Title: A Life of William Shakespeare

Author: Sir Sidney Lee

Release date: November 12, 2007 [eBook #23464]

Most recently updated: March 16, 2013

Language: English

Credits: Transcribed from the 1899 Smith, Elder and Co. edition by Les Bowler

Transcribed from the 1899 Smith, Elder and Co. edition by Les Bowler.

by

SIDNEY LEE.

WITH PORTRAITS AND FACSIMILES

FOURTH EDITION

LONDON

SMITH, ELDER, & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE

1899

[All rights reserved]

p. ivPrinted November 1898 (First Edition).

Reprinted December 1898 (Second

Edition); December 1898

(Third Edition); February 1899 (Fourth

Edition).

This work is based on the article on Shakespeare which I contributed last year to the fifty-first volume of the ‘Dictionary of National Biography.’ But the changes and additions which the article has undergone during my revision of it for separate publication are so numerous as to give the book a title to be regarded as an independent venture. In its general aims, however, the present life of Shakespeare endeavours loyally to adhere to the principles that are inherent in the scheme of the ‘Dictionary of National Biography.’ I have endeavoured to set before my readers a plain and practical narrative of the great dramatist’s personal history as concisely as the needs of clearness and completeness would permit. I have sought to provide students of Shakespeare with a full record of the duly attested facts and dates of their master’s career. I have avoided merely æsthetic criticism. My estimates of the value of Shakespeare’s plays and poems are intended solely to fulfil the obligation that lies on the biographer of indicating p. visuccinctly the character of the successive labours which were woven into the texture of his hero’s life. Æsthetic studies of Shakespeare abound, and to increase their number is a work of supererogation. But Shakespearean literature, as far as it is known to me, still lacks a book that shall supply within a brief compass an exhaustive and well-arranged statement of the facts of Shakespeare’s career, achievement, and reputation, that shall reduce conjecture to the smallest dimensions consistent with coherence, and shall give verifiable references to all the original sources of information. After studying Elizabethan literature, history, and bibliography for more than eighteen years, I believed that I might, without exposing myself to a charge of presumption, attempt something in the way of filling this gap, and that I might be able to supply, at least tentatively, a guide-book to Shakespeare’s life and work that should be, within its limits, complete and trustworthy. How far my belief was justified the readers of this volume will decide.

I cannot promise my readers any startling revelations. But my researches have enabled me to remove some ambiguities which puzzled my predecessors, and to throw light on one or two topics that have hitherto obscured the course of Shakespeare’s career. Particulars that have not been before incorporated in Shakespeare’s biography will be found in my treatment of the following subjects: the conditions under which ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’ and the p. vii‘Merchant of Venice’ were written; the references in Shakespeare’s plays to his native town and county; his father’s applications to the Heralds’ College for coat-armour; his relations with Ben Jonson and the boy actors in 1601; the favour extended to his work by James I and his Court; the circumstances which led to the publication of the First Folio, and the history of the dramatist’s portraits. I have somewhat expanded the notices of Shakespeare’s financial affairs which have already appeared in the article in the ‘Dictionary of National Biography,’ and a few new facts will be found in my revised estimate of the poet’s pecuniary position.

In my treatment of the sonnets I have pursued what I believe to be an original line of investigation. The strictly autobiographical interpretation that critics have of late placed on these poems compelled me, as Shakespeare’s biographer, to submit them to a very narrow scrutiny. My conclusion is adverse to the claim of the sonnets to rank as autobiographical documents, but I have felt bound, out of respect to writers from whose views I dissent, to give in detail the evidence on which I base my judgment. Matthew Arnold sagaciously laid down the maxim that ‘the criticism which alone can much help us for the future is a criticism which regards Europe as being, for intellectual and artistic [vii] purposes, one great confederation, p. viiibound to a joint action and working to a common result.’ It is criticism inspired by this liberalising principle that is especially applicable to the vast sonnet-literature which was produced by Shakespeare and his contemporaries. It is criticism of the type that Arnold recommended that can alone lead to any accurate and profitable conclusion respecting the intention of the vast sonnet-literature of the Elizabethan era. In accordance with Arnold’s suggestion, I have studied Shakespeare’s sonnets comparatively with those in vogue in England, France, and Italy at the time he wrote. I have endeavoured to learn the view that was taken of such literary endeavours by contemporary critics and readers throughout Europe. My researches have covered a very small portion of the wide field. But I have gone far enough, I think, to justify the conviction that Shakespeare’s collection of sonnets has no reasonable title to be regarded as a personal or autobiographical narrative.

In the Appendix (Sections III. and IV.) I have supplied a memoir of Shakespeare’s patron, the Earl of Southampton, and an account of the Earl’s relations with the contemporary world of letters. Apart from Southampton’s association with the sonnets, he promoted Shakespeare’s welfare at an early stage of the dramatist’s career, and I can quote the authority of Malone, who appended a sketch of Southampton’s history to his biography of Shakespeare (in the p. ix‘Variorum’ edition of 1821), for treating a knowledge of Southampton’s life as essential to a full knowledge of Shakespeare’s. I have also printed in the Appendix a detailed statement of the precise circumstances under which Shakespeare’s sonnets were published by Thomas Thorpe in 1609 (Section V.), and a review of the facts that seem to me to confute the popular theory that Shakespeare was a friend and protégé of William Herbert, third Earl of Pembroke, who has been put forward quite unwarrantably as the hero of the sonnets (Sections VI., VII., VIII.) [ix] I have also included in the Appendix (Sections IX. and X.) a survey of the voluminous sonnet-literature of the Elizabethan poets between 1591 and 1597, with which Shakespeare’s sonnetteering efforts were very closely allied, as well as a bibliographical note on a corresponding feature of French and Italian literature between 1550 and 1600.

Since the publication of the article on Shakespeare in the ‘Dictionary of National Biography,’ I have received from correspondents many criticisms and suggestions which have enabled me to correct some errors. But a few of my correspondents have exhibited so ingenuous a faith in those forged p. xdocuments relating to Shakespeare and forged references to his works, which were promulgated chiefly by John Payne Collier more than half a century ago, that I have attached a list of the misleading records to my chapter on ‘The Sources of Biographical Information’ in the Appendix (Section I.) I believe the list to be fuller than any to be met with elsewhere.

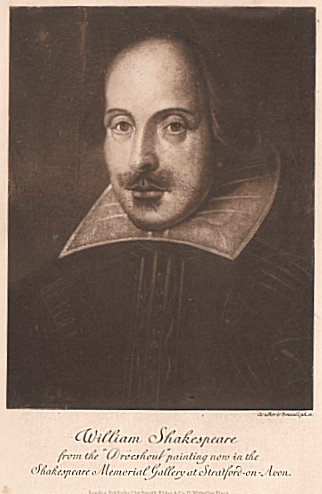

The six illustrations which appear in this volume have been chosen on grounds of practical utility rather than of artistic merit. My reasons for selecting as the frontispiece the newly discovered ‘Droeshout’ painting of Shakespeare (now in the Shakespeare Memorial Gallery at Stratford-on-Avon) can be gathered from the history of the painting and of its discovery which I give on pages 288-90. I have to thank Mr. Edgar Flower and the other members of the Council of the Shakespeare Memorial at Stratford for permission to reproduce the picture. The portrait of Southampton in early life is now at Welbeck Abbey, and the Duke of Portland not only permitted the portrait to be engraved for this volume, but lent me the negative from which the plate has been prepared. The Committee of the Garrick Club gave permission to photograph the interesting bust of Shakespeare in their possession, [x] but, owing to the fact that it is moulded in black terra-cotta no satisfactory negative could be obtained; the p. xiengraving I have used is from a photograph of a white plaster cast of the original bust, now in the Memorial Gallery at Stratford. The five autographs of Shakespeare’s signature—all that exist of unquestioned authenticity—appear in the three remaining plates. The three signatures on the will have been photographed from the original document at Somerset House, by permission of Sir Francis Jenne, President of the Probate Court; the autograph on the deed of purchase by Shakespeare in 1613 of the house in Blackfriars has been photographed from the original document in the Guildhall Library, by permission of the Library Committee of the City of London; and the autograph on the deed of mortgage relating to the same property, also dated in 1613, has been photographed from the original document in the British Museum, by permission of the Trustees. Shakespeare’s coat-of-arms and motto, which are stamped on the cover of this volume, are copied from the trickings in the margin of the draft-grants of arms now in the Heralds’ College.

The Baroness Burdett-Coutts has kindly given me ample opportunities of examining the two peculiarly interesting and valuable copies of the First Folio [xi] in her possession. Mr. Richard Savage, of Stratford-on-Avon, the Secretary of the Birthplace Trustees, and Mr. W. Salt Brassington, the Librarian of the Shakespeare Memorial at Stratford, have courteously replied p. xiito the many inquiries that I have addressed to them verbally or by letter. Mr. Lionel Cust, the Director of the National Portrait Gallery, has helped me to estimate the authenticity of Shakespeare’s portraits. I have also benefited, while the work has been passing through the press, by the valuable suggestions of my friends the Rev. H. C. Beeching and Mr. W. J. Craig, and I have to thank Mr. Thomas Seccombe for the zealous aid he has rendered me while correcting the final proofs.

October 12, 1898.

|

I—PARENTAGE AND BIRTH |

||

|

Distribution of the name of Shakespeare |

||

|

The poet’s ancestry |

||

|

The poet’s father |

||

|

His settlement at Stratford |

||

|

The poet’s mother |

||

|

1564, April |

The poet’s birth and baptism |

|

|

Alleged birthplace |

||

|

II—CHILDHOOD, EDUCATION, AND MARRIAGE |

||

|

The father in municipal office |

||

|

Brothers and sisters |

||

|

The father’s financial difficulties |

||

|

1571-7 |

Shakespeare’s education |

|

|

His classical equipment |

||

|

Shakespeare’s knowledge of the Bible |

||

|

1575 |

Queen Elizabeth at Kenilworth |

|

|

1577 |

Withdrawal from school |

|

|

1582, Dec. |

The poet’s marriage |

|

|

Richard Hathaway of Shottery |

||

|

Anne Hathaway |

||

|

Anne Hathaway’s cottage |

||

|

The bond against impediments |

||

|

1583, May |

Birth of the poet’s daughter Susanna |

|

|

Formal betrothal probably dispensed with |

||

|

Early married life |

||

|

Poaching at Charlecote |

||

|

Unwarranted doubts of the tradition |

||

|

Justice Shallow |

||

|

1585 |

The flight from Stratford |

|

|

IV—ON THE LONDON STAGE |

||

|

1586 |

The journey to London |

|

|

Richard Field, Shakespeare townsman |

||

|

Theatrical employment |

||

|

A playhouse servitor |

||

|

The acting companies |

||

|

The Lord Chamberlain’s company |

||

|

Shakespeare, a member of the Lord Chamberlain’s company |

||

|

The London theatres |

||

|

Place of residence in London |

||

|

Actors’ provincial tours |

||

|

Shakespeare’s alleged travels |

||

|

In Scotland |

||

|

In Italy |

||

|

Shakespeare’s rôles |

||

|

His alleged scorn of an actor’s calling |

||

|

V—EARLY DRAMATIC WORK |

||

|

The period of his dramatic work, 1591-1611 |

||

|

His borrowed plots |

||

|

The revision of plays |

||

|

Chronology of the plays |

||

|

Metrical tests |

||

|

1591 |

Love’s Labour’s Lost |

|

|

1591 |

Two Gentlemen of Verona |

|

|

1592 |

Comedy of Errors |

|

|

1592 |

Romeo and Juliet |

|

|

1592, March |

Henry VI |

|

|

1592, Sept. |

Greene’s attack on Shakespeare |

|

|

Chettle’s apology |

||

|

Divided authorship of Henry VI |

||

|

Shakespeare’s coadjutors |

||

|

Shakespeare’s assimilative power |

||

|

Lyly’s influence in comedy |

||

|

Marlowe’s influence in tragedy |

||

|

1593 |

Richard III |

|

|

1593 |

Richard II |

|

|

Shakespeare’s acknowledgments to Marlowe |

||

|

1593 |

Titus Andronicus |

|

|

1594, August |

The Merchant of Venice |

|

|

Shylock and Roderigo Lopez |

||

|

1594 |

King John |

|

|

1594, Dec. |

Comedy of Errors in Gray’s Inn Hall |

|

|

Early plays doubtfully assigned to Shakespeare |

||

|

Arden of Feversham (1592) |

||

|

Edward III |

||

|

Mucedorus |

||

|

Faire Em (1592) |

||

|

1593, April |

Publication of Venus and Adonis |

|

|

1594, May |

Publication of Lucrece |

|

|

Enthusiastic reception of the poems |

||

|

Shakespeare and Spenser |

||

|

Patrons at Court |

||

|

VII—THE SONNETS AND THEIR LITERARY HISTORY |

||

|

The vogue of the Elizabethan sonnet |

||

|

Shakespeare’s first experiments |

||

|

1594 |

Majority of his Shakespeare’s composed |

|

|

Their literary value |

||

|

Circulation in manuscript |

||

|

Their piratical publication in 1609 |

||

|

A Lover’s Complaint |

||

|

Thomas Thorpe and ‘Mr. W. H.’ |

||

|

The form of Shakespeare’s sonnets |

||

|

Their want of continuity |

||

|

The two ‘groups’ |

||

|

Main topics of the first ‘group’ |

||

|

Main topics of the second ‘group’ |

||

|

The order of the sonnets in the edition of 1640 |

||

|

Lack of genuine sentiment in Elizabethan sonnets |

||

|

Their dependence on French and Italian models |

||

|

Sonnetteers’ admissions of insincerity |

||

|

Contemporary censure of sonnetteers’ false sentiment |

||

|

Shakespeare’s scornful allusions to sonnets in his plays |

||

|

VIII—THE BORROWED CONCEITS OF THE SONNETS |

||

|

Slender autobiographical element in Shakespeare’s sonnets |

||

|

The imitative element |

||

|

Shakespeare’s claims of immortality for his sonnets a borrowed conceit |

||

|

Conceits in sonnets addressed to a woman |

||

|

The praise of ‘blackness’ |

||

|

The sonnets of vituperation |

||

|

Gabriel Harvey’s Amorous Odious sonnet |

||

|

Jodelle’s Contr’ Amours |

||

|

Biographic fact in the ‘dedicatory’ sonnets |

||

|

The Earl of Southampton the poet’s sole patron |

||

|

Rivals in Southampton’s favour |

||

|

Shakespeare’s fear of another poet |

||

|

Barnabe Barnes probably the chief rival |

||

|

Other theories as to the chief rival’s identity |

||

|

Sonnets of friendship |

||

|

Extravagances of literary compliment |

||

|

Patrons habitually addressed in affectionate terms |

||

|

Direct references to Southampton in the sonnets of friendship |

||

|

His youthfulness |

||

|

The evidence of portraits |

||

|

Sonnet cvii. the last of the series |

||

|

Allusions to Queen Elizabeth’s death |

||

|

Allusions to Southampton’s release from prison |

||

|

X—THE SUPPOSED STORY OF INTRIGUE IN THE SONNETS |

||

|

Sonnets of melancholy and self-reproach |

||

|

The youth’s relations with the poet’s mistress |

||

|

Willobie his Avisa (1594) |

||

|

Summary of conclusions respecting the sonnets |

||

|

XI—THE DEVELOPMENT OF DRAMATIC POWER |

||

|

1594-95 |

Midsummer Night’s Dream |

|

|

1595 |

All’s Well that Ends Well |

|

|

1595 |

The Taming of The Shrew |

|

|

Stratford allusions in the Induction |

||

|

Wincot |

||

|

1597 |

Henry IV |

|

|

Falstaff |

||

|

1597 |

The Merry Wives of Windsor |

|

|

1598 |

Henry V |

|

|

Essex and the rebellion of 1601 |

||

|

Shakespeare’s popularity and influence |

||

|

Shakespeare’s friendship with Ben Jonson |

||

|

The Mermaid meetings |

||

|

1598 |

Meres’s eulogy |

|

|

Value of his name to publishers |

||

|

1599 |

The Passionate Pilgrim |

|

|

1601 |

The Phœnix and the Turtle |

|

|

Shakespeare’s practical temperament |

||

|

His father’s difficulties |

||

|

His wife’s debt |

||

|

1596-9 |

The coat of arms |

|

|

1597, May 4. |

The purchase of New Place |

|

|

1598 |

Fellow-townsmen appear to Shakespeare for aid |

|

|

Shakespeare’s financial position before 1599 |

||

|

Shakespeare’s financial position after 1599 |

||

|

His later income |

||

|

Incomes of fellow actors |

||

|

1601-1610 |

Shakespeare’s formation of his estate at Stratford |

|

|

1605 |

The Stratford tithes |

|

|

1600-1609 |

Recovery of small debts |

|

|

XIII—MATURITY OF GENIUS |

||

|

Literary work in 1599 |

||

|

1599 |

Much Ado about Nothing |

|

|

1599 |

As You Like It |

|

|

1600 |

Twelfth Night |

|

|

1601 |

Julius Cæsar |

|

|

The strife between adult actors and boy actors |

||

|

Shakespeare’s references to the struggle |

||

|

1601 |

Ben Jonson’s Poetaster |

|

|

Shakespeare’s alleged partisanship in the theatrical warfare |

||

|

1602 |

Hamlet |

|

|

The problem of its publication |

||

|

The First Quarto, 1603 |

||

|

The Second Quarto, 1604 |

||

|

The Folio version, 1623 |

||

|

Popularity of Hamlet |

||

|

1603 |

Troilus and Cressida |

|

|

Treatment of the theme |

||

|

1603, March 26 |

Queen Elizabeth’s death |

|

|

James I’s patronage |

||

|

XIV—THE HIGHEST THEMES OF TRAGEDY |

||

|

1604, Nov. |

Othello |

|

|

1604, Dec. |

Measure for Measure |

|

|

1606 |

Macbeth |

|

|

1607 |

King Lear |

|

|

1608 |

Timon of Athens |

|

|

1608 |

Pericles |

|

|

1608 |

Antony and Cleopatra |

|

|

1609 |

Coriolanus |

|

|

The placid temper of the latest plays |

||

|

1610 |

Cymbeline |

|

|

1611 |

A Winter’s Tale |

|

|

1611 |

The Tempest |

|

|

Fanciful interpretations of The Tempest |

||

|

Unfinished plays |

||

|

The lost play of Cardenio |

||

|

The Two Noble Kinsmen |

||

|

Henry VIII |

||

|

The burning of the Globe Theatre |

||

|

XVI—THE CLOSE OF LIFE |

||

|

Plays at Court in 1613 |

||

|

Actor-friends |

||

|

1611 |

Final settlement at Stratford |

|

|

Domestic affairs |

||

|

1613, March |

Purchase of a house in Blackfriars |

|

|

1614, Oct. |

Attempt to enclose the Stratford common fields |

|

|

1616, April 23rd. |

Shakespeare’s death |

|

|

1616, April 25th. |

Shakespeare’s burial |

|

|

The will |

||

|

Shakespeare’s bequest to his wife |

||

|

Shakespeare’s heiress |

||

|

Legacies to friends |

||

|

The tomb in Stratford Church |

||

|

Shakespeare’s personal character |

||

|

XVII—SURVIVORS AND DESCENDANTS |

||

|

Mrs. Judith Quiney, (1585-1662) |

||

|

Mrs. Susanna Hall (1583-1649) |

||

|

The last descendant |

||

|

Shakespeare’s brothers, Edmund, Richard, and Gilbert |

||

|

XVIII—AUTOGRAPHS, PORTRAITS, AND MEMORIALS |

||

|

Spelling of the poet’s name |

||

|

Autograph signatures |

||

|

Shakespeare’s portraits |

||

|

The Stratford bust |

||

|

The ‘Stratford portrait’ |

||

|

Droeshout’s engraving |

||

|

The ‘Droeshout’ painting |

||

|

Later portraits |

||

|

The Chandos portrait |

||

|

The ‘Jansen’ portrait |

||

|

The ‘Felton’ portrait |

||

|

The ‘Soest’ portrait |

||

|

Miniatures |

||

|

The Garrick Club bust |

||

|

Alleged death-mask |

||

|

Memorials in sculpture |

||

|

Memorials at Stratford |

||

|

Quartos of the poems in the poet’s lifetime |

||

|

Posthumous quartos of the poems |

||

|

The ‘Poems’ of 1640 |

||

|

Quartos of the plays in the poet’s lifetime |

||

|

Posthumous quartos of the plays |

||

|

1623 |

The First Folio |

|

|

The publishing syndicate |

||

|

The prefatory matter |

||

|

The value of the text |

||

|

The order of the plays |

||

|

The typography |

||

|

Unique copies |

||

|

The Sheldon copy |

||

|

Estimated number of extant copies |

||

|

Reprints of the First Folio |

||

|

1632 |

The Second Folio |

|

|

1663-4 |

The Third Folio |

|

|

1685 |

The Fourth Folio |

|

|

Eighteenth-century editions |

||

|

Nicholas Rowe (1674-1718) |

||

|

Alexander Pope (1688-1744) |

||

|

Lewis Theobald (1688-1744) |

||

|

Sir Thomas Hanmer (1677-1746) |

||

|

Bishop Warburton (1698-1779) |

||

|

Dr. Johnson (1709-1783) |

||

|

Edward Capell (1713-1781) |

||

|

George Steevens (1736-1800) |

||

|

Edmund Malone (1741-1812) |

||

|

Variorum editions |

||

|

Nineteenth-century editors |

||

|

Alexander Dyce (1798-1869) |

||

|

Howard Staunton (1810-1874) |

||

|

Nikolaus Delius (1813-1888) |

||

|

The Cambridge edition (1863-6) |

||

|

Other nineteenth-century editions |

||

|

XX—POSTHUMOUS REPUTATION |

||

|

Views of Shakespeare’s contemporaries |

||

|

Ben Jonson tribute |

||

|

English opinion between 1660 and 1702 |

||

|

Dryden’s view |

||

|

Restoration adaptations |

||

|

English opinion from 1702 onwards |

||

|

Stratford festivals |

||

|

Shakespeare on the English stage |

||

|

The first appearance of actresses in Shakespearean parts |

||

|

David Garrick (1717-1779) |

||

|

John Philip Kemble (1757-1823) |

||

|

Mrs. Sarah Siddons (1755-1831) |

||

|

Edmund Kean (1787-1833) |

||

|

Recent revivals |

||

|

Shakespeare in English music and art |

||

|

Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery |

||

|

Shakespeare in America |

||

|

Translations |

||

|

Shakespeare in Germany |

||

|

German translations |

||

|

Modern German critics |

||

|

Shakespeare on the German stage |

||

|

Shakespeare in France |

||

|

Voltaire’s strictures |

||

|

French critics’ gradual emancipation from Voltairean influence |

||

|

Shakespeare on the French stage |

||

|

Shakespeare in Italy |

||

|

In Holland |

||

|

In Russia |

||

|

In Poland |

||

|

In Hungary |

||

|

In other countries |

||

|

XXI—GENERAL ESTIMATES |

||

|

General estimate |

||

|

Shakespeare’s defects |

||

|

Character of Shakespeare’s achievement |

||

|

Its universal recognition |

||

|

APPENDIX |

||

|

I—THE SOURCES OF BIOGRAPHICAL KNOWLEDGE |

||

|

Contemporary records abundant |

||

|

First efforts in biography |

||

|

Biographers of the nineteenth century |

||

|

Stratford topography |

||

|

Specialised studies in biography |

||

|

Epitomes |

||

|

Aids to study of plots and text |

||

|

Concordances |

||

|

Bibliographies |

||

|

Critical studies |

||

|

Shakespearean forgeries |

||

|

John Jordan (1746-1809) |

||

|

The Ireland forgeries (1796) |

||

|

List of forgeries promulgated by Collier and others (1835-1849) |

||

|

II—THE BACON-SHAKESPEARE CONTROVERSY |

||

|

Its source |

||

|

Toby Matthew’s letter of 1621 |

||

|

Chief exponents of the theory |

||

|

Its vogue in America |

||

|

Extent of the literature |

||

|

Absurdity of the theory |

||

|

Shakespeare and Southampton |

||

|

Southampton’s parentage |

||

|

1573, Oct. 6 |

Southampton’s birth |

|

|

His education |

||

|

Recognition of Southampton’s beauty in youth |

||

|

His reluctance to marry |

||

|

Intrigue with Elizabeth Vernon |

||

|

1598 |

Southampton’s marriage |

|

|

1601-3 |

Southampton’s imprisonment |

|

|

Later career |

||

|

1624, Nov. 10 |

His death |

|

|

IV—THE EARL OF SOUTHAMPTON AS A LITERARY PATRON |

||

|

Southampton’s collection of books |

||

|

References in his letters to poems and plays |

||

|

His love of the theatre |

||

|

Poetic adulation |

||

|

1593 |

Barnabe Barnes’s sonnet |

|

|

Tom Nash’s addresses |

||

|

1595 |

Gervase Markham’s sonnet |

|

|

1598 |

Florio’s address |

|

|

The congratulations of the poets in 1603 |

||

|

Elegies on Southampton |

||

|

V—THE TRUE HISTORY OF THOMAS THORPE AND ‘MR. W. H.’ |

||

|

The publication of the ‘Sonnets’ in 1609 |

||

|

The text of the dedication |

||

|

Publishers’ dedications |

||

|

Thorpe’s early life |

||

|

His ownership of the manuscript of Marlowe’s Lucan |

||

|

His dedicatory address to Edward Blount in 1600 |

||

|

Character of his business |

||

|

Shakespeare’s sufferings at publishers hands |

||

|

The use of initials in dedications of Elizabethan and Jacobean books |

||

|

Frequency of wishes for ‘happiness’ and ‘eternity’ in dedicatory greetings |

||

|

Five dedications by Thorpe |

||

|

‘W. H.’ signs dedication of Southwell’s ‘Poems’ |

||

|

‘W. H.’ and Mr. William Hall |

||

|

The ‘onlie begetter’ means ‘only procurer’ |

||

|

Origin of the notion that ‘Mr. W. H.’ stands for William Herbert |

||

|

The Earl of Pembroke known only as Lord Herbert in youth |

||

|

Thorpe’s mode of addressing the Earl of Pembroke |

||

|

VII—SHAKESPEARE AND THE EARL OF PEMBROKE |

||

|

Shakespeare with the acting company at Wilton in 1603 |

||

|

The dedication of the First Folio in 1623 |

||

|

No suggestion in the sonnets of the youth’s identity with Pembroke |

||

|

Aubrey’s ignorance of any relation between Shakespeare and Pembroke |

||

|

VIII—THE ‘WILL’ SONNETS |

||

|

Elizabethan meanings of ‘will’ |

||

|

Shakespeare’s uses of the word |

||

|

Shakespeare’s puns on the word |

||

|

Arbitrary and irregular use of italics by Elizabethan and Jacobean printers |

||

|

The conceits of Sonnets cxxxv.-vi. interpreted |

||

|

Sonnet cxxxv |

||

|

Sonnet cxxxvi |

||

|

Sonnet cxxxiv |

||

|

Sonnet cxliii |

||

|

IX—THE VOGUE OF THE ELIZABETHAN SONNET, 1591-1597 |

||

|

1557 |

Wyatt’s and Surrey’s Sonnets published |

|

|

1582 |

Watson’s Centurie of Love |

|

|

1591 |

Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella |

|

|

I. |

Collected sonnets of feigned love |

|

|

1592 |

Daniel’s Delia |

|

|

Fame of Daniel’s sonnets |

||

|

1592 |

Constable’s Diana |

|

|

1593 |

Barnabe Barne’s sonnets |

|

|

1593 |

Watson’s Tears of Fancie |

|

|

1593 |

Giles Fletcher’s Licia |

|

|

1593 |

Lodge’s Phillis |

|

|

1594 |

Drayton’s Idea |

|

|

1594 |

Percy’s Cœlia |

|

|

Zepheria |

||

|

1595 |

Barnfield’s sonnets to Ganymede |

|

|

1595 |

Spenser’s Amoretti |

|

|

1595 |

Emaricdulfe |

|

|

1595 |

Sir John Davies’s Gullinge Sonnets |

|

|

1596 |

Linche’s Diella |

|

|

1596 |

Griffin Fidessa |

|

|

1596 |

Thomas Campion’s sonnets |

|

|

1596 |

William Smith’s Chloris |

|

|

1597 |

Robert Tofte’s Laura |

|

|

Sir William Alexander’s Aurora |

||

|

Sir Fulke Greville’s Cœlica |

||

|

Estimate of number of love-sonnets issued between 1591 and 1597 |

||

|

II. |

Sonnets to patrons, 1591-1597 |

|

|

III. |

Sonnets on philosophy and religion |

|

|

X—BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ON THE SONNET IN FRANCE, 1550-1600 |

||

|

Ronsard (1524-1585) and ‘La Pléiade’ |

||

|

The Italian sonnetteers of the sixteenth century |

442n. |

|

|

Philippe Desportes (1546-1606) |

||

|

Chief collections of French sonnets published between 1550 and 1584 |

||

|

Minor collections of French sonnets published between 1553 and 1605 |

||

|

INDEX |

Shakespeare came of a family whose surname was borne through the middle ages by residents in very many parts of England—at Penrith in Cumberland, at Kirkland and Doncaster in Yorkshire, as well as in nearly all the midland counties. The surname had originally a martial significance, implying capacity in the wielding of the spear. [1a] Its first recorded holder is John Shakespeare, who in 1279 was living at ‘Freyndon,’ perhaps Frittenden, Kent. [1b] The great mediæval guild of St. Anne at Knowle, whose members included the leading inhabitants of Warwickshire, was joined by many Shakespeares in the fifteenth century. [1c] p. 2In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the surname is found far more frequently in Warwickshire than elsewhere. The archives of no less than twenty-four towns and villages there contain notices of Shakespeare families in the sixteenth century, and as many as thirty-four Warwickshire towns or villages were inhabited by Shakespeare families in the seventeenth century. Among them all William was a common Christian name. At Rowington, twelve miles to the north of Stratford, and in the same hundred of Barlichway, one of the most prolific Shakespeare families of Warwickshire resided in the sixteenth century, and no less than three Richard Shakespeares of Rowington, whose extant wills were proved respectively in 1560, 1591, and 1614, were fathers of sons called William. At least one other William Shakespeare was during the period a resident in Rowington. As a consequence, the poet has been more than once credited with achievements which rightly belong to one or other of his numerous contemporaries who were identically named.

The poet’s ancestry cannot be defined with absolute certainty. The poet’s father, when applying for a grant of arms in 1596, claimed that his grandfather (the poet’s great-grandfather) received for services rendered in war a grant of land in Warwickshire from Henry VII. [2] No precise confirmation of this pretension has been discovered, and it may be, after the manner of heraldic genealogy, fictitious. But there is a probability that the poet p. 3came of good yeoman stock, and that his ancestors to the fourth or fifth generation were fairly substantial landowners. [3a] Adam Shakespeare, a tenant by military service of land at Baddesley Clinton in 1389, seems to have been great-grandfather of one Richard Shakespeare who held land at Wroxhall in Warwickshire during the first thirty-four years (at least) of the sixteenth century. Another Richard Shakespeare who is conjectured to have been nearly akin to the Wroxhall family was settled as a farmer at Snitterfield, a village four miles to the north of Stratford-on-Avon, in 1528. [3b] It is probable that he was the poet’s grandfather. In 1550 he was renting a messuage and land at Snitterfield of Robert Arden; he died at the close of 1560, and on February 10 of the next year letters of administration of his goods, chattels, and debts were issued to his son John by the Probate Court at Worcester. His goods were valued at £35 17s. [3c] Besides the son John, Richard of Snitterfield certainly had a son Henry; while a Thomas Shakespeare, a considerable landholder at p. 4Snitterfield between 1563 and 1583, whose parentage is undetermined, may have been a third son. The son Henry remained all his life at Snitterfield, where he engaged in farming with gradually diminishing success; he died in embarrassed circumstances in December 1596. John, the son who administered Richard’s estate, was in all likelihood the poet’s father.

About 1551 John Shakespeare left Snitterfield, which was his birthplace, to seek a career in the neighbouring borough of Stratford-on-Avon. There he soon set up as a trader in all manner of agricultural produce. Corn, wool, malt, meat, skins, and leather were among the commodities in which he dealt. Documents of a somewhat later date often describe him as a glover. Aubrey, Shakespeare’s first biographer, reported the tradition that he was a butcher. But though both designations doubtless indicated important branches of his business, neither can be regarded as disclosing its full extent. The land which his family farmed at Snitterfield supplied him with his varied stock-in-trade. As long as his father lived he seems to have been a frequent visitor to Snitterfield, and, like his father and brothers, he was until the date of his father’s death occasionally designated a farmer or ‘husbandman’ of that place. But it was with Stratford-on-Avon that his life was mainly identified.

In April 1552 he was living there in Henley Street, a thoroughfare leading to the market town of Henley-in-Arden, and he is first mentioned in the borough records as paying in that month a fine of p. 5twelve-pence for having a dirt-heap in front of his house. His frequent appearances in the years that follow as either plaintiff or defendant in suits heard in the local court of record for the recovery of small debts suggest that he was a keen man of business. In early life he prospered in trade, and in October 1556 purchased two freehold tenements at Stratford—one, with a garden, in Henley Street (it adjoins that now known as the poet’s birthplace), and the other in Greenhill Street with a garden and croft. Thenceforth he played a prominent part in municipal affairs. In 1557 he was elected an ale-taster, whose duty it was to test the quality of malt liquors and bread. About the same time he was elected a burgess or town councillor, and in September 1558, and again on October 6, 1559, he was appointed one of the four petty constables by a vote of the jury of the court-leet. Twice—in 1559 and 1561—he was chosen one of the affeerors—officers appointed to determine the fines for those offences which were punishable arbitrarily, and for which no express penalties were prescribed by statute. In 1561 he was elected one of the two chamberlains of the borough, an office of responsibility which he held for two years. He delivered his second statement of accounts to the corporation in January 1564. When attesting documents he occasionally made his mark, but there is evidence in the Stratford archives that he could write with facility; and he was credited with financial aptitude. The municipal accounts, which were checked by tallies and counters, were audited by him after he p. 6ceased to be chamberlain, and he more than once advanced small sums of money to the corporation.

With characteristic shrewdness he chose a wife of assured fortune—Mary, youngest daughter of Robert Arden, a wealthy farmer of Wilmcote in the parish of Aston Cantlowe, near Stratford. The Arden family in its chief branch, which was settled at Parkhall, Warwickshire, ranked with the most influential of the county. Robert Arden, a progenitor of that branch, was sheriff of Warwickshire and Leicestershire in 1438 (16 Hen. VI), and this sheriff’s direct descendant, Edward Arden, who was himself high sheriff of Warwickshire in 1575, was executed in 1583 for alleged complicity in a Roman Catholic plot against the life of Queen Elizabeth. [6] John Shakespeare’s wife belonged to a humbler branch of the family, and there is no trustworthy evidence to determine the exact degree of kinship between the two branches. Her grandfather, Thomas Arden, purchased in 1501 an estate at Snitterfield, which passed, with other property, to her father Robert; John Shakespeare’s father, Richard, was one of this Robert Arden’s Snitterfield tenants. By his first wife, whose name is not known, Robert Arden had seven daughters, of whom all but two married; John Shakespeare’s wife seems to have been the youngest. Robert Arden’s second wife, Agnes or Anne, widow of John Hill (d. 1545), a substantial farmer of Bearley, survived him; but by her he had no issue. When he died at the end of 1556, he owned a farmhouse at Wilmcote p. 7and many acres, besides some hundred acres at Snitterfield, with two farmhouses which he let out to tenants. The post-mortem inventory of his goods, which was made on December 9, 1556, shows that he had lived in comfort; his house was adorned by as many as eleven ‘painted cloths,’ which then did duty for tapestries among the middle class. The exordium of his will, which was drawn up on November 24, 1556, and proved on December 16 following, indicates that he was an observant Catholic. For his two youngest daughters, Alice and Mary, he showed especial affection by nominating them his executors. Mary received not only £6. 13s. 4d. in money, but the fee-simple of Asbies, his chief property at Wilmcote, consisting of a house with some fifty acres of land. She also acquired, under an earlier settlement, an interest in two messuages at Snitterfield. [7] But, although she was well provided with worldly goods, she was apparently without education; several extant documents bear her mark, and there is no proof that she could sign her name.

John Shakespeare’s marriage with Mary Arden doubtless took place at Aston Cantlowe, the parish church of Wilmcote, in the autumn of 1557 (the church registers begin at a later date). On September 15, 1558, his first child, a daughter, Joan, was baptised in the church of Stratford. A second child, another daughter, Margaret, was baptised on December 2, 1562; but both these children died in infancy. The poet William, the first son and third child, was p. 8born on April 22 or 23, 1564. The latter date is generally accepted as his birthday, mainly (it would appear) on the ground that it was the day of his death. There is no positive evidence on the subject, but the Stratford parish registers attest that he was baptised on April 26.

Some doubt is justifiable as to the ordinarily accepted scene of his birth. Of two adjoining houses forming a detached building on the north side of Henley Street, that to the east was purchased by John Shakespeare in 1556, but there is no evidence that he owned or occupied the house to the west before 1575. Yet this western house has been known since 1759 as the poet’s birthplace, and a room on the first floor is claimed as that in which he was born. [8] The two houses subsequently came by bequest of the poet’s granddaughter to the family of the poet’s sister, Joan Hart, and while the eastern tenement was let out to strangers for more than two centuries, and by them converted into an inn, the ‘birthplace’ was until 1806 occupied by the Harts, who latterly carried on there the trade of butcher. The fact of its long occupancy by the poet’s collateral descendants accounts for the identification of the western rather than the eastern tenement with his birthplace. Both houses were purchased in behalf of subscribers to a public fund on September 16, 1847, and, after extensive restoration, were converted into a single domicile for the purposes of a public museum. They were presented under a deed of p. 9trust to the corporation of Stratford in 1866. Much of the Elizabethan timber and stonework survives, but a cellar under the ‘birthplace’ is the only portion which remains as it was at the date of the poet’s birth. [9]

In July 1564, when William was three months old, the plague raged with unwonted vehemence at Stratford, and his father liberally contributed to the relief of its poverty-stricken victims. Fortune still favoured him. On July 4, 1565, he reached the dignity of an alderman. From 1567 onwards he was accorded in the corporation archives the honourable prefix of ‘Mr.’ At Michaelmas 1568 he attained the highest office in the corporation gift, that of bailiff, and during his year of office the corporation for the first time entertained actors at Stratford. The Queen’s Company and the Earl of Worcester’s Company each received from John Shakespeare an official welcome. [10] On September 5, 1571, he was chief p. 11alderman, a post which he retained till September 30 the following year. In 1573 Alexander Webbe, the husband of his wife’s sister Agnes, made him overseer of his will; in 1575 he bought two houses in Stratford, one of them doubtless the alleged birthplace in Henley Street; in 1576 he contributed twelvepence to the beadle’s salary. But after Michaelmas 1572 he took a less active part in municipal affairs; he grew irregular in his attendance at the council meetings, and signs were soon apparent that his luck had turned. In 1578 he was unable to pay, with his colleagues, either the sum of fourpence for the relief of the poor or his contribution ‘towards the furniture of three pikemen, two bellmen, and one archer’ who were sent by the corporation to attend a muster of the trained bands of the county.

Meanwhile his family was increasing. Four children besides the poet—three sons, Gilbert (baptised October 13, 1566), Richard (baptised March 11, 1574), and Edmund (baptised May 3, 1580), with a daughter Joan (baptised April 15, 1569)—reached maturity. A daughter Ann was baptised September 28, 1571, and was buried on April 4, 1579. To meet his growing liabilities, the father borrowed money from his wife’s kinsfolk, and he and his wife p. 12mortgaged, on November 14, 1578, Asbies, her valuable property at Wilmcote, for £40 to Edmund Lambert of Barton-on-the-Heath, who had married her sister, Joan Arden. Lambert was to receive no interest on his loan, but was to take the ‘rents and profits’ of the estate. Asbies was thereby alienated for ever. Next year, on October 15, 1579, John and his wife made over to Robert Webbe, doubtless a relative of Alexander Webbe, for the sum apparently of £40, his wife’s property at Snitterfield. [12a]

John Shakespeare obviously chafed under the humiliation of having parted, although as he hoped only temporarily, with his wife’s property of Asbies, and in the autumn of 1580 he offered to pay off the mortgage; but his brother-in-law, Lambert, retorted that other sums were owing, and he would accept all or none. The negotiation, which was the beginning of much litigation, thus proved abortive. Through 1585 and 1586 a creditor, John Brown, was embarrassingly importunate, and, after obtaining a writ of distraint, Brown informed the local court that the debtor had no goods on which distraint could be levied. [12b] On September 6, 1586, John was deprived of his alderman’s gown, on the ground of his long absence from the council meetings. [12c]

Happily John Shakespeare was at no expense for the education of his four sons. They were entitled to free tuition at the grammar school of Stratford, which was reconstituted on a mediæval foundation by Edward VI. The eldest son, William, probably entered the school in 1571, when Walter Roche was master, and perhaps he knew something of Thomas Hunt, who succeeded Roche in 1577. The instruction that he received was mainly confined to the Latin language and literature. From the Latin accidence, boys of the period, at schools of the type of that at Stratford, were led, through conversation books like the ‘Sententiæ Pueriles’ and Lily’s grammar, to the perusal of such authors as Seneca Terence, Cicero, Virgil, Plautus, Ovid, and Horace. The eclogues of the popular renaissance poet, Mantuanus, were often preferred to Virgil’s for beginners. The rudiments of Greek were occasionally taught in Elizabethan grammar schools to very promising pupils; but such coincidences as have been detected between expressions in Greek plays and in Shakespeare seem due to accident, and not to any study, either at school or elsewhere, of the Athenian drama. [13]

p. 14Dr. Farmer enunciated in his ‘Essay on Shakespeare’s Learning’ (1767) the theory that Shakespeare knew no language but his own, and owed whatever knowledge he displayed of the classics and of Italian and French literature to English translations. But several of the books in French and Italian whence Shakespeare derived the plots of his dramas—Belleforest’s ‘Histoires Tragiques,’ Ser Giovanni’s ‘Il Pecorone,’ and Cinthio’s ‘Hecatommithi,’ for examplep. 15—were not accessible to him in English translations; and on more general grounds the theory of his ignorance is adequately confuted. A boy with Shakespeare’s exceptional alertness of intellect, during whose schooldays a training in Latin classics lay within reach, could hardly lack in future years all means of access to the literature of France and Italy.

With the Latin and French languages, indeed, and with many Latin poets of the school curriculum, Shakespeare in his writings openly acknowledged his acquaintance. In ‘Henry V’ the dialogue in many scenes is carried on in French, which is grammatically accurate if not idiomatic. In the mouth of his schoolmasters, Holofernes in ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’ and Sir Hugh Evans in ‘Merry Wives of Windsor,’ Shakespeare placed Latin phrases drawn directly from Lily’s grammar, from the ‘Sententiæ Pueriles,’ and from ‘the good old Mantuan.’ The influence of Ovid, especially the ‘Metamorphoses,’ was apparent throughout his earliest literary work, both poetic and dramatic, and is discernible in the ‘Tempest,’ his latest play (v. i. 33 seq.) In the Bodleian Library there is a copy of the Aldine edition of Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ (1502), and on the title is the signature Wm. She., which experts have declared—not quite conclusively—to be a genuine autograph of the poet. [15] Ovid’s Latin text was certainly not unfamiliar to him, but his closest adaptations of Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ often reflect the phraseology of the popular English version by p. 16Arthur Golding, of which some seven editions were issued between 1565 and 1597. From Plautus Shakespeare drew the plot of the ‘Comedy of Errors,’ but it is just possible that Plautus’s comedies, too, were accessible in English. Shakespeare had no title to rank as a classical scholar, and he did not disdain a liberal use of translations. His lack of exact scholarship fully accounts for the ‘small Latin and less Greek’ with which he was credited by his scholarly friend, Ben Jonson. But Aubrey’s report that ‘he understood Latin pretty well’ need not be contested, and his knowledge of French may be estimated to have equalled his knowledge of Latin, while he doubtless possessed just sufficient acquaintance with Italian to enable him to discern the drift of an Italian poem or novel. [16]

Of the few English books accessible to him in his schooldays, the chief was the English Bible, either in the popular Genevan version, first issued in a complete form in 1560, or in the Bishops’ revision of 1568, which the Authorised Version of 1611 closely followed. References to scriptural characters and incidents are not conspicuous in Shakespeare’s plays, but, such as they are, they are drawn from all parts of the Bible, and indicate that general acquaintance with the narrative of both Old and New Testaments which a clever boy would be certain to acquire either in the schoolroom or at church on Sundays. Shakespeare quotes or adapts p. 17biblical phrases with far greater frequency than he makes allusion to episodes in biblical history. But many such phrases enjoyed proverbial currency, and others, which were more recondite, were borrowed from Holinshed’s ‘Chronicles’ and secular works whence he drew his plots. As a rule his use of scriptural phraseology, as of scriptural history, suggests youthful reminiscence and the assimilative tendency of the mind in a stage of early development rather than close and continuous study of the Bible in adult life. [17a]

Shakespeare was a schoolboy in July 1575, when Queen Elizabeth made a progress through Warwickshire on a visit to her favourite, the Earl of Leicester, at his castle of Kenilworth. References have been detected in Oberon’s vision in Shakespeare’s ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ (II. ii. 148-68) to the fantastic pageants and masques with which the Queen during her stay was entertained in Kenilworth Park. Leicester’s residence was only fifteen miles from Stratford, and it is possible that Shakespeare went thither with his father to witness some of the open-air festivities; but two full descriptions which were published in 1576, in pamphlet form, gave Shakespeare knowledge of all that took place. [17b] Shakespeare’s opportunities of recreation outside Stratford were in any case restricted during his schooldays. His father’s financial p. 18difficulties grew steadily, and they caused his removal from school at an unusually early age. Probably in 1577, when he was thirteen, he was enlisted by his father in an effort to restore his decaying fortunes. ‘I have been told heretofore,’ wrote Aubrey, ‘by some of the neighbours that when he was a boy he exercised his father’s trade,’ which, according to the writer, was that of a butcher. It is possible that John’s ill-luck at the period compelled him to confine himself to this occupation, which in happier days formed only one branch of his business. His son may have been formally apprenticed to him. An early Stratford tradition describes him as ‘a butcher’s apprentice.’ [18] ‘When he kill’d a calf,’ Aubrey proceeds less convincingly, ‘he would doe it in a high style and make a speech. There was at that time another butcher’s son in this towne, that was held not at all inferior to him for a naturall witt, his acquaintance, and coetanean, but dyed young.’

At the end of 1582 Shakespeare, when little more than eighteen and a half years old, took a step which was little calculated to lighten his father’s anxieties. He married. His wife, according to the inscription on her tombstone, was his senior by eight years. Rowe states that she ‘was the daughter of one Hathaway, said to have been a substantial yeoman in the neighbourhood of Stratford.’

On September 1, 1581, Richard Hathaway, ‘husbandman’ of Shottery, a hamlet in the parish of Old p. 19Stratford, made his will, which was proved on July 9, 1582, and is now preserved at Somerset House. His house and land, ‘two and a half virgates,’ had been long held in copyhold by his family, and he died in fairly prosperous circumstances. His wife Joan, the chief legatee, was directed to carry on the farm with the aid of her eldest son, Bartholomew, to whom a share in its proceeds was assigned. Six other children—three sons and three daughters—received sums of money; Agnes, the eldest daughter, and Catherine, the second daughter, were each allotted £6 13s. 4d, ‘to be paid at the day of her marriage,’ a phrase common in wills of the period. Anne and Agnes were in the sixteenth century alternative spellings of the same Christian name; and there is little doubt that the daughter ‘Agnes’ of Richard Hathaway’s will became, within a few months of Richard Hathaway’s death, Shakespeare’s wife.

The house at Shottery, now known as Anne Hathaway’s cottage, and reached from Stratford by field-paths, undoubtedly once formed part of Richard Hathaway’s farmhouse, and, despite numerous alterations and renovations, still preserves many features of a thatched farmhouse of the Elizabethan period. The house remained in the Hathaway family till 1838, although the male line became extinct in 1746. It was purchased in behalf of the public by the Birthplace trustees in 1892.

No record of the solemnisation of Shakespeare’s marriage survives. Although the parish of Stratford p. 20included Shottery, and thus both bride and bridegroom were parishioners, the Stratford parish register is silent on the subject. A local tradition, which seems to have come into being during the present century, assigns the ceremony to the neighbouring hamlet or chapelry of Luddington, of which neither the chapel nor parish registers now exist. But one important piece of documentary evidence directly bearing on the poet’s matrimonial venture is accessible. In the registry of the bishop of the diocese (Worcester) a deed is extant wherein Fulk Sandells and John Richardson, ‘husbandmen of Stratford,’ bound themselves in the bishop’s consistory court, on November 28, 1582, in a surety of £40, to free the bishop of all liability should a lawful impediment—‘by reason of any precontract’ [i.e. with a third party] or consanguinity—be subsequently disclosed to imperil the validity of the marriage, then in contemplation, of William Shakespeare with Anne Hathaway. On the assumption that no such impediment was known to exist, and provided that Anne obtained the consent of her ‘friends,’ the marriage might proceed ‘with once asking of the bannes of matrimony betwene them.’

Bonds of similar purport, although differing in significant details, are extant in all diocesan registries of the sixteenth century. They were obtainable on the payment of a fee to the bishop’s commissary, and had the effect of expediting the marriage ceremony while protecting the clergy from the consequences of any possible breach of canonical law. But they were not p. 21common, and it was rare for persons in the comparatively humble position in life of Anne Hathaway and young Shakespeare to adopt such cumbrous formalities when there was always available the simpler, less expensive, and more leisurely method of marriage by ‘thrice asking of the banns.’ Moreover, the wording of the bond which was drawn before Shakespeare’s marriage differs in important respects from that adopted in all other known examples. [21] In the latter it is invariably provided that the marriage shall not take place without the consent of the parents or governors of both bride and bridegroom. In the case of the marriage of an ‘infant’ bridegroom the formal consent of his parents was absolutely essential to strictly regular procedure, although clergymen might be found who were ready to shut their eyes to the facts of the situation and to run the risk of solemnising the marriage of an ‘infant’ without inquiry as to the parents’ consent. The clergyman who united Shakespeare in wedlock to Anne Hathaway was obviously of this easy temper. Despite the circumstance that Shakespeare’s bride was of full age and he himself was by nearly three years a minor, the Shakespeare bond stipulated merely for the consent of the bride’s ‘friends,’ and ignored the bridegroom’s parents altogether. Nor was this the only irregularity in the document. In other pre-matrimonial covenants p. 22of the kind the name either of the bridegroom himself or of the bridegroom’s father figures as one of the two sureties, and is mentioned first of the two. Had the usual form been followed, Shakespeare’s father would have been the chief party to the transaction in behalf of his ‘infant’ son. But in the Shakespeare bond the sole sureties, Sandells and Richardson, were farmers of Shottery, the bride’s native place. Sandells was a ‘supervisor’ of the will of the bride’s father, who there describes him as ‘my trustie friende and neighbour.’

The prominence of the Shottery husbandmen in the negotiations preceding Shakespeare’s marriage suggests the true position of affairs. Sandells and Richardson, representing the lady’s family, doubtless secured the deed on their own initiative, so that Shakespeare might have small opportunity of evading a step which his intimacy with their friend’s daughter had rendered essential to her reputation. The wedding probably took place, without the consent of the bridegroom’s parents—it may be without their knowledge—soon after the signing of the deed. Within six months—in May 1583—a daughter was born to the poet, and was baptised in the name of Susanna at Stratford parish church on the 26th.

Shakespeare’s apologists have endeavoured to show that the public betrothal or formal ‘troth-plight’ which was at the time a common prelude to a wedding carried with it all the privileges of marriage. But neither Shakespeare’s detailed description of a p. 23betrothal [23] nor of the solemn verbal contract that ordinarily preceded marriage lends the contention much support. Moreover, the whole circumstances of the case render it highly improbable that Shakespeare and his bride submitted to the formal preliminaries of a betrothal. In that ceremony the parents of both contracting parties invariably played foremost parts, but the wording of the bond precludes the assumption that the bridegroom’s parents were actors in any scene of the hurriedly planned drama of his marriage.

A difficulty has been imported into the narration of the poet’s matrimonial affairs by the assumption of his identity with one ‘William Shakespeare,’ to whom, according to an entry in the Bishop of Worcester’s register, a license was issued on November 27, 1582 (the day before the signing of the Hathaway bond), authorising his marriage with Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton. The theory that the maiden name of Shakespeare’s wife was Whateley is quite untenable, and it is unsafe to assume that the bishop’s clerk, when making a note of the grant of the license in his register, erred so extensively as to write Anne p. 24Whateley of Temple Grafton’ for ‘Anne Hathaway of Shottery.’ The husband of Anne Whateley cannot reasonably be identified with the poet. He was doubtless another of the numerous William Shakespeares who abounded in the diocese of Worcester. Had a license for the poet’s marriage been secured on November 27, [24] it is unlikely that the Shottery husbandmen would have entered next day into a bond ‘against impediments,’ the execution of which might well have been demanded as a preliminary to the grant of a license but was wholly supererogatory after the grant was made.

Anne Hathaway’s greater burden of years and the likelihood that the poet was forced into marrying her by her friends were not circumstances of happy augury. Although it is dangerous to read into Shakespeare’s dramatic utterances allusions to his personal experience, the emphasis with which he insists that a woman should take in marriage ‘an elder than herself,’ [25a] and that prenuptial intimacy is productive of ‘barren hate, sour-eyed disdain, and discord,’ suggest a personal interpretation. [25b] To both these unpromising features was added, in the poet’s case, the absence of a means of livelihood, and his course of life in the p. 26years that immediately followed implies that he bore his domestic ties with impatience. Early in 1585 twins were born to him, a son (Hamnet) and a daughter (Judith); both were baptised on February 2. All the evidence points to the conclusion, which the fact that he had no more children confirms, that in the later months of the year (1585) he left Stratford, and that, although he was never wholly estranged from his family, he saw little of wife or children for eleven years. Between the winter of 1585 and the autumn of 1596—an interval which synchronises with his first literary triumphs—there is only one shadowy mention of his name in Stratford records. In April 1587 there died Edmund Lambert, who held Asbies under the mortgage of 1578, and a few months later Shakespeare’s name, as owner of a contingent interest, was joined to that of his father and mother in a formal assent given to an abortive proposal to confer on Edmund’s son and heir, John Lambert, an absolute title to the estate on condition of his cancelling the mortgage and paying £20. But the deed does not indicate that Shakespeare personally assisted at the transaction. [26]

Shakespeare’s early literary work proves that while in the country he eagerly studied birds, flowers, and trees, and gained a detailed knowledge of horses and dogs. All his kinsfolk were farmers, and with them he doubtless as a youth practised many field sports. Sympathetic references to hawking, hunting, coursing, and angling abound in his early plays and p. 27poems. [27] And his sporting experiences passed at times beyond orthodox limits. A poaching adventure, according to a credible tradition, was the immediate cause of his long severance from his native place. ‘He had,’ wrote Rowe in 1709, ‘by a misfortune common enough to young fellows, fallen into ill company, and, among them, some, that made a frequent practice of deer-stealing, engaged him with them more than once in robbing a park that belonged to Sir Thomas Lucy of Charlecote near Stratford. For this he was prosecuted by that gentleman, as he thought, somewhat too severely; and, in order to revenge that ill-usage, he made a ballad upon him, and though this, probably the first essay of his poetry, be lost, yet it is said to have been so very bitter that it redoubled the prosecution against him to that degree that he was obliged to leave his business and family in Warwickshire and shelter himself in London.’ The independent testimony of Archdeacon Davies, who was vicar of Saperton, Gloucestershire, late in the seventeenth century, is to the effect that Shakespeare ‘was much given to all unluckiness in stealing venison and rabbits, particularly from Sir Thomas Lucy, who had him oft whipt, and sometimes imprisoned, and at last made him fly his native county to his great advancement.’ The law of Shakespeare’s day (5 Eliz. cap. 21) p. 28punished deer-stealers with three months’ imprisonment and the payment of thrice the amount of the damage done.

The tradition has been challenged on the ground that the Charlecote deer-park was of later date than the sixteenth century. But Sir Thomas Lucy was an extensive game-preserver, and owned at Charlecote a warren in which a few harts or does doubtless found an occasional home. Samuel Ireland was informed in 1794 that Shakespeare stole the deer, not from Charlecote, but from Fulbroke Park, a few miles off, and Ireland supplied in his ‘Views on the Warwickshire Avon,’ 1795, an engraving of an old farmhouse in the hamlet of Fulbroke, where he asserted that Shakespeare was temporarily imprisoned after his arrest. An adjoining hovel was locally known for some years as Shakespeare’s ‘deer-barn,’ but no portion of Fulbroke Park, which included the site of these buildings (now removed), was Lucy’s property in Elizabeth’s reign, and the amended legend, which was solemnly confided to Sir Walter Scott in 1828 by the owner of Charlecote, seems pure invention. [28]

The ballad which Shakespeare is reported to have fastened on the park gates of Charlecote does not, as Rowe acknowledged, survive. No authenticity can be allowed the worthless lines beginning ‘A parliament member, a justice of peace,’ which were p. 29represented to be Shakespeare’s on the authority of an old man who lived near Stratford and died in 1703. But such an incident as the tradition reveals has left a distinct impress on Shakespearean drama. Justice Shallow is beyond doubt a reminiscence of the owner of Charlecote. According to Archdeacon Davies of Saperton, Shakespeare’s ‘revenge was so great that’ he caricatured Lucy as ‘Justice Clodpate,’ who was (Davies adds) represented on the stage as ‘a great man,’ and as bearing, in allusion to Lucy’s name, ‘three louses rampant for his arms.’ Justice Shallow, Davies’s ‘Justice Clodpate,’ came to birth in the ‘Second Part of Henry IV’ (1598), and he is represented in the opening scene of the ‘Merry Wives of Windsor’ as having come from Gloucestershire to Windsor to make a Star-Chamber matter of a poaching raid on his estate. The ‘three luces hauriant argent’ were the arms borne by the Charlecote Lucys, and the dramatist’s prolonged reference in this scene to the ‘dozen white luces’ on Justice Shallow’s ‘old coat’ fully establishes Shallow’s identity with Lucy.

The poaching episode is best assigned to 1585, but it may be questioned whether Shakespeare, on fleeing from Lucy’s persecution, at once sought an asylum in London. William Beeston, a seventeenth-century actor, remembered hearing that he had been for a time a country schoolmaster ‘in his younger years,’ and it seems possible that on first leaving Stratford he found some such employment in a neighbouring village. The p. 30suggestion that he joined, at the end of 1585, a band of youths of the district in serving in the Low Countries under the Earl of Leicester, whose castle of Kenilworth was within easy reach of Stratford, is based on an obvious confusion between him and others of his name. [30] The knowledge of a soldier’s life which Shakespeare exhibited in his plays is no greater and no less than that which he displayed of almost all other spheres of human activity, and to assume that he wrote of all or of any from practical experience, unless the evidence be conclusive, is to underrate his intuitive power of realising life under almost every aspect by force of his imagination.

To London Shakespeare naturally drifted, doubtless trudging thither on foot during 1586, by way of Oxford and High Wycombe. [31a] Tradition points to that as Shakespeare’s favoured route, rather than to the road by Banbury and Aylesbury. Aubrey asserts that at Grendon near Oxford, ‘he happened to take the humour of the constable in “Midsummer Night’s Dream”’—by which he meant, we may suppose, ‘Much Ado about Nothing’—but there were watchmen of the Dogberry type all over England, and probably at Stratford itself. The Crown Inn, (formerly 3 Cornmarket Street) near Carfax, at Oxford, was long pointed out as one of his resting-places.

To only one resident in London is Shakespeare likely to have been known previously. [31b] Richard p. 32Field, a native of Stratford, and son of a friend of Shakespeare’s father, had left Stratford in 1579 to serve an apprenticeship with Thomas Vautrollier, the London printer. Shakespeare and Field, who was made free of the Stationers’ Company in 1587, were soon associated as author and publisher; but the theory that Field found work for Shakespeare in Vautrollier’s printing-office is fanciful. [32a] No more can be said for the attempt to prove that he obtained employment as a lawyer’s clerk. In view of his general quickness of apprehension, Shakespeare’s accurate use of legal terms, which deserves all the attention that has been paid it, may be attributable in part to his observation of the many legal processes in which his father was involved, and in part to early intercourse with members of the Inns of Court. [32b]

Tradition and common-sense alike point to one of the only two theatres (The Theatre or The Curtain) that existed in London at the date of his arrival as an early scene of his regular occupation. The compiler of ‘Lives of the Poets’ (1753) [32c] was the first to relate the story that p. 33his original connection with the playhouse was as holder of the horses of visitors outside the doors. According to the same compiler, the story was related by D’Avenant to Betterton; but Rowe, to whom Betterton communicated it, made no use of it. The two regular theatres of the time were both reached on horseback by men of fashion, and the owner of The Theatre, James Burbage, kept a livery stable at Smithfield. There is no inherent improbability in the tale. Dr. Johnson’s amplified version, in which Shakespeare was represented as organising a service of boys for the purpose of tending visitors’ horses, sounds apocryphal.

There is every indication that Shakespeare was speedily offered employment inside the playhouse. In 1587 the two chief companies of actors, claiming respectively the nominal patronage of the Queen and Lord Leicester, returned to London from a provincial tour, during which they visited Stratford. Two subordinate companies, one of which claimed the patronage of the Earl of Essex and the other that of Lord Stafford, also performed in the town during the same year. Shakespeare’s friends may have called the attention of the strolling players to the homeless youth, rumours of whose search for employment about the London theatres had doubtless reached Stratford. From such incidents seems to have sprung the opportunity which offered Shakespeare fame and fortune. According to Rowe’s vague statement, ‘he was received into the company then in being at first in a very mean rank.’ p. 34William Castle, the parish clerk of Stratford at the end of the seventeenth century, was in the habit of telling visitors that he entered the playhouse as a servitor. Malone recorded in 1780 a stage tradition ‘that his first office in the theatre was that of prompter’s attendant’ or call-boy. His intellectual capacity and the amiability with which he turned to account his versatile powers were probably soon recognised, and thenceforth his promotion was assured.

Shakespeare’s earliest reputation was made as an actor, and, although his work as a dramatist soon eclipsed his histrionic fame, he remained a prominent member of the actor’s profession till near the end of his life. By an Act of Parliament of 1571 (14 Eliz. cap. 2), which was re-enacted in 1596 (39 Eliz. cap. 4), players were under the necessity of procuring a license to pursue their calling from a peer of the realm or ‘personage of higher degree;’ otherwise they were adjudged to be of the status of rogues and vagabonds. The Queen herself and many Elizabethan peers were liberal in the exercise of their licensing powers, and few actors failed to secure a statutory license, which gave them a rank of respectability, and relieved them of all risk of identification with vagrants or ‘sturdy beggars.’ From an early period in Elizabeth’s reign licensed actors were organised into permanent companies. In 1587 and following years, besides three companies of duly licensed boy-actors that were formed from the choristers of St. Paul’s Cathedral and the Chapel p. 35Royal and from Westminster scholars, there were in London at least six companies of fully licensed adult actors; five of these were called after the noblemen to whom their members respectively owed their licenses (viz. the Earls of Leicester, Oxford, Sussex, and Worcester, and the Lord Admiral, Charles, lord Howard of Effingham), and one of them whose actors derived their license from the Queen was called the Queen’s Company.

The patron’s functions in relation to the companies seem to have been mainly confined to the grant or renewal of the actors’ licenses. Constant alterations of name, owing to the death or change from other causes of the patrons, render it difficult to trace with certainty each company’s history. But there seems no doubt that the most influential of the companies named—that under the nominal patronage of the Earl of Leicester—passed on his death in September 1588 to the patronage of Ferdinando Stanley, lord Strange, who became Earl of Derby on September 25, 1592. When the Earl of Derby died on April 16, 1594, his place as patron and licenser was successively filled by Henry Carey, first lord Hunsdon, Lord Chamberlain (d. July 23, 1596), and by his son and heir, George Carey, second lord Hunsdon, who himself became Lord Chamberlain in March 1597. After King James’s succession in May 1603 the company was promoted to be the King’s players, and, thus advanced in dignity, it fully maintained the supremacy p. 36which, under its successive titles, it had already long enjoyed.

It is fair to infer that this was the company that Shakespeare originally joined and adhered to through life. Documentary evidence proves that he was a member of it in December 1594; in May, 1603 he was one of its leaders. Four of its chief members—Richard Burbage, the greatest tragic actor of the day, John Heming, Henry Condell, and Augustine Phillips were among Shakespeare’s lifelong friends. Under this company’s auspices, moreover, Shakespeare’s plays first saw the light. Only two of the plays claimed for him—‘Titus Andronicus’ and ‘3 Henry VI’—seem to have been performed by other companies (the Earl of Sussex’s men in the one case, and the Earl of Pembroke’s in the other).