, a paranoiac, shoots ex-President Theodore Roosevelt in the right side with a 38-caliber bullet as the ex-President is standing in an automobile in front of Hotel Gilpatrick, Milwaukee. Schrank is immediately arrested, after a struggle to recover the revolver and protect him from violence. Col. Roosevelt, bleeding from his wound, is driven to the Auditorium, Milwaukee, and speaks to an audience of 9,000 for eighty minutes. Immediately after his speech he is taken to the Johnston Emergency hospital, Milwaukee, where his wound is dressed. At 12:30 o'clock he is taken on a special train to Chicago, then to Mercy hospital.

October 15, 1912—Schrank is arraigned in District court, Milwaukee, and admits having fired the shot. He is bound over to Municipal court for preliminary hearing.

October 18, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt passes crisis in Mercy hospital, Chicago.

October 21, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt leaves Chicago for his home at Oyster Bay, R.I.

October 22, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt reaches home after a trip not seriously impairing his condition.

October 26, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt takes first walk out of doors.

October 27, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt celebrates his fifty-fourth birthday.

October 30, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt speaks to an audience of 16,000 in Madison Square Garden, New York, over 30,000 having been turned away. He is given an ovation lasting forty-five minutes.

November 1, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt again speaks to an audience filling Madison Square Garden. But for his request that it cease so that he could speak, the ovation would have exceeded that of October 30.

November 3, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt makes his last campaign speech at Oyster Bay, R.I.

November 5, 1912—Ex-President Roosevelt votes at Oyster Bay, R.I.

November 12, 1912—John Flammang Schrank pleads guilty to assault with intent to murder before Judge August C. Backus in Municipal court, Milwaukee. Judge Backus appoints a commission of five Milwaukee alienists to determine, as officers of the court, Schrank's sanity.

November 14, 1912—The sanity commission begins examinations of Schrank.

November 22, 1912—The sanity commission reports to Judge A. C. Backus in Municipal court, Milwaukee, that Schrank is insane and was insane at the time he shot ex-President Roosevelt. Schrank is committed to the Northern Hospital for the Insane at Oshkosh, Wis. Judge Backus in making the commitment orders that in the event of recovery Schrank shall face trial on the charge of assault with intent to kill.

November 25, 1912—Schrank is taken to the Northern Hospital for the Insane, Oshkosh, Wis., by deputies from the office of the sheriff of Milwaukee county.

CHAPTER I.

THE SHOT IS FIRED.

RELATED BY HENRY F. COCHEMS AFTER THE SHOOTING.

At 8:10 o'clock on the night of Oct. 14, 1912, an attempt was made to assassinate Ex-President Theodore Roosevelt in the city of Milwaukee. Col. Roosevelt had dined at the Hotel Gilpatrick with the immediate members of his traveling party. The time having arrived to leave for the Auditorium, where he was due to speak, he left his quarters, and, emerging from the front of the hotel, crossing the walk, stepped into a waiting automobile.

Instantly that he appeared a wild acclaim of applause and welcome greeted him. He settled in his seat, but, responsive to the persistent roar of the crowd, which extended in dense masses for over a block in every direction, he rose in acknowledgement, raising his hat in salute.

At this instant there cracked out the vicious report of a pistol shot, the flash of the gun showing that the would-be assassin had fired from a distance of only four or five feet.

Instantly there was a wild panic and confusion. Elbert E. Martin, one of Col. Roosevelt's stenographers, a powerful athlete and ex-football player, leaped across the machine and bore the would-be assassin to the ground. At the same moment Capt. A. O. Girard, a former Rough Rider and bodyguard of the ex-President, and several policemen were upon him. Col. Roosevelt's knees bent just a trifle, and his right hand reached forward on the door of the car tonneau. Then he straightened himself and reached back against the upholstered seat, but in the same instant he straightened himself, he again raised his hat, a reassuring smile upon his face, apparently the coolest and least excited of any one in the frenzied mob, who crowding in upon the man who fired the shot, continued to call out:

"Kill him, kill him."

I had stepped into the car beside Col. Roosevelt, about to take my seat when the shot was fired. Throwing my arm about the Colonel's waist, I asked him if he had been hit, and after Col. Roosevelt saying in an aside, "He pinked me, Harry," called out to those who were wildly tearing at the would-be assassin:

"Don't hurt him; bring him to me here!"

The sharp military tone of command was heard in the midst of the general uproar, and Martin, Girard and the policemen dragged Schrank toward where Mr. Roosevelt stood. Arriving at the side of the car, the revolver, grasped by three or four hands of men struggling for possession, was plainly visible, and I succeeded in grasping the barrel of the revolver, and finally in getting it from the possession of a detective. Mr. Martin says that Schrank still had his hands on the revolver at that time. The Colonel then said:

"Officers, take charge of him, and see that there is no violence done to him."

The crowd had quickly cleared from in front of the automobile, and we drove through, Col. Roosevelt waving a hand, the crowd now half-hysterical with frenzied excitement.

After rounding the corner I drew the revolver from my overcoat pocket and saw that it was a 38-caliber long which had been fired. As the Colonel looked at the revolver he said:

"A 38-Colt has an ugly drive."

Mr. McGrath, one of the Colonel's secretaries riding at his right side, said:

"Why, Colonel, you have a hole in your overcoat. He has shot you."

The Colonel said:

"I know it," and opened his overcoat, which disclosed his white linen, shirt, coat and vest saturated with blood. We all instantly implored and pleaded with the Colonel to drive with the automobile to a hospital, but he turned to me with a characteristic smile and said:

"I know I am good now; I don't know how long I may be. This may be my last talk in this cause to our people, and while I am good I am going to drive to the hall and deliver my speech."

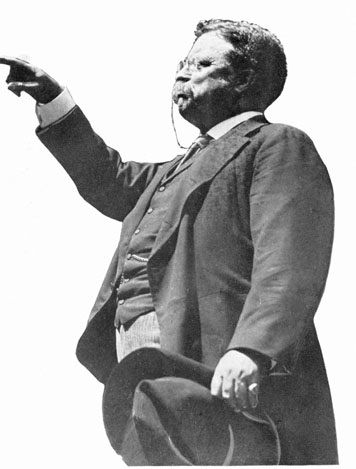

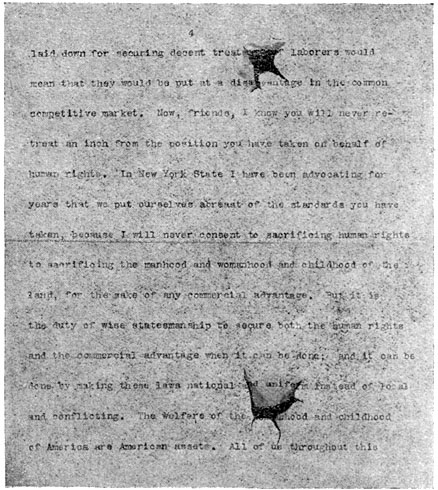

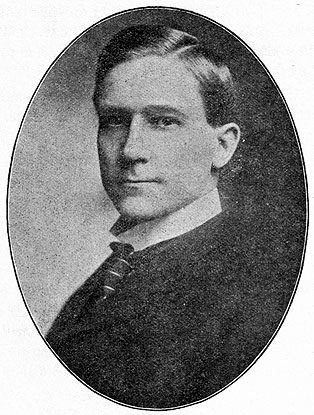

Shirts Worn by Ex-President Roosevelt

Showing Extent of Bleeding from Wound

While He Spoke to 9,000 People.

By the time we had arrived at the hall the shock had brought a pallor to his face. On alighting he walked firmly to the large waiting room in the back of the Auditorium stage, and there Doctors Sayle, Terrell and Stratton opened his shirt, exposing his right breast.

Just below the nipple of his right breast appeared a gaping hole. They insisted that under no consideration should he speak, but the Colonel asked:

"Has any one a clean handkerchief?"

Some one extending one, he placed it over the wound, buttoned up his clothes and said:

"Now, gentlemen, let's go in," and advanced to the front of the platform.

I, having been asked to present him to the audience, after admonishing the crowd that there was no occasion for undue excitement, said that an attempt to assassinate Col. Roosevelt had taken place; that the bullet was still in his body, and that he would attempt to make his speech as promised.

As the Colonel stepped forward, some one in the audience said audibly:

"Fake," whereupon the Colonel smilingly said:

"No, it's no fake," and opening his vest, the blood-red stain upon his linen was clearly visible.

A half-stifled expression of horror swept through the audience.

About the first remark uttered in the speech, as the Colonel grinned broadly at the audience, was:

"It takes more than one bullet to kill a Bull Moose. I'm all right, no occasion for any sympathy whatever, but I want to take this occasion within five minutes after having been shot to say some things to our people which I hope no one will question the profound sincerity of."

Throughout his speech, which continued for an hour and twenty minutes, the doctors and his immediate staff of friends, sitting closely behind him, expected that he might at any moment collapse. I was so persuaded of this that I stepped over the front of the high platform to the reporters' section immediately beneath where he was speaking, so that I might catch him if he fell forward.

These precautions, however, were unnecessary, for, while his speech lacked in the characteristic fluency of other speeches, while the shock and pain caused his argument to be somewhat labored, yet it was with a soldierly firmness and iron determination, which more than all things in Roosevelt's career discloses to the country the real Roosevelt, who at the close of his official service as President in 1909 left that high office the most beloved public figure in our history since Lincoln fell, and the most respected citizen of the world. As was said in an editorial in the Chicago Evening Post:

"There is no false sentiment here; there is no self-seeking. The guards are down. The soul of the man stands forth as it is. In the Valley of the Shadow his own simple declaration of his sincerity, his own revelation of the unselfish quality of his devotion to the greatest movement of his generation, will be the standard by which history will pass upon Theodore Roosevelt its final judgment. This much they cannot take from him, no matter whether he is now to live or to die."

To the men of America, who either love or hate Roosevelt personally, these words from his speech must carry an imperishable lesson:

"The bullet is in me now, so that I cannot make a very long speech. But I will try my best.

"And now, friends, I want to take advantage of this incident to say as solemn a word of warning as I know how to my fellow Americans.

"First of all, I want to say this about myself: I have altogether too many important things to think of to pay any heed or feel any concern over my own death.

"Now I would not speak to you insincerely within five minutes of being shot. I am telling you the literal truth when I say that my concern is for many other things. It is not in the least for my own life.

"I want you to understand that I am ahead of the game anyway. No man has had a happier life than I have had—a happier life in every way.

"I have been able to do certain things that I greatly wished to do, and I am interested in doing other things.

"I can tell you with absolute truthfulness that I am very much uninterested in whether I am shot or not.

"It was just as when I was colonel of my regiment. I always felt that a private was to be excused for feeling at times some pangs of anxiety about his personal safety, but I cannot understand a man fit to be a colonel who can pay any heed to his personal safety when he is occupied, as he ought to be occupied, with the absorbing desire to do his duty.

"I am in this cause with my whole heart and soul; I believe in the Progressive movement—a movement for the betterment of mankind, a movement for making life a little easier for all our people, a movement to try to take the burdens off the man and especially the woman in this country who is most oppressed.

"I am absorbed in the success of that movement. I feel uncommonly proud in belonging to that movement.

"Friends, I ask you now this evening to accept what I am saying as absolute truth when I tell you I am not thinking of my own success, I am not thinking of my own life or of anything connected with me personally."

The disabling of Col. Roosevelt at this tragic moment was a great strategic loss in his campaign. The mind of the country was in a pronounced state of indecision. He had started at Detroit, Mich., one week before and had planned to make a great series of sledge hammer speeches upon every vital issue in the campaign, which plan took him to the very close of the fight. He had planned to put his strongest opponent in a defensive position, the effect of which, now that all is over, no man can measure. Stricken down, an immeasurable loss was sustained. In the years that lie before, when misjudgment and misstatements, which are the petty things born of prejudice, and which die with the breath that gives them life, shall have passed away, this incident and the soldierly conduct of the brave man who was its victim will have a real chastening and wholesome historical significance.

Page from Ex-President Roosevelt's Manuscript of Speech Showing Bullet Holes.

CHAPTER II.

SPEAKS TO GREAT AUDIENCE.[1]

Standing with his coat and vest opened, holding before him manuscript of the speech he had prepared to deliver, through which were two perforations by Schrank's bullet, the ex-President was given an ovation which shook the mammoth Auditorium, Milwaukee.

The audience seemed unable to realize the truth of the statement of Henry F. Cochems, who had introduced Col. Roosevelt, that the ex-President had been shot. Col. Roosevelt had opened his vest to show blood from his wound.

Even then many in the audience did not comprehend that they were witnessing a scene destined to go down in history—an ex-President of the United States, blood still flowing from the bullet wound of a would-be assassin, delivering a speech from manuscript perforated by the bullet of the assailant.

Col. Roosevelt said:

"Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible," he said. "I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a bull moose. (Cheers.) But fortunately I had my manuscript, so you see I was going to make a long speech (holds up manuscript with bullet hole) and there is a bullet—there is where the bullet went through and it probably saved me from it going into my heart. The bullet is in me now, so that I can not make a very long speech, but I will try my best. (Cheers.)

"And now, friends, I want to take advantage of this incident and say a word of a solemn warning, as I know how to my fellow countrymen. First of all, I want to say this about myself: I have altogether too important things to think of to feel any concern over my own death, and now I can not speak to you insincerely within five minutes of being shot. I am telling you the literal truth when I say that my concern is for many other things. It is not in the least for my own life. I want you to understand that I am ahead of the game, anyway. (Applause and cheers.) No man has had a happier life than I have led; a happier life in every way. I have been able to do certain things that I greatly wished to do and I am interested in doing other things. I can tell you with absolute truthfulness that I am very much uninterested in whether I am shot or not. It was just as when I was colonel of my regiment. I always felt that a private was to be excused for feeling at times some pangs of anxiety about his personal safety, but I can not understand a man fit to be a colonel who can pay any heed to his personal safety when he is occupied as he ought to be occupied with the absorbing desire to do his duty. (Applause and cheers.)

"I am in this cause with my whole heart and soul. I believe that the progressive movement is for making life a little easier for all our people; a movement to try to take the burdens off the men and especially the women and children of this country. I am absorbed in the success of that movement.

"Friends, I ask you now this evening to accept what I am saying as absolutely true, when I tell you I am not thinking of my own success. I am not thinking of my life or of anything connected with me personally. I am thinking of the movement. I say this by way of introduction because I want to say something very serious to our people and especially to the newspapers. I don't know anything about who the man was who shot me tonight. He was seized at once by one of the stenographers in my party, Mr. Martin, and I suppose is now in the hands of the police. He shot to kill. He shot—the shot, the bullet went in here—I will show you (opened his vest and shows bloody stain in the right breast; stain covered the entire lower half of his shirt to the waist).

"I am going to ask you to be as quiet as possible for I am not able to give the challenge of the bull moose quite as loudly. Now I do not know who he was or what party he represented. He was a coward. He stood in the darkness in the crowd around the automobile and when they cheered me and I got up to bow, he stepped forward and shot me in the darkness.

"Now friends, of course, I do not know, as I say, anything about him, but it is a very natural thing that weak and vicious minds should be inflamed to acts of violence by the kind of awful mendacity and abuse that have been heaped upon me for the last three months by the papers in the interest of not only Mr. Debs but of Mr. Wilson and Mr. Taft. (Applause and cheers.)

"Friends, I will disown and repudiate any man of my party who attacks with such foul slander and abuse any opponent of any other party (applause) and now I wish to say seriously to all the daily newspapers, to the republican, the democratic and the socialist parties that they cannot month in and month out and year in and year out make the kind of untruthful, of bitter assault that they have made and not expect that brutal violent natures, or brutal and violent characters, especially when the brutality is accompanied by a not very strong mind; they cannot expect that such natures will be unaffected by it.

"Now friends, I am not speaking for myself at all. I give you my word, I do not care a rap about being shot not a rap. (Applause.)

"I have had a good many experiences in my time and this is one of them. What I care for is my country. (Applause and cheers.) I wish I were able to impress upon my people—our people, the duty to feel strongly but to speak the truth of their opponents. I say now, I have never said one word against any opponent that I can not—on the stump—that I can not defend. I have said nothing that I could not substantiate and nothing that I ought not to have said—nothing that I—nothing that looking back at I would not say again.

"Now friends, it ought not to be too much to ask that our opponents (speaking to some one on the stage) I am not sick at all. I am all right. I can not tell you of what infinitesimal importance I regard this incident as compared with the great issues at stake in this campaign and I ask it not for my sake, not the least in the world, but for the sake of our common country, that they make up their minds to speak only the truth, and not to use the kind of slander and mendacity which if taken seriously must incite weak and violent natures to crimes of violence. (Applause.) Don't you make any mistake. Don't you pity me. I am all right. I am all right and you can not escape listening to the speech either. (Laughter and applause.)

"And now, friends, this incident that has just occurred—this effort to assassinate me, emphasizes to a peculiar degree the need of this progressive movement. (Applause and cheers.) Friends, every good citizen ought to do everything in his or her power to prevent the coming of the day when we shall see in this country two recognized creeds fighting one another, when we shall see the creed of the 'Havenots' arraigned against the creed of the 'Haves.' When that day comes then such incidents as this tonight will be commonplace in our history. When you make poor men—when you permit the conditions to grow such that the poor man as such will be swayed by his sense of injury against the men who try to hold what they improperly have won, when that day comes, the most awful passions will be let loose and it will be an ill day for our country.

"Now, friends, what we who are in this movement are endeavoring to do is to forestall any such movement by making this a movement for justice now—a movement in which we ask all just men of generous hearts to join with the men who feel in their souls that lift upward which bids them refuse to be satisfied themselves while their fellow countrymen and countrywomen suffer from avoidable misery. Now, friends, what we progressives are trying to do is to enroll rich or poor, whatever their social or industrial position, to stand together for the most elementary rights of good citizenship, those elementary rights which are the foundation of good citizenship in this great republic of ours.

"My friends are a little more nervous than I am. Don't you waste any sympathy on me. I have had an A1 time in life and I am having it now.

"I never in my life had any movement in which I was able to serve with such wholehearted devotion as in this; in which I was able to feel as I do in this that common weal. I have fought for the good of our common country. (Applause.)

"And now, friends, I shall have to cut short much of the speech that I meant to give you, but I want to touch on just two or three of the points.

"In the first place, speaking to you here in Milwaukee, I wish to say that the progressive party is making its appeal to all our fellow citizens without any regard to their creed or to their birthplace. We do not regard as essential the way in which a man worships his God or as being affected by where he was born. We regard it as a matter of spirit and purpose. In New York, while I was police commissioner, the two men from whom I got the most assistance were Jacob Ries, who was born in Denmark and Oliver Van Briesen, who was born in Germany, both of them as fine examples of the best and highest American citizenship as you could find in any part of this country.

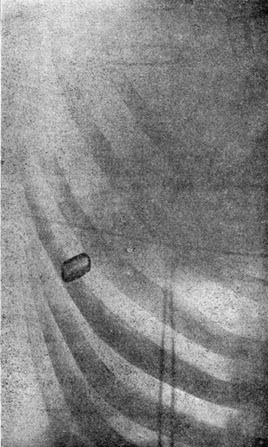

X-Ray Photograph Showing Bullet as it Remains in Theodore Roosevelt.

"I have just been introduced by one of your own men here, Henry Cochems. His grandfather, his father and that father's seven brothers all served in the United States army and they entered it four years after they had come to this country from Germany (applause). Two of them left their lives, spent their lives on the field of battle—I am all right—I am a little sore. Anybody has a right to be sore with a bullet in him. You would find that if I was in battle now I would be leading my men just the same. Just the same way I am going to make this speech.

"At one time I promoted five men for gallantry on the field of battle. Afterward it happened to be found in making some inquiries about that I found that it happened that two of them were Protestants, two Catholics and one a Jew. One Protestant came from Germany and one was born in Ireland. I did not promote them because of their religion. It just happened that way. If all five of them had been Jews, I would have promoted them, or if all five had been Protestants I would have promoted them; or if they had been Catholics. In that regiment I had a man born in Italy who distinguished himself by gallantry, there was a young fellow, a son of Polish parents, and another who came here when he was a child from Bohemia, who likewise distinguished themselves, and friends, I assure you, that I was incapable of considering any question whatever, but the worth of each individual as a fighting man. If he was a good fighting man, then I saw that Uncle Sam got the benefit from it. That is all. (Applause.)

"I make the same appeal in our citizenship. I ask in our civic life we in the same way pay heed only to the man's quality of citizenship to repudiate as the worst enemy that we can have whoever tries to get us to discriminate for or against any man because of his creed or his birthplace.

"Now, friends, in the same way I want our people to stand by one another without regard to differences or class or occupation. I have always stood by the labor unions. I am going to make one omission tonight. I have prepared my speech because Mr. Wilson had seen fit to attack me by showing up his record in comparison with mine. But I am not going to do that tonight. I am going to simply speak of what I myself have done and of what I think ought to be done in this country of ours. (Applause.)

"It is essential that there should be organizations of labor. This is an era of organization. Capital organizes and therefore labor must organize. (Applause.)

"My appeal for organized labor is twofold, to the outsider and the capitalist I make my appeal to treat the laborers fairly, to recognize the fact that he must organize, that there must be such organization, that it is unfair and unjust—that the laboring man must organize for his own protection and that it is the duty of the rest of us to help him and not hinder him in organizing. That is one-half of the appeal that I make.

"Now the other half is to the labor man himself. My appeal to him is to remember that as he wants justice, so he must do justice. I want every labor man, every labor leader, every organized union man to take the lead in denouncing crime or violence. (Applause.) I want them to take the lead (applause) in denouncing disorder and inciting riot, that in this country we shall proceed under the protection of our laws and with all respect to the laws and I want the labor men to feel in their turn that exactly as justice must be done them so they must do justice. That they must bear their duty as citizens, their duty to this great country of ours and that they must not rest content without unless they do that duty to the fullest degree. (Interruption.)

"I know these doctors when they get hold of me they will never let me go back and there are just a few things more that I want to say to you.

"And here I have got to make one comparison between Mr. Wilson and myself simply because he has invited it and I can not shrink from it.

"Mr. Wilson has seen fit to attack me, to say that I did not do much against the trusts when I was president. I have got two answers to make to that. In the first place what I did and then I want to compare what I did while I was president with what Mr. Wilson did not do while he was governor. (Applause and laughter.)

"When I took office as president"—(turning to stage) "How long have I talked?"

Answer: "Three-quarters of an hour."

"Well, I will take a quarter of an hour more. (Laughter and applause.) When I took office the anti-trust law was practically a dead letter and the interstate commerce law in as poor a condition. I had to revive both laws. I did. I enforced both. It will be easy enough to do now what I did then, but the reason that it is easy now is because I did it when it was hard. (Applause and cheers.)

"Nobody was doing anything. I found speedily that the interstate commerce law by being made more perfect could be a most useful instrument for helping solve some of our industrial problems with the anti-trust law. I speedily found that almost the only positive good achieved by such a successful lawsuit as the Northern Securities suit, for instance, was for establishing the principle that the government was supreme over the big corporation, but that by itself, or that law did not do—did not accomplish any of the things that we ought to have accomplished, and so I began to fight for the amendment of the law along the lines of the interstate commerce, and now we propose, we progressives, to establish an interstate commission having the same power over industrial concerns that the interstate commerce commission has over railroads, so that whenever there is in the future a decision rendered in such important matters as the recent suits against the Standard Oil, the sugar—no, not that—tobacco—the tobacco trust—we will have a commission which will see that the decree of the court is really made effective; that it is not made a merely nominal decree.

"Our opponents have said that we intend to legalize monopoly. Nonsense. They have legalized monopoly. At this moment the Standard Oil and Tobacco trust monopolies are legalized; they are being carried on under the decree of the Supreme Court. (Applause.)

"Our proposal is really to break up monopoly. Our proposal is to put in the law—to lay down certain requirements and then require the commerce commission—the industrial commission to see that the trusts live up to those requirements. Our opponents have spoken as if we were going to let the commission declare what the requirements should be. Not at all. We are going to put the requirements in the law and then see that the commission makes the trust. (Interruption.) You see they don't trust me. (Laughter.) That the commission requires them to obey that law.

"And now, friends, as Mr. Wilson has invited the comparison I only want to say this: Mr. Wilson has said that the states are the proper authorities to deal with the trusts. Well, about 80 per cent of the trusts are organized in New Jersey. The Standard Oil, the tobacco, the sugar, the beef, all those trusts are organized in New Jersey and Mr. Wilson—and the laws of New Jersey say that their charters can at any time be amended or repealed if they misbehave themselves and it gives the government—the laws give the government ample power to act about those laws and Mr. Wilson has been governor a year and nine months and he has not opened his lips. (Applause and cheers.) The chapter describing of what Mr. Wilson has done about the trusts in New Jersey would read precisely like a chapter describing the snakes in Ireland, which ran: 'There are no snakes in Ireland.' (Laughter and applause.) Mr. Wilson has done precisely and exactly nothing about the trusts.

"I tell you and I told you at the beginning I do not say anything on the stump that I do not believe. I do not say anything I do not know. Let any of Mr. Wilson's friends on Tuesday point out one thing or let Mr. Wilson point out one thing he has done about the trusts as governor of New Jersey. (Applause.)

"And now, friends, I want to say one special thing here——"

(Col. Roosevelt turned to the table upon the stage to reach for his manuscript, but found it in the hands of some one upon the stage. He demanded it back with the words: "Teach them not to grab," which provoked laughter.)

"And now, friends, there is one thing I want to say specially to you people here in Wisconsin. All that I have said so far is what I would say in any part of this union. I have a peculiar right to ask that in this great contest you men and women of Wisconsin shall stand with us. (Applause.) You have taken the lead in progressive movements here in Wisconsin. You have taught the rest of us to look to you for inspiration and leadership. Now, friends, you have made that movement here locally. You will be doing a dreadful injustice to yourselves; you will be doing a dreadful injustice to the rest of us throughout this union if you fail to stand with us now that we are making this national movement (applause) and what I am about to say now I want you to understand if I speak of Mr. Wilson I speak with no mind of bitterness. I merely want to discuss the difference of policy between the progressive and the democratic party and to ask you to think for yourselves which party you will follow. I will say that, friends, because the republican party is beaten. Nobody need to have any idea that anything can be done with the republican party. (Cheers and applause.)

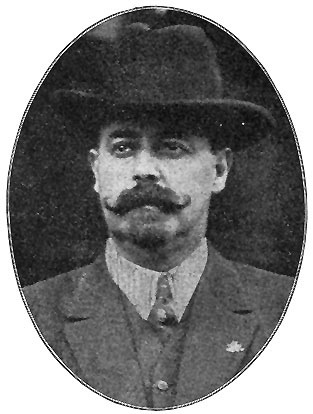

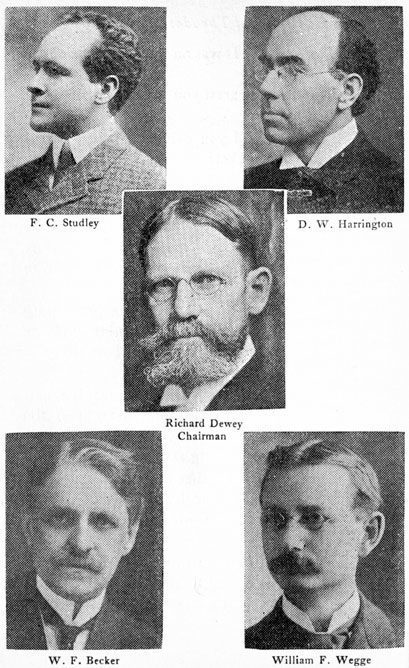

John Flammang Schrank.

"When the republican party—not the republican party—when the bosses in the control of the republican party, the Barneses and Penroses last June stole the nomination and wrecked the republican party for good and all. (Applause.) I want to point out to you, nominally, they stole that nomination from me, but really it was from you. (Applause.) They did not like me and the longer they live the less cause they will have to like me. (Applause and laughter.) But while they do not like me, they dread you. You are the people that they dread. They dread the people themselves, and those bosses and the big special interests behind them made up their mind that they would rather see the republican party wrecked than see it come under the control of the people themselves. So I am not dealing with the republican party. There are only two ways you can vote this year. You can be progressive or reactionary. Whether you vote republican or democratic it does not make any difference, you are voting reactionary." (Applause.)

Col. Roosevelt stopped to take a drink of water and the doctors remonstrated with him to stop talking, to which he replied: "It is getting to be better and better as time goes on. (Turning to the audience) If these doctors don't behave themselves I won't let them look at me at all." (Laughter and applause.)

"Now the democratic party in its platform and through the utterances of Mr. Wilson has distinctly committed itself to old flintlock, muzzle loaded doctrine of states right and I have said distinctly that we are for the people's right. We are for the rights of the people. If they can be obtained best through the national government, then we are for national rights. We are for the people's rights however it is necessary to secure them.

"Mr. Wilson has made a long essay against Senator Beveridge's bill to abolish child labor. It is the same kind of an argument that would be made against our bill to prohibit women from working more than eight hours a day in industry. It is the same kind of argument that would have to be made, if it is true, it would apply equally against our proposal to insist that in continuous industries there shall be by law one day's rest in seven and a three-shift eight hour day. You have labor laws here in Wisconsin, and any Chamber of Commerce will tell you that because of that fact there are industries that will not come into Wisconsin. They prefer to stay outside where they can work children of tender years; where they can work women fourteen and sixteen hours a day, where, if it is a continuous industry, they can work men twelve hours a day and seven days a week.

"Now, friends, I know that you of Wisconsin would never repeal those laws even if they are to your commercial hurt, just as I am trying to get New York to adopt such laws even though it will be to New York's commercial hurt. But if possible, I want to arrange it so that we can have justice without commercial hurt, and you can only get that if you have justice enforced nationally. You won't be burdened in Wisconsin with industries not coming to the state if the same good laws are extended all over the other states. (Applause.) Do you see what I mean? The states all compete in a common market and it is not justice to the employers of a state that has enforced just and proper laws to have them exposed to the competition of another state where no such laws are enforced. Now the democratic platform, their speaker declares that we shall not have such laws. Mr. Wilson has distinctly declared that you shall not have a national law to prohibit the labor of children, to prohibit child labor. He has distinctly declared that we shall not have law to establish a minimum wage for women.

"I ask you to look at our declaration and hear and read our platform about social and industrial justice and then, friends, vote for the progressive ticket without regard to me, without regard to my personality, for only by voting for that platform can you be true to the cause of progress throughout this union." (Applause.)

All through his talk, it was evident that his physicians feared his injury had been more serious than he was willing to admit. That a man with a bullet embedded in his body could stand up there and insist on giving the audience the speech which they had come to hear was almost incredible and it was plain the physicians as well as the other friends of the colonel on the stage were greatly alarmed.

Col. Roosevelt, however, would have none of it. "Sit down, sit down," he said to those who, when he faltered once or twice, half rose to come towards him. He insisted that he was having a good time in spite of his injury.

Finally a motherly looking woman, a few rows of seats back from the stage rose and said, "Mr. Roosevelt, we all wish you would be seated."

To this the colonel quickly replied: "I thank you, madam, but I don't mind it a bit."

To those on the stage, who wished he would adopt the suggestion of being seated, he said: "Good gracious if you saw me in the saddle at the head of my troops with a bullet in me you would not mind."

The only time Col. Roosevelt gave up and took a seat was when he came to a quotation from La Follette's weekly which paid him a tribute of praise for his work as president. This was read by Assemblyman T. J. Mahon, while the colonel rested.

At the conclusion of the reading Col. Roosevelt said that he was the same man now that he was then. He had not been president since 1909 so that what he was described as being then he was now.

T. J. Mahon read this editorial from La Follette's magazine of March 13, 1909:

"Roosevelt steps from the stage gracefully. He has ruled his party to a large extent against its will. He has played a large part of the world's work for the past seven years. The activities of his remarkably forceful personality have been so manifold that it will be long before his true rating will be fixed in the opinion of the race. He is said to think that the three great things done by him are the undertaking of the construction of the Panama canal and its rapid and successful carrying forward, the making of peace between Russia and Japan, and the sending around the world of the fleet.

"These are important things but many will be slow to think them his great services. The Panama canal will surely serve mankind when in operation; and the manner of organizing this work seems to be fine. But no one can yet say whether this project will be a gigantic success or a gigantic failure; and the task is one which must in the nature of things have been undertaken and carried through some time soon, as historic periods go, anyhow. The peace of Portsmouth was a great thing to be responsible for, and Roosevelt's good offices undoubtedly saved a great and bloody battle in Manchuria. But the war was fought out, and the parties ready to quit, and there is reason to think that it is only when this situation was arrived at that the good offices of the President of the United States were, more or less indirectly, invited. The fleet's cruise was a strong piece of diplomacy, by which we informed Japan that we will send our fleet wherever we please and whenever we please. It worked out well.

"But none of these things, it will seem to many, can compare with some of Roosevelt's other achievements. Perhaps he is loath to take credit as a reformer, for he is prone to spell the word with question marks, and to speak despairingly of 'reform.'

"But for all that, this contention of 'reformers' made reform respectable in the United States, and this rebuke of 'muck-rakers' has been the chief agent in making the history of 'muck-raking' in the United States a national one, conceded to be useful. He has preached from the White House many doctrines; but among them he has left impressed on the American mind the one great truth of economic justice couched in the pithy and stinging phrase 'the square deal.' The task of making reform respectable in a commercialized world, and of giving the national a slogan in a phrase, is greater than the man who performed it is likely to think.

"And, then, there is the great and statesmanlike movement for the conservation of our national resources, into which Roosevelt so energetically threw himself at a time when the nation as a whole knew not that we are ruining and bankrupting ourselves as fast as we can. This is probably the greatest thing Roosevelt did, undoubtedly. This globe is the capital stock of the race. It is just so much coal and oil and gas. This may be economized or wasted. This same thing is true of phosphates and other mineral resources. Our water resources are immense, and we are only just beginning to use them. Our forests have been destroyed; they must be restored. Our soils are being depleted; they must be built up and conserved.

"These questions are not of this day only, or of this generation. They belong all to the future. Their consideration requires that high moral tone which regards the earth as the home of a posterity to whom we owe a sacred duty.

"This immense idea, Roosevelt, with high statesmanship, dinned into the ears of the nation until the nation heeded. He held it so high that it attracted the attention of the neighboring nations of the continent, and will so spread and intensify that we will soon see world's conferences devoted to it.

"Nothing can be greater or finer than this. It is so great and so fine that when the historian of the future shall speak of Theodore Roosevelt, he is likely to say that he did many notable things, among them that of inaugurating the movement which finally resulted in the square deal, but that his greatest work was inspiring and actually beginning a world movement for staying terrestrial waste and saving for the human race the things upon which, and upon which alone, a great and peaceful and progressive and happy race life can be founded.

"What statesman in all history has done anything calling for so wide a view and for a purpose more lofty?"

1 (Return)

Stenographic Report from The Milwaukee Sentinel.

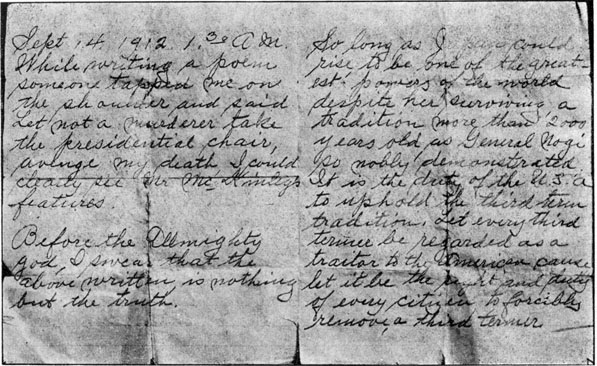

Page One of Letter Found in Schrank's Pocket.

CHAPTER III.

ROOSEVELT IN THE EMERGENCY.

After Colonel Roosevelt had finished speaking at the Auditorium, the effect of the shock and loss of blood from the shot, was quite manifest in his appearance. Despite this fact, however, he walked with firm step to an automobile waiting at the rear of the big hall, and guarded by a group of friends, was driven rapidly to the Johnston Emergency hospital. Preparation had there been made for a careful examination and for treatment by Dr. Scurry L. Terrell, who attended Col. Roosevelt during his entire trip, Dr. R. G. Sayle and Dr. T. A. Stratton, both of Milwaukee.

At the hospital, Dr. Joseph Colt Bloodgood, a surgeon of the faculty of Johns-Hopkins university, was invited into the consultation. The Colonel's first thought had been to reassure Mrs. Roosevelt and family against any unnecessary fear, and before he received treatment, he sent a long reassuring telegram, together with a telegram to Seth Bullock, whose telegram was one of the first of the stream of telegrams which began pouring in for news of the patient's condition.

During the preliminary examination of the wound by the doctors in the Johnston Emergency hospital, preparations were completed to secure X-ray pictures under the direction of Dr. J. S. Janssen, Roentgenologist, Milwaukee. Dr. Janssen secured his views and left for his laboratory to develop the negatives.

While these negatives were being secured, it was determined by the doctors that no great additional danger would be incurred if Col. Roosevelt were moved to a train, and by special train to Chicago, which plan he had proposed, so that he might be nearer to the center of his fight. He was moved by ambulance to the train, which left Milwaukee shortly after midnight.

In the meantime, the completion of the X-ray pictures disclosed the fact that the bullet laid between the fourth and fifth ribs, three and one-half inches from the surface of the chest, on the right side, and later examinations disclosed that it had shattered the fourth rib somewhat, and was separated by only a delicate tissue from the pleural cavity.

By a miracle it had spent its force, for had it entered slightly farther, it would almost to a certainty have ended Col. Roosevelt's life.

Upon Dr. Janssen's report of the location of the bullet, there was a period of indecision, during which the train waited, before the surgeons concluded that the patient might be taken to Chicago, despite the deep nature of the wound, without seriously impairing his chances.

Arriving at Chicago about 3 in the morning of October 15, an ambulance was procured and the Colonel taken to Mercy hospital, where he was attended by Dr. John B. Murphy, Dr. Arthur Dean Bevan and Dr. S. L. Terrell.

A week later, during which the surgeons concluded that the wound was not mortal, and having recovered his strength somewhat, he was taken East to his home at Oyster Bay.

The bullet lies where it imbedded itself. It has not been disturbed by probes, because surgeons have concluded that such an effort would incur additional danger.

That the shot fired by Schrank didn't succeed in murdering Col. Roosevelt is a miracle of good fortune. A "thirty-eight" long Colt's cartridge, fired from a pistol frame of "forty-four" caliber design, so built because it gives a heavier drive to the projectile, fired at that close range, meant almost inevitable death.

The aim was taken at a lower portion of Col. Roosevelt's body, but a bystander struck Schrank's arm at the moment of explosion, and elevated the direction of the shot. After passing through the Colonel's heavy military overcoat, and his other clothing, it would have certainly killed him had it not struck in its course practically everything which he carried on his person which could impede its force.

In his coat pocket he had fifty pages of manuscript for the night's speech, which had been doubled, causing the bullet to traverse a hundred pages of manuscript.

It had struck also his spectacle case on the outer concave surface of the gun metal material of which the case was constructed. It had passed through a double fold of his heavy suspenders before reaching his body.

Had anyone of those objects been out of the range of the bullet, Schrank's dastardly purpose would have been accomplished beyond any conjecture.

Just before he went to the operating room in the Emergency hospital Col. Roosevelt directed the following telegram to Mrs. Roosevelt and gave orders that if the telegraph office at Oyster Bay was closed the message should be taken to Sagamore Hill by taxicab.

"Am in excellent shape, made an hour and half speech. The wound is a trivial one. I think they will find that it merely glanced on a rib and went somewhere into a cavity of the body; it certainly did not touch a lung and isn't a particle more serious than one of the injuries any of the boys used continually to be having. Am at the Emergency hospital at the moment, but anticipate going right on with my engagements. My voice seems to be in good shape. Best love to Ethel.

"Theodore Roosevelt."

The first bulletin issued by surgeons at the Johnston Emergency hospital was:

"The bleeding was insignificant and the wound was immediately cleansed, externally and dressed with sterile gauze by R. G. Sayle, of Milwaukee, consulting surgeon of the Emergency hospital. As the bullet passed through Col. Roosevelt's clothes, doubled manuscript and metal spectacle case, its force was much diminished. The appearance of the wound also presented evidence of a much bent bullet. The colonel is not suffering from shock and is in no pain. His condition was so good that the surgeons did not object to his continuing his journey in his private car to Chicago where he will be placed under surgical care."

(Signed)

"Dr. S. L. Terrell.

"Dr. R. G. Sayle.

"Dr. Joseph Colt Bloodgood,

of the faculty of Johns-Hopkins University.

"Dr. T. A. Stratton."

The following bulletin was issued just before Col. Roosevelt was taken to the special train which carried him to Chicago:

"Col. Roosevelt has a superficial flesh wound below the right breast with no evidence of injury to the lung.

"The bullet is probably lodged somewhere in the chest walls, because there is but one wound and no signs of any injury to the lung.

"His condition was so good that the surgeons did not try to locate the bullet, nor did they try to probe for it."

"Dr. S. L. Terrell.

"Dr. R. G. Sayle."

CHAPTER IV.

CAREFUL OF COLLAR BUTTONS.

Miss Regine White, Superintendent of the Johnston Emergency Hospital, cut the gory shirts from Colonel Roosevelt and, after he had been attended by surgeons, tied the hospital shirt, with "Johnston Emergency Hospital" emblazoned across the front, about him.

Miss White, describing the ex-President's stay in the hospital, said:

"Col. Roosevelt is the most unusual patient who ever was ministered to in the Johnston Emergency Hospital, in that he was absolutely calm and unperturbed, and influenced every one about him to be so, although excitement and unrest were in the very atmosphere, and he was suffering much.

"Col. Roosevelt had not been in the hospital fifteen minutes before every one he came in contact with was willing to swear allegiance to the Bull Moose party, and personal allegiance to, the genial Bull Moose himself. He was so friendly and cordial, so natural and free, so happy and genial and so inclined to 'jolly' us all that we felt on terms of intimate friendship with him almost immediately, and yet through all this freedom of manner he maintained a dignity that never for an instant let us forget we were in the presence of a great man.

"It is almost unbelievable that he could have been as unruffled and apparently unconcerned as he was when he really was suffering, and when he did not know how serious the wound was."

"GOD HELP POOR FOOL."

"I asked the colonel how he felt about the prosecution of the man who shot him," said Miss White, "and he said, 'I've not decided yet, but God help the poor fool under any circumstances!' and the tone he used was one of kindly sympathy and sincerity, and without one trace of malice or sarcasm.

"He seemed kindly interested in everything that any one said to him. Miss Elvine Kucko, one of our nurses, shook hands with him when he was about to go and said she was sorry the shooting had happened in our city. The colonel consoled her by saying it might have happened anywhere. I broke in with a remark to the effect that he would have felt even worse had it been perpetrated by a Milwaukeean, and that we were glad it was a New Yorker who did the deed.

"'You cruel little woman!' the patient ejaculated, and I remembered then that New York was the ex-President's state."

When he was ready to go, Miss White offered him a sealed envelope and told him his cuff buttons, shirt studs and collar buttons were in it.

"No, you can't do that with me," he said, "I want to see! I don't intend to get down to Chicago without the flat button for the back of my collar."

Miss White joined him in a laugh as she pulled open the envelope and counted each one separately into his hand. That flat bone button that he treasured hid itself under one of the others and he had to have a second count before he was satisfied that he was not going to be inconvenienced by its loss when he should next care to wear a collar.

Doctors and nurses questioned the ex-President's coat being warm enough, but he assured them that the coat was one he had worn in the Spanish-American war, that it was of military make and would keep him warm enough in a steam-heated Pullman.

When the bandages were being strapped on the colonel's chest to keep the dressing in place, one of the doctors, Fred Stratton, a young giant, didn't put one fold as Miss White thought it ought to be. She ordered it put right, and the colonel began to laugh, which isn't to be wondered at when one remembers that Miss White is a tiny, wee bit of fluffy humanity who doesn't look a bit like what one would expect, the superintendent of a big hospital and looked a pigmy beside the big doctor.

Page Two of Letter Found in Schrank's Pocket.

"That's nothing," said Dr. R. G. Sayle, "she's been bossing us doctors for the past twenty years!"

"Oh, please—not quite that long——" began Miss White.

"Well, we'll knock off two and make it eighteen," the colonel interposed.

When the wound was dressed doctors and nurses tried to persuade the patient to remain over night, but without success.

"I know if Mrs. Roosevelt were here she would insist upon your staying," Miss White said.

"Young woman, if Mrs. Roosevelt were here I am certain she would insist upon my leaving immediately," her husband made reply, and gazed at the four pretty nurses surrounding him.

When the patient was brought up the elevator and led into the "preparation" room, the first thing to do was to prepare him for care of his wound. Miss White took his eye glasses. The Colonel objected and said he did not want those out of his sight. But when Miss White assured him she would give the glasses her personal attention he seemed content with the arrangement.

One of the physicians asked for a chair for Col. Roosevelt. Miss White said the operating table was ready, and the colonel immediately acquiesced and laid down on the carefully scrubbed pine slab on an iron frame, which has carried the weight of tramps, laborers and other unfortunates picked up in the street, but never before that of an ex-President of the United States.

Miss White was a little diffident about exposing the fact that the president had said a swear word, but she finally admitted that he remarked:

"I don't care a d——n about finding the bullet but I do hope they'll fix it up so I need not continue to suffer."

The doctors washed the wound area, painted it with iodine, itself a somewhat painful operation, and proceeded to the dressing.

One of the doctors told Col. Roosevelt that Miss White was a suffragist, and that after his kind treatment he ought to be converted. Miss White said the Big Bull Moose was a suffragist and that was one of the big planks of his party and the colonel laughed and said of course he believed in it.

When the party left for Chicago Dr. R. G. Sayle took with his antisepticized surgeon's gloves, surgical dressing and instruments to be used in case of hemorrhage before Chicago was reached.

Not a souvenir of the ex-President's visit remains in the hospital. His shirt was turned over to the police, and a blood-soaked handkerchief which was bound upon the wound, and which was picked up by one of the nurses, was found to have an "S" in the corner, so it was evident that it either did not belong to the ex-President or he had not always owned it, and this was discarded.

The Mercy Hospital nurses were appreciative of Col. Roosevelt.

"He was the best patient I ever had," said Miss Welter, and the sentiment was endorsed by Miss Fitzgerald.

"He was consideration itself. He never had a word of complaint all the time he was at the hospital, and his chief worry seemed to be that we were not comfortable. We had expected to find him 'strenuous' and possibly disagreeable. On the contrary, we found him most docile. He chafed at being kept in bed, but he tried not to show it, and he never was ill-humored or peevish, as many patients in a similar position are."

CHAPTER V.

ARRIVAL AT MERCY HOSPITAL.

Arriving at Mercy Hospital, Chicago, Col. Roosevelt was given further examination on October 15. Several bulletins of his condition were issued. The last official bulletin given out by his staff physicians, J. B. Murphy, A. D. Bevan and Scurry L. Terrell, showed a most favorable condition.

Mrs. Roosevelt reached Chicago with her son Theodore and her daughter Ethel, was driven directly to Mercy Hospital and took charge of her husband as soon as she had greeted him. She was quite composed on her arrival and placidly directed affairs all through. As a result of her presence, the colonel's visiting list was materially cut down, he devoted less time to reading telegrams, and discussed the campaign very little.

Part of the morning he spent in reading cablegrams of sympathy and congratulation on his escape from Emperor William, King George, the President of France, the King of Italy, the King of Spain, the President of Portugal and the Crown Prince and Princess of Germany.

Among his few callers were Col. Cecil Lyon, Medill McCormick, Dr. Alexander Lambert, his family physician, who accompanied Mrs. Roosevelt to Chicago, Dr. Evans of Chicago and Dr. Woods-Hutchinson, a writer on medical topics, a warm personal friend.

As soon as he saw Dr. Lambert the colonel said:

"Lambert, you'd have let me finish that speech if you'd been there after I was shot, wouldn't you?"

"Perhaps so," returned the doctor, a little dubiously, "but I should have made sure you were not seriously hurt first."

Before Mrs. Roosevelt arrived the colonel was insistent that he be allowed to go to Oyster Bay shortly. After a talk with Mrs. Roosevelt, he said he would leave that question to her.

"It will probably be ten days at least before we go," she said. "It is too far distant to attempt a prophecy."

A more careful examination of the X-ray photographs taken of the patient disclosed the fact that his fourth rib was slightly splintered by the impact of the bullet lodged against it. This accounted for the discomfort that the colonel suffered.

Mrs. Roosevelt was insistent on taking her husband home at the earliest moment consistent with safety.

The colonel passed an easy day. He continued to exhibit the utmost indifference to the motives of Schrank, who sought his life. "His name might be Czolgosz or anything else as far as I am concerned," he said to one of his visitors. "I never heard of him before and know nothing about him."

To another friend he expressed the opinion that the man was a maniac afflicted with a paranoia on the subject of the third term. He showed no curiosity about him and did not discuss him, although he talked considerably about the shooting.

"You know," he said to Dr. Murphy, "I have done a lot of hunting and I know that a thirty-eight caliber pistol slug fired at any range will not kill a bull moose."

Before he went to sleep, Col. Roosevelt called for hot water and a mirror and sitting in bed, carefully shaved himself. Mrs. Roosevelt, tired out after her long journey, also retired early, at 10 o'clock.

The following bulletin, issued by the surgeons on the morning of October 15, described the wound inflicted by Schrank's bullet:

"Col. Roosevelt's hurt is a deep bullet wound of the chest wall without striking any vital organ in transit. The wound was not probed. The point of entrance was to the right of and one inch below the level of the right nipple. The range of the bullet was upward and inward, a distance of four inches, deeply in the chest wall. There was no evidence of the bullet penetrating into the lung. Pulse, 90; temperature, 99.2; respiration, 20; leucocyte count, .82 at 10 a.m. No operation to remove bullet is indicated at the present time. Condition hopeful, but wound so important as to demand absolute rest for a number of days."

(Signed)

"Dr. John B. Murphy.

"Dr. Arthur B. Bevan.

"Dr. Scurry L. Terrell.

"Dr. R. G. Sayle."

The arrival of Col. Roosevelt in Mercy Hospital, Chicago, was described by John B. Pratt, of the International News service, a correspondent traveling with the ex-President during the campaign, as follows:

"Any way, if I had to die, I wanted to die with my boots on." Lying on a hospital bed completely filled by his great bulk, Theodore Roosevelt made this answer to a question by Dr. Terrell.

He had just talked with the newspaper men who were with his party enroute. Terrell, coming in at the conclusion of the conversation, expressed the fear that the ex-President was exerting himself beyond his strength.

"You do too much," said Terrell. "The most uncomfortable hour I ever spent in my life was while I sat on that platform in Milwaukee wondering where that bullet was and in how imminent danger you were. How could you be so incautious as to make a speech then? It was all very well for you to say the shot was not fatal but how could you tell?"

The colonel grinned, raised his arm heavily, trying not to show the pain that came with every movement.

"I did not think the wound was dangerous," he said. "I was confident that it was not in a place where much harm could follow and therefore I wished to make the speech. Anyway, even if it went against me—well, if I had to die—" and the colonel chuckled grimly, "I thought I'd rather die with my boots on."

The newspaper men who were with him when out of the darkness came the bullet that still menaces his life, felt that in that sentence he had epitomized his unfaltering courage. Never once since has he wavered in courage. Physically overcome he once sank back, and came as near to fainting as so strong a man can. All the rest of the time he has been as serene as a man unhurt.

It was in the gray of this morning's daylight that we caught our first glimpse of him after the shooting. Standing in the corridor of his private car as it lay in the North-Western station in Chicago, we heard Dr. Terrell say:

"Now is a chance to see the old warrior, he is coming out."

The door of his state room creaked and swung open slowly. As it swung back within loomed the figure that attracts attention everywhere. The colonel stepped out slowly, his shoulders thrown back and his bearing soldierly. He stretched out two fingers to one of the party.

"Ah, old comrade," he said, "shake. The newspaper boys are my friends," he added, as he proceeded toward the door of the car. "I'm glad to see them."

"You had a pretty rough time last night, colonel," suggested somebody.

"We did have a middling lively time, didn't we?" said the colonel with a broad grin.

"Pretty plucky of you," said another man. "Everybody agrees to that."

"Fiddlesticks," and the colonel stepped out on the platform and down the steps.

He had indignantly refused a stretcher and even balked at an ambulance, but finally agreed that this was the best means of conveyance to the hospital.

He walked past a silent crowd, a crowd that wanted to cheer, but did not dare, but stood, without a smile as he went by. To them all he waved a hand. Just as he was leaving the steps a flashlight flared forth, the sharp report of the powder startling everybody.

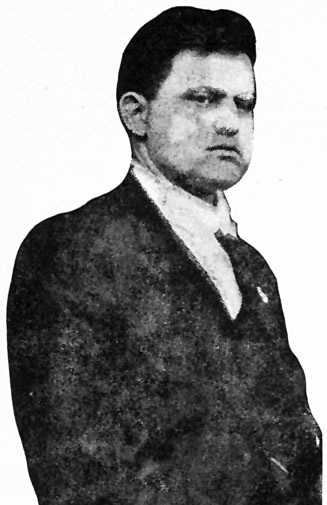

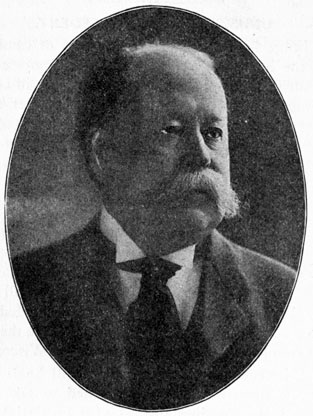

Capt. A. O. Girard.

"Ah, shot again," said the colonel, without a tremor.

Before climbing into the ambulance he turned to the newspaper men who had come out to see him off.

"I want to see you newspaper men at the hospital at 3 o'clock. I want all the old guard there." Then he started up the steps of the automobile conveyance with a firm step and tried to seat himself firmly on the cushion. But he had counted on more strength than he possessed. With a smothered exclamation he sank back among them, his head dropping and his figure one of pathetic helplessness.

At 3 o'clock he welcomed the newspaper men sitting up in bed with his massive chest hidden beneath an undershirt.

"I came away in too big a hurry to get my pajamas," he explained, apologetically.

"Here they are, bless their hearts. They never desert me," the colonel cried, as the visitors were ushered in.

His face had lost the gray of the early morning and resumed its normal tint. He never looked better and certainly never looked larger. He filled the narrow hospital cot completely, from side to side, and from end to end.

Two beautiful rooms had been secured for him at Mercy Hospital, one of the biggest and finest institutions in the west. The four windows of the sick room faced two on Calumet avenue and two on Twenty-sixth street, in a quiet part of town, away from the smoke and the roar of the elevated trains. To make the air more salubrious an oxygen apparatus had been placed in the room, which liberated just enough gas to make the air fresh and to give it an autumn twang.

In response to a question as to how he felt, he replied with a laugh: "I feel as well as a man feels who has a bullet in him."

"But haven't you any pain?" asked someone.

"Well," the colonel said, dryly, "A man with a bullet in him is lucky if he doesn't experience a little pain."

Here Dr. Terrell, always on watch, held up a warning hand.

"You must not talk much," he said.

"I'll boss this job," said Roosevelt. "You go away and let me do this thing."

Just then the door opened to admit Elbert E. Martin, the herculean stenographer who had grabbed Schrank before he could fire a second shot.

"Here he is," cried the colonel, waving his hand, "here is the man that did it."

Martin had brought a lot of telegrams. The colonel, lying partly propped up adjusted the great tortoise shell glasses and proceeded to look them over. With one of them he seemed especially pleased. It came from Madison, Wis., and was as follows:

"Permit me to express my profound regret that your life should have been in peril and to express my congratulations upon your fortunate escape from serious injury. I trust that you will speedily recover.

(Signed)

"Robert M. La Follette."

"Let me see that again," he said, after turning it back to Martin. When he had read it a second time he said: "Here, take this," and dictated:

"Senator Robert M. La Follette—Thanks sincerely for your kind expressions of sympathy."

Half an hour the colonel spent looking over and answering private telegrams, dictating always in a clear, strong voice. When he had done he talked with the newspaper men of former experiences of the kind he had just gone through and of cranks at Sagamore Hill and at the White House.

"But I never had a bullet in me before," he said.

CHAPTER VI.

GETS BACK INTO CAMPAIGN.

October 17, convinced that he was beyond all possible danger, Col. Roosevelt resumed the active campaign from his sick room in Mercy Hospital by dictating a statement in which he requested his political opponents to continue the fight as if nothing had happened to him.

The colonel awoke feeling as he expressed it, "like a bull moose." In the afternoon he overcame Mrs. Roosevelt's objections to work long enough to send for Stenographer Martin and dictate the statement that put him back into politics.

Then he answered dispatches from President Taft, Cardinal Gibbons, and several other of those who had sent messages of sympathy.

He carefully reread the dispatch from President Taft and dictated this reply:

"I appreciate your sympathetic inquiry and wish to thank you for it."

"Sign that Theodore Roosevelt," he said to Martin.

To Cardinal Gibbons he sent this:

"I am deeply touched by your kind words."

To Woodrow Wilson: "I wish to thank you for your very warm sympathy."

His statement dictated to Stenographer Martin asking the campaign to continue despite Schrank's shot was as follows:

"I wish to express my cordial agreement with the manly and proper statement of Mr. Bryan at Franklin, Ind., when in arguing for a continuance of the discussion of the issues at stake in the contest he said:

"'The issues of this campaign should not be determined by the act of an assassin. Neither Col. Roosevelt nor his friends should ask that the discussion should be turned away from the principles that are involved. If he is elected President it should be because of what he has done in the past and what he proposes to do hereafter.'

"I wish to point out, however, that neither I nor my friends have asked that the discussion be turned away from the principles that are involved. On the contrary, we emphatically demand that the discussion be carried on precisely as if I had not been shot. I shall be sorry if Mr. Wilson does not keep on the stump and feel that he owes it to himself and to the American people to continue on the stump.

"I wish to make one more comment on Mr. Bryan's statement. It is of course perfectly true that in voting for me or against me, consideration must be paid to what I have done in the past and to what I propose to do. But it seems to me far more important that consideration should be paid to what the progressive party proposes to do.

"I cannot too strongly emphasize the fact upon which we progressives insist that the welfare of any one man in this fight is wholly immaterial compared to the greatest fundamental issues involved in the triumph of the principles for which our cause stands. If I had been killed the fight would have gone on exactly the same. Gov. Johnson, Senator Beveridge, Mr. Straus, Senator Bristow, Miss Jane Addams, Giffford Pinchot, Judge Ben Lindsay, Raymond Robbins, Mr. Prendergast and the hundreds of other men now on the stump are preaching the doctrine that I have been preaching and stand for, and represent just the same cause. They would have continued the fight in exactly the same way if I had been killed, and they are continuing it in just the same way now that I am for the moment laid up.

"So far as my opponents are concerned, whatever could with truth and propriety have been said against me and my cause before I was shot can with equal truth and equal propriety be said against me and it now should be so said, and the things that cannot be said now, are merely the things that ought not to have been said before. This is not a contest about any man; it is a contest concerning principles.

"If my broken rib heals fast enough to relieve my breathing I shall hope to be able to make one or two speeches yet in this campaign; in any event, if I am not able to make them the men I have mentioned above and the hundreds like them will be stating our case right to the end of the campaign and I trust our opponents will be stating their case also.

"Theodore Roosevelt."

October 19, Gov. Hiram W. Johnson, of California, candidate for Vice-President on the National Progressive ticket, was summoned to Mercy Hospital by Col. Roosevelt.

The governor hastened to the hospital and conferred with Roosevelt for an hour. The ex-President urged upon Johnson that he return to California to hold his office as governor. Johnson had two years to serve of his term and under the law he would forfeit the governorship if he did not get back. The law there provides that no governor shall absent himself from office for more than two months running. Johnson had been away all but a few days of that period.

"Governor, I realize the sacrifice you have made in keeping so long away from your office," began the colonel, in serious tone. "I am told that if you do not hurry back they will take the governorship away from you. Now, I want you to go back. Leave the campaign to me. I can handle it all right. Soon I'm going out on the stump and I'll lead the fight myself."

Gov. Johnson marveled at the bold idea that Roosevelt, convalescing from the bullet wound, would take command again.

"You can't do it, colonel," he protested. "You will need to build up your strength. I won't——"

"Fiddlesticks," interrupted the colonel. "You'll do what I say. I never felt any stronger in my life. It's all a matter of being able to breathe easier with this splintered rib. That won't bother me more than a few days. Then they can't hold me back."

Flatly Gov. Johnson informed Col. Roosevelt that he wanted to stay in the fight.

"I'm needed," he went on. "I'm going to let them take the governorship. I'll resign."

Leaning out from the arm chair in which he sat, Roosevelt whacked his right fist down on the table before him. A sharp pain went through the breast pierced by the bullet.

"I tell you, governor, you'll not do it," fairly cried the colonel, so vehemently that Mrs. Roosevelt, in the next room, stepped to the doorway.

"You must be quiet, Theodore," spoke Mrs. Roosevelt, lifting a warning finger.

"Yes, that's right," agreed the colonel, "but the governor here is recalcitrant and I've got to speak roughly to him."

After a brisk interchange of opinion as to the feasibility of the governor giving up the campaign the two violently taking opposite sides, bidding the colonel an affectionate good-bye, Gov. Johnson left the hospital. As he passed out to an automobile, Johnson said he had promised the colonel to talk the matter over with other leaders before deciding what to do.

"He insists that I return to California and I insist I won't," explained the governor. "We couldn't agree."

Later Gov. Johnson conferred at his hotel with William Allen White, Francis J. Heney and other Bull Moose leaders. The governor was obdurate in his decision to stick in the race.

"Col. Roosevelt is in no shape to take up the responsibility," he maintained. "It is but an evidence of his magnanimity that he urges me to return to California. I'd rather lost the job than desert the colonel now."

Attorney General U. S. Webb of California on October 20 issued the following opinion, however, which did away with possibility of Gov. Johnson losing his office:

Elbert E. Martin.

"There is a code section in the state limiting the absence of the governor and other officials from the state to sixty days, but the legislature of 1911 by resolution, removed the limitations on the governor and other high state officials. In addition to that the constitution of the United States specifically provides the conditions under which a state official may be removed, and it does not include this particular condition. There is no reason why Gov. Johnson cannot remain outside the state as long as he sees fit and there is nothing the legislature can do to remove him for remaining away more than sixty days."

CHAPTER VII.

BACK AT SAGAMORE HILL.

The trip of ex-President Roosevelt from Mercy Hospital, Chicago, to his home at Oyster Bay, beginning the morning of October 21 over the Pennsylvania road is described here by one of the correspondents who traveled with him. Under date of October 21, he wrote at Pittsburg, Pa.:

"On a mellow autumn day whose warmth seemed to breathe a tender sympathy, Col. Roosevelt traveled from Chicago today on his way to Oyster Bay on the most extraordinary trip ever undertaken by a candidate for the presidency.

"Unable because of sheer weakness to show himself on the platform of his private car, the stricken Bull Moose leader, with blinds drawn in his stateroom, listened with throbbing heart to the soft murmuring of eager throngs as they clustered at the stations along the way. As the train rolled into Pittsburg tonight the colonel, shaken up by the jostling of the train, meekly confessed to Dr. Alexander Lambert, his New York physician, who with Dr. Scurry Terrell, are making the trip with him, that he was 'tired out.'

"'I'm going to put in a sound night of sleep,' he sighed, 'I'll be all right again in the morning.'