AN APOLOGY FOR THE LIFE OF

MR. COLLEY CIBBER.

VOLUME THE SECOND.

NOTE.

510 copies printed on this fine deckle-edge demy 8vo paper for England and

America, with the portraits as India proofs after letters.

Each copy is numbered, and the type distributed.

No.

AN APOLOGY FOR THE LIFE OF

MR. COLLEY CIBBER

WRITTEN BY HIMSELF

A NEW EDITION WITH NOTES AND SUPPLEMENT

BY

ROBERT W. LOWE

WITH TWENTY-SIX ORIGINAL MEZZOTINT PORTRAITS BY

R. B. PARKES, AND EIGHTEEN ETCHINGS

BY ADOLPHE LALAUZE

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOLUME THE SECOND

LONDON

JOHN C. NIMMO

14, King William Street, Strand

MDCCCLXXXIX

Chiswick Press

PRINTED BY CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. E.C.

CONTENTS.

LIST OF MEZZOTINT PORTRAITS.

NEWLY ENGRAVED BY R. B. PARKES.

VOLUME THE SECOND.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Colley Cibber, in the character of "Sir Novelty Fashion, newley created Lord Foppington," in Vanbrugh's play of "The Relapse; or, Virtue in Danger." From the painting by J. Grisoni. The property of the Garrick Club. | Frontispiece |

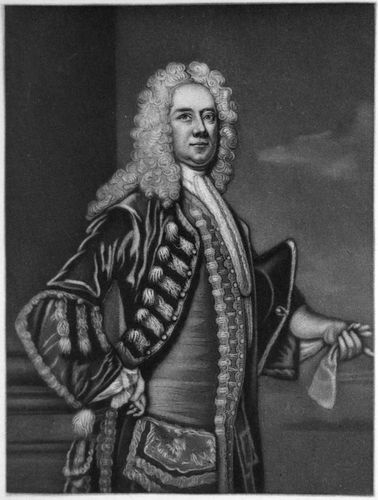

| II. | Owen Swiney. After the painting by John Baptist Vanloo. | 54 |

| III. | Anne Oldfield. From the picture by Jonathan Richardson. | 70 |

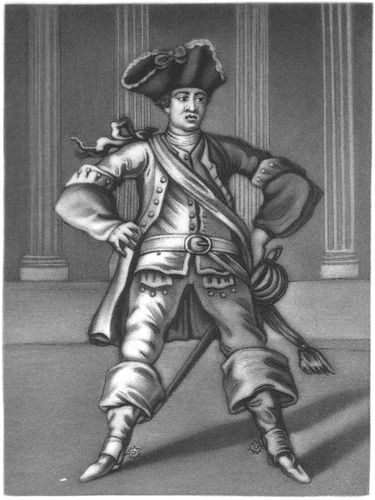

| IV. | Theophilus Cibber, in the character of "Antient Pistol". | 86 |

| V. | Hester Santlow (Mrs. Barton Booth). After an original picture from the life. | 104 |

| VI. | Robert Wilks. After the painting by John Ellys, 1732. | 122 |

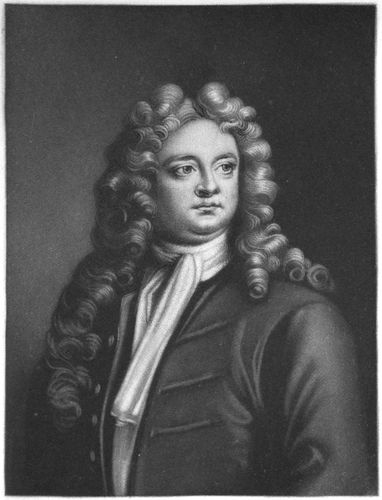

| VII. | Richard Steele. From the painting by Jonathan Richardson, 1712. | 172 |

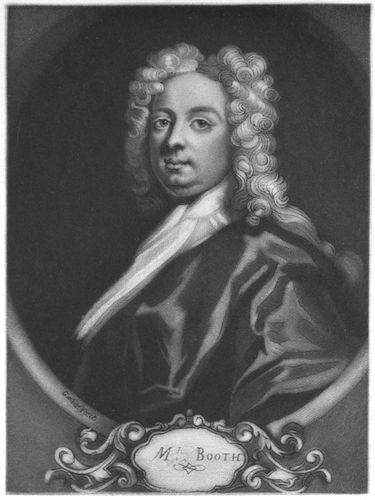

| VIII. | Barton Booth. From the picture by George White. | 206 |

| IX. | Susanna Maria Cibber. After a painting by Thomas Hudson. | 222 |

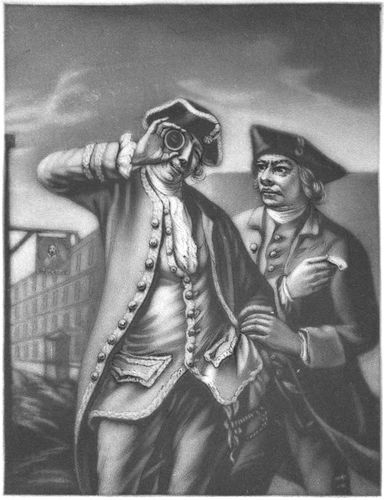

| X. | Charles Fleetwood. "Sir Fopling Flutter Arrested." "Drawn from a real Scene." John Dixon ad vivum del et fect. | 254 |

| XI. | Alexander Pope, at the age of 28. After the picture by Sir Godfrey Kneller, painted in 1716. | 272 |

| XII. | Susanna Maria Cibber, in the character of Cordelia, "King Lear," act iii. After the picture by Peter Van Bleeck. | 288 |

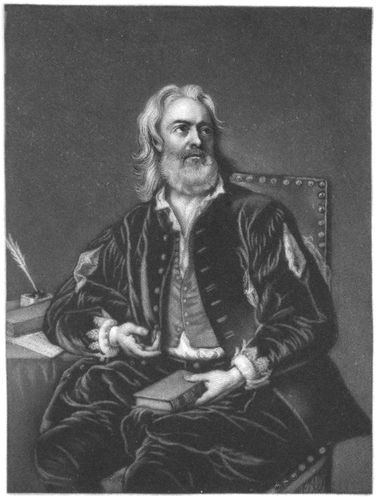

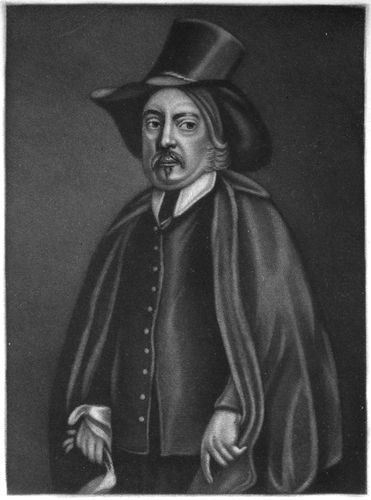

| XIII. | Cave Underhill, in the character of Obadiah, "The Fanatic Elder." After the picture by Robert Bing, 1712. | 306 |

LIST OF CHAPTER HEADINGS.

NEWLY ETCHED FROM CONTEMPORARY DRAWINGS BY ADOLPHE LALAUZE.

Volume the Second.

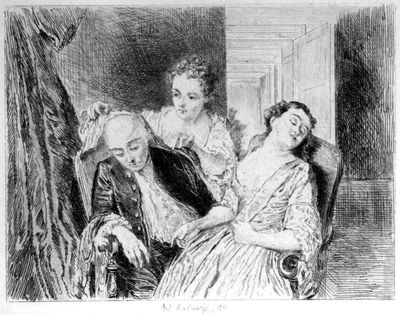

| X. | Scene illustrating Cibber's "Careless Husband." After the picture by Philip Mercier. |

| XI. | Coffee-House Scene of Cibber's Day, "drawn from the life" by G. Vander Gucht. |

| XII. | Scene illustrating "The Italian Opera," with Senesino, Cuzzoni, &c. From a contemporary design. |

| XIII. | Scene illustrating Farquhar's "Recruiting Officer." After the picture by Philip Mercier. |

| XIV. | Scene illustrating Addison's "Cato." After the contemporary design by Lud. du Guernier. |

| XV. | Scene illustrating Vanbrugh and Cibber's "Provoked Husband." After the contemporary design by J. Vanderbank. |

| XVI. | Scene illustrating Vanbrugh's "Provoked Wife." After the contemporary design by Arnold Vanhaecken. |

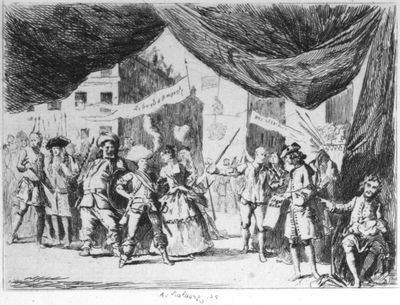

| XVII. | "The Stage Mutiny," with portraits of Theophilus Cibber as "Antient Pistol," Mrs. Wilks, and others, in character; Colley Cibber as Poet Laureate, with his lap filled with bags of money. From a pictorial satire of the time. |

| XVIII. | Anthony Aston's "The Fool's Opera." |

AN APOLOGY FOR THE LIFE OF

MR. COLLEY CIBBER, &c.

CHAPTER X.

The recruited Actors in the Hay-Market encourag'd by a Subscription. Drury-Lane under a particular Management. The Power of a Lord-Chamberlain over the Theatres consider'd. How it had been formerly exercis'd. A Digression to Tragick Authors.

Having shewn the particular Conduct of the Patentee in refusing so fair an Opportunity of securing to himself both Companies under his sole Power and Interest, I shall now lead the Reader, after a short View of what pass'd in this new Establishment of the Hay-Market Theatre, to the Acci2dents that the Year following compell'd the same Patentee to receive both Companies, united, into the Drury-Lane Theatre, notwithstanding his Disinclination to it.

It may now be imagin'd that such a Detachment of Actors from Drury-Lane could not but give a new Spirit to those in the Hay-Market; not only by enabling them to act each others Plays to better Advantage, but by an emulous Industry which had lain too long inactive among them, and without which they plainly saw they could not be sure of Subsistence. Plays by this means began to recover a good Share of their former Esteem and Favour; and the Profits of them in about a Month enabled our new Menager to discharge his Debt (of something more than Two hundred Pounds) to his old Friend the Patentee, who had now left him and his Troop in trust to fight their own Battles. The greatest Inconvenience they still laboured under was the immoderate Wideness of their House, in which, as I have observ'd, the Difficulty of Hearing may be said to have bury'd half the Auditors Entertainment. This Defect seem'd evident from the much better Reception several new Plays (first acted there) met with when they afterwards came to be play'd by the same Actors in Drury-Lane: Of this Number were the Stratagem[1] and the Wife's Resent3ment;[2] to which I may add the Double Gallant.[3] This last was a Play made up of what little was tolerable in two or three others that had no Success, and were laid aside as so much Poetical Lumber; but by collecting and adapting the best Parts of them all into one Play, the Double Gallant has had a Place every Winter amongst the Publick Entertainments these Thirty Years. As I was only the Compiler of this Piece I4 did not publish it in my own Name; but as my having but a Hand in it could not be long a Secret, I have been often treated as a Plagiary on that Account: Not that I think I have any right to complain of whatever would detract from the Merit of that sort of Labour, yet a Cobler may be allow'd to be useful though he is not famous:[4] And I hope a Man is not blameable for doing a little Good, tho' he cannot do as much as another? But so it is—Twopenny Criticks must live as well as Eighteenpenny Authors![5]

While the Stage was thus recovering its former Strength, a more honourable Mark of Favour was shewn to it than it was ever known before or since to have receiv'd. The then Lord Hallifax was not only the Patron of the Men of Genius of this Time, but had likewise a generous Concern for the Reputation and Prosperity of the Theatre, from whence the most elegant Dramatick Labours of the Learned, he knew, had often shone in their brightest Lustre. A Proposal therefore was drawn up and addressed to that Noble Lord for his Approbation and Assistance to raise a publick Subscription for Reviving Three Plays of the best Authors, with the full Strength of the Company; every Subscriber to have Three Tickets for the first Day of each Play for5 his single Payment of Three Guineas. This Subscription his Lordship so zealously encouraged, that from his Recommendation chiefly, in a very little time it was compleated. The Plays were Julius Cæsar of Shakespear; the King and no King of Fletcher, and the Comic Scenes of Drydens Marriage à la mode and of his Maiden Queen put together;[6] for it was judg'd that, as these comic Episodes were utterly independent of the serious Scenes they were originally written to, they might on this occasion be as well Episodes either to the other, and so make up five livelier Acts between them: At least the Project so well succeeded, that those comic Parts have never since been replaced, but were continued to be jointly acted as one Play several Years after.

By the Aid of this Subscription, which happen'd in 1707, and by the additional Strength and Industry of this Company, not only the Actors (several of which were handsomely advanc'd in their Sallaries) were duly paid, but the Menager himself, too, at the Foot of his Account, stood a considerable Gainer.

At the same time the Patentee of Drury-Lane went on in his usual Method of paying extraordinary Prices to Singers, Dancers, and other exotick Performers, which were as constantly deducted out of the sinking Sallaries of his Actors: 'Tis true his Actors perhaps might not deserve much more than he gave them; yet, by what I have related, it is plain he chose not to be troubled with such as visibly had deserv'd more: For it seems he had not purchas'd his Share of the Patent to mend the Stage, but to make Money of it: And to say Truth, his Sense of every thing to be shewn there was much upon a Level with the Taste of the Multitude, whose Opinion and whose Money weigh'd with him full as much as that of the best Judges. His Point was to please the Majority, who could more easily comprehend any thing they saw than the daintiest things that could be said to them. But in this Notion he kept no medium; for in my Memory he carry'd it so far that he was (some few Years before this time) actually dealing for an extraordinary large Elephant at a certain Sum for every Day he might think fit to shew the tractable Genius of that vast quiet Creature in any Play or Farce in the Theatre (then standing) in Dorset-Garden. But from the Jealousy which so formidable a Rival had rais'd in his Dancers, and by his Bricklayer's assuring him that if the Walls were to be open'd wide enough for its Entrance it might endanger the fall of the House, he gave up his Project, and with it so hopeful a Prospect of7 making the Receipts of the Stage run higher than all the Wit and Force of the best Writers had ever yet rais'd them to.[7]

About the same time of his being under this Disappointment he put in Practice another Project of as new, though not of so bold a Nature; which was his introducing a Set of Rope-dancers into the same Theatre; for the first Day of whose Performance he had given out some Play in which I had a material Part: But I was hardy enough to go into the Pit and acquaint the Spectators near me, that I hop'd they would not think it a Mark of my Disrespect to them, if I declin'd acting upon any Stage that was brought to so low a Disgrace as ours was like to be by that Day's Entertainment. My Excuse was so well taken that I never after found any ill Consequences, or heard of the least Disapprobation of it: And the whole Body of Actors, too, protesting against such an Abuse of their Profession, our cautious Master was too much alarm'd and intimidated to repeat it.

After what I have said, it will be no wonder that all due Regards to the original Use and Institution of the Stage should be utterly lost or neglected: Nor was the Conduct of this Menager easily to be alter'd while he had found the Secret of making Money out8 of Disorder and Confusion: For however strange it may seem, I have often observ'd him inclin'd to be cheerful in the Distresses of his Theatrical Affairs, and equally reserv'd and pensive when they went smoothly forward with a visible Profit. Upon a Run of good Audiences he was more frighted to be thought a Gainer, which might make him accountable to others, than he was dejected with bad Houses, which at worst he knew would make others accountable to him: And as, upon a moderate Computation, it cannot be supposed that the contested Accounts of a twenty Year's Wear and Tear in a Play-house could be fairly adjusted by a Master in Chancery under four-score Years more, it will be no Surprize that by the Neglect, or rather the Discretion, of other Proprietors in not throwing away good Money after bad, this Hero of a Menager, who alone supported the War, should in time so fortify himself by Delay, and so tire his Enemies, that he became sole Monarch of his Theatrical Empire, and left the quiet Possession of it to his Successors.

If these Facts seem too trivial for the Attention of a sensible Reader, let it be consider'd that they are not chosen Fictions to entertain, but Truths necessary to inform him under what low Shifts and Disgraces, what Disorders and Revolutions, the Stage labour'd before it could recover that Strength and Reputation wherewith it began to flourish towards the latter End of Queen Anne's Reign; and which it continued to enjoy for a Course of twenty Years9 following. But let us resume our Account of the new Settlement in the Hay-Market.

It may be a natural Question why the Actors whom Swiney brought over to his Undertaking in the Hay-Market would tie themselves down to limited Sallaries? for though he as their Menager was obliged to make them certain Payments, it was not certain that the Receipts would enable him to do it; and since their own Industry was the only visible Fund they had to depend upon, why would they not for that Reason insist upon their being Sharers as well of possible Profits as Losses? How far in this Point they acted right or wrong will appear from the following State of their Case.

It must first be consider'd that this Scheme of their Desertion was all concerted and put in Execution in a Week's Time, which short Warning might make them overlook that Circumstance, and the sudden Prospect of being deliver'd from having seldom more than half their Pay was a Contentment that had bounded all their farther Views. Besides, as there could be no room to doubt of their receiving their full Pay previous to any Profits that might be reap'd by their Labour, and as they had no great Reason to apprehend those Profits could exceed their respective Sallaries so far as to make them repine at them, they might think it but reasonable to let the Chance of any extraordinary Gain be on the Side of their Leader and Director. But farther, as this Scheme had the Approbation of the Court, these Actors in10 reality had it not in their Power to alter any Part of it: And what induced the Court to encourage it was, that by having the Theatre and its Menager more immediately dependent on the Power of the Lord Chamberlain, it was not doubted but the Stage would be recover'd into such a Reputation as might now do Honour to that absolute Command which the Court or its Officers seem'd always fond of having over it.

Here, to set the Constitution of the Stage in a clearer Light, it may not be amiss to look back a little on the Power of a Lord Chamberlain, which, as may have been observ'd in all Changes of the Theatrical Government, has been the main Spring without which no Scheme of what kind soever could be set in Motion. My Intent is not to enquire how far by Law this Power has been limited or extended; but merely as an Historian to relate Facts to gratify the Curious, and then leave them to their own Reflections: This, too, I am the more inclin'd to, because there is no one Circumstance which has affected the Stage wherein so many Spectators, from those of the highest Rank to the Vulgar, have seem'd more positively knowing or less inform'd in.

Though in all the Letters Patent for acting Plays, &c. since King Charles the First's Time there has been no mention of the Lord Chamberlain, or of any Subordination to his Command or Authority, yet it was still taken for granted that no Letters Patent, by the bare Omission of such a great Officer's Name,11 could have superseded or taken out of his Hands that Power which Time out of Mind he always had exercised over the Theatre.[8] The common Opinions then abroad were, that if the Profession of Actors was unlawful, it was not in the Power of the Crown to license it; and if it were not unlawful, it ought to be free and independent as other Professions; and that a Patent to exercise it was only an honorary Favour from the Crown to give it a better Grace of Recommendation to the Publick. But as the Truth of this Question seem'd to be wrapt in a great deal of Obscurity, in the old Laws made in former Reigns relating to Players, &c. it may be no Wonder that the best Companies of Actors should be desirous of taking Shelter under the visible Power of a Lord Chamberlain who they knew had at his Pleasure favoured and protected or born hard upon them: But be all this as it may, a Lord Chamberlain (from whencesoever his Power might be derived) had till of later Years had always an implicit Obedience paid to it: I shall now give some few Instances in what manner it was exercised.

What appear'd to be most reasonably under his Cognizance was the licensing or refusing new Plays,12 or striking out what might be thought offensive in them: Which Province had been for many Years assign'd to his inferior Officer, the Master of the Revels; yet was not this License irrevocable; for several Plays, though acted by that Permission, had been silenced afterwards. The first Instance of this kind that common Fame has deliver'd down to us, is that of the Maid's Tragedy of Beaumont and Fletcher, which was forbid in King Charles the Second's time, by an Order from the Lord Chamberlain. For what Reason this Interdiction was laid upon it the Politicks of those Days have only left us to guess. Some said that the killing of the King in that Play, while the tragical Death of King Charles the First was then so fresh in People's Memory, was an Object too horribly impious for a publick Entertainment. What makes this Conjecture seem to have some Foundation, is that the celebrated Waller, in Compliment to that Court, alter'd the last Act of this Play (which is printed at the End of his Works) and gave it a new Catastrophe, wherein the Life of the King is loyally saved, and the Lady's Matter made up with a less terrible Reparation. Others have given out, that a repenting Mistress, in a romantick Revenge of her Dishonour, killing the King in the very Bed he expected her to come into, was shewing a too dangerous Example to other Evadnes then shining at Court in the same Rank of royal Distinction; who, if ever their Consciences should have run equally mad, might have had frequent Opportunities of putting13 the Expiation of their Frailty into the like Execution. But this I doubt is too deep a Speculation, or too ludicrous a Reason, to be relied on; it being well known that the Ladies then in favour were not so nice in their Notions as to think their Preferment their Dishonour, or their Lover a Tyrant: Besides, that easy Monarch loved his Roses without Thorns; nor do we hear that he much chose to be himself the first Gatherer of them.[9]

The Lucius Junius Brutus of Nat. Lee[10] was in the same Reign silenced after the third Day of Acting it; it being objected that the Plan and Sentiments of it had too boldly vindicated, and might enflame republican Principles.

A Prologue (by Dryden) to the Prophetess was forbid by the Lord Dorset after the first Day of its being spoken.[11] This happen'd when King William was prosecuting the War in Ireland. It must be14 confess'd that this Prologue had some familiar, metaphorical Sneers at the Revolution itself; and as the Poetry of it was good, the Offence of it was less pardonable.

The Tragedy of Mary Queen of Scotland[12] had been offer'd to the Stage twenty Years before it was acted: But from the profound Penetration of the Master of the Revels, who saw political Spectres in it that never appear'd in the Presentation, it had lain so long upon the Hands of the Author; who had at last the good Fortune to prevail with a Nobleman to favour his Petition to Queen Anne for Permission to have it acted: The Queen had the Goodness to refer the Merit of his Play to the Opinion of that noble Person, although he was not her Majesty's Lord Chamberlain; upon whose Report of its being every way an innocent Piece, it was soon after acted with Success.

Reader, by your Leave——I will but just speak a Word or two to any Author that has not yet writ one Line of his next Play, and then I will come to my Point again——What I would say to him is this—Sir, before you set Pen to Paper, think well and principally of your Design or chief Action, towards15 which every Line you write ought to be drawn, as to its Centre: If we can say of your finest Sentiments, This or That might be left out without maiming the Story, you would tell us, depend upon it, that fine thing is said in a wrong Place; and though you may urge that a bright Thought is not to be resisted, you will not be able to deny that those very fine Lines would be much finer if you could find a proper Occasion for them: Otherwise you will be thought to take less Advice from Aristotle or Horace than from Poet Bays in the Rehearsal, who very smartly says—What the Devil is the Plot good for but to bring in fine things? Compliment the Taste of your Hearers as much as you please with them, provided they belong to your Subject, but don't, like a dainty Preacher who has his Eye more upon this World than the next, leave your Text for them. When your Fable is good, every Part of it will cost you much less Labour to keep your Narration alive, than you will be forced to bestow upon those elegant Discourses that are not absolutely conducive to your Catastrophe or main Purpose: Scenes of that kind shew but at best the unprofitable or injudicious Spirit of a Genius. It is but a melancholy Commendation of a fine Thought to say, when we have heard it, Well! but what's all this to the Purpose? Take, therefore, in some part, Example by the Author last mention'd! There are three Plays of his, The Earl of Essex,[13] Anna16 Bullen,[14] and Mary Queen of Scots, which, tho' they are all written in the most barren, barbarous Stile that was ever able to keep Possession of the Stage, have all interested the Hearts of his Auditors. To what then could this Success be owing, but to the intrinsick and naked Value of the well-conducted Tales he has simply told us? There is something so happy in the Disposition of all his Fables; all his chief Characters are thrown into such natural Circumstances of Distress, that their Misery or Affliction wants very little Assistance from the Ornaments of Stile or Words to speak them. When a skilful Actor is so situated, his bare plaintive Tone of Voice, the Cast of Sorrow from his Eye, his slowly graceful Gesture, his humble Sighs of Resignation under his Calamities: All these, I say, are sometimes without a Tongue equal to the strongest Eloquence. At such a time the attentive Auditor supplies from his own Heart whatever the Poet's Language may fall short of in Expression, and melts himself into every Pang of Humanity which the like Misfortunes in real Life could have inspir'd.

After what I have observ'd, whenever I see a Tragedy defective in its Fable, let there be never so many fine Lines in it; I hope I shall be forgiven if I impute that Defect to the Idleness, the weak Judgment, or barren Invention of the Author.

If I should be ask'd why I have not always my self follow'd the Rules I would impose upon others;17 I can only answer, that whenever I have not, I lie equally open to the same critical Censure. But having often observ'd a better than ordinary Stile thrown away upon the loose and wandering Scenes of an ill-chosen Story, I imagin'd these Observations might convince some future Author of how great Advantage a Fable well plann'd must be to a Man of any tolerable Genius.

All this I own is leading my Reader out of the way; but if he has as much Time upon his Hands as I have, (provided we are neither of us tir'd) it may be equally to the Purpose what he reads or what I write of. But as I have no Objection to Method when it is not troublesome, I return to my Subject.

Hitherto we have seen no very unreasonable Instance of this absolute Power of a Lord Chamberlain, though we were to admit that no one knew of any real Law, or Construction of Law, by which this Power was given him. I shall now offer some Facts relating to it of a more extraordinary Nature, which I leave my Reader to give a Name to.

About the middle of King William's Reign an Order of the Lord Chamberlain was then subsisting that no Actor of either Company should presume to go from one to the other without a Discharge from their respective Menagers[15] and the Permission of18 the Lord Chamberlain. Notwithstanding such Order, Powel, being uneasy at the Favour Wilks was then rising into, had without such Discharge left the Drury-Lane Theatre and engag'd himself to that of Lincolns-Inn-Fields: But by what follows it will appear that this Order was not so much intended to do both of them good, as to do that which the Court chiefly favour'd (Lincolns-Inn-Fields) no harm.[16] For when Powel grew dissatisfy'd at his Station there too, he return'd to Drury-Lane (as he had before gone from it) without a Discharge: But halt a little! here, on this Side of the Question, the Order was to stand in force, and the same Offence against it now was not to be equally pass'd over. He was the next Day taken up by a Messenger and confin'd to the Porter's-Lodge, where, to the best of my Remembrance, he remain'd about two Days; when the Menagers of Lincolns-Inn-Fields, not thinking an Actor of his19 loose Character worth their farther Trouble, gave him up; though perhaps he was releas'd for some better Reason.[17] Upon this occasion, the next Day, behind the Scenes at Drury-Lane, a Person of great Quality in my hearing enquiring of Powel into the Nature of his Offence, after he had heard it, told him, That if he had had Patience or Spirit enough to have staid in his Confinement till he had given him Notice of it, he would have found him a handsomer way of coming out of it.

Another time the same Actor, Powel, was provok'd20 at Will's Coffee-house, in a Dispute about the Playhouse Affairs, to strike a Gentleman whose Family had been sometimes Masters of it; a Complaint of this Insolence was, in the Absence of the Lord-Chamberlain, immediately made to the Vice-Chamberlain, who so highly resented it that he thought himself bound in Honour to carry his Power of redressing it as far as it could possibly go: For Powel having a Part in the Play that was acted the Day after, the Vice-Chamberlain sent an Order to silence the whole Company for having suffer'd Powel to appear upon the Stage before he had made that Gentleman Satisfaction, although the Masters of the Theatre had had no Notice of Powel's Misbehaviour: However, this Order was obey'd, and remain'd in force for two or three Days, 'till the same Authority was pleas'd or advis'd to revoke it.[18] From the Measures this injur'd Gentleman took for his Redress, it may be judg'd how far it was taken for granted that a Lord-Chamberlain had an absolute Power over the Theatre.

I shall now give an Instance of an Actor who had the Resolution to stand upon the Defence of his21 Liberty against the same Authority, and was reliev'd by it.

In the same King's Reign, Dogget, who tho', from a severe Exactness in his Nature, he could be seldom long easy in any Theatre, where Irregularity, not to say Injustice, too often prevail'd, yet in the private Conduct of his Affairs he was a prudent, honest Man. He therefore took an unusual Care, when he return'd to act under the Patent in Drury-Lane, to have his Articles drawn firm and binding: But having some Reason to think the Patentee had not dealt fairly with him, he quitted the Stage and would act no more, rather chusing to lose his whatever unsatisfy'd Demands than go through the chargeable and tedious Course of the Law to recover it. But the Patentee, who (from other People's Judgment) knew the Value of him, and who wanted, too, to have him sooner back than the Law could possibly bring him, thought the surer way would be to desire a shorter Redress from the Authority of the Lord-Chamberlain.[19] Accordingly, upon his Complaint a Messenger was immediately dispatch'd to Norwich, where Dogget then was, to bring him up in Custody: But doughty Dogget, who had Money in his Pocket and the Cause of Liberty at his Heart, was not in the least intimidated22 by this formidable Summons. He was observ'd to obey it with a particular Chearfulness, entertaining his Fellow-traveller, the Messenger, all the way in the Coach (for he had protested against Riding) with as much Humour as a Man of his Business might be capable of tasting. And as he found his Charges were to be defray'd, he, at every Inn, call'd for the best Dainties the Country could afford or a pretended weak Appetite could digest. At this rate they jollily roll'd on, more with the Air of a Jaunt than a Journey, or a Party of Pleasure than of a poor Devil in Durance. Upon his Arrival in Town he immediately apply'd to the Lord Chief Justice Holt for his Habeas Corpus. As his Case was something particular, that eminent and learned Minister of the Law took a particular Notice of it: For Dogget was not only discharg'd, but the Process of his Confinement (according to common Fame) had a Censure pass'd upon it in Court, which I doubt I am not Lawyer enough to repeat! To conclude, the officious Agents in this Affair, finding that in Dogget they had mistaken their Man, were mollify'd into milder Proceedings, and (as he afterwards told me) whisper'd something in his Ear that took away Dogget's farther Uneasiness about it.

By these Instances we see how naturally Power only founded on Custom is apt, where the Law is silent, to run into Excesses, and while it laudably pretends to govern others, how hard it is to govern itself. But since the Law has lately open'd its23 Mouth, and has said plainly that some Part of this Power to govern the Theatre shall be, and is plac'd in a proper Person; and as it is evident that the Power of that white Staff, ever since it has been in the noble Hand that now holds it, has been us'd with the utmost Lenity, I would beg leave of the murmuring Multitude who frequent the Theatre to offer them a simple Question or two, viz. Pray, Gentlemen, how came you, or rather your Fore-fathers, never to be mutinous upon any of the occasional Facts I have related? And why have you been so often tumultuous upon a Law's being made that only confirms a less Power than was formerly exercis'd without any Law to support it? You cannot, sure, say such Discontent is either just or natural, unless you allow it a Maxim in your Politicks that Power exercis'd without Law is a less Grievance than the same Power exercis'd according to Law!

Having thus given the clearest View I was able of the usual Regard paid to the Power of a Lord-Chamberlain, the Reader will more easily conceive what Influence and Operation that Power must naturally have in all Theatrical Revolutions, and particularly in the complete Re-union of both Companies, which happen'd in the Year following.

CHAPTER XI.

Some Chimærical Thoughts of making the Stage useful: Some, to its Reputation. The Patent unprofitable to all the Proprietors but one. A fourth Part of it given away to Colonel Brett. A Digression to his Memory. The two Companies of Actors reunited by his Interest and Menagement. The first Direction of Operas only given to Mr. Swiney.

From the Time that the Company of Actors in the Hay-Market was recruited with those from Drury-Lane, and came into the Hands of their new Director, Swiney, the Theatre for three or four Years following suffer'd so many Convulsions, and was thrown every other Winter under such different Interests and Menagement before it came to a firm25 and lasting Settlement, that I am doubtful if the most candid Reader will have Patience to go through a full and fair Account of it: And yet I would fain flatter my self that those who are not too wise to frequent the Theatre (or have Wit enough to distinguish what sort of Sights there either do Honour or Disgrace to it) may think their national Diversion no contemptible Subject for a more able Historian than I pretend to be: If I have any particular Qualification for the Task more than another it is that I have been an ocular Witness of the several Facts that are to fill up the rest of my Volume, and am perhaps the only Person living (however unworthy) from whom the same Materials can be collected; but let them come from whom they may, whether at best they will be worth reading, perhaps a Judgment may be better form'd after a patient Perusal of the following Digression.

In whatever cold Esteem the Stage may be among the Wise and Powerful, it is not so much a Reproach to those who contentedly enjoy it in its lowest Condition, as that Condition of it is to those who (though they cannot but know to how valuable a publick Use a Theatre, well establish'd, might be rais'd) yet in so many civiliz'd Nations have neglected it. This perhaps will be call'd thinking my own wiser than all the wise Heads in Europe. But I hope a more humble Sense will be given to it; at least I only mean, that if so many Governments have their Reasons for their Disregard of their Theatres, those26 Reasons may be deeper than my Capacity has yet been able to dive into: If therefore my simple Opinion is a wrong one, let the Singularity of it expose me: And tho' I am only building a Theatre in the Air, it is there, however, at so little Expence and in so much better a Taste than any I have yet seen, that I cannot help saying of it, as a wiser Man did (it may be) upon a wiser Occasion:

Give me leave to play with my Project in Fancy.

I say, then, that as I allow nothing is more liable to debase and corrupt the Minds of a People than a licentious Theatre, so under a just and proper Establishment it were possible to make it as apparently the School of Manners and of Virtue. Were I to collect all the Arguments that might be given for my Opinion, or to inforce it by exemplary Proofs, it might swell this short Digression to a Volume; I shall therefore trust the Validity of what I have laid down to a single Fact that may be still fresh in the Memory of many living Spectators. When the Tragedy of Cato was first acted,[21] let us call to mind the noble Spirit of Patriotism which that Play then infus'd into the Breasts of a free People that crowded to it; with what affecting Force was that most elevated of Human Virtues recommended? Even the false Pretenders to it felt an unwilling Conviction,27 and made it a Point of Honour to be foremost in their Approbation; and this, too, at a time when the fermented Nation had their different Views of Government. Yet the sublime Sentiments of Liberty in that venerable Character rais'd in every sensible Hearer such conscious Admiration, such compell'd Assent to the Conduct of a suffering Virtue, as even demanded two almost irreconcileable Parties to embrace and join in their equal Applauses of it.[22] Now, not to take from the Merit of the Writer, had that Play never come to the Stage, how much of this valuable Effect of it must have been lost? It then could have had no more immediate weight with the Publick than our poring upon the many ancient Authors thro' whose Works the same Sentiments have been perhaps less profitably dispers'd, tho' amongst Millions of Readers; but by bringing such Sentiments to the Theatre and into Action, what a superior Lustre did they shine with? There Cato breath'd again in Life; and though he perish'd in the Cause of Liberty, his Virtue was victorious, and left the Triumph of it in the Heart of every melting Spectator. If Effects like these are laudable, if the Representation of such Plays can carry Conviction with so much Pleasure to the Understanding, have28 they not vastly the Advantage of any other Human Helps to Eloquence? What equal Method can be found to lead or stimulate the Mind to a quicker Sense of Truth and Virtue, or warm a People into the Love and Practice of such Principles as might be at once a Defence and Honour to their Country? In what Shape could we listen to Virtue with equal Delight or Appetite of Instruction? The Mind of Man is naturally free, and when he is compell'd or menac'd into any Opinion that he does not readily conceive, he is more apt to doubt the Truth of it than when his Capacity is led by Delight into Evidence and Reason. To preserve a Theatre in this Strength and Purity of Morals is, I grant, what the wisest Nations have not been able to perpetuate or to transmit long to their Posterity: But this Difficulty will rather heighten than take from the Honour of the Theatre: The greatest Empires have decay'd for want of proper Heads to guide them, and the Ruins of them sometimes have been the Subject of Theatres that could not be themselves exempt from as various Revolutions: Yet may not the most natural Inference from all this be, That the Talents requisite to form good Actors, great Writers, and true Judges were, like those of wise and memorable Ministers, as well the Gifts of Fortune as of Nature, and not always to be found in all Climes or Ages. Or can there be a stronger modern Evidence of the Value of Dramatick Performances than that in many Countries where the Papal Religion prevails29 the Holy Policy (though it allows not to an Actor Christian Burial) is so conscious of the Usefulness of his Art that it will frequently take in the Assistance of the Theatre to give even Sacred History, in a Tragedy, a Recommendation to the more pathetick Regard of their People. How can such Principles, in the Face of the World, refuse the Bones of a Wretch the lowest Benefit of Christian Charity after having admitted his Profession (for which they deprive him of that Charity) to serve the solemn Purposes of Religion? How far then is this Religious Inhumanity short of that famous Painter's, who, to make his Crucifix a Master-piece of Nature, stabb'd the Innocent Hireling from whose Body he drew it; and having heighten'd the holy Portrait with his last Agonies of Life, then sent it to be the consecrated Ornament of an Altar? Though we have only the Authority of common Fame for this Story, yet be it true or false the Comparison will still be just. Or let me ask another Question more humanly political.

How came the Athenians to lay out an Hundred Thousand Pounds upon the Decorations of one single Tragedy of Sophocles?[23] Not, sure, as it was merely a Spectacle for Idleness or Vacancy of Thought to gape at, but because it was the most rational, most instructive and delightful Composition that Human Wit had yet arrived at, and consequently the most worthy to be the Entertainment of a wise and warlike Nation: And it may be still a Question whether30 the Sophocles inspir'd this Publick Spirit, or this Publick Spirit inspir'd the Sophocles?[24]

But alas! as the Power of giving or receiving such Inspirations from either of these Causes seems pretty well at an End, now I have shot my Bolt I shall descend to talk more like a Man of the Age I live in: For, indeed, what is all this to a common English Reader? Why truly, as Shakespear terms it—Caviare to the Multitude![25] Honest John Trott will tell you, that if he were to believe what I have said of the Athenians, he is at most but astonish'd at it; but that if the twentieth Part of the Sum I have mentioned were to be apply'd out of the Publick money to the Setting off the best Tragedy the nicest Noddle in the Nation could produce, it would probably raise the Passions higher in those that did Not like it than in those that did; it might as likely meet with an Insurrection as the Applause of the People, and so, mayhap, be fitter for the Subject of a Tragedy than for a publick Fund to support it.——Truly, Mr. Trott, I cannot but own that I am very much of your Opinion: I am only concerned that the Theatre has not a better Pretence to the Care and further Consideration of those Governments where it is tolerated; but as what I have said31 will not probably do it any great Harm, I hope I have not put you out of Patience by throwing a few good Wishes after an old Acquaintance.

To conclude this Digression. If for the Support of the Stage what is generally shewn there must be lower'd to the Taste of common Spectators; or if it is inconsistent with Liberty to mend that Vulgar Taste by making the Multitude less merry there; or by abolishing every low and senseless Jollity in which the Understanding can have no Share; whenever, I say, such is the State of the Stage, it will be as often liable to unanswerable Censure and manifest Disgraces. Yet there was a Time, not yet out of many People's Memory, when it subsisted upon its own rational Labours; when even Success attended an Attempt to reduce it to Decency; and when Actors themselves were hardy enough to hazard their Interest in pursuit of so dangerous a Reformation. And this Crisis I am my self as impatient as any tir'd Reader can be to arrive at. I shall therefore endeavour to lead him the shortest way to it. But as I am a little jealous of the badness of the Road, I must reserve to myself the Liberty of calling upon any Matter in my way, for a little Refreshment to whatever Company may have the Curiosity or Goodness to go along with me.

When the sole Menaging Patentee at Drury-Lane for several Years could never be persuaded or driven to any Account with the Adventurers, Sir Thomas Skipwith (who, if I am rightly inform'd, had an equal32 Share with him[26]) grew so weary of the Affair that he actually made a Present of his entire Interest in it upon the following Occasion.

Sir Thomas happen'd in the Summer preceding the Re-union of the Companies to make a Visit to an intimate Friend of his, Colonel Brett, of Sandywell, in Gloucestershire; where the Pleasantness of the Place, and the agreeable manner of passing his Time there, had raised him to such a Gallantry of Heart, that in return to the Civilities of his Friend the Colonel he made him an Offer of his whole Right in the Patent; but not to overrate the Value of his Present, told him he himself had made nothing of it these ten Years: But the Colonel (he said) being a greater Favourite of the People in Power, and (as he believ'd) among the Actors too, than himself was, might think of some Scheme to turn it to Advantage, and in that Light, if he lik'd it, it was at33 his Service. After a great deal of Raillery on both sides of what Sir Thomas had not made of it, and the particular Advantages the Colonel was likely to make of it, they came to a laughing Resolution That an Instrument should be drawn the next Morning of an Absolute Conveyance of the Premises. A Gentleman of the Law well known to them both happening to be a Guest there at the same time, the next Day produced the Deed according to his Instructions, in the Presence of whom and of others it was sign'd, seal'd, and deliver'd to the Purposes therein contain'd.[27]

This Transaction may be another Instance (as I have elsewhere observed) at how low a Value the Interests in a Theatrical License were then held, tho' it was visible from the Success of Swiney in that very Year that with tolerable Menagement they could at no time have fail'd of being a profitable Purchase.

The next Thing to be consider'd was what the Colonel should do with his new Theatrical Commission, which in another's Possession had been of so little Importance. Here it may be necessary to premise that this Gentleman was the first of any Consideration since my coming to the Stage with whom I had contracted a Personal Intimacy; which might be the Reason why in this Debate my Opinion had some Weight with him: Of this Intimacy, too, I am the more tempted to talk from the natural Pleasure34 of calling back in Age the Pursuits and happy Ardours of Youth long past, which, like the Ideas of a delightful Spring in a Winter's Rumination, are sometimes equal to the former Enjoyment of them. I shall, therefore, rather chuse in this Place to gratify my self than my Reader, by setting the fairest Side of this Gentleman in view, and by indulging a little conscious Vanity in shewing how early in Life I fell into the Possession of so agreeable a Companion: Whatever Failings he might have to others, he had none to me; nor was he, where he had them, without his valuable Qualities to balance or soften them. Let, then, what was not to be commended in him rest with his Ashes, never to be rak'd into: But the friendly Favours I received from him while living give me still a Pleasure in paying this only Mite of my Acknowledgment in my Power to his Memory. And if my taking this Liberty may find Pardon from several of his fair Relations still living, for whom I profess the utmost Respect, it will give me but little Concern tho' my critical Readers should think it all Impertinence.

This Gentleman, then, Henry, was the eldest Son of Henry Brett, Esq; of Cowley, in Gloucestershire, who coming early to his Estate of about Two Thousand a Year, by the usual Negligences of young Heirs had, before this his eldest Son came of age, sunk it to about half that Value, and that not wholly free from Incumbrances. Mr. Brett, whom I am speaking of, had his Education, and I might say,35 ended it, at the University of Oxford; for tho' he was settled some time after at the Temple, he so little followed the Law there that his Neglect of it made the Law (like some of his fair and frail Admirers) very often follow him. As he had an uncommon Share of Social Wit and a handsom Person, with a sanguine Bloom in his Complexion, no wonder they persuaded him that he might have a better Chance of Fortune by throwing such Accomplishments into the gayer World than by shutting them up in a Study. The first View that fires the Head of a young Gentleman of this modish Ambition just broke loose from Business, is to cut a Figure (as they call it) in a Side-box at the Play, from whence their next Step is to the Green Room behind the Scenes, sometimes their Non ultra. Hither at last, then, in this hopeful Quest of his Fortune, came this Gentleman-Errant, not doubting but the fickle Dame, while he was thus qualified to receive her, might be tempted to fall into his Lap. And though possibly the Charms of our Theatrical Nymphs might have their Share in drawing him thither, yet in my Observation the most visible Cause of his first coming was a more sincere Passion he had conceived for a fair full-bottom'd Perriwig which I then wore in my first Play of the Fool in Fashion in the Year 1695.[28] For it is to be noted that the Beaux of those Days were of a quite different Cast from the modern Stamp, and had36 more of the Stateliness of the Peacock in their Mien than (which now seems to be their highest Emulation) the pert Air of a Lapwing. Now, whatever Contempt Philosophers may have for a fine Perriwig, my Friend, who was not to despise the World, but to live in it, knew very well that so material an Article of Dress upon the Head of a Man of Sense, if it became him, could never fail of drawing to him a more partial Regard and Benevolence than could possibly be hoped for in an ill-made one.[29] This perhaps may soften the grave Censure which so youthful a Purchase might otherwise have laid upon him: In a Word, he made his Attack upon this Perriwig, as your young Fellows generally do upon a Lady of Pleasure, first by a few familiar Praises of her Person, and then a civil Enquiry into the Price of it. But upon his observing me a little surprized at the Levity of his Question about a Fop's Perriwig, he began to railly himself with so much Wit and Humour upon the Folly of his Fondness for it, that he struck me with an equal Desire of granting any thing in my37 Power to oblige so facetious a Customer. This singular Beginning of our Conversation, and the mutual Laughs that ensued upon it, ended in an Agreement to finish our Bargain that Night over a Bottle.

If it were possible the Relation of the happy Indiscretions which passed between us that Night could give the tenth Part of the Pleasure I then received from them, I could still repeat them with Delight: But as it may be doubtful whether the Patience of a Reader may be quite so strong as the Vanity of an Author, I shall cut it short by only saying that single Bottle was the Sire of many a jolly Dozen that for some Years following, like orderly Children, whenever they were call'd for, came into the same Company. Nor, indeed, did I think from that time, whenever he was to be had, any Evening could be agreeably enjoy'd without him.[30] But the long continuance of our Intimacy perhaps may be thus accounted for.

He who can taste Wit in another may in some sort be said to have it himself: Now, as I always38 had, and (I bless my self for the Folly) still have a quick Relish of whatever did or can give me Delight: This Gentleman could not but see the youthful Joy I was generally raised to whenever I had the Happiness of a Tête à tête with him; and it may be a moot Point whether Wit is not as often inspired by a proper Attention as by the brightest Reply to it. Therefore, as he had Wit enough for any two People, and I had Attention enough for any four, there could not well be wanting a sociable Delight on either side. And tho' it may be true that a Man of a handsome Person is apt to draw a partial Ear to every thing he says; yet this Gentleman seldom said any thing that might not have made a Man of the plainest Person agreeable. Such a continual Desire to please, it may be imagined, could not but sometimes lead him into a little venial Flattery rather than not succeed in it. And I, perhaps, might be one of those Flies that was caught in this Honey. As I was then a young successful Author and an Actor in some unexpected Favour, whether deservedly or not imports not; yet such Appearances at least were plausible Pretences enough for an amicable Adulation to enlarge upon, and the Sallies of it a less Vanity than mine might not have been able to resist. Whatever this Weakness on my side might be, I was not alone in it; for I have heard a Gentleman of Condition say, who knew the World as well as most Men that live in it, that let his Discretion be ever so much upon its Guard, he never fell into Mr. Brett's39 Company without being loth to leave it or carrying away a better Opinion of himself from it. If his Conversation had this Effect among the Men; what must we suppose to have been the Consequence when he gave it a yet softer turn among the Fair Sex? Here, now, a French Novellist would tell you fifty pretty Lies of him; but as I chuse to be tender of Secrets of that sort, I shall only borrow the good Breeding of that Language, and tell you in a Word, that I knew several Instances of his being un Homme à bonne Fortune. But though his frequent Successes might generally keep him from the usual Disquiets of a Lover, he knew this was a Life too liquorish to last; and therefore had Reflexion enough to be govern'd by the Advice of his Friends to turn these his Advantages of Nature to a better use.

Among the many Men of Condition with whom his Conversation had recommended him to an Intimacy, Sir Thomas Skipwith had taken a particular Inclination to him; and as he had the Advancement of his Fortune at Heart, introduced him where there was a Lady[31] who had enough in her Power to disencumber him of the World and make him every way easy for Life.

While he was in pursuit of this Affair, which no time was to be lost in (for the Lady was to be in40 Town but for three Weeks) I one Day found him idling behind the Scenes before the Play was begun. Upon sight of him I took the usual Freedom he allow'd me, to rate him roundly for the Madness of not improving every Moment in his Power in what was of such consequence to him. Why are you not (said I) where you know you only should be? If your Design should once get Wind in the Town, the Ill-will of your Enemies or the Sincerity of the Lady's Friends may soon blow up your Hopes, which in your Circumstances of Life cannot be long supported by the bare Appearance of a Gentleman.——But it is impossible to proceed without some Apology for the very familiar Circumstance that is to follow——Yet, as it might not be so trivial in its Effect as I fear it may be in the Narration, and is a Mark of that Intimacy which is necessary should be known had been between us, I will honestly make bold with my Scruples and let the plain Truth of my Story take its Chance for Contempt or Approbation.

After twenty Excuses to clear himself of the Neglect I had so warmly charged him with, he concluded them with telling me he had been out all the Morning upon Business, and that his Linnen was too much soil'd to be seen in Company. Oh, ho! said I, is that all? Come along with me, we will soon get over that dainty Difficulty: Upon which I haul'd him by the Sleeve into my Shifting-Room, he either staring, laughing, or hanging back all the way. There, when I had lock'd him in, I began to strip off41 my upper Cloaths, and bad him do the same; still he either did not, or would not seem to understand me, and continuing his Laugh, cry'd, What! is the Puppy mad? No, no, only positive, said I; for look you, in short, the Play is ready to begin, and the Parts that you and I are to act to Day are not of equal consequence; mine of young Reveller (in Greenwich-Park[32]) is but a Rake; but whatever you may be, you are not to appear so; therefore take my Shirt and give me yours; for depend upon't, stay here you shall not, and so go about your Business. To conclude, we fairly chang'd Linnen, nor could his Mother's have wrap'd him up more fortunately; for in about ten Days he marry'd the Lady.[33] In a Year or two after his Marriage he was chosen a Member of that Parliament which was sitting when42 King William dy'd. And, upon raising of some new Regiments, was made Lieutenant-Colonel to that of Sir Charles Hotham. But as his Ambition extended not beyond the Bounds of a Park Wall and a pleasant Retreat in the Corner of it, which with too much Expence he had just finish'd, he, within another Year, had leave to resign his Company to a younger Brother.

This was the Figure in Life he made when Sir Thomas Skipwith thought him the most proper Person to oblige (if it could be an Obligation) with the Present of his Interest in the Patent. And from these Anecdotes of my Intimacy with him, it may be less a Surprise, when he came to Town invested with this new Theatrical Power, that I should be the first Person to whom he took any Notice of it. And notwithstanding he knew I was then engag'd, in another Interest, at the Hay-Market, he desired we might consider together of the best Use he could make of it, assuring me at the same time he should think it of none to himself unless it could in some Shape be turn'd to my Advantage. This friendly Declaration, though it might be generous in him to make, was not needful to incline me in whatever might be honestly in my Power, whether by Interest or Negotiation, to serve him. My first Advice,43 therefore, was, That he should produce his Deed to the other Menaging Patentee of Drury-Lane, and demand immediate Entrance to a joint Possession of all Effects and Powers to which that Deed had given him an equal Title. After which, if he met with no Opposition to this Demand (as upon sight of it he did not) that he should be watchful against any Contradiction from his Collegue in whatever he might propose in carrying on the Affair, but to let him see that he was determin'd in all his Measures. Yet to heighten that Resolution with an Ease and Temper in his manner, as if he took it for granted there could be no Opposition made to whatever he had a mind to. For that this Method, added to his natural Talent of Persuading, would imperceptibly lead his Collegue into a Reliance on his superior Understanding, That however little he car'd for Business he should give himself the Air at least of Enquiry into what had been done, that what he intended to do might be thought more considerable and be the readier comply'd with: For if he once suffer'd his Collegue to seem wiser than himself, there would be no end of his perplexing him with absurd and dilatory Measures; direct and plain Dealing being a Quality his natural Diffidence would never suffer him to be Master of; of which his not complying with his Verbal Agreement with Swiney, when the Hay-Market House was taken for both their Uses, was an Evidence. And though some People thought it Depth and Policy in him to keep things often in44 Confusion, it was ever my Opinion they over-rated his Skill, and that, in reality, his Parts were too weak for his Post, in which he had always acted to the best of his Knowledge. That his late Collegue, Sir Thomas Skipwith, had trusted too much to his Capacity for this sort of Business, and was treated by him accordingly, without ever receiving any Profits from it for several Years: Insomuch that when he found his Interest in such desperate Hands he thought the best thing he could do with it was (as he saw) to give it away. Therefore if he (Mr. Brett) could once fix himself, as I had advis'd, upon a different Foot with this hitherto untractable Menager, the Business would soon run through whatever Channel he might have a mind to lead it. And though I allow'd the greatest Difficulty he would meet with would be in getting his Consent to a Union of the two Companies, which was the only Scheme that could raise the Patent to its former Value, and which I knew this close Menager would secretly lay all possible Rubs in the way to; yet it was visible there was a way of reducing him to Compliance: For though it was true his Caution would never part with a Straw by way of Concession, yet to a high Hand he would give up any thing, provided he were suffer'd to keep his Title to it: If his Hat were taken from his Head in the Street, he would make no farther Resistance than to say, I am not willing to part with it. Much less would he have the Resolution openly to oppose any just45 Measures, when he should find one, who with an equal Right to his and with a known Interest to bring them about, was resolv'd to go thro' with them.

Now though I knew my Friend was as thoroughly acquainted with this Patentee's Temper as myself, yet I thought it not amiss to quicken and support his Resolution, by confirming to him the little Trouble he would meet with, in pursuit of the Union I had advis'd him to; for it must be known that on our side Trouble was a sort of Physick we did not much care to take: But as the Fatigue of this Affair was likely to be lower'd by a good deal of Entertainment and Humour, which would naturally engage him in his dealing with so exotick a Partner, I knew that this softening the Business into a Diversion would lessen every Difficulty that lay in our way to it.

However copiously I may have indulg'd my self in this Commemoration of a Gentleman with whom I had pass'd so many of my younger Days with Pleasure, yet the Reader may by this Insight into his Character, and by that of the other Patentee, be better able to judge of the secret Springs that gave Motion to or obstructed so considerable an Event as that of the Re-union of the two Companies of Actors in 1708.[34] In Histories of more weight, for want of such Particulars we are often deceiv'd in the true Causes of Facts that most concern us to be let into; which sometimes makes us ascribe to Policy, or false46 Appearances of Wisdom, what perhaps in reality was the mere Effect of Chance or Humour.

Immediately after Mr. Brett was admitted as a joint Patentee, he made use of the Intimacy he had with the Vice-Chamberlain to assist his Scheme of this intended Union, in which he so far prevail'd that it was soon after left to the particular Care of the same Vice-Chamberlain to give him all the Aid and Power necessary to the bringing what he desired to Perfection. The Scheme was, to have but one Theatre for Plays and another for Operas, under separate Interests. And this the generality of Spectators, as well as the most approv'd Actors, had been some time calling for as the only Expedient to recover the Credit of the Stage and the valuable Interests of its Menagers.

As the Condition of the Comedians at this time is taken notice of in my Dedication of the Wife's Resentment to the Marquis (now Duke) of Kent, and then Lord-Chamberlain, which was publish'd above thirty Years ago,[35] when I had no thought of ever troubling the World with this Theatrical History, I see no Reason why it may not pass as a Voucher of the Facts I am now speaking of; I shall therefore give them in the very Light I then saw them. After some Acknowledgment for his Lordship's Protection of our (Hay-Market) Theatre, it is further said——

"The Stage has, for many Years, 'till of late, groan'd under the greatest Discouragements, w47hich have been very much, if not wholly, owing to the Mismenagement of those that have aukwardly govern'd it. Great Sums have been ventur'd upon empty Projects and Hopes of immoderate Gains, and when those Hopes have fail'd, the Loss has been tyrannically deducted out of the Actors Sallary. And if your Lordship had not redeem'd them—This is meant of our being suffer'd to come over to Swiney——they were very near being wholly laid aside, or, at least, the Use of their Labour was to be swallow'd up in the pretended Merit of Singing and Dancing."

What follows relates to the Difficulties in dealing with the then impracticable Menager, viz.

"—And though your Lordship's Tenderness of oppressing is so very just that you have rather staid to convince a Man of your good Intentions to him than to do him even a Service against his Will; yet since your Lordship has so happily begun the Establishment of the separate Diversions, we live in hope that the same Justice and Resolution will still persuade you to go as successfully through with it. But while any Man is suffer'd to confound the Industry and Use of them by acting publickly in opposition to your Lordship's equal Intentions, under a false and intricate Pretence of not being able to comply with them, the Town is likely to be more entertain'd with the private Dissensions than the publick Performance of either, and the Actors in a perpetual Fear and Necessity of petitioning your Lordship every Season for new Relief."

Such was the State of the Stage immediately preceding the time of Mr. Brett's being admitted a joint Patentee, who, as he saw with clearer Eyes what was its evident Interest, left no proper Measures unattempted to make this so long despair'd-of Union practicable. The most apparent Difficulty to be got over in this Affair was, what could be done for Swiney in consideration of his being oblig'd to give up those Actors whom the Power and Choice of the Lord-Chamberlain had the Year before set him at the Head of, and by whose Menagement those Actors had found themselves in a prosperous Condition. But an Accident at this time happily contributed to make that Matter easy. The Inclination of our People of Quality for foreign Operas had now reach'd the Ears of Italy, and the Credit of their Taste had drawn over from thence, without any more particular Invitation, one of their capital Singers, the famous Signior Cavaliero Nicolini: From whose Arrival, and the Impatience of the Town to hear him, it was concluded that Operas being now so completely provided could not fail of Success, and that by making Swiney sole Director of them the Profits must be an ample Compensation for his Resignation of the Actors. This Matter being thus adjusted by Swiney's Acceptance of the Opera only to be perform'd at the Hay-Market House, the Actors49 were all order'd to return to Drury-Lane, there to remain (under the Patentees) her Majesty's only Company of Comedians.[36]

CHAPTER XII.

A short View of the Opera when first divided from the Comedy. Plays recover their Credit. The old Patentee uneasy at their Success. Why. The Occasion of Colonel Brett's throwing up his Share in the Patent. The Consequences of it. Anecdotes of Goodman the Actor. The Rate of favourite Actors in his Time. The Patentees, by endeavouring to reduce their Price, lose them all a second time. The principal Comedians return to the Hay-Market in Shares with Swiney. They alter that Theatre. The original and present Form of the Theatre in Drury-Lane compar'd. Operas fall off. The Occasion of it. Farther Observations upon them. The Patentee dispossess'd of Drury-Lane Theatre. Mr. Collier, with a new License, heads the Remains of that Company.

Plays and Operas being thus established upon separate Interests,[37] they were now left to make the best of their way into Favour by their different Merit. Although the Opera is not a Plant of our Native Growth, nor what our plainer Appetites are fond of, and is of so delicate a Nature that witho51ut excessive Charge it cannot live long among us; especially while the nicest Connoisseurs in Musick fall into such various Heresies in Taste, every Sect pretending to be the true one: Yet, as it is call'd a Theatrical Entertainment, and by its Alliance or Neutrality has more or less affected our Domestick Theatre, a short View of its Progress may be allow'd a Place in our History.

After this new Regulation the first Opera that appear'd was Pyrrhus. Subscriptions at that time were not extended, as of late, to the whole Season, but were limited to the first Six Days only of a new Opera. The chief Performers in this were Nicolini, Valentini, and Mrs. Tofts;[38] and for the inferior Parts the best that were then to be found. Whatever Praises may have been given to the most famous Voices that have been heard since Nicolini, upon the whole I cannot but come into the Opinion that still prevails among several Persons of Condition who are able to give a Reason for their liking, that no Singer since his Time has so justly and gracefully acquitted himself in whatever Character he appear'd as Nicolini. At most the Difference between him and the greatest Favourite of the Ladies, Farinelli, amounted but to this, that he 52might sometimes more exquisitely surprize us, but Nicolini (by pleasing the Eye as well as the Ear) fill'd us with a more various and rational Delight. Whether in this Excellence he has since had any Competitor, perhaps will be better judg'd by what the Critical Censor of Great Britain says of him in his 115th Tatler, viz.

"Nicolini sets off the Character he bears in an Opera by his Action, as much as he does the Words of it by his Voice; every Limb and Finger contributes to the Part he acts, insomuch that a deaf Man might go along with him in the Sense of it. There is scarce a beautiful Posture in an old Statue which he does not plant himself in, as the different Circumstances of the Story give occasion for it—He performs the most ordinary Action in a manner suitable to the Greatness of his Character, and shews the Prince even in the giving of a Letter or dispatching of a Message, &c."[39]

His Voice at this first time of being among us (for he made us a second Visit when it was impair'd) had all that strong53, clear Sweetness of Tone so lately admir'd in Senesino. A blind Man could scarce have distinguish'd them; but in Volubility of Throat the former had much the Superiority. This so excellent Performer's Agreement was Eight Hundred Guineas for the Year, which is but an eighth Part more than half the Sum that has since been given to several that could never totally surpass him: The Consequence of which is, that the Losses by Operas, for several Seasons, to the End of the Year 1738, have been so great, that those Gentlemen of Quality who last undertook the Direction of them, found it ridiculous any longer to entertain the Publick at so extravagant an Expence, while no one particular Person thought himself oblig'd by it.

Mrs. Tofts,[40] who took her first Grounds of 54Musick here in her own Country, before the Italian Taste had so highly prevail'd, was then not an Adept in it:[41] Yet whatever Defect the fashionably Skilful might find in her manner, she had, in the general Sense of her Spectators, Charms that few of the most learned Singers ever arrive at. The Beauty of her fine proportion'd Figure, and exquisitely sweet, silver Tone of her Voice, with that peculiar, rapid Swiftness of her Throat, were Perfections not55 to be imitated by Art or Labour. Valentini I have already mention'd, therefore need only say farther of him, that though he was every way inferior to Nicolini,[42] yet, as he had the Advantage of giving us our first Impression of a good Opera Singer, he had still his Admirers, and was of great Service in being so skilful a Second to his Superior.

Three such excellent Performers in the same kind of Entertainment at once, England till this Time had never seen: Without any farther Comparison, then, with the much dearer bought who have succeeded them, their Novelty at least was a Charm that drew vast Audiences of the fine World after them. Swiney, their sole Director, was prosperous, and in one Winter a Gainer by them of a moderate younger Brother's Fortune. But as Musick, by so profuse a Dispensation of her Beauties, could not always supply our dainty Appetites with equal Variety, nor for ever please us with the same Objects, the Opera, after one luxurious Season, like the fine Wife of a roving Husband, began to loose its Charms, and every Day discover'd to our Satiety Imperfections which our former Fondness had been blind to: But of this I shall observe more in its Place: in the mean time, let us enquire into the Productions of our native Theatre.

It may easily be conceiv'd, that by this entir56e Re-union of the two Companies Plays must generally have been perform'd to a more than usual Advantage and Exactness: For now every chief Actor, according to his particular Capacity, piqued himself upon rectifying those Errors which during their divided State were almost unavoidable. Such a Choice of Actors added a Richness to every good Play as it was then serv'd up to the publick Entertainment: The common People crowded to them with a more joyous Expectation, and those of the higher Taste return'd to them as to old Acquaintances, with new Desires after a long Absence. In a Word, all Parties seem'd better pleas'd but he who one might imagine had most Reason to be so, the (lately) sole menaging Patentee. He, indeed, saw his Power daily mould'ring from his own Hands into those of Mr. Brett,[43] whose Gentlemanly manner of making every one's Business easy to him, threw their old Master under a Disregard which he had not been us'd to, nor could with all his happy Change of Affairs support. Although57 this grave Theatrical Minister of whom I have been oblig'd to make such frequent mention, had acquired the Reputation of a most profound Politician by being often incomprehensible, yet I am not sure that his Conduct at this Juncture gave us not an evident Proof that he was, like other frail Mortals, more a Slave to his Passions than his Interest; for no Creature ever seem'd more fond of Power that so little knew how to use it to his Profit and Reputation; otherwise he could not possibly have been so discontented, in his secure and prosperous State of the Theatre, as to resolve at all Hazards to destroy it. We shall now see what infallible Measures he took to bring this laudable Scheme to Perfection.

He plainly saw that, as this disagreeable Prosperity was chiefly owing to the Conduct of Mr. Brett, there could be no hope of recovering the Stage to its former Confusion but by finding some effectual Means to make Mr. Brett weary of his Charge: The most probable he could for the Present think of, in this Distress, was to call in the Adventurers (whom for many Years, by his Defence in Law, he had kept out) now to take care of their visibly improving Interests.[44] This fair Appearance of Equity being known to be his own Proposal, he rightly guess'd would incline these Adventurers to form a Majority of Votes on his Side in all Theatrical Questions, and consequently become a Check upon the Power of58 Mr. Brett, who had so visibly alienated the Hearts of his Theatrical Subjects, and now began to govern without him. When the Adventurers, therefore, were re-admitted to their old Government, after having recommended himself to them by proposing to make some small Dividend of the Profits (though he did not design that Jest should be repeated) he took care that the Creditors of the Patent, who were then no inconsiderable Body, should carry off the every Weeks clear Profits in proportion to their several Dues and Demands. This Conduct, so speciously just, he had Hopes would let Mr. Brett see that his Share in the Patent was not so valuable an Acquisition as perhaps he might think it; and probably make a Man of his Turn to Pleasure soon weary of the little Profit and great Plague it gave him. Now, though these might be all notable Expedients, yet I cannot say they would have wholly contributed to Mr. Brett's quitting his Post, had not a Matter of much stronger Moment, an unexpected Dispute between him and Sir Thomas Skipwith, prevailed with59 him to lay it down: For in the midst of this flourishing State of the Patent, Mr. Brett was surpriz'd with a Subpœna into Chancery from Sir Thomas Skipwith, who alledg'd in his Bill that the Conveyance he had made of his Interest in the Patent to Mr. Brett was only intended in Trust. (Whatever the Intent might be, the Deed it self, which I then read, made no mention of any Trust whatever.) But whether Mr. Brett, as Sir Thomas farther asserted, had previously, or after the Deed was sign'd, given his Word of Honour that if he should ever make the Stage turn to any Account or Profit, he would certainly restore it: That, indeed, I can say nothing to; but be the Deed valid or void, the Facts that apparently follow'd were, that tho' Mr. Brett in his Answer to this Bill absolutely deny'd his receiving this Assignment either in Trust or upon any limited Condition of what kind soever, yet he made no farther Defence in the Cause. But since he found Sir Thomas had thought fit on any Account to sue for the Restitution of it, and Mr. Brett being himself conscious that, as the World knew he had paid no Consideration for it, his keeping it might be misconstrued, or not favourably spoken of; or perhaps finding, tho' the Profits were great, they were constantly swallowed up (as has been observ'd) by the previous Satisfaction of old Debts, he grew so tir'd of the Plague and Trouble the whole Affair had given him, and was likely still to engage him in, that in a few Weeks after he withdrew himself from all Concern with th60e Theatre, and quietly left Sir Thomas to find his better Account in it. And thus stood this undecided Right till, upon the Demise of Sir Thomas, Mr. Brett being allow'd the Charges he had been at in this Attendance and Prosecution of the Union, reconvey'd this Share of the Patent to Sir George Skipwith, the Son and Heir of Sir Thomas.[45]

Our Politician, the old Patentee, having thus fortunately got rid of Mr. Brett, who had so rashly brought the Patent once more to be a profitable Tenure, was now again at Liberty to chuse rather to lose all than not to have it all to himself.

I have elsewhere observ'd that nothing can so effectually secure the Strength, or contribute to the Prosperity of a good Company, as the Directors of it having always, as near as possible, an amicable Understanding with three or four of their best Actors, whose good or ill-will must naturally make a wide Difference in their profitable or useless manner of serving them: While the Principal are kept reasonably easy the lower Class can never be troublesome without hurting themselves: But when a valuable Actor is hardly treated, the Master must be a very cunning Man that finds his Account in it. We shall now see how far Experience will verify this Observation.

The Patentees thinking themselves secure in being61 restor'd to their former absolute Power over this now only Company, chose rather to govern it by the Reverse of the Method I have recommended: For tho' the daily Charge of their united Company amounted not, by a good deal, to what either of the two Companies now in Drury-Lane or Covent-Garden singly arises, they notwithstanding fell into their former Politicks of thinking every Shilling taken from a hired Actor so much clear Gain to the Proprietor: Many of their People, therefore, were actually, if not injudiciously, reduced in their Pay, and others given to understand the same Fate was design'd them; of which last Number I my self was one; which occurs to my Memory by the Answer I made to one of the Adventurers, who, in Justification of their intended Proceeding,[46] told me that my Sallary, tho' it should be less than it was by ten Shillings a Week, would still be more than ever Goodman had, who was a better Actor than I could pretend to be: To which I reply'd, This may be true, but then you know, Sir, it is as true that Goodman was forced to go upon the High-way for a Livelihood. As this was a known Fact of Goodman, my mentioning it on that Occasion I believe was of Service to me; at least my Sallary was not reduced after it. To say a Word or two more of62 Goodman, so celebrated an Actor in his Time, perhaps may set the Conduct of the Patentees in a clearer Light. Tho' Goodman had left the Stage before I came to it, I had some slight Acquaintance with him. About the Time of his being expected to be an Evidence against Sir John Fenwick in the Assassination-Plot,[47] in 1696, I happen'd to meet him at Dinner at Sir Thomas Skipwith's, who, as he was an agreeable Companion himself, liked Goodman for the same Quality. Here it was that Goodman, without Disguise or sparing himself, fell into a laughing Account of several loose Passages of his younger Life; as his being expell'd the University of Cambridge for being one of the hot-headed Sparks who63 were concern'd in the cutting and defacing the Duke of Monmouth's Picture, then Chancellor of that Place. But this Disgrace, it seems, had not disqualified him for the Stage, which, like the Sea-Service, refuses no Man for his Morals that is able-bodied: There, as an Actor, he soon grew into a different Reputation; but whatever his Merit might be, the Pay of a hired Hero in those Days was so very low that he was forced, it seems, to take the Air (as he call'd it) and borrow what Money the first Man he met had about him. But this being his first Exploit of that kind which the Scantiness of his Theatrical Fortune had reduced him to, King James was prevail'd upon to pardon him: Which Goodman said was doing him so particular an Honour that no Man could wonder if his Acknowledgment had carried him a little farther than ordinary into the Interest of that Prince: But as he had lately been out of Luck in backing his old Master, he had now no way to get home the Life he was out upon his Account but by being under the same Obligations to King William.

Another Anecdote of him, though not quite so dishonourably enterprizing, which I had from his own Mouth at a different Time, will equally shew to what low Shifts in Life the poor Provision for good Actors, under the early Government of the Patent, reduced them. In the younger Days of their Heroism, Captain Griffin and Goodman were confined by their moderate Sallaries to the Oeconomy64 of lying together in the same Bed and having but one whole Shirt between them: One of them being under the Obligation of a Rendezvous with a fair Lady, insisted upon his wearing it out of his Turn, which occasion'd so high a Dispute that the Combat was immediately demanded, and accordingly their Pretensions to it were decided by a fair Tilt upon the Spot, in the Room where they lay: But whether Clytus or Alexander was obliged to see no Company till a worse could be wash'd for him, seems not to be a material Point in their History, or to my Purpose.[48]