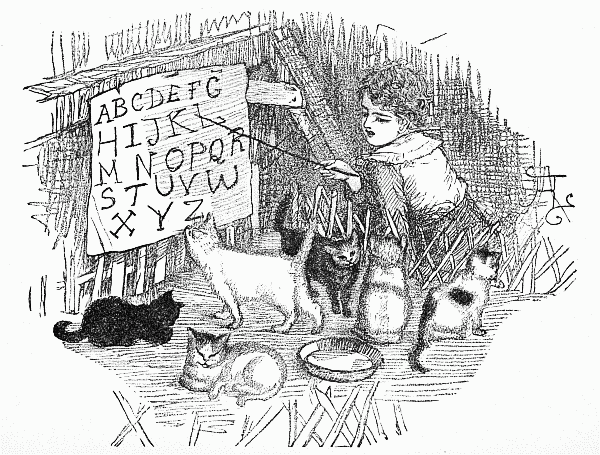

"Johnny spent hours and hours reading the letters over to the kittens."—Page 38.

"Johnny spent hours and hours reading the letters over to the kittens."—Page 38.

Title: Mammy Tittleback and Her Family: A True Story of Seventeen Cats

Author: Helen Hunt Jackson

Illustrator: Addie Ledyard

Release date: July 24, 2010 [eBook #33240]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Sharon Verougstraete and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

AUTHOR OF "RAMONA," "NELLY'S SILVER MINE," "BITS OF TALK," ETC.

Letters From a Cat.

Mammy Tittleback and her Family.

The Hunter Cats of Connorloa.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

BOSTON: ROBERTS BROTHER'S. 1886.

Mammy Tittleback

and

Her Family.

A TRUE STORY OF SEVENTEEN CATS.

By H. H.,

AUTHOR OF "BITS OF TALK," "BITS OF TRAVEL," "BITS OF TALK FOR YOUNG

FOLKS," "NELLY'S SILVER MINE," AND "LETTERS FROM A CAT."

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY ADDIE LEDYARD.

BOSTON:

ROBERTS BROTHERS.

1886.

Copyright, 1881,

The Preface is at the end of the book, and nobody must read it till after reading the book. It will spoil all the fun to read it first.

| I. | ||

| MAMMY TITTLEBACK. | ||

| II. | ||

| Juniper, | Mammy Tittleback's first kittens. | |

| Mousiewary, | ||

| III. | ||

| Spitfire, | Mammy Tittleback's second family of kittens. |

|

| Blacky, | ||

| Coaley, | ||

| Limbab, | ||

| Lily, | ||

| Gregory 2D, | ||

| IV. | ||

| Tottontail, | Mammy Tittleback's adopted kittens. | |

| Tottontail's Brother, |

||

| (sometimes called | ||

| Grandfather), | ||

| V. | ||

| Beauty, | Mammy Tittleback's first grandkittens, being the first kittens of Mousiewary. |

|

| Clover, | ||

Mammy Tittleback is a splendid great tortoise-shell cat,—yellow and black and white; nearly equal parts of each color, except on her tail and her face. Her tail is all black; and her face is white, with only a little black and yellow about the ears and eyes. Her face is a very kind-looking face, but[10] her tail is a fierce one; and when she is angry, she can swell it up in a minute, till it looks almost as big as her body.

Nobody knows where Mammy Tittleback was born, or where she came from. She appeared one morning at Mr. Frank Wellington's, in the town of Mendon in Pennsylvania. Phil and Fred Wellington, Mr. Frank Wellington's boys, liked her looks, and invited her to stay; that is, they gave her all the milk she wanted to drink, and that is the best way to make a cat understand that you want her to live with you. So she stayed, and Phil and Fred named[11] her Mammy Tittleback after a cat they had read about in the "New York Tribune."

Phil and Fred have two cousins who often go to visit them. Their names are Johnny and Rosy Chapman; and if it had not been for Johnny and Rosy Chapman, there would never have been this nice story to tell about Mammy Tittleback: for Phil and Fred are big boys, and do not care very much about cats; they like to see them around, and to make them comfortable; but Johnny and Rosy are quite different. Johnny is only eight and Rosy six, and they love cats and kittens better than any[12]thing else in the world; and when they went to spend this last summer at their Uncle Frank Wellington's, and found Mammy Tittleback with six little kittens, just born, they thought such a piece of luck never had happened before to two children.

Juniper and Mousiewary had been born the year before. Phil named these. Juniper was a splendid great fellow, nearly all white. At first he was called "Junior," but they changed it afterward to "Juniper," because, as Phil said, they didn't know what his father's name was, and there wasn't any sense in calling him "Junior,"[13] and, besides, "Juniper" sounded better.

Mousiewary was white, with a black and yellow head. Phil called her "Mousiewary" because she would lie still so long watching for a mouse. She was a year and a half old when Johnny and Rosy went to their Uncle Frank's for this visit, and she had two little kittens of her own that could just run about. They were wild little things, and very fierce, so Phil had called them the Imps. But Johnny and Rosy soon got them so tame that this name did not suit them any longer, and then they named them over again "Beauty" and "Clover."[14]

Mammy Tittleback's second family of kittens were born in the barn, on the hay. After a while she moved them into an old wagon that was not used. This was very clever of her, because they could not get out of the wagon and run away. But pretty soon she moved them again, to a place which the children did not approve of at all; it was a sort of hollow in the ground, under a great pile of fence rails that were lying near the cowshed.

This did not seem a nice place, and the children could not imagine why she moved them there. I think, myself, she moved them to try and [15]hide them away from the children. I don't believe she thought it was good for the kittens to be picked up so many times a day, and handled, and kissed, and talked to. I dare say she thought they'd never have a chance to grow if she couldn't hide them away from Johnny and Rosy for a few weeks. You see, Johnny and Rosy never left them alone for half a day. They were always carrying them about. When people came to the house to see their Aunt Mary, the children would cry, "Don't you want to see our six kittens? We'll bring them in to you." Then they would run out to the barn, take a[16] basket, fill it half full of hay, and very gently lay all the kittens in it, and Johnny would take one handle and Rosy the other, and bring it to the house. They always put Mammy Tittleback in too; but before they had carried her far, she generally jumped out, and walked the rest of the way by their side. She would never leave them a minute till they had carried the kittens safe back again to their nest. She did not try to prevent their taking them, for she knew that neither Johnny nor Rosy would hurt one of them any more than she would; but I have no doubt in her heart she disliked to have the kittens touched.

The children worried a great deal about this last place that Mammy Tittleback had selected for her nursery. They thought it was damp; and they were afraid the rails would fall down some day and crush the poor little kittens to death; and what was worst of all, very often when they went there to look at them, they could not get any good sight of them at all, they would be so far in among the rails.

At last a bright idea struck Johnny. He said he would build a nice house for them.

"You can't," said Rosy.

"I can too," said Johnny. "'Twon't[18] be a house such as folks live in, but it'll do for cats."

"Will it be as nice as a dog's house, Johnny?" asked Rosy.

"Nicer," said Johnny; "that is, it'll be prettier. 'Twon't be so close. Cats don't need it so close; but it'll be prettier. It's going to have flags on it."

"Flags! O Johnny!" exclaimed Rosy. "That'll be splendid; but we haven't got any flags."

"I know where I can get as many as I want," said Johnny,—"down to the club-room. They give flags to boys there."

"What for, Johnny?" asked Rosy.[19]

"Oh, just to carry," replied Johnny proudly. "They like to have boys carrying their flags round."

"Do you suppose they'll like to have them on a cat's house?" asked Rosy.

"Why not?" said Johnny; and Rosy did not know what to say.

Very hard Johnny worked on the house; and it was a queer-looking house when it was done, but it was the only one I ever heard of that was built on purpose for cats. It was about eight feet square; the central support of it was an old saw-horse turned up endwise, with a mason's trestle on top; the roof was made of[20] old rails, and had two slopes to it, like real houses' roofs; the sides were uneven, because on one side the rails rested on an old pig-trough, and on the other on a wooden trestle which was higher than the trough. This unevenness troubled Johnny, but it really made the house prettier. The space under this roof was divided by rows of small stakes into three compartments,—one large one for Mammy Tittleback and her six youngest kittens; Mousiewary and her two kittens in another smaller room; and the adopted kittens and Juniper in a third. I haven't told you yet about the adopted kittens, but I[21] will presently. These three rooms had each a tin pan set in the middle, and fixed firm in its place by small stakes driven into the ground around it. Johnny was determined to teach the cats to keep in their own rooms, and that each family must eat by itself. It wasn't so hard to bring this about as you would have supposed, because Johnny and Rosy spent nearly all their time with the cats, and every time any cat or kitten stepped over the little wall of stakes into the apartment of another family, it was very gently lifted up and put back again into its own room, and stroked and told in gentle voice,[22]—

"Stay in your own room, kitty."

And at meal-times there was very little trouble, after the first few days, with anybody but Juniper. All the rest learned very soon which milk-pan belonged to them, and would run straight to it, as soon as Johnny called them. But Juniper was an independent cat; and he persisted in walking about from room to room, pretty much as he pleased. You see he was the only unemployed cat in the set. Mammy Tittleback had her hands full,—I suppose you ought to say paws full when you are speaking of cats,—with six kittens of her own and two adopted ones; and Mousie[23]wary was just as busy with her two kittens as if she had had ten; but Juniper had nobody to look after except himself. He was a lazy cat too. He always used to walk slowly to his meals. The rest would all be running and jumping in their hurry to get to the house when Johnny and Rosy called them; but Juniper would come marching along as slowly as if he were in no sort of hurry, in fact, as if he didn't care whether he had anything to eat or not. But once he got to the pan he would drink fully his share, and more too.[24]

Now I must tell you about the adopted kittens. They belonged to a wild cat who lived in the garden. Nobody knew anything about this cat. She was a kind of a beggar and thief cat, Johnny said. She wouldn't let you take care of her, or get near her; and the only reason she took up her abode in the garden with her kittens was so as to be near the milk-house, and have a chance now and[25] then to steal milk out of the great kettles. One day the children found the poor thing dead in the chicken yard. What killed her there was nothing to show, but dead she was, and no mistake; so the children carried her away and buried her, and then went to look for her little kittens. There were four of them, and the poor little things were half dead from hunger. Their mother must have been dead some time before the children found her. They were too young to be fed, and the only chance for saving their lives was to get Mammy Tittleback to adopt them.

"She's got an awful big family[26] now," said Phil, "but we might try her."

"She won't know but they're her own, if we don't let them all suck at once," said Johnny; "but it wouldn't be fair to cheat her that way."

"Won't know!" said Phil. "That's all you know about cats! She'll know they ain't hers as quick as she sees them."

It was a very droll sight to see Mammy Tittleback when the strange kittens were put down by her side. She was half asleep, and some of her own kittens had gone to sleep sucking their dinners; but the instant these poor famished little things were put[27] down by her, two of them began to suck as if they had never had anything to eat before, since they were born. Mammy Tittleback opened her eyes, and jumped up so quick she knocked all the kittens head over heels into a heap. Then she began smelling at kitten after kitten, and licking her own as she smelled them, till she came to the strangers, when she growled a little, and sniffed and sniffed; if cats could turn up their noses, she'd have turned up hers, but as she couldn't she only growled and pushed them with her paw, and looked at them, all the time sniffing contemptuously. Johnny[28] and Rosy were nearly ready to cry.

"Is she 'dopting 'em?" whispered Rosy.

"Keep still, can't you!" said Phil; "don't interrupt her. Let her do as she wants to."

The children held their breaths and watched. It looked very discouraging. Mammy Tittleback walked round and round, looking much perplexed and not at all pleased. One minute she would stand still and stare at the pile of kittens, as if she did not know what to make of it; then she would fall to smelling and licking her own. At last, by mistake [29]perhaps, she gave a little lick to one of the orphans.

"Oh, oh," screamed Johnny, "she's going to, she's licked it;" at which Phil gave Johnny a great shake, and told him to be quiet or he'd spoil everything. Presently Mammy Tittleback lay down again and stretched herself out, and in less than a minute all six of her own kittens and the two strongest of the strangers were sucking away as hard as ever they could.

The children jumped for joy; but their joy was dampened by the sight of the other two feeble little kittens, who lay quite still and did not try to crowd in among the rest.[30]

"Are they dead?" asked Rosy.

"No," said Johnny, picking them up,—"no; but I guess they will die pretty soon, they don't maow." And he laid them down very gently close in between Mammy Tittleback's hind legs.

"Well, they might as well," remarked Phil. "Eight kittens are enough. Mammy Tittleback can't bring up all the kittens in the town, you needn't think. She's a real old brick of a cat to take these two. I hope the others will die anyhow."

"O Phil," said Rosy, "couldn't we find some other cat to 'dopt these two?" Rosy's tender heart ached[31] as hard at the thought of these motherless little kittens as if they had been a motherless little boy and girl.

"No," said Phil, "I don't know any other cat round here that's got kittens."

"But, Phil," persisted Rosy, "isn't there some cat that hasn't got any kittens that would like some?"

Phil looked at Rosy for a minute without speaking, then he burst out laughing and said to Johnny, "Come on; what's the use talking?"

Then Rosy looked very much hurt, and ran into the house to ask her Aunt Mary if she didn't know of any cat that would adopt the two[32] poor little kittens that Mammy Tittleback wouldn't take.

The next morning, when the children went out to visit their cats, the two feeble little kittens were dead, so that put an end to all trouble on that score, and left only thirteen cats for the children to take care of.

It is wonderful how fast young cats grow. It seemed only a few days before all eight of these little kittens were big enough to run around, and a very pretty sight it was to see them following Johnny and Rosy wherever they went.

Spitfire was Johnny's favorite from the beginning. He was a sharp, spry[33] fellow, not very good-natured to anybody but Johnny. Rosy was really afraid of him, even while he was little; but Johnny made him his chief pet, and told him everything that happened.

Mammy Tittleback had divided her own colors among her kittens very oddly. "Spitfire" was all yellow and white; "Coaley" was black as a coal, and that was why he was called "Coaley." "Blacky" was black and white; "Limbab," white with gray spots; "Gregory Second," gray with white spots; and "Lily" was as white as snow, for which reason she got her pretty name. Rosy wanted her called[34] "White Lily," but the boys thought it too long. Where there were so many cats, they said, none of the names ought to be more than two syllables long, if you could help it. "Gregory" had to be called "Gregory Second," because there was another Gregory already, an old cat over at Grandma Jameson's, and it was for him that this kitten was named; and "Tottontail" had to be called "Tottontail," because he was all over gray, with just a little bit of white at the tip of his tail, like a cottontail rabbit. And his brother was exactly like him, only a little bit less white on his tail, so it seemed best to call him "Tot[35]tontail's Brother;" and he had such a funny way of putting his ears back, it made him look like an old man; so sometimes they could not help calling him "Grandfather." Altogether there seemed to be a very good reason for every name in the whole family, and I think there was just as good a reason for calling "Lily" "White Lily." However, as Phil said, "anybody could see she was white; and nobody ever heard of a black lily anyhow, and it saved time to say just 'Lily.'"

Mr. Frank Wellington's house was an old-fashioned square wooden house, with a wide hall running straight through it from front to back; at the back was a broad piazza with a railing around it, and steps leading down into the back yard. Grape-vines grew on the sides of this piazza, and a splendid great polonia-tree, which had heart-shaped leaves as big as dinner-plates, grew close [37]enough to it to shade it. This was where Mrs. Wellington used to sit with her sewing on summer afternoons; and she often thought that there couldn't be a prettier sight in all the world than Rosy Chapman running among the verbena beds with her long yellow curls flying behind, her little bare white feet glancing up and down among the bright blossoms, and half a dozen kittens racing after her. Rosy loved to race with them better than anything else; though sometimes she would sit down in her little rocking-chair, holding her lap full of them, and rocking them to sleep. But Johnny made a[38] more serious business of it. Johnny wanted to teach them. He had read about learned pigs and trained fleas, and he was sure these kittens were a great deal brighter than either pigs or fleas could possibly be; so what do you think Johnny did? He printed the alphabet in large letters on a sheet of white pasteboard, nailed it up on the inside of the largest room in the cats' house, and spent hours and hours reading the letters over to the kittens. He had a scheme of putting the letters on separate square bits of pasteboard or paper pasted on wood, and teaching the kittens to pick them out; but before he did[39] that, he wanted to be sure that they knew them by sight on the paper he had nailed up, and he never became sure enough of that to go on any farther in his teaching. In fact, he never got any farther than to succeed in keeping them still for a few minutes while he read the letters aloud. The cat that kept still the longest, he said, was the best scholar that day; he put their names down in a little book, and gave them good and bad marks according as they behaved, just as he and Rosy used to get marks in school.

After Johnny got all his flags up, the cats' house looked very pretty. It had four flags on it; one was a[40] big one with the stars and stripes, and "Our Republic" in big letters on it; one was a "Garfield and Arthur" flag, which had been given to Johnny by the Garfield Club in Mendon; underneath this was a small white one Johnny made himself, with "Hurrah for Both" on it in rather uneven letters; then at two of the corners of the house were small red, white, and blue flags of the common sort. But the glory of all was a big flag on a flagstaff twenty feet high, which Uncle Frank put up for the boys. This also was a "Garfield and Arthur" flag, and a very fine one it was too. The kit[41]tens used to look up longingly at all these bright flags blowing in the wind above their house; but Johnny had taken care to put them high enough to be beyond their reach even when they climbed up to the ridgepole. They would have made tatters of them all in five seconds if they could have ever got their claws into them.

As soon as the kittens were big enough to enjoy playing with a mouse, or, perhaps, taking a bite of one, Mammy Tittleback returned to her old habits of mouse-catching. There had never been such a mouser as she on the farm. It is really true that[42] she had several times been known to catch six mice in five minutes by Mr. Frank Wellington's watch; and once she did a thing even more wonderful than that. This Phil described to me himself; and Phil is one of the most exact and truthful boys, and never makes any story out bigger than it is.

The place where they used to have the best fun seeing Mammy Tittleback catch mice was in the cornhouse. The floor of the cornhouse was half covered with cobs from which the corn had been shelled; in one corner these were piled up half as high as the wall. The mice[43] used to hide among these, and in the cracks in the walls; the boys would take long sticks, push the cobs about, and roll them from side to side. This would frighten the mice and make them run out. Mammy Tittleback stood in the middle of the floor ready to spring for them the minute they appeared. One day the boys were doing this, and two mice ran out almost at the same minute and the same way. Mammy Tittleback caught the first one in her mouth; they thought she would lose the second one. Not a bit of it. Quick as a flash she pounced on that one[44] too, and, without letting go of the one she already had in her teeth, she actually caught the second one! Two live mice at once in her mouth! They were not alive many seconds, though; one craunch of Mammy Tittleback's teeth killed them both, and she dropped them on the floor, and was all ready to catch the next ones. Did anybody ever hear of such a mouser as that?

Another story also Phil told me about the kittens which I should have found it hard to believe if I had read it in a book; but which I know must be true, because Phil told it. One day, after the kittens had grown so big[45] that they used to go everywhere, the children went off for a long walk in the fields, and four of the kittens went with them. When the children climbed fences the kittens crawled through, and they had no trouble till they came to a brook. The children just tucked up their trousers and waded through, first putting the kittens all down together in a hollow at the roots of a tree, and telling them to stay still there till they came back. They hadn't gone many steps on the other side when they heard first one splash, then two, then three; and, looking round, what should they see but three of those little kittens swim[46]ming for dear life across the brook, their poor little noses hardly above the water? It was as much as ever they got across; but they did, and scrambled out on the other side looking like drowned rats. These were Spitfire and Gregory Second and Blacky; Tottontail was the fourth. He did not appear, and he was not to be seen, either, where they had put him down on the other side. At last they spied him racing up stream as hard as he could go. He ran till he came to a place where the brook was only a little thread of water in the grass, and there he very sensibly stepped across; the only one of the [47]whole party, cats or children, who got over without wet feet. Now who can help believing that Tottontail thought it all out in his head, just as a boy or a girl would who had never learned to swim? It was very wonderful that Spitfire and Gregory and Blacky should have plunged in to swim across, when they had never done such a thing before in all their lives, and of course must have hated the very touch of water, as all cats do; but I think it was still more wonderful in Tottontail to have reasoned that if he ran along the stream for a little distance, he might possibly come to a place where he could get[48] over by an easier way than swimming, and without wetting his feet.

The summer was gone before the children felt as if it had fairly begun. Each of them had had a flower-bed" of his own, and ever so many of the flowers had gone to seed before the children had finished their first weeding. The little cats had enjoyed the gardens as much as the children had. When the beds were first planted, and the green plants were just peeping up, the kittens were very often scolded, and sometimes had their ears gently boxed, to keep them from walking on the beds; but by August, when the weeds and the flowers were all[49] up high and strong together, they raced in and out among them as much as they pleased, and had fine frolics under the poppies and climbing hollyhock stems.

When the time of Johnny's and Rosy's visit drew near its end, Johnny felt very sad at the thought of leaving his kittens. They were "just at the prettiest age," he said; "just beginning to be some comfort," after all the pains he had taken to train them; and he was very much afraid they would not be so well taken care of after he had gone. Fred was going away to school for the winter, and Phil, he thought,[50] would never have patience to feed thirteen cats each day. However, he did all that he could to make them comfortable for the winter. He boarded up the sides of their house snug and warm, so that they need not suffer from cold; and he made his Aunt Mary promise to give them plenty of milk twice a day. Then, when the time came, he bade them all good-by one by one, and had a long farewell talk with his favorite Spitfire. Rosy, too, felt very sad at leaving them, but not so sad as Johnny.

Johnny and Rosy and their mother were to spend the winter at their [51]Grandma Jameson's, in the town of Burnet, only twelve miles from Mendon, and Johnny said to Spitfire,—

"It isn't as if we were going so far off, we couldn't ever come to see you. We'll be back some day before Christmas."

"Maow," said Spitfire.

"I'm perfectly sure he understands all I say," said Johnny. "Don't you, Spitfire?"

"Maow, maow," replied Spitfire.

"There!" said Johnny triumphantly; "I knew he did."

It was the middle of October when Johnny and Rosy left their Aunt[52] Mary's and went to Grandma Jameson's. Much to their delight, they found four cats there.

"A good deal better than none," said Johnny.

"Yes," said Rosy, "but they're all old. They won't play tag. They're real old cats."

"Anyhow, they're better than none," replied Johnny resolutely. "They're good to hold, and Snowball's a splendid mouser."

These cats' names were "Snowball," "Lappit," "Stonepile," and "Gregory." This was the old "Gregory" after whom the kitten "Gregory Second" over at Mendon had been[53] named. "Gregory" had been in the Jameson family a good many years.

There was another character who had been in the Jameson family a good many years, about whom I must tell you, because he will come in presently in connection with this history of the cats. In fact, he has more to do with the next part of the history than even Johnny and Rosy have. This is an old colored man who takes care of Grandma Jameson's farm for her. He is as good[55] an old man as "Uncle Tom" was, in "Uncle Tom's Cabin," and I'm sure he must be as black. He lives in a little house in a grove of chestnut and oak trees, just across the meadow from Grandma Jameson's; and, summer and winter, rain or shine, he is to be seen every morning at daylight coming up the lane ready for his day's work. His name is Jerry; he is well known all over Burnet, and he is one of the old men that nobody ever passes by without speaking. "Hullo, Jerry!" "How de do, Jerry?" "Is that you, Jerry?" are to be heard on all sides as Jerry goes through the street.[56]

There is a mule, too, that Jerry drives, which is almost as well known as Jerry. There is a horse also on the farm; but the horse is so fat he can't go as fast as the mule does. So the mule and the horse have gradually changed places in their duties; the horse does the farm work and the mule goes to town on errands; and there is no more familiar sight in all the town of Burnet than the Jameson Rockaway drawn by the mule Nelly, with old Jerry sitting sidewise on the low front seat, driving. There isn't a week in the year that Jerry doesn't go down to the railway station at least once, and sometimes sev[57]eral times, in this way, to bring some of Grandma Jameson's children or grandchildren or nieces or nephews or friends to come and make her a visit. Her house is one of the houses that never seems to be so full it can't hold more. You know there are some such houses; the more people come, the merrier, and there is always room made somehow for everybody to sleep at night.

You wouldn't think to look at the house that it could hold many people; it is not large. In truth, I cannot myself imagine, often as I have stayed in the dear old place, where all the people have slept when I have[58] known twelve or more to come down to breakfast of a morning, all looking as if they had had a capital night's rest. Jerry is always glad as anybody in the house when visitors come; yet it makes him no end of work, carrying them and their luggage back and forth to town, with all the rest of the errands he has to do. Nelly is pretty old, and the Rockaway is small, and many a time Jerry has to make two trips to get one party of people up to the house, with all that belongs to them in the way of trunks and bags and bundles; but he likes it. He pulls off his old drab felt hat, and bows, and holds out both hands, and[59] everybody who comes shakes hands with Jerry, first of all, at the station.

One day, late in last October, Jerry was at the post-office waiting for the mail; when it came in, there was a postal card from Mendon for Mrs. Jameson, and as the postmistress is Mrs. Jameson's own niece, she thought she would look at the message on the card, and see if all were well at Mr. Frank Wellington's. This was what she found written on the card,—

"Meet company at the three o'clock train."

That was the train which had just come in and brought the mail.[60]

"Oh, dear!" said she. "Jerry, it is well I looked at this card. It is from Mr. Wellington, and he says there will be company down by the three o'clock train, to go to Grandma's. You must turn round and go right to the station; they will be waiting, and wondering why nobody's there to meet them."

"That's a fact," said Jerry; "they've done sure, wonderin' by this time; 'spect they've walked up; but I'll go down 'n' see."

So Jerry made as quick time as he could coax out of the mule, down to the railway station. The train had been gone more than half an hour,[61] and the station was quiet and deserted by all except the station-master, who was waiting for the up-train, which would be along in an hour.

"Been anybody here to go up to our house?" asked Jerry. "We got a postal, sayin' there'd be company down on the three o'clock."

"Well," replied the station-master, looking curiously at Jerry, "there was some company came on that train for your folks."

"What became on 'em?" said Jerry. "Hev they walked?"

"Well, no; they hain't walked; they're in the Freight Depot," said the man rather shortly.[62]

Jerry thought this was the queerest thing he ever heard of.

"In the Freight Depot!" exclaimed he. "What'd they go there for? Who be they?"

"You'll find 'em there," replied the man, and turned on his heel.

Still more bewildered, Jerry hurried to the Freight Depot, which was on the opposite side of the railroad track, a little farther down. Now I am wondering if any of you children will guess who the "company" were that had come from Mendon by the three o'clock train to go to Grandma Jameson's. It makes me laugh so to think of it, that I can hardly write[63] the words. I don't believe I shall ever get to be so old that it won't make me laugh to think about this batch of visitors to Grandma Jameson's.

It was nothing more nor less than all Johnny Chapman's cats! Yes, all of them,—Mammy Tittleback, Juniper, Mousiewary, Spitfire, Blacky, Coaley, Limbab, Lily, Gregory Second, Tottontail, Tottontail's Brother, Beauty, Clover. There they all were, large as life, and maowing enough to make you deaf. Poor things! it wasn't that they were uncomfortable, for they were in a very large box, with three sides made of slats, so they had[64] plenty of room and plenty of air; but of course they were frightened almost to death. The box was addressed in very large letters to

Captain Johnny Chapman

and

First Lieutenant Rose Chapman.

Above this was printed in still bigger letters,

THE GARFIELD CLUB.

Some of the men who were at the station when the box came, were made very angry by this. They did not know anything about the history of the cats; and of course they could not[65] see that the thing had any meaning at all, except as an insult to the Garfield Club in Burnet. It was just before Election, you see, and at that time all men in the United States are so excited they become very touchy on the subject of politics; and all the Garfield men who saw this great box of mewing cats labelled the "Garfield Club" thought the thing had been done by some Democrat to play off a joke on the Republicans. So they went to a paint-shop, and got some black paint, and painted, on the other side of the box, "Hancock Serenaders." That was the only thing they could think of to pay off the Demo[66]crats whom they suspected of the joke.

Jerry knew what it meant as soon as he saw the box. He had heard from Johnny and Rosy all about their wonderful cats over at Uncle Frank's, and how terribly they missed them; but it had never crossed anybody's mind that Uncle Frank would send them after the children. Poor Jerry didn't much like the prospect of his ride from the station to the house; however, he put the box into the Rockaway, got home with it as quickly as possible, and took it immediately to the barn.

Then he went into the house with[67] the mail, as if nothing had happened. Jerry was something of a wag in his way, as well as Mr. Frank Wellington; so he handed the letters to Mrs. Chapman without a word, and stood waiting while she looked them over. As soon as she read the postal she exclaimed,—

"Oh, Jerry, this is too bad. There's company down at the station; came by the three o'clock train. You'll have to go right back and get them. I wonder who it can be."

"They've come, ma'am," said Jerry quietly.

"Come!" exclaimed Mrs. Chapman; "come? Why, where are[68] they?" and she ran out on the piazza. Jerry stopped her, and coming nearer said, in a low, mysterious tone,—

"They're in the barn, ma'am!"

"Jerry! In the barn! What do you mean?" exclaimed Mrs. Chapman. And she looked so puzzled and frightened that Jerry could not keep it up any longer.

"It's the cats, ma'am," he said; "them cats of Johnny's from Mr. Wellington's: all of 'em. The men to the station said there was forty; but I don't think there's more 'n twenty; mebbe not so many 's that; they're rowin' round so, you can't count 'em very well."[69]

"Oh, dear! oh, dear!" said Mrs. Chapman. "What won't Frank Wellington do next!" Then she found her mother, and told her, and they both went out to the barn to look at the cats. Jerry lifted up one of the slats so that he could put in a pail of milk for them; and as soon as they saw friendly faces, and heard gentle voices, and saw the milk, they calmed down a little, but they were still terribly frightened. Grandma Jameson could not help laughing, but she was not at all pleased.

"I think Frank Wellington might have been in better business," she said. "We do not want any more[70] cats here; the winter is coming, when they must be housed. What is to be done with the poor beasts?"

"Oh, we'll give most of them away, mother," said Mrs. Chapman. "They're all splendid kittens; anybody'll be glad of them."

"I do not think thee will find any dearth of cats in the village; it seems to be something most families are supplied with: but thee can do what thee likes with them; they can't be kept here, that is certain," replied Mrs. Jameson placidly, and went into the house.

Mrs. Chapman and Jerry decided that the cats should be left in the box[71] till morning, and the children should not be told until then of their arrival.

When Mrs. Chapman was putting Johnny and Rosy to bed, she said,—

"Johnny, if Uncle Frank should send your cats over here, you would have to make up your mind to give some of them away. You know, Grandma couldn't keep them all!"

"What makes you think he'll send them over?" cried Johnny. "He didn't say he would."

"No," replied Mrs. Chapman, "I know he didn't; but I think it is very likely he found them more trouble, after you went away, than he thought they would be."[72]

"I got them fixed real comfortable for the winter," said Johnny. "Their house is all boarded up, so 't will be warm; but I'd give anything to have them here. There's plenty of room in the barn. They needn't even come into the house."

It took a good deal of reasoning and persuading to bring Johnny to consent to the giving away of any of his beloved cats, in case they were sent over from Mendon; but at last he did, and he and Rosy fell asleep while they were trying to decide which ones they would keep, and which ones they would give away, in case they had to make the choice.[73]

In the morning, after breakfast, the news was told them, that the cats had arrived the night before and were in the barn. Almost before the words were out of their mother's mouth they were off like lightning to see them. Jerry was on hand ready to open the box, and the whole family gathered to see the prisoners set free. What a scene it was! As soon as the slats were broken enough to give room,[74] out the cats sprang, like wild creatures, heads over heels, heels over heads, the whole thirteen in one tumbling mass. They ran in all directions as fast as they could run, poor Rosy and Johnny in vain trying to catch so much as one of them.

"They're crazy like," said Jerry; "they've been scared enough to kill 'em; but they'll come back fast enough. Ye needn't be afeard," he added kindly to Johnny, who was ready to burst out crying, to see even his beloved Spitfire darting away like a strange wildcat of the woods. Sure enough, very soon the little ones began to stick their heads out from[75] behind beams and out of corners, and to take cautious steps towards Johnny, whose dear voice they recognized as he kept saying, pityingly,—

"Poor kitties, poor kitties, come here to me; poor kitties, don't you know me?" In a few minutes he had Spitfire in his arms, and Rosy had Blacky, the one she had always loved best. Mammy Tittleback, Juniper, and Mousiewary had escaped out of the barn, and disappeared in the woods along the mill-race. They were much more frightened than the kittens, and had reason to be, for they knew very well that it was an extraordinary thing which had happened to[76] them, whereas the little ones did not know but it often happened to cats to be packed up in boxes and take journeys in railway trains, and now that they saw Johnny and Rosy, they thought everything was all right.

In the mean time the cats of the house, Snowball, Gregory, Stonepile, and Lappit, hearing the commotion and caterwauling in the barn, had come out to see what was going on. On the threshold they all stopped, stock still, set up their backs, and began to growl. The little kittens began to sneak off again towards hiding-places. Snowball came for[77]ward, and looked as if she would make fight, but Johnny drove her back, and said very sharply, "Scat! scat! we don't want you here." On hearing these words, Gregory and the others turned round and walked scornfully away, as if they would not take any more notice of such young cats; but Snowball was very angry, and continued to hang about the barn, every now and then looking in, and growling, and swelling up her tail, and she never would, to the last, make friends with one of the new-comers.

Release had come too late for poor Gregory Second and Lily. They had never been strong as the others, and[78] the fright of the journey was too much for them. Early on the morning after their arrival, Gregory Second was found dead in the barn. The children gave him a grand funeral, and buried him in the meadow behind the house. There were staying now at Mrs. Jameson's two other grandchildren of hers, Johnny and Katy Wells; and the two Johnnies and Katy and Rosy went out, in a solemn procession, into the field to bury Gregory. Each child carried a cat in its arms, and the rest of the cats followed on, and stood still, very serious, while Gregory was laid in the ground. The boys filled up the grave, [79]made a good-sized mound over it, and planted a little evergreen-tree at one end. They also set very firmly, on the top of the mound, what Johnny called "a kind of marble monument." It was the marble bottom of an old kerosene lamp. When this was all done, the children sang a hymn, which they had learned in their school.

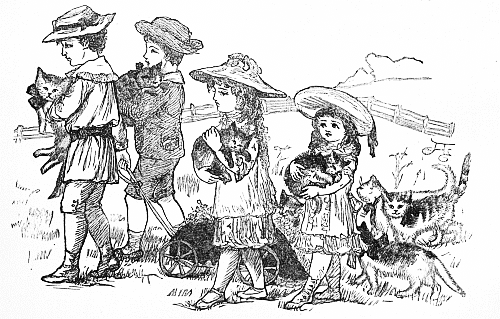

"The children gave him a grand funeral. Each carried a cat in its arms, and the rest of the cats followed on."—Page 78.

"The children gave him a grand funeral. Each carried a cat in its arms, and the rest of the cats followed on."—Page 78.

THE OLD BLACK CAT.

Who so full of fun and glee,

Happy as a cat can be?

Polished sides so nice and fat,

Oh, how I love the old black cat!

Poor kitty! O poor kitty!

Sitting so cozy under the stove.

[80]

CHORUS.

Pleasant, purring, pretty pussy,

Frisky, full of fun and fussy?

Mortal foe of mouse and rat,

Oh, I love the old black cat!

Yes, I do!

Some will like the tortoise-shell;

Others love the white so well;

Let them choose of this or that,

But give to me the old black cat.

Poor kitty! O poor kitty!

Sitting so cozy under the stove.

CHORUS.

Pleasant, purring, pretty pussy, etc.

When the boys, to make her run,

Call the dogs and set them on,

Quickly I put on my hat,

And fly to save the old black cat.

[81]Poor kitty! O poor kitty!

Sitting so cozy under the stove.

CHORUS.

Pleasant, purring, pretty pussy, etc.

This song had come to Burnet years before, in a magazine. There was no other printed copy of the song; but, year after year, the Burnet children had sung it at school, and every child in town knew it by heart.

It cannot be said to be exactly a funeral hymn, and Gregory was a gray cat and not a black one, which made it still less appropriate; but it was the only song they knew about cats, so they sang it slow, and made it do.[82] Just as they were finishing it a big dog came darting down from the other side of the mill-race, leaped over the race, barking loud, and sprang in among them.

This gave the relatives a great scare. All those that were standing on the ground scrambled up the nearest trees as fast as they could; and even those that were being held in the children's arms scratched and fought to get down, that they might run away too. So the funeral ended very suddenly in great disorder, and with altogether more laughing than seemed proper at a funeral.

The next day Lily died and was[83] buried by the side of Gregory, but with less ceremony than had been used the day before. Over her grave was put a high glass monument, which made much more show than the one of marble on Gregory's grave. That was only a flat slab, which lay on the grass; but Lily's was a glass lamp which had by some accident got a little broken. This, set bottom side up, pressed down firmly into the earth, made a fine show, and could be seen a good way off, "the way a monument ought to be," Johnny said; and he searched diligently to find something equally high and imposing for Gregory's grave, but could not find it.[84]

In the course of a few days the remaining kittens and cats were all given away, except Mammy Tittleback and Blacky. They were selected as being on the whole the best ones to keep. Mammy Tittleback is so good a mouser that she would be a useful member of any family, and Blacky bids fair to grow up as good a mouser as she. What became of Juniper and Mousiewary was never known. They were seen now and then in the neighborhood of the house, but never stayed long, and finally disappeared altogether.

Mammy Tittleback, I am sorry to say, did not take the loss of her fam[85]ily in the least to heart; after the first week or two she seemed as contented and as much at home in her new quarters as if she had lived there all her life. What she has thought about it all, there is no knowing; but as she and Blacky lie asleep under the stove, of an evening, you'd never suspect, to look at them, that they had had such a fine summer house to live in last year, or had ever belonged to a "Garfield Club," and taken a railway journey.

[Listen]

This story of Mammy Tittleback and her family was told to me last winter, at Christmas time, in Grandma Jameson's house, by Johnny and Rosy Chapman and their mother, and by Phil Wellington and his mother, and by Johnny and Katy Wells, and by Grandma Jameson herself, and by "Aunt Maggie" Jameson, Grandma Jameson's daughter, and by "Aunt Hannah," Grandma Jameson's sister, and by "Cousin Fanny," the postmistress who had the first[90] sight of the postal card, and by Jerry, who had the worst of the whole business, bringing the box of cats from the railway-station up to the house.

I don't mean that each of these persons told me the whole story from beginning to end. I was not at Grandma Jameson's long enough for that; I was there only Christmas day and the day after. But I mean that all these people told me parts of the story, and every time the subject was mentioned somebody would remember something new about it, and the longer we talked about it the more funny things kept coming up to the very last, and I don't doubt that when I go there again next summer, Phil and Johnny will begin where they left off and[91] tell me still more things as droll as these. The story about the little kittens swimming over the brook I did not hear until the morning I was coming away. Just as I was busy packing Phil came running up to my room, saying, "There's one more thing we forgot the cats did," and then he told me the story of the swimming. Then I said, "Tell me some more, Phil; I don't believe you've told me half yet."

"Well," he said, "you see, they were doing things all the time, and we didn't think much about 'em. That's the reason we can't remember," which remark of Phil's has a good lesson in it when you come to look at it closely. It would make a good text for a little sermon to preach to children[92] that very often have to say, "I forgot," about something they ought to have done.

Things that we think very much about we never forget, any more than we do persons that we love very dearly and think very much of. So "I forgot" is not very much of an excuse for not having done a thing; it is only another way of saying "I didn't attend to it enough to make it stay in my mind," or, "I didn't care enough about it to remember it."

I heard the greater part of this story on Christmas night. Johnny and Rosy and Phil and Katy had a great frolic telling it. In the midst of it Johnny exclaimed, "Don't you want to see Mammy Tittleback?"

"Indeed I do," I replied. So he ran out[93] to the barn and brought her in in his arms. Snowball was already there. She was lying on the hearth when Mammy Tittleback was brought in, and I began to praise her, saying what a beauty she was, and how handsome the yellow, black, and white colors in her fur were. Snowball got up, and began to walk about uneasily and to rub up against us, as if she wanted to be noticed also.

"Snowball's a nice cat too," said Phil, picking her up, "'most as good as Mammy Tittleback."

"Blacky's the nicest," said Rosy, who was rocking in her rocking-chair, and hugging Blacky up close to her face. "Blacky's the nicest of them all." Upon which everybody fell to telling what a tyrant Blacky had[94] become; how she would be held in somebody's lap all the time, and that even Aunt Hannah had had to give up to Blacky. Even Aunt Hannah, whom nobody in the house, not even Grandma Jameson herself, ever thinks of going against in the smallest thing, because she is such a beautiful and venerable old lady,—even Aunt Hannah had had to give up to Blacky.

Aunt Hannah is over eighty years old but she is never idle. She never has time to hold cats in her lap; and, besides, I do not think she loves cats so well as the rest of her family do. As often as Blacky jumped up in her lap, Aunt Hannah would very gently set her on the floor; but in five minutes Blacky would be up again. At last,[95] when she found Aunt Hannah really would not hold her in her lap, she took it in her head to lie in Aunt Hannah's work-basket, close by her side; and just as often as Aunt Hannah put her out of her lap she would spring into the work-basket, and curl herself up like a little puff-ball of fur among the spools. This was even worse to Aunt Hannah than to have her on her knees, and she would take her out of the work-basket less gently than she lifted her out of her lap, and set her on the floor. Then Blacky would jump right up on her lap again, and so they had it,—Aunt Hannah and Blacky,—first lap, and then work-basket, till poor Aunt Hannah got as nearly out of patience as a lovely old lady of the Society of Friends[96] ever allows herself to be. She got so out of patience that she made a very nice, soft, round cushion stuffed with feathers, and kept it always at hand for Blacky to lie on. Then when Blacky jumped on her knees, she laid her on the cushion; instantly Blacky would spring into the work-basket, and when she took her out of that, right up in her lap again. On that cushion she would not lie. At last Aunt Hannah was heard to say, "I believe it is of no use, I'll have to give up to thee, little cat;" and now Blacky lies in Aunt Hannah's work-basket whenever she feels like lying there instead of in Rosy's little chair or in somebody's lap; and I dare say by the time I go to Burnet again, I shall find that Aunt Hannah has given up [97]in the matter of the lap also, and is holding Blacky on her knees as many hours a day as anybody else in the house.

There was a great deal of discussion among the children as to the places where the little kittens were living now, and as to which ones were given away, and which ones had run away.

I suppose when Jerry had a half-dozen kittens to give away all at once, he couldn't stop to select them very carefully, or to sort them out by name, or recollect where each one went.

"I know where Spitfire is," said Johnny; "I saw him yesterday."

"Where?" said Phil.

"I won't tell," said Johnny, "but I know."[98]

"Juniper, he ran away. He'll take care of himself. He used to come back once in a while. We'd see him round the barn. Mousiewary, she comes sometimes now; I saw her the other day. She's real smart."

"Well, old Mammy Tittleback's the best of 'em all," said Phil, catching her up and trying to make her snuggle down in his lap. But Mammy Tittleback did not like to be held. She wriggled away, jumped down, and walked restlessly toward the kitchen door. Phil followed, opened the door, and let her go out. "She won't let you pet her," he said; "she's a real business cat, she always was. She likes to stay in the barn and hunt rats better than anything in the world, except when it's so cold she can't."[99]

"She used to let me hold her sometimes in the summer," said Rosy.

"Oh, that was different. She had to be staying round then, doing nothing, to look after the kittens," replied Phil. "She wasn't wasting any time then being held, but she won't let you hold her now more 'n two or three minutes at a time. She jumps right down, and goes off as if she was sent for."

After the children had gone to bed, Mrs. Chapman told us a very droll part of the history of the cats' journey,—what might be called the sequel to it. The Democrats were not the only people in the village who took offence at the sight of the cats. There is a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty[100] to Animals in Burnet, and some of the people who belonged to this society, when they heard of the affair, took it into their heads that Mr. Frank Wellington had done a very cruel thing in shutting so many cats up in a box together. It was a very good illustration of the way stories grow big in many times telling, the way the number of those cats went on growing bigger and bigger every time the story was told. At last they got it up as high as forty-five; and there really were some people in town who believed that forty-five cats had come from Mendon to Burnet in that box. "Jerry says they haven't ever had it lower than twenty-five," said Mrs. Chapman. "It runs all the way from forty-five to twenty-five,[101] but twenty-five is the lowest, and there was one man in the town who really did threaten pretty seriously to enter a complaint against Frank Wellington with the society, but I guess he was laughed out of it. It is almost a pity he didn't do it, it would have been such a joke all round."

This is all I have to tell you about Mammy Tittleback and her family now. When I go back to Burnet next summer, I hope I shall find her with six more little kittens, and Johnny and Rosy as happy with them as they were with Spitfire, Blacky, Coaley, Limbab, Lily, and Gregory Second.

THE END.

Transcriber's Note

Punctuation has been standardised.

Table of Contents has been added for the reader's convenience.

Page 7, changed "Limbat" to "Limbab" on Genealogical Tree

Page 7, changed "Lilly" to "Lily" on Genealogical Tree

Illustration following Page 96, changed "Blackie" to "Blacky" (Now Blacky lies)