FROM DR. FRANKLIN’S BROOM-CORN SEED. See Page 223.

Title: Illustrated Science for Boys and Girls

Author: Anonymous

Release date: June 17, 2008 [eBook #25822]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

ILLUSTRATED SCIENCE

FOR

BOYS AND GIRLS.

BOSTON:

D. LOTHROP & COMPANY,

FRANKLIN STREET.

Copyright, 1881,

By D. Lothrop & Company.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| Page | |

| How Newspapers are made. | 11 |

| Umbrellas. | 38 |

| Paul and the Comb-makers. | 54 |

| In the Gas-works. | 69 |

| Racing a Thunder-storm. | 86 |

| August’s “’Speriment.” | 103 |

| The Birds Of Winter. | 125 |

| Something About Light-houses. | 141 |

| “Buy a Broom! Buy a Broom!” | 158 |

| Talking by Signals. | 171 |

| Jennie finds out how Dishes are made. | 183 |

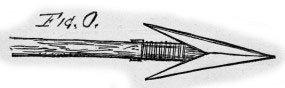

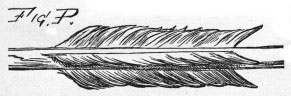

| Archery For Boys. | 192 |

| Dolly’s Shoes. | 202 |

| A Glimpse of some Montana Beavers. | 208 |

| How Logs go to Mill. | 211 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Page | |

| Frontispiece | |

| The N. Y. Tribune Building at Night. | 13 |

| A Contributor to the Waste-Paper Basket. | 16 |

| Office of the Editor-In-Chief. | 17 |

| Regular Contributors | 19 |

| How Some of the News is Gathered | 22 |

| Type-Setter’s Case In Pi. | 22 |

| Type-Setters’ Room. | 23 |

| Taking “Proofs.” | 24 |

| In the Stereotypers’ Room. | 25 |

| Finishing the Plate. | 27 |

| Printing Presses of the Past and Present | 30 |

| A News-Dealer. | 33 |

| A Bad Morning for the News-Boys. | 36 |

| “Any Answers come for Me?” | 37 |

| The First Umbrella. | 38 |

| What Jonas saw adown the Future. | 39 |

| Lord of the Twenty-Four Umbrellas. | 42 |

| A “Duck’s Back” Umbrella. | 44 |

| An Umbrella Handle Au Naturel. | 46 |

| Cutting the Covers. | 47 |

| Finishing the Handle. | 50 |

| Sewing “Pudding-Bag” Seams. | 51 |

| Completing the Umbrella | 53 |

| Master Paul did not feel Happy. | 55 |

| My Lady’s Toilet. | 58 |

| The New Circle Comb | 61 |

| Ancient or Modern—Which? | 62 |

| “In Some Remote Corner Of Spain.” | 65 |

| A Retort. | 72 |

| Kitty in the Gas-Works. | 77 |

| The Metre. | 77 |

| The Gasometre. | 83 |

| Inflating the “Buffalo.” | 87 |

| A Plucky Dog. | 91 |

| Our Balloon Camp. | 94 |

| The Professor’s Dilemma. | 99 |

| The Wreck of the “Buffalo.” | 101 |

| The Incubator. | 105 |

| How the Chicken is Packed. | 117 |

| How the Shell is Cracked. | 118 |

| The Artificial Mother. | 120 |

| The Chickadee. | 126 |

| The Black Snow-Bird. | 129 |

| The Snow Bunting. | 133 |

| The Brown Creeper. | 134 |

| Nuthatches. | 136 |

| The Downy Woodpecker. | 138 |

| Fourth Order Light-House. | 141 |

| A Modern Light-House | 144 |

| Light-House on Mt. Desert. | 147 |

| Light-House at “The Thimble Shoal” | 151 |

| First Class Light-Ship. | 154 |

| The Blind Broom-Maker of Barnstable. | 159 |

| A Gay Cavalcade. | 160 |

| The Comedy of Brooms. | 163 |

| Up in the Attic. | 164 |

| Plant the Broom! | 166 |

| The Tragedy of Brooms. | 169 |

| In Obedience to the Signals. | 177 |

| The Potter’s Wheel. | 184 |

| The Kiln and Saggers. | 186 |

| Mould for a cup. | 188 |

| Handle Mould. | 188 |

| Making a Sugar-Bowl. | 189 |

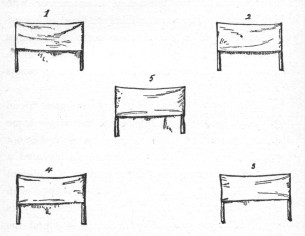

| Rest for flat Dishes. | 191 |

| The Target. | 201 |

| Dolly’s Shoes | 204 |

| A Maine Wood-Chopper. | 211 |

| A River-Driver. | 214 |

| “The Liberated Logs came sailing along.” | 216 |

| Through the Sluice. | 218 |

ILLUSTRATED SCIENCE FOR

BOYS AND GIRLS.

We will suppose that it is a great newspaper, in a great city, printing daily 25,000, or more, copies. Here it is, with wide columns, with small, compact type, with very little space wasted in head lines, eight large pages of it, something like 100,000 words printed upon it, and sold for four cents—25,000 words for a cent. It is a great institution—a power greater than a hundred banking-houses, than a hundred politicians, than a hundred clergymen. It collects and scatters news; it instructs and entertains with valuable and sprightly articles; it forms and concentrates public opinion; it in one way or another, brings its influence to bear 12 upon millions of people, in its own, and other lands. Who would not like to know something about it?

And there is Tom, first of all, who declares that he is going to be a business man, and who already has a bank-book with a good many dollars entered on its credit side—there is Tom, I say, asking first of all: “How much does it cost? and where does the money come from? and is it a paying concern?” Tom shall not have his questions expressly answered; for it isn’t exactly his business; but here are some points from which he may figure:

“How much does it cost?” Well, there is the publishing department, with an eminent business man at its head, with two or three good business men for his assistants, and with several excellent clerks and other employès. Then there is the Editor-in-Chief, and the Managing Editor, and the City Editor, and a corps of editors of different departments, besides reporters—thirty or forty men in all, each with some special literary gift. Then there are thirty or forty men setting type; a half-dozen proof-readers; a half-dozen stereotypers; the engineer and foreman and assistants below stairs, who do the printing; and several men employed in the mailing department. Then there are tons and tons of paper to be bought each week; ink, new type, heavy bills for 13 postage; many hundreds of dollars a week for telegraphic dispatches; and the interest on the money invested in an expensive building; expensive machinery, and an expensive stock of printers’ materials—nothing being said of the pay of correspondents of the paper at the State Capitol, at Washington, at London, at Paris, etc. Tom is enough of a business man, already, I know, to figure up the weekly expenses of such an establishment at several thousands of dollars—a good many hundreds at each issue of the paper.

“And where does the money come from?” Partly from the sale of papers. Only four cents apiece, and only a part of that goes to the paper; but, then, 25,000 times, say two-and-a-half cents, is $625, which it must be confessed, is quite a respectable sum for quarter-dimes to pile up in a single day. But the greater part of the money comes from advertisements. Nearly half of the paper is taken up with them. If you take a half-dozen lines to the advertising clerk, he will charge you two or three dollars; and there are several hundred times as much as your small advertisement in each paper. So you may guess what an income the advertising yields. And the larger, the more popular, and the more widely read the paper, the better will be the prices which advertisers 14 will pay, and the more will be the advertisements. And so the publisher tries to sell as many papers as he can, partly because of the money which he gets for them, but more, because the more he sells the more advertising will he get, and the better rates will he charge for it. So, Tom, if you ever become the publisher of a newspaper, you must set your heart on getting an editor who will make a paper that will sell—whatever else he does or does not do.

“And is it a paying concern?” Well, I don’t think the editors think they get very large pay, nor the correspondents, nor the reporters, nor the printers, nor the pressmen. They work incessantly; it is an intense sort of work; the hours are long and late; the chances of premature death are multiplied. I think they will all say: “We aren’t in this business for the money that is in it; we are in it for the influence of it, for the art of it, for the love of it; but then, we are very glad to get our checks all the same.” As to whether the paper pays the men who own it—which was Tom’s question: I think that that “depends” a great deal on the state of trade, on the state of politics, and on the degree to which the paper will, or will not, scruple to do mean things. A great many papers would pay better, if they were meaner. It would be a great deal easier to make a good paper, if you did not 15 have to sell it. When, then, Jonathan shall have become a minister, he doesn’t want to bear down too hard on a “venal press” in his Fast Day and Thanksgiving sermons. Perhaps, by that time, Tom will be able to explain why.

“How, now, is this paper made?” “But,” interrupts Jonathan, “before they make it, I should like to know where they get the 100,000 words to put into it; I have been cudgeling my brains for now two weeks to get words enough to fill a four page composition—say 200 words, coarse.”

The words which are put into it are, besides the advertisements, chiefly: 1. News; 2. Letters and articles on various subjects; 3. Editorial articles, reviews, and notes; 4. Odds and ends.

The “letters and articles on various subjects” come from all sorts of people: some from great writers who get large pay for even a brief communication; some from paid correspondents in various parts of the world; some from all sorts of people who wish to proclaim to the world some grievance of theirs, or to enlighten the world with some brilliant idea of theirs—which generally loses its luster the day the article is printed. A large proportion of letters and articles from this last class of people get sold for waste-paper before the printer sees them. This is 16 one considerable source of income to the paper, of which I neglected to tell Tom.

As for the “odds and ends”—extracts from other papers, jokes, and various other scraps tucked in here and there—a man with shears and paste-pot has a 17 good deal to do with the making of them. If you should see him at work, you would want to laugh at him—as if he were, for all the world, only little Nell cutting and pasting from old papers, a “frieze” for her doll’s house. But when his “odds and ends,” tastefully scattered here and there through the paper, come under the reader’s eye, they make, I am bound to say, a great deal of very hearty laughter which is not that laughter of ridicule which the sight of him at his work might excite.

About the “news,” I must speak more fully. The “editorial articles, reviews, and notes,” we shall happen upon when we visit the office.

A part of the news comes by telegraph from all parts of the world. Some of it is telegraphed to the paper by its correspondents, and the editors call it “special,” because it is especially to them. Perhaps there is something in it which none of the other papers have yet heard of. But the general telegraphic news, from the old-world and the new, is gathered up by the “Associated Press.” That is to say, the leading papers form an Association and appoint men to send them news from the chief points in America and in Europe. These representatives of the Associated Press are very enterprising, and 18 they do not allow much news of importance to escape them. The salaries of these men, and the cost of the telegraphic dispatches, are divided up among the papers of the Association, so that the expense to each paper is comparatively small. Owing to this association of papers, hundreds of papers throughout the country publish a great deal of matter on the same day which is word-for-word alike.

Two devices in this matter of Associated Press dispatches save so much labor, that I think you will like me to describe them.

One is this: Suppose there are a dozen papers in the same city which are entitled to the Associated Press dispatches. Instead of making a dozen separate copies, which might vary through mistakes, one writing answers for all the dozen. First, a sheet of prepared tissue paper is laid down, then a sheet of a black, smutty sort of paper, then two sheets of tissue paper, then a sheet of black paper, and so on, until as many sheets of tissue paper have been piled up, as there are copies wanted. Upon the top sheet of paper, the message is written, not with pen, or pencil, but with a hard bone point, which presses so hard that the massive layers of tissue paper take off from the black paper a black line wherever the bone point has pressed. Thus a dozen pages are 19 written with one writing, and off they go, just alike, to the several newspaper offices. The printers call this queer, tissue-paper copy—“manifold.”

The other device is a telegraphic one. Suppose the Associated Press agent in New York is sending a dispatch to the Boston papers. There are papers belonging to the Association at, say, New Haven, Hartford, Springfield and Worcester. Instead of sending a message to each of these points, also, the message goes to Boston, and operators at New Haven, Hartford, Springfield, and Worcester, listen to it as it goes through, and copy it off. Thus one operator at New York is able to talk to perhaps a score of papers, in various parts of New England, or elsewhere, at once.

But in a large city there is a great deal of city and suburban news. Take for example, New York; and there is that great city, and Brooklyn, and Jersey City, and Hoboken, and Newark, and Elizabeth, to be looked after, as well as many large villages near at hand. And there is great competition between the papers, which shall get the most, the exactest, and the freshest, news. Consequently, each day, a leading New York paper will publish a page or more of local news. The City Editor has charge of collecting this news. He has, perhaps, twenty or twenty-five 20 men to help him—some in town, and others in the suburbs.

His plan for news collecting will be something like this: He will have his secretary keep two great journals, with a page in each devoted to each day. One of these, the “blotter,” will be to write things in which are going to happen. Everything that is going to happen to-morrow, the next day, the next, and so on, the secretary will make a memorandum of or paste a paragraph in about upon the page for the day on which the event will happen. Whatever he, or the City Editor, hears or reads of, that is going to happen, they thus put down in advance, until by and by, the book gets fairly fat and stout with slips which have been pasted in. But, this morning, the City Editor wants to lay out to-day’s work. So his secretary turns to the “blotter,” at to-day’s page, and copies from it into to-day’s page in the second book all the things to happen to-day—a dozen, or twenty, or thirty—a ship to be launched, a race to come off, a law-case to be opened, a criminal to be executed, such and such important meetings to be held, and so on. By this plan, nothing escapes the eye of the City Editor who, at the side of each thing to happen, writes the name of the reporter whom he wishes to have write the event up. This second book 21 is called the “assignment book;” and, when it is made out, the reporters come in, find their orders upon it, and go out for their day’s work, returning again at evening for any new assignments. Besides this, they, and the City Editor, keep sharp ears 22 and eyes for anything new; and so, amongst them, the city and suburbs are ransacked for every item of news of any importance. The City Editor is a sort of general. He keeps a close eye on his men. He finds out what they can best do, and sets them at that. He gives the good workers better and better work; the poor ones he gradually works out of the office. Those who make bad mistakes, or fail to get the news, which some other paper gets, are frequently “suspended,” or else discharged out-and-out. Failing to get news which other papers get, is called being “beaten,” and no reporter can expect to get badly “beaten” many times without losing his position.

And now, Tom, and Jonathan, and even little Nell, we’ll all be magicians to-night, like the father of Miranda, in “The Tempest,” and transport ourselves in an instant right to one of those great newspaper offices.

It is six o’clock. The streets are dark. The gaslights are glaring from hundreds of lamp-posts. Do you see the highest stories of all those buildings brilliant with lights? Those are the type-setters’ rooms of as many great newspapers. In a twinkling we are several stories up toward the top of one of these buildings. These are the Editorial Rooms. 23 We’ll make ourselves invisible, so that they’ll not suspect our presence, and will do to-night just as they always do.

Up over our heads, in the room of the type-setters, are a hundred columns, or more, of articles already set—enough to make two or three newspapers. The Foreman of the type-setters makes copies of these on narrow strips of paper with a hand-press, and 24 sends them down to the Editor-in-Chief. These copies on narrow strips of paper, are called “proofs,” because, when they are read over, the person reading them can see if the type has been set correctly—can prove the correctness or incorrectness of the type-setting.

The Editor-in-Chief runs rapidly through these proofs, and marks, against here and there one, “Must,” which means that it “must” be published in to-morrow’s paper. Against other articles he marks, “Desirable,” which means that the articles are “desirable” to be used, if there is room for them. Many of the articles he makes no mark against, because they can wait, perhaps a week, or a month. By having a great many articles in type all the time, they never lack—Jonathan will be glad to know—for something to put into the paper. Jonathan might well take the hint, and write his compositions well in advance. Against some of the articles, the word “Reference” is written, which indicates that when the article is published an editorial article or note with “reference” to it must also be published. Before the Editor-in-Chief is through, perhaps he marks against one or two articles the word “Kill,” which means that the article is, after all, not wanted in the paper, and that the type of it may be taken 25 apart—the type-setters say “distributed”—without being printed.

When the Editor-in-Chief is through with the proofs, perhaps he has a consultation with the Managing Editor—the first editor in authority after him—about some plans for to-night’s paper, or for to-morrow, or for next week. Perhaps, then, he summons in the Night Editor. The Night Editor is the man who stays until almost morning, who overlooks everything that goes into the paper, and who puts everything in according to the orders of the Editor-in-Chief, or of the Managing Editor. Well, he tells the Night Editor how he wants to-morrow’s paper made, what articles to make the longest, and what ones to put in the most important places in the paper. Then, perhaps, the City Editor comes knocking at the door, and enters, and he and the Editor-in-Chief talk over some stirring piece of city news, and decide what to say in the editorial columns about it.

After the Editor-in-Chief has had these consultations, perhaps he begins to dictate to his secretary letters to various persons, the secretary taking them down in short-hand, as fast as he can talk, and afterwards copying them out and sending them off. That is the sort of letter-writing which would suit little Nell—just to say off the letter, and not to have to write 26 it—which, in her case, means “printing” it in great, toilsome capitals. After dictating perhaps a dozen letters, it may be that the Editor-in-Chief dictates in the same manner, an editorial article, or some other matter which he wishes to have appear in the paper. Thus he spends several hours—perhaps the whole night—in seeing people, giving directions, dictating letters and articles, laying out new plans, and exercising a general headship over all things.

Turning, now, from his room, we observe in the great room of the editors, a half dozen men or more seated at their several desks—the Managing Editor and the Night Editor about their duties; two or three men looking over telegraph messages and getting them ready for the type-setters; two or three men writing editorial, and other articles.

From this room we turn to the great room of the City Department. There is the City Editor, in his little, partitioned-off room, writing an editorial, we will suppose, on the annual report of the City Treasurer, which has to-day been given to the public. At desks, about the great room, a half-dozen reporters are writing up the news which they have been appointed to collect; and another, and another, comes in every little while.

Over there, is the little, partitioned-off room for the Assistant City Editor. It is this man’s duty, with his assistant, to prepare for the type-setters all the articles which come from the City Department. There are stacks and stacks of them. Each reporter thinks his subject is the most important, and writes it up fully; and, when it is all together, perhaps there is a third or a half more than there is room in the paper to print. So the Assistant City Editor, and his Assistant, who come to the office at about five o’clock in the afternoon, read it all over carefully, correct it, cut out that which it is not best to use, group all the news of the same sort so that it may come under one general head, put on suitable titles, decide what sort of type to put it in, etc.,—a good night’s work for both of them. They also write little introductions to the general subjects, and so harmonize and modify the work of twenty or twenty-five reporters, as to make it read almost as if it were written by one man, with one end in view.

The editors of the general news have to do much the same thing by the letters of correspondents, and by the telegraphic dispatches.

While this sort of work goes on, hour after hour, with many merry laughs and many good jokes interspersed to make the time fly the swifter, we will 29 wander about the establishment. Here, in the top story of the building, is the room of the type-setters. Every few minutes, from down-stairs in the Counting Room, comes a package of advertisements to be put into type; and from the Editorial Rooms a package of news and general articles for the same purpose. They do not trouble to send them up by a messenger. A tube, with wind blown through it very fast, brings up every little while a little leathern bag, in which are the advertisements or the articles—the “copy” as the type-setters call it.

In this room are thirty or forty type-setters. Each one of them has his number. When the copy comes up, a man takes it and cuts it up into little bits, as much as will make, say, a dozen lines in the paper, and numbers the bits—“one,” “two,” etc., to the end of the article. Type-setter after type-setter comes and takes one of these little bits, and in a few moments sets the type for it, and lays it down in a long trough, with the number of the bit of copy laid by the side of it. We will suppose that an article has been cut up into twenty bits. Twenty men will each in a few moments be setting one of these bits, and, in a few minutes more they will come and lay down the type and the number of the bit in the long trough, in just the right order of the number of the bits—“one,” “two,” etc. Then all the type will be 30 slid together, and a long article will thus be set in a few minutes, which it would take one or two men several hours to set. It is by this means that long articles can in so short a time be put into type. Each man who takes a bit, has to make his last line fill out to the end of the line; and, because there are sometimes not words enough, so that he has to fill out with some extra spaces between the words, you may often see in any large daily paper every two inches, or so, a widely spaced line or two showing how the type-setter had to fill out his bit with spaces—only he would call the bit, a “take.”

I said that each type-setter has his number. We will suppose that this man, next to us, is number “twenty-five.” Then he is provided with a great many pieces of metal, just the width of a column, with his number made on them—thus: “TWENTY-FIVE.” Every time he sets a new bit of copy, he puts one of these “twenty-fives” at the top; and when all the bits of type in the long trough are slid together the type is broken up every two inches or so, with “twenty-five,” “thirty-seven,” “two,” “eleven,” and so on, at the top of the bits which the men, whose numbers these are, have set. When a proof of the article is taken, these several numbers appear; and, if there are mistakes, it appears from these numbers, what type-setters made them, and 31 they have to correct them. Also, of each article, a single “proof” is taken on colored paper. These colored paper “proofs” are cut up the next day, and all the pieces marked “twenty-five,” “thirty-seven,” and so on, go to the men who have these numbers, and when pasted together show how much type, number “twenty-five,” “thirty-seven,” and so on, are to be paid for setting—for the type-setters are paid according to the amount of type which they set.

FAC-SIMILE OF “PROOF” SHOWING “TAKES.”

As fast as the proofs are taken they go into the room of the proof-readers to be corrected. The bits 32 of copy are pasted together again, and one man holds the copy while another reads the proof aloud. The man holding the copy notices any points in which the proof does not read like the copy, and tells the man who is reading it. The man reading it corrects the variations from copy, and corrects all the other mistakes which he can discover, and then the type-setters have to change the type so as to make it right. There the proof readers sit hard at work, reading incredibly fast, and making rapid and accurate corrections; then the “copy” is locked up, and no one can get at it, except the Managing Editor or Editor-in-Chief gives an order to see it. This precaution is taken, in order to make certain who is responsible for any mistakes which appear in the paper—the editors, or the type-setters.

By this time it is nearly midnight, and the editors, type-setters, etc., take their lunches. They either go out to restaurants for them, or have them sent in—hot coffee, sandwiches, fruit, etc.—a good meal for which they are all glad to stop.

And now the Foreman of the type-setters sends to the Night Editor that matter enough is in type to begin the “make-up”—that is, to put together the first pages of the paper. There the beautiful type stands, in long troughs, all corrected now, the great 33 numbers of the type-setters removed from between the bits of type—the whole ready to be arranged into page after page of the paper. So the Night Editor makes a list of the articles which he wants on the page which is to be made up; the Foreman puts them in in the order which the Night Editor indicates; the completed page is wedged securely into an iron frame, and then is ready to be stereotyped.

The room of the stereotypers is off by itself. There is a furnace in it, and a great caldron of melted type metal. They take the page of the paper which has just been made up; put it on a hot steam chest; spat down upon the type some thick pulpy paper soaked so as to make it fit around the type; spread plaster of Paris on the back, so as to keep the pulpy paper in shape; and put the whole under the press which more perfectly squeezes the pulpy paper down 34 upon the type, and causes it to take a more perfect impression of the type. The heat of the steam chest warms the type, and quickly dries the pulpy paper and the plaster of Paris. Then the pulpy paper is taken off, and curved with just such a curve as the cylinders of the printing-press have, and melted type metal is poured over it, which cools in a moment; when, lo, there is a curving plate of type-metal just like the type! The whole process of making this plate takes only a few minutes. They use such plates as these, rather than type, in printing the great papers chiefly for reasons like these: 1. Because plates save the wear of type; 2. Because they are easier handled; 3. Because they can be made curving, to fit the cylinders of the printing presses as it would be difficult to arrange the type; 4. Because several plates can be made from the same type, and hence several presses can be put at work at the same time printing the same paper; 5. Because, if anything needs to be added to the paper, after the presses have begun running, the type being left up-stairs can be changed and new plates made, so that the presses need stop only a minute for the new plates to be put in—which is a great saving of time.

But, coming down into the Editorial Rooms again—business Tom, and thoughtful Jonathan, and sleepy 35 little Nell—all is excitement. Telegrams have just come in telling of the wreck of an ocean steamer, and men are just being dispatched to the steamer’s office to learn all the particulars possible, and to get, if it may be, a list of the passengers and crew. And now, just in the midst of this, a fire-alarm strikes, and in a few moments the streets are as light as day with the flames of a burning warehouse in the heart of the business part of the city. More men are sent off to that; and, what with the fire and the wreck, every reporter, every copy-editor, every type-setter and proof-reader are put to their hardest work until the last minute before the last page of the paper must be sent down to the press-rooms. Then, just at the last, perhaps the best writer in the office dashes off a “leader” on the wreck sending a few lines at a time to the type-setters—a leader which, though thought out, written, set, corrected, and stereotyped in forty minutes, by reason of its clearness, its wisdom, and its brilliancy, is copied far and wide, and leads the public generally to decide where to fix the blame, and how to avoid a like accident again. There is the work of the “editorial articles, reviews, and notes”—to comment on events which happen, and to influence the minds of the public as the editorial management of the paper regards to 36 be wise. There is all sorts of this editorial writing—fun, politics, science, literature, religion—and he who says, with his pen, the say of such a newspaper, wields an influence which no mind can measure.

Well, the fire, and the wreck, have thoroughly awakened even little Nell. And so down, down we go, far under ground, to the Press-rooms. There the noise is deafening. Two or three presses are at work. At one end of the press is a great roll of paper as big as a hogshead and a mile or more long. This immense roll of paper is unwinding very fast, and going in at one end of the machine; while at the other end, faster than you can count, are coming out finished papers—the papers printed on both sides, cut up, folded, and counted, without the touch of a hand—a perfect marvel and miracle of human ingenuity. The sight is a sight to remember for a lifetime. Upon what one here sees, hinges very much of the thinking of a metropolis and of a land.

And now, here come the mailing clerks, to get their papers to send off—with great accuracy and speed of directing and packing—by the first mails which leave the city within an hour and a half, at five and six o’clock in the morning. And after them come the newsboys, each for his bundle; and soon the frosty morning air in the gray dawn is alive 37 with the shouting of the latest news in this and a dozen other papers.

This, I am sure, is too fast a world even for business Tom: so let us “spirit” ourselves back to our beds in the quiet, slow-moving, earnest country—Tom and Jonathan and little Nell and I—home, and to sleep—and don’t wake us till dinner-time!

About one hundred and thirty years ago, an Englishman named Jonas Hanway, who had been a great traveller, went out for a walk in the city of London, carrying an umbrella over his head.

Every time he went out for a walk, if it rained or if the sun shone hotly, he carried this umbrella, and all along the streets, wherever he appeared, men and boys hooted and laughed; while women and girls, in doorways and windows, giggled and stared at the strange sight, for this Jonas Hanway was the first man to commonly carry an umbrella in the city of London, 40 and everybody, but himself, thought it was a most ridiculous thing to do.

But he seems to have been a man of strength and courage, and determined not to give up his umbrella even if all London made fun of him. Perhaps, in imagination, he saw adown the future, millions of umbrellas—umbrellas enough to shelter the whole island of England from rain.

Whether he did foresee the innumerable posterity of his umbrella or not, the “millions” of umbrellas have actually come to pass.

But Jonas Hanway was by no means the first man in the world to carry an umbrella. As I have already mentioned, he had travelled a great deal, and had seen umbrellas in China, Japan, in India and Africa, where they had been in use for so many hundreds of years that nobody knows when the first one was made. So long ago as Nineveh existed in its splendor, umbrellas were used, as they are yet to be found sculptured on the ruins of that magnificent capital of Assyria, as well as on the monuments of Egypt which are very, very old; and your ancient history will tell you that the city of Nineveh was founded not long after the flood. Perhaps it was that great rain, of forty days and forty nights, that put in the minds of Noah, or some of his sons, the idea to build an umbrella! 41

Although here in America the umbrella means nothing but an umbrella, it is quite different in some of the far Eastern countries. In some parts of Asia and Africa no one but a royal personage is allowed to carry an umbrella. In Siam it is a mark of rank. The King’s umbrella is composed of one umbrella above another, a series of circles, while that of a nobleman consists of but one circle. In Burmah it is much the same as in Siam while the Burmese King has an umbrella-title that is very comical: “Lord of the twenty-four umbrellas.”

The reason why the people of London ridiculed Jonas Hanway was because at that time it was considered only proper that an umbrella should be carried by a woman, and for a man to make use of one was very much as if he had worn a petticoat.

There is in one of the Harleian MSS. a curious picture showing an Anglo-Saxon gentleman walking out, with his servant behind him carrying an umbrella; the drawing was probably made not far from five hundred years ago, when the umbrella was first introduced into England. Whether this gentleman and his servant created as much merriment as Mr. Hanway did, I do not know; neither can I tell you why men from that time on did not continue to use the umbrella. If I were to make a “guess” about it, I should say that they thought it would not be “proper,” for it was 42 considered an unmanly thing to carry one until a hundred years ago when the people of this country first began to use them. And it was not until twenty years later, say in the year 1800, that the “Yankees” began to make their own umbrellas. But since that time there have been umbrellas and umbrellas!

The word umbrella comes from the Latin word umbra, which means a “little shade;” but the name, most probably, was introduced into the English language from the Italian word ombrella. Parasol means “to ward off the sun,” and another very pretty name, not much used by Americans, for a small parasol, is “parasolette.”

It would be impossible for me to tell you how many umbrellas are made every year in this country. A gentleman connected with a large umbrella manufactory in the city of Philadelphia gave me, as his estimate, 7,000,000.

This would allow an umbrella to about one person in six, according to the census computation which places the population of the United States at 40,000,000 of people. And one umbrella for every six persons is certainly not a very generous distribution. Added to the number made in this country, are about one-half million which are imported, chiefly from France and England. 43 You who have read “Robinson Crusoe,” remember how he made his umbrella and covered it with skins, and that is probably the most curious umbrella you can anywhere read about. Then there have been umbrellas covered with large feathers that would shed rain like a “duck’s back,” and umbrellas with coverings of oil-cloth, of straw, of paper, of woollen stuffs, until now, nearly all umbrellas are covered either with silk, gingham, or alpaca. And this brings us to the manufacture of umbrellas in Philadelphia, where there are more made than in any other city in America.

If you will take an umbrella in your hand and examine it, you will see that there are many more different things used in making it than you at first supposed.

First, there are the “stick,” made of wood, “ribs,” “stretchers” and “springs” of steel; the “runner,” “runner notch,” the “ferule,” “cap,” “bands” and “tips” of brass or nickel; then there are the covering, the runner “guard” which is of silk or leather, the “inside cap,” the oftentimes fancy handle, which may be of ivory, bone, horn, walrus tusk, or even mother-of-pearl, or some kind of metal, and, if you will look sharply, you will find a rivet put in deftly here and there. 44

For the “sticks” a great variety of wood is used; although all the wood must be hard, firm, tough, and capable of receiving both polish and staining. The cheaper sticks are sawed out of plank, chiefly, of maple and iron wood. They are then “turned” (that is made round), polished and stained. The “natural sticks,” not very long ago, were all imported from England. But that has been changed, and we now send England a part of our own supply, which consists principally of hawthorne and huckleberry, which come from New York and New Jersey, and of oak, ash, hickory, and wild cherry.

If you were to see these sticks, often crooked and gnarled, with a piece of the root left on, you would 45 think they would make very shabby sticks for umbrellas. But they are sent to a factory where they are steamed and straitened, and then to a carver, who cuts the gnarled root-end into the image of a dog or horse’s head, or any one of the thousand and one designs that you may see, many of which are exceedingly ugly. The artist has kindly made a picture for you of a “natural” stick just as it is brought from the ground where it grows, and, then again, the same stick after it has been prepared for the umbrella.

Of the imported “natural” sticks, the principal are olive, ebony, furze, snakewood, pimento, cinnamon, partridge, and bamboo. Perhaps you do not understand that a “natural” stick is one that has been a young tree, having grown to be just large enough for an umbrella stick, when it was pulled up, root and all, or with at least a part of the root. If, when you buy an umbrella that has the stick bent into a deep curve at the bottom for the handle, you may feel quite sure that it is of partridge wood, which does not grow large enough to furnish a knob for a handle, but, when steamed, admits of being bent.

The “runner,” “ferule,” “cap,” “band,” etc., form what is called umbrella furniture and for these articles there is a special manufactory. Another manufactory 46 cuts and grooves wire of steel into the “ribs” and “stretchers.” Formerly ribs were made out of cane or whalebone; but these materials are now seldom used. When the steel is grooved, it is called a “paragon” frame, which is the lightest and best made. It was invented by an Englishman named Fox, seventeen or eighteen years ago. The latest improvement in the manufacture of “ribs” is to give them an inward curve at the bottom, so that they will fit snugly around the stick, and which dispenses with the “tip cup,”—a cup-shaped piece of metal that closed over the tips.

Of course we should all like to feel that we Americans have wit enough to make everything used in making an umbrella. And so we have in a way; but it must be confessed that most of the silk used for umbrella covers, is brought from France. Perhaps 47 if the Cheney Brothers who live at South Manchester in Connecticut, and manufacture such elegant silk for ladies’ dresses, and such lovely scarfs and cravats for children, were to try and make umbrella silk, we would soon be able to say to the looms of France, “No more umbrella silk for America, thank you; we are able to supply our own!”

But the “Yankees” do make all their umbrella gingham, which is very nice. And one gingham factory that I have heard about has learned how to dye gingham such a fast black, that no amount of rain or 48 sun changes the color. The gingham is woven into various widths to suit umbrella frames of different size, and along each edge of the fabric a border is formed of large cords. As to alpaca, a dye-house is being built, not more than a “thousand miles” from Philadelphia on the plan of English dye-houses, so that our home-made alpacas may be dyed as good and durable a black as the gingham receives; for although nobody minds carrying an old umbrella, nobody likes to carry a faded one. Although there are umbrellas of blue, green and buff, the favorite hue seems to be black.

And now that we have all the materials together to make an umbrella, let us go into a manufactory and see exactly how all the pieces are put together.

First, here is the stick, which must be “mounted.” By that you must understand that there are two springs to be put in, the ferule put on the top end, and if the handle is of other material than the stick, that must be put on.

The ugliest of all the work is the cutting of the slots in which the springs are put. These are first cut by a machine; but if the man who operates it is not careful, he will get some of his fingers cut off. But after the slot-cutting machine does its work, there is yet something to be done by another man with a 49 knife before the spring can be put in. After the springs are set, the ferule is put on, and when natural sticks are used, as all are of different sizes, it requires considerable time and care to find a ferule to fit the stick, as well as in whittling off the end of the stick to suit the ferule. And before going any farther 50 you will notice that all the counters in the various work-rooms are carpeted. The carpet prevents the polished sticks from being scratched, and the dust from sticking to the umbrella goods.

After the handle is put on the stick and a band put on for finish or ornament, the stick goes to the frame-maker, who fastens the stretchers to the ribs, strings the top end of the ribs on a wire which is fitted into the “runner notch;” then he strings the lower ends of the “stretchers” on a wire and fastens it in the “runner,” and then when both “runners” are securely fixed the umbrella is ready for the cover.

As this is a very important part of the umbrella, several men and women are employed in making it. In the room where the covers are cut, you will at first notice a great number of V shaped things hanging against the wall on either side of the long room. These letter Vs are usually made of wood, tipped all around with brass or some other fine metal, and are of a great variety of sizes. They are the umbrella cover patterns, as you soon make out. To begin with, the cutter lays his silk or gingham very smoothly out on a long counter, folding it back and forth until the fabric lies eight or sixteen times in thickness, the layers being several yards in length. (But I must go back a little and tell you that both edges of the 51 silk, or whatever the cover is to be, has been hemmed by a woman, on a sewing machine before it is spread out on the counter). Well, when the cutter finds that he has the silk smoothly arranged, with the edges even, he lays on his pattern, and with a sharp knife quickly draws it along two sides of it, and in a twinkling you see the pieces for perhaps two umbrellas cut out; this is so when the silk, or material, is sixteen layers thick and the umbrella cover is to have but eight pieces.

After the cover is cut, each piece is carefully examined by a woman to see that there are no holes nor defects in it, for one bad piece would spoil a whole umbrella.

Then a man takes the pieces and stretches the cut edges. This stretching must be so skilfully done that the whole length of the edge be evenly stretched. This stretching is necessary in order to secure a good fit on the frame.

After this the pieces go to the sewing-room, where they are sewed together by a woman, on a sewing-machine, in what is called a “pudding-bag” seam. The sewing-machine woman must have the machine-tension just right or the thread of the seam will break when the cover is stretched over the frame.

The next step in the work is to fasten the cover to 52 the frame, which is done by a woman. After the cover is fastened at the top and bottom, she half hoists the umbrella, and has a small tool which she uses to keep the umbrella in that position, then she fastens the seams to the ribs; and a quick workwoman will do all this in five minutes, as well as sew on the tie, which has been made by another pair of hands. Then the cap is put on and the umbrella is completed.

But before it is sent to the salesroom, a woman smooths the edge of the umbrella all around with a warm flat-iron. Then another woman holds it up to a window where there is a strong light, and hunts for holes in it. If it is found to be perfect the cover is neatly arranged about the stick, the tie wrapped about it and fastened, and the finished umbrella goes to market for a buyer.

After the stick is mounted, how long, think you does it take to make an umbrella?

Well, my dears—it takes only fifteen minutes!

So you see that in the making of so simple an every-day article as an umbrella, that you carry on a rainy day to school, a great many people are employed; and to keep the world supplied with umbrellas thousands and thousands of men and women are 53 kept busy, and in this way they earn money to buy bread and shoes and fire and frocks for the dear little folks at home, who in turn may some day become umbrella makers themselves.

Little Paul Perkins—Master Paul his uncle called him—did not feel happy. But for the fact that he was a guest at his uncle’s home he might have made an unpleasant exhibition of his unhappiness; but he was a well-bred city boy, of which fact he was somewhat proud, and so his impatience was vented in snapping off the teeth of his pocket-combs, as he sat by the window and looked out into the rain.

It was the rain which caused his discontent. Only the day before his father, going from New York to Boston on business, had left Paul at his uncle’s, some distance from the “Hub,” to await his return. It being the lad’s first visit, Mr. Sanford had arranged a very full programme for the next day, including a trip in the woods, fishing, a picnic, and in fact quite 55 enough to cover an ordinary week of leisure. Over and over it had been discussed, the hours for each feature apportioned, and through the night Paul had lived the programme over in his half-waking dreams.

And now that the eventful morning had come, it brought a drizzling, disagreeable storm, so that Mr. 56 Sanford, as he met his nephew, was constrained to admit that he did not know what they should find to supply the place of the spoiled programme.

“And my little nephew is so disappointed that he has ruined his pretty comb, into the bargain,” said the uncle.

“I was—was trying to see what it was made of,” Paul stammered, thrusting the handful of teeth into his coat pocket. “I don’t see how combs are made. Could you make one, uncle?”

“I never made one,” Mr. Sanford replied, “but I have seen very many made. There is a comb-shop not more than a half-mile away, and it is quite a curiosity to see how they make the great horns, rough and ugly as they are, into all sorts of dainty combs and knicknacks.”

“What kind of horns, uncle?”

“Horns from all parts of the country, Paul. This shop alone uses nearly a million horns a year, and they come in car-loads from Canada, from the great West, from Texas, from South America, and from the cattle-yards about Boston and other Eastern cities.”

“You don’t mean the horns of common cattle?”

“Yes, Paul; all kinds of horns are used, though some are much tougher and better than others. The 57 cattle raised in the Eastern, Middle and Western States furnish the best horns, and there is the curious difference that the horns of six cows are worth no more than those of a single ox. Many millions of horn combs are made every year in Massachusetts; perhaps more than in all the rest of the country. If you like we will go down after breakfast and have a look at the comb-makers.”

Paul was pleased with the idea, though he would much rather have passed the day as at first proposed. He was not at all sorry that he had broken up his comb, and even went so far as to cut up the back with his knife, wondering all the while how the smooth, flat, semi-transparent comb had been produced from a rough, round, opaque horn.

By and by a mail stage came rattling along, without any passengers, and Mr. Sanford took his nephew aboard. They stopped before a low, straggling pile of buildings, located upon both sides of a sluggish looking race-way which supplied the water power, covered passage-ways connecting different portions of the works.

“Presently, just over this knoll,” said his uncle, “you will see a big pile of horns, as they are unloaded from the cars.”

They moved around the knoll, and there lay a monstrous pile of horns thrown indiscriminately together.

“Really there are not so many as we should think,” said Mr. Sanford, as Paul expressed his astonishment. “That is only a small portion of the stock of this shop. I will show you a good many more.”

He led the way to a group of semi-detached buildings in rear of the principal works, and there Paul saw great bins of horns, the different sizes and varieties carefully assorted, the total number so vast that the immense pile in the open yard began to look small in contrast.

At one of the bins a boy was loading a wheelbarrow, and when he pushed his load along a plank track through one of the passage-ways Mr. Sanford and his nephew followed. As the passage opened into another building, the barrow was reversed and its load deposited in a receptacle a few feet lower.

In this room only a single man was employed, and the peculiar character of his work at once attracted the attention of Paul. In a small frame before him was suspended a very savage-looking circular saw, running at a high rate of speed. The operator caught 60 one of the great horns by its tip, gave it a turn through the air before his eyes, seized it in both hands and applied it to the saw. With a sharp hiss the keen teeth severed the solid tip from the body of the horn, 61 and another movement trimmed away the thin, imperfect parts about the base. The latter fell into a pile of refuse at the foot of the frame, the tip was cast into a box with others; the horn, if large, was divided into two or more sections, a longitudinal slit sawn in one side, and the sections thrown into a box.

“This man,” said Mr. Sanford, “receives large pay and many privileges, on account of the danger and unpleasant nature of his task. He has worked at this saw for about forty years, and in that time has handled, according to his record, some twenty-five millions of horns, or over two thousand for every working day. He has scarcely a whole finger or thumb upon either hand—many of them are entirely gone; but most of these were lost during his apprenticeship. The least carelessness was rewarded by the loss of a finger, for the saw cannot be protected with guards, as in lumber-cutting.”

Paul watched the skilful man with the closest interest, shuddering to see how near his hands passed and repassed to the merciless saw-teeth as he sent a ceaseless shower of parts of horns rattling into their respective boxes. Before he left the spot Paul took a pencil and made an estimate. 62

“Why, uncle,” he said, “to cut so many as that, he must saw over three horns every minute for ten hours a day. I wouldn’t think he could handle them so fast.”

Then, as he saw how rapidly one horn after another was finished, he drew forth his little watch and found that the rugged old sawyer finished a horn every ten seconds with perfect ease.

“Would you like to learn this trade?” the old fellow asked. He held up his hands with the stumps of fingers and thumbs outspread; but Paul only laughed and followed his uncle.

They watched a boy wheeling a barrow-load of the horns as they came from the saw, and beheld them placed in enormous revolving cylinders, through which a stream of water was running, where they remained until pretty thoroughly washed. Being removed from these, they were plunged into boilers ranged along one side of the building, filled with hot water.

“Here they are heated,” said Mr. Sanford, “to clear them from any adhering matter that the cold water does not remove, and partially softened, ready for the next operation.”

From the hot water the horns were changed to a 63 series of similar caldrons at the other side of the room, filled with boiling oil. Paul noticed that when the workmen lifted the horns from these vats their appearance was greatly changed, being much less opaque, and considerably plastic, opening readily at the longitudinal cut made by the saw. As the horns were taken from the oil they were flattened by unrolling, and placed between strong iron clamps which were firmly screwed together, and put upon long tables in regular order.

“Now I begin to see how it is done,” Paul said, though he was thinking all the time of questions that he would ask his uncle when there were no workmen by to overhear.

“The oil softens the horn,” said Mr. Sanford, “and by placing it in this firm pressure and allowing it to remain till it becomes fixed, the whole structure is so much changed that it never rolls again. Some combs, you will notice, are of a whitish, opaque color, like the natural horn, while others have a smooth appearance, are of amber color, and almost transparent. The former are pressed between cold irons and placed in cold water, while the others are hot-pressed, it being ‘cooked’ in a few minutes. These plates of horn may be colored; and there are a great many 64 ‘tortoise-shell’ combs and other goods sold which are only horn with a bit of color sprinkled upon it.

“The solid tips of the horns, and all the pieces that are worth anything cut off in making the combs, are made up into horn jewelry, chains, cigar-holders, knife-handles, buttons, and toys of various kinds. These trinkets are generally colored more or less, and many a fashionable belle, I suppose, would be surprised to know the amount of money paid for odd bits of horn under higher sounding names. But the horn is tough and serviceable, at any rate, and that is more than can be said of many of the cheats we meet with in life.”

The next room, in contrast with all they had passed through previously, was neat and had no repulsive odors. Here the sheets of horn as they came from the presses were first cut by delicate circular saws into blanks of the exact size for the kind of combs to be made, after which they were run through a planer, which gave them the proper thickness.

“What do you mean by ‘blanks’?” Paul asked, as his uncle used the term.

“You can look in the dictionary to find its exact meaning,” was the answer. “But you will see what it is in practice at this machine.”

They stepped to another part of the room; and here Paul saw the “blanks” placed in the cutting-machine standing over a hot furnace, where, after being softened by the heat, they were slowly moved along, while a pair of thin chisels danced up and down, cutting through the centre of the blank at each stroke. When it had passed completely through, an assistant took the perforated blank and pulled it carefully apart, showing two combs, with the teeth interlaced. After separation they were again placed together to harden under pressure, when the final operations consisted of bevelling the teeth on wheels covered with sand-paper, rounding the backs, rounding and pointing the teeth; after which came the polishing, papering and putting in boxes.

“I suppose they go all over the country,” said Paul as he glanced into the shipping-room.

“Much further than that,” was the reply. “We never know how far they go; for the wholesale dealers, to whom the combs are shipped from the manufactory, send them into all the odd corners of the earth. Every little dealer must sell combs, and in the very nature of the business they frequently pass through a great many hands before reaching the user, so at the last price is many times what the 67 makers received for them. I suppose it often happens that horns which have been sent thousands of miles to work up are returned to the very regions from which they came, in some other form, increased very many fold in value by their long journey. Or a horn may come from the remoter parts of South America to be wrought here in Massachusetts, and then be shipped from point to point till it reaches some remote corner of Africa, Spain, or Siberia, as an article of barter. And even different parts of the same horn may be at the same moment decking the person of a New York dandy and unsnarling the tangled locks of a Russian Tchuktch.”

While Paul was watching the deft fingers of the girls who filled the boxes and affixed the labels, his uncle stepped through a door communicating with the office, and soon returned with three elegant pocket-combs.

“One of these,” he said, “represents a horn which came from pampas of Buenos Ayres; this one, in the original, dashed over the boundless plains of Texas; and here is another, toughened by the hot, short summers and long, bitter winters of Canada. Take them with you in memory of this cheerless rainy day.” 68

Paul could not help a little sigh as he thought again of the pleasures he had enjoyed in anticipation; but still he answered bravely, “Thank you; never mind the rain, dear uncle. All the New York boys go off in the woods when they get away from home; but not many of them ever heard how combs are made, and I don’t suppose a quarter of them even know what they are made of. I can tell them a thing or two when I get home.”

Philip and Kitty were curled up together on the lounge in the library, reading Aldrich’s “Story of a Bad Boy.” It was fast growing dark in the corner where they were, for the sun had gone down some time before, but they were all absorbed in Tom Bailey’s theatricals, and did not notice how heavy the shadows were getting around them. Papa came in by-and-by.

“Why, little folks, you’ll spoil your eyes reading here; I’d better light the gas for you,” and he took out a match from the box on the mantle.

“O, let me, please,” cried Philip, jumping up and running to the burner. So he took the match, and climbed up in a chair with it. Scr-a-tch! and the new-lit jet gave a glorified glare that illuminated everything in the room, from the Japanese vase on the 70 corner bracket to the pattern of the rug before the open fire. But as Philip turned it off a little it grew quieter, and finally settled down into a steady, respectable flame. Philip always begged to light the gas. It had not been long introduced in the little town where he lived, and the children thought it a very fine thing to have it brought into the house, and secretly pitied the boys and girls whose fathers had only kerosene lamps.

“Why can’t you blow out gas, just as you do a kerosene light?” asked Kitty, presently, leaving the Bad Boy on the lounge, and watching the bright little crescent under the glass shade.

“Because,” explained papa, “unless you shut it off by turning the little screw in the pipe, the gas will keep pouring out into the room all the time, and if it isn’t disposed of by being burned up, it will mix with the air and make it poisonous to breathe. A man at the hotel here, a few nights ago, blew out the gas because he did not know any better, and was almost suffocated before he realized the trouble and opened his window.”

“And where does the gas come from in the first place?” pursued Kitty.

“Why, from the gas-works, of course,” said Philip in a very superior way, for he was a year the elder of 71 the two. “That brick building over by Miller’s Hill—don’t you know—that we pass in going to Aunt Hester’s.”

“I know that as well as you do, Philip Lawrence,” said Kitty with some dignity. “What I wanted to know was what it’s made out of. What is it, papa?”

“Out of coal,” said papa. “They put the coal in ovens and heat it till the gas it contains is separated from the other parts of the coal, and driven off by itself. Then it is purified and made ready for use.”

“Out of coal? How funny! I wish I could see all about it,” said Philip, looking more interested.

“And so do I wish I could,” added Kitty.

“I don’t see why it cannot be done,” said papa. “If you really care to see it, and won’t mind a few bad smells, I will ask Mr. Carter to-morrow morning, when he can take you around and explain things.”

The next day when Mr. Carter was asked about it, he said, “O, come in any day you like. About three in the afternoon would be a good time, because we are always newly-filling the retorts then.” This sounded very nice and imposing to the children, and at three the next afternoon they started out with papa. The gas-house certainly did smell very badly as they drew near it, and dainty Kitty sniffed in considerable disgust. Philip suggested that perhaps she had better not go in after all; he didn’t believe girls ever did go into such places. And upon that Kitty 72 valiantly declared she did not mind it a bit, and sternly set her face straight.

Mr. Carter met them at the door. “You are just in time to see the retorts opened,” said he, and led the way directly into a large and very dingy room, along one side of which was built out a sort of huge iron cupboard with several little iron doors. The upper ones were closed tight, but some of the lower ones were open a crack, and a very bright fire could be seen inside. Everything around was dirty and gloomy, and these gleams of fire from the little iron doors made the place look weird and ghostly. Long iron pipes reached from each of the upper doors up to one very large horizontal pipe or cylinder near the ceiling overhead. This cylinder ran the whole length of the room, and, at its farther end, joined another iron pipe which passed through the wall.

“Those are the furnace-doors down below,” said Mr. Carter to the children. “What you see burning inside of them is coke. Coke is what is left of the coal after we have taken the gas and tar out of it. The upper doors open into the retorts, or ovens, that we fill every five hours with the coal from which we want to get gas. Each retort holds about two hundred pounds, and from that amount we get a thousand cubic feet of gas.” 73

“Is it just common coal;” asked Kitty, “like what people burn in stoves?”

“Not exactly. It is a softer kind, containing more of a substance called hydrogen than the sorts that are generally used for fuel. Several different varieties are used: ‘cherry,’ ‘cannel,’ ‘splint,’ and so on, and they come from mines in different parts of England and Scotland, chiefly. Glasgow, Coventry and Newcastle send us a great deal.”

Philip started as if a bright idea had struck him. “Is that what people mean when you’re doing something there’s no need of, and they say ‘you’re carrying coals to Newcastle?’”

“Yes. You see such an enterprise would be absurd. Just notice the man yonder with the long iron rod! He is going to open one of the retorts, take out the old coal—only it is now coke—and put in a fresh supply.”

A workman in a grimy, leather apron loosened one of the retort doors, and held up a little torch. Immediately a great sheet of flame burst out, and then disappeared.

He took the door quite off, and there was a long, narrow oven with an arched top, containing a huge bed of red-hot coals. 74

“What a splendid place to pop corn!” exclaimed Kitty.

Papa laughed. “You would find it warm work,” said he, “unless you’d a very long handle to your corn-popper.” And Kitty thought so too, as she went nearer the fiery furnace.

“You see,” said Mr. Carter, “these red-hot coals have been changed a great deal by the heat. They have given up all their gas and tar, and are themselves no longer coal, but coke. We shovel out this coke and use it as fuel in the furnaces down below to help heat up the next lot. Then new coal is put into the retorts, and they are closed up with iron plates, like that one lying ready on the ground.”

“It’s all muddy ’round the edge,” observed Kitty.

“Yes, that paste of clay is to make it air-tight. The heat hardens the clay very quickly, so all the little cracks around the edge are plastered up. When the coal is shut up in the ovens, or retorts, the heat, as I just told you, divides it up into the different substances of which it is made; that is, into the coke which you have seen, a black, sticky liquid called tar, the illuminating gas, and more or less ammonia, sulphur, and other things that must be got rid of. Almost all these things are saved and used for one purpose or another, though they may be of no use to 75 us here. If we have more coke than we ourselves need it is sold for fuel. The coal-tar goes for roofing and making sidewalks, or sometimes (though you wouldn’t think it possible, as you look at the sticky, bad-smelling, black stuff) in the manufacture of the most lovely dyes, like that which colored Miss Kitty’s pink ribbon. The ammonia is used for medicine and all sorts of scientific preparations, in bleaching cloth, and in the printing of calicoes and cambrics.”

“When the materials of the coal are separated as I told you in the retorts, most of the tar remains behind, and is drawn off; but some gets up the pipes. That large, horizontal cylinder is always nearly half full of it. The gas, which is very light, you know, rises through the upper pipes leading from the retorts, and bubbles up through the tar in the bottom of the cylinder. Then it passes along the farther end of the cylinder, and into the condensing pipes.”

He opened a door, and they went through into the next room. Here the large pipe which came through the wall of the room they had just left, led to a number of clusters of smaller pipes that were jointed and doubled back and forth upon each other, cob-house fashion.

“When the gas goes through these pipes,” said Mr. Carter, “it gets pretty well cooled down, for the 76 pipes are kept cold by having so great an amount of surface exposed to draughts of air around them. And when the gas is cooled the impurities are cooled too, so that many of them take a liquid form and can be drawn off.”

The next room they entered had a row of great, square chests on each side, as they walked through.

“These are the purifiers,” explained Mr. Carter again. “They are boxes with a great many fan-like shelves inside, projecting out in all directions, and covered thickly with a paste made of lime.”

“Lime like what the masons used when they plastered the new kitchen?” asked Philip.

“About the same thing. The boxes are made air-tight, and the gas enters the first box at one of the lower corners. Then before it can get through the connecting-pipe into the next box, it has to wind its way around among these plates coated with lime. This lime takes up the sulphur and other things that we do not want in the gas, and so by the time it gets through all the boxes it is quite pure and fit to use.”

Then the party all went into the room where the gas was measured. It was a little office with a queer piece of furniture in it; something that looked like a very large drum-shaped clock, with several different dials or faces. This, Mr. Carter said, was the metre 77 or measurer, and by looking at the dials it could be told exactly how much gas was being made every day.

“As soon as the gas gets through the purifiers,” said he, “it comes, by an iron pipe, in here, and is made to pass through and give an account of itself before any of it is used. And now I suppose you would like to know how it does report its own amount, wouldn’t you?”

Philip and Kitty both were sure they did want to know, so he sketched a little plan of the metre on a piece of paper, and then went on to explain it:

“This shows how the metre would look if you could cut it through in the middle. The large drum-shaped box A. A. is hollow, and filled a little more than half way up with water. Inside it is a smaller hollow drum, B. B. so arranged as to turn easily from right to left, on the horizontal axis C. This axis is a hollow pipe by which the gas comes from the purifiers to enter the several chambers of the metre in turn, through small openings called 78 valves. The partitions P. P. P. P. divide the drum B. B. into—let us say—four chambers, 1, 2, 3, 4, all of the same size, and capable of holding a certain known amount of air or gas. The chamber 1 is now filled with gas, 3 with water, and 2 and 4 partly with gas and partly with water. The valves in the pipe C are so arranged that the gas will next pour into the chamber 2. This it does with such force as to completely fill it, lifting it quite out of the water and into the place that 1 had occupied before. Then as 1 is driven over to the place which 4 had occupied, the gas with which it was filled passes out by another pipe and off to the large reservoir you will see by and by, its place being filled with water. At the same time 4 is driven around to the place of 3, and 3 to that of 2. The water always keeps the same level, and simply waits for the chambers to come round and down to be filled.

“Next, 3, being in the place of 2, receives its charge of gas from the entrance pipe, is in turn lifted up into the central position, and sends all the other chambers around one step further. And when the drum gets completely around once, so that the chambers stand in the same places as at first, you know each chamber must have been once filled with gas and then emptied of it. If then we know that each 79 chamber will hold, say two and a half cubic feet of gas, we are sure that every time the drum has turned fully around it has received and sent off four times two and a half feet, or ten feet in all. Now we connect the axis C with a train of wheel-work, something like that in a clock, and this wheel-work moves the pointers on the dials in front, so that as the gas in passing in and out of the chambers turns the drum on the axis, it turns the dial pointers also.

“The right hand dial marks up to one hundred. While its pointer is passing completely around once, the pointer on the next dial (which marks up to one thousand) is moving a short space and preserving the record of that one hundred; and then the first pointer begins over again. The two pointers act together just like the minute and hour hands on a clock. Then the next dial marks up to ten thousand, and acts in turn like an hour-hand to the thousands’ dial as a minute-hand, and so on. You see each dial has its denominations, ‘thousands,’ ‘hundred thousands,’ or whatever it may be, printed plainly below it. And now, when we want to read off the dials, we begin at the left, taking in each case the last number a pointer has passed, and read towards the right, just as you have learned to do with any numbers in your ‘Eaton’s Arithmetic.’ There is one thing 80 more to remember, however; the number you read means not simply so many cubic feet of gas but so many hundred cubic feet.”

Philip and Kitty immediately set to work to read the dials on the office metre, and found that they were not now so very mysterious.

“But how do you know how much people use?” asked Philip. “There is something like this metre, only smaller, down cellar at home, and a man came and looked at it the other day, to see how much gas had been burned in the house he said, when I asked him what he was going to do.”

“The metre you have at home works in the same way as this,” said Mr. Carter, “and the dial-plates are read in the same way. But the gas that your little metre registers is only that which you take from the main supply-pipe, to light your parlors and bed-rooms.

“When a stream of gas from the main enters the house, it has to pass through the metre the very first thing, before any of it is used; and each little metre keeps as strict an account of what passes through from the main to the burners, as the large one here in the office does of that which passes from the purifiers to the reservoir. But there is this difference between the two: the gas keeps pouring through the office metre as long as we keep making it in the retorts, 81 but it passes through your metre at home only just as long as you keep drawing it off at the burners. So if we find by looking at the metre that 5450 feet have passed through during a given time, we send in our bill to your papa for that amount, knowing it must have been burned in the house.

“But most likely the metre doesn’t say anything directly about 5450. It says, perhaps, 11025. ‘How can that be?’ you would think. ‘We haven’t burned so much as that,’ and you haven’t—during this one quarter. But after the metre had been inspected at the end of the last quarter, the pointers did not go back to the beginning of the dials and start anew; they kept right on from the place where they were, so that 11025 is the amount you paid for last time and the amount you want to pay for this time, lumped together. Now this is what we do. We turn to our books and see how much you were charged with last time, and subtracting that record from the present record leaves the amount you have used since the last time of payment.

“Then suppose another case. Your metre registers only as far as 100,000. At the end of the last quarter it marked 97850; now it records but 3175. How would you explain that, master Philip?”

Philip looked puzzled a moment, and then said, 82

“I should think it must have finished out the hundred thousand and begun over again.”

“Exactly. And to find the amount for this quarter you would add together the remainder of the hundred thousand (2150) and the 3175, and get 5325, the real record. But I guess you’ve had arithmetic enough for the present, so we’ll go out now and see the gasometer, or gas reservoir.”

They all went out of doors then, papa, Mr. Carter, Philip and Kitty, across a narrow court-yard. There was a huge, round box, or drum, with sides as high as those of the carriage-house at home, but with no opening anywhere, “like a great giant’s bandbox,” thought Kitty. Four stout posts, much taller still than the “bandbox” itself, were set at equal distances around it, and their extremities were joined by stout beams which passed across over the top of the gasometer.

As the children went up nearer to it, they saw it was made of great plates of iron firmly riveted together, and that it did not rest on the ground, as they had supposed, but in the middle of a circular tank of water.

“After the gas has been made and purified and measured,” said Mr. Carter, “it is brought by underground pipes into this gasometer, and from here 83 drawn off by other pipes into the houses. The weight of this iron shell bearing down upon the gas, gives pressure or force enough to drive the gas anywhere we wish.”

“But why do you put the—the iron thing in water, instead of on the ground?” asked Kitty.

“So as to make it air-tight, and give it a chance to move freely up and down. Of course if the iron shell were empty its own weight would make it sink directly to the bottom of the water-tank and stay there. But gas, you know, is so much lighter than 84 common air that it always makes a very strong effort to rise higher and higher, carrying along whatever encloses it. You saw that illustrated in the balloon that went up last Fourth of July. Now, as the gas from the works pours into the reservoir from beneath, it is strong enough to lift the iron box up a little in the water. Of course that gives a little more room. Then as more gas comes in to take up this room, the gasometer keeps on rising slowly. We make sure of its not rising above the water and letting the gas leak out, by means of the beams you see stretched across above it. They are all ready to hold it down in a safe position if the need should come.

“On the other hand, as the people in town draw off the gas to burn, the gasometer would, of course, tend to sink down gradually. So we have the water-tanks made deep enough to allow for every possible necessity in that direction. In very cold weather we keep the water from freezing by passing a current of hot steam into it. If it should ever freeze, the gasometer might as well be on the ground, for it could not move up and down, or be trusted to keep the gas from leaking out around the edges. With these precautions, however, we know it is perfectly trustworthy.”

“I saw it one morning early, when I was out coasting on the hill,” said Philip, “and it wasn’t more than half as high as it is now.” 85

“A great deal had been drawn off during the night and we had not been making any more during the time to take its place.”

“Does it ever get burned out too much?”

“No, there’s no danger of it. We make enough to allow a good large margin above what we expect will be used.”

The children looked about a little longer, and then, with good-byes and many thanks to Mr. Carter, walked home again with papa, over the crisp, hard snow.

Next week Philip had a composition to write at school. He took “Gas” for his subject, and wrote:

“Gas that you burn is made out of soft coal. They put it in Ovens and cook it until it is not coal any longer. The Ovens are so hot you cant go anywhare near them but the men do With poles and big lether aprons. I would not like to shovle in the coal. I would rather have a Balloon. They use two or three tons every day. it makes coke and Tar and the gas that goes up the pipes. They make the gas clean and mesure it in a big box of water, and tell how much there is by looking at the clock faces in front. Then it goes into a big round box made of iron and then we burn it. but I do not like to smell of it. you must not blow it out for if you do you will get choked. This is all I Remember about gas.

“Philip Raymond Lawrence.”