Fig. 1.—Multiple Fracture of both Bones of Leg.

Fig. 1.—Multiple Fracture of both Bones of Leg.

Title: Manual of Surgery Volume Second: Extremities—Head—Neck. Sixth Edition.

Author: Alexis Thomson

Alexander Miles

Release date: March 29, 2009 [eBook #28428]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Chris Logan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: The inverted 'Y' symbol used in this book has been transcribed as [inverted Y].

VOLUME SECOND

EXTREMITIES—HEAD—NECK

SIXTH EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED

WITH 288 ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

HENRY FROWDE and HODDER & STOUGHTON

THE LANCET BUILDING

1 & 2 BEDFORD STREET, STRAND, W.C. 2

| First Edition | 1904 |

| Second Edition | 1907 |

| Third Edition | 1909 |

| Fourth Edition | 1912 |

| ""Second Impression | 1913 |

| Fifth Edition | 1915 |

| ""Second Impression | 1919 |

| Sixth Edition | 1921 |

Printed in Great Britain by

Morrison and Gibb Ltd., Edinburgh

| page | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I | |

| Injuries of Bones | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Injuries of Joints | 32 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Injuries in the Region of the Shoulder and Upper Arm | 44 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Injuries in the Region of the Elbow and Forearm | 79 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Injuries in the Region of the Wrist and Hand | 102 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Injuries in the Region of the Pelvis, Hip-Joint, and Thigh | 122 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Injuries in the Region of the Knee and Leg | 155 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Injuries in Region of Ankle and Foot | 185 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Diseases of Individual Joints | 201 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Deformities of the Extremities | 241 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Scalp | 319 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| The Cranium and its Contents | 328 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Injuries of the Skull | 361 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Diseases of the Brain and Membranes | 373 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Diseases of the Cranial Bones | 406 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The Vertebral Column and Spinal Cord | 411 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| Diseases of the Vertebral Column and Spinal Cord | 431 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| Deviations of the Vertebral Column | 461 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| The Face, Orbit, and Lips | 474 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| The Mouth, Fauces, and Pharynx | 496 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| The Jaws, including the Teeth and Gums | 507 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| The Tongue | 528 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| The Salivary Glands | 543 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| The Ear | 553 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| The Nose and Naso-Pharynx | 567 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| The Neck | 582 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| The Thyreoid Gland | 604 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| The Œsophagus | 616 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| The Larynx, Trachea, and Bronchi | 634 |

| INDEX | 645 |

| fig. | page | |

|---|---|---|

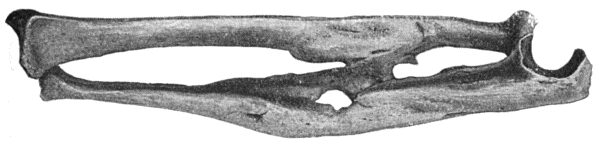

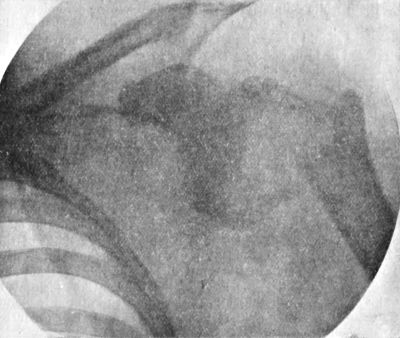

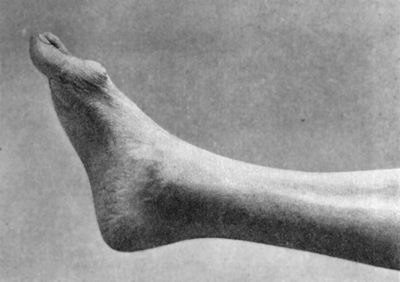

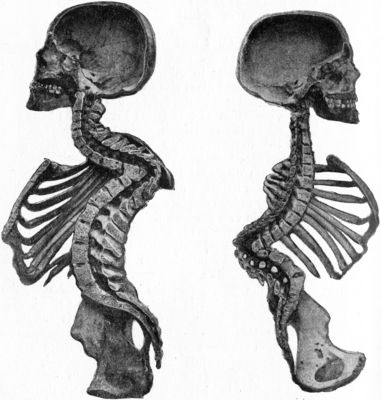

| 1. | Multiple Fracture of both Bones of Leg | 4 |

| 2. | Radiogram showing Comminuted Fracture of both Bones of Forearm | 5 |

| 3. | Oblique Fracture of Tibia; with partial Separation of Epiphysis of Upper End of Fibula; and Incomplete Fracture of Fibula in Upper Third | 6 |

| 4. | Excess of Callus after Compound Fracture of Bones of Forearm | 9 |

| 5. | Multiple Fractures of both Bones of Forearm showing Mal-union | 11 |

| 6. | Radiogram of Un-united Fracture of Shaft of Ulna | 13 |

| 7. | Excessive Callus Formation after Infected Compound Fracture of both Bones of Forearm | 27 |

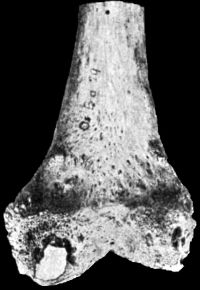

| 8. | Partial Separation of Epiphysis, with Fracture running into Diaphysis | 29 |

| 9. | Complete Separation of Epiphysis | 29 |

| 10. | Partial Separation with Fracture of Epiphysis | 29 |

| 11. | Complete Separation with Fracture of Epiphysis | 29 |

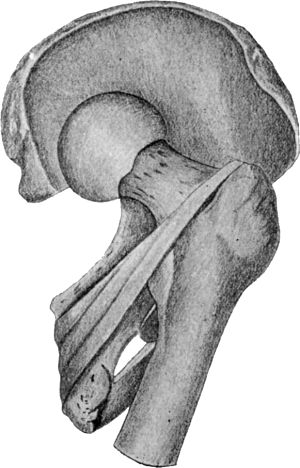

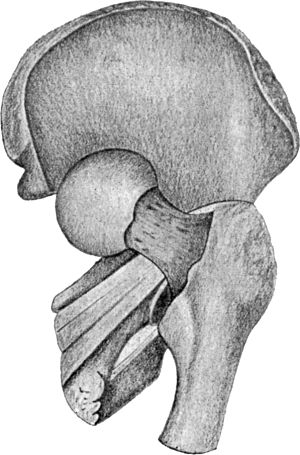

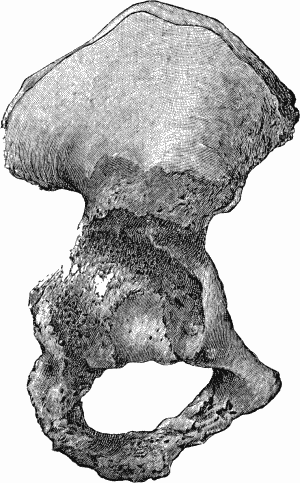

| 12. | Os Innominatum showing new Socket formed after Old-standing Dislocation | 41 |

| 13. | Oblique Fracture of Right Clavicle in Middle Third, united | 45 |

| 14. | Fracture of Acromial End of Clavicle | 46 |

| 15. | Adhesive Plaster applied for Fracture of Clavicle | 49 |

| 16. | Forward Dislocation of Sternal End of Right Clavicle | 51 |

| 17. | Diagram of most common varieties of Dislocation of the Shoulder | 53 |

| 18. | Sub-coracoid Dislocation of Right Shoulder | 55 |

| 19. | Sub-coracoid Dislocation of Humerus | 56 |

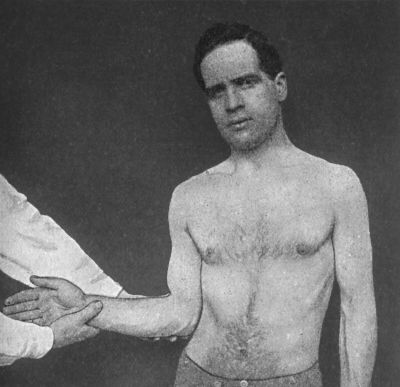

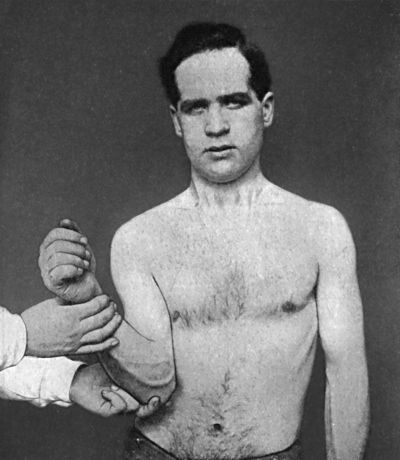

| 20. | Kocher's Method of reducing Sub-coracoid Dislocation—First Movement | 57 |

| 21. | Kocher's Method—Second Movement | 58 |

| 22. | Kocher's Method—Third Movement | 59 |

| 23. | Miller's Method of reducing Sub-coracoid Dislocation—First Movement | 60 |

| 24. | Miller's Method—Second Movement | 61 |

| 25. | Dislocation of Shoulder with Fracture of Neck of Humerus | 64 |

| 26. | Transverse Fracture of Scapula | 68 |

| 27. | Fracture of Surgical Neck of Humerus, united with Angular Displacement | 70 |

| 28. | Impacted Fracture of Neck of Humerus | 71 |

| 29. | Ambulatory Abduction Splint for Fracture of Humerus | 72 |

| 30. | Radiogram of Separation of Upper Epiphysis of Humerus | 73 |

| 31. | “Cock-up” Splint | 77 |

| 32. | Gooch Splints for Fracture of Shaft of Humerus; and Rectangular Splint to secure Elbow | 77 |

| 33. | Radiogram of Supra-condylar Fracture of Humerus in a Child | 81 |

| 34. | Radiogram of T-shaped Fracture of Lower End of Humerus | 83 |

| 35. | Radiogram of Fracture of Olecranon Process | 86 |

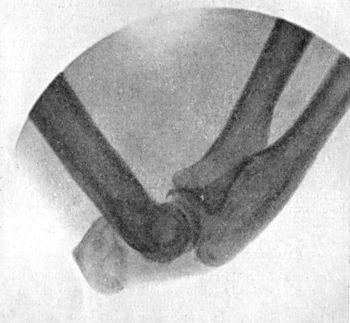

| 36. | Backward Dislocation of Elbow in a Boy | 89 |

| 37. | Bony Outgrowth in relation to insertion of Brachialis Muscle | 90 |

| 38. | Radiogram of Incomplete Backward Dislocation of Elbow | 91 |

| 39. | Forward Dislocation of Elbow, with Fracture of Olecranon | 93 |

| 40. | Radiogram of Forward Dislocation of Head of Radius, with Fracture of Shaft of Ulna | 95 |

| 41. | Greenstick Fracture of both Bones of the Forearm | 98 |

| 42. | Gooch Splints for Fracture of both Bones of Forearm | 99 |

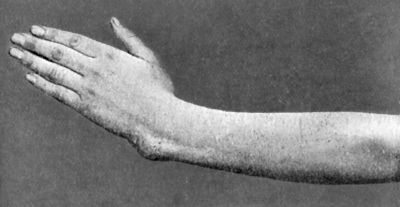

| 43. | Colles' Fracture showing Radial Deviation of Hand | 103 |

| 44. | Colles' Fracture showing undue prominence of Ulnar Styloid | 103 |

| 45. | Radiogram showing the Line of Fracture and Upward Displacement of the Radial Styloid in Colles' Fracture | 104 |

| 46. | Radiogram of Chauffeur's Fracture | 107 |

| 47. | Radiogram of Smith's Fracture | 108 |

| 48. | Manus Valga following Separation of Lower Radial Epiphysis in Childhood | 109 |

| 49. | Radiogram showing Fracture of Navicular (Scaphoid) Bone | 111 |

| 50. | Dorsal Dislocation of Wrist at Radio-carpal Articulation | 113 |

| 51. | Radiogram showing Forward Dislocation of Navicular Bone | 114 |

| 52. | Extension Apparatus for Oblique Fracture of Metacarpals | 117 |

| 53. | Radiogram of Bennett's Fracture of Base of Metacarpal of Right Thumb | 118 |

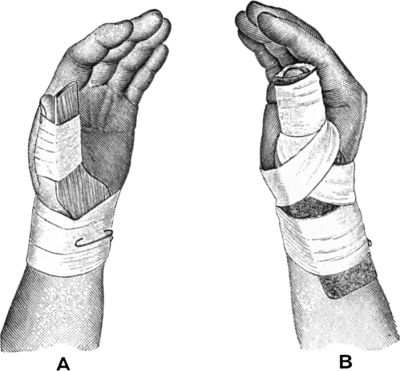

| 54. | Splints for Bennett's Fracture | 119 |

| 55. | Multiple Fracture of Pelvis through Horizontal and Descending Rami of both Pubes, and Longitudinal Fracture of left side of Sacrum | 123 |

| 56. | Fracture of Left Iliac Bone; and of both Pubic Arches | 124 |

| 57. | Many-tailed Bandage and Binder for Fracture of Pelvic Girdle | 125 |

| 58. | Nélaton's Line | 128 |

| 59. | Bryant's Line | 129 |

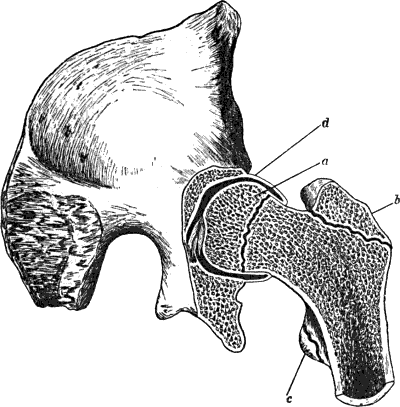

| 60. | Section through Hip-Joint to show Epiphyses at Upper End of Femur, and their relation to the Joint | 130 |

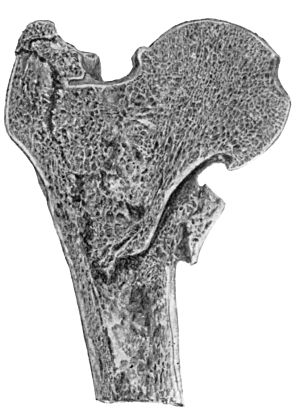

| 61. | Fracture through Narrow Part of Neck of Femur on Section | 131 |

| 62. | Impacted Fracture through Narrow Part of Neck of Femur | 132 |

| 63. | Fracture of Neck of Right Femur, showing Shortening, Abduction, and Eversion of Limb | 133 |

| 64. | Fracture of Narrow Part of Neck of Femur | 134 |

| 65. | Coxa Vara following Fracture of Neck of Femur in a Child | 136 |

| 66. | Non-impacted Fracture through Base of Neck | 137 |

| 67. | Fracture through Base of Neck of Femur with Impaction into the Trochanters | 137 |

| 68. | Non-impacted Fracture through Base of Neck | 138 |

| 69. | Fracture of the Femur just below the small Trochanter, united, showing Flexion and Lateral Rotation of Upper Fragment | 140 |

| 70. | Adjustable Double-inclined Plane | 141 |

| 71. | Diagram of the most Common Dislocations of the Hip | 142 |

| 72. | Dislocation of Right Femur on to Dorsum Ilii | 143 |

| 73. | Dislocation on to Dorsum Ilii | 144 |

| 74. | Dislocation into the Vicinity of the Ischiatic Notch | 145 |

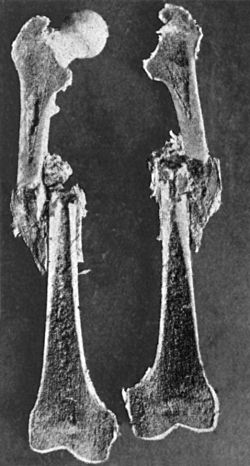

| 75. | Longitudinal Section of Femur showing Fracture of Shaft with Overriding of Fragments | 148 |

| 76. | Radiogram of Steinmann's Apparatus applied for Direct Extension to the Femur | 150 |

| 77. | Hodgen's Splint | 151 |

| 78. | Long Splint with Perineal Band | 152 |

| 79. | Fracture of Thigh treated by Vertical Extension | 153 |

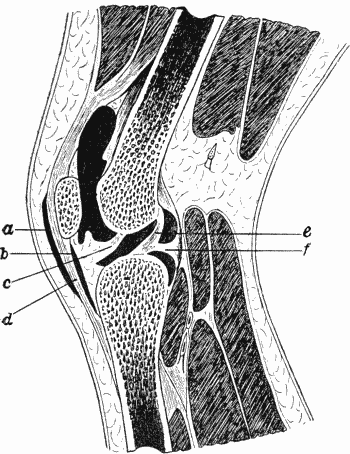

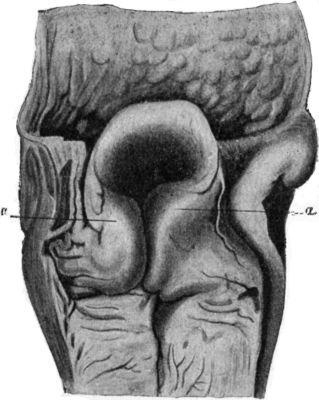

| 80. | Section of Knee-joint showing Extent of Synovial Cavity | 156 |

| 81. | Extension applied by means of Ice-tong Callipers for Fracture of Femur | 158 |

| 82. | Radiogram of Separation of Lower Epiphysis of Femur, with Backward Displacement of the Diaphysis | 160 |

| 83. | Separation of Lower Epiphysis of Femur, with Fracture of Lower End of Diaphysis | 161 |

| 84. | Radiogram of Fracture of Head of Tibia and upper Third of Fibula | 163 |

| 85. | Radiogram illustrating Schlatter's Disease | 164 |

| 86. | Diagram of Longitudinal Tear of Posterior End of Right Medial Semilunar Meniscus | 171 |

| 87. | Radiogram of Fracture of Patella | 173 |

| 88. | Fracture of Patella, showing wide Separation of Fragments | 175 |

| 89. | Radiogram of Transverse Fracture of both Bones of Leg by Direct Violence | 178 |

| 90. | Radiogram of Oblique Fracture of both Bones of Leg by Indirect Violence | 178 |

| 91. | Box Splint for Fractures of Leg | 180 |

| 92. | Box Splint applied | 181 |

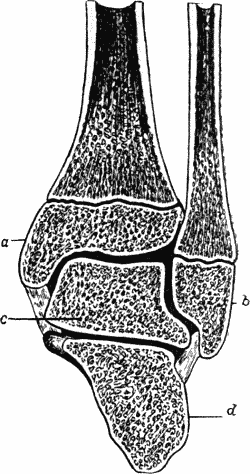

| 93. | Section through Ankle-joint showing relation of Epiphyses to Synovial Cavity | 186 |

| 94. | Radiogram of Pott's Fracture, with Lateral Displacement of Foot | 187 |

| 95. | Ambulant Splint of Plaster of Paris | 189 |

| 96. | Dupuytren's Splint applied to Correct Eversion of Foot | 190 |

| 97. | Syme's Horse-shoe Splint applied to Correct Backward Displacement of Foot | 191 |

| 98. | Radiogram of Fracture of Lower End of Fibula, with Separation of Lower Epiphysis of Tibia | 192 |

| 99. | Radiogram of Backward Dislocation of Ankle | 195 |

| 100. | Compound Dislocation of Talus | 197 |

| 101. | Radiogram of Fracture-Dislocation of Talus | 198 |

| 102. | Radiogram of Dislocation of Toes | 199 |

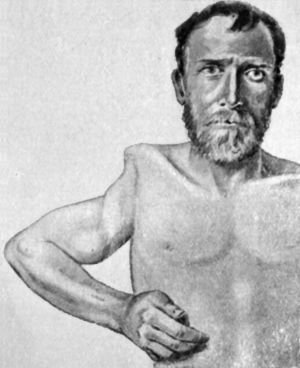

| 103. | Arthropathy of Shoulder in Syringomyelia | 203 |

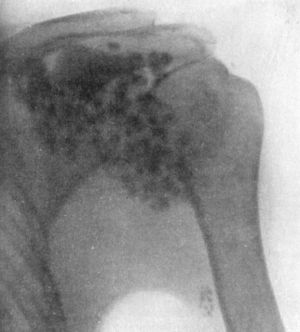

| 104. | Radiogram of Specimen of Arthropathy of Shoulder in Syringomyelia | 204 |

| 105. | Radiogram showing Multiple partially Ossified Cartilaginous Loose Bodies in Shoulder-joint | 205 |

| 106. | Diffuse Tuberculous Thickening of Synovial Membrane of Elbow | 206 |

| 107. | Contracture of Elbow and Wrist following a Burn in Childhood | 207 |

| 108. | Advanced Tuberculous Disease of Acetabulum with Caries and Perforation into Pelvis | 210 |

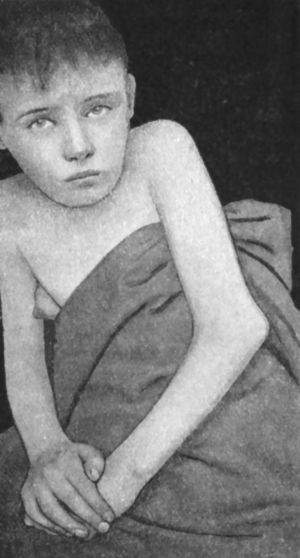

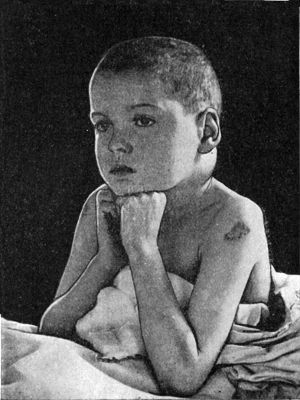

| 109. | Early Tuberculous Disease of Right Hip-joint in a Boy | 212 |

| 110. | Disease of Left Hip; showing Moderate Flexion and Lordosis | 213 |

| 111. | Disease of Left Hip; Disappearance of Lordosis on further Flexion of the Hip | 213 |

| 112. | Disease of Left Hip; Exaggeration of Lordosis | 214 |

| 113. | Thomas' Flexion Test, showing Angle of Flexion at Diseased Hip | 214 |

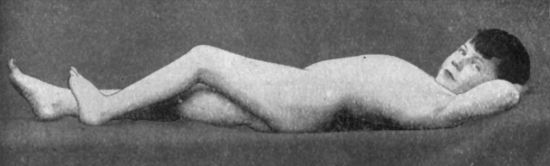

| 114. | Tuberculous Disease of Left Hip: Third Stage | 215 |

| 115. | Advanced Tuberculous Disease of Left Hip-joint in a Girl | 216 |

| 116. | Extension by Adhesive Plaster and Weight and Pulley | 220 |

| 117. | Stiles' Double Long Splint to admit of Abduction of Diseased Limb | 221 |

| 118. | Thomas' Hip-splint applied for Disease of Right Hip | 222 |

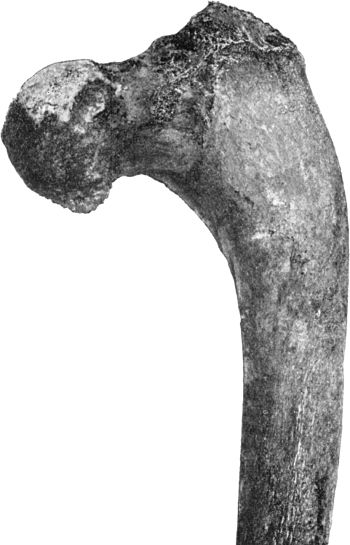

| 119. | Arthritis Deformans, showing erosion of Cartilage and lipping of Articular Edge of Head of Femur | 225 |

| 120. | Upper End of Femur in advanced Arthritis Deformans of Hip | 226 |

| 121. | Femur in advanced Arthritis Deformans of Hip and Knee Joints | 227 |

| 122. | Tuberculous Synovial Membrane of Knee | 230 |

| 123. | Lower End of Femur from an Advanced Case of Tuberculous Arthritis of the Knee | 231 |

| 124. | Advanced Tuberculous Disease of Knee, with Backward Displacement of Tibia | 233 |

| 125. | Thomas' Knee-splint applied | 236 |

| 126. | Tuberculous Disease of Right Ankle | 239 |

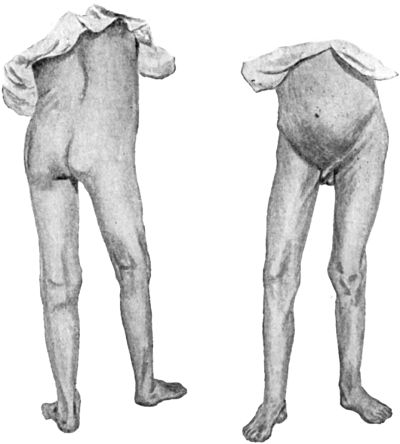

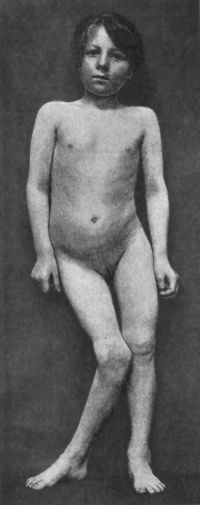

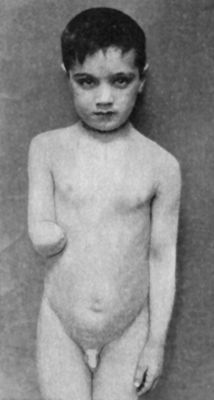

| 127. | Female Child showing the results of Poliomyelitis affecting the Left Lower Extremity | 243 |

| 128. | Radiogram of Double Congenital Dislocation of Hip in a Girl | 249 |

| 129. | Innominate Bone and Upper End of Femur from a case of Congenital Dislocation of Hip | 250 |

| 130. | Congenital Dislocation of Left Hip in a Girl | 251 |

| 131. | Contracture Deformities of Upper and Lower Limbs resulting from Spastic Cerebral Palsy in Infancy | 255 |

| 132. | Rachitic Coxa Vara | 258 |

| 133. | Coxa Vara, showing Adduction Curvature of Neck of Femur associated with Arthritis of the Hip and Knee | 260 |

| 134. | Bilateral Coxa Vara, showing Scissors-leg Deformity | 260 |

| 135. | Genu Valgum and Genu Varum | 265 |

| 136. | Female Child with Right-sided Genu Valgum, the result of Rickets | 266 |

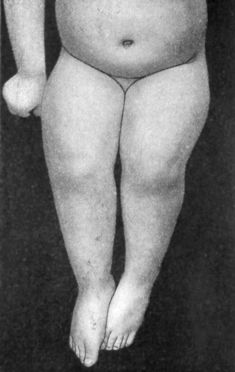

| 137. | Double Genu Valgum; and Rickety Deformities of Arms | 267 |

| 138. | Radiogram of Case of Double Genu Valgum in a Child | 268 |

| 139. | Genu Valgum in a Child. Patient standing | 269 |

| 140. | Genu Valgum. Same Patient as Fig. 139, sitting | 270 |

| 141. | Bow-knee in Rickety Child | 271 |

| 142. | Bilateral Congenital Club-foot in an Infant | 274 |

| 143. | Radiogram of Bilateral Congenital Club-foot in an Infant | 275 |

| 144. | Congenital Talipes Equino-varus in a Man | 277 |

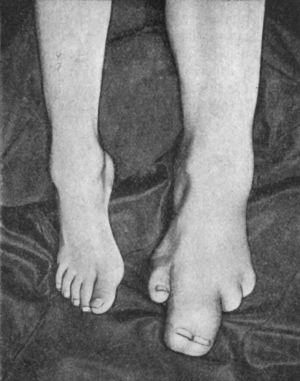

| 145. | Bilateral Pes Equinus in a Boy | 280 |

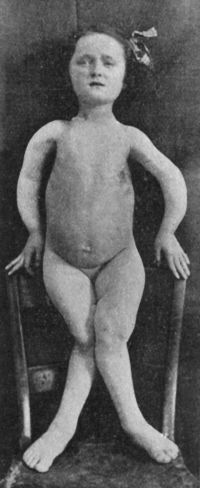

| 146. | Extreme form of Pes Equinus in a Girl | 281 |

| 147. | Skeleton of Foot from case of Pes Equinus due to Poliomyelitis | 282 |

| 148. | Pes Calcaneo-valgus with excessive arching of Foot | 284 |

| 149. | Pes Calcaneo-valgus, the result of Poliomyelitis | 285 |

| 150. | Pes Cavus in Association with Pes Equinus, the Result of Poliomyelitis | 286 |

| 151. | Radiogram of Foot of Adult, showing Changes in the Bones in Pes Cavus | 286 |

| 152. | Adolescent Flat-Foot | 287 |

| 153. | Flat-Foot, showing Loss of Arch | 288 |

| 154. | Imprint of Normal and of Flat Foot | 290 |

| 155. | Bilateral Pes Valgus and Hallux Valgus in a Girl | 293 |

| 156. | Radiogram of Spur on Under Aspect of Calcaneus | 295 |

| 157. | Radiogram of Hallux Valgus | 296 |

| 158. | Radiogram of Hallux Varus or Pigeon-Toe | 298 |

| 159. | Hallux Rigidus and Flexus in a Boy | 299 |

| 160. | Hammer-Toe | 300 |

| 161. | Section of Hammer-Toe | 301 |

| 162. | Congenital Hypertrophy of Left Lower Extremity in a Boy | 302 |

| 163. | Supernumerary Great Toe | 303 |

| 164. | Congenital Elevation of Left Scapula in a Girl: also shows Hairy Mole over Sacrum | 304 |

| 165. | Winged Scapula | 305 |

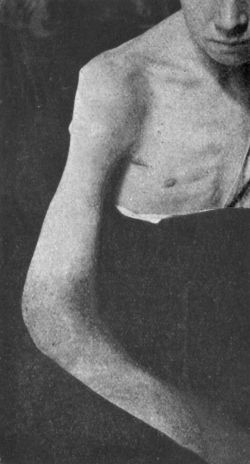

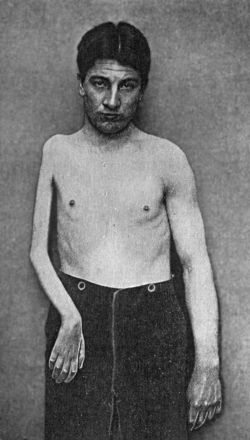

| 166. | Arrested Growth and Wasting of Tissues of Right Upper Extremity | 307 |

| 167. | Lower End of Humerus from case of Cubitus Varus | 309 |

| 168. | Intra-Uterine Amputation of Forearm | 310 |

| 169. | Radiogram of Arm of Patient shown in Fig. 168 | 310 |

| 170. | Congenital Absence of Left Radius and Tibia in a Child | 311 |

| 171. | Club-Hand, the Result of Imperfect Development of Radius | 312 |

| 172. | Congenital Contraction of Ring and Little Fingers | 314 |

| 173. | Dupuytren's Contraction | 315 |

| 174. | Splint used after Operation for Dupuytren's Contraction | 316 |

| 175. | Supernumerary Thumb | 317 |

| 176. | Trigger Finger | 318 |

| 177. | Multiple Wens | 324 |

| 178. | Adenoma of Scalp | 325 |

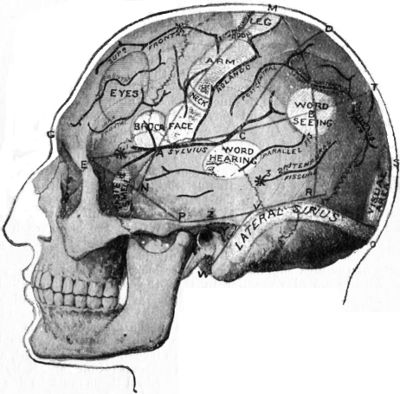

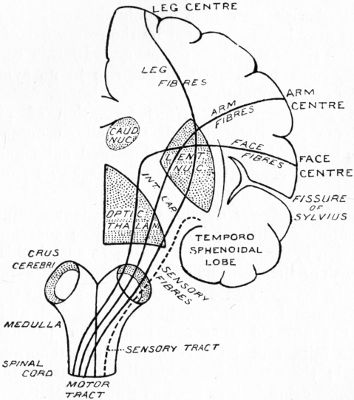

| 179. | Relations of the Motor and Sensory Areas to the Convolutions and to Chiene's Lines | 330 |

| 180. | Diagram of the Course of Motor and Sensory Nerve Fibres | 333 |

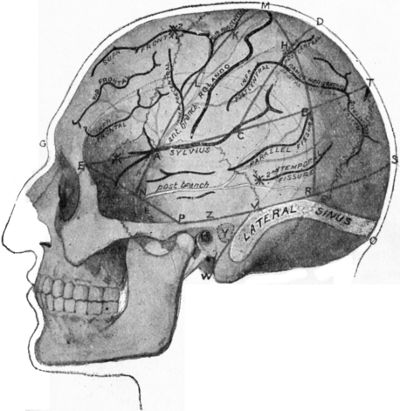

| 181. | Chiene's Method of Cerebral Localisation | 336 |

| 182. | To illustrate the Site of Various Operations on the Skull | 337 |

| 183. | Localisation of Site for Introduction of Needle in Lumbar Puncture | 338 |

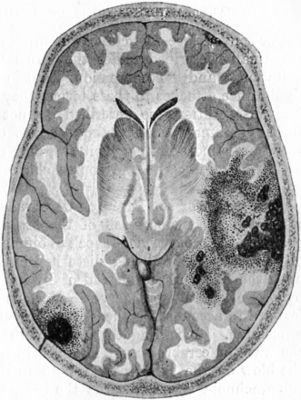

| 184. | Contusion and Laceration of Brain | 343 |

| 185. | Charts of Pyrexia in Head Injuries | 348 |

| 186. | Relations of the Middle Meningeal Artery and Lateral Sinus to the Surface as indicated by Chiene's Lines | 353 |

| 187. | Extra-Dural Clot resulting from Hæmorrhage from the Middle Meningeal Artery | 354 |

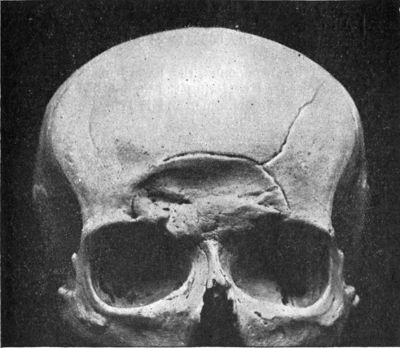

| 188. | Depressed Fracture of Frontal Bones with Fissured Fracture | 365 |

| 189. | Depressed and Comminuted Fracture of Right Parietal Bone: Pond Fracture | 365 |

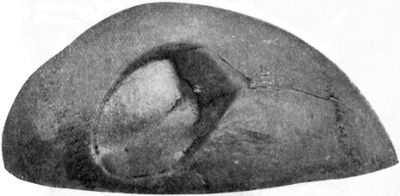

| 190. | Pond Fracture of Left Frontal Bone, produced during Delivery | 366 |

| 191. | Transverse Fracture through Middle Fossa of Base of Skull | 368 |

| 192. | Diagram of Extra-Dural Abscess | 374 |

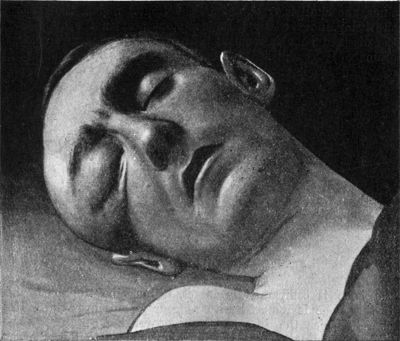

| 193. | Pott's Puffy Tumour in case of Extra-Dural Abscess following Compound Fracture of Orbital Margin | 375 |

| 194. | Diagram of Sub-Dural Abscess | 376 |

| 195. | Diagram illustrating sequence of Paralysis, caused by Abscess in Temporal Lobe | 380 |

| 196. | Chart of case of Sinus Phlebitis following Middle Ear Disease | 384 |

| 197. | Occipital Meningocele | 388 |

| 198. | Frontal Hydrencephalocele | 389 |

| 199. | Nævus at Root of Nose, simulating Cephalocele | 390 |

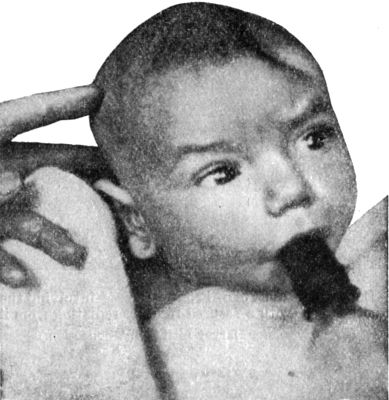

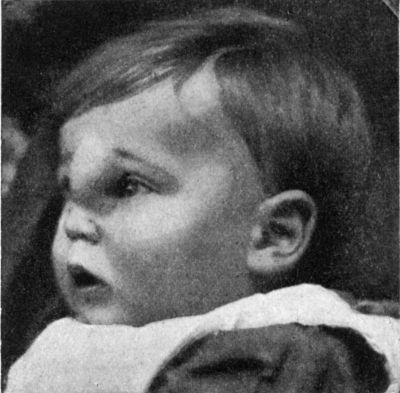

| 200. | Hydrocephalus in a Child | 391 |

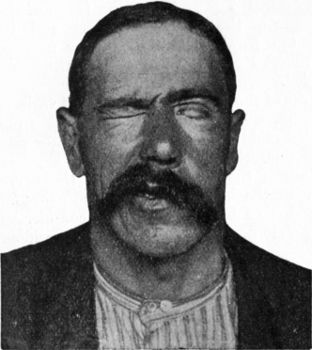

| 201. | Patient suffering from Left Facial Paralysis | 402 |

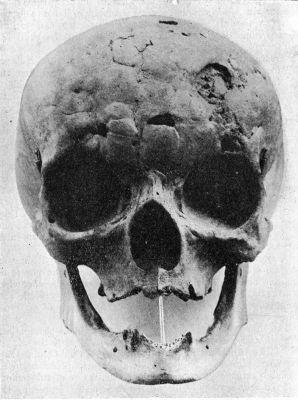

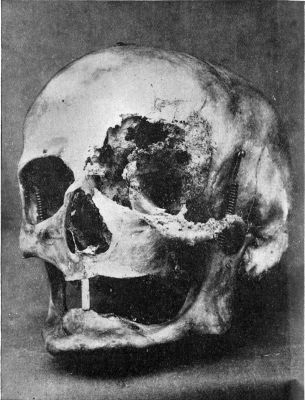

| 202. | Skull of Woman illustrating the appearances of Tertiary Syphilis of Frontal Bone—Corona Veneris—in the Healed Condition | 408 |

| 203. | Sarcoma of Orbital Plate of Frontal Bone in a Child at Age of 11 months and 18 months | 409 |

| 204. | Destruction of Bones of Left Orbit, caused by Rodent Cancer | 410 |

| 205. | Distribution of the Segments of the Spinal Cord | 417 |

| 206. | Attitude of Upper Extremities in Traumatic Lesions of the Sixth Cervical Segment | 418 |

| 207. | Compression Fracture of Bodies of Third and Fourth Lumbar Vertebræ | 426 |

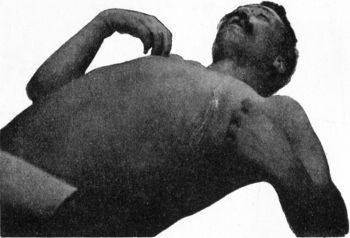

| 208. | Fracture-Dislocation of Ninth Thoracic Vertebra | 428 |

| 209. | Fracture of Odontoid Process of Axis Vertebra | 429 |

| 210. | Tuberculous Osteomyelitis affecting several Vertebræ at Thoracico-Lumbar Junction | 432 |

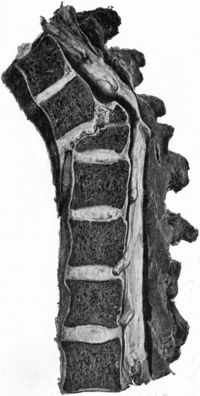

| 211. | Osseous Ankylosis of Bodies (a) of Dorsal Vertebræ, (b) of Lumbar Vertebræ following Pott's Disease | 434 |

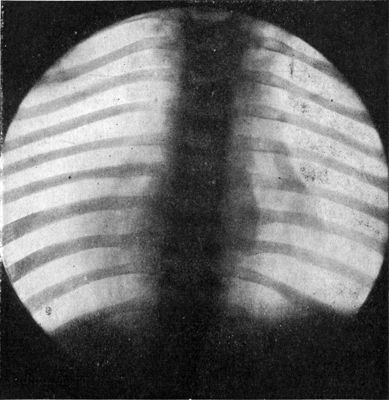

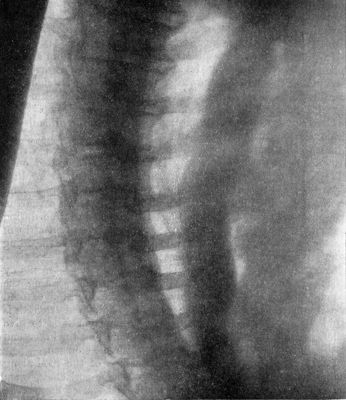

| 212. | Radiogram of Museum Specimen of Pott's Disease in a Child | 435 |

| 213. | Radiogram of Child's Thorax showing Spindle-shaped Shadow at Site of Pott's Disease of Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Thoracic Vertebræ | 437 |

| 214. | Attitude of Patient suffering from Tuberculous Disease of the Cervical Spine | 441 |

| 215. | Thomas' Double Splint for Tuberculous Disease of the Spine | 442 |

| 216. | Hunch-back Deformity following Pott's Disease of Thoracic Vertebræ | 443 |

| 217. | Attitude in Pott's Disease of Thoracico-Lumbar Region of Spine | 444 |

| 218. | Arthritis Deformans of Spine | 449 |

| 219. | Meningo-Myelocele of Thoracico-Lumbar Region | 454 |

| 220. | Meningo-Myelocele of Cervical Spine | 454 |

| 221. | Meningo-Myelocele in Thoracic Region | 456 |

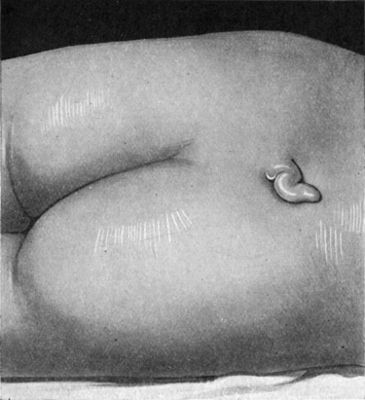

| 222. | Tail-like Appendage over Spina Bifida Occulta in a Boy | 457 |

| 223. | Congenital Sacro-Coccygeal Tumour | 458 |

| 224. | Scoliosis following upon Poliomyelitis affecting Right Arm and Leg | 463 |

| 225. | Rickety Scoliosis in a Child | 464 |

| 226. | Vertebræ from case of Scoliosis showing Alteration in Shape of Bones | 466 |

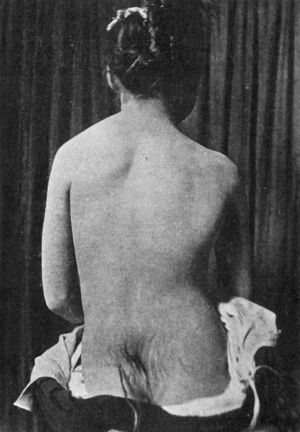

| 227. | Adolescent Scoliosis in a Girl | 467 |

| 228. | Scoliosis with Primary Curve in Thoracic Region | 468 |

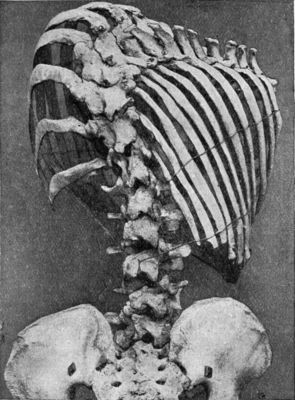

| 229. | Scoliosis showing Rotation of Bodies of Vertebræ, and widening of Intercostal Spaces on side of Convexity | 469 |

| 230. | Diagram of Attitudes in Klapp's Four-Footed Exercises for Scoliosis | 473 |

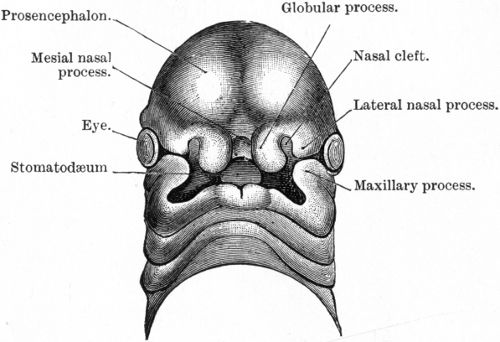

| 231. | Head of Human Embryo about 29 days old | 475 |

| 232. | Simple Hare-Lip | 476 |

| 233. | Unilateral Hare-Lip with Cleft Alveolus | 477 |

| 234. | Double Hare-Lip in a Girl | 478 |

| 235. | Double Hare-Lip with Projection of the Os Incisivum | 479 |

| 236. | Asymmetrical Cleft Palate extending through Alveolar Process on Left Side | 480 |

| 237. | Illustrating the Deformities caused by Lupus Vulgaris | 483 |

| 238. | Sarcoma of Orbit causing Exophthalmos and Downward Displacement of the Eye, and Projecting in Temporal Region | 488 |

| 239. | Sarcoma of Eyelid in Child | 489 |

| 240. | Dermoid Cyst at Outer Angle of Orbital Margin | 490 |

| 241. | Macrocheilia | 492 |

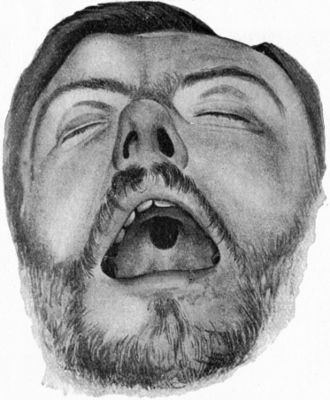

| 242. | Squamous Epithelioma of Lower Lip in a Man | 493 |

| 243. | Advanced Epithelioma of Lower Lip | 494 |

| 244. | Recurrent Epithelioma in Glands of Neck adherent to Mandible | 495 |

| 245. | Cancrum Oris | 497 |

| 246. | Perforation of Palate, the Result of Syphilis, and Gumma of Right Frontal Bone | 498 |

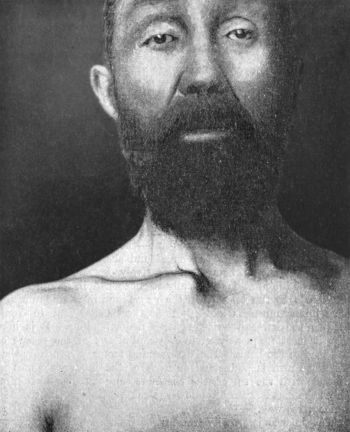

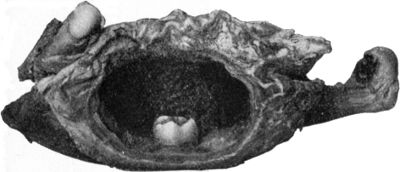

| 247. | Cario-necrosis of Mandible | 510 |

| 248. | Diffuse Syphilitic Disease of Mandible | 512 |

| 249. | Epulis of Mandible | 513 |

| 250. | Sarcoma of the Maxilla | 515 |

| 251. | Malignant Disease of Left Maxilla | 516 |

| 252. | Dentigerous Cyst of Mandible containing Rudimentary Tooth | 517 |

| 253. | Osseous Shell of Myeloma of Mandible | 518 |

| 254. | Multiple Fracture of Mandible | 520 |

| 255. | Four-Tailed Bandage applied for Fracture of Mandible | 522 |

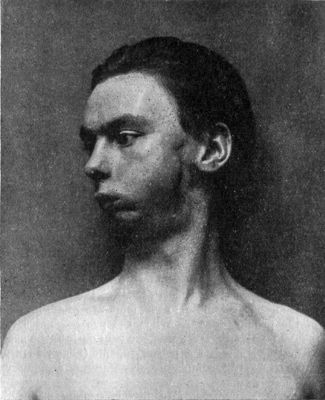

| 256. | Defective Development of Mandible from Fixation of Jaw due to Tuberculous Osteomyelitis in Infancy | 526 |

| 257. | Leucoplakia of the Tongue | 531 |

| 258. | Papillomatous Angioma of Left Side of Tongue in a Woman | 538 |

| 259. | Dermoid Cyst in Middle Line of Neck | 539 |

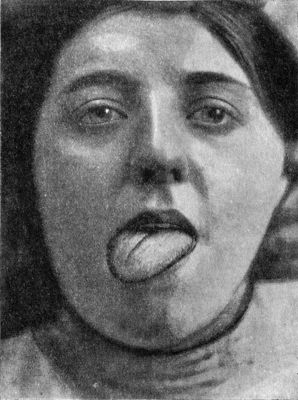

| 260. | Temporary Unilateral Paralysis of Tongue | 541 |

| 261. | Series of Salivary Calculi | 545 |

| 262. | Acute Suppurative Parotitis | 546 |

| 263. | Mixed Tumour of Parotid | 550 |

| 264. | Mixed Tumour of the Parotid of over twenty years' duration | 551 |

| 265. | Acute Mastoid Disease showing Œdema and Projection of Auricle | 565 |

| 266. | Rhinophyma or Lipoma Nasi | 569 |

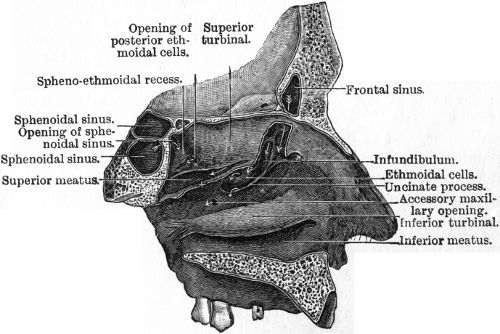

| 267. | The Outer Wall of Left Nasal Chamber after removal of the Middle Turbinated Body | 571 |

| 268. | Congenital Branchial Cyst in a Woman | 584 |

| 269. | Bilateral Cervical Ribs | 586 |

| 270. | Transient Wry-Neck | 587 |

| 271. | Congenital Wry-Neck in a Boy | 589 |

| 272. | Congenital Wry-Neck seen from behind to show Scoliosis | 590 |

| 273. | Recovery from Suicidal Cut-Throat after Low Tracheotomy and Gastrostomy | 596 |

| 274. | Hygroma of Neck | 599 |

| 275. | Lympho-Sarcoma of Neck | 600 |

| 276. | Branchial Carcinoma | 601 |

| 277. | Parenchymatous Goitre in a Girl | 606 |

| 278. | Larynx and Trachea surrounded by Goitre | 607 |

| 279. | Section of Goitre shown in Fig. 278 to illustrate Compression of Trachea | 607 |

| 280. | Multiple Adenomata of Thyreoid in a Woman | 611 |

| 281. | Cyst of Left Lobe of Thyreoid | 612 |

| 282. | Exophthalmic Goitre | 614 |

| 283. | Radiogram of Safety-Pin impacted in the Gullet and Perforating the Larynx | 620 |

| 284. | Denture Impacted in Œsophagus | 621 |

| 285. | Radiogram, after swallowing an Opaque Meal, in a Man suffering from Malignant Stricture of Lower End of Gullet | 626 |

| 286. | Diverticulum of the Œsophagus at its Junction with the Pharynx | 627 |

| 287. | Larynx from case of Sudden Death due to Œdema of Ary-Epiglottic Folds | 637 |

| 288. | Papilloma of Larynx | 641 |

The injuries to which a bone is liable are Contusions, Open Wounds, and Fractures.

Contusions of Bone are almost of necessity associated with a similar injury of the overlying soft parts. The mildest degree consists in a bruising of the periosteum, which is raised from the bone by an effusion of blood, constituting a hæmatoma of the periosteum. This may be absorbed, or it may give place to a persistent thickening of the bone—traumatic node.

Open Wounds of Bone of the incised and contused varieties are usually produced by sabres, axes, butcher's knives, scythes, or circular saws. Punctured wounds are caused by bayonets, arrows, or other pointed instruments. They are all equivalent to compound, incomplete fractures.

A fracture may be defined as a sudden solution in the continuity of a bone.

A pathological fracture has as its primary cause some diseased state of the bone, which permits of its giving way on the application of a force which would be insufficient to break a healthy bone. It cannot be too strongly emphasised that when a bone is found to have been broken by a slight degree of violence, the presence of some pathological condition should be suspected, and a careful examination made with the X-rays and by other means, before arriving at a conclusion as to the cause of the fracture. Many cases are on record in which such an accident has first drawn attention to the presence of a new-growth, or other serious lesion in the bone. The following conditions, which are more fully described with diseases of bone, may be mentioned as the causes of pathological fractures.

Atrophy of bone may proceed to such an extent in old people, or in those who for long periods have been bed-ridden, that slight violence suffices to determine a fracture. This most frequently occurs in the neck of the femur in old women, the mere catching of the foot in the bedclothes while the patient is turning in bed being sometimes sufficient to cause the bone to give way. Atrophy from the pressure of an aneurysm or of a simple tumour may erode the whole thickness of a bone, or may thin it out to such an extent that slight force is sufficient to break it. In general paralysis, and in the advanced stages of locomotor ataxia and other chronic diseases of the nervous system, an atrophy of all the bones sometimes takes place, and may proceed so far that multiple fractures are induced by comparatively slight causes. They occur most frequently in the ribs or long bones of the limbs, are not attended with pain, and usually unite satisfactorily, although with an excessive amount of callus. Attendants and nurses, especially in asylums, must be warned against using force in handling such patients, as otherwise they may be unfairly blamed for causing these fractures.

Among diseases which affect the skeleton as a whole and render the bones abnormally fragile, the most important are rickets, osteomalacia, and fibrous osteomyelitis. In these conditions multiple pathological fractures may occur, and they are prone to heal with considerable deformity. In osteomalacia, the bones are profoundly altered, but they are more liable to bend than to break; in rickets the liability is towards greenstick fractures.

Of the diseases affecting individual bones and predisposing them to fracture may be mentioned suppurative osteomyelitis, hydatid cysts, tuberculosis, syphilitic gummata, and various forms of new-growth, particularly sarcoma and secondary cancer. It is not unusual for the sudden breaking of the bone to be the first intimation of the presence of a new-growth. In adolescents, fibrous osteomyelitis affecting a single bone, and in adults, secondary cancer, are the commonest local causes of pathological fracture.

Intra-uterine fractures and fractures occurring during birth are usually associated with some form of violence, but in the majority of cases the fœtus is the subject of constitutional disease which renders the bones unduly fragile.

Traumatic fractures are usually the result of a severe force acting from without, although sometimes they are produced by muscular contraction.

When the bone gives way at the point of impact of the force, the violence is said to be direct, and a “fracture by compression” results, the line of fracture being as a rule transverse. The soft parts overlying the fracture are more or less damaged according to the weight and shape of the impinging body. Fracture of both bones of the leg from the passage of a wheel over the limb, fracture of the shaft of the ulna in warding off a stroke aimed at the head, and fracture of a rib from a kick, are illustrative examples of fractures by direct violence.

When the force is transmitted to the seat of fracture from a distance, the violence is said to be indirect, and the bone is broken by “torsion” or by “bending.” In such cases the bone gives way at its weakest point, and the line of fracture tends to be oblique. Thus both bones of the leg are frequently broken by a person jumping from a height and landing on the feet, the tibia breaking in its lower third, and the fibula at a higher level. Fracture of the clavicle in its middle third, or of the radius at its lower end, from a fall on the outstretched hand, are common accidents produced by indirect violence. The ribs also may be broken by indirect violence, as when the chest is crushed antero-posteriorly and the bones give way near their angles. In fractures by indirect violence the soft parts do not suffer by the violence causing the fracture, but they may be injured by displacement of the fragments.

In fractures by muscular action the bone is broken by “traction” or “tearing.” The sudden and violent contraction of a muscle may tear off an epiphysis, such as the head of the fibula, the anterior superior iliac spine, or the coronoid process of the ulna; or a bony process may be separated, as, for example, the tuberosity of the calcaneus, the coracoid process of the scapula, or the larger tubercle (great tuberosity) of the humerus. Long bones also may be broken by muscular action. The clavicle has snapped across during the act of swinging a stick, the humerus in throwing a stone, and the femur when a kick has missed its object. Fractures of ribs have occurred during fits of coughing and in the violent efforts of parturition.

Before concluding that a given fracture is the result of muscular action, it is necessary to exclude the presence of any of the diseased conditions that lead to pathological fracture.

Although the force acting upon the bone is the primary factor in the production of fractures, there are certain subsidiary factors to be considered. Thus the age of the patient is of importance. During infancy and early childhood, fractures are less common than at any other period of life, and are usually transverse, incomplete, and of the nature of bends. During adult life, especially between the ages of thirty and forty, the frequency of fractures reaches its maximum. In aged persons, although the bones become more brittle by the marrow spaces in their interior becoming larger and filled with fat, fractures are less frequent, doubtless because the old are less exposed to such violence as is likely to produce fracture.

Males, from the nature of their occupations and recreations, sustain fractures more frequently than do females; in old age, however, fractures are more common in women than in men, partly because their bones are more liable to be the seat of fatty atrophy from senility and disease, and partly because of their clothing—a long skirt—they are more exposed to unexpected or sudden falls.

Clinical Varieties of Fractures.—The most important subdivision of fractures is that into simple and compound.

In a simple or subcutaneous fracture there is no communication, directly or indirectly, between the broken ends of the bone and the surface of the skin. In a compound or open fracture, on the other hand, such a communication exists, and, by furnishing a means of entrance for bacteria, may add materially to the gravity of the injury.

A simple fracture may be complicated by the existence of a wound of the soft parts, which, however, does not communicate with the broken bone.

Fractures, whether simple or compound, fall into other clinical groups, according to (1) the degree of damage done to the bone, (2) the direction of the break, and (3) the relative position of the fragments.

(1) According to the Degree of Damage done to the Bone.—A fracture may be incomplete, for example in greenstick fractures, which occur only in young persons—usually below the age of twelve—while the bones are still soft and flexible. They result from forcible bending of the bone, the osseous tissue on the convexity of the curve giving way, while that on the concavity is compressed. The clavicle and the bones of the forearm are those most frequently the seat of greenstick fracture (Fig. 41). Fissures occur on the flat bones of the skull, the pelvic bones, and the scapula; or in association with other fractures in long bones, when they often run into joint surfaces. Depressions or indentations are most common in the bones of the skull.

The bone at the seat of fracture may be broken into several pieces, constituting a comminuted fracture. This usually results from severe degrees of direct violence, such as are sustained in railway or machinery accidents, and in gun-shot injuries (Fig. 2).

Sub-periosteal fractures are those in which, although the bone is completely broken across, the periosteum remains intact. These are common in children, and as the thick periosteum prevents displacement, the existence of a fracture may be overlooked, even in such a large bone as the femur.

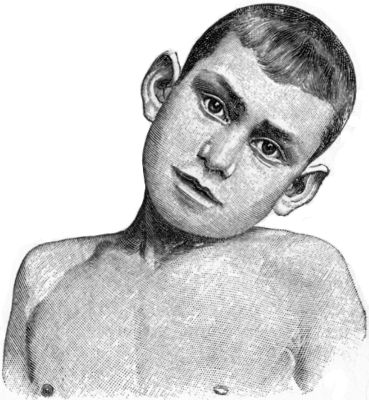

Fig. 3.—Showing (1) Oblique fracture of Tibia; (2)

Oblique fracture with partial separation of Epiphysis of upper end of

Fibula; (3) Incomplete fracture of Fibula in upper third. Result of

railway accident. Boy æt. 16.

Fig. 3.—Showing (1) Oblique fracture of Tibia; (2)

Oblique fracture with partial separation of Epiphysis of upper end of

Fibula; (3) Incomplete fracture of Fibula in upper third. Result of

railway accident. Boy æt. 16.

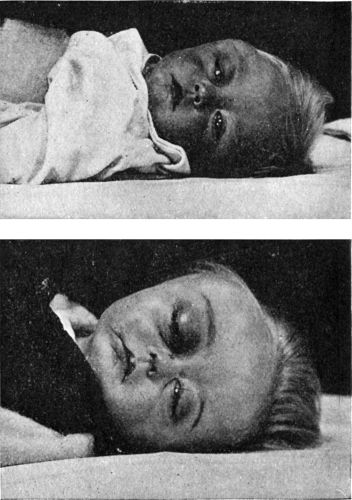

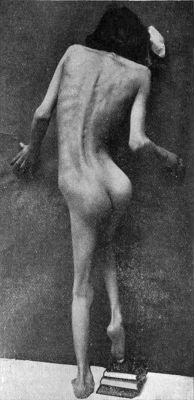

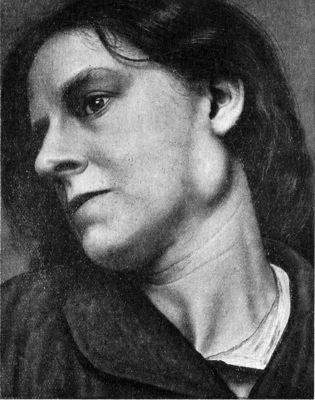

A bone may be broken at several places, constituting a multiple fracture (Fig. 1).

Separation of bony processes, such as the coracoid process, the epicondyle of the humerus, or the tuberosity of the calcaneus, may result from muscular action or from direct violence. Separation of epiphyses will be considered later.

(2) According to the Direction of the Break.—Transverse fractures are those in which the bone gives way more or less exactly at right angles to its long axis. These usually result from direct violence or from end-to-end pressure. Longitudinal fractures extending the greater part of the length of a long bone are exceedingly rare. Oblique fractures are common, and result usually from indirect violence, bending, or torsion (Fig. 3). Spiral fractures result from forcible torsion of a long bone, and are met with most frequently in the tibia, femur, and humerus.

(3) According to the Relative Position of the Fragments.—The bone may be completely broken across, yet its ends remain in apposition, in which case there is said to be no displacement. There may be an angular displacement—for example, in greenstick fracture. In transverse fractures of the patella or of the olecranon there is often distraction or pulling apart of the fragments (Fig. 35). The broken ends, especially in oblique fractures, may override one another, and so give rise to shortening of the limb (Fig. 2). Where one fragment is acted upon by powerful muscles, a rotatory displacement may take place, as in fracture of the radius above the insertion of the pronator teres, or of the femur just below the small trochanter. The fragments may be depressed, as in the flat bones of the skull or the nasal bones. At the cancellated ends of the long bones, particularly the upper end of the femur and humerus, and the lower end of the radius, it is not uncommon for one fragment to be impacted or wedged into the substance of the other (Fig. 28).

Causes of Displacement.—The factors which influence displacement are chiefly mechanical in their action. Thus the direction and nature of the fracture play an important part. Transverse fractures with roughly serrated ends are less liable to displacement than those which are oblique with smooth surfaces. The direction of the causative force also is a dominant factor in determining the direction in which one or both of the fragments will be displaced. Gravity, acting chiefly upon the distal fragment, also plays a part in determining the displacement—for example, in fractures of the thigh or of the leg, where the lower segment of the limb rolls outwards, and in fractures of the shaft of the clavicle, where the weight of the arm carries the shoulder downwards, forwards, and medially. After the break has taken place and the force has ceased to act, displacement may be produced by rough handling on the part of those who render first aid, the careless or improper application of splints or bandages, or by the weight of the bedclothes.

In certain situations the contraction of unopposed, or of unequally opposed, groups of muscles plays a part in determining displacement. For example, in fracture immediately below the lesser trochanter of the femur, the ilio-psoas tends to tilt the upper fragment forward and laterally; in supra-condylar fracture of the femur, the muscles of the calf pull the lower fragment back towards the popliteal space; and in fracture of the humerus above the deltoid insertion, the muscles inserted into the inter-tubercular (bicipital) groove adduct the upper fragment.

In a simple fracture the vessels of the periosteum and the marrow being torn at the same time as the bone is broken, blood is poured out, and clots around and between the fragments. This clot is soon permeated by newly formed blood vessels, and by leucocytes and fibroblasts, the latter being derived from proliferation of the cells of the marrow and periosteum. The granulation tissue thus formed resembles in every particular that described in the repair of other tissues, except that the fibroblasts, being the offspring of cells which normally form bone, assume the functions of osteoblasts, and proceed to the formation of bone. The new bone may be formed either by a direct conversion of the fibrous tissue into osseous tissue, the osteoblasts arranging themselves concentrically in the recesses of the capillary loops, and secreting a homogeneous matrix in which lime salts are speedily deposited; or there may be an intermediate stage of cartilage formation, especially in young subjects, and in cases where the fragments are incompletely immobilised. The newly formed bone is at first arranged in little masses or in the form of rods which unite with each other to form a network of spongy bone, the meshes of which contain marrow.

The reparative material, consisting of granulation tissue in the process of conversion into bone, is called callus, on account of its hard and unyielding character. In a fracture of a long bone, that which surrounds the fragments is called the external or ensheathing callus, and may be likened to the mass of solder which surrounds the junction of pipes in plumber-work; that which occupies the position of the medullary canal is called the internal or medullary callus; and that which intervenes between the fragments and maintains the continuity of the cortical compact tissue of the shaft is called the intermediate callus. This intermediate callus is the only permanent portion of the reparative material, the external and internal callus being only temporary, and being largely re-absorbed through the agency of giant cells.

Detached fragments or splinters of bone are usually included in the callus and ultimately become incorporated in the new bone that bridges the gap.

In time all surplus bone is removed, the medullary canal is re-formed, the young spongy bone of the intermediate callus becomes more and more compact, and thus the original architectural arrangement of the bone may be faithfully reproduced. If, however, apposition is not perfect, some of the new bone is permanently required and some of the old bone is absorbed in order to meet the altered physiological strain upon the bone resulting from the alteration in its architectural form. In overriding displacement, even the dense cortical bone intervening between the medullary canal of the two fragments is ultimately absorbed and the continuity of the medullary canal is reproduced.

The amount of callus produced in the repair of a given fracture is greater when movement is permitted between the broken ends. It is also influenced by the character of the bone involved, being less in bones entirely ossified in membrane, such as the flat bones of the skull, than in those primarily ossified in cartilage.

If the fragments are widely separated from one another, or if some tissue, such as muscle, intervenes between them, callus may not be able to bring about a bony union between the fragments, and non-union results.

Bones divided in the course of an operation, for example in osteotomy for knock-knee, or wedge-shaped resection for bow-leg, are repaired by the same process as fractures.

Excess of Callus.—In comminuted fractures, and in fractures in which there is much displacement, the amount of callus is in excess, but this is necessary to ensure stability. In fractures in the vicinity of large joints, such as the hip or elbow, the formation of callus is sometimes excessive, and the projecting masses of new bone restrict the movements of the joint. When exuberant callus forms between the bones in fractures of the forearm, pronation and supination may be interfered with (Fig. 4). Certain nerve-trunks, such as the radial (musculo-spiral) in the middle of the arm, or the ulnar at the elbow-joint, may become included in or pressed upon by callus.

Absorption of Callus.—It sometimes happens that when an acute infective disease, especially one of the exanthemata, supervenes while a fracture is undergoing repair, the callus which has formed becomes softened and is absorbed. This may occur weeks or even months after the bone has united, with the result that the fragments again become movable, and it may be a considerable time before union finally takes place.

Tumours of Callus.—Tumours, such as chondroma and sarcoma, and cysts which are probably of the same nature as those met with in osteomyelitis fibrosa, are liable to occur in callus, or at the seat of old fractures, but the evidence so far is inconclusive as to the causative relationship of the injury to the new-growth. They are treated on the same lines as tumours occurring independently of fracture.

Badly United Fracture—Mal-Union.—Union with marked displacement of the fragments is most common in fractures that have not been properly treated—as, for example, those occurring in sailors at sea; and in cases in which the comminution was so great that accurate apposition was rendered impossible. It may also result from imperfect reduction, or because the apparatus employed permitted of secondary displacement. Restlessness on the part of the patient from intractability, delirium tremens, or mania, is the cause of mal-union in some cases; sometimes it has resulted because the patient was expected to die from some other lesion and the fracture was left untreated.

Whether or not any attempt should be made to improve matters depends largely on the degree of deformity and the amount of interference with function.

When interference is called for, if the callus is not yet firmly consolidated, it may be possible, under an anæsthetic, to bend the bone into position or to re-break it, either with the hands or by means of a strong mechanical contrivance known as an osteoclast. In the majority of cases, however, an open operation yields results which are more certain and satisfactory. When the deformity is comparatively slight, the bone is divided with an osteotome and straightened; when there is marked bending or angling, a wedge is taken from the convexity, as in the operation for bow-leg. To maintain the fragments in apposition it may be necessary to employ pegs, plates, bone-grafts, or other mechanical means. Splints and extension are then applied, and the condition is treated on the same lines as a compound fracture.

Delayed Union.—At the time when union should be firm and solid, it may be found that the fragments are only united by a soft cartilaginous callus, which for a prolonged period may undergo no further change, so that the limb remains incapable of bearing weight or otherwise performing its functions. The normal period required for union may be extended from various causes. The most important of these is general debility, but the presence of rickets or tuberculosis, or an intercurrent acute infectious disease, may delay the reparative process. The influence of syphilis, except in its gummatous form, in interfering with union is doubtful. The influence of old age as a factor in delaying union has been overestimated; in the great majority of cases, fractures in old people unite as rapidly and as firmly as those occurring at other periods of life.

Treatment.—The general condition of the patient should be improved, by dieting and tonics. One of the most reliable methods of hastening union in these cases is by inducing passive hyperæmia of the limb after the method advocated by Bier, and this plan should always be tried in the first instance. An elastic bandage is applied above the seat of fracture, sufficiently tightly to congest the limb beyond, and, to concentrate the congestion in the vicinity of the fracture, an ordinary bandage should be applied from the distal extremity to within a few inches of the break. The hyperæmia should be maintained for several hours (six to twelve) daily. An apparatus should be adjusted to enable the patient to get into the open air, and in fractures of the lower extremity the patient should move about with crutches in the intervals, putting weight on the fractured bone. This method of treatment should be persevered with for three or four weeks, and the limb should be massaged daily while the constricting bandage is off.

Among the other methods which have been recommended are the injection between the fragments of oil of turpentine (Mikulicz), a quantity of the patient's own blood (Schmieden), or alcohol and iodine; the forcible rubbing of the ends together, under an anæsthetic if necessary; and the administration of thyreoid extract. If these methods fail, the case should be treated as one of un-united fracture. As a rule, satisfactory union is ultimately obtained, although much patience is required.

Non-Union.—Sometimes the fragments become united by a dense band of fibrous tissue, and the reparative process goes no further—fibrous union. This is frequently the case in fractures of the patella, the olecranon, and the narrow part of the neck of the femur.

False Joint—Pseudarthrosis.—In rare cases the ends of the fragments become rounded and are covered with a layer of cartilage. Around their ends a capsule of fibrous tissues forms, on the inner aspect of which a layer of endothelium develops and secretes a synovia-like fluid. This is met with chiefly in the humerus and in the clavicle.

Failure of Union—“Un-united Fracture.”—As the time taken for union varies widely in different bones, and ossification may ultimately ensue after being delayed for several months, a fracture cannot be said to have failed to unite until the average period has been long overpassed and still there is no evidence of fusion of the fragments. Under these conditions failure of union is a rare complication of fractures. In adults it is most frequently met with in the humerus, the radius and ulna (Fig. 6), and the femur; in children in the bones of the leg and in the forearm.

In a radiogram the bones in the vicinity of the fracture, particularly the distal fragment, cast a comparatively faint shadow, and there may even be a clear space between the fragments. When the parts are exposed by operation, the bone is found to be soft and spongy and the ends of the fragments are rarefied and atrophied; sometimes they are pointed, and occasionally absorption has taken place to such an extent that a gap exists between the fragments. The bone is easily penetrated by a bradawl, and if an attempt is made to apply plates, the screws fail to bite. These changes are most marked in the distal fragment.

The want of union is evidently due to defective activity of the bone-forming cells in the vicinity of the fracture. This may result from constitutional dyscrasia, or may be associated with a defective blood supply, as when the nutrient artery is injured. Interference with the trophic nerve supply may play a part, as cases are recorded by Bognaud in which union of fractures of the leg failed to take place after injuries of the spinal medulla causing paraplegia. The condition has been attributed to local causes, such as the interposition of muscle or other soft tissue between the fragments, or to the presence of a separated fragment of bone or of a sequestrum following suppuration. In our experience such factors are seldom present.

If the treatment recommended for delayed union fails, recourse must be had to operation, the most satisfactory procedure being to insert a bone graft in the form of an intra-medullary splint. In certain cases met with in the bones of the leg in children, the degree of atrophy of the bones is such that it has been found necessary to amputate after repeated attempts to obtain union by operative measures have failed.

In the tibia we have found that with the double electric saw a rod of bone can be rapidly and accurately cut, extending well above as well as below the site of fracture but unequally in the two directions; the rod is then reinserted into the trough from which it was taken with the ends reversed, so that a strong bridge of bone is provided at the seat of non-union.

In the first place, the history of the accident should be investigated, attention being paid to the nature of the violence—whether a blow, a twist, a wrench, or a crush, and whether the violence was directly or indirectly applied. The degree of the violence may often be judged approximately from the instrument inflicting it—whether, for example, a fist, a stick, a cart wheel, or a piece of heavy machinery. The position of the limb at the time of the injury; whether the muscles were braced to meet the blow or were lax and taken unawares; and the patient's sensations at the moment, such as his feeling something snap or tear, may all furnish information useful for purposes of diagnosis.

Signs of Fracture.—The most characteristic signs of fracture are unnatural mobility, deformity, and crepitus.

Unnatural mobility—that is, movement between two segments of a limb at a place where movement does not normally occur—may be evident when the patient makes attempts to use his limb, or may only be elicited when the fragments are seized and moved in opposite directions. Deformity, or the part being “out of drawing” in comparison with the normal side, varies with the site and direction of the break, and depends upon the degree of displacement of the fragments. Crepitus is the name applied to the peculiar grating or clicking which may be heard or felt when the fractured surfaces are brought into contact with one another.

The presence of these three signs in association is sufficient to prove the existence of a fracture, but the absence of one or more of them does not negative this diagnosis. There are certain fallacies to be guarded against. For example, a fracture may exist and yet unnatural mobility may not be present, because the bones are impacted into one another, or because the fracture is an incomplete one. Again, the extreme tension of the swollen tissues overlying the fracture may prevent the recognition of movement between the fragments. Deformity also may be absent—as, for instance, when there is no displacement of the fragments, or when only one of two parallel bones is broken, as in the leg or forearm. Similarly, crepitus may be absent when impaction exists, when the fragments completely override one another, or are separated by an interval, or when soft tissues, such as torn periosteum or muscle, are interposed between them. A sensation simulating crepitus may be felt on palpating a part into which blood has been extravasated, or which is the seat of subcutaneous emphysema. The creaking which accompanies movements in certain forms of teno-synovitis and chronic joint disease, and the rubbing of the dislocated end of a bone against the tissues amongst which it lies, may also be mistaken for the crepitus of fracture.

It is not advisable to be too diligent in eliciting these signs, because of the pain caused by the manipulations, and also because vigorous handling may do harm by undoing impaction, causing damage to soft parts or producing displacement which does not already exist, or by converting a simple into a compound fracture.

It is often necessary for purposes of diagnosis to administer a general anæsthetic, particularly in injuries of deeply placed bones and in the vicinity of joints. Before doing so, the appliances necessary for the treatment of the injury should be made ready, in order that the fracture may be reduced and set before the patient regains consciousness.

Radiography in the Diagnosis of Fractures.—While radiography is of inestimable value in the diagnosis of many fractures and other injuries, particularly in the vicinity of joints, the student is warned against relying too implicitly on the evidence it seems to afford.

A radiogram is not a photograph of the object exposed to the X-rays but merely a picture of its shadow, or rather of a series of shadows of the different structures, which vary in opacity. As the rays emanate from a single point in the vacuum tube, and as they are not, like the sun's rays, approximately parallel, the shadows they cast are necessarily distorted. Hence, in interpreting a radiogram, it is necessary to know the relative positions of the point from which the rays proceed, the object exposed, and the plate on which the shadow is registered. The least distortion takes place when the object is in contact with the plate, and the shadow of that part of the object which lies perpendicularly under the light is less distorted than that of the parts lying outside the perpendicular. The light and the plate remaining constant, the amount of distortion varies directly with the distance between the object and the plate.

To ensure accuracy in the diagnosis of fracture by the X-rays, it is necessary to take two views of the limb—one in the sagittal and the other in the coronal plane. By the use of the fluorescent screen, the best positions from which to obtain a clear impression of the fracture may be determined before the radiograms are taken. Stereoscopic radiograms may be of special value in demonstrating the details of a fracture that is otherwise doubtful.

Imperfect technique and faulty interpretation of the pictures obtained lead to certain fallacies. In young subjects, for example, epiphysial lines may be mistaken for fractures, or the ossifying centres of epiphyses for separated fragments of bone. The os trigonum tarsi has been mistaken for a fracture of the talus. In the vicinity of joints the bones may be crossed by pale bands, due to the rays traversing the cavity of the joint. In this way fracture of the olecranon or of the clavicle may be simulated. The neck of the femur may appear to be fractured if a foreshortened view is taken.

It is possible, on the other hand, to overlook a fracture—for example, if there is no displacement, or if the line of fracture is crossed by the shadow of an adjacent bone. In deeply placed bones such as those about the hip, or in bones related to dense, solid viscera—for example, ribs, sternum, or dorsal vertebræ—it is sometimes difficult to obtain conclusive evidence of fracture in a radiogram.

It is to be borne in mind also, and especially from the medico-legal point of view, that, as early callus does not cast a deep shadow in a radiogram, the appearance of fracture may persist after union has taken place. The earliest shadow of callus appears in from fourteen to twenty-one days, and can hardly be relied upon till the fourth or sixth week. The disturbed perspective produced by divergence of the rays may cause the fragments of a fracture to appear displaced, although in reality they are in good position. If the limb and the plate are not parallel, the bones may appear to be distorted, and errors in diagnosis may in this way arise. In this relation it should be mentioned that perfect apposition of the fragments and anatomically accurate restoration of the outline of the bones are not always essential to a good functional result.

As most of the remaining signs are common to all the lesions from which fractures have to be distinguished, their diagnostic value must be carefully weighed.

Interference with Function.—As a rule, a broken bone is incapable of performing its normal function as a lever or weight-bearer; but when a fracture is incomplete, when the fragments are impacted, or when only one of two parallel bones is broken, this does not necessarily follow. It is no uncommon experience to find a patient walk into hospital with an impacted fracture of the neck of the femur or a fracture of the fibula; or to be able to pronate and supinate the forearm with a greenstick fracture of the radius or a fracture of the ulna.

Pain.—Three forms of pain may be present in fractures: pain independent of movement or pressure; pain induced by movement of the limb; and pain elicited on pressure or “tenderness.” In injuries by direct violence, pain independent of movement and pressure is never diagnostic of fracture, as it may be due to bruising of soft tissues. In injuries resulting from indirect violence, however, pain localised to a spot at some distance from the point of impact is strongly suggestive of fracture—as, for example, when a patient complains of pain over the clavicle after a fall on the hand, or over the upper end of the fibula after a twist of the ankle. Pain elicited by attempts to move the damaged part, or by applying pressure over the seat of injury, is more significant of fracture. Pain elicited at a particular point on pressing the bone at a distance, “pain on distal pressure,”—for example, pain at the lower end of the fibula on pressing near its neck, or at the angle of a rib on pressing near the sternum,—is a valuable diagnostic sign of fracture. When nerve-trunks are implicated in the vicinity of a fracture, pain is often referred along the course of their distribution.

Localised swelling comes on rapidly, and is due to displacement of the fragments and to hæmorrhage from the torn vessels of the marrow and periosteum.

Discoloration accompanies the swelling, and is often widespread, especially in fracture of bones near the surface and when the tension is great. It is not uncommon to find over the ecchymosed area, especially over the shin-bone, large blebs containing blood-stained serum. In fractures of deep-seated bones, discoloration may only show on the surface after some days, and at a distance from the break.

Alterations in the relative position of bony landmarks are valuable diagnostic guides. Alteration in the length of the limb, usually in the direction of shortening, is also an important sign. Before drawing deductions, care must be taken to place both limbs in the same position and to determine accurately the fixed points for measurement, and also to ascertain if the limbs were previously normal.

Shock is seldom a prominent symptom in uncomplicated fractures, although in old and enfeebled patients it may be serious and even fatal. During the first two or three days after a fracture there is almost invariably some degree of traumatic fever, indicated by a rise of temperature to 99° or 100° F.

Complications.—Injuries to large arteries are not common in simple fractures. The popliteal artery, however, is liable to be compressed or torn across in fractures of the lower end of the femur; extravasation of blood from the ruptured artery and gangrene of the limb may result. If large veins are injured, thrombosis may occur, and be followed by pulmonary embolism.

Injuries to nerve-trunks are comparatively common, especially in fractures of the arm, where the radial (musculo-spiral) nerve is liable to suffer.

The nerve may be implicated at the time of the injury, being compressed, bruised, lacerated, or completely torn across by broken fragments, or it may be involved later by the pressure of callus. The symptoms depend upon the degree of damage sustained by the nerve, and vary from partial and temporary interference with sensation and motion to complete and permanent abrogation of function.

In rare instances fat embolism is said to occur, and fat globules are alleged to have been found in the urine. In persons addicted to excess of alcohol, delirium tremens is a not infrequent accompaniment of a fracture which confines the patient to bed.

Prognosis in Simple Fractures.—Danger to life in simple fractures depends chiefly on the occurrence of complications. In old people, a fracture of the neck of the femur usually necessitates long and continuous lying on the back, and bronchitis, hypostatic pneumonia, and bed-sores are prone to occur and endanger life. Fractures complicated with injury to internal organs, and fractures in which gangrene of the limb threatens, are, of course, of grave import.

The prognosis as regards the function of the limb should always be guarded, even in simple fractures. Incidental complications are liable to arise, delaying recovery and preventing a satisfactory result, and these not only lead to disappointment, but may even form a ground for actions for malpraxis.

The chief and most frequent cause of permanent disability after fracture is angular displacement. A comparatively small degree of angularity may lead to serious loss of function, especially in the lower limb; the joints above and below the fracture are placed at a disadvantage, arthritic changes result from the abnormal strain to which they are subjected, and rarefaction of the bone may also ensue.

Fibrous union is a common result in fractures of the neck of the femur in old people and in certain other fractures, such as fracture of the patella, of the olecranon, coronoid and coracoid processes, and although this does not necessarily involve interference with function, the patient should always be warned of the possibility.

Impairment of growth and eventual shortening of the limb may result from involvement of an epiphysial junction.

Stiffness of joints is liable to follow fractures implicating articular surfaces, or it may result from arthritic changes following upon the injury.

Osseous ankylosis is not a common sequel of simple fractures, but locking of joints from the mechanical impediment produced by the union of imperfectly reduced fragments, or from masses of callus, is not uncommon, especially in the region of the elbow.

Wasting of the muscles and œdema of the limb often delay the complete restoration of function. Delayed union, want of union, and the formation of a false joint have already been referred to.

Treatment.—The treatment of a fracture should be commenced as soon after the accident as possible, before the muscles become contracted and hold the fragments in abnormal positions, and before the blood and serum effused into the tissues undergo organisation.

Care must be taken during the transport of the patient that no further damage is done to the injured limb. To this end the part must be secured in some form of extemporised splint, the apparatus being so designed as to control not only the broken fragments, but also the joints above and below the fracture.

When the ordinary method of removing the clothes involves any risk of unduly moving the injured part, they should be slit open along the seams.

The patient should be placed on a firm straw, horse-hair, or spring mattress, stiffened in the case of fractures of the pelvis or lower limbs by fracture-boards inserted beneath the mattress. Special mattresses constructed in four pieces, to facilitate the nursing of the patient, are sometimes used.

In many cases, particularly in muscular subjects, in restless alcoholic patients, and in those who do not bear pain well, a general anæsthetic is a valuable aid to the accurate setting of a fracture, as well as a means of rendering the diagnosis more certain.

The procedure popularly known as “setting a fracture” consists in restoring the displaced parts to their normal position as nearly as possible, and is spoken of technically as the reduction of the fracture.

The Reduction of Fractures.—In some cases the displacement may be overcome by relaxing the muscles acting upon the fragments, and this may be accomplished by the stroking movements of massage. In most cases, however, it is necessary, after relaxing the muscles, to employ extension, by making forcible but steady traction on the distal fragment, while counter-extension is exerted on the proximal one, either by an assistant pulling upon that portion of the limb, or by the weight of the patient's body. The fragments having been freed, and any shortening of the limb corrected in this way, the broken ends are moulded into position—a process termed coaptation.

The reduction of a recent greenstick fracture consists in forcibly straightening the bend in the bone, and in some cases it is necessary to render the fracture complete before this can be accomplished.

In selecting a means of retaining the fragments in position after reduction, the various factors which tend to bring about re-displacement must be taken into consideration, and appropriate measures adopted to counteract each of these.

In addition to retaining the broken ends of the bone in apposition, the after-treatment of a fracture involves the taking of steps to promote the absorption of effused blood and serum, to maintain the circulation through the injured parts, and to favour the repair of damaged muscles and other soft tissues. Means must also be taken to maintain the functional activity of the muscles of the damaged area, to prevent the formation of adhesions in joints and tendon sheaths, and generally to restore the function of the injured part.

Practical Means of Effecting Retention—By Position.—It is often found that only in one particular position can the fragments be made to meet and remain in apposition—for example, the completely supine position of the forearm in fracture of the radius just above the insertion of the pronator teres. Again, in certain cases it is only by relaxing particular groups of muscles that the displacement can be undone—as, for instance, in fracture of the bones of the leg, or of the femur immediately above the condyles, where flexion of the knee, by relaxing the calf muscles, permits of reduction.

Massage and Movement in the Treatment of Fractures.—Lucas-Championnière, in 1886, first pointed out that a certain amount of movement between the ends of a fractured bone favours their union by promoting the formation of callus, and advocated the treatment of fractures by massage and movement, discarding almost entirely the use of splints and other retentive appliances. We were early convinced by the teaching of Lucas-Championnière, and have adopted his principles in fractures.

In the majority of cases the massage and movement are commenced at once, but circumstances may necessitate their being deferred for a few days. The measures adopted vary according to the seat and nature of the fracture, but in general terms it may be stated that after the fracture has been reduced, the ends of the broken bone are retained in position, and gentle massage is applied by the surgeon or by a trained masseur. The lubricant may either be a powder composed of equal parts of talc and boracic acid, or an oily substance such as olive oil or lanolin. The rubbing should never cause pain, but, on the contrary, should relieve any pain that exists, as well as the muscular spasm which is one of the most important causes of pain and of displacement in recent fractures. The parts on the proximal side of the injured area are first gently stroked upwards to empty the veins and lymphatics, and to disperse the effused blood and serum. The process is then applied to the swollen area, and gradually extended down over the seat of the fracture and into the parts beyond. In this way the circulation through the damaged segment of the limb is improved, the veins are emptied of blood, the removal of effused fluid is stimulated, and the muscular irritability allayed. The joints of the limb are gently moved, care being taken that the broken ends of the bone are not displaced. After the rubbing has been continued for from fifteen to twenty minutes, the limb is placed in a comfortable position, and retained there by pillows, sand-bags, or, if found more convenient, by a light form of splint.

The massage is repeated once each day; the sittings last from ten to fifteen minutes. The sequence should be, first, massage; second, passive movement; and third, active movement. At first massage predominates, and more passive than active movement; gradually massage is lessened and movements are increased, active movements ultimately preponderating.

Splints and other Appliances.—The appropriate splints for individual fractures and the method of applying them will be described later; but it may here be said that the general principle is that when dealing with a part where there is a single bone, as the thigh or upper arm, the splint should be applied in the form of a ferrule to surround the break; while in situations where there are two parallel bones, as in the forearm and leg, the splint should take the form of a box.

Simple wooden splints of plain deal board or yellow pine, sawn to the appropriate length and width; or Gooch's splinting, which consists of long strips of soft wood, glued to a backing of wash-leather, are the most useful materials. Gooch's splinting has the advantage that when applied with the leather side next the limb it encircles the part as a ferrule; while it remains rigid when the wooden side is turned towards the skin. Perforated sheet lead or tin, stiff wire netting, and hoop iron also form useful splints.

When it is desirable that the splint should take the shape of the part accurately, a plastic material may be employed. Perhaps the most convenient is poroplastic felt, which consists of strong felt saturated with resin. When heated before a fire or placed in boiling water, it becomes quite plastic and may be accurately moulded to any part, and on cooling it again becomes rigid. The splint should be cut from a carefully fitted paper pattern. Millboard, leather, or gutta-percha softened in hot water, and moulded to the part, may also be employed.

In conditions where treatment by massage and movement is impracticable, and where movable splints are inconvenient, splints of plaster of Paris, starch, or water-glass are sometimes used, especially in the treatment of fractures of the leg. When employed in the form of an immovable case, they are open to certain objections—for example, if applied immediately after the accident they are apt to become too tight if swelling occurs; and if applied while swelling is still present, they become slack when this subsides, so that displacement is liable to occur.

When it is desired to enclose the limb in a plaster case, coarse muslin bandages, 3 yards long, and charged with the finest quality of thoroughly dried plaster of Paris, are employed. The “acetic plaster bandages” sold in the shops set most quickly and firmly. Boracic lint or a loose stocking is applied next the skin, and the bony prominences are specially padded. The plaster bandage is then placed in cold water till air-bubbles cease to escape, by which time it is thoroughly saturated, and, after the excess of water is squeezed out, is applied in the usual way from below upward. From two to four plies of the bandage are required. In the course of half an hour the plaster should be thoroughly set. To facilitate the removal of a plaster case the limb should be immersed for a short time in tepid water.

A convenient and efficient splint is made by moulding two pieces of poroplastic felt to the sides of the limb, and fixing them in position with an elastic webbing bandage; this apparatus can be easily removed for the daily massage.

Padding is an essential adjunct to all forms of splints. The whole part enclosed in the splint must be covered with a thick layer of soft and elastic material, such as wool from which the fat has not been removed. All hollows should be filled up, and all bony projections specially protected by rings of wadding so arranged as to take the pressure off the prominent point and distribute it on the surrounding parts. Opposing skin surfaces must always be separated by a layer of wool or boracic lint. A bandage should never be applied to the limb underneath the splints and pads, as congestion or even gangrene may be induced thereby.

Operative Treatment of Simple Fractures.—Operation in simple fracture is specially called for (1) in fracture into or near a joint where a permanently displaced fragment will cause locking of the joint; (2) when fragments are drawn apart, as in fractures of the patella or olecranon; (3) when displacement, especially shortening, cannot be remedied by other means; (4) when complications are present, such as a torn nerve-trunk or a main artery; (5) when non-union is to be feared, as in certain cases of fracture of the neck of the femur in old people. Under such circumstances it is necessary to expose the fracture by operation, and to place the fragments in accurate apposition, if necessary, fixing them in position by wires, pegs, plates, or screws (Op. Surg., p. 52). Operative interference is usually delayed till about five to seven days after the injury, by which time the effect of other measures will have been estimated, accurate information obtained by means of the X-rays regarding the nature of the lesion and the position of the fragments, and the tissues recovered their normal powers of resistance. Such operations, however, are not to be undertaken lightly, as they are often difficult, and if infection takes place the results may be disastrous. Arbuthnot Lane and Lambotte advocate a more general resort to operative measures, even in simple and uncomplicated fractures, and it must be conceded that in many fractures an open operation affords the only means of securing accurate apposition and alignment of the fragments.

Both before and after operation, massage and movement are to be carried out, as in fractures treated by other methods.

The essential feature of a compound fracture is the existence of an open wound leading down to the break in the bone. The wound may vary in size from a mere puncture to an extensive tearing and bruising of all the soft parts.

A fracture may be rendered compound from without, the soft parts being damaged by the object which breaks the bone—as, for example, a cart wheel, a piece of machinery, or a bullet. Sloughing of soft parts resulting from the pressure of improperly applied splints, also, may convert a simple into a compound fracture. On the other hand, a simple fracture may be rendered compound from within—for example, a sharp fragment of bone may penetrate the skin; this is the least serious variety of compound fracture.

As a rule, it is easy to recognise that the fracture is compound, as the bone can either be seen or felt.

The prognosis depends on the success which attends the efforts to make and to keep the wound aseptic, as well as on the extent of damage to the tissues. When asepsis is secured, repair takes place as in simple fracture, only it usually takes a little longer; sometimes the reason for the delay is obvious, as when the compound fracture is the result of a more severe form of violence and where there is comminution and loss of one or more portions of bone that would have contributed to the repair. Sometimes the delay cannot be so explained; Bier suggested that it is due to the escape of blood at the wound, whereas in simple fractures the blood is retained and assists in repair.

If sepsis gains the upper hand in a compound fracture there is, firstly, the risk of infection of the marrow—osteomyelitis—which in former times was liable to result in pyæmia; in the second place, not only do loose fragments tend to die and be thrown off as sequestra, but the ends of the fragments themselves may undergo necrosis; involving as this does the dense cortical bone of the shaft, the dead bone is slow in being separated, and until it is separated and thrown off, no actual repair can take place. The sepsis stimulates the bone-forming tissues and new bone is formed in considerable amount, especially on the surface of the shaft in the vicinity of the fracture; in macerated specimens it presents a porous, crumbling texture. Sometimes the new bone—which corresponds to the involucrum of an osteomyelitis—imprisons a sequestrum and prevents its extrusion, in which case one or more sinuses may persist indefinitely. Cases are met with where such sinuses have existed for the best part of a long life and have ultimately become the seat of epithelioma.

It should be noted that all the above changes can be followed in skiagrams.

Treatment.—The leading indication is to ensure asepsis. Even in the case of a small punctured wound caused by a pointed fragment coming through the skin it is never wise to assume that the wound is not infected. It is much safer to enlarge such a wound, pare away the bruised edges, and disinfect the raw surfaces.