Emily Sarah Holt

"The White Lady of Hazelwood"

Preface.

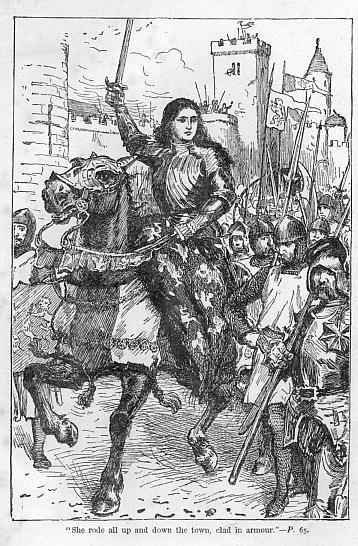

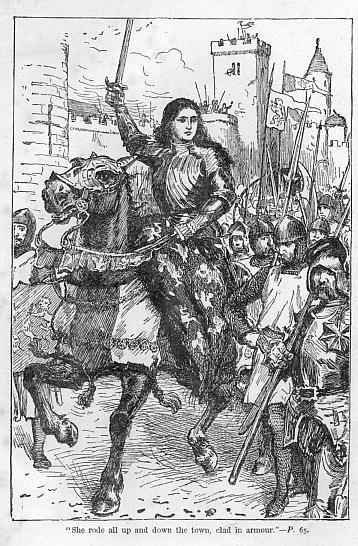

On the crowded canvas of the fourteenth century stands out as one of its most prominent figures that of the warrior Countess of Montfort. No reader of Froissart’s Chronicle can forget the siege of Hennebon, and the valiant part she played in the defence of her son’s dominions. Actuated by more personal motives than the peasant maid, she was nevertheless the Joan of Arc of her day, and of Bretagne.

What became of her?

After the restoration of her son, we see no more of that brave and tender mother. She drops into oblivion. Her work was done. Those who have thought again of her at all have accepted without question the only extant answer—the poor response of a contemporary romance, according to which she dwelt in peace, and closed an honoured and cherished life in a castle in the duchy of her loving and grateful son.

It has been reserved for the present day to find the true reply—to draw back the veil from the “bitter close of all,” and to show that the hardest part of her work began when she laid down her sword, and the ending years of her life were the saddest and weariest portion. Never since the days of Lear has such a tale been told of a parent’s sacrifice and of a child’s ingratitude. In the royal home of the Duke of Bretagne, there was no room for her but for whose love and care he would have been a homeless fugitive. The discarded mother was imprisoned in a foreign land, and left to die.

Let us hope that as it is supposed in the story, the lonely, broken heart turned to a truer love than that of her cherished and cruel son—even to His who says “My mother” of all aged women who seek to do the will of God, and who will never forsake them that trust in Him.

Chapter One.

At the Patty-Maker’s Shop.

“Man wishes to be loved—expects to be so:

And yet how few live so as to be loved!”

Rev. Horatius Bonar, D.D.

It was a warm afternoon in the beginning of July—warm everywhere; and particularly so in the house of Master Robert Altham, the patty-maker, who lived at the corner of Saint Martin’s Lane, where it runs down into the Strand. Shall we look along the Strand? for the time is 1372, five hundred years ago, and the Strand was then a very different place from the street as we know it now.

In the first place, Trafalgar Square had no being. Below where it was to be in the far future, stood Charing Cross—the real Eleanor Cross of Charing, a fine Gothic structure—and four streets converged upon it. That to the north-west parted almost directly into the Hay Market and Hedge Lane, genuine country roads, in which both the hay and the hedge had a real existence. Southwards ran King Street down to Westminster; and northwards stood the large building of the King’s Mews, where his Majesty’s hawks were kept. Two hundred years later, bluff King Hal would turn out the hawks to make room for his horses; but as yet the word mews had its proper signification of a place where hawks were mewed or confined. At the corner of the Mews, between it and the patty-maker’s, ran up Saint Martin’s Lane; its western boundary being the long blank wall of the Mews, and its eastern a few houses, and then Saint Martin’s Church. Along the Strand, eastwards, were stately private houses on the right hand, and shops upon the left. Just below the cross, further to the south, was Scotland Yard, the site of the ancient Palace of King David of Scotland, and still bearing traces of its former grandeur; then came the Priory of Saint Mary Rouncival, the town houses of six Bishops, the superb mansion of the Earl of Arundel, and the house of the Bishops of Exeter, interspersed with smaller dwellings here and there. A long row of these stretched between Durham Place and Worcester Place, behind which, with its face to the river, stood the magnificent Palace of the Savoy, the city habitation of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, eldest surviving son of the reigning King. The Strand was far narrower than now, and the two churches, instead of being in the middle, broke the monotony of the rows of houses on the north side. Let us look more especially at the long row which ran unbroken from the corner of Saint Martin’s Lane to the first church, that of “our Lady and the holy Innocents atte Stronde.”

What would first strike the eye was the signboards, gaily painted, and swinging in the summer breeze. Every house had one, for there were no numbers, and these served the purpose; consequently no two similar ones must be near each other. People directed letters to Master Robert Altham, “at the Katherine Wheel, by Saint Martin’s Church, nigh the King’s Mews,” when they had any to write; but letters, except to people in high life or in official positions, were very rare articles, and Master Altham had not received a full dozen in all the seven-and-twenty years that he had lived in the Strand and made patties. Next door to him was John Arnold, the bookbinder, who displayed a Saracen’s head upon his signboard; then came in regular order Julian Walton, the mercer, with a wheelbarrow; Stephen Fronsard, the girdler, with a cardinal’s hat; John Silverton, the pelter or furrier, with a star; Peter Swan, the Court broiderer, with cross-keys; John Morstowe, the luminer, or illuminator of books, with a rose; Lionel de Ferre, the French baker, with a vine; Herman Goldsmith, the Court goldsmith, who bore a dolphin; William Alberton, the forcermonger, who kept what we should call a fancy shop for little boxes, baskets, etcetera, and exhibited a fleur-de-lis; Michael Ladychapman, who sported a unicorn, and sold goloshes; Joel Garlickmonger, at the White Horse, who dealt in the fragrant vegetable whence he derived his name; and Theobald atte Home, the hatter, who being of a poetical disposition, displayed a landscape entitled, as was well understood, the Hart’s Bourne. Beyond these stretched far away to the east other shops—those of a mealman, a lapidary, a cordwainer—namely, a shoemaker; a lindraper, for they had not yet added the syllable which makes it linen; a lorimer, who dealt in bits and bridles; a pouchmonger, who sold bags and pockets; a parchment-maker; a treaclemonger, a spicer, a chandler, and a pepperer, all four the representatives of our modern grocer; an apothecary; a scrivener, who wrote for the numerous persons who could not write; a fuller, who cleaned clothes; a tapiser, who sold tapestry, universally used for hangings of rooms; a barber, an armourer, a spurrier, a scourer, a dyer, a glover, a turner, a goldbeater, an upholdester or upholsterer, a toothdrawer, a buckler-maker, a fletcher (who feathered arrows), a poulter or poulterer, a vinter or wine-merchant, a pewterer, a haberdasher, a pinner or pin-maker, a skinner, a hamper-maker, and a hosier. The list might be prolonged through fifty other trades, but we have reached Temple Bar. So few houses between Saint Martin’s Lane and Temple Bar! Yes, so few. Ground was cheap, and houses were low, and it cost less to cover much ground than to build high. Only very exalted mansions had three floors, and more than three were unknown even to imagination. Moreover, the citizens of London had decided ideas of the garden order. They did not crush their houses tight together, as if to squeeze out another inch, if possible. Though their streets were exceedingly narrow, yet nearly every house had its little garden; and behind that row to which we are paying particular attention, ran “le Covent Garden,” the Abbot of Westminster’s private pleasure ground, and on its south-east was Auntrous’ Garden, bordered by “the King’s highway, leading from the town of Seint Gylys to Stronde Crosse.” The town of Seint Gylys was quite a country place, and as to such remote villages as Blumond’s Bury or Iseldon, which we call Bloomsbury and Islington, nobody thought of them in connection with London, any more than with Nottingham or Durham.

The houses were much more picturesque than those of modern build. There was no attempt at uniformity. Each man set his house down as it suited him, and some thatches turned to the east and west, while others fronted north and south. There were few chimneys, except in the larger houses, and no shop windows; a large wooden shutter fixed below the window covered it at night, and in the day it was let down to hang, tablewise, as a counter whereon the goods sold by the owner were displayed.

The Strand was one of the few chief streets where various trades congregated together. Usually every street had its special calling, and every trade its own particular street. Some of the latter retain their significant names even yet—Hosier Lane, Cordwainer Street, Bread Street, Soper’s Lane, the Poultry, Silver Street, Ironmonger’s Lane, and Paternoster Row, in which last lived the text-writers and rosary-makers. The mercers lived mainly in Cheapside, the drapers in Lombard Street (they were mostly Italians, as the name shows), the furriers in Saint Mary Axe, the fishmongers in Knightriders’ Street, the brewers by the Thames, the butchers in Eastcheap, and the goldsmiths in Guthrum’s (now Gutter) Lane.

But it is time to inquire what kind of patties were inviting the passer-by on Mr Altham’s counter. They were a very large variety: oyster, crab, lobster, anchovy, and all kinds of fish; sausage-rolls, jelly, liver, galantine, and every sort of meat; ginger, honey, cream, fruit; cheese-cakes, almond and lemon; little open tarts called bry tarts, made of literal cheese, with a multitude of other articles—eggs, honey or sugar, and spices; and many another compound of multifarious and indigestible edibles; for what number of incongruities, palatable or sanitary, did our forefathers not put together in a pie! For one description of dainty, however, Mr Altham would have been asked on this July afternoon in vain. He would have deemed it next door to sacrilege to heat his oven for a mince pie, outside the charmed period between Christmas Eve and Twelfth Day.

On the afternoon in question, Mr Altham stepped out of his door to speak with his neighbour the girdler, and no sooner was he well out of the way than another person walked into it. This was a youth of some eighteen years, dressed in a very curious costume. Men did not affect black clothes then, except in mourning; and the taste of few led them to the sombre browns and decorous greys worn by most now. This young gentleman had on a tunic of dark red, in shape not unlike a butcher’s blue frock, which was fastened round the hips by a girdle of black leather, studded with brass spangles. His head was covered by a loose hood of bright blue, and his hose or stockings—for stockings and trousers were in one—were a light, bright shade of apple-green. Low black shoes completed this showy costume, but it was not more showy than that of every other man passing along the street. Our young man seemed rather anxious not to be seen, for he cast sundry suspicious glances in the direction of the girdler’s, and having at length apparently satisfied himself that the patty-maker was not likely to return at once, he darted across the street, and presented himself at the window of the corner shop. Two girls were sitting behind it, whose ages were twenty and seventeen. These young ladies were scarcely so smart as the gentleman. The elder wore a grey dress striped with black, over which was a crimson kirtle or pelisse, with wide sleeves and tight grey ones under them; a little green cap sat on her light hair, which was braided in two thick masses, one on each side of the face. The younger wore a dress of the same light green as the youth’s hose, with a silvery girdle, and a blue cap.

“Mistress Alexandra!” said the youth in a loud whisper.

The elder girl took no notice of him. The younger answered as if she had just discovered his existence, though in truth she had seen him coming all the time.

“O Clement Winkfield, is that you? We’ve no raffyolys (Sausage-rolls) left, if that be your lack.”

“I thank you, Mistress Ricarda; but I lack nought o’ the sort. Mistress Alexandra knoweth full well that I come but to beg a kind word from her.”

“I’ve none to spare this even,” said the elder, with a toss of her head.

“But you will, sweet heart, when you hear my tidings.”

“What now? Has your mother bought a new kerchief, or the cat catched a mouse?”

“Nay, sweet heart, mock me not! Here be grand doings, whereof my Lord talked this morrow at dinner, I being awaiting. What say you to a goodly tournament at the Palace of the Savoy?”

“I dare reckon you fell asleep and dreamed thereof.”

“Mistress Alexandra, you’d make a saint for to swear! Howbeit, if you reck not thereof,—I had meant for to practise with my cousin at Arundel House, for to get you standing room with the maids yonder; but seeing you have no mind thereto—I dare warrant Mistress Joan Silverton shall not say me nay, and may be Mistress Argenta—”

“Come within, Clement, and eat a flaune,” said Ricarda in a very different tone, taking up a dish of cheese-cakes from the counter. “When shall the jousting be?”

“Oh, it makes no bones, Mistress Ricarda. Your sister hath no mind thereto, ’tis plain.”

However, Clement suffered himself to be persuaded to do what he liked, and Ricarda going close to her sister to fetch a plate, whispered to her a few words of warning as to what she might lose by too much coldness, whereupon the fair Alexandra thawed somewhat, and condescended to seem slightly interested in the coming event. Ricarda, however, continued to do most of the talking.

Clement Winkfield was scullion in the Bishop of Durham’s kitchen, and would have been considered in that day rather a good match for a tradesman’s daughter; for anything in the form of manufacture or barter was then in a very mean social position. Domestic service stood much higher than it does now; and though Mr Altham’s daughters were heiresses in a small way, they could not afford to despise Clement Winkfield, except as a political stratagem.

“And what like shall the jousting be, Clement?” asked Ricarda, when that young gentleman had been satisfactorily settled on a form inside the shop, with a substantial cheese-cake before him—not a mere mouthful, but a large oval tart from which two or three people might be helped.

“It shall be the richest and rarest show was seen this many a day, my mistress,” replied Clement, having disposed of his first bite. “In good sooth, Mistress, but you wot how to make flaunes! My Lord hath none such on his table.”

“That was Saundrina’s making,” observed Ricarda with apparent carelessness.

“Dear heart! That’s wherefore it’s so sweet, trow,” responded Clement gallantly.

Alexandra laughed languidly. “Come now, Clem, tell us all about the jousting, like a good lad as thou art, and win us good places to see the same, and I will make thee a chowet-pie (liver-pie) of the best,” said she, laying aside her affected indifference.

“By my troth, I’ll talk till my tongue droppeth on the floor,” answered the delighted Clement; “and I have heard all of Will Pierpoint, that is in my Lord of Arundel his stable, and is thick as incle-weaving with one of my Lord of Lancaster his palfreymen. The knights be each one in a doublet of white linen, spangled of silver, having around the sleeves and down the face thereof a border of green cloth, whereon is broidered the device chosen, wrought about with clouds and vines of golden work. The ladies and damsels be likewise in green and white. For the knights, moreover, there be masking visors, fourteen of peacocks’ heads, and fourteen of maidens’ heads, the one sort to tilt against the other. My Lord Duke of Lancaster, that is lord of the revels, beareth a costume of white velvet paled with cramoisie (striped with crimson velvet), whereon be wrought garters of blue, and the Lady of Cambridge, that is lady of the jousts, and shall give the prizes, shall be in Inde-colour (blue), all wrought with roses of silver. There be at this present forty women broiderers a-working in the Palace, in such haste they be paid mighty high wage—fourpence halfpenny each one by the day.”

In order to understand the value of these payments, we must multiply them by about sixteen. The wages of a broideress, according to the present worth of money, were, when high, six shillings a day.

“And the device, what is it?”

“Well, I counsel not any man to gainsay it. ‘It is as it is’—there you have it.”

“Truly, a merry saying. And when shall it be, Clem?”

Mistress Alexandra was quite gracious now.

“Thursday shall be a fortnight, being Saint Maudlin’s Day, at ten o’ the clock in the forenoon. Will hath passed word to me to get me in, and two other with me. You’ll come, my mistresses? There’ll not be room for Mistress Amphillis; I’m sorry.”

Alexandra tossed her head very contemptuously.

“What does Amphillis want of jousts?” said she. “She’s fit for nought save to sift flour and cleanse vessels when we have a-done with them. And she hasn’t a decent kirtle, never name a hood. I wouldn’t be seen in her company for forty shillings.”

“Saundrina’s been at Father to put her forth,” added Ricarda, “if he could but hear of some service in the country, where little plenishing were asked. There’s no good laying no money out on the like of her.”

A soft little sound at the door made them look round. A girl was standing there, of about Clement’s age—a pale, quiet-looking girl, who seemed nervously afraid of making her presence known, apparently lest she should be blamed for being there or anywhere. Alexandra spoke sharply.

“Come within and shut the door, Amphillis, and stare not thus like a goose! What wouldst?”

Amphillis neither came in nor shut the door. She held it in her hand, while she said in a shy way, “The patties are ready to come forth, if one of you will come,” and then she disappeared, as if frightened of staying a minute longer than she could help.

“‘Ready to come forth!’” echoed Ricarda. “Cannot the stupid thing take them forth by herself?”

“I bade her not do so,” explained her sister, “but call one of us—she is so unhandy. Go thou, Ricarda, or she’ll be setting every one wrong side up.”

Ricarda, with a martyr-like expression—which usually means an expression very unlike a martyr’s—rose and followed Amphillis. Alexandra, thus left alone with Clement, became so extra amiable as to set that not over-wise youth on a pinnacle of ecstasy, until she heard her father’s step, when she dismissed him hastily.

She did not need to have been in a hurry, for the patty-maker was stopped before he reached the threshold, by a rather pompous individual in white and blue livery. Liveries were then worn far more commonly than now—not by servants only, but by officials of all kinds, and by gentlemen retainers of the nobles—sometimes even by nobles themselves. To wear a friend’s livery was one of the highest compliments that could be paid. Mr Altham knew by a glance at his costume that the man who had stopped him bore some office in the household of the Duke of Lancaster, since he not only wore that Prince’s livery, but bore his badge, the ostrich feather ermine, affixed to his left sleeve.

“Master Altham the patty-maker, I take it?”

“He, good my master, and your servant.”

“A certain lady would fain wit of you, Master, if you have at this present dwelling with you a daughter named Amphillis?”

“I have no daughter of that name. I have two daughters, whose names be Alexandra and Ricarda, that dwell with me; likewise one wedded, named Isabel. I have a niece named Amphillis.”

“That dwelleth with you?”

“Ay, she doth at this present, sithence my sister, her mother, is departed (dead); but—”

“You have had some thought of putting her forth, maybe?”

Mr Altham looked doubtful.

“Well! we have talked thereof, I and my maids; but no certain end was come to thereabout.”

“That is it which the lady has heard. Mistress Walton the silkwoman, at the Wheelbarrow, spake with this lady, saying such a maid there was, for whom you sought service; and the lady wotteth (knows) of a gentlewoman with whom she might be placed an’ she should serve, and the service suited your desires for her.”

“Pray you, come within, and let us talk thereon at our leisure. I am beholden to Mistress Walton; she knew I had some thoughts thereanent (about it), and she hath done me a good turn to name it.”

The varlet, as he was then called, followed Mr Altham into the shop. Aralet is a contraction of this word. But varlet, at that date, was a term of wide signification, including any type of personal attendant. The varlet of a duke would be a gentleman by birth and education, for gentlemen were not above serving nobles even in very menial positions. People had then, in some respects, “less nonsense about them” than now, and could not see that it was any degradation for one man to hand a plate to another.

Alexandra rose when the varlet made his appearance. She did not keep a heart, and she did keep a large stock of vanity. She was consequently quite ready to throw over Clement Winkfield as soon as ever a more eligible suitor should present himself; and her idea of mankind ranged them in two classes—such as were, and such as were not, eligible suitors for Alexandra Altham.

Mr Altham, however, led his guest straight through the shop and upstairs, thus cutting short Miss Altham’s wiles and graces. He took him into what we should call his study, a very little room close to his bedchamber, and motioned him to the only chair it contained; for chairs were rare and choice things, the form or bench being the usual piece of furniture. Before shutting the door, however, he called—“Phyllis!”

Somebody unseen to the varlet answered the call, and received directions in a low voice. Mr Altham then came in and shut the door.

“I have bidden the maid bring us hypocras and spice,” said he; “so you shall have a look at her.”

Hypocras was a very light wine, served as tea now is in the afternoon, and spice was a word which covered all manner of good things—not only pepper, sugar, cinnamon, and nutmegs, but rice, almonds, ginger, and even gingerbread.

Mr Tynneslowe—for so the varlet was named—sat down in the chair, and awaited the tray and Amphillis.

Chapter Two.

The Goldsmith’s Daughter.

“I can live

A life that tells on other lives, and makes

This world less full of evil and of pain—

A life which, like a pebble dropped at sea,

Sends its wide circles to a hundred shores.”

Rev. Horatius Bonar, D.D.

The coming hypocras interested Mr Tynneslowe more than its bearer. He was privately wondering, as he sat awaiting it, whether Mr Altham would have any in his cellar that was worth drinking, especially after that of his royal master. His next remark, however, had reference to Amphillis.

“It makes little matter, good Master, that I see the maid,” said he. “The lady or her waiting-damsels shall judge best of her. You and I can talk over the money matters and such. I am ill-set to judge of maids: they be kittle gear.”

“Forsooth, they be so!” assented Mr Altham, with a sigh: for his fair and wayward Alexandra had cost him no little care before that summer afternoon. “And to speak truth, Master Tynneslowe, I would not be sorry to put the maid forth, for she is somewhat a speckled bird in mine house, whereat the rest do peck. Come within!”

The door of the little chamber opened, and Amphillis appeared carrying a tray, whereon was set a leather bottle flanked by two silver cups, a silver plate containing cakes, and a little silver-gilt jar with preserved ginger. Glass and china were much too rare and costly articles for a tradesman to use, but he who had not at least two or three cups and plates of silver in his closet was a very poor man. Of course these, by people in Mr Altham’s position, were kept for best, the articles commonly used being pewter or wooden plates, and horn cups.

Amphillis louted to the visitor—that is, she dropped what we call a charity school-girl’s “bob”—and the visitor rose and courtesied in reply, for the courtesy was then a gentleman’s reverence. She set down the tray, poured out wine for her uncle and his guest into the silver cups, handed the cakes and ginger, and then quietly took her departure.

“A sober maid and a seemly, in good sooth,” said Mr Tynneslowe, when the door was shut. “Hath she her health reasonable good? She looks but white.”

“Ay, good enough,” said the patty-maker, who knew that Amphillis was sufficiently teased and worried by those lively young ladies, her cousins, to make any girl look pale.

“Good. Well, what wages should content you?”

Mr Altham considered that question with pursed lips and hands in his pockets.

“Should you count a mark (13 shillings 4 pence) by the year too much?”

This would come to little over ten pounds a year at present value, and seems a very poor salary for a young lady; but it must be remembered that she was provided with clothing, as well as food and lodging, and that she was altogether free from many expenses which we should reckon necessaries—umbrellas and parasols, watches, desks, stamps, and stationery.

“Scarce enough, rather,” was the unexpected answer. “Mind you, Master Altham, I said a lady.”

Master Altham looked curious and interested. We call every woman a lady who has either money or education; but in 1372 ranks were more sharply defined. Only the wives and daughters of a prince, peer, or knight were termed ladies; the wives of squires and gentlemen were gentlewomen; while below that they were simply called wives or maids, according as they were married or single.

“This lady, then, shall be—Mercy on us! sure, Master Tynneslowe, you go not about to have the maid into the household of my Lady’s Grace of Cambridge, or the Queen’s Grace herself of Castile?”

The Duke of Lancaster having married the heiress of Castile, he and his wife were commonly styled King and Queen of Castile.

Mr Tynneslowe laughed. “Nay, there you fly your hawk at somewhat too high game,” said he; “nathless (nevertheless), Master Altham, it is a lady whom she shall serve, and a lady likewise who shall judge if she be meet for the place. But first shall she be seen of a certain gentlewoman of my lady’s household, that shall say whether she promise fair enough to have her name sent up for judgment. I reckon three nobles (one pound; present value, 6 pounds) by the year shall pay her reckoning.”

“Truly, I would be glad she had so good place. And for plenishing, what must she have?”

“Store sufficient of raiment is all she need have, and such jewelling as it shall please you to bestow on her. All else shall be found. The gentlewoman shall give her note of all that lacketh, if she be preferred to the place.”

“And when shall she wait on the said gentlewoman?”

“Next Thursday in the even, at Master Goldsmith’s.”

“I will send her.”

Mr Tynneslowe declined a second helping of hypocras, and took his leave. The patty-maker saw him to the door, and then went back into his shop.

“I have news for you, maids,” said he.

Ricarda, who was arranging the fresh patties, looked up and stopped her proceedings; Alexandra brought her head in from the window. Amphillis only, who sat sewing in the corner, went on with her work as if the news were not likely to concern her.

“Phyllis, how shouldst thou like to go forth to serve a lady?”

A bright colour flushed into the pale cheeks.

“I, Uncle?” she said.

“A lady!” cried Alexandra in a much shriller voice, the word which had struck her father’s ear so lightly being at once noted by her. “Said you a lady, Father? What lady, I pray you?”

“That cannot I say, daughter. Phyllis, thou art to wait on a certain gentlewoman, at Master Goldsmith’s, as next Thursday in the even, that shall judge if thou shouldst be meet for the place. Don thee in thy best raiment, and mind thy manners.”

“May I go withal, Father?” cried Alexandra.

“There was nought said about thee. Wouldst thou fain be put forth? I never thought of no such a thing. Maybe it had been better that I had spoken for you, my maids.”

“I would not go forth to serve a city wife, or such mean gear,” said Alexandra, contemptuously. “But in a lady’s household I am well assured I should become the place better than Phyllis. Why, she has not a word to say for herself,—a poor weak creature that should never—”

“Hush, daughter! Taunt not thy cousin. If she be a good maid and discreet, she shall be better than fair and foolish.”

“Gramercy! cannot a maid be fair and discreet belike?”

“Soothly so. ’Tis pity she is not oftener.”

“But may we not go withal, Father?” said Ricarda.

“Belike ye may, my maid. Bear in mind the gentlewoman looks to see Amphillis, not you, and make sure that she wist which is she. Then I see not wherefore ye may not go.”

Any one who had lived in Mr Altham’s house from that day till the Thursday following would certainly have thought that Alexandra, not Amphillis, was the girl chosen to go. The former made far more fuss about it, and she was at the same time preparing a new mantle wherein to attend the tournament, of which Amphillis was summoned to do all the plain and uninteresting parts. The result of this preoccupation would have been very stale pastry on the counter, if her father had not seen to that item for himself. Ricarda was less excited and egotistical, yet she talked more than Amphillis.

The Thursday evening came, and the three girls, dressed in their best clothes, took their way to the Dolphin. The Court goldsmith was a more select individual than Mr Altham, and did not serve in his own shop, unless summoned to a customer of rank. The young men who were there had evidently been prepared for the girls’ coming, and showed them upstairs with a fire of jokes which Alexandra answered smartly, while Amphillis was silent under them.

They were ushered into the private chamber of the goldsmith’s daughter, who sat at work, and rose to receive them. She kissed them all, for kissing was then the ordinary form of greeting, and people only shook hands when they wished to be warmly demonstrative.

“Is the gentlewoman here, Mistress Regina?”

“Sit you down,” said Mistress Regina, calmly. “No, she is not yet come. She will not long be. Which of you three is de maiden dat go shall?”

“That my cousin is,” said Alexandra, making fun of the German girl’s somewhat broken English, though in truth she spoke it fairly for a foreigner. But Amphillis said gently—

“That am I, Mistress Regina; and I take it full kindly of you, that you should suffer me to meet this gentlewoman in your chamber.”

“So!” was the answer. “You shall better serve of de three.”

Alexandra had no time to deliver the rather pert reply which she was preparing, for the door opened, and the young man announced “Mistress Chaucer.”

Had the girls known that the lady who entered was the wife of a man before whose fame that of many a crowned monarch would pale, and whose poetry should live upon men’s lips when five hundred years had fled, they would probably have looked on her with very different eyes. But they knew her only as a Lady of the Bedchamber, first to the deceased Queen Philippa, and now to the Queen of Castile, and therefore deserving of all possible subservience. Of her husband they never thought at all. The “chiel amang ’em takin’ notes” made no impression on them: but five centuries have passed since then, and the chiel’s notes are sterling yet in England.

Mistress Chaucer sat down on the bench, and with quiet but rapid glances appraised the three girls. Then she said to Amphillis—

“Is it thou whom I came to see?”

Amphillis louted, and modestly assented, after which the lady took no further notice of the two who were the more anxious to attract her attention.

“And what canst thou do?” she said.

“What I am told, Mistress,” said Amphillis.

“Ach!” murmured Regina; “you den can much do.”

“Ay, thou canst do much,” quietly repeated Mistress Chaucer. “Canst dress hair?”

Amphillis thought she could. She might well, for her cousins made her their maid, and were not easily pleased mistresses.

“Thou canst cook, I cast no doubt, being bred at a patty-shop?”

“Mistress, I have only dwelt there these six months past. My father was a poor gentleman that died when I was but a babe, and was held to demean himself by wedlock with my mother, that was sister unto mine uncle, Master Altham. Mine uncle was so kindly as to take on him the charge of breeding me up after my father died, and he set my mother and me in a little farm that ’longeth to him in the country: and at after she departed likewise, he took me into his house. I know somewhat of cookery, an’ it like you, but not to even my good cousins here.”

“Oh, Phyllis is a metely fair cook, when she will give her mind thereto,” said Alexandra with a patronising air, and a little toss of her head—a gesture to which that young lady was much addicted.

A very slight look of amusement passed across Mistress Chaucer’s face, but she did not reply to the remark.

“And thy name?” she asked, still addressing Amphillis.

“Amphillis Neville, and your servant, Mistress.”

“Canst hold thy peace when required so to do?” Amphillis smiled. “I would endeavour myself so to do.”

“Canst be patient when provoked of other?”

“With God’s grace, Mistress, I so trust.” Alexandra’s face wore an expression of dismay. It had never occurred to her that silence and patience were qualities required in a bower-maiden, as the maid or companion to a lady was then called; for the maid was the companion then, and was usually much better educated than now—as education was understood at that time. In Alexandra’s eyes the position was simply one which gave unbounded facilities for flirting, laughing, and giddiness in general. She began to think that Amphillis was less to be envied than she had supposed.

“And thou wouldst endeavour thyself to be meek and buxom (humble and submissive) in all things to them that should be set over thee?”

“I would so, my mistress.”

“What fashions of needlework canst do?”

“Mistress, I can sew, and work tapestry, and embroider somewhat if the pattern be not too busy (elaborate, difficult). I would be glad to learn the same more perfectly.”

Mistress Chaucer rose. “I think thou wilt serve,” said she. “But I can but report the same—the deciding lieth not with me. Mistress Regina, I pray you to allow of another to speak with this maid in your chamber to-morrow in the even, and this time it shall be the lady that must make choice. Not she that shall be thy mistress, my maid; she dwelleth not hereaway, but far hence.”

Amphillis cared very little where her future duties were to lie. She was grateful to her uncle, but she could hardly be said to love him; and her cousins had behaved to her in such a style, that the sensation called forth towards them was a long way from love. She felt alone in the world; and it did not much signify in what part of that lonely place she was set down to work. The only point about which she cared at all was, that she was rather glad to hear she was not to stay in London; for, like old Earl Douglas, she “would rather hear the lark sing than the mouse cheep.”

The girls louted to Mistress Chaucer, kissed Regina, and went down into the shop, which they found filled with customers, and Master Herman himself waiting on them, they being of sufficient consequence for the notice of that distinguished gentleman. On the table set in the midst of the shop—which, like most tables at that day, was merely a couple of boards laid across trestles—was spread a blue cloth, whereon rested various glittering articles—a silver basin, a silver-gilt bottle, a cup of gold, and another of a fine shell set in gold, a set of silver apostle spoons, so-called because the handle of each represented one of the apostles, and another spoon of beryl ornamented with gold; but none of them seemed to suit the customers, who were looking for a suitable christening gift.

“Ach! dey vill not do!” ejaculated Master Herman, spreading out his fat fingers and beringed thumbs. “Then belike we must de jewels try. It is a young lady, de shild? Gut! den look you here. Here is de botoner of perry (button-hook of goldsmith’s work), and de bottons—twelf—wrought wid garters, wid lilies, wid bears, wid leetle bells, or wid a reason (motto)—you can haf what reason you like. Look you here again, Madam—de ouches (brooches)—an eagle of gold and enamel, Saint George and de dragon, de white hart, de triangle of diamonds; look you again, de paternosters (rosaries), dey are lieblich! gold and coral, gold and pearls, gold and rubies; de rings, sapphire and ruby and diamond and smaragdus (emerald)—ach! I have it. Look you here!”

And from an iron chest, locked with several keys, Master Herman produced something wrapped carefully in white satin, and took off the cover as if he were handling a baby.

“Dere!” he cried, holding up a golden chaplet, or wreath for the head, of ruby flowers and leaves wrought in gold, a large pearl at the base of every leaf—“dere! You shall not see a better sight in all de city—ach! not in Nuremburg nor Cöln. Dat is what you want—it is schön, schön! and dirt sheap it is—only von hundert marks. You take it?”

The lady seemed inclined to take it, but the gentleman demurred at the hundred marks—66 pounds, 13 shillings and 4 pence, which, reduced to modern value, would be nearly eleven hundred pounds; and the girls, who had lingered as long as they reasonably could in their passage through the attractive shop, were obliged to pass out while the bargain was still unconcluded.

“I’d have had that chaplet for myself, if I’d been that lady!” said Alexandra as they went forward. “I’d never have cast that away for a christening gift.”

“Nay, but her lord would not find the money,” answered Ricarda.

“I’d have had it, some way,” said her sister. “It was fair enough for a queen. Amphillis, I do marvel who is the lady thou shalt serve. There’s ever so much ado ere the matter be settled. ’Tis one grander than Mistress Chaucer, trow, thou shalt see to-morrow even.”

“Ay, so it seems,” was the quiet answer.

“Nathless, I would not change with thee. I’ve no such fancy for silence and patience. Good lack! but if a maid can work, and dress hair, and the like, what would they of such weary gear as that?”

“Maids be not of much worth without they be discreet,” said Amphillis.

“Well, be as discreet as thou wilt; I’ll none of it,” was the flippant reply of her cousin.

The young ladies, however, did not neglect to accompany Amphillis on her subsequent visit. Regina met them at the door.

“She is great lady, dis one, I am sure,” said she. “Pray you, mind your respects.”

The great lady carried on her conversation in French, which in 1372 was the usual language of the English nobles. Its use was a survival from the Norman Conquest, but the Norman-French was very far from pure, being derided by the real French, and not seldom by Englishmen themselves. Chaucer says of his prioress:—

“And French she spake full fair and fetously (cleverly),

After the scole of Stratford-atte-Bow,

For French of Paris was to hire (her) unknow.”

This lady, the girls noticed, spoke the French of Paris, and was rather less intelligible in consequence. She put her queries in a short, quick style, which a little disconcerted Amphillis; and she had a weary, irritated manner. At last she said shortly—

“Very well! Consider yourself engaged. You must set out from London on Lammas Day (August 1st), and Mistress Regina here, who is accustomed to such matters, will tell you what you need take. A varlet will come to fetch you; take care you are ready. Be discreet, and do not get into any foolish entanglements of any sort.”

Amphillis asked only one question—Would the lady be pleased to tell her the name and address of her future mistress?

“Your mistress lives in Derbyshire. You will hear her name on the way.”

And with a patronising nod to the girls, and another to Regina, the lady left the room.

“Lammas Day!” cried Alexandra, almost before the door was closed. “Gramercy, but we can never be a-ready!”

“Ach! ja, but you will if you hard work,” said Regina.

“And the jousting!” said Ricarda.

“What for the jousting?” asked Regina. “You are not knights, dat you joust?”

“We should have seen it, though: a friend had passed his word to take us, that wist how to get us in.”

“We’ll go yet, never fear!” said her sister. “Phyllis must work double.”

“Den she will lose de sight,” objected Regina.

“Oh, she won’t go!” said Alexandra, contemptuously. “Much she knows about tilting!”

“What! you go, and not your cousin? I marvel if you about it know more dan she. And to see a pretty sight asks not much knowing.”

“I’m not going to slave myself, I can tell you!” replied Alexandra. “Phyllis must work. What else is she good for?”

Regina left the question unanswered. “Well, you leave Phyllis wid me; I have something to say to her—to tell her what she shall take, and how she must order herself. Den she come home and work her share—no more.”

The sisters saw that she meant it, and they obeyed, having no desire to make an enemy of the wealthy goldsmith’s daughter.

Chapter Three.

Who can she be?

“O thou child of many prayers!

Life hath quicksands—life hath snares.”

Longfellow.

“Now, sit you down on de bench,” said Regina, kindly. “Poor maid! you tremble, you are white. Ach! when folks shall do as dey should, dey shall not do as dey do no more. Now we shall have von pleasant talking togeder, you and I. You know de duties of de bower-woman? or I tell dem you?”

“Would you tell me, an’ it please you?” answered Amphillis, modestly. “I do not know much, I dare say.”

“Gut! Now, listen. In de morning, you are ready before your lady calls; you keep not her awaiting. Maybe you sleep in de truckle-bed in her chamber; if so, you dress more quieter as mouse, you wake not her up. She wakes, she calls—you hand her garments, you dress her hair. If she be wedded lady, you not to her chamber go ere her lord be away. Mind you be neat in your dress, and lace you well, and keep your hair tidy, wash your face, and your hands and feet, and cut short your nails. Every morning you shall your teeth clean. Take care, take much care what you do. You walk gravely, modestly; you talk low, quiet; you carry you sad (Note 1) and becomingly. Mix water plenty with your wine at dinner: you take not much wine, dat should shocking be! You carve de dishes, but you press not nobody to eat—dat is not good manners. You wash hands after your lady, and you look see there be two seats betwixt her and you—no nearer you go (Note 2). You be quiet, quiet! sad, sober always—no chatter fast, no scamper, no loud laugh. You see?”

“I see, and I thank you,” said Amphillis. “I hope I am not a giglot.”

“You are not—no, no! Dere be dat are. Not you. Only mind you not so become. Young maids can be too careful never, never! You lose your good name in one hour, but in one year you win it not back.”

And Regina’s plump round face went very sad, as if she remembered some such instance of one who was dear to her.

“Ach so!—Well! den if your lady have daughters young, she may dem set in your care. You shall den have good care dey learn courtesy (Note 3), and gaze not too much from de window, and keep very quiet in de bower (Note 4). And mind you keep dem—and yourself too—from de mans. Mans is bad!”

Amphillis was able to say, with a clear conscience, that she had no hankering after the society of those perilous creatures.

“See you,” resumed Regina, with some warmth, “dere is one good man in one hundert mans. No more! De man you see, shall he be de hundert man, or one von de nine and ninety? What you tink?”

“I think he were more like to be of the ninety and nine,” said Amphillis with a little laugh. “But how for the women, Mistress Regina? Be they all good?”

Regina shook her head in a very solemn manner.

“Dere is bad mans,” answered she, “and dey is bad: and dere is bad womans, and dey is badder; and dere is bad angels, and dey is baddest of all. Look you, you make de sharpest vinegar von de sweetest wine. Amphillis, you are good maid, I tink; keep you good! And dat will say, keep you to yourself, and run not after no mans, nor no womans neider. You keep your lady’s counsel true and well, but you keep no secrets from her. When any say to you, ‘Amphillis, you tell not your lady,’ you say to yourself, ‘I want noting to do wid you; I keep to myself, and I have no secrets from my lady.’ Dat is gut!”

“Mistress Regina, wot you who is the lady I am to serve?”

“I know noting, no more dan you—no, not de name of de lady you dis evening saw. She came from de Savoy—so much know I, no more.”

Amphillis knew that goldsmiths were very often the bankers of their customers, and that their houses were a frequent rendezvous for business interviews. It was, therefore, not strange at all that Regina should not be further in the confidence of the lady in question.

“Now you shall not tarry no later,” said Regina, kissing her. “You serve well your lady, you pray to God, and you keep from de mans. Good-night!”

“Your pardon granted, Mistress Regina, but you have not yet told me what I need carry withal.”

“Ach so! My head gather de wool, as you here say. Why, you take with you raiment enough to begin—dat is all. Your lady find you gowns after, and a saddle to ride, and all dat you need. Only de raiment to begin, and de brains in de head—she shall not find you dat. Take wid you as much of dem as you can get. Now run—de dark is gekommen.”

It relieved Amphillis to find that she needed to carry nothing with, her except clothes, brains, and prudence. The first she knew that her uncle would supply; for the second, she could only take all she had; and as to the last, she must do her best to cultivate it.

Mr Altham, on hearing the report, charged his daughters to see that their cousin had every need supplied; and to do those young ladies justice, they took fairly about half their share of the work, until the day of the tournament, when they declared that nothing on earth should make them touch a needle. Instead of which, they dressed themselves in their best, and, escorted by Mr Clement Winkfield, were favoured by permission to slip in at the garden door, and to squeeze into a corner among the Duke’s maids and grooms.

A very grand sight it was. In the royal stand sat the King, old Edward the Third, scarcely yet touched by that pitiful imbecility which troubled his closing days; and on his right hand sat the queen of the jousts, the young Countess of Cambridge, bride of Prince Edmund, with the Duke of Lancaster on her other hand, the Duchess being on the left of the King. All the invited ladies were robed uniformly in green and white, the prize-giver herself excepted. The knights were attired as Clement had described them. I am not about to describe the tournament, which, after all, was only a glorified prize-fight, and, therefore, suited to days when few gentlemen could read, and no forks were used for meals. We call ourselves civilised now, yet some who consider themselves such, seem to entertain a desire to return to barbarism. Human nature, in truth, is the same in all ages, and what is called culture is only a thin veneer. Nothing but to be made partaker of the Divine nature will implant the heavenly taste.

The knights who were acclaimed victors, or at least the best jousters on the field, were led up to the royal stand, and knelt before the queen of the jousts, who placed a gold chaplet on the head of the first, and tied a silken scarf round the shoulders of the second and third. Happily, no one was killed or even seriously injured—not a very unusual state of things. At a tournament eighteen years later, the Duke of Lancaster’s son-in-law, the last of the Earls of Pembroke, was left dead upon the field.

Alexandra and Ricarda came back very tired, and not in exceptionally good tempers, as Amphillis soon found out, since she was invariably a sufferer on these occasions. They declared themselves, the next morning, far too weary to put in a single stitch; and occupied themselves chiefly in looking out of the window and exchanging airy nothings with customers. But when Clement came in the afternoon with an invitation to a dance at his mother’s house, their exhausted energies rallied surprisingly, and they were quite able to go, though the same farce was played over again on the ensuing morning.

By dint of working early and late, Amphillis was just ready on the day appointed—small thanks to her cousins, who not only shirked her work, but were continually summoning her from it to do theirs. Mr Altham gave his niece some good advice, along with a handsome silver brooch, a net of gold tissue for her hair, commonly called a crespine or dovecote, and a girdle of black leather, set with bosses of silver-gilt. These were the most valuable articles that had ever yet been in her possession, and Amphillis felt herself very rich, though she could have dispensed with Ricarda’s envious admiration of her treasures, and Alexandra’s acetous remarks about some people who were always grabbing as much as they could get. In their father’s presence these observations were omitted, and Mr Altham had but a faint idea of what his orphan niece endured at the hands—or rather the tongues—of his daughters, who never forgave her for being more gently born than themselves.

Lammas Day dawned warm and bright, and after early mass in the Church of Saint Mary at Strand—which nobody in those days would have dreamed of missing on a saint’s day—Amphillis placed herself at an upstairs window to watch for her escort. She had not many minutes to wait, before two horses came up the narrow lane from the Savoy Palace, and trotting down the Strand, stopped at the patty-maker’s door. After them came a baggage-mule, whose back was fitted with a framework intended to sustain luggage.

One horse carried a man attired in white linen, and the other bore a saddle and pillion, the latter being then the usual means of conveyance for a woman. On the saddle before it sat a middle-aged man in the royal livery, which was then white and red. The man in linen alighted, and after a few minutes spent in conversation with Mr Altham, he carried out Amphillis’s luggage, in two leather trunks, which were strapped one on each side of the mule. As soon as she saw her trunks disappearing, Amphillis ran down and took leave of her uncle and cousins.

“Well, my maid, God go with thee!” said Mr Altham. “Forget not thine old uncle and these maids; and if thou be ill-usen, or any trouble hap thee, pray the priest of thy parish to write me a line thereanent, and I will see what can be done.”

“Fare thee well, Phyllis!” said Alexandra, and Ricarda echoed the words.

Mr Altham helped his niece to mount the pillion, seated on which, she had to put her arms round the waist of the man in front, and clasp her hands together; for without this precaution, she would have been unseated in ten minutes. There was nothing to keep her on, as she sat with her left side to the horse’s head, and roads in those days were rough to an extent of which we, accustomed to macadamised ways, can scarcely form an idea now.

And so, pursued for “luck” by an old shoe from Ricarda’s hand, Amphillis Neville took her leave of London, and rode forth into the wide world to seek her fortune.

Passing along the Strand as far as the row of houses ran, at the Strand Cross they turned to the left, and threading their way in and out among the detached houses and little gardens, they came at last into Holborn, and over Holborn Bridge into Smithfield. Under Holborn Bridge ran the Fleet river, pure and limpid, on its way to the silvery Thames; and as they emerged from Cock Lane, the stately Priory of Saint Bartholomew fronted them a little to the right. Crossing Smithfield, they turned up Long Lane, and thence into Aldersgate Street, and in a few minutes more the last houses of London were left behind them. As they came out into the open country, Amphillis was greeted, to her surprise, by a voice she knew.

“God be wi’ ye, Mistress Amphillis!” said Clement Winkfield, coming up and walking for a moment alongside, as the horse mounted the slight rising ground. “Maybe you would take a little farewell token of mine hand, just for to mind you when you look on it, that you have friends in London that shall think of you by nows and thens.”

And Clement held up to Amphillis a little silver box, with a ring attached, through which a chain or ribbon could be passed to wear it round the neck. A small red stone was set on one side.

“’Tis a good charm,” said he. “There is therein writ a Scripture, that shall bear you safe through all perils of journeying, and an hair of a she-bear, that is good against witchcraft; and the carnelian stone appeaseth anger. Trust me, it shall do you no harm to bear it anigh you.”

Amphillis, though a sensible girl for her time, was not before her time, and therefore had full faith in the wonderful virtues of amulets. She accepted the silver box with the entire conviction that she had gained a treasure of no small value. Simple, good-natured Clement lifted his cap, and turned back down Aldersgate Street, while Amphillis and her escort went on towards Saint Albans.

A few miles they rode in silence, broken now and then by a passing remark from the man in linen, chiefly on the deep subject of the hot weather, and by the sumpterman’s frequent requests that his mule would “gee-up,” which the perverse quadruped in question showed little inclination to do. At length, as the horse checked its speed to walk up a hill, the man in front of Amphillis said—

“Know you where you be journeying, my mistress?”

“Into Derbyshire,” she answered. “Have there all I know.”

“But you wot, surely, whom you go to serve?”

“Truly, I wot nothing,” she replied, “only that I go to be bower-woman to some lady. The lady that saw me, and bound me thereto, said that I might look to learn on the road.”

“Dear heart! and is that all they told you?”

“All, my master.”

“Words must be costly in those parts,” said the man in linen.

“Well,” answered the other, drawing out the word in a tone which might mean a good deal. “Words do cost much at times, Master Saint Oly. They have cost men their lives ere now.”

“Ay, better men than you or me,” replied the other. “Howbeit, my mistress, there is no harm you should know—is there, Master Dugan?—that you be bounden for the manor of Hazelwood, some six miles to the north of Derby, where dwell Sir Godfrey Foljambe and his dame.”

“No harm; so you tarry there at this present,” said Master Dugan.

“Ay, I’ve reached my hostel,” was the response.

“Then my Lady Foljambe is she that I must serve?”

The man in linen exchanged a smile with the man in livery.

“You shall see her the first, I cast no doubt, and she shall tell you your duties,” answered Dugan.

Amphillis sat on the pillion, and meditated on her information as they journeyed on. There was evidently something more to tell, which she was not to be told at present. After wondering for a little while what it might be, and deciding that her imagination was not equal to the task laid upon it, she gave it up, and allowed herself to enjoy the sweet country scents and sounds without apprehension for the future.

For six days they travelled on in this fashion, about twenty miles each day, staying every night but one at a wayside inn, where Amphillis was always delivered into the care of the landlady, and slept with her daughter or niece; once at a private house, the owners of which were apparently friends of Mr Dugan. They baited for the last time at Derby, and about two o’clock in the afternoon rode into the village of Hazelwood.

It was only natural that Amphillis should feel a little nervous and uneasy, in view of her introduction to her new abode and unknown companions. She was not less so on account of the mystery which appeared to surround the nameless mistress. Why did everybody who seemed to know anything make such a secret of the affair?

The Manor house of Hazelwood was a pretty and comfortable place enough. It stood in a large garden, gay with autumn flowers, and a high embattled wall protected it from possible enemies. The trio rode in under an old archway, through a second gate, and then drew up beneath the entrance arch, the door being—as is yet sometimes seen in old inns—at the side of the arch running beneath the house. A man in livery came forward to take the horses.

“Well, Master Saint Oly,” said he; “here you be!”

“I could have told thee that, Sim,” was the amused reply. “Is all well? Sir Godfrey at home?”

“Ay to the first question, and No to the second.”

“My Lady is in her bower?”

“My Lady’s in the privy garden, whither you were best take the damsel to her.”

Sim led the horses away to the stable, and Saint Oly turned to Amphillis.

“Then, if it please you, follow me, my mistress; we were best to go to my Lady at once.”

Amphillis followed, silent, curious, and a little fluttered.

They passed under the entrance arch inwards, and found themselves in a smaller garden than the outer, enclosed on three sides by the house and its adjacent outbuildings. In the midst was a spreading tree, with a form underneath it; and in its shade sat a lady and a girl about the age of Amphillis. Another girl was gathering flowers, and an elderly woman was coming towards the tree from behind. Saint Oly conducted Amphillis to the lady who sat under the tree.

“Dame,” said he, “here, under your good leave, is Mistress Amphillis Neville, that is come to you from London town, to serve her you wot of.”

This, then, was Lady Foljambe. Amphillis looked up, and saw a tall, handsome, fair-complexioned woman, with a rather grave, not to say stern, expression of face. “Good,” said Lady Foljambe. “You are welcome, Mistress Neville. I trust you can do your duty, and not giggle and chatter?”

The girl who sat by certainly giggled on hearing this question, and Lady Foljambe extinguished her by a look.

“I will do my best, Dame,” replied Amphillis, nervously.

“None can do more,” said her Ladyship more graciously. “Are you aweary with your journey?”

“But a little, Dame, I thank you. Our stage to-day was but short.”

“You left your friends well?” was the next condescending query.

“Yes, Dame, I thank you.”

Lady Foljambe turned her head. “Perrote!” she said.

“Dame!” answered the elderly woman.

“Take the damsel up to your Lady’s chambers, and tell her what her duties will be.—Mistress Neville, one matter above all other must I press upon you. Whatever you see or hear in your Lady’s chamber is never to come beyond. You will company with my damsels, Agatha—” with a slight move of her head towards the girl at her side—“and Marabel,”—indicating by another gesture the one who was gathering flowers. “Remember, in your leisure times, when you are talking together, no mention of your Lady must ever be made. If you hear it, rebuke it. If you make it, you may not like that which shall follow. Be wise and discreet, and you shall find it for your good. Chatter and be giddy, and you shall find it far otherwise. Now, follow Mistress Perrote.”

Amphillis louted silently, and as silently followed.

The elderly woman, who was tall, slim, and precise-looking, led her into the house, and up the stairs.

When two-thirds of them were mounted, she turned to the left along a passage, lifted a heavy curtain which concealed its end, and let it drop again behind them. They stood in a small square tower, on a little landing which gave access to three doors. The door on the right hand stood ajar; the middle one was closed; but the left was not only closed, but locked and barred heavily. Mistress Perrote led the way into the room on the right, a pleasant chamber, which looked out into the larger garden.

At the further end of the room stood a large bed of blue camlet, with a canopy, worked with fighting griffins in yellow. A large chest of carved oak stood at the foot. Along the wall ran a settle, or long bench, furnished with blue cushions; and over the back was thrown a dorsor of black worsted, worked with the figures of David and Goliath, in strict fourteenth-century costume. The fireplace was supplied with andirons, a shovel, and a fire-fork, which served the place of a poker. A small leaf table hung down by the wall at one end of the settle, and over it was fixed a round mirror, so high up as to give little encouragement to vanity. On hooks round the walls were hangings of blue tapestry, presenting a black diamond pattern, within a border of red roses.

“Will you sit?” said Mistress Perrote, speaking in a voice not exactly sharp, but short and staccato, as if she were—what more voluble persons often profess to be—unaccustomed to public speaking, and not very talkative at any time. “Your name, I think, is Amphillis Neville?”

Amphillis acknowledged her name.

“You have father and mother?”

“I have nothing in the world,” said Amphillis, with a shake of her head, “save an uncle and cousins, which dwell in London town.”

“Ha!” said Mistress Perrote, in a significant tone. “That is wherefore you were chosen.”

“Because I had no kin?” said Amphillis, looking up.

“That, and also that you were counted discreet. And discreet you had need be for this charge.”

“What charge?” she asked, blankly.

“You know not?”

“I know nothing. Nobody would tell me anything.”

Mistress Perrote’s set features softened a little.

“Poor child!” she said. “You are young—too young—to be given a charge like this. You will need all your discretion, and more.”

Amphillis felt more puzzled than ever.

“You may make a friend of Marabel, if you choose; but beware how you trust Agatha. But remember, as her Ladyship told you, no word that you hear, no thing that you see, must be suffered to go forth of these chambers. You may repeat nothing! Can you do this?”

“I will bear it in mind,” was the reply. “But, pray you, if I may ask—seeing I know nothing—is this lady that I shall serve an evil woman, that you caution me thus?”

“No!” answered Mistress Perrote, emphatically. “She is a most terribly injured— What say I? Forget my words. They were not discreet. Mary, Mother! there be times when a woman’s heart gets the better of her brains. There be more brains than hearts in this world. Lay by your hood and mantle, child, on one of those hooks, and smooth your hair, and repose you until supper-time. To-morrow you shall see your Lady.”

Note 1. Sad, at this time, did not mean sorrowful, but serious.

Note 2. These are the duties of a bower-woman, laid down in the Books of Courtesy at that time.

Note 3. Then a very expressive word, including both morals and manners.

Note 4. A private sitting-room for ladies.

Chapter Four.

The White Lady.

“The future is all dark,

And the past a troubled sea,

And Memory sits in the heart,

Wailing where Hope should be.”

Supper was ready in the hall at four o’clock, and Amphillis found herself seated next below Agatha, the younger of Lady Foljambe’s damsels. It was a feast-day, so that meat was served—a boar’s head, stewed beef, minced mutton, squirrel, and hedgehog. The last dainty is now restricted to gypsies, and no one eats our little russet friend of the bushy tail; but our forefathers indulged in both. There were also roast capons, a heron, and chickens dressed in various ways. Near Amphillis stood a dish of beef jelly, a chowet or liver-pie, a flampoynt or pork-pie, and a dish of sops in fennel. The sweets were Barlee and Mon Amy, of which the first was rice cream, and the second a preparation of curds and cream.

Amphillis looked with considerable interest along the table, and at her opposite neighbours. Lady Foljambe she recognised at once; and beside her sat a younger lady whom she had not seen before. She applied to her neighbour for information.

“She?” said Agatha. “Oh, she’s Mistress Margaret, my Lady’s daughter-in-law; wife to Master Godfrey, that sits o’ t’ other side of his mother; and that’s Master Matthew, o’ this side. The priest’s Father Jordan—a fat old noodle as ever droned a psalm through his nose. Love you mirth and jollity?”

“I scarce know,” said Amphillis, hesitatingly. “I have had so little.”

Agatha’s face was a sight to see.

“Good lack, but I never reckoned you should be a spoil-sport!” said she, licking her spoon as in duty bound before she plunged it in the jelly—a piece of etiquette in which young ladies at that date were carefully instructed. The idea of setting a separate spoon to help a dish had not dawned upon the mediaeval mind.

“I shall hate you, I can tell you, if you so are. Things here be like going to a funeral all day long—never a bit of music nor dancing, nor aught that is jolly. Mistress Margaret might be eighty, so sad and sober is she; and as for my Lady and Mistress Perrote, they are just a pair of old jog-trots fit to run together in a quirle (the open car then used by ladies, something like a waggonette). Master Godfrey’s all for arms and fighting, so he’s no better. Master Matthew’s best of the lot, but bad’s the best when you’ve a-done. And he hasn’t much chance neither, for if he’s seen laughing a bit with one of us, my Lady’s a-down on him as if he’d broke all the Ten Commandments, and whisks him off ere you can say Jack Robinson; and if she whip you not, you may thank the saints or your stars, which you have a mind. Oh, ’tis a jolly house you’ve come to, that I can tell you! I hoped you’d a bit more fun in you than Clarice—she wasn’t a scrap of good. But I’m afraid you’re no better.”

“I don’t know, really,” said Amphillis, feeling rather bewildered by Agatha’s reckless rattle, and remembering the injunction not to make a friend of her. “I suppose I have come here to do my duty; but I know not yet what it shall be.”

“I detest doing my duty!” said Agatha, energetically.

“That’s a pity, isn’t it?” was the reply.

Agatha laughed.

“Come, you can give a quip-word,” said she. “Clarice was just a lump of wood, that you could batter nought into,—might as well sit next a post. Marabel has some brains, but they’re so far in, there’s no fetching ’em forth. I declare I shall do somewhat one o’ these days that shall shock all the neighbourhood, only to make a diversion.”

“I don’t think I would,” responded Amphillis. “You might find it ran the wrong way.”

“You’ll do,” said Agatha, laughing. “You are not jolly, but you’re next best to it.”

“Whose is that empty place on the form?” asked Amphillis, looking across.

“Oh, that’s Master Norman’s—Sir Godfrey’s squire—he’s away with him.”

And Agatha, without any apparent reason, became suddenly silent.

When supper was over, the girls were called to spin, which they did in the large hall, sitting round the fire with the two ladies and Perrote. Amphillis, as a newcomer, was excused for that evening; and she sat studying her neighbours and surroundings till Mistress Perrote pronounced it bed-time. Then each girl rose and put by her spindle; courtesied to the ladies, and wished them each “Good-even,” receiving a similar greeting; and the three filed out of the inner door after Perrote, each possessing herself of a lighted candle as she passed a window where they stood. At the solar landing they parted, Perrote and Amphillis turning aside to their own tower, Marabel and Agatha going on to the upper floor. (The solar was an intermediate storey, resembling the French entresol.) Amphillis found, as she expected, that she was to share the large blue bed and the yellow griffins with Perrote. The latter proved a very silent bedfellow. Beyond showing Amphillis where she was to place her various possessions, she said nothing at all; and as soon as she had done this, she left the room, and did not reappear for an hour or more. As Amphillis lay on her pillow, she heard an indistinct sound of voices in an adjoining room, and once or twice, as she fancied, a key turned in the lock. At length the voices grew fainter, the hoot of the white owl as he flew past the turret window scarcely roused her, and Amphillis was asleep—so sound asleep, that when Perrote lay down by her side, she never made the discovery.

The next morning dawned on a beautiful summer day. Perrote roused her young companion about four o’clock, with a reminder that if she were late it would produce a bad impression upon Lady Foljambe. When they were dressed, Perrote repeated the Rosary, Amphillis making the responses, and they went down to the hall.

Breakfast was at this time a luxury not indulged in by every one, and it was not served before seven o’clock. Lady Foljambe patronised it. At that hour it was accordingly spread in the hall, and consisted of powdered beef, boiled beef, brawn, a jug of ale, another of wine, and a third of milk. The milk was a condescension to a personal weakness of Perrote; everybody else drank wine or ale.

Amphillis was wondering very much, in the private recesses of her mind, how it was that no lady appeared whom she could suppose to be her own particular mistress; and had she not received such strict charges on the subject, she would certainly have asked the question. As it was, she kept silence; but she was gratified when, after breakfast, having been bidden to follow Perrote, that worthy woman paused to say, as they followed the passage which led to their own turret—

“Now, Amphillis Neville, you shall see your Lady.”

She stopped before the locked and barred door opposite to their own, unfastened it, and led Amphillis into the carefully-guarded chamber.

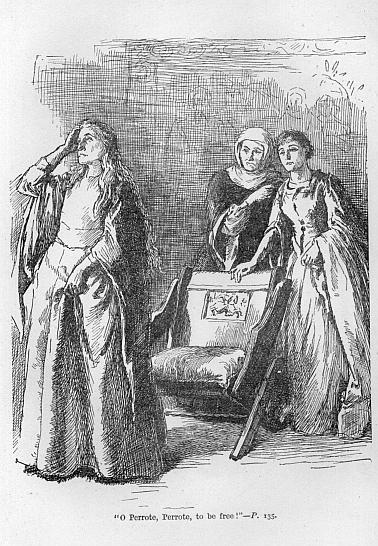

The barred room proved to be an exceedingly pleasant one, except that it was darker than the other, for it looked into the inner garden, and therefore much less sun ever entered it. A heavy curtain of black worsted, whereon were depicted golden vines and recumbent lions, stretched across the room, shutting off that end which formed the bedchamber. Within its shelter stood a bed of green silk wrought with golden serpents and roses; a small walnut-wood cabinet against the wall; two large chests; a chair of carved walnut-wood, upholstered in yellow satin; a mirror set in silver; and two very unusual pieces of furniture, which in those days they termed folding-chairs, but which we should call a shut-up washstand and dressing-table. The former held an ewer and basin of silver-gilt, much grander articles than Amphillis had ever seen, except in the goldsmith’s shop. In front of the curtain was a bench with green silk cushions, and two small tables, on one of which lay some needlework; and by it, in another yellow satin chair, sat the solitary inhabitant of the chamber, a lady who appeared to be about sixty years of age. She was dressed in widow’s mourning, and in 1372 that meant pure snowy white, with chin and forehead so covered by barb and wimple that only the eyes, nose, and mouth were left visible. This lady’s face was almost as white as her robes. Even her lips seemed colourless; and the fixed, weary, hopeless expression was only broken by two dark, brilliant, sunken eyes, in which lay a whole volume of unread history—eyes that looked as if they could flash with fury, or moisten with pity, or grow soft and tender with love; eyes that had done all these, long, long ago! so long ago, that they had forgotten how to do it. Sad, tired, sorrowful eyes—eyes out of which all expectation had departed; which had nothing left to fear, only because they had nothing left to hope. They were turned now upon Amphillis.

“Your Grace’s new chamber-dame,” said Mistress Perrote, “in the room of Clarice. Her name is Amphillis Neville.”

The faintest shadow of interest passed over the sorrowful eyes.

“Go near,” said Perrote to Amphillis, “and kiss her Grace’s hand.”

Amphillis did as she was told. The lady, after offering her hand for the kiss, turned it and gently lifted the girl’s face.

“Dost thou serve God?” she said, in a voice which matched her eyes.

“I hope so, Dame,” replied Amphillis.

“I hope nothing,” said the mysterious lady. “It is eight years since I knew what hope was. I have hoped in my time as much as ever woman did. But God took away from me one boon after another, till now He hath left me desolate. Be thankful, maid, that thou canst yet hope.”

She dropped her hand, and went back to her work with a weary sigh.

“Dame,” said Perrote, “your Grace wot that her Ladyship desires not that you talk in such strain to the damsels.”

The white face changed as Amphillis had thought it could not change, and the sunken eyes shot forth fire.

“Her Ladyship!” said the widow. “Who is Avena Foljambe, that she looketh to queen it over Marguerite of Flanders? They took my lord, and I lived through it. They took my daughter, and I bare it. They took my son, my firstborn, and I was silent, though it brake my heart. But by my troth and faith, they shall not still my soul, nor lay bonds upon my tongue when I choose to speak. Avena Foljambe! the kinswoman of a wretched traitor, that met the fate he deserved—why, hath she ten drops of good blood in her veins? And she looks to lord it over a daughter of Charlemagne, that hath borne sceptre ere she carried spindle!”

Mistress Perrote’s calm even voice checked the flow of angry words.

“Dame, your Grace speaks very sooth (truth). Yet I beseech you remember that my Lady doth present (represent) an higher than herself—the King’s Grace and no lesser.”

The lady in white rose to her feet.

“What mean you, woman? King Edward of Windsor may be your master and hers, but he is not mine! I owe him no allegiance, nor I never sware any.”

“Your son hath sworn it, Dame.”

The eyes blazed out again.

“My son is a hound!—a craven cur, that licks the hand that lashed him!—a poor court fool that thinks it joy enough to carry his bauble, and marvel at his motley coat and his silvered buttons! That he should be my son,—and his!”

The voice changed so suddenly, that Amphillis could scarcely believe it to be the same. All the passionate fury died out of it, and instead came a low soft tone of unutterable pain, loneliness, and regret. The speaker dropped down into her chair, and laying her arm upon the little table, hid her face upon it.

“My poor Lady!” said Perrote in tender accents—more tender than Amphillis had imagined she could use.

The lady in white lifted her head.

“I was not so weak once,” she said. “There was a time when man said I had the courage of a man and the heart of a lion. Maiden, never man sat an horse better than I, and no warrior ever fought that could more ably handle sword. I have mustered armies to the battle ere now; I have personally conducted sieges, I have headed sallies on the camp of the King of France. Am I meek pigeon to be kept in a dovecote? Look around thee! This is my cage. Ha! the perches are fine wood, sayest thou? the seed is good, and the water is clean! I deny it not. I say only, it is a cage, and I am a royal eagle, that was never made to sit on a perch and coo! The blood of an hundred kings is thrilling all along my veins, and must I be silent? The blood of the sovereigns of France, the kingdom of kingdoms,—of the sea-kings of Denmark, of the ancient kings of Burgundy, and of the Lombards of the Iron Crown—it is with this mine heart is throbbing, and man saith, ‘Be still!’ How can I be still, unless I were still in death? And man reckoneth I shall be a-paid for my lost sword with a needle, and for my broken sceptre he offereth me a bodkin!”

With a sudden gesture she brushed all the implements for needlework from the little table to the floor.

“There! gather them up, which of you list. I lack no such babe’s gear. If I were but now on my Feraunt, with my visor down, clad in armour, as I was when I rode forth of Hennebon while the French were busied with the assault on the further side of the town,—forth I came with my three hundred horse, and we fired the enemy’s camp—ah, but we made a goodly blaze that day! I reckon the villages saw it for ten miles around or more.”

“But your Grace remembereth, we won not back into the town at after,” quietly suggested Perrote.

“Well, what so? Went we not to Brest, and there gathered six hundred men, and when we appeared again before Hennebon, the trumpets sounded, and the gates were flung open, and we entered in triumph? Thy memory waxeth weak, old woman! I must refresh it from mine own.”

“Please it, your good Grace, I am nigh ten years younger than yourself.”

“Then shouldest thou be the more ’shamed to have so much worser a memory. Why, hast forgot all those weeks at Hennebon, that we awaited the coming of the English fleet? Dost not remember how I went down to the Council with thyself at mine heels, and the child in mine arms, to pray the captains not to yield up the town to the French, and the lither loons would not hear me a word? And then at the last minute, when the gates were opened, and the French marching up to take possession, mindest thou not how I ran to yon window that giveth toward the sea, and there at last, at last! the English fleet was seen, making straight sail for us. Then flung I open the contrary casement toward the street, and myself shouted to the people to shut the gates, and man the ramparts, and cry, ‘No surrender!’ Ah, it was a day, that! Had there been but time, I’d never have shouted—I’d have been down myself, and slammed that gate on the King of France’s nose! The pity of it that I had no wings! And did I not meet the English Lords and kiss them every one (Note 1), and hang their chambers with the richest arras in my coffers? And the very next day, Sir Walter Mauny made a sally, and destroyed the French battering-ram, and away fled the French King with ours in pursuit. Ha, that was a jolly sight to see! Old Perrote, hast thou forgot it all?”

We are accustomed in the present day to speak of the deliverer of Hennebon as Sir Walter Manny. That his name ought really to be spelt and sounded Mauny, is evidenced by a contemporary entry which speaks of his daughter as the Lady of Maweny.