Title: In Pastures New

Author: George Ade

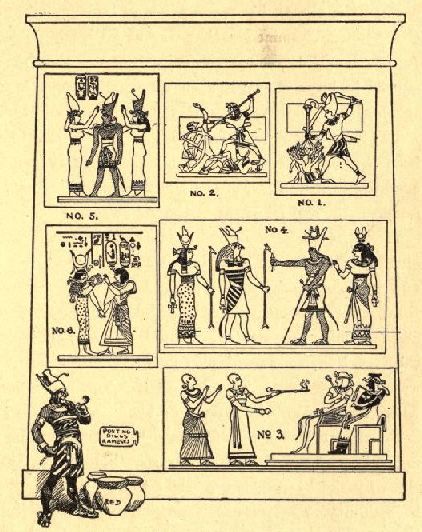

Illustrator: Albert Levering

Release date: December 22, 2011 [eBook #38364]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

Holds it the same as a slide trombone

BY

GEORGE ADE

TORONTO

THE MUSSON BOOK COMPANY, LIMITED

1906

Copyright, 1906, by

McCLURE, PHILLIPS & CO.

Published, October, 1906

Copyright, 1906, by George Ade

Many of the letters appearing in this volume were printed in a syndicate of newspapers in the early months of 1906. With these letters have been incorporated extracts from letters written to the Chicago Record in 1895 and 1898. For the use of the letters which first appeared in the Chicago Record, acknowledgment is due Mr. Victor F. Lawson.

CONTENTS

In London

In Paris

| VII. | How an American Enjoys Life for Eight Minutes at a Time |

| VIII. | A Chapter of French Justice as Dealt Out in the Dreyfus Case |

| IX. | The Story of What Happened to an American Consul |

In Naples

| X. | Mr. Peasley and His Vivid Impressions of Foreign Parts |

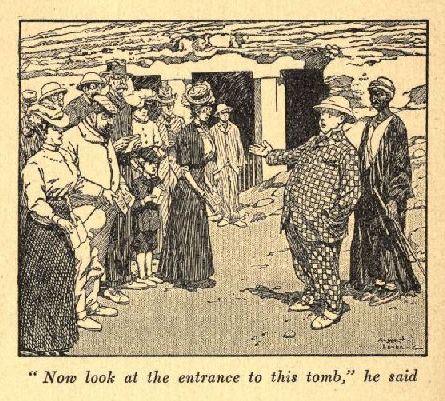

In Cairo

In Cairo

| XX. | Mr. Peasley and his Final Size-up of Egypt |

GETTING ACQUAINTED WITH THE

ENGLISH LANGUAGE

It may be set down as a safe proposition that every man is a bewildered maverick when he wanders out of his own little bailiwick. Did you ever see a stock broker on a stock farm, or a cow puncher at the Waldorf?

A man may be a large duck in his private puddle, but when he strikes deep and strange waters he forgets how to swim.

Take some captain of industry who resides in a large city of the Middle West. At home he is unquestionably IT. Everyone knows the size of his bank account, and when he rides down to business in the morning the conductor of the trolley holds the car for him. His fellow passengers are delighted to get a favouring nod from him. When he sails into the new office building the elevator captain gives him a cheery but deferential "good morning." In his private office he sits at a $500 roll top desk from Grand Rapids, surrounded by push buttons, and when he gives the word someone is expected to hop. At noon he goes to his club for luncheon. The head waiter jumps over two chairs to get at him and relieve him of his hat and then leads him to the most desirable table and hovers over him even as a mother hen broods over her first born.

This Distinguished Citizen, director of the First National Bank, trustee of the Cemetery Association, member of the Advisory Committee of the Y.M.C.A., president of the Saturday Night Poker Club, head of the Commercial Club, and founder of the Wilson County Trotting Association, is a whale when he is seated on his private throne in the corn belt. He rides the whirlwind and commands the storm. The local paper speaks of him in bated capital letters, and he would be more or less than human if he failed to believe that he was a very large gun.

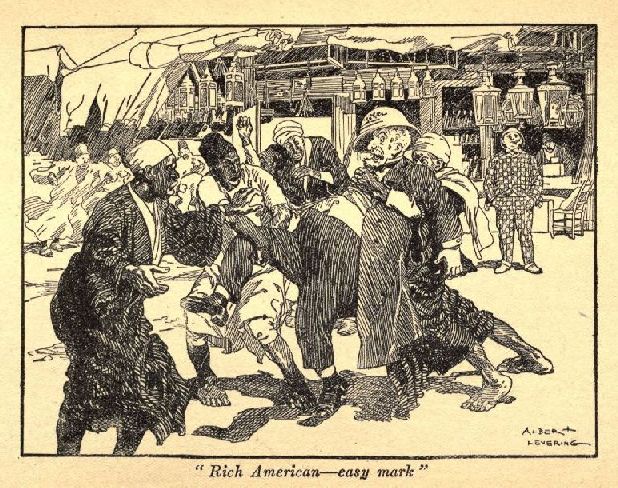

Take this same Business Behemoth and set him down in Paris or Rome or Naples. With a red guide book clutched helplessly in his left hand and his right hand free, so that he can dig up the currency of the realm every thirty seconds, he sets forth to become acquainted with mediæval architecture and the work of the old masters. He is just as helpless and apprehensive as a country boy at Coney Island. The guides and cabmen bullyrag him. Newsboys and beggars pester him with impunity. Children in the street stop to laugh at his Kansas City hat known to the trade as a Fedora. When he goes into a shop the polite brigand behind the showcase charges him two prices and gives him bad money for change.

Stop to laugh at his Kansas City hat

Why? Because he is in a strange man's town, stripped of his local importance and battling with a foreign language. The man who cannot talk back immediately becomes a weakling.

What is the chief terror to travel? It is the lonesomeness of feeling that one cannot adapt himself to the unfamiliar background and therefore is sure to attract more or less attention as a curio. And in what city does this feeling of lonesomeness become most overwhelming? In London.

The American must go to England in order to learn for a dead certainty that he does not speak the English language. On the Continent if he kicks on the charges and carries a great deal of hand luggage and his clothes do not fit him any too well he may be mistaken for an Englishman. This great joy never awaits him in London.

I do not wish to talk about myself, yet I can say with truthfulness that I have been working for years to enrich the English language. Most of the time I have been years ahead of the dictionaries. I have been so far ahead of the dictionaries that sometimes I fear they will never catch up. It has been my privilege to use words that are unknown to Lindley Murray. Andrew Lang once started to read my works and then sank with a bubbling cry and did not come up for three days.

It seems that in my efforts to enrich the English language I made it too rich, and some who tried it afterward complained of mental gastritis. In one of my fables, written in pure and undefiled Chicago, reference was made to that kind of a table d'hôte restaurant which serves an Italian dinner for sixty cents. This restaurant was called a "spaghetti joint." Mr. Lang declared that the appellation was altogether preposterous, as it is a well-known fact that spaghetti has no joints, being invertebrate and quite devoid of osseous tissue, the same as a caterpillar. Also he thought that "cinch" was merely a misspelling of "sink," something to do with a kitchen. Now if an American reeking with the sweet vernacular of his native land cannot make himself understood by one who is familiar with all the ins and outs of our language, what chance has he with the ordinary Londoner, who gets his vocabulary from reading the advertisements carried by sandwich men?

This pitiful fact comes home to every American when he arrives in London—there are two languages, the English and the American. One is correct; the other is incorrect. One is a pure and limpid stream; the other is a stagnant pool, swarming with bacilli. In front of a shop in Paris is a sign, "English spoken—American understood." This sign is just as misleading as every other sign in Paris. If our English cannot be understood right here in England, what chance have we among strangers?

One of the blessed advantages of coming here to England is that every American, no matter how old he may be or how often he has assisted at the massacre of the mother tongue, may begin to get a correct line on the genuine English speech. A few Americans, say fifty or more in Boston and several in New York, are said to speak English in spots. Very often they fan, but sometimes they hit the ball. By patient endeavor they have mastered the sound of "a" as in "father," but they continue to call a clerk a clerk, instead of a "clark," and they never have gained the courage to say "leftenant." They wander on the suburbs of the English language, nibbling at the edges, as it were. Anyone living west of Pittsburg is still lost in the desert.

It is only when the Pilgrim comes right here to the fountain head of the Chaucerian language that he can drink deep and revive his parched intellect. For three days I have been camping here at the headwaters of English. Although this is my fourth visit to London and I have taken a thorough course at the music halls and conversed with some of the most prominent shopkeepers on or in the Strand, to say nothing of having chatted almost in a spirit of democratic equality with some of the most representative waiters, I still feel as if I were a little child playing by the seashore while the great ocean of British idioms lies undiscovered before me.

Yesterday, however, I had the rare and almost delirious pleasure of meeting an upper class Englishman. He has family, social position, wealth, several capital letters trailing after his name (which is long enough without an appendix), an ancestry, a glorious past and possibly a future. Usually an American has to wait in London eight or ten years before he meets an Englishman who is not trying to sell him dress shirts or something to put on his hair. In two short days—practically at one bound—I had realised the full ambition of my countrymen.

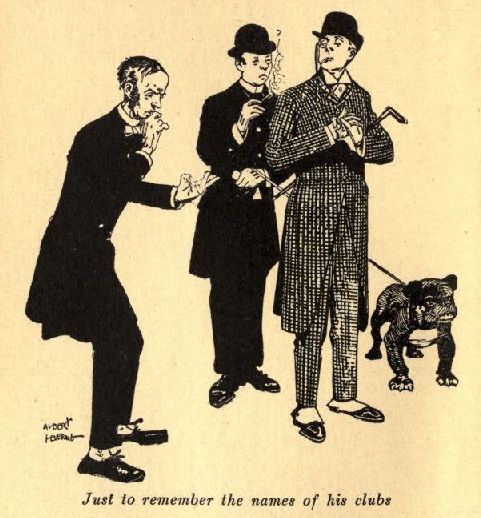

Before being presented to the heavy swell I was taken into the chamber of meditation by the American who was to accompany me on this flight to glory. He prepared me for the ceremony by whispering to me that the chap we were about to meet went everywhere and saw everybody; that he was a Varsity man and had shot big game and had a place up country, and couldn't remember the names of all his clubs—had to hire a man by the year just to remember the names of his clubs.

May I confess that I was immensely flattered to know that I could meet this important person? When we are at long range we throw bricks at the aristocracy and landed gentry, but when we come close to them we tremble violently and are much pleased if they differentiate us from the furniture of the room.

Just to remember the names of his clubs

Why not tell the truth for once? I was tickled and overheated with bliss to know that this social lion was quite willing to sit alongside of me and breathe the adjacent atmosphere.

Also I was perturbed and stage frightened because I knew that I spoke nothing but the American language, and that probably I used my nose instead of my vocal chords in giving expression to such thoughts as might escape from me. Furthermore, I was afraid that during our conversation I might accidentally lapse into slang, and I knew that in Great Britain slang is abhorred above every other earthly thing except goods of German manufacture. So I resolved to be on my guard and try to come as near to English speech as it is possible for anyone to come after he has walked up and down State street for ten years.

My real and ulterior motive in welcoming this interview with a registered Englishman was to get, free of charge, an allopathic dose of 24-karat English. I wanted to bask in the bright light of an intellect that had no flickers in it and absorb some of the infallibility that is so prevalent in these parts.

We met. I steadied myself and said:—"I'm glad to know you—that is, I am extremely pleased to have the honour of making your acquaintance."

He looked at me with a kindly light in his steel blue eye, and after a short period of deliberation spoke as follows:—"Thanks."

"Thanks"

"The international developments of recent years have been such as should properly engender a feeling of the warmest brotherhood between all branches of the Anglo-Saxon race," I said. "I don't think that any fair-minded American has it in for Great Britain—that is, it seems to me that all former resentment growing out of early conflicts between the two countries has given way to a spirit of tolerant understanding. Do you not agree with me?"

He hesitated for a moment, as if not desiring to commit himself by a hasty or impassioned reply, and then delivered himself as follows:—"Quite."

"It seems to me," I said, following the same line of thought, "that fair-minded people on both sides of the water are getting sore—that is, losing patience with the agitators who preach the old doctrine that our attitude toward Great Britain is necessarily one of enmity. We cannot forget that when the European Powers attempted to concert their influence against the United States at the outset of the late war with Spain you bluffed them out—that is, you induced them to relinquish their unfriendly intentions. Every thoughtful man in America is on to this fact—that is, he understands how important was the service you rendered us—and he is correspondingly grateful. The American people and the English people speak the same language, theoretically. Our interests are practically identical in all parts of the world—that is, we are trying to do everybody, and so are you. What I want to convey is that neither nation can properly work out its destiny except by co-operating with the other. Therefore any policy looking toward a severance of friendly relations is unworthy of consideration."

"Rot!" said he.

"Just at present all Americans are profoundly grateful to the British public for its generous recognition of the sterling qualities of our beloved Executive," I continued. "Over in the States we think that 'Teddy' is the goods—that is, the people of all sections have unbounded faith in him. We think he is on the level—that is, that his dominant policies are guided by the spirit of integrity. As a fair-minded Briton, who is keeping in touch with the affairs of the world, may I ask you your candid opinion of President Roosevelt?"

After a brief pause he spoke as follows:—"Ripping!"

"The impulse of friendliness on the part of the English people seems to be more evident year by year," I continued. "It is now possible for Americans to get into nearly all the London hotels. You show your faith in our monetary system by accepting all the collateral we can bring over. No identification is necessary. Formerly the visiting American was asked to give references before he was separated from his income—that is, before one of your business institutions would enter into negotiations with him. Nowadays you see behind the chin whisker the beautiful trade mark of consanguinity. You say, 'Blood is thicker than water,' and you accept a five-dollar bill just the same as if it were an English sovereign worth four dollars and eighty-six cents."

"Jolly glad to get it," said he.

"Both countries have adopted the gospel of reciprocity," I said, warmed by this sudden burst of enthusiasm. "We send shiploads of tourists over here. You send shiploads of English actors to New York. The tourists go home as soon as they are broke—that is, as soon as their funds are exhausted. The English actors come home as soon as they are independently rich. Everybody is satisfied with the arrangement and the international bonds are further strengthened. Of course, some of the English actors blow up—that is, fail to meet with any great measure of financial success—when they get out as far as Omaha, but while they are mystifying the American public some of our tourists are going around London mystifying the British public. Doubtless you have seen some of these tourists?"

The distinguished person nodded his head in grave acquiescence and then said with some feeling:—"Bounders!"

"In spite of these breaches of international faith the situation taken as a whole is one promising an indefinite continuation of cordial friendship between the Powers," I said. "I am darned glad that such is the case; ain't you?"

"Rather," he replied.

Then we parted.

It was really worth a long sea voyage to be permitted to get the English language at first hand; to revel in its unexpected sublimities, and gaze down new and awe-inspiring vistas of rhetorical splendour.

A month before sailing I visited the floating skyscraper which was to bear us away. It was hitched to a dock in Hoboken, and it reminded me of a St. Bernard dog tied by a silken thread. It was the biggest skiff afloat, with an observatory on the roof and covered porches running all the way around. It was a very large boat.

After inspecting the boat and approving of it, I selected a room with southern exposure. Later on, when we sailed, the noble craft backed into the river and turned round before heading for the Old World, and I found myself on the north side of the ship, with nothing coming in at the porthole except a current of cold air direct from Labrador.

This room was on the starboard or port side of the ship—I forget which. After travelling nearly one million miles, more or less, by steamer, I am still unable to tell which is starboard and which is port. I can tell time by the ship's bell if you let me use a pencil, but "starboard" means nothing to me. In order to make it clear to the reader, I will say that the room was on the "haw" side of the boat. I thought I was getting the "gee" side as the vessel lay at the dock, but I forgot that it had to turn around in order to start for Europe, and I found myself "haw." I complained to one of the officers and said that I had engaged a stateroom with southern exposure. He said they couldn't back up all the way across the Atlantic just to give me the sunny side of the boat. This closed the incident. He did explain, however, that if I remained in the ship and went back with them I would have southern exposure all the way home.

I complained to one of the officers

Our ship was the latest thing out. To say that it was about seven hundred feet long and nearly sixty feet beam and 42,000 tons displacement does not give a graphic idea of its huge proportions. A New Yorker might understand if told that this ship, stood on end, would be about as tall as two Flatiron buildings spliced end to end.

Out in Indiana this comparison was unavailing, as few of the residents have seen the Flatiron Building and only a small percentage of them have any desire to see it. So when a Hoosier acquaintance asked me something about the ship I led him out into Main Street and told him that it would reach from the railroad to the Presbyterian church. He looked down street at the depot and then he looked up street at the distant Presbyterian church, and then he looked at me and walked away. Every statement that I make in my native town is received with doubt. People have mistrusted me ever since I came home years ago and announced that I was working.

Evidently he repeated what I had said, for in a few minutes another resident came up and casually asked me something about the ship and wanted to know how long she was. I repeated the Presbyterian church story. He merely remarked "I thought 'Bill' was lyin' to me," and then went his way.

It is hard to live down a carefully acquired reputation, and therefore the statement as to the length of the vessel was regarded as a specimen outburst of native humour. When I went on to say that the boat would have on board three times as many people as there were in our whole town, that she had seven decks, superimposed like the layers of a jelly cake, that elevators carried passengers from one deck to another, that a daily newspaper was printed on board, and that a brass band gave concerts every day, to say nothing of the telephone exchange and the free bureau of information, then all doubt was dispelled and my local standing as a dealer in morbid fiction was largely fortified.

The chief wonder of our new liner (for all of us had a proprietary interest the moment we came aboard) was the system of elevators. Just think of it! Elevators gliding up and down between decks the same as in a modern office building. Very few passengers used the elevators, but it gave us something to talk about on board ship and it would give us something to blow about after we had returned home.

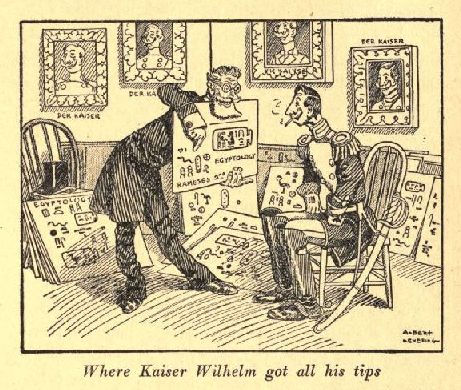

Outside of the cage stood a young German with a blonde pompadour and a jacket that came just below his shoulder blades. He was so clean he looked as if he had been scrubbed with soap and then rubbed with holystone. Every German menial on board seemed to have two guiding ambitions in life. One was to keep himself immaculate and the other was to grow a U-shaped moustache, the same as the one worn by the Kaiser.

The boy in charge of the elevator would plead with people to get in and ride. Usually, unless he waylaid them, they would forget all about the new improvement and would run up and down stairs in the old-fashioned manner instituted by Noah and imitated by Christopher Columbus.

This boy leads a checkered career on each voyage. When he departs from New York he is the elevator boy. As the vessel approaches Plymouth, England, he becomes the lift attendant. At Cherbourg he is transformed into a garçon d'ascenseur, and as the ship draws near Hamburg he is the Aufzugsbehueter, which is an awful thing to call a mere child.

Goodness only knows what will be the ultimate result of present competition between ocean liners. As our boat was quite new and extravagantly up-to-date, perhaps some information concerning it will be of interest, even to those old and hardened travellers who have been across so often that they no longer set down the run of the ship and have ceased sending pictorial post-cards to their friends at home.

In the first place, a telephone in every room, connected with a central station. The passenger never uses it, because when he is a thousand miles from shore there is no one to be called up, and if he needs the steward he pushes a button. But it is there—a real German telephone, shaped like a broken pretzel, and anyone who has a telephone in his room feels that he is getting something for his money.

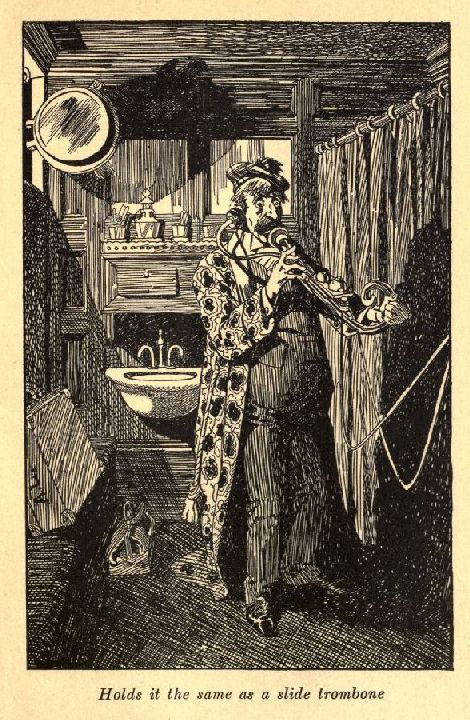

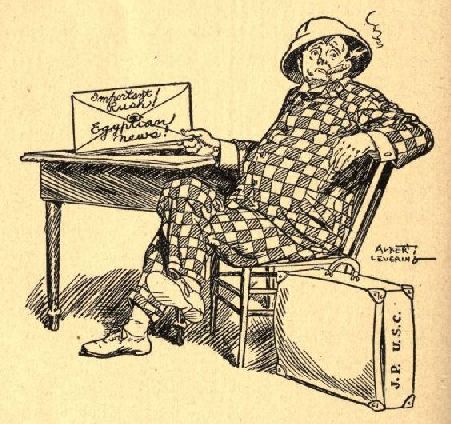

After two or three lessons any American can use a foreign telephone. All he has to learn is which end to put to his ear and how to keep two or three springs pressed down all the time he is talking. In America he takes down the receiver and talks into the 'phone. Elsewhere he takes the entire telephone down from a rack and holds it the same as a slide trombone.

Holds it the same as a slide trombone

In some of the cabins were electric hair curlers. A Cleveland man who wished to call up the adjoining cabin on the 'phone, just to see if the thing would work, put the hair curler to his ear and began talking into the dynamo. There was no response, so he pushed a button and nearly ruined his left ear. It was a natural mistake. In Europe, anything attached to the wall is liable to be a telephone.

On the whole, I think our telephone system is superior to that of any foreign cities. Our telephone girls have larger vocabularies, for one thing. In England the "hello" is never used. When an Englishman gathers up the ponderous contrivance and fits it against his head he asks:—"Are you there?" If the other man answers "No," that stops the whole conversation.

Travellers throughout the world should rise up and unite in a vote of thanks to whoever it was that abolished the upper berth in the newer boats. Mahomet's coffin suspended in mid air must have been a cheery and satisfactory bunk compared with the ordinary upper berth. Only a trained athlete can climb into one of them. The woodwork that you embrace and rub your legs against as you struggle upward is very cold. When you fall into the clammy sheets you are only about six inches from the ceiling. In the early morning the sailors scour the deck just overhead and you feel as if you were getting a shampoo. The aërial sarcophagus is built deep, like a trough, so that the prisoner cannot roll out during the night. It is narrow, and the man who is addicted to the habit of "spraddling" feels as if he were tied hand and foot.

In nearly all of the staterooms of the new boat there were no upper berths, and the lower ones were wide and springy—they were almost beds, and a bed on board ship is something that for years has been reserved as the special luxury of the millionaire.

I like the democracy of a shipboard community. You take the most staid and awe-inspiring notable in the world, bundle him in a damp storm-coat and pull a baggy travelling cap down over his ears and there is none so humble as to do him reverence. One passenger may say to another as this great man teeters along the deck, squinting against the wind: "Do you know who that man is?"

"No, who is it?"

"That's William Bilker, the millionaire philanthropist. He owns nearly all the coke ovens in the world—has built seven theological seminaries. He's going to Europe to escape a Congressional investigation."

That is the end of it so far as any flattering attentions to Mr. Bilker are concerned. If he goes in the smoking-room some beardless youth will invite him to sit in a game of poker. His confidential friend at the table may be a Montana miner, a Chicago real estate agent or a Kentucky horseman. He may hold himself aloof from the betting crowd and discourage those who would talk with him on deck, but he cannot by any possibility be a man of importance. Compared with the captain, for instance, he is a worm. And the captain draws probably $2500 a year. It must be a lot of fun to stay on board ship all the time. Otherwise the ocean liner could not get so many high class and capable men to work for practically nothing.

On the open sea a baby is much more interesting than a railway president and juveniles in general are a mighty welcome addition to the passenger list. If a child in the house is a wellspring of pleasure, then a child on a boat is nothing less than a waterspout. The sea air, with its cool vapours of salt and iodine, may lull the adult into one continuous and lazy doze, but it is an invigorant to the offspring. We had on board children from Buffalo, Chicago, Jamestown, Poughkeepsie, Worcester, Philadelphia, and other points. These children traded names before the steamer got away from the dock, and as we went down the bay under a bright sunshine they were so full of emotion that they ran madly around the upper decks, shrieking at every step. Nine full laps on the upper deck make a mile, and one man gave the opinion that the children travelled one hundred miles that first afternoon. This was probably an exaggeration.

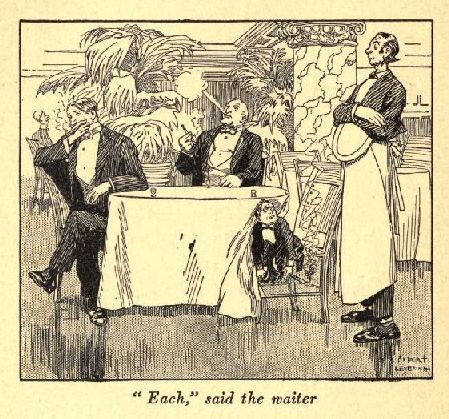

The older people lay at full length in steamer chairs and drowsed like so many hibernating bears. That is, they slept when they were not eating. The boat was one of a German line, and on a German boat the passenger's first duty is to gorge. In the smoking-room the last night out there was a dispute as to the number of meals, whole or partial, served every day. One man counted up and made it nine. Another, who was trying to slander the company, made the number as low as five. A count was taken and the following schedule was declared to be accurate and official:

6 a.m.—Coffee and rolls in the dining room.

8 to 10 a.m.—Breakfast in the dining room.

11 a.m.—Sandwiches and bouillon on deck.

12:35 p.m.—Luncheon.

4 p.m.—Cakes and lemonade on deck.

6 p.m.—Dinner.

9 p.m.—Supper (cold) in dining room.

10 to 11:30 p.m.—Sandwiches (Swiss cheese, caviar, tongue, beef, cervelat wurst, etc.) in the smoking-room.

It will be noted that anyone using ordinary diligence is enabled to stay the pangs of hunger at least eight times a day. But the company in order to cover all emergencies, has made the humane provision that articles of food may be obtained at any hour, either in the smoking room or dining room, or by giving the order to a steward. It is said that geese being fattened for the market or encouraged to develop the liver are tied to the ground so that they cannot take any harmful exercise, and large quantities of rich food are then pushed into them by means of a stick. Anyone who has spent a lazy week on a German steamer can sympathise with the geese.

Of course we had wireless messages to give us an occasional throb of excitement. Wireless telegraphy, by the way, is more or less of an irritant to the traveller. The man with stocks purchased and lawsuits pending, and all sorts of deals under way, knows that he can be reached (probably) in some sort of a zig-zag manner by wireless telegraphy, no matter where he may be on the wide ocean, and so, most of the time, he is standing around on one foot waiting for bad news. On shore he doesn't fret so much about possible calamities, but as soon as he gets away from Sandy Hook he begins to draw mental pictures of the mistakes being made by lunk-headed subordinates, and then he hangs around the Marconi station up on the sun deck, waiting for his most horrible fears to be confirmed.

In 1895, during my first voyage to Europe, I wrote the following in one of my letters, intending it as a mild pleasantry:

"Some day, perhaps, there will be invented a device by which ocean steamers may tap the Atlantic cable for news bulletins and stock quotations, or else receive them by special transmission through the water, and then the last refuge will be denied the business slave who is attempting to get away from his work."

And to think that ten years later the miracle of shooting a message through an open window and across five hundred miles of nothing but atmosphere has become a tame and every-day occurrence!

On the steamer I met an old friend—Mr. Peasley, of Iowa. We first collided in Europe in 1895, when both of us were over for the first time and were groping our way about the Continent and pretending to enjoy ourselves. About the time I first encountered Mr. Peasley he had an experience which, in all probability, is without parallel in human history. Some people to whom I have told the story frankly disbelieved it, but then they did not know Mr. Peasley. It is all very true, and it happened as follows:—

Mr. Peasley had been in Rotterdam for two days, and after galloping madly through churches, galleries, and museums for eight hours a day he said that he had seen enough Dutch art to last him a million years, at a very conservative estimate, so he started for Brussels. He asked the proprietor of the hotel at Rotterdam for the name of a good hotel in Brussels and the proprietor told him to go to the Hotel Victoria. He said it was a first-class establishment and was run by his brother-in-law. Every hotel keeper in Europe has a brother-in-law running a hotel in some other town.

Mr. Peasley was loaded into a train by watchful attendants, and as there were no Englishmen in the compartment he succeeded in getting a good seat right by the window and did not have to ride backward. Very soon he became immersed in one of the six best sellers. He read on and on, chapter after chapter, not heeding the flight of time, until the train rolled into a cavernous train shed and was attacked by the usual energetic mob of porters and hotel runners. Mr. Peasley looked out and saw that they had arrived at another large city. On the other side of the platform was a large and beautiful 'bus marked "Hotel Victoria." Mr. Peasley shrieked for a porter and began dumping Gladstone bags, steamer rugs, cameras, and other impedimenta out through the window. The man from the Victoria put these on top of the 'bus and in a few minutes Mr. Peasley was riding through the tidy thoroughfares and throwing mental bouquets at the street-cleaning department.

When he arrived at the Victoria he was met by the proprietor, who wore the frock coat and whiskers which are the world-wide insignia of hospitality.

"Your brother-in-law in Rotterdam told me to come here and put up with you," explained Mr. Peasley. "He said you were running a first-class place, which means, I s'pose, first class for this country. If you fellows over here would put in steam heat and bathrooms and electric lights and then give us something to eat in the bargain your hotels wouldn't be so bad. I admire the stationery in your writing rooms, and the regalia worn by your waiters is certainly all right, but that's about all I can say for you."

The proprietor smiled and bowed and said he hoped his brother-in-law in Rotterdam was in good health and enjoying prosperity, and Mr. Peasley said that he, personally, had left with the brother-in-law enough money to run the hotel for another six months.

After Mr. Peasley had been conducted to his room he dug up his Baedeker and very carefully read the introduction to Brussels. Then he studied the map for a little while. He believed in getting a good general idea of the lay of things before he tackled a new town. He marked on the map a few of the show places which seemed worth while, and then he sallied out, waving aside the smirking guide who attempted to fawn upon him as he paused at the main entrance. Mr. Peasley would have nothing to do with guides. He always said that the man who had to be led around by the halter would do better to stay right at home.

It was a very busy afternoon for Mr. Peasley. At first he had some difficulty in finding the places that were marked in red spots on the map. This was because he had been holding the map upside down. By turning the map the other way and making due allowance for the inaccuracies to be expected in a book written by ignorant foreigners, the whole ground plan of the city straightened itself out, and he boldly went his way. He visited an old cathedral and two art galleries, reading long and scholarly comments on the more celebrated masterpieces. Some of the paintings were not properly labelled, but he knew that slipshod methods prevailed in Europe—that a civilisation which is on the downhill and about to play out cannot be expected to breed a business-like accuracy. He wrote marginal corrections in his guide book and doctored up the map a little, several streets having been omitted, and returned to the hotel at dusk feeling very well repaid. From the beginning of his tour he had maintained that when a man goes out and gets information or impressions of his own unaided efforts he gets something that will abide with him and become a part of his intellectual and artistic fibre. That which is ladled into him by a verbose guide soon evaporates or oozes away.

At the table d'hôte Mr. Peasley had the good fortune to be seated next to an Englishman, to whom he addressed himself. The Englishman was not very communicative, but Mr. Peasley persevered. It was his theory that when one is travelling and meets a fellow Caucasian who is shy or reticent or suspicious the thing to do is to keep on talking to him until he feels quite at ease and the entente cordiale is fully established. So Mr. Peasley told the Englishman all about Iowa and said that it was "God's country." The Englishman fully agreed with him—that is, if silence gives consent. There was a lull in the conversation and Mr. Peasley, seeking to give it a new turn, said to his neighbour, "I like this town best of any I've seen. Is this your first visit to Brussels?"

"I have never been to Brussels," replied the Englishman.

"That is, never until this time," suggested Mr. Peasley. "I'm in the same boat. Just landed here to-day. I've heard of it before, on account of the carpet coming from here, and of course everybody knows about Brussels sprouts, but I had no idea it was such a big place. It's bigger than Rock Island and Davenport put together."

The Englishman began to move away, at the same time regarding the cheerful Peasley with solemn wonderment. Then he said:—

"My dear sir, I am quite unable to follow you. Where do you think you are?"

"Brussels—it's in Belgium—capital, same as Des Moines in Iowa."

"My good man, you are not in Brussels. You are in Antwerp."

"Antwerp!"

"Certainly."

"Why, I've been all over town to-day, with a guide book, and——" He paused and a horrible suspicion settled upon him. Arising from the table he rushed to the outer office and confronted the manager.

"What's the name of this town I'm in?" he demanded.

"Antwerp," replied the astonished manager.

Mr. Peasley leaned against the wall and gasped.

"Well, I'll be ——!" he began, and then language failed him.

"You said you had a brother-in-law in Rotterdam," he said, when he recovered his voice.

"That is quite true."

"And the Victoria Hotel—is there one in Brussels and another in Antwerp?"

"There is a Victoria Hotel in every city in the whole world. The Victoria Hotel is universal—the same as Scotch whiskey."

"And I am now in Antwerp?"

"Most assuredly."

Mr. Peasley went to his room. He did not dare to return to face the Englishman. Next day he proceeded to Brussels and found that he could work from the same guide book just as successfully as he had in Antwerp.

When I met him on the steamer he said that during all of his travels since 1895 he never had duplicated the remarkable experience at Antwerp. As soon as he alights from a train he goes right up to someone and asks the name of the town.

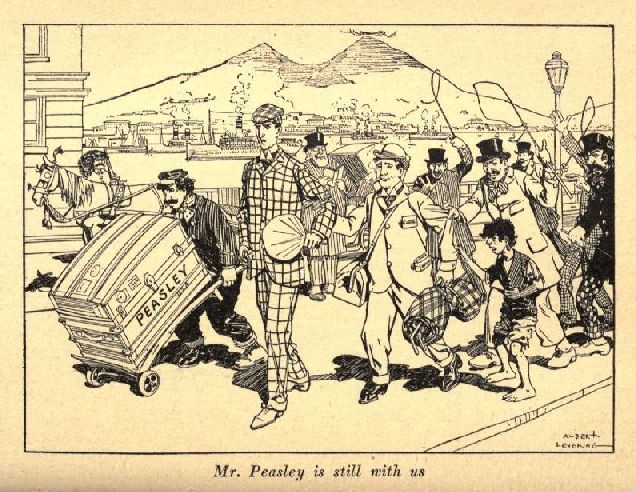

We did not expect to have Mr. Peasley with us in London. He planned to hurry on to Paris, but he has been waiting here for his trunk to catch up with him. The story of the trunk will come later.

As we steamed into Plymouth Harbour on a damp and overcast Sabbath morning, Mr. Peasley stood on the topmost deck and gave encouraging information to a man from central Illinois who was on his first trip abroad. Mr. Peasley had been over for six weeks in 1895, and that gave him license to do the "old traveller" specialty.

In beginning a story he would say, "I remember once I was crossing on the Umbria," or possibly, "That reminds me of a funny thing I once saw in Munich." He did not practise to deceive, and yet he gave strangers the impression that he had crossed on the Umbria possibly twelve or fourteen times and had spent years in Munich.

The Illinois man looked up to Mr. Peasley as a modern Marco Polo, and Mr. Peasley proceeded to unbend to him.

"A few years ago Americans were very unpopular in England," said Mr. Peasley. "Every one of them was supposed to have either a dynamite bomb or a bunch of mining stock in his pocket. All that is changed now—all changed. As we come up to the dock in Plymouth you will notice just beyond the station a large triumphal arch of evergreen bearing the words, 'Welcome, Americans!' Possibly the band will not be out this morning, because it is Sunday and the weather is threatening, but the Reception Committee will be on hand. If we can take time before starting for London no doubt a committee from the Commercial Club will haul us around in open carriages to visit the public buildings and breweries and other points of interest. And you'll find that your money is counterfeit out here. No use talkin', we're all one people—just like brothers. Wait till you get to London. You'll think you're right back among your friends in Decatur."

It was too early in the morning for the Reception Committee, but there was a policeman—one solitary, water-logged, sad-eyed policeman—waiting grewsomely on the dock as the tender came alongside. He stood by the gangplank and scrutinised us carefully as we filed ashore. The Illinois man looked about for the triumphal arch, but could not find it. Mr. Peasley explained that they had taken it in on account of the rain.

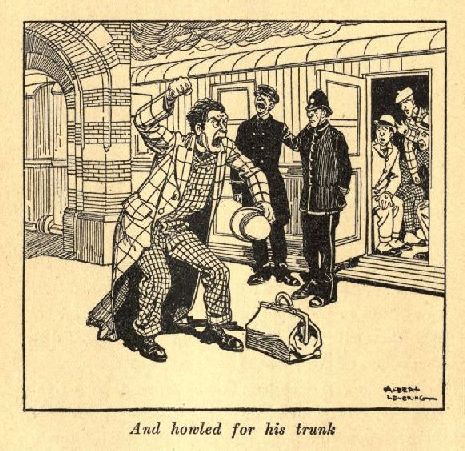

While the passengers were kept herded into a rather gloomy waiting room, the trunks and larger baggage were brought ashore and sorted out according to the alphabetical labels in an adjoining room to await the customs examination. When the doors opened there was a rush somewhat like the opening of an Oklahoma reservation. In ten minutes the trunks had been passed and were being trundled out to the special train. Above the babel of voices and the rattle of wheels arose the sounds of lamentation and modified cuss words. Mr. Peasley could not find his trunk. It was not with the baggage marked "P." It was not in the boneyard, or the discard, or whatever they call the heap of unmarked stuff piled up at one end of the room. It was not anywhere.

The other passengers, intent upon their private troubles, pawed over their possessions and handed out shillings right and left and followed the line of trucks out to the "luggage vans," and Mr. Peasley was left alone, still demanding his trunk. The station agent and many porters ran hither and thither, looking into all sorts of impossible places, while the locomotive bell rang warningly, and the guard begged Mr. Peasley to get aboard if he wished to go to London. Mr. Peasley took off his hat and leaned his head back and howled for his trunk. The train started and Mr. Peasley, after momentary indecision, made a running leap into our midst. There were six of us in a small padded cell, and five of the six listened for the next fifteen minutes to a most picturesque and impassioned harangue on the subject of the general inefficiency of German steamships and English railways.

And howled for his trunk

"Evidently the trunk was not sent ashore," someone suggested to Mr. Peasley. "If the trunk did not come ashore you could not reasonably expect the station officials to find it and put it aboard the train."

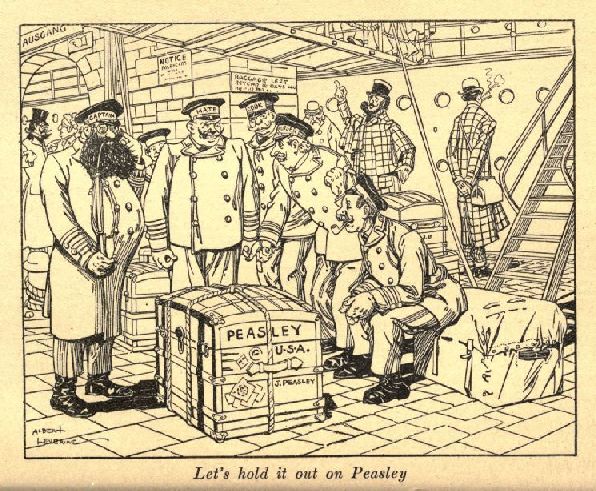

"But why didn't it come ashore?" demanded Mr. Peasley. "Everyone on the boat knew that I was going to get off at Plymouth. It was talked about all the way over. Other people got their trunks, didn't they? Have you heard of any German being shy a trunk? Has anybody else lost anything? No; they went over the passenger list and said, 'If we must hold out a trunk on anyone, let's hold it out on Peasley—old good thing Peasley.'"

Let's hold it out on Peasley

"Are you sure it was put on board at Hoboken?" he was asked.

"Sure thing. I checked it myself, or, rather, I got a fellow that couldn't speak any English to check it for me. Then I saw it lowered into the cellar, or the subway, or whatever they call it."

"Did you get a receipt for it?"

"You bet I did, and right here she is."

He brought out a congested card case and fumbled over a lot of papers, and finally unfolded a receipt about the size of a one-sheet poster. On top was a number and beneath it said in red letters at least two inches tall, "This baggage has been checked to Hamburg."

We called Mr. Peasley's attention to the reading matter, but he said it was a mistake, because he had been intending all the time to get off at Plymouth.

"Nevertheless, your trunk has gone to Hamburg."

"Where is Hamburg?"

"In Germany. The Teuton who checked your baggage could not by any effort of the imagination conceive the possibility of a person starting for anywhere except Hamburg. In two days your trunk will be lying on a dock in Germany."

"Well, there's one consolation," observed Mr. Peasley; "the clothes in that trunk won't fit any German."

When he arrived in London he began wiring for his trunk in several languages. After two days came a message couched in Volapuk or some other hybrid combination, which led him to believe that his property had been started for London.

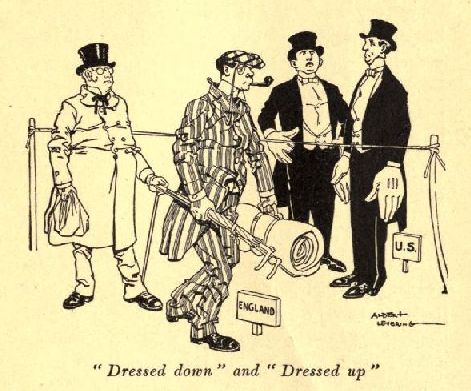

Mr. Peasley spent a week in the world's metropolis with no clothes except a knockabout travelling outfit and what he called his "Tuxedo," although, over here they say "dinner jacket." In Chicago or Omaha Mr. Peasley could have got along for a week without any embarrassment to himself or others. Even in New York the "Tuxedo" outfit would have carried him through, for it is regarded as a passable apology for evening dress, provided the wearer wishes to advertise himself as a lonesome "stag." But in London there is no compromise. In every hotel lobby or dining-room, every restaurant, theatre or music hall, after the coagulated fog of the daytime settles into the opaque gloom of night, there is but one style of dress for any mortal who does not wish to publicly pose as a barbarian. The man who affects a "Tuxedo" might as well wear a sweater. In fact it would be better for him if he did wear a sweater, for then people would understand that he was making no effort to dress; but when he puts on a bobtail he conveys the impression that he is trying to be correct and doesn't understand the rules.

An Englishman begins to blossom about half-past seven p.m. The men seen in the streets during the day seem a pretty dingy lot compared with a well-dressed stream along Fifth Avenue. Many of the tall hats bear a faithful resemblance to fur caps. The trousers bag and the coat collars are bunched in the rear and all the shoes seem about two sizes too large. Occasionally you see a man on his way to a train and he wears a shapeless bag of a garment made of some loosely woven material that looks like gunnysack, with a cap that resembles nothing so much as a welsh rabbit that has "spread." To complete the picture, he carries a horse blanket. He thinks it is a rug, but it isn't. It is a horse blanket.

If the Englishman dressed for travel is the most sloppy of all civilised beings, so the Englishman in his night regalia is the most correct and irreproachable of mortals. He can wear evening clothes without being conscious of the fact that he is "dressed up." The trouble with the ordinary American who owns an open-faced suit is that he wears it only about once a month. For two days before assuming the splendour of full dress he broods over the approaching ordeal. As the fateful night draws near he counts up his studs and investigates the "white vest" situation. In the deep solitude of his room he mournfully climbs into the camphor-laden garments, and when he is ready to venture forth, a tall collar choking him above, the glassy shoes pinching him below, he is just as much at ease as he would be in a full suit of armour, with casque and visor.

"Dressed down" and "Dressed up"

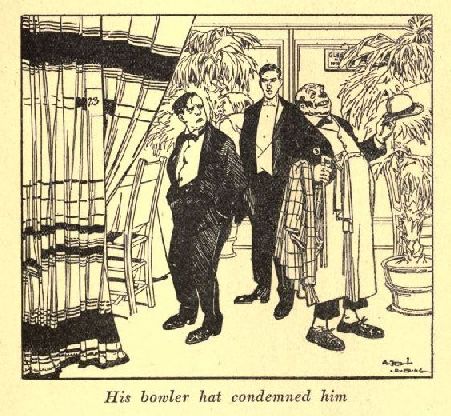

However, all this is off the subject. Here was Mr. Peasley in London, desirous of "cutting a wide gash," as he very prettily termed it, plenty of good money from Iowa burning in his pocket, and he could not get out and "associate" because of a mere deficiency in clothing.

At the first-class theatres his "bowler" hat condemned him and he was sent into the gallery. When he walked into a restaurant the head waiter would give him one quick and searching glance and then put him off in some corner, behind a palm. Even in the music halls the surrounding "Johnnies" regarded him with wonder as another specimen of the eccentric Yankee.

His bowler hat condemned him

We suggested to Mr. Peasley that he wear a placard reading "I have some clothes, but my trunk is in Hamburg." He said that as soon as his swell duds arrived he was going to put them on and revisit all of the places at which he had been humiliated and turned down, just to let the flunkeys know that they had been mistaken.

Mr. Peasley was greatly rejoiced to learn one day that he could attend a football game without wearing a special uniform. So he went out to see a non-brutal game played according to the Association rules. The gentle pastime known as football in America is a modification and overdevelopment of the Rugby game as played in Great Britain. The Association, or "Seeker" game, which is now being introduced in the United States as a counter-irritant for the old-fashioned form of manslaughter, is by far the more popular in England. The Rugby Association is waning in popularity, not because of any outcry against the character of the play or any talk of "brutality," but because the British public has a more abiding fondness for the Association game.

In America we think we are football crazy because we have a few big college games during October and November of each year. In Great Britain the football habit is something that abides, the same as the tea habit.

We are hysterical for about a month and then we forget the game unless we belong to the minority that is trying to debrutalise it and reduce the death rate.

Here it was, February in London, and on the first Saturday after our arrival forty-five Association games and thirty-eight Rugby games were reported in the London papers. At sixteen of the principal Association games the total attendance was over two hundred and fifty thousand and the actual receipts at these same games amounted to about $45,000. There were two games at each of which the attendance was over thirty thousand, with the receipts exceeding $5,000. A very conservative estimate of the total attendance at the games played on this Saturday would be five hundred thousand. In other words, on one Saturday afternoon in February the attendance at football games was equal to the total attendance at all of the big college games during an entire season in the United States. No wonder that the English newspapers are beginning to ask editorially "Is football a curse?" There is no clamour regarding the roughness of the game, but it is said to cost too much money and to take up too much time for the benefits derived.

The game to which Mr. Peasley conducted us was played in rather inclement weather—that is, inclement London weather—which means that it was the most terrible day that the imagination can picture—a dark, chilly, drippy day, with frequent downpours. It has been said that one cannot obtain icewater in London. This is a mistake. We obtained it by the hogshead.

In spite of the fact that the weather was bad beyond description, seventeen thousand spectators attended the game and saw it through to a watery finish.

Mr. Peasley looked on and was much disappointed. He said they used too many players and the number of fatalities was not at all in keeping with the advertised importance of the game. It was a huge crowd, but the prevailing spirit of solemnity worried Mr. Peasley. He spoke to a native standing alongside of him and asked:—"What's the matter with you folks over here? Don't you know how to back up a team? Where are all of your flags and ribbons, your tally-hos and tin horns? Is this a football game or a funeral?"

"Why should one wear ribbons at a football game?" asked the Englishman.

"Might as well put a little ginger into the exercises," suggested Mr. Peasley. "Do you sing during the game?"

"Heavens, no. Sing? Why should one sing during a football game? In what manner is vocal music related to an outdoor pastime of this character?"

"You ought to go to a game in Iowa City. We sing till we're black in the face—all about 'Eat 'em up, boys,' 'Kill 'em in their tracks,' and 'Buck through the line.' What's the use of coming to a game if you stand around all afternoon and don't take part? Have you got any yells?"

"What are those?"

"Can you beat that?" asked Mr. Peasley, turning to us. "A football game without any yells!"

The game started. By straining our eyes we could make out through the deep gloom some thirty energetic young men, very lightly clad, splashing about in all directions, and kicking in all sorts of aimless directions. Mr. Peasley said it was a mighty poor excuse for football. No one was knocked out; there was no bucking the line; there didn't even seem to be a doctor in evidence. We could not follow the fine points of the contest. Evidently some good plays were being made, for occasionally a low, growling sound—a concerted murmur—would arise from the multitude banked along the side lines.

"What is the meaning of that sound they are making?" asked Mr. Peasley, turning to the native standing alongside of him.

"They are cheering," was the reply.

"They are what?"

"Cheering."

"Great Scott! Do you call that cheering? At home, when we want to encourage the boys we get up on our hind legs and make a noise that you can hear in the next township. We put cracks in the azure dome. Cheering! Why, a game of croquet in the court house yard is eight times as thrilling as this thing. Look at those fellows juggling the ball with their feet. Why doesn't somebody pick it up and butt through that crowd and start a little rough work?"

The native gave Mr. Peasley one hopeless look and moved away.

We could not blame our companion for being disappointed over the cheering. An English cheer is not the ear-splitting demoniacal shriek, such as an American patriot lets out when he hears from another batch of precincts.

The English cheer is simply a loud grunt, or a sort of guttural "Hey! hey!" or "Hurray!"

When an English crowd cheers the sound is similar to that made by a Roman mob in the wings of a theatre.

After having once heard the "cheering" one can understand the meaning of a passage in the Parliamentary report, reading about as follows: "The gentleman hoped the house would not act with haste. (Cheers). He still had confidence in the committee (cheers), but would advise a careful consideration (cheers), etc."

It might be supposed from such a report that Parliament was one continuous "rough house," but we looked in one day and it is more like a cross between a Presbyterian synod and bee-keepers' convention.

About four o'clock we saw a large section of the football crowd moving over toward a booth at one end of the grounds. Mr. Peasley hurried after them, thinking that possibly someone had started a fight on the side and that his love of excitement might be gratified after all. Presently he returned in a state of deep disgust.

"Do you know why all those folks are flockin' over there?" he asked. "Goin' after their tea. Tea! Turnin' their backs on a football game to go and get a cup of tea! Why, that tea thing over there is worse than the liquor habit. Do you know, when the final judgment day comes and Gabriel blows his horn and all of humanity is bunched up, waitin' for the sheep to be cut out from the goats and put into a separate corral, some Englishman will look at his watch and discover that it's five o'clock and then the whole British nation will turn its back on the proceedings and go off looking for tea."

After we had stood in the rain for about an hour someone told Mr. Peasley that one team or the other had won by three goals to nothing, and we followed the moist throng out through the big gates.

"Come with me," said Mr. Peasley, "and I will take you to the only dry place in London."

So we descended to the "tuppenny tube."

One good thing about London is that, in spite of its enormous size, you are there when you arrive. Take Chicago, by way of contrast. If you arrive in Chicago along about the middle of the afternoon you may be at the station by night.

The stranger heading into Chicago looks out of the window at a country station and sees a policeman standing on the platform. Beyond is a sign indicating that the wagon road winding away toward the sunset is 287th street, or thereabouts.

"We are now in Chicago," says someone who has been over the road before.

The traveller, surprised to learn that he has arrived at his destination, puts his magazine and travelling cap into the valise, shakes out his overcoat, calls on the porter to come and brush him, and then sits on the end of the seat waiting for the brakeman to announce the terminal station. After a half-hour of intermittent suburbs and glorious sweeps of virgin prairie he begins to think that there is some mistake, so he opens his valise and takes out the magazine and reads another story.

Suddenly he looks out of the window and notices that the train has entered the crowded city. He puts on his overcoat, picks up his valise and stands in the aisle, so as to be ready to step right off as soon as the train stops.

The train passes street after street and rattles through grimy yards and past towering elevators, and in ten minutes the traveller tires of standing and goes back to his seat. The porter comes and brushes him again, and he looks out at several viaducts leading over to a skyline of factories and breweries, and begins to see the masts of ships poking up in the most unexpected places. At last, when he has looked at what seems to be one hundred miles of architectural hash floating in smoke and has begun to doubt that there is a terminal station, he hears the welcome call, "Shuh-kawgo!"

When you are London bound the train leaves the green country (for the country is green, even in February), dashes into a region of closely built streets, and you look out from the elevated train across an endless expanse of chimney-pots. Two or three stations, plated with enameled advertising signs, buzz past. The pall of smoky fog becomes heavier and the streets more crowded. Next, the train has come to a grinding stop under a huge vaulted roof. The noise of the wheels give way to the roar of London town.

You step down and out and fall into the arms of a porter who wishes to carry your "bags." You are in the midst of parallel tracks and shifting trains. Beyond the platform is a scramble of cabs. The sounds of the busy station are joined into a deafening monotone. You shout into the ear of your travelling companion to get a "four-wheeler" while you watch the trunks.

He struggles away to hail a four-wheeler. You push your way with the others down toward the front of the train to where the baggage is being thrown out on the platform. You seize a porter and engage him to attend to the handling of the trunks. As you point them out he loads them onto a truck. Your companion arrives in a wild-eyed search for you.

"I've got a four-wheeler," he gasps. "All the baggage here?"

"Yes, yes, yes."

Everybody is excited and hopping about, put into a state of hysteria by the horrible hubbub and confusion.

"It's number 48."

The porter handling the truck leads the way to the cab platform and howls "Forty-ite! Forty-ite!"

"'Ere you are," shouts forty-eight, who is wedged in behind two hansoms.

By some miracle of driving he gets over or under or past the hansoms and comes to the platform. The steamer trunks are thrown on top and the porter, accepting the shilling with a "'k you, sir," slams the door behind you.

Then you can hear your driver overhead managing his way out of the blockade.

"Pull a bit forward, cahn't you?" he shouts. Then to someone else, "'Urry up, 'urry up, cahn't you?"

You are in a tangle of wheels and lamps, but you get out of it in some way, and then the rubber tires roll easily along the spattering pavement of a street which seems heavenly quietude.

This is the time to lean back and try to realise that you are in London. The town may be common and time-worn to those people going in and out of the shops, but to you it is a storehouse of novelties, a library of things to be learned, a museum of the landmarks of history.

We could read the names on the windows, and they were good homely Anglo-Saxon names. We didn't have to get out of the four-wheeler and go into the shops to convince ourselves that Messrs. Brown, Jones, Simpson, Perkins, Jackson, Smith, Thompson, Williams, and the others were serious men of deferential habits, who spoke in hollow whispers of the king, drank tea at intervals and loved a pipe of tobacco in the garden of a Sunday morning.

Some people come to London to see the Abbey and the Tower, but I fear that our trusty little band came to see the shop windows and the crowds in the streets.

May the weak and imitative traveller resist the temptation to say that Fleet street is full of publishing houses, that the British museum deserves many visits, that the Cheshire Cheese is one of the ancient taverns, that the new monument in front of the Courts of Law marks the site of old Temple Bar, that the chapel of King Henry VII. is a superb example of its own style of decoration, and that one is well repaid for a trip to Hampton Court. Why seek to corroborate the testimony of so many letter-writers?

Besides, London does not consist of towers, abbeys, and museums. These are the remote and infrequent things. After you have left London and try to call back the huge and restless picture to your mind, the show places stand dimly in the background. The London which impressed you and made you feel your own littleness and weakness was an endless swarm of people going and coming, eddying off into dark courts, streaming toward you along sudden tributaries, whirling in pools at the open places, such as Piccadilly Circus and Trafalgar Square. Thousands of hansom cabs dashed in and out of the street traffic, and the rattling omnibuses moved along every street in a broken row, and no matter how long you remained in London you never saw the end of that row.

You go out in London in the morning, and if you have no set programme to hamper you, you make your way to one of those great chutes along which the herds of humanity are forever driven.

If you follow the guide-book it will lead you to a chair in which a king sat 300 years ago. If you can get up an emotion by straining hard enough and find a real pleasure in looking at the moth-eaten chair, then you should follow the guide-book. If not, escape from the place and go to the street. The men and women you find there will interest you. They are on deck. The chair is a dead splinter of history. All the people in the street are the embodiment of that history. For purposes of actual observation I would rather encounter a live cabman than the intangible, atmospheric suggestion of Queen Elizabeth.

After you have been in London once you understand why your friends who have visited it before were never able to tell you about it so that you could understand. It is too big to be put under one focus. The traveller takes home only a few idiotic details of his stay. He says that he had to pay for his programme at the theatre, and that he couldn't get ice at some of the restaurants.

"But tell us about London," says the insistent friend who has constructed a London of his own out of a thousand impressions gathered from books and magazines. Then the traveller says that London is large, he doesn't remember how many millions, and very busy, and there wasn't as much fog as he had expected, and as for the people they were not so much different from Americans, although you never had any difficulty in identifying an American in London. The traveller's friends listen in disappointment and agree that he got very little out of his trip, and that when they go to London they will come back and tell people the straight of it.

As a matter of fact, London is principally a sense of dizziness. This dizziness comes of trying to keep an intent gaze on too many human performances. The mind is in a blur. The impressions come with rolling swiftness. There is no room for them. The traveller overflows with them. They spill behind him. You could track an American all around London by the trail of excess information which he drops in his pathway.

Of course, I have kept a journal, but that doesn't help much. It simply says that we went out each day and then came back to the hotel for dinner. There was not much chance for personal experiences, because in London you are not a person. You are simply a drop of water in a sea, and any molecular disturbances which may concern you are of small moment compared to the general splash.

Advice to those following along behind. Stock up on heavy flannels and do not bother about a passport.

Before we became old and hardened travellers we were led to believe that any American who appeared at a frontier without a passport would be hurried to a dungeon or else marched in the snow all the way to Siberia.

When I first visited the eastern hemisphere (I do love to recall the fact that I have been over here before), our little company of travellers prepared for European experiences by reading a small handbook of advice. The topics were arranged alphabetically, and the specific information set out under each heading was more valuable and impressive at the beginning of the trip than it was after we had come home and read it in the cold light of experience. We paid particular heed to the following:

"PASSPORTS—Every American travelling in Europe should carry a passport. At many frontiers a passport, properly 'vised,' must be shown before the traveller will be allowed to enter the country. A passport is always valuable as an identification when money is to be drawn on a letter of credit. Very often it will secure for the bearer admission to palaces, galleries and other show places which are closed to the general public. It is the most ready answer to any police inquiry, and will serve as a letter of introduction to all consular offices."

We read the foregoing and sent for passports before we bought our steamship tickets.

I have been a notary public; I have graduated from a highschool; I have taken out accident insurance, and once, in a careless moment, I purchased one thousand shares of mining stock. In each instance I received a work of art on parchment—something bold and black and Gothic, garnished with gold seals and curly-cues. But for splendour of composition and majesty of design, the passport makes all other important documents seem pale and pointless. There is an American eagle at the top, with his trousers turned up, and beneath is a bold pronouncement to the world in general that the bearer is an American citizen, entitled to everything that he can afford to buy. No man can read his own passport without being more or less stuck on himself. I never had a chance to use the one given to me years ago, but I still keep it and read it once in a while to bolster up my self-respect.

When we first landed at Liverpool each man had his passport in his inside coat pocket within easy reach, so that in case of an insult or an impertinent question he could flash it forth and say: "Stand back! I am an American citizen!" After a week in London we went to the bank to draw some more money. The first man handed in his letter of credit and said: "If necessary, I have a pass——"

Before he could say any more the cashier reached out a little scoop shovel loaded with sovereigns and said: "Twenty pounds, sir."

We never could find a banker who wanted to look at our passports or who could be induced to take so much as a glance at them. I said to one banker: "We have our passports in case you require any identification." He said: "Rully, it isn't necessary, you know. I am quite sure that you are from Chicago."

We couldn't determine whether this was sheer courtesy on his part or whether we were different.

After we were on the continent we hoped that some policeman would come to the hotel and investigate us, so that we could smile coolly and say: "Look at that," at the same time handing him the blue envelope. Then to note his dismay and to have him apologise and back out. But the police never learned that we were in town.

As for the art galleries and palaces, we had believed the handbook. We fancied that some day or other one of us would approach the entrance to a palace and that a gendarme would step out and say: "Pardon, monsieur, but the palace is closed to all visitors to-day."

"To most visitors, you mean."

"To all, monsieur."

"I think not, do you know who I am?"

"No, monsieur."

"Then don't say a word about anything being closed until you find out. I am an American. Here is my passport. Fling open the doors!"

At which the gendarme would prostrate himself and the American would pass in, while a large body of English, French and German tourists would stand outside and envy him.

Alas, it was a day-dream. Every palace that was closed seemed to be really closed, and when we did find the gendarme who was to be humiliated, we discovered that we couldn't speak his language, and, besides, we felt so humble in his presence that we wouldn't have ventured to talk to him under any circumstances.

We travelled in England, Ireland, Holland, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and France, crossing and recrossing frontiers, and we never encountered a man, woman or child who would consent to look at our passports.

On the other hand, the cable code is something that no tourist should be without. Whenever he is feeling blue or downcast he can open the code book and get a few hearty laughs. Suppose he wishes to send a message to his brother in Toledo. The code permits him to concentrate his message into the tabloid form and put a long newsy letter into two or three words. He opens the blue book and finds that he can send any of the following tidings to Toledo:

Adjunctio—Apartments required are engaged and will be ready for occupation on Wednesday.

Amalior—Bills of lading have not been endorsed.

Animatio—Twins, boy and girl, all well.

Collaria—Received invitation to dinner and theatre, Illaqueo—Have a fly at the station to meet train arriving at eight o'clock.

Napina—Machinery out of order. Delay will be great.

Remissus—Can you obtain good security?

And so on, page after page. Theoretically, this vest pocket volume is a valuable helpmate, but when Mr. Peasley wanted to cable Iowa to have his Masonic dues paid and let Bill Levison take the river farm for another year and try to collect the money from Joe Spillers, the code book did not seem to have the proper equivalents.

We had with us on the boat an American who carried a very elaborate code book. All the way up from Plymouth to London he was working on a cablegram to his wife. When he turned it over to the operator, this is the joyous message that went singing through the water back to New York:

"LIZCAM, New York. Hobgoblin buckwheat explosion manifold cranberry suspicious.

"JAMES."

He showed us a copy and seemed to be very proud of it.

"That's what you save by having a code," he explained.

"What will Lizcam think when he receives that?"

"He? That's my wife's registered cable address. 'Liz' for Lizzie and 'Cam' for Campbell. Her maiden name was Lizzie Campbell."

"Well, what does that mean about a buckwheat hobgoblin having a suspicious explosion?"

"Oh, those words are selected arbitrarily to represent full sentences in the code. When my wife gets that cable she will look up those words one after the other and elaborate the message so that it will read like this:

He showed us the following:

"Mrs. Chauncey Cupple, Mount Joy Hotel, New York——Dear Wife: Well, here we are at London, after a very pleasant voyage, all things considered. We had only two days of inclement weather and I was not seasick at any time. We saw a great many porpoises, but no whales. The third day out I won the pool on the run. Formed the acquaintance of several pleasant people. (Signed) James."

"It's just as good as a letter," said the man from Buffalo.

"Yes, and I save fifty-eight words," said Cupple. "I wouldn't travel without a code."

"Why don't you tack on another word and let her know how many knots we made each day?" asked the Buffalo man, but his sarcasm was wasted.

A week later I met Mr. Cupple and he said that the cablegram had given his wife nervous prostration.

Mr. Cupple is not a careful penman and the cable operator had read the last word of the message as "auspicious" instead of "suspicious." A reference to the code showed that the mistake changed the sense of the message.

"Suspicious—Formed the acquaintance of several pleasant people.

"Auspicious—After a futile effort to work the pumps the captain gave orders to lower the boats. The passengers were in a panic, but the captain coolly restrained them and gave orders that the women and children should be sent away first."

The message, as altered in transmission, caused Mrs. Cupple some uneasiness, and, also, it puzzled her. It was gratifying to know that her husband had enjoyed the voyage and escaped seasickness, but she did not like to leave him on the deck of the ship with a lot of women and children stepping up to take the best places in the boat. Yet she could not believe that he had been lost, otherwise, how could he have filed a cablegram at London?

She wanted further particulars, but she could not find in the code any word meaning "Are you drowned?"

So she sent a forty-word inquiry to London, and when Mr. Cupple counted the cost of it he cabled back:

"All right. Ignore code."

A man is always justly proud of the information which has just come to hand. He enjoys a new piece of knowledge just as a child enjoys a new Christmas toy. It seems impossible for him to keep his hands off of it. He wants to carry it around and show it to his friends, just as a child wants to race through the neighbourhood and display his new toy.

Within a week the toy may be thrown aside, having become too familiar and commonplace, and by the same rule of human weakness the man will toss his proud bit of information into the archives of memory and never haul it out again except in response to a special demand.

These turgid thoughts are suggested by the behaviour of an American stopping at our hotel. He is here for the first time, and he has found undiluted joy in getting the British names of everything he saw. After forty-eight hours in London he was gifted with a new vocabulary, and he could not withstand the temptation to let his brother at home know all about it. The letter which he wrote was more British than any Englishman could have made it.

In order to add the sting of insult to his vainglorious display of British terms he inserted parenthetical explanations at different places in his letter. It was just as if he had said, "Of course, I'll have to tell you what these things mean, because you never have been out of America, and you could not be expected to have the broad and comprehensive knowledge of a traveller."

This is the letter which he read to us last evening:

"DEAR BROTHER: I send you this letter by the first post (mail) back to America to let you know that I arrived safely. In company with several pleasant chaps with whom I had struck up an acquaintance during our ride across the pond (ocean) I reached the landing stage (dock) at Southampton at 6 o'clock Saturday. It required but a short time for the examination of my box (trunk) and my two bags (valises), and then I booked (bought a ticket) for London. My luggage (baggage) was put into the van (baggage car) and registered (checked) for London. I paid the porter a bob (a shilling, equal to 24 cents in your money), and then showed my ticket to the guard (conductor), who showed me into a comfortable first-class carriage (one of the small compartments in the passenger coach), where I settled back to read a London paper, for which I had paid tuppence (4 cents in your money). Directly (immediately after) we started I looked out of the window, and was deeply interested in this first view of the shops (small retail establishments) and the frequent public houses (saloons). Also we passed through the railway yards, where I saw many drivers (engineers) and stokers (firemen) sitting in the locomotives, which did not seem to be as large as those to which you are accustomed in America.

"Our ride to London was uneventful. When we arrived at London I gave my hand luggage into the keeping of a porter and claimed the box which had been in the van. This was safely loaded on top of a four-wheeled hackney carriage (four-wheeled cab), and I was driven to my hotel, which happened to be in (on) the same street, and not far from the top (the end) of the thoroughfare. Arrived at the hotel, I paid the cabby (the driver) a half-crown (about 60 cents in your money), and went in to engage an apartment. I paid seven shillings (about $1.75) a day, this to include service (lights and attendance), which was put in at about 18 pence a day. The lift (elevator) on which I rode to my apartment was very slow. I found that I had a comfortable room, with a grate, in which I could have a fire of coals (coal). As I was somewhat seedy (untidy) from travel, I went to the hair-dresser's (the barber), and was shaved. As it was somewhat late I did not go to any theatre, but walked down the Strand and had a bite in a cook-shop (restaurant). The street was crowded. Every few steps you would meet a Tommy Atkins (soldier) with his 'doner' (best girl). I stopped and inquired of a bobby (policeman) the distance to St. Paul's (the cathedral), and decided not to visit it until the next morning.

"Yesterday I put in a busy day visiting the abbey (Westminster) and riding around on the 'buses (omnibuses) and tram cars (street cars). In the afternoon I went up to Marble Arch (the entrance to Hyde Park), and saw many fashionables; also I looked at the Row (Rotten Row, a drive and equestrian path in Hyde Park). There were a great many women in smart gowns (stylish dresses), and nearly all the men wore frock coats (Prince Alberts), and top hats (silk hats). There are many striking residential mansions (apartment houses) facing the park, and the district is one of the most exclusive up west (in the west end of London). Sunday evening is very dull, and I looked around the smoking-room of the hotel. Nearly every man in the room had a 'B and S' (brandy and soda) in front of him, although some of them preferred 'polly' (apollinaris) to the soda. A few of them drank fizz (champagne); but, so far as I have observed, most of the Englishmen drink spirits (whiskey), although they very seldom take it neat (straight), as you do at home. I went to bed early and had a good sleep. This morning when I awoke I found that my boots (shoes), which I had placed outside the door the night before, had been neatly varnished (polished). The tub (bath) which I had bespoken (ordered) the night before was ready, and I had a jolly good splash."

We paused in our admiring study of the letter and remarked to the author that "jolly good splash" was very good for one who had been ashore only two days.

"Rahther," he said.

"I beg pardon?"

"Rahther, I say. But you understand, of course, that I'm giving him a bit of spoof."

"A bit of what?"

"Spoof—spoof. Is it possible that you have been here since Saturday without learning what 'spoof' means? It means to chaff, to joke. In the States the slang equivalent would be 'to string' someone."

"How did you learn it?"

"A cabby told me about it. I started to have some fun with him, and he told me to 'give over on the spoof.' But go ahead with the letter. I think there are several things there that you'll like."

So we resumed.

"For breakfast I had a bowl of porridge (oatmeal) and a couple of eggs, with a few crumpets (rolls). Nearly all day I have been looking in the shop windows marvelling at the cheap prices. Over here you can get a good lounge suit (sack suit) for about three guineas (a guinea is twenty-one shillings); and I saw a beautiful poncho (light ulster) for four sovereigns (a sovereign is a pound, or twenty shillings). A fancy waistcoat (vest) costs only twelve to twenty shillings ($3 to $5), and you can get a very good morning coat (cutaway) and waistcoat for three and ten (three pounds and ten shillings). I am going to order several suits before I take passage (sail) for home. Thus far I have bought nothing except a pot hat (a derby), for which I paid a half-guinea (ten shillings and sixpence). This noon I ate a snack (light luncheon) in the establishment of a licensed victualer (caterer), who is also a spirit merchant (liquor dealer). I saw a great many business men and clarks (clerks) eating their meat pies (a meat pie is a sort of a frigid dumpling with a shred of meat concealed somewhere within, the trick being to find the meat), and drinking bitter (ale) or else stout (porter). Some of them would eat only a few biscuit (crackers) for their lunch. Others would order as much as a cut of beef, or, as we say over here, a 'lunch from the joint.' This afternoon I have wandered about the busy thoroughfares. All the street vehicles travel rapidly in London, and you are chivied (hurried) at every corner."

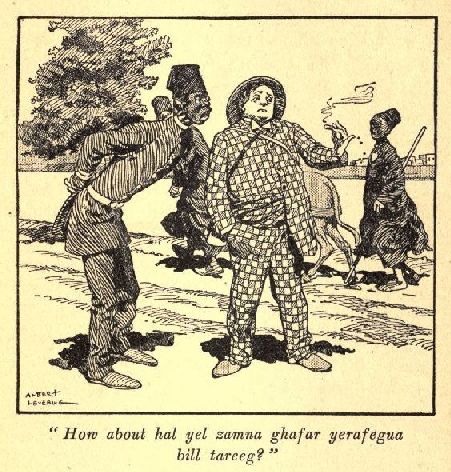

"You have learned altogether too much," said Mr. Peasley. Where did you pick up that word 'chivy'?"