"Axe in hand."

Original etching by Adrian Marcel.

Title: Avarice--Anger: Two of the Seven Cardinal Sins

Author: Eugène Sue

Illustrator: Adrian Marcel

Release date: November 13, 2010 [eBook #34308]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

Illustrated Cabinet Edition

Illustrated with Etchings by

Adrian Marcel

Dana Estes & Company

Publishers

Boston

Copyright, 1899

By Francis A. Niccolls & Co.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| AVARICE. | ||

|---|---|---|

| I. | An Unfortunate Choice | 13 |

| II. | A Touching Example of Unselfish Devotion | 25 |

| III. | A Shameful Deception | 36 |

| IV. | The Voice of the Tempter | 46 |

| V. | Father and Son | 57 |

| VI. | A Father's Ambition | 65 |

| VII. | The Forged Letter | 72 |

| VIII. | A Startling Discovery | 78 |

| IX. | Commandant de la Miraudière's Antecedents | 86 |

| X. | The Mystery Explained | 97 |

| XI. | Hidden Treasure | 106 |

| XII. | A Voice from the Grave | 113 |

| XIII. | The Miser Extolled | 118 |

| XIV. | Plans for the Future | 122 |

| XV. | Madame Lacombe's Unconditional Surrender | 126 |

| XVI. | A Capricious Beauty | 132 |

| XVII. | The Hôtel Saint-Ramon | 139 |

| XVIII. | A Novel Entertainment | 146 |

| XIX. | A Change of Owners | 152 |

| XX. | The Return | 159 |

| XXI. | The Awakening | 166 |

| ANGER. | ||

| I. | The Duel | 177 |

| II. | Another Ebullition of Temper | 186 |

| III. | The Warning | 194 |

| IV. | Those Whom the Gods Destroy They First Make Mad" | 199 |

| V. | Deadly Enmity | 208 |

| VI. | A Cunning Scheme | 217 |

| VII. | Home Pleasures | 225 |

| VIII. | The Captain's Narrative | 234 |

| IX. | Conclusion of the Captain's Narrative | 240 |

| X. | Segoffin's Dissimulation | 248 |

| XI. | Sabine's Confession | 255 |

| XII. | Suzanne's Enlightenment | 265 |

| XIII. | Onésime's Conquest | 271 |

| XIV. | Arguments For and Against | 279 |

| XV. | An Unwelcome Visitor | 287 |

| XVI. | Segoffin's Ruse | 294 |

| XVII. | The Voice of the Tempter | 302 |

| XVIII. | "My Mother's Murderer Still Lives!" | 309 |

| XIX. | After the Storm | 316 |

| XX. | The Midnight Attack | 322 |

| XXI. | A Last Appeal | 329 |

| XXII. | Conclusion | 338 |

| PAGE | |

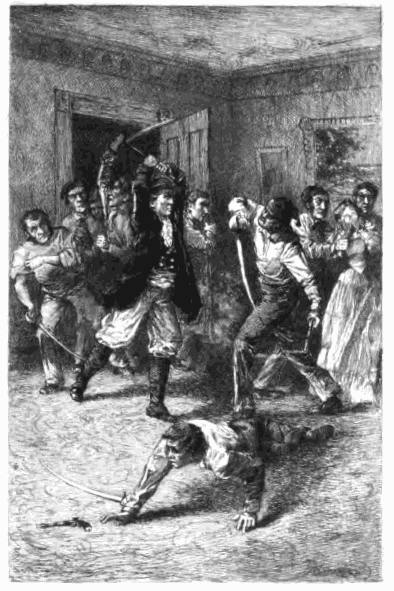

| "Axe in hand" | Frontispiece |

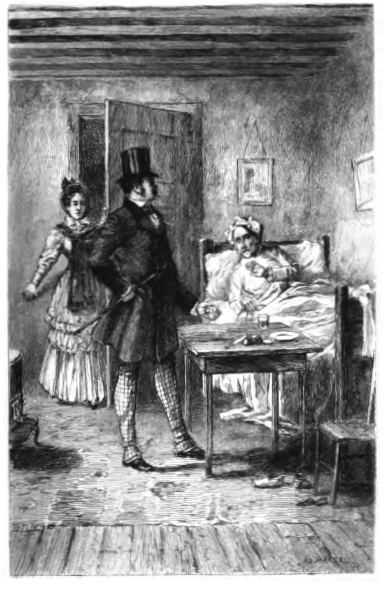

| "'Go away and let me alone'" | 53 |

| "'My star has not deserted me'" | 155 |

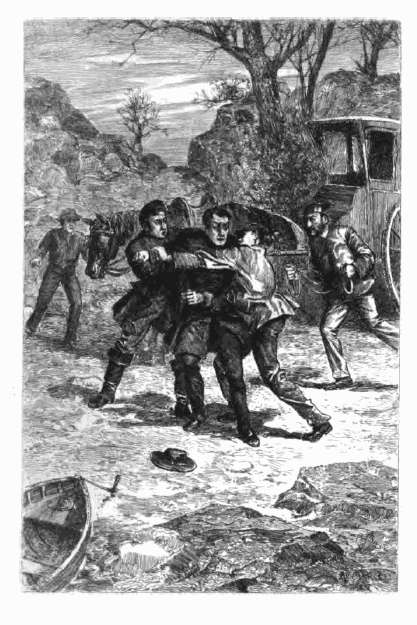

| "Several men rushed upon him" | 236 |

Avarice and Anger.

The narrow street known for many long years as the Charnier des Innocents (the Charnel-house of the Innocents), near the market, has always been noted for the large number of scriveners who have established their booths in this densely populated part of Paris.

One fine morning in the month of May, 18—, a young girl about eighteen years of age, who was clad in working dress, and whose charming though melancholy face wore that peculiar pallor which seems to be a sort of sinister reflection of poverty, was walking thoughtfully down the Charnier des Innocents. Several times she paused as if in doubt in front of as many scriveners' booths, but either because the proprietors seemed too young or too unprepossessing in appearance or too busy, she went slowly on again.

Seeing, in the doorway of the last booth, an old man with a face as good and kind as it was venerable, the young girl did not hesitate to enter the modest little establishment.

The scrivener, struck in his turn by the young girl's remarkable beauty and modest bearing, as well as her timid and melancholy air, greeted her with almost paternal affability as she entered his shop, after which he closed the door; then drawing the curtain of the little window, the good man motioned his client to a seat, while he took possession of his old leather armchair.

Mariette—for that was the young girl's name—lowered her big blue eyes, blushed deeply, and maintained an embarrassed, almost painful, silence for several seconds. Her bosom rose and fell tumultuously under the small gray shawl that she wore over her faded calico gown, while the hands she had clasped in her lap trembled violently.

The old scrivener, anxious to reassure the poor girl, said to her, almost affectionately, "Come, come, my child, compose yourself. Why should you feel this embarrassment? You came to ask me to write some request or petition for you, or, perhaps, a letter, did you not?"

"Yes, monsieur, it was—it was to ask you to write a letter for me that I came."

"Then you do not know how to write?"

"No, monsieur," replied Mariette, blushing still more deeply, as if ashamed of her ignorance, whereupon the scrivener, regretting that he had thus humiliated his client, said, kindly:

"You certainly cannot suppose me capable of blaming you for your ignorance. On the contrary, it is a sincere compassion I feel for persons who, for want of an education, are compelled to come to me, to apply to a third party, who may betray their confidence, and, perhaps, even ridicule them! And yet they are compelled to confide their dearest and most secret thoughts to these strangers. It is very hard, is it not?"

"It is, indeed, monsieur," replied Mariette, touched by these words. "To be obliged to apply to a stranger to—"

The young girl did not finish the sentence, but blushed deeply, and her eyes filled with tears.

Gazing at his youthful client with even greater interest, the scrivener said:

"Do not be so troubled, my child. You have neither garrulousness nor ridicule to fear from me. I have always regarded as something indescribably touching and sacred the confidence which persons who have been deprived of the advantages of an education are obliged to repose in me."

Then, with a kindly smile, he added: "But pray do not suppose for one moment, mademoiselle, that I say this to glorify myself at the expense of my confreres, and to get their clients away from them. No, I am saying exactly what I think and feel; and at my age, one certainly may be allowed to do that."

Mariette, more and more surprised at the old man's words, said, gratefully:

"I thank you, monsieur; you relieve me very much by thus understanding and excusing my embarrassment. It is very hard not to know how to read and write," she added, sighing," but, alas! very often one cannot help it."

"I am sure, my poor child, that in your case, as in the case of many other young girls who apply to me, it is not the good-will but the opportunity that is lacking. Many of these young girls, from being obliged to take care of their young brothers and sisters while their parents are busy away from home, have had no chance to attend school. Others were apprenticed at an early age—"

"Like myself, monsieur," said Mariette, smiling. "I was apprenticed when I was only nine years old, and up to that time I had been obliged to remain at home and take care of a little brother, who died a short time before my father and mother."

"Poor child! your history is very similar to that of most young girls of your station in life. But, since your term of apprenticeship expired, have you made no effort to acquire a little education?"

"Since that time I have had to work all day and far into the night to earn enough to keep my godmother and myself alive, monsieur," said Mariette, sadly.

"Alas! yes, time is bread to the labourer, and only too often he has to choose whether he shall die of hunger or live in ignorance."

Then, becoming more and more interested, he added: "You spoke of your godmother just now; so your father and mother are both dead, I suppose?"

"Yes, as I told you a little while ago," replied Mariette, sadly. "But pardon me, monsieur, for taking up so much of your time instead of telling you at once what I want you to write for me."

"I am sure my time could not have been better spent, for I am an old man, and I have had a good deal of experience, and I feel sure that you are a good and worthy girl. But now about the letter. Do you prefer to give me a rough idea of what you wish to write and let me put it in my own words, or do you prefer to dictate the letter?"

"I would rather dictate it, monsieur."

"Then I am ready," said the old man, putting on his spectacles, and seating himself at his desk with his eyes fixed upon the paper so as not to increase his client's embarrassment by looking at her.

So, after a moment's hesitation, Mariette, with downcast eyes, proceeded to dictate, as follows:

"Monsieur Louis."

On hearing this name, the old scrivener made a slight movement of surprise,—a fact that was not noticed by Mariette, who repeated, in a less trembling voice this time, "Monsieur Louis."

"I have written that," said the scrivener, still without looking at Mariette, whereupon the latter continued, hesitating every now and then, for, in spite of her confidence in the old man, it was no easy matter to reveal her secret thoughts to him:

"I am greatly troubled, for I have heard nothing from you, though you promised to write me while you were away."

"While you were away," repeated the scrivener, whose face had suddenly become thoughtful, and who was saying to himself, with a vague anxiety: "This is a singular coincidence. His name is Louis, and he is away."

"I hope you are well, M. Louis," Mariette continued, "and that it is not on account of any illness that you have not written to me, for then I should have two causes of anxiety instead of one.

"To-day is the sixth of May, M. Louis, the sixth of May, so I could not let the day pass without writing to you. Perhaps the same thought will occur to you, and that day after to-morrow I shall receive a letter from you, as you will receive one from me. Then I shall know that it was not on account of forgetfulness or sickness that you have delayed writing to me so long. In that case, how happy I shall be! So I shall wait for day after to-morrow with great impatience. Heaven grant that I may not be disappointed, M. Louis."

Mariette stifled a sigh as she uttered these last words, and a tear rolled down her cheek.

A long pause followed. The features of the scrivener who was bending over his desk could not be seen by the young girl, but they were assuming a more and more anxious expression; and two or three times he tried to steal a furtive glance at his client, as if the interest he had felt in her had given place to a sort of distrust caused by grave apprehensions on his part.

The young woman, keeping her eyes still fixed upon her lap, continued:

"I have no news to tell you, M. Louis. My godmother is still very ill. Her sufferings seem to increase, and that renders her much more irritable. In order that I may be with her as much as possible, I sew at home now most of the time, instead of going to Madame Jourdan's, so the days seem long and gloomy; for the work done in the shop with my companions was almost a pleasure, and seemed to progress much more rapidly. So I am obliged to work far into the night now, and do not get much sleep, as my godmother suffers much more at night than in the daytime, and requires a great deal of attention from me. Sometimes I do not even wake when she calls me because I am so dead with sleep, and then she scolds, which is very natural when she suffers so.

"You can understand, of course, that my life at home is not very happy, and that a friendly word from you would be a great comfort, and console me for many things that are very unpleasant.

"Good-bye, M. Louis. I expected to have written to you through Augustine, but she has gone back to her home now, and I have been obliged to apply to another person, to whom I have dictated this letter. Ah, M. Louis, never have I realised the misfortune of not knowing how to read or write as much as I do at this present time.

"Farewell, M. Louis, think of me, I beg of you, for I am always thinking of you.

"With sincere affection I once more bid you adieu."

As the young girl remained silent for a minute or two after these words, the old man turned to her and asked:

"Is that all, my child?"

"Yes, monsieur."

"And what name is to be signed to this letter?"

"The name of Mariette, monsieur."

"Mariette only?"

"Mariette Moreau, if you think best, monsieur. That is my family name."

"Signed, Mariette Moreau," said the old man, writing the name as he spoke.

Then, having folded the letter, he asked, concealing the secret anxiety with which he awaited the girl's reply:

"To whom is this letter to be addressed, my child?"

"To M. Louis Richard. General delivery, Dreux."

"I thought as much," secretly groaned the old man, as he prepared to write the address Mariette had just given him.

If the young girl had not been so deeply preoccupied she could hardly have failed to notice the change in the expression of the scrivener's face,—a change which became still more noticeable when he discovered for a certainty for whom this missive was intended. It was with a look of positive anger now that he furtively watched Mariette, and he seemed unable to make up his mind to write the address she had just given him, for after having written upon the envelope the words, "To Monsieur," he dropped his pen, and said to his client, forcing a smile in order to conceal alike his resentment and his apprehensions:

"Now, my child, though this is the first time we ever saw each other, it seems to me you feel you can trust me a little already."

"That is true, monsieur. Before I came here, I feared I should not have the courage to dictate my letter to an entire stranger, but your manner was so kind that I soon got over my embarrassment."

"I certainly see no reason why you should feel the slightest embarrassment. If I were your own father, I could not find a word of fault with the letter you have just written to—to M. Louis, and if I were not afraid of abusing the confidence you say that you have in me, I should ask—but no, that would be too inquisitive."

"You would ask me what, monsieur?"

"Who this M. Louis Richard is?"

"That is no secret, monsieur. M. Louis is the clerk of a notary whose office is in the same building as the shop in which I work. It was in this way that we became acquainted on the sixth of May, just one year ago to-day."

"Ah! I understand now why you laid such stress upon that date in your letter."

"Yes, monsieur."

"And you love each other, I suppose,—don't blush so, child,—and expect to marry some day, probably?"

"Yes, monsieur."

"And M. Louis's family consents to the marriage?"

"M. Louis has no one but his father to consult, and we hope he will not refuse his consent."

"And the young man's father, what kind of a person is he?"

"The best of fathers, M. Louis says, and bears his present poverty with great courage and cheerfulness, though he used to be very well off. M. Louis and his father are as poor now, though, as my godmother and I are. That makes us hope that he will not oppose our marriage."

"And your godmother, my child,—it seems to me she must be a great trial to you."

"When one suffers all the time, and has never had anything but misfortunes all one's life, it is very natural that one should not be very sweet tempered."

"Your godmother is an invalid, then?"

"She has lost one of her hands, monsieur, and she has a lung trouble that has confined her to the bed for more than a year."

"Lost her hand,—how?"

"She used to work in a mattress factory, monsieur, and one day she ran a long, crooked needle into her hand. The wound became inflamed from want of care, for my godmother had not time to give it the attention it should have had, and the doctors were obliged to cut her arm off. The wound reopens now and then, and causes her a great deal of pain."

"Poor woman!" murmured the scrivener, absently.

"As for the lung trouble she has," continued Mariette, "many women who follow that trade contract the disease, the doctors say, from breathing the unwholesome dust from the old mattresses they make over. My godmother is bent almost double, and nearly every night she has such terrible fits of coughing that I have to hold her for hours, sometimes."

"And your godmother has nothing but your earnings to depend on?"

"She cannot work now, monsieur, of course."

"Such devotion on your part is very generous, I must say."

"I am only doing my duty, monsieur. My godmother took care of me after my parents died, and paid for a three years' apprenticeship for me. But for her, I should not be in a position to earn my living, so it is only right that she should profit now by the assistance she gave me years ago."

"But you must have to work very hard to support her and yourself?"

"Yes; I have to work from fifteen to eighteen hours a day, monsieur."

"And at night you have to nurse her instead of taking the rest you so much need?"

"Who else would nurse her, monsieur?"

"But why doesn't she try to get into some hospital?"

"They will not take her into a hospital because the lung trouble she has is incurable. Besides, I could not desert her like that."

"Ah, well, my child, I see that I was not mistaken. You are a good, noble-hearted girl, there is no doubt of it," added the old man, holding out his hand to Mariette.

As he did, either through awkwardness, or intentionally, the scrivener overturned the inkstand that stood on his desk in such a way that a good part of the contents ran over the letter, which lacked only the address to complete it.

"Good heavens! How unfortunate, the letter is covered with ink, monsieur!" exclaimed Mariette.

"How awkward in me!" responded the old man, with a disgusted air. "Still, it doesn't matter very much, after all. It was a short letter. I write very rapidly, and it will not take me more than ten minutes to copy it for you, my child. At the same time, I will read it aloud so you can see if there is any change you would like to make in it."

"I am truly sorry to give you so much trouble, monsieur."

"It serves me right, as it was all my fault," responded the old man, cheerfully.

And he began to read the letter aloud as he wrote, exactly as if he were recopying it, as he proceeded with the reading. Nevertheless, from the scrivener's manner it seemed evident that a violent struggle was going on in his breast, for sometimes he sighed and knit his brows, sometimes he seemed confused and kept his eyes sedulously averted from the ingenuous face of Mariette, who sat with one elbow resting upon the table, and her head supported on her hand, watching with envious eyes the rapid movements of the old man's pen, as it traced characters which were undecipherable to her, but which would, as she fondly supposed, convey her thoughts to the man she loved.

The young girl expressing no desire to make the slightest change in her artless missive, the scrivener handed it to her after having carefully sealed it.

"And now, monsieur, how much do I owe you?" timidly inquired the girl, drawing a little purse containing two small silver corns and a few sous from her pocket.

"Fifty centimes," replied the old man after a moment's hesitation, remembering, perhaps, that it was at the cost of a day's bread that the poor girl was writing to her lover; "fifty centimes," repeated the scrivener, "for you understand, of course, my child, that I expect you to pay for only one of the letters I have written. I alone am responsible for my awkwardness."

"You are certainly very honest, monsieur," said Mariette, touched by what she considered a proof of generosity on the part of the scrivener. Then, after having paid for her letter, she added:

"You have been so kind to me, monsieur, that I shall venture to ask a favour of you."

"Speak, my child."

"If I have any other letters to write, it would be almost impossible for me to apply to any one but you, monsieur."

"I shall be at your service."

"But this is not all, monsieur. My godmother is as I am. She can neither read nor write. I had a friend I could depend upon, but she is out of town. In case I should receive a letter from M. Louis, would you be kind enough to read it to me?"

"Certainly, my child. I will read your letters to you with pleasure. Bring them all to me," replied the old man, with much inward gratification. "It is I who should thank you for the confidence you manifest in me. I hope I shall soon see you again, and that you leave here much more easy in mind than when you came."

"I certainly could not expect such kindness as you have shown me from any one else."

"Farewell, then, my child, and be sure that you consider me your reader and secretary henceforth. It really seems as if we must have known each other a dozen years."

"That is true, monsieur. Au revoir."

"Au revoir, my child."

Mariette had hardly left the booth when a postman appeared in the doorway, and holding out a letter to the old scrivener, said, cordially:

"Here, Father Richard, is a letter from Dreux."

"A letter from Dreux!" exclaimed the old man, seizing it eagerly. "Thank you, my friend." Then, examining the handwriting, he said to himself: "It is from Ramon! What is he going to tell me? What does he think of my son? Ah! what is going to become of all the fine plans Ramon and I formed so long ago?"

"There are six sous to pay on it, Father Richard," said the postman, arousing the old scrivener from his reverie.

"Six sous! the devil! isn't it prepaid?"

"Look at the stamp, Father Richard."

"True," said the scrivener, sighing heavily, as he reluctantly drew the ten sous piece he had just received from his pocket and handed it to the postman.

While this was going on, Mariette was hastening homeward.

Mariette soon reached the gloomy and sombre thoroughfare known as the Rue des Prêtres St. Germain-l'Auxerrois, and entered one of the houses opposite the grim walls of the church. After traversing a dark alley, the girl began to climb a rickety stairway as dark as the alley itself, for the only light came through a courtyard so narrow that it reminded one of a well.

The porter's room was on the first landing only a few steps from the stairway, and Mariette, pausing there, said to the woman who occupied it:

"Madame Justin, did you have the goodness to go up and see if my godmother wanted anything?"

"Yes, Mlle. Mariette, I took her milk up to her, but she was in such a bad humour that she treated me like a dog. Had it not been for obliging you, I would have let the old crosspatch alone, I can tell you."

"You must not be too hard on her, Madame Justin; she suffers so much."

"Oh, you are always making excuses for her, I know. It shows how good-hearted you are, but it doesn't prevent your godmother from being a hateful old thing. Poor child, you certainly are having your purgatory in advance. If there is no paradise for you hereafter you will certainly be cheated out of your rightful dues. But wait a minute, I have a letter for you."

"A letter?" exclaimed Mariette, her heart throbbing with relief and hope, "a letter from some one out of the city?"

"Yes, mademoiselle, it is postmarked Dreux, and there are six sous to pay on it. Here it is, and see, on the corner of the envelope the writer has put the words, 'Very urgent.'"

Mariette seized the letter and slipped it into her bosom; then, drawing out her little purse again, she took from it her last ten sous piece and paid the woman, after which she hastened up to her room, pleased and at the same time anxious and sad; pleased at having received a letter from Louis, anxious concerning the significance of those words, "Very urgent," written in a corner of the envelope, and sad because several hours must elapse before she would know the contents of the letter, for she dared not absent herself again after having left her godmother alone so long.

It was with a sort of dread that she finally opened the door of the room on the fifth floor that she occupied with her godmother. The poor woman was lying on the only bed the two women possessed. A thin mattress now rolled up out of the way in a corner, but laid on the floor at night, served as a bed for Mariette. A table, an old bureau, two chairs, a few cooking utensils hanging on the wall near the fireplace, were the only articles of furniture in the dimly lighted room, but everything was scrupulously clean.

Madame Lacombe—for that was the invalid's name—was a tall, frightfully pale, and emaciated woman, about fifty years of age, with a peevish, disagreeable face. Bent nearly double in the bed, one could see of her only her mutilated arm swathed in bandages, and her irascible face, surrounded by an old cap from which a wisp of gray hair crept out here and there, while her bluish lips were continually distorted by a bitter and sardonic smile.

Madame Lacombe seemed to be suffering greatly. At all events she was in an execrable temper, and her hollow eyes gleamed ominously. Making an effort to turn herself in bed, so as to get a look at her godchild, she exclaimed, wrathfully:

"Where on earth have you been all this time, you gadabout?"

"I have been gone barely an hour, godmother."

"And you hoped to find me dead when you got back, didn't you, now? Oh, you needn't deny it. You've had enough of me, yes, too much. The day my coffin lid is screwed down will be a happy day for you, and for me, too, for it is too bad, too bad for any one to have to suffer as I do," added the poor woman, pressing her hand upon her bosom, and groaning heavily.

Mariette dried the tears her godmother's sarcastic words had excited, and approaching the sufferer, said, gently:

"You had such a bad night last night that I hoped you would be more comfortable to-day and get a little sleep while I was out."

"If I suffer or if I starve to death it makes no difference to you, evidently, provided you can run the streets."

"I went out this morning because I was absolutely obliged to, godmother, but before I left I asked Madame Justin—"

"I'd as lief see a death's-head as that creature, so when you want to get rid of me you have only to send her to wait on me."

"Shall I dress your arm, godmother?"

"No, it is too late for that now. You stayed away on purpose. I know you did."

"I am sorry I was late, but won't you let me dress it now?"

"I wish to heaven you would leave me in peace."

"But your arm will get worse if you don't have it dressed."

"And that is exactly what you want."

"Oh, godmother, don't say that, I beg of you."

"Don't come near me! I won't have it dressed, I say."

"Very well, godmother," replied the girl, sighing. Then she added, "I asked Madame Justin to bring up your milk. Here it is. Would you like me to warm it a little?"

"Milk? milk? I'm tired of milk! The very thought of it makes me sick at my stomach. The doctor said I was to have good strong bouillon, with a chop and a bit of chicken now and then. I had some Monday and Wednesday—but this is Sunday."

"It is not my fault, godmother. I know the doctor ordered it, but one must have money to follow his directions, and it is almost impossible for me to earn twenty sous a day now."

"You don't mind spending money on clothes, I'm sure. When my comfort is concerned it is a very different thing."

"But I have had nothing but this calico dress all winter, godmother," answered Mariette, with touching resignation. "I economise all I can, and we owe two months' rent for all that."

"That means I am a burden to you, I suppose. And yet I took you in out of the street, and had you taught a trade, you ungrateful, hard-hearted minx!"

"No, godmother, I am not ungrateful. When you are not feeling as badly as you are now you are more just to me," replied Mariette, restraining her tears; "but don't insist upon going without eating any longer. It will make you feel so badly."

"I know it. I've got dreadful cramps in my stomach now."

"Then take your milk, I beg of you, godmother."

"I won't do anything of the kind! I hate milk, I tell you."

"Shall I go out and get you a couple of fresh eggs?"

"No, I want some chicken."

"But, godmother, I can't—"

"Can't what?"

"Buy chicken on credit."

"I only want a half or a quarter of one. You had twenty-four sous in your purse this morning."

"That is true, godmother."

"Then go to the rôtisseur and buy me a quarter of a chicken."

"But, godmother, I—"

"Well?"

"I haven't that much money any longer, I have only a few sous left."

"And those two ten sous pieces; what became of them?"

"Godmother—"

"Where are those two ten sous pieces, tell me?"

"I—I don't know," repeated the poor girl, blushing. "They must have slipped out of my purse. I—I—"

"You lie. You are blushing as red as a beet."

"I assure you—"

"Yes, yes, I see," sneered the sick woman, "while I am lying here on my death-bed you have been stuffing yourself with dainties."

"But, godmother—"

"Get out of my sight, get out of my sight, I tell you! Let me lie here and starve if you will, but don't let me ever lay eyes on you again! You were very anxious for me to drink that milk! There was poison in it, I expect, I am such a burden to you."

At this accusation, which was as absurd as it was atrocious, Mariette stood for a moment silent and motionless, not understanding at first the full meaning of those horrible words; but when she did, she recoiled, clasping her hands in positive terror; then, unable to restrain her tears, and yielding to an irresistible impulse, she threw herself on the sick woman's neck, twined her arms around her, and covering her face with tears and kisses, exclaimed, wildly:

"Oh, godmother, godmother, how can you?"

This despairing protest against a charge which could have originated only in a disordered brain restored the invalid to her senses, and, realising the injustice of which she had been guilty, she, too, burst into tears; then taking one of Mariette's hands in one of hers, and trying to press the young girl to her breast with the other, she said, soothingly:

"Come, come, child, don't cry so. What a silly creature you are! Can't you see that I was only joking?"

"True, godmother, I was very stupid to think you could be in earnest," replied Mariette, passing the back of her hand over her eyes to dry her tears, "but really I couldn't help it."

"You ought to have more patience with your poor godmother, Mariette," replied the sick woman, sadly. "When I suffer so it seems as if I can hardly contain myself."

"I know it, I know it, godmother! It is easy enough to be just and amiable when one is happy, while you, poor dear, have never known what happiness is."

"That is true," said the sick woman, feeling a sort of cruel satisfaction in justifying her irritability by an enumeration of her grievances, "that is true. Many persons may have had a lot like mine, but no one ever had a worse one. Beaten as an apprentice, beaten by my husband until he drank himself to death, I have dragged my ball and chain along for fifty years, without ever having known a single happy day."

"Poor godmother, I understand only too well how much you must have suffered."

"No, child, no, you cannot understand, though you have known plenty of trouble in your short life; but you are pretty, and when you have on a fresh white cap, with a little bow of pink ribbon on your hair, and you look at yourself in the glass, you have a few contented moments, I know."

"But listen, godmother, I—"

"It is some comfort, I tell you. Come, child, be honest now, and admit that you are pleased, and a little proud too, when people turn to look at you, in spite of your cheap frock and your clumsy laced shoes."

"Oh, so far as that is concerned, godmother, I always feel ashamed, somehow, when I see people looking at me. When I used to go to the workroom there was a man who came to see Madame Jourdan, and who was always looking at me, but I just hated it."

"Oh, yes, but for all that it pleases you way down in your secret heart; and when you get old you will have something pleasant to think of, while I have not. I can't even remember that I was ever young, and, so far as looks are concerned, I was always so ugly that I never could bear to look in the glass, and I could get no husband except an old drunkard who used to beat me within an inch of my life. I didn't even have a chance to enjoy myself after his death, either, for I had a big bill at the wine-shop to pay for him. Then, as if I had not trouble enough, I must needs lose my health and become unable to work, so I should have died of starvation, but for you."

"Come, come, godmother, you're not quite just," said Mariette, anxious to dispel Madame Lacombe's ill-humour. "To my certain knowledge, you have had at least one happy day in your life."

"Which day, pray?"

"The day when, at my mother's death, you took me into your home out of charity."

"Well?"

"Well, did not the knowledge that you had done such a noble deed please you? Wasn't that a happy day for you, godmother?"

"You call that a happy day, do you? On the contrary it was one of the very worst days I ever experienced."

"Why, godmother?" exclaimed the girl, reproachfully.

"It was, for my good-for-nothing husband having died, as soon as his debts were paid I should have had nobody to think of but myself; but after I took you, it was exactly the same as if I were a widow with a child to support, and that is no very pleasant situation for a woman who finds it all she can do to support herself. But you were so cute and pretty with your curly head and big blue eyes, and you looked so pitiful kneeling beside your mother's coffin, that I hadn't the heart to let you go to the Foundling Asylum. What a night I spent asking myself what I should do about you, and what would become of you if I should get out of work. If I had been your own mother, Mariette, I couldn't have been more worried, and here you are talking about that having been a happy day for me. No; if I had been well off, it would have been very different! I should have said to myself: 'There is no danger, the child will be provided for.' But to take a child without any hope of bettering its condition is a very serious thing."

"Poor godmother!" said the young girl, deeply affected. Then smiling through her tears in the hope of cheering the sick woman, she added:

"Ah, well, we won't talk of days, then, but of moments, for I'm going to convince you that you have at least been happy for that brief space of time, as at this present moment, for instance."

"This present moment?"

"Yes, I'm sure you must be pleased to see that I have stopped crying, thanks to the kind things you have been saying to me."

But the sick woman shook her head sadly.

"When I get over a fit of ill-temper like that I had just now, do you know what I say to myself?" she asked.

"What is it, godmother?"

"I say to myself: 'Mariette is a good girl, I know, but I am always so disagreeable and unjust to her that way down in the depths of her heart she must hate me, and I deserve it.'"

"Come, come, godmother, why will you persist in dwelling upon that unpleasant subject, godmother?" said the girl, reproachfully.

"You must admit that I am right, and I do not say this in any faultfinding way, I assure you. It would be perfectly natural. You are obliged almost to kill yourself working for me, you nurse me and wait on me, and I repay you with abuse and hard words. My death will, indeed, be a happy release for you, poor child. The sooner the undertaker comes for me, the better."

"You said, just now, that when you were talking of such terrible things it was only in jest, and I take it so now," responded Mariette, again trying to smile, though it made her heart bleed to see the invalid relapsing into this gloomy mood again; but the latter, touched by the grieved expression of the girl's features, said:

"Well, as I am only jesting, don't put on such a solemn look. Come, get out the chafing-dish and make me some milk soup. While the milk is warming, you can dress my arm."

Mariette seemed as pleased with these concessions on the part of her godmother as if the latter had conferred some great favour upon her. Hastening to the cupboard she took from a shelf the last bit of bread left in the house, crumbled it in a saucepan of milk, lighted the lamp under the chafing-dish, and then returned to the invalid, who now yielded the mutilated arm to her ministrations, and in spite of the repugnance which such a wound could not fail to inspire, Mariette dressed it with as much dexterity as patience.

The amiability and devotion of the young girl, as well as her tender solicitude, touched the heart of Madame Lacombe, and when the unpleasant task was concluded, she remarked:

"Talk about Sisters of Charity, there is not one who deserves half as much praise as you do, child."

"Do not say that, godmother. Do not the good sisters devote their lives to caring for strangers, while you are like a mother to me? I am only doing my duty. I don't deserve half as much credit as they do."

"Yes, my poor Mariette, I would talk about my affection for you. It is a delightful thing. I positively made you weep awhile ago, and I shall be sure to do the same thing again to-morrow."

Mariette, to spare herself the pain of replying to her godmother's bitter words, went for the soup, which the invalid seemed to eat with considerable enjoyment after all, for it was not until she came to the last spoonful that she exclaimed:

"But now I think of it, child, what are you going to eat?"

"Oh, I have already breakfasted, godmother," replied the poor little deceiver. "I bought a roll this morning, and ate it as I walked along. But let me arrange your pillow for you. You may drop off to sleep, perhaps, you had such a bad night."

"But you were awake even more than I was."

"Nonsense! I am no sleepyhead, and being kept awake a little doesn't hurt me. There, don't you feel more comfortable now?"

"Yes, very much. Thank you, my child."

"Then I will take my work and sit over there by the window. It is so dark to-day, and my work is particular."

"What are you making?"

"Such an exquisite chemise of the finest linen lawn, godmother. Madame Jourdan told me I must be very careful with it. The lace alone I am to put on it is worth two hundred francs, which will make the cost of each garment at least three hundred francs, and there are two dozen of them to be made. They are for some kept woman, I believe," added Mariette, naïvely.

The sick woman gave a sarcastic laugh.

"What are you laughing at, godmother?" inquired the girl, in surprise.

"A droll idea that just occurred to me."

"And what was it, godmother?" inquired Mariette, rather apprehensively, for she knew the usual character of Madame Lacombe's pleasantries.

"I was thinking how encouraging it was to virtue that an honest girl like yourself, who has only two or three patched chemises to her back, should be earning twenty sous a day by making three hundred franc chemises for—Oh, well, work away, child, I'll try to dream of a rest from my sufferings."

And the sick woman turned her face to the wall and said no more.

Fortunately, Mariette was too pure-hearted, and too preoccupied as well, to feel the bitterness of her godmother's remark, and when the sick woman turned her back upon her the girl drew the very urgent letter the portress had given her from her bosom, and laid it in her lap where she could gaze at it now and then as she went on with her sewing.

Discovering, a little while afterward, that her godmother was asleep, Mariette, who up to that time had kept the letter from Louis Richard—the scrivener's only son—carefully concealed in her lap, broke the seal and opened the missive. An act of vain curiosity on her part, for, as we have said, the poor girl could not read. But it was a touching sight to see her eagerly gaze at these, to her, incomprehensible characters.

She perceived with a strange mingling of anxiety and hope that the letter was very short. But did this communication, which was marked "Very urgent" on a corner of the envelope, contain good or bad news?

Mariette, with her eyes riveted upon these hieroglyphics, lost herself in all sorts of conjectures, rightly thinking that so short a letter after so long a separation must contain something of importance,—either an announcement of a speedy return, or bad news which the writer had not time to explain in full.

Under these circumstances, poor Mariette experienced one of the worst of those trials to which persons who have been deprived of the advantages of even a rudimentary education are exposed. To hold in one's hand lines that may bring you either joy or sorrow, and yet be unable to learn the secret! To be obliged to wait until you can ask a stranger to read these lines and until you can hear from other lips the news upon which your very life depends,—is this not hard?

At last this state of suspense became so intolerable that, seeing her godmother continued to sleep, she resolved, even at the risk of being cruelly blamed on her return,—for Madame Lacombe's good-natured fits were rare,—to hasten back to the scrivener; so she cautiously rose from her chair so as not to wake the sick woman, and tiptoed to the door, but just as she reached it a bitter thought suddenly checked her.

She could not have the scrivener read her letter without asking him to reply to it. At least it was more than probable that the contents of the letter would necessitate an immediate reply, consequently she would be obliged to pay the old man, and Mariette no longer possessed even sufficient money to buy bread for the day, and the baker, to whom she already owed twenty francs, would positively refuse, she knew, to trust her further. Her week's earnings which had only amounted to five francs, as her godmother had taken up so much of her time, had been nearly all spent in paying a part of the rent and the washerwoman, leaving her, in fact, only twenty-five sous, most of which had been used in defraying the expenses of her correspondence with Louis, an extravagance for which the poor child now reproached herself in view of her godmother's pressing needs.

One may perhaps smile at the harsh recriminations to which she had been subjected on account of this trifling expenditure, but, alas! twenty sous does not seem a trifling sum to the poor, an increase or decrease of that amount in their daily or even weekly earnings often meaning life or death, sickness or health, to the humble toiler for daily bread.

To save further expense, Mariette thought for a moment of asking the portress to read the letter for her, but the poor girl was so shy and sensitive, and feared the rather coarse, though good-natured woman's raillery so much, that she finally decided she would rather make almost any sacrifice than apply to her. She had one quite pretty dress which she had bought at a second-hand clothes store and refitted for herself, a dress which she kept for great occasions and which she had worn the few times she had gone on little excursions with Louis. With a heavy sigh, she placed the dress, together with a small silk fichu, in a basket to take it to the pawnbroker; and with the basket in her hand, and walking very cautiously so as not to wake her godmother, the girl approached the door, but just as she again reached it Madame Lacombe made a slight movement, and murmured, drowsily:

"She's going out again, I do believe, and—"

But she fell asleep again without finishing the sentence.

Mariette stood for a moment silent and motionless, then opening the door with great care she stole out, locking it behind her and removing the key, which she left in the porter's room as she passed. She then hastened to the Mont de Piété, where they loaned her fifty sous on her dress and fichu, and, armed with this money, Mariette flew back to the Charnier des Innocents to find the scrivener.

Since Mariette's departure, and particularly since he had read the letter received from Dreux that morning, the old man had been reflecting with increasing anxiety on the effect this secret which he had discovered by the merest chance would have upon certain projects of his own. He was thus engaged when he saw the same young girl suddenly reappear at the door of his shop, whereupon, without concealing his surprise, though he did not betray the profound uneasiness his client's speedy return caused him, the scrivener said:

"What is it, my child? I did not expect you back so soon."

"Here is a letter from M. Louis, sir," said the young girl, drawing the precious missive from her bosom, "and I have come to ask you to read it to me."

Trembling with anxiety and curiosity, the girl waited as the scrivener glanced over the brief letter, concealing with only a moderate degree of success the genuine consternation its contents excited; then, uttering an exclamation of sorrowful indignation, he, to Mariette's intense bewilderment and dismay, tore the precious letter in several pieces.

"Poor child! poor child!" he exclaimed, throwing the fragments under his desk, after having crumpled them in his hands.

"What are you doing, monsieur?" cried Mariette, pale as death.

"Ah, my poor child!" repeated the old man, with an air of deep compassion.

"Good heavens! Has any misfortune befallen M. Louis?" murmured the girl, clasping her hands imploringly.

"No, my child, no; but you must forget him."

"Forget him?"

"Yes; believe me, it would be much better for you to renounce all hope, so far as he is concerned."

"My God! What has happened to him?"

"There are some things that are much harder to bear than ignorance, and yet I was pitying you a little while ago because you could not read."

"But what did he say in the letter, monsieur?"

"Your marriage is no longer to be thought of."

"Did M. Louis say that?"

"Yes, at the same time appealing to your generosity of heart."

"M. Louis bids me renounce him, and says he renounces me?"

"Alas! yes, my poor child. Come, come, summon up all your courage and resignation."

Mariette, who had turned as pale as death, was silent for a moment, while big tears rolled down her cheeks; then, stooping suddenly, she gathered up the crumpled fragments of the letter and handed them to the scrivener, saying, in a husky voice:

"I at least have the courage to hear all. Put the pieces together and read the letter to me, if you please, monsieur."

"Do not insist, my child, I beg of you."

"Read it, monsieur, in pity read it!"

"But—"

"I must know the contents of this letter, however much the knowledge may pain me."

"I have already told you the substance of it. Spare yourself further pain."

"Have pity on me, monsieur. If you do really feel the slightest interest in me, read the letter to me,—in heaven's name, read it! Let me at least know the extent of my misfortune; besides, there may be a line, or at least a word, of consolation."

"Well, my poor child, as you insist," said the old man, adjusting the fragments of the letter, while Mariette watched him with despairing eyes, "listen to the letter."

And he read as follows:

"'My dear Mariette:—I write you a few lines in great haste. My soul is full of despair, for we shall be obliged to renounce our hopes. My father's comfort and peace of mind, in his declining years, must be assured at any cost. You know how devotedly I love my father. I have given my word, and you and I must never meet again.

"'One last request. I appeal both to your delicacy and generosity of heart. Make no attempt to induce me to change this resolution. I have been obliged to choose between my father and you; perhaps if I should see you again, I might not have the courage to do my duty as a son. My father's future is, consequently, in your hands. I rely upon your generosity. Farewell! Grief overpowers me so completely that I can no longer hold my pen.

"'Once more, and for ever, farewell.

"'Louis.'"

While this note was being read, Mariette might have served as a model for a statue of grief. Standing motionless beside the scrivener's desk, with inertly hanging arms, and clasped hands, her downcast eyes swimming with tears, and her lips agitated by a convulsive trembling, the poor creature still seemed to be listening, long after the old man had concluded his reading.

He was the first to break the long silence that ensued.

"I felt certain that this letter would pain you terribly, my dear child," he said, compassionately.

But Mariette made no reply.

"Do not tremble so, my child," continued the scrivener. "Sit down; and here, take a sip of water."

But Mariette did not even hear him. With her tear-dimmed eyes still fixed upon vacancy, she murmured, with a heart-broken expression on her face:

"So it is all over! There is nothing left for me in the world. It was too blissful a dream. I am like my godmother, happiness is not for such as me."

"My child," pleaded the old man, touched, in spite of himself, by her despair, "my child, don't give way so, I beg of you."

The words seemed to recall the girl to herself. She wiped her eyes, then, gathering up the pieces of the torn letter, she said, in a voice she did her best to steady:

"Thank you, monsieur."

"What are you doing?" asked Father Richard, anxiously. "What is the use of preserving these fragments of a letter which will awaken such sad memories?"

"The grave of a person one has loved also awakens sad memories," replied Mariette, with a bitter smile, "and yet one does not desert that grave."

After she had collected all the scraps of paper in the envelope, Mariette replaced it in her bosom, and, crossing her little shawl upon her breast, turned to go, saying, sadly: "I thank you for your kindness, monsieur;" then, as if bethinking herself, she added, timidly:

"Though this letter requires no reply, monsieur, after all the trouble I have given you, I feel that I ought to offer—"

"My charge is ten sous, exactly the same as for a letter," replied the old man, promptly, accepting and pocketing the remuneration with unmistakable eagerness, in spite of the conflicting emotions which had agitated him ever since the young girl's return. "And now au revoir, my child," he said, in a tone of evident relief; "our next meeting, I hope, will be under happier circumstances."

"Heaven grant it, monsieur," replied Mariette, as she walked slowly away, while Father Richard, evidently anxious to return home, closed the shutters of his stall, thus concluding his day's work much earlier than usual.

Mariette, a prey to the most despairing thoughts, walked on and on mechanically, wholly unconscious of the route she was following, until she reached the Pont au Change. At the sight of the river she started suddenly like one awaking from a dream, and murmured, "It was my evil genius that brought me here."

In another moment she was leaning over the parapet gazing down eagerly into the swift flowing waters below. Gradually, as her eyes followed the course of the current, a sort of vertigo seized her. Unconsciously, too, she was slowly yielding to the fascination such a scene often exerts, and, with her head supported on her hands, she leaned farther and farther over the stream.

"I could find forgetfulness there," the poor child said to herself. "The river is a sure refuge from misery, from hunger, from sickness, or from a miserable old age, an old age like that of my poor godmother. My godmother? Why, without me, what would become of her?"

Just then Mariette felt some one seize her by the arm, at the same time exclaiming, in a frightened tone:

"Take care, my child, take care, or you will fall in the river."

The girl turned her haggard eyes upon the speaker, and saw a stout woman with a kind and honest face, who continued, almost affectionately:

"You are very imprudent to lean so far over the parapet, my child. I expected to see you fall over every minute."

"I was not noticing, madame—"

"But you ought to notice, child. Good Heavens! how pale you are! Do you feel sick?"

"No, only a little weak, madame. It is nothing. I shall soon be all right again."

"Lean on me. You are just recovering from a fit of illness, I judge."

"Yes, madame," replied Mariette, passing her hand across her forehead. "Will you tell me where I am, please?"

"Between the Pont Neuf and the Pont au Change, my dear. You are a stranger in Paris, perhaps."

"No, madame, but I had an attack of dizziness just now. It is passing off, and I see where I am now."

"Wouldn't you like me to accompany you to your home, child?" asked the stout woman, kindly. "You are trembling like a leaf. Here, take my arm."

"I thank you, madame, but it is not necessary. I live only a short distance from here."

"Just as you say, child, but I'll do it with pleasure if you wish. No? Very well, good luck to you, then."

And the obliging woman continued on her way.

Mariette, thus restored to consciousness, as it were, realised the terrible misfortune that had befallen her all the more keenly, and to this consciousness was now added the fear of being cruelly reproached by her godmother just at a time when she was so sorely in need of consolation, or at least of the quiet and solitude that one craves after such a terrible shock.

Desiring to evade the bitter reproaches this long absence was almost sure to bring down upon her devoted head, and remembering the desire her godmother had expressed that morning, Mariette hoped to gain forgiveness by gratifying the invalid's whim, so, with the forty sous left of the amount she had obtained at the Mont de Piété still in her pocket, she hastened to a rôtisseur's, and purchased a quarter of a chicken there, thence to a bakery, where she bought a couple of crisp white rolls, after which she turned her steps homeward.

A handsome coupé was standing at the door of the house in which Mariette lived, though she did not even notice this fact, but when she stopped at the porter's room as usual, to ask for her key, Madame Justin exclaimed:

"Your key, Mlle. Mariette? Why, that gentleman called for it a moment ago."

"What gentleman?"

"A decorated gentleman. Yes, I should say he was decorated. Why, the ribbon in his buttonhole was at least two inches wide. I never saw a person with such a big decoration."

"But I am not acquainted with any decorated gentleman," replied the young girl, much surprised. "He must have made a mistake."

"Oh, no, child. He asked me if the Widow Lacombe didn't live here with her goddaughter, a seamstress, so you see there could be no mistake."

"But didn't you tell the gentleman that my godmother was an invalid and could not see any one?"

"Yes, child, but he said he must have a talk with her on a very important matter, all the same, so I gave him the key, and let him go up."

"I will go and see who it is, Madame Justin," responded Mariette.

Imagine her astonishment, when, on reaching the fifth floor, she saw the stranger through the half-open door, and heard him address these words to Madame Lacombe:

"As your goddaughter has gone out, my good woman, I can state my business with you very plainly."

When these words reached her ears, Mariette, yielding to a very natural feeling of curiosity, concluded to remain on the landing and listen to the conversation, instead of entering the room.

The speaker was a man about forty-five years of age, with regular though rather haggard features and a long moustache, made as black and lustrous by some cosmetic as his artistically curled locks, which evidently owed their raven hue to artificial means. The stranger's physiognomy impressed one as being a peculiar combination of deceitfulness, cunning, and impertinence. He had large feet and remarkably large hands; in short, despite his very evident pretensions, it was easy to see that he was one of those vulgar persons who cannot imitate, but only parody real elegance. Dressed in execrable taste, with a broad red ribbon in the buttonhole of his frock coat, he affected a military bearing. With his hat still on his head, he had seated himself a short distance from the bed, and as he talked with the invalid he gnawed the jewelled handle of a small cane that he carried.

Madame Lacombe was gazing at the stranger with mingled surprise and distrust. She was conscious, too, of a strong aversion, caused, doubtless, by his both insolent and patronising air.

"As your goddaughter is out, my good woman, I can state my business with you very plainly."

These were the words that Mariette overheard on reaching the landing. The conversation that ensued was, in substance, as follows:

"You asked, monsieur, if I were the Widow Lacombe, Mariette Moreau's godmother," said the sick woman tartly. "I told you that I was. Now, what do you want with me? Explain, if you please."

"In the first place, my good woman—"

"My name is Lacombe, Madame Lacombe."

"Oh, very well, Madame Lacombe," said the stranger, with an air of mock deference, "I will tell you first who I am; afterwards I will tell you what I want. I am Commandant de la Miraudière." Then, touching his red ribbon, he added, "An old soldier as you see—ten campaigns—five wounds."

"That is nothing to me."

"I have many influential acquaintances in Paris, dukes, counts, and marquises."

"What do I care about that?"

"I keep a carriage, and spend at least twenty thousand francs a year."

"While my goddaughter and I starve on twenty sous a day, when she can earn them," said the sick woman, bitterly. "That is the way of the world, however."

"But it is not fair, my good Mother Lacombe," responded Commandant de la Miraudière, "it is not fair, and I have come here to put an end to such injustice."

"If you've come here to mock me, I wish you'd take yourself off," retorted the sick woman, sullenly.

"Mock you, Mother Lacombe, mock you! Just hear what I have come to offer you. A comfortable room in a nice apartment, a servant to wait on you, two good meals a day, coffee every morning, and fifty francs a month for your snuff, if you take it, or for anything else you choose to fancy, if you don't,—well, what do you say to all this, Mother Lacombe?"

"I say—I say you're only making sport of me, that is, unless there is something behind all this. When one offers such things to a poor old cripple like me, it is not for the love of God, that is certain."

"No, Mother Lacombe, but for the love of two beautiful eyes, perhaps."

"Whose beautiful eyes?"

"Your goddaughter's, Mother Lacombe," replied Commandant de la Miraudière, cynically. "There is no use beating about the bush."

The invalid made a movement indicative of surprise, then, casting a searching look at the stranger, inquired:

"You know Mariette, then?"

"I have been to Madame Jourdan's several times to order linen, for I am very particular about my linen," added the stranger, glancing down complacently at his embroidered shirt-front. "I have consequently often seen your goddaughter there; I think her charming, adorable, and—"

"And you have come to buy her of me?"

"Bravo, Mother Lacombe! You are a clever and sensible woman, I see. You understand things in the twinkling of an eye. This is the proposition I have come to make to you: A nice suite of rooms, newly furnished for Mariette, with whom you are to live, five hundred francs a month to run the establishment, a maid and a cook who will also wait on you, a suitable outfit for Mariette, and a purse of fifty louis to start with, to say nothing of the other presents she will get if she behaves properly. So much for the substantials. As for the agreeable part, there will be drives in the park, boxes at the theatre,—I know any number of actors, and I am also on the best of terms with some very high-toned ladies who give many balls and card-parties,—in short, your goddaughter will have a delightful, an enchanted life, Mother Lacombe, the life of a duchess. Well, how does all this strike you?"

"Very favourably, of course," responded the sick woman, with a sardonic smile. "Such cattle as we are, are only fit to be sold when we are young, or to sell others when we are old."

"Ah, well, Mother Lacombe, to quiet your scruples, if you have any, you shall have sixty francs a month for your snuff, and I shall also make you a present of a handsome shawl, so you can go around respectably with Mariette, whom you are never to leave for a moment, understand, for I am as jealous as a tiger, and have no intention of being made a fool of."

"All this tallies exactly with what I said to Mariette only this morning. 'You are an honest girl,' I said to her, 'and yet you can scarcely earn twenty sous a day making three hundred franc chemises for a kept woman.'"

"Three hundred franc chemises ordered from Madame Jourdan's? Oh, yes, Mother Lacombe, I know. They are for Amandine, who is kept by the Marquis de Saint-Herem, an intimate friend of mine. It was I who induced her to patronise Madame Jourdan,—a regular bonanza for her, though the marquis is very poor pay, but he makes all his furnishers as well as all his mistresses the fashion. This little Amandine was a clerk in a little perfumery shop on the Rue Colbert six months ago, and Saint-Herem has made her the rage. There is no woman in Paris half as much talked about as Amandine. The same thing may happen to Mariette some day, Mother Lacombe. She may be wearing three hundred franc chemises instead of making them. Don't it make you proud to think of it?"

"Unless Mariette has the same fate as another poor girl I knew."

"What happened to her, Mother Lacombe?"

"She was robbed."

"Robbed?"

"She, too, was promised mountains of gold. The man who promised it placed her in furnished apartments, and at the end of three months left her without a penny. Then she killed herself in despair."

"Really, Mother Lacombe, what kind of a man do you take me for?" demanded the stranger, indignantly. "Do I look like a scoundrel, like a Robert Macaire?"

"I don't know, I am sure."

"I, an old soldier who have fought in twenty campaigns, and have ten wounds! I, who am hand and glove with all the lions of Paris! I, who keep my carriage and spend twenty thousand francs a year! Speak out, what security do you want? If you say so, the apartment shall be furnished within a week, the lease made out in your name, and the rent paid one year in advance; besides, you shall have the twenty-five or thirty louis I have about me to bind the bargain, if you like."

And as he spoke, he drew a handful of gold from his pocket and threw it on the little table by the sick woman's bed, adding: "You see I am not like you. I am not afraid of being robbed, Mother Lacombe."

On hearing the chink of coin, the invalid leaned forward, and cast a greedy, covetous look upon the glittering pile. Never in her life had she had a gold coin in her possession, and now she could not resist the temptation to touch the gleaming metal, and let it slip slowly through her fingers.

"I can at least say that I have handled gold once in my life," the sick woman murmured, hoarsely.

"It is nothing to handle it, Mother Lacombe. Think of the pleasure of spending it."

"There is enough here to keep one in comfort five or six months," said the old woman, carefully arranging the gold in little piles.

"And remember that you and Mariette can have as much every month if you like, Mother Lacombe, in good, shining gold, if you wish it."

After a long silence, the sick woman raised her hollow eyes to the stranger's face, and said:

"You think Mariette pretty, monsieur. You are right, and there is not a better-hearted, more deserving girl in the world. Well, be generous to her. This money is a mere trifle to a man as rich as you are. Make us a present of it."

"Eh?" exclaimed the stranger, in profound astonishment.

"Monsieur," said the consumptive, clasping her hands imploringly, "be generous, be charitable. This sum of money is a mere trifle to you, as I said before, but it would support us for months. We should be able to pay all we owe. Mariette would not be obliged to work night and day. She would have time to look around a little, and find employment that paid her better. We should owe five or six months of peace and happiness to your bounty. It costs us so little to live! Do this, kind sir, and we will for ever bless you, and for once in my life I shall have known what happiness is."

The sick woman's tone was so sincere, her request so artless, that the stranger, who could not conceive of any human creature being stupid enough really to expect such a thing of a man of his stamp, felt even more hurt than surprised, and said to himself:

"Really, this is not very flattering to me. The old hag must take me for a country greenhorn to make such a proposition as that."

So bursting into a hearty laugh, he said, aloud:

"You must take me for a philanthropist, or the winner of the Montyon prize, Mother Lacombe. I am to make you a present of six hundred francs, and accept your benediction and eternal gratitude in return, eh?"

The sick woman had yielded to one of those wild and sudden hopes that sometimes seize the most despondent persons; but irritated by the contempt with which her proposal had been received, she now retorted, with a sneer:

"I hope you will forgive me for having so grossly insulted you, I am sure, monsieur."

"Oh, you needn't apologise, Mother Lacombe. I have taken no offence, as you see. But we may as well settle this little matter without any further delay. Am I to pocket those shining coins you seem to take so much pleasure in handling, yes or no?"

And he stretched out his hand as if to gather up the gold pieces.

With an almost unconscious movement, the sick woman pushed his hand away, exclaiming, sullenly:

"Wait a minute, can't you? You needn't be afraid that anybody is going to eat your gold."

"On the contrary, that is exactly what I would like you to do, on condition, of course—"

"But I know Mariette, and she would never consent," replied the sick woman, with her eyes still fixed longingly upon the shining coins.

"Nonsense!"

"But she is an honest girl, I tell you. She might listen to a man she loved, as so many girls do, but to you, never. She would absolutely refuse. She has her ideas—oh, you needn't laugh."

"Oh, I know Mariette is a virtuous girl. Madame Jourdan, for whom your goddaughter has worked for years, has assured me of that fact; but I know, too, that you have a great deal of influence over her. She is dreadfully afraid of you, Madame Jourdan says, so I am sure that you can, if you choose, persuade or, if need be, compel Mariette to accept—what? Simply an unlooked-for piece of good fortune, for you are housed like beggars and almost starving, that is evident. Suppose you refuse, what will be the result? The girl, with all her fine disinterestedness, will be fooled sooner or later by some scamp in her own station in life, and—"

"That is possible, but she will not have sold herself."

"That is all bosh, as you'll discover some day when her lover deserts her, and she has to do what so many other girls do to save herself from starving."

"That is very possible," groaned the sick woman. "Hunger is an evil counsellor, I know, when one has one's child as well as one's self to think of. And with this gold, how many of these poor girls might be saved! Ah! if Mariette is to end her days like them, after all, what is the use of struggling?"

For a minute or two the poor woman's contracted features showed that a terrible conflict was raging in her breast. The gold seemed to exercise an almost irresistible fascination over her; she seemed unable to remove her eyes from it; but at last with a desperate effort she closed them, as if to shut out the sight of the money, and throwing herself back on her pillow, cried, angrily:

"Go away, go away, and let me alone."

"What! you refuse my offer, Mother Lacombe?"

"Yes."

"Positively?"

"Yes."

"Then I've got to pocket all this gold again, I suppose," said the stranger, gathering up the coins, and making them jingle loudly as he did so. "All these shining yellow boys must go back into my pocket."

"May the devil take you and your gold!" exclaimed the now thoroughly exasperated woman. "Keep your money, but clear out. I didn't take Mariette in to ruin her, or advise her to ruin herself. Rather than eat bread earned in such way, I would light a brazier of charcoal and end both the girl's life and my own."

Madame Lacombe had scarcely uttered these words before Mariette burst into the room, pale and indignant, and throwing herself upon the sick woman's neck, exclaimed:

"Ah, godmother. I knew very well that you loved me as if I were your own child!"

Then turning to Commandant de la Miraudière, whom she recognised as the man who had stared at her so persistently at Madame Jourdan's, she said contemptuously:

"I beg that you will leave at once."

"But, my dear little dove—"

"I was there at the door, monsieur, and I heard all."

"So much the better. You know what I am willing to do, and I assure you—"

"Once more, I must request you to leave at once."

"Very well, very well, my little Lucrece, I will go, but I shall allow you one week for reflection," said the stranger, preparing to leave the room.

But on the threshold he paused and added:

"You will not forget my name, Commandant de la Miraudière, my dear. Madame Jourdan knows my address."

After which he disappeared.

"Ah, godmother," exclaimed the girl, returning to the invalid, and embracing her effusively, "how nobly you defended me!"

"Yes," responded the sick woman, curtly, freeing herself almost roughly from her goddaughter's embrace, "and yet with all these virtues, one perishes of hunger."

"But, godmother—"

"Don't talk any more about it, for heaven's sake!" cried the invalid, angrily. "It is all settled. What is the use of discussing it any further? I have done my duty; you have done yours. I am an honest woman; you are an honest girl. Great good it will do you, and me, too; you may rest assured of that."

"But, godmother, listen to me—"

"We shall be found here some fine morning stiff and cold, you and I, with a pan of charcoal between us. Ah, ha, ha!"

And with a shrill, mirthless laugh, the poor creature, embittered by years of misfortune, and chafing against the scruples that had kept her honest in spite of herself, put an end to the conversation by abruptly turning her back upon her goddaughter.

Mariette went out into the hall where she had left the basket containing the sick woman's supper. She placed the food on a small table near the bed, and then went and seated herself silently by the narrow window, where, drawing the fragments of her lover's letter from her pocket, she gazed at them with despair in her soul.

On leaving Mariette, the commandant said to himself:

"I'm pretty sure that last shot told in spite of what they said. The girl will change her mind and so will the old woman. The sight of my gold seemed to dazzle the eyes of that old hag as much as if she had been trying to gaze at the noonday sun. Their poverty will prove a much more eloquent advocate for me than any words of mine. I do not despair, by any means. Two months of good living will make Mariette one of the prettiest girls in Paris, and she will do me great credit at very little expense. But now I must turn my attention to business. A fine little discovery it is that I have just made, and I think I shall be able to turn it to very good account."

Stepping into his carriage, he was driven to the Rue Grenelle St. Honoré. Alighting in front of No. 17, a very unpretentious dwelling, he said to the porter:

"Does M. Richard live here?"

"A father and son of that name both live here, monsieur."

"I wish to see the son. Is M. Louis Richard in?"

"Yes, monsieur. He has only just returned from a journey. He is with his father now."

"Ah, he is with his father? Well, I would like to see him alone."

"As they both occupy the same room, there will be some difficulty about that."

The commandant reflected a moment, then, taking a visiting card bearing his address from his pocket, he added these words in pencil: "requests the honour of a visit from M. Louis Richard to-morrow morning between nine and ten, as he has a very important communication which will brook no delay, to make to him."

"Here are forty sous for you, my friend," said M. de la Miraudière to the porter, "and I want you to give this card to M. Louis Richard."

"That is a very easy way to earn forty sous."

"But you are not to give the card to him until to-morrow morning as he goes out, and his father is not to know anything about it. Do you understand?"

"Perfectly, monsieur, and there will be no difficulty about it as M. Louis goes out every morning at seven o'clock, while his father never leaves before nine."

"I can rely upon you, then?"

"Oh, yes, monsieur, you can regard the errand as done."

Commandant de la Miraudière reëntered his carriage and drove away.

Soon after his departure a postman brought a letter for Louis Richard. It was the letter written that same morning in Mariette's presence by the scrivener, who had addressed it to No. 17 Rue de Grenelle, Paris, instead of to Dreux as the young girl had requested.

We will now usher the reader into the room occupied by the scrivener, Richard, and his son, who had just returned from Dreux.

The father and son occupied on the fifth floor of this old house a room that was almost identical in every respect with the abode of Mariette and her godmother. Both were characterised by the same bareness and lack of comfort. A small bed for the father, a mattress for the son, a rickety table, three or four chairs, a chest for their clothing—these were the only articles of furniture in the room.

Father Richard, on his way home, had purchased their evening repast, an appetising slice of ham and a loaf of fresh bread. These he had placed upon the table with a bottle of water, and a single candle, whose faint light barely served to render darkness visible.

Louis Richard, who was twenty-five years of age, had a frank, honest, kindly, intelligent face, while his shabby, threadbare clothing, worn white at the seams, only rendered his physical grace and vigour more noticeable.

The scrivener's features wore a joyful expression, slightly tempered, however, by the anxiety he now felt in relation to certain long cherished projects of his own.

The young man, after having deposited his shabby valise on the floor, tenderly embraced his father, to whom he was devoted; and the happiness of being with him again and the certainty of seeing Mariette on the morrow made his face radiant, and increased his accustomed good humour.

"So you had a pleasant journey, my son," remarked the old man, seating himself at the table.

"Very."

"Won't you have some supper? We can talk while we eat."

"Won't I have some supper, father? I should think I would. I did not dine at the inn like the other travellers, and for the best of reasons," added Louis, gaily, slapping his empty pocket.

"You have little cause to regret the fact, probably," replied the old man, dividing the slice of ham into two very unequal portions, and giving the larger to his son. "The dinners one gets at wayside inns are generally very expensive and very poor."

As he spoke, he handed Louis a thick slice of bread, and the father and son began to eat with great apparent zest, washing down their food with big draughts of cold water.

"Tell me about your journey, my son," remarked the old man.

"There is very little to tell, father. My employer gave me a number of documents to be submitted to M. Ramon. He read and studied them very carefully, I must say. At least he took plenty of time to do it,—five whole days, after which he returned the documents with numberless comments, annotations, and corrections."

"Then you did not enjoy yourself particularly at Dreux, I judge."

"I was bored to death, father."

"What kind of a man is this M. Ramon, that a stay at his house should be so wearisome?"

"The worst kind of a person conceivable, my dear father. In other words, an execrable old miser."

"Hum! hum!" coughed the old man, as if he had swallowed the wrong way. "So he is a miser, is he? He must be very rich, then."

"I don't know about that. One may be stingy with a small fortune as well as with a big one, I suppose; but if this M. Ramon's wealth is to be measured by his parsimony, he must be a multi-millionaire. He is a regular old Harpagon."

"If you had been reared in luxury and abundance, I could understand the abuse you heap upon this old Harpagon, as you call him; but we have always lived in such poverty that, however parsimonious M. Ramon may be, you certainly cannot be able to see much difference between his life and ours."

"Ah, father, you don't know what you're talking about."

"What do you mean?"

"Well, M. Ramon keeps two servants; we have none. He occupies an entire house; we both eat and sleep in this garret room. He has three or four courses at dinner, we take a bite of anything that comes handy, but for all that we live a hundred times better than that skinflint does."

"But I don't understand, my son," said Father Richard, who for some reason or other seemed to be greatly annoyed at the derogatory opinion his son expressed. "There can be no comparison between that gentleman's circumstances and ours."