Bertram Mitford

"The Induna's Wife"

Prologue.

Twilight was fast closing in upon the desolate site of the old Kambúla Camp, and the short, sharp thunderstorm which at the moment of outspanning had effectually drenched the scant supply of fuel, rendering that evening’s repast, of necessity, cold commons, had left in its wake a thin but steady downpour. Already the line of low hills hard by was indistinct in the growing gloom, and a far-reaching expanse of cold and treeless plains made up a surrounding as mournful and depressing as could be.

The waggon stood outspanned in the tall grass, which, waist high, was about as pleasant to stand in as the drift of a river. Just above, the conical ridge, once crested with fort and waggon laagers, and swarming with busy life, and the stir and hum of troops on hard active service, now desolate and abandoned—the site, indeed, still discernible if only by ancient tins, and much fragmentary residue of the ubiquitous British bottle. Below, several dark patches in the grass marked the resting-place of hundreds of Zulu dead—fiery, intrepid warriors—mown down in foil and sweeping rush, with lips still framing the war cry of their king, fierce resolute hands still gripping the deadly charging spear. Now a silent and spectral peace rested upon this erewhile scene of fierce and furious war, a peace that in the gathering gloom had in it something that was weird, boding, oppressive. Even my natives, usually prone to laughter and cheery spirits, seemed subdued, as though loth to pass the night upon this actual site of vast and tolerably recent bloodshed; and the waggon leader, a smart but unimaginative lad, showed a suspicious alacrity in driving back the span from drinking at the adjacent water-hole. Yes! It is going to be a detestable night.

Hard biscuit and canned jam are but a poor substitute for fizzling rashers and wheaten cakes, white as snow within and hot from the gridiron; yet there is a worse one, and that is no biscuit at all. Moreover, there is plenty of whisky, and with that and a pipe I proceed to make myself as snug as may be within the waggon, which is not saying much, for the tent leaks abominably. But life in the Veldt accustoms one to such little inconveniences, and soon, although the night is yet young—has hardly begun, in fact—I find myself nodding, and becoming rapidly and blissfully oblivious to cold splashes dropping incontinently from new and unexpected quarters.

The oxen are not yet made fast to the disselboom for the night, and one of my natives is away to collect them. The others, rolled in their blankets beneath the waggon, are becoming more and more drowsy in the hum of their conversation. Suddenly this becomes wide-awake and alert. They are sitting up, and are, I gather from their remarks, listening to the approach of something or somebody. Who—what is it? There are no wild animals to reckon with in that part of the country, save for a stray leopard or so, and Zulus have a wholesome shrinking from moving abroad at night, let alone on such a night as this. Yet on peering forth, a few seconds reveal the approach of somebody. A tall form starts out of the darkness and the long wet grass, and from it the deep bass tones of the familiar Zulu greeting: “Nkose!”

Stay! Can it be? I ought indeed to know that voice; yet what does its owner here thus and at such an hour? This last, however, is its said owner’s business exclusively.

“Greeting, Untúswa! Welcome, old friend,” I answered. “Here is no fire to sit by, but the inside of the waggon is fairly dry; at any rate not so wet as outside. And there is a dry blanket or two and a measure of strong tywala to restore warmth, likewise snuff in abundance. So climb up here, winner of the King’s Assegai, holder of the White Shield, and make thyself snug, for the night is vile.”

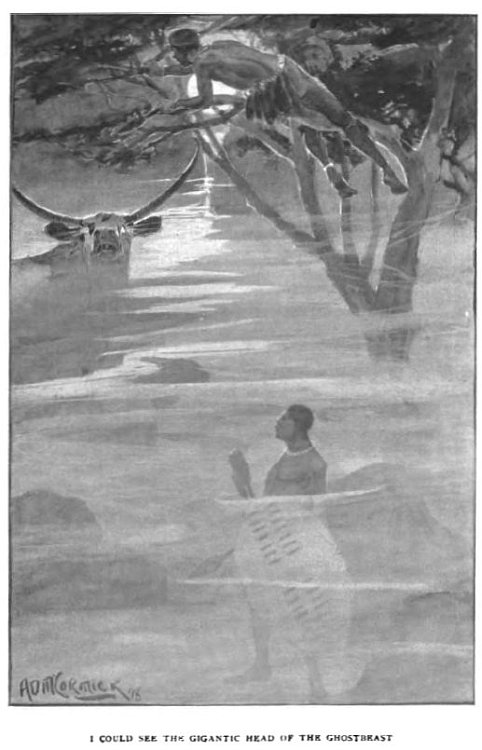

Now, as this fine old warrior was in the act of climbing up into the waggon, there came a sound of trampling and the clash of horns, causing him to turn his head. The waggon leader, having collected the span, was bringing it in to attach to the yokes for the night, for it promised soon to be pitch dark, and now the heads of the oxen looked spectral in the mist. One especially, a great black one, with wide branching horns rising above the fast gathering sea of vapour, seemed to float upon the latter—a vast head without a trunk. The sight drew from Untúswa a shake of the head and a few quick muttered words of wonderment. That was all then, but when snug out of the drizzling rain, warmed by a measure of whisky, and squatting happy and comfortable in a dry blanket, snuff-box in hand, he began a story, and I—well, I thought I was in luck’s way, for a wet and cheerless and lonely evening stood to lose all its depression and discomfort if spent in listening to one of old Untúswa’s stories.

Chapter One.

The Tale of the Red Death.

There was that about the look of your oxen just now, Nkose—shadowed like black ghosts against the mist—that brought back to my old mind a strange and wonderful time. And the night is yet young. Nor will that tale take very long in telling, unless—ah, that tale is but the door opening into a still greater one; but of that we shall see—yes, we shall see.

I have already unfolded to you, Nkose, all that befell at the Place of the Three Rifts, and how at that place we met in fierce battle and rolled back the might of Dingane and thus saved the Amandebeli as a nation. Also have I told the tale of how I gained the White Shield by saving the life of a king, and how it in turn saved the life of a nation. Further have I told how I took for principal wife Lalusini, the sorceress, in whose veins ran the full blood of the House of Senzangakona, the royal House of Zululand, and whom I had first found making strange and powerful múti among the Bakoni, that disobedient people whom we stamped flat.

For long after these events there was peace in our land. The arm of Dingane was stretched out against us no more, and Umzilikazi, our king, who had meditated moving farther northward, had decided to sit still in the great kraal, Kwa’zingwenya, yet a little longer. But though we had peace from our more powerful enemies, the King would not suffer the might of our nation to grow soft and weak for lack of practice in the arts of war—oh, no. The enrolling of warriors was kept up with unabated vigour, and the young men thus armed were despatched at once to try their strength upon tribes within striking distance, and even far beyond the limits of the same. Many of these were mountain tribes, small in numbers, but brave and fierce, and gave our fiery youths just as much fighting as they could manage ere wetting their victorious spears in blood.

Now, although we had peace from our more formidable foes, yet the mind of the King seemed not much easier on that account, for all fears as to disturbance from without being removed, it seemed that Umzilikazi was not wholly free from dread of conspiracy within. And, indeed, I have observed that it is ever so, Nkose. When the greater troubles which beset a man, and which he did not create, beset him no longer, does he not at once look around to see what troubles he can create for himself? Whau! I am old. I have seen.

So it was with Umzilikazi. The fear of Dingane removed, the recollection of the conspiracy of Tyuyumane and the others returned—that conspiracy to hand over our new nation to the invading Amabuna—that conspiracy which so nearly succeeded, and, indeed, would have completely, but for the watchfulness and craft of the old Mosutu witch doctor. Wherefore, with this suspicion ever in the King’s mind we, izinduna, seemed to have fallen upon uneasy times. Yet the principal object of dislike and distrust to the Great Great One was not, in the first place, one of ourselves. No councillor or fighting man was it, but a woman—and that woman Lalusini, my principal wife.

“Ha, Untúswa!” would the King say, talking dark, but his tone full of gloomy meaning. “Ha, Untúswa, but thine amahlose (Tutelary spirits) watch over thee well. Tell me, now, where is there a man the might of whose spear and the terror of whose name sweeps the world—whose slumbers are lulled by the magic of the mighty, and who is greater even than kings? Tell me, Untúswa, where is such a man?”

“I think such is to be found not far hence, Great Great One. Even in this house,” I answered easily, yet with a sinking fear of evil at heart, for his words were plain in their meaning; my successes in war surpassed by none; my beautiful wife, the great sorceress of the Bakoni, the wandering daughter of Tshaka the Terrible. And his tone—ah, that, too, spoke.

“Even in this house! Yeh bo! Untúswa—thou sayest well,” went on the King softly, his head on one side, and peering at me with an expression that boded no good. “Even in this house! Ha! Name him, Untúswa. Name him.”

“Who am I that I should sport with the majesty of the King’s name?” I answered. “Is not the son of Matyobane—the Founder of Mighty Nations—the Elephant of the Amandebeli—such a man? Doth not his spear rule the world, and the terror of his name—au!—who would hear it and laugh? And is not the bearer of that name greater than other kings—greater even than the mighty one of the root of Senzangakona—whose might has fled before the brightness of the great king’s head-ring? And again, who sleeps within the shadow of powerful and propitious magic but the Father and Founder of this great nation?”

“Very good, Untúswa. Very good. Yet it may be that the man of whom I was speaking is no king at all—great, but no king.”

“No king at all! Hau! I know not such a man, Father of the World,” I answered readily. “There is but one who is great, and that is the King. All others are small—small indeed.”

I know not how much further this talk would have gone, Nkose; and indeed of it I, for my part, was beginning to have more than enough. For, ever now, when Umzilikazi summoned me to talk over matters of state, would he soon lead the conversation into such channels; and, indeed, I saw traps and pitfalls beneath every word. But now the voice of an inceku—or household attendant—was heard without singing the words of sibonga, and by the way in which he praised we knew he desired to announce news of importance. At a sign from the King I admitted the man.

“There are men without, O Divider of the Sun,” he began—when he had made prostration—“men from the kraals of Maqandi-ka-Mahlu, who beg the protection of the King’s wise ones. The Red Magic has been among them again.”

“Ha! The Red Magic!” said Umzilikazi, with a frown. “It seems I have heard enough of such childish tales. Yet, let the dogs enter and whine out their own story.”

Through the door of the royal dwelling, creeping on hands and knees, came two men. They were not of our blood, but of a number whom the King had spared, with their wives and children, and had located in a region some three days to the northward as far as a swift walker could travel. It was a wild and mountainous land—a land of black cliffs and thunderous waterfalls—cold, and sunless, and frowning—a meet abode of ghosts and all evil things. Here they had been located, and, being skilled in ironwork, were employed in forging spear-heads and axes for our nation. They were in charge of Maqandi-ka-Mahlu—a man of our race, and a chief—and who, having been “smelt out” by our witch doctors, the King had spared—yet had banished in disgrace to rule over these iron-workers in the region of ghosts and of gloom.

Their tale now was this: The stuff which they dug from the bowels of the earth to make the metal for our spears and axes was mostly procured in a long, deep, gloomy valley, running right up into the heart of the mountains. Here they bored holes and caves for digging the stuff. But, for some time past, they had not been able to go there—for the place had become a haunt of tagati. A terrible ghost had taken up its abode in the caves, and did a man wander but the shortest space of time from his fellows, that man was never again seen.

He was seen, though, but not alive. His body was found weltering in blood, and ripped, not as with a spear, but as though by the horn of a fierce and furious bull. This had befallen several times, and had duly been reported to the King—who would know everything—but Umzilikazi only laughed, saying that he cared nothing that the spirits of evil chose to devour, from time to time, such miserable prey as these slaves. There were plenty more of them, and if the wizard animals, who dwelt in the mountains, wanted to slay such, why, let them.

But now, the tale which these men told was serious. They could no more go to that place for the terror which haunted it. They had tried keeping together, so that none might fall a prey to the evil monster—and, for some while, none had. But there came a day when travelling thus, in a body close together, through the gloom of the forest, a sudden and frightful roaring, as of the advance of a herd of savage bulls, burst upon them. Some fell, half dead with fear; others, crying out that they could see fearful shapes, with gigantic horns and flaming eyes, moving among the trees, rushed blindly in all directions. Of thirty men who had entered that dreadful valley, ten only came forth, nor of these could any be persuaded to return and see what had happened to the remaining score. But the seer, Gasitye, who knew no terror of things of the other world, had ventured in. Twenty bodies had he seen—lying scattered—no two together—no, not anywhere two together—and all had died the Red Death.

“And was this by day or by night?” said the King, who had been listening with great attention to this tale.

“By day, O Ruler of the World. While yet the sun was straight overhead,” replied the men.

“Well, I care not,” said Umzilikazi, with a sneer. “Go back now and cause your seer, Gasitye, to charm away that tagati, and that soon, lest I visit him and you with the fate of those who make witchcraft. Shall we keep a dog who cannot guard our house? For to what other use can we turn such a dog? Begone.”

There was despair upon the faces of the two messengers as the meaning of these words became plain to them—and in truth were they between two perils, even as one who travels, and, being beset by a great fire, fleeth before it, only to find himself stopped by a mighty and raging river, whose flood he cannot hope to cross. Yet the man who had spoken, instead of immediate obedience, ventured further to urge his prayer with the intrepidity and hopeless courage of such despair.

“Who are we that we should weary the ears of the Father of the Great?” he went on. “Yet, even a dog cannot entirely guard a house if he is but a small dog, and they who would enter are many and strong. He can but give warning of their approach—and this is what we have done. But the King’s magicians are many and powerful, and ours are weak. Besides, O Black Elephant, how shall metal be procured for the spears of the Great Great One’s warriors, when the place where it is procured is guarded by the horns of the ghost-bulls, who slay all who go in?”

Now, I thought those slaves must indeed have touched the lowest depth of despair and terror, that they dared to use such speech to the King. And upon the countenance of Umzilikazi came that look which was wont to mean that somebody would never behold another sun to rise.

“Enough!” he said, pointing at the two messengers with his short-handled spear. “Return ye hence. For the rest of you—hearken now, Untúswa. Send one half of thy regiment of ‘Scorpions’ under an experienced captain, that they may drive the whole of the people of Maqandi within this Ghost-Valley. Then let them draw a line across the month thereof, and slay every one who shall attempt to escape. So shall the people of Maqandi either slay this ghost or be slain by it. I care not which. Go?”

I rose to carry out the King’s orders, and upon the faces of the grovelling messengers was an awful expression of set, hopeless despair. But, before I could creep through the low doorway, a sign from Umzilikazi caused me to halt. At the same time, a frightful hubbub arose from without—the hubbub of a volume of deep, excited voices—mingled with a wild bellowing, which was enough to make a man deaf.

“I think these ghost-bulls are upon us, too,” said the King, with an angry sneer. “Look forth, Untúswa, and see whether all the world has gone mad.”

Quickly I gained the gate in the woven fence which surrounded the isigodhlo. From far and near people were flocking, while the great open space within the kraal was becoming more and more densely packed; and, making their way through the blackness of the crowd, which parted eagerly to give them passage, came a weird and hideous throng, decked with horrid devices of teeth and claws and the skulls of beasts, their bodies hung with clusters of bleeding entrails and all the fooleries which our izanusi hang about themselves to strike terror into the fearful. These, leaping and bounding in the air, rushed forward till it seemed they were about to bear me down and pour into the isigodhlo itself. But they halted—halted almost in the very gate—and redoubled their bellowings, howling about the Valley of the Red Death and the woe which should come upon our nation. And all the people, their faces turned earthward, howled in response. Looking upon this, I bethought me that there seemed truth in the King’s words, and that all the world had indeed gone mad. Making a sign to the izanusi to desist their howlings—a sign, however, which they did not obey—I returned to the royal presence to report what I had seen.

“Send my guard, Untúswa, to beat back this mob,” said the King. “This must be looked into. As for these”—pointing to the messengers—“custody them forth, for it may be I have further use for them.”

Quickly I went out to issue my orders, and hardly had I done so, than the King himself came forward, and making a sign to myself and two or three other izinduna to attend him, sat himself down at the head of the open space. The while the roars of bonga which greeted his appearance mingled with the howling of the gang of witch doctors and the shouting and blows of the royal guard, beating back the excited crowd with their sticks and shields. In very truth, Nkose, it seemed as though the whole nation were gathered there.

Suddenly a silence fell upon the multitude, and even the bellowing of the izanusi was stayed, as there came through the throng, creeping upon their hands and knees, nearly a score of men. Their leader was a fine and well-built warrior of middle age, whom I knew as a fierce and fearless fighter, and they had returned from “eating up” the kraal of one of the subject tribes in accordance with the King’s mandate. Now the leader reported having carried out his orders fully. The evil-doers were destroyed, their houses burnt, and their cattle swept off as forfeit to the King.

“It is well,” said Umzilikazi. “Yet not for that ye have obeyed your orders has the whole nation gone mad.”

“There is more to tell, Great Great One,” answered the warrior, upon whose countenance, and upon the countenances of his band, I could descry signs of dread. “In returning we had to pass through the land of Maqandi. Two of us fell to the Red Death.”

“To the Red Death?” repeated the King, speaking softly and pleasantly. “Ha! How and where was that, Hlatusa?”

Then the leader explained how he had allowed two of his followers to wander into the Ghost Valley in pursuit of a buck they had wounded. They had not returned, and when sought for had been found lying some little distance apart, each terribly ripped and covered with blood, as though they had been rolled in it.

“So?” said the King, who had been listening attentively with his head on one side. “So, Hlatusa? And what did you do next, Hlatusa?”

“This, Black Elephant,” answered the man. “Every corner of that tagati place did we search, but found in it no living thing that could have done this—ghost or other. In every cave and hole we penetrated, but nothing could we find, Father of the Wise.”

“In this instance, Father of the Fools,” sneered Umzilikazi, a black and terrible look taking the place of the pleasant and smiling expression his face had hitherto worn. “Yet, stay. What else did you find there? No sign, perchance?”

“There was a sign, Divider of the Sun,” replied Hlatusa, who now considered himself, and they that were with him, already dead. “There was a sign. The hoof-mark as of a huge bull was imprinted in the ground beside the bodies.”

“And wherefore did ye not rout out that bull and return hither with his head, O useless ones?” said the King.

“No bull was it, but a ghost, Great Great One,” replied the leader. And they who had been with him murmured strongly in support of his words.

“Now have I heard enough,” said Umzilikazi. “You, Hlatusa, you I send forth at the head of twenty men, and you return, having lost two—not on the spears of a fighting enemy, but in strange fashion. And no one do ye hold accountable for this, but return with a child-tale about ghosts and the hoof-mark of a ghost-bull. Hamba gahle, Hlatusa. The alligators are hungry. Take him hence!”

With these fatal words the throng of slayers sprang forward to seize him. But Hlatusa waited not to be seized. Rising, he saluted the King; then turning, he stalked solemnly and with dignity to his doom—down through the serried ranks of the people, down through the further gate of the kraal, away over the plain, keeping but two paces in front of his guards. A dead silence fell upon all, and every face was turned his way. We saw him stand for a moment on the brow of the cliff which overhung the Pool of the Alligators, wherein evil-doers were cast. Then we saw him leap; and in the dead silence it seemed we could hear the splash—the snapping of jaws and the rush through the water of those horrible monsters, now ever ravening for the flesh of men.

Chapter Two.

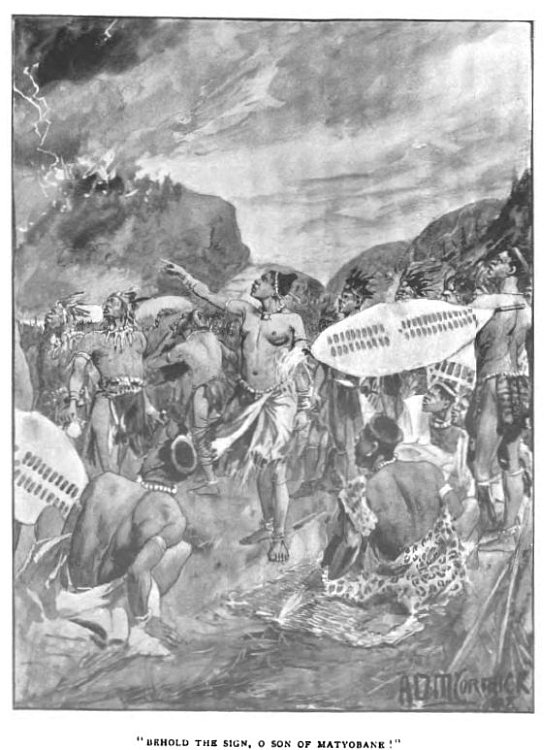

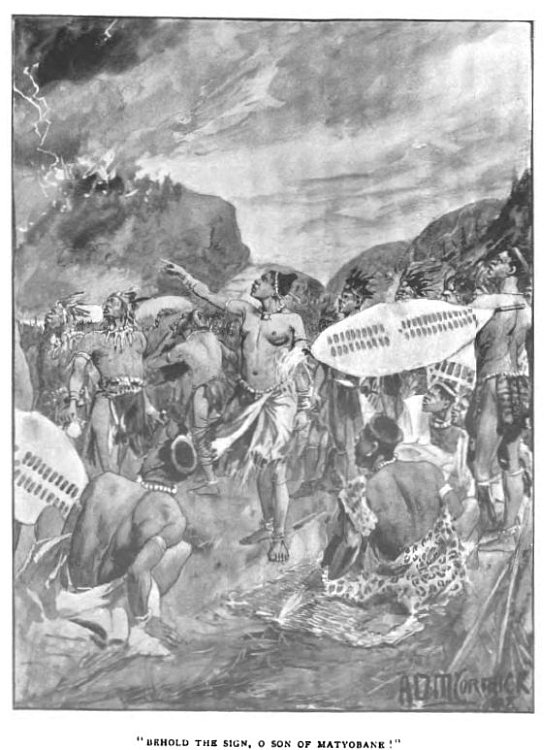

“Behold the Sign!”

The silence was broken by a long, muttering roll of thunder. Masses of dark cloud were lying low down on the further sky, but overhead the sun darted his beams upon us in all the brightness of his mid-day fierceness, causing the great white shield held above the King to shine like polished metal. To many of us it seemed that the thunder-voice, coming as it did, was an omen. The wizard spell of the Red Death seemed to lie heavy upon us; and now that two of ourselves had fallen to its unseen terror, men feared, wondering lest it should stalk through the land, laying low the very pick and flower of the nation. Murmurs—deep, threatening, ominous—rose among the dense masses of the crowd. The King had decreed one victim, the people demanded another; for such was the shape which now those murmurs took.

Umzilikazi sat in gloomy silence. He liked not the sacrifice of good and brave fighting men, and the thing that had happened had thrown him into a dark mood indeed. Not until the murmurs became loud and deafening did he seem to notice them. Then the izanusi, deeming that their moment had come, took up the tale. Shaking their hideous ornaments and trappings, they came howling before the King; calling out that such dark witchcraft was within the nation as could not fail to destroy it. But upon these the Great Great One gazed with moody eyes, giving no sign of having heard them; and I, watching, wondered, for I knew not what was going to follow. Suddenly the King looked up.

“Enough of your bellowings, ye snakes, ye wizard cheats!” he thundered. “I have a mind to send ye all into this Ghost Valley, to slay the thing or be slain by it. Say; why are ye not ridding me of this evil thing which has crept into the nation?”

“That is to be done, Ruler of the World!” cried the chief of the izanusi. “That is to be done; but the evil-doer is great—great!”

“The evil-doer is great—great!” howled the others, in response.

“Find him, then, jackals, impostors!” roared the King. “Whau! Since old Masuka passed into the spirit-land never an izanusi have we known. Only a crowd of bellowing jackal-faced impostors.”

For, Nkose, old Masuka was dead. He had died at a great age, and had been buried with sacrifices of cattle as though one of our greatest chiefs. In him, too, I had lost a friend, but of that have I more to tell.

Now some of the izanusi dived in among the crowd and returned dragging along several men. These crawled up until near the King, and lay trembling, their eyes starting from their heads with fear. And now, for the first time, a strange and boding feeling came over me, as I recognised in these some of the Bakoni, who had been at a distance when we stamped flat that disobedient race, and had since been spared and allowed to live among us as servants.

“Well, dogs! What have ye to say?” quoth the King. “Speak, and that quickly, for my patience today is short.”

Whau! Nkose! They did speak, indeed, those dogs. They told how the Red Death was no new thing—at least to them—for periodically it was wont to make its appearance among the Bakoni. When it did so, it presaged the succession of a new chief; indeed, just such a manifestation had preluded the accession to the supreme chieftainship of Tauane, whom we had burned amid the ashes of his own town. The Red Death was among the darker mysteries of the Bakoni múti.

Not all at once did this tale come out, Nkose, but bit by bit, and then only when the Great Great One had threatened them with the alligators—even the stake of impalement—if they kept back aught. And I—I listening—Hau! My blood seemed first to freeze, then to boil within me, as I saw through the ending of that tale. The darker mysteries of the Bakoni múti!—preluding the accession of a new king? The countenance of the Great Great One grew black as night.

“It is enough,” he said. “Here among us, at any rate, is one to whom such mysteries are not unknown. The Queen of the Bakoni múti—who shall explain them better than she?”

The words, taken up by the izanusi and bellowed aloud, soon went rolling in chorus among the densely-packed multitude, and from every mouth went up shouts for Lalusini—the Queen of the Bakoni múti. Then, Nkose, the whole plot burst in upon my mind. Our witch doctors had always hated my inkosikazi, because she was greater than they; even as they had always hated me, because I had old Masuka on my side, and was high in the King’s favour, and therefore cared nothing about them, never making them gifts. Now their chance had come, since old Masuka was dead and could befriend me no more, and my favour in the King’s sight was waning. Moreover, they had long suspected that of Lalusini the Great Great One would fain be rid; yet not against her had they dared to venture upon the “smelling out” in the usual way, lest she proved too clever for them; for the chief of the izanusi had a lively recollection of the fate of Notalwa and Isilwana, his predecessors. Wherefore they had carefully and craftily laid their plot, using for the purpose the meanest of the conquered peoples whose very existence we had by that time forgotten.

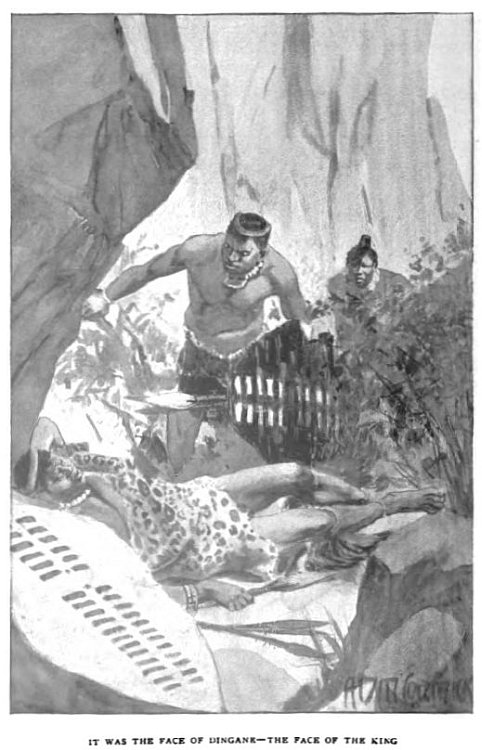

Now the shouts for Lalusini were deafening, and should have reached my kraal, which, from where I sat, I could just see away against the hillside. But the shouters had not long to shout, for again a way was opened up, and through it there advanced she whom they sought.

No dread or misgiving was on the face of my beautiful wife, as she advanced with a step majestic and stately as became her royal blood. She drew near to the King, then halted, and, with hand upraised, uttered the “Bayéte” for no prostration or humbler mode of address was Umzilikazi wont to exact from her, the daughter of Tshaka the Terrible, by reason of her mighty birth. Thus she stood before the King, her head slightly thrown back, a smile of entire fearlessness shining from her large and lustrous eyes.

“Greeting, Daughter of the Great,” said Umzilikazi, speaking softly. “Hear you what these say?”

“I have heard them, son of Matyobane,” she answered.

“Ha! Yet they spoke low, and thou wert yet afar off,” went on the King craftily.

“What is that to me, Founder of a New Nation? Did I not hear the quiver of the spear-hafts of Mhlangana’s host long before it reached the Place of the Three Rifts?”

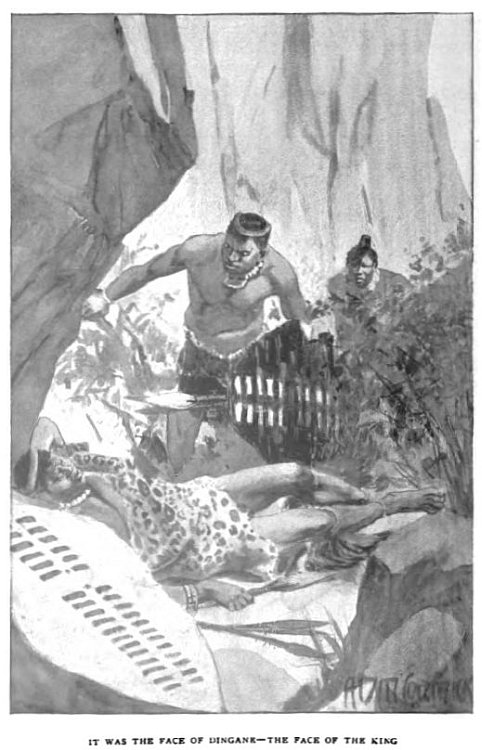

“The Place of the Three Rifts,” growled the King. “Hau! It seems to me we have heard overmuch of that tale. Here, however, is a new tale, not an old one. What of the Red Death? Do these dogs lie?” pointing to the grovelling Bakoni.

Lalusini glanced at them for a moment—the deepest scorn and disgust upon her royal features—the disgust felt by a real magician for those who would betray the mysteries of their nation’s magic, and I, gazing, felt I would rather encounter the most deadly frown that ever rested on the face of the King himself than meet such a look upon that of my inkosikazi, if directed against myself.

“They lie, Great Great One,” she answered shortly.

Then the King turned such a deadly look upon the crouching slaves that these cried aloud in their fear. They vociferated that they were telling the truth, and more—that they themselves had witnessed the operations of the Red Death among their own people; that Lalusini herself and her mother, Laliwa, had actually brought about the destruction of Tauane’s predecessor by its means, and that that of Tauane himself had been decreed—that it always meant the accession of a new ruler.

Now I, sitting near Umzilikazi, knew well what was passing in his mind. As he grew older he had become more and more sour and suspicious. Now he was thinking that he himself was destined to die in blood, even as that Great One, Tshaka, had died, that I, his second fighting induna, his favourite war-councillor, should succeed him, and so win back not only the seat of Matyobane, but the throne of Senzangakona for this sorceress—this splendid daughter of Tshaka the Terrible. So, too, would the death of Tshaka be avenged. And in Umzilikazi’s look I could read my own doom, and yet, Nkose, even at that moment not of myself did I think. I had only eyes for the tall, shapely form of my beautiful wife thus put upon her trial before the King and the whole nation. Then Umzilikazi spoke.

“It seems we have spared too many slaves of this race of Abatagati. Take these hence,” pointing to the grovelling Bakoni. “The alligators are hungry.”

There was a roar of delight from all who heard. The slayers flung themselves upon the shrieking slaves, dragging them away by the heels as they rolled upon the ground imploring mercy, for they were too sick with terror to stand upon their legs. Shouts of hate and wrath followed them as they were hurried away to the pool of death. Indeed, such a rain of blows and kicks fell upon them from those through whose midst they were dragged that it seemed doubtful whether most of them would ever reach the alligators alive. For, Nkose, although in dead silence and pitied by all, Hlatusa had gone through these same people to his doom, he was one of ourselves, and a brave fighter; but these were of an inferior and conquered race, and withal miserable cowards, wherefore our people could not restrain their hatred and contempt.

“Hold!” roared the King, before the slayers had quite dragged these dogs outside the kraal, and at his voice again silence fell upon the throng. “Hold! After feeding upon the flesh of a brave man I will not that my alligators be poisoned with such carrion as this. There may yet be more royal meat for them,” he put in, in a lower tone, and with a savage and deadly sneer. Then, raising his voice, “Let these dogs be taken up to yonder hill and burnt.”

A roar of delight broke from all, mingled with shouts of bonga as to the King’s justice and wisdom. And none were more pleased, I thought, than the slayers, men of fierce and savage mind, who, from constantly meting out torture and death, loved their occupation the more the farther they pursued it.

For awhile there was silence. Away upon a round-topped hillock, within sight of all, the slayers were collecting great piles of dry wood, and upon these the condemned slaves were flung, bound. Then amid the fierce roar and crackle of the flames wild tortured shrieks burst from those who writhed there and burned, and to the people the shrieks were the pleasantest of sounds, for the terror of the Red Death had strangely fastened upon all minds, and they could not but hold that these who thus died had in some way brought the curse of it upon them.

Again upon the stillness arose a long roll of thunder—this time loud and near, for the great cloud which had been lying low down upon the further sky was now towering huge and black, almost above the very spot where burned those wretches, and the pointed flash which followed seemed to dart in and out of the smoke which rose from the crackling wood pile. The multitude, watching, began to murmur about an omen.

“Talk we now of this thing of evil,” said Umzilikazi, at last. “Thou, Lalusini, art a pestilent witch. For long hast thou been among us. For long has thy greatness been honoured, thou false prophetess, whose promise is as far from fulfilment as ever. Now thou shalt travel the way of those whose predictions are false.”

Black and bitter wrath was in the King’s mind. Hardly could he contain himself, hardly could he speak for rage. He must stop perforce, half choking for breath. And I, Nkose, I sitting there, how did I contain myself, as I was obliged to behold my beautiful wife—whom I loved with a love far surpassing that which I felt for King and nation, or my own life a hundred times over—standing thus awaiting the word which should adjudge her to a shameful and agonising death! Hau! I am an old man now—a very old man—still can I see it before me; the huge kraal like a full moon, the yellow domes of the huts within the ring fences, the great open space in the middle black with listening people, bright with distended eyeballs, and gleaming teeth showing white between parted lips, and away beyond this the heavy smoke-wreath mounting from the glowing wood-pile, the cries and groans of the expiring slaves, the blackness of the thunder cloud, the fierce pale glare of the sun upon the assegais of the armed guard, and upon the blaze of white of the great shield held above the King. Yeh-bo—I see it all—the angry infuriated countenance of Umzilikazi, the dread anxiety on the faces of the other izinduna, which was as the shrinking before a great and terrible storm about to burst. Haul and I see more. I see, as I saw it then, the face of my beautiful wife, Lalusini, Daughter of the Mighty—as she stood there before the Great One, in whose hand was death—proud, fearless, and queenly. And she was awaiting her doom.

Now she threw back her head, and in her eyes shone the light which must oft-times have shone in the eyes of that Mighty One from whom she had sprung. Then she spoke:

“In the hand of the King is death, and even the greatest of those who practise sorcery cannot withstand such—at least not always. But know this, son of Matyo-bane, with my death shall utterly perish all hope of the seat of Senzangakona to thee and thine. Further, know that, without my help, the very House of Matyobane shall in two generations be rooted up and utterly destroyed, scattered to the winds, and the people of the Amandebeli shall become even as Amaholi to those who are stronger.”

Those who heard these words murmured in awe, for over Lalusini’s face had come that inspired look which it wore when the spirit of divination was on her. But the King was beside himself with fury, and his features were working as those of a man who has gone mad.

“So!” he hissed. “So! And I sit in my seat only by permission of a witch—by permission of one who is greater than I! So I am no longer a King!” he mocked. “Yet two bulls cannot rule in one kraal. So, sister, thou shalt have a high throne to rule this nation from—as high a throne as had the traitor Tyuyumane before thee.” Then raising his voice—for they had hitherto talked in a tone low enough to be heard only by the King and the few who sat in attendance round him—“Make ready the stake—the stake of impalement—for the inkosikazi of Untúswa. Make ready a high throne for the Queen of the Bakoni múti.”

Whau, Nkose! I had fought at the side of Umzilikazi ever since I could fight. I had stood beside him when, single-handed, we hunted fierce and dangerous game. I had stood beside him in every peril, open or secret, that could beset the path of the founder of a great and warrior nation, who must ever rule that nation with a strong and iron hand. In short, there was no peril to which the King had been exposed that I had not shared, and yet, Nkose, I who sat there among the izinduna, unarmed and listening, knew that never, since the day of his birth, had he gone in such peril of instant death as at that moment when he sat there, his own broad spear in his right hand, and guarded by the shields and gleaming assegais of his body-guard—pronouncing the words which should consign my inkosikazi to a death of shame and of frightful agony. For the spell of Lalusini’s witchcraft lay potent and sweet upon my soul—and I was mad—yet not so mad but that as I sat there unarmed, I could measure the few paces that intervened between myself and the Great Great One—could mark how carelessly he held the broad-bladed spear within his grasp.

Even the slayers—for not all had gone forth to the burning of the Bakoni—even the slayers stared as though half stupefied, hesitating to lay hands upon that queenly form, standing there erect and unutterably majestic. Upon us the spell of the moment was complete. We leaned forward as we sat, we izinduna, and for the rest of us it was as though stone figures sat there watching, not living men of flesh and bones. For myself, I know not how I looked. But how I felt—ah! it was well my thoughts were buried. The armed guards, too, seemed bewildered with awe and amazement. The moment had come. The Red Death had indeed presaged the accession of a new King—but for the daughter of Tshaka the Mighty, the swift and merciful stroke of a royal spear should end her life, instead of the stake of agony and shame. For myself I cared not. I was mad. The whole world was whizzing round.

Through it all I heard the voice of Lalusini.

“Pause a moment, Ruler of the Great,” she was saying, and her voice was firm and sweet and musical as ever, and utterly without fear. “Pause a moment for a sign.”

She had half turned, and with one hand was pointing towards the ascending smoke-cloud towering above the hill of death. A sharp, crashing peal of thunder shook the world, and the lightning-gleam seemed to flash down right upon the smouldering pile. A silence was upon all as, with upturned faces, King, izinduna, guards, slayers, the whole multitude sat motionless, waiting for what should next befall. Not long had we to wait.

Lalusini stood, her eyes turned skyward, her hand outstretched, her lips moving. To many minds there came the recollection of her as she had thus stood, long ago, singing the Song of the Shield—that glorious war-song which had inspired each of our warriors with the daring of ten, which had saved the day to us at the Place of the Three Rifts. Then there came such a deafening crash that the very earth rocked and reeled; and from the rent thunder cloud a jagged stream of fire poured itself down upon the remainder of the burning wood, scattering logs, sparks, cinders, and the bones of the tortured slaves, whirling them in a mighty shower far and wide over the plain. Those of the slayers who still lingered around the spot lay as dead men.

“Behold the sign, O son of Matyobane!” cried Lalusini, in clear, ringing tones, turning again to the King. “Yonder are the dogs who lied against me. The heavens above would not suffer their very bones to rest, but have scattered them far and wide over the face of the world. No others have met with harm.”

Now all began to cry aloud that indeed it was so; and from the multitude a great murmur of wonderment went up. For then those of our men who had been struck down were seen to rise and walk slowly down towards the kraal—stupified, but alive and unharmed. Then I, who could no longer sit still, came before the King.

“A boon, Great Great One,” I cried. “Suffer me to go and root out this mystery of the Red Death, and slay for ever this evil thing that causeth it; I alone. So shall it trouble the land no more.”

A hum of applause rose from among my fellow izinduna, who joined with me in praying that my undertaking be allowed.

“Ever fearless, Untúswa,” said the King, half sneering; yet I could see that the wrathful mood was fast leaving him. “Yet thou art half a magician thyself, and this thing seems a thing of fearful and evil witchcraft. But hear me. Thou shalt proceed to the Valley of the Red Death, but with no armed force; and before this moon is full thou shalt slay this horror, that its evil deeds may be wrought no more. If success is thine, it shall be well with thee and thine; if failure, thou and thy house shall become food for the alligators; and as for thine inkosikazi, the stake which she has for the time being escaped shall still await her. I have said it, and my word stands. Now let the people go home.”

With these words Umzilikazi rose and retired within the isigodhlo, and, as the rain began to fall in cold torrents, in a very short time the open space was clear, all men creeping within the huts to take shelter and to talk over the marvel that had befallen. But while only the izanusi retired growling with discontent, all men rejoiced that Lalusini had so narrowly escaped what had seemed a certain doom.

Such doom, too, Nkose, had the King himself narrowly escaped; but that all men did not know, it being, indeed, only known to me.

Chapter Three.

An Ominous Parting.

You will see, Nkose, that my times now were stormy and troublesome, and indeed I have ever observed that as it is with nations and people so it is with individuals. There comes a time when all is fair—all is power and strength and richness—then comes a decline, and neither nation nor individual is as before.

Such a time had come upon myself. After the battle of the Three Rifts, when we had rolled back the might of Dingane—a matter, indeed, wherein I had fully borne my part—there had followed a time of great honour and of rest. I was, next to the King, the greatest man in the nation, for Kalipe, the chief fighting induna, was getting on in age, and would fain have seen me in his place, having no jealousy of me. I had taken to wife the beautiful sorceress whose love I had longed to possess; moreover, the King had rid me of Nangeza, whose tongue and temper had become too pestilent for any man to bear aught of. My cattle had increased, and spread over the land, and they who owned me as chief were many, and comprised some of the best born and of the finest fighting men in the nation. Yet this was not to last, and as age and security increased for Umzilikazi, his distrust of me gained too, and now I knew he would almost gladly be rid of me, and quite gladly of Lalusini, my principal wife. Yes. To this had things come. I, Untúswa, the second in command of the King’s troops, who had largely borne part in the saving of our nation, who had even been hailed as king by the flower of the Zulu fighting indunas, had now to set out upon a ghost hunt, and, in the event of failure, the penalty hanging over me was such as might have fallen upon a miserable cheat of an izanusi.

Thus pondering I took my way back to my principal kraal, followed by Lalusini and others of my wives and followers who had separated from the throng and joined themselves on to me when the order was given to disperse. Arrived there, I entered my hut, accompanied by Lalusini alone. Then I sat down and took snuff gloomily and in silence. This was broken by Lalusini.

“Wherefore this heaviness, holder of the White Shield?” she said. “Do you forget that you have a sorceress for inkosikazi?”

For a while I made no reply, but stood gazing at her with a glance full of admiration and love. For, standing there, tall and beautiful and shapely, it seemed to me that Lalusini looked just as when I first beheld her in the rock cave high up on the Mountain of Death. Time had gone by since I had taken her to wife, yet she seemed not to grow old as other women do. My two former wives, Fumana and Nxope, were no longer young and pleasing, but Lalusini seemed ever the same. Was it her magic that so kept her? She had borne me no children, but of this I was rather glad than otherwise, for we loved each other greatly, and I desired that none should come between to turn her love away from me, as children would surely do. For my other wives it mattered nothing, but with Lalusini it was different. I loved her, Nkose, as some of you white people love your women. Whau! Do you not allow your women to walk side by side with you instead of behind? This I have seen in my old age. And those among us who have been at Tegwini (Durban) tell strange tales of white men who go out with their women, that they might load themselves with all the little things their women had bought from the traders. Few of us could believe that, Nkose—the tale is too strange; and yet it was somewhat after this manner that I loved Lalusini—I, the second induna of the King’s warriors, I, who since I was but a boy had slain with my own hand more of the King’s enemies than I could count. I, moreover, who had known what the ingratitude and malice of women could do, in the person of my first wife, Nangeza, for whom I had sacrificed my fidelity to the King and the nation—even my life itself. But with Lalusini, ah! it was very different. No evil or sullen mood was ever upon her; nor did she ever by look or word give me to understand that a daughter of the House of Senzangakona, the royal house of Zululand, might perchance be greater than even the second induna of a revolted and fugitive tribe, now grown into a nation. Even her counsels, which were weighty and wise, she would put forward as though she had not caused me to win the White Shield—had not saved our nation at the Place of the Three Rifts.

“It seems to me, Lalusini,” I said at last, “it seems to me that in this nation there is no longer any room for us two. I have served Umzilikazi faithfully and well. I have more than once snatched back the life of the King, when it was tottering on the very brink of the Dark Unknown, but kings are ever ungrateful; and now I and my house are promised the death of the traitor. The destruction of the Red Terror, which is my ordeal, is no real trial at all—it is but a trick. The King would be rid of us, and, whether I succeed or whether I fail, the Dark Unknown is to be our portion.”

Lalusini bent her head with a murmur of assent, but made no remark.

“And now I am weary of this ingratitude,” I went on, sinking my voice to a whisper, but speaking in a tone of fierce and gloomy determination. “What has been done before can be done again. I have struck down more of the enemies of our nation than the King himself. One royal spear—one white shield is as good to sit under as another; and—it is time our new nation sat down under its second king.”

“Great dreams, Untúswa,” said Lalusini, with a smile that had something of sadness in it.

“Great acts shouldst thou say rather, for I am no dreamer of dreams,” I answered bitterly. “Ha! do I not lead the whole nation in war? for, of late, Kalipe is old, and stiff in the limbs. One swift stroke of this broad spear, and the nation will be crying ‘Bayéte’ to him who is its leader in war. Ah! ah! What has happened before can happen again.”

But here I stopped, for I was referring darkly to the death of that Great Great One, the mighty Tshaka, from whose loins my inkosikazi had sprung. Yet no anger did she show.

“So shall we be great together at last, Lalusini, and my might in war, and thy múti combined, shall indeed rule the world,” I went on. “Ha! I will make believe to go on this tagati business, but to-night I will return in the darkness, and to-morrow—whau!—it may indeed be that the appearance of the Red Death has presaged the accession of a new King—even as those dogs, who were burnt to-day, did declare. How now for that, Lalusini?”

“The throne of Dingiswayo is older than that of Senzangakona, and both are older than that of Matyobane,” she answered. “Yet I know not—my múti tells me that the time is not yet. Still, it will come—it will come.”

“It will come—yes, it will come—when we two have long since been food for the alligators,” I answered impatiently. “The King’s word is that I slay this horror—this tagati thing—by the foil of the moon. What if I fail, Lalusini?”

“Fail? Fail? Does he who rolled back the might of the Twin Stars of Zulu talk about failure? Now, nay, Untúswa—now, nay,” she answered, with that strange and wonderful smile of hers.

“I know not. Now cast me ‘the bones,’ Lalusini, that I may know what success, if any, lieth before me against the Red Terror.”

“The bones? Ha! Such methods are too childish for such as I, Untúswa,” she answered lightly. “Yet—wait—”

She ceased to speak and her face clouded, even as I had seen it when she was about to fall into one of her divining trances. Anxiously I watched her. Her lips moved, but in silence. Her eyes seemed to look through me, into nowhere. Then I saw she was holding out something in her hand. Bending over I gazed. She had held nothing when we sat down nor was there any place of concealment whence she could have produced anything. But that which lay in her hand was a flat bag, made of the dressed skin of an impala. Then she spoke—and her voice was as the voice of one who talks in a dream.

“See thou part not from this, Untúswa. Yet seek not to look within—until such time as thy wit and the wit of others fail thee—or the múti will be of no avail—nay more, will be harmful. But in extremity make use of what is herein—in extremity only—when at thy wit’s end.”

Still held by her eyes, I reached forth my hand and took the múti bag, securing it round my neck by a stout leather thong which formed part of the hide from whence the bag had been cut. As I did so, Lalusini murmured of strange things—of ghost caves, and of whole impis devoured in alligator-haunted swamps—and of a wilder, weirder mystery still, which was beyond my poor powers of understanding—I being but a fighter and no izanusi at all. Then her eyes grew calm, and with a sigh as of relief she was herself again.

Now I tried to go behind what she had been saying, but it was useless. She had returned from the spirit world, and being once more in this, knew not what she had seen or said while in the other. Even the múti pouch, now fastened to my neck, she glanced upon as though she had never seen it before.

“Go now, Untúswa,” she said.

We embraced each other with great affection, and Lalusini with her own hands armed me with my weapons—the white shield, and the great dark-handled assegai which was the former gift of the King, also my heavy knobkerrie of rhinoceros horn, and three or four light casting spears—but no feather crest or other war adornments did I put on. Then I stepped forth.

No armed escort was to accompany me, for I must do this thing alone. But I had chosen one slave to bear such few things as I should require. Him I found awaiting me at the gate of the kraal.

It was evening when I stepped forth—evening, the busiest and cheeriest time of the day—yet my kraal was silent and mournful as though expecting every moment the messengers of death. The cattle within their enclosure stood around, lowing impatiently, for the milking was neglected; and men, young and old, sat in gloomy groups, and no women were to be seen. These murmured a subdued farewell, for not only was I, their chief and father, about to sally forth upon an errand of horror and of gloom, but in the event of failure on my part, who should stand between them and the King’s word of doom?

Through these I strode with head erect as though proceeding to certain success—to a sure triumph. When without the gate I turned for a moment to look back. The rim of the sinking sun had just kissed the tips of the forest trees on the far sky-line, and his rays, like darts of fire, struck full upon my largest hut, which was right opposite the great gate of the kraal. And there against the reed palisade in front of the door stood Lalusini, who had come to see the last of me, ere I disappeared into gloom and distance. Au! I can see her now, my beautiful wife, as she stood there, her tall and splendid form robed as it were in waving flames of fire, where the last glory of the dying sun fell full upon her. And through the dazzle of this darting light, her gaze was fixed upon me, firm and unflinching. Yes, I can see her now as I saw her then, and at times in my dreams, Nkose, old man as I am, my heart feels sore and heavy and broken as it did then. For as I returned her parting gesture of farewell, and plunged into the forest shades, at that moment a voice seemed to cry in my ears that I should behold her no more. In truth was I bewitched.

“Will you not rest a while, lord, and suffer me to prepare food, for we have travelled fast and far?”

The voice was that of my attendant slave, and it struck upon my ears as a voice from the spirit world, so wrapped up was I in the gloom of my own thoughts. Now I glanced at the sky and judged the night to be more than half through. And we had marched since the setting of the sun. But the light of the half moon was sufficient for us, for the forest trees were of low stature and we were seldom in complete darkness.

“Rest a while? Not so, Jambúla,” I answered. “Are we not on the King’s errand? and from hence to the full of the moon is not far.”

“The forest is loud with the roarings of strange ghost-beasts, my father; and the time of night when such have most power must already be here. And we are but two,” he urged, though with great deference.

“And what are such to me—to me!” I answered, “I who am under the protection of great and powerful múti? Go to, Jambúla. Art thou turning fearful as time creeps upon thee?”

“I fear nothing within touch of thy múti, father,” he answered, liking not the question.

And then, indeed, I became alive to the meaning of the man’s words, for strange and fearful noises were abroad among the shadows on either hand, low sad wailings as of the ghosts of them that wander in darkness and pain, mingling with the savage howls of ramping beasts into whose grim bodies the spirits of many fighters had passed, to continue their fierce warring upon such as still trod this earth in the flesh. And over and above these came the mighty, muffled, thunderous roar of a lion.

But those sounds, many and terrifying as they were, held no fears for me—indeed, they had hitherto fallen upon deaf ears—so filled was my soul with forebodings of another kind. Now, however, a quick, startled murmur on the part of my follower caused me to halt.

Right in front I saw a huge shape—massive and shaggy—and I saw the green flash of eyes, and the baring of mighty jaws in the moonlight. Then up went the vast head, and a quivering thunderous roar shook the night.

Then the beast crouched. It was of enormous size in the half light. Was it only a lion—or a ghost-beast, which would spread and spread till its hugeness overshadowed the world? If the latter, mere weapons were powerless against it.

Jambúla stepped to my side, every muscle of his frame tense with the excitement of the moment. His shield was thrust, forward, and his right hand gripped the haft of a broad-bladed stabbing spear. But I—no movement did I make towards using a weapon. I advanced straight upon the beast, and as I did so, some force I knew not caused my hand to rest upon the múti bag which hung upon my breast.

With a snarling roar the beast moved forward a little, preparing for its rush. We were but ten paces apart. Then the fierce lashing of the tail ceased, the awful eyes seemed to glare with fear where rage had fired them before—the thunder of the threatening roar became as the shrill whine of a crowd of terrified women—and, backing before me as I advanced, the huge beast slunk away in the cover, and we could hear its frightened winnings growing fainter and fainter in the distance.

By this, Nkose, two things were clear—that the shape, though that of a huge and savage lion, was but a shape to give cover to something which was not of this world—and that Lalusini’s múti was capable of accomplishing strange and wonderful results.

Chapter Four.

The Abode of the Terror.

Through the whole of the following day, and the night after, we travelled; and on the next morning, before the son had arisen, we came upon a large kraal. The land lay enshrouded in heavy mist, and the hoarse barking of many dogs sounded thick and muffled. Armed men sprang to the gate to inquire our errand, but one word from my slave, Jambúla, caused them to give us immediate admission. This was the kraal of Maqandi-ka-Mahlu, the chief over the workers in iron, in whose midst the horror named the Red Death had broken forth.

As I strode across the centre space—the domes of the encircling huts looming shadowy through the mist—Maqandi himself came forth to meet me. Yet although showing me this mark of deference, I liked not his manner, which was sullen, and somewhat lacking in the respect due from an inferior and disgraced chief towards one who dwelt at the right hand of the King, and who was, moreover, the second in command of the King’s army. But it seemed to me that fear was in his mind, for he could not think that an induna of my rank would arrive alone, attended by one slave, and I think he expected every moment the signal which should bring my followers swarming into the kraal to put him and his to the assegai and his possessions to the flames.

“What is the will of the Great Great One, son of Ntelani?” he said, as we sat together within his hut alone. “Hau! I am an old man now, and troubles grow thick on every side. I have no people, and am but taskmaster over a set of miserable slaves—I, who fought with the assegai and led warriors to victory at the Place of the Three Rifts, even as you did yourself, Untúswa. Yes, troubles are upon me on every side, and I would fain sit down at rest within the Dark Unknown.”

I looked at Maqandi, and I pitied him. He had, indeed, grown old since we had fought together in that great battle. His face was lined and his beard had grown grey; and his hair—which, being in some measure in disgrace, he had neglected to shave—seemed quite white against the blackness of his head-ring. Yet with all his desire to sleep the sleep of death, there was in his eyes a look of fear; such a look as may be descried in the faces of those to whom the witch-finder’s rod draws very near. Yes, I pitied him.

“The will of the Great Great One is not with thee for the present, Maqandi,” I said, desiring to reassure him. “Now, hearken, and give me such aid as I need, and it may be that the head-ring of the son of Mahlu may yet shine once more in its place among the nation.”

“Ha! Sayest thou so, holder of the White Shield?” he answered quickly, a look of joy lighting up his face. “Is not all I have at the disposal of the second induna of the King?”

“That is rightly said, Maqandi,” I replied. “For never yet did I fail those who did well by me. And now we will talk.”

I unfolded my plan to the chief over the ironworkers, and as I did so his face grew sad and heavy again—for I could see he doubted my success in ridding the land of this terror—and then would not he, too, be sacrificed to the anger of the King? But I enjoined upon him silence and secrecy—telling him that his part lay in strictly obeying my orders and supplying my need. This, so far, lay in requiring two of the slave ironworkers to be in attendance upon me at sundown, for I intended proceeding to the Valley of the Red Death that very night.

Food was brought in, and tywala, and we ate and drank. Then I lay down and slept—slept hard and soundly throughout the heat and length of the day.

When I awoke the sun was declining from his highest point in the heavens. My slave Jambúla was already waiting and armed before the door of my hat. Beside him, too, were those I required to be in attendance. Both went before me, uttering words of bonga.

“Why are these armed?” I said, noting that the two ironworkers carried spears and axes. “I need no armed force. Let them leave their weapons here.”

A look of fear spread over the faces of both slaves at these words, and they reckoned themselves already dead men. For although weapons could be of no avail against a thing of tagati and of terror, such as had already laid low so many of their number, and indeed two of our own tried warriors, in a death of blood, yet it is in the nature of man to feel more confident when his hand holds a spear. But at my word they dropped their weapons and stood helpless.

Now, Nkose, not without reason did I so act. The King’s word had been that I should slay this horror accompanied by no armed force, and although two such miserable fighters as this race of slaves could supply were of no more use with arms in their hands than without, yet I would not give Umzilikazi any chance of saying I had not fulfilled his conditions. Besides, I had a purpose to which I intended putting these two, wherein weapons would avail them nothing at all.

I took leave of Maqandi-ka-Mahlu and set forth—I and Jambúla and the two workers in iron. Such men of our people as I encountered saluted me in gloomy silence, and as I passed the kraals of the iron-workers the people came forth and prostrated themselves on the ground, for my importance was twofold; I represented the majesty of the King, and further, some inkling had got abroad that my errand lay to investigate, and, if possible, bring to an end the terror of the Red Magic.

From the kraal of Maqandi we could already see the great mountain range in whose heart lay the locality of this terror, and shortly, ere the last rays of the sun faded from the world, we stood before a dark and narrow defile. We had left behind the dwellings of men, though plentiful traces of their occupation would meet our eyes, being left by the iron-working parties. Through this defile a thin trickle of water ran, though in times of rain and storm the place showed signs of pouring down a mighty and formidable flood. High overhead the slopes were covered with thick bush and forest trees, and above this, again, walls of red-faced rock seemed to cleave the sky. As we entered this gloomy place the terror on the faces of the slaves deepened, and even I, Nkose, felt not so easy in my mind as I would have it appear.

Soon we came out into more open ground; open immediately around us, for on raising my eyes I saw that we were in a large valley, or hollow. A ring of immense cliffs shut in the place as with a wall, nor, save the way by which we had come in, could my glance, keen and searching as it was, descry any means by which a man might find a way out.

The bottom of this strange valley was nearly level, and well grown with tall forest trees and undergrowth; not so thick, however, but that there were grassy open spaces, bestrewn with large rocks and boulders. But from the level floor of the hollow robe little or no slope. The great iron faces of the cliffs rose immediately, either in terraces or soaring up to a great height. Such was the aspect of the Valley of the Red Death.

That it was indeed the dreaded valley, the looks on the faces of the two iron-workers were sufficient to show. But I, gazing earnestly around and noting that there was but one way in or out, reckoned that the first part of my errand would not be hard—to find the accursed thing. Then a further examination of the cliffs, and I felt not so sure, for irregularly along their faces were black spots of all shapes and sizes. These were the mouths of caves.

Now, as we stood there, the light of day had all but faded from the world, and already one or two stars were peeping over the rim of the vast cliff-wall rearing up misty and dim to the height of the heavens. Little sound of life was there, from bird, or beast, or insect; and this of itself added to the grey and ghostly chill which seemed to brood over the place; for in that country night was wont to utter with more voices than day. But the golden bow of a young moon, bright and clear, gave a sufficient light to make out anything moving, save under the black darkness of the trees.

“What is thy name?” I said suddenly, turning to one of the slaves.

“Suru, father,” he replied.

“Well then, Suru, attend,” I said. “Remain here, in this open space beside this small rock, and stir not hence until I send for or call thee. To fail in thy orders in the smallest particular is death.”

But the man sank on the ground at my feet.

“Slay me now, father,” he entreated, “for death by one blow of the spear of the mighty do I prefer to the awfulness and horror of the death which shall come upon me here alone.”

“But death by one blow of the spear shall not be thy portion, oh fool,” I answered, mocking him. “Ah, ah! No such easy way is thine, oh dog, oh slave. The stake of impalement shall be thy lot, oh Suru. Think of it, thou hast never seen it. Ask Jambúla here how long a man may live when seated upon that sharp throne. For days and days may he beg for death, with blackened face and bursting eyeballs and lolling tongue, and every nerve and muscle cracking and writhing with the fiery torture. Why surely the death which this ghost could bring upon thee here would be mercy compared with such a death as that. But I think I will leave thee no choice. Bind him, Jambúla. Even a bound sentinel is better than none, though more helpless. If Suru will not keep his watch a free man he shall keep it bound. Ah, ah!”

That settled all his doubts. As Jambúla made a step towards him, Suru cried out to me to pardon his first hesitation, and to allow him to obey my orders at any rate unbound. I agreed to this, for he was frightened enough, and indeed, Nkose, as he moved away to take up the position I had assigned to him, his look was that of one who stands on the brink of the Pool of the Alligators with the slayers beside him.

Leaving Suru to his solitary post, I moved back with Jambúla and the other slave to near the neck of the narrow passage by which we had entered the hollow, for I wanted to see whether the thing of dread came in when night fell, or whether it abode within the place itself. This we could do, for I chose a position a little way up the hillside, whence, by the light of the moon, I could command a clear space over which anything approaching from without could not but pass. So we sat beneath a cluster of rocks, and watched, and watched.

Night had fallen, mysterious and ghostly. The stars burned bright in the heavens, yet it seemed as though some black cloud of fear hung above, blurring their light. From the open country far beyond came the cry of hyaenas, and the sharp barking yelp of the wild hunting dog calling to its mates; but in the drear gloom of this haunted valley, no sound of bird or beast was there to break the silence. So the night watches rolled on.

I know not whether I slept, Nkose; it may be that I partly did; but there came a feeling over me as of the weight of some great terror, and indeed it seemed to hold me as though I could not move. Was it an evil dream? Scarcely, for, as with a mighty effort, I partly threw off the spell, my glance fell upon the face of Jambúla.

He was gazing upward—gazing behind him—gazing behind him and me. His jaw had fallen as that of a man not long dead, and his eyeballs seemed bursting from their sockets, and upon his face was the same awful look of fear as that worn by the slave, Suru, when left to his solitary watch. I followed his glance, and then I too felt the blood run chill within me.

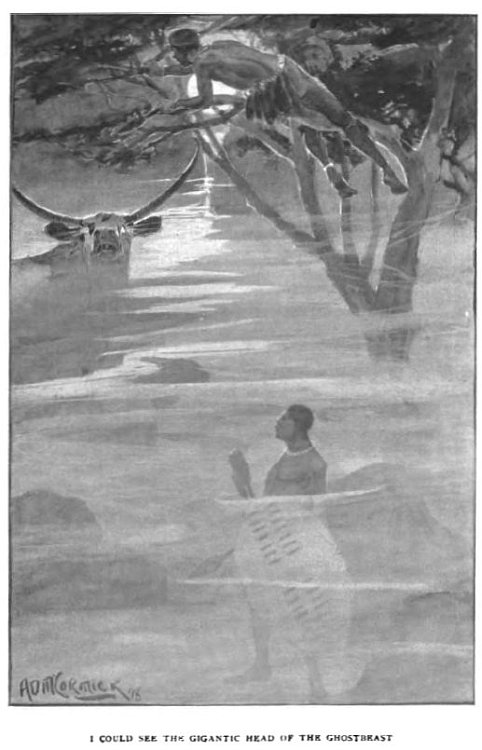

Rising above the rocks, at the foot of which we sat, a pair of great branching horns stood forth black against the sky. Slowly, slowly, the head followed, till a pair of flaming eyes shone beneath, seeming to burn us as we crouched there. But the size of it! Whau! No animal that ever lived—even the largest bull in the King’s herd—ever attained to half the size. Thoughts of the tagati terror rushed through my mind. Should I creep round the rocks and slay the monster, while its attention was taken up watching my slaves? Would it indeed fall to mortal weapon? And at that moment, I, the fearless, the foremost in the fiercest battle, the second commander of the King’s armies, felt my heart as water within me. But before I could decide on any plan the thing vanished—vanished as I gazed.

It was coming round the rocks, of course. In a moment we should receive its onslaught, and three more would be added to the number of the victims of the Red Death.

But—after? I thought of my beautiful wife, writhing her life out upon the stake of agony. I thought of my kinsmen and followers given over to the death of the alligators, and in a moment my heart grew strong again. I felt nerved with the strength of ten men. Let the thing come; and gripping my broad assegai, the royal spear, and my great white shield, the royal gift, I stood above the two scared and cowering slaves, ready to give battle to this terror from the unseen world. And in the short space of silence, of waiting, it seemed that I lived the space of my whole life.

But as I thus waited there rang forth upon the night a shrill, wild echoing yell—such a cry as might issue from the throat of one suffering such unheard of torments as the mind of man could ever invent. It pealed forth again louder, more quavering, rending the night with its indescribable notes of terror and agony—and it rose from where we had left the slave, Suru, to keep his grisly watch alone in the blackness of the forest. There was silence, but immediately that was rent by another sound—a terrible sound, too—the savage growling roars as of an infuriated bull—receding further and further from the place whence the death cry had arisen, together with a crashing sound as though a great wind were rushing away further and further up the haunted valley.

For long did that fearful death-yell ring in my ears, as I stood throughout the night watches, grasping my spear, every moment expecting the onslaught of the thing—for, of course, it would return, where more victims awaited. Then the thought came to me that it only dared attack and slay the unarmed; that at the sight of a warrior like myself, armed and ready for battle, it had retired to vent its rage upon an easier prey; and this thought brought strength and encouragement, for I would find no great difficulty in slaying such. But with the thought came another. The two men of Hlatusa’s band had been slain as easily and mysteriously as the iron-working slaves—slain in broad daylight—and they were well-armed warriors, and men of tried valour. In truth, the undertaking seemed as formidable as ever.

Even that night came to an end, and the cheerfulness and warmth of the newly-arisen sunbeams put heart even into the two badly-frightened slaves; and, feeling strong in my presence, their fears yielded to curiosity to learn the exact fate of Suru—not that any of us really doubted what that fate had been.

With spear held ready, and none the less alert because it was day, and the valley was now flooded with the broad light of the sun, I quickly made my way down, followed by Jambúla and the other, to where I had left the slave the night before. It was as I thought. There he lay—dead; crushed and crumpled into a heap of body and limbs. He had tried to run. I could see that by the tracks, but before he had run ten steps the terrible ghost-bull had overtaken him and flung him forward. The great hole made by the entering horn gaped wide between his ribs, and, tearing forward, had half ripped him in two. The grass around was all red and wet with half-congealed blood, and in the midst, imprinted deep and clear as in the muddy earth after rain, two great hoof marks, and those of such a size as to be imprinted by no living animal.

So now I had seen with my own eyes a victim of the terror of the Red Death, and now I myself must slay this horror. But how to slay a great and terrible ghost—a fearful thing not of this world?

Chapter Five.

Gasitye the Wizard.

For long I stood there thinking. I looked at the ground, all red and splashed with blood. I looked at the distorted body of the dead slave and the great gaping wound which had let out the life—the sure and certain mark of the dreaded Red Death—always dealt as it was, in the same part of the body—and for all my thought I could think out no method of finding and slaying this evil thing. Then I thought of the múti—the amulet which Lalusini had hung around my neck. Should I look within it? Her words came back to me. “Seek not to look within until such time as thy wit and the wit of others fail thee.” Yet, had not that time come? I could think of no plan. The monster was not of this world. No weapon ever forged could slay it; still there must be a way. Ha! “the wit of others!” Old Masuka had departed to the land of spirits himself. He might have helped me. Who could those “others” be, of whom my sorceress-wife had spoken while her spirit was away among the spirits of those unseen?

“Remain here,” I said suddenly, to Jambúla and the other slave. “Remain here, and watch, and stir not from this spot until I return.”

They made no murmur against this—yet I could see they liked not the order. But I gave no thought to them as I moved forward with my eyes fixed upon the tracks of the retreating monster.

The bloody imprint of the huge hoofs was plain enough, and to follow these was a work of no difficulty. Soon, however, as the hoofs had become dry, it was not so easy. Remembering the crashing noise I had heard as the thing rushed on its course, I examined the bushes and trees. No leaves or twigs were broken off such as could not but have happened with such a heavy body plunging through them. Then the hoof-marks themselves suddenly ceased, and with that, Nkose, the blood once more seemed to tingle within me, for if the thing had come no further was it not lying close at hand—those fiery eyes perhaps at that very moment watching me—those awful horns even now advancing silent and stealthy to rip and tear through my being? Ha! It seemed to me that this hunting of a terrible ghost was a thing to turn the bravest man into a coward.

Then as I stood, my hearing strained to its uttermost, my hand gripping my broad spear ready at any rate to fight valiantly for life, and all that life involved, something happened which well-nigh completed the transformation into a coward of a man who had never known fear.

For now a voice fell upon my ears—a voice low and quavering, yet clear—a voice with a strange and distant sound as though spoken afar off.

“Ho! fearless one who art now afraid! Ho! valiant leader of armies! Ho! mighty induna of the Great King! Thou art as frightened as a little child. Ha, ha, ha!”

This last was very nearly true, Nkose—but hearing it said, and the hideous mocking laugh that followed, very nearly turned it into a lie.

“I know not who speaks,” I growled, “save that by the voice it is a very old man. Were it not so he should learn what it means to name me a coward.”

“Ha, ha, ha!” screamed the voice again. “Brave words, O holder of the King’s assegai. Why, thy voice shakes almost as much as mine. Come hither—if thou art not afraid.”

From where the bush grew darkest and thickest the voice seemed to come. I moved cautiously forward, prepared at every step to fall into some trap—to meet with some manifestation of abominable witchcraft. For long did I force my way through the thick growth, but cautiously ever, and at last stood once more in the open. Then astonishment was my lot. Right before me rose a great rock wall. I had reached the base of one of the heights which shut in the hollow.

“Welcome, Untúswa,” cackled the voice again. “Art thou still afraid?”

Now, Nkose, I could see nobody; but remembering the Song of the Shield, and how Lalusini had caused it to sound forth from the cliff to hearten us during the battle—she herself being some way off—I was not so much amazed as I might have been, for the voice came right out of the cliff.

“If thou art not afraid, Untúswa,” it went on, “advance straight, and touch the rock with thy right hand.”

I liked not this order, but, Nkose, I had ever had to do with magicians, and had dipped somewhat into their art, as I have already shown. Here, I thought, was more sorcery to be looked into, and how should I root out the sorcery of the Red Magic save by the aid of other sorcery? So I advanced boldly, yet warily. And then, indeed, amazement was my lot.

For, as my right hand touched it, the hard rock moved, shivered. Then a portion of this smooth, unbroken wall seemed to fall inward, leaving a black gaping hole like a doorway, through which a man might enter upright.

“Ho, ho! Untúswa!” cackled the voice again, now from within the hole. “Welcome, valiant fighter. Enter. Yet, wilt thou not leave thy weapons outside?”

“Not until I stand once more in the presence of him who sent me do I disarm, O Unknown One. And now, where art thou? for I like better to talk to a man with a voice than to a voice without the man.”

“And how knowest thou that I am a man, O Fearless One? Yet, enter, weapons and all. Ha! Knowest thou not this voice?”

Whau! It seemed to me then that my flesh crept indeed, for I did know that voice. Ah, yes, well indeed; and it was the voice of one who had long since sat down in the sleep of death—the voice of old Masuka, the mightiest magician our nation had ever seen.

Then, indeed, did I enter, for, even though dead, the voice was that of one who had done naught but well by me during life, and I feared not a change the other way now. I entered, and, as I did so, I stood in darkness once more. The rock wall had closed up behind me.

Now my misgivings returned, for, Nkose, no living man, be he never so brave, can find himself suddenly entombed within the heart of the earth alone, the voice of one who has long been dead talking with him in the black, moist darkness, and not feel some alarm. Again the voice spoke, and this time it was not that of Masuka, but the mocking cackle which had at first startled me.

“Ho, ho! Untúswa, the valiant, the fearless. Dost thou not tremble—thou who art even now within the portal of the Great Unknown? Did ever peril of spear, or of the wrath of kings, make thy face cold as it now is? Ha, ha!”