Title: Harper's Young People, October 26, 1880

Author: Various

Release date: June 25, 2009 [eBook #29238]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

| Vol. I.—No. 52. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, October 26, 1880. | Copyright, 1880, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

"What's your name, boy?"

The question came so suddenly that the boy nearly tumbled from the fence upon which he was perched, as Judge Barton stopped squarely in front of him, and waited for an answer.[Pg 762]

"Wilbert Fairlaw, sir," was the timid reply.

"Go to school?"

"No, sir."

"Do any work?"

"Yes, sir; I 'tend marm's cows and fetch wood."

"Well, that's something. But don't you think there's plenty to do in this part of the world that's better than kicking your heels against the fence all the morning? Now just look around, my boy, until you find something that wants fixing up, and take off your coat and go at it. You won't have to look far about here." And the Judge gave a contemptuous glance toward the widow Fairlaw's neglected farm. "Take my word for it, boy," he added, "work's a mint—work's a mint." And then he turned away, walking with dignified pace toward the Willows—the name of his place.

Now I think that most boys would have been tempted to talk back, but Wilbert only sat still and looked after the man as he walked away, and then down at his bare feet.

"It's all true. Somehow our place does look badly, but I can't 'tend to everything," he thought, "like a hired man; an' if I did try to patch things, likely I'd get a lickin' for doin' something I oughtn't. I don't see as it makes any difference whether I work or not. It's all the same about here; but, oh, I would like to have something to do for pay, so I could have a little money—ever so little—and I could feel it in my pocket, and know it was there. I wonder what the Judge meant by saying, 'Work's a mint.' I guess it is something about getting paid. How I wish I had a little money! but I would like to earn it myself."

"Here, bub, get a bucket, will you, and bring my nag some water?"

This time it was a keen-looking young man sitting in a light wagon who addressed him.

"Now stir your pegs, bub, and here's a nickel for you."

Wilbert was already on the way to the well, for he was always quite willing to do a favor, and so he didn't hear the last sentence. Then he unfastened the check-rein by standing upon a horse-block, and gave the tired animal a pail of water.

The driver meanwhile searched his pockets in vain for a nickel.

"Got any change, bub?"

"No, sir."

"Well, then, never mind; here's a quarter to start your fortune. I guess it'll do you more good than it would me," and away he drove at a lively pace up the road, and Wilbert sat down in the grass by the road-side, too happy even to whistle or dance.

So people sometimes paid for having their horses watered? Why not keep watch for teams, and have a bucket ready? There was plenty of travel over the road. Carriage-loads of excursionists went by to the "Glen"—a resort about six miles distant—almost daily, and the only place to water on the way was always made muddy by the pigs.

But people wouldn't be willing to wait while he went clear to the well every time for water, especially when there were two horses.

Behind the barn lay an unused trough, made for feeding pigs. Wilbert tied a rope around it, and hitching the one old horse his mother owned to this, dragged it to a point in the road where the shadow of a large chestnut-tree rested most of the day. Then he built a stone support about it, out of the plentiful supply of bowlders in the fields. Next the water was to be brought. It took a long time to carry enough with one pail to even half fill the trough, and then the very first farmer who drove along the road stopped his horses, and looking with some surprise at Wilbert's "improvement," let his animals drink most of the contents, and was off before Wilbert returned from the pump.

Several teams watered during the morning, and one man tossed the boy ten cents. How pleasantly his two coins jingled, to be sure!

Early the next morning Wilbert was on his way to a ravine which lay back of the big chestnut-tree. He carried a spade, and began to dig where the grass was greenest, and slime was gathered upon the stones. At a depth of two feet he saw the hole fill with water, which speedily became clear, as he sat down to rest, and soon trickled down the slope.

Then he went to that repository of all odds and ends, the shed back of the barn, and selected a number of boards left over when the fence was built; with these and some nails he made a trough to carry the water down the hill, placing them one end upon another in forked stakes, and after two days of hard work was delighted to find that his trough was easily filled with clear cool spring-water.

Upon that day he made twenty cents, and a good-natured peddler gave him a large sponge, and taught him how to rinse out the parched mouths of the horses.

He rode to town with the peddler, and bought a handsome bucket with his money, feeling sure that he would soon get it all back.

Business was now fairly under way, and many were the praises bestowed by passers-by upon his work. Some paid, and others only said "Thank you." The crusty Judge, who had a kind heart in spite of his rough ways, halted his team, and after learning from Wilbert that it was all his own work, told his driver always to stop there when passing, and said he thought he had better pay for the season in advance, and so handed the boy a dollar.

One day Wilbert sat by his trough under the chestnut, looking very thoughtful. He knew that summer would soon be over, and was thinking of the coming winter days, when his occupation would be gone. He had earned quite a nice little sum—ten dollars or more—and had formed and rejected many plans for using it to the best advantage. He became quite unhappy through his uncertain frame of mind. You see, even the possession of money is a cause of sorrow sometimes. There was one thing settled. He had determined to buy a new woollen shawl for his mother with a part of his riches.

Wilbert took his money out of his pocket, and counted it for perhaps the hundredth time. While thus engaged his attention was drawn to a cloud of dust in the road, out of which a pair of black ponies dashed at full speed. They seemed to be running away. Men were shouting to the pale-faced boy who held the reins, and who was presently thrown violently from his seat, and now lay still and senseless by the road-side. There was but a moment in which to form a resolve. Wilbert seized a loose board from the fence and held it squarely across the road, throwing it with all his strength toward the ponies. Thus attacked, they became confused, and turned to the road-side, upsetting the watering-trough, and stopped. Wilbert scrambled up out of the dust into which he had been thrown by the force of his effort, and caught the reins. Two men ran to the horses' heads, while another brought the injured boy to the spot.

"I guess we had better get him home as soon as we can," said one of the men. "He's stopping over to the Judge's, and is his nephew. Here, you, Wilbert, just git in, and hold his head up, while I manage these little scamps. Things ain't much broken, considering how the critters run."

So they drove back to the Willows. Wilbert went in with the man, secretly wondering at the beautiful rooms, the rich carpets, pictures, and easy-chairs. They surpassed anything he had ever seen or dreamed of. Then Wilbert was sent after the doctor, and made himself so handy that it was agreed he should stay and help nurse Clarence, for that was the boy's name.[Pg 763]

For six weeks the injured lad lay in bed, and Wilbert remained faithfully by him. As Clarence grew stronger, the boys became very fond of each other, though they had never met before the accident, Clarence having just arrived from Boston on a visit to his uncle.

He told Wilbert that his father was a manufacturer, and that his mother was dead. The young visitor had a great many books, some of which Wilbert found time to read while watching by the bedside. One of these was a story of the life of George Stephenson, who invented the first locomotive. This was such a favorite with Wilbert that the sick boy gave it to him.

All that he read set him to thinking. Why couldn't he too invent something, and become famous? Long after everybody else slept Wilbert lay in bed with his eyes wide open, until he had thought out a plan for hitching horses to carriages in such a manner that they couldn't run away.

The very next day he walked to the village and bought a few tools and such material as he thought his device would require, and then set about making a model.

The Judge good-naturedly laughed at his "notion," as he termed it, but allowed him to work at it all of his spare time. "Work's a mint," said he, "and such work ain't mischief, at any rate."

At last Wilbert had his model completed, save a single part, and was obliged to make another trip to the village to get the proper material. When he returned he was alarmed by the discovery that his model was gone. He ran down stairs to the study, but held back as he saw the Judge and a stranger intently examining his missing work.

"I always believe," said the Judge, "in letting boys work out their notions. It don't hurt 'em, and it teaches 'em patience."

"Of course, of course," replied the stranger. "For instance, this 'notion,' as you call it, will never do. It isn't the thing at all; but see here, Judge, examine this hub. There's a 'notion' in that worth something. I tell you what it is, any boy who can stumble on such an idea, even by accident, has got good stuff in him."

Just then the Judge caught sight of Wilbert.

"Here's the lad himself. And so," said he to the boy, with a great show of severity, "this is all that your work for two weeks has brought out. Mr. Congdon here, Clarence's father, says your invention ain't worth anything. What do you say to that? Your work ain't much of a mine, after all, is it?"

Wilbert felt very much like choking with vexation and grief. He couldn't bear to have fun made of his model, especially before a stranger, but he wisely remained silent.

"So your name is Wilbert?" inquired Mr. Congdon. "Well, now, Wilbert, I want you to let me take this toy of yours home with me. I have come after Clarence. We leave this evening for Boston. Trust me with it, and you won't regret doing so."

So Mr. Congdon left with Wilbert's companion and his "notion," after which the boy seemed lost for a few days. He went back to the old farm, and handed his mother the wages the Judge had paid him, and an order for a new suit of clothes kindly added by Mrs. Barton.

Toward the close of the year he sat one night, reading, as usual, by candle-light, and oddly enough it happened to be Christmas-eve, when a rap came at the door, and Judge Barton entered. He held in his hand an important-looking envelope, which he reached toward Wilbert, saying, "Here's a Christmas gift for you, boy. Work's a mint—work's a mint. Yes, indeed, it's better than a gold mine, for it brings its reward already coined."

Now, you see, Wilbert had never had but one letter before in his life, and that was a little boyish scrawl from Clarence, and no wonder he opened the big envelope timidly. The contents began, "Know all men by these presents," and here Wilbert looked again into the envelope to see where the presents it spoke of were hidden.

The Judge explained that this was a paper from the United States Patent-office, granting a patent to Wilbert Fairlaw for an improved carriage hub.

"Now," said the Judge, "that patent was secured for you by Mr. Congdon, who got the hint for the hub from that 'notion' of yours. It will sell for considerable money, but I advise you to hold it. I think, Mrs. Fairlaw"—turning to the widow—"that you had better let your boy go to school for a couple of years. I'll see that the royalty on the manufacture of this hub will pay for his keeping; and when he is old enough, he can do as he thinks best about the patent."

Ten Christmas-eves have come and gone since that visit by the Judge, and many changes have occurred. The old house has been partly rebuilt, and Mrs. Fairlaw still lives there. The Judge, too, is living, and comes down frequently to see the "firm" and the new factory, which stands close by the ravine and the big chestnut-tree. The name of the firm and its purpose is seen upon the large sign:

When the Judge came over upon his first visit to the works after business was started, he was conducted to the long work-room, full of whizzing machinery, by Wilbert and Clarence, and shown, greatly to his delight, his favorite motto, which was painted across the wall:

A NUTTING PARTY—BUMPING THE HICKORY-TREE.

A NUTTING PARTY—BUMPING THE HICKORY-TREE.

Posy and Bob Parker, of Baltimore, went to visit their cousins in England. Posy, who was a little girl, was surprised to see the customs and observances supposed to belong in England to different days. On Michaelmas-day (September 29), for instance, her uncle's family all dined upon roast goose, because Queen Elizabeth, having received at dinner news of the defeat of the Armada on that day, stuck her royal knife into the breast of a fat goose before her, and declared that thenceforward no Englishman should have good luck who did not eat goose upon St. Michael's Day.

When All-hallow Eve came (October 31) the children and their cousins were invited to a beautiful old country place five miles across the Yorkshire moors to keep Halloween.

"But what is Halloween kept for, anyway, uncle?" said little Posy, as they rode over the moors that evening.

"'Really and truly,' Posy, as you would say, the night of October 31 is the vigil of All-saints' Day, one of the four high festivals in the Roman Catholic Church, and a day on which all Christians who hold to ancient forms commemorate the noble doings of the holy dead. But the All-hallow's frolics you will see this evening have nothing whatever to do with Christianity. They are relics of old paganism, of the days when 'millions of spiritual creatures' were supposed to be allowed that night 'to walk the earth'—ghosts, fairy folk, witches, gnomes, and brownies, all creatures of the fancy whose home is fairy-land."

"What is the proper thing to eat on Halloween, uncle?" said Posy.

"To eat, little Posy?"

"Yes, uncle. Every great occasion in England seems to me to have something proper to eat on that day."

"Oh, now I understand you. Apples and nuts, Posy. A vigil was always a fast in the olden time, so those who kept Halloween could have no substantial dainties for their supper."[Pg 764]

"Nurse Birkenshaw used to call it Nut-crack Day," cried Posy's eldest cousin. "But here we are!"

They were ushered into a low long room on the ground-floor, paved with flag-stones, having an immense hearth at one end. Inside the chimney, and on each side of the blazing fire built of logs and turf, were two oak benches, so that six guests could literally sit in the chimney-corner. This recess was made beautiful by blue and white Dutch tiles.

About thirty people soon assembled. From the ceiling hung a stick about two feet long, and five feet from the floor. On one end of this stick was stuck an apple, to the other hung a small bag stuffed loosely with white sand. On one side of the room were three great washing tubs filled with water. Three crocks stood on a side table, and baskets filled with apples, walnuts, chestnuts, and fresh filberts were placed about the room.

The performance began by reading "Tam o' Shanter," accompanied by illustrations, made by a magic lantern. When this was over, and lights were again brought into the room, the tubs of water were drawn forward. Twelve apples were set floating in each tub. Three little boys had their arms pinioned, and water-proof capes were put over their clothes. Then each one was led up to a tub, and told to name one of the girls present; if he could catch an apple in his teeth, she would be his next year's valentine. Fun, splashing, and laughter followed for five minutes; then time was up, and three more boys took their turn. After many such trials Posy's big cousin (an old hand, with a big mouth) brought up a little apple, another fellow caught an apple by its stalk, and Bob (good at a dive), after plunging his face to the bottom of the tub, and holding his apple steady between his nose and chin, rose with it in his teeth, triumphant but dripping.

After this had gone on for some time with varying success, the wet boys were sent off to change their clothes, and the girls' turn came. Many more apples were put into the tubs, and each girl in turn was told to hold a fork as high as she could in her right hand over the tub, and drop it on the apples. If she could spear one, she might choose her valentine. The boys joined in this also, but hardly so many apples were speared as had been caught in the boys' teeth, and the victors in the tub fishery set up a shout of triumph.

Next boys and girls had their hands tied behind them, and took turns to run up to the apple on the stick suspended by a string. This string had been twisted by the master of the revels, and the stick turned round rapidly. The fun was to jump up, and with their teeth to seize the apple. If they missed (which, of course, they did nearly every time), the bag of sand swung round and hit them on the face, to the amusement of the company.

Meantime there were many nuts roasting on the hearth, each named for a boy or girl. If one bearing a boy's name swelled up and popped away, his lady-love would lose him; if it flared up and blazed, he was thinking about her tenderly. If two nuts named for two lovers blazed at once, they would soon be a happy couple.

Some of the older boys and girls of the party were then blindfolded, and hand in hand were conducted to the gate of the walled kitchen-garden, where they were told to find their way into the cabbage patch, where each was to pull up a cabbage stump. When they returned with their prizes to the house, great fun and much dirt were the result. Posy's eldest cousin had brought in a big crooked cabbage stalk, with plenty of mould hanging to its roots: he was to marry a tall, stout, misshapen wife with a large fortune. Miss Clara, the young lady of the house, brought in a tall and slender stalk, with little soil adhering to it; so by-and-by, as some one said, she would marry a tall, straight, penniless bridegroom.

Then the table with the three crocks was brought into the middle of the room. Into one crock was poured fresh water, into another soapy water, and the third was empty. Posy, among the rest, was blindfolded, and led up to the table. She was instructed to dip her fingers into one of[Pg 765] the crocks. She felt around, and at last dipped into the one that held the soapy water: she was told that she would marry a widower. Miss Clara dipped into clear water, and would marry a bachelor. One of the other girls put her fingers into the empty crock, and would die an old maid.

By this time it was nearly midnight—time for the fairy folk as well as children to be in bed. But Miss Clara first went up stairs to an empty room, and holding a candle in one hand, ate an apple before the looking-glass. Captain Strickland (slender and tall) crept softly up stairs after her, and as she ate her last mouthful, she saw his face over her shoulder. She dropped her candle, with a scream, and they came quietly down after a while in the dark together.

Miss Clara's elder sister had meantime gone out into the flower garden, taking with her a ball of blue yarn. This she flung from her as far as possible, keeping hold, however, of one end, and dragging it after her. As she went back to the house she sang,

"Who holds my thread? who holds my clew?

For he loves me, and I him, too."

Suddenly the ball of yarn refused to follow her. She jerked at it in vain. She dared not let her clew break, because if she should lose the lover supposed to be holding its other end, she would die unmarried. "Let me see you! let me see you!" she cried, eagerly, and a figure drew near her in the darkness. An arm covered with dark cloth was almost round her. She drew away with a scream, and began to run, pursued by Bob, the young American, who had stolen away from the other guests to follow her, and whose appearance produced much laughter; for Bob was twelve, and she was seven-and-twenty.

The children had not cared much for these last two tests. They had been popping nuts and eating apples. They were now called to supper. There was at the end of a long table a great tureen of soured oatmeal porridge. The master of the house, who was of Scotch descent, called it "sowens," and declared that every one present must eat some with butter and salt if he desired to have luck till next All-hallow Eve. There were other good things on the table, however, much better, Posy thought, than sour porridge. And when supper was over the children went off to bed, solemnly assured by their elders that the fairy folk—the witches, ghosts, and so on—had already gone to their beds under the earth, not being permitted, even on such a night as Halloween, to sit up any longer.

When Benny Mallow went to bed at night, after the great exhibition, he suddenly remembered that he had forgotten to ask what the grand total of the receipts for the Beantassel family had been. Under ordinary circumstances he would have got out of bed, dressed himself, and scoured the town for full information before he slept. On this particular night, however, he did not give the subject more than a moment of thought, for his mind was full of greater things. Paul Grayson an Indian?[Pg 766] Why, of course: how had he been so stupid as not to think of it before? Paul was only dark, while Indians were red, but then it was easy enough for him to have been a half-breed; Paul was very straight, as Indians always were in books; Paul was a splendid shot with a rifle, as all Indians are; Paul had no parents—well, the tableau made by Paul's own friend Mr. Morton, who knew all about him, explained plainly enough how Indian boys came to be without fathers and mothers.

Even going to sleep did not rid Benny of these thoughts. He saw Paul in all sorts of places all through the night, and always as an Indian. At one time he was on a wild horse, galloping madly at a wilder buffalo; then he was practicing with bow and arrow at a genuine archery target; then he stood in the opening of a tent made of skins; then he lay in the tall grass, rifle in hand, awaiting some deer that were slowly moving toward him. He even saw Paul tomahawk and scalp a white boy of his own size, and although the face of the victim was that of Joe Appleby, the hair somehow was long enough to tie around the belt which Paul, like all Indians in picture-books, wore for the express purpose of providing properly for the scalps he took.

So fully did Benny's dreams take possession of him, that although he had been awake for two hours the next morning before he met Paul, he was rather startled and considerably disappointed to find his friend in ordinary dress, without a sign of belt, scalp, or tomahawk about him. Still, of course Paul was an Indian, and Benny promptly determined that no one should beat him in getting information about the young man's earlier life; so Benny opened conversation abruptly by asking, "Where do you begin to cut when you want to take a man's scalp off?"

"Why, who are you going to scalp, little fellow?" asked Paul.

"Oh, nobody," said Benny, in confusion. "I'd like to know, that's all."

"I'm afraid you'll have to ask some one else, then," said Paul, with a laugh. "Try me on something easier."

"Then how do you ride a wild horse without saddle or bridle?" asked Benny.

"Worse and worse," said Paul. "See here, Benny, have you been reading dime novels, and made up your mind to go West?"

"Not exactly," said Benny; "but," he continued, "I wouldn't mind going West if I had some good safe fellow to go with—some one who has been there and knows all about it."

"Well, I know enough about it to tell you to stay at home," said Paul.

This was proof enough, thought Benny; so although he was aching to ask Paul many other questions about Indian life, he hurried off to assure the other boys that it was all right—that Paul was an Indian, and no mistake. The consequence was that when Paul approached the school-house half of the boys advanced slowly to meet him, and then they clustered about him, and he became conscious of being looked at even more intently than on the day of his first appearance. He did not seem at all pleased by the attention; he looked rather angry, and then turned pale; finally he hurried up stairs into the school-room and whispered something to the teacher, at which Mr. Morton shook his head and patted Paul on the shoulder, after which the boy regained his ease and took his seat.

But at recess he again found himself the centre of a crowd, no member of which seemed to care to begin any sort of game. Paul stopped short, looked around him, frowned, and asked, "Boys, what is the matter with me?"

"Nothing," replied Will Palmer.

"Then what are you all crowding around me for?"

No one answered for a moment, but finally Sam Wardwell said, "We want you to tell us stories."

"Stories about Indians," explained Ned Johnston.

Paul laughed. "You're welcome to all I know," said he; "but I don't think they're very interesting. Really, I can't remember a single one that's worth telling."

This was very discouraging; but Canning Forbes, who was so smart that, although he was only fourteen years of age, he was studying mental philosophy, whispered to Will Palmer that people never saw anything interesting about their own daily lives.

"You can tell us something about birch canoes, can't you?" asked Ned Johnston, by way of encouragement.

"Oh yes," Paul replied; "they're made out of bark, with hoops and strips of wood inside, to give them shape and make them strong."

"How do they fasten up the ends?" asked Ned.

"They first sew or tie them together with strings, and then they put pitch over the seams to make them water-tight."

"Did you ever see the Indians race in birch canoes?" asked Sam.

"Oh yes, often," Paul replied; "and they make fast time too, I can tell you."

"Did you ever race yourself?" asked Benny.

"No," said Paul, "but I learned to paddle a canoe pretty well. I'd rather have a good row-boat, though, than any birch I ever saw. If you run one of them on a sharp stone, it may be cut open, unless it's pretty new."

"How do the Indians kill buffaloes?" asked Will Palmer.

"Why, just as white men do—they shoot them with rifles. Nearly all the Indians have rifles nowadays."

This was very unromantic, most of the boys thought, for an Indian without bows and arrows could not be very different from a white man. Still, something wonderful would undoubtedly come before Paul was done talking.

"Are buffaloes really so terrible-looking as the story-papers say?" asked Bert Sharp.

"Well, they don't look exactly like pets," said Paul. "A bull buffalo, in the winter season, when he has a full coat of hair, looks fiercer than a lion."

"Do the Indians really kill or torture all the white people they catch?" asked Canning Forbes.

"I don't know; I suppose so, but perhaps they're not all as bad as some white people say."

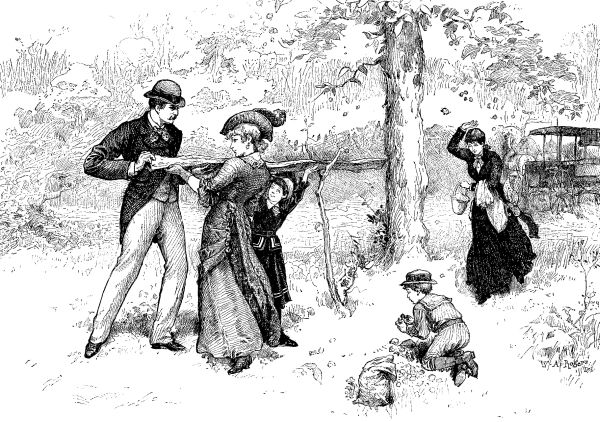

"YOU'RE A CHIEF'S SON, AREN'T YOU?"

"YOU'RE A CHIEF'S SON, AREN'T YOU?"

Canning shook his head encouragingly at Will Palmer: evidently this young Indian had a manly spirit, and was not going to have his people abused. There was a moment or two of silence, each boy wondering what next to ask. Finally, Napoleon Nott said,

"You're a chief's son, aren't you?"

"What?" exclaimed Paul, so sharply that Notty dodged behind Will Palmer, and put his hand to his head as if to protect his scalp.

"I meant," said Notty, tremblingly— "I meant to ask what tribe you belonged to."

"I? What tribe? Notty, what are you talking about?"

Notty did not answer, so Paul looked around at the other boys, but they also were silent.

"Notty," said Paul, "what on earth are you thinking about? Do you imagine I'm an Indian?"

"I thought you were," said Notty, very meekly; "and," he continued, "so did all the other boys."

"Well, that's good," said Paul, laughing heartily. "What made you think so, fellows?"

"Benny told us," explained Ned.

"Benny?" exclaimed Paul. "What put that fancy into your head?"

"I—I dreamed it," said Benny, almost ready to cry for shame and disappointment.

"And you told all the other boys?"

"Yes, I believed it; I really did, or I never would have said it."

Then Paul laughed again—a long, hearty laugh it was,[Pg 767] but no one helped him. Most of the boys felt as if in some way Paul had cheated them. As for Ned Johnston, he evidently did not believe Paul, for he began to ask questions.

"If you're not an Indian, how do you know so much about a birch canoe?"

"Why, I've seen dozens of them in Maine, where I used to live; the Indians make them there."

"Wild Indians?" asked Ned, and all the boys listened eagerly for the answer.

"No," said Paul, contemptuously; "they're the tamest kind of tame ones."

This was dreadful, yet Ned thought he would try once more. "How did you come to know so much about buffaloes?" he asked.

"I saw two in Central Park, in New York," Paul replied. "Oh, boys! boys! you're dreadfully sold."

"Say, Paul," said Benny, edging to the front, and looking appealingly at his friend, "you've been away out West anyhow, haven't you?—because you told me you knew about it." Benny awaited the answer with fear and trembling, for he felt he never would hear the end of the affair if he did not get some help from Paul.

"No, I've never been farther West than Laketon," was the disheartening reply. "All I know of the West I've learned from books and newspapers."

"Dear me!" sighed Benny; and for the first time in his life he wished the bell would ring, and give him an excuse to get away. Within a moment his wish was gratified, and he scampered up stairs very briskly, but not before Bert Sharp had caught up with him, and called him "Smarty," and asked him if he hadn't some more dreams that he could go about telling as truth. Poor Benny's only consolation, as he took his seat, was that Notty had been the first to suggest the Indian theory, and he ought therefore to bear a part of whatever abuse might come of the mistake.

At any rate he had learned that Paul had been in Maine and New York; certainly that was more than he had known an hour before.

Boys and girls now travel so much and so far that no doubt a great number of "Harper's Young People" will have an opportunity to see these fine little fellows, perhaps some pleasant day next summer. Mr. Morris has drawn them just as they are leaving their school for their weekly parade.

This school is in Chelsea, England, and is for the support and education of seven hundred boys and three hundred girls, whose fathers have either been killed in battle or died on foreign stations, or whose mothers have died while their fathers were on duty in foreign lands. The school is a fine building of brick and stone, and the front entrance, out of which you see the boys filing, has a spacious stone portico, supported by four noble pillars of the Doric order, the frieze bearing the following inscription: "The Royal Military Asylum for the Children of Soldiers of the Regular Army."

The Asylum is inclosed by high walls, except before the great front, where there is an iron railing. The grounds connected with this part are beautifully laid out in flower and grass plats, and shaded with fine trees. Attached to each wing are spacious play-grounds, as well as a number of covered arcades. In the latter the children play when the weather is too wet or cold for open-air exercise.

All the domestic affairs are regulated by Commissioners appointed by the Queen's sign-manual, and the officials consist of a commandant, adjutant, and secretary, chaplain, quartermaster, surgeon, matron, and various other persons; for everything about the school is conducted according to military discipline.

The boys are taught reading, writing, and arithmetic, and after they are eleven years of age they are employed on alternate days in works of industry. Five hours daily in summer and four in winter is the time required of them, and in this short period they make every article of clothing they require for their own use. About one hundred boys work as tailors, fifty each day alternately; about one hundred are employed in a similar manner as shoe-makers, capmakers, and coverers and repairers of the school's books. Besides, there are two sets or companies of knitters and of shirtmakers, and others who are engaged as porters, gardeners, etc. Everything is done by those who work at the trades, except the cutting out. This branch, requiring experience, is managed by old regimental shoe-makers, tailors, etc., who, with aged sergeants and corporals and their wives, manage the affairs of the institution.

The school also furnishes its own drum and fife corps and a very fine military band, the players, of course, devoting a proper proportion of their time to the practice on their instruments. Friday is the best day on which to visit the school, for on that day the entire force is turned out for a dress parade. The boys are then dressed in full uniform—red jackets, blue trousers, and little black caps—and with their flags flying, drums beating, and band playing, they march to the parade-ground, where they give a fine exhibition drill. After the parade they are trained in various difficult and skillful gymnastic exercises.

There is no compulsion on any boy to join the army; but when any regiment is in want of recruits, a notice is placed in the school-rooms, and any boys above fourteen years of age who wish to go into the army are allowed to join that regiment. For those who prefer trades or other occupations situations are provided, and if at the end of a certain number of years they can produce certificates of good conduct from those who employ them, they are publicly rewarded in the chapel of the institution.

The girls, in addition to the usual branches of a good common-school education, are taught needle-work of all kinds, and fitted for lady's-maids, dressmakers, cooks, and the various higher positions of household services. Their dress is uniform, and consists of blue petticoats, red gowns, and straw hats.

The school is supported by an annual grant from Parliament, and by the gift of one day's pay in every year from the whole army.

The awful fact is beyond a doubt,

The cage was open, and Dick flew out.

"What shall I do?" cries Pet, half wild,

And Nurse Deb says, "Why, bress you, child,

I knows a plan dat'll nebber fail:

Jes put some salt on yer birdie's tail."

"Why, you silly old nurse, 'twould never do;

That plan is worthy a goose like you.

What! salt for birds. No, sugar, I say;

I'll coax him back to me right away."

But wicked Dick, with his round black eyes,

He wouldn't be caught in this gentle wise.

Mamma comes in, and she sees the plight;

It will take her wits to set it right:

That big bandana on Deb's black head,

Ere Dick can jump, 'tis over him spread;

Then two soft hands they hold him fast:

The bright little rogue is caught at last.

As into his cage the truant goes

Pet says, "Now, nurse, I do suppose

That salt and sugar, though two nice things,

Are not a match for a birdie's wings;

And, Deb, I think we must just allow,

When a thing's to be done, mamma knows how."

[Pg 768]

!["SONS OF THE BRAVE."—From a Painting by P. R. Morris, A.R.A.—[See Page 767.]](images/ill_005.jpg) "SONS OF THE BRAVE."—From a Painting by P. R. Morris, A.R.A.—[See Page 767.]

"SONS OF THE BRAVE."—From a Painting by P. R. Morris, A.R.A.—[See Page 767.]

"There, boys, that's the pumpkin."

"That'll do, Phil; but what'll your father say? Doesn't he mean to take that pumpkin to town?"

"Well, no, I guess not. Anyhow, he said I might have it."

"Did you tell him what it's for?"

"Of course I did. Only I guess he guessed near enough that I didn't mean to make any pies."

"What did he say, Phil?"

"Why, he laughed right out—it's easy to get him laughing—and he said if we could invent anything ugly enough to scare the Sewing Society, we might have a cart-load of pumpkins, if we'd see that they were pitched into the big feed kettle after we got done with them, so they could be boiled for the cows."

"Isn't that a whopper, though! Biggest pumpkin I ever saw. Let's go right at it."

Clint Burgess had his knife out, and was opening the big blade, but Prop Corning stopped him.

"Hold on, Clint. Let's practice on some of the little ones first. Besides, we don't want to carry the big one too far after it's done. We might drop it and break it."

"That's so," said Clint. "I say, Phil, where'll we go?"

"Up behind the corn-crib—close to the barn; best place in the world to hide 'em till we want 'em. The Sewing Society don't half get here till pretty near tea-time."

"We'll show 'em something."

"Teach the girls, too, not to laugh at fellows of our age."

"It's too bad. When a man gets to be thirteen, it's time they let him come in to tea."

That was where the rules of the Plumville Sewing Society were pinching the self-esteem of Phil Merritt and his two friends, and Phil's father and his uncle and his two grown-up brothers had gravely expressed their entire sympathy, even to the extent of furnishing unlimited pumpkins.

That was a large pumpkin. It had grown by itself in a corner of the corn field, where it had plenty of room, and, as Clint Burgess remarked when they were rolling it in behind the corn-crib, "it had just sat still and swelled."

Prop Corning was the best hand any of them knew of with a jackknife, and he knew all about jack-o'-lanterns; but they all had learned more by the time they had worked up four of the smaller pumpkins.

"They look more like big apples alongside that other."

"That's the King Pumpkin."

"That's it," shouted Prop. "We'll make the King Jack-o'-lantern. I'll show you! Phil, you run to the house for a big iron spoon."

"To scoop with? I know. The rind'll be awful thick."

So they found it; and the outer shell was so hard that Phil went to the tool-room after one of his father's small key saws and a gimlet.

"Now we won't break our knives, nor the shell either."

"Nor cut our fingers. But we must keep every piece of shell we cut out," said Prop. "I've got a big idea in my head."

"Big as that pumpkin?"

"Big as the whole Sewing Society. We want a piece out of the top first, about six inches square."

The top piece came out nicely, and it was a wonder what a mass of seeds and pulp was pulled out after it.

Then the spoon was plied till the boys all had a turn at getting tired of scraping, and then Prop Corning went to work with the little saw.

"I'll just cut through the rind," he said, "and we won't make a hole anywhere. We'll cut the pieces out so they'll all stick in again, and then we'll scoop the places thin from the inside—thin as we want 'em, and no thinner. When we come to light it up out here after dark, and try it, we can scrape any spots thinner if they need it."

"That's the way. You never know just how a jack-o'-lantern's going to look till after you've got a candle in it," said Clint Burgess, very seriously. "We must make this one so it would scare a cow if she'd been eating pumpkins all day."

"There," remarked Prop, "that round spot down there'll stand for his chin. Now for his mouth. We must make it turn up at the corners, and have teeth like a mill saw."

That was the hardest kind of a thing to do, and do it right; but Prop was a patient worker, and there was nothing to be said against such a mouth as he sawed for that pumpkin.

"He mustn't have too much nose. Two round holes at the bottom: they're his smellers. Then a long slit away up to above his eyes; that's the bridge of his nose, and they'll have to imagine the rest of it."

"Can we give him any cheeks?" asked Phil, doubtfully.

"Yes, but there mustn't too much light come through 'em. It's to be a Goblin King, and they always have most fire coming out of their mouths and eyes."

Clint and Phil both admitted that Prop was right about that, but they ventured to suggest, "He won't be a King worth a cent if we don't give him some kind of a crown."

"Crown? You wait and see. His teeth won't be anything to the crown we'll put on him. But I mustn't lose a square inch of the rind. He must have ears too—a half-moon on each side—and you can let any amount of blaze shine out there."

It was a long job of sculptor work; but when it was done the three boys could hardly take their eyes away from it. Not until Prop had carefully fitted back to their places all the pieces of rind he had sawed out.

There was nothing to be done after that but for Prop and Clint to go home and attend to their "chores," and for Phil to go after his cows; but the Sewing Society had an experience before it that evening.

It was just as Phil Merritt said it would be about their coming together, and his mother had never before seen him so cheerful and willing about doing all he could, and about not going in to tea with the rest. His father noticed it too, and he whispered to him, once, "Phil, did you take the pumpkin?"

"Don't let 'em know a word about it, father," said Phil, anxiously. "You'll see, by-and-by."

"All right, Phil. I'll wait."

He had to wait until about nine o'clock, and some of the ladies were almost ready to go home, when suddenly there was a great noise out by the front gate.

"What's that?"

"Dear me!"

"Something's happened!"

Whoever made that sound must have been dreadfully unhappy about something; they all felt sure of that—and there was a grand rush to the front door and the windows.

"Sakes alive!"

"What can it be?"

"Mrs. Merritt, there's somethin' awful a-stickin' on the top of one o' your gate posts."

So there was, indeed. Something very large and round, and that looked very dark in spite of strange, mysterious rays of light that crept out of it here and there.

The whole gate post looked like a wooden man without any arms, but with more head than would have answered for half a dozen such men.

Nobody in the house heard Prop Corning whisper at that moment across the front-door walk, "Keep down, Clint, keep under the bushes. We're all ready. Pull[Pg 771] out his chin." And then he added, in a lower whisper, "Ain't I glad I brought along my kite-string?—we've used it 'most all up, but we can show 'em that King."

One of the ladies, a second later, gave a little scream, and exclaimed, "Look at it now!—it's on fire."

"Dear me!" added another, "it's got a mouth."

"And a nose."

"And a cheek."

"Oh, Deacon Merritt, eyes too."

There was a subdued chuckle down there among the lilac-bushes, as if somebody were listening to all that was said by the growing crowd on the front-door step, and another whisper went across the walk: "Clint, give him his right ear. The left sticks. I'm afraid I'll pull him off the post."

"There it is."

"Here comes mine too. Now for his crown. Jerk your half."

"Oh!" "Oh!" "Oh!" More than a dozen ladies of all ages said "Oh!" in the same breath, and Deacon Merritt himself exclaimed:

"Capital! capital! The boys have done it. It's by all odds the best jack-o'-lantern I ever saw in my life. It's a King Jack-o'-lantern."

There is lying beside me on the table as I write a sampler, worked in pink, green, blue, and dull purple-red silks, on which I read these wise sentences, "Order is the first law of Nature and of Nature's God," "The moon, stars, and tides vary not a moment," and "The sun knoweth the hour of its going down." Below, inclosed in a wreath of tambour-work,[1] are two words, "Appreciate Time." Under the first four alphabets (there are five in all) comes the date, "September 19, 1823," and in the lower corner another date, "October 24," when the square was completed, with the name of the child who wrought it, long since grown to womanhood, and now nearly forty years dead, but there recorded, in pink silk cross stitch, as "aged eight years."

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

And these dainty stitches, set so exactly, assure me that the little girls for whom I write are not too young to embroider neatly. Will you let its two mottoes remind you that a few moments carefully used each day will make you as good needle-women as your grandmothers were, and that your work-boxes or baskets should be in such order that you can find your thimbles in the dark, and can tell each several shade of wool by lamp-light? But I leave you to apply the mottoes for yourselves.

If you are to begin work with me, will you buy a few crewel-needles, No. 5 or 6, and two or three shades of crewel of any given color, such as old blue, dull mahogany, or pomegranate reds, or old gold shading into gold browns? These are colors that will always be useful.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

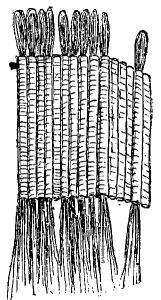

First, your wools must be prepared so they can be used in making tidies, or anything that must be washed. The best crewels are not twisted, and will wash; still, as you are never sure of getting the best, it is well to unwind your skeins, pour scalding water on the wools, and rinse them well in it, squeeze out the water, shake the wools thoroughly, and hang them up. When dry, cut the skein across where it is tied double, and with a bodkin and string, or with a long hair-pin, draw the crewel into its case. This case (see Fig. 1) is made by folding together a long piece of thin cotton cloth a foot wide, and running parallel lines across its width half an inch or so apart. When the wools are drawn in in groups—reds, blues, greens, yellows, each by themselves, carefully arranged as to shades—cut the upper end so you need not be tempted to use too long needlefuls, and there your wools are neatly put away, and soon you can distinguish any shade by its position in the case, no matter how deceptive the lamp-light may be. Still, you will not need your case till you have a dozen different colors. If you buy your wools at first by the dozen, which is the cheaper way, be sure that your pinks, blues, greens, etc., have, so far as may be, a yellowish tone. Remember that yellow is the color of sunlight, and that without it your work will look cold and lifeless; and always avoid vivid greens and reds.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

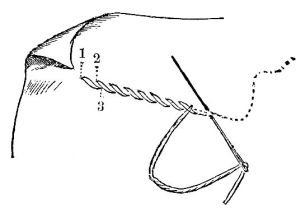

First learn the stem stitch, and you can practice on any bit of coarse linen or crash. Draw a line with a pencil (see dotted line Fig. 2); then put your needle in at the back, bringing it out at 1; then put it in at 2, taking up on the needle the threads of cloth from 2 to 3, so making a stitch that is long on the upper but short on the under side of your cloth. The needle points toward you, but your work runs from you, and you put in the needle to the right of your thread. When you wish a wide stem, slant your stitches across the line; if it must be narrow, take up the threads exactly on the line, or you can make two or more rows of stem stitch where you wish the line broadened.

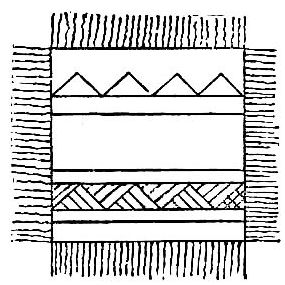

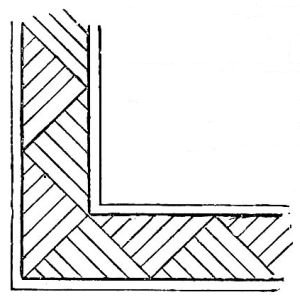

Stem stitch can be used by beginners in many ways. Squares of duck, fringed out on the edges, and overcast or hem-stitched, can have simple borders or stripes of any desired width worked in this stitch (see Fig. 3). You can draw the lines yourself with a pencil and ruler; those lines which slant in one direction may be worked in one shade, those slanting in the opposite direction in another shade. The heavier lines can be worked with double crewel, and these squares make very pretty tidies to protect the arms of chairs. Figs. 4, 5, and 6 are set patterns that can be used for borders upon doylies, towels, or table-covers. They should be worked with crewels, outlining crewels—exceedingly fine wools—or fine silks, according to the quality of the linen or other stuffs used. Stem stitch is the foundation of good modern embroidery, and we must not go on with the building until this foundation is laid.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

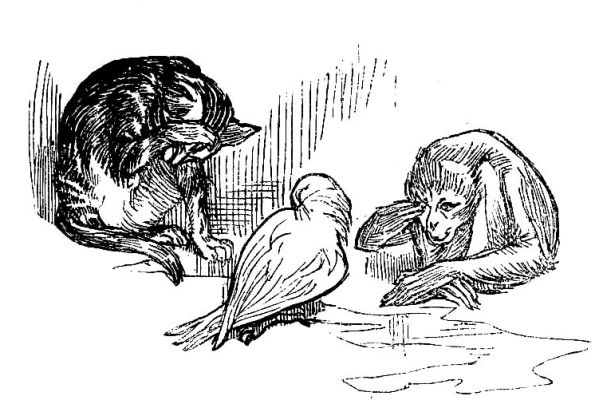

A pussy cat, a parrot, and a monkey once lived together in a funny little red house, with one great round window like a big eye set in the front. And they were a very happy family as long as they had an old woman to cook their dinner and mend their clothes. But one sad day the old woman was taken ill and died, and then the cat, the parrot, and the monkey were left to take care of themselves and the red house, and very little they knew about it.

"Who will cook the porridge now?" asked the cat.

"And who will make the beds?" asked the parrot.

"And who will sweep the floor?" asked the monkey.

But none could answer, and they thought and thought a long time, but could come to no decision, until at last the parrot nodded his head wisely, and said, "We must learn to do them ourselves."

"But who will teach us?" asked Miss Pussy.

"I know," said the monkey. "We will go to town, and watch how the men and women cook their meals and take care of their homes, and then we will be able to do the same."

"So we will," said the other two, and all three immediately put on their scarlet cloaks and blue sun-bonnets, and set off for the town, but they were in such haste that they forgot to lock the door.

They had not been gone long when a ragged little girl, with bare feet and sunburned face, came up the dusty road, and she was very tired and very hungry. Her real name nobody knew, not even herself, but she was always called Filbert, because her hair, eyes, and skin were all as brown as a nut.

"Oh dear! oh dear!" sighed Filbert, as she dragged her weary feet along, "I wish I had a fairy godmother, like the girl in the fairy book, for then I could wear silk dresses every day, and ride in a golden coach."

Just then she spied the funny little house, and thought, "Well, as I am not so lucky as to have a rich godmother, I will go in here and ask for a drink of milk, and rest awhile on the door-step."

So she went up to the door and knocked, but nobody came. Again rap-tap-tap; still nobody; and at last she lifted the latch and walked in.

"Oh, what a cunning little place!" cried Filbert, "and nobody home: so I will help myself."

In the closet she found meal and milk, which she boiled over the fire, and ate with a great relish. Then she went all over the house, exploring the nooks and corners of every room, and wondering what had become of the people who lived there.

She also thought it very queer that in so pretty a house, where almost everything was neat and well kept, the floors should be dirty and the beds not yet made up.

At last the little girl, who had walked far along the dusty road in the hot sun that morning, found herself growing very tired and sleepy, and as the tumbled beds did not look very inviting, she went down stairs and took a nap in a large rocking-chair that had belonged to the old woman. When she was quite rested, she helped herself to a needle and thread out of the work-basket, and went to work to mend her dress, which was badly torn. Just as she had sewed up the last rent she heard steps outside, and glancing out of the round window, saw the pussy cat, the parrot, and the monkey coming in at the gate.

Frightened nearly out of her wits at sight of the queer trio, Filbert jumped up, and ran and hid behind the curtain.

In came the three, as gay as could be, chattering and laughing.

"For I have learned to cook porridge," said the cat.

"And I have learned to make beds," said the parrot.

"And I have learned to sweep the floor," said the monkey.

"Then do let us hurry," cried all three, "for we are hungry and sleepy, and the house is very, very dusty."

The cat set to work first, mixed the meal and milk, and[Pg 773] set it over the fire to boil; and it smelled so good they all felt hungrier than ever; but when they came to taste the porridge they found it was burned, and pussy had forgotten the salt.

"Bah! bah!" cried the parrot and monkey, throwing down their spoons in disgust; "you can't cook, and we shall have to go to bed hungry."

"We can't go to our beds either unless you hurry and make them," said the cat, who was vexed at having failed.

So the parrot set to, and tried to spread the clothes on the bed with her beak; but as fast as she pulled them up one side, they slipped off the other, and at last she gave up in despair.

"Oh dear, we shall have to sleep on the floor," cried the other two.

"Then you had better sweep it first," retorted the parrot.

So the monkey took the broom and began to sweep, but only succeeded in raising such a dust that they were nearly blinded, and had to run out of the house and sit on the door-step until it settled.

And they were so discouraged that they cried, and cried, until their tiny handkerchiefs were wet through, and the tears ran down and formed quite a pool in front of the door.

"It's of no use to try and keep house by ourselves," said the monkey; "we shall have to go to some museum and board."

"What! leave our own pretty little house, where we have lived so long," said the cat.

"I'll stay here and starve before I'll go to the old museum," said the parrot. And overcome with grief at the idea of breaking up their happy home they embraced, and sobbed aloud on each other's necks.

Now Filbert had watched all that was going on, and felt very sorry for the little creatures; so as soon as they left the room she slipped out from behind the curtain, and in a few minutes did all they had tried so hard to accomplish, and returned to her hiding-place just as the three came in, saying sadly to one another, "The dust must have settled, so we will try and sleep on the floor and forget how hungry we are; and to-morrow we will go to town again, and try very much harder than we did to-day to learn how to keep house."

But here they stopped short and stared in surprise, for the floor was as clean and bright as a new penny; the little white beds were tucked smoothly up, and on the table smoked three bowls of nice hot porridge.

"What good fairy has been here!" they all exclaimed.

"A nut-brown maiden, nut-brown maiden," chirped a cricket on the hearth.

"And where has she gone?" they asked.

"Behind the curtain, behind the curtain," sang the cricket.

And in a twinkling Filbert was dragged, blushing and trembling, from her hiding-place.

"Who are you, and how came you here?" asked the cat.

"My name is Filbert, and I came in to rest," said the girl, "for I have no friends and no home."

"And can you cook and sweep and sew?" asked the parrot.

"Yes, indeed, and many other things."

"Oh! will you stay and live with us?" asked the monkey.

"What will you give me?" asked Filbert.

"A good home," said the cat.

"Brand-new clothes," said the parrot.

"And a brass, a silver, and a gold penny every week," said the monkey.

So Filbert staid, and was as happy as a bird in the one-eyed house. She sang so cheerfully as she went about her work that things seemed almost to do themselves for her. The monkey watched in admiration whenever she swept the floor, and wondered why there was no dust. They all learned to love her dearly, and were as good as fairy godmothers to her, giving her everything she wished, and her pile of pennies grew so fast that she became quite rich; and, at last, if she had chosen, could have married a prince.[Pg 774]

The present Number closes the first volume of Young People, and we wish to express our great pleasure at the thought that thousands and thousands of children who one year ago were strangers to us are now our little friends, and, we might say, seem to us like one large family. We have done our best to amuse and instruct them, and to make them happy; and by giving them weekly a rich fund of beautiful pictures, stories, poems, and instructive reading, to awaken in them noble thoughts and impulses, a desire for information, and also to teach them to think for themselves.

Through the letters addressed to our Post-office Box we have become acquainted with large numbers of our readers, and feel as much interest in their little enjoyments, their pets, their studies, and their plans for the future as if they were personally known to us.

Our Post-office Box is the most complete department of its kind in existence. We print all the letters we possibly can, and would be glad to print every one if our space allowed, for each contains some pretty bit of childish life which we are sure would be delightful to other little folks. Our letters come to us from all parts of the globe—from every corner of the United States and Canada; from England, Germany, France, and Italy; from the West Indies and South America; and even from distant islands far across the sea. It would seem that wherever there are English-speaking children, even in the most remote localities, Young People has found its way to their hands; and critical and exacting as little folks are, their expressions of delight in their "little paper" are unqualified.

Our exchange department has developed a fact that is very gratifying, and that is that boys and girls throughout the country are interested in making collections of minerals, pressed flowers and ferns, ocean curiosities, and other specimens of nature's beautiful and perfect handiwork. It affords us much pleasure to bring them into communication with each other for the exchange of these instructive objects, thus cultivating in them a desire for useful information, which, as they grow older, may develop, in many instances, in ways which will lead to a life-long benefit to themselves and others.

It has also afforded us the greatest satisfaction to answer the numerous and varied questions of our inquisitive little readers; and except in instances where the answer, were it given correctly, would occupy too much space in our columns, or be too scientific for the comprehension of the youthful querist, we have left but two or three questions to be noticed.

We thank all of our readers most sincerely for the hearty expressions of approval and delight which we have received; and we promise them that the new volume of Young People shall continue to bring them weekly an entertaining and instructive variety of stories and papers by the most popular writers, good puzzles of all kinds, directions for making various articles useful to boys and girls, and a very full and interesting Post-office Box. We are confident that before the end of the second volume we shall make friends with thousands of little people whose handwriting is still unknown to us.

Dorset, Canada.

I am fourteen years old, and I live in the northern part of Canada. My sister takes Young People. I liked the story of "The Moral Pirates" very much. Our nearest neighbor is about six miles away. There are lots of lakes here in which are a great many speckled and salmon trout, and there are troops of red deer in the woods. I have killed thirteen myself. We have two hounds which run the deer in the lakes, and we have birch-bark canoes in which we row. There is a sporting club comes here every year from New York and Toronto.

Erastus W. L.

I am seven years old. I live North, among the rocks and mountains and lakes of Canada. I never went to school, except once for five weeks, but I can read in the Fourth Reader. I have a pet cat and a chicken, and papa says he will catch me a fawn. I love Young People very much.

Nettie L.

My sister Nettie and I can crochet, and we would be very much obliged if Gracie Meads would send us the pattern she wrote about in her letter. We would send her some flower seeds in return.

Addie Lockman,

Dorset P. O., Haliburton, Ontario, Canada.

Marengo, Iowa.

I like Young People very much, but I like best of all the Post-office Box, and all the pretty things. I am going to make a Manes life-boat, and a cucuius.

My sister has two white mice and a brown one, and I have a canary-bird. One of our white mice was sick, but is getting better.

Can any one tell me a good way to make a scrap-book?

I am beginning a collection of stamps. I have only eight different kinds, but will soon have more. I am also collecting birds' eggs and nests. I would like to know what bird lays a white egg speckled with brown.

Jessie Lee R.

There are several varieties of birds that lay white eggs speckled with brown. The king-bird's egg has brown blotches on one end, and is speckled all over; the wood-peewit lays a small white egg speckled with brown, the spots forming a ring around one end; the egg of the meadow-lark is long and white, with brown spots on the large end; swallows' eggs are white, covered with brown spots; and other common varieties of birds lay eggs of a similar appearance.

Claremont, Minnesota.

I have taken Young People ever since it was published, and I like it very much. I enjoy reading the letters from all the children in the Post-office Box. I am thirteen years old.

There is nothing much to do here except go to school and play. My father keeps a store, and during the summer I worked for him. School began on the 4th of October. I have ten chickens, and am building a coop for them; and I have a very large cat named Buff. I am saving money now to buy a cornet.

Will you tell me whether the stamps the readers of Young People are collecting are used or new? I have quite a number of used ones.

George H. H.

The stamps in the albums of young collectors, if they are genuine issues, have, with but few exceptions, done service on some letter or package before they find their way to the collector's hands. Unless they are too much defaced by postal marks they form as valuable specimens as if they were new, and are perhaps more interesting. To obtain full collections of new foreign stamps would be difficult and very expensive.

Asheville, North Carolina.

I like Harper's Young People very much. I have a paint-box, and I am going to color all the pretty pictures. I have a pony named Tiny, two cats, and a canary which sings delightfully. I am eight years old.

Emily T. H.

Boston, Massachusetts.

Little "Wee Tot" wishes to say that she is getting a great many requests for ocean curiosities. She can not possibly answer all the letters, but whoever will send her a box of pretty curiosities in minerals, insects, birds' eggs, skulls and skeletons of reptiles, rare postage stamps, coins, relics, Revolutionary mementos, ancient newspapers, or anything else that is of value, shall receive an equivalent in things from the ocean.

Last week "Wee Tot" received through the Post-office a beautiful Indian bow and three arrows from the Indian country, and yesterday she received fifty-six baby water-snakes and some beautiful butterflies.

With much love to you, dear Young People,

"Wee Tot" Brainard,

257 Washington Street, Boston, Massachusetts.

Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

I can give some good directions to Daisy F. for pressing sea-weeds. The implements used are a dish of water, a camel's-hair brush, sheets of paper, blotting-paper, and linen or cotton rags. After cleaning all the sand and dirt from the weeds, put one in a dish of water, and slip a sheet of paper under it. Then lift it carefully nearly out of the water, and arrange all the little branches naturally with the brush. Now lay the paper which contains the weed on a piece of blotting-paper: over it put a rag, so that the weed is entirely covered by it, and over that another piece of blotting-paper, and on this in turn lay another sheet of paper upon which a weed has been floated. Proceed in this manner until you have a pile ready. Place it between two boards, and leave it under heavy pressure for three or four days, until it is dry. Then remove the blotting-papers and rags very gently, taking care not to pull the sea-weeds from the paper on which they are pressed.

William A. L.

When floating certain kinds of sea-weeds on to the paper it will be found necessary to cut away, with a sharp, fine-pointed scissors, many superfluous stems and branches, as otherwise the sea-weed when pressed will present a matted appearance, and much of the delicacy be lost.

Brooklyn, New York.

I have taken Young People from the first number, and have learned a great deal from it.

I have a collection of three thousand five hundred and thirty-one stamps, no two alike, six hundred and six of which are American varieties. I would like to know if any reader has one as large.

The young chemists' club have elected me President, and I am desired to thank the readers of Harper's Young People for the experiments they have sent, and to request them to favor the club with more.

Charles H. W.

Dubuque, Iowa.

I like Young People so much! and I always read all the letters in the Post-office Box.

Ann A. N. is just my age, and I would like to tell her some more things that a birdie likes. There is a little seed called millet, which I get at the market in the heads as it grows, and the birdies love to pick out the little round seeds. A bit of cabbage leaf is a treat to them, and any one living in the country can give birds the long seed heads of the plantain, or the little satchel-like seeds of the pouch-weed. I sometimes give my birds a little hard-boiled egg, but one must be careful not to give enough of these things to make the bird too fat.

Tell Anna Wierum it would be better to put her cuttings in warm moist sand for a few days, until they throw out little white roots; then wrap each in a bit of florist's moss or cotton-wool, and put a bit of oiled paper around the roots. Very thin brown paper, oiled with butter or lard, will do, so it will not absorb moisture. Pack all carefully in a small pasteboard box, and tie it up instead of sealing it. A package tied, with no writing in it, goes cheaply through the mails as third-class matter.

Will any correspondent tell me how to keep goldfish healthy in a globe?

Georgia G. S.

I would like to exchange rare foreign stamps. I have fifteen hundred in my collection. I would especially like to obtain new issues.

W. Page Gardner,

16 Hanson Street, Boston, Massachusetts.

I would like to exchange postmarks for birds' eggs with any reader of Young People. To any one who will send me ten varieties of birds' eggs, I will send twenty-five postmarks, or for five varieties, I will send twelve postmarks.

James Thompson,

Middlefield, Geauga County, Ohio.

Can any correspondent tell me where I can get a catalogue of birds' eggs? I am starting a collection of eggs, and would like to exchange an egg of a brown thrush for one of a meadow-lark.

Milton D. Close,

Berlin Heights, Erie County, Ohio.

If any reader of Young People will send me twenty different foreign postage stamps, I will send by return mail a Chinese coin.

Willie B. Gordon,

P. O. Box 116, Upper Sandusky, Ohio.

I would like to exchange birds' eggs with any of the readers of Young People. To any one who will send me a list, and the number of each kind he has for exchange, I will send my list in return.

Fred C. Todd,

Milltown, New Brunswick.

I would like to exchange a little of the soil of Virginia for that of any of the Western States. I am twelve years old.

H. Jacob, Darlington Heights,

Prince Edward County, Virginia.

I have received a letter from a correspondent desiring exchange, but there is no name or address. I think the postmark is Harrison, but am not sure. Please publish this, as I do not wish the writer to think it is my fault that no attention is paid to his letter.

William Winslow,

74 De Soto Street, St. Paul, Minnesota.

I have a collection of postage stamps and a number of duplicates. To any correspondent sending me twenty good stamps, I will send the same number in return.

Can any one tell me the price of silk-worm cocoons?

Philip Tyng,

403 North Madison Street, Peoria, Illinois.

I take Young People. I am very much interested in the Post-office Box, because I like to read of the boys and girls who make collections. I am collecting[Pg 775] postmarks and minerals, and I will gladly exchange a specimen of iron ore for any other mineral.

Bennie C. Graham,

165 West Goodale Street, Columbus, Ohio.

I would like to exchange United States and foreign coins with any reader of Young People.

William F. Saltmarsh,

512 North New Jersey St., Indianapolis, Indiana.

I have been gathering autumn leaves, and preparing them for decorating lace curtains, picture-frames, and other things. They are mostly maple, as we have very few others here. I would like to send some to any little girl or boy in exchange for sea-shells or other ocean treasures. To any one sending me an address I will send some leaves right away.

Nellie S. G. Vaughan,

Chazy, Clinton County, New York.

I have a cabinet in which I have a number of war relics. I also have an aquarium. I would like to exchange foreign and United States postmarks and stamps with any readers of Young People.

W. Paul D. Moross,

Care of C. A. Morass & Co.,

Chattanooga, Tennessee.

I have several kinds of Norwegian stamps, and if any stamp collector will send me some shells, sea-weeds, or any such things, I will be very glad to send some of my stamps in return.

Elizabeth Koren,

Decorah, Winnesheik County, Iowa.

I would like to exchange postmarks or stamps with any one in the United States or Canada.

Clifford Potts,

412 Walnut Street, Reading, Pennsylvania.

A little girl who is making an interesting collection of monograms would be very glad to exchange with any boy or girl. Please address

E. M., P. O. Box 1132,

Plainfield, New Jersey.

I am just beginning a collection of monograms. As yet I have but very few, but I would be very glad to exchange with any readers of Young People.

Isabelle Van Brunt,

27 West Thirtieth Street, New York City.

All boys from fourteen to twenty are invited to become members of a debating club on a legal basis. The debates are carried on by mail. For further information address the recording secretary,

N. L. Collamer,

Room 49, Treasury Department, Washington, D. C.

I would like to exchange stamps or postmarks with any readers of Young People.

I have mislaid the address of May A. J. Cornish, of Washington, and if she will kindly send it to me I will answer her letter requesting exchange.

George G. Omerly,

616 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

E. M. W.—Many thanks for your trouble in copying the pretty version of the legend of the forget-me-not. But as it is very long, and is not new, we can not print it.

A. C.—The military organization of the ancient Romans which was called a legion numbered from 3000 to 6000 men. It combined cavalry and infantry and all the constituent elements of an army. Originally only Roman citizens of property were admitted to the legion, but at a later period the enrollment of all classes became common.—There are so many large printing establishments in New York city that it is difficult to answer your other question. The best thing for you to do is to make a personal application to any one you may select.

Charlie.—You will find the advertisement of the "Royal Middy" costume in Young People No. 27.—The Indian ponies of the far West are very serviceable and hardy little animals. The Canadian ponies and Texan mustangs are useful, but sometimes too vicious for a little boy like you. A shaggy little Shetland is pretty, if you can obtain one.

W. S. W.—Your florist friend will know better than we can tell you in what way to procure you a plant of the Venus's-flytrap. He can, no doubt, send you some young roots. As the plant is only a cluster of leaves, low on the ground, from which springs a single stalk, about six inches high, crowned with a bunch of white flowers, it can not easily be propagated by cuttings. It is a matter of dispute if this plant feeds upon the insects it captures or not. The unfortunate fly imprisoned in its leaves is macerated in a juice which the leaf again absorbs, but the plant would probably thrive as well from the nourishment derived from the sun and air and earth alone.

Harry I. F.—We can not print your request for exchange, as you gave no address, not even the town in which you live.—We can not give addresses of correspondents, but if you have any questions to ask of the one you name, you can write them to the Post-office Box, and if they are suitable, we will print your letter.

N. W. J.—We have not made the arrangements about which you inquire. We thank you sincerely for your pretty letter and your kind intentions.

Miriam B., Florence N., Harry F. H., and many others.—We refer you to the introductory note to the Post-office Box of Young People No. 45 for the reason why your requests for exchange are not published. Such collections as yours are very pretty and interesting, but as our Post-office Box is not large enough to contain every pretty thing, we can only print those requests for exchanges of articles which we consider in some way instructive.

1. First, a household pet. Second, a surface. Third, an animal. Fourth, a measure.

Winnie.

2. First, a narrow board. Second, vitality. Third, at a distance. Fourth, a portion of time.

H. N. T.

Central letter.—In valetudinarianism.

Top.—A vegetable. Something found in nearly every newspaper. An untruth. Snug. A metal. A letter.

Right.—Having many names. A register of deaths. Having two ways. One who assumes a part. Excommunication. A letter.

Left.—A root. Decrease. An officer of a university. Pertaining to a wall. A loud noise. A letter.

Down.—To personify. Dimly. A violent revolutionist. A cone-bearing tree. A small cask. A letter.

Centrals read downward spell a word applied to certain species of minerals; read across, a word signifying a counter-accusation.

Rip Van Winkle.

A familiar verse:

M—r—h—d—l—t—l—l—m—,

I—s—l—e—e—a—w—i—e—s—n—w;

A—d—v—r—w—e—e—h—t—a—y—e—t

T—e—a—b—a—s—r—t—g—.

Little Rosie.

| S | P | A | R | E | H | E | A | T | H | |

| P | A | N | E | L | E | X | T | R | A | |

| A | N | G | L | E | A | T | L | A | S | |

| R | E | L | I | C | T | R | A | C | T | |

| E | L | E | C | T | H | A | S | T | E |

| O | ||||||

| F | R | O | ||||

| F | E | T | I | D | ||

| O | R | T | O | L | A | N |

| O | I | L | E | D | ||

| D | A | D | ||||

| N |

| D | I | R | E | F | U | L |

| N | O | M | A | D | ||

| Y | E | A | ||||

| R | ||||||

| A | S | S | ||||

| D | R | O | L | L | ||

| Q | U | I | N | I | N | E |

October.

Charade on page 728—Vane, vein, vain.

Bicycle riding is the best as well as the healthiest of out-door sports; is easily learned and never forgotten. Send 3c. stamp for 24-page Illustrated Catalogue, containing Price-Lists and full information.

Within a year of its first appearance Harper's Young People has secured a leading place among the periodicals designed for juvenile readers. The object of those who have the paper in charge is to provide for boys and girls from the age of six to sixteen a weekly treat in the way of entertaining stories, poems, historical sketches, and other attractive reading matter, with profuse and beautiful illustrations.

The conductors of Harper's Young People proceed upon the theory that it is not necessary, in order to engage the attention of youthful minds, to fill its pages with exaggerated and sensational stories, to make heroes of criminals, or throw the glamour of romance over bloody deeds. Their design is to make the spirit and influence of the paper harmonize with the moral atmosphere which pervades every cultivated Christian household. The lessons taught are those which all parents who desire the welfare of their children would wish to see inculcated. Harper's Young People aims to do this by combining the best literary and artistic talent, so that fiction shall appear in bright and innocent colors, sober facts assume such a holiday dress as to be no longer dry or dull, and mental exercise, in the solution of puzzles, problems, and other devices, become a delight.

The cordial approval extended to Harper's Young People by the intelligent and exacting audience for whose special benefit it was projected shows that its conductors have not miscalculated the requirements of juvenile periodical literature. The paper has attained a wide circulation in the United States, Canada, Europe, the West Indies, and South America. The "Post-office Box," the most complete department of the kind ever attempted, contains letters from almost every quarter of the globe, and not only serves to bring the boys and girls of different states and countries into pleasant acquaintance, but, through its exchanges and answers to questions, to extend their knowledge and quicken their intelligence.

The Bound Volume for 1880 has been gotten up in the most attractive manner, the cover being embellished with a tasteful and appropriate design. It will be one of the most handsome, entertaining, and useful books for boys and girls published for the ensuing holidays.

Four Cents a Number. Single Subscriptions for one year, $1.50 each; Five Subscriptions, one year, $7—payable in advance: postage free. Subscriptions will be commenced with the Number current at the time of receipt of order, except in cases where the subscribers otherwise direct.

The Second Volume will begin with No. 53, to be issued November 2, 1880. Subscriptions should be sent in before that date, or as early as possible thereafter.