Title: Dorothy at Skyrie

Author: Evelyn Raymond

Release date: October 20, 2012 [eBook #41117]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

New York

THE PLATT & PECK CO.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Early Visitors | 9 |

| II. | An Unfortunate Affair | 22 |

| III. | On the Road to South Meadow | 41 |

| IV. | The Learned Blacksmith | 56 |

| V. | An Accident and an Apparition | 69 |

| VI. | More Peculiar Visitors | 85 |

| VII. | At the Office of a Justice | 96 |

| VIII. | A Walk and Its Ending | 112 |

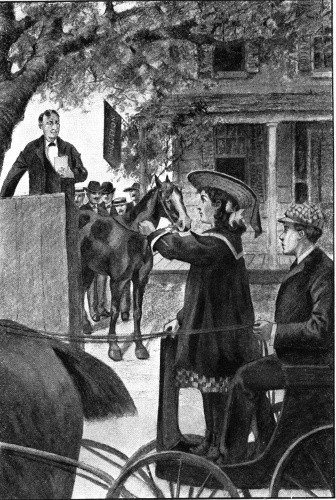

| IX. | A Live Stock Sale | 127 |

| X. | At Milking-Time | 143 |

| XI. | Helpers | 158 |

| XII. | Seth Winters and His Friends | 177 |

| XIII. | A Beneficent Bee | 195 |

| XIV. | An Astonishing Question | 210 |

| XV. | Concerning Several Matters | 227 |

| XVI. | The Fate of Daisy-Jewel | 245 |

| XVII. | On the Road to the Circus | 259 |

| XVIII. | That South Meadow | 275 |

| XIX. | Dorothy Has Another Secret | 293 |

| XX. | All's Well That Ends Well | 308 |

"Hello! How-de-do?"

This salutation was so sudden and unexpected that Dorothy Chester jumped, and rising from the grass, where she had been searching for wild strawberries, beheld a row of pink sunbonnets behind the great stone wall.

Within the sunbonnets were three equally rosy faces, of varying sizes, each smiling broadly and each full of a friendly curiosity. It was from the biggest face that the voice had come, and Dorothy responded with a courteous "Good-morning!" then waited for further advances. These came promptly.

"I'm Alfaretta Babcock; this one's Baretta Babcock; and this other one, she's Claretta Babcock. The baby that's to home and can't walk yet—only just creep—she's Diaretta Babcock."

Dorothy laughed. The alphabetical names attached to these several "Babcocks" sounded very funny and she couldn't help her amusement, even if it were rude. However, no rudeness was suspected, and Alfaretta laughed in return, then walked a few steps to the bar-way, with her sisters following. These she hoisted upon the rails, and putting her hands upon the topmost one vaulted over it with an ease that astonished the city-bred Dorothy.

"Why! how well you did that! Like a regular gymnast!" she exclaimed, admiringly, and observing that this was a girl of about her own age though much larger and stronger in build, as the broad back now turned toward her showed.

Alfaretta did not reply, except to bid the children on the other side of the bars to "hop over," and when they were too timid to "hop" without aid she seized their hands and pulled them across, letting them drop on the long grass in a haphazard way that made Dorothy gasp and exclaim:

"Oh! you'll hurt them!"

Alfaretta faced about and keenly scrutinized Dorothy's face, demanding:

"You makin' fun, or not?"

"Fun? I don't see anything funny in such tumbles as those, and I surely wasn't making fun of the way you sprang over that fence. I wish I was as nimble."

"Pooh! That's nothing. I'm the best climber anywheres on the mounting. I can beat any boy 'round, even if I do wear petticoats. I'll learn you if you want me to," offered the visitor, generously.

"Thank you," said Dorothy, rather doubtfully. She did not yet know how necessary climbing might be, in her new country life, but her aspirations did not tend that way. Then thinking that this trio of Babcocks might have come upon an errand to Mrs. Chester, she inquired: "Did you want to see my mother?"

Alfaretta sat down on a convenient bowlder and her sisters did the same, while she remarked:

"You may as well set, yourself, for we come to see you more'n anybody else. Besides, you haven't got any mother. I know all about you."

"Indeed! How can that be, since I came to Skyrie only last night? And I came out to find some wild strawberries for my father's breakfast—we haven't had it yet."

If this was intended for a polite hint that it was too early in the day for visiting it fell pointless, for Alfaretta answered, without the slightest hesitation:

"We haven't, neither. We've come to spend the day. Ma she said she thought you might be lonesome and 'twasn't no more'n neighborly to start in to once. More'n that, she's glad to get us out the way, 'cause she's going down mounting to the 'other village' to 'Liza Jane's store—Claretta, stop suckin' your thumb! Dorothy Chester don't do that, and ma said she'd put some more that picra on it if you don't quit—to buy us some gingham for dresses. She heard 'Liza Jane had got in a lot real cheap and she's going to get a web 'fore it's all picked over."

Tired of standing, Dorothy had also dropped down upon the bowlder and now was regarding her uninvited guests with much of the same curiosity they were bestowing upon her, and Alfaretta obligingly shoved her smallest sister off the rock to make more room for their hostess.

"Don't do that! What makes you so rough with them? Besides, I must go. Mother will need me and I don't see any berries," said Dorothy, springing up. "Excuse me, please."

As she stooped to pick up the tin pail she had left on the grass, Alfaretta snatched it from her grasp and was off down the slope, calling back:

"Come on, then! I know where they're thicker 'n molasses in the winter time!"

With their unvarying imitation of their elder sister the two little girls likewise scampered away, and fearing she would lose mother Martha's new "bucket" Dorothy followed also. Across a little hollow in the field and up another rise Alfaretta led the way and there fulfilled her promise, for the northern hillside was red with the fruit. With little outcries of delight all of them went down upon their knees and began to gather it; the younger ones greedily stuffing their mouths till their faces were as red as the berries, but Alfaretta scrupulously dropping all but a few extra-sized ones into the rapidly filling pail. But she kept close to Dorothy and laughingly forced these finer ones between her protesting lips, demanding once:

"Ever go berryin' before, Dorothy C.?"

"Not—this kind of 'berrying,'" answered the other, with a keen recollection of the "berrying" she had done for the truck-farmer, Miranda Stott. "But how happened you to call me that 'Dorothy C.' as only my own people do? Who told you about me?"

"Why—everybody, I guess. Anyhow, I know all about you. See if I don't. You was a 'foundling' on the Chesterses' doorstep and they brought you up. You was kidnapped, and that there Barlow boy that Mis' Calvert's brought to Deerhurst helped you to get away. Mis' Calvert, she saw you in a lane, or somethin', and fetched you back to that Baltimore city where the both of you lived. Then she brought you here, too, 'cause Mr. Chester he's got something the matter with his legs and has had to come to the mounting and live on Skyrie farm. If he makes a livin' off it it'll be more'n anybody else ever done, ma says. The old man that owned it 'fore he gave it to Mis' Chester, he was crazy as a loon. Believed there was a gold mine, or somethin' like that, under the south medder—'D you ever hear such a thing! Ma says all the gold'll ever be dug out o' Skyrie is them rocks he put into his stone walls. The whole farm was just clear rocks, ma says, and that's why the walls are four five feet thick, some of 'em more. There wasn't no other place to put 'em and besides he wanted it that way. The whole of Skyrie farm is bounded—Ever study jogaphy? Know how to bound the states? Course. I s'pose you've been to school more'n I have: but I can bound Skyrie for you all right. On the north by a stone wall, 'joining Judge Satterlee's place: on the south by a stone wall right against Cat Hollow—that's where I live, other side the mounting but real nigh, cut 'cross lots. On the east—I guess that's Mis' Calvert's woods; an' west—Oh! fiddlesticks—I don't know whose land that is, but it's kept off by more stone wall an' the thickest of the lot. Where the stone wall had to be left open for bar-ways, to drive through, he went to work and nailed up the bars. That's why I had to hop over, 'stead of letting 'em down. Say, our pail is filling real fast. Pity you hadn't a bigger one. After we've et breakfast we can come and get a lot for Mis' Chester to preserve. Ma she's done hers a'ready. Let's rest a minute."

Dorothy agreed. She was finding this new acquaintance most attractive, despite the forwardness of her manner, for there was the jolliest of smiles constantly breaking out on the round, freckled face, and the blue eyes expressed a deal of admiration for this city girl, so unlike herself in manner and appearance. Her tongue had proved fully as nimble as her fingers, and now while she rested she began afresh:

"Ma says I could talk the legs off an iron pot, if I tried, and I guess you're thinkin' so too. Never mind. Can't help it. Ain't it queer to be adopted? There was a power of money, real, good money, offered for you, wasn't there! My heart! Think of one girl bein' worth so much to anybody! It was all in the papers, but ma says likely we never would have noticed it, only Mis' Satterlee she showed it to ma, account of Mis' Chester moving up here an' going nigh crazy over losin' you. Ma she washes for the Satterlees, and they give us their old papers. Pa he loves to read. Ma says he'd rather set an' read all day than do a stroke to earn an honest livin'. Pa says if your folks had so many children as he has and some of 'em got away he wouldn't offer no reward for 'em, he wouldn't. But ma said: 'Now, pa, you hush! You'd cry your eyes out if Diaretta fell into the rain-barrel, or anything!' We ain't all ma's children. Four of 'em's named Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. They're hired out to work, 'cause they're older 'n what I am, and three is dead. Say, that's awful fine stuff your dress is made of. Do you wear that kind all the time? and shoes, too?"

"Yes, this is an everyday frock that dear Mrs. Calvert had made for me and gave me. She is my father's friend and is sorry for him, and does things for me, I reckon, just to help him. Of course, I wear shoes—when I have them!" laughed Dorothy, carefully refraining from looking at Alfaretta's own bare feet.

"What you laughing at?" demanded that observant young person, already joining in the mirth without knowing its cause.

"I was thinking how I was once allowed to buy a pair of shoes for myself and picked them out so small they nearly crippled me. And I have been barefooted, too, sometimes, when I was trying to escape from the truck-farm;" and once started upon the subject, Dorothy did not hesitate to complete the narrative of her adventures and, indeed, of all her short, simple life, as already related by me in another book called, "Dorothy Chester."—how she had been picked up on the doorstep by Mrs. Chester and brought up as that lady's own child—how she had been kidnapped and taken to the truck farm—how honest Jim Barlow had proved her best friend—and how at last the rich Mrs. Calvert had restored her to her foster parents at this picturesque if rather dilapidated home in the Highlands of the Hudson.

Alfaretta was likewise confidential, and with each passing moment and each fresh remembrance the liking between the two little maids strengthened. Finally, with a trifle of gloom, the country girl disclosed the fact:

"Pa he's the scolder to our house, but ma she's the licker. She says she ain't going to spoil her children by sparing rods when our 'upper lot' is full of 'em. The rods, I mean. She doesn't, neither. That's true as preachin'."

"Why, Alfaretta! Are you ever whipped? A big girl like you?"

"Huh! I may be bigger 'n you but I ain't much older. When's your birthday?"

"The second of April."

"My heart! If that don't beat the Dutch! Mine's the first. So we must be next door to twins. But lickin's! You just come to Cat Hollow any Saturday night, 'bout sundown, and you'll be in the nick of time to get a whack yourself. Ma says she's real impartial, 'cause she takes us in turn. One week she begins with me and the next time with Claretta. Diaretta ain't old enough yet to fall into line, and the boys were let off soon as they went to work and fetched in money. Ma says all of us need a lickin' once a week, anyhow, and she don't have time to bother with it only Saturday nights, after we all get washed. When do you get licked, yourself, Dorothy C.?"

"When? Never! Never in my whole life has anybody struck me. I—I wouldn't bear it—I couldn't!" cried Dorothy, indignantly. "But I mustn't stop here any longer. We've more than enough berries for breakfast and I'm so hungry. Besides, we're out of sight of the house and my father John will worry. He said last night, when he had me in his arms again after so long and so much happening, that he meant to keep me right beside him for the rest of his life. Of course, he didn't mean that exactly, and he was asleep when I came out. I waked up so early, with all the birds singing round, and oh! I think this wonderful old mountain is almost too beautiful to be true! Seems as if I'd come to fairyland, sure enough! I'm going now."

Dorothy said this with a faint hope that her visitors might depart without taxing Mrs. Chester to provide them a meal. She knew that no food was ever wasted in mother Martha's frugal household and but sufficient for three ever prepared, unless there was due warning of more to partake. Twice three would halve the rations and—at that moment, with appetite sharpened by early rising and the cool mountain air—the young hostess felt as if she could not endure the halving process.

However, her hope proved useless, for with a shout and bound, Baretta started for the cottage and Claretta kept her a close second, both crying loudly:

"I'm hungry, too! I'm hungry, too!"

Alfaretta was off with a rush, carrying the pail of berries and bursting in upon the astonished Mrs. Chester, with the announcement:

"We've come to spend the day! We're Mis' Babcock's children. See all the berries I've picked you? Is breakfast ready? 'Cause we are if it ain't!"

"Where—is—Dorothy C.?" questioned the housemistress, recognizing the extended pail as her own, wondering how it had come into this girl's hands, and failing to see any sign of her daughter, no matter how closely she peered outward.

"Why, sakes alive! Where is she?" echoed Alfaretta, with great surprise, also searching the landscape. "A minute ago she was tagging me, close, and now she isn't! My heart! What if she's gone and got herself kidnapped again!"

But nothing so dire had happened. Crossing the grassy stretch before the cottage Dorothy had caught sight of Jim Barlow's familiar figure, coming along the tree-bordered lane which led to Deerhurst, and had hurried to meet him. The shrubbery hid her from view of Mrs. Chester and the Babcock girls, and for a moment mother Martha's heart sank with the same dread she had known while her beloved child had been absent from her. "Kidnapped!" If Alfaretta had tried she couldn't have hit upon a more terrifying word to her hearer.

"O Jim! Did ever anybody see such a beautiful, beau-ti-ful spot as this? Let me hold Peter's chain—the darling dog! No, he won't get away from me! I shan't let him. You can lead Ponce—but why did you bring them? Did Mrs. Calvert know? How do you like Deerhurst? Are you going to be happy there? Shall you have a chance to study some? Must you work in the garden all the time? Oh! I want to know everything all at once and you are so slow to talk! But, Jim dear, just stop a minute and look—look! Isn't our new home lots prettier than the little brick house where we used to live—77 Brown Street, Baltimore! Do stop and look—please do!"

Obedient Jim did pause, for this small maid could always compel him to her will, though he felt he was half-disobedient to his real mistress, Mrs. Cecil, in doing so. She had sent him with a basket of fruit from her own fine garden for the family at Skyrie and had bidden him take the Great Danes along to give them their morning exercise. They were wild with delight over the outing, and their vigorous gambols not only threatened to upset the basket hung on his arm but made him caution:

"Look out, Dorothy Chester! That there dog'll get away, an' then what'll happen?"

"Why—he'll get away, silly! You just said so yourself! But I won't let him—Quiet, Peter, bad dog! Down, sir, down! No, I'm not one bit afraid of you now, even if once you did nearly kill me and scared me out of my senses! O Jim! I'm so happy—so happy! Almost too happy to live. If my precious father were only well! That's the one thing isn't just perfect."

In her joy Dorothy gave her tall friend a rapturous pat on the shoulder, and though a swift flush rose to his sunburned cheek he shook off her caress as he would the touch of a troublesome insect. In his eyes this little maid whom he had rescued from her imprisonment on Mrs. Stott's truck-farm was the most wonderful of human beings, with her dainty, graceful ways and her lovely, mobile face. All the same—she was a girl, and for girls, as such, James Barlow had a boyish contempt.

But she did not resent his action, indeed scarcely noticed it as, whirling about to suit her movements to those of Peter, she still pointed to her new home:

"They say the man who built that house was queer, but seems to me he was very wise. All of stone, so, it looks almost like a big rock and part of the mountain itself. Such cute little, tiny-paned windows! Such a funny stairway going up to the second floor on the outside! There's a little one inside—so narrow and twisted, Jim, that even I can hardly walk straight up it but have to go sidewise. Then the back of the house is even with the ground. I mean that the biggest, best room of all, which is father John's, opens right on the garden. Two stories and a cellar in front, only a wee low story behind! Like a piece of the hillside it's on. Then the vines! Did you ever see such beauties? Oh! I love it, I love it, already, and I've only been here one night. What will it be when I've lived a long time there!"

"Huh! You'll get sick enough of it—'fore long too. S'pose you hain't heard it's haunted—but I have, an' 'tis!"

"Jim Barlow! How ridiculous and—how delightful! What sort of a 'haunt' is it? Masculine, feminine, or neuter?" demanded Dorothy C., clapping her hands.

"Look out! Don't you let go that dog! You hold him tight, I tell you!" returned the lad, as her sudden action loosened the chain attached to Peter's collar. But she caught it again, deftly, and faced her friend, vexed that she saw in his face no answering enthusiasm to her own over the "loveliness" of Skyrie cottage.

"I haven't let go—yet, Master 'Fraid-cat! And you shall say my home is pretty!" she protested, imperatively. "Say it quick, too, 'cause I haven't had my breakfast and I have company waiting to eat it with me. Say it, Jim, say it!"

The boy laughed. He was very happy himself, that sunshiny morning, and felt more at ease than he had done for many days, because, at last, he was once more clad in blouse and overalls and knew that he had a busy day of congenial work before him. True, these working garments were new and of the best quality, provided by his new employer, but like in cut and comfort to those he had always worn. His feet alone bothered him, for a barefooted person could not be permitted about Deerhurst and his shoes were stiff and troublesome. Now there's nothing more trying to one's temper than feet which "hurt," and it was physical discomfort mostly that made the lad's tongue sharp and his mood unsympathetic; and thus goaded to an enthusiasm he did not feel he retorted:

"Well, it's purty enough, then, but that ruff must leak like a sieve."

"It's all mossy green on one side——"

"Where the shingles is rotten."

"And the dear little window-panes are like an old-fashioned picture!"

"A right smart of 'em is cracked or burst entirely."

"O Jim! How very unromantic you are! But you cannot say but that the vines are beautiful!"

"I've heard they're fust-class for givin' folks the rheumatiz."

Dorothy's enthusiasm ebbed. Rheumatism was the one malady that sometimes affected mother Martha's health. But she was not to be dashed by forebodings, and pointing to the garden declared:

"You cannot say a thing against our garden, anyway. Think of all that room for roses and posies and everything nice!"

"Garden? I call it a reg'lar weed-patch."

Dorothy heaved a sigh which seemed to come from her very shoes.

"You're—you're perfectly horrid, Jim Barlow. But I heard you say, once, while we were working on that truck-farm, that the thing you most longed for—after your education—was to own land. Look yonder, all that ground, inside those big stone walls, is ours, ours! Mr. Barlow. Behold and envy! Even on that untilled land flowers grow. See them?"

"Pshaw! Them's mullein. Ain't no surer sign o' poor soil than a passel o' mullein stalks. Stuns and mullein—Your pa's got a job ahead of him! Now I'm goin' on. I was told to give this basket to Mis' Chester and this note I've got in my jumper pocket to Mr. I'd ruther you'd take 'em, only I was told; and we've stood here foolin' so long, I've got to hurry like lightnin'. Take care that dog!"

With that Jim set his aching feet once more in the path of duty and Dorothy C. marched along beside him, her head held high in disdain but with a twinkle in her eye and mischief in her heart. Jim didn't like girls! Well, there was Alfaretta Babcock waiting for him, and he should be made to go through a formal introduction in punishment for his want of sympathy! She managed that he should precede her through the narrow doorway, into the very presence of the unknown, and chuckled in delight over his sudden, awkward pause, his flustered manner, and his attempt to back out of the little kitchen.

Mrs. Chester had gone up the stairs, to help her husband around the corner of the house and down the slope to the kitchen where breakfast was waiting and the three Misses Babcock with it. They sat in a row on the old lounge, their pink sunbonnets folded upon their blue-print laps, alert with the novelty of their situation and for "what next."

"Miss Alfaretta Babcock—Mr. James Barlow, of Baltimore. The Misses Baretta and Claretta Babcock—Mr. Barlow," announced Dorothy with perfect gravity, yet anticipating a funny, awkward scene. But she was unprepared for what really did happen, as Alfaretta promptly left the lounge, swept a most remarkable courtesy before the bashful lad, and seizing both his hands—dog-chain and all—in her own plump ones, exclaimed:

"Oh! Ain't I glad I come! You're the 'hero' that Mis' Judge Satterlee calls you! I meant to get to know you, soon's ever I could, but this beats the Dutch! I saw you in Mis' Calvert's carriage, last night all dressed up, and I was scared of you, but I ain't now. You might be just Matthew, or Mark, or Luke, though you're too tall for John. He's my littlest brother. Pshaw! To think any plain kind of a boy, same's them, could be a 'hero.' Ain't that queer? Did you come to breakfast, too? You fetched yours in a basket, didn't you? I would, too, but ma she hadn't nothing nice cooked up, and she was sort of scared offerin' city folks country victuals. My! Here comes Mis' Chester and her man. Won't they be tickled to see you!"

For a moment, after Alfaretta seized him, Jim looked full as flustered as Dorothy had desired: then all his awkwardness vanished before the hearty good will of the girl and he found himself shaking her hands with a warmth of cordiality equaling her own. She was as honest and simple-natured as himself, and instead of being amused by their meeting Dorothy soon felt something much nearer envy of Alfaretta's power to win liking and confidence.

Then she saw through the window father John limping down the path on his crutches, and hurried out to meet him; also to ask of the housemistress:

"Isn't there something I can do to help? How can we feed so many people? for, mother dear, Jim's come, too!"

"Oh! that's all right, deary. I cooked a lot of stuff, yesterday; made a feast for your homecoming. We'll have to use for breakfast what was meant for dinner. I was dismayed by those children coming, but I'm more than glad to have that boy here. We all owe him much, Dolly darling;" and mother Martha caught her restored child in a grateful embrace.

Poor Jim was far more ill at ease in the presence of Mr. and Mrs. Chester than he had been with Alfaretta: fidgeting under their thanks and praises, which they had vainly tried to express during their brief interview of the night before, and honestly astonished that anybody should make such ado over so trifling a matter.

"'Twan't nothin'. Not a mite. Anybody'd ha' felt sorry for a girl was coaxed away from her folks, that-a-way. Pshaw! Don't! No. I've had my breakfast a'ready. I couldn't. Mis' Calvert, the old lady, she sent me to fetch this basket o' garden sass to Mis' Chester: an' this letter was for you, sir. I was to give it to you an' nobody elst. I'm obleeged to ye, ma'am, but I couldn't. I couldn't, nohow. I'm—I'm chock-full!"

With this rather inelegant refusal, Jim turned his back on the neatly-spread table and fled through the doorway, dragging Ponce with him, overturning the too curious Claretta upon the floor, and making a vain effort to loosen Peter's chain from the arm of the chair where Dorothy had hastily fastened it.

The result was disaster. Both dogs jerked themselves free and gayly dashed forward toward the road leading down the mountain to the villages at its foot, instead of that leafy lane which would have brought them home to their own kennel. Their long chains dangled behind them, or whirled from side to side, catching in wayside obstructions, but in no wise hindering their mad rush.

Scarcely less mad was poor Jim's speed following in pursuit, and the day that had begun so joyously for him was destined to end in gloom. Only the week previous there had been an alarm of "mad dog" in the twin villages, "Upper" and "Lower" Riverside, and local authority was keen to corral any unmuzzled canines; and when these formidable Great Danes of Mrs. Calvert tore wildly through the street, people hastily retreated indoors, while the two constables with pistols, joined by a few brave citizens, gave Peter and Ponce a race for their lives.

To them it was all fun. Never, in their city restricted career, had they dreamed of such wide stretches over which to exercise their mighty limbs; and, heretofore, during their summer stays at Deerhurst they had been closely kept within bounds. They were so big that many people were frightened by that mere fact of size and it had been useless for their doting mistress to assure her neighbors that:

"They are as gentle as kittens unless they are interfered with. They always recognize the difference between honest persons and tramps."

The argument was not convincing. Even a "tramp" might be honest and, in any case, would certainly object to being bitten; therefore the beautiful creatures had lived their days out at the end of a chain and now, for the first, tasted the sweets of liberty.

The affair ended by the dogs escaping and finally making their way home almost unobserved, very weary, and reposing with an air of great innocence before their kennel door, where Ephraim the colored coachman discovered them and ejaculated in great surprise:

"Fo' de lan' o' love! How come dese yeah dogs done gone got dey chains broke? 'Peahs lak somebody gwine a spite my Miss Betty fo' keepin' 'em, anyhow. Mebbe"—here Ephraim's black face turned a shade paler—"mebbe—somepin's gwine to happen! Dere sholy is! Mebbe—mebbe some dem burgaleers I'se heerd of gwine—gwine——"

Visions of disasters too dire to be put into words cut short the old man's speech, and hastily fetching pieces of rope he proceeded to refasten the dogs to the kennel staples, and was much surprised that they submitted so quietly. Then, being as wise as he was faithful, he resolved to say nothing, at present, to the lady of Deerhurst about this incident, reflecting that:

"My Miss Betty she ain' sca'ed o' nobody, burgaleers er nothin'. Ef ol' Eph done tol' her erbout dis yeah succumstance she's boun' to set up de whole endurin' night a-lookin' out fo' trouble, wid dat dere pistol-volver in her han's, all ready fo' to shoot de fust creachah puts foot on groun'. Lak's not shoot de wrong one too. She's done got a pow'ful quick tempah, my Miss Betty has, same's all my Somerset family had, bein' fust quality folks lak dey was. No, suh! Dere's times fo' to talk an' dere's times fo' to keep yo' mouf shut. Dis yeah's one dem times, shuah ernuf."

So, fully satisfied which of these "times" the present chanced to be, the old coachman departed stableward to attend upon his beloved bays and to make ready for his mistress's morning drive.

Meanwhile, on the street of Lower Riverside, Jim Barlow had come to fresh grief. In his frantic chase of the runaway dogs he had almost caught up with Ponce, who suddenly darted into an open doorway of the post-office just as a gentleman emerged from it, carrying a pile of letters and papers just arrived in the early mail. A collision of the three was inevitable, and Ponce was the only one who came out from it intact.

With outstretched arms, believing that he had already captured one of the Great Danes, poor Jim threw himself headlong upon the gentleman, who staggered under the unexpected blow and fell backward upon the floor, with the lad atop. In the ensuing struggle to rise they forgot the dog, the animal rushing out of doors again as swiftly as he had rushed within.

Instantly there was great commotion. The postmaster hurried to the rescue, as did the crowd of other persons awaiting the distribution of the mail; but the assaulted gentleman proved as agile as he was furious and, as he gained his own feet, Jim found himself being shaken till he lost his balance again and went down at the stranger's side.

"You unmannerly lubber! How dare you? I say, how dare you knock me down like that? Set your dog on me, would you? Do you know who I am?"

The lad was slow to anger, but once roused could be as furious as the other. His natural impulse was greater than his knowledge of the world, and his answer was to send a telling blow into the gentleman's face. This was "assault" in truth, and oddly enough seemed to restore the victim to perfect coolness. With a bow he accepted the return of the eyeglasses which had been knocked from his nose during the mêlée and turned to the perturbed postmaster, saying:

"Mr. Spence, where is the nearest justice of the peace?"

"Why—why, Mr. Montaigne, sir, I think he——"

"Simmons is out of town. He and Squire Randall have both gone to Newburgh on that big case, you know," interposed a bystander.

"Sure enough. Well then, Mr. Montaigne, the nearest justice available this morning is Seth Winters, the blacksmith, up-mountain. Right near your own place, sir, you know."

"Thanks. Do you know this boy?"

"Never saw him before," answered Mr. Spence. Then, as Jim started to make his way outward through the crowd, he laid a firmly detaining hand upon his shoulder and forced him to remain or again resort to violence. "But I'll find out, sir, if you wish."

"Do so, please. Or I presume a constable can do that for me. As for you, young ruffian—we shall meet again."

With that the gentleman flicked off some of the dust which had lodged upon his fine clothing, again carefully readjusted his glasses, and stepped out to the smart little trap awaiting his convenience. Everything about the equipage and his own appearance betokened wealth, as well as did the almost servile attentions of his fellow townsmen; though one old man to whom he was a stranger inquired:

"That the fellow who's built that fine house on the Heights, beyond Deerhurst?"

Mr. Spence wheeled about and demanded in surprise:

"What? you here, Winters? And don't you know your own mountain neighbors? Did you see the whole affair?"

"I do not know that gentleman, though, of course, I do know his employees, who have brought his horses to me to be shod. Nor do I call anybody a 'neighbor' till I've found him such. The accident of living side by side can't make neighbors. My paper, please? We're going to have a glorious day."

It was noticeable that while the roughly clad old man was speaking, the excited voices of the others in the office had quieted entirely, and that as he received his weekly paper—his "one extravagance"—they also remembered and attended to the business which had brought them there.

As Mr. Winters left the place he laid his hand upon Jim's shoulder and said:

"Come with me, my lad. Our roads lie together."

The boy glanced into the rugged yet benignant face turned toward him and saw something in it which calmed his own anger; and without a word he turned and followed.

"Goodness! If the young simpleton hasn't gone off with the Squire of his own accord!" remarked one they had left behind.

But untutored Jim Barlow knew nothing of law or "justices." All he knew was that he had looked into the eyes of a friend and trusted him.

For a moment the group in the kitchen at Skyrie were dismayed by Jim Barlow's sudden departure and the escape of the dogs. Then Dorothy, who knew him best, declared:

"He'll catch them. Course. Jim always can do what he wants to do; and—shall we never, never, have our breakfast? Why, Alfaretta, you thoughtful girl! Why didn't I know enough to do that myself? Not leave it to you, the 'company'!"

Mrs. Chester turned back from the doorway, where she had been trying to follow the dogs' movements, and saw that their guest had quietly possessed herself of a colander from the closet and had hulled the berries into it; and that she was now holding it over the little sink and gently rinsing the fruit with cold water.

The housemistress smiled her prompt approval, though she somewhat marveled at this stranger's assured manner, which made her as much at home in another's house as in her own.

"Why, Alfaretta, how kind! Thank you very much. How fragrant those wild berries are! You must have a good mother to have been taught such helpful ways."

"Yes, ma'am. She's smarter'n lightnin', ma is. She's a terrible worker, too, and pa he says she tires him out she's so driv' all the time. Do you sugar your strawberries in the dish? or let folks do it theirselves, like Mis' Judge Satterlee does? She's one the 'ristocratics lives up-mounting here and a real nice woman, even if she is rich. Pa he says no rich folks can be nice. He says everybody'd ought to have just the same lot of money and no difference. But ma says 't if pa had all the money there was he'd get rid of it quicker'n you could say Jack Robinson. She says if 'twas all divided just the same 'twouldn't be no time at all 'fore it would all get round again to the same hands had it first. She says the smart ones 'd get it and the lazy ones 'd lose it—Claretta Babcock! Wipe your nose. Ma put a nice clean rag in your pocket, and come to breakfast. It's ready, ain't it, Mis' Chester?"

The greatly amused Mr. Chester had taken a chair by the window and drawn Dorothy to his side; whence, without offering her own services, she had watched the proceedings of mother Martha and Alfaretta. The one had carefully unpacked the basket which Jim had brought, and found it contained not only some fine fruit but a jar of honey, a pan of "hot bread"—without which no southern breakfast is considered complete—and half a boiled ham. For a moment, as the mistress of Skyrie surveyed these more substantial offerings she was inclined to resent them. A bit of fruit—that was one thing; but, poor though she might be, she had not yet arrived at the point of being grateful for "cold victuals"!

Yet she was almost as promptly ashamed of the feeling and remembered a saying of her wiser husband's: "It takes more grace to accept a favor than to bestow one." Besides, with these three hungry visiting children, the addition to her pantry stores would be very timely.

"Such a breakfast as this is! I never laughed so much at any meal in my life!" cried Dorothy, at last finding a chance to edge in a word of her own between Alfaretta's incessant chatterings. "But, Alfaretta, do they always call you by your whole, full name?"

"No, they don't. Most the time I'm just Alfy, or Sis. Baretta she's mostly just Retty; and Clary's Clary. Saves time, that way; though ma says no use having high-soundin' names without using 'em, so she never clips us herself. Pa he does. He says life's too short and he ain't got time to roll his tongue 'round so much. But ma she tells him 't a man 't never does anything else might as well talk big words as little ones. Pa he's a Nanarchist. Ever see one? They're awful queer-lookin'; least pa is, an' I s'pose the rest is just like him. His hair's real red and he never combs it. He'd disdain to! And he's got the longest, thickest whiskers of anybody in Riverside, Upper or Lower, or Newburgh either. He's terrible proud of his whiskers, but ma don't like 'em. She says they catch dirt and take away all his ambition. She says if he'd cut 'em off and look more like other men she'd be real proud of him, he's such a good talker. Ma says I'm just like him, that way," naïvely concluded this entertaining young person, who saw no reason why her own family affairs should not become public property. Then without waiting for her hostess to set her the example she coolly pushed back from the table, announcing with satisfaction: "I'm done: and I've et real hearty too. Where's your dishpan at, Mis' Chester? I'll wash up for you, then we can all go outdoors and look 'round. I s'pose you've been down to the gold mine, ain't you?"

"Gold mine? Is there one on these premises? Why, that's the very thing we need!" laughed father John, working his chair backward from leg to leg and taking the crutches Dorothy brought him. Even yet she could not keep the look of pity from her brown eyes whenever she saw the once active postman depend upon these awkward, "wooden feet," as he jestingly called them.

But he had become quite familiar with them now, and managed to get about the old farm with real alacrity, and had already laid many ingenious plans for working it. He had a hopeful, sunny nature, and never looked upon the dark side of things if he could help it. As he often told his wife, she "could do enough of that for both of them:" and though he had now fallen upon dark days he looked for every ray of sunshine that might brighten them.

Not the least of these was the safe return of his adopted daughter, and with her at hand he felt that even his lameness was a mere trifle and not at all a bar to his success. Succeed he would—he must! There was no other thing left possible. What if his feet had failed him? Was he not still a man, with a clear head and infinite patience? Besides, as he quoted to Martha: "God never shuts one door but He opens another."

Now as he rose to go outdoors with Dorothy he remembered the letter Jim Barlow had brought him. Letter? It appeared rather like some legal document, with its big envelope and the direction written upon it: "Important. Not to be opened until after my death, unless I personally direct otherwise. (Signed), Elisabeth Cecil Somerset-Calvert." The envelope was addressed to himself, by his own full name, and "in case of his death," to his wife, also by her full title. The date of a few days previous had been placed in an upper corner, and the whole matter was, evidently, one of deliberate consideration.

Calling Mrs. Chester aside he showed it to her and they both realized that they had received some sort of trust, to be sacredly guarded: but why should such have been intrusted to them—mere humble acquaintances of the great lady who had bestowed it? and where could it be most safely kept?

After a moment's pondering mother Martha's face lost its perplexity and, taking the paper from her husband's hand, she whispered:

"I know! I've just thought of a place nobody would ever suspect. I'll hide it and tell you—show and when——"

Then all at once they perceived the too bright eyes of Alfaretta Babcock fixed upon them with a curiosity that nothing escaped. In their interest concerning the letter they had forgotten her, busy at her task in the rear of the room, and the others had already gone out of doors; yet even in the one brief glimpse she caught of that long, yellow envelope, she knew its every detail. Of course, she was too far away to distinguish the words written upon it, but she could have described to a nicety where each line was placed and its length. Nor did she hesitate to disclose her knowledge, as she exclaimed:

"My! That was a big letter that 'hero' boy brought, wasn't it? Have you read it yet? Ain't you going to? Pshaw! I'd like to know what it's all about. I would so, real well. Ma she likes to hear letters read, too, and once we got one from my aunt who lives out west. My aunt is my pa's sister, an' she wanted him to move out there an' make a man of himself; but ma she said he couldn't do that no matter what part of the country he lived in, so he might's well stay where he was, where she was raised and folks 'round knew she was the right sort if he wasn't. So we stayed: but ma she carried that letter round a-showin' it to folks till it got all wore to rags, and Diary got it in her mouth an' nigh choked to death, tryin' to swaller it. So that was the end o' that!" concluded Miss Babcock, giving her dishcloth a wring and an airy flirt, which would have annoyed the careful housemistress had she been there to see.

However, at the very beginning of Alfaretta's present harangue, she had perceived that it would be a lengthy one and had slipped away without explaining to her husband where she would put the letter. Mr. Chester also drew himself up on his crutches and swung across the floor and out of doors. Alfaretta's gossip, which had at first amused him, now bored him, and he was ashamed for her that she had so little respect for her parents as to relate their differences to strangers. Unconsciously, he put into his usual friendly manner a new sternness: but this had no further effect upon the talkative girl than to make her probe her memory for something more interesting. Following him through the doorway she laid her hand on his shoulder and begged:

"Say, Mr. Chester, let me fetch that big wheel-chair o' yours an' let me roll you down through the south medder to the mine. To where it's covered, I mean. I can do it first-rate. I'm as strong as strong! See my arms? That comes from helpin' ma with the wash. Once I done it all alone and Mis' Judge Satterlee she said 'twas 'most as good as ma 'd have done. Do let me, Mr. Chester! I'd admire to!"

The ex-postman looked around and whistled. There was no use in trying to oppose or frown upon this amazing little maid, whose round face was the embodiment of good-nature, and whose desire to help anybody and everybody was so sincere. Besides, there was in her expression an absence of that "pity" which hurt his pride, even when seen upon his darling Dorothy's own face. She seemed to accept his crutches and rolling chair as quite in the natural order of things, like her own sturdy bare feet and her big red arms.

"Well, my lass, certainly you are kindness itself. I thought I had hobbled over nearly the whole of this little farm, but I chanced upon no 'mine' of any sort, though if there's one existing I'd mightily like to find it. But I don't think you could roll me very far on this rough ground. Wheel-chairs are better fitted to smooth floors and pavements than rocky fields."

Alfaretta paid no attention to his objection, except to spin the chair out from its corner of the kitchen, or living-room, and to place it ready for his use. She was as full of delight and curiosity concerning this helpful article as over every other new thing she saw, and promptly expressed herself thus:

"I'm as proud as Punch to be let handle such an elegant chair. My heart! Ain't them leather cushions soft as chicken feathers! And the wheels go round easy as fallin' off a log. I'd admire to be lame myself if I could be rid around in such a sort o' carriage as this. Must have cost a pile of money. How much was it, Mr. Chester?"

"I don't know. It was a gift from my old comrades at the post-office: but don't, child, don't 'admire' to possess anything so terrible as this helplessness of mine! With your young healthful body you are rich beyond measure."

For the first time she saw an expression of gloom and almost despair cloud the cheerful face of her new acquaintance, and though she thought him very silly to consider health as good as wealth she did not say so; but with real gentleness helped him to swing his crippled body into the chair and set off at a swift pace across the field.

All the others had preceded them; even Mrs. Chester having joined the group, determined not to lose sight of her Dorothy again, even for a few moments: and also resolved that, for once, she would forego her usual industry and make a happy holiday.

For a time all went well. The ground near the house was not so very rough and the slope southward was a gentle one. The chair rolled easily enough and, for a wonder, Alfaretta's tongue was still. Not since he had arrived at Skyrie had father John had so comfortable a chance to look over the land; and whatever gloom he had for a moment shown soon gave way before the beauty of the day and the delight of feasting his eyes upon Dorothy's trim little figure, skipping along before him.

Presently she came running back to join him and with her own hand beside Alfy's, on the handle of his chair, to start that talkative body on a fresh topic.

"Tell us about the ghost Jim Barlow said 'haunts' dear Skyrie, Alfy, please. You've heard of it, too, course."

"Heard? I should say I had! Why, everybody knows that, an' I can't scarce believe you don't yourself. Pshaw! Then maybe you wouldn't have moved up-mounting if you had ha' known. When she heard you was comin' ma she said how 't you must be real brave folks. She wouldn't live here if you'd give her the hull farm. I—I seen—it once—myself!" concluded Alfaretta, dropping her voice to an awestruck whisper and thrusting her head forward to peer into father John's face and see if he believed her.

He laughed and Dorothy clapped her hands, demanding:

"What was he like? Was it a 'he' or a lady 'haunt'? How perfectly romantic and delightful! Tell, tell, quick!"

Alfaretta's face assumed a look of great solemnity and a shiver of real fear ran over her. These new people might laugh at the Skyrie ghost, but to her it was no laughing matter. Indeed, she had such a dread of the subject that it had been the one her loquacious tongue had abjured, leaving it to the newcomer, Jim Barlow, to introduce it. But now—Well! If they wanted to hear about the dreadful thing it might be wise to gratify them.

"He's a—'he.' Everybody says that who's seen 'him,'" began the narrator, still in an unnaturally subdued tone.

"Good enough!" ejaculated Mr. Chester, gayly, entering into the spirit of fun he saw shining on Dorothy's face, and glad indeed that his impressionable child did not take this statement seriously. "Good enough! He'll be company for me, for I greatly miss men companions."

"I guess you won't like him for no companion, Mr. Chester. Why, the very place he stays the most is in—that very—room you—come out of to your breakfast—where you stay, too!" cried Alfaretta, impressively. "But other times he lives in the gold mine."

Father John looked back at Dorothy and merrily quoted a verse—slightly altered to fit the occasion:

Dorothy as merrily and promptly joined in this remodeled ditty of the "Purple Cow," but they were destined never to complete it; because, absorbed in her own relation and astonished at their light treatment of it, Alfaretta ceased to observe the smoothness or roughness of their path and inadvertently propelled the wheel-chair into a wide, open ditch, whose edge was veiled by a luxurious growth of weeds.

An instant later the wheels were uppermost, the two girls had been projected upon them, and poor father John buried beneath the whole.

As the old man called Winters left the post-office he struck out for the mountain road, a smooth macadamized thoroughfare kept in perfect order for the benefit of the wealthy summer residents of the Heights, whither it led: but he soon left it for a leafy ravine that ran alongside and was rich with the sights and sounds of June.

Whether he did this from habit, being an ardent lover of nature, or because he knew that all anger must be soothed by the songs of birds and the perfume of flowers, can only be guessed. Certain it is that if he sought to obtain the latter result for his disturbed companion, who had as silently followed him into the shady by-way as he had from the crowded office, he fully succeeded.

The ravine, like the road, climbed steadily upward, and the noisy little stream that tumbled through it made a soothing accompaniment to the bird songs: and in his own delight of listening the old man almost forgot his fellow traveler. Almost, but not quite; for just at a point where the gully branched eastward and he paused to admire, a sigh fell on Seth Winters's ear, and set him face backward, smiling cheerily and remarking:

"This is one of my resting-spots. Let's stop a minute. The moss—or lichen—on this bowlder must be an inch thick. Dry as a feather cushion, too, because the sun strikes this particular place as soon as it rises above old Beacon, across the river. Sit, please."

He seated himself as he spoke, and Jim dropped down beside him.

"Beautiful, isn't it, lad? And made for just us two to appreciate, it may be: for I doubt if any others ever visit this hidden nook. Think of the immeasurable wealth of a Providence who could create such a wonder for just two insignificant human beings. Ah! but it takes my breath away!" and as if in the presence of Deity itself, the blacksmith reverently bared his head.

Unconsciously, Jim doffed his own new straw hat; though his companion smiled, realizing that the action was due to example merely, or even to a heated forehead. But he commended, saying:

"That's right. A man can think better with his head uncovered. If it wouldn't rouse too much idle talk I'd never wear a hat, the year round."

To this the troubled lad made no reply. Indeed, he scarcely noticed what was said, he was so anxious over the affair of the morning; and, with another prodigious sigh, he suddenly burst forth;

"What in the world 'll I do!"

"Do right, of course. That's easy."

"Huh! But when a feller don't know which is right—Pshaw!"

"You might as well tell me the whole story. I'm bound to hear it in the end, you know, because I'm the justice of the peace whom that angry gentleman was in pursuit of. If his common sense doesn't get the better of his anger, you'll likely be served a summons to appear before me and answer for your 'assault.' But—he hasn't applied to me yet; and until he does I've a right to hear all you have to say. Better begin at the beginning of things."

Jim looked up perplexed. He had only very vague ideas of justice as administered by law and, at present, he cared little about that. If he could make this fine old fellow see right into his heart, for a minute, he was sure he would be given good advice. He even opened his lips to speak, but closed them again with a sense of the uselessness of the attempt. So that it was with the surprise of one who first listens to a "mind reader" that he heard Seth Winters say:

"I know all about you. If you can't talk for yourself, my lad, I'll talk for you. You are an orphan. As far as you know there isn't a human being living who has any claim to your services by reason of blood relationship. You worked like a bond slave for an exacting old woman truck-farmer until pity got the better of your abnormal sense of 'duty,' when you ran away and helped a kidnapped girl to reach her friends. In recognition of your brave action my neighbor, Mrs. Betty Calvert, has taken you in hand to give you a chance to make a man of yourself. She is going to test your character further and, if you prove worthy, will give you the education you covet more than anything else in life. She brought you here last night and this morning trusted you with two important matters: the delivery to a certain gentleman, whom as yet I do not know, of a confidential letter: and the care of her Great Danes, creatures which she looks upon as almost wiser than human beings and considers her stanchest friends. The latter safely reached Mr. Chester's hands; but—the Danes? What shall we do about the Danes, Jim Barlow?"

"Thun—der—a—tion! You must be one them air wizards I heerd Mis' Stott tell about, 't used to be in that Germany country where she was raised. Why—pshaw! I feel as if you'd turned me clean inside out! How—how come it?"

"In the most natural way. The men who print newspapers search closely for a bit of 'news,' and so your simple story got into the columns of my weekly. Besides, Mrs. Betty Calvert and I are lifelong friends. Our fathers' estates in old Maryland lay side by side. She's a gossip, Betty is, and who so delightful to gossip with as an old man who's known your whole life from A to izzard? So when she can't seat herself in my little smithy and hinder my work by chattering there, she must needs put all her thoughts and actions on a bit of writing paper and send it through the post. Now, my lad, I've talked to you more than common. Do you know why?"

"No, I don't, and it sounds like some them yarns Dorothy C. used to make up whilst we was pickin' berries in the sun, just to make it come easier like. She can tell more stories, right out her plain head 'n a feller 'd believe! She's awful clever, Dorothy is—and spell! My sakes! If I could spell like her I'd be sot up. But I don't see how just bein' befriended by Mis' Calvert made you talk to me so much."

The blacksmith laughed, and answered:

"Indeed, lad, it wasn't that. That big-hearted woman has so many protégés that one more or less scarcely interests me. Only for something in themselves. Well, it was something in yourself. Down there in the office, while I stood behind a partition and nobody saw me—I would hide anywhere to keep out of a quarrel!—I saw you, the very instant after Mr. Montaigne had shaken you and you'd struck back, lift your foot and step aside because a poor little caterpillar was crawling across the floor and you were in danger of crushing it. It was a very little thing in itself, but a big thing to have been done by a boy in the terrific passion you were. It was one of God's creatures, and you spared it. I believe you're worth knowing. But I'd like to have that belief confirmed by hearing what you are going to do next. Let us go on."

They both rose and each carrying his hat in his hand, the better to facilitate "thinking," went silently onward again. It was a long climb, something more than two miles, but the ravine ended at length in a meadow on the sloping hillside, which Seth Winters crossed by a tiny footpath. Then they were upon the smooth white road again. Before them rose the fine mansions of those residents designated by Alfaretta as the "aristocratics," and scattered here and there among these larger estates were the humbler homes of the farmer folk who had dwelt "up-mounting" long before it had become the fashionable "Heights."

Not far ahead lay Deerhurst, the very first of the expensive dwellings to be erected amid such a wilderness of rocks and trees: its massive stone walls half-hidden by the ivy clambering over them, its judiciously trimmed "vistas" through which one might look northward to the Catskills and downward to the valley bordering the great Hudson.

Just within the clematis-draped entrance-pillars stood the picturesque lodge where the childless couple lived who had charge of the estate and with whom Jim was to stay. He had been assigned a pleasant upper chamber, comfortably fitted up with what seemed to its humble occupant almost palatial splendor. Best of all, there hung upon the wall of this chamber a little book-rack filled with well-selected literature. And, though the boy did not know this, the books had been chosen to meet just his especial case by Seth Winters himself, at the behest of his old friend, Mrs. Calvert, immediately upon her decision to bring Jim to Deerhurst.

Even now, one volume lay on the window ledge, where the happy lad had risen to study it as soon as daylight came. He fancied that he could see it, even at this distance, and another of his prodigious sighs issued from his lips.

"Well, lad. We have come to the parting of the ways, at least for the present. My smithy lies yonder, beyond that turn of the road and behind the biggest oak tree in the country. Behind the shop is another mighty fellow, known all over this countryside as the 'Great Balm of Gilead.' It's as old, maybe, as 'the everlasting hills,' and seems to hold the strength of one. I've built an iron fence around it, to protect its bark from the knives of silly people who would carve their names upon it, and—it's well worth seeing. Good-by."

"Hold on! Say. You seem so friendly like, mebbe—mebbe you could give me a job."

"No, I couldn't," came the answer with unexpected sharpness, yet a tinge of regret.

"Why not? I'm strong—strong as blazes, for all I'm kind of lean 'count of growin' so fast. And I'm steady. If you could see Mirandy Stott, she'd have to 'low that, no matter how mad she was about my leavin'. Give me a job, won't ye?"

"No. I thought you were going to do right. Good-morning;" and, as if he wholly gave up his apparent interest in the lad, Seth Winters, known widely and well as the "Learned Blacksmith," strode rapidly homeward to his daily toil, feeling that he had indeed wasted his morning; and he was a man to whom every hour was precious.

Jim's perplexity was such that he would far rather run away and turn his back on all these new helpful friends than return to Deerhurst and confess his unfaithfulness to his duty. He fancied he could hear Mrs. Cecil saying:

"Well, I tried you and found you wanting. I shall never trust you again. You can go where you please, for you've had your chance and wasted it."

Of course, even in fancy, he couldn't frame sentences just like these, but the spirit of them was plain enough to his mind. The dogs—One thought of these, at that moment, altered everything. It had been commented upon by all the retainers of the house of Calvert that such discriminating animals had made instant friends with the uncouth farm boy. This had flattered his pride and his fondness for all dumb creatures had made them dear to him beyond his own belief. Poor Ponce! Poor Peter! If they suffered because of his negligence—Well, he must make what atonement he could!

His doubts sank to rest though his reluctance to follow the dictates of his conscience did not; and it was by actual force he dragged his unwilling feet through the great stone gateway and along the driveway to that shady veranda where he saw the mistress of Deerhurst sitting, ready waiting for her morning drive and the arrival of Ephraim. As Jim approached she looked at him curiously. Why should he come by that road when he was due from another? and why was he not long ago transplanting those celery seedlings which she had directed him should be his first day's labor?

As he reached the wide steps he snatched off his hat again; not, as she fancied, from an instinctive respect to her but to cool his hot face, and without prelude jerked out the whole of his story:

"Mis' Calvert, ma'am, I've lost your dogs. I've been in a fight. I'm going to be arrested an' took afore a judge-blacksmith. Likely I'll be jailed. 'Tain't no sort o' use sayin' I'm sorry—that don't even touch to what I feel inside me. You give me a chance an'—an'—I wasn't worth it. I'll go, now, and—and soon's I can get a job an' earn somethin' I'll send you back your clothes. Good-by."

"Stop! Wait! You lost my dogs!" cried Mrs. Cecil, springing up and in a tone which brooked no disobedience: a tone such as a high-born dame might sometimes use to an inferior but was rarely heard from this real gentlewoman; a tone that, despite the humility and self-contempt he felt at that moment, stung the unhappy youth like a whip-lash. "Explain. At once. If they're lost they must be found. That you've been foolish enough to fight and get arrested—that's your own affair—nothing to me; but my dogs, my priceless, splendid, irreplaceable Great Danes! Boy, you might as well have struck me on my very heart. Where? When? Oh! if I had never, never seen you!"

Poor Jim said nothing. He stood waiting with bowed head while she lavished her indignation upon him, and realizing, for the first, how great a part of a lonely old life even dumb animals may become. When, for want of breath, or further power to contemn, she sank back in her stoop chair, he turned to go, a dejected, disappointed creature that would have moved Mrs. Cecil's heart to pity, had she opened her eyes to look. But she had closed them in a sort of hopeless despair, and he had already retraced his footsteps some distance toward the outer road when there sounded upon the air that which sent her to her feet again—this time in wild delight—and arrested him where he stood.

At once, following those joyful barks, that both hearers would have recognized anywhere, came the leaping, springing dogs; dangling their broken chains and the freshly gnawed and broken ropes—with which old Ephraim had unwisely reckoned to restrain them from the sweets of a once tasted liberty.

But even amid her sudden rejoicing where had been profound sorrow, the doting mistress of the troublesome Great Danes felt a sharp tinge of jealousy.

"They're safe, the precious creatures! But—they went to that farm boy first!"

The screams of Dorothy and Alfaretta brought Mrs. Chester hurrying back to them and as she saw what had happened her alarm increased, for it seemed impossible that a helpless person, like her husband, should go through such an accident and come out safe.

For a moment her strength left her and she turned giddy with fear, believing that she had brought her invalid here only to be killed. The next instant she was helping the girls to free themselves from the tangle of wheels, briars, and limbs; and then all three took hold of the heavy chair to lift it from the prostrate man.

"John! John! Are you alive? Speak—do speak if you love me!" cried poor mother Martha, frantic with anxiety.

But for a time, even after they had lifted him to the bank above, Mr. Chester lay still with closed eyes and no sign of life about him. There was a bruise upon his forehead where he had struck against a rock in falling; and, seeing him so motionless, poor Dorothy buried her face in her hands and sobbed aloud:

"Oh! I've killed him! I've killed my precious father!"

"There is a bridge across the ditch just yonder!—Why didn't you see it! How could you—" began Mrs. Chester; yet got no further in her up-braidings, for father John opened his eyes and looked confusedly about him.

Either the sound of voices or the liberal dash of cold water, which thoughtful Alfaretta had rushed away to bring and throw upon him, had restored him to consciousness, and his beclouded senses rapidly became normal. It had been a great shock but, more fortunately than his frightened wife at first dared to believe, there were no broken bones, and it was with intense thankfulness that she now picked up his crutches and handed them to him at his demand.

"Well, I reckon wooden feet are safest, after all! I've never—I'll never go without them. Good thing I brought them—No, thank you! Walking's good!" he cried, with all his usual spirit though in a weak voice.

They had managed to get the chair into position and found it as uninjured as its owner. A few scratches here and there marred the polish of the frame and one cushion had sustained an ugly rent. It had been a very expensive purchase for the donors and an ill-advised one. A lighter, cheaper chair would have been far more serviceable; and, as father John tried to steady himself upon his crutches, he regarded it with his familiar, whimsical smile that comforted them all more readily than words:

"The boys might as well have given me an automobile! Wouldn't have been much more clumsy—nor dangerous!" he declared, trying to swing himself forward from the spot where he stood, striving to steady himself upon his safer "wooden feet."

"O John! how can you joke? You might be—be dead!" wailed mother Martha, weeping and unnerved for the first time, now that all danger was past.

"And that's the best 'joke' of all. I might be but I'm not. So let's all heave—heave away! for that pleasant shore of a wide lounge and a—towel! With the best intentions—I've been ducked pretty wet!"

"That was my fault! I'm awful sorry but—but—that time John Babcock he fell off the barn roof ma she flung a whole pail of water right out the rain-barrel onto him and that brung him to quicker'n scat. So I remembered and I'm real sorry now," explained Alfaretta, more abashed than ordinarily: and in her own heart feeling that the guilt of carelessness which caused the accident had been more hers than Dorothy's. "And nobody needn't scold Dolly C. 'Cause she didn't know about the bridge over an' I did, and——"

"No, no! My fault, my very own!" interposed Dorothy hastily.

"Let nobody blame nobody! All's well that ends well! Alfaretta mustn't regret her serviceable memory nor my drenching, for she's a wise little maid and I owe my 'coming to,' to her 'remembering.' As for you, Dolly darling, let me see another tear in your eye and I will 'scold' in earnest. Now, Martha, wife, I'll give it up. I'm rather shaky on my pins yet and the chair it must be, if I'm to put myself in connection with that lounge. I shan't need the towel after all. I've just let myself 'dreen,' as my girl used to do with the dishes, sometimes!"

He talked so cheerily and so naturally that he almost deceived them into believing that he was not a whit the worse for his tumble, and as they helped him to be seated and began to push him up the slope toward the cottage, he whistled as merrily as he had used to do upon his postal route.

"And you ain't goin' to the gold mine after all?" asked Alfy, much disappointed. It was a spot she had hitherto shunned on account of its ghostly reputation, but was eager to visit now in company with these owners of it, who scoffed at the "haunt." She wanted to show them she was right and see what they would say then.

"Gold mine? Trash! If there had been such a thing on this farm, a man as clever as my uncle Simon Waterman would have used some of the 'gold' to keep things in better shape. I don't want to hear any more of that nonsense, nor to have you, Dorothy, go searching for the place. Our first trip to hunt for gold has been a lesson to us all," said mother Martha, with such sharpness that Alfaretta stared and the others, who knew her better, realized that this was a time to keep silence.

More than once that day was the good housewife tempted to send the three visiting Babcocks home, but was too courteous to do so. She longed to have her daughter to herself, and to discuss with her not only the happenings of the past but plans for the future. Besides this desire, she also saw, at last, how badly shaken by his fall her husband was and that he needed perfect quiet—a thing impossible to procure with Alfaretta Babcock in the cottage.

However, the day wore away at length. The girl showed herself as useful in the dinner-getting and clearing away as she had done at breakfast time; also, she and her sisters brought to it as keen an appetite, so that, after all, the clearing away was not so great a matter as might be.

Dorothy kept the smaller girls out of doors, helping them to make a playhouse with bits of stones, to stock it with broken crockery and holly-hock dolls, and to entrance them with her store of fairy tales to such a degree that Baretta decided:

"I'm comin' again, Dorothy Chester. I'm comin' ever' single day they is."

"Oh, no! You mustn't do that!" gasped the surprised young hostess. "I will have to work a great deal to help my mother and I shan't have time for visiting."

"Me come, too, Do'thy Chetter," lisped Claretta. "Me like playhouth futh-rate. Me come to-mowwow day, maybe."

Dorothy said no more, but found a way to end their plans by getting a book for herself, and becoming so absorbed in it that they ceased to find her interesting and wandered off by themselves to rummage in the old barn; and, finally, to grow so tired of the whole place that they began to howl with homesickness.

Dorothy let them howl. She had recently been promoted to the reading of Dickens, and enthralled by the adventures of Barnaby Rudge she had wandered far in spirit from that mountain farm and the disgruntled Babcocks. Curled up on the grass beneath a low-branched tree she forgot everything, and for a long time knew nothing of what went on about her.

Meantime, to keep Alfaretta's tongue beyond reach of her husband's ears, Mrs. Chester had gone down into the cellar of the cottage which, her visitor informed her, had once been the "dairy." Until now, since her coming to Skyrie, the housemistress had occupied herself only in getting the upper rooms cleaned and furnished with such of her belongings as she had brought with her, and in attendance upon father John. She had not attempted any real farm work, though she had listened to his plans with patient unbelief in his power to accomplish any of them.

"If Dorothy should be found," had been his own conclusion of all his schemes, during the time of their uncertainty concerning her; and afterward, when news of her safety and early coming had reached them, he merely changed this form to: "Now that Dorothy is found."

Everything had its beginning and end in "Dorothy." For her the garden was to be made, especially the flower beds in it; the farm rescued from its neglected condition and made a well-paying one, that Dorothy might be educated; and because of Dorothy's love of nature the whole property must be rendered delightfully picturesque.

Now Dorothy had really come; and, unfortunately, as Mrs. Chester expressed it:

"I can see to the bottom of our pocket-book, John dear, and it's not very deep down. Plans and talk are nice but it takes money to carry them out. As for your doing any real work yourself, you can't till you get well. 'Twould only hinder your doing so if you tried. We'll have to hire a man to work the ground for us and clear it of weeds. If we can get him to do it 'on shares,' so much the better; if he won't do that—Oh! hum! To think of folks having more dollars than they can spend and we just enough to starve on!"

This talk had been on that very day before, while they sat impatiently awaiting her arrival, and it had made John Chester wince. While his life had been in danger, even during all their time of doubt concerning their adopted child, Martha had been gentleness and hopefulness indeed. She had seemed to assume his nature and he hers: but now that their more serious fears were removed, each had returned to his own again; she become once more a fretter over trifles and he a jester at them.

"Don't say that, dear wife. I don't believe we will starve; or that we'll have to beg the superfluous dollars of other people," he had answered, hiding his regret for his own lost health and comfortable salary.

But the much-tried lady was on the highroad toward trouble-borrowing and bound to reach her end.

"I might as well say it as think it, John. I never was one to keep things to myself that concern us both, as you did all that time you knew you was going lame and never told me. Besides the man, we must have a horse, or two of them. Maybe mules would come cheaper, if they have 'em around here. We'll have to get a cow, of course. Milk and butter save a lot of butcher stuff. Then we must get a pig. The pig will eat up the sour milk left after the butter's made——"

"My dear, don't let him eat up the buttermilk, too! Save that for Dorothy and me, please. Remember how the little darling used to coax for a nickel to run to the 'corner' and buy a quart of it, when we'd been digging extra hard in our pretty yard. And don't forget, in your financial reckonings, to leave us a few cents to buy roses with. I've been thinking how well some climbing 'Clothilde Souperts' would look, trained against that barn wall, with, maybe, a row of crimson 'Jacks,' or 'Rohans' in front. Dorothy would like that, I guess. I must send for a new lot of florists' catalogues, since you didn't bring my old ones."

"I hadn't room; and I hope you won't. We've not one cent to waste on plants, let alone dollars. Besides, once you and Dorothy get your heads together over one those books you want all that's in it, from cover to cover. There's things I want, too, but I put temptation behind me. The whole farm's run to weeds and posies, anyhow. No need to buy more."

Father John had thought it wise to change the subject. Martha was the best of wives, but there were some things in which she failed to sympathize. He therefore remarked, what he honestly believed:

"I think it's wonderful, little woman, how you can remember so much about farming, when you haven't lived on one since you were a child."

"Children remember better than grown folks. I don't forget how I used to have to churn in a dash-churn, till my arms ached fit to drop off. And I learned to milk till I could finish one cow in a few minutes; but it nearly broke my fingers in two, at first. I wonder if I can milk now! I'll have to try, anyway, soon as we get the cow. I guess you'd better write an advertisement for the Local News, and I'll go to Mrs. Calvert's place and ask her coachman to post it when he goes down the mountains to meet the folks. Just to think we shall have our blessed child this very night before we sleep!" ended the housemistress, with a return of her good spirits.

Father John laughed with almost boyish gayety. Dorothy was coming! Everything would be right. So he hobbled across to his own old desk which Martha had placed in the cheeriest corner of the room assigned to him, looking back over his shoulder to inquire:

"Shall it be for a cow, a horse, or that milk-saving pig? Or all three at one fell swoop? Must I say second-hand or first-class? I never lived on a farm, you know, and enjoyed your advantages of knowledge: and, by the way, what will we do with the creatures when we get them? I haven't been into that barn yet, but it looks shaky."

"John Chester! Folks don't keep pigs in their barns! They keep them in pens. Even an ex-postman ought to know enough for that. And make the thing short. The printers charge so much a word, remember."

"All right. 'Brevity is the soul of wit.' I'll condense."

Whistling over his task, Mr. Chester soon evolved the following "Want Ad.":

"Immediate. Pig. Cow. Horse. Skyrie."

This effusion, over which he chuckled considerably, he neatly folded and addressed to the publisher of the local newspaper and left on his desk for his wife to read, then hobbled back to his bed to sleep away the time till Dorothy came, if he could thus calm his happy excitement. But it never entered his mind that his careful wife would not read and reconstruct the advertisement before she dispatched it to its destination.

However, this she did not do. She simply sealed and delivered it to old Ephraim, just as he was on the point of starting for his mistress at the Landing: and the result of its prompt appearance in the weekly sheet, issued the next morning, was not just what either of the Chesters would have desired.

After all, Alfaretta was good company down in that old cellar-dairy, poking into things, explaining the probable usage of much that Martha did not understand. For instance:

"That there great big wooden thing in the corner's a dog-churn. Ma says 'twas one more o' old Si Waterman's crazy kinks. He had the biggest kind of a dog an' used to make him do his churnin'. Used to try, anyhow. See? This great barrel-like thing is the churn. That's the treadmill 'Hendrick Hudson'—that was the dog's name—had to walk on. Step, step, step! an' never get through! Ma says 'twas no wonder the creatur' 'd run away an' hide in the woods soon's churnin' days come round. He knew when Tuesday an' Friday was just as well as folks. Then old Si he'd spend the whole mornin' chasing 'Hudson'—he was named after the river or something—from Pontius to Pilate; an' when he'd catch him, Si'd be a good deal more tuckered out an' if he'd done his churnin' himself."

Martha laughed, and rolling the big, barrel-churn upon its side was more than delighted to see it fall apart, useless.

"How could he ever get cream enough to fill such a thing? Or enough water to keep it clean? And look, Alfy! what a perfect rat-hole of dirt and rubbish is under it. That old dog-churn must come down first thing. I've a notion to take that rusty ax yonder and knock it to pieces myself," she remarked and turned her back for a moment, to examine the other portions of her future dairy.

Now good-natured Alfaretta was nothing if not helpful, and quite human enough to enjoy smashing something. Before Mrs. Chester could turn around, the girl had caught up the ax and with one vigorous blow from her strong arm sent the dog-churn, already tumbling to pieces with age, with a deafening rattle down upon the stone floor.

The sound startled John Chester from his restful nap, silenced the outcries of the little Babcocks, and sent Dorothy to her feet, in frightened bewilderment. For there before her, in the flesh, stood the hero of the very book she dropped as she sprang up—Barnaby Rudge himself!

"Barnaby Rudge! Fiddlesticks! That ain't his name nor nothing like it. He's Peter Piper. He's out the poorhouse or something. He ain't like other folks. He's crazy, or silly-witted, or somethin'. How-de-do, Peter?" said Alfaretta, as Dorothy, closely followed by the little Babcocks and the "apparition" himself, dashed down into the dust-clouded dairy where Mrs. Chester stood still, gazing in bewilderment at the demolished dog-churn.