George Manville Fenn

"A Fluttered Dovecote"

Chapter One.

Memory the First—Mamma Makes a Discovery.

Oh, dear!

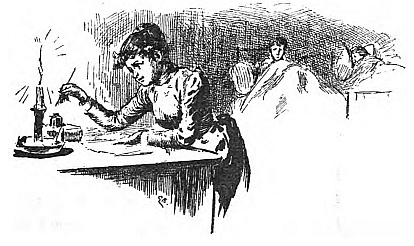

You will excuse me for a moment? I must take another sheet of paper—I, Laura Bozerne, virgin and martyr, of Chester Square, Belgravia—for that last sheet was all spotted with tears, and when I applied my handkerchief, and then the blotting-paper, the glaze was gone and the ink ran.

Ce n’est que le premier pas qui coûte, the French say, but it is not true. However, I have made up my mind to write this history of my sufferings, so to begin.

Though what the world would call young—eighteen—I feel so old—ah! so old—and my life would fill volumes—thick volumes—with thrilling incidents; but a natural repugnance to publicity forces me to confine myself to the adventures of one single year, whose eventful hours were numbered, whose days were one chaos of excitement or rack of suspense. How are the scenes brought vividly before my mind’s eye as I turn over the leaves of my poor blotted diary, and recognise a tear blister here, and recall the blistering; a smear there; or find the writing illegible from having been hastily closed when wet, on account of the prying advance of some myrmidon of tyranny when the blotting-paper was not at hand. Faces too familiar rise before me, to smile or frown, as my associations with them were grave or gay. Now I shudder—now I thrill with pleasure; now it is a frown that contracts my brow, now a smile curls my lip; while the tears, “Oh, ye tears!”—by the way, it is irrelevant, but I have the notes of a poem on tears, a subject not yet hackneyed, while it seems to me to be a theme that flows well—“tears, fears, leers, jeers,” and so on.

Oh! if I had only possessed yellow hair and violet eyes, and determination, what I might have been! If I had only entered this great world as one of those delicious heroines, so masculine, so superior, that our authors vividly paint—although they might be engravings, they are so much alike. If I had but stood with flashing eyes a Lady Audley, a Mrs Armitage, the heroine of “Falkner Lyle,” or any other of those charming creatures, I could have been happy in defying the whips and stings, and all that sort of thing; but now, alas! alack!—ah, what do I say?—my heart is torn, wrecked, crushed. Hope is dead and buried; while love—ah, me!

But I will not anticipate. I pen these lines solely to put forth my claims for the sympathy of my sex, which will, I am sure, with one heart, throb and bleed for my sorrows. That my readers may never need a similar expression of sympathy is the fond wish of a wrecked heart.

Yes, I am eighteen, and dwelling in a wilderness—Chester Square is where papa’s residence (town residence) is situated. But it is a wilderness to me. The flowers coaxed by the gardener to grow in the square garden seem tame in colour and inodorous; the gate gives me a shudder as I pass through, when it grits with the dust in its hinges, and always loudly; while mischievous boys are constantly inserting small pebbles in the dusty lock to break the wards of the key. It is a wilderness to me; and though this heart may become crusted with bitterness, and too much hardened and callous, yet never, ah! never, will it be what it was a year ago. I am writing this with a bitter smile upon my lips, which I cannot convey to paper; but I have chosen the hardest and scratchiest pen I could find, I am using red ink, and there are again blurs and spots upon the paper where tears have removed the glaze—for I always like very highly glazed note.

I did think of writing this diary in my own life’s current, but my reason told me that it would only be seen by the blackened and brutal printers; and therefore, as I said before, I am using red ink, and sitting writing by the front drawing-room window, where it is so much lighter, where the different passing vehicles can be seen, and the noise of those horrid men saying “Ciss, ciss,” in the mews at the back cannot be heard.

Ah! but one year ago, and I was happy! I recall it as if but yesterday. We were sitting at breakfast, and I remember thinking what a pity it was to be obliged to sit down, and crease and take the stiffening out of the clean muslin I wore, one that really seemed almost perfection as I came downstairs, when suddenly mamma—who was reading that horrid provincial paper—stopped papa just as he raised a spoonful of egg to his lips, and made him start so that he dropped a portion upon his beard.

“Excelsior!” exclaimed mamma. “Which is?” said papa, making the table-cloth all yellow.

“Only listen,” said mamma, and she commenced reading an atrocious advertisement, while I was so astonished at the unwonted vivacity displayed, that I left off skimming the last number of The World, and listened as well while she read the following dreadful notice:—

“The Cedars, Allsham.—Educational Establishment for a limited number of young ladies”—(limited to all she could get). “Lady principal, Mrs Fortesquieu de Blount”—(an old wretch); “French, Monsieur de Tiraille; German, Fraülein Liebeskinden; Italian, Signor Pazzoletto; singing, Fraülein Liebeskinden, R.A.M., and Signor Pazzoletto, R.A.M.” (the result of whose efforts was to make us poor victims sing in diphthongs or the union of vowels—Latin and Teutonic); “pianoforte, Fraülein Liebeskinden; dancing and deportment, Monsieur de Kittville; English, Mrs Fortesquieu de Blount, assisted by fully qualified teachers. This establishment combines the highest educational phases with the comforts of a home,”—(Now is it not as wicked to write stories as to say them? Of course it is; and as, according to the paper, their circulation was three thousand a week, and there are fifty-two weeks in a year, that wicked old tabby in that one case told just one hundred and six thousand fibs in the twelvemonth; while if I were to analyse the whole advertisement, comme ça, the amount would be horrible)—“Mrs Fortesquieu de Blount having made it her study to eliminate every failing point in the older systems of instructions and scholastic internal management, has formed the present institution upon a basis of the most firm, satisfactory, and lasting character.” (Would you think it possible that mammas who pride themselves upon their keenness would be led away and believe such nonsense?) “The staff of assistants has been most carefully selected—the highest testimonials having in every case been considered of little avail, unless accompanied by tangible proof of long and arduous experience.”

Such stuff! And then there was ever so much more—and there was quite a quarrel once about paying for the advertisement, it came to so much—about forks and spoons and towels, and advantages of situation in a sanitary point of view, and beauty of scenery, and references to bishops, priests, and deacons, deans and canons, two M.D.s and a Sir Somebody Something, Bart. I won’t mention his name, for I’m sure he must be quite sufficiently ashamed of it by this time, almost as much so as those high and mighty peers who have been cured of their ailments for so many years by the quack medicines. But there, mamma read it all through, every bit, mumbling dreadfully, as she always has ever since she had those new teeth with the patent base.

“Well, but there isn’t anything about excelsior,” said papa.

“No, of course not,” said mamma. “I meant that it was the very thing for Laura. Finishing, you know.”

“Well, it does sound pretty good,” said papa. “I don’t care so long as it isn’t Newnham or Girton, and wanting to ride astride horses.”

“My dear!” said mamma.

“Well, that’s what they’re all aiming at now,” cried papa. “We shall have you on horseback in Rotten Row next.”

“My love!”

“I should do a bit of Banting first,” continued papa, with one of those sneers against mamma’s embonpoint which do make her so angry.

And then, after a great deal of talking and arguing, in which of course mamma must have it all her own way, and me not consulted a bit, they settled that mamma was to write to Allsham, and then if the letter in reply proved satisfactory, she was to go down at once and see the place. If she liked it, I was to spend a year there for a finishing course of education; for they would not call it—as I spitefully told papa they ought to—they would not call it sending me back to school; and it was too bad, after promising that the two years I passed in the convent at Guisnes should be the last.

Yes: too bad. I could not help it if my grammar was what papa called, in his slangy way, “horribly slack.” I never did like that horrid parsing, and I’m sure it comes fast enough with reading. Soeur Celine never found fault with my French grammatical construction when I wrote letters to her, and I wrote one that very day; for it did seem such a horrid shame to treat me in so childish a way.

And while I was writing—or rather, while I was sitting at the window, thinking of what to say, and biting the end of my pen—who should come by but the new curate, Mr Saint Purre, of Saint Sympathetica’s, and when he saw how mournful I looked, he raised his hat with such a sad smile, and passed on.

By the way, what an improvement it is, the adoption of the beard in the church. Mr Saint Purre’s is one of the most beautiful black, glossy, silky beards ever seen; and I’m sure I thought so then, when I was writing about going back to school—a horrible, hateful place! How I bit my lips and shook my head! I could have cried with vexation, but I would not let a soul see it; for there are some things to which I could not stoop. In fact, after the first unavailing remonstrance, if it had been to send me to school for life, I would not have said another word.

For only think of what mamma said, and she must have told papa what she thought. Such dreadful ideas.

“You are becoming too fond of going to church, Laura,” she said with a meaning look. “I’m afraid we did wrong in letting you go to the sisters.”

“Absurd, mamma!” I cried. “No one can be too religious.”

“Oh, yes, my dear, they can,” said mamma, “when they begin to worship idols.”

“What do you mean, mamma?” I cried, blushing, for there was a curious meaning in her tone.

“Never mind, my dear,” she said, tightening her lips. “Your papa quite agreed with me that you wanted a change.”

“But I don’t, mamma,” I pleaded.

“Oh yes you do, my dear,” she continued, “you are getting wasted and wan, and too fond of morning services. What do you think papa said?”

“I don’t know, mamma.”

“He said, ‘That would cure it.’”

She pronounced the last word as if it was spelt “ate,” and I felt the blood rush to my cheeks, feeling speechless for a time, but I recovered soon after, as I told myself that most likely mamma had no arrière-pensée.

If it had been a ball, or a party, or fête, the time would have gone on drag, drag, dawdle, dawdle, for long enough. But because I was going back to school it must rush along like an express train. First, there were the answers back to mamma’s letters, written upon such stiff thick paper that it broke all along the folds; scented, and with a twisty, twirly monogram-thing done in blue upon paper and envelope; while the writing—supposed to be Mrs de Blount’s, though it was not, for I soon found that out, and that it was written, like all the particular letters, by Miss Furness—was of the finest and most delicate, so fine that it seemed as if it was never meant to be read, but only to be looked at, like a great many more ornamental things we see every day done up in the disguise of something useful.

Well, there were the letters answered, mamma had been, and declared to papa that she was perfectly satisfied, for everything was as it should be, and nothing seemed outré—that being a favourite word of mamma’s, and one out of the six French expressions she remembers, while it tumbles into all sorts of places in conversation where it has no business.

I did tell her, though, it seemed outré to send me back to one of those terrible child prisons, crushing down my young elastic soul in so cruel a way; but she only smiled, and said that it was all for my good.

Then came the day all in a hurry; and I’m sure, if it was possible, that day had come out of its turn, and pushed and elbowed its way into the front on purpose to make me miserable.

But there it was, whether or no; and I’d been packing my boxes—first a dress, then a tear, then another dress, and then another tear, and so on, until they were full—John said too full, and that I must take something out or they would not lock. But there was not a single thing that I could possibly have done without, so Mary and Eliza both had to come and stand upon the lid, and then it would not go quite close, when mamma came fussing in to say how late it was, and she stood on it as well; so that there were three of them, like the Graces upon a square pedestal. But we managed to lock it then; and John was cording it with some new cord, only he left that one, because mamma said perhaps they had all better stand on the other box, in case it would not lock; while when they were busy about number two, if number one did not go off “bang,” like a great wooden shell, and burst the lock off, when we had to be content with a strap.

Nobody minded my tears—not a bit; and there was the cab at the door at last, and the boxes lumbered down into the hall, and then bumped up, as if they wanted to break them, on to the roof of the cab; and mamma all the while in a regular knot trying to understand “Bradshaw” and the table of the Allsham and Funnleton Railway. Papa had gone to the City, and said good-bye directly after breakfast; and when mamma and I went out, the first thing mamma must do was to take out her little china tablets and pencil, and put down the cabman’s number; if the odious, low wretch did not actually wink at me—such insolence.

When we reached the station, if my blood did not quite boil when mamma would stop and haggle with the horrible tobaccoey wretch about sixpence of the fare, till there was quite a little crowd, when the money was paid, and the tears brought into my eyes by being told that the expenses of my education necessitated such parsimony; and that, too, at a time when I did not wish for a single fraction of a penny to go down to that dreadful woman at Allsham. But that was always the way; and some people are only too glad to make excuses and lay their meannesses upon some one else. Of course, I am quite aware that it is very shocking to speak of mamma in this manner; but then some allowance must be made for my wretched feelings, and besides, I don’t mean any harm.

Chapter Two.

Memory the Second—The Cedars, Allsham.

I sincerely hope the readers of all this do not expect to find any plot or exciting mystery; because, if they do, they will be most terribly disappointed, since I am not leading them into the realms of fiction. No lady is going to be poisoned; there is no mysterious murder; neither bigamy, trigamy, nor quadrigamy; in fact, not a single gamy in the book, though once bordering upon that happy state. Somebody does not turn out to be somebody else, and anybody is not kept out of his rightful property by a false heir, any more than a dreadfully good man’s wife runs away from him with a very wicked roué, gets injured in a railway accident, and then comes back to be governess to her own children, while her husband does not know her again.

Oh, no! there is no excitement of that kind, nothing but a twelvemonth’s romance of real life; the spreading of the clouds of sorrow where all was sunshine; the descent of a bitter blight, to eat into and canker a young rose-bud. But there, I won’t be poetical, for I am not making an album.

I was too much out of humour, and too low-spirited, to be much amused with the country during my journey down; while as to reading the sort of circular thing about the Cedars and the plan of operations during the coming session, now about to commence, I could not get through the first paragraph; for every time I looked up, there was a dreadful foreign-looking man with his eyes fixed upon me, though he pretended to be reading one of those Windsor-soap-coloured paper-covered Chemin-de-Fer novels, by Daudet, that one buys on the French railways.

Of course we should not have been subjected to that annoyance—shall I call it so?—only mamma must throw the expenses of my education at my head, and more; and say it was necessary we should travel second-class, though I’m sure papa would have been terribly angry had he known.

I had my tatting with me, and took it out when I laid the circular aside; but it was always the same—look up when I would, there were his sharp, dark, French-looking eyes fixed upon me; while I declare if it did not seem that in working my pattern I was forming a little cotton-lace framework to so many bright, dark eyes, which kept on peering out at me, till the porter shouted out “’sham, All—sham,” where the stranger also descended and watched us into the station fly.

Mamma said that if we came down second-class, we would go up to the Cedars in a decent form; and we did, certainly, in one of the nastiest, stably-smelling, dusty, jangling old flys I was ever in. The window would not stop up on the dusty side, while on the other it would not let down; and I told mamma we might just as well have brought the trunks with us, and not left them for the station people to send, for all the difference it would have made. But mamma knew best, of course, and it was no use for me to speak.

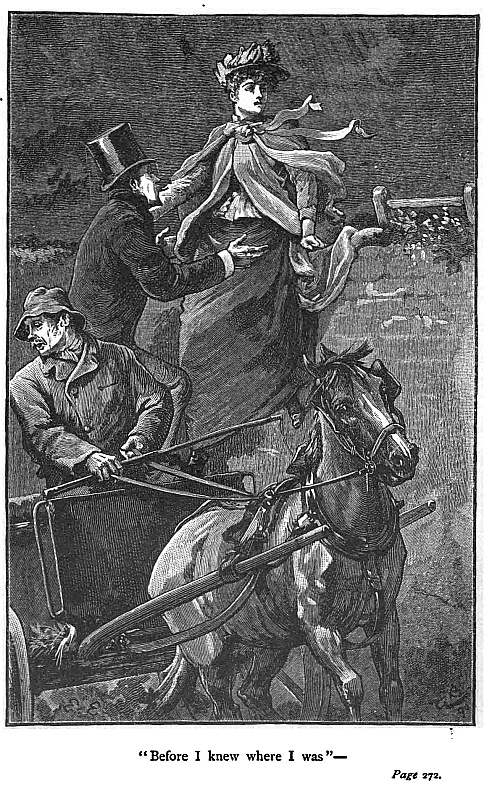

But I wish to be just; and I must say that the Cedars was a very pretty place to look at, just outside Allsham town; though of course its prettiness was only for an advertisement, and not to supply home comfort to the poor little prisoners within. We entered by a pair of large iron gates, where upon the pillars on either side were owls, with outstretched wings—put there, of course, to remind parents of the goddess Minerva; but we all used to say that they were likenesses of Mrs Blount and the Fraülein. There was a broad gravel sweep up to the portico, while in front was a beautiful velvet lawn with a couple of cedar trees, whose graceful branches swept the grass.

“Mrs and Miss Bozerne,” said mamma to the footman, a nasty tall, thin, straggley young man, with red hair that would not brush smooth, and a freckly face, a horrible caricature of our John, in a drab coat and scarlet plushes, and such thin legs that I could not help a smile. But he was terribly thin altogether, and looked as if he had been a page-boy watered till he grew out of knowledge, and too fast; and he clung to the door in such a helpless way, when he let us in, that he seemed afraid to leave it again, lest he should fall.

“This way, ladies,” he said, with a laugh-and-water sort of a smile; and he led us across a handsome hall, where there were four statues and a great celestial globe hanging from the ceiling—only the globe hanging; though I’m sure it would have been a charity and a release for some young people if a few of the muses had shared the fate of the globe—at all events, that four. First and foremost of all was Clio. I wish she had been hung upon a date tree!

“This way, ladies,” said the tall creature, saving himself once more from tippling over by seizing the drawing-room door-handle, and then, as he turned and swung by it, sending the blood tingling into my cheeks by announcing—

“Mrs and Miss Bosom.”

Any one with a heart beating beneath her own can fancy our feelings. Of course I am aware that some unfeeling, ribald men—I do not include thee, oh, Achille!—would have turned the wretch’s blunder into a subject for jest; but thanks to the goddess of Bonheur, there was none of the race present, and Mrs Fortesquieu de Blount came mincing forward, smiling most benignly in her pet turban.

A dreadful old creature—I shall never forget her! Always dressed in black satin, a skin parting front, false teeth, and a thick gold chain hung over her shoulders; while the shocking old thing always thrust everything artificial that she wore right under your eyes, so that you could not fail to see how deceptive she was.

She was soon deep in conversation with mamma; while I looked wearily round the room, which was full to overflowing with all sorts of fancy work, so that you could not stir an inch without being hooked, or caught, or upsetting something. There were antimacassars, sofa-cushions, fire-screens, bead-mats, wool-mats, crochet-mats, coverings for the sofa, piano, and chimney-piece, candle-screens, curtains, ottomans, pen wipers—things enough, in short, to have set up a fancy fair. And, of course, I knew well enough what they all meant—presents from pupils who had been foolish enough to spend their money in buying the materials, and then working them up to ornament the old tabby’s drawing-room.

Well, I don’t care. It’s the truth; she was a horrible old tabby, with nothing genuine or true about her, or I would not speak so disrespectfully. She did not care a bit for her pupils, more than to value them according to how much they brought her in per annum, so that the drawing-room boarders—there were no parlour boarders there, nothing so common—stood first in her estimation.

I felt so vexed that first day, sitting in the drawing-room, I could have pulled off the old thing’s turban; and I’m sure that if I had the false front would have come with it. There she was, pointing out the different crayon-drawings upon the wall; and mamma, who cannot tell a decent sketch from a bad one, lifting up her hand and pretending to be in ecstasies.

Do you mean to tell me that they did not both know how they were deceiving one another? Stuff! Of course they did, and they both liked it. Mamma praised Mrs Blount, and Mrs Blount praised mamma and her “sweet child”; and I declare it was just like what the dreadful American man said in his horrid, low, clever book—that was so funny, and yet one felt ashamed at having laughed—where he writes to the newspaper editor to puff his show, and promises to return the favour by having all his printing done at his office; and papa read it so funnily, and called it “reciprocity of allaying the irritation of the dorsal region,” which we said was much more refined than Mr Artemus Ward’s way of putting it.

I was quite ashamed of mamma, that I was, for it did seem so little; and, oh! how out of patience I was! But there, that part of the interview came to an end, and a good thing too; for I knew well enough a great deal of it was to show off before me, for of course Mrs Blount had shown mamma the drawings and things before.

So then we were taken over the place, and introduced to the teachers and the pupils who had returned, and there really did seem to be some nice girls; but as for the teachers—of all the old, yellow, spectacled things I ever did see, they were the worst; while as for the German Fraülein, I don’t know what to say bad enough to describe her, for I never before did see any one so hooked-nosed and parroty.

Then we went upstairs to see the dormitories—there were no bedrooms—and afterwards returned to the drawing-room, where the lady principal kissed me on both cheeks and said I was most welcome to her establishment, and I declare I thought she meant to bite me, for her dreadful teeth went snap, though perhaps, like mamma’s, they were not well under control.

Then mamma had some sherry, and declared that she was more enchanted with the place than she had been at her last visit; and she hoped I should be very happy and very good, and make great progress in my studies. When Mrs Blount said she was quite certain that I should gratify my parents’ wishes in every respect, and be a great credit to the establishment; and I knew she was wondering all the time how many silk dresses and how many bonnets I had brought, for everything about the place was show, show always, and I soon found out how the plainly-dressed girls were snubbed and kept in the background. As for Miss Grace Murray, the half-teacher, half-pupil, who had her education for the assistance she gave with the younger girls, I’m sure it was shameful—such a sweet, gentle, lovable girl as she was—shameful that she should have been so ill-treated. I speak without prejudice, for she never was any friend of mine, but always distrusted me, and more than once reported what I suppose she was right in calling flippant behaviour; but I could not help it. I was dreadfully wicked while at the Cedars.

At last the fly bore mamma away, and I wanted to go to my dormitory, to try and swallow down my horrible grief and vexation, which would show itself; while that horrible Mrs Blunt—I won’t call her anything else, for her husband’s name was spelt without the “o,” and he was a painter and glazier in Tottenham Court Road—that horrible Mrs Blunt kept on saying that it was a very proper display of feeling, and did me great credit; and patting me on the back and calling me “my child,” when all the time I could have boxed her ears.

There I was, then, really and truly once more at school, and all the time feeling so big, and old, and cross, and as if I was being insulted by everything that was said to me.

The last months I spent at Guisnes the sisters made pleasant for me by behaving with a kind of respect, and a sort of tacit acknowledgment that I was no longer a child; and, oh, how I look back now upon those quiet, retired days! Of course they were too quiet and too retired; but then anything seemed better than being brought down here; while as to religion, the sisters never troubled themselves about my not being the same as themselves, nor tried to make a convert of me, nor called me heretic, or any of that sort of thing. All the same it was quite dreadful to hear Aunt Priscilla go on at papa when I was at home for the vacation, telling him it was sinful to let me be at such a place, and that it was encouraging the sisters to inveigle me into taking the veil. That we should soon have the Papists overrunning the country, and relighting the fires in Smithfield, and all such stuff as that; while papa used very coolly to tell her that he most sincerely hoped that she would be the first martyr, for it would be a great blessing for her relatives.

That used to offend her terribly, and mamma too; but it served her right for making such a fuss—the place being really what they called a pension, and Protestant and Catholic young ladies were there together. Plenty of them were English, and the old sisters were the dearest, darlingest, quietest, lovablest creatures that ever lived, and I don’t believe they would have roasted a fly, much more an Aunt Priscilla.

And there I was, then, though I could hardly believe it true, and was at school; and as I said before, I wanted to get up to my dormitory. I said “my,” but it was not all mine; for there were two more beds in the room.

As soon as I got up there, and was once more alone, I threw myself down upon my couch, and had such a cry. It was a treat, that was; for I don’t know anything more comforting than a good cry. There’s something softening and calming to one’s bruised and wounded feelings; just as if nature had placed a reservoir of tears ready to gently flood our eyes, and act as a balm in times of sore distress. It was so refreshing and nice; and as I lay there in the bedroom, with the window open, and the soft summer breeze making the great cedar trees sigh, and the dimity curtains gently move, I gazed up into the bright blue sky till a veil seemed to come over my eyes, and I went fast asleep.

There I was in the train once more, with the eyes of that foreign-looking man regularly boring holes through my lids, until it was quite painful; for, being asleep, of course I kept them closely shut. It was like a fit of the nightmare; and as to this description, if I thought for a moment that these lines would be read by man—save and except the tradesmen engaged in their production—I would never pen them. But as the editor and publisher will be careful to announce that they are for ladies only, I write in full.

First of all the eyes seemed to be quite small, but, oh! so piercing; while I can only compare the sensation to that of a couple of beautiful, bright, precious stone seals, making impressions upon the soft wax of my brain. And they did, too—such deeply-cut, sharp impressions as will never be effaced.

Well, as I seemed to be sitting in the train, the eyes appeared to come nearer, and nearer, and nearer, till I could bear it no longer; and I opened mine to find that my dream was a fact, and that there really were a pair of bright, piercing orbs close to mine, gazing earnestly at me, so that I felt that I must scream out; but as my lips parted to give utterance to a shrill cry, it was stayed, for two warm lips rested upon mine, to leave there a soft, tender kiss; and it seemed so strange that my dream should have been all true.

But there, it was not all true; though I was awake and there were a pair of beautiful eyes looking into mine, and the soft, red lips just leaving their impression; and as I was fighting hard to recover my scattered senses, a sweet voice whispered—

“Don’t cry any more, dear, please.”

I saw through it all, for the dear girl who had just spoken was Clara Fitzacre; but just behind, and staring hard at me with her great, round, saucer eyes, was a fat, stupid-looking girl, whose name I soon learned was Martha Smith—red-faced and sleepy, and without a word to say for herself. As for Clara, I felt to love her in a moment, she was so tender and gentle, and talked in such a consolatory strain.

“I’m so glad to find that you are to be in our room,” said Clara, who was a tall, dark-haired, handsome girl. “We were afraid it would turn out to be some cross, frumpy, stuck-up body, weren’t we, Patty?”

“I’m sure I don’t know,” said the odious thing, whose words all sounded fat and sticky. “I thought you said that you wouldn’t have anybody else in our room. I wish it was tea-time.”

“But I should not have said so if I had known who was coming,” said Clara, turning very red. “But Patty has her wish, for it is tea-time; so sponge your poor eyes, and let me do your hair, and then we’ll go down. You need not wait, Patty.”

Patty Smith did not seem as if she wished to wait, for she gave a great, coarse yawn, for all the world like a butcher’s daughter, and then went out of the room.

“She is so fat and stupid,” said Clara, “that it has been quite miserable here; and I’m so glad that you’ve come, dear.”

“I’m not,” said I, dismally. “I don’t like beginning school over again.”

“But then we don’t call this school,” said Clara.

“But it is, all the same,” I said. “Oh, no,” said Clara, kindly; “we only consider that we are finishing our studies here, and there are such nice teachers.”

“How can you say so!” I exclaimed indignantly. “I never saw such a set of ugly, old, cross-looking—”

“Ah, but you’ve only seen the lady teachers yet. You have not seen Monsieur Achille de Tiraille, and Signor Pazzoletto—such fine, handsome, gentlemanly men; and then there’s that dear, good-tempered, funny little Monsieur de Kittville.”

I could not help sighing as I thought of Mr Saint Purre, and his long, black, silky beard; and how nice it would have been to have knelt down and confessed all my troubles to him, and I’m sure I should have kept nothing back.

“All the young ladies are deeply in love with them,” continued Clara, as she finished my hair; “so pray don’t lose your heart, and make any one jealous.”

“There is no fear for me,” I said, with a deep sigh; and then, somehow or another, I began thinking of the church, and wondering what sort of a clergyman we should have, and whether there would be early services like there were at Saint Vestment’s, and whether I should be allowed to attend them as I had been accustomed.

I sighed and shivered, while the tears filled my eyes; for it seemed that all the happy times of the past were gone for ever, and life was to be a great, dreary blank, full of horrible teachers and hard lessons. Though, now one comes to think of it, a life could not be a blank if it were full of anything, even though they were merely lessons.

I went down with Clara to tea, and managed to swallow a cup of the horribly weak stuff; but as to eating any of the coarse, thick bread-and-butter, I could not; though, had my heart been at rest, the sight of Patty Smith devouring the great, thick slices, as if she was absolutely ravenous, would have quite spoiled my repast. At first several of the pupils were very kind and attentive, but seeing how put out and upset I was, they left me alone till the meal was finished; while, though I could not eat, I could compare and think how different all this was from what I should have had at home, or at dinner parties, or where papa took me when we went out. For he was very good that way, and mamma did not always know how we had dined together at Richmond and Blackwall. Such nice dinners, too, as I had with him in Paris when he came to fetch me from the sisters. He said it was experience to see the capital, and certainly it was an experience that I greatly liked. There is such an air of gaiety about a café; and the ices—ah!

And from that to come down to thick bread-and-butter like a little child!

After tea I was summoned to attend Mrs Blunt in her study—as if the old thing ever did anything in the shape of study but how to make us uncomfortable, and how to make money—and upon entering the place, full of globes, and books, and drawings, I soon found that she had put her good temper away with the cake and wine, as a thing too scarce with her to be used every day.

The reason for my being summoned was that I might be examined as to my capabilities; and I found the lady principal sitting in state, supported by the Fraülein and two of the English teachers—Miss Furness and Miss Sloman.

I bit my lips as soon as I went in, for, I confess it freely, I meant to be revenged upon that horrible Mrs Blunt for tempting mamma with her advertisement; and I determined that if she was to be handsomely paid for my residence at the Cedars, the money should be well earned.

And now, once for all, let me say that I offer no excuse for my behaviour; while I freely confess to have been, all through my stay at the Cedars, very wicked, and shocking, and reprehensible.

“I think your mamma has come to a most sensible determination, Miss Bozerne,” said Mrs Blunt, after half an hour’s examination. “What do you think, ladies?”

“Oh, quite so,” chorused the teachers.

“Really,” said Mrs Blunt, “I cannot recall having had a young lady of your years so extremely backward.”

Then she sat as if expecting that I should speak, for she played with her eyeglass, and occasionally took a glance at me; but I would not have said a word, no, not even if they had pinched me.

“But I think we can raise the standard of your acquirements, Miss Bozerne. What do you say, ladies?”

“Oh, quite so,” chorused the satellites, as if they had said it hundreds of times before; and I feel sure that they had.

“And now,” said Mrs Blunt, “we will close this rather unsatisfactory preliminary examination. Miss Bozerne, you may retire.”

I was nearly at the door—glad to have it over, and to be able to be once more with my thoughts—when the old creature called me back.

“Not in that way, Miss Bozerne,” she exclaimed, with a dignified, cold, contemptuous air, which made me want to slap her—“not in that way at the Cedars, Miss Bozerne. Perhaps, Miss Sloman, as the master of deportment is not here, you will show Miss Laura Bozerne the manner in which to leave a room.—Your education has been sadly neglected, my child.”

This last she said to me with rather an air of pity, just as if I was only nine or ten years old; and, as a matter of course, being rather proud of my attainments, I felt dreadfully annoyed.

But my attention was now taken up by Miss Sloman, a dreadfully skinny old thing, in moustachios, who had risen from her seat, and began backing towards the door in an awkward way, like two clothes-props in a sheet, till she contrived to catch against a little gipsy work-table and overset it, when, cross as I felt, I could not refrain from laughing.

“Leave the room, Miss Bozerne,” exclaimed Mrs Blunt, haughtily.

This to me! whose programme had been rushed at when I appeared at a dance, and not a vacant place left. Oh, dear! oh, dear! I feel the thrill of annoyance even now.

Of course I made my way out of the room to where Clara was waiting for me; and then we had a walk out in the grounds, with our arms round each other, just as if we had been friends for years; though you will agree it was only natural I should cling to the first lovable thing which presented itself to me in my then forlorn condition.

Chapter Three.

Memory the Third—Infelicity. Again a Child.

The next day was wet and miserable; and waiting about, and feeling strange and uncomfortable, as I did, made matters ever so much worse.

We were all in the schoolroom; and first one and then another stiff-backed, new-smelling book was pushed before me, and the odour of them made me feel quite wretched, it was so different to what of late I had been accustomed. For don’t, pray, think I dislike the smell of a new book—oh, no, not at all, I delight in it; but then it must be from Mudie’s, or Smith’s, or the Saint James’s Square place, while as for these new books—one was that nasty, stupid old Miss Mangnall’s “Questions,” and another was Fenwick de Porquet’s this, and another Fenwick de Porquet’s that, and, soon after, Noehden’s German Grammar, thrust before me with a grin by the Fraülein. At last, as if to drive me quite mad, as a very culmination of my miseries, I was set, with Clara Fitzacre and five more girls, to write an essay on “The tendencies towards folly of the present age.”

“What shall I say about it, ma’am?” I said to Miss Furness, who gave me the paper.

“Say?” she exclaimed, as if quite astonished at such a question. “Why, give your own opinions upon the subject.”

“Oh, shouldn’t I like to write an essay, and give my own opinions upon you,” I said to myself; while there I sat with the sheets of paper before me, biting and indenting the penholder, without the slightest idea how to begin.

I did think once of dividing the subject into three parts or heads, like Mr Saint Purre did his sermons; but there, nearly everybody I have heard in public does that, so it must be right. So I was almost determined to begin with a firstly, and then go on to a secondly, and then a thirdly; and when I felt quite determined, I wrote down the title, and under it “firstly.” I allowed the whole of the first page for that head, put “secondly” at the beginning of the second page, and “thirdly” upon the next, which I meant to be the longest.

Then I turned back, and wondered what I had better say, and whether either of the girls would do it for me if I offered her a shilling.

“What shall I say next,” I asked myself, and then corrected my question; for it ought to have been, “What shall I say first?” And then I exclaimed under my breath, “A nasty, stupid, spiteful old thing, to set me this to do, on purpose to annoy me!” just as I looked on one side and found the girl next me was nearly at the bottom of her sheet of paper, while I could do nothing but tap my white teeth with my pen.

I looked on the other side, where sat Miss Patty Smith, glaring horribly down at her blank paper, nibbling the end of her pen, and smelling dreadfully of peppermint; and her forehead was all wrinkled up, as if the big atlas were upon her head, and squeezing down the skin.

Just then I caught Clara’s eye—for she was busy making a great deal of fuss with her blotting-paper, as if she had quite ended her task—when, upon seeing my miserable, hopeless look, she came round and sat down by me.

“Never mind the essay,” she whispered; “say you had the headache. I dare say it will be correct, won’t it? For it always used to give me the headache when I first came.”

“Oh, yes,” I said, with truth, “my head aches horribly.”

“Of course it does, dear,” said Clara; “so leave that rubbish. It will be dancing in about five minutes.”

“I say,” drawled Miss Smith to Clara, “what’s tendencies towards folly? I’m sure I don’t know.”

“Patty Smith’s,” said Clara, in a sharp voice; and the great fat, stupid thing sat there, glaring at her with her big, round eyes, as much as to say, “What do you mean?”

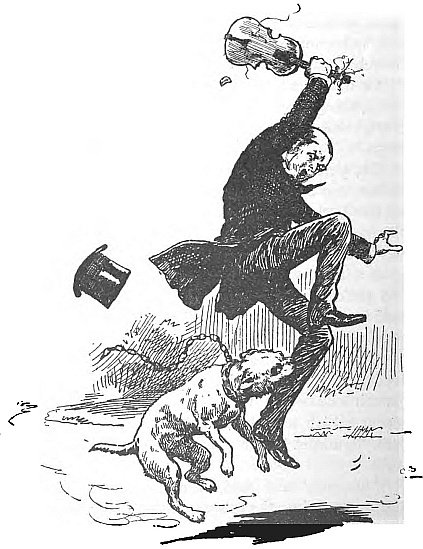

Sure enough, five minutes had not elapsed before we were summoned to our places in the room devoted to dancing and calisthenic exercises; and, as a matter of course, I was all in a flutter to see the French dancing master, who would be, I felt sure, a noble-looking refugee—a count in disguise—and I felt quite ready to let him make a favourable impression; for one cannot help sympathising with political exiles, since one has had a Louis Napoleon here in difficulties. But there, I declare it was too bad; and I looked across at Clara, who had slipped on first, and was holding her handkerchief to her mouth to keep from laughing as she watched my astonished looks; for you never did see such a droll little man, and I felt ready to cry with vexation at the whole place.

There he stood—Monsieur de Kittville—the thinnest, funniest little man I ever saw off the stage. He seemed to have been made on purpose to take up as little room as possible in the world and he looked so droll and squeezy, one could not feel cross long in his presence. If I had not been in such terribly low spirits, I’m sure I must have laughed aloud at the funny, capering little fellow, as he skipped about, now here and now there—going through all the figures, and stopping every now and then to scrape through the tune upon his little fiddle.

But it would have been a shame to laugh, for he was so good and patient; and I know he could feel how some of the girls made fun of him, though he bore it all amiably and never said a word.

I know he must have thought me terribly stupid, for there was not one girl so awkward, and grumpy, and clumsy over the lesson. But think, although it was done kindly enough, what did I want with being pushed here, and poked there, and shouted at and called after in bad English, when I had been used to float round and round brilliantly-lighted rooms in dreamy waltzes and polkas, till day-break? And I declare the very thoughts of such scenes at a time like this were quite maddening.

Finished! I felt as if I should be regularly finished long before the year had expired; and, after the short season of gaiety I had enjoyed in London, I would far rather have gone back to Guisnes and spent my days with dear old Soeur Charité in the convent. After all, I fancy papa was right when he said it was only a quiet advertising dodge—he will say such vulgar things, that he picks up in the City—and that it was not a genuine convent at all. I mean one of those places we used to read about, where they built the sisters up in walls, and all that sort of thing. But there: things do grow so dreadfully matter-of-fact, and so I found it; for here was I feeling, not so dreadfully young, but so horribly old, to be back at school.

The place seemed so stupid; the lessons seemed stupid; girls, teachers, everything seemed stupid. There were regular times for this, and regular times for that, and one could not do a single thing as one liked. If I went upstairs to brush my hair, and sat down before the glass, there would be a horrible, cracked voice crying, “Miss Bozerne, young ladies are not allowed in the dormitories out of hours;” and then I had to go down.

For the old wretch hated me because I was young and handsome, I am sure. Yes: I was handsome then, I believe; before all these terrible troubles came upon me, and made me look so old—ah! so old. And, oh! it was dreadful, having one’s time turned into a yard measure, and doled out to one in quarter-inches for this and half-inches for that, and not have a single scrap to do just what one liked with. Perhaps I could have borne it the better if I had not been used to do just as I liked at home. For mamma very seldom interfered; and I’m sure I was as good as could be always, till they nearly drove me out of my mind with this horrible school.

For it was a school, and nothing else but a school; and as they all ill-used me, and trod upon me like a worm in the path, why, of course I turned and annoyed them all I could at the Cedars, and persisted in calling it school. Finishing establishment—pah! Young ladies, indeed—fah! Why, didn’t I get to know about Miss Hicks being the grocer’s daughter, and being paid for in sugar? And wasn’t Patty Smith the butcher’s girl? Why, she really smelt of meat, and her hair always looked like that of those horrible butcher-boys in London, who never wear caps, but make their heads so shiny and matty with fat. Patty was just like them; and I declare the nasty thing might have eaten pomatum, she used such a quantity. Why, she used to leave the marks of her head right through her nightcap on to the pillow; and I once had the nasty thing put on my bed by mistake, when if it didn’t smell like the crust of Mrs Blunt’s apple-dumplings, and set me against them more than ever.

Dear, sensitive reader, did you ever eat finishing establishment “poudings aux pommes” as Mrs Blunt used to call them?—that is to say school apple-dumplings, or as we used to call them “pasty wasters.” If you never did, never do; for they are horrible. Ours used to be nasty, wet, slimy, splashy things, that slipped about in the great blue dish. And one did slide right off once on to the cloth, when the servant was putting it upon the table; and then the horrible thing collapsed in a most disgusting way, and had to be scraped up with a spoon. Ugh! such a mess! I declare I felt as if I was one of a herd of little pigs, about to be fed; and I told Clara so, when she burst out laughing, and Miss Furness ordered her to leave the table. If they would only have boiled the dreadful dumplings in basins, it would not have mattered so much; but I could see plainly enough that they were only tied up loosely in cloths, so that the water came in to make them wet and pappy; while they were always made in a hurry, and the crust would be in one place half-an-inch, and in another three inches thick; and I always had the thick mass upon my plate. Then, too, they used to be made of nasty, viciously acid apples, with horrible cores that never used to be half cut out, and would get upon your palate and then would not come off again. Oh, dear! would I not rather have been a hermit on bread and water and sweet herbs than have lived upon Mrs Blunt’s greasy mutton—always half done—and pasty wasters!

The living was quite enough to upset you, without anything else, and it used to make me quite angry, for one always knew what was for dinner, and it was always the same every week. It would have been very good if it had been nicely cooked, no doubt, but then it was not; and I believe by having things nasty there used to be quite a saving in the expenditure. “Unlimited,” Mrs Blunt told mamma the supplies were for the young ladies; but only let one of the juniors do what poor little Oliver Twist did—ask for more—and just see what a look the resident teacher at the head of the table would give her. It was a great chance if she would ask again. But there, I must tell you about our living. Coffee for breakfast that always tasted like Patty Smith’s Spanish liquorice wine that she used to keep in a bottle in her pocket—a nasty toad! Thick bread-and-butter—all crumby and dab, as if the servant would not take the trouble to spread the butter properly. For tea there was what papa used to tease mamma by calling “a mild infusion,” though there was no comparison between our tea and Allsham tea, for mamma always bought hers at the Stores, and Allsham tea was from Miss Hicks’s father’s; and when we turned up our noses at it, and found fault, she said it was her pa’s strong family Congou, only there was so little put in the pot; while if they used not to sweeten the horrible pinky-looking stuff with a treacley-brown sugar; and as for the milk—we do hear of cows kicking over the milking pail, and I’m sure if the bluey-looking stuff poured into our tea had been shown to any decent cow, and she had been told that it was milk, she would have kicked it over in an instant.

And, oh! those dinners at the Cedars! On Sundays we had beef—cold beef—boiled one week, roast the next. On Mondays we had a preparation of brown slime with lumps of beef in it, and a spiky vandyke of toast round the dish, which was called “hash,” with an afterpiece of “mosh posh” pudding—Clara christened it so—and that was plain boiled rice, with a white paste to pour over it out of a butter boat, while the rice itself always tasted of soapsuds. Tuesday was roast shoulder of mutton day. Wednesday, stewed steak—such dreadful stuff!—which appeared in two phases, one hard and leathery, the other rag and tattery. Thursday, cold roast beef always—when they might just as well have let us have it hot—and pasty wasters, made of those horrible apples, which seemed to last all the year round, except midsummer vacation time, when the stock would be exhausted; but by the time the holidays were over, the new ones came in off the trees—the new crops—and, of course, more sour, and vicious, and bitter than ever. We used to call them vinegar pippins; and I declare if that Patty Smith would not beg them of the cook, and lie in bed and crunch them, while my teeth would be quite set on edge with only listening to her.

Heigho! I declare if it isn’t almost as hard work to get through this description of the eatables and drinkables at the Cedars as it was in reality. Let me see, where was I? Oh, at Thursday! Then on Fridays it was shoulder of mutton again, with the gravy full of sixpences; and, as for fat—oh! they used to be so horribly fat, that I’m sure the poor sheep must have lived in a state of bilious headache all their lives, until the butcher mercifully killed them; while—only fancy, at a finishing establishment!—if that odious Patty Smith did not give Clara and me the horrors one night by an account of how her father’s man—I must do her the credit of saying that she had no stuck-up pride in her, and never spoke of her “esteemed parent” as anything but father; for only fancy a “papa,” with a greasy red face, cutting steaks, or chopping at a great wooden block, and crying “What-d’yer-buy—buy—buy?” Let’s see—oh! of how her father’s man killed the sheep; and I declare it was quite dreadful; and I said spitefully to Clara afterwards that I should write by the next post and tell mamma how nicely my finishing education was progressing, for I knew already how they killed sheep. Well, there is only one more day’s fare to describe—Saturday’s, and that is soon done, for it was precisely the same as we had on the Wednesday, only the former used mostly to be the tattery days and the latter the hard ones.

Now, of course, I am aware that I am writing this is a very desultory manner; but after Mrs Blunt’s rules and regulations, what can you expect? I am writing to ease my mind, and therefore I must write just as I think; and as this is entirely my own, I intend so to do, and those may find fault who like. I did mean to go through the different adventures and impressions of every day; but I have given up that idea, because the days have managed to run one into the other, and got themselves confused into a light and shady sad-coloured web, like Miss Furness’s scrimpy silk dress that she wore on Sundays—a dreadful antique thing, like rhubarb shot with magnesia; for the nasty old puss always seemed to buy her things to give her the aspect of having been washed out, though with her dreadfully sharp features and cheesey-looking hair—which she called auburn—I believe it would have been impossible to make her look nice.

Whenever there was a lecture, or a missionary meeting, or any public affair that Mrs Blunt thought suitable, we used all to be marched off, two and two; while the teachers used to sit behind us and Mrs Blunt before, when she would always begin conversing in a strident voice, that every one could hear in the room, before the business of the evening began—talking upon some French or German author, a translation of whose works she had read, quite aloud, for every one to hear—and hers was one of those voices that will penetrate—when people would, of course, take notice, and attention be drawn to the school. Of course there were some who could see through the artificial old thing; but for the most part they were ready to believe in her, and think her clever.

Then the Misses Bellperret’s young ladies would be there too, if it was a lecture, ranged on the other side of the Town Hall. Theirs was the dissenting school—one which Mrs Blunt would not condescend to mention. It used to be such fun when the lecture was over, and we had waited for the principal part of the people to leave, so that the school could go out in a compact body. Mrs Blunt used to want us to go first, and the Misses Bellperret used to want their young ladies to go first. Neither would give way; so we were mixed up altogether, greatly to Mrs Blunt’s disgust and our delight in both schools; for really, you know, I think it comes natural for young ladies to like to see their teachers put out of temper.

But always after one of these entertainments, as Mrs Blunt called them—when, as a rule, the only entertainment was the fun afterwards—there used to be a lecture in Mrs B.’s study for some one who was charged with unladylike behaviour in turning her head to look on the other side, or at the young gentlemen of the grammar-school—fancy, you know, thin boys in jackets, and with big feet and hands, and a bit of fluff under their noses—big boys with squeaky, gruff, half-broken voices, who were caned and looked sheepish; and, I declare, at last there would be so many of these lectures for looking about, that it used to make the young ladies worse, putting things into their heads that they would never have thought of before. Not that I mean to say that was the case with me, for I must confess to having been dreadfully wicked out of real spite and annoyance.

Chapter Four.

Memory the Fourth—A Terrible Surprise.

I don’t know what I should have done if it had not fallen to my lot to meet with a girl like Clara Fitzacre, who displayed quite a friendly feeling towards me, making me her confidante to such an extent that I soon found out that she was most desperately—there, I cannot say what, but that a sympathy existed between her and the Italian master, Signor Pazzoletto.

“Such a divinely handsome man, dear,” said Clara one night, as we lay talking in bed, with the moon streaming her rays like a silver cascade through the window; while Patty Smith played an accompaniment upon her dreadful pug-nose. And then, of course, I wanted to hear all; but I fancy Clara thought Patty was only pretending to be asleep, for she said no more that night, but the next day during lessons she asked me to walk with her in the garden directly they were over, and of course I did, when she began again,—

“Such a divinely handsome man, dear! Dark complexion and aquiline features. He is a count by rights, only he has exiled himself from Italy on account of internal troubles.”

I did not believe it a bit, for I thought it more likely that he was some poor foreigner whom Mrs Blunt had managed to engage cheaply; so when Clara spoke of internal troubles, I said, spitefully,—“Ah, that’s what mamma talks about when she has the spasms and wants papa to get her the brandy. Was the Signor a smuggler, and had the troubles anything to do with brandy?”

“Oh, no, dear,” said Clara, innocently, “it was something about politics; but you should hear him sing ‘Il balen’ and ‘Ah, che la morte’. It quite brings the tears into my eyes. But I am getting on with my Italian so famously.”

“So it seems,” I said, maliciously; “but does he know that you call him your Italian?”

“Now, don’t be such a wicked old quiz,” said Clara. “You know what I mean—my Italian lessons. We have nearly gone through ‘I Miei Prigioni’, and it does seem so romantic. You might almost fancy he was Silvio Pellico himself. I hope you will like him.”

“No, you don’t,” I said, mockingly. “I’m sure I do,” said Clara; “I said like, didn’t I?”

I was about to reply with some sharp saying, but just then I began thinking about the Reverend Theodore Saint Purre and his sad, patient face, and that seemed to stop me.

“But I know whom you will like,” said Clara. “Just stop till some one comes—you’ll see.”

“And who may that be, you little goose?” I cried, contemptuously.

“Monsieur Achille de Tiraille, young ladies,” squeaked Miss Furness. “I hope the exercises are ready.”

Clara looked at me with her handsome eyes twinkling, and then we hurried in, or rather Clara hurried me in; and we went into the classroom. Almost directly after, the French master was introduced by Miss Sloman, who frowned at me, and motioned to me to remain standing. I had risen when he entered, and then resumed my seat; for I believe Miss Sloman took a dislike to me from the first, because I laughed upon the day when she overset the little table while performing her act of deportment.

But I thought no more of Miss Sloman just then, for I knew that Clara’s eyes were upon me, and I could feel the hot blood flushing up in my cheeks and tingling in my forehead; while I knew too—nay, I could feel, that another pair of eyes were upon me, eyes that I had seen in the railway carriage, at the station, in my dreams; and I quite shivered as Miss Sloman led me up to the front of a chair where some one was sitting, and I heard her cracked-bell voice say,—

“The new pupil, Monsieur Achille: Miss Bozerne.”

I could have bitten my lips with anger for being so startled and taken aback before the dark foreign gentleman of whom I have before spoken.

Oh, me! sinner that I am, I cannot tell much about that dreadful afternoon. I have only some recollection of stumbling through a page of Télémaque in a most abominable manner, so badly that I could have cried—I, too, who would not condescend to make use of Mr Moy Thomas as a translator, but read and revelled in “Les Miserables” and doated on that Don Juan of a Gilliat in “Les Travailleurs de Mer” though I never could quite understand how he could sit still and be drowned, for the water always seems to pop you up so when you’re bathing; but, then, perhaps it is different when one is going to drown oneself, and in spite of the horrors which followed I never quite made up my mind to do that.

There I was, all through that lesson—I, with my pure French accent and fluent speech, condemned to go on blundering through a page of poor old Télémaque, after having almost worshipped that dear old Dumas, and fallen in love with Bussy, and Chicot, and Athos, and Porthos, and Aramis, and D’Artagnan, and I don’t know how many more—but stop; let me see. No, I did not like Porthos of the big baldric, for he was a great booby; but as for Chicot—there, I must consider. I can’t help it; I wandered then—I wandered all the time I was at Mrs Blunt’s, wandered from duty and everything. But was I not prisoned like a poor dove, and was it not likely that I should beat my breast against the bars in my efforts to escape? Ah, well! I am safe at home once more, writing and revelling in tears—patient, penitent, and at peace; but as I recall that afternoon, it seems one wild vision of burning eyes, till I was walking in the garden with Clara and that stupid Patty Smith.

“Don’t be afraid to talk,” whispered Clara, who saw how distraite I was; “she’s only a child, though she is so big.”

I did not reply, but I recalled her own silence on the previous night.

“You won’t tell tales, will you, Patty?” said Clara.

“No,” said Patty, sleepily; “I never do, do I? But I shall, though,” with a grin lighting up her fat face—“I shall, though, if you don’t do the exercise for me that horrid Frenchman has left. I can’t do it, and I sha’n’t, and I won’t, so now then.”

And then the great, stupid thing made a grimace like a rude child.

It was enough to make one slap her, to hear such language; for I’m sure Monsieur de Tiraille was so quiet and gentlemanly, and—and—well, he was not handsome, but with such eyes. I can’t find a word to describe them, for picturesque won’t do. And then, too, he spoke such excellent English.

I suppose I must have looked quite angrily at Patty, for just then Clara pinched my arm.

“I thought so,” said she, laughing; “you won’t make me jealous, dear, about the Signor, now, will you, you dear, handsome girl? I declare I was quite frightened about you at first.”

“Don’t talk such nonsense,” I said, though I could not help feeling flattered. “Whatever can you mean?”

“Oh, nothing at all,” said Clara, laughing. “You can’t know what I mean. But come and sit down here, the seat is dry now. Are not flowers sweet after the rain?”

So we went and sat down under the hawthorn; and then Clara, who had been at the Cedars two years, began to talk about Monsieur Achille, who was also a refugee, and who was obliged to stay over here on account of the French President; and a great deal more she told me, but I could not pay much attention, for my thoughts would keep carrying me away, so that I was constantly going over the French lesson again and again, and thinking of how stupid I must have looked, and all on in that way, when it did not matter the least bit in the world; and so I kept telling myself.

“There!” exclaimed Clara, all at once; “I never did know so tiresome a girl. Isn’t she, Patty, tiresome beyond all reason?”

But Patty was picking and eating the sour gooseberries—a nasty pig!—and took not the slightest notice of the question.

“It is tiresome,” said Clara again; “for I’ve been talking to you for the last half-hour, about what I am sure you would have liked to know, and I don’t believe that you heard hardly a word; for you kept on saying ‘um!’ and ‘ah,’ and ‘yes’; and now there’s the tea-bell ringing. But I am glad that you have come, for I did want a companion so badly. Patty is so big and so stupid; and all the other girls seem to pair off when they sleep in the same rooms. And, besides, when we are both thinking—that is, both—both—you know. There, don’t look like that! How droll it is of you to pretend to be so innocent, when you know all the while what I mean!”

I could not help laughing and squeezing Clara’s hand as I went in; for somehow I did not feel quite so dumpy and low-spirited as I did a few hours before; and, as I sat over the thick bread-and-butter they gave us—though we were what, in more common schools, they would have called parlour boarders—I began to have a good look about me, and to take a little more notice of both pupils and teachers, giving an eye, too, at Mrs Fortesquieu de Blount.

Only to think of the artfulness of that woman, giving herself such a grand name, and the stupidity of people themselves to be so taken in. But so it was; for I feel sure it was nothing else but the “Fortesquieu de Blount” which made mamma decide upon sending me to the Cedars. And there I sat, wondering how it would be possible for me to manage to get through a whole year, when I declare if I did not begin to sigh terribly. It was the coming back to all this sort of thing, after fancying it was quite done with; while the being marched out two and two, as we had been that day, all round the town and along the best walks, for a perambulating advertisement of the Cedars, Allsham, was terrible to me. It seemed so like making a little girl of me once more, when I was so old that I could feel a red spot burning in each cheek when I went out; and I told Clara of them, but she said they were caused by pasty wasters and French lessons, and not by annoyance; while, when I looked angrily round at her, she laughed.

It would not have mattered so much if the teachers had been nice, pleasant, lady-like bodies, and would have been friendly and kind; but they would not, for the sole aim of their lives seemed to be to make the pupils uncomfortable, and find fault; and the longer I was there the more I found this out, which was, as a matter of course, only natural. If we were out walking—now we were walking too fast, so that the younger pupils could not keep up with us; or else we were said to crawl so that they were treading on our heels; and do what we would, try how we would, at home or abroad, we were constantly wrong. Then over the lessons they were always snapping and catching us up and worrying, till it was quite miserable. As to that Miss Furness, I believe honestly that nothing annoyed her more than a lesson being said perfectly, and so depriving her of the chance of finding fault.

Now pray why is it that people engaged in teaching must always be sour and disappointed-looking, and ready to treat those who are their pupils as if they were so many enemies? I suppose that it is caused by the great pressure of knowledge leaving room for nothing mild and amiable. Of course Patty Smith was very stupid; but it was enough to make the poor, fat, pudgy thing ten times more stupid to hear how they scolded her for not doing her exercises. I declare it was quite a charity to do them for her, as it was not in her nature to have done them herself. There she would sit, with her forehead all wrinkled up, and her thick brows quarrelling, while her poor eyes were nearly shut; and I’m sure her understanding was quite shut up, so that nothing could go either in or out.

Oh! I used to be so vexed, and could at any time have pulled off that horrid Mrs Blunt’s best cap when she used to bring in her visitors, and then parade them through the place, displaying us all, and calling up first one and then another, as if to show off what papa would call our points.

The vicar of Allsham used to be the principal and most constant visitor; and he always made a point of taking great interest in everything, and talking to us, asking us Scripture questions; coming on a Monday—a dreadful old creature—so as to ask us about the sermon which he preached on the previous morning. They were all such terrible sermons that no one could understand—all about heresies, and ites, and saints with hard names; and he had a bad habit of seeing how many parentheses he could put inside one another, like the lemons from the bazaars, till you were really quite lost, and did not know which was the original, or what it all meant; and I’m sure sometimes he did not know where he had got to, and that was why he stopped for quite two minutes blowing his nose so loudly. I’m afraid I told him very, very wicked stories sometimes when he questioned me; while if he asked me once whether I had been confirmed, he asked me twenty times.

I’m sure I was not so very wicked before I went down to Allsham; but I quite shudder now when I think of what a wretch I grew, nicknaming people and making fun of serious subjects; and oh, dear! I’m afraid to talk about them almost.

The vicar sat in his pew in the nave in the afternoon, and let the curate do all the service; and I used to feel as if I could box his ears, for he would stand at the end of his seat, half facing round, and then, in his little, fat, round, important way, go on gabbling through the service, as if he wasn’t satisfied with the way the curate was reading it, and must take it all out of his mouth. He upset the poor young man terribly, and the clerk too; so that the three of them used to tie the service up in a knot, or make a clumsy trio of it, with the school children tripping up their heels by way of chorus.

Then, too, the old gentleman would be so loud, and would not mind his points, and would read the responses in the same fierce, defiant way in which he said the Creed in the morning, just as if he was determined that everybody should hear how he believed. And when the curate was preaching, he has folded his arms and stared at the poor young fellow, now shaking his head, and now blowing his nose; while the curate would turn hot, and keep looking down at him as much as to say, “May I advance that?” or “Won’t that do, sir?” till it was quite pitiful.

The vicar used to bring his two daughters with him to the Cedars, to pat, and condescend, and patronise, and advise: two dreadful creatures that Clara called the giraffes, they were so tall and thin, and hook-nosed, and quite a pair in appearance. They dressed exactly alike, in white crape long shawls and lace bonnets in summer; and hooked on to their father, one on each arm, as the fat, red-faced, little old gentleman used to come up the gravel walk, he was just like a chubby old angel, with a pair of tall, scraggy, half-open wings.

But though the two old frights were so much alike in appearance, they never agreed upon any point; and the parishioners had a sad time of it with first one and then the other. They were always leaving books for the poor people’s reading, and both had their peculiar ideas upon the subject of what was suitable. They considered that they knew exactly what every one ought to read, and what every one else ought to read was just the very reverse of what they ought to read themselves. But there, they do not stand alone in that way, as publishers well know when they bring out so many works of a kind that they are sure customers will buy—not to read, but to give away—very good books, of course.

It was all very well to call them the giraffes, and that did very well for their height; but as soon as I found out how one was all for one way, and the other immediately opposed to her sister, declaring she was all wrong, I christened them—the Doxies—Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy. It was very dreadful—wasn’t it?—and unladylike, and so on; but it did seem to fit, and all the girls took it up and enjoyed it; only that odious Celia Blang must tell Miss Furness, and Miss Furness must tell Mrs Blunt, and then of course there was a terrible hubbub, and I was told that it was profane in one sense, bad taste in another, and disgusting language in another; for the word “doxy” was one that no lady should ever bring her lips to utter. When if I did not make worse of it—I mean in my own conscience—by telling a most outrageous story, and saying I was sorry, when I wasn’t a bit.

Oh, the visitors! I was sick of them; for it was just as if we girls were kept to show. I used to call the place Mrs Blunt’s Menagerie, and got into a scrape about that; for everything I said was carried to the principal—not that I cared, only it made me tell those stories, and say I was sorry when I was not.

The curate and his poor unfortunate wife came sometimes. A curious-looking couple they were, too, who seemed as if they had found matrimony a mistake, and did not approve of it; for they always talked in a quiet, subdued way, and walked as far apart from one another as they could.

The curate had not much to say for himself; but he made the best he could of it, and stretched his words out a tremendous length, saying pa-a-ast and la-a-ast; so that when he said the word everlasting in the service, it was perfectly terrible, and you stared at him in dismay, as if there really never would be an end to it.

We used to ask one another, when he had gone, what he had been talking about; but we never knew—only one had two or three long-stretched-out words here, and a few more there. But it did not matter; and I think we liked him better than his master, the vicar. As for his wife, she had a little lesson by heart, and she said it every time she came, with a sickly smile, as she smoothed one side at a time of her golden locks, which always looked rough; and hers were really golden locks—about eight-carat gold, I should say, like Patty Smith’s trumpery locket; for they showed the red coppery alloy very strongly—too strongly for my taste, which favours pale gold.

Pray do not for a moment imagine that I mean any vulgar play upon words, and am alluding to any vegetable in connection with the redness of the Mrs Curate’s hair; for she was a very decent sort of woman, if she would not always have asked me how I was, and how was mamma, and how was papa, and how I liked Allsham, and whether I did not think Mrs de Blount a pattern of deportment. And then, as a matter of course, I was obliged to tell another story; so what good could come to me from the visits of our vicar and his followers?

Chapter Five.

Memory the Fifth—I Get into Difficulties.

I declare my progress with my narrative seems for all the world like papa carving a pigeon-pie at a picnic: there were the claws sticking out all in a bunch at the top, as much as to say there were plenty of pigeons inside; but when he cut into it, there was just the same result as the readers must find with this work—nothing but disappointing bits of steak, very hard and tiresome. But I can assure you, like our cook at home, that all the pigeons were put in, and if you persevere you will be as successful as papa was at last, though I must own that pigeon is rather an unsatisfactory thing for a hungry person.

Heigho! what a life did I live at the Cedars: sigh, sigh, sigh, morning, noon, and night. I don’t know what I should have done if it had not been for the garden, which was very nice, and the gardener always very civil. The place was well kept up—of course for an advertisement; and when I was alone in the garden, which was not often, I used to talk to the old man or one of his underlings, while they told me of their troubles. It is very singular, but though I thought the place looked particularly nice, I learnt from the old man that it was like every garden I had seen before, nothing to what it might be if there were hands enough to keep it in order. I spoke to papa about that singular coincidence, and he laughed, and said that it was a problem that had never yet been solved:—how many men it would take to keep a garden in thorough order.

There was one spot I always favoured during the early days of my stay. It was situated on the north side of the house, where there was a dense, shady horse-chestnut, and beneath it a fountain in the midst of rockery—a fountain that never played, for the place was too oppressive and dull; but a few tears would occasionally trickle over the stones, where the leaves grew long and pallid, and the blossoms of such flowers as bloomed here were mournful, and sad, and colourless. It seemed just the spot to sit and sigh as I bent over the ferns growing from between the lumps of stone; for you never could go, even on the hottest days without finding some flower or another with a tear in its eye.

I hope no one will laugh at this latter conceit, and call it poetical or trivial; for if I like to write in a sad strain, and so express my meaning when I allude to dew-wet petals, where is the harm?

But to descend to everyday life. I talked a great deal just now about the different visitors we had, and the behaviour of our vicar in the church; and really it was a very nice little church, though I did not like the manners of some of the people who frequented it.

Allsham being a small country town, as a matter of course it possessed several grandees, some among whom figured upon Mrs Blunt’s circular; and it used to be so annoying to see about half-a-dozen of these big people cluster outside the porch in the churchyard, morning and afternoon, to converse, apparently, though it always seemed to me that they stood there to be bowed to by the tradesmen and mechanics. They never entered the church themselves until the clergyman was in the reading-desk, and the soft introductory voluntary was being played on the organ by the Fraülein, who performed in the afternoon, the organist in the morning. Then the grandees would come marching in slowly and pompously as a flock of geese one after another into a barn, proceeding majestically to their pews; when they would look into their hats for a few moments, seat themselves, and then stare round, as much as to say, “We are here now. You may begin.”

It used to annoy me from its regularity and the noise their boots made while the clergyman was praying; for they might just as well have come in a minute sooner; but then it was the custom at Allsham, and I was but a visitor.

I did not get into any trouble until I had been there a month, when Madame Blunt must give me an imposition of a hundred lines for laughing at her, when I’m sure no one could have helped it, try ever so hard. In the schoolroom there was a large, flat, boarded thing, about a foot high, all covered with red drugget; and upon this used to stand Mrs Blunt’s table and chair, so that she was a great deal higher than anyone else, and could easily look over the room. Then so sure as she began to sit down upon this dais, as she used to call it, there was a great deal of fuss and arranging of skirts, and settling of herself into her chair, which she would then give two or three pushes back, and then fidget forward; and altogether she would make more bother than one feels disposed to make sometimes upon being asked to play before company, when the music-stool requires so much arranging.

Now, upon the day in question she had come in with her head all on one side, and pulling a sad long face, pretending the while to be very poorly, because she was half-an-hour late, and we had been waiting for the lesson she was down in the table to give. Then, as we had often had it before, and knew perfectly well what was coming, she suddenly caught sight of the clock.

“Dear me, Miss Sloman! Bless my heart, that clock is very much too fast,” she would exclaim. “It cannot be nearly so late as that.”

“I think it is quite right, Mrs de Blount,” Miss Sloman would say, twitching her moustache.

“Oh, dear me, no, Miss Sloman; nothing like right. My pendule is quite different.”

Of course we girls nudged one another—that is not a nice word, but kicked or elbowed seems worse; and then, thinking I did not know, Clara whispered to me that her ladyship always went on like that when she was down late of a morning. But I had noticed it several times before; while there it was, always the same tale, and the silly old ostrich never once saw that we could see her when she had run her stupid old head in the sand.

Well, according to rule, she came in, found fault with the clock, but took care not to have it altered to match her gimcrack French affair in her bedroom, which she always called her pendule. Then she climbed on to the daïs; and, as usual, she must be very particular about the arrangement of the folds of her satin dress, which was one of the company or parent-seeing robes, now taken into everyday use.

“Look out,” whispered Clara to me.