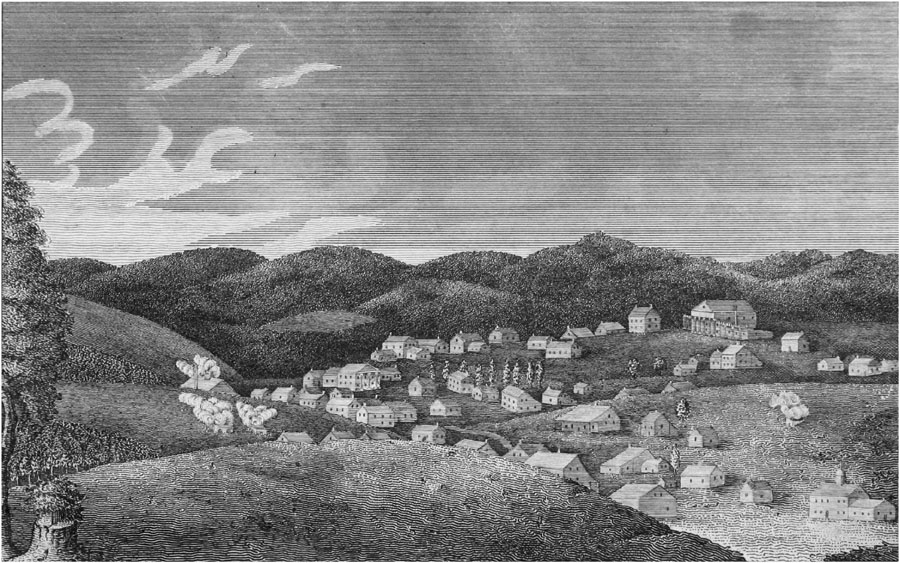

POTOSI alias Mine à Burlon.

Title: Scenes and Adventures in the Semi-Alpine Region of the Ozark Mountains of Missouri and Arkansas

Author: Henry Rowe Schoolcraft

Release date: July 9, 2011 [eBook #36675]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Julia Miller, Barbara Kosker and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

HENRY R. SCHOOLCRAFT.

These early adventures in the Ozarks comprehend my first exploratory effort in the great area of the West. To traverse the plains and mountain elevations west of the Mississippi, which had once echoed the tramp of the squadrons of De Soto—to range over hills, and through rugged defiles, which he had once searched in the hope of finding mines of gold and silver rivalling those of Mexico and Peru; and this, too, coming as a climax to the panorama of a long, long journey from the East—constituted an attainment of youthful exultation and self-felicitation, which might have been forgotten with its termination. But the incidents are perceived to have had a value of a different kind. They supply the first attempt to trace the track of the Spanish cavaliers west of the Mississippi. The name of De Soto is inseparably connected with the territorial area of Missouri and Arkansas, which he was the first European to penetrate, and in the latter of which he died.

Four-and-thirty years have passed away, since the travels here brought to view, were terminated. They comprise a period of exciting and startling events in our history, social and political. With the occupancy of Oregon, the annexation [Pg vi]of Texas, the discoveries in California, and the acquisition of New Mexico, the very ends of the Union appear to have been turned about. And the lone scenes and adventures of a man on a then remote frontier, may be thought to have lost their interest. But they are believed to possess a more permanent character. It is the first and only attempt to identify De Soto's march west of the Mississippi; and it recalls reminiscences of scenes and observations which belong to the history of the discovery and settlement of the country.

Little, it is conceived, need be said, to enable the reader to determine the author's position on the frontiers of Missouri and Arkansas in 1818. He had passed the summer and fall of that year in investigating the geological structure and mineral resources of the lead-mine district of Missouri. He had discovered the isolated primitive tract on the sources of the St. Francis and Grand rivers—the "Coligoa" of the Spanish adventurer—and he felt a strong impulse to explore the regions west of it, to determine the extent of this formation, and fix its geological relations between the primitive ranges of the Alleghany and Rocky mountains.

Reports represented it as an alpine tract, abounding in picturesque valleys and caves, and replete with varied mineral resources, but difficult to penetrate on account of the hostile character of the Osage and Pawnee Indians. He recrossed the Mississippi to the American bottom of Illinois, to lay his plan before a friend and fellow-traveller in an earlier part of his explorations, Mr. Ebenezer Brigham, of Massachusetts, who agreed to unite in the enterprise. He then proceeded to St. Louis, where Mr. Pettibone, a Connecticut man, and a fellow-voyager on the Alleghany river, determined also to unite in this interior journey. The place of rendezvous was appointed [Pg vii]at Potosi, about forty miles west of the Mississippi. Each one was to share in the preparations, and some experienced hunters and frontiersmen were to join in the expedition. But it turned out, when the day of starting arrived, that each one of the latter persons found some easy and good excuse for declining to go, principally on the ground that they were poor men, and could not leave supplies for their families during so long a period of absence. Both the other gentlemen came promptly to the point, though one of them was compelled by sickness to return; and my remaining companion and myself plunged into the wilderness with a gust of adventure and determination, which made amends for whatever else we lacked.

It is only necessary to add, that the following journal narrates the incidents of the tour. The narrative is drawn up from the original manuscript journal in my possession. Outlines of parts of it, were inserted in the pages of the Belles-lettres Repository, by Mr. Van Winkle, soon after my return to New York, in 1819; from whence they were transferred by Sir Richard Phillips to his collection of Voyages and Travels, London, 1821. This latter work has never been republished in the United States.

In preparing the present volume, after so considerable a lapse of time, it has been thought proper to omit all such topics as are not deemed of permanent or historical value. The scientific facts embraced in the appendix, on the mines and mineralogy of Missouri, are taken from my publication on these subjects. In making selections and revisions from a work which was at first hastily prepared, I have availed myself of the advantage of subsequent observation on the spot, as well as of the suggestions and critical remarks made by men of judgment and science.

[Pg viii]A single further remark may be made: The term Ozark is applied to a broad, elevated district of highlands, running from north to south, centrally, through the States of Missouri and Arkansas. It has on its east the striking and deep alluvial tract of the Mississippi river, and, on its west, the woodless buffalo plains or deserts which stretch below the Rocky Mountains. The Osage Indians, who probably furnish origin for the term, have occupied all its most remarkable gorges and eminences, north of the Arkansas, from the earliest historical times; and this tribe, with the Pawnees ("Apana"), are supposed to have held this position ever since the days of De Soto.

Washington, January 20, 1853.

| Introduction | 13 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Junction of the Ohio with the Mississippi—Difficulty of Ascending the latter with a Barge—Its turbid and rapid Character—Incidents of the Voyage—Physical Impediments to its Navigation—Falling-in Banks—Tiawapati—Animals—Floating Trees—River at Night—Needless and laughable Alarm—Character of the Shores—Men give out—Reach the first fast Lands—Mineral Products—Cape Girardeau—Moccasin Spring—Non-poetic geographical Names—Grand Tower—Struggle to pass Cape Garlic. | 22 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Pass Cape Garlic—Obrazo River—Cliffs—Emigrants—Cape St. Comb—Bois Brule Bottom—Paroquet—Fort Chartres—Kaskaskia—St. Genevieve—M. Breton—The Mississippi deficient in Fish—Antiquities—Geology—Steamer—Herculaneum—M. Austin, Esq., the Pioneer to Texas—Journey on foot to St. Louis—Misadventures on the Maramec—Its Indian Name—Carondelet—St. Louis, its fine Site and probable future Importance—St. Louis Mounds not artificial—Downward Pressure of the diluvial Drift of the Mississippi. | 32 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Resolve to proceed further West—Night Voyage on the Mississippi in a Skiff—An Adventure—Proceed on foot West to the Missouri Mines—Incidents by the Way—Miners' Village of Shibboleth— Compelled by a Storm to pass the Night at Old Mines—Reach Potosi—Favourable Reception by the mining Gentry—Pass several Months in examining the Mines—Organize an Expedition to explore Westward—Its Composition—Discouragements on setting out—Proceed, notwithstanding—Incidents of the Journey to the Valley of Leaves. | 43 |

| [Pg x]CHAPTER IV. | |

| Horses elope—Desertion of our Guide—Encamp on one of the Sources of Black River—Head-waters of the River Currents—Enter a romantic Sub-Valley—Saltpetre Caves—Description of Ashley's Cave—Encampment there—Enter an elevated Summit—Calamarca, an unknown Stream—encounter four Bears—North Fork of White River. | 54 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Descend the Valley—Its Difficulties—Horse rolls down a Precipice—Purity of the Water—Accident caused thereby—Elkhorn Spring—Tower Creek—Horse plunges over his depth in Fording, and destroys whatever is deliquescent in his pack—Absence of Antiquities, or Evidences of ancient Habitation—a remarkable Cavern—Pinched for Food—Old Indian Lodges—The Beaver—A deserted Pioneer's Camp— Incident of the Pumpkin. | 65 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Abandon our Camp and Horse in search of Settlements—Incidents of the first Day—Hear a Shot—Camp in an old Indian Lodge—Acorns for Supper—Kill a Woodpecker—Incidents of the second Day—Sterile Ridges—Want of Water—Camp at Night in a deep Gorge—Incidents of the third Day—Find a Horse-path, and pursue it— Discover a Man on Horseback—Reach a Hunter's Cabin—Incidents there—He conducts us back to our old Camp—Deserted there without Provisions—Deplorable State—Shifts—Taking of a Turkey. | 74 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Proceed West—Bog our Horse—Cross the Knife Hills—Reach the Unica, or White River—Abandon the Horse at a Hunter's, and proceed with Packs—Objects of Pity—Sugar-Loaf Prairie—Camp under a Cliff—Ford the Unica twice—Descend into a Cavern—Reach Beaver River, the highest Point of Occupancy by a Hunter Population. | 83 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Obstacle produced by the Fear of Osage Hostility—Means pursued to

overcome it—Natural Monuments of Denudation in the Limestone

Cliffs—Purity of the Water—Pebbles of Yellow Jasper—Complete

the Hunters' Cabins—A Job in Jewellery—Construct a Blowpipe from Cane—What is thought of Religion. |

93 |

| [Pg xi]CHAPTER IX. | |

| Proceed into the Hunting-Country of the Osages—Diluvial Hills and Plains—Bald Hill—Swan Creek—Osage Encampments—Form of the Osage Lodge—The Habits of the Beaver—Discover a remarkable Cavern in the Limestone Rock, having natural Vases of pure Water—Its geological and metalliferous Character—Reach the Summit of the Ozark Range, which is found to display a broad Region of fertile Soil, overlying a mineral Deposit. | 101 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Depart from the Cave—Character of the Hunters who guided the

Author—Incidents of the Route—A beautiful and fertile Country,

abounding in Game—Reach the extreme north-western Source of White

River—Discoveries of Lead-ore in a Part of its Bed—Encamp, and

investigate its Mineralogy—Character, Value, and History of the

Country—Probability of its having been traversed by De Soto in 1541. |

109 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Severe winter Weather on the Summit of the Ozarks—False Alarm of Indians—Danger of my Furnace, etc., being hereafter taken for Antiquities—Proceed South—Animal Tracks in the Snow—Winoca or Spirit Valley—Honey and the Honey-Bee—Buffalo- Bull Creek—Robe of Snow—Mehausca Valley—Superstitious Experiment of the Hunters—Arrive at Beaver Creek. | 115 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Descend White River in a Canoe—Its pure Water, Character, and Scenery—Places of Stopping—Bear Creek—Sugar-Loaf Prairie—Big Creek—A River Pedlar—Pot Shoals—Mouth of Little North Fork—Descend formidable Rapids, called the Bull Shoals—Stranded on Rocks—A Patriarch Pioneer—Mineralogy—Antique Pottery and Bones—Some Trace of De Soto—A Trip by Land—Reach the Mouth of the Great North Fork. | 120 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Detention at the Mouth of the Great North Fork—Natural History of the Vicinity—Great Blocks of Quartz—Imposing Precipices of the Calico Rock—A Characteristic of American Scenery—Cherokee Occupancy of the Country between the White and Arkansas Rivers—Its Effects on the Pioneers—Question of the Fate of the Indian Races—Iron-ore—Descent to the Arkansas Ferries—Leave the River at this Point—Remarks on its Character and Productions. | 128 |

| [Pg xii]CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Ancient Spot of De Soto's crossing White River in 1542—Lameness produced by a former Injury—Incidents of the Journey to the St. Francis River—De Soto's ancient Marches and Adventures on this River in the search after Gold—Fossil Salt—Copper—The ancient Ranges of the Buffalo. | 134 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Proceed North—Incidents of the Route—A severe Tempest of Rain, which swells the Stream—Change in the Geology of the Country—The ancient Coligoa of De Soto—A primitive and mineral Region—St. Michael—Mine a La Motte—Wade through Wolf Creek—A Deserted House—Cross Grand River—Return to Potosi. | 142 |

| PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE WEST. | |

| Two Letters, addressed to the Hon. J. B. Thomas, U. S. Senate, Washington. | 146 |

| APPENDIX. | |

| MINERALOGY, GEOLOGY, AND MINES. | |

| 1. A View of the Lead-Mines of Missouri. | 153 |

| 2. A Catalogue of the Minerals of the Mississippi Valley | 198 |

| 3. Mineral Resources of the Western Country. A Letter to Gen. C. G. Haines. | 215 |

| GEOGRAPHY. | |

| 1. Missouri. | 222 |

| 2. Hot Springs of Washita. | 231 |

| 3. Memoir of White River. | 233 |

| 4. List of Steamboats on the Mississippi River in 1819. | 239 |

| ANTIQUITIES AND INDIAN HISTORY. | |

| 1. Articles of curious Workmanship found in ancient Indian Graves. | 241 |

| 2. Ancient Indian Cemetery found in the Maramec Valley. | 243 |

De Soto, in 1541, was the true discoverer of the Mississippi river, and the first person who crossed it, who has left a narrative of that fact; although it is evident that Cabaca de Vaca, the noted survivor of the ill-fated expedition of Narvaez in 1528, must, in his extraordinary pilgrimage between Florida and the eastern coasts of the gulf of California, have crossed this river, perhaps before him; but he has not distinctly mentioned it in his memoir. Narvaez himself was not the discoverer of the mouth of the Mississippi, as some persons have conjectured, inasmuch as he was blown off the coast and lost, east of that point. The most careful tracing of the narrative of his voyage in boats along the Florida shore, as given by De Vaca, does not carry him beyond Mobile bay, or, at farthest, Perdido bay.[1]

De Soto's death frustrated his plan of founding a colony of Spain in the Mississippi valley; and that stream was allowed to roll its vast volume into the gulf a hundred and thirty-two years longer, before it attracted practical notice. Precisely at the end of this time, namely, in 1673, Mons. Jolliet, accompanied by James Marquette, the celebrated enterprising missionary of New France, entered the stream at the confluence of the Wisconsin, in accordance with the policy, and a plan of exploration, of the able, brave, and efficient governor-general of Canada, the Count Frontenac. Marquette and his companion, who was the chief of the expedition, but whose [Pg 14]name has become secondary to his own, descended it to the mouth of the Arkansas, the identical spot of De Soto's demise. La Salle, some five or six years later, continued the discovery to the gulf; and Hennepin extended it upward, from the point where Marquette had entered it, to the falls of St. Anthony, and the river St. Francis. And it is from this era of La Salle, the narrators of whose enlarged plans, civic and ecclesiastical, recognised the Indian geographical terminology, that it has retained its Algonquin name of Mississippi.

It is by no means intended to follow these initial facts by recitals of the progress of the subsequent local discoveries in the Mississippi valley, which were made respectively under French, British, and American rule. Sufficient is it, for the present purpose, to say, that the thread of the discovery of the Mississippi, north and west of the points named, was not taken up effectively, till the acquisition of Louisiana. Mr. Jefferson determined to explore the newly acquired territories, and directed the several expeditions of discovery under Lewis and Clark, and Lieut. Z. M. Pike. The former traced out the Missouri to its sources, and followed the Columbia to the Pacific; while the latter continued the discovery of the Mississippi river above St. Anthony's falls where Hennepin, and perhaps Carver, had respectively left it. The map which Pike published in 1810 contained, however, an error of a capital geographical point, in regard to the actual source of the Mississippi. He placed it in Turtle lake, at the source of Turtle river of upper Lac Cedre Rouge, or Cass lake, which lies in the portage to Red lake of the great Red River of the North, being in the ordinary route of the fur trade to that region.

In 1820, Mr. Calhoun, who determined to erect a cordon of military posts to cover the remotest of the western settlements, at the same time that he despatched Major Long to ascend to the Yellowstone of the Missouri, directed the extreme upper Mississippi to be examined and traced out to its source. This expedition, led by Gov. Cass, through the upper lakes, reached the mouth of Turtle river of the large lake beyond the upper cataract of the Mississippi, which has since borne the name of the intrepid leader of the party. It was [Pg 15]satisfactorily determined that Turtle lake was not the source, nor even one of the main sources, of the Mississippi; but that this river was discharged, in the integrity of its volume, into the western end of Cass lake. To determine this point more positively, and trace the river to its source, another expedition was organized by the Department of War in 1832, and committed to me. Taking up the line of discovery where it had been left in 1820, the river was ascended up a series of rapids about forty miles north, to a large lake called the Amigegoma; a few miles above which, it is constituted by two forks, having a southern and western origin, the largest and longest of which was found[2] to originate in Itasca lake, in north latitude 37° 13'—a position not far north of Ottertail lake, in the highlands of Hauteur des Terres.

So far as the fact of De Soto's exploration of the country west of the Mississippi, in the present area of Missouri and Arkansas, is concerned, it is apprehended that the author of these incidents of travel has been the first person to identify and explore this hitherto confused part of the celebrated Spanish explorer's route. This has been traced from the narrative, with the aid of the Indian lexicography, in the third volume of his Indian History (p. 50), just published, accompanied by a map of the entire route, from his first landing on the western head of Tampa bay. Prior to the recital of these personal incidents, it may serve a useful purpose to recall the state of geographical information at this period.

The enlarged and improved map of the British colonies, with the geographical and historical analysis, accompanying it, of Lewis Evans, which was published by B. Franklin in 1754, had a controlling effect on all geographers and statesmen of the day, and was an important element in diffusing a correct geographical knowledge of the colonies at large, and particularly of the great valley of the Mississippi, agreeably to modern ideas of its physical extent. It was a great work for the time, and for many years remained the standard of reference. In some of its features, it was never excelled. Mr. Jefferson [Pg 16]quotes it, in his Notes on Virginia, and draws from it some interesting opinions concerning Indian history, as in the allusion to the locality and place of final refuge of the Eries. It was from the period of the publication of this memoir that the plan of an "Ohio colony," in which Dr. Franklin had an active agency, appears to have had its origin.

Lewis Evans was not only an eminent geographer himself, but his map and memoir, as will appear on reference to them, embrace the discoveries of his predecessors and contemporary explorers, as Conrad Wiser and others, in the West. The adventurous military reconnoissance of Washington to fort Le Bœuf, on lake Erie, was subsequent to this publication.

Evans's map and analysis, being the best extant, served as the basis of the published materials used for the topographical guidance of General Braddock on his march over the Alleghany mountains. Washington, himself an eminent geographer, was present in that memorable march; and so judicious and well selected were its movements, through defiles and over eminences, found to be, that the best results of engineering skill, when the commissioners came to lay out the great Cumberland road, could not mend them. Such continued also to be the basis of our general geographical knowledge of the West, at the period of the final capture of fort Du Quesne by General Forbes, and the change of its name in compliment to the eminent British statesman, Pitt.

The massacre of the British garrison of Michilimackinac in 1763, the investment of the fort of Detroit in the same year by a combined force of Indian tribes, and the development of an extensive conspiracy, as it has been termed, against the western British posts under Pontiac, constituted a new feature in American history; and the military expeditions of Cols. Bouquet and Bradstreet, towards the West and North-west, were the consequence. These movements became the means of a more perfect geographical knowledge respecting the West than had before prevailed. Hutchinson's astronomical observations, which were made under the auspices of Bouquet, fixed accurately many important points in the Mississippi valley, and furnished a framework for the military narrative of the expedition. In [Pg 17]fact, the triumphant march of Bouquet into the very strongholds of the Indians west of the Ohio, first brought them effectually to terms; and this expedition had the effect to open the region to private enterprise.

The defeat of the Indians by Major Gladwyn at Detroit had tended to the same end; and the more formal march of Colonel Bradstreet, in 1764, still further contributed to show the aborigines the impossibility of their recovering the rule in the West. Both these expeditions, at distant points, had a very decided tendency to enlarge the boundaries of geographical discovery in the West, and to stimulate commercial enterprise.

The Indian trade had been carried to fort Pitt the very year of its capture by the English forces; and it may serve to give an idea of the commercial daring and enterprise of the colonists to add, that, so early as 1766, only two years after Bouquet's expedition, the leading house of Baynton, Wharton & Morgan, of Philadelphia, had carried that branch of trade through the immense lines of forest and river wilderness to fort Chartres, the military capital of the Illinois, on the Mississippi.[3] Its fertile lands were even then an object of scarcely less avidity.[4] Mr. Alexander Henry had, even a year or two earlier, carried this trade to Michilimackinac; and the English flag, the symbol of authority with the tribes, soon began to succeed that of France, far and wide. The Indians, finding the French flag had really been struck finally, submitted, and the trade soon fell, in every quarter, into English hands.

The American revolution, beginning within ten years of this time, was chiefly confined to the regions east of the Alleghanies. The war for territory west of this line was principally carried on by Virginia, whose royal governors had more than once marched to maintain her chartered rights on the Ohio. Her blood had often freely flowed on this border, and, while the great and vital contest still raged in the Atlantic colonies, she ceased not with a high hand to defend it, attacked as it was by the fiercest and most deadly onsets of the Indians.

[Pg 18]In 1780, General George Rogers Clark, the commander of the Virginia forces, visited the vicinity of the mouth of the Ohio, by order of the governor of Virginia, for the purpose of selecting the site for a fort, which resulted in the erection of fort Jefferson, some few miles (I think) below the influx of the Ohio, on the eastern bank of the Mississippi. The United States were then in the fifth year of the war of independence. All its energies were taxed to the utmost extent in this contest; and not the least of its cares arose from the Indian tribes who hovered with deadly hostility on its western borders. It fell to the lot of Clark, who was a man of the greatest energy of character, chivalric courage, and sound judgment, to capture the posts of Kaskaskia and Vincennes, in the Illinois, with inadequate forces at his command, and through a series of almost superhuman toils. And we are indebted to these conquests for the enlarged western boundary inserted in the definitive treaty of peace, signed at Paris in 1783. Dr. Franklin, who was the ablest geographer among the commissioners, made a triumphant use of these conquests; and we are thus indebted to George Rogers Clark for the acquisition of the Mississippi valley.

American enterprise in exploring the country may be said to date from the time of the building of fort Jefferson; but it was not till the close of the revolutionary war, in 1783, that the West became the favorite theatre of action of a class of bold, energetic, and patriotic men, whose biographies would form a very interesting addition to our literature. It is to be hoped that such a work may be undertaken and completed before the materials for it, are beyond our reach. How numerous this class of men were, and how quickly they were followed by a hardy and enterprising population, who pressed westward from the Atlantic borders, may be inferred from the fact that the first State formed west of the Ohio river, required but twenty years from the treaty of peace for its complete organization. Local histories and cyclical memoirs have been published in some parts of the West, which, though scarcely known beyond the precincts of their origin, possess their chief value as affording a species of historical material for this investigation. [Pg 19]Pioneer life in the West must, indeed, hereafter constitute a prolific source of American reminiscence; but it may be doubted whether any comprehensive work on the subject will be effectively undertaken, while any of this noble band of public benefactors are yet on the stage of life.

The acquisition of Louisiana, in 1803, became the period from which may be dated the first efforts of the United States' government to explore the public domain. The great extent of the territory purchased from France, stretching west to the Pacific ocean—its unknown boundaries on the south, west, and north—and the importance and variety of its reputed resources, furnished the subjects which led the Executive, Mr. Jefferson, to direct its early exploration. The expeditions named of Lewis and Clark to Oregon, and of Pike to the sources of the Mississippi, were the consequence. Pike did not publish the results of his search till 1810. Owing to the death of Governor Meriwether Lewis, a still greater delay attended the publication of the details of the former expedition, which did not appear till 1814. No books had been before published, which diffused so much local geographical knowledge. The United States were then engaged in the second war with Great Britain, during which the hostility of the western tribes precluded explorations, except such as could be made under arms. The treaty of Ghent brought the belligerent parties to terms; but the intelligence did not reach the country in season to prevent the battle of New Orleans, which occurred in January 1815.

Letters from correspondents in the West, which were often published by the diurnal press, and the lectures of Mr. W. Darby on western and general geography, together with verbal accounts and local publications, now poured a flood of information respecting the fertility and resources of that region, and produced an extensive current of emigration. Thousands were congregated at single points, waiting to embark on its waters. The successful termination of the war had taken away all fear of Indian hostility. The tribes had suffered a total defeat at all points, their great leader Tecumseh had fallen, and there was no longer a basis for any new combinations to oppose the [Pg 20]advances of civilization. Military posts were erected to cover the vast line of frontiers on the west and north, and thus fully to occupy the lines originally secured by the treaty of 1783. In 1816, Mr. J. J. Astor, having purchased the North-west Company's posts, lying south of latitude 49°, established the central point of his trade at Michilimackinac. A military post was erected by the government at the falls of St. Anthony, and another at Council Bluffs on the Missouri. The knowledge of the geography and resources of the western country was thus practically extended, although no publication, so far as I am aware, was made on this subject.

In the fall of 1816, I determined to visit the Mississippi valley—a resolution which brought me into the situations narrated in the succeeding volume. In the three ensuing years I visited a large part of the West, and explored a considerable portion of Missouri and Arkansas, in which De Soto alone, I believe, had, in 1542, preceded me. My first publication on the results of these explorations was made at New York, in 1819. De Witt Clinton was then on the stage of action, and Mr. Calhoun, with his grasping intellect, directed the energies of the government in exploring the western domain, which, he foresaw, as he told me, must exercise a controlling influence on the destinies of America.

In the spring of 1818, Major S. H. Long, U. S. A., was selected by the War Office to explore the Missouri as high as the Yellowstone, and, accompanied by a corps of naturalists from Philadelphia, set out from Pittsburgh in a small steamer. The results of this expedition were in the highest degree auspicious to our knowledge of the actual topography and natural history of the far West, and mark a period in their progress. It was about this time that Colonel H. Leavenworth was directed to ascend the Mississippi, and establish a garrison at the mouth of the St. Peter's or Minnesota river. Early in 1820, the War Department directed an exploratory expedition to be organized at Detroit, under the direction of Lewis Cass, Esq., Governor of Michigan Territory, for the purpose of surveying the upper lakes, and determining the area at the sources of the Mississippi—its physical character, topography, [Pg 21]and Indian population. In the scientific corps of this expedition, I received from the Secretary of War the situation of mineralogist and geologist, and published a narrative of it. This species of public employment was repeated in 1821, during which I explored the Miami of the Lakes, and the Wabash and Illinois; and my position assumed a permanent form, in another department of the service, in 1822, when I took up my residence in the great area of the upper lakes.

It is unnecessary to the purposes of this sketch to pursue these details further than to say, that the position I occupied was favorable to the investigation of the mineral constitution and natural history of the country, and also of the history, antiquities, and languages and customs, of the Indian tribes. For a series of years, the name of the author has been connected with the progress of discovery and research on these subjects. Events controlled him in the publication of separate volumes of travels, some of which were, confessedly, incomplete in their character, and hasty in their preparation. Had he never trespassed on public attention in this manner, he would not venture, with his present years, and more matured conceptions of a species of labor, where the difficulties are very great, the chances of applause doubtful, and the rewards, under the most favorable auspices, very slender. As it is, there is a natural desire that what has been done, and may be quoted when he has left this feverish scene and gone to his account, should be put in the least exceptionable form. Hence the revision of these travels.

[1] Vide Narr. of Cabaca de Vaca, Smith's Tr., 1851.

[2] 291 years after De Soto's discovery, and 159 after Marquette's.

[3] MS. Journal of Matthew Clarkson, in the possession of Wm. Duane, Esq., Philadelphia.

[4] Ibid.

JUNCTION OF THE OHIO WITH THE MISSISSIPPI—DIFFICULTY OF ASCENDING THE LATTER WITH A BARGE—ITS TURBID AND RAPID CHARACTER—INCIDENTS OF THE VOYAGE—PHYSICAL IMPEDIMENTS TO ITS NAVIGATION—FALLING-IN BANKS—TIAWAPATI—ANIMALS—FLOATING TREES—RIVER AT NIGHT—NEEDLESS AND LAUGHABLE ALARM—CHARACTER OF THE SHORES—MEN GIVE OUT—REACH THE FIRST FAST LANDS—MINERAL PRODUCTS—CAPE GIRARDEAU—MOCCASIN SPRING—NON-POETIC GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES—GRAND TOWER—STRUGGLE TO PASS CAPE GARLIC.

I reached the junction of the Ohio with the Mississippi on the last day of June, 1818, with feelings somewhat akin to those of one who performs a pilgrimage;—for that Algonquin name of Mississippi had been floating through my mind ever since boyhood, as if it had been invested with a talismanic power.

The reading of books of geography, however, makes but a feeble impression on the mind, compared to the actual objects. Born on one of the tributaries of the Hudson—a stream whose whole length, from the junction of the Mohawk, is less than two hundred miles—I had never figured to myself rivers of such magnificent length and velocity. I had now followed down the Ohio, in all its windings, one thousand miles; it was not only the longest, but the most beautiful river which I had [Pg 23]ever seen; and I felt something like regret to find it at last swallowed up, as it were, by the turbid and repulsive Mississippi. The latter was at its summer flood, and rushed by like a torrent, which seemed to be overcharged with the broken-down materials of half a continent.

De Soto had been the first European to gaze upon this heady mass of waters, urging downward everything that comes within their influence, and threatening to carry even their own banks into the gulf. We came, in a large, heavily-manned barge, to the very point of the influx of the Ohio, where Cairo is now located. It was early in the afternoon; but the captain of our craft, who was a stout-hearted fellow, of decision of character and a full-toned voice, deemed it best to come-to here, and wait till morning to grapple with the Mississippi. There were some old arks on the point, which had been landed in high water, and were now used as houses; but I retained my berth in the barge, and, after looking around the vicinity, amused myself by angling from the sides of the vessel. The only fish I caught was a gar—that almost single variety of the voracious species in these waters, which has a long bill, with sharp teeth, for arousing its prey, apparently, from a muddy bottom. The junction of two such streams as the Ohio and Mississippi, exhibits a remarkable struggle. For miles, along the eastern shores of the Mississippi, the clear blue waters of the Ohio are crowded to the banks; while the furious current of the former, like some monster, finally gulps it down, though the mastery is not obtained, I am told, till near the Chickasaw bluffs.

Early in the morning (1st July), the voice of the captain was heard, and the men paraded the sides of the deck, with their long poles shod with iron; and we were soon in the gurgling, muddy channel, struggling along its eastern shore. The men plied their poles with the skill of veterans, planting them as near the margin of the channel as possible, and placing the head of the pole against the shoulder, while they kept their footing by means of slats nailed across the footway. With every exertion, we made but five miles the first day. This slowness of ascent was, however, very favorable to observation. I was the only passenger on board, except two adventurers [Pg 24]from the Youghioghany, in Western Pennsylvania, who had freighted the barge, and were in the position of supercargoes. Such tugging and toiling I had never before seen. It seemed to me that no set of men could long stand it. The current ran as if it were charged with power to sweep everything down its course. Its banks were not proof against this impetuosity, and frequently fell in, with a noise and power which threatened to overwhelm us. This danger was often increased by the floating trees, which had fallen into the stream at higher points. And when, after a severe day's toil, the captain ordered the boat to be moored for the night, we felt an insecurity from the fear that the bank itself might prove treacherous before morning.

Nothing in the structure of the country appeared to present a very fixed character. The banks of the river were elevated from ten to fifteen feet above the water, and consisted of a dark alluvium, bearing a dense forest. When they became too precipitous, which was an indication that the water at these points was too deep for the men to reach bottom with their poles, they took their oars, and crossed to the other bank. When night came on, in these damp alluvions, and darkness was added to our danger, the scene was indeed gloomy. I remember, this evening, we tried most perseveringly to drink our tea by a feeble light, which appeared to be a signal for the collection of insects far and near, who, by their numbers and the fierceness of their attacks, made it impossible to bring our cups to our mouths without stopping to brush away the fierce and greedy hordes of mosquitoes. Amongst the growth, cane and cotton-wood were most conspicuous.

I had a specimen of boatman manners to-day, which should not certainly be a subject of surprise, considering the rough-and-ready life and character of that class. Having laid down on the top deck of the barge a mineralogical specimen to which I attached value, and gone temporarily away, I found, on my return, that it had been knocked to pieces by one of the men, who acted, probably, like the boy who broke the fiddle, "to get the music out" of it. On expressing my disapproval of this, to one who evidently had not the most distant idea of the [Pg 25]scientific value of "a stone," he made some trite remark, that "there was more where this came from," and then, stretching himself up at his full length of six feet, with sinews which had plainly become tense and hard from the use of the setting-pole, he exclaimed, "Help yourself!"

July 2d. The toils of this day were similar to those of the last. It was a perpetual struggle to overcome the force of the current by poles placed in the bed, and, when that became too deep, we sought for shallower shores. We encountered the same growth of trees along the banks. The land became somewhat more elevated. The insects were in such hordes, that it was amazing. We proceeded but about six miles to-day, and they were miles of incessant toil.

July 3d. To the ordinary dangers and efforts of this day, were added the frequent occurrence of snags and sawyers, or planters—terms which denote some of the peculiar impediments of Mississippi navigation. The captain of our craft, who was a courageous and vigilant man, was continually on the look-out to avoid these dangers, and put-to, at night, at the foot of a large cane-covered island, by which he avoided, in some measure, the sweep of the current, but was yet in jeopardy from falling-in banks. He requested me, in this exigency, to take a pole, and, from the bow, sound for bottom, as we crossed the river, to avoid shoals. This I did successfully. We estimated our ascent this day at seven miles.

July 4th. The perils and toils of the crew did not prevent their remembrance of the national anniversary; and the captain acknowledged their appeal in the morning by an extra measure of "old Monongahela." We then set forward against the wild, raging current. From the appearance of the wild turkey and large grey squirrel ashore, it is probable that we are passing out of the inundated region. In other respects, the face of the country and its productions appear the same. After ascending about six miles, when the time approached for looking out for a place to moor for the night, a storm of wind [Pg 26]suddenly arose, which dashed the water into the barge. We put ashore in haste, at a precipitous bank of an island, which fell in during the night very near to us, and put us in momentary peril. To leave our position in the dark, would be to take the risk of running afoul of snags, or encountering floating trees; but as early as the light appeared on the morning of the 5th, we left the spot immediately, crossing to the western bank. By diligence we made eight miles this day, which brought us to the first settlement at Tiawapeta bottom, on the Missouri shore. This is the first land that appears sufficiently elevated for cultivation. The settlement consists of six or eight farms, where corn, flax, hemp, potatoes, and tobacco, are abundantly raised. The peach and apple-tree also thrive. I observed the papaw and persimmon among the wild fruits.

July 6th. The downward movement of the water, and its gurgling and rush as it meets with obstacles, is very audible after the barge has been fastened to the shore for the night, when its fearful impetuosity, surcharged as it is with floating wrecks of forest life, is impressive to the listener, while night has thrown her dark pall over the scene.

Early in the morning, the oarsmen and polemen were at their masculine toils. I had feared that such intense application of muscle, in pushing forward the boat, would exhaust their strength; and we had not gone over three miles this day, when we were obliged to lay-by for the want of more competent hands. The complaining men were promptly paid, and furnished with provisions to return. While detained by this circumstance, we were passed by a boat of similar construction to our own, laden with planks from Olean, on the sources of the Alleghany river, in New York. This article had been transported already more than thirteen hundred miles, on its way to a market at St. Louis, where it was estimated to be worth sixty dollars per thousand feet.

While moored along this coast, the day after we had thus escaped from the treacherous island, we seemed to have taken shelter along a shore infested by wild beasts. "Grizzly bear!" was the cry at night. We were all alarmed by a snorting and [Pg 27]disturbance at the water's edge, a short distance below us, which, it was soon evident, proceeded from a large, light-colored, and furious animal. So far, all agreed. One of our Pennsylvanians, who had a choice rifle, prepared himself for the attack. The captain, who had no lack of resolution, and would, at any rate, have become bold by battling the Mississippi river for six or seven days, had some missiles; and all prepared to be useful on the occasion. As I carried nothing more deadly than a silver crucible and some acids, I remained on the upper deck of the barge. From this elevation I soon saw, by the dim moonlight, the whole party return, without having fired a gun. It turned out that the cause of this unusual disturbance was a large white hog, which had been shot in the head and snout with swan-shot, by some cruel fellows, the preceding day, and came at night to mitigate its burning and festering wounds by bathing in the river.

July 7th. Having procured some additional hands, our invincible captain pressed stoutly forward, and, at an early hour, we reached the head of Tiawapeta bottom, where a short stop was made. At this point, the bed of the Mississippi appears to be crossed by a chain of rocks, which oppose, however, no obstruction to its navigation. Such masses of it as appear on shore, are silico-carbonates of lime, and seem to belong to the metalliferous system of Missouri. About half a mile above the commencement of this chain, I observed, at the foot of an elevation near the water's edge, a remarkable stratum of white aluminous earth, of a rather dry and friable character, resembling chalk, and which, I afterwards observed, was extensively used by mechanics in Missouri as a substitute for that article. Masses, and in some instances nodules, of hornstone, resembling true flint, are found imbedded in it; yet it is not to be confounded with the chalk formation. It yields no effervescence with nitric, and is wholly destitute of carbonic, acid. Portions of the stratum are colored deeply by the red oxide of iron. Scattered along the shores of the river at this place, I observed large, angular masses of pudding-stone, consisting chiefly of silicious pebbles and sand, cemented by oxide of iron.

[Pg 28]I now began to breathe more freely. For seven days we had been passing through such a nascent region, down which the Mississippi swept at so furious a rate, that I never felt sure, at night, that I should behold another day. Had the barge, any day, lost her heading and got athwart the stream, nothing could have prevented the water from rushing over her gunwales, and sweeping her to destruction. And the whole district of the alluvial banks was subject to be momentarily undermined, and frequently tumbled in, with the noise and fury of an avalanche, threatening destruction to whatever was in the vicinity.

Owing to the increased firmness of the shore, and the reinforcement of hands, we ascended this day ten miles. We began to feel in better spirits.

July 8th. The calcareous and elevated formation of rocks, covered with geological drift, continued constantly along the Missouri shore; for it was this shore, and not the Illinois side, that we generally hugged. This drift, on ascending the elevations, consisted of a hard and reddish loam, or marly clay, filled with pebble-stones of various kinds, and fragments and chips of hornstone, chert, common jasper, argillaceous oxide of iron, radiated quartz, and quartz materials, betokening the disruption, in ancient eras, of prior formations. The trees observed on the diluvial elevations were oaks, sassafras, and, on the best lands, walnut, but of sparse growth; with a dense forest of cotton-wood, sycamore, and elm, on the alluvions. On ascending the river five miles, we came to the town of Cape Girardeau, consisting of about fifty wooden buildings of all sorts, with a post-office and two stores. We were now at the computed distance of fifty miles above the influx of the Ohio. We went no farther that day. This gave me an opportunity to explore the vicinity.

I had not yet put my foot ashore, when a fellow-passenger brought me a message from one of the principal merchants of the place, desiring me to call at his store, and aid him in the examination of some drugs and medicines which he had newly received. On reaching his store, I was politely ushered into [Pg 29]a back room, where some refreshments were handsomely set out. The whole thing was, in fact, designed as a friendly welcome to a professional man, who came neither to sell nor buy, but simply to inquire into the resources and natural history of the country. At this trait of hospitality and appreciation in a stranger, I took courage, and began to perceive that the West might be relied on.

I found the town of Cape Girardeau situated on an elevation of rich, red, marly soil, highly charged with oxide of iron, which is characteristic of the best arable soils of the mine country. This soil appears to be very readily dissolved in water, and carried off rapidly by rains, which furnishes a solution to the deep gulfs and gorges that disfigure many parts of the cultivated high grounds. If such places were sown with the seeds of grass, it would give fixity to the soil, and add much to the beauty of the landscape.

July 9th. We resumed our journey up the rapid stream betimes, but, with every exertion, ascended only seven miles. The river, in this distance, preserves its general character; the Missouri shores being rocky and elevated, while the vast alluvial tracts of the Illinois banks spread out in densely wooded bottoms. But, while the Missouri shores create the idea of greater security by their fixity, and freedom from treacherous alluvions, this very fixity of rocky banks creates jets of strong currents, setting around points, which require the greatest exertions of the bargemen to overcome. To aid them in these exigencies, the cordelle is employed. This consists of a stout rope fastened to a block in the bow of the barge, which is then passed over the shoulders of the men, who each at the same time grasp it, and lean hard forward.

July 10th. To me, the tardiness of our ascent, after reaching the rock formations, was extremely favorable, as it facilitated my examinations. Every day the mineralogy of the western banks became more interesting, and I was enabled daily to add something to my collection. This day, I picked up a large fragment of the pseudo pumice which is brought [Pg 30]down the Missouri by its summer freshets. This mineral appears to have been completely melted; and its superficies is so much enlarged by vesicles filled with air, and its specific gravity thereby so much reduced, as to permit it to float in water. We encamped this evening, after an ascent of seven miles, at a spot called the Moccasin Spring, which is contained in a crevice in a depressed part of the limestone formation.

July 11th. This day was signalized by our being passed by a small steamer of forty tons burden, called the Harriet, laden with merchandise for St. Louis. Viewed from our stand-point, she seemed often nearly stationary, and sometimes receded, in her efforts to stem the fierce current; but she finally ascended, slowly and with labor. The pressure of the stream, before mentioned, against the rocky barrier of the western banks, was found, to-day, to be very strong. With much ado, with poles and cordelle, we made but five miles.

July 12th. We passed the mouth of Great Muddy river, on the Illinois shore, this morning. This stream, it is said, affords valuable beds of coal. The name of the river does not appear to be very poetic, nor very characteristic, in a region where every tributary stream is muddy; the Mississippi itself being muddy above all others. But, thanks to the Indians, they have not embodied that idea in the name of the Father of rivers; its greatness, with them, being justly deemed by far its most characteristic trait.

About two miles above this locality, we came to one of the geological wonders of the Mississippi, called the Grand Tower. It is a pile of limestone rocks, rising precipitously from the bed of the river in a circular form, resembling a massive castle. The height of this geological monument may be about one hundred feet. It is capped by some straggling cedars, which have caught a footing in the crevices. It might, with as much propriety as one of the Alps, be called the Jungfrau (Virgin); for it seems impossible that any human being should ever have ascended it. The main channel of the river passes east of it. There is a narrower channel on the west, which is apparently [Pg 31]more dangerous. We crossed the river below this isolated cliff, and landed at some cavernous rocks on the Illinois side, which the boatmen, with the usual propensity of unlettered men, called the Devil's Oven. We then recrossed the river, and, after ascending a distance along the western shore, were repulsed in an attempt, with the cordelle, to pass Garlic Point. The captain then made elaborate preparations for a second attempt, but again failed. A third effort, with all our appliances, was resolved on, but with no better success; and we came-to, finally, for the night, in an eddy below the point, having advanced, during the day, seven miles. If we did not make rapid progress, I had good opportunities of seeing the country, and of contemplating this majestic river in one of its most characteristic phases—namely, its summer flood. I pleased myself by fancying, as I gazed upon its rushing eddies of mud and turbid matter, that I at least beheld a part of the Rocky mountains, passing along in the liquid state! It was a sight that would have delighted the eyes of Hutton; for methinks the quantity of detritus and broken-down strata would not have required, in his mind, many cycles to upbuild a continent.

Mountains to chaos are by waters hurled,

And re-create the geologic world.

PASS CAPE GARLIC—OBRAZO RIVER—CLIFFS—EMIGRANTS—CAPE ST. COMB—BOIS BRULE BOTTOM—PAROQUET—FORT CHARTRES—KASKASKIA—ST. GENEVIEVE—M. BRETON—THE MISSISSIPPI DEFICIENT IN FISH—ANTIQUITIES—GEOLOGY—STEAMER—HERCULANEUM—M. AUSTIN, ESQ., THE PIONEER TO TEXAS—JOURNEY ON FOOT TO ST. LOUIS—MISADVENTURES ON THE MARAMEC—ITS INDIAN NAME—CARONDELET—ST. LOUIS, ITS FINE SITE AND PROBABLE FUTURE IMPORTANCE—ST. LOUIS MOUNDS NOT ARTIFICIAL—DOWNWARD PRESSURE OF THE DILUVIAL DRIFT OF THE MISSISSIPPI.

July 13th. We renewed the attempt to pass Cape Garlic at an early hour, and succeeded after a protracted and severe trial. But two of our best men immediately declared their unwillingness to proceed farther in these severe labors, in which they were obliged to pull like oxen; and they were promptly paid off by the captain, and permitted to return. The crew, thus diminished, went on a short distance further with the barge, and came-to at the mouth of the Obrazo river, to await the effort of our commander to procure additional hands. We had not now advanced more than two miles, which constituted the sum of this day's progress. While moored here, we were passed by four boats filled with emigrants from Vermont and Western New York, destined for Boon's Lick, on the Missouri. I embraced the occasion of this delay to make some excursions in the vicinity.

July 14th. Having been successful in obtaining a reinforcement of hands from the interior, we pursued the ascent, and made six miles along the Missouri shore. The next day (15th) [Pg 33]we ascended seven miles. This leisurely tracing of the coast revealed to me some of the minutest features of its geological structure. The cliffs consist of horizontal strata of limestone, resting on granular crystalline sandstone. Nothing can equal the beauty of the varying landscape presented for the last two days. There has appeared a succession of the most novel and interesting objects. Whatever pleasure can be derived from the contemplation of natural objects, presented in surprising and picturesque groups, can here be enjoyed in the highest degree. Even art may be challenged to contrast, with more effect, the bleak and rugged cliff with the verdant forest, the cultivated field, or the wide-extended surface of the Mississippi, interspersed with its beautiful islands, and winding majestically through a country, which only requires the improvements of civilized and refined society, to render it one of the most delightful residences of man. Nor is it possible to contemplate the vast extent, fertility, resources, and increasing population of this immeasurable valley, without feeling a desire that our lives could be prolonged to an unusual period, that we might survey, an hundred years hence, the improved social and political condition of the country, and live to participate in its advantages, improvements, and power.

All the emigrants whom we have passed seem to be buoyed up by a hopeful and enterprising character; and, although most of them are manifestly from the poorest classes, and are from twelve to fifteen hundred miles on their adventurous search for a new home, from none have I heard a word of despondency.

July 16th. I observed to-day, at Cape St. Comb, large angular fragments of a species of coarse granular sandstone rock, which appear to be disjecta membra of a much more recent formation than that underlying the prevalent surface formation.

The gay and noisy paroquet was frequently seen, this day, wheeling in flocks over the river; and at one point, which was revealed suddenly, we beheld a large flock of pelicans standing along a low, sandy peninsula. Either the current, during [Pg 34]to-day's voyage, was less furious, or the bargemen exerted more strength or skill; for we ascended ten miles, and encamped at the foot of Bois Brule (Burnt-wood) bottom. The term "bottom" is applied, in the West, to extensive tracts of level and arable alluvial soil, whether covered by, or denuded of, native forest trees. We found it the commencement of a comparatively populous and flourishing settlement, having on the next day (17th) passed along its margin for seven miles. Its entire length is twelve miles.

July 18th. The most prominent incidents of this day were the passing, on the Illinois shore, of the celebrated site of fort Chartres, and the influx of the Kaskaskia (or, as it is abbreviated by the men, Ocaw or Caw) river—a large stream on the eastern shore. These names will recall some of the earliest and most stirring scenes of Illinois history. The town of Kaskaskia, which is the present seat of the territorial government, is seated seven miles above its mouth.

Fort Chartres is now a ruin, and, owing to the capricious channel of the Mississippi, is rapidly tumbling into it. It had been a regular work, built of stone, according to the principles of military art. Its walls formerly contained not only the chief element of military power in French Illinois, but also sheltered the ecclesiastics and traders of the time. In an old manuscript journal of that fort which I have seen, a singular custom of the Osages is mentioned, on the authority of one Mons. Jeredot. He says (Dec. 22, 1766) that they have a feast, which they generally celebrate about the month of March, when they bake a large (corn) cake of about three or four feet diameter, and of two or three inches thickness. This is cut into pieces, from the centre to the circumference; and the principal chief or warrior arises and advances to the cake, when he declares his valor, and recounts his noble actions. If he is not contradicted, or none has aught to allege against him, he takes a piece of the cake, and distributes it among the boys of the nation, repeating to them his noble exploits, and exhorting them to imitate them. Another then approaches, and in the same manner recounts his achievements, and proceeds as [Pg 35]before. Should any one attempt to take of the cake, to whose character there is the least exception, he is stigmatized and set aside as a poltroon.

It is said by some of the oldest and most intelligent inhabitants of St. Louis, that about 1768, when the British had obtained possession of fort Chartres, a very nefarious transaction took place in that vicinity, in the assassination of the celebrated Indian chief Pontiac. Tradition tells us that this man had exercised great influence in the North and West, and that he resisted the transfer of authority from the French to the English, on the fall of Canada. Carver has a story on this subject, detailing the siege of Detroit in 1763, which has been generally read. The version of Pontiac's death in Illinois, is this:—While encamped in this vicinity, an Illinois Indian, who had given in his adherence to the new dynasty of the English, was hired by the promise of rum, by some English traders, to assassinate the chief, while the latter was reposing on his pallet at night, still vainly dreaming, perhaps, of driving the English out of America, and of restoring his favorite Indo-Gallic empire in the West.

July 19th. We ascended the Mississippi seven miles yesterday, to which, by all appliances, we added eleven miles to-day, which is our maximum ascent in one day. Five miles of this distance, along the Missouri shore, consists of the great public field of St. Genevieve. This field is a monument of early French policy in the days of Indian supremacy, when the agricultural population of a village was brought to labor in proximity, so that any sudden and capricious attack of the natives could be effectively repelled. We landed at the mouth of the Gabarie, a small stream which passes through the town. St. Genevieve lies on higher ground, above the reach of the inundations, about a mile west of the landing. It consists of some three hundred wooden houses, including several stores, a post-office, court-house, Roman Catholic church, and a branch of the Missouri Bank, having a capital of fifty thousand dollars. The town is one of the principal markets and places of shipment for the Missouri lead-mines. Heavy stacks of lead in [Pg 36]pigs, are one of the chief characteristics which I saw in, and often piled up in front of its storehouses; and they give one the idea of a considerable export in this article.

July 20th. I devoted this day to a reconnoissance of St. Genevieve and its environs. The style of building reminds one of the ancient Belgic and Dutch settlements on the banks of the Hudson and Mohawk—high-pointed roofs to low one-story-buildings, and large stone chimneys out-doors. The streets are narrow, and the whole village as compact as if built to sustain a siege. The water of the Mississippi is falling rapidly, and leaves on the shores a deposit of mud, varying from a foot to two feet in depth. This recent deposit appears to consist essentially of silex and alumine, in a state of very intimate mixture. An opinion is prevalent throughout this country, that the water of the Mississippi, with every impurity, is healthful as a common drink; and accordingly the boatmen, and many of the inhabitants on the banks of the river, make use of no other water. An expedient resorted to at first, perhaps, from necessity, may be continued from an impression of the benefits resulting from it. I am not well enough acquainted with the chemical properties of the water, or the method in which it operates on the human system, to deny its utility; but, to my palate, clear spring-water is far preferable. A simple method is pursued for clarifying it: a handful of Indian meal is sprinkled on the surface of a vessel of water, precipitating the mud to the bottom, and the superincumbent water is left in a tolerable state of purity.

July 21st. We again set forward this morning. On ascending three miles, we came to Little Rock ferry—a noted point of crossing from the east to the west of the Mississippi. The most remarkable incident in the history of this place is the residence of an old French soldier, of an age gone by, who has left his name in the geography of the surrounding country. M. Breton, the person alluded to, is stated to be, at this time, one hundred and nine years of age. Tradition says that he was at Braddock's defeat—at the siege of Louisbourg—at the [Pg 37]building of fort Chartres, in the Illinois—and at the siege of Bergen-op-Zoom, in Flanders. While wandering as a hunter, after his military services had ended, in the country about forty miles west of the Mississippi, he discovered the extensive lead-mines which continue to bear his name.

We ascended this day twelve miles, which is the utmost stretch of our exertions against the turbid and heavy tide of this stream. Our captain (Ensminger) looked in the evening as if he had been struggling all day in a battle, and his men took to their pallets as if exhausted to the last degree.

July 22d. I have seen very little, thus far, in the Mississippi, in the shape of fish. The only species noticed has been the gar; one of which I caught, as described, from the side of the boat, while lying at the mouth of the Ohio. Of all rivers in the West, I should think it the least favorable to this form of organized matter. Of the coarse species of the catfish and buffalo-fish which are found in its waters, I suppose the freshet has deprived us of a sight.

Of antiquities, I have seen nothing since leaving the Ohio valley till this day, when I picked up, in my rambles on shore, an ancient Indian dart, of chert. The Indian antiquities on the Illinois shore, however, are stated to be very extensive. Near the Kaskaskia river are numerous mounds and earthworks, which denote a heavy ancient population.

The limestone cliffs, at the place called Dormant Rocks, assume a very imposing appearance. These precipitous walls bear the marks of attrition in water-lines, very plainly impressed, at great heights above the present water-level; creating the idea that they may have served as barriers to some ancient ocean resting on the grand prairies of Illinois.

We were passed, near evening, by the little steamer Harriet, on her descent from St. Louis. This vessel is the same that was noticed on the 11th, on her ascent, and is the only representative of steam-power that we have observed.[5] Our ascent this day was estimated at thirteen miles.

[Pg 38]July 23d. Passing the Platten creek, the prominence called Cornice Rock, and the promontory of Joachim creek, an ascent of five miles brought us to the town of Herculaneum. This name of a Roman city buried for ages, gives, at least, a moral savor of antiquity to a country whose institutions are all new and nascent. It was bestowed, I believe, by Mr. Austin, who is one of the principal proprietors of the place. It consists of between thirty and forty houses, including three stores, a post-office, court-house, and school. There are three shot-towers on the adjoining cliffs, and some mills, with a tan-yard and a distillery, in the vicinity. It is also a mart for the lead-mine country.

I had now ascended one hundred and seventy miles from the junction of the Ohio. This had required over twenty-two days, which gives an average ascent of between seven and eight miles per day, and sufficiently denotes the difficulty of propelling boats up this stream by manual labor.

At Herculaneum I was introduced to M. Austin, Esq.—a gentleman who had been extensively engaged in the mining business while the country was yet under Spanish jurisdiction, and who was favorably known, a few years after, as the prime mover of the incipient steps to colonize Texas. Verbal information, from him and others, appeared to make this a favorable point from which to proceed into the interior, for the purpose of examining its mineral structure and peculiarities. I therefore determined to leave my baggage here until I had visited the territorial capital, St. Louis. This was still thirty miles distant, and, after making the necessary preparations, I set out, on the 26th of the month, on foot. In this journey I was joined by my two compagnons de voyage from Pennsylvania and Maryland. We began our march at an early hour. The summer had now assumed all its fervor, and power of relaxation and lassitude on the muscles of northern constitutions. We set out on foot early, but, as the day advanced, the sun beat down powerfully, and the air seemed to owe all its paternity to tropical regions. It was in vain we reached the summit land. There was no breeze, and the forest trees were too few and widely scattered to afford any appreciable shade.

[Pg 39]The soil of the Missouri uplands appears to possess a uniform character, although it is better developed in some localities than in others. It is the red mineral clay, which, in some of its conditions, yields beds of galena throughout the mine country, bearing fragments of quartz in some of its numerous varieties. In these uplands, its character is not so well marked as in the districts further west; geologically considered, however, it is identical in age and relative position. The gullied character of the soil, and its liability to crumble under the effect of rain, and to be carried off, which was first noticed at Cape Girardeau, is observed along this portion of the river, and is most obvious in the gulfy state of the roads.

What added greatly to our fatigue in crossing this tract, was the having taken a too westerly path, which gave us a roundabout tramp. On returning to the main track, we forded Cold river, a rapid and clear brook; a little beyond which, we reached a fine, large, crystal spring, the waters of which bubbled up briskly and bright, and ran off from their point of outbreak to the river we had just crossed, leaving a white deposit of sulphur. The water is pretty strongly impregnated with this mineral, and is supposed to have a beneficial effect in bilious complaints. The scenery in the vicinity of the spring is highly picturesque, and the place is capable of being made a delightful resort.

Five miles more brought us to the banks of the Maramec river, where we arrived at dark, and prevailed with the ferryman to take us across, notwithstanding the darkness of the night, and the rain, which, after having threatened a shower all the afternoon, now began to fall. The Maramec is the principal stream of the mine country, and is the recipient of affluents, spreading over a large area. The aboriginal name of this stream, Mr. Austin informed me, should be written "Marameg." The ferryman seemed in no hurry to put us over this wide river, at so late an hour, and with so portentous a sky as hung over us, threatening every moment to pour down floods upon us. By the time we had descended from his house into the valley, and he had put us across to the opposite shore, it was dark. We took his directions for finding the house at [Pg 40]which we expected to lodge; but it soon became so intensely dark, that we pursued a wrong track, which led us away from the shelter we sought. Satisfied at length that we had erred, we knew not what to do. It then began to pour down rain. We groped about a while, but finally stood still. In this position, we had not remained long, when the faint tinkling of a cow-bell, repeated leisurely, as if the animal were housed, fell on our ears. The direction of the sound was contrary to that we had been taking; but we determined to grope our way cautiously toward it, guided at intervals by flashes of lightning which lit up the woods, and standing still in the meanwhile to listen. At length we came to a fence. This was a guide, and by keeping along one side of it, it led us to the house of which we were in search. We found that, deducting our misadventure in the morning, we had advanced on our way, directly, but about fifteen miles.

July 27th. We were again on our path at a seasonable hour, and soon passed out of the fertile and heavily timbered valley of the Maramec. There now commenced a gentle ridge, running parallel to the Mississippi river for twelve miles. In this distance there was not a single house, nor any trace that man had bestowed any permanent labor. It was sparsely covered with oaks, standing at long distances apart, with the intervening spaces profusely covered with prairie grass and flowers. We frequently saw the deer bounding before us; and the views, in which we sometimes caught glimpses of the river, were of a highly sylvan character. But the heat of the day was intense, and we sweltered beneath it. About half-way, we encountered a standing spring, in a sort of open cavern at the foot of a hill, and stooped down and drank. We then went on, still "faint and wearily," to the old French village of Carondelet, which bears the soubriquet of Vede-pouche (empty sack). It contains about sixty wooden buildings, arranged mostly in a single street. Here we took breakfast.

Being now within six miles of the place of our destination, and recruited and refreshed, we pushed on with more alacrity. The first three miles led through a kind of brushy heath, which [Pg 41]had the appearance of having once been covered with large trees that had all been cut away for firing, with here and there a dry trunk, denuded and white, looking like ghosts of a departed forest. Patches of cultivation, with a few buildings, then supervened. These tokens of a better state of things increased in frequency and value till we reached the skirts of the town, which we entered about four o'clock in the afternoon.

St. Louis impressed me as a geographical position of superlative advantages for a city. It now contains about five hundred and fifty houses, and five thousand inhabitants. It has forty stores, a post-office, a land-office, two chartered banks, a court-house, jail, theatre, three churches, one brewery, two distilleries, two water-mills, a steam flouring-mill, and other improvements. These elements of prosperity are but indications of what it is destined to become. The site is unsurpassed for its beauty and permanency; a limestone formation rising from the shores of the Mississippi, and extending gradually to the upper plain. It is in north latitude 38° 36', nearly equidistant from the Alleghany and the Rocky mountains. It is twelve hundred miles above New Orleans, and about one thousand below St. Anthony's falls.

No place in the world, situated so far from the ocean, can at all compare with St. Louis for commercial advantages. It is so situated with regard to the surrounding country, as to become the key to its commerce, and the storehouse of its wealth; and if the whole western region be surveyed with a geographical eye, it must rest with unequalled interest on that peninsula of land formed by the junction of the Missouri with the Mississippi—a point occupied by the town of St. Louis. Standing near the confluence of two such mighty streams, an almost immeasurable extent of back country must flow to it with its produce, and be supplied from it with merchandise. The main branch of the Missouri is navigable two thousand five hundred miles, and the most inconsiderable of its tributary streams will vie with the largest rivers of the Atlantic States. The Mississippi, on the other hand, is navigable without interruption for one thousand miles above St. Louis. Its affluents, the De Corbeau, Iowa, Wisconsin, St. Pierre, Rock river, Salt [Pg 42]river, and Desmoines, are all streams of the first magnitude, and navigable for many hundred miles. The Illinois is navigable three hundred miles; and when the communication between it and the lakes, and between the Mississippi and lake Superior, and the lake of the Woods—between the Missouri and the Columbia valley—shall be effected; communications not only pointed out, but, in some instances, almost completed by nature; what a chain of connected navigation shall we behold! And by looking upon the map, we shall find St. Louis the focus where all these streams are destined to be discharged—the point where all this vast commerce must centre, and where the wealth flowing from these prolific sources must pre-eminently crown her the queen of the west.

My attention was called to two large mounds, on the western bank of the Mississippi, a short distance above St. Louis. I have no hesitation in expressing the opinion that they are geological, and not artificial. Indian bodies have been buried in their sides, precisely as they are often buried by the natives in other elevated grounds, for which they have a preference. But the mounds themselves consist of sand, boulders, pebbles, and other drift materials, such as are common to undisturbed positions in the Mississippi valley generally.

Another subject in the physical geography of the country attracted my notice, the moment the river fell low enough to expose its inferior shores, spits, and sand-bars. It is the progressive diffusion of its detritus from superior to inferior positions in its length. Among this transported material I observed numerous small fragments of those agates, and other silicious minerals of the quartz family, which characterize the broad diluvial tracts about its sources and upper portions.

[5] I found fifty steamers of all sizes on the Mississippi and its tributaries, of which a list is published in the Appendix.

RESOLVE TO PROCEED FURTHER WEST—NIGHT VOYAGE ON THE MISSISSIPPI IN A SKIFF—AN ADVENTURE—PROCEED ON FOOT WEST TO THE MISSOURI MINES—INCIDENTS BY THE WAY—MINERS' VILLAGE OF SHIBBOLETH—COMPELLED BY A STORM TO PASS THE NIGHT AT OLD MINES—REACH POTOSI—FAVORABLE RECEPTION BY THE MINING GENTRY—PASS SEVERAL MONTHS IN EXAMINING THE MINES—ORGANIZE AN EXPEDITION TO EXPLORE WESTWARD—ITS COMPOSITION—DISCOURAGEMENTS ON SETTING OUT—PROCEED, NOTWITHSTANDING—INCIDENTS OF THE JOURNEY TO THE VALLEY OF LEAVES.

I was kindly received by some persons I had before known, particularly by a professional gentleman with whom I had descended the Alleghany river in the preceding month of March, who invited me to remain at his house. I had now proceeded about seventeen hundred miles from my starting-point in Western New York; and after passing a few days in examining the vicinity, and comparing facts, I resolved on the course it would be proper to pursue, in extending my journey further west and south-west. I had felt, for many years, an interest in the character and resources of the mineralogy of this part of what I better knew as Upper Louisiana, and its reported mines of lead, silver, copper, salt, and other natural productions. I had a desire to see the country which De Soto had visited, west of the Mississippi, and I wished to trace its connection with the true Cordillera of the United States—the Stony or Rocky mountains. My means for undertaking this were rather slender. I had already drawn heavily on these in my outward trip. But I felt (I believe from early reading) an irrepressible desire to explore this region. I was a good [Pg 44]draughtsman, mapper, and geographer, a ready penman, a rapid sketcher, and a naturalist devoted to mineralogy and geology, with some readiness as an assayer and experimental chemist; and I relied on these as both aids and recommendations—as, in short, the incipient means of success.

When ready to embark on the Mississippi, I was joined by my two former companions in the ascent from the mouth of the Ohio. It was late in the afternoon of one of the hottest summer days, when we took our seats together in a light skiff at St. Louis, and pushed out into the Mississippi, which was still in flood, but rapidly falling, intending to reach Cahokia that night. But the atmosphere soon became overcast, and, when night came on, it was so intensely dark that we could not discriminate objects at much distance. Floating, in a light pine skiff, in the centre of such a stream, on a very dark night, our fate seemed suspended by a thread. The downward pressure of the current was such, that we needed not to move an oar; and every eye was strained, by holding it down parallel to the water, to discover contiguous snags, or floating bodies. It became, at the same time, quite cold. We at length made a shoal covered with willows, or a low sandy islet, on the left, or Illinois shore. Here, one of my Youghioghany friends, who had not yet got over his penchant for grizzly bears, returned from reconnoitering the bushes, with the cry of this prairie monster with a cub. It was too dark to scrutinize, and, as we had no arms, we pushed on hurriedly about a mile further, and laid down, rather than slept, on the shore, without victuals or fire. At daylight, for which we waited anxiously, we found ourselves nearly opposite Carondelet, to which we rowed, and where we obtained a warm breakfast. Before we had finished eating, our French landlady called for pay. Whether anything on our part had awakened her suspicions, or the deception of others had rendered the precaution necessary, I cannot say. Recruited in spirits by this meal, and by the opening of a fine, clear day, we pursued our way, without further misadventure, about eighteen miles, and landed at Herculaneum.