CRUISINGS in the CASCADES and other HUNTING ADVENTURES

G. O. SHIELDS

(COQUINA)

G. O. Shields

Cruisings in the Cascades.

A NARRATIVE OF

Travel, Exploration, Amateur Photography,

Hunting, and Fishing,

WITH SPECIAL CHAPTERS ON

HUNTING THE GRIZZLY BEAR, THE BUFFALO, ELK, ANTELOPE,

ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT, AND DEER; ALSO ON TROUTING IN

THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS; ON A MONTANA ROUND-UP;

LIFE AMONG THE COWBOYS, ETC.

By G. O. SHIELDS,

("COQUINA")

AUTHOR OF "RUSTLINGS IN THE ROCKIES," "HUNTING IN THE GREAT WEST," "THE BATTLE OF THE BIG HOLE," ETC.

CHICAGO AND NEW YORK:

Rand, Mcnally & Company, Publishers.

1889.

Copyright, 1889, by Rand, Mcnally & Co.

The articles herein on Elk, Bear, and Antelope Hunting are reprinted by the courtesy of Messrs. Harper & Brothers, in whose Magazine they were first published; and those on Buffalo Hunting and Trouting are reproduced from "Outing" Magazine, in which they first appeared.

"Come live with me and be my love.

And we will all the pleasures prove

That hills and valleys, dales and fields,

Woods or steepy mountains, yield."

—Marlowe.

"Earth has built the great watch-towers of the mountains, and they lift their heads far up into the sky, and gaze ever upward and around to see if the Judge of the World comes not."

—Longfellow.

[7]

PREFACE.

And now, how can I suitably apologize for having inflicted another book on the reading public? I would not attempt it but that it is the custom among authors. And, come to think of it, I guess I won't attempt it anyway. I will merely say, by way of excuse, that my former literary efforts, especially my "Rustlings in the Rockies," have brought me in sundry dollars, in good and lawful money, which I have found very useful things to have about the house. If this volume shall meet with an equally kind reception at the hands of book buyers, I shall feel that, after all, I am not to blame for having written it.

THE AUTHOR.

Chicago, March, 1889.

[9]

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

The Benefits, Mental and Physical, of Mountain Climbing—A Never-failing Means of Obtaining Sound Sleep and a Good Appetite—The Work to be in Proportion to the Strength of the Climber—People Who Would Like to See, but are Too Lazy to Climb—How the Photograph Camera May Enhance the Pleasures and Benefits of Mountain Climbing—Valuable Souvenirs of Each Ascent—How "These Things are Done in Europe"—An Effective Cure for Egotism. 17

CHAPTER II.

The Cascade Mountains Compared with the Rockies—Characteristics and Landmarks of the Former—The Proper Season for Cruising in the Cascades—Grand Scenery of the Columbia—Viewing Mount Tacoma from the City of Tacoma—Men Who Have Ascended this Mysterious Peak—Indian Legends Concerning the Mountain—Evil Spirits, Who Dwell in Yawning Caverns—The View from the Mountain—Crater Lake and the Glaciers—Nine Water-falls in Sight from One Point. 25

CHAPTER III.

The City of Seattle—A Booming Western Town—Lumbering and Salmon Canning—Extensive Hop Ranches—Rich Coal and Iron Mines—Timber Resources of Puget Sound—Giant Firs and Cedars—A Hollow Tree for a House—Big Timber Shipped to England—A Million Feet of Lumber from an Acre of Land—Novel Method of Logging—No Snow in Theirs—A World's Supply of Timber for a Thousand Years. 35

[10]CHAPTER IV.

Length, Breadth, and Depth of Puget Sound—Natural Resources of the Surrounding Country—Flora and Fauna of the Region—Great Variety of Game Birds and Animals—Large Variety of Game and Food Fishes—A Paradise for Sportsman or Naturalist—A Sail Through the Sound—Grand Mountains in Every Direction—The Home of the Elk, Bear, Deer, and Salmon—Sea Gulls as Fellow Passengers—Photographed on the Wing—Wild Cattle on Whidby Island—Deception Pass; its Fierce Current and Wierd Surroundings—Victoria, B. C.—A Quaint Old, English-looking Town. 42

CHAPTER V.

Through English Bay—Water Fowls that Seem Never to Have Been Hunted—Rifle Practice that was Soon Interrupted—Peculiarities of Burrard Inlet—Vancouver and Port Moody—A Stage Ride to Westminster—A Stranger in a Strange Land—Hunting for a Guide—"Douglass Bill" Found and Employed—An Indian Funeral Delays the Expedition. 53

CHAPTER VI.

The Voyage up the Frazier—Delicious Peaches Growing in Sight of Glaciers—The Detective Camera Again to the Front—Good Views from the Moving Steamer—A Night in an Indian Hut—The Sleeping Bag a Refuge from Vermin—The Indian as a Stamping Ground for Insects—He Heeds Not Their Ravages. 59

CHAPTER VII.

A Breakfast with the Bachelor—Up Harrison River in a Canoe—Dead Salmon Everywhere—Their Stench Nauseating—The Water Poisoned with Carrion—A Good Goose Spoiled with an Express Bullet—Lively Salmon on the Falls—Strange Instinct of this Noble Fish—Life Sacrificed in the Effort to Reach its Spawning Grounds—Ranchmen Fishing with Pitchforks, and Indians with Sharp Sticks—Salmon Fed to Hogs, and Used as Fertilizers; the Prey of Bears, Cougars, Wild Cats, Lynxes, Minks, Martins, Hawks, and Eagles. 66

[11]CHAPTER VIII.

The River Above the Rapids—A Lake Within Basaltic Walls—Many Beautiful Waterfalls—Mount Douglas and its Glaciers—A Trading Post of the Hudson Bay Fur Company—The Hot Springs; an Ancient Indian Sanitarium—Anxiously Waiting for "Douglass Bill"—Novel Method of Photographing Big Trees. 75

CHAPTER IX.

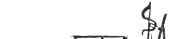

An Early Morning Climb—A Thousand Feet Above the Lake—Fresh Deer Signs in Sight of the Hotel—Three Indians Bring in Three Deer—"Douglass Bill" Proves as Big a Liar as Other Indians—Heading off a Flock of Canvas Backs—A Goodly Bag of these Toothsome Birds—A Siwash Hut—A Revolting Picture of Dirt, Filth, Nakedness, and Decayed Fish—Another Guide Employed—Ready on Short Notice—Off for the Mountain. 82

CHAPTER X.

Characteristics of the Flathead Indians—Canoeists and Packers by Birth and Education—A Skillful Canoe Builder—Freighting Canoes—Fishing Canoes—Traveling Canoes—Two Cords of Wood for a Cargo, and Four Tons of Merchandise for Another—Dress of the Coast Indians. 89

CHAPTER XI.

Climbing the Mountain in a Rainstorm-Pean's Dirty Blankets—His Careful Treatment of His Old Musket—A Novel Charge for Big Game—The Chatter of the Pine Squirrel—A Shot Through the Brush—Venison for Supper—A Lame Conversation: English on the One Side, Chinook on the Other—The Winchester Express Staggers the Natives—Peculiarities of the Columbia Black Tail Deer. 97

CHAPTER XII.

The Chinook Jargon; an Odd Conglomeration of Words; the Court Language of the Northwest; a Specimen Conversation—A Camp on the Mountain Side—How the Indian Tried [12] to Sleep Warm—The Importance of a Good Bed when Camping—Pean is taken Ill—His Fall Down a Mountain—Unable to go Further, We Turn Back—Bitter Disappointment 102

CHAPTER XIII.

The Return to the Village—Two New Guides Employed—Off for the Mountains Once More—The Tramp up Ski-ik-kul Creek Through Jungles, Gulches, and Cañons—And Still it Rains—Ravages of Forest Fires—A Bed of Mountain Feathers—Description of a Sleeping Bag; an Indispensable Luxury in Camp Life; an Indian Opinion of It 107

CHAPTER XIV.

Meditations by a Camp Fire—Suspicions as to the Honesty of My Guides; at Their Mercy in Case of Stealthy Attack—A Frightful Fall—Broken Bones and Intense Suffering—A Painful and Tedious Journey Home—A Painful Surgical Operation—A Happy Denouement 113

CHAPTER XV.

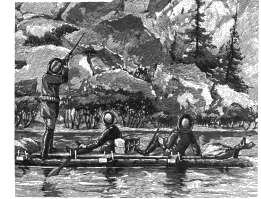

The Beauties of Ski-ik-kul Creek; a Raging Mountain Torrent; Rapids and Waterfalls Everywhere; Picturesque Tributaries—Above the Tree Tops—The Pleasure of Quenching Thirst—A Novel Spear—A Fifteen-Pound Salmon for Supper—The Indians' Midnight Lunch—A Grand Camp Fire—At Peace with All Men 118

CHAPTER XVI.

Seymour Advises a Late Start for Goat Hunting; but His Council is Disregarded—We Start at Sunrise—A Queer Craft—Navigating Ski-ik-kul Lake—A "Straight-up" Shot at a Goat—Both Horns Broken Off in the Fall—More Rain and Less Fun—A Doe and Kid—Successful Trout Fishing—Peculiarities of the Skowlitz Tongue; Grunts, Groans and Whistles—John has Traveled—Seymour's Pretended Ignorance of English 125

CHAPTER XVII.

[Pg 13] En Route to the Village Again—A Water-Soaked Country—"Oh, What a Fall was There, My Countrymen!"—Walking on Slippery Logs—More Rain—Wet Indians—"Semo He Spile de Grouse"—A Frugal Breakfast—High Living at Home—A Bear He did a Fishing Go; but He was Caught Instead of the Fish, and His Skin is Bartered to the Unwashed Siwashes. 132

CHAPTER XVIII.

John and His Family "At Home"—An Interesting Picture of Domestic Economy—Rifle Practice on Gulls and Grebes—Puzzled Natives—"Phwat Kind of Burds is Them?"—A day on the Columbia—The Pallisades from a Steamer—Photographing Bad Lands from a Moving Train. 141

CHAPTER XIX.

Deer Hunting at Spokane Falls—Ruin Wrought by an Overloaded Shotgun: A Tattered Vest and a Wrecked Watch—Billy's Bear Story—The Poorest Hunter Makes the Biggest Score—A Claw in Evidence—A Disgusted Party. 146

CHAPTER XX.

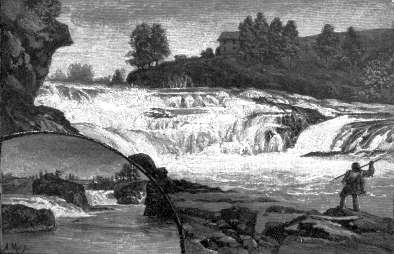

A Fusilade on the Mule Deer—Two Does as the Result—A Good Shot Spoiled—View from the Top of Blue Grouse Mountain—A Grand Panorama; Lakes, Mountains, Prairies and Forests—Johnston's Story—Rounding Up Wild Hogs—A Trick on the Dutchman—A Bucking Mule and a Balky Cayuse—Falls of the Spokane River. 153

CHAPTER XXI.

Hunting the Grizzly Bear—Habitat and Characteristics—A Camp Kettle as a Weapon of Defense—To the Rescue with a Winchester—Best Localities for Hunting the Grizzly—Baiting and Still-Hunting—A Surprise Party in the Trail—Two Bulls-eyes and a Miss—Fresh Meat and Revelry in Camp. 164

[14] CHAPTER XXII.

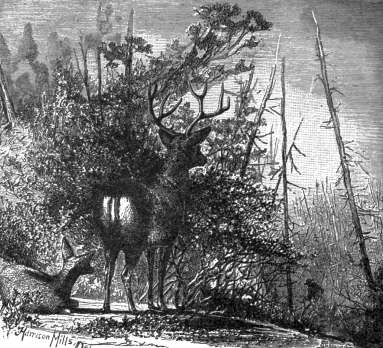

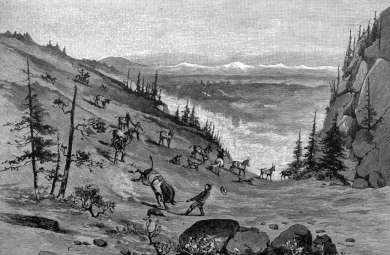

Elk Hunting in the Rocky Mountains—Characteristics of the Elk—His Mode of Travel—A Stampede in a Thicket—The Whistle of the Elk, the Hunter's Sweetest Music—Measurements of a Pair of Antlers—Saved by Following an Elk Trail—The Work of Exterminators—The Elk Doomed. 181

CHAPTER XXIII.

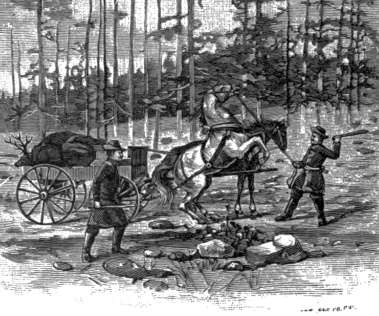

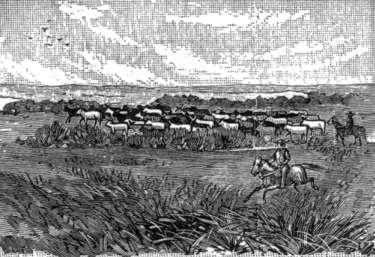

Antelope Hunting in Montana—A Red Letter Day on Flat Willow—Initiating a Pilgrim—Sample Shots—Flagging and Fanning—Catching Wounded Antelopes on Horseback—Four Mule-Loads of Meat. 194

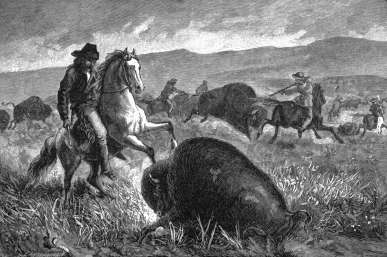

CHAPTER XXIV.

Buffalo Hunting on the Texas Plains—A "Bull Train" Loaded with Skins—A Sensation in Fort Worth—En Route to the Range—Red River Frank's Mission—A Stand on the Herd—Deluged with Buffalo Blood—A Wild Run by Indians—Tossed into the Air and Trampled into the Earth. 213

CHAPTER XXV.

Hunting the Rocky Mountain Goat—Technical Description of the Animal—Its Limited Range—Dangers Incurred in Hunting It—An Army Officer's Experience—A Perilous Shot—A Long and Dangerous Pursuit—Successful at Last—Carrying the Trophies to Camp—Wading up Lost Horse Creek—Numerous Baths in Icy Water—An Indian's Fatal Fall—Horses Stampeded by a Bear—Seven Days on Foot and Alone—Home at Last. 236

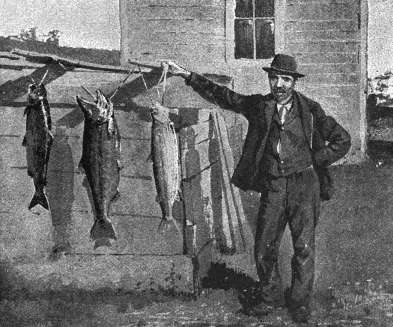

CHAPTER XXVI.

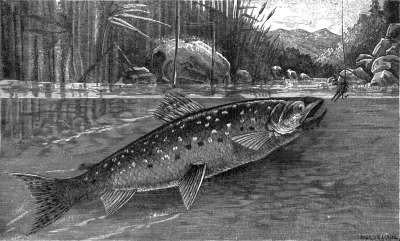

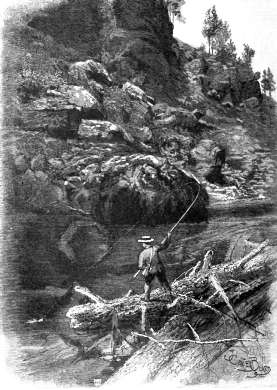

Trouting in the Mountains—Gameness of the Mountain Trout—A Red Letter Day on the Bitter Root—Frontier Tackle and Orthodox Bait—How a Private Soldier Gets to the Front as an Angler—A Coot Interrupts the Sport, and a Rock Interrupts the Coot—Colonel Gibson takes a Nine-Pounder—A Native Fly Fisherman—Grand Sport on Big Spring Creek—How Captain Hathaway does the Honors—Where Grand Sport may be Found. 257

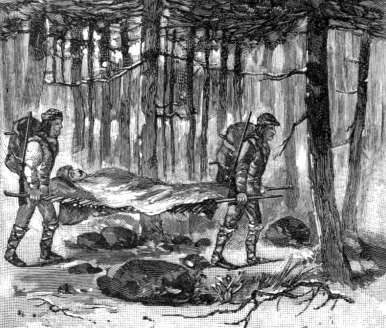

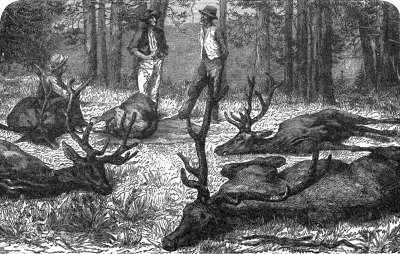

[15]CHAPTER XXVII.

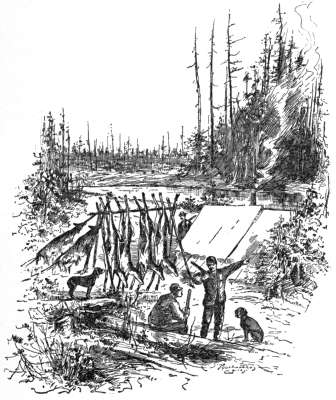

Deer Hunting in Northern Wisconsin—On the Range at Daylight—The Woods Full of Game—Missing a Standing "Broadside" at Thirty Yards—Several Easy Shots in Rapid Succession; the only Fruits Shame and Chagrin—Nervousness and Excitement Finally Give Way to Coolness and Deliberation—A Big Buck at Long Range—A Steady Aim and a Ruptured Throat—A Blind Run Through Brush and Fallen Trees—Down at Last—A Noble Specimen—His Head as a Trophy 280

CHAPTER XXVIII.

Among the Pines—A Picture of Autumnal Loveliness—Cordial Welcome to a Logging Camp—A Successful Shot—The Music of the Dinner Horn—A Throat Cut and a Leg Broken—A Stump for a Watch-Tower—The Raven Homeward Bound—A Suspicious Buck—A Mysterious Presence—Dead Beside His Mate—Three Shots and Three Deer 288

CHAPTER XXIX.

A Typical Woodsman—Model Home in the Great Pine Forest—A Lifetime in the Wilderness—A Deer in a Natural Trap—Disappointment and Despondency—"What, You Killed a Buck!"—Sunrise in the Woods—An Unexpected Shot—A Free Circus and a Small Audience—A Buck as a Bucker—More Venison 296

CHAPTER XXX.

Cowboy Life—The Boys that Become Good Range Riders—Peculiar Tastes and Talents Required for the Ranch—Wages Paid to Cowboys—Abuse and Misrepresentation to which They are Subjected—The "Fresh Kid," and the Long-Haired "Greaser"—The Stranger Always Welcome at the Ranch—A Dude Insulted—A Plaid Ulster, a Green Umbrella, and a Cranky Disposition—Making a Train Crew Dance—An Uncomplimentary Concert—No Sneak Thieves on the Plains—Leather Breeches, Big Spurs, and a Six-Shooter in a Sleeping [16] Car—Fear Gives Way to Admiration—The Slang of the Range—The "Bucker," and the "Buster"—The Good Cow-Horse—Roping for Prizes—Snaking a Bear with a Lariat—A Good School for Boys—Communion with Nature Makes Honest Men. 304

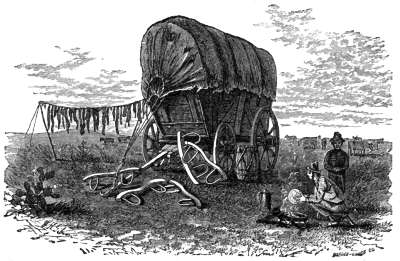

CHAPTER XXXI.

A Montana Roundup—Ranges and Ranches on Powder River; Once the Home of the Buffalo, the Elk, the Antelope; now the Home of the Texas Steer and the Cowboy—The Great Plains in Spring Attire—A Gathering of Rustlers—"Chuck Outfits" to the Front—Early Risers—Taming an "Alecky" Steer—A Red-Hot Device—Branding and Slitting—The Run on the Mess Wagon—"Cutting Out" and "Throwing Over"—A Cruel Process. 327

CRUISINGS IN THE CASCADES.

[17]

CHAPTER I.

"Mountains are the beginning and the end of all natural scenery."

—Ruskin.

OR anyone who has the courage, the hardihood, and the physical strength to endure the exercise, there is no form of recreation or amusement known to mankind that can yield such grand results as mountain climbing. I mean from a mental as well as from a physical standpoint; and, in fact, it is the mind that receives the greater benefit. The exertion of the muscular forces in climbing a high mountain is necessarily severe; in fact, it is more than most persons unused to it can readily endure; and were it not for the inspiration which the mind derives from the experience when the ascent is made it would be better that the subject should essay some milder form of exercise. But if one's strength be sufficient to endure the labor of ascending a grand mountain peak, that extends to or above timber line, to the regions of perpetual snow and ice, or even to a height that gives a general view of the surrounding country, the compensation [19][18] must be ample if one have an eye for the beauties of nature, or any appreciation of the grandeur of the Creator's greatest works.

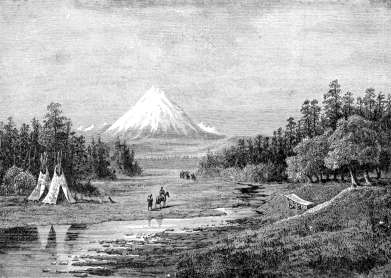

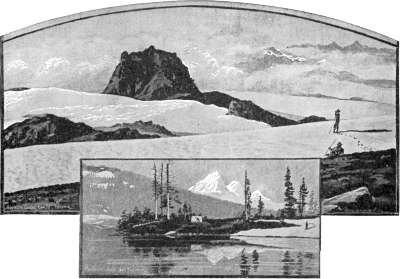

MOUNT HOOD.

Vain, self-loving man is wont to consider himself the noblest work of God, but let him go to the top of one of these lofty mountains, surrounded by other towering peaks, and if he be a sane man he will soon be convinced that his place in the scale of creation is far from the top. Let him stand, for instance, on the summit of Mount Hood, Mount Tacoma, or Mount Baker, thousands of feet above all surrounding peaks, hills, and valleys, where he may gaze into space hundreds of miles in every direction, with naught to obstruct his view, face to face with his Creator, and if he have aught of the love of nature in his soul, or of appreciation of the sublime in his mental composition, he will be moved to exclaim with the Apostle, "What is man that Thou art mindful of him, or the son of man that Thou visitest him?" He will feel his littleness, his insignificance, his utter lack of importance, more forcibly perhaps than ever before. It seems almost incredible that there should be men in the world who could care so little for the grandest, the sublimest sights their native land affords, as to be unwilling to perform the labor necessary to see them to the best possible advantage; and yet it is so, for I have frequently heard them say:

"I should like very much to see these grand sights you describe, but I never could afford to climb those high mountains for that pleasure; it is too hard work for me."

And, after all, the benefits to be derived from mountain climbing are not wholly of an intellectual [21] character; the physical system may be benefited by it as well. It is a kind of exercise that in turn brings into use almost every muscle in the body, those of the legs being of course taxed most severely, but those of the back do their full share of the work, while the arms are called into action almost constantly, as the climber grasps bushes or rocks by which to aid himself in the ascent. The lungs expand and contract like bellows as they inhale and exhale the rarified atmosphere, and the heart beats like a trip-hammer as it pumps the invigorated blood through the system. The liver is shaken loose from the ribs to which it has perchance grown fast, and the stomach is aroused to such a state of activity as it has probably not experienced for years. Let any man, especially one of sedentary habits, climb a mountain 5,000 feet high, on a bright, pleasant day, when

"Night's candles are burnt out and jocund day

Stands tiptoe on the misty mountain tops."

MOUNT TACOMA.

There let him breathe the rare, pure atmosphere, fresh from the portals of heaven, and my word for it he will have a better appetite, will eat heartier, sleep sounder, and awake next morning feeling more refreshed than since the days of his boyhood.

Although the labor be severe it can and should be modulated to the strength and capabilities of the person undertaking the task. No one should climb faster than is compatible with his strength, and halts should be made every five or ten minutes, if need be, to allow the system ample rest. In this manner a vast amount of work may be accomplished [22] in a day, even by one who has had no previous experience in climbing.

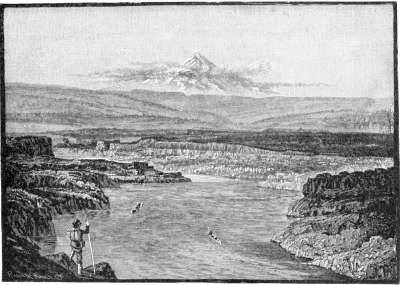

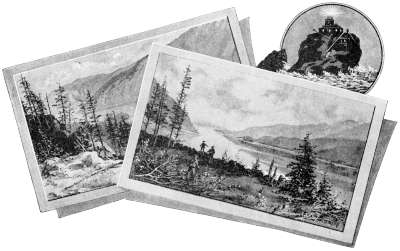

ON THE COLUMBIA.

The benefits and pleasures of mountain climbing are much better understood and appreciated in Europe than in this country. Nearly every city of England, France, Spain, Germany, and other European countries has an Alpine, Pyrenese, or Himalayan club. The members of these clubs spend their [23] summer outings in scaling the great peaks of the mountains after which the societies are named, or other ranges, and the winter evenings in recounting to each other their experiences; and many a man, by his association with the clubs and by indulgence in this invigorating pastime develops from a delicate youth into a muscular, sturdy, athletic man in a few years.

The possible value of mountain climbing as a recreation and as a means of gaining knowledge, has been greatly enhanced, of late years, by the introduction of the dry-plate system in photography, and since the small, light, compact cameras have been constructed, which may be easily and conveniently carried wherever a man can pack his blankets and a day's supply of food. With one of these instruments fine views can be taken of all interesting objects and bits of scenery on the mountain, and of the surrounding country. The views are interesting and instructive to friends and to the public in general, and as souvenirs are invaluable to the author. And from the negatives thus secured lantern slides may be made, and from these, by the aid of the calcium light, pictures projected on a screen that can only be excelled in their beauty and attractiveness by nature herself.

GLACIERS ON MOUNT TACOMA.

[25]

CHAPTER II.

ACH succeeding autumn, for years past, has found me in some range of mountains, camping, hunting, fishing, climbing, and taking views. The benefits I have derived from these expeditions, in the way of health, strength, and vigor, are incalculable, and the pleasures inexpressible. My last outing was in the Cascade Range, in Oregon and Washington Territory, where I spent a month in these delightful occupations, and it is with a view of encouraging and promoting a love for these modes of recreation that this record is written.

"I live not in myself, but I become

Portion of that around me; and to me

High mountains are a feeling, but the hum

Of human cities torture."

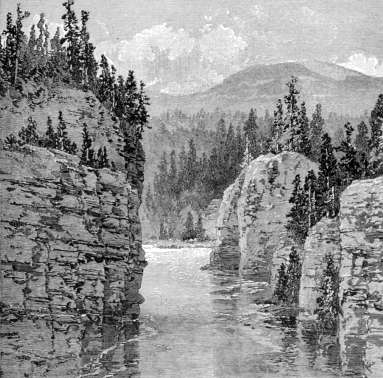

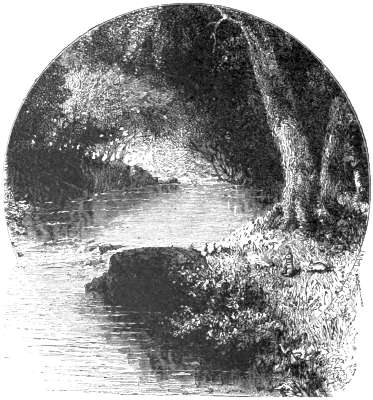

A VIEW IN THE CASCADES.

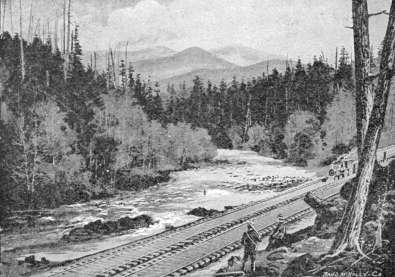

The Cascade Range of mountains extends from Southern Oregon through Washington Territory, away to the northward in British Columbia. In width, from east to west, it varies from fifty to one hundred miles. It is the most densely-timbered range on the continent, and yet is one of the highest and most rugged. It may not possess so many ragged, shapeless crags and dark cañons as the Rocky Range, and yet everyone who has ever traversed both accords to the [27] Cascades the distinction of being the equal, in picturesqueness and grandeur, of the Rockies, or, in fact, of any other range in the country. As continental landmarks, Mounts Pitt, Union, Thielson, Jefferson, Hood, Adams, St. Helens, Tacoma, Baker, Stuart, Chiam, Douglass, and others are unsurpassed. Their hoary crests tower to such majestic heights as to be visible, in some instances, hundreds of miles, and their many glaciers feed mighty rivers upon whose bosoms the commerce of nations is borne. Mount Jefferson is 9,020 feet high; Mount Adams, 9,570; Mount St. Helens, 9,750; Mount Baker, 10,800, Mount Hood, 11,025, and Mount Tacoma, 14,444. There are many other peaks that rise to altitudes of 7,000 to 9,000 feet, and from these figures one may readily form something of an idea of the general height and beauty of the Cascade Range. The foot-hills are generally high, rolling, and picturesque, and so heavily timbered that in many places one cannot see a hundred yards in any direction. Higher up the range, however, this heavy timber is replaced by smaller trees, that stand farther apart, and the growth of underbrush is not so dense; consequently, the labor of travel is lightened and the range of vision is extended. The geological formation in the Cascades is varied. Igneous rock abounds; extensive basaltic cliffs and large bodies of granite, limestone, sandstone, etc., are frequently met with, and nearly all the table-lands, in and about the foot-hills, are composed of gravel drift, covered with vegetable mold. The Cascades may be explored with comfort later in the fall than the Rockies or other more eastern ranges, the winter setting in on the former much later than [29] on the latter, although the winter rains usually come in November. September and October are the most pleasant months for an outing in the Cascades.

ONEONTA GORGE, COLUMBIA RIVER, OREGON.

* * * It was late in October when my wife and I started from Chicago for a tour of a month among the bristling peaks of the Cascades and the picturesque islands of Puget Sound. A pleasant ride of fifteen hours on the Wisconsin Central Railroad to St. Paul, and another of three days and nights on the grand old Northern Pacific, brought us face to face with the glittering crests and beetling cliffs that were the objects of our pilgrimage. As the tourist goes west, the first view of the range is obtained at the Dalles of the Columbia river, from whence old Mount Hood, thirty-five miles distant, rears its majestic head high into the ethereal vault of heaven, and neighboring peaks, of lesser magnitude, unfold themselves to the enraptured vision. As the train whirls down the broad Columbia river, every curve, around which we swing with dazzling speed, reveals to our bewildered gaze new forms of beauty and new objects of wonder. So many descriptions of the scenery along this mystic stream have been written, that every reading man, woman, and child in the land must be familiar with it, and I will not repeat or attempt to improve upon any of them. To say the most extravagant representations are not exaggerated, is to speak truly, and no one can know how beautiful some of these towers and cliffs are until he has seen them.

The train arrived at Portland, that old and far-famed metropolis of the North Pacific coast, at half past ten o'clock in the morning, and after twenty-four [30] hours pleasantly spent in viewing its many points of interest and the snow-covered mountains thereabouts, we again boarded the Northern Pacific train and sped toward Tacoma, where we arrived at six o'clock in the evening. Here we passed another day in looking over a booming Western city, whose future prosperity and greatness have been assured by its having been chosen as the tide-water terminus of the Northern Pacific Railway. Tacoma is situated on Commencement Bay, an arm of Puget Sound, and has a harbor navigable for the largest ocean steamships. The vast forests of pine, fir, and cedar, with which it is surrounded, give Tacoma great commercial importance as a lumbering town, and the rich agricultural valleys thereabout assure home production of breadstuffs, vegetables, meats, etc., sufficient to feed its army of workingmen. Rich coal fields, in the immediate neighborhood, furnish fuel for domestic and manufacturing purposes at merely nominal prices. All the waters hereabouts abound in salmon, several varieties of trout and other food-fishes, while in the woods and mountains adjacent, elk, deer, and bears are numerous; so the place will always be a popular resort for the sportsman and the tourist. The chief attraction of the city, however, for the traveler, will always be the fine view it affords of Mount Tacoma. This grand old pinnacle of the Cascade Range, forty-five miles distant, lifts its snow-mantled form far above its neighbors, which are themselves great mountains, while its glacier-crowned summit rises, towers, and struggles aloft 'til——

"Round its breast the rolling clouds are spread,

Eternal sunshine settles on its head;"

[31] and its crown is almost lost in the limitless regions of the deep blue sky.

From the verandas of the Tacoma House one may view Mount Tacoma until wearied with gazing. The Northern Pacific Railway runs within fifteen miles of the base of it, and from the nearest point a trail has been made, at a cost of some thousands of dollars, by which tourists may ascend the mountain on horseback, to an altitude of about 10,000 feet, with comparative comfort; but he who goes above that height must work his passage. There are several men who claim the distinction of being the only white man that has ever been to the top of this mountain. Others declare that it has been ascended only twice; but we have authentic information of at least three successful and complete ascents having been made. Indian legends people the mountain with evil spirits, which are said to dwell in boiling caldrons and yawning caverns—

"Calling shapes, and beck'ning shadows dire,

And airy tongues that syllable men's names."

Tradition says their wild shrieks and groans may be heard therein at all times; and no Indians are known ever to have gone any great distance up Mount Rainier, as they call it. White men have tried to employ the native red men as guides and packers for the ascent, but no amount of money can tempt them to invade the mysterious cañons and cliffs with which the marvelous pile is surrounded. They say that all attempts to do so, by either white or red men, must result in certain destruction. Undoubtedly the first ascent was made about thirty years ago, by General (then Lieutenant) Kautz, and [32] Lieutenant Slaughter, of the United States Army, who were then stationed at Steilacoom, Washington Territory. They took pack animals, and with an escort of several men ascended as far as the animals could go. There they left them and continued the climb on foot. They were gone nine days, from the time of leaving their mules until they returned to the animals, and claimed, no doubt justly, to have gone to the top of Liberty Cap, the highest of the three distinct summits that form the triplex corona; the others being known as the Summit and the Dome. The next ascent, so far as known, was made in 1876 by Mr. Hazard Stevens, who gave an account of his experiences in the Atlantic Monthly for November, of that year. In 1882, Messrs. Van Trump and Smith, of San Francisco, made a successful ascent, and in the same year an Austrian tourist who attempted to ascend the mountain, got within three hundred feet of the top, when his progress was arrested by an avalanche, and he came very near losing his life. Mr. L. L. Holden, of Boston, went to within about six hundred feet of the summit in 1883, and Mr. J. R. Hitchcock claims to have reached it in 1885.

From the point gained by the trail above mentioned, the tourist may look down upon the glaciers of the North Fork of the Puyallup River, 3,000 feet below, while on the other hand, the glaciers of the cañon of the Carbon may be seen 4,000 feet beneath him. Away to the north, glimmering and glinting under the effulgent rays of the noonday sun, stretches that labyrinth of waters known as Puget Sound—

"Whose breezy waves toss up their silvery spray;"

[33] while the many islands therein, draped in their evergreen foliage, look like emeralds set in a sheet of silver. Many prominent landmarks in British Columbia are seen, while to the north and south stretches the Cascade Range, to the west the Olympic, and to the southwest the Coast Range. All these are spread out before the eye of the tourist in a grand panorama unsurpassed for loveliness. Crater Lake forms one of the mysteries of Mount Tacoma. About its ragged, ice-bound and rock-ribbed shores are many dark caverns, from which the Indians conceived their superstitious fears of this mysterious pile. An explorer says of one of these chambers:

"Its roof is a dome of brilliant green, with long icicles pendant therefrom; while its floor is composed of the rocks and débris that formed the side of the crater, worn smooth by the action of water and heated by a natural register, from which issue clouds of steam."

The grand cañon of the Puyallup is two and a half miles wide, and from its head may be seen the great glacier, 300 feet in thickness, which supplies the great volume of water that flows through the Puyallup river. From here no less than nine different waterfalls, varying in height from 500 to 1,500 feet, are visible; and visitors are sometimes thrilled with the magnificent spectacle of an avalanche of thousands of tons of overhanging ice falling with an overwhelming crash into the cañon, roaring and reverberating in a way that almost makes the great mountain tremble. Fed by the lake, torrents pour over the edge of the cliff, and the foaming waters, forming a perpetual veil of seemingly silver lace,[34] fall with a fearful leap into the arms of the surging waves below. Mount Tacoma will be the future resort of the continent, and many of its wondrous beauties yet remain to be explored.

VIEW ON GREEN RIVER NEAR MOUNT TACOMA.

[35]

CHAPTER III.

HE Oregon Railway & Navigation Company's steamers leave Tacoma, for Seattle, at four o'clock in the morning, and at six-thirty in the evening, so we were unable to see this portion of the sound until our return trip. Seattle is another of those rushing, pushing, thriving, Western towns, whose energy and dash always surprise Eastern people. The population of the city is 15,000 souls; it has gas-works, water-works, and a street railway, and does more business, and handles more money each year than many an Eastern city of 50,000 or more.

The annual lumber shipments alone aggregate over a million dollars, from ten saw-mills that cost over four millions, and the value of the salmon-canning product is nearly a million more. The soil of the valleys adjacent to Seattle is peculiarly adapted to hop-raising, and that industry is extensively carried on by a large number of farmers. Some of the largest and finest hop-ranches in the world are located in the vicinity, and their product is shipped to [36] various American and European ports, over 100,000 tons having been shipped in 1888, bringing the growers the handsome sum of $560,327.

During the fifteen years since the beginning of this important cultivation, the hop crop is said never to have failed, nor has it been attacked by disease, nor deteriorated by reason of the roots being kept on the same land without replanting. It is believed that the Dwamish, the White River, and the Puyallup Valleys could easily produce as many hops as are now raised in the United States, if labor could be obtained to pick them. Indians have been mainly relied upon to do the picking, and they have flocked to the Sound from nearly all parts of the Territory, even from beyond the mountains. Many have come in canoes from regions near the outlet of the Sound, from British Columbia, and even from far off Alaska, to engage temporarily in this occupation; then to purchase goods and return to their wigwams. They excel the whites in their skill as pickers, and, as a rule, conduct themselves peaceably.

Elliot Bay, on which Seattle is built, affords a fine harbor and good anchorage, while Lakes Union and Washington, large bodies of fresh water—the former eleven and the latter eighteen feet above tide level—lie just outside the city limits, opposite. There are rich coal mines at hand, which produce nearly a million dollars worth each year. Large fertile tracts of agricultural lands, in the near vicinity, produce grain, vegetables, and fruits of many varieties, and in great luxuriance. Iron ore of an excellent quality abounds in the hills and [37] mountains back of the city, and with all these natural resources and advantages at her command, Seattle is sure to become a great metropolis in the near future. The climate of the Puget Sound country is temperate; snow seldom falls before Christmas, never to a greater depth than a few inches in the valleys and lowlands, and seldom lies more than a few days at a time. My friend, Mr. W. A. Perry, of Seattle, in a letter dated December 6, says:

"The weather, since your departure, has been very beautiful. The morning of your arrival was the coldest day we have had this autumn. Flowers are now blooming in the gardens, and yesterday a friend who lives at Lake Washington sent me a box of delicious strawberries, picked from the vines in his garden in the open air on December 4, while you, poor fellow, were shivering, wrapped up in numberless coats and furs, in the arctic regions of Chicago. Why don't you emigrate? There's lots of room for you on the Sumas, where the flowers are ever blooming, where the summer never dies, where the good Lord sends the tyee (great) salmon to your very door; and where, if you want to shoot, you have your choice from the tiny jacksnipe to the cultus bear or the lordly elk."

There are thousands of acres of natural cranberry marshes on the shores of the sound, where this fruit grows wild, of good quality, and in great abundance. It has not been cultivated there yet, but fortunes will be made in that industry in the near future.

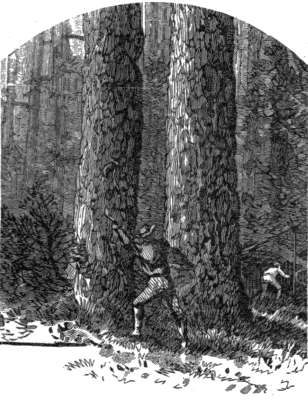

But the crowning glory of Puget Sound, and its greatest source of wealth, are the vast forests of [39] timber. It is scarcely advisable to tell the truth concerning the size to which some of the giant firs and cedars grow in this country, lest I be accused of exaggeration; but, for proof of what I say, it will only be necessary to inquire of any resident of the Sound country. There are hundreds of fir and cedar trees in these woods twenty to twenty-five feet in diameter, above the spur roots, and over three hundred feet high. A cube was cut from a fir tree, near Vancouver, and shipped to the Colonial Exhibition in London in 1886, that measured nine feet and eight inches in thickness each way. The bark of this tree was fourteen inches thick. Another tree was cut, trimmed to a length of three hundred and two feet, and sent to the same destination, but this one, I am told, was only six feet through at the butt.

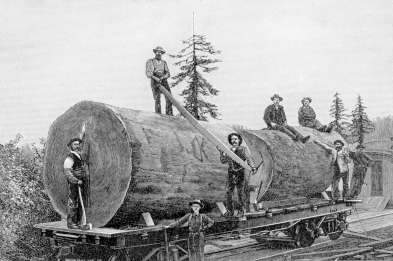

PUGET SOUND SAW-LOGS.

From one tree cut near Seattle six saw-logs were taken, five of which were thirty feet long, each, and the other was twenty-four feet in length. This tree was only five feet in diameter at the base, and the first limb grew at a height of two feet above where the last log was cut off, or over one hundred and seventy feet from the ground. A red cedar was cut in the same neighborhood that measured eighteen feet in diameter six feet above the ground; and there is a well-authenticated case of a man, named Hepburn, having lived in one of these cedars for over a year, while clearing up a farm. The tree was hollow at the ground, the cavity measuring twenty-two feet in the clear and running up to a knot hole about forty feet above. The homesteader laid a floor in the hollow, seven or eight feet above the ground, and [40] placed a ladder against the wall by which to go up and down. On the floor he built a stone fireplace, and from it to the knot hole above a stick and clay chimney. He lived upstairs and kept his horse and cow downstairs. It may be well to explain that he was a bachelor, and thus save the reader any anxiety as to how his wife and children liked the situation.

The "Sumas Sapling" stands near Sumas Lake, northeast of Seattle. It is a hollow cedar, twenty-three feet in the clear, on the ground, and is estimated to be fifteen feet in diameter twenty feet above the ground. I have, in several instances, counted more than a hundred of these mammoth trees on an acre of land, and am informed that one tract has been out off that yielded over 1,000,000 feet of lumber per acre. In this case the trees stood so close together that many of the stumps had to be dug out, after the trees had been felled, before the logs could be gotten out. The system of logging in vogue here differs widely from that practiced in Wisconsin, Michigan, Maine, and elsewhere. No snow or ice are required here, and, in fact, if snow falls to any considerable depth while crews are in the woods a halt is called until it goes off.

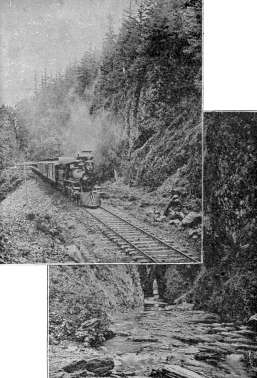

Corduroy roads are built into the timber as fast as required, on which the teams travel, so that it is not necessary that the ground should be even frozen. Skids, twelve to eighteen inches thick, are laid across, these roads, about nine feet apart, and sunk into the ground so as to project about six inches above the surface; the bark is peeled off the top, they are kept greased, and the logs are "snaked" over them with four to seven yoke of cattle, as may be required.[41] The wealthier operators use steam locomotives and cars, building tracks into the timber as fast and as far as needed. This great timber belt is co-extensive with Puget Sound, the Straits of Georgia, and the Cascade Mountains. I believe that at the present rate at which lumber is being consumed, there is fir, pine, and cedar enough in Washington Territory and British Columbia to last the world a thousand years.

[42]

CHAPTER IV.

UGET SOUND is a great inland sea, extending nearly 200 miles from the ocean, having a surface of about 2,000 square miles, and a shore line of 1,594 miles, indented with numerous bays, harbors, and inlets, each with its peculiar name; and it contains numerous islands inhabited by farmers, lumbermen, herdsmen, and those engaged in quarrying lime and building stone. Nothing can surpass the beauty of these waters and their safety. Not a shoal exists within the Sound, the Straits of Juan de Fuca, Admiralty Bay, Hood's Canal, or the Straits of Georgia, that would in any way interrupt their navigation by a seventy-four-gun ship. There is no country in the world that possesses waters equal to these. The shores of all the inlets and bays are remarkably bold, so much so that a ship's side would touch the shore before her keel would touch the ground. The country by which these waters are surrounded has a remarkably salubrious climate.

The region affords every advantage for the accommodation of a vast commercial and military marine, with conveniences for docks, and there are a great many sites for towns and cities, which at all times would be well supplied with water, and the surrounding country, which is well adapted to agriculture, [43] would supply all the wants of a large population. No part of the world affords finer islands, sounds, or a greater number of harbors than are found within these waters. They are capable of receiving the largest class of vessels, and are without a single hidden danger. From the rise and fall of the tide (18 feet), every facility is afforded for the erection of works for a great maritime nation. The rivers also furnish hundreds of sites for water-power for manufacturing purposes. On this Sound are already situated many thriving towns and cities, besides those already mentioned, bidding for the commerce of the world.

The flora of the Sound region is varied and interesting. A saturated atmosphere, constantly in contact with the Coast Range system of upheaval, together with the warm temperature, induces a growth of vegetation almost tropical in its luxuriance. On the better soils, the shot-clay hills and uplands, and on the alluvial plains and river bottoms, grow the great trees, already mentioned, and many other species of almost equal beauty, though of no commercial value.

"The characteristic shrubs are the cornels and the spiræas, many species. These, with the low thickets of salal (Gaultheria shallon), Oregon grape (berries), and fern (chiefly pteris, which is the most abundant), and the tangle of the trailing blackberry (Rubus pedatus) make the forests almost impenetrable save where the ax or the wild beast or the wilder fire have left their trails.

"The dense shade of the forest gives little opportunity for the growth of the more lowly herbs. [45] Where the fire has opened these shades to the light the almost universal fireweed (epilobium) and the lovely brown fire-moss (funaria) abound. In swamps and lowlands the combustion of decay, almost as quick and effective as fire itself, opens large spaces to the light; and here abound chiefly the skunk cabbage of the Pacific coast (lysichiton) and many forms of the lovliest mosses, grown beyond belief save by those who have looked upon their tropical congeners. Hypnums and Mniums make the great mass which meet the eye; and among the many less obvious forms a careful search will reveal many species characteristic of this coast alone. The lower forms of the cryptogams, the lichens and the fungi, abound in greatest profusion as might be expected. The chief interest in these, in the present state of our knowledge of them, springs from their disposition to invade the more valuable forms of vegetation which follow advancing civilization."

VIEWS ON PUGET SOUND.

I measured one fungus, which I found growing upon the decaying trunk of a mammoth fir, that was thirteen inches thick and thirty-four inches wide. I have frequently seen mosses growing on rotten logs, in the deep shades of these lonely forests, that were twelve to sixteen inches deep, and others hanging from branches overhead three feet or more in length. There are places in these dense forests where the trees stand so close and their branches are so intertwined that the sun's rays never reach the ground, and have not, perhaps for centuries; and it is but natural that these shade and moisture loving plants should grow to great size in such places.

The fauna of this Territory includes the elk, black-tailed [46] deer, Cervus columbianus; the mule-deer, Cervus macrotus; the Virginia deer, Cervus virginianus; the caribou, the Rocky Mountain goat, Rocky Mountain sheep, the grizzly and black bear. Among the smaller mammals there are the raccoon, the cougar, wild cat, gray wolf, black wolf, prairie wolf or coyote, gray and red fox, fisher, mink, martin, beaver, otter, sea otter, red squirrel, ermine, muskrat, sea lion, fur and hair seals, wolverine, skunk, badger, porcupine, marmot, swamp hare, jack-rabbit, etc. Of birds and wild fowls there is a long list, among which may be mentioned several varieties of geese and brant, including the rare and toothsome black brant, which in season hovers in black clouds about the sand spits; the canvas back, redhead, blue bill, teal, widgeon, shoveler, and various other ducks; ruffed, pinnated, and blue grouse; various snipes and plovers; eagles, hawks, owls, woodpeckers, jays, magpies, nuthatches, warblers, sparrows, etc. There are many varieties of game and food fishes in the Sound and its tributaries, in addition to the salmon and trout already mentioned. In short, this whole country is a paradise for the sportsman and the naturalist, whatever the specialty of either.

We left Seattle, en route for Victoria, at seven o'clock on a bright, crisp November morning. The air was still, the bay was like a sheet of glass, and only long, low swells were running outside. We had a charming view of the Cascade Mountains to the east and the Olympics to the west, all day. The higher peaks were covered with snow, and the sunlight glinted and shimmered across them in playful,[47] cheery mood. Deep shadows fell athwart dark cañons, in whose gloomy depths we felt sure herds of elk and deer were nipping the tender herbage, and along whose raging rivers sundry bears were doubtless breakfasting on salmon straight. Old Mount Baker's majestic head, rising 10,800 feet above us and only fifty miles away, was the most prominent object in the gorgeous landscape, and one on which we never tired of gazing. We had only to cast our eyes from the grand scene ashore to that at our feet, and vice versa, to—

"See the mountains kiss high heaven,

And the waves clasp one another."

A large colony of gulls followed the steamer, with ceaseless beat of downy wings, from daylight till dark, and after the first hour they seemed to regard us as old friends. They hovered about the deck like winged spirits around a lost child. Strange bird thus to poise with tireless wing over this watery waste day after day! Near the route of the vessel one of the poor creatures lay dead, drifting sadly and alone on the cold waves. Mysterious creature, with—

"Lack lustre eye, and idle wing,

And smirched breast that skims no more,

Hast thou not even a grave

Upon the dreary shore,

Forlorn, forsaken thing?"

Our feathered fellow-passengers greeted us with plaintive cries whenever we stepped out of the cabin, dropping into the water in pursuit of every stray bit of food that was thrown overboard from the cook-room. My wife begged several plates of stale bread [48] from the steward, and, breaking it into small pieces, threw handfuls at a time into the water.

OUR FEATHERED FELLOW-PASSENGERS.

Twenty or thirty of the birds would drop in a bunch where the bread fell, and a lively scramble would ensue for the coveted food. The lucky ones would quickly corral it, however, when the whole flight, rising again, would follow and soon overtake the vessel. Then they would cluster around their patron, cooing, and coaxing for more of the welcome bounty. I took out my detective camera and made a number of exposures on the gulls, which resulted very satisfactorily. Many of the prints show them sadly out of focus, but this was unavoidable, as I focused at [49] twenty feet, and of course all that were nearer or farther away, at the instant of exposure, are not sharp. Many, however, that were on wing at the time of making the exposure, and at the proper distance from the lens, are clearly and sharply cut.

These pictures form a most interesting study for artists, anatomists, naturalists, and others, the wings being shown in every position assumed by the birds in flight. The shutter worked at so high a pressure that only one or two birds in the entire series show any movement at all, and they are but very slightly blurred. When we consider that the steamer, as well as the gulls, was in motion—running ten miles an hour—trembling and vibrating from stem to stern, and that, in many cases, the birds were going in an opposite direction from that of the vessel, the results obtained are certainly marvelous. It may interest some of my readers to know that I used an Anthony detective camera, making a four-by-five-inch picture, to which is fitted a roll holder, and in all the work done on this trip, I used negative paper. I also obtained, en route, several good views of various islands, and points of interest on the mainland, while the boat was in motion.

There are many beautiful scenes in and about the Sound; many charming islands, clothed in evergreen foliage, from whose interiors issue clear, sparkling brooks of fresh water; while the mainland shores rise abruptly, in places, to several hundreds of feet, bearing their burdens of giant trees. There are perpendicular cut banks on many of the islands and the mainland shores, thirty, forty, or fifty feet high, [51] almost perpendicular, made so by the hungry waves having eaten away their foundations, and the earth having fallen into the brine, leaving exposed bare walls of sand and gravel. On Whidby Island, one of the largest in the Sound, there was, up to a few years ago, a herd of wild cattle, to which no one made claim of ownership, and which were, consequently, considered legitimate game for anyone who cared to hunt them. They were wary and cunning in the extreme. The elk or deer, native and to the manor born, could not be more so. But, alas, these cattle were not to be the prey of true, conscientious sportsmen; for the greed of the market hunter and the skin hunter exceeded the natural cunning of the noble animals, and they have been nearly exterminated; only ten or twelve remain, and they will soon have to yield up their lives to the insatiable greed of those infamous butchers.

DECEPTION PASS, PUGET SOUND.

One of the most curious and interesting points in the sound is Deception Pass. This is a narrow channel or passage between two islands, only fifty yards wide, and about two hundred yards long. On either side rise abrupt and towering columns of basaltic rock, and during both ebb and flow the tide runs through it, between Padilla and Dugalla Bays, with all the wild fury and bewildering speed of the maelstrom. This pass takes its name from the fact of there being three coves near—on the west coast of Whidby Island—that look so much like Deception that they are often mistaken for it at night or during foggy weather, even by experienced navigators. All the skill and care of the best pilots are required to make the pass in safety, and the bravest of them [52] heave a sigh of relief when once its beetling cliffs and seething abysses are far astern. Gulls hover about this weird place, and eagles soar above it at all hours, as if admiring its pristine beauties, yet in superstitious awe of the dark depths. Mount Erie, two miles away, rising to a height of 1,300 feet, casting its deep shadows across the pass and surrounding waters, completes a picture of rare beauty and grandeur.

We reached Victoria, that quaint, old, aristocratic, ultra-English town, just as the sun was sinking beneath the waves, that rolled restlessly on the surface of Juan de Fuca Strait. We were surprised to see so substantial and well-built a town as this, and one possessing so much of the air of age and independence, so far north and west. One might readily imagine, from the exterior appearance of the city and its surroundings, that he were in the province of Quebec instead of that of British Columbia. My wife felt that she must not remain longer away from home at present, and we were to part here; therefore, in the early morning she embarked for home, while I transferred my effects and self to the steamer Princess Louise, bound for Burrard Inlet.

[53]

CHAPTER V.

T daylight in the morning we entered English Bay, having crossed the strait during the night. The sun climbed up over the snow-mantled mountains into a cloudless sky, and his rays were reflected from the limpid, tranquil surface of the bay:

"Blue, darkly, deeply, beautifully blue,"

as if from the face of a mirror. A few miles to the east, the triple-mouthed Frazer empties its great volume of fresh, cold, glacier-tinted fluid into the briny inland sea, and its delta, level as a floor, stretches back many miles on either side of the river to the foot-hills of the Cascades. Thousands of ducks sat idly and lazily in the water, sunning themselves, pruning their feathers, and eyeing us curiously but fearlessly, as we passed, sometimes within twenty-five or thirty yards of them. A few geese crossed hither and thither, in low, long, dark lines, uttering their familiar honk, honk; but they were more wary than their lesser cousins, and kept well out of range. I asked the purser if there was any rule against shooting on board, and he said no; to go down on the after main deck, and shoot until I was tired. I took my Winchester express from the case, went below and opened on the ducks. They at once found [54] it necessary to get out of the country, and their motion, and that of the vessel combined, caused me to score several close misses, but I finally found the bull's-eye, so to speak, and killed three in rapid succession. Then the mate came down and said:

"We don't allow no one to be firin' off guns on board."

"I have the purser's permission," I said.

"Well," he replied, "the captain's better authority than the purser on this here boat," whereupon he returned to the cabin deck, and so did I. I was not seriously disappointed, however, for I cared little for the duck shooting; I was in quest of larger game, and only wanted to practice a little, to renew acquaintance and familiarity with my weapon. Early in the day we entered Burrard Inlet, a narrow, crooked, and peculiarly shaped arm of the salt water, that winds and threads its way many miles back into the mountains, so narrow in places, that a boy may cast a stone across it, and yet so deep as to be navigable for the largest ocean steamship. The inlet is so narrow and crooked that a stranger, sailing into it for the first time, would pronounce it a great river coming down from the mountains. Through this picturesque body of water our good boat cleft the shadows of the overhanging mountains until nearly noon, when we landed at Vancouver, the terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway. In consequence of this important selection, the place is a busy mart of trade. The clang of saw and hammer, the rattle of wheels, the general din of a building boom, are such as to tire one's nerves in a few hours. Later in the day we reached Port Moody. This town was originally [55] designated as the tide-water terminus of the road, and had its brief era of prosperity and speculation in consequence; but now that the plan has been changed it has been reduced to a mere way station, and has relapsed into the dullest kind of dullness.

From here I staged across the divide to New Westminster, on the Frazer river, the home of Mr. J. C. Hughs, who had invited me there to hunt Rocky Mountain goats with him. I was grieved beyond measure, however, to learn on my arrival that he was dangerously ill, and went at once to his house, but he was unable to see me. He sank rapidly from the date of his first illness, died two days after my arrival, and I therefore found myself in a strange land, with no friend or acquaintance to whom I could go for information or advice.

My first object, therefore, was to find a guide to take me into the mountains, and although I found several pretended sportsmen, I could hear of no one who had ever killed a goat, except poor Hughs, and a Mr. Fannin, who had formerly lived there, but had lately moved away, so of course no one knew where I could get a guide. Several business men, of whom I asked information, inquired at once where I was from, and on learning that I was an American, simply said "I don't know," and were, or at least pretended to be, too busy to talk with me. They seemed to have no use for people from this side of the boundary line, and this same ill-feeling toward my Nation (with a big N) was shown me in other places, and on various occasions, while in the province. I found, however, one gracious exception, in New Westminster, in the [56] person of Mr. C. G. Major, a merchant, who, the moment I made known to him my wish, replied:

"Well, sir, the best guide and the best hunter in British Columbia left here not three minutes ago. He is an Indian who lives on Douglass Lake, and I think I can get him for you. If I can, you are fixed for a good and successful hunt."

This news, and the frank, manly, cordial greeting that came with it, were surprising to me, after the treatment I had been receiving. Mr. Major invited me into his private office, gave me a chair by the fire, and sent out a messenger to look for "Douglass Bill," the Indian of whom he had spoken. This important personage soon came in. Mr. Major told him what I wanted, and it took but a few minutes to make a bargain. He was a solid, well-built Indian, had an intelligent face, spoke fair English, and had the reputation of being, as Mr. Major had said, an excellent hunter. Mr. Major further said he considered Bill one of the most honest, truthful Indians he had ever known, and that I could trust him as implicitly as I could any white man in the country.

This arrangement was made on Saturday night, but Bill said he could not start on the hunt until Wednesday morning, as his mother-in-law had just died, and he must go and help to bury her on Tuesday. The funeral was to take place on the Chilukweyuk river, a tributary of the Frazer, about fifty miles above New Westminster, and it was arranged that I should go up on the steamer, and meet him at the mouth of Harrison river, another tributary stream, on Wednesday morning. We were then to go up the Harrison to the hunting grounds. I was [57] delighted at the prospect of a successful hunt, with so good a guide, and cheerfully consented to wait the necessary three days for the red man to perform the last sad rites of his tribe over the remains of the departed kloochman, but I was doomed to disappointment.

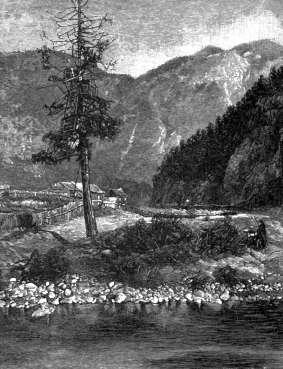

A VIEW ON THE FRAZER.

[59]

CHAPTER VI.

OR many years I had read, heard, and dreamed of the Frazer, that mysterious stream which flows out from among the icy fastnesses of the Cascades, in the far-off confines of British Columbia. For many years had I longed to see with my own eyes some of the grand scenery of the region it drains, and now, at last, that mighty stream flowed at my feet. How eagerly I drank in the beauty of the scene! How my heart thrilled at the thought that I stood face to face with this land of my dreams and was about to explore a portion, at least, of the country in which this great river rises. The beautiful lines penned by Maria Brooks, on the occasion of her first visit to the St. Lawrence, came vividly to my mind:

"The first time I beheld thee, beauteous stream,

How pure, how smooth, how broad thy bosom heaved;

What feelings rushed upon my heart! a gleam

As of another life my kindling soul received."

I left New Westminster at seven o'clock Monday morning on the steamer Adelaide, for the mouth of Harrison river, sixty miles up the Frazer. There were over twenty Indians on board, going up to the mouth of the Chilukweyuk, to attend the funeral of Douglass Bill's deceased relative. As soon as I [60] learned their destination I inquired if he were among them, but they said he was not. He had come aboard before we left, but for some reason had decided to go on another boat that left half an hour ahead of the Adelaide. The voyage proved intensely interesting. The Frazer is from a quarter to half a mile wide, and is navigable for large steamers for a hundred miles above its mouth. There are portions of the valley that are fertile, thickly settled, and well cultivated. The valleys of some of its tributaries are also good farming districts, and grain, fruits, and vegetables of various kinds grow in abundance. At the mouth of the Chilukweyuk I saw fine peaches that had grown in the valley, within ten miles of perpetual snow. The river became very crooked as we neared the mountains, and finally we entered the gorge, or cañon, where the rocky-faced mountains rise, sheer from the water's edge, to heights of many hundreds of feet, and just back of them tower great peaks, clad in eternal snows. The little camera was again brought into requisition and, as we rounded some of these picturesque bends and traversed some of the beautiful reaches, I secured many good views, though the day was cloudy and lowery. The boat being in motion, I was, of course, compelled to make the shortest possible exposures, and was, therefore, unable to get fine details in the shadows; yet many of the prints turned out fairly well.

We saw several seals in the river on the way up, and the captain informed me that at certain seasons they were quite plentiful in the Frazer and all the larger streams in the neighborhood. They go up [61] the Frazer to the head of navigation and he could not say how much farther. He said that on one occasion a female seal and her young were seen sporting in the water ahead of the steamer, and that when the vessel came within about fifty yards they dove. Nothing more was seen of the puppy, and the captain thought it must have been caught in the wheel and killed, for the mother followed the vessel several miles, whining, looking longingly, pitifully, and beseechingly at the passengers and crew. She would swim around and around the steamer, coming close up, showing no fear for her own safety, whatever, but seeming to beg them to give back her baby. She appeared to have lost sight of it entirely, whatever its fate, and to think it had been captured and taken on board. Her moaning and begging, her intense grief, were pitiable in the extreme, and brought tears to the eyes of stout, brawny men. Finally she seemed completely exhausted with anguish and her exertions and gradually sank out of sight. My informant said he hoped never to witness another such sight.

We arrived at the mouth of Harrison river at six o'clock in the evening. There is a little Indian village there called by the same name as the river, and Mr. J. Barker keeps a trading post on the reservation, he being the only white man living there. He made me welcome to the best accommodations his bachelor quarters afforded, but said the only sleeping-room he had was full, as two friends from down the river were stopping with him for the night, and that I would have to lodge with one of the Indian families. He said there was one kloochman (the [62] Chinook word for squaw) who was a remarkably neat, cleanly housekeeper, who had a spare room, and who usually kept any strangers that wished to stop over night in the village. While we were talking the squaw in question came in and Mr. Barker said to her:

"Mary, yah-kwa Boston man tik-eh moo-sum me-si-ka house po-lak-le." (Here is an American who would like to sleep in your house to-night.) To which she replied:

"Yak-ka hy-ak" (he can come), and the bargain was closed.

I remained at the store and talked with Mr. Barker and his friends until ten o'clock, when he took a lantern and piloted me over to the Indian rancherie, where I was to lodge. I took my sleeping-bag with me and thanked my stars that I did, for notwithstanding the assurances given me by good Mr. Barker that the Indian woman was as good a housekeeper as the average white woman, I was afraid of vermin. I have never known an Indian to be without the hemipterous little insect, Pediculus (humanus) capitis. Possibly there may be some Indians who do not wear them; I simply say I have never had the pleasure of knowing one, and I have known a great many, too. I seriously doubt if one has ever yet lived many days at a time devoid of the companionship of these pestiferous little creatures. In fact, an Indian and a louse are natural allies—boon companions—and are as inseparable as the boarding-house bed and the bedbug. The red man is so inured to the ravages of his parasitic companion, so accustomed to have him rustling [63] around on his person and foraging for grub, that he pays little or no attention to the insect, and seems hardly to feel its bite.

You will rarely see an Indian scratch his head or, in fact, any portion of his person, as a white man does when he gets a bite. Lo gives forth no outward sign that he is thickly settled, and it is only when he sits or lies down in the hot sun that the inhabitants of his hair and clothing come to the front; then you may see them crawling about like roaches in a hotel kitchen. Or, when he has lain down on a board, or your tent canvas, or any light-colored substance and got up and gone away, leaving some of his neighbors behind, then you know he is—like others of his race—the home of a large colony of insects.

When Mary and her husband, George, saw my roll of bedding, which they supposed to be simply blankets, they protested to Mr. Barker that I would not need them, that there was "hy-iu mit-lite pa-se-se" (plenty of covering on the bed). I told them, however, that I could sleep better in my own blankets and preferred to use them. I took the bundle into my room, spread the sleeping-bag on the bed and crawled into it. The outer covering of the bag being of thick, hard canvas, I hoped it would prove an effectual barrier against the assaults of the vermin, and that they might not find the portal by which I entered, and so it proved.

George and Mary live in a very well-built, comfortable, one-story frame cottage, divided into two rooms; the kitchen, dining-room, parlor and family sleeping-room all in one, and the spare room being the other.[64] The house has four windows and one door, a shingle roof and a board floor. They have a cooking-stove, several chairs, a table, cupboard, etc. The bedstead on which I slept was homemade, but neat and substantial. It was furnished with a white cotton tick, filled with straw, feather pillows, several clean-looking blankets, and a pair of moderately clean cotton sheets. I have slept in much worse-looking beds in hotels kept by white people.

GEORGE AND MARY.

This Indian village, Harrison river, or Skowlitz, as the Indians call both the river and the village, is composed of about twenty families, living in houses [65] of about the same class and of the same general design as the one described, although some are slightly larger and better, while others are not quite so good. All have been built by white carpenters, or the greater part of the work was done by them, and the lumber and other materials were manufactured by white men. None of the dwellings have ever been painted inside or out, but there is a neat mission church in the village that has been honored with a coat of white paint. There are a few log shacks standing near, that look very much as if they had been built by native industry. The frame houses, I am informed, were erected by the Government and the church by the Catholic Missionary Society.

[66]

CHAPTER VII.

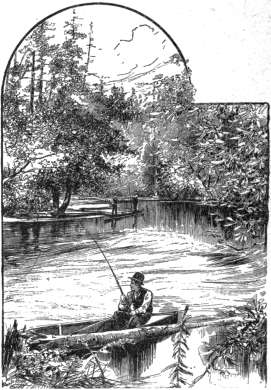

was not compelled to eat with George and Mary, for Mr. Barker had kindly invited me to breakfast with him, and when I reached his store, at the breakfast hour in the morning, I found a neat inviting-looking table in the room back of the store, loaded with broiled ham, baked potatoes, good bread and butter, a pot of steaming coffee, etc.; all of which we enjoyed intensely. Mr. Barker informed me there was a cluster of hot springs ten miles up the river, at the foot of Harrison Lake, the source of Harrison river, near which a large hotel had lately been built. Upon inquiry as to a means of getting up there, I learned that he had employed a couple of Indians to take some freight up that morning in a canoe, and that I could probably secure a passage with them. As Harrison Lake, or rather the mountains surrounding it, were the hunting-grounds which Douglass Bill had selected, and as we would have to pass these hot springs en route, I decided to go there and wait for him. I therefore arranged with Barker to send him up to the springs, when he should call for me at the store, and took passage in the freight canoe.

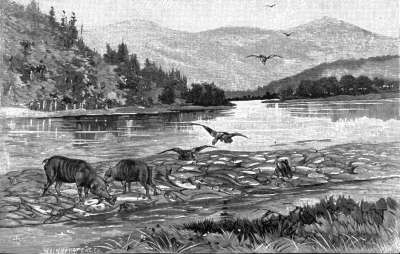

The Harrison river is a large stream that cuts its way through high, rugged mountains, and the water [67] has a pronounced milky tinge imparted by the glaciers from which its feeders come, away back in the Cascades. It is a famous salmon stream, and thousands of these noble fishes, of mammoth size, that had lately gone up the river and into the small creeks to spawn, having died from disease, or having been killed in the terrible rapids they had to encounter, were lying dead on every sand bar, lodged against every stick of driftwood, or were slowly floating in the current. Their carcasses lined the shore all along the lower portion of the river, and the hogs, of which the Indians have large numbers, were feasting on the putrid masses as voraciously as if they had been ears of new, sweet corn. The stench emitted by these festering bodies was nauseating in the extreme; and the water, ordinarily so pure and palatable, was now totally unfit for use. I counted over one hundred of these dead fishes on a single sand bar of less than half an acre in extent. Cruising amid such surroundings was anything but pleasant, and I was glad the current was slow here so that, though going up stream, we were able to make good progress, and soon got away from this nauseating sight.

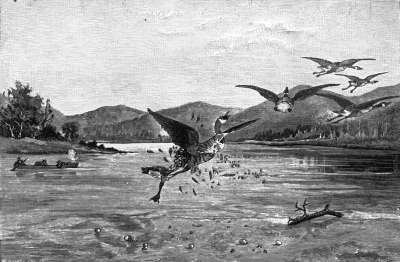

About a mile above the village we rounded a bend in the river, where it spread out to nearly a quarter of a mile in width, and on a sand bar in the middle of the stream, sat a flock of geese. I picked up my rifle and took a shot at them, but the ball cut a ditch in the water nearly fifty yards this side, and went singing over their heads into the woods beyond. They did not seem lo enjoy such music, and taking wing started for some safer feeding-ground, carrying [69] on a lively conversation in goose Latin, probably about any fool who would try to kill geese at that distance. I turned loose on them again, and in about a second after pulling the trigger one of them seemed to explode, as if hit by a dynamite bomb. For a few seconds the air was full of fragments of goose, which rained down into the water like a shower of autumn leaves. My red companions enjoyed the result of this shot hugely, and a canoe load of Indians from up river, who were passing at the time, set up a regular war whoop. We pulled over and got what was left of the goose, and found that my express bullet had carried away all his stern rigging, his rudder, one of his paddles, and a considerable portion of his hull. The water was covered with fragments of sail, provisions of various kinds, and sundry bits of cargo and hull. Charlie picked up so much of the wreck as hung together, and said in his broken, laconic English:

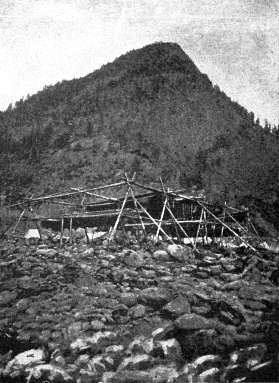

DEAD SALMON ON HARRISON RIVER.

"Dat no good goose gun. Shoot him too much away."

There were plenty of ducks, coots, grebes, and gulls on the river, and I had fine sport with them whenever I cared to shoot.

A mile above where I killed the goose we entered a long reach of shoal rapids, where all the brawn and skill of the Indians were required to stem the powerful current and the immense volume of water. The rapids are over a mile long, and it took us nearly two hours to reach their head. As soon as we were well into them we came among large numbers of live, healthy salmon. Many of them were running down the stream, some up, while others seemed not to be [71] going anywhere in particular, but just loafing around, enjoying themselves. They were wild, but, owing to the water being so rough and rapid, we frequently got within two or three feet of them before they saw us, and the Indians killed two large ones with their canoe poles. Occasionally we would corner a whole school of them in some little pocket, where the water was so shallow that their dorsal fins would stick out, and where there was no exit but by passing close to the canoe. When alarmed they would cavort around like a herd of wild mustangs in a corral, until they would churn the water into a foam; then, emboldened by their peril, they would flash out past us with the velocity of an arrow. They were doing a great deal of jumping; frequently a large fish, two or three feet long, would start across the stream, and make four or five long, high leaps out of the water, in rapid succession, only remaining in the water long enough after each jump to gain momentum for the next. I asked Charlie why they were doing this, if they were sick, or if something was biting them.

WRECKED BY AN EXPRESS BULLET

"No," he said. "Play. All same drunk—raise hell!"

These salmon run up the rivers and creeks to deposit their spawn, and seem possessed of an insane desire to get as far up into the small brooks as they possibly can. They frequently pursue their mad course up over boiling, foaming, roaring rapids, and abrupt, perpendicular falls, where it would seem impossible for any living creature to go—regardless of their own safety or comfort. They are often found in dense schools in little creeks away up near their [72] sources, where there is not water enough to cover their bodies, and where they become an easy prey to man, or to wild beasts. In such cases, Indians kill them with spears and sharp sticks, or even catch and throw them out with their hands.

Or if their journeyings take them among farms or ranches, as is often the case, the people throw them out on the banks with pitch-forks, and after supplying their household necessities, they cart the noble fish away and feed them to their hogs, or even use them to fertilize their fields. I have seen salmon wedged into some of the small streams until you could almost walk on them. The banks of many creeks, far up in the foot-hills, are almost wholly composed of the bones of salmon. In traveling through dense woods I have often heard, at some distance ahead, a loud splashing and general commotion in water, as if of a dozen small boys in bathing. This would, perhaps, be the first intimation I had that I was near water, and, on approaching the source of the noise, I have found it to have been made by a school of these lordly salmon, wedged into one of the little streams, thrashing the creek into suds in their efforts to get to its head.

After depositing their spawn the poor creatures, already half dead from bruises and exhaustion incurred in their perilous voyage up stream, begin to drift down. But how different, now, from the bright, silvery creatures that once darted like rays of living light through the sea. Unable to control their movements in the descent, even as well as in the ascent, they drift at the cruel mercy of the stream. They are driven against rough bowlders, submerged logs [73] and snags, or through raging rapids by the fury of the torrent, until hundreds, yes thousands, of them are killed outright, and thousands more die from sheer exhaustion.

I have seen salmon with their noses broken and torn off; others with a lower jaw torn away; some with sides, backs, or bellies bruised and bleeding; others with their tails whipped and split into shreds, and still others with their entrails torn out by snags. In this sad plight they are beset at every turn in the river by their natural enemies. Bears, cougars, minks, wild cats, fishers, eagles, hawks, and worst and most destructive of all, men, await them everywhere, and it would be strange, indeed, if one in each thousand that left the salt water should live to return. The few that do so, are, of course, so weak that they fall an easy prey to the seals, sharks, and other enemies, that wait with open mouths to engulf them. So, all the leaping, rushing multitude that entered the river a few months ago, have, ere this, gone to their doom, but their seed is planted in the icy brook, far away in the mountains, and their young will soon come forth to take the place of the parents that have passed away. The instinct of reproduction must, indeed, be an absorbing passion in poor dumb creatures, when they will thus sacrifice life in the effort to deposit their ova where the offspring may best be brought into being.

INDIAN SPEARING SALMON.

[74]

CHAPTER VIII.

BOVE the rapids we had a lovely reach of river, from a quarter to half a mile wide, with no perceptible current. Impelled by our united efforts, our light cedar canoe shot over the water as lightly and almost as swiftly as the gulls above us sped through the air. I took one of the poles and used it while the Indians plied their paddles, and for a distance of nearly two miles the depth of water did not vary two inches from four and a half feet. The bottom was composed of a hard, white sand, into which the pole, with my weight on it, sunk less than an inch; in fact, the current is so slight, the width of the river so great, and the general character of the water such, that it might all be termed a lake above the falls; though the foot of the lake, as designated on the map, has a still greater widening five miles above the head of the falls.

Abrupt basaltic walls, 500 to 1,000 feet high and nearly perpendicular, rise from the water's edge on either side. On the more sloping faces of these, vegetation has obtained root-room, little bunches of soil have formed, and various evergreens, alders, water hazels, etc., grow vigorously. [77] Half a foot of snow had lately fallen on the tops of these mountains, and a warm, southwest wind and the bright sun were now sending it down into the river in numerous plunging streams of crystal fluid. For thousands of years these miniature torrents have, at frequent intervals, tumbled down here, and in all that time have worn but slight notches in the rocky walls.

A TRIBUTARY OF THE HARRISON.

Shrubs have grown up along and over these small waterways, and as the little rivulets come coursing down, dodging hither and thither under overhanging clumps of green foliage, leaping from crag to crag and curving from right to left and from left to right, around and among frowning projections of invulnerable rock, glinting and sparkling in the sunlight, they remind one of silvery satin ribbons, tossed by a summer breeze, among the brown tresses of some winsome maiden. I took several views of these little waterfalls, but their transcendent beauty can not be intelligently expressed on a little four-by-five silver print.

Several larger streams also put into the Harrison, that come from remote fastnesses, and seem to carve their way through great mountains of granite. Their shores are lined with dense growths of conifers, and afford choice retreats for deer, bears, and other wild animals.