Title: Book Collecting: A Guide for Amateurs

Author: J. Herbert Slater

Release date: December 19, 2011 [eBook #38345]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Margo Romberg and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

A GUIDE FOR AMATEURS

Editor of Book Prices Current; formerly Editor of Book Lore; Author of

The Library Manual; Engravings and their Value; The Law

relating to Copyright and Trade Marks, etc., etc.

LONDON

SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO.

PATERNOSTER SQUARE

1892

| PAGE. | |

| CHAPTER I. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | 20 |

| CHAPTER IV. | 25 |

| CHAPTER V. | 34 |

| CHAPTER VI. | 44 |

| CHAPTER VII. | 51 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | 62 |

| CHAPTER IX. | 74 |

| CHAPTER X. | 100 |

| CHAPTER XI. | 112 |

| PRINCIPAL SECOND-HAND BOOKSELLERS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM WHO PUBLISH CATALOGUES. | 121 |

THE Bibliophile, as he is somewhat pedantically termed, probably dates his existence from the time when books began to be multiplied in sufficient quantities to render the acquisition of duplicate copies by the public a matter of possibility, but his opportunities of amassing a large number of volumes can hardly be said to have arisen until many years after the invention of printing.

The most ancient manuscript extant has been identified with the reign of Amenophis, who ruled in Egypt no less than 1600 years before the Christian era, and this manuscript, old as it is, shows such superior execution that there can be little, if any, doubt that caligraphy in its oldest—that is, its hieroglyphic—form must be referred for its origin to a period still more remote. Diodorus Siculus relates that Rameses II. founded a library in one of the chambers of the Memnonium at Thebes, and deposited therein the 42 sacred books of Thoth, which had they been in existence now would be nearly 5000 years old. In those days, however, education was looked upon as the peculiar property of the priesthood; the library had sealed doors; even the very books themselves must have been wholly unintelligible to all but the favoured few whose duty it was to preserve them with religious care. All the early Egyptian manuscripts extant have served in their day an ecclesiastical rather than a secular object, and all of them abound with mythological stories more or less recondite. To [2] use the art of writing for any less sacred purpose would have been held disrespectful to the educated class and resented accordingly. Ptolemy Sotor, who reigned over Egypt about the year 280 B.C., appears to have been the first to break through the artificial barrier which the priestcraft of age upon age had succeeded in building up; and his magnificent twin library at Alexandria, known as the Bruchium and Serapeum, which was partly stocked with the confiscated books of travellers who touched at the port, became in course of time the most famous in the world, and would most probably have been so at this day had it not been destroyed by Theodosius and his army, as a sacrifice at the shrine of ignorance and superstition. With the destruction of the library at Alexandria, containing, as it did, books which can never be replaced, the literary importance of the Egyptians came to an end; thenceforward all that remained was the consciousness of having instructed others better able to preserve their independence than they were themselves. Yet after all it is somewhat extraordinary that Egypt should have been not merely the first to encourage a love of literature, but also the last; for simultaneously with the destruction of the Bruchium and Serapeum were ushered in the first centuries of the dark ages, when the ability to read and write was looked upon as unworthy the status of a free man, unless indeed he were a priest, and when fire and sword were brought into requisition for the purpose of annihilating everything that suggested mental culture.

In the eras which intervened between the reign of Rameses the Constructor and that of Theodosius the Destroyer, Pisistratus had founded his public library at Athens, and collected the poems of Homer which had previously been scattered in detached portions throughout Greece; and Plato, the prince of ancient book hunters, had given no less than 100 attic minæ—nearly £300 of our money—for three small treatises of Philolaus the Pythagorean. Aristotle too, unless he has been sadly maligned, thought 300 minæ a fair exchange for a little pile of books which had formerly belonged to Speusippus, thereby setting an example to that French king of after ages who pawned his gold and silver plate to obtain means wherewith to purchase a coveted copy of Lacertius, as Gabriel Naudé calls the great Epicurean biographer. In Rome also Lucullus had furnished his house with books and thrown [3] open his doors to all who wished to consult them. Atticus the famous publisher had turned out a thousand copies of the second book of Martial's Epigrams, with its 540 lines of verse, bound and endorsed in the space of a single hour, and the booksellers carried on a flourishing trade in their shops in the Argeletum and the Vicus Sandalarius, exhibiting catalogues on the side posts of their doors exactly as the second-hand dealers in London and elsewhere do now. Of all this vast enterprise of Greece and Rome not a trace remains: only the sepulchral writings of mother Egypt and the clay tablets of Assyria.

History tells us how the luxurious rich of Athens and Rome regarded their books as so many pieces of furniture, and engaged learned slaves to read aloud at their banquets; and if the example of Plato were followed to any extent, doubtless large sums of money were spent on rare originals which had passed through the hands of a succession of dilettanti, and acquired thereby a reputation for genuineness, which they could not have gained in any other manner. Seneca indeed ridicules the vulgar emulation which prompted some of his contemporaries to collect volumes of which, he says, they knew nothing except the outsides, many of them possibly barely that. It has been ever so: in England to-day there are many who would have felt the lash of Nero's tutor across their shoulders.

When the public no longer took pleasure in mental culture, and the whole world was overrun with hordes of barbarians intent upon destruction, learning of every kind was banished to the monasteries, and the monks became the only book lovers, making it their business to transcribe, generation after generation, the volumes which had been saved from the general conflagration. It is entirely through their efforts that the old classics have been preserved to our day; we have to thank them, and them alone, for the preservation of the Bible itself. Even in the monasteries, however, the same spirit of emulation which had prompted Greek to compete with Greek, and Roman with Roman, became apparent in course of time. Ordinary transcripts, though never numerous, began to be looked upon as hardly pretentious enough, and the larger houses established scriptoria, where trained monks sat the livelong day, painfully tracing letter after letter on the purest vellum, while Bibliolatrists added illuminated borders and miniatures in a style that would task the skill of our best artists of to-day. This [4] competition led to the exchange of manuscripts, or to their loan for a brief period, so that by degrees monastic libraries assumed large proportions, numbering many hundreds of neatly bound volumes, which, on being opened, looked as though printed, so accurately and carefully had the copying been done. This explains how Fust, the inventor, or one of the inventors, of printing, was enabled to deceive the people of Paris, for he flooded the market there with printed copies of the Bible which he sold for 50 crowns each, instead of for 400 or 500 crowns, which would have been a fair price had they been in manuscript. The book buyers of Paris thought they were in manuscript, until the recurrence of one or two defective types cast from the same matrix caused an inquiry. Fust was arrested, not for the fraud but for witchcraft, and to save his life he explained his process. Thus did the old order give place to the new.

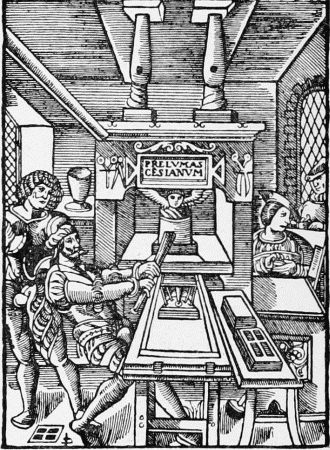

In a very few years after the discovery of Fust's secret the whole of the western portion of Europe was dotted with printing presses. Before 1499 there were 236 in operation; and six years after Gutenberg had completed his Bible of 42 lines there were no less than 50 German cities and towns in which presses had been established. Considering that this only brings us down to about the year 1462, it is evident with what rapidity the art of printing was seized upon through the length and breadth of the country of its probable origin.

In 1475 our own famous printer Caxton was being instructed in the office of Colard Mansion at Bruges, and in 1477, if not earlier,[1] he settled as a printer at Westminster, thus laying the foundation of our English industry and establishing a native press which has continued to grow year by year until it has assumed its present enormous proportions. Authorities, however, point out that improvement in the art of printing did not come by age or experience, for, curiously enough, the science—for such it really is—was almost perfect from its origin, and, so far as this country is concerned, has distinctly deteriorated since the death of Caxton and his pupils Wynkyn de Worde, Faques, and Pynson. The typefounders of that early period [5] were as expert as many at the present day and immeasurably superior to most. The greatest care appears to have been exercised in the casting, and competition did not engender the slovenly haste which is only too apparent in many of our modern publications. It is probable that, simultaneously with the introduction of printing into England, a certain limited few, most likely ecclesiastics and powerful nobles, would commence to collect works from the press of Caxton, and subsequently from the foreign presses. In 1545 the Earl of Warwick's library consisted of 40 printed books, in 1691 that of the Rev. Richard Baxter of 1448. It is not until a comparatively modern period that any single man has been able to mass together thousands of volumes during the course of a single lifetime, for it is only recently that printing has been used on every trivial occasion, and in the manufacture of books which would originally have been deemed unworthy of the application of the art.

At the present day books constitute one of the necessities of life and private libraries one of its luxuries. The collector has such ample scope for the exercise of his favourite pursuit that it has long since become a question not so much of accumulating a large number of miscellaneous volumes, as of exercising a rigid discrimination and confining one's attention to works of a certain class, to the almost entire exclusion of all others. Thus, some book hunters collect first, or, at any rate, early, editions of popular modern authors, such, for example, as Dickens, Thackeray, and Lever; others collect old editions of the Scriptures, a few, the expensive early printed volumes which are every year becoming absorbed into the public libraries, and consequently growing more scarce. A small number attempt to form an extensive all-round library, but they rarely, if ever, succeed, partly because life is too short for the purpose, and money too limited in quantity. Occasionally a large collection comes to the auctioneer's hammer, but in nearly every instance it will be found that it represents the labours of several generations of owners, each of whom has contributed the principal publications of his day or taken advantage of any proffered bargain which he may have happened to come across during the course of his lifetime.

The book lover however is not content with mere acquisition, he feels it his duty to know something of the inner life, so to speak, of each volume on his shelf—something, [6] that is to say, beyond the outside lettering. He wishes to know the chief incidents in the history of the person who wrote it, under what circumstances it was written and why, how many editions have been published, whether the particular copy is perfect, how much it is worth from a pecuniary point of view, and occasionally the nature of the contents. The word "occasionally" may be considered by some as used in an objectionable sense, implying in fact that book lovers are not always in the habit of reading what they possess. Let the collector of Bibles say whether he is in the habit of reading the various editions which he has been at such pains to collect, and it will then be time enough to inquire into the practices of other collectors who, like himself, though in different departments, may not consider themselves justified in spending the amount of time necessary for careful and satisfactory study. In truth, if all books were read, it is only reasonable to suppose that all libraries would be small; and, as we know the contrary to be the fact, we must acknowledge the truth of the main proposition to a very large extent. The happiness of the book lover, as we know him when in the plenitude of his glory, consists by no means in reading, but in the contemplation of his possessions from afar; an inane treatise on theology becomes the object of his daily prayers when bound in morocco and stamped with the Golden Fleece of Longepierre.

In this short dissertation we have but little to do with the contents of any book. This knowledge can be acquired as circumstances and opportunity offer; we deal rather with extraneous details which are necessary to be known by everyone who aspires to form a collection of books for himself and would know something of the history of each.

Every bibliographer, and also every collector of any eminence, has within reach certain books of reference which experience has shown to be absolutely necessary. Chief among these is Lowndes' Bibliographer's Manual of which two editions have been issued. The first was published in 1834; the second in seven parts from 1857-61, with an appendix volume in 1864, having been re-issued from the stereotype plates without a date in 1871. The latter may frequently be picked up at auction sales for about 25s., but there is this peculiarity about the work, that it really would not seem to be very material which edition is purchased. The book is imperfect and full of errors: it cannot be relied on, and the second edition, which [7] was edited by the late Mr. H. G. Bohn, the eminent bookseller, is as untrustworthy as the first edition. The original plan, which has never been departed from, was to give the names of English authors in alphabetical order, placing under each the title of the works he wrote, with the date of each edition, number of volumes, in many cases the collation, and finally the sums realised at auction. Nothing fluctuates so greatly as auction values, and it is not surprising, therefore, to find that not a single entry in Lowndes under this head can be accepted at the present day. Some of the variations between past and present prices are ludicrous in the extreme, and there is no doubt that anyone who attempted to obtain his knowledge of the value of books from Lowndes' Manual would find himself in possession of a mass of old-time information which would be rather a hindrance to him than otherwise. The Manual is useful because it gives a full and tolerably complete list of English authors, and collates many of their works with considerable care; it is, moreover, the authority quoted by cataloguers, and, being a copyright publication, practically bars the way to any rival work on the same subject. For these and other reasons it is indispensable.

To ascertain the value of a book is an exceedingly difficult operation; in fact, there are many who assert that it is impossible to do so. Booksellers' prices, as disclosed in their catalogues, are not much to go by, for it is notorious that a West End dealer will often charge more than one who is established further East. Again, some London booksellers charge more or less than provincial ones, according to circumstance and the character of their customers. Until recently there were only two ways of becoming an adept in this department, the first and best by practical experience, a method which is not, of course, available to any but dealers and their assistants; and the second, by indexing retail catalogues and striking an average. A third method, that of taking the average of auction sales, was not available until recently, for it is too troublesome, for any save those whose business it is, to attend sales by auction all day long for nine months out of the twelve, in order to obtain the necessary materials.

In 1886, I conceived the idea of fully reporting all sales of any importance taking place either in London or the provinces, and in December of that year the necessary arrangements were completed, with the modification that for the present, at any rate, no notice was to be taken of any book which did not realise at [8] least 20s. by auction. This publication, the success of which amply demonstrates the necessity for its existence, is named Book Prices Current, and already five volumes are published, and a sixth will be ready at the beginning of next year (1893). As a book of this kind would be useless without a full index, the greatest possible care has been taken to make it as complete and as accurate as possible. From Book Prices Current a very good idea of the average value of almost any book may be obtained. Careful note of the way in which the particular volume is bound must, of course, be taken, for this, as might be expected, makes a great difference in the price.

The French are supposed to be much better bibliographers than our own countrymen, and if the character of the authoritative works published in either country is a criterion of national merit there cannot be much, if any, doubt that this is so. Lowndes' Bibliographer's Manual takes no notice of books published abroad, and, as they are in the majority, it becomes necessary to seek an additional guide. This is afforded by Brunet's Manuel du Libraire et de l'Amateur de Livres, published at Paris in 6 vols. from 1860-65, and usually found, with the Appendix on Géographie, 1870, and 2 vol. Supplément, 1878-80. In its place it is a much better book than Lowndes', but it is very expensive, frequently bringing as much as £10 and £12 by auction. Here again, however, the values are quite unreliable, and, as in the case of Lowndes', there is no index of subjects whatever. From the three works mentioned very much may undoubtedly be learned about almost any book provided the author's name be known; but as it frequently happened that many authors chose, for reasons satisfactory to themselves, to conceal their names altogether, or in the much commoner instance of the name being forgotten by or unknown to the searcher, an index of subjects becomes a necessity. This is partly supplied by Watt's Bibliotheca Britannica in 4 vols. 4to, 1824, two volumes being devoted to authors and two to subjects, there being also cross references from one to the other. This inestimable work occupied the author the greater portion of his life, and is a monument of industry and research. The auction value amounts to £3 within a fraction, this being one of the few books which has a fixed market price all over the kingdom. Good copies in handsome bindings frequently occur, and are worth £4 to £5. The English Catalogue, initiated by the late Mr. Sampson Low, is a periodical which [9] makes its appearance annually, and, unlike all the other works I have mentioned, is confined entirely to current literature. The title of every work published during the year is given, with the month in which it was issued, the price, and publisher's name, the whole being arranged in one line under the name of the author. At intervals, which do not appear to be strictly defined, collective editions of these annual catalogues, arranged in one alphabet, are published, as well as of the indexes of the titles which are appended to each annual issue.[2]

It is obvious that a work of this kind must be of the greatest utility, and as the English Catalogue is merely a continuation of the London Catalogue and the British Catalogue, the former of which commenced so far back as the year 1811, it will be seen that a comprehensive view can be taken of the whole range of English literature from that date to the present. The Catalogue has not, however, always been so carefully prepared as it is now, and consequently in the earlier days many publications were omitted. When this is the case Lowndes and Watt will be found of material assistance, the latter especially. A complete set of these catalogues, unfortunately, is very difficult to obtain, and as the earlier ones are not indispensable, it may be perhaps advisable to forego them and to commence in 1814. The volumes to be acquired therefore would be London Catalogue, 1816-51; English Catalogue, 1835-63, 1863-71, 1872-80, 1881-89; with the accompanying subject indexes to the London Catalogue, 1814-46; and to the English Catalogue, 1835-55, 1856-75, 1874 (sic)-80. It will be noticed that the dates sometimes overlap each over, but this is an advantage rather than a drawback. Among the other books frequently consulted by both dealers and amateurs are Mr. Swan Sonnenschein's The Best Books; the Reference Catalogue of Current Literature, and Halkett & Laing's Dictionary of Anonymous and Pseudonymous Literature of Great Britain, in 4 vols. These are mentioned together because they are essentially subject indexes and the best of their kind.

Sonnenschein's The Best Books, already in a second and vastly improved edition, is a comparatively recent publication, in which, under subjects arranged systematically, are placed [10] the best current books, whether ancient or modern, on each subject, with the prices, sizes, publisher's name and dates of the first and last editions of each. There are about 50,000 works included, and they together give a very good idea of all the material in the various departments of research which the specialist is likely to have occasion to read or refer to. Old books are included where they are of actual present-day value to the student. The selection is not, of course, entirely made by the author, as it is impossible for him to have read a hundredth part of the books recommended; most probably the list has been compiled from the works of specialists, the various encyclopædias, and so forth; but however this may be, it is a very useful one in the hands of a person capable of discrimination (towards which the numerous critical and bibliographical notes and the system of asterisks are a great help), especially if he live near one or other of the large libraries now springing up in different parts of the country.

The Reference Catalogue of Current Literature, a cumbrous and unwieldy tome, the last issue of which was out of print within a couple of months of its publication, consists of a large number of publishers' catalogues arranged in alphabetical order. Each work mentioned is indexed, and this has been accomplished so fully and accurately that almost any book to be bought new in the market makes its appearance here.

Halkett & Laing's Dictionary is, as the title implies, a record of the anonymous and pseudonymous literature of Great Britain. If an author wrote under an assumed name or anonymously, his real name will be found here, together with a short account of his publications. This work can hardly be said to be indispensable, but it is, notwithstanding, exceedingly useful, and well worth the three and a half guineas which will have to be expended upon it.

Among other works which at one time were thought more of than they are now is Quaritch's Catalogue of Books, in one thick volume, 1880, and a supplement which is back-dated 1875-7. The chief value of this lay not only in the prices, which were, as in every other bookseller's catalogue, appended to the items, but in the extraordinary number of the entries, which cover the whole range of British and foreign literature. Even now the work is useful, but there is no doubt that it is gradually decreasing in importance, owing to the high-class works of reference which have lately made their appearance. [11] As to values, Book Prices Current gives them much more satisfactorily than any bookseller can pretend or afford to do, while most of the bibliographical notes and references are to be found in one or other of the works I have mentioned.

The collector who, as yet, is not sufficiently advanced to

fully realise the difficulties he will have to surmount before he

can bring together a judicious assortment of books, will at any

rate begin to see that the knowledge requisite to enable him to

do so is of no mean order. The preliminaries will take him a

long time to master, and he will find that the expense is a factor

by no means to be despised. Even the books mentioned are

not all that he may have to procure, for if, after consideration,

he should decide to devote his attention exclusively to one

branch of Bibliography, there are other books of reference to be

purchased, and a special course of study must be entered upon

and carefully followed, if he would hope to be successful.

Thus, should he decide to make Dickens or Thackeray his one

author, as so many people are doing now, he will need a guide

to direct his course. Memory is so treacherous that he can

take nothing on trust, and time so short that he cannot afford

to journey two sides of the triangle when he might have taken

the third. These special works for special departments are set

out and enlarged upon in the following chapter, but before

referring to them it may not be superfluous to remind the reader

that a book of reference only possesses a relative value. It

is quite possible to have a whole library within reach and yet to

be ignorant of the proper method of using it. Some of our

best writers had no library worthy the name, but the few books

they had they knew—knew, that is to say, how to extract the information

they required, which book to consult, how it was

arranged, and what might be expected of it. Though a book

collector is not necessarily a book reader, he will have to be

absolute master of his works of reference, or he will find every

volume on his shelf a useless incumbrance. Where to possess

all the absolute facts is of importance, the newest works are,

generally speaking, most likely to be the best; but this is very

far from being applicable to a library in all its departments.

Yet even in the case of works of a general nature a careful and

economic selection may be made, so as to cover, in a small

compass, much valuable ground.

[1] The Dictes and Sayinges of the Philosophers, Caxton's first book which bears a date, was finished in November, 1477; and it is upon the strength of this that the Caxton Quarcentenary Festival was held in 1877. There can be little doubt, however, that he printed many books of which no copies remain, some of which were probably earlier than The Dictes.

[2] In the annual volume for 1891 a new scheme has been started, the

authors and titles entries appearing in one alphabet in "dictionary

form".

THE first sale of books by auction which is recorded as having taken place in England was held in Warwick Lane exactly 213 years ago, and Dr. Lazarus Seaman, whose library was dispersed on the occasion in question, appears to have confined his attention strictly to Latin Bibles of the 16th century, the cumbrous works of the Puritan divines, and the great editions of the Fathers—huge folios thought so little of that, allowing for the change in the value of money, they can now for the most part be bought from the booksellers for less than they could then at auction. The reason which prompted this old collector to limit his purchases to works of a single class was in all probability much the same as that which prevails under similar circumstances at the present time, namely, a natural desire for finality, the outcome of an experience which shows plainly enough that in order to form a complete collection of anything its scope must be reduced to the smallest possible compass. As a matter of fact Dr. Seaman appears to have embarked on a somewhat extensive undertaking, for in the period mentioned by far the greater majority of works issued from the press were of a religious nature. Still the incident is valuable from an antiquarian point of view, as it forms a good precedent for a large body of modern collectors who, like Seaman, follow the prevailing fashion of the day. This fashion on being analysed will be found to vary at different periods and to be of longer or shorter duration according to a variety of circumstances which appear to be entirely without the range of argumentative discussion.

In the year 1699, for example, a book was published, [13] entitled Entretiens sur les Contes de Fées, in which one of the characters is described as saying, "For some time past you know to what an extent the editions of the Elzevirs have been in demand. The fancy for them has penetrated far and wide to such an extent, indeed, that I know a man who starves himself for the sake of accumulating as many of these books as he can lay his hands on." In the chapter devoted to the Elzevir press, these important publications are treated as fully as space permits, so that at present it will be sufficient to say that for nearly 200 years many generations of collectors have made painstaking attempts to form a complete library of these little books, which, after all, excel only in the quality of the paper and the beauty of the type. For real scholarly merit the editions of Gryphius or Estienne are much to be preferred, but this makes no difference. The Elzevirs were fashionable, much more so than they are now, and accordingly they were valued. It is, moreover, quite possible that they may again rise in popular favour, in which event those far-seeing individuals who are even now imitating the example of the collector mentioned in the Entretiens will reap a rich harvest in case they choose to avail themselves of it. The great guide-book on the productions of this famous press is that by Alphonse Willems, entitled Les Elzevier, Histoire et Annales Typographiques, published at Brussels in 1880, with the Etudes sur la Bibliographie Elzevirienne of Dr. G. Berghman, a kind of supplement to it, published at Stockholm in 1885.[3]

Each publication is given in the order in which it was issued, and what will be found especially useful is an appendix containing a list of the spurious Elzevirs issued from the Dutch presses and of the forgeries which have from time to time been foisted on the confiding amateur. With the assistance of this work, the Elzevir collector cannot go very far wrong, though he will undoubtedly have much to learn from his own practical experience. He will become more or less perfect in his lesson in time, and may take comfort in the reflection [14] that nothing so quickly ensures perfection as a limited series of bad mistakes. As examples of the Elzevir press are of "right" and "wrong" editions, with and without red lines, and are, moreover, usually measured in millimetres with the assistance of a rule which the enthusiastic collector invariably carries about with him wherever he goes, it is evident that there is much to learn and a great deal to be carried in the memory before the amateur can trust himself to become his own mentor.

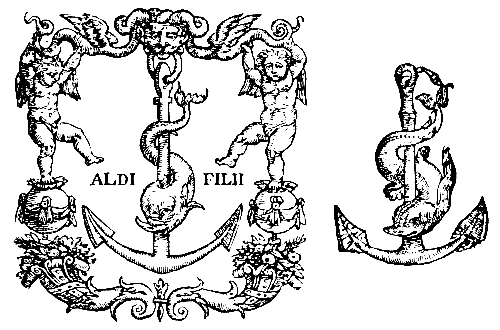

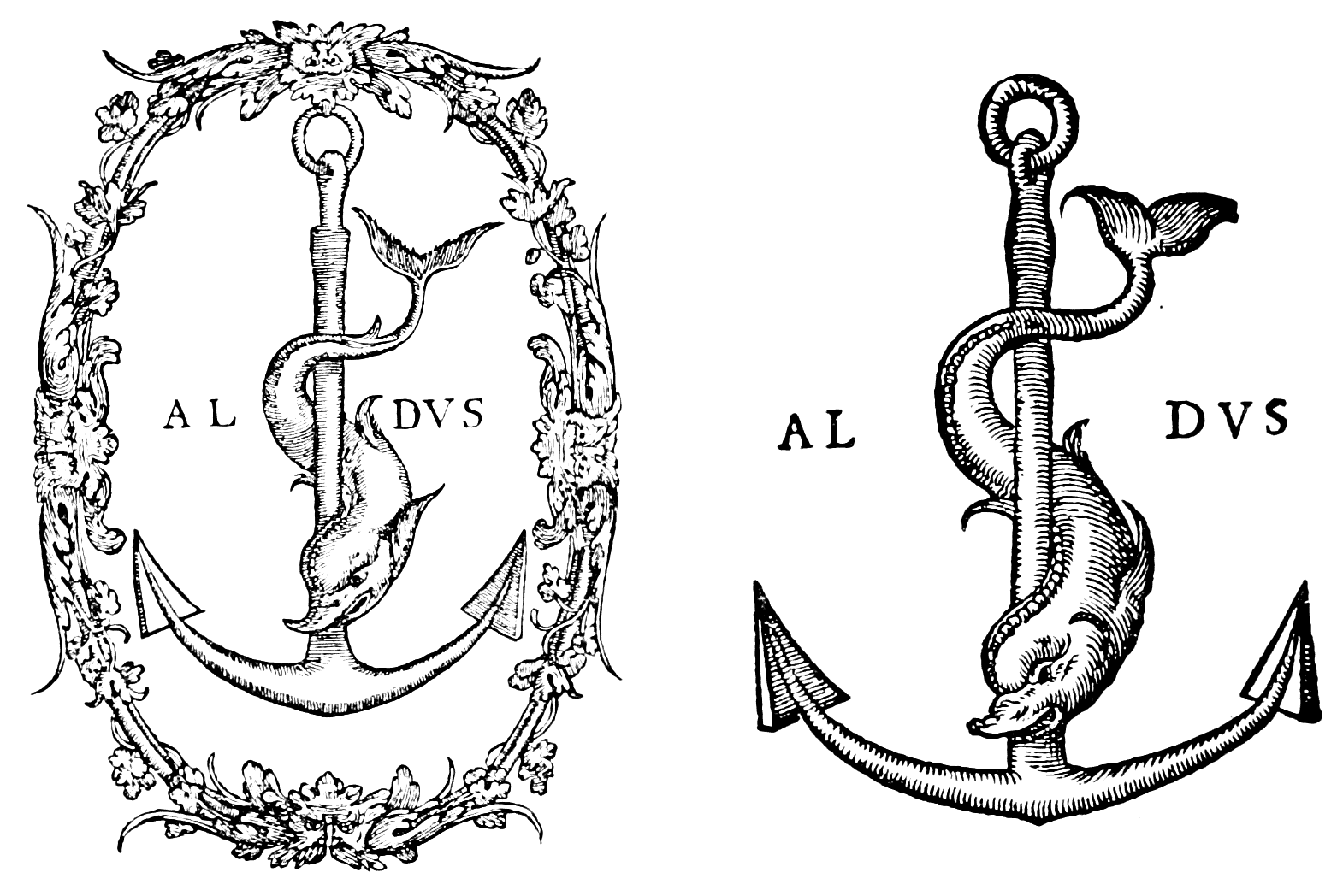

Difficult as the subject of the Elzevir press is, that of the Aldine press is more so. It was established much earlier—viz., about 1489—and examples are more numerous and altogether more confusing. As a general rule they are also more expensive, and none but rich collectors can afford to compete for examples of the best class. Still, good specimens may occasionally be got for reasonable sums; and as a guide to the subject as a whole Renouard's Annales de l'Imprimerie des Alde (1st ed., 2 vols., Paris, 1803; 2nd, 3 vols., ib., 1825; 3rd, 1 vol., ib., 1834) occupies a unique position. This work is arranged on a similar plan to the Elzevier and is quite as indispensable to the specialist. An ordinary copy of the 2nd ed. will cost about 30s., but the more recent edition can sometimes be got for considerably less.

Those fortunate persons who succeed in forming a good library of early printed books usually consult Dibdin's Bibliotheca Spenceriana, which professes to be nothing more than a descriptive catalogue of books of the 15th century in the incomparable collection of Earl Spencer. It is, however, full of notes by one of the best of English bibliographers. The British Museum Catalogue of Early Printed Books in English, 3 vols., 1884, which is carried down to 1640, and Maitland's Early Printed Books in Lambeth Library, 1843, carried down to 1600, are also frequently consulted. These works are of course supplementary to Lowndes' Bibliographer's Manual and Watt's Bibliotheca Britannica, which, as previously explained, are on the shelves of every collector worthy the name, be he a specialist or not. The department of early printed books may, however, be left without further comment, as not one person out of many thousands is able for obvious reasons to devote his serious attention to it. Public libraries and similar institutions, which may be said to have a continuing existence, frequently contain a good show of works of this class, and, in the opinion of many, are the only suitable repositories for them.

Privately printed books are those which are issued either [15] from a private press or for the benefit of private friends. They are never published in the ordinary acceptation of that term, and cannot be bought at first hand. A good collection of these is of course difficult, though by no means impossible, to acquire; and for the benefit of those who may wish to devote themselves to this department—uninteresting as it undoubtedly is—Martin's Privately Printed Books (1834, 2nd ed., 1854), in 1 vol. 8vo, is readily available. Many of these so-called "books" consist merely of single sheets of letterpress; others, on the contrary, are more pretentious. In the former case they are more correctly termed "broadsides"; and R. Lemon's Catalogue of the Collection of Broadsides, in the possession of the Society of Antiquaries (8vo, 1866), though by no means a perfect book, is certainly the best that can be procured for our purpose.

Early printed American books, or those which in any way relate to the American Continent, provided only they were published during the 16th or 17th centuries, have lately become exceedingly scarce. In June, 1888, nine small quarto tracts, bound in one volume, brought, £66 by auction, a record entirely surpassed by the preceding lot, which, consisting of twelve similar tracts only, brought no less a sum than £555. These prices are of course highly exceptional; but so great is the desire to obtain books of this class that the amounts in question, exorbitant though they may appear to be, were perhaps not excessive.

The amateur may in this instance follow the rule with every confidence. Should he at any time see a work relating to America, no matter where printed so long as it is dated before the year 1700, he should on no account pass it by without very careful consideration; and the same remark applies, though to a less extent, to all books printed in Scotland before that date. In both cases it is probable that the specimen offered for sale will have a most unprepossessing exterior, and in some instances the price asked may be small. This frequently happens, since the more uneducated class of dealers commence by valuing a book from its appearance, and while a coloured plate or two would at once put them on the qui vive there is generally nothing about books of this kind which looks valuable. It is no disparagement to the trade as a whole to say that some booksellers, particularly those who carry [16] on business in small provincial towns, are absolutely ignorant of anything more than the first principles of their trade, and it is out of these that bargains are made. Henry Stevens' Catalogue of the American Books in the Library of the British Museum (1886, 8vo) is from the pen of a late famous bookseller who made many "bargains" in his time and whose profound knowledge of the insides as well as of the outsides of his very valuable collection was in every way worthy of his success.

Shakespearian collectors cannot do better than consult the article "Shakespeare" in Lowndes' Bibliographer's Manual, where every known edition, translation, and commentary professes to be catalogued and also in many cases collated and described. Some of Halliwell-Phillipps' works, though not absolutely indispensable, are nevertheless exceedingly useful.

Bible collectors do not as a rule notice editions later than what is styled the "Vinegar" Bible, published in 1717. They commence with Coverdale's issue of 1535, and proceed onward in regular order, for the most part arranging their collection not according to date but under the various "versions". This subject is very extensive and exceedingly difficult to handle, so much so that, without a competent guide, it will be found impossible to make satisfactory progress. This is provided in Cotton's Editions of the Bible and Parts thereof in English (1821, 2nd ed., 1852), and J. R. Dore's Old Bibles (1876, 2nd ed., 1888). Mr. Dore is probably the best living authority upon English Bibles and Testaments, and his book is in itself amply sufficient for the amateur. It is published by Eyre & Spottiswoode at 5s.

For works on botany consult Pritzel's Thesaurus Literaturæ Botanicæ (Leipsic, 1847-51, 2nd ed., 1872-7, 4to); and for books exclusively relating to tobacco, some of which are very rare and valuable, W. Bragge's Bibliotheca Nicotiana (priv. prin., r. 8vo, 1880).

Angling and the whole of the literature devoted to it is dealt with in Westwood's new Bibliotheca Piscatoria (1883), and swimming in R. Thomas' Bibliographical List of Works on Swimming (1868, 8vo).

The Greek and Latin Classics were at one time great favourites with all classes of collectors, but of late they have fallen considerably from their high estate. Many of the early [17] editions, being printed by famous houses, as the editio princeps of Virgil's works was, which sold for £590 at the Hopetoun House dispersion, a few months ago, are still eagerly sought after, but not quâ classics—merely as specimens of ancient typography. Ordinary editions of Horace, Virgil, Sallust, Plato, Livy, and the rest can be bought now for a fourth or fifth part of the sum they would have cost thirty or forty years ago, and, from all appearances, they are likely to decline still further in the market. The great work on this subject is Dibdin's Rare and Valuable Editions of the Greek and Latin Classics (2 vols., 1827), which can sometimes be bought by auction for as little as £1.

Art books are so numerous, and so readily subdivided into an infinite number of classes, that they are rarely, if ever, collected as a whole. Amateurs invariably use the Universal Catalogue of Books on Art, which was compiled by order of the Lords of the Committee of the Council on Education, and published between the years 1870-7 (in 3 vols. sm. 4to). It is a work that would be exceedingly difficult to improve upon, though as time goes on it will of course be necessary to add to it.

Works on Shorthand are catalogued by J. W. Gibson (Pitman & Sons, 1887), on Magic and Witchcraft in Scribner's Bibliotheca Diabolica (New York, 1874), while books on music and all about them are noted in C. Engel's Literature of National Music (1879, 8vo).

We now come to the point when a short description of the more modern methods of book collecting becomes a matter of necessity. For some years it has been the fashion to collect not so much works of a certain class as of particular authors, chiefly those which are embellished with plates. By common consent first editions are, with a few exceptions, alone worthy of note; and it is also an axiom that where a book was originally published in parts, those parts must on no account be bound up in volume form. If the collector should be so ill advised as to bind the parts, notwithstanding the decrees of fashion to the contrary, he may save his position no little by binding in the title-pages and also the lists of advertisements, but if he neglects to do this, then his case is hopeless. This is an example of the ridiculous rules which have been laid down by a generation of autocratic book lovers, not one of whom could in all probability give a satisfactory reason for his dicta. [18] It is, however, the rule, and will have to be followed, since great pecuniary loss is certain to follow the slightest infraction of it. Although the amateur does not buy his books to sell again, still I apprehend it is a satisfaction to know that, in case he should ever be compelled, though against his will, to sell them, he will be able to do so without losing by his bargain. Original editions of Dickens' works find a ready market, at ever-increasing prices; but in addition to his better-known books, the very titles of which have now become household words, there are others which are not so generally known, such, for example, as the Curious Dance, the Village Coquettes and many small pieces which are scattered about the pages of the magazines, and are usually classed under the heading Dickensiana. The same remarks, but even perhaps to a still greater extent, apply to Thackeray and his works, for that great author worked for many years before his genius became recognised. The bibliographer who has smoothed the way for the Dickens and Thackeray collector is Mr. C. P. Johnson, in his Hints to Collectors of Original Editions of the Works of Charles Dickens (1885), and his Hints to Collectors of Original Editions of the Works of W. M. Thackeray (1885).

The same author's Early Writings of William Makepeace Thackeray (1888) contains a list of all the pieces which can now be identified, and of the places where they are to be found, so as to put it readily in the power of the biographer, the collector, and the student to refer to them if he will. The Snob, Gownsman, National Omnibus, National Standard, The Constitutional, and Fraser's Magazine all contain essays, articles, or tales from his able pen, which, but for Mr. Johnson's patient efforts, might have been lost in course of time, when the evidence to identify them would have been wanting.

Bibliographies of the works of Carlyle, Swinburne, Ruskin, and Tennyson, as well as those of Dickens and Thackeray, have been compiled by R. H. Shepherd, and of the works of Hazlitt, Leigh Hunt, and Lamb by Alexander Ireland.

That famous artist George Cruikshank illustrated a large number of books, all of which are eagerly sought after by certain bodies of collectors. As in the case of other illustrated books, the value mainly depends upon the earliness of impression of the plates, and the condition; and consequently original editions are more highly esteemed than those which followed. Some capacity for judging engravings is required of the amateur [19] who makes this branch of the subject a speciality, but in other respects he will find almost everything he is likely to require in G. W. Reid's Descriptive Catalogue of the Works of George Cruikshank (London, 1871, 8vo).

Bewick collectors have an infallible guide in the Rev. T. Hugo's Bewick Collector, a Descriptive Catalogue of the Works of T. and J. Bewick (published, with the supplement, in 2 vols., 1866-8, 8vo). It is related of this author that he once found a battered and ragged specimen of a child's book got up on strong-laid paper by the famous engraver. Only one or two copies are known to exist, as Bewick found the enterprise too expensive to pay, and accordingly discontinued it. The owner of this treasure was an old woman, who had derived her infant ideas of lions and tigers from its well-thumbed leaves, and who refused to part with an old friend, though sorely and even desperately pressed to do so.

How often is the enthusiastic book hunter thwarted when

his hopes are on the point of being realised; how often must

he succumb to what he may consider to be nothing better

than prejudice or obstinacy? This is a question which every

amateur learns in time to answer for himself.

[3] To those who do not read French or do not possess Les Elzevier, Mr. Goldsmid's The Elzevir Presses, published as part of his Bibliotheca Curiosa, may be of some assistance. It is a species of compendium of the work of M. Willems, and was issued in 1889. It is somewhat faulty and incomplete; but not without its value to beginners in the study of the Elzevir press.

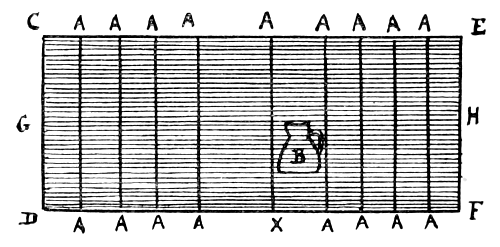

THE mould used by paper-makers is a kind of sieve of an

oblong shape, bottomed with the very finest wire strands, all of

which run horizontally from end to end. From top to bottom,

and about an inch apart, are placed "chain wires," and on the

right-hand side of the mould the wire water-mark, which,

together with the wire-marks, appears semi-transparent. The

reason of this is that both water-mark and wires are slightly

raised, and of course the pulp is thinner there than anywhere

else. Any ordinary sheet of paper held up to the light will

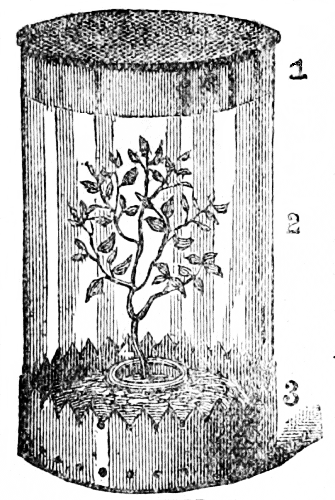

show this, and serve to extra illustrate the following diagram.

Paper-maker's Mould: Jug Water-mark.

Paper-maker's Mould: Jug Water-mark.

Here CDEF is the mould which the workman drops into

a vat of pulp, the fine strands run from G to H all the way

down the mould, AA, &c., are the chain wires, and B is the

[21]

water-mark, in this case a jug. The water in the pulp of

course runs through the sieve, leaving a layer of soft matter,

which after a while hardens into a sheet of paper. The water-mark

was at one time the trade mark of the maker, but subsequently

became merely a symbol denoting the size of the

sheet of paper before it was folded. The smallest sheet was

water-marked with a jug, as above, and termed "pot"; the

next had a cap and bells, hence our term "foolscap"; the

next a horn, hence "post". Others had a "crown," and so

on. At the present day all water-marks have once more

become trade symbols, and cannot be depended upon to

afford any evidence of size; but at one time—i.e., before the

year 1750—this was not so, and, therefore, these water-marks,

irrespective of their antiquarian value, serve a useful purpose—namely,

to point out in cases of doubt whether any given book

is an octavo, quarto, or folio, or a variation of any of these

sizes.

To refer once more to the diagram. Take a sheet of paper supposed to have come from the mould and double it in half at the line AX. The water-mark will in that event appear in the centre of the half sheet, and the folded paper is of folio size. Now fold the paper the contrary way, and the water-mark will appear at the bottom, but cut in half; the paper thus folded is quarto (4to). Now fold it the contrary way again, and a section of the water-mark will appear at the top; the paper thus folded is octavo (8vo). We can go on folding, and in every subsequent case the watermark will appear at the edges, while, as the paper gets smaller and smaller, the sizes are styled 12mo, 16mo, 32mo, and so forth.

In the example given, a book made of the sheet of paper in question would be a pot folio, pot 4to, pot 8vo, and so on; but as larger-sized papers were used, another book might be a post 8vo, or a crown 4to, &c., according to circumstances.

As stated, this is one way of finding out the size of an old book; but there is another way—by means of the "signatures," which consist of small letters or figures at the foot of the page of nearly every book. The leaves (not pages) must be counted between signature and signature, and then if there are two leaves the book is a folio, if four a 4to, if eight an 8vo, if twelve a 12mo, if sixteen a 16mo, and if thirty-two a 32mo. Take, as an example, this very book you hold in your hand, [22] and it will be found that there are eight leaves between signature and signature; hence it is an 8vo, though a small one, owing, of course, to the small size of the paper from which it has been made, viz., crown. Had it been a little smaller (still preserving its oblong shape) it would have been a foolscap 8vo, if somewhat larger a demy 8vo, if larger still a royal 8vo, and largest of all imperial 8vo. The quartos and folios are governed by identical rules, and hence in the trade the sizes of books are very numerous.

Simple as this method of computation may appear, a great deal of controversy has taken place on the subject—so much so, indeed, that there are people to be found who stoutly maintain, and adduce proof to show, that what looks like a 4to is in reality an 8vo, or vice versâ. It would be out of place to enter into a discussion of this nature, and, therefore, I should advise the young collector to count the leaves between signature and signature, and to abide by the result, regardless of all the learned arguments of specialists. If there are no signatures, and the book is an old one, then study the position of the water-mark.

As examples, it will be sufficient to note that the Illustrated London News is folio, Punch is 4to, and the Cornhill and nearly all the monthly magazines are large 8vos. There is a large number of varieties of each size, but on the whole books which approximate to the sizes of magazines are of the sizes named. Occasionally in judging by the eye in this manner a mistake may be made; but of one thing there is no doubt, that a vast amount of argument would have to be expended upon the subject before the judgment could be proved to be wrong.

Paper-makers at one period made their sheets in frames of a given size, so that it was a comparatively easy matter to distinguish the size of a book at a glance. Now-a-days, however, there appears to be but little uniformity in this respect, and the difficulty is consequently considerably increased. The following measurements will, however, be found approximately correct, and they may be utilised in a practical manner by taking a sheet of brown paper of the required size and folding it as previously mentioned, thus forming crown 8vos, crown 4tos, elephant folios, &c., at will. The practice is good, and it will not need to be often repeated.

| a sheet of | foolscap | measures about | 17 in. x 13 in. |

| " | post | " | 19 in. x 15 in. |

| " | crown | " | 20 in. x 15 in. |

| " | demy | " | 22 in. x 17 in. |

| " | royal | " | 24 in. x 19 in. |

| " | imperial | " | 30 in. x 22 in. |

| " | elephant | " | 28 in. x 23 in. |

| " | atlas | " | 34 in. x 26 in. |

The only paper used, as a general rule, for making up into 8vo books is foolscap, post, crown, demy, royal, and imperial; 4to books are made up of all the sizes; though elephant and atlas are chiefly devoted to folios.

I now take leave of this branch of the subject, and return to water-marks, which, as previously stated, were formerly used, as they are now, for trade marks, and as trade marks only.

Before the year 1320, paper was very rarely used to write upon, but still there are a few examples of it having been so employed extant, the chief of which is an account-book preserved at the Hague, commencing with the year 1301. The water-mark on the paper of this book is a globe surmounted by a cross, while on paper of a little later date the rude representation of a jug frequently appears. The globe and the jug are consequently the most ancient water-marks yet discovered, and these became the principal marks on paper, then exclusively manufactured in Holland and Belgium. The "can and reaping hook" appeared a little later, so did the "two cans," the "open hand," and the "half fleur-de-lis," all executed, as might be expected, in the rudest possible manner.

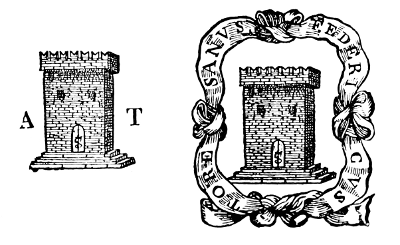

The Holbein family at Ravensburg—a town famous to this day for the manufacture of paper—used a "bull's head". Fust and Schœffer (circa 1460) used a "clapper" or rattle, which has a somewhat curious history. At Ravensburg there was an hospital for lepers, and whenever any of the inmates had occasion to leave the building he was strictly enjoined to flourish a rattle with which he was provided, so that healthy folk could get out of his way. Paper made at the town is often found marked with the rattle, that having grown, by reason of its frequent use, into an institution of the place.

The next marks in point of date are in all probability the "unicorn," "anchor," and the "P" and "Y," the initials of[24] Philip of Burgundy and his wife Isabella, who were married in 1430.

The famous English printer Caxton (c. A.D. 1424-91)[4] used the "bull's head" paper from Ravensburg, the "P" and "Y," the "open hand," and the "unicorn"; sometimes even the "bunch of grapes," which came from Italy.

The first folio of Shakespeare's works (1623) has paper marked with a "fool's cap" among other devices. The "post horn," another favourite device, which has given the name to a particular size of paper—namely, "post"—was first used about the year 1670, when the General Post Office was established, and it became the fashion for the postman to blow a horn.

In modern times paper-marks have become so numerous

that it would be next to impossible to classify them; nor would

it be of much advantage to the book collector even if it could

be done. With old marks it is different, for fac-simile reprints

of scarce and ancient volumes are frequently detected by

looking at the water-mark on the paper. Of course, this also

may be imitated, but there is often considerable difficulty

in attaining the requisite degree of perfection; and, under any

circumstance, some little knowledge of the early history and

appearance of water-marks will be found useful as well as

interesting. The best books to consult on the subject are

Herring's Paper and Papermaking and Sotheby's Principia

Typographica, 1858, the latter of which is a masterpiece of

learning and constructive skill.

[4] It is very improbable that Caxton was born in 1412, as nearly all his biographers state, but about ten or twelve years later. Evidence of this is contained in the records preserved at Mercers' Hall, Cheapside, London, where his name is inscribed as having been apprenticed in the year 1438, the age at which apprenticeship was entered upon being most commonly between twelve and fourteen years.

IT must be borne in mind that the title-page of a book, though constituting a very old method of showing at a glance the nature of the contents, together with the place of publication and frequently also the date, is by no means the earliest means of attaining that object. The title-page, such as we see it, was first adopted in England in 1490, the year before Caxton's death, having been introduced on the Continent in 1470;[5] but previously—and, indeed, for some years after that date—the Colophon was in general use.

The term "Colophon" has its origin in the Greek proverb, "to put the colophon to the matter," that is, the "finishing stroke," and contains the place or year (or both), date of publication, printer's name, and other particulars considered necessary at the time for the identification of the volume. It frequently commences somewhat after the following form: Explicit liber qui dicitur, &c.[6] The colophon, moreover, is always found on the last page, and sometimes takes the form of an inverted pyramid. In the early days, when the printer was not unfrequently author or translator as well, the completion of a work upon which he had probably been engaged for many months—or, perhaps, in some instances, years—was rightly regarded as matter for much self-congratulation, as well as for thanks to the Divine Power, by whose permission alone he had [26] been enabled to persevere. Hence the Psalterium of Fust and Schœffer, a folio of 175 lines to the page, and remarkable as being the first book in which large capital letters, printed in colours, were employed, has for its colophon a very characteristic inscription, which may be translated as follows:—

"This book of Psalms, decorated with antique initials and sufficiently emphasised with rubricated letters, has been thus made by the masterly invention of printing and also type-making, without the writing of a pen, and is consummated to the service of God through the industry of Johann Fust, citizen of Mentz, and Peter Schœffer, of Gernsheim, in the year of our Lord MCCCCLVII., on the eve of the Assumption".

This Psalter is also the first known book which bears any date at all, and for that and other reasons is one of the most highly prized of volumes.

From what has been said, the reader will no doubt clearly understand that it does not follow that, because an old book is minus a title-page, it is necessarily imperfect. He should turn to the last leaf for the colophon; but should that be wanting also, it is probable that the book is deficient, though even this is not a conclusive test. In cases of doubt the volume must be collated, that is, critically compared with some other specimen: each leaf must be examined carefully, and notes made of any differences that may appear during the course of the examination. There is a business-like way and the reverse of tabulating these notes, so much so that an adept can see at a glance whether it has been performed by a competent man. The following is the collation of a copy of the first edition of the famous Genevan version of the Bible printed by Rowland Hall in 1560, 4to: "Four prel. leaves. Text, Genesis to ii. Maccabees, 474 ll. folioed, N. T. 122 leaves, 'A Briefe Table' HH h iii to LLl iii., 13 ll. followed by 1 p. 'The order of the yeres from Paul's conversion,' &c., rev. blank."

At first sight this may appear somewhat technical, but when a few of these collations are compared with actual copies of the works to which they refer, there will be no difficulty in understanding all the rest. The above, for instance, would read, when set out at full length, as follows: "There are four preliminary leaves, and then follows the Bible text proper, which, from Genesis to the 2nd of Maccabees, is on 474 numbered leaves. The New Testament, which follows, has 122 leaves; [27] then comes 'A Briefe Table,' extending from signature HH h iii to LL l iii, and comprising 13 leaves, followed by one page, 'The order of the yeres from Paul's conversion,' &c. The reverse side of this page is blank." The words "page" and "leaf" have distinct meanings, the latter, of course, containing two of the former, unless, indeed, one side happens to be blank, as in the above example. If both sides are blank, the description would be simply "i 1 blank".

From 1457—the date of Fust and Schœffer's Psalter, already described as being the first printed book disclosing on its face the year of publication—until comparatively recent times, it was customary to use Roman numerals on the colophon or title-page, as the case might be. This system of notation is so well understood, or can be so speedily mastered from almost any arithmetical treatise, that it is hardly worth while to enlarge upon it here. On some old books, however, there is a dual form of the "D" representing 500, which is sometimes the cause of considerable perplexity; e.g., MIƆXL standing for the year 1540. In this example the I is equivalent to D; in fact, it would appear as if the former numeral were merely a mutilation of the latter. Again, the form CIƆ is equivalent to M or 1000. A few instances will make the distinction apparent:—

| M IƆ XXIV or M D XXIV |

= 1524; |

| CIƆ IƆ CLXXXV or M D CLXXXV |

= 1661; |

| CIƆ IƆ CLXXXV or M D CLXXXVIII |

= 1685; |

The only part of a title-page which gives any real difficulty

to a person who has a fair knowledge of the Latin language, in

which most of these old books were printed, is the name of

the place of publication, which, being in a Latinised form,

frequently bears but a slight resemblance to the modern

appellation. Dr. Cotton, many years ago now, collected a

large number of these Latin forms, partly from his own

reading and partly from the works of various bibliographers

who had chanced occasionally to mention them in their works,

and at the present day his collection stands unapproachable in

point of the number of entries, as well as in general accuracy.

The use of this compilation will be apparent to those who have

occasion to consult it even for the first time, while to advanced

[28]

collectors, who are not satisfied with mere possession, it will be

found indispensable. The title-page of a book now before me

runs as follows: "Kanuti Episcopi Vibergensis Quedam breves

expositõs s legum et jurium cõcordantie et allegatiões circa leges

iucie"; at the foot is "Ripis, M. Brand, MIƆIIII". The

question immediately arises: Where is Ripis, the place where

the book was evidently printed by Brand? The best gazetteer

may be consulted in vain, for the title is obsolete now; it is, in

fact, the Roman name for Riben, a small place in Denmark.

In like manner, Firenze frequently stands for Florence, Brixia

for Breschia, Aug. Trinob. (Augusta Trinobantum) for London,

Mutina for Modena, and so on. This being the case, some

kind of tabulation becomes absolutely necessary, and the best

that occurs to my mind is to place the Latin titles of all the

chief centres of printing in alphabetical order, and append to

each the English equivalent. The date is that of the first book

known to have been printed at the particular town against

which it is set. As the list is not complete, and could not be

made so without the sacrifice of a great deal of space, the

reader is referred to Dr. Cotton's Typographical Antiquities

for any further information he may require. The omissions

will be found, however, to consist, for the most part, of unimportant

places, from many of which only some half-dozen books

or less are known to have been issued, so that the following list

will be found sufficient in the vast majority of cases:—

| 1486. | Abbatis Villa | Abbeville. |

| 1621. | Abredonia | Aberdeen. |

| 1493. | Alba | Acqui (in Italy). |

| 1480. | Albani Villa | St. Albans. |

| 1501. | Albia | Albia (in Savoy). |

| 1480. | Aldenarda | Oudenarde. |

| 1473. | Alostum | Alost (in Flanders). |

| 1467. | Alta Villa | Eltville, or Elfeld (near Mayence). |

| 1523. | Amstelœdamum | Amsterdam. |

| 1476. | Andegavum | Angers. |

| Aneda | Edinburgh. | |

| 1491. | Angolismum | Angoulême. |

| 1482. | Antverpia | Antwerp. |

| 1482. | Aquila | Aquila (near Naples). |

| 1456(?). | Argentina, or Argentoratum | Strassburg. |

| 1477. | Asculum | Ascoli (in Ancona). |

| 1474.[29] | Athenæ Rauracæ | Basle. |

| 1517. | Atrebatum | Arras. |

| 1469. | Augusta Vindelicorum | Augsburg. |

| 1480. | Augusta Trinobantum | London. |

| 1481. | Auracum | Urach (in Wurtemberg). |

| 1490. | Aurelia | Orleans. |

| 1490. | Aureliacum | Orleans. |

| 1497. | Avenio | Avignon. |

| 1462. | Bamberga | Bamberg. |

| 1478. | Barchine | Barcelona. |

| 1497. | Barcum | Barco (in Italy). |

| 1474. | Basilea | Basle. |

| 1470. | {Berona, or Beronis Villa } | Beron Minster (in Switzerland). |

| 1487. | Bisuntia | Besançon. |

| 1471. | Bononia | Bologna. |

| 1485. | Bravum Burgi | Burgos. |

| 1472. | Brixia | Breschia. |

| 1475. | Brugæ | Bruges. |

| 1486. | Brunna | Brunn. |

| 1476. | Bruxellæ | Brussels. |

| 1473. | Buda | Buda. |

| 1485. | Burgi | Burgos. |

| 1484. | Buscum Ducis | Bois-le-duc. |

| 1478. | Cabelia | Chablies (in France). |

| 1480. | Cadomum | Caen. |

| 1475. | Cæsar Augusta, or Caragoça | Saragossa. |

| 1484. | Camberiacum | Chambery. |

| 1521. | Cantabrigia | Cambridge. |

| 1497. | Carmagnola | Carmagnola. |

| 1622. | Carnutum | Chartres. |

| 1494. | Carpentoratum | Carpentras. |

| 1486. | Casale Major | Casal-Maggiore. |

| 1475. | Cassela | Caselle (in Piedmont). |

| 1484. | Chamberium | Chambery. |

| 1482. | Coburgum | Coburg. |

| 1466. | Colonia | Cologne. |

| 1466. | Colonia Agrippina | Cologne. |

| 1466. | Colonia Claudia | Cologne. |

| 1460. | Colonia Munatiana | Basle. |

| 1466. | Colonia Ubiorum | Cologne. |

| 1474.[30] | Comum | Como. |

| 1516. | Conimbrica | Coimbra. |

| 1505. | Constantia | Constance. |

| 1487. | Cordova | Cordova. |

| 1469. | Coria | Soria (in Old Castile). |

| 1500(about). | Cracovia | Cracow (Poland). |

| 1472. | Cremona | Cremona. |

| 1480. | Culemburgum | Culembourg (in Holland). |

| 1478. | Cusentia | Cosenza. |

| 1475. | Daventria | Deventer (in Holland). |

| 1477. | Delphi | Delft. |

| 1491. | Divio | Dijon. |

| 1490. | Dola | Dol (in France). |

| 1564. | Duacum | Douay. |

| Eblana | Dublin. | |

| 1509. | Eboracum | York. |

| Edemburgum | Edinburgh. | |

| 1440(?). | Elvetrorum Argentina | Strassburg. |

| 1491. | Engolismum | Angoulême. |

| 1482. | Erfordia | Erfurt. |

| 1472. | Essium | Jesi (in Italy). |

| 1473. | Esslinga | Esslingen (in Wurtemberg). |

| 1531. | Ettelinga | Etlingen. |

| 1471. | Ferrara | Ferrara. |

| 1471. | Firenze | Florence. |

| 1472. | Fivizanum | Fivzziano (in Tuscany). |

| 1471. | Florentia | Florence. |

| 1495. | Forum Livii | Forli (in Italy). |

| 1504. | Francofurtum ad Mœnum | Frankfort on the Maine. |

| 1504. | Francofortum ad Oderam | Frankfort on the Oder. |

| 1495. | Frisinga | Freysingen. |

| 1470. | Fulgineum | Foligno (in Italy). |

| 1487. | Gaietta | Gaeta. |

| 1490. | Ganabum | Orleans. |

| 1483. | Gandavvm, or Gand | Ghent. |

| 1478. | Geneva | Geneva. |

| 1474. | Genua | Genoa. |

| 1483. | Gerunda | Gerona (in Spain). |

| 1477. | Gouda | Gouda. |

| 1490. | Gratianopolis | Grenoble. |

| 1493. | Hafnia | Copenhagen. |

| Haga Comitum | The Hague. | |

| 1491.[31] | Hamburgum | Hamburg. |

| 1491. | Hamnionia | Hamburg. |

| 1483. | Harlemum (probably earlier date) | Haarlem. |

| 1504. | Helenopolis | Frankfort on the Maine. |

| 1479. | Herbipolis | Wurtzburg. |

| 1476. | Hispalis, or Colonia Julia Romana | Seville. |

| 1483. | Holmia | Stockholm. |

| 1487. | Ingolstadium | Ingolstadt. |

| 1473. | Lauginga | Laugingen (in Bavaria). |

| 1483. | Leida | Leyden. |

| 1495. | Lemovicense Castrum | Limoges. |

| 1566. | Leodium | Liège. |

| 1503. | Leucorea | Wittemburg. |

| 1480. | Lipsia | Leipsic. |

| 1485. | Lixboa | Lisbon. |

| 1474(?). | Londinum | London. |

| 1474. | Lovanium | Louvain. |

| 1475. | Lubeca | Lubec. |

| 1477. | Luca | Lucca. |

| 1473. | Lugdunum | Lyons. |

| 1483. | Lugdunum Batavorum | Leyden. |

| 1499. | Madritum | Madrid. |

| 1483. | Magdeburgum | Magdeburg. |

| 1442(?). | Maguntia | Mayence. |

| 1732. | Mancunium | Manchester. |

| 1472. | Mantua | Mantua. |

| 1527. | Marpurgum | Marburg. |

| 1473. | Marsipolis | Mersburg. |

| 1493. | Matisco | Maçon. |

| 1470. | Mediolanum | Milan. |

| 1473. | Messana | Messina. |

| 1500. | Monachium | Munich. |

| 1470. | Monasterium | Munster (in Switzerland). |

| 1472. | Mons Regalis | Mondovi (in Piedmont). |

| 1475. | Mutina | Modena. |

| 1510. | Nanceium | Nancy. |

| 1471. | Neapolis | Naples. |

| 1493. | Nannetes | Nantes. |

| 1525. | Nerolinga | Nordlingen (in Suabia). |

| 1480. | Nonantula | Nonantola (in Modena). |

| 1469. | Norimberga | Nuremberg. |

| 1479. | Novi | Novi (near Genoa). |

| 1479.[32] | Noviomagium | Nimeguen. |

| 1533. | Neocomum | Neuchatel. |

| 1494. | Oppenhemium | Oppenheim. |

| 1468. | Oxonia | Oxford (the date is disputed). |

| 1477. | Panormum | Palermo. |

| 1471. | Papia | Pavia. |

| 1470. | Parisii | Paris. |

| 1472. | Parma | Parma. |

| 1481. | Patavia | Passau (in Bavaria). |

| 1472. | Patavium | Padua. |

| 1475. | Perusia | Perugia. |

| 1479. | Pictavium | Poitiers. |

| 1483. | Pisa | Pisa. |

| 1472. | Plebisacium | Piobe de Sacco (in Italy). |

| 1478. | Praga | Prague. |

| 1495. | Ratiastum Lemovicum | Limoges. |

| 1485. | Ratisbona | Ratisbon. |

| 1480. | Regium | Reggio. |

| 1482. | Reutlinga | Reutlingen. |

| 1484. | Rhedones | Rennes. |

| 1503. | Ripa or Ripis | Ripen (in Denmark). |

| 1467. | Roma | Rome. |

| 1487. | Rothomagum | Rouen. |

| 1479. | Saena | Siena. |

| 1480. | Salmantice | Salamanca. |

| 1470. | Savillianum | Savigliano (in Piedmont). |

| 1474. | Savona | Savona. |

| 1483. | Schedamum | Schiedam. |

| 1479. | Senæ | Siena. |

| 1484. | Soncino | Soncino (Italy). |

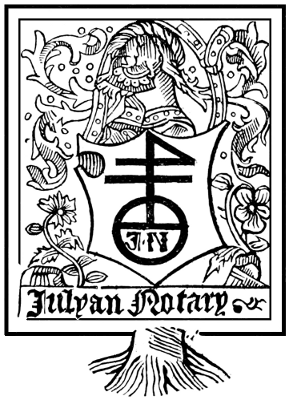

| 1514. | Southwark | Southwark. |

| 1471. | Spira | Spires (in Pavaria). |

| 1465. | Sublacense Monasterium. An independent monastery about two miles distant from Subiaco, in the Campagna di Roma. | |

| 1484. | Sylva Ducis | Bois-le-duc. |

| 1471. | Tarvisium | Treviso (in Italy). |

| 1474. | Taurinum | Turin. |

| 1468. | Theatrum Sheldonianum (the date is disputed) | Oxford. |

| 1521. | Tigurum | Zurich. |

| 1479. | Tholosa | Toulouse. |

| 1480. | Toletum | Toledo. |

| 1473. | Trajectum ad Rhenum | Utrecht. |

| 1504.[33] | Trajectum ad Viadrum | Frankfort on the Oder. |

| 1471. | Trajectum Inferius | Utrecht. |

| 1470. | Trebia | Trevi (in Italy). |

| 1483. | Trecæ | Troyes. |

| 1440 (?). | Tribboccorum | Strassburg. |

| 1483. | Tricasses | Troyes. |

| 1476. | Tridentum Trent (in the Tyrol). | |

| 1498. | Tubinga | Tübingen. |

| 1521. | Turigum | Zurich. |

| 1496. | Turones | Tours. |

| 1479. | Tusculanum | Toscolano (in Italy). |

| 1471(?). | Ulma | Ulm. |

| 1471. | Ultrajectum | Utrecht. |

| 1485. | Ulyssipo | Lisbon. |

| 1481. | Urbinum | Urbino. |

| 1474. | Valentia | Valentia. |

| 1474. | Vallis S. Mariæ

near Mentz, now suppressed). | |

| 1469. | Venetiæ | Venice. |

| 1485. | Vercellæ | Vercelli. |

| 1470. | Verona | Verona. |

| 1487. | Vesontio | Besançon. |

| 1473. | Vicentia | Vicenza. |

| 1517. | Vilna | Wilna (in Russia). |

| 1482. | Vindobona | Vienna. |

| 1503. | Vitemberga | Wittemburg. |

| 1488. | Viterbium | Viterbo. |

| Vratislavia | Breslau. | |

| 1474. | Westmonasterium | Westminster. |

| 1475. | Wirceburgum | Wurtzburg. |

[5] Vide Pollard's Last Words on the History of the Title-page (Lond., 1891).

[6] Some recent French publishers, such as Quantin and Rouveyre, have imitated the practice in their editions for bibliophiles.

THE reasons which contribute to make up the pecuniary value of a book depend on a variety of circumstances by no means easy of explanation. It is a great mistake to suppose that because a given work is scarce, in the sense of not often being met with, it is necessarily valuable. It may certainly be so, but, on the other hand, plenty of books which are acquired with difficulty are hardly worth the paper they are printed upon, perhaps because there is no demand for them, or possibly because they are imperfect or mutilated.

One of the first lessons I learned when applying myself to the study of old books was never, on any account or under any circumstances, to have anything to do with imperfect copies, and I have not so far had any occasion to regret my decision. It is perfectly true that no perfect copies are known of some works, such, for example, as the first or 1562-3 English edition of Fox's Book of Martyrs; but books of this class will either never be met with during a lifetime, or will form, if met with, an obvious exception to the rule. Fragments of genuine Caxtons, again, sometimes sell by auction for two or three pounds a single leaf, and even a very imperfect copy of any of his productions would be considered a good exchange for a large cheque; but these are exceptions and nothing more— exceptions, moreover, of such rare practical occurrence as to be [35] hardly worth noting. In the vast majority of instances, when a book is mutilated it is ruined; even the loss of a single plate out of many will often detract fifty per cent. or more from the normal value, while if the book is "cut down" the position is worse. This lesson as a rule is only learned by experience, and many young collectors resolutely shut their eyes to the most apparent of truisms, until such time as the consequences are brought fairly home to them. It is exceedingly dangerous to purchase imperfect or mutilated books, or to traffic in them at all. This position will be enlarged upon during the progress of the present chapter.

To return to the reasons which contribute to the value of a book, it may be mentioned that "suppression" is one of the chief. This is a natural reason; others are merely artificial, which may be in full force to-day but non-existent to-morrow, depending as they do upon mere caprice and the vagaries of fashion: with these I have, in this volume at any rate, nothing to do.

De Foe, in his Essay on Projects, observes: "I have heard a bookseller in King James's time say that if he would have a book sell, he would have it burned by the hands of the common hangman," by which he presupposed the existence of some little secret horde which should escape the general destruction, and which would consequently rise to ten times its value directly the persecution was diverted into other channels. This is so, for where an edition has been suppressed, and most of the copies destroyed, the remainder acquire an importance which the whole issue would never have enjoyed had it been left severely alone. The Inquisition has been the direct cause of elevating hundreds of books to a position far above their merit, and the same may be said of Henry VIII., who sent Catholic as well as Protestant books wholesale to the flames; of Mary, who condemned the latter; of Edward VI., who acquiesced in the destruction of the former; and of Elizabeth and the two succeeding sovereigns, who delighted in a holocaust of political pamphlets and libels.

The Inquisition, with that brutal bigotry which characterised most of its proceedings, almost entirely destroyed Grafton's Paris Bible of 1538, with the result that the printing presses, types, and workmen were brought to London, and the few copies saved were completed here, to be sold on rare occasions [36] at the present day for as much as £160 apiece. There is nothing in the Bible more than in any other; it is not particularly well printed, but it has a history, just as the Scotch Bassandyne Bible has, though in that case the persecution was directed against persons who declined to have the book in their houses, ready to be shown to the tax collector whenever he chose to call. One Dr. James Drake, who in the year 1703 had the temerity to publish in London his Historia Anglo-Scotica, which contained, as was alleged, many false and injurious reflections upon the sovereignty and independence of the Scottish nation, had the pleasure of hearing that his work had been publicly burned at the Mercat Cross of Edinburgh, a pleasure which was doubtless considerably enhanced when another venture—the Memorial—shared the same fate in London, two years later. Drake had the honour of hearing himself censured from the throne, of being imprisoned, and of having his books burned, distinctions which some people sigh for in vain at the present day. As a consequence, the Historia and the Memorial are both desirable books, and Drake's name has been rescued from oblivion.

William Attwood's Superiority and Direct Dominion of the Imperial Crown of England over the Crown and Kingdom of Scotland (London, 4to, 1705) is another book of good pedigree which would never have been worth the couple of guineas a modern bookseller will ask for it, had it not been burned by jealous Scotchmen immediately on its appearance.

The massacre of St. Bartholomew produced a large crop of treatises, and any contemporary book on the Huguenot side is worth preservation, for a general search was made throughout France, and every work showing the slightest favour to the Protestants was seized and destroyed. Among them was Claude's Défense de la Réformation (1683), which was burned not only abroad, but in England as well, so great an ascendency had the French Ambassador acquired over our Court.

Bishop Burnet's Pastoral letter to the Clergy of his Diocese (1689) was condemned and burned for ascribing the title of William III. to the Crown, to the right of conquest. The Emilie and the Contrat Social of Jean Jacques Rousseau shared the same fate, as did also Les Histoires of d'Aubigné and Augustus de Thou.

Baxter's Holy Commonwealth went the way of all obnoxious books, in 1688; the Boocke of Sportes upon the Lord's Day, in 1643; the Duke of Monmouth's proclamation declaring James [37] to be an usurper, in 1685; Claude's Les Plaintes des Protestans, in 1686.

Harris' Enquiry into the Causes of the Miscarriage of the Scots Colony at Darien (Glasgow, 1700); Bastwicke's Elenchus Religionis Papisticæ (1634); Blount's King William and Queen Mary, Conquerors, &c. (1692); the second volume of Wood's Athenæ Oxoniensis (1793); De Foe's Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702); Pocklington's Sunday no Sabbath and Altare Christianum (1640); Sacheverel's Two Sermons (1710); and Coward's Second Thoughts concerning the Human Soul (1702), were all burned by the hangman, and copies destroyed wherever found.