TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The numbers in the right margin refer to the page numbers of the original printed book, they appear just where the corresponding page begins, e.g., page 113 contains the text between “p. 113” and “p. 114”.

The illustrations in the printed book were placed in unnumbered pages inserted between the numbered text pages (the first illustration was in the frontispiece). In this version the illustrations have been inserted right after the passage they refer to.

At the end of the book there are several pages of advertisement for other books of the publisher, these pages have an independent numbering in the printed book, here they are numbered 1′–22′.

In the present edition some typographic errors or inconsistencies have been corrected. In the HTML version these corrections are marked with a dotted underline, and the printed text usually appears in a “pop-up hint” when hovering the cursor on it.

A. L. BURT, PUBLISHER.

CORPORAL ’LIGE’S RECRUIT.

By James Otis.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Recruiting | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| A Secluded Camp | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| An Unpleasant Surprise | 45 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Letter | 64 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Nathan Beman | 88 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A Squad of Four | 112 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Ticonderoga | 141 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| An Interruption | 169 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| A Bold Stroke | 204 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Crown Point | 229 |

vi

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

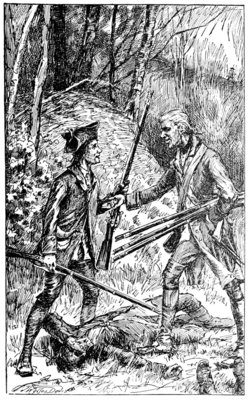

| • The old man marched down the street with such a swagger as he evidently believed befitting a soldier. | 27 |

| • “Is it all right, Corporal?” Isaac asked timidly. | 57 |

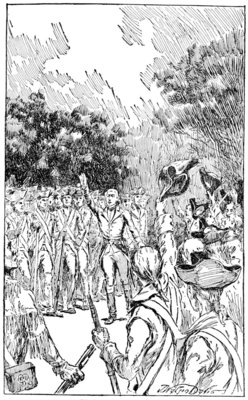

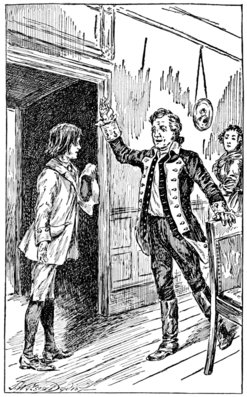

| • “Silence in the ranks!” the Colonel said sternly. | 104 |

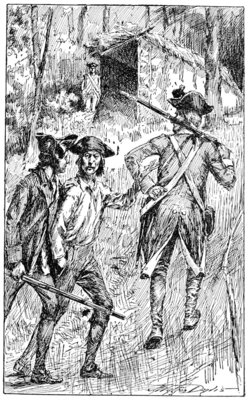

| • “But the Corporal wouldn’t lie,” Isaac said solemnly. | 114 |

| • Before he could speak, Colonel Allen cried: “I order you instantly to surrender, in the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress.” | 168 |

| • “So the Fort has been taken by our People,” Captain Baker cried, clasping the messenger by the hand. | 232 |

1

CHAPTER I. RECRUITING.

There was great excitement among the citizens of the town of Pittsfield in the province of Massachusetts on the first day of May in the year 1775.

Master Edward Mott and Noah Phelps, forming a committee appointed by the Provincial Assembly of Connecticut, had arrived on the previous evening charged with an important commission, the making known of which had so aroused the inhabitants of the peaceful settlement that it was as if the reports of the muskets fired at Lexington and Concord were actually ringing in their ears.

These two gentlemen had with them a 2 following of sixteen men, equipped as if for battle, and the arrival of so large an armed body had aroused the curiosity of the good people until all were painfully eager to learn the reason for what seemed little less than an invasion.

When it was whispered around that Master Mott and Phelps had, immediately upon their arrival, inquired for Colonel James Easton and Master John Brown, and were even then closeted with those citizens, the more knowing ones predicted that this coming had much to do with the warlike preparations that were making in Boston and New York, designed to put a check upon the unlawful doings of his majesty the king.

When morning came, that is to say, on this first day of May, it was generally understood throughout the settlement that the Provincial Assembly of Connecticut had agreed upon a 3 plan to seize the munitions of war at Ticonderoga for the use of that body of men known as the American army, then gathered at Cambridge and Roxbury in the province of Massachusetts.

The gossips of Pittsfield stated that one thousand dollars had been advanced from the Provincial Treasury of Connecticut to pay the expenses of the expedition; that the sixteen men making up the following of the committee were recruits who had pledged themselves to capture this important fortress which formed the key of communication between New York and the Canadas, and that they proposed to march through the country to Shoreham, opposite Ticonderoga, recruiting as they went, with the belief that on arriving there their force would be sufficiently large to capture the fort.

The boys as well as the men were highly 4 excited, as was but natural, by such rumors, and a certain Isaac Rice, who prided himself upon being fourteen years old, instead of gathering with his companions, listening eagerly to every word which dropped from the lips of the older members of the community, conceived the idea of applying to what he believed to be the fountain-head of all information regarding military matters.

This supposedly wise man was none other than Corporal Elijah Watkins, generally known as “Corporal ’Lige,” sometimes spoken of as “Master Watkins;” but always to Isaac Rice, “the corporal.”

He was looked upon as an old man when he served under Abercrombie at Ticonderoga in ’58, and believed of a surety he was as well informed in military affairs as Isaac Rice, his ardent disciple, fancied him to be.

5Ever ready to give advice on important matters; not backward about criticising the alleged mistakes of his superiors, and holding himself as with the idea that during the late troubles with the French he had learned all the art of warfare; but yet with such possibly disagreeable qualities, Corporal ’Lige had shown himself to be a brave soldier, willing at any time to do more even than was his duty.

The old man was sitting outside the door of a tiny log building which he called home, smoking peacefully, much as he might have done had the committee from Connecticut never passed that way, and this apparent indifference surprised the boy.

“Why, corporal, don’t you know what’s going on in the town? Haven’t you heard that they are talking of taking the fort at Ticonderoga, and running the king out of the country?”

6“First and foremost, Isaac lad, are you so ignorant as to think the king is here in this ’ere province to be run out? An’ then agin, can’t you realize that talkin’s one thing an’ doin’s another?”

“Yes; but, corporal, haven’t you heard the news?”

“If you mean so far as concerns the committee from Connecticut, Isaac, I have heard it, and what’s more, Master Noah Phelps talked with me before ever he went to see Colonel Easton. He knew where he could get information about Ticonderoga, for bless your soul, lad, wasn’t I there in ’58? An’ would you find a stick or stone around the place that I can’t call to mind?”

“Did Master Phelps come to see you first?”

“Well, yes, lad, it ’mounted to much the same thing. I was down the road when he come into town, an’ seein’ me he acted like 7 as if a great load had been lifted off his shoulders, ’cause he knowed I could tell him a thing or two if I was minded. ‘Good-evenin’ to you, Corporal ’Lige,’ he said sweet as honey in the honeycomb, and I passed the time of day with him, kind of suspicionin’ something of this same business was goin’ on. ‘Want to take a little trip up through the country?’ he asked friendly-like, and do you know, lad, the whole plan come to me in a minute, an’ I says to him, says I, ‘Master Phelps, you can count me in, if it so be yo’re goin’ toward the lakes.’ ‘That’s where we’re bound for, Corporal ’Lige,’ says he, ‘and I’ll put your name down.’ I said, says I, ‘It’s rations, an’ somethin’ in the way of pay, I reckon?’ an’ he allowed as that part of it would be all fixed, especially with me, ’cause you see, lad, it wouldn’t be much good for these people what never knew anything 8 ’bout war, to start out leavin’ me behind. Why, bless your heart, I allow that’s why they come through Pittsfield, jest for the purpose of seein’ Corporal ’Lige.”

The old man ceased speaking to puff dense volumes of smoke from his pipe, and Isaac Rice gazed at him in wonder and amaze.

That the committee from Connecticut had visited the town for the sole and only reason of inducing the corporal to join the force, there was no question in his mind, and now, more implicitly than ever before, did he believe that throughout all the provinces there could be found no abler soldier than Corporal ’Lige.

“Yes, lad, I’m goin’ with the committee, more to tell ’em what they ought to do, as you might say, than to serve as a private soldier, for you see I know Ticonderoga root and branch. I could tell you the whole story 9 from the meanin’ of the name down to who is in command of it this very minute, if there was time.”

“But there is, corporal. The committee are talkin’ to Colonel Easton and Master Brown now, and don’t count on leaving here before to-morrow.”

“What do they want of the colonel?”

“I don’t know; but they are stopping at his house.”

“I ain’t sayin’ but that the colonel is as good a soldier as you’ll find around here; but bless your soul, lad, though it ain’t for me to say it, he could learn considerable from Corporal ’Lige if he was to spend a few hours every now and then listenin’.”

“But tell me all you can about Ticonderoga, corporal.”

The old man looked around furtively as if half-expecting the committee from Connecticut, 10 or Colonel Easton, might be coming to ask his advice on some disputed point, and then, shaking his forefinger now and again at the lad much as though to prevent contradiction, he began:

“In the first place the folks ’round here call it ‘Ticonderoga’ when it ain’t anything of the kind. The real name is ‘Cheonderoga,’ which is Iroquois lingo for ‘Sounding Water,’ being called so, I allow, because the falls at Lake George make a deal of noise. The French built breastworks there in ’55, which they christened Fort Carillon. Now you see it’s a mighty strong place owin’ to the situation, and its bein’ located on a point which, so I’ve heard said, rises more’n a hundred feet above the level of the water. The solid part of it—that is to say, the land—is only about five hundred acres. Three sides are surrounded by water, an’ in the rear is a swamp. That 11 much for the advantages of the spot, so to speak. Now I was there in July of ’58 when Montcalm held the fort with four thousand men. Lord Howe was second in command of General Abercrombie’s forces, and Major Putnam, down here, was with the crowd. That’s when the major wouldn’t let his lordship go into the battle first; but banged right along ahead until we come to the first breastworks, finding it so strong that the troops were marched back to the landin’ place and went into bivouac for the night. It was the sixth day of July; on the eighth we tried it again; but the fort couldn’t be carried, an’ the blood that was shed there, lad, all under the British flag, would come pretty nigh drownin’ every man, woman an’ child in this ’ere settlement. On the twenty-sixth of July in the year 1759, General Amherst with eleven thousand men scared the French out; 12 they didn’t fire a gun, but abandoned the fortification and fled to Crown Point. Since that time the king’s forces have held it.”

“How many are there now?” Isaac asked, not so much for the purpose of gaining information as to tempt the old man to continue his story.

“I can’t rightly say, lad, though it’s somewhere in the neighborhood of fifty. The commandant is, or was when I last heard, one Captain Delaplace, and it is said that he’s a thorough soldier, though I’m allowin’ he hasn’t got any too much of a force with him.”

“Do you think the Connecticut gentlemen can raise men enough between here and there to take a fort which resisted General Abercrombie’s entire army?”

“That remains to be seen, lad. If they are willin’ to act on such advice as can be got 13 from some people hereabouts, I allow there’s a good chance for it, more especially if the Green Mountain boys take a hand in the matter, as Master Phelps thinks probable. In that case Colonel Ethan Allen would most likely be in command.”

“And you are really going, corporal?” asked Isaac.

“Yes, lad, it don’t seem as though I ought to hang back back when I’m needed. If all we hear from the other provinces is true, you’ll be old enough to take a hand in the scrimmage before the fightin’s over, so here’s a chance to serve an apprenticeship. If it so be you’re of the mind I’ll take you under my wing, an’ by the time we get back you’ll have a pretty decently good idea of a soldier’s trade.”

“Do you really mean it, corporal?” and Isaac sprang to his feet in excitement. “Do 14 you really mean that I may go with you just as if I was of age to carry a gun?”

“Ay, lad, if it so be your mother an’ father are willin’, an’ I can’t see why they shouldn’t agree, seein’s how they know the company you’ll be in. It would seem different if you talked of goin’ with the general run of recruits, who are green hands at this kind of work.”

“But will the committee allow a lad of my age to go as a soldier?”

“Isaac, my boy, when Corporal ’Lige says to Master Phelps, says he, ‘This ’ere lad is goin’ under my wing, so to speak,’ why bless your heart, that’s the end of the whole business. They’ve got to have me, an’ won’t stand out about your joinin’ when it’s known my heart is set on it.”

“Will you come now while I ask my mother?”

15“Well, lad, I ain’t prepared to say as how I will; but this much I’m promisin’: Go to her an’ find out how she’s feelin’ about the matter. If there’s any waverin’ in her mind I’ll step in—you see I’ll be the reserves in this case—an’ when I charge she’s bound to surrender. But if it so happens that she’s dead set against it at the start, why, you had best not vex her by tryin’ to push the matter.”

Having perfect faith in the corporal’s wisdom Isaac was thoroughly satisfied with this decision, and after the old man had promised to await his return at that point, the lad set out for home at full speed.

Perhaps if Isaac had been the only son of his mother he would have found it difficult to gain her permission for such an adventure as Corporal ’Lige had proposed.

There were five other boys in the family, 16 and Isaac was neither the oldest nor the youngest.

The fact that Mrs. Rice had so many did not cause her to be unmindful of any, but less timorous perhaps, about parting with one.

However it may be, the lad gained the desired permission providing his father would assent, and this last was little more than a formality.

Master Rice was found among the throng of citizens in front of the inn where recruiting was going on briskly.

The opportunity served to give the good man a certain semblance of patriotism when he showed himself willing that one of his sons should go for a soldier, and he would have had the boy sign the rolls then and there, but that Isaac demurred.

It was not in his mind to enlist save in the 17 company and after being again assured of the corporal’s protection, therefore he insisted on presenting himself as the old man’s recruit rather than his father’s offering.

Corporal ’Lige was well pleased when Isaac returned with a detailed account of all that had taken place, and said approvingly:

“You have shown yourself to be a lad of rare discretion, Isaac Rice, and I will take it upon myself to see that such forethought brings due reward. Suppose you had signed the rolls at the inn? What would you be then? Nothin’ more than a private.”

“But that is all I shall be when I sign them with you, corporal.”

“It may appear that way, I’m free to admit lad; but still you will be a deal higher than any non-commissioned officer, because you’ll be under my wing, and when we have taken Ticonderoga, though I ain’t admitting that’s 18 the proper name of the fort—when we’ve taken that, I say, you’ll be fit for any kind of a commission that you’re qualified to hold.”

“Yes,” Isaac replied doubtfully, and then he fell to speculating as to whether even though Corporal ’Lige did not “take him under his wing,” he might not be fit to fill any position for which “he was qualified.”

While he was thus musing a messenger came from Master Phelps saying the recruiting was coming to an end in this town, and the party would set out that same afternoon on their way to Bennington, expecting to enlist volunteers from Colonel Easton’s regiment of militia as they passed through the country.

“Never you fear but that I’ll be right at my post of duty when the command is given to form ranks,” Corporal ’Lige said to the messenger, and after the latter had departed 19 he added as he turned to the boy, “Now, Isaac, lad, you can see what they think of Corporal ’Lige. Colonel Easton and Master Brown are hangin’ ’round the inn instead of waitin’ for the committee to visit them. An’ what do I do? Why, I stay quietly here, knowin’ they can’t well get along without me, an’ instead of coolin’ my heels among a lot of raw recruits, I’m sent for when the time is come, as if I was a staff officer. That’s one thing you want to bear in mind. If you don’t count yourself of any importance, other people are mighty apt to pass you by as a ne’er-do-well.”

“But I haven’t enlisted yet, corporal.”

“Of course you have. When you said to me ‘I’m ready to go as your apprentice in this ’ere business,’ it was jest the same as if you’d signed the rolls. I’ll arrange all that matter with Master Phelps, my lad. Now do you 20 hasten home; get what you can pick up in the way of an outfit; borrow your father’s gun, and kind of mention the fact to your mother that the more she gives in the way of provisions the better you’ll be fed, for you an’ me are likely to mess together.”

“How much are you going to take, corporal?”

“That will depend a good deal on what kind of a supply your mother furnishes. I’m willin’ to admit she’s nigh on to as good a cook as can be found in Pittsfield, an’ will take my chances on what she puts up for you, providin’ there’s enough of it.”

“Of course you are to take your musket?”

“I should be a pretty poor kind of a soldier if I didn’t, lad—the same one I used under Abercrombie,” and he pointed with his thumb toward the interior of the dwelling where, as Isaac knew, a well-worn weapon 21 hung on hooks just over the fireplace. “It’s one of the king’s arms, an’ I reckon will do as good service against him as it did for him, which is saying considerable, lad, as Major Putnam can vouch for. Now set about making ready, for we two above all others must not be behind-hand when the column moves.”

A fine thing it was to be a soldier, so Isaac thought as he went leisurely from Corporal ’Lige’s log hut to his home; he was forced to pass through the entire length of the village, stopping here and there to acquaint a friend with what he believed to be a most important fact.

Among all the lads in Pittsfield of about his own age he was the only one who proposed to enlist, and from all he heard and saw there could be no question but that he was envied by his companions.

22From the youngest boy to the oldest man, the citizens were in such a ferment of excitement as gave recruits the idea that to enlist was simply providing amusement for themselves during a certain number of days, and, with the exception of those experienced in such matters, no person believed for a moment that the brave ones who were rallying at their country’s call would suffer hardships or privations.

In fact, this going forth to capture the fort at Ticonderoga was to be a pleasure excursion rather than anything else, and Isaac Rice believed he was the most fortunate lad in the province of Massachusetts.

His outfit did not require that his mother should spend very much time upon it.

The clothes he wore comprised the only suit he owned, and when two shirts and three pairs of stockings had been made into a parcel 23 of the smallest possible size, and he had borrowed his father’s gun, powder horn and shot pouch, the equipment was complete.

Then came the most important of the preparations, to Isaac’s mind, for he knew the corporal would criticize it closely—the store of provisions.

Had he been allowed his own bent the remainder of the Rice family might have been put on short allowance, for, with a view to pleasing the corporal, he urged that this article of food, and then that, should be put into the bag which served him as a haversack, until the larder must have been completely emptied but for his mother’s emphatic refusal to follow such suggestions.

If Mrs. Rice did not shed bitter tears over Isaac when he left her to join the recruits, it was because she shared the opinion of many others in Pittsfield, and felt positive the lad 24 would soon return, none the worse for his short time of soldiering.

It was but natural she should take a most affectionate farewell of him, however, even though believing he would be in no especial danger, and a glimpse of the tears which his mother could not restrain caused an uncomfortable swelling in the would-be soldier’s throat.

This leaving home, even to march away by the side of Corporal ’Lige, was not as pleasant as he had supposed, and for the moment he ceased to so much as think of the provision-bag.

“Now, see here, mother,” he said, with a brave attempt at indifference. “I’m not counting on doing anything more than help take the fort, and since the corporal is to be with us, that can’t be a long task.”

“You will ever be a good boy, Isaac?”

25“Of course, mother.”

“And you will write me a letter, if it so be you find the opportunity?”

This was not a pleasing prospect to the boy, for he had never found it an easy task to make a fair copy of the single line set down at the top of his writing-book; but his heart was sore for the moment, and he would have promised even more in order to check his mother’s tears.

Therefore it was he agreed to make her acquainted with all his movements, so far as should be possible, and, that done, it seemed as if the sting was taken in a great measure from the parting.

Feeling more like a man than ever before in his life, Isaac set forth from his home with a heavy musket over his shoulder, and the bag of provisions hanging at his back, glancing neither to the right nor to the left 26 until he arrived at the corporal’s dwelling.

An exclamation of surprise and delight burst from his lips when he saw the old man, armed and equipped as he had been in ’58, wearing the uniform of a British soldier, even though by thus setting out he was proving his disloyalty to the king.

“Well you do look fine, corporal. I dare wager there are none who will set forth from this town as much a soldier as you!”

“I reckon Colonel Easton will come out great with his militia uniform; but what does it amount to except for the value of the gold lace that’s on it? All I’m wearin’ has seen service, an’ though it ain’t for me to say it, I shouldn’t be surprised if him as is inside this ’ere red coat could tell the militia colonel much regarding his duty.”

“Of course you can, corporal, every one 27 knows that, an’ I’m expecting to see you put next in command to Colonel Allen, if it so be he goes.”

“Not quite that, lad, not quite that, for there’s jealousy in the ranks the same as outside of them, though I warrant many of ’em will be glad to ask Corporal ’Lige’s advice before this ’ere business is over. Now let’s have a look to your stores, and we’ll be off.”

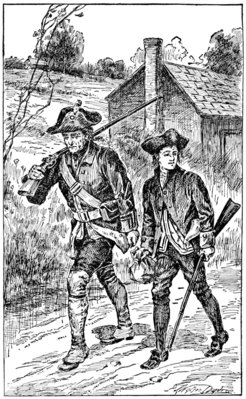

The examination of the impromptu haversack appeared to be satisfactory to the old man, and without doing more in the way of securing his dwelling from intruders than shutting the outer door, he marched down the street with such a swagger as he evidently believed befitting a soldier.

THE OLD MAN MARCHED DOWN THE STREET WITH SUCH A SWAGGER AS HE EVIDENTLY BELIEVED BEFITTING A SOLDIER.

Corporal ’Lige’s Recruit, p. 27.

Isaac followed meekly at his heels, troubling his head not one whit because he lacked a uniform, but believing he shared to a certain 28 degree in Corporal ’Lige’s gorgeousness and martial bearing.

The two came to a halt outside the inn, standing stiffly at “attention,” and there they remained until Master Phelps was forced to go out and bid the old man enter, that the formality of signing the rolls might be gone through with, after which Isaac Rice was duly entitled to call himself a militiaman.

29CHAPTER II. A SECLUDED CAMP.

When these raw recruits departed from the town—Corporal ’Lige insisted that they did not march—they were followed for several miles by nearly all the men and boys in the vicinity.

The old man was greatly exercised because Colonel Easton, who now assumed command, allowed such an unsoldierly proceeding as that his troops should walk arm in arm with their friends, each in his own manner and at his own convenience.

Had the corporal been invested with the proper authority he would have had these raw recruits marshaled into ranks and forced 30 to step in unison, carrying their muskets at the same angle, and otherwise conforming themselves to his idea of soldierly bearing—all this he would have had them do; but whether he could have brought about such a condition of affairs is extremely problematical.

“I allowed Colonel James Easton came somewhere near bein’ a soldier, even though he is only a militiaman,” the corporal said in a tone of intense dissatisfaction to Isaac as the two marched solemnly side by side in the midst of their disorderly companions, “and I did think we could set out from here and capture Ticonderoga, if all hands were willin’ to put their shoulders to the wheel; but I take back that statement, lad, and am sorry I ever was so foolish as to enlist. I ought to have known better when I saw the crowd that was signin’ the rolls.”

31“Why, what’s the matter, corporal?” and Isaac looked around in surprise, for until this moment he had believed everything was progressing in proper military fashion.

“Matter?” Corporal ’Lige cried angrily. “Look around and see how these men are comportin’ themselves, an’ then you’ll know. Here are them as should be soldiers, seein’s they’ve signed the rolls, mixed up with citizens till you couldn’t tell one from the other unless personally acquainted with all hands. Then how are they marchin’? Why, a flock of geese couldn’t straggle along in any more ungainly fashion.”

“I shouldn’t suppose it would make any difference how they marched so that they got there in time,” Isaac ventured to suggest timidly.

“Shouldn’t, eh? Then what’s the good of calling themselves soldiers? Why don’t 32 they start out like a crowd of farmers an’ try their hand at taking the fort?”

“Well?” Isaac replied calmly. “Why shouldn’t they? They are not soldiers, you know, corporal, and so long’s the fort is taken why wouldn’t it be as well if they didn’t try to ape military manners?”

The old man gazed sternly at the boy while one might have counted ten, and then said in a tone of sadness:

“It’s a shame, Isaac Rice, that after bein’ with me all these years, an’ hearin’ more or less regardin’ military matters, you shouldn’t have more sense.”

“Why, what have I said now, corporal? Is it any harm to think that farmers might take a fort?”

“Of course it is, lad. If anything of that kind could happen, what’s the use of having soldiers?”

33“But I suppose it is necessary to have an army if there’s going to be war,” Isaac replied innocently, and this last was sufficient to completely fill the vials of the old man’s wrath.

That this pupil of his should fail at the very first opportunity to show a proper spirit, was to him most disappointing, and during the half-hour which followed he refused to speak, even though Isaac alternately begged his pardon for having been so ignorant and expressed regret that he had said anything which might give offense.

During all this while the citizens of Pittsfield were following the recruits in a most friendly manner, believing it their duty to thus cheer those who might soon be amid the carnage of battle, and perhaps not one realized how seriously he was by such method offending Corporal ’Lige.

34Isaac’s father was among this well-intentioned following, as were two of the lad’s brothers, and when these representatives of the Rice family, having walked as far as the head of the household deemed necessary, were about to turn back, they ranged themselves either side of the corporal and his pupil, in order to bid the latter farewell.

“I expect you will give a good account of yourself, Isaac, when it comes to fighting, and I feel all the more confident in regard to it because you are under the wing of a man who knows what it is to be a soldier.”

This compliment was intended for Corporal ’Lige as a matter of course; but he paid no other attention to it than to say:

“If the lad had profited by my teachings, he’d know that he has no right to talk with outsiders while he’s in the ranks.”

“That’s exactly it,” Mr. Rice replied, 35 wholly oblivious that the corporal was administering what he believed to be a most severe rebuke. “That is exactly it, my son, and you will do well to remember that you cannot fail in your duty so long as you take pattern from the corporal.”

The old soldier gave vent to what can be described only as a “snort” of contempt; and the boy’s sorrow was as nothing compared with what it had been when bidding good-by to his mother.

After the young Rices had turned their faces homeward in obedience to the orders of the elder Rice, Isaac gave more heed to copying the movements of the corporal, thereby atoning in a certain measure for his previous injudicious remarks.

The boy firmly believed that no more able soldier could be found in all the colonies than this same Corporal ’Lige, and had any person 36 ventured to remark that the expedition might be as well off without him, Isaac would have set the speaker down as one lacking common sense.

Take the corporal out of the ranks, and young Rice would have said there was no possibility either Crown Point or Ticonderoga could be captured.

Thus it was that an order from Colonel Allen, Colonel Easton, or Seth Warner was as nothing compared with one from Corporal ’Lige, in the mind of Isaac Rice; but there were many in the ranks who did not have such an exalted opinion of the old soldier, and these were free with their criticisms and unfavorable remarks, much against the raw recruit’s peace of mind, as well as the corporal’s annoyance.

It was because of these light-headed volunteers, who saw only in this expedition a 37 novel and agreeable form of junketing, out of which it was their duty to extract all the sport possible regardless of the feelings of others, that Corporal ’Lige withdrew himself, so to speak, from his comrades, and barely acknowledged the salutes of any save his superior officers.

At the end of the second day’s journey he refused to go into camp with them; but applied to the captain of his company for permission to advance yet a short distance further, at which point he could join the troops when they came forward next morning. It was known by all the expedition, even including those who were making the old soldier the butt of their mirth, that he was held in high esteem by Colonel Ethan Allen, and the request, although irregular, was readily granted, after a warning against the perils attendant upon such a course.

38“It is better you stay with the troops, corporal,” the captain said kindly, “although I have no hesitation in saying you are free to do as you choose.”

“And I do not choose to remain in the encampment for all the young geese—who fancy that by signing the rolls they have become soldiers—to sharpen their wits upon, therefore I would halt by myself, taking only the recruit I claim as my own, for company.”

“I will have a care that you are not annoyed again,” the officer replied in a kindly tone; but this was not to Corporal ’Lige’s liking.

“If a soldier can only keep his self-respect by running to his superior officers like a schoolboy when matters are not to his fancy it is time he left the ranks. After we have smelt burning powder I fancy these youngsters 39 will keep a civil tongue in their heads, and until then I had best care for myself.”

This was such good logic that the captain could oppose no solid argument against it, therefore the old soldier received permission for himself and “his recruit” to form camp wherever it should please him, provided, however, that they remained in the ranks while the command was advancing.

Not until after the matter had been thus settled did the captain take it upon himself to warn the corporal that it was not wholly safe to thus separate from his companions.

“It is well known that our movements are being watched by both Tories and Indians,” he said in a friendly manner, such as would not offend the obstinate old soldier, “and you can well fancy that they would not hesitate to do some mischief to any of the expedition whom they might come upon alone.”

40“I can take care of myself, and also the boy,” Corporal ’Lige replied stiffly, as he saluted his superior officer with unusual gravity, and with this the subject was dropped.

Then the old man said to his recruit, as he motioned him aside that others might not get information concerning his purpose:

“We’ll draw such rations as may be served out, lad, and then push ahead to where we can be in the company of sensible people, meaning our two selves.”

Isaac would have felt decidedly more safe if he could remain with the main body of troops, for he had heard the captain’s caution; but he did not think it wise to give such a desire words, and by his silence signified that he was ready to do whatsoever his instructor should deem to be for the best.

The rations served these volunteers who 41 proposed to reduce the forts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point ere they yet knew a soldier’s duties were not generous, and he who, from a desire to avoid seeming greedy, delayed in applying for them, generally found himself without food, save he might be so fortunate as to beg some from his more provident companions.

Corporal ’Lige was exceedingly friendly to his stomach; he made it a rule never to allow modesty to deprive him of a full share of whatever might be served out, therefore it was he had drawn rations for himself and Isaac almost before the troops came to a halt, and the hindermost were yet marching into camp, weary and travel-stained, when he said to his small comrade:

“There is nothing to keep us here longer, and the sooner we are at a goodly distance from these silly youngsters who fancy that 42 the taking of a musket in their hands makes them soldiers, the better I shall be pleased.”

Isaac gave token of willingness to continue the march by shouldering his weapon once more, and the two set off, attracting no attention from their companions-in-arms, each of whom had little thought save to minister to his own comfort, for this soldiering was rapidly becoming more of a task and less of a pleasure-tour than had been at first supposed.

Not until he was fully a mile from the foremost of the main body did the corporal give any evidence of an intention to halt, and then he showed remarkably good judgment in his selection of a camping-place.

At the edge of a small brook about fifty yards from the main road over which they had been traveling, he threw down his knapsack, 43 and announced in a tone of satisfaction that they would spend the night there.

“It is not too far away, and yet at such a distance that we shall not be forced to listen to the gabbling of those geese,” he said as he set about building a small campfire in order to prepare the food he had procured. “Make yourself comfortable, Isaac Rice, for it is a soldier’s solemn duty to gain all the rest he can.”

“Do you think we shall be safe here?” the boy asked almost timidly, for it seemed little short of a crime to question any proposition made by the corporal.

“Safe, lad? What’s to prevent? If you keep your ears open for stories of danger while you are with the army, you’ll never know peace of mind, for there are always those faint-hearted ones ready to exaggerate the falling of a leaf into the coming of the 44 enemy. I have as much regard for my own safety as for yours, and I say that here we can camp in peace and safety.”

This was sufficient for the corporal’s recruit, and he set about making himself comfortable, with the conviction that none knew better than his comrade the general condition of affairs.

45CHAPTER III. AN UNPLEASANT SURPRISE.

Surely this camping by themselves was exceedingly pleasant, Isaac thought, as the old soldier took upon himself the duties of cook, leaving his recruit with nothing to do save watch him as he worked.

On the previous night they had slept in the midst of a noisy throng who chattered and made merry until an exceedingly late hour, thus preventing the more weary from sleeping, and everywhere in the air, hanging like clouds, was the dust raised by the feet of so many men.

Now these two were in the seclusion of the woods, with a carpet of grass for a bed; the 46 rippling brook to lull them to slumber, and nothing more noisy than the insect life everywhere around to disturb their slumbers.

Corporal ’Lige was in a rare good humor. He prepared an appetizing meal, although his materials were none of the best, and when it had been eaten, seated himself by Isaac’s side with pipe in his mouth, ready and willing to spin yarns of his previous experience as a soldier.

The boy was an eager listener; but after a certain time even the tones of the old soldier’s voice were not sufficient to banish the sleep elves, and his eyes closed in unconsciousness just when his comrade had arrived at the most exciting portion of his narrative.

“Perhaps I shan’t be so willin’ the next time you want to hear what I’ve seen in this world,” Corporal ’Lige said testily when he observed that his audience was asleep, and 47 then, knocking the ashes carefully from his pipe, he lay down by the side of his small companion.

It seemed to Isaac that he had hardly more than closed his eyes in unconsciousness when he was aroused by the pressure of some heavy substance upon his hand, and looking up quickly he saw, in the dim light, three men standing over the corporal.

The foot of one of these strangers was upon the boy’s hand, as if he did not think Isaac of sufficient importance either to warrant his taking him prisoner, or to so much as step aside that he might be spared pain.

Before hearing a single word, Isaac understood that these late-comers were no friends of the corporal’s, and he endured the pain in silence, hoping that by so doing he might escape observation.

It was hardly probable the strangers failed 48 to see him, for he had been lying within a few feet of his companion; but that he was not the object of their regard could be readily understood.

The man who had thus pinned the boy to the earth by his heel wore moccasins rather than boots, otherwise Isaac would have received severe injury, and as it was, the corporal’s recruit suffered considerable pain before the foot was finally removed; but yet made no sound.

So far as he could judge by the conversation, these strangers must have been in camp some time before he was awakened, for when he first opened his eyes they were in the midst of an unpleasant conversation with the old soldier, such as had evidently been carried on for some moments.

“If he don’t choose to tell, string him up to a tree,” one of the party cried impatiently 49 at the moment Isaac first became conscious that matters were not running smoothly in this private encampment. “A dead rebel is of more good than a live one, and we have no time to lose.”

“Hang me, if that’s what you’re hankerin’ for!” Corporal ’Lige cried in a voice that sounded thick and choked as if a heavy pressure was upon his throat. “Even though I knew more concernin’ this ’ere expedition than I do, not a word should I speak.”

“We’ll soon see whether you’re so willing to dance on nothing,” the first speaker cried vindictively, and then came noises as if the man was making ready to carry his threat into execution.

“Give him another chance,” one of the Tories suggested. “Let the old fool tell us all he knows of Allen’s plans, an’ we’ll leave him none the worse for our coming.”

50“I know nothing!” the corporal cried in a rage. “Do you reckon the colonel would lay out his campaign before me?”

“It is said he did so before you left Pittsfield.”

“Whoever says that is a liar; but even though he had made the fullest explanations, I would not reveal the plans to you. You must think I’m a mighty poor kind of a soldier if I don’t know how to die rather than play the traitor.”

“You’ll soon have a chance of proving what you can do!” the third man cried angrily, and then it was he stepped forward, leaving Isaac free to do as he thought best.

That these three Tories were bent on hanging the old soldier, or at least so nearly doing so as to frighten him into disclosing all he knew regarding Colonel Allen’s plans, there could be no question, and young Rice, 51 trembling with fear though he was, had no other thought than as to how it might be possible for him to aid his comrade.

It did not seem probable the men were ignorant regarding the boy’s presence, and the only explanation which can be made as to why they failed to secure him is that he was so nearly a child as to appear of but little consequence. They evidently had no thought that he could in any way thwart their purpose, and, therefore, no heed was given to him.

It can readily be imagined that Isaac did not waste much time in speculations as to why he was allowed to remain at liberty.

Now was come the moment when he might repay some portion of the debt he believed he owed Corporal ’Lige, and the only anxiety in his mind was lest he should not do it in proper military fashion.

52He could not even so much as guess what a genuine soldier would do under the same circumstances; but he had a very good idea as to how a boy might extricate himself from such a difficulty, and lost no time in beginning the work.

The three men were so busily engaged trying to frighten the corporal into telling them what he might know of Colonel Allen’s forces as not to heed the noise Isaac made when he rolled himself toward the bushes in that direction where the two muskets had been set up against a tree under the foliage in such manner that they might not be affected by the dew.

It was impossible for him to say exactly what these intruders were doing to Corporal ’Lige, but, from the noises, he judged they had first made a prisoner of the old man by seizing him around the throat, perhaps while 53 he was yet asleep, and now there was every indication that they were making ready to carry out the threat of hanging.

“Give him another chance to tell what he knows,” one of the men cried, and immediately afterward the old soldier replied:

“String me up if you will, for there’s no need of waiting any longer with the idea that I’m goin’ to give you any information, even if I have it.”

“Then up with him!” the man who had first spoken shouted, and Isaac, without looking in that direction, heard the confused noises which told him the enemy were trying to raise the old man to his feet.

By this time the boy had his hand on one of the muskets, and his first impulse was to discharge it full at the intruders; but before he could act, the thought came that there were two shots at his disposal, and he ought 54 to so plan as to make both of them count. He believed it was necessary to work with the utmost speed, lest these three Tories should have hung the corporal before he was ready to interfere, and yet a certain number of seconds were absolutely necessary before he could carry out that plan which had suddenly come into his mind.

With both muskets under his arm he crept cautiously a few paces onward until screened by the foliage, and then raising one of the weapons, took deliberate aim at the nearest enemy.

There was no thought in his mind that he was thus compassing the death of a human being. He only knew his comrade’s life was in danger, and that a well-directed shot might save him.

The three men had by this time gotten a rope around Corporal ’Lige’s neck, and, finding 55 that it was difficult to raise the old man to his feet, were throwing the halter over the limb of the nearest tree as a method of saving labor.

One of the Tories, he who appeared to be the elder, and who was directing the movements of the others, stood a few paces from his comrades, and, taking deliberate aim at him, Isaac shouted:

“Throw down your weapons, and surrender, or you are dead men!”

The words had but just been spoken when he discharged the musket, and a scream of pain from the living target told that the bullet had sped true to its mark.

The two men who were as yet unarmed dropped the rope they were holding and sprang toward their weapons, which had been left on the ground near by; but before they could reach them, Isaac had emptied a 56 second musket, and another cry of pain rang out.

“Throw down your weapons and surrender, or you are dead men!” he shouted again, and at this the third Tory, who must have believed there was more than one man in the thicket, took to his heels in alarm, while Corporal ’Lige, who had received no worse injury than a severe choking, seized upon the three muskets which were lying close beside him.

Even now, when two of the intruders were wounded and the third running for dear life, Isaac was doubtful as to whether he should show himself.

He remained in concealment, while the corporal gazed around him in surprise for a dozen seconds or more, and gave no token of his whereabouts until the old man shouted:

“Hello, friends! Show yourselves!”

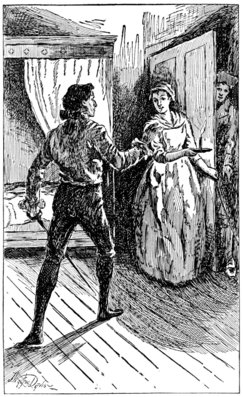

57“Is it all right?” Isaac asked timidly, and in a tone which was little better than a squeak. “Is it all right, corporal?”

“Come in here, Isaac Rice. Can it be it was you who fired those shots?”

The raw recruit came forward almost timidly, and Corporal ’Lige, shifting the three muskets he had taken possession of over on to his left arm, seized the boy by the hand.

“I’ve done a good bit of soldierin’ in my day, lad; seen surprises, an’ ambushes, an’ attacks of a similar kind without number; but never did I know of anything that was done with more neatness an’ dispatch than this same job of yours, which has saved my neck from bein’ stretched. I’m proud of you, lad!”

Isaac was overwhelmed by this praise, yet not to such an extent but that there was a 58 great fear in his mind lest he had taken a human life, and he asked anxiously:

“Do you suppose I hurt either of them seriously, Corporal ’Lige?” and he pointed to where the wounded men lay.

“It is to be hoped you killed ’em both, so that we may be spared any further trouble with the vermin,” and not until then did the corporal condescend to give any attention to those enemies who had been so sadly worsted by a boy.

Just at this moment the wounded Tories suffered more in mind than in body, for they now understood who had made the attack upon them, and it can readily be fancied that both were ashamed at having been thus defeated in their purpose by one whom they had considered of so little importance that no effort was made to deprive him of his liberty when they surprised the encampment.

59It was with the most intense relief that young Rice heard the corporal’s report, which was to the effect that he who had acted as leader of the party had a severe but apparently not exceedingly dangerous wound in the shoulder, while his comrade was suffering from a bullet-hole in the leg.

“They’re disabled, lad, but not killed, an’ the first bit of soldierin’ that you have been called on to do is like to give great credit with such as Colonel Allen and Colonel Easton. Tell me how you happened to think of overcoming them in this shape?”

“I didn’t think of it,” the boy replied. “It seemed to me you were like to be hanged and I only did what was in my power.”

“I came nigher to havin’ my neck stretched than ever before, an’ as it was, the villainous Tories pulled mighty hard on that rope, before you effected the rescue; but, lad, you 60 must have thought! This attack you made in such a soldierly fashion wasn’t the result of chance, an’ that I’ll go bail.”

It was useless to make any attempt at convincing Corporal ’Lige of what was only the truth.

The old man was so determined to look upon the rescue as a soldierly act that he would not accept any other explanation, and the boy ceased his fruitless efforts by asking:

“What is to be done with these two Tories?”

“I reckon they must be got back to camp, although it would be no more than servin’ ’em right if we put an end to their miserable lives without further parley.”

“Oh, you wouldn’t kill them in cold blood, Corporal ’Lige?” Isaac cried in alarm.

“No; I don’t reckon I would, though that’s what ought to be done with ’em. It’s plain 61 you an’ I can’t lug the two a matter of a mile or more, so one must stand guard over ’em while the other goes back to the camp. I’m leavin’ it to you to say which service you’ll perform, for after this night’s work I’m willin’ to admit that my recruit has in him the makin’s of a better soldier than I can ever hope to be.”

The boy gave no heed to this praise at the time, although later he remembered the words with pleasure.

Now there was in his mind a fear lest the corporal should desire him to guard the prisoners, and, the more imminent danger over, he was growing exceedingly timorous.

“I’ll go back to the encampment if it so please you, Corporal ’Lige, because I can run faster than you.”

“As you will, lad, as you will. Explain to Colonel Ethan Allen what has happened here 62 and let him say how these venomous snakes are to be treated.”

During this conversation neither of the wounded men had spoken; but now, as the boy was about to set out for the encampment, he who had evidently acted as the leader cried sharply:

“Hold on a bit! What is the sense of sending us into your camp when we are like to die? Why not give us a show for our lives?”

“In what way?” Corporal ’Lige asked sternly.

“By allowing us to go to our homes.”

“That will do,” the old soldier said angrily. “After your attempt to kill me I’m not such a simple as to let you go scot free. Get you gone, lad, and make the report to Colonel Allen as soon as may be.”

The wounded Tory continued to plead with 63 the corporal; but Isaac did not wait to hear anything more.

He set out at full speed down the road in the direction where the troops were encamped, running at his best pace, and fearing each instant lest that Tory who had made his escape should suddenly come upon him.

64CHAPTER IV. THE LETTER.

When Isaac was come within hailing distance of the few sentinels who had been posted to guard against a surprise, he was astonished at being halted after having announced who he was, and the laxness of military discipline can be understood when it is said that, after being recognized by the recruit at that particular post, the boy was allowed to enter the encampment without further question.

Colonel Allen was not better lodged than his men. A lean-to formed of a few boughs was the only shelter he had, and Isaac was forced to search among the sleeping soldiers 65 several moments before discovering the whereabouts of the commander.

Once this had been done it was but the work of a few seconds to acquaint the officer with what had occurred, and at this evidence that the Tories were dogging the little army, more than one recruit who had boasted the loudest as to what he would do when the time for fighting should come, turned suspiciously pale as he approached to hear all Isaac was saying.

“Why did Corporal Watkins camp by himself?” Colonel Allen asked when the boy concluded his report.

“Because some of the men poke fun at him, allowin’ that he’s too old to be of service, an’ far too crochety to make any fist at bein’ a soldier,” Isaac replied promptly.

“I wish from the bottom of my heart that I had one hundred men like him, rather than 66 some of the braggarts who do not know there is such a work as the manual of arms,” the colonel said in a loud voice, as if desirous that all should hear. “Tell the corporal that he will camp with this force in the future, and I shall make it my especial business to learn who it is that dares make matters uncomfortable for him.”

Then, to the captain of the company to which Corporal ’Lige was attached, an order was given that a squad of men be sent forward to bring in the prisoners, and when this had been obeyed the old soldier, as a matter of course, returned with them.

From that night Isaac heard nothing more regarding the wounded Tories. It was said they had been sent back to Pittsfield under a strong guard, and certain it is they disappeared from the encampment before daybreak, but neither the boy nor the corporal 67 could find a single man who had seen them depart.

This incident, and it was hardly to be spoken of as anything of importance, together with Colonel Allen’s remark, served to render Corporal ’Lige’s life more pleasant, for those who had used him as the butt of their mirth began to understand that he was superior to themselves, in a soldierly way, and more than one sought his advice on various occasions.

At sunset on the seventh day of May the raw recruits had arrived at Castleton, fourteen miles east of Skenesborough, and Isaac himself has given the details of that straggling march through the country, in the first letter written to his mother after setting out as a soldier:

“May the Eighth, 1775.“My Dear Mother, Father, and Children:“We have been camping here in this 68 thicket since last night, and if there is anybody in all the company more tired of soldiering than I am, I would like to meet him. I wore a hole in the heel of my stocking on the second day, and got such a blister because of it that I’ve been obliged to go barefoot ever since.

“We have had plenty to eat, for the folks along the road were most kind; but it’s sleeping that has been the worst on me, though the corporal says I never can hope to be a soldier till I’m able to lay down in three or four inches of water and get as much rest as I would at home in bed. I tell him I don’t hope to be one any more, for I’ve had about enough of it, though of course I shall stick by the company till we’ve taken the fort, and it’s pretty certain we shall do that, because now there are two hundred and seventy men in the ranks.

“Colonel Easton enlisted thirty-nine of his militia before we got to Bennington, and 69 there we were joined by the Green Mountain Boys under the command of Colonel Ethan Allen.

“It surprised me to find that a good many of the people don’t believe we are doing right in trying to take away the fort from the king’s troops, and the corporal says that unless this thing is a success we are all like to be hanged for traitors, because his majesty will make an example of them who are foremost in the work—which means us.

“Two hours after we halted last night Colonel Benedict Arnold, who is said to have gone from New Haven as captain of a company, to Cambridge, arrived here with a few men and a large amount—so it seems to me—of military supplies.

“Although knowing that Colonel Allen is in charge of this force, he claimed the right to take command, and, so the corporal says, made display of a commission signed by the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, declaring 70 that it entitled him to take charge of all the troops. Now, although I’m not a soldier—the corporal says I never will be—I’ve got sense enough to understand that if I enlisted under Colonel Easton, and was willing he should give way to Colonel Allen so we might have the Green Mountain Boys with us, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety have got nothing to do with saying who shall lead in the battle—though I hope to goodness we shan’t see one.

“The corporal says that no committee is going to scare Ethan Allen, and it’s certain, so those of the Green Mountain Boys with whom I’ve talked say, that this stranger won’t get himself into command of the company, even though, as is said, he brings one hundred pounds in money, two hundred pounds’ weight of gunpowder, the same of leaden balls, and one thousand flints, to carry all of which, and himself, he has ten horses.

71“Now, the corporal claims that these things, including the money, are munitions of war, and that if Colonel Arnold doesn’t deliver them over to Colonel Allen, they will be taken from him, and he, Corporal ’Lige, I mean, went early this morning to Master Phelps, offering to see to it that this property was delivered up to us; but for some reason or other—neither the corporal nor I can understand what—his offer was not accepted.

“I have heard it said, and the corporal is of the opinion it is true, that when the council of war was held last night before this gentleman from New Haven arrived, Colonel Allen was chosen commander of the whole expedition, Colonel Easton second in command, and Seth Warner third. It was decided that the greater number of us, with the principal officers, would march from here to Shoreham—which you know is opposite Ticonderoga—and Captain Herrick with thirty men would at the same time go to Skenesborough to 72 capture young Major Skene, whose father, the governor, is now in England; seize all the boats they can find, and join us at Shoreham. Captain Douglas is to go to Panton with a small troop, and get whatever craft is in the water roundabout. The corporal says he shall be quite well satisfied with this arrangement, providing the remainder of the plan is mapped out as he thinks right.

“However, nobody seems to know whether Colonel Arnold will manage to get his commission from the Massachusetts Committee of Safety recognized as good and sufficient authority for him to lord it over our people, and we ask each other what will become of his munitions of war in case he doesn’t, or how may the plans be changed if he does?”

“What I can’t understand in this whole business is why the corporal shouldn’t be the third officer in command, instead of Master Warner, who I have no doubt is a very worthy gentleman; but of course cannot 73 claim to be any such soldier as Corporal ’Lige. He says there’s always a lot of jealousy among officers in the army, and that’s why he isn’t to be given a chance to show how much he can do.”

“The food I brought from home was used up the second day—the corporal had what he called a ‘coming appetite’—and perhaps it was just as well, for I had all the load any fellow could want to carry. I never believed before leaving home that father’s musket was so heavy; I held it over my shoulder until it seemed as if the flesh was worn right down to the bone; then lugged it in my hand till my arm ached as if it was going to drop off, and I verily believe I would have thrown the thing away but that Corporal ’Lige said a soldier didn’t amount to very much unless he had a weapon of some kind.”

“The corporal says I am to give you his dutiful compliments, and to say that if his 74 life is spared, by the blessing of God, he will capture Ticonderoga before we come back.

“As for me, I wish I was at home now, though it will be a fine thing if we do what the old man says is our duty in these times, without being hanged.

“I haven’t yet found out why people think there is so much honor to be gained in being a soldier. To my mind it’s much like any other way of running around the country; but the corporal says if he had the management of affairs things would be different, because he’d keep the men right up to their work, though I don’t see how it could well be done. For my part, I shouldn’t carry a musket over my shoulder when I was lame and tired just because any man said so. It would be as well whatever fashion I lugged it, providing the labor was lessened; but the corporal says it would make all the difference in the world if we marched the same as we would at a muster.

75“I love you all very much, and shall be precious glad to find myself at home again.

“From your obedient and dutiful son,

“Isaac Rice.”

In this letter the young recruit, who although having enjoyed the teachings of Corporal ’Lige, was certainly not a soldier at heart, has told the main facts in the case regarding the halt of the militia at Castleton; but it will be observed that his modesty was too great to permit of his mentioning the brave part he played in the rescue of Corporal ’Lige from the Tories.

He has failed, however, most probably through ignorance, in giving Colonel Arnold’s authority for claiming his right to lead the expedition.

That officer had brought to Cambridge from New Haven a company of which he was 76 the captain, and upon arriving there at once reported to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety that it would be possible, before the forts had been reinforced, to seize the works at Ticonderoga and Crown Point with a comparatively small body of men.

He proceeded to organize an expedition for such a purpose, and to this end was supplied with the money and munitions of war mentioned by Isaac, together with a colonel’s commission, which gave him the chief command of troops, not exceeding four hundred in number, which he might raise to accompany him against the lake fortresses.

Upon arriving at Stockbridge, in the province of Massachusetts, he learned that another expedition had set out—that is to say the same one Corporal ’Lige and Isaac accompanied—and after engaging officers and men to the number of fourteen he hastened 77 onward, overtaking the militia as Isaac has said.

In this camp where military discipline was conspicuous by its absence, the recruits, who had learned within the hour what had been decided upon the night previous by the council of war, soon ascertained the position which the officer from New Haven claimed, and knew exactly what he proposed to do by virtue of his commission.

Even though the men had not learned such facts from their officers, those recruits who accompanied Colonel Arnold would have at once made the matter public.

At about the time Isaac finished the letter to his mother the encampment was in a state bordering on insubordination.

Colonel Arnold’s recruits raised in Stockbridge insisted that their leader should command the forces, not only because he was 78 authorized to do so, but owing to the fact that he had the money and ammunition necessary to carry out the plan, while the members of Colonel Allen’s regiment, known as the Green Mountain Boys were equally determined that such honor as might be gained should be their colonel’s, and in a brief space of time these new-fledged patriots were ripe for riot.

Now was come the hour when Corporal ’Lige had shown him some portion of that consideration which he believed due his experience in military affairs.

Those members of Colonel Easton’s militia regiment which had joined the expedition, jealous because their leader had given way to Colonel Allen, now demanded loudly and publicly that he must lead the party or they would turn back.

Inasmuch, however, as this portion of the 79 troops amounted to fifty or thereabouts, they had a small showing when the Green Mountain boys, who were more than two hundred strong, came forth in turn with their threats.

Colonel Allen was to be retained first in command, as had been decided upon the previous evening, or they should march back to Bennington without an hour’s delay.

On the other hand, the men from Stockbridge insisted that Colonel Arnold was the lawful commander because he was the only one who held a commission for such purpose, and threatened that neither money nor munitions of war should be given up unless his claims were fully recognized.

On this morning of the eighth of May the men were divided into three divisions according to their opinions, and it seemed much as if the officers were willing they should settle it without interference, for 80 those highest in command remained in council among themselves, giving no heed to the threats which were uttered here and there until it seemed positive personal encounters must soon take the place of words.

The men from round about Pittsfield, recognizing the need of a leader in what might properly be termed a mutiny, selected Corporal ’Lige as if by common consent, and Isaac had but just written his mother’s name on the missive which had cost him so much labor, when he and the corporal were surrounded by the faction to which belonged their neighbors and friends.

One of these, a butcher, whose home was in Pittsfield, thus addressed the old man, using at the beginning of his remark just that compliment best calculated to please him.

“You, who have had so much experience 81 in military affairs, Corporal ’Lige, should be able to settle this matter without any great loss of time, for according to my way of thinking it must be arranged among the men themselves, or not at all.”

“I have seen plenty of fightin’,” the corporal began slowly, as if undecided what words had best be used; “but it was in the king’s army, as you well know, and there every one in command held their commission from his majesty, which plainly said he was to be the leader. Now it seems in this ’ere case that the only officer who has any real authority is the one from New Haven——”

A chorus of derisive howls interrupted the old man, and not a few of his neighbors accused him of being a traitor because he was apparently on the point of giving his decision in favor of the stranger.

Waiting patiently until they had exhausted 82 their anger, and were silent once more, he continued placidly:

“As I said before it seems to me the only one with any show of authority is the officer from New Haven; but,” and Corporal ’Lige emphasized this word, “but what do you know of this ’ere Massachusetts Committee of Safety? Accordin’ to my way of figurin’, that body of men are lookin’ out for matters round about Boston, and we’ve got with us recruits all the way from Pittsfield up to Bennington, none of whom are given overmuch to heedin’ what the Boston folks think is right or wrong. Therefore I say, that while the officer from New Haven seems to have the only real authority, it strikes me that his commission does not extend as far as this ’ere spot, where we are encamped.”

Again he was interrupted; but this time by cries expressive of satisfaction and good will.

83“We were the ones who started the idea of taking the fort,” a recruit from Pittsfield cried, “and that being the case I hold we’ve got the right to say who shall lead us.”

“But the Green Mountain Boys won’t go except their colonel is in command,” another added, and a third cried:

“The men of Stockbridge will hold to Colonel Arnold, and won’t go on under another.”

“Well, I’ve heard all that before,” Corporal ’Lige said in a tone of fine irony. “If you have come to me to repeat the same story that has been goin’ ’round the encampment since daybreak, why then you are wastin’ your time. If you want my opinion so that this thing can be put right in short order, hold your tongues, an’ I’ll give it.”

“Let Corporal ’Lige finish.”

“He is soldier enough to know what should be done.”

84“Go on, corporal, go on.”

This evidence of popularity was most pleasing to the old man, and smiling benignantly upon those nearest, he said, with the air of one who cannot be in the wrong:

“This is how it must be done: Let them as come with Colonel Easton, stick to him; the Green Mountain Boys shall hang to the tail of Colonel Allen’s coat, and the Stockbridge men may follow Colonel Arnold. That makes three bands of us. Now, mark you, lads, there are three sides to that ’ere fort—one apiece. Let us meet here at whatever hour you will, and then start on the minute, each troop taking a different course, an’ them who arrive first an’ capture the fortification, gets the credit.”

“But we are needing what Colonel Arnold brought with him,” someone cried.

“Ay, and you would have heard me fix that 85 if you’d waited. Where did this ’ere Massachusetts Committee of Safety get these munitions of war an’ this money? Why, they got it out of the province, of course. And where did we come from? Why, we come from the province of Massachusetts, of course. Then who does this money and these munitions of war belong to? Why, they belong to us, of course. Now, as near as I have heard, there are only fourteen following Colonel Arnold. How long will it take us to lay our hands on all that stuff? Then I guarantee that Colonel Easton—for if he wants me to do it I’ll help him in conducting the campaign—will march straight through an’ take Ticonderoga before you’ve had time to say Jack Robinson. Never mind what the Green-Mountain Boys do, an’ as for the Stockbridge men, they ain’t enough for the countin’.”

86The advice which Corporal ’Lige had given met with the unqualified approval of all whom he addressed, and instantly shouts were raised in his honor until those recruits who were not in the secret looked about them in alarm and dismay as if fearing an attack.

Isaac was frightened, of that there could be no mistake.

It seemed to him as if an immediate and unquestionably dangerous encounter could not be prevented, for already were the men hanging about Corporal ’Lige in a dense body as bees hang about their queen when swarming, all urging that he lead them on to wrest from the Stockbridge men the property which he had proven did not belong to them.

Isaac glanced this way and then as if trying to determine in which direction it would 87 be safest to flee, but at this moment his eyes fell upon a lad of about his own age, who had come in from the highway and was staring about him in perplexity.

88CHAPTER V. NATHAN BEMAN.

In his fear and trouble it seemed to Isaac as if this stranger might render him some valuable assistance.

It was as if he stood alone amid the recruits, now that Corporal ’Lige had been claimed, so to speak, as leader of the Pittsfield faction, and the lad needed some one to whom he could appeal for advice.

Therefore it was that while the new-comer was staring about him as if distracted by the tumult, Isaac approached in the most friendly manner as he asked:

“Are you a recruit?”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Do you belong to the soldiers here?”

89“Do you call these soldiers?” the stranger asked almost contemptuously.

“Well, if they ain’t, what do you call them?”

“They look to me like a crowd of folks what was goin’ to have a fight pretty soon.”

“That’s jest what I’m afraid of. Say, do you live near here?”

“No, I came from Shoreham. We heard there was a crowd comin’ to take Fort Ticonderoga, an’ seein’s how they didn’t get along very fast, I thought I’d come an’ hunt ’em up. Do you count yourself a soldier?”

“I did when I left Pittsfield; but I’ve kind’er got over that feelin’ now. What’s your name?”

“Nathan Beman.”

“Mine’s Isaac Rice.”

“What made you come out with a crowd like this?”

90“All the folks ’round our way was enlisting, and they said it was the duty of everybody to fight against the king. Besides that the corporal was going, an’ he agreed to put me through in great shape.”

“Who’s the corporal?”

“That’s him over there with the red coat on.”

“Do you allow an old chap like him could put anybody through in very great shape?”

“You mustn’t talk like that about Corporal ’Lige where anybody will hear you. Why, he’s a regular soldier; fought under General Abercrombie in ’58, an’ I reckon if it hadn’t been for him the king’s troops would have got it terrible bad.”

“An’ that’s about the way they did get it.”

“Well, Corporal ’Lige is here now, an’ it’ll be different. Did you ever see the fort?”

“See it? Why, I’m over there pretty near 91 very week. Our folks sell eggs an’ chickens an’ such truck to the garrison, an’ I know the place jest like I do my own home.”

“Do you s’pose we can take it?”

“There seems to be a sight of you here; but I shouldn’t want to make a guess till after I’d seen whether there’s going to be a row among all hands or not. Father says when thieves fall out honest men get their due.”

However frightened Isaac might be, he was not disposed to allow any boy of his own size to call the members of this army thieves, even though they were in a state of insubordination, and forgetting all his fears he demanded sternly:

“Who are you calling thieves?”

“Now, you needn’t get so huffy, ’cause I didn’t mean anything,” Nathan replied quietly, and yet with no show of alarm; 92 “but father is always sayin’ that, an’ I s’pose it means—well I don’t know what, except that all hands of you are fightin’ here, an’ it looks like as if Captain Delaplace would get the best of it.”

“Who’s he?”

“The commandant of the fort, of course.”

“Well, see here, Nathan, it begins to look as though there was goin’ to be a row for a fact, and I hoped you lived close by so I could go to your house till it was over.”

“But you’re a soldier, ain’t you?”

“Not much of one.”

“Well, if you’ve enlisted, a fight is right where you belong,” and Nathan appeared to think this settled the matter beyond any argument.

“I ain’t so certain of that; but even if I do belong in a fight I shan’t stay in one. It seems like as if Corporal ’Lige had turned 93 me off, an’ all he’s thinking about is helping our crowd get the best of the Stockbridgers.”

“Well, there ain’t anything very dangerous here yet awhile; suppose we wait an’ see how things turn? I don’t care overmuch for fightin’ myself; but that’s no reason why I shouldn’t want to know whether there’s likely to be a row or not.”

Isaac admired the courage of his new acquaintance and immediately adopted him as a protector, taking up his position a pace or two in the rear of Nathan as he watched the threatening movements.

The recruits from Pittsfield and vicinity were standing in close order with the corporal at their head, evidently ready for whatever turn might come in affairs.

Some of them retained their weapons; but the majority appeared to have more confidence in their fists, and with arms bared to 94 the elbow were awaiting the word which would precipitate them upon the small body from Stockbridge who guarded the treasure.

This last detachment had either learned of the advice given by Corporal ’Lige, or scented danger because they were so few in numbers as compared with the other two factions, and were standing shoulder to shoulder ready to resist an expected attack.

A short distance away the Green-Mountain Boys remained strictly by themselves; but not giving any sign of taking part in the lawless proceedings. So long as Ethan Allen was considered the head of the expedition they were satisfied to stand aloof from any brawl.

As has been said before, the leading officers were nowhere to be seen; some of the better informed declared they were in the shelter near by which had been used as 95 their quarters during the night, and with Colonel Arnold were discussing the question of superiority in rank.

Corporal ’Lige hesitated to give the word which should precipitate the riot.

He had been elevated to the position of leader and perhaps the responsibility weighed heavily upon him, for certain it is that after advising what should be done, he evinced a disposition to retire from what might be the scene of a conflict.

“Look here, old man, we’re ready to do as you have said. Now give the word and lead us on to those recruits. We’ll soon find out what they’re made of,” one of the men said as the corporal turned toward the rear much as though intending to join Isaac and Nathan:

“Yes, give the word. This is your plan, and we’re ready to carry it out as you have said!”

96“Fair an’ easy; fair an’ easy, comrades,” Corporal ’Lige said soothingly. “A good general doesn’t depend wholly on his plan until he’s made certain of the enemy’s position. You don’t allow that we can rush in hilter-skilter an’ hope to work our purpose, eh?”

“Why not? There are only a dozen of them to near fifty of us.”

“But look at Colonel Allen’s regiment.”

“Well, what of them? They are not in this quarrel, for their commander is leader of the expedition so far.”

“No, they are not in it,” the corporal said; “but what assurance have we they won’t take a hand as soon as we begin operations? Don’t you allow they know what the Stockbridge men brought with them?”

“Why, everybody in camp knows that.”

“Then do you suppose they’re goin’ to 97 stand by idly while we take the money and munitions?”

The men began to murmur among themselves, and Corporal ’Lige appeared well satisfied that they should thus consume the time; but before many minutes had passed one and another spoke derisively of the old man, asking what his plan was good for if he didn’t dare carry it out, or why he had not made mention of what Colonel Allen’s men might do in event of his suggestion being acted upon?

At first the corporal was not minded to take heed of these disparaging remarks; but as the clamor increased he was forced to defend himself, and made answer sharply:

“The plan was good, and the only one likely to succeed. When I got that far with it you jumped to the idea that it should be worked out at once. Now all the while I 98 was keeping my eye fixed on Colonel Allen’s men, tryin’ to make up my mind what they’d do when we struck the first blow, and I haven’t decided yet.”

“You’re a coward! You claimed to be an old soldier, and to know more of warfare than any one in this encampment, not excepting the commanders, but yet you don’t dare lead fifty men against a dozen!”

“If I don’t dare it isn’t because I’m afraid of bodily injury; but I can’t afford to stake my reputation as a soldier where the chances are likely to be so heavy against us. It’s one thing to have a good plan, an’ just as important to know when to carry it out. If we hang together an’ are ready to take advantage of the first opportunity that comes, then we’ll be showing our strength; but not by rushing in hilter-skilter like a crowd of boys primed for a rough-an’-tumble fight.”