Title: Just Irish

Author: Charles Battell Loomis

Release date: August 9, 2012 [eBook #40465]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

JUST IRISH

CHARLES BATTELL LOOMIS

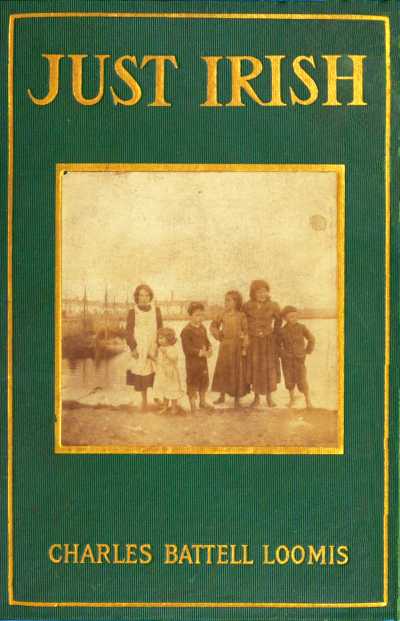

Lismore Castle

CHARLES BATTELL LOOMIS

Author of "Cheerful Americans," "A Bath in an

English Tub," "A Holiday Touch,"

"The Knack of It," "Little

Maude's Mamma,"

Etc., Etc.,

With many illustrations from photographs by the Author.

BOSTON

RICHARD G. BADGER

THE GORHAM PRESS

1911

Copyright 1909 and 1910 by Richard G. Badger

All rights reserved

The Gorham Press, Boston

Dedicated

to

my first friends

in

Ireland,

the Todds of 'Derry

THE first edition of this book was printed before I had thought to write a preface.

Now, my readers may not care for a preface, but as a writer I do not feel that a book is completed until the author has said a word or two.

You don't hand a man a glass of wine or even an innocuous apple in silence: you say, "Here's looking at you," or, "Have an apple?" and the recipient says, "Thanks, I don't care if I do," or, "Thanks, I don't eat apples." In either case you have done what you expected of yourself, and that, let me tell you, is no small satisfaction.

So now that my publisher has thought it worth while to get out an illustrated edition of this unpretentious record of pleasant (though rainy) days in Ireland, it is my pleasure to say to all who may be about to pick it up, "Don't be afraid of it—it won't hurt you. It was written by a Protestant, but while he was in Ireland his only thought was that God was good to give him such a pleasant time and to make people so well disposed toward him. It was written by a man without a drop of Irish blood in his veins (as far as he knows), but he felt that he was among his brothers in race, because their ideas so chimed in with his, and every one made him so comfortable."

This is a good opportunity to thank those of Irish birth or extraction who in their papers and magazines said such nice things about the book.

The pictures, all snap shots, were taken by me, and even the Irish atmosphere was friendly to my purpose, and gave me considerable success. A pleasanter five weeks of travel I never had, and if you who read this have never visited Ireland, don't get too old before doing so. And if you do visit it give yourself up to it, and you'll have a good time.

Here's the book—like it if you can, drop it if you don't. Never waste time over a book that is not meant for you.

| I. | A Taste of Irish Hospitality | 15 |

| II. | Around about Lough Swilly | 27 |

| III. | A Joyful Day in Donegal | 41 |

| IV. | The Dull Gray Skies of Ireland | 52 |

| V. | The Joys of Third-Class Travel | 62 |

| VI. | A Few Irish Stories | 74 |

| VII. | Snapping and Tipping | 83 |

| VIII. | Random Remarks on Things Corkonian | 97 |

| IX. | A Visit to Mount Mellaray | 108 |

| X. | A Dinner I Didn't Have | 123 |

| XI. | What Ireland Wants | 134 |

| XII. | A Hunt for Irish Fairies | 143 |

| XIII. | In Galway with a Camera | 156 |

| XIV. | The New Life in Ireland | 167 |

JUST IRISH

A Taste of Irish Hospitality

"IRISH hospitality." I have often heard the term used, but I did not suppose that I should get such convincing evidence of it within twelve hours of my arrival at this northern port.

This is to be a straightforward relation of what happened to some half dozen Americans, strangers to each other, a week ago, and strangers to all Ireland upon arrival.

In details it is somewhat unusual, but in spirit I am sure it is characteristic of what might have befallen good Americans in any one of the four provinces.

To be dumped into the tender that came down the Foyle to meet the Caledonia at Moville at the chilly hour of[Pg 16] two in the morning seemed at the time a hardship. We had wanted to see the green hills of old Ireland and here were blackness and bleakness and crowded humanity.

But the loading process was long drawn out, and when at last we began our ascent of the Foyle there were indubitable symptoms of morning in the eastern skies, and we saw that our entrance into the tender was like the entrance of early ones into a theater before the lights are turned up. After a while the curtain is lifted and the scenic glories are revealed to eyes that have developed a proper amount of eagerness and receptivity.

With the first steps of day a young Irishman returning to his native land mounted a seat and recited an apostrophe, "The top of the mornin' to ye," and then a mist lifting suddenly, Ireland, dewily green and soft and fair, lay revealed before our appreciative eyes.

A Real Irish Bull

The sun, when he really began his morning brushwork, painted the trees and grasses in more vivid greens, but there was a suggestiveness of early spring in the first soft tones that was fully valued by eyes that had been used to leaden skies for more than half the days of the voyage.

But I am no poet to paint landscapes on paper, so we will consider ourselves landed at Londonderry and furnished with a few hours of necessary sleep, and anxious to begin our adventures.

Our party consisted of a half dozen whose itineraries were to run in parallels for a time. There were four ladies and two of us were men. One of the men had to come to Ireland on business, and he found he had awaiting him an invitation to lunch that day with a country gentleman with whom he had corresponded on business matters.

As the one least strange to the country this American had tendered his good offices, American fashion, to the ladies who would be traveling without male companions after we left them, and so he dispatched a messenger with a note to the effect that he must regretfully decline, and stating his reasons for so doing.

While we were lunching at the hotel a return note came to him, this time from the good man's wife, cordially asking that we all come and have afternoon tea.

Here was a chance to see an Irish household that was hailed with delight by all, a delight that was not unappreciative of the warmth of the invitation.

We would go to the pleasant country house, but—our trunks had not come. Would our traveler's togs worthily represent our country?

But our friend said, "Don't let clothes stand between us and this thing. I'm sure this lady will be glad to welcome us as Americans, and for my part I never reflect credit on my tailor, and people[Pg 19] never clamor for his address when they see me. As for you ladies, I'd think any tea of mine honored by such fetching gowns, if that's the proper term. I'm going to write her that we're coming just as we are."

So he sent another messenger out into the country—telephones seem as scarce as snakes here—saying, well, he used a good assortment of words and arranged them worthily.

The two young girls of the party clamored for jaunting cars, and so two were ordered for four o'clock. One of them had red cushions and was as glittering in its glass and gold as a circus wagon.

My friend, on ordering this one, said to the "jarvey" (by the way, they call them drivers here in this part of Ireland, but jarvey has always seemed so delightfully Irish that I prefer to stick to it), "Get another car as nice as this."

"Sure, there's none as nice as this,"[Pg 20] said he, pride forcing the confession, "but I'll get a good one."

It was a beautiful day except for the extreme heat—and yet they say it always rains in Ireland. I felt that it must be exceptional, and said to the waiter at lunch, "I suppose it's unusual to have such weather as this?" "Sure, every day is like this," said he with patriotic mendacity.

When the jaunty jaunting cars drew up a little before four o'clock there were portentous black clouds in the sky, but the jarvies assured us that they were there more for looks than anything else—that there might be a matter of a spit or two, but that we'd have a fine afternoon.

So we mounted the sides of the cars, and holding on to the polished rails, as we had been told was the proper fashion, we set out bravely on our way, little wotting what a wetting all Ireland was soon to have.

In a half hour or so we would be walking over Irish lawns and admiring Irish laces as they decked the forms of gaily clad femininity gathered for sociability and tea alongside the rhododendrons and fuchsia bushes.

Government Cottage, rent a shilling a week

A few drops of rain fell, but the wind was south and we seemed to be going east.

"Isn't this gay?" called the young girls, as we jiggled along in holiday mood. Suddenly a silver bolt of jagged lightning cleft the sky to the south, and almost instantaneously a peal of thunder that sounded as if it had been born and bred on Connecticut hills, so loud was it, told us that the people living to the south of us were going to get wet.

And then we came to a bend in the road and turned south.

"Ah, 'twill be nothin'," said our driver, in answer to a question.

To give up what one has undertaken is a poor way of playing a game and we were all for going on. "It's not so far,"[Pg 22] said the jarvey, but this was a sort of truth that depended on what he was comparing the distance with. It was not so far as Dublin, for instance, but 'twas far enough as the event proved.

We put on our cravenettes, hoisted what umbrellas we had, and gave the blankets an extra tucking in and after that—the deluge!

Bang, kerrassh! A bolt from heaven followed by a bolt from each horse. A sort of echo as it were. The drivers reined them in and ours started to seek shelter under a tree.

As I sometimes read the newspapers when at home I told our driver to keep in the open.

The lightning now became more and more frequent and was so close that we let go our hold on the brass rails, preferring to pitch out rather than act as conductor on a jaunting car—such things as conductors being unknown anyway.

It was terrifying, and to add to my discomfort I found I was sitting in a pool of water, the rain having an Irish insinuatingness about it that was irresistible. And now, just to show us what could be gotten up on short notice for American visitors, it began to hail and the wind blew it in long, white, slanting, winter-like lines across the air and into our faces, and the roads having become little brooks, the horses had to be urged to the driver's utmost of threats and cajolery.

I thought of that waiter who had told me it was always sunny in Ireland and I wished him out in the pelting storm.

"I've not seen the like in twinty yairs, sirr," said the driver.

To go back was to get the storm in fuller fury, for the wind had shifted. To go ahead was to arrive like drowned rats, but we were anxious for shelter, and still the driver said, "It's not far," and so we went on. I have been in many places in all sorts of weathers, but[Pg 24] it is years since I've been out in such a storm. The hailstones were not as large as hen's eggs, but they were as large as French peas.

There was not a dry stitch on us and the red of the gay cushion went through to my skin. My cravenette treacherously refused to let the water depart from me, but shed it on the wrong side—which may be an Irish bull, for all I know.

"Here we are now, sirr," said our driver, as he turned in at a beautiful driveway. A winding drive of a minute or two and we arrived like wet hens—all of us—at the house of these people who had never heard of us until that day.

But the warmth of the welcome from our host and hostess who came out to the door to greet us made us not only glad we had come, but even glad we were wet.

Had there been the least stiffness we should have wished the storm far enough[Pg 25] (and indeed all Ireland did wish it, for it turned out to be the most tremendous thunder and hailstorm in a score or more of years), but our new found friends frankly laughed with us at our funny appearance, and we were hurried off to various rooms to change our clothes.

Our protestations of regret at putting them to trouble were met with protestations of delight at being able to serve us, and as my host brought me some union garments that had been made for a man of three times my size and I wrapped them round and round me until they were giddy, I was glad I had not turned back to spend a damp afternoon in a lonely hotel.

The rest of the party fared well in getting clothes that became them, but when I was fully dressed I looked like Francis Wilson in Erminie. As I turned up my sleeves and triple turned up my trousers I knew I would be good for a laugh in any theater in Christendom.

There was but one thing to do—go down and look unconscious of my misfit appearance. It would never do to stay in my room through a mistaken sense of personal dignity.

So I went down, and meeting host and hostess and my compatriots, a laugh went up that would have broken the ice in a Pittsburgh millionaire's drawing room.

And then we were taken to the tearoom and in a few minutes I forgot that I was no longer the glass of fashion and the mold of form, for I was made to feel that I was just a friend who had dropped in (or, perhaps, dripped in would be better), and when a couple of hours later we drove home through the soft Irish verdure, doubly green after its rough but invigorating bath, we all felt that Irish hospitality was no mere traveler's tale, but a thing that had intensity and not a little emotion in it.

Horses in County Kerry

Around about Lough Swilly

TO a tired New Yorker who has sixteen days at his disposal I would recommend a day on Lough Swilly at Rathmullan. It is separated from the island of Manhattan by little else than the Atlantic, and every one knows that a sea voyage is good for a wearied man.

Take a boat for Londonderry from the foot of Twenty-fourth Street, and then for the mere cost of a shilling (if you travel third class, and that is the way to fall in with characters) you will be railroaded and ferried to Rathmullan, where you'll find as clean an inn and as faithful service as heart could wish. And such scenery!

And every one will be glad to see you, because you are from America. ("Welcome[Pg 28] from the other side," and a hearty hand grip from leathery hands.)

Of course a day is a short time in which to get the full benefit of the peaceful atmosphere of the place and perhaps you will stay on as we are doing for several days.

Then you can return for a shilling to 'Derry, take Saturday's steamer to the foot of Twenty-fourth Street, New York, and you'll soon be walking the streets of the metropolis filled with pleasant memories of one of nature's beauty spots.

Lough Swilly is an arm of the Atlantic and its waters are salt. At Rathmullan the lough is surrounded by lofty green hills, mostly treeless, gently sloping to the water, and for the better part of the time softened in tone by an Indian summer haze indescribably beautiful.

We came down according to the program I have outlined, and traveled third class for the reason I have stated, but as the only other occupant of the coach was[Pg 29] a lone "widow woman" we were unable to get any characteristic conversation. In fact, up here in Donegal, as far as I have observed, the natives talk more like the Scotch than they do like the Irish made known to us by certain actors. When I get south I expect to hear rich brogues, but here the burr is Scotch.

We were ferried from Fahan in a side-wheel steamer, and soon the painfully neat-looking white houses of Rathmullan lay before us and we disembarked, and carrying our own grips unmolested (a sure sign of an unusual place) we made our way up the stone pier between restless steers who were waiting for us to get out of the way so that they could go to the slaughter house. There had been a cattle fair that day in Rathmullan.

We knew little of the town save what Stephen Gwynn says of it in his delightful "Highways and Byways in Donegal and Antrim."

There is a most picturesque and ivy-grown[Pg 30] ruin of an abbey dating back to the fifteenth century. It is much more beautiful than Kenilworth.

We bent our steps to the plain-looking little inn, and entering the taproom we asked for lodgings for the night. The inn is kept by a widow who still bears trace of a beauty that must have been transcendent in her girlhood. As it is, she could serve as a model to some artist for an allegorical painting representing "Sorrowful Ireland"; the arched eyebrows, the melting eyes, the long, classic nose, and the grieving mouth—very Irish and very lovely.

We have seen many pretty women here in Ireland, but in her day this inn keeper must have been the peer of any.

Her husband kept the inn formerly, but as an Irishman told me, "He died suddenly. Throuble with the head," said he, tapping his own. "'Twas heart disease, I think." This is the first Irish bull I've heard.

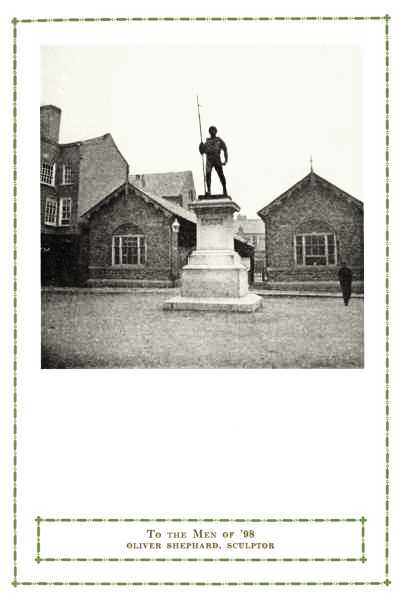

To the Men of '98 OLIVER SHEPHARD, SCULPTOR

My companion thought he would like a room fronting Lough Swilly and so did I.

The maid who had taken charge of us said that that wouldn't be possible, as the only available rooms having such an outlook had been engaged by wire.

"But," said my insistent friend, who is the type of American who gets what he wants by smiles if possible, but who certainly gets it, "they won't be here to-day, will they?"

"No, not to-day; to-morrow."

"Well, let us have the rooms for to-night."

"But, will ye give them up when they come?" said she, still hesitating.

"Surely. Depend upon it. Count on us to vamoose just as soon as you give the word."

"But these people come every year," said she tenaciously.

"I don't wonder at it," said O'Donnell.

(My friend is of Irish descent.) "I[Pg 31]

[Pg 32]

would, too, if I didn't live so far away.

Don't you worry, honey. We'll just go

out like little lambs as soon as you give

the word."

There was something delightfully quaint in the notion that because people were coming to the rooms to-morrow night we ought not to have them to-night—the girl was perfectly sincere. She evidently knew the lure of sunrise on the mountains and the lake and feared her ability to oust us once we were ensconced.

"We're passing on to-morrow and will be just as careful of the rooms," said O'Donnell in the tone of one who talks to a child, and the pretty maid succumbed, and our valises were deposited in the coveted rooms.

But just as she left us she said once more, "You'll go when they come, won't you?"

"We sure will," said O'Donnell, with a solemnity that carried conviction with it. "Now about dinner," said he; "we'd[Pg 33] like dinner at six thirty. It's now four."

"We haven't begun to serve dinners at night yet," said the maid. The summer season had evidently not begun.

"Oh, that's too bad," said O'Donnell, "but you'll make an exception in our case now, won't you?"

She thought a minute, and O'Donnell smiled on her.

I can imagine ice banks melting under that smile.

"I suppose we could give you hot roast chicken," said she.

"Why, of course you could. Roast chicken is just what you could give us, and potatoes with their jackets on——"

"And soup," said the girl, evidently excited over the prospect.

"Yes, we'll leave the rest to you."

So we went out and walked through the lovely countryside, noting that in Ireland fuchsias grow to the proportions of our lilac bushes and are loaded with the pretty red flowers.

We were unable to name most of the trees we saw (but that sometimes happens in America), yet we were both sure we had not seen their like at home. And the freshness of them all, the brilliant quality of their green, fulfilled all expectations.

We took a long walk and arrived at the inn with appetites sharpened.

Friends in America had told me that I'd not fare very well in Ireland except in the large towns. I would like to ask at what small hotel—New York or Chicago or Philadelphia—I would get as well cooked or as well served a dinner as was brought to me in Londonderry for three shillings and sixpence.

If one is looking for Waldorf magnificence and French disguises he'll not find them here unless it is at Dublin, but if one is blessed with a good appetite and is willing to put up with plain cooking I fancy he will do better here than at like hotels at home.

Prosperity in Limerick

The Irish are such good cooks that we in the east (of America) have been employing them for two generations. Let us not forget that.

We entered the dining-room and had an appetizing soup and then the Irish potatoes (oh, such Irish potatoes!) and anything tenderer or better cooked than the chicken it would have been hard to find. We looked at each other and decided that we would not go on to Port Salon next day, but would spend another night in Rathmullan, and we said so to the maid.

"But you'll take other rooms?" said she, alarmed at once.

"Oh, yes, honey, we'll go anywhere you put us."

Now you know we had an itinerary, and to stay longer at Rathmullan was to cut it short somewhere else, but the stillness and calm, the purple shadows on the mountains and the lake (Lough Swilly means Lake of Shadows), had us[Pg 36] gripped and we were content to stay and make the most of it.

A simple, golden rule sort of people the inhabitants are. We came on a man clipping hawthorn bushes and asked him how far it was to a certain point and whether we could "car" it there.

He told us we could and then he said, "Were ye thinkin' of hirin' a car, sir?"

"Yes," said O'Donnell.

"I have one," said he.

"Well," said O'Donnell, "we've talked to the landlady about hiring hers——"

"Ah, yes," said the man. "Sure I don't want ye to take mine if she expects to rint hers."

Such altruism!

We had comfortable beds in the rooms that had been engaged by wire "for to-morrow," and indeed they were so comfortable that we never saw the sunrise at all. But the view from our windows was worth the price of the rooms and that was—listen!—two shillings and sixpence apiece!

Wheat porridge and fresh eggs (oh, so fresh!) and yellow cream and graham bread and jam for breakfast. What more do you want?

Oh, yes, I know your kind, my dear sir.

"What! no steak? No chops, and fried ham and buckwheat cakes and oranges and grapefruit and hot rolls? What sort of a hotel is this for an American? You tell the landlady that they don't know how to run hotels in this country. You tell her to come to God's country, that's what. Then she'll learn how."

Yes, then she'll learn how to set out ten or twelve dinkey little saucers of peas and corn and beans and turnips and rice, all tasting alike.

But Mr. O'Donnell and I will continue to like the simplicity of this inn.

We astonished the easy-going natives by climbing the mountain on Inch Island in the morning for the magnificent view[Pg 38] and going fishing for young cod in the afternoon. The young fellow who took us out had the somewhat Chinese name of Toye, but he was Irish.

When it came time to settle for the use of the boat and his services for a matter of two hours he wanted to leave it with us.

"No, sir," said O'Donnell. "Your Uncle Dudley doesn't do business that way," with one of his beaming smiles.

"Oh, I don't know what to charge, sir, pay me what's right."

"That's just it. I don't know what's right."

"Well, ye were not out so long. Is two shillin's apiece right?"

"Very good, indeed, and here's sixpence extra for you," said O'Donnell, paying him.

"Oh, thank you, sir," said the boy, evidently thinking the tip far too much.

But as we had caught forty-eight fish in the hour we were at the fishing grounds [Pg 39]we felt that it was worth it. Sixpence—and to be sincerely thanked for it! There are those who are not money grubbers.

Mackerel Seller, Bundoran, Donegal

They use a tackle here that they call "chop sticks"—two pieces of bamboo fastened at right angles, from which depend the gut and hooks, while back of them is the heavy sinker. The sinker rests on the bottom and the ugly red "lugs" (bait) play around in the water until they are gulped by the voracious coddlings, or cod. We had small hooks and caught only the youngsters.

Time after time we threw in our lines, got "two strikes" at once and pulled in two cod as fast as we could pull in the line.

No sport in the way of fight on the part of the party of the second part, but not a little excitement in thus hauling in toothsome food.

We had them for supper and I tell you, O tired business man, if you want[Pg 40] to know how good fish can taste, come over here and go a-fishin'. Like us you will stay on and on.

Oh, yes, about those other people. No, we didn't get out of our rooms, because the landlady had relatives in America and so she made other arrangements for her expected guests and we stayed on and overlooked Lough Swilly.

Americans are popular over here. But I hope they won't spoil these simple folk with either excessive tipping or excessive grumbling.

A Joyful Day in Donegal

HOLLAND is noted the world over for its neatness. The Dutch housewives spend a good part of each morning in scrubbing the sidewalks in front of their houses. Philadelphia is also a clean town and there you will see house-maids out scrubbing the front stoops and the brick pavements. Now a good part of the inhabitants of Donegal emigrate to Philadelphia. (We in America all know the song, "For I'm Off to Philadelphia in the Morning.") Well, the third neatest place that occurs to me is Rathmullan, in Lough Swilly, in County Donegal.

Whether Philadelphia is neat because of the Irish or the Irish of Donegal go to Philadelphia because it is neat, I leave to others to determine.

All my life I've read and have been told that the north of Ireland was very different from the south; that the people were better off and more thrifty, but I did not expect to see such scrupulous neatness. The houses are mostly white and severely plain in line, built of stone faced with plaster, sometimes smooth and sometimes rough finished, but always in apple-pie order (unless they were on parade the three days I was there). Even the alleys are sweet and clean, and where the people keep their pigs is a mystery to me. I snapped one, but he was being driven hither and thither after the manner of Irish pigs, and may not have lived in Rathmullan at all.

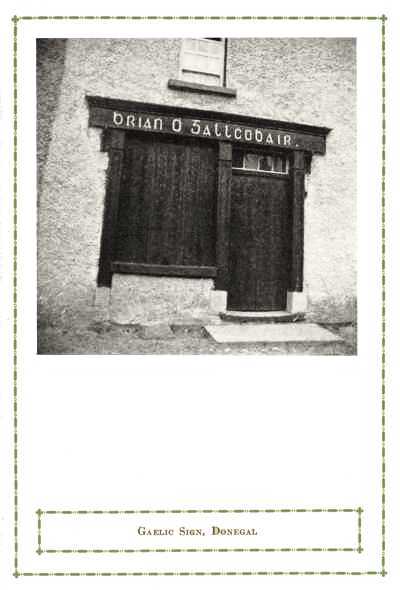

Here in the town of Donegal while the houses are not of Philadelphia neatness, they show evidence of housewifely care, and if there is abject poverty it is carefully concealed. (I have been a week in Ireland and I have not seen a beggar or a drunken man, although I have kept my eyes moving rapidly.)

In Donegal

How often must an emigrant who has elected to live in noisome tenements in American cities long for the white cottages and the green lanes and noble mountains and verdant valleys of Donegal!

Every hotel at which I have stopped so far has had hot and cold water baths and I have only been to small towns.

I heard a bathing story from a vivacious Irish lady at an evening gathering that may never have seen American printer's ink.

She said that in former times a lady stopping at a primitive hotel in the west of Ireland asked for a bath. She was told by the maid that a colonel was performing his ablutions in the room in which the bathing pan was set.

"But he'll not be long, I'm thinkin', miss," said the maid.

This lady waited awhile in her room, and at last growing impatient, she stepped out into the hall and found the maid with her eye to the keyhole of the bathroom.

On hearing the lady's footstep she turned around quite unabashed and said, "He'll be ready in a minute, miss. He's just after gettin' out of the tub."

This story was told me in a drawing-room with many young people present, so it must be true, but candor compels me to say that I have observed nothing of the kind on this trip. There are no terrors like those of a bath in an English tub of which I had occasion to speak last year.

Speaking of anecdotes, I heard one that concerned the father of the man who showed us through the lovely ruins of McSwiney's castle at Rathmullan. Son, father, and grandfather have all in their turn acted as caretakers of the ruins, and proud enough is the son of his position.

But it is of the father that the story goes.

The wife of an English admiral, whose family were in the habit of being buried in the graveyard adjoining the abbey[Pg 45] whenever they died, departed this life, and to "Jimmy" fell the task of digging her grave.

Meeting the admiral some two weeks later he said, "It'll be ten shillings for yon grave."

"Is it ten shillings, man?" said the admiral. "Why that's extortionate. I'll pay five shillings and that's a shilling more than usual, but I'll not pay ten shillings."

"Ah, well," said Jimmy, composedly, "if ye'll not pay ten shillings then I'll dig her up again." And the admiral, knowing Jimmy to be a man of his word, paid him what does not look to be an exorbitant price.

Among the most impressive ruins in the world are those of the Grianan (or summer palace) of Aileach on Elagh mountain. Here is a circular fort of rocks some three hundred feet in circumference that antedates Christ's nativity by from two thousand to three thousand[Pg 46] years. It is supposed to have been a temple of the sun worshippers and occupies a magnificent and awesome position from which to see either the arrival or the departure of the sun god, for the half of County Donegal lies north, south, east, and west at your feet. Such an extended view is seldom vouchsafed to the dwellers within towns and I don't wonder that the sun worshippers built there a temple to their deity.

There it still stands, its walls eighteen feet high and twelve feet thick. It has been somewhat restored by Dr. Bernard, of Derry, but does not seem to vie with the Giant's Causeway as an attraction to visitors. There were only three persons there when we went up, but there is a holy well just outside of it and from the number of bandages fluttering in the wind there I imagine that a good many maimed people manage to scale the steep ascent.

I said that Elagh mountain afforded[Pg 47] a fine view for the dwellers within towns. It is only six miles by car and a mile by foot (I suppose seven miles in any manner would cover it) from Derry.

By the way, for ease and comfort to a naturally lazy man, commend me to a jaunting car. The cushioned top with which they cover the "well" that lies between the sidewise seats is an admirable place on which to "slop over" and loll on from the seat, and so far from being an insecure perch, it is just as safe as a dog cart or a buggy. And the motion is pleasantly stimulating to the system. The well-built, vigorous, well-fed cob trots with the regularity of a metronome or a London cab horse, reeling off mile after mile. We did our twelve miles to and from Elagh mountain in less than two hours and at a cost of three shillings apiece, exclusive of the sixpenny tip. They don't do those things as cheap in New York or Chicago.

At Donegal my friend had to see a solicitor[Pg 48] on business and after it was over he came to me and said that the solicitor would like to take us sailing down Donegal Bay. I was delighted to go, but I wondered whether we would walk down to the bay or ride there. I knew that it was several miles out, for I had seen it across the wet sands that stretch from the town's center seaward.

My uncertainty was soon dispelled, for two minutes' walk brought us to where the bare sands had been a few hours before, and lo, Donegal Bay had come to us and the solicitor's boat was riding on the water waiting to be off. A tide is a handy thing to have about.

As one leaves the inlet and looks back he gets a picture that might have been composed by an exceedingly successful landscape gardener. The trim little town showing a bit of the ruins of Donegal castle and one graceful church spire, wooded hills running up from the town on either side; back of all this hills of[Pg 49] greater magnitude, destitute of trees, and then, towering up in the distance, the great, gaunt Barnesmore that forms part of a heaven-kissing train.

We sailed well out into the bay with favoring winds, and had most noble views of purple mountains on every side, but when we turned to go back the wind made off to sea, laughing at us, and we came back laggingly, but in plenty of time for a cozy supper in the solicitor's home and an all evening chat with him.

We had never met until that day, but his welcome was as hearty as if he had been anxiously awaiting our coming.

As I got off the train at Donegal a heavy hand clapped me on the shoulder, and, turning, I saw Seumas McManus, whose Irish stories are so well known in America.

He lives at Mount Charles, a village lying three Irish miles from Donegal, and nothing would do but my friend and I must have dinner with him.

We accepted with pleasure, and next day walked up there, meeting more pretty girls returning from mass than it seemed right for two to meet when there were so many people in the world who seldom see a pretty face. But we tried to bear our good fortune meekly and strode on, quite conscious in the warm sun that an Irish mile has an English mile beaten by many yards. That ought to be cause for satisfaction to any Irishman.

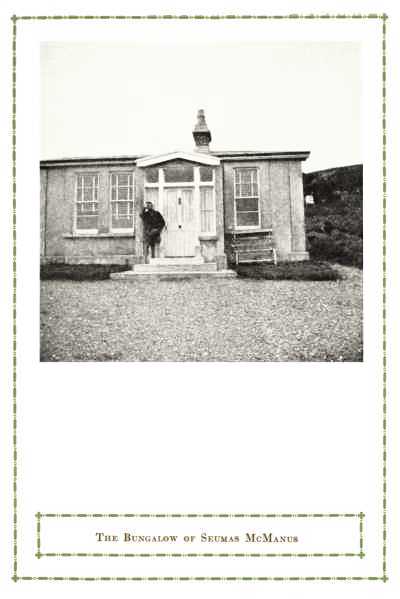

McManus has a bungalow on top of Mount Charles, and at his feet lie seven counties. They have a way of throwing counties at your feet in this part of Ireland that makes the view superb. The furthermost land that is his to look at on a clear day lies a hundred miles to the south.

Such a view ought to stimulate a man to noble thoughts, and I was not surprised to learn that McManus is a member of the Sinn Fein (Shinn Fane) Society (it means, "Ourselves Alone"), [Pg 51]what one might call bloodless revolutionists, although it comprises much of the best blood and the youngest blood in Ireland.

The Bungalow of Seumas McManus

McManus is an ardent believer in a glorious future for Ireland when she shall have shaken off the shackles that bind her, and as a good American, I wrote in his guest book, "May Ireland come to her own before I die."

The Dull Gray Skies of Ireland

I AM coming more and more to believe that we have better weather in America than we give the poor country credit for. What passes for good weather here would make a poor substitute for the American article. I will not deny that it is soft and insinuating, but it is also not to be depended upon. I went out to climb a wild-looking mountain near Bundoran, on the northwest coast. To my inexperienced eye the day looked promising—that is promising rain—but the driver, of whom I had ordered a car to take me to the base of the mountain, said there'd be no rain. All those ugly clouds hovering over the summit of it were merely reminders that there was such a thing as rain, and so we started.

A Sky Line at Bundoran

And here let me make a few remarks about Irish weather in general. You are out walking in a fine "mizzle," that penetrates ordinary cloth with the utmost ease, and you meet a countryman to whom you observe "Not very pleasant." "Oh, it's a bit soft, but it's pleasant enough." What a blessing it is to be easily satisfied.

You strike a day without sun and positively chilly, and the natives assure you it is fine, that they had awful weather last week, but that, according to the barometer, the weather is going to be steady for awhile. They have borrowed the barometer habit from the English, and it really is a comfort when you're going for a long walk or drive to see that it points to fair. "Fair to middling" would be better.

Well, my driver and I set out for the

mountain, and on the way I asked him[Pg 53]

[Pg 54]

the question I ask all of the peasants

with whom I hold conversation, "Would

you like to go to America?"

"Sure I would. I'll not be stayin' here long. I've an aunt an' a brother an' a cousin an' a sister an' an uncle beyant. There's no chance here."

I wonder whether the reason why there is no chance is because the Irishman is lacking in application. I fell in with a delightful man at a little town in County Fermanagh. I wanted a little thing done to my watch and I asked him how long it would take to do it.

He assured me that he was driven to death with work and was up till late every night trying to get ahead, but that he would try to find time to mend my watch some time before seven o'clock, when he nominally closed. Then he followed me to the door of his shop and began to ask me questions about America, which I was glad to answer, as I had a half hour to kill before starting for[Pg 55] some sight or other, and I killed that half hour most agreeably with the little man's help. He pointed out different passers by and told me their life histories. And every once in a while he would say, "I've not had a day off for nearly a year, not even bank holiday. Never a minute for anything but work. I've an order now that's going to keep me busy, except for the time I'll give to your watch, all the rest of the day. And dinner eaten in my workshop to save time."

I told him I wished he wasn't so driven, but I knew how it was with a man who did good work, and then I bade him good day and didn't go near there until seven in the evening. I found him outside the shop discussing the strike of the constabulary at Belfast with a neighbor.

"Awfully sorry, sir, but I've been so busy to-day that I've been unable to finish that job. It'll not take over twenty minutes when I get to it. Can you come in the morning?"

I told him I could, say about eight o'clock.

"Oh, dear no. We don't open the shops until nine."

"Very well, then, nine will do."

And having some more time that I wished to kill I entered into a discussion with him and his neighbor as to the extent to which the constabulary disaffection would spread, and it was eight o'clock when I went back to my hotel.

Next morning I was at the shop at nine and he was just taking down the shutters. Said he'd worked until ten the night before, but seemed further behind than before. If I'd come up into his workroom he'd fix my watch while I waited.

Up there he had some photographs to show me that he had taken a year ago and had only just found time to develop, and we talked photography for a matter of twenty minutes, and then he fixed my watch in a jiffy when he got to work.

The Rocks at Bundoran on the West Coast

He's typical not only of Irishmen, but of Yankees, too—men who can work fast if you seal their mouths.

I was sorry I had to journey on, because our talks had been pleasant and it had never once entered his head that he was wasting that time of which he had so little, although he dealt in watches.

But to return to my driver.

When we reached the base of the mountain he put the horse up in a stone stable that belonged to a poor woman. Think of a poor woman housing her cow in a stone stable, built to stand the wear and tear of generations!

We had no sooner begun our climb

of the hill or mountain than the rain

came down in earnest, and my shoes

were soon wet through, but I persevered,

somewhat to the disappointment of the

boy, who was better used to being wet on

his car than on foot. But when we[Pg 57]

[Pg 58]

reached the top the view of all Donegal

bay and the mountains beyond, and

many other bits of geography not half as

beautiful on the map as they are in nature,

repaid me for my climb and wetting.

And when I said, "It's too bad it rained just as we got here," my driver said, "It's always rainin' on the mountains," although when he was getting me for a passenger he had assured me it wouldn't rain on the mountain.

We made our way down through the wet, but still beautifully purple heather, and just as we reached the level the rain stopped. It was as if our feet upon the mountain had precipitated the rain.

But at the close of the drive I found a comfortable inn and a most agreeable dinner of fresh caught fish, and that mutton that we never seem to get in America, and I still felt that the climb was worth the wetting.

But the weather never ceases to astonish me. Dull gray skies at home[Pg 59] would depress me, but here I am thankful for dull gray skies if they only stop leaking long enough to enable me to do my accomplished task of walking or driving.

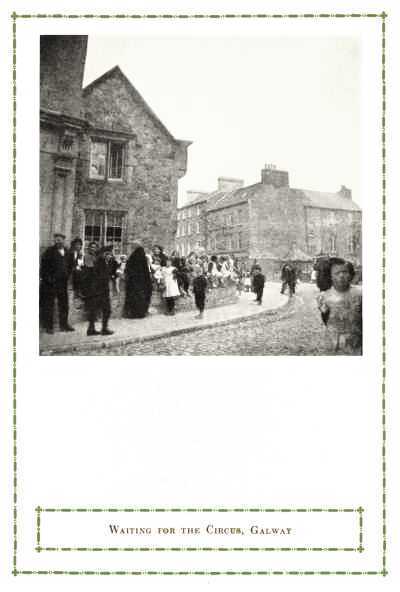

But real rain has no terrors for countryman or city man in Ireland. I attended a concert at the exhibition in Dublin (and it would not have been a tax on the imagination to pretend one was at Lunar Park in Coney Island or at the French Exposition or the Pan-American). There was the usual bandstand, and the Dublin populace to the extent of several thousands were seated on little chairs listening to the combined bands of H. M. Second Life Guards, the Eighty-seventh Royal Irish Fusiliers (Faugh-a-Ballaghs) and the Forty-second Royal Highlanders (the Black Watch).

Outside the circle of those in seats passed and repassed a slowly promenading crowd made up of pretty Dublin girls and their escorts, with mustaches as spindle-waxed as ever any Frenchman's,[Pg 60] a sprinkling of English, and the ever-present Americans, with their alert eyes, the Americans straw-hatted, the English derbied, and the Irish, almost to a man, wearing huge, soft green or gray-visored cloth caps.

Suddenly the rain began to fall.

I know at least two Americans who put for shelter, but the Irish people present merely put up umbrellas and went on promenading and sitting and listening to the music. Gay strains from "The Mikado" (there were no Japanese present), somber umbrellas, colorful millinery and drizzling rain. An American crowd would have made for the main exhibition building, but I doubt if the Dubliners noticed that it was raining. Their umbrellas went up under subconscious direction.

After the concert the crowds went home in the double-decker electric trams, and every seat on the roof of every car was filled by the holiday crowd, although[Pg 61] the rain was still coming down in a relentless fashion.

In the north they would have called it a bit soft. I know we felt like mush when we arrived at our hotel.

The Joys of Third-Class Travel

IN Ireland, if you wish to travel third class, it is well to get into a carriage marked "non smoking." If there is no sign on it it is a smoking compartment, quite probably, the custom here being often the direct opposite of that in Great Britain.

If you are traveling with women in the party the second class is advisable, but the third has this advantage—it saves you money that you can spend on worthless trinkets that may be confiscated by our customs house officers.

I have been ten days in the north of Ireland and I met my first drunken man in a third-class carriage.

Will the W. C. T. U. kindly make a note of this? Allow me to repeat for[Pg 63] the benefit of those who took up the paper after I had begun—I have been ten days in Ireland and have traveled afoot, acar, and on train and tram through half a dozen northern counties and have been on the outlook for picturesque sights, and I saw my first drunken man yesterday afternoon—the afternoon of the tenth day.

He was in a third-class smoking compartment, and in my hurry to make my train I stepped in without noticing the absence of the sign.

He was a very old and rather nice-looking, clean-shaven man, and his instincts were for the most part of the kindliest, but he would have irritated Charles Dickens exceedingly, for he was an inveterate spitter, of wonderful aim, and, like the beautiful lady in the vaudeville shows whose husband surrounds her with knives without once touching her, I was surrounded but unharmed. When the old man saw my straw hat a gleam of interest came into[Pg 64] his dull eye, and he came over and sat down right opposite me.

"Are ye a Yankee?" said he. I assured him that I was. "I thought so be your hat, but you don't talk like a Yankee." So I handed him out a few "by Goshes," which he failed to recognize and told me plainly that he doubted my nationality. Except for my hat I was no Yankee. Now my hat was made in New York, but I knew that this was a subtlety that would pass him, so I again proclaimed my nationality, and he asked me with great politeness if I objected to his smoking (keeping up his fusillade all the time) and I with polite insincerity told him that I didn't. For his intentions were of the kindliest. I believe he would have stopped spitting if I had asked him to, but I hated to deprive so old a man of so quiet a pleasure.

The talk now turned to the condition of Ireland, and he told me in his maudlin, thickly articulated way that Ireland was on the eve of a great industrial revival. As I had repeatedly heard this from the lips of perfectly sober people I believed it. I told him that he would live to see a more prosperous Ireland.

Geese in Galway

This he refused to believe and once more asked me if I was as American as my hat. I assured him that perhaps I was even more so and that his grandchildren would surely live to see Triumphant Ireland. This he accepted gladly, and coming to his place of departure, bade me kindly farewell, and stumbled over his own feet out of the compartment. And I immediately changed to one where smoking was not allowed.

It was on the same journey that I

stopped at a place called Omagh, and

while waiting for a connection we were

at the station some time. I was reading,

but suddenly became conscious that some

young people were having a very happy

time, for peal after peal of laughter rang[Pg 65]

[Pg 66]

through the station. After awhile I looked

up and found that I was the cause of all

this joy on the part of young Ireland.

There were three or four girls absolutely

absorbed in me and my appearance.

I supposed it was again the American

hat, but suddenly one of the girls

"pulled a face" that I recognized as a

caricature of my own none too merry

countenance, and the group went off into

new peals of merriment.

"How pleasant a thing it is," thought I, "that by the mere exhibition of the face nature gave me in America I can amuse perfect strangers in a far-off land," and I smiled benignantly at the young women, which had the effect of nearly sending them into hysterics.

Life was a little darker for them after the train pulled out, but I could not stay in Omagh for the mere purpose of exciting their risibles by the exposition of my gloomy features.

Everywhere I go I am a marked man.[Pg 67] I feared for a time that there was something the matter with my appearance, but at Enniskillen I fell in with a young locomotive engineer from California, and he told me that he too aroused attention wherever he went, and that in Cork youngsters followed him shouting "Yankee!" Fancy a "Yankee" from California!

At Enniskillen I went for a walk with this young engine driver and we passed two pretty young girls, of whom he inquired the way to the park. It seems that the young women were on their way there themselves and they very obligingly showed us how to go. It occurred to the gallant young Californian that such an exhibition of kindliness was worth rewarding, and he asked the ladies if they did not care to stroll through the park. They, having nothing else to do and the evening being fine, consented, and we made a merry quartette.

I have been somewhat disappointed in[Pg 68] the Irishman as a wit in my actual contact with him on his native heath, but these girls showed that wit was still to be found. They were very quick at decorous repartee, and although my San Francisco friend neglected to introduce me to them (possibly because he did not know their names), I paid a tribute to their gifts of conversation.

Nor should it be imagined for a moment that they were of that sisterhood so deservedly despised by that estimable and never to be too well thought of Mrs. Grundy—they were simply working girls who were out for an evening stroll and who saw in a chance conversation with representatives of the extreme east and west of America an opportunity for mental improvement.

They were, it may be, unconventional, but how much more interesting are such people than those whose lives are ordered by rule.

We left the young women in the park[Pg 69] intent upon the glories of a day that was dying hard (after eighteen hours of daylight) and as we made our way to the hotel we agreed that a similar readiness to converse with strangers on the part of young women in New York would have given reasonable cause for various speculations.

But Ireland has a well-earned reputation for a certain thing, which the just published table of vital statistics for the year 1906 goes far to strengthen.

In the morning the young locomotive pusher and myself had attended a cattle show at Enniskillen fair grounds.

I don't mind saying that I had stayed over a day in order to go to the fair, for I have not read Irish literature for nothing, and I was perfectly willing to see a fight and ascertain the strength of a shillelagh as compared with a Celtic skull.

It was a great day for Enniskillen and for the Enniskillen Guards, who were out in force. There were also pretty[Pg 70] maidens from all the surrounding counties and not a few of the gentry who had been attracted by the jumping contests.

But—what a disappointment.

Irishmen? Why, you'll see more Irishmen any pleasant day below Fourteenth Street in New York. And those that were there were so painfully well behaved and quiet. And as for speaking the Irish dialect—well, I wish that some of the Irish comedians who have been persuaded that Irishmen wear green whiskers would come over here and listen to Irishmen speak. They wouldn't understand them, they speak so like other people.

For ginger and noise and varied interests any New England cattle show has this one beaten to a pulp—if one may use so common an expression in a newspaper.

The noisiest things there were the bulls, and they were vociferous and huge. But the men were soft spoken and there seemed little of the "Well, I swan! I[Pg 71] hain't seen you for more'n two years. How's it goin'?" "Oh, fair to middlin'. Able to set up an' eat spoon vittles" atmosphere in the place, although undoubtedly it was a great gathering of people who seldom met. Not a single side show. Not a three-card monte man or a whip seller or a vendor of non-intoxicants.

There was just one man selling what must have been mock oranges, for such mockeries of oranges I never saw. They were the size of peaches and the engineer told me they were filled with dusty pulp.

I bought none.

The racing and fence jumping in the afternoon were interesting, but there was no wild Yankee excitement on the part of the crowd and no hilarity. There was only one man that I noticed as having taken more than was necessary, and the only effect it had on him was to unlock the flood gates of an incoherent eloquence[Pg 72] that caused a great deal of amusement to those who were able to extricate a sequence of ideas from the alcoholic freshet of words.

One venerable-looking man, with a flowing white beard of the sort formerly worn by Americans of the requisite years, fell from a fence where he was viewing the jumping and was knocked out for a time. He had been "overcome by the heat," at which, out of respect to him, I took off my overcoat. The Irish idea of heat is different from the New York one.

The splendid old fellow had served thirty-three years on the police force and had been a police pensioner for thirty-one years, and as he must have been twenty-one when he joined the force he was upwards of eighty-five.

Would Edward Everett Hale view a race from a picket fence? There is something in the Irish air conducive to longevity. In the evening I saw the old man standing in the doorway of a[Pg 73] temperance hotel talking with men some seventy years younger than he.

A local tradesman told me that in the town of Enniskillen where formerly any public gathering was sure to be followed by a public fight, he had seen the Catholic band and the Orangemen's band playing amicably the same tune (I'll bet it wasn't "The Wearing of the Green"), as they marched side by side up the main street.

The world do move.

A Few Irish Stories

IF you enter Ireland by the north, as I did, you will not hear really satisfying Irish dialect until you reach Dublin. The dialect in the north is very like Scotch, yet if it were set down absolutely phonetically it would be neither Scotch nor Irish to the average reader, but a new and hard dialect, and he would promptly skip the story that was clothed in this strange dress.

But in Dublin one hears two kinds of speech, the most rolling, full and satisfying dialect and also the most perfect English to be found in the British Isles.

It is a delight to hear one's mother tongue spoken with such careless precision, with just the suspicion of a brogue to it. I am told it is really the way that English was spoken when the most successful playwright was not Shaw, but Shakespeare.

Dublin Bay

The folk tale that follows was told me, not by a Dublin jarvey, but by a Dublin artist whose command of the right word was as great as his command of his brush.

He regaled me with many stories of Irishmen and Ireland and never let pass a chance to abuse the English in the most amusingly good-natured way. To him the English as a race were a hateful, selfish lot. Most of the Englishmen he knew personally were exceptions to this rule, but he was convinced that the average Englishman was a man who was nurtured in selfishness and hypocritical puritanism.

But this is far afield from his story of the first looking glass.

Once upon a time (said my friend)[Pg 76] a man was out walking by the edge of the ocean and he picked up a looking glass.

Into the glass he looked and he saw there the face of himself.

"Oh," said he, "'tis a picture of my father," and he took it to his cabin and hung it on the wall. And often he would go to look at it, and always he said, "'Tis a picture of my father."

But one day he took to himself a wife, and when she went to the mirror and looked in she said:

"I thought you said this was a picture of your father. Sure, it is a picture of an ugly, red-headed woman. Who is she?"

"What have ye?" said the man. "Step away and let me to it."

So she stepped away and let him to it and he looked at it again.

"Ah," said he with a sigh (for his father was dead), "'tis a picture of my father."

"Step away," said she, "and let me[Pg 77] see if it's no eyes at all I have. What have you with pictures of women?"

So he stepped away and let her to it, and she looked in it again.

"An ugly, red-headed woman it is," said she. "You had a lover before me," and she was very angry.

"Sure we'll leave it to the priest," said he.

And when the priest passed by they called him in and said, "Father, tell us what it is that this picture is about. I say it is my father, who is dead."

"And I say it is a red-haired woman I never saw," said the woman.

"Step away," said the priest, with authority, "and let me to it."

So they stepped away and let the priest to it, and he looked at it.

"Sure neither you nor the woman was right. What eyes have ye? It is a picture of a holy father. I will take it to adorn the church."

And he took it away with him, to[Pg 78] the gladness of the wife, who hated the woman her husband had in the frame, and to the grief of the man, who could see his father no more.

But in the church was the picture of a holy man.

Quite the folklore quality.

I heard a story of a well-known Dublin priest, Father Healy, very witty and very kindly, who was invited by a millionaire, probably a brewer, to go on a cruise with him.

Over the seas they sailed and landed at many ports, and the priest could not put his hand into his pocket, for he was the guest of the millionaire.

At last they returned to Dublin and the millionaire, being a man of simplicity of character, the two took a tram to their destination.

"Now it's my turn," said the priest, with a twinkle in his eye, and, putting his hand in his pocket, he paid the fare for the two.

A Dublin Ice Cart

And here's another.

Two Irishmen were in Berlin at a music hall, and just in front of them sat two officers with their shakos on their heads.

Leaning forward, with a reputation for courtesy to sustain, one of the Irishmen said, pleasantly, "Please remove your helmet; I can't see the stage for the plume."

By way of reply the German officer insolently flipped the Irishman in the face with his glove.

In a second the Irishman was on his feet and in another second the officer's face was bleeding from a crashing blow.

Satisfaction having been thus obtained, the two Irishmen left the cafe and returned to their hotel, where they boasted of the affair.

Fortunately kind friends at once showed them the necessity of immediately crossing the frontier.

That the Irishman had not been run[Pg 80] through by the officer's sword was due to the fact that he was a foreigner.

Speaking of fights, the other day an American friend of mine was taking a walk in Dublin and he came on a street fight. Four men were engaged in it, and no one else was interfering. Passers by glanced over their shoulders and walked on. Two women, evidently related to the contestants, stood by awaiting the result.

My friend mounted a flight of steps and watched the affair with unaffected interest.

A member of the Dublin constabulary happened to pass the street, and, glancing down, saw to his disgust that it was up to him to stop a fight.

Slowly he paced toward them, giving them time to finish at least one round.

But the two women saw him coming and, rushing into the mixture of fists and arms and legs, hustled the combatants into the house, and the policeman went[Pg 81] along his beat twirling, not his club, but his waxed mustache.

I told a Dublin man of this incident, deploring my luck in not having come across it with my camera in my hand.

He said: "That policeman was undoubtedly sorry that he happened on the row. He would much have preferred to let them fight it out while he sauntered by on another street all unknowing. Not that he was afraid to run them in, but that an Irishman loves a fight."

Another sight that I saw myself at a time when my camera was not with me was two little boys, not five years apiece, engaged in a wrestling match under the auspices of their father, who proudly told me that they were very good at it. The little fellows shook hands, flew at each other, and wrestled for all they were worth. And from the time they clinched until one or the other was thrown they were laughing with joy. They wrestled[Pg 82] for several rounds, but the laughter never left them.

How much better it is for little children to learn to fight under the watchful and appreciative eye of a kind father than to learn at the hands of vindictive strangers.

O'Connell's Monument, Dublin

Snapping and Tipping

THE poor man never knows the cares and responsibilities that beset the man of wealth, and the man without a kodak does not know how keen is the disappointment of a picture missed—be the cause what it may.

Heretofore I have traveled care free for two reasons: one was I never had any money to speak of, and the other was I never carried a camera. I looked at the superb view, or the picturesque street group, solely for its passing interest, with never a thought of locking it up in a black box for the future delectation of my friends, and to bore transient visitors who, as I have noticed, always begin to look up their time tables when the snapshot[Pg 84] album is produced of a rainy Sunday afternoon.

But this year some one with the glib tongue of a salesman persuaded me of the delights that were consequent on the pressing of a button, and I purchased a camera of the sort that makes its owner a marked man.

The first two or three days I was as conscious as a man who has just shaved his mustache on a dare, and who expects his wife home from the country any minute. I fancied that every one knew I was a novice, although even I hadn't seen any of my pictures as yet.

I snapped a number of friends on the steamer, and even had the audacity to make the captain look pleasant—but in his case it came natural, and really, when it was printed, even strangers could hear his hearty laugh whenever they looked at the picture, so true to life was it.

Of course it was beginner's luck, but as I went on snapping and getting the[Pg 85] films developed I found that I had picked up a fine lens, and the pictures I was taking were really worth while, and then—

Say, have you ever had hen fever? Has your pulse ever quickened at sight of an egg you could call your own? Have you ever breathed hard, when the old hen led forth thirteen fluffy chickens and you reflected that thirteen chickens would reach the egg-laying stage in seven months, and that if each of them hatched out thirteen you would have one hundred and sixty-nine inside of a year—and then have you gone out and bought twenty old hens, so as to have wholesale success—with deplorable results? If you have done all these things you know what a man does whose first snapshots are successful. I laid in supplies of films till my pockets bulged and my purse looked lean.

And the first time the sun shone after landing at 'Derry, I went out to see the Giant's Causeway—and left my camera behind me.

Then I experienced for the first time the sensation as of personal loss, when the views that might have been mine were left where they grew.

On my way back I came on a hardened old sinner of sixty odd years teaching a little kiddie of four to smoke a cigarette. If I had had my camera I could have batted the old man over the head with it. But it was in the hotel.

When I show my views to visitors they will say, "And didn't you go to the Giant's Causeway?" nor will they accept my reason for the lack of a view. And I feel that the set is incomplete.

As time went on I noticed several things that are probably obvious to every amateur. One was that on the days on which I remembered to take my camera I saw very commonplace subjects and only snapped because I had the habit. Another was that no matter how fine the weather was when I set out with my camera, it was sure to cloud up, just as we reached the castle or met the pretty peasant girl, who was only too willing to be taken.

On the Road to Lismore, in a Rain Storm

One day I was walking from Cappoquin to Lismore, all unconscious of what lay before me, and just for wantonness I took trees and pictures that might have been in any country. At last I had but two films left, and then the meeting of several droves of cattle coming from Lismore told me that it must be Fair Day there. Just then lovely, noble, glorious Lismore castle burst on my view and I had to take it.

And then I came on the fair and saw pictures at every turn.

Funny little donkeys with heads quite buried in burlap bags the while they sought for oats, gay-petticoated and pretty-faced women in groups, grizzled farmers that looked the part, waterbutts on wheels in Rembrandtesque passageways, leading to sunlit courtyards beyond—regular prize winners if one had any sort of luck.

And then a man with an ingratiating brogue asked me to take him and his cart and almost before I knew it I had taken a sow that weighed all of five hundred pounds, and my snapshooting was over for the day.

You may be sure that next day I went well prepared, but Fair Day is only once a month, and fair days are not much more plentiful, and it rained all day, and the only thing I saw worth taking was a sort of Don Quixote windmill that had been run by a horse probably years before the expression "the curse o' Crummel" (Cromwell) came to be used, and I was in a swiftly moving train and there was a woman in the way—oh! there's no doubt that camerading is fascinating, but it is also vexatious.

Still, my advice to those about to travel is—take a camera. If it's a very rainy Sunday you may want them to leave on an early train.

Tipping is a subject that is always[Pg 89] worth discussing. A man does not like to give less than the usual tip, and he ought not to give more, because it makes it hard for the next man, who may not be able to afford much of an expenditure.

Tipping in Ireland is a very mild thing compared to continental tipping. I'll never forget my first experience in Amsterdam. I have spent many agreeable and useful years since then, and the world has been better for my presence, for eighty-four months at least, since that day, but the comic opera features of that first wholesale tipping stand out as if I heard the whole thing last night at some Broadway theater.

There were two of us, and we had spent two delightful days in Amsterdam, doing the picture galleries and confirming Baedeker as hard as we could, and now we must give up the two huge rooms on the first floor that we occupied at the Grand Hotel (to give it a name) and make our way to other Dutch hostelries.

I said to Massenger, "How about tipping? Does it obtain in Holland?"

"Oh, yes," said Massenger, with a gleam in his eye. "It obtains all right. You leave it to them."

"How much shall I leave to them?" said I, looking at the small coins I had withdrawn from my pocket.

"Well, we have been royally treated, and there are a good many waiters and chambermaids and 'portiers,' and a proprietor or two, and the equivalent for boots, and the 'bus driver."

"But how are we to get them all?"

"Just pay your bill and you'll get them all right," said Massenger. (I should explain that whoever travels with me is called Massenger. It saves trouble.)

I did not quite understand, but I signified my intention of paying my bill, and the proprietor or his steward was all bows and smiles, and handed it to me, at the same time ringing a bell.

Then the chorus began to assemble.[Pg 91] Lads and maidens in the persons of waiters whom I had never seen, and chambermaids of whom I had never heard, began to swarm into the office.

After they had ranged themselves picturesquely the boots began to arrive. Some from neighboring hotels who had heard the bell came running in, and grouped themselves behind the maids. Then a head waiter who looked like a tenor came seriously in and I expected that in a moment I would hear:

I looked at Massenger and asked him what it all meant.

"It's in our honor," said he. "We've got to shell out."

And sure enough it was. We had to disgorge pro rata to all the assembled ones, and Massenger said afterward that he thought one or two of the guests came in for certain of our gratuities.

When we stepped into the 'bus, quite innocent of coins of any sort, I listened, expecting to hear:

They got it all right, but I was quite unnerved for some time. The attack had been so sudden.

In Ireland there is nothing to equal this for system, and a copper does make a man feel grateful—or at least it does make him express gratitude. I have yet to hear curses in Ireland.

But when you visit private houses you don't know what to do. Tips are expected there—not by everybody, but by maid and coachman, anyhow, and you wonder what is the right thing to do.

To be sure you have caused trouble. You have placed your boots outside your door, just as you have latterly learned to do at home, and it was a maid who gave them that dull polish that wears out in a half hour. Leave polish behind when you leave America—that seems, by the way, to be the motto of a good many traveling Americans, but I referred to the kind that you can see your face in when imparted by an Italian.

Milk Wagon, Mallow

I had an experience when on my way to visit Lady ——, in County Monaghan, in the central part of Ireland.

Just how much to tip a coachman of a "Lady" I did not know. A shilling did not seem enough, and two shillings seemed a good deal, and the fellow did not have the arrogance of an English coachman. He was simple and kindly, and was willing to talk to me, although he never ventured a word unless I spoke to him.

When I had alighted at Ballybully

station a ragged man had seized my

valise, and on ascertaining my destination[Pg 93]

[Pg 94]

had carried it to a smart jaunting

car driven by a liveried driver. I offered

him a copper, and he looked at it and

said, "Sure, you're too rich a man to be

contint with that."

So to contint meself I gave him sixpence, just what I had paid for having my trunk carried one hundred and eighty miles, and climbed to the car.

On the way to the estate of Lady Clancarty (to give her a name also) I figured on what I'd better give. To give too much would be as bad as to give too little. Still, if it cost a sixpence for my suit case to go a hundred yards, a three-mile drive should be worth a half pound at least.

At last, just as we were driving in at the lodge gates, I foresaw that I must make haste—as it would never do to hand out my tip in the presence of my hostess—so I reached over the "well" and handed two shillings to the driver. He seemed surprised and pulled a bit[Pg 95] hard on the left line. There was a swerve, a loud snap, and the step of the car was broken short off against the gate!

I was conscience-stricken, but said not a word for a minute. Then the driver said, "I've been driving for twinty-three years and niver had an accident before."

He had jumped out and thrown the step into the "well" between us.

I had visions of the sacking of the old family driver, and all because I had not known how much of a gratuity to give him.

But when I offered to make up the damage he said, "Indeed an' I'll be able to fix it myself." And fix it he did, so that no one was the wiser.

But the pain of those few moments when I expected to be driven into the presence of my hostess with the car a wreck will not soon fade.

As a matter of fact, it was a good half mile to the house after we left the lodge, and when we arrived I jumped from[Pg 96] the seat without using the step, and no one ever knew the humiliation that had come to the driver after twenty-three years.

Random Remarks on Things Corkonian

THEY told me that Cork was a very dirty city. They even said it was filthy, and they said it in such a way as to reflect on Irishmen in general and Corkonians in particular.

Yes, they said that Cork was a dirty city, and so I found it—almost as dirty as New York. This may sound like a strong statement, but I mean it.

When I arrived in Cork I saw a hill and made for it at once, because after railway there is nothing that so takes the kinks out of a fellow's legs as a walk up a stiff hill. And anyhow I was on a walking tour.

I arrived at the top about sunset. On reading this sentence over I find that it[Pg 98] sounds as if the hill was an all-day journey, but it was only a matter of a few squares, and when I started the sun had long since made up its mind to set.

In Ireland the sun takes on Irish ways, and is just a little dilatory. It always means to set, and it always does set in time to avoid being out in the dark, but it's "an unconscionably long time a dying."

At the summit of the hill I saw a church steeple that appealed to my esthetic sense, and I asked a little boy what church it was.

"Shandon churrch, sirr," said he with the rapid and undulating utterance of the Corkonian.

"Where the bells are?" said I.

"Yes," said he, smiling. "And over beyont is the Lee."

"The pleasant waters of the river Lee," I quoted at him, and he smiled again. Probably every traveler who goes to Cork quotes the lovely old bit of doggerel,[Pg 99] but the Corkonian smiles and smiles.

The river Lee runs through the center of Cork, and at evening it is a favorite place for fishing, also for learning to swim on dry land.

The fishermen seem to fish for the love of casting, and the little boys swim on the pavement—two pursuits as useless as they are pleasant. Over the bridge the fishermen leaned, and cast their lines in anything but pleasant places—for the river is malodorous—and the little boys stood on benches and dived to the pavement, where they spat and then went through the motions of swimming.

There were dozens of the little boys, and most of them seemed to be brothers. Some of them were quite expert in diving backward, and all of them were dirty, but they seemed to be happy. I could not help thinking how soon the Celtic mind begins to use symbols, for it was easy to[Pg 100] see that when the boys spat it signified a watering place to them. I dare say they were breaking a city ordinance in spitting, and if they knew that they were that much happier—stolen sweets are the sweetest.

During the time I watched the setting sun—which was still at it and, by the way, performed some lovely variations on a simple color scheme in the sky—not even an eel was caught, but the fishermen cast under the bridge, let their bait float down the (un) pleasant waters, and drew in their lines again and again—mute examples of a patience that one does not associate with Ireland.

At last I left them and started out to find Shandon church, which seemed but a few squares away.

My pathway led through the slums, and up a hill so steep that I hope horses only use it as a means of descent. I passed one fireside where the folks looked cosy and happy and warm. It was a summer evening, but chilly, and the[Pg 101] place into which I looked was a shop for the sale of coal. Shoemakers' children are generally barefooted, but these people were burning their own coal, and the mother and the dirty children sprawled around the store or home, in a shadow-casting way, that would have delighted Mynheer Rembrandt if he had passed by.

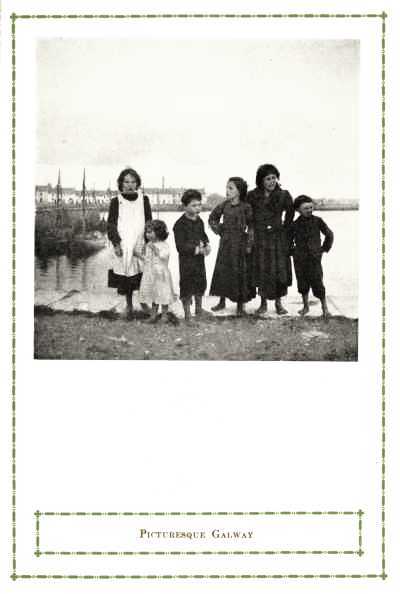

I was struck with the population of Cork. It was most of it on the sidewalk, and nearly all of it was under sixteen. Pretty faces, too, among them, and happy looking. I think that sympathy would have been wasted on them. They had so much more room than they would have had in New York, and they were not any dirtier—than New Yorkers of the same class.

After I had reached the top of the hill I turned and looked for Shandon church and it was gone. I asked a boy what had become of it, and he told me that in following my winding way through the convolutions known as streets I had[Pg 102] gotten as far from the church as I could in the time. He told me pleasantly just how to go to get to the church, and it involved going to the foot of the hill and beginning again.

I asked a number of times after that, and always got courteous but rapid answers. The Irish are great talkers, but the Corkonian could handicap himself with a morning's silence, and beat his brothers from other counties before evening.

At last I came on the church, passing, just before I reached it, the Greencoat Hospital National School, with its quaint and curious (to quote three of Poe's words) statues of a green-coated boy and girl.

I asked a man when the bells began to ring (for I had been told that they only rang at night).

"'Every quar-rter of an hour, sirr, they'll be ringing in a couple of minutes, sirr."

Green Coat Hospital, Cork

One likes to indulge in a bit of sentiment sometimes, and I stood and waited to hear the bells of Shandon that sound so grand on the pleasant waters of the river Lee. I had left the Lee to the fishermen and the make-believe swimmers, but the bells would sound sweetly here under the tower that held them.

A minute passed, and then another, and then I heard music—music that called forth old memories of days long since dead. How it pealed out its delight on the (icy) air of night. And how well I knew the tune:

No, it was not the chimes, but a nurse in the hospital at a piano. Before she had finished, Shandon bells began, but they played what did not blend with what she sang, and I went on my way thinking on the potency of music.

I passed on down where the river Lee flowed, and the fishermen were still fishing, but the little boys had tired of swimming.

Two signs met me at nearly every corner. One read, "James J. Murphy & Co.," and the other "Beamish & Crawford," or "Crawford & Beamish," I forget which. Both marked the places of publicans (and sinners, I doubt not), and both were brewers' names. The publican's own name never appeared, but these names were omnipresent.

Again I thought of Shandon bells, and the romantic song, "Down Where the Wurzburger Flows," and leaving the Lee still flowing I sought my hotel.

I would like to make a revolutionary statement, that is more often thought than uttered, but before I make it, I would like to say that there are two classes of travelers: those who think there is nothing in Europe that compares with similar things in America, and those who think there is nothing in America that can hold a candle to similar things in Europe.

I hope I belong to neither class. If[Pg 105] I mistake not, I am a Pharisee, and thank my stars that I am not as other men are. Most of us are Pharisees, but few will admit it.

I began being a Pharisee when I was a small child, and that is the time that most people begin.

I kept it up. In this, I am—like the multitude.

Having thus stated my position, let me go on to say, that I am perfectly willing to admit that this or that bit of scenery in France, or Switzerland, or England, or Ireland, lays over anything of the sort I ever saw in America, if I think it does, and I am equally willing to say, that America has almost unknown bits that are far better than admired and poet-ridden places in Europe.

Twin Lakes in Connecticut is one of them, and Killarney is a poet-ridden place.