Title: History, Manners, and Customs of the North American Indians

Author: Old Humphrey

Editor: Thomas O. Summers

Release date: September 22, 2008 [eBook #26688]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Irma Spehar and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

REVISED BY THOMAS O. SUMMERS, D.D.

Nashville, Tenn.:

SOUTHERN METHODIST PUBLISHING HOUSE.

1859.

This volume is one of a series of books from the ready and prolific pen of the late George Mogridge—better known by his nom de plume, “Old Humphrey.” Most of his works were written for the London Religious Tract Society, and were originally issued under the auspices of that excellent institution. In revising them for our catalogue, we have found it necessary to make scarcely any alterations. A “Memoir of Old Humphrey, with Gleanings from his Portfolio”—a charming biography—accompanies our edition of his most interesting works.

Every Sunday-school and Family Library should be supplied with the entertaining and useful productions of Old Humphrey’s versatile and sanctified genius.

T. O. SUMMERS.

Nashville, Tenn., Sept. 27, 1855.

The present volume is in substance a reprint from a work published by the London Religious Tract Society, and is, we believe, chiefly compiled from the works of our enterprising countryman, Catlin. It is rendered especially attractive by the spirited and impressive pictorial illustrations of Indian life and scenery with which it abounds.

Great changes have occurred in late years, in the circumstances and prospects of the Indian tribes, and neither their number nor condition can be ascertained with much accuracy. We have endeavoured to make the present edition as correct as possible, and have omitted some parts of the original work which seemed irrelevant, or not well authenticated. We have also made such changes in the phraseology as its republication in this country requires.

It was on a wild and gusty day, that Austin and Brian Edwards were returning home from a visit to their uncle, who lived at a distance of four or five miles from their father’s dwelling,[8] when the wind, which was already high, rose suddenly; and the heavens, which had for some hours been overclouded, grew darker, with every appearance of an approaching storm. Brian was for returning back; but to this Austin would by no means consent. Austin was twelve years of age, and Brian about two years younger. Their brother Basil, who was not with them, had hardly completed his sixth year.

The three brothers, though unlike in some things—for Austin was daring, Brian fearful, and Basil affectionate—very closely resembled each other in their love of books and wonderful relations. What one read, the other would read; and what one had learned, the other wished to know.

Louder and louder blew the wind, and darker grew the sky, and already had a distant flash and growling thunder announced the coming storm, when the two brothers arrived at the rocky eminence where, though the wood was above them, the river rolled nearly a hundred fathoms below. Some years before, a slip of ground had taken place at no great distance from the spot, when a mass of earth, amounting to well nigh half an acre, with the oak trees that grew upon it, slid down, all at once, towards the river. The rugged rent occasioned by the slip of earth, the great height of the road above the river, the rude rocks that here and there presented themselves, and the giant oaks of the wood frowning on the dangerous path, gave it a character at once highly picturesque and fearful. Austin, notwithstanding the[9] loud blustering of the wind, and the remonstrance of his brother to hasten on, made a momentary pause to enjoy the scene.

In a short time the two boys had approached the spot where a low, jutting rock of red sand-stone, around which the roots of a large tree were seen clinging, narrowed the path; so that there was only the space of a few feet between the base of the rock and an abrupt and fearful precipice.

Austin was looking down on the river, and Brian was holding his cap to prevent it being blown from his head, when, between the fitful blasts, a loud voice, or rather a cry, was heard. “Stop, boys, stop! come not a foot farther on peril of your lives!” Austin and Brian stood still, neither of them knowing whence came the cry, nor what was the danger that threatened them; they were, however, soon sensible of the latter, for the rushing winds swept through the wood with a louder roar, and, all at once, part of the red sand-stone rock gave way with the giant oak whose roots were wrapped round it, when the massy ruin, with a fearful crash, fell headlong across the path, and right over the precipice. Brian trembled with affright, and Austin turned pale. In another minute an active man, somewhat in years, was seen making his way over such parts of the fallen rock as had lodged on the precipice. It was he who had given the two brothers such timely notice of their danger, and thereby saved their lives.

Austin was about to thank him, but hardly had he began to speak, when the stranger stopped[10] him. “Thank God, my young friends,” said he with much emotion, “and not me; for we are all in his hands. It is his goodness that has preserved you.” In a little time the stranger had led Austin and Brian, talking kindly to them all the way, to his comfortable home, which was at no great distance from the bottom of the wood.

Scarcely had they seated themselves, when the storm came on in full fury. As flash after flash seemed to rend the dark clouds, the rain came down like a deluge, and the two boys were thankful to find themselves in so comfortable a shelter. Brian’s attention was all taken up with the storm while Austin was surprised to see the room all hung round with lances, bows and arrows, quivers, tomahawks, and other weapons of Indian warfare together with pouches, girdles, and garments of great beauty, such as he had never before seen. A sight so unexpected both astonished and pleased him, and made a deep impression on his mind.

It was some time before the storm had spent its rage, so that the two brothers had some pleasant conversation with the stranger, who talked to them cheerfully. He did not, however, fail to dwell much on the goodness of God in their preservation; nor did he omit to urge on them to read, on their return home, the first two verses of the forty-sixth Psalm, which he said might dispose them to look upwards with thankfulness and confidence. Austin and Brian left the stranger, truly grateful for the kindness which had been shown them; and the former felt determined[11] it should not be his fault, if he did not, before long, make another visit to the place.

When the boys arrived at home, they related, in glowing colours, and with breathless haste, the adventure which had befallen them. Brian dwelt on the black clouds, the vivid lightning, and the rolling thunder; while Austin described, with startling effect, the sudden cry which had arrested their steps near the narrow path, and the dreadful crash of the red sand-stone rock, when it broke over the precipice, with the big oak-tree that grew above it. “Had we not been stopped by the cry,” said he, “we must in another minute have been dashed to pieces.” He then, after recounting how kind the stranger had been to them, entered on the subject of the Indian weapons.

Though the stranger who had rendered the boys so important a service was dressed like a common farmer, there was that in his manner so superior to the station he occupied, that Austin, being ardent and somewhat romantic in his notions, and wrought upon by the Indian weapons and dresses he had seen, thought he must be some important person in disguise. This belief he intimated with considerable confidence, and assigned several good reasons in support of his opinion.

Brian reminded Austin of the two verses they were to read; and, when the Bible was produced, he read aloud, “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble. Therefore will not we fear, though the earth be removed, and[12] though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea.”

“Ah,” said Austin, “we had, indeed, a narrow escape; for if the mountains were not carried into the sea, the rock fell almost into the river.”

On the morrow, Mr. Edwards was early on his way, to offer his best thanks, with those of Mrs. Edwards, to the stranger who had saved the lives of his children. He met him at the door, and in an interview of half an hour Mr. Edwards learned that the stranger was the son of a fur trader; and that, after the death of his father, he had spent several years among the Indian tribes, resting in their wigwams, hunting with them, and dealing in furs; but that, having met with an injury in his dangerous calling, he had at last abandoned that mode of life. Being fond of solitude, he had resolved, having the means of following out his plans, to purchase a small estate, and a few sheep; he should then be employed in the open air, and doubted not that opportunities would occur, wherein he could make himself useful in the neighbourhood. There was, also, another motive that much influenced him in his plans. His mind had for some time been deeply impressed with divine things, and he yearned for that privacy and repose, which, while it would not prevent him from attending on God’s worship, would allow him freely to meditate on His holy word, which for some time had been the delight of his heart.

He told Mr. Edwards, that he had lived there for some months, and that, on entering the wood[13] the day before, close by the narrow path, he perceived by the swaying of the oak tree and moving of the sand-stone rock, that there was every probability of their falling: this had induced him to give that timely warning which had been the means, by the blessing of God, of preserving the young lads from their danger.

Mr. Edwards perceived, by his conversation and manners, that he was of respectable character; and some letters both from missionaries and ministers, addressed to the stranger, spoke loudly in favour of his piety. After offering him his best thanks, in a warm-hearted manner, and expressing freely the pleasure it would give him, if he could in any way act a neighbourly part in adding to his comfort, Mr. Edwards inquired if his children might be permitted to call at the house, to inspect the many curiosities that were there. This being readily assented to, Mr. Edwards took his departure with a very favourable impression of his new neighbour, with whom he had so unexpectedly been made acquainted.

Austin and Brian were, with some impatience, awaiting their father’s return, and when they knew that the stranger who had saved their lives had actually passed years among the Indians, on the prairies and in the woods: that he had slept in their wigwams; hunted beavers, bears, and buffaloes with them; shared in their games; heard their wild war-whoop, and witnessed their battles, their delight was unbounded. Austin took large credit for his penetration in discovering that their new friend was not a common shepherd,[14] and signified his intention of becoming thoroughly informed of all the manners and customs of the North American Indians.

Nothing could have been more agreeable to the young people than this unlooked-for addition to their enjoyment. They had heard of the Esquimaux, of Negroes, Malays, New Zealanders, Chinese, Turks, and Tartars; but very little of the North American Indians. It was generally agreed, as leave had been given them to call at the stranger’s, that the sooner they did it the better. Little Basil was to be of the party; and it would be a difficult thing to decide which of the three brothers looked forward to the proposed interview with the greatest pleasure.

Austin, Brian, and Basil, had at different times found abundant amusement in reading of parrots, humming birds, and cocoa nuts; lions, tigers, leopards, elephants, and the horned rhinoceros; monkeys, raccoons, opossums, and sloths; mosquitoes, lizards, snakes, and scaly crocodiles; but these were nothing in their estimation, compared with an account of Indians, bears, and buffaloes, from the mouth of one who had actually lived among them.

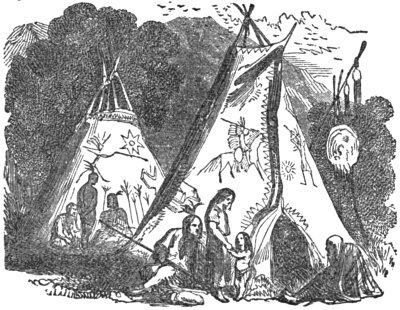

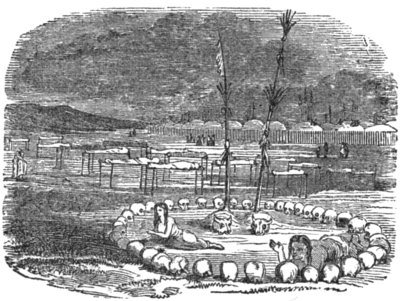

Indian Scenery.

Indian Scenery.

Austin Edwards was too ardent in his pursuits not to make the intended visit to the cottage near the wood the continued theme of his conversation with his brothers through the remainder of the day; and, when he retired to rest, in his dreams he was either wandering through the forest defenceless, having lost his tomahawk, or flying over the prairie on the back of a buffalo, amid the yelling of a thousand Indians.

The sun was bright in the skies when the three brothers set out on their anticipated excursion. Austin was loud in praise of their kind preserver, but he could not at all understand how any one, who had been a hunter of bears and buffaloes,[16] could quietly settle down to lead the life of a farmer; for his part, he would have remained a hunter for ever. Brian thought the hunter had acted a wise part in coming away from so many dangers; and little Basil, not being quite able to decide which of his two brothers was right, remained silent.

As the two elder brothers wished to show Basil the place where they stood when the oak tree and the red sand-stone rock fell over the precipice with a crash; and as Basil was equally desirous to visit the spot, they went up to it. Austin helped his little brother over the broken fragments which still lay scattered over the narrow path. It was a sight that would have impressed the mind of any one; and Brian looked up with awe to the remaining part of the rifted rock, above which the fallen oak tree had stood. Austin was very eloquent in his description of the sudden voice of the stranger, of the roaring wind as it rushed through the wood, and of the crashing tree and falling rock. Basil showed great astonishment; and they all descended from the commanding height, full of the fearful adventure of the preceding day.

When they were come within sight of the wood, Brian cried out that he could see the shepherd’s cottage; but Austin told him that he ought not to call the cottager a shepherd, but a hunter. It was true that he had a flock of sheep, but he kept them more to employ his time than to get a living by them. For many years he had lived among the Indians, and hunted buffaloes with them; he was,[17] therefore, to all intents and purposes, a buffalo hunter, and ought not to be called a shepherd. This important point being settled—Brian and Basil having agreed to call him, in future, a hunter, and not a shepherd—they walked on hastily to the cottage.

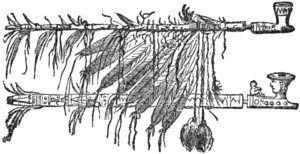

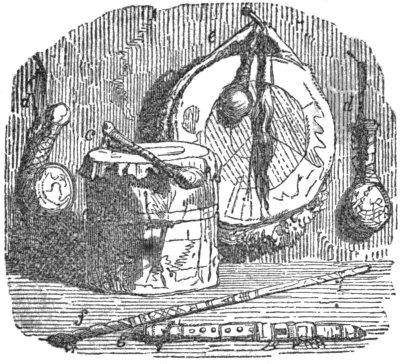

In five minutes after, the hunter was showing and explaining to his delighted young visitors the Indian curiosities which hung around the walls of his cottage, together with others which he kept with greater care. These latter were principally calumets, or peace-pipes; mocassins, or Indian shoes; war-eagle dresses, mantles, necklaces, shields, belts, pouches and war-clubs of superior workmanship. There was also an Indian cradle, and several rattles and musical instruments: these altogether afforded the young people wondrous entertainment. Austin wanted to know how the Indians used their war-clubs; Brian inquired how they smoked the peace-pipe; and little Basil was quite as anxious in his questions about a rattle, which he had taken up and was shaking to and fro. To all these inquiries the hunter gave satisfactory replies, with a promise to enter afterwards on a more full explanation.

In addition to these curiosities, the young people were shown a few specimens of different kinds of furs: as those of the beaver, ermine, sable, martin, fiery fox, black fox, silver fox, and squirrel. Austin wished to know all at once, where, and in what way these fur animals were caught; and, with this end in view, he contrived to get the hunter into conversation on the subject.[18] “I suppose,” said he, “that you know all about beavers, and martins, and foxes, and squirrels.”

Hunter. I ought to know something about them, having been in my time somewhat of a Voyageur, a Coureur des bois, a Trapper, and a Freeman; but you will hardly understand these terms without some little explanation.

Austin. What is a Coureur des bois?

Brian. What is a Voyageur?

Basil. I want to know what a Trapper is.

Hunter. Perhaps it will be better if I give you a short account of the way in which the furs of different animals are obtained, and then I can explain the terms, Voyageur, Coureur des bois, Trapper, and Freeman, as well as a few other things which you may like to know.

Brian. Yes, that will be the best way.

Austin. Please not to let it be a short account, but a long one. Begin at the very beginning, and go on to the very end.

Hunter. Well, we shall see. It has pleased God, as we read in the first chapter of the book of Genesis, to give man “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” The meaning of which is, no doubt, not that he may cruelly abuse them, but that he may use them for his wants and comforts, or destroy them when they annoy and injure him. The skins of animals have been used as clothing for thousands of years; and furs have become so general in dresses and ornaments, that, to obtain them, a regular trade[19] has long been carried on. In this traffic, the uncivilized inhabitants of cold countries exchange their furs for useful articles and comforts and luxuries, which are only to be obtained from warmer climes and civilized people.

Austin. And where do furs come from?

Hunter. Furs are usually obtained in cold countries. The ermine and the sable are procured in the northern parts of Europe and Asia; but most of the furs in use come from the northern region of our own country.

If you look at the map of North America, you will find that between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans the space is, in its greatest breath, more than three thousand miles; and, from north to south, the country stretches out, to say the least of it, a thousand miles still further. The principal rivers of North America are the Mackenzie, Missouri, Mississippi, Ohio, and St. Lawrence. The Mississippi is between three and four thousand miles long. Our country abounds with lakes, too: Ontario and Winipeg are each near two hundred miles long; Lakes Huron and Erie are between two and three hundred; Michigan is four hundred, and Lake Superior nearly five hundred miles long.

Brian. What a length for a lake! nearly five hundred miles! Why, it is more like a sea than a lake.

Hunter. Well, over a great part of the space that I have mentioned, furry animals abound; and different fur companies send those in their employ to boat up the river, to sail through the lakes, to[20] hunt wild animals, to trap beavers, and to trade with the various Indian tribes which are scattered throughout this extensive territory.

Austin. Oh! how I should like to hunt and to trade with the Indians!

Hunter. Better think the matter over a little before you set off on such an expedition. Are you ready to sail by ship, steam-boat, and canoe, to ride on horseback, or to trudge on foot, as the case may require; to swim across brooks and rivers; to wade through bogs, and swamps, and quagmires; to live for weeks on flesh, without bread or salt to it; to lie on the cold ground; to cook your own food; and to mend your own jacket and mocassins? Are you ready to endure hunger and thirst, heat and cold, rain and solitude? Have you patience to bear the stings of tormenting mosquitoes; and courage to defend your life against the grizzly bear, the buffalo, and the tomahawk of the red man, should he turn out to be an enemy?

Brian. No, no, Austin. You must not think of running into such dangers.

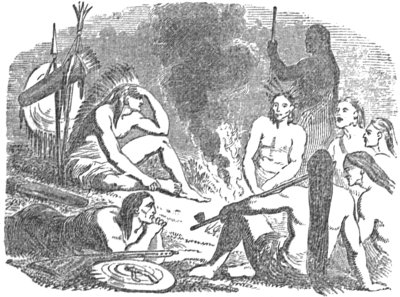

Hunter. I will now give you a short account of the fur trade. About two hundred years ago, or more, the French made a settlement in Canada, and they soon found such advantage in obtaining the furry skins of the various animals wandering in the woods and plains around them, that, after taking all they could themselves, they began to trade with the Indians, the original inhabitants of the country, who brought from great distances skins of various kinds. In a rude camp, formed[21] of the bark of trees, these red men assembled, seated themselves in half circles, smoked their pipes, made speeches, gave and received presents, and traded with the French people for their skins. The articles given in exchange to the Indian hunters, were knives, axes, arms, kettles, blankets, and cloth: the brighter the colour of the cloth, the better the Indians were pleased.

Austin. I think I can see them now.

Basil. Did they smoke such pipes as we have been looking at?

Hunter. Yes; for almost all the pipes used by the red men are made of red stone, dug out of the same quarry, called pipe-stone quarry; about which I will tell you some other time. One bad part of this trading system was, that the French gave the Indians but a small part of the value of their skins; and besides this they charged their own articles extravagantly high; and a still worse feature in the case was, that they supplied the Indians with spirituous liquors, and thus brought upon them all the evils and horrors of intemperance.

This system of obtaining furs was carried on for many years, when another practice sprang up. Such white men as had accompanied the Indians in hunting, and made themselves acquainted with the country, would paddle up the rivers in canoes, with a few arms and provisions, and hunt for themselves. They were absent sometimes for as much as a year, or a year and a half, and then returned with their canoes laden with rich furs. These white men were what I called Coureurs des bois, rangers of the woods.[22]

Austin. Ah! I should like to be a coureur des bois.

Hunter. Some of these coureurs des bois became very lawless and depraved in their habits, so that the French government enacted a law whereby no one, on pain of death, could trade in the interior of the country with the Indians, without a license. Military posts were also established, to protect the trade. In process of time, too, fur companies were established; and men, called Voyageurs, or canoe men, were employed, expressly to attend to the canoes carrying supplies up the rivers, or bringing back cargoes of furs.

Basil. Now we know what a Voyageur is.

Hunter. You would hardly know me, were you to see me dressed as a voyageur. Just think: I should have on a striped cotton shirt, cloth trousers, a loose coat made of a blanket, with perhaps leathern leggins, and deer-skin mocassins; and then I must not forget my coloured worsted belt, my knife and tobacco pouch.

Austin. What a figure you would cut! And yet, I dare say, such a dress is best for a voyageur.

Hunter. Most of the Canadian voyageurs were good-humoured, light-hearted men, who always sang a lively strain as they dipped their oars into the waters of the lake or rolling river; but steam-boats are now introduced, so that the voyageurs are but few.

Basil. What a pity! I like those voyageurs.

Hunter. The voyageurs, who were out for a long period, and navigated the interior of the[23] country, were called North-men, or Winterers, while the others had the name of Goers and Comers. Any part of a river where they could not row a laden canoe, on account of the rapid stream, they called a Décharge; and there the goods were taken from the boats, and carried on their shoulders, while others towed the canoes up the stream: but a fall of water, where they were obliged not only to carry the goods, but also to drag the canoes on land up to the higher level, they called a Portage.

Austin. We shall not forget the North-men, and Comers and Goers, nor the Décharges and Portages.

Basil. You have not told us what a Trapper is.

Hunter. A Trapper is a beaver hunter. Those who hunt beavers and other animals, for any of the fur companies, are called Trappers; but such as hunt for themselves take the name of Freemen.

Austin. Yes, I shall remember. Please to tell us how they hunt the beavers.

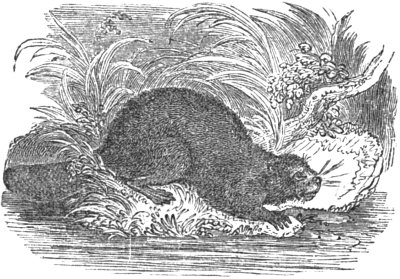

Hunter. Beavers build themselves houses on the banks of creeks or small rivers, with mud, sticks, and stones, and afterwards cover them over with a coat of mud, which becomes very hard. These houses are five or six feet thick at the top; and in one house four old beavers, and six or eight young ones, often live together. But, besides their houses, the beavers take care to have a number of holes in the banks, under water, called washes, into which they can run for shelter, should their houses be attacked. It is the business of the trappers to find out all these washes,[24] or holes; and this they do in winter, by knocking against the ice, and judging by the sound whether it is a hole. Over every hole they cut out a piece of ice, big enough to get at the beaver. No sooner is the beaver-house attacked, than the animals run into their holes, the entrances of which are directly blocked up with stakes. The trappers then either take them through the holes with their hands, or haul them out with hooks fastened to the end of a pole or stick.

Austin. But why is a beaver hunter called a trapper? I cannot understand that.

Hunter. Because beavers are caught in great numbers in steel traps, which are set and baited on purpose for them.

Brian. Why do they not catch them in the summer?

Hunter. The fur of the beaver is in its prime in the winter; in the summer, it is of inferior quality.[25]

Austin. Do the trappers catch many beavers? I should think there could not be very many of them.

Hunter. In one year, the Hudson’s Bay Company alone sold as many as sixty thousand beaver-skins; and it is not a very easy matter to take them, I can assure you.

Austin. Sixty thousand! I did not think there were so many beavers in the world.

Hunter. I will tell you an anecdote, by which you will see that hunters and trappers have need to be men of courage and activity. A trapper, of the name of Cannon, had just had the good fortune to kill a buffalo; and, as he was at a considerable distance from his camp, he cut out the tongue and some of the choice bits, made them into a parcel, and slinging them on his shoulders by a strap passed round his forehead, as the voyageurs carry packages of goods, set out on his way to the camp. In passing through a narrow ravine, he heard a noise behind him, and looking round, beheld, to his dismay, a grizzly bear in full pursuit, apparently attracted by the scent of the meat. Cannon had heard so much of the strength and ferocity of this fierce animal, that he never attempted to fire, but slipping the strap from his forehead, let go the buffalo meat, and ran for his life. The bear did not stop to regale himself with the game, but kept on after the hunter. He had nearly overtaken him, when Cannon reached a tree, and throwing down his rifle, climbed up into it. The next instant Bruin was at the foot of the tree, but as this species of[26] bear does not climb, he contented himself with turning the chase into a blockade. Night came on. In the darkness, Cannon could not perceive whether or not the enemy maintained his station; but his fears pictured him rigorously mounting guard. He passed the night, therefore, in the tree, a prey to dismal fancies. In the morning the bear was gone. Cannon warily descended the tree, picked up his gun, and made the best of his way back to the camp, without venturing to look after his buffalo-meat.

Austin. Then the grizzly bear did not hurt him, after all.

Brian. I would not go among those grizzly bears for all in the world.

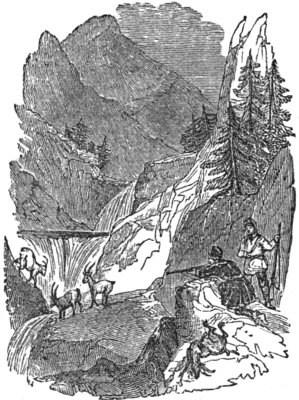

Austin. Do the hunters take deer as well as other animals?

Hunter. Deer, though their skins are not so valuable as many furs, are very useful to hunters and trappers; for they not only add to their stock of peltries, but also supply them with food. When skins have been tanned on the inside, they are called furs; but, before they are tanned, they are called peltries. Deer are trapped much in the same way as buffaloes are. A large circle is enclosed with twisted trees and brushwood, with a very narrow opening, in the neighbourhood of a well-frequented deer path. The inside of the circle is crowded with small hedges, in the openings of which are set snares of twisted thongs, made fast at one end to a neighbouring tree. Two lines of small trees are set up, branching off outwardly from the narrow entrance of the[27] circle; so that the further the lines of trees extend from the circle, the wider is the space between them. As soon as the deer are seen moving in the direction of the circle, the hunters get behind them, and urge them on by loud shouts. The deer, mistaking the lines of trees set up for enemies, fly straight forward, till they enter the snare prepared for them. The circle is then surrounded, to prevent their quitting it, while some of the hunters go into it, blocking up the entrance, and kill the deer with their bows and arrows, and their spears.

Basil. I am sorry for the poor deer.

Brian. And so am I, Basil.

Hunter. Hunters are often obliged to leave food in particular places, in case they should be destitute on their return that way. They sometimes, too, leave property behind them, and for this purpose they form a cache.

Austin. What is a cache?

Hunter. A cache is a hole, or place of concealment; and when any thing is put in it, great care is required to conceal it from enemies, and indeed from wild animals, such as wolves and bears.

Austin. Well! but if they dig a deep hole, and put the things in it, how could anybody find it? A wolf and a bear would never find it out.

Hunter. Perhaps not; unless they should smell it.

Austin. Ay! I forgot that. I must understand a little more of my business before I set up for a hunter, or a trapper; but please to tell us all about a cache.[28]

Hunter. A cache is usually dug near a stream, that the earth taken out of the hole may be thrown into the running water, otherwise it would tell tales. Then the hunters spread blankets, or what clothes they have, over the surrounding ground, to prevent the marks of their feet being seen. When they have dug the hole they line it with dry grass, and sticks, and bark, and sometimes with a dry skin. After the things to be hidden are put in, they are covered with another dry skin, and the hole is filled up with grass, stones, and sticks, and trodden down hard, to prevent the top from sinking afterwards: the place is sprinkled with water to take away the scent; and the turf, which was first cut away, before the hole was dug, is laid down with care, just as it was before it was touched. They then take up their blankets and clothes, and leave the cache, putting a mark at some distance, that when they come again they may know where to find it.

Austin. Capital! I could make a cache now, that neither bear, nor wolf, nor Indian could find.

Brian. But if the bear did not find the cache, he might find you; and then what would become of you?

Austin. Why I would climb a tree, as Cannon did.

Hunter. Most of the furs that are taken find their way to London; but every year the animals which produce them become fewer. Besides the skins of larger animals, the furs of a great number of smaller creatures are valuable; and these, varying in their habits, require to be taken in a different[29] manner. The bison is found on the prairies, or plains; the beaver, on creeks and rivers; the badger, the fox, and the rabbit, burrow in the ground; and the bear, the deer, the mink, the martin, the raccoon, the lynx, the hare, the musk-rat, the squirrel, and ermine, are all to be found in the woods. In paddling up the rivers in canoes, and in roaming through the woods and prairies, in search of these animals, I have mingled much with Indians of different tribes; and if you can, now and then, make a call on me, you will perhaps be entertained in hearing what I can tell you about them. The Indians should be regarded by us as brothers. We ought to feel interested in their welfare here, and in their happiness hereafter. The fact that we are living on lands once the residence of these roaming tribes, and that they have been driven far into the wilderness to make room for us, should lead us not only to feel sympathy for the poor Indians, but to make decided efforts for their improvement. Our missionary societies are aiming at this great object, but far greater efforts are necessary. We have the word of God, and Christian Sabbaths, and Christian ministers, and religious ordinances, in abundance, to direct and comfort us; but they are but scantily supplied with these advantages. Let us not forget to ask in our prayers, that the Father of mercies may make known his mercy to them, opening their eyes, and influencing their hearts, so that they may become true servants of the Lord Jesus Christ.

The delight visible in the sparkling eyes of the[30] young people, as they took their leave, spoke their thanks. On their way home, they talked of nothing else but fur companies, lakes, rivers, prairies, and rocky mountains; buffaloes, wolves, bears, and beavers; and it was quite as much as Brian and Basil could do, to persuade their brother Austin from making up his mind at once to be a voyageur, a coureur des bois, or a trapper. The more they were against it, so much the more his heart seemed set upon the enterprise; and the wilder they made the buffaloes that would attack him, and the bears and wolves that would tear him to pieces, the bolder and more courageous he became. However, though on this point they could not agree, they were all unanimous in their determination to make another visit the first opportunity.

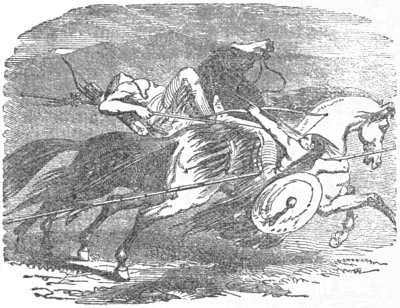

Indian Cloak.

Indian Cloak.

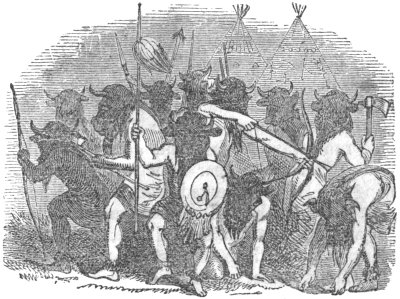

Chiefs of different Tribes.

Chiefs of different Tribes.

The next time the three brothers did not go to the red sand-stone rock, but the adventure which took place there formed a part of their conversation. They found the hunter at home, and, feeling now on very friendly and familiar terms with him, they entered at once on the subject that was nearest their hearts. “Tell us, if you please,” said Austin, as soon as they were seated, “about the very beginning of the red men.”

“You are asking me to do that,” replied the hunter, “which is much more difficult than you suppose. To account for the existence of the original inhabitants, and of the various tribes of Indians which are now scattered throughout the whole of North America, has puzzled the[32] heads of the wisest men for ages; and, even at the present day, though travellers have endeavoured to throw light on this subject, it still remains a mystery.”

Austin. But what is it that is so mysterious? What is it that wise men and travellers cannot make out?

Hunter. They cannot make out how it is, that the whole of America—taking in, as it does, some parts which are almost always covered with snow, and other parts that are as hot as the sun can make them—should be peopled with a class of human beings distinct from all others in the world—red men, who have black hair, and no beards. If you remember, it is said, in the first chapter of Genesis, “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.” And, in the second chapter, “And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed.” Now, it is known, by the names of the rivers which are mentioned in the chapter, that the garden of Eden was in Asia; so that you see our first parents, whence the whole of mankind have sprung, dwelt in Asia.

Austin. Yes, that is quite plain.

Hunter. Well, then, you recollect, I dare say, that when the world was drowned, all mankind were destroyed, except Noah and his family in the ark.

Brian. Yes; we recollect that very well.

Hunter. And when the ark rested, it rested on Mount Ararat, which is in Asia also. If you[33] look on the map of the world, you will see that the three continents, Europe, Asia, and Africa, are united together; but America stands by itself, with an ocean rolling on each side of it, thousands of miles broad. It is easy to suppose that mankind would spread over the continents that are close together, but difficult to account for their passing over the ocean, at a time when the arts of ship-building and navigation were so little understood.

Austin. They must have gone in a ship, that is certain.

Hunter. But suppose they did, how came it about that they should be so very different from all other men? America was only discovered about four hundred years ago, and then it was well peopled with red men. Besides, there have been discovered throughout our country, monuments, ruins, and sites of ancient towns, with thousands of enclosures and fortifications. Articles, too, of pottery, sculpture, glass, and copper, have been found at times, sixty or eighty feet under the ground, and, in some instances, with forests growing over them, so that they must have been very ancient. The people who built these fortifications and towers, and possessed these articles in pottery, sculpture, glass, and copper, lived at a remote period, and must have been, to a considerable degree, cultivated. Who these people were, and how they came to America, no one knows, though many have expressed their opinions. But, even if we did know who they were, how could we account for the present race[34] of Indians in North America being barbarous, when their ancestors were so highly civilized? These are difficulties which, as I said, have puzzled the wisest heads for ages.

Austin. What do wise men and travellers say about these things?

Hunter. Some think, that as the frozen regions of Asia, in one part, are so near the frozen regions of North America—it being only about forty miles across Behring’s Straits—some persons from Asia might have crossed over there, and peopled the country; or that North America might have once been joined to Asia, though it is not so now; or that, in ancient times, some persons might have drifted, or been blown there by accident, in boats or ships, across the wide ocean. Some think these people might have been Phenicians, Carthagenians, Hebrews, or Egyptians; while another class of reasoners suppose them to have been Hindoos, Chinese, Tartars, Malays, or others. It seems, however, to be God’s will often to humble the pride of his creatures, by baffling their conjectures, and hedging up their opinions with difficulties. His way is in the sea, and his path in the great waters, and his footsteps are not known. He “maketh the earth empty, and maketh it waste, and turneth it upside down, and scattereth abroad the inhabitants thereof.”

Austin. Well, if you cannot tell us of the Indians in former times, you can tell us of the Indians that there are, for that will be a great deal better.[35]

Brian. Yes, that it will.

Hunter. You must bear in mind, that some years have passed since I was hunting and trapping in the woods and prairies, and that many changes have taken place since then among the Indians. Some have been tomahawked by the hands of the stronger tribes; some have given up their lands to the whites, and retired to the west of the Mississippi; and thousands have been carried off by disease, which has made sad havoc among them. I must, therefore, speak of them as they were. Some of the tribes, since I left them, have been utterly destroyed; not one living creature among them being left to speak of those who have gone before them.

Austin. What a pity! They want some good doctors among them, and then diseases would not carry them off in that way.

Hunter. I will not pretend to give you an exact account of the number of the different tribes, or the particular places they now occupy; for though my information may be generally right, yet the changes which have taken place are many.

Austin. Please to tell us what you remember, and what you know; and that will quite satisfy us.

Hunter. A traveller[1] among the Indian tribes has published a book called “Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians;” and a most interesting and entertaining account it is. If ever you can lay hold of it, it will afford you great amusement. [36]Perhaps no man who has written on the Indians has seen so much of them as he has.

[1] Mr. Catlin

Brian. Did you ever meet Catlin?

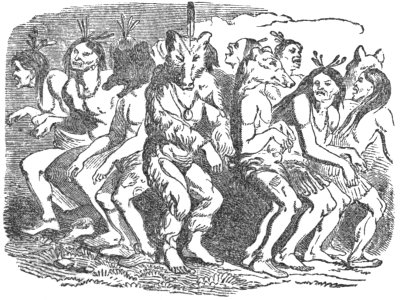

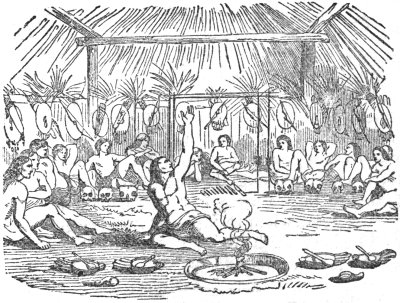

Hunter. O yes, many times; and a most agreeable companion I found him. He has lectured in most of our cities, and shown the beautiful collection of Indian dresses and curiosities collected during his visits to the remotest tribes. If you can get a sight of his book, you will soon see that he is a man of much knowledge, and possessing great courage, energy, and perseverance. I will now, then, begin my narrative; and if you can find pleasure in hearing a description of the Indians, with their villages, wigwams, war-whoops, and warriors; their manners, customs, and superstitions; their dress, ornaments, and arms; their mysteries, games, huntings, dances, war-councils, speeches, battles, and burials; with a fair sprinkling of prairie dogs, and wild horses; wolves, beavers, grizzly bears, and mad buffaloes; I will do my best to give you gratification.

Austin. These are the very things that we want to know.

Hunter. I shall not forget to tell you what the missionaries have done among the Indians; but that must be towards the latter end of my account. Let me first show you a complete table of the number and names of the tribes. It is in the Report made to Congress by the Commissioners of Indian Affairs for 1843-4.[37]

Statement showing the number of each tribe of Indians, whether natives of, or emigrants to, the country west of the Mississippi, with items of emigration and subsistence.

| Names of tribes. | Number of each tribe indigenous to the country west of the Mississippi. | Number removed of each tribe wholly or partially removed. | Present western population of each tribe wholly or partially removed. | Number remaining east of each tribe. | Number removed since date of last annual report. | Number of each now under subsistence west. | Daily expense of subsisting them. |

| Chippewas, Ottowas, and Pottawatomies, and Pottawatomies of Indiana | — | 5,779 | 2,298 | 92[a] | |||

| Creeks | — | 24,594 | 24,594 | 744 | |||

| Choctaws | — | 15,177 | 15,177 | 3,323 | |||

| Minatarees | 2,000 | ||||||

| Florida Indians | — | 3,824 | 3,824 | — | 212 | 212 | $7 68½ |

| Pagans | 30,000 | ||||||

| Cherokees | — | 25,911 | 25,911 | 1,000 | |||

| Assinaboins | — | 7,000 | |||||

| Swan Creek and Black River Chippewas | — | 62 | 62 | 113 | |||

| Appachees | 20,280 | ||||||

| Crees | 800 | [38] | |||||

| Ottowas and Chippewas, together with Chippewas of Michigan | — | — | — | 7,055 | |||

| Arrapahas | 2,500 | ||||||

| New York Indians | — | — | — | 3,293 | |||

| Gros Ventres | 3,300 | ||||||

| Chickasaws | — | 4,930 | 4,930 | 80[b] | 288[c] | 198[d] | 9 40½ |

| Eutaws | 19,200 | ||||||

| Stockbridges and Munsees, and Delawares and Munsees | — | 180 | 278 | 320 | |||

| Sioux | 25,000 | ||||||

| Quapaws | 476 | ||||||

| Iowas | 470 | ||||||

| Kickapoos | — | 588 | 505 | ||||

| Sacs and Foxes of Mississippi | 2,348[e] | ||||||

| Delawares | — | 826 | 1,059 | ||||

| Shawnees | — | 1,272 | 887 | ||||

| Sacs of Missouri | 414[e] | [39] | |||||

| Weas | — | 225 | 176 | 30 | |||

| Osages | 4,102 | ||||||

| Piankeshaws | — | 162 | 98 | ||||

| Kanzas | 1,588 | ||||||

| Peorias and Kaskaskias | — | 132 | 150 | ||||

| Omahas | 1,600 | ||||||

| Senecas from Sandusky | — | 251 | 251 | ||||

| Otoes and Missourias | 931 | ||||||

| Senecas and Shawnees | — | 211 | 211 | ||||

| Pawnees | 12,500 | ||||||

| Winnebagoes | — | 4,500 | 2,183 | ||||

| Camanches | 19,200 | ||||||

| Kiowas | 1,800 | ||||||

| Mandans | 300 | ||||||

| Crows | 4,000 | ||||||

| Wyandots of Ohio | — | 664 | — | 50[g] | 664 | ||

| Poncas | 800 | ||||||

| Miamies | — | — | — | 661 | |||

| Arickarees | 1,200 | ||||||

| Menomonies | — | — | — | 2,464 | |||

| Cheyenes | 2,000 | ||||||

| Chippewas of the Lakes | — | — | — | 2,564 | |||

| Blackfeet | 1,300 | ||||||

| Caddoes | 2,000 | ||||||

| Snakes | 1,000 | [40] | |||||

| Flatheads | 800 | ||||||

| Oneidas of Green Bay | — | — | — | 675 | |||

| Stockbridges of Green Bay | — | — | — | 207 | |||

| Wyandots of Michigan | — | — | — | 75 | |||

| Pottawatomies of Huron | — | — | — | 100 | |||

| 168,909 | 89,288 | 83,594 | 22,846 | 1,164 | 410 | 17 09 |

[a] These 92 are Ottowas of Maumee.

[b] This, as far as appears from any data in the office; but, in point of fact, there are most probably no, or very few, Chickasaws remaining east.

[c] In this number is included a party, assumed to be 100, who clandestinely removed themselves; but they are withheld from the next column, because, it is not yet known what arrangement has been made for their subsistence, though instructions on that subject have been addressed to the Choctaw agent.

[d] Ten of these emigrated as far back as January, 1842; but, as the number was so small, the arrangements for their subsistence were postponed until they could be included in some larger party, such as that which subsequently arrived.

[e] These Indians do not properly belong to this column, but are so disposed of because the table is without an exactly appropriate place for them. Originally, their haunts extended east of the river, and some of their possessions on this side are among the cessions by our Indians to the Government, but their tribes have ever since been gradually moving westward.

[g] This number is conjectural, but cannot be far from the truth, as Mr. McElvaine, the sub-agent, states that but 8 or 10 families still remain.[41]

Hunter. And now, place before you a map of North America. See how it stretches out north and south from Baffin’s Bay to the Gulf of Mexico, and east and west from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. What a wonderful work of the Almighty is the rolling deep! “The sea is His, and he made it: and his hands formed the dry land.” Here are the great Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario; and here run the mighty rivers, the Mississippi, the Missouri, the Ohio, and the St. Lawrence: the Mississippi itself is between three and four thousand miles long.

Basil. What a river! Please to tell us what are all those little hills running along there, one above another, from top to bottom.

Hunter. They are the Rocky Mountains. Some regard them as a continuation of the Andes of South America; so that, if both are put together, they will make a chain of mountains little short of nine thousand miles long. North America, with its mighty lakes, rivers, and mountains, its extended valleys and prairies, its bluffs, caverns, and cataracts, and, more than all, its Indian inhabitants, beavers, buffaloes, and bisons, will afford us something to talk of for some time to come; but the moment you are tired of my account, we will stop.

Austin. We shall never be tired; no, not if you go on telling us something every time we come, for a whole year. But do tell us, how did these tribes behave to you, when you were among them?[42]

Hunter. I have not a word of complaint to make. The Indians have been represented as treacherous, dishonest, reserved, and sour in their disposition; but, instead of this, I have found them generally, though not in all cases, frank, upright, hospitable, light-hearted, and friendly. Those who have seen Indians smarting under wrongs, and deprived, by deceit and force, of their lands, hunting-grounds, and the graves of their fathers, may have found them otherwise: and no wonder; the worm that is trodden on will writhe; and man, unrestrained by Divine grace, when treated with injustice and cruelty, will turn on his oppressor.

Austin. Say what you will, I like the Indians.

Hunter. That there is much of evil among Indians is certain; much of ignorance, unrestrained passions, cruelty, and revenge: but they have been misrepresented in many things. I had better tell you the names of some of the chiefs of the tribes, or of some of the most remarkable men among them.

Austin. Yes; you cannot do better. Tell us the names of all the chiefs, and the warriors, and the conjurors, and all about them.

Hunter. The Blackfeet Indians are a very warlike people; Stu-mick-o-súcks was the name of their chief.

Austin. Stu-mick-o-súcks! What a name! Is there any meaning in it?

Hunter. O yes. It means, “the back fat of the buffalo;” and if you had seen him and Peh-tó-pe-kiss, “the ribs of the eagle,” another chief[43] dressed up in their splendid mantles, buffaloes’ horns, ermine tails, and scalp-locks, you would not soon have turned your eyes from them.

Brian. Who would ever be called by such a name as that? The back fat of the buffalo!

Hunter. The Camanchees are famous on horseback. There is no tribe among the Indians that can come up to them, to my mind, in the management of a horse, and the use of the lance: they are capital hunters. The name of their chief is Eé-shah-kó-nee, or “the bow and quiver.” I hardly ever saw a larger man among the Indians than Ta-wáh-que-nah, the second chief in power. Ta-wáh-que-nah means “the mountain of rocks,” a very fit name for a huge Indian living near the Rocky Mountains. When I saw Kots-o-kó-ro-kó, or “the hair of the bull’s neck,” (who is, if I remember right, the third chief,) he had a gun in his right hand, and his warlike shield on his left arm.

Austin. If I go among the Indians, I shall stay a long time with the Camanchees; and then I shall, perhaps, become one of the most skilful horsemen, and one of the best hunters in the world.

Brian. And suppose you get thrown off your horse, or killed in hunting buffaloes, what shall you say to it then?

Austin. Oh, very little, if I get killed; but no fear of that. I shall mind what I am about. Tell us who is the head of the Sioux?

Hunter. When I was at the upper waters of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, Ha-wón-je-tah,[44] or “the one horn,” was chief; but since then, being out among the buffaloes, a buffalo bull attacked and killed him.

Basil. There, Austin! If an Indian chief was killed by a buffalo, what should you do among them? Why they would toss you over their heads like a shuttlecock.

Hunter. Wee-tá-ra-sha-ro, the head chief of the Pawnee Picts, is dead now, I dare say; for he was a very old, as well as a very venerable looking man. Many a buffalo hunt with the Camanchees had he in his day, and many a time did he go forth with them in their war-parties. He had a celebrated brave of the name of Ah′-sho-cole, or “rotten foot,” and another called Ah′-re-kah-na-có-chee, “the mad elk.” Indians give the name of brave to a warrior who has distinguished himself by feats of valour, such as admit him to their rank.

Brian. I wonder that they should choose such long names. It must be a hard matter to remember them.

Hunter. There were many famous men among the Sacs. Kee-o-kuk was the chief. Kee-o-kuk means “the running fox.” One of his boldest braves was Má-ka-tai-me-she-kiá-kiák, “the black hawk.” The history of this renowned warrior is very curious. It was taken down from his own lips, and has been published. If you should like to listen to the adventures of Black Hawk, I will relate them to you some day, when you have time to hear them, as well as those of young Nik-ka-no-chee, a Seminole.[45]

Austin. We will not forget to remind you of your promise. It will be capital to listen to these histories.

Hunter. When I saw Wa-sáw-me-saw, or “the roaring thunder,” the youngest son of Black Hawk, he was in captivity. Náh-se-ús-kuk, “the whirling thunder,” his eldest son, was a fine looking man, beautifully formed, with a spirit like that of a lion. There was a war called The Black Hawk war, and Black Hawk was the leader and conductor of it; and one of his most famous warriors was Wah-pe-kée-suck, or “white cloud;” he was, however, as often called The Prophet as the White Cloud. Pam-a-hó, “the swimmer;” Wah-pa-ko-lás-kak, “the track of the bear;” and Pash-ce-pa-hó, “the little stabbing chief;” were, I think, all three of them warriors of Black Hawk.

Basil. The Little Stabbing Chief! He must be a very dangerous fellow to go near, if we may judge by his name: keep away from him, Austin, if you go to the Sacs.

Austin. Oh! he would never think of stabbing me. I should behave well to all the tribes, and then I dare say they would all of them behave well to me. You have not said any thing of the Crow Indians.

Hunter. I forget who was at the head of the Crows, though I well remember several of the warriors among them. They were tall, well-proportioned, and dressed with a great deal of taste and care. Pa-ris-ka-roó-pa, called “the two crows,” had a head of hair that swept the ground after him as he walked along.[46]

Austin. What do you think of that, Basil? No doubt the Crows are fine fellows. Please to mention two or three more.

Hunter. Let me see; there was Eé-heé-a-duck-chée-a, or “he who binds his hair before;” and Hó-ra-to-ah, “a warrior;” and Chah-ee-chópes, “the four wolves;” the hair of these was as long as that of Pa-ris-ka-roó-pa. Though they were very tall, Eé-heé-a-duck-chée-a being at least six feet high, the hair of each of them reached and rested on the ground.

Austin. When I go among the Indians, the Crows shall not be forgotten by me. I shall have plenty to tell you of, Brian, when I come back.

Brian. Yes, if you ever do come back; but what with the sea, and the rivers, and the swamps, and the bears, and the buffaloes, you are sure to get killed. You will never tell us about the Crows, or about any thing else.

Hunter. There was one of the Crows called The Red Bear, or Duhk-pits-o-hó-shee.

Brian. Duhk-pitch a—Duck pits—I cannot pronounce the word—why that is worse to speak than any.

Austin. Hear me pronounce it then: Duhk-pits-o-hoot-shee. No; that is not quite right, but very near it.

Basil. You must not go among the Crows yet, Austin; you cannot talk well enough.

Hunter. Oh, there are much harder names among some of the tribes than those I have mentioned; for instance there is Aú-nah-kwet-to-hau-páy-o, “the one sitting in the clouds;” and[47] Eh-tohk-pay-she-peé-shah, “the black mocassin;” and Kay-ée-qua-da-kúm-ée-gish-kum, “he who tries the ground with his foot;” and Mah-to-rah-rish-nee-éeh-ée-rah, “the grizzly bear that runs without fear.”

Brian. Why these names are as long as from here to yonder. Set to work, Austin! set to work! For, if there are many such names as these among the Indians, you will have enough to do without going to a buffalo hunt.

Austin. I never dreamed that there were such names as those in the world.

Basil. Ay, you will have enough of them, Austin, if you go abroad. You will never be able to learn them, do what you will. Give it up, Austin; give it up at once.

Though Brian and Basil were very hard on Austin on their way home, about the long names of the Indians, and the impossibility of his ever being able to learn them by heart, Austin defended himself stoutly. “Very likely,” said he, “after all, they call these long names very short, just as we do; Nat for Nathaniel, Kit for Christopher, and Elic for Alexander.”

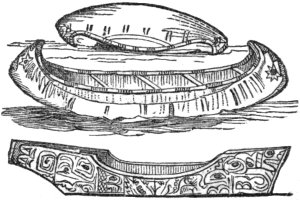

Wigwams.

Wigwams.

It was not long before Austin, Brian, and Basil were again listening to the interesting accounts given by their friend, the hunter; and it would have been a difficult point to decide whether the listeners or the narrator derived most pleasure from their occupation. Austin began without delay to speak of the aborigines of North America.

“We want to know,” said he, “a little more about what these people were, and when they were first found out.”

Hunter. When America was first discovered, the inhabitants, though for the most part partaking of one general character, were not without variety. The greater part, as I told you, were, both in hot[49] and cold latitudes, red men with black hair, and without beards. They, perhaps, might have been divided into four parts: the Mexicans and Peruvians, who were, to a considerable extent, civilized; the Caribs, who inhabited the fertile soil and luxuriant clime of the West Indies; the Esquimaux, who were then just the same people as they are now, living in the same manner by fishing; and the Red Men, or North American Indians.

Austin. Then the Esquimaux are not Red Indians.

Hunter. No; they are more like the people who live in Lapland, and in the North of Asia; and for this reason, and because the distance across Behring’s Straits is so short, it is thought they came from Asia, and are a part of the same people. The red men are, however, different; and as we agreed that I should tell you about the present race of them, perhaps I may as well proceed.

Austin. Yes. Please to tell us first of their wigwams, and their villages, and how they live.

Brian. And what they eat, and what clothes they wear.

Basil. And how they talk to one another.

Austin. Yes; and all about their spears and tomahawks.

Hunter. The wigwams of the Indians are of different kinds: some are extremely simple, being formed of high sticks or poles, covered with turf or the bark of trees; while others are very handsome. The Sioux, the Blackfeet, and the Crows,[50] form their wigwams nearly in the same manner; that is, by sewing together the skins of buffaloes, after properly dressing them, and making them into the form of a tent. This covering is then supported by poles. The tent has a hole at the top, to let out the smoke, and to let in the light.

Austin. Ay, that is a better way of making a wigwam than covering over sticks with turf.

Hunter. The wigwams, or lodges, of the Mandans are round. A circular foundation is dug about two feet deep; timbers six feet high are set up all around it, and on these are placed other long timbers, slanting inwards, and fastened together in the middle, like a tent, leaving space for light and for the smoke to pass. This tent-like roof is supported by beams and upright posts, and it is covered over outwardly by willow boughs and a thick coating of earth; then comes the last covering of hard tough clay. The sun bakes this, and long use makes it solid. The outside of a Mandan lodge is almost as useful as the inside; for there the people sit, stand, walk, and take the air. These lodges are forty, fifty, or sixty feet wide.

Brian. The Mandan wigwam is the best of all.

Hunter. Wigwams, like those of the Mandans, which are always in the same place, and are not intended to be removed, are more substantial than such as may be erected and taken down at pleasure. Some of the wigwams of the Crow Indians, covered as they are with skins dressed almost white, and ornamented with paint, porcupine quills and scalp-locks, are very beautiful.

Austin. Yes; they must look even better than[51] the Mandan lodges, and they can be taken down and carried away.

Hunter. It would surprise you to witness the manner in which an encampment of Crows or Sioux strike their tents or wigwams. I have seen several hundred lodges all standing; in two or three minutes after, all were flat upon the prairie.

Austin. Why, it must be like magic.

Hunter. The time has been fixed, preparations made, the signal given, and all at once the poles and skin coverings have been taken down.

Brian. How do they carry the wigwams away with them?

Hunter. The poles are dragged along by horses and by dogs; the smaller ends being fastened over their shoulders, while on the larger ends, dragging along the ground, are placed the coverings, rolled up together. The dogs pull along two poles, each with a load, while the horses are taxed according to their strength. Hundreds of horses and dogs, thus dragging their burdens, may be seen slowly moving over the prairie with attendant Indians on horseback, and women and girls on foot heavily laden.

Brian. What a sight! and to what length they must stretch out; such a number of them!

Hunter. Some of their villages are large, and fortified with two rows of high poles round them. A Pawnee Pict village on the Red River, with its five or six hundred beehive-like wigwams of poles, thatched with prairie grass, much pleased me. Round the village there were fields of maize, melons and pumpkins growing.[52]

The Indians hunt, fish, and some of them raise corn for food; but the flesh of the buffalo is what they most depend upon.

Austin. How do the Indians cook their food?

Hunter. They broil or roast meat and fish, by laying it on the fire, or on sticks raised above the fire. They boil meat, also, making of it a sort of soup. I have often seated myself, squatting down on a robe spread for me, to a fine joint of buffalo ribs, admirably roasted; with, perhaps, a pudding-like paste of the prairie turnip, flavoured with buffalo berries.

Austin. That is a great deal like an English dinner—roast beef and a pudding.

Hunter. The Indians eat a great deal of green corn, pemican, and marrow fat. The pemican is buffalo meat, dried hard, and pounded in a wooden mortar. Marrow fat is what is boiled out of buffalo bones; it is usually kept in bladders. They eat, also, the flesh of the deer and other animals: that of the dog is reserved for feasts and especial occasions. They have, also, beans and peas, peaches, melons and strawberries, pears, pumpkins, chinkapins, walnuts and chestnuts. These things they can get when settled in their villages; but when wandering, or on their war parties, they take up with what they can find. They never eat salt with their food.

Basil. And what kind of clothes do they wear?

Hunter. Principally skins, unless they trade with the whites, in which case they buy clothes of different kinds. Some wear long hair, some cut their hair off and shave the head. Some[53] dress themselves with very few ornaments, but others have very many. Shall I describe to you the full dress of Máh-to-tóh-pa, “the four bears.”

Austin. Oh, yes; every thing belonging to him.

Hunter. You must imagine, then, that he is standing up before you, while I describe him, and that he is not a little proud of his costly attire.

Austin. I fancy that I can see him now.

Hunter. His robe was the soft skin of a young buffalo bull. On one side was the fur; on the other, were pictured the victories he had won. His shirt, or tunic, was made of the skins of mountain sheep, ornamented with porcupine quills and paintings of his battles. From the edge of his shoulder-band hung the long black locks that he had taken with his own hand from his enemies. His head-dress was of war-eagle quills, falling down his back to his very feet; on the top of his head stood a pair of buffalo horns, shaven thin, and polished beautifully.

Brian. What a figure he must have made!

Hunter. His leggings were tight, decorated with porcupine quills and scalp-locks: they were made of the finest deer skins, and fastened to a belt round the waist. His mocassins, or shoes, were buckskin, embroidered in the richest manner; and his necklace, the skin of an otter, having on it fifty huge claws, or rather talons, of the grizzly bear.

Austin. What a desperate fellow! Bold as a lion, I will be bound for it. Had he no weapons about him?

Hunter. Oh, yes! He held in his left hand a[54] two-edged spear of polished steel, with a shaft of tough ash, and ornamented with tufts of war-eagle quills. His bow, beautifully white, was formed of bone, strengthened with the sinews of deer, drawn tight over the back of it; the bow-string was a three-fold twist of sinews. Seldom had its twang been heard, without an enemy or a buffalo falling to the earth; and rarely had that lance been urged home, without finding its way to some victim’s heart.

Austin. Yes; I thought he was a bold fellow.

Hunter. He had a costly shield of the hide of a buffalo, stiffened with glue and fringed round with eagle quills and antelope hoofs; and a quiver of panther skin, well filled with deadly shafts. Some of their points were flint, and some were steel, and most of them were stained with blood. He carried a pipe, a tobacco sack, a belt, and a medicine bag; and in his right hand he held a war club like a sling, being made of a round stone wrapped up in a raw hide and fastened to a tough stick handle.

Austin. What sort of a pipe was it?

Basil. What was in his tobacco sack?

Brian. You did not say what his belt was made of.

Hunter. His pipe was made of red pipe-stone, and it had a stem of young ash, full three feet long, braided with porcupine quills in the shape of animals and men. It was also ornamented with the beaks of woodpeckers, and hairs from the tail of the white buffalo. One thing I ought not to omit; on the lower half of the pipe, which[55] was painted red, were notched the snows, or years of his life. By this simple record of their lives, the red men of the forest and the prairie may be led to something like reflection.

Basil. What was in his tobacco sack?

Hunter. His flint and steel, for striking a light, and his tobacco, which was nothing more than the bark of the red willow. His medicine bag was beaver skin, adorned with ermine and hawks’ bills; and his belt, in which he carried his tomahawk and scalping-knife, was formed of tough buckskin, firmly fastened round his loins.

Austin. Please to tell us about the scalping knife. It must be a fearful instrument.

Hunter. All instruments of cruelty, vengeance and destruction are fearful, whether in savage or civilized life. What are we, that wrath and revenge and covetousness should be fostered in our hearts! What is man, that he should shed the blood of his brother! Before the Indians had dealing with the whites, they made their own weapons: their bows were strung with the sinews of deer; their arrows were headed with flint; their knives were sharpened bone; their war-clubs were formed of wood, cut into different shapes, and armed with sharp stones; and their tomahawks, or hatchets, were of the same materials: but now, many of their weapons, such as hatchets, spear-heads, and knives, are made of iron, being procured from the whites, in exchange for the skins they obtain in the chase. A scalping-knife is oftentimes no more than a rudely formed butcher’s[56] knife, with one edge, and the Indians wear them in beautiful scabbards under their belts.

Austin. How does an Indian scalp his enemy?

Hunter. The hair on the crown of the head is seized with the left hand; the knife makes a circle round it through the skin, and then the hair and skin together, sometimes with the hand, and sometimes with the teeth, are forcibly torn off! The scalp may be, perhaps, as broad as my hand.

Brian. Terrible! Scalping would be sure to kill a man, I suppose.

Hunter. Not always. Scalps are war trophies, and are generally regarded as proofs of the death of an enemy; but an Indian, inflamed with hatred and rage, and excited by victory, will not always wait till his foe has expired before he scalps him. The hair, as well as the scalp, of a fallen foe is carried off by the victorious Indian, and with it his clothes are afterwards ornamented. It is said, that, during the old French war, an Indian slew a Frenchman who wore a wig. The warrior stooped down, and seized the hair for the purpose of securing the scalp. To his great astonishment, the wig came off, leaving the head bare. The Indian held it up, and examining it with great wonder, exclaimed, in broken English, “Dat one big lie.”

Brian. How the Indian would stare!

Basil. He had never seen a wig before, I dare say.

Hunter. The arms of Indians, offensive and defensive, are, for the most part, those which I have mentioned—the club, the tomahawk, the bow[57] and arrow, the spear, the shield and the scalping-knife. But the use of fire-arms is gradually extending among them. Some of their clubs are merely massy pieces of hard, heavy wood, nicely fitted to the hand, with, perhaps, a piece of hard bone stuck in the head part; others are curiously carved into fanciful and uncouth shapes; while, occasionally, may be seen a frightful war-club, knobbed all over with brass nails, with a steel blade at the end of it, a span long.

Austin. What a terrible weapon, when wielded by a savage!

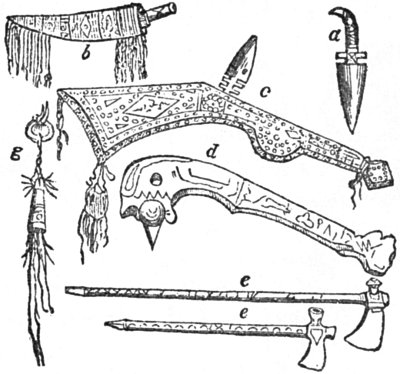

a, scalping-knife. b, ditto, in sheath. c, d, war-clubs.

e, e, tomahawks. g, whip.

a, scalping-knife. b, ditto, in sheath. c, d, war-clubs.

e, e, tomahawks. g, whip.

Brian. I would not go among the Indians, with their clubs and tomahawks, for a thousand dollars.

Basil. Nor would I: they would be sure to kill me.

Hunter. The tomahawk is often carved in a strange manner; and some of the bows and arrows[58] are admirable. The bow formed of bone and strong sinews is a deadly weapon; and some Indians have boasted of having sent an arrow from its strings right through the body of a buffalo.

Austin. What a strong arm that Indian must have had! Through a buffalo’s body!

Hunter. The quiver is made of the skin of the panther, or the otter; and some of the arrows it contains are usually poisoned.

Brian. Why, then, an arrow is sure to kill a person, if it hits him.

Hunter. It is not likely that an enemy, badly wounded with a poisoned arrow, will survive; for the head is set on loosely, in order that, when the arrow is withdrawn, the poisoned barb may remain in the wound. How opposed are these cruel stratagems of war to the precepts of the gospel of peace, which are “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you!”

Basil. What will you do, Austin, if you go among the Indians, and they shoot you with a poisoned arrow?

Austin. Oh, I shall carry a shield. You heard that the Indians carry shields.

Hunter. The shields of the Crows and Blackfeet are made of the thick skin of the buffalo’s neck: they are made as hard as possible, by smoking them, and by putting glue upon them obtained from the hoofs of animals; so that they will not only turn aside an arrow, but even a musket ball, if they are held a little obliquely.[59]

Austin. There, Basil! You see that I shall be safe, after all; for I shall carry a large shield, and the very hardest I can get anywhere.

Hunter. Their spears have long, slender handles, with steel heads: the handles are a dozen feet long, or more, and very skilful are they in the use of them; and yet, such is the dread of the Indian when opposed to a white man, that, in spite of his war horse and his eagle plumes, his bow and well-filled quiver, his long lance, tomahawk and scalping-knife, his self-possession forsakes him. He has heard, if not seen, what the white man has done; and he thinks there is no standing before him. If he can surprise him, he will; but, generally, the red man fears to grapple with a pale face in the strife of war, for he considers him clothed with an unknown power.

Austin. I should have thought that an Indian would be more than a match for a white man.

Hunter. So long as he can crawl in the grass or brushwood, and steal silently upon him by surprise, or send a shaft from his bow from behind a tree, or a bullet from his rifle from the brow of a bluff, he has an advantage; but, when he comes face to face with the white man, he is superstitiously afraid of him. The power of the white man, in war, is that of bravery and skill; the power of the red man consists much in stratagem and surprise. Fifty white men, armed, on an open plain, would beat off a hundred red men.

Brian. Why is it that the red men are always fighting against one another? They are all[60] brothers, and what is the use of their killing one another?

Hunter. Most of the battles, among the Indians, are brought about by the belief that they are bound to revenge an injury to their tribe. There can be no peace till revenge is taken; they are almost always retaliating one on another. Then, again, the red men have too often been tempted, bribed, and, in some cases, forced to fight for the white man.

Brian. That is very sad, though.

Hunter. It is sad; but when you say red men are brothers, are not white men brothers too? And have they not been instructed in the truths of Christianity, and the gospel of peace, which red men have not, and yet how ready they are to draw the sword! War springs from sinful passions; and until sin is subdued in the human heart, war will ever be congenial to it.

Austin. What do the Indians call the sun?

Hunter. The different tribes speak different languages, and therefore you must tell me which of them you mean.

Austin. Oh! I forgot that. Tell me what any two or three of the tribes call it.

Hunter. A Sioux calls it wee; a Mandan, menahka; a Tuscarora, hiday; and a Blackfoot, cristeque ahtose.

Austin. The Blackfoot is the hardest to remember. I should not like to learn that language.

Brian. But you must learn it, if you go among them; or else you will not understand a word they say.[61]

Austin. Well! I shall manage it somehow or other. Perhaps some of them may know English; or we may make motions one to another. What do they call the moon?

Hunter. A Blackfoot calls it coque ahtose; a Sioux, on wee; a Riccaree, wetah; a Mandan, esto menahka; and a Tuscarora, autsunyehaw.

Brian. I wish you joy of the languages you have to learn, Austin, if you become a wood-ranger, or a trapper. Remember, you must learn them all; and you will have quite enough to do, I warrant you.

Austin. Oh! I shall learn a little at a time. We cannot do every thing at once. What do the red men call a buffalo?

Hunter. In Riccaree, it is watash; in Mandan, ptemday; in Tuscarora, hohats; in Blackfoot, eneuh.

Basil. What different names they give them!

Hunter. Yes. In some instances they are alike, but generally they differ. If you were to say “How do you do?” as is the custom with us; you must say among the Indians, How ke che wa? Chee na e num? Dati youthay its? or, Tush hah thah mah kah hush? according to the language in which you spoke. I hardly think these languages would suit you so well as your own.

Brian. They would never suit me; but Austin must learn every word of them.

Austin. Please to tell us how to count ten, and then we will ask you no more about languages. Let it be in the language of the Riccarees.[62]

Hunter. Very well. Asco, pitco, tow wit, tchee tish, tchee hoo, tcha pis, to tcha pis, to tcha pis won, nah e ne won, nah en. I will just add, that weetah, is twenty; nahen tchee hoo, is fifty; nah en te tcha pis won, is eighty; shok tan, is a hundred; and sho tan tera hoo, is a thousand.

Austin. Can the Indians write?

Hunter. Oh no; they have no use for pen and ink, excepting some of the tribes near the whites. In many of the different treaties which have been made between the white and the red man, the latter has put, instead of his name, a rough drawing of the animal or thing after which he had been called. If the Indian chief was named “War hatchet,” he made a rough outline of a tomahawk. If his name was “The great buffalo” then the outline of a buffalo was his signature.

Basil. How curious!

Hunter. The Big turtle, the Fish, the Scalp, the Arrow, and the Big canoe, all draw the form represented by their names in the same manner. If you were to see these signatures, you would not think these Indian chiefs had ever taken lessons in drawing.

Brian. I dare say their fish, and arrows, and hatchets, and turtles, and buffaloes, are comical figures enough.

Hunter. Yes: but the hands that make these feeble scrawls are strong, when they wield the bow or the tomahawk. A white man in the Indian country, according to a story that is told, met a Shawnese riding a horse, which he recognised as his own, and claimed it as his property.[63] The Indian calmly answered: “Friend, after a little while I will call on you at your house, when we will talk this matter over.” A few days afterwards, the Indian came to the white man’s house, who insisted on having his horse restored to him. The other then told him: “Friend, the horse which you claim belonged to my uncle, who lately died; according to the Indian custom, I have become heir to all his property.” The white man not being satisfied, and renewing his demand, the Indian immediately took a coal from the fire-place, and made two striking figures on the door of the house; the one representing the white man taking the horse, and the other himself in the act of scalping him: then he coolly asked the trembling claimant whether he could read this Indian writing. The matter was thus settled at once, and the Indian rode off.

Austin. Ay; the white man knew that he had better give up the horse than be scalped.

After the hunter had told Austin and his brothers that he should be sure to have something new to tell them on their next visit, they took their departure, having quite enough to occupy their minds till they reached home.

“Black Hawk! Black Hawk!” cried out Austin Edwards, as he came in sight of the hunter, who was just returning to his cottage as Austin and his brothers reached it. “You promised to tell us all about Black Hawk, and we are come to hear it now.”