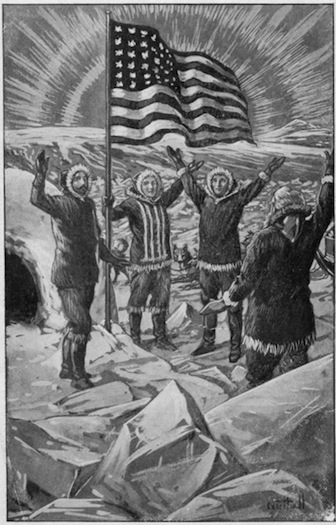

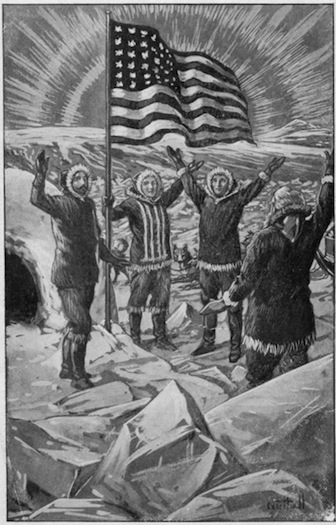

“And now, a cheer for the first boys at the North Pole!”

Title: First at the North Pole; Or, Two Boys in the Arctic Circle

Author: Edward Stratemeyer

Illustrator: Charles Nuttall

Release date: February 25, 2012 [eBook #38968]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Contents

“And now, a cheer for the first boys at the North Pole!”

FIRST AT THE NORTH POLE

OR

TWO BOYS IN THE ARCTIC CIRCLE

BY

EDWARD STRATEMEYER

Author of

Oliver Bright’s Search, Richard Dare’s Venture,

The Last Cruise of the Spitfire, True to

Himself, Joe, the Surveyor,

Shorthand Tom, Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY CHARLES NUTTALL

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS :: NEW YORK

Published, December, 1909

Copyright, 1909, by Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

All rights reserved

First at the North Pole

PREFACE

“First at the North Pole,” relates the particulars of a marvelous journey from our New England coast to that portion of our globe sometimes designated as “the top of the world.”

Filled with such dreams as come to all explorers, Barwell Dawson fitted out the Ice King for a trip to the north. Because of what had happened, it was but natural that he should invite Andy and Chet to accompany him, and equally natural that they should hasten to accept the invitation.

The boys knew that they would have no easy time of it, yet they did not dream of the many perils that awaited the entire party. Once the staunch steamer was in danger of being crushed by an immense iceberg, in which event this chronicle would not have been written. Again, the boys and the others had a fierce fight with polar bears and with a savage walrus. When the ship was jammed hard and fast in the ice a start was made by the exploring party, accompanied by some Esquimaux and several dog sledges. All had heard of the marvelous achievements of Cook and Peary, and all were fired with a great ambition to go and do likewise. With the thermometer often at fifty degrees below zero, they pushed on steadily, facing death more than once. To add to their troubles they had sickness in camp, and snow-blindness, and once some Esquimaux, becoming scared, rebelled and tried to run off with their supplies. Then, when the North Pole was at last gained, it became the gravest kind of a problem how to return to civilization alive.

In penning this volume I have had a twofold purpose in mind: the first to show what pure grit and determination can do under the most trying of circumstances, and the second to give my readers an insight into Esquimaux life and habits, and to relate what great explorers like Franklin, Kane, Hall, DeLong, Nansen, Cook, and Peary have done to open up this weird and mysterious portion of our globe.

Edward Stratemeyer.

November 15, 1909.

“What be you a-goin’ to do today, Andy?”

“I’m going to try my luck over to the Storburgh camp, Uncle Si. I hardly think Mr. Storburgh will have an opening for me, but it won’t hurt to ask him.”

“Did you try Sam Hickley, as I told you to?” continued Josiah Graham, as he settled himself more comfortably before the open fireplace of the cabin.

“Yes, but he said he had all the men he wanted.” Andy Graham gave something of a sigh. “Seems to me there are more lumbermen in this part of Maine than there is lumber.”

“Humph! I guess you ain’t tried very hard to git work,” grumbled the old man, drawing up his bootless feet on the rungs of his chair, and spreading out his hands to the generous blaze before him. “Did you see them Plover brothers?”

“No, but Chet Greene did, day before yesterday, and they told him they were laying men off instead of taking ’em on.”

“Humph! I guess thet Chet Greene don’t want to work. He’d rather fool his time away in the woods, huntin’ and fishin’.”

“Chet is willing enough to work if he can get anything to do. And hunting pays, sometimes. Last week he got a fine deer and one of the rich hunters from Boston paid him a good price for it.”

“Humph! Thet ain’t as good as a stiddy, payin’ job. I don’t want you to be a-lazin’ your time away in the woods,—I want you to grow up stiddy an’ useful. Besides, we got to have money, if we want to live.”

“Aren’t you going to try to get work, Uncle Si?” asked the boy anxiously, as he gazed at the large and powerful-looking frame of the man before him.

“To be sure I’m a-goin’ to go to work—soon as I’m fit. But I can’t do nuthin with my feet an’ my stomach goin’ back on me, can I?”

“I thought your dyspepsia was about over—you’ve eaten so well the past week. And you’ve walked considerably lately. If you got something easy——”

“Now, don’t you go to tellin’ me what to do!” cried the old man, wrathfully. “I’m a sick man, that’s what I am. I ain’t able to work, an’ it’s up to you as a dootiful nevvy to git work an’ support us both. Now you jest trot off to the Storburgh camp, an’ don’t you come home till you git work. An’ after this, you better give up havin’ anything to do with thet good-fer-nuthin, lazy Chet Greene.”

The boy’s eyes flashed for an instant and he was on the point of making a bitter reply to his relative. But then his mouth closed suddenly and he turned away. In silence he drew off his slippers, donned his big boots, and put on his overcoat and his winter cap. Then he pulled on his gloves, slung a game bag over his shoulder, and reached for a gun that stood behind a door.

“Wot you takin’ thet fer?” demanded Josiah Graham, with his eyes on the gun. “Didn’t I tell you to look fer a job?”

“That’s what I’m going to do,” was the reply. “But if I come across any game on the way I want the chance to bring it down.”

“Humph! I know how boys are! Rather loaf around the woods than work, any time.”

“Uncle Si, if you say another word——” began the youth, and then he stopped short, turned on his heel, and walked from the cabin, closing the door none too gently behind him.

It was certainly a trying situation, and as he stepped out into the snow Andy felt as if he never wanted to go back and never wanted to see his Uncle Si again.

“It’s his laziness, nothing else,” murmured the boy to himself, as he trudged off. “He’s as able to work as I am. He always was lazy—father said so. Oh, dear; I wish he had never come to Pine Run!”

Andy was a youth of seventeen, of medium height, but with well-developed chest and muscles. His face was a round one, and usually good to look at, although at present it was drawn down because of what had just occurred.

The boy was an orphan, the son of a man who in years gone by had bought and sold lumber throughout the northern section of Maine. His mother had been taken away when he was a small lad, and then he and his father had left town and come to live in the big cabin from which Andy was now trudging so rapidly. An old colored woman had come along, to do the cooking and other household work.

A log jam on the river had caused Mr. Graham’s death two years before this tale opens, and for a short time Andy had been left utterly alone, there being no near neighbors and no relatives to take care of the orphan. True, he had been offered a home by a lumber dealer of Bangor, but the man was such a harsh fellow that Andy shrank from going with him.

Then, one day, much to everybody’s surprise, Josiah Graham appeared on the scene and announced his intention to settle down and live with his nephew. Josiah was an older half-brother to Andy’s father, and the boy had often heard of him as a shiftless, lazy ne’er-do-well, who drifted from one town to another, seldom keeping a job longer than two or three weeks or a month. He did not drink, but he loved to smoke, and to tell stories of what he had done or was going to do.

“I’m a-goin’ to take Andy in hand an’ make a man of him,” he declared, shortly after his arrival. “A young feller like him needs a guardeen.” And then he had his trunk carted to the cabin and, without asking Andy’s permission, proceeded to settle down and make himself comfortable.

At first it looked as if matters might go along smoothly enough, for Josiah Graham managed to obtain a position as time-keeper at one of the lumber camps, where Andy was employed as a chopper. But soon the man’s laziness manifested itself, and when he did not do his work properly he was discharged.

“It was the boss’s fault, ’twasn’t mine,” he told Andy, but the youth knew better. Then he got into a quarrel with the negro woman who did the housework and told her to go away.

“’Twill be one less to feed,” he said to his nephew. “We can do our own work.” But he did not do a stroke extra, and it fell to Andy’s share to sweep, and wash dishes, and make his own bed. Uncle Si wanted him to make the other bed too, but he refused.

“If you want it made, you can make it yourself!” declared Andy, with spirit. “You are not working at the camp, while I am.” This led to a lively quarrel. After that Josiah Graham did make up the bed a few times, but usually when he crawled into it at night it was in the same mussed-up condition as when he had crawled out in the morning.

Another quarrel came over the question of money. The uncle wanted Andy to hand over all his earnings, but this the lad refused to do. Josiah Graham had already gotten possession of the fifteen hundred dollars left by Andy’s father, but this was lost in a wildcat speculation in lumber for which the old man was morally, if not legally, responsible. The youth felt that he must be cautious or his uncle might make him penniless.

“I’ll pay the bills and give you a dollar a week,” he told Josiah Graham. “That will buy those tablets you take for your dyspepsia. You had better give up smoking.”

“Smoking is good for the dyspepsy,” was the reply. “You give me the money an’ I’ll pay the bills,” and then, when Andy still refused, the uncle waited until pay-day and went to the lumber camp and collected his nephew’s wages. This brought on more trouble, and, because of this, Andy lost his position.

It was midwinter, and to get another job was by no means easy. The youth tramped from place to place, but without success. The money in the hands of Josiah Graham was running low, and he was constantly “nagging” Andy to go and do something. He was perfectly able to look for work himself, but was too indolent to make the effort. He preferred to sit in front of the blazing fire and give advice. Once or twice a week he would shuffle off to the village, two miles away, to sit behind the pot stove in the general store and listen to the news.

“The laziest man in the whole district,” declared the storekeeper. “It’s a pity he showed up to bother Andy Graham. I think the boy could have done better without him.” And this verdict was shared by many. But nobody dared to tell Josiah Graham, for fear of provoking a quarrel with the man.

As mentioned before, Andy’s father had left fifteen hundred dollars. He had also bequeathed to his son, when he should become of age, an interest in a large timber tract in upper Michigan. On his deathbed the father had secretly given his son some papers referring to the land, telling him to beware or some “lumber sharks” would get the better of him and take his property away. Andy now had these papers hidden in a box under his bed. He had not told his uncle of them, feeling that his relative was not capable of looking after his rights. Andy’s education was somewhat limited, yet he knew a great deal more than did Josiah Graham, who had been too lazy to attend school, even when he had the chance.

“I’ll keep the papers secret,” the lad told himself, “and some day, when I get the chance and have the money, I’ll go down to Bangor or Portland and get a lawyer to look into the matter for me. If I let Uncle Si have them he’ll allow the land sharks to cheat me out of everything.”

Andy’s father had been more or less of a hunter, and the boy took naturally to a rifle and a shotgun. He was a fair marksman, and the winter previous had laid low three deer and a great variety of small game. One of the deer had been brought down on a windy day and at long range, and of that shot he was justly proud. The venison and other meat had come in handy at the cabin, and the deer skins and the horns of a buck had brought him in some money that was badly needed.

“If I can’t get a job, I’m going hunting for a few days,” said Andy half aloud, as he trudged through the snow. “It’s better than doing nothing, Uncle Si to the contrary. Maybe I can get Chet to go along. I don’t think he has anything else to do. Somehow or other, it seems to be awfully dull around here this winter. Maybe I would have done better if I had tried my luck down in one of the towns.”

Andy had to pass through the village of Pine Run, consisting of a general store, blacksmith shop, church, and a score of houses. As he approached the settlement he saw a horse and cutter coming toward him at a smart rate of speed. In the cutter sat a man of about thirty, dressed in a fine fur overcoat.

“Whoa!” called the man to his steed, as he approached the youth, and the horse soon came to a halt. “Say, can you tell me, is this the road to Moose Ridge?” he asked.

“It’s one of the roads,” answered Andy.

“Then there is another?”

“Yes, sir, just beyond that fringe of trees yonder.”

“Which is the best road?”

“What part of the Ridge do you want to go to?”

“Up to a place called the Blasted Pines.”

“Then you had better take the other road. You won’t get through this way.”

“You are sure of that? I don’t want to make any mistake.”

“Yes, I am sure. I’ve been up there hunting myself,” added Andy. He saw that the cutter contained a game bag and two gun cases.

“Is the hunting any good?”

“It was last year. I haven’t been up there this year. I got a fine big deer up there. Maybe I’ll get up there later—if I can’t find work.”

“Out of employment, eh?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, if you come up there perhaps we’ll meet again,” said the man, and started to turn the cutter back to the other road. “Much obliged for the information.”

“You’re welcome,” answered Andy. And then he watched the turnout swing around and dash away for the other road.

Little did he dream of the strange circumstances under which he was to meet this man again, or of what that encounter was to bring forth.

Leaving the village behind him, Andy struck out bravely for the Storburgh lumber camp, three miles up the river. The thermometer was low but there was no wind, and he did not mind the cold, for he had plenty of good red blood in his veins. All he was worried about was the question of getting work. He knew that he must have money, and that it could not very well be obtained without employment.

“If I were a fellow in a fairy story book I might find a bag of gold,” he mused. “But as I’m only a Yankee lad, I guess I’ll have to hustle around for all I get. Even if I went hunting and brought down a deer or two, or a moose, that wouldn’t bring in enough. If I were a regular guide I might get a job with that gentleman in the cutter. He looked as if he had money to spend. He must be a stranger in these parts, or he wouldn’t ask about the road to Moose Ridge.”

It was nearly noon when Andy came in sight of the lumber camp. From a distance he heard the ringing sounds of the axes, and the shouts of the men to “stand from under” as a mighty monarch of the forest was about to fall. Skirting the “yard,” he approached the building which was known as the office.

“Is Mr. Storburgh around?” he asked, of the young man in charge.

“He is not,” was the reply, and the clerk scarcely looked up from the sheet upon which he was figuring.

“When will he be here?”

“I don’t know—he’s gone to New York.”

“Do you know if he has an opening for a chopper, or on the teams?”

“No opening whatever. We laid off four men last week, and we’re going to lay off four more this coming Saturday.”

The clerk went on figuring, and in silence Andy withdrew. He had had a walk of nearly five miles for nothing. Was it any wonder that he was disheartened?

“It’s the same story everywhere,” he told himself, as he moved away slowly. “I might tramp to the Elroy place—that’s six miles from here—but what’s the use? I’ll wear out boot-leather for nothing. I guess Uncle Si and I will have to pull up stakes or starve.”

Not knowing what else to do, Andy walked along to where a number of men were at work. Just then the twelve o’clock whistle sounded, and the workers “knocked off” for their midday meal.

“Hello, Andy!” sung out a cheery voice, and, turning, the boy saw a brawny chopper named Bill Carrow approaching. Carrow had once worked with Mr. Graham, and knew the son fairly well.

“Hello,” returned the youth. “Going to feed the inner man?” and he smiled.

“That’s what, son. How are you?” And the lumberman shook hands.

“Fairly well, but I’d feel better if I had a job.”

“Out of work, eh? That’s too bad. I don’t suppose there is any opening here.”

“The clerk said there wasn’t any—said they were discharging hands instead of taking ’em on.”

“That’s true. Business is bad—account of the panic last year, you know.” Bill Carrow paused a moment. “Had your dinner?”

“No, but I can wait until——”

“You ain’t going to wait. You come with me and I’ll fill you up. Your father did the same for me many a time. Come on.”

Andy was hungry, and could not resist this kindly invitation. Soon the pair were eating a plain but substantial dinner, which Carrow procured from the camp cook. It was disposed of in a corner of the mess cabin, apart from the other lumbermen. As they ate the lumberman asked the youth about himself and his uncle.

“That uncle of yours ought to be ashamed of himself, that’s my opinion of it,” said Bill Carrow. “If I was you, I’d not lift my finger to support him. He was the laziest young feller I ever knew, and it’s nothing but laziness now. He ought to be supporting you instead of you supporting him.”

“I can support myself—if he’d only leave me alone and not try to get my money away from me.”

“He squandered that money your father left—I know all about it. I’d make him go to work.”

“I can’t make him do anything.”

“The boys ought to go over and ride him on a rail, or tar and feather him. I guess that would wake him up.”

“Oh, I hope they don’t do that! He’s a bad man when he gets in a rage.” Andy did not want any more trouble than had already fallen to his portion.

“By the way, Andy, did a man named Hopton call on you lately?” asked Carrow, after a pause.

“Hopton? I never heard of him. Who is he?”

“Why, as near as I can learn, he is a real estate man—deals in timber and farm lands. He came here a week or so ago, thinking you had a job here. I told him where you lived, and I supposed he called on you.”

“I didn’t see him. What did he want?”

“He wouldn’t say—leastwise, I didn’t ask him, seeing’s it was none of my business. But he did ask me, confidential like—after he found out that I had known your father well—if your folks had any timber lands over in Michigan.”

“Oh!” Andy uttered the exclamation before he had time to think. “Did he—that is, did he ask about any land in particular?”

“No. I told him I didn’t think you owned any land anywhere. He looked satisfied at that and went away. But I thought he called on you.”

“Where was he from?”

“I don’t know. But they might tell you at the office. Have you got any land?”

It was an awkward question. Andy did not wish to tell a falsehood, nor did he wish to disclose the secret left by his parent. He bit off a mouthful of bread and pretended to choke upon it.

“Hi, look out, or you’ll choke to death!” cried Bill Carrow, slapping him on the back. Then Andy ran to the door and continued to cough, until the awkward question was forgotten. Other workmen came up, and the talk became general. Perhaps Carrow suspected that the boy did not wish to answer him, for he did not refer to the matter again.

After thanking his friend for the dinner, Andy walked back to the office. He found the clerk smoking a pipe and reading a Bangor newspaper, having finished his midday meal a few minutes previously.

“It’s no use,” he said, as Andy came in. “We can’t possibly take you on.”

“I came back to get a little information, if you’ll be kind enough to give it. Do you know a man named Hopton?”

“Why, yes. I suppose you mean A. Q. Hopton, the real estate dealer.”

“Does he deal in timber lands?”

“I think he does.”

“Where is he from?”

“He has an office in Portland, and another in Grand Rapids, Michigan.”

“Do you know where he is now?”

“No. He was here on business some days ago. Perhaps he went back to Portland.”

“Thank you.”

“Want to buy a few thousand acres of land?” and the clerk chuckled at his joke.

“No, I thought I could sell him a linen duster to keep the icicles off when he’s on the road,” answered Andy, with a grin. And then, as there seemed nothing more to say, he walked away, and was soon leaving the Storburgh lumber camp behind him.

What he had heard set him to thinking deeply. What did this A. Q. Hopton know about the lumber tract in Michigan? Was it valuable, and did it really belong to his father’s estate?

“I wish I knew more about such things,” mused Andy. “The last time I tried to read the papers over I couldn’t make head or tail of them. I guess it would take a smart lawyer to get to the bottom of it—and a lawyer would want a lot of money for the work. I wonder——” And then Andy came to a sudden halt.

Was it possible that Mr. A. Q. Hopton had called at the cabin during his absence and interviewed Uncle Si? And if so, how much had Uncle Si been able to tell the real estate dealer? Had the two gone on a hunt for the papers, and, if so, had they found the documents?

“If Uncle Si has gone into any kind of a deal on this without consulting me, I’ll—I’ll bring him to account for it!” cried the youth, vehemently. “After this he has got to leave my affairs alone. He lost that fifteen hundred dollars—he’s not going to lose that timber land, too.”

It occurred to Andy that the best thing he could do would be to get home at once and interview his uncle. For the time being he lost his interest in looking for work, and also lost his desire to go gunning.

“I’ve tramped far enough for one day, anyway,” he told himself. “I’ll just stop at the store for a few things, and then go straight home.”

It was a long walk to the village, and once there he was glad enough to rest while the storekeeper put up the few things he desired. These he paid for in cash, for he did not wish to risk a refusal should he ask for trust.

“Your uncle was here—got some tobacco,” said the storekeeper. “He said you would pay for it.”

“He’ll have to pay for it himself, Mr. Sands,” answered Andy, firmly.

“Yes? All right, Andy, just as you say.”

“I pay for what I buy, and he can do the same.”

“Well, I don’t blame you, my boy.” And the look of the storekeeper spoke volumes. He handed over some change that was due. “By the way, did you know there was a real estate dealer in town to see you?” he inquired.

“A Mr. Hopton?”

“That’s the man.”

“When?”

“To-day,—only a few hours ago. I was telling him where you lived when your uncle came along for the tobacco. They talked a while together, and then went off.”

“Towards our place?”

“Yes, they took that road. The real estate man had a sleigh, and your uncle got in with him.”

“What did Mr. Hopton want?”

“I don’t know exactly. I heard some words about papers, and your uncle said he had them. Mr. Hopton said something about three hundred dollars in cash—but I don’t know what it was.”

Andy’s heart leaped into his throat. Was it possible that his uncle had found the timber claim papers, and was going to let Mr. A. Q. Hopton have them for three hundred dollars?

“He sha’n’t do it—I’ll stop him—I must stop him!” the boy told himself, and catching up his bundles he left the general store, and struck out for home as fast as his tired limbs would carry him.

Ever since his father had left him the papers Andy had thought they might be of considerable value, but now he was more convinced than ever of their importance.

“For all I know, that claim may be worth a fortune,” he reasoned. “Anyway, it’s worth something, or that man wouldn’t be so anxious to get the papers.”

The youth tried his best to increase his speed, but the snow was deep in spots, and his long journey to the Storburgh camp had tired him, so it took some time to get even within sight of the cabin that was his home. To the rear, under the shed, he saw a horse and cutter.

“He is there, that’s sure,” he told himself. “I wonder what they are doing?”

The path to the cabin wound in and out among some trees, so that those inside could not witness his approach unless they were on the watch. As the youth came closer a sudden thought struck him, and he darted behind some bushes, made a detour, and came up in the shed. Here there was a back door opening into a summer kitchen.

Placing his bundles on a shelf in the shed, Andy softly opened the door to the summer kitchen and entered the place. Here there was another door, opening into the general living room of the cabin. It was not well hung, and stood open several inches.

“Well, I know something about timber lands,” he heard his uncle saying. “If they are wuth anything, they are generally wuth considerable.”

“I am offering you more than this claim is worth,” was the reply from Mr. A. Q. Hopton. He was standing in front of the fire warming himself, while Josiah Graham was hunched up in his usual attitude in the easy chair. Both men were smoking cigars, the real estate man having stood treat.

“Wot makes you so anxious to git the papers?” went on Josiah Graham.

“My client simply wants to clear away this flaw, as I told you,” answered A. Q. Hopton, smoothly. “Of course he could go ahead and claim everything just as it is, and I don’t think you could do a thing, but he prefers to treat everybody right. Mr. Graham gave a hundred dollars for this claim, so when you get three hundred for it you are getting a big price.”

“Humph!” Josiah Graham fell back on his favorite exclamation. “If I—that is, if I let you have them papers, Andy may object.”

“How can he? You’re his guardian, aren’t you?”

“Sure I am, but——”

“Then you have a right to do as you please. You don’t want me to buy the papers from him, do you?”

“No! no! You give the money to me!” cried Josiah Graham, in alarm. “He don’t know the vally of a dollar, an’ I do. If he had thet three hundred dollars he’d squander it in no time.”

“Very well, give me the papers and I’ll write you out a check.”

“Can’t you give me cash? It ain’t no easy matter fer me to git a check cashed up here.” Josiah Graham did not add that he was afraid the check might be worthless, although that was in his mind.

“I don’t carry three hundred dollars in my clothes. I can give you fifty in cash though,” went on the real estate agent, as he saw the old man’s face fall. “And if you wish, I’ll get one of the lumber bosses up here to vouch for the check.”

“Humph! I suppose thet will have to do then. But—er—one thing more, Mr. Hopton——”

“What is that?”

Josiah Graham leaned forward anxiously.

“Don’t you let the boy know about this right away. You give me a chanct to tell him myself.”

“Just as you wish. You’re his guardian, and I’ll not interfere with you. Get the papers and I’ll give you the check and the cash right now.” And the real estate agent drew a pocketbook and a checkbook from his inside coat.

Andy had listened to the conversation with bated breath. So far as worldly experience went he was but a boy, yet he realized that, in some way, this Mr. A. Q. Hopton was trying to swindle him out of his inheritance, and that his Uncle Si was willing to aid the schemer just for the sake of getting possession of the three hundred dollars.

As his uncle arose to enter the room in which his nephew slept, the boy slipped into the cabin. Like a flash he darted to his bedroom, jumped inside, and shut and bolted the door after him.

“Hi there! What’s this?” cried the real estate dealer, in astonishment.

“It’s—it’s the boy, my nevvy!” gasped Josiah Graham. “He come in through the back door! He must have been a-listenin’ to our talk.”

“Is that so? That’s too bad.” The real estate agent was dazed by the sudden turn of affairs. “He had a gun with him.”

“Yes, he took it with him when he went for work.” Josiah Graham walked over to the door and tried it. “Andy, open that door.”

“I will not,” was the answer.

“Was you a-listenin’ to our talk?”

“I was.”

“Humph! Nice thing fer a boy to do!”

“I guess I had a right to listen,” was the cool answer. As he spoke, Andy was examining the box in which he had stored the papers. He found things much disarranged, showing that his uncle had gone through the contents during his absence. But the papers were there, and the sight of them caused him to breathe a sigh of relief.

“They sha’n’t have these papers, no matter what happens,” he said to himself, and stuffed the documents into an inside pocket.

“Open thet door!” commanded Josiah Graham, and his voice now sounded harsh and threatening.

“I guess you had better teach that boy manners,” was Mr. A. Q. Hopton’s comment.

“I’ll teach him sumthin’!” answered the old man. “Open thet door, I say, an’ come out here.”

“You want to get those papers,” said Andy. He was wondering what to do next.

“Well, ain’t I your guardeen, an’ ain’t I got a right to ’em?”

“The papers are mine, and I’m not going to give them up,” answered Andy, doggedly. “I don’t like that Mr. Hopton, and he’s not going to get the papers. I’m going to turn them over to a lawyer.”

At these words the real estate man was much disturbed.

“That boy is an imp,” he said, in a low voice. “I’d not let him talk to me that way if I were you.”

“I ain’t goin’ to,” answered Josiah Graham. “Andy, you open thet door, or I’ll bust it in!”

“Don’t you dare break down the door!” answered Andy, in increased alarm. “If you do—I’ll—I’ll—Well, remember, I’ve got my gun—and it’s loaded, too.”

“Don’t ye shoot! Don’t ye shoot!” yelled Uncle Si, in sudden terror, and he backed away several steps. “Don’t ye dare! Oh, was ever there sech a boy!”

“Do you think he’d dare to shoot?” asked the real estate dealer.

“I dunno. He’s got lots o’ spirit sometimes.”

“Maybe we had better try to reason with him.”

“All right.” Josiah Graham raised his voice. “Andy, this is all—er—foolishness. Come out o’ there.”

To this the youth did not answer. He was considering what he had best do next. He did not want to shoot anybody, and he was afraid that the two men would in some manner get the better of him and take away the papers.

“Andy, do ye hear me? Come out—I ain’t goin’ to hurt ye.”

“You’ll take those papers away from me.”

“He is going to sell me the papers, and at a good price,” broke in A. Q. Hopton.

“I don’t want to sell—to you,” answered Andy. He was moving around the bedroom rapidly, having decided on a course of action.

“I’m your guardeen, an’ I know wot’s best,” broke in Josiah Graham. “Open the door, an’ no more foolin’ about it.”

“I don’t recognize you as my guardian,” was Andy’s reply. As he spoke he tiptoed his way to the window and opened it. Then he threw out a small bundle, and his gun and game bag followed.

“I am your guardeen!” stormed Josiah Graham. “You open the door!”

Instead of answering, Andy pushed a chair to the window. In another instant he had mounted it, and then he crawled through the opening. He landed in a heap in the snow, and scrambled up immediately. With bundle, gun, the game bag in his possession, he ran back of the shed and then down the road leading to the village.

At that minute he did not know where he was going, or what he was going to do. He had the precious papers in his pocket, and his one idea was to keep these away from his uncle and Mr. A. Q. Hopton.

“I’ll not go back until I’ve stored the papers in a safe place,” he told himself, finally. “I wonder who would keep them for me without asking too many questions?”

Although the sun hung low in the west, it was still light, and reaching a turn in the road, Andy stopped to look back. Much to his chagrin, he saw that his flight had already been discovered.

“They are coming after me!” he murmured, as he saw the horse and cutter flash into view. His uncle and the real estate dealer were on the seat, and the latter was urging the horse into a run through the heavy snow.

Unfortunately for Andy, there was but one road in that vicinity, and that ended at the Graham cabin. On all sides were the pine woods, with their scrub timber and underbrush, still partly laden with the fall of snow of the week previous.

“If I stick to the road they’ll catch me sure, and if I leave it I’ll have to go right into the woods, and they’ll easily see my trail,” he reasoned.

He broke into a run, and thus managed to pass another bend of the highway. Behind him he heard the jingle of the sleighbells as the cutter drew closer. In a few minutes more his pursuers would be upon him.

“I’ll chance it in the woods,” he muttered, and, reaching a spot where the undergrowth was thick, he leaped between the bushes and then walked on to a clump of pines. He was barely under the pines when he heard the cutter dash past. The men were talking excitedly, but he could not make out what was being said.

As the jingle of the sleighbells grew more distant, another thought came to Andy’s mind, one that made him smile grimly in spite of the seriousness of the situation.

“Might as well return and get something to eat,” he told himself. “They won’t come back right away.”

It did not take him long to retrace his steps to the cabin. The cutter, with its occupants, had kept on towards the village, so he had the place entirely to himself. He quickly found something to eat and to drink, and made a substantial meal. Then he placed a few more of his belongings in his bundle.

“It won’t do for me to stay here as long as I have the papers with me,” he told himself. “I guess I’d better try to get to the old Smith cabin for tonight. Then I can make up my mind what to do in the morning.”

The Smith cabin was a deserted place nearly a mile away. To reach it, Andy had to tramp directly through the woods. But the youth did not mind this, for he had often been out hunting in the vicinity.

“I might get a shot at something,” he mused. “A rabbit or a couple of birds wouldn’t go bad for breakfast.”

He lost no time in striking out. Half the distance was covered when he saw a big rabbit directly in his path. He blazed away, and the game fell dead. Then he caught sight of a squirrel, and brought that down also.

“Now I’ll have something besides crackers and bacon when I’m hungry,” he told himself, with satisfaction.

Soon he came in sight of the old Smith place. Much to his surprise, smoke was curling from the chimney, and he saw the ruddy glare of an open fire within.

“Somebody is here,” he thought. “Some hunter most likely. Wonder who it can be.” And he strode forward to find out.

“Hello, Andy!”

“Hello, Chet! I never expected to find you here! This is a real pleasure!” And Andy rushed into the old cabin, threw down his luggage, and grasped another lad by the hand.

“And I never expected you to come here tonight,” said Chetwood Greene, as a smile lit up his somewhat square face. “I thought I was booked to camp here alone. What brought you, hunting?”

“Not exactly. It’s a long story, Chet. Say, I’m glad you have a fire. I’m half frozen from tramping through the woods. The snow was pretty deep in spots.”

“I know all about it, for I have been out all day. Here, draw up to the blaze. I was just getting supper ready. You’ve got some game, I see. I had very little luck—three rabbits and a wild turkey. I looked for deer, but it was no use.”

“You’ve got to go pretty well back for deer these days,” answered Andy.

“Thought you were going to strike Storburgh for a job.”

“So I did, but it’s the same story everywhere.”

“Too bad! Well, you are no worse off than myself. I’m sick of even asking for work. I’ve about made up my mind to try my luck at hunting. I guess I can bring down enough to live on, and that’s better than starving.”

Chetwood Greene, always called Chet for short, was about the same age as Andy, but a trifle taller. He had a square chin, and dark, piercing eyes, that fairly shot forth fire when Chet was provoked. He was a good fellow in the main, but he had a hasty temper that occasionally got him into much trouble. Andy liked him very much, and the two boys were more or less chums.

There was a mystery surrounding Chet which few folks in that district knew. Many supposed that both of his parents were dead. But the fact of the matter was that Chet’s father disappeared when the lad was fourteen years old. Some thought him dead, while others imagined he had run away to escape punishment incidental to a large transaction in lumber. Some signatures were forged, and it was held that Tolney Greene was guilty. He protested his innocence, but failed to stand trial, running away “between two days,” as it was termed. He was traced to New Bedford, and there it was reported that he had last been seen boarding a sailing vessel outward bound. What had become of him after that, nobody knew.

Mrs. Greene had believed her husband innocent, and it grieved her greatly to be thus deserted. She tried to bear up, however, but during the following winter contracted pneumonia, and died, leaving Chet alone in the world.

Nobody seemed to want anything to do with the lad—thinking him the son of a forger, and possibly a suicide. Some tried to talk to him, but when they mentioned the supposed guilt of his parent, he flew into a rage.

“My father wasn’t guilty, and you needn’t say so!” he stormed. “If you say it I’ll lick you!” And then he knocked one man flat. He was subdued after a while, but he refused utterly to live with those who offered him a home, saying he did not want to be an object of charity, and that he could get along alone. He took his belongings, and a little money left by his mother, and moved to another part of the State—close to where Andy resided. Here he lived with an old guide for a while, and then got employment at one of the lumber camps. The old guide had departed during the past year for the Adirondacks, and Chet was now living alone, in a cabin that had seen better days.

It had been no easy matter for Andy and Chet to become chums. At first when they met, at a lumber camp where both were employed, Chet was silent and morose. But little by little, warmed by Andy’s naturally sunny disposition, he “thawed out,” and told his story in all its details. He knew a few things that the general public did not know, and these he confided to Andy.

“My father went off on a whaler named the Betsey Andrews,” he once said. “He said he would come back some day and clear himself. The mate wrote to my mother that my father’s mind was affected a little, but he hoped he would be all right by the end of the trip.”

“Well, hasn’t the Betsey Andrews got back yet?” had been Andy’s question.

“No.”

“Where is she?”

“That’s the worst part of it—nobody knows.”

“Do you think she was lost?”

“I hope not—but I don’t know,” had been Chet’s somewhat sad answer. He lived in daily hope of hearing from his parent again.

Chet knew Andy’s story, of Josiah Graham’s meanness and laziness, and of the papers left by Andy’s father, and he now listened with deep interest to what his chum had to tell about the visit of Mr. A. Q. Hopton, and of the escape through the bedroom window.

“Now what do you make of the whole thing, Chet?” asked Andy, after he had finished his recital.

“It looks to me as if this real estate dealer was mighty anxious to get the papers,” was the answer. “And that means that the papers are valuable.”

“Just what I think.”

“Your uncle has no right to sell ’em for three hundred dollars, or any other amount,” pursued Chet. “I understand enough about law to know that he’s got to get a court order to sell property. To my way of thinking, he’d like to do this on the sly, and pocket the three hundred. He’s no good, even if he is your uncle.”

“He’s only my father’s half-brother, and he always was a poor stick. I wish I knew of some lawyer to go to.”

“Why not try Mr. Jennings, over at Lodgeport? I’ve heard he’s a good man, and smart, too.”

“I might try him. But it’s a twelve-mile tramp.”

“Never mind, I’ll go along, and we may be able to pick up some game on the way,” answered Chet.

The boys talked the matter over for two hours, during which time Chet prepared supper, and the two ate it. Then Andy fixed the fire for the night, and the boys turned in, tired out from their long tramps through the snow.

It took some time for Andy to get to sleep, for the events of the day had disturbed him greatly. But at last he dozed off, and neither he nor Chet awoke until it was daylight.

“Phew! but it’s cold!” cried Chet, as he put his head out of doors. “And it snowed a little last night, too.”

“Is it snowing now?” questioned Andy, anxiously. His mind was on the trip to Lodgeport. A heavy fall of snow might mean much delay.

“No, the storm is clearing away.”

“Then let us get breakfast and start.”

Both of the youths had been camping so often that they knew exactly what to do. The fire was stirred up, and fresh wood put on, and they prepared a couple of cups of coffee, and broiled two squirrels. They had bread and crackers, and a little cheese, and thus made quite a good breakfast.

The meal over, they lost no time in packing up, and placing the larger portion of their outfits in hiding in the old cabin. To carry them to Lodgeport would have been too much of a load.

“We can carry a little food and our guns,” said Chet. “If we can’t get back tonight, we can return tomorrow. I don’t believe anybody will come here during that time.”

“I hope I don’t meet Uncle Si—or Mr. Hopton,” said Andy.

“We can watch out and easily keep out of their way.”

To get to the road that led to Lodgeport, the two lads had to cross a heavy patch of timber. Here, under the pines, it was intensely cold, and they had to move along rapidly to keep their blood in circulation.

“Talk about Greenland’s icy mountains, I guess this is bad enough!” cried Chet, as he slapped his hands to keep them warm.

“We’ll soon be out in the sunlight again,” answered Andy. But he was mistaken, for by the time they reached the open country once more, the sun had gone under a fringe of light clouds, so it was as cold as ever.

At the end of four miles they passed through one of the lumber settlements, and then, leaving the wagon road, took to a trail running in the neighborhood of Moose Ridge.

“I met a man yesterday who was coming out to the Ridge to hunt,” said Andy. “Wonder if he’ll have any success.”

“Hunting is not as good as it might be,” answered his chum. “The best of the game was killed off at the very beginning of the season. Still, he may get some deer, or a moose, if he’s a good hunter.”

“I’d like to get a moose myself, Chet.”

“Oh, so would I. If you see one, kindly point him out to me.” And Chet’s usually serious face showed a grin.

“I will—after I have brought him down with my gun,” answered Andy, and then both laughed.

Less than fifteen minutes later they came on the trail of a deer. The marks were so fresh, both boys could not resist the temptation to go after the game. They plunged through some bushes, and Andy went headlong into a hollow.

“Wuow!” he spluttered, as the snow got into his ears and down his neck. “What a tumble!”

“Maybe you’re training for a circus,” cried Chet.

“Not out here—and in this cold. Help me up, will you?”

Chet gave his chum a hand, and slowly Andy came out of the hollow. He had dropped his firearm, but this was easily recovered from the snowdrift.

“I don’t want another such tumble,” said the unfortunate one, as he tried to get the snow out of his coat collar. “I’m cold enough already.”

Once more they went on, after the deer, but the game had evidently heard their voices and taken fright, for when they came to a long, open stretch, no living creature was in sight.

Another mile was covered in the direction of Lodgeport, and then they reached one end of the rock elevation locally termed Moose Ridge. Here there was a good-sized cliff, with smaller cliffs branching off in various directions.

“There used to be some good hunting around here,” said Chet, as, having climbed a small rise, they paused to catch their breath. “I once brought down a dandy buck over yonder.”

He had scarcely spoken, when from a distance ahead there sounded out the crack of a rifle, followed, a few moments later, by a second report.

“Somebody is out!” cried Andy. “Wonder if he hit what he was aiming at.”

“Maybe we’ll see. Come ahead.”

“I hope he isn’t shooting this way.”

“The reports came from the top of the big cliff.”

The two boys moved on, keeping their eyes on the alert for the possible appearance of the hunter who had fired the two shots.

“Look! look!” cried Andy, suddenly, and pointing over the top of a small tree that stood between them and the big cliff ahead.

“What did you see?”

“Maybe I was mistaken, but I thought I saw a man tumble off the cliff!”

“A man? Perhaps it was a deer, or a moose.”

“No, it looked like a man to me. Come on! If he fell to the bottom he may be killed!”

Andy set off as rapidly as the depth of the snow permitted, and Chet followed in his footsteps. Soon they rounded half a dozen trees and came in full view of the big cliff. Both uttered cries of horror, and with good reason.

Halfway down the edge of the cliff was a narrow ledge, and on this rested the body of a man,—a hunter, as was shown by his gun and game bag. He had tumbled from the top of the cliff, and the fall had rendered him unconscious. He lay half over the edge of the ledge, and was in imminent danger of falling still further and killing himself.

“Is he dead?” questioned Chet, in a strained voice.

“I don’t know—but I don’t think so,” answered Andy. “He has certainly had a nasty tumble.”

“It looks to me as if he was going to tumble the rest of the way, unless he holds on.”

“Let us see if we can’t help him.”

Both youths stood their guns against a tree, and made their way to the bottom of the cliff. As they did this, they saw the man’s body shift slightly, and then came a low moan.

“He’s alive!” cried Andy. “Hi, there!” he shouted. “Look out for yourself, or you’ll get another tumble!”

To this, the man on the ledge did not answer. But the boys, listening intently, heard him moan again.

“I wonder if we can get at him?” mused Chet. “I don’t see any way up the cliff from here, do you?”

“Oh, we must find a way to get to him!” cried Andy.

“Maybe we can catch him if he falls. If we—Look out!”

Andy leaped to one side, and the next instant the man’s gun dropped down on the rocks and fell in the snow. The game bag followed. They now saw the man in his unconscious state turn partly over.

“He’ll fall sure, unless we help him,” said Chet. “But I don’t know what to do.”

“I have it,” returned his chum. “Come on.”

“Where to?”

“I’ll show you.”

Wondering what his friend had in mind to do, Chet followed Andy to where was located an ash sapling of fair size. It had been broken off about two feet above the ground—how, they could not tell.

“We can put that against the cliff, and use it as a ladder,” said Andy.

“Provided we can get it over, Andy.”

Both began to tug at the sapling, and at last got it free from the stump end. Then they fairly rushed with it to the bottom of the cliff.

“You hold the end, and I’ll raise it up,” said Chet, who was a little the stronger of the two. “We can put the top right against the man, and that will keep him from rolling down.”

“If it will reach that far.”

“I think it will.”

Their experience as lumbermen stood them in good stead, and while Andy kept the bottom of the ash sapling from slipping in the snow, his chum raised it slowly but steadily, until it stood upright. Then Chet let it go over against the cliff with care, so that the man might not be further injured. The little tree reached several feet above the man’s head.

“I’ll go up and see what I can do for him,” said Andy, throwing off his overcoat. “You steady the tree, Chet.”

“All right. But be careful.”

From early boyhood days Andy had been a good climber, and he went up the ash sapling with ease. The young tree was strong, so there was no danger of its breaking beneath his weight. Soon his feet touched the ledge, and he knelt down beside the hurt man.

“Why, I know him!” he called down to his chum. “He’s the man I told you about—the one who asked me about the road to Moose Ridge.”

“Pull him back, before he has a chance to slip,” ordered Chet, and this Andy did. The movement made the man groan, and presently he opened his eyes for an instant.

“Oh, what a fall!” he murmured, and then relapsed into unconsciousness again.

“We’ll have to get him down from here and try to do something for him,” announced Andy. “He has a bad cut behind his left ear. I can’t do anything for him up here—it’s too slippery.”

“Can’t you climb down the tree with him? I’ll hold it steady.”

“I’ll try it.”

Andy made his preparations with care, for what he proposed to attempt was difficult and dangerous. A tumble to the rocks at the foot of the cliff might mean broken limbs, if not worse.

With care he raised the unconscious form up and placed it over his shoulder. Then he turned around, and, inch by inch, felt his way out on the sapling.

“I’m coming!” he called. “Hold it, Chet, or we’ll both come down!”

“I’ll hold it,” was the confident reply.

Gripping the knees of the man with his left hand, Andy held on to the sapling with his right. Stepping and sliding, he came down slowly. The young tree bent and threatened once to slip to one side, but Chet braced it with all his strength. In a minute more Andy was down, and had stretched the man out on the snow. The boy was panting from his exertions.

“I suppose we ought to have a doctor for him,” said Chet, as he made an examination of the unfortunate one’s wounds. “But I don’t know of any around here.”

“Nor do I. We can’t leave him here,—he’ll freeze to death. Where do you suppose we ought to take him?”

“I don’t know of a single place within a mile,—and I don’t suppose we ought to carry him as far as that. He may be hurt inside, and if he is, it won’t do to move him too much.”

Much perplexed by the situation which confronted them, the two boys talked the matter over. It was so cold at the foot of the cliff that to remain there was out of the question. At last Chet suggested moving to a clump of pine trees, where they might fix up some sort of temporary shelter and build a fire. They picked up their guns and the belongings of the man, and Chet took the unfortunate over his shoulder. He groaned several times, but did not speak or open his eyes.

“He is certainly hurt quite seriously,” said Andy. “I hope he doesn’t die on our hands.”

“Do you know his name, or where he comes from?”

“No, but I guess we can find that out by looking in his pockets. He must have cards or a notebook, or something.”

“He looks as if he was well off. That gun is an A No. 1 piece.”

“Yes, and look at the fine clothing he is wearing.”

It was a hard walk, and they had to take turns in carrying the unconscious man. To add to the gloom of the situation, it now commenced to snow again.

Presently they reached a spot that looked good to them. There were a series of rocks to the northward, backed up by a thick growth of pines. At the foot of the rocks grew some brushwood.

Chet had calculated to spend some time hunting, and had with him a hatchet, with which to cut firewood. In a very few minutes he had cut out some of the brushwood, leaving a cleared space about eight feet square. Over the top of the cleared space he threw some saplings and pine branches, and then “wove in” pine branches around the sides. By this means he soon had a shelter ready, which, while it was by no means air-tight, was a great deal better than nothing. On the floor of the shelter he placed other pine branches, and there he and Andy made the suffering man as comfortable as possible. As soon as they had reached the spot, Andy had started up a fire, right in front of the opening, and this now gave out a warmth that was much appreciated.

With some warm water made from melted snow, the lads washed the wounds of the man, and then bound them up with strips torn from their shirts. They used other water for making coffee, and poured some of this down the man’s throat. They also rubbed his hands and wrists, doing what they could think of to revive him.

In the meantime the snow continued to come down, lightly at first, and then so thickly that the entire landscape around the shelter was blotted out.

“It’s going to be a corker of a storm,” announced Chet, as he gazed out.

“I can’t see a thing anywhere,” was Andy’s answer. “Wonder how long it will last.”

“Several hours, maybe.”

“I don’t see how we are going to get a doctor to come here while it is like this.”

“Better not try to find one. If you go out, you may lose your way.”

They replenished the fire, and cut a good stock of wood, and then sat down to watch the man. In one of his pockets they found a card-case.

“His name is Barwell Dawson,” announced Andy, “and he comes from Brooklyn.”

“What business is he in?”

“It doesn’t say.”

That the stranger was rich was quite evident. He wore a fine gold watch and chain, and an elegant diamond ring. In one pocket he had a wallet filled with bills of large denomination.

“He is one of your high-toned sportsmen,” announced Chet. “Some of ’em come up to Maine every fall to hunt.”

“It’s a wonder he didn’t have a guide, Chet.”

“Oh, some of ’em think they can do better without one.”

Suddenly the man opened his eyes wide, stared around for a moment, and then sat up. The change was so unexpected that the boys were amazed.

“Where—Who are you?” he stammered.

“You’ve had a bad fall—came down over the cliff,” answered Andy.

“What? Oh, yes, so I did. I—I——” The man felt of his head. “Why, I’m all bandaged up!”

“You got cut pretty badly,” said Chet. “We’re wondering if you broke any bones.”

“Yes?” The man gave a little groan. “I’m hurt, that’s sure. Oh!” And then he put his hand to his side.

“You had better keep quiet for a while,” said Andy, gently. “It won’t do you any good to stir around. We’d get a doctor, only it’s snowing so we’re afraid we might miss the trail.”

“Snowing? It wasn’t snowing when I fell.”

“That was nearly two hours ago.”

“And I’ve been knocked out all that time?” The man fell back on the pine boughs. “No wonder I feel so broken up.”

He closed his eyes, and the boys thought he was going to faint. Chet got some more coffee.

“Here, drink this, it will do you good,” he said, and placed the tin cup to the sufferer’s lips. The man gulped down the beverage, and it seemed to give him a little strength. Presently he sat up again.

“Did you two see me take the tumble?” he questioned, with a weak attempt at a smile.

“I saw you,” answered Andy. “You didn’t come all the way over the cliff. You struck a ledge and hung there, and we got you down and brought you here.”

“I see.”

“We were afraid some of your bones were broken,” put in Chet. “Are they?”

“I don’t know.” Slowly the man moved his arms and his legs. He winced a little.

“All right but my left ankle,” he announced. “I reckon that got a bad twist. Beats the Dutch, doesn’t it?” he added, with another attempt at a smile.

“It’s too bad,” returned Andy.

“No, you don’t understand. I mean my coming to Maine to do a little quiet hunting, and then to get knocked out like this. Why, I’ve hunted all over this globe,—the West, India, Africa, and even in the Arctic regions—and hardly got a scratch. I didn’t think anything could happen to me on a quiet little trip like this.”

The two boys listened to the man’s words with keen interest. He had hunted in the wild West, in India, Africa, and even in the Arctic regions! Surely he was a sportsman out of the ordinary.

“You’re like old Tom Casey,” said Andy. “He fought the forest fires here for years, and never got singed, and then went home one day and burnt his arm on a red-hot stove. I hope the ankle isn’t bad.”

“I can’t tell about that until I stand on it. Give me a lift, will you?”

Both boys helped the man to his feet. He took a couple of steps, and was then glad enough to return to the pine couch.

“It’s no use—I can’t walk, yet,” he murmured.

“Do you think you need a doctor?” asked Chet.

“Hardly—although I’d call him in if he was handy. I’m pretty tough, although I may not look it. Who are you?”

“My name is Chet Greene, and this is a friend of mine, Andy Graham.”

“I am glad to know you, and very thankful for what you have done for me. I’ll make it right with you when I’m able to get around. My name is Dawson—Barwell Dawson. I’m a traveler and hunter, and occasionally I write articles for the magazines—hunting articles mostly.”

“Oh, are you the man who once wrote a little book about bears—how they really live and what they do, and all that?” cried Andy.

“Yes, I’m the same fellow.”

“I’ve got that book at home—you once gave it to my father, when I was about eight years old.”

“Is that so? I don’t remember it.”

“My father was up on the Penobscot, lumbering. He went out with you into the woods and you found a honey tree. You gave him the book for his little boy—that was me.”

“Oh, yes, I remember it now!” cried Barwell Dawson. “So that was your father. How is he?”

“My father is dead,” answered Andy, and his voice dropped a little.

“Indeed! I am sorry to hear it. And your mother?”

“She is dead, too.”

“Then you are alone in the world? Do you live near?”

“I live two miles from Pine Run, with an uncle. It was I who told you how to get to Moose Ridge, when you were driving on the wrong road.”

“Oh, yes, I thought I had seen you somewhere.”

Here the conversation lapsed, for Barwell Dawson was still weak. He lay back and closed his eyes, and the boys did not disturb him.

It continued to snow, until the fresh fall covered the old to the depth of several inches. The boys kept the campfire going, and cooked such game as they had brought along.

“We are booked to stay here for a while, that’s certain,” observed Chet. “No Lodgeport today.”

After a while Barwell Dawson sat up again, and gladly partook of the food offered to him. His injuries consisted of a hard shaking up, a bruised ankle, and several cuts on his head.

“I am thankful that no bones are broken, and that I did not get killed,” he said, and then he requested them to give the details of the rescue from the ledge. The boys related their story, to which he listened closely.

“It was fine of you to get me down,” he declared. “Fine! I’ll have to reward you.”

“I don’t want any reward,” answered Andy, promptly.

“Nor do I,” added Chet.

“Well, you ought to let me do something for you,” persisted the one who had been rescued.

“You might tell us of some of your hunting adventures,” said Andy, with a smile. “I’d like to hear about hunting in the far West and other places.”

“So would I,” added Chet. “If I had the money, I’d like to do like you have done, travel all over the world and hunt.” And his eyes glistened with anticipation.

“What do you do now?”

“Nothing at present. We can’t get an opening at any of the lumber camps.”

“I understand business is very dull this season.”

After that Barwell Dawson asked for more particulars concerning the boys, and they told him how they were situated. He was surprised to learn that Chet was practically alone in the world.

“It is certainly hard luck,” he said, kindly. “You must let me do something for you.”

Then, after his ankle had been bathed in hot water, and bound up, the hunter and traveler told them of his trips to various portions of the globe, and how he had hunted deer and moose in one place, bears and mountain lions in another, and tigers and other wild beasts elsewhere. He had two very interested listeners.

“It must be great!” murmured Chet. “Oh, that would suit me down to the ground—to go out that way!”

“I have made one trip to the north,” continued Barwell Dawson, “and I am soon going to make another.”

“You mean to Canada?” queried Andy.

“Not exactly. I am going to Greenland, and then into the polar regions. I want to hunt seals, polar bears, and musk oxen.”

“You’ll be frozen to death!”

“Hardly,” answered the hunter. “On my previous trip I stood the cold very well, and this time I shall go much better prepared. Somehow, I like hunting in the Arctic Circle better than hunting anywhere else. Besides, I wish to—But never mind that now,” and Barwell Dawson broke off rather abruptly. Then he told a story of a hunt after polar bears that made Chet’s eyes water.

“That’s the stuff!” whispered Chet to Andy. “That beats a deer hunt all hollow!”

“Yes, provided the polar bear doesn’t eat you up.”

“Huh! I’d not be afraid. I don’t believe a polar bear is any more dangerous than a moose.”

“I saw a moose just before I had the tumble,” said Barwell Dawson. “I climbed up the cliff after him, but I couldn’t get very close. I took two shots at him, but he got away.”

“If we are going to be snowed up here we ought to try for some game,” said Chet. “Maybe I can stir up some rabbits, or something.”

It was decided that he should go out, leaving Andy to look after Mr. Dawson and the campfire.

“But don’t go far,” cautioned Andy. “The snow is coming down so thick that you may get lost.”

“Oh, I’ll take care of myself,” answered Chet.

He knew it would be a bad move to go out into the open, so he kept to the timber, blazing a tree here and there as he went along. He knew very little game would be stirring.

“If I get anything it will be more accident than anything else,” he reasoned. “No animal is going to stir out in this storm.”

He was just passing under a big spruce tree when, chancing to glance up, he saw a sight that quickened his pulse. On a limb close at hand were several wild turkeys, huddled together to keep warm.

With great caution he moved to one side, to get a good aim. Then, raising his gun, he blazed away. There was a whirr and a flutter, and two of the turkeys came down, one dead and the other wounded. Rushing forward, Chet caught the wounded bird by the neck, and soon put it out of its misery.

“That’s a good start,” he told himself, with much satisfaction. “I hope my luck continues.”

Placing the game in his bag, he went forward again, looking for more signs of birds, and also for signs of squirrels and rabbits.

It was growing dark, and Chet began to think it was time to turn back, when he saw some rabbits in a thick clump of bushes. He sprang in after them, and they leaped out into the snow and across a small opening. Then, before he could fire, they were out of sight again.

“You shan’t get away from me as easily as that,” the youth muttered to himself, and ran out into the opening. Here the snow was so thick he could see but little, yet he kept on, and soon reached more brushwood. He saw some branches close to the snow move, and blazed away in the dark.

His aim proved true, for when he came up he found one rabbit dead. Another had been wounded, as the blood on the snow showed. In all haste he made after the limping game. But the rabbit had considerable life left in it, and dove deep into the brushwood. But at last it had to give up, and Chet secured the additional game without much trouble.

It had grown dark rapidly, and in some anxiety the young hunter turned back, in an endeavor to retrace his steps. This was no easy matter, for the snow was coming down as thickly as ever, and he could scarcely see two yards ahead of him.

“It won’t do for me to get lost out here,” he reasoned. “If I don’t get back, Andy will be worried to death.”

Bending to meet the snow—for the wind was now blowing briskly, Chet pushed forward until another clump of trees was gained. Walking was becoming irksome, and he panted for breath. Under the trees he paused to get his bearings.

“I must be right,” he thought. Yet, try his best, he could not locate any of the trees he had blazed a short while before.

Any other lad might have become frightened at the prospect, but Chet was used to being alone, and he simply resolved to move forward with increased caution.

“If the worst comes, I can fire three shots in succession. Andy will know what that means,” he reasoned. On previous trips to the woods the boys had arranged that three shots meant, “I am lost. Where are you?” A single shot was to be the answer—repeated, of course, as often as necessary.

Another hundred feet were covered, and Chet was looking vainly for one of the blazed trees, when an unexpected sound broke upon his ears.

It was an unusual and uncanny noise, and he stopped short to listen. It came from a clump of spruces to his left.

“Now, what can that be?” he asked himself. “I never heard a noise like that before.”

He listened, and presently the sound was repeated. To him it seemed as if some unseen giant were in deep distress.

Chet was not superstitious, or he might have thought he heard a ghost. He knew there must be some rational reason for the unusual noise, and he resolved to investigate.

“Anybody there?” he cried, as he raised his gun in front of him, and tried to peer through the snow-laden air.

There was no answer, nor was the peculiar sound repeated. With cautious steps he advanced toward the clump of spruces. Underneath all was now as dark as night could make it.

Again he paused, something warning him to be extra cautious. His nerves were now at a high tension, for he felt something unusual was coming.

An instant later it came. Through the snow and darkness Chet caught a momentary gleam of a pair of eyes shining like two balls of fire. Then a bulky form shot out of the darkness, and bumped up against him, hurling him flat. Ere he could arise, the form leaped over him, and went limping off, puffing and snorting as it did so.

“A moose!” gasped Chet, as he felt in the snow for his gun. “And wounded! It must be the one Mr. Dawson tried to get!”

He thought the big beast was retreating, but soon found out otherwise. The moose was badly wounded, and ugly in the extreme. Around he wheeled, and then came straight for Chet. The lad could not locate his gun, and, feeling his peril, darted for the nearest tree and leaped high up among the branches.

“Phew! that was a narrow escape!”

Such were Chet’s words as he drew himself higher up into the tree. The big beast below had come up, and struck the tree a blow that made it shiver from top to bottom. Had he not been holding on tightly the boy would have been hurled down, and at the very feet of the moose.

The animal was full-grown, powerful, and with wide and heavy antlers. He had been wounded in one of the forelegs, but was still able to stand. Now he stood under the spruce, on three legs, gazing up at Chet speculatively.

“Like to smash me, wouldn’t you?” murmured the youth. “Well, I guess not—not if I know it!”

Chet wished with all his heart that he had his gun. But the weapon was out of sight under the snow, and the moose was standing over the spot.

What to do next, the lad did not know. The moose did not show any inclination to leave. He breathed heavily, as if his wound hurt him, but Chet was certain that there was still a good deal of fight in the creature.

“Perhaps he’ll keep me here all night,” thought the boy, dismally.

Presently an idea came to him to call for help. Andy might hear him, and come up with his gun.

“That shelter is a long way off, but it won’t do any harm to try it,” Chet reasoned, and expanding his chest, he let out a yell at the top of his lung power. He repeated the cry several times, and then listened with strained ears. No answer came back but the gentle sighing of the rising wind, as it swept through the woods.

“Huddled inside the shelter, I suppose, to keep warm,” Chet murmured, dismally. “I might yell my head off and it wouldn’t do a bit of good. I’ll have to try something else.”

What that something else was to be was not clear. He moved from one branch to another to investigate, then a thought struck him, and he resolved to act upon it.

With caution, so as not to attract the attention of the moose, he climbed far out on a branch of the spruce, and thus gained a grip on the wide-spreading limb of another tree. He swung himself to this, and crawling along and past the trunk of the second tree, moved to the end of a branch on the opposite side.

He was now a good twenty-five feet from where the moose was standing. Would it be wise to drop down in the snow and make a dash for liberty?

“If he catches me, he’ll kill me—he’s so ugly from that wound,” Chet told himself. “If it wasn’t so awful cold, I’d stay here till morning.”

Cautiously he lowered himself toward the snow below. He was on the point of dropping when he heard the moose move. The animal came on the rush, and in drawing up into the tree again, Chet had one foot scraped by the moose’s antlers.

“No escape that way,” he told himself, and lost no time in pulling himself still higher into the tree.

Thus far he had managed to keep warm, but now, as he sat down to rest, and to study the situation, he became colder and colder. Occasionally the wind drove in some of the snow, to add to his discomfort.

Presently Chet thought of another idea, and wondered why it had not occurred to him before. He knew that all wild animals dread fire. He resolved to make himself a torch, and try that on the moose.

Making sure that he had his matches, he got out his jackknife and cut off the driest branch that he could find. Then, holding it with care, he struck a match, shielding it from the wind as best he could, and lit the end of the branch. At first it did not ignite very well, but he “nursed” the tiny flame, and soon it blazed up into quite a torch.

“Now we’ll see how you like this,” Chet muttered, and started to climb to the lower branch once more.

With eyes that still blazed, the moose had watched the flaring up of the light. At first he was all curiosity, but as the flame grew larger he gave a snort of fear. Far back in the past he had felt the effects of a forest fire, and now he thought he saw another such conflagration starting up. As Chet swung down he turned and limped off, moving faster at every step.

“Hurrah! that did the trick!” cried the boy, in deep satisfaction, and then, as he saw the moose plowing off through the deepening snow, he jumped to the ground and rushed off to where he had dropped his gun. Perhaps he could lay the beast low after all.

As luck would have it, Chet did not have to look long for the firearm. The moose had kicked the snow from part of the barrel, and the glare of the torch lit upon this. In a trice the youth had the gun in his hand. The moose was disappearing in the snow and darkness, but taking hasty aim, he fired.

The animal went on, but Chet felt certain his shot had gone true. Hastily reloading, so that he might have both barrels ready in case he wanted them, he set off after the game as fast as the now heavy fall of snow would allow. He was a true sportsman, and made up his mind that now he had his firearm once again, the moose should not escape him.

As is well known, although a moose is one of the swiftest of wild animals on clear ground, or even on the rocks and in the woods, the creature is at a disadvantage in soft snow, because of its small legs and hoofs. Its weight causes it to sink to the very bottom of every hollow.

Chet had advanced less than two hundred feet when he saw the moose floundering in the snow behind some bushes over which it had leaped.

“Now I’ve got you!” cried the boy, and advancing fearlessly, he took careful aim and blazed away. The animal went down, thrashed around, sending the snow in all directions, and then lay still.

Not to be caught in any trap, Chet reloaded once more, and then came up with caution. But the big creature was dead, and the heart of the young hunter bounded with delight. It was an event to lay low such a monarch of the forest as this.

“As big a moose as I’ve seen brought in from these parts,” he mused. “Won’t Andy be surprised when he sees the game! But Mr. Dawson deserves some of the credit—he hit the moose first.”

What to do with his prize Chet did not know. To haul it to the temporary camp alone, and through such deep snow, was impossible. And if he left it where it was, some wolves or other wild beasts might get at it.

“I’ll kick the snow over it, and let it go at that,” he finally decided. “It’s time I got back. It’s so dark it won’t be long before I can’t see a thing.”

Sticking his torch in the snow, he made a mound over the game, and on top stuck a stick with his handkerchief tied to it. Then he retraced his steps to the clump of spruces, and searched once again for the blazes he had made on the trees.

At last, just as he was about to shoot off his gun as a signal of distress, he found one of the blazes, and a minute later discovered another. He now had the proper direction in mind, and set off as rapidly as his weary limbs and the ever-increasing depth of snow would permit.

“Hullo, Chet! Where are you?”

It was a call from Andy, sounding out just as the young hunter came in sight of the campfire. Andy was growing anxious, and had come forth from the shelter several times in an endeavor to locate his chum.

“Here I am,” was the answer. “Christopher, but I’m tired!”

“Any luck?”

“A little. How are those for wild turkeys?”

“Fine! Now we’ll have a good breakfast, anyway.”

“How is Mr. Dawson?”

“He says he feels pretty easy. But his ankle is badly swollen. Say, he’s a splendid man, and one of the greatest hunters you ever heard of, Chet. And he’s rich, too—he owns a ranch out West and a bungalow down on the Jersey coast, and a yacht, and I don’t know what all.”

“You can tell him I brought down the moose he wounded.”

“What!” And Andy’s eyes showed his astonishment.

“It’s true. The moose almost laid me low first, but I got the best of him after all.”

“Where is the animal?”

“About a quarter of a mile from here. I covered him with snow, and put a stick and my handkerchief over the spot.”

“Did he attack you?”

“He certainly did,” answered Chet.

Both boys entered the temporary shelter. Barwell Dawson was awake, and he and Andy listened with keen attention to the story Chet had to tell.

“It must have been the moose I hit,” said Barwell Dawson. “But I think he’s your game anyway, Chet.”

“Well, we can divide up,” answered the young hunter, modestly.

The tramp in the snow, and the excitement, had made Chet weary, and he was glad enough to lie down and go to sleep. During his absence, Andy had cut more pine boughs and piled them around the sides and on top of the shelter, so it was now fairly cozy, although not nearly as good as a cabin would have been.

In the morning Andy was the first to stir. He found the entrance to the shelter blocked by snow, and the campfire was all but out. The snow had stopped coming down, but the air seemed to be still full of it.

“We’ve got to get out of here, or we’ll be snowed in for certain,” he told Chet, and then kicked the snow aside and started up the fire, and commenced to get breakfast. They cooked one of the wild turkeys, and it proved delicious eating to the lads, although Mr. Dawson thought the meat a trifle strong.

The man who had had the tumble over the cliff declared that he felt quite like himself, aside from his ankle, which still pained him. The swelling of the member had gone down some, which was a good sign.

“I guess your uncle will wonder what has become of you,” said Chet to Andy. “I suppose he’ll hunt all over the village for you.”

“Let him hunt, Chet. I am not going back until I find out about that timber land, and about what sort of man that Hopton is. The more I think of it, the more I’m convinced that Mr. A. Q. Hopton is a swindler and is trying to swindle both Uncle Si and myself.”

“Well, it’s no credit to your uncle to stand in with him.”

“Of course it isn’t—and I’ll give Uncle Si a piece of my mind when I get the chance.”

“I don’t think you’re going to get to Lodgeport today.”

“Well, it doesn’t matter much. I don’t think there is any great hurry about this business. The matter has rested ever since father died.”

This talk took place outside the shelter, so Barwell Dawson did not hear it. Inside, the man dressed his ankle, while the boys cleared away the remains of the morning meal, and started the fire afresh with more pine sticks.

“We really ought to try to get out of here,” said Andy, after an hour had passed. “I think it will snow again by night, and it would be rough to be snow-bound in such a place as this.”

“I’d like to get out myself, but I am afraid I can’t walk,” said Barwell Dawson, with a sigh. “A bruised ankle is worse than a broken arm—when it comes to traveling,” he added, with a grim smile.

“Supposing we took turns at carrying you?” suggested Chet. “I think we could do it.”

“How far?”