KENSINGTON RHYMES

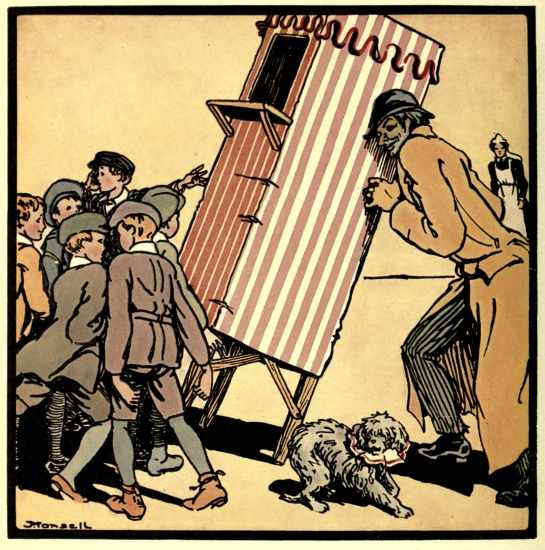

THE PUNCH AND JUDY SHOW

K E N S I N G T O N

R H Y M E S

BY COMPTON MACKENZIE

ILLUSTRATED BY J. R. MONSELL

LONDON: MARTIN SECKER

NUMBER FIVE JOHN STREET ADELPHI

First published 1912

PRINTED BY

BALLANTYNE & COMPANY LTD

AT THE BALLANTYNE PRESS

TAVISTOCK STREET COVENT GARDEN

LONDON

TO

ETHEL LONG

CONTENTS

| PAGE |

| OUR HOUSE | 11 |

| OUR SQUARE | 15 |

| THE DANCING CLASS | 17 |

| MY SISTER AT A PARTY | 22 |

| KISSING GAMES | 26 |

| A BALLAD OF THE ROUND POND | 28 |

| TOWN AND COUNTRY | 35 |

| POOR LAVENDER GIRLS | 37 |

| SUMMER HOLIDAYS | 39 |

| THE UNPLEASANT MOON | 42 |

| SUGGESTIONS ABOUT SLEEP | 44 |

| THE RARE BURGLAR | 47 |

| THE GERMAN BAND | 49 |

| THE DECEITFUL RAT-TAT | 53 |

| THE CAGE IN THE PILLAR BOX | 54 |

| THE FORTUNATE COALMEN | 57 |

| THE PAVEMENT ARTIST | 60 |

| SWEEPS | 63 |

| GREENGROCERS | 65 |

| CHRISTMAS NOT FAR OFF | 66 |

| THE DISAPPOINTMENT | 67 |

| TREASURE TROVE | 68 |

| A VISIT TO MY AUNT | 73 |

| DON QUIXOTE | 77 |

| THE WET DAY | 84 |

| LAST WORDS | 87 |

KENSINGTON RHYMES

OUR house is very high and red,

The steps are very white,

The balcony is full of flowers,

The knocker's very bright.

The hall has got a coloured lamp,

A rack for father's hat,

And pegs for coats: a curious word[A]

Is printed on the mat.

The kitchen ticks too loud at night,

It is a horrid place;

Black-beetles run about the floor

At a most dreadful pace.

The cellar is quite black with coal,

The cat goes scratching there;

People go tramping past above,

But nobody knows where.

The dining-room has rosy walls,

And silver knives and forks,

And when I listen at the door,

I hear the popping corks.

The library smells like new boots,

It is a woolly room;

The housemaid comes at eight o'clock

And sweeps it with a broom.

The staircase has a thousand rods

That rattle if you kick,

And when the twilight makes it blue

I rush up very quick.

The landing is a dismal place,

The bannisters creak so,

The door-knobs twinkle horribly,

The gas is always low.

The drawing-room is cold and white,

The chairs have crooked legs;

Silk ladies rustle in and out

While Fido sits and begs.

The bathroom is a trickling room,

And always smells of paint,

The cupboard's full of medicine

For fever, cold or faint.

My bedroom is a brassy room

With pictures on the wall:

It's rather full of nurse's clothes

But then my own are small.

Our house is very high and red,

The steps are very white,

The balcony is full of flowers,

The knocker's very bright.

OUR square is really most select,

Infectious children, dogs and cats

Are not allowed to come inside,

Nor any people from the flats.

I have a sweetheart in the square,

I bring her pebbles that I find,

And curious shapes in mould, and sticks,

And kiss her when she does not mind.

She wears a dress of crackling white,

A shiny sash of pink or blue,

And over these a pinafore,

And she comes out at half-past two.

Her legs are tall and thin and black,

Her eyes are very large and brown,

And as she walks along the paths,

Her frock moves slowly up and down.

We all have sweethearts in our square,

And when the winter comes again,

We shall go to the dancing-class

And watch them walking through the rain.

THE DANCING CLASS

EACH week on Friday night at six

Our dancing-class begins:

Two ladies dressed in white appear

And play two violins.

It's really meant for boys at school,

But girls can also come,

And when you walk inside the room

You hear a pleasant hum.

The older boys wear Eton suits,

The younger boys white tops;

We stand together in a row

And practise curious hops.

The dancing-master shows the step

With many a puff and grunt;

He has a red silk handkerchief

Stuck grandly in his front.

He's awfully excitable,

His wrists are very strong,

He drags you up and down the room

Whenever you go wrong.

And when you're going very wrong,

The girls begin to laugh;

And when you're pushed back in your place,

The boys turn round and chaff.

We've learnt the polka and the waltz,

We've got the ladies' chain;

Although he says our final bows

Give him enormous pain.

The floor is very slippery,

It's difficult to walk

From one end to the other end

Unless you sort of stalk.

And when the steps have all been done,

He takes you by the arm

To choose a partner for the dance—

It makes you get quite warm.

You have to bow and look polite,

And ask with a grimace

The pleasure of the next quadrille,

And slouch into your place.

He always picks out girls you hate,

I really don't know why,

And when you look across the room

It almost makes you cry

To see the girl you would have picked

Dance with another boy

Without a single smile for you,

Determined to annoy.

Your heart beats very loud and quick,

Your breath comes very fast,

You pinch your partner in the chain—

But dances end at last.

You think you will not look at her,

You look the other way;

Yet when she beckons with her fan,

You instantly obey.

How quick the evening gallops by

And eight o'clock comes soon,

But not till you've arranged to meet

To-morrow afternoon.

I HEAR the piano, the party's begun;

Hurry up! hurry up! there is going to be fun.

Leave your wrap in the hall and tie up your shoes,

There isn't a moment, a moment to lose.

Take a peep at the dining-room as you go by,

Lemonade, claret cup, orange wine you will spy:

And they're going to have two sorts of ices this year,

Both strawberry-cream and vanilla, I hear.

Twelve dances are down on the programme, I see.

Oh, do up your gloves, she is waiting for me!

I hear the piano, the polka's begun!

Oh, why does your beastly old sash come undone!

That's right, are your ready? now don't you forget

To say how d'ye do and express your regret

That Miss Perkins[B] is laid up in bed with a cold—

It isn't my place—just you do as you're told.

I say, look at Frank,[C] he's behaving as though

He was playing with cads in a field full of snow;

He's sliding about on the slippery floor

All over the room with the kid from next door.

It's a jolly good thing that Miss Perkins' in bed,

They'll probably send old Eliza[D] instead.

When we hear that she's come, we'll just not attend,

Or tell her we never go home till the end.

They give all the maids when they come, orange wine—

I say, do you think I might ask her for nine.

All right, only don't say I danced more than twice;

If you do, I'll say you have had more than one ice.

Mother said that you could? She said one of each?

You'd better look out or I'll jolly well peach.

You don't care if I do? All right, just you wait!

You'll tell Mrs. Jones we were not to be late?

I'm not pinching at all, you beastly young sneak!

You won't follow me round when we play hide and seek!

There's Dorothy![E] Pax! You can eat what you like,

And to-morrow I'll give you a ride on my bike.

POSTMAN'S Knock! Postman's Knock!

A letter for the girl next door,

And two pence, please, to pay.

Kiss in the Ring! Kiss in the Ring!

She's fallen down upon the floor,

I don't know what to say.

Postman's Knock! Postman's Knock!

I wish that I had asked for more;

At games you must obey.

Kiss in the Ring! Kiss in the Ring!

When running after her I tore

Her frock the other day.

Postman's Knock! Postman's Knock!

A letter for the girl next door,

And a shilling she must pay.[F]

THE Round Pond is a fine pond

With fine ships sailing there,

Cutters, yachts and men-o'-war,

And sailor-boys everywhere.

Paper boats they hug the shore,

And row-boats move with string

But cutters, yachts and larger ships

Sail on like anything.

THE ROUND POND

It was the schooner Kensington,

Set out one Saturday:

The wind was blowing from the east,

The sky was cold and grey.

Her crew stood on the quarter-deck

And stared across the sea,

With two brass cannon in the stern

For the Royal Artillery.

The Royal Tin Artillery

Had faced the sea before,

They had fallen in the bath one night

And heard the waste-plug roar.

They were rescued by the nursery maid

And put on the ledge to dry;

And they looked more like the Volunteers

Than the Royal Artillery.

For the blue had all come off their clothes,

And they afterwards wore grey;

But they stood by the cannon like Marines

That famous Saturday.

The crew of the schooner Kensington

Were Dutchmen to a man,

With wooden legs and painted eyes;

But the Captain he was bran.

His blood was of the brownest bran

And his clothes were full of tucks;

But he fell in the sea half-way across,

And was eaten up by ducks.

We launched the boat at half-past three,

And stood on the bank to watch,

And some friends of mine who were fishing there

Had a wonderful minnow-catch.

Fifteen minnows were caught at once

In an ancient ginger jar,

When a shout went up that the Kensington

Was heeling over too far.

Too far for a five-and-sixpenny ship

That was warranted not to upset;

But she righted herself in half a tick

Though the crew got very wet.

The crew got very wet indeed;

The Artillery all fell down,

And lay on their backs for the rest of the voyage

For fear they were going to drown.

The schooner Kensington sailed on

Across the wild Round Pond,

And we ran along the gravel-bank

With a hook stuck into a wand.

A hook stuck into a wand to guide

The schooner safe ashore

To incandescent harbour lights

And a dock on the school-room floor.

But suddenly the wind dropped dead.

And a calm came over the sea,

And a terrible rumour got abroad

It was time to go home to tea.

We whistled loud, we whistled long,

The whole of that afternoon;

But there wasn't wind enough to float

A twopenny pink balloon.

And the other chaps upon the bank

Looked anxiously out to sea;

For their sweethearts and sisters were going home,

And they feared for the cake at tea.

. . . . . . .

It was the schooner Kensington

Came in at dead of night

With many another gallant ship

And one unlucky kite.

The keeper found them at break of day,

And locked them up quite dry

In his little green hut, with a notice that

On Monday we must apply.

So on Sunday after church we went

To stare at them through the door;

And we saw the schooner Kensington

Keel upwards on the floor.

But though we stood on the tips of our toes,

And craned our necks to see,

We could not spot the wooden-legged crew

Or the Royal Artillery.

THEY say that country children have

Most fierce adventures every night,

With owls and bats and giant moths

That flutter to the candle-light.

They say that country children search

For earwigs underneath the sheets,

That creeping animals abound

Upon the wooden window-seats.

They say that country children wash

Their hands in water full of things,

Tadpoles and newts and wriggling eels,

Until their hands are pink with stings.

But this I know, that if they slept

Far, far away from owls and bats,

Their hearts would thump tremendously

To hear outside two fighting cats.

Two cats that surely must come through

The inky window-pane and jump,

With gleaming eyes, upon my bed—

Ah, then indeed their hearts would thump.

LAVENDER, lavender!

Summer's in town!

Blue skies and marguerites,

Mother's new gown!

Lavender, lavender!

Summer's in town!

Blue seas and yellow sands,

Children have flown.

Lavender, lavender!

Bunchy and sweet!

No one wants lavender

All down our street.

Lavender girls in London never learn to play,

Give them a penny, a penny before you go away.

GOOD-NIGHT

WHEN I was small and went to bed

Before the sun went down,

My cot was woven out of gold

Like a princess's gown.

And in the garden every night,

I used to hear the birds,

And from the people on the lawn

A pleasant sound of words.

The garden was quite full of pinks

Whose smell came blowing in

Through windows open very wide

Where gnats would dance and spin.

And as I lay in my cool cot,

I'd think of daylight hours,

Poppies and ox-eyed daisies white,

And all the roadside flowers

Now lifting up their drooping heads

In the long-shadow time;

I'd listen for my mother's step

The narrow stairs to climb.

And as she bent to say good-night

And heard me say my prayer,

She seemed a bit of mignonette,

She was so sweet and fair.

And just as I was dozing off,

I'd hear some jolly talk

Of aunts and uncles setting out

To take their supper-walk.

I'd hear their voices die away

In the green curly lane;

But I was always fast asleep

When they came back again.

THE moon is not much use to me,

She rises far too late:

I'm fonder of the friendly fire

That crackles in the grate.

But when I wake up in the night

And find the fire asleep,

His ashes make a horrid noise

And mice begin to creep.

And then the moon crawls in between

The curtains and the floor,

And when I turn my face away,

She's crawling round the door.

Oh, then I wish she was the fire,

I like his light the most;

He does not give the furniture

A sort of shaking ghost.

I hide my head beneath the clothes

And shut my eyes up tight,

And then I see queer dancing wheels

And spots of coloured light.

They do not comfort me at all,

But pass the time away

Until I hear the milkman's can

And know that it is day.

I'VE heard it said that the dustman

Is responsible for our sleep,

That he puts a pinch of dust in our eyes

When the stars begin to peep.

If this is true it would quite explain

The horrible dreams that come,

For the dustman looks a rough sort of chap,

And his cart smells awfully rum.

THE DUSTMAN

I've tried to talk to the dustman,

But his voice is fearfully hoarse;

And once I put a penny in the bin—

It was taken out of course.

But for all the good it did my dreams,

I need not have put it in;

Perhaps he thought that the penny had slipped

By accident into the bin.

It seems absurd in this civilised age[G]

That our dreams should still be bad;

If the dustman is responsible

I think he must be mad.

It's horrid enough to lie awake,

And count the knobs on the bed;

But it's horrider far to go to sleep,

In fact I'd sooner be dead.

I expect that then if one had bad dreams

And woke up in a fright,

There would be an angel somewhere about

To strike a cheerful light.

And your governess is not always glad,

If you wake her up to say

That a witch has been chasing you down a street

Where the people have gone away.

IT'S extremely unusual, my mother declares,

For a burglar to sleep at the top of the stairs:

The policemen, she says, are so terribly sure

That daily the number of burglars gets fewer.

They are caught by the dozen as morning comes round

And dragged off to cells very deep underground:

And there they repent of their wicked bad lives,

With occasional visits from children and wives.

So every night when I lie in my bed,

I listen to hear the policeman's deep tread.

I've a whistle that hangs on a piece of white cord,

And it's much more consoling than any tin sword:

For I know, if I blow, the policeman will come

And make the old burglar look awfully glum.

THE GERMAN BAND

I LOVE to lie in bed and hear

The jolly German band.

Why people do not care for it

I cannot understand.

They do not mind the orchestra.

And that makes far more noise;

They quite forget that music is

A thing that one enjoys.

When grown-up people come and call,

I have to play for them;

And once a deaf old lady said

My playing was a gem.

But it's not true for them to say

The Carnival de Venise[H]

With three wrong notes is better than

A band that plays with ease.

It comes each week at eight o'clock,

And when I hear it play,

I am a knight upon a horse

And riding far away.

The lines upon the blanket are

Six armies marching past,

Six armies marching on a plain,

Six armies marching fast.

Of course I am the general,

I'm riding at the head;

But suddenly the music stops

And then I'm back in bed.

Each time it plays brings different thoughts,

Exciting, sad and good.

I'm sailing in a sailing ship,

I'm walking in a wood.

I'm going to the pantomime,

I'm at the hippodrome.

But when the music stops, why then

I always am at home.

In winter when it's dark at eight,

The jolly German band

Drives all unpleasant thoughts away

Just like a fairy-wand.

In summer when it's light at eight,

The German band still plays;

It makes me think of pleasant things

And seaside holidays.

I've heard that it plays out of tune,

And upsets talking, and

I've heard it called a nuisance, but

I love the German band.

THE postman has given a loud rat-tat,

Perhaps it's a parcel for me:

Elizabeth does go slowly

To open the door and see.

Oh dear, it's only a telegram,

To wait on the stand in the hall

Till Father comes home in the evening

Or Mother comes back from a call.

I WONDER if an animal

Lives in the pillar-box,

For when the postman opens it

You see a cage with locks.

And surely letters do not want

A cage with bars and clamps;

They have no wings, they could not fly,

They're held by sticky stamps.

Perhaps the postman keeps a pet,

A savage beast of prey;

For lions, seals and diving-birds

Are fed three times a day.

And all those figures on the plate

Are meant perhaps for you

To learn what time the beast is fed

Like others at the Zoo.

And now I come to think of it,

The postman's coat and hat

Is not unlike a keeper's who

Feeds animals with fat.

Besides, he always shuts the door

With a tremendous bang,

As if he feared to see stick out

An irritable fang.

But then again I never heard

The faintest roar or squeak,

I never saw a sniffing nose

Or spied a hooky beak.

So after all perhaps there's not

A bird, a beast or snake.

And yet to-morrow I shall post

A slice of cherry-cake.

IT is a pleasant thing to watch

The coalmen at their work;

They do not seem to mind the dark

Where many dangers lurk.

The braver of them goes below

Into the cellar black,

And calls out in a cheerful voice

To bring another sack.

The other grunts and groans a lot

Beneath his load of coal,

And down the ladder goes with care

Until he gains the hole.

He turns his burden upside down,

The inside rattles out,

And a delicious smell of coal

Gets everywhere about.

The braver one takes up his spade

And shovels it away;

The other wipes his shiny face,

And asks the time of day.

But it is very strange to me

That neither seems to want

To put the ladder down the hole

And climb down where I can't.

A man, they say, once broke his leg

By falling down a grating,

And nearly died for want of food,

Because they kept him waiting

A week before they pulled him out

And took him to his home,

From which he never more went forth

The London streets to roam.

But coalmen do not run these risks,

They have no nurse to frown,

So they might spend the whole long day

In climbing up and down.[I]

I THINK that I should like to be

A pavement artist best,

For he has every kind of chalk

Spread in a cosy nest.

I have ten pieces in a box,

Black, yellow, white and blue,

Pink, red, brown, orange, grey and green,

But these are far too few.

THE PAVEMENT ARTIST

He has a hundred different shades,

And most uncommon sorts;

He can draw salmon, queens and chops,

Wrecks, mutinies and forts.

His cannon have enormous puffs

Of the most curly smoke,

Because he has so many 'greys,'

Far more than other folk.

His girls are a delicious pink,

And mine are rather pale;

But then I have to be more strict

For fear my pink should fail.

His fields have got a splendid green;

They're full of flowers bright;

But mine are covered up with snow

Because my paper's white.

And yet with all these jolly chalks,

The artist seems in pain;

Perhaps because his pictures get

Rubbed out by showers of rain.

But what I cannot understand

Is why each paving-stone

Has not a drawing on its face,

Why such a few are done.

Our walks would be much pleasanter,

If all the dullest streets

Were illustrated like a book

And gay as flags or sweets.

Of course a lot would get all smudged

By careless people's tracks,

But some would tread as I do now

Only upon the cracks.

MY nurse declares that sweeps are kind,

Without the slightest inclination

To steal away a well-dressed child

Except by nurse's invitation.

Nurse says that children do not climb

The tall black chimneys any more;

She even says (this must be wrong)

Sweeps enter by the area door.

But I have seen a chimney-sweep

Go whooping up and down our street;

And on his back he had a sack—

I bet with something good to eat.

GREENGROCERS, greengrocers,

In your green shops,

With cabbages and cauliflowers

And tough turnip-tops.

Mother buys daffodils,

And apples for me:

But nurse she buys radishes

To eat with her tea.

NOVEMBER fogs, November fogs,

A month to Christmas day.

The world is cold and dirty,

But the muffin man is gay.

He rings his bell, he rings his bell

All through the afternoon:

He rings his bell to let us know

That Christmas will come soon.

THE Punch and Judy man's in sight,

He's coming down our street,

He's stopping just before our house—

Shut up! I bagged that seat.

I say, the Colonel opposite[J]

Is sending him away,

Because he says his wife is ill

And can't bear noise to-day.

AFTER a winter walk, it's nice

To see the baked-potato man

Poking his stove and picking out

The best potatoes from his pan.

A baked potato on a spike

Is very like a pirate's head;

I always think of them again

Long after when I've gone to bed.

I bought one coming home from school,

And as I turned into our street,

The lamp-posts in the yellow fog

Sailed like a wicked pirate fleet.

And all the people in the fog

Were sailor-men upon a quay;

The pavement smelt of tar and salt:

I thought I heard quite close the sea.

I heard a whisper as I went,

'The Jolly Roger's at the peak';

A bullfinch in a lighted room

Was a parrot in a far-off creek.

The parlour-maid at Twenty-two

Was black-eyed Susan, and beyond,

The plane-tree was a cocoa-palm;

The crossing-sweeper was marooned.

And as I got close to our house,

I was an English midshipman;

My satchel was an old sea-chest,

My copy-book a treasure-plan.

And then a wondrous thing occurred,

The strangest thing I ever knew:

I found a shining sixpence, though

I don't suppose you'll think it true.

I hardly dared to look at it,

Afraid that it would only prove

A bit of tin, a Bovril coin,

And not a proper treasure-trove.

I told my brother and he thought

We'd better hide it out of sight,

In case the pirates should attack

Our bedroom on that foggy night.

The baked potato in my coat

Was just exactly Captain Kidd;

So both of us declared at once

That there the sixpence must be hid.

We took our sister's sailor-doll

And put his clothes upon a stick,

And spent the evening doing this

Instead of my arithmetic.

We made a glorious cocked-hat

Of paper-painted Prussian blue,

We put the pirate on the stick,

And stuck the sixpence first with glue.

Deep in my mother's window-box

Next day we buried Captain Kidd;

My sister never could find out

Where all her sailor-clothes were hid.

We made a map to show the place

And wrote directions in red ink;

But when we dug the treasure up,

I dropped it down the kitchen sink.

AUNT JANE with whom I sometimes stay

Has a very curious house,

As quiet as Aunt Jane herself,

As quiet as a mouse.

It's always Autumn when I go

And raining every day:

The garden's full of shrubs and paths

I'm sent out there to play.

The paths are green and full of moss,

The shrubs are wet and dark:

It's like a secret corner in

A sort of nightmare park.

I walk about the paths alone

And look at roots and leaves,

And once behind a laurel bush

I saw a Pierrot's[K] sleeves.

I thought of him that night in bed,

I was afraid he'd climb

And peep against the window-pane

And say a horrid rhyme.

And when I heard the rain outside

Dripping upon the sill,

I thought I heard his footsteps too,

And oh, I did lie still.

I saw his shadow dance about

Like a shadow on a sheet;

I saw his eyes, like currants black,

And his white velvet feet.

My aunt's house is a quiet house,

The servants never speak:

She goes to sleep each afternoon:

I stay there for a week.

The rooms have got a woolly smell,

They're full of little things—

Tall clocks and fat blue china bowls

And birds with coloured wings.

I tinkle all the candlesticks

Upon the mantelpiece:

They wave long after I have gone,

And never seem to cease.

The drawing-room is full of shawls,

With footstools everywhere,

And prickly cushions stuck upright

Upon each bristly chair.

I'm glad when I go home again

Into the shining lamps

And comfortable sound of streets,

And see my book of stamps.

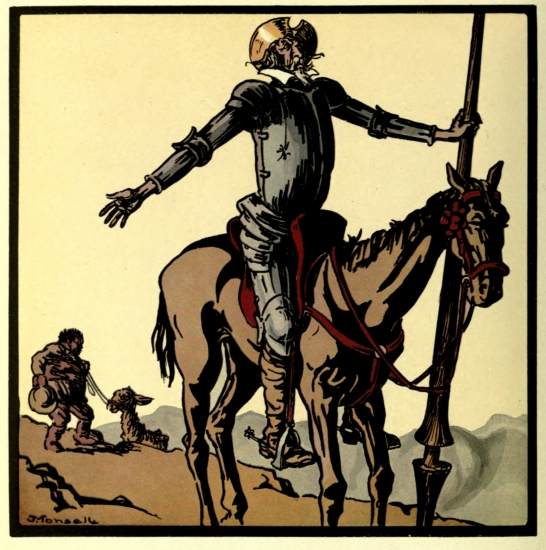

DON QUIXOTE

THE clock is striking four o'clock,

It is not time for tea.

Although the night is marching up

And I can hardly see.

I'm reading in the library

In a most enormous chair;

The fire is just the very kind

That makes you want to stare.

I'm looking at the largest book

That ever yet was seen;

They say I shall not understand

This tale till I'm fourteen.

Don Quixote is the name of it

With pictures on each page;

The way that he was treated puts

Me in a fearful rage.

Don Quixote was a tall thin man

Whose thoughts were just like mine,

He saw queer things, he heard queer sounds

Though he was more than nine.

He used to lie in bed and watch

The hilly counterpane.

And see strange little knights-at-arms

Go riding down a plain.

His room was simply crowded with

Enchanters, dwarfs and elves,

And dragons used to go to sleep

Upon the darkest shelves.

He used to think that common things

Were really very strange,

Like me who saw a goblin once

Upon our kitchen-range.

He saw big giants in the clouds

Marching and fighting there:

He used to listen to the leaves

And think it was a bear.

He found some armour that belonged

To people long ago,

And rode away to fight and save

Princesses from the foe.

But every one behaved to him

As if they were his nurse:

They said he was old-fashioned and

They said he was a curse.

He used to play at 'let's pretend'

And charge a flock of sheep;

He used to read in bed at night

Instead of going to sleep.

There was not anything of which

He could not make a game;

He must have been a jolly chap—

Don Quixote was his name.

He had adventures every day,

He simply made them come;

But all his family shook their heads

And said that he was rum.

They burnt his books, they shut him up,

They threw enormous stones.

Some beastly fellows beat him too

And almost broke his bones.

It makes me simply furious,

It nearly makes me cry

To see him lying in the road—

I hope he will not die.

He did not mean to misbehave,

He wanted just to play;

Some people think my games are bad—

They did the other day.

A cousin came to stay with us

To see the Lord Mayor's Show,

And we were playing 'Ancient Greeks,'

A game you all must know.

Andromeda we gave to her,

Perseus was given to me;

My kiddy brother was the beast,

The nursery floor the sea.

We tied her to the rock with string,

The rock was Nurse's bed,

Medusa's head was Nurse's hat—

We ruined it, she said.

And as the floor was rather dry,

We got the water-jug,

And slooshed it all about the room

And simply sopped the rug.

My kiddy brother was the beast,

I killed him with the poker;

My kiddy cousin screamed and yelled

As if we meant to soak her.

So we were punished just because

We played at 'let's pretend.'

Don Quixote would have understood,

He would have been our friend.

Hullo! there goes the bell for tea;

They've lighted up the hall,

And I must go and wash my hands

And fetch Miss Perkins' shawl.

THE wettest days in London

Are quite a jolly spree:

Our house is like an island,

The wet street like a sea.

The rain beats on our windows

And splashes on the sill;

But the dining-room's a jungle,

The staircase is a hill.

Our camping-ground's the nursery,

The hall's a coral-reef;

My sister's cot's a schooner,

And Nurse an Indian chief.

Miss Perkins is a pirate,

The maids are cannibals;

They have orgies in the pantry

Unless a person calls.

We've guns and swords and pistols,

We've several sorts of flags;

By shooting on the hillside

We've got some splendid bags.

We found a grand volcano

Close to the servants' room,

It really was the cistern,

But it made a fearful boom.

In all our expeditions

My brother is the crew,

I'm midshipman and captain—

Of course it's rather few,

But then my kiddie sister

Has got to be the beasts

Which we go out a-hunting

In order to have feasts.

Our feasts are bread and butter,

And sometimes bread and jam—

That is, if when we're shooting

No doors are made to slam.

The wettest days in London

Are quite a jolly spree;

And sometimes, though not often,

Our friends come in to tea.

IF, Percy, you have money in your pocket,

For Algernon I hope you'll buy this book,

But when you've bought it, do let Algy read it,

And let your kiddy sister have a look.

This good advice applies to you, young Godfrey,

To Wilfred and to Michael and to Claude,

To James, Guy, Basil, Archibald and Eustace,

And also to Diana, Joan and Maud.

Philip, to you the last must be spoken;

Tell people of this book round Kensington;

Mention with kind encouragement the Author,

And get the money from your Uncle John.

THE END