Title: Old Mackinaw; Or, The Fortress of the Lakes and its Surroundings

Author: W. P. Strickland

Release date: September 9, 2007 [eBook #22550]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. Author's spelling has been maintained.

Page 312: The amount of barrels is obviously an error of the typograph, but the proper amount not being know, it has been left in place. "It is probable that they are now capable of manufacturing 1,25,000 barrels of flour annually, and this quantity would require 5,625,000 bushels of wheat."

The inconsistencies of the typographer or author for punctuation (or lack of) in amount have not been corrected.]

Philadelphia: James Challen & Son,

New York: CARLTON & PORTER. — Cincinnati: POE & HITCHCOCK.

Chicago: W. H. DOUGHTY. — Detroit: PUTNAM, SMITH & CO.

Nashville: J. B. McFERRIN.

1860.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year, 1860, by

JAMES CHALLEN & SON,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States, in

and for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

PHILADELPHIA:

STEREOTYPED BY S. A. GEORGE,

607 SANSOM STREET.

In the preparation of this volume a large number of works have been consulted, among which the author desires to acknowledge his indebtedness to the following: "The Travels of Baron La Hontan," published in English and French, 1705; "Relations des Jesuits," in three vols., octavo; "Marquette's Journal;" Schoolcraft's works, in three volumes; "Shea's Catholic Missions and Discovery of the Mississippi" "American Annals;" "Lanman's History of Michigan;" "Parkman's Siege of Pontiac;" "Annals of the West;" "Foster and Whitney's Geological Report;" "Ferris' Great West;" "Disturnell's Trip to the Lakes;" "Lanman's Summer in the Wilderness;" "Pietzell's Lights and Shades of Missionary Life;" (p. 004) "Life of Rev. John Clark;" "Lectures before the Historical Society of Michigan;" "Mansfield's Mackinaw City;" "Andrews' Report of Lake Trade;" "Heriot's Canada;" "Presbyterian Missions," &c., &c. He desires particularly to mention the works of Schoolcraft, which have thrown more light on Indian history than the productions of any other author. He also desires to acknowledge his indebtedness to Wm. M. Johnson, Esq., of Mackinac Island, for his valuable contributions to the history of that interesting locality. The statistics in relation to that portion of the country embraced in the work are taken from the most recent sources, and are believed to be perfectly reliable.

We are indebted to J. W. Bradley, of Philadelphia, the publisher of "The North American Indians," for the beautiful frontispiece in this work. Mr. Catlin, the author, visited every noted tribe, and, by residing among them, was initiated into many of their secret and hidden mysteries. It is a valuable work.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XV.

Mackinaw and its surroundings — Indian legends — Hiawatha — Ottawas and Ojibwas — Paw-pau-ke-wis — San-ge-man — Kau-be-man — An Indian custom — Dedication to the spirits — Au-se-gum-ugs — Exploits of San-ge-man — Point St. Ignatius — Magic lance — Council of Peace — Conquests of San-ge-man.

Mackinaw, with its surroundings, has an interesting and romantic history, going back to the earliest times. The whole region of the Northwest, with its vast wildernesses and mighty lakes, has been traditionally invested with a mystery. The very name of Mackinaw, in the Indian tongue, signifies the dwelling-place of the Great Genii, and many are the legends written and unwritten connected with its history. If the testimony of an old Indian chief at Thunder Bay can be credited, it was at old Mackinaw that Mud-je-ke-wis, the father of Hiawatha, lived and died.

Traditional history informs us that away back in (p. 010) a remote period of time, the Ottawas and the Ojibwas took up their journey from the Great Salt Lake towards the setting sun. These tribes were never stationary, but were constantly roving about. They were compared by the neighboring tribes to Paw-pau-ke-wis, a name given by the Indians to the light-drifting snow, which blows over the frozen ground in the month of March, now whirling and eddying into gigantic and anon into diminutive drifts. Paw-pau-ke-wis signifies running away. The name was given to a noted Indian chief, fully equal in bravery and daring to Hiawatha, Plu-re-busta, or Man-a-bosho.

The Ottawas and Ojibwas dwelt for a time on the Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron. While the tribes dwelt here, two distinguished Indian youths, by the name of San-ge-man and Kau-be-man, remarkable for their sprightliness, attracted the attention of their particular tribes. Both were the youngest children of their respective families. It was the custom of the Indians to send their boys, when young, to some retired place a short distance from their village, where they were to fast until the manitoes or spirits of the invisible world should appear to them. Temporary lodges were constructed for their accommodation. Those who could not endure (p. 011) the fast enjoined upon them by the Metais or Medicine-men, never rose to any eminence, but were to remain in obscurity. Comparatively few were able to bear the ordeal; but to all who waited the appointed time, and endured the fast, the spiritual guardian appeared and took the direction and control of their subsequent lives. San-ge-man in his first trial fasted seven days, and on the next he tasted food, having been reduced to extreme debility by his long abstinence, during which his mind became exceedingly elevated. In this exaltation his spiritual guide appeared to him. He was the spirit of the serpent who rules in the centre of the earth, and under the dark and mighty waters. This spirit revealed to him his future destiny, and promised him his guardianship through life. San-ge-man grew up and became remarkably strong and powerful. From his brave and reckless daring he was both an object of love and fear to the Ottawas.

About this time, as the legend runs, the former inhabitants of the Manitoulin Island and the adjoining country, who have the name of the Au-se-gum-a-ugs, commenced making inroads upon the settlements of the combined bands, and killed several of their number. Upon this the Ojibwas and Ottawas mustered a war party. San-ge-man, (p. 012) though young, offered himself as a warrior; and, full of heroic daring, went out with the expedition which left the Island in great numbers in their canoes, and crossed over to the main land on the northeast. After traveling a few days they fell upon the war path of their enemies, and soon surprised them. Terrified, they fled before the combined forces; and in the chase, the brave and daring youth outstripped all the rest and succeeded in taking a prisoner in sight of the enemies' village. On their return the Ojibwas and Ottawas were pursued, and being apprised of it by San-ge-man, they made good their escape, while the young brave, being instructed by his guardian spirit, allowed himself to be taken prisoner. His hands were tied, and he was made to walk in the midst of the warriors. At night they encamped, and after partaking of their evening meal, commenced their Indian ceremonies of drumming and shaking the rattle, accompanied with war songs. San-ge-man was asked by the chief of the party, if he could che-qwon-dum, at the same time giving him the rattle. He took it and commenced singing in a low, plaintive tone, which made the warriors exclaim, "He is weak-hearted, a coward, an old woman". Feigning great weakness and cowardice, he stepped up to the (p. 013) Indian to whom he had surrendered his war club; and taking it, he commenced shaking the rattle, and as he danced round the watch-fire, increasing his speed, and, gradually raising the tone of his voice, he ended the dance by felling a warrior with his club, exclaiming, "a coward, ugh!" Then with terrific yells and the power of a giant, he continued his work of death at every blow. Affrighted, the whole party fled from the watch-fire and left him alone with the slain, all of which he scalped, and returned laden with these terrible trophies of victory to join his companions who returned to the Island.

San-ge-man having by his valor obtained a chieftainship over the Ottawas, started out on the war path and conquered all the country east and north of Lake Huron. The drum and rattle were now heard resounding through all the villages of the combined forces, and they extended their conquests to Saut St. Mary. For the purpose of bettering their condition they removed from the Island to the Detour, or the mouth of the St. Mary's river, where they occupied a deserted village, and there separated, part going up to the Saut, which had also been deserted, and the other portion tarrying in the above village for a year.

(p. 014) At the expiration of this time San-ge-man led a war party towards the west, and reached the present point St. Ignatius, on the north side of the straits where he found a large village. There was also another village a little east of Point St. Ignatius, at a place now called Moran's Bay, and still another at Point Au Chenes on the north shore of Lake Michigan, northeast of the Island of Mackinaw. At these places, old mounds, ditches, and gardens were found, which had existed from an unknown period. From this point a trail led to the Saut through an open country, and these ancient works can be distinctly traced to this day though covered with a heavy growth of timber.

After a hard fight with the inhabitants of these villages, San-ge-man at length succeeded in conquering them, and after expelling them burned all their lodges with the exception of a few at Point St. Ignatius. The inhabitants of this village fled across the straits southward from Point St. Ignatius and located at the point now known as Old Mackinaw, or Mackinaw City.

In the mean time, San-ge-man had returned to the Detour and removed his entire band to Point St. Ignatius. In the following spring while the Ottawas were out in their fields planting corn, a party of (p. 015) Au-se-gum-ugs crossed over from Old Mackinaw, on the south side of the straits, and killed two of the Ottawa women. San-ge-man at once selected a party of tried warriors, and going down the straits pursued the Au-se-gum-ugs to the River Cheboy-e-gun, whither they had gone on a war expedition against the Mush-co-dan-she-ugs. On a sandy bay a little west of the mouth of the river, they found their enemies' canoes drawn up, they having gone into the interior. Believing that they would soon return, San-ge-man ordered his party to lie in ambush until their return. They were not long in waiting, for on the following day they made their appearance, being heated and weary with their marches, they all stripped and went into the Lake to bathe previous to embarking for Mackinaw. Unsuspicious of danger they played with the sportive waves as they dashed upon the shore, and were swimming and diving in all directions, when the terrific yell of armed warriors broke upon their ears. It was but the work of a moment and one hundred defenseless Indians perished in the waters. When the sad intelligence came to the remainder of the tribe at Mackinaw, they fled towards the Grand River country.

The village now deserted possessing superior attractions to San-ge-man and his warriors, the Ottawas (p. 016) crossed the straits and took possession, and here he remained until after he unfairly succeeded in obtaining the magic lance.

It was while here that a large delegation of Indians of the Mush-co-dan-she-ugs from the Middle village, Bear River, and Grand Traverse came to shake hands and smoke the pipe of peace with him. They had heard of his fame as a mighty warrior. The occasion was one of great rejoicing to the inhabitants of Mackinaw, and all turned out to witness the gathering. San-ge-man and his warriors appeared in council, dressed in richest furs, their heads decorated with eagle feathers, and tufts of hair of many colors. Among all the chiefs there assembled, for proud and noble bearing none excelled the Ottawa. A fur robe covered with scalp-locks hung carelessly over his left shoulder leaving his right arm free while speaking. As the result of these deliberations the bands became united and thus the territory of the Ottawa chief was enlarged.

It was from this point that he sallied forth every summer in war excursions toward the south, conquering the country along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, extending his conquests to Grand River, and overrunning the country about the present site of Chicago. It was here that he received reinforcements (p. 017) from his old allies the Ojibwas, and extended his conquests down the Illinois River until he reached the "father of waters."

From this place he went forth to the slaughter of the Iroquois at the Detour, and expelled them from the Island of Mackinaw and Point St. Ignatius. From hence he went armed to wage an unnatural war against his relatives the Ojibwas, and was slain by the noble chief Kau-be-man, and it was to this place that the sad news came back of his fate. Thus much for the Indian history of Old Mackinaw.

Equally romantic is the history of the early missionaries and voyagers to this great centre of the Indian tribes. On the far-off shores of the northwestern lakes the Jesuit Missionaries planted the cross, erected their chapels, repeated their pater nosters and ave marias, and sung their Te Deums, before the cavaliers landed at Jamestown or the Puritans at Plymouth. Among the Ottawas of Saut St. Marie and the Ojibwas and Hurons of Old Mackinaw, these devoted self-sacrificing followers of Ignatius Loyola commenced their ministrations upwards of two hundred years ago. They were not only the first missionaries among the savages of this northwestern wilderness, but they were the first discoverers and explorers of the mighty lakes and rivers (p. 018) of that region. In advance of civilization they penetrated the dense unbroken wilderness, and launched their canoes upon unknown rivers, breaking the silence of their shores with their vesper hymns and matin prayers. The first to visit the ancient seats of heathenism in the old world, they were the first to preach the Gospel among the heathen of the new.(Back to Content)

Indian Spiritualists — Medicine men — Legends — The Spirit-world — Difference between Indian and Modern Spiritualists — Chusco the Spiritualist — Schoolcraft's testimony of — Mode of communicating with spirits — Belief in Satanic agency — Interesting account of Clairvoyance.

The earliest traditions of the various Indian tribes inhabiting this country prove that they have practiced jugglery and all other things pertaining to the secret arts of the old uncivilized nations of the world. Among all the tribes have been found the priests of the occult sciences, and to this day we find Metais, Waubonos, Chees-a-kees and others bearing the common designation of Medicine men. In modern parlance we would call them Professors of Natural Magic, or of Magnetism, or Spiritualism. The difference however between these Indian professors of magic and those of modern date is, that while the latter travel round the country exhibiting their wonderful performances to gaping crowds, at a (p. 020) shilling a head, the former generally shrink from notoriety, and, instead of being anxious to display their marvelous feats, have only been constrained, after urgent entreaty and in particular cases, to exhibit their powers. The Indian magicians have shown more conclusively their power as clairvoyants and spiritualists, than all the rapping, table-tipping mediums of the present day.

Numerous interesting and beautiful Indian legends show their belief in a spiritual world—of a shadowy land beyond the great river. Whether this was obtained by revelations from their spiritual mediums, or derived from a higher source of inspiration, we know not; but most certain it is, that in no belief is the Indian more firmly grounded than that of a spirit-world.

The Indian Chees-a-kees or spiritualists had a different and far more satisfactory mode of communicating with departed spirits than ever modern spiritualists have attained to, or perhaps ever will. Forming, as they did, a connecting link or channel of communication between this world and the world of spirits, they did not affect to speak what the spirit had communicated; or, perhaps, to state it more fully, their organs of speech were not employed by the spirits to communicate revelations (p. 021) from the spirit world; but the spirits themselves spoke, and the responses to inquiries were perfectly audible to them and to all present. In this case all possibility of collusion was out of the question, and the inquirer could tell by the tones of the voice as as well as the manner of the communication, whether the response was genuine or not.

Chusco, a noted old Indian who died on Bound Island several years ago, was a spiritualist. He was converted through the labors of Protestant Missionaries, led for many years an exemplary Christian life, and was a communicant in the Presbyterian Church on the Island up to the time of his death. Mr. Schoolcraft in his "Personal Memoirs," in which he gives most interesting reminiscences, running through a period of thirty years among numerous Indian tribes of the northwest, and who has kindly consented to allow us to make what extracts we may desire from his many interesting works, says that "Chusco was the Ottawa spiritualist, and up to his death he believed that he had, while in his heathen state, communication with spirits". Whenever it was deemed proper to obtain this communication, a pyramidal lodge was constructed of poles, eight in number, four inches in diameter, and from twelve to sixteen feet in height. These poles were (p. 022) set firmly in the ground to the depth of two feet, the earth being beaten around them. The poles being securely imbedded, were then wound tightly with three rows of withes. The lodge was then covered with ap-puck-wois, securely lashed on. The structure was so stoutly and compactly built, that four strong Indians could scarcely move it by their mightiest efforts. The lodge being ready, the spiritualist was taken and covered all over, with the exception of his head, with a canoe sail which was lashed with bois-blanc cords and knotted. This being done, his feet and hands were secured in a like firm manner, causing him to resemble a bundle more than anything else. He would then request the bystanders to place him in the lodge. In a few minutes after entering, the lodge would commence swaying to and fro, with a tremulous motion, accompanied with the sound of a drum and rattle. The spiritualist then commenced chanting in a low, melancholy tone, gradually raising his voice, while the lodge, as if keeping time with his chant, vibrated to and fro with greater violence, and seemed at times as if the force would tear it to pieces.

In the midst of this shaking and singing, the sail and the cords, with which the spiritualist was bound, would be seen to fly out of the top of the (p. 023) lodge with great violence. A silence would then ensue for a short time, the lodge still continuing its tremulous vibrations. Soon a rustling sound would be heard at the top of the lodge indicating the presence of the spirit. The person or persons at whose instance the medium of the spiritualist was invoked, would then propose the question or questions they had to ask of the departed.

An Indian spiritualist, residing at Little Traverse Bay, was once requested to enter a lodge for the purpose of affording a neighboring Indian an opportunity to converse with a departed spirit about his child who was then very sick. The sound of a voice, unfamiliar to the persons assembled, was heard at the top of the lodge, accompanied by singing. The Indian, who recognized the voice, asked if his child would die. The reply was, "It will die the day after to-morrow. You are treated just as you treated a person a few years ago. Do you wish the matter revealed." The inquirer immediately dropped his head and asked no further questions. His child died at the time the spirit stated, and reports, years after, hinted that it had been poisoned, as the father of the deceased child had poisoned a young squaw, and that it was this same person who made the responses.

(p. 024) Old Chusco, after he became a Christian, could not, according to the testimony of Schoolcraft, be made to waver in his belief, that he was visited by spirits in the exhibitions connected with the tight-wound pyramidal, oracular lodge; but he believed they were evil spirits. No cross-questioning could bring out any other testimony. He avowed that, aside from his incantations, he had no part in the shaking of the lodge, never touching the poles at any time, and that the drumming, rattling, singing, and responses were all produced by these spirits.

The following account of Chusco, or Wau-chus-co, from the pen of William M. Johnson, Esq., of Mackinaw Island, will be found to be deeply interesting:

"Wau-chus-co was a noted Indian spiritualist and Clairvoyant, and was born near the head of Lake Michigan—the year not known. He was eight or ten years old, he informed me, when the English garrison was massacred at Old Fort Missilimackinac. He died on Round Island, opposite the village and island of Mackinaw, at an advanced age.

"As he grew up from childhood, he found that he was an orphan, and lived with his uncle, but under the care of his grandmother. Upon attaining the age of fifteen his grandmother and uncle (p. 025) urged him to comply with the ancient custom of their people, which was to fast, and wait for the manifestations of the Gitchey-monedo,—whether he would grant him a guardian spirit or not, to guide and direct him through life. He was told that many young men of his tribe tried to fast, but that hunger overpowered their wishes to obtain a spiritual guardian; he was urged to do his best, and not to yield as others had done.

"Wau-chus-co died in 1839 or '40. He had, for more than ten years previous to his death, led an exemplary Christian life, and was a communicant of the Presbyterian Church on this Island, up to the time of his death. A few days previous to his death, I paid him a visit. 'Come in, come in, nosis!' (grandson) said he. After being seated, and we had lit our pipes; I said to him, 'Ne-me-sho-miss, (my grandfather,) you are now very old and feeble; you cannot expect to live many days; now, tell me the truth, who was it that moved your chees-a-kee lodge when you practiced your spiritual art?' A pause ensued before he answered:—'Nosis, as you are in part of my nation, I will tell you the truth: I know that I will die soon. I fasted ten days when I was a young man, in compliance with the custom of my tribe. While my body was feeble from long (p. 026) fasting, my soul increased in its powers; it appeared to embrace a vast extent of space, and the country within this space, was brought plainly before my vision, with its misty forms and beings—I speak of my spiritual vision. It was, while I was thus lying in a trance, my soul wandering in space, that animals, some of frightful size and form, serpents of monstrous size, and birds of different varieties and plumage, appeared to me and addressed me in human language, proposing to act as my guardian spirits. While my mind embraced these various moving forms, a superior intelligence in the form of man, surrounded by a wild, brilliant light, influenced my soul to select one of the bird-spirits, resembling the kite in look and form, to be the emblem of my guardian spirit, upon whose aid I was to call in time of need, and that he would be always prepared to render me assistance whenever my body and soul should be prepared to receive manifestations. My grandmother roused me to earth again, by inquiring if I needed food: I ate, and with feeble steps, soon returned to our lodge.

"'The first time that I ever chees-a-keed, was on a war expedition toward Chicago, or where it is now located—upon an urgent occasion. We were afraid that our foes would attack us unawares, and as we (p. 027) were also short of provisions, our chief urged me incessantly, until I consented. After preparing my soul and body, by fasting on bitter herbs, &c., I entered the Chees-a-kee lodge, which had been prepared for me:—the presence of my guardian spirit was soon indicated by a violent swaying of the lodge to and fro. "Tell us! tell us! where our enemies are?" cried out the chief and warriors. Soon, the vision of my soul embraced a large extent of country, which I had never before seen—every object was plainly before me—our enemies were in their villages, unsuspicious of danger; their movements and acts I could plainly see; and mentally or spiritually, I could hear their conversation. Game abounded in another direction. Next day we procured provisions, and a few days afterward a dozen scalps graced our triumphant return to the village of the Cross. I exerted my powers again frequently among my tribe, and, to satisfy them, I permitted them to tie my feet and hands, and lash me round with ropes, as they thought proper. They would then place me in the Chees-a-kee lodge, which would immediately commence shaking and swaying to and fro, indicating the presence of my guardian spirit: frequently I saw a bright, luminous light at the top of the lodge, and the words of the spirit would be (p. 028) audible to the spectators outside, who could not understand what was said; while mentally, I understood the words and language spoken.

"'In the year 1815, the American garrison at this post expected a vessel from Detroit, with supplies for the winter—a month had elapsed beyond the time for her arrival, and apprehensions of starvation were entertained; finally, a call was made to me by the commanding officer, through the traders. After due preparation I consented; the Chees-a-kee lodge was surrounded by Indians and whites; I had no sooner commenced shaking my rattle and chanting, than the spirits arrived; the rustling noise they made through the air, was heard, and the sound of their voices was audible to all.

"'The spirits directed my mind toward the southern end of Lake Huron—it lay before me with its bays and islands; the atmosphere looked hazy, resembling our Indian Summer; my vision terminated a little below the mouth of the St. Clair River—there lay the vessel, disabled! the sailors were busy in repairing spars and sails. My soul knew that they would be ready in two days, and that in seven days she would reach this Island, (Mackinaw,) by the south channel, [at that time an unusual route,] and I so revealed it to the inquirers. On the day I mentioned (p. 029) the schooner hove in sight, by the south channel. The captain of the vessel corroborated all I had stated.

"'I am now a praying Indian (Christian). I expect soon to die, Nosis. This is the truth: I possessed a power, or a power possessed me, which I cannot explain or fully describe to you. I never attempted to move the lodge by my own physical powers—I held communion with supernatural beings or souls, who acted upon my soul or mind, revealing to me the knowledge which I have related to you.'

"The foregoing merely gives a few acts of the power exhibited by this remarkable, half-civilized Indian. I could enumerate many instances in which this power has been exhibited among our Indians. These Chees-a-kees had the power of influencing the mind of an Indian at a distance for good or evil, even to the deprivation of life among them: so also in cases of rivalship, as hunters or warriors. This influence has even extended to things material, while in the hands of those influenced. The soul or mind—perhaps nervous system of the individual, being powerfully acted upon by a spiritual battery, greater than the one possessed more or less by all human beings."

(p. 030) In Schoolcraft's "American Indians" an interesting account is given of a woman-spiritualist, who bore the name of the "Prophetess of Che-moi-che-goi-me-gou." Among the Indians she was called "The woman of the blue-robed cloud." The account was given by herself after she had become a member of the Methodist Church and renounced all connection with spirits. The following is her narrative:—

"When I was a girl of about twelve or thirteen years of age, my mother told me to look out for something that would happen to me. Accordingly, one morning early, in the middle of winter, I found an unusual sign, and ran off, as far from the lodge as I could, and remained there until my mother came and found me out. She knew what was the matter, and brought me nearer to the family lodge, and bade me help her in making a small lodge of branches of the spruce tree. She told me to remain there, and keep away from every one, and as a diversion, to keep myself employed in chopping wood, and that she would bring me plenty of prepared bass-wood bark to twist into twine. She told me she would come to see me, in two days, and that in the mean time I must not even taste snow.

(p. 031) "I did as directed; at the end of two days she came to see me. I thought she would surely bring me something to eat, but to my disappointment she brought nothing. I suffered more from thirst than hunger, though I felt my stomach gnawing. My mother sat quietly down and said (after ascertaining that I had not tasted anything), 'My child, you are the youngest of your sisters, and none are now left me of all my sons and children, but you four' (alluding to her two elder sisters, herself and a little son, still a mere lad). 'Who,' she continued, 'will take care of us poor women? Now, my daughter, listen to me, and try to obey. Blacken your face and fast really, that the Master of Life may have pity on you and me, and on us all. Do not, in the least, deviate from my counsels, and in two days more, I will come to you. He will help you, if you are determined to do what is right, and tell me, whether you are favored or not, by the true Great Spirit; and if your visions are not good, reject them.' So saying, she departed.

"I took my little hatchet and cut plenty of wood, and twisted the cord that was to be used in sewing ap-puk-way-oon-un, or mats for the use of the family. Gradually I began to feel less appetite, but my thirst continued; still I was fearful of touching the snow (p. 032) to allay it, by sucking it, as my mother had told me that if I did so, though secretly, the Great Spirit would see me, and the lesser spirits also, and that my fasting would be of no use. So I continued to fast till the fourth day, when my mother came with a little tin dish, and filling it with snow, she came to my lodge, and was well pleased to find that I had followed her injunctions. She melted the snow, and told me to drink it. I did so, and felt refreshed, but had a desire for more, which she told me would not do, and I contented myself with what she had given me. She again told me to get and follow a good vision—a vision that might not only do us good, but also benefit mankind, if I could. She then left me, and for two days she did not come near me, nor any human being, and I was left to my own reflections. The night of the sixth day, I fancied a voice called to me, and said: 'Poor child! I pity your condition; come, you are invited this way;' and I thought the voice proceeded from a certain distance from my lodge. I obeyed the summons, and going to the spot from which the voice came, found a thin, shining path, like a silver cord, which I followed. It led straight forward, and, it seemed, upward. After going a short distance I stood still and saw on my right hand the new moon, (p. 033) with a flame rising from the top like a candle, which threw around a broad light. On the left appeared the sun, near the point of its setting. I went on, and I beheld on my right the face of Kau-ge-gag-be-qua, or the everlasting woman, who told me her name, and said to me, 'I give you my name, and you may give it to another. I also give you that which I have, life everlasting. I give you long life on the earth, and skill in saving life in others. Go, you are called on high.'

"I went on, and saw a man standing with a large, circular body, and rays from his head, like horns. He said, 'Fear not, my name is Monedo Wininees, or the Little man Spirit. I give this name to your first son. It is my life. Go to the place you are called to visit.' I followed the path till I could see that it led up to an opening in the sky, when I heard a voice, and standing still, saw the figure of a man standing near the path, whose head was surrounded with a brilliant halo, and his breast was covered with squares. He said to me: 'Look at me, my name is O-shau-wau-e-geeghick, or the Bright Blue Sky. I am the veil that covers the opening into the sky. Stand and listen to me. Do not be afraid. I am going to endow you with gifts of life, and put you in array that you may withstand and (p. 034) endure.' Immediately I saw myself encircled with bright points which rested against me like needles, but gave me no pain, and they fell at my feet. This was repeated several times, and at each time they fell to the ground. He said, 'wait and do not fear, till I have said and done all I am about to do.' I then felt different instruments, first like awls, and then like nails stuck into my flesh, but neither did they give me pain, but, like the needles, fell at my feet as often as they appeared. He then said, 'that is good,' meaning my trial by these points. 'You will see length of days. Advance a little further,' said he. I did so, and stood at the commencement of the opening. 'You have arrived,' said he, 'at the limit you cannot pass. I give you my name, you can give it to another. Now, return! Look around you. There is a conveyance for you. Do not be afraid to get on its back, and when you get to your lodge, you must take that which sustains the human body.' I turned, and saw a kind of fish swimming in the air, and getting upon it as directed, was carried back with celerity, my hair floating behind me in the air. And as soon as I got back, my vision ceased.

"In the morning, being the sixth day of my fast, my mother came with a little bit of dried trout. (p. 035) But such was my sensitiveness to all sounds, and my increased power of scent, produced by fasting, that before she came in sight I heard her, while a great way off, and when she came in, I could not bear the smell of the fish or herself either. She said, 'I have brought something for you to eat, only a mouthful, to prevent your dying.' She prepared to cook it, but I said, 'Mother, forbear, I do not wish to eat it—the smell is offensive to me.' She accordingly left off preparing to cook the fish, and again encouraged me to persevere, and try to become a comfort to her in her old age, and bereaved state, and left me.

"I attempted to cut wood, as usual, but in the effort I fell back on the snow, from weariness, and lay some time; at last I made an effort and rose, and went to my lodge and lay down. I again saw the vision, and each person who had before spoken to me, and heard the promises of different kinds made to me, and the songs. I went the same path which I had pursued before, and met with the same reception. I also had another vision, or celestial visit, which I shall presently relate. My mother came again on the seventh day, and brought me some pounded corn boiled in snow-water, for she said I must not drink water from lake or river. After taking it, I related my vision to her. She said it (p. 036) was good, and spoke to me to continue my fast three days longer. I did so; at the end of which she took me home, and made a feast in honor of my success, and invited a great many guests. I was told to eat sparingly, and to take nothing too hearty or substantial; but this was unnecessary, for my abstinence had made my senses so acute, that all animal food had a gross and disagreeable odor.

"After the seventh day of my fast (she continued), while I was lying in my lodge, I saw a dark, round object descending from the sky like a round stone, and enter my lodge. As it came near, I saw that it had small feet and hands like a human body. It spoke to me and said, 'I give you the gift of seeing into futurity, that you may use it for the benefit of yourself and the Indians—your relations and tribes-people.' It then departed, but as it went away, it assumed wings, and looked to me like the red-headed woodpecker.

"In consequence of being thus favored, I assumed the arts of a medicine-woman and a prophetess: but never those of a Wabeno. The first time I exercised the prophetical art, was at the strong and repeated solicitations of my friends. It was in the winter season, and they were then encamped west of the Wisacoda, or Brule River, of Lake Superior, (p. 037) and between it and the plains west. There were, beside my mother's family and relatives, a considerable number of families. They had been some time at the place, and were near starving, as they could find no game. One evening the chief of the party came into my mother's lodge. I had lain down, and was supposed to be asleep, and he requested of my mother that she would allow me to try my skill to relieve them. My mother spoke to me, and after some conversation, she gave her consent. I told them to build the Jee-suk-aun, or prophet's lodge strong, and gave particular directions for it. I directed that it should consist of ten posts or saplings, each of a different kind of wood, which I named. When it was finished, and tightly wound with skins, the entire population of the encampment assembled around it, and I went in, taking only a small drum. I immediately knelt down, and holding my head near the ground, in a position as near as may be prostrate, began beating my drum, and reciting my songs or incantations. The lodge commenced shaking violently, by supernatural means. I knew this by the compressed current of air above, and the noise of motion. This being regarded by me, and by all without, as a proof of the presence of the spirits I consulted, I ceased beating (p. 038) and singing, and lay still, waiting for questions in the position I at first assumed.

"The first question put to me was in relation to the game, and where it was to be found. The response was given by the orbicular spirit, who had appeared to me. He said, 'How short-sighted you are! If you will go in a west direction, you will find game in abundance.' Next day the camp was broken up, and they all moved westward, the hunters, as usual, going far ahead. They had not proceeded far beyond the bounds of their former hunting circle, when they came upon tracks of moose, and that day they killed a female and two young moose, nearly full-grown. They pitched their encampment anew, and had abundance of animal food in this new position.

"My reputation was established by this success, and I was afterward noted in the tribe, in the art of a medicine-woman, and sung the songs which I have given to you."(Back to Content)

Marquette's visit to Iroquois Point — Chapel and Fort — Old Mackinaw — The French Settlement in the Northwest — Erection of Chapel and Fort — The Gateway of Commerce — The Rendezvous of Traders, Trappers, Soldiers, Missionaries, and Indians — Description of Fort — Courriers des Bois — Expedition of Marquette and Joliet to Explore the Mississippi — Green Bay — Fox River — Wisconsin — Mississippi — Peoria Indians — Return Trip — Kaskaskia Indians — St. Xavier Missions — Mission to "the Illinois" — Marquette's Health declines — Starts out on Return trip to Mackinaw — Dies and is Buried at mouth of Marquette River — Indians remove his Remains to Mackinaw — Funeral Cortege — Ceremonies — Burial in the Chapel — Changes of time — Schoolcraft on the Place of Marquette's Burial — Missilimackinac — Name of Jesuit Missions.

In the year 1670, the devoted and self-sacrificing missionary, Jean Marquette, with a company of Indians of the Huron tribe, subsequently known as the Wyandots from the Georgian Bay, on the northeastern extremity of Lake Huron, entered for the first time the old Indian town on the northern (p. 040) side of the Mackinaw Straits. During the time he was planting his colony, and erecting his chapel at Iroquois Point, which he afterward designated St. Ignace, he resided on the Mackinaw Island. In 1671, he furnished an account of the island and its surroundings, which was published in "The Relations Des Jesuits". He says:

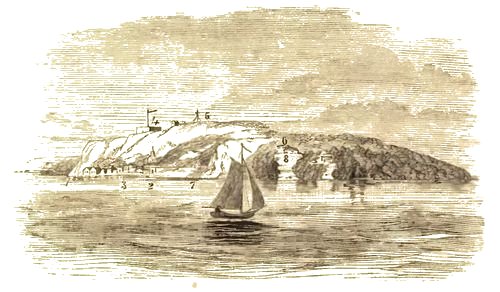

"Missilimackinac is an island famous in these regions, of more than a league in diameter, and elevated in some places by such high cliffs as to be seen more than twelve leagues off. It is situated just in the strait forming the communication between Lakes Huron and Illinois (Michigan). It is the key, and, and as it were, the gate for all the tribes from the south, as the Saut, (St. Marie) is for those of the north, there being in this section of country only those two passages by water, for a great number of nations have to go by one or other of these channels, in order to reach the French settlements.

"This presents a peculiarly favorable opportunity, both for instructing those who pass here, and also for obtaining easy access and conveyance to their places of abode.

"This place is the most noted in these regions for the abundance of its fisheries; for, according to (p. 041) the Indian saying, 'this is the home of the fishes.' Elsewhere, although they exist in large numbers, it is not properly their 'home,' which is in the neighborhood of Missilimackinac.

"In fact, beside the fish common to all the other tribes, as the herring, carp, pike, gold-fish, white-fish and sturgeon, there are found three varieties of the trout—one common; the second of a larger size, three feet long and one foot thick; the third monstrous, for we cannot otherwise describe it—it being so fat that the Indians, who have a peculiar relish for fats, can scarcely eat it. Besides, the supply is such that a single Indian will take forty or fifty of them through the ice, with a single spear, in three hours.

"It is this attraction which has heretofore drawn to a point so advantageous, the greater part of the savages, in this country driven away by fear of the Iroquois. The three tribes at present living on the Baye des Puans (Green Bay) as strangers, formerly dwelt on the main land near the middle of this island—some on the borders of Lake Illinois, others on the borders of Lake Huron. A part of them, called Sauteurs, had their abode on the main land at the West, and the others look upon this place as their country for passing the winter, when there are (p. 042) no fish at the Saut. The Hurons, called Etonontathronnons, have lived for some years in the same island, to escape the Iroquois. Four villages of Ottawas had also their abode in this quarter.

"It is worthy of notice that those who bore the name of the island, and called themselves Missilimackinac, were so numerous, that some of the survivors yet living here assure us that they once had thirty villages, all inclosed in a fortification of a league and a half in circuit, when the Iroquois came and defeated them, inflated by a victory they had gained over three thousand men of that nation, who had carried their hostilities as far as the country of the Agnichronnons.

"In one word, the quantity of fish, united with the excellence of the soil for Indian corn, has always been a powerful attraction to the tribes in these regions, of which the greater part subsist only on fish, but some on Indian corn. On this account many of these same tribes, perceiving that the peace is likely to be established with the Iroquois, have turned their attention to this point so convenient for a return to their own country, and will follow the examples of those who have made a beginning on the islands of Lake Huron, which by this means will soon be peopled from one end to (p. 043) the other, an event highly desirable to facilitate the instruction of the Indian race, whom it would not be necessary to seek by journeys of two or three hundred leagues on these great lakes, with inconceivable danger and hardships.

"In order to aid the execution of the design, signified to us by many of the savages, of taking up their abode at this point, where some have already passed the winter, hunting in the neighborhood, we ourselves have also wintered here, in order to make arrangements for establishing the mission of St. Ignace, from whence it will be easy to have access to all the Indians of Lake Huron, when the several tribes shall have settled each on its own lands.

"With these advantages, the place has also its inconveniences, particularly for the French, who are not yet familiar, as are the savages, with the different kinds of fishery, in which the latter are trained from their birth; the winds and the tides occasion no small embarrassment to the fishermen.

"The winds: For this is the central point between the three great lakes which surround it, and which seem incessantly tossing ball at each other. For no sooner has the wind ceased blowing from Lake Michigan than Lake Huron hurls back the (p. 044) gale it has received, and Lake Superior in its turn, sends forth its blasts from another quarter, and thus the game is played from one to the other—and as these lakes are of vast extent, the winds cannot be otherwise than boisterous, especially during the autumn."

"Old Mackinaw," the Indian name of which is Pe-quod-e-non-ge, an Indian town on the south side of the Straits, became the place of the first French settlement northwest of Fort Frontenac, or Cadaraeque on Lake Ontario. The settlement was made by father Marquette, in 1671. Pe-quod-e-non-ge, as we have seen in a previous Chapter, with its coasts and islands before it, has been the theatre of some of the most exciting and interesting events in Indian history, previous to the arrival of the "white man." It was the Metropolis of a portion of the Ojibwa, and Ottawa nations. It was there that their Congresses met, to adopt a policy which terminated in the conquest of the country south of it—it was there that the tramping feet of thousands of plumed and painted warriors shook Pe-quod-e-non-ge, while dancing their war dances—it was from there that the startling sound of the war yell of these thousands was wafted to the adjacent coast and islands, making the peaceful welkin ring with (p. 045) their unearthly shouts of victory or death. In process of time a Chapel and Fort were erected, and it became a strong-hold and trading post of the greatest importance to the entire region of the northwest, being the gateway of commerce between the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi, and also the grand avenue to the Upper Lakes of the north, and the rendezvous of the traders, merchants, trappers, soldiers, missionaries and Indians of the whole northwest. Villages of Hurons and Ottawas were located in the vicinity of the Fort and Chapel. The Fort inclosed an area of about several acres, and was surrounded with cedar pickets. The remains of the fort and buildings can still be seen. On an eminence not far from the fort, the Ottawas erected a fortification. Within the inclosure of the Fort and adjoining the Chapel, the Jesuits erected a College, the first institution of the kind in the Western country. It was also the great depot for the Courriers des Bois, or rangers of the woods, who, from their distant excursions, would congregate here. The goods which they had brought from Canada, for the purpose of exchanging for furs with the Indians of Green Bay and Illinois, and along the shores of Lake Superior, and the region lying between that and the banks of the Mississippi, had to (p. 046) be deposited here, and they were usually on hand a long time before they could be disposed of and transferred to the distant marts of trade.

In the year 1672, while Marquette was engaged in his duties as priest at the Chapel, the site of which now bears the name of St. Ignatius, and also employed in instructing the Indian youth of the villages, he was visited by Joliet, a member of the same order who bore a commission from Frontenac, then Governor of Canada, empowering him to select Marquette as a companion and enter upon a voyage of discovery. The winter was spent by these men in making preparations to carry out the commands of their superiors. The specific object of their mission was to explore the Mississippi, which was supposed to empty into the Gulf of California. That all possible information might be gained in regard to this unknown river, Marquette held conversations with all the noted Indian explorers and trappers, as well as the rangers of the woods within his reach. From the information thus gained he made out a map of the river, including its source and direction, and all the streams known to empty into it.

Spring at length came, and on a bright, beautiful morning in the month of May, having bid adieu to his charge at his mission, and commended his flock (p. 047) to God, Marquette and his companion, with five others selected for the purpose, entered their bark canoes with paddles in hand, and St. Ignatius was soon lost to the sight of the devoted missionary forever. After sailing along the Straits they entered Lake Michigan, and continued their voyage until they arrived at Green Bay, passed the mouth of the Menominee River, finally reaching that of the Fox River. On the 7th of June, having sailed upwards of two hundred miles, the voyagers reached the mission of St. Francis Xavier. They had now reached the limit of all former French or English discoveries. The new and unknown West spread out before them, and the thousand dangers and hardships by river and land, heightened by tales of horror related to them by the Indians, were presented to their imagination. Resolutely determined to prosecute the enterprise committed to their charge, they knelt upon the shore of Fox River to renew their devotions and obtain the divine guidance and protection. Encouraged by past success, and urged on by a strong faith, they launched their canoes upon the bosom of the Fox River, and breaking the silence of its shores by the dip of their paddles, they sailed up its current. When they reached the rapids of that river, it was with difficulty (p. 048) they were enabled to proceed. There was not power enough in the paddles of the two canoes to stem the current, and they were obliged to wade up the rapids on the jagged rocks, and thus tow them along. Having made the voyage of the Fox they arrived at the portage, and taking their canoes containing their provision and clothes upon their shoulders, they reached the Wisconsin and launched them upon that stream. They had no longer to breast a rapid current, as the waters of the Wisconsin flowed west. With renewed courage they prosecuted their voyage, and after ten days their hearts were made glad at the sight of the broad and beautiful river which they were entering, and which they supposed would bear them to the far-off western sea. They had reached the "father of waters." No sight could be more charming than that which presented itself to their vision as they beheld on either side, alternately stretching away to a vast distance, immense forests of mountain and plain.

At length, on the 25th of June, as they were sailing along near the eastern shore, they discovered foot-prints in the sand. At sight of these they landed and fastening their canoes, that they might again look upon the face of human beings, they followed an Indian path which led up the (p. 049) bank. They were not long in finding two Indian villages, which proved to be those of the "Pewa-rias" and "Moing-wenas." In answer to a question proposed by Marquette, who addressed them in Indian, and inquired who they were; they answered, "We are Illinois." After an exchange of friendly greetings with these peaceable Indians, the voyagers re-embarked and passed on down the river. They continued on their downward passage until they reached the mouth of the Missouri, which poured its turbid flood into the Mississippi; and still further until they passed the mouth of the Ohio, and then on down until they passed the Arkansas, and arrived within thirty miles of the mouth of the Mississippi. It was not necessary to proceed any further to satisfy the explorers that the river entered into the Gulf of Mexico, instead of that of California.

Having accomplished the end of the expedition, the company started out upon their return trip on the 17th of July. When they reached the mouth of the Illinois river, they determined on returning by that route to Mackinaw. Arriving at the portage of that river they fell in with a tribe of Indians who called themselves the Kaskaskias, who kindly volunteered to conduct them to Lake Michigan, (p. 050) where in due time they arrived. After sailing along the western shore of the lake they again found themselves at Green Bay, and were heartily welcomed by the brethren at the mission of St. Francis Xavier. Worn down with fatigue, Marquette determined to remain here to recruit his health before returning to his missionary labors. He spent his time at this mission post in copying his journal of the voyage down the Mississippi and back, which he accompanied by a map of the river and country, and sent by the Ottawa flotilla to his superiors at Montreal. The return of this flotilla brought him orders for the establishment of a mission among the Illinois, with whom he had so friendly an interview on his exploring voyage. Having passed the winter and succeeding summer at the St. Xavier mission, he started out in the fall for Kaskaskia. The difficulties of the journey were such, it having to be accomplished by land and water, that his health, which had been greatly enfeebled by his former voyage, was not sufficient to enable him to endure the cold winds of winter which had set in before the completion of the journey. On reaching the Chicago River it was found closed, and he did not consider it prudent to undertake an over-land journey. He therefore resolved (p. 051) to winter at that point, and giving his Indian companions who accompanied him the proper instructions and pious counsel, he sent them back to Green Bay. Two Frenchmen made an arrangement to remain with him during the winter. The nearest persons to their lodge were fifty miles distant. They were French trappers and traders, one of whom bore the title of a doctor. This latter person being informed of Marquette's ill-health paid him a visit, and did what he could for his relief. He also received friendly offices from the Indians in the neighborhood, a party of whom proposed to carry him and all his baggage to the contemplated mission at Kaskaskia. His health, however, was such that it did not allow him to accept their kind offer, and he was obliged to remain in his camp during the winter.

Spring at length returned after a long and dreary winter, and Marquette, with some Indian companions, started out for the upper waters of the Illinois River. In about two weeks he reached Kaskaskia, and at once entered upon the duties of his mission. After having instructed the Indians, so as to enable them to understand the objects of his mission to them, he called them all together in the open prairie, where he had erected a rude altar surmounted (p. 052) by the cross, and adorned with pictures of the Virgin Mary. The chiefs and warriors, and the whole tribe, were addressed by him in their native tongue. He made a number of presents to them, the more effectually to gain their affections and confidence, and then related to them the simple story of the cross, after which he celebrated mass. The scene was truly impressive, and the effect upon the sons of the forest was all that the missionary could desire. Bright and cheering were the prospects of converting the Kaskaskias to Christianity, but the devoted missionary was doomed to disappointment. His former malady returned, and assumed a type of so alarming a nature, that he was satisfied his labors on earth would soon come to an end.

Thoughts of his beloved mission at Mackinaw, where he had spent so many days in preaching to Ottawas and Hurons, and in teaching their youth Christian science, filled his mind; and the Christian, not to say natural, desire of his heart, was again to bow in the Chapel of St. Ignatius, and again behold the parents and children of his former charge. Having received the last rites of the church he set out to the lake, accompanied by the Kaskaskias who sorrowed much at his departure, but who were (p. 053) comforted by the dying missionary, who assured them that another would soon be sent to take his place. When they reached the shore of Lake Michigan the Indians returned, and with his two French companions Marquette embarked in a canoe upon its waters. As they coasted along the eastern shore of the lake the health of Marquette continued to fail, and he at last became so weak that when they landed to encamp for the night they had to lift him out of the canoe. Much further they could not proceed, as the journey of life with the missionary was rapidly drawing to a close.

Conscious of his approaching dissolution, as they were gently gliding along the shore, he directed his companions to paddle into the mouth of a small river which they were nearing, and pointing to an eminence not far from the bank, he languidly said, "Bury me there." That river, to this day, bears the name of the lamented Marquette. On landing they erected a bark cabin, and stretched the dying missionary as comfortably as they could beneath its humble roof. Having blessed some water with the usual ceremonies of the Catholic Church, he gave his companions directions how to proceed in his last moments. He instructed them also in regard to the manner in which they were to arrange his (p. 054) body when dead, and the ceremonies to be performed when it was committed to the earth. He then, for the last time, heard the confessions of his companions, encouraging them to rely on the mercy and protection of God, and then sent them away to take the repose they so much needed. After a few hours he felt that he was about taking his last sleep, and calling them, he took his crucifix and placing it in their hands, pronounced in a clear voice his profession of faith, thanking the Almighty for the favor of permitting him to die a Jesuit Missionary. Then calmly folding his arms upon his breast with the name of Jesus on his lips, and his eyes raised to heaven, while over his face beamed the radiance of immortality, he passed away to the land of the blest.

In conformity with the directions of the deceased, in due time his companions prepared the body for burial, and to the sound of his Chapel bell bore it slowly and solemnly to the place designated, where they committed it to the dust, and erected a rude cross to point out to the passing traveler the place of his grave.

James Marquette was of a most ancient and honorable family of the city of Laon, France. Born at the ancient seat of his family, in the year 1637, he was, through his pious mother, Rose de la Salle, (p. 055) allied to the venerable John Baptist de la Salle, the founder of the institute known as the Brothers of the Christian Schools. At the age of seventeen he entered the Society of Jesus, and after two years of study and self-examination had passed away, he was, as is usual with the young Jesuits, employed in teaching, which position he held for twelve years. No sooner had he been invested with the priesthood, than his desire to become in all things an imitator of his chosen patron, St. Francis Xavier, induced him to seek a mission in some land that knew not God, that he might labor there to his latest breath, and die unaided and alone. His desire was gratified. For nine years he labored among the Indians, and was able to preach to them in ten different languages; but he rests from his labors, and his works follow him. He died, May 18, 1675.

The Indians of Mackinaw and vicinity, and also those of Kaskaskia, were in great sorrow when the tidings of Marquette's death reached them. Not long after this melancholy event, a large company of Ojibwas, Ottawas, and Hurons, who had been out on a hunting expedition, landed their canoes at the mouth of the Marquette river, with the intention of removing his remains to Mackinaw. They had heard of his desire to have his body interred in (p. 056) the consecrated ground of St. Ignatius, and they had resolved that the dying wish of the missionary should be fulfilled. As they stood around in silence and gazed upon the cross that marked the place of his burial, the hearts of the stern warriors were moved. The bones of the missionary were dug up and placed in a neat box of bark made for the occasion, and the numerous canoes which formed a large fleet started from the mouth of the river with nothing but the sighs of the Indians, and the dip of the paddles to break the silence of the scene. As they advanced towards Mackinaw, the funeral cortege was met by a large number of canoes bearing Ottawas, Hurons, and Iroquois, and still others shot out ever and anon to join the fleet.

When they arrived in sight of the Point, and beheld the cross of St. Ignatius as if painted against the northern sky, the missionaries in charge came out to the beach clad in vestments adapted to the occasion. How was the scene heightened when the priests commenced, as the canoe bearing the remains of Marquette neared the shore, to chant the requiem for the dead. The whole population was out, entirely covering the beach, and as the procession marched up to the Chapel with cross and prayer, and tapers burning, and laid the bark box (p. 057) beneath a pall made in the form of a coffin, the sons and daughters of the forest wept. After the funeral service was ended, the coffin was placed in a vault in the middle of the church, where the Catholic historian says, "Marquette reposes as the guardian angel of the Ottawa missions."

"He was the first and last white man who ever had such an assembly of the wild sons of the forest to attend him to his grave.

"So many stirring events succeeded each other after this period—first, the war between the English Colonists, and the French; then the Colonists with the Indians, the Revolutionary War, the Indian Wars, and finally the War of 1812, with the death of all those who witnessed his burial, including the Fathers who officiated at the time, whose papers were lost, together with the total destruction and evacuation of this mission station for many years, naturally obliterated all recollections of the transaction, which accounts for the total ignorance of the present inhabitants of Point St. Ignatius respecting it. The locality of his grave is lost; but only until the Archangel's trump, at the last, shall summon him from his narrow grave, with those plumed and painted warriors who now lie around him."

The Missionaries who succeeded Marquette, at (p. 058) Mackinaw, continued their labors until 1706, when, finding it useless to continue the mission, or struggle any longer with superstition and vice, they burned down their College and Chapel, and returned to Quebec. The governor, alarmed at this step, at last promised to enforce the laws against the dissolute French, and prevailed on Father Marest to return. Soon after the Ottawas, discontented at Detroit, a French post, which was served by the Recollects, and where the blood of a Recollect had been shed in a riot, began to move back to Mackinaw, and the mission was renewed. In 1721, Charlevoix visited this mission, and this is the last we hear of it.

Nearly two hundred years have passed away since that event. The Chapel of St. Ignatius has passed away, and with it the Chapel, and Fort, and College at Old Mackinaw. Nothing is left but the stone walls and stumps of the pickets which surrounded them, and which may be seen to this day. To the Catholic, this consecrated spot, the site of one of their first Chapels, and their first College in the great northwest, must possess unusual interest. As there is a difference of opinion in relation to the burial place of Marquette, whether it was on the north or south side of the Straits, we give the (p. 059) following from "Schoolcraft's Discovery of the Sources of the Mississippi." He says: "They carried his body to the Mission of Old Mackinaw, of which he was the founder, where it was interred. It is known that the Mission of Mackinaw fell on the downfall of the Jesuits. When the post of Mackinaw was removed from the peninsula to the island, which was about 1780, the bones of the Missionary were transferred to the old Catholic burial ground, in the village on the island. There they remained till a land or property question arose to agitate the Church, and when the crisis happened the whole grave-yard was disturbed, and his bones, with others, were transferred to the Indian village of La Crosse, which is in the vicinity of L'Arbre Croche, Michigan."

There is a difference of opinion also as to the point from whence Marquette and his companions started for the discovery of the Mississippi. Schoolcraft says: "Wherever Missilimackinac is mentioned in the Missionary letters, or in the history of this period, it is the ancient Fort on the apex of the Michigan peninsula that is alluded to." In his Introduction to the above work, he says, that "Father Marquette, after laying the foundation of Missilimackinac, proceeded in company with Sieur Joliet, (p. 060) up the Fox River of Green Bay, and crossing the portage into the Wisconsin, entered the Mississippi in 1673."

It is an established fact, that Marquette organized the Mission at Old Mackinaw, in the year 1671, subsequently to that at the opposite point, and that he remained there until the year 1673, when he embarked with Joliet on his exploring tour of the Mississippi. Charlevoix places the Mission of St. Ignace, on the south side of the Straits, adjoining the Fort, and has made no such designation on the north side, showing at least that this mission was more modern than the other. Nearly all the Jesuit Missions bore the name of St. Ignatius, in honor of their founder, as those of the Franciscans bore the name of St. Francis. Ignatius Loyola and Francis Xavier were the founders of these sects.(Back to Content)

La Salle's visit to Mackinaw — English traders — La Hontan's visit — Mackinaw an English fort — Speech of a Chippewa Chief — Indian stratagem — Massacre of the English at the fort — Escape of Mr. Alexander Henry — Early white settlement of Mackinaw — Present description — Relations of the Jesuits — Remarkable phenomena — Parhelia — Subterranean river.

In the summer of 1679 the Griffin, built by La Salle and his company on the shore of Lake Erie, at the present site of the town of Erie, passed up the St. Clair, sailed over the Huron, and entering the Straits, found a safe harbor at Old Mackinaw. La Salle's expedition passed eight or nine years at this place, and from hence they penetrated the country in all directions. At the same time it continued to be the summer resort of numerous Indian tribes who came here to trade and engage in the wild sports and recreations peculiar to the savage race. As a city of peace, it was regarded in the same light that (p. 062) the ancient Hebrews regarded their cities of Refuge, and among those who congregated here all animosities were forgotten. The smoke of the calumet of peace always ascended, and the war cry never as yet has been heard in its streets.

In Heriot's Travels, published in 1807, we find the following interesting item:

'In 1671 Father Marquette came hither with a party of Hurons, whom he prevailed on to form a settlement. A fort was constructed, and it afterward became an important spot. It was the place of general assemblage for all the French who went to traffic with the distant nations. It was the asylum of all savages who came to exchange their furs for merchandise. When individuals belonging to tribes at war with each other came thither, and met on commercial adventure, their animosities were suspended.'

Notwithstanding San-ge-man and his warriors had braved the dangers of the Straits and had slain a hundred of their enemies whose residence was here, yet it was not in the town that they were slain. No blood was ever shed by Indian hands within its precincts up to this period, and had it remained in possession of the French the terrible scenes subsequently enacted within its streets would in all probability (p. 063) never have occurred, and Old Mackinaw would have been a city of Refuge to this day.

The English, excited by the emoluments derived from the fur trade, desired to secure a share in this lucrative traffic of the northwestern Lakes. They, accordingly, in the year 1686, fitted out an expedition, and through the interposition of the Fox Indians, whose friendship they secured by valuable presents; the expedition reached Old Mackinaw, the "Queen of the Lakes," and found the El Dorado they had so long desired.

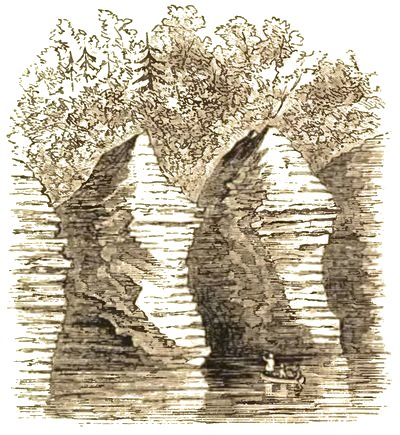

The following interesting description, from Parkman's "History of the Conspiracy of Pontiac," of a voyage by an English merchant to Old Mackinaw about this time, will be in place here: "Passing the fort and settlement of Detroit, he soon enters Lake St. Clair, which seems like a broad basin filled to overflowing, while along its far distant verge a faint line of forests separates the water from the sky. He crosses the lake, and his voyagers next urge his canoe against the current of the great river above. At length Lake Huron opens before him, stretching its liquid expanse like an ocean to the furthest horizon. His canoe skirts the eastern shore of Michigan, where the forest rises like a wall from the water's edge, and as he advances onward, an (p. 064) endless line of stiff and shaggy fir trees hung with long mosses, fringe the shore with an aspect of desolation. Passing on his right the extensive Island of Bois Blanc, he sees nearly in front the beautiful Island of Mackinaw rising with its white cliffs and green foliage from the broad breast of waters. He does not steer toward it, for at that day the Indians were its only tenants, but keeps along the main shore to the left, while his voyagers raise their song and chorus. Doubling a point he sees before him the red flag of England swelling lazily in the wind, and the palisades and wooden bastions of Fort Mackinaw standing close upon the margin of the lake. On the beach canoes are drawn up, and Canadians and Indians are idly lounging. A little beyond the fort is a cluster of white Canadian houses roofed with bark and protected by fences of strong round pickets. The trader enters the gate and sees before him an extensive square area, surrounded by high palisades. Numerous houses, barracks, and other buildings form a smaller square within, and in the vacant place which they enclose appear the red uniforms of British soldiers, the grey coats of the Canadians, and the gaudy Indian blankets mingled in picturesque confusion, while a multitude of squaws (p. 065) with children of every hue stroll restlessly about the place. Such was old fort Mackinaw in 1763."

La Hontan, who visited Mackinaw in 1688, says: "It is a place of great importance. It is not above half a league distant from the Illinese (Michigan) Lake. Here the Hurons and Ottawas have each of them a village, the one being severed from the other by a single palisade, but the Ottawas are beginning to build a fort upon a hill that stands but one thousand or twelve hundred paces off. In this place the Jesuits have a little house or college adjoining to a church, and inclosed with pales that separate it from the village of the Hurons. The Courriers de Bois have but a very small settlement here, at the same time it is not inconsiderable, as being the staple of all the goods that they truck with the south and west savages; for they cannot avoid passing this way when they go to the seats of the Illinese and the Oumamis on to the Bay des Puanto, and to the River Mississippi. Missilimackinac is situated very advantageously, for the Iroquese dare not venture with their sorry canoes to cross the stright of the Illinese Lake, which is two leagues over; besides that the Lake of the Hurons is too rough for such slender boats, and as they cannot come to it by water, so they cannot approach it by land by reason of the (p. 066) marshes, fens, and little rivers which it would be very difficult to cross, not to mention that the stright of the Illinese Lake lies still in their way."

As rivals of the French, the English were never regarded with favor by the various Indian tribes. Constant encroachments by the English from year to year, though they were lavish of their gifts did not tend to soften the hostility of the tribes. Thus matters continued until Mackinaw passed into the hands of the English, which event took place after the fall of Quebec in the year 1759. This transfer of jurisdiction from a people that the Indians loved to one that they experienced a growing hate for during three-quarters of a century, filled them with a spirit of revenge. Such was the dislike of the Indians of Mackinaw to the English, that when Alexander Henry visited that place in 1761, he was obliged to conceal the fact that he was an Englishman and disguise himself as a Canadian voyager. On the way he was frequently warned by the Indians to turn back, as he would not be received at Mackinaw, and as there were no British soldiers there as yet, he was assured that his visit would be attend with great hazard. He still persisted, however, and finally, with his canoes laden with goods he reached the fort, which, we have before remarked, was surrounded (p. 067) with palisades, and occupied the high ground immediately back from the beach. When he entered the village he met with a cold reception, and the inhabitants did all in their power to alarm and discourage him.

Soon after his arrival he received the very unpleasant intelligence, that a large number of Chippewas were coming from the neighboring villages in their canoes to call upon him. Under ordinary circumstances this information would not have excited any alarm, but as the French of Mackinaw as well as the Indians were alike hostile to the English trader, it was no difficult matter to apprehend danger. At length the Indians, about sixty in number, arrived, each with a tomahawk in one hand and a scalping knife in the other. The garrison at this time contained about ninety soldiers, a commander and two officers. Beside the small arms, on the bastions were mounted two small pieces of brass cannon. Beside Henry, there were four English merchants at the fort. After the Indians were introduced to Henry and his English brethren, their chief presented him with a few strings of wampum and addressed them as follows:

"Englishmen, it is to you that I speak, and I demand your attention. You know that the French (p. 068) King is our father. He promised to be such, and we in turn promised to be his children. This promise we have kept. It is you that have made war with this our father. You are his enemy, and how then could you have the boldness to venture among us, his children. You know that his enemies are ours. We are informed that our father, the King of France, is old and infirm, and that being fatigued with making war upon your nation, he has fallen asleep. During this sleep you have taken advantage of him and possessed yourselves of Canada. But his nap is almost at an end. I think I hear him already stirring and inquiring for his children, and when he does awake what must become of you? He will utterly destroy you. Although you have conquered the French you have not conquered us. We are not your slaves. These lakes, these woods and mountains are left to us by our ancestors, they are our inheritance and we will part with them to none. Your nation supposes that we, like the white people, cannot live without bread, and pork, and beef, but you ought to know that He, the Great Spirit and Master of Life, has provided food for us in these spacious lakes and on these woody mountains.

"Our father, the King of France, employed our young men to make war upon your nation. In this (p. 069) warfare many of them have been killed, and it is our custom to retaliate until such time as the spirits of the slain are satisfied. But the spirits of the slain are to be satisfied in one of two ways; the first is by the spilling the blood of the nation by which they fell, the other by covering the bodies of the dead, and thus allaying the resentment of their relations. This is done by making presents. Your king has never sent us any presents, nor entered into any treaty with us, wherefore he and we are still at war, and until he does these things we must consider that we have no other father or friend among the white men than the King of France. But for you, we have taken into consideration that you have ventured among us in the expectation that we would not molest you. You do not come around with the intention to make war. You come in peace to trade with us, and supply us with necessaries, of which we are in much need. We shall regard you, therefore, as a brother, and you may sleep tranquilly without fear of the Chippewas. As a token of friendship we present you with this pipe to smoke."

Henry was afterwards visited by a party of two hundred Ottawa warriors from L'Arbre Croche, about (p. 070) seventy miles southwest of Mackinaw. One of the Chiefs addressed him thus:—

"Englishmen: We, the Ottawas, were some time since informed of your arrival in this country, and of your having brought with you the goods we so much need. At this news we were greatly pleased, believing that, through your assistance, our wives and children would be able to pass another winter; but, what was our surprise, when a few days ago we were informed the goods which we had expected were intended for us were on the eve of departure for distant countries, some of which are inhabited by our enemies. These accounts being spread, our wives and children came to us crying, and desiring that we should go to the Fort to learn with our ears the truth or falsehood. We accordingly embarked, almost naked as you see, and on our arrival here we have inquired into the accounts, and found them true. We see your canoes ready to depart, and find your men engaged for the Mississippi and other distant regions. Under these circumstances we have considered the affair, and you are now sent for that you may hear our determination, which is, that you shall give each of our men, young and old, merchandise and ammunition to the amount of fifty beaver skins on credit, and for which (p. 071) I have no doubt of their paying you in the summer, on their return from their wintering."