Title: A Walk and a Drive.

Author: Thomas Miller

Release date: January 24, 2012 [eBook #38661]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by the University of Florida Digital Collections.)

"She was very pleased to have her mug filled—the mug which she had brought on purpose."

"She was very pleased to have her mug filled—the mug which she had brought on purpose."

| SIX VOLUMES. |

| ON THE JOURNEY. |

| A WALK AND A DRIVE. |

| THE DUCKS AND PIGS. |

| THE WOUNDED BIRD. |

| A SAD ADVENTURE. |

| THE DOCTOR'S VISIT. |

Nurse said it was not time yet, and that she was very sleepy; but when the little girl had climbed into[8] her bed, and given her a great many soft kisses, and told her how much she wanted to take a walk before breakfast, the kind nursey first rubbed her eyes, then opened them, and then got out of bed.

While she was dressing, Rosy began to put on her own shoes and stockings and some of her clothes; for she had already learnt to do a great deal for herself.

She peeped out of window to look for the birds, but for some time she could not see any.

Rosy thought this very strange, for she remembered how she used to hear the dear little birdies sing when she had been in the country[9] in England; but nurse could not explain the puzzle; so Rosy settled that it was to be a question for her papa. Of course he would know; he always knew everything.

When they were quite ready, nurse said,—

"Now, my darling, if you like, we will go and get your milk for breakfast; for I know where it is to be had, and nice, new, good milk I hope it may be, to make my little Trotty very fat."

"Is not Rosy fat now?" asked the little girl, in surprise, and feeling first her plump cheeks and then her round arms with her stumpy little fingers.

"O, pretty well," said nurse laughing, "but you may be fatter yet, and I like fat little girls."

They had not to walk far before they came to the place where the milk was sold. It was called a farm; and nurse took Rosy in, and said she should see the dairy if the good woman would let her.

Rosy did not know what a dairy meant; but she supposed that it was something curious, and tripped merrily along, wondering what she should see, till they came to a room which had a floor made of red tiles, on which stood at least ten or twelve large open bowls full of new milk.

Now Rosy happened to be very[11] fond of milk; and as she was just then quite ready for her breakfast, she was very pleased to have her mug filled,—the mug which she had brought on purpose, as nurse told her,—and then take a good drink.

"Ah, nurse, how good it is!" she cried; "but what is all this sticking to my lips? It is not white like our milk. See, there is something on the top of it!" and she held out her mug to show her.

"Ah, that's cream, good cream. We did not get milk like this in Paris," said nurse; "and I'm sure we don't in London. There's no water here, is there, madame?"

But madame did not understand English; so nurse was obliged, by looking very pleased, to make her see that she thought her milk very good.

"But it's very bad of the other people to put water in my milk," said Rosy, frowning. "I shall ask my papa to scold them when we go home; and I shall take a great mugful of this nice milk to show my grandmamma."

"Well, now say good by prettily in French, as your papa teaches you," said nurse, "and then we'll go home, and I dare say we shall find some more milk there."

"Adieu, madame," said the little[13] girl, and off she trotted again, as ready to go as she had been to come.

They say "madame" to every one in France, you know, and not to rich ladies only.

Now there are beautiful hills all round the back of Cannes, and a little way up one of these was the house where Rosy was going to live. She did so like running up and down hills! and there were two or three little ones between the farm and this house, which was called a villa.

When she got on to the top of one, she cried out,—

"Ah, there's the sea, I do declare![14] and there's a boat on it with a white sail! Shall we go in a boat some day?"

"I don't know," said nurse, "you must ask your mamma; but you don't want to be sick, do you?"

"I won't be sick," cried the little girl. "Rosy is never sick in a beau'ful boat like that. I'll ask my mamma," and she bustled on.

"Stay, stay!" cried nurse, "you're going too far, my pet; this is the way; look, who stands up there?"

Rosy looked up, and there was the villa with its green blinds high up over her head; and some one stood outside the door calling her by name.

O, what a number of steps there were for those little legs to climb before she reached her papa!

They went up by the side of a garden, which was itself like a lot of wide steps, and on each step there was a row of vines, not trained against a wall as we train our vines in England, but growing on the ground like bean plants.

Rosy saw lots of such nice grapes that her little mouth quite watered, and she would have liked to have stopped to pick some; but then she knew that would be stealing, because they were not hers. And I hope that Rosy would not have stolen even if nurse had not been[16] following her, or her papa watching her.

She got the grapes, too, without picking them; for when she had climbed up to the very top, there was papa waiting for her with a beautiful bunch in his hand. And he said,—

"Come in, Rosy; mamma wants her breakfast very badly. See, mamma, what a pair of roses your little girl has been getting already!"

Rosy knew very well what that meant, for she rubbed her cheeks with her little fat hands, and then tumbled her merry little head about her mamma's lap to "roll the roses off," as she said.

But that little head was too full of thoughts to stay there long.

There was so much to tell and to talk about, and that dairy took a long time to describe. Then when papa asked if she had seen the dear cows that gave the milk, she thought that that would be a capital little jaunt for to-morrow, and clapped her hands with glee.

"So you are going to find some new pets, Rosy," he said, "to do instead of Mr. Tommy and the kittens?"

"Ah, papa, but there are no dickies here—I mean, hardly any," she answered. "We looked so for the birdies all, all the time; but[18] only two came, and went away again directly."

"We must go out and see the reason of that," said papa, smiling,—"you and I, Rosy, directly after breakfast. We must go and tell the dear birds that Rosy has come."

They went only a little way up the road, and then they came to a field, on one side of which were some high bushes. Rosy knew where to look for birds, and peeped very anxiously amidst the boughs[20] till she saw something hopping. Then she pulled her papa's hand, and let him know that she wanted him to stoop down and look too.

He looked, and then whispered,—

"Yes, Rosy. There is a pretty little robin; let us go round the other side and see if we can make him come out with these crumbs which I have brought with me."

So they went softly to the gate, and were just going in, when papa said,—

"Stop, Rosy; look what that man has got in his hand."

Then she looked, and saw a man with a very long gun and two dogs.

"What is he going to do, papa?"[21] asked the little girl, drawing back; "will he shoot us if we go in?"

"O, no, Rosy; don't be afraid. It is the robin that he wants to shoot and not us. So now you see how it is that the dicky-birds don't sing much at Cannes. It is because they shoot so many of them."

Poor little Rosy! She loved so much to watch the little birds and hear them sing! And when she thought of this dear robin being shot quite dead, and that perhaps there was a nest somewhere with little ones who would have no mamma, she began to cry, and to call the man "a cruel fellow."

She was not much comforted by[22] being told that such little birds were eaten there; so that if the man could shoot one, he would get some money for it which might buy bread for his little ones. But she was rather glad to hear that the little robins must be able by that time of year to take care of themselves, and had left the nest some time; and much more pleased, when, soon after, she saw the dear robin fly right away, so that the man with the gun was not likely to shoot that one at any rate.

Then papa said, "I shouldn't wonder if mamma would like to go out this morning. Shall we go back and see?"

"Rosy was very much pleased when soon after

she saw the robin fly right away."

"Rosy was very much pleased when soon after

she saw the robin fly right away."

Rosy thought that would be very nice; and then her papa lifted up his little girl, and showed her all the beautiful hills that were behind them. There were some that had peaked tops, and some rather roundish; and just in one place she could see some hills a very long way off, that seemed to climb right up into the sky and were all white on the top. He told her that those hills were called mountains, because they were so very high,—a great deal too high for Rosy to walk up, and that the white stuff which she saw was snow.

"We don't have snow when it is warm in England, Rosy, do we?"[26] said papa, "nor yet here, but up there, you see, it is so cold that the snow never melts. Those are called 'the snow Alps.'"

Rosy had nearly forgotten the poor birds now, because there were so many other things to think about. She saw some poppies a little way off, and then some blue flowers; and they were so pretty that she was quite obliged to stop a good many times to pick some for dear mamma. The wind was very high too, and it blew little Rosy's hat right off, so that papa and she had both to run after it.

Mamma was ready for a walk when they got in, but she staid to[27] put Rosy's flowers in water; and they looked very gay and pretty. Nurse and every one admired them; and Rosy said that she was not a bit tired, and was quite sure that she could go for another long, long walk.

But papa said that though Rosy might be a little horse, her mamma was not, and that it was a long way to the town and to the shops where she wanted to go; so he would go and get a carriage for them.

Now, though Rosy certainly was very tired of trains, she found a basket pony-carriage a very different thing, and enjoyed her ride so much that she was obliged to change[28] pretty often from her mamma's lap to her papa's and back again, just because she was too happy to sit still.

The ponies went along merrily too, as if they were nearly as happy. They had bells on their necks which jingled delightfully, and every now and then they met a carriage, or even a cart, the horses of which had bells too. So they had plenty of music.

They went up one hill and down another, and the ponies ran so fast, and turned round the corners of the roads so quickly, that sometimes mamma was afraid that the carriage would be upset, and that they[29] would all be "tipped out in a heap." Rosy thought it would be good fun if they were. She often rolled about herself, like a little ball, without hurting herself; and she thought that papa and mamma would only get a little dusty, and that it would be a nice little job for her to brush the dust off when she got home.

Just then a number of boys and girls came along the road to meet them, and Rosy saw that all the little ones wore caps, not hats or bonnets. There was one baby with large black eyes, whom she would have liked to kiss and hug. It was so fat and pretty. But it was dressed in a way that she had never seen[30] any baby dressed before, for its feet and legs were put into a sort of large bag, so that it could not kick like other children; and Rosy wondered how it could laugh so merrily.

When the carriage came near this little party the man did not hold the reins of his horses tight as an English coachman would have done. He only screamed out to the children, "Gare! gare!" which Rosy's papa told her meant "Get out of the way."

And when they were all past there came next a great wagon, piled up with the trunks of trees. The horses which drew this had no[31] bells; but they had a funny sort of post sticking up high between their ears, with lots of things hanging on to it. They had also three pink tassels hanging on their faces, one in front and one on each side. These tassels shook as they went along, and looked so pretty that Rosy thought to herself that if ever she had a toy horse again she would ask nurse to make some little tassels for it just like them. Her papa had told her, too, that they were to keep off the flies, which teased the poor horses very often dreadfully. And of course Rosy would not like her horse to be teased.

But the carriage went on while[32] she was thinking this; and soon they saw four old women coming along the road with large baskets, full of some green stuff, on their heads. The little girl did not say anything as they went by, but she looked very particularly to see how they were dressed.

Now I must tell you why she did this.

In the first place, then, she had never seen any old women a bit like them before.

They walked all in a row with their baskets on their heads, and with their hands stuck into their sides, and they talked very fast as they came along. On their heads[33] they wore very, very large hats, with small crowns. Rosy had never seen such hats before, and she heard her mamma say that she had never seen them either. Under these great hats they had nice white caps, with colored handkerchiefs over them, which hung down behind. They had, besides, other colored handkerchiefs over their shoulders, and two of them had red gowns.

Now Rosy had had a present given her in Paris. It was a piece of French money, worth ten English pennies; and with this money she had bought ten Dutch dolls, which nursey was going to dress for her.[34] At first she meant them to make an English school; but now that she had seen so many funny people she thought she would like her dolls to be dressed like the people in Cannes, because then they would just show her dear grandmamma how very nice they looked, and how very different to English people.

She was very quiet for a little while, because she was making this grand plan; but they soon turned out of the narrow street, and all at once she saw the sea again.

They had come now to what was called the "port," and there were all the great ships which had come home lately, and were waiting to[35] go out again,—one, two, three, four, five, six, all in a row, quite quiet, and "taking their naps," as Rosy's papa said, "after all their hard work."

He lifted Rosy out first, and said that they would go and look at them, while mamma went into the shops.

Rosy was not quite sure whether she was pleased at that, because sometimes her mamma bought her very nice things, such as toys, or sugar-plums, or cakes, when she took her out shopping. But they soon found plenty to look at, and some funny men with blue coats and cocked hats amused the little girl[36] very much. Her papa wondered why she looked at them so often; but then he did not know Rosy's grand scheme, and how she was thinking of asking nurse to dress one doll just like them. She kept this little plan quite a secret till she got back to her nurse.

It was half the fun to have a secret.

Rosy jumped up in a minute, crying out,—

"The cows! the cows! Shall we go and see them?"

"If you will make great haste," said the nurse; "but it is getting late."

Rosy never got dressed more[38] quickly. She did not much like even to wait for her morning splash; and while her curls were being combed, she kept saying, "Won't it do, nurse?" and then rather hindering by holding up her little face for a kiss.

As soon as she was quite ready she bustled off, and got down stairs first. Whom should she see there but papa himself, with his hat on?

He said that he would take her to see the cows, and even carry her a little way if she got tired.

How very kind that was! But would such a great girl as Rosy get tired?

O, dear, no; at least, so she said, for Rosy did not like to be thought a baby now, though somehow or other it did sometimes happens that after a long walk her feet would ache a little bit, and then papa's shoulder made a very comfortable seat.

She was half afraid now that nursey might be sorry not to see the cows, and ran back to whisper that if she liked she might dress one of the dollies instead. That was meant for a treat, you know; and nursey laughed, and said,—

"Perhaps, we shall see;" and gave her another kiss.

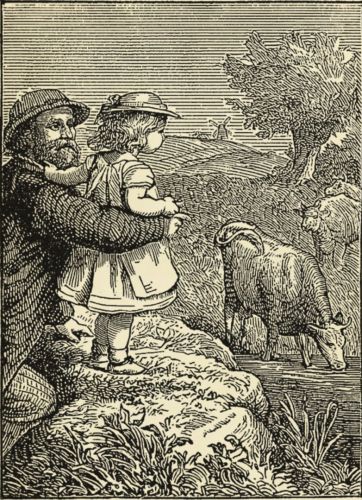

Then Rosy showed her papa where the farm was; and when they came near, they saw the farmer's wife standing at the door, as if she expected her little visitor.

Rosy did not forget to say,—

"Bon jour, madame," which means "Good morning" in English, you know.

Papa asked in French if they could see the cows, and the good woman was kind enough to take them round to the water where they were drinking.

There was a black one, and a black and white one, and a red one, and another with red spots. We cannot find room for them all in the[41] picture; but you will see the one which was drinking.

Rosy admired them very much, and wanted to go as near as she could that she might see them well; for although they were so very big and had such long legs, she was not a bit afraid of them. She never was afraid of anything when her papa was by, because he was so very strong—stronger than all the world she thought.

"Who made the cows, Rosy?" asked her papa, when she had looked at them a little while.

"God," said Rosy, softly; "God made everything, didn't he, papa? Why did he make the cows?" she asked, after thinking a minute.

"To give us good milk, such as you had yesterday, Rosy, and to make you and other little girls and boys fat and strong. Was not that very good of God!"

"Yes, papa," said Rosy, again.

"Then will you remember that, my little one, when you say, by and by, 'I thank God for my nice bread and milk'?"

Rosy said she would, and then she asked,—

"And do the pretty cows give us coffee, too, papa?"

"And do the pretty cows give us coffee, too, papa."

"And do the pretty cows give us coffee, too, papa."

"No, no, my silly little Rosy; don't you recollect that we buy that at the grocer's shop? We must go some day and ask him to let you see it ground up to powder. The coffee comes from a long, long way off. It grows on a tree in a very hot country, and looks like little berries till they put it into a mill and turn a handle. Then the berries are ground up to powder, and we put some boiling water over the powder, and when it gets cool we drink it. Haven't you seen mamma pour it out into the cup and put some sugar and milk in for herself and papa?"

Rosy remembered now; but she

had not taken much notice before,

because she did not like coffee at

all. She liked her nice milk much

better; and so when she went away

with her papa she called out,[45]

[46]—

"Good by, dear cowies, and thank you very much for my nice milk."

Rosy wanted to walk round the other side where there was a very gentle, kind-looking cow, that was not in the water, because she thought that she would like to stroke her; but her papa told her to look at those two great horns. And he said that cows did not like little girls to take liberties with them unless they knew them, and that this cow did not know her, and might think her very saucy, and poke out her horns to teach her to keep a proper distance. If she did, he said he thought Rosy would not[47] like that poke, for it might hurt her, so he advised her to keep quite out of the good cow's way.

Then she stood at a little distance to watch her drinking, and Rosy's papa said,—

"See how she enjoys it! Cows like to come here sometimes, like little girls; but French cows don't get out of their houses so often as English ones."

"Don't they, papa?" said Rosy. "Then I should think they must often wish to go to England."

Papa laughed, and said,—

"Perhaps they would wish it if they knew how their English cousins enjoy themselves; but I think they[48] look pretty happy; don't you, Rosy?"

Rosy said,—

"Yes, papa; but how funnily the cow drinks! She puts her head into the water."

"And you think that if she were a polite cow she would not think of doing such a vulgar thing, but would wait till they gave her a glass; eh, Rosy?"

"She hasn't got any hands, papa," cried Rosy, "so she couldn't, I 'spose."

"No," said papa; "so I think that we must excuse and forgive the poor thing, until Rosy can teach her a better plan."

And Rosy trotted home by his side, thinking how much she should like to try drinking after the cow's fashion.

Her mamma took off her hat and her little jacket, and said,—

"So, Rosy, you have brought me two more roses."

"But my roses don't smell, mamma," said Rosy, laughing and patting her own fat cheeks, as she always did when mamma said that. Then she made haste to scramble up[51] on to her little chair, and pull her nice basin of bread and milk close to her. She looked at her papa after she had said her little grace, and said,—

"I didn't forget, papa."

Then she began to eat away as if she liked it very much; and when she had eaten a little, her mamma said,—

"Look here, Rosy."

And Rosy turned round and saw a whole spoonful of egg waiting for her to eat it. Mamma was holding it for her; and it looked so yellow and so delicious!

Rosy opened her mouth, but she did not take it all in at once. It[52] was too good for that, and she thought it better to make it last a little.

But some of the yellow would stick on Rosy's lips; so mamma wiped it off, and then Rosy put her arms round her neck and kissed her, and said,—

"So nice, dear mamma."

Then mamma said,—

"At the end of the garden, Rosy, there lives the good hen that gave us this nice egg, and a great many other hens, and very fine cocks too,—the cocks that you heard crowing this morning. Shall we go and see them after breakfast?"

"O, yes, yes, yes!" cried Rosy,[53] clapping her hands, "that will be fun. I've almost done mine;" and the little girl made great haste to finish her bread and milk; but mamma said,—

"Ah, but not quite directly. I've not done my breakfast. If you have done yours, you had better go and see what nurse is doing, and ask her to get ready to come and hear papa read about Daniel in the lions' den."

Rosy did not mind waiting for that, for she was never tired of hearing that story. I dare say that some of her young friends know it too.

Her mamma got ready soon after,[54] and they both went round to a part of the garden which Rosy had not seen before.

There they saw that one piece was railed off from all the rest, and that a hen-house was inside it.

Rosy's mamma opened a gate in the railing, and took her little girl into the enclosure amongst all the cocks and hens.

The cocks did not seem much to like this, and they both made a great crowing, and then marched off into the farthest corner, with a lot of hens after them.

Rosy said,—

"O, mamma, show them the nice seed, and then they won't go away!"

But her mamma answered,—

"Not yet, Rosy; let us go first and look at these good ladies that are walking about inside their house. We can have a good look at them before they get away. See, they can't get out if we stand at the door."

"Ah, look at these beauties, all over speckly feathers," cried Rosy, as she ran forward to catch one.

She put out her little arms to seize her; but the hen seemed to think this a great liberty from so small a child, and instead of running away, she turned and opened her beak in a very angry manner.

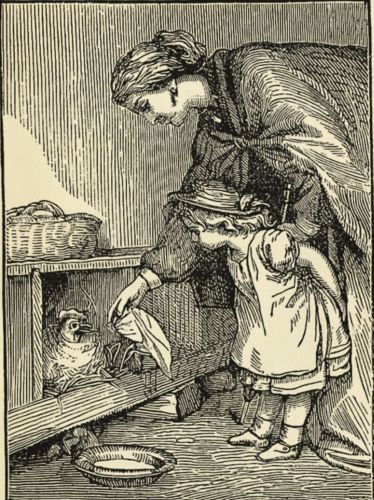

"Take care, Rosy," said her[56] mamma, as the little girl drew back half frightened. "This hen seems rather a fierce lady. I will give her some seed to persuade her to be quiet. Perhaps she has got something there that she does not choose us to see. I wonder what it can be."

Rosy took one more peep, and then called out,—

"O, mamma, mamma, some little chickens, I do declare! If you stoop down you can see them running about behind her,—such dear, pretty, soft little creatures! Do get me one to play with."

"Little chickens!" said mamma; "why, they must have come out of[57] their shells very late in the year if they are little ones still, and I am afraid their mother won't let me touch them."

"Do chickens come out of shells?" said Rosy, making very large eyes, and looking quite puzzled.

"Yes, Rosy, out of just such shells as our eggs had this morning; and if in the summer we had given this good hen five or six of her own eggs in this little house of hers, she would have sat upon them, and spread her wings over them to keep them warm; and there she would have staid so patiently all day long, and day after day, until the dear little chickens were ready to come too."

"And wouldn't the hen get tired?" said Rosy. "I shouldn't like to stay still so long."

"No, I don't think you would," said her mamma, chucking her little girl under the chin; "but then, you see, you are like the little chickens, and not like the mamma hen. I think you will find that she has not got tired even yet, for if you peep down again you will see that she is keeping two of the little chickens warm under her even now. Little chickens are like little babies, and they very soon get cold, so they like keeping very close to their mammas."

"Are the little chickens naughty sometimes?" asked Rosy.

"If you stoop down you will see that she is keeping two

of the little chickens warm under her."

"If you stoop down you will see that she is keeping two

of the little chickens warm under her."

"Well, I don't know, Rosy; but I know that I have often thought it very pretty to see how they will all run to their mother when the great hen clucks for them."

"O, mamma, I should so like to hear her cluck," cried Rosy, clapping her hands.

"Well, Rosy, you go a little way off, and keep quite quiet; and then I will see if I can tempt the good lady out of her nest with some of this nice seed."

So Rosy ran away, and her mamma

stepped back a few paces and

threw down some of the seed.

The hen saw it directly, and looked

for an instant as if she would like[61]

[62]

some very much; and she did not

wait long, but soon stepped out of

her house, and began picking up the

seed.

Just at that moment a cat came creeping along the outside of the paling, and watching to see if she could pounce on one of the little chickens. The hen saw the cat, and began to stretch out her neck very fiercely, as if she meant to fly at its eyes, and then began to cluck for her little ones, which all came running to her as fast as their legs would carry them.

Rosy's little eyes sparkled with pleasure, and she went up and put her hand into her mamma's, and said softly,[63]—

"Wasn't it nice?"

"Yes, Rosy," said her mamma, "and I hope that my little chicken will always run to my side as quickly as these did to their mother. You see she knew that they were in danger when they didn't themselves; and so do I sometimes when my Rosy thinks she is quite safe."

Transcriber's Notes:

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

Page 7, "the" changed to "she" (so that she)