Transcriber's Note: Corrections are underlined with a thin dotted

line—hovering over them will reveal an explanatory transcriber's note.

Hyphenation of the word 'antebellum' has been regularized

(ante-bellum → antebellum), and several spelling and punctuation irregularies between the

index and the main text have been corrected without note.

Several alphabetization errors in the index were also corrected. All other

spelling and punctuation is as it appeared in the original.

Two identical footnotes on pages 42-43 have been merged into one (Footnote 16).

The Table of Contents did not appear in the original—it has been added by the transcriber.

NEGRO FOLK RHYMES

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

Negro Folk Rhymes

Wise and Otherwise

WITH A STUDY

BY

THOMAS W. TALLEY,

OF FISK UNIVERSITY

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1922

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Copyright, 1922,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and printed. Published January, 1922.

Press of

J. J. Little & Ives Company

New York, U. S. A.

| PAGE |

| INTRODUCTION | v |

| PART I: NEGRO FOLK RHYMES | 1 |

| Dance Rhyme Section | 1 |

| Dance Rhyme Song Section | 14 |

| Play Rhyme Section | 73 |

| Pastime Rhyme Section | 93 |

| Love Rhyme Section | 127 |

| Love Song Rhyme Section | 131 |

| Courtship Rhyme Section | 135 |

| Courtship Song Rhyme Section | 141 |

| Marriage Rhyme Section | 143 |

| Married Life Rhyme Section | 144 |

| Nursery Rhyme Section | 149 |

| Wise Saying Section | 207 |

| Foreign Section | 216 |

| PART II: A STUDY IN NEGRO FOLK RHYMES | 228 |

| GENERAL INDEX | 327 |

| COMPARATIVE STUDY INDEX | 337 |

[Pg v]

INTRODUCTION

Of the making of books by individual authors there is no end; but a

cultivated literary taste among the exceptional few has rendered almost

impossible the production of genuine folk-songs. The spectacle,

therefore, of a homogeneous throng of partly civilized people dancing to

the music of crude instruments and evolving out of dance-rhythm a

lyrical or narrative utterance in poetic form is sufficiently rare in

the nineteenth century to challenge immediate attention. In Negro Folk

Rhymes is to be found no inconsiderable part of the musical and poetic

life-records of a people; the compiler presents an arresting volume

which, in addition to being a pioneer and practically unique in its

field, is as nearly exhaustive as a sympathetic understanding of the

Negro mind, careful research, and labor of love can make it. Professor

Talley of Fisk University has spared himself no pains in collecting and

piecing together every attainable scrap and fragment of secular rhyme

which might help in adequately interpreting the inner life of his own

people.

[Pg vi]

Being the expression of a race in, or just emerging from bondage, these

songs may at first seem to some readers trivial and almost wholly devoid

of literary merit. In phraseology they may appear crude, lacking in that

elegance and finish ordinarily associated with poetic excellence; in

imagery they are at times exceedingly winter-starved, mediocre, common,

drab, scarcely ever rising above the unhappy environment of the singers.

The outlook upon life and nature is, for the most part, one of

imaginative simplicity and child-like naïveté; superstitions crowd in

upon a worldly wisdom that is elementary, practical, and obvious; and a

warped and crooked human nature, developed and fostered by

circumstances, shows frequently through the lines. What else might be

expected? At the time when these rhymes were in process of being created

the conditions under which the American Negro lived and labored were not

calculated to inspire him with a desire for the highest artistic

expression. Restricted, cramped, bound in unwilling servitude, he looked

about him in his miserable little world to see whatever of the beautiful

or happy he might find; that which he discovered is pathetically slight,

but, such as it is, it served to keep alive his stunted artist-soul

under the most adverse circumstances. [Pg vii]He saw the sweet pinks under a

blue sky, or observed the fading violets and the roses that fall, as he

passed to a tryst under the oak trees of a forest, and wrought these

things into his songs of love and tenderness. Friendless and otherwise

without companionship he lived in imagination with the beasts and birds

of the great out-of-doors; he knew personally Mr. Coon, Brother Rabbit,

Mr. 'Possum and their associates of the wild; Judge Buzzard and Sister

Turkey appealed to his fancy as offering material for what he supposed

to be poetic treatment. Wherever he might find anything in his lowly

position which seemed to him truly useful or beautiful, he seized upon

it and wove about it the sweetest song he could sing. The result is not

so much poetry of a high order as a valuable illustration of the

persistence of artist-impulses even in slavery.

In some of these folk-songs, however, may be found certain qualities

which give them dignity and worth. They are, when properly presented,

rhythmical to the point of perfection. I myself have heard many of them

chanted with and without the accompaniment of clapping hands, stamping

feet, and swaying bodies. Unfortunately a large part of their liquid

melody and flexibility of movement is lost through confinement in cold

print; but when[Pg viii]

they are heard from a distance on quiet summer nights

or clear Southern mornings, even the most fastidious ear is satisfied

with the rhythmic pulse of them. That pathos of the Negro character

which can never be quite adequately caught in words or transcribed in

music is then augmented and intensified by the peculiar quality of the

Negro voice, rich in overtones, quavering, weird, cadenced, throbbing

with the sufferings of a race. Or perhaps that well-developed sense of

humor which has, for more than a century, made ancestral sorrows

bearable finds fuller expression in the lilting turn of a note than in

the flashes of wit which abundantly enliven the pages of this volume.

There is one lyric in particular which, in evident sincerity of feeling,

simple and unaffected grace, and regularity of form, appeals to me as

having intrinsic literary value:

She hug' me, an' she kiss' me,

She wrung my han' an' cried.

She said I wus de sweetes' thing

Dat ever lived or died.

She hug' me an' she kiss' me.

Oh Heaben! De touch o' her han'!

She said I wus de puttiest thing

In de shape o' mortal man.

[Pg ix]I told her dat I love' her,

Dat my love wus bed-cord strong;

Den I axed her w'en she'd have me,

An' she jes' say, "Go 'long!"

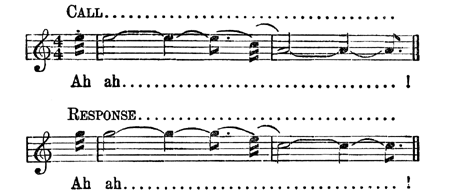

There is also a dramatic quality about many of these rhymes which must

not be overlooked. It has long been my observation that the Negro is

possessed by nature of considerable, though not as yet highly developed,

histrionic ability; he takes delight in acting out in pantomime whatever

he may be relating in song or story. It is not surprising, then, to find

that the play-rhymes, originating from the "call" and "response," are

really little dramas when presented in their proper settings. "Caught By

The Witch" would not be ineffective if, on a dark night, it were acted

in the vicinity of a graveyard! And one ballad—if I may be permitted to

dignify it by that name—called "Promises of Freedom" is characterized

by an unadorned narrative style and a dramatic ending which are

associated with the best English folk-ballads. The singer tells simply

and, one feels, with a grim impersonality of how his mistress promised

to set him free; it seemed as if she would never die—but "she's somehow

gone"! His master likewise made promises,

[Pg x]Yes, my ole Mosser promise' me;

But "his papers" didn't leave me free.

A dose of pizen he'pped 'im along.

May de Devil preach 'is

fūner'l song.

The manner of this conclusion is strikingly like that of the Scottish

ballad, "Edward,"

The curse of hell frae me sall ye beir,

Mither, Mither,

The curse of hell frae me sall ye beir,

Sic counseils ye gave to me O.

In both a story of cruelty is suggested in a single artistic line and

ended with startling, dramatic abruptness.

In fact, these two songs probably had their ultimate origin in not

widely dissimilar types of illiterate, unsophisticated human society.

Professor Talley's "Study in Negro Folk Rhymes," appended to this volume

of songs, is illuminating. One may not be disposed to accept without

considerable modification his theories entire; still his account from

personal, first-hand knowledge of the beginnings and possible evolution

of certain rhymes in this collection is apparently authentic. Here we

have again, in the nineteenth century, the record of a singing, dancing

people creating by a process[Pg xi] approximating communal authorship a mass

of verse embodying tribal memories, ancestral superstitions, and racial

wisdom handed down from generation to generation through oral tradition.

These are genuine folk-songs—lyrics, ballads, rhymes—in which are

crystallized the thought and feeling, the universally shared lore of a

folk. Recent theorizers on poetic origins who would insist upon

individual as opposed to community authorship of certain types of

song-narrative might do well to consider Professor Talley's

characteristic study. And students of comparative literature who love to

recreate the life of a tribe or nation from its song and story will

discover in this collection a mine of interesting material.

Fisk University, the center of Negro culture in America, is to be

congratulated upon having initiated the gathering and preservation of

these relics, a valuable heritage from the past. Just how important for

literature this heritage may prove to be will not appear until this

institution—and others with like purposes—has fully developed by

cultivation, training, and careful fostering the artistic impulses so

abundantly a part of the Negro character. A race which has produced,

under the most disheartening conditions, a mass of folk-poetry such[Pg xii] as

Negro Folk Rhymes may be expected to create with unlimited

opportunities for self-development, a literature and a distinctive music

of superior quality.

Walter Clyde Curry.

Vanderbilt University,

September 30, 1921.

[Pg 1]

Dance Rhyme Section

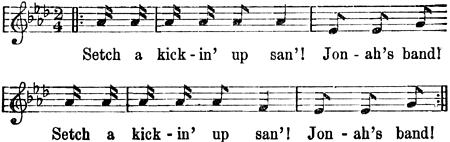

JONAH'S BAND PARTY

Setch a kickin' up san'! Jonah's Ban'!

Setch a kickin' up san'! Jonah's Ban'!

"Han's up sixteen! Circle to de right!

We's gwine to git big eatin's here to-night."

Setch a kickin' up san'! Jonah's Ban'!

Setch a kickin' up san'! Jonah's Ban'!

"Raise yo' right foot, kick it up high,

Knock dat [1]Mobile Buck in de eye."

Setch a kickin' up san'! Jonah's Ban'!

Setch a kickin' up san'! Jonah's Ban'!

"Stan' up, flat foot, [1]Jump dem Bars!

[1]Karo back'ards lak a train o' kyars."

Setch a kickin' up san'! Jonah's Ban'!

Setch a kickin' up san'! Jonah's Ban'!

"Dance 'round, Mistiss, show 'em de p'int;

Dat Nigger don't know how to [1]Coonjaint."

[Pg 2]

LOVE IS JUST A THING OF FANCY

Love is jes a thing o' fancy,

Beauty's jes a blossom;

If you wants to git yō' finger bit,

Stick it at a 'possum.

Beauty, it's jes skin deep;

Ugly, it's to de bone.

Beauty, it'll jes fade 'way;

But Ugly'll hōl' 'er own.

STILL WATER CREEK

'Way down yon'er on Still Water Creek,

I got stalded an' stayed a week.

I see'd Injun Puddin and Punkin pie,

But de black cat stick 'em in de yaller cat's eye.

'Way down yon'er on Still Water Creek,

De Niggers grows up some ten or twelve feet.

Dey goes to bed but dere hain't no use,

Caze deir feet sticks out fer de chickens t' roost.

I got hongry on Still Water Creek,

De mud to de hub an' de hoss britchin weak.

I stewed bullfrog chitlins, baked polecat pie;

If I goes back dar, I shō's gwine to die.

[Pg 3]

'POSSUM UP THE GUM STUMP

'Possum up de gum stump,

Dat raccoon in de holler;

Twis' 'im out, an' git 'im down,

An' I'll gin you a half a doller.

'Possum up de gum stump,

Yes, cooney in de holler;

A pretty gal down my house

Jes as fat as she can waller.

'Possum up de gum stump,

His jaws is black an' dirty;

To come an' kiss you, pretty gal,

I'd run lak a gobbler tucky.

'Possum up de gum stump,

A good man's hard to fīn';

You'd better love me, pretty gal,

You'll git de yudder kīn'.

[Pg 4]

JOE AND MALINDA JANE

Ole Joe jes swore upon 'is life

He'd make Merlindy Jane 'is wife.

W'en she hear 'im up 'is love an' tell,

She jumped in a bar'l o' mussel shell.

She scrape 'er back till de skin come off.

Nex' day she die wid de Whoopin' Cough.

WALK, TALK, CHICKEN WITH YOUR HEAD PECKED!

Walk, talk, chicken wid yō' head pecked!

You can crow w'en youse been dead.

Walk, talk, chicken wid yō' head pecked!

You can hōl' high yō' bloody head.

You's whooped dat Blue Hen's Chicken,

You's beat 'im at his game.

If dere's some fedders on him,

Fer dat you's not to blame.

Walk, talk, chicken wid yō' head pecked!

You beat ole Johnny Blue!

Walk, talk, chicken wid yō' head pecked!

Say: "Cock-a-doo-dle-doo—!"

[Pg 5]

TAILS

De coon's got a long ringed bushy tail,

De 'possum's tail is bare;

Dat rabbit hain't got no tail 'tall,

'Cep' a liddle bunch o' hair.

De gobbler's got a big fan tail,

De pattridge's tail is small;

Dat peacock's tail 's got great big eyes,

But dey don't see nothin' 'tall.

CAPTAIN DIME

Cappun Dime is a fine w'ite man.

He wash his face in a fry'n' pan,

He comb his head wid a waggin wheel,

An' he die wid de toothache in his heel.

Cappun Dime is a mighty fine feller,

An' he shō' play kyards wid de Niggers in de cellar,

But he will git drunk, an' he won't smoke a pipe,

Den he will pull de watermillions 'fore dey gits ripe.

[Pg 6]

CROSSING THE RIVER

I went down to de river an' I couldn' git 'cross.

I jumped on er mule an' I thought 'e wus er hoss.

Dat mule 'e wa'k in an' git mired up in de san';

You'd oughter see'd dis Nigger make back fer de lan'!

I want to cross de river but I caint git 'cross;

So I mounted on a ram, fer I thought 'e wus er hoss.

I plunged him in, but he sorter fail to swim;

An' I give five dollars fer to git 'im out ag'in.

Yes, I went down to de river an' I couldn' git 'cross,

So I give a whole dollar fer a ole blin' hoss;

Den I souzed him in an' he sink 'stead o' swim.

Do you know I got wet clean to my ole hat brim?

T-U-TURKEY

T-u, tucky, T-u, ti.

T-u, tucky, buzzard's eye.

T-u, tucky, T-u, ting.

T-u, tucky, buzzard's wing.

Oh, Mistah Washin'ton! Don't whoop me,

Whoop dat Nigger Back 'hind dat tree.

[Pg 7]He stole tucky, I didn' steal none.

Go wuk him in de co'n field jes fer fun.

CHICKEN IN THE BREAD TRAY

"Auntie, will yō' dog bite?"—

"No, Chile! No!"

Chicken in de bread tray

A makin' up dough.

"Auntie, will yō' broom hit?"—

"Yes, Chile!" Pop!

Chicken in de bread tray;

"Flop! Flop! Flop!"

"Auntie, will yō' oven bake?"—

"Yes. Jes fry!"—

"What's dat chicken good fer?"—

"Pie! Pie! Pie!"

"Auntie, is yō' pie good?"—

"Good as you could 'spec'."

Chicken in de bread tray;

"Peck! Peck! Peck!"

[Pg 8]

MOLLY COTTONTAIL, OR, GRAVEYARD RABBIT

Ole Molly Cottontail,

At night, w'en de moon's pale;

You don't fail to tu'n tail,

You always gives me leg bail.[2]

Molly in de Bramble-brier,

Let me git a little nigher;

Prickly-pear, it sting lak fire!

Do please come pick out de brier!

Molly in de pale moonlight,

Yō' tail is shō a pretty white;

You takes it fer 'way out'n sight.

"Molly! Molly! Molly Bright!"

Ole Molly Cottontail,

You sets up on a rotten rail!

You tears through de graveyard!

You makes dem ugly [3]hants wail.

Ole Molly Cottontail,

Won't you be shore not to fail

[4]To give me yō' right hīn' foot?

My luck, it won't be fer sale.

[Pg 9]

Juba dis, an' Juba dat,

Juba [6]skin dat Yaller Cat. Juba! Juba!

Juba jump an' Juba sing.

Juba, [6]cut dat Pigeon's Wing. Juba! Juba!

Juba, kick off Juba's shoe.

Juba, dance dat [6]Jubal Jew. Juba! Juba!

Juba, whirl dat foot about.

Juba, blow dat candle out. Juba! Juba!

Juba circle, [6]Raise de Latch.

Juba do dat [6]Long Dog Scratch. Juba! Juba!

[Pg 10]

ON TOP OF THE POT

Wild goose gallop an' gander trot;

Walk about, Mistiss, on top o' de pot!

Hog jowl bilin', an' tunnup greens hot,

Walk about, Billie, on top o' de pot!

Chitlins, hog years, all on de spot,

Walk about, ladies, on top o' de pot!

[7]

STAND BACK, BLACK MAN

Oh!

Stan' back, black man,

You cain't shine;

Yō' lips is too thick,

An' you hain't my kīn'.

[Pg 11]

Aw!

Git 'way, black man,

You jes haint fine;

I'se done quit foolin'

Wid de nappy-headed kind.

Say?

Stan' back, black man!

Cain't you see

Dat a kinky-headed chap

Hain't nothin' side o' me?

NEGROES NEVER DIE

Nigger! Nigger never die!

He gits choked on Chicken pie.

Black face, white shiny eye. Nigger! Nigger!

Nigger! Nigger never knows!

Mashed nose, an' crooked toes;

Dat's de way de Nigger goes. Nigger! Nigger!

Nigger! Nigger always sing;

Jump up, cut de Pidgeon's wing;

Whirl, an' give his feet a fling. Nigger! Nigger!

[Pg 12]

JAWBONE

Samson, shout! Samson, moan!

Samson, bring on yō' Jawbone.

Jawbone, walk! Jawbone, talk!

Jawbone, eat wid a knife an fo'k.

Walk, Jawbone! Jinny, come alon'!

Yon'er goes Sally wid de bootees on.

Jawbone, ring! Jawbone, sing!

Jawbone, kill dat wicked thing.

INDIAN FLEA

Injun flea, bit my knee;

Kaze I wouldn' drink ginger tea.

Flea bite hard, flea bite quick;

Flea bite burn lak dat seed tick.

Hit dat flea, flea not dere.

I'se so mad I pulls my hair.

I go wild an' fall in de creek.

To wash 'im off, I'd stay a week.

[Pg 13]

AS I WENT TO SHILOH

As I went down

To Shiloh Town;

I rolled my barrel of Sogrum down.

Dem lasses rolled;

An' de hoops, dey bust;

An' blowed dis Nigger clear to Thundergust!

JUMP JIM CROW

Git fus upon yō' heel,

An' den upon yō' toe;

An ebry time you tu'n 'round,

You jump Jim Crow.

Now fall upon yō' knees,

Jump up an' bow low;

An' ebry time you tu'n 'round,

You jump Jim Crow.

Put yō' han's upon yō' hips,

Bow low to yō' beau;

An' ebry time you tu'n 'round,

You jump Jim Crow.

[Pg 14]

Dance Rhyme Song Section

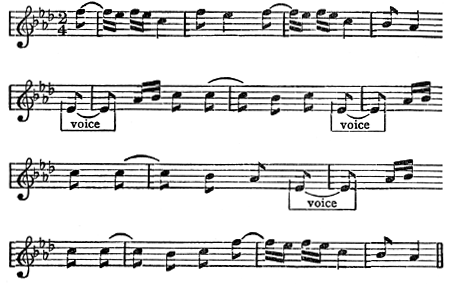

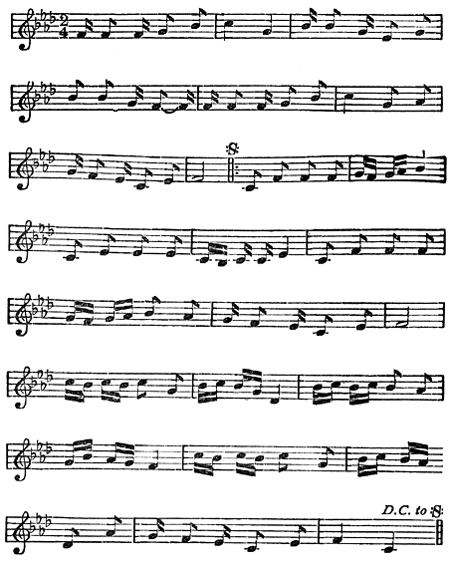

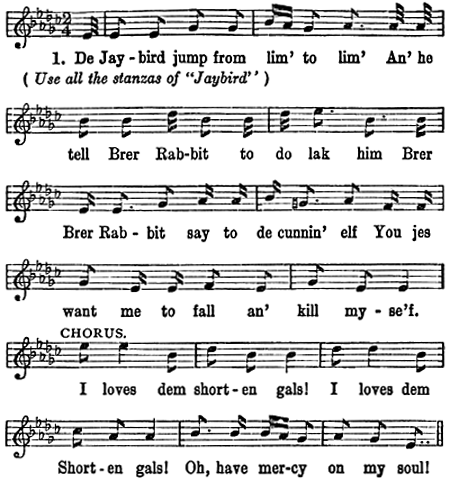

[Listen]

JAYBIRD

De Jaybird jump from lim' to lim',

An' he tell Br'er Rabbit to do lak him.

[Pg 15]Br'er Rabbit say to de cunnin' elf:

"You jes want me to fall an' kill myself."

Dat Jaybird a-settin' on a swingin' lim'.

He wink at me an' I wink at him.

He laugh at me w'en my gun "crack."

It kick me down on de flat o' my back.

Nex' day de Jaybird dance dat lim'.

I grabs my gun fer to shoot at him.

W'en I "crack" down, it split my chin.

"Ole Aggie Cunjer" fly lak sin.

Way down yon'er at de risin' sun,

Jaybird a-talkin' wid a forked tongue.

[8]He's been down dar whar de bad mens dwell.

"Ole Friday Devil," fare—you—well!

OFF FROM RICHMOND

I'se off from Richmon' sooner in de mornin'.

I'se off from Richmon' befō' de break o' day.

I slips off from Mosser widout pass an' warnin'

Fer I mus' see my Donie wharever she may stay.

[Pg 16]

HE IS MY HORSE

One day as I wus a-ridin' by,

Said dey: "Ole man, yō' hoss will die"—

"If he dies, he is my loss;

An' if he lives, he is my hoss."

Nex' day w'en I come a-ridin' by,

Dey said: "Ole man, yō' hoss may die."—

"If he dies, I'll tan 'is skin;

An' if he lives, I'll ride 'im ag'in."

Den ag'in w'en I come a-ridin' by,

Said dey: "Ole man, yō' hoss mought die."—

"If he dies, I'll eat his co'n;

An' if he lives, I'll ride 'im on."

[9]

JUDGE BUZZARD

Dere sets Jedge Buzzard on de Bench.

Go tu'n him off wid a monkey wrench!

Jedge Buzzard try Br'er Rabbit's case;

An' he say Br'er Tarepin win dat race.

Here sets Jedge Buzzard on de Bench.

Knock him off wid dat monkey wrench!

[Pg 17]

SHEEP AND GOAT

Sheep an' goat gwine to de paster;

Says de goat to de sheep: "Cain't you walk a liddle faster?"

De sheep says: "I cain't, I'se a liddle too full."

Den de goat say: "You can wid my ho'ns in yō' wool."

But de goat fall down an' skin 'is shin

An' de sheep split 'is lip wid a big broad grin.

JACKSON, PUT THAT KETTLE ON!

Jackson, put dat kittle on!

Fire, steam dat coffee done!

Day done broke, an' I got to run

Fer to meet my gal by de risin' sun.

My ole Mosser say to me,

Dat I mus' drink [10]sassfac tea;

But Jackson stews dat coffee done,

An' he shō' gits his po'tion: Son!

[Pg 18]

DINAH'S DINNER HORN

It's a cōl', frosty mornin',

An' de Niggers goes to wo'k;

Wid deir axes on deir shoulders,

An' widout a bit o' [11]shu't.

Dey's got ole husky ashcake,

Widout a bit o' fat;

An' de white folks'll grumble,

If you eats much o' dat.

I runs down to de henhouse,

An' I falls upon my knees;

It's 'nough to make a rabbit laugh

To hear my tucky sneeze.

I grows up on dem meatskins,

I comes down on a bone;

I hits dat co'n bread fifty licks,

I makes dat butter moan.

It's glory in yō' honor!

An' don't you want to go?

I sholy will be ready

Fer dat dinnah ho'n to blow.

[Pg 19]Dat ole bell, it goes "Bangity—bang!"

Fer all dem white folks bo'n.

But I'se not ready fer to go

Till Dinah blows her ho'n.

"Poke—sallid!" "Poke—sallid!"

Dat ole ho'n up an' blow.

Jes think about dem good ole greens!

Say? Don't you want to go?

MY MULE

Las' Saddy mornin' Mosser said:

"Jump up now, Sambo, out'n bed.

Go saddle dat mule, an' go to town;

An' bring home Mistiss' mornin' gown."

I saddled dat mule to go to town.

I mounted up an' he buck'd me down.

Den I jumped up from out'n de dust,

An' I rid him till I thought he'd bust.

[Pg 20]

BULLFROG PUT ON THE SOLDIER CLOTHES

Bullfrog put on de soldier clo's.

He went down yonder fer to shoot at de crows;

Wid a knife an' a fo'k between 'is toes,

An' a white hankcher fer to wipe 'is nose.

Bullfrog put on de soldier clo's.

He's a "dead shore shot," gwineter kill dem crows.

He takes "Pot," an' "Skillet" from de Fiddler's Ball.

Dey're to dance a liddle jig while Jim Crow fall.

Bullfrog put on de soldier clo's.

He went down de river fer to shoot at de crows.

De powder flash, an' de crows fly 'way;

An' de Bullfrog shoot at 'em all nex' day.

SAIL AWAY, LADIES!

Sail away, ladies! Sail away!

Sail away, ladies! Sail away!

Nev' min' what dem white folks say,

May de Mighty bless you. Sail away!

[Pg 21]Nev' min' what yō' daddy say,

Shake yō' liddle foot an' fly away.

Nev' min' if yō' mammy say:

"De Devil'll git you." Sail away!

THE BANJO PICKING

Hush boys! Hush boys! Don't make a noise,

While ole Mosser's sleepin'.

We'll run down de Graveyard, an' take out de bones,

An' have a liddle Banjer pickin'.

I takes my Banjer on a Sunday mornin'.

Dem ladies, dey 'vites me to come.

We slips down de hill an' picks de liddle chune:

"Walk, Tom Wilson Here Afternoon."

[12]"Walk Tom Wilson Here Afternoon";

"You Cain't Dance Lak ole Zipp Coon."

Pick [12]"Dinah's Dinner Ho'n" "Dance 'Round de Room."

"Sweep dat Kittle Wid a Bran' New Broom."

[Pg 22]

OLD MOLLY HARE

Ole Molly har'!

What's you doin' thar?

"I'se settin' in de fence corner, smokin' seegyar."

Ole Molly har'!

What's you doin' thar?

"I'se pickin' out a br'or, settin' on a Pricky-p'ar."

Ole Molly har'!

What's you doin' thar?

"I'se gwine cross de Cotton Patch, hard as I can t'ar."

Molly har' to-day,

So dey all say,

Got her pipe o' clay, jes to smoke de time 'way.

"De dogs say 'boo!'

An' dey barks too,

I hain't got no time fer to talk to you."

[Pg 23]

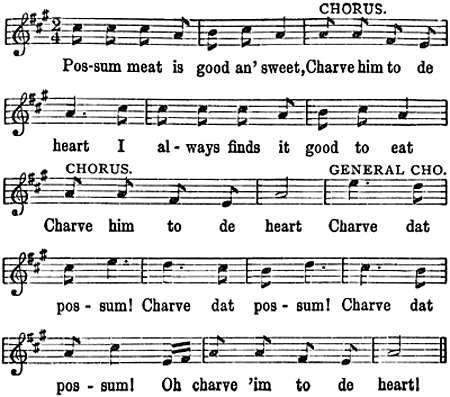

ONE NEGRO TUNE USED WITH "AN OPOSSUM HUNT"

[Listen]

AN OPOSSUM HUNT

'Possum meat is good an' sweet,

I always finds it good to eat.

My dog tree, I went to see.

A great big 'possum up dat tree.

I retch up an' pull him in,

Den dat ole 'possum 'gin to grin.

[Pg 24]I tuck him home an' dressed him off,

Dat night I laid him in de fros'.

De way I cooked dat 'possum sound,

I fust parboiled, den baked him brown.

I put sweet taters in de pan,

'Twus de bigges' eatin' in de lan'.

DEVILISH PIGS

I wish I had a load o' poles,

To fence my new-groun' lot;

To keep dem liddle bitsy debblish pigs

Frum a-rootin' up all I'se got.

Dey roots my cabbage, roots my co'n;

Dey roots up all my beans.

Dey speilt my fine sweet-tater patch,

An' dey ruint my tunnup greens.

I'se rund dem pigs, an' I'se rund dem pigs.

I'se gittin' mighty hot;

An' one dese days w'en nobody look,

Dey'll root 'round in my pot.

[Pg 25]

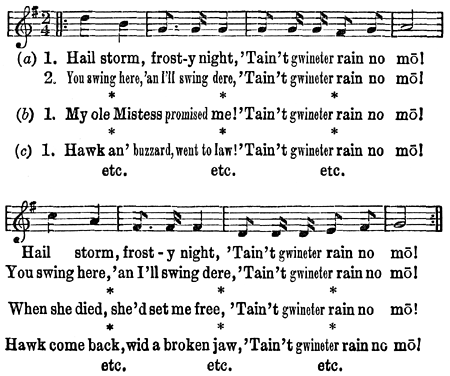

PROMISES OF FREEDOM

My ole Mistiss promise me,

W'en she died, she'd set me free.

She lived so long dat 'er head got bal',

An' she give out'n de notion a dyin' at all.

My ole Mistiss say to me:

"Sambo, I'se gwine ter set you free."

But w'en dat head git slick an' bal',

De Lawd couldn' a' killed 'er wid a big green maul.

My ole Mistiss never die,

Wid 'er nose all hooked an' skin all dry.

But my ole Miss, she's somehow gone,

An' she lef' "Uncle Sambo" a-hillin' up co'n.

Ole Mosser lakwise promise me,

W'en he died, he'd set me free.

But ole Mosser go an' make his Will

Fer to leave me a-plowin' ole Beck still.

[Pg 26]Yes, my ole Mosser promise me;

But "his papers" didn' leave me free.

A dose of pizen he'ped 'im along.

May de Devil preach 'is fūner'l song.

WHEN MY WIFE DIES

W'en my wife dies, gwineter git me anudder one;

A big fat yaller one, jes lak de yudder one.

I'll hate mighty bad, w'en she's been gone.

Hain't no better 'oman never nowhars been bo'n.

W'en I comes to die, you mus'n' bury me deep,

But put Sogrum molasses close by my feet.

Put a pone o' co'n bread way down in my han'.

Gwineter sop on de way to de Promus' Lan'.

W'en I goes to die, Nobody mus'n' cry,

Mus'n' dress up in black, fer I mought come back.

But w'en I'se been dead, an' almos' fergotten;

You mought think about me an' keep on a-trottin'.

Railly, w'en I'se been dead, you needn' bury me at tall.

You mought pickle my bones down in alkihall;

Den fold my han's "so," right across my breas';

An' go an' tell de folks I'se done gone to "res'."

[Pg 27]

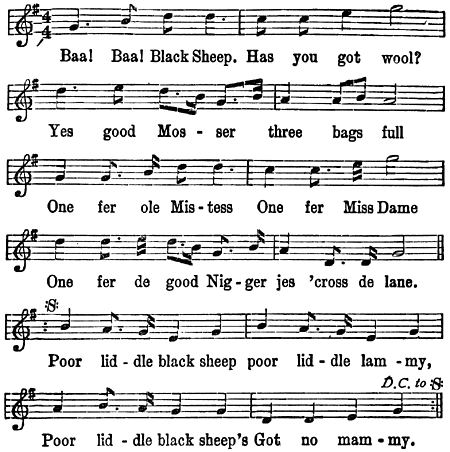

ONE TUNE USED WITH "BAA! BAA! BLACK SHEEP!"

[Listen]

BAA! BAA! BLACK SHEEP

"Baa! Baa! Black Sheep,

Has you got wool?"

"Yes, good Mosser,

Free bags full.

One fer ole Mistis,

One fer Miss Dame,

[Pg 28]An' one fer de good Nigger

Jes across de lane."

Pōōr liddle Black Sheep,

Pōōr liddle lammy;

Pōōr liddle Black Sheep's

Got no mammy.

HE WILL GET MR. COON

Ole Mistah Coon, at de break o' day,

You needn' think youse gwineter git 'way.

Caze ole man Ned, he know how to run,

An' he's shō' gone fer to git 'is gun.

You needn' clam to dat highes' lim',

You cain't git out'n de retch o' him.

You can stay up dar till de sun done set.

I'll bet you a dollar dat he'll git you yet.

Ole Mistah Coon, you'd well's to give up.

You had well's to give up, I say.

Caze ole man Ned is straight atter you,

An' he'll git you shō' this day.

[Pg 29]

BRING ON YOUR HOT CORN

Bring along yō' hot co'n,

Bring along yō' col' co'n;

But I say bring along,

Bring along yō' [13]Jimmy-john.

Some loves de hot co'n,

Some loves de col' co'n;

But I loves, I loves,

I loves dat Jimmy-john.

THE LITTLE ROOSTER

I had a liddle rooster,

He crowed befō' day.

'Long come a big owl,

An' toted him away.

But de rooster fight hard,

An' de owl let him go.

Now all de pretty hens

Wants dat rooster fer deir beau.

[Pg 30]

SUGAR IN COFFEE

Sheep's in de meader a-mowin' o' de hay.

De honey's in de bee-gum, so dey all say.

My head's up an' I'se boun' to go.

Who'll take sugar in de coffee-o?

I'se de prettiest liddle gal in de county-o.

My mammy an' daddy, dey bofe say so.

I looks in de glass, it don't say, "No";

So I'll take sugar in de coffee-o.

[14]

THE TURTLE'S SONG

Mud turkle settin' on de end of a log,

A-watchin' of a tadpole a-turnin' to a frog.

He sees Br'er B'ar a-pullin' lak a mule.

He sees Br'er Tearpin a-makin' him a fool.

Br'er B'ar pull de rope an' he puff an' he blow;

But he cain't git de Tearpin out'n de water from below.

Dat big clay root is a-holdin' dat rope,

Br'er Tearpin's got 'im fooled, an' dere hain't no hope.

[Pg 31]

Mud turkle settin' on de end o' dat log;

Sing fer de tadpole a-turnin' to a frog,

Sing to Br'er B'ar a-pullin' lak a mule,

Sing to Br'er Tearpin a-makin' 'im a fool:—

"Oh, Br'er Rabbit! Yō' eyes mighty big!"

"Yes, Br'er Turkle! Dey're made fer to see."

"Oh, Br'er Tearpin! Yō' house mighty cu'ous!"

"Yes, Br'er Turkle, but it jest suits me."

"Oh, Br'er B'ar! You pulls mighty stout."

"Yes, Br'er Turkle! Dat's right smart said!"

"Right, Br'er B'ar! Dat sounds bully good,

But you'd oughter git a liddle mō' pull in de head."

RACCOON AND OPOSSUM FIGHT

De raccoon an' de 'possum

Under de hill a-fightin';

Rabbit almos' bust his sides

Laughin' at de bitin'.

[Pg 32]De raccoon claw de 'possum

Along de ribs an' head;

'Possum tumble over an' grin,

Playin' lak he been dead.

COTTON EYED JOE

Hol' my fiddle an' hol' my bow,

Whilst I knocks ole Cotton Eyed Joe.

I'd a been dead some seben years ago,

If I hadn' a danced dat Cotton Eyed Joe.

Oh, it makes dem ladies love me so,

W'en I comes 'roun' pickin' ole Cotton Eyed Joe!

Yes, I'd a been married some forty year ago,

If I hadn' stay'd 'roun' wid Cotton Eyed Joe.

I hain't seed ole Joe, since way las' Fall;

Dey say he's been sol' down to Guinea Gall.

[Pg 33]

RABBIT SOUP

Rabbit soup! Rabbit sop!

Rabbit e't my tunnup top.

Rabbit hop, rabbit jump,

Rabbit hide behin' dat stump.

Rabbit stop, twelve o'clock,

Killed dat rabbit wid a rock.

Rabbit's mine. Rabbit's skin'.

Dress 'im off an' take 'im in.

Rabbit's on! Dance an' whoop!

Makin' a pot o' rabbit soup!

OLD GRAY MINK

I once did think dat I would sink,

But you know I wus dat ole gray mink.

Dat ole gray mink jes couldn' die,

W'en he thought about good chicken pie.

He swum dat creek above de mill,

An' he's killing an' eatin' chicken still.

[Pg 34]

RUN, NIGGER, RUN!

Run, Nigger, run! De [15]Patter-rollers'll ketch you.

Run, Nigger, run! It's almos' day.

Dat Nigger run'd, dat Nigger flew,

Dat Nigger tore his shu't in two.

All over dem woods and frou de paster,

Dem Patter-rollers shot; but de Nigger git faster,

Oh, dat Nigger whirl'd, dat Nigger wheel'd,

Dat Nigger tore up de whole co'n field.

SHAKE THE PERSIMMONS DOWN

De raccoon up in de 'simmon tree.

Dat 'possum on de groun'.

De 'possum say to de raccoon: "Suh!"

"Please shake dem 'simmons down."

[Pg 35]De raccoon say to de 'possum: "Suh!"

(As he grin from down below),

"If you wants dese good 'simmons, man,

Jes clam up whar dey grow."

THE COW NEEDS A TAIL IN FLY-TIME

Dat ole black sow, she can root in de mud,

She can tumble an' roll in de slime;

But dat big red cow, she git all mired up,

So dat cow need a tail in fly-time.

Dat ole gray hoss, wid 'is ole bob tail,

You mought buy all 'is ribs fer a dime;

But dat ole gray hoss can git a kiver on,

Whilst de cow need a tail in fly-time.

Dat Nigger Overseer, dat's a-ridin' on a mule,

Cain't make hisse'f white lak de lime;

Mosser mought take 'im down fer a notch or two,

Den de cow'd need a tail in fly-time.

[Pg 36]

JAYBIRD DIED WITH THE WHOOPING COUGH

De Jaybird died wid de Whoopin' Cough,

De Sparrer died wid de colic;

'Long come de Red-bird, skippin' 'round,

Sayin': "Boys, git ready fer de Frolic!"

De Jaybird died wid de Whoopin' Cough,

De Bluebird died wid de Measles;

'Long come a Nigger wid a fiddle on his back,

'Vitin' Crows fer to dance wid de Weasels.

Dat Mockin'-bird, he romp an' sing;

Dat ole Gray Goose come prancin'.

Dat Thrasher stuff his mouf wid plums,

Den he caper on down to de dancin'.

Dey hopped it low, an' dey hopped it high;

Dey hopped it to, an' dey hopped it by;

Dey hopped it fer, an' dey hopped it nigh;

Dat fiddle an' bow jes make 'em fly.

[Pg 37]

WANTED! CORNBREAD AND COON

I'se gwine now a-huntin' to ketch a big fat coon.

Gwineter bring him home, an' bake him, an' eat him wid a spoon.

Gwineter baste him up wid gravy, an' add some onions too.

I'se gwineter shet de Niggers out, an' stuff myse'f clean through.

I wants a piece o' hoecake; I wants a piece o' bread,

An' I wants a piece o' Johnnycake as big as my ole head.

I wants a piece o' ash cake: I wants dat big fat coon!

An' I shō' won't git hongry 'fore de middle o' nex' June.

LITTLE RED HEN

My liddle red hen, wid a liddle white foot,

Done built her nes' in a huckleberry root.

She lay mō' aigs dan a flock on a fahm.

Anudder liddle drink wouldn' do us no harm.

[Pg 38]My liddle red hen hatch fifty red chicks

In dat liddle ole nes' of huckleberry sticks.

Wid one mō' drink, ev'y chick'll make two!

Come, bring it on, Honey, an' let's git through.

RATION DAY

Dat ration day come once a week,

Ole Mosser's rich as Gundy;

But he gives us 'lasses all de week,

An' buttermilk fer Sund'y.

Ole Mosser give me a pound o' meat.

I e't it all on Mond'y;

Den I e't 'is 'lasses all de week,

An' buttermilk fer Sund'y.

Ole Mosser give me a peck o' meal,

I fed and cotch my tucky;

But I e't dem 'lasses all de week,

An' buttermilk fer Sund'y.

Oh laugh an' sing an' don't git tired.

We's all gwine home, some Mond'y,

To de honey ponds an' fritter trees;

An' ev'ry day'll be Sund'y.

[Pg 39]

MY FIDDLE

If my ole fiddle wus jes in chune,

She'd bring me a dollar ev'y Friday night in June.

W'en my ole fiddle is fixed up right,

She bring me a dollar in nearly ev'y night.

W'en my ole fiddle begin to sing,

She make de whole plantation ring.

She bring me in a dollar an' sometime mō'.

Hurrah fer my ole fiddle an' bow!

DIE IN THE PIG-PEN FIGHTING

Dat ole sow said to de barrer:

"I'll tell you w'at let's do:

Let's go an' git dat broad-axe

And die in de pig-pen too."

"Die in de pig-pen fightin'!

Yes, die, die in de wah!

Die in de pig-pen fightin',

Yes, die wid a bitin' jaw!"

[Pg 40]

MASTER IS SIX FEET ONE WAY

Mosser is six foot one way, an' free foot tudder;

An' he weigh five hunderd pound.

Britches cut so big dat dey don't suit de tailor,

An' dey don't meet half way 'round.

Mosser's coat come back to a claw-hammer p'int.

(Speak sof' or his Bloodhound'll bite us.)

His long white stockin's mighty clean an' nice,

But a liddle mō' holier dan righteous.

FOX AND GEESE

Br'er Fox wa'k out one moonshiny night,

He say to hisse'f w'at he's a gwineter do.

He say, "I'se gwineter have a good piece o' meat,

Befō' I leaves dis townyoo.

Dis townyoo, dis townyoo!

Yes, befō' I leaves dis townyoo!"

[Pg 41]Ole mammy Sopentater jump up out'n bed,

An' she poke her head outside o' de dō'.

She say: "Ole man, my gander's gone.

I heared 'im w'en he holler 'quinny-quanio,'

'Quinny-quanio, quinny-quanio!'

Yes, I heared 'im w'en he holler 'quinny-quanio.'"

GOOSEBERRY WINE

Now 'umble Uncle Steben,

I wonders whar youse gwine?

Don't never tu'n yō' back, Suh,

On dat good ole gooseberry wine!

Oh walk chalk, Ginger Blue!

Git over double trouble.

You needn' min' de wedder

So's de win' don't blow you double.

Now!

Uncle Mack! Uncle Mack!

Did you ever see de lak?

Dat good ole sweet gooseberry wine

Call Uncle Steben back.

[Pg 42]

I'D RATHER BE A NEGRO THAN A POOR WHITE MAN

My name's Ran, I wuks in de san';

But I'd druther be a Nigger dan a pō' white man.

Gwineter hitch my oxes side by side,

An' take my gal fer a big fine ride.

Gwineter take my gal to de country stō';

Gwineter dress her up in red calico.

You take Kate, an' I'll take Joe.

Den off we'll go to de pahty-o.

Gwineter take my gal to de Hullabaloo,

Whar dere hain't no [16]Crackers in a mile or two.

Interlocution:

(Fiddler) "Oh, Sal! Whar's de milk strainer cloth?"

[Pg 43]

(Banjo Picker) "Bill's got it wropped 'round his ole sore leg."

(Fiddler) "Well, take it down to de gum spring an' give it a cold water

rench; I 'spizes nastness anyway. I'se got to have a clean cloth fer de milk."

He don't lak whisky but he jest drinks a can.

Honey! I'd druther be a Nigger dan a pō' white man.

I'd druther be a Nigger, an' plow ole Beck

Dan a white [16]Hill Billy wid his long red neck.

THE HUNTING CAMP

Sam got up one mornin'

A mighty big fros'.

Saw "A louse, in de huntin' camp

As big as any hoss!"

[Pg 44]Sam run 'way down de mountain;

But w'en Mosser got dar,

He swore it twusn't nothin'

But a big black b'ar.

THE ARK

Ole Nora had a lots o' hands

A clearin' new ground patches.

He said he's gwineter build a Ark,

An' put tar on de hatches.

He had a sassy Mo'gan hoss

An' gobs of big fat cattle;

An' he driv' em all aboard de Ark,

W'en he hear de thunder rattle.

An' den de river riz so fas'

Dat it bust de levee railin's.

De lion got his dander up,

An' he lak to a broke de palin's.

An' on dat Ark wus daddy Ham;

No udder Nigger on dat packet.

He soon got tired o' de Barber Shop,

Caze he couln' stan' de racket.

[Pg 45]An' den jes to amuse hisse'f,

He steamed a board an' bent it, Son.

Dat way he got a banjer up,

Fer ole Ham's de fust to make one.

Dey danced dat Ark from ēen to ēen,

Ole Nora called de Figgers.

Ole Ham, he sot an' knocked de chunes,

De happiest of de Niggers.

GRAY AND BLACK HORSES

I went down to de woods an' I couldn' go 'cross,

So I paid five dollars fer an ole gray hoss.

De hoss wouldn' pull, so I sōl' 'im fer a bull.

De bull wouldn' holler, so I sōl' 'im fer a dollar.

De dollar wouldn' pass, so I throwed it in de grass.

Den de grass wouldn' grow. Heigho! Heigho!

Through dat huckleberry woods I couldn' git far,

So I paid a good dollar fer an ole black mar'.

W'en I got down dar, de trees wouldn' bar;

So I had to gallop back on dat ole black mar'.

"Bookitie-bar!" Dat ole black mar'; "Bookitie-bar!" Dat ole black mar'.

Yes she trabble so hard dat she jolt off my ha'r.

[Pg 46]

RATTLER

Go call ole Rattler from de bo'n.

Here Rattler! Here!

He'll drive de cows out'n de co'n,

Here Rattler! Here!

Rattler is my huntin' dog.

Here Rattler! Here!

He's good fer rabbit, good fer hog,

Here Rattler! Here!

He's good fer 'possum in de dew.

Here Rattler! Here!

Sometimes he gits a chicken, too.

Here Rattler! Here!

BROTHER BEN AND SISTER SAL

Ole Br'er Ben's a mighty good ole man,

He don't steal chickens lak he useter.

He went down de chicken roos' las' Friday night,

An' tuck off a dominicker rooster.

[Pg 47]Dere's ole Sis Sal, she climbs right well,

But she cain't 'gin to climb lak she useter.

So yonder she sets a shellin' out co'n

To Mammy's ole bob-tailed rooster.

Yes, ole Sis Sal's a mighty fine ole gal,

She's shō' extra good an' clever.

She's done tuck a notion all her own,

Dat she hain't gwineter marry never.

Ole Sis Sal's got a foot so big,

Dat she cain't wear no shoes an' gaiters.

So all she want is some red calico,

An' dem big yaller yam sweet taters.

Now looky, looky here! Now looky, looky there!

Jes looky!—Looky 'way over yonder!—

Don't you see dat ole gray goose

A-smilin' at de gander?

SIMON SLICK'S MULE

Dere wus a liddle kickin' man,

His name wus Simon Slick.

He had a mule wid cherry eyes.

Oh, how dat mule could kick!

[Pg 48]An', Suh, w'en you go up to him,

He shet one eye an' smile;

Den 'e telegram 'is foot to you,

An' sen' you half a mile!

NOBODY LOOKING

Well: I look dis a way, an' I look dat a way,

An' I heared a mighty rumblin'.

W'en I come to find out, 'twus dad's black sow,

A-rootin' an' a-grumblin'.

Den: I slipped away down to de big White House.

Miss Sallie, she done gone 'way.

I popped myse'f in de rockin' chear,

An' I rocked myse'f all day.

Now: I looked dis a way, an' I looked dat a way,

An' I didn' see nobody in here.

I jes run'd my head in de coffee pot,

An' I drink'd up all o' de beer.

[Pg 49]

HOECAKE

If you wants to bake a hoecake,

To bake it good an' done;

Jes' slap it on a Nigger's heel,

An' hol' it to de sun.

Dat snake, he bake a hoecake,

An' sot de toad to mind it;

Dat toad he up an' go to sleep,

An' a lizard slip an' find it!

My mammy baked a hoecake,

As big as Alabamer.

She throwed it 'g'inst a Nigger's head

An' it ring jes' lak a hammer.

De way you bakes a hoecake,

In de ole Virginy 'tire;

You wrops it 'round a Nigger's heel,

An' hōl's it to de fire.

[Pg 50]

I WENT DOWN THE ROAD

I went down de road,

I went in a whoop;

An' I met Aunt Dinah

Wid a chicken pot o' soup.

Sing: "I went away from dar; hook-a-doo-dle, hook-a-doo-dle."

"I went away from dar; hook-a-doo-dle-doo!"

I drunk up dat soup,

An' I let her go by;

An' I tōl' her nex' time

To bring Missus' pot pie.

Sing: "Oh far'-you-well; hook-a-doo-dle, hook-a-doo-dle;

Oh far'-you-well, an' a hook-a-doo-dle-doo!"

THE OLD HEN CACKLED

De ole hen she cackled,

An' stayed down in de bo'n.

She git fat an' sassy,

A-eatin' up de co'n.

[Pg 51]De ole hen she cackled,

Git great long yaller laigs.

She swaller down de oats,

But I don't git no aigs.

De ole hen she cackled,

She cackled in de lot,

De nex' time she cackled,

She cackled in de pot.

I LOVE SOMEBODY

I loves somebody, yes, I do;

An' I wants somebody to love me too.

Wid my chyart an' oxes stan'in' 'roun',

Her pretty liddle foot needn' tetch de groun'.

I loves somebody, yes, I do,

Dat randsome, handsome, Stickamastew.

Wid her reddingoat an' waterfall,

She's de pretty liddle gal dat beats 'em all.

[Pg 52]

WE ARE "ALL THE GO"

Yes! We's "All-de-go," boys; we's "All-de-go."

Me an' my Lulu gal's "All-de-go."

I jes' loves my sweet pretty liddle Lulu Ann,

But de way she gits my money I cain't hardly understan'.

W'en she up an' call me "Honey!" I fergits my name is Sam,

An' I hain't got one nickel lef' to git a me a dram.

Still: We's "All-de-go," boys; we's "All-de-go."

Me an' my Lulu gal's "All-de-go."

She's always gwine a-fishin', w'en she'd oughter not to go;

An' now she's all a troubled wid de frostes an' de snow.

I tells you jes one thing dat I'se done gone an' foun':

De Nigs cain't git no livin' 'round de Cō't House steps an' town.

[Pg 53]

AUNT DINAH DRUNK

Ole Aunt Dinah, she got drunk.

She fell in de fire, an' she kicked up a chunk.

Dem embers got in Aunt Dinah's shoe,

An' dat black Nigger shō' got up an' flew.

I likes Aunt Dinah mighty, mighty well,

But dere's jes' one thing I hates an' 'spize:

She drinks mō' whisky dan de bigges' fool,

Den she up an' tell ten thousand lies.

Yes, I won't git drunk an' kick up a chunk.

I won't git drunk an' kick up a chunk.

I won't git drunk an' kick up a chunk,

'Way down on de ole Plank Road.

Oh shoo my Love! My turkle dove.

Oh shoo my Love! My turkle dove.

Oh shoo my Love! My turkle dove.

'Way down on de ole Plank Road.

[Pg 54]

THE OLD WOMAN IN THE HILLS

Once: Dere wus an ole 'oman

Dat lived in de hills;

Put rocks in 'er stockin's,

An' sent 'em to mill.

Den: De ole miller swore,

By de pint o' his knife;

Dat he never had ground up

No rocks in his life.

So: De ole 'oman said

To dat miller nex' day:

"You railly must 'scuse me,

It's de onliest way."

"I heared you made meal,

A-grindin' on stones.

I mus' 'ave heared wrong,

It mus' 'ave been bones."

[Pg 55]

A SICK WIFE

Las' Sadday night my wife tuck sick,

An' what d'you reckon ail her?

She e't a tucky gobbler's head

An' her stomach, it jes' fail her.

She squall out: "Sam, bring me some mint!

Make catnip up an' sage tea!"

I goes an' gits her all dem things,

But she throw 'em back right to me.

Says I: "Dear Honey! Mind nex' time!"

"Don't eat from 'A to Izzard'"

"I thinks you won' git sick at all,

If you saves pō' me de gizzard."

MY WONDERFUL TRAVEL

I come down from ole Virginny,

'Twas on a Summer day;

De wedder was all frez up,

'An' I skeeted all de way!

Hand my banjer down to play,

Wanter pick fer dese ladies right away;

"W'en dey went to bed,

Dey couldn' shet deir eyes,"

An' "Dey was stan'in' on deir heads,

A-pickin' up de pies."

[17]

I WOULD NOT MARRY A BLACK GIRL

I wouldn' marry a black gal,

I'll tell you de reason why:

When she goes to comb dat head

De naps'll 'gin to fly.

I wouldn' marry a black gal,

I'll tell you why I won't:

When she'd oughter wash her face—

Well, I'll jes say she don't.

I woudn' marry a black gal,

An' dis is why I say:

When you has her face around,

It never gits good day.

[Pg 57]

HARVEST SONG

Las' year wus a good crap year,

An' we raised beans an' 'maters.

We didn' make much cotton an' co'n;

But, Goodness Life, de taters!

You can plow dat ole gray hoss,

I'se gwineter plow dat mulie;

An' w'en we's geddered in de craps,

I'se gwine down to see Julie.

I hain't gwineter wo'k on de railroad.

I hates to wo'k on de fahm.

I jes wants to set in de cool shade,

Wid my head on my Julie's ahm.

You swing Lou, an' I'll swing Sue.

Dere hain't no diffunce 'tween dese two.

You swing Lou, I'll swing my beau;

I'se gwineter buy my gal red calico.

[Pg 58]

YEAR OF JUBILEE

Niggers, has you seed ole Mosser;

(Red mustache on his face.)

A-gwine 'roun' sometime dis mawnin',

'Spectin' to leave de place?

Nigger Hands all runnin' 'way,

Looks lak we mought git free!

It mus' be now de [18]Kingdom Come

In de Year o' Jubilee.

Oh, yon'er comes ole Mosser

Wid his red mustache all white!

It mus' be now de Kingdom Come

Sometime to-morrer night.

Yanks locked him in de smokehouse cellar,

De key's throwed in de well:

It shō' mus' be de Kingdom Come.

Go ring dat Nigger field-bell!

[Pg 59]

SHEEP SHELL CORN

Oh: De Ram blow de ho'n an' de sheep shell co'n;

An' he sen' it to de mill by de buck-eyed Whippoorwill.

Ole Joe's dead an' gone but his [19]Hant blows de ho'n;

An' his hound howls still from de top o' dat hill.

Yes: De Fish-hawk said unto Mistah Crane;

"I wishes to de Lawd dat you'd sen' a liddle rain;

Fer de water's all muddy, an de creek's gone dry;

If it 'twasn't fer de tadpoles we'd all die."

Oh: When de sheep shell co'n wid de rattle of his ho'n

I wishes to de Lawd I'd never been bo'n;

Caze when de Hant blows de ho'n, de sperits all dance,

An' de hosses an' de cattle, dey whirls 'round an' prance.

[Pg 60]

Oh: Yonder comes Skillet an' dere goes Pot;

An' here comes Jawbone 'cross de lot.

Walk Jawbone! Beat de Skillet an' de Pan!

You cut dat Pigeon's Wing, Black Man!

Now: Take keer, gemmuns, an' let me through;

Caze I'se gwineter dance wid liddle Mollie Lou.

But I'se never seed de lak since I'se been bo'n,

When de sheep shell co'n wid de rattle of his ho'n!

PLASTER

Chilluns:

Mammy an' daddy had a hoss,

Dey want a liddle bigger.

Dey sticked a plaster on his back

An' drawed a liddle Nigger.

Den:

Mammy an' daddy had a dog,

His tail wus short an' chunky.

Dey slapped a plaster 'round dat tail,

An' drawed it lak de monkey.

[Pg 61]Well:

Mammy an' daddy's dead an' gone.

Did you ever hear deir story?

Dey sticked some plasters on deir heels,

An' drawed 'em up to Glory!

UNCLE NED

Jes lay down de shovel an' de hoe.

Jes hang up de fiddle an' de bow.

No more hard work fer ole man Ned,

Fer he's gone whar de good Niggers go.

He didn' have no years fer to hear,

Didn' have no eyes fer to see,

Didn' have no teeth fer to eat corn cake,

An' he had to let de beefsteak be.

Dey called 'im "Ole Uncle Ned,"

A long, long time ago.

Dere wusn't no wool on de top o' his head

In de place whar de wool oughter grow.

When ole man Ned wus dead,

Mosser's tears run down lak rain;

But ole Miss, she wus a liddle sorter glad,

Dat she wouldn' see de ole Nigger 'gain.

[Pg 62]

THE MASTER'S "STOLEN" COAT

Ole Mosser bought a brand new coat,

He hung it on de wall.

Dat Nigger [20]stole dat coat away,

An' wore it to de Ball.

His head look lak a Coffee pot,

His nose look lak de spout,

His mouf look lak de fier place,

Wid de ashes all tuck out.

His face look lak a skillet lid,

His years lak two big kites.

His eyes look lak two big biled aigs,

Wid de yallers in de whites.

His body 'us lak a stuffed toad frog,

His foot look lak a board.

Oh-oh! He thinks he is so fine,

But he's greener dan a gourd.

[Pg 63]

[21]

I WOULDN'T MARRY A YELLOW OR A WHITE NEGRO GIRL

I sho' loves dat gal dat dey calls Sally [22]"Black,"

An' I sorter loves some of de res';

I first loves de gals fer lovin' me,

Den I loves myse'f de bes'.

I wouldn' marry dat yaller Nigger gal,

An' I'll tell you de reason why:

Her neck's drawed out so stringy an' long,

I'se afeared she 'ould never die.

I wouldn' marry dat White Nigger gal,

(Fer gracious sakes!) dis is why:

Her nose look lak a kittle spout;

An' her skin, it hain't never dry.

DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS

Don't ax me no questions,

An' I won't tell you no lies;

But bring me dem apples,

An' I'll make you some pies.

[Pg 64]An' if you ax questions,

'Bout my havin' de flour;

I fergits to use 'lasses

An' de pie'll be all sour.

Dem apples jes wa'k here;

An' dem 'lasses, dey run.

Hain't no place lak my house

Found un'er de sun.

THE OLD SECTION BOSS

I once knowed an ole Sexion Boss but he done been laid low.

I once knowed an ole Sexion Boss but he done been laid low.

He "Caame frum gude ole Ireland some fawhrty year ago."

W'en I ax 'im fer a job, he say: "Nayger, w'at can yer do?"

W'en I ax 'im fer a job, he say: "Nayger, w'at can yer do?"

"I can line de track; tote de jack, de pick an' shovel too."

[Pg 65]Says he: "Nayger, de railroad's done, an' de chyars is on de track,"

Says he: "Nayger, de railroad's done, an' de chyars is on de track,"

"Transportation brung yer here, but yō' money'll take yer back."

I went down to de Deepo, an' my ticket I shō' did draw.

I went down to de Deepo, an' my ticket I shō' did draw.

To take me over dat ole Iron Mountain to de State o' Arkansaw.

As I went sailin' down de road, I met my mudder-in-law.

I wus so tired an' hongry, man, dat I couldn' wuk my jaw.

Fer I hadn't had no decent grub since I lef' ole Arkansaw.

Her bread wus hard corndodgers; dat meat, I couldn' chaw.

Her bread wus hard corndodgers; dat meat, I couldn' chaw.

You see; dat's de way de Hoosiers feeds way out in Arkansaw.

[Pg 66]

THE NEGRO AND THE POLICEMAN

"Oh Mistah Policeman, tu'n me loose;

Hain't got no money but a good excuse."

Oh hello, Sarah Jane!

Dat ole Policeman treat me mean,

He make me wa'k to Bowlin' Green.

Oh hello, Sarah Jane!

De way he treat me wus a shame.

He make me wear dat Ball an' Chain.

Oh hello, Sarah Jane!

I runs to de river, I can't git 'cross;

Dat Police grab me an' swim lak a hoss.

Oh hello, Sarah Jane!

I goes up town to git me a gun,

Dat ole Police shō' make me run.

Oh hello, Sarah Jane!

I goes crosstown sorter walkin' wid a hump

An' dat ole Police shō' make me jump.

Oh hello, Sarah Jane!

Sarah Jane, is dat yō' name?

Us boys, we calls you Sarah Jane.

Well, hello, Sarah Jane!

[Pg 67]

HAM BEATS ALL MEAT

Dem white folks set up in a Dinin' Room

An' dey charve dat mutton an' lam'.

De Nigger, he set 'hind de kitchen door,

An' he eat up de good sweet ham.

Dem white folks, dey set up an' look so fine,

An' dey eats dat ole cow meat;

But de Nigger grin an' he don't say much,

Still he know how to git what's sweet.

Deir ginger cakes taste right good sometimes,

An' deir Cobblers an' deir jam.

But fer every day an' Sunday too,

Jest gimme de good sweet ham.

Ham beats all meat,

Always good an' sweet.

Ham beats all meat,

I'se always ready to eat.

You can bake it, bile it, fry it, stew it,

An' still it's de good sweet ham.

[Pg 68]

SUZE ANN

Yes: I loves dat gal wid a blue dress on,

Dat de white folks calls Suze Ann.

She's jes' dat gal what stole my heart,

'Way down in Alabam'.

But: She loves a Nigger about nineteen,

Wid his lips all painted red;

Wid a liddle fuz around his mouf;

An' no brains in his head.

Now: Looky, looky Eas'! Oh, looky, looky Wes'!

I'se been down to ole Lou'zan';

Still dat ar gal I loves de bes'

Is de gal what's named Suze Ann.

Oh, head 'er! Head 'er! Ketch 'er!

Jump up an' [23]"Jubal Jew."

Fer de Banger Picker's sayin':

He hain't got nothin' to do.

WALK TOM WILSON

Ole Tom Wilson, he had 'im a hoss;

His legs so long he couldn' git 'em 'cross.[Pg 69]

He laid up dar lak a bag o' meal,

An' he spur him in de flank wid his toenail heel.

Ole Tom Wilson, he come an' he go,

Frum cabin to cabin in de county-o.

W'en he go to bed, his legs hang do'n,

An' his foots makes poles fer de chickens t' roost on.

Tom went down to de river, an' he couldn' go 'cross.

Tom tromp on a 'gater an' 'e think 'e wus a hoss.

Wid a mouf wide open, 'gater jump from de san',

An' dat Nigger look clean down to de Promus' Lan'.

Wa'k Tom Wilson, git out'n de way!

Wa'k Tom Wilson, don't wait all de day!

Wa'k Tom Wilson, here afternoon;

Sweep dat kitchen wid a bran' new broom.

CHICKEN PIE

If you wants to make an ole Nigger feel good,

Let me tell you w'at to do:

Jes take off a chicken from dat chicken roost,

An' take 'im along wid you.

Take a liddle dough to roll 'im up in,

An' it'll make you wink yō' eye;

Wen dat good smell gits up yō' nose,

Frum dat home-made chicken pie.

[Pg 70]Jes go round w'en de night's sorter dark,

An' dem chickens, dey can't see.

Be shore dat de bad dog's all tied up,

Den slip right close to de tree.

Now retch out yō' han' an' pull 'im in,

Den run lak a William goat;

An' if he holler, squeeze 'is neck,

An' shove 'im un'er yō' coat.

Bake dat Chicken pie!

It's mighty hard to wait

When you see dat Chicken pie,

Hot, smokin' on de plate.

Bake dat Chicken pie!

Yes, put in lots o' spice.

Oh, how I hopes to Goodness

Dat I gits de bigges' slice.

I AM NOT GOING TO HOBO ANY MORE

My mammy done tol' me a long time ago

To always try fer to be a good boy;

To lay on my pallet an' to waller on de flō';

An' to never leave my daddy's house.

I hain't never gwineter hobo no mō'. By George!

I hain't never gwineter hobo no mō'.

[Pg 71]Yes, befō' I'd live dat ar hobo life,

I'll tell you what I'd jes go an' do:

I'd court dat pretty gal an' take 'er fer my wife,

Den jes lay 'side dat ar hobo life.

I hain't never gwineter hobo no mō'. By George!

I hain't never gwineter hobo no mō'.

FORTY-FOUR

If de people'll jes gimme

Des a liddle bit o' peace,

I'll tell 'em what happen

To de Chief o' Perlice.

He met a robber

Right at de dō'!

An' de robber, he shot 'im

Wid a forty-fō'!

He shot dat Perliceman.

He shot 'im shō'!

What did he shoot 'im wid?

A forty-fō'.

Dey sent fer de Doctah

An' de Doctah he come.

He come in a hurry,

He come in a run.[Pg 72]

He come wid his instriments

Right in his han',

To progue an' find

Dat forty-fō', Man!

De Doctah he progued;

He progued 'im shō'!

But he jes couldn' find

Dat forty-fō'.

Dey sent fer de Preachah,

An' de preachah he come.

He come in a walk,

An' he come in to talk.

He come wid 'is Bible,

Right in 'is han',

An' he read from dat chapter,

Forty-fō', Man!

Dat Preachah, he read.

He read, I know.

What Chapter did he read frum?

'Twus Forty-fō'!

[Pg 73]

Play Rhyme Section

BLINDFOLD PLAY CHANT

Oh blin' man! Oh blin' man!

You cain't never see.

Just tu'n 'round three times

You cain't ketch me.

Oh tu'n Eas'! Oh tu'n Wes'!

Ketch us if you can.

Did you thought dat you'd cotch us,

Mistah blin' man?

FOX AND GEESE PLAY

[24](Fox Call) "Fox in de mawnin'!"

(Goose Sponse) "Goose in de evenin'!"

(Fox Call) "How many geese you got?"

(Goose Sponse) "More 'an you're able to ketch!"

[Pg 74]

HAWK AND CHICKENS PLAY

[25](Chicken's Call)

"Chickamee, chickamee, cranie-crow."

I went to de well to wash my toe.

W'en I come back, my chicken wus gone.

W'at time, ole Witch?

(Hawk Sponse) "One"

(Hawk Call) "I wants a chick."

(Chicken's Sponse) "Well, you cain't git mine."

(Hawk Call) "I shall have a chick!"

(Chicken's Sponse) "You shan't have a chick!"

CAUGHT BY THE WITCH PLAY

(Human Call) "Molly, Molly, Molly-bright!"

(Witch Sponse) "Three scō' an' ten!"

(Human Call) "Can we git dar 'fore candle-light?"

(Witch Sponse) "Yes, if yō' legs is long an' light."

(Conscience's Warning Call) "You'd better watch out,

Or de witches'll git yer!"

[Pg 75]

[26]

GOOSIE-GANDER PLAY RHYME

"Goosie, goosie, goosie-gander!

What d'you say?"—"Say: 'Goose!'"—

"Ve'y well, go right along, Honey!

I tu'ns yō' years a-loose."

"Goosie, goosie, goosie-gander!

What d'you say?"—"Say: 'Gander'"

"Ve'y well. Come in de ring, Honey!

I'll pull yō' years way yander!"

HAWK AND BUZZARD

Once: De Hawk an' de buzzard went to roost,

An' de hawk got up wid a broke off tooth.

Den: De hawk an' de buzzard went to law,

An' de hawk come back wid a broke up jaw.

But lastly: Dat buzzard tried to plead his case,

Den he went home wid a smashed in face.

[Pg 76]

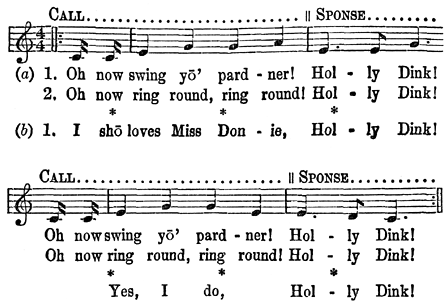

LIKES AND DISLIKES

I sho' loves Miss Donie! Oh, yes, I do!

She's neat in de waist,

Lak a needle in de case;

An' she suits my taste.

I'se gwineter run wid Mollie Roalin'! Oh, yes, I will!

She's pretty an' nice

Lak a bottle full o' spice,

But she's done drap me twice.

I don't lak Miss Jane! Oh no, I don't.

She's fat an' stout,

Got her mouf sticked out,

An' she laks to pout.

SUSIE GIRL

Ring 'round, Miss Susie gal,

Ring 'round, "My Dovie."

Ring 'round, Miss Susie gal.

Bless you! "My Lovie."

[Pg 77]Back 'way, Miss Susie gal.

Back 'way, "My Money."

Now come back, Miss Susie gal.

Dat's right! "My Honey."

Swing me, Miss Susie gal.

Swing me, "My Starlin'."

Jes swing me, my Susie gal.

Yes "Love!" "My Darlin'."

SUSAN JANE

I know somebody's got my Lover;

Susan Jane! Susan Jane!

Oh, cain't you tell me; help me find 'er?

Susan Jane! Susan Jane!

If I lives to see nex' Fall;

Susan Jane! Susan Jane!

I hain't gwineter sow no wheat at all.

Susan Jane! Susan Jane!

'Way down yon'er in de middle o' de branch;

Susan Jane! Susan Jane!

De ole cow pat an' de buzzards dance.

Susan Jane! Susan Jane!

[Pg 78]

PEEP SQUIRREL

Peep squir'l, ying-ding-did-lum;

Peep squir'l, it's almos' day,

Look squir'l, ying-ding-did-lum,

Look squir'l, an' run away.

Walk squir'l, ying-ding-did-lum;

Walk squir'l, fer dat's de way.

Skip squir'l, ying-ding-did-lum;

Skip squir'l, all dress in gray.

Run squir'l! Ying-ding-did-lum!

Run squir'l! Oh, run away!

I cotch you squir'l! Ying-ding-did-lum!

I cotch you squir'l! Now stay, I say.

DID YOU FEED MY COW?

"Did yer feed my cow?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Will yer tell me how?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Oh, w'at did yer give 'er?" "Cawn an' hay."

"Oh, w'at did yer give 'er?" "Cawn an' hay."

[Pg 79]"Did yer milk 'er good?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Did yer do lak yer should?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Oh, how did yer milk 'er?" "Swish! Swish! Swish!"

"Oh, how did yer milk 'er?" "Swish! Swish! Swish!"

"Did dat cow git sick?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Wus she kivered wid tick?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Oh, how wus she sick?" "All bloated up."

"Oh, how wus she sick?" "All bloated up."

"Did dat cow die?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Wid a pain in 'er eye?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Oh, how did she die?" "Uh-! Uh-! Uh-!"

"Oh, how did she die?" "Uh-! Uh-! Uh-!"

"Did de Buzzards come?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Fer to pick 'er bone?" "Yes, Mam!"

"Oh, how did they come?" "Flop! Flop! Flop!"

"Oh, how did they come?" "Flop! Flop! Flop!"

A BUDGET

If I lives to see nex' Spring

I'se gwineter buy my wife a big gold ring.

[Pg 80]If I lives to see nex' Fall,

I'se gwinter buy my wife a waterfall.

"When Christmas comes?" You cunnin' elf!

I'se gwineter spen' my money on myself.

THE OLD BLACK GNATS

Dem ole black gnats, dey is so bad

I cain't git out'n here.

Dey stings, an' bites, an' runs me mad;

I cain't git out'n here.

Dem ole black gnats dey sings de song,

"You cain't git out'n here.

Ole Satan'll git you befō' long;

You cain't git out'n here."

Dey burns my years, gits in my eye;

An' I cain't git out'n here.

Dey makes me dance, dey makes me cry;

An' I cain't git out'n here.

I fans an' knocks but dey won't go 'way!

I cain't git out'n here.

Dey makes me wish 'twus Jedgment Day;

Fer I cain't git out'n here.

[Pg 81]

SUGAR LOAF TEA

Bring through yō' [27]Sugar-lō'-tea, bring through yō' [27]Candy,

All I want is to wheel, an' tu'n, an' bow to my Love so handy.

You tu'n here on Sugar-lō'-tea, I'll tu'n there on Candy.

All I want is to wheel, an' tu'n, an' bow to my Love so handy.

Some gits drunk on Sugar-lō'-tea, some gits drunk on Candy,

But all I wants is to wheel, an' tu'n, an' bow to my Love so handy.

GREEN OAK TREE! ROCKY'O

Green oak tree! Rocky'o! Green oak tree! Rocky'o!

Call dat one you loves, who it may be,

To come an' set by de side o' me.

"Will you hug 'im once an' kiss 'im twice?"

"W'y! I wouldn' kiss 'im once fer to save 'is life!"

Green oak tree! Rocky'o! Green oak tree! Rocky'o!

[Pg 82]

KISSING SONG

A sleish o' bread an' butter fried,

Is good enough fer yō' sweet Bride.

Now choose yō' Lover, w'ile we sing,

An' call 'er nex' onto de ring.

"Oh my Love, how I loves you!

Nothin' 's in dis worl' above you.

Dis right han', fersake it never.

Dis heart, you mus' keep forever.

One sweet kiss, I now takes from you;

Caze I'se gwine away to leave you."

KNEEL ON THIS CARPET

Jes choose yō' Eas'; jes choose yō' Wes'.

Now choose de one you loves de bes'.

If she hain't here to take 'er part

Choose some one else wid all yō' heart.

Down on dis chyarpet you mus' kneel,

Shore as de grass grows in de fiel'.

Salute yō' Bride, an' kiss her sweet,

An' den rise up upon yō' feet.

[Pg 83]

SALT RISING BREAD

I loves saltin', saltin' bread.

I loves saltin', saltin' bread.

Put on dat skillet, nev' mind de lead;

Caze I'se gwineter cook dat saltin' bread;

Yes, ever since my mammy's been dead,

I'se been makin' an' cookin' dat saltin' bread.

I loves saltin', saltin' bread.

I loves saltin', saltin' bread.

You loves biscuit, butter, an' fat?

I can dance Shiloh better 'an dat.

Does you turn 'round an' shake yō' head?—

Well; I loves saltin', saltin' bread.

I loves saltin', saltin' bread.

I loves saltin', saltin' bread.

W'en you ax yō' mammy fer butter an' bread,

She don't give nothin' but a stick across yō' head.

On cracklin's, you say, you wants to git fed?

Well, I loves saltin', saltin' bread.

[Pg 84]

PRECIOUS THINGS

Hol' my rooster, hōl' my hen,

Pray don't tetch my [28]Gooshen Ben'.

Hol' my bonnet, hōl' my shawl,

Pray don't tetch my waterfall.

Hōl' my han's by de finger tips,

But pray don't tetch my sweet liddle lips.

HE LOVES SUGAR AND TEA

Mistah Buster, he loves sugar an' tea.

Mistah Buster, he loves candy.

Mistah Buster, he's a Jim-dandy!

He can swing dem gals so handy.

Charlie's up an' Charlie's down.

Charlie's fine an' dandy.

Ev'ry time he goes to town,

He gits dem gals stick candy.

Dat Niggah, he love sugar an' tea.

Dat Niggah love dat candy.[Pg 85]

Fine Niggah! He can wheel 'em 'round,

An' swing dem ladies handy.

Mistah Sambo, he love sugar an' tea.

Mistah Sambo love his candy.

Mistah Sambo; he's dat han'some man

What goes wid sister Mandy.

HERE COMES A YOUNG MAN COURTING

Here comes a young man a courtin'! Courtin'! Courtin'!

Here comes a young man a-courtin'! It's Tidlum Tidelum Day.

"Say! Won't you have one o' us? Us, Sir? Us, Sir?

Say! Won't you have one o' us, Sir?" dem brown skin ladies say.

"You is too black an' rusty! Rusty! Rusty!

You is too black an' rusty!" said Tidlum Tidelum Day.

"We hain't no blacker 'an you, Sir! You, Sir! You, Sir!

We hain't no blacker 'an you, Sir!" dem brown skin ladies say.

[Pg 86]"Pray! Won't you have one o' us, Sir? Us, Sir? Us, Sir?

Pray! Won't you have one o' us, Sir?" say yaller gals all gay.

"You is too ragged an' dirty! Dirty! Dirty!

You is too ragged an' dirty!" said Tidlum Tidelum Day.

"You shore is got de bighead! Bighead! Bighead!

You shore is got de bighead! You needn' come dis way.

We's good enough fer you, Sir! You, Sir! You, Sir!

We's good enough fer you, Sir!" dem yaller gals all say.

"De fairest one dat I can see, dat I can see, dat I can see,

De fairest one dat I can see," said Tidlum Tidelum Day.

"My Lulu, come an' wa'k wid me, wa'k wid me, wa'k wid me.

My Lulu, come an' wa'k wid me. 'Miss Tidlum Tidelum Day.'"

[Pg 87]

ANCHOR LINE

I'se gwine out on de Anchor Line, Dinah!

I won't git back 'fore de summer time, Dinah!

W'en I come back be "dead in line,"

I'se gwineter bring you a dollar an' a dime,

Shore as I gits in from de Anchor Line, Dinah!

If you loves me lak I loves you, Dinah!

No Coon can cut our love in two, Dinah!

If you'll jes come an' go wid me,

Come go wid me to Tennessee,

Come go wid me; I'll set you free,—Dinah!

SALLIE

Sallie! Sallie! don't you want to marry?

Sallie! Sallie! do come an' tarry!

Sallie! Sallie! Mammy says to tell her when.

Sallie! Sallie! She's gwineter kill dat turkey hen!

Sallie! Sallie! When you goes to marry,

(Sallie! Sallie!) Marry a fahmin man(!)

(Sallie! Sallie!) Ev'ry day'll be Mond'y,

(Sallie! Sallie!) Wid a hoe-handle in yō' han'!

[Pg 88]

[29]

SONG TO THE RUNAWAY SLAVE

Go 'way from dat window, "My Honey, My Love!"

Go 'way from dat window! I say.

De baby's in de bed, an' his mammy's lyin' by,

But you cain't git yō' lodgin' here.

Go 'way from dat window, "My Honey, My Love!"

Go 'way from dat window! I say;

Fer ole Mosser's got 'is gun, an' to Miss'ip' youse been sōl';

So you cain't git yō' lodgin' here.

Go 'way from dat window, "My Honey, My Love!"

Go 'way from dat window! I say.[Pg 89]

De baby keeps a-cryin'; but you'd better un'erstan'

Dat you cain't git yō' lodgin' here.

Go 'way from dat window, "My Honey, My Love!"

Go 'way from dat window! I say;

Fer de Devil's in dat man, an' you'd better un'erstan'

Dat you cain't git yō' lodgin' here.

DOWN IN THE LONESOME GARDEN

Hain't no use to weep, hain't no use to moan;

Down in a lonesome gyardin.

You cain't git no meat widout pickin' up a bone,

Down in a lonesome gyardin.

Look at dat gal! How she puts on airs,

Down in de lonesome gyardin!

But whar did she git dem closes she w'ars,

Down in de lonesome gyardin?

It hain't gwineter rain, an' it hain't gwineter snow;

Down in my lonesome gyardin.

You hain't gwinter eat in my kitchen doo',

Nor down in my lonesome gyardin.

[Pg 90]

LITTLE SISTER, WON'T YOU MARRY ME?

Liddle sistah in de barn, jine de weddin'.

Youse de sweetest liddle couple dat I ever did see.

Oh Love! Love! Ahms all 'round me!

Say, liddle sistah, won't you marry me?

Oh step back, gal, an' don't you come a nigh me,

Wid all dem sassy words dat you say to me.

Oh Love! Love! Ahms all 'roun' me!

Oh liddle sistah, won't you marry me?

RAISE A "RUCUS" TO-NIGHT

Two liddle Niggers all dressed in white, (Raise a rucus to-night.)

Want to go to Heaben on de tail of a kite. (Raise a rucus to-night.)

De kite string broke; dem Niggers fell; (Raise a rucus to-night.)

Whar dem Niggers go, I hain't gwineter tell. (Raise a rucus to-night.)

[Pg 91]A Nigger an' a w'ite man a playin' seben up; (Raise a rucus to-night.)

De Nigger beat de w'ite man, but 'ē's skeered to pick it up. (Raise a rucus to-night.)

Dat Nigger grabbed de money, an' de w'ite man fell. (Raise a rucus to-night.)

How de Nigger run, I'se not gwineter tell. (Raise a rucus to-night.)

Look here, Nigger! Let me tell you a naked fac'; (Raise a rucus to-night.)

You mought a been cullud widout bein' dat black; (Raise a rucus to-night.)

Dem 'ar feet look lak youse shō' walkin' back; (Raise a rucus to-night.)

An' yō' ha'r, it look lak a chyarpet tack. (Raise a rucus to-night.)

Oh come 'long, chilluns, come 'long,

W'ile dat moon are shinin' bright.

Let's git on board, an' float down de river,

An' raise dat rucus to-night.

[Pg 92]

SWEET PINKS AND ROSES

Sweet pinks an' roses, strawbeers on de vines,

Call in de one you loves, an' kiss 'er if you minds.

Here sets a pretty gal,

Here sets a pretty boy;

Cheeks painted rosy, an' deir eyes battin' black.

You kiss dat pretty gal, an' I'll stan' back.

[Pg 93]

Pastime Rhyme Section

SATAN

De Lawd made man, an' de man made money.

De Lawd made de bees, an' de bees made honey.

De Lawd made ole Satan, an' ole Satan he make sin.

Den de Lawd, He make a liddle hole to put ole Satan in.

Did you ever see de Devil, wid his iron handled shovel,

A scrapin' up de san' in his ole tin pan?

He cuts up mighty funny, he steals all yō' money,

He blinds you wid his san'. He's tryin' to git you, man!

JOHNNY BIGFOOT

Johnny, Johnny Bigfoot!

Want a pair o' shoes?

Go kick two cows out'n deir skins.

Run Brudder, tell de news!

[Pg 94]

THE THRIFTY SLAVE

Jes wuk all day,

Den go huntin' in de wood.

Ef you cain't ketch nothin',

Den you hain't no good.

Don't look at Mosser's chickens,

Caze dey're roostin' high.

Big pig, liddle pig, root hog or die!

WILD NEGRO BILL

I'se wild Nigger Bill

Frum Redpepper Hill.

I never did wo'k, an' I never will.

I'se done killed de Boss.

I'se knocked down de hoss.

I eats up raw goose widout apple sauce!

I'se Run-a-way Bill,

I knows dey mought kill;

But ole Mosser hain't cotch me, an' he never will!

[Pg 95]

YOU LOVE YOUR GIRL

You loves yō' gal?

Well, I loves mine.

Yō' gal hain't common?

Well, my gal's fine.

I loves my gal,

She hain't no goose—

Blacker 'an blackberries,

Sweeter 'an juice.

FRIGHTENED AWAY FROM A CHICKEN-ROOST

I went down to de hen house on my knees,

An' I thought I heared dat chicken sneeze.

You'd oughter seed dis Nigger a-gittin' 'way frum dere,

But 'twusn't nothin' but a rooster sayin' his prayer.

How I wish dat rooster's prayer would en',

Den perhaps I mought eat dat ole gray hen.

[Pg 96]

BEDBUG

De June-bug's got de golden wing,

De Lightning-bug de flame;

De Bedbug's got no wing at all,

But he gits dar jes de same.

De Punkin-bug's got a punkin smell,

De Squash-bug smells de wust;

But de puffume of dat ole Bedbug,

It's enough to make you bust.

Wen dat Bedbug come down to my house,

I wants my walkin' cane.

Go git a pot an' scald 'im hot!

Good-by, Miss Lize Jane!