Title: A Pair of Schoolgirls: A Story of School Days

Author: Angela Brazil

Illustrator: John Campbell

Release date: August 9, 2010 [eBook #33389]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By ANGELA BRAZIL

"Angela Brazil has proved her undoubted talent for writing a story of schoolgirls for other schoolgirls to read."—Bookman.

LONDON: BLACKIE & SON, Ltd., 50 OLD BAILEY, E.C.

A

Pair of Schoolgirls

A Story of School Days

BY

ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN CAMPBELL

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

Printed in Great Britain by

Blackie & Son, Limited, Glasgow

| Chap. | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | A School Election | 9 |

| II. | What Dorothy Overheard | 24 |

| III. | A Retrospect | 39 |

| IV. | Dorothy makes a Friend | 55 |

| V. | A Literature Exercise | 68 |

| VI. | A Promise | 84 |

| VII. | Alison's Home | 101 |

| VIII. | A Short Cut | 120 |

| IX. | Dorothy Scores | 132 |

| X. | Martha Remembers | 151 |

| XI. | Alison's Uncle | 169 |

| XII. | The Subterranean Cavern | 181 |

| XIII. | A School Anniversary | 199 |

| XIV. | Water Plantain | 216 |

| XV. | A Confession | 229 |

| XVI. | The William Scott Prize | 244 |

| Page | |

|---|---|

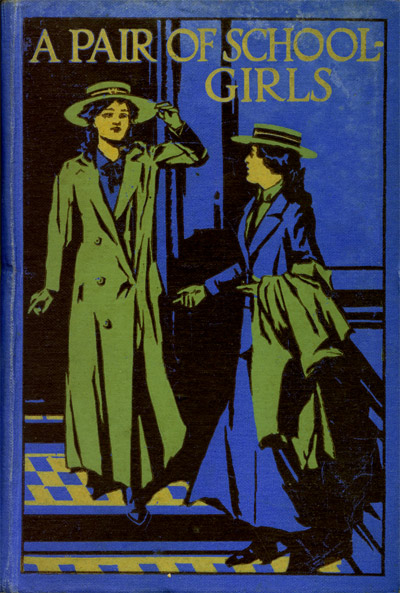

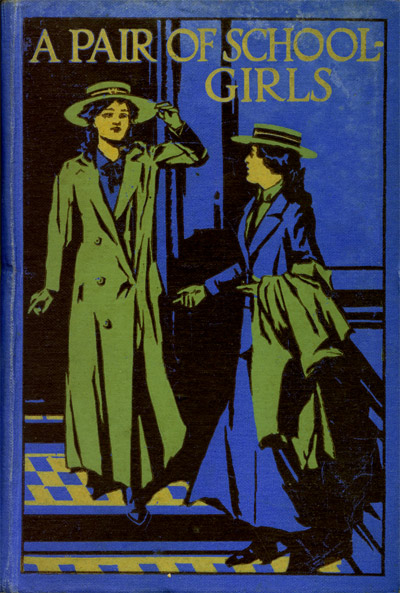

| "'You're the absolute image!' declared Alison" | Frontispiece 110 |

| The New Girl | 56 |

| In Discreet Hiding | 124 |

| A Lesson in Golf | 178 |

| A Nursing Experience | 212 |

It was precisely five minutes past eleven on the first day of the autumn term, and Avondale College, which for seven whole weeks had been lonely and deserted, and given over to the tender mercies of paperhangers, painters, and charwomen, once more presented its wonted aspect of life and bustle. The reopening was a very important event in the opinion of everybody concerned, partly because it marked the beginning of a fresh school year, and partly because the building had been altered and enlarged, many changes made in the curriculum, and many new names added to the already long list in the register. Three hundred and eighty-seven pupils had assembled that morning in the great lecture hall, the largest number on record at the College; five additional classes had[10] been formed, and there were six extra mistresses. At the eleven o'clock interval the place seemed swarming with girls; they thronged the staircase and passages, filled the pantry, blocked the dressing-rooms, and overflowed into the playground and the gymnasium—girls of all sorts and descriptions, from the ten-year-olds who had just come up (rather solemn and overawed) from the Preparatory to those elect and superior damsels of seventeen who were studying for their Matriculation.

By the empty stove in the Juniors' Common Room stood half a dozen "betwixt-and-betweens", whose average age probably worked out at fourteen and a quarter, though Mavie Morris was a giantess compared with little Ruth Harmon. The six heads were bent together in closest proximity, and the six tongues were particularly active, for after the long summer holidays there was such a vast amount to talk about that it seemed almost impossible to discuss all the interesting items of news with sufficient rapidity.

"The old Coll. looks no end," said Grace Russell. "It's so smart and spanky now—one hardly knows it! Pictures in the classrooms, flowers on the chimneypieces, a stained glass window in the lecture hall, busts on brackets all along the corridor wall, and the studio floor polished! Every single place has been done up from top to bottom."

"I'd like it better if it didn't smell so abominably[11] of new paint," objected Noëlle Kennedy. "When I opened the studio door, the varnish stuck to my fingers. However, the school certainly looks much nicer. Why, even the book cupboard has been repapered."

"That's because you splashed ink on the wall last term. Don't you remember how fearfully cross Miss Hardy was about it?"

"Rather! She insisted that I'd done it on purpose, and couldn't and wouldn't believe it was an accident. Well, thank goodness we've done with her! I'm glad teachers don't move up with their forms. I'm of the opposite opinion to Hamlet, and I'd rather face the evils that I don't know than those I do. Miss Pitman can't possibly be any worse, and she may chance to be better."

"I say, it's rather a joke our being in the Upper Fourth now, isn't it?" remarked Ruth Harmon.

"I'm glad we've all gone up together," said Dorothy Greenfield. "There's only Marjory Poulton left behind, and she won't be missed. We're exactly the same old set, with the addition of a few new girls."

"Do you realize," said Mavie Morris, "that we're the top class in the Lower School now, and that one of us will be chosen Warden? There'll be an election this afternoon."

"Why, so there will! What a frantic excitement! We shall all have to canvass in the dinner-hour.[12] I wonder if Miss Tempest has put up the list of candidates yet? I vote we go to the notice board and see; there's just time before the bell rings."

Off scrambled the girls at once, pushing and jostling one another in their eagerness to get to the lecture hall. There was a crowd collected round the notice board, but they elbowed their way to the front notwithstanding. Yes, the list was there, in the head mistress's own handwriting, and they scanned it with varying comments of joy or disappointment, according as their names were present or absent.

"Hurrah!"

"Disgusting!"

"No luck for me!"

"I don't call it fair!"

"You're on, Dorothy Greenfield, and so am I."

"I say, girls, which of you'll promise to vote for me?"

Avondale College was a large day school. Its pupils were drawn from all parts of Coleminster and the surrounding district, many coming in by train or tramcar, and some on bicycles. Under the headmistress-ship of Miss Tempest its numbers had increased so rapidly that extra accommodation had become necessary; and not only had the lecture hall and dressing-rooms been enlarged, but an entire new wing had been added to the building. Avondale[13] prided itself greatly upon its institutions. It is not always easy for a day school to have the same corporate life as a boarding school; but Miss Tempest, in spite of this difficulty, had managed to inaugurate a spirit of union among her pupils, and to make them work together for the general good of the community. She wished the College to be, not merely a place where textbooks were studied, but a central point of light on every possible subject. She encouraged the girls to have many interests outside the ordinary round of lessons, and by the help of various self-governing societies to learn to be good citizens, and to play an intelligent and active part in the progress of the world. A Nature Study Union, a Guild of Arts and Crafts, a Debating Club, a Dramatic Circle, and a School Magazine all flourished at Avondale. The direction of these societies was in the hands of a select committee chosen from the Fifth and Sixth Forms, but in order that the younger girls might be represented, a member of the Upper Fourth was elected each year as "Warden of the Lower School", and was privileged to attend some of the meetings, and to speak on behalf of the interests of the juniors.

Naturally this post was an exceedingly coveted honour: the girl who held it became the delegate and mouthpiece of the lower forms, an acknowledged authority, and the general leader of the rest. It was the custom to elect the warden by ballot on[14] the afternoon of the reopening day. Six candidates were selected by Miss Tempest, and these were voted for by the members of the several divisions of the Third and Fourth Forms.

Among the six chosen for this election, none was more excited about her possible chances than Dorothy Greenfield, and as our story centres round her and her doings she merits a few words of description. She was a tall, slim, rather out-of-the-common-looking girl, and though at present she was passing through the ugly duckling stage, she had several good points, which might develop into beauty later on. Her large dark grey eyes, with their straight, well-marked brows, made you forgive her nondescript nose. She lacked colour, certainly, but her complexion was clear, and, despite her rather thin cheeks, the outline of her face was decidedly pleasing. Her mouth was neat and firm, and her chin square; and she had a quantity of wavy, fluffy brown hair that had an obstreperous way of escaping from its ribbon and hanging over her ears. During the past six months Dorothy had shot up like Jack's beanstalk, and she was still growing fast—an awkward process, which involved a certain angularity of both body and mind. She was apt to do things by fits and starts; she formed hot attachments or took violent prejudices; she was amiable or irritable according to her mood, and though capable of making herself most attractive,[15] could flash out with a sharp retort if anybody offended her. She had a favourable report in the school: she was generally among those marked "excellent" in her form, and she was above the average at hockey and tennis, had played a piano solo at the annual concert, won "highly commended" at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition, and contributed an article to the School Magazine.

Possessing such a good all-round record, therefore, Dorothy might have as reasonable a possibility of success as anybody else at the coming election, and she could not help letting her hopes run high. The ballot was to be taken at half-past three, which left little time for canvassing; but she meant to do the best for herself that circumstances would allow. She was a day boarder, so, when morning classes were over, she strolled into the Juniors' Common Room to discuss her chances. Already some papers were pinned up claiming attention for the various candidates:

"Vote for Val Barnett, the hockey champion."

"Hope Lawson begs all her friends to support her in the coming election."

"Grace Russell solicits the favour of your votes."

"Noëlle Kennedy relies upon the kindness of the Lower School."

"Hallo, Dorothy!" said Mavie Morris. "Aren't you going to add your quota to the general lot? All the others are getting up their appeals. I[16] wish Miss Tempest had put me on the list of likelies!"

"I can't think why she didn't," replied Dorothy. "I should say you're far more suitable than Noëlle Kennedy."

"Why, so do I, naturally. But there! it can't be helped. I'm not among the elect, so I must just grin and bear it. Is this your appeal? Let me look."

She seized the piece of paper from Dorothy's hand, and, scanning it eagerly, read the following lines:

"What do you think of it?" asked Dorothy. "I made it up during the history lesson, and wrote it on my knee under the desk. One wants[17] something rather different from other people's, and I thought perhaps no one else would have a rhyming address."

"It's not bad," commented Mavie, "but you do brag."

"I've apologized for it. One must state one's qualifications, or what's the use of being a candidate? Look at Val's notice—she calls herself the hockey champion."

"No one takes Val too seriously. I don't believe she's the ghost of a chance, though she did win the cup last season. One needs more than that for a warden; brains count as well as muscles."

"I know; that's why I tried poetry."

"Please don't call that stuff poetry. Half of the lines won't scan."

There was a pucker between Dorothy's dark eyebrows as she snatched back her literary bantling.

"I don't suppose that matters. Everybody isn't so viper-critical," she retorted. "Shall I pin it up here or in the gym.?"

"It will be more seen here; but I warn you, Dorothy, I don't think the girls will like it."

"Why not?"

"Well, it's clever enough, but it's cheeky. I'm afraid somehow it won't catch on. If you take my advice, you'll tear it up and just write 'Vote for Dorothy Greenfield' instead."

But taking other people's advice was not at[18] present included in Dorothy's scheme of existence; she much preferred her own ideas, however crude.

"I'll leave it as it is," she answered loftily. "It can't fail to attract attention anyhow."

"As you like. By the by, if you're going round canvassing, there's been a new——"

But Dorothy did not wait to listen. She was annoyed at Mavie's scant appreciation of her poetic effort; and having manifested her independence by pinning the offending verses on the notice board, she stalked away, trying to look nonchalant. She was determined to use every means at hand to ensure success, and her best plan seemed to be to go round personally soliciting votes.

"I'll tackle the dinner girls now," she thought, "and I expect there'll be just time to catch the others when they come back in the afternoon. Thank goodness the election is only among the Third and Fourth! It would be terrible if one had to go all round the school. Why, I never asked Mavie! How stupid! But she's certain to be on my side; she detests Val, and she's not particularly fond of Hope either, though of course there's Grace. Had I better go back and make sure of her?"

On the whole she decided that as she had left Mavie in rather a high and mighty manner, it would seem a little beneath her dignity to return at once and beg a favour, so she went into the playground instead to beat up possible electors.[19] She was not the first in the field, by any means. Already Valentine Barnett and her satellites were hard at work coaxing and wheedling, while the emissaries of Doris Earnshaw and Noëlle Kennedy were urging the qualifications of their particular favourites. Hope Lawson was seated on the see-saw in company with a number of small girls from the Lower Second.

"What's she doing that for?" thought Dorothy. "Those kids haven't got votes. It's sheer waste of time to bother with them. She's actually put her arm round that odious little Maggie Muir, and taken Nell Boughton on her knee! I shouldn't care to make myself so cheap. I suppose she's letting Blanche Hall and Irene Jackson do her canvassing for her."

Dorothy was, however, too much occupied with her own affairs to concern herself greatly about her neighbours' movements. To put her claims adequately before each separate elector was no mean task, and time fled all too quickly. She used what powers of persuasion she possessed, and flattered herself that she had made an impression in some quarters; but very few of the girls would give any definite promises. Many of them, especially those of the Middle and Lower Thirds, seemed to enjoy the importance of owning something which it was in their power to withhold.

"I'm waiting till I've heard what you all six[20] have to say for yourselves," said Kitty Palgrave condescendingly. "I shan't make up my mind until the very last minute."

"It's so difficult to choose between you," added Ellie Simpson, a pert little person of twelve.

Their tone verged on the offensive, and in any other circumstances Dorothy would have administered a snub. As it was, she pocketed her pride, and merely said she hoped they would remember her. She heard them snigger as she turned away, and longed to go back and shake them; but discretion prevailed.

"One has to put up with this sort of thing if one wants to get returned Warden," she reflected. "All the same, it's sickening to be obliged to truckle to young idiots like that."

She had not by any means found all the possible voters, so she decided to return to the Juniors' Common Room. Mavie had gone, but a number of other girls stood near the notice board talking, and reading the appeals of the various candidates. Dorothy strolled up to see how her verses were being received. They made a different impression on different minds, to judge from the comments that met her ears.

"It's ripping!" exclaimed Bertha Warren.

"Says she can run the show, does she?" sneered Joyce Hickson.

"I call it just lovely!" gushed Addie Parker.

[21] "Her trumpeter's dead, certainly!" giggled Phyllis Fowler. "Hallo, Dorothy! I didn't see you were there."

"I'm going to vote for you, Dorothy," said Bertha, "and so is Addie. Phyllis has promised Hope, and Joyce is on Val's side. If you like, I'll canvass for you here, while you do the gym. You'd better not waste any time, because the others are hard at it, and it's best to get first innings if you can."

Dorothy hastily agreed, and hurried off to the gymnasium, where she was fortunate enough to catch some of her own classmates. They were all sucking enormous peppermint "humbugs", and were almost speechless in consequence; but they had the politeness to listen to her, which was more than she had experienced from some of the girls.

"Very sorry!" replied Annie Gray, talking with difficulty. "You should have asked us sooner. Val's been round, and simply coerced us."

"She made it a hockey versus lacrosse contest, and of course we plumped for hockey," murmured Elsie Bellamy.

"Val's simply ripping at hockey!"

"Is that all you care for?" exclaimed Dorothy scornfully. "Val has nothing else to recommend her."

"Hasn't she? What about peppermint 'humbugs'?[22] I call them a very substantial recommendation."

"Did Val give you those?"

"Rather! She put on her hat and bolted out into High Street and bought a whole pound. Lucky Miss James didn't catch her as she dodged back!"

"She's handing them round to everybody," added Helen Walker. "I wish I had taken two."

For once Dorothy's pale cheeks put on a colour. She could not restrain her indignation.

"How atrociously and abominably mean!" she burst out. "Why, it's just bribery, pure and simple. I didn't think Val was capable of such a sneaking trick. She knows quite well how unfair it is to the rest of us."

"Why, you could have done the same if you'd liked," laughed Elsie. "It's not too late now. I've a preference for caramels, if you ask me."

"I'd be ashamed!" declared Dorothy. "Surely you ought to give your votes on better grounds than 'humbugs' or caramels? Such a thing has never been done before at the Coll."

"All the more loss for us," giggled Helen flippantly.

"Do you mean to tell me you don't care whether a candidate behaves dishonourably or not?"

"Not I, if she's jolly."

"I'm disgusted with you, absolutely disgusted![23] If you haven't a higher ideal of what's required in a warden, you don't deserve to have votes at all."

"Draw it mild, Dorothy!" chirped Elsie.

"I won't. I'll tell you what I think of you: you're a set of greedy things! There isn't one of you with a spark of public spirit, and if the election is going to be run on these lines, I——"

But Dorothy's tirade was interrupted by the dinner bell; and the objects of her scorn, hastily swallowing the offending peppermints, decamped at a run, leaving her to address a group of empty chairs. She followed more leisurely, fuming as she went. She knew she had been foolish and most undiplomatic to lose her temper so utterly, but the words had rushed out before she could stop them.

"They wouldn't have voted for me in any case," she said to herself, "so it really doesn't matter, after all, they're only a minority. I expect it will prove a very even affair, perhaps a draw, and that no one will have a complete walk-over."

At half-past three, exactly in the middle of the French reading-lesson, Miss James, the school secretary, entered the Upper Fourth room with a sheaf of voting papers in her hand. These were dealt round to all the girls, with the exception of the candidates, and Miss James gave a brief explanation of what was required.

"On each paper you will find six names. You must put a cross to the one you wish to choose for your warden. Do not write anything at all, but fold the paper and hand it in to Miss Pitman, who will place it in this box, which I shall call for in five minutes."

So saying, she bustled away in a great hurry to perform a similar errand in the next classroom. The six candidates tried to sit looking disinterested and unconscious while their fates were being decided. Hope Lawson hunted out words in the dictionary, Valentine Barnett made a parade of arranging the contents of her pencil box, and the others opened books and began preparation. Not[25] a word was allowed to be spoken. In dead silence the girls recorded their crosses and handed in their papers, and the last was hardly dropped into the ballot box before Miss James reappeared. The result of the election was to be announced at four o'clock, therefore there were still twenty minutes of suspense. Miss Pitman went on with the French reading as if nothing had happened, and Dorothy made a gallant effort to fix her attention on Le Jeune Patriote, and to forget that Miss Tempest and Miss James were hard at work in the library counting votes. Nobody's translation was particularly brilliant that afternoon; everyone was watching the clock and longing for the end of the lesson. When the bell rang there was a general scuffle; books were seized and desk lids banged, and though Miss Pitman called the Form to order and insisted upon a decorous exit from the room, the girls simply pelted down the stairs to the lecture hall. In a few moments the whole school had assembled. There was not long to wait, for exactly at the stroke of four Miss Tempest walked on to the platform and made the brief announcement:

"Hope Lawson has been elected Warden of the Lower School by a majority of fifty votes."

Dorothy left the lecture hall with her head in a whirl. That Hope should have won by such an enormous majority was most astonishing. She[26] could not understand it. Conversation was strictly forbidden on the staircase, but the moment she reached the gymnasium door she burst into eager enquiries.

"Yes, it's a surprise to everybody," said Ruth Harmon. "I thought myself that Val would get it. All the Lower Fourth and most of the Upper Third were for her."

"Then how could Hope possibly score by fifty?"

"She did it with the kids, I suppose."

"But the First and Second weren't voting?"

"Indeed they were! Do you mean to say you never knew? Why, Miss James gave it out this morning."

"Of all sells!" gasped Dorothy. "I heard nothing about it! It's the first year those kids have ever taken part in the election. Why couldn't some of you tell me?"

"I was just going to," said Mavie, "but you stalked away and wouldn't listen. It's your own fault, Dorothy."

"You might have run after me."

"You looked so lofty, I didn't feel disposed."

"Val didn't know either," interposed Bertha Warren. "She never canvassed in the First or the Second; no more did Grace or Noëlle. I'm not certain if any of you knew except Hope. Only a few were in the room when Miss James gave it out."

[27] "Then she's taken a most mean advantage," said Dorothy. "I understand now why she was sitting on the see-saw making herself so extremely pleasant. It's not fair! Miss James ought to have announced to the whole school that such a change had been made."

"Go and tell her so!" sneered Phyllis Fowler.

"Those who lose always call things unfair," added Joyce Hickson.

Dorothy walked away without another word. She did not wish to be considered jealous, and her common sense told her that she had already said more than enough. She was too proud to ask for sympathy, and felt that her most dignified course was to accept her defeat in silence. She thought she would rather not speak even to her friends, so, ignoring violent signals from Bertha Warren and Addie Parker, she went at once to put on her outdoor clothes. The dressing-room, to provide greater accommodation, had not only hooks round the walls, but double rows of hat-stands down the middle, with lockers for boots underneath. As Dorothy sat changing her shoes, she could hear three girls talking on the other side of the hat-stand, though, owing to the number of coats which were hanging up, the speakers were hidden from her. She recognized their voices, however, perfectly well.

"I'm rather surprised at Hope getting it," Helen[28] Walker was saying. "I thought Val was pretty safe. I voted for her, of course."

"A good many voted for Dorothy," replied Evie Fenwick.

"I know. I thought she might have had a chance even against Val. She'll be dreadfully disgusted."

"I'm very glad Hope was chosen," said Agnes Lowe. "After all, she's far the most suitable for Warden; she's ever so much cleverer than Val."

"But not more than Dorothy!"

"No; but she's a girl of better position, and that counts for something. Her father was Mayor last year, and her mother is quite an authority on education, and speaks at meetings."

"Well, Dorothy's aunt writes articles for magazines. One often sees the name 'Barbara Sherbourne' in the newspapers. Dorothy's tremendously proud of her."

"Dorothy needn't take any credit to herself on that account," returned Agnes, "for, as it happens, Miss Sherbourne isn't her aunt at all; she's no relation."

"Are you sure?"

"Absolutely. I know for a fact that Dorothy is nothing but a waif, a nobody, who is being brought up for charity. Miss Sherbourne adopted her when she was a baby."

At this most astounding piece of information,[29] Dorothy, who had followed the conversation without any thought of eavesdropping, flung her slippers into her locker and stalked round to the other side of the hat-stand.

"Agnes Lowe, what do you mean by telling such an absolute story?" she asked grimly.

"I'd no idea you were there!" returned Agnes.

"Listeners never hear any good of themselves," laughed Helen.

"I'm extremely glad I overheard. It gives me a chance to deny such rubbish. I shall expect Agnes to make an instant apology."

Dorothy's tone was aggressive; she waited with a glare in her eyes and a determined look about her mouth. Agnes did not flinch, however.

"I'm sorry you heard what I said, Dorothy," she replied. "It wasn't meant for you; but it's true, all the same, and I can't take back my words."

"How can it be true?"

Agnes put on her hat hastily and seized her satchel.

"You'd better ask Miss Sherbourne. Probably everyone in Hurford knows about it except yourself. Come, Helen, I'm ready now," and she hurried away with her two friends, evidently anxious to escape further questioning.

Dorothy took up her pile of home-lesson books and followed them; but they must have raced down[30] the passage, for when she reached the door they were already disappearing round the corner of the playground. It was useless to think of pursuing them; she had barely time, as it was, to catch her train, and she must walk fast if she meant to be at the station by half-past four. She scurried along High Street, keeping a watchful eye on the town hall clock in the intervals of dodging passengers on the pavements and dashing recklessly over crossings. At Station Road she quickened her footsteps to a run, and tore up the flight of stairs that was the shortest cut to the ticket office. Fortunately she possessed a contract, so she had no further delay, and was able to scuttle across the platform into the Hurford train. The guard, who knew her well by sight, smiled as he slammed the door of her compartment.

"A near shave to-day, missy! I see you're back at school," he remarked, then waved his green flag.

Dorothy sank down breathlessly. To miss the 4.30 would have meant waiting three-quarters of an hour—a tiresome experience which she had gone through before, and had no desire to repeat. She was lucky, certainly; but now that the anxiety of catching the train was over, the reaction came, and she felt both tired and cross. What an enormously long time it seemed since she had started that morning, and what a horrid day it had been![31] She leaned back in a corner of the compartment and took a mental review of everything that had happened at school: her expectation of winning the election, her canvassing among the girls, their many ill-natured remarks, Val's method of bribery, and Hope's unfair advantage. She was bitterly chagrined at missing the wardenship, and the thought that she might have had a chance of success if she had known of the voting powers of the First and Second Forms only added to her disappointment. She was indignant and out of temper with Mavie, with Hope, with the whole of her little world; everything had seemed to go wrong, and, to crown all, Agnes Lowe had dared to call her a nobody and a charity child! What could Agnes mean? It was surely a ridiculously false accusation, made from spite or sheer love of teasing. She, Dorothy Greenfield, a waif! The idea was impossible. Why, she had always prided herself upon her good birth! The Sherbournes were of knightly race, and their doings were mentioned in the county history of Devonshire as far back as Queen Elizabeth's reign. Of course, her name was Greenfield, not Sherbourne; but she was of the same lineage, and she had pasted the family crest inside her school books. She would trace out her pedigree that very evening right to Sir Thomas Sherbourne, who helped to fit out a ship to fight the Armada; and she would take a copy[32] to school to-morrow and show it to Agnes, who could not fail to be convinced by such positive evidence. Yes, the girls should see that, far from being a nobody, she was really of a better family than Hope Lawson, whose claims to position rested solely on her father's public services to the city of Coleminster.

And yet under all her assurance there lurked an uneasy sensation of doubt. She had taken it for granted that her mother was a Sherbourne; but she remembered now that when she had spoken of her as such, Aunt Barbara had always evaded the subject. Nobody ever mentioned her parents. She had thought it was because they were dead; but surely that was not a sufficient reason for the omission? Could there be another and a stronger motive for thus withholding all knowledge about them? Several things occurred to her—hints that had been dropped by Martha, the maid, which, though not comprehended, had remained in her memory—looks, glances, half-spoken sentences let fall by Aunt Barbara's friends—a hundred nothings too small in themselves to be noticed, but, counted in the aggregate, quite sufficient to strengthen the unwelcome suspicion that had suddenly awakened.

"Rubbish!" thought Dorothy, with an effort to dispel the black shadow. "I'll ask Aunt Barbara, and I've no doubt she'll easily explain it all and set everything right."

[33] By this time the train had passed Ash Hill, Burnlea, and Latchworth, and had arrived at Hurford, Dorothy's station. She stepped out of the compartment, so preoccupied with her reflections that she would have forgotten her books, if a fellow-passenger had not handed them to her. She scarcely noticed the Rector and his children, who were standing on the platform, and, turning a deaf ear to the youngest boy, who called to her to wait for them, she hurried off alone along the road.

It was a pleasant walk to her home, between green hedges, and with a view of woods and distant hills. Hurford was quite a country place, and could boast of thatched cottages, a market cross, and a pair of stocks, although it lay barely twelve miles from the great manufacturing city of Coleminster. Dorothy's destination was a little, quaint, old-fashioned stone house that stood close by the roadside at the beginning of the village street. A thick, well-clipped holly hedge protected from prying eyes a garden where summer flowers were still blooming profusely, a strip of lawn was laid out for croquet, and a small orchard, at the back, held a moderate crop of pears and apples. Dorothy ran in through the creeper-covered porch, slammed her books on the hall table, then, descending two steps, entered the low-ceiled, oak-panelled dining-room, and rushed to[34] fling her arms round a lady who was sitting doing fancy work near the open window.

"Here I am at last, Auntie! Oh, I feel as if I hadn't seen you for a hundred years! I'm in the Upper Fourth, but it's been a hateful day. I never thought school was so horrid before. I'm very disappointed and disgusted and abominably cross."

"Poor little woman! What's the matter?" said Aunt Barbara, taking Dorothy's face in her hands, as the girl knelt by her side, and trying to kiss away the frown that rested there. "You certainly don't look as if you had been enjoying yourself."

"Enjoying myself? I should think not! We had an election for the wardenship, and my name was on the list, and I might perhaps have won if the others hadn't been so mean; but I didn't, and Hope Lawson has got it!"

"We can't always win, can we? Never mind! It's something that your name was on the list of candidates. All the girls who lost will be feeling equally disappointed. Suppose you just forget about it, go and take off your things, and tell Martha to make some buttered toast."

Dorothy laughed. Already her face had lost its injured and woeful expression.

"That's as good as saying: 'Don't make a fuss about nothing'. All right, Auntie, I'm going. But I warn you that this is only a respite, and I[35] mean to give you a full and detailed list of all my particular grievances after tea. So make up your mind to it, and brace your dear nerves!"

Miss Barbara Sherbourne was a most charming personality. She was young enough to be still very pretty and attractive, but old enough to take broad views of life, and to have attained that independence of action which is the prerogative of middle age. She was a clever and essentially a cultured woman; she had lived abroad in her youth, and the glamour of old Italian cities and soft, southern skies still seemed to cling to her. She was a good amateur musician, could sketch a little, and had lately obtained some success in writing. Ever since Dorothy could remember, she and Aunt Barbara and Martha, the maid, had lived together at Holly Cottage, a particularly harmonious trio, liking their own mode of life, and quite independent of the outside world. The little house seemed to fit its inmates, and, in spite of its small accommodation, to provide just what was wanted for each. First there was the old-fashioned dining-room, with its carved oak furniture, blue china, and rows of shining pewter; its choice prints on the walls, its bookshelves, overflowing with interesting volumes; and the desk where Aunt Barbara wrote in the mornings—a room that seemed made especially for comfort, and reached its acme of cosiness on a cold winter's[36] day, when arm-chairs were drawn up to the blazing fire that burnt in the quaint dog grate. Then there was the little drawing-room, with its piano and music rack, and its great Japanese cabinet, full of all kinds of treasures from foreign places. When Dorothy was a tiny girl it had been her Sunday afternoon treat to be allowed to investigate the mysteries of this cabinet, to open its numerous drawers and sliding panels, and to turn over the miscellaneous collection of things it contained; and she still regarded it in the light of an old friend. The artistic decorations, the chintz hangings, the water-colour paintings of Italian scenes, all helped to give an æsthetic effect to the room, and to make a very pleasant whole. The kitchen was, of course, Martha's particular domain, but even here there were books and pictures, and a table reserved for writing desk and work basket. I fear Martha did not often busy herself with pens and paper, for she held head-learning in good-natured contempt; but she appreciated her mistress's effort to make her comfortable, and polished the brass-topped inkpot diligently, if she seldom used it. Peterkin, the grey Persian cat, generally sat in the arm-chair, or on Martha's knee, which he much preferred, when he got the chance; and Draco, the green parrot, hobbled up and down his perch at the sunny window, repeating his stock of phrases, begging for titbits, or imitating smacking kisses.

[37] Just at the top of the stairs was Dorothy's special sanctum. It had formerly been her nursery, and still contained her old dolls' house, put away in a corner, though her toys were now replaced by schoolgirl possessions. Here she kept her tennis racket, her hockey stick, her camera and photographic materials, her collections of stamps, crests, and picture postcards; there was a table where she could use paste or glue, or indulge in various sticky performances forbidden in the dining-room, and a cupboard where oddments could be stored without the painful necessity of continually keeping them tidily arranged. She could try experiments in sweet making, clay modelling, bookbinding, or any of the other arts and crafts that were represented at the annual school exhibition; in fact, it was a dear, delightful "den", where she could conduct operations without being obliged to move her things away, and might make a mess in defiance of Martha's chidings.

Dorothy often took a peep into her sanctum on her return from Avondale, but to-day she ran straight to her bedroom. She was anxious to finish tea and have a talk with Aunt Barbara. She felt she could not rest until she had mentioned Agnes Lowe's remarks, and either proved or disproved their truth. It was not a question that she could raise, however, when Martha was coming into and going out of the dining-room[38] with hot water and toast; and it was only after she had cajoled Miss Sherbourne to the privacy of the summer-house, and had related her other school woes, that the girl ventured to broach the subject.

"I know it's nonsense, Auntie, but I thought I'd like to tell you, all the same," she concluded, and waited for a denial with a look of anxiety in her eyes that belied her words.

Miss Sherbourne did not at once reply. Apparently she was considering what answer to make.

"I knew you would ask me this some day, Dorothy," she said at last. "It seemed unnecessary for you to know before, but you are growing older so fast that it is time you learnt your own story."

Dorothy turned her face sharply away. She did not want even Aunt Barbara to see how her mouth was quivering.

"Is it true, then?" she asked, in a strangled voice.

"Yes, dear child. In a sense it is all absolutely true."

More than thirteen years before this story begins, Miss Barbara Sherbourne happened to be travelling on the Northern Express from Middleford to Glasebury. She had chosen a corner of the compartment with her back to the engine, had provided herself with books and papers, had ordered a cup of afternoon tea to be brought from the restaurant car precisely at four o'clock, and had put a piece of knitting in her handbag with which to occupy herself in case she grew tired of reading or watching the landscape. After these preparations she anticipated a comfortable journey, and she leaned back in her corner feeling at peace with herself and all the world. Her fellow-passengers consisted of two old ladies, evidently returning home after a holiday in the South; a morose-looking man with a bundle of Socialist tracts, and a middle-aged woman, who, with a baby on her knee, occupied the opposite corner. Nobody spoke a word, except an occasional necessary one about the opening or closing of a window, and all settled down to[40] read books and papers, or to enjoy the luxury of a snooze while the train sped swiftly northwards. The baby was sleeping peacefully, its lips parted, its long lashes resting on its flushed cheeks, and one little hand flung out from under the white woolly shawl which was wrapped closely round it. It made a pretty picture as it lay thus, and Miss Sherbourne's eyes returned again and again to dwell on the soft lines of the chubby neck and dimpled chin. She was fond of studying her fellow-creatures, and she could not quite reconcile the appearance of the child with that of the woman who held it in her arms. The latter was plainly though tidily dressed, and did not look like an educated person. There was nothing of refinement in her face: the features were heavy, the mouth even a trifle coarse. Her gloveless hands were work-worn, and her wedding ring was of a cheap gold. The general impression she gave was that of a superior working woman, or the wife of a small tradesman. The baby did not resemble her in the least: it was fair, and pretty, and daintily kept, its bonnet and coat and the shawl in which it was wrapped were of finest quality, and the tiny boot that lay on the carriage seat was a silk one.

Miss Barbara could not help speculating about the pair. She amused herself first with vainly trying to trace a likeness, then with wondering[41] whether the woman were really the mother of the child, and if so, how she managed to dress it so well, and whether she realized that its clothes looked out of keeping with her own attire. Finally she gave up guessing, in sheer despair of arriving at any possible conclusion.

The train had been ten minutes late in starting, and was making up for lost time by an increase in speed as it dashed across a tract of moorland. The oscillation was most marked, and walls and telegraph posts seemed to fly past so quickly as to dazzle the sight. Miss Sherbourne closed her eyes; the whirling landscape made her head ache, and the swaying of the carriage had become very unpleasant. She took hold of the strap to steady herself, and was debating whether it would be better to close the rattling window, when, without further warning, there came a sudden and awful crash, the impact of which hurled the baby on to her knee, and telescoped the walls of the compartment. For a few seconds she was stunned with the shock. When she recovered consciousness she found herself lying on her side under a pile of wreckage, instinctively clutching the little child in her arms. She moved her limbs cautiously, and satisfied herself that she was unhurt; part of the roof had fallen slantwise, and by so doing had just saved her from injury, penning her in a corner of the overturned carriage. The smashed[42] window was underneath, about eighteen inches above the ground, for the train in toppling over had struck a wall, and lay at an inclined angle.

From all around came piteous groans and cries for help, but Miss Sherbourne could see nobody, the broken woodwork cutting her off completely from the rest of the compartment. The baby in her arms was screaming with fright. Fortunately for herself, she preserved presence of mind and a resourceful brain. She did not lose her head in this emergency, and her first idea was to find some means of escape. She stretched out her hand and broke away the pieces of shivered glass till the window beneath her was free; then, still clasping the child, she managed to crawl through the opening on to the line below. So narrow was the space between the ground and the wreckage above her that she was forced to lie flat and writhe herself along. It was a slow and painful progress, and the light was so dim that she could scarcely see, while at any moment she expected to find her way blocked by fallen woodwork. Yet that was her one chance of safety, and at any cost she must persevere. She never knew how far she crawled; to her it seemed miles, though probably it was no greater distance than the length of the carriage: but at last she spied daylight, and, struggling through a hole above her head, she climbed over the ruins of a luggage compartment,[43] and so on to the bank of grass edging the line.

The wind was blowing strongly over the moor, so strongly that she had difficulty in keeping her feet as she staggered into the shelter of the wall. The scene before her was one of horror and desolation. She saw at once the cause of the accident—the express had dashed into an advancing train, and the two engines lay smashed by the terrific force of the collision. A few passengers who, like herself, had managed to make their escape stood by the line—some half-dazed and staring helplessly, others already attempting to rescue those who were pinned under the wreckage. The guard, his face livid and streaming with blood, was running to the nearest signal box to notify the disaster, and some labourers were hurrying from a group of cottages near, bringing an axe and a piece of rope. To the end of her life Miss Barbara will never recall without a shudder the pathetic sights she witnessed as the injured were dragged from the splintered carriages. But the worst was yet to come. Almost immediately a cry of "Fire!" was raised, and the flames, starting from one of the overturned engines and fanned by the furious wind, gained a fierce hold on the broken woodwork, which flared up and burned like tinder.

"Come awa'!" screamed a countrywoman, seizing Miss Sherbourne almost roughly by the arm.[44] "You with a bairn! Bring it to our hoose yonder out o' the wind. The men are doing a' they can, and we canna help 'em. It's no fit sight for women. Come, I tell ye! Th' train's naught but a blazin' bonfire, and them as is under it's as good as gone. Don't look! Don't look! Come, in the Lord's name!"

"Then may He have mercy on their souls!" said Miss Barbara, as with bowed head she allowed herself to be led away.

The news of the accident was telegraphed down the line, and as speedily as possible a special train, bearing doctors and nurses, arrived on the spot. The sufferers were carried to the little village of Greenfield, close by, and attended to at once, some who were well enough to travel going on by a relief train, while others who were more seriously injured remained until they could communicate with their friends. The fire, meanwhile, had done its fatal work, and little was left of any of the carriages but heaps of charred ashes. Those who had escaped comparatively unhurt had, with the aid of the few farm labourers who were near at the time, worked with frantic and almost superhuman endeavour to rescue any fellow-passengers within their reach; but they had at last been driven back by the fury of the flames and forced to abandon their heroic task. No one could even guess the extent of the death roll. From the extreme rapidity with which[45] the fire had taken hold and spread, it was feared that many must have perished under the wreckage, but their names could not be ascertained until the news of the disaster was spread over the country, and their friends reported them as missing.

Twenty-four hours later Miss Barbara Sherbourne sat in the parlour of the Red Lion Hotel at Greenfield. She had remained there partly because she was suffering greatly from shock, and partly because she felt responsible for the welfare of the little child whom she had been able to save. The account of its rescue was circulated in all the morning papers, so she expected that before long some relation would arrive to claim it. The woman who had accompanied it was not among the list of the rescued, and Miss Barbara shuddered afresh at the remembrance of the burning carriages.

"It's a bonnie bairn, too, and takes wonderful notice," said Martha, Miss Sherbourne's faithful maid, for whom she had telegraphed. "Those to whom it belongs will be crazy with joy to find it safe. Dear, dear! To think its poor mother has gone, and to such an awful death!"

The baby girl was indeed the heroine of the hour. The story of her wonderful escape appealed to everybody; newspaper reporters took snapshots of her, and many people begged to be allowed to see her out of sheer curiosity or interest. So far, though she had been interviewed almost continuously[46] from early morning, not one among the numbers who visited her recognized her in the least. Fortunately she was of a friendly disposition, and though she had had one or two good cries, she seemed fairly content to be nursed by strangers, and took readily to the bottle that was procured for her. At about six o'clock Miss Barbara and Martha sat alone with her in the inn parlour. The afternoon train had departed, bearing with it most of yesterday's sufferers and their friends, so it was hardly to be expected that any more visitors would arrive that evening. The baby sat on Miss Barbara's knee, industriously exercising the only two wee teeth it possessed upon an ivory needlecase supplied from Martha's pocket. Outside the light was fading, and rain was beginning to fall, so the bright fire in the grate was the more attractive.

"I'm glad we didn't attempt to go home to-night, Martha," said Miss Sherbourne. "I expect I shall feel better to-morrow, and I shall leave much more comfortably when this little one has been claimed. No doubt somebody will turn up for her in the morning. It's too late for anyone else to come to-day."

"There's a carriage arriving now," replied Martha, rising and going to the window. "Somebody's getting out of it. Yes, and she's coming in here, too, I verily believe."

[47] Martha was not mistaken. A moment afterwards the door was opened, and the landlord obsequiously ushered in a stranger. The lady was young, and handsomely dressed in deep mourning. Her face was fair and pretty, though it showed signs of the strongest agitation. She was deadly pale, her eyes had a strained expression, and her lips twitched nervously. Without a word of introduction or explanation she walked straight to the child, and stood gazing at it with an intensity which it was painful to behold, catching her breath as if speech failed her.

"Do you recognize her?" asked Miss Barbara anxiously, turning her nursling so that the light from the lamp fell full on its chubby face.

"No! No!" gasped the stranger. "I don't know it. I can't tell whose it is in the least."

She averted her face as she spoke; her mouth was quivering, and her hands trembled.

"You've lost a baby of this age in the accident, maybe?" enquired Martha.

"No; I have lost nobody. I only thought—I expected——" She spoke wildly, almost hysterically, casting swift, uneasy glances at the child, and as quickly turning away her eyes.

"You expected?" said Miss Sherbourne interrogatively, for the stranger had broken off in the middle of the sentence.

"Nothing—nothing at all! I'm sorry to have[48] troubled you. I must go at once, for my carriage is waiting."

"Then you don't know the child?"

"I don't," the stranger repeated emphatically; "not in the slightest. I tell you I have never seen it in my life before!"

She left the room as abruptly as she had entered, without even the civility of a good-bye; addressed a few hurried words in a low tone to the landlord in the hall, then, entering her conveyance, drove off into the rapidly gathering darkness.

"There's something queer about her," said Martha, watching the departure over the top of the short window blind. "She was ready to take her oath that she'd never set eyes on the child before, but the sight of it sent her crazy. Deny what she may, if you ask me, it's my firm opinion she was telling a lie."

"Surely no one would refuse to acknowledge it!" exclaimed Miss Barbara. "She seemed so terribly agitated and upset, she must have expected to find some other baby, and have been disappointed."

"Disappointed!" sniffed Martha scornfully. "Aye, she was disappointed at finding what she expected. Agitated and upset, no doubt, but the trouble was, she knew the poor bairn only too well."

In spite of the publicity given by the newspapers,[49] no friends turned up to claim the little girl. Nobody seemed to recognize her, or was able to supply the least clue to her parentage. It was impossible even to ascertain at what station the woman, presumably her mother, had joined the train. She was already settled in the corner when Miss Sherbourne entered the compartment, and though a description of her was circulated, none of the porters remembered noticing her particularly. All the carriages had been full, and there had been several other women with young children in the accident. Any luggage containing papers or articles which might have led to her identification had been destroyed in the fire. The baby's clothing was unmarked. Day after day passed, and though many visits were paid and enquiries made, the result was invariably the same, and in a short time popular interest, always fleeting and fickle, died completely away.

After staying nearly a fortnight at the Red Lion Hotel, in the hope that the missing relatives might come at last to the scene of the disaster, Miss Sherbourne returned to her own home, taking with her the child which so strange a chance had given into her charge. For some months she still made an endeavour to establish its identity; she put advertisements in the newspapers and enlisted the services of the police, but all with no avail: and when a year had passed she realized that her[50] efforts seemed useless. Her friends urged her strongly to send the little foundling to an orphanage, but by that time both she and Martha had grown so fond of it that they could not bear the thought of a parting.

"I'll adopt her as my niece, if you're willing to take your share of the trouble, Martha," said Miss Barbara.

"Don't call it trouble," returned Martha. "The bairn's the very sunshine of the house, and it would break my heart if she went."

"Very well; in future, she's mine. I shall name her Dorothy Greenfield, because Dorothy means 'a gift of God', and it was at Greenfield that the accident occurred. I feel that Fate flung her into my arms that day, and surely meant me to keep her. She was a direct 'gift', so I accept the responsibility as a solemn charge."

Miss Sherbourne's decision met with considerable opposition from her relations.

"You're quixotic and foolish, Barbara, to think of attempting such a thing," urged her aunt. "It's absurd, at your age, to saddle yourself with a child to bring up. Why, you may wish to get married!"

"No, no," said Miss Barbara hastily, her thoughts on an old heartache that obstinately refused to accept decent burial; "that will never be—now. You must not take that contingency into consideration at all."

[51] "You may think differently in a year or two, and it would be cruelty to the child to bring her up as a lady and then hand her over to an institution."

"I should not do her that injustice. I take her now, and promise to keep her always."

"But with your small means you really cannot afford it."

"I am sure I shall be able to manage, and the child herself is sufficient compensation for anything I must sacrifice; she's a companion already."

"Well, I don't approve of it," said Aunt Lydia, with disfavour. "If you want companionship, you can always have one of your nieces to stay a week or two with you."

"It's not the same; they have their own homes and their own parents, and are never anything but visitors at my house. However fond they may be of me, I feel I am only a very secondary consideration in their lives. I can't be content with such crumbs of affection. Little Dorothy seems entirely mine, because she has nobody else in the world to love her."

"Then you actually intend to assume the full responsibility of her maintenance, and to educate her in your own station—a child sprung from who knows where?"

"Certainly. I shall regard her absolutely as my[52] niece, and I shall never part with her unless someone should come and show a higher right than mine to claim her."

Having exhausted all their arguments, Miss Sherbourne's relatives gave her up in despair. She was old enough to assert her own will and manage her own affairs, and if she liked to spend a large proportion of her scanty income on bringing up a foundling,—well, she need not expect any help from them in the matter. They ignored the child, and never asked it to their houses, refusing to recognize that it had any claim to be treated on an equality with their own children, and disapproving from first to last of the whole proceeding.

It was part of Miss Barbara's plan to let little Dorothy grow up in complete ignorance of her strange history. She did not wish her to realize that she was different from other children, or to allow any slight to be cast upon her, or any unkind references made to her dependent position. For this reason she removed into Yorkshire, and settled down at the village of Hurford, where the circumstances of the case were not known, and Dorothy could be received as her niece without question. She left the little girl at home with Martha when she went to stay with her relations, whom she succeeded in influencing so far that she persuaded them to refrain from all allusions[53] to Dorothy's parentage when they paid return visits to Holly Cottage. Dorothy had often wondered why Aunt Lydia and Aunt Constance treated her so stiffly, but, like most children, she divided the world into nice and nasty people, and simply included them in the latter category, without an inkling of the real reason for their coldness. That she was never asked to their homes did not trouble her in the least; she would have regarded such a visit as a penance. Martha kept the secret rigidly. In her blunt, uncompromising fashion she adored the child, and was glad to have her in the house. Though she did not spare scoldings, and enforced a rigorous discipline concerning the kitchen regions, she looked after Dorothy's welfare most faithfully, especially during Miss Sherbourne's absence, and always took the credit for having a half-share in her upbringing.

And now more than thirteen years had passed away, and the chubby baby had grown into a tall girl who must be verging upon fourteen. Time, which had brought a line or two to Miss Barbara's face, and a chance grey thread among her brown locks, had also brought her a modest measure of success. She had always possessed a taste for literary work, and in the quiet village of Hurford she had been able to write undisturbed. Her articles, reviews, and short stories appeared in various magazines and papers, and by this method[54] of adding to her income she had been able to send Dorothy to Avondale College. It was quite an easy journey by train from Hurford to Coleminster, and the school was considered one of the best in the north of England. The girl had been there for four years, and had made satisfactory progress, though she had not shown a decided bent for any special subject. What her future career might be, Fate had yet to determine.

Dorothy set off for school on the morning after the election in a very sober frame of mind. Aunt Barbara had made her acquainted with most of the facts mentioned in our last chapter, and she now thoroughly understood her own position. To a girl of her proud temperament the news had indeed come as a great humiliation. Instead of bringing a copy of her pedigree to convince Agnes Lowe that she was one of the Sherbournes of Devonshire, she would now be obliged to ignore the subject. She did not expect it would be mentioned openly again, but there might be hints or allusions, and the mere fact that the girls at school should know was sufficiently mortifying.

"Agnes was perfectly right," she thought bitterly. "I am a waif, a nobody, with no relations, and no place of my own in the world. I suppose I am exactly what she called me—a charity child! I wonder how she heard the story? But it really does not matter who told her; the[56] secret has leaked out somehow, and no doubt it will soon be bruited all over the College. It was time I knew about it myself; but oh dear, how different I feel since yesterday!"

Thus Dorothy mused, all unconscious that the shuttle of Fate was already busy casting fresh threads into the web of her life, and that the next few minutes would bring her a meeting with one whose fortunes were closely interwoven with her own, and whose future friendship would lead to strange and most unexpected issues. The train had reached Latchworth, where a number of passengers were waiting on the platform. The door of Dorothy's compartment was flung open, and a girl of about her own age entered, wearing the well-known Avondale ribbon and badge on her straw hat. Dorothy remembered noticing her among the new members who had been placed yesterday in the Upper Fourth, though she had had no opportunity of speaking to her, and had not even learnt her name. A pretty, fair-haired lady was seeing her off, and turned to Dorothy with an air of relief.

"You are going to the College?" she asked pleasantly. "Oh, I am so glad! Then Alison will have somebody to travel with. Will you be good-natured, and look after her a little at school? She knows nobody yet."

"I'll do my best," murmured Dorothy.

[57] "It will be a real kindness. It is rather an ordeal to be a complete stranger among so many new schoolfellows. Birdie, you must be sure to come back with this girl, then I shall feel quite happy about you. You have your books and your umbrella? Well, good-bye, darling, until five o'clock."

The girl stood waving her hand through the window until the train was out of the station, then she came and sat down in the seat next to Dorothy. She had a plump, rosy, smiling face, very blue eyes, and straight, fair hair. Her expression was decidedly friendly.

Dorothy was hardly in a genial frame of mind, but she felt bound to enter into conversation.

"You're in the Upper Fourth, aren't you?" she began, by way of breaking the ice.

"Yes, and so are you. Aren't you Dorothy Greenfield, who was put up for the Lower School election?"

"And lost it!" exclaimed Dorothy ruefully. "I don't believe I'll ever canvass again, whatever office is vacant. The thing wasn't managed fairly. You haven't told me your name yet."

"Alison Clarke, though I'm called Birdie at home."

"Do you live at Latchworth?"

"Yes, at Lindenlea."

"That pretty house on the hill? I always notice[58] it from the train. Then you must have just come. It has been to let for two years."

"We removed a month ago. We used to live at Leamstead."

"How do you like the Coll.?"

"I can't tell yet. I expect I shall like it better when I know the girls. I'm glad you go in by this train, because it's much jollier to have somebody to travel backwards and forwards with. Mother took me yesterday and brought me home, but of course she can't do that every day."

Dorothy marched into school that morning feeling rather self-conscious. She could not be sure whether her story had been circulated or not, but she did not wish it to be referred to, nor did she want to enter into any explanations. She imagined that her classmates looked at her in rather a pitying manner. The bare idea put her on the defensive. Her pride could not endure pity, even for losing the Wardenship, so she kept aloof and spoke to nobody. It was easy enough to do this, since Hope Lawson was the heroine of the hour, and the girls, finding Dorothy rather cross and unsociable, left her to her own devices. At the mid-morning interval she took a solitary walk round the playground, and at one o'clock, instead of joining the rest of the day boarders in the gymnasium, she lingered behind in the classroom.

"What's wrong with Dorothy Greenfield?" asked[59] Ruth Harmon. "She's so grumpy, one can't get a word out of her."

"Sulking because she missed the election, I suppose," said Val Barnett.

"That's not like Dorothy. She flares up and gets into tantrums, but she doesn't sulk."

"And she doesn't generally bear a grudge about things," added Grace Russell.

"I believe I can guess," said Mavie Morris. "I heard yesterday that she isn't really Miss Sherbourne's niece at all; she was adopted when she was a baby, and she doesn't even know who her parents were."

"Well, she can't help that."

"Of course she can't; but you know Dorothy! She's as proud as Lucifer, and Agnes Lowe called her a waif and a nobody."

"Agnes Lowe wants shaking."

"Well, she didn't mean Dorothy to overhear her. She's very sorry about it."

"I'm more sorry for Dorothy. So that's the reason she's looking so glum! Isn't she coming to the meeting?"

"I don't know. She's up in the classroom."

"Someone fetch her."

"I'll go," said Mavie. "It's a shame to let her stay out of everything. She's as prickly as a hedgehog to-day, and will probably snap my head off, but I don't mind. She may have a temper,[60] but she's one of the jolliest girls in the Form, all the same."

"So she is. It's fearfully hard on her if what Agnes Lowe says is really true. I vote we try to be nice to her, to make up."

"Any girl who refers to it would be a cad."

"Well, look here! Let us try to get her made secretary of our 'Dramatic'."

"Right you are! I'll propose her myself."

Mavie ran quickly upstairs to the classroom.

"Aren't you coming, Dorothy? It's the committee meeting of the 'Dramatic', you know. The others are all waiting; they sent me to fetch you."

"You'll get on just as well without me," growled Dorothy, with her head inside her desk.

"Nonsense! Don't be such a goose. I tell you, everybody's waiting."

"Dorothy's jealous of Hope," piped Annie Gray, who, as monitress, was performing her duty of cleaning the blackboard.

"I'm not! How can you say such a thing? I don't care in the least about the Wardenship."

"Then come and show up at the meeting, just to let them see you're not sulking, at any rate," whispered Mavie. "Do be quick! I can't wait any longer."

Dorothy slammed her desk lid, but complied. Though she would rather have preferred her own[61] society that day, she did not wish her conduct to be misconstrued into jealousy or sulks.

"Go on, Mavie, and I'll follow," she replied abruptly, but not ungraciously.

As she strolled downstairs she noticed Alison Clarke standing rather aimlessly on the landing, as if she did not quite know where to go or what to do. Dorothy's conscience gave her a prick. She had quite forgotten Alison, who, as a new girl, must be feeling decidedly out of things at the College. She certainly might have employed the eleven-o'clock interval much more profitably in befriending the new-comer than in mooning round the playground by herself, brooding over her own troubles. However, it was not too late to make up for the omission.

"Hallo!" she exclaimed. "Not a very breezy occupation to stand reading the Sixth Form timetable, is it?"

"I've nothing better to do," replied Alison, whose rosy face looked a trifle forlorn. "I don't know a soul here yet, or the ways of the place."

"You know me! Come along to the gym.; we're going to have a committee meeting."

Alison brightened visibly.

"What's the meeting about?" she asked, as she stepped briskly with Dorothy along the passage.

"It's our 'Dramatic'. You see, we who stay for dinner get up little plays among ourselves.[62] Each Form acts one or two every term. They're nothing grand—not like the swell things they have at the College Dramatic Union—and we only do them before the other girls in the gym., but they're great fun, all the same."

"I love acting!" declared Alison, with unction.

"Ever done any?"

"Rather! We were keen on it at the school I went to in Leamstead. I was 'Nerissa' once, and 'Miss Matty' in Scenes from Cranford, and 'The March Hare' in Alice in Wonderland. I have the mask still, and the fur costume, and Miss Matty's cap and curls."

"Any other properties?"

"Heaps—in a box at home. There are Miss Matty's mittens and cross-over, and her silk dress."

"Good! I must tell the girls that. We requisition everything we can. Where are they having the meeting, I wonder? Oh, there's Mavie beckoning to us near the horizontal bar!"

The day boarders belonging to the Upper Fourth were collected in a corner of the gymnasium, waiting impatiently for a few last arrivals. They made room for Dorothy and Alison, and as Annie Gray followed in a moment or two, the meeting began almost immediately. Hope Lawson, by virtue of her Wardenship, took the chair. The first business of the society was to choose a secretary.

"I beg to propose Dorothy Greenfield," said[63] Grace Russell, putting in her word before anyone else had an opportunity, and looking at Ruth Harmon.

"And I beg to second the proposal," said Ruth, rising to the occasion.

Nobody offered the slightest opposition, and Dorothy was elected unanimously. Very much surprised, but extremely pleased, she accepted the notebook and stump of pencil that were handed her as signs of office.

"The next thing is to choose a play," said Hope, "and I think we can't do better than take one of these Scenes from Thackeray. Miss Pinkerton's Establishment for Young Ladies is lovely."

"Who'd be Miss Pinkerton?"

"It depends on the costume. She ought to have curls, and a cap and mittens, and a silk dress."

"Can we fish them up from anywhere?"

"Didn't you say you'd had them for Miss Matty?" whispered Dorothy to Alison; adding aloud: "This new girl, Alison Clarke, has the complete costume at home, and she's accustomed to acting. I say she'd better take Miss Pinkerton."

"One can't give the best part to a new girl," objected Annie Gray.

"It's not the best part; it's nothing to Becky Sharp."

"Well, it's the second best, anyhow."

[64] "Oh, never mind that! Let her try. If you find she can't manage it, you can put in somebody else instead. Give her a chance to show what she can do, at any rate," pleaded Dorothy.

"We'd destined Miss Pinkerton for you," murmured Grace Russell.

"Then I'll resign in favour of Alison. Let me take Miss Swartz, or one of the servants—I don't mind which."

It was characteristic of Dorothy that, having reproached herself for neglecting Alison, she was at once ready to renounce anything and everything for her benefit. She never did things by halves, and, considering that she had made a promise in the train, she meant to keep it; moreover, she had really taken a fancy to the new-comer's beaming face.

"So be it!" said Hope. "Put it down provisionally—Miss Pinkerton, Alison Clarke. Now the great business is to choose Becky. Oh, bother! There's the dinner bell! It always rings at the wrong minute. No, we can't meet again at two, because I have my music lesson. We must wait till to-morrow."

Dorothy escorted her protégée to the dining-room, and, when dinner was over, spent the remaining time before school in showing her the library, the museum, and the other sights of the College.

[65] "You don't feel so absolutely at sea now?" she enquired.

"No, I'm getting quite at home, thanks to you. It's such a comfort to have somebody to talk to. Yesterday was detestable."

At three o'clock the Upper Fourth had a literature lesson with Miss Tempest. It was held in the lecture hall instead of their own classroom, and just as the girls were filing in at the door, Dorothy made the horrible discovery that in place of her Longfellow she had brought an English history book. It was impossible to go back, for Miss Pitman was standing on the stairs.

"What am I to do?" she gasped. "How could I have been so idiotically stupid?"

"Can't you look on with somebody?" suggested Alison, who was walking with her.

"Miss Tempest will notice, and ask the reason. She's fearfully down on us if we forget anything. I'm in the front row, too, worse luck!"

"Then take my Longfellow and give me your History. Perhaps I shan't be asked to read. We'll chance it, anyhow," said Alison, changing the two books before Dorothy had time to object.

"No, no; it's too bad!" began Dorothy; but at that moment Miss Pitman called out: "What are you two girls waiting for? Move on at once!" and they were obliged to pass into the lecture hall and go to their seats.

[66] Fortune favoured them that afternoon. Miss Tempest, in the course of the lesson, twice asked Dorothy to read passages, and completely missed out Alison, who sat rejoicing tremulously in the back row.

"You don't know from what you've saved me," said the former, as she returned the book when the class was over. "I should have been utterly undone without your Longfellow."

"It's like the fable of the mouse and the lion," laughed Alison. "I must say I felt a little nervous when Miss Tempest looked in my direction. I thought once she was just going to fix on me. All's well that ends well, though."

"And I won't be such a duffer again," declared Dorothy.

"Mother, dearest," said Alison Clarke that evening, "I didn't think the College half so horrid to-day as I did yesterday. I like Dorothy Greenfield, she's such a jolly girl. She took me all round the place and showed me everything, and told me what I might do, and what I mustn't. We went to the Dramatic meeting—at least, it wasn't the real College Dramatic, but one in our own Form—and I got chosen for Miss Pinkerton. Dorothy's going to be Miss Swartz, I expect. We've arranged to travel together always. She's going to wave her handkerchief out of the window[67] the second the train gets to Latchworth, so that I can go into her carriage; and we shall wait for each other in the dressing-room after school."

"I thought she looked a nice girl," said Mrs. Clarke. "She has such a bright, intelligent face, and she answered so readily and pleasantly when I spoke to her. I'm glad to hear she took you under her wing, and showed you the Avondale ways. You'll soon feel at home there now, Birdie."

"Oh, I shall get along all right! Miss Tempest is rather tempestuous, and Miss Pitman's only tolerable, but the acting is going to be fun. As for Dorothy, she's ripping!"

The fickle goddess of fortune, having elected to draw together the lives of Dorothy Greenfield and Alison Clarke, had undoubtedly begun her task by sending the latter to live near Coleminster. Mrs. Clarke told all her friends that it was by the merest chance she had seen and taken Lindenlea. She had decided that the climate of Leamstead was too relaxing; and when, on a motor tour with a cousin in the North, she happened to pass through the village of Latchworth, and noticed the pretty, rambling old house to let on the top of the hill, she had at once insisted upon stopping, obtaining the keys, and looking over it. And she had so immediately and entirely fallen in love with its pleasant, sunny rooms and delightful garden that she had interviewed the agent without further delay, and arranged to take it on a lease.

"It's the very kind of place I've always longed for!" she declared—"old-fashioned enough to be picturesque, yet with every modern comfort: a good coach-house and stable, a meadow large[69] enough to keep a Jersey cow in, a splendid tennis court, and the best golf links in the neighbourhood close by. Another advantage is that Alison can go to Avondale College. The house is so near to the station that she can travel by train into Coleminster every day, and return at four o'clock. I'm never able to make up my mind to spare her to go to a boarding school; but, on the other hand, I don't approve of girls being taught at home by private governesses. The College exactly solves the problem. No one can say I'm not giving her a good education, and yet I shall see her every day, and have her all Saturday and Sunday with me. It's no use possessing a daughter unless she can be something of a companion, and I always think Nature meant a mother to bring up her own child, particularly when she's a precious only chick like mine."

Alison had no memory of her father, who had died in her infancy. Her mother had been as both parents to her, and had supplied the place of brothers and sisters as well. Poor Mrs. Clarke could not help fussing over her one treasure, and Alison's education, amusements, clothes, and, above all, health, were her supreme interests in life. The girl was inclined to be delicate; she had suffered as a child from bronchial asthma, and though she had partly outgrown the tendency, an occasional attack still alarmed her mother.

[70] It was largely on Alison's account that Mrs. Clarke had taken Lindenlea. She thought the open, breezy situation on the top of a hill likely to suit her far better than the house at Leamstead, which had been situated too close to the river; and she knew that the neighbourhood of Coleminster was considered specially bracing for those troubled with throat or chest complaints. At fourteen Alison was one of those over-coddled, petted, worshipped only daughters who occasionally, in defiance of all ordinary rules, seem to escape becoming pampered and selfish. She had a very sweet and sensible disposition, and a strong sense of justice. In her heart of hearts she hated to be spoilt or in any way favoured. She would have liked to be one of a large family, and she greatly envied girls with younger brothers and sisters to care for. Dearly as she loved her mother, it was often a real trial to her to be idolized in public. She was quick to catch the amused smile of visitors who listened while her praises were sung, and the everlasting subject of her health was discussed; and to detect the disapproval with which they noticed her numerous indulgences. She felt it unfair that strangers, and even friends, seemed to consider her selfish for receiving all the good things showered upon her. She could not disappoint her mother by refusing any of them, though she would gladly have handed them on[71] to someone less fortunate than herself. To her credit, she never once allowed her mother to suspect that this over-fond and anxious affection made her appear singular, and occasionally even a subject of ridicule among other girls. She submitted quite patiently to the cosseting and worrying about her health, only sighing a little over the superfluous wraps and needless tonics, and wishing, though never for less love, certainly for less close and fretting attention.

Perhaps as the direct result of this adoration at home, Alison was a pleasant companion at school, quite ready to give up her own way on occasion, and enjoying the sensation of sharing alike with everyone else. She was soon on good terms with her classmates, for she was merry and humorous as well as accommodating. Her friendship with Dorothy increased daily. As they travelled backwards and forwards by train together they were necessarily thrown much in each other's company, and they earned the nicknames of "David" and "Jonathan" in the Form.