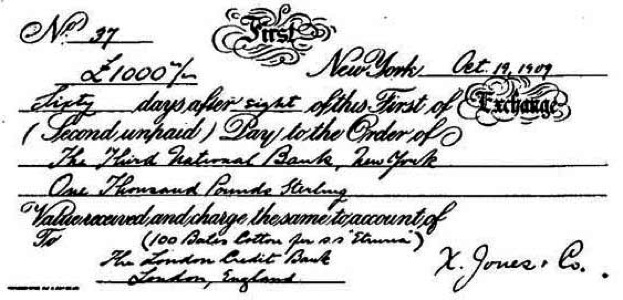

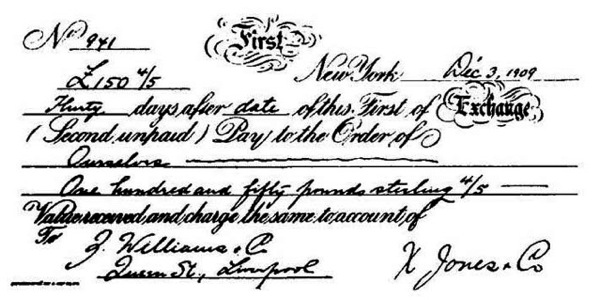

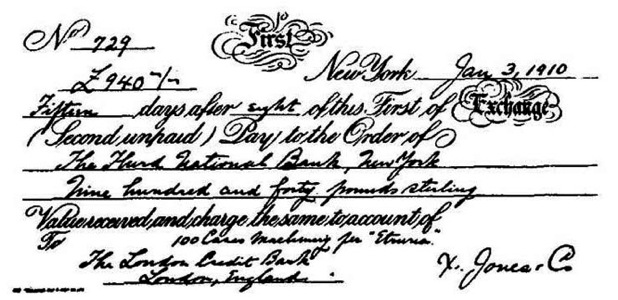

Form of Commercial Long Bill

Title: Elements of Foreign Exchange: A Foreign Exchange Primer

Author: Franklin Escher

Release date: July 10, 2009 [eBook #29364]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian

Libraries)

| PAGE | ||

| Chapter I. | What Foreign Exchange is and What Brings it into Existence | 3 |

| The various forms of obligation between the bankers and merchants of one country and the bankers and merchants of another, which result in the drawing of bills of exchange. | ||

| Chapter II. | The Demand for Bills of Exchange | 15 |

| A discussion of the six sources from which spring the demand for the various kinds of bills of exchange. | ||

| Chapter III. | The Rise and Fall of Exchange Rates | 25 |

| Operation of the five main influences tending to make exchange rise as opposed to the five main influences tending to make | ||

| Chapter IV. | The Various Kinds of Exchange | 45 |

| A detailed description of: Commercial "Long" Bills—Clean Bills—Commercial "Short" Bills—Drafts drawn against securities sold abroad—Bankers' demand drafts—Bankers' "long" drafts. | ||

| Chapter V. | The Foreign Exchange Market | 59 |

| How the exchange market is constituted. The bankers, dealers and brokers who make it up. How exchange rates are established. The relative importance of different kinds of exchange. | ||

| Chapter VI. | How Money Is Made in Foreign Exchange. The Operations of the Foreign Department | 68 |

| An intimate description of: Selling demand bills against remittances of demand bills—Selling cables against remittances of demand bills—Selling demand drafts against remittances of "long" exchange—The operation of lending foreign money here—The drawing of finance bills—Arbitraging in Foreign Exchange—Dealing in exchange "futures." | ||

| Chapter VII. | Gold Exports and Imports | 106 |

| The primary movement of gold from the mines to the markets, and its subsequent distribution along the lines of favorable exchange rates. Description (with presentation of actual figures) of: The export of gold bars from New York to London—Import of gold bars from London—Export of gold bars to Paris under the "triangular operation." Shipments to Argentina. | ||

| London as a "free" gold market and the ability of the Central Banks in Europe to control the movement of gold. | ||

| Chapter VIII. | Foreign Exchange in its Relation to International Security Trading | 130 |

| Europe's "fixed" and "floating" investment in American bonds and stocks a constant source of international security trading. Consequent foreign exchange business. Financing foreign speculation in "Americans." Description of the various kinds of bond and stock "arbitrage." | ||

| Chapter IX. | The Financing of Exports and Imports | 141 |

| A complete description of the international banking system by which merchandise is imported into and exported from the United States. An actual operation followed through its successive steps. | ||

"Where can I find a little book from which I can get a clear idea of how foreign exchange works, without going too deeply into it?"—that question, put to the author dozens of times and by many different kinds of people, is responsible for the existence of this little work. There are one or two well-written textbooks on foreign exchange, but never yet has the author come across a book which covered this subject in such a way that the man who knew little or nothing about it could pick up the book and within a few hours get a clear idea of how foreign exchange works,—the causes which bear upon its movement, its influence on the money and security markets, etc.

That is the object of this little book—to cover the ground of foreign exchange, but in such a way as to make the subject interesting and its treatment readable and comprehensible to the man without technical knowledge. Foreign exchange is no easy subject to understand; there are few important subjects which are. But, on the other hand, neither is it the complicated and abstruse subject which so many people seem to consider it—an idea only too often born of a look into some of the textbooks on exchange, with their formidable pages of tabulations, formulas, and calculations of all descriptions. For the average man there is little of interest in these intricacies of the subject. Many of the shrewdest and most successful exchange bankers in New York City, indeed, know less about them than do some of their clerks. What is needed is rather a clear and definite knowledge of the movement of exchange—why it moves as it does, what can be read from its movements, what effects its movements exert on the other markets. It is in the hope that something may be added to the general understanding of these important matters that this little book is offered to the public.

CHAPTER I

WHAT FOREIGN EXCHANGE IS AND WHAT BRINGS IT INTO EXISTENCE

Underlying the whole business of foreign exchange is the way in which obligations between creditors in one country and debtors in another have come to be settled—by having the creditor draw a draft directly upon the debtor or upon some bank designated by him. A merchant in New York has sold a bill of goods to a merchant in London, having thus become his creditor, say, for $5,000. To get his money, the merchant in New York will, in the great majority of cases, draw a sterling draft upon the debtor in London for a little over £1,000. This draft his banker will readily enough convert for him into dollars. The buying and selling and discounting of countless such bills of exchange constitute the very foundation of the foreign exchange business.

Not all international obligations are settled by having the creditor draw direct on the debtor. Sometimes gold is actually sent in payment. Sometimes the debtor goes to a banker engaged in selling drafts on the city where the obligation exists, gets such a draft from him and sends that. But in the vast majority of cases payment is effected as stated—by a draft drawn directly on the buyer of the goods. John Smith in London owes me money. I draw on him for £100, take the draft around to my bank and sell it at, say, 4.86, getting for it a check for $486.00. I have my money, and I am out of the transaction.

Obligations continually arising in the course of trade and finance between firms in New York and firms in London, it follows that every day in New York there will be merchants with sterling drafts on London which they are anxious to sell for dollars, and vice versa. The supply of exchange, therefore, varies with the obligations of one country to another. If merchants in New York, for instance, have sold goods in quantity in London, a great many drafts on London will be drawn and offered for sale in the New York exchange market. The supply, it will of course be apparent, varies. Sometimes there are many drafts for sale; sometimes very few. When there are a great many drafts offering, their makers will naturally have to accept a lower rate of exchange than when the supply is light.

The par of exchange between any two countries is the price of the gold unit of one expressed in the money of the other. Take England and the United States. The gold unit of England is the pound sterling. What is the price of as much gold as there is in a new pound sterling, expressed in American money? $4.8665. That amount of dollars and cents at any United States assay office will buy exactly as much gold as there is contained in a new British pound sterling, or sovereign, as the actual coin itself is called. 4.8665 is the mint par of exchange between Great Britain and the United States.

The fact that the gold in a new British sovereign (or pound sterling) is worth $4.8665 in our money by no means proves, however, that drafts payable in pounds in London can always be bought or sold for $4.8665 per pound. To reduce the case to a unit basis, suppose that you owed one pound in London, and that, finding it difficult to buy a draft to send in payment, you elected to send actual gold. The amount of gold necessary to settle your debt would cost $4.8665, in addition to which you would have to pay all the expenses of remitting. It would be cheaper, therefore, to pay considerably more than $4.8665 for a one-pound draft, and you would probably bid up until somebody consented to sell you the draft you wanted.

Which goes to show that the mint par is not what governs the price at which drafts in pounds sterling can be bought, but that demand and supply are the controlling factors. There are exporters who have been shipping merchandise and selling foreign exchange against the shipments all their lives who have never even heard of a mint par of exchange. All they know is, that when exports are running large and bills in great quantity are being offered, bankers are willing to pay them only low rates—$4.83 or $4.84, perhaps, for the commercial bills they want to sell for dollars. Conversely, when exports are running light and bills drawn against shipments are scarce, bankers may be willing to pay 4.87 or 4.88 for them.

For a clear understanding of the mechanics of the exchange market there is necessary a clear understanding of what the various forms of obligations are which bring foreign exchange into existence. Practically all bills originate from one of the following causes:

1. Merchandise has been shipped and the shipper draws his draft on the buyer or on a bank abroad designated by him.

2. Securities have been sold abroad and the seller is drawing on the buyer for the purchase price.

3. Foreign money is being loaned in this market, the operation necessitating the drawing of drafts on the lender.

4. Finance-bills are being drawn, i.e., a banker abroad is allowing a banker here to draw on him in pounds sterling at 60 or 90 days' sight in order that the drawer of the drafts may sell them (for dollars) and use the proceeds until the drafts come due and have to be paid.

1. Looking at these sources of supply in the order in which they are given, it is apparent, first, what a vast amount of foreign exchange originates from the direct export of merchandise from this country. Exports for the period given below have been as follows:

| 1913 | $2,465,884,000 |

| 1912 | 2,204,322,000 |

| 1911 | 2,049,320,000 |

| 1910 | 1,744,984,000 |

| 1909 | 1,663,011,000 |

Not all of this merchandise is drawn against; in some cases the buyer abroad chooses rather to secure a dollar draft on some American bank and to send that in payment. But in the vast majority of cases the regular course is followed and the seller here draws on the buyer there.

There are times, therefore, when exchange originating from this source is much more plentiful than at others. During the last quarter of each year, for instance, when the cereal and cotton crop exports are at their height, exchange comes flooding into the New York market from all over the country, literally by the hundreds of millions of dollars. The natural effect is to depress rates—sometimes to a point where it becomes possible to use the cheaply obtainable exchange to buy gold on the other side.

In a following chapter a more detailed description of the New York exchange market is given, but in passing, it is well to note how the whole country's supply of commercial exchange, with certain exceptions, is focussed on New York. Chicago, Philadelphia, and one or two other large cities carry on a pretty large business in exchange, independent of New York, but by far the greater part of the commercial exchange originating throughout the country finds its way to the metropolis. For in New York are situated so many banks and bankers dealing in bills of exchange that a close market is always assured. The cotton exporter in Memphis can send the bills he has drawn on London or Liverpool to his broker in New York with the fullest assurance that they will be sold to the bankers at the highest possible rate of exchange anywhere obtainable.

2. The second source of supply is in the sale abroad of stocks and bonds. Here again it will be evident how the supply of bills must vary. There are times when heavy flotations of bonds are being made here with Europe participating largely, at which times the exchange drawn against the securities placed abroad mounts up enormously in volume. Then again there are times when London and Paris and Berlin buy heavily into our listed shares and when every mail finds the stock exchange houses here drawing millions of pounds, marks, and francs upon their correspondents abroad. At such times the supply of bills is apt to become very great.

Origin of bills from this source, too, is apt to exert an important influence on rates, in that it is often sudden and often concentrated on a comparatively short period of time. The announcement of a single big bond issue, often, where it is an assured fact that a large part of it will be placed abroad, is enough to seriously depress the exchange market. Bankers know that when the shipping abroad of the bonds begins, large amounts of bills drawn against them will be offered and that rates will in all probability be driven down.

Announcements of such issues, as well as announcements that a block of this or that kind of bonds has been placed abroad with some foreign syndicate, are apt to come suddenly and often find the exchange market unprepared. For the supply of exchange originated thereby, it must be remembered, is not confined to the amount actually drawn against bonds sold but includes also all the exchange which other bankers, in their anticipation of lower rates, hasten to draw. The exchange market is, indeed, a sensitive barometer, from which those who understand it can read all sorts of coming developments. It often happens that buying or selling movements in our securities by the foreigners are so clearly forecasted by the action of the exchange market that bankers here are able to gain great advantage from what they are able to foresee.

3. The third great source of supply is in the drafts which bankers in one country draw upon bankers in another in the operation of making international loans. The mechanism of such transactions will be treated in greater detail later on, but without any knowledge of the subject whatever, it is plain that the transfer of banking capital, say from England to the United States, can best be effected by having the American house draw upon the English bank which wants to lend the money. In the finely adjusted state of the foreign exchanges nowadays, loans are continually being made by bankers in one country to bankers and merchants in another. Very little of the capital so transferred goes in the form of gold. A London house decides to loan, say, $100,000 in the American market. The terms having been arranged, the London house cables its New York correspondent to draw for £20,000, at 60 or 90 days' sight, as the case may be. The New York house, having drawn the draft, sells it in the exchange market, realizing on it the $100,000, which it then proceeds to loan out according to instructions.

The arranging of these loans, it will be seen, means the continuous creation of very large amounts of foreign exchange. As the financial relationships between our bankers and those of the Old World have been developed, it has come about that European money is being put out in this market in increasing volume. Conditions of money, discount, and exchange are constantly being watched for the opportunity to make loans on favorable terms, and the aggregate of foreign money loaned out here at times reaches very large figures. In 1901 Europe had big amounts of money outstanding in the New York market, and again in 1906 very large sums of English and French capital were temporarily placed at our disposal. But in the summer of 1909 all records were surpassed, American borrowings in London and Paris footing up to at least half a billion dollars. Such loans, running only a couple of months on the average and then being sometimes paid off, but more often shifted about or renewed, give rise to the drawing of immense amounts of foreign exchange.

4. Drawing of so-called "finance-bills," of which a complete description will be found in chapters IV and VI, is the fourth source whence foreign exchange originates. Whenever money rates become decidedly higher in one of the great markets than in the others, bankers at that point who have the requisite facilities and credit, arrange with bankers in other markets to allow them (the bankers at the point where money is high) to draw 60 or 90 days' sight bills. These bills can then be disposed of in the exchange market, dollars being realized on them, which can then be loaned out during the whole life of the bills. The advantages or dangers of such an operation will not be touched upon here, the purpose of this chapter being merely to set forth clearly the sources from which foreign exchange originates.

And when money is decidedly higher in New York than in London an immense volume of foreign exchange does originate from this source. A number of firms and banks, with either their own branches in London or with correspondents there to whom they stand very close, are in a position where they can draw very large amounts of finance bills whenever they deem it profitable and expedient to do so. Eventually, of course, these 60 and 90 day bills come due and have to be settled by remittances of demand exchange, but in the meantime the house which drew them will have had the unrestricted use of the money. In a market like New York this is only too often a prime consideration. With money rates soaring as they do so frequently here, a banker can pay almost any commission his correspondent abroad demands and still come out ahead on the transaction.

These are the principal sources from which foreign exchange originates—shipments of merchandise, sales abroad of securities, transfer of foreign banking capital to this side, sale of finance-bills. Other causes of less importance—interest and profits on American capital invested in Europe, for instance—are responsible for the existence of some quantity of exchange, but the great bulk of it originates from one of the four sources above set forth. In the next chapter effort will be made to show whence arises the demand which pretty effectually absorbs all the supply of exchange produced each year.

CHAPTER II

THE DEMAND FOR BILLS OF EXCHANGE

Turning now to consideration of the various sources from which springs the demand for foreign exchange, it appears that they can be divided about as follows:

1. The need for exchange with which to pay for imports of merchandise.

2. The need for exchange with which to pay for securities (American or foreign) purchased by us in Europe.

3. The necessity of remitting abroad the interest and dividends on the huge sums of foreign capital invested here, and the money which foreigners domiciled in this country are continually sending home.

4. The necessity of remitting abroad freight and insurance money earned here by foreign companies.

5. Money to cover American tourists' disbursements and expenses of wealthy Americans living abroad.

6. The need for exchange with which to pay off maturing foreign short-loans and finance-bills.

1. Payment for merchandise imported constitutes probably the most important source of demand for foreign exchange. Merchandise brought into the country for the period given herewith has been valued as follows:

| 1913 | $1,813,008,000 |

| 1912 | 1,653,264,000 |

| 1911 | 1,527,226,000 |

| 1910 | 1,556,947,000 |

| 1909 | 1,311,920,000 |

Practically the whole amount of these huge importations has had to be paid for with bills of exchange. Whether the merchandise in question is cutlery manufactured in England or coffee grown in Brazil, the chances are it will be paid for (under a system to be described hereafter) by a bill of exchange drawn on London or some other great European financial center. From one year's end to the other there is constantly this demand for bills with which to pay for merchandise brought into the country. As in the case of exports, which are largest in the Fall, there is much more of a demand for exchange with which to pay for imports at certain times of the year than at others, but at all times merchandise in quantity is coming into the country and must be paid for with bills of exchange.

2. The second great source of demand originates out of the necessity of making payment for securities purchased abroad. So far as the American participation in foreign bond issues is concerned, the past few years have seen very great developments. We are not yet a people, as are the English or the French, who invest a large proportion of their accumulated savings outside of their own country, but as our investment surplus has increased in size, it has come about that American investors have been going in more and more extensively for foreign bonds. There have been times, indeed, as when the Japanese loans were being floated, when very large amounts of foreign exchange were required to pay for the bonds taken by American individuals and syndicates.

Security operations involving a demand for foreign exchange are, however, by no means confined to American participation in foreign bond issues. Accumulated during the course of the past half century, there is a perfectly immense amount of American securities held all over Europe. The greater part of this investment is in bonds and remains untouched for years at a stretch. But then there come times when, for one reason or another, waves of selling pass over the European holdings of "Americans," and we are required to take back millions of dollars' worth of our stocks and bonds. Such selling movements do not really get very far below the surface—they do not, for instance, disturb the great blocks of American bonds in which so large a proportion of many of the big foreign fortunes are invested, but they are apt to be, nevertheless, on a scale which requires large amounts of exchange to pay for what we have had to buy back.

The same thing is true with stocks, though in that case the selling movements are more frequent and less important. Europe is always interested heavily in American stocks, there being, as in the case of bonds, a big fixed investment of capital, beside a continually fluctuating "floating-investment." In other words, aside from their fixed investments in our stocks, the foreigners are continually speculating in them and continually changing their position as buyers and sellers. Selling movements such as these do not materially affect Europe's set position on our stocks, but they do result at times in very large amounts of our stocks being dumped back upon us—sometimes when we are ready for them, sometimes when the operation is decidedly painful, as in the Fall of 1907. In any case, when Europe sells, we buy. And when we buy, and at the rate of millions of dollars' worth a day, there is a big demand for exchange with which to pay for what we have bought.

3. So great is the foreign investment of capital in this country that the necessity of remitting the interest and dividends alone means another continuous demand for very large amounts of foreign exchange. Estimates of how much European money is invested here are little better than guesses. The only sure thing about it is that the figures run well up into the billions and that several hundred millions of dollars' worth of interest and dividends must be sent across the water each year. There are, in the first place, all the foreign investments in what might be called private enterprise—the English money, for instance, invested in fruit orchards, gold and copper mines, etc., in the western states. Profits on this money are practically all remitted back to England, but no way exists of even estimating what they amount to. Aside from that there are all the foreign holdings of bonds and stocks in our great public corporations, holdings whose ownership it is impossible to trace. Only at the interest periods at the beginning and middle of each year does it become apparent how large a proportion of our bonds are held in Europe and how great is the demand for exchange with which to make the remittances of accrued interest. At such times the incoming mails of the international banking houses bulge with great quantities of coupons sent over here for collection. For several weeks on either side of the two important interest periods, the exchange market feels the stimulus of the demand for exchange with which the proceeds of these masses of coupons are to be sent abroad.

4. Freights and insurance are responsible for a fourth important source of demand for foreign exchange. A walk along William Street in New York is all that is necessary to give a good idea of the number and importance of the foreign companies doing business in the United States. In some form or other all the premiums paid have to be sent to the other side. Times come, of course, like the year of the Baltimore fire, when losses by these foreign companies greatly outbalance premiums received, the business they do thus resulting in the actual creation of great amounts of foreign exchange, but in the long run—year in, year out—the remitting abroad of the premiums earned means a steady demand for exchange.

With freights it is the same proposition, except that the proportion of American shipping business done by foreign companies is much greater than the proportion of insurance business done by foreign companies. Since the Civil War the American mercantile marine instead of growing with the country has gone steadily backward, until now the greater part of our shipping is done in foreign bottoms. Aside from the other disadvantages of such a condition, the payment of such great sums for freight to foreign companies is a direct economic drain. An estimate that the yearly freight bill amounts to $150,000,000 is probably not too high. That means that in the course of every year there is a demand for that amount of exchange with which to remit back what has been earned from us.

5. Tourists' expenditures abroad are responsible for a further heavy demand for exchange. Whether it is because Americans are fonder of travel than the people of other countries or whether it is because of our more or less isolated position on the map, it is a fact that there are far more Americans traveling about in Europe than people belonging to any other nation. And the sums spent by American tourists in foreign lands annually aggregate a very large amount—possibly as much as $175,000,000—all of which has eventually to be covered by remittances of exchange from this side.

Then again there must be considered the expenditures of wealthy Americans who either live abroad entirely or else spend a large part of their time on the other side. During the past decade it has come about that every European city of any consequence has its "American Colony," a society no longer composed of poor art students or those whose residence abroad is not a matter of volition, but consisting now of many of the wealthiest Americans. By these expatriates money is spent extremely freely, their drafts on London and Paris requiring the frequent replenishment, by remittances of exchange from this side, of their bank balances at those points. Furthermore, there must be considered the great amounts of American capital transferred abroad by the marriage of wealthy American women with titled foreigners. Such alliances mean not only the transfer of large amounts of capital en bloc, but mean as well, usually, an annual remittance of a very large sum of money. No account of the money drained out of the country in this way is kept, of course, but it is an item which certainly runs up into the tens of millions.

6. Lastly, there is the demand for exchange originating from the paying off of the short-term loans which European bankers so continuously make in the American market. There is never a time nowadays when London and Paris are lending American bankers less than $100,000,000 on 60 or 90 day bills, while the total frequently runs up to three or four times that amount. The sum of these floating loans is, indeed, changing all the time, a circumstance which in itself is responsible for a demand for very great amounts of foreign exchange.

Take, for instance, the amount of French and English capital employed in this market in the form of short-term loans; $250,000,000 is probably a fair estimate of the average amount, and 90 days a fair estimate of the average time the loans run before being paid off or renewed. That means that the quarter of a billion dollars of floating indebtedness is "turned over" four times a year and that means that every year the rearrangement of these loans gives rise to a demand for a billion dollars' worth of foreign exchange. These loaning operations, it must be understood, both originate exchange and create a demand for it. They are mentioned, therefore, in the preceding chapter, as one of the sources from which exchange originates, and now as one of the sources from which, during the course of every year, springs a demand for a very great quantity of exchange.

The six sources of demand for exchange, then, are for the payment for imports; for securities purchased abroad; for the remitting abroad of interest on foreign capital invested here and the money which foreigners in this country send home; for remitting freight and insurance profits earned by foreign companies here; for tourists' expenses abroad; and lastly, for the paying off of foreign loans. From these sources spring practically all the demand for exchange. In the last chapter there were set forth the principal sources of supply. With a clear understanding of where exchange comes from and of where it goes, it ought now to be possible for the student of the subject to grasp the causes which bear on the movement of exchange rates. That subject will accordingly be taken up in the next chapter.

CHAPTER III

THE RISE AND FALL OF EXCHANGE RATES

Granted that the obligations to each other of any two given countries foot up to the same amount, it is evident that the rate of exchange will remain exactly at the gold par—that in New York, for instance, the price of the sovereign will be simply the mint value of the gold contained in the sovereign. But between no two countries does such a condition exist—take any two, and the amount of the obligation of one to the other changes every day, which causes a continuous fluctuation in the exchange rate—sometimes up from the mint par, sometimes down.

Before going on to discuss the various causes influencing the movement of exchange rates, there is one point which should be very clearly understood. Two countries, at least, are concerned in the fluctuation of every rate. Take, for example, London and New York, and assume that, at New York, exchange on London is falling. That in itself means that, in London, exchange on New York is rising.

For the sake of clearness, in the ensuing discussion of the influences tending to raise and lower exchange rates, New York is chosen as the point at which these influences are operative. Consideration will be given first to the influences which cause exchange to go up. In a general way, it will be noticed, they conform with the sources of demand for exchange given in the previous chapter. They may be classified about as follows:

1. Large imports, calling for large amounts of exchange with which to make the necessary payments.

2. Large purchases of foreign securities by us, or repurchase of our own securities abroad, calling for large amounts of exchange with which to make payment.

3. Coming to maturity of issues of American bonds held abroad.

4. Low money rates here, which result in a demand for exchange with which to send banking capital out of the country.

5. High money rates at some foreign centre which create a great demand for exchange drawn on that centre.

1. Heavy imports are always a potent factor in raising the level of exchange rates. Under whatever financial arrangement or from whatever point merchandise is imported into the United States, payment is almost invariably made by draft on London, Paris, or Berlin. At times when imports run especially heavy, demand from importers for exchange often outweighs every other consideration, forcing rates up to high levels. A practical illustration is to be found in the inpour of merchandise which took place just before the tariff legislation in 1909. Convinced that duties were to be raised, importers rushed millions of dollars' worth of merchandise of every description into the country. The result was that the demand for exchange became so great that in spite of the fact that it was the season when exports normally meant low exchange, rates were pushed up to the gold export point.

2. Heavy purchasing movements of our own or foreign securities, on the other side, are the second great influence making for high exchange. There come times when, for one reason or another, the movement of securities is all one way, and when it happens that for any cause we are the ones who are doing the buying, the exchange market is likely to be sharply influenced upward by the demand for bills with which to make payments. Such movements on a greater or less scale go on all the time and constitute one of the principal factors which exchange managers take into consideration in making their estimate of possible exchange market fluctuations.

It is interesting, for instance, to note the movement of foreign exchange at times when a heavy selling movement of American stocks by the foreigners is under way. Origin of security-selling on the Stock Exchange is by no means easy to trace, but there are times when the character of the brokers doing the selling and the very nature of the stocks being disposed of mean much to the experienced eye. Take, for instance, a day when half a dozen brokers usually identified with the operations of the international houses are consistently selling such stocks as Missouri, Kansas & Texas, Baltimore & Ohio, or Canadian Pacific—whether or not the inference that the selling is for foreign account is correct can very probably be read from the movement of the exchange market. If it is the case that the selling comes from abroad and that we are buying, large orders for foreign exchange are almost certain to make their appearance and to give the market a very strong tone if not actually to urge it sharply upward. Such orders are not likely to be handled in a way which makes them apparent to everybody, but as a rule it is impossible to execute them without creating a condition in the exchange market apparent to every shrewd observer. And, as a matter of fact, many an operation in the international stocks is based upon judgment as to what the action of the exchange market portends. Similarly—the other way around—exchange managers very frequently operate in exchange on the strength of what they judge or know is going to happen in the market for the international stocks. With the exchange market sensitive to developments, knowledge that there is to be heavy selling in some quarter of the stock market, from abroad, is almost equivalent to knowledge of a coming sharp rise in exchange on London.

Perhaps the best illustration of how exchange can be affected by foreign selling of our securities occurred just after the beginning of the panic period in October of 1907. Under continuous withdrawals of New York capital from the foreign markets, exchange had sold down to a very low point. Suddenly came the memorable selling movement of "Americans" by English and German investors. Within two or three days perhaps a million shares of American stocks were jettisoned in this market by the foreigners, while exchange rose by leaps and bounds nearly 10 cents to the pound, to the unheard-of price of 4.91. Nobody had exchange to sell and almost overnight there had been created a demand for tens of millions of dollars' worth.

3. The coming to maturity of American bonds held abroad is another influencing factor closely kept track of by dealers in exchange. So extensive is the total foreign investment in American bonds that issues are coming due all the time. Where some especially large issue runs off without being funded with new bonds, demand for exchange often becomes very strong. Especially is this the case with the short-term issues of the railroads and most especially with New York City revenue warrants which have become so exceedingly popular a form of investment among the foreign bankers. In spite of its mammoth debt, New York City is continually putting out revenue warrants, the operation amounting, in fact, to the issue of its notes. Of late years Paris bankers, especially, have found the discounting of these "notes" a profitable operation and have at times taken them in big blocks.

Whenever one of these blocks of revenue warrants matures and has to be paid off, the exchange market is likely to be strongly affected. Accumulation of exchange in preparation is likely to be carried on for some weeks ahead, but even at that the resulting steady demand for bills often exerts a decidedly stimulating influence. Experienced exchange managers know at all times just what short-term issues are coming due, about what proportion of the bonds or notes have found their way to the other side, just how far ahead the exchange is likely to be accumulated. Repayment operations of this kind are often almost a dominant, though usually temporary, influence on the price of exchange.

4. Low money rates are the fourth great factor influencing foreign exchange upward. Whenever money is cheap at any given center, and borrowers are bidding only low rates for its use, lenders seek a more profitable field for the employment of their capital. It has come about during the past few years that so far as the operation of loaning money is concerned, the whole financial world is one great market, New York bankers nowadays loaning out their money in London with the same facility with which they used to loan it out in Boston or Philadelphia. So close have become the financial relationships between leading banking houses in New York and London that the slightest opportunity for profitable loaning operations is immediately availed of.

Money rates in the New York market are not often less attractive than those in London, so that American floating capital is not generally employed in the English market, but it does occasionally come about that rates become abnormally low here and that bankers send away their balances to be loaned out at other points. During long periods of low money, indeed, it often happens that large lending institutions here send away a considerable part of their deposits, to be steadily employed for loaning out and discounting bills in some foreign market. Such a time was the long period of stagnant money conditions following the 1907 panic. Trust companies and banks who were paying interest on large deposits at that time sent very large amounts of money to the other side and kept big balances running with their correspondents at such points as Amsterdam, Copenhagen, St. Petersburg, etc.,—anywhere, in fact, where some little demand for money actually existed. Demand for exchange with which to send this money abroad was a big factor in keeping exchange rates at their high level during all that long period.

5. High money rates at some given foreign point as a factor in elevating exchange rates on that point might almost be considered as a corollary of low money here, but special considerations often govern such a condition and make it worth while to note its effect. Suppose, for instance, that at a time when money market conditions all over the world are about normal, rates, for any given reason, begin to rise at some point, say London. Instantly a flow of capital begins in that direction. In New York, Paris, Berlin and other centers it is realized that London is bidding better rates for money than are obtainable locally, and bankers forthwith make preparations to increase the sterling balances they are employing in London. Exchange on that particular point being in such demand, rates begin to rise, and continue to rise, according to the urgency of the demand.

Particular attention will be given later on to the way in which the Bank of England and the other great foreign banks manipulate the money market and so control the course of foreign exchange upon themselves, but in passing it is well to note just why it is that when the interest rate at any given point begins to go up, foreign exchange drawn upon that point begins to go up, too. Remittances to the point where the better bid for money is being made, are the very simple explanation. Bankers want to send money there, and to do it they need bills of exchange. An urgent enough demand inevitably means a rise in the quotation at which the bills are obtainable. Which suggests very plainly why it is that when the Directors of the Bank of England want to raise the rate of exchange upon London, at New York or Paris or Berlin, they go about it by tightening up the English money market.

The foregoing are the principal causes making for high exchange. The causes which make up for low rates must necessarily be to a certain extent merely the converse, but for the sake of clearness they are set down. The division is about as follows:

1. Especially heavy exports of merchandise.

2. Large purchases of our stocks by the foreigners and the placing abroad of blocks of American bonds.

3. Distrust on our part of financial conditions existing at some point abroad where there are carried large deposits of American capital.

4. High money rates here.

5. Unprofitably low loaning rates at some important foreign centre where American bankers ordinarily carry large balances on deposit.

1. Just as unusually large imports of commodities mean a sharp demand for exchange with which to pay for them, unusually large exports mean a big supply of bills. In a previous chapter it has been explained how, when merchandise is shipped out of the country, the shipper draws his draft upon the buyer, in the currency of the country to which the merchandise goes. When exports are heavy, therefore, a great volume of bills of exchange drawn in various kinds of currency comes on the market for sale, naturally depressing rates.

Exports continue on a certain scale all through the year, but, like imports, are heavier at some times than others. In the Fall, for instance, when the year's crops are being exported, shipments out of the country invariably reach their zenith, the export nadir being approached in midsummer, when the crop has been mostly exported and shipments of manufactured goods are running light.

From the middle of August, when the first of the new cotton crop begins to find its way to the seaport, until the middle of December, when the bulk of the corn and wheat crop exports have been completed, exchange in very great volume finds its way into the New York market. Normally this is the season of low rates, for which reason many shippers of cotton and grain, who know months in advance approximately how much they will ship, contract ahead of time with exchange dealers in New York for the sale of the bills they know they will have. By so doing, shippers are often able to obtain very much better rates. They can then protect themselves, at least, from the extremely low rates which they may be forced to take if they wait and accept going rates at a time when shippers all over the country are trying to sell their bills at the same time.

How great is the rush of exchange into market may be seen from the statistics of cotton exports during the period given below. Not all of this cotton goes out during the last four months of the year, but the greater part of it does and, furthermore, cotton, while the most important, is only one of the domestic products exported in the autumn.

| Money Value of Cotton Exported | |

|---|---|

| 1913 | $547,357,000 |

| 1912 | 565,849,000 |

| 1911 | 585,318,000 |

| 1910 | 450,447,000 |

| 1909 | 417,390,000 |

During the autumn months, under normal conditions, the advantage is all with the buyer of foreign exchange. By every mail huge packages of bills, drawn against shipments of cotton, wheat and corn, come pouring into the New York market. Bankers' portfolios become crowded with bills; remittances by each steamer, in the case of some of the big bankers, run up, literally, into the millions of dollars. Naturally, any one wanting bankers' exchange is usually able to secure it at a low price.

2. With regard to the second influence making for low exchange, sale of American bonds or stocks abroad, no season can be set when the influence is more likely to be operative than at any other, unless, possibly, it be the Spring, when money rates are more apt to be low and bond issues larger than at any other time of the year. No time, however, can be definitely set—there are years when the bulk of the new issues are brought out in the Spring and other years when the Fall season sees most of the new financing. But whatever the time of the year, one thing is certain—the issue of any amount of American bonds with Europe participating largely means a full supply of foreign exchange not only during the time the issues are actually being brought out, but for long afterward.

There used to be a saying among exchange dealers that cotton exports make exchange faster than anything, but nowadays bond sales abroad have come to take first place. For foreign participation in syndicates formed to underwrite new issues almost invariably means the drawing of bills representing the full amount of the foreign participation. A syndicate is formed, for instance, to take off the hands of the X Y Z railroad $30,000,000 of new bonds, the arrangement being that the railroad is to receive its money at once and that the syndicate is to take its own time about working off the bonds. Half the amount, say, has been allotted to foreign houses. Immediately, the drawing of £3,000,000, or francs 75,000,000, as the case may be, begins. The foreign houses have to raise the money, and in nine cases out of ten, their way of doing it is to arrange with some representative abroad to let them draw long drafts, against the deposit of securities on this side. These drafts, in pounds or francs, at sixty to ninety days' sight, they can sell in the exchange market for dollars, thus securing the money they have agreed to turn over to the railroad. In the meantime, during the life of the drafts they have set afloat and before they come due and have to be paid off, the bankers here can go about selling the bonds and getting back their money. Perhaps before the sixty or ninety days, as the case may be, are over, the syndicate may have sold out all its bonds and its foreign members have been put in a position where they can pay off all the drafts they set afloat originally in order to raise the money.

Very often, however, it will happen that on account of one reason or another, sixty days pass or ninety days pass without the syndicate having been able to dispose of its bonds. In that case the long bills drawn on the foreign bankers have to be "renewed"—that being a process for which ample provision has, of course, been made. In a succeeding chapter, full description of how long bills of exchange coming due are renewed will be made. Just here it is only necessary to say that most or all of the money necessary to pay off the maturing bills is raised by selling another batch of "sixties" or "nineties," an operation which throws the maturity two or three months further ahead.

From this outline of the way foreign participation in American bond issues is financed, it can be seen that every time a big issue of bonds of a railroad or industrial in which European investors are actively interested, is brought out, it means a large supply of foreign exchange created and suddenly thrown on the exchange market for sale. Not any more suddenly or publicly than the bankers concerned can help, but still necessarily so to a great degree, because big bond issues can only be made with the full knowledge and coöperation of a large part of the public. Bankers who know in advance of large issues likely to be made and in which they know they will be asked to participate, often sell "futures" covering the exchange they foresee their participation will bring into existence, but as a general rule it may be set down that heavy issues, involving the sale abroad of large amounts of bonds, are a most depressing factor on the foreign exchange market. Especially so, as the participants who have agreed to turn over the money to the railroad, must sell bills to raise it, even if the horde of speculators and "trailers" who are always on the lookout for such opportunities, make every effort to sell the market out from under their feet.

3. Uneasiness with regard to the stability of the financial situation at some point abroad where American bankers usually carry large balances is another circumstance which often depresses the exchange market sharply. "Trouble in the Balkans" and "trouble over the Moroccan situation" are two bugbears which have for years back furnished the keynote for many swoops downward in the exchange market, and for years after this book is published will probably continue to do so. Money on deposit at a point several thousand miles away is naturally very sensitive, and the least suspicion of financial trouble is sufficient to cause its withdrawal. Withdrawal of bankers' balances from a foreign city means offerings of exchange drawn on that point with resultant decline in rates.

In the everyday life of the exchange market, political developments of an unfavorable character and war rumors are about the most frequent and potent influences toward the condition of uneasiness above referred to. Few war rumors ever come to anything, but there are times when they circulate with astonishing frequency and persistence and cause decided uneasiness concerning financial conditions at important points. At such times bankers having money on deposit at those points are apt to become influenced by the drift of sentiment and to draw down their balances. Here, again, operators in exchange, keenly on the alert for such chances, will very likely begin to sell the exchange market short and often succeed in breaking it to a degree entirely unwarranted by the known facts.

4. But of all the sure depressing influences on exchange, none is more sure than a rise in the money market. More gradual usually than a decline caused by such an influence as the sale of American bonds abroad, the influence of a rising level of money rates is nevertheless far more certain.

The theory of this "counter" movement in money rates and exchange is simply that when money rates rise, say at a point like New York, American bankers find it profitable to draw in their deposits from all over Europe for the purpose of using the money in New York. Such a process means a wholesale drawing of bills of exchange on all the leading European cities, with consequent offering of the bills and price-depression in the leading American exchange markets.

The number of banks scattered all over the United States which keep running deposit accounts in the leading European cities has become surprisingly great during the past ten years, and a movement to bring home this capital has to go only a little way before it reaches very large proportions. That is exactly what happens when money rates at a point like New York become decidedly more attractive than they are over on the other side. Arrangements with foreign correspondents usually call for a minimum balance of considerable size, which must be left intact, but under ordinary circumstances there is considerable leeway, and when the better opportunity for loaning presents itself here, drafts on balances abroad, in large aggregate amount, are apt to be drawn and sold in this market. Especially is this the case when the cause of the higher money level appears to be deep-rooted and the outlook is for a continuance of the condition for some time to come.

5. Lastly, as a depressing factor, there is to be considered the condition which arises when money at some important foreign center, such as London or Paris, begins to ease decidedly. Large receipts of gold from the mines, a bettering political outlook—these or many other causes may bring it about that money in London, for instance, after a period of high rates, may ease off faster than in Berlin or Hamburg. As a result, American bankers having large balances in London and finding it difficult to employ them profitably there, any longer, either withdraw them entirely or have the money transferred to some other point. In either case the operation will result in depressing the rate of exchange on London, for the American banker will either draw on London himself or, if he wants to transfer the money to Berlin or Hamburg, will instruct the German bankers by cable to draw for his account on London. In whatever way it is accomplished, the withdrawal of capital from any banking point tends to lower the rate of foreign exchange on that point.

These are the main influences bearing on the fluctuation of exchange. Needless to say they are not exerted all one way, or one at a time, as set forth. The international money markets are a most decidedly complex proposition, and there is literally never a time when several influences tending to put rates up are not conflicting with several influences tending to put rates down. The actual movement of the rate represents the relative strength of the two sets of influences. To be able to "size up" the influences present and to gauge what movement of rates they will result in, is an operation requiring, first, knowledge, then judgment. The former qualification can perhaps be derived, in small degree, from study of the foregoing pages. The latter is a matter of mental calibre and experience.

CHAPTER IV

THE VARIOUS KINDS OF EXCHANGE

Before taking up the question of the activities of the foreign exchange department and the question of how bankers make money dealing in exchange, it may be well to fix in mind clearly what the various forms of foreign exchange are. Following is a description of the most important classes of bills bought and sold in the New York market:

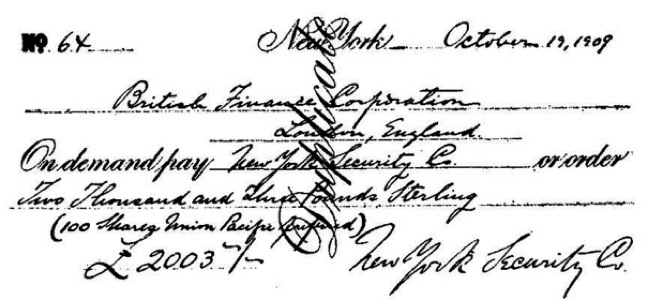

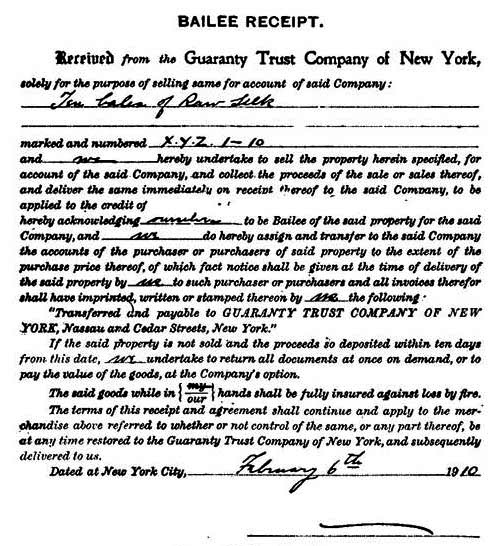

1. Commercial Long Bills

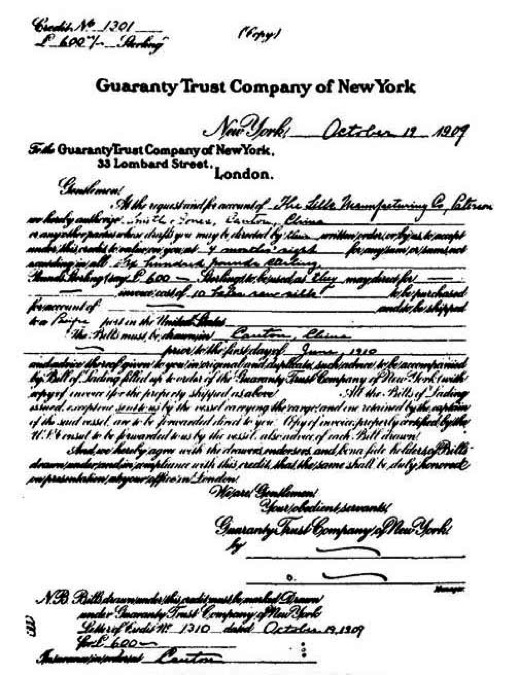

Drafts drawn by shippers of merchandise upon buyers abroad, or upon the banking representatives of the buyers abroad, at thirty days' sight or more. The drafts may be accompanied by shipping documents or may be "clean." The former kind of bill making up the greater part of the whole amount of foreign exchange dealt in in the New York market, will be described first.

Suppose a cotton dealer in Memphis to have sold one hundred bales of cotton to a spinner in Liverpool, the arrangement being that the English buyer is to be drawn on at sixty days' sight. The first thing the Memphis merchant does is to ship the cotton on its way to Liverpool, receiving from the railroad company a receipt known as a "bill of lading." At the same time he arranges for the insurance of the cotton, receiving from the insurance company a little certificate stating that the insurance has been effected.

The next step is for the Memphis shipper to draw the draft on the Liverpool buyer—or upon some bank abroad designated by the buyer. This draft is drawn in pounds sterling for the equivalent of the dollar value of the cotton and made payable sixty days after the party abroad on whom it is drawn has seen it and written "accepted" across its face. This draft, the bill of lading received from the shipping company, and the insurance certificate received from the insurance company are then pinned together and constitute a complete "commercial long bill with documents attached."

Other less important documents go with such a bill. Sometimes invoices showing the weight and price of the cotton go along with it and sometimes there is also attached a "hypothecation slip" which formally turns over the right to the goods to the Memphis or New York banker who buys the draft and accompanying documents from the Memphis cotton shipper. Sometimes, too, insurance is effected by the buyer abroad, in which case there may be no insurance certificate. But in the main, one of these "documentary" commercial bills consists of the draft itself, the bill of lading, and an insurance certificate.

Having pinned the document and the draft together, the Memphis cotton shipper is in possession of an instrument which he can dispose of for dollars. This he does either by selling it to his bank in Memphis or by sending it to New York, in order that it may be sold there in the exchange market at the current rate of exchange. Say, the bill of exchange is drawn on London at sixty days' sight, for £1,000. The buying price for such a draft will be, perhaps, 4.84. The Memphis shipper gets his check for $4,840, and is out of the transaction. The bill has passed into a banker's hands, who will send it abroad—deposit it in some foreign bank where he keeps a balance.

As to the rate of 4.84 received by the shipper, it is to be noted that had the bill been drawn at less than sixty days' sight, he would have received more dollars for it, while if it had been drawn at more than sixty days' sight, he would have received less for it. The longer the banker who takes the draft off the shipper's hands has to wait until he can get his money back on it, the lower, naturally, the rate of exchange he is willing to pay. On the same day that demand drafts are selling at 4.87, sixty-day drafts may be selling at 4.84 and ninety-day drafts at 4.83.

Assume, in this particular case, that the draft has been taken off the shipper's hands by some foreign exchange banker in New York. By the very first steamer the latter will forward it to his banking correspondent abroad, with instructions to present it at once to the parties on whom it is drawn, in order that they may mark it "accepted—payable such-and-such-a-date." After that the bill is a double obligation of the drawer and the drawee, and may be discounted in the open market, for cash.

Just here it is necessary to digress and state that documentary commercial bills are of two kinds—"acceptance" bills and "payment" bills. In the case of the first-named, the documents are delivered to the party on whom the bill is drawn as soon as he "accepts" the bill, which puts him in a position to get possession of the merchandise at once. In the case of a "payment" bill, the credit of the man on whom it is drawn is not good enough to entitle him to such a privilege, and the only way he can get actual possession of the goods is to actually pay the draft under a rebate-of-interest arrangement. All bills drawn on banks are naturally "acceptance" bills; and being discountable and thus immediately convertible into cash abroad, command a better rate of exchange in the New York market than "payment" bills, which may be allowed to run all the way to maturity before a single pound sterling is paid on them.

Except in the case of the shipment of perishable merchandise—grain shipped in bulk, for instance. In that case the buyer on the other side cannot afford to let the draft run, because the merchandise would spoil. He is simply forced to pay it under rebate, in order to get possession of the grain. And the rebate being always less than the discount rate, less pounds sterling come off the face of the bill in the process of rebating than of discounting. For which reason sixty-day bills drawn against shipments of grain—documents deliverable only on payment under rebate—command a better rate of exchange even than the very best of cotton "acceptance" bills drawn on banks.

2. Clean Bills

Where the drafts of the merchants of one country drawn upon the merchants or bankers of another are unaccompanied by shipping documents they are said to be "clean." Bills of this kind may originate from the transfer of capital from one country to another or may represent drawings against shipments of merchandise previously made. It is not unusual, indeed, where the relationship between some foreign merchant and some American merchant is very close, for the one to ship merchandise to the other without drawing drafts against the shipment until some little time afterward. It might happen, for instance, that a cotton manufacturing firm in France wanted to import a lot of raw cotton from the United States, but did not want to be drawn upon at the time. Under such circumstances the American house might ship the goods and send over the documents to the buyer, postponing its drawing for some time. Eventually, of course, the American house would reimburse itself by drawing, but the documents having gone forward long before, the drafts would be what is known as "clean."

Later on, in the chapter on the actual money-making operations of the foreign department, the risk in buying various kinds of bills will be fully explained, but in passing it may be mentioned that "clean" bills are of such a nature that bankers will touch them only when drawn by the very best houses. With a documentary bill, the banker holds the bill of lading, and if there is any trouble about the acceptance or payment of a draft, can simply seize the goods and sell them. But in the case of a "clean" bill, he has absolutely no security. The standing of the maker of the bill and what he knows about the maker's right to draw the bill is all he has to go by in determining whether to buy it or not.

3. Documentary Commercial Bills Drawn at Short Sight

A comparatively small part of our exports are sold on a basis where the draft drawn is at less than thirty days' sight, but there are a good many small bills of this kind continually coming into the market. Drafts drawn against manufactured articles and against such products as cheese, butter, dried fruits, etc., are apt to be drawn for, with shipping documents attached, at anywhere from three to thirty days' sight, but there is no rule about it. Where the "usance"—the time the bill has to run—is only a few days, documents are apt to be deliverable only on payment of the bills.

4. Drafts Drawn Against Securities

Exchange of this kind is naturally of the highest class, the stocks or bonds against which it is drawn being almost always attached to the bill of exchange. In the case of syndicate participations by large houses, the bonds may be shipped abroad privately and exchange against them drawn and sold independently, in which case, of course, no security is attached, but as a rule the bonds or stocks go with the draft. A, in New York, executes an order to buy for B in London, one hundred Union Pacific preferred shares on the New York Stock Exchange. The stock comes into A's office, and he pays for it with the proceeds of a sterling draft he draws on B. The stock itself he attaches to this sterling draft. Whoever buys the draft of him gets the stock with it and keeps possession of it till the draft is presented and paid in London.

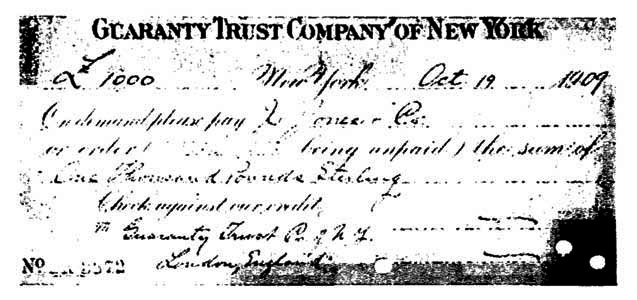

5. Bankers' Checks or Demand Drafts on Their Correspondents Abroad

Bankers who do a foreign exchange business, keeping large balances in several European centers, are continually drawing and selling their demand drafts—"checks," they are called, or "demand"—upon these foreign balances. Such checks are always to be had in great volume in the exchange market, the banker's business being to draw and sell exchange, and his degree of willingness being merely a matter of rate. There come times, of course, when bankers have every reason to leave their foreign balances undisturbed, but even at such times the bid of a high enough rate will usually bring about the drawing of bills.

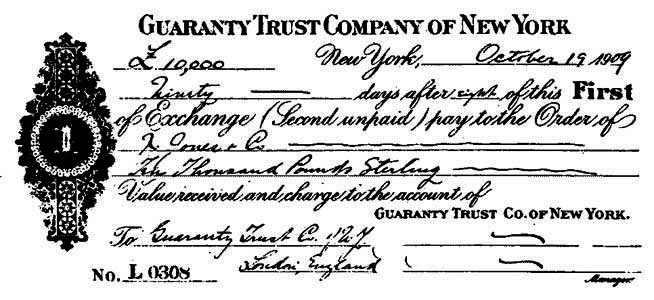

6. Bankers' Long Drafts

In describing the nature of bankers' drawings of long bills, great care must be taken to differentiate between the different kinds of long bills being bought and sold in the exchange market. A finance bill looks exactly the same as a long bill drawn by a banker for a commercial customer who wants to anticipate the payment abroad for an incoming shipment of wool or shellac, but the nature and origin of the two bills are radically different. The three main kinds of bankers' long bills will thus be taken up in the following order:

A. Bills Drawn in the Regular Course of Business

Such is the nature of foreign exchange business that bankers engaged in it are continually drawing their sixty and ninety days' sight bills in response to their own and their customers' needs. One example which might be cited is that of the importer who has a payment to make on the other side, sixty days from now, but who, having the money on hand, wants to make it at once. Under some circumstances such an importer might remit a demand draft on the basis of receiving a rebate of interest for the unexpired sixty days, but more likely he would go to a banker and buy from him a sixty days' sight draft for the exact amount of pounds he owed. The cost of such a draft—which would mature at the time the debt became due—would be less than the cost of a demand draft, the importer getting his rebate of interest out of the cheaper price he pays for the pounds he needs. Prepayments of this sort are responsible every day for very large drawings of bankers' long bills.

B. Long Bills Issued in the Operation of Lending Foreign Money

Bills of this kind represent by far the greater proportion of bankers' long bills sold in the exchange market. European bankers keep an enormous amount of floating capital loaned out in this market, in the making and renewing of which loans long bills are created as follows:

A banker on the other side decides to loan out, say, £100,000 in the New York market. Arrangements having been made, he cables his New York representative to draw ninety days' sight drafts on him for £100,000, the proceeds of which drafts are then loaned out for account of the foreign house. The matter of collateral, risk of exchange and, indeed, all the other detail, will be fully described in the succeeding chapters on how bankers make money out of exchange. For the time being it is merely necessary to note that every time a loan of foreign capital is made here—and there are days when millions of pounds are so loaned out—bankers' long bills for the full amount of the loans are created and find their way into the exchange market.

C. Bankers' Long Bills Drawn for the Purpose of Raising Money

Finance bills constitute the third kind of bankers' long exchange. In this case, again, detailed discussion must be put off until the chapter on foreign-exchange-bankers' operations, but the fact that bills of this kind constitute so important a part of the bankers' long bills to be had in the market, necessitates their classification in this place. Every time a banker here starts to use his credit abroad for the purpose of raising money—and there are times when the privilege is pretty freely availed of—he does it by drawing sixty or ninety days' sight drafts on his correspondents abroad. Finance bills, it may be said without question, are one of the most interesting forms of foreign exchange banking—at the same time one of the most useful and one of the most abused of privileges coming to the domestic banker by reason of his having strong banking connections abroad.

CHAPTER V

THE FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET

The foreign exchange market is in every sense "open"—anyone with bills to buy or sell and whose credit is all right can enter it and do business on a par with anyone else. There is no place where the trading is done, no membership, license or anything of the kind. The "market," in fact, exists in name only; it is really constituted of a number of banks, dealers and brokers, with offices in the same section of the city, and who do business indiscriminately among themselves—sometimes personally, sometimes by telephone, by messenger, or by the aid of the continuously circulating exchange brokers.

The system is about as follows: The larger banks and banking houses have a foreign exchange manager, or partner, taking care of that part of the business, whose office is usually so situated as to make him accessible to the brokers who come in from the outside, and whose telephoning and wiring facilities are very complete. These larger houses have no brokers or "outside" men in their employ. The manager knows very well that plenty of chance to do business, buying or selling, will be brought in to him by the brokers and that his wires keep him constantly in touch with his fellow bankers.

Next come the big dealers in exchange, some of whom do a regular exchange business of their own, the same as the bankers, but who also have men out on the street "trading" between large buyers and sellers of bills. Such houses are necessarily closely in touch with banks, bankers, exporters, and importers all over the country, and have always large orders on hand to buy and sell exchange. Some of the bills they handle they buy and use for the conduct of their own business with banks abroad, but the more important part of what they do is to deal in foreign exchange among the banks. They are known as always having on hand for sale large lines of commercial and bankers' bills, while on the other hand they are always ready to buy, at the right price.

After this class of houses come the regular brokers—the independent and unattached individuals who spend their time trying to bring buyer and seller together, and make a commission out of doing it. In a market like New York the number of exchange brokers is very large. Like bond-brokerage, the business requires little in the way of office facilities or capital, and is attractive to a good many persons who are willing to accept the small income to be made out of it in return for being in a business where they are independent.

Foreign exchange brokerage, like all other employment of the middleman, is not what it used to be. Before the business became overcrowded as it is now, exchange brokers made their quarter-cent in the pound commission, and could depend on a respectable income. But nowadays brokers swarm among the foreign exchange bankers and dealers, doing business on any commission they can get, which is not infrequently as little as 1/128 of one per cent., say, $1.50, for buying or selling francs 100,000. In handling sterling, the broker is lucky if he makes his five points (5/100 of a cent per pound), which means that for turning over £10,000 he would be rewarded with the sum of $5. Under such conditions it is not difficult to see how hard it is to make any money to speak of out of foreign exchange brokerage.

The dealers, of course, fare much better. Handling commercial bills where the question of credit affects the price, they have a chance to make more of a profit, and buying and selling bills for their own account they naturally are entitled to make more than the man without capital, who simply tries to get in between the buyer and the seller. Dealing in exchange, especially for out-of-town clients, is a highly profitable business, but one which takes time, brains, experience and money to build up. Dealers representing large out-of-town sellers of exchange are very much in the position of the New York agents of manufacturing companies who sell goods on commission.

There being no regular market in which foreign exchange rates are made, it follows that the establishment of rates each morning and during the course of each day will be according to the supply and demand for bills. On any given morning by ten o'clock the bankers will all have received their cables quoting money and exchange rates in the foreign centers, and will all have pretty well made up their minds as to what the rate for demand bills on London ought to be. A banker, for instance, has £10,000 he wants to sell as early in the morning as possible, and from his foreign cables figures that 4.86 is about the right price. He offers it at that, but learns that another banker is offering exchange at 4.8595. He offers his own at that price, and somebody comes along, taking both lots and bidding 4.86 for £50,000 more. Somebody else bids 4.86 for other large lots, refusing, however, to pay 4.8605. The market is established at that point.

For the time being. A cable message from abroad may induce some banker to bid 4.8605 or 4.8610, or it may cause him to throw on the market such an amount of exchange as may break the price down to 4.85-3/4. Rates are constantly changing, and changing at times almost from minute to minute. Yet so complete is the system of telephones and brokers that any exchange manager can tell just about what is taking place in any other part of the market. Not infrequently, of course, sales are made simultaneously at slightly different rates, but, as a rule, if a trade is made at 4.86 on Cedar Street, 4.86 will be the rate on Exchange Place. It is remarkable how closely each manager keeps in touch with what is going on in every part of the market. And the great number of brokers continually circulating around and trying to "get in between" for five points is in itself a powerful influence toward keeping rates exactly the same in all parts of the market at once.

"Posted rates" mean little with regard to current conditions, being simply the bankers' public notice of the rate at which he will sell bills for trifling amounts. Exchange bankers dislike to draw small drafts and usually can be induced to do so only by the offer of a much higher rate than that current for a large amount. A banker might offer to sell you £10,000 at 4.87, but if you said you wanted only £10, he would be likely to point to his posted rate and charge you 4.88. Considering that in transactions based on the best bills the banker only figures on making from $10 to $20 profit on each £10,000, it may readily be seen why he is not anxious to sell a £10 draft.

As to the actual fluctuation of exchange, while it is true that rates at times rise and fall with all the violence so often displayed in the security markets, most of the time they move within a comparatively narrow range. On an ordinary business day, for instance, the change is not apt to run over fifteen points (15/100 of a cent per pound). In the morning, demand sterling may be at, say, 4.86; at noon a moderate demand for bills may carry the rate, first, to 4.8605, then to 4.8610; and finally, perhaps, to 4.8615. On fairly large offerings of bills the market might then recede to, say, 4.8605, ending the day five points up. And that would be an ordinary day—by no means the kind of a day the exchange market always sees, but a day corresponding to a stock market session in which the market leaders rise or fall a point or so.

There are times, of course, when very different conditions prevail. An unexpected rise in the bank rate in London, the announcement of a big loan or any one of many different happenings, are apt to cause a reduction in the exchange market and a bewildering movement of rates up and down. At such times a rise or fall of fifty points in sterling within half an hour is not at all out of the ordinary, while in times of panic, or when great crises impend, the fluctuations will be three or four times as great. During the latter part of October, 1907, and in November, the exchange market fluctuated with greater violence than, perhaps, at any other time since the gold standard was firmly established. Thrown completely out of gear by the premium of 3-1/2 per cent. a day for currency during the panic time, the exchange markets for some time would rise and fall several cents in the pound on the same day. Completely baffled by this erratic movement, many bankers temporarily withdrew entirely from the market.

As to the relative importance of the different kinds of exchange, sterling, of course, occupies the most prominent position. What proportion of the total of exchange dealt in in the New York market consists of sterling it is impossible to determine, but that it is as great as the volume of all the other kinds of exchange put together can safely be said. Many big dealers, indeed, make a specialty of sterling, and if they handle any other bills at all, do so only on a very small scale. As to whether francs or marks come next in volume, there is a difference of opinion. With Germany our direct financial transactions are probably considerably larger than with France, but the position of Paris as a banking centre makes the French capital figure prominently in many operations where the French market is not directly concerned. Despite the fact that sterling easily predominates, the volume of franc and mark bills, too, is enormous. Drafts on Paris for from three to five million francs and on Berlin for as many marks are not at all infrequently traded in in the exchange market, and at times bills for very much larger amounts have been drawn and offered for sale.

Bills drawn in other kinds of currency—guilders on Holland, for instance, form an important part of the foreign exchange dealt in in a market like New York, but are subservient in their rate fluctuations to the movement of sterling, marks, and francs. The latter are, indeed, the three great classes of exchange, and are the basis of at least nine-tenths of all foreign exchange operations.

In the following chapter will be taken up the various forms of activity of the foreign exchange department. No attempt is made to state out of which kind of business bankers make most money, but before looking into the more detailed description of how exchange business is conducted, it may be well to fix in mind the fact that it is out of the "straight" forms of foreign exchange business that the most profit is made. Highly complicated operations are indulged in by some managers with more theoretical than practical sense, and money is at times made out of them, but on the whole the real money is made out of the kinds of business about to be described. To the author's certain knowledge, the exchange business of one of the largest houses in New York was for years thus limited to what might be called "straight" operations. While the profits might at times have been materially increased by the introduction of a little more of a speculative element into the business, the house made money on a large scale and avoided the losses inevitable where business is conducted along speculative lines.

CHAPTER VI

HOW MONEY IS MADE IN FOREIGN EXCHANGE. THE OPERATIONS OF THE FOREIGN DEPARTMENT