|

|

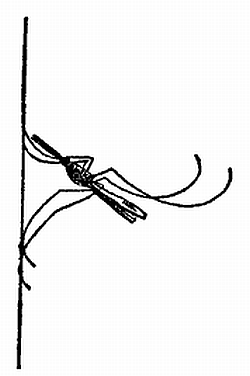

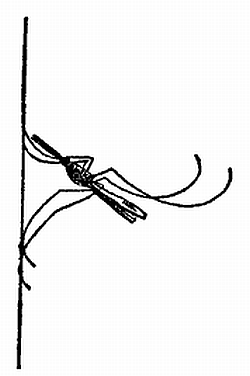

| Fig. 1. ANOPHELES. (Malarial Mosquito.) |

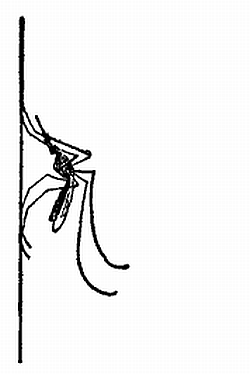

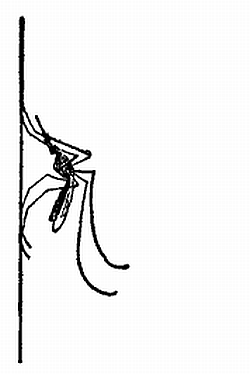

Fig. 2. CULEX. (Common Mosquito.) |

Title: Health on the Farm: A Manual of Rural Sanitation and Hygiene

Author: H. F. Harris

Release date: September 28, 2008 [eBook #26718]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tom Roch, Marcia Brooks and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images produced by Core Historical

Literature in Agriculture (CHLA), Cornell University)

Inconsistencies with regards to hyphenated words have been left as in the original. Inconsistencies in spelling and other unexpected spelling have been retained as in the original book.

From Kitchen to Garret. By Virginia Terhune Van de Water.

Neighborhood Entertainments. By Renée B. Stern, of the Congressional Library.

Home Water-works. By Carleton J. Lynde, Professor of Physics in Macdonald College, Quebec.

Animal Competitors. By Ernest Ingersoll.

Health on the Farm. By Dr. H. F. Harris, Secretary, Georgia State Board of Health.

Co-operation Among Farmers. By John Lee Coulter.

Roads, Paths and Bridges. By L. W. Page, Chief of the Office of Public Roads, U. S. Department of Agriculture.

Farm Management. By C. W. Pugsley, Professor of Agronomy and Farm Management in the University of Nebraska.

Electricity on the Farm. By Frederick M. Conlee.

The Farm Mechanic. By L. W. Chase, Professor of Farm Mechanics in the University of Nebraska.

The Satisfactions of Country Life. By Dr. James W. Robertson, Principal of Macdonald College, Quebec.

This is the day of the small book. There is much to be done. Time is short. Information is earnestly desired, but it is wanted in compact form, confined directly to the subject in view, authenticated by real knowledge, and, withal, gracefully delivered. It is to fulfill these conditions that the present series has been projected—to lend real assistance to those who are looking about for new tools and fresh ideas.

It is addressed especially to the man and woman at a distance from the libraries, exhibitions, and daily notes of progress, which are the main advantage, to a studious mind, of living in or near a large city. The editor has had in view, especially, the farmer and villager who is striving to make the life of himself and his family broader and brighter, as well as to increase his bank account; and it is therefore in the humane, rather than in a commercial direction, that the Library has been planned.

The average American little needs advice on the conduct of his farm or business; or, if he thinks he does, a large supply of such help in farming and trading as books and periodicals can give, is available to him. But many a man who is well to do and knows how to continue to make money, is ignorant how to spend it in a way to bring to himself, and confer upon his wife and children, those conveniences, comforts and niceties which alone make money worth acquiring and life worth living. He hardly realizes that they are within his reach.

For suggestion and guidance in this direction there is a real call, to which this series is an answer. It proposes to tell its readers how they can make work easier, health more secure, and the home more enjoyable and tenacious of the whole family. No evil in American rural life is so great as the tendency of the young people to leave the farm and the village. The only way to overcome this evil is to make rural life less hard and sordid; more comfortable and attractive. It is to the solving of that problem that these books are addressed. Their central idea is to show how country life may be made richer in interest, broader in its activities and its outlook, and sweeter to the taste.

To this end men and women who have given each a lifetime of study and thought to his or her specialty, will contribute to the Library, and it is safe to promise that each volume will join with its eminently practical information a still more valuable stimulation of thought.

Ernest Ingersoll.

Notwithstanding the extraordinary advances in a material way that have been accomplished in this country within the last few decades, it is a significant and most alarming fact that progress in hygienic matters has lagged far behind. Why this is, it would be very difficult to say,—for the reason that the causes are perhaps many. Chief among these, probably, is the fact that our progress along industrial lines has occupied the entire time of the majority of our best intellects, and it is also in no small degree the consequence of a fatalism that regards disease as a direct visitation of providence and therefore a thing which man may not avoid. Another cause in some instances is the[Pg 4] pride of our people in their homes and respective localities, which causes them to repel with indignation the suggestion that any special measures are necessary in order to conserve the public health where they reside. Ignorant as the average man is of the causes that produce sickness and the means by which this result is accomplished, he is naturally not in a position to form a correct judgment concerning such matters, and as a consequence, sees no reasons for taking the precautions that are necessary in order to ward off disease. This ignorance, it must be confessed with sorrow, is in a measure the fault of the medical profession, which has not in the vast majority of instances lived up to its ideals in this connection. Petty and unworthy rivalry has played an extremely important part in this failure of medical men to do their duty in this particular—none of the physicians of a community being, as a rule, willing that others should instruct the public, however vital this might be for the general good. As a consequence, that class of vultures known as medical quacks has furnished to the laity by far the greater proportion of their instruction[Pg 5] on hygienic subjects, with the result that the average man has a greater misconception and less real knowledge of such matters than of anything else in which he is vitally interested.

Another, and very curious explanation for our general disregard of the laws of health is that our strong belief in ourselves impels us to think that however much others may suffer from things generally regarded as unhygienic, we, ourselves, will be immune. This belief is fostered by the fact that in early life there often seems no end to our capacity to endure, and we find ourselves constantly defying without apparent harm, what we are told by others is directly contrary to all rules of proper living. But it is unfortunately true also that the reserve force and great power of resistance that enables us to do these things begins to wane towards the end of the third decade of life, and we, therefore, find ourselves sooner or later breaking down after we have become thoroughly convinced that we were made of iron, and that while other people might not be able to do as we were, it could not possibly result in evil in our own cases.[Pg 6]

What a pity it is that the young will not learn from the experience of those who have gone before them! Could they only do so, how much suffering and woe could be avoided in this world. Unfortunately, however, there are few men so constituted that they are willing to be guided by the experience of those who have preceded them, and there is but a faint possibility, therefore, that any good can be accomplished by warning the coming generation of the troubles in store for them should they not heed the advice of those who have suffered before them. Notwithstanding this, the writer feels that these words of warning should be spoken to the young, since they, alas, are the only ones to be benefited by such advice.

As you value your happiness materially, and as you desire a healthy old age and a long life, inform yourselves as to the few simple laws that govern human existence, and attempt so far as lies in your power to follow them. If you do not do this, disaster will follow as surely as the night follows the day.

Apathy of the Public as to Hygiene.—As a partial consequence, probably, of all the reasons[Pg 7] mentioned, along with others, there exists in the popular mind a curious apathy concerning hygienic matters—an apathy so great that it is scarcely possible to get the average man to discuss, much less to put in practice the all-important laws that govern health. As a result of the work of the various State boards of health and of the Public Health and Marine Hospital Service, this condition of affairs happily shows some signs of abatement, and we certainly have reasons to believe that the future promises great things along these lines. No sign of this change is more significant than the awakening of the press of the country to the vast importance of instructing the public in health matters, and their changed attitude toward the charlatans and quacks who live by promising the impossible. Largely subsidized by the infamous vendors of patent medicine, our newspapers and magazines still lend their columns to these human vampires who prey pre-eminently on the ignorance and credulity of the hopelessly-diseased poor; but within recent years some of our foremost journals show signs of an awakening of conscience, and a very few have[Pg 8] even gone so far as to exclude advertisements of this character altogether.

It has been said, certainly with more or less truth, that we are creatures of our surroundings, but whether we accept this in its broadest sense or not, there can be no question that our well being is most intimately connected with those things with which we come into every day contact. Nothing is more important for us to recognize than that our diseases are contracted from neighboring subjects just in proportion as we are closely associated with them. From our fellowmen we contract, as everyone knows, a large number of diseases, either by direct contact or by means of the air that surrounds us. From the earth we get hook-worms and other animal parasites, either by coming directly in contact with it or through eating uncooked fruits and vegetables. From water we get typhoid fever, dysentery, cholera, and many other parasitic diseases. From our food we likewise contract dangerous maladies such as tapeworms from uncooked meats and fish and the deadly trichina from raw hog meat. With decomposed breads we take the poisons that[Pg 9] produce pellagra, kak-ke, ergotism and acrodinia. From uncooked fruits and vegetables we get dysentery, typhoid fever, cholera, and parasitic diseases. Spoiled beans give us the deadly lathyrismus. From decomposed meat and fish we get ptomaine poisoning. Mosquitoes convey to us malaria, yellow fever and a parasite known as the filaria. The dreaded sleeping-sickness of Africa comes through the bites of a small fly; the bedbug is believed to be the means of conveying a frightful disease known as kala-azar, and the house-fly often brings to us the germs that produce typhoid fever, dysentery, and probably other diseases as well.

The bubonic plague, which is one of the most frightful diseases known, is conveyed to man by the rat and mouse.[1] Hydrophobia is usually contracted from the bite of the dog, and it is a well-known fact that this animal often harbors a minute tapeworm, a single egg of which, when swallowed by the human being, is often followed by death. Both dogs and cats probably[Pg 10] convey diphtheria, and both unquestionably often have within their intestinal tracts tapeworms that occasionally infect children. With the exception of the rare disease known as glanders, the horse is not believed to be directly responsible for any of the maladies from which the human being suffers, but it is well established that fully 95 per cent. of house-flies hatch in the manure of these animals, and they, therefore, become indirectly responsible for some of the most serious diseases affecting the human being. It is thus seen that almost every object with which man comes in intimate contact is capable of conveying to him the poison of one or more diseases. If it were possible for us to separate ourselves completely from everything with which we are ordinarily associated there can be no question that the span of human life would be greatly increased, and that death from bacterial and parasitic diseases generally would no longer occur. All this is said not with the object of startling the reader, but to warn him of the dangers that surround him on every hand, and to urge a recognition of that which can so materially prolong his[Pg 11] life. Fortunately these sources of infection may be almost entirely done away with by a few simple rules of life, and the health and longevity of mankind must necessarily be directly proportionate to the care with which we observe them.

It is now in order to discuss in detail the subject of personal hygiene.

[1] See the volume in this Library, Animal Competitors, by Ernest Ingersoll, for the agency of rats and mice in the introduction and dissemination of plague and other diseases; and the means of destroying these pests of the farm.

It is happily the case that in America the importance of personal cleanliness is more thoroughly understood, and is more generally practiced than any of the other important hygienic procedures. While it is true that there are many—particularly those of foreign extraction, and who live for the most part in the larger cities—to whom an occasional bath appeals only as a painful necessity, a very large percentage of those born in this country bathe regularly. It should be thoroughly understood that a daily bath is essential, not only from the standpoint of cleanliness, but from the fact that this practice is in the highest degree conducive to health. It should never be forgotten that by cleanliness infectious materials are removed from the surface of the body, and at the same time the skin is put into a condition to eliminate from the system those waste products[Pg 13] which it is its special function to remove. The close relationship of the proper activity of the skin to health is perhaps not generally sufficiently appreciated—for it is true that the body cannot remain normal when the secretory power of its glands is impaired, and that even death quickly follows when they cease to functionate altogether.

Advice as to Bathing.—Much difference of opinion exists as to the proper temperature of the water for bathing, some holding that it should be quite cold, while others are equally positive that it should be warm. Unfortunately it is impossible to give fixed rules concerning this somewhat important matter, for there is every reason to believe that it should be determined in each individual case according to circumstances, and that, therefore, both may be right. Some persons unquestionably do better with one, and some with the other. It has been established clearly that the cold bath is highly stimulating, and where not too prolonged, and when followed by vigorous rubbing, is undoubtedly healthful for a large number of people. The cold bath is often used by physicians[Pg 14] in the treatment of diseases of low vitality. Many persons however, are unpleasantly affected by bathing in water of a temperature much below that of the body; particularly is this true of women, and the like may be said of thin and nervous persons of the other sex. It is claimed by the advocates of the cold bath that those who practice this procedure daily are practically immune from colds, but this, certainly, is not always true; on the contrary the writer has seen instances where the cold bath has unquestionably led to chronic nasal catarrh, with increased tendency to inflammatory conditions of the air passages. It is also the case that baths of this description tend in some persons to prevent a normal accumulation of fat beneath the skin, and keep individuals of this kind unnaturally lean.

The warm bath is perhaps, on the whole, more popular than the cold, since it is preferred usually by children and women, and is practiced by a considerable proportion of adult males. It is unquestionably somewhat enervating, and at best fails entirely to give the agreeable stimulation experienced by those who take a[Pg 15] cold plunge. It is, however, to be preferred in those instances where cold water produces disagreeable effects, and if the bath be not too long continued it is followed by no ill results. Persons who become lean under cold baths not uncommonly take on flesh when they begin to use warm ones. It is unquestionably true that the latter is to be preferred in hot climates.

The sea bath is invigorating not only from the water being cool, but as a consequence of the pleasurable excitement with which it is attended. Its greatest disadvantage lies in the fact that there is a tendency to overdo it, many persons remaining in the water for hours. Ten or fifteen minutes is as long as the average person should indulge in sea-bathing, and it is a question if even those who are young and vigorous should remain in the water longer than half an hour.

Bathing of any kind should be indulged in before meals, the best time being before breakfast in the morning.

Care of the Teeth.—Nothing in connection with the subject of personal hygiene is of more importance than keeping the teeth properly[Pg 16] cleansed. The fact is not generally appreciated that sound teeth stand in a most intimate relationship with good health, and that disastrous consequences are sure to follow sooner or later where these most important structures are neglected.

While it is true that in a person of vigorous health one or two decayed teeth do not, as a rule, occasion obvious trouble at once, ill effects are sure sooner or later to be felt. For one thing, a person without good teeth cannot chew his food well. Those who begin by neglecting what at first are slight defects in the teeth seem to acquire in the course of time a sort of habit of doing this, and ultimately disregard and fail to have corrected the more serious diseases of the dental structures. Nothing is more common than for the practicing physician to find patients with one or more teeth partially gone, or, even worse, with only the exposed roots remaining.

Where cavities exist, food is constantly forced into them, and undergoing decomposition, the breath of their owner becomes foul, and portions of decayed food mixed with multitudes of[Pg 17] bacteria are constantly swallowed; sooner or later there inevitably follows under such circumstances catarrhal conditions of the stomach, which reaches a point in some individuals where the health is seriously threatened. Not only do bad teeth produce trouble in the way just mentioned, but there is every reason to believe that germs that produce disease—particularly those that cause consumption—not uncommonly find their way to the interior of the body through the resulting cavities.

It is the duty of everyone to properly cleanse the teeth at least once daily—to do so after each meal would be even still better. This should be done with a moderately soft brush, with which it is unnecessary to use tooth-powders or lotions—though many prefer to do so. Where something of the kind is desired, ordinary lime-water is perhaps as satisfactory as anything else; peroxide of hydrogen, diluted eight or ten times with water, to which a pinch or two of ordinary cooking soda has been added, undoubtedly aids the cleansing process, and has the advantage that it leaves a pleasant after-taste in the mouth. In brushing the teeth care[Pg 18] should be taken that every part of the tooth receives attention, it being not sufficient, as is so often done, merely to brush the front. It should be the practice of everyone to have the teeth looked over at least once a year by a good dentist, as even where cleansing is diligently performed decay frequently sets in on their inner sides.

The utmost care should be taken of the permanent teeth especially, and as long as it is possible to prevent it no one should be allowed to pull them. There can be no doubt that life is shortened by the early loss of the permanent teeth in most, if not in all, cases—not to count loss in health and happiness that follows their absence.

Clothing,—Material and Color.—Clothing will be considered in this article only as regards its function of properly protecting the body, which it does by preventing the escape of heat, thus keeping the body warm, or, under other circumstances, by keeping out excessive heat or cold.

Materials of which clothing is made differ very greatly in their ability to accomplish the[Pg 19] object just mentioned, some being comparatively poor conductors of heat and hence fulfill the desired function admirably, while others, for opposite reasons, are of comparatively little value for this purpose. In general it may be said that structures of animal origin, such as wool and silk, are much poorer heat conductors than those obtained from the vegetable world, and as a consequence the former are justly held in much higher esteem as material for clothing than the latter. It should not be forgotten, however, that the protective value of a fabric also depends upon the manner in which it is woven, since those that are loosely constructed are much warmer, other things being equal, than those that are put together more closely; this depends upon the fact that in the former there are innumerable small cavities between the fibers in which air is contained, and as this substance is a very poor conductor of heat, it follows that a garment made loosely and containing many such chambers is warmer than where the number is less. It may well be the case that a fabric constructed of a material which is a poor conductor of heat and closely woven[Pg 20] may be actually cooler than another composed of a substance which is a much better conductor of heat but of a loose texture.

The efficiency of different materials of which clothing is made also depends upon their capacity to absorb water. This may be done in two ways: the water may simply collect between the fibers, in which case it may be in a large measure removed by wringing, or it may be actually absorbed into the substance composing the fabric, and, as a consequence, the latter, even though containing much moisture, do not appear damp. Fabrics made from vegetable materials, as cotton or linen, have little power of actually absorbing water, and hence they become wet on the slightest addition of moisture, while on the other hand those of animal origin have the capacity of absorbing water, and appear dry even after the addition of this substance in considerable amounts. A person, therefore, dressed in cotton fabrics will find after active perspiration has begun that his clothing quickly becomes moist, while if he have on woolen garments this will not occur. It is particularly noteworthy that water is[Pg 21] gradually removed by evaporation from animal fabrics, which causes a general cooling without producing a chill; it is therefore readily understood that woolen clothing is much to be preferred where active exercise is being taken.

Color is also of some importance in determining the value of a fabric for protecting the body from the sun's heat. Within recent times we have learned a great deal respecting the wonderful penetrating power of the invisible light rays, and we have every reason to believe that these modify to a very considerable degree every process going on within the body. The violet and ultra-violet rays are those that unquestionably exert most influence, and it has been suggested that they may be broken up and rendered innocuous by covering the body with materials having a reddish-yellow color. It is not necessary to put these materials on the outside where they would be conspicuous, but they may be used as lining for hats and clothing; and there are good reasons to believe that if their use were generally adopted suffering and actual loss of life from overheating would be greatly reduced, particularly in warm countries.[Pg 22]

Work and Rest.—Very slowly the people of our country are beginning to realize that it is quite as necessary to rest as to work, though unfortunately in some quarters a strenuous life is urged as being only secondary in importance to possessing a big family; that there is an intimate association between the two there can be no doubt, since the latter beyond peradventure would entail the former. It has ever been the habit and misfortune of sages now and then to desert the field of their own peculiar activities and to make incursions into unknown regions—generally giving advice with a dogmatism and finality proportionate to their ignorance of the subject under discussion.

As a matter of fact the average American works entirely too much, and while he sometimes accumulates an immense fortune with astounding rapidity, to his sorrow he often learns later that he has likewise acquired a damaged heart, premature thickening of his blood-vessels or nervous dyspepsia with all of its attendant evils. Descended as we are in a large measure from the most vigorous and adventurous Europeans of the last few centuries, and coming into[Pg 23] possession of a new world where everything was to be done, this tendency to overwork is most natural,—and for this reason is all the more to be combated. That we have been able so successfully to carry the burden for several generations is indeed remarkable, but there are not wanting numerous indications that the strain is beginning to tell. If we do not call a halt, and devote more time to rest and agreeable pastimes, disastrous consequences are sure to follow, and we will become in the course of time a race of neurasthenics and degenerates. Attention should likewise be directed to the fact that men do not develop to the highest point of mentality who devote their entire time to work, as leisure is absolutely essential for thought and the development of all that is best in man.

Let us then cast aside the shallow and ignorant preachments of those who do not understand the subject, and devote a reasonable time to the reading of good books, to thought, to the cultivation of the arts and sciences, and to pleasurable pastimes. In these particulars we are far behind Europe, and we shall never take[Pg 24] our place as an intellectual people until we radically change our method of life. A nation must dream before becoming great. Let it not be understood from the foregoing that the writer would in the slightest degree minimize the necessity for a reasonable amount of work, for he thoroughly appreciates that without labor neither the individual nor the nation itself could remain sound—it is only urged that excessive work is quite as much to be feared as none at all.

Health and Labor.—As to the number of hours that should be devoted to labor no rule can be laid down. It all depends on the age, physical and mental vigor of the individual, and likewise, to a considerable degree, on the character of the work. Occupations requiring intense mental or physical strain can only be kept up for short periods of continuous application, while, on the other hand, quite naturally, those of a less strenuous nature would permit longer hours. The young man, in pride of perfect bodily and mental vigor, too often assumes, because he has been able in the past to do pretty much anything that pleased him without ill-effect,[Pg 25] that he can continue to do the same through life. No greater mistake could be made.

Anything that has a tendency to undermine the health, repeated sufficiently often, will ultimately cause a complete breakdown. How often do we see the strength and beauty of early manhood blighted and turned to premature old age and death as a consequence of disregarding the warnings that have just been given! How frequently do we observe young men rejoicing in the emancipation from home and school and spurred on by the fatal delusion that while others might suffer they will not, becoming in the end the victim of that arch enemy of early manhood, consumption! Every practicing doctor has seen this, not once, but hundreds of times, and in the vast majority of instances he can say with truth that the frightful result is a consequence of overwork—too often associated with nocturnal dissipation. The man who works during the day, and devotes his nights to alcohol and gay company when he should be sleeping, will assuredly, sooner or later—and usually sooner—suffer the inevitable consequences.[Pg 26]

To those who live sedentary lives, active out-door exercise is very essential, but inasmuch as this little volume is being written for those who live a saner and more healthful existence, it is not deemed necessary to discuss here this phase of the subject.

Value of Sleep.—Closely connected with the subject just discussed is sleep. Here also we have no rules, or laws, from which we can clearly determine the amount required in individual cases. Overwise philosophers have asserted that seven hours for a man, eight hours for a woman, and nine hours for a fool, was the allotted time for sleep. As a matter of fact, the necessity for repose varies greatly in different individuals, some of them requiring less while others demand more. It is a safe rule to follow that every man should sleep as long as he naturally desires, for nature is a much better mentor than any man could be—however learned. The majority of men require at least eight hours of sleep for the day and night, and this should be secured if possible at such a time as will permit it to be undisturbed; hence it is that man usually prefers to sleep at night, and,[Pg 27] all things considered, it is probably the time best suited for his repose. We read many marvelous stories of certain great men who required little or no sleep. Within recent years the press has frequently contained articles recounting the extraordinary fact that a certain prominent inventor of this country lived daily on a mere spoonful or so of food, and only slept a few hours now and then when there was nothing else particularly to do. Such stories should be accepted only on absolute proof, as, irrespective of their utter improbability, one may observe that they are generally insisted upon in and out of season with a pertinacity that would indicate that they were conceived and are scattered abroad with the sole idea of impressing the general public with what a marvelous and unusual person the individual in question is. There can be no reasonable doubt that they are merely evidences of childish vanity and puerile mendacity, and are only referred to here for the reason that young persons, ignorant of the laws of health, might attempt to emulate them, with results that could be but disastrous. Nothing so preserves youth, health,[Pg 28] and good looks as a sufficient amount of sleep, and it is pre-eminently the secret of long life.

Reference will be made in the chapter on the Hygiene of Infancy to the necessity of children sleeping as much as is possible. It will do no harm to say again here that nothing is so essential for the proper development of the body as sleep, and that it is absolutely a crime to awaken a child except under circumstances of absolute necessity.

Precautions in Respect to Eating.—A sufficient amount of sleep, and a proper quantity of digestible and nutritious food, thoroughly cooked and carefully masticated, are the things which above all others are most important for the maintenance of health. In the chapter on Foods, the nutritive values and digestibility of the various articles eaten by man will be discussed with sufficient thoroughness to instruct the reader as to a wholesome dietary; it is, therefore, not necessary here to go into the matter fully, but the subject is so important that a few general remarks will not be out of place.

Eating should never, so far as is possible, be hurried. Nothing is more important for the[Pg 29] proper digestion of food than its thorough mastication, and this can only be accomplished when sufficient time is allowed for eating. It is not necessary that this be done to the extreme advocated by some, but it is certainly of the highest importance that the food be so thoroughly chewed that it is reduced to fine particles, and that it should be so soaked in saliva that it may be swallowed without the aid of liquids of any kind.

It is also desirable that food should not be taken while the individual is tired, so that it is a good plan where this condition exists for one to lie down for a short time before eating.

Regularity in eating is likewise of importance, it being best to take the meals at stated periods; the consumption of food at irregular hours often leads to indigestion and is a practice which should not be indulged in.

It is highly desirable to have food served under agreeable circumstances, digestion being accomplished in a much more satisfactory manner if pleasant conversation be indulged in during the meal, and if the food be of an appetizing character. Nothing is of more importance[Pg 30] in connection with this subject than to have the food properly prepared. Not only is thorough cooking important from the standpoint of making foods digestible, but as is shown in another part of this volume, grave and sometimes fatal diseases are contracted by a neglect of this important procedure.

Fruits, contrary to what is generally thought, contain but little nourishment, and severely tax the digestive powers of those who have a tendency to dyspepsia. When eaten at all, they should be perfectly ripe and fresh, and should always be taken after meals rather than before.

Drinks,—Coffee, Tea, Milk, etc.—Much misconception exists, among people generally, and even among the medical profession, concerning the proper amount of water that should be drunk. While this substance is unquestionably the most wholesome of all drinks, there exists no necessity for taking it in great quantities at times when the system does not call for it. It would perhaps be a good rule for all to form the habit of drinking little while eating, the reason for which will be explained hereafter.

Coffee is exceedingly popular both on account[Pg 31] of its delicious odor and taste when properly made, and for the reason that it is highly stimulating. While it is borne by young and vigorous persons of either sex with apparent impunity, there frequently comes a time in life when it can no longer be drunk without ill effects. As a general rule, dyspeptics do not bear it well.

Tea, if properly prepared, is a most palatable beverage, and one that is generally better borne than coffee. It is more wholesome when taken without lemon juice, and like coffee it is less disposed to produce trouble if largely diluted with milk, or if taken without cream or sugar.

Cocoa and chocolate are often used as substitutes for tea or coffee, and where they agree with the individual are perhaps as wholesome as either. Both, however, contain considerable quantities of fat, and as they are frequently prepared with cream, or very rich milk, they are not as a rule well borne.

While milk might be considered as being almost as much a food as a drink still the fact that it is fluid, and that it contains a very large percentage of water, causes it to be regarded[Pg 32] as a beverage. When taken slowly—and this precaution is particularly necessary where it is fresh and sweet—milk is a drink that should be regarded as being on a par with water. It contains no injurious substances, but sour milk should, as a rule, be avoided by dyspeptics.

The cardinal principle in taking beverages of any kind at mealtime is that they should be drunk alone after the food has been swallowed, as when they are taken with the purpose of softening the latter, mastication is seriously interfered with and the proper soaking of the food in the saliva prevented.

Alcoholic Beverages.—Alcoholic drinks are so fully discussed in a latter part of this book that here it may merely be stated that they cannot be regarded as having food-value to any degree, and so far as the matter is at present understood, appear to be entirely superfluous, and even positively injurious. If taken at all, they should be consumed in extreme moderation, after meals rather than before. The young especially should be particularly warned against the use of all beverages of this class.

A Word on “Soft Drinks.”—Mention should[Pg 33] also be made of those drinks commonly sold at soda-fountains. The vast majority of them may be taken occasionally without any appreciable ill effects, but the habitual use of beverages containing considerable quantities of syrup is not entirely wholesome. Particularly is this true where the drink contains stimulating drugs, such as do some of those most advertised. Some of them are, if no worse, the equivalent of a strong cup of coffee, and should, therefore, no more be taken every hour or two during the day than a cup of the substance just mentioned. If their use is persisted in, it is sure to be followed by indigestion, and in many instances nervous disorders of even a serious character. The reader should also be warned against the use of drinks containing medicine for the relief of pain—particularly those that are advertised as remedies for headache. Practically without exception, all such drinks contain coal-tar preparations that greatly depress the heart, and have in a number of instances been followed by death. Drugs of this character should be taken with the utmost circumspection, and only on the prescription of a competent physician.[Pg 34]

Tobacco.—Tobacco, of all nerve sedatives, is the most universally used. In moderation it could not be said that it is followed by any apparent ill effects in the majority of people, but if used in excess oftentimes sets up serious disturbances. It is peculiarly injurious to boys, and should never be indulged in until manhood is reached. Some persons seem to possess a natural immunity to the ill effects of nicotine, and appear to be able throughout their lives to chew or smoke tobacco in any amount without harmful results; such instances are, however, rare—its excessive use being usually followed by symptoms that may be of a serious nature. Of the two methods of use perhaps smoking is less open to objection, though it is unquestionably true that chewing is not so apt to cause disturbances of the heart. Smoking affects the stomach, but not to the extent that chewing does.

The bearing of intelligently located houses of proper construction on health is not so generally understood, even by physicians, as the facts warrant, and, of course, is even less well recognized by the non-medical public. It is true that some attention has been given to the matter of location, but even in this connection there prevails a woful ignorance among all classes as to just how the diseases are transmitted that are most influenced in this way. As a result of recent advances in medicine it has been clearly shown that at least some of the diseases that are most influenced by locality may be easily avoided, and as a consequence we find that the views of the modern sanitarians have necessarily undergone a certain amount of change in this direction. On the other hand recognition of the necessity of hygienic construction[Pg 36] has not been sufficiently accentuated,—since it is possible by proper attention to the details of building to do away entirely with at least two of the diseases that have heretofore been the principal drawbacks to life in all tropical and sub-tropical countries. Much importance likewise attaches to houses being thoroughly ventilated, and to their being sufficiently roomy to properly accommodate their inmates. The following table shows the striking relationship that mortality bears to over-crowding:—

| City. | Mean number of inhabitants to each house. | Average death-rate per 1,000 inhabitants. |

| London | 8 | 24 |

| Berlin | 32 | 25 |

| Paris | 35 | 28 |

| St. Petersburg | 52 | 41 |

| Vienna | 55 | 47 |

Many other statistics could be quoted, but all follow the general trend of those just given.

Choice of Site.—In our rural districts the inhabitants have a wide latitude in the matter of the selection of the location for their houses,[Pg 37] and it is usually the case that our people are sufficiently intelligent to make the best use of their opportunities in this direction. It may, however, be mentioned that it is generally considered that building-sites in the neighborhood of cemeteries are not favorable locations, nor should houses be erected in the vicinity of a manufacturing plant that gives off injurious gases, or obnoxious materials of other kinds. Inasmuch as we now know that malaria is transmitted by a certain mosquito, and that by properly screening the house their attacks may be avoided, the necessity no longer exists for avoiding the vicinity of lakes and rivers as building-sites; such localities being as a rule pleasant and often picturesque, they would naturally under ordinary circumstances be selected, and there now remains no reason why this may not be done,—provided that the house is so constructed that mosquitoes can be effectually prevented from gaining entrance.

Of much importance is the selection of a locality where good and pure water can be easily procured, as otherwise disastrous consequences are sure to follow.[Pg 38]

The soil should be of a light and porous character, easily permeable by water, and free from the decomposing remains of excretions of man or animals. There is much reason for the belief also that the level of the ground-water plays a somewhat important part in the salubrity of any given locality, and it is generally considered that this should be at least ten feet below the surface. It is generally thought, and probably with truth, that those sites are most healthful which have their location on a basis of granite, or other rock-foundation; in such localities there is usually a considerable slope of the general surface of the ground, with the result that water rapidly runs off after rains, and consequently stagnant pools, which might serve as a breeding place for mosquitoes and bacteria, do not form. Soils through which water easily permeates are likewise, as a rule, healthy, though this depends in a measure upon whether or not they contain a very considerable proportion of vegetable matter. Clay foundations are healthful where there is a considerable slope to the surface of the ground, but where this does not exist the soil is damp, owing[Pg 39] to its impermeability, and often has stagnant pools upon its surface. Marls and alluvial soils are not regarded as being wholesome, but it is not unlikely that their bad reputation is largely due to the fact that they generally exist in the neighborhood of rivers and other considerable bodies of water where mosquitoes are numerous. There are no reasons going to show that cultivated lands are unhealthy—even where they receive yearly abundant additions of manure. Where it is necessary to build in damp localities the site should be thoroughly drained, and the space upon which the house is constructed should be carefully covered with some impermeable cement.

Building Materials.—Of all building materials, the one most commonly employed in America is wood. This arises from the fact that in the past we have had unlimited quantities of timber from which lumber could be procured at a price so reasonable that no other material could ordinarily be considered. That the wooden house has some advantages cannot be denied; its walls rapidly cool following the torrid days that so commonly occur during the[Pg 40] summer in almost all portions of the United States, and it is usually well ventilated as a result of the numerous fissures naturally existing in its structure.

Next to wood, bricks are most commonly used for building purposes, and have many advantages, among which are their handsome effect, their stability, and their being poor conductors of heat; the last mentioned is of considerable importance, since it keeps both heat and frost from rapidly permeating the interior, and as a consequence houses constructed of this material are cooler in summer and warmer in winter.

Other materials occasionally used are concrete, granite, marble, and sandstone, any of which, on account of their durable character and the beauty that they lend to structures made from them, may be selected for building purposes, but inasmuch as they are rarely used in rural districts, a detailed consideration of their peculiar advantages for building purposes is not deemed here necessary.

The internal wall-coating of houses deserves more consideration than is commonly accorded it, since the dyes used for coloring wall-paper[Pg 41] and curtains in some instances contain noxious materials. Chief among those that are dangerous are the bright green pigments which commonly contain arsenic as their principal constituent; where these or other poisonous substances are employed in interior decorations the air, wherever the room is kept closed, may become more or less impregnated with poisonous gases, and serious consequences to the inmates may ensue.

Screening Indispensable to Health.—Nothing is more important in connection with house construction than having every opening thoroughly screened. We have learned that both malaria and yellow fever are transmitted always by certain kinds of mosquitoes, and it therefore, becomes a matter of the greatest importance to effectually prevent the entrance of these insects. It cannot be too strongly insisted upon that we absolutely know that the statement just made is correct, and that avoiding the diseases referred to becomes as a consequence entirely a matter of preventing the entrance of mosquitoes into houses.[Pg 42]

|

|

| Fig. 1. ANOPHELES. (Malarial Mosquito.) |

Fig. 2. CULEX. (Common Mosquito.) |

The Anopheles mosquito, which is the one that transmits malaria, often exists in localities where the more common varieties do not occur, and on account of the habits of this insect their presence is liable to be overlooked. They seldom attempt to bite during the day, and it is only rarely the case that they try to do so at night in a well lighted room;—particularly where movement of any kind is going on. During the day this mosquito remains perfectly quiet in the dark corners of the house, and is very fond of resting on cobwebs, presenting, when doing so, an appearance strikingly similar to that of fragments of leaves, soot or of other natural objects that are frequently found[Pg 43] suspended on such structures. On account of these peculiarities and for the further reason that the insect bites mainly just following daybreak, when the victim is profoundly unconscious in sleep, its presence often remains undetected, and as a consequence we occasionally hear from those who do not take the trouble to inform themselves that malaria exists in this or that locality where mosquitoes do not occur.

The yellow-fever mosquito bites for the most part during the day, but will do so at any time when there is light. In districts where this disease occurs it is quite as important to prevent its entrance as that of the malarial mosquito. Not only does screening prevent malaria and yellow fever, but it keeps out flies and other insects that unquestionably bring with them the germs of other diseases.

There now remains no doubt that several affections, notably typhoid fever and dysentery, are frequently communicated by means of the common house-fly, which spends its time alternately on the fecal material around privies or in other filth, and in our kitchens and dining-rooms; it is one of the most astounding evidences[Pg 44] of the power of habit, in the face of common sense and ordinary decency, that we have not long ago taken active steps to rid ourselves of its disgusting presence. Fortunately in screens we have a perfect barrier to the entrance of flies, and no house can be considered complete without being thoroughly equipped with these all-necessary appliances.

It is scarcely possible to overestimate the economy that results from the use of screens; among the various means employed for conserving the public health they take first rank, and undoubtedly insure those who live in houses to which they have been added an immunity against the costly effects of disease that could scarcely be computed. A house would be more habitable without chairs, beds, or tables than screens, since in the absence of the former we may be healthy, though somewhat uncomfortable, but without the latter serious disorders are pretty certain, sooner or later, to make their appearance.

It is of considerable importance to use a screen the mesh of which is sufficiently fine. Where mosquitoes exist, the screen should be of[Pg 45] such fineness that at least sixteen, or better eighteen meshes be in each inch of the gauze. Where it is absolutely certain that mosquitoes are not to be feared, the spaces may be somewhat larger—but always of such size as will prevent the entrance of the smallest fly.

Air-space Required.—It is of much importance from a hygienic standpoint that the rooms of dwellings should be sufficiently large. The height should never be less than eight feet, and the living-room should be made as large as circumstances will permit. Bed-chambers should contain at least 1,000 cubic feet of air space for each adult, with somewhat less for children, though it should never be forgotten that the more the better; this means that each person should have the equivalent of a room which is at least 10 x 12 x 9 feet.

Heating.—Americans are extravagant in the matter of heating to a degree that astonishes the average foreigner, and it is by no means sure that we do not go to unhygienic extremes in this direction. It is not, perhaps, true that the excessive heat itself could be considered as especially hurtful, but it is too often the case that[Pg 46] the conditions required to secure the degree of heat preferred by us are incompatible with proper ventilation, and hence are to be condemned. It is generally considered that the temperature of living-rooms should be somewhere about 70°F.; for many persons this is lower than would be entirely comfortable, and as a consequence our houses in the winter are frequently kept nearer 80°F. than the figure just given. The reader should be urged to see to it that, at whatever temperature his habitation is kept, a sufficient amount of ventilation be secured.

There are many different methods of heating, the most satisfactory of which are by means of hot water or steam; a modified form of the latter is the so-called vapor method, which in recent years has proven extremely satisfactory. Hot air, supplied by a furnace is also extensively used, and for the reason that by this method fresh air from the outside is constantly brought into the house, it is theoretically to be commended; practically, however, a considerable difficulty is experienced in securing an equable distribution of this heat throughout the[Pg 47] various parts of the house, and as a consequence it has not achieved the popularity that it would otherwise have done.

Inasmuch as the installation of plants for heating by the methods just referred to entails quite an expense, and for the further reason that they require coal for satisfactory operating, they have not been employed in the rural districts of America to any considerable extent. The farmer, for the most part, depends on the old open fireplace where wood is plentiful and the weather does not become excessively cold, while in those portions of the country where the temperatures in winter go very low, the stove is generally employed. Of the two methods, the former is much the more hygienic where it can be used successfully, but over a greater portion of the United States this cannot be done owing to the cold winter climate.

The principal objection to the stove lies in the fact that the heat that comes from it is very dry, and that where its walls have to be heated excessively, unpleasant odors are apt to be generated; the former is usually and ought always to be obviated by keeping upon the stove[Pg 48] a vessel of water, the vapors from which moisten the atmosphere, and the latter by having the stove of such size that it will not require excessive heating in order to warm the room in which it is placed. Wherever possible the open fireplace is to be preferred to the stove for the reason that it very thoroughly ventilates the room.

Ventilation.—In order that the health of the inmates may be conserved proper ventilation of all habitations is essential. However cold the weather may be, an abundance of fresh air should be allowed to enter all parts of the house. In the average wooden dwelling there are so many cracks that good ventilation is generally secured without opening doors or windows, but where the construction does not permit this, openings for the entrance of air should be left in the most convenient and suitable places. Windows may be slightly raised and draughts prevented by proper screening, or what is even better, rooms should be so constructed that they have openings at the top and at the bottom to allow free ventilation. Openings towards the upper portion of rooms are especially important[Pg 49] in hot weather, as the warm air rises to the ceiling and escapes only very slowly where such exits do not exist. Lowering windows from the top aids materially in allowing the hot air to escape, but this is not altogether so satisfactory as having openings higher up on the walls, or in the ceiling.

Disposal of Sewage.—No problem that confronts the dweller in the rural district is of greater importance than the proper disposal of sewage. It is unfortunately impossible in most instances for the farmer to have in his house a system of water-works, and, therefore, all dish-waters and slops are thrown into the yard, and a privy is used instead of a modern water-closet. Where the lay of the land is such that water readily runs off, or the soil is of a character that permits rapid absorption, throwing slops on the ground around the house may not constitute a danger to the inmates, but nothing is more certain than that the old fashioned privy is a dire menace to the health of all those in its vicinity.

Not only are infectious materials brought into houses by flies, from fecal matter and other[Pg 50] excretions, but they are carried away by the rains and sometimes contaminate sources of water-supply. It is furthermore extremely probable that bacteria in particles of dust from dried fecal material may be carried by the winds from privies into wells and houses, and as a consequence diseases may be spread; of perhaps still more importance—and certainly of far greater moment all over the southern portions of the country—is the fact that hook-worm disease and other infections caused by animal parasites are transmitted from man to man as the result of our adherence to the old fashioned privy.

As will be explained in the chapter devoted to the common communicable diseases, the eggs of the hook-worm pass from the intestine along with the feces of those who are victims of this parasite and reaching the ground, hatch out in the course of a few days minute hook-worm embryos, which crawl away and permeate the soil in the vicinity; later collecting in little pools that form after rains, or in dew-drops during the night, they attach themselves to the skin of barefooted children who come in contact with such[Pg 51] collections of water, and boring into the body ultimately, through a circuitous route, reach the intestines. Here they undergo further development, and in a short time become mature hook-worms, which in their turn lay eggs, and the life cycle begins over again. It is thus seen that a child having hook-worm disease becomes a menace, on account of the privy, to its brothers and sisters, and of course quite commonly receives back into its own body, worms that had previously escaped as eggs.

In the same way eggs of the two common tapeworms pass out with the feces, and the offal containing them being eaten by hogs in the one case, or being scattered in the vicinity and taken in with grass by cows in the other, have their shells dissolved off as soon as they reach the stomachs of these animals, and there are liberated small embryos that bore through the walls of the stomach and later find their way into the muscular tissues of these beasts, and there lie dormant until eaten by man with imperfectly cooked meat; after being swallowed, the embryo parasite passes to the intestine and soon becomes a fully developed tapeworm.[Pg 52]

Particular reference at this point should be directed to the evil effects, which are even still greater than those that come from the privy, of permitting children and hired helpers to scatter their feces indiscriminately in corners of the yard, the apple-orchard, or in the horse-lot; under such circumstances, where hook-worm disease is once introduced, the soil in the course of a short time becomes thoroughly permeated with the embryos of this worm, and, as a consequence, all of the children who play in the infected area barefooted, as is customary in the country, are sooner or later infected with these parasites. It is thus seen that soil-pollution from fecal material is a most dangerous thing, and, particularly in the southern portion of the United States, deserves the most earnest consideration of everyone. We should see to it that our children only evacuate their bowels in properly constructed closets; and it is the duty of the head of every family to provide such a place for the accommodation of those who are dependent on him.

Proper Construction of Out-door Privies.—The most practical and generally satisfactory[Pg 53] device heretofore invented for the disposal of the sewage of communities unprovided with water-works is what is known as the Rochdale, or dry-closet, system. By this system a privy, at a distance from the dwelling, is constructed in the ordinary manner, with the exception that instead of being open at the back it is tightly closed. In the space beneath the seat receptacles are placed for receiving the urine and feces. These may consist of pails of wood or better of galvanized iron; or a single box occupying the whole space. If wooden receptacles are used, they should be thoroughly coated on the inside with tar, to prevent both leakage and the soaking of the liquids into the wood. One such structure, which the writer knows has been wholly satisfactory has a brick foundation with walls two feet high around the front and sides, within which rests a shallow tarred box. It ensures perfect cleanliness.

In any case this space under the seat is tightly closed, being guarded by doors that open outward, through which the pails or box may be introduced and removed for emptying.

Each privy contains a box in which is placed[Pg 54] either wood ashes or dry powdered earth, with a small shovel by which a sufficient quantity of the dust to cover the deposit is thrown into the pail after each evacuation. It is remarkable how completely this shovelful of earth or ashes destroys all disagreeable smell. The privy should be provided with at least two opposite windows, both of which should be thoroughly screened. The entrance should have a door that is closed with a spring, so that it cannot be carelessly or accidentally left open when vacant. At intervals the pails containing the feces are removed, and the contents are carried to a distance and buried.

Another plan that is quite satisfactory where iron pails are used, is to place a quantity of water in the vessels for receiving the feces, and then to pour in a small quantity of kerosene; the latter substance forms a layer over the water that keeps out flies, and does away largely with the disagreeable odors that are likely to emanate.

If any contagious disease exists among those who use such a closet, the fecal material should be carefully sterilized before being removed, as[Pg 55] by means of corrosive sublimate, carbolic acid, chlorinated lime, or any one of the many commercial disinfectants containing crysylic acid, all of which may be obtained at any drug store. If carbolic acid or other liquid antiseptics be used the amount by volume should be equal to about five per cent. of the material to be treated; the proportion of corrosive sublimate should be at least 1 to 1,000 where this disinfectant is used. Along with whatever antiseptic is chosen, water should be added in sufficient quantity to permit the whole to be rendered semi-fluid, and the mixture should then be thoroughly stirred, and the chemical left to act for some hours before emptying the receptacle. By far the most satisfactory method of sterilizing infected material, however, is by boiling, since disease-germs are killed by such a temperature in a few moments. Where iron receptacles are used, therefore, the simplest method is to set them upon an open fire in the yard for a little while.

A privy constructed after the manner just described possesses some advantages even over the regulation water-closets that are used in[Pg 56] cities, since they are cheaper in original cost, require less repairs, and are uninjured by a freezing temperature. The amount of care required to keep them in proper condition is not excessive, and they are so infinitely superior from a hygienic standpoint to the old-time privy that no sort of comparison is possible.

It should always be remembered that the principal advantages of this closet are that where it is used we are able to collect all of the evacuations, which may then be properly deodorized with soil or ashes, and that it may then be finally disposed of in such a way that it cannot be reached by hogs or other animals; of very great importance also is the screening of the closet, since only in this way is it possible to prevent flies from gaining entrance to the fecal material in the receiving pails.

Water supply.[2]—In the location of houses and schools an eye should always be had to[Pg 57] selecting a site where it is possible to obtain good, pure water. To those fortunate dwellers in the mountainous regions of our country this is usually a matter of little difficulty, since it is always possible to find a location in the neighborhood of which the purest spring water may be obtained. In less favored regions the well becomes the main reliance, while cisterns are used in some portions of our country, in which water is collected during the rainy seasons of the year. Of the two, the former is undoubtedly to be preferred, provided a pump be used instead of the old fashioned bucket. The writer is strongly of the opinion that a very large proportion of the contamination to which sources of water-supply are subject comes from the bucket being drunk from or handled by persons with contagious diseases, or from germs[Pg 58] being blown into the well with dust, or carried in by means of insects and small animals. It is inconceivable that any appreciable amount of contamination from the surface can reach the underground streams that supply wells in localities that are thinly populated, though it is unquestionably true that a well might be infected as a result of the entrance of surface-water where its top is not properly protected. On the other hand we have in an open well or cistern every facility afforded for the entrance of bacteria.

It is unquestionably of the utmost importance that wells be carefully covered over, and every precaution should be taken to prevent surface-water leaking into them around their edges. In order to comply with these conditions a pump is essential, since it is the only means by which water can be brought to the surface without exposing the contents of the well to contamination. It is likewise of the first importance to have the walls of the well curbed to a sufficient depth to prevent the possibility of seepage from the surface. It is, of course, also quite necessary that the well be of sufficient[Pg 59] depth—the lower we go the more likely are we to secure a perfectly pure water. In regions where the water rises to within eight or ten feet, or less, of the surface, the possibility of the well being contaminated during the rainy season by seepage is considerably increased, and the waters of such wells should be used only after analyses have shown that they are pure; where this cannot be done, the water should be boiled before being drunk. Of course, the possibilities of contamination are greatly increased if the locality be thickly inhabited.

As has been before remarked, cisterns are more liable to contamination from the air than are wells, chiefly owing to the fact that they are supplied by water that is conducted into them by gutters from the tops of houses. There is no question that during the dry seasons dust containing many kinds of bacteria is deposited all over the tops of houses and remains there until washed away by the rains. While it is true that the sunlight quickly kills most germs that produce disease a certain number of them would inevitably escape, and having gained entrance[Pg 60] to a cistern, would be likely to multiply and later cause trouble. It is thus seen that however pure the rain-water may originally have been—and it is among the purest of all waters—it is likely to become contaminated in the process of collection, and may ultimately in this way become the source of disease. Where any doubt exists as to the purity of such water it should be boiled before use.

Surface-streams also occasionally supply drinking-water in rural districts, and while the use of such waters may not always be attended by danger, their contamination by disease-producing germs is much more to be feared than when they are derived from wells or springs; where streams arise from and keep their course through uninhabited districts the probabilities are strong that their waters are pure and fit for use, but where they run through cultivated fields, and particularly where they pass in the neighborhood of houses, their waters should never be looked upon as being drinkable,—except after being boiled or properly filtered. Inasmuch as adequate filtration is exceedingly difficult to carry out, and requires a somewhat[Pg 61] extensive and costly plant, this is, as a rule, not feasible for the dweller in country districts, and boiling, therefore, remains the only satisfactory method of rendering the water fit for use where doubt exists as to its purity.

Location of Pens and Stables for Animals.—Animals should always be housed at some little distance from the dwelling. While it is true that man does not often contract directly diseases from hogs, sheep, horses and cattle, there are some maladies of a most serious character that come to us in this way, and we should, therefore, always guard against their occurrence by removing ourselves as far as is possible from sources of possible infection. The matter also has an æsthetic side, as odors of a disagreeable character may prove very annoying where animals are kept too close to the house. It is likewise of importance that stables should be, if possible, on lower ground than the dwelling, since during rains materials from their dung may be washed around and under the house, and may possibly gain access to the well.

Every care should be taken to keep hog-pens[Pg 62] and stables clean, since otherwise very foul smells are engendered that oftentimes find their way to neighboring houses. There is also a suspicion that some of the germs that produce disease find the conditions suitable for their stables and pig-sties.

In this connection it might be well to warn those unacquainted with the subject against the all too common practice of close association with dogs, since it is well established that in addition to hydrophobia they may transmit, while apparently in perfect health, maladies of a deadly character to the human being. It cannot be too often emphasized that the less intimate our association with the lower animals is, the greater the likelihood of our escaping many serious diseases.

[2] This subject is fully treated in another volume of this Library, entitled Home Water-works, written by Prof. Carleton J. Lynde. It shows where water should be sought, and how it may be supplied under perfectly safe conditions to the household, with descriptions of machinery, estimates of expense, etc. This thoroughly practical book meets a widely recognized need for information, and is written by a specialist. Thousands of men living in rural parts of the United States and Canada, out of reach of a public water-system, have equipped their homes with water-supply conveniences equal to any found in the cities. Thousands more who could well afford to do so and who could do so advantageously, have not done so for various reasons—because the idea has not occurred to them, or because they did not know how to go about it, or because they mistakenly thought the expense too great. To all such this book should prove of the greatest practical help.

No characteristic of the Caucasian mind is more marked, and none more universally affects his actions than a constant, gnawing suspicion that the things going on around him are not being done in the proper way, and consequently an irrepressible desire to experiment, and if possible, to change everything. Such a spirit is unquestionably the basis of what we call progress, and, in so far as it conduces to the health and happiness of mankind, is entitled to our most hearty commendation. On the other hand, it cannot be denied that too often we endeavor to bring about changes with but an imperfect understanding of the basic principles at issue, and naturally, under such circumstances, our efforts are crowned with anything but success. In other words, an enlightened investigation of the whys and wherefores of any[Pg 64] existing state of affairs may and often does, lead to improvement, while, on the other hand, ignorant meddling is likely to be followed by disastrous consequences.

Nowhere do we see the bad results of false conceptions more marked than in our treatment of infants and children.

Particularly do young infants suffer in this way, as they are pounced upon as soon as they enter the world by every old “granny” and negro “mammy” in the neighborhood, and plied with abominable concoctions that would be productive of homicide if we were to attempt forcibly to administer them to grown men, and whose only effect on the defenseless little sufferer is to cause colic and indigestion. Many times has the writer seen a wee, tiny little mortal, who was too young and weak to even protest, bundled up with a mountain of flannels in the hottest weather of July and August. True to the superstition that the warmer we kept an infant the better, too frequently we see them confined to hot stuffy rooms when they should be out in the sunshine, or under the trees. Instead of being allowed to gain health and strength in the forests, which are the schoolhouses of nature, the miserable little wretch is later sent to a public school as soon as he or she can be trusted to go alone on the streets, and the tiny victim too frequently contracts diphtheria, scarlet fever, whooping-cough, measles, or some other disease as a reward of [Pg 65]merit. Truly we see to it that the helpless innocents early realize the truth of the melancholy and hopeless biblical lament that “man's days here are few and full of trouble.”

We should rear our children with as little interference as possible, allowing them the utmost freedom compatible with their safety, and permitting them to do those things that nature and instinct demand. Above all let them sleep as much and as long as they will, insist that they live in the open air, and encourage them in every possible way to perfect their physical education by those active amusements that they instinctively prefer. After they have established a sound and rugged constitution ample time will be left for them to develop mentally.

Feeding of Nursing Infants.—The most important thing in connection with the feeding of infants is to always remember that nature has provided in their mother's milk, when sufficiently abundant and normal in quality, everything in the way of food and drink that they require. During the three days that usually intervene between birth and the coming of the milk in the mother's breast, infants may be[Pg 66] given from time to time small quantities of pure water, but under no circumstances should anything else be allowed. During this period the child may be put to the breast four or five times in the twenty-four hours, for, while it gets but little in the way of nourishment, there is even at this time a watery fluid secreted in the breast that goes far towards supplying everything that the infant needs for the time being.

A child should never nurse longer than twenty minutes at one time. It is likewise of importance that the time of nursing be strictly regulated.

Particularly during the first year it is of the utmost importance to watch with an intelligent eye the growth and development of the child. Where the milk agrees with it it has a good color and gains regularly in weight; it cries but little, and is good natured, and thoroughly contented. Should it, on the other hand, lose weight, appear fretful and listless, and sleep badly, there is something wrong, and the mother should at once have her milk examined by a competent physician.[Pg 67]

In case the mother does not give sufficient nourishment there is no objection to partially feeding the infant on modified cow's milk—the method of the preparation of which will be considered later on.

Where colic occurs it generally means that the infant is getting a diet too rich in albuminous foods, which should be corrected by advising the mother to take an abundance of out-door exercise, and to avoid all causes of worry so far as is possible.

Vomiting freely is a very common occurrence in small children, and is usually the result of too much food being taken at a time. It also occurs, particularly some time after feeding, as a result of indigestion, which is frequently the consequence of the milk being too rich in fats. Wherever an infant shows signs of trouble it is well to advise the mother to use a diet less rich in meats, and to caution her against over-eating.

Children should be weaned at the end of their first year. This had best be brought about gradually, by, in the beginning, feeding the child once daily, and then gradually increasing[Pg 68] the frequency, at the same time proportionately leaving off the nursing. Where children are not thriving, it is often a good practice to wean earlier, in which case modified cow's milk, taken from a bottle, must be substituted.

Artificial Feeding.—While it is true that children often thrive for a time on the various baby-foods with which the market is so abundantly supplied, it is, nevertheless, the case that where fed in this way they are very apt to develop rickets or scurvy, and not uncommonly show evidences of bad nutrition in loss of weight and strength, becoming peevish and fretful, and sleeping badly.

Much better than any of the artificial foods is properly modified cow's milk, which, with care, may be prepared in such a manner as to take the place of mother's milk in the vast majority of instances. In order, however, that this be successfully carried out, much care and attention is necessary.

At this point it is well to stress the fact that the mother's milk differs from that of the cow in some quite important particulars, and it is only by intelligently[Pg 69] taking these differences into consideration that it is possible for us to prepare an artificial food that will be satisfactory. Principal among these differences are that cow's milk contains three times as much albuminous material as that of the human being, and that it is less rich by about half in milk-sugar; furthermore, the former is acid in reaction, while the latter is neutral, or faintly alkaline. It will be seen, then, that in order to prepare a modified cow's milk that will approximate that of the human being it is necessary to dilute it with water sufficiently to cause the albumin to approach in proportion that of mother's milk, and at the same time some alkali must be added to neutralize the excessive acidity. Modified milk prepared, however, from the whole cow's milk, would contain much less fat than is desirable, so that we must use in making it the upper third of the whole milk after it has been allowed to remain undisturbed for a number of hours; in other words, in making modified cow's milk we use a large proportion of the cream, with a less amount of the other constituents.

The following table for calculating the proper proportion of milk to be used at the various periods of the infant's life may be recommended, as it gives quite as satisfactory results as those that are more elaborate; it also gives the frequency of feeding and the proper amounts that should be used. The table was devised by Dr. C. E. Boynton, of Atlanta, Georgia.

| Fat percentage desired. |

Quantity ounces at feeding. |

No. of feedings in 24 hours. |

Intervals by day. |

||

| Premature | 1.00 | ¼ - ¾ | 12 - 18 | 1 - 1½ | hrs. |

| 1 - 4 day | 1.00 | 1 - 1½ | 6 - 10 | 2 - 4 | " |

| 5 - 7 " | 1.50 | 1 - 2 | 10 | 2 | " |

| 2 - week | 2.00 | 2 - 2½ | 10 | 2 | " |

| 3 - " | 2.50 | 2 - 2½ | 10 | 2 | " |

| 4 - 8 " | 3.00 | 2½ - 4 | 9 | 2½ | " |

| 2 - month | 3.00 | 3 - 5 | 8 | 2½ | " |

| 4 - " | 3.50 | 3 - 5½ | 7 | 3 | " |

| 5 - " | 3.50 | 4 - 6 | 7 | 3 | " |

| 6 - 10 month | 4.00 | 5 - 8 | 6 | 3 | " |

| 11 - month | 4.00 | 6 - 9 | 5 | 4 | " |

| 12 - " | 4.00 | 7 - 9 | 5 | 4 | " |

| 13 - " | 4.00 | 7 - 10 | 5 | 4 | " |

In making calculations from this table it is assumed that the milk from the upper third of the bottle, after it has been allowed to sit for at least four hours, contains 10% of fat, and this is therefore called 10% milk. The calculation is made as follows:—10% milk is to the fat percentage desired, as the amount which we wish to make up is to X. For example, if we wish to prepare twenty ounces of milk for an infant two months old, we will note by referring to the table that 3% is the amount of fat that is desirable for a milk for a child of this age, and the formula will be constructed as follows:—

10:3::20:X. X = 60/10. X = 6.

Six ounces is then the amount of 10% milk that must be used for making twenty ounces of modified [Pg 71]milk,—this being mixed with one ounce of lime-water and thirteen ounces of boiled water. It should never be forgotten that while milk modified by the foregoing formula is suitable for most children, it is by no means always satisfactory, and we may, therefore, be compelled to do a considerable amount of experimenting in some cases before arriving at the correct formula.