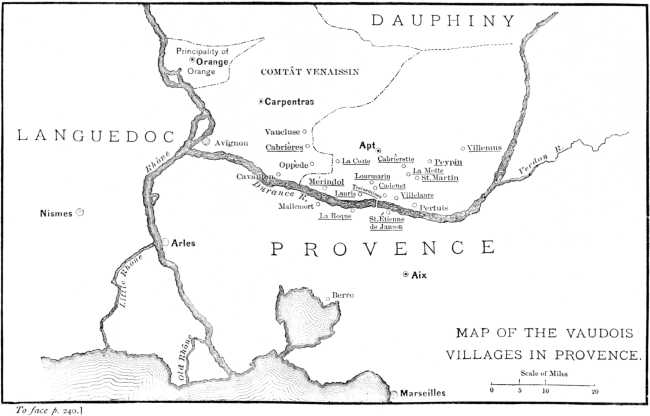

MAP OF THE VAUDOIS VILLAGES IN PROVENCE.

To face p. 240.

Title: History of the Rise of the Huguenots, Vol. 1

Author: Henry Martyn Baird

Release date: September 24, 2007 [eBook #22762]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sigal Alon, Daniel J. Mount, Taavi Kalju and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Occupying nearly four columns, appeared in the New York Tribune of Dec. 30th, 1879, from which the following is extracted.

"It embraces the time from the accession of Francis I. in 1515, to the death of Charles IX. in 1574, at which epoch the doctrines of the Reformation had become well-grounded in France, and the Huguenots had outgrown the feebleness of infancy and stood as a distinct and powerful body before the religious world. In preparing the learned and elaborate work, which will give the name of the author an honourable place on the distinguished list of American historians, Professor Baird has made a judicious use of the researches and discoveries which, during the last thirty years, have shed a fresh light on the history of France at the era of the Reformation. Among the ample stores of knowledge which have been laid open to his inquiries are the archives of the principal capitals of Europe, which have been thoroughly explored for the first time during that period. Numerous manuscripts of great value, for the most part unknown to the learned world, have been rescued from obscurity. At the side of the voluminous chronicles long since printed, a rich abundance of contemporary correspondence and hitherto inedited memoirs has accumulated, which afford a copious collection of life-like and trustworthy views of the past. The secrets of diplomacy have been revealed. The official statements drawn up for the public may now be tested by the more truthful and unguarded accounts conveyed in cipher to all the foreign courts of Europe. Of not less importance, perhaps, than the official publications are the fruits of private research, among which are several valuable collections of original documents. While the author has not failed to enrich his pages with the materials derived from these and similar sources, he has made a careful and patient study of the host of original chronicles, histories, and kindred productions which have long been more or less familiar to the world of letters. The fruits of his studious labours, as presented in these volumes, attest his diligence, his fidelity, his equipoise of judgment, his fairness of mind, his clearness of perception, and his accuracy of statement.

"While the research and well-digested erudition exhibited in this work are eminently creditable to the learning and scholarship of the author, its literary execution amply attests the excellence of his taste, and his judgment and skill in the art of composition. His work is one of the most important recent contributions to American literature, and is entitled to a sincere greeting for its manifold learning and scholarly spirit."

Hazell, Watson, and Viney, Printers, London and Aylesbury

The period of about half a century with which these volumes are concerned may properly be regarded as the formative age of the Huguenots of France. It included the first planting of the reformed doctrines, and the steady growth of the Reformation in spite of obloquy and persecution, whether exercised under the forms of law or vented in lawless violence. It saw the gathering and the regular organization of the reformed communities, as well as their consolidation into one of the most orderly and zealous churches of the Protestant family. It witnessed the failure of the bloody legislation of three successive monarchs, and the equally abortive efforts of a fourth monarch to destroy the Huguenots, first with the sword and afterward with the dagger. At the close of this period the faith and resolution of the Huguenots had survived four sanguinary wars into which they had been driven by their implacable enemies. They were just entering upon a fifth war, under favorable auspices, for they had made it manifest to all men that their success depended less upon the lives of leaders, of whom they might be robbed by the hand of the assassin, than upon a conviction of the righteousness of their cause, which no sophistry of their opponents could dissipate. The Huguenots, at the death of[Pg iv] Charles the Ninth, stood before the world a well-defined body, that had outgrown the feebleness of infancy, and had proved itself entitled to consideration and respect. Thus much was certain.

The subsequent fortunes of the Huguenots of France—their wars until they obtained recognition and some measure of justice in the Edict of Nantes; the gradual infringement upon their guaranteed rights, culminating in the revocation of the edict, and the loss to the kingdom of the most industrious part of the population; their sufferings "under the cross" until the publication of the Edict of Toleration—these offer an inviting field of investigation, upon which I may at some future time be tempted to enter.[1]

The history of the Huguenots during a great part of the period covered by this work, is, in fact, the history of France as well. The outlines of the action and some of the characters that come upon the stage are, consequently, familiar to the reader of general history. The period has been treated cursorily in writings extending over wider limits, while several of the most striking incidents, including, especially, the Massacre of St. Bartholomew's Day, have been made the subject of special disquisitions. Yet, although much study and ingenuity have been expended in elucidating the more difficult and obscure points, there is, especially in the English language, a lack of works upon the general theme, combining painstaking investigation into the[Pg v] older (but not, necessarily, better known) sources of information, and an acquaintance with the results of modern research.

The last twenty-five or thirty years have been remarkably fruitful in discoveries and publications shedding light upon the history of France during the age of the Reformation and the years immediately following. The archives of all the principal, and many of the secondary, capitals of Europe have been explored. Valuable manuscripts previously known to few scholars—if, indeed, known to any—have been rescued from obscurity and threatened destruction. By the side of the voluminous histories and chronicles long since printed, a rich store of contemporary correspondence and hitherto inedited memoirs has been accumulated, supplying at once the most copious and the most trustworthy fund of life-like views of the past. The magnificent "Collection de Documents Inédits sur l'Histoire de France," still in course of publication by the Ministry of Public Instruction, comprehends in its grand design not only extended memoirs, like those of Claude Haton of Provins, but the even more important portfolios of leading statesmen, such as those of Secretary De l'Aubespine and Cardinal Granvelle (not less indispensable for French than for Dutch affairs), and the correspondence of monarchs, as of Henry the Fourth. The secrets of diplomacy have been revealed. Those singularly accurate and sensible reports made to the Doge and Senate of Venice, by the ambassadors of the republic, upon their return from the French court, can be read in the collections of Venetian Relations of Tommaseo and Albèri, or as summarized by Ranke and Baschet. The official statements drawn up for the eyes of the public may now be confronted with and tested by the more truthful and unguarded accounts conveyed in cipher to all the foreign courts of Europe. Including the partial collections of[Pg vi] despatches heretofore put in print, we possess, regarding many critical events, the narratives and opinions of such apt observers as the envoys of Spain, of the German Empire, of Venice, and of the Pope, of Wurtemberg, Saxony, and the Palatinate. Above all, we have access to the continuous series of letters of the English ambassadors and minor agents, comprising Sir Thomas Smith, Sir Nicholas Throkmorton, Walsingham, Jones, Killigrew, and others, scarcely less skilful in the use of the pen than in the art of diplomacy. This English correspondence, parts of which were printed long ago by Digges, Dr. Patrick Forbes, and Haynes, and other portions by Hardwick, Wright, Tytler-Fraser, etc., can now be read in London, chiefly in the Record Office, and is admirably analyzed in the invaluable "Calendars of State Papers (Foreign Series)," published under the direction of the Master of the Rolls. Too much weight can scarcely be given to this source of information and illustration. One of the learned editors enthusiastically remarks concerning a part of it (the letters of Throkmorton[2]): "The historical literature of France, rich as it confessedly is in memoirs and despatches of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, possesses (as far as I am aware) no series of papers which can compare either in continuity, fidelity, or minuteness, with the correspondence of Throkmorton.... He had his agents and his spies everywhere throughout France."

Little, if at all, inferior in importance to governmental publications, are the fruits of private research. Several voluminous collections of original documents deserve special mention. Not to speak of the publications of the national French Historical[Pg vii] Society, the "Société de l'Histoire du Protestantisme Français" has given to the world, in its monthly Bulletin, so many hitherto inedited documents, besides a great number of excellent monographs, that the volumes of this periodical, now in its twenty-eighth year, constitute in themselves an indispensable library of reference. That admirable biographical work, "La France Protestante," by the brothers Haag (at present in course of revision and enlargement); the "Correspondance des Réformateurs dans les Pays de Langue Française," by M. Herminjard (of which five volumes have come out), a signal instance of what a single indefatigable student can accomplish; the collections of Calvin's Letters, by M. Jules Bonnet; and the magnificent edition of the same reformer's works, by Professors Baum, Cunitz, and Reuss, a treasury of learning, rich in surprises for the historical student—all these merit more particular description than can here be given. The biography of Beza, by Professor Baum, the history of the Princes of Condé, by the Due d'Aumale, the correspondence of Frederick the Pious, edited by Kluckholn, etc., contribute a great deal of previously unpublished material. The sumptuous work of M. Douen on Clément Marot and the Huguenot Psalter sheds new light upon an interesting, but until now obscure subject. The writings of Farel and his associates have been rescued from the oblivion to which the extreme scarcity of the extant copies consigned them; and the "Vray Usage de la Croix," the "Sommaire," and the "Manière et Fasson," can at last be read in elegant editions, faithful counterparts of the originals in every point save typographical appearance. The same may be said of such celebrated but hitherto unattainable rarities as the "Tigre" of 1560, scrupulously reproduced in fac-simile, by M. Charles Read, of Paris, from the copy belonging to the Hôtel-de-Ville, and the fugi[Pg viii]tive songs and hymns which M. Bordier has gathered in his "Chansonnier Huguenot."

No little value belongs, also, to certain contemporary journals of occurrences given to the world under the titles of "Journal d'un Bourgeois de Paris sous le règne de François Ier," "Cronique du Roy Françoys, premier de ce nom," "Journal d'un curé ligueur de Paris sous les trois derniers Valois (Jehan de la Fosse)," "Journal de Jean Glaumeau de Bourges," etc.

The revival of interest in the fortunes of their ancestors has led a considerable number of French Protestants to prepare works bearing upon the history of Protestantism in particular cities and provinces. Among these may be noted the works of MM. Douen and Rossier, on Picardy; Recordon, on Champagne; Lièvre, on Poitou; Bujeaud, on Angoumois; Vaurigaud, on Brittany; Arnaud, on Dauphiny; Coquerel, on Paris; Borrel, on Nismes; Callot and Delmas, on La Rochelle; Crottet, on Pons, Gémozac, and Mortagne; Corbière, on Montpellier, etc. Although these books differ greatly in intrinsic importance, and in regard to the exercise of historical criticism, they all have a valid claim to attention by reason of the evidence they afford of individual research.

Of the new light thrown upon the rise of the Huguenots by these and similar works, it has been my aim to make full use. At the same time I have been convinced that no adequate knowledge of the period can be obtained, save by mastering the great array of original chronicles, histories, and kindred productions with which the literary world has long been acquainted, at least by name. This result I have, accordingly, endeavored to reach by careful and patient reading. It is unnecessary to specify in detail the numerous authors through whose writings it became my laborious but by no means un[Pg ix]grateful task to make my way, for the marginal notes will indicate the exact line of the study pursued. It may be sufficient to say, omitting many other names scarcely less important, that I have assiduously studied the works of De Thou, Agrippa d'Aubigné, La Place, La Planche; the important "Histoire Ecclésiastique," ascribed to Theodore de Bèze; the "Actiones et Monimenta" of Crespin; the memoirs of Castelnau, Vieilleville, Du Bellay, Tavannes, La Noue, Montluc, Lestoile, and other authors of this period, included in the large collections of memoirs of Petitot, Michaud and Poujoulat, etc.; the writings of Brantôme; the Commentaries of Jean de Serres, in their various editions, as well as other writings attributed to the same author; the rich "Mémoires de Condé," both in their original and their enlarged form; the series of important documents comprehended in the "Archives curieuses" of Cimber and Danjou; the disquisitions collected by M. Leber; the histories of Davila, Florimond de Ræmond, Maimbourg, Varillas, Soulier, Mézeray, Gaillard; the more recent historical works of Sismondi, Martin, Michelet, Floquet; the volumes of Browning, Smedley, and White, in English, of De Félice, Drion, and Puaux, in French, of Barthold, Von Raumer, Ranke, Polenz, Ebeling, and Soldan, in German. The principal work of Professor Soldan, in particular, bounded by the same limits of time with those of the present history, merits, in virtue of accuracy and thoroughness, a wider recognition than it seems yet to have attained. My own independent investigations having conducted me over much of the ground traversed by Professor Soldan, I have enjoyed ample opportunity for testing the completeness of his study and the judicial fairness of his conclusions.

The posthumous treatise of Professor H. Wuttke, "Zur Vorgeschichte der Bartholomäusnacht," published in Leipsic since[Pg x] the present work was placed in the printer's hands, reached me too late to be noticed in connection with the narrative of the events which it discusses. Notwithstanding Professor Wuttke's recognized ability and assiduity as a historical investigator, I am unable to adopt the position at which he arrives.

I desire here to acknowledge my obligation for valuable assistance in prosecuting my researches to my lamented friend and correspondent, Professor Jean Guillaume Baum, long and honorably connected with the Académie de Strasbourg, than whom France could boast no more indefatigable or successful student of her annals, and who consecrated his leisure hours during forty years to the enthusiastic study of the history of the French and Swiss Reformation. If that history is better understood now than when, in 1838, he submitted as a theological thesis his astonishingly complete "Origines Evangelii in Gallia restaurati," the progress is due in great measure to his patient labors. To M. Jules Bonnet, under whose skilful editorship the Bulletin of the French Protestant Historical Society has reached its present excellence, I am indebted for help afforded me in solving, by means of researches among the MSS. of the Bibliothèque Rationale at Paris, and the Simler Collection at Zurich, several difficult problems. To these names I may add those of M. Henri Bordier, Bibliothécaire Honoraire in the Department of MSS. (Bibliothèque Rationale), of M. Raoul de Cazenove, of Lyons, author of many highly prized monographs on Huguenot topics, and of the Rev. John Forsyth, D.D., who have in various ways rendered me valuable services.

Finally, I deem it both a duty and a privilege to express my warm thanks to the librarians of the Princeton Theological Seminary and of the Union Theological Seminary in this city; and[Pg xi] particularly to the successive superintendents and librarians of the Astor Library—both the living and the dead—by the signal courtesy of whom, the whole of that admirable collection of books has been for many years placed at my disposal for purposes of consultation so freely, that nothing has been wanting to make the work of study in its alcoves as pleasant and effective as possible.

University of the City of New York,

September 15, 1879.

| BOOK I. | ||

| CHAPTER I | ||

| Page | ||

| France in the Sixteenth Century | 3 | |

| Extent at the Accession of Francis I. | 3 | |

| Gradual Territorial Growth | 4 | |

| Subdivision in the Tenth Century | 5 | |

| Destruction of the Feudal System | 5 | |

| The Foremost Kingdom of Christendom | 6 | |

| Assimilation of Manners and Language | 8 | |

| Growth and Importance of Paris | 9 | |

| Military Strength | 10 | |

| The Rights of the People overlooked | 11 | |

| The States General not convoked | 12 | |

| Unmurmuring Endurance of the Tiers État | 13 | |

| Absolutism of the Crown | 14 | |

| Partial Checks | 15 | |

| The Parliament of Paris | 16 | |

| Other Parliaments | 17 | |

| The Parliaments claim the Right of Remonstrance | 17 | |

| Abuses in the Parliament of Bordeaux | 19 | |

| Origin and Growth of the University | 20 | |

| Faculty of Theology, or Sorbonne | 22 | |

| Its Authority and Narrowness | 23 | |

| Multitude of Students | 24 | |

| Credit of the Clergy | 25 | |

| Liberties of the Gallican Church | 25 | |

| Pragmatic Sanction of. St. Louis (1268) | 26 | |

| Conflict of Philip the Fair with Boniface VIII. | 27 | |

| [Pg xiv]The "Babylonish Captivity" | 28 | |

| Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges (1438) | 29 | |

| Rejoicing at the Council of Basle | 31 | |

| Louis XI. undertakes to abrogate the Pragmatic Sanction | 32 | |

| But subsequently re-enacts it in part | 33 | |

| Louis XII. publishes it anew | 35 | |

| Francis I. sacrifices the Interests of the Gallican Church | 35 | |

| Concordat between Leo X. and the French King | 36 | |

| Dissatisfaction of the Clergy | 37 | |

| Struggle with the Parliament of Paris | 37 | |

| Opposition of the University | 39 | |

| Patronage of the King | 41 | |

| The "Renaissance" | 41 | |

| Francis's Acquirements overrated | 42 | |

| His Munificent Patronage of Art | 42 | |

| The Collége Royal, or "Trilingue" | 43 | |

| An Age of Blood | 44 | |

| Barbarous Punishment for Crime | 45 | |

| And not less for Heresy | 46 | |

| Belief in Judicial Astrology | 47 | |

| Predictions of Nostradamus | 47 | |

| Reverence for Relics | 49 | |

| For the Consecrated Wafer | 50 | |

| Internal Condition of the Clergy | 51 | |

| Number and Wealth of the Cardinals | 51 | |

| Non-residence of Prelates | 52 | |

| Revenues of the Clergy | 52 | |

| Vice and Hypocrisy | 53 | |

| Brantôme's Account of the Clergy before the Concordat | 54 | |

| Aversion to the Use of the French Language | 56 | |

| Indecent Processions—"Processions Blanches" | 59 | |

| The Monastic Orders held in Contempt | 60 | |

| Protests against prevailing Corruption | 61 | |

| The "Cathari," or Albigenses | 61 | |

| Nicholas de Clemangis | 63 | |

| John Gerson | 64 | |

| Jean Bouchet's "Deploration of the Church" | 65 | |

| Changes in the Boundaries of France during the 16th Century | 66 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| 1512-1525. | ||

| The Reformation in Meaux | 67 | |

| Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples | 67 | |

| Restores Letters to France | 68 | |

| [Pg xv]Wide Range of his Studies | 68 | |

| Guillaume Farel, his Pupil | 68 | |

| Devotion of Teacher and Scholar | 69 | |

| Lefèvre publishes a Latin Commentary on the Pauline Epistles (1512) | 70 | |

| Enters into Controversy with Natalis Beda (1518) | 71 | |

| The Sorbonne's Declaration (Nov. 9, 1521) | 71 | |

| Briçonnet, Bishop of Meaux | 72 | |

| His First Reformatory Efforts | 72 | |

| Invites Lefèvre and Farel to Meaux | 73 | |

| Effects of the Preaching of Roussel and others | 74 | |

| De Roma's Threat | 76 | |

| Lefèvre publishes a Translation of the New Testament (1523) | 77 | |

| The Results surpass Expectation | 79 | |

| Bishop Briçonnet's Weakness | 80 | |

| Forbids the "Lutheran" Doctors to preach | 81 | |

| Lefèvre and Roussel take Refuge in Strasbourg | 84 | |

| Jean Leclerc whipped and branded | 87 | |

| His barbarous Execution at Metz | 88 | |

| Pauvan burned on the Place de Grève | 89 | |

| The Hermit of Livry | 92 | |

| Briçonnet becomes a Jailer of "Lutherans" | 92 | |

| Lefèvre's Writings condemned by the Sorbonne (1525) | 93 | |

| He becomes Tutor of Prince Charles | 94 | |

| Librarian at Blois | 94 | |

| Ends his Days at Nérac | 95 | |

| His Mental Anguish | 95 | |

| Michel d'Arande and Gérard Roussel | 96 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| 1523-1525. | ||

| Francis I. and Margaret of Angoulême—Early Reformatory Movements and Struggles | 99 | |

| Francis I. and Margaret of Angoulême | 99 | |

| The King's Chivalrous Disposition | 100 | |

| Appreciates Literary Excellence | 101 | |

| Contrast with Charles V. | 101 | |

| His Religious Convictions | 102 | |

| His Fear of Innovation | 102 | |

| His Loose Morality | 103 | |

| Margaret's Scholarly Attainments | 104 | |

| Her Personal Appearance | 105 | |

| Her Participation in Public Affairs | 106 | |

| Her First Marriage to the Duke of Alençon | 106 | |

| Obtains a Safe-Conduct to visit her Brother | 106 | |

| [Pg xvi]Her Second Marriage, to Henry, King of Navarre | 107 | |

| Bishop Briçonnet's Mystic Correspondence | 108 | |

| Luther's Teachings solemnly condemned by the University | 108 | |

| Melanchthon's Defence | 109 | |

| Regency of Louise de Savoie | 109 | |

| The Sorbonne suggests Means of extirpating the "Lutheran Doctrines" (Oct. 7, 1523) | 110 | |

| Wide Circulation of Luther's Treatises | 112 | |

| François Lambert, of Avignon | 112 | |

| Life among the Franciscans | 113 | |

| Lambert, the first French Monk to embrace the Reformation | 113 | |

| He is also the First to Marry | 114 | |

| Jean Châtellain at Metz | 114 | |

| Wolfgang Schuch at St. Hippolyte | 115 | |

| Farel at Montbéliard | 117 | |

| Pierre Caroli lectures on the Psalms | 118 | |

| The Heptameron of the Queen of Navarre | 119 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| 1525-1533. | ||

| Increased Severity—Louis de Berquin | 122 | |

| Captivity of Francis I. | 122 | |

| Change in the Religious Policy of Louise | 123 | |

| A Commission appointed to try "Lutherans" | 124 | |

| The Inquisition heretofore jealously watched | 125 | |

| The Commission indorsed by Clement VII. | 126 | |

| Its Powers enlarged by the Bull | 128 | |

| Character of Louis de Berquin | 128 | |

| He becomes a warm Partisan of the Reformation | 129 | |

| First Imprisonment (1523) | 130 | |

| Released by Order of the King | 130 | |

| Advice of Erasmus | 131 | |

| Second Imprisonment (1526) | 131 | |

| Francis from Madrid again orders his Release | 132 | |

| Dilatory Measures of Parliament | 132 | |

| Margaret of Angoulême's Hopes | 133 | |

| Francis violates his Pledges to Charles V. | 134 | |

| Must conciliate the Pope and Clergy | 135 | |

| Promises to prove himself "Very Christian" | 137 | |

| The Council of Sens (1528) | 138 | |

| Cardinal Duprat | 138 | |

| Vigorous Measures to suppress Reformation | 139 | |

| The Councils of Bourges and Lyons | 139 | |

| [Pg xvii]Financial Help bought by Persecution | 140 | |

| Insult to an Image and an Expiatory Procession | 141 | |

| Other Iconoclastic Excesses | 143 | |

| Berquin's Third Arrest | 143 | |

| His Condemnation to Penance, Branding, and Perpetual Imprisonment | 145 | |

| He Appeals | 145 | |

| Is suddenly Sentenced to Death and Executed | 146 | |

| Francis Treats with the Germans | 147 | |

| And with Henry VIII. of England | 148 | |

| Francis meets Clement at Marseilles | 148 | |

| Marriage of Henry of Orleans to Catharine de' Medici | 148 | |

| Francis Refuses to join in a general Scheme for the Extermination of Heresy | 149 | |

| Execution of Jean de Caturce, at Toulouse | 150 | |

| Le Coq's Evangelical Sermon | 151 | |

| Margaret attacked at College of Navarre | 152 | |

| Her "Miroir de l'Ame Pécheresse" condemned | 152 | |

| Rector Cop's Address to the University | 153 | |

| Calvin, the real Author, seeks Safety in Flight | 154 | |

| Rough Answer of Francis to the Bernese | 155 | |

| Royal Letter to the Bishop of Paris | 156 | |

| Elegies on Louis de Berquin | 157 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| 1534-1535. | ||

| Melanchthon's Attempt at Conciliation, and the Year of the Placards | 159 | |

| Hopes of Reunion in the Church | 159 | |

| Melanchthon and Du Bellay | 160 | |

| A Plan of Reconciliation | 160 | |

| Its Extreme Concessions | 161 | |

| Makes a Favorable Impression on Francis | 162 | |

| Indiscreet Partisans of Reform | 162 | |

| Placards and Pasquinades | 163 | |

| Féret's Mission to Switzerland | 164 | |

| The Placard against the Mass | 164 | |

| Excitement produced in Paris (Oct. 18, 1534) | 167 | |

| A Copy posted on the Door of the Royal Bedchamber | 167 | |

| Anger of Francis at the Insult | 167 | |

| Political Considerations | 168 | |

| Margaret of Navarre's Entreaties | 168 | |

| Francis Abolishes the Art of Printing (Jan. 13, 1535) | 169 | |

| [Pg xviii]The Rash and Shameful Edict Recalled | 170 | |

| Rigid Investigation and many Victims | 171 | |

| The Expiatory Procession (Jan. 21, 1535) | 173 | |

| The King's Speech at the Episcopal Palace | 176 | |

| Constancy of the Victims | 177 | |

| The Estrapade | 177 | |

| Flight of Clément Marot and others | 179 | |

| Royal Declaration of Coucy (July 16, 1535) | 179 | |

| Alleged Intercession of Pope Paul III. | 180 | |

| Clemency again dictated by Policy | 181 | |

| Francis's Letter to the German Princes | 182 | |

| Sturm and Voré beg Melanchthon to come | 182 | |

| Melanchthon's Perplexity | 183 | |

| He is formally invited by the King | 184 | |

| Applies to the Elector for Permission to go | 184 | |

| But is roughly refused | 185 | |

| The Proposed Conference reprobated by the Sorbonne | 187 | |

| Du Bellay at Smalcald | 188 | |

| He makes for Francis a Protestant Confession | 189 | |

| Efforts of French Protestants in Switzerland and Germany | 191 | |

| Intercession of Strasbourg, Basle, etc. | 191 | |

| Unsatisfactory Reply by Anne de Montmorency | 193 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| 1535-1545. | ||

| Calvin and Geneva—More Systematic Persecution by the King | 193 | |

| Changed Attitude of Francis | 193 | |

| Occasioned by the "Placards" | 194 | |

| Margaret of Navarre and Roussel | 195 | |

| The French Reformation becomes a Popular Movement | 196 | |

| Independence of Geneva secured by Francis | 197 | |

| John Calvin's Childhood | 198 | |

| He studies in Paris and Orleans | 199 | |

| Change of Religious Views at Bourges | 199 | |

| His Commentary on Seneca's "De Clementia" | 200 | |

| Escapes from Paris to Angoulême | 201 | |

| Leaves France | 202 | |

| The "Christian Institutes" | 202 | |

| Address to Francis the First | 203 | |

| Calvin wins instant Celebrity | 204 | |

| The Court of Renée of Ferrara | 205 | |

| Her History and Character | 206 | |

| Calvin's alleged Visit to Aosta | 207 | |

| [Pg xix]He visits Geneva | 208 | |

| Farel's Vehemence | 209 | |

| Calvin consents to remain | 210 | |

| His Code of Laws for Geneva | 210 | |

| His View of the Functions of the State | 210 | |

| Heretics to be constrained by the Sword | 211 | |

| Calvin's View that of the other Reformers | 212 | |

| And even of Protestant Martyrs | 212 | |

| Calvin longs for Scholarly Quiet | 213 | |

| His Mental Constitution | 214 | |

| Ill-health and Prodigious Labors | 214 | |

| Friendly and Inimical Estimates | 214 | |

| Violent Persecutions throughout France | 216 | |

| Royal Edict of Fontainebleau (June 1, 1540) | 218 | |

| Increased Severity, and Appeal cut off | 218 | |

| Exceptional Fairness of President Caillaud | 219 | |

| Letters-Patent from Lyons (Aug. 30, 1542) | 220 | |

| The King and the Sacramentarians | 221 | |

| Ordinance of Paris (July 23, 1543) | 221 | |

| Heresy to be punished as Sedition | 222 | |

| Repression proves a Failure | 222 | |

| The Sorbonne publishes Twenty-five Articles | 223 | |

| Francis gives them the Force of Law (March 10, 1543) | 224 | |

| More Systematic Persecution | 224 | |

| The Inquisitor Mathieu Ory | 224 | |

| The Nicodemites and Libertines | 225 | |

| Margaret of Navarre at Bordeaux | 226 | |

| Francis's Negotiations in Germany | 227 | |

| Hypocritical Representations made by Charles, Duke of Orleans | 228 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| 1545-1547. | ||

| Campaign against the Vaudois of Mérindol and Cabrières, and Last Days of Francis I. | 230 | |

| The Vaudois of the Durance | 230 | |

| Their Industry and Thrift | 230 | |

| Embassy to German and Swiss Reformers | 232 | |

| Translation of the Bible by Olivetanus | 233 | |

| Preliminary Persecutions | 234 | |

| The Parliament of Aix | 235 | |

| The Atrocious "Arrêt de Mérindol" (Nov. 18, 1540) | 236 | |

| Condemned by Public Opinion | 237 | |

| Preparations to carry it into Effect | 237 | |

| President Chassanée and the Mice of Autun | 238 | |

| [Pg xx]The King instructs Du Bellay to investigate | 239 | |

| A Favorable Report | 240 | |

| Francis's Letter of Pardon | 241 | |

| Parliament's Continued Severity | 241 | |

| The Vaudois publish a Confession | 242 | |

| Intercession of the Protestant Princes of Germany | 242 | |

| The new President of Parliament | 243 | |

| Sanguinary Royal Order, fraudulently obtained (Jan. 1, 1545) | 244 | |

| Expedition stealthily organized | 245 | |

| Villages burned—their Inhabitants murdered | 246 | |

| Destruction of Mérindol | 247 | |

| Treacherous Capture of Cabrières | 248 | |

| Women burned and Men butchered | 248 | |

| Twenty-two Towns and Villages destroyed | 249 | |

| A subsequent Investigation | 251 | |

| "The Fourteen of Meaux" | 253 | |

| Wider Diffusion of the Reformed Doctrines | 256 | |

| The Printer Jean Chapot before Parliament | 256 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| 1547-1559. | ||

| Henry the Second and the Organization of the French Protestant Churches | 258 | |

| Impartial Estimates of Francis the First | 258 | |

| Henry, as Duke of Orleans | 259 | |

| His Sluggish Mind | 260 | |

| His Court | 261 | |

| Diana of Poitiers | 262 | |

| The King's Infatuation | 262 | |

| Constable Anne de Montmorency | 263 | |

| His Cruelty | 264 | |

| Disgraced by Francis, but recalled by Henry | 265 | |

| Duke Claude of Guise, and John, first Cardinal of Lorraine | 266 | |

| Marriage of James the Fifth of Scotland to Mary of Lorraine | 268 | |

| Francis the Dauphin affianced to Mary of Scots | 268 | |

| Francis of Guise and Charles of Lorraine | 268 | |

| Various Estimates of Cardinal Charles of Lorraine | 270 | |

| Rapacity of the new Favorites | 272 | |

| Servility toward Diana of Poitiers | 273 | |

| Persecution to atone for Moral Blemishes | 274 | |

| "La Chambre Ardente" | 275 | |

| Edict of Fontainebleau against Books from Geneva (Dec. 11, 1547) | 275 | |

| Deceptive Title-pages | 275 | |

| The Tailor of the Rue St. Antoine | 276 | |

| [Pg xxi]Other Victims of Intolerance | 278 | |

| Severe Edicts and Quarrels with Rome | 278 | |

| Edict of Châteaubriand (June 27, 1551) | 279 | |

| The War against Books from Geneva | 280 | |

| Marshal Vieilleville refuses to profit by Confiscation | 282 | |

| The "Five Scholars of Lausanne" | 283 | |

| Interpositions in their Behalf ineffectual | 284 | |

| Activity of the Canton of Berne | 286 | |

| Progress of the Reformation in Normandy | 287 | |

| Attempt to establish the Spanish Inquisition | 287 | |

| Opposition of Parliament | 288 | |

| President Séguier's Speech | 289 | |

| Coligny's Scheme of American Colonization | 291 | |

| Villegagnon in Brazil | 292 | |

| He brings Ruin on the Expedition | 293 | |

| First Protestant Church in Paris | 294 | |

| The Example followed in the Provinces | 296 | |

| Henry the Second breaks the Truce | 297 | |

| Fresh Attempts to introduce the Spanish Inquisition | 298 | |

| Three Inquisitors-General | 299 | |

| Judges sympathize with the Victims | 300 | |

| Edict of Compiègne (July 24, 1557) | 301 | |

| Defeat of St. Quentin (August 10, 1557) | 302 | |

| Vengeance wreaked upon the Protestants | 302 | |

| Affair of the Rue St. Jacques (Sept. 4, 1557) | 303 | |

| Treatment of the Prisoners | 304 | |

| Malicious Rumors | 305 | |

| Trials and Executions | 307 | |

| Intercession of the Swiss Cantons and Others | 308 | |

| Constancy of Some and Release of Others | 311 | |

| Controversial Pamphlets | 311 | |

| Capture of Calais (January, 1558) | 312 | |

| Registry of the Inquisition Edict | 312 | |

| Antoine of Navarre, Condé, and other Princes favor the Protestants | 313 | |

| Embassy of the Protestant Electors | 313 | |

| Psalm-singing on the Pré aux Clercs | 314 | |

| Conference of Cardinals Lorraine and Granvelle | 315 | |

| D'Andelot's Examination before the King | 317 | |

| His Constancy in Prison and temporary Weakness | 318 | |

| Paul IV.'s Indignation at the King's Leniency | 320 | |

| Anxiety for Peace | 321 | |

| Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis (April 3, 1559) | 322 | |

| Sacrifice of French Interests | 323 | |

| Was there a Secret Treaty for the Extermination of Protestants? | 324 | |

| The Prince of Orange learns the Designs of Henry and Philip | 325 | |

| Danger of Geneva | 320 | |

| Parliament suspected of Heretical Leanings | 329 | |

| [Pg xxii]The "Mercuriale" | 330 | |

| Henry goes in Person to hear the Deliberations (June 10, 1559) | 332 | |

| Fearlessness of Du Bourg and Others | 334 | |

| Henry orders their Arrest | 335 | |

| First National Synod (May 26, 1559) | 335 | |

| Ecclesiastical Discipline adopted | 336 | |

| Marriages and Festivities of the Court | 338 | |

| Henry mortally wounded in the Tournament (June 30, 1559) | 339 | |

| His Death (July 10, 1559) | 340 | |

| "La Façon de Genève"—the Protestant Service | 341 | |

| Farel's "Manière et Fasson" (1533) | 342 | |

| Calvin's Liturgy (1542) | 343 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| July, 1559-May, 1560. | ||

| Francis the Second and the Tumult of Amboise | 346 | |

| Epigrams on the Death of Henry | 346 | |

| The Young King | 347 | |

| Catharine de' Medici | 348 | |

| Favors the Family of Guise | 350 | |

| Who make themselves Masters of the King | 351 | |

| Constable Montmorency retires | 352 | |

| Antoine, King of Navarre | 354 | |

| His Remissness and Pusillanimity | 355 | |

| The Persecution continues | 359 | |

| Denunciation and Pillage at Paris | 360 | |

| The Protestants address Catharine | 362 | |

| Pretended Orgies in "La Petite Genève" | 365 | |

| Cruelty of the Populace | 366 | |

| Traps for Heretics | 367 | |

| Trial of Anne du Bourg | 368 | |

| Intercession of the Elector Palatine | 370 | |

| Du Bourg's Last Speech | 371 | |

| His Execution and its Effect | 372 | |

| Florimond de Ræmond's Observations | 374 | |

| Revulsion against the Tyranny of the Guises | 375 | |

| Calvin and Beza discountenance Armed Resistance | 377 | |

| De la Renaudie | 379 | |

| Assembly of Malcontents at Nantes | 380 | |

| Plans well devised | 381 | |

| Betrayed by Des Avenelles | 382 | |

| The "Tumult of Amboise" | 383 | |

| Coligny gives Catharine good Counsel | 384 | |

| [Pg xxiii]The Edict of Amnesty (March, 1560) | 385 | |

| A Year's Progress | 386 | |

| Confusion at Court | 387 | |

| Treacherous Capture of Castelnau | 388 | |

| Death of La Renaudie | 389 | |

| Plenary Commission given to the Duke of Guise | 389 | |

| A Carnival of Blood | 391 | |

| The Elder D'Aubigné and his Son | 393 | |

| Francis and the Prince of Condé | 393 | |

| Condé's Defiance | 394 | |

| An alleged Admission of Disloyal Intentions by La Renaudie | 394 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| May-December, 1560. | ||

| The Assembly of Notables at Fontainebleau, and the Close of the Reign of Francis the Second | 397 | |

| Rise of the Name of the Huguenots | 397 | |

| Their Sudden Growth | 399 | |

| How to be accounted for | 400 | |

| Progress of Letters | 400 | |

| Marot's and Beza's Psalms | 402 | |

| Morality and Martyrdom | 402 | |

| Character of the Protestant Ministers | 402 | |

| Testimony of Bishop Montluc | 403 | |

| Preaching in the Churches of Valence | 404 | |

| The Reformation and Morals | 406 | |

| Francis orders Extermination | 406 | |

| Large Congregations at Nismes | 407 | |

| Mouvans in Provence | 407 | |

| A Popular Awakening | 408 | |

| Pamphlets against the Guises | 409 | |

| Catharine consults the Huguenots | 409 | |

| Edict of Romorantin (May, 1560) | 410 | |

| No Abatement of Rigorous Persecution | 411 | |

| Spiritual Jurisdiction differing little from the Inquisition | 411 | |

| Chancellor Michel de l'Hospital | 412 | |

| Continued Disquiet—Montbrun | 414 | |

| Assembly of Notables at Fontainebleau (Aug. 21, 1560) | 415 | |

| The Chancellor's Address | 416 | |

| The Finances of France | 416 | |

| Admiral Coligny presents the Petitions of the Huguenots | 416 | |

| Bishop Montluc ably advocates Toleration | 418 | |

| Bishop Marillac's Eloquent Speech | 420 | |

| Coligny's Suggestions | 421 | |

| [Pg xxiv]Passionate Rejoinder of the Duke of Guise | 422 | |

| The Cardinal of Lorraine more calm | 423 | |

| New Alarms of the Guises | 424 | |

| The King of Navarre and Condé summoned to Court | 425 | |

| Advice of Philip of Spain | 426 | |

| Navarre's Irresolution embarrasses Montbrun and Mouvans | 427 | |

| The "Fashion of Geneva" embraced by many in Languedoc | 428 | |

| Elections for the States General | 430 | |

| The King and Queen of Navarre | 431 | |

| Beza at the Court of Nérac | 432 | |

| New Pressure to induce Navarre and Condé to come | 433 | |

| Navarre Refuses a Huguenot Escort | 434 | |

| Disregards Warnings | 435 | |

| Is refused Admission to Poitiers | 435 | |

| Condé arrested on arriving at Orleans | 436 | |

| Return of Renée de France | 437 | |

| Condé's Intrepidity | 437 | |

| He is Tried and Condemned to Death | 439 | |

| Antoine of Navarre's Danger | 440 | |

| Plan for annihilating the Huguenots | 441 | |

| Sudden Illness and Death of Francis the Second | 442 | |

| The "Epître au Tigre de la France" | 445 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| December, 1560-September, 1561. | ||

| The Reign of Charles the Ninth, to the Preliminaries of the Colloquy of Poissy | 449 | |

| Sudden Change in the Political Situation | 449 | |

| The Enemy of the Huguenots buried as a Huguenot | 450 | |

| Antoine of Navarre's Opportunity | 451 | |

| Adroitness of Catharine de' Medici | 452 | |

| Financial Embarrassments | 453 | |

| Catharine's Neutrality | 453 | |

| Opening of the States General of Orleans | 454 | |

| Address of Chancellor L'Hospital | 455 | |

| Cardinal Lorraine's Effrontery | 457 | |

| De Rochefort, Orator for the Noblesse | 457 | |

| L'Ange for the Tiers État | 458 | |

| Arrogant Speech of Quintin for the Clergy | 458 | |

| A Word for the poor, down-trodden People | 459 | |

| Coligny presents a Huguenot Petition | 461 | |

| The States prorogued | 461 | |

| [Pg xxv]Meanwhile Prosecutions for Religion to cease | 462 | |

| Return of Fugitives | 463 | |

| Charles writes to stop Ministers from Geneva | 463 | |

| Reply of the Genevese | 464 | |

| Condé cleared and reconciled with Guise | 465 | |

| Humiliation of Navarre | 466 | |

| The Boldness of the Particular Estates of Paris | 467 | |

| Secures Antoine more Consideration | 467 | |

| Intrigue of Artus Désiré | 468 | |

| General Curiosity to hear Huguenot Preaching | 468 | |

| Constable Montmorency's Disgust | 469 | |

| The "Triumvirate" formed | 471 | |

| A Spurious Statement | 471 | |

| Massacres of Protestants in Holy Week | 474 | |

| The Affair at Beauvais | 474 | |

| Assault on the House of M. de Longjumeau | 476 | |

| New and Tolerant Royal Order | 476 | |

| Opposition of the Parisian Parliament | 477 | |

| Popular Cry for Pastors | 479 | |

| Moderation of the Huguenot Ministers | 479 | |

| Judicial Perplexity | 481 | |

| The "Mercuriale" of 1561 | 481 | |

| The "Edict of July" | 483 | |

| Its Severity creates extreme Disappointment | 484 | |

| Iconoclasm at Montauban | 485 | |

| Impatience with Public "Idols" | 487 | |

| Calvin endeavors to repress it | 487 | |

| Re-assembling of the States at Pontoise | 488 | |

| Able Harangue of the "Vierg" of Autun | 489 | |

| Written Demands of the Tiers État | 490 | |

| A Representative Government demanded | 492 | |

| The French Prelates at Poissy | 493 | |

| Beza and Peter Martyr invited to France | 494 | |

| Urgency of the Parisian Huguenots | 496 | |

| Beza comes to St. Germain | 497 | |

| His previous History | 497 | |

| Wrangling of the Prelates | 498 | |

| Cardinal Châtillon communes "under both Forms" | 499 | |

| Catharine and L'Hospital zealous for a Settlement of Religious Questions | 499 | |

| A Remarkable Letter to the Pope | 500 | |

| Beza's flattering Reception | 502 | |

| He meets the Cardinal of Lorraine | 503 | |

| Petition of the Huguenots respecting the Colloquy | 505 | |

| Informally granted | 507 | |

| Last Efforts of the Sorbonne to prevent the Colloquy | 508 | |

| [Pg xxvi]CHAPTER XII. | ||

| September, 1561-January, 1562. | ||

| The Colloquy of Poissy and the Edict of January | 509 | |

| The Huguenot Ministers and Delegates | 509 | |

| Assembled Princes in the Nuns' Refectory | 510 | |

| The Prelates | 511 | |

| Diffidence of Theodore Beza | 512 | |

| Opening Speech of Chancellor L'Hospital | 512 | |

| The Huguenots summoned | 513 | |

| Beza's Prayer and Address | 514 | |

| His Declaration as to the Body of Christ | 519 | |

| Outcry of the Theologians of the Sorbonne | 519 | |

| Beza's Peroration | 520 | |

| Cardinal Tournon would cut short the Conference | 521 | |

| Catharine de' Medici is decided | 522 | |

| Advantages gained | 522 | |

| The Impression made by Beza | 522 | |

| His Frankness justified | 524 | |

| The Prelates' Notion of a Conference | 526 | |

| Peter Martyr arrives | 527 | |

| Cardinal Lorraine replies to Beza | 528 | |

| Cardinal Tournon's new Demand | 529 | |

| Advancing Shadows of Civil War | 530 | |

| Another Session reluctantly conceded | 531 | |

| Beza's Reply to Cardinal Lorraine | 532 | |

| Claude d'Espense and Claude de Sainctes | 532 | |

| Lorraine demands Subscription to the Augsburg Confession | 533 | |

| Beza's Home Thrust | 534 | |

| Peter Martyr and Lainez the Jesuit | 536 | |

| Close of the Colloquy of Poissy | 537 | |

| A Private Conference at St. Germain | 538 | |

| A Discussion of Words | 540 | |

| Catharine's Premature Delight | 541 | |

| The Article agreed upon Rejected by the Prelates | 541 | |

| Catharine's Financial Success | 543 | |

| Order for the Restitution of Churches | 544 | |

| Arrival of Five German Delegates | 544 | |

| Why the Colloquy proved a Failure | 546 | |

| Catharine's Crude Notion of a Conference | 547 | |

| Character of the Prelates | 547 | |

| Influence of the Papal Legate, the Cardinal of Ferrara | 548 | |

| Anxiety of Pius the Fourth | 548 | |

| The Nuncio Santa Croce | 549 | |

| [Pg xxvii]Master Renard turned Monk | 551 | |

| Opposition of People and Chancellor | 551 | |

| The Legate's Intrigues | 552 | |

| His Influence upon Antoine of Navarre | 554 | |

| Contradictory Counsels | 555 | |

| The Triumvirate leave in Disgust | 556 | |

| Hopes entertained by the Huguenots respecting Charles | 557 | |

| Beza is begged to remain | 559 | |

| A Spanish Plot to kidnap the Duke of Orleans | 559 | |

| The Number of Huguenot Churches | 560 | |

| Beza secures a favorable Royal order | 560 | |

| Rapid Growth of the Reformation | 561 | |

| Immense Assemblages from far and near | 562 | |

| The Huguenots at Montpellier | 563 | |

| The Rein and not the Spur needed | 565 | |

| Marriages and Baptisms at Court "after the Geneva Fashion" | 565 | |

| Tanquerel's Seditious Declaration | 566 | |

| Jean de Hans | 567 | |

| Philip threatens Interference in French Affairs | 567 | |

| "A True Defender of the Faith" | 568 | |

| Roman Catholic Complaints of Huguenot Boldness | 570 | |

| The "Tumult of Saint Médard" | 571 | |

| Assembly of Notables at St. Germain | 574 | |

| Diversity of Sentiments | 575 | |

| The "Edict of January" | 576 | |

| The Huguenots no longer Outlaws | 577 | |

When, on the first day of the year 1515, the young Count of Angoulême succeeded to the throne left vacant by the death of his kinsman and father-in-law, Louis the Twelfth, the country of which he became monarch was already an extensive, flourishing, and well-consolidated kingdom. The territorial development of France was, it is true, far from complete. On the north, the whole province of Hainault belonged to the Spanish Netherlands, whose boundary line was less than one hundred miles distant from Paris. Alsace and Lorraine had not yet been wrested from the German Empire. The "Duchy" of Burgundy, seized by Louis the Eleventh immediately after the death of Charles the Bold, had, indeed, been incorporated into the French realm; but the "Free County" of Burgundy—la Franche Comté, as it was briefly designated—had been imprudently suffered to fall into other hands, and Besançon was the residence of a governor appointed by princes of the House of Hapsburg. Lyons was a frontier town; for the little districts of Bresse and Bugey, lying between the Saône and Rhône, belonged to the Dukes of Savoy. Further to the south, two fragments of foreign territory were completely enveloped by the domain of the French king.[Pg 4] The first was the sovereign principality of Orange, which, after having been for over a century in the possession of the noble House of Châlons, was shortly to pass into that of Nassau, and to furnish the title of William the Silent, the future deliverer of Holland. The other and larger one was the Comtât Venaissin, a fief directly dependent upon the Pope. Of irregular shape, and touching the Rhone both above and below Orange, the Comtât Venaissin nearly enclosed the diminutive principality in its folds. Its capital, Avignon, having forfeited the distinction enjoyed in the fourteenth century as the residence of the Roman Pontiffs, still boasted the presence of a Legate of the Papal See, a poor compensation for the loss of its past splendor. On the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, the Spanish dominions still extended north of the principal chain of the Pyrenees, and included the former County of Roussillon.

But, although its area was somewhat smaller than that of the modern republic, France in the sixteenth century had nearly attained the general dimensions marked out for it by great natural boundaries. Four hundred years had been engrossed in the pursuit of territorial enlargement. At the close of the tenth century the Carlovingian dynasty, essentially foreign in tastes and language, was supplanted by a dynasty of native character and capable of gathering to its support all those elements of strength which had been misunderstood or neglected by the feeble descendants of Charlemagne. But it found the royal authority reduced to insignificance and treated with open contempt. By permitting those dignities which had once been conferred as a reward for pre-eminent personal merit to become hereditary in certain families, the crown had laid the foundation of the feudal system; while, by neglecting to enforce its sovereign claims, it had enabled the great feudatories to make themselves princes independent in reality, if not in name. So low had the consideration of the throne fallen, that when Hugh Capet, Count of Paris, in 987 assumed the title of king of France, basing his act partly on an election by nobles, partly on force of arms, the transaction elicited little opposition from the rival lords who might have been expected to resent his usurpation.[Pg 5]

France contained at this time six principal fiefs—four in the north and two in the south—each nearly or fully as powerful as the hereditary dominions of Hugh, while probably more than one excelled them in extent. These limited dominions, on the resources of which the new dynasty was wholly dependent in the struggle for supremacy, embraced the important cities of Paris and Orleans, but barely stretched from the Somme to the Loire, and were excluded from the ocean by the broad possessions of the dukes of Normandy on both sides of the lower Seine. The great fiefs had each in turn yielded to the same irresistible tendency to subdivision. The great feudatory was himself the superior of the tenants of several subordinate, yet considerable, fiefs. The possessors of these again ranked above the viscounts of cities and the provincial barons. A long series of gradations in dignity ended at the simple owners of castles, with their subject peasants or serfs. In no country of Europe had the feudal system borne a more abundant harvest of disintegration and consequent loss of power.[3]

The reduction of the insubordinate nobles on the patrimonial estates of the crown was the first problem engaging the attention of the early Capetian kings. When this had at length been solved, with the assistance of the scanty forces lent by the cities—never amounting, it is said, to more than five hundred men-at-arms[4]—Louis the Fat, a prince of resplendent ability, early in the twelfth century addressed himself to the task of making good the royal title to supremacy over the neighboring provinces. Before death compelled him to forego the prosecution of his ambitious designs, the influence of the monarchy had been extended over eastern and central France—from Flanders, on the north, to the volcanic mountains of Auvergne, on the south. Meanwhile the oppressed subjects of the petty tyrants, whether within or around his domains, had learned to look for redress to the sovereign[Pg 6] lord who prided himself upon his ability and readiness to succor the defenceless. His grandson, the more illustrious Philip Augustus (1180-1223), by marriage, inheritance, and conquest added to previous acquisitions several extensive provinces, of which Normandy, Maine, and Poitou had been subject to English rule, while Vermandois and Yalois had enjoyed a form of approximate independence under collateral branches of the Capetian family.

The conquests of Louis the Fat and of Philip Augustus were consolidated by Louis the Ninth—Saint Louis, as succeeding generations were wont to style him—an upright monarch, who scrupled to accept new territory without remunerating the former owners, and even alienated the affection of provinces which he might with apparent justice have retained, by ceding them to the English, in the vain hope of cementing a lasting peace between the rival states.[5]

The same pursuit of territorial aggrandizement under successive kings extended the domain of the crown, in spite of disaster and temporary losses, until in the sixteenth century France was second to no other country in Europe for power and material resources. United under a single head, and no longer disturbed by the insubordination of the turbulent nobles, lately humbled by the craft of Louis the Eleventh, this kingdom awakened the warm admiration of political judges so shrewd as the diplomatic envoys of the Venetian Republic. "All these provinces," exclaimed one of these agents, in a report made to the Doge and Senate soon after his return, "are so well situated, so liberally provided with river-courses, harbors, and mountain ranges, that it may with safety be asserted that this realm is not only the most noble in Christendom, rivalling in antiquity our own most illus[Pg 7]trious commonwealth, but excels all other states in natural advantages and security."[6] Another of the same distinguished school of statesmen, taking a more deliberate survey of the country, gives utterance to the universal estimate of his age, when averring that France is to be regarded as the foremost kingdom of Christendom, whether viewed in respect to its dignity and power, or the rank of the prince who governs it.[7] In proof of the first of these claims he alleges the fact that, whereas England had once been, and Naples was at that moment dependent upon the Church, and Bohemia and Poland sustained similar relations to the Empire, France had always been a sovereign state. "It is also the oldest of European kingdoms, and the first that was converted to Christianity," remarks the same writer; adding, with a touch of patriotic pride, the proviso, "if we except the Pope, who is the universal head of religion, and the State of Venice, which, as it first sprang into existence a Christian commonwealth, has always continued such."[8]

Other diplomatists took the same view of the power and resources of this favored country. "The kingdom of France," said Chancellor Bacon, in a speech against the policy of rendering open aid to Scotland, and thus becoming involved in a war with the French, "is four times as large as the realm of England, the men four times as many, and the revenue four times as much, and it has better credit. France is full of expert captains and old soldiers, and besides its own troops it may entertain as many Almains as it is able to hire."[9][Pg 8]

Meantime France was fast becoming more homogeneous than it had ever been since the fall of the Roman power. As often as the lines of the great feudal families became extinct, or these families were induced or compelled to renounce their pretensions, their fiefs were given in appanage to younger branches of the royal house, or were more closely united to the domains of the crown, and entrusted to governors of the king's appointment.[10] In either case the actual control of affairs was placed in the hands of officers whose highest ambition was to reproduce in the provincial capital the growing elegance of the great city on the Seine where the royal court had fixed its ordinary abode. The provinces, consequently, began to assimilate more and more to Paris, and this not merely in manners, but in forms of speech and even in pronunciation. The rude patois, since it grated upon the cultivated ear, was banished from polite society, and, if not consigned to oblivion, was relegated to the more ignorant and remoter districts. Learning held its seat in Paris, and the scholars who returned to their homes after a sojourn in its academic halls were careful to avoid creating doubts respecting the thoroughness of their training by the use of any dialect but that spoken in the neighborhood of the university. As the idiom of Paris asserted its supremacy over the rest of France, a new tie was constituted, binding together provinces diverse in origin and history.

The spirit of obedience pervading all classes of the population contributed much to the national strength. The great nobles had lost their excessive privileges. They no longer attempted, in the seclusion of their ancestral estates, to rival the magnificence or defy the authority of the king. They began to prefer the capital to the freer retreat of their[Pg 9] castles. During the reign of Francis the First, and still more during the reign of his immediate successors, costly palaces for the accommodation of princely and ducal families were reared in the neighborhood of the Louvre.[11] It was currently reported that more than one fortune had been squandered in the hazardous experiment of maintaining a pomp befitting the courtier. Ultimately the poorer grandees were driven to the adoption of the wise precaution of spending only a quarter of the year in the enticing but dangerous vicinity of the throne.[12]

The cities, also, whose extensive privileges had constituted one of the most striking features of the political system of mediæval Europe, had been shorn of their exorbitant claims founded upon royal charters or prescriptive usage. The kings of France, in particular, had favored the growth of the municipalities, in order to secure their assistance in the reduction of refractory vassals. Flourishing trading communities had sprung up on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and of the ocean, and on the banks of the navigable rivers emptying into them. These corporations had secured a degree of independence proportioned, for the most part, to the weakness of their neighbors. The policy of the crown had been, while generously conferring privileges of great importance upon the cities lying within the royal domain, to make still more lavish concessions in favor of the municipalities upon or contiguous to the lands of the great feudatories.[13]

No sooner, however, did the humiliation of the landed nobility render it superfluous to conciliate the good-will of the proud and opulent citizens, than the readiest means were sought for reducing them to the level of ordinary subjects. Paris especially, once almost a republic, had of late learned submission and docility.[14] By the change, however, the capital[Pg 10] had lost neither wealth nor inhabitants, being described as very rich and populous, covering a vast area, and wholly given up to trade.[15] In the absence of an accurate census, the number of its inhabitants was variously stated at from 300,000 souls to nearly thrice as many; but all accounts agreed in placing Paris among the foremost cities of the civilized world.[16]

With the military resources at his command, the king had the means of rendering himself formidable abroad and secure at home. The French cavalry, consisting of gentlemen whose duty and honorable distinction it was to follow the monarch in every expedition, still sustained the reputation for the impetuous ardor and the irresistible weight of its charges which it had won during the Middle Ages. If it had encountered unexpected rebuffs on the fields of Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt, the chivalry of France had been too successful in other engagements to lose courage and enthusiasm. The nobles, both old and young, were still ready at any time to flock to their prince's standard when unfurled for an incursion into Naples or the Milanese. Never had they displayed more alacrity or self-sacrificing devotion than when young Francis the First set out upon his campaigns in Italy.[17] The[Pg 11] French infantry was less trustworthy. The troops raised in Normandy, Brittany, and Languedoc were reported to be but poorly trained to military exercises; but the foot-soldiers supplied by some of the frontier provinces were sturdy and efficient, and the gallant conduct of the Gascons at the disastrous battle of St. Quentin was the subject of universal admiration.[18]

What France lacked in cavalry was customarily supplied by the Reiters, whose services were easily purchased in Germany. The same country stood ready to furnish an abundance of Lansquenets (Lanzknechten), or pikemen, who, together with the Swiss, in a great measure replaced the native infantry. A Venetian envoy reported, in 1535, that the French king could, in six weeks at longest, set on foot a force of forty-eight thousand men, of whom twenty-one thousand, or nearly one-half, would be foreign mercenaries. His navy, besides his great ship of sixty guns lying in the harbor of Havre, numbered thirty galleys, and a few other vessels of no great importance.[19]

The power gained by the crown through the consolidation of the monarchy had been acquired at the expense of the popular liberties. In the prolonged struggle between the king, as lord paramount, and his insubordinate vassals, the rights of inferior subjects had received little consideration. From the strife the former issued triumphant, with an asserted claim to unlimited power. The voice of the masses was but feebly heard in the States General—a convocation of all three orders called at irregular intervals. Upon the ordinary policy of government, this, the only representative body, exercised no permanent control. If, in its occasional sessions, the deputies of the Tiers État exhibited a disposition to intermeddle in those political concerns which the crown claimed as its exclusive prerogative, the king and his advisers found in their audacity an additional motive for postponing as long as possible a resort to an expedient so disa[Pg 12]greeable as the assembling of the States General. Already had monarchs begun to look with suspicion upon the growing intelligence of untitled subjects, who might sooner or later come to demand a share in the public administration.

It was, therefore, only when the succession to the throne was contested, or when the perils attending the minority of the prince demanded the popular sanction of the choice of a regent, or when the flames of civil war seemed about to burst forth and involve the whole country in one general conflagration, that the royal consent could be obtained for convening the States General. During the first half of the sixteenth century the States General were not once summoned, unless the designation of States be accorded to one or two convocations partaking rather of the character of "Assemblies of Notables," and intended merely to assist in extricating the monarch from temporary embarrassment.[20] The repeated wars of Louis the Twelfth, of Francis the First, and of Henry the Second were waged without any reference of the questions of their expediency and of the mode of conducting them to the tribunal of popular opinion. Thousands of brave Frenchmen found bloody graves beyond the Alps; Francis the First fell into the hands of his enemies, and after a weary captivity with difficulty regained his freedom; a new faith arose in France, threatening to subvert existing ecclesiastical institutions; yet in the midst of all this bloodshed, confusion and perplexity the people were left unconsulted.[21] From the accession of Charles[Pg 13] the Eighth, in 1483, to that of Charles the Ninth, in 1560, the history of representative government in France is almost a complete blank. So long was the period during which the States General were suspended, that, when at length it was deemed advisable to convene them again, the chancellor, in his opening address, felt compelled to enter into explanations respecting the nature and functions of a body which perhaps not a man living remembered to have seen in session.[22] Yet, while the desuetude into which had fallen the laudable custom of holding the States every year, or, at least, on occasion of any important matter for deliberation, might properly be traced to the flood of ambition and pride which had inundated the world, and to the inordinate covetousness of kings,[23] there were not wanting considerations to mitigate the disappointment of the people. Chief among them, doubtless, in the view of shrewd observers, was the fact that the assembling of the States was the invariable prelude to an increase of taxation, and that never had they met without benefiting the king's exchequer at the expense of the purses of his subjects.[24]

Meanwhile the nation bore with exemplary patience the accumulated burdens under which it staggered. Natives and foreigners alike were lost in admiration of its wonderful pow[Pg 14]ers of endurance. No one suspected that a terrible retribution for this same people's wrongs might one day overtake the successor of a long line of kings, each of whom had added his portion to the crushing load. The Emperor Maximilian was accustomed to divert himself at the expense of the French people. "The king of France," said he, "is a king of asses; there is no weight that can be laid upon his subjects which they will not bear without a murmur."[25] The warrior and historian Rabutin congratulated the monarchs of France upon God's having given them, in obedience, the best and most faithful people in the whole world.[26] The Venetian, Matteo Dandolo, declared to the Doge and Senate that the king might with propriety regard as his own all the money in France, for, such was the incomparable kindness of the people, that whatever he might ask for in his need was very gladly brought to him.[27] It was not strange, perhaps, that the ruler of subjects so exemplary in their eagerness to replenish his treasury as soon as it gave evidence of being exhausted, came to take about the same view of the matter. Accordingly, it is related of Francis the First that, being asked by his guest, Charles the Fifth, when the latter was crossing France on his way to suppress the insurrection of Ghent, what revenue he derived from certain cities he had passed through, the king promptly, replied: "Ce que je veux"—"What I please."[28][Pg 15]

Yet it must be noted, in passing, that the studied abasement of the Tiers État had already begun to bear some fruit that should have alarmed every patriotic heart. It was, as we have seen, impossible to obtain good French infantry except from Gascony and some other border provinces. The place that should have been held by natives was filled by Germans and Swiss. What was the reason? Simply that the common people had lost the consciousness of their manhood, in consequence of the degraded position into which the king, and the privileged classes, imitating his example, had forced them. "Because of their desire to rule the people with a rod of iron," says Dandolo, "the gentry of the kingdom have deprived them of arms. They dare not even carry a stick, and are more submissive to their superiors than dogs!"[29] No wonder that all efforts of Francis to imitate the armies of free states, by instituting legions of arquebusiers, proved fruitless.[30] Add to this that trade was held in supreme contempt,[31] and the picture is certainly sufficiently dark.

Yet, while, through the absence of any effectual barrier to the exercise of his good pleasure, the king's authority was ultimately unrestricted, it must be confessed that there existed, in point of fact, some powerful checks, rendering the abuse of the royal prerogative, for the most part, neither easy nor expedient. Parliament, the municipal corporations, the university, and the clergy, weak as they often proved in a direct struggle with the crown, nevertheless exerted an influence that ought not to be overlooked. The most headstrong prince hesitated to disregard the remonstrances of any one of these bodies, and their united protest sometimes led to the abandonment of schemes of great promise for the royal treasury. It is true that parliament, university, and char[Pg 16]tered borough owed their existence and privileges to the royal will, and that the power that created could also destroy. But time had invested with a species of sanctity the venerable institutions established by monarchs long since dead, and the utmost stretch of royal displeasure went not in its manifestation further than the mere threat to strip parliament or university of its privileges, or, at most, the arrest and temporary imprisonment of the more obnoxious judges or scholars.

The Parliament of Paris was the legitimate successor of that assembly in which, in the earlier stage of the national existence, the great vassals came together to render homage to the lord paramount and aid him by their deliberations. This feudal parliament was transformed into a judicial parliament toward the end of the thirteenth century. With the change of functions, the chief crown officers were admitted to seats in the court. Next, the introduction of a written procedure, and the establishment of a more complicated legislation, compelled the illiterate barons and the prelates to call in the assistance of graduates of the university, acquainted with the art of writing and skilled in law. These were appointed by the king to the office of counsellors.[32] In 1302, parliament, hitherto migratory, following the king in his journeys, was made stationary at Paris. Its sessions were fixed at two in each year, held at Easter and All Saints respectively. The judicial body was subdivided into several "chambers," according to the nature of the cases upon which it was called to act.

From this time the Parliament of Paris assumed appellate jurisdiction over all France, and became the supreme court of justice. But the burden of prolonged sessions, and the necessity now imposed upon the members of residing at least four months out of every year in the capital, proved an irksome restraint both to prelates and to noblemen. Their attendance, therefore, began now to be less constant. As early as in 1320 the bishops and other ecclesiastical officers were excused, on the ground that their duty to their dioceses and sacred functions demanded their presence elsewhere. From[Pg 17] the general exemption the Bishop of Paris and the Abbot of St. Denis alone were excluded, on account of their proximity to the seat of the court. About the beginning of the fifteenth century, the members, taking advantage of the weak reign of Charles the Sixth, made good their claim to a life-tenure in their offices.[33]

The rapid increase of cases claiming the attention of the Parliament of Paris suggested the erection of similar tribunals in the chief cities of the provinces added to the original estates of the crown. Before the accession of Francis the First a provincial parliament had been instituted at Toulouse, with jurisdiction over the extensive domain once subject to the illustrious counts of that city; a second, at Grenoble, for Dauphiny; a third, at Bordeaux, for the province of Guyenne recovered from the English; a fourth, at Dijon, for the newly acquired Duchy of Burgundy; a fifth, at Rouen, to take the place of the inferior "exchequer" which had long had its seat there; and a sixth, at Aix-en-Provence, for the southeast of France.[34]

To their judicial functions, the Parliament of Paris, and to a minor degree the provincial parliaments, had insensibly added other functions purely political. In order to secure publicity for their edicts, and equally with the view of establishing the authenticity of documents purporting to emanate from the crown, the kings of France had early desired the insertion of all important decrees in the parliamentary records. The registry was made on each occasion by express order of the judges, but with no idea on their part that this form was essential to the validity of a royal ordinance. Presently, however, the novel theory was advanced that parliament had the right of refusing to record an obnoxious law, and that, without the formal recognition of parliament, no edict[Pg 18] could be allowed to affect the decisions of the supreme or of any inferior tribunal.

In the exercise or this assumed prerogative, the judges undertook to send a remonstrance to the king, setting forth the pernicious consequences that might be expected to flow from the proposed measure if put into execution. However unfounded in history, the claim of the Parliament of Paris appears to have been viewed with indulgence by monarchs most of whom were not indisposed to defer to the legal knowledge of the counsellors, nor unwilling to enhance the consideration of the venerable and ancient body to which the latter belonged. In all cases, however, the final responsibility devolved upon the sovereign. Whenever the arguments and advice of parliament failed to convince him, the king proceeded in person to the audience-chamber of the refractory court, and there, holding a lit-de-justice, insisted upon the immediate registration, or else sent his express command by one of his most trusty servants. The judges, in either case, were forced to succumb—often, it must be admitted, with a very bad grace—and admit the law to their records. We shall soon have occasion to note one of the most striking instances of this unequal contest between king and parliament, in which power rather than right or learning won the day. In spite, however, of occasional checks, parliament manfully and successfully maintained its right to throw obstacles in the way of hasty or inconsiderate legislation. In this it was often efficiently assisted by the Chancellor of France, the highest judicial officer of the crown, to whom, on his assuming office, an oath was administered containing a very explicit promise to exercise the right of remonstrance with the king before affixing the great seal of state to any unjust or unreasonable royal ordinance.[35][Pg 19]

Not that either the Parliament of Paris or the provincial parliaments were free of grave defects deserving the severe animadversion of impartial observers. It was probably no worse with the Parliament of Bordeaux than with its sister courts;[36] yet, when Charles the Ninth visited that city in 1564, honest Chancellor L'Hospital seized the opportunity to tell the judges some of their failings. The royal ordinances were not observed. Parliamentary decisions ranked above commands of the king. There were divisions and violence. In the civil war some judges had made themselves captains. Many of them were avaricious, timid, lazy and inattentive to their duties. Their behavior and their dress were "dissolute." They had become negligent in judging, and had thrown the burden of prosecuting offences upon the shoulders of the king's attorney, originally appointed merely to look after the royal domain. They had become the servants of the nobility for hire. There was not a lord within the jurisdiction of the Parliament of Bordeaux but had his own chancellor in the court to look after his interests.[37] It was sufficiently characteristic that the same judicial body of which such things were said to its face (and which neither denied their truth nor grew indignant), should have been so solicitous for its dignity as to send the monarch, upon his approach to the city, an earnest petition that its members should not be constrained to kneel when his Majesty entered their court-room! To which the latter dryly responded, "their genuflexion would not make him any less a king than he already was."[38][Pg 20]

Among the forces that tended to limit the arbitrary exercise of the royal authority, the influence of the University of Paris is entitled to a prominent place. Nothing had added more lustre to the rising glory of the capital than the possession of the magnificent institution of learning, the foundation of which was lost in the mist of remote antiquity. Older than the race of kings who had for centuries held the French sceptre, the university owed its origin, if we are to believe the testimony of its own annals, to the munificent hand of Charlemagne, in the beginning of the ninth century. Careful historical criticism must hesitate to accept as conclusive the slender proof offered in support of the story.[39] It is, perhaps, safer to regard one of the simple schools instituted at an early period in connection with cathedrals and monasteries as having contained the humble germ from which the proud university was slowly developed. But, by the side of this original foundation there had doubtless grown up the schools of private instructors, and these had acquired a certain prominence before the confluence of scholars to Paris from all quarters rendered necessary an attempt to introduce order into the complicated system, by the formation of that union of all the teachers and scholars to which the name of universitas was ultimately given.