Title: The Azure Rose: A Novel

Author: Reginald Wright Kauffman

Release date: December 29, 2011 [eBook #38436]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, Sam W. and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A Novel

BY

REGINALD WRIGHT KAUFFMAN

Author of “Jim,” “The House of Bondage,”

“The Mark of The Beast,” “Our Navy at Work,” etc.

NEW YORK

THE MACAULAY COMPANY

Copyright, 1919

By The Macaulay Co.

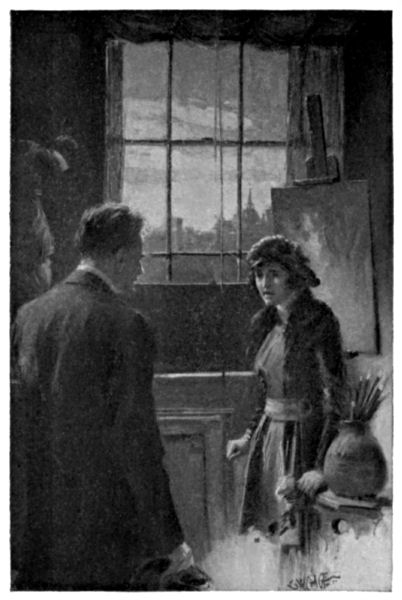

“Oh!” she cried. “I had just come in and I thought—I thought it was my room.”

For

My Friend and Secretary,

LANCE-CORPORAL ARNOLD ROBSON,

No. 10864, “C” Company, Sixth Battalion,

Yorkshire Regiment—“The Green Howards”—

Who, Leading His Squad, Died for His Country

At Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, 21st August, 1915,

Aged Twenty.

A novel about Paris that is not about the war requires even now, I am told, some word of explanation. Mine is brief:

This story was conceived before the war began. I came to the task of putting it into its final shape after nine months passed between the Western Front and a Paris war-torn and war-darkened, both physically and spiritually. Yet, though I had found the old familiar places, and the ever young and ever familiar people, wounded and sad, I did not long have to seek for the Parisian bravery in pain and the Parisian smile shining, rainbowlike, through the tears. Nothing can conquer France and nothing can lastingly hurt Paris. They are, as a famous wit said of our own so different Boston, a state of mind. Had the German succeeded in the Autumn of 1914 or the Spring of 1918, France would have remained, and Paris. What used to happen in the Land of Love and [Pg viii] the City of Lights will happen there again and be always happening, so that my story is at once a retrospect and a prophecy.

Realizing these things, I have found it a pleasure to make this book. A book without problems and without horrors, its sole purpose is to give to the reader some of that pleasure which went to its making. Wars come and go; but for every man the Door Opposite stands open beside the Seine, the hurdy-gurdy plays “Annie Laurie” in the Street of the Valley of Grace and—a Lady of the Rose is waiting.

R. W. K.

Columbia, Penna.,

Christmas Day, 1918.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | In Which, if not Love, at Least Anger, Laughs at Locksmiths | 13 |

| II. | Providing the Gentle Reader with a Card of Admission to the Nest of the Two Doves | 36 |

| III. | In Which a Fool and His Money Are Soon Parted | 49 |

| IV. | A Damsel in Distress | 64 |

| V. | Which Tells How Cartaret Returned to the Rue du Val-de-Grâce, and What He Found There | 84 |

| VI. | Cartaret Sets Up Housekeeping | 102 |

| VII. | Of Domestic Economy, of Day-Dreams, and of a Far Country and Its Sovereign Lady | 118 |

| VIII. | Chiefly Concerning Strawberries | 144 |

| IX. | Being the True Report of a Chaperoned Déjeuner | 154 |

| X. | An Account of an Empty Purse and a Full Heart, in the Course of Which the Author Barely Escapes Telling a Very Old Story | 169 |

| [Pg x]XI. | Tells How Cartaret’s Fortune Turned Twice in a Few Hours and How He Found One Thing and Lost Another | 192 |

| XII. | Narrating How Cartaret Began His Quest of the Rose | 206 |

| XIII. | Further Adventures of an Amateur Botanist | 222 |

| XIV. | Something or Other About Traditions | 253 |

| XV. | In Which Cartaret Takes Part in the Revival of an Ancient Custom | 273 |

| XVI. | And Last | 300 |

THE AZURE ROSE

Je ne connais point la nature des anges, parce que je ne suis qu’homme; il n’y a que les théologiens qui la connaissent.—Voltaire: Dictionnaire Philosophique.

He did not know why he headed toward his own room—it could hold nothing that he guessed of to welcome him, except further tokens of the dejection and misery he carried in his heart—but thither he went, and, as he drew nearer, his step quickened. By the time that he entered the rue du Val de Grâce, he was moving at something close upon a run.

He hurried up the rising stairs and into the dark hall, and, as he did so, was possessed by the sense that somebody had as hurriedly ascended [Pg 14] just ahead of him. The door to his room was never locked, and now he flung it wide.

The last of the afterglow had all but faded from the sky, and only the faintest twilight, a rose-pink twilight, came into the studio. Rose-pink: he thought of that at once and thought, too, that these sky-roses had a sweeter scent than the roses of earth, for there was about this once-familiar place an odor more delicate and tender than any he had ever known before. It was dim, illusive; it was like a musical poem in an unknown tongue, and yet, unlike French scents and hot-house flowers, it subtly suggested open spaces and mountain-peaks. Cartaret had a quick vision of sunlight upon snow-crests. He wondered how such a perfume could find its way through the narrow, dirty streets of the Latin Quarter and into his poor room.

And then, in the dim light, he saw a figure standing there.

Cartaret stopped short.

An hour ago he had left the place empty. Now, when he so wanted solitude, it had been [Pg 15] invaded. There was an intruder. It was—— yes, the Lord have mercy on him, it was a girl!

“Who’s there?” demanded Cartaret.

He was so startled that he asked the question in English and with his native American accent. The next moment, he was more startled when the strange girl answered him in English, though an English oddly precise.

“It is I,” she said.

“It is I,” was what she said first, and, as she said it, Cartaret noted that her voice was a wonderfully soft contralto. What she next said was uttered as he further discovered himself to her by an involuntary movement that brought him within the rear window’s shaft of afterglow. It was:

“What are you doing here?”

She spoke with patent amazement, and there were, between the words, four perceptible pauses.

What was he doing there? What was she? What light there was came from behind her: he could not at all make out her features; he had [Pg 16] only her voice to go by—only her voice and her manner of regal possession—and with neither was he acquainted. Good Heavens, hadn’t he a right to come unannounced into the one place in Paris that he might still call his own? It surely was his own. He looked distractedly about him.

“I thought,” said Cartaret, “that this was my room.”

His glance, bewildered as it was, nevertheless assured him that he had not been mistaken. His accustomed eye detected everything that the twilight might hide from the eye of a stranger.

Here was all his student-litter. Here were the good photographs of good pictures, bought second-hand; the bad copies of good pictures, made by Cartaret himself during long mornings in the Louvre, where impudent tourists, staring at his work, jolted his elbow and craned their necks beside his cheek; there were the plaster-casts on brackets—casts of antiques more mutilated than the antiques themselves; and here, too, were the rows of lost endeavors in the shape of discarded canvases banked on the floor along the walls and [Pg 17] sometimes jutting far out into the room. Two or three chairs were scattered about, one with a broken leg—he remembered the party at which it was broken; across from the fire-place was Cartaret’s bed that a tarnished Oriental cover (made in Lyons) converted by day into a divan; and close beside the rear window, flanked by the table on which he mixed his colors, stood, almost at the elbow of this imperious intruder, Cartaret’s own easel with a virgin canvas in position, waiting to receive the successor to that picture which he had sold for a song a few hours ago.

What was he doing here, indeed! He liked that.

And she was still at it:

“How dare you think so?” she persisted.

The slight pauses between her words lent them more weight than, even in his ears, they otherwise would have possessed. She came a step nearer, and Cartaret saw that she was breathing quickly and that the bit of lace above her heart rose and fell irregularly.

“How dare you?” she repeated.

[Pg 18] She was close enough now for him to decide that she was quite the most striking girl he had ever seen. Her figure, without a touch of exaggeration, was full and yet lithe: it moved with the grace of the athlete. Her skin was rosy and white—the rose of health and the clear cream of sane living.

It was, however, her manner that had led Cartaret first to doubt his own senses, and then to doubt hers. This girl spoke like a queen resenting a next-to-impossible familiarity. He had half a mind to leave the place and allow her to discover her own mistake, the nature of which—his room ran the length of the old house and half its width, being separated from a similar room by only a dark and draughty hallway—now suddenly revealed itself to him. He seriously considered leaving her alone to the advent of her humiliation.

Then he looked at her again. Her hair, in sharp contrast to the tint of her face, was a shining blue-black; though her features were almost classical in their regularity, her mouth was [Pg 19] generous and sensitive, and, under even black brows and through long, curling lashes, her eyes shone frank and blue. Cartaret decided to remain.

“You are an artist?” he inquired.

“Leave this room!” She stamped a little foot. “Leave this room instantly!”

Cartaret stooped to one of the canvases that were piled against the wall nearest him. He turned its face to her.

“And this is some of your work?” he asked.

He had meant to be only light and amusing, but when he saw the effect of his action, he cursed himself for a heavy-witted fool: the girl glanced first at the picture and then wildly about her. She had at last realized her mistake.

“Oh!” she cried. Her delicate hands went to her face. “I had just come in and I thought—I thought it was my room!”

He registered a memorandum to kick himself as soon as she had gone. He moved awkwardly forward, still between her and the door.

“It’s all right,” he said. “Everybody drops in [Pg 20] here at one time or another, and I never lock my door.”

“But you do not understand!” She was still speaking through her unjeweled fingers: “Sir, we moved into this house only this morning. I went out for the first time ten minutes since. My maid did not want me to go, but I would do it. Our room—I understand now that our room is the other one: the one across the hallway. But I came back hurriedly, a little frightened by the streets, and I turned—Oh-h!” she ended, “I must go—I must go immediately!”

She dropped her hands and darted forward, turning to her right. Cartaret lost his head: he turned to his right. Each saw the mistake and sought the left; then darted to the right again.

“Let me pass!” commanded the girl.

Cartaret, inwardly condemning his stupidity, suddenly backed. He backed into the half open door; it shut behind him with a sharp snap.

“I’m not dancing,” he said. “I know it looks like it, but I’m not—truly.”

[Pg 21] “Then stand aside and let me pass.”

He stood aside.

“Certainly,” said he; “that is what I was trying to do.”

With her head high, she walked by him to the door and turned the knob: the door would not open.

Than the scorn that she turned upon him then, he had never seen anything more magnificent—or more beautiful. “What is this?” she asked.

He did not know.

“It’s probably stuck,” he suggested. She was beginning to terrify him. “If you’ll allow me——”

He bent to the knob, his hand just brushing hers, which was quickly withdrawn. He pulled: the door would not give. He took the knob in both hands and raised it: no success. He bore all his weight down upon the knob: the door remained shut.

He looked up at her attempting the smile of apology, but her eyes, as soon as they encountered his, were raised to a calm regard of the panel [Pg 22] above his head. Cartaret’s gaze returned to the door and, presently, encountered the old deadlatch that antedated his tenancy and that he had never once used: it was a deadlatch of a type antiquated even in the Latin Quarter, tough and enduring; years ago it had been pushed back and held open by a small catch; the knob whereby it was originally worked from inside the room had been broken off; and now the catch had slipped, the spring-bolt had shot home and, the knob being broken, the girl and Cartaret were as much prisoners in the room as if the lock had been on the other side of the door.

The American broke into a nervous laugh.

“What now?” asked the girl, her eyes hard.

“We’re caught,” said Cartaret.

She could only repeat the word:

“Caught?”

“Yes. I’m sorry. It was my stupidity; I suppose I jolted the door rather hard when I bumped into it, doing that tango just now. Anyhow, this old lock’s sprung into action and we’re fastened in.”

[Pg 23] The girl looked at him sharply. A difficult red climbed her cheeks.

“Open that door,” she ordered.

“But I can’t—not right away. I’ll have to try to——”

“Open that door instantly.”

“But I tell you I can’t. Don’t you see?” He pointed to the offending deadlatch. In embarrassed sentences, he explained the situation.

She did not appear to listen. She had the air of one who has prejudged a case.

“You are trying to keep me in this room,” she said.

Her tone was steady, and her eyes were brave; but it was evident that she quite believed her statement.

Cartaret colored in his turn.

“Nonsense,” said he.

“Then open the door.”

“I tell you the lock has slipped.”

“If that is so, use your key.”

“I haven’t any key,” protested Cartaret. “And even if I had——”

[Pg 24] “You have no key to your own room?” She raised her eyes scornfully. “I understood you to say very positively that I was trespassing in your room.”

“Great Scott!” cried Cartaret. “Of course it’s my room. You make me wish it wasn’t, but it is. It is my room, but you can see for yourself there’s no keyhole to the confounded lock on this side of the door, and never was. Look here.” Again he pointed to the deadlatch: “If you’ll only come a little nearer and look——”

“Thank you,” she said. “I shall remain where I am.” She had put her hand among the lace over her breast; now the hand, withdrawn, held an unsheathed knife. “And if you come one step nearer to me,” she calmly concluded, “I will kill you.”

It was the sole dream-touch needed to perfect his sense of the entire episode’s unreality. In his poor room, a princess that he had never seen before—that, surely, he was not seeing now!—some royal figure out of a lost Hellenic tragedy; her breast visibly cumbered by the heavy air of [Pg 25] modern Paris, her wonderful eyes burning with the cold fire of resolution, she told him that she would kill him if he approached her. And she would do it; she would kill him with less compunction than she would feel in crushing an offending moth!

Cartaret had instinctively jumped at the first flash of the weapon. Now his laughter returned. A vision could not be impeded by a sprung lock.

“But you’re not here,” he said.

She did not shift by so much as a hairbreadth her position of defense, yet, ever so slightly, her eyes widened.

“And I’m not, either,” he persisted. “Don’t you see? Things like this don’t happen. One of us is asleep and dreaming—and I must be that one.”

Plainly she did not follow him, but his laughter had been so boyishly innocent as to make her patently doubtful of her own assumption. He crowded that advantage.

“Honestly,” he said, “I didn’t mean any harm——”

[Pg 26] “You at least place yourself in a strange position,” the girl interrupted, though the hand that held the knife was lowered to her side.

“But if you really doubt me,” he continued, “and don’t want to wait until I pick this lock, let me call from the window and get somebody in the street to send up the concierge.”

“The street?” She evidently did not like this idea. “No, not the street. Why do you not ring for him?”

Cartaret’s gesture included the four walls of the room:

“There’s no bell.”

Still a little suspicious of him, her blue eyes scanned the room to confirm his statement.

“Then why not call him from the window in the back?”

“Because his quarters are at the front of the house, and he wouldn’t hear.”

“Would no one hear?”

“There’s nobody in the garden at this time of day. You had really better let me call to the [Pg 27] first person that goes along the street. Somebody is always going along, you know.”

He made two strides toward the front window.

“Come back!”

He turned to find her with her face scarlet. She had raised the knife.

“Break the lock,” she said.

“But that will take time.”

“Break the lock.”

“All right; only why don’t you want me to call for help?”

“And humiliate me still further?” One small foot, cased in an absurdly light patent-leather slipper with a flashing buckle, tapped the floor angrily. “I have been foolish, and your folly has made me more foolish, but I will not have it known to all the world how foolish I have been. Break the lock at once—now—immediately.”

Cartaret divined that this was eminently a time for silence: she was alive, she was real, and she was human. He opened a drawer in the table, dived under the divan, plunged behind a curtain in one corner, and at last found a shaky hammer [Pg 28] and a nicked chisel with which he returned to the locked door.

“I’m not much of a carpenter,” he said, by way of preparatory apology.

The girl said nothing.

He was angry at himself for having appeared to such heavy disadvantage. Consequently, he was unsteady. His first blow missed. His strength turned to mere violence, and he showered futile blows upon the butt of the chisel. Then a misdirected blow hit the thumb of his left hand. He swore softly and, having sworn, heard her laugh.

He looked up: the knife had disappeared. He was pleased at the change to merriment that her face discovered; but, as he looked, he realized that her mirth was launched against his efforts, and he was pleased no longer. His rage directed itself from him to her.

“I’m sorry you don’t approve,” he said sulkily. “For my part, I am quite willing to stop, I assure you.”

If an imperious person may be said to have [Pg 29] tossed her head, then it should here be said that this imperious person now tossed hers.

“Now, shall I go to the window and yell into the street?” he savagely inquired.

Her high-tilted chin, her crimsoned cheeks and the studiously managed lack of expression in her eyes were proofs that she had heard him. Nevertheless, she persisted in her disregard of his suggestion.

Cartaret’s mood became more ugly. He resolved to make her pay attention.

“I’ll do it,” he said, and turned away from the door.

That brought the answer. She looked at him in angry horror.

“And make us the laughing-stock of the neighborhood?” she cried. “Is it not enough that you have shut me in here, that you have insulted me, that——”

“Insulted you?” He stood with the hammer in one hand and the chisel in the other, a rather unromantic figure of protest. “I never did anything of the sort.”

[Pg 30] He made a flourish and dropped the hammer. When he picked it up, he saw that she stood there, looking over his bent head, with eyes sternly kept serene; but he saw also that her cheeks remained aglow and that her breath came short.

“I never did anything of the sort,” he went on. “How could I?”

“How could you?” She clenched her hands.

“I don’t mean that.” He could have bitten out his tongue. He floundered in a marsh of confusion. “I mean—I mean—Oh, I don’t know what I mean, except that I beg you to believe I am incapable of the impudence you charge! I came in here and found the most beautiful woman——”

She recoiled.

“You speak so to me?”

It was out: he had to go ahead now. He did not at all recognize himself: this was not American; it was wholly Gallic.

“I can’t help it,” he said, “you are.”

“Go to work,” said the girl.

“But I want you to understand——”

[Pg 31] Two tears, twin diamonds of mortification, shone in her blue eyes.

“You have humiliated me, and mortified me, and insulted me!” she persisted. Her white throat swallowed the chagrin, and anger returned to take its place. “If you are what you pretend to be, you will go back to your work of opening that door. If I were the strong man that you are, I should have broken it open long ago.”

She had a handsome ferocity. Cartaret put one broad shoulder to the door and both hands to the knob. There was a tremendous wrenching and splitting: the door swung open. He turned and bowed.

“It’s open,” he said.

To his amazement, her mood had entirely changed. Whether his action had served as proof of his declared sincerity, or whether her brief reflection on his words had itself served him this good turn, he could not guess; but he saw now that her eyes had softened and that her underlip quivered.

[Pg 32] “Good afternoon,” said Cartaret.

“Good-by,” said she.

She moved toward the door, then stopped.

“I hope that you will pardon me,” she said, and she spoke as if she were not accustomed to asking pardon. “I have been too quick and very foolish. You must know that I am new to Paris—new to France—new to cities—and that I have heard strange stories of Parisians and of the men of the large towns.”

Cartaret was more than mollified, but he took a grip upon his emotions and resolved to pursue this advantage.

“At least,” he said, “you should have seen that I was your own sort.”

“My own—my own sort?” She did not seem to comprehend.

“Well, of your own class, then.” This girl had an impish faculty for making him say things that sounded priggish: “You should have seen I was of your own class.”

Again her eyes widened. Then she tossed her head and laughed a little silvery laugh.

[Pg 33] He fancied the laugh disdainful, and thought so the more when she seemed to detect his suspicion and tried to allay it by an alteration of tone.

“I mean exactly that,” he said.

She bit her red lip, and Cartaret noted that her teeth were even and white.

“Forgive me,” she begged.

She put out her hand so frankly that he would have forgiven her anything. He took the hand and, as it nestled softer than any satin in his, he felt his heart hammer in his breast.

“Forgive me,” she was repeating.

“I hope you’ll forgive me,” he muttered. “At any rate, you can’t forget me: you’ll have to remember me as the greatest boor you ever met.”

She shook her head.

“It was I that was foolish.”

“Oh, but it wasn’t! I——”

He stopped, for her eyes had fallen from his and rested on their clasped hands. He released her instantly.

“Good-by,” she said again.

[Pg 34] “Good—— But surely I’m to see you once in a while!”

“I do not know.”

“Why, we’re neighbors! You can’t mean that you won’t let me——”

“I do not know,” she said. “Good-by.”

She went out, drawing-to the shattered door behind her.

Cartaret leaned against the panel and listened shamelessly.

He heard her cross the hall and open the door to the opposite room; he heard her suspiciously greeted by another voice—a voice that he gladly recognized as feminine—and in a language that was wholly unfamiliar to him: a language that sounded somehow Oriental. Then he heard the other door shut, and he turned to the comfortless gloom of his own quarters.

He sat down on the bed. He had forgotten a riotous dinner that was to have been his final Parisian folly, forgotten his poverty, forgotten his day of disappointment and his desire to go back to Ohio and the law. He remembered only [Pg 35] the events of the last quarter-hour and the girl that had made them what they were.

As he sat there, there seemed to come again into the silent room the perfume he had noticed when he returned. It seemed to float in on the twilight, still dimly pink behind the roofs of the gray houses along the Boul’ Miche’: subtle, haunting, an odor more delicate and tender than any he had ever known before.

He raised his head. He saw something white lying on the floor—lying where, a few moments since, he had stood. He went forward and picked it up.

It was a flower like a rose—a white rose—but unlike any rose of which Cartaret had any knowledge. It was small, but perfect, its pure petals gathered tight against its heart, and from its heart came the perfume that had seemed to him like a musical poem in an unknown tongue.

For a second time Cartaret had that quick vision of the sunlight upon snow-crests and the virgin sheen of unattainable mountain tops....

Dans ces questions de crédit, il faut toujours frapper l’imagination. L’idée de génie, c’est de prendre dans la poche des gens l’argent qui n’y est pas encore.—Zola: L’Argent.

Until just before the appearance of Charlie Cartaret’s rosy vision, this had been a day of darkness and wet. Rain—a dull, hopeless, February rain—fell with implacable monotony. It descended in fine spray, as if too lazy to hurry, yet too spiteful to stop. It made all Paris miserable; but, as is the way with Parisian rains, it was a great deal wetter on the Left Bank of the Seine than on the Right.

No rain—not even in those happy times before the great war—ever washed the Left Bank clean, and this one only made it a marsh. A [Pg 37] curtain of fog fell sheer between the Isle de la Cité and the Quai des Augustins; the twin towers of St. Sulpice staggered up into a pall of fog and were lost in it. The gray houses hunched their shoulders, lowered their heads, drew their mansard hats and gabled caps over their noses and stood like rows of patient horses at a cabstand under the gray downpour. Now and again a real cab scuttled along the streets, its skinny beast clop-clopping over the wooden paving, or slipping among the cobbled ways, its driver hidden under a mountainous pile of woolen great-coat and rubber cape. Even the taxis lacked the proud air with which they habitually splash pedestrians, and such pedestrians as business forced upon the early afternoon thoroughfares went with heads bowed like the houses’ and umbrellas leveled like flying-jibs.

In front of the little Café Des Deux Colombes, the two marble-topped tables which occupied its scant frontage on the rue Jacob were deserted by all save their four iron-backed chairs [Pg 38] with wet seats and their twin water-bottles into which, with mathematical precision, water dropped from a pair of holes in the sagging canvas overhead. Inside, however, there were lighted gas-jets, the proprietor and the proprietor’s wife—presumably the pair of doves for whom the Café was named—and a man that was trying to look like a customer.

Gaston François Louis Pasbeaucoup had an apron tied about his middle, and, standing before the intended patron’s table, leaned what weight he had—it was not much—upon his finger-tips. His mustache was fierce enough to grace the upper lip of a deputy from the Bouches-du-Rhône and generous enough to spare many a contribution to the plat-du-jour; but his mustache was the only large thing about him—always excepting Madame his wife, who was ever somewhere about him and who was just now, two hundred and twenty pounds of evidence to the good food of the Deux Colombes, stuffed into a wire cage at one end of the bar, and bulging out of it, her eyebrows meeting over her [Pg 39] pug-nose and the heap of hair leaping from her head nearly to the ceiling, while her lips and fingers were busy adding the bills from déjeuner.

“It would greatly pleasure me to accommodate monsieur,” Pasbeaucoup was whispering, “but monsieur must know that already——”

The sentence ended in a deprecating glance over the speaker’s shoulder in the general direction of mighty Madame.

“Already? Already what then?” demanded the intending customer.

He was lounging on the wall-seat behind his table, and he had an aristocratic air surprisingly at variance with his garments. His black jacket shone too highly at the elbows, and its short sleeves betrayed an unnecessary length of red wrist. His black boots gasped for repair; a soft black hat, pushed to the back of his black hair, still dripped from an unprotected voyage along the rainy street, and his neckcloth, which was also long and soft and black, showed a spot or two not put there by its makers. These were patently matters beyond their owner’s command [Pg 40] and beneath the dignity of his attention. Against them one was compelled to set a manner truly lofty, which was enhanced by a pair of burning, deep-placed eyes, a thin white face and, sprouting from either side of his lower jaw, near the chin, two wisps of ebon whisker. He frowned majestically, and he smoked a caporal cigarette as if it were a Havana cigar.

“Already what?” he loudly repeated. “If it is possible! I patronize your cabbage of a café for five years, and now you put me off with your alreadys!”

Pasbeaucoup, his fingers still resting on the table, danced in embarrassment and rolled his eyes in a manner that plainly enough warned monsieur not to let his voice reach the caged lady.

“I was but about to say that monsieur already owes us the trifling sum of——”

“Sixty francs, twenty-five!”

The tone that announced these fateful numerals was so tremendous a contralto as to be [Pg 41] really bass. It came from the wire cage and belonged to Madame.

Pasbeaucoup sank into the nearest chair. He spread out his hands in a gesture that eloquently said:

“Now you’ve done it! I can’t shield you any longer!”

The debtor, albeit he was still a young man, did not appear unduly impressed. The table was across his knees, but he rose as far as it would permit and removed his hat with a flourish that sent a spray of water directly over Madame’s monument of hair. Disregarding the blatant fact that she was quite the most remarkable feature of the room, he vowed that he had not observed her upon entering, was desolated because of his oversight and ravished now to have the pleasure of once more beholding her in all her accustomed grace and charm.

Madame shrugged her shoulders higher than the walls of the cage.

“Sixty francs, twenty-five,” she said, without looking up from her task.

[Pg 42] Ah, yes: his little account. Monsieur recalled that: there was a little account; but, so truly as his name was Seraphin and his passion Art, what a marvelous head Madame had for figures. It was of an exactitude magnificent!

When he paused, Madame said:

“Sixty francs, twenty-five.”

“But surely, Madame——” Seraphin Dieudonné was politely amazed; he did not desire to credit her with an impoliteness, and yet she seemed to imply that, unless he paid this absurdly little sum, there might be some delay in serving him in this so excellent establishment.

“C’est ça,” said Madame. “The delay will be entire.”

“Incomprehensible!” Seraphin put a bony hand to his heart. “Do you not know—all the world of the Quartier knows—that I have, Madame, but three days’ work more upon my magnum opus—a week at the utmost—and that then it can sell for not a sou less than fifteen thousand francs?”

Madame’s face never changed expression when [Pg 43] she talked; it always seemed set at the only angle that would balance her monument of hair. She now said:

“What all the world of the Quartier knows is that your last magnum opus you sold to that simpleton Fourget in the rue St. André des Arts; that even from him you could squeeze but a hundred francs for it; and that he has not yet been able to find a customer.”

At first Seraphin seemed slow to credit the scorn that Madame was at such pains to reveal. He made one valiant effort to overlook it, and failed; then he made an effort no less valiant to meet her with the ridiculous majesty in which he habitually draped himself. It was as if, unable to make her believe in him, he at least wanted her to believe that his long struggle with poverty and an indifferent public had served only to increase his confidence in his own genius and to rear between him and the world a wall through which the arrows of the scornful could hardly pass. But this attempt succeeded no more than its predecessor: as he half stood, half [Pg 44] bent before this landlady of a fifth-rate café, a tardy pink crept up his white face and painted the skin over his cheek-bones; his eyelids fluttered, and his mouth worked. The man was hungry.

“Madeleine!” whispered Pasbeaucoup, compassion for the debtor almost overcoming fear of the wife.

Seraphin wet his lips.

“Madame——” he began.

“Sixty francs, twenty-five,” said Madame. “Ca y est!”

As she said it, the door of the Deux Colombes opened and another patron, at once evidently a more welcome patron, presented himself. He was a plump little man with hands that were thinly at contrast with the rest of him. He was fairly well dressed, but far better fed, and so contented with his lot as to have no eye for the evident lot of Seraphin. He was Maurice Houdon, who had decided some day to be a great composer and who meanwhile overcharged a few English and American pupils for lessons [Pg 45] on the piano and borrowed money from any that would trust him. He stormed Dieudonné, leaned over the intervening table and embraced him.

“My dear friend!” he cried, his arms outflung, his fingers rattling rapid arpeggios upon invisible pianos. “You are indeed well found. I have news—such news!” He thrust back his head and warbled a laugh worthy of the mad-scene in Lucia. “Listen well.” Again he embraced the unresisting Seraphin. “This night we dine here; we make a collation—a symposium: we feed both our bodies and our souls. I shall sit at the head of the table in the little room on the first floor, and you will sit at the foot. Armand Garnier will read his new poem; Devignes will sing my latest song; Philippe Varachon and you will discourse on your arts; and I—perhaps I shall let you persuade me to play the fugue that I go to write for the death of the President: it is all but ready against the day that a president chooses to die.”

[Pg 46] But Seraphin’s thoughts were fixed on the food for the body.

“You make no jest with me, Maurice?”

“Jest with you? I jest with you? No, my friend. I do not jest when I invite a guest to dine with me.”

“I comprehend,” said Dieudonné; “but who is to be the host?”

At that question, Pasbeaucoup rose from his chair, and Madame, his wife, tried to thrust her nose, which was too short to reach, through the bars of her cage. The composer struck a chord on his breast and bowed.

“True: the host,” said he. “I had forgotten. I have found a veritable patron of my art. He has had the room above mine for two years, and I did not once before suspect him. He is an American of the United States.”

Madame’s contralto shook her prison bars:

“There is no American that can appreciate art.”

“True, Madame,” admitted Houdon, bowing profoundly; “there is no American that can [Pg 47] appreciate art, and there is no American millionaire that can help patronizing it.”

“Eh, he is a millionaire, then, this American?” demanded Madame, audibly mollified.

“He has that honor.”

“And his name?”—Madame wanted to make a memorandum of that name.

Houdon struck another chord. It was as if he were sounding a fanfare for the entrance of his hero.

“Charles Cartaret.” He pronounced the first name in the French fashion and the second name “Cartarette.”

Seraphin’s reply to this announcement rather spoiled its effect. He laughed, and his laughter was high and mocking.

“Cartaret!” he cried. “Charlie Cartaret! But I know him well.”

“Eh?”—The composer was reproachful—“And you never presented him to me?”

“It never happened that you were by.”

“My faith! Why should I be? Am I not Houdon? You should have brought him to me. [Pg 48] Is it that you at the same time consider yourself my friend and do not bring to me your millionaire?”

Seraphin’s laughter waxed.

“But he is not my millionaire: he is your millionaire only. I know well that he is as poor as we are.”

The musician’s imaginary melody ceased: one could almost hear it cease. He gazed at Seraphin as he might have gazed at a madman.

“But that room rents for a hundred francs a month!”

“He is in debt for it.”

“And his name is that of a rich American well known.”

“An uncle who does not like him.”

“And he has offered to provide this collation.”

Seraphin shrugged.

“M. Cartaret’s credit,” said he, with a glance at Madame, “seems to be better than mine. I tell you he is only a young art-student, enough genteel, and the relation of a man enough rich, but for himself—poof!—he is one of us.”

Money’s the still sweet-singing nightingale.—Herrick: Hesperides.

Seraphin Dieudonné told the truth: at that moment Charlie Cartaret—for all this, remember, preceded the coming of the Vision—at that moment Cartaret was seated in his room in the rue du Val-de-Grâce, wondering how he was to find his next month’s rent. His trouble was that he had just sold a picture, for the first time in his life, and, having sold it, he had rashly engaged to celebrate that good fortune by a feast which would leave him with only enough to buy meals for the ensuing three weeks.

He was a rather fine-looking, upstanding young fellow of a type essentially American. In the days, not long distant, when the goal at [Pg 50] the other end of the gridiron had been the only goal of his ambition, he had put hard muscles on his hardy frame; later he had learned to shoot in Arizona; and he even now would have looked more at home along Broadway or Halsted Street than he did in the rue St. Jacques or the Boulevard St. Michel. He was tow-haired and brown-eyed and clean-shaven; he was generally hopeful, which is another way of saying that he was still upon the flowered slope of twenty-five.

Cartaret had inherited his excellent constitution, but his family all suffered from one disease: the disease of too much money on the wrong side of the house. When oil was found in Ohio, it was found in land belonging to his father’s brother, but Charlie’s father remained a poor lawyer to the end of his days. Uncle Jack had children of his own and a deserved reputation for holding on to his pennies. He sent his niece to a finishing-school, where she could be properly prepared for that state of life to which it had not pleased Heaven to call her, [Pg 51] and he sent his nephew to college. When the former child was finished, he found her a place as companion to an ancient widow in Toledo and dismissed her from his thoughts; when Charlie was through with college—which is to say, when the faculty was through with him for endeavoring to plant a fraternity in a plot of academic soil that forbade the seed of Greek-letter societies—he asked him what he intended to do now—and asked it in a tone that plainly meant:

“What further disgrace are you planning to bring upon our name?”

Charlie replied that he wanted to be an artist.

“I might have guessed it,” said his uncle. “How long’ll it take?”

Young Cartaret, knowing something about art, had not the slightest idea.

“Well,” said the by-product of petroleum, “if you’ve got to be an artist, be one as far away from New York as you can. They say Paris is the best place to learn the business.”

“It is one of the best places,” said Charlie.

[Pg 52] The elder Cartaret wrote a check.

“Take a boat to-morrow,” he ordered. “I’ll pay your board and tuition for two years: that’s time enough to learn any business. After two years you’ll have to make out for yourself.”

So Charlie had worked hard for two years. That period ended a week ago, and his uncle’s checks ended with it. He had stayed on and hoped. To-day he had carried a picture through the rain to Seraphin’s benefactor, the dealer Fourget; and the soft-hearted Fourget had bought it. Cartaret, on his return, met Houdon in the lower hall and before the American was well aware of it, he was pledged to the feast of which Maurice was bragging to Dieudonné.

Charlie dug into his pocket and fished out all that was in it: a matter of two hundred and ten francs. He counted it twice over.

“No use,” he said. “I can’t make it any larger. I wonder if I ought to take a smaller room.”

Certainly there was more room here than he wanted, but he had grown to love the place: [Pg 53] even then, when he had still to see it in the rose-pink twilight of romance, in the afterglow that was a dawn—even then, before the apparition of the strange Lady—he loved it as his sort of man must love the scenes of those struggles which have left him poor. Its front windows opened upon the street full of student-life and gossip, its rear windows looked on a little garden that was pretty with the concierge’s flowers all Summer long and merry with the laughter of the concierge’s children on every fair day the whole year round. The light was good enough, the location excellent; the service was no worse than the service in any similar house in Paris.

“But I have been a fool,” said Cartaret.

He looked again at his money, and then he looked again about the room. The difference between a fool and a mere dilettante in folly is this: that the latter knows his folly as he indulges it, whereas the former recognizes it, if ever, only too late.

[Pg 54] “If I’d been able to study for only one year more,” he said.

It was the wail of retrospection that, sooner or later, every man, each in his own way and according to his chances and his character for seizing them, is bound to utter. It was what we all say and what, in saying, we each think unique. Happy he that says it, and means it, in time to profit!

“Yes,” said Cartaret, “I’ve been a fool. But I won’t be a quitter,” he added. “I’ll go and order that dinner.”

Thus Charles Cartaret in the afternoon.

He had put on a battered, broad-brimmed hat of soft black felt, which was picturesquely out of place above his American features, and a still more battered English rain-coat, which did not at all belong with the hat, and, thus fortified against the rain, he hurried into the hall. As he closed the door of his studio behind him, he fancied that he heard a sound from the room across from his own, and so stood listening, his hand upon the knob.

[Pg 55] “That’s queer,” he reflected. “I thought that room was still to let.”

He listened a moment longer, but the sound, if sound there had been, was not repeated, so he pulled his hat-brim over his eyes and descended to the street.

The rain had lessened, but the fog held on, and the thoroughfares were wet and dismal. Cartaret cut down the rue du Val-de-Grâce to the Avenue de Luxembourg and through the gardens with their dripping statues and around the museum, whence he crossed to the sheltered way between those bookstalls that cling like ivy to the walls of the Odéon, and so, by the steep descent of the rue de Tournon and the rue de Seine, came to the rue Jacob and the Café Des Deux Colombes.

Seraphin and Maurice were still there. They received him as their separate natures dictated, the former with a restrained dignity, the latter with the dignity of a monarch so secure of his title that he can afford to condescend to an air of democracy. Seraphin bowed; Maurice [Pg 56] embraced and, embracing, tapped the diatonic scale along Cartaret’s vertebræ. Pasbeaucoup, in trembling obedience to a cryptic nod from the caged Madame, hovered in the background.

“I have come,” said Cartaret, whose French was the easy and inaccurate French of the American art-student, “to order that dinner.” He half turned to Pasbeaucoup, but Houdon was before him.

“It is done,” announced the musician, as if announcing a favor performed. “I have relieved you of that tedium. We are to begin with an hors-d’oeuvre of anchovies and——”

Madame had again nodded, this time less cryptically and more violently, at her husband, and Pasbeaucoup, between twin terrors, timidly suggested:

“Monsieur Cartaret comprehends that it is only because of the so high cost of necessities that it is necessary for us to request——”

He stopped there, but the voice from the cage boomed courageously:

“The payment in advance!”

[Pg 57] “A custom of the establishment,” explained Houdon grandly, but shooting a venomous glance in the direction of Madame.

Seraphin came quietly from behind his table and, slipping a thin arm through Cartaret’s, drew him, to the speechless amazement of the other participants in this scene, toward the farthest corner of the café.

“My friend,” he whispered, “you must not do it.”

“Eh?” said Cartaret. “Why not? It’s a queer thing to be asked, but why shouldn’t I do it?”

Seraphin hesitated. Then, regaining the conquest over self, he put his lips so close to the American’s ear that the Frenchman’s wagging wisps of whisker tickled his auditor’s cheek.

“This Houdon is but a pleasant coquin,” he confided. “He will suck from you the last sou’s worth of your blood.”

Cartaret smiled grimly.

“He won’t get a fortune by it,” he said.

“That is why I do not wish him to do it: [Pg 58] I know well that you cannot afford these little dissipations. I do not wish to see my friend swindled by false friendship. Houdon is a good boy, but, Name of a Name, he has the conscience of a pig!”

“All right,” said Cartaret suddenly, for Seraphin was appealing to a sense of economy still fresh enough to be sensitive, “since he’s ordered the dinner, we’ll let him pay for it.”

“Alas,” declared Dieudonné, sadly shaking his long hair, “poor Maurice has not the money.”

“Oh!”—A gleam of gratitude lighted Cartaret’s blue eyes—“Then you are proposing that you do it?”

“My friend,” inquired Seraphin, flinging out his arms as a man flings out his arms to invite a search of his pockets, “you know me: how can I?”

Cartaret blushed at his ineptitude. He knew Dieudonné well enough to have been aware of his poverty and liked him well enough to be tender toward it. “But,” he nevertheless pardonably [Pg 59] inquired, “if that’s the way the thing stands, who’s to pay? One of the other guests?”

“We are all of the same financial ability.”

“Then I don’t see——”

“Nor do I. And”—Seraphin’s high resolution clattered suddenly about his ears—“after all, the dinner has been ordered, and I am very hungry. My friend,” he concluded with a happy return of his dignity, “at least I have done you this service: you will buy the dinner, but you will not both buy it and be deceived.”

Cartaret turned, with a smile no longer grim, to the others.

“Seraphin,” he said, “has persuaded me. Madame, l’addition, if you please.”

Pasbeaucoup trotted to the cage, bringing back to Cartaret the long slip of paper that Madame had ready for him. Cartaret glanced at only the total and, though he flushed a little, paid without comment.

“And now,” suggested Houdon, “now let us play a little game of dominoes.”

Seraphin, from the musician’s shoulder, [Pg 60] frowned hard at Cartaret, but Cartaret was in no mood to heed the warning. He was angry at himself for his extravagance and decided that, having been such a fool as to fling away a great deal of his money, he might now as well be a greater fool and fling it all away. Besides, he might be able to win from Houdon, and, even if Houdon could not pay, there would be the satisfaction of revenge. So he sat down at one of the marble-topped tables and began, with a great clatter, to shuffle the dominoes that obsequious Pasbeaucoup hurriedly fetched. Within two hours, Seraphin was head over ears in the musician’s debt, and the American was paying into Houdon’s palm all but about ten francs of the money that he had so recently earned. He rose smilingly.

“You do not go?” inquired Houdon.

Cartaret nodded.

“But the dinner?”

“Don’t you worry; I’ll be back for that—I don’t know when I’ll get another.”

“Then permit me,” Houdon condescended, [Pg 61] “to order a bock. For the three of us.” He generously included the hungry Seraphin. “Come, we shall drink to your better fortune next time.”

But Cartaret excused himself. He said that he had an engagement with a dealer, which was not true, and which was understood to be false, and he went into the street.

The last of the rain, unnoticed during Cartaret’s fevered play, had passed, and a red February sun was setting across the Seine, behind the higher ground that lies between L’Etoile and the Place du Trocadero. The river was hidden by the point of land that ends in the Quai D’Orsay, but, as Cartaret crossed the broad rue de Vaugirard, he could see the golden afterglow and, silhouetted against it, the high filaments of the Eiffel Tower.

What an ass he had been, he bitterly reflected, as he passed again through the Luxembourg Gardens, where now the statues glistened in the fading light of the dying afternoon. What a mad ass! If a single stroke of almost [Pg 62] pathetically small good luck made such a fool of him, it was as well that his uncle and not his father had come into a fortune.

His thought went back with a new tenderness to his father and to his own and his sister Cora’s early life in that small Ohio town. He had hated the dull routine and narrow conventionality of the place. There the most daring romance of youth had been to walk with the daughter of a neighbor along the shaded streets in the Summer evenings, and to hang over the gate to the front yard of the house in which she lived, tremblingly hinting at a delicious tenderness, which one never dared more adequately to express, until a threatening parental voice called the girl to shelter. His life, since those days, had been more stirring, and sometimes more to be regretted; but he had loved it and thought it absurd sentiment on Cora’s part to insist that their tiny income go to keeping up the little property—the three-story brick house and wide front and back-yard along Main Street—which had been their home. Yet now [Pg 63] he felt, and was half ashamed of feeling, a strong desire to go back there, a pull at his heartstrings for a return to all that he was once so anxious to quit forever.

He wondered if it could be possible that he was tired of Paris. He even wondered if it were possible that he could not be a successful artist—he had never wanted to be a rich one—whether the sensible course would not be to go home and study law while there was yet time....

And then——

Then, in the rose-pink twilight, the beginning of the Dream Wonderful: that scent of the roses from the sky; that quick memory of sunlight upon snow-crests; that first revelation of the celestial Lady transfiguring the earthly commonplace of his room!

Charlie Cartaret would have told you—indeed, he frequently did tell his friends—that the mere fact of a man being an artist was no proof that he lacked in the uncommon sense commonly known as common. Cartaret was quite insistent upon this and, as evidence in favor of his contention, he was accustomed to point to C. Cartaret, Esq. He, said Cartaret, was at once an artist and a practical man: it was wholly impossible, for instance, to imagine him capable of any silly romance.

Nevertheless, when left alone in his room by the departure of the Lady on that February evening, he sat for a long time with the strange [Pg 65] rose between his fingers and a strange look in his eyes. He regarded the rose until the last ray of light had altogether faded from the West. Only then did he recall that he had invited sundry persons to dine with him at the Café Des Deux Colombes, and when he had made ready to go to them, the rose was still in his reluctant hand.

Cartaret looked about him stealthily. He had been in the room for some hours and he should have been thoroughly aware that he was alone in it; but he looked, as all guilty men do, to right and left to make sure. Then, like a naughty child, he turned his back to the street-window.

He stood thus a bare instant, yet in that instant his hand first raised something toward his lips, and then bestowed that same something somewhere inside his waistcoat, a considerable distance from his heart, but directly over the rib beneath which ill-informed people believe the heart to be. This accomplished, he exhibited a rigorously practical face to the room [Pg 66] and swaggered out of it, ostentatiously humming a misogynistic drinking-song:

Armand Garnier, one of the men that were to dine with Cartaret to-night, had written the words of which this is a free translation, and Houdon had composed the air—he composed it impromptu for Devignes over an absinthe, after laboring upon it in secret for an entire week—but Cartaret, when he reached the note that stood for the last word here given, came to an abrupt stop; he was facing the door of the room opposite his own. He continued facing it for quite a minute, but he heard nothing.

“M. Refrogné,” he said, when he thrust his head into the concierge’s box downstairs, “if—er—if anybody should inquire for me this evening, [Pg 67] you will please tell them that I am dining at the Café Des Deux Colombes.”

Nothing could be seen in the concierge’s box, but from it came a grunt that might have been either assent or dissent.

“Yes,” said Cartaret, “in the rue Jacob.”

Again the ambiguous grunt.

“Exactly,” Cartaret agreed; “the Café Des Deux Colombes, in the rue Jacob, close by the rue Bonaparte. You—you’re quite sure you won’t forget?”

The grunt changed to an ugly chuckle, and, after the chuckle, an ugly voice said:

“Monsieur expects something unusual: he expects an evening visitor?”

“Confound it, no!” snapped Cartaret. He had been wildly hoping that perhaps The Girl might need some aid or direction that evening and might seek it of him. “Not at all,” he pursued, “but you see——”

“How then?” inquired the voice.

Cartaret’s hand went to his pocket and drew [Pg 68] forth one of the few franc-pieces that remained there.

“Just, please, remember what I’ve said,” he requested.

In the darkness of the box into which it was extended, his hand was grasped by a larger and rougher hand, and the franc was deftly extracted.

“Merci, monsieur.”

A barely appreciable softening of the tone encouraged Cartaret. He balanced himself from foot to foot and asked:

“Those people—the ones, you understand, that have rented the room opposite mine?”

Refrogné understood but truly.

“Well—in short, who are they, monsieur?”

“Who knows?” asked Refrogné in the darkness. Cartaret could feel him shrug.

“I rather thought you might,” he ventured.

The darkness was silent; a good concierge answers questions, not general statements.

“Where—don’t you know where they come from?”

[Pg 69] There was speech once more. Refrogné, it said, neither knew nor cared. In the rue du Val de Grâce people continually came and went—all manner of people from all manner of places—so long as they paid their rent, it was no concern of Refrogné’s. For all the information that he possessed, the two people of whom monsieur inquired might be natives of Cochin-China. Mademoiselle evidently wanted to be an artist, as scores of other young women, and Madame, her guardian and sole companion, evidently wanted Mademoiselle to be nothing at all. There were but two of them, thank God! The younger spoke much French with an accent terrible; the elder understood French, but spoke only some pig of a language that no civilized man could comprehend. That was all that Refrogné had to tell.

Cartaret went on toward the scene of his dinner-party. He wished he did not have to go. On the other hand, he was sure he had thrown Refrogné a franc to no purpose: the Lady of the Rose was little likely to seek him! He found [Pg 70] the evening cold and his rain-coat inadequate. He began humming the drinking-song again.

They were singing it outright, in a full chorus, when he entered the little room on the first floor of the Café Des Deux Colombes. The table was already spread, the feast already started. The unventilated room was flooded with light and full of the steam of hot viands.

Maurice Houdon, his red cheeks shining, his black mustache stiffly waxed, sat at the head of the table as he had promised to do, performing the honors with a regal grace and playing imaginary themes with every flourish of address to every guest: a different theme for each. On his right was a vacant place, the sole apparent reference to the host of the evening; on his left, Armand Garnier, the poet, very thin and cadaverous, with long dank locks and tangled beard, his skin waxen, his lantern-jaw emitting no words, but working lustily upon the food. Next to Cartaret’s place bobbed the pear-shaped Devignes, leading the chorus, as became the only professional singer in the company. Across from him [Pg 71] was Philippe Varachon, the sculptor, whose nose always reminded Cartaret of an antique and long lost bit of statuary, badly damaged in exhumation; and at the foot Seraphin was seated, the first to note Cartaret’s arrival and the only one to apologize for not having delayed the dinner.

He got up immediately, and his whiskers tickled the American’s cheek with the whisper:

“It was ready to serve, and Madame swore that it would perish. My faith, what would you?”

Pasbeaucoup was darting among the guests, wiping fresh plates with a napkin and his dripping forehead with his bare hand. Cartaret felt certain that the little man would soon confuse the functions of the two.

“Ah-h-h!” cried Houdon. He rose from his place and endeavored to restore order by beating with a fork upon an empty tumbler, as an orchestral conductor taps his baton—at the same time nodding fiercely at Pasbeaucoup to refill the tumbler with red wine. He was the sole member of the company not long known to their host, [Pg 72] but he said: “Messieurs, I have the happiness to present to you our distinguished American fellow-student, M. Charles Cartarette. Be seated among us, M. Cartarette,” he graciously added; “pray be seated.”

Cartaret sat down in the place kindly reserved for him, and the interruption of his appearance was so politely forgotten that he wished he had not been such a fool as to make it. The song was resumed. It was not until the salad was served and Pasbeaucoup had retired below-stairs to assist in preparing the coffee, that Houdon turned again to Cartaret and executed what was clearly to be the Cartaret theme.

“We had despaired of your arrival, Monsieur,” said he.

Cartaret said he had observed signs of something of the sort.

“Truly,” nodded Houdon. His tongue rolled a ball of salad into his cheek and out of the track of speech. “Doubtless you had the one living excuse, however.”

“I don’t follow you,” said Cartaret.

[Pg 73] Houdon leered. His fingers performed on the table-cloth something that might have been the motif of Isolde.

“I have heard,” said he, “your American proverb that there are but two adequate excuses for tardiness at dinner—death and a lady—and I am charmed, monsieur, to observe that you are altogether alive.”

If Cartaret’s glance indicated that he would like to throttle the composer, Cartaret’s glance did not misinterpret.

“We won’t discuss that, if you please,” said he.

But Houdon was incapable of understanding such glances in such a connection. He tapped for the attention of his orchestra and got it.

“Messieurs,” he announced, “our good friend of the America of the North has been having an adventure.”

Everybody looked at Cartaret and everybody smiled.

“Delicious,” squeaked Varachon through his broken nose.

[Pg 74] “Superb,” trilled the pear-shaped singer Devignes.

Garnier’s lantern-jaws went on eating. Seraphin Dieudonné caught Cartaret’s glance imploringly and then shifted, in ineffectual warning, to Houdon.

“But that was only what was to be expected, my children,” the musician continued. “What can we poor Frenchmen look for when a blond Hercules of an American comes, rich and handsome, to our dear Paris? Only to-day I observed, renting an abode in the house that Monsieur and I have the honor to share, a young mademoiselle, the most gracious and beautiful, accompanied by a tuteur, the most ferocious; and I noted well that they went to inhabit the room but across the landing from that of M. Cartarette. Behold all! At once I said to myself: ‘Alas, how long will it be before this confiding——’”

He stopped short and looked at Cartaret, for Cartaret had grasped the performing hand of the composer and, in a steady grip, forced it quietly to the table.

[Pg 75] “I tell you,” said Cartaret, gently, “that I don’t care to have you talk in this strain.”

“How then?” blustered the amazed musician.

“If you go on,” Cartaret warned him, “you will have to go on from the floor; I’ll knock you there.”

“Maurice!” cried Seraphin, rising from his chair.

“Messieurs!” piped Devignes.

Varachon growled at Houdon, and Garnier reached for a water-bottle as the handiest weapon of defense. Houdon and Cartaret were facing each other, erect, each waiting for the other to make a further move, the former red, the latter white, with anger. There followed that flashing pause of quiet which is the precursor of battle.

The battle, however, was not forthcoming. Instead, through the silence, there came a roar of voices that diverted the attention of even the chief combatants. It was a roar of voices from the café below: a heavy rumble that was unmistakably Madame’s and a clatter of [Pg 76] unintelligible shrieks and demands that were feminine but unclassifiable. Now one voice shouted and next the other. Then the two joined in a mighty explosion, and little Pasbeaucoup was shot up the stairs and among the diners as if he were the first rock from the crater of an emptying volcano.

He staggered against the table and jolted the water-bottle out of the poet’s hand.

“Name of a Name!” he gasped. “She is a veritable tigress, that woman there!”

They had no time then to inquire whom he referred to, though they knew that, however justly he might think it, he would never, even in terror like the present, say such a thing of his wife. The words were no sooner free of his lips than a larger rock was vomited from the volcano, and a still larger, the largest rock of the three, came immediately after.

Everybody was afoot now. They saw that Pasbeaucoup cowered against the wall in a fear terrible because it was greater than his fear for Madame; they saw that Madame, who was the [Pg 77] third rock, was clinging to the apron-strings of another woman, who was rock number two, and they saw that this other woman was a stocky figure, who carried in her hand a curious, wide head-dress, and who wore a parti-colored apron that began over her ample breasts and ended by brushing against her equally ample boots, and a black skirt of simple stuff and extravagant puffs, surmounted by a short-skirted blouse or basque of the same material. Her face was round and wrinkled like a last winter’s apple on the kitchen-shelf; but her eyes shone red, her hands beat the air vigorously, and from her lips poured a lusty torrent of sounds that might have been protestations, appeals or curses, yet were certainly, considered as words, nothing that any one present had ever heard before.

She ran forward; Madame ran forward. The stranger shouldered Madame; Madame dragged her back. The stranger cried out more of her alien phrases; Madame shouted French denunciations. The Gallic diners formed a grinning circle, eager to lose no detail of the sort of [Pg 78] wrangle that a Frenchman loves best to watch: a wrangle between women.

Cartaret made his way through the ring and put his hand on the stranger’s shoulder. She seemed to understand, and relapsed into quiet, attentive but alert.

“Now,” said Cartaret, “one at a time, please. Madame, what is the trouble?”

“Trouble?” roared Madame. Her face did not change expression, but she held her arms akimbo, pug-nose and strong chin poked defiantly at the strange interloper. “You may well say it, trouble!”

She put her position strongly and at length. She had been in the caisse, with no one of the world in the café, when, crying barbarous threats incomprehensible, this she-bandit, this—this anarchiste infâme, had burst in from the street, disrupting the peace of the Deux Colombes and endangering its well-known quiet reputation with the police.

That was the gist of it. When it was delivered, Cartaret faced the stranger.

[Pg 79] “And you, Madame?” he asked, in French.

The stranger strode forward as a pugilist steps from his corner for the round that he expects to win the fight for him. She clapped her wide head-dress upon her head, where it settled itself with a rakish tilt.

“Holy pipe!” cried Houdon. “In that I recognize her. It is the ferocious tuteur!”

Cartaret’s interest became tense.

“What did you want here?” he urged, still speaking French.

The stranger said, twice over, something that sounded like “Kar-kar-tay.”

“She is mad,” squeaked Varachon.

“She is worse; she is German,” vowed Madame.

Cartaret raised his hand to silence these contentions.

“Do you understand me?” he urged.

The wide head-dress flapped a vehement assent.

“But you can’t answer?”

The head-dress fluttered a negative, and the [Pg 80] mouth mumbled a negative in a French so thick, hesitant and broken as to be infinitely less expressive than the shake of the head.

Cartaret remembered what the concierge Refrogné had told him. To the circle of curious people he explained:

“She can understand a little French, but she cannot speak it.”

Madame snorted. “Why then does she come to this place so respectable if she cannot talk like a Christian?”

“Because,” said Cartaret, “she evidently thought she would be intelligently treated.”

It was clear to him that she would not have come had her need not been desperate. He made another effort to discover her nationality.

“Who of you speaks something besides French?” he asked of the company.

Not Madame; not Seraphin or Houdon: they were ardent Parisians and of course knew no language but their own. As for Garnier, as a French poet and a native of the pure-tongued Tours, he would not have soiled his lips with [Pg 81] any other speech had he known another. Varachon, it turned out, was from the Jura, and had picked up a little Swiss-German during a youthful liaison at Pontarlier. He tried it now, but the stranger only shook her head-dress at him.

“She knows no German,” said Varachon.

“Such German!” sniffed Houdon.

“Chut! This proves rather that she knows it too well,” grumbled Madame. “She but wishes to conceal it; probably she is a German spy.”

Devignes said he knew Italian, and he did seem to know a sort of Opera-Italian, but it, too, was useless.

Cartaret had an inspiration.

“Spanish!” he suggested. “Does any one know any Spanish?”

Pasbeaucoup did; he knew two or three phrases—chiefly relating to prices on the menu of the Deux Colombes—but to him also the awful woman only shook her head in ignorance.

Cartaret took up the French again.

[Pg 82] “Can you not tell me what you want here?” he pleaded.

“Kar-kar-tay,” said the stranger.

“Ah!” cried Seraphin, clapping his hands. “Does not Houdon say that she makes her abode in the same house that you make yours? She seeks you, monsieur. ‘Kar-kar-tay,’ it is her manner of endeavoring to say Cartarette.”

At the sound of that name, the stranger nodded hard.

“Oui, oui!” she cried.

She understood that her chief inquisitor was Cartaret, and it was indeed Cartaret that she sought. She flung herself on her knees to him. When he hurriedly raised her, she caught at the skirt of his coat and nearly pulled it from him in an attempt to drag him to the stairs.

Cartaret looked sharply at Houdon. The musician having been so recently saved from the wrath of his host, was momentarily discreet: he hid his smile behind one of the thin bands that contrasted so sharply with his plump cheeks.

[Pg 83] “Messieurs,” said Cartaret, “I am going with this lady.”

They all edged forward.

“And I am going alone,” added the American. “I wish you good-night.”

“You will be knifed in the street,” said Madame. Her tone implied: “And it will serve you right.”

None of the others seemed to mind his going; the wrangle over, they were ready for their coffee and liqueurs. Houdon was frankly relieved. Only Seraphin protested.

“And you will leave your dinner unfinished?” he cried.

Cartaret was taking his hat and rain-coat from the row of pegs on the wall where, among the other guests’, he had hung them when he entered. He nodded his answer to Seraphin’s query.

“Leave your dinner?” said Seraphin. “But my God, it is paid for!”

“Good-night,” said Cartaret, and was plunged down the stairs by the strangely-garbed woman tugging at his hand.

La timidité est un grand péché contre l’amour.—Anatole France: La Rotisserie de la Reine Pédauque.

If that strange old woman in the rakish head-dress was in a hurry, Cartaret, you may be sure, was in no mood for tarrying by the way. He left the Café des Deux Colombes, picturing The Girl of the Rose desperately ill, and he was resolved not only to be the first to come to her aid, but to have none of the restaurant’s suspicious company for a companion. Then, no sooner had he passed through the empty room on the ground-floor of Mme. Pasbeaucoup’s establishment and gone a few steps toward the rue de Seine, than he began to fear that perhaps the house to which he was apparently being conducted—The Girl’s house and [Pg 85] his own—had taken fire; or that the cause of the duenna’s mission was some like misfortune which would be better remedied, so far as The Girl’s interests were concerned, if there were more rescuers than one.

“What is the matter?” he begged his guide to inform him, as they hurried through the darkened streets.

His guide lifted both hands to her face.

“Is mademoiselle ill?”

The duenna shook her head in an emphatic negative.

“The place isn’t on fire?” His tone was one of petition, as if, should he pray hard enough, she might avert the catastrophe he now dreaded; or as if, by touching her sympathies, he could release some hidden spring of intelligible speech.

The old woman, however, only shook her head again and hurried on. Cartaret was glad to find that she possessed an agility impossible for a city-bred woman of her apparent age, and he was still more relieved when they reached their lodging-house and discovered it in [Pg 86] apparently the same condition as that in which he had left it.

Their ascent of the stairs was like a race—a race ending in a dead-heat. At the landing, Cartaret turned, of course, toward his neighbor’s door; to his amazement, the old woman pulled him to his own.

He opened it and struck a match: the room was empty. He held the match until it burnt his fingers.

The old woman pushed him toward his table, on which stood a battered lamp. She pointed to the lamp.

“But your mistress?” asked Cartaret.

The duenna pointed to the lamp.

“Shall I light it?”

She nodded.

He lit the lamp. The flame grew until it illuminated a small circle about the table.

“Now what?” Cartaret inquired.

Again that odd gesture toward the nose and mouth.

“I don’t understand,” said Cartaret.

[Pg 87] She picked up the lamp and made as if to search the floor for something. Then she held out the lamp to him.

“Oh”—it began to dawn on Cartaret—“you’ve lost something?”

“Oui, oui!”

He took the lamp, and they both fell on their knees. Together they began a minute inspection of the dusty floor. Cartaret’s mind was more easy now: at least his Lady suffered no physical distress.

“It’s like a sort of religious ceremony,” muttered the American, as, foot by foot, they crawled and groped over the grimy boards....

“Was it money you lost?” he inquired.

No, it was not money.

The search continued. Cartaret crawled under the divan, while the duenna held the cover high to admit the light. He blackened his hands in the fire-place and transferred a little of the soot to his few extra clothes that hung behind the corner curtain—but only a little; most of the soot preferred his hands.

[Pg 88] “I never knew before that the room was so large,” he gasped.

They had covered two-thirds of the floor-space when a new thought struck him. Still crouching on his knees, he once more tried his companion.

“I can’t find it,” he said; “but I’d give a good deal to know what I’m looking for. What were you doing in here when you lost it, anyway?”

She shook her head, with her hand on her breast. Then she pointed to the door and nodded.

“You mean your mistress lost it?”

“Oui.”

“Well, then, let’s get her. She can tell me what I’m after.”

He half rose; but the woman seized his arm. She broke into loud sounds, patently protestations.

“Nonsense,” said Cartaret. “Why not? Come on; I’ll knock at her door.”

The duenna would not have her mistress disturbed. The ancient voice rose to a shriek.

[Pg 89] “But I say yes.”

The shriek grew louder. With amazing strength, the old woman forced his unsuspecting body back to its former position; she came near to jolting the lamp from his hand.

It was then that Cartaret heard a lesser noise behind them: a voice, the low sweet voice of The Rose-Lady, asked, in the duenna’s strange tongue, a question from the doorway. Cartaret turned his head.

She was standing there in the dim light, a sort of kimono gathered about her, her sandaled feet peeping from its lower folds, the lovely arm that held the curious dressing-gown in place bare to the elbow. She was smiling at the answer that her guardian had already given her; Cartaret thought her even more beautiful than when he had seen her before.

The duenna had scuttled forward on her knees and, amid a series of cries, was pressing the hem of the kimono to her lips. The Girl’s free hand was raising the petitioner.

[Pg 90] “I am sorry that you have been disturbed by Chitta,” she was saying.

Cartaret understood then that he was addressed. Moreover, he became conscious that he was by no means at his best on his knees, with his clothes even more rumpled than usual, his hands black and, probably, his face no better. He scrambled to his feet.

“It’s been no trouble,” he said awkwardly.

“I should say that it had been a good deal,” said the Girl. “Chitta is so very superstitious. Did you find it?”

“No,” said Cartaret. “At least I don’t think so.”

The Girl puckered her pretty brow.

“I mean,” explained Cartaret, coming nearer, but thankful that he had left the lamp on the floor behind him, whence its light would least reveal his soiled hands and face—“I mean that I haven’t the least idea what I was looking for.”

The Girl burst into rippling laughter.

“Not the least,” pursued the emboldened [Pg 91] American. “You see, I left word with Refrogné—that’s the concierge—that I was dining with some friends at the Deux Colombes—that’s a café—when I went out; and I suppose she—I mean your—your maid, isn’t it?—made him understand that she—I mean your maid again—wanted me—you know, I don’t generally leave word; but this time I thought that perhaps you—I mean she—or, anyhow, I had an idea——”

He knew that he was making a fool of himself, so he was glad when she came serenely to his assistance and gallantly shifted the difficulty to her own shoulders.

“It was too bad of Chitta to take you away from your dinner.”

Chitta had slunk into the shadows, but Cartaret could descry her glaring at him.

“That was of no consequence,” he said; he had forgotten what the dinner cost him.

“But, sir, for a reason of so great an absurdity!” She put one hand on the table and leaned on it. “I must tell you that there is in my country a superstition——”

[Pg 92] She hesitated. Cartaret, his heart leaping, leaned forward.

“What is your country, mademoiselle?” he asked.

She did not seem to hear that. She went on:

“It is really a superstition so much absurd that I am slow to speak to you of it. They believe, our peasants, that it brings good luck when they take it with them across our borders; that only it can ensure their return, and that, if it is lost, they will never come back to their home-land.” Her blue eyes met his gaze. “They, sir, love their home-land.”

Cartaret was certain that the land which could produce this presence, at once so human and so spiritual, was well worth loving. He wanted to say so, but another glance at her serene face checked any impulse that might seem impertinent.

“I, too, love my country, although I am not superstitious,” the Girl pursued, “so I had brought it with me from my country. I brought it with me to Paris, and I lost it. We go early to [Pg 93] sleep, the people of my race; I had not missed it when I went to bed; but then Chitta missed it; and I told her that I thought that I had perhaps dropped it here. She ran before I could recall her—and I fell straightway asleep. She tells me that she had seen you go out, sir, and that she went to the concierge, as you supposed, to discover where you had gone, for she thought, she says, that your door was locked.” The corners of the Girl’s mouth quivered in a smile. “I trust that she would not have trespassed when you were gone, even if your door was open. Until I heard her shriek but now, I had no idea that she would pursue you. I regret for your sake that she disturbed you, but I also regret for her sake that it was not found.”

Cartaret had guessed the answer to his question before he asked it. His cheeks burned for the consequences, but he put the query:

“What was lost?” he inquired.

“Ah, I thought that I had said it: a flower.”

“A—a rose?”

[Pg 94] The hand that held her kimono pressed a little closer to her breast.

“Then you have found it?”