An Introduction to the study of the Art of Japan

1911

Contents

- Introduction by Iwaya Sazanami

- Introduction by Hirai Kinza

- Preface

- CHAPTER ONE. PERSONAL EXPERIENCES

- CHAPTER TWO. ART IN JAPAN

- CHAPTER THREE. LAWS FOR THE USE OF BRUSH AND MATERIALS

- CHAPTER FOUR. LAWS GOVERNING THE CONCEPTION AND EXECUTION OF A PAINTING

- CHAPTER FIVE. CANONS OF THE AESTHETICS OF JAPANESE PAINTING

- CHAPTER SIX. SUBJECTS FOR JAPANESE PAINTING

- CHAPTER SEVEN. SIGNATURES AND SEALS

- EXPLANATION OF HEAD-BANDS

- PLATES EXPLANATORY OF THE FOREGOING TEXT ON THE LAWS OF JAPANESE PAINTING

- Footnotes

Illustrations

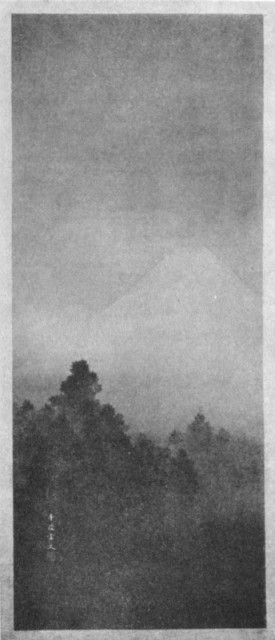

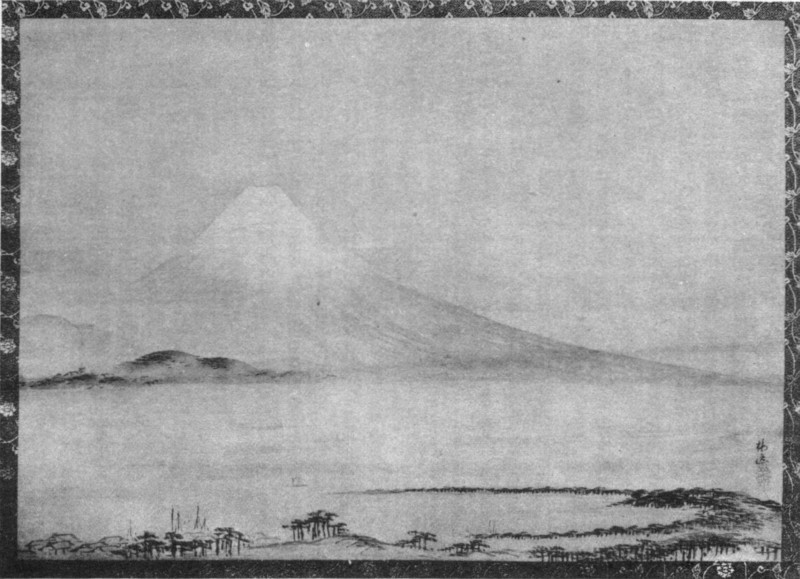

- Fujiyama, by Murata Tanryu. Plate I.

- The Tea Ceremony, by Miss Uyemura Shoen. Plate II.

- Chickens in Spring, by Mori Tessan. Plate III.

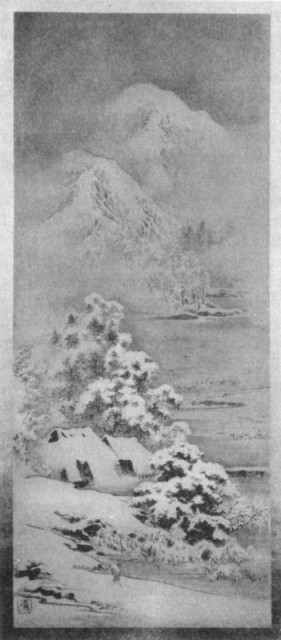

- Snow Scene in Kaga, by Kubota Beisen. Plate IV.

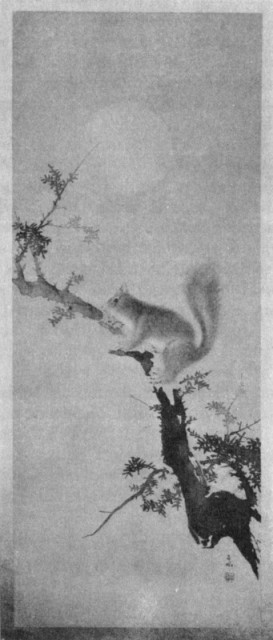

- Tree Squirrel, by Mochizuki Kimpo. Plate V.

- Tiger, by Kishi Chikudo. Plate VI.

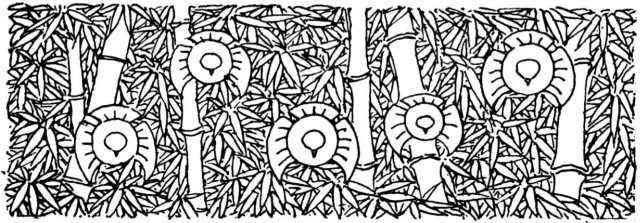

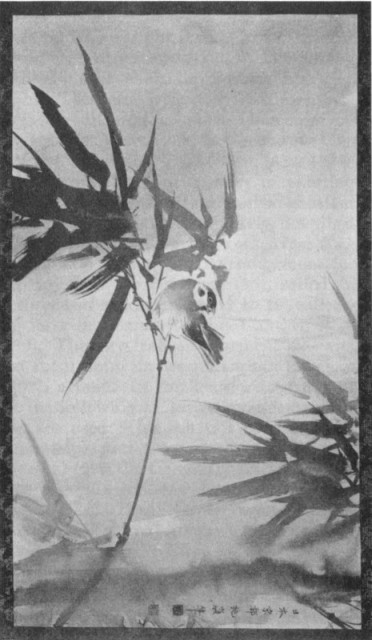

- Bamboo, Sparrow and Rain. Plate VII.

- Fujiyama from Tago no Ura, by Yamamoto Baietsu. Plate VIII.

- Most Careful Method of Laying on Color. Plate VIIII.

- The Next Best Method. Plate X.

- The Light Water-Color Method. Plate XI.

- Color With Outlines Suppressed. Plate XII.

- Color Over Lines. Plate XIII.

- Light Reddish-Brown Method. Plate XIV.

- The White Pattern. Plate XV.

- The Black or Sumi Method. Plate XVI.

- The Rule of Proportion in Landscapes. Plate XVII.

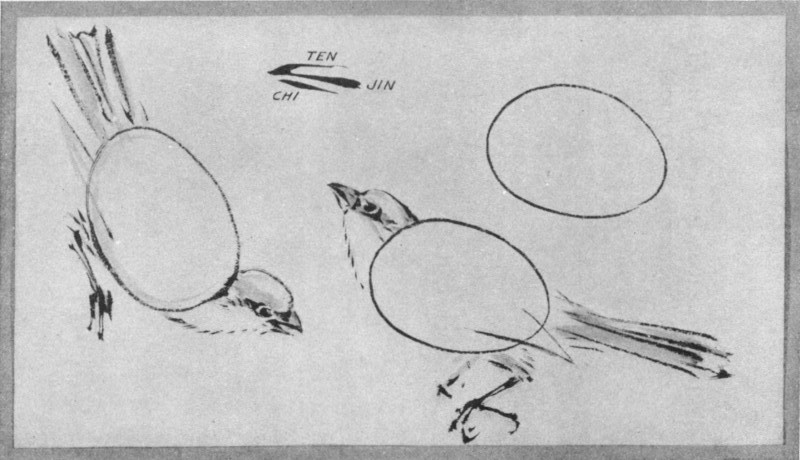

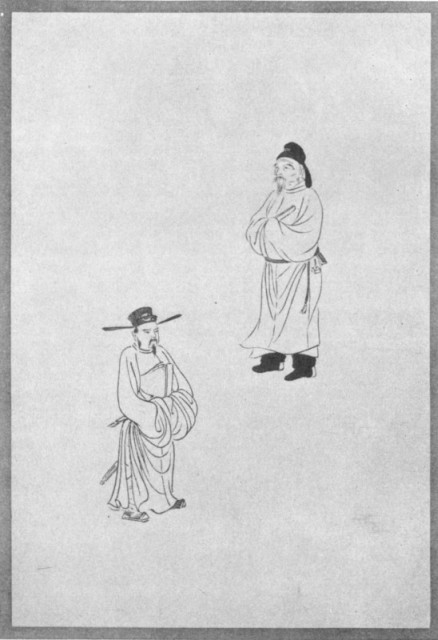

- Heaven, Earth, Man. Plate XVIII.

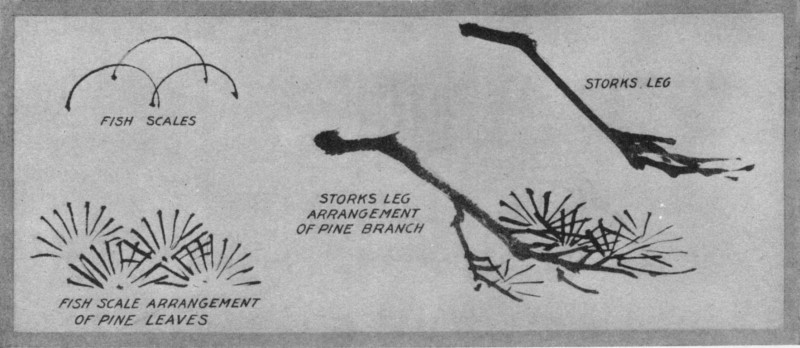

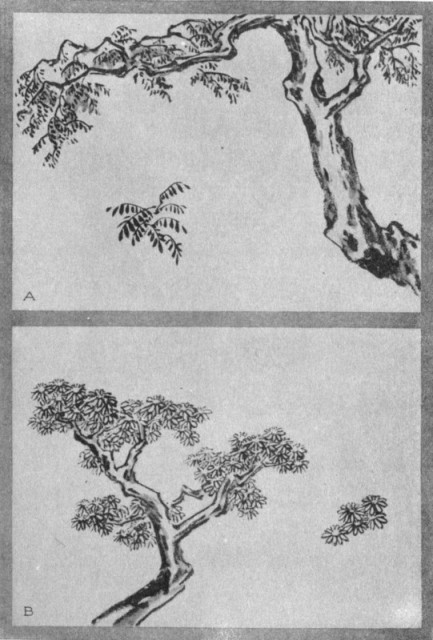

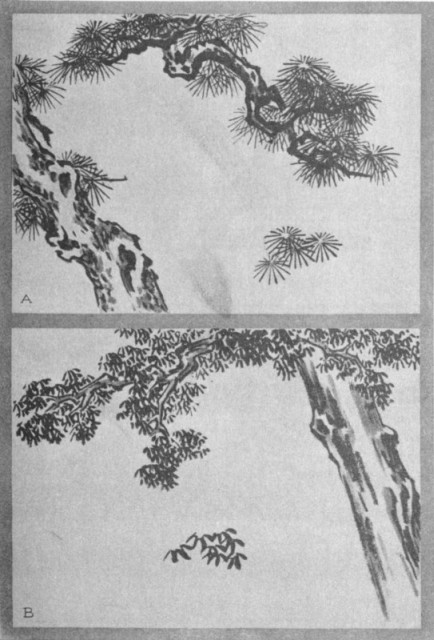

- Pine Tree Branches. Plate XIX.

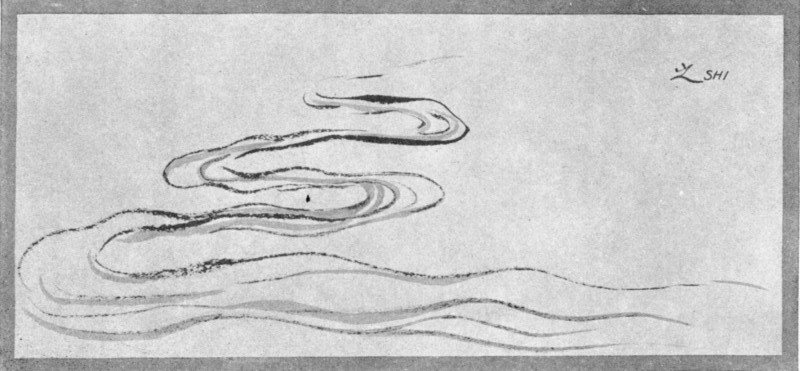

- Winding Streams. Plate XX.

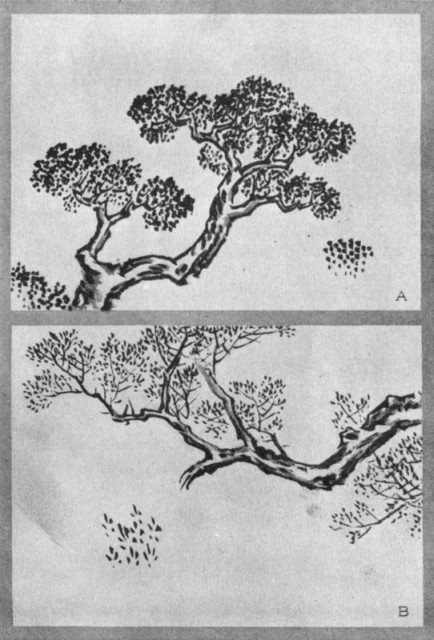

- A Tree and Its Parts. Plate XXI.

- Bird and Its Subdivisions. Plate XXII.

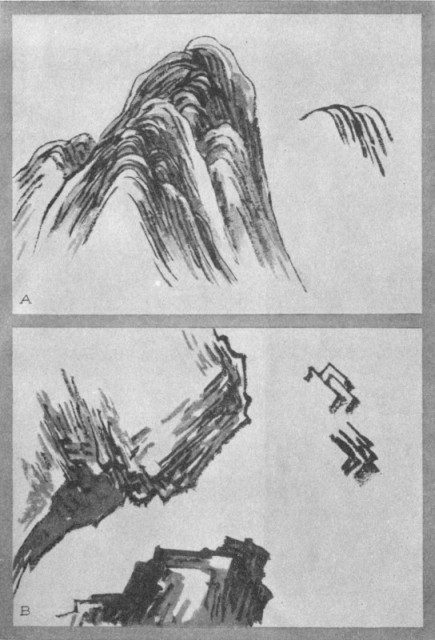

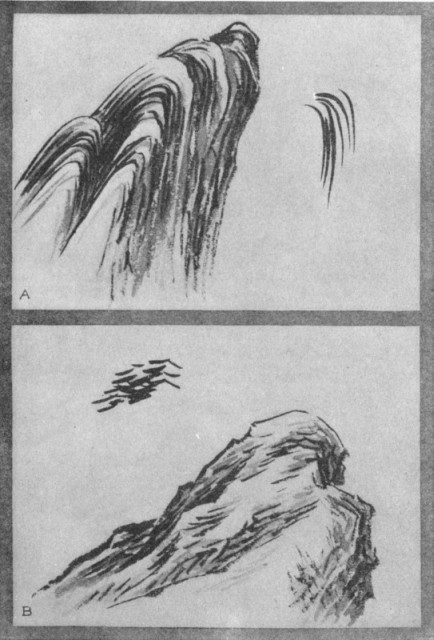

- Peeled Hemp-Bark Method for Rocks and Ledges (a) The Axe strokes (b). Plate XXIII.

- Lines or Veins of Lotus Leaf (a). Alum Crystals (b). Plate XXIV.

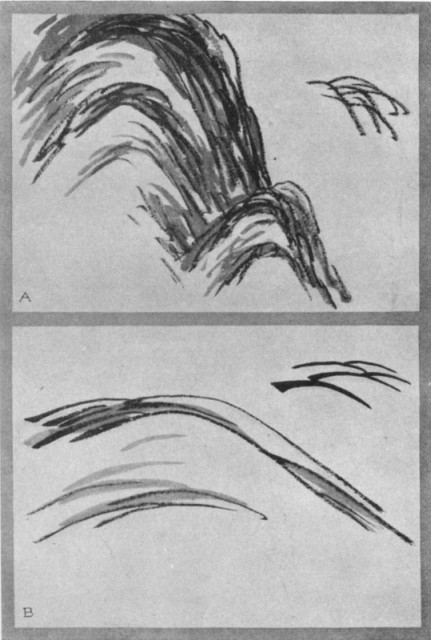

- Loose Rice Leaves (a). Withered Kindling Twigs (b). Plate XXV.

- Scattered Hemp Leaves (a). Wrinkles on the Cow's Neck (b). Plate XXVI.

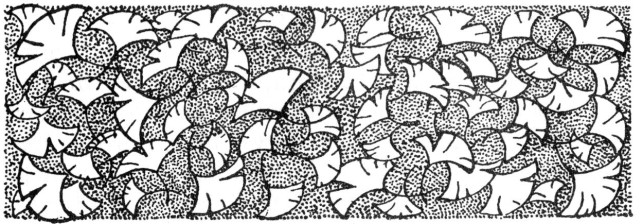

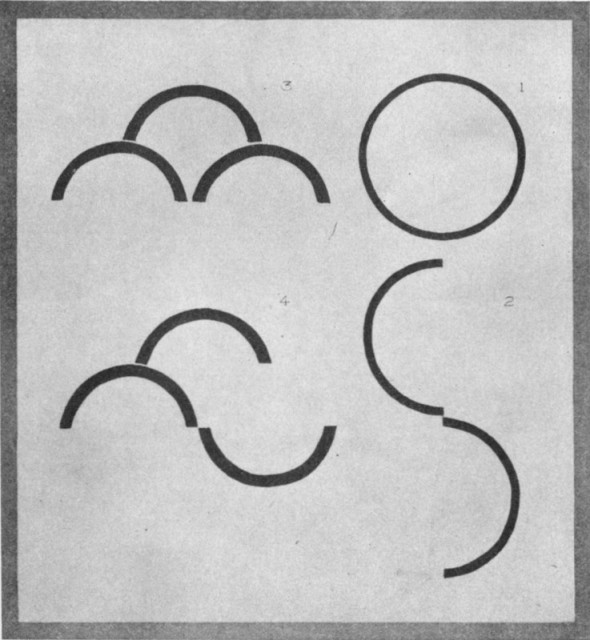

- The Circle (1). Semi-Circle (2). Fish Scales (3). Moving Fish Scales (4). Plate XXVII.

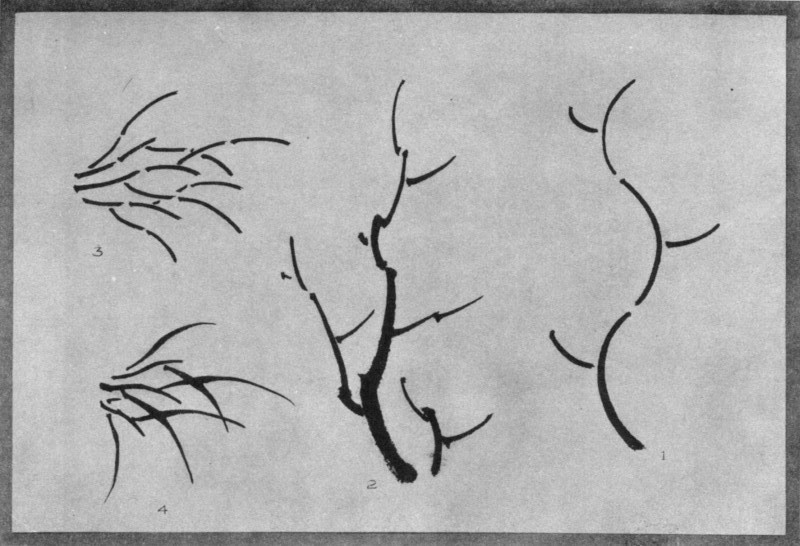

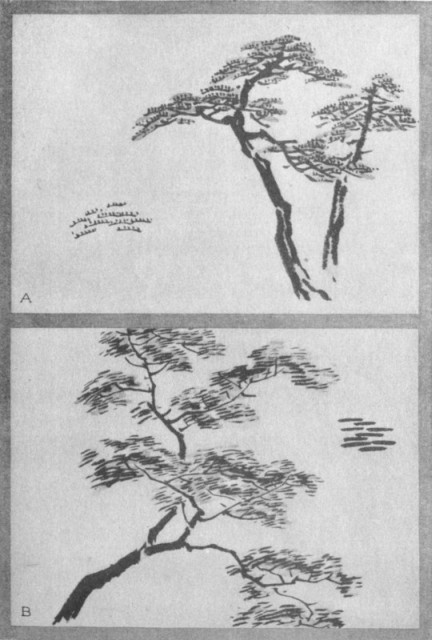

- Theory of Tree Growth (1). Practical Application (2). Grass Growth in Theory (3). In Practice (4). Plate XXVIII.

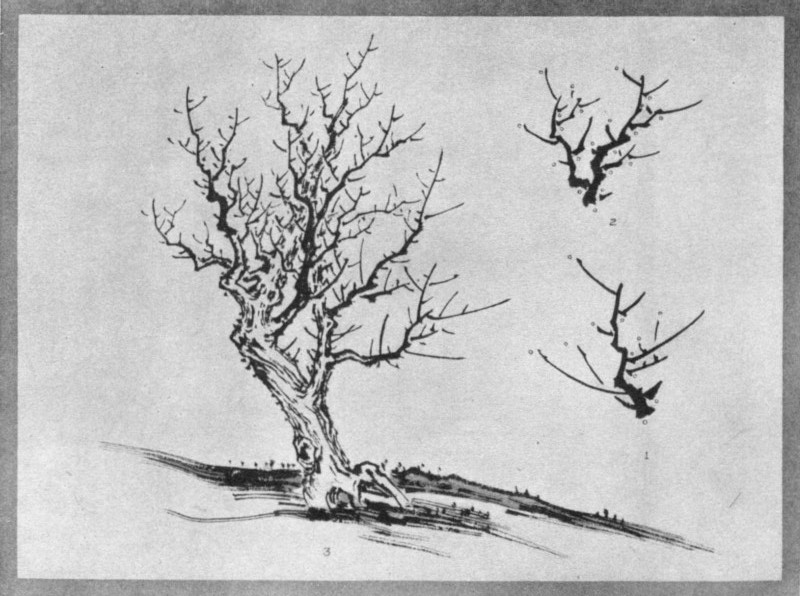

- Skeleton of a Forest Tree (1) Same Developed (2). Tree Completed in structure (3). Plate XXIX.

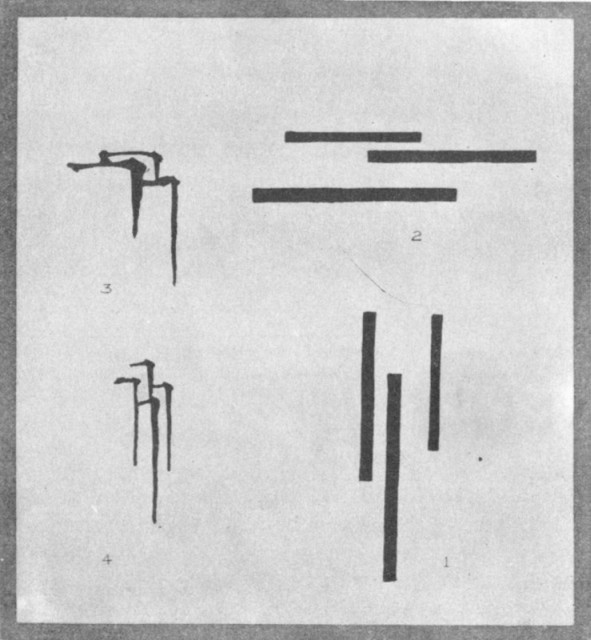

- Perpendicular Lines for Rocks (1). Horizontal Lines for Rocks (2). Rock Construction as Practiced in Art (3 and 4). Plate XXX.

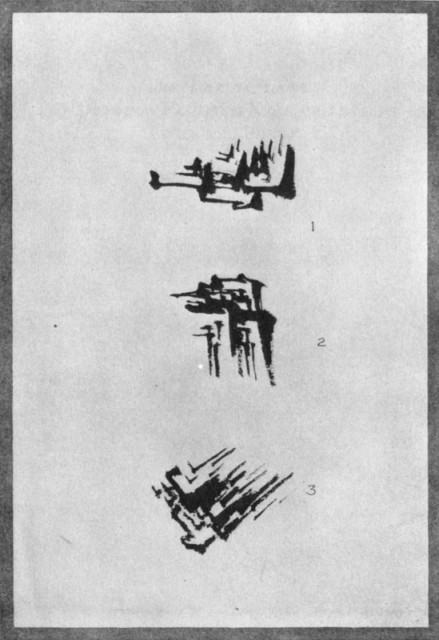

- Different Ways of Painting Rocks and Ledges. Plate XXXI.

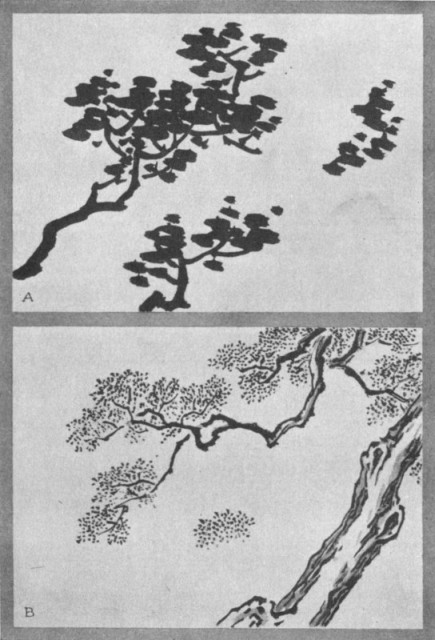

- Wistaria Dot (a). Chrysanthemum Dot (b). Plate XXXII.

- Wheel-Spoke Dot (a). Kai Ji Dot (b). Plate XXXIII.

- Pepper-Seed Dot (a). Mouse-Footprint Dot (b). Plate XXXIV.

- Serrated Dot (a). Ichi Ji dot (b). Plate XXXV.

- Heart Dot (a). Hitsu Ji Dot (b). Plate XXXVI.

- Rice Dot (a). Haku Yo Dot (b). Plate XXXVII.

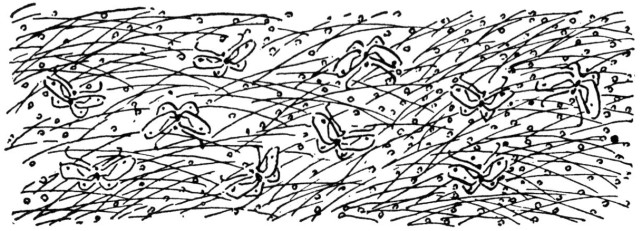

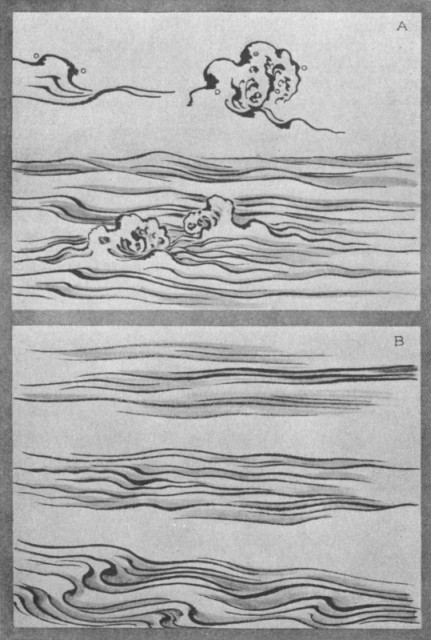

- Waves (a). Different Kinds of Moving Waters (b). Plate XXXVIII.

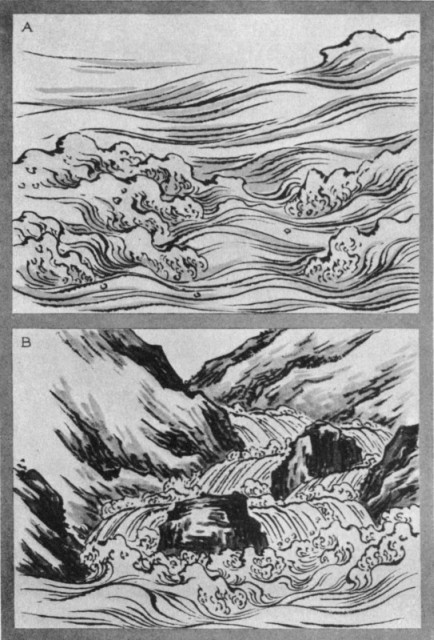

- Sea Waves (a). Brook Waves (b). Plate XXXIX.

- Storm Waves. Plate XL.

- Silk-Thread Line (upper). Koto string Line (lower). Plate XLI.

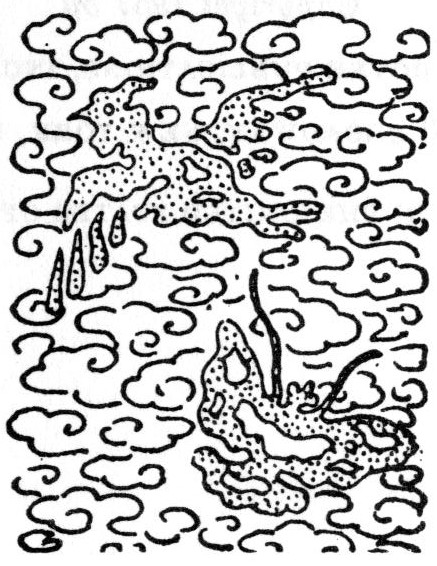

- Clouds, Water Lines (upper). Iron-Wire Line (lower). Plate XLII.

- Nail-Head, Rat-Tail Line (upper). Tsubone Line (lower). Plate XLIII.

- Willow-Leaf Line (upper). Angle-Worm Line (lower). Plate XLIV.

- Rusty-Nail and Old-Post Line (upper). Date-Seed Line (lower). Plate XLV.

- Broken-Reed Line (upper). Gnarled-Knot Line (lower). Plate XLVI.

- Whirling-Water Line (upper). Suppression Line (lower). Plate XLVII.

- Dry-Twig Line (upper). Orchid-Leaf Line (lower). Plate XLVIII.

- Bamboo-Leaf Line (upper). Mixed style (lower). Plate XLIX.

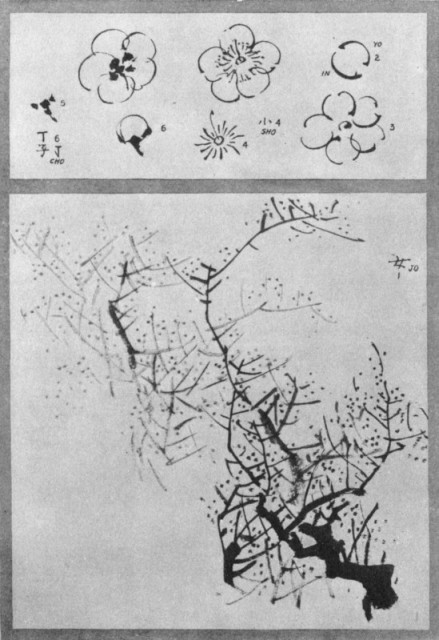

- The Plum Tree and Blossom. Plate L.

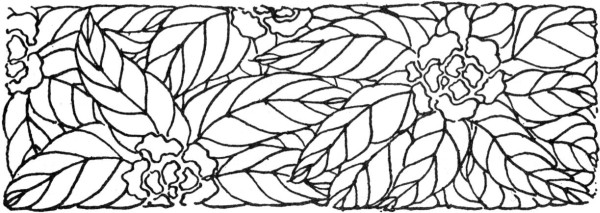

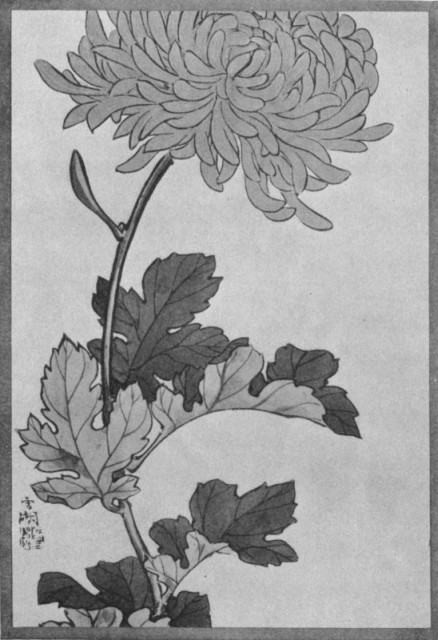

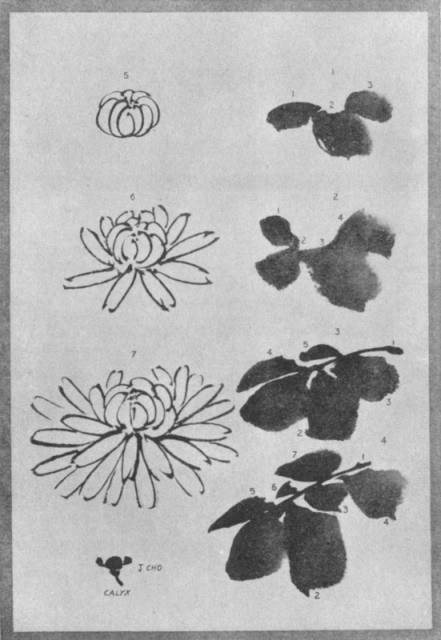

- The Chrysanthemum Flower and Leaves. Plate LI.

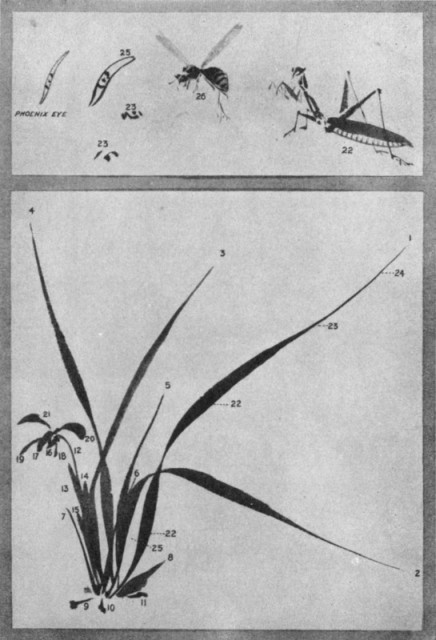

- The Orchid Plant and Flower. Plate LII.

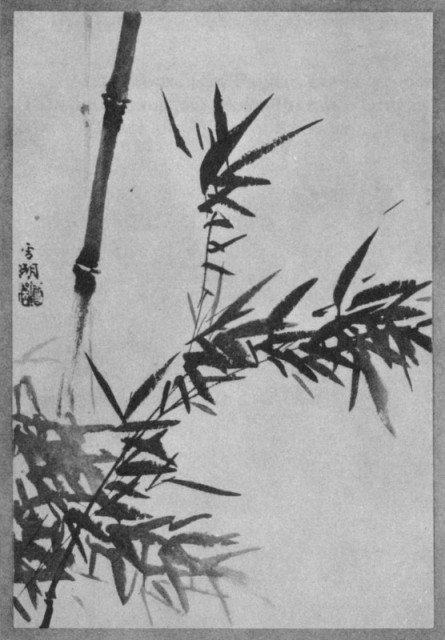

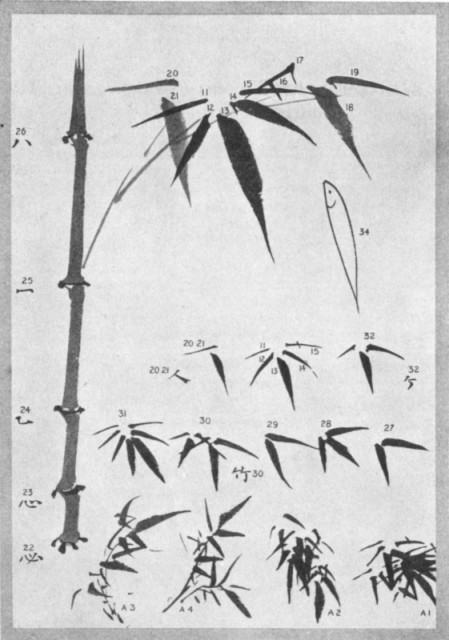

- The Bamboo Plant and Leaves. Plate LIII.

- Sunrise Over the Ocean (1). Horai San (2). Sun, storks and Tortoise (3, 4, 5). Plate LIV.

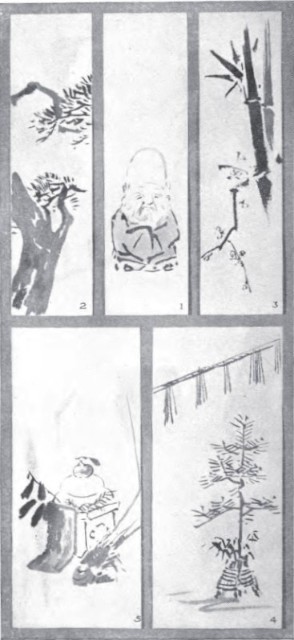

- Fuku Roku Ju (1). The Pine Tree (2). Bamboo and Plum (3). Kado Matsu and Shimenawa (4). Rice Cakes (5). Plate LV.

- Sun and Waves (1). Rice Grains(2). Cotton Plant (3). Battledoor (4). Treasure Ship (5). Plate LVI.

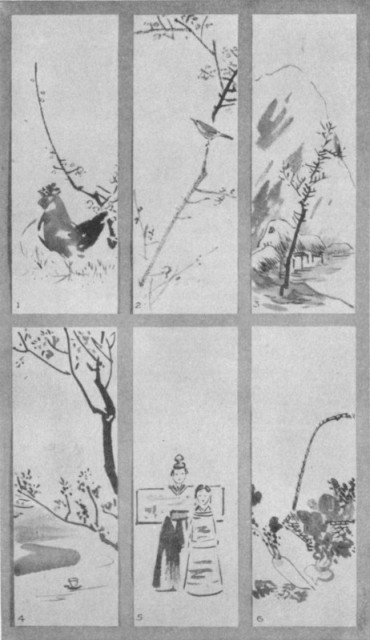

- Chickens and the Plum Tree (1). Plum and Song Bird (2). Last of the Snow (3). Peach Blossoms (4). Paper Dolls (5). Nana Kusa (6). Plate LVII.

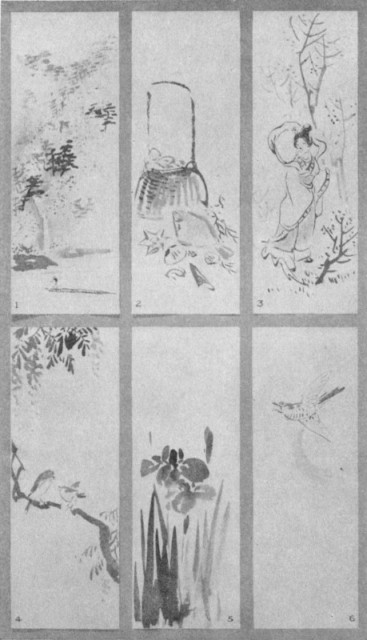

- Cherry Trees (1). Ebb Tide (2). Saohime (3). Wistaria (4). Iris (5). Moon and Cuckoo (6). Plate LVIII.

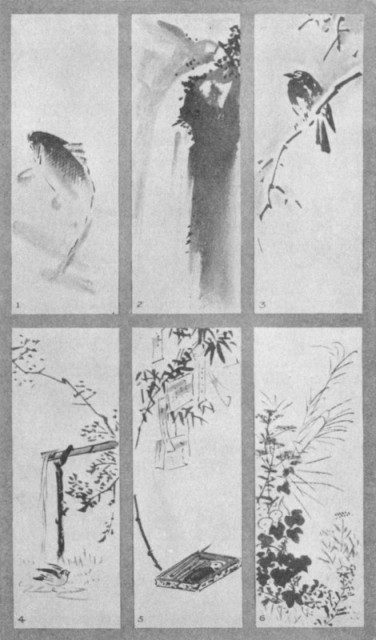

- Carp (1). Waterfall (2). Crow and Snow (3). Kakehi (4). Tanabata (5). Autumn Grasses (6). Plate LIX.

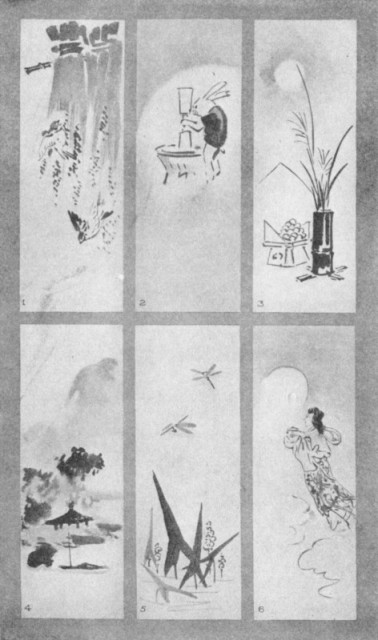

- Stacked Rice and Sparrows (1). Rabbit in the Moon (2). Megetsu (3). Mist Showers (4). Water Grasses (5). Joga (6). Plate LX.

- Chrysanthemum (1). Tatsutahime (2). Deer and Maples (3). Geese and the Moon (4). Fruits of Autumn (5). Monkey and Persimmons (6). Plate LXI.

- Squirrel and Grapes (1). Kayenu Matsu (2). Evesco or Ebisu (3). Zan Kiku (4). First Snow (5). Oharame (6). Plate LXII.

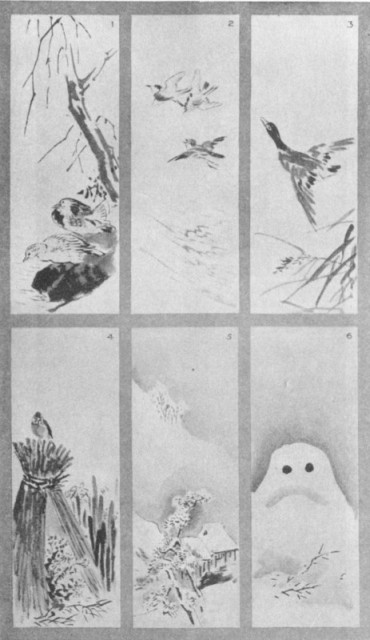

- Mandarin Ducks (1). Chi Dori (2). Duck Flying (3). Snow Shelter (4). Snow Scene (5). Snow Daruma (6). Plate LXIII.

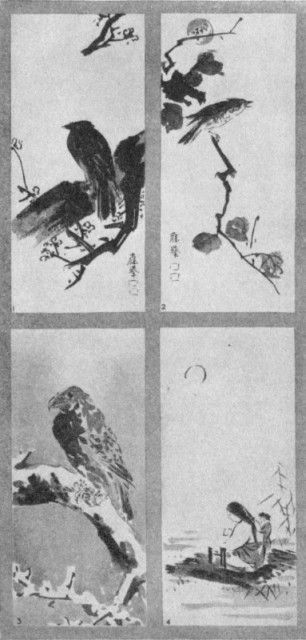

- Crow and Plum (1). Bird and Persimmon (2). Nukume Dori (3). Kinuta uchi (4). Plate LXIV.

- Spring (1). Summer (2). Autumn (3). Winter (4). Plate LXV.

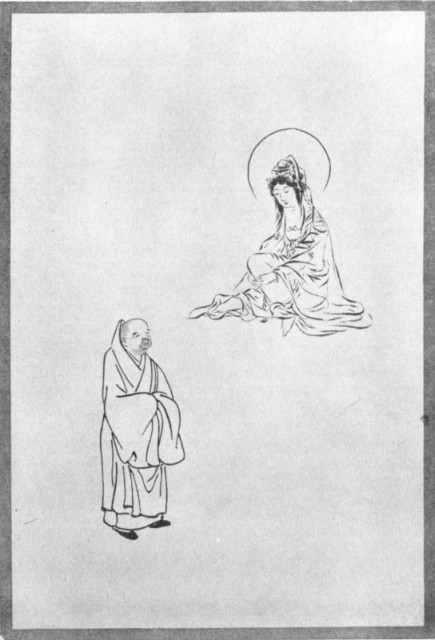

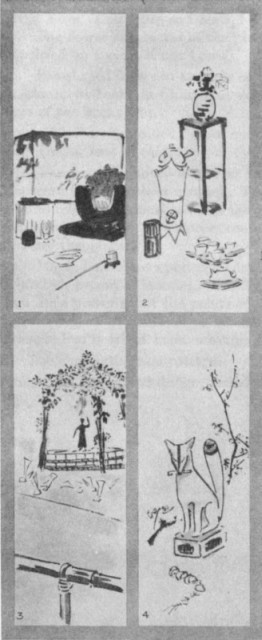

- Cha no Yu (1). Sen Cha (2). Birth of Buddha (3). Inari (4). Plate LXVI.

DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF KUBOTA BEISEN A GREAT ARTIST AND A KINDLY MAN, WHOSE HAPPINESS WAS IN HELPING OTHERS AND WHOSE TRIUMPHANT CAREER HAS SHED ENDURING LUSTRE UPON THE ART OF JAPANESE PAINTING

Introduction by Iwaya Sazanami1

[pg v]First of all, I should state that in the year 1909 I accompanied the Honorable Japanese Commercial Commissioners in their visit to the various American capitals and other cities of the United states, where we were met with the heartiest welcome, and for which we all felt the most profound gratitude. We were all so happy, but I was especially so; indeed, it would be impossible to be more happy than I felt, and particularly was this true of one day, namely, the twenty-seventh of November of the year named, when Henry P. Bowie, Esq., invited us to his residence in San Mateo, where we found erected by him a Memorial Gate to commemorate our victories in the Japanese-Russian War; and its dedication had been reserved for this day of our visit. Suspended above the portals was a bronze tablet inscribed with letters written by my late father, Ichi Roku. The evening of that same day we were invited by our host to a reception extended to us in San Francisco by the Japan Society of America, where I had the honor of delivering a short address on Japanese folk-lore. In adjoining halls was exhibited a large collection of Japanese writings and paintings, the latter chiefly the work of the artist, Kubota Beisen, while the writings were from the brush of my deceased father, between whom and Mr. Bowie there existed the relations of the warmest friendship and mutual esteem.

Two years or more have passed and I am now in receipt of information from Mr. Shimada Sekko that Mr. Bowie is about to publish a work upon the laws of Japanese painting and I am requested to write a preface to the same. I am well aware how unfitted I am for such an undertaking, but in view of all I have here related I feel I am not permitted to refuse.

Indeed, it seems to me that the art of our country has for many years past been introduced to the public of Europe and America in all sorts of ways, and hundreds of books about Japanese art have appeared in several foreign languages; but I have been privately alarmed for the reason that a great many such books contain either superficial observations made during sightseeing sojourns of six months or a year in our country or are but hasty commentaries, compilations, extracts or references, chosen here and there from other [pg vi] volumes. All work of this kind must be considered extremely superficial. But Mr. Bowie has resided many years in Japan. He thoroughly understands our institutions and national life; he is accustomed to our ways, and is fully conversant with our language and literature, and he understands both our arts of writing and painting. Indeed, I feel he knows about such matters more than many of my own countrymen; added to this, his taste is instinctively well adapted to the Oriental atmosphere of thought and is in harmony with Japanese ideals. And it is he who is the author of the present volume. To others a labor of the kind would be very great; to Mr. Bowie it is a work of no such difficulty, and it must surely prove a source of priceless instruction not only to Europeans and Americans, but to my own countrymen, who will learn not a little from it. Ah, how fortunate do we feel it to be that such a book will appear in lands so far removed from our native shores. Now that I learn that Mr. Bowie has written this book the happiness of two years ago is again renewed, and from this far-off country I offer him my warmest congratulations, with the confident hope that his work will prove fruitfully effective.

August 17, 1911

Introduction by Hirai Kinza2

[pg vii]Seventeen years ago, at a time when China and Japan were crossing swords, Mr. Henry P. Bowie came to me in Kyoto requesting that I instruct him in the Japanese language and in the Chinese written characters. I consented and began his instruction. I was soon astonished by his extraordinary progress and could hardly believe his language and writing were not those of a native Japanese. As for the Chinese written characters, we learn them only to know their meaning and are not accustomed to investigate their hidden significance; but Mr. Bowie went so thoroughly into the analysis of their forms, strokes and pictorial values that his knowledge of the same often astounded and silenced my own countrymen. In addition to this, having undertaken to study Japanese painting, he placed himself under one of our most celebrated artists and, daily working with unabated zeal, in a comparatively short time made marvelous progress in that art. At one of our public art expositions he exhibited a painting of pigeons flying across a bamboo grove which was greatly admired and praised by everyone, but no one could believe that this was the work of a foreigner. At the conclusion of the exposition he was awarded a diploma attesting his merit. Many were the persons who coveted the painting, but as it had been originally offered to me, I still possess it. From time to time I refresh my eyes with the work and with much pleasure exhibit it to my friends. Frequently after this Mr. Bowie, always engaged in painting remarkable pictures in the Japanese manner, would exhibit them at the various art exhibitions of Japan, and was on two occasions specially honored by our Emperor and Empress, both of whom expressed the wish to possess his work, and Mr. Bowie had the honor of offering the same to our Imperial Majesties.

His reputation soon spread far and wide and requests for his paintings came in such numerous quantities that to comply his time was occupied continuously.

Now he is about to publish a work on Japanese painting to enlighten and instruct the people of Western nations upon our art. As I believe such a book must have great influence in promoting sentiments of kindliness between Japan and America, by causing the [pg viii] feelings of our people and the conditions of our national life to be widely known, I venture to offer a few words concerning the circumstances under which I first became acquainted with the author.

Meiji-Yosa Amari Yotose-Hazuke.

Preface

This volume contains the substance of lectures on on the laws and canons of Japanese painting delivered before the Japan Society of America, the Sketch Club of San Francisco, the Art students of stanford University, the Saturday Afternoon Club of Santa Cruz, the Arts and Crafts Guild of San Francisco, and the Art Institute of the University of California.

The interest the subject awakened encourages the belief that a wider acquaintance with essential principles underlying the art of painting in Japan will result in a sound appreciation of the artist work of that country.

Japanese art terms and other words deemed important have been purposely retained and translated for the benefit of students who may desire to seriously pursue Japanese painting under native masters. Those terms printed in small capitals are Chinese in origin; all others in italics are Japanese.

All of the drawings illustrative of the text have been specially prepared by Mr. Shimada Sekko, an artist of research and ability, who, under David starr Jordan, has long been engaged on scientific illustrations in connection with the Smithsonian Institution.

The author apologizes for all references herein to personal experiences, which he certainly would have omitted could he regard the following pages as anything more than an informal introduction of the reader to the study of Japanese painting.

KEN WAN CHOKU HITSU

A firm arm and a perpendicular brush

CHAPTER ONE. PERSONAL EXPERIENCES

In the year 1893 I went on a short visit to Japan, and becoming interested in much I saw there, the following year I made a second journey to that country. Taking up my residence in Kyoto, I determined to study and master, if possible, the Japanese language, in order to thoroughly understand the people, their institutions, and civilization. My studies began at daybreak and lasted till midday. The afternoons being unoccupied, it occurred to me that I might, with profit, look into the subject of Japanese painting. The city of Kyoto has always been the hotbed of Japanese art. At that time the great artist, Ko No Bairei, was still living there, and one of his distinguished pupils, Torei Nishigawa, was highly recommended to me as an art instructor. Bairei had declared Torei's ability was so great that at the age of eighteen he had learned all he could teach him. Torei was now over thirty years of age and a perfect type of his kind, overflowing with skill, learning, and humor. He gave me my first lesson and I was simply entranced.

[pg 4]It was as though the skies had opened to disclose a new kingdom of art. Taking his brush in hand, with a few strokes he had executed a masterpiece, a loquot (biwa) branch, with leaves clustering round the ripe fruit. Instinct with life and beauty, it seemed to have actually grown before my eyes. From that moment dated my enthusiasm for Japanese painting. I remained under Nishigawa for two years or more, working assiduously on my knees daily from noon till nightfall, painting on silk or paper spread out flat before me, according to the Japanese method.

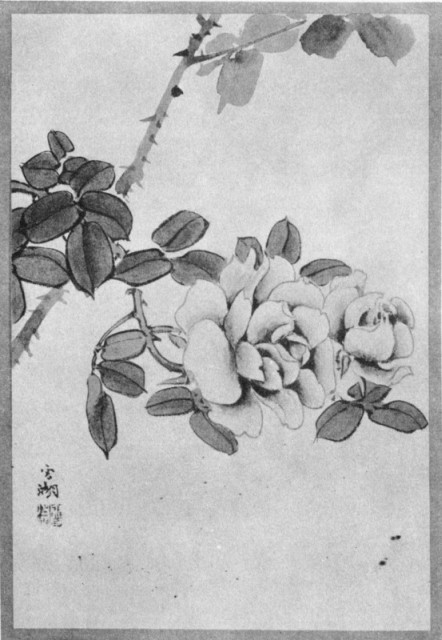

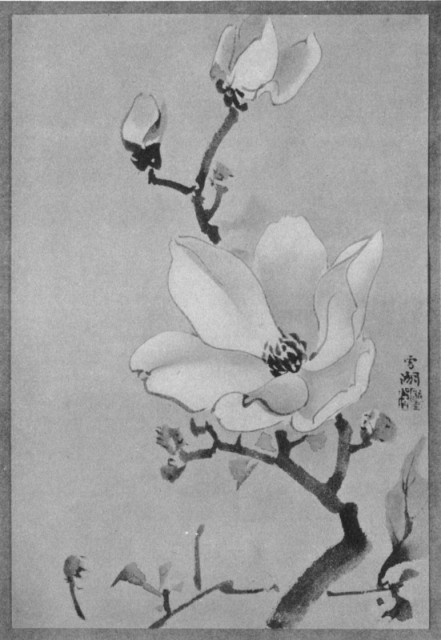

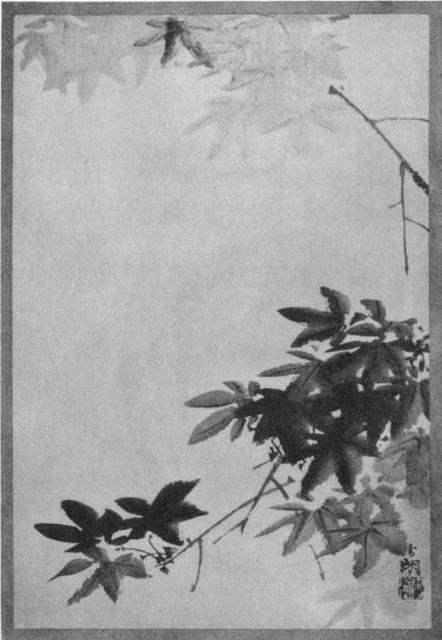

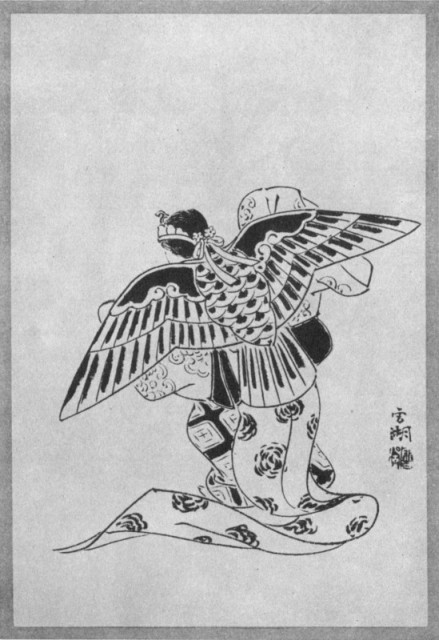

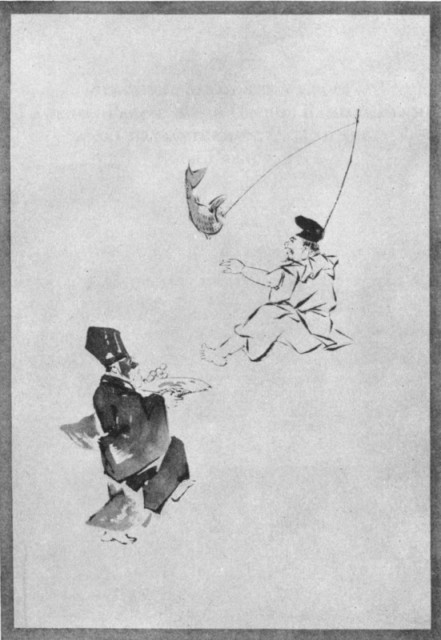

Japanese painters are generally classed according to what they confine themselves to producing. Some are known as painters of figures (jim butsu) or animals (do butsu), others as painters of landscapes (san sui), others still as painters of flowers and birds (ka cho), others as painters of religious subjects (butsu gwa), and so on. Torei was a painter of flowers and birds, and these executed by him are really as beautiful as their prototypes in nature. On plate VII is given a specimen of his work. He is now a leading artist of Osaka, where he has done much to revive painting in that commercial city.

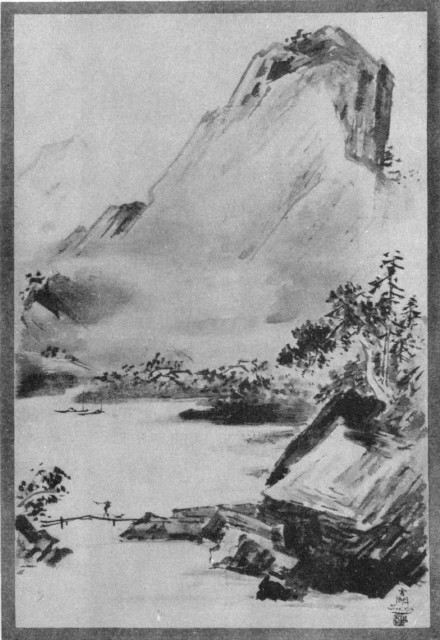

As I desired to get some knowledge of Japanese landscape painting, I was fortunate in next obtaining instruction from the distinguished Kubota Beisen, one of the most popular and gifted artists in the empire.

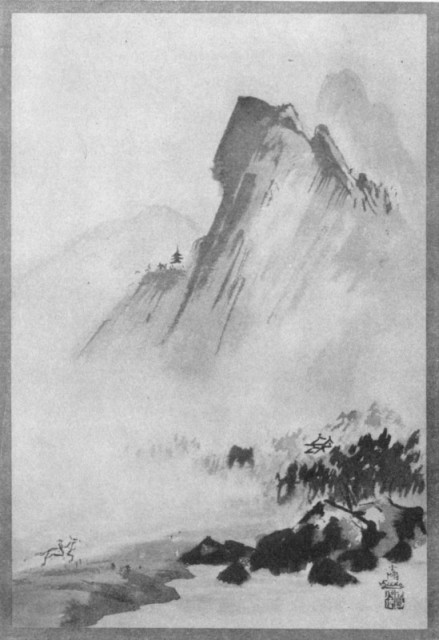

In company with several of his friends and former pupils I called upon him. After the usual words of [pg 5] ceremony he was asked if he would kindly paint something for our delight. Without hesitation he spread a large sheet of Chinese paper (toshi) him and in a few moments we beheld a crow clinging to the branches of a persimmon tree and trying to peck at the fruit, which was just a trifle out of reach. The work seemed that of a magician. I begged him then and there to give me instruction. He consented, and thus began an acquaintance and friendship which lasted until his death a few years ago. I worked faithfully under his guidance during five years, every day of the week, including Sundays. I never tired; in fact, I never wanted to stop. Every stroke of his brush seemed to have magic in it. (Plate IV.) In many ways he was one of the cleverest artists Japan has ever produced. He was an author as well as a painter, and wrote much on art. At the summit of his renown he was stricken hopelessly blind and died of chagrin,—he could paint no more.

While living in Tokio for a number of years I painted constantly under two other artists—Shimada Sekko, now distinguished for fishes; and Shimada Bokusen, a pupil of Gaho, and noted for landscape in the Kano style; so that, after nine years in all of devotion and labor given to Japanese painting, I was able to get a fairly good understanding of its theory and practice.

It may seem strange that one not an Oriental should become thus interested in Japanese painting and devote so much time and hard work to it; but the fact is, if one seriously investigates that art [pg 6] he readily comes under the sway of its fascination. As the people of Japan love art in all its manifestations, the foreigner who paints in their manner finds a double welcome among them; thus, ideal conditions are supplied under which the study there of art can be pursued.

My memory records nothing but kindness in that particular. During my long residence in Kyoto there were constantly sent to me for my enjoyment and instruction precious paintings by the old masters, to be replaced after a short time by other works of the various schools. For such attention I was largely indebted to the late Mr. Kumagai, one of Kyoto's most highly esteemed citizens and art patrons. Without multiplying instances of the generous nature of the Japanese and their interest in the endeavors of a foreigner to study their art, I will mention the gift from the Abbot of Ikegami of two original dragon paintings, executed for that temple by Kano Tanyu. In Tokio my dwelling was the frequent rendezvous of many of the leading artists of that city and gassaku painting was invariably our principal pastime. The great poet, Fukuha Bisei, now gone, would frequently join us, and to every painting executed he would add the embellishment of his charming inspirations in verse, written thereon in his inimitable kana script. This nobleman had taught the art of poetry to H. I. M. Mutsu Hito, to the preceding Emperor, and to the present Crown Prince.

CHAPTER TWO. ART IN JAPAN

[pg 7]In approaching a brief exposition of the laws of Japanese painting it is not my purpose to claim for that art superiority over every other kind of painting; nor will I admit that it is inferior to other schools of painting. Rather would I say that it is a waste of time to institute comparisons. Let it be remembered only that no Japanese painting can be properly understood, much less appreciated, unless we possess some acquaintance with the laws which control its production. Without such knowledge, criticism—praising or condemning a Japanese work of art—is without weight or value.

Japanese painters smile wearily when informed that foreigners consider their work to be flat, and at best merely decorative; that their pictures have no middle distance or perspective, and contain no shadows; in fact, that the art of painting in Japan is still in its infancy. In answer to all this suffice it to say that whatever a Japanese painting fails to contain has been purposely omitted. With Japanese artists it is a question of judgment and taste [pg 8] as to what shall be painted and what best left out. They never aim at photographic accuracy or distracting detail. They paint what they feel rather than what they see, but they first see very distinctly. It is the artistic impression (sha i) which they strive to perpetuate in their work. So far as perspective is concerned, in the great treatise of Chu Kaishu entitled, “The Poppy-Garden Art Conversations,” a work laying down the fundamental laws of landscape painting, artists are specially warned against disregarding the principle of perspective called en kin, meaning what is far and what is near. The frontispiece to the present volume illustrates how cleverly perspective is produced in Japanese art (Plate I).

Japanese artists are ardent lovers of nature; they closely observe her changing moods, and evolve every law of their art from such incessant, patient, and careful study.

These laws (in all there are seventy-two of them recognized as important) are a sealed book to the uninitiated. I once requested a learned Japanese to translate and explain some art terms in a work on Japanese painting. He frankly declared he could not do it, as he had never studied painting.

The Japanese are unconsciously an art-loving people. Their very education and surroundings tend to make them so. When the Japanese child of tender age first takes his little bowl of rice, a pair of tiny chop-sticks is put into his right hand. He grasps them as we would a dirk. His mother then shows him how he should manipulate them. [pg 9] He has taken a first lesson in the use of the brush. With practice he becomes skilful, and one of his earliest pastimes is using the chop-sticks to pick up single grains of rice and other minute objects, which is no easy thing to do. It requires great dexterity. He is insensibly learning how to handle the double brush (ni hon fude) with which an artist will, among other things, lay on color with one brush and dilute or shade off (kumadori) the color with another, both brushes being held at the same time in the same hand, but with different fingers.

At the age of six the child is sent to school and taught to write with a brush the phonetic signs Japanese (forty-seven in number) which constitute the Japanese syllabary. These signs represent the forty-seven pure sounds of the Japanese language and are used for writing. They are known as katakana and are simplified Chinese characters, consisting of two or three strokes each. With them any word in Japanese can be written. It takes a year for a child to learn all these signs and to write them from memory, but they are an excellent training for both the eye and the hand.

His next step in education is to learn to write these same sounds in a different script, called hiragana. These characters are cursive or rounded in form, while the katakana are more or less square. The hiragana are more graceful and can be written more rapidly, but they are more complicated.

From daily practice considerable training in the use of the brush and the free movement of the right arm and wrist is secured, and the eye is taught [pg 10] insensibly the many differences between the square and the cursive form. Before the child is eight years old he has become quite skilful in writing with the brush both kinds of kana.

He is next taught the easier Chinese characters,—Chinese kanji and ideographs. These are most ingeniously constructed and are of great importance in the further training of the eye and hand.

So greatly do these wonderfully conceived written forms appeal to the artistic sense that a taste for them thus early acquired leads many a Japanese scholar to devote his entire life to their study and cultivation. Such writers become professionals and are called shoka. Probably the most renowned in all China was Ogishi. Japan has produced many such famous men, but none greater than Iwaya Ichi Roku, who has left an immortal name.

From what has been said about writing with the brush, it will be understood how the youth who may determine to follow art as a career is already well prepared for rapid strides therein. His hand and arm have acquired great freedom of movement. His eye has been trained to observe the varying lines and intricacies of the strokes and characters, and his sentiments of balance, of proportion, of accent and of stroke order, have been insensibly developed according to subtle principles, all aiming at artistic results.

The knowledge of Chinese characters and the their ability to write them properly are considered of prime importance in Japanese art. A first counsel given me by Kubota Beisen was to commence that [pg 11] study, and he personally introduced me to Ichiroku who, from that time, kindly supervised my many years of work in Chinese writing, a pursuit truly engrossing and captivating.

In all Japanese schools the rudiments of art are taught, and children are trained to perceive, feel, and enjoy what is beautiful in nature. There is no city, village, or hamlet in all Japan that does not contain its plantations of plum and cherry blossoms in spring, its peonies and lotus ponds in summer, its chrysanthemums in autumn, and camelias, mountain roses and red berries in winter. The school children are taken time and again to see these, and revel amongst them. It is a part of their education. Excursions, called undokai, are organized at stated intervals during the school term and the scholars gaily tramp to distant parts of the country, singing patriotic and other songs the while and enjoying the view of waterfalls, broad and winding rivers, autumn maples, or snow-capped mountains. In addition to this, trips are taken to all famous temples and historical places including, where conveniently near, the three great views of Japan,—Matsushima, Ama No Hashi Date, and Myajima. Thus a taste for landscape is inculcated and becomes second nature. Furthermore, the scholars are encouraged to closely watch every form of life, including butterflies, crickets, beetles, birds, goldfish, shell-fish, and the like; and I have seen miniature landscape gardens made by Japanese children, most cleverly reproducing charming views [pg 12] and contained in a shallow box or tray. This gentle little art is called bonsai or hako niwa.

My purpose in alluding to all this is to indicate that a boy on leaving school has absorbed already much artistic education and is fairly well equipped for beginning a special course in the art schools of the empire.

These schools differ in their methods of instruction, and many changes have been introduced in them during the present reign, or Meiji period, but substantially the course takes from three to four years and embraces copying (isha mitori), tracing (mosha, tsuki-utsushi), reducing (shukuzu, chijime-ru), and composing (shiko, tsukuri kata).

In copying, the teacher usually first paints the particular subject and the student reproduces it under his supervision. Kubota's invariable method was to require the pupil on the following day to reproduce from memory (an ki) the subject thus copied. This engenders confidence. In tracing, thin paper is placed over the picture and the outlines (rin kaku) are traced according to the exact order in which the original subject was executed, an order which is established by rule; thus a proper style and brush habit are acquired. The correct sequence of the lines and parts of a painting is of the highest importance to its artistic effect.

In reducing the size of what is studied, the laws of proportion are insensibly learned. This is of great use afterwards in sketching (shassei). I believe that in the habit of reproducing, as taught in [pg 13] the schools, lies the secret of the extraordinary skill of the Japanese artisan who can produce marvelous effects in compressing scenery and other subjects course within the very smallest dimensions and yet preserve correct proportions and balance. Nothing can excel in masterly reduction the miniature landscape work of the renowned Kaneiye, as exhibited in his priceless sword guards (tsuba).

Sketching comes later in the course and is taught only after facility has been acquired in the other three departments. It embraces everything within doors and without—everything in the universe which has form or shape goes into the artist's sketch-book (ken kon no uchi kei sho arumono mina fun pon to nasu)—and forms part of the course in composition, which is intended to develop the imaginative faculties (sozo). Kubota was so skilful in sketching that while traveling rapidly through a country he could faithfully reproduce the salient features of an extended landscape, conformable to the general rule in sketching, that what first attracts the eye is to be painted first, all else becoming subordinate to it in the scheme. Again, he could paint the scenery and personages of any historical song (joruri) as it was being sung to him, reproducing everything therein described and finishing his work in exact time with the last bar of the music. His arm and wrist were so free and flexible that his brush skipped about with the velocity of a dragon-fly. As an offhand painter (sekijo), or as a contributor to an impromptu picture in which several artists will in turn participate, [pg 14] such joint composition being known as gassaku, Kubota stood facile princeps among modern Japanese artists. The Kyoto painters have always been most gifted in that kind of accomplishment. In their day Watanabe Nangaku, a pupil of Okyo, Bairei, and Hyakunen, all of Kyoto, were famous as sekijo painters.

The art student having completed his course is now qualified to attach himself to some of the great artists, into whose household he will be admitted and whose deshi or art disciple he becomes from that time on. The relation between such master (sensei) and his pupil (deshi) is the most kindly imaginable. Indeed, deshi is a very beautiful word, meaning a younger brother, and was first applied to the Buddhist disciples of Shakka. The master treats him as one of his family and the pupil reveres the master as his divinity. Greater mutual regard and affection exist nowhere and many pupils remain more or less attached to the master's household until his death. To the most faithful and skilful of these the master bestows or bequeaths his name or a part of it, or his nom de plume (go); and thus it is that the celebrated schools (ryugi or ha or fu) of Japanese painting have been formed and perpetuated, beginning with Kanaoka, Tosa, Kano, and Okyo, and brought down to posterity through the devoted, and I might say sacred efforts of their pupils, to preserve the methods and traditions of those great men. Pupils of the earlier painters took their masters' family names, which accounts for so many Tosas and Kanos.

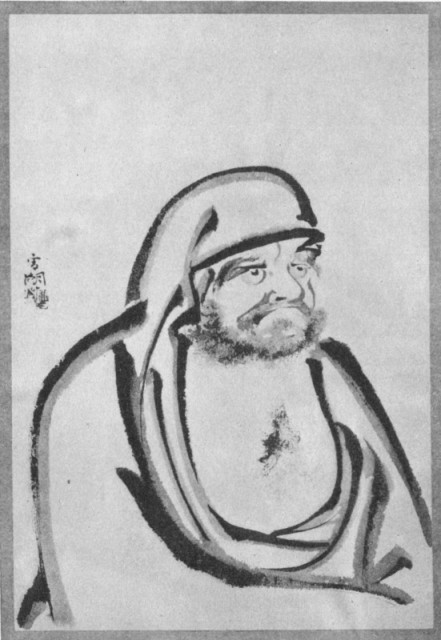

[pg 15]Great painters have always been held in high esteem in Japan, not only by their pupils, but also by the whole nation. Chikudo, the distinguished tiger painter, Bairei, one of the most renowned of the shijo ha or Maruyama school, Hashimoto Gaho, a pupil of Kano Massano and a leading exponent of the Kano style (Kano ha), and Katei, a Nangwa artist, all only recently deceased, were glorified in their lifetime. Strange to say, no one ever saw Gaho with brush in hand. He never would paint before his pupils or in any one's presence. His instructions were oral. On the other hand, Kubota Beisen was always at his best when painting before crowds of admirers.

Prior to the Meiji period the great painters attached to the household of a Daimyo were called O Eshi. Painters who sold their paintings were styled E kaki. Now all painters are called gwa ka. Engravers, sculptors, print makers and the like were and still are denominated shokunin, meaning artisans. The comprehensive term “fine arts” (bijutsu) is of quite recent creation in Japan.

To say a few words about the different schools of painting in Japan, there were great artists there, many centuries before Italy had produced Michael Angelo or Raphael. The art of painting began more than fifteen hundred years ago and has continued in uninterrupted descent from that remote time down to this forty-fourth year of Meiji, the present emperor's reign. No other country in the civilized world can produce such an art record. One thousand years before America was discovered, [pg 16] five hundred years before England had a name, and long before civilization had any meaning in Europe, there were artists in Japan following the profession of painting with the same ardor and the same intelligence they are now bestowing upon their art in this twentieth century of our era.

When Buddhism was introduced there in the sixth century, a great school of Buddhist artists began its long career. Among the names that stand out from behind the mist of ages is that of Kudara no Kawanari, who came from Corea.

In the ninth century lived the celebrated Kose Kanaoka. He painted in what was called the pure Japanese style, yamato e, yamato being the earliest name by which Japan was designated. He painted portraits and landscapes, and his school having a great following, lasted through five centuries. Kose Kimi Mochi, his pupil, Kimitada and Hirotaka were distinguished disciples of Kanaoka.

The Tosa school came next, beginning with Tosa Motomitsu, followed by Mitsunaga, Nobuzane and Mitsunobu. It dates back to the period of the Kamakura Shogunate eight hundred years ago. Its artists confined themselves principally to painting court scenes, court nobles, and the various ceremonies of court life. This school always used color in its paintings.

After Tosa came the schools of Sumiyoshi, Takuma, Kassuga, and Sesshu. Sesshu was a genius of towering proportions and an indefatigable artist of the very highest rank as a landscape painter. He had a famous pupil named Sesson.

[pg 17]Following Sesshu came the celebrated school of Kano artists, founded in the sixteenth century by Kano Masanobu. It took Japan captive. It had a tremendous vogue and following, and has come down to the present day through a succession of great painters. There were two branches, one in Edo (Tokyo), which included Kano Masanobu, Motonobu, his son, Eitoku, Motonobu's pupil, and later, Tanyu (Morinobu) Tanshin, his pupil, Koetsu, Naonobu, Tsunenobu, Morikage, Itcho, and finally Hashimoto Gaho, its latest distinguished representative, who is but recently deceased. The other branch, known as the Kyoto Kano, included the famous San Raku, Eino, San Setsu, and others. By some critics San Raku is placed at the head of all the Kano artists.

The Kano painters are remarkable for the boldness and living strength of the brush strokes (fude no chicara or fude no ikioi), as well as for the brilliancy or sheen (tsuya) and shading of the sumi. This latter effect—the play of light and shade in the stroke, considered almost a divine gift—is called bokushoku, and recalls somewhat the term chiaroscuru. The range of subjects of the Kano painters was originally limited to classic Chinese scenery, treated with simplicity and refinement, and to Chinese personages, sages and philosophers; color was used sparingly.

Other schools, more or less offshoots of the Kano style (ryu) of painting, came next—e. g., Korin and his imitator, Hoitsu, the daimyo of Sakai, who was said to use powdered gold and precious stones in [pg 18] his pigments. Korin has never had his equal as a painter on lacquer. His work is said to be le regal des delicats.

Another disciple of the Kano school, and a pupil of Yutei, was Maruyama Okyo, who founded in turn a school of art which is the most widely spread and flourishing in Japan today. Maruyama, not Okyo, was the family name of that artist. The name Okyo originated thus: Maruyama, much admiring an ancient painter named Shun Kyo, took the latter half of that name, Kyo, and prefixing an “O” to it, made it Okyo, which he then adopted. His style is called shi jo fu, shi jo being the name of that part of Kyoto where he resided, and fu meaning style or manner, and its characteristic is artistic fidelity to the objects represented. By some it is called the realistic school, and includes such well-known household names as Goshun, pupil of Busson, Sosen, the great monkey painter, Tessan (Plate III.) and his son, Morikwansai, Bairei, Chi-kudo, the tiger painter, Hyakunen and his three pupils, Keinen, Shonen and Beisen, Kawabata Gyokusho, Torei, Shoen, and Takeuchi Seiho.

There are still other schools (ryugi) which might be mentioned, including that of the nangwa, or Chinese southern painters, of Chinese origin and remarkable for the gracefulness of the brush stroke, the effective treatment of the masses and for the play of light and shade throughout the composition. Among the great nangwa painters are Taigado, Chikuden, Baietsu (Plate VIII) and Katei. To this school is referred a style of painting affected [pg 19] exclusively by the professional writers of Chinese characters, and called bunjingwa. To these I will allude further on. The versatile artist, Tani Buncho, created a school which had many adherents, including the distinguished Watanabe Kwazan and Eiko of Tokyo, lately deceased, one of its best exponents.

The art of painting is enthusiastically pursued at the present time in Kyoto, Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka. In Tokyo, Hashi Moto Gaho was generally conceded to be, up to the time of his death in 1908, the foremost artist in Japan. Although of the Kano school, he greatly admired European art, and the treatment of the human figure in some of his latest paintings recalls the manner of the early Flemish artists.

My first meeting with Gaho was at his home. While waiting for him, I observed suspended in the tokonoma, or alcove, a narrow little kakemono by Kano Moto Nobu, representing an old man upon a donkey crossing a bridge. A small bronze vase containing a single flower spray was the sole ornament in the room. This gave the keynote to Gaho's character—classic simplicity, ever reflected in his work. He had many followers. His method of instruction with advanced pupils was to give them subjects such as “A Day in Spring,” “Solitude,” “An Autumn Morning,” or the like, and he was most insistent upon all the essentials to the proper effect being introduced. His criticisms were always luminous and sympathetic. He advised his students to copy everything good, but to imitate [pg 20] no-one,—to develop individuality. He left three very distinguished and able pupils—Gyokudo, Kan Zan and Boku Sen.

Since Gaho's death, Kawabata Gyokusho, an Okyo artist, is the recognized leader of the capital. In Kyoto, Takeuchi Seiho, an early pupil of Bairei, now occupies the foremost place, although Shonen and Keinen, pupils of Hyakunen, still hold a high rank.

Recurring to the time of Tosa, there is another school beginning under Matahei and perpetuated through many generations of popular artists, including Utamaro, Yeisen and Hokusai, and coming down to the present date. This is the Ukiyo e or floating-world-picture school. It is far better known through its prints than its paintings. The great painters of Japan have never held this school in any favor. At one time or another I have visited nearly every distinguished artist's studio in Japan, and I know personally most of the leading artists of that country. I have never seen a Japanese print in the possession of any of them, and I know their sentiments about all such work. A print is a lifeless production, and it would be quite impossible for a Japanese artist to take prints into any serious consideration. They rank no higher than cut velvet scenery or embroidered screens. I am aware that such prints are in great favor with many enthusiasts and that collectors highly value them; but they do not exemplify art as the Japanese understand that term. It must be admitted, however, that the prints have been of service in several [pg 21] ways. They first attracted the world's attention to the subject of Japanese art in general. Commencing with an exhibition of them in London a half century ago, the prints of Ukiyo or genre subjects came rapidly into favor and ever since have commanded the notice and admiration of collectors in Europe and America. Many people are even under the impression that the prints represent Japanese painting, which, of course, is a great mistake. There have been artists in Japan who, in the Ukiyo e manner, have painted kakemono, byobu and makimono. The word kakemono is applied to a painting on silk or paper, wound upon a wooden roller and unrolled and hung up to be seen. Kakeru means to suspend and mono means an object, hence kakemono, a suspended object. byobu signifies wind protector or screen; makimono, meaning a wound thing, is a painting in scroll form. It is not suspended, but simply unrolled for inspection. Such original work by Matahei and others is extant. But most of the Ukiyo e, or pictures in the popular style, are prints struck from wood blocks and are the joint production of the artist, the wood engraver, the color smearer and the printer, all of whom have contributed to and are more or less entitled to credit for the result; and that is one reason why the artist-world of Japan objects to or ignores them; they are not the spontaneous, living, palpitating production of the artist's brush. It is well known that artists of the Ukiyo e school frequently indicated only by written instructions how their outline drawings for the prints should be colored, [pg 22] leaving the detail of such work to the color smearer. Apart from the fact that the colors employed were the cheapest the market afforded, and are found often to be awkwardly applied, there is too much about the prints that is measured, mechanical and calculated to satisfy Japanese art in its highest sense. Frequently more than one engraver was employed upon a single print. The engravers had their specialties; some were engaged for the coiffure or head-dress (mage), other for the lines of the face, others for the dress (kimono), others still for pattern (moyo), et cetera. The most skilful engravers in Yedo were called kashira bori and were always employed on Utamaro and Hokusai prints. Many of the colors of these prints in their soft, neutral shades, are rapturously extolled by foreign connoisseurs as evidence of the marvelous taste of the Japanese painter. But, really, time more than art is to be credited with toning down such tints to their present delicate hues. In this respect, like Persian rugs, they improve with age and exposure. An additional objection to most of the prints is that they reproduce trivial, ordinary, every-day occurrences in the life of the mass of the people as it moves on. They are more or less plebian. The prints being intended for sale to the common people, the subjects of them, however skilfully handled, had to be commonplace. They were not purchased by the nobility or higher classes. Soldiers, farmers, and others bought them as presents (miage) for their wives and children, and they were generally sold for a penny apiece, so that in Japan [pg 23] prints were a cheap substitute for art with the lower classes, just as Raspail says garlic has always been the camphor of the poor in France. The practice of issuing Ukiyo e prints at very low prices still continues in Tokyo, where every week or two such colored publications are sprung up in front of the book-stalls and are still as eagerly purchased by the common people as they were in Tokugawa days.

The prices the old prints now bring are out of all proportion to their intrinsic value, yet, such is the crescendo craze to acquire them that Japan has been almost drained of the supply, the number of prints of the best kind being limited, like that of Cremona violins of the good makers.

Prints are genuine originals of a first or subsequent issue, called respectively, sho han and sai han, or they are reproductions more or less cleverly copied upon new blocks, or they are fraudulent imitations (ganbutsu) of the original issues, often difficult to detect. The very wormholes are burnt into them with senko or perfume sticks and clever workmen are employed to make such and other trickery successful. A long chapter could be written about their dishonest devices. Copies of genuine prints (hon koku), made from new blocks after the manner of the ancient ones, abound, and were not intended to pass for originals. Yedo, where the print industry was chiefly carried on, has had so many destructive conflagrations that most of the old Ukiyo e blocks have been destroyed. At Nagoya the house of To Heki Do still preserves the original blocks of the mangwa or miscellaneous drawings of [pg 24] Hokusai, but they are much worn. Prints are known by various names, such as ezoshi (illustrations), nishiki e, edo e (Yedo pictures), sunmono and insatsu. It may be of interest to know that the print blocks, when so worn as to be no longer serviceable for prints, are sometimes converted into fire-boxes (hibachi) and tobacco trays (tobacco bon) which, when highly polished, are decorative and unique.

Perhaps a useful purpose prints have served is to record the manners and customs of the people of the periods when they were struck off. They show not only prevailing styles of dress and headdress, but also the pursuits and amusements of the common folk. They are excellent depositaries of dress pattern (moyo) or decoration, upon which fertile subject Japan has always been a leading authority. In the early Meiji period print painters frequently delegated such minute pattern work to their best pupils, whose seals (in) will be found upon the prints thus elaborated. The prints preserve the ruling fashions of different periods in combs and other hair ornaments, fans, foot-gear, single and multiple screens, fire-boxes and other household ornaments and utensils. They also furnish specimens of temple and house architecture, garden plans, flower arrangements (ike bana), bamboo, twig and other fences. Again, they reproduce the stage, with its famous actors in historical dramas; battle scenes, with warriors and heroes; characters in folk-lore and other stories, and wrestling matches, with the popular champions; and we will often find upon [pg 25] the face of the print good reproductions of Chinese and Japanese writing, in poems and descriptive prose pieces. Hokusai illustrated much of the classic poetry of China and Japan, as well as the senjimon, or Thousand Character Chinese classic, a work formerly universally taught in the Japanese schools. The original characters for this remarkable compilation were taken from the writings of Ogishi. The prints have aided in teaching elementary history to the young; the knowledge of Japanese children in this connection is often remarkable and may be attributed to the educational influence of the Ukiyo e publications.

So there are certainly good words to be said for the prints, but they are not Japanese art in its best sense, however interesting as a subordinate phase of it, and in no sense are they Japanese painting.

If limited to a choice of one artist of the Ukiyo e school, no mistake would be made, I think, in selecting Hiroshige, whose landscapes fairly reproduce the sentiment of Japanese scenery, although the prints bearing his name fall far short of reproducing that artist's color schemes. Hokusai's reputation with foreigners is greater than Hiroshige's, but Japanese artists do not take Hokusai seriously. His pictures, they declare, reflect the restlessness of his disposition; his peaks of Fuji are all too pointed, and his manner generally is exaggerated and theatrical. Utamaro's women of the Yoshiwara are certainly careful studies in graceful line drawing,—as correct as Greek drapery in marble.

[pg 26]Iwasa Matahei, the founder of the popular school, was a pupil of Mitsunori, a Kyoto artist and follower of Tosa. Matahei disliked Tosa subjects and preferred to depict the fleeting usages of the people, so he was nicknamed Fleeting World or Ukiyo Matahei, and thus originated the name Ukiyo e or pictures of every-day life. There are no genuine Matahei prints. He dates back to the seventeenth century. Profile faces in original screen paintings by him have an Assyrian cast of countenance, the eye being painted as though seen in full face.

Hishikawa Moronobu was his follower and admirer. He was an artist of Yedo. Nishikawa Sukenobu belonged to the Kano school and was a pupil of Kano Eiko. He adopted the Ukiyo e style and depicted the pastimes of women and the portraits of actors. He lived two hundred and twenty years ago and in his time prints came greatly into vogue. Torii Kyonobu painted women and actors and invented the kind of pictured theatrical powers which are still in fashion, placarded at the entrance to theaters and showing striking incidents in the play.

Suzuki Harunobu never painted actors, preferring to reproduce the feminine beauties of his time. It was to his careful work that was first applied the term nishiki e or brocade pictures, on account of the charm of his decorative manner. He lived one hundred and thirty years ago.

Among the many able foreign writers on Japanese prints Fenollosa stands prominent. He resided for a long time in Japan, understood and spoke the [pg 27] language, and lived the life of the people. He was in great sympathy with them and with their art and enjoyed exceptional opportunities for seeing and studying the best treasures of that country. Had he possessed the training necessary to paint in the Japanese style I do not think he would have devoted so much time to Japanese woodcuts. Visiting me at Kyoto, where I was busily engaged in painting, “Ah!” he cried, “that is what I have always longed to do. Sooner or later I shall follow your example.” But he never did. Instead, he issued a large work on Japanese prints. His death was a real loss to the art literature of Japan. During eight years he was in the service of the Japanese government ransacking, cataloguing and photographing the multitudinous art treasures, paintings, kakemono, makimono, and byobu (pictures, scrolls and screens), to be found in the various Buddhist and other temples and monasteries scattered throughout the empire. The last time we met, he remarked, “How can one willingly leave this land of light? Japan, to my mind, stands for whatever is beautiful in nature and true in art; here I hope to pass the remaining years of my life.” Such was his genuine enthusiasm, engendered by a long acquaintance with art and everything else beautiful in that country. Japan impresses in this way all who see it under proper conditions, but unfortunately the ordinary traveler, pushed for time, and whose acquaintance is limited to professional guides, never gets much beyond the sights, the shops and the curio dealers.

[pg 28]

The question is often asked, “Is there any good book on Japanese painting?” I know of none in any language except Japanese. The following are among the best works on the subject:

| A History of Japanese Painting (Hon Cho Gashi), by Kano Eno. | |

| A Treasure Volume (bampo zen sho), by Ki Moto Ka Ho. | |

| The Painter's Convenient Reference (Goko Ben Ran), by Arai Haku Seki. | |

| A Collection of Celebrated Japanese Paintings (Ko Cho Meiga shu e), by Hiyama Gi Shin. | |

| Ideas on Design in Painting (To Ga Ko), by Saito Heko Maro. | |

| A Discourse on Japanese Painting (Honcho Gwa San), by Tani Buncho. | |

| Important Reflections on All Kinds of Painting (Gwa Jo Yo Ryaku), by Arai Kayo. | |

| A Treatise on Famous Japanese Paintings (Fu So Mei Gwa Den), by Hori Nao Kaku. | |

| Observations on Ancient Pictures (Ko Gwa Bi Ko), by Asa Oka Kotei. | |

| A Treatise on Famous Painters (Fu So Gwa Jin), by Ko Shitsu Ryo Chu. | |

| A Treatise on Japanese Painting (Yamato Nishiki Kem Bun Sho), by Kuro Kama Shun Son. | |

| A Treatise on the Laws of Painting (Gwafu), by Ran Sai, a pupil of Chinanpin. The work is voluminous and is both of great use and authority. | |

| Cho Chu Gwa Fu, by Chiku To. | |

| Sha Zan Gakugwa Hen, by Buncho. |

Translations of all these works into English are greatly to be desired.

There is much that has been sympathetically written and published about Japanese paintings both in Europe and America, but however laudatory, it might be all summed up under the title, “Impressions of an Outsider.” Such writings lack [pg 29] the authority which only constant labor in the field of practical art can confer. A Japanese artist, by which I mean a painter, is long in making. From ten to fifteen years of continuous study and application are required before much skill is attained. During that time he gradually absorbs a knowledge of the many principles, precepts, maxims and methods, which together constitute the corpus or body of art doctrine handed down from a remote antiquity and preserved either in books or perpetuated by tradition. Along with these are innumerable art secrets called hiji or himitsu, never published, but orally imparted by the masters to their pupils—not secrets in a trick sense, but methods of execution discovered after laborious effort and treasured as valued possessions. It is obvious, then, how incapable of writing technically upon the subject must anyone be who has not gone through such curriculum and had drilled into him all that varied instruction which makes up the body of rules applicable to that art.

I have read many seriously written appreciations of Japanese paintings published in various modern languages, and even some amiable imaginings penned for foreigners by Japanese who fancy they know by instinct what only can be acquired after long study and practice with brush in hand. All such writers are characterized in Japan by a very polite term, shiroto—which means amateur. It also has a secondary signification of emptiness.

CHAPTER THREE. LAWS FOR THE USE OF BRUSH AND MATERIALS

Upon a subject as technical as that of Japanese painting, to endeavor to impart correct information in a way that shall be both instructive and entertaining is an undertaking of no little difficulty. The rules and canons of any art when enumerated, classified and explained, are likely to prove trying, if not wearisome reading. Yet, if our object be to acquire accurate knowledge, we must consent to make some sacrifice to attain it, and there is no royal road to a knowledge of Japanese painting.

We have little or no opportunity in America, excepting in one or two cities, to see good specimens of the work of the great painters of Japan. Furthermore, such work in kakemono form is seen to much disadvantage when exhibited in numbers strung along the walls of a museum. Japanese kakemono (hanging paintings) are best viewed singly, suspended in the recess of the tokonoma, or alcove. A certain seclusion is essential to the [pg 31] enjoyment of their delicate and subtle effects; the surroundings should be suggestive of leisure and repose, which the Japanese word shidzuka, often employed in art language, well describes.

The Japanese technique, by which I understand the established manner in which their effects in painting are produced, differs widely from that of European art. The Japanese brushes (Jude and hake), colors and materials influence largely the method of painting. The canons or standards by which Japanese art is to be judged are quite special to Japan and are scarcely understood outside of it. Since the subject is technical, to treat it in a popular way is to risk the omission of much that is essential. I will endeavor, at any rate, to give an outline of its fundamental principles, first saying a word or two about the tools and materials.

In Japanese painting no oils are used. Sumi (a black color in cake form) and water-colors only are employed, while Chinese and Japanese paper and specially prepared silk take the place of canvas or other material.

Japanese artists do not paint on easels; while at work they sit on their heels and knees, with the paper or silk spread before them on a soft material, called mosen, which lies upon the matting or floor covering. After one becomes accustomed to this position, he finds it gives, among other things, a very free use of the right arm and wrist.

Silk (e ginu) is prepared for painting by first attaching it with boiled rice mucilage to a stretching frame. A sizing of alum and light glue (called [pg 32] dosa) is next applied, care being taken not to wet the edges of the silk attached to the frame, which would loosen the silk.

It has been found that paper lasts much longer than silk, and also can be more easily restored when cracked with age.

The artists of the Tosa school used a paper various kinds called tori no ko, into the composition of which egg-shells entered. This paper was a special product of Ichi Zen.

The Kano artists used both tori no ko and a paper made from the mulberry plant, also a product of Ichi Zen, and known as hosho. For ordinary tracing a paper called tengu jo is used. In Okyo's time, Chinese paper made from rice-plant leaves came into vogue. It is manufactured in large sheets and is called toshi. It is a light straw color, and is very responsive to the brush stroke, except when it “catches cold,” as the Japanese say. It should be kept in a dry place.

The Tosa artists used paper almost to the exclusion of silk. The Kano school largely employed silk for their paintings. Okyo also usually painted on silk.

Japanese artists seldom outline their work. In painting on silk, a rough sketch in sumi is sometimes placed under the silk for guidance. Outlining on paper is done with straight willow twigs of charcoal, called yaki sumi, easily erased by brushing with a feather.

There are strict, and when once understood, reasonable and helpful laws for the use of the [pg 33] brush (yohitsu), the use of sumi (yoboku) and the use of water-colors (sesshoku). These laws reach from what seems merely the mechanics of painting into the highest ethics of Japanese art.

The law of yo hitsu requires a free and skilful handling of the brush, always with strict attention to the stroke, whether dot, line or mass is to be made; the brush must not touch the silk or paper before reflection has determined what the stroke or dot is to express. Neither negligence nor indifference is tolerated.

An artist, be he ever so skilful, is cautioned not to feel entirely satisfied with his use of the brush, as it is never perfect and is always susceptible of improvement. The brush is the handmaid of the artist's soul and must be responsive to his inspiration. The student is warned to be as much on his guard against carelessness when handling the brush as if he were a swordsman standing ready to attack his enemy or to defend his own life; and this is the reason: Everything in art conspires to prevent success. The softness of the brush requires the stroke to be light and rapid and the touch delicate. The brush, when dipped first into the water, may absorb too much or not enough, and the sumi or ink taken on the brush may blot or refuse to spread or flow upon the material, or it may spread in the wrong direction. The Chinese paper (toshi) which is employed in ordinary art work may be so affected by the atmosphere as to refuse to respond, and the brush stroke must be regulated accordingly. All such matters have to [pg 34] be considered when the brush is being used, and if the spirit of the artist be not alert, the result is failure. (it ten ichi boku ni chiu o su beki.)

Vehicle of the subtle sentiment to be expressed in form, the brush must be so fashioned as to receive and transmit the vibrations of the artist's inner self. Much care, much thought and skill have been expended in the manufacture of the brush.

In China, the art of writing preceded painting, and the first brushes made were writing brushes, and the more writing developed into a wonderful art, the more attention was bestowed upon the materials composing the writing brush. Such brushes were originally made with rabbit hair, round which was wrapped the hair of deer and sheep, and the handles were mulberry stems. Later on, as Chinese characters became more complex and writing more scientific, the brushes were most carefully made of fox and rabbit hair, with handles of ivory, and they were kept in gold and jeweled boxes. Officials were enjoined to write all public documents with brushes having red lacquer handles, red being a positive or male (yo) color. Ogishi, the greatest of the Chinese writers, used for his brushes the feelers from around the rat's nose and hairs taken from the beak of the kingfisher.

In Japan, hair of the deer, badger, rabbit, sheep, squirrel, and wild horse all enter into the manufacture of the artist's brush, which is made to order, long or short, soft or strong, stiff or pliable. For laying on color, the hair of the badger is preferred. The sizes and shapes of brushes used differ [pg 35] according to the subject to be painted. There are brushes for flowers and birds, human beings, landscapes, lines of the garments, lines of the face, for laying on color, for shading, et cetera.

A distinguishing feature in Japanese painting is the strength of the brush stroke, technically called fude no chikara or fude no ikioi. When representing an object suggesting strength, such, for instance, as a rocky cliff, the beak or talons of a bird, the tiger's claws, or the limbs and branches of a tree, the moment the brush is applied the sentiment of strength must be invoked and felt throughout the artist's system and imparted through his arm and hand to the brush, and so transmitted into the object painted; and this nervous current must be continuous and of equal intensity while the work proceeds. If the tree's limbs or branches in a painting by a Kano artist be examined, it will astonish any one to perceive the vital force that has been infused into them. Even the smallest twigs appear filled with the power of growth—all the result of fude no chikara. Indeed, when this principle is understood, and in the light of it the trees of many of the Italian and French artists are critically viewed, they appear flabby, lifeless, and as though they had been done with a feather. They lack that vigor which is attained only by fude no chikara, or brush strength.

In writing Chinese characters in the rei sho manner this same principle is carefully inculcated. The characters must be executed with the feeling of their being carved on stone or engraved on [pg 36] steel—such must be the force transmitted through the arm and hand to the brush. Thus executed the writings seem imbued with living strength.

It is related of Chinanpin, the great Chinese painter, that an art student having applied to him for instruction, he painted an orchid plant and told the student to copy it. The student did so to his own satisfaction, but the master told him he was far away from what was most essential. Again and again, during several months, the orchid was reproduced, each time an improvement on the previous effort, but never meeting with the master's approval. Finally Chinanpin explained as follows: The long, blade-like leaves of the orchid may droop toward the earth but they all long to point to the sky, and this tendency is called cloud-longing (bo un) in art. When, therefore, the tip of the long slender leaf is reached by the brush the artist must feel that the same is longing to point to the clouds. Thus painted, the true spirit and living force (kokoromochi) of the plant are preserved.

Kubota recommended to art students and artists to a practice with lines which is excellent for acquiring and retaining firmness and freedom of the arm, with steady and continuous strength in the stroke. With a brush held strictly perpendicular to the paper horizontal lines are painted, first from right to left, the entire width of the toshi or other paper, each line with equal thickness and unwavering intensity of power throughout its entire length. The thickness of the line will depend upon the amount of hair in the brush that is allowed to [pg 37] touch the paper; if only the tip of the brush be used, the line will be slender or thin; but, whether a broad band or a delicate tracing, it must be uniform throughout and filled with living force. Next, the lines are painted from left to right in the same way and with the same close attention to uniform thickness and continuous flow of nervous strength from start to finish. Then, the increasingly difficult task is to paint them from top to bottom of the toshi, and finally, most difficult and most important of all these exercises, the parallel lines are traced from bottom to top of the paper. The thinner the line the more difficult it is to execute, because of the tendency of the hand to tremble. Indeed, the difficulty is supreme. Let any one who is interested try this; it is an exercise for the most expert. Such lines resemble the sons filés on the violin, where a continuous sustained tone of equal intensity is produced by drawing the bow from heel to tip so slowly over the strings that it hardly moves. Practicing lines in the way indicated gives steadiness and strength, qualities in demand at every instant in Japanese art. Observe a Japanese artist paint the young branch of a plum tree shooting from the trunk. The new year's growth starting, it may be, from the bottom of the toshi will be projected to the top. Examine it carefully and it will be found to conform to that principle of jude no chikara which transfers a living force into the branch. I have seen European artists in Japan vainly try offhand to produce such effects; but these depend on long and patient practice.

[pg 38]A Japanese artist will frequently ignore the boundaries of the paper upon which he paints by beginning his stroke upon the mosen and continuing it upon the paper—or beginning it upon the paper and projecting it upon the mosen. This produces the sentiment or impression of great strength of stroke. It animates the work. And in this energetic kind of painting, if drops of sumi accidentally fall from the brush upon the painting they are regarded as giving additional energy to it. Similarly, if the stroke on the trunk or branch of a tree shows many thin hair lines where the intention was that the line should be solid, this also is regarded as an additional evidence of stroke energy and is always highly prized.

The same principle applies in the art of Chinese writing; but this effect must not be the result of calculation—it must be what in art is called shi zen, meaning spontaneous.

In painting the hair of monkeys, bears and the like, the pointed brush is flattened and spread out (wari fude) so that each stroke of the same will reproduce numberless thin lines, corresponding to the hairs of the animal. Sosen thus painted. In modern times Kimpo (Plate V) is justly renowned for such work.

Many artists become wonderfully expert in the use of the flat brush, from one to four inches wide, called hake, by means of which instantaneous effects such as rain, rocks, mountain chains and snow scenes are secured. Some artists acquire a special reputation for skill in the use of the hake.

[pg 39]The brush should be often and thoroughly rinsed during the time that it is used and washed and dried when not employed. In Kyoto, Osaka and Tokyo there are famous manufacturers of artists' brushes, and names of makers such as Nishimura, Sugiyama, Hakkado, Onkyodo and Kiukyodo are familiar to all the artists of the country.

The use of sumi (yoboku) is the really distinguishing feature of Japanese painting. Not only is this black color (sumi) used in all water color work, but it is frequently the only color employed; and a painting thus executed, according to the laws of Japanese art, is called sumi e and is regarded as the highest test of the artist's skill. Colors can cheat the eye (damakasu) but sumi never can; it proclaims the master and exposes the tyro.

The terms “study in black and white,” “India ink drawing” and the like, since all are only makeshift translations, are misleading. The Chinese term “bokugwa” is the exact equivalent of sumi e and both mean and describe the same production. Sumi e is not an “ink picture,” since no ink is used in its production. Ink is the very opposite of sumi both in its composition and effect. Ink is an acid and fluid. Sumi is a solid made from the soot obtained by burning certain plants (for the best results juncus communis, bull rush, or the sessamen orientalis), combined with glue from deer horn. This is molded into a black cake which, drying thoroughly if kept in ashes, improves with age. In much of the good sumi crimson (beni) is added for the sheen, and musk perfume (Jako) is [pg 40] introduced for antiseptic purposes. When a dead finish or surface (tsuya o keshi) is desired, as, for instance, where the female coiffure is to be painted and a lusterless ground is needed for contrast with the shining strands of the hair, a little white pulverized oyster shell, called go fun, is mixed, with the sumi. Commercial India ink resembles sumi in appearance, but is very inferior to it in quality. The methods of sumi manufacture are carefully guarded secrets. China during the Ming dynasty, three centuries ago, produced the best sumi, although China sumi (toboku) employed twelve centuries past shows both in writing and in painting as distinctly and brilliantly today as though it were but recently manufactured. Nara, near Kyoto, was the birthplace of Japanese sumi, and the house of Kumagai (Kyukyodo) for centuries has had its manufacturers in that city. In Tokyo a distinguished maker, whose sumi many of the artists there prefer, is Baisen. He has devoted fifty years of his life to the study and compounding of this precious article. He possesses some great secrets of manufacture which may die with him. In Okyo's time there was a dark blue sumi called ai en boku but the art and secret of its manufacture are lost.

In using sumi the cake is moistened and rubbed on a slab called suzuri, producing a semi-fluid. The well-cleaned brush is dipped first into clear water and then into the prepared sumi. When the sumi is taken on the brush it should be used without delay; otherwise it will mingle with the [pg 41] water of the brush and destroy the desired balance between the water and the sumi. For careful work the sumi is first transferred on the brush from the suzuri to a white saucer, where it is tested. It is a singular fact that the color of sumi will differ according to the manner in which it is rubbed upon the stone. The best results are obtained when a young maiden is employed for the purpose, her strength being just suitable.

It is very important while painting with sumi to renew its strength frequently by fresh applications of the cake to the slab. The color and richness of sumi left upon the slab soon fade; and though when used this may not be apparent, when the sumi dries on the paper or silk its weakness is speedily perceived.

By the dexterous use of sumi colors may be successfully suggested, materials apparently reproduced and by what is termed bokushoku, or the brush-stroke play of light and shade, the very rays of the sun may be imprisoned within the four corners of a picture. Artists are readily recognized in their work by their manner of using or laying on sumi. The color, the sheen, the shadings and the flow of the ink enable us even to determine the disposition or state of mind of the artist at the time of painting, so sensitive, so responsive is sumi to the mood of the artist using it. There is much of engaging interest in connection with this subject. Artists become most difficult to satisfy on the subject of the various kinds of sumi, which differ as much in their special qualities as the tones [pg 42] of celebrated violins. It is interesting to observe how different the color or richness of the same sumi becomes according to the varying skill with which it is applied.

The mineral character of the suzuri has also much to do with the production of the best and richest black tones.

The most valuable stone for suzuri is known throughout the entire oriental world as tan kei and is found in the mountain of Fuka in China. This stone has gold streaks through it, with small dots called bird's eyes. The water which flows from Fuka mountain is blue. The color of the rock is violet. A favorite color for the suzuri (in Chinese called ken) is lion's liver. Formerly much ceremony was observed in mining for this stone and sheep and cattle were offered in sacrifice, else it was believed that the stone would be struck by a thunderbolt and reduced to ashes in the hands of its possessor. The suzuri is also made in China from river sediment fashioned and baked. Still another method is to make the suzuri from paper and the varnish of the lacquer tree. Such are called paper suzuri (shi ken). In Thibet suzuri are made from the bamboo root. In Japan the best stones for suzuri are found near Hiroshima in Kiushu, the grain being hard and fine.

The skilful use of water colors is called sesshoku. It is more difficult to paint with sumi alone than use of water to paint with the aid of colors, which can hide defects never to be concealed in a sumi e, where painting over sumi a second time is disastrous. Japanese painters as a rule are sparing of colors, the slightest amount used discreetly and with restraint generally sufficing. Many artists have not the color sense or dislike color and seldom use it. Kubota often declared he hoped to live until he might feel justified in discarding color and employing sumi alone for any and all effects in painting.

There are eight different ways of painting in color. I will enumerate them, with their technical, descriptive terms:

In the best form of color painting (goku zai shiki) (Plate IX) the color is most carefully laid on, being applied three times or oftener if necessary. On account of these repeated coats this form is called tai chaku shoku. This style of painting is reserved for temples, gold screens, palace ceilings and the like. Tosa and Yamato e painters generally followed this manner.

The next best method of coloring (chu zai shiki) (Plate X) is termed chaku shoku, or the ordinary application of color. The Kano and Shijo schools use this method extensively, as did also the Ukiyo e painters.

The light water-color method, called tan sai (Plate XI), is employed in the ordinary style of painting kakemono and is much used by the Okyo school.

The most interesting form of painting, technically called bokkotsu (Plate XII), is that in which all outlines are suppressed and sumi or color is used for the masses. Another Japanese term for the same is tsuketate.

[pg 44]

The method of shading, called goso (Plate XIII), invented by a Chinese artist, Godoshi, who lived one thousand years ago, consists in applying dark brown color or light sumi wash over the sumi lines. This style was much employed by Kano painters and for art printing.

The light reddish-brown color, technically called senpo shoku (Plate XIV), is mostly used in printing pictures in book form.

Another form similarly used is called hakubyo (Plate XV) or white pattern, no color being employed.

Lastly, there is the sumi picture or sumi e (Plate XVI), technically called suiboku,—to which reference has already been made—where sumi only is employed, black being regarded as a color by Japanese artists.

A well-known method by which the autumnal tints of forest leaves are produced is to take up with the brush one after another and in the following order these colors: Yellow-green (ki iro), brown (tai sha), red (shu), crimson (beni), and last, and on the very tip of the brush, sumi. The brush thus charged and dexterously applied gives a charming autumn effect, the colors shading into each other as in nature.

There are five parent colors in Japanese art: parent colors Blue (sei), yellow (au), black (koku), white (byaku), combinations and red (seki). These in combination (cho go) originate other colors as follows: Blue and yellow produce green (midori); blue and black, dark blue (ai nezumi); blue and white, sky-blue (sora iro); [pg 45] blue and red, purple (murasaki); yellow and black, dark green (unguisu cha); yellow and red, orange (kaba); black and red, brown (tobiiro); black and combinations white, gray (nezumiiro). These secondary colors in combination produce other tones and shades required. Powdered gold and silver, and crimson made from the saffron plant are also employed. The colors, excepting yellow, are prepared for use by mixing them with light glue upon a saucer. With yellow, water alone is used. In addition to all the foregoing there are other expensive colors used in careful work and known as mineral earths (iwamono). They are blue (gunjo), dark or Prussian blue (konjo), light bluish-green (gunroku), green (rokusho), light green (byakugun), pea green (cha-roku sho) and light red (sango matsu).

The use of primary colors in a painting in proximity to secondary ones originated by them is color to be avoided, as both lose by such contrast; and when a color-scheme fails to give satisfaction it will usually be found that this cardinal principle of harmony, called iro no kubari, has been disregarded by the artist. Color in art is the dress, the apparel in which the work is clad. It must be suitably combined, restrained, and attract no undue attention (medatsunai). True color sense is a special gift.

CHAPTER FOUR. LAWS GOVERNING THE CONCEPTION AND EXECUTION OF A PAINTING

When a Japanese artist is preparing to paint a picture he considers first the space the picture is to occupy and its shape, whether square, oblong, round or otherwise; next, the distribution of light and shade, and then the placing of the objects in the composition so as to secure harmony and effective contrasts. In settling these questions he relies largely on the laws of proportion and design.

The principles of proportion (ichi) and design (isho) are closely allied. They aim to supply and express with sobriety what is essential to the composition, proportion determining the just arrangement and distribution of the component parts, and design the manner in which the same shall be handled. In a landscape, proportion may require the balancing effect of buildings and trees, while design will determine how the same may be picturesquely presented; for instance, by making the [pg 47] trees partially hide the buildings, thus provoking a desire to see more than is shown. Such suggestion or stimulation of the imagination is called yukashi. The Japanese painter is early taught the value of suppression in design—l'art d'ennuyer est de tout dire.

A well-known rule of proportion, quaintly expressed in the original Chinese and which is more or less adhered to in practice, requires in a landscape painting that if the mountain be, for example, ten feet high the trees should be one foot, a horse one inch and a man the size of a bean. Jo san seki ju, sun ba to jin (Plate XVII).

Design, called in art isho zuan or takumi, is largely the personal equation of the artist. It is his power of presenting and expressing what he treats in an original manner. The subject may not be new, but its treatment must be fresh and attractive. Much will depend upon the learning and the technical ability of the artist. In the matter of design the artists of Tokyo have always differed from those of Kyoto, the former aiming at lively and even startling effects, while the latter seek to produce a quieter or more subdued (otonashi) result.