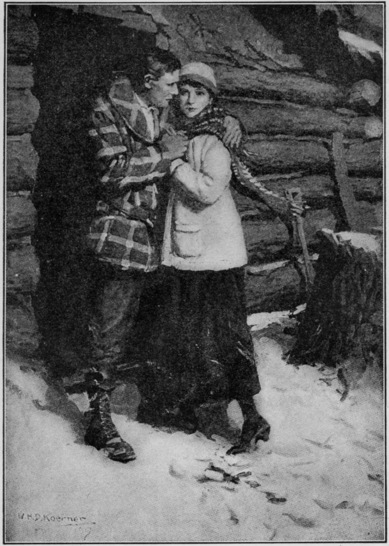

“God bless you, Madge,” said the man. “I will come soon.” See page 306

Title: The Peace of Roaring River

Author: George Van Schaick

Illustrator: W. H. D. Koerner

Release date: October 28, 2009 [eBook #30349]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

“God bless you, Madge,” said the man. “I will come soon.” See page 306

|

Copyright, 1918

BY SMALL, MAYNARD & COMPANY

(INCORPORATED)

Second Printing

| I. | The Woman Scorned | 13 |

| II. | What Happened to a Telegram | 26 |

| III. | Out of a Wilderness | 42 |

| IV. | To Roaring River | 71 |

| V. | When Gunpowder Speaks | 102 |

| VI. | Deeper in the Wilderness | 124 |

| VII. | Carcajou Is Shocked | 152 |

| VIII. | Doubts | 165 |

| IX. | For the Good Name of Carcajou | 189 |

| X. | Stefan Runs | 211 |

| XI. | A Visit Cut Short | 223 |

| XII. | Help Comes | 237 |

| XIII. | A Widening Horizon | 251 |

| XIV. | The Hoisting | 279 |

| XV. | The Peace of Roaring River | 290 |

| “God bless you, Madge,” said the man. “I will come soon.” See page 306 | Frontispiece |

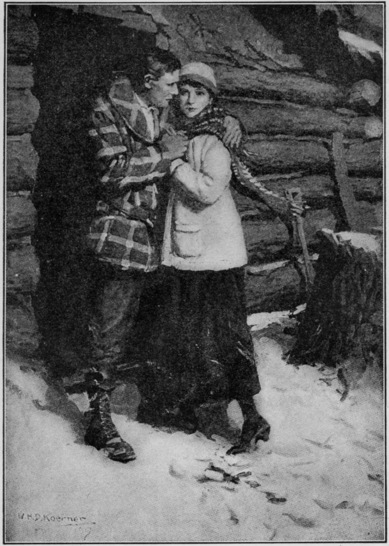

| Truth flashed upon her! In a few moments she would see for the first time the man she was to marry | 98 |

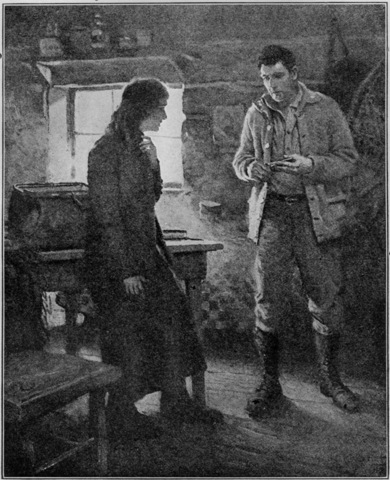

| “I’m glad you were not hurt. Rather unexpected, wasn’t it” | 122 |

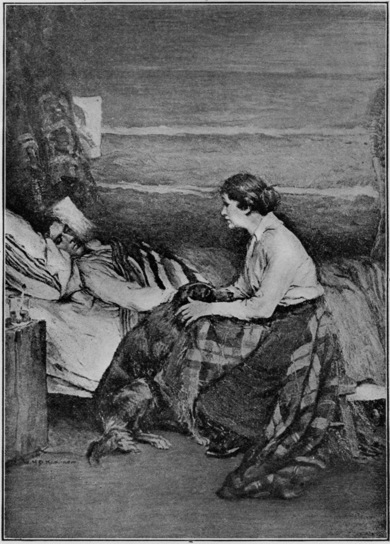

| He put out a brown hand and touched the girl’s arm | 270 |

THE PEACE OF ROARING RIVER

THE PEACE OF ROARING RIVER

To the village of Carcajou came a young man in the spring. The last patches of snow were disappearing from under the protecting fronds of trees bursting into new leaf. From the surface of the lakes the heavy ice had melted and broken, and still lay in shattered piles on the lee shores. Black-headed chickadees, a robin or two, and finally swallows had appeared, following the wedges of geese returning from the south on their way to the great weedy shoals of James’ Bay.

The young man had brought with him a couple of heavy packs and some tools, but this did not suffice. He entered McGurn’s store, after hesitating between the Hudson’s Bay Post and the newer building. A newcomer he was, and something of a tenderfoot, but he made no pretence of knowing it all. A gigantic Swede he addressed gave him valued advice, 14 and Sophy McGurn, daughter of the proprietor, joined in, smilingly.

She was a rather striking girl, of fiery locks and, it was commonly reported, of no less flaming temper. To Hugo Ennis, however, she showed the most engaging traits she possessed. The youth was good-looking, well built, and his attire showed the merest trifle of care, such as the men of Carcajou were unused to bestow upon their garb. The bill finally made out by Sophia amounted to some seventy dollars.

“Come again, always glad to see you,” called the young lady as Hugo marched out, bearing a part of his purchases.

For a month he disappeared in the wilderness and finally turned up again, for a few more purchases. On the next day he left once more with Stefan, the big Swede, and nothing of the two was seen again until August, when they returned very ragged, looking hungry, their faces burned to a dull brick color, their limbs lankier and, if anything, stronger than ever. The two sat on the verandah of the store and Hugo counted out money his companion had earned as guide and helper. When they entered the store Miss Sophia smiled again, graciously, and nodded a head adorned with a bit of new ribbon. There 15 were a few letters waiting for Hugo, which she handed out, as McGurn’s store was also the local post-office. The young man chatted with her for some time. It was pleasant to be among people again, to hear a voice that was not the gruff speech of Stefan, given out in a powerful bass.

“More as two months ve traipse all ofer,” volunteered the latter. “Ye-es, Miss Sophy, ma’am, ve vork youst like niggers. Und it’s only ven ve gets back real handy here, by de pig Falls, dat ve strike someting vhat look mighty good. Hugo here he build a good log-shack. He got de claim all fix an’ vork on it some to vintertime. Nex spring he say he get a gang going. Vants me for foreman, he do.”

This was pleasant news. Hugo would be a neighbor, for what are a dozen miles or so in the wilderness? He would be coming back and forth for provisions, for dynamite, for anything he needed.

“We had a fine trip anyway, and saw a lot of country,” declared Hugo, cheerfully.

“Ve get one big canoe upset in country close in by Gowganda,” said Stefan again. “Vidout him Hugo I youst git trowned.”

“That wasn’t anything,” exclaimed Hugo, hastily.

“It was one tamn pig ting for me, anyvays,” declared Stefan, roaring out with contented laughter.

Miss Sophy was not greatly pleased when Hugo civilly declined an invitation to have dinner with her ma and pa. The young man was disappointing. He spoke cheerfully and pleasantly but appeared to take scant notice of her new ribbon, to pay little heed to her grey-blue eyes.

After this, once or twice a week, Hugo would come in again, for important or trifling purchases. It might be a hundred pounds of flour or merely a new pipe. He was the only man in Carcajou who took off his cap to her when he entered the store, but when she would have had him lean over the counter and chat with her he seemed to be just as pleased to gossip with lumberjacks and mill-men, or even with Indians who might come in for tobacco or tea and were reputed to have vast knowledge of the land to the North. Once he half promised to come to a barn-dance in which Scotty Humphrey would play the fiddle, and she watched for him, eagerly, but he never turned up, explaining a few days later that his dog Maigan, an acquisition of a couple of months before, had gone lame and that it would have been a shame to leave the poor old fellow alone.

Sophy met him in the village street and he actually bowed to her without stopping, as if there might be more important business in the world than gossiping with a girl. She began to feel, after a time, that she actually disliked him. The station agent, Kid Follansbee, admired her exceedingly, and had timidly ventured some words of hopeful flirtation as a preliminary to more serious proposals. Two or three other youths of Carcajou only needed the slightest sign of encouragement, and there was a conductor of the passenger train who used to blow kisses at her, once in a while, from the steps of the Pullman. In spite of all this Sophy continued to smile and talk softly, whenever he entered the store, and he would answer civilly and cheerfully, and ask the price of lard or enquire for the fish-hooks that had been ordered from Ottawa. He would pat the head of the big dog that was always at his heels, throw a coin on the counter, slip his change in his pocket and go out again, as if time had mattered, when, as she knew perfectly well, he really hadn’t much to do. The poor fellow, she decided, was really stupid, in spite of his good looks.

The worst of it all was that some folks had taken notice of her efforts to attract Hugo’s attention. The people of Carcajou were good-natured 18 but prone to guffaws. One or two asked her when the wedding would take place, and roared at her indignant denials.

In the meanwhile Hugo was utterly ignorant of the feelings that had arisen in Miss Sophy McGurn’s bosom. He worked away at a great rocky ledge, and loud explosions were not uncommon at the big falls of Roaring River. Also he cut a huge pile of firewood against the coming of winter, and, from time to time, would take a rod and lure from the river some of the fine red square-tailed trout that abounded in its waters. A few books on mining and geology, and an occasional magazine, served his needs of mental recreation. A French Canadian family settled about a mile north of his shack soon grew friendly with him. There were children he was welcomed by, and a batch of dogs that tried in vain to tear Maigan to pieces, until with club and fang they were taught better manners. To the young man’s peculiar disposition such surroundings were entirely satisfactory. There was a freedom in it, a sense of personal endeavor, a hope of success, that tinted his world in gladdening hues.

When autumn came he shouldered his rifle and went out to the big swampy stretches of the upper river, where big cow moose and 19 their ungainly young, soon to be abandoned, wallowed in the oozy bottoms of shallow ponds and lifted their heads from the water, chewing away at the dripping roots of lily-pads. There were deer, also, and he caught sight of one or two big bull-moose but forebore to shoot, for the antlers were still in velvet and there was not enough snow on the ground to sledge the great carcasses home. He contented himself with a couple of bucks, which he carried home and divided with his few neighbors, also bringing some of the meat to Stefan’s wife at Carcajou. Later on he killed two of the big flathorns, hung the huge quarters to convenient trees and went back to Papineau’s, the Frenchman’s place, for the loan of his dog-team.

After this came the winter with heavy falls of snow and cold that sent the tinted alcohol in the thermometer at the station down very close to the bulb. Carcajou and its inhabitants seemed to go to sleep. The village street was generally deserted. Even the dogs stayed indoors most of the day, hugging the cast-iron stoves. At this time all the Indians were away at their winter hunting grounds, and many of the lumberjacks had gone further south where the weather did not prevent honest toil. The big sawmill was utterly silent and the river, 20 wont to race madly beneath the railroad bridge, had become a jumbled mass of ice and rock.

The only men who kept up steady work in and near Carcajou formed the section gang on the railroad. One day, in the middle of winter, and in quickly gathering shadows, Pete Coogan, their foreman, was walking the track back towards the village and had reached the big cut whose other end led to the bridge at Carcajou. The wind bit hard as it howled through the opening in the hill and the man walked wearily, pulling away at a short and extinct pipe and thinking of little but the comfort that would be his after he reached his little house and kicked off his heavy Dutch stockings. A hot and hearty meal would be ready for him, and after this he would light another pipe and listen to his wife’s account of the village doings. Since before daylight he had been toiling hard with his men, in a place where tons of ice and snow had thundered down a mountainside and covered the rails, four or five feet deep. The work had been hurried, breathless, anxious, but finally they had been able to remove the warning signals after clearing the track in time to let the eastbound freight thunder by, with a lowing of cold, starved cattle tightly 21 packed and a squealing of hogs by the legion. A frost-encased man had waived a thickly-mittened hand at them from the top of a lumber car, and the day’s work was over, all but clearing a great blocked culvert, lest an unexpected thaw or rain might flood the right of way. To these men it was all in the day’s work and unconscious passengers snored away in their berths, unknowing of the heroic toil their safety required.

So Pete walked slowly, his grizzled head bent against the blast as he struggled between the metals, listening. At a sudden shrieking roar he moved deliberately to one side, his back resting against a bank of snow left by the giant circular plough whose progress, on the previous day, had been that of a slow but irresistible avalanche. A crashing whistle tore the air and the wind of the rushing train pulled at his clothes and swirled sharp flakes into his eyes. Yet he dimly saw something white flutter down to his feet and he picked it up. It chanced to be a paper tossed out by some careless hand, a rather disreputable sheet printed some thousand miles away, one of the things that lie like scabs on the outer hide of civilization. It was much too dark and cold for him to think of removing a mitten and searching for the glasses in his coat 22 pocket. But the respect is great, in waste places, for the printed word. There news of the great outside world trickles in slowly, and he carefully stuffed the thing between two of the big horn buttons of his red-striped mackinaw.

There were but a few minutes more of toil for him. At last he passed over the bridge, in a flurry of swirling ice-crystals, and finally made his way into McGurn’s store, which is across the way from the railway depot.

“Cold night,” he announced, stamping his feet near the door.

“Follansbee he says they report fifty below at White River,” a man sitting by the stove informed him.

Coogan nodded and approached the counter.

“Give me a plug, Miss Sophy,” he told the girl who sat at a rough counter, adding figures. “The wind’s gettin’ real sharp and I got the nose most friz off’n my face.”

The girl rose, with a yawn, and handed him the tobacco. She swept his ten-cent piece in a drawer and sat down again. One of the men lounging about the great white-topped stove in the middle of the room pointed to Coogan’s coat.

“Ye’re that careless, Pete,” he said. “I ’low that’s a bundle o’ thousand dollar bills as is droppin’ off’n yer coat.”

The old section foreman looked down.

“Oh! I’d most forgot. This here’s some kind o’ paper I picked up on the track. Beats anything how passengers chucks things off. Mike Smith ’most got killed last week with an empty bottle. Lucky he had his big muskrat cap on. May be ye’d like to see it, Miss Sophy? Guess my old woman wouldn’t have no use for it as it don’t seem to have any picters in it.”

He was about to place it on the counter when one of the men took it from his hand and held it under the hanging oil lamp.

“Why!” he chuckled, somewhat raspingly. “It’s just what Sophy needs real bad. Ye wants ter study that real careful, Sophy. It’ll show ye as there’s just as good fish in the sea as was ever took out of it.”

The girl leaned far out over the counter and snatched the paper away from him.

“Yes, there’s just as good fish as that there Ennis lad,” repeated the man.

A single glance had acquainted Sophy with the title. It was the Matrimonial Journal. She flung it down to her feet, angrily.

“You get out of here with your Ennis!” she cried. “I wouldn’t––wouldn’t marry him if he was the last man on earth. I––I just despise him!”

“And that’s real lucky for ye,” snickered the man. “I heard him say––lemme see––yes, ’bout three-four days ago, as he wasn’t nowise partial ter carrots. It’s a wegetable as he couldn’t never bear the sight of.”

The girl’s hand went up to her fine head of auburn hair and a deep red rose from her cheeks to its roots. Her narrow lips became a mere slit in her face and her steely eyes flashed.

“And––and he’s the kind as thinks himself a gentleman!” she hissed out. “Get out o’ here, all of ye! There ain’t a man in Carcajou as I’d wipe my boots on. Clear out o’ here, I tell ye!”

The three men left, Pete silently and disapprovingly, the other two guffawing.

“I don’t believe as how that lad Ennis ever said anything o’ the kind,” declared the foreman. “He’s a fine bye, he is, and it ain’t like him.”

“Of course he didn’t,” the village joker assured him. “But ’twas too much of a chance ter get a rise out er Sophy for me to lose it. Ain’t she the hot-tempered thing? Just the same she wuz dead sot on gettin’ him, we all know that, an’ she’s mad clear through.”

“Well, I don’t see as yer got any call ter 25 rile the gal, just the same,” ventured Pete. “Like enough she can’t help herself, she can’t, and just because she got a temper like a sorrel mare ain’t no good reason ter be hurtin’ her feelin’s.”

But the other two chuckled again and started towards the big boarding-house, whose ceilings and walls were beautifully covered with stamped metal plates guaranteed to last for ever and sell for old iron afterwards. Its corrugated iron roof, to most of Carcajou’s population, represented the very last word in architectural glory.

Within the store Miss Sophy was biting her nails, excitedly, and felt all the fury of the woman scorned.

Customers were rare on such terribly cold nights. For a long time Sophy McGurn held her chin in the palm of her hand, staring about her from time to time, without seeing anything but the visions her anger evolved. Presently, however, she took up the small bag of mail and sorted out a few letters and papers, placing them in the individual boxes. But while she worked the heightened color of her face remained and her teeth often closed upon her lower lip. There was a postal card addressed to Hugo Ennis. She turned it over, curiously, but it proved to be an advertisement of some sort of machinery and she threw it from her, impatiently.

“Supper’s ready, Sophy,” cried a shrill voice. “Train’s in and father’ll be here in a minute. Get the table fixed.”

“I’m coming,” she answered.

For a minute she busied herself putting down plates and knives and forks. She heard her father coming in. He had been away on 27 some business at the next station. She heard him kicking off his heavy felt shoes and he came into the room in his stocking-feet.

“Hello, Ma! Hello, Sophy! Guess ye’ve been settin’ too close to the hot stove, ain’t ye? Yer face is red as a beet.”

“My face is all right!” she exclaimed, angrily. “Them as don’t like it can look the other way!”

Her mother, a quiet old soul, looked at her in silence and dished out the broiled ham and potatoes. The old gentleman snickered but forebore to add more fuel to the fire. He was a prudent man with a keen appreciation of peace. They sat down. Under a chair the old cat was playing with her lone kitten, sole remnant of a large litter. An aggressive clock with a boldly painted frame was beating loudly. Beneath the floor the oft-repeated gnawing of a mouse or rat went on, distractingly. From the other side of the road, in spite of double-windows and closed doors, came the wail of an ill-treated violin.

“One of these days I’m goin’ over to Carreau’s an’ smash that fiddle,” suddenly asserted Sophy, truculently. “It’s gettin’ on my nerves. Talk o’ cats screechin’!”

“I wouldn’t do that, Sophy,” advised her mother, patiently. “Not but what it’s mighty 28 tryin’, sometimes, for Cyrille he don’t ever get further’n them two first bars of ‘The Campbells are comin’.’”

Sophy sniffed and poured herself out strong tea. She drank two cups of it but her appetite was evidently poor, for she hardly touched her food. Her father was engaged in a long explanation of the misdeeds of a man who had sold him inferior pork, as she folded her napkin, slipped it into her ring, and went back into the store. Here she sat on her stool again, tapping the counter with closed knuckles. Her eyes chanced to fall upon the paper she had thrown down on the floor, and she picked it up and began to read. Pete Coogan, when he had brought it into the store, unknowingly had set big things in motion. He would have been amazed at the consequences of his act.

Presently Sophy became deeply interested. The pages she turned revealed marvelous things. Even to one of her limited attainments in the way of education and knowledge of the world the artificiality of many of the advertisements was apparent. Others made her wonder. It was marvelous that there were so many gentlemen of good breeding and fine prospects looking hungrily for soul-mates, and such a host of women, young or, in 29 a few instances, confessing to the early thirties, seeking for the man of their dreams, for the companion who would understand them, for the being who would bring poetry into their lives. Some, it is true, hinted at far more substantial requirements. But these, in the brief space of a few lines, were but hazily revealed. Among the men were lawyers needing but slight help to allow them to reach wondrous heights of forensic prosperity. There were merchants utterly bound to princely achievement. Also there was a sprinkling of foreign gentlemen suggesting that they might exchange titles of high nobility for some little superfluity of wealth. Good looks were not so essential as a kindly, liberal disposition, they asserted, and also hinted that youth in their brides was less important than the quality of bank accounts. The ladies, as described by themselves, were tall and handsome, or small and vivacious. Some esteemed themselves willowy while others acknowledged Junoesque forms. But all of them, of either sex, high or short, thin or stout, appeared to think only of bestowing undying love and affection for the pure glory of giving, for the highest of altruistic motives. Other and more trivial things were spoken of, as a rule, in a second short paragraph which, to 30 the initiated, would have seemed rather more important than the longer announcements. At any rate, that which they asked in exchange for the gifts they were prepared to lavish always appeared to be quite trivial, at first sight.

Sophy McGurn, as she kept on reading, was not a little impressed. Yet, gradually, a certain native shrewdness in her nature began to assert itself. She had helped her father in the store for several years and knew that gaudy labels might cover inferior goods. She by no means believed all the things she read. At times she even detected exaggeration, lack of candor, motives less allowable than the ones so readily advanced.

“Guess most of them are fakes,” she finally decided, not unwisely. “But there’s some of them must get terribly fooled. I––I wonder....”

Her cogitations were interrupted by a small boy who entered and asked for a stamped envelope. A few people, later on, came in to find out if there was any mail for them. But during the intervals she kept on poring over those pages. One by one the lights of Carcajou were going out. Carreau’s fiddle had stopped whining long before. The cat lay asleep in the wood-box, near the stove, with the kitten nestled against her. Old McGurn 31 called down to her that it was time for bed, but the girl made no answer.

Yes, it was a marvelous idea that had come to her. She saw a dim prospect of revenge. It was as if the frosted windows had gradually cleared and let in the light of the stars. Hugo Ennis had made a laughing-stock of her. He didn’t like carrots, forsooth! She was only too conscious of the failure of her efforts to attract him. But he had noticed them and commented on them to others, evidently. It was enough to make one wild!

The oil in the swinging lamp had grown very low and the light dim by the time she finished a letter, in which she enclosed some money. Then she stamped it and placed it in the bag that would be taken up in the morning, for the eastbound express. Finally she placed the heavy iron bar against the front door and went up the creaking stairs to her room as the loud-ticking clock boomed out eleven strokes, an unearthly hour for Carcajou.

A couple of weeks later a copy of the Matrimonial Journal was forwarded to A.B.C., P.O. Box 17, Carcajou, Ontario, Canada. Miss Sophy McGurn retired with it to her room, looked nervously out of the window, lest any one might have observed her, 32 and searched the pages feverishly. Yes! There it was! Her own words appeared in print!

A wealthy young man owning a silver mine in Canada would like to correspond with a young lady who would appreciate a fine home beside a beautiful river. In exchange for all that he can bestow upon her he only seeks in the woman he will marry an affectionate and kindly disposition suited to his own. Write A.B.C., P.O. Box 17, Carcajou, Ontario, Can.

During the next few days it was with unwonted eagerness that Sophy opened the mail bags. Finally there came a letter, followed by five, all in different handwritings and in the same mail. For another week or ten days others dribbled in. They were all from different women, cautiously worded, asking all manner of questions, venturing upon descriptions of themselves. Unanimously they proclaimed themselves bubbling over with affection and kindliness. The girl was impressed with the wretched spelling of most of them, with the evident tone of artificiality, with the patent fact that the writers were looking for a bargain. All these letters, even the most poorly written, gave Sophy the impression that the correspondents were dangerous people, she knew not why, and might perhaps hoist her with her own petard. She studied them over and over again, with a feeling of 33 disappointment, and reluctantly decided that the game was an unsafe one.

Two days had gone by without a letter to A.B.C. when at last one turned up. At once it seemed utterly different, giving an impression of bashfulness and timidity that contrasted with the boldness or the caution of the others. That night, with a hand disguised as best she could, the girl answered it. She knew that several days must elapse before she could obtain a reply and awaited it impatiently. It was this, in all probabilities, that made her speak snappishly to people who came to trade in the store or avail themselves of the post-office.

“I’m a fool,” she told herself a score of times. “They all want the money to come here and it must be enough for the return journey. This last one ain’t thought of it, but she’ll ask also, in her next letter, I bet. And I haven’t got it to send; and if I had it I wouldn’t do so. They might pocket it and never turn up. And anyway I might be getting in trouble with the postal authorities. Guess I better not answer when it comes. I’ll have to find some other way of getting square with him.”

By this time she regretted the dollars spent from her scant hoard for the advertisement, 34 but the reply came and the game became a passionately interesting one. She answered the letter again, using a wealth of imagination.

“She’ll sure answer this one, but then I’ll say I’ve changed my mind and have decided that I ain’t going to marry. Takes me really for a man, she does. Must be a fool, she must. And she ain’t asked for money, ain’t that funny? If she writes back she’ll abuse me like a pickpocket, anyway. Won’t he be mad when he gets the letter!”

Sophy’s general knowledge of postal matters and of some of the more familiar rules of law warned her that she was skating on thin ice. Yet her last letter had ventured rather far. In her first letter she had merely signed with the initials, but this time she had boldly used Hugo Ennis’s name. She thought she would escape all danger of having committed a forgery by simply printing the letters.

“And besides, there ain’t any one can tell I ever wrote those letters,” she reassured herself, perhaps mistakenly. “If there’s ever any enquiry I’ll stick to it that some one just dropped them in the mail-box and I forwarded them as usual. When it comes to her answers they’ll all be in Box 17, unopened, and I can say I held them till called for, according to rules. I never referred to them in 35 what I wrote. Just told her to come along and promised her all sorts of things.”

Again she waited impatiently for an answer, which never came. Instead of it there was a telegram addressed to Hugo Ennis, which was of course received by Follansbee, the station agent, who read it with eyes rather widely opened. He transcribed the message and entrusted it to big Stefan, the Swede, who now carried mail to a few outlying camps.

“It’s a queer thing, Stefan,” commented Joe. “Looks like there’s some woman comin’ all the way from New York to see yer friend Hugo.”

“Vell, dat’s yoost his own pusiness, I tank,” answered the Swede, placidly.

“Sure enough, but it’s queer, anyways. Did he ever speak of havin’ some gal back east?”

“If he had it vould still be his own pusiness,” asserted Stefan, biting off a chew from a black plug and stowing away the telegram in a coat pocket. Hugo Ennis was his friend. Anything that Hugo did was all right. Folks who had anything to criticize in his conduct were likely to incur Stefan’s displeasure.

The big fellow’s dog-team was ready. At his word they broke the runners out of the 36 snow, barking excitedly, but for the time being they were only driven across the way to the post-office for the mail-bag.

Sophy handed the pouch to him, her face none too agreeable.

“Dat all vhat dere is for Toumichouan?” asked the man.

“Yes, that’s all,” answered the girl, snappily. “There’s a parcel here for Papineau and a letter for Tom Carew’s wife. If you see any one going by way of Roaring River tell him to stop there and let ’em know.”

“You can gif ’em to me, too,” said Big Stefan. “I’m goin’ dat vay. I got one of dem telegraft tings for Hugo Ennis.”

Sophy rushed out from behind the counter.

“Let me see it!” she said.

“No, ma’am,” said Stefan, calmly. “It is shut anyvays, de paper is. Follansbee he youst gif it to me. I tank nobotty open dat telegraft now till Hugo he get it.”

He tucked the mail-bag and the parcel under one arm and went out, placing the former in a box that was lashed to the toboggan. Then he clicked at his dogs, who began to trot off easily towards the rise of ground at the side of the big lake. It was a sheet of streaky white, smooth or hummocky according to varying effects of wind and falling levels. 37 Far out on its surface he saw two black dots that were a pair of ravens, walking in dignified fashion and pecking at some indistinguishable treasure trove. At the summit of the rise he clicked again and the dogs went on faster, the man running behind with the tireless, flat-footed gait of the trained traveler of the wilderness.

In the meanwhile old McGurn was busy in the store and Sophy put on her woollen tuque and her mitts.

“I’m going over to the depot and see about that box of Dutch socks,” she announced.

“’T ain’t due yet,” observed her father.

“I’m going to see, anyway,” she answered.

In the station she found Joe Follansbee in his little office. The telegraphic sounder was clicking away, with queer sudden interruptions, in the manner that is so mysterious to the uninitiated.

“Are you busy, Joe?” she asked him, graciously.

“Sure thing!” answered the young fellow, grinning pleasantly. “There’s the usual stuff. The 4.19 is two hours late, and I’ve had one whole private message. Gettin’ to be a busy place, Carcajou is.”

“Who’s getting messages? Old man Symonds at the mill?”

“Ye’ll have to guess again. It’s a wire all the way from New York.”

“What was it about, Joe?” she asked, in her very sweetest manner.

Indeed, the inflection of her voice held something in it that was nearly caressing. Kid Follansbee had long admired her, but of late he had been quite hopeless. He had observed the favor in which Ennis had seemed to stand before the girl, and had perhaps been rather jealous. It was pleasant to be spoken to so agreeably now.

“We ain’t supposed to tell,” he informed her, apologetically. “It’s against the rules. Private messages ain’t supposed to be told to anyone.”

“But you’ll tell me, Joe, won’t you?” she asked again, smiling at him.

It was a chance to get even with the man he deemed his rival and he couldn’t very well throw it away.

“Well, I will if ye’ll promise not to repeat it,” he said, after a moment’s hesitation. “It’s some woman by the name of Madge who’s wired to Ennis she’s coming.”

“But when’s she due, Joe?”

“It just says ‘Leaving New York this evening. Please have some one to meet me. Madge Nelson.’”

“For––for the land’s sakes!”

She turned, having suddenly become quite oblivious of Joe, who was staring at her, and walked back slowly over the hard-packed snow that crackled under her feet in the intense cold.

“I––I don’t care,” she told herself, doggedly. “I––I guess she’ll just tear his eyes out when she finds out she’s been fooled. She’ll be tellin’ everybody and––and they’ll believe her, of course, and––and like enough they’ll laugh at him, now, instead of me.”

During this time Stefan rode his light toboggan when the snow was not too hummocky, or when the grade favored his bushy-tailed and long-nosed team. At other times he broke trail for them or, when the old tote-road allowed, ran alongside. With all his fast traveling it took him nearly three hours to reach the shack that stood on the bank, just a little way below the great falls of Roaring River. Here he abandoned the old road that was so seldom traveled since lumbering operations had been stopped in that district, owing to the removal of available pine and spruce. At a word from him the dogs sat down in their traces, their wiry coats giving out a thin vapor, and he went down the path to the log building. The door was closed and he had 40 already noted that no film of smoke came from the stove-pipe. While it was evident that Ennis was not at home Stefan knocked before pushing his way in. The place was deserted, as he had conjectured. Drawing off his mitt he ascertained that the ashes in the stove were still warm. There was a rough table of axe-hewn boards and he placed the envelope on it, after which he kindled a bit of fire and made himself a cup of hot tea that comforted him greatly. After this it took but a minute to bind on his heavy snowshoes again and he rejoined his waiting dogs, starting off once more in the hard frost, his breath steaming and once more gathering icicles upon his short and stubby yellow moustache.

It was only in the dusk of the short winter’s day that Hugo Ennis returned to his home, carrying his gun, with Maigan scampering before him. It was quite dark within the shack and he placed the bag that had been on his shoulders upon the table of rough planks. After this he drew off his mitts and unfastened his snowshoes after striking a light and kindling the oil lamp. Then he pulled a couple of partridges and a cold-stiffened hare out of the bag, which he then threw carelessly in a corner. Whether owing to the dampness of melting snow or the stickiness of fir-balsam 41 on the bottom of the bag, the envelope Stefan had left for him stuck to it and he never saw the telegram that had been sent from the far-away city.

A couple of days before Sophy’s advertisement appeared in the Matrimonial Journal a girl rose from her bed in one of the female wards of the great hospital on the banks of the East River, in New York. On the day before the visiting physician had stated that she might be discharged. She was not very strong yet but the hospital needed every bed badly. Pneumonia and other diseases were rife that winter.

A kindly nurse carried her little bag for her down the aisle of the ward and along the wide corridor till they reached the elevator. Madge Nelson was not yet very steady on her feet; once or twice she stopped for a moment, leaning against the walls owing to slight attacks of dizziness. The car shot down to their floor and the girl entered it.

“Good-by and good luck, my dear,” said the kindly nurse. “Take good care of yourself!”

Then she hurried back to the ward, where 43 another suffering woman was being laid on the bed just vacated.

Madge found herself on the street, carrying the little bag which, in spite of its light weight, was a heavy burden for her. The air was cold and a slight drizzle had followed the snow. The chilly dampness made her teeth chatter. Twice she had to hold on to the iron rails outside the gates of the hospital, for a moment’s rest. After this she made a brave effort and, hurrying as best she could, reached Third Avenue and waited for a car. There was room in it, fortunately, and she did not have to stand up. Further down town she got out, walked half a block west, and stopped before a tenement-house, opening the door. The three flights up proved a long journey. She collapsed on a kitchen chair as soon as she entered. A woman who had been in the front room hastened to her.

“So you’re all right again,” she exclaimed. “Last week the doctor said ’t was nip and tuck with you. You didn’t know me when I stood before ye. My! But you don’t look very chipper yet! I’ll make ye a cup of hot tea.”

Madge accepted the refreshment gratefully. It was rather bitter and black but at least it was hot and comforting. Then she 44 went and sought the little bed in the dim hall-room, whose frosted panes let in a yellow and scanty light. For this she had been paying a dollar and a half a week, and owed for the three she had spent in the hospital. Fortunately, she still had eleven dollars between herself and starvation. After paying out four-fifty the remainder might suffice until she found more work.

She was weary beyond endurance and yet sleep would not come to her, as happens often to the overtired. Before her closed eyes a vague panorama of past events unrolled itself, a dismal vision indeed.

There was the coming to the great city, after the widowed mother’s death, from a village up the state. The small hoard of money she brought with her melted away rather fast, in spite of the most economical living. But at last she had obtained work in a factory where they made paper boxes and paid a salary nearly, but not quite, adequate to keep body and soul together. From this she had drifted to a place where they made shirts. Here some hundreds of motor-driven sewing-machines were running and as many girls bent over the work, feverishly seeking to exceed the day’s stint and make a few cents extra. A strike in this place sent her to another, 45 with different work, which kept her busy till the hands were laid off for part of the summer.

And always, in every place, she toiled doggedly, determinedly, and her pretty face would attract the attention of foremen or even of bosses. Chances came for improvement in her situation, but the propositions were nearly always accompanied by smirks and smiles, by hints never so well covered but that they caused her heart to beat in indignation and resentment. Sometimes, of course, they merely aroused vague suspicions. Two or three times she accepted such offers. The result always followed that she left the place, hurriedly, and sought elsewhere, trudging through long streets of mercantile establishments and factories, looking at signs displayed on bits of swinging cardboard or pasted to dingy panes.

Throughout this experience, however, she managed to escape absolute want. She discovered the many mysteries which, once revealed, permit of continued existence of a sort. The washing in a small room, that had to be done on a Sunday; the making of small and unnutritious dishes on a tiny alcohol stove; the reliance on suspicious eggs and milk turned blue; the purchase of things 46 from push-carts. She envied the girls who knew stenography and typewriting, and those who were dressmakers and fitters and milliners, all of which trades necessitate long apprenticeship. The quiet life at home had not prepared her to earn her own living. It was only after the mother’s death that an expired annuity and a mortgage that could not be satisfied had sent her away from her home, to become lost among the toilers of a big city.

For a year she had worked, and her clothing was mended to the verge of impending ruin, and her boots leaked, and she had grown thin, but life still held out hope of a sort, a vague promise of better things, some day, at some dim period that would be reached later, ever so much later, perhaps. For she had still her youth, her courage, her indomitable tendency towards the things that were decent and honest and fair.

At last she got a better position as saleswoman in one of the big stores, whereupon her sky became bluer and the world took on rosier tints. She was actually able to save a little money, cent by cent and dime by dime, and her cheerfulness and courage increased apace.

It was at this time that typhoid struck her down and the big hospital saw her for the 47 first time. For seven long weeks she remained there, and when finally she was able to return to the great emporium she found that help was being laid off, owing to small trade after the holidays. She sought further but the same conditions prevailed and she was thankful to find harder and more scantily paid work in another factory, in which she packed unending cases with canned goods that came in a steady flow, over long leather belts.

So she became thinner again, and wearier, but held on, knowing that the big stores would soon seek additional help. The winter had come again, and with it a bad cough which, perforce, she neglected. One day she could not rise from her bed and the woman who rented a room to her called in the nearest doctor who, after a look at the patient and a swift, understanding gaze at the surroundings, ordered immediate removal to the hospital.

So now she was out of the precincts of suffering again, but the world had become a very hard place, an evil thing that grasped bodies and souls and churned them into a struggling, crying, weeping mass for which nothing but despair loomed ahead. She would try again, however. She would finish wearing out the soles of her poor little boots in a further hunt for work. At last sleep came to her, and the 48 next morning she awoke feeling hungry, and perhaps a bit stronger. Some sort of sunlight was making its way through the murky air. She breakfasted on a half-bottle of milk and a couple of rolls and went out again, hollow-eyed, weary looking, to look for more work.

For the best part of three days she staggered about the streets of the big city, answering advertisements found in a penny paper, looking up the signs calling for help, that were liberally enough displayed in the manufacturing district.

Then, one afternoon, she sank down upon a bench in one of the smaller parks, utterly weary and exhausted. Beside her, on the seat, lay a paper which she picked up, hoping to find more calls for willing workers. But despair was clutching at her heart. In most of the places they had looked at her and shaken their heads. No! They had just found the help they wanted. The reason of her disappointments, she realized, lay in the fact that she looked so ill and weary. They did not deem her capable of doing the needed work, in spite of her assurances.

So she held up the paper and turned over one or two pages, seeking the title. It was the Matrimonial Journal! It seemed like a scurrilous joke on the part of fate. What had she 49 to do with matrimony; with hopes for a happy, contented home and surcease of the never-ending search for the pittance that might keep her alive? She hardly knew why she folded it and ran the end into the poor little worn plush muff she carried. When she reached her room again she lighted the lamp and looked it over. It was merely something with which to pass a few minutes of the long hours. She read some of those advertisements and the keen instinct that had become hers in little less than two years of hard city life made her feel the lack of genuineness and honesty pervading those proposals and requests. When she chanced to look at that far demand from Canada, however, she put the paper down and began to dream.

Her earlier and blessed years had been spent in a small place. Her memory went back to wide pastures and lowing cattle, to gorgeously blossoming orchards whose trees bent under their loads of savory fruit, long after the petals had fallen. She felt as if she could again breathe unpolluted air, drink from clear springs and sit by the edges of fields and watch the waves of grain bending with flashes of gold before the breezes. Time and again she had longed for these things; the mere thought of them brought a hunger 50 to her for the open country, for the glory of distant sunsets, for the sounds of farm and byre, for the silently flowing little river, bordered with woodlands that became of gold and crimson in the autumn. She could again see the nesting swallows, the robins hopping over grasslands, the wild doves pairing in the poplars, the chirping chickadees whose tiny heads shone like black diamonds, as they flitted in the bushes. The memory of it all brought tears to her eyes.

What a wonderful outlook this thing presented, as she read it again. A home by a beautiful river! A prosperous youth who needed but kindliness and affection to make him happy! Why had he not found a suitable mate in that country? She remembered hearing, or reading somewhere, that women are comparatively few in the lands to which men rush to settle in wildernesses. And perhaps the women he had met were not of the education or training he had been accustomed to.

The idea of love, as it had been presented by the men she had been thrown with, in factory and office, was repugnant to her. But, if this was true, the outlook was a different one. Not for a moment did she imagine that it was a place wherein a woman might live in idleness and comparative luxury. No! 51 Such a man would require a helpmeet, one who would do the work of his house, one who would take care of the home while he toiled outside. What a happy life! What a wondrous change from all that she had experienced! There were happy women in the world, glorying in maternity, watching eagerly for the home-coming of their mates, blessed with the love of a good man and happy to return it in full measure. It seemed too good to be true. She stared with moistened eyes. If this was really so the man had doubtless already received answers and chosen. There must be so many others looking like herself for a haven of safety, for deliverance from lives that were unendurable. Who was she that she should aspire to this thing? To such a man she could bring but health impaired, but the remnants of her former strength. In a bit of looking-glass she saw her dark-rimmed eyes and deemed that she had lost all such looks as she had once possessed.

Yet something kept urging her. It was some sort of a fraud, doubtless. The man was probably not in earnest. A letter from her would obtain no attention from him. A minute later she was seated at the table, in spite of all these misgivings, and writing to 52 this man she had never seen or heard of. She stated candidly that life had been too hard for her and that she would do her best to be a faithful and willing helper to a man who would treat her kindly. It was a poor little despairing letter whose words sounded like a call for rescue from the deep. After she had finished it she threw it aside, deciding that it was useless to send it. An hour later she rushed out of the house, procured a stamp at the nearest drug-store, and threw the letter in a box at the street-corner. As soon as it was beyond her reach she would have given anything to recall it. Her pale face had become flushed with shame. A postman came up just then, who took out a key fastened to a brass chain. She asked him to give her back her letter. But he swept up all the missives and locked the box again, shaking his head.

“Nothing doing, miss,” he told her, gruffly.

Before her look of disappointment he halted a few seconds to explain some measure, full of red-tape, by which she might perhaps obtain the letter again from the post-office. To Madge it seemed quite beyond the powers of man to accomplish such a thing. And, moreover, the die was cast. The thing might as well go. She would never hear from it again.

The next day she found work in a crowded loft, poorly ventilated and heated, and came home to throw herself upon her bed, exhausted. Her landlady’s children were making a terrible noise in the next room, and the racket shot pains through her head. On the morrow she was at work again, and kept it up to the end of the week. When she returned on Saturday, late in the afternoon, with her meagre pay-envelope in her ragged muff, she had forgotten all about her effort to obtain freedom.

“There’s a letter for ye here, from foreign parts,” announced Mrs. MacRae. “Leastwise ’t ain’t an American stamp.”

Madge took it from her, wondering. A queer tremor came over her. The man had written!

Once in her room she tore the envelope open. The handwriting was queer and irregular. But a man may write badly and still be honest and true. And the words she read were wonderful. This individual, who merely signed A. B. C., was eager to have her come to him. She would be treated with the greatest respect. If the man and the place were not suited to her she would naturally be at liberty to return immediately. It was unfortunate that his occupations absolutely prevented 54 his coming over at once to New York to meet her. If she would only come he felt certain that she would be pleased. The hosts of friends he had would welcome her.

Thus it ran for three pages and Madge stared at the light, a tremendous longing tearing at her soul, a great fear causing her heart to throb.

She forgot the meagre supper she had brought with her and finally sat down to write again. Like the first letter it was a sort of confession. She acknowledged again that life no longer offered any prospect of happiness to her. After she looked again in the little glass she wrote that she was not very good-looking. To her own eyes she now appeared ugly. But she said she knew a good deal about housekeeping, which was true, and was willing to work and toil for a bit of kindness and consideration. Her face was again red as she wrote. There was something in all this that shocked her modesty, her inborn sense of propriety and decency. But, after all, she reflected that men and women met somehow, and became acquainted. And the acquaintance, in some cases, became love. And the love eventuated in the only really happy life a man or a woman could lead.

Nearly another week went by before the second answer arrived. It again urged her to come. It spoke of the wonderful place Carcajou was, of the marvel that was Roaring Falls, of the greatness of the woodlands of Ontario. Indeed, for one of her limited attainments, Sophy’s letter was a remarkable effort. This time the missive was signed in printed letters: HUGO ENNIS. This seemed queer. But some men signed in very puzzling fashion and this one had used this method, in all likelihood, in order that she might be sure to get the name right. And it was a pleasant-sounding name, rather manly and attractive.

The letter did not seem to require another answer. Madge stuffed it under her pillow and spent a restless night. On the next day her head was in a whirl of uncertainty. She went as far as the Grand Central Station and inquired about the price of a ticket to Carcajou. The man had to look for some time before he could give her the information. It was very expensive. The few dollars in her pocket were utterly inadequate to such a journey, and she returned home in despair.

On the Monday morning, at the usual hour, she started for the factory. She was about to take the car when she turned back and made 56 her way to her room again. Her mind was made up. She would go!

She opened a tiny trunk she had brought with her from her country home and searched it, swiftly, hurriedly. She was going. It would not do to hesitate. It was a chance. She must take it!

She pulled out a little pocketbook and opened it swiftly. Within it was a diamond ring. It had been given to her mother by her father, in times of prosperity, as an engagement ring. And she had kept it through all her hardships, vaguely feeling that a day might come when it might save her life. She had gone very hungry, many a time, with that gaud in her possession. She had felt that she could not part with it, that it was something that had been a part of her own dear mother, a keepsake that must be treasured to the very last. And now the moment had come. She placed the little purse in her muff, clenched her hand tightly upon it, and went out again into the street.

She looked out upon the thoroughfare in a new, impersonal way. She felt as if now she were only passing through the slushy streets on her way to new lands. From the tracks of the Elevated Road dripped great drops of turbid water. The sky was leaden and an 57 easterly wind, in spite of the thaw, brought the chill humidity that is more penetrating than colder dry frost.

She hastened along the sidewalk flooded with the icy grime of the last snowfall. It went through the thin soles of her worn boots. Once she shivered in a way that was suggestive of threatened illness and further resort to the great hospital. Before crossing the avenue she was compelled to halt, as the great circular brooms of a monstrous sweeper shot forth streams of brown water and melting snow. Then she went on, casting glances at the windows of small stores, and finally stopped before a little shop, dark and uninviting, whose soiled glass front revealed odds and ends of old jewelry, watches, optical goods and bric-a-brac that had a sordid aspect. She had long ago noticed the ancient sign disposed behind the panes. It bore the words:

“We buy Old Gold and Jewelry”

For a moment only she hesitated. Her breath came and went faster as if a sudden pain had shot through her breast. But at once she entered the place. From the back of the store a grubby, bearded, unclean old man wearing a black skullcap looked at her keenly over the edge of his spectacles.

“I––I want to sell a diamond,” she told him, uneasily.

He stared at her again, studying her poor garb, noticing the gloveless hands, appraising the worn garments she wore. He was rubbing thin long-fingered hands together and shaking his head, in slow assent.

“We have to be very careful,” his voice quavered. “We have to know the people.”

“Then I’ll go, of course,” she answered swiftly, “because you don’t know me.”

The atmosphere of the place was inexpressibly distasteful to her and the old man’s manner was sneaking and suspicious. She felt that he suspected her of being a thief. Her shaking hand was already on the doorknob when he called her back, hurrying towards her.

“What’s your hurry? Come back!” he called to her. “Of course I can’t take risks. There’s cases when the goods ain’t come by honest. But you look all right. Anyway ’t ain’t no trouble to look over the stuff. Let me see what you’ve got. There ain’t another place in New York where they pay such good prices.”

She returned, hesitatingly, and handed to him a small worn case that had once been covered with red morocco. He opened it, 59 taking out the ring and moving nearer the window, where he examined it carefully.

“Yes. It’s a diamond all right,” he admitted, paternally, as if he thus conferred a great favor upon her. “But of course it’s very old and the mounting was done years and years ago, and it’s worn awful thin. Maybe a couple of dollars worth of gold, that’s all.”

“But the stone?” she asked, anxiously.

“One moment, just a moment, I’m looking at it,” he replied, screwing a magnifying glass in the socket of one of his eyes. “Diamonds are awful hard to sell, nowadays––very hard, but let me look some more.”

He was turning the thing around, estimating the depth of the gem and studying the method of its cutting.

“Very old,” he told her again. “They don’t cut diamonds that way now.”

“It belonged to my mother,” she said.

“Of course, of course,” he quavered, repellently, so that her cheeks began to feel hot again. She was deeply hurt by his tone of suspicion. The sacrifice was bad enough––the implication was unbearable.

“I don’t think you want it,” she said, coldly. “Give it back to me. I can perhaps do better at a regular pawnshop.”

But he detained her again, becoming smooth and oily. He first offered her fifty dollars. She truthfully asserted that her father had paid a couple of hundred for it. After long bargaining and haggling he finally agreed to give her eighty-five dollars and, worn out, the girl accepted. She was going out of the shop, with the money, when she stopped again.

“It seems to me that I used to see pistols, or were they revolvers, in your show window,” she said.

He lifted up his hands in alarm.

“Pistols! revolvers! Don’t you know there’s the Sullivan law now? We ain’t allowed to sell ’em––and you ain’t allowed to buy ’em without a license––a license from the police.”

“Oh! That’s a pity,” said Madge. “I’m going away from New York and I thought it might be a good idea to have one with me.”

The old man looked keenly at her again, scratching one ear with unkempt nails. Finally he drew her back of a counter, placing a finger to his lips.

“I’m taking chances,” he whispered. “I’m doing it to oblige. If ye tell any one you got it here I’ll say you never did. My word’s as good as yours.”

“I tell you I’m going away,” she repeated. “I––I’m never coming to this city again––never as long as I live. But I want to take it with me.”

When she finally went out she carried a cheap little weapon worth perhaps four dollars, and a box of cartridges, for which she paid him ten of the dollars he had handed out to her. It was with a sense of inexpressible relief that she found herself again on the avenue, in spite of the drizzle that was coming down. The air seemed purer after her stay in the uninviting place. Its atmosphere as well as the old man’s ways had made her feel as if she had been engaged in a very illicit transaction. She met a policeman who was swinging his club, and the man gave her an instant of carking fear. But he paid not the slightest heed to her and she went on, breathing more freely. It was as if the great dark pall of clouds hanging over the city was being torn asunder. At any rate the world seemed to be a little brighter.

She went home and deposited her purchase, going out again at once. She stopped at a telegraph office where the clerk had to consult a large book before he discovered that messages could be accepted for Carcajou in the Province of Ontario, and wrote out the 62 few words announcing her coming. After this she went into other shops, carefully consulting a small list she had made out. Among other things she bought a pair of stout boots and a heavy sweater. With these and a very few articles of underwear, since she could spare so little, she returned to the Grand Central and purchased the needed ticket, a long thing with many sections to be gradually torn off on the journey. Berths on sleepers, she decided, were beyond her means. Cars were warm, as a rule, and as long as she wasn’t frozen and starving she could endure anything. Not far from the house she lived in there was an express office where a man agreed to come for her trunk, in a couple of hours.

Then she climbed up to Mrs. MacRae’s.

“I’m going to leave you,” announced the girl. “I––I have found something out of town. Of course I’ll pay for the whole week.”

The woman expressed her regret, which was genuine. Her lodger had never been troublesome and the small rent she paid helped out a very poor income mostly derived from washing and scrubbing.

“I hope it’s a good job ye’ve found, child,” she said. “D’ye know for sure what kind o’ 63 place ye’re goin’ to? Are you certain it’s all right?”

“Oh! If it isn’t I’ll make it so,” answered Madge, cryptically, as she went over to her room. Here, from beneath the poor little iron bed, she dragged out a small trunk and began her packing. For obvious reasons this did not take very long. It was a scanty trousseau the bride was taking with her to the other wilderness. After her clothes and few other possessions had been locked in, the room looked very bare and dismal. She sat on the bed, holding a throbbing head that seemed very hot with hands that were quite cold. After a time the expressman came and removed the trunk. There was a lot of time to spare yet and Madge remained seated. Thoughts by the thousand crowded into her brain––the gist of them was that the world was a terribly harsh and perilous place.

“I––I can’t stay here any longer!” she suddenly decided, “or I’ll get too scared to go. I––I must start now! I’ll wait in the station.”

So she bade Mrs. MacRae good-by, after handing her a dollar and a half, and received a tearful blessing. Then, carrying out a small handbag, she found herself once more on the sidewalk and began to breathe more freely. 64 The die was cast now. She was leaving all this mud and grime and was gambling on a faint chance of rest and comfort, with her dead mother’s engagement ring, the very last thing of any value that she had hitherto managed to keep. It was scarcely happiness that she expected to find. If only this man might be good to her, if only he placed her beyond danger of immediate want, if only he treated her with a little consideration, life would become bearable again!

As she walked along the avenue the pangs of hunger came to her, keenly. For once she would have a sufficient meal! She entered a restaurant and ordered lavishly. Hot soup, hot coffee, hot rolls, a dish of steaming stew with mashed potatoes, and finally a portion of hot pudding, furnished her with a meal such as she had not tasted for months and months. A sense of comfort came to her, and she placed five cents on the table as a tip to the girl who had waited on her. She was feeling ever so much better as she went out again. She had spent fifty cents for one meal, like a woman rolling in wealth. At a delicatessen shop she purchased a loaf of bread and a box of crackers, with a little cold meat. She knew that meals on trains were very expensive.

As she reached the station she felt that she 65 had burned her bridges behind her. She could never come back, since the few dollars that were left would never pay for her return.

“But I’m not coming back,” she told herself grimly. “I’m my own master now.”

She felt the bottom of her little bag. Yes, the pistol was there, a protector from insult or a means towards that end she no longer dreaded.

“No! I’ll never come back!” she repeated to herself. “I’ll never see this city again. It––it’s been too hard, too cruelly hard!”

The girl was glad to sit down at last on one of the big benches in the waiting-room. It was nice and warm, at any rate, and the seat was comfortable enough. Her arm had begun to ache from carrying the bag, and she had done so much running about that her legs felt weary and shaky. A woman sitting opposite looked at her for an instant and turned away. There was nothing to interest any one in the garments just escaping shabbiness, or in the pale face with its big dark-rimmed eyes. People are very unconscious, as a rule, of the tragedy, the drama or the comedy being enacted before their eyes.

Gradually Madge began to feel a sense of 66 peace stealing over her. She was actually beginning to feel contented. It was a chance worth taking, since things could never be worse. And then there was that thing in her bag. Presently a woman came to sit quite close to her with a squalling infant in her arms and another standing at her knee. She was a picture of anxiety and helplessness. But after a time a man came, bearing an old cheap suit-case tied up with clothes-line, who spoke in a foreign tongue as the woman sighed with relief and a smile came over her face.

Yes! That was it! The coming of the man had solved all fears and doubts! There was security in his care and protection. With a catch in her breathing the girl’s thoughts flew over vast unknown expanses and went to that other man who was awaiting her. Her vivid imagination presented him like some strange being appearing before her under forms that kept changing. The sound of his voice was a mystery to her and she had not the slightest idea of his appearance. That advertisement stated that he was young and the first letter had hinted that he possessed fair looks. Yet moments came in which the mere idea of him was terrifying, and this, in swiftly changing moods, changed to forms that seemed to bring 67 her peace, a surcease of hunger and cold, of unavailing toil, of carking fear of the morrow.

At times she would look about her, and the surroundings would become blurred, as if she had been weeping. The hastening people moved as if through a heavy mist and the announcer’s voice, at intervals, boomed out loudly and called names that suggested nothing to her. Again her vision might clear and she would notice little trivial things, a bewildered woman dragging a pup that was most unwilling, a child hauling a bag too heavy for him, a big negro with thumbs in the armholes of his vest, yawning ponderously. For the hundredth time she looked at the big clock and found that she still had over an hour to wait for her train. Again she lost sight of the ever-changing throngs, of the massive structure in which she seemed to be lost, and the roar of the traffic faded away in the long backward turning of her brain, delving into the past. There was the first timid yet hopeful coming to the big city and the discovery that a fair high-school education, with some knowledge of sewing and fancywork, was but poor merchandise to exchange for a living. Her abundance of good looks, at that time, had proved nothing but a hindrance and a danger. Then had come the 68 bitter toil for a pittance, and sickness, and the hospital, and the long period of convalescence during which everything but the ring had been swept away. She had met the sharp tongues of slatternly, disappointed landladies, while she looked far and wide for work. At first she had been compelled to ask girls on the street for the meaning of cards pasted on windows or hanging in doorways. Words such as “Bushel girls on pants” or “Stockroom assistants” had signified nothing to her. Month by month she had worked in shops and factories where the work she exacted from her ill-nourished body sapped her strength and thinned her blood. Nor could she compete with many of the girls, brought up to such labor, smart, pushing, inured to an existence carried on with the minimum of food and respirable air.

The red came to her cheeks again as she remembered insults that had been proffered to her. It deepened further as she thought of that paper picked up on a bench of a little city square. The fear of having made a terrible mistake returned to her, more strongly than ever. Her efforts towards peace now seemed immodest, bold, unwomanly. But that first vision had been so keen of a quiet-voiced man extending a strong hand to welcome 69 and protect as he smiled at her in pleasant greeting! Her vague notions of a far country in which was no wilderness of brick and mortar but only the beauty of smiling fields or of scented forests had filled her heart with a passionate longing. And the last thing the doctor had told her, in the hospital, was that she ought to live far away from the city, in the pure air of God’s country. It was with a hot face and a throbbing heart that she now remembered the poor little letters she had written. Even the sending of that telegram now filled her with shame. And yet....

With clamorous voice the man was announcing her train. After a heart-rending moment’s hesitation she hastened to where a few people were waiting. The gates opened and she was pushed along. It was as if her own will could no longer lead her, as if she were being carried by a strong tide, with other jetsam, towards shores unknown.

At last she was seated in an ordinary coach, than which man has never devised sorrier accommodation for a long journey. Finally the train started and she sought to look out of the window but obtained only a blurred impression of columns and pillars lighted at intervals by flickering bulbs. They made her eyes ache. But presently she made out, to her 70 left, the dark surface of a big river. A few more lights were glinting upon it, appearing and disappearing. Vaguely she made out the outlines of a few vessels that were battling against the drifting ice, for she could see myriad sparks flying from what must have been the smokestacks of tugs or river steamers.

Her fellow passengers were mostly laborers or emigrants going north or west. The air was tainted with the scent of garlic. Children began to cry and later grew silent or merely fretful. Finally the languor of infinite weariness came over the girl and she lay back, uncomfortably, and tried to sleep. At frequent intervals she awoke and sat up again, with terror expressed in her face and deep blue eyes. Once she fell into a dream and was so startled that she had to restrain herself from rushing down the aisle and seeking to escape from some unknown danger that seemed to be threatening her.

Again she passed a finger over the blurred glass and sought to look out. The train seemed to be plunging into strange and grisly horrors. Overwrought as she was a flood of tears came to her eyes and seemed to bring her greater calm, so that at last she fell into a deeper sleep, heavy, visionless, no longer attended with sudden terrors.

At last the morning came and Madge awoke. At first she could not realize where she was. Her limbs ached from their cramped position and a pain was gnawing at her, which meant hunger. In spite of the heaters in the car a persistent chilliness had come over her, and all at once she was seized by an immense discouragement. She felt that she was now being borne away to some terrible place. Those people called it Roaring River. Now that she thought of it the very name represented something that was gruesome and panicky. But then she lay back and reflected that its flood would be cleaner and its bed a better place to leap into, if her fears were realized, than the turbid waters of the Hudson. She knew that she was playing her last stake. It must result in a life that could be tolerated or else in an end she had battled against, to the limit of endurance.

She quietly made a meal of the provisions she had brought. Her weary brain no longer 72 reacted to disturbing thoughts and vague fears and she felt that she was drifting, peacefully, to some end that was by this time nearly indifferent to her. The day wore on, with a long interval in Ottawa, where she dully waited in the station, the restaurant permitting her to indulge in a comforting cup of coffee. All that she saw of the town was from the train. There was a bridge above the tracks, near the station, and on the outskirts there were winding and frozen waterways on which some people skated. As she went on the land seemed to take an even chillier aspect. The snow was very deep. Farms and small villages were half buried in it. The automobiles and wheeled conveyances of New York had disappeared. Here and there she could see a sleigh, slowly progressing along roads, the driver heavily muffled and the horse traveling in a cloud of vapor. When night came they were already in a vast region of rock and evergreen trees, of swift running rivers churning huge cakes of ice, and the dwellings seemed to be very few and far between. The train passed through a few fairly large towns, at first, and she noted that the people were unfamiliarly clad, wearing much fur, and the inflections of their voices were strange to her. By this time the train was 73 running more slowly, puffing up long grades and sliding down again with a harsh grinding of brakes that seemed to complain. When the moon rose it shone over endless snow, broken only by dim, solid-looking masses of conifers. Here and there she could also vaguely discern rocky ledges upon which gaunt twisted limbs were reminders of devastating forest fires. There were also great smooth places that must have been lakes or the beds of wide rivers shackled in ice overlaid with heavy snow. Whenever the door of the car was opened a blast of cold would enter, bitingly, and she shivered.

Came another morning which found her haggard with want of sleep and broken with weariness. But she knew that she was getting very near the place and all at once she began to dread the arrival, to wish vainly that she might never reach her destination, and this feeling continued to grow keener and keener.

Finally the conductor came over to her and told her that the train was nearing her station. Obligingly he carried her bag close to the door and she stood up beside him, swaying a little, perhaps only from the motion of the car. The man looked at her and his face expressed some concern but he remained silent until the train stopped.

Madge had put on her thin cloak. The frosted windows of the car spoke of intense cold and the rays of the rising sun had not yet passed over the serrated edges of the forest.

“I’m afraid you’ll find it mighty cold, ma’am,” ventured the conductor. “Hope you ain’t got to go far in them clothes. Maybe your friends ’ll be bringing warmer things for you. Run right into the station; there’s a fire there. Joe ’ll bring your baggage inside. Good morning, ma’am.”

She noticed that he was looking at her with some curiosity, and her courage forsook her once more. It was as if, for the first time in her life, she had undertaken to walk into a lion’s cage, with the animal growling and roaring. She felt upon her cheeks the bite of the hard frost, but there was no wind and she was not so very cold, at first. She looked about her as the train started. Scattered within a few hundred yards there were perhaps two score of small frame houses. At the edge of what might have been a pasture, all dotted with stumps, stood a large deserted sawmill, the great wire-guyed sheet-iron pipe leaning over a little, dismally. A couple of very dark men she recognized as Indians looked at her without evincing the slightest show of interest. From a store across the 75 street a young woman with a thick head of red hair peeped out for an instant, staring at her. Then the door closed again. After this a monstrously big man with long, tow-colored wisps of straggling hair showing at the edges of his heavy muskrat cap, and a ragged beard of the same color, came to her as she stood upon the platform, undecided, again a prey to her fears. The man smiled at her, pleasantly, and touched his cap.

“Ay tank you’re de gal is going ofer to Hugo Ennis,” he said, in a deep, pleasant voice.

She opened her mouth to answer but the words refused to come. Her mouth felt unaccountably dry––she could not swallow. But she nodded her head in assent.

“I took de telegraft ofer to his shack,” the Swede further informed her, “but Hugo he ain’t here yet. I tank he come soon. Come inside de vaiting-room or you freeze qvick. Ain’t you got skins to put on?”

She shook her head and he grasped her bag with one hand and one of her elbows with the other and hurried her into the little station. Joe Follansbee had a redhot fire going in the stove, whose top was glowing. The man pointed at a bench upon which she could sit and stood at her side, shaving tobacco from a 76 big black plug. She decided that his was a reassuring figure and that his face was a good and friendly one.

“Do you think that––that Mr. Ennis will come soon?” she finally found voice to ask.

“Of course, ma’am. You yoost sit qviet. If Hugo he expect a leddy he turn up all right, sure. It’s tvelve mile ofer to his place, ma’am, and he ain’t got but one dog.”

She could not quite understand what the latter fact signified. What mattered it how many dogs he had? She was going to ask for further explanation when the door opened and the young woman who had peeped at her came in. She was heavily garbed in wool and fur. As she cast a glance at Madge she bit her lips. For the briefest instant she hesitated. No, she would not speak, for fear of betraying herself, and she went to the window of the little ticket-office.

“Anything for us, Joe?” she asked.

“No. There’s no express stuff been left,” he answered. “Your stuff’ll be along by freight, I reckon. Wait a moment and I’ll give you the mail-bag.”

“You can bring it over. It––it doesn’t matter about the goods.”

She turned about, hastily, and nodded to big Stefan. Then she peered at Madge again, 77 with a sidelong look, and left the waiting-room.

As so often happens she had imagined this woman who was coming as something entirely different from the reality. She had evolved vague ideas of some sort of adventuress, such as she had read of in a few cheap novels that had found their way to Carcajou. In spite of the mild and timid tone of the letters she had prepared to see some sort of termagant, or at least a woman enterprising, perhaps bold, one who would make it terribly hot for the man she would believe had deceived her and brought her on a fool’s errand. This little thin-faced girl who looked with big, frightened eyes was something utterly unexpected, she knew not why.

“And––and she ain’t at all bad-looking,” she acknowledged to herself, uneasily. “She don’t look like she’d say ‘Boo’ to a goose, either. But then maybe she’s deceiving in her looks. A woman who’d come like that to marry a man she don’t know can’t amount to much. Like enough she’s a little hypocrite, with her appearance that butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth. And my! The clothes she’s got on! I wonder if she didn’t look at me kinder suspicious. Seemed as if she was taking me in, from head to foot.”

In this Miss Sophy was probably mistaken. Madge had looked at her because the garb of brightly-edged blanketing, the fur cap and mitts, the heavy long moccasins, all made a picture that was unfamiliar. There was perhaps some envy in the look, or at least the desire that she also might be as well fended against the bitter cold. She had the miserable feeling that comes over both man and woman when feeling that one’s garments are out of place and ill-suited to the occasion. Once Madge had seen a moving-picture representing some lurid drama of the North, and some of the women in it had worn that sort of clothing.

Big Stefan had lighted his pipe and sought a seat that creaked under his ponderous weight. He opened the door of the stove and threw two or three large pieces of yellow birch in it.

“Guess it ain’t nefer cold vhere you comes from,” he ventured. “You’ll haf to put on varm tings if you goin’ all de vay to Roaring Rifer Falls.”

“I’m afraid I have nothing warmer than this,” the girl faltered. “I––I didn’t know it was so very cold here. And––and I’m nicely warmed up now, and perhaps I won’t feel it so very much.”

“You stay right here an’ vait for me,” he told her, and went out of the waiting-room, hurriedly. But he opened the door again.

“If Hugo he come vhile I am avay, you tell him I pring youst two three tings from my voman for you. I’m back right avay. So long, ma’am!”