Bertram Mitford

"A Veldt Vendetta"

Chapter One.

A Voyage of Discovery.

I had not a friend in the world.

My own fault? No doubt. It is usually said so, at any rate, so of course must be true. For I, Kenrick Holt, who do this tale unfold, am not by nature and temperament an expansive animal, rather the reverse, being constitutionally reticent; and, is it not written that the world takes you at your own valuation? Still, I had managed to muddle on through life somehow, and gain a living so far—which was satisfactory, but in an uncongenial and sedentary form of occupation—which was not. Incidentally I owned to the ordinary contingent of acquaintances, but at the period of which I write I had not a friend in the world—only brothers.

Of these, one owned an abominable wife, the other a snug country living, which combination of circumstances may account for the fact that we had rather less to do with each other on the whole than the latest conjunction of club acquaintances. Incidentally, too, I owned relatives, but for ordinary reasons, not material to this narrative, they didn’t count.

“Great events from little causes spring” is a truism somewhat shiny at the seams. In the present instance the “little cause” took the form of an invite from the last-mentioned of my two brethren—he who drew comfortable subsidy for shepherding a few rustics in the national creed to wit—to run down and get through a week with him at his vicarage.

I was out of sorts and “hipped,” not so much through overwork as through remaining in town too long at a stretch: for, except a day off now and then up the river, I had stuck to my office all through the hot months, and it was now September. In passing, it may be mentioned I held a secretaryship to a not very long floated company; a fairly good berth—as long as it lasted. As long as it lasted! There lay the rub. For I had held two similar berths before!

Well, this invite came in pat. A blow of country air would do me all the good in the world just then. The invite was something of an event, as may be conjectured in the light of certain foregoing remarks; still, that didn’t matter. Nothing did—according to my then philosophy—except lack of the needful, and an abominable noise when one wanted to go to sleep. The first I had experienced more than once, the second I was destined to—and notably if I accepted the invite. However, that didn’t weigh. The only thing that remained was to pack up and send a wire.

I had packed, and found out a convenient train. But the first thing in the morning brought a counter-wire—

“Sorry must put you off dick and bertha got scarlatina holt.”

Here was a nuisance—the said Dick and Bertha being among the certain arch-contributors in prospective to the second of the things that matter in life, as referred to above. Yes, it was a nuisance. I was all ready to start, and the weather was perfect; just that soft, golden, hazy kind of September weather that is exquisite in the country, and here was I, doomed to the reek of asphalt and wood paving once more, just as I was rejoicing in the prospect of a week of emancipation therefrom. Well, I would go somewhere, but it wasn’t the same thing, for I am not partial to solitary jaunts, albeit in most matters self-concentrated. At any rate, I would not go back to work.

I strolled round to the club, thinking out an objective the while. There were few habitués there, but a sprinkling of strangers, for we were housing another kindred institution pending its summer cleaning. Among these was a man I knew, and as we got talking over our “split” I found he was in the same predicament as myself.

“Don’t know where to go?” he said. “I’ll tell you. There’s a jolly little place on the Dorsetshire coast—Whiddlecombe Regis—right out of the public beat, only known to a few, and they always go back there. Jolly pretty country, first-rate bathing, and not bad sea fishing. Let’s run down together for a week or so. We can capture a train from Waterloo at a decent hour to-morrow. Waiter, just fetch me the ABC, will you?”

The ABC was fetched, and we put our heads together over it, and in the result the following afternoon saw us deposited—after a five-mile coach ride from the nearest station—in front of the principal inn at Whiddlecombe Regis.

It was a delightfully picturesque and retired place, with its one long steep street, and flat massive church tower; and seemed to deserve all the encomium which Bindley had bestowed upon it. It nestled snugly in its own bay, which was guarded by bold headlands, all crimson and gold with heather and gorse, shooting out into the sparkling blue of a summer sea. Not a cloud was in the sky, and against the soft haze in the offing a trail of smoke here and there marked out the flight of a passing steamer.

Our “decent train from Waterloo” had proved to be a dismally early one, consequently we found ourselves at our destination at an early hour of the afternoon. So after we had lunched—plainly but exceedingly well—I suggested we should go down to the beach and take on a good pull if there was a light boat to be had, and a sail if there was not.

But Bindley was not an ideal travelling companion; I had found that out in more than one trifling particular on the way down. Nor did he now jump at my suggestion with the alacrity it deserved—or at any rate which I thought it did. He made various objections. It was too hot—and so forth. He felt more like taking it easy. What was the good in coming away for a rest if one began by grinding one’s soul out? he said.

However, I was bursting with long-pent-up energy. The glorious open air, after the reek and fogginess of London had already begun to put new life into me, and the smooth blue of the sea and its fresh salt whiff invited its exploration. So I left Bindley to laze in peace and took my way down to the beach. For a moment I had felt inclined to fall in with his idea, or at any rate to wait an hour or two until he felt inclined to fall in with mine, but the feeling passed. How little I knew what the next twelve hours or so were destined to bring forth!

The beach at Whiddlecombe Regis held everything in common with the beach at half a hundred similar places. There were the same fishing boats and the same whiff thereof—some with their brown sails up and drying, and two or three of their blue jerseyed owners doing odd jobs about them; others alone and deserted, with nets hung over the side to dry. Children were paddling in the little sparkling rims of froth left by each ripple of the tide, and under the redolent shelter of the boats aforesaid their nurses and governesses, seated beneath sunshades, gossipped, or looked up from the Family Herald to inspect the passing male stranger and grumble at the heat.

“Boat, sir?”

The hail, proceeded from a weather-beaten seafarer. I was beyond the fishing craft by now, and in front lay, drawn up on the beach, a dozen or so of rowing boats and—marvellous to relate—among them one, light and an outrigger.

“Well, I feel like an hour’s pull,” I answered. “This one will do.”

The salt looked out seaward a moment. Then he said—

“Well, sir, she be only good in smooth water, and it’s that now. Be you much in the way of boats, sir?”

“Rather,” I answered readily, for I fancied myself in the sculling line, it being one of my favourite forms of recreation. And I suppose I looked my words, for my amphibious friend ran the pair-oar down into the water without more ado.

Though not a skiff, the craft was light and well built, and in a very few moments I was sending her over the smooth waters of the bay at a pace which should soon render the village of Whiddlecombe Regis a mere blur against a wall of green hillside and crimson-clad down—and that without any effort. The exhilaration of it was glorious—the swift easy glide, the free open sea, the cloudless blue sky above, and the racing headlands. Beyond these other promontories appeared; only to be merged in their turn into the spreading extent of the fast-receding coastline. The boat went beautifully. I had got her over half a dozen miles in no time. I would make it a round dozen straight out; then back—and get in at dusk, in nice time for dinner.

What an ass Bindley was to come down to a place like this merely for the fun of going to sleep, I thought, as I skimmed onwards; and then it occurred to me that as this was the only craft of the kind on the beach, I should have missed the splendid exhilaration afforded by my present exercise, as she was certainly not built to carry two, and I had thoughts of hiring her for the time I should be down here, so as to ensure always being able to take her out when wanted.

I had, as near as could be judged by time, about accomplished my prescribed dozen miles, and was pulling the boat round to return, when in spite of the exercise I felt chilly. Then as I faced out to seaward and perceived the cause I felt chillier still—and with reason.

Fog.

Creeping up swiftly, insidiously, like a dark curtain over the sea it was already upon me. Heavens! how I pulled. But pull I never so lustily, send the light craft foaming through the water as I was doing, the dread enemy was swifter still—and all too subtle. Already the coastline was half blotted out, and the remainder blurred and indistinct, but up-Channel the sea was still clear. Well, by holding a straight course now, and keeping what little wind there was upon my right ear, I could still fetch the land even if I did not soon run into clear weather again.

But the smother deepened, lying thick upon the surface. Already the air seemed darkening, and now a distance of half a dozen yards on either hand was all that was visible—sometimes not as much.

Was it demoralisation evoked by this sudden blotting out of the world around, as I found myself alone in the dark vastness of this spectral silence?—for now I felt tired and was obliged to rest on my sculls more than once. And again and again, though hot and perspiring, I shivered.

Now through the silence came the whooping of a steamer’s siren. Another, further out, answered in ghostly hoot. Heavens! what did this mean? Had I, while resting, been insidiously turned round and was now sculling my utmost out into mid-Channel—and—right into the path of passing shipping? And with the thought it occurred to me that no sound of the shore—the striking of a church clock or the bark of a dog, for instance, reached my ears. The thought was an uncomfortable one—almost appalling. One thing was clear. Further rowing was of no use at all.

Again rose the hoot of that spectral foghorn, and as it ceased I lifted up my voice and shouted like mad. But the steamer was probably not near enough for those on board of her to hear my yell, and from the repetition of the sound she seemed to be passing.

It was now almost dark. Shivering violently, I put on my coat and waistcoat—which I had thrown off when beginning my pull—but they were light summer flannels and of small protection—and looked the situation in the face. Here was I, in a cockleshell of a craft, which even the smallest rising of the sea would inevitably swamp, shut in by thick impenetrable fog anywhere out towards mid-Channel, and drifting Heaven knew where, with nothing to eat, nothing to drink, and a long night before me to do it in. I might be picked up, but it was even more likely I might be run down, and with the thought I seemed to see a black, towering cut-water rush foaming from the oily smother, to crash into my little craft and bear me down drowning and battered beneath the grim iron keel.

Time went by; it must have been hours—to me it seemed years. In the overwhelming unearthly blackness of the fog I sat and shivered, a prey to the most unutterably helpless feeling. If it were only daylight, and the fog would lift, I should be picked up in no time in so congested a waterway as the Channel was at this point. But such a consideration now only served to enhance the horror of the position, for it wanted hours and hours to daylight, and here I was, with no means of showing a light except a matchbox containing some dozen and a half of wax vestas, and right in the way of anything that came along. That was an idea anyhow. I might light a pipe. The glow, tiny as it was, might attract notice in the dark. But though a greater smoker than the average I am not one of those who can enjoy tobacco on an empty stomach, and the latter condition being all there, I soon had to desist, and think of the cosy dinner we should now long since have been sitting down to, Bindley and I, in the snug inn at Whiddlecombe Regis; which, whether it lay north, south, east or west of me at that moment, Heaven only knew.

It may be guessed I had expended a good deal of lung power in periodical shouting. I had heard fog-horns whooping from time to time, but more or less distant, and once I had heard the powerful beat of a propeller and the rush of a great liner, quite near by. But as Fate would have it, at that critical point I had shouted myself well-nigh voiceless, and the clank and clatter on board and the wash of her way must have drowned my feeble attempts, for she passed on, and presently a succession of waves furrowed up by her passage caused my little cockleshell to dance in the most lively fashion. Thus I was left alone in the blackness once more, sick and faint with hunger, and my teeth chattering with the cold, to such an extent that it seemed to me the very noise they made ought in itself to attract the attention of passing craft.

After that I seemed to fall into a state of semi-somnolence for a time, out of which I was roused by the motion of the boat. I awoke with a start. There was a freshening in the air, as though a breeze were springing up; and indeed such was the case. The fog, too, had lifted, for I could see stars. But the momentary exultation evoked by this idea subsided in a new alarm. The sea was getting up, and I needed not a reminder of the old salt from whom I had hired the boat that the latter was only good for smooth water. Here was a new peril, and a very real one. And there was a decidedly “open sea” kind of whiff about the freshening breeze.

I pulled the boat round so as to keep her head to the waves, which seemed to be increasing every moment. Their splash wetted me, rendering the cold more biting than ever, and then—a strange roaring sound bellowed in my ears. A huge green eye shot forward in the darkness, and a tall dark mass towered foaming above me. At that moment I opened my mouth and emitted the most awful yell that ever proceeded from human throat. Then came the crash—as I knew it would. I seemed to be shot forward into space, then dragged through leagues of cold and rushing waters, while gripping something hard and resisting as though life depended on it. Then another shock, and I knew no more.

Chapter Two.

A Waif.

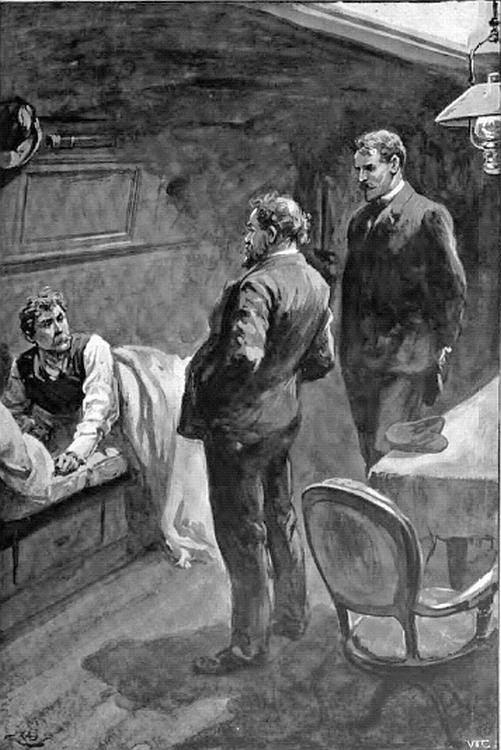

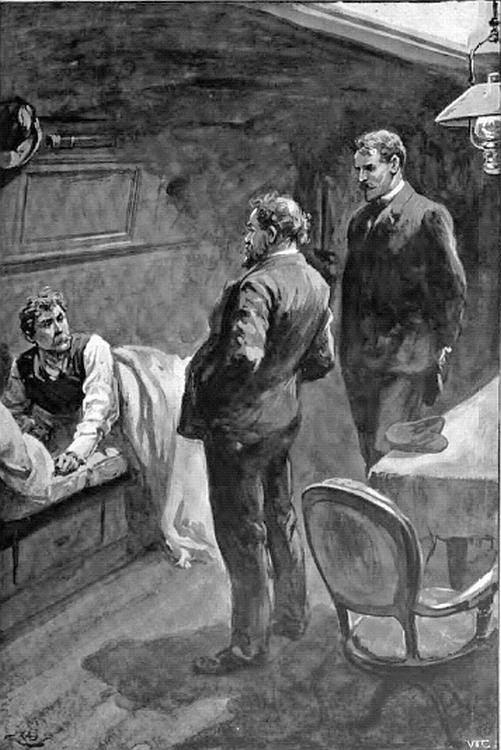

“Seems to be coming to, don’t he?”

“Not quite. Better leave him alone a bit longer.”

Was I dead, and were these voices of another world? Hardly. They had a homely and British intonation which savoured too much of this one. Then I grew confused, and dozed off again.

Was I dreaming, or where was I? shaped out the next thought as I heard the voices again. Lying with closed eyes, returning consciousness began to assert itself. A certain heaving movement, which could be produced by nothing else than a ship at sea, made itself felt—a movement not unknown to me, for I had made a voyage to Australia and back earlier in my hitherto uneventful career—and a pounding, vibrating sound, which jarred somewhat roughly upon my awakened nerves, told that the vessel was a steamship. Opening my eyes drowsily, I saw that I was lying in a bunk, and the fresh air blowing in through an open skylight was breezy and salt. There was no mistaking my present quarters. I was in a ship’s cuddy. A table, covered with a faded cloth of many colours, stood in the middle of the room, and the slant of an apparently useless pillar running from floor to ceiling, and through the same, could only be that of a mast.

“Feeling better now, sir?”

Two men had glided into the room and were watching me. One was tall, slim, and well made, with a clear-cut face and dark pointed beard, the other red and broad and burly; and when they spoke I recognised the voices I had heard before.

“Yes, thanks. At least I think so,” I answered faintly.

“Better give him a tot of rum. That’ll bring him to,” said the broad red man, in a voice that rumbled.

“Not much. Grog on top of that whack on the head he got would be the death of him. Oh, steward! tell the doctor to send along that broth,” he called out to some one outside.

“Where am I?” was my next and obvious question.

“Board the Kittiwake, bound for East London. Cargo, iron rails,” answered the broad red man.

“Let’s see. You ran me down, didn’t you?” I said confusedly.

“Run you down? Well, sonny, you lurched your ironclad against our bows in a way that was reckless. And you warn’t carrying no lights neither, which is clean contrary to Board o’ Trade regulations, and dangerous to shippin’.”

“What a narrow squeak I must have had. Are you the captain?”

“No, sir. This here’s the captain, Captain John Morrissey,” and he turned to the good-looking, dark-bearded man, whom at first I had taken for the ship’s surgeon.

“Narrow squeak’s hardly the word for it, Mr Holt,” said this man in a pleasant voice. “It’s more of a miracle than I’ve seen in all my experience of sea-going. Ah, I see the doctor has sent you your broth; you’d better take it, and I wouldn’t talk too much just yet, if I were you.”

“You carry a doctor, then. Are you a liner?”

Both laughed at this.

“No, no, Mr Holt,” answered the captain. “Doctor’s a seafaring term for the ship’s cook, and I believe in this instance you’ll find his prescriptions do you more good than those of the real medico.”

I sipped the broth, and felt better; but still had a very confused, not to say achy, feeling about the head, and again began to feel drowsy.

“I suppose I’ll be all right by the time we get in,” I said. “Right enough to land, shan’t I?”

The broad red man rumbled out a deep guffaw. The captain’s face took on a strange look—comical and warning at the same time.

“You’ll be all right long before we get in, Mr Holt,” he said. “Now, if you take my advice, you’ll go to sleep again.”

I did take it, and I must have slept for a long time. Once or twice I half woke, and it seemed to be night, for all was dark save for a faint light coming in through the closed portholes, and the lulling rocking movement and swish of the water soon sent me off again. Even the throb of the propeller was soothing in its regularity.

“You’ve had a good sleep, sir. Feel better this morning, sir?”

It was broad daylight, and the motion of the ship had changed to a very decided roll. I sat up in my bunk.

“Shall we be in soon, steward?” I asked, recognising that functionary.

“Be in soon? Why, hardly, sir,” he answered, looking puzzled. “We don’t touch nowhere.”

“No, I suppose not. But where are we now?”

“Well into the Bay.”

“The Bay! What Bay?”

“Bay o’ Biscay, sir,” he replied, looking as though he thought the effects of my buffeting had impaired my reasoning faculties.

“Bay of Biscay!” I echoed. “The Channel, you mean. The captain said we were bound for East London.”

“So we are, sir, and we’re heading there at nine knots an hour. We shan’t do so much, though, if this sou’wester keeps up.”

An idea struck me, but it was a confused one.

“Steward,” I said, sitting bolt upright. “Will you oblige me with a piece of information. Where the devil is East London?”

“Eastern end of the Cape Colony, Mr Holt; and a bad port of call, whichever way you take it.”

The answer came from the captain, who entered at that moment. The steward went on with his occupation, that of laying the table for breakfast.

“Great Scott!” I cried, as the truth dawned upon me. “But—”

“I see how it stands,” said the captain with a smile. “You thought East London meant the East India Docks. I didn’t set you right at the time, because you might have got into a state of excitement, and rest was the word just then. Now I think you are fairly on your legs again.”

“But—botheration! I don’t want to take a voyage to the Cape. I suppose you can put me ashore somewhere, so I can get back.”

“I’m afraid not. We don’t touch anywhere. But I think even the voyage is the lesser evil of the two. Better than lying at the bottom of the Channel, I mean.”

“Well, certainly. Don’t think me ungrateful, Captain Morrissey; but this will mean a lot to me. I shall lose my berth, for one thing.”

“Even that isn’t worse than losing your life, and you had a narrow squeak of that. By the way, were you sculling across the Channel for a bet?”

“Haw, haw, haw!” rumbled the broad red man, who had rolled in in time to catch this question.

I joined in the laugh, and told them how I came to be found in such a precarious plight. Then I learned how my rescue had been effected, and indeed miraculous hardly seemed the word for it. But that the steamer was going dead slow in the fog, and I had clung to her straight stern with the grip of death, I should have been crushed down beneath her and cut to pieces by the propeller. Even then they had hauled me on board with difficulty. The boat, of course, had been knocked to matchwood.

“You had a gold watch and chain upon you, a pocket-book, and some money?” said the captain. “How much was there?”

“Let me see; five pounds and some change. I forget how much.”

The captain disappeared through a door, and immediately re-entered.

“Count that,” he said.

I picked up a five-pound note, two sovereigns, and some silver change.

“Seven pounds, nine and a halfpenny,” I said. “Yes, that’s about what it was.”

“That’s all right. I took care of it for you. Here’s your watch and chain. I ventured to open the pocket-book to find out your identity. Now, if you’ll take my advice you’ll get up and join us at breakfast.”

I took it, and soon the captain and I and the broad red man, who was the chief mate, and rejoiced in the name of Chadwick, were seated at table, and I don’t know that grilled chops and mashed potato—for the fresh meat supply had not yet run out—ever tasted better. The while we discussed the situation.

“The nearest point I could land you at would be the Canaries,” the captain was saying, “and I daren’t do that. My owners are deadly particular, and it might be as much as my bunk was worth—and I’ve got a family to support.”

“Well, I haven’t,” I answered, “so I wouldn’t allow you to take any risk of the kind on my account, captain, even if you were willing to. But—what about passing steamers?”

The two sailors looked at each other.

“The fact is,” went on the captain, “it’s blowing not only fresh, but strong. The glass is dropping in a way that points to the next few days finding us with our hands all full. After that we shan’t sight anything much this side of the Cape, and it’ll hardly be worth your while to tranship then. I’m afraid you’ll have to make up your mind to do the whole passage with us.”

I recognised the force of this, and that it was a case of resigning myself to the inevitable. And the thought ran through my mind how strange are the workings of events. But for my brother’s invite I should have been safe and snug and humdrum in my City office. But for the cancelling of that invite I should never have found my way to Whiddlecombe Regis, or even have heard of such a place; and now here I was, after a perilous experience, launched upon the high seas, bound for a distant colony, and that without any will of my own in the matter. Well, when I got there, I could always arrange a return passage. I had some means of my own—not enough to keep me without working, unless I chose to live upon what would amount to the wages of an artisan. Therefore there was nothing to cause me serious anxiety, unless it were that my berth would probably be filled up. But, as I have hinted, the tenure of it was somewhat precarious, so some consolation lay that way, and I could doubtless find another. So I reasoned, forgetting that after all we are blind and helpless instruments in the hands of Fate, a lesson which my experience so far might well have reminded me—certainly in total unconsciousness of what stirring experiences, perilous and otherwise, lay between now and when I should once more behold the English coastline.

“You seem a good sailor, at any rate, Mr Holt,” said the captain, breaking in upon my meditations.

“Why, I never thought of feeling seasick,” I answered. “It didn’t occur to me.”

“No? Well, you’re all right then. If we’ve done, I would suggest a turn on deck. If we get a bad blow, you may not be able to get there for a while, so better make the most of it now.”

Chapter Three.

Southward.

A stirring and lively scene met my gaze as I emerged from the companion-way. A great waste of roaring tumbling seas, their dull green mountainous masses breaking off into foamy crests as they swooped down upon us, only to swing under the keel and roar on afresh in a moving mountain beyond. The sky, a great flying scud which glimpses of sickly sunshine strove here and there to pierce. White gulls hovered and darted, squealing; and, thrown out in a cloud of proud magnificence against the inky sky to the westward, a homeward-bound ship, under a full spread of canvas, was thundering over the boil of billows, dashing the white spray before her in cataracts.

From the poop-deck I could see for the first time what manner of craft I was in. The Kittiwake was an iron steamer of just under two thousand tons, brig rigged; and the water was pouring from her forecastle as she dipped her nose into the meeting of the green seas. Some of the hands were running up the foresail to the accompaniment of a shrill nautical chant, and the broad red man, clad in oilskins, had just gone up to relieve the second mate on the bridge. To a landsman’s eye, the aspect of the weather quarter looked black and threatening to the last degree, and it hardly needed the captain’s warning that a dusty time, which would keep all hands busy, was in front of us.

“You were saying you had no incubus in the matter of family dependent on you, Mr Holt,” the captain remarked as we paced the short poop-deck, which was literally, as he put it, fisherman’s walk—three steps and overboard. “But I hope you’ve left no one behind who’ll be anxious about you.”

“Not a soul,” I answered. “I have no friends, only relations, and their only anxiety—at least, on the part of one of two of the nearest—will be as to how soon they can file claims to what little I possess.”

The other laughed drily at this, and there was a twinkle of sympathetic fun in his eyes.

“After them, the most anxious person will be the man who let me the boat,” I said. “But I can compensate him, with interest, later on.”

I thought of Bindley, and how my disappearance might possibly spoil his holiday; but then, I didn’t suppose it would. He was one of those men who ought to go about by themselves; in fact, I wondered why he had moved me to join him in this jaunt, seeing that his idea of companionable travelling was to go to sleep most of the time or to read the papers all through dinner. No, he wouldn’t mind. On the contrary, it would give him matter to oraculise upon.

The next three days were something to remember, and we spent most of them and the corresponding nights either hove to or going dead slow. I had been through rough weather before, but never such an experience as that, and, to tell the truth, never do I want to again. Black darkness, only qualified by a dim oil lamp—for the captain had insisted on my remaining below—thunderous roaring, crashing and poundings as though the ship were being ground in pieces between two mighty icebergs. And then the inert uncertainty of it! Every upheave seemed to be followed by a downward settling plunge, as though the ship were already on her way to the bottom. The steward and I stole furtive looks at each other from white faces as we moved about, nearly knee-deep in water, and I think the same thought was in both our minds, that each sickening plunge was going to be the last. Seriously, that momentary expectation of death, condemned the while to utter inaction and surrounded by every circumstance of appalling tumult and darkness and horror, is about as unnerving a thing as can find place in any man’s experience, and it was long before the recollection of it passed from my mind.

Assuredly, too, I shall never forget the scene that greeted my first appearance on deck, after the subsidence of the storm.

The steamer, which before, though lacking the spick-and-span smartness of a crack liner, was, for a cargo boat, wonderfully clean and ship-shape, now had all the appearance of a wreck. Everything movable on her decks had been swept away. Three out of her four boats were gone, and the green seas came pouring over the main deck, to run off through a great breach in her bulwarks. Crates of poultry and a live sheep alike had disappeared, and she wore the aspect of a woe-begone hulk. However, we had weathered the gale, and the engines had stood out nobly.

The captain and chief mate, too, looked hardly the same men. The former was pale and sallow, and the latter, though still broad, could no longer be described as red. The long spell of sleeplessness and terrible anxiety had told upon them, and the eyes of both were dull and opaque. I did not address them, as they were busily engaged in “shooting the sun,” it being the first time that luminary had been available for the purpose since the beginning of the gale.

“Running down the Portuguese coast, and a sight nearer in than we ought to be,” said the captain, joining me. “Well, Mr Holt, you’ve had a new experience, and I’m not sure I haven’t myself, for I can hardly call to mind a worse blow, especially with such a cargo, and loaded down as we are. The boat won’t rise properly, you see—hasn’t a fair chance. Well, we shan’t get any more of it, unless we come in for a dusting off the Cape coast.”

We ran into lovely weather—day after day of cloudless skies and glassy seas; but the heat on the line was something to remember, and we had none of the luxuries of a first-class passenger ship—no long drinks or iced lager, or cool salads and oranges. Salt provisions and ship biscuit and black tea, with a tot of grog before turning in, constituted our luxurious fare, and the heat had brought out innumerable cockroaches, which did their level best to contribute towards its seasoning. But there were compensations. For instance, I had made up my mind to leave all care and anxiety behind, to throw it off utterly, and trust to luck; and having done this, in spite of drawbacks, I began to enjoy the situation amazingly.

I had long since come to the conclusion that the captain was one of the nicest fellows I had ever met. He was utterly unlike any preconceived and conventional idea of the merchant skipper. He never swore or hustled his crew, or laid down the law, or did any of those things which story has immemorially associated with his cloth. And he was refined and cultured, and could talk well on matters outside his professional experience. He was rather a religious man, too, though he never put it forward, but I frequently saw him reading books of Catholic authorship or compilation, so guessed at his creed. As an Irishman, too, he was quite outside the preconceived type in that he was neither quick-tempered nor impulsive, and in his speech it was difficult to detect anything but the faintest trace of brogue. Chadwick, the first mate, who soon recovered all his original redness, was a rough diamond, whose table manners perhaps might not have been appreciated in the saloon of a first-class liner, yet he was an excellent fellow, and the same held good of the chief engineer. But the second mate, King, I own to disliking intensely. He was a dark-bearded, sallow-faced young man, with a cockney drawl and an infallible manner. He was certainly the most argumentative fellow I have ever met. There was no subject under heaven on which he would not undertake to set us all right. The captain bore with him in good-humouredly contemptuous silence. Chadwick used to sledgehammer him with a growl and a flat contradiction, but it was like sledge-hammering a flea on an eider-down cushion. He hopped up livelier than ever, with a challenge to his superior to prove his contradiction.

One day he had been trying my patience to the very utmost, when duty called him elsewhere. I turned to the chief engineer, who had formed one of the group, with something like relief.

“Upon my word, McBean, that messmate of yours is appropriately named.”

“Who? King?”

“Yes.”

“And why?”

“Because he ‘can do no wrong.’”

“Ay,” said the Scot. “And do ye thenk the king can do no wrang?”

I looked at McBean. But the rejoinder was perfectly and innocently serious.

I do not propose to dwell further on the voyage, for it was uneventful, and therefore like a score of other such voyages. But to myself it was very enjoyable, in spite of passing drawbacks, and more so than ever when one night Chadwick pointed out the Agulhas light—very far away, for we had given that perilous coast particularly wide sea room—and I knew that a few days would see us at our destination.

For the said few days we could see the loom of the coast line on our port beam, high, in parts mountainous, but indistinct, for the skipper knew enough of that coast to appreciate the value of sea room. Finally we drew in nearer, and I could make out green stretches sloping upward from the shore and intersected here and there by strips of dark jungle. A dull unceasing roar was borne outward, denoting that the lines of white water lashing this mysterious-looking coast represented heavy surf. Then in the distance there hove in sight a squat lighthouse and the roofs of a few houses.

“There’s your land of promise, Holt,” said the captain, joining me. “We shall be at anchor by three o’clock. Meanwhile you’d better go down to dinner.”

Strange to say, I felt disinclined to do anything of the kind. The voyage was over, and I had a distinct and forlorn feeling that I was about to be literally turned adrift, and I believe at that moment I would have decided to return by the Kittiwake even as I had come; but such a course was impossible, for after she had discharged she was to leave for Bombay, in ballast. So I leaned over the side, gazing somewhat resentfully at this fair land, with its infinite range of possibilities, of which at that moment I was hardly thinking at all. For over and above the impending farewells, I was wondering how on earth I was going to get along in a strange land where I knew not a soul, with seven pounds nine and a half penny as my present assets.

Chapter Four.

On a Strange and Distant Shore.

“Well, good-bye, Holt. Wish you every luck if I don’t see you again, but I expect I shall if you stop on a day or two at the hotel yonder. I’ll be getting a run on shore—when I can.”

Thus the captain, and then came Chadwick, and the chief engineer—all wishing me a most hearty good-bye. Even toward the obnoxious King I felt quite affectionately disposed. The crew too were singing out, “Good luck to you, sir.”

I could hardly say anything in return, for I felt parting with these excellent fellows and good comrades, whose involuntary guest I had been during four weeks. Then I slid down the rope ladder on to the great surf boat which had been signalled alongside to take me off.

There were other vessels in the roadstead, sailing craft and a white-hulled, red-funnelled coasting steamer of the Castle line. It was a dull, sunless afternoon, which enhanced my depressed and forlorn feeling considerably. The surf boat was one of several that had been discharging cargo from the other shipping, which was stowed away in her hold, leaving room for me in the very small space open at either end. She was worked by a hawser and half a dozen black fellows, and a very rough specimen of a white man, with a great tangled beard, and a stock of profanity both original and extensive.

“Now, mister,” sang out this worthy, as I was waving last farewells to those on board, “stow that—and yer bloomin’ carcase too, unless yer want yer ruddy nut cracked with the blanked rope. Get down into the bottom of the boat.”

The warning, though rough, was all needed, for hardly had I obeyed it, when bang—whigge! the great hawser flew taut like some huge bowstring, just where my head had been a moment before. For a little while I judged it expedient literally to lie low, but when I eventually looked up, it was to behold an immense green wall of water towering aft. It curled and hissed—then broke upon us with a thunderous crash, and for half a minute I didn’t know whether we were in the boat or in the sea; and had hardly time to take breath when another followed.

“Hang on, mister, hang on,” bellowed the captain, after the first storm of profanity which burst from him had spent itself. “Hang on for all you’re worth. There’s more coming.”

I took his advice. There was a quick gliding movement, an upheave and a bump—and then—crash came one of the mighty rollers as before. Another and another followed, and at length, half drowned, I realised we were in smooth water again, and ventured cautiously to look up.

We were in the mouth of a fine river, banked by high bluffs covered with thick virgin forest. On the left bank lay a township of sorts, and the lighthouse I had seen. The darkies were warping along merrily now, their skins glistening with their recent wetting. Behind, lay such a very hell of raging surf as to set me wondering whether we could really have come through it and lived.

“Blanked heavy bar on to-day, mister,” said the skipper of the lighter, cramming a pipe from a rubber pouch. “My word, but you’ve got a ducking. Five bob please, for landing you.”

I handed over the amount, and asked him about accommodation.

“Keightley’s—up yonder,” he said. “That’s the only hotel on the West bank. There’s a German shanty a mile or so higher up t’other bank, but you’ll be better here. Going on to ‘King,’ I take it?”

“Where?”

“‘King’—King Williamstown,” he explained.

I was about to reply that I was a picked-up castaway, but thought better of it in time. Such would be presumed to be destitute, and thus might find initial difficulties as to accommodation. So I only answered that that would do me.

Now a most weird noise attracted my attention, and I found that it proceeded from a sight hardly less weird. Covering a ricketty jetty which we were slowly approaching, a crowd of strange beings were preparing for our reception after their own fashion. Some were clothed in brick red blankets and some were clothed in nothing, but all were smeared from head to foot with red ochre—and, as they swayed and contorted, a thunder of deep bass voices accompanying the high yelling recitative of him who led the chant, and beat time in measured stamping on the boards, I wondered that the structure did not collapse and strew the river with the lot of them. But their wild aspect and the grinning and contortions gave me the idea of a crowd of hugely exaggerated baboons in the last stage of drunken frenzy. But they were not drunk at all. It was only the raw savage, disporting himself after his own form of lightheadedness.

Up to this time my ideas as to the Kafir of South-Eastern Africa had been vague. If I had thought of him at all it had been as a meek, harmless kind of black, rather downtrodden than otherwise, and to whom a kick and a curse would constitute a far more frequent form of reward than a sixpence. But now as I stepped upon the jetty at East London, my views on that head underwent a complete and lasting change. For these ochre-smeared beings were brawny savages, at once powerful and lithe of frame and with a bold independent look in their rolling eyes, which, although their countenances were in the main good-humoured, seemed to show that they were able and willing to hold their own if called upon to do so. More than one of the group towered above me, and I am not short. They crowded around, vociferating in their own tongue, and tried to seize the bundle I carried—this, by the way, contained a change of clothing which Morrissey had insisted on my accepting—and I began to think of showing fight, when the surf-boat skipper came to my aid with the explanation that they merely wanted to carry it for me, for a consideration. But I was glad to get rid of the vociferous musky-smelling crowd—little thinking what strange and wild experiences awaited me yet at the hands of the savage inhabitants of this land, of whom these were fair representatives. And here I was, thrown up, as it were, upon this inhospitable coast, without a dry stitch of clothing upon me.

Soon I found myself the fortunate possessor of a small whitewashed room in the only “hotel” the place boasted—and its leading features were flies and various weird and unknown specimens of the beetle tribe, both small and great, which, attracted by the light, would come whizzing in, blundering against the greasy flare which had attracted them—to their discomfiture, or into my face—to mine; but at length I fell asleep, to the unintermittent thunder of the surf upon the bar. But the said sleep was troubled and fitful. The door, half glazed, was door and window combined, and the night being sultry, this must perforce be left open, and in the result I don’t know how many frogs startled me out of my slumbers by a weird, searching croak right at my bedside, but I do know that at least three rats were playing hopscotch upon my counterpane at once. And these, and other unconsidered trifles, ensured that precious little sleep fell to my lot the first night I passed upon the soil of Southern Africa, whither I had been thrown under so strange and unforeseen a combination of circumstances.

Chapter Five.

Of an Early Adventure.

I awoke in the morning feeling but poorly rested, and having assimilated an indifferent breakfast, which however was quite passable after four weeks of ship fare, set out to interview the manager of the local branch of the Standard Bank. I was business man enough to feel misgivings as to any success attending the object of my interview, and so far was justified by results. The manager—a youngish man, and the usual Scotchman—listened to my story politely enough—sympathetically too. But when it came to hard business, opening an account pending the time I could communicate with my own bankers, the difficulty began. He did not exactly disbelieve my story: my proposal to bring forward Captain Morrissey in corroboration went far against that. But then how could Captain Morrissey vouch as to my means? On my own showing he could by no possibility do so, and indeed to no one, in view of my business experience as aforesaid, did such an argument more fully appeal than to myself. As to reference home, why, England in those days was over three weeks distant, otherwise seven or eight before an answer could be had. Didn’t I know any one locally who could vouch for me? Of course I didn’t—considering the circumstances under which I had found myself here. Well, he was exceedingly sorry he could not accommodate me—on his own responsibility. He would, however, refer the matter to the general manager, and would then be only too happy, etc., etc. And so I was very politely bowed out.

Well, I couldn’t blame him. Business is business, and I might have been just the predatory adventurer he had no proof I was not. But for all that I went out feeling very disconsolate. My seven pounds nine and a halfpenny wouldn’t last long, and I had already begun to bore into it. What was I to do next—yes—what the devil was I to do next?

I thought I would cross the river for one thing, and take a walk along the shore on the other side. I believe I had a sort of foolish idea that the mere sight of the Kittiwake lying close in at anchor, constituted a kind of link between other times and my homeless and friendless condition on this strange and far away shore; and some thoughts of shipping on board her as an able seaman, and so working my passage round home, even entered my head. Anyway, I crossed over on the pontoon, and walking along the bush road which skirted the east bank, at length came out upon the green slope which stretches down to the sandy beach within the bight of the roadstead.

The vessels were riding to their anchorage, and the rattle of swinging out cargo, and the yells and chatter of Kafirs working the surf boats, was borne across the water. The bar had gone down considerably since the previous day, yet there was still some surf on, and it came thundering up the beach, all milky and blue in the radiance of the unclouded sun—which said sun began to wax uncommonly warm, by the same token. However, the voyage had inured me to tropical heat, which this wasn’t; wherefore I sat down to take a rest, and smoke a pipe.

Now as I sat there, moodily gazing out to seaward, an object caught my eye. It was beyond the further line of surf, and it looked uncommonly like the head of something swimming. Yet, who would be fool enough to swim out beyond that line of rollers, with their powerful and dangerous undertow? Besides, I had heard that sharks were plentiful on that coast.

I stared at the thing as it rose on the summit of a long wave. Yes, it was a head, and—great heaven! it was the head of a child; the sunlight falling full upon a little white face, and just a glimpse of gold as it touched the head, revealed that much beyond a doubt. And, as though to add to the mystery of the situation, a cry rang out over the roar of the breakers, which sounded most startlingly like a cry for help.

I was on my feet in a moment. Not a soul was in sight along the shore. In less than another moment I had thrown off my coat and kicked off my boots, and as I dashed into the surf another cry came pealing through the roar—this time more urgent, more piteous than before. I shouted in encouragement and then it required all my strength and experience in the water to get through that hell of boiling breakers, and avoid being rolled and pounded and thrown ignominiously back half drowned. Were it not indeed that I am a strong swimmer, and, what is better still, thoroughly at home in the water, such is precisely what would have happened.

A horrible fear came upon me as I got beyond the broken line. Was I too late? Then the object of my search rose upon the wave within a few yards of me.

It was, as I had thought, the face of a child—of a pretty little girl of twelve or thirteen. She wore a blue bathing dress, which allowed plenty of freedom for swimming, and her golden-brown hair was gathered in a thick plait. But in the large blue eyes was a look of terror, a kind of haunted look.

“Here, you’re all right now,” I shouted as I reached her. “Don’t be scared. Lean on me, and rest. Then we’ll swim in together. Hold on to my shoulder now. That’s right.”

The little one seemed exhausted, for she could hardly gasp out—

“We must go in quick. Sharks—two of them—after me,” and again she stared wildly over her shoulder with that terrified and haunted look. And indeed a very uncomfortable feeling came over myself, for there I was, over a hundred yards from shore, treading water, with a badly frightened child hanging on to my shoulder, the breakers in front and this other peril behind.

Peril indeed! Seldom, if ever, have I known such a chilling of the blood as that which now went through my frame. A black glistening object was sliding through the water, five-and-twenty yards away, perhaps less—a rakish triangular object, with which I was familiar enough by that time to identify as the dorsal fin of a shark, and a large one too. And, great heaven! even nearer still on the other side was another of those dreadful glistening fins.

“We’ll scare them effectually,” I said, with a hollow and ghastly grin of assumed levity. And springing half out of the water I emitted a most fiendish yell, while falling back again with a mighty splash. It was effective, for the two hateful objects sheered off, gliding away a short distance—but only a short distance.

“Come now,” I said, making a most prodigious splashing. “We must get in. Swim with me. Hold my hand if you are tired.”

“No, I’m all right now,” said the plucky little thing, beginning to strike out quite easily and naturally. Then I saw her face pale, and she stole a quick, terrified look over her shoulder, and I felt mine do ditto. For there—keeping pace with us, one on each side, and about the same distance at which we had first sighted them, moved the two horrors. They were trying to get ahead of us, to cut us off before we could reach the broken water, wherein they dare not venture.

I once knew a man who had escaped from the foundering of the ill-fated Birkenhead, and he attributed his exemption to the fact that time had lacked wherein to divest himself of his clothing before starting to swim ashore—for two sailors, who had been able to strip, were pulled under, one on each side of him. And now this idea flashed a wonderful hope into my mind, for I was almost fully clothed and my little companion wore a bathing dress. But her strokes were quick and spasmodic, and she panted. Terror was sapping her natural confidence in the water.

“This won’t do,” I cried in a loud hectoring voice. “Keep cool, can’t you, and don’t be a little idiot.”

The bullying tone told, as I intended it should. The look she gave me was amusingly resentful and contemptuous. But she ceased to swim wildly. At the same time our slimy enemies increased their distance, doubtless alarmed at the sound of my voice, which I also intended. To my unspeakable and heartfelt relief we were now on the upheave of the curling combers, and those horrible fins were still behind.

But we were not out of the wood yet—no, not by any means; for here before us lay a peril almost as formidable in itself. My little companion swam gracefully and with ease, but when we came within the breakers I kept tight hold of her, and indeed such precaution was needed, for she began to regain her terrors as the huge combers whirled us high in the air, to throw us, half smothered into a hissing cauldron of milky foam. However, they threw us forward, and by using my judgment I managed so that we should ride more and more in on the crest of each roller. And the undertow at the very last proved the most difficult of all to withstand, and twice we were dragged irresistibly backward, to be pounded by the breaking thunder of the next onrushing comber. At last we were through, and I believe but for the incentive afforded by the very act of saving life, I should have collapsed—anyway, the child could never have gained that beach unaided.

We stood, panting and dripping, and looking at each other for some moments. Then I said, as I pulled on my boots—

“Well, young lady, you seem to have had something of a swim. Where did you go into the water, and what on earth made you venture out so far, may I ask?”

She explained that she was staying at a seaside camp whose tents were pitched just beyond a few rocks a little way further on. The water was sheltered there, and there was no difficulty in getting a smooth swim. But she had somehow got too far to the right, and just as she was turning to come in again, she had seen the triangular fin of a shark cleaving the surface at no great distance, and coming towards her—then another, much nearer. This, together with the knowledge of the distance necessary to return, unless she could try to land through the surf, had unnerved and flurried her, resulting in exhaustion.

“Well, I believe it’s jolly lucky for you I happened to be at hand,” I said reprovingly. “Now, don’t you go running any such silly risks again, or you may not get off so easily. You’d better cut back now, and get dressed, or you’ll catch cold.”

“No fear. The sun’s much too hot for that,” she answered, laughing up into my face.

She was, as I have said, a pretty child, with large blue eyes and a clear skin somewhat sun-tanned. She had a pretty voice too, and spoke with a peculiar intonation, not unpleasing, and a little way of dipping the letter “r” where it occurred to end a word—which I afterwards found was the prevailing method of speech among most of those born in the Cape Colony.

I picked up my hat and coat intending to see her safely, at any rate until within sight of her people.

“What’s your name?” I said, as we walked along, at first in silence.

“Iris.”

“Iris—what?”

But before she could answer, two girls appeared round the pile of rocks, which we had nearly gained. They looked startled at seeing me, then scared, and no doubt I looked a little wild, for a rational white man walking along the beach in soaked and dripping clothes was not an everyday object. Then they advanced shyly and somewhat awkwardly, and it occurred to me that they did not look quite the equals in the social scale of my little friend.

The latter whispered to me, hurriedly and concernedly.

“Don’t tell them anything about me—about finding me as you did. I shall never be allowed to go into the water again. Don’t tell them. Promise you won’t.”

What could I do but give the required promise? Then the little one, with a hurried good-bye, skipped off to join the two, who were awaiting her—rather awkwardly—at a little distance off.

“Ungrateful little animal!” I thought to myself. “She would never have seen land again but for me—that’s as certain as that she’s on it now.”

Child-like, her first thought had been for herself—smothering even the barest expression of thanks. I did not want to be thanked for saving her little life, still I thought she might have shown a trifle more appreciation, child though she was. And as I wended my way back, my clothes fast drying on me under the powerful rays of the midday sun, another and a meaner thought struck me, begotten, I hope, of my lonely and forlorn condition. I did not want gratitude; still, the incident might have availed to make me friends of some sort in this strange and far away land, and of such I had none.

In a state of corresponding depression, I sat down to dinner. There were two other men present, rough specimens of the small agricultural class, who performed marvellous feats of attempted knife swallowing; and as I divided my energies between keeping off the swarming flies and taking in the necessary sustenance, I began to wonder what on earth I should do to get a living until the two months necessary to hear from England had elapsed. Indeed, I began almost to regret my steady refusal of Captain Morrissey’s proffered loan; for that prince of good fellows had been really hurt because I had refused to borrow a ten pound note from him—which, he said, was most of what he had with him; but what did he want with money anyhow then, he urged, being on board ship all the time?

“Say, mister!” said a voice in my ear, accompanied by a characteristically familiar touch on the shoulder. “There’s a gentleman asking for you.”

I looked up and beheld the frowzy, perspiring barkeeper, in his usual shirt-sleeves. A visitor for me? Why, Morrissey, of course—or was it the bank manager come to say he had thought better of his refusal, and I could open an account within modest limits right there? The grimy barkeeper seemed as an angel with a message as I followed him somewhat hastily to the front room. Then disappointment awaited. The room contained neither of these, but one stranger, and him I didn’t know from Adam.

Chapter Six.

Of the Unexpected.

The stranger, who was looking out of the window, turned as I entered, and I saw a tall good-looking young fellow, some three or four years my junior.

“Don’t you know me?” he said, with a smile.

“I’m afraid I don’t,” I answered, feeling thoroughly puzzled, and the thought flashed through my mind he must be some relative of the child I had rescued.

“I wondered if you would,” he went on. “I’m Matterson—Brian Matterson. We were at old Wankley’s together.”

“By Jove! Why, so it is. I’m awfully glad to meet you. It’s small wonder if I didn’t know you again, Matterson. You were a youngster then, and it must be quite a dozen years ago, if not more.”

“About that,” he answered; and by this time we were “pump-handling” away like anything.

“How on earth did you find me out, though?” I asked. “I don’t know a soul in the land.”

“That’s just it. I got on your spoor by the merest fluke. Was in at the bank this morning on business, and while I was yarning with Marshbanks I saw your card lying on the table. That made me skip, I can tell you, for I thought there couldn’t be two Kenrick Holts; if it had been Tom or George, or any name like that, of course it wouldn’t have been so certain. Marshbanks said you had called on him not very long before me, and he was sorry to have to disappoint you, because you looked a decent sort of chap; but still, biz was biz.”

“Oh, I don’t blame him in the least,” I said. “I fully recognise that maxim myself.”

“Well, I told him if you were the chap I thought, he need raise no further indaba about accommodating you, because I’d take the responsibility. So we’ll stroll round presently and look him up, and put the thing all right.”

“Awfully good of you, Matterson. In fact, you’ve no idea what running against you like this means to me, apart from the ordinary pleasure of meeting an old pal. Did the manager tell you how I got here?”

“Yes, and it struck me that a shipwrecked mariner leaving home suddenly like you did might have come, well—hum!—rather unprepared, so I lost no time in putting you right with Marshbanks. And now, what are your plans?”

“Why, to get back home again.”

“I wouldn’t hurry about that if I were you. Why not come and stay with us a bit? The governor’ll be delighted, if you can put up with things a bit plain. We can show you a little of the country, and what life on a stock farm is like. A little in the way of sport too, though there’s a sight too many Kafirs round us for that to be as good as it ought.”

“My dear chap, I shall be only too delighted. You can imagine how gay and festive I’ve been feeling, thrown up here like a stranded log, not knowing a living soul, and with seven pound nine and a halfpenny—and that already dipped into—for worldly wealth until I could hear from home.”

“By Jove! Is that all? Well, it’s a good job I spotted your card on Marshbanks’ table.”

“Here, we’ll have a drink to our merry meeting,” I said, rapping on the table by way of hailing the perspiring barman aforesaid. “What’s yours, Matterson?”

“Oh, a French and soda goes down as well as anything. Only, as this is my country, the drinks are mine too, Holt. So don’t put your hand in your pocket now. Here’s luck! Welcome to South Africa.”

We had been schoolfellows together, as Brian Matterson had said, but the three or four years between our ages, though nothing now, had been everything then. I remembered him a quiet, rather melancholy sort of boy on his first arrival from his distant colonial home, and in his capacity of new boy had once or twice protected him from the rougher pranks of bigger fellows. But he had soon learned to take his own part, never having been any sort of a fool, and, possibly by reason of his earliest training, had turned out as good at games and athletics as many bigger and older fellows than himself. We had little enough to do with each other then by reason of the difference in our ages, yet we might have been the greatest chums if the genuine cordiality wherewith he now welcomed me here—in this, to me, distant and strange country—went for anything.

We strolled round to the bank, and the manager was full of apologies, but I wouldn’t hear any, telling him I quite understood his position, and would almost certainly have acted in the same way myself. Then, our business satisfactorily disposed of, Brian and I went round to a store or two to procure a little clothing and a trunk, for my wardrobe was somewhat scanty. But such things as I could procure would not have furnished good advertisements for a first-rate London tailor or hosier.

“Don’t you bother about that, Holt,” Brian said. “You don’t want much in the way of clothes in our life. Fit doesn’t matter—wear and comfort’s everything.” And I judged I could not do better than be guided by his experience.

We were to start early the next morning, and had nearly two days’ drive before us. This was not their district town, Brian explained to me; indeed, it was the merest chance that he was down here at all, but his father and a neighbour or two had been trying the experiment of shipping their wool direct to England, and he had come down to attend to it. He was sending the waggons back almost empty, but we would return in his buggy. At my suggestion that my surprise visit might prove inconvenient to his people he simply laughed.

“We don’t bother about set invites in this country, Holt,” he said. “Our friends are always welcome, though of course they mustn’t expect the luxury of a first-class English hotel. You won’t put us out, so make your mind quite easy as to that.”

Late in the afternoon we parted. Brian was due to drive out to a farm eight or ten miles off—on business of a stock-dealing nature—and sleep, but it was arranged he should call for me in the morning any time after sunrise.

There is a superstition current to the effect that when things are at their worst they mend, and assuredly this last experience of mine was a case confirming it. An hour or so ago here was I, stranded, a waif and a stray, upon a very distant shore, a stranger in a strange land, wondering what on earth I was going to do next, either to keep myself while in it or get out of it again. And now I had all unexpectedly found a friend, and was about to set forth with that friend upon a pleasure visit fraught with every delightful kind of novelty. There was one crumple in the rose-leaf, however. We were starting early the next morning, and I should have no opportunity of seeing Morrissey and my excellent friends of the Kittiwake again. I went round to the agents, however, and inquired if there was no way of sending any note or message to the ship, and was disgusted to find that there was none that day. The bar had risen again in the afternoon, and there was no prospect of any one from the shipping in the roadstead coming ashore. So I left a note for the captain, expressing—well, a great deal more than I could ever have told in so many words.

I was up in good time next morning, and had just got outside of a muddy concoction whose principal flavour was wood-fire smoke, and was euphemistically termed coffee, when Brian Matterson drove up in a Cape cart.

“Hallo, Holt,” he sang out. “You’re in training early. You see, with us a fellow has to turn out early, if only that everybody else does, even if he himself has nothing particular to do. Well, in this case I might have given you a little longer, because I’ve got to pick up a thing or two at the store, and it won’t be open just yet, and then my little sister’s coming to have a look at me at the pontoon by way of good-bye. She’s staying with some people down here at a seaside camp—I brought her down when I came four days ago—and wants to say good-bye, you know. She’s a dear little kid, and I wouldn’t disappoint her for anything. Now trot out your luggage, and we’ll splice it on behind.”

We got hold of a sable myrmidon who was “boots” and general handyman about the place, a queer good-humoured aboriginal with his wool grown long and standing out like unravelled rope around his head, and having hauled out my new trunk, bound it on behind the trap with the regulation raw hide reim. Then we thought we might as well have some breakfast before starting, and did.

It was about seven o’clock when we started, but the sun’s rays were already manifest, even through the shelter of the canvas awning. The horses, a pair of flea-bitten roans, were not much to look at, being smallish, though sturdy and compact, but in hard condition, and up to any amount of work. We picked up some things at the store, and then it seemed to me we had hardly started before we pulled up again. There was the white of a sunshade by the roadside, and under it the flutter of a feminine dress. I recognised one of the girls who had come out to meet the little one to whose aid I had so opportunely come the day before, and—great heavens!—with her was my little friend herself.

“Hallo, Iris,” sung out Brian Matterson. “Get up, now; I’ve got to take you back. Just had a note from Beryl to say you re to go back at once. Jump up, now.”

The little one laughed, showing a row of white teeth, and shook her pretty head.

“No fear,” she replied. “Keep that yarn for next time, Brian.” Then, catching sight of me, she started and stared, reduced to silence. The while I was conscious of being introduced to Miss Somebody or other, whose name I couldn’t for the life of me catch, and, judging from the stiff awkwardness wherewith she acknowledged the introduction, I was sure she could not catch mine. Then, in answer to some vehement signalling on the part of the child, Brian got down and went a little way with her apart, where the two seemed immersed in animated conversation, leaving me to inform the awkward girl that it was a fine morning and likely to continue hot, and to indulge in similar banalities.

Brian reascended to his seat, and relieved me of the reins. I, the while, faithful to my plighted word, showed no sign of ever having seen the child before, seeming indeed to see a certain reminder of the same in her sparkling pretty little face as she half-shyly affected to make my acquaintance. Brian kissed her tenderly, and we drove on. But before we had had gone far he turned on me suddenly.

“Holt, I don’t know how to thank you, or what to say. I’ve just heard from Iris what you did yesterday. Man, you saved her life—her life, do you hear?—and what that means to me—to us—why, blazes take it, you’ve seen her!—I don’t know how I can convey the idea better.”

He was all afire with agitation—indeed, to such an extent as to astonish me, for I had set him down as rather a cool customer, and not easily perturbed. Now he continued to wax eloquent, and it made me uncomfortable. So I endeavoured to cut him short.

“All right, old chap. It isn’t worth jawing about. Only too glad I was on hand at the time. Besides, nothing at all to a fellow who can swim. I say, though, I was admiring the way the little girl was at home in the water; still, she’s small, and those beastly breakers have a devil of an undertow, you know. She oughtn’t to be allowed out like that with nobody to look after her.”

“That’s just it. But she bound me to secrecy, like she did you, for fear of not being allowed in again. I made her promise not to do it again though, as a condition of keeping dark.”

And then he went on to expatiate on Miss Iris’ swimming perfections, and indeed every other perfection, to an extent that rather prejudiced me against her if anything, as likely to prove a spoilt handful. However, it got him out of the gratitude groove, which was all I wanted just then.

That couple of days’ journey was quite one of the most delightful experiences of my life. Our way lay over beautiful rolling country dotted with flowering mimosa, and here and there intersected with a dark forest-filled kloof; and bright-winged birds flashed sheeny from our path, and on every hand the hum of busy insects made music on the warm air. Yes, it was warm; in the middle of the day very much so. But the evening was simply divine, in its hushed dewiness rich with the unfolding fragrance of innumerable subtle herbs, for we took advantage of a glorious moon to travel in the coolness. Now and again we would pass a large Kafir kraal, whose clustering beehive-shaped huts stood white in the moonlight, and thence an uproar of stamping and shouting, accompanying the rhythm of a savage song, showed that its wild denizens were holding high festivity at any rate; and the sound of the barbarous revel rising loud and clear upon the still night air, came to me with an effect that was wholly weird and imposing.

“Seems as if I had suddenly leaped outside civilisation altogether,” I remarked as we passed one of these kraals, whose inhabitants paused in their revelry to send after us a long loud halloo, partly good-humoured, partly insolent. And I gave my companion the benefit of my preconceived notions of the Kafir, whereat he laughed greatly.

“It’s funny how these notions get about, Holt,” he said. “Now you have seen a glimpse of your meek, down-trodden black—only he’s generally red—since you landed, and you can the more easily realise it when I tell you he’d cut all our throats with the greatest pleasure in life if he dared. There are enough of them to do it any night in the year; but, providentially, there’s never any cohesion among savages, and these chaps won’t trust each other, which is our salvation, for they simply swarm as to numbers. What do you say? Shall we outspan and make a night of it on the veldt? There’s an accommodation house a mile or so further on, but it’s a beastly hole, and the people none too civil.”

Of course I voted for camping, and as Brian’s forethought had provided a supply of cold meat and bread and cheese, as well as a bottle of grog, we fared (relatively) sumptuously, and thereafter the last thing I knew was my first pipe dropping out of my mouth very soon indeed after I had lighted it.

We inspanned early the next morning, and as we progressed our way became more hilly. Thick bush came down to the road in many places, and twice we forded a drift of a river, whose muddy and turbid current rose to the axles. The high broken country, copiously bush-clad, was delightful to the eye, but oh, the heat of the sun in those scorching valley bottoms, where, when we were not jolting over uneven masses of stone, were wallowing painfully through inches and inches of thick red dust. Now and then we would pass a string of transport waggons, or a traveller on horseback, and in the middle of the day we outspanned at a farm of the rougher kind. Towards evening we entered a long, wild, beautiful valley resonant with the cooing of doves and other sounds of evening peace, the bleating of homing flocks and the lowing of cattle; and as we rounded a bush-clad spur and a homestead came into view I felt no surprise that Brian Matterson should turn to me with the remark—

“Here we are at last, Holt; and there’s Beryl, on the look-out for us.”

Chapter Seven.

Beryl.

He reined up the Cape cart at the gate of a picturesque verandah-fronted house which stood against a background of wild and romantic bush scenery. Not for this, however, had I any eyes at that moment; only for the personality which was framed as it were within a profusion of white cactus blossoms which overhung the garden gate.

“Well, Beryl!” he sang out, as we got out of the trap. “Here’s an old school chum I picked up by the merest fluke down at East London. I brought him out here to see a little African life, so for the present I’ll hand him over to you. Give him a cool chair on the stoep, and a ditto drink, while I go and see to the outspanning, and to things in general. Dad still away, I suppose?”

“Yes. He’ll be back this evening, though. I’m expecting him every minute.”

“So long, then.”

Now I have already explained that I am by nature a reticent animal, and may add that I have a sneaking horror of being taken for a susceptible one. Wherefore I had refrained from questioning Brian on the way hither, as to the outward appearance or inner characteristics of his elder sister, and he, while mentioning the fact that he had another sister, who kept house for them—for their mother was long since dead—and a younger brother, had not entered into details.

But it would be idle to pretend I had not been indulging, and that mightily, in all sorts of speculation upon the subject, and that within my own mind. Would she resemble the little one to whose aid I had come—prove a grown-up replica of her? If so, she would be something to look at, I concluded. Yet, now that I beheld her, my first impression of Beryl Matterson was a strange mingling of interest and disappointment. Tall and very graceful of carriage, she stood there, with outstretched hand of welcome. The tint of the smooth skin was that of a dark woman, yet she had eyes of a rich violet blue—large, deep, thoughtful—and her abundant brown hair was drawn back in a wavy ripple from the temples.

But that her glance, so straight and scrutinising as it met mine, became melting and tender as it rested upon her brother, I should have set her down as of a cold disposition, and withal a trifle too resolute for a woman, especially for one of her age. As it was, I hardly knew what to think. She did not greatly resemble Brian, who though also tall and handsome was very dark; yet I suspected his to be the gentler disposition of the two.

“You are very welcome, Mr Holt,” she said. “How strange that Brian should have met you down there.”

“It was not only strange but providential, for I was literally a shipwrecked mariner thrown up on your shore without a dry stitch on me.”

And I told her briefly the plight I had found myself in, when Brian had come to the rescue. She listened with great interest.

“Well, I am more than ever glad he did. But what an experience! The landing one, though, I have been through myself; the bar at East London can be too terrific for words. By the way, we have a little sister staying down there now with some friends. We thought the sea-bathing would do her good, and she’s so fond of it. Did you see her, perhaps?”

“Yes. She met us outside the town to say good-bye. What a pretty child she is.”

“She is, and nicely she gets spoiled on the strength of it,” laughed Beryl, but the laugh was wholly a pleasant one, without a tinge of envy or resentment in it.

We chatted a little, and then she proposed we should stroll out and look at the garden and some tiny ostrich chicks she was trying to rear, and flinging on a large rough straw hat which was infinitely becoming, she led the way, down through an avenue of fig trees, and opened a light gate in the high quince hedge.

Then as I stood within the coolness of the garden, which covered some acreage of the side of the slope, I gained a most wonderful impression of the place that was destined to prove my home for a long time to come, and in whose joys and sorrows—yes, and impending tragedies of dark vendetta and bloodshed—I was fated to be associated. Below the house lay the sheep kraals, and already a woolly cataract was streaming into one of the thorn-protected enclosures, while another awaited its turn at a little distance off. The cattle kraal, too, was alive with dappled hides, and one unintermittent “moo” of restless and hungry calves, while a blue curling smoke reek from the huts of the Kafir farm servants rose upon the still evening atmosphere. What is there about that marvellous African sunset glow? I have seen it many a time since, under far different conditions—under the steamy heat of the lower Zambesi region, and amid piercing cold with many degrees of frost on the high Karoo; in the light dry air of the Kalahari, and in the languorous, semi-tropical richness of beautiful Natal; but never quite as I saw it that evening, standing beside Beryl Matterson. It was as a scene cut out of Eden, that wondrous changing glow which rested upon the whole valley, playing upon the rolling sea of foliage like the sweep of golden waves, striking the iron face of a noble cliff with a glint of bronze, then dying, to leave a pearly atmosphere redolent of distilling aromatic herbs, tuneful with the cooing of myriad doves and the whistle of plover and the hum of strange winged insects coming forth on their nightly quests.

“Let’s see. How long is it since you and Brian saw each other last, Mr Holt?” said my companion as we strolled between high quince hedges.

“Why, it must have been quite twelve years, rather over than under. And most of the time has not been good, as far as I was concerned. The financial crash that forced me to leave school when I did, kept me for years in a state of sedentary drudgery for a pittance. Something was saved out of the wreck at last, but by that time I had grown ‘groovy’ and fought shy of launching out into anything that involved risk. I preferred to keep my poor little one talent in a napkin, to the possibility of losing it in the process of turning it into two.”

She looked interested as she listened. The face which I had thought hard grew soft, sympathetic, and wholly alluring.

“There’s a good deal in that,” she laughed. “I must say I have often thought the poor one-talent man was rather hardly used. By the way, when Brian was sent to England to school it was with the idea of making a lawyer or a doctor of him, but he would come back to the farm. It was rather a sore point with our father for quite a long time after, but now he recognises that it is all for the best. My father is not what the insurance people call a ‘good’ life, Mr Holt.”

“I’m very sorry to hear that. What is wrong? Heart?”

“Yes. But I am boring you with all these family details, but having been Brian’s school chum seems to make you almost as one of ourselves.”

“Pray rid yourself of the impression that you are boring me, Miss Matterson—on the contrary, I am flattered. But I must not obtain your good opinion under false pretences. The fact is, Brian and I were not exactly school chums. There was too much difference between our ages—at that time, of course; which makes it all the more friendly and kind of him to have brought me here now.”

“Oh, that doesn’t make any difference. If you weren’t chums then you will be now, so it’s all the same.”

Then we talked about other things, and to my inquiries relating to this new land—new to me, that is—Beryl gave ready reply.

“You will have to return the favour, Mr Holt,” she said with a smile. “There are many things I shall ask you about by-and-by. After all, this sort of life is a good deal outside the world, and I have never been to England, you know. I am only a raw Colonial.”