The Project Gutenberg eBook of Mooswa & Others of the Boundaries

Title: Mooswa & Others of the Boundaries

Creator: William Alexander Fraser

Illustrator: Arthur Heming

Release date: February 27, 2013 [eBook #42226]

Most recently updated: March 17, 2013

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

MOOSWA & OTHERS

OF THE BOUNDARIES

By W. A. FRASER

Illustrated by ARTHUR HEMING

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

NEW YORK

MDCCCC

Copyright, 1900, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

UNIVERSITY PRESS -- JOHN WILSON

AND SON -- CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

Contents

Introduction

The Dwellers of the Boundaries

Choosing the King

The Value of their Fur

The Law of the Boundaries

The Building of the Shack

The Exploration of Carcajou

The Setting Out of the Traps

The Otter Slide

The Trapping of Wolverine

The Coming of the Train Dogs

The Trapping of Black Fox

The Run of the Wolves

Carcajou's Revenge

Pisew Steals The Boy's Food

The Punishing of Pisew

The Caring for The Boy

François at The Landing

Mooswa brings Help to The Boy

Illustrations

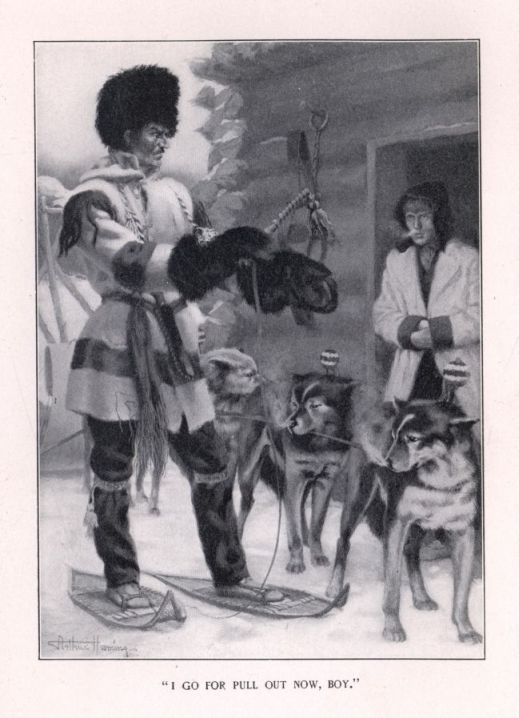

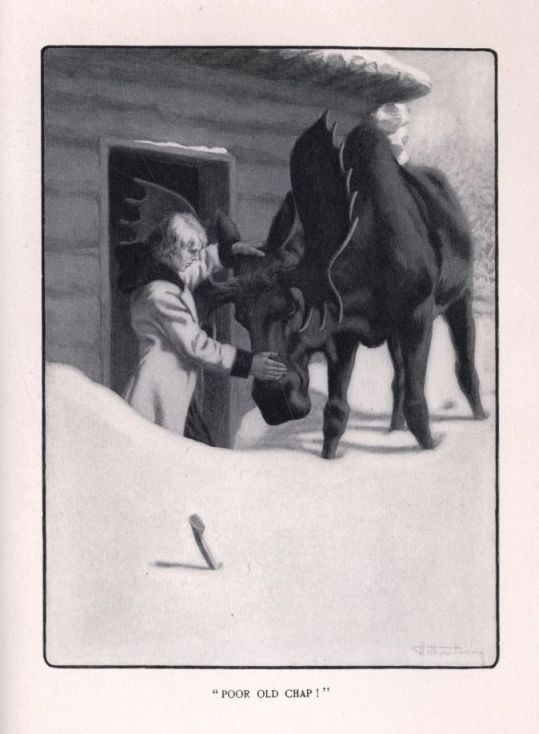

From drawings by Arthur Heming

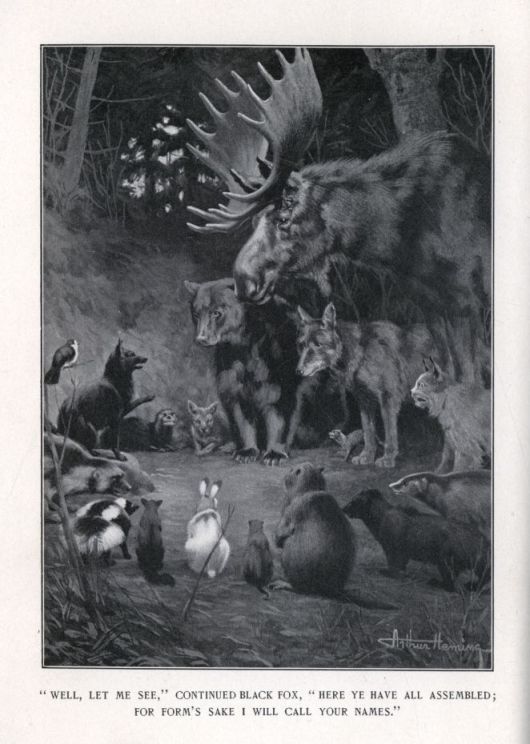

"Well, let me see," continued Black Fox, "here Ye have all assembled; for form's sake I will call your names" . . . Frontispiece

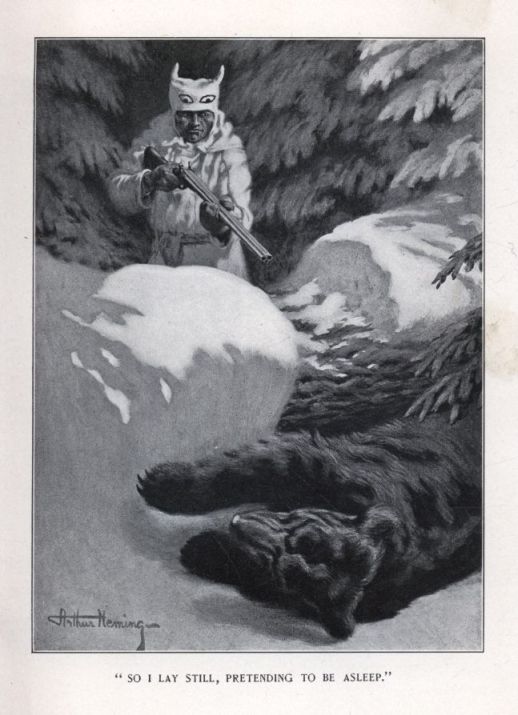

"So I lay still, pretending to be asleep"

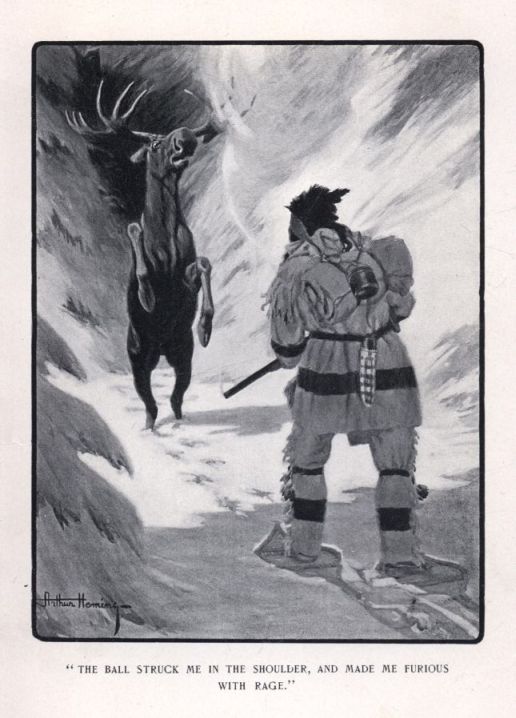

"The ball struck me in the shoulder, and made me furious with rage"

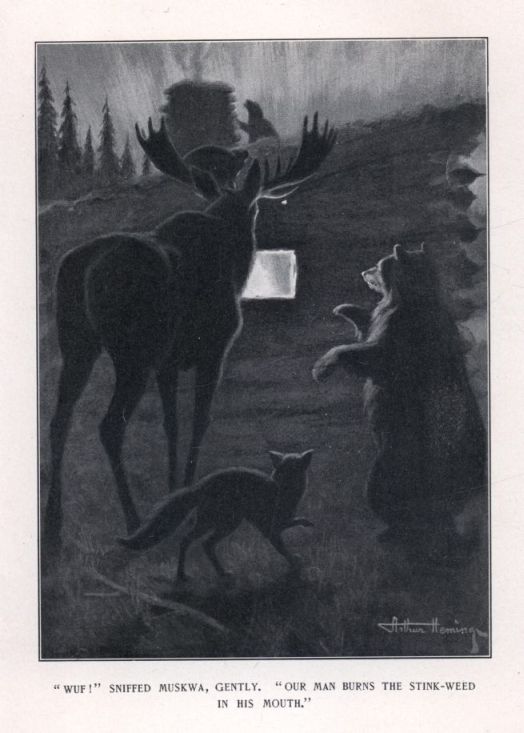

"Wuf!" sniffed Muskwa, gently. "Our Man burns the stink-weed in his mouth"

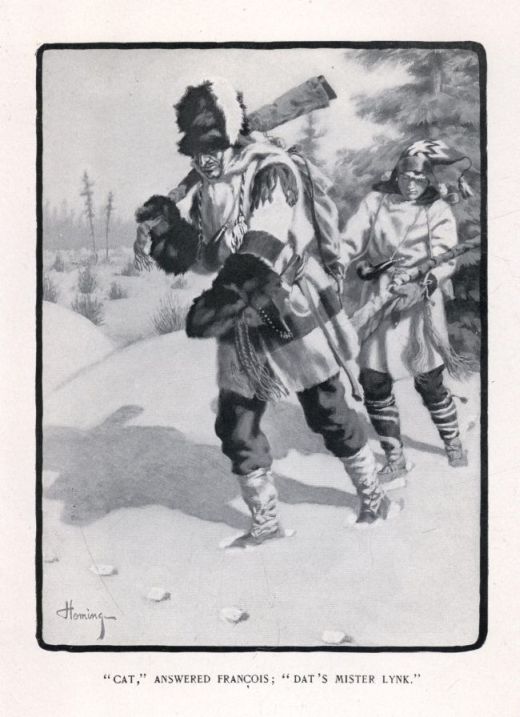

"Cat," answered François; "dat's Mister Lynk"

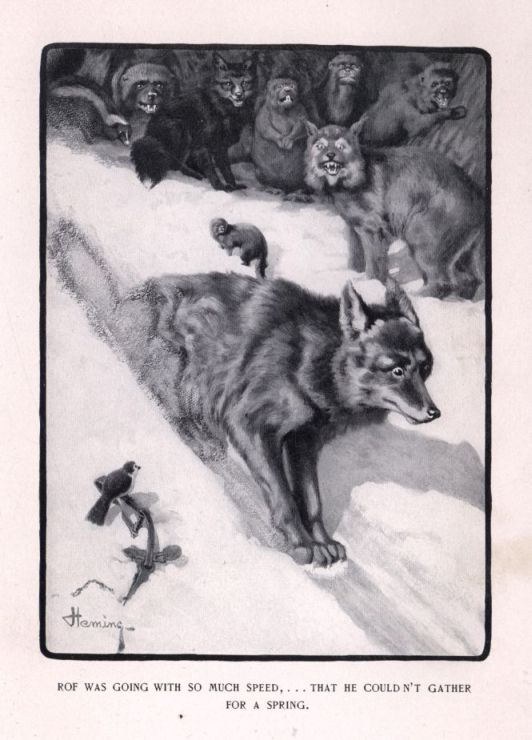

Rof was going with so much speed, ... that he couldn't gather for a spring

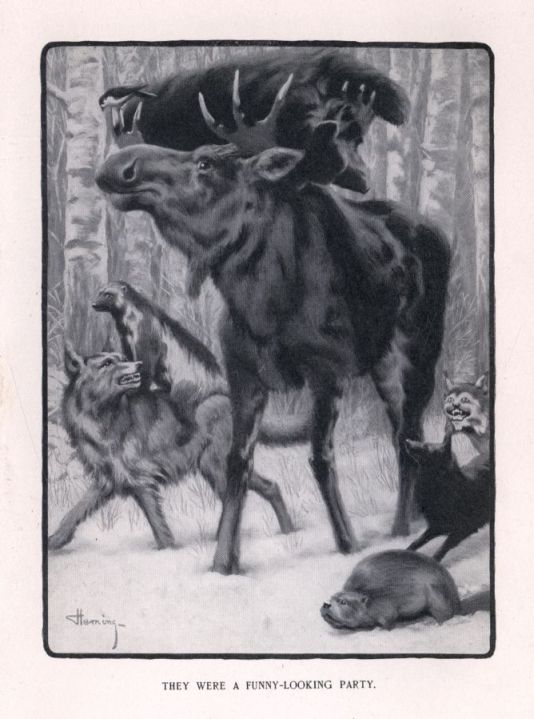

They were a funny-looking party

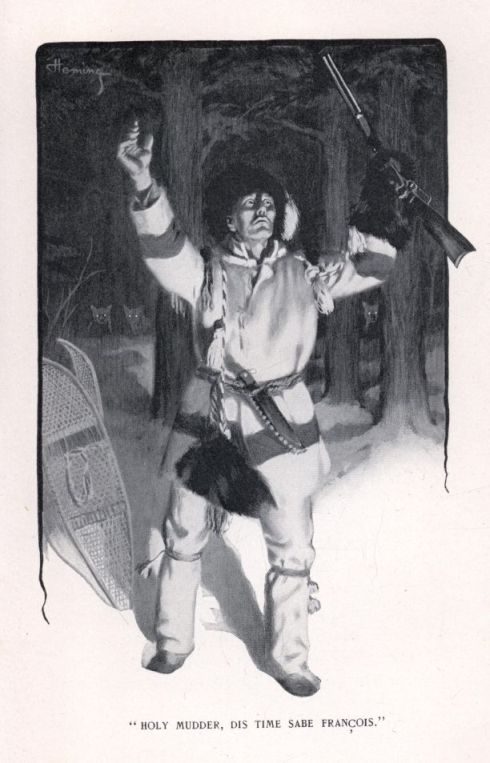

"Holy Mudder, dis time sabe François"

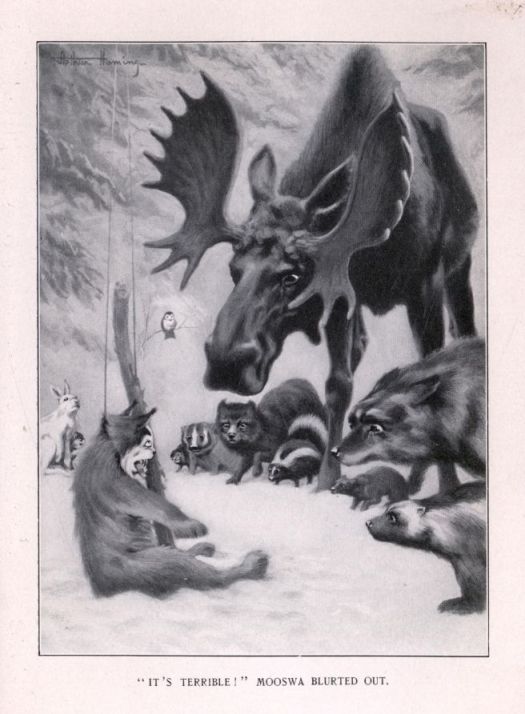

"It's terrible!" Mooswa blurted out

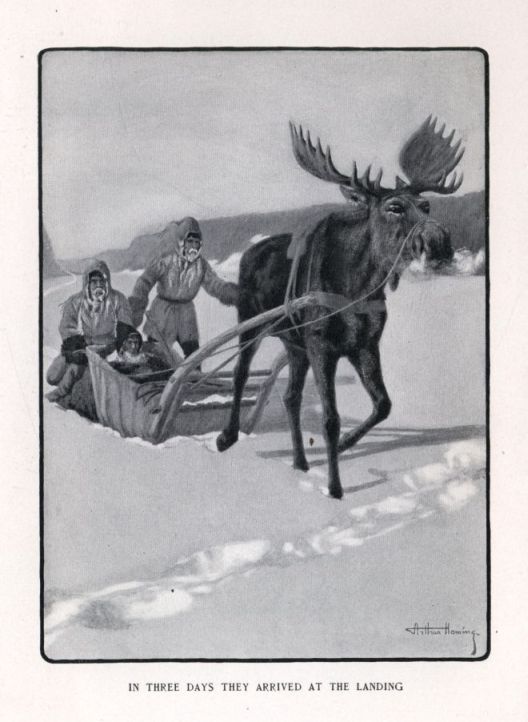

In three days they arrived at The Landing

Introduction

This simple romance of a simple people, the furred dwellers of the Northern forests, came to me from time to time during the six seasons I spent on the Athabasca and Saskatchewan Rivers in the far North-West of Canada.

Long evenings have passed pleasantly, swiftly, as sitting over a smouldering camp-fire I have listened to famous Trappers as they spoke with enthusiastic vividness of the most fascinating life in the world,--the fur-winner's calling.

If the incidents and tales in this book fail of interest the fault is mine, for, coming from their lips, they pleased as did the song of the Minstrel in the heroic past.

Several of the little tales are absolutely true. Black Fox was trapped as here described, by a Half-breed, Johnnie Groat, who was with me for a season.

Carcajou has raided, not one, but many shacks through the chimney, as fifty Trappers in the North-West could be brought to testify. The trapping of this clever little animal by means of a hollow stump, all other schemes having failed, was an actual occurrence. It is a well known fact that many a Trapper has had to abandon his "marten road" and move to another locality when Carcajou has set up to drive him out.

Mooswa is still plentiful in the forests of the Athabasca, and is the embodiment of dignity among animals.

There is no living thing more characteristic of the Northern land than Whisky-Jack, the Jay. Wherever a traveller stops, on plain or in forest, and uncovers food, there will be one or two of these saucy, thieving birds. Where they nest, or how, is much of a mystery. I never met but one man who claimed to have found Jack's nest, and this man, a Trapper, was of rather an imaginative turn of mind.

The Rabbit of that land is really a hare, never burrowing, but living quite in the open. As told in the story they go on multiplying at a tremendous rate for six years; the seventh, a plague carries a great number of them off, and very few are seen for the next couple of years. The supply of fur depends almost entirely upon the rabbit--he is the food reserve for the other forest dwellers.

Blue Wolf is also an actuality. Once in a while one of the gray wolves grows larger than his fellows, and wears a rich blue-gray coat. I have one of these pelts in my house now--they are very rare, and are known to the Traders and Trappers as Blue Wolf.

Perhaps this story is too simple, too light, too prolific of natural history, too something or other--I don't know; I have but tried to tell the things that appeared very fascinating to me under the giant spruce and the white-barked poplars, with the dark-faced Indians and open-handed white Trappers sitting about a spirit-soothing camp-fire.

THE DWELLERS OF THE BOUNDARIES AND

THEIR NAMES IN THE CREE

INDIAN LANGUAGE

MOOSWA, the Moose. Protector of The Boy.

MUSKWA, the Bear.

BLACK FOX, King of the Boundaries.

THE RED WIDOW, Black Fox's Mother.

CROSS-STRIPES, Black Fox's Baby Brother.

ROF, the Blue Wolf. Leader of the Gray Wolf Pack.

CARCAJOU, the Wolverine. Lieutenant to Black King, and known as the "Devil of the Woods."

PISEW, the Lynx. Possessed of a cat-like treachery.

UMISK, the Beaver. Known for his honest industry.

WAPOOS, the Rabbit (really a Hare). The meat food for Man and Beast in the Boundaries.

WAPISTAN, the Marten. With fur like the Sable.

NEKIK, the Otter. An eater of Fish.

SAKWASEW, the Mink. Would sell his Mother for a Fish.

WUCHUSK, the Muskrat. A houseless vagabond who admired Umisk, the Beaver.

SIKAK, the Skunk. A chap to be avoided, and who broke up the party at Nekik's slide.

WENUSK, the Badger.

WUCHAK, the Fisher.

WHISKY-JACK, the Canada Jay. A sharp-tongued Gossip.

COUGAR, EAGLE, BUFFALO, ANT, and CARIBOU.

WIE-SAH-KE-CHACK. Legendary God of the Indians, who could change himself into an animal at will.

FRANÇOIS, French Half-breed Trapper.

NICHEMOUS, Half-breed hunter who tried to kill Muskwa.

TRAPPERS, HALF-BREEDS, and TRAIN DOGS.

ROD, The Boy. Son of Donald MacGregor, formerly Factor to Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Resolution.

When Rod was a little chap, Mooswa had been brought into Fort Resolution as a calf, his mother having been killed, and they became playmates. Then MacGregor was moved to Edmonton, and Rod was brought up in civilization until he was fourteen, when he got permission to go back to the Athabasca for a Winter's trapping with François, who was an old servant of the Factor's. This story is of that Winter. Mooswa had been turned loose in the forest by Factor MacGregor when leaving the Fort.

THE BOUNDARIES. The great Spruce forests and Muskeg lands lying between the Saskatchewan River, the Arctic Ocean, and the Rocky Mountains--being the home of the fur-bearing animals.

Mooswa

And Others of the Boundaries

CHOOSING THE KING

The short, hot Summer, with its long-drawn-out days full of coaxing sunshine, had ripened Nature's harvest of purple-belled pea-vine, and yellow-blossomed gaillardia, and tall straight-growing moose weed; had turned the heart-shaped leaves of the poplars into new sovereigns that fell with softened clink from the branches to earth, waiting for its brilliant mantle--a fairy mantle all splashed blood-red by crimson maple woven in a woof of tawny bunch-grass and lace-fronded fern.

Oh, but it was beautiful! that land of the Boundaries, where Black Fox was King; and which stretched from the Saskatchewan to where the Peace first bounded in splashing leaps from the boulder-lined foothills of the Rockies; all beautiful, spruce-forested, and muskeg-dotted--the soft muskegs knee deep under a moss carpet of silver and green.

The Saskatoons, big brother to the Huckleberry, were drying on the bush where they had ripened; the Raspberries had grown red in their time and gladdened the heart of Muskwa, the Bear; the Currants clustered like strings of black pearls in the cool beds of lazy streams, where pin-tailed Grouse, and Pheasant in big, red cravat, strutted and crouked in this glorious feeding-ground so like a miniature vineyard; the Cranberries nestled shyly in the moss; and the Wolf and Willow-berries gleamed like tiny white stars along the banks of the swift-running, emerald-green Saskatchewan and Athabasca. All this was in the heritage land of Black Fox, and Muskwa, and Mooswa.

It was at this time, in the full Autumn, that Whisky-Jack flew North and South, and East and West, and called to a meeting the Dwellers that were in the Boundaries. This was for the choosing of their King, a yearly observance, and for the settling of other matters.

When they had gathered, Black Fox greeted the Animals:--

"Good Year to you, Subjects, and much eating, each unto his own way of life!"

Whisky-Jack preened his mischievous head, ruffled his blue-gray feathers, broke into the harsh, cackling laugh of the Jay, and sneered, "Eating! always of eating; and never a more beautiful song to you, or--"

"Less thieving to you, eh, Mister Jay," growled Muskwa. "You who come by your eating easily have it not so heavily on your mind as we Toilers."

"Well, let me see," continued Black Fox, with reflective dignity, "here Ye have all assembled; for form's sake I will call your names."

From Mooswa to Wapoos each one of the Dwellers as his name was spoken stepped forward in the circle and saluted the King.

"Jack has been a faithful messenger," said Black King; "but where are Cougar, and Buffalo, and Eagle?"

"They had notice, thank you, Majesty, for your praise. Cougar says the mountain is his King, and that he wouldn't trust himself among a lot of Plain Dwellers."

"He's a Highway Robber and an Outlaw, anyway, so it doesn't matter," asserted Carcajou.

"You wouldn't talk that way if he were at your throat, my fat little Friend," lisped Whisky-Jack. "Buffalo is afraid of Man, and won't come; nearly all his brothers have been killed off, and he is hiding in the Spruce woods near Athabasca Lake."

"I saw a herd of them last Summer," declared Mooswa; "fine big fellows they have grown to be, too. Their hair is longer, and blacker, and curlier than it was when they were on the Plains. There's no more than fifty of them left alive in all the North woods; it's awful to think of how they were slaughtered. That's why I stick to the Timber Boundaries."

"Eagle won't come, Your Majesty, because Jay's chatter makes his head ache," declared Carcajou.

"Blame me," cried Whisky-Jack, "if anybody doesn't turn up at the meeting--say it's my fault; I don't mind."

"You know why we meet as usual?" queried Black Fox, placing his big white-tipped brush affectedly about his feet.

"That they do," piped Whisky-Jack; "it's because they're afraid of losing their hides. I'm not--nobody tries to rob me."

"Worthless Gabbler!" growled Muskwa.

"Jack is right," declared Black Fox; "if we do not help each other with the things we have learned, our warm coats will soon be on the shoulders of the White Men's Wives."

"Is that why the Men are always chasing us?" asked Beaver, turning his sharp-pointed head with the little bead eyes toward the King.

"Not in your case," snapped Whisky-Jack, "for they eat you, old Fat Tail. I heard the two White Men who camped on our river last Winter say that your Brother, whom they caught when they raided your little round lodge, tasted like beefsteak, whatever that is.--He, he! And François the Guide ate his tail and said it was equal to fat bacon."

"Unthinking Wretch!" cried Umisk angrily, bringing his broad tail down on a stone like the crack of a pistol.

"I picked his bones," taunted the Jay; "he was dead, and cooked too, so it didn't matter."

"Cannibal!" grunted Bear.

"They eat you also, Muskwa; only when they're very hungry though,--they say your flesh is like bad pork, strong and tough."

Black Fox interrupted the discord. "Comrades," he pleaded, "don't mind Jack; he's only a Jay, and you know what chatterers they are. He means well--does he not tell us when the Trappers are coming, and where the Traps are?"

"Yes, and steal the Bait so you won't get caught," added Jay. "Oh, I am good--I help you. You're a lot of crawling fools--all but the King. You can run, and fight, but you don't know things. That's because you don't associate with Man, and sit in his camp as I do."

"I've been in his camp," asserted Carcajou, picking up a small stone slyly to shy at Jack.

"Not when he was home," retorted the Jay; "you sneaked in to steal when he was away."

"Stop!" commanded the King, angrily. "Your chatter spoils everything, do stop!"

Whisky-Jack spread his feathers till he looked like a woollen ball, and subsided.

"This is the end of the year," continued Black Fox, "and the great question is, are you satisfied with the rule--is it good?"

Wolverine spoke: "I have been Lieutenant to the Black King for four years--I am satisfied. When our enemies, the Trappers, have tried to catch us by new wiles His Majesty has told us how to escape."

"Did he, always?" demanded the Bird. "Who knew of the little White Powder that François put in the Meat--the White Medicine Powder he had in a bottle? Neither you, Carcajou, nor Black King, nor any one tasted that--did you? Even now you do not know the name of it; but I can tell you--it's strychnine. Ha, ha! but that was funny. They put it out, and I, Whisky-Jack, whom you call a Tramp, told you. I, Jack the Gabbler, flew till my wings were tired warning you to beware."

"You might have saved yourself the trouble," retorted Wolverine; "Black King would have found it with his nose. Can he not tell even if any Man has touched the Meat that is always a Bait?"

"Stupid!" exclaimed Jack; "do you think the Men are such fools? They handle not the Bait which is put in the Traps--they know that all the brains you chaps have are in your noses. Catch François, the Half-breed, doing that; he's too clever. He cuts it with a long knife, and handles it with a stick. The little White Powder that is the essence of death is put in a hole in the Meat. I know; I've seen them at it. Haven't their Train-Dogs noses also--and didn't two of them that time eat the Bait, and die before they had travelled the length of a Rabbit-run. I saw them--they grew stiff and quiet, like the White Man who fell in the snow last Winter when he was lost. But I'm satisfied with Black Fox; and you can be his Lieutenant--I don't care."

"Yes," continued Carcajou, "who among us is more fitted to be King? Muskwa is strong, and big, and brave; but soon he will go into his house, and sleep until Spring. What would become of us with no King for months?"

"Yes, I'm sleepy," answered Bear--"and tired. I've tramped up and down the banks of the river eating white Buffalo-berries and red Cranberries until I'm weary. They are so small, and I am so big; it keeps me busy all day."

"You've got stout on it," chuckled Jack. "I wish I could get fat."

"You talk too much, and fret yourself to death over other people's business," growled Bear. "You're a meddling Tramp."

"Muskwa," said Mink, "there are bushels and bushels of big, juicy, Black Currants up in the Muskeg, near the creek I fish in--I wish I could eat them. Swimming, swimming all day after little frightened Fish, that are getting so cunning. Why, they hide under sticks, and get up in shallow water among the stones, so that I can hardly see them. It must be pleasant to sit up on your quarters, nice and dry, pull down the bushes and eat great, juicy Berries. I wish I lived on fruit."

"No you don't," snarled Jay; "you'd sell your Mother for a fish."

"If you're quite through wrangling," interrupted Wolverine, "I'll go on talking about the King. Who is better suited than Black Fox? Is it Mooswa? He would make a very magnificent-looking King. See his great horns. He would protect us--just now; but do you not know that in the Spring they will drop off, and our Comrade will be like a Man without hands all Summer. Why, even his own Wife won't look at him while he is in that condition. Then the young horns come out soft and pulpy, all covered with velvet, and until they get hard again are tender, and he's afraid to strike anything with them. You see, we must have somebody that is King all the year round. Why, Mooswa couldn't tell us about the Bait; he can't put his nose to the ground; he can't even eat grass, because of his short neck."

"I wish I could," sighed the Moose. "I get tired of the purple-headed Moose-weed, and the leaves and twigs. The young grass looks so sweet and fresh. But Carcajou is right; I was made this way--I don't know why, though."

"No, you weren't!" objected Whisky-Jack; "you're such a lordly chap when you get your horns in good order, and have gone around so much with that big nose stuck up in the air, that you've just got into that shape--He, he! I've seen Men like you. The Hudson's Bay Factor, at Slave Lake, is just your sort. Bah! I don't want you for a King."

The Bull Moose waved his tasselled beard back and forth angrily, and stamped a sharp, powerful fore-foot on the ground like a trip-hammer.

Black Fox interfered again. "Why do you make everybody angry, you silly Bird?" he said to the Jay. "Do you learn this bitter talk from listening to your Men friends while you are waiting for their scraps?"

"Perhaps so; I learn many things from them, and you learn from me. But go on, Bully Carcajou. Tell us all why we're not fit to be Kings. Perhaps Rof, there, would like to hear of his failings."

"I don't want to be King," growled Rof, the big Blue Wolf, surlily.

"No, your manners are against you," sneered Jack; "you'd do better as executioner."

"Well," commenced Carcajou, taking up the challenge, "to tell you the truth, we're all just a little afraid of Rof. We don't want a despotic Ruler if we can help it. I don't wish to hurt his feelings, but when Blue Wolf got hungry his subjects might suffer."

"I don't want him for King," piped Mink; "his jaws are too strong and his legs too long."

"Oh, I couldn't stay here," declared Blue Wolf, "and manage things for you fellows. Next month I'm going away down below Grand Rapids. My Brother has been hunting there with a Pack of twenty good fellows, and says the Rabbits are so thick that he's actually getting fat;" and Wolf licked his steel jaws with a hungry movement that made them all shudder. His big lolling tongue looked like a firebrand.

"You needn't fret," squeaked Jay; "we don't want you. We don't want a rowdy Ruler. I saw you fighting with the Train Dogs over at Wapiscaw last Winter. You're as disgraceful as any domestic cur."

"Now, Pisew--" began Carcajou.

As he mentioned the Lynx's name, a smile went round the meeting. Whisky-Jack took a fit of chuckling laughter, until he fell off his perch. This made him cranky in an instant. "Of all the silly Sneaks!" he exclaimed scornfully, as he fluttered up on a small Jack-pine, and stuck out his ruffled breast. "That Spear-eared Creature for King! Oh, my! Oh, my! that's too rich! He'd have you all catching Rabbits for him to eat. Kings are great gourmands, I know, but they don't eat Field Mice, and Frogs, and Snails, and trash of that sort--not raw, anyway."

Carcajou proceeded more gravely with his objection. "As I said before, this is purely a matter of business with us; and anything I say must not be taken as a personal affront."

"Of course not, of course not," interrupted Jack. "Go on with your candid observations, Hump-back."

"We all know our Friend's weakness for perfume," continued Wolverine.

"Do you call Castoreum a perfume?" questioned Whisky-Jack. "It's a vile, diabolical stink--that's what it is. Why, the Trappers won't keep it in their Shacks--it smells so bad; they bury it outside. Nobody but a gaunt, brainless creature, like the Cat there, would risk his neck for a whiff of that horrible-smelling stuff."

"Order!" commanded Black King; "you get so personal, Jack. You know that our Comrade, Beaver, furnishes the Castoreum, don't you?"

"Yes, I know; and he ought to be ashamed of it."

"It's not my fault," declared Umisk; "your friends, the cruel Trappers, don't get it from us till we're dead."

"Well, never mind about that," objected Carcajou. "We know, and the Trappers know, that Lynx is the easiest caught of all our fellows; if he were our King they'd snare him in a week--then we'd be without a Ruler. We must have some one that not only can take care of us, but of himself too."

"Pisew can't do that--he can't take care of his own family," twittered Jay. "His big furry feet make a trail in the snow like Panther's, and then when you come up to him, he's just a great starved Cat, with less brains than a Tadpole."

Carcajou suddenly reared on his hind quarters and let fly the stone with his short, strong, right arm at the Bird. "Evil Chatterer!" he exclaimed angrily, "you are always making mischief."

Jack hopped nimbly to one side, cocked his saucy silvered head downward, and piped: "Proceed with the meeting; the Prince of all Mischief-makers, Carcajou, the Devil of the Woods, lectures us on morality."

"Yes, let us proceed with the discussion," commanded Black Fox.

"Brothers," said the Moose, in a voice that was strangely plaintive, coming from such a big, deep throat, "I am satisfied with Black Fox for King; but if anything were to happen requiring us to choose another, one of almost equal wisdom, I should like to nominate Beaver. We know that when the world was destroyed by the great flood, and there was nothing but water, that Umisk took a little mud, made it into a ball with his handy tail, and the ball grew, and they built it up until it became dry land again. Wiesahkechack has told us all about that. I have travelled from the Athabasca across Peace River, and up to the foothills of the big mountains, to the head-waters of the Smoky, and have seen much of Brother Umisk's clever work, and careful, cautious way of life. I never heard any one say a word against his honesty."

"That's something," interrupted Jay; "that's more than can be said for many of us."

The big melancholy eyes of the Moose simply blinked solemnly, and he proceeded: "Brother Umisk has constructed dams across streams, and turned miles of forest into rich, moist Muskeg, where the loveliest long grasses grow--most delicious eating. These dams are like the great hard roads you have seen the White Men cut through our country to pull their stupid carts over; I can cross the softest Muskeg on one and my sharp hoofs hardly bury to the fetlock. Is that not work worthy of an Animal King? And he has more forethought, more care for the Winter, than any of us. Some of you have seen his stock of food."

"I have," eagerly interrupted Nekik, the Otter.

"And I," said Fisher.

"I too, Mooswa," cried Mink.

"I have seen it," quoth Muskrat; "it's just beautiful!"

"You tell them about Umisk's food supply, Brother Muskrat," commanded the Moose. "I can't dive under the water like you and see it ready stored, but I have observed the trees cut down by his chisel-teeth."

"You make me blush," remonstrated Beaver, modestly.

"Beautiful White Poplar trees," went on Mooswa; "and always cut so they fall just on the edge of the stream. Is that not clever for one of us? Man can't do it every time."

"Trowel Tail only cuts the leaning trees--that's why!" explained Whisky-Jack.

Mooswa was too haughty to notice the interruption, but continued his laudation of Beaver's cunning work.

"Then our Brother Umisk cuts the Poplar into pieces the length of my leg; and, while I think of it, I'd like to ask him why he leaves on the end of each stick a piece like the handle of a rolling-pin."

"What's a rolling-pin?" gasped Jay.

"Something the Cook throws at your head when you're trying to steal his dinner," interjected Carcajou.

Lynx laughed maliciously at this thrust. "Isn't Wolverine a witty chap?" he said, fawningly, to Blue Wolf.

"I know what that cunning little end is for," declared Muskrat; "I'll tell you what Beaver does with the sticks under water, and then you'll understand."

Black King yawned as though all this bored him. "He doesn't like to hear his rival praised," sneered Whisky-Jack; "it makes him sleepy."

"Well," continued Wuchusk, "Beaver floats the Poplar down to his pond, to a little place just up stream from his lodge, with a nice, soft bottom. There he dives swiftly with each piece, and the small round end you speak of, Mooswa, sticks in the mud, see? Oh, it is clever; I wish I could do it,--but I can't. I have to rummage around all Winter for my dinner. All the sticks stand there close together on end; the ice forms on top of the water, and nobody can see them. When Umisk wants his dinner, he swims up the pond, selects a nice, fat, juicy Poplar, pulls it out of the mud, floats it in the front door of his pretty, round-roofed lodge, strips off the rough covering, and eats the white, mealy inner-bark. It's delicious! No wonder Beaver is fat."

"I should think it would be indigestible," said Lynx. "But isn't Umisk kind to his family--dear little Chap!"

"Must be hard on the teeth," remarked Mink. "I find fishbones tough enough."

"Oh, it's just lovely!" sighed Beaver. "I like it."

"What do you do with the logs after you've eaten the crust?" asked Black King, pretending to be interested.

"Float them down against the dam," answered Beaver. "They come in handy for repairing breaks."

"What breaks the dam?" mumbled Blue Wolf, gruffly.

"I know," screamed Jay; "the Trappers. I saw François knock a hole in one last Winter. That's how he caught your cousins, Umisk, when they rushed to fix the break."

"How do you know when it's damaged, Beaver?" queried Mooswa. "Supposing it was done when you were asleep--you don't make your bed in the water, I suppose."

"No, we have a nice, dry shelf all around on the inside of the lodge, just above--we call it the second-story; but we keep our tails in the water always, so as soon as it commences to lower we feel it, you know."

"That is wise," gravely assented Mooswa. "Have I not said that Umisk is almost as clever as our King?"

"He may be," chirruped Jay; "but François never caught the Black King, and he catches many Beaver. Last winter he took out a Pack of their thick, brown coats, and I heard him say there were fifty pelts in it."

"That's just it," concurred Carcajou. "I admire Umisk as much as anybody. He's an honest, hard-working little chap, and looks after his family and relations better than any of us; but if there was any trouble on we couldn't consult him, for at the first crack of a Firestick, or bark of a Train Dog, he's down under the water, and either hidden away in his lodge, or in one of the many hiding-holes he has dug in the banks for just such emergencies. We must have some one who can get about and warn us all."

"I object to him because he's got Fleas," declared Jay, solemnly.

"Fleas!" a chorus of voices exclaimed in indignant protest.

The Coyote, who had been digging viciously at the back of his ear with a sharp-clawed foot, dropped his leg, got up, and stretched himself, with a yawn, hoping that nobody had observed his petulant scratching.

"That's silly!" declared Mooswa. "A chap that lives under the water have Fleas?"

"Is it?" piped Whisky-Jack. "What's his thick fur coat, with the strong, black guard-hairs for? Do you suppose that doesn't keep his hide dry? If one of you land-dwellers were out in a stiff shower you'd be wet to the skin; but he won't, though he stay under water a month. If he hasn't got Fleas, what is that double nail on his left hind-foot for?"

"Perhaps he hasn't got a split-nail," ventured Fisher--"I haven't."

"Nor I!" declared Mink.

"My nails are all single!" asserted Muskrat.

"Look for yourselves if you don't believe me," commanded Jack. "If he hasn't got it, I'll take back what I said, and you can make him King if you wish."

This made Black Fox nervous. "Will you show our Comrades your toes, please?" he commanded Beaver, with great politeness.

Umisk held up his foot deprecatingly. There sure enough, on the second toe, was a long, black, double claw, like a tiny pincers. "What did I tell you?" shrieked Jack. "He can pin a Flea with that as easily as Mink seizes a wriggling Trout. He's got half-a-dozen different kinds of Fleas, has Umisk. I won't have a King who is little better than a bug-nursery. A King must be above that sort of thing."

"This is all nonsense," exclaimed Carcajou angrily, for he had fleas himself; "it's got nothing to do with the matter. Umisk has to live under the ice nearly all Winter, and would be of no more service to us than Muskwa--that's the real objection."

"My!" cried Beaver, patting the ground irritably with his trowel-tail, "one really never knows just how vile he is till he gets running for office. Besides, I don't want to be King--I'm too busy. Perhaps sometime when I was here governing the Council, François, or another enemy, would break my dam and murder the whole family; besides, it's too dusty out here--I like the nice, clean water. My feet get sore walking on the land."

"Oh, he doesn't want to be King!" declared Jay, ironically. "Next! next! Who else is there, Frog-legged Carcajou?"

"Well, there's Muskrat," suggested Lynx; "I like him."

"Yes, to eat!" interrupted Whisky-Jack. "If Wuchusk were King, we'd come home some day and find that he'd been eaten by one of his own subjects--by the sneaking Lynx--'Slink' it should be."

"You shouldn't say that," declared Black Fox; "because you're our Mail Carrier you shouldn't take so many liberties."

"I'm only telling the truth. It has always been the custom at these meetings for each one to speak just what he thought, and no hard feelings afterward."

Carcajou pulled his long, curved claws through his whiskers reflectively. "What's the use of wrangling like this--we're as silly as a lot of Men. Last Winter when I was down at Grand Rapids I sat up on the roof of a Shack listening to those two-legged creatures squabbling. They were all arguing fiercely about the different ways of getting to Heaven. According to each one he was on the right road, and the rest were all wrong. Fresh Meat! but it was stupid; for I gathered from what they said that the one way to get there was to be good; only each had a different way."

"What place did you say?" queried the Jay.

"Grand Rapids."

"No, no! the place they all wanted to go to."

"Heaven."

"Where's that?"

"I don't know, and you needn't bother; for the Men said it was a place for the good, only."

Beaver's fat sides fairly shook as he chuckled delightedly over the snub Carcajou had given Jack.

"Ha, ha!" roared Bear; "Sweet Berries! but Humpback is too many for you, Birdie," and the woods echoed with his laughter.

"Rats!" screamed the Jay; "that's the subject under discussion. Our friend wanders from his theme trying to be personal."

"Oh, nobody's personal here," sighed Lynx. "I'm a 'Slink,' but that doesn't count."

"Yes, talking of Rats," recommenced Carcajou, "like Lynx, I admire our busy little Brother, Beaver, though I never ate one in my life--"

"Pisew did!" chirruped the bird-voice from over their heads.

"Though I never ate one," solemnly repeated Wolverine; "but if Umisk won't do for King, there is no use discussing Wuchusk's chances. He has all Trowel Tail's failings, without his great wisdom, and even can't build a decent house, though he lives in one. Half the time he hasn't anything to eat for his family; you'll see him skirmishing about Winter or Summer, eating Roots, or, like our friends Mink and Otter, chasing Fish. Anyway, I get tired of that horrible odour of musk always. His house smells as bad as a Trapper's Shack with piles of fur in it--I hate people who use musk, it shows bad taste; and to carry a little bag of it around with one all the time--it's detestable!"

"You should take a trip to the Barren Lands, my fastidious friend, as I did once," interposed Mooswa, "and get a whiff of the Musk Ox. Much Fodder! it turned my stomach."

"You took too much of it, old Blubbernose," yelled Jay, fiendishly; "Wolverine hasn't got a nose like the head of a Sturgeon Fish. Anyway, you're out of it, Mister Rat; if the Lieutenant says you're not fit for King, why you're not--I must say I'm glad of it."

"There are still the two cousins, Otter, and Mink," said Carcajou.

"Fish Thieves--both of them," declared Whisky-Jack. "So is Fisher, only he hasn't nerve to go in the water after Fish; he waits till Man catches and dries them, then robs the cache. That's why they call him Fisher--they should name him Fish-stealer."

"Look here, Jack," retorted Wolverine, "last Winter I heard François say that you stole even his soap."

"I thought it was butter," chuckled Jay--"it made me horribly sick. But their butter was so bad, I thought the soap was an extra good pat of it."

"I may say," continued Carcajou, "that these two cousins, Otter and Mink, like Muskrat, have too limited a knowledge for either to be Chief of the Boundaries. While they know all about streams and water powers, they'd be lost on land. Why, in deep snow, Nekik with his short, little legs makes a track as though somebody had pulled a log along--that wouldn't do."

"I don't want to be King!" declared Otter.

"Nor I!" added Mink.

"And we don't want you--so that settles it; all agreed!" cried Whisky-Jack, gleefully. "Nothing like having peace and harmony in the meeting. It always comes to the same thing: people's names are put up, they're blackguarded and abused, and in the end nobody's fit for the billet but Black Fox; and Carcajou, of course, is his Lieutenant."

"We have now considered everybody's claims," began Carcajou--

"You've modestly forgotten yourself," interrupted Whisky-Jack. "You'd make a fine, fat, portly Ruler."

"No, I withdraw in favour of Black Fox, and we won't even mention your name. Black Fox has been a good King; he has saved many of us from a Trap; besides, he wears the Royal Robe. Look at him! his Mother and all his Brothers and Sisters are red, except Stripes, the Baby, who is a Cross; does that not show that he has been selected for royal honours? Among ourselves each one is like his Brother--there is little difference. The Minks are alike, the Otter are alike, the Wolves are alike--all are alike; except, of course, that one may be a little larger or a little darker than the other. Look at the King's magnificent Robe--blacker than Fisher's coat; and the silver tip of the white guard-hairs make it more beautiful than any of our jackets."

"It's just lovely!" purred Pisew, with a fine sycophantic touch.

"I'm glad I haven't a coat like that," sang out Jay; "His Majesty will be assassinated some day for it. Do you fellows know what he's worth to the Trappers--do any of you know your market value? I thought not--let me tell you."

"For the sake of a mild Winter, don't--not just now," pleaded Carcajou. "Let us settle this business of the King first, then you can all spin yarns."

"Yes, we're wasting time," declared Umisk. "I've got work to do on my house, so let us select a Chief, by all means. There's Coyote, and Wapoos, and Sikak the Skunk, who have not yet been mentioned." But each of these, dreading Jack's sharp tongue, hastily asserted they were not in the campaign as candidates.

"Well, then," asked Carcajou, "are you all agreed to have Black Fox as Leader until the fulness of another year?"

"I'm satisfied!" said Bear, gruffly.

"It's an honour to have him," ventured Pisew the Lynx.

"He's a good enough King," declared Nekik the Otter.

"I'm agreed!" exclaimed Beaver; "I want to get home to my work."

"Long live the King!" barked Blue Wolf.

"Long live the King!" repeated Mink, and Fisher, and the rest of them in chorus.

"Now that's settled," announced Wolverine.

"Thank you, Comrades," said Black Fox; "you honour me. I will try to be just, and look after you carefully. May I have Wolverine as Lieutenant again?"

They all agreed to this.

THE VALUE OF THEIR FUR

"Now that's serious business enough for one day," declared the King; "Jack, you may tell us about the fur, and perhaps some of the others also have interesting tales to relate."

Whisky-Jack hopped down from his perch, and strutted proudly about in the circle.

"Mink," he began, snapping his beak to clear his throat, "you can chase a silly, addle-headed Fish into the mud and eat him, but you don't know the price of your own coat. Listen! The Black King's jacket is worth more than your fur and all the others put together. I heard the Factor at Wapiscaw tell his clerk about it last Winter when I dined with him."

"You mean when you dined with the Train Dogs," sneered Pisew.

"You'll dine with them some day, and their stomachs will be fuller than yours," retorted the Bird. "Mink, your pelt is worth a dollar and a half--'three skins,' as the Company Men say when they are trading with the Indians, for a skin means fifty cents. You wood-dwellers didn't know that, I suppose."

"What do they sell my coat for?" queried Beaver.

"Six dollars--twelve skins, for a prime, dark one. Kit-Beaver, that's one of your Babies, old Trowel Tail, sells for fifty cents--or is given away. You, Fisher, and you, Otter, are nip and tuck--eight or ten dollars, according to whether your fur is black or of a dirty coffee colour. But there's Pisew; he's got a hide as big as a blanket, and it sells for only two dollars. Do you know what they do with your skin, Slink? They line long cloaks for the White Wives with it; because it's soft and warm,--also cheap and nasty. He, he! old Feather-bed Fur.

"Now, Wapistan, the Marten, they call a little gentleman. It's wonderful how he has grown in their affections, though. Why, I remember, five years ago the Company was paying only three skins for prime Marten; and what do you suppose your hide sells for now, wee Brother?"

"Please don't," pleaded Marten, "it's a painful subject; I wish they couldn't sell it at all. I'm almost afraid to touch anything to eat--there's sure to be a Trap underneath. The other day I saw a nice, fat White Fish head, and thought Mink had left a bite for me; but when I reached for it, bang! went a pair of steel jaws, scraping my very nose. Fat Fish! it was a close shave--I'm trembling yet; the jagged teeth looked so viciously cruel. If my leg had got in them I know what I should have had to do."

"So do I," asserted Jack.

"What would he have done, Babbler--you who know all things?" asked Lynx.

"Died!" solemnly croaked Jay.

"I should have had to cut off my leg, as a cousin of mine did," declared Wapistan. "He's still alive, but we all help him get a living now. I wish my skin was as cheap as Muskrat's."

"Oh, bless us! he's only worth fifteen cents," remonstrated Jack. "His wool is but used for lining--put on the inside of Men's big coats where it won't show. But your fur, dear Pussy Marten, is worth eight dollars; think of that! Of course that's for a prime pelt. That Brother of yours, sitting over there with the faded yellow jacket, wouldn't fetch more than three or four at the outside; but I'll give you seven for yours now, and chance it--shouldn't wonder if you'd fetch twelve when they skin you, for your coat is nice and black."

"I suppose there's no price on your hide," whined Lynx; "it's nice to be of no value in the world--isn't it?"

"There's always a price on brains; but that doesn't interest you, Silly, does it? You're not in the market. Your understanding runs to a fine discrimination in perfumes--prominent odours, like Castoreum, or dead Fish. If you were a Man you'd have been a hair-dresser.

"Muskwa, your pelt's a useful one; still it doesn't sell for a very great figure. Last year at Wapiscaw I saw pictures on the Factor's walls of men they call Soldiers, and they had the queerest, great, tall head-covers, made from the skins of cousins of yours. And the Factor also had a Bear pelt on the floor, which he said was a good one, worth twenty dollars--that's your value dead, twenty dollars.

"Mooswa's shaggy shirt is good; but they scrape the hair off and make moccasins of the leather. Think of that, Weed-eater; perhaps next year the Trappers will be walking around in your hide, killing your Brother, or your Daddy, or some other big-nosed, spindle-legged member of your family. The homeliest man in the whole Chippewa tribe they have named 'The Moose,' and he's the ugliest creature I ever saw; you'd be ashamed of him--he's even ashamed of himself."

"What's the hide worth?" asked Carcajou.

"Seven dollars the Factor pays in trade, which is another name for robbery; but I think it's dear at that price, with no hair on, for it is tanned, of course--the Squaws make the skin into leather. You wouldn't believe, though, that they'd ever be able to skin Bushy-tail, would you?"

"What! the Skunk?" cried Lynx. "Haven't the Men any noses?"

"Not like yours, Slink; but they take his pelt right enough; and the white stripes down his back that he's so proud of are dyed, and these Men, who are full of lies, sell it as some kind of Sable. And Marten, too, they sell him as Sable--Canadian Sable."

"I'm sure we are all enjoying this," suggested Black King, sarcastically.

"Yes, Brothers," assented Whisky-Jack, "Black Fox's silver hide is worth more than all the rest put together. Sometimes it fetches Five Hundred Dollars!"

"Oh!" exclaimed Otter, enviously; "is that true, Jack?"

"It is, Bandy-legs--I always speak the truth; but it is only a fad. A tribe of Men called Russians buy Silver Fox; it is said they have a lot of money, but, like Pisew, little brains. For my part, I'd rather have feathers; they don't rub off, and are nicer in every way. Do you know who likes your coat, Carcajou?"

"The Russians!" piped Mink, like a little school-boy.

"Stupid Fish-eater! Bigger fools than the Russians buy Wolverine--the Eskimo, who live away down at the mouth of the big river that runs to the icebergs."

"What are icebergs, Brother?" asked Mink.

"Pieces of ice," answered Jack. "Now you know everything, go and catch a Goldeye for your supper."

"Goldeye don't come up the creeks, you ignorant Bird," retorted Sakwasew. "I wish they did, though; one can see their big, yellow eyes so far in the water--they're easily caught."

"Suckers are more useful," chimed in Fisher; "when they crowd the river banks in Autumn, eating those black water-bugs, I get fat, and hardly wet a foot; I hate the water, but I do like a plump, juicy Sucker."

"Not to be compared to a Goldeye or Doré," objected Mink; "they're too soft and flabby."

"Fish, Fish, Fish! always about Fish, or something to eat, with you Water-Rats," interrupted Carcajou, disgustedly. "Do let us get back to the subject. Do you know what the Men say of our Black King, Comrades?"

"They call him The Devil!" declared Jay.

"No they don't," objected Carcajou; "they aver he's Wiesahkechack, the great Indian God, who could change himself into Animals--that's what they think. You all know François, the French Half-breed, who trapped at Hay River last Winter."

"He killed my First Cousin," sighed Marten.

"I lost a Son by him--poisoned," moaned Black King's Mother, the Red Widow, who had been sitting quietly during the meeting watching with maternal pride the form of her son.

"Yes, he tried to catch me," boasted Carcajou, "but I outwitted him, and threw a Number Four Steel Trap in the river. He had a fight with a Chippewa Indian over it--blamed him for the theft. Oh, I enjoyed that. I was hidden under a Spruce log, and watched François pummel the Indian until he ran away. I don't understand much French, but the Half-breed used awful language. I wish they'd always fight amongst themselves."

"Why didn't the Chippewa squeeze François till he was dead?--that's what I should have done," growled Muskwa. "Do you remember Nichemous, the Cree Half-breed, who always keeps his hat tied on with a handkerchief?"

"I saw him once," declared Black Fox.

"Well, he tried to shoot me--crept up close to a log I was lying behind, and poked his Ironstick over it, thinking I was asleep. That was in the Winter--I think it was the Second of February: but do you know, sometimes I get my dates mixed. One year I forgot in my sleep, and came out on the First to see what the weather was like. Ha, ha! fancy that; coming out on the First and thought it was the Second."

"What has that got to do with Nichemous, old Garrulity?" squeaked Whisky-Jack.

Muskwa licked his gray nose apologetically for having wandered from the subject. "Well, as I have said, it was the Second of February; I had been lying up all Winter in a tremendously snug nest in a little coulee that runs off Pembina River. Hunger! but I was weak when I came out that day."

"I should think you would have been," sympathized the Bird, mockingly.

"I had pains, too; the hard Red-willow Berries that I always eat before I lay up were griping me horribly--they always do that--they're my medicine, you know."

"Muskwa is getting old," interrupted Jay. "He's garrulous--it's his pains and aches now."

Bear took no notice of the Bird. "I was tired and cross; the sun was nice and warm, and I lay down behind a log to rest a little. Suddenly there was a sound of the crisp hide of the snow cracking, and at first I thought it was something to eat coming,--something for my hunger. I looked cautiously over the tree, and there was Nichemous trailing me; his snow-shoe had cut through the crust; but it was too late to run, for that Ironstick of his would have reached; so I lay still, pretending to be asleep. Nichemous crept up, oh, so cunningly. He didn't want to wake poor old Muskwa, you see--not until he woke me with the bark of his Ironstick. Talk about smells, Mister Lynx. Wifh! the breath of that when it coughs is worse than the smell of Coyote--it's fairly blue in the air, it's so bad."

"Where was Nichemous all this time?" cried Jack, mockingly.

"Have patience, little shaganappi (cheap) Bird. Nichemous saw my trail leading up to the log, but could not see it going away on the other side. I had just one eye cocked up where I could watch his face. Wheeze! it was a study. He'd raise one foot, shove it forward gently, put that big gut-woven shoe down slowly on the snow, and carry his body forward; then the other foot the same way, so as not to disturb me. Good, kind Nichemous! What a queer scent he gave to the air. Have any of you ever stepped on hot coals, and burned your foot?"

"I have!" cried Blue Wolf; "I had a fight with three Train Dogs once, at Wapiscaw, when their Masters were asleep. It was all over a miserable frozen White Fish that even the Dogs wouldn't eat. They were husky fighters. Wur-r-r! we rolled over and over, and finally I fetched up in the camp-fire."

"Then you know what your paw smelled like when the coals scorched it; and that is just the nasty scent that came down the air from Nichemous--like burnt skin. I could have nosed him a mile away had he been up wind, but he wasn't at first. When Nichemous got to the big log, he reached his yellow face over, with the Ironstick in line with his nose, and I saw murder in his eyes, so I just took one swipe at the top of his head with my right paw and scalped him clean. Whu-u-o-o-f-f-! but he yelled. The Ironstick barked as he went head first into the snow, and its hot breath scorched my arm--underneath where there's little hair; but the round iron thing it spits out didn't touch me. I gave Nichemous a squeeze, threw him down, and went away. I was mad enough to have slain him, but I'm glad I didn't. It's not good to kill a Man. You see I was cross," he added, apologetically, "and my head ached from living in that stuffy hole all Winter."

"Didn't it hurt your paw?" queried Jack. "I should have thought your fingers would have been tender from sucking them so much while you were sleeping in the nest."

"That's what saved Nichemous's life," answered Muskwa. "My fist was swollen up like a moss-bag, else the blow would have crushed his skull. But I knocked the fur all off the top; and his wife, who is a great medicine woman, couldn't make it grow again; though she patched the skin up some way or other. That is why you'll see Nichemous's hat tied on with a red handkerchief always."

"I also know of this Man," wheezed Otter. "Nichemous stepped on my slide once when he was poaching my preserve--I had it all nice and smooth, and slippery, and the silly creature, without a claw to his foot, tried to walk on it."

"What happened, Long-Back?" asked Jack, eagerly.

"Well, he went down the slide faster than ever I did, head first; but, would you believe it, on his back."

"Into the water?" queried Muskrat. "That wouldn't hurt him."

"He was nearly drowned," laughed Nekik. "The current carried him under some logs, but he got out, I'm sorry to say. That's the worst of it, we never manage to kill these Men."

"I killed one once," proclaimed Mooswa--"stamped him with my front feet, and his friends never found him; but I wouldn't do it again, the look in his eyes was awful--no, I'll never do it again."

"They'll kill you some day, Marrow-Bones," declared Jay, blithely.

"That's what this Man tried to do."

"Tell us about it, Comrade," cried Carcajou, "for I like to hear of the tables being turned once in a while. Why, Mistress Carcajou frightens the babies to sleep by telling them that François, or Nichemous, or some other Trapper will catch them if they don't close their eyes and stop crying--it's just awful to live in continual dread of Man."

"He was an Indian named Grasshead," began Mooswa, lying down to tell the little tale comfortably. "I had just crossed the Athabasca on the ice; he'd been watching, no doubt, and as I went up the bank his Firestick coughed, and the ball struck me in the neck. Of course I cleared off into the woods at a great rate."

"Didn't stop to thank the Man, eh, old Pretty Legs?" questioned Jack, ironically.

"There was a treacherous crust on the snow; sometimes it would bear me up, and sometimes I would go through up to my chest, for it was deep. Grasshead wore those big shoes that Muskwa speaks of, and glided along the top; but my feet are small and hard, you know, and cut the crust."

"See!" piped Jay, "there's where pride comes in. All of you horned creatures are so proud of your little feet, and unless the ground is hard you soon get done up."

"Well," continued Mooswa, "sometimes I'd draw away many miles from the Indian. Once I circled wide, went back close to my trail, laid down in a thicket, and watched for him. He passed quite close, trailing along easily on top of the snow, chewing a piece of dried moose-meat--think of that, Brothers! stuck in his loose shirt was dried-meat, cut from the bodies of some of my relatives; even the shirt itself was made from one of their hides. His little eyes were vicious and cruel; and several times I heard him give the call of our wives, which is, 'Wh-e-a-u-h-h-h!' That was that I might come back, thinking it was one of my tribe calling. All day he trailed me that way, and twice I rested as I speak of. Then Grasshead got cunning. He travelled wide of my trail, off to one side, meaning to come upon me lying down or circling. The second day of his pursuit I was very tired, and the Indian was always coming closer and closer.

"Getting desperate, I laid a trap for him. It was the Firestick I feared really; for without that he was no match for me. With our natural strength, he with his arms and teeth, and I with my hoofs and horns, I could kill him easily. Why, once I slew three Wolves, nearly as large as Rof; they were murderous chaps who tackled me in the night. It wouldn't do to fight Grasshead where the crust was bad on the deep snow, so I made for a Jack-pine bluff."

"I know," interrupted Black Fox, nodding his head; "nice open ground with no underbrush to bother--just the place for a rush when you've marked down your Bird. Many a Partridge I've pinned in one of those bluffs."

"Yes," went on Mooswa, "the pine needles kill out everything but the silver-green moss. The snow wasn't very deep there; it was an ideal place for a charge--nothing to catch one's horns, or trip a fellow. As Grasshead came up he saw me leaning wearily against a tree, and thought I was ready to drop. I was tired, but not quite that badly used up. You all know, Comrades, how careful an Indian is not to waste the breath of his Ironstick; he will creep, and creep, and sneak, just like--"

"Lynx," suggested Whisky-Jack.

"Well, Grasshead, seeing that I couldn't get away, as he thought, came cautiously to within about five lengths, meaning to make sure of my death, you know, Brothers; and just as he raised his Ironstick I charged. He didn't expect that--it frightened him. The ball struck me in the shoulder, and made me furious with rage. The Indian turned to run; but I cut him down, and trampled him to death--I ground him into the frozen earth with my antlers. He gave the queer Man-cry that is of fear and pain--it's awful! I wish he hadn't followed me--I wish I hadn't killed him."

"You were justified, Mooswa," said Black King; "there is no blame--that is the Law of the Forest:--

"'First we run for our lives,Then we fight for our lives:And we turn at bay when the killer drives."

"Bravo, bravo!" applauded Whisky-Jack. "Don't fret about the Indian, old Jelly-Nose. I'm glad you killed him. I've heard the White Trappers say that the only good Indians are the dead ones."

"My own opinion is that Indians are a fat-meat sight better than the Whites," declared Carcajou; "they don't tell as many lies, and they won't steal. They never lock a door here, but they do in the Whiteman's land. An Indian just puts his food down any place, or up on a cache, and nobody touches it; only, of course, the White Men who were here in the Boundaries last year looking for the yellow-sand--they stole from the caches."

"Nobody?" screamed Jay. "Nobody? What do you call yourself, Carcajou? How many bags of flour have you ripped open that didn't belong to you? How many pounds of bacon have melted away because of your hot mouth? I know. I've heard Ambrose, and François, and every other Trapper from the Landing to Fort Simpson swear you're the biggest thief since the time of Wiesahkechack. Why, you're as bad as a White Man by your own showing."

"Gently, Brother, gently. Didst ever hear your Men Friends tell the story of the pot and the kettle? Besides, is it unfair that I, or any of us, take a little from those who come here to steal the coats off our backs, and the lives from our hearts?"

"Indeed thou art the pot, Carcajou," retorted Jack; "but what do I steal? True, I took the piece of soap thinking it was butter; but that was a trifle, not the size of a Trap Bait; and if I take the Meat out of their Traps I do so that my Comrades may not be caught?"

"It is written in the Law of the Forest that is not stealing," said Black King, solemnly. "The Bait that is put in the Trap is for those of the Forest, so come it they be not caught; and even though the Trappers say otherwise, there is no wrong in taking it."

"I also take the Bait-meat," cried Wolverine, "for the good of my Brothers; but I spring the Trap too, lest by accident they put their foot in it."

"I also know Nichemous," broke in Umisk, the Beaver. "He cut a hole in the roof of my house one day, first blocking up the front door thinking we were inside, and meaning to catch us; he had his trouble for nothing, for I got the whole family out just in the nick of time; but I'd like to make him pay for repairs to the roof. I don't know any animal so bad as a Man, unless it's a Hermit Beaver."

"What's a Hermit Beaver, you of the little fore-feet?" asked Jay.

Umisk sighed wearily. "For a Bird that has travelled as much as you have, Jack, you are wondrous devoid of knowledge. Have you never seen Red Jack, the Hermit?"

"I have," declared Pisew, "he has a piece out of the side of his tail."

"Perhaps you have, perhaps you have; but all hermits are marked that way--that's the sign. You see, once in a while a Beaver is born lazy--won't work--will do nothing but steal other people's Poplar and eat it. First we reason with him, and try to encourage him to work; if that fails we bite a piece out of his tail as a brand, and turn him out of the community. I marked Red Jack that way myself; I boarded him for a whole Winter, though, first."

"Served him right," concurred Whisky-Jack.

"Yes, Nichemous is a bad lot," said Carcajou, reflectively; "but he's no worse than François."

Black Fox rose, stretched himself, yawned, and said: "The Meeting is over for to-day; three spaces of darkness from this we meet here again; there is some business of the Hunting Boundaries to do, and Wapoos has a complaint to make."

"I'm off," whistled Whisky-Jack. "Good-bye, Your Majesty. You fellows have got to hunt your dinner, I'm going to dine with some Men--I like my food cooked."

Each of the Animals slipped away, leaving Black Fox and his Mother, the Red Widow.

"I'm proud of you, my Son," said the Fox Mother. "Come home with me, I've got something rare for dinner."

"What is it, Dame?"

"A nice, fat Wavey" (kind of goose).

"What! Wawao, who nests in the Athabasca Lake? You make my mouth water, Mother. These Mossberry-fed Partridge are so dry they give me indigestion; besides, I never saw them so scarce as they are this year."

"It was the great fire the river Boatmen started in the Summer which burnt up all their eggs that makes them so scarce, Son. Do you not remember how we had to fly to the river, and lie for days with our noses just above water to escape the heat?"

"It's an ill wind, Mother, that blows nobody good, for it nearly cured me of fleas. My fur is not like Beaver's. But the Wavies fly high, and do not nest hereabout--how came you by the Fat Bird?"

"A Hunter hurt it with his Firestick, and it fell in the water with a broken wing. I was watching. I think he is still looking down the river for his Wavey."

THE LAW OF THE BOUNDARIES

Three days later, as had been spoken in the Council, Black King, accompanied by three Fox Brothers, and his Mother the Red Widow, crept cautiously into the open space that was fringed by a tangle of Red and Gray Willows, inside of which grew a second frieze of Raspberry Bushes, sat on his haunches and peered discontentedly, furtively about. There was nobody, nothing in sight--nothing but the dilapidated old Hudson's Bay Company's Log Shack that had been a Trading Post, and against which Time had leaned so heavily that the rotted logs were sent sprawling in a disconsolate heap.

"This does not look overmuch like our Council Court, does it, Dame?" he asked of the Red Widow. "I, the King, am first to arrive--ah, here is Rof!" as Blue Wolf slouched into the open, his froth-lined jaws swinging low in suspicious watchfulness.

"I'm late," he growled, sniffing at each bush and stump as he made the circuit of the Court. "What! only Your Majesty and the Red Widow here as yet. It's bad form for our Comrades to keep the King waiting."

While Blue Wolf was still speaking the Willows were thrust open as though a tree had crashed through them, and Mooswa's massive head protruded, just for all the world as if hanging from a wall in the hall of some great house. His Chinese-shaped eyes blinked at the light. "May I be knock-kneed," he wheezed plaintively, "if it didn't take me longer to do those thirty miles this morning than I thought it would--the going was so soft. I should have been here on time, though, if I hadn't struck just the loveliest patch of my favourite weed at Little Rapids--where the fire swept last year, you know."

"That's what the Men call Fire-weed," cried Carcajou, pushing his strong body through the fringe of berry bushes.

"That's because they don't know," retorted Mooswa; "and because it always grows in good soil after the Fire has passed, I suppose."

"Where does the seed come from, Mooswa?" asked Lynx, who had come up while they were talking. "Does the Fire bring it?"

"I don't know," answered the Bull Moose.

"It is not written in Man's books, either," affirmed Carcajou.

"Can the King, who is so wise, tell us?" pleaded Fisher, who had arrived.

"Manitou sends it!" Black Fox asserted decisively.

"The King answers worthily," declared Wolverine. "If Mooswa can stand in the Fire-flower until it tops his back, and eat of the juice-filled stalk without straining his short neck until his belly is like the gorge of a Sturgeon, what matters how it has come. Let the Men, who are silly creatures, bother over that. Manitou has sent it, and it is good; that is enough for Mooswa."

"You are late, Nekik," said the King, severely; "and you, too, Sakwasu."

"I am lame!" pleaded Otter.

"My ear is bleeding!" said Mink.

"Who got the Fish?" queried Carcajou. They both tried to look very innocent.

"What Fish?" asked Black Fox.

"My Fish," replied Mink.

"Mine!" claimed Otter, in the same breath.

Wolverine winked solemnly at the Red Widow.

"Yap! that won't do--been fighting!" came from the King.

"It was a Doré, Your Majesty," pleaded Sakwasu, "and I caught him first."

"Just as I dove for him," declared Otter, "Sakwasu followed after and tried to take him from me--a great big Fish it was. I've been fishing for four years, but this was the biggest Doré I ever saw--why, he was the length of Pisew."

"A Fisherman's lie," quoth the Red Widow.

"Who got the Doré? That's the main question," demanded Carcajou.

"He escaped," replied Nekik, sorrowfully; "and we have come to the Meeting without any breakfast."

"Bah! Bah! Bah!" laughed Blue Wolf; "that's rich! Hey, Muskwa, you heard the end of the story--isn't it good?"

"I, too, have had no breakfast," declared Muskwa, "so I don't see the point--it's not a bit funny. Seven hard-baked Ant Hills have I torn up in the grass-flat down by the river, and not a single dweller in one of them. My arms ache, for the clay was hard; and the dust has choked up my lungs. Wuf-f-f! I could hardly get my breath coming up the hill, and I have more mortar in my lungs than Ants in my stomach."

"Are there no Berries to be had, then, Muskwa?" asked Wapistan.

"Oh, yes; there are Berries hereabouts, but they're all hard and bitter. The white Dogberries, and the pink Buffalo-berries, and the Wolf-willow berries--what are they? Perhaps not to be despised in this Year of Famine, for they pucker up one's stomach until a Cub's ration fills it; but the Saskatoons are now dry on the Bush, and I miss them sorely. Gluck! they're the berries--full of oil, not vinegar; a feed of them is like eating a little Sucking Pig."

"What's a Sucking Pig?" queried Lynx; "I never saw one growing."

"I know," declared Carcajou. "The Priest over at Wapiscaw had six little white fellows in a small corral. They had voices like Pallas, the Black Eagle. I could always tell when they were being fed, their wondrous song reached a good three miles."

"That's where I got mine," remarked Muskwa, looking cautiously about to see that there were no eavesdroppers; "I had three, and the Priest keeps three. But talking of food, one Summer I crossed the great up-hills that Men call Rockies, and along the rivers of that land grows just the loveliest Berry any poor Bear ever ate."

"Saskatoons?" queried Carcajou.

"No, the Salmon Berry--great, yellow, juicy chaps, the size of Mooswa's nose."

"Fat Birds! what a sized Berry!" ejaculated the Widow, dubiously.

"Well, almost as big," modified Muskwa; "and sweet and nippy. Ugh! ugh! It was like eating a handful of the fattest black Ants you ever tasted."

"I don't eat Ants," declared the Red Widow.

"Neither did I this morning, I'm sorry to say," added Bear, hungrily.

"Weren't they hairy little Beggars, Muskwa?" asked Blue Wolf, harking back longingly to the meat food.

"What, the Salmon Berries?"

"No; the Padre's little Pigs at Wapiscaw."

"Yes, somewhat; I had bristles in my teeth for a week--awfully coarse fur they wore. But they were noisy little rats--the screeching gave me an earache. Huf, huf, huh! You should have seen the Factor, who is a fat, pot-bellied little Chap, built like Carcajou, come running with his short Otter-shaped legs when he heard me among the Pigs."

"What did you do, Muskwa--weren't you afraid?" asked the Red Widow.

"I threw a little Pig out of the corral and he took to the Forest. The Factor in his excitement ran after him, and I laughed so much to see this that I really couldn't eat a fourth Pig."

"But you did well," cried Black King; "there's nothing like a good laugh at meal-time to aid digestion."

"I thought they would eat like that, Muskwa," continued Blue Wolf. "You remember the thick, white-furred animals they once brought to the Mission at Lac La Biche?"

"Sheep," interposed Mooswa, "I remember them; stupid creatures they were--always frightened by something; and always bunching up together like the Plain Buffalo, so that a Killer had more slaying than running to do amongst them."

"That was the worst of it," declared Blue Wolf. "My Pack acted as foolishly as Man did with the Buffalo--killed them all off in a single season, for that very reason."

"And for that trick Man put the blood-bounty on your scalp," cried Carcajou.

"Oh, the bounty doesn't matter so long as I keep the scalp on my own head. But, as I was going to say, the queer fur they had got into my teeth, and made me fair furious. Where one Sheep would have sufficed for my supper, I killed three--though I'm generally of an even temper. The Priest did much good in this country--"

"Bringing in the Sheep, eh?" interrupted Carcajou.

"Perhaps, perhaps; each one according as his interests are affected."

"The Priests are a benefit," asserted Marten. "The Father at Little Slave Lake had a corral full of the loveliest tame Grouse--Chickens, they called them. They were like the Sheep, silly enough to please the laziest Hunter."

"Did you join the Mission, Brother?" asked Carcajou, licking his chops hungrily.

"For three nights," answered Wapistan, "then I left it, carrying a scar on my hip from the snap of a white bob-tailed Dog they call a Fox-terrier. A busy, meddlesome, yelping little cur, lacking the composure of a Dweller in the Boundaries. I became disgusted at his clatter and cleared out."

"A Fox what?" asked the Red Widow. "He was not of our tribe to interfere with a Comrade's Kill."

"It must have been great hunting," remarked Black King, his mouth watering at the idea of a corral full of Chickens.

"It was!" asserted Wapistan. "All in a row they sat, shoulder to shoulder--it was night, you know. They simply blinked at me with their glassy eyes, and exclaimed, 'Peek! Peek!' until I cut their throats. Yes, the Mission is a good thing."

"It is," concurred Black King--"they should establish more of them. But where in the world is Chatterbox, the Jay?"

"Gabbler the Fool must have trailed in with a party of Men going down the river," suggested Carcajou. "Nothing but eating would keep him away from a party of talkers."

"Well, Comrades," said Black King, "shall the Boundaries be the same as last year? Are there any changes to be made?"

"I roam everywhere; is that not so, King?" asked Muskwa.

"Yes; but not eat everywhere. There is truce for the young Beaver, because workmen are not free to the Kill."

"I have not eaten of Trowel Tail's Children," declared Muskwa, proudly. "I have kept the Law of the Boundaries."

"And yet he has lost two sons," said Black Fox, looking sternly about.

A tear trickled down the sandy beard of Beaver and glistened on his black nose.

"Two sturdy Sons, Your Majesty, a year old. Next year, or the year after, they would have gone out and built lodges of their own. Such plasterers I never saw in my life. Why, their work was as smooth as the inner bark of the Poplar; and no two Beavers on the whole length of Pelican River could cut down a tree with them."

"Oh, never mind their virtues, Trowel Tail," interrupted Carcajou, heartlessly; "they are dead--that is the main thing; and who killed them, the question. Who broke the Boundary Law is what we want to know."

"Whisky-Jack should be here during the inquiry," grumbled the King. "He's our detective--Jack sees everything, tells everything, and finds out everything. Shouldn't wonder but he knows--strange that he's not with us."

"Must have struck some Men friends, Your Majesty," said the Bull Moose. "As I drank at the river, twenty miles up, one of those floating houses the Traders use passed with two Men in it. There was the smell of hot Meat came to me, and if Jack was within a Bird's scent of the river, which is a long distance, he also would know of the food."

"Very likely, Mooswa," rejoined Black King. "A cooked pork rind would coax Jay from his duty any time. We must go on with the enquiry without him. Who broke the Law of the Boundaries and killed Umisk's two Sons?" he demanded sternly.

"I didn't," wheezed Mooswa, rubbing his big, soft nose caressingly down Beaver's back, as the latter sat on one of the old stumps. "I have kept the law. Like Muskwa I roam from lake to lake, and from river to river; but I kill no one--that is, with one exception."

"That was within the law," asserted the King, "for we kill in our own defence."

"I think it was Pisew," whispered the Red Widow. "See the Sneak's eye. Call him up, O Son, and command him to look straight into your Royal Face and say if he has kept the law."

"Pisew," commanded Black Fox, "come closer!"

Lynx started guiltily at the call of his name. There was something soft and unpleasant in the slipping sound of his big muffled feet as he walked toward the King.

"Has Pisew kept the Law of the Boundaries?" asked Black King, sternly, looking full in the mustached face of the slim-bodied cat.

Lynx turned his head sideways, and his eyes sought to avoid those of the questioner.

"Your Majesty, I roam from the Pelican on one side, to Fish Creek on the other; and the law is that therein I, who eat flesh, may kill Wapoos the Rabbit. This year it has been hard living, Your Majesty--hard living. Because of the fire, Wapoos fled beyond the waters of the creeks, and I have eaten of the things that could not fly the Boundaries--Mice, and Frogs, and Slugs: a diet that is horrible to think of. Look, Your Majesty, at my gaunt sides--am I not like one that is already skinned by the Trappers?"

"He is making much talk," whispered the Red Widow, "to the end that you forget the murder of Trowel Tail's Sons."

"Didst like Beaver Meat?" queried Black King, abruptly.

"I am not the slayer of Umisk's children," denied Lynx. "It was Wapoos, or Whisky-Jack; they are mischief makers, and ready for any evil."

"Oh, you silly liar!" cried Carcajou, in derision. "Wapoos the Rabbit kill a Beaver? Why not say the Moon came down and ate them up. Thou hast a sharp nose and a full appetite, but little brain."

"He is a poor liar!" remarked the Red Widow.

"I have kept the law," whined Lynx. "I have eaten so little that I am starved."

"What shall we do, Brothers, about the murdered Sons of Umisk? Beaver is the worker of our lands. But for him, and the dams he builds, the Muskegs would soon dry up, the fires would burn the Forests, and we should have no place to live. If we kill the Sons, presently there will be no workers--nobody but ourselves who are Killers." Black Fox thus put the case wisely to the others.

"Gr-a-a-h-wuh! let me speak," cried Blue Wolf. "Pisew has done this thing. If any in my Pack make a kill and I come to speak of it, do I not know from their eyes that grow tired, which it is?"

Said the Lieutenant, Carcajou: "I think you are right, Rof; but you can't hang a Comrade because he has weak eyes. No one has seen Pisew make the kill. We must have a new law, Your Majesty. That if again Kit-Beaver, or Cub-Fox, or Babe-Wapoos, or Young-Anyone is slain for eating, we shall all, sitting in Council, decide who is to pay the penalty. I think that will stop this murderous poaching."

"It will," whispered the Red Widow. "Lynx will never touch one of them again. He knows what Carcajou means."

"That is a new law, then," cried the King. "If any of Umisk's children are killed by one of us, sitting in Council we shall decide who is to be executed for the crime."

"Please, Your Majesty," squeaked Rabbit, "I keep the Boundary Law, but others do not. From Beaver's dam to the Pelican, straighter than a Man's trail, are my three Run-ways. My Cousin's family has three more; and in the Muskeg our streets run clear to view. Beyond our Run-ways we do not go. Nor do we build houses in violation of the law--only roads are we allowed, and these we have made. In the Muskeg parks, the nice open places Beaver has formed by damming back the waters, we labor.

"When the young Spruce are growing, and would choke up the park, we strip the bark off and they die, and the open is still with us. Neither do we kill any Animal, nor make trouble for them--keeping well within the law. Are we not ourselves food for all the Animal Kingdom? Lynx lives off us, and Marten lives off us, and Fox lives off us, and Wolf and Bear sometimes. Neither I nor my Tribe complains, because that law is older than the laws we make ourselves.

"But have we not certain rights which are known to the Council? For one hour in the morning, and one hour in the evening, just when the Sun and the Stars change their season of toil, are we not to be free from the Hunting?"

"Yes, it is written," replied Black King, "that no one shall kill Wapoos at the hour of dusk and the hour of dawn. Has anyone done so?"

"If they have, it's a shame!" cried Carcajou. "I do not eat Wapoos; but if everything else fails--if the Fish fail, if there are no Berries, if the Nuts and the Seeds are dried in the heart before they ripen, we still have Wapoos to carry us over. The Indians know this--it is of their history; and many a time has Wapoos, the Rabbit, our Little Brother, saved them from starvation."

"Who has slain Wapoos at the forbidden hour?" thundered Black King.

Again there was denial all around the circle; and again everybody felt convinced that Lynx was the breaker of the law. Said Black Fox: "It is well because of the new ruling we have passed, I think. If again Wapoos is killed or hunted at the forbidden hours, we shall decide in Council who must die."

"Also, O King," still pleaded Rabbit, "for all time have we claimed another protection. You know our way of life. For seven years we go on peopling the streets of our Muskeg Cities, growing more plentiful all the time, until there is a great population. Then comes the sickness on The Seventh Year, and we die off like Flies."

"It has been so for sixty years," assented Mooswa. "My father, who is sixty, has always known of this thing."

"For a hundred times sixty, Brother," quoth Carcajou; "it is so written in the legends of the Indians."

"It is a queer sickness," continued Wapoos. "The lumps come in our throats, and under our arms, and it kills. Your Majesty knows the Law of the Seventh Season."

"Yes, it is that no one shall eat Wapoos that year, or next."

"Most wise ruling!" concurred Carcajou. "The Rabbits with the lumps in their necks are poisonous. Besides, when there are so few of them, if they were eaten, the food supply of the Boundaries would be forever gone. A most wise rule."

"Has any one violated this protection-right?" asked the King.

"Yes, Your Majesty. This is the Seventh Year, is it not?" said Rabbit.

"Bless me! so it is," exclaimed Mooswa, thoughtfully. "I, who do not eat Rabbits, have paid no attention to the calendar. I wondered what made the woods so silent and dreary; that's just it. No pudgy little Wapooses darting across one's path. Why, now I remember, last year, The Year of the Plenty, when I laid down for a rest they'd be all about me. Actually sat up on my side many a time."

"Yes, it's the Seventh Year," whined Lynx; "look how thin I am. Perhaps miles and miles of river bank, and not even a Frog to be had."

"Alas! it's the Plague-year," declared Wapoos; "and my whole family were stricken with the sickness. They died off one--by--one--" Here he stopped, and covered his big, sympathetic eyes with soft, fur-ruffed hands. His tender heart choked.

Mooswa sniffed through his big nose, and browsed absent-mindedly off the Gray-willows. My! but they were bitter--he never ate them at any time; but one must do something when a Father is talking about his dead Children.

"Did they all die, Wapoos?" asked Otter; and in his black snake-like eyes there actually glistened a tear of sympathy.

"Yes; and our whole city was almost depopulated."

"Dreadful!" cried Carcajou.

"The nearest neighbor left me was a Widow on the third main Run-way--two cross-paths from my lane. All her family died off, even the Husband. We were a great help to each other in the way of consolation, and became fast friends. Yesterday morning, when I called to talk over our affliction, there was nothing left of her but a beautiful, white, fluffy tail."

"Horrible! oh, the Wretch!" screamed Black Fox's Mother; "to treat a Widow that way--eat her!"

"If I knew who did it," growled Muskwa, savagely, "I would break his neck with one stroke of my fist. Poor little Wapoos! come over here. Eat these Black Currants that I've just picked--I don't want them."

"That is a most criminal breach of the law," said the King, with emphasis. "If Wapoos can prove who did it, we'll give the culprit quick justice."

"Flif--fluf, flif--fluf," came the sound of wings at this juncture, and with an erratic swoop Whisky-Jack shot into the circle.

He was trembling with excitement--something of tremendous importance had occurred; every blue-gray feather of his coat vibrated with it. He strutted about to catch his breath, and his walk was the walk of one who feels his superiority.

"Good-morning, Glib-tongue!" greeted Carcajou.

"Welcome, Clerk!" said the King, graciously.

"Hop up on my antler," murmured Mooswa, condescendingly; "you'll get your throat full of dust down there."