Title: Curious Epitaphs

Editor: William Andrews

Release date: April 25, 2012 [eBook #39532]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

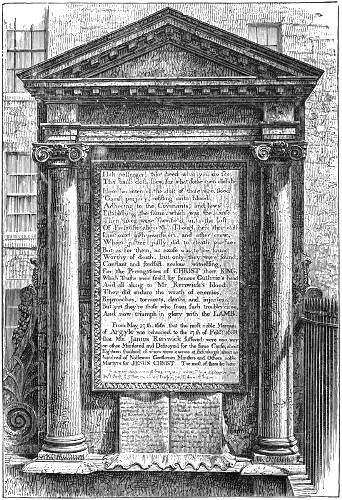

MARTYRS’ MONUMENT, EDINBURGH.

Curious

Epitaphs

Collected and Edited with Notes

By William Andrews

LONDON:

WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO., 5, FARRINGDON AVENUE, E.C.

1899.

THIS BOOK IS

DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF

CUTHBERT BEDE, B.A.,

Author of “Verdant Green,” etc.,

AS A TOKEN OF GRATITUDE FOR

LITERARY ASSISTANCE AND SYMPATHY

GIVEN IN YEARS AGONE,

BUT NOT FORGOTTEN.

W. A.

This work first appeared in 1883 and quickly passed out of print. Some important additions are made in the present volume. It is hoped that in its new form the book may find favour with the public and the press.

William Andrews.

The Hull Press,

May Day, 1899.

Contents.

| PAGE | |

| Epitaphs on Tradesmen | 1 |

| Typographical Epitaphs | 24 |

| Good and Faithful Servants | 35 |

| Epitaphs on Soldiers and Sailors | 49 |

| Epitaphs on Musicians and Actors | 73 |

| Epitaphs on Sportsmen | 92 |

| Bacchanalian Epitaphs | 105 |

| Epitaphs on Parish Clerks and Sextons | 119 |

| Punning Epitaphs | 134 |

| Manxland Epitaphs | 141 |

| Epitaphs on Notable Persons | 149 |

| Miscellaneous Epitaphs | 209 |

| Index | 235 |

CURIOUS EPITAPHS.

Many interesting epitaphs have been placed to the memory of tradesmen. Often they are not of an elevating character, nor highly poetical, but they display the whims and oddities of men. We will first present a few relating to the watch and clock-making trade. The first specimen is from Lydford churchyard, on the borders of Dartmoor:—

Here lies, in horizontal position,

the outside case of

George Routleigh, Watchmaker;

Whose abilities in that line were an honour

to his profession.

Integrity was the Mainspring, and prudence the

Regulator,

of all the actions of his life.

Humane, generous, and liberal,

his Hand never stopped

till he had relieved distress.

[Pg 2]So nicely regulated were all his motions,

that he never went wrong,

except when set a-going

by people

who did not know his Key;

even then he was easily

set right again.

He had the art of disposing his time so well,

that his hours glided away

in one continual round

of pleasure and delight,

until an unlucky minute put a period to

his existence.

He departed this life

Nov. 14, 1802,

aged 57:

wound up,

in hopes of being taken in hand

by his Maker;

and of being thoroughly cleaned, repaired,

and set a-going

in the world to come.

In the churchyard of Uttoxeter, a monument is placed to the memory of Joseph Slater, who died November 21st, 1822, aged 49 years:—

| Here lies one who strove to equal time, A task too hard, each power too sublime; Time stopt his motion, o’erthrew his balance-wheel, Wore off his pivots, tho’ made of hardened steel; Broke all his springs, the verge of life decayed, And now he is as though he’d ne’er been made. Such frail machine till time’s no more shall rust, [Pg 3]And the archangel wakes our sleeping dust; Then in assembled worlds in glory join, And sing—“The hand that made us is divine.” |

Our next is from Berkeley, Gloucestershire:—

| Here lyeth Thomas Peirce, whom no man taught, Yet he in iron, brass, and silver wrought; He jacks, and clocks, and watches (with art) made And mended, too, when others’ work did fade. Of Berkeley, five times Mayor this artist was, And yet this Mayor, this artist, was but grass. When his own watch was down on the last day, He that made watches had not made a key To wind it up; but useless it must lie, Until he rise again no more to die. Died February 25th, 1665, aged 77. |

The following is from Bolsover churchyard, Derbyshire:—

Here

lies, in a horizontal position, the outside

case of

Thomas Hinde,

Clock and Watch-maker,

Who departed this life, wound up in hope of

being taken in hand by his Maker, and being

thoroughly cleaned, repaired, and set a-going

in the world to come,

On the 15th of August, 1836,

In the 19th year of his age.

Respecting the next example, Mr. Edward Walford, M.A., wrote to the Times as follows: Close to the south-western corner of the parish[Pg 4] churchyard of Hampstead there has long stood a square tomb, with a scarcely decipherable inscription, to the memory of a man of science of the last century, whose name is connected with the history of practical navigation. The tomb, having stood there for more than a century, had become somewhat dilapidated, and has lately undergone a careful restoration at the cost and under the supervision of the Company of Clock-makers, and the fact is recorded in large characters on the upper face. The tops of the upright iron railings which surround the tomb have been gilt, and the restored inscription runs as follows:—

In memory of Mr. John Harrison, late of Red Lion-square, London, inventor of the time-keeper for ascertaining the longitude at sea. He was born at Foulby, in the county of York, and was the son of a builder of that place, who brought him up to the same profession. Before he attained the age of 21, he, without any instruction, employed himself in cleaning and repairing clocks and watches, and made a few of the former, chiefly of wood. At the age of 25 he employed his whole time in chronometrical improvements. He was the inventor of the gridiron pendulum, and the method of preventing the effects of heat and cold upon time-keepers by two bars fixed together; he introduced the secondary spring, to keep them going while winding up, and was the inventor of most (or all) the improvements in clocks and watches during his time. In the year 1735 his first time keeper [Pg 5]was sent to Lisbon, and in 1764 his then much improved fourth time-keeper having been sent to Barbadoes, the Commissioners of Longitude certified that he had determined the longitude within one-third of half a degree of a great circle, having not erred more than forty seconds in time. After sixty years’ close application to the above pursuits, he departed this life on the 24th day of March, 1776, aged 83.

In an epitaph in High Wycombe churchyard, life is compared to the working of a clock. It runs thus:—

| Of no distemper, Of no blast he died, But fell, Like Autumn’s fruit, That mellows long, Even wondered at Because he dropt not sooner. Providence seemed to wind him up For fourscore years, Yet ran he nine winters more; Till, like a clock, Worn out with repeating time, The wheels of weary life At last stood still. In Memory of John Abdidge, Alderman. Died 1785. |

We have some curious specimens of engineers’ epitaphs. A good example is copied from the churchyard of Bridgeford-on-the-Hill, Notts:—

[Pg 6]Sacred to the memory of John Walker, the only son of Benjamin and Ann Walker, Engineer and Pallisade Maker, died September 22nd, 1832, aged 36 years.

| Farewell, my wife and father dear; My glass is run, my work is done, And now my head lies quiet here. That many an engine I’ve set up, And got great praise from men, I made them work on British ground, And on the roaring seas; My engine’s stopp’d, my valves are bad, And lie so deep within; No engineer could there be found To put me new ones in. But Jesus Christ converted me And took me up above, I hope once more to meet once more, And sing redeeming love. |

Our next is on a railway engine-driver, who died in 1840, and was buried in Bromsgrove churchyard:—

| My engine now is cold and still, No water does my boiler fill; My coke affords its flame no more; My days of usefulness are o’er; My wheels deny their noted speed, No more my guiding hand they need; My whistle, too, has lost its tone, Its shrill and thrilling sounds are gone; My valves are now thrown open wide; My flanges all refuse to guide, My clacks also, though once so strong, [Pg 7]Refuse to aid the busy throng: No more I feel each urging breath; My steam is now condensed in death. Life’s railway o’er, each station’s passed, In death I’m stopped, and rest at last. Farewell, dear friends, and cease to weep: In Christ I’m safe; in Him I sleep. |

In the Ludlow churchyard is a headstone to the memory of John Abingdon “who for forty years drove the Ludlow stage to London, a trusty servant, a careful driver, and an honest man.” He died in 1817, and his epitaph is as follows:—

| His labor done, no more to town, His onward course he bends; His team’s unshut, his whip’s laid up, And here his journey ends. Death locked his wheels and gave him rest, And never more to move, Till Christ shall call him with the blest To heavenly realms above. |

The epitaph we next give is on the driver of the coach that ran between Aylesbury and London, by the Rev. H. Bullen, Vicar of Dunton, Bucks, in whose churchyard the man was buried:—

| Parker, farewell! thy journey now is ended, Death has the whip-hand, and with dust is blended; Thy way-bill is examined, and I trust Thy last account may prove exact and just. When he who drives the chariot of the day, Where life is light, whose Word’s the living way, [Pg 8]Where travellers, like yourself, of every age, And every clime, have taken their last stage, The God of mercy, and the God of love, Show you the road to Paradise above! |

Lord Byron wrote on John Adams, carrier, of Southwell, Nottinghamshire, an epitaph as follows:—

| John Adams lies here, of the parish of Southwell, A carrier who carried his can to his mouth well; He carried so much, and he carried so fast, He could carry no more—so was carried at last; For the liquor he drank, being too much for one, He could not carry off—so he’s now carri-on. |

On Hobson, the famous University carrier, the following lines were written:—

| Here lies old Hobson: death has broke his girt, And here! alas, has laid him in the dirt; Or else the ways being foul, twenty to one He’s here stuck in a slough and overthrown: ’Twas such a shifter, that, if truth were known, Death was half glad when he had got him down; For he had any time these ten years full, Dodged with him betwixt Cambridge and the Bull; And surely Death could never have prevailed, Had not his weekly course of carriage failed. But lately finding him so long at home, And thinking now his journey’s end was come, And that he had ta’en up his latest inn, In the kind office of a chamberlain Showed him the room where he must lodge that night, Pulled off his boots and took away the light. [Pg 9]If any ask for him it shall be said, Hobson has supt and’s newly gone to bed. |

In Trinity churchyard, Sheffield, formerly might be seen an epitaph on a bookseller, as follows:—

| In Memory of Richard Smith, who died April 6th, 1757, aged 52. |

| At thirteen years I went to sea; To try my fortune there, But lost my friend, which put an end To all my interest there. To land I came as ’twere by chance, At twenty then I taught to dance, And yet unsettled in my mind, To something else I was inclined; At twenty-five laid dancing down, To be a bookseller in this town, Where I continued without strife, Till death deprived me of my life. Vain world, to thee I bid farewell, To rest within this silent cell, Till the great God shall summon all To answer His majestic call, Then, Lord, have mercy on us all. |

The following epitaph was written on James Lackington, a celebrated bookseller, and eccentric character:—

| Good passenger, one moment stay, And contemplate this heap of clay; ’Tis Lackington that claims a pause, [Pg 10]Who strove with death, but lost his cause: A stranger genius ne’er need be Than many a merry year was he. Some faults he had, some virtues too (the devil himself should have his due); And as dame fortune’s wheel turn’d round, Whether at top or bottom found, He never once forgot his station, Nor e’er disown’d a poor relation; In poverty he found content, Riches ne’er made him insolent. When poor, he’d rather read than eat, When rich books form’d his highest treat, His first great wish to act, with care, The sev’ral parts assigned him here; And, as his heart to truth inclin’d, He studied hard the truth to find. Much pride he had,—’twas love of fame, And slighted gold, to get a name; But fame herself prov’d greatest gain, For riches follow’d in her train. Much had he read, and much had thought, And yet, you see, he’s come to nought; Or out of print, as he would say, To be revised some future day: Free from errata, with addition, A new and a complete edition. |

At Rugby, on Joseph Cave, Dr. Hawksworth wrote:—

Near this place lies the body of

Joseph Cave,

Late of this parish;

Who departed this life Nov. 18, 1747,

Aged 79 years.

[Pg 11]He was placed by Providence in a humble station; but industry abundantly supplied the wants of nature, and temperance blest him with content and wealth. As he was an affectionate father, he was made happy in the decline of life by the deserved eminence of his eldest son,

Edward Cave,

who, without interest, fortune, or connection, by the native force of his own genius, assisted only by a classical education, which he received at the Grammar School of this town, planned, executed, and established a literary work called

The Gentleman’s Magazine,

whereby he acquired an ample fortune, the whole of which devolved to his family.

Here also lies

The body of William Cave,

second son of the said Joseph Cave, who died May 2, 1757, aged 62 years, and who, having survived his elder brother,

Edward Cave,

inherited from him a competent estate; and, in gratitude to his benefactor, ordered this monument to perpetuate his memory.

| He lived a patriarch in his numerous race, And shew’d in charity a Christian’s grace: Whate’er a friend or parent feels he knew; His hand was open, and his heart was true; In what he gain’d and gave, he taught mankind A grateful always is a generous mind. Here rests his clay! his soul must ever rest, Who bless’d when living, dying must be blest. |

The well-known blacksmith’s epitaph, said to be written by the poet Hayley, may be found in many churchyards in this country. It formed the[Pg 12] subject of a sermon delivered on Sunday, the 27th day of August, 1837, by the then Vicar of Crich, Derbyshire, to a large assembly. We are told that the vicar appeared much excited, and read the prayers in a hurried manner. Without leaving the desk, he proceeded to address his flock for the last time; and the following is the substance thereof: “To-morrow, my friends, this living will be vacant, and if any one of you is desirous of becoming my successor he has now an opportunity. Let him use his influence, and who can tell but he may be honoured with the title of Vicar of Crich. As this is my last address, I shall only say, had I been a blacksmith, or a son of Vulcan, the following lines might not have been inappropriate:—

| My sledge and hammer lie reclined, My bellows, too, have lost their wind; My fire’s extinct, my forge decayed, And in the dust my vice is laid. My coal is spent, my iron’s gone, My nails are drove, my work is done; My fire-dried corpse lies here at rest, And, smoke-like, soars up to be bless’d. |

If you expect anything more, you are deceived; for I shall only say, Friends, farewell, farewell!” The effect of this address was too visible to pass unnoticed. Some appeared as if awakened from a[Pg 13] fearful dream, and gazed at each other in silent astonishment; others for whom it was too powerful for their risible nerves to resist, burst into boisterous laughter, while one and all slowly retired from the scene, to exercise their future cogitations on the farewell discourse of their late pastor.

From Silkstone churchyard we have the following on a potter and his wife:—

In memory of John Taylor, of Silkstone, potter, who departed this life, July 14th, Anno Domini 1815, aged 72 years.

Also Hannah, his wife, who departed this life, August 13th. 1815, aged 68 years.

| Out of the clay they got their daily bread, Of clay were also made. Returned to clay they now lie dead, Where all that’s left must shortly go. To live without him his wife she tried, Found the task hard, fell sick, and died. And now in peace their bodies lay, Until the dead be called away, And moulded into spiritual clay. |

On a poor woman who kept an earthenware shop at Chester, the following epitaph was composed:—

| Beneath this stone lies Catherine Gray, Changed to a lifeless lump of clay; By earth and clay she got her pelf, And now she’s turned to earth herself. [Pg 14]Ye weeping friends, let me advise, Abate your tears and dry your eyes; For what avails a flood of tears? Who knows but in a course of years, In some tall pitcher or brown pan, She in her shop may be again. |

Our next is from the churchyard of Aliscombe, Devonshire:—

Here lies the remains of James Pady, brickmaker, late of this parish, in hope that his clay will be re-moulded in a workmanlike manner, far superior to his former perishable materials.

| Keep death and judgment always in your eye, Or else the devil off with you will fly, And in his kiln with brimstone ever fry: If you neglect the narrow road to seek, Christ will reject you, like a half-burnt brick! |

In the old churchyard of Bullingham, on the gravestone of a builder, the following lines appear:—

| This humble stone is o’er a builder’s bed, Tho’ raised on high by fame, low lies his head. His rule and compass are now locked up in store. Others may build, but he will build no more. His house of clay so frail, could hold no longer— May he in heaven be tenant of a stronger! |

In Colton churchyard, Staffordshire, is a mason’s tombstone decorated with carving of square and[Pg 15] compass, in relief, and bearing the following characteristic inscription:—

| Sacred to the memory of James Heywood, Who died May 4th, 1804, in the 55th year of his age. |

| The corner-stone I often times have dress’d; In Christ, the corner-stone, I now find rest. Though by the Builder he rejected were, He is my God, my Rock, I build on here. |

In the churchyard of Longnor, the following quaint epitaph is placed over the remains of a carpenter:—

| In Memory of Samuel Bagshaw late of Har- ding-Booth who depar- ted this life June the 5th 1787 aged 71 years. |

| Beneath lie mouldering into Dust A Carpenter’s Remains. A man laborious, honest, just: his Character sustains. In seventy-one revolving Years He sow’d no Seeds of Strife; With Ax and Saw, Line, Rule and Square, employed his careful life. But Death who view’d his peaceful Lot His Tree of Life assail’d His Grave was made upon this spot, and his last Branch he nail’d. |

Here are some witty lines on a carpenter[Pg 16] named John Spong, who died 1739, and is buried in Ockham churchyard:—

| Who many a sturdy oak has laid along, Fell’d by Death’s surer hatchet, here lies John Spong. Post oft he made, yet ne’er a place could get And lived by railing, tho’ he was no wit. Old saws he had, although no antiquarian; And stiles corrected, yet was no grammarian. Long lived he Ockham’s favourite architect, And lasting as his fame a tomb t’ erect, In vain we seek an artist such as he, Whose pales and piles were for eternity. |

Our next is from Hessle, near Hull, and is said to have been inscribed on a tombstone placed over the remains of George Prissick, plumber and glazier:—

| Adieu, my friend, my thread of life is spun; The diamond will not cut, the solder will not run; My body’s turned to ashes, my grief and troubles past, I’ve left no one to worldly care—and I shall rise at last. |

On a dyer, from the church of St. Nicholas, Yarmouth, we have as follows:—

| Here lies a man who first did dye, When he was twenty-four, And yet he lived to reach the age, Of hoary hairs, fourscore. But now he’s gone, and certain ’tis He’ll not dye any more. |

[Pg 17]In Sleaford churchyard, on Henry Fox, a weaver, the following lines are inscribed:—

| Of tender thread this mortal web is made, The woof and warp and colours early fade; When power divine awakes the sleeping dust, He gives immortal garments to the just. |

Our next epitaph, from Weston, is placed over the remains of a useful member of society in his time:—

| Here lies entomb’d within this vault so dark, A tailor, cloth-drawer, soldier, and parish clerk; Death snatch’d him hence, and also from him took His needle, thimble, sword, and prayer-book. He could not work, nor fight,—what then? He left the world, and faintly cried, “Amen!” |

On an Oxford bellows-maker, the following lines were written:—

| Here lyeth John Cruker, a maker of bellowes, His craftes-master and King of good fellowes; Yet when he came to the hour of his death, He that made bellowes, could not make breath. |

The next epitaph, on Joseph Blakett, poet and shoemaker of Seaham, is said to be from Byron’s pen:—

| Stranger! behold interr’d together The souls of learning and of leather. Poor Joe is gone, but left his awl— You’ll find his relics in a stall. [Pg 18]His work was neat, and often found Well-stitched and with morocco bound. Tread lightly—where the bard is laid We cannot mend the shoe he made; Yet he is happy in his hole, With verse immortal as his sole. But still to business he held fast, And stuck to Phœbus to the last. Then who shall say so good a fellow Was only leather and prunella? For character—he did not lack it, And if he did—’twere shame to Black it! |

The following lines are on a cobbler:—

| Death at a cobbler’s door oft made a stand, But always found him on the mending hand; At length Death came, in very dirty weather, And ripp’d the soul from off the upper leather: The cobbler lost his awl,—Death gave his last, And buried in oblivion all the past. |

Respecting Robert Gray, a correspondent writes: He was a native of Taunton, and at an early age he lost his parents, and went to London to seek his fortune. Here, as an errand boy, he behaved so well, that his master took him apprentice, and afterwards set him up in business, by which he made a large fortune. In his old age he retired from trade and returned to Taunton, where he founded a hospital. On his monument is the following inscription:—

| Taunton bore him; London bred him; Piety train’d him; Virtue led him; Earth enrich’d him; Heaven possess’d him; Taunton bless’d him; London bless’d him: This thankful town, that mindful city, Share his piety and pity, What he gave, and how he gave it, Ask the poor, and you shall have it. Gentle reader, may Heaven strike Thy tender heart to do the like; And now thy eyes have read his story, Give him the praise, and God the glory. |

He died at the age of 65 years, in 1635.

In Rotherham churchyard the following is inscribed on a miller:—

| In memory of Edward Swair, who departed this life, June 16, 1781. |

| Here lies a man which Farmers lov’d Who always to them constant proved; Dealt with freedom, Just and Fair— An honest miller all declare. |

On a Bristol baker we have the following:—

Here lie Tho. Turar, and Mary, his wife. He was twice Master of the Company of Bakers, and twice Churchwarden of this parish. He died March 6, 1654. She died May 8th, 1643.

| Like to the baker’s oven is the grave, Wherein the bodyes of the faithful have A setting in, and where they do remain In hopes to rise, and to be drawn again; [Pg 20]Blessed are they who in the Lord are dead, Though set like dough, they shall be drawn like bread. |

On the tomb of an auctioneer in the churchyard at Corby, in the county of Lincoln, is the following:—

| Beneath this stone, facetious wight Lies all that’s left of poor Joe Wright; Few heads with knowledge more informed, Few hearts with friendship better warmed; With ready wit and humour broad, He pleased the peasant, squire, and lord; Until grim death, with visage queer, Assumed Joe’s trade of Auctioneer, Made him the Lot to practise on, With “going, going,” and anon He knocked him down to “Poor Joe’s gone!” |

In Wimbledon churchyard is the grave of John Martin, a natural son of Don John Emanuel, King of Portugal. He was sent to this country about the year 1712, to be out of the way of his friends, and after several changes of circumstances, ultimately became a gardener. It will be seen from the following epitaph that he won the esteem of his employers:—

To the memory of John Martin, gardener, a native of Portugal, who cultivated here, with industry and success, the same ground under three masters, forty years.

| Though skilful and experienced, He was modest and unassuming; [Pg 21]And tho’ faithful to his masters, And with reason esteemed, He was kind to his fellow-servants, And was therefore beloved. His family and neighbours lamented his death, As he was a careful husband, a tender father, and an honest man. |

This character of him is given to posterity by his last master, willingly because deservedly, as a lasting testimony of his great regard for so good a servant.

He died March 30th, 1760. Aged 66 years.

| For public service grateful nations raise Proud structures, which excite to deeds of praise; While private services, in corners thrown, Howe’er deserving, never gain a stone. But are not lilies, which the valleys hide, Perfect as cedars, tho’ the valley’s pride? Let, then, the violets their fragrance breathe, And pines their ever-verdant branches wreathe Around his grave, who from their tender birth Upreared both dwarf and giant sons of earth, And tho’ himself exotic, lived to see Trees of his raising droop as well as he. Those were his care, while his own bending age, His master propp’d and screened from winter’s rage, Till down he gently fell, then with a tear He bade his sorrowing sons transport him here. But tho’ in weakness planted, as his fruit Always bespoke the goodness of his root, The spirit quickening, he in power shall rise With leaf unfading under happier skies. |

The next is on the Tradescants, famous [Pg 22]gardeners and botanists at Lambeth. In 1657 Mr. Tradescant, junr., presented to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, a remarkable cabinet of curiosities:—

| Know, stranger, ere thou pass, beneath this stone Lye John Tradescant, grandsire, father, son; The last died in his spring; the other two Liv’d till they had travell’d art and nature through; As by their choice collections may appear, Of what is rare, in land, in sea, in air; Whilst they (as Homer’s Iliad in a nut) A world of wonders in one closet shut; These famous antiquarians, that had been Both gard’ners to the ROSE AND LILY QUEEN, Transplanted now themselves, sleep here; and when Angels shall with trumpets waken men, And fire shall purge the world, then hence shall rise, And change this garden for a paradise. |

We have here an epitaph on a grocer, culled from the Rev. C. W. Bardsley’s “Memorials of St. Anne’s Church,” Manchester. In a note about the name of Howard, the author says: “Poor John Howard’s friends gave him an unfortunate epitaph—one, too, that reflected unkindly upon his wife. It may still be seen in the churchyard.—Here lyeth the body of John Howard, who died Jan. 2, 1800, aged 84 years; fifty years a respectable grocer, and[Pg 23] an honest man. As it is further stated that his wife died in 1749, fifty years before, it would seem that her husband’s honesty dated from the day of her decease. Mrs. Malaprop herself, in her happiest moments, could not have beaten this inscription.”

The trade of printer is rich in technical terms available for the writer of epitaphs, as will be seen from the following examples.

Our first inscription is from St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster, placed in remembrance of England’s benefactor, the first English printer:—

To the memory of

William Caxton,

who first introduced into Great Britain

the Art of Printing;

And who, A.D. 1477 or earlier, exercised that art in the

Abbey of Westminster.

This Tablet,

In remembrance of one to whom the literature of this

country is so largely indebted, was raised,

anno Domini MDCCCXX.,

by the Roxburghe Club,

Earl Spencer, K.G., President.

In St. Giles’ Cathedral Church, Edinburgh, is the Chepman aisle, founded by the man who introduced printing into North Britain. Dr. William Chambers, by whose munificence this stately church was restored, had placed in the[Pg 25] aisle, bearing Chepman’s name, a brass tablet having the following inscription:—

To the Memory of

Walter Chepman,

designated the Scottish Caxton,

who under the auspices of James IV.

and his Queen, Margaret, introduced

the art of printing into Scotland

1507 ![[symbol]](images/symbol25.jpg) founded this aisle in

founded this aisle in

honour of the King, Queen, and

their family, 1513. Died 1532.

This tablet is gratefully inscribed by

William Chambers, ll.d.

The next is in memory of one Edward Jones, ob. 1705, æt. 53. He was the “Gazette” Printer of the Savoy, and the following epitaph was appended to an elegy, entitled, “The Mercury Hawkers in Mourning,” and published on the occasion of his death:—

| Here lies a Printer, famous in his time, Whose life by lingering sickness did decline. He lived in credit, and in peace he died, And often had the chance of Fortune tried. Whose smiles by various methods did promote Him to the favour of the Senate’s vote; And so became, by National consent, The only Printer of the Parliament. Thus, by degrees, so prosp’rous was his fate, He left his heirs a very good estate. |

[Pg 26]It has been truthfully said that the life of Benjamin Franklin is stranger than fiction. He was a self-made man, gaining distinction as a printer, journalist, author, electrician, natural philosopher, statesman, and diplomatist. The “Autobiography and Letters of Benjamin Franklin” has been extensively circulated, and must ever remain a popular book; young men and women cannot fail to peruse its pages without pleasure and profit.

In collections of epitaphs and books devoted to literary curiosities, a quaint epitaph said to have been written by Franklin frequently finds a place. He was not, however, the original composer of the epitaph, but imitated it for himself. Jacob Tonson, a famous bookseller, died in 1735, and a Latin epitaph was written on him by an Eton scholar. It is printed in the Gentleman’s Magazine, February, 1736, with a diffuse paraphrase in English verse. The following is at all events a conciser version:—

The volume

of

his life being finished

here is the end of

Jacob Tonson.

Weep authors and break your pens;

[Pg 27]Your Tonson effaced from the book,

is no more,

but print the last inscription on the title

page of death,

for fear that delivered to the press

of the grave

the Editor should want a title:

Here lies a bookseller,

The leaf of his life being finished,

Awaiting a new edition,

Augmented and corrected.

The following is Franklin’s epitaph for himself:

The body

of

Benjamin Franklin,

Printer

(Like the cover of an old book,

its contents torn out,

And stript of its lettering and gilding),

Lies here, food for worms.

But the work itself shall not be lost,

For it will, as he believed, appear once more,

In a new and more elegant edition,

Revised and corrected

By

The Author.

But it is not at all certain that Franklin was not the earlier writer, for the epitaph was certainly a production of the first years of manhood—probably 1727. There are other epitaphs from[Pg 28] which he may have taken the idea; that, on the famous John Cotton at Boston, for instance, in which he is likened to a Bible:—

| A living, breathing Bible; tables where Both covenants at large engraven were; Gospel and law in his heart had each its column, His head an index to the sacred volume! His very name a title-page; and, next, His life a commentary on the text. Oh, what a moment of glorious worth, When in a new edition he comes forth! Without errata, we may think ’twill be, In leaves and covers of Eternity. |

There is a similar conceit in the epitaph on John Foster, the Boston printer. Franklin would probably have seen both of these.

On the 17th April, 1790, at the age of eighty-four years, passed away the sturdy patriot and sagacious writer. His mortal remains rest with those of his wife in the burial-ground of Christ Church, Philadelphia. A plain flat stone covers the grave, bearing the following simple inscription:—

| Benjamin | } | ||

| AND | Franklin. | ||

| Deborah | |||

| 1790. | |||

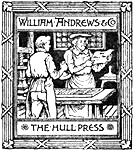

This is the inscription which he directed, in his will, to be placed on his tomb. We give a[Pg 29] picture of the quiet corner where the good man and his worthy wife are buried. English as well as American visitors to the city usually wend their way to the last resting-place of the famous man we delight to honour.

FRANKLIN’S GRAVE.

A printer’s sentiment inscribed to the memory of Franklin is worth reproducing:—

Benjamin Franklin, the * of his profession; the type of honesty; the ! of all; and although the ☞ of death put a . to his existence, each § of his life is without a ||.

Dr. Franklin’s parents were buried in one grave[Pg 30] in the old Grancey Cemetery, beside Park Street Church, Boston, Mass. He placed a marble monument to their memory, bearing the following inscription:—

Josiah Franklin

and

Abiah, his wife,

Lie here interred.

They lived lovingly together, in wedlock,

Fifty-five years;

And without an estate, or any gainful employment,

By constant labour and honest industry

(With God’s blessing),

Maintained a large family comfortably;

And brought up thirteen children and seven

grand-children

Reputably.

From this instance, reader,

Be encouraged to diligence in thy calling,

And distrust not Providence.

He was a pious and prudent man,

She a discreet and virtuous woman.

Their youngest son,

In filial regard to their memory,

Places this stone.

J. F., Born 1655; Died 1744 ÆT 89.

A. F., Born 1667; Died 1752 ÆT 85.

It is satisfactory to learn that, when the stone became dilapidated, the citizens of Boston replaced it with a granite obelisk.

A notable epitaph was that of George Faulkner,[Pg 31] alderman and printer, of Dublin, who died in 1775:—

| Here sleeps George Faulkner, printer, once so dear To humorous Swift, and Chesterfield’s gay peer; So dear to his wronged country and her laws; So dauntless when imprisoned in her cause; No alderman e’er graced a weighter board, No wit e’er joked more freely with a lord. None could with him in anecdotes confer; A perfect annal-book, in Elzevir. Whate’er of glory life’s first sheets presage, Whate’er the splendour of the title-page, Leaf after leaf, though learned lore ensues; Close as thy types and various as thy news; Yet, George, we see that one lot awaits them all, Gigantic folios, or octavos small; One universal finis claims his rank, And every volume closes in a blank. |

In the churchyard of Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, is a good specimen of a typographical epitaph, placed in remembrance of a noted printer, who died in the year 1818. It reads as follows:—

Here lie the remains of L. Gedge, Printer.

Like a worn-out character, he has returned to the Founder,

Hoping that he will be re-cast in a better and

more perfect mould.

Our next example is profuse of puns, some of which are rather obscure to younger readers,[Pg 32] owing to the disuse of the old wooden press. It is the epitaph of a Scotch printer:—

Sacred to the memory of

Adam Williamson,

Pressman-printer, in Edinburgh,

Who died Oct. 3, 1832,

Aged 72 years.

All my stays are loosed;

My cap is thrown off; my head is worn out;

My box is broken;

My spindle and bar have lost their power;

My till is laid aside;

Both legs of my crane are turned out of their path;

My platen can make no impression;

My winter hath no spring;

My rounce will neither roll out nor in;

Stone, coffin, and carriage have all failed;

The hinges of my tympan and frisket are immovable;

My long and short ribs are rusted;

My cheeks are much worm-eaten and mouldering

away:

My press is totally down:

The volume of my life is finished,

Not without many errors;

Most of them have arisen from bad composition, and

are to be attributed more to the chase than the

press;

There are also a great number of my own;

Misses, scuffs, blotches, blurs, and bad register;

But the true and faithful Superintendent has undertaken

to correct the whole.

When the machine is again set up

(incapable of decay),

[Pg 33]A new and perfect edition of my life will appear,

Elegantly bound for duration, and every way fitted

for the grand Library of the Great Author.

The next specimen is less satisfactory, because devoid of the hope that should encircle the death of the Christian. It is the epitaph which Baskerville, the celebrated Birmingham printer and type founder, directed to be placed upon a tomb of masonry in the shape of a cone, and erected over his remains:—

Stranger

Beneath this cone, in unconsecrated ground,

A friend to the liberties of mankind

Directed his body to be inurned.

May the example contribute to emancipate thy mind

from the idle fears of superstition, and the

wicked arts of priestcraft.

It is recorded that “The tomb has long since been overturned, and even the remains of the man himself desecrated and dispersed till the final day of resurrection, when the atheism which in his later years he professed will receive assuredly so complete and overwhelming a refutation.”

In 1599 died Christopher Barker, one of the most celebrated of the sixteenth century typographers, printer to Queen Elizabeth—to whom, in fact, the present patent held by Eyre and Spottiswoode can be traced back in unbroken succession.

| Here Barker lies, once printer to the Crown, Whose works of art acquired a vast renown. Time saw his worth, and spread around his fame, That future printers might imprint the same. But when his strength could work the press no more And his last sheets were folded into store, Pure faith, with hope (the greatest treasure given), Opened their gates, and bade him pass to heaven. |

We will bring to a close our examples of typographical epitaphs with the following, copied from the graveyard of St. Michael’s, Coventry, on a worthy printer who was engaged over sixty years as a compositor on the Coventry Mercury:—

Here

lies inter’d

the mortal remains

of

John Hulm,

Printer,

who, like an old, worn-out type,

battered by frequent use,

reposes in the grave.

But not without a hope that at some future time

he might be cast in the mould of righteousness,

And safely locked-up

in the chase of immortality.

He was distributed from the board of life

on the 9th day of Sept., 1827,

Aged 75.

Regretted by his employers,

and respected by his fellow artists.

Our graveyards contain many tombstones inscribed to the memory of old servants. Frequently these memorials have been raised by their employers to show appreciation for faithful discharge of duty and good conduct of life. A few specimens of this class of epitaph can hardly fail to interest the reader.

Near to Chatsworth, Derbyshire, the seat of the Duke of Devonshire, is the model village of Edensor, with its fine church, from the design of Sir Gilbert Scott, reared on the site of an old structure. The church and graveyard contain numerous touching memorials to the memory of noblemen and their servants. In remembrance of the latter the following are of interest. The first is engraved on a brass plate near the chancel arch:—

| Here lies ye Body of Mr. Iohn Phillips some- time Housekeeper of Chatsworth, who de- parted this life on ye 28th of May 1735, in ye 73rd year of his age, and 60th of his service in ye Most Noble family of His Grace the Duke of Devonshire. [Pg 36] Pray let my Bones together lie Until that sad and joyful Day, When from above a Voice shall say, Rise, all ye dead, lift up your Eyes, Your great Creator bids you rise; Then do I hope with all ye Just To shake off my polluted dust, And in new Robes of Glory Drest To have access amongst ye Bless’d. Which God in his infinite Mercy Grant For the sake & through ye merits of my Redeemer Jesus Christ ye Righteous. Amen. |

A tombstone in the churchyard to the memory of James Brousard, who died in 1762, aged seventy-six years, states:—

| Ful forty years as Gardener to ye D. of Devonshire, to propigate ye earth with plants it was his ful desire; but then thy bones, alas, brave man, earth did no rest afoard, but now wee hope ye are at rest with Jesus Christ our Lord. |

On a gravestone over the remains of William Mather, 1818, are the following lines:—

| When he that day with th’ Waggon went, He little thought his Glass was spent; But had he kept his Plough in Hand, He might have longer till’d the Land. |

We obtain from a memorial stone at Disley Church a record of longevity:—

Here Lyeth Interred the

[Pg 37]Body of Joseph Watson, Bur-

ied June the third 1753,

Aged 104 years. He was

Park Keeper at Lyme more

than 64 years, and was ye First

that Perfected the art of Dri-

ving ye Stags. Here also Lyeth

the Body of Elizabeth his

wife, Aged 94 years, to whom

He had been married 73 years.

Reader take Notice, the Long-

est Life is Short.

On the authority of Mr. J. P. Earwaker, the historian of East Cheshire, it is recorded of the above that “in the 103rd year of his age he was at the hunting and killed a buck with the honourable George Warren, in his Park at Poynton, whose activity gave pleasure to all the spectators there present. Sir George was the fifth generation of the Warren family he had performed that diversion with in Poynton Park.”

We have from Petersham, Surrey, the next example:—

Near the tomb of

a Worthy Family

lies the Body of

Sarah Abery,

who departed this life

The 3rd day of August 1795

Aged 83 Years.

[Pg 38]Having lived in the Service

of that Family

Sixty Years.

She was a good Christian

an Honest Woman

and

a faithful Servant.

At Great Marlow a stone states that Mary Whitty passed sixty-three years as a faithful servant in one family. She died in 1795 at the age of eighty-two years.

Our next example is from Burton-on-Trent:—

Sacred

to the memory of

Sampson Adderly

An Honest, Sober, Modest Man

(A Character how rarely found;)

Whose peaceful Life a circle ran

More hallow’d makes this hallow’d ground

In Service thirty years he spent

And Dying left his well got gains;

To feed and cloth, a Mother bent

By Age’s slow consuming pains:

A tender Master, Mistress kind,

And Friends, (for many a friend had he)

Lament the loss, but time will find

His gain through blest Eternity

He was near thirty Years

a Servant in the Cotton Family

and died in its attendance at Buxton

the 30th of September 1760 Aged 48.

[Pg 39]Also adjoining to him

was laid his Aged Parent

who died the 21st of February following.

From a gravestone at Sutton Coldfield we have a record of a long and industrious life:—

Sacred

to the memory of

John Fisher, day labourer,

who died May 17th in the Year 1806

in the 91st Year of his Age,

having served two Masters at Moore Hall

in this Parish, upwards of fifty years,

Faithfully, Industriously, and Cheerfully.

He was in his Imployment

eight weeks before he died.

This Stone is inscribed to his Memory

by his last Master, as a pattern to Posterity.

Our next inscription is from Eltham, Kent:—

Here

lie the Remains of

Mr. James Tappy

who departed this life on the 8th of

September 1818, Aged 84.

After a faithful Service of

60 years in one Family,

by each individual in which,

He lived respected,

And died lamented

by the sole Survivor.

At Besford, Worcestershire, is a gravestone to the memory of Nathaniel Bell and his wife, both[Pg 40] of whom lived over sixty years each in the Sebright family.

At Kempsey, Worcestershire, is a tombstone on which appears the remarkable record of seventy-seven years in the service of one family:—

To the Memory of

Mrs. Sarah Armison,

who died on the 27th of April

1817

Aged 88 years.

77 of which she passed in the

Service of the Family

of Mrs. Bell

Justly and deservedly lamented

by them,

for integrity, rectitude

of Conduct, and Amiable

Disposition.

We have not noted a more extended period than the foregoing passed in domestic service.

At Tidmington, Worcestershire, is a gravestone to the memory of Sarah Lanchbury, who died at the age of seventy-seven years; she was the servant of one gentleman fifty-six years.

A stone in the old abbey church at Pershore, in the same county, bears an inscription as follows:—

To

[Pg 41]the Memory

of

Sarah Andrews: a faithful Domestic

of

Mr. Herbert Woodward

of this Place

In whose Service she died

on the 10th Feby, 1814

Aged 80

having filled the Duties of her humble

Station with unblemished Integrity

for the long Period

of

52 Years.

From Petworth, Sussex, we have the following:—

| In Memory of Sarah Betts, widow, who passed nearly 50 Years in one Service and died January 2, 1792 Aged 75. |

| Farewell! dear Servant! since thy heavenly Lord Summons thy worth to its supreme reward. Thine was a spirit that no toil could tire, “When Service sweat for duty, not for hire.” From him whose childhood cherished by thy care, Weathered long years of sickness and despair, Take what may haply touch the best above, Truth’s tender praise! and tears of grateful love. |

In the year 1807, died, at the age of eighty-five years, Mary Baily. She was buried at Epsom, and her gravestone says: “She passed sixty[Pg 42] years of her life in the faithful discharge of her duties in the service of one family, by whom she was honoured, respected, and beloved.”

A gravestone at Beckenham, Kent, bears testimony to long and faithful service:—

In memory

of

John King

who departed this Life 29th of

December 1774 aged 75 years.

He was 61 years Servant

to

Mr. Francis Valentine,

Joseph

Valentine, and Paul

Valentine,

from Father to Son,

without ever

Quitting their Service,

Neglecting

his Duty, or being

Disguised

in Liquor.

From the same graveyard the next inscription is copied:—

Sacred to the Memory of

William Chapman

of this Parish,

who died December the

25th 1793

Aged 77 years.

[Pg 43]Sixty years of his life were passed under the Burrell Family, three successive Generations of which he served with such Intelligence and fidelity, as to obtain from each the sincerest respect and Friendship, leaving behind him at his Death the Character of a truly Honest and good Man.

The poet Pope caused to be placed on the outside of Twickenham Church a tablet bearing the following inscription:—

To the Memory of

Mary Beach

Who died Nov. 5th 1725,

Aged 78.

Alexander Pope

whom she nursed in his infancy

and constantly attended for

38 years, in gratitude

to a faithful old

servant

erected this Stone.

When George III. was king, Jenny Gaskoin taught a Dames’ School at Great Limber, a rural Lincolnshire village. From the stories respecting her which have come down to us it would appear that her qualifications for the position of teacher were somewhat limited. It is related that in the children’s reading lessons words often occurred which the good lady was unable to pronounce or explain. She was too politic, [Pg 44]however, to confess her ignorance on such occasions, and had resource to the artful evasion of saying, “Never mind it, bairns; it is a bad word; skip it.”

Dame Gaskoin had a son who obtained the situation of a “helper” in the royal stables. For a slight offence the youth was whipped by the Prince of Wales, when in a momentary fit of anger. It would appear that the Prince regretted his conduct, for he promoted the boy to give him redress for the dressing he had bestowed. Young Gaskoin had the good fortune to be able to introduce his sister Mary into the service of the princesses. By exemplary conduct she obtained the esteem of the royal family. The maiden on one occasion ventured to observe that the rye-bread of Lincolnshire, such as her mother made, was far superior to that which was used at court. This caused the request to be made, or rather a command given, that some of the aforesaid bread should be forwarded as a specimen. The order was complied with, and gave complete satisfaction. The good schoolmistress was afterwards desired to send periodically up to town bread for the royal table.

During a visit to the metropolis to see her daughter the old lady had the honour of an[Pg 45] interview with the princesses. She wore a mob cap of simple form, which took the fancy of the royal ladies to such a degree that it was introduced at court under the name of “Gaskoin Mob-Cap.”

We have little to add, save that the daughter remained in the royal service, attending especially upon the person of the Princess Amelia, and the labour and anxiety she underwent in ministering to the princess in her last illness, combined with sorrow for her death, caused her to follow her royal mistress to the grave after a short interval. In the cloisters of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, is a memorial creditable to the monarch who erected it, and the humble handmaid whom it commemorates:—

King George 3d

caused to be interred

near this place the body of

Mary Gaskoin,

Servant to the late Pss Amelia

And this tablet to be erected

In testimony of

His grateful sense of

the faithful services

And attachment of

An amiable young woman

to his beloved Daughter

Whom she survived

[Pg 46]Only three Months

She died the 19th of February 1811

Aged 31 years.

Over the remains of freed slaves we have read several interesting inscriptions. A running footman was buried in the churchyard of Henbury, near Bristol. The poor fellow, a negro, as the tradition says, died of consumption incurred as a consequence of running from London!

“Here

Lieth the Body of

Scipio Africanus

Negro Servant to ye Right

Honourable Charles William

Earl of Suffolk and Brandon

who died ye 21 December

1720, aged 18 years.”

On the footstone are these lines:—

| “I, who was born a Pagan and a Slave, Now sweetly sleep, a Christian in my grave. What though my hue was dark, my Saviour’s sight Shall change this darkness into radiant light. Such grace to me my Lord on earth has given To recommend me to my Lord in Heaven, Whose glorious second coming here I wait With saints and angels him to celebrate.” |

Our next is from Hillingdon, near Uxbridge:—

Here lyeth

Toby Plesant

An African Born.

He was early in life rescued from West Indian Slavery by [Pg 47]a Gentleman of this Parish which he ever gratefully remembered and whom he continued to serve as a Footman honestly and faithfully to the end of his Life. He died the 2d of May 1784 Aged about 45 years.

Many visitors to Morecambe pay a pilgrimage to Sambo’s grave. A correspondent kindly furnishes us with the following particulars of poor Sambo, who is buried far from his native land. Sunderland Point, he says, a village on the coast near Lancaster, was, before the advent of Liverpool, the port for Lancaster, and is credited with having received the first cargo of West India cotton which reached this country. Some rather large warehouses were built there about a century ago, now adapted to fishermen’s cottages for the few fisher folk who still linger about the little port. Near the ferry landing on the Morecambe side there is a strange looking tree, which tradition says was raised from a seed brought from the West Indies, and the natives call it the cotton tree, because every year it strews the ground with its white blossoms. Close to the shore, with only a low stone wall dividing it from the restless sea, is a solitary grave in the corner of a field, which is called “Sambo’s grave.” Poor Sambo came over to this country with a cotton cargo, fell ill at Sunderland Point, and died; and[Pg 48] there being no churchyard near, he was laid in mother earth in an adjoining field. The house is still pointed out in which the negro died, and some sixty years afterwards it occurred to Mr. James Watson that the fact of this dark-skinned brother dying so far from home among strangers was sufficiently pathetic to warrant a memorial. Accordingly he caused the following to be inscribed on a large stone laid flat on the grave, which indicates that he was a slave of probably an English master about a century before the days of negro emancipation in the colonies:—

| Here lies Poor Sambo, A faithful negro, who (Attending his master from the West Indies), Died on his arrival at Sunderland. |

| For sixty years the angry winter’s wave Has, thundering, dashed this bleak and barren shore, Since Sambo’s head laid in this lonely grave, Lies still, and ne’er will hear their turmoil more. Full many a sand-bird chirps upon the sod, And many a moonlight elfin round him trips, Full many a summer sunbeam warms the clod, And many a teeming cloud upon him drips. But still he sleeps, till the awakening sounds Of the archangel’s trump new life impart; Then the Great Judge, His approbation founds Not on man’s colour, but his worth of heart. H. Bell, del. (1796.) |

We give a few of the many curious epitaphs placed to the memory of soldiers and sea-faring men. Our initial epitaph is taken from Longnor churchyard, Staffordshire, and it tells the story of an extended and eventful life:—

In memory of William Billinge, who was Born in a Corn Field at Fawfield head, in this Parish, in the year 1679. At the age of 23 years he enlisted into His Majesty’s service under Sir George Rooke, and was at the taking of the Fortress of Gibralter in 1704. He afterwards served under the Duke of Marlborough at Ramillies, fought on the 23rd of May, 1706, where he was wounded by a musket-shot in his thigh. Afterwards returned to his native country, and with manly courage defended his sovereign’s rights in the Rebellion in 1715 and 1745. He died within the space of 150 yards of where he was born, and was interred here the 30th January, 1791, aged 112 years.

Billeted by death, I quartered here remain,

And when the trumpet sounds I’ll rise and march again.

On a Chelsea Hospital veteran we have the following interesting epitaph:—

Here lies William Hiseland,

A Veteran, if ever Soldier was,

[Pg 50]Who merited well a Pension,

If long service be a merit,

Having served upwards of the days of Man.

Ancient, but not superannuated;

Engaged in a Series of Wars,

Civil as well as Foreign,

Yet maimed or worn out by neither.

His complexion was Fresh and Florid;

His Health Hale and Hearty;

His memory Exact and Ready.

In Stature

He exceeded the Military Size;

In Strength

He surpassed the Prime of Youth;

And

What rendered his age still more Patriarchal,

When above a Hundred Years old

He took unto him a Wife!

Read! fellow Soldiers, and reflect

That there is a Spiritual Warfare,

As well as a Warfare Temporal.

Born the 1st August, 1620,

Died the 17th of February, 1732,

Aged One Hundred and Twelve.

At Bremhill, Wiltshire, the following lines are placed to the memory of a soldier who reached the advanced age of 92 years:—

| A poor old soldier shall not lie unknown, Without a verse and this recording stone. ’Twas his, in youth, o’er distant lands to stray, Danger and death companions of his way. Here, in his native village, stealing age [Pg 51]Closed the lone evening of his pilgrimage. Speak of the past—of names of high renown, Or brave commanders long to dust gone down, His look with instant animation glow’d, Tho’ ninety winters on his head had snow’d. His country, while he lived, a boon supplied, And Faith her shield held o’er him when he died. |

The following inscription is engraved on a piece of copper affixed to one of the pillars in Winchester Cathedral:—

| A Memoriall. |

| For the renowned Martialist Richard Boles of ye Right Worshypful family of the Boles, in Linckhorne Sheire: Colonell of a Ridgment of Foot of 1300, who for his Gratious King Charles ye First did wounders at the Battell of Edge Hill; his last Action, to omit all others was att Alton in the County of Southampton, was surprised by five or Six Thousand of the Rebells, who caught him there Quartered to fly to the church, with near fourscore of his men who there fought them six or seven Houers, and then the Rebells breaking in upon them he slew with his sword six or seven of them, and then was slayne himself, with sixty of his men aboute him |

| 1641. |

| His Gratious Sovereign hearing of his death, gave him his high comendation in ys pationate expression, Bring me a moorning scarffe, i have lost One of the best Commanders in this Kingdome. Alton will tell you of his famous fight Which ys man made and bade the world good night [Pg 52]His verteous life feared not Mortality His body must his vertues cannot Die. Because his Bloud was there so nobly spent, This is his Tomb, that church his monument. |

| Ricardus Boles in Art. Mag. Composuit, Posuitque, Dolens, An. Dm. 1689. |

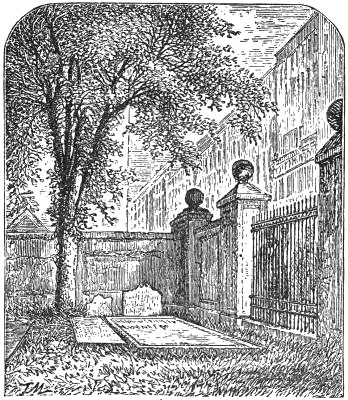

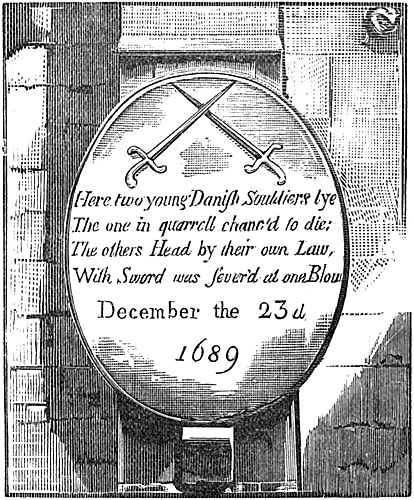

On one of the buttresses on the south side of St. Mary’s Church, at Beverley, is an oval tablet, to commemorate the fate of two Danish soldiers, who, during their voyage to Hull, to join the service of the Prince of Orange, in 1689, quarrelled, and having been marched with the troops to Beverley, during their short stay there sought a private meeting to settle their differences by the sword. Their melancholy end is recorded in a doggerel epitaph, of which we give an illustration.

In the parish registers the following entries occur:—

| 1689, | December 16.— | Daniel Straker, a Danish trooper buried. |

| " | December 23.— | Johannes Frederick Bellow, a Danish trooper, beheaded for killing the other, buried. |

“The mode of execution was,” writes the Rev. Jno. Pickford, M.A., “it may be presumed, by a broad two-handed sword, such a one as Sir Walter Scott has particularly described in[Pg 53] ‘Anne of Geierstein,’ as used at the decapitation of Sir Archibald de Hagenbach, and which the executioner is described as wielding with such address and skill. The Danish culprit was, like the oppressive knight, probably bound and seated in a chair; but such swords as those depicted on the tablet could not well have been used for the purpose, for they are long, narrow in the blade, and perfectly straight.”

TABLET IN ST. MARY’S CHURCH, BEVERLEY.

We have in the diary of Abraham de la Pryme, the Yorkshire antiquary, some very interesting[Pg 54] particulars respecting the Danes. Writing in 1689, the diarist tells us: “Towards the latter end of the aforegoing year, there landed at Hull about six or seven thousand Danes, all stout fine men, the best equip’d and disciplin’d of any that was ever seen. They were mighty godly and religious. You would seldom or never hear an oath or ugly word come out of their mouths. They had a great many ministers amongst them, whome they call’d pastours, and every Sunday almost, ith’ afternoon, they prayed and preach’d as soon as our prayers was done. They sung almost all their divine service, and every ministre had those that made up a quire whom the rest follow’d. Then there was a sermon of about half-an-houre’s length, all memoratim, and then the congregation broke up. When they administered the sacrament, the ministre goes into the church and caused notice to be given thereof, then all come before, and he examined them one by one whether they were worthy to receive or no. If they were he admitted them, if they were not he writ their names down in a book, and bid them prepare against the next Sunday. Instead of bread in the sacrament, I observed that they used wafers about the bigness and thickness of a sixpence. They held it no sin[Pg 55] to play at cards upon Sundays, and commonly did everywhere where they were suffered; for indeed in many places the people would not abide the same, but took the cards from them. Tho’ they loved strong drink, yet all the while I was amongst them, which was all this winter, I never saw above five or six of them drunk.”

The diarist tells us that the strangers liked this country. It appears they worked for the farmers, and sold tumblers, cups, spoons, etc., which they had imported, to the English. They acted in the courthouse a play in their own language, and realised a good sum of money by their performances. The design of the piece was “Herod’s Tyranny—The Birth of Christ—The Coming of the Wise Men.”

A correspondent states that in Battersea Church there is a handsome monument to Sir Edward Wynter, a captain in the East India Company’s service in the reign of Charles II., which records that in India, where he had passed many years of his life, he was

| A rare example, and unknown to most, Where wealth is gain’d, and conscience is not lost; Nor less in martial honour was his name, Witness his actions of immortal fame. [Pg 56]Alone, unharm’d, a tiger he opprest, And crush’d to death the monster of a beast. Thrice twenty mounted Moors he overthrew, Singly, on foot, some wounded, some he slew, Dispersed the rest,—what more could Samson do? True to his friends, a terror to his foes, Here now in peace his honour’d bones repose. |

Below, in bas-relief, he is represented struggling with the tiger, both the combatants appearing in the attitude of wrestlers. He is also depicted in the performance of the yet more wonderful achievement, the discomfiture of the “thrice twenty mounted Moors,” who are all flying before him.

In Yarmouth churchyard, a monumental inscription tells a painful story as follows:—

To the memory of George Griffiths, of the Shropshire Militia, who died Feb. 26th, 1807, in consequence of a blow received in a quarrel with his comrade.

| Time flies away as nature on its wing, I in a battle died (not for my King). Words with my brother soldier did take place, Which shameful is, and always brings disgrace. Think not the worse of him who doth remain, For he as well as I might have been slain. |

We have also from Yarmouth the next example:—

To the memory of Isaac Smith, who died March 24th, 1808, and Samuel Bodger, who died April 2nd, 1808, both of the Cambridgeshire Militia.

| The tyrant Death did early us arrest, And all the magazines of life possest: No more the blood its circling course did run, But in the veins like icicles it hung; No more the hearts, now void of quickening heat, The tuneful march of vital motion beat; Stiffness did into every sinew climb, And a short death crept cold through every limb. |

The next example is from Bury St. Edmunds:—

| William Middleditch, Late Serjeant-Major of the Grenadier Guards, Died Nov. 13, 1834, aged 53 years. |

| A husband, father, comrade, friend sincere, A British soldier brave lies buried here. In Spain and Flushing, and at Waterloo, He fought to guard our country from the foe; His comrades, Britons, who survive him, say He acted nobly on that glorious day. |

Edward Parr died in 1811, at the age of 38 years, and was buried in North Scarle churchyard. His epitaph states:—

| A soldier once I was, as you may see, My King and Country claim no more from me. In battle I receiv’d a dreadful ball Severe the blow, and yet I did not fall. When God commands, we all must die it’s true Farewell, dear Wife, Relations all, adieu. |

A tablet in Chester Cathedral reads as follows:—

| To the Memory of [Pg 58]John Moore Napier Captain in Her Majesty’s 62nd Regiment Who died of Asiatic Cholera in Scinde on the 7th of July, 1846 Aged 29 years. |

| The tomb is no record of high lineage; His may be traced by his name; His race was one of soldiers. Among soldiers he lived; among them he died; A soldier falling, where numbers fell with him, In a barbarous land. Yet there was none died more generous, More daring, more gifted, or more religious. On his early grave Fell the tears of stern and hardy men, As his had fallen on the graves of others. |

A British soldier lies buried under the shadow of the fine old Minster of Beverley. He died in 1855, and his epitaph states:—

| A soldier lieth beneath the sod, Who many a field of battle trod: When glory call’d, his breast he bar’d, And toil and want, and danger shar’d. Like him through all thy duties go; Waste not thy strength in useless woe, Heave thou no sigh and shed no tear, A British soldier slumbers here. |

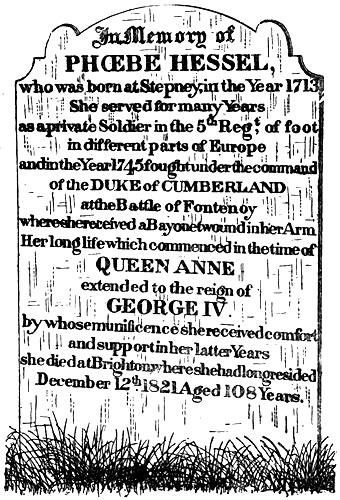

A GRAVESTONE IN BRIGHTON CHURCHYARD.

[Pg 61]The stirring lives of many female soldiers have furnished facts for several important historical works, and rich materials for the writers of romance. We give an illustration of the stone erected by public subscription in Brighton churchyard over the remains of a notable female warrior, named Phœbe Hessel. The inscription tells the story of her long and eventful career. The closing years of her life were cheered by the liberality of George IV. During a visit to Brighton, when he was Prince Regent, he met old Phœbe, and was greatly interested in her history. He ascertained that she was supported by a few benevolent townsmen, and the kind-hearted Prince questioned her respecting the amount that would be required to enable her to pass the remainder of her days in comfort. “Half-a-guinea a week,” said Phœbe Hessel, “will make me as happy as a princess.” That amount by order of her royal benefactor was paid to her until the day of her death. She told capital stories, had an excellent memory, and was in every respect most agreeable company. Her faculties remained unimpaired to within a few hours of her death. On September 22nd, 1821, she was visited by a person of some literary taste, and the following particulars were obtained respecting her life. The writer states:—“I have seen to-day an extraordinary character in the person of Phœbe Hessel, a poor woman stated to[Pg 62] be 108 years of age. It appears that she was born in March, 1715, and at fifteen formed a strong attachment to Samuel Golding, a private in the regiment called Kirk’s Lambs, which was ordered to the West Indies. She determined to follow her lover, enlisted into the 5th regiment of foot, commanded by General Pearce, and embarked after him. She served there five years without discovering herself to anyone. At length they were ordered to Gibraltar. She was likewise at Montserrat, and would have been in action, but her regiment did not reach the place till the battle was decided. Her lover was wounded at Gibraltar and sent to Plymouth; she then waited on the General’s lady at Gibraltar, disclosed her sex, told her story, and was immediately sent home. On her arrival, Phœbe went to Samuel Golding in the hospital, nursed him there, and when he came out, married and lived with him for twenty years; he had a pension from Chelsea. After Golding’s death, she married Hessel, has had many children, and has been many years a widow. Her eldest son was a sailor with Admiral Norris; he afterwards went to the East Indies, and, if he is now alive, must be nearly seventy years of age. The rest of the family are dead. At an advanced[Pg 63] age she earned a scanty livelihood at Brighton by selling apples and gingerbread on the Marine Parade.

“I saw this woman to-day in her bed, to which she is confined from having lost the use of her limbs. She has even now, old and withered as she is, a characteristic countenance, and, I should judge from her present appearance, must have had a fine, though perhaps a masculine style of head when young. I have seen many a woman at the age of sixty or seventy look older than she does under the load of 108 years of human life. Her cheeks are round and seem firm, though ploughed with many a small wrinkle. Her eyes, though their sight is gone, are large and well formed. As soon as it was announced that somebody had come to see her, she broke the silence of her solitary thoughts and spoke. She began in a complaining tone, as if the remains of a strong and restless spirit were impatient of the prison of a decaying and weak body. ‘Other people die, and I cannot,’ she said. Upon exciting her recollection of former days, her energy seemed roused, and she spoke with emphasis. Her voice was strong for an old person; and I could easily believe her when, upon being asked if her sex was[Pg 64] not in danger of being detected by her voice, she replied that she always had a strong and manly voice. She appeared to take a pride in having kept her secret, declaring that she told it to no man, woman, or child, during the time she was in the army; ‘for you know, Sir, a drunken man and a child always tell the truth. But,’ said she, ‘I told my secret to the ground. I dug a hole that would hold a gallon, and whispered it there.’ While I was with her, the flies annoyed her extremely; she drove them away with a fan, and said they seemed to smell her out as one that was going to the grave. She showed me a wound she had received in her elbow by a bayonet. She lamented the error of her former ways, but excused it by saying, ‘When you are at Rome, you must do as Rome does.’ When she could not distinctly hear what was said, she raised herself in the bed and thrust her head forward with impatient energy. She said when the king saw her, he called her ‘a jolly old fellow.’ Though blind, she could discern a glimmering light, and I was told would frequently state the time of day by the effect of light.”

The next is copied from a time-worn stone in Weem churchyard, near Aberfeldy, Perthshire:—

[Pg 65]In memory of Captain James Carmichael, of Bockland’s Regiment.—Died 25th Nov. 1758:

| Where now, O Son of Mars, is Honour’s aim? What once thou wast or wished, no more’s thy claim. Thy tomb, Carmichael, tells thy Honour’s Roll, And man is born, as thee, to be forgot. But virtue lives to glaze thy honours o’er, And Heaven will smile when brittle stone’s no more. |

The following is inscribed on a gravestone in Fort William Cemetery:—

Sacred

To the Memory of

Captain Patrick Campbell,

Late of the 42nd Regiment,

Who died on the xiii of December,

MDCCCXVI.,

Aged eighty-three years,

A True Highlander,

A Sincere Friend,

And the best deerstalker

Of his day.

A gravestone in Barwick-in-Elmet, Yorkshire, states:—

| Here lies, retired from busy scenes, A first lieutenant of Marines, Who lately lived in gay content On board the brave ship “Diligent.” Now stripp’d of all his warlike show, And laid in box of elm below, Confined in earth in narrow borders, He rises not till further orders. |

[Pg 66]The next is from Dartmouth churchyard:—

Thomas Goldsmith, who died 1714.

He commanded the “Snap Dragon,” as Privateer belonging to this port, in the reign of Queen Anne, in which vessel he turned pirate, and amass’d much riches.

| Men that are virtuous serve the Lord; And the Devil’s by his friends ador’d; And as they merit get a place Amidst the bless’d or hellish race; Pray then, ye learned clergy show Where can this brute, Tom Goldsmith, go? Whose life was one continued evil, Striving to cheat God, Man, and Devil. |

We find the following at Woodbridge on Joseph Spalding, master mariner, who departed this life Sept. 2nd, 1796, aged 55:—

| Embark’d in life’s tempestuous sea, we steer ’Midst threatening billows, rocks and shoals; But Christ by faith, dispels each wavering fear, And safe secures the anchor of our souls. |

In Selby churchyard, the following is on John Edmonds, master mariner, who died 5th Aug., 1767:—

| Tho’ Boreas, with his blustering blasts Has tost me to and fro, Yet by the handiwork of God, I’m here enclosed below. And in this silent bay I lie [Pg 67]With many of our fleet, Until the day that I set sail My Saviour Christ to meet. |

Another, on the south side of Selby churchyard:—

| The boisterous main I’ve travers’d o’er, New seas and lands explored, But now at last, I’m anchor’d fast, In peace and silence moor’d. |

In the churchyard, Selby, near the north porch, in memory of William Whittaker, mariner, who died 22nd Oct., 1797, we read—

| Oft time in danger have I been Upon the raging main, But here in harbour safe at rest Free from all human pain. |

Southill Church, Bedfordshire, contains a plain monument to the memory of Admiral Byng, who was shot at Portsmouth:—

To the perpetual disgrace of public justice,

The Honourable John Byng, Vice-Admiral of the Blue,

fell a martyr to political persecution, March 14,

in the year 1757;

when bravery and loyalty were insufficient securities for

the life and honour of a naval officer.

The following epitaph, inscribed on a stone in Putney churchyard, is nearly obliterated:—

| Lieut. Alex. Davidson [Pg 68]Royal Navy has Caus’d this Stone to be Erected to the Memory of Harriot his dearly beloved Wife who departed this Life Jan 24 1808 Aged 38 Years. |

| I have crossed this Earth’s Equator Just sixteen times And in my Country’s cause have brav’d far distant climes In Howe’s Trafalgar and several Victories more Firm and unmov’d I heard the Fatal Cannons roar Trampling in human blood I felt not any fear Nor for my Slaughter’d gallant Messmates shed A tear But of A dear Wife by Death unhappily beguil’d Even the British Sailor must become A child Yet when from this Earth God shall my soul unfetter I hope we’ll meet in Another World and a better. |

Some time ago a correspondent of the Spectator stated: “As you are not one to despise ‘unconsidered trifles’ when they have merit, perhaps you will find room for the following epitaph, on a Deal boatman, which I copied the other day from a tombstone in a churchyard in that town:—

In memory of George Phillpot,

Who died March 22nd, 1850, aged 74 years.

| Full many a life he saved With his undaunted crew; He put his trust in Providence, And cared not how it blew. |

A hero; his heroic life and deeds, and the philosophy of religion, perfect both in theory and practice, which inspired them, all described in[Pg 69] four lines of graphic and spirited verse! Would not ‘rare Ben’ himself have acknowledged this a good specimen of ‘what verse can say in a little?’ Whoever wrote it was a poet ‘with the name.’

“There is another in the same churchyard which, though weak after the above, and indeed not uncommon, I fancy, in seaside towns, is at least sufficiently quaint:—

Memory of James Epps Buttress, who, in rendering assistance to the French Schooner, “Vesuvienne,” was drowned, December 27th, 1852, aged 39.

Though Boreas’ blast and Neptune’s wave

Did toss me to and fro,

In spite of both, by God’s decree,

I harbour here below;

And here I do at anchor ride

With many of our fleet,

Yet once again I must set sail,

Our Admiral, Christ, to meet.

Also two sons, who died in infancy, &c.

The ‘human race’ typified by ‘our fleet,’ excites vague reminiscences of Goethe and Carlyle, and ‘our Admiral Christ’ seems not remotely associated in sentiment with the ‘We fight that fight for our fair father Christ,’ and ‘The King will follow Christ and we the King,’ of our grand poet. So do the highest and the lowest meet. But the heartiness, the vitality, nay, almost vivacity, of[Pg 70] some of these underground tenantry is surprising. There is more life in some of our dead folk than in many a living crowd.”

The following five epitaphs are from Hessle Road Cemetery, Hull:—

| William Easton, Who was lost at sea, In the fishing smack Martha, In the gale of January, 1865. Aged 30 years. |

| When through the torn sail the wild tempest is streaming; When o’er the dark wave the red lightning is gleaming, No hope lends a ray the poor fisher to cherish. Oh hear, kind Jesus; save, Lord, or we perish! |

| In affectionate remembrance of Thomas Crackles, Humber Pilot, who was drowned off The Lincolnshire Coast, During the gale, October 19th, 1869. Aged 24 years. |

| How swift the torrent rolls That hastens to the sea; How strong the tide that bears our souls On to Eternity. |

| In affectionate remembrance of David Collison, Who was drowned in the “Spirit of the Age,” Off Scarborough, Jan. 6th, 1864. Aged 36 years. |

| I cannot bend over his grave, He sleeps in the secret sea; And not one gentle whisp’red wave Can tell that place to me. Although unseen by human eyes, And mortal know’d it not; Yet Christ knows where his body lies, And angels guard the spot. |

| Robert Pickering, who was Drowned from the smack “Satisfaction,” On the Dutch coast, May 7, 1869. Aged 18 years. |

| The waters flowed on every side, No chance was there to save; At last compelled, he bowed and died, And found a watery grave. |

| In affectionate remembrance of William Harrison, 53 years Mariner of Hull, Who died October 5th, 1864. Aged 70 years. |

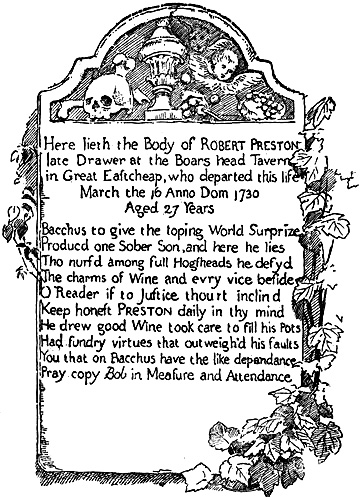

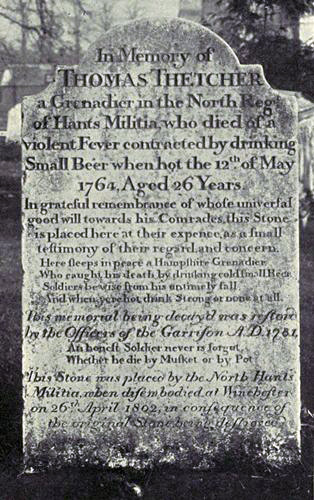

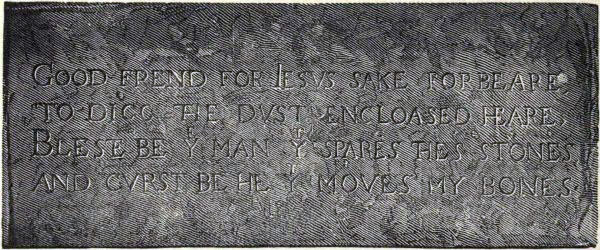

| Long time I ploughed the ocean wide, A life of toil I spent; But now in harbour safe arrived From care and discontent. My anchor’s cast, my sails are furled, And now I am at rest. Of all the parts throughout the world, Sailors, this is the best. |