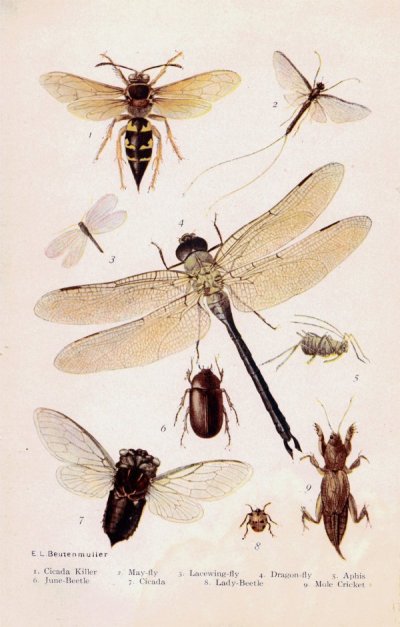

E. L. Beutenmuller

1. Cicada Killer 2. May-fly 3. Lacewing-fly 4. Dragon-fly 5. Aphis

6. June-Beetle 7. Cicada 8. Lady-Beetle 9. Mole Cricket

Title: Little Busybodies: The Life of Crickets, Ants, Bees, Beetles, and Other Busybodies

Author: Jeannette Augustus Marks

Julia Moody

Release date: June 27, 2007 [eBook #21948]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

|

LITTLE BUSYBODIES THE LIFE OF CRICKETS, ANTS, BEES BEETLES, AND OTHER BUSYBODIES BY JEANNETTE MARKS AND JULIA MOODY OF MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE ILLUSTRATED

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS NEW YORK AND LONDON MCMIX |

|

STORY-TOLD SCIENCE FOR CHILDREN FROM EIGHT TO FOURTEEN YEARS OF AGE Other Books for the Series: CRUSTY COUSINS: Crabs, Spiders, etc. SHELL DWELLERS AND URCHINS: Clams, Oysters, Snails, Starfish, Sea Urchins HATCHING WATER BABIES: Fish and Frogs BIRD WITS LITTLE MAMMALS FLOWERS A series intended to cover simple types of plant and animal life, arranged in logical order HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS, N. Y. |

|

Copyright, 1909, by Harper & Brothers. All rights reserved. Published April, 1909. |

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| A Word to the Children and the Wise | v | ||

| I | The Journey | 1 | |

| II | Rangeley Village | 11 | |

| III | The Little Army (Locusts and Grasshoppers) | 21 | |

| IV | Fiddlers (Crickets) | 34 | |

| V | How Katy Did (Katydids) | 43 | |

| VI | Fishing (Dragon-flies) | 50 | |

| VII | The Swimming-Pool (The May-fly) | 61 | |

| VIII | The Rainy Day (Leaf and Tree Hoppers) | 68 | |

| IX | The Prize (Lace-Wing, Ant-Lion, and Caddis-Worm) | 77 | |

| X | A Nagging Family (Flies and Mosquitoes) | 90 | |

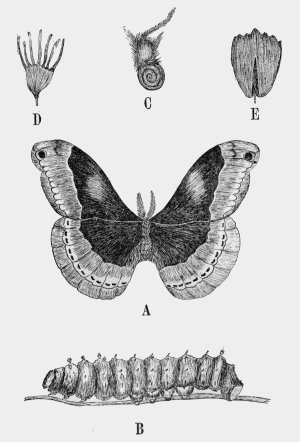

| XI | Camping Out (Butterflies and Moths) | 103 | |

| XII | Camp-In-The-Clouds (Butterflies and Moths, continued) | 114 | |

| XIII | Storm-Bound (Beetles) | 122 | |

| XIV | A Day'S Hunting (Bees) | 136 | |

| XV | Leaving Camp (Wasps) | 153 | |

| XVI | Eyes And No Eyes (Ants) | 167 |

Note.—We do not think it practicable to give classifications except as they exist unnamed in the above titles: (1) straight winged: locusts, grasshoppers, crickets, katydids; (2) tooth-shaped: dragon-flies; (3) ephemerals: may-flies; (4) half-winged: leaf and tree hoppers; (5) nerve-winged: lace-wings, ant-lions, and caddis-worms; (6) two-winged: flies and mosquitoes; (7) scaly winged: butterflies and moths; (8) sheath-winged: beetles; (9) membranous-winged: bees, wasps, and ants.

We hope that the children who read this book will like the boys and girls who are in it. They are real, and the good times they have are real, as any boy or girl who has lived out-of-doors will know. And the stories are true. Peter is not always good. But do you expect a child always to be good? We do not. Sometimes, too, the frolics turn into a scramble to catch a dragon-fly that will not be caught, and there are accidents. Also, Betty and Jack work hard to win a prize which the guide gives to the child who learns most about ants.

Of course it would be impossible for five children to go in search of locusts, grasshoppers, crickets, katydids, dragon-flies, May-flies, leaf-hoppers, lace-wings, caddis-worms, butterflies, beetles, bees, wasps—and so many other six-legged creatures that among them they have wings and legs enough to fill a new Pandora's box—without having a good deal happen. And a good deal does happen. It is all true enough, and every word about the six-legged busybodies is true as true. The other books, too, that come after this in our Story-Told Science Series will be every word true.

And we who wrote this book? Well, we, too, have been children. We used to climb trees and turn somersaults; why—But that is another story! And we remember so well what it used to be like to have to learn dull things we did not wish to know. So we said to ourselves, as we looked over our spectacles at each other, "No, they sha'n't be told a single uninteresting fact; they sha'n't be dull, poor dears, as we were so long ago, before we put on spectacles and began to call ourselves wise."

And so, although we sat down and wrote a book just about long enough for a school-year's work; although we felt very proud because our stories had more wonderful six-legged creatures than any book written for children; although we took pains to have in the book only such little creatures as any one of us could see any day; although we hoped that mothers and teachers would say, "At last, this is a book the children and I can like and find useful!" or, "There, that will help as a starting-point to tell about the bees and the flowers!" or, "This story about the flies will teach the children what it means to be clean!" Although, I say, we hoped all these things, yet our chief hope was that we might give all sorts of children a good time.

So we put our spectacles on and looked very wise, and took a quantity of ink on our pens and began to write. And we wrote and wrote and wrote. And part of the time, while one of us was writing and hoping the stories would be so interesting the children would want to write about them, too, the other was drawing and labelling each sketch so plainly that any child could understand it, even if the ears were quite where they could not be expected to be, or there were more eyes than, seemingly, one creature ought to have, or wings and legs served to make music, as no sensible child could possibly guess.

And now we can't do better than wish you a good time before we say good-bye. We wish you to enjoy all the frolics, to feel how jolly it is to be out-of-doors in the woods and fields and lakes, climbing, canoeing, picnicing, and swimming.

But still more, we hope that you will realize that more wonderful than the most wonderful fairy story ever told is the marvel of the created life of these little insects; we want you to come to know something of their joys and troubles; we want you to learn how to be kind to them, and how they may be useful to you; and we want you to find out for yourselves the places they take in the great plan of creation.

In other words, we want you to think and feel about the lives of these six-legged busybodies, and see for yourselves how much even a butterfly can add to the interest and beauty of living. Does this seem a little bit like a sermon? Well, you see, we forgot we had kept on our spectacles so long, and somehow spectacles always turn into sermons. Perhaps it is because both begin with the letter S.

And now this is all of our short word to the wise. We expect to make each one of our books better than the last, and you can help us to do this by writing any suggestions you may have. We shall be glad to hear from children, big or little.

J. M. and J. M.

South Hadley, Massachusetts,

January 27, 1909.

"It will be stories all summer, won't it?" said Betty to her mother.

"Yes, dear."

"And hunting, too?" said Jimmie.

"Hunting with your new gun and hunting with your camera."

Jimmie unfastened the case of his new camera and looked in. What a beautiful one it was, and what pictures he meant to take, and how the camera would impress Ben Gile! Jimmie looked about proudly. He knew no other boy in that whole great train had a camera like the one his father had given him.

"Mother, when will it be lunch?" asked Betty.

"I'm as hungry as a bear," declared Jimmie.

"And hear Kitty mewing; she's hungry, too." Betty looked at the big round basket, whose cover kept restlessly stirring.

"Did you leave something in the baggage-car for Max to eat?" Mrs. Reece asked Jimmie.

"Yes, mum. It's one o'clock; can't we have something now?"

"As late as that! No wonder you chickens are hungry for—"

"Chicken!" squealed Betty.

"And ham sandwiches!" added Jimmie.

"And chocolate cake!"

"And root-beer!"

"And peppermints!"

"Ssh!" said Mrs. Reece, "or every one in the car will know what little piggies you are. Ask Lizzie for the basket."

Every minute the air was growing cooler. The children could smell the pine woods, and once in a while the train flashed by a great big sawmill, or a lake set like a sapphire in the deep green of the forests. And the hills were rolling nearer and nearer in great shadows. The children ate their luncheon contentedly, looking out of the windows and thinking of the mountains there would be to climb, the ponds, the streams to fish, the pictures to take, and the stories they were to hear the summer long.

"Mother," said Betty, eating her second piece of chocolate cake—"mother, what will Ben Gile tell us this summer?"

"Let me see," said her mother, "perhaps it will be about the little creatures—grasshoppers and katydids, butterflies and bees."

"Goody!"

"Pooh!" said Jimmie, "I don't see what you want to know of those old things. I'd much rather hear about porcupines. There isn't anything to say about a grasshopper except that it hops."

"Isn't there, my son? Well, that shows that you don't use your eyes. Suppose some one said there was nothing to say about you except that you whistle?"

"Well, what is there about an old grasshopper, anyhow?"

"I don't know, but Ben will."

"But tell us something, mum," urged Jimmie, who loved his mother dearly, and was certain she knew more than anybody else, in part because she had been to college, but chiefly because she was his mother.

"Let me see," said Mrs. Reece, "I shall have to think about it." Both of the children came as close to her as they could, while she continued:

"What a strange world it would be if there were no insects in it! We should have no little crickets chirping in the sunny fields or in the dark corners and cracks of our houses. There would be no katydids singing all night, no clacking of the locusts in the tall grass along dusty roads, no drowsy hum of bees. There would be no little ants and big ants digging out underground tunnels and carrying the grains of sand as far from their doorways as possible. There would be no brightly colored moths and butterflies flitting from flower to flower. We should find no sparkling fairy webs spun anew for us every morning."

"But, mother, all these creatures aren't insects," said Jimmie.

"Yes, they are, dear. It is hard to believe that they all belong to the same family called insecta, but they do."

"Mother, what's that word mean?"

"It doesn't mean anything more than cut up into parts. You see, Betty, all these insect bodies are made up of separate rings joined nicely together. If you look carefully you will find that behind the head there is another distinct part. This is called the thorax, which means chest. Behind that there is a pointed part of the body, which is called the abdomen. Then, if you look again, you will see that all these little creatures are alike in that they have six jointed legs."

"And are they all good, like the bee and the butterfly?" asked Betty, who wasn't always a good little girl herself, and who thought it would be much nicer if insects were naughty sometimes.

"Not all, dear," answered Mrs. Reece; "some do us real service, but others are troublesome; insects are such hungry little fellows, and they don't have chocolate cake every day to keep them from getting hungry. They are hungry when they are babies and hungry when they grow up. Some eat all they can see—like a little boy I know—and some prefer the tender leaves and twigs. Some care only for the sweet sap flowing into the new leaves and buds. And still others like best the tender new roots of plants."

"Mother, what are the baddest ones?" asked Betty.

"Pooh! I know," said Jimmie; "the beetles are, because they eat everything. Why, they'd eat the buttons off your coat or the nose off your face or—"

"Jim! Jim! do tell the truth! The beetles, and bugs, too, are the most troublesome. Many of the bugs are such tiny little creatures that it is hard to realize that they can hurt a plant. But bugs have sucking beaks. With these beaks they bore into the leaves or the buds of the plant, and then by means of tiny muscles at the back of the mouth they pump up the sap. To be sure, one little pump could do no harm; but think of millions of little sucking beaks, millions of little pumps busy at work on a single plant! Do you remember the pansies mother had in the winter, and how they were all covered by green plant-lice? Well, those are bugs called aphids. You remember they were pale green, just the color of the plant, and so transparent and soft they looked most harmless. The scale insects are very troublesome, too, but mother doesn't know anything about them."

"Oh, I know what they are," announced Jimmie, "they get into the fruit trees."

"And sometimes onto shrubs, too. Mother has heard of a scale insect out in California which has been a great nuisance to fruit-growers. A certain ladybug finds this cottony-cushion scale a tender morsel, so many ladybugs were taken out there to help the owners of the fruit farms get rid of the scale."

"Did they carry them all the way out, mother?"

"Yes," answered Jimmie; "they got a Pullman car for them, and Mr. and Mrs. Ladybug and family travelled in style."

"Mother, tell Jim to be still." Betty, not unlike other little sisters, hated to be teased by her brother.

"And now, let me see," said Mrs. Reece. "I don't know that I can tell you any more until I know more myself. Yes, I do know what baby beetles are called. They are called grubs, and they live in the ground until it is time for them to turn into grown-up beetles. While they are babies they eat as much and as fast as they can, as no baby but a beetle should. The more they eat the sooner they come out into the bright world as a June-bug or some other kind of beetle. They eat all the tender little roots they can find. This is very nice—"

"For Mary Ann, but rather hard on Abraham."

"You horrid boy," said Betty, "you don't even let me hear a story in peace! It's very nice what, mother?"

"It's very nice for the little grubs, but it's rather hard on the plants, for if too many roots are nibbled away the plants die. The caterpillars are great eaters, too."

Betty leaned over and whispered something to her mother; then they both giggled.

"I know what you're saying," said Jimmie, but after that he was quieter.

"Sometimes a caterpillar will thrive on just one kind of a plant; it may be carrot, it may be milkweed. On that it feeds until it has grown as large as possible. Then it spins itself a nice silken cocoon, or rolls itself up in a soft leaf and takes a long, long nap. And now it is time for us to take a nap, too, for we shall soon reach Bemis, and then there will be still two long lakes to cross and a carry to walk."

The next morning great was the stir in the town, for it was known by the village children that Betty and Jimmie had come, and by the grown-ups that Mrs. Reece was there. All winter long the children had looked forward to their coming, for it meant jolly times: picnics, parties, expeditions, and games. Then, too, Ben Gile would begin to tell them wonderful things. Through the winter he had been teaching school, and it was only when the ice broke up in the big lake and the beavers decided to stop sleeping that Ben Gile came back to his guiding.

There was great excitement about Turtle Lodge. Lizzie kept flying out with rugs, and then forgetting they hadn't been brushed and flying in again. The cat was playing croquet with the balls and spools of an open work-basket, and Max had discovered an old straw hat which tasted very good to him. Only Mrs. Reece kept her head and stayed indoors, moving about quietly from room to room, putting the house in that beautiful order which little children never think about.

Out on the grass that sloped down to the street, which, in its turn, tumbled head over heels down to the lake, Betty and Jimmie were playing with their playmates. They were all so wild with joy that every time Jimmie saw another boy he shouted, "Come over!" when the boy was coming, anyway, just as fast as he could.

Up, up from the foot of the lake climbed an old man; up, up, up the steep street he came, his white hair shaking and shining in the brisk June breeze, his long, white beard caught every once in a while by the wind and tossed sideways.

"Mother," called Jimmie, "Ben Gile is coming!"

Out came Mrs. Reece to greet the old man.

Then, one by one, the children spoke with Ben Gile.

"You're having a good time before you can say Jack Robinson, aren't you?"

"Yes, sir," came in a chorus of voices. Then, "Tell us a story; tell us a story!"

"Not to-day," said the old man. "Why, you want a story before you've had time to turn around."

Betty stuck her head out from behind her mother. "Mother said you would tell us about crickets and moths, and everything."

"Well, well, well," murmured the old man, "did she? But I can't tell a story to-day. I'll tell you, though, something, so that when you come to collect the little creatures you'll know what to do. All sit down."

They all sat down cross-legged on the ground, the old man in the middle.

"Here, you big Jim-boy, catch me that butterfly."

There was a wild rush, and the bright wings were soon caught.

"There, you've torn off one of its legs," said the old man.

Jimmie looked troubled. "I didn't mean to, sir."

"Do you know how it hurts to have your leg torn off, boy? Do you know, children?"

"No," came in a chorus.

The guide took out a piece of paper and drew a picture on it. "There, every part of that little fellow's body I've drawn has muscles, such fine muscles no naked eye could ever see them. I'll show them to you under the microscope in my cabin. Those muscles move the body, and each muscle is controlled by threads, still more fine, called nerves."

The old man reached out like a flash and pinched Jimmie.

"Ouch!" cried the boy, and there was a shout of laughter from the children.

"You felt that?"

"I guess I did," said Jim, sulkily.

"Well, that's because you're made something the same way this butterfly is. When anything hurts us it's because some of our nerves are hurt, and quick as a flash the news travels to the brain, and we try to get away from the thing that causes pain—a pinch, perhaps, or, still worse, the hurt of a poor leg that has been torn off."

"But a butterfly hasn't any brain," objected Jimmie, who was still cross.

"Hasn't it? Well, we'll see. Now, you watch my pencil." He pointed to the head of the butterfly. "This little fellow has a very tiny brain there. Also running through the body, from end to end, is a little tube through which the food passes. It is in the head above this tube where the tiny brain is, and from which two little threads run down around the tube and join to form another little knot of nerve cells like that of the brain. Then, from this second one there runs a series of little knots united by fine threads the entire length of the body, one in each ring of the body. Do you understand that?"

"Yes," piped up Betty, "mother told us an insect is made up of rings, and—and—" she stammered, surprised at her own boldness, "the word means cut up into parts."

"Good! Why, that's a real bright girl. Well, from each one of these knots nerves go to the muscles of the body."

"It's just like a lot of beads on a string," said Hope Stanton.

"So it is, child. So, you see, if we handle an insect roughly, squeezing it too hard, or breaking a leg or a wing, a message is sent to one of these little beads or knots or nerve cells, and the poor, helpless creature suffers pain."

"But I didn't mean to hurt that butterfly!"

"No, of course you didn't. The only way to do," said the old man, "is to catch them in a net. Make it of bobinet with a rounded bottom, sewing it to a wire ring and fastening it to a handle that is the right weight and length for your arm."

"But then, after you caught it, how could you keep it, sir?" asked Betty.

"There are two merciful ways," said the old man, "of killing insects, but neither way is safe for children to try. Put a few drops of chloroform on a piece of cotton under a tumbler turned upside down. Put the insect inside. It will soon fall asleep without pain. The other is a cyanide bottle. I have one down at the cabin. It must be kept tightly corked and never smelled. The cyanide in the bottle is hard and dry. Several insects may be put into the bottle at the same time. Once there they die very quickly. After large insects are killed the wings should be folded over the back, and they should be placed in a little case like this. See, I'm folding a piece of paper to form a three-cornered case. Then I bend down one edge to keep the little case closed."

At this moment out flew Lizzie with a curtain which she was going to shake.

"Here, here!" shouted the old man, "don't shake that; catch that caterpillar on it. I want it."

Lizzie made a good-natured grab at the caterpillar, and then there was a cry of pain. "Oh, begorra, begorra, I'm stung by a wasp, I am! Ow!" But she still kept tight hold of the caterpillar as she danced about.

"No," said the guide, "you're not stung by any wasp. Bring me that! There, open your hand. You see, the caterpillar stung you."

"Oh my, what a beauty!" exclaimed the children. "But caterpillars don't sting."

"Oh yes, they do," continued Ben Gile, with a twinkle in his eye; "ask Lizzie." Lizzie was looking at the palm of her hand, which showed how badly it had been stung.

"Now, you see, we'll need something to pick up these little creatures with—a pair of forceps or something of that kind. At least, you must be very careful."

"And what else do we need?" asked the children.

"A little hand lens will magnify the small parts of an insect a great deal. It will show you all the tiny hairs on the body, and the little rings and the feelers and the facets of the eyes, and many another wonderful thing."

"What are we going to put the bugs in?" inquired Jimmie.

"Lizzie will get you a small wooden box," said Mrs. Reece.

Lizzie went off grumbling something about guides and bites and insects, but soon she came back with a nice box, and in a minute all the children's heads were clustered about Ben Gile as he showed them how to line the box with a layer of cork, how to steam the insects a little if they were dry, and then how to put the long, slender pins through the chest of the insect and stick it into the cork.

Ben Gile shook his head. As his hair was long and white, and his hands moved with his head, just as if he were a lot of dried branches moving in the wind, it was enough to frighten little Betty. "Plagues of Egypt! Plagues of Egypt!" he kept muttering. Now, Betty had been to school a long time—I think it must have been as much as two whole years, which is a very long time for school and a very short time for climbing trees—now, Betty had been to school and knew better. She crept behind a big beech-tree, but she stuck her little head out and said, in a trembling voice:

"It was locusts, sir, wasn't it—and wild honey?"

Betty wasn't at all certain that any kind of honey could be a plague.

"It was locusts, child—yes, you're right," answered the old man. "Locusts it was; but you eat wild honey."

Betty came out from behind the tree and whispered, "You eat them both?"

"So men did in the Bible," said Ben Gile, and washing his sugar-pails, and putting his maple sugar camp—a very sweet place for a little girl to be when there are still piles of maple sugar packed away on the shelves—in order for the summer.

In all her short life Betty had never known another old man like him. In the winter he taught school; in spring he made maple sugar; in summer he was guiding about the ponds or looking up into the trees most of the time; and in the fall he cut wood before he went back to teaching; but what was oddest of all to Betty was that he knew the squirrels and deer and rabbits as well as he seemed to know little girls or little boys. There was a story told in those woods about his taming even a trout so that one morning it hopped out of the water and followed him everywhere he went—hop, hop, flop behind him. And in the evening, as Ben Gile and his tame trout were passing by the pond again, the trout fell in and was drowned. But, dear me, that is a fish story, and you mustn't believe any fish stories whatever except those your father tells! Still, if your grandpa is fond of fishing, you may believe his fish stories, too.

Betty came out farther from behind the tree. "Please, sir, do you eat grasshoppers?"

"Not yet, my dear." The old man's eyes twinkled. "I knew a little boy once"—Betty was wondering whether this old man had ever been a little boy himself—"I knew a little boy once who wasn't afraid to swallow even a caterpillar, but I think that little boy never thought of eating a grasshopper." The old man shook his head gravely. "No, not a grasshopper."

"Please, sir," said Betty, coming right up to the bucket he was washing in the brook—"please, sir, do you know any stories about grasshoppers?"

Ben Gile laid his finger along his nose and thought. Betty was sure he knew a hundred million stories, and that he could tell her something about anything she might ask for in all the world.

"Well, once upon a time," the old man began, "there was another old man who was a great deal wiser than I am, and a great deal richer, my dear, for he owned a whole kingdom and lived in a palace, and his name was—"

"Solomon!" called out Betty, dancing up and down, out of pride in her own wisdom.

"Right! And this other old man said:

"There are four things which are little upon the earth, but they are exceedingly wise:

"The ants are a people not strong, yet they prepare their meat in the summer;

"The conies are but a feeble folk, yet make they their houses in the rocks;

"The locusts have no king, yet go they forth all of them by bands;

"The spider taketh hold with her hands and is in kings' palaces."

"But that's not a story."

The guide shook his head. "You don't know a story, child, when you hear one. It began, 'Once upon a time,' didn't it?"

"Yes, sir; but please tell me another."

"Well, there are others in the Bible, my dear, about locusts and grasshoppers."

"But, please, sir," said Betty, who was almost ready to cry, she was so teased—"please tell me one of your own stories."

Ben Gile began to swash his bucket up and down, up and down, in the stream until the water fairly rocked. Then he pulled the bucket out of the water, set it beside him, and reached out after a locust.

"Here he is." There was a long pause. Betty thought he would never go on. "Well, once upon a time there was a little army and all its uniforms were brown and green, and from the meanest soldier in the ranks to the lieutenant-commander this little army was made up of insects who belonged to the same tribe. Let me see—there were the grasshoppers and the locusts and the katydids and the crickets."

"Please, sir, were they cousins?"

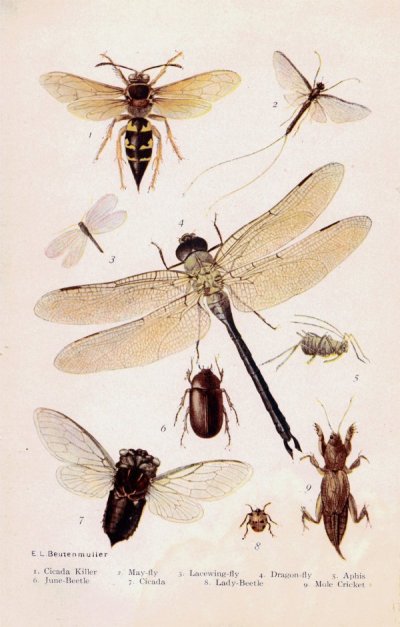

"I think they were, my dear. Yes, first cousins, and, unlike even my first cousins, they all have wings, and straight wings like this."

The guide gently spread out one of the wings.

"Just where the back of your chest is these wings grow—two pairs of wings, my dear, and two pairs of wings mean a good deal more than two pairs of new shoes. This first pair is straight and narrow and hard, because it is meant to cover the gauzy wings underneath. Puff!"

Away flew the locust.

"You see, he doesn't use his first pair, but holds them out straight from his body while he spreads out the gauzy ones like a—like a—"

"Fan!" shouted Betty, quite forgetting the tiny squirrel who had come up near her, and, at her shout, nearly jumped out of his little red jacket.

"A yellow fan," said the old man. "And some have a red fan. Well, I think," said he, reaching for his pail, "there isn't going to be any more of this story."

"Not any more? But there must be more, sir; I've seen hundreds and hundreds of them on a dusty road, and, please, they're just the color of the dirt."

The guide shook his head. "Not to-day."

By this time Betty was so eager to have him go on that she had forgotten all about being afraid of him. "And when they whir up from the road, sir, they say, 'Clack! clack! clack!'"

The old man made a sound like the noise of a locust.

"How does it make its mouth move, sir?"

"It doesn't make its mouth move, child. It makes the noise by striking the edges of the gauzy wings and hard wing covers together. See, this way!" And the old man struck his arm and leg together. "It has another fiddle, too, which it uses when it makes the long, rasping, drowsy sound of summer days. Then it rubs the rough edges of its hind leg against the edge of its wing-cover."

"Please, is it happy, then?" asked Betty.

"Just as happy as a healthy locust, who lives in long, sweet-smelling grass and is contented with his own singing, can be, and that is very happy."

"Oh!" said Betty, "it doesn't use its mouth, then? Jimmie said it did."

"Jimmie's a stupid boy. See this fellow." The old man held the locust toward Betty. "With its upper lip, broad, you see; and there is the lower lip made in two scallops, and there's a short feeler on either side, and another pair of soft jaws with a feeler. Hidden away under those parts is a pair of dark-brown, horny jaws which open like two big swinging gates."

"What makes them so big?"

"The better to eat you with, my dear." The guide worked his jaws until Betty, half afraid and half pleased, screamed and ran behind a tree. "Oh, how they can eat!" growled the old man, "more than any little girl or boy I ever knew! Years and years ago, when your mamma was a baby, they mounted up into the air from the Rocky Mountains and flew eastward in a great cloud. Down they swooped upon the fertile valleys in rustling hordes, and ate everything in sight—grass, grains, vegetables, and bushes. They ate and ate and ate until they had eaten up fifty million dollars' worth of food, and the poor farmer could hear nothing but the sound of the chewing of those ever-swinging jaws. Now, be off, little girl, or my pails won't be clean."

"Oh, please, sir, just tell me how they jump and breathe."

"Dear, dear, see this fellow!" He had wet a little grain of maple sugar, and a tiny meadow grasshopper which had alighted on his knee was pushing the sweet stuff into its mouth with both fore legs. "Child, you must never," said the old man, savagely, "push your food in that way."

"Please, sir," answered Betty, "I never do, because I eat with my fork and my knife. Please, sir, are they happy when they jump?"

"Looks like a horse, doesn't it?" asked the old man. "It's made for jumping. Think of all the training it takes to make a jumper of your brother at school. Well, this chap can jump ten times as far. It's born with a better jump than the longest-legged boy you ever saw. But the locust might get its head cut off when jumping if it weren't for this little saddle that covers the soft part of the neck. Mr. Locust can't always look before he leaps, as a little girl can, and the knife edge of a blade of grass would cut its head right off if it weren't for this saddle. See, here are its long leaping-legs, and on the back edge of these are some spines to keep it from slipping, and the feet are padded with several soft little cushions that keep it from chin-chopping itself to pieces when it lands after a long jump. And here, my dear, are little rest-legs just behind the front legs. With these Mr. Locust hangs on to a blade of grass when tired—a fine idea, child; every little boy and girl ought to have some rest-legs like the locust. And the locust has some extra eyes, too."

Ben Gile was going so fast now that Betty was listening to him, mouth open, as he pointed with a blade of grass to one thing after another.

"You see, the locust has two big eyes, and there in the middle of the forehead it has three little eyes, and with five eyes there isn't much it can't see. And here on the body are two tiny shining oval windows. These are ear-laps, and that, my dear, is the way it hears. And upon the sides of the body (the thorax—that is, just the chest) and his abdomen are tiny holes. The air enters through these, and that is the way Mr. Locust breathes."

"Oh," said Betty, "then it hasn't got any nose? I thought everything in the world had a nose."

"And this little body," the old man went on, "is as strong as a grub hoe. With it the locust makes holes in fence rails, logs, stumps, and the earth, and in those holes mother locust lays her eggs. See, those four spines are for boring holes. With these Mrs. Locust bores a hole in the ground, and then with these same spines she guides the bundles of eggs into the hole and covers them up with a gummy stuff. There the eggs stay until next spring, when, my dear, out comes a little hopper with no wings, and this little hopper is called a nymph. It grows and splits its skin, grows and splits its skin, and with its new skin—it has five or six skins, and leaves all its old clothes hanging around on the bushes—its wings grow bigger and bigger. At last it flies off just as its mother and father did a year ago."

Ben Gile tossed the locust into the air and called out, "Shoo!" clapping his hands loudly together. Out from the woods came two baby deer, a wise, gentle old cow; from the cabin came a mother cat and three kittens and a big black dog; and from the trees scampered down a half a dozen squirrels.

"Time for dinner."

Betty went up to him and whispered something in his ear. The old man nodded his head solemnly, and the little girl went trotting along the path to Rangeley Village.

There was the greatest scurrying around in the fields on the edge of the woods about Ben Gile's cabin. Little girls and boys were flitting hither and thither with pretty nets and small boxes strapped over their shoulders. Inside the boxes there seemed to be just as much hopping about as there was outside.

By-and-by the guide put his head out of his cabin door and called, "How many have you?"

"Oh, lots and lots!" the children answered.

"Bring them in." And the children trooped into the cabin, which they thought quite the most wonderful place in the world. Its walls were lined with books and cases. The books were not only in English, but also in French, German, Italian, Latin, Greek, and other languages, and the cases were filled with scores of specimens, the most beautiful butterflies, moths, beetles, birds, flowers, and rare stones. The floor of the cabin was covered by different kinds of skins. Besides, there were telescopes, field-glasses, magnifying-glasses, specimen cases, old weapons, and a flute. And by the great wide fireplace, in front of which the guide was cooking biscuits and cookies in a reflector oven, lay several kittens, the old black dog, Thor, and a dappled fawn which Thor was licking.

"Those crickets sound like pop-guns," said the old man, slipping more cookies into the oven and setting a pan of biscuits on a shelf by the hearth.

"Oh, please," said little Hope, "we've got bushels of them!"

"Now we'll let those cookies bake while we 'tend to the fiddlers. Are four pans of cookies enough for five children?"

"Yes, yes."

"Now, Hope, let me have your bushel box. H'm," he murmured, peeping in, "all dressed for the party. What color?"

"Brown, sir."

"Black, too," said Betty; "and on a few," she added, "there's a stripe or a weeny spot of color."

"Oho!" exclaimed the old man, "what have we here?" He took a pale little creature from Hope's basket.

"Why, it's white and green tinted," called Jimmie. "That isn't a cricket."

"Isn't it? Well, it's a first cousin which lives in the trees and loves its tree home so much, like the sensible little fellow it is, that it sings 'Tr-e-e-e, tr-e-e-e,' as fast as it can trill all summer long. But it is very harmful to the tree, because when egg-laying time comes it cuts a long slit in the trees in which to lay its eggs. Just a minute!" The old man shifted the position of the baker, and out came such a good odor of cookies that all the children sniffed with delight. "Here, Jack," he said, to a brown little fellow in ragged clothes and bare feet, "you have a singer in your box."

"I didn't catch but one," said the lad.

"Briers aren't good for bare legs, are they? Never mind, your crickets won't eat one another."

"Eat one another?" cried the children.

"Yes, crickets are cannibals, like some other insects, and they frequently eat a near relation or a friend, as the people in the Fiji Islands used to do. This is a nice brown little chap, Jack. Do you know how he makes his music?"

"Why, I suppose," said the boy, "he opens his mouth the way Mr. Tucker does in the church choir, and—"

There was a shout of laughter from Jimmie, who was sure he knew a great deal.

"Well," said the guide to Jim, "then how does it make its music, since you know?"

"Not with its mouth."

"Then how?"

"I don't know, sir," stammered Jimmie, who found he didn't know as much as he thought he did.

"When Mr. Cricket sings," went on the hermit, "it lifts its two wing covers so that the edges meet like the pointed roof of a house. Then your little fiddler, Jack, rubs one edge against the other."

All this time Peter Beech had been waving his hand about, the way children do in school, and giving big sniffs.

"Please, sir, the cookies are burning."

"Bless my soul!" The guide whisked the cookies away.

"Please, sir," said Jack, "are we going to have something soon?" Jack did not look as if he had his share of food to eat, for he was as thin as the fawn which had curled up near him. Jack had twelve brothers and sisters, and a father who wasn't what he ought to be, so there were times when there was no food for Jack.

"Yes, my son," said the guide, kindly, for the old man could guess how hungry the lad was. "But, first, where do you suppose the crickets and katydids have their ears?"

"Near those big eyes," called Peter.

"No, no, on the joint of the fore leg is a little membrane, which is just a thinner, tighter place in the skin of the leg. There!" Ben Gile had the fore leg of Jack's cricket stretched under the magnifying-glass. The children could see plainly the film of tight skin. "Underneath the thin, tight skin is a fine nerve which, when the air makes the skin shake, changes the motion into sound. Mrs. Cricket listens with her fore leg while Mr. Cricket sings his love-song to her."

At this the children laughed and laughed, and comical little Peter put up his leg as if listening.

"Here, Pete, give me your box. Do you remember what I told you about Mrs. Locust, Betty, and the way she lays her eggs?"

"Yes, sir. She has four straight spines at the end of her body, and after she has bored a hole with her body she guides the eggs in with the four spines."

"Good! Well, Mrs. Cricket wears at the end of her body a long spear. See this cricket of Peter's. Now she bores her hole with this spear and then guides her eggs carefully into the hole. Why, see here, Pete, what have you got here?"

The children gazed eagerly over the old man's shoulder.

"My, isn't it like velvet!" exclaimed Peter.

"And isn't it brown!" added Hope.

"But look at its stumpy front legs!" called Jack, who had forgotten his empty stomach in the excitement about this little creature, which looked like a cricket and yet was so different.

"And its little beads of eyes!" said Betty.

"Do you know what it is?" No one knew. "Well, it's a mole cricket. You rarely ever see one because they live underground and bore their way along just like moles, leaving tiny tracks and nibbling the roots of tender plants. You see, it doesn't need eyes any more than the mole does. But it does need those thickened fore legs to do its underground digging. Now, children, run out into the fields and let your crickets go. Be careful not to hurt them. We'll have supper, and after supper we'll catch a katydid."

Out ran the children. Soon they were setting the long wooden tables under the trees with delicious trout the boys had caught, with hot biscuits and jugs of maple syrup, with berries and cookies, with milk from the old cow, who, contentedly chewing her cud, was looking at them through the low crotch of a tree, and with little cakes of maple sugar which the guide had moulded into the shape of hearts.

Never did trout, cookies, and maple sugar disappear so quickly; never were such appetites; never such laughing, and such interesting stories told by the guide.

"Hush!" said Ben Gile. "Do you hear that?"

"Yes," cried Peter.

"What is it?"

"It's a katydid," said Betty, "over there."

"Listen, children, what does it say?"

"It says, 'Chic-a-chee, chic-a-chee,' over and over again," answered Jack.

"Pooh," interrupted Jimmie, "it says, 'Katy did, Katy didn't!'"

"It says, 'Katy broke a china plate; yes, she did; no, she didn't,'" called Betty.

"Yes, she did; no, she didn't!" the children shouted, merrily, together.

"Well," said the old man, "anyway, it's all about what Katy did do and what Katy didn't do. Probably Mr. Katy, like other good husbands in the world, is singing of the wonderful things Katy did do and the naughty things she didn't do. That is Mr. Katy's love-song. Ah, he finds Mrs. Katy very charming—her beautiful wings, her gracefully waving antennæ, her knowing, shining eyes! Now, listen again. Katydid carries its musical instrument at the base of its wing cover. On each side is a tiny membrane and a strong vein. When the wing covers are rubbed together the membrane speaks, and you hear—"

"Katy did, Katy didn't!" shouted the children.

"Do you think you know where they are? Well, take these lanterns"—the guide had lighted half a dozen—"and find them."

The children scurried off, certain of a quick victory. In the woods about the cabin you could hear them shouting: "It's here!" "No, it isn't!" "Where is it?"

"A will-o'-the-wisp," murmured the old man; "may they never have a harder one to find!"

By-and-by the children came trotting back. They couldn't find the katydid in any place, and they had looked everywhere.

"Couldn't? How did you look?" He took one of the lanterns, went to a near-by tree, and held the lantern close to the leaves. "Here it is! Why, it's a great fellow!"

The children trooped into the cabin after him, crowding to look at the katydid.

"I thought they were brown," said Hope.

"So did I," echoed Betty.

"See, you can't tell this fellow from the leaf, it is such a bright, fresh green. Woe to the katydid if it were anything but this bright green! Just think how easily the birds would find them. What nice salad Katy would make for a young robin!"

"Do the birds eat katydids?" asked the children, in surprise.

"Oh yes, and they haven't any stated luncheon or supper time for doing it. They are very informal. One time is as good as another, and the oftener the merrier. If Katy doesn't keep very quiet and demure, like her leafy background, whist! and Father Robin or Mother Bluebird has a meal for the youngsters."

"Is that why it doesn't sing by day?" asked Peter.

"They wait till the birds go to bed, I suppose. See what a comical look this fellow has, waving its long, fine, silky antennæ about. Probably it's trying to find out what it is on, looking out for another nice green leaf to eat. They do a lot of damage eating leaves from the trees."

"What's that?" asked Betty, pointing to the edge of a leaf.

"Well, you have sharp eyes," said the old man. "Mrs. Katydid has laid her eggs there. See, the eggs are rounded and flattened, and each egg laps a little over the one in front of it. Once another man saw a row of katydid eggs laid as neatly as could be on the edge of a clean linen collar. I'll keep these eggs; then, in the spring, the young ones will hatch out. They will grow and shed their skins from time to time, just the way the locusts do. Ah, they leave so many old clothes about that they need an old clothes man! I wish I could tell you about the katydid I knew once upon a time who spent her days collecting old clothes, and how she made a fortune selling them to—"

Ben Gile paused and sighed deeply.

"Selling them to what?" shouted the children.

"I can't tell that to you," replied the old man, shaking his head sadly. "It's the story of 'How Katy Did.' I have to be very careful, for Mr. John Burroughs, who is a wiser old man than I am, says I mustn't. Lately the scientists almost killed one man I know, and a good, clever, useful man, for telling that story—very savage, very savage."

The children began to look troubled. "Will Mr. Burroughs hurt us?" inquired Hope. "My papa would—"

"No, no, child, you're too small. He likes something big, and he's especially fond of the Big Stick."

"Is that what he does his beating with?" Jack's eyes were frightened.

"He hunts with the Big Stick," answered the guide. "Dear me, where are we? It's half-past eight, and you children should have been in bed this time long, long ago. Hurry! Skip! Get the lanterns or we'll all be scolded."

And they scampered for the village, the guide driving them before him, and all the lights waving to and fro like so many crazy fireflies.

Have you ever started off on a bright, cool morning to fish? At the last it seems as if you would never get started, which, I suppose, is partly the eagerness to be gone; then you do get off, only to find you've forgot the can of worms or the salt for the luncheon-basket.

Jimmie and Betty were prancing on the lawn in front of Turtle Lodge. Jimmie had his camera over his back and a jointed steel rod done up in a neat little case in his hands, on his feet long rubber boots. Betty wore a big straw hat; she carried a little rod like Jim's and a pretty little knapsack, which held part of the luncheon. They were waiting for Jack and Ben Gile, who were to go with them to fish a stream that lay far back from the pond. It was to be a great day's sport. They had a creel and a rod for Jack; for the guide they needed to take nothing, for he had the most wonderful collection of rods and flies they had ever seen.

At last they saw him coming up the hill, Jack with him. Hastily they kissed Mrs. Reece, and ran shouting and jumping toward the old man and the boy, Lizzie after them, for they had left half the luncheon on the grass. "Faith!" she panted, catching up with them, "and what can you be doing without the victuals, I'd like to know?"

The guide took part of the bundles and Jack the rest. Off they went gayly talking and laughing.

Soon they were following the stream, Jack catching his line and fly in the alders almost every time he cast.

Jack was too poor ever to have had any rod except an alder stick cut beside the stream, a short line and hook, and any worm or grasshopper he might find. He was wonderfully proud of the rod he held. The children meant to give it to him at the end of the summer. But Jack did not know this good news yet.

Ben Gile led the way, and almost every time he cast his fly there was a swirl, the end of the slender rod bent, there was a minute of excitement, and then upon the bank lay a beautiful speckled trout. On, on, on they went over the cool, green leaves and bright red berries of the partridge vine, and past raspberries wherever the sun had struck in through the heavy trees to ripen them. The stream was running more and more swiftly as they travelled up grade; quick water was growing more frequent and the pools deeper.

At last they came to a deep, round pool, and the guide said, "Now, Jim, you've the first try."

Jimmie cast his fly, there was a strike, a plunge, and out, out, out ran Jimmie's line. The boy's face turned quite pale. "What shall I do, sir?"

"You have a big one," answered Ben, calmly. "If you can play him long enough we may get him; otherwise he'll get your fly and line. Steady there, steady; let out a little more line, and now reel in a bit."

It seemed like hours to Jimmie as he let the line out and reeled it in again. Really, it was only a few minutes before the guide said: "Seems to be getting a little tired; bring him in closer. That's it. There!"

They had no landing-net with them, so at the last moment Ben Gile seized the line, and out came a two-pound trout. Jimmie's eyes were popping nearly out of his head, and Betty was jumping about and clapping her hands.

"Some," said the boy.

"Well, this is the best place we shall find to eat our luncheon. We'll camp here. Now for the fire! Boys, get the wood and a small strip of birch bark! Then these two stones will hold the frying-pan. Now for the fish; we'll keep that big one of yours and I'll mount it for you, if you'd like me to. We'll eat the little fellows. After luncheon we must catch more for your mother, Betty, and for Jack to take home with him."

Soon the frying-pan was hot, and the trout were sizzling and curling up with the bacon in the pan. Never did a luncheon taste so good as that, with fried trout and bacon, and hard-boiled eggs, soda biscuits, and a mammoth apple pie. They listened to the fire crackling; they looked up into the shining trees; they watched the water beyond the pool go tumbling downhill.

Finally the old man said, "It's going to be a clear day to-morrow."

The children gazed up into the sky.

At this Ben Gile laughed. "Don't look at the sky, look at your plates."

Puzzled by this, the children did look at their plates.

"But there's nothing left to look at," said Jack.

"That's just it. There's an old saying that people who eat all their food make a clear day for the morrow. Now," he continued, "I'll smoke my pipe of peace before we go on. Just look at that fellow darting about over the pool!"

"Oh!" cried Betty, "it's a darning-needle, and it will sew up my mouth and my eyes—oh, oh!"

"Nonsense, child, that's silly. The dragon-fly is a very useful and a very harmless fellow. It's a pity that there are so many superstitions about it."

"There's another name for it," said Jack—"devil's darning-needle."

"And in the South the darkies call it the mule-killer, and believe it has power to bring snakes to life. It's all nonsense. They are not only harmless to human beings but also very useful, for they eat flies and mosquitoes at a great rate. Once upon a time I fed a dragon-fly forty house flies in two hours. And they eat beetles and spiders and centipedes. And sometimes they eat one another."

"Like the crickets?" said Betty.

"Yes, like the crickets. Just see that fellow dart about. The sharpest sort of angles. There, it has something! It caught that lace-wing in its leg-basket."

"Leg-basket!" exclaimed the children.

"Yes; it draws its six legs together, and makes a sort of basket right under its head. Then the dragon-fly devours what it catches by these strong-toothed jaws. It is a hungry fellow, it is."

The old man puffed away quietly for a few minutes, while the children watched the darning-needle and hoped Ben Gile would say something soon.

"Those scientists," he continued, "who are working on flying-machines could learn a good deal from this fellow. The dragon-fly is made for flight. A long, slender, tapering body that cuts the air, moved by four narrow, gauzy wings, and steered by that pointed abdomen. They eat, mate, and lay their eggs while they are flying. I don't know that they are still for more than a few seconds."

"Can you find their eggs?" asked Betty.

"Yes; their eggs are laid in the water or fastened to the stems of water plants. See that damsel fly, the slender, smaller, pretty-colored darning-needle? Well, it goes entirely under water, cuts a slit in the stem with the sharp end of the abdomen, and lays the eggs in the groove it has made. And they lay thousands of eggs."

"When they hatch out, what do they look like?" asked Jack, who grew daily more interested in the creatures about him, and who, in the years to come, was destined to be a great scientist.

"It looks a little like the mother," said Ben Gile, taking out his pipe, "but not much. It goes through a great many changes before it is really grown up. All told, the growth takes from a few months to a whole year. The young one, called a nymph, is an ugly little fellow, dingy black with six sprawling legs, two staring eyes, and a big lower lip which covers up its cruel face like a mask. It is a true ogre, lurking under stones and in rubbish at the bottom of the pond seeking whom it may devour. It eats the smaller and weaker nymphs."

"Oh," said Betty, studying the picture the guide had drawn, "what an ugly, ugly fellow!"

"It changes its skin a good many times, and sometimes it looks a little better while the skin is still clean and light gray. But it soon turns dingy again. See these three little leaf-shaped gills I've drawn?"

"They are like the screw on a steamer," commented Jimmie.

"They are, a little. Well, this chap uses these gills for the same purpose as the steamer uses its screw—to scull through the water."

"What happens when it changes?" asked Jack.

"After the nymph has its full growth, some sunny morning soon after daylight, it makes its way up out of the water on to a stem and waits quietly for the old dark skin to split. Then out crawls a soft-skinned creature with gauzy wings. But the body is so moist and weak it has to wait awhile for the warm sunshine to harden the skin and strengthen the muscle. When this is done the new dragon-fly, with its glistening body, flies out from the pond in the bright, warm light."

"Then does it live forever?" asked Betty.

"No; it dies after twenty-five to forty-five days of its flight. Here, Jack, catch that fellow!"

There was a wild scramble, but every time Jack just missed the dragon-fly. Finally Betty lent him her broad hat, and at last Jack caught the insect.

"Gee! aren't its eyes big?"

"And beautiful, too," said the guide. "They are made up of thousands of facets (a facet is just a small, plain surface) as many as thirty thousand facets in one eye. Some look up, some look down, some look out, some look in; so that there is nothing that escapes the sight of this hawk of the air. Look at the wings on this fellow, and look at the picture I drew for you of the nymph. Well, this fellow's wings begin in the nymph as tiny sacs, or pads, made by the pushing out of the wall of the body. Running all through between the two layers of the wing are thickened lines of chitin, which divide and subdivide, forming this fine network. In the new wing, protected by these thickenings, are air-tubes, which divide and branch into all parts of the wing. But as the wing reaches its full growth most of the air-tubes die." The guide paused. "We are talking too much and fishing too little. Time to go on. Put out the fire, boys. Be sure that it's out. Run water all around it. Now we're off!" And up, up, up the brook they went.

Two or three days after the fishing expedition the boys had gathered together at the swimming-pool, Ben Gile with them. They had been racing, and climbing trees, and were very warm. "Come, boys," said the guide, "let's sit down a minute before you go into the water. It won't do to bathe when you're too warm. Look round on the stones under the water and see what you can find."

"Look at this," called Peter; "it's just like a sponge."

"It is a fresh-water sponge."

"I didn't suppose sponges grew in these parts at all," said Jimmie.

"Oh yes, there are many of them in the ponds."

"See this, sir," shouted Jack; "what funny little legs it has!"

"That's a May-fly or shad-fly nymph. He was hiding carefully under that stone and keeping out of the way of the dragon-fly nymph, who would so gladly gobble him up."

"It's prettier," said Jimmie, "than that dragon-fly nymph you drew a picture of."

"So it is. See, here on each side of its body are these fine little gill-plates, moving, moving, moving, so that they may get as much fresh air as possible out of the water. Each gill-plate is a tiny sac, and within these are the fine branches of the air-tubes. It's wonderful the way these creatures breathe."

"Don't they breathe just the way we do?" asked Jack.

"No; throughout the body of an insect is a system of tiny white tubes. Some day we'll look at these tubes under the microscope, and you will see that they are made up of rings. From end to end of the tube is a fine thread of chitin twisted in a close spiral like a spring. It is these little coils which look like rings. The coiled thread holds the little tube open so that the air may pass readily. But your little fellow, Jack, cannot have pores on the sides of the body like the last nymph. It lives under water, and the water would get into its tubes; instead, it has tracheal gills."

"That's a pretty big word," said Peter, looking up at the guide. He was growing impatient, and wished to begin the swim. If he had known what that swim was to mean to him, probably he would not have been so anxious.

"They aren't so hard to understand; they are just little oval sacs, inside of which is a limb of the air tube divided into tiny branches. The fresh air in the water passes through the thin wall of the gill and is taken by the air-tubes to all parts of the body, while the impure air passes out in the water. This is all that breathing means in any creature—a changing of impure for pure air."

"Then that is what my nymph is doing," asked Jack, "when it wiggles its gills so?"

"Just that. Your May-fly nymph, Jack, hatched from a tiny egg first. But it grows rapidly, and splits and sheds its skin sometimes as often as twenty times. During the last few months wings appear, which grow a little larger with each shedding of the skin. Finally, after three years—sometimes three years spent in growing and hiding away from its enemies—the little nymph floats up to the surface of the water. In a few minutes the old skin splits along the back, and from it flies forth a frail little May-fly. Its body is very soft and delicate. Its four wings are of a gauzy texture. At the tip of the body are two long, fine hairs. Its jaws are small and weak, but the life of this little creature is so short that it never eats. Up it flies into the air with thousands of its brothers and sisters, whirls in a mad dance for a few hours, then falls exhausted to the ground to die.

"Well, now I think we'd better go into the water," ended the guide. "You boys can go in just as you are." For three little boys had been sitting undressed in the bright sunshine. "Good for their pores," Ben Gile had told them, which is all very true.

Soon there was the greatest splashing and paddling and shouts of, "My goodness, isn't the water cold!" "Can you swim this way?" "How far can you go, anyway?"

Jimmie and the guide were swimming around near the shore when suddenly, two hundred feet ahead of them, they saw Peter disappear in what they supposed was shallow water. Jack was half-way the distance between the guide and Peter. It did not take him an instant to realize what had happened. But before he could get to the place where Peter had gone down, the lad had come up, struggled, and gone down again. As he came up once more Jack caught him by his curly hair, turned over on his back, holding Peter's head high out of the water, and swam calmly for the shallow place. Once there, the old man took Peter in his arms and hurried to shore, where they rolled him until they had the water out of him. Not a word was said, and modest, quiet Jack did not seem to think that he had been brave.

When Peter opened his eyes he said, "Guess my pores weren't in the right place."

It was a rainy day. Poor Betty flattened her little nose against the window-panes of Turtle Lodge a dozen times. But outside all she could see were just the long, straight lines of the down-coming rain and an empty road leading downhill to the edge of the pond; all she could hear was the drum of the water upon the roof. Inside, Jimmie was developing films in his laboratory, and was not in the least interested in what Betty might be doing.

"Oh, mother," called Betty, "I am so tired; there isn't anything to do!"

"Why don't you sew on a dress for Belinda?" asked Mrs. Reece.

"Belinda has too many clothes; she has more than I have, mother, and she's a naughty dolly to-day."

"Well, let me see—get Lizzie to let you make cake."

"Lizzie's cross, and I'm afraid to. I wish the guide were here. He's never cross, and never too busy to tell you something that's interesting." Betty looked out of the window. "He's coming now! Goody! Goody!"

When old Ben Gile reached the steps there was a little girl dancing inside the door and still shouting "Goody!"

"What's this?"

"You'll tell me a story, won't you?"

"Tell you a story! Dear, dear, I never knew such a little greedy for stories. I've brought you something."

Betty's face was shining now. She had forgotten the rain, the dreary day, cross Lizzie, and everything. Ben Gile took a box out of his pocket. "What is it?" she asked.

"I have a box full of little elves for you."

"Elves!" exclaimed Betty.

"Yes, little elves, little brownies."

"Come into the study, where there is a fire." Mrs. Reece led the way. "Then you can tell us all about these elves." They sat down around the fire, and Mrs. Reece continued, "Don't you think it would be fun to pop corn while we're hearing about the brownies?"

Betty was delighted, and ran for a corn-popper, and soon there was the merry sound of crackling wood, popping corn, and happy voices—all sounds that proved so tempting that before long Jimmie joined the others.

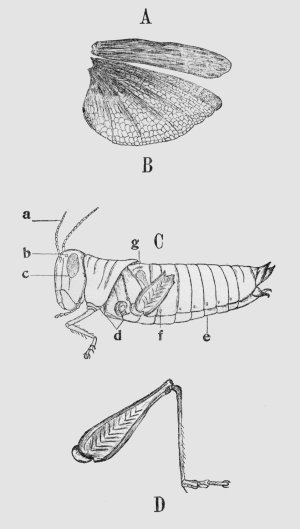

"My little elf is a bug," began the hermit.

"A bug an elf?"

"Yes, a bug; and when he doesn't look like an elf, he looks like a king with a high crown on his head or a naughty boy with a dunce cap."

"Let's see him, please," said Betty.

The old man opened his box. Inside lay a lot of little creatures with backs like beechnuts. "See, look through the lens!"

Betty laughed. "Oh, aren't they funny! The eyes are so big and so far apart."

"And the lines on their heads make them look as if they were gazing through heavy-bowed spectacles," said Mrs. Reece.

"There is a very wise man, and his name is Mr. Comstock, who says that Nature must have been in a joking mood when she made these little tree and leaf hoppers, they are so impish and knowing-looking. Ah, they are the naughty brownies of the insect world!"

"Betty, Betty," called Mrs. Reece, "your popcorn is burning!"

"Mother, I don't care to pop any more; let me just listen now. What makes them bad?"

"Well, they are born with a naughty desire to suck everything they can get their tiny sucking beaks upon. They hop around in great numbers on the fruit trees and pierce the leaves with their sharp beaks. Then, with a tubelike lower lip, they suck up the sap. They also make slits in the twigs in which to lay their eggs. In the following spring the eggs hatch, and there is a fresh supply of tree-hoppers ready to begin the mischief their parents left off only when they died."

"And what is the difference between the leaf-hoppers and the tree-hoppers?" asked Mr. Reece.

"Not much. They are cousins—cousins in naughtiness. The leaf-hoppers are a great nuisance. Every year they destroy from one-fourth to one-fifth of the grass that springs up. They also suck the sap of the rose, the grape-vine, and of many grains. These sturdy fellows live during the winter by hiding under the rubbish in the fields and vineyards, ready when the warm spring does come to begin their naughty work."

"What makes a little fellow like this able to do so much damage?" asked Jimmie, who had come in, his hands all stained with chemicals.

"Well, it is well covered by this horny substance called chitin, and then it is very active. You see, the chitin acts both as armor-plate for the soft parts and also as a firm support to the many muscles. As many as two thousand separate, tiny muscles have been counted in a certain caterpillar. That shows how very active insects are."

"And they all have such big eyes they can see everything," said Betty.

"So they have—bigger eyes than the old wolf of the story had."

"You remember, I told you about the thousands of facets in the big eyes of the darning-needle? Not contented with these large eyes, most insects have three small eyes arranged in the form of a triangle on the front of the head."

"This bug has feelers, too," said Jimmie.

"So it has. Insects use these feelers, or antennæ, for all sorts of purposes—some for touch, some for smell, some for hearing. Ants exchange greetings by touching antennæ, and recognize a friend or an enemy by the odor. The antennæ of a male mosquito are covered with fine hairs. When Mrs. Mosquito sings, all the tiny hairs on Mr. Mosquito's feelers are set in motion, and he becomes aware of Mrs. Mosquito."

Mrs. Reece laughed. "That's a new kind of romance!"

"Mother, what's a romance?" asked Betty.

"You'll know, dear, in time."

"Notice this imp's mouth," said the guide. "It's made for sucking. But there's a great difference in the mouths of insects: some are made for biting, some for lapping, some for piercing, and some for sucking. The butterfly, which lives on nectar in the depths of the flowers, has a long, coiled tube which scientists call a proboscis. This it unrolls and buries in the throat of the flower. Mrs. Mosquito has a file and pump, for it is she, and not her husband, who does all the singing and biting. The male mosquito has nothing more than a mouth for sucking nectar. And I told you about the biting jaws of the locust with which it nibbles grass and leaves."

"And does the tree-hopper breathe the way the locust does—through those pores on the side?"

"Yes, child," said the old man, "and the air-pores are protected by fine hairs which surround the openings, just the way the hairs in your nostrils keep the dust from getting up your nose and into your throat."

"Things in the bugs," said Betty, "are so like us."

"The world becomes more and more like one great whole as you grow older," added Ben Gile. "Those are interesting elves I've been telling you about, aren't they?"

"I didn't know bug elves could be so interesting."

"Now run and get us some of the fresh cake Lizzie has been baking," said Mrs. Reece. "I hope it will taste as good as it smells."

There were two canoes going up the little river which led out from the pond. In the first were Ben Gile with Betty, Hope, and Jack. In the second Jimmie and Peter paddled Mrs. Reece. They had trout rods, although they did not plan to fish very much, and well-filled luncheon-baskets, magnifying-glasses, cameras, boxes, and various other things.

In two weeks they were to go on a camping expedition, and to-day's trip was taken chiefly to find a good place for the first night's stop.

The children were all excitement about the camping, which was to be the last jollity of their happy summer, and they asked so many questions about what they were to take with them, and they asked the same questions over so many times, that at last Mrs. Reece put her hands on her ears and called to the guide, who was paddling vigorously ahead.

"Well," he called back, "a frying-pan and an axe, and perhaps a tent." He allowed his canoe to drop nearer Mrs. Reece's. "What naughty children you are," he continued, "to bother the life out of your poor mother! I know of some other children, too, who are very naughty. I see one flying now."

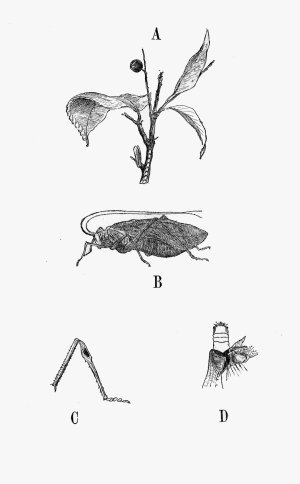

"That pretty little thing," exclaimed Betty, "with the gauzy wings?"

"Yes, that pretty little thing; its wings have many, many veins. When Lace-Wing is a baby and is called a larva, it does not look like this, for its jaws are strong and very sharp. After it has eaten and grown for some time it makes a house for itself, where it rolls up for a nap. While it is lying very still in this little house many things are happening."

"What happens?" asked Jack.

"Well, it is changing from a baby to a grown-up, and while it is growing up into an insect it is called a pupa. Don't mistake this for papa—it does not look like your papa at all."

Betty thought this was very funny, because her father was a great big man over six feet tall.

"After its wings are made and it looks just like its mamma, Lace-Wing crawls out of its house and flies away."

"Has it any cousins, like the locust?" asked Betty.

"Yes, it has cousins; the ant-lion and caddis-fly both belong to this family. But little Lace-Wing, with its beautiful green body, gauzy wings, and golden eyes, is the most graceful member of the family."

"How do they live when they are babies?" asked Hope.

"When they are babies," said Ben Gile, opening his eyes wide and speaking in a loud, deep voice, "they go about like lions seeking whom they may devour."

Betty was frightened.

"No, no, child," said Mrs. Reece, "not a real lion."

"Just an aphis-lion," explained the guide, his eyes twinkling. "They are called aphis-lions because they are very cruel to the little green plant-lice I told you about. You remember, the plant-lice live on plants, and with their sucking beaks pump the sap from the plants. The aphis-lions crawling over the plants come across the little aphid. Quick as a wink they stick their sharp claws in the soft body of the plant-louse and drink the blood with their sharp-pointed jaws. They are very fond of eggs, too, and Mamma Lace-Wing is careful of her eggs, because she knows the mischievous ways of her children."

"What does Mamma Lace-Wing do with her eggs?" inquired Mrs. Reece.

"Each egg which she lays has a tiny stem, and the stems are fastened to a leaf or twig. When the babies hatch out they crawl down onto the leaf and hunt around for something to eat. Perhaps if they knew more they would crawl up the little egg stems and eat their own brothers and sisters."

"Oh, what cannibals!" cried Betty.

"Yes, it is not pleasant, this Fiji Island of the insects, but it is their nature."

"They do seek their meat from God," murmured Mrs. Reece.

"Yes, it is a mystery," answered the old man. "But, dear me, I have forgotten my story. Well, in about ten days they find a nicely sheltered spot and spin a little silken cocoon about themselves. In this they stay for a couple of weeks, while they are changing into grown-up lace-wings. When they are finished they cut a round door in their silken house, spread their gauzy wings, stretch their delicate green bodies, rub their eyes in wonder at the sunny world, and fly away to lay some little eggs on slender stems just like those which their mothers laid and from which they came."

"See," said Jimmie, "what a place for camping!"

"But it is too near home," objected Peter. "We could get here in two hours."

"So we could," admitted Jimmie.

"Tell us something about the cousins, sir," said Jack.

"We can't have much more now," replied the guide, "for we shall have to stop for luncheon soon. But I'll tell you about a little fellow called the ant-lion. Along the side of almost any country path or road, if you keep your eyes open, you may notice some day little pits of sand with sloping sides, and down at the bottom of this is a hole. The hole is very dark, and unless you look sharply you will think it just a hole. But if you examine it you will see a little head and two little sharp, curved jaws. These are the jaws of the ant-lion, lying in wait to gobble up the first passer-by. The rest of the body is in a little tunnel burrowed out in the sand. They get their name, I suppose, because they think an ant an excellent dinner. They lie there knowing very well that Mr. and Mrs. Ant will surely slip on the steep-sloping sides. And if by any chance they don't, these ant-lions have been seen to throw up sand with their heads in order to hit a helpless little ant and knock it down into the pit."

The children exclaimed at this cleverness.

"After it has eaten its fill, this cruel, greedy fellow makes a little room for itself of fine grains of sand firmly held together with silky fibres. In this room it lies quietly, sometimes all winter, until it changes into a grown-up ant-lion with four long, narrow wings. Then Mrs. Ant-Lion lays her eggs in the sand, and when the young ones hatch out they build the 'pits of destruction' which I told you about. What book is it, children, that uses the 'pit of destruction' so often as a figure?"

"The Bible!" shouted Peter, who was the minister's son in Rangeley Village.

"Good! Now, no more for the present, and here we are at a splendid place for luncheon—clear spring, dry ground, handy wood, and all."

The canoe beached noiselessly on the river's edge, the boys jumped out with a whoop, and soon luncheon and frying-pans were out of the canoes, and there was the sound of the axe chopping the dry wood, the good smell of smoke, and the sizzling of bacon. Betty and Hope went for water. The boys fetched wood. Mrs. Reece and the guide took care of the luncheon, Mrs. Reece spreading the table on the ground, and the guide frying the potatoes and bacon.

"Oh, mother," said Jimmie, "what does make things taste so good out-of-doors?"

"I'm sure I don't know."

"And, mother," asked Betty, "what does make everything so pretty?"

"You ask mother a hard question."

"And oh, Mrs. Reece," exclaimed Jack, his thin, eager face shining with excitement, "everything in the world is so wonderful!"

"It's all so different in the winter," said Peter, in between bites of bread-and-butter. "It isn't half so nice, but I suppose it would be lovely if we could have you and Mr. Gile—"

"You dear child!"

"It is about three miles above here," the guide spoke, "on the last of the Dead River Ponds, where we shall find our first camping ground. I want you to look at it."

"And we'll be gone days and days."

"Goody! goody!" called Betty, clapping her hands. "And we'll sleep out-of-doors, cook out-of-doors, and do everything out-of-doors."

Every one smiled with her, for there was not a person there who was not looking forward with happiness to this trip.

"Before we start on I'll smoke my pipe," said the old man.

"Then, please, sir, won't you tell us something else?" asked Betty.

"Why, I have nothing left in my head, you child."

"Oh, please, sir, you said there was another cousin called the caddis-worm."

"So I did," said the old man. "Fetch me that stone, Jack." He pointed to a stone lying in the water. Jack brought it to him, and he broke something off from it. "What's that?"

"That's a stick," answered Betty.

"No, that's not a stick, that's a caddis-worm. This little fellow,

unlike some spoiled children I know, has to find its own dinner, change

its own clothes, tuck itself into bed, and build its own house. And it

is brighter than some children I know," said the old man, looking kindly

at Peter. "The caddis-worm builds itself different kinds of houses. Some

of the houses are shaped like the horns you blow on the Fourth of July,

and one kind of house is made of the finest sand, fastened together with

bands of finest silk, which the caddis spins. Our caddis-worm has

patience," said the old man, shaking his head and looking at

Jimmie—"patience, plenty of patience." He puffed away at his pipe for a

few seconds. "Some build rougher houses, choosing small pebbles instead

of sand. Of these it builds a long tube. Others make a little green

summer cottage with twigs, grasses, and pine-needles, from which they

build an attractive bungalow by laying down four pieces and crossing the

ends like this: ![]() These cottages are built about an inch long, and in

them the young caddis-worms have a cool and cosey summer home. Often

these little houses have silken hangings inside. The little owners

fasten the hooks at the ends of their bodies to these and moor

themselves securely."

These cottages are built about an inch long, and in

them the young caddis-worms have a cool and cosey summer home. Often

these little houses have silken hangings inside. The little owners

fasten the hooks at the ends of their bodies to these and moor

themselves securely."

"What do you call it a worm for?" asked Mrs. Reece.

"Well, it looks a little like a worm. It has a long, slender body, but it has six jointed legs, which real worms don't have. See this fellow!" Ben Gile pulled the worm out of its case.

"Oh, see! part of the body is so pale and soft!"

"That, child, is because it is always covered by the little house. The front end and the legs, however, are darker. That's sunburn, I suppose."

"When young Master Caddis-Worm goes out for a swim or a walk it pushes its six legs out-of-doors, and walks along, carrying its house with it. Very convenient, you see! No doors to lock! And if it gets tired it does not have to walk home; it just walks in and goes to sleep under a nice, smooth stone. Some roam about and some stay at home. These creatures are pretty much like human beings in their ways.

"One of the young caddis-worms prefers fishing to walking, like some other young fellows I know. On a stone near its house it spins a fine web, turned up-stream, so that any tender little insects floating down-stream get lodged in it. An easy way to get your dinner—just to go to a net and eat."

The guide paused for a long time, clouds of smoke circling about his white beard and white hair. The children thought he would never go on. "I've had something on my mind for days," he said, "and I'll speak of it now. The boy or girl who learns most about the ants before September 15th shall win a prize. This prize is to be a magnifying-glass, a book of colored plates of the insects, very beautiful and very big, and a five-dollar gold piece."