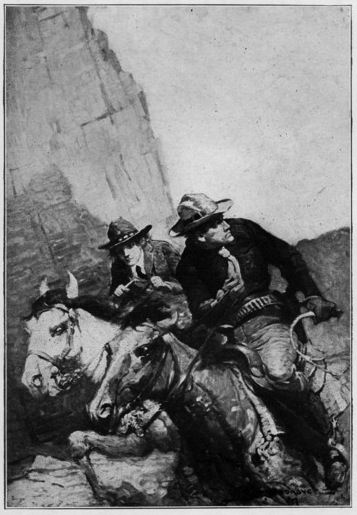

“Ride Low—They’re Coming!”

THE RUSTLER

OF WIND RIVER

By G. W. OGDEN

WITH FRONTISPIECE

By FRANK E. SCHOONOVER

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Published by Arrangement with A. C. McClurg & Company

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1917

Published March, 1917

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER |

|

PAGE |

| I |

Strange Bargainings |

1 |

| II |

Beef Day |

11 |

| III |

The Ranchhouse by the River |

28 |

| IV |

The Man in the Plaid |

41 |

| V |

If He was a Gentleman |

55 |

| VI |

A Bold Civilian |

66 |

| VII |

Throwing the Scare |

81 |

| VIII |

Afoot and Alone |

89 |

| IX |

Business, not Company |

102 |

| X |

“Hell’s a-goin’ to Pop” |

119 |

| XI |

The Señor Boss Comes Riding |

131 |

| XII |

“The Rustlers!” |

147 |

| XIII |

The Trail at Dawn |

160 |

| XIV |

When Friends Part |

182 |

| XV |

One Road |

196 |

| XVI |

Danger and Dignity |

215 |

| XVII |

Boots and Saddles |

227 |

| XVIII |

The Trail of the Coffee |

240 |

| XIX |

“I Beat Him to It” |

252 |

| XX |

Love and Death |

268 |

| XXI |

The Man in the Door |

280 |

| XXII |

Paid |

298 |

| XXIII |

Tears in the Night |

303 |

| XXIV |

Banjo Faces Into the West |

312 |

| XXV |

“Hasta Luego” |

322 |

THE RUSTLER OF WIND RIVER

CHAPTER I

STRANGE BARGAININGS

When a man came down out of the mountains

looking dusty and gaunt as the stranger did,

there was no marvel in the matter of his eating five

cans of cove oysters. The one unaccountable thing

about it was that Saul Chadron, president of the

Drovers’ Association, should sit there at the table

and urge the lank, lean starveling to go his limit.

Usually Saul Chadron was a man who picked his

companions, and was a particular hand at the

choosing. He could afford to do that, being of

the earth’s exalted in the Northwest, where people

came to him and put down their tribute at his feet.

This stranger, whom Chadron treated like a long-wandering

friend, had come down the mountain trail

that morning, and had been hanging about the

hotel all day. Buck Snellin, the proprietor—duly

licensed for a matter of thirty years past by the

United States government to conduct his hostelry in

the corner of the Indian reservation, up against the

2

door of the army post—did not know him. That

threw him among strangers in that land, indeed, for

Buck knew everybody within a hundred miles on every

side.

The stranger was a tall, smoky man, hollow-faced,

grim; adorned with a large brown mustache which

drooped over his thin mouth; a bony man with

sharp shoulders, and a stoop which began in the

region of the stomach, as if induced by drawing in

upon himself in times of poignant hunger, which he

must have felt frequently in his day to wear him down

to that state of bones; with the under lid of his left

eye caught at a point and drawn down until it showed

red, as if held by a fishhook to drain it of unimaginable

tears.

There was a furtive look in his restless, wild-animal

eyes, smoky like the rest of him, and a surliness about

his long, high-ridged nose which came down over his

mustache like a beak. He wore a cloth cap with ear

flaps, and they were down, although the heat of

summer still made the September air lively enough

for one with blood beneath his skin. He regaled himself

with fierce defiance, like a captive eagle, and had

no word in return for the generous importunities of

the man who was host to him in what evidently was a

long-deferred meal.

Chadron paid the bill when the man at last finished

packing his internal cavities, and they went together

into the hotel office which adjoined the dining-room.

The office of this log hotel was a large, gaunt

3

room, containing a few chairs along the walls, a small,

round table under the window with the register upon

it, a pen in a potato, and a bottle of ink with trickled

and encrusted sides. The broad fireplace was bleak

and black, blank-staring as a blind eye, and the sun

reached through the window in a white streak across

the mottled floor.

There was the smell of old pipes, old furs, old

guns, in the place, and all of them were present to

account for themselves and dispel any shadow of

mystery whatever—the guns on their pegs set in

auger-holes in the logs of the walls, the furs of wild

beasts dangling from like supports in profusion

everywhere, and the pipes lying on the mantel with

stems hospitably extended to all unprovided guests.

Some of them had been smoked by the guests who

had come and gone for a generation of men.

The stranger stood at the manteltree and tried the

pipes’ capacity with his thick-ended thumb, finding

one at last to his requirements. Tall as Saul

Chadron stood on his own proper legs, the stranger

at his shoulder was a head above him. Seven feet he

must have towered, his crown within a few inches of

the smoked beams across the ceiling, and marvelously

thin in the running up. It seemed that the wind

must break him some blustering day at that place in

his long body where hunger, or pain, or mischance

had doubled him over in the past, and left him

creased. The strong light of the room found pepperings

of gray in his thick and long black hair.

Chadron himself was a gray man, with a mustache

and beard like a cavalier. His shrewd eyes were

sharp and bright under heavy brows, his brown face

was toughened by days in the saddle through all seasons

of weather and wind. His shoulders were broad

and heavy, and even now, although not dressed for

the saddle, there was an up-creeping in the legs of

his trousers, and a gathering at the knees of them,

for they were drawn down over his tall boots.

That was Chadron’s way of doing the nice thing

when he went abroad in his buckboard. He had

saddle manners and buckboard manners, and even

office manners when he met the cattle barons in Cheyenne.

No matter what manners he chanced to be

wearing, one remembered Saul Chadron after meeting

him, and carried the recollection of him to the

sundown of his day.

“We can talk here,” said Chadron, giving the other

a cigar.

The tall man broke the cigar and ground part of it

in his palm, looking with frowning thoughtfulness

into the empty fireplace as the tobacco crushed in his

hard hand. He filled the pipe that he had chosen,

and sat with his long legs stretched out toward the

chimney-mouth.

“Well, go on and talk,” said he.

His voice came smothered and hoarse, as if it lay

beneath all the oysters which he had rammed into his

unseen hollow. It was a voice in strange harmony

with the man, such a sound as one would have

5

expected to come out of that surly, dark-lipped, thin

mouth. There was nothing committal about it, nothing

exactly identifying; an impersonal voice, rather,

and cold; a voice with no conscience behind it,

scarcely a soul.

“You’re a business man, Mark—”

“Huh!” said Mark, grunting a little cloud of

smoke from the bowl of his pipe in his sarcastic

vehemence.

“And so am I,” continued Chadron, unmoved.

“Words between us would be a waste of time.”

“You’re right; money talks,” said Mark.

“It’s a man’s job, or I wouldn’t have called you

out of your hole to do it,” said Chadron, watching

the man slyly for the effect.

“Pay me in money,” suggested Mark, unwarmed

by the compliment. “Is it nesters ag’in?”

“Nesters,” nodded the cattleman, drawing his

great brows in a frown. “They’re crowdin’ in so

thick right around me that I can’t breathe comfortable

any more; the smell of ’em’s in the wind.

They’re runnin’ over three of the biggest ranches up

here besides the Alamito, and the Drovers’ Association

wants a little of your old-time holy scare throwed

into the cussed coyotes.”

Mark nodded in the pause which seemed to have

been made for him to nod, and Chadron went on.

“We figger that if a dozen or two of ’em’s cleaned

out, quick and mysterious, the rest’ll tuck tail and

sneak. It’s happened that way in other places more

6

than once, as you and I know. Well, you’re the man

that don’t have to take lessons.”

“Money talks,” repeated Mark, still looking into

the chimney.

“There’s about twenty of them that counts, the

rest’s the kind you can drive over a cliff with a whip.

These fellers has strung their cussed bob-wire fences

crisscross and checkerboard all around there up the

river, and they’re gittin’ to be right troublesome.

Of course they’re only a speck up there yet, but

they’ll multiply like fleas on a hot dog if we let ’em

go ahead. You know how it is.”

There was a conclusiveness in Chadron’s tone as

he said that. It spoke of a large understanding

between men of a kind.

“Sure,” grunted the man Mark, nodding his head

at the chimney. “You want a man to work from

the willers, without no muss or gun-flashin’, or rough

houses or loud talk.”

“Twenty of them, their names are here, and some

scattered in between that I haven’t put down, to be

picked up as they fall in handy, see?”

“And you’re aimin’ to keep clear, and stand back

in the shadder, like you always have done,” growled

Mark. “Well, I ain’t goin’ to ram my neck into no

sheriff’s loop for nobody’s business but my own from

now on. I’m through with resks, just to be

obligin’.”

“Who’ll put a hand on you in this country unless

we give the word?” Chadron asked, severely.

“How do I know who’s runnin’ the law in this dang

country now? Maybe you fellers is, maybe you

ain’t.”

“There’s no law in this part of the country bigger

than the Drovers’ Association,” Chadron told him,

frowning in rebuke of Mark’s doubt of security.

“Well, maybe there’s a little sheriff here and there,

and a few judges that we didn’t put in, but they’re

down in the farmin’ country, and they don’t cut no

figger at all. If you was fool enough to let one of

them fellers git a hold on you we wouldn’t leave you

in jail over night. You know how it was up there in

the north.”

“But I don’t know how it is down here.” Mark

scowled in surly unbelief, or surly simulation.

“There’s not a judge, federal or state, that could

carry a bale of hay anywhere in the cattle country,

I tell you, Mark, that we don’t draw the chalk line

for.”

“Then why don’t you do the job yourselves, ’stead

of callin’ a peaceable man away from his ranchin’?”

“You’re one kind of a gentleman, Mark, and I’m

another, and there’s different jobs for different men.

That ain’t my line.”

“Oh hell!” said Mark, laying upon the words an

eloquent stress.

“All you’ve got to do is keep clear of the reservation;

don’t turn a card here, no matter how easy it

looks. We can’t jerk you out of the hands of the

army if you git mixed up with it; that’s one place

8

where we stop. The reservation’s a middle ground

where we meet the nesters—rustlers, every muddy-bellied

wolf of ’em, and we can prove it—and pass

’em by. They come and go here like white men, and

nothing said. Keep clear of the reservation; that’s

all you’ve got to do to be as safe as if you was layin’

in bed on your ranch up in Jackson’s Hole.”

Chadron winked as he named that refuge of the

hunted in the Northwest. Mark appeared to be

considering something weightily.

“Oh, well, if they’re rustlers—nobody ain’t got

no use for a rustler,” he said.

“There’s men in that bunch of twenty”—tapping

the slip of paper with his finger—“that started

with two cows a couple of years ago that’s got fifty

and sixty head of two-year-olds now,” Chadron feelingly

declared.

“How much’re you willin’ to go?” Mark put the

question with a suddenness which seemed to betray

that he had been saving it to shoot off that way, as a

disagreeable point over which he expected a quarrel.

He squinted his draggled left eye at Chadron, as if he

was taking aim, while he waited for a reply.

“Well, you have done it for fifty a head,” Chadron

said.

“Things is higher now, and I’m older, and the

resk’s bigger,” Mark complained. “How fur apart

do they lay?”

“You ought to get around in a week or two.”

“But that ain’t figgerin’ the time a feller has to

9

lay out in the bresh waitin’ and takin’ rheumatiz in

his j’ints. I couldn’t touch the job for the old figger;

things is higher.”

“Look here, Mark”—Chadron opened the slip

which he had wound round his finger—“this one is

worth ten, yes, all, the others. Make your own price

on him. But I want it done; no bungled job.”

Mark took the paper and laid his pipe aside while

he studied it.

“Macdonald?”

“Alan Macdonald,” nodded Chadron. “That

feller’s opened a ditch from the river up there on my

land and begun to irrigate!”

“Irrigatin’, huh?” said Mark, abstractedly,

moving his finger down the column of names.

“He makes a blind of buyin’ up cattle and fattenin’

’em on the hay and alfalfer he’s raisin’ up there

on my good land, but he’s the king-pin of the

rustlers in this corner of the state. He’ll be in here

tomorrow with cattle for the Indian agent—it’s beef

day—and you can size him up. But you’ve got to

keep your belly to the ground like a snake when you

start anything on that feller, and you’ve got to make

sure you’ve got him dead to rights. He’s quick with

a gun, and he’s sure.”

“Five hundred?” suggested Mark, with a crafty

sidelong look.

“You’ve named it.”

“And something down for expenses; a feller’s got

to live, and livin’s high.”

Chadron drew out his wallet. Money passed into

Mark’s hand, and he put it away in his pocket along

with the list of names.

“I’ll see you in the old place in Cheyenne for the

settlement, if you make good,” Chadron told him.

Mark waved his hand in lofty depreciation of the

hint that failure for him was a possible contingency.

He said no more. For a little while Chadron stood

looking down on him as he leaned with his pipe over

the dead ashes in the fireplace, his hand in the breast

of his coat, where he had stored his purse. Mark

treated the mighty cattleman as if he had become a

stranger to him, along with the rest of the world in

that place, and Chadron turned and went his way.

Fort Shakie was on its downhill way in those

days, and almost at the bottom of the decline.

It was considered a post of penance by enlisted men

and officers alike, nested up there in the high plateau

against the mountains in its place of wild beauty and

picturesque charm.

But natural beauty and Indian picturesqueness do

not fill the place in the soldierly breast of fair civilian

lady faces, nor torrential streams of cold mountain

water supply the music of the locomotive’s toot.

Fort Shakie was being crept upon by civilization,

true, but it was coming all too slow for the booted

troopers and belted officers who must wear away the

months in its lonely silences.

Within the memory of officers not yet gray the

post had been a hundred and fifty miles from a railroad.

Now it was but twenty; but even that short

leap drowned the voice of the locomotive, and the

dot at the rails’ end held few of the endearments

which make soldiering sweet.

Soon the post must go, indeed, for the need of it

had passed. The Shoshones, Arapahoes, and Crows

had forgotten their old animosities, and were traveling

with Buffalo Bill, going to college, and raising

alfalfa under the direction of a government farmer.

12

The Indian police were in training to do the soldiers’

work there. Soon the post must stand abandoned,

a lonely monument to the days of hard riding, long

watches, and bleak years. Not a soldier in the

service but prayed for the hastening of the day.

No, there was not much over at Meander, at the

railroad’s end, to cheer a soldier’s heart. It was an

inspiring ride, in these autumn days, to come to

Meander, past the little brimming lakes, which

seemed to lie without banks in the green meadows

where wild elk fed with the shy Indian cattle; over

the white hills where the earth gave under the hoofs

like new-fallen snow. But when one came to it

through the expanding, dusty miles, the reward of his

long ride was not in keeping with his effort.

Certainly, privates and subalterns could get drunk

there, as speedily as in the centers of refinement, but

there were no gentlemanly diversions at which an

officer could dispel the gloom of his sour days in

garrison.

The rough-cheeked girls of that high-wind country

were well enough for cowboys to swing in their wild

dances; just a rung above the squaws on the reservation

in the matter of loquacity and of gum. Hardly

the sort for a man who had the memory of white

gloves and gleaming shoulders, and the traditions of

the service to maintain.

Of course there was the exception of Nola

Chadron, but she was not of Meander and the railroad’s

end, and she came only in flashes of summer

13

brightness, like a swift, gay bird. But when Nola

was at the ranchhouse on the river the gloom lifted

over the post, and the sour leaven in the hearts of

unmarried officers became as sweet as manna in the

cheer of the unusual social outlet thus provided.

Nola kept the big house in a blaze of joy while

she nested there through the summer days. The sixteen

miles which stretched between it and the post

ran out like a silver band before those who rode

into the smile of her welcome, and when she flitted

away to Cheyenne, champagne, and silk hats in the

autumn, a grayness hovered again over the military

post in the corner of the reservation.

Later than usual Nola had lingered on this fall,

and the social outlet had remained open, like a

navigable river over which the threat of ice hung

but had not yet fallen. There were not lacking those

who held that the lodestone which kept her there at

the ranchhouse, when the gaieties of the season beckoned

elsewhere, was in the breast of Major Cuvier

King. Fatal infatuation, said the married ladies at

the post, knowing, as everybody knew in the service,

that Major King was betrothed to Frances Landcraft,

the colonel’s daughter.

No matter for any complications which might come

of it, Nola had remained on, and the major had

smiled on her, and ridden with her, and cut high

capers in the dance, all pending the return of

Frances and her mother from their summering at Bar

Harbor in compliance with the family traditions.

14

Now Frances was back again, and fortune had thrown

a sunburst of beauty into the post by centering her

and Nola here at once. Nola was the guest of the

colonel’s daughter, and there were flutterings in

uniformed breasts.

Beef day was an event at the agency which never

grew old to the people at the post. Without beef

day they must have dwindled off to acidulous shadows,

as the Indians who depended upon it for more

solid sustenance would have done in the event of its

discontinuation by a paternal government.

There were phases of Indian life and character

which one never saw save on beef day, which fell on

Wednesday of each week. Guests at the post

watched the bright picture with the keen interest of

a pageant on the stage; tourists came over by stage

from Meander in the summer months by the score to

be present; the resident officers, and their wives and

families—such as had them—found in it an ever-recurring

source of interest and relief from the tedium

of days all alike.

This beef day, the morning following the meeting

between Saul Chadron and his mysterious guest, a

chattering group stood on the veranda of Colonel

Landcraft’s house in the bright friendly sun. They

were waiting for horses to make the short journey to

the agency—for one’s honesty was questioned, his

sanity doubted, if he went afoot in that country even

a quarter of a mile—and gayest among them was

Nola Chadron, the sun in her fair, springing hair.

Nola’s crown reached little higher than a proper

soldier’s heart, but what she lacked in stature she

supplied in plastic perfection of body and vivacity

of face. There was a bounding joyousness of life in

her; her eager eyes reflecting only the anticipated

pleasures of today. There was no shadow of yesterday’s

regret in them, no cloud of tomorrow’s doubt.

On the other balance there was Frances Landcraft,

taller by half a head, soldierly, too, as became her

lineage, in the manner of lifting her chin in what

seemed a patrician scorn of small things such as a

lady should walk the world unconscious of. The

brown in her hair was richer than the clear agate of

her eyes; it rippled across her ear like the scroll of

water upon the sand.

There was a womanly dignity about her, although

the threshold of girlhood must not have been far

behind her that bright autumnal morning. Her nod

was equal to a stave of Nola’s chatter, her smile worth

a league of the light laughter from that bounding

little lady’s lips. Not that she was always so silent

as on that morning, there among the young wives of

the post, at her own guest’s side. She had her hours

of overflowing spirits like any girl, but in some

company she was always grave.

When Major King was in attendance, especially,

the seeing ones made note. And there were others,

too, who said that she was by nature a colonel among

women, haughty, cold and aloof. These wondered

how the major ever had made headway with her up to

16

the point of gaining her hand. Knowing ones smiled

at that, and said it had been arranged.

There were ambitions on both sides of that match,

it was known—ambition on the colonel’s part to

secure his only child a station of dignity, and what

he held to be of consequence above all achievements

in the world. Major King was a rising man, with

two friends in the cabinet. It was said that he would

be a brigadier-general before he reached forty.

On the major’s side, was the ambition to strengthen

his political affiliations by alliance with a family of

patrician strain, together with the money that his

bride would bring, for Colonel Landcraft was a

weighty man in this world’s valued accumulations.

So the match had been arranged.

The veranda of the colonel’s house gave a view of

the parade grounds and the long avenue that came

down between the officers’ houses, cottonwoods lacing

their limbs above the road. There was green in the

lawns, the flash of flowers between the leaves and

shrubs, white-gleaming walls, trim walks, shorn

hedges. It seemed a pleasant place of quiet beauty

that bright September morning, and a pity to give it

up by and by to dust and desolation; a place where

men and women might be happy, but for the gnawing

fire of ambition in their hearts.

Mrs. Colonel Landcraft was not going. Indians

made her sick, she said, especially Indians sitting

around in the tall grass waiting for the carcasses to

be cut up and apportioned out to them in bloody

17

chunks. But there seemed to be another source of

her sickness that morning, measuring by the grave

glances with which she searched her daughter’s face.

She wondered whether the major and Frances had

quarreled; and if so, whether Nola Chadron had been

the cause.

They were off, with the colonel and a lately-assigned

captain in the lead. There was a keener

pleasure in this beef day than usual for the colonel,

for he had new ground to sow with its wonders, which

were beginning to pale in his old eyes which had seen

so much of the world.

“Very likely we’ll see the minister’s wife there,”

said he, as they rode forward, “and if so, it will be

worth your while to take special note of her. St.

John Mathews, the Episcopalian minister over there

at the mission—those white buildings there among

the trees—is a full-blooded Crow. One of the pioneer

missionaries took him up and sent him back East

to school, where in time he entered the ministry and

married this white girl. She was a college girl, I’ve

been told, glamoured by the romance of Mathews’

life. Well, it was soon over.”

The colonel sighed, and fell silent. The captain,

feeling that it was intended that he should, made

polite inquiry.

“The trouble is that Mathews is an Indian out of

his place,” the colonel resumed. “He returned here

twenty years or so ago, and took up his work among

his people. But as he advanced toward civilization,

18

his wife began to slip back. Little by little she

adopted the Indian ways and dress, until now you

couldn’t tell her from a squaw if you were to meet

her for the first time. She presents a curious psychological

study—or perhaps biological example of

atavism, for I believe there’s more body than soul in

the poor creature now. It’s nature maintaining the

balance, you see. He goes up; she slips back.

“If she’s there, she’ll be squatting among the

squaws, waiting to carry home her husband’s allotment

of warm, bloody beef. She doesn’t have to do

it, and it shames and humiliates Mathews, too, even

though they say she cuts it up and divides it among

the poorer Indians. She’s a savage; her eyes sparkle

at the sight of red meat.”

They rounded the agency buildings and came upon

an open meadow in which the slaughterhouses stood

at a distance from the road. Here, in the grassy

expanse, the Indians were gathered, waiting the distribution

of the meat. The scene was barbarically

animated. Groups of women in their bright dresses

sat here and there on the grass, and apart from them

in gravity waited old men in moccasins and blankets

and with feathers in their hair. Spry young men

smoked cigarettes and talked volubly, garbed in the

worst of civilization and the most useless of savagery.

One and all they turned their backs upon the

visitors, the nearest groups and individuals moving

away from them with the impassive dignity of their

race. There is more scorn in an Indian squaw’s back,

19

turned to an impertinent stranger, than in the faces

of six matrons of society’s finest-sifted under similar

conditions.

Colonel Landcraft led his party across the meadow,

entirely unconscious of the cold disdain of the people

whom he looked down upon from his superior heights.

He could not have understood if any there had felt

the trespass from the Indians’ side—and there was

one, very near and dear to the colonel who felt it so—and

attempted to explain. The colonel very likely

would have puffed up with military consequence

almost to the bursting-point.

Feeling, delicacy, in those smeared, smelling creatures!

Surliness in excess they might have, but

dignity, not at all. Were they not there as beggars

to receive bounty from the government’s hand?

“Oh, there’s Mrs. Mathews!” said Nola, with the

eagerness of a child who has found a quail’s nest in

the grass. She was off at an angle, like a hunter on

the scent. Colonel Landcraft and his guest followed

with equal rude eagerness, and the others swept after

them, Frances alone hanging back. Major King was

at Nola’s side. If he noted the lagging of his fiancée

he did not heed.

The minister’s wife, a shawl over her head, her

braided hair in front of her shoulders like an Indian

woman, rose from her place in startled confusion.

She looked as if she would have fled if an avenue had

been open, or a refuge presented. The embarrassed

creature was obliged to stand in their curious eyes,

20

and stammer in a tongue which seemed to be growing

strange to her from its uncommon use.

She was a short woman, growing heavy and shapeless

now, and there was gray in her black hair. Her

skin was browned by sun, wind, and smoke to the

hue of her poor neighbors and friends. When she

spoke in reply to the questions which poured upon

her, she bent her head like a timid girl.

Frances checked her horse and remained behind,

out of range of hearing. She was cut to the heart

with shame for her companions, and her cheek burned

with the indignation that she suffered with the harried

woman in their midst. A little Indian girl came

flying past, ducking and dashing under the neck of

Frances’ horse, in pursuit of a piece of paper which

the wind whirled ahead of her. At Frances’ stirrup

she caught it, and held it up with a smile.

“Did you lose this, lady?” she asked, in the very

best of mission English.

“No,” said Frances, bending over to see what it

might be. The little girl placed it in her hand and

scurried away again to a beckoning woman, who

stood on her knees and scowled over her offspring’s

dash into the ways of civilized little girls.

It was a narrow strip of paper that she had rescued

from the wind, with the names of several men written

on it in pencil, and at the head of the list the name

of Alan Macdonald. Opposite that name some crude

hand had entered, with pen that had flowed heavily

under his pressure, the figures “$500.”

Frances turned it round her finger and sat waiting

for the others to leave off their persecution of the

minister’s wife and come back to her, wondering in

abstracted wandering of mind who Alan Macdonald

might be, and for what purpose he had subscribed

the sum of five hundred dollars.

“I think she’s the most romantic little thing in

the world!” Nola was declaring, in her extravagant

surface way as they returned to where Frances sat

her horse, her wandering eyes on the blue foothills,

the strip of paper prominent about her finger. “Oh,

honey! what’s the matter? Did you cut your

finger?”

“No,” said Frances, her serious young face lighting

with a smile, “it’s a little subscription list, or

something, that somebody lost. Alan Macdonald

heads it for five hundred dollars. Do you know

Alan Macdonald, and what his charitable purpose

may be?”

Nola tossed her head with a contemptuous sniff.

“They call him the ‘king of the rustlers’ up the

river,” said she.

“Oh, he is a man of consequence, then?” said

Frances, a quickening of humor in her brown eyes,

seeing that Nola was up on her high horse about it.

“We’d better be going down to the slaughter-house

if we want to see the fun,” bustled the colonel,

wheeling his horse. “I see a movement setting in that

way.”

“He’s just a common thief!” declared Nola, with

22

flushed cheek and resentful eye, as Frances fell in

beside her for the march against the abattoir.

Frances still carried the paper twisted about her

finger, reserving her judgment upon Alan Macdonald,

for she knew something of the feuds of that

hard-speaking land.

“Anyway, I suppose he’d like to have his paper

back,” she suggested. “Will you hand it to him

the next time you meet him?”

Frances was entirely grave about it, although it

was only a piece of banter which she felt that Nola

would appreciate. But Nola was not in an appreciative

mood, for she was a full-blooded daughter of the

baronial rule. She jerked her head like a vicious

bronco and reined hurriedly away from Frances as

she extended the paper.

“I’ll not touch the thing!” said Nola, fire in her

eyes.

Major King was enjoying the passage between

the girls, riding at Nola’s side with his cavalry hands

held precisely.

“If I’m not mistaken, the gentleman in question

is there talking to Miller, the agent,” said he, nodding

toward two horsemen a little distance ahead.

“But I wouldn’t excite him, Miss Landcraft, if I

were you. He’s said to be the quickest and deadliest

man with a weapon on this range.”

Major King smiled over his own pleasantry.

Frances looked at Nola with brows lifted inquiringly,

as if waiting her verification. Then the grave young

23

lady settled back in her saddle and laughed merrily,

reaching across and touching her friend’s arm in

conciliating caress.

“Oh, you delightful little savage!” she said. “I

believe you’d like to take a shot at poor Mr. Macdonald

yourself.”

“We never start anything on the reservation,”

Nola rejoined, quite seriously.

Miller, the Indian agent, rode away and left Macdonald

sitting there on his horse as the military party

approached. He spurred up to meet the colonel,

and to present his respects to the ladies—a hard

matter for a little round man with a tight paunch,

sitting in a Mexican saddle. The party halted, and

Frances looked across at Macdonald, who seemed to

be waiting for Miller to rejoin him.

Macdonald was a supple, sinewy man, as he appeared

across the few rods intervening. His coat

was tied with his slicker at the cantle of his saddle,

his blue flannel shirt was powdered with the white

dust of the plain. Instead of the flaring neckerchief

which the cowboys commonly favored, Macdonald

wore a cravat, the ends of it tucked into the bosom

of his shirt, and in place of the leather chaps of

men who ride breakneck through brush and bramble,

his legs were clad in tough brown corduroys, and

fended by boots to his knees. There were revolvers

in the holsters at his belt.

Not an unusual figure for that time and place,

but something uncommon in the air of unbending

24

severity that sat on him, which Frances felt even at

that distance. He looked like a man who had a

purpose in his life, and who was living it in his own

brave way. If he was a cattle thief, as charged,

thought she, then she would put her faith against

the world that he was indeed a master of his trade.

They were talking around Miller, who was going

to give them places of vantage for the coming show.

Only Frances and Major King were left behind,

where she had stopped her horse to look curiously

across at Alan Macdonald, king of the rustlers, as

he was called.

“It may not be anything at all to him, and it may

be something important,” said Frances, reaching out

the slip to Major King. “Would you mind handing

it to him, and explaining how it came into my

hands?”

“I’ll not have anything to do with the fellow!”

said the major, flushing hotly. “How can you ask

such a thing of me? Throw it away, it’s no concern

of yours—the memorandum of a cattle thief!”

Frances drew herself straight. Her imperious

chin was as high as Major King ever had carried

his own in the most self-conscious moment of his

military career.

“Will you take it to him?” she demanded.

“Certainly not!” returned the major, haughtily

emphatic. Then, softening a little, “Don’t be silly,

Frances; what a row you make over a scrap of blowing

paper!”

“Then I’ll take it myself!”

“Miss Landcraft!”

“Major King!”

It was the steel of conventionality against the flint

of womanly defiance. Major King started in his

saddle, as if to reach out and restrain her. It was

one of those defiantly foolish little things which

women and men—especially women—do in moments

of pique, and Frances knew it at the time. But she

rode away from the major with a hot flush of insubordination

in her cheeks, and Alan Macdonald

quickened from his pensive pose when he saw her

coming.

His hand went to his hat when her intention became

unmistakable to him. She held the little paper out

toward him while still a rod away.

“A little Indian girl gave me this; she found it

blowing along—they tell me you are Mr. Macdonald,”

she said, her face as serious as his own. “I

thought it might be a subscription list for a church,

or something, and that you might want it.”

“Thank you, Miss Landcraft,” said he, his voice

low-modulated, his manner easy.

Her face colored at the unexpected way of this

man without a coat, who spoke her name with the

accent of refinement, just as if he had known her,

and had met her casually upon the way.

“I have seen you a hundred times at the post and

the agency,” he explained, to smooth away her confusion.

“I have seen you from afar.”

“Oh,” said she, as lame as the word was short.

He was scanning the written paper. Now he

looked at her, a smile waking in his eyes. It moved

in slow illumination over his face, but did not break

his lips, pressed in their stern, strong line. She saw

that his long hair was light, and that his eyes were

gray, with sandy brows over them which stood on

end at the points nearest his nose, from a habit of

bending them in concentration, she supposed, as he

had been doing but a moment before he smiled.

“No, it isn’t a church subscription, Miss Landcraft,

it’s for a cemetery,” said he.

“Oh,” said she again, wondering why she did not

go back to Major King, whose horse appeared

restive, and in need of the spur, which the major

gave him unfeelingly.

At the same time she noted that Alan Macdonald’s

forehead was broad and deep, for his leather-weighted

hat was pushed back from it where his fair, straight

hair lay thick, and that his bony chin had a little

croft in it, and that his face was long, and hollowed

like a student’s, and that youth was in his eyes in

spite of the experience which hardships of unknown

kind had written across his face. Not a handsome

man, but a strong one in his way, whatever that

way might be.

“I am indebted to you for this,” said he, drawing

forth his watch with a quick movement as he spoke,

opening the back cover, folding the little paper carefully

away in it, “and grateful beyond words.”

“Good-bye, Mr. Macdonald,” said she, wheeling

her horse suddenly, smiling back at him as she rode

away to Major King.

Alan Macdonald sat with his hat off until she was

again at the major’s side, when he replaced it over

his fair hair with slow hand, as if he had come from

some holy presence. As for Frances, her turn of

defiance had driven her clouds away. She met the

major smiling and radiant, a twinkling of mischief

in her lively eyes.

The major was a diplomat, as all good soldiers,

and some very indifferent ones, are. Whatever his

dignity and gentler feelings had suffered while she

was away, he covered the hurt now with a smile.

“And how fares the bandit king this morning?”

he inquired.

“He seems to be in spirits,” she replied.

The others were out of sight around the buildings

where the carcasses of beef had been prepared. Nobody

but the major knew of Frances’ little dash out

of the conventional, and the knowledge that it was

so was comfortable in his breast.

“And the pe-apers,” said he, in melodramatic

whisper, “were they the thieves’ muster roll?”

“He isn’t a thief,” said she, with quiet dignity,

“he’s a gentleman. Yes, the paper was important.”

“Ha! the plot deepens!” said Major King.

“It was a matter of life and death,” said she,

with solemn rebuke for his levity, speaking a truer

word than she was aware.

28

CHAPTER III

THE RANCHHOUSE BY THE RIVER

Saul Chadron had built himself into that

house. It was a solid and assertive thing of

rude importance where it stood in the great plain,

the river lying flat before it in its low banks like a

gray thread through the summer green. There was

a bold front to the house, and a turret with windows,

standing like a lighthouse above the sea of meadows

in which his thousand-numbered cattle fed.

As white as a dove it sat there among the cottonwoods

at the riverside. A stream of water led into

its gardens to gladden them and give them life. Years

ago, when Chadron’s importance was beginning to

feel itself strong upon its legs, and when Nola was

a little thing with light curls blowing about her blue

eyes, the house had grown up under the wand of

riches in that barren place.

The post at Fort Shakie had been the nearest

neighbor in those days, and it remained the nearest

neighbor still, with the exception of one usurper and

outcast homesteader, Alan Macdonald by name, who

had invaded the land over which Chadron laid his

extensive claim. Fifteen miles up the river from

the grand white house Macdonald had strung his

barbed wire and carried in the irrigation ditch to

his alfalfa field. He had chosen the most fertile spot

29

in the vast plain through which the river swept, and

it was in the heart of Saul Chadron’s domain.

After the lordly manner of the cattle “barons,”

as they were called in the Northwest, Chadron set

his bounds by mountains and rivers. Twenty-five

hundred square miles, roughly measured, lay within

his lines, the Alamito Ranch he called it—the Little

Cottonwood. He had no more title to that great

sweep of land than the next man who might come

along, and he paid no rental fee to nation nor state

for grazing his herds upon it. But the cattle barons

had so apportioned the land between themselves, and

Saul Chadron, and each member of the Drovers’

Association, had the power of their mighty organization

to uphold his hand. That power was incontestable

in the Northwest in its day; there was no

higher law.

This Alan Macdonald was an unaccountable man,

a man of education, it was said, which made him

doubly dangerous in Saul Chadron’s eyes. Saul himself

had come up from the saddle, and he was not

strong on letters, but he had seen the power of learning

in lawyers’ offices, and he respected it, and handled

it warily, like a loaded gun.

Chadron had sent his cowboys up the river when

Macdonald first came, and tried to “throw a holy

scare into him,” as he put it. The old formula did

not work in the case of the lean, long-jawed, bony-chinned

man. He was polite, but obdurate, and his

quick gray eyes seemed to read to their inner process

30

of bluff and bluster as through tissue paper before

a lamp. When they had tried to flash their guns on

him, the climax of their play, he had beaten them to

it. Two of them were carried back to the big ranchhouse

in blankets, with bullets through their fleshy

parts—not fatal wounds, but effective.

The problem of a fighting “nester” was a new one

to the cattlemen of that country. For twenty years

they had kept that state under the dominion of the

steer, and held its rich agricultural and mineral lands

undeveloped. The herbage there, curing in the dry

suns of summer as it stood on the upland plains,

provided winter forage for their herds. There was

no need for man to put his hand to the soil and

debase himself to a peasant’s level when he might

live in a king’s estate by roaming his herds over the

untamed land.

Homesteaders who did not know the conditions

drifted there on the westward-mounting wave, only

to be hustled rudely away, or to pay the penalty of

refusal with their lives. Reasons were not given,

rights were not pleaded by the lords of many herds.

They had the might to work their will; that was

enough.

So it could be understood what indignation

mounted in the breast of tough old Saul Chadron

when a pigmy homesteader put his firm feet down

on the ground and refused to move along at his

command, and even fought back to maintain what he

claimed to be his rights. It was an unprecedented

31

stand, a dangerous example. But this nester had

held out for more than two years against his forces,

armed by some invisible strength, it seemed, guarded

against ambuscades and surprises by some cunning

sense which led him whole and secure about his nefarious

ways.

Not alone that, but other homesteaders had come

and settled near him across the river on two other

big ranches which cornered there against Chadron’s

own. These nesters drew courage from Macdonald’s

example, and cunning from his counsel, and stood

against the warnings, persecutions, and attempts at

forceful dislodgment. The law of might did not seem

to apply to them, and there was no other source equal

to the dignity of the Drovers’ Association—at least

none to which it cared to carry its grievances and

air them.

So they cut Alan Macdonald’s fences, and other

homesteaders’ fences, in the night and drove a thousand

or two cattle across his fields, trampling the

growing grain and forage into the earth; they persecuted

him in a score of harassing, quick, and

hidden blows. But this homesteader was not to be

driven away by ordinary means. Nature seemed to

lend a hand to him, he made crops in spite of the

cattlemen, and was prospering. He had taken root

and appeared determined to remain, and the others

were taking deep root with him, and the free, wide

range was coming under the menace of the fence

and the lowly plow.

That was the condition of things in those fair

autumn days when Prances Landcraft returned to

the post. The Drovers’ Association, and especially

the president of it, was being defied in that section,

where probably a hundred homesteaders had settled

with their families of long-backed sons and daughters.

They were but a speck on the land yet, as

Chadron had told the smoky stranger when he had

engaged him to try his hand at throwing the “holy

scare.” But they spread far over the upland plain,

having sought the most favored spots, and they were

a blight and a pest in the eyes of the cattlemen.

Nola had flitted back to the ranchhouse, carrying

Frances with her to bring down the curtain on her

summer’s festivities there in one last burst of joy.

The event was to be a masquerade, and everybody

from the post was coming, together with the few from

Meander who had polish enough to float them, like

new needles in a glass of water, through frontier society’s

depths. Some were coming from Cheyenne,

also, and the big house was dressed for them, even

to the bank of palms to conceal the musicians, in

the polite way that society has of standing something

in front of what it cannot well dispense with,

yet of which it appears to be ashamed.

It was the afternoon of the festal day, and Nola

sighed happily as she stood with Frances in the ballroom,

surveying the perfection of every detail.

Money could do things away off there in that corner

of the world as well as it could do them in Omaha

33

or elsewhere. Saul Chadron had hothouses in which

even oranges and pineapples grew.

Mrs. Chadron was in the living-room, with its big

fireplace and homely things, when they came chattering

out of the enchanted place. She was sitting

by the window which gave her a view of the dim gray

road where it came over the grassy swells from

Meander and the world, knitting a large blue sock.

Mrs. Chadron was a cow-woman of the unimproved

school. She was a heavy feeder on solids, and she

liked plenty of chili peppers in them, which combination

gave her a waist and a ruddiness of face like a

brewer. But she was a good woman in her fashion,

which was narrow, and intolerant of all things which

did not wear hoofs and horns, or live and grow mighty

from the proceeds of them. She never had expanded

mentally to fit the large place that Saul had made

for her in the world of cattle, although her struggle

had been both painful and sincere.

Now she had given it up, and dismissed the troubles

of high life from her fat little head, leaving Nola

to stand in the door and do the honors with credit

to the entire family. She had settled down to her

roasts and hot condiments, her knitting and her afternoon

naps, as contentedly as an old cat with a

singed back under a kitchen stove. She had no

desire to go back to the winter home in Cheyenne,

with its grandeur, its Chinese cook, and furniture

that she was afraid to use. There was no satisfaction

in that place for Mrs. Chadron, beyond the

34

swelling pride of ownership. For comfort, peace,

and a mind at ease, give her the ranchhouse by the

river, where she could set her hand to a dish if she

wanted to, no one thinking it amiss.

“Well, I declare! if here don’t come Banjo Gibson,” said she,

her hand on the curtain, her red face

near the pane like a beacon to welcome the coming

guest. There was pleasure in her voice, and anticipation.

The blue sock slid from her lap to the floor,

forgotten.

“Yes, it’s Banjo,” said Nola. “I wonder where

he’s been all summer? I haven’t seen him in an age.”

“Who is he?” Frances inquired, looking out at

the approaching figure,

“The troubadour of the North Platte, I call him,”

laughed Nola; “the queerest little traveling musician

in a thousand miles. He belongs back in the days

of romance, when men like him went playing from

castle to court—the last one of his kind.”

Frances watched him with new interest as he drew

up to the big gate, which was arranged with weights

and levers so that a horseman could open and close

it without leaving the saddle. The troubadour rode

a mustang the color of a dry chili pepper, but with

none of its spirit. It came in with drooping head,

the reins lying untouched on its neck, its mane and

forelock platted and adorned fantastically with vari-colored

ribbons. Rosettes were on the bridle, a fringe

of leather thongs along the reins.

The musician himself was scarcely less remarkably

35

than the horse. He looked at that distance—now

being at the gate—to be a dry little man of middle

age, with a thirsty look about his throat, which was

long, with a lump in it like an elbow. He was a

slender man and short, with gloves on his hands, a

slight sandy mustache on his lip, and wearing a dun-colored

hat tilted a little to one side, showing a waviness

almost curly in his glistening black hair. He

carried a violin case behind his saddle, and a banjo

in a green covering slung like a carbine over his

shoulder.

“He’ll know where to put his horse,” said Mrs.

Chadron, getting up with a new interest in life, “and

I’ll just go and have Maggie stir him up a bite to

eat and warm the coffee. He’s always hungry when

he comes anywhere, poor little man!”

“Can he play that battery of instruments?”

Prances asked.

“Wait till you hear him,” nodded Nola, a laugh

in her merry eyes.

Then they fell to talking of the coming night,

and of the trivial things which are so much to youth,

and to watching along the road toward Meander for

the expected guests from Cheyenne, who were to come

up on the afternoon train.

Regaled at length, Banjo Gibson, in the wake of

Mrs. Chadron, who presented him with pride, came

into the room where the young ladies waited with

impatience the waning of the daylight hours. Banjo

acknowledged the honor of meeting Miss Landcraft

36

with extravagant words, which had the flavor of a

manual of politeness and a ready letter-writer in

them. He was on more natural terms with Nola,

having known her since childhood, and he called her

“Miss Nola,” and held her hand with a tender lingering.

His voice was full and rich, a deep, soft note in

it like a rare instrument in tune. His small feet

were shod in the shiningest of shoes, which he had

given a furbishing in the barn, and a flowing cravat

tied in a large bow adorned his low collar. There

were stripes in the musician’s shirt like a Persian

tent, but it was as clean and unwrinkled as if he had

that moment put it on.

Banjo Gibson—if he had any other christened

name, it was unknown to men—was an original. As

Nola had said, he belonged back a few hundred years,

when musical proficiency was not so common as now.

The profession was not crowded in that country,

happily, and Banjo traveled from ranch to ranch

carrying cheer and entertainment with him as he

passed.

He had been doing that for years, having worked

his way westward from Nebraska with the big cattle

ranches, and his art was his living. Banjo’s arrival

at a ranch usually resulted in a dance, for which he

supplied the music, and received such compensation

as the generosity of the host might fix. Banjo never

quarreled over such matters. All he needed was

enough to buy cigarettes and shirts.

Banjo seldom played in company with any other

musician, owing to certain limitations, which he

raised to distinguishing virtues. He played by “air,”

as he said, despising the unproficiency of all such as

had need of looking on a book while they fiddled.

Knowing nothing of transposition, he was obliged to

tune his banjo—on those rare occasions when he

stooped to play “second” at a dance—in the key

of each fresh tune. This was hard on the strings, as

well as on the patience of the player, and Banjo liked

best to go it single-handed and alone.

When he heard that musicians were coming from

Cheyenne—a day’s journey by train—to play for

Nola’s ball, his face told that he was hurt, but his

respect of hospitality curbed his words. He knew

that there was one appreciative ear in the mansion

by the river that no amount of “dago fiddlin’” ever

would charm and satisfy like his own voice with the

banjo, or his little brown fiddle when it gave out the

old foot-warming tunes. Mrs. Chadron was his

champion in all company, and his friend in all places.

“Well, sakes alive! Banjo, I’m as tickled to see

you as if you was one of my own folks,” she declared,

her face as warm as if she had just gorged on the

hottest of hot dishes which her Mexican cook, Maggie,

could devise.

“I’m glad to be able to make it around ag’in, thank

you, mom,” Banjo assured her, sentiment and soul

behind the simple words. “I always carry a warm

place in my heart for Alamito wherever I may stray.”

Nola frisked around and took the banjo from its

green cover, talking all the time, pushing and placing

chairs, and settling Banjo in a comfortable place.

Then she armed him with the instrument, making

quite a ceremony of it, and asked him to play.

Banjo twanged the instrument into tune, hooked

the toe of his left foot behind the forward leg of his

chair, and struck up a song which he judged would

please the young ladies. Of Mrs. Chadron he was

sure; she had laughed over it a hundred times. It

was about an adventure which the bard had shared

with his gal in a place designated in Banjo’s uncertain

vocabulary as “the big cook-quari-um.” It

began:

Oh-h-h, I stopped at a big cook-quari-um

Not very long ago,

To see the bass and suckers

And hear the white whale blow.

The chorus of it ran:

Oh-h-h-h, the big sea-line he howled and he growled,

The seal beat time on a drum;

The whale he swallered a den-vereel

In the big cook-quari-um.

From that one Banjo passed to “The Cowboy’s

Lament,” and from tragedy to love. There could be

nothing more moving—if not in one direction, then

in another—than the sentimental expression of

Banjo’s little sandy face as he sang:

I know you were once my true-lov-o-o-o,

But such a thing it has an aind;

My love and my transpo’ts are ov-o-o-o,

But you may still be my fraind-d-d.

Sundown was rosy behind the distant mountains,

a sea of purple shadows laved their nearer feet, when

Banjo got out his fiddle at Mrs. Chadron’s request

and sang her “favorite” along with the moving tones

of that instrument.

Dau-ling I am growing-a o-o-eld,

Seel-vo threads a-mong tho go-o-ld—

As he sang, Nola slipped from the room. He was

finishing when she sped by the window and came

sparkling into the room with the announcement that

the guests from far Cheyenne were coming. Frances

was up in excitement; Mrs. Chadron searched the

floor for her unfinished sock.

“What was that flashed a-past the winder like a

streak a minute ago?” Banjo inquired.

“Flashed by the window?” Nola repeated, puzzled.

Frances laughed, the two girls stopping in the

door, merriment gleaming from their young faces like

rays from iridescent gems.

“Why, that was Nola,” Frances told him, curious

to learn what the sentimental eyes of the little musician

foretold.

“I thought it was a star from the sky,” said

Banjo, sighing softly, like a falling leaf.

As they waited at the gate to welcome the guests,

40

who were cantering up with a curtain of dust behind

them, they laughed over Banjo’s compliment.

“I knew there was something behind those eyes,”

said Frances.

“No telling how long he’s been saving it for a

chance to work it off on somebody,” Nola said. “He

got it out of a book—the Mexicans all have them,

full of brindies, what we call toasts, and silly soft

compliments like that.”

“I’ve seen them, little red books that they give

for premiums with the Mexican papers down in

Texas,” Frances nodded, “but Banjo didn’t get that

out of a book—it was spontaneous.”

“I must write it down, and compare it with the

next time he gets it off.”

“Give him credit for the way he delivered it, no

matter where he got it,” Frances laughed. “Many

a more sophisticated man than your desert troubadour

would have broken his neck over that. He’s

in love with you, Nola—didn’t you hear him sigh?”

“Oh, he has been ever since I was old enough to

take notice of it,” returned Nola, lightly.

“Oh, my luv’s like a falling star,” paraphrased

Frances.

“Not much!” Nola denied, more than half serious.

“Venus is ascendant; you keep your eye on her and

see.”

41

CHAPTER IV

THE MAN IN THE PLAID

There was no mistaking the assiduity with

which Major King waited upon Nola Chadron

that night at the ball, any more than there was a

chance for doubt of that lively little lady’s identity.

He sought her at the first, and hung by her side

through many dances, and promenaded her in the

garden walks where Japanese lanterns glimmered

dimly in the soft September night, with all the close

attention of a farrier cooling a valuable horse.

Perhaps it was punishment—or meant to be—for

the insubordination of Frances Landcraft in

speaking to the outlawed Alan Macdonald on last

beef day. If so, it was systematically and faithfully

administered.

Nola was dressed like a cowgirl. Not that there

were any cowgirls in that part of the country, or

anywhere else, who dressed that way, except at the

Pioneer Week celebration at Cheyenne, and in the

romantic dramas of the West. But she was so

attired, perhaps for the advantage the short skirt

gave her handsome ankles—and something in silk

stockings which approached them in tapering grace.

She was improving her hour, whether out of exuberant

mischief or in deadly earnest the ladies from

the post were puzzled to understand, and if headway

42

toward the already pledged heart of Major King

was any indication of it, her star was indeed ascendant.

Frances Landcraft appeared at the ball as an

Arabian lady, meaning in her own interpretation of

the masking to stand as a representation of the

“Thou,” who is endearingly and importantly capitalized

in the verses of the ancient singer made famous

by Irish-English Fitzgerald. Her disguise was sufficient,

only that her hair was so richly assertive.

There was not any like it in the cattle country; very

little like it anywhere. It was a telltale, precious

possession, and Major King never could have made

good a plea of hidden identity against it in this

world.

Frances had consolation enough for his alienation

and absence from her side if numbers could compensate

for the withdrawal of the fealty of one. She

distributed her favors with such judicial fairness that

the tongue of gossip could not find a breach. At

least until the tall Scotsman appeared, with his defiant

red hair and a feather in his bonnet, his plaid

fastened across his shoulder with a golden clasp.

Nobody knew when he arrived, or whence. He

spoke to none as he walked in grave stateliness among

the merry groups, acknowledging bold challenges and

gay banterings only with a bow. The ladies from

the post had their guesses as to who he might be,

and laid cunning little traps to provoke him into betrayal

through his voice. As cunningly he evaded

them, with unsmiling courtesy, his steady gray eyes

only seeming to laugh at them behind his green

mask.

Frances had finished a dance with a Robin Hood—the

slender one in billiard-cloth green—there being

no fewer than four of them, variously rounded, diversely

clad, when the Scot approached her where

she stood with her gallant near the musicians’ brake

of palms.

A flask of wine, a book of verse—and Thou

Beside me singing in the wilderness—

said the tall Highlandman, bending over her shoulder,

his words low in her ear. “Only I could be

happy without the wine,” he added, as she faced him

in quick surprise.

“Your penetration deserves a reward—you are

the first to guess it,” said she.

“Three dances, no less,” said he, like a usurer

demanding his toll.

He offered his arm, and straightway bore her off

from the astonished Robin Hood, who stood staring

after them, believing, perhaps, that he was the victim

of some prearranged plan.

The spirit of his free ancestors seemed to be in

the lithe, tall Highlander’s feet. There was no dancer

equal to him in that room. A thistle on the wind

was not lighter, nor a wheeling swallow more graceful

in its flight.

Many others stopped their dancing to watch that

44

pair; whisperings ran round like electrical conjectures.

Nola steered Major King near the whirling

couple, and even tried to maneuver a collision, which

failed.

“Who is that dancing with Frances Landcraft?”

she breathed in the major’s ear.

“I didn’t know it was Miss Landcraft,” he replied,

although he knew it very well, and resolved to find

out who the Scotsman was, speedily and completely.

“My enchanted hour will soon pass,” said the

Scot, when that dance was done, “and I have been

looking the world over for you.”

“Dancing all the way?” she asked him lightly.

“Far from it,” he answered, his voice still muffled

and low.

They were standing withdrawn a little from the

press in the room after their second dance, when

Major King came by. The major was a cavalier

in drooping hat, with white satin cape, and sword

by his side, and well enough known to all his friends

in spite of the little spat of mustache and beard. As

the major passed he jostled the Scot with his shoulder

with a rudeness openly intentional.

The major turned, and spoke an apology. Frances

felt the Highlander’s muscles swell suddenly where

her hand lay on his arm, but whatever had sprung

into his mind he repressed, and acknowledged the

major’s apology with a lofty nod.

The music for another dance was beginning, and

couples were whirling out upon the floor.

“I don’t care to dance again just now, delightfully

as you carry a clumsy one like me through—”

“A self-disparagement, even, can’t stand unchallenged,”

he interrupted.

“Mr. Macdonald,” she whispered, “your wig is

awry.”

They were near the door opening to the illumined

garden, with its late roses, now at their best, and

hydrangea clumps plumed in foggy bloom. They

stepped out of the swirl of the dance like particles

thrown from a wheel, not missed that moment even

by those interested in keeping them in sight.

“You knew me!” said he, triumphantly glad, as

they entered the garden’s comparative gloom.

“At the first word,” said she.

“I came here in the hope that you would know

me, and you alone—I came with my heart full of

that hope, and you knew me at the first word!”

There was not so much marvel as satisfaction, even

pride for her penetration, in it.

“Somebody else may have recognized you, too—that

man who brushed against you—”

“He’s one of your officers.”

“I know—Major King. Do you know him?”

“No, and he doesn’t know me. He can have no interest

in me at all.”

“Very well; set your beautiful red wig straight

and then tell me why you wanted to come here among

your enemies. It seems to me a hardy challenge, a

most unnecessary risk.”

“No risk is unnecessary that brings me to you,”

he said, his voice trembling in earnestness. “I dared

to come because I hoped to meet you on equal

ground.”

“You’re a bold man—in more ways than one.”

She shook her head as in rebuke of his temerity.

“But you don’t believe I’m a thief,” said he, conclusively.

“No; I have made public denial of it.” She

laughed lightly, but a little nervously, an uneasiness

over her that she could not define.

“An angel has risen to plead for Alan Macdonald,

then!”

“Why should you need anybody to plead for you

if there’s no truth in their charges? What is a man

like you doing in this wild place, wasting his life in

a land where he isn’t wanted?”

They had turned into a path that branched beyond

the lanterns. The white gravel from the river bars

with which it was paved glimmered among the

shadowy shrubs. Macdonald unclasped his plaid

from his shoulders and transferred it to hers. She

drew it round her, wrapping her arms in it like a

squaw, for the wind was coming chill from the mountains

now.

“It is soon said,” he answered, quite willingly.

“I am not hiding under any other man’s name—the

one they call me by here is my own. I was a ‘son of

a family,’ as they say in Mexico, and looked for distinction,

if not glory, in the diplomatic service. Four

47

years I grubbed, an under secretary in the legation

at Mexico City, then served three more as consul at

Valparaiso. An engineer who helped put the railroad

through this country told me about it down there

when the rust of my inactive life was beginning to

canker my body and brain. I threw up my chance for

diplomatic distinction and came off up here looking

for life and adventure, and maybe a copper mine. I

didn’t find the mine, but I’ve had some fun with the

other two. Sometimes I’d like to lose the adventure

part of it now—it gets tiresome to be hunted, after

a while.”

“What else?” she asked, after a little, seeing that

he walked slowly, his head up, his eyes far away on

the purple distances of the night, as if he read a

dream.

“I settled in this valley quite innocently, as others

have done, before and after me, not knowing conditions.

You’ve heard it said that I’m a rustler—”

“King of the rustlers,” she corrected.

“Yes, even that. But I am not a rustler. Everybody

up here is a rustler, Miss Landcraft, who

doesn’t belong to, or work for, the Drovers’ Association.

They can’t oust us by merely charging us

with homesteading government land, for that hasn’t

been made a statutory crime yet. They have to

make some sort of a charge against us to give the

color of justification to the crimes they practice on

us, and rustler is the worst one in the cattlemen’s

dictionary. It stands ahead of murder and arson in

48

this country. I’m not saying there are no rustlers

around the edges of these big ranches, for there are

some. But if there are any among the settlers up

our way we don’t know it—and I think we’d pretty

soon find out.”

They turned and walked back toward the house.

“I don’t see why you should trouble about it; this

plainly isn’t your place,” she said.

“First, I refused to be driven out by Chadron

and the rest because the thing got on my mettle. I

knew that I was right, and that they were simply

stealing the public domain. Then, as I hung on, it

became apparent that there was a man’s work cut

out for somebody up here. I’ve taken the ready-made

job.”

“Tell me about it.”

“There’s a monstrous injustice being practiced,

systematically and cruelly, against thousands of

homeless people who come to this country in innocent

hope every year. They come here believing it’s the

great big open-handed West they’ve heard so much

about, carrying everything with them that they

own. They cut the strings that hold them to the

things they know when they face this way, and when

they try to settle on the land that is their inheritance,

this copper-bottomed combination of stockmen drives

them out. If they don’t go, they shoot them. You’ve

heard of it.”

“Not just that way,” said she, thoughtfully.

“No, they never shoot anybody but a rustler, the

49

way the world hears of it,” said he, in resentment.

“But they’ll hear another story on the outside one

of these days. I’m in this fight up to the eyes to

break the back of this infernal combination that’s

choking this state to death. It’s the first time in

my life that I ever laid my hand to anything for

anybody but myself, and I’m going to see it through

to daylight.”

“But there must be millions behind the cattlemen,

Mr. Macdonald.”

“There are. It seems just about hopeless that a

handful of ragged homesteaders ever can make a

stand against them. But they’re usurping the public

domain, and they’ll overreach themselves one of these

days. Chadron has title to this homestead, but that’s

every inch of land that he’s got a legal right over.

In spite of that, he lays the claim of ownership to

the land fifteen miles north of here, where I’ve nested.

He’s been telling me for more than two years that I

must clear out.”

“You could give it up, and go back to your work

among men, where it would count,” she said.

“There are things here that count. I couldn’t put

a state on the map—an industrial and progressive

one, I mean—back home in Washington, or sitting

with my feet on the desk in some sleepy consulate.

And I’m going to put this state on the map where it

belongs. That’s the job that’s cut out for me here,

Miss Landcraft.”

He said it without boast, but with such a stubborn

50

note of determination that she felt something lift

within her, raising her to the plane of his aspirations.

She knew that Alan Macdonald was right about it,

although the thing that he would do was still dim in

her perception.

“Even then, I don’t see what a ranch away off up

here from anywhere ever will be worth to you, especially

when the post is abandoned. You know the

department is going to give it up?”

“And then you—” he began in consternation,

checking himself to add, slowly, “no, I didn’t know

that.”

“Perhaps in a year.”

“It can’t make much difference in the value of

land up this valley, though,” he mused. “When the

railroad comes on through—and that will be as soon

as we break the strangle hold of Chadron and men

like him—this country will develop overnight.

There’s petroleum under the land up where I am,

lying shallow, too. That will be worth something

then.”

The music of an old-style dance was being played.

Now the piping cowboy voice of some range cavalier

rose, calling the figures. The two in the garden path

turned with one accord and faced away from the

bright windows again.

“They’ll be unmasking at midnight?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“I’m afraid I can’t go in again, then. The hour

of my enchantment is nearly at its end.”

“You shouldn’t have come,” she chided, yet not

in severity, rather in subdued admiration for his reckless

bravery. “Suppose they—”

“Mac! O Mac!” called a cautious, low voice from

a hydrangea bush close at hand.

“Who’s there?” demanded Macdonald, springing

forward.

“They’re onto you, Mac,” answered the voice from

the shrub, “they’re goin’ to do you hurt. They’re

lookin’ for you now!”

There was a little rustling in the leaves as the

unseen friend moved away. The voice was the voice

of Banjo Gibson, but not even the shadow of the

messenger had been seen.

“You should have gone before—hurry!” she

whispered in alarm.

“Never mind. It was a risk, and I took it, and

I’d take it again tomorrow. It gave me these minutes

with you, it was worth—”

“You must go! Where’s your horse?”

“Down by the river in the willows. I can get to

him, all right.”

“They may come any minute, they—”

“No, they’re dancing yet. I expected they’d find

me out; they know me too well. I’ll get a start of

them, before they even know I’m gone.”

“They may be waiting farther on—why don’t

you go—go! There—listen!

“They’re saddling,” he whispered, as low sounds

of haste came from the barnyard corral.

“Go—quick!” she urged, flinging his plaid across

his arm.

“I’m going—in one moment more. Miss Landcraft,

I’ll ride away from you tonight perhaps never

to see you again, and if I speak impetuously before

I leave you, forgive me before you hear the words—they’ll

not hurt you—I don’t believe they’ll shame

you.”

“Don’t say anything more, Mr. Macdonald—even

this delay may cost your life!”