Title: Priests, Women, and Families

Author: Jules Michelet

Release date: April 28, 2010 [eBook #32157]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

When it was first proposed to publish an English Translation of this admirable work, its gifted Author wrote to the Translator to the following effect: "This work cannot be without interest to the people of England, among whom, at this moment, the Jesuits are so madly pursuing their work. Nothing is more strange than their chimerical hopes of speedily converting England."

Indeed, their intrigues and manoeuvres were thought at that time—1845—to be "chimerical," even by many who were forced to join in the Jesuit Crusade. One of the Bishops, directed by Dr. Wiseman to use the "Litany for the Conversion of England," replied, "You may as well pray that the blackamoor may be made white." He was ordered to Rome, and six months' detention there quieted his opposition to the Jesuit schemes intended to "bend or break" his country.

In presenting a New Issue of "PRIESTS, WOMEN, AND FAMILIES", we meet a want—a necessity—of Society. The CONFESSIONAL UNMASKED, which so faithfully portrayed the Romish and Ritualistic Priest, and which was so unjustly and illegally suppressed by the violence and intrigues of Priests and those whom they "directed," was too plain in its utterances for general reading. Its testimony as a WITNESS was and is of the highest importance; but we fully concur with the Author of this "work of art" that it should not be disfigured by the portraits of Priests.

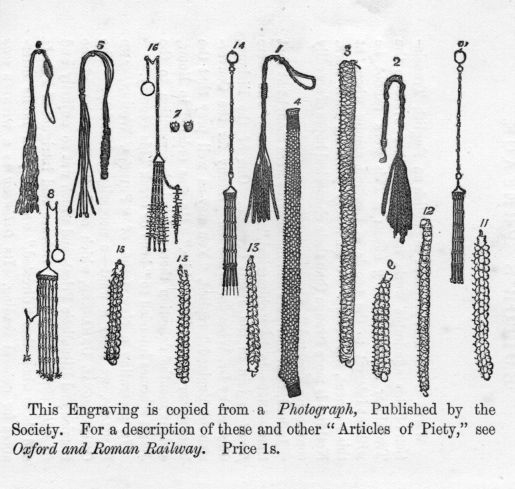

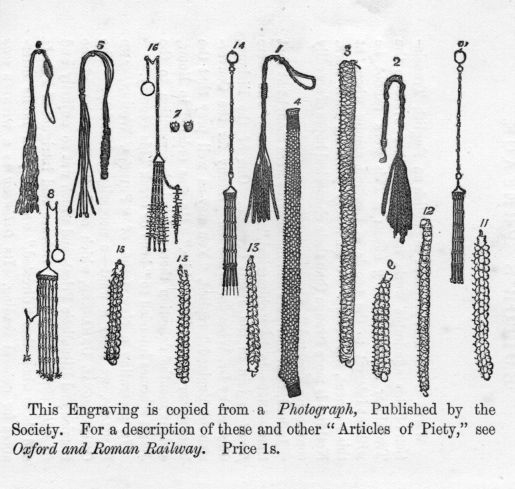

The following Illustrations are a proof that something ought to be done on behalf of the deluded creatures who, under the pretence of becoming the "Brides of Christ," are subjected to "indignities" and cruelty, not tolerated anywhere else.

Instruments of Torture are now practised upon Nuns in Romish Convents in London and in all parts of the country.

The Romish "Articles of Piety," named on the next page, were bought at "Little's Ecclesiastical Warehouse", 20, Cranbourne Street, and at the Convent of the "Sisters of the Assumption of the Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament," London.

Such Instruments of Torture are fitter for the worshippers of Baal, than for the worshippers of God; and a person using them upon cattle would lay himself open to a prosecution by the "Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals." Both the parties who purchased these articles are intimately known to Mr. Steele, the Secretary of the Protestant Evangelical Mission and Electoral Union.

COPIES OF BILLS GIVEN TO PURCHASERS.

No. 1. Jan. 15, 1868.

Ecclesiastical Warehouse,

20, Cranbourne Street.

s. d.

To Hair Shirt .................. 12 6

To Discipline .................. 4 0

Two Do., had last week ......... 3 6

To Massive Waist Chain ......... 8 6

Two Armlets, 3s. 6d. & 1s. 6d. 5 0

One Hair Band .................. 5 0

£1 18 6

Rec. C. Cuddon. for F. A. LITTLE

No. 2. Convent of the Assumption,

24, Kensington Sq.

s. d.

One Iron Discipline ........... 7 0

One Nut ....................... 2 6

Total ............. 9 6

Rec. Sr. M. Bernardine, May 1, 1869.

No. 3. Convent of the Assumption,

24, Kensington Sq.

s. d.

Iron Discipline ............... 5 6

Two Bracelets ................. 1 6

One Nut ....................... 2 6

9 6

Paid S--: Sep. --, 1869.

No. 4. Little's Ecclesiastical

Warehouse, 20, Cranbourne Street.

s. d.

To Discipline (9 tails) ....... 6 6

" Ditto (7 tails) ............ 2 3

" Chain Band ................. 6 6

Ditto Smaller ................. 4 6

19 9

Received with thanks, Sep. --, 1869.

Christian Reader,—It is your duty to testify, on God's behalf, against the Blasphemy and Cruelty of Romanism. The Maker and Preserver of man is the loving Father who gave His only begotten Son to die for us; and thus make atonement for our sin. "By Him all that believe are justified from all things."—Acts xiii. 38, 39; Micah vi. 6-8; John iii. 16; Rom. iii. 20-26; Heb. ix. 22.

Saint Liguori, the Doctor of the Romish Church, commends the use of Disciplines to the "True Spouse of Christ" thus:—

"Disciplines, or Flagellations, are a species of mortification, strongly recommended by St. Francis de Sales, and universally adopted in Religious Communities of both sexes. All the modern Saints, without a single exception, have continually practised this sort of penance. It is related of St. Lewis Gonzaga, that he often scourged himself into blood three times a-day. And at the point of death, not having sufficient strength to use the lash, he besought the Provincial to have him disciplined from head to foot."

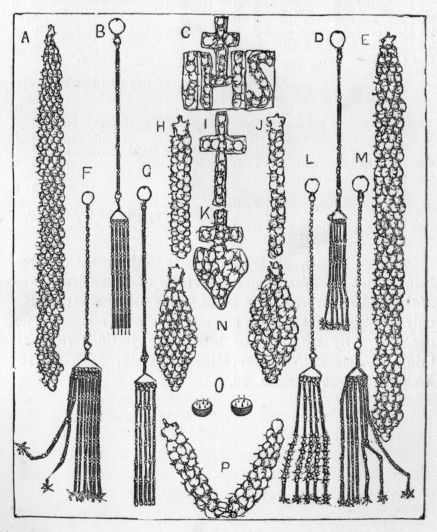

A. This is a band for going round the body to "mortify the flesh." It is made of Iron wire, and the ends of each link form Spikes which range in length from the sixteenth of an inch to half an inch.

B. This is a Flagellum, made of strong iron wire. It has five tails to represent the "Five wounds;" and at the end of each tail there is a Spike, about an inch long, to pierce the flesh. It will be seen that the lowermost joints are the heaviest, so as to increase the severity of the blows.

C. This is a Cross resting upon an "I. H. S."—Jesus the Saviour of Man. It is for wearing on the breast, and is made of iron, as, indeed, all the other articles represented in the engraving are. It is covered over with spikes on the side next the body.

D. This is another Flagellum, commemorative of the "Five wounds." At the end of each tail there is a kind of Rowel with sharp points. It is impossible to use this without cutting the flesh.

E. This Belt is similar to A, but of stronger material. This belt sometimes becomes imbedded in the flesh of the devoted victim of "the Church."

F. This Flagellum has Nine tails, to represent the nine months during which "The Word was made flesh." The "Cat-and-nine-tails" and the "Incarnation"!!

G. This Flagellum is a modification of B, D, and L.

H, J, P. These are Bands for the limbs, and, like A and E, are covered with spikes.

I. This is a Cross similar to that resting upon the "I. H. S." above.

K. This is a Cross and Heart to be worn over the seat of the affections, to show that all "natural affection" is to be crucified. This was painfully illustrated in the case of a young lady who had left her home and entered one of these Conventual Establishments to the great grief of her parents. Her father called at the convent to see her. She was brought to him, and on his expostulating with her, and soliciting her return home, he observed that she pressed her hands against her breast, and seemed to suffer excruciating pain. After a little, blood oozed through her dress, and she was then withdrawn by the "Sisters."

L. This Flagellum may be called the Mother Superior's "Wild Cat."

M. This Flagellum has Seven tails, to represent the "Seven Dolours" of the Virgin; and a doleful tale they tell.

N. These two Nets of Iron wire, covered over with spikes, are for the most cruel and immodest purposes. We dare not describe them.

O. Each of these two hemispheres, together forming a Nut, has five brass spikes, which are used for imprinting the Stigmata or "Five wounds" of Christ upon the Religious.

Were such cruelties perpetrated upon the Heathen, all our Christian Churches would resound with appeals to the sympathy of the people to come to the help of the sufferers, whether Fanatics or Victims. This would be commendable. Why, then, is the same course not adopted on behalf of Nuns, who, as Rev. Pierce Connelly says, "are not only slaves, but who are, de facto, by a Satanic consecration, secret prisoners for life, and may any day be put an end to, or much worse, with less risk of vengeance here in England than in Italy or Spain!"—Extracted from the Annual Report of the Protestant Evangelical Mission and Electoral Union, January, 1873.

The following pages—intended to restore Domestic Life to French Society—formed the Preface to the Third Edition of Priests, Women, and Families, by M. Michelet, of which celebrated work, "THE PROTESTANT EVANGELICAL MISSION" have published an Edition in English.

This book has produced upon our adversaries an effect we had not anticipated. It has made them lose every sense of propriety and self-respect:—nay, more, even that respect for the sanctuary which it was their duty to teach us. From the pulpits of their crowded churches they preach against a living man, calling him by his name, and invoking upon the author and his book the hatred of those who know not how to read, and who will never read this work. The heads of the clergy must, indeed, have felt themselves touched to the quick, to let loose these furious preachers upon us.

We have hit the mark too fairly, it should seem. Woman!—this was the point on which they were sensitive. Direction, the spiritual guidance of women, is the vital part of ecclesiastical authority; and they will fight for it to the death. Strike, if you will, elsewhere, but not here. Attack the dogma—all well and good; they may, perhaps, make a show of violence, or perpetrate some empty declamation; but if you should happen to meddle with this particular point, the thing becomes serious, and they no longer contain themselves. It is a sad sight to see pontiffs, elders of the people, gesticulating, stamping, foaming at the mouth, and gnashing their teeth.[1] Young men, do not look; epileptic convulsions have occasionally a contagious effect upon the spectators. Let us leave them and depart; we must resume our studies without loss of time: "Art is long, life is short."

I remember having read in the correspondence of Saint Charles Borromeo, that one of his friends, a person of authority and importance, having censured some Jesuit or other who was too fond of confessing nuns, the latter came in a fury to insult him. The Jesuit knew his strength: being a preacher then in vogue, well off at court, and still better at the court of Rome, he thought he need not stand upon ceremony. He went to the greatest extremes, was violent, insolent, as much as he pleased: his grave censor remained cool. The Jesuit could no longer keep within the bounds of decency, and made use of the vilest expressions. The other, calm and firm, answered nothing; he let him continue his declamation, threats, and violent gestures; he only looked at his feet. "Why were you always looking at his feet?" inquired an eye-witness, as soon as the Jesuit, was gone. "Because," replied the noble man calmly, "I fancied I saw the cloven hoof peeping out every now and then; and this man, who seemed possessed with a devil, might be the tempter himself, disguised as a Jesuit."

One prelate predicts in sorrow that we are sending the priests to martyrdom.

Alas, this martyrdom is what they themselves demand, either aloud or in secret, namely—marriage.

We think, without enumerating the too well known inconveniences of their present state, that if the priest is to advise the family, it is good for him to know what a family is; that as a married man, of a mature age and experience, one who has loved and suffered, and whom domestic affections have enlightened upon the mysteries of moral life, which are not to be learned by guessing, he would possess at the same time more affection and more wisdom.

It is true the defenders of the clergy have lately drawn such a picture of marriage, that many persons perhaps will henceforth dread the engagement. They have far exceeded the very worst things that novelists and modern socialists have ever said against the legal union. Marriage, which lovers imprudently seek as a confirmation of love, is, according to them, but a warfare: we marry in order to fight. It is impossible to degrade lower the virtue of matrimony. The sacrament of union, according to these doctors, is useless, and can do nothing unless a third party be always present between the partners—i.e., the combatants—to separate them.

It had been generally believed that two persons were sufficient for matrimony: but this is all altered; and we have the new system, as set forth by themselves, composed of three elements: 1st, man, the strong, the violent; 2ndly, woman, a being naturally weak; 3rdly, the priest, born a man, and strong, but who is kind enough to become weak and resemble woman; and who, participating thus in both natures, may interpose between them.

Interpose! interfere between two persons who were to be henceforth but one! This changes wonderfully the idea which, from the beginning of the world, has been entertained of marriage.

But this is not all; they avow that they do not pretend to make an impartial interference that might favour each of the parties, according to reason. No, they address themselves exclusively to the wife: she it is whom they undertake to protect against her natural protector. They offer to league with her in order to transform the husband. If it were once firmly established that marriage, instead of being unity in two persons, is a league of one of them with a stranger, it would become exceedingly scarce. Two to one! the game would seem too desperate; few people would be bold enough to face the peril. There would be no marriages but for money; and these are already too numerous. People in difficulties would doubtless not fail to marry; for instance, a merchant placed by his pitiless creditor between marriage and a warrant.

To be transformed, re-made, remodelled, and changed in nature! A grand and difficult change! But there would be no merit in it, if it was not of one's free will, and only brought about by a sort of domestic persecution, or household warfare.

First of all, we must know whether transformation means amelioration, whether it be intended by transformation to ascend higher and higher in moral life, and become more virtuous and wise. To ascend would be well and good; but if it should be to fall lower?

And first of all, the wisdom they offer us does not imply knowledge. "What is the use of knowledge and literature? They are mere toys of luxury, vain and dangerous ornaments of the mind, both strangers to the soul." Let us not contest the matter, but pass over this empty distinction that opposes the mind to the soul, as if ignorance was innocence, and as if they could have the gifts of the soul and heart with a poor, insipid, idiotic literature!

But where is their heart? Let us catch a glimpse of it. How is it that those who undertake to develope it in others dispense with giving any proof of it in themselves? But this living fountain of the heart is impossible to be hidden, if we really have it within us. It springs out in spite of everything; if you were to stop it on one side, it would run out by the other. It is more difficult to be confined than the flowing of great rivers:—try to shut up the sources of the Rhone or Rhine! These are vain metaphors, and very ill-placed, I allow: to what deserts of Arabia must I not resort to find more suitable ones?

We are in a church: see the crowd, the dense mass of people who after having wandered far, enter here weary and athirst, hoping to find some refreshment; they wait with open mouths. Will there even be one small drop of dew?

No; a decent, proper, blunt-looking man ascends the pulpit: he will not affect them; he confines himself to proofs. He makes a grand display of reasoning, with high logical pretensions and much solemnity in his premises. Then come sudden, sharp conclusions; but for middle term there is none: "These things require no proof." Why, then, miserable reasoner, did you make so much noise about your proofs?

Well! do not prove! only love! and we will let you off everything else. Say only one word from the heart to comfort this crowd. All that variegated mass of living heads, that you see so closely assembled around your pulpit are not blocks of stone, but so many living souls. Those yonder are young men, the rising generation, our future society. They are of happy dispositions, full of spirit, fresh and entire, such as God made them, and untamed; they rush forward incautiously even to the very brink of precipices. What! youth, danger, futurity, and hopes clouded with fear—does not all this move you? Will nothing open your fatherly heart?

Mark, too, that brilliant crowd of women and flowers: in all that splendour so delightful to the eye there is much suffering. I pray you to speak one word of comfort to them. You know they are your daughters, who come every evening so forlorn to weep at your feet. They confide in you, and tell you everything; you know their wounds. Try to find some consoling word—surely that cannot be so difficult. What man is there who, in seeing the heart of a woman bleeding before him, would not feel his own heart inspired with words to heal it? A dumb man, for want of words, would find what is worth more, a flood of tears!

What shall we say of those who, in presence of so many desponding, sickly, and confiding persons, give them, as their only remedy, the spirit of an academy, glittering commonplaces, old paradoxes, Bonaparteism, socialism, and what not? There is in all this, we must confess, a sad dryness and a great want of feeling.

Ah! you are dry and harsh! I felt this the other day (it was in December last), when I read on the walls, as I was passing by, an order from the archbishop. It was a case of suicide; a poor wretch had killed himself in the church of Saint-Gervais. Was it misery, passion, madness, spleen, or moral weakness in this melancholy season? No cause was mentioned; the body alone was there with the blood on the marble slabs; but no explanation. By what gradation of griefs, disappointments, and anguish had he been induced to commit this unnatural act? What steps of moral purgatory had he descended before he reached the bottom of the abyss? Who could say? No one. But any man with a gleam of imagination in his heart, sees in this solemn mystery something to make him weep and pray. That man is not Mr. Affre: read the mandate. There is compassion for the blood-stained church, and pity for the polluted stones; but for the dead only a malediction. But, whether a Christian or not, guilty or not, is he not still a man, my lord bishop? Could you not, whilst you were condemning suicide, let fall one word of pity by the way? No, no sentiment of humanity, nothing for the poor soul, which, besides its misfortune (which must have been terrible, indeed, since it could not support it), departs all alone and accursed, to attempt that perilous flight of the other life and judgment.

Another very different fact had given me some time before a similar impression. I had gone on business to the house of the venerable Sister * * *.

She was absent; and two persons, a lady and an aged priest, were waiting, like myself, in the small parlour. The lady seemed actuated by some motive of beneficence: the priest, as they are lords and masters in every Religious house, seemed to be quite at home, and, to beguile the time, was writing letters at the sister's bureau. At the conclusion of every note, he listened to the lady for a moment. The latter, whose gentle face bore traces of grief, impressed one at once with the goodness of her disposition: perhaps she would not have attracted my attention, but there was something in her that interested me. Was it passion or grief? I overheard without listening—she had lost her son.

An only son, full of affection, spirits, and courage; a young hero, who, leaving the Polytechnic school, had abandoned everything, riches, high life, pleasure, happiness, and such a mother! And regardless alike of safety and danger, had rushed to Marseilles, thence to Algiers, to the enemy, and to death.

The poor woman, wholly occupied with this idea, snatched, from time to time, a little moment to put in a word; she wanted to speak to him, and appeal to his compassion. The scene was infinitely touching and natural, without any theatrical effect. Her moderate grief and sighs, without tears, affected me the more.

She was evidently wasting her breath. The thoughts of the priest were elsewhere. It was not possible for him not to listen; he was forced to say something or other (the lady was rich, and her carriage was waiting at the door); but he got off as cheap as he could: "Yes, Madam, Providence tries us. It strikes us for our good. These are very painful trials," &c., &c. Such vague and cold words did not discourage the lady; she drew her chair nearer, thinking he would hear her better: "Ah! Sir, how shall I tell you? Ah! how can you understand so heavy a calamity?" She would have made a dead man weep.

Did you ever see the heart-rending sight of the poor pointer, that has been wounded by a shot, writhing at his master's feet, and licking his hands, as if praying to him to help him? The comparison will appear, perhaps, strange to those who have not seen the reality. However, at that moment, I felt it in my heart. That woman, mortally wounded, yet so gentle in her grief, seemed to be writhing at the feet of the priest, and to entreat his compassion.

I looked at that priest: he was vulgar and unfeeling, such as we see so often, neither wicked nor good; there was nothing to indicate a heart of iron, but he was as if made of wood. I saw plainly that no one word of all which his ear had received had entered his soul. One sense was wanting. But why torment a blind man by speaking to him of colours? He answers vaguely; occasionally he may guess pretty nearly; but how can it be helped? he cannot see.

And do not think that the feelings of the heart can be guessed at more easily. A man without wife or child might study the mysterious working of a family in books and the world for ten thousand years, without ever knowing one word about them. Look at these men; it is neither time, opportunity, nor facility that they lack to acquire knowledge; they pass their lives with women who tell them more than they tell their husbands; they know and yet they are ignorant: they know all a woman's acts and thoughts, but they are ignorant precisely of what is the best and most intimate part of her character, and the very essence of her being. They hardly understand her as a lover (of God or man), still less as a wife, and not at all as a mother. Nothing is more painful than to see them sitting down awkwardly by the side of a woman to caress her child: their manner towards it is that of flatterers or courtiers—anything but that of a father.

What I pity most in the man condemned to celibacy is not only the privation of the sweetest joys of the heart, but that a thousand objects of the natural and moral world are, and ever will be, a dead letter to him. Many have thought, by living apart, to dedicate their lives to science; but the reverse is the case: in such a morose and crippled life science is never fathomed; it may be varied and superficially immense; but it escapes, for it will not reside there. Celibacy gives a restless activity to researches, intrigues, and business, a sort of huntsman's eagerness, a sharpness in the subtleties of school-divinity and disputation; this is at least the effect it had in its prime. If it makes the senses keen and liable to temptation, certainly it does not soften the heart. Our terrorists in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were monks.[2] Monastic prisons were always the most cruel.[3] A life systematically negative, a life without its functions, developes in man instincts that are hostile to life; he who suffers, is willing to make others suffer. The harmonious and fertile parts of our nature, which on the one hand incline to goodness, and on the other to genius and high invention, can hardly ever withstand this partial suicide.

Two classes of persons necessarily contract much insensibility—surgeons and priests. By constantly witnessing sufferings and death, we become by degrees dead in our sympathetic faculties. Let us, however, remark this difference, that the insensibility of the surgeon is not without its utility: if he was affected by his operation he might tremble. The business of the priest, on the contrary, requires that he should be affected; sympathy would be generally the most efficacious remedy to cure the soul. But independently of what we have just said about the natural harshness of this profitless life, we must observe that the priest, in contradiction with a society, the whole of whose progress he condemns, becomes less and less benevolent for the sinner and the rebel. The physician who does not like his patient is less likely than another to cure him.

It is a sad reflection to think that these men, who have so little sympathy, and who are, moreover, soured by contention, should happen to have in their hands the most gentle portion of mankind; that which has preserved the most affection, and ever remained the most faithful to nature, and which, in the very corruption of morals, is still the least corrupted by interest and hateful passions.

That is to say, that the least loving govern those who love the most.

In order to know well what use they make of this empire over women, which they claim as their own privilege, we must not confine ourselves to their flattering and wheedling ways with fashionable ladies, but inquire of the poor women whom they are able to treat unceremoniously, those especially, who, being in convents, are at the mercy of the ecclesiastical superiors, and whom they keep under lock and key, and undertake to protect alone.

We are not quite satisfied with this protection. For a long time we thought all was right; we were even simple enough to say to ourselves that the law could see nothing amiss in this kingdom of grace. But hark! from those gentle asylums, those images of paradise, we hear sobs and sighs.

I shall not speak here of the convents that have become real houses of correction, nor of the events at Sens, Avignon, and Poictiers, nor of the suicides that have taken place, alas! much nearer home.

No, I shall speak only of the most honourable houses and the most holy nuns. How are they protected by ecclesiastical authority?

First, as to the Soul, or conscience, that dearest possession, on account of which they sacrifice all the pleasures of this world; is it true that the sisters of the hospitals who passed for Jansenists have been latterly persecuted, to make them denounce their supposed secret directors; and that they have obtained a truce only through the threatening mediation of a magistrate, who is a celebrated orator and a firm Gallican?

Again, as to the Body, or personal liberty, which the slave gains as soon as ever he does but touch the sacred soil of France—does ecclesiastical authority secure this to the nuns? Is it true that a Carmelite nun, within sixty leagues of Paris, was kept chained for several months in her convent, and afterwards shut up for nine years in a madhouse?

Is it true that a Benedictine nun was put into a sort of in pace, and afterwards into a room full of mad women, where nothing was heard but the horrible cries, howlings, and impure language of ruined women, who, from one excess to another, have become raving mad?[4]

This woman, whose only crime was good sense and a taste for writing and drawing flowers, served her establishment a long time as housekeeper and governess: she had taught most of the sisters to read. What does she ask for? The punishment of her enemies? No: only the consolation of confessing, and taking the sacrament; spiritual food for her old age.

People may say, "Perhaps the bishop did not know?" The bishop knew all: "he was much moved"—but he did nothing. The chaplain of the house knew they were going to put a nun in pace. "He sighed "—but did nothing. The Vicaire-Général did not sigh, but sided with the party against the nun: his ultimatum was that she should die of hunger, or return to her dungeon.

Who showed himself the real bishop in this business?—The Magistrate. Who was the real priest? The Advocate, a studious young man, whom science had withdrawn from the bar, but who, seeing this unfortunate woman devoid of all succour, for whom no one durst either print or plead (under the ridiculous system of terror), took up the affair, spoke, wrote, and acted; taking every necessary step, making journeys in the depth of winter, and sacrificing both his money and his time—six months of his life. May God pay him back with interest!

Which is the good Samaritan in this case? Who proved himself the neighbour of the wretched woman? Who picked up the bleeding victim from the road, before whom the Pharisees had passed? Who is the real priest, the true father?

A witty writer of the day uses the term my fathers, in speaking of the magistrates who interpose in the affairs of the Church. He speaks deridingly, but they deserve the name. Who bestows it upon them? The afflicted who are the members of Christ, and who, as such, are also the Church, I should think. Yes, they call them fathers on account of their paternal equity. Their helpful interposition had too long been repelled from the threshold of the convents by these crafty words: "What are you going to do? Should you enter here, you would disturb the peace of these quiet asylums, and startle these timid virgins!" Why! they themselves call for our assistance: we hear their shrieks from the streets!

All of us laymen, of whatever denomination, whether magistrates, politicians, authors, or solitary thinkers, ought to take up the cause of women more seriously than we have hitherto done.

We cannot leave them where they now are, in hands so harsh and unfeeling, and which are, moreover, unsafe in more than one respect.

Nothing can be more important or more worthy of uniting us together.

Let us, I pray you, come to an understanding about it; it is the most holy of all causes: let there be then a cessation from religious strife. We can recommence our disputes afterwards as much as we please.

And first let us frankly confess the truth to one another. The evil when confessed and known has a better chance of being remedied. Whom ought we to accuse in the present state of things?

Let us not accuse the Jesuits, who carry on their Jesuitical trade, nor the priests, who are dangerous, restless, and violent, only because they are unhappy. No; we ought rather to accuse ourselves.

If dead men return in broad daylight, if these Gothic phantoms haunt our streets at noon-day, it is because the living have let the spirit of life grow weak within them. How is it that these men re-appear among us, after having been buried by history with all funeral rites, and laid by the side of other ancient orders? The very sight of them is a solemn token and a serious warning.

This has been allowed to take place, O ye men of the present day, to bring you to your senses, and to remind you of what you ought to be. If the future that is within you were revealed in its full light, who would turn his eyes towards the departing shadows of darkness and night? It is for you to find, and for you to make, the future. This is not a thing that you must expect to find ready made. If the future is already in you as a bud, transmitted from the most distant ages, let it grow there as the desire for progress and amelioration, a paternal wish for the happiness of those who are to follow you. Love in anticipation your unknown son, for he will be born. Men call him "The time to come." Then work for him.

The day when fellow-mortals will perceive in you the man of future and a magnanimous mind, families will be rallied. Woman will follow you everywhere, if she can say to herself, "I am the wife of a strong man."

Modern strength appears in the powerful liberty with which you go on disengaging the reality from the forms, and the spirit from the dead letter. But why do you not reveal yourself to the companion of your life, in that which is for you your life itself? She passes away days and years by your side, without seeing or knowing the grandeur that is within you. If she saw you walk free, strong, and prosperous in action and in science, she would not remain chained down to material idolatry, and bound to the sterile letter; she would rise to a faith far more free and pure, and you would be as one in faith. She would preserve for you this common treasure of religious life, where you might seek for comfort when your mind is languid; and when your various toils, studies, and business have weakened the vital unity within you, she would bring back your thoughts and life to God, the true, the only unity.

I shall not attempt to crowd a large volume into a small Preface. I shall only add one word, which at once expresses and completes my thought.

Man ought to nourish woman. He ought to feed spiritually (and materially if he can) her who nourishes him with her love, her milk, and her very life. Our adversaries give women bad food; but we give them none at all.

To the women of the richer class, those brilliant ones whom people suppose so happy, to these we give no spiritual food.

And to the women of the poorer class, solitary, industrious, and destitute, who try hard to gain their bread, we do not even give our assistance to help them to find their material food.

These women, who are or will be mothers, are left by us to fast (either in soul or in body), and we are punished especially by the generation that issues from them, for our neglecting to give them the staff of life.

I like to believe that good-will, generally, is not wanting—only time and attention. People live in a hurry, and can hardly be said to live: they follow with a huntsman's eagerness this or that petty object, and neglect what is important.

You man of business or study, who are so energetic and indefatigable, you have no time, say you, to associate your wife with your daily progress; you leave her to her ennui, idle conversations, empty sermons, and silly books; so that, falling below herself, less than woman, even less than a child, she will have neither moral action, influence, or maternal authority over her own offspring. Well! you will have the time, as old age advances, to try in vain to do all over again what is not done twice, to follow in the steps of a son, who, from college to the schools, and from thence into the world, hardly knows his family; and who, if he travels a little, and meets you on his return, will ask you your name. The mother alone could have made you a son; but to do so you ought to have made her what a woman ought to be, strengthened her with your sentiments and ideas, and nourished her with your life.

If I look beyond the family and domestic affections, I find our negligence towards women resembles hard-heartedness; the cruel effects which result from it recoil upon ourselves.

You think yourself good and kind-hearted; you are not insensible to the fate of poor women; an old one reminds you of your mother, a young one of your daughter. But you have not the time either to see or know that the old one and the young one are both literally dying with hunger.

Two machines are constantly working to exterminate them:—the convent, that immense Workshop, that works for little or nothing, not relying on its labour for subsistence. Then the large shop, with sleeping partners, that buys of the convent, and destroys by degrees the smaller shops which employed the workwomen. The latter has but two chances left—the Seine, or to find at night some heartless wretch who takes advantage of her hunger—suicide or dishonour.

Men receive about as much as women from public charity: this is unjust. They have infinitely more resources. They are stronger, have a greater variety of work, more initiative, a more active impulse, more locomotion, if I may so express myself, to go and hunt out work. They travel, emigrate, and find engagements. Not to mention countries where manual labour is very dear, I know of provinces in France, where it is very difficult to find either journeymen or man-servants. Man can wander to and fro. Woman remains at home and dies.

Let this workwoman, whom the opposition of the convent has crushed, crawl to the gate of the convent—can she find an asylum there? She would want, in default of dowry, the active protection of an influential priest, a protection reserved for devout persons, such as have had the time to follow the "Mois de Marie"—Devotions to the Virgin—the Catechisms of Perseverance, &c., &c., and who have been, for a long time past, under ecclesiastical authority. This protection is often very dearly purchased; and for what? To get permission to pass one's life shut up within walls, to be obliged to counterfeit a devotion one has not! Death cannot be worse.

They die then, quietly, decently, and alone. They will never be seen coming down from their garrets into the street to walk about with the motto, "To live working or die fighting." They will make no disturbances; we have nothing to fear from them. It is for this very reason, that we are the more bound to assist them. Shall we then feel our hearts affected only for those of whom we are afraid?

Men of money, if I must speak to you in your own money language, I will tell you, that as soon as we shall have an economical government, it will not hesitate to lay out its money for women, to help them to maintain themselves by their industry.

Not only do these sickly women crowd our hospitals, and leave them only to return, but the offspring of these poor exhausted creatures, if they do not die in the Foundling, will be, like their mothers, the habitual inmates of those hospitals. A miserably poor woman is a whole family of sick persons in perspective.

Whether we be philosophers, physiologists, political economists, or statesmen, we all know that the excellency of the race, the strength of the people, come especially from the woman. Does not the nine months' support of the mother establish this? Strong mothers have strong children.

We all are, and ever shall be, the debtors of women. They are mothers; this says everything. He who would bargain about the work of those who are the joy of the present and the destiny of the future, must needs have been born in misery and damnation. Their manual labour is a very secondary consideration; that is especially our part. What do they make?—Man: this is a superior work. To be loved, to bring forth both physically and morally, to educate man (our barbarous age does not quite understand this yet), this is the business of woman.

"Fons omnium viventium!" What can ever be added to this sublime saying?

Whilst writing all this, I have had in my mind a woman, whose strong and serious mind would not have failed to support me in these contentions: I lost her thirty years ago (I was a child then); nevertheless, ever living in my memory, she follows me from age to age.

She suffered with me in my poverty, and was not allowed to share my better fortune. When young I made her sad, and now I cannot console her. I know not even where her bones are: I was too poor then to buy earth to bury her!

And yet I owe her much. I feel deeply that I am the son of woman. Every instant in my ideas and words (not to mention my features and gestures), I find again my mother in myself. It is my mother's blood which gives me the sympathy I feel for by-gone ages, and the tender remembrance of all those who are now no more.

What return then could I, who am myself advancing towards old age, make her for the many things I owe her? One, for which she would have thanked me—this protest in favour of women and mothers: and I place it at the head of a book believed by some to be a work of controversy. They are wrong.

The longer it lives, if it should live, the plainer will it be seen, that, in spite of polemical emotion, it was a work of history, a work of faith, of truth, and of sincerity:—on what, then, could I have set my heart more?

[1] This will not appear exaggerated to those who have read the furious libel of the Bishop of Chartres. A newspaper asks me why I did not prosecute him for defamation. This mad violence is much less guilty than the treacherous insinuations they make in their books and newspapers, in the saloons, &c. Now they attribute to me whatever has been done by other Michelets, to whom I am not even related (for instance, Michelet of Languedoc, a poet and soldier under the Restoration); now they pretend to believe, though I had told them the contrary at the end of my preface, that this book is my lecture of 1844. Then, again, they get up a little petition from Marseilles, to pray for the dismissal of the professor. So far from wishing to stifle the voice of my adversaries, I have claimed for their writings the same liberty I asked for my own. Lesson of the 27th of February, 1845:—"I see among you the greater part of those who had aided me to maintain in this chair the liberty of discussion. We will respect this liberty in our adversaries. This is not chivalry, it is simply our duty. It is, moreover, essential to the cause of truth, that no objection be suppressed; but that each party may be at liberty to state their reasons. You may be sure that truth will prevail and conquer. We pass away; but truth lasts and triumphs. Yet, as long as her adversaries may have any thing to say, her triumph is mingled with doubt."

[2] For the fifteenth century, see my History of France, A.D. 1413.

[3] Mabillon on Monastic Imprisonment, posthumous works, vol. ii. p. 327.

[4] We should, perhaps, have reserved these facts for some future occasion, if they had not been already divulged by the newspapers and reviews. Besides, several magistrates have expressed their opinions on many analogous facts in the same locality. A solicitor-general writes to the underprefect:—"I have reason to be as convinced as you, that Madame * * * was in full possession of her senses. A longer imprisonment would most certainly have made her really mad," &c. A letter from the Solicitor-General Sorbier, quoted by Mr. Tilliard, in favour of Marie Lemonnier, p. 65.

The following brief Memoir of the Author of "Priests, Women, and Families" was written for, and embodied in, the "Dictionary of Universal Biography," published by Mackenzie about 1862.

Another Memoir of this celebrated Historian of France was given in The Times, Feb. 12, 1874, two days after his decease. The Times states that he "died of heart disease":—

"Michelet, Jules, one of the greatest of contemporary French writers, was born at Paris on the 21st of August, 1798. In the introduction to his little book, 'Le Peuple,' Michelet has told the story of his early life. He was the son of a small master printer, of Paris, who was ruined by one of the Emperor Napoleon's arbitrary measures against the Press, by which the number of printers in Paris was suddenly reduced. For the benefit of his creditors, the elder Michelet, with no aid but that of his family, printed, folded, bound, and sold some trivial little works, of which he owned the copyright; and the Historian of France began his career by 'composing' in the typographical, not the literary, sense of the word. At twelve he had picked up a little Latin from a friendly old bookseller who had been a village schoolmaster; and his brave parents, in spite of their penury, decided that he should go to college. He entered the Lycée Charlemagne, where he distinguished himself, and his exercises attracted the notice of Villemain. He supported himself by private teaching until, in 1821, he obtained, by competition, a professorship in his college. His first publications were two chronological summaries of modern history, 1825-26. In 1827 he essayed a higher flight by the publication, not only of his 'Précis de l'Histoire Moderne,' but by that of his volume on the Scienza Nuova of Vico ('Principes de la Philosophie d'Histoire'), the then little-known father of the so-called philosophy of history, whose work was thus first introduced to the French public, and, indeed, to that of England. These two works procured him a professorship at the école normale. After the Revolution of the Three Days, the now distinguished professor was placed at the head of the historical section of the French archives, a welcome position, which gave him the command of new and unexplored material for the History of France. The first work in which he displayed his peculiar historical genius, was his 'Histoire Romaine,' 1831, embracing only the History of the Roman Republic. From 1833, dates the appearance of his great 'History of France,' of which still uncompleted work, twelve volumes had appeared in 1860. In 1834, Gruizot made the dawning Historian of France his suppléant, or substitute, in the Chair of History connected with the Faculty of Letters; and in 1838 he was appointed Professor of History in the College de France. Meanwhile, besides instalments of his 'History of France,' he had published several works, among them (1835) his excellent and interesting 'Memoires de Luther,' in which, by extracts from Luther's Table-talk and Letters, the great reformer was made to tell himself the history of his life; the 'OEuvres Choises de Vico;' and the philosophical and poetical 'Origines du Droit Francais.' In the education controversy of the later years of Louis Philippe's reign, Michelet and his friend Edgar Quinet vehemently opposed the pretensions of the clerical party, and carried the war into the enemies' camp by the publication of their joint work, 'Les Jesuites,' 1843, followed, in 1844, by Michelet's 'Du Pretre, de la Femme, et la Famille,' translated into English as 'Priests, Women, and Families.' Guizot bowed to the ecclesiastical storm which these works invoked, and suspended the lectures of the two anti-clerical professors. To 1846 belongs Michelet's eloquent and touching little book, 'Le Peuple.' The Revolution of February, 1848, restored Michelet to his functions. He waived, however, the political career which was now opened to him, and laboured at his grandiose 'History of the French Revolution,' of which the first volume had appeared in 1847. In 1851 he was again suspended—this time by the ministry of the Prince President—from his professional functions, and on account of his democratic teachings. After the coup d'etat he refused to take the oaths, and lost all his public employments. Since then he has been occupied with his 'History of France,' and of the French Revolution, and with the production of other and some minor works. It is not among the last that must be classed his two striking volumes, 'L'Oiseau,' 1856, and 'L'Insecte,' 1857, the result of a retreat from a pressure of a new political system into the realm of nature. In 'L'Amour,' 1858, and 'La Femme,' 1859, the intrusion of physiology into the domain of thought and feeling was too much for English tastes. In 'La Mer,' 1861, Michelet addresses himself to the natural history and the poetry of the sea."

Religious Re-action in 1600—Influence of the Jesuits over Women and Children—Savoy; the Vaudois; Violence and Gentleness—St. François de Sales

St. François de Sales and Madame de Chantal—Visitation—Quietism—Results of Religious Direction

Loneliness of Woman—Easy Devotion—Worldly Theology of the Jesuits—Women and Children advantageously made use of—Thirty Years' War, 1618-1648—Gallant Devotion—Religious Novels—Casuists

Convents—Convents in Paris—Convents contrasted; the Director—Dispute about the Direction of the Nuns—The Jesuits Triumph through Calumny

Re-action of Morality—Arnaud, 1643; Pascal, 1657—The Jesuits lose Ground—They gain over the King and the Pope—Discouragement of the Jesuits; their Corruption—They Protect the Quietists—Desmarets—Morin burnt, 1663—Immorality of Quietism

Continuation of Moral Re-action—Tartuffe, 1664—Real Tartuffes—Why Tartuffe is not a Quietist

Apparition of Molinos, 1675—His Success at Rome—French Quietists—Madame Guyon and her Director—"The Torrents"—Mystic Death—Do we return from it?

Fenelon as Director—His Quietism—"Maxims of Saints," 1697—Fenelon and Madame de la Maisonfort

Bossuet as Director—Bossuet and Sister Cornuau—Bossuet's Imprudence—He is a Quietist in Practice—Devout Direction inclines to Quietism—Moral Paralysis

Molinos' "Guide"—Part Played in it by the Director; Hypocritical Austerity—Immoral Doctrine; Approved by Rome, 1675—Molinos Condemned at Rome, 1687—His Morals—His Morals Conformable to his Doctrine—Spanish Molinosists—Mother Agueda

No more Systems: an Emblem—The Heart—Sex—The Immaculate—The Sacred Heart—Mario Alacoque—The Seventeenth Century is the Age of Equivocation—Chimerical Politics of the Jesuits—Father Colombière—England—Papist Conspiracy—First Altar of the Sacred Heart—The Ruin of the Galileans, Quietists, and Port-Royal—Theology annihilated in the Eighteenth Century—Materiality of the Sacred Heart—Jesuitical Art

Resemblances and Differences between the seventeenth and nineteenth Centuries—Christian Art—It is we who have restored the Church—What the Church adds to the Power of the Priest—The Confessional

Confession—Present Education of the Young Confessor—The Priest in the Middle Ages—1st, believed—2ndly, was mortified—3rdly, knew—4thly, interrogated less—The Dangers of the Young Confessor—How he Strengthens his Tottering Position

Confession—The Confessor and the Husband—How they Detach the Wife—The Director—Directors in Concert—Ecclesiastical Policy

Habit—Power of Habit—Its Insensible Beginning; its Progress—Second Nature; often fatal—A Man taking Advantage of his Power—Can we get clear of it?

On Convents—Omnipotence of the Director—Condition of the Nuns, Forlorn and Wretched—Convents made Bridewells and Bedlams—Captation—Barbarous Discipline; Struggle between the Superior Nun and the Director; Change of Directors—The Magistrate

Absorption of the Will—Government of Acts, Thoughts, and Wills—Assimilation of the Soul—Transhumanation—To become the God of another—Pride and Desire

Desire. Terrors of the other World—The Physician and his Patient—Alternatives; Postponements—Effects of Fear in Love—To be All-powerful and Abstain—Struggles between the Spirit and the Flesh—Moral Death more Potent than Physical Life—It will not revive

Schism in Families—The Daughter; by whom Educated—Importance of Education—The Advantage of the First Instructor—Influence of Priests upon Marriage—Which they Retain after that Ceremony

Woman—The Husband does not Associate with the Wife—He seldom knows how to Initiate her into his Thoughts—What Mutual Initiation would be—The Wife Consoles Herself with her Son—He is taken from her; her Loneliness and Ennui—A pious young Man—The Spiritual and the Worldly Man—Who is now the Mortified Man

The Mother—Alone for a Long Time, she can bring up her Child—Intellectual Nourishment—Gestation, Incubation, Education—The Child Guarantees the Mother, and she the Child—She protects his Originality, which Public Education must Limit—The Father even Limits it, the Mother Defends it—Her Weakness; she wishes her Son to be a Hero—Her Heroic Disinterestedness

Love—Love wishes to raise and not absorb—False Theory of our Adversaries; Dangerous Practice—Love wishes to form an Equal who may love freely—Love in the World, in the Civil World—And in Families, not understood by the Middle Ages—Family Religion

ONE WORD TO THE PRIESTS:—We do not Attack Priests, but their Unhappy and Dangerous Position—Not Rome but France is the Pope—Our Sympathy for Priests, Victims of the Laws—Priests and Soldiers—Priest means Old Man

RELIGIOUS REACTION IN 1600.—INFLUENCE OF THE JESUITS OVER WOMEN AND CHILDREN.—SAVOY; THE VAUDOIS; VIOLENCE AND MILDNESS.—ST. FRANCOIS DE SALES.

Everybody has seen in the Louvre Guide's graceful picture representing the Annunciation. The drawing is incorrect, the colouring false, and yet the effect is seducing. Do not expect to find in it the conscientiousness and austerity of the old schools; you would look also in vain for the vigorous and bold touch of the masters of the Renaissance. The sixteenth century has passed away, and everything assumes a softer character. The figure with which the painter has evidently taken the most pleasure is the angel, who, according to the refinement of that surfeited period, is a pretty-looking singing boy—a cherub of the Sacristy. He appears to be sixteen, and the Virgin from eighteen to twenty years of age. This Virgin—by no means ideal, but real, and the reality slightly adulterated—is no other than a young Italian maiden whom Guido copied at her own house, in her snug oratory, and at her convenient praying-desk (prie-Dieu), such as were then used by ladies.

If the painter was inspired by anything else, it was not by the Gospel, but rather by the devout novels of that period, or the fashionable sermons uttered by the Jesuits in their coquettish-looking churches. The Angelic Salutation, the Visitation, the Annunciation, were the darling subjects upon which they had, for a long time past, exhausted every imagination of seraphic gallantry. On beholding this picture by Guide, we fancy we are reading the Bernardino. The angel speaks Latin like a young learned clerk; the Virgin, like a boarding-school young lady, responds in soft Italian, "O alto signore," &c.

This pretty picture is important as a work characteristic of an already corrupt age; being an agreeable and delicate work, we are the more easily led to perceive its suspicious graces and equivocal charms.

Let us call to mind the softened forms which the devout reaction of this age—that of Henry IV.—then assumed. We are lost in astonishment when we hear, as it were on the morrow of the sixteenth century, after wars and massacres, the lisping of this still small voice. The terrible preachers of the Sixteen,—the monks who went armed with muskets in the processions of the League—are suddenly humanised, and become gentle. The reason is, they must lull to sleep those whom they have not been able to kill. The task, however, was not very difficult. Everybody was worn out by the excessive fatigue of religious warfare, and exhausted by a struggle that afforded no result, and from which no one came off victorious. Every one knew too well his party and his friends. In the evening of so long a march there was nobody, however good a walker he might be, who did not desire to rest: the indefatigable Henry of Beam, seeking repose like the rest, or wishing to lull them into tranquillity, afforded them the example, and gave himself up with a good grace into the hands of Father Cotton and Gabrielle.

Henry IV. was the grandfather of Louis XIV., and Cotton the great uncle of Father La Chaise—two royalties, two dynasties; one of kings, the other of Jesuit confessors. The history of the latter would be very interesting. These amiable fathers ruled throughout the whole of the century, by dint of absolving, pardoning, shutting their eyes, and remaining ignorant. They effected great results by the most trifling means, such as little capitulations, secret transactions, back-doors, and hidden staircases.

The Jesuits could plead that, being the constrained restorers of Papal authority, that is to say, physicians to a dead body, the means were not left to their choice. Dead beat in the world of ideas, where could they hope to resume their warfare, save in the field of intrigue, passion, and human weaknesses?

There, nobody could serve them more actively than Women. Even when they did not act with the Jesuits and for them, they were not less useful in an indirect manner, as instruments and means,—as objects of business and daily compromise between the penitent and the confessor.

The tactics of the confessor did not differ much from those of the mistress. His address, like hers, was to refuse sometimes, to put off, to cause to languish, to be severe, but with moderation, then at length to be overcome by pure goodness of heart. These little manoeuvres, infallible in their effects upon a gallant and devout king, who was moreover obliged to receive the sacrament on appointed days, often put the whole State into the Confessional. The king being caught and held fast, was obliged to give satisfaction in some way or other. He paid for his human weaknesses with political ones; such an amour cost him a state-secret, such a bastard a royal ordinance. Occasionally, they did not let him off without bail. In order to preserve a certain mistress, for instance, he was forced to give up his son. How much did Father Cotton forgive Henry IV. to obtain from him the education of the dauphin.[1]

In this great enterprise of kidnapping man everywhere, by using woman as a decoy, and by woman getting possession of the child, the Jesuits met with more than one obstacle, but one particularly serious—their reputation of Jesuits. They were already by far too well known. We may read in the letters of St. Charles Borromeo, who had established them at Milan and {36} singularly favoured them, what sort of character he gives them—intriguing, quarrelsome, and insolent under a cringing exterior. Even their penitents, who found them very convenient, were nevertheless at times disgusted with them. The most simple saw plainly enough that these people, who found every opinion probable, had none themselves. These famous champions of the faith were sceptics in morals: even less than sceptics, for speculative scepticism might leave some sentiment of honour; but a doubter in practice, who says Yes on such and such an act, and Yes on the contrary one, must sink lower and lower in morality, and lose not only every principle, but in time every affection of the heart!

Their very appearance was a satire against them. These people, so cunning in disguising themselves, were made up of lying; it was everywhere around them, palpable and visible. Like brass badly gilt, like the holy toys in their gaudy churches, they appeared false at the distance of a hundred paces: false in expression, accent, gesture, and attitude; affected, exaggerated, and often excessively fickle. This inconstancy was amusing, but it also put people on their guard. They could well learn an attitude or a deportment; but studied graces, and a bending, undulating, and serpentine gait are anything but satisfactory. They worked hard to appear a simple, humble, insignificant, good sort of people. Their grimace betrayed them.

These equivocal-looking individuals had, however, in the eyes of the women a redeeming quality: they were passionately fond of children. No mother, grandmother, or nurse could caress them more, or could find better some endearing word to make them smile. In the churches of the Jesuits the good saints of the order, St. Xavier or St. Ignatius, are often painted as grotesque nurses, holding the divine darling (poupon) in their arms, fondling and kissing it. They began also to make on their altars and in their fantastically-ornamented chapels those little paradises in glass cases, where women are delighted to see the wax child among flowers. The Jesuits loved children so much, that they would have liked to educate them all.

Not one of them, however learned he might be, disdained to be a tutor, to give the principles of grammar, and teach the declensions.

There were, however, many people among their own friends and penitents, even those who trusted their souls to their keeping, who, nevertheless, hesitated to confide their sons to them. They would have succeeded far less with women and children, if their good fortune had not given them for ally a tall lad, shrewd and discreet, who possessed precisely what they had lacked to inspire confidence,—a charming simplicity.

This friend of the Jesuits, who served them so much the better as he did not become one of them, invented, in an artless manner, for the profit of these intriguers, the manner, tone, and true style of easy devotion, which they would have ever sought for in vain. Falsehood would never assume the shadow of reality as it can do, if it was always and entirely unconnected with truth.

Before speaking of François de Sales, I must say one word about the stage on which he performs his part.

The great effort of the Ultramontane reaction about the year 1600 was at the Alps, in Switzerland and Savoy. The work was going on bravely on each side of the mountains, only the means were far from being the same: they showed on either side a totally different countenance—here the face of an angel, there the look of a wild beast; the latter physiognomy was against the poor Vaudois in Piedmont.

In Savoy, and towards Geneva, they put on the angelic expression, not being able to employ any other than gentle means against populations sheltered by treaties, and who would have been protected against violence by the lances of Switzerland.

The agent of Rome in this quarter was the celebrated Jesuit, Antonio Possevino[2], a professor, scholar, and diplomatist, as {38} well as the confessor of the kings of the North. He himself organised the persecutions against the Vaudois of Piedmont; and he formed and directed his pupil, François de Sales, to gain by his address the Protestants of Savoy.

Ought I to speak of this terrible history of the Vaudois, or pass it over in silence? Speak of it! It is far too cruel—no one will relate it without his pen hesitating, and his words being blotted by his tears.[3] If, however, I did not speak of it, we should never behold the most odious part of the system, that artful policy which employed the very opposite means in precisely the same cases; here ferocity, there an unnatural mildness. One word, and I leave the sad story. The most implacable butchers were women, the penitents of the Jesuits of Turin. The victims were children! They destroyed them in the sixteenth century: there were four hundred children burnt at one time in a cavern. In the seventeenth century they kidnapped them. The edict of pacification, granted to the Vaudois in 1655, promises, as a singular favour, that their children under twelve years of age shall no longer be stolen from them; above that age it is still lawful to seize them.

This new sort of persecution, more cruel than massacres, characterises the period when the Jesuits undertook to make themselves universally masters of the education of children. These pitiless plagiarists[4], who dragged them away from their mothers, wanted only to bring them up in their fashion, make them abjure their faith, hate their family, and arm them against their brethren.

It was, as I have said, a Jesuit professor, Possevino, who renewed the persecution about the time at which we are now arrived. The same, while teaching at Padua, had for his pupil young François de Sales, who had already passed a year in Paris, at the college of Clermont. He belonged to one of those families of Savoy, as much distinguished by their devotion as by their valour, who carried on wars long against Geneva. He was endowed with all the qualities requisite for the war of seduction, which they then desired to commence—a gentle and sincere devotion, a lively and earnest speech, and a singular charm of goodness, beauty, and gentleness. Who has not remarked this charm in the smile of the children of Savoy, who are so natural, yet so circumspect?

Every favour of Heaven must, we certainly believe, have been showered upon him, since in this bad age, bad taste, and bad party, among the cunning and false people who made him their tool, he remained, however, St. François de Sales. Everything he has said or written, without being free from blemishes, is charming, full of affection, of an original gentleness and genius, which, though it may excite a smile, is nevertheless very affecting. Everywhere we find, as it were, living fountains springing up, flowers after flowers, and rivulets meandering as in a lovely spring morning after a shower. It might be said, perhaps, that he amuses himself so much with flowerets, that his nosegay is no longer such as shepherdesses gather, but such as would suit a flower-girl, as his Philothea would say: he takes them all, and takes too many; there are some colours among them badly matched, and have a strange effect. It is the taste of that age, we must confess; the Savoyard taste in particular does not fear ugliness; and a Jesuit education does not lead to the detestation of falsehood.

But even if he had not been so charming a writer, his bewitching personal qualities would still have had the same effect. His fair mild countenance, with rather a childish expression, pleased at first sight. Little children, in their nurses' arms, as soon as they saw him, could not take their eyes off him. He was equally delighted with them, and would exclaim, as he fondly caressed them, "Here is my little family." The children ran after him, and the mothers followed their children.

Little family? or little intrigue? The words (ménage manège) are somewhat similar; and though a child in appearance, the good man was at bottom very deep. If he permitted the nuns a few trifling falsehoods[5], ought we to believe he never granted the same indulgence to himself? However it may be, actual falsehood appeared less in his words than in his position; he was made a bishop in order to give the example of sacrificing the rights of the bishops to the Pope. For the love of peace, and to hide the division of the Catholics by an appearance of union, he did the Jesuits the important service of saving their Molina accused at Rome; and he managed to induce the Pope to impose silence on the friends, as well as the enemies, of Grace.

This sweet-tempered man did not, however, confine himself to the means of mildness and persuasion. In his zeal as a converter, he invoked the assistance of less honourable means—interest, money, places; lastly, authority and terror. He made the Duke of Savoy travel from village to village, and advised him at last to drive away the remaining few who still refused to abjure their faith.[6] Money, very powerful in this poor country, seemed to him a means at once so natural and irresistible, that he went even into Geneva, to buy up old Theodore de Bèze, and offered him, on the part of the Pope, a pension of four thousand crowns.

It was an odd sight to behold this man, the bishop and titular prince of Geneva, beating about the bush to circumvent his native city, and organising a war of seduction against it by France and Savoy. Money and intrigue did not suffice; it was necessary to employ a softer charm to thaw and liquify the inattackable iceberg of logic and criticism. Convents for females were founded, to attract and receive the newly-converted, and to offer them a powerful bait composed of love and mysticism. These convents have been made famous by the names of Madame de Chantal and Madame Guyon. The former established in them the mild devotion of the Visitation; and it was there that the latter wrote her little book of Torrents, which seems inspired, like Rousseau's Julie (by the bye, a far less dangerous composition), by the Charmettes, Meillerie, and Clarens.

[1] The masterpiece of the Jesuit was to get the shepherd-poet Des Yveteaux, the most empty-headed man in France, named tutor, reserving to himself the moral and religious part of education.

[2] See his Life, by Dorigny, p. 505.; Bonneville, Life of St. François, p. 19, &c.

[3] Read the three great Vaudois historians, Gilles, Léger, and Arnaud.

[4] Plagiarius, in its proper sense, means, as is well known, a man-stealer.

[5] Little lies, little deceits, little prevarications. See, for instance, OEuvres, vol. viii. pp. 196, 223, 342.

[6] Nouvelles Lettres Inédites, published by Mr. Datta, 1835, vol. i. p. 247. See also, for the intolerance of St. François, pp. 130, 131, 136, 141, and vol. ix. of the OEuvres, p. 335, the bounden duty of kings to put to the sword all the enemies of the Pope.

ST. FRANCOIS DE SALES AND MADAME DE CHANTAL.—VISITATION.—QUIETISM.—RESULTS OF RELIGIOUS DIRECTION.

Saint François de Sales was very popular in France, and especially in the provinces of Burgundy, where a fermentation of religious passions had continued in full force ever since the days of the League. The parliament of Dijon entreated him to come and preach there. He was received by his friend André Frémiot, who from being a counsellor in Parliament had become Archbishop of Bourges. He was the son of a president much esteemed at Dijon, and the brother of Madame de Chantal, consequently the great-uncle of Madame de Sévigné, who was the grand-daughter of the latter.

The biographers of St. François and Madame de Chantal, in order to give their first meeting an air of the romantic and marvellous, suppose, but with little probability on their side, that they were unacquainted; that one had scarcely heard the other spoken of; that they had seen each other only in their dreams or visions. In Lent, when the Saint preached at Dijon, he distinguished her among the crowd of ladies, and, on descending from the pulpit, exclaimed, "Who is then this young widow, who listened so attentively to the Word of God?" "My sister," replied the Archbishop, "the Baroness de Chantal."

She was then (1604) thirty-two years of age, and St. Francis thirty-seven; consequently, she was born in 1572, the year of St. Bartholomew. From her very infancy she was somewhat austere, passionate, and violent. When only six years old, a Protestant gentleman happening to give her some sugar-plums, she threw them into the fire, saying, "Sir, see how the heretics will burn in hell, for not believing what our Lord has said. If you gave the lie to the king, my papa would have you hung; what must the punishment be then for having so often contradicted our Lord!"

With all her devotion and passion, she had an eye to real advantages. She had very ably conducted the household and fortune of her husband, and those of her father and father-in-law were managed by her with the same prudence. She took up her abode with the latter, who, otherwise, had not left his wealth to her young children.

We read with a sort of enchantment the lively and charming letters by which the correspondence begins between St. François de Sales, and her whom he calls "his dear sister and daughter." Nothing can be more pure and chaste, but at the same time, why should we not say so, nothing more ardent. It is curious to observe the innocent art, the caresses, the tender and ingenious flattery with which he envelopes these two families, the Frémiots and the Chantals. First, the father, the good old president Frémiot, who in his library begins to study religious books and dreams of salvation; next, the brother, the ex-chancellor, the Archbishop of Bourges; he writes expressly for him a little treatise on the manner of preaching. He by no means neglects the father-in-law, the rough old Baron de Chantal, an ancient relic of the wars of the League, the object of the daughter-in-law's particular adoration. But he succeeds especially in captivating the young children; he shows his tenderness in a thousand ways, by a thousand pious caresses, such as the heart of a woman, and that woman a mother, had scarcely been able to suggest. He prays for them, and desires these infants to remember him in their prayers.

Only one person in this household was difficult to be tamed, and this was Madame de Chantal's confessor. It is here, in this struggle between the Director and the Confessor, that we learn what address, what skilful manoeuvres and stratagems, are to be found in the resources of an ardent will. This confessor was a devout personage, but of confined and shallow intellect, and small means. The Saint desires to become his friend,—he submits to his superior wisdom the advice he is about to give. He skilfully comforts Madame de Chantal, who entertained some misgiving about her spiritual infidelity, and who, finding herself moving on an agreeable sloping path, was fearful she had left the rough road to salvation. He carefully entertains this scruple in order the better to do away with it; to her inquiry whether she ought to impart it to her confessor, he adroitly gives her to understand that it may be dispensed with.

He declares then as a conqueror, who has nothing to fear, that far from being, like the other, uneasy, jealous, and peevish, who required implicit obedience, he on the contrary imposes no obligations, but leaves her entirely free—no obligation, save that of Christian friendship, whose tie is called by St. Paul "the bond of perfectness:" all other ties are temporal, even that of obedience; but that of charity increases with time: it is free from the scythe of death,—"Love is strong as death," saith the Song of Solomon. He says to her, on another occasion, with much ingenuousness and dignity: "I do not add one grain to the truth; I speak before God, who knows my heart and yours; every affection has a character that distinguishes it from the others; that which I feel for you has a peculiar character, that gives me infinite consolation, and to tell you all, is extremely profitable to me. I did not wish to say so much, but one word produces another, and then I know you will be careful." (Oct. 14, 1604.)

From this moment, having her constantly before his eyes, he associates her not only with his religious thoughts, but, what astonishes us more, with his very acts as a priest. It is generally before or after mass that he writes to her; it is of her, of her children, that he is thinking, says he, "at the moment of the communion." They do penance the same days, take the communion at the same moment, though separate. "He offers her to God, when he offers Him His Son!" (Nov. 1, 1605.)

This singular man, whose serenity was never for a moment affected by such a union, was able very soon to perceive that the mind of Madame de Chantal was far from being as tranquil as his own. Her character was strong, and she felt deeply. The middle class of people, the citizens and lawyers, from whom she was descended, were endowed from their birth with a keener mind, and a greater spirit of sincerity and truth, than the elegant, noble, but enfeebled families of the sixteenth century. The last comers were fresh; you find them everywhere ardent and serious in literature, warfare, and religion; they impart to the seventeenth century the gravity and holiness of its character. Thus this woman, though a saint, had nevertheless depths of unknown passion.

They had hardly been separated two months when she wrote to him that she wanted to see him again. And indeed they met half-way in Franche-Comte, in the celebrated pilgrimage of St. Claude. There she was happy; there she poured out all her heart, and confessed to him for the first time; making him the sweet engagement of entrusting to his beloved hand the vow of obedience.

Six weeks had not passed away before she wrote to him that she wanted to see him again. Now she is bewildered by passions and temptations; all around her is darkness and doubts; she doubts even of her faith; she has no longer the strength of exercising her will; she would wish to fly—alas! she has no wings; and in the midst of these great but sad feelings, this serious person seems rather childish; she would like him to call her no longer "madam," but his sister, his daughter, as he did before.

She uses in another place this sad expression,—"There is something within me that has never been satisfied."—(Nov. 21, 1604.)

The conduct of St. François deserves our attention. This man, so shrewd at other times, will now understand but half. Far from inducing Madame de Chantal to adopt a religious life, which would have put her into his power, he tries to strengthen her in her duties of mother and daughter towards her children and the two old men who required also her maternal care. He discourses with her of her duties, business, and obligations. As to her doubts, she must neither reflect nor reason about them. She must occasionally read good books; and he points out to her, as such, some paltry mystic treatises. If the she-ass should kick (it is thus he designates the flesh and sensuality), he must quiet her by some blows of discipline.

He appears at this time to have been very sensible that an intimacy between two persons so united by affection was not without inconvenience. He answers with prudence to the entreaties of Madame de Chantal: "I am bound here hand and foot; and as for you, my dear sister, does not the inconvenience of the last journey alarm you?"

This was written in October on the eve of a season rude enough among the Alps and at Jura: "We shall see between this and Easter."

She went at this period to see him at the house of his mother; then, finding herself all alone at Dijon, she fell very ill. Occupied with the controversy of this time, he seemed to be neglecting her. He wrote to her less and less; feeling, doubtless, the necessity of making all haste in this rapid journey. All this year (1605) was passed, on her part, in a violent struggle between temptations and doubts; at last she scarcely knew how to make up her mind, whether to bury herself with the Carmelites, or marry again.

A great religious movement was then taking place in France: this movement, far from being spontaneous, was well devised, very artificial, but, nevertheless, immense in its results. The rich and powerful families of the Bar had, by their zeal and vanity, impelled it forward. At the side of the oratory founded by Cardinal de Bérulle, Madame Acarie, a woman singularly active and zealous, a saint engaged in all the devout intrigues (known also as the blessed Mary of the incarnation), established the Carmelites in France, and the Ursulines in Paris. The impassioned austerity of Madame de Chantal urged her towards the Carmelites; she consulted occasionally one of their superiors, a doctor of the Sorbonne.[1] St. François de Sales perceived the danger, and he no longer endeavoured to contend against her. He accepted Madame de Chantal from that very moment. In a charming letter he gives her, in the name of his mother, his young sister to educate.

It seems that as long as she had this tender pledge she was in some degree calmer; but it was soon taken from her. This child, so cherished and so well taken care of, died in her arms at her own house. She cannot disguise from the Saint, in the excess of her grief, that she had asked God to let her rather die herself; she went so far as to pray that she might rather lose one of her own children!

This took place in November (1607). It is three months after that we find in the letters of the Saint the first idea of getting nearer to him a person so well tried, and who seemed to him, moreover, to be an instrument of the designs of God.