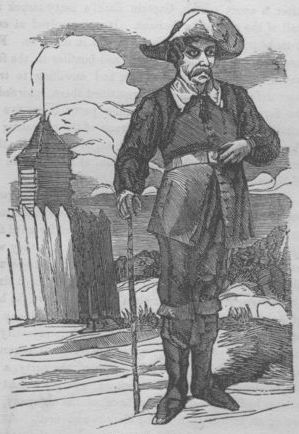

THE WOUNDED PIONEER.

Title: Heroes and Hunters of the West

Author: John Frost

Release date: October 19, 2008 [eBook #26965]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE WOUNDED PIONEER.

HEROES

AND

HUNTERS OF THE WEST:

COMPRISING

SKETCHES AND ADVENTURES

OF

BOONE, KENTON, BRADY, LOGAN, WHETZEL,

FLEEHART, HUGHES, JOHNSTON, &c.

PHILADELPHIA:

H. C. PECK & THEO. BLISS.

1860.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1853,

BY H. C. PECK & THEO. BLISS,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the Eastern District

of Pennsylvania.

CONTENTS.

| Daniel Boone. | 11 |

| Simon Kenton. | 19 |

| George Rogers Clarke. | 24 |

| Benjamin Logan. | 32 |

| Samuel Brady. | 38 |

| Lewis Whetzel. | 45 |

| Caffree, M’Clure, and Davis. | 58 |

| Charles Johnston. | 66 |

| Joseph Logston. | 74 |

| Jesse Hughes. | 81 |

| Siege of Fort Henry. | 87 |

| Simon Girty. | 103 |

| Joshua Fleehart. | 118 |

| Indian Fight on the Little Muskingum. | 129 |

| Escape of Return J. Meigs. | 137 |

| Estill’s Defeat. | 144 |

| A Pioneer Mother. | 154 |

| The Squatter’s Wife and Daughter. | 167 |

| Captain William Hubbell. | 173 |

| Murder of Cornstalk and his Son. | 185 |

| The Massacre of Chicago. | 189 |

| The Two Friends. | 211 |

| Desertion of a young White Man, from a party of Indians. | 219 |

| Morgan’s Triumph. | 229 |

| Massacre of Wyoming. | 233 |

| Heroic Women of the West. | 243 |

| Indian Strategem Foiled. | 250 |

| Blackbird. | 265 |

| A Desperate Adventure. | 268 |

| Adventure of Two Scouts. | 276 |

| A Young Hero of the West. | 299 |

PREFACE.

To the lovers of thrilling adventure, the title of this work would alone be its strongest recommendation. The exploits of the Heroes of the West, need but a simple narration to give them an irresistible charm. They display the bolder and rougher features of human nature in their noblest light, softened and directed by virtues that have appeared in the really heroic deeds of every age, and form pages in the history of this country destined to be read and admired when much that is now deemed more important is forgotten.

It is true, that, with the lights of this age, we regard many of the deeds of our western pioneer as aggressive, barbarous, and unworthy of civilized men. But there is no truly noble heart that will not swell in admiration of the devotion and disinterestedness of Benjamin Logan, the self-reliant energy of Boone and Whetzel, and the steady firmness and consummate military skill of George Rogers Clarke. The people of this country need records of the lives of such men, and we have attempted to present these in an attractive form.

CAPTURE OF BOONE.

HEROES OF THE WEST.

In all notices of border life, the name of Daniel Boone appears first—as the hero and the father of the west. In him were united those qualities which make the accomplished frontiersman—daring, activity, and circumspection, while he was fitted beyond most of his contemporary borderers to lead and command.

Daniel Boone was born either in Virginia or Pennsylvania, and at an early age settled in North Carolina, upon the banks of the Yadkin. In 1767, James Findley, the first white man who ever visited Kentucky, returned to the settlements of North Carolina, and gave such a glowing account of that wilderness, that Boone determined to venture into it, on a hunting expedition. Accordingly, in 1769, accompanied by Findley and four others, he commenced his journey. Kentucky was found to be all that the first adventurer had represented, and the hunters had fine sport. The country was uninhabited, but, during certain seasons, parties of the northern and southern Indians visited it upon hunting expeditions. These parties frequently engaged in fierce conflicts, and hence the beautiful region was known as the “dark and bloody ground.”

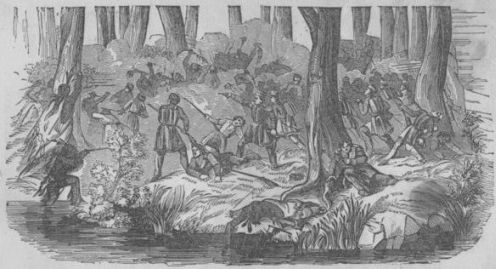

BATTLE OF BLUE LICKS.

On the 22d of December, 1769, Boone and one of his companions, named John Stuart, left their encampment on the Red river, and boldly followed a buffalo path far into the forest. While roving carelessly from canebrake to canebrake, they were suddenly alarmed by the appearance of a party of Indians, who, springing from their place of concealment, rushed upon them with a swiftness which rendered escape impossible. The hunters were seized, disarmed, and made prisoners. Under these terrible circumstances, Boone’s presence of mind was admirable. He saw that there was no chance of immediate escape; but he encouraged his companion and constrained himself to follow the Indians in all their movements, with so constrained an air, that their vigilance began to relax.

DANIEL BOONE.

On the seventh evening of the captivity of the hunter, the party encamped in a thick cane-break, and having built a large fire lay down to rest. About midnight, Boone, who had not closed his eyes, ascertained from the deep breathing of all around him, that the whole party, including Stuart, was in a deep sleep. Gently extricating himself from the savages who lay around him, he awoke Stuart, informed him of his determination to escape, and exhorted him to follow without noise. Stuart obeyed with quickness and silence. Rapidly moving through the forest, guided by the light of the stars and the barks of the trees, the hunters reached their former camp the next day, but found it plundered and deserted, with nothing remaining to show the fate of their companions. Soon afterwards, Stuart was shot and scalped, and Boone and his brother who had come into the wilderness from North Carolina, were left alone in the forest. Nay, for several months, Daniel had not a single companion, for his brother returned to North Carolina for ammunition. The hardy hunter was exposed to the greatest dangers, but he contrived to escape them all. In 1771, Boone and his brother returned to North Carolina, and Daniel, having sold what property he could not take with him, determined to take his family to Kentucky, and make a settlement. He was joined by others at “Powel’s Valley,” and commenced the journey, at the head of a considerable party of pioneers. Being attacked by the Indians, the adventurers were compelled to return, and it was not until 1774, that the indomitable Boone succeeded in conveying his family to the banks of the Kentucky, and founding Boonesborough. In the meantime, James Harrod had settled at the station called Harrodsburgh. Other stations were founded by Bryant and Logan—daring pioneers; but Boonesborough was the chief object of Indian hostility, and was exposed to almost incessant attack, from its foundation until after the bloody battle of Blue Licks. During this time, Daniel Boone was regarded as the chief support and counsellor of the settlers, and in all emergencies, his wisdom and valor was of the greatest service. He met with many adventures, and made some hair-breadth escapes, but survived all his perils and hardships and lived to a green old age, enjoying the respect and confidence of a large and happy community, which his indomitable spirit had been chiefly instrumental in founding. He never lost his love of the woods and the chase, and within a few weeks of his death might have been seen, rifle in hand, eager in the pursuit of game.

SIMON KENTON.

LOGAN.

Simon Kenton was born in Fauquier county, Virginia, on the 15th of May, 1755. His parents were poor, and until the age of sixteen his days seem to have been passed in the laborious drudgery of a farm. When he was about sixteen, an unfortunate occurrence threw him upon his own resources. A robust young farmer, named Leitchman, and he were rival suitors for the hand of a young coquette, and she being unable to decide between them, they took the matter into their own hands and fought a regular pitched battle at a solitary spot in the forest. After a severe struggle, Kenton triumphed, and left his antagonist upon the ground, apparently in the agonies of death. Without returning for a suit of clothing, the young conqueror fled westward, assumed the name of Butler, joined a party of daring hunters, and visited Kentucky, (1773.) In the wilderness he became an accomplished and successful hunter and spy, but suffered many hardships.

In 1774, the Indian war, occasioned by the murder of the family of the chief, Logan, broke out, and Kenton entered the service of the Virginians as a spy, in which capacity he acted throughout the campaign, ending with the battle of Point Pleasant. He then explored the country on both sides of the Ohio, and hunted in company with a few other, in various parts of Kentucky. When Boonesborough was attacked by a large body of Indians, Simon took an active part in the defence, and in several of Boone’s expeditions, our hero served as a spy, winning a high reputation.

In the latter part of 1777, Kenton, having crossed the Ohio, on a horse-catching expedition, was overtaken and made captive by the Indians. Then commenced a series of tortures to which the annals of Indian warfare, so deeply tinged with horrors, afford few parallels. Having kicked and cuffed him, the savages tied him to a pole, in a very painful position, where they kept him till the next morning, then tied him on a wild colt and drove it swiftly through the woods to Chilicothe. Here he was tortured in various ways. The savages then carried him to Pickaway, where it was intended to burn him at the stake, but from this awful death, he was saved through the influence of the renegade, Simon Girty, who had been his early friend. Still, Kenton was carried about from village to village, and tortured many times. At length, he was taken to Detroit, an English post, where he was well-treated; and he recovered from his numerous wounds. In the summer of 1778, he succeeded in effecting his escape, and, after a long march, reached Kentucky.

SIMON GIRTY.

Kenton was engaged in all the Indian expeditions up to Wayne’s decisive campaign, in 1794, and was very serviceable as a spy. Few borderers had passed through so many hardships, and won so bright a reputation. He lived to a very old age, and saw the country, in which he had fought and suffered, formed into the busy and populous state of Ohio. In his latter days, he was very poor, and, but for the kindness of some distinguished friends, would have wanted for the necessaries of life.

In natural genius for military command, few men of the west have equalled George Rogers Clarke. The conception and execution of the famous expedition against Kaskaskia and Vincennes displayed many of those qualities for which the best generals of the world have been eulogized, and would have done honor to a Clive.

Clarke was born in Albermarle county, Virginia, in September, 1753. Like Washington, he engaged, at an early age, in the business of land surveying, and was fond of several branches of mathematics. On the breaking out of Dunmore’s war, Clarke took command of a company, and fought bravely at the battle of Point Pleasant, being engaged in the only active operation of the right wing of the Virginians against the Indians. Peace was concluded soon after, by Lord Dunmore, and Clarke, whose gallant bearing had been noticed, was offered a commission in the royal service. But this he refused, as he apprehended that his native country would soon be at war with Great Britain.

GEORGE ROGERS CLARKE.

Early in 1775, Clarke visited Kentucky as the favorite scene of adventure, and penetrated to Harrodsburgh. His talents were immediately appreciated by the Kentuckians, and he was placed in command of all the irregular troops in that wild region. In 1776, the young commander exerted himself with extraordinary ability to secure a political organization and the means of defence to Kentucky, and was so successful as to win the title of the founder of the commonwealth.[A]

In partisan service against the Indians, Clarke was active and efficient; but his bold and comprehensive mind looked to checking savage inroads at their sources. He saw at a glance, that the red men were stimulated to outrages by the British garrisons of Detroit, Vincennes and Kaskaskia, and was satisfied that to put an end to them, those posts must be captured. Having sent two spies to reconnoitre Kaskaskia and Vincennes, and gained considerable intelligence of the situation of the enemy, the enterprising commander sought aid from the government of Virginia to enable him to carry out his designs. After some delay, money, supplies, and a few companies of troops were obtained. Clarke then proceeded to Corn Island, opposite the present city of Louisville. Here the objects of the expedition were disclosed. Some of the men murmured, and others attempted to desert; but the energy of Colonel Clarke secured obedience and even enthusiasm.

The little band soon commenced its march through a wild and difficult country, and on the 4th of July, 1778, reached a spot within a few miles of the town of Kaskaskia. Clarke made his arrangements for a surprise with great skill and soon after dark, the town was captured without shedding a drop of blood. The inhabitants were at first terror-stricken and expected to be massacred, but they were soon convinced of their mistake by the bearing and representations of the Virginia commander. Cahokia was captured shortly afterwards, without difficulty.

Clarke’s situation was now extremely critical, and he duly appreciated the fact. Vincennes was still in front, so garrisoned, that it seemed madness to attempt its capture by direct attack. But a bold offensive movement could alone render the conquests which had been made, permanent and advantageous. A French priest, named Gibault, secured the favor of the inhabitants of Vincennes for the American interest, and the Indians of the neighborhood were conciliated by the able management of Colonel Clarke, who knew how to win the favor of the men better than any other borderer; but on the 29th of January, 1779, intelligence was received at Kaskaskia, where Clarke was then posted, that Governor Hamilton had taken possession of Vincennes, and meditated the re-capture of the other posts, preparatory to assailing the whole frontier, as far as Fort Pitt.

BATTLE OF POINT PLEASANT.

Clarke determined to act upon the offensive immediately, as his only salvation. Mounting a galley with two four-pounders and four swivels, and manning it with forty-six men, he dispatched it up the Wabash, to the White River, and on the 7th of February, 1779, marched from Kaskaskia at the head of only one hundred and seventy men, over the drowned lands of the Wabash, against the British post. The march of Arnold by way of the Kennebec to Canada can alone be placed as a parallel with this difficult expedition. The indomitable spirit of Clarke sustained the band through the most incredible fatigues. On the 28th the expedition approached the town, still undiscovered. The American commander then issued a proclamation, intended to produce an impression that his force was large and confident of success, and invested the fort. So vigorously was the siege prosecuted that the garrison was reduced to straits, and Governor Hamilton compelled to capitulate. (24th of February, 1779.) This was a brilliant achievement and reflected the highest honor upon Colonel Clarke and his gallant band. Detroit was now in full view, and Clarke was confident he could capture it if he had but five hundred men; but he could not obtain that number, till the chances of success were annihilated, and thus his glorious expedition terminated. The object of the enterprise, however, which was the checking of Indian depredations, was accomplished. Clarke afterwards engaged in other military enterprises and held high civil offices in Kentucky; but at the capture of Vincennes his fame reached its greatest brilliancy, and posterity will not willingly let it die.

The real heroic spirit, which delights in braving the greatest dangers in the cause of humanity, was embodied in Benjamin Logan, one of the first settlers in Kentucky. This distinguished borderer was born in Augusta county, Virginia. At an early age he displayed the noble impulses of his heart; for upon the death of his father, when the laws of Virginia allowed him, as the eldest son, the whole property of the intestate, he sold the farm and distributed the money among his brothers and sisters, reserving a portion for his mother. At the age of twenty-one, Logan removed to the banks of the Holston, where he purchased a farm, and married. He served in Dunmore’s war. In 1775, he removed to Kentucky, and soon became distinguished among the hardy frontiersmen for firmness, prudence, and humanity. In the following year he returned for his family, and brought them to a small settlement called Logan’s Fort, not far from Harrodsburgh.

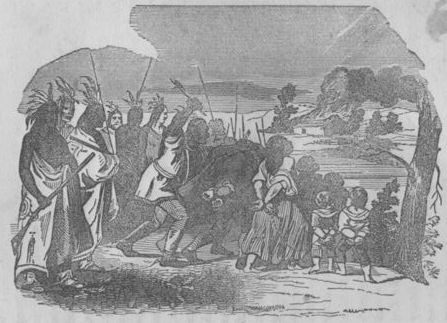

LOGAN JOURNEYING INTO KENTUCKY.

On the morning of the 20th of May, 1777, the women were milking the cows at the gate of the little fort, and some of the garrison attending them, when a party of Indians appeared and fired at them. One man was shot dead, and two more wounded, one of them mortally. The whole party instantly ran into the fort, and closed the gate. The enemy quickly showed themselves at the edge of the canebrake, within rifle-shot of the gate, and seemed numerous and determined. A spectacle was now presented to the garrison which awakened interest and compassion. A man, named Harrison, had been severely wounded, and still lay near the spot where he had fallen. The poor fellow strove to crawl towards the fort, and succeeded in reaching a cluster of bushes, which, however, were too thin to shelter his person from the enemy. His wife and children in the fort were in deep distress at his situation. The case was one to try the hearts of men. The numbers of the garrison were so small, that it was thought folly to sacrifice any more lives in striving to save one seemingly far spent. Logan endeavored to persuade some of the men to accompany him in a sally; but the danger was so appalling that only one man, John Martin, could be induced to make the attempt. The gate was opened, and the two sallied forth, Logan leading the way. They had advanced about five steps, when Harrison made a vigorous attempt to rise, and Martin, supposing him able to help himself, sprang back within the gate. Harrison fell at full-length upon the grass. Logan paused a moment after the retreat of Martin, then sprang forward to the spot where Harrison lay, seized the wounded man in his arms, and in spite of a tremendous shower of balls poured from every side, reached the fort without receiving a scratch, though the gate and picketing near him were riddled and his clothes pierced in several places.

Soon afterwards, the heroic Logan again performed an act of self-devotion. The fort was vigorously assailed, and although the little garrison made a brave defence, their destruction seemed imminent, on account of the scarcity of ammunition. Holston was the nearest point where supplies could be obtained. But who would brave so many dangers in the attempt to procure it? No one but Logan. After encouraging his men to hope for his speedy return, he crawled through the Indian encampment on a dark night, proceeded by by-paths, which no white man had then trodden, reached Holston, obtained a supply of powder and lead, returned by the same almost inaccessible paths, and got safe within the walls of the fort. The garrison was inspired with fresh courage, and in a few days, the appearance of Colonel Bowman, with a body of troops, compelled the savages to retire.

Logan led several expeditions into the Indian country, and won a high renown as one of the boldest and most successful of Kentucky’s heroes. When the Indian depredations were, in a great measure, checked, he devoted himself to civil affairs, and exerted considerable influence upon the politics of the country. Throughout his career, he was beloved and respected as a fearless, honest, and intelligent man.

Captain Samuel Brady was the Daniel Boone of Western Pennsylvania. As brave as a lion, as swift as a deer, and as cautious as a panther, he gave the Indians reason to tremble at the mention of his name. As the captain of the rangers he was the favorite of General Brodhead, the commander of the Pennsylvania forces, and regarded by the frontier inhabitants as their eye and arm.

The father and brother of Captain Brady being killed by the Indians, it is said that our hero vowed to revenge their murder, and never be at peace with the Indians of any tribe. Many instances of such dreadful vows, made in moments of bitter anguish, occur in the history of our border, and, when we consider the circumstances, we can scarcely wonder at the number, though, as Christians, we should condemn such bloody resolutions.

GENERAL BRODHEAD.

Many of Brady’s exploits are upon record; and they are entitled to our admiration for their singular daring and ingenuity. One of the most remarkable is known in border history as Brady’s Leap. The energetic Brodhead, by an expedition into the Indian country, had delivered such destructive blows that the savages were quieted for a time. The general kept spies out, however, for the purpose of guarding against sudden attacks on the settlements. One of the scouting parties, under the command of Captain Brady, had the French creek country assigned as their field of duty. The captain reached the waters of Slippery Rock, without seeing any signs of Indians. Here, however, he came on a trail, in the evening, which he followed till dark, without overtaking the enemy. The next morning the pursuit was renewed, and Brady overtook the Indians while they were at their morning meal. Unfortunately, another party of savages was in his rear, and when he fired upon those in front, he was in turn fired upon from behind. He was now between two fires, and greatly outnumbered. Two of his men fell, his tomahawk was shot from his side, and the enemy shouted for the expected triumph. There was no chance of successful defence in the position of the rangers, and they were compelled to break and flee.

Brady ran towards the creek. The Indians pursued, certain of making him captive, on account of the direction he had taken. To increase their speed, they threw away their guns, and pressed forward with raised tomahawk. Brady saw his only chance of escape, which was to leap the creek, afterwards ascertained to be twenty-two feet wide and twenty deep. Determined never to fall alive into the hands of the Indians, he made a mighty effort, sprang across the abyss of waters and stood rifle in hand upon the opposite bank. As quick as lightning, he proceeded to load his rifle. A large Indian, who had been foremost in pursuit, came to the opposite bank, and after magnanimously doing justice to the captain by exclaiming “Blady make good jump!” made a rapid retreat.

Brady next went to the place appointed as a rendezvous for his party, and finding there three of his men, commenced his homeward march, about half defeated. Three Indians had been killed while at their breakfast. The savages did not return that season, to do any injury to the whites, and early in the fall, moved off to join the British, who had to keep them during the winter, their corn having been destroyed by General Brodhead. Brady survived all his perils and hardships and lived to see the Indians completely humbled before those whites on whom they had committed so many outrages.

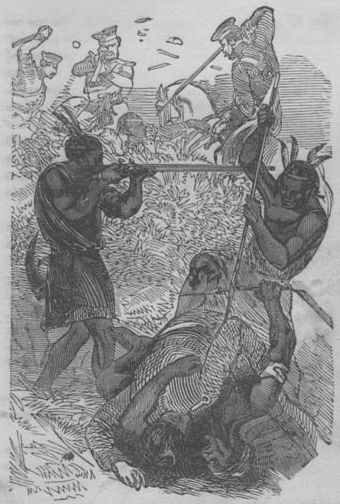

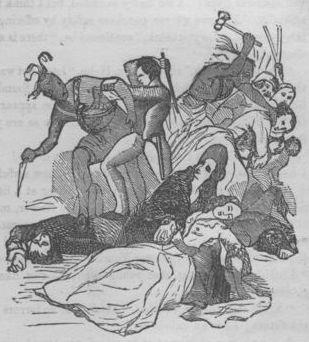

MASSACRE OF MRS. WHETZEL AND HER CHILDREN.

The Whetzel family is remembered in the west for the courage, resolution, and skill in border warfare displayed by four of its members. Their names were Martin, Lewis, Jacob, and John. Of these, Lewis won the highest renown, and it is doubtful whether Boone, Brady, or Kenton equaled him in boldness of enterprise.

In the hottest part of the Indian war, old Mr. Whetzel, who was a German, built his cabin some distance from the fort at Wheeling. One day, during the absence of the two oldest sons, Martin and John, a numerous party of Indians surrounded the house, killed, tomahawked and scalped old Mr. Whetzel, his wife, and the small children, and carried off Lewis, who was then about thirteen years old, and Jacob who was about eleven. Before the young captives had been carried far, Lewis contrived their escape. When these two boys grew to be men, they took a solemn oath never to make peace with the Indians as long as they had strength to wield a tomahawk or sight to draw a bead, and they kept their oath.

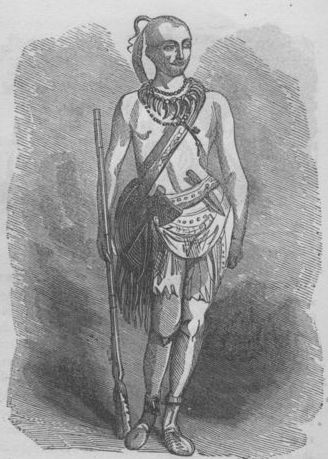

The appearance of Lewis Whetzel was enough to strike terror into common men. He was about five feet ten inches high, having broad shoulders, a full breast, muscular limbs, a dark skin, somewhat pitted by the small pox, hair which, when combed out, reached to the calves of his legs, and black eyes, whose excited and vindictive glance would curdle the blood. He excelled in all exercises of strength and activity, could load his rifle while running with almost the swiftness of a deer, and was so habituated to constant action, that an imprisonment of three days, as ordered by General Harmar, was nearly fatal to him. He had the most thorough self-reliance as his long, solitary and perilous expeditions into the Indian country prove.

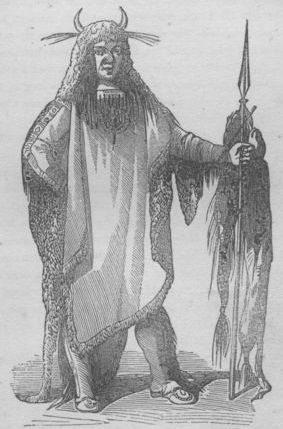

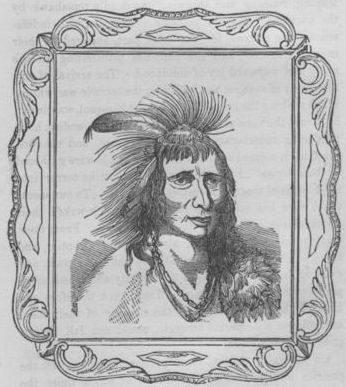

INDIAN CHIEF.

In the year of 1782, Lewis Whetzel went with Thomas Mills, who had been in the campaign, to get a horse, which he had left near the place where St. Clairsville now stands. At the Indian Spring, two miles above St. Clairsville, on the Wheeling road, they were met by about forty Indians, who were in pursuit of the stragglers from the campaign. The Indians and the white men discovered each other about the same time. Lewis fired first, and killed an Indian; the fire from the Indians wounded Mr. Mills, and he was soon overtaken and killed. Four of the Indians then singled out, dropped their guns, and pursued Whetzel. Whetzel loaded his rifle as he ran. After running about half a mile, one of the Indians having got within eight or ten steps of him, Whetzel wheeled round and shot him down, ran on, and loaded as before. After going about three-quarters of a mile further, a second Indian came so close to him, that when he turned to fire, the Indian caught the muzzle of his gun, and as he expressed it, he and the Indian had a severe wring for it; he succeeded, however, in bringing the gun to the Indian’s breast, and killed him on the spot. By this time, he, as well as the Indians, were pretty well tired; the pursuit was continued by the remaining two Indians. Whetzel, as before, loaded his gun, and stopped several times during the chase. When he did so the Indians treed themselves. After going something more than a mile, Whetzel took advantage of a little open piece of ground, over which the Indians were passing, a short distance behind him, to make a sudden stop for the purpose of shooting the foremost, who got behind a little sapling, which was too small to cover his body. Whetzel shot, and broke his thigh; the wound, in the issue, proved fatal. The last of the Indians then gave a little yell, and said, “No catch dat man—gun always loaded,” and gave up the chase; glad, no doubt, to get off with his life.

Another of this daring warrior’s exploits is worthy of a place beside the most remarkable achievements of individual valor. In the year 1787, a party of Indians crossed the Ohio, killed a family, and scalped with impunity. This murder spread great alarm through the sparse settlements and revenge was not only resolved upon, but a handsome reward was offered for scalps. Major McMahan, who often led the borderers in their hardy expeditions, soon raised a company of twenty men, among whom was Lewis Whetzel. They crossed the Ohio and pursued the Indian trail until they came to the Muskingum river. There the spies discovered a large party of Indians encamped. Major McMahan fell back a short distance, and held a conference when a hasty retreat was resolved upon as the most prudent course, Lewis Whetzel refused to take part in the council, or join in the retreat. He said he came out to hunt Indians; they were now found and he would either lose his own scalp or take that of a “red skin.” All arguments were thrown away upon this iron-willed man; he never submitted to the advice or control of others. His friends were compelled to leave him a solitary being surrounded by vigilant enemies.

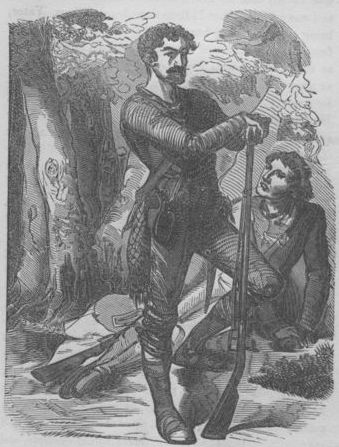

LEWIS WHETZEL’S SINGULAR ESCAPE.

As soon as the major’s party had retired beyond the reach of danger, Whetzel shouldered his rifle, and marched off into a different part of the country, hoping that fortune would place a lone Indian in his way. He prowled through the woods like a panther, eager for prey, until the next evening, when he discovered a smoke curling up among the bushes. Creeping softly to the fire, he found two blankets and a small copper kettle, and concluded that it was the camp of two Indians. He concealed himself in the thick brush, in such a position that he could see the motions of the enemy. About sunset the two Indians came in, cooked and ate their supper, and then sat by the fire engaged in conversation. About nine o’clock one of them arose, shouldered his rifle, took a chunk of fire in his hand, and left the camp, doubtless in search of a deer-lick. The absence of this Indian was a source of vexation and disappointment to Whetzel, who had been so sure of his prey. He waited until near break of day, and still the expected one did not return. The concealed warrior could delay no longer. He walked cautiously to the camp, found his victim asleep, and drawing a knife buried it in the red man’s heart. He then secured the scalp, and set off for home, where he arrived only one day after his companions. For the scalp, he claimed and received the reward.

Here is another of Lewis Whetzel’s remarkable exploits. Returning home from a hunt, north of the Ohio, he was walking along in that reckless manner, which is a consequence of fatigue, when his quick eye suddenly caught sight of an Indian in the act of raising his gun to fire. Both sprung like lightning to the woodman’s forts, large trees, and there they stood for an hour, each afraid of the other. This quiet mode of warfare did not suit the restless Whetzel, and he set his invention to work to terminate it. Placing his bear-skin cap on the end of his ramrod, he protruded it slightly and cautiously as if he was putting his head to reconnoitre, and yet was hesitating in the venture. The simple savage was completely deceived. As soon as he saw the cap, he fired and it fell. Whetzel then sprang forward to the astonished red man, and with a shot from the unerring rifle brought him to the ground quite dead. The triumphant ranger then pursued his march homeward.

But it was in a deliberate attack upon a party of four Indians that our hero displayed the climax of daring and resolution. While on a fall hunt, on the Muskingum, he came upon a camp of four savages, and with but little hesitation resolved to attempt their destruction. He concealed himself till midnight, and then stole cautiously upon the sleepers. As quick as thought, he cleft the skull of one of them. A second met the same fate, and as a third attempted to rise, confused by the horrid yells, which Whetzel gave with his blows, the tomahawk stretched him in death. The fourth Indian darted into the darkness of the wood and escaped, although Whetzel pursued him for some distance. Returning to camp, the ranger scalped his victims and then left for home. When asked on his return, “What luck?” he replied, “Not much. I treed four Indians, and one got away.” Where shall we look for deeds of equal daring and hardihood? Martin, Jacob, and John Whetzel were bold warriors; and in the course of the Indian war, they secured many scalps; but they never obtained the reputation possessed by their brother, Lewis. All must condemn cruelty wherever displayed, but it is equally our duty to render just admiration to courage, daring, and indomitable energy, qualities in which the Whetzel brothers have rarely if ever been excelled.

LEWIS WHETZEL’S STRATAGEM.

General Clark, the companion of Lewis in the celebrated tour across the Rocky Mountains, having heard much of Lewis Whetzel, in Kentucky, determined to secure his services for the exploring expedition. After considerable hesitation, Whetzel consented to go, and accompanied the party during the first three months’ travel, but then declined going any further, and returned home. Shortly after this, he left again on a flat-boat, and never returned. He visited a relation, named Sikes, living about twenty miles in the interior, from Natchez, and there made his home, until the summer of 1808, when he died, leaving a fame for valor and skill in border warfare, which will not be allowed to perish.

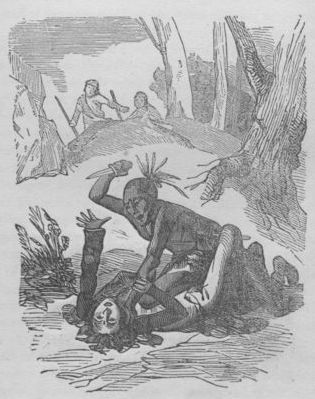

About 1784, horse-stealing was as common as hunting to the whites and Indians of the west. Thefts and reprisals were almost constantly made. Some southern Indians having stolen horses from Lincoln county, Kentucky, three young men, named Caffree, M’Clure, and Davis, set out in pursuit of them. Coming in sight of an Indian town, near the Tennessee river, they met three red men. The two parties made signs of peace, shook hands, and agreed to travel together. Both were suspicious, however, and at length, from various indications, the whites became satisfied of the treacherous intentions of the Indians, and resolved to anticipate then. Caffree being a very powerful man, proposed that he himself should seize one Indian, while Davis and M’Clure should shoot the other two. Caffree sprang boldly upon the nearest Indian, grasped his throat firmly, hurled him to the ground, and drawing a cord from his pocket attempted to tie him. At the same instant, Davis and M’Clure attempted to perform their respective parts. M’Clure killed his man, but Davis’s gun missed fire. All three, i. e. the two white men, and the Indian at whom Davis had flashed, immediately took trees, and prepared for a skirmish, while Caffree remained upon the ground with the captured Indian—both exposed to the fire of the others. In a few seconds, the savage at whom Davis had flashed, shot Caffree as he lay upon the ground and gave him a mortal wound—and was instantly shot in turn by M’Clure who had reloaded his gun. Caffree becoming very weak, called upon Davis to come and assist him in tying the Indian, and directly afterwards expired. As Davis was running up to the assistance of his friend—the Indian released himself, killed his captor, sprung to his feet, and seizing Caffree’s rifle, presented it menacingly at Davis, whose gun was not in order for service, and who ran off into the forest, closely pursued by the Indian. M’Clure hastily reloaded his gun and taking the rifle which Davis had dropped, followed them for some distance into the forest, making all signals which had been concerted between them in case of separation. All, however, was vain—he saw nothing more of Davis, nor could he ever afterwards learn his fate. As he never returned to Kentucky, however, he probably perished.

A SOUTHERN INDIAN.

M’Clure, finding himself alone in the enemy’s country, and surrounded by dead bodies, thought it prudent to abandon the object of the expedition and return to Kentucky. He accordingly retraced his steps, still bearing Davis’ rifle in addition to his own. He had scarcely marched a mile, before he saw advancing from the opposite direction, an Indian warrior, riding a horse with a bell around its neck, and accompanied by a boy on foot. Dropping one of the rifles, which might have created suspicion, M’Clure advanced with an air of confidence, extending his hand and making other signs of peace. The opposite party appeared frankly to receive his overtures, and dismounting, seated himself upon a log, and drawing out his pipe, gave a few puffs himself, and then handed it to M’Clure. In a few minutes another bell was heard, at the distance of half a mile, and a second party of Indians appeared upon horseback. The Indian with M’Clure now coolly informed him by signs that when the horseman arrived, he (M’Clure) was to be bound and carried off as a prisoner with his feet tied under the horse’s belly. In order to explain it more fully, the Indian got astride of the log, and locked his legs together underneath it. M’Clure, internally thanking the fellow for his excess of candor, determined to disappoint him, and while his enemy was busily engaged in riding the log, and mimicking the actions of a prisoner, he very quietly blew his brains out, and ran off into the woods. The Indian boy instantly mounted the belled horse, and rode off in an opposite direction. M’Clure was fiercely pursued by several small Indian dogs, that frequently ran between his legs and threw him down. After falling five or six times, his eyes became full of dust and he was totally blind. Despairing of escape, he doggedly lay upon his face, expecting every instant to feel the edge of the tomahawk. To his astonishment, however, no enemy appeared, and even the Indian dogs after tugging at him for a few minutes, and completely stripping him of his breeches, left him to continue his journey unmolested. Finding every thing quiet, in a few moments he arose, and taking up his gun continued his march to Kentucky.

CAFFREE KILLED BY THE INDIAN.

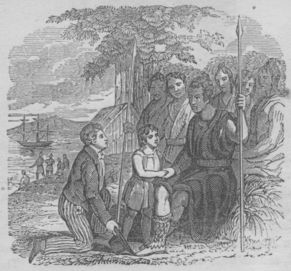

In March, 1790 a boat, containing four men and two women, passing down the Ohio, was induced by some renegade whites to approach the shore, near the mouth of the Sciota, and then attacked by a large party of Indians. A Mr. John May and one of the women were shot dead, and the others then surrendered. The chief of the band was an old warrior, named Chickatommo, and under his command were a number of renowned red men. When the prisoners were distributed, a young man named Charles Johnson, was given to a young Shawnee chief who is represented to have been a noble character. His name was Messhawa, and he had just reached the age of manhood. His person was tall and seemingly rather fitted for action than strength. His bearing was stately, and his countenance expressive of a noble disposition. He possessed great influence among those of his own tribe, which he exerted on the side of humanity. On the march, Messhawa repeatedly saved Johnson from the tortures which the other savages delighted to inflict, and the young captive saw some displays of generous exertion on the part of the chief which are worthy of a place in border history.

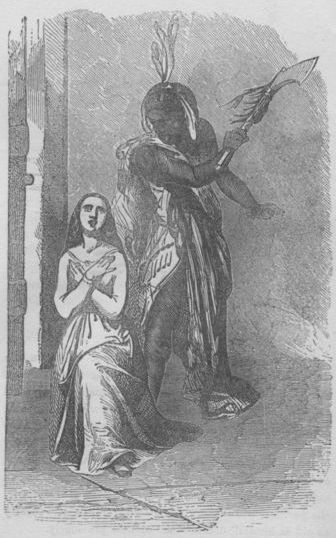

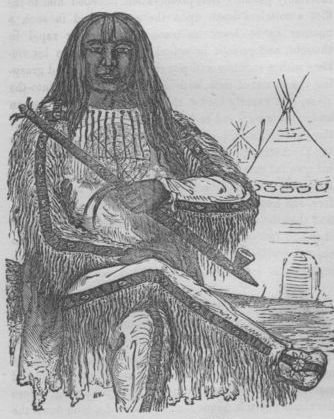

MESSHAWA.

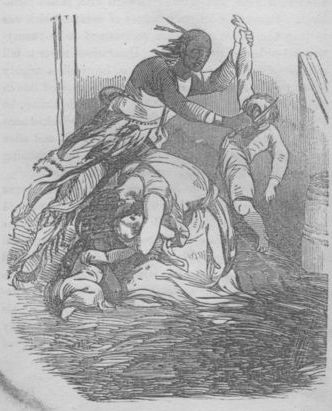

The warriors painted themselves in the most frightful colors, and performed a war dance, with the usual accompaniments. A stake, painted in alternate stripes of black and vermilion, was fixed in the ground, and the dancers moved in rapid but measured evolutions around it. They recounted, with great energy, the wrongs they had received from the whites.—Their lands had been taken from them—their corn cut up—their villages burnt—their friends slaughtered—every injury which they had received was dwelt upon, until their passions had become inflamed beyond control. Suddenly, Chickatommo darted from the circle of dancers, and with eyes flashing fire, ran up to the spot where Johnston was sitting, calmly contemplating the spectacle before him. When within reach he struck him a furious blow with his fist, and was preparing to repeat it, when Johnston seized him by the arms, and hastily demanded the cause of such unprovoked violence. Chickatommo, grinding his teeth with rage, shouted “Sit down, sit down!” Johnston obeyed, and the Indian, perceiving the two children within ten steps of him, snatched up a tomahawk, and advanced upon them with a quick step, and a determined look. The terrified little creatures instantly arose from the log on which they were sitting, and fled into the woods, uttering the most piercing screams, while their pursuer rapidly gained upon them with uplifted tomahawk. The girl, being the youngest, was soon overtaken, and would have been tomahawked, had not Messhawa bounded like a deer to her relief. He arrived barely in time to arrest the uplifted tomahawk of Chickatommo, after which, he seized him by the collar and hurled him violently backward to the distance of several paces. Snatching up the child in his arms, he then ran after the brother, intending to secure him likewise from the fury of his companion, but the boy, misconstruing his intention, continued his flight with such rapidity, and doubled several times with such address, that the chase was prolonged to the distance of several hundred yards. At length Messhawa succeeded in taking him. The boy, thinking himself lost, uttered a wild cry, which was echoed by his sister, but both were instantly calmed. Messhawa took them in his arms, spoke to them kindly, and soon convinced them that they had nothing to fear from him. He quickly reappeared, leading them gently by the hand, and soothing them in the Indian language, until they both clung to him closely for protection.

No other incident disturbed the progress of the ceremonies, nor did Chickatommo appear to resent the violent interference of Messhawa.

CHICKATOMMO.

After undergoing many hardships, Johnston was taken to Sandusky, where he was ransomed by a French trader. Messhawa took leave of his young captive with many expressions of esteem and friendship. This noble chief was in the battle of the Fallen Timber and afterwards became a devoted follower of the great Tecumseh—thus proving that while he was as humane as a civilized man, he was patriotic and high-spirited enough to resent the wrongs of his people. He was killed at the battle of the Thames, where the power of the Shawnees was for ever crushed.

Big Joe Logston was a noted character in the early history of the west. He was born and reared among the Alleghany mountains, near the source of the north branch of the Potomac, some twenty or thirty miles from any settlement. He was tall, muscular, excelled in all the athletic sports of the border, and was a first-rate shot. Soon after Joe arrived at years of discretion, his parents died, and he went out to the wilds of Kentucky. There, Indian incursions compelled him to take refuge in a fort. This pent up life was not at all to Joe’s taste. He soon became very restless, and every day insisted on going out with others to hunt up cattle. At length no one would accompany him, and he resolved to go out alone. He rode the greater part of the day without finding any cattle, and then concluded to return to the fort. As he was riding along, eating some grapes, with which he had filled his hat, he heard the reports of the two rifles; one ball passed through the paps of his breast, which were very prominent, and the other struck the horse behind the saddle, causing the beast to sink in its tracks.

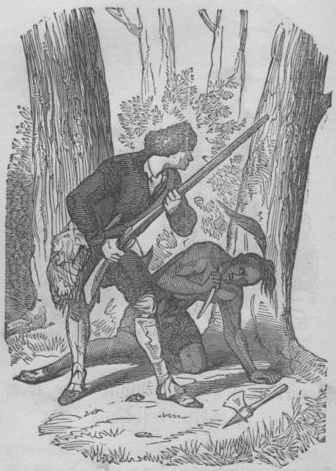

INDIANS AMBUSHED FOR JOE LOGSTON.

Joe was on his feet in an instant and might have taken to his heels with the chances of escape greatly in his favor. But to him flight was never agreeable. The moment the guns were fired, an Indian sprang forward with an uplifted tomahawk; but as Joe raised his rifle, the savage jumped behind two saplings, and kept springing from one to the other to cover his body. The other Indian was soon discovered behind a tree loading his gun. When in the act of pushing down his bullet, he exposed his hips and Joe fired a load into him. The first Indian then sprang forward and threw his tomahawk at the head of the white warrior, who dodged it. Joe then clubbed his gun and made at the savage, thinking to knock him down. In striking, he missed, and the gun now reduced to the naked barrel, flew out of his hands. The two men then sprang at each other with no other weapons than those of nature. A desperate scuffle ensued. Joe could throw the Indian down, but could not hold him there. At length, however, by repeated heavy blows, he succeeded in keeping him down, and tried to choke him with the left hand while he kept the right free for contingencies. Directly, Joe saw the savage trying to draw a knife from its sheath, and waiting till it was about half way out, he grasped it quickly and sank it up to the handle in the breast of his foe, who groaned and expired.

Springing to his feet, Joe saw the Indian he had crippled, propped against a log, trying to raise his gun to fire, but falling forward, every time he made the attempt. The borderer, having enough of fighting for one day, and not caring to be killed by a crippled Indian, made for the fort, where he arrived about nightfall. He was blood and dirt from crown to toe, and without horse, hat, or gun.

The next morning a party went to Joe’s battle-ground. On looking round, they found a trail, as if something had been dragged away, and at a little distance they came upon the big Indian, covered up with leaves. About a hundred yards farther, they found the Indian Joe had crippled, lying on his back, with his own knife sticking up to the hilt in his body, just below the breast bone, evidently to show that he had killed himself. Some years after this fight, Big Joe Logston lost his life in a contest with a gang of outlaws. He was one of those characters who were necessary to the settlement of the west, but who would not have been highly esteemed in civilized society.

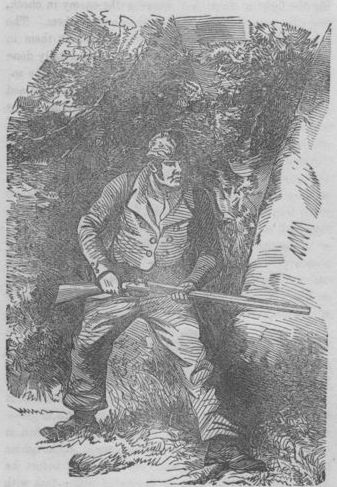

INDIAN IN AMBUSH

Jesse Hughes was born and reared in Clarksburgh, Harrison county, Virginia, on the head-waters of the Monongahela. He was a light-built, active man, and from his constant practice became one of the best hunters and Indian fighters on the frontier. Having a perfect knowledge of all the artifices of the Indians, he was quick to devise expedients to frustrate them. Of this, the following exploit is an illustration. At a time of great danger from Indian incursions, when the citizens in the neighborhood where in a fort at Clarksburgh, Hughes one morning observed a lad very hurriedly engaged in fixing his gun.

“Jim,” said he, “what are you doing that for?”

“I am going to shoot a turkey that I hear gobbling on the hill side,” replied Jim.

“I hear no turkey,” said Hughes.

“Listen,” said Jim. “There, didn’t you hear it? Listen again!”

“Well,” said Hughes, after hearing it repeated, “I’ll go and kill it.”

“No you won’t. It’s my turkey. I heard it first,” said Jim.

“Well,” said Hughes, “but you know I am the best marksman; and besides, I don’t want the turkey, you may have it.”

The lad then agreed that Hughes should go and kill it for him. Hughes went out of the fort on the side that was farthest from the supposed turkey, and running along the river, went up a ravine and came in on the rear, where, as he expected, he saw an Indian, sitting on a chestnut stump, surrounded by sprouts, gobbling and watching to see if any one would come from the fort to kill the turkey. Hughes crept up and shot him dead. The successful ranger then took off the scalp, and went into the fort, where Jim was waiting for the prize.

“There, now,” said Jim, “you have let the turkey go. I would have killed it if I had gone.”

“No,” said Hughes, “I didn’t let it go,” and he threw down the scalp. “There, take your turkey, Jim; I don’t want it.”

The lad nearly fainted, as he thought of the death he had so narrowly escaped, owing to the keen perception and good management of Mr. Hughes.

The sagacity of our border hero was fully proved upon another occasion. About 1790, the Indians visited Clarksburgh, in the night, and contrived to steal a few horses, with which they made a hasty retreat. About daylight the next morning, a party of twenty-five or thirty men, among whom was Jesse Hughes, started in pursuit. They found a trail just outside of the settlement, and from the signs, supposed that the marauding party consisted of eight or ten Indians. A council was held to determine how the pursuit should be continued. Mr. Hughes was opposed to following the trail. He said he could pilot the party to the spot where the Indians would cross the Ohio, by a nearer way than the enemy could go, and thus render success certain. But the captain of the party insisted on following the trail. Mr. Hughes then pointed out the dangers of such a course. Suddenly, the captain, with unreasonable obstinacy, called aloud to those who were brave to follow him and let the cowards go home. Hughes knew the captain’s remark was intended for him, but smothered his indignation and went on with the party.

They had not pursued very far when the trail went down a drain, where the ridge on one side was very steep, with a ledge of rocks for a considerable distance. On the top of the cliff, two Indians lay in ambush, and when the company got opposite to them, they made a noise, which caused the whites to stop; that instant two of the company were mortally wounded, and before the rangers could get round to the top of the cliff, the Indians made their escape with ease. This was as Hughes had predicted. All then agreed that the plan rejected by the captain was the best, and urged Hughes to lead them to the Ohio river. This he consented to do, though fearful that the Indians would cross before he could reach the point. Leaving some of the company to take care of the wounded men, the party started, and arrived at the Ohio the next day, about an hour after the Indians had crossed. The water was yet muddy in the horses’ trails, and the rafts that the red men had used were floating down the opposite shore. The company was now unanimous for returning home. Hughes said he wanted to find out who the cowards were. He said that if any of them would go with him, he would cross the river, and scalp some of the Indians. Not one could be found to accompany the daring ranger, who thus had full satisfaction for the captain’s insult. He said he would go by himself, and take a scalp, or leave his own with the savages. The company started for home, and Hughes went up the river three or four miles, then made a raft, crossed the river, and camped for the night. The next day, he found the Indian trail, pursued it very cautiously, and about ten miles from the Ohio, came upon the camp. There was but one Indian in it; the rest were all out hunting. The red man was seated, singing, and playing on some bones, made into a rude musical instrument, when Hughes crept up and shot him. The ranger then took the scalp, and hastened home in triumph, to tell his adventures to his less daring companions.

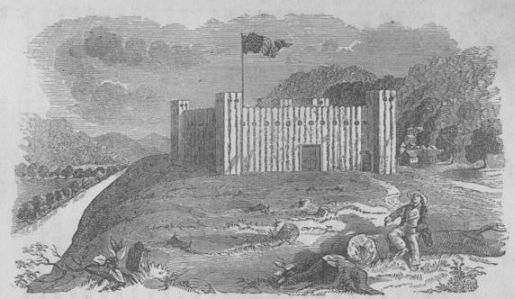

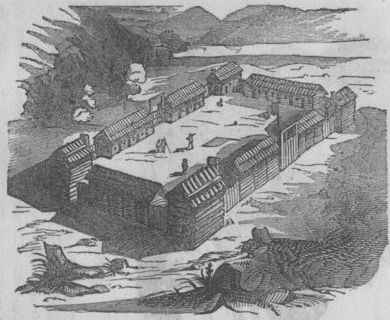

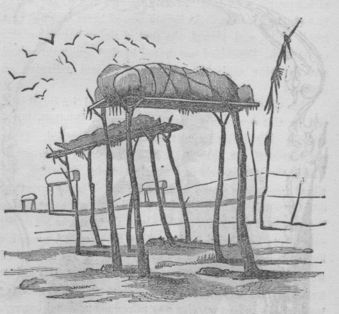

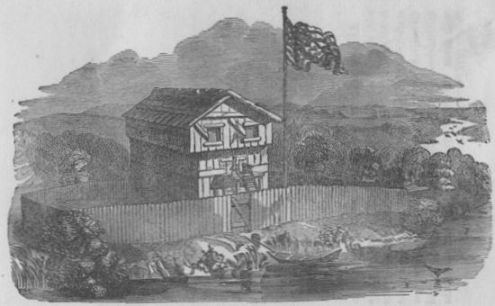

FORT HENRY.

The siege of Fort Henry, at the mouth of Wheeling creek, in the year 1777, is one of the most memorable events in Indian warfare—remarkable for the indomitable bravery displayed by the garrison in general, and for some thrilling attendant incidents. The fort stood immediately on the left bank of the Ohio river, about a quarter of a mile above Wheeling creek, and at much less distance from an eminence which rises abruptly from the bottom land. The space inclosed was about three quarters of an acre. In shape the fort was a parallelogram, having a block-house at each corner with lines of pickets eight feet high between. Within the inclosures was a store-house, barrack-rooms, garrison-well, and a number of cabins for the use of families. The principal entrance was a gateway on the eastern side of the fort. Much of the adjacent land was cleared and cultivated, and near the base of the hill stood some twenty-five or thirty cabins, which form the rude beginning of the present city of Wheeling. The fort is said to have been planned by General George Rogers Clarke; and was constructed by Ebenezer Zane and John Caldwell. When first erected, it was called Fort Fincastle but the name was afterwards changed in compliment to Patrick Henry the renowned orator and patriotic governor of Virginia.

At the time of the commencement of the siege, the garrison of Fort Henry numbered only forty-two men, some of whom were enfeebled by age while others were mere boys. All, however, were excellent marksmen, and most of them, skilled in border warfare. Colonel David Shepherd, was a brave and resolute officer in whom the borderers had full confidence. The store-house was well-supplied with small arms, particularly muskets, but sadly deficient in ammunition.

In the early part of September, 1777, it was ascertained that a large Indian army was concentrating on the Sandusky river, under the command of the bold, active, and skilful renegade, Simon Girty. Colonel Shepherd had many trusty and efficient scouts on the watch; but Girty deceived them all and actually brought his whole force of between four and five hundred Indians before Fort Henry before his real object was discovered.

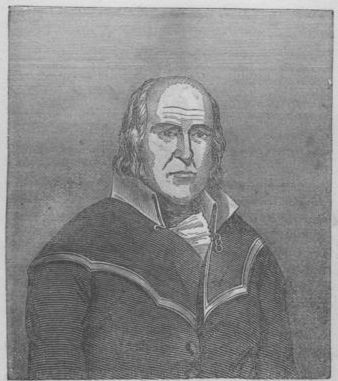

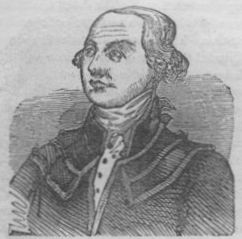

PATRICK HENRY.

On the 26th, an alarm being given all the inhabitants in the vicinity repaired to the fort for safety. At break of day, on the 27th, Colonel Shepherd, wishing to dispatch an express to the nearest settlements for aid, sent a white man and a negro to bring in some horses. While these men were passing through the cornfield south of the fort, they encountered a party of six Indians, one of whom raised his gun and brought the white man to the ground. The negro fled and reached the fort without receiving any injury. As soon as he related his story, Colonel Shepherd dispatched Captain Mason, with fourteen men, to dislodge the Indians from the cornfield. Mason marched almost to the creek without finding any Indians, and was about to return, when he was furiously assailed in front, flank and rear by the whole of Girty’s army. Of course, the little band was thrown into confusion, but the brave captain rallied his men, and taking the lead, hewed a passage through the savage host. In the struggle, more than half of the party were slain, and the gallant Mason severely wounded. An Indian fired at the captain at the distance of five paces and wounded, but did not disable him. Turning about, he hurled his gun, felled the savage to the earth, and then succeeded in hiding himself in a pile of fallen timbers, where he was compelled to remain to the end of the siege. Only two of his men survived the fight, and they owed their safety to the heaps of logs and brush which abounded in the cornfield.

As soon as the perilous situation of Captain Mason became known at the fort, Captain Ogle was sent out with twelve men, to cover his retreat. This party fell into an ambuscade and two-thirds of the number were slain upon the spot. Captain Ogle found a place of concealment, where he was obliged to remain until the end of the siege. Sergeant Jacob Ogle, though mortally wounded, managed to escape, with two soldiers into the woods.

The Indian army now advanced to the assault, with terrific yells. A few shots from the garrison, however, compelled them to halt. Girty then changed the order of attack. Parties of Indians were placed in such of the village-houses as commanded a view of the block-houses. A strong party occupied the yard of Ebenezer Zane, about fifty yards from the fort, using a paling fence as a cover, while the main force was posted under cover on the edge of a cornfield to act as occasion might require.

Girty then appeared at the window of a cabin, with a white flag in his hand, and demanded the surrender of the fort in the name of his Britanic majesty. At this time, the garrison numbered only twelve men and two boys. Yet the gallant Colonel Shepherd promptly replied to the summons, that the fort should never be surrendered to the renegade. Girty renewed his proposition, but before he could finish his harangue, a thoughtless youth fired at the speaker and brought the conference to an abrupt termination. Girty disappeared, and in about fifteen minutes, the Indians opened a heavy fire upon the fort, and continued it without much intermission for the space of six hours. The fire of the little garrison, however, was much more destructive than that of the assailants. About one o’clock, the Indians ceased firing and fell back against the base of the hill.

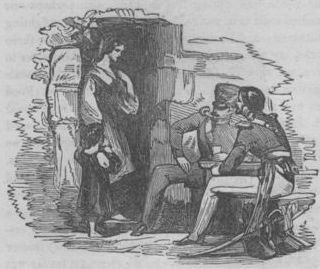

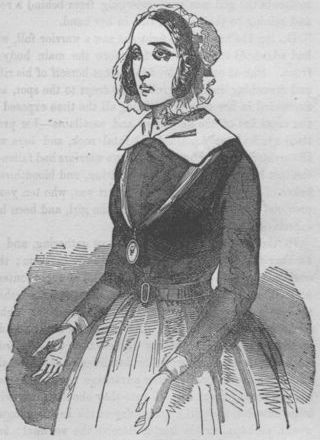

THE ALARM AT FORT HENRY.

The colonel resolved to take advantage of the intermission to send for a keg of powder, which was known to be in the house of Ebenezer Zane, about sixty yards from the fort. Several young men promptly volunteered for this dangerous service; but Shepherd could only spare one, and the young men could not determine who that should be. At this critical moment, a young lady, sister of Ebenezer Zane, came forward, and asked that she might be permitted to execute the service; and so earnestly did she argue for the proposition, that permission was reluctantly granted. The gate was opened, and the heroic girl passed out. The opening of the gate arrested the attention of several Indians who were straggling through the village, but they permitted Miss Zane to pass without molestation. When she reappeared with the powder in her arms, the Indians, suspecting the character of her burden, fired a volley at her, but she reached the fort in safety. Let the name of Elizabeth Zane be remembered among the heroic of her sex.

About half-past two o’clock, the savages again advanced and renewed their fire. An impetuous attack was made upon the south side of the fort, but the garrison poured upon the assailants a destructive fire from the two lower block-houses. At the same time, a party of eighteen or twenty Indians, armed with rails and billets of wood, rushed out of Zane’s yard and made an attempt to force open the gate of the fort. Five or six of the number were shot down, and then the attempt was abandoned. The Indians then opened a fire upon the fort from all sides, except that next the river, which afforded no shelter to besiegers. On the north and east the battle raged fiercely. As night came on the fire of the enemy slackened. Soon after dark, a party of savages advanced within sixty yards of the fort, bringing a hollow maple log which they had loaded to the muzzle and intended to use it as a cannon. The match was applied and the wooden piece bursted, killing or wounding several of those who stood near it. The disappointed party then dispersed.

Late in the evening, Francis Duke, son-in-law of Colonel Shepherd, arriving from the Forks of Wheeling, was shot down before he could reach the fort. About four o’clock next morning, Colonel Swearingen, with fourteen men, arrived from Cross Creek, and was fortunate enough to fight his way into the fort without losing a single man.

This reinforcement was cheering to the wearied garrison. More relief was at hand. About daybreak, Major Samuel M’Culloch, with forty mounted men from Short Creek, arrived. The gate was thrown open, and the men, though closely beset by the enemy, entered the fort. But Major M’Culloch was not so fortunate. The Indians crowded round and separated him from the party. After several ineffectual attempts to force his way to the gate, he turned and galloped off in the direction of Wheeling Hill.

DARING FEAT OF ELIZABETH ZANE.

When he was hemmed in by the Indians before the fort, they might have taken his life without difficulty, but they had weighty reasons for desiring to take him alive. From the very commencement of the war, his reputation as an Indian hunter was as great as that of any white man on the north-western border. He had participated in so many rencontres that almost every warrior possessed a knowledge of his person. Among the Indians his name was a word of terror; they cherished against him feelings of the most phrenzied hatred, and there was not a Mingo or Wyandotte chief before Fort Henry who would not have given the lives of twenty of his warriors to secure to himself the living body of Major M’Culloch. When, therefore, the man whom they had long marked out as the first object of their vengeance, appeared in their midst, they made almost superhuman efforts to acquire possession of his person. The fleetness of M’Culloch’s well-trained steed was scarcely greater than that of his enemies, who, with flying strides, moved on in pursuit. At length the hunter reached the top of the hill, and, turning to the left, darted along the ridge with the intention of making the best of his way to Shor’ creek. A ride of a few hundred yards in that direction brought him suddenly in contact with a party of Indians who were returning to their camp from a marauding excursion to Mason’s Bottom, on the eastern side of the hill. This party being too formidable in numbers to encounter single-handed, the major turned his horse about and rode over his own track, in the hope of discovering some other avenue to escape. A few paces only of his countermarch had been made, when he found himself confronted by his original pursuers, who had, by this time, gained the top of the ridge, and a third party was discovered pressing up the hill directly on his right. He was now completely hemmed in on three sides, and the fourth was almost a perpendicular precipice of one hundred and fifty feet descent, with Wheeling creek at its base. The imminence of his danger allowed him but little time to reflect upon his situation. In an instant he decided upon his course. Supporting his rifle in his left hand and carefully adjusting his reins with the other, he urged his horse to the brink of the bluff, and then made the leap which decided his fate. In the next moment the noble steed, still bearing his intrepid rider in safety, was at the foot of the precipice. M’Culloch immediately dashed across the creek, and was soon beyond reach of the Indians.

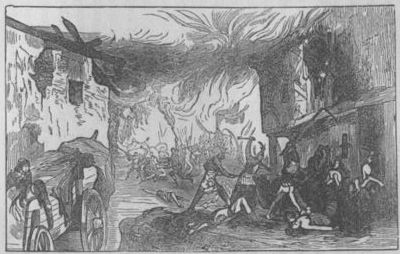

After the escape of the major, the Indians concentrated at the foot of the hill, and soon after set fire to all the houses and fences outside of the fort, and killed about three hundred cattle. They then raised the siege and retired.

The whole loss sustained by the whites during this remarkable siege, was twenty-six men killed and four or five wounded. The loss of the enemy was from sixty to one hundred men. As they removed their dead, exact information on the subject could not be obtained.

The gallant Colonel Shepherd deserved the thanks of the frontier settlers for his conduct on this occasion, and Governor Henry appointed him county lieutenant as a token of his esteem. A number of females, who were in the fort, undismayed by the dreadful strife, employed themselves in running bullets and performing various little services; and thus excited much enthusiasm among the men. Perhaps, a more heroic band was never gathered together in garrison than that which defended Fort Henry, and it would be unjust to mention any one as particularly distinguished. We have named the commander only because of his position.

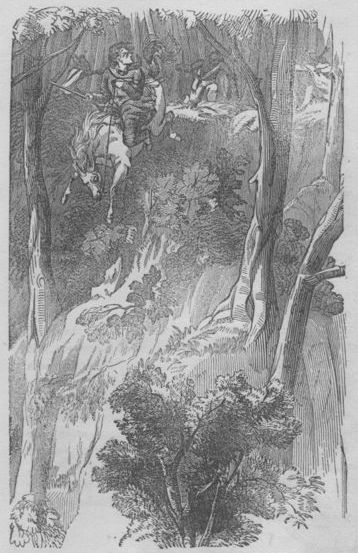

TREMENDOUS LEAP OF MAJOR M’CULLOCH.

During the long warfare maintained between the pioneers of the west and the Indians, the latter were greatly assisted by some renegade white men. Of these, Simon Girty was the most noted and influential. He led several important expeditions against the settlements of Virginia and Kentucky, displayed much courage, energy, and conduct, and was the object of bitter hatred on the frontier. Recent investigations into the stirring events of his career have shown that however bad he might have been, much injustice has been done his memory by border historians.

Simon Girty was born and reared in Western Pennsylvania, near the Virginia line. His parents are said to have been very dissipated, and this, perhaps, had some influence in disgusting him with life in the settlements. Becoming skilled in woodcraft, he served with young Simon Kenton, as a scout upon the frontiers. He joined the Virginia army in Dunmore’s wars, and, it is said, showed considerable ambition to become distinguished as a soldier. He was disappointed, and so far from gaining promotion, was, for a trifling offence, publicly disgraced, it is said, through the influence of Colonel Gibson. The proud spirit of Girty could not brook such a blow. With a burning thirst for revenge, he fled from the settlements, and took refuge among the Wyandottes.

The talents of the renegade were of the kind and of the degree to secure influence among the red men. He excelled the majority of them in council and field, and neither forgave a foe, nor forgot a friend. He was successful in many expeditions after plunder and scalps, and spared none because they were of his own race. He was cruel as many of the borderers were cruel. Becoming an Indian, he had an Indian’s hatred of the whites. The borderers seldom showed a red man mercy, and they could not expect any better treatment in return.

The exertions of Girty to save his friend, Simon Kenton, from a horrible death, have been noticed in another place. That he did not make such exertions more frequently on the side of humanity is scarcely a matter of wonder—inasmuch as he could not have done so consistently with a due regard to his own safety. After he had become a renegade, the borderers would not permit a return; and as he was forced to reside among the Indians, he was right in securing their favor. Besides saving Kenton, he posted his brother, James Girty, upon the banks of the Ohio, to warn passengers in boats not to be lured to the shore by the arts of the Indians, or of the white men in their service. This was a pure act of humanity. The conduct of Girty on another memorable occasion, the burning of Colonel William Crawford, was more suspicious.

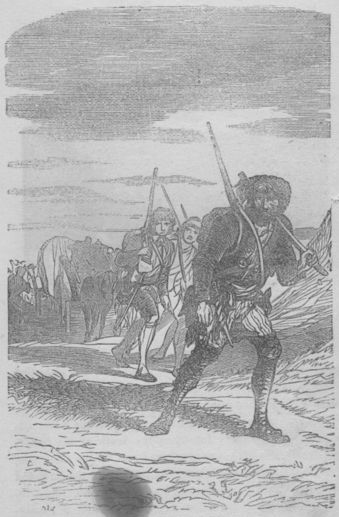

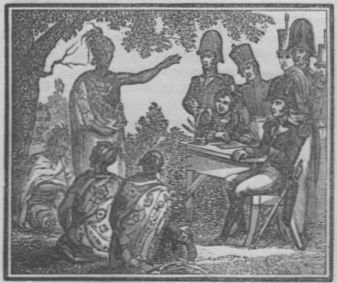

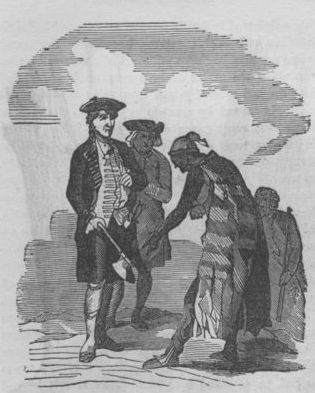

COLONEL CRAWFORD AND HIS FRIENDS, PRISONERS.

In the early part of the year 1782, the incursions of the Indians became so harassing and destructive to the inhabitants of Western Pennsylvania, that an expedition against the Wyandotte towns was concerted, and the command given to Colonel Crawford. On the 22d of May, the army, consisting of four hundred and fifty men, commenced its march, and proceeded due west as far as the Moravian towns, where some of the volunteers deserted. The main body, however, marched on, with unabated spirit. The Indians, discovering the advance of the invaders gathered a considerable force, and took up a strong position, determined to fight. Crawford moved forward in order of battle, and on the afternoon of the 6th of June, encountered the enemy. The conflict continued fiercely until night, when the Indians drew off, and Crawford’s men slept on the field. In the morning, the battle was renewed, but at a greater distance, and, during the day, neither party suffered much. The delay, however, was fatal to Crawford; for the Indians received large reinforcements. As soon as it was dark, a council of war was held, and it was resolved to retreat as rapidly as possible. By nine o’clock, all the necessary arrangements had been made, and the retreat began in good order. After an advance of about a hundred yards, a firing was heard in the rear, and the troops, seized with a panic, broke and fled in confusion, each man trying to save himself. The Indians came on rapidly in pursuit and plied the tomahawk and scalping-knife without mercy. Colonel Crawford and Dr. Knight were captured, at a distance from the main body—which was soon dispersed in every direction.

On the morning of the 10th of June, Crawford, Knight, and nine other prisoners, were conducted to the old town of Sandusky. The main body of the Indians halted within eight miles of the village; but as Colonel Crawford expressed great anxiety to speak with Simon Girty, who was then at Sandusky, he was permitted to go under the care of the Indians. On the morning of the 11th of June, the colonel was brought back from Sandusky on purpose to march into town with the other prisoners. To Knight’s inquiry as to whether he had seen Girty, he replied in the affirmative, and added, that the renegade had promised to use his influence for the safety of the prisoners, though as the Indians were much exasperated by the recent outrages of the whites at Guadenhutten upon the unresisting Moravian red men, he was fearful that all pleading would be in vain.

Soon afterwards, Captain Pipe, the great chief of the Delawares, appeared. This distinguished warrior had a prepossessing appearance and bland manners, and his language to the prisoners was kind. His purposes, however, were bloody and revengeful. With his own hands he painted every prisoner black! As they were conducted towards the town, the captives observed the bodies of four of their friends, tomahawked and scalped. This was regarded as a sad presage. In a short time, they overtook the five prisoners who remained alive. They were seated on the ground, and surrounded by a crowd of Indian squaws and boys, who taunted and menaced them. Crawford and Knight were compelled to sit down apart from the rest, and immediately afterwards the doctor was given to a Shawnee warrior, to be conducted to their town. The boys and squaws then fell upon the other prisoners, and tomahawked them in a moment. Crawford was then driven towards the village, Girty accompanying the party on horseback.

Presently, a large fire was seen, around which were more than thirty warriors, and about double that number of boys and squaws. As soon as the colonel arrived, he was stripped naked, and compelled to sit on the ground. The squaws and boys then fell upon him, and beat him severely with their fists and sticks. In a few minutes, a large stake was fixed in the ground, and piles of hickory poles were spread around it.

Colonel Crawford’s hands were then tied behind his back; a strong rope was produced, one end of which was fastened to the ligature between his wrists, and the other tied to the bottom of the stake. The rope was long enough to permit him to walk round the stake several times and then return. Fire was then applied to the hickory poles, which lay in piles at the distance of six or seven yards from the stake.

The colonel observing these terrible preparations, called to Girty, who sat on horseback, at the distance of a few yards from the fire, and asked if the Indians were going to burn him. Girty replied in the affirmative. The colonel heard the intelligence with firmness, merely observing that he would bear it with fortitude. When the hickory poles had been burnt asunder in the middle, Captain Pipe arose and addressed the crowd, in a tone of great energy, and with animated gestures, pointing frequently to the colonel, who regarded him with an appearance of unruffled composure. As soon as he had ended, a loud whoop burst from the assembled throng, and they all rushed at once upon the unfortunate Crawford. For several seconds, the crowd was so great around him, that Knight could not see what they were doing; but in a short time, they had dispersed sufficiently to give him a view of the colonel.

His ears had been cut off, and the blood was streaming down each side of his face. A terrible scene of torture now commenced. The warriors shot charges of powder into his naked body, commencing with the calves of his legs, and continuing to his neck. The boys snatched the burning hickory poles and applied them to his flesh. As fast as he ran around the stake, to avoid one party of tormentors, he was promptly met at every turn by others, with burning poles, red hot irons, and rifles loaded with powder only; so that in a few minutes nearly one hundred charges of powder had been shot into his body, which had become black and blistered in a dreadful manner. The squaws would take up a quantity of coals and hot ashes, and throw them upon his body, so that in a few minutes he had nothing but fire to walk upon.

CAPTAIN PIPE.

In the extremity of his agony, the unhappy colonel called aloud upon Girty, in tones which rang through Knight’s brain with maddening effect: “Girty! Girty!! shoot me through the heart!! Quick! quick!! Do not refuse me!!”

“Don’t you see I have no gun, colonel!!” replied the renegade, bursting into a loud laugh, and then turning to an Indian beside him, he uttered some brutal jests upon the naked and miserable appearance of the prisoner. While this awful scene was being acted, Girty rode up to the spot where Dr. Knight stood, and told him that he had now had a foretaste of what was in reserve for him at the Shawnee towns. He swore that he need not expect to escape death, but should suffer it in all the extremity of torture.

Knight, whose mind was deeply agitated at the sight of the fearful scene before him, took no notice of Girty, but preserved an impenetrable silence. Girty, after contemplating the colonel’s sufferings for a few moments, turned again to Knight, and indulged in a bitter invective against a certain Colonel Gibson, from whom, he said, he had received deep injury; and dwelt upon the delight with which he would see him undergo such tortures as those which Crawford was then suffering. He observed, in a taunting tone, that most of the prisoners had said, that the white people would not injure him, if the chance of war was to throw him into their power; but that for his own part, he should be loath to try the experiment. “I think, (added he with a laugh,) that they would roast me alive, with more pleasure than those red fellows are now broiling the colonel! What is your opinion, doctor? Do you think they would be glad to see me?” Still Knight made no answer, and in a few minutes Girty rejoined the Indians.

The terrible scene had now lasted more than two hours, and Crawford had become much exhausted. He walked slowly around the stake, spoke in a low tone, and earnestly besought God to look with compassion upon him, and pardon his sins. His nerves had lost much of their sensibility, and he no longer shrunk from the firebrands with which they incessantly touched him. At length he sunk in a fainting fit upon his face, and lay motionless. Instantly an Indian sprung upon his back, knelt lightly upon one knee, made a circular incision with his knife upon the crown of his head, and clapping the knife between his teeth, tore the scalp off with both hands. Scarcely had this been done, when a withered hag approached with a board full of burning embers, and poured them upon the crown of his head, now laid bare to the bone. The colonel groaned deeply, arose, and again walked slowly around the stake! But why continue a description so horrible? Nature at length could endure no more, and at a late hour in the night, he was released by death from the hands of his tormentors.[B]

Whether Girty really took pleasure in the torture of Colonel Crawford, or was forced by circumstances to seem to enjoy it is a question which historians have generally been in too much haste to determine. It is well known that at the time of Crawford’s expedition the Indians were very much exasperated by the cold-blooded slaughter of the Moravian red men at Guadenhutten—an atrocity without a parallel in border warfare, and to have seemed merciful to the whites for a single moment would have been fatal to Girty. Indeed, it is said, that, when he spoke of ransoming the colonel, Captain Pipe threatened him with death at the stake. Let justice be rendered even to the worst of criminals.

Dr. Knight, made bold or desperate by the torture he had witnessed, effected his escape from the Shawnee warrior to whose care he was committed, and after much suffering, reached the settlements. From him the greater portion of the account of Crawford’s death is derived, and corrected by the statements of Indians present on the occasion. Simon Girty never forsook the Indians among whom he had made his home; but his influence gradually diminished. Some accounts say that he perished in the battle of the Thames; while others assert that he lived to extreme old age in Canada, where his descendants are now highly respected citizens.

Extraordinary strength and activity, with the most daring courage and a thorough knowledge of life in the woods, won for Joshua Fleehart a high reputation among the first settler’s of Western Virginia and Ohio. When the Ohio Company founded its settlement at Marietta, in April, 1778, Fleehart was employed as a scout and a hunter. In this service he had no superior north of the Ohio. At periods of the greatest danger, when the Indians were known to be much incensed against the whites, he would start from the settlement with no companion but his dog, and ranging within about twenty miles of an Indian town, would build his cabin and trap and hunt during nearly the whole season. On one occasion this reckless contempt of danger almost cost the hunter his life.

JOSHUA FLEEHART.

Having became tired of the sameness of garrison life, and panting for that freedom among the woods and hills to which he had always been accustomed, late in the fall of 1795, he took his canoe, rifle, traps, and blanket, with no one to accompany him, leaving even his faithful dog in the garrison with his family. As he was going into a dangerous neighborhood, he was fearful lest the voice of his dog might betray him. With a daring and intrepidity which few men possess, he pushed his canoe up the Sciota river a distance of fifteen or twenty miles, into the Indian country, amidst their best hunting-grounds for the bear and the beaver, where no white man had dared to venture. These two were the main object of his pursuit, and the hills of Brush creek were said to abound in bear, and the small streams that fell into the Sciota were well suited to the haunts of the beaver.

The spot chosen for his winter’s residence was within twenty-five or thirty miles of the Indian town of Chillicothe, but as they seldom go far to hunt in the winter, he had little to fear from their interruption. For ten or twelve weeks he trapped and hunted in this solitary region unmolested; luxuriating on the roasted tails of the beaver, and drinking the oil of the bear, an article of diet which is considered by the children of the forest as giving health to the body, with strength and activity to the limbs. His success had equalled his most sanguine expectations, and the winter passed away so quietly and so pleasantly, that he was hardly aware of its progress. About the middle of February, he began to make up the peltry he had captured into packages, and to load his canoe with the proceeds of his winter’s hunt, which for safety had been secreted in the willows, a few miles below the little bark hut in which he had lived. The day before that which he had fixed on for his departure, as he was returning to his camp, just at evening, Fleehart’s acute ear caught the report of a rifle in the direction of the Indian towns, but at so remote a distance, that none but a backwoodsman could have distinguished the sound. This hastened his preparations for decamping. Nevertheless he slept quietly, but rose the following morning before the dawn; cooked and ate his last meal in the little hut to which he had become quite attached.

FLEEHART SHOOTING THE INDIAN.