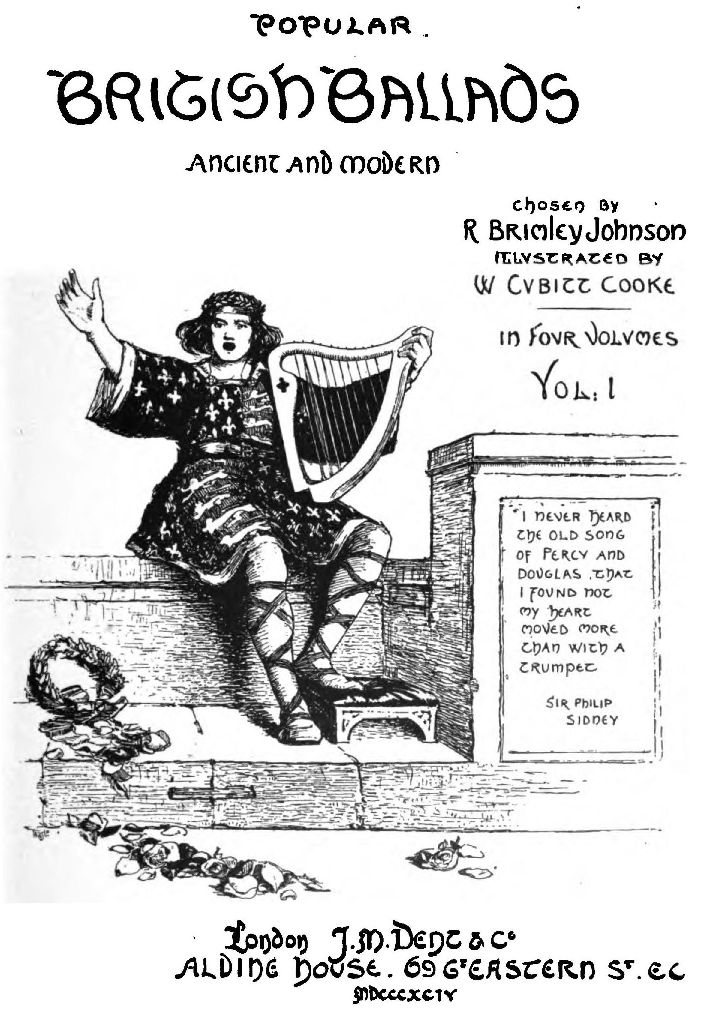

Title: Popular British Ballads, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 1 (of 4)

Editor: R. Brimley Johnson

Illustrator: W. Cubitt Cooke

Release date: March 28, 2014 [eBook #45241]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by Google Books

CONTENTS

LITTLE MUSGRAVE AND LADY BARNARD

THE BLIND BEGGAR'S DAUGHTER OF BEDNALL GREEN

FAIR MARGARET AND SWEET WILLIAM.

ADAM BEL, CLYM OF THE CLOUGH,AND WILLIAM OF CLOUDESLE

ROBIN HOOD AND GUY OF GISBORNE

CAPTAIN CAR, OR EDOM O' GORDON.

LADY ISABEL AND THE ELF-KNIGHT

THERE WAS A MAID CAME OUT OF KENT

1. The word "ballad" is admittedly of very wide significance. Meaning originally "a song intended as the accompaniment to a dance," it was afterwards applied to "a light simple song of any kind" with a leaning towards the sentimental or romantic; and, in its present use, is defined by Dr Murray as "a simple spirited poem in short stanzas, in which some popular story is graphically told." Passing over the obsolete sense of "a popular song specially celebrating or scurrilously attacking some person or institution," we may note that Dr Johnson calls a ballad "a song," and quotes a statement from Watts that it once "signified a solemn and sacred song as well as a trivial, when Solomon's Song was called the 'The Ballad of Ballads,' but now it is applied to nothing but trifling verse."

Ballad-collectors, however, have never strictly regarded any one of these definitions, and to me their catholicity seems worthy of imitation. I have demanded no more of a ballad than that it should be a simple spirited narrative; and, though excluding the pure lyrics and metrical romances found in Percy's Reliques or elsewhere, I have been guided in doubtful cases rather by intuition than by rule. I have included poems written in every variety of metre except blank verse, and even the latter may seem to be represented by Blake's Fair Elinor.

Moreover, this is a collection of poems, not of archaeological specimens or verses on great historic events; and the ballads have been chosen according to my judgment of their artistic merits.

2. Vols. I. and II. contain the best traditionary ballads of England and Scotland, with a small group of Peasant Ballads still sung in country districts. Vols. III. and IV. contain selected modern experiments in the art of ballad-writing by English, Scotch, and Welsh poets, with a mixed group of Irish ballads; those on foreign or classical subjects being in each case excluded.

a. The text of the old ballads has been carefully prepared from the best authorities, and the spelling is modernised so far as can be done without injuring the rhythm or accentuation. Brief historical or explanatory notes are printed in the Table of Contents, and obsolete terms are explained in footnotes.

No attempt has been made to settle disputed dates of composition, but the ballads are arranged in groups according to the collection (e.g. Percy's Reliques, Scott's Minstrelsy, etc.) in which they were first included, and thus brought before the notice of the literary public. The groups are arranged according to the dates of publication of the collections.

b. For the Peasant Ballads one text is seldom more authoritative than another, and minor differences have to be settled by personal judgment. The versions here offered, have, in many cases, been prepared from those popular in different parts of England. They are believed to represent the most poetical form of the songs which were the favourites of the elder generation, and which are being now superseded by the shorter and more sensational effusions of the music-hall. They are arranged according to their subjects.

c. The modern ballads are arranged chronologically, according to the dates of birth of their authors, and are intended to be, so far as possible, representative of our best poets. Parodies and dialect poems have been purposely omitted, because they form classes by themselves and are essentially different in spirit from both the traditionary and the literary ballads. This restriction does not involve the omission of all poems with humorous subjects or treatment.

By calling these ballads "modern" I do not wish to imply that every one of them was written later than those in Vols. I. and II., since it is practically certain that some of the Peasant group belong to this century. They are modern in the sense of being literary productions by known authors, which were offered to the public in a printed form from the first.

d. Irish ballads, written in English, are comparatively modern, but they belong to the traditionary manner and, whether the work of ballad-mongers or of poets, need not be separated from the few translations from the Irish which have been thought suitable for this collection. They too are arranged chronologically.

e. A similar group of Welsh ballads was projected, but after a careful investigation of the principal periodicals and collections, and some correspondence with students of Welsh literature, I have concluded that, for English readers at least, there exist but few Welsh ballads of any merit; and that the poetic genius of the nation could not be fairly represented by such a selection.

3. a. Every student of our old ballads owes an immeasurable debt of gratitude to Professor F. J. Child, whose monumental collections * have covered the entire field. I have naturally followed his guidance in the choice of texts and used his transcripts from manuscripts, having received his cordial permission to do so, in letters of kind advice and sympathy.

* "English and Scottish Ballads," in 8 vols. (Houghton,

Mifflin & Co.); "The English and Scottish Ballads"—in the

course of publication—Parts i.-viii. having already

appeared (Houghton, Mifflin & Co.).

My thanks are also due to Dr Furnivall and Professor Hales for answers to questions and permission to follow their reprint of The Percy Folio; to Professor Skeat for the use of his transcript of The Hunting of the Cheviot; to Mr W. C. Hazlitt for a portion of an old copy of Adam Bell, Clym of the Clough, and William Cloudeslè; and to the Council of the Folk-lore Society for the version of the Unquiet Grave which appeared in their Record.

b. In the preparation of the Peasant group I have received great assistance from the Rev. S. Baring-Gould, who has generously put at my disposal the results of his life-long studies in this subject, given me advice and information at every turn, and allowed me the free use of all his own manuscript and printed material. Without his help and encouragement this part of the work could never have been completed.

My thanks are also due to numerous members of the Folk-lore Society, both in London and the provinces, among whom I would particularly mention Miss C. S. Burne, author of Shropshire Folk-lore, and Mrs Balfour of Northumberland.

I have received much assistance also from Miss Lucy E. Broadwood, who has united with Mr J. A. Fuller-Maitland and the Leadenhall Press, Ltd., in permitting me to reprint from her English County Songs.

For replies to various questions on these subjects I am indebted to Messrs A. T. Quiller-Couch, W. E. A. Axon, Edward Peacock, the Rev. J. C. Atkinson, Judge Hughes, Miss Field, and Miss G. Chanter. Messrs G. Bell & Sons have kindly allowed me to reprint "Sir Arthur and charming Mollee" from their Ancient Poems, Ballads, and Songs of the Peasantry of England.

c. For the use of copyright matter my thanks are further due to Messrs Macmillan & Co., the publishers of Charles Kingsley, and Miss Rossetti; to Messrs Smith, Elder & Co., of Robert Browning; to Messrs Chatto & Windus, of G. W. Thombury; to Messrs Elis & Elvey, of D. G. Rossetti; Messrs Ward, Lock & Bowden, of Henry Kingsley; Messrs Kegan Paul & Co., of Mrs Hamilton-King; Messrs Messina & Co., Melbourne, of A. L. Gordon; and Mr C. Baxter, the agent of Mr R. L. Stevenson.

I am also indebted to Sir George Young, Bart., for information concerning W. M. Praed; to. Mr Sebastian Evans; Mrs W. B. Scott; Mrs Dobell; Dr George MacDonald; Miss Jean Ingelow and her publishers, Messrs Longmans, Green & Co.; Mrs Isa Craig Knox; Mrs Calverly; Dr Garnett; Mrs Cory and the publisher of the late William Cory, Mr George Allen; Mr A. C. Swinburne; Madame Darmsteter; Miss Grant; Mr Ernest Rhys; Mr R. Buchanan; Mr John Davidson; Mr Rudyard Kipling and his publishers, Messrs Methuen & Co., and Messrs Thacker & Co.; and Miss G. Chanter.

Having found every endeavour vain to discover the address of the Misses Hawker, I have ventured to reprint The Doom of St Madron, by the late R. S. Hawker, without their permission, the publishers, Messrs Kegan Paul & Co., offering no objection so far as they are concerned. From the works of Tennyson, Mr Wm. Morris, and a few others, I should have made selections, had not the permission been, to my great regret, withheld.

d. In the preparation of the Irish group I have been very materially assisted by Mr Alfred Percival Graves, who has advised my selection and given me the free use of all his own work; and by Mr David J. O'Donoghue, author of the Dictionary of the Poets and Poetry of Ireland, who has devoted much time to supplying me with information of all kinds, and directing me to the work of comparatively unknown authors.

For the use of copyright matter I am also indebted to Mrs Allingham; to Professor E. F. Savage-Armstrong, for his own work, and that of his brother, the late Edward J. Armstrong; to Lady Ferguson; Miss Emily H. Hickey; Mr Michael Hogan; Mr Wm. Winter and Messrs C. Scribner & Sons, for a poem by Fitzjames O'Brien; Messrs Routledge & Sons for poems by S. Lover; to Mr T. D. Sullivan, M.P.; Mrs K. Tynan (Hinkson); Mr Aubrey de Vere and his publishers, Messrs Macmillan & Co.; Mr W. B. Yeats; and Dr Sigerson.

Finally, I have to thank Mr Theodore Watts and Mr Alfred H. Miles, editor of The Poets and Poetry of the Century, for information on certain questions of copyright.

R. Brimley Johnson.

Llandaff House, Cambridge,

August 3rd, 1894.

There were three ravens sat on a tree,

Downe, a downe, hay downe, hay downe,

There were three ravens sat on a tree,

With a downe,

There were three ravens sat on a tree,

They were as black as they might be,

With a downe, derrie, derrie, derrie, downe, downe.

The one of them said to his mate,

"Where shall we our breakfast take?"—

"Down in yonder green field,

There lies a knight slain under his shield.

"His hounds they lie down at his feet,

So well they can their master keep.

=His hawks they flie so eagerly,

There's no fowl dare him come nigh."

Down there comes a fallow doe,

As great with young as she might go.

She lift up his bloody head,

And kist his wounds that were so red.

She got him up upon her back,

And carried him to earthen lake.

She buried him before the prime,

She was dead herself ere even-song time.

God send every gentleman,

Such hawks, such hounds, and such a leman.

As it fell one holy-day, hay down,

As many be in the year,

When young men and maids together did go

Their matins and mass to hear,

Little Musgrave came to the church door,

The priest was at private mass;

But he had more mind of the fair women,

Then he had of our lady's grace.

The one of them was clad in green,

Another was clad in pall;

And then came in my lord Barnards wife,

The fairest amonst them all.

She cast an eye on little Musgrave,

As bright as the summer sun,

And then bethought this little Musgrave,

"This lady's heart have I won."

Quoth she, "I have loved thee, little Musgrave,

Full long and many a day:"

"So have I loved you, fair lady,

Yet never word durst I say."

"I have a bower at Bucklesfordbery,

Full daintily it is dight;

If thou wilt wend thither, thou little Musgrave,

Thou's lig in mine arms all night."

Quoth he, "I thank ye, fair lady,

This kindness thou showest to me;

But whether it be to my weal or woe,

This night I will lig with thee."

With that he heard a little tiny page,

By his lady's coach as he ran:

"Allthough I am my lady's footpage,

Yet I am lord Barnard's man.

"My lord Barnard shall know of this,

Whether I sink or swim:"

And ever where the bridges were broke,

He laid him down to swim.

"Asleep, or wake! thou lord Barnard,

As thou art a man of life;

For little Musgrave is at Bucklesfordbery,

Abed with thy own wedded wife."

"If this be true, thou little tiny page,

This thing thou tellest to me,

Then all the land in Bucklesfordbery

I freely will give to thee.

"But if it be a lie, thou little tiny page,

This thing thou tellest to me,

On the highest tree in Bucklesfordbery

Then hanged shalt thou be."

He called up his merry men all:—

"Come saddle me my steed;

This night must I to Bucklesfordbery,

For I never had greater need."

And some of them whistl'd, and some of them sung,

And some these words did say,

And ever when my lord Barnard's horn blew,

"Away, Musgrave, away!"

"Methinks I hear the thresel-cock,

Methinks I hear the jay;

Methinks I hear my Lord Barnard,—

And I would I were away."

"Lie still, lie still, thou little Musgrave,

And huggell me from the cold;

'Tis nothing but a shephard's boy,

A driving his sheep to the fold.

"Is not thy hawk upon a perch?

Thy steed eats oats and hay,

And thou a fair lady in thine arms,—

And wouldst thou be away?"

With that my lord Barnard came to the door,

And lit a stone upon;

He plucked out three silver keys,

And he open'd the doors each one.

He lifted up the coverlet,

He lifted up the sheet;

"How now, how now, thou little Musgrave,

Doest thou find my lady sweet?"

"I find her sweet," quoth little Musgrave,

"The more 'tis to my pain;

I would gladly give three hundred pounds

That I were on yonder plain."

"Arise, arise, thou little Musgrave,

And put thy clothés on;

It shall ne'er be said in my country,

I have killed a naked man.

"I have two swords in one scabbard,

Full dear they cost my purse;

And thou shalt have the best of them,

And I will have the worse."

The first stroke that little Musgrave stroke,

He hurt Lord Barnard sore;

The next stroke that Lord Barnard stroke,

Little Musgrave ne'er struck more.

With that bespake this fair lady,

In bed whereas she lay;

"Although thou'rt dead, thou little Musgrave,

Yet I for thee will pray;

"And wish well to thy soul will I,

So long as I have life;

So will I not for thee, Barnard,

Although I am thy wedded wife."

He cut her paps from off her breast,

Great pity it was to see,

That some drops of this lady's heart's blood

Ran trickling down her knee.

"Woe worth you, woe worth, my merry men all,

You were ne er born for my good;

Why did you not offer to stay my hand,

When ye saw me wax so wood!

"For I have slain the bravest sir knight

That ever rode on steed;

So have I done the fairest lady

That ever did woman's deed.

"A grave, a grave," Lord Barnard cried,

To put these lovers in;

But lay my lady on the upper hand,

For she came of the better kin,"

There was twa sisters in a bowr,

Edinburgh, Edinburgh,

There was twa sisters in a bow'r,

Stirling for aye,

There was twa sisters in a bowr,

There came a knight to be their wooer,

Bonny Saint Johnston stands upon Tay.

He courted the eldest wi' glove an' ring,

But he loved the youngest above a' thing.

He courted the eldest wi' brooch an' knife,

But loved the youngest as his life;

The eldest she was vexed sair,

An' much envied her sister fair;

Into her bower she could not rest,

Wi' grief an' spite she almost brast.

Upon a morning fair an' clear

She cried upon her sister dear:

O sister come to yon sea-stran',

And see our father's ships come to lan'.

She's ta'en her by the milk-white han',

And led her down to yon sea-stran'.

The youngest stood upon a stane,

The eldest came an' threw her in;

She took her by the middle sma',

An' dash'd her bonny back to the jaw;

O sister, sister, take my han',

An I'se make you heir to a' my lan'.

O sister, sister, take my middle,

And ye's get my gold and my golden girdle.

O sister, sister, save my life,

And I swear I'se never be nae man's wife.

"Foul fa the han' that I should take,

It twin'd me an' my wardle's make."

"Your cherry cheeks and yallow hair,

Gars me gae maiden for evermair."

Sometimes she sank, an' sometimes she swam,

Till she cam down yon bonny mill dam;

O out it came the miller's son,

An' saw the fair maid swimmin' in.

"O father, father, draw your dam!

Here's either a mermaid, or a swan."

The miller quickly drew the dam,

An' there he found a drown'd woman;

You couldna see her yallow hair,

For gold and pearl that were sae rare;

You couldna see her middle sma,

For golden girdle that was sae braw;

Ye couldna see her fingers white

For golden rings that was sae gryte.

And by there came a harper fine,

That harped to the king at dine.

When he did look that lady upon,

He sigh'd and made a heavy moan;

He's taen three locks o' her yallow hair,

And wi' them strung his harp sae fair.

The first tune he did play and sing

Was—"Farewell to my father the king."

The nexten tune that he played syne

Was—"Farewell to my mother the queen."

The lasten tune that he play'd then

Was—"Wae to my sister, fair Ellen!"

The Perse out of Northumberland,

And a vow to God made he,

That he would hunt in the mountains

Of Cheviot within days three,

In the magger of doughtè Douglas,

And all that ever with him be.

The fattest harts in all Cheviot

He said he would kill, and carry them away:

"By my faith," said the doughty Douglas again,

"I will let that hunting if that I may."

Then the Perse out of Banborowe came,

With him a mighty meany;

With fifteen hundrith archers bold of blood and bone,

They were chosen out of shires three.

This began on a Monday at morn,

In Cheviot the hillys so he;

The child may rue that is un-born,

It was the more pity.

Then the wyld thorow the woodès went,

On every sydë shear;

Greyhounds thorow the grevis glent,

For to kill their deer.

Thus began in Cheviot the hills abone,

Early on a Monnyn day;

By that it drew to the hour of noon,

A hundrith fat harts dead there lay.

They blew a mort upon the bent,

They sembled on sydës shear;

The drivers thorow the woodès went,

For to raise the deer;

Bowmen byckarte upon the bent

With their broad arrows clear.

To the quarry then the Perse went,

To see the brittling of the deer.

He said, "It was the Douglas promise

This day to meet me here;

But I wist he would fail, verament:"

A great oath the Perse swear.

At the last a squire of Northumberland

Looked at his hand full nigh;

He was ware o* the doughty Douglas coming,

With him a mighty meany;

Both with spear, bille, and brand;

It was a mighty sight to see;

Hardier men, both of heart nor hand,

Were not in Christiantè.

There were twenty hundrith spear-men good,

Withowtè any fail;

They were born along by the water o' Twyde,

Ith' bounds of Tividale.

"Leave of the brittling of the deer," he said,

"And to your bows look ye take good heed;

For never sith ye were on your mothers born

Had ye never so mickle need."

The doughty Douglas on a steed

He rode all his men beforne;

His armour glittered as did a glede;

A bolder bairn was never born.

"Tell me whose men ye are," he says,

"Or whose men that ye be:

Who gave you leave to hunt in this Cheviot chase,

In the spite of mine and me?"

The first man that ever him an answer made,

It was the good lord Perse:

"We will not tell thee whose men we are," he says,

"Nor whose men that we be;

But we will hunt here in this chase,

In the spite of thine and of thee.

"The fattest harts in all Cheviot

We have killed, and cast to carry them a-way:"

"Be my troth," said the doughty Douglas again,

"Therefore the one of us shall die this day."

Then said the doughty Douglas

Unto the lord Perse:

"To kill all these guiltless men,

Alas, it were great pity!

"But, Perse, thou art a lord of land,

I am an Earl called within my contre -,

Let all our men upon a party stand,

And do the battle of thee and of me."

"Now Cristes corpse on his crown," said the lord Perse,

"Whosoever there-to says nay;

By my troth, doughty Douglas," he says,

"Thou shalt never see that day.

"Neither in England, Scotland, nor France,

Nor for no man of a woman born,

But, and fortune be my chance,

I dare meet him, one man for one."

Then bespake a squire of Northumberland,

Richard Wytharyngton was him name;

"It shall never be told in South-England," he says,

"To king Harry the fourth for shame.

"I wot you bin great lordes twa,

I am a poor squire of land;

I will never see my captain fight on a field,

And stand myself, and lookè on,

But while I may my weapon wield,

I will not [fail] both heart and hand."

That day, that day, that dreadfull day!

The first fit here I find;

And you will hear any more a' the hunting a' the Cheviot,

Yet is there more behind.

The English men had their bows yebent,

Their hearts were good enough;

The first of arrows that they shot off,

Seven score spear-men they slough.

Yet bides the Earl Douglas upon the bent,

A captain good enough,

And that was seenè verament,

For he wrought home both woe and wouche.

The Douglas parted his host in three,

Like a cheffe chieftan of pride,

With sure spears of mighty tree,

They come in on every side:

Through our English archery

Gave many a wound full wide;

Many a doughty they gard to die,

Which gained them no pride.

The English men let their bows be,

And pulled out brands that were bright;

It was a heavy sight to see

Bright swords on basnets light.

Thorow rich mail and maniple,

Many sterne the stroke down straight;

Many a freyke that was full free,

There under foot did light.

At last the Douglas and the Perse met,

Like to captains of might and of main;

They swept together till they both swat,

With swords that were of fine myllàn.

These worthè freykes for to fight,

There-to they were full fain,

Till the blood out of their basnets sprent,

As ever did hail or rain.

"Yield thee, Perse," said the Douglas,

"And i' faith I shall thee bring

Where thou shalt have an earl's wages

Of Jamy our Scottish king.

"Thou shalt have thy ransom free,

I hight thee here this thing,

For the manfullest man yet art thou,

That ever I conquered in field fighting."

"Nay," said the lord Perse,

"I told it thee beforne,

That I would never yielded be

To no man of a woman born."

With that there cam an arrow hastely,

Forth of a mighty wane;

It hath striken the earl Douglas

In at the breast bane.

Thorow liver and lungs, baith

The sharp arrow is gane,

That never after in all his life-days,

He spake mo words but ane:

That was, "Fight ye, my merry men, whiles ye may,

For my life-days ben gane."

The Perse leaned on his brand,

And saw the Douglas dee;

He took the dead man by the hand,

And said, "Woe is me for thee!

"To have saved thy life, I would have parted with

My landes for years three,

For a better man, of heart nor of hand,

Was not in all the north contre."

Of all that see a Scottish knight,

Was called Sir Hew the Monggombyrry;

He saw the Douglas to the death was dight,

He spended a spear, a trusty tree:—

He rode upon a courser

Through a hundrith archery:

He never stinted, nor never blane,

Till he came to the good lord Perse.

He set upon the lord Perse

A dint that was full sore;

With a sure spear of a mighty tree

Clean thorow the body he the Persè bare,

A'the tother side that a man might see

A large cloth yard and mair:

Two better captains were not in Christiantè,

Than that day slain were there.

An archer of Northumberland

Sae slain was the lord Persè;

He bare a bend-bow in his hand,

Was made of trusty tree.

An arrow, that a cloth yard was lang,

To th' hard steel haled he;

A dint that was both sad and sore,

He set on Sir Hewe the Monggomberry.

The dint it was both sad and sore,

That he of Monggomberry set;

The swan-feathers, that his arrow bore,

With his heart-blood they were wet.

There was never a freyke one foot would flee,

But still in stour did stand,

Hewing on each other, while they might dree,

With many a baleful brand.

This battle began in Cheviot

An hour befor the noon,

And when even-song bell was rang,

The battle was not half done.

They took... on eithar hand

By the light of the moon;

Many had no strength for to stand,

In Cheviot the hills aboun.

Of fifteen hundrith archers of England

Went away but seventy and three;

Of twenty hundrith spear-men of Scotland,

But even five and fifty:

But all were slain Cheviot within;

They had no strength to stand on high;

The child may rue that is unborn,

It was the more pity.

There was slain with the lord Perse,

Sir John of Agerstone,

Sir Roger, the hind Hartly,

Sir William, the bold Hearone.

Sir Jorg, the worthè Loumle,

A knight of great renown,

Sir Raff, the rich Rugbè,

With dints were beaten down.

For Wetharryngton my heart was woe,

That ever he slain should be;

For when both his legs were hewn in two,

Yet he kneeled and fought on his knee.

There was slain with the doughty Douglas,

Sir Hew the Monggomberry,

Sir Davy Lydale, that worthy was,

His sisters son was he:

Sir Charls o' Murrè in that place,

That never a foot would flee;

Sir Hew Maxwell, a lord he was,

With the Douglas did he dee.

So on the morrow they made them biers

Of birch and hazel so gray;

Many widows with weepng tears

Came to fetch their makes away.

Tivydale may carp of care,

Northumberland may make great moan,

For two such captains as slain were there,

On the March-party shall never be none.

Word is commen to Eddenburrow,

To Jamy the Scottish king,

That doughty Douglas, lieu-tenant of the Merches

He lay slain Cheviot with-in.

His handes did he weal and wring,

He said, "Alas, and woe is me!"

Such an other captain Scotland within,

He said, i-faith should never be.

Word is commen to lovely London,

Till the fourth Harry our king,

That Lord Persè, lieu-tenant of the Marches

He lay slain Cheviot within.

"God have mercy on his soul," said king Harry,

"Good lord, if thy will it be!

I have a hundrith captains in England," he said,

"As good as ever was he:

But Persè, and I brook my life,

Thy death well quit shall be."

As our noble king made his a-vow,

Like a noble prince of renown,

For the death of the lord Persè

He did the battle of Hombyll-down:

Where six and thirty Scottish knights

On a day were beaten down:

Glendale glittered on their armour bright,

Over castle, tower, and town.

This was the Hunting of the Cheviot;

That tear began this spurn:

Old men that knowen the ground well enough,

Call it the battle of Otterburn.

At Otterburn began this spurn

Upon a Monnyn day:

There was the doughty Douglas slain,

The Perse never went away.

There was never a time on the March-partys

Sen the Douglas and the Perse met,

But it was marvel, and the red blude ran not,

As the rain does in the street.

Jesu Christ our bales bete,

And to the bliss us bring!

Thus was the Hunting of the Cheviot:

God send us all good ending!

This song's of a beggar who long lost his sight,

And had a fair daughter, most pleasant and bright;

And many a gallant brave suitor had she,

And none was so comely as pretty Bessee.

And though she was of complexion most fair,

Yet seeing she was but a beggar his heir,

Of ancient housekeepers despised was she,

Whose sons came as suitors to pretty Bessee.

Wherefore in great sorrow fair Bessee did say,

"Good father and mother, let me now go away,

To seek out my fortune, whatever it be;"

This suit then was granted to pretty Bessee.

This Bessee, that was of a beauty most bright,

They clad in gray russet, and late in the night

From father and mother alone parted she,

Who sighed and sobbed for pretty Bessee.

She went till she came to Stratford-at-Bow,

Then she knew not whither or which way to go;

With tears she lamented her sad destiny,

So sad and so heavy was pretty Bessee.

She kept on her journey until it was day,

And went unto Rumford along the highway;

And at the King's Arms entertained was she,

So fair and well-favoured was pretty Bessee.

She had not been there one month at an end,

But master and mistress and all was her friend;

And every brave gallant that once did her see

Was straightway in love with pretty Bessee.

Great gifts they did send her of silver and gold,

And in their songs daily her love they extoll'd;

Her beauty was blazed in every degree,

So fair and so comely was pretty Bessee.

The young men of Rumford in her had their joy;

She shewed herself courteous, but never too coy,

And at their commandment still she would be,

So fair and so comely was pretty Bessee.

Four suitors at once unto her did go,

They craved her favour, but still she said no;

"I would not have gentlemen marry with me,"—

Yet ever they honoured pretty Bessee.

Now one of them was a gallant young knight,

And he came unto her disguised in the night;

The second, a gentleman of high degree,

Who wooed and sued for prétty Bessee.

A merchant of London, whose wealth was not small,

Was then the third suitor, and proper withal;

Her master's own son the fourth man must be,

Who swore he would die for pretty Bessee.

"If that thou wilt marry with me," quoth the knight,

"Ill make thee a lady with joy and delight;

My heart is enthralled in thy fair beauty,

Then grant me thy favour, my pretty Bessee."

The gentleman said, "Come marry with me,

In silks and in velvets my Bessee shall be;

My heart lies distracted, oh hear me!" quoth he,

"And grant me thy love, my dear pretty Bessee."

"Let me be thy husband," the merchant did say,

"Thou shalt live in London most gallant and gay;

My ships shall bring home rich jewels for thee,

And I will for ever love pretty Bessee."

Then Bessee she sighed, and thus she did say;

"My father and mother I mean to obey;

First get their goodwill, and be faithful to me,

And you shall enjoy your dear pretty Bessee."

To every one of them that answer she made;

Therefore unto her they joyfully said,

"This thing to fulfill we all now agree;

But where dwells thy father, my pretty Bessee?"

"My father," quoth she, "is soon to be seen;

The silly blind beggar of Bednall Green,

That daily sits begging for charity,

He is the kind father of pretty Bessee.

"His marks and his token are knowen full well;

He always is led by a dog and a bell;

A poor silly old man, God knoweth, is he,

Yet he is the true father of pretty Bessee."

"Nay, nay," quoth the merchant, "thou art not for me;"

"She," quoth the innholder, "my wife shall not be;"

"I loathe," said the gentleman, "a beggar's degree,

Therefore, now farewell, my pretty Bessee."

"Why then," quoth the knight, "hap better or worse,

I weigh not true love by the weight of the purse,

And beauty is beauty in every degree;

Then welcome to me, my dear pretty Bessee.

"With thee to thy father forthwith I will go."

"Nay, forbear," quoth his kinsman, "it must not be so:

A poor beggar's daughter a lady sha'nt be;

Then take thy adieu of thy pretty Bessee."

As soon then as it was break of the day,

The knight had from Rumford stole Bessee away;

The young men of Rumford, so sick as may be,

Rode after to fetch again pretty Bessee.

As swift as the wind to ride they were seen,

Until they came near unto Bednall Green,

And as the knight lighted most courteously,

They fought against him for pretty Bessee.

But rescue came presently over the plain,

Or else the knight there for his love had been slain;

The fray being ended, they straightway did see

His kinsman come railing at pretty Bessee.

Then bespoke the Blind Beggar, "Altho' I be poor,

Rail not against my child at my own door;

Though she be not decked in velvet and pearl,

Yet I will drop angels with thee for my girl;

"And then if my gold should better her birth,

And equal the gold you lay on the earth,

Then neither rail you, nor grudge you to see

The Blind Beggar's daughter a lady to be.

"But first, I will hear, and have it well known,

The gold that you drop it shall be all you own;"

"With that," they replied, "contented we be;"

"Then here's," quoth the beggar, "for pretty Bessee."

With that an angel he dropped on the ground,

And dropped, in angels, full three thousand pound;

And oftentimes it proved most plain,

For the gentleman's one, the beggar dropped twain.

So that the whole place wherein they did sit

With gold was covered every whit;

The gentleman having dropt all his store,

Said, "Beggar, your hand hold, for I have no more.

"Thou hast fulfilled thy promise aright;"

"Then marry my girl," quoth he to the knight;

"And then," quoth he, "I will throw you down,

An hundred pound more to buy her a gown."

The gentlemen all, who his treasure had seen,

Admired the Beggar of Bednall Green.

And those that had been her suitors before,

Their tender flesh for anger they tore.

Thus was the fair Bessee matched to a knight,

And made a lady in others' despite:

A fairer lady there never was seen

Than the Blind Beggar's daughter of Bednall Green.

But of her sumptuous marriage and feast,

And what fine lords and ladies there prest,

The second part shall set forth to your sight,

With marvellous pleasure, and wished for delight.-

Of a blind beggar's daughter so bright,

That late was betrothed to a young knight,

All the whole discourse thereof you did see,

But now comes the wedding of pretty Bessee.

It was in a gallant palace most brave,

Adorned with all the cost they could have,

This wedding it was kept most sumptuously,

And all for the love of pretty Bessee.

And all kind of dainties and delicates sweet

Was brought to their banquet, as it was thought meet;

Partridge, and plover, and venison most free,

Against the brave wedding of pretty Bessee.

The wedding thro' England was spread by report,

So that a great number thereto did resort,

Of nobles and gentles of every degree,

And all for the fame of pretty Bessee.

To church then away went this gallant young knight,

His bride followed after, an angel most bright,

With troops of ladies, the like was ne'er seen,

As went with sweet Bessee of Bednall Green.

This wedding being solemnized then,

With music performed by skilfullest men,

The nobles and gentles sat down at that tide,

Each one beholding the beautiful bride.

But after the sumptuous dinner was done,

To talk and to reason a number begun,

And of the Blind Beggar's daughter most bright,

And what with his daughter he gave to the knight.

Then spoke the nobles, "Much marvel have we

This jolly blind beggar we cannot yet see!"

"My lords," quoth the bride, "my father so base

Is loathe with his presence these states to disgrace."

"The praise of a woman in question to bring,

Before her own face, is a flattering thing;

But we think thy father's baseness," quoth they,

"Might by thy beauty be clean put away."

They no sooner this pleasant word spoke,

But in comes the beggar in a silken cloak,

A velvet cap and a feather had he,

And now a musician, forsooth, he would be.

And being led in, from catching of harm,

He had a dainty lute under his arm;

Said, "Please you to hear any music of me,

A song I will give you of pretty Bessee."

With that his lute he twanged straightway,

And thereon began most sweetly to play,

And after a lesson was played two or three,

He strained out this song most delicately:—

"A beggars daughter did dwell on a green,

Who for her beauty might well be a queen,

A blithe bonny lass, and dainty was she,

And many one called her pretty Bessee.

"Her father he had no goods nor no lands,

But begged for a penny all day with his hands,

And yet for her marriage gave thousands three,

Yet still he hath somewhat for pretty Bessee.

"And here if any one do her disdain,

Her father is ready with might and with main,

To prove she is come of noble degree,

Therefore let none flout at my pretty Bessee."

With that the lords and the company round

With a hearty laughter were ready to swound;

At last said the lords, "Full well we may see,

The bride and the bridegrooms beholden to thee."

With that the fair bride all blushing did rise,

With crystal water all in her bright eyes;

"Pardon my father, brave nobles," quoth she,

"That through blind affection thus doats upon me.

"If this be thy father," the nobles did say,

"Well may he be proud of this happy day,

Yet by his countenance well may we see,

His birth with his fortune could never agree.

"Arid therefore, blind beggar, we pray thee bewray,

And look that the truth to us thou dost say,

Thy birth and thy parentage what it may be,

E'en for the love thou bearest to pretty Bessee."

"Then give me leave, ye gentles each one,

A song more to sing and then I'll begone;

And if that I do not win good report,

Then do not give me one groat for my sport:—

"When first our king his fame did advance,

And sought his title in delicate France,

In many places great perils past he,

But then was not born my pretty Bessee.

"And at those wars went over to fight,

Many a brave duke, a lord, and a knight,

And with them young Monford of courage so free,

But then was not born my pretty Bessee.

"And there did young Monford with a blow on the face

Lose both his eyes in a very short space;

His life had been gone away with his sight,

Had not a young woman gone forth in the night.

"Among the slain men, her fancy did move

To search and to seek for her own true love,

Who seeing young Monford there gasping to die,

She saved his life through her charity.

"And then all our victuals in beggars' attire,

At the hands of good people we then did require;

At last into England, as now it is seen,

We came, and remained in Bednall Green.

"And thus we have lived in Fortune's despite,

Though poor, yet contented, with humble delight,

And in my old years, acomfort to me,

God sent me a daughter called pretty Bessee.

"And thus, ye nobles, my song I do end,

Hoping by the same no man to offend;

Full forty long winters thus I have been,

A silly blind beggar of Bednall Green."

Now when the company every one

Did hear the strange tale he told in his song,

They were amazed, as well as they might be,

Both at the blind beggar and pretty Bessee,

With that the fair bride they all bid embrace,

Saying, "You are come of an honourable race;

Thy father likewise is of high degree,

And thou art right worthy a lady to be."

Thus was the feast ended with joy and delight;

A happy bridegroom was made the young knight,

Who lived in great joy and felicity,

With his fair lady, dear pretty Bessee.

As it befell in midsummer time,

When birds sing sweetly on every tree,

Our noble King, King Henry the eighth,

Over the river of Thames past he.

He was no sooner over the river,

Down in a forest to take the air,

But eighty merchants of London city

Came kneeling before King Henry there.

"O ye are welcome, rich merchants,

[Good sailors, welcome unto me! ]"

They swore by the rood, they were sailors good,

But rich merchants they could not be.

"To France nor Flanders dare we not pass,

Nor Bordeaux voyage we dare not fare;

And all for a false robber that lies on the seas,

Who robs us of our merchant's ware."

King Henry was stout, and he turned him about,

And swore by the Lord that was mickle of might,

"I thought he had not been in the world throughout,

That durst have wrought England such unright."

But ever they sighed, and said, "Alas!"

Unto King Harry this answer again;

"He is a proud Scot, that will rob us all,

If we were twenty ships, and he but one."

The king lookt over his left shoulder,

Amongst his lords and barons so free;

"Have I never lord in all my realm,

Will fetch yond traitor unto me?"

"Yes, that dare I," says my Lord Charles Howard;

Near to the king whereas he did stand;

"If that your grace will give me leave,

Myself will be the only man."

"Thou shalt have six hundred men," saith our king;

"And choose them out of my realm so free;

Besides mariners, and boys,

To guide the great ship on the sea."

"I'll go speak with Sir Andrew," ssyn Charles, my lord Howard;

"Upon the sea,' if he be there,

I will bring him and his ship to shore.

Or before my prince I will never come near."

The first of all my lord did call,

A noble gunner he was one,

This man was threescore years and ten;

And Peter Simon was his name.

"Peter," says he, "I must sail to the sea,

To seek out an enemy; God be my speed!

Before all others I have chosen thee,

Of a hundred gunners thou'st be my head."

"My lord," says he, "if you have chosen me

Of a hundred gunners to be the head,

Hang me at your main-mast tree,

If I miss my mark past three pence bread."

The next of all my lord he did call,

A noble bowman he was one;

In Yorkshire was this gentleman borne,

And William Horsley was his name.

"Horsley," says he, "I must sail to the sea,

To seek out an enemy; God be my speed!

Before all others I have chosen thee;

Of a hundred bowmen thou'st be my head."

"My lord," says he, "if you have chosen me

Of a hundred bowmen to be the head,

Hang me at your main-mast tree,

If I miss my mark past twelve pence bread."

With pikes, and guns, and bowmen bold,

This noble Howard is gone to the sea;

On the day before mid-summer even,

And out at Thames mouth sailed they.

They had not sailed days three,

Upon their journey they took in hand,

But there they met with a noble ship,

And stoutly made it both stay and stand.

"Thou must tell me thy name," says Charles, my lord Howard,

"Or who thou art, or from whence thou came,

Yea, and where thy dwelling is,

To whom and where thy ship does belong."

"My name," says he, "is Henry Hunt,

With a pure heart, and a penitent mind;

I and my ship they do belong

Unto the Newcastle that stands upon Tyne."

"Now thou must tell me, Harry Hunt,

As thou hast sailed by day and by night,

Hast thou not heard of a stout robber;

Men calls him Sir Andrew Barton, knight?"

But ever he sighed, and said, "Alas!

Full well, my lord, I know that wight;

He robbed me of my merchant's ware,

And I was his prisoner but yesternight.

"As I was sailing upon the sea,

And [a] Bordeaux voyage as I did fare,

He clasped me to his hatch-board,

And robbed me of all my merchant ware.

And I am a man, both poor and bare,

And every man will have his own of me,

And I am bound towards London to fare,

To complain to my prince Henry."

"That shall not need," says my Lord Howard;

"If thou canst let me this robber see,

For every penny he has taken thee froe

Thou shalt be rewarded a shilling," quoth he.

"Now God forefend," says Henry Hunt,

"My lord, you should work so far amiss!

God keep you out of that traitor's hands!

For you wot full little what a man he is.

"He is brass within, and steel without,

And beams he bears in his topcastle strong;

His ship hath ordinance clean round about,

Besides, my lord, he is very well manned.

He hath a pinnace, is dearly dight,

St. Andrew's cross, that is his guide;

His pinnace bears ninescore men and more,

Besides fifteen canons on every side.

"If you were twenty ships, and he but one,

Either in hatchboard or in hall,

He would overcome you every one,

And if his beams they do down fall."

"This is cold comfort," says my lord Howard,

"To welcome a stranger thus to the sea:

I'll bring him and his ship to shore,

Or else into Scotland he shall carry me."

"Then you must get a noble gunner, my lord,

That can set well with his eye,

And sink his pinnace into the sea,

And soon then overcome will he be.

And when that you have done this,

If you chance Sir Andrew for to board,

Let no man to his topcastle go

And I will give you a glass, my lord.

"And then you need to fear no Scot,

Whether you sail by day or by night;

And to-morrow by seven of the clock,

You shall meet with Sir Andrew Barton, knight.

I was his prisoner but yesternight,

And he hath taken me sworn," quoth he;

"I trust my L[ord] God will me forgive

And if that oath then broken be."

"You must lend me six pieces, my lord," quoth he,

"Into my ship, to sail the sea,

And to-morrow by nine of the clock

Your Honour again then will I see."

And the hatch-board where Sir Andrew lay

Is hatched with gold dearly dight:

"Now by my faith," says Charles, my lord Howard,

"Then yonder Scot is a worthy wight.

Take in your ancients, and your standards,

Yea that no man shall them see;

And put me forth a white willow wand,

As merchants use to sail the sea."

But they stirred neither top nor mast *;

But Sir Andrew they passed by;

"What English are yonder," said Sir Andrew,

"That can so little courtesy?

"I have been admiral over the sea

More than these years three,

There is never an English dog nor Portingall

Can pass this way without leave of me.

But now yonder pedlars they are past:

Which is no little grief to me:

Fetch them back," says Sir Andrew Barton,

"They all shall hang at my main-mast tree."

With that the pinnace it shot off;

That my Lord Howard might it well ken;

It stroke down my lord's fore-mast,

And killed fourteen of my lord his men.

"Come hither, Simon," says my lord Howard,

"Look that thy words be true thou said;

I'll hang thee at my main-mast tree,

If thou miss thy mark past twelve pence bread."

* i.e. did not salute.

Simon was old, but his heart it was bold;

He took down a piece and laid it full low,

He put in chain yards nine,

Besides other great shot less and more,

With that he let his gun-shot go;

So well he settled it with his eye,

The first sight that Sir Andrew saw,

He see his pinnace sunk in the sea.

When he saw his pinnace sunk,

Lord, in his heart he was not well!

"Cut my ropes! it is time to be gone!

Ill fetch yond pedlars back mysel'."

When my lord Howard saw Sir Andrew loose,

Lord! in his heart that he was fain;

"Strike on your drums, spread out your

ancients,

Sound out your trumpets, sound out amain."

"Fight on, my men," says Sir Andrew Barton,

"Weet, howsoever this gear will sway;

It is my lord admiral of England,

Is come to seek me on the sea."

Simon had a son, with shot of a gun—

Well Sir Andrew might it ken;—

He shot it in at a privy place,

And killed sixty more of Sir Andrew's men.

Harry Hunt came in at the other side;

And at Sir Andrew he shot then;

He drove down his fore-mast tree,

And killed eighty more of Sir Andrew's men.

"I have done a good turn," says Harry Hunt;

"Sir Andrew is not our king's friend;

He hoped to have undone me yesternight,

But I hope I have quit him well in the end."

"Ever alas!" said Sir Andrew Barton,

"What should a man either think or say?

Yonder false thief is my strongest enemy,

Who was my prisoner but yesterday.

Come hither to me, thou Gordon good,

And be thou ready at my call,

And I will give thee three hundred pound,

If thou wilt let my beams down fall."

With that he swarved the main-mast tree,

So did he it with might and main;

Horsley, with a bearing arrow,

Stroke the Gordon through the brain;

And he fell into the hatches again,

And sore of this wound that he did bleede:

Then word went through Sir Andrew's men,

That the Gordon he was dead.

"Come hither to me, James Hamilton,

Thou art my sister's son, I have no more;

I will give [thee] six hundred pound

If thou wilt let my beams down fall.

With that he swarved the main-mast tree,

So did he it with might and main;

Horsley, with another broad arrow,

Strake the yeoman through the brain.

That he fell down to the hatches again,

Sore of his wound that he did bleed:

Covetousness gets no gain,

It is very true, as the Welshman said.

But when he saw his sister's son slain,

Lord! in his heart he was not well:

"Go fetch me down my armour of proof,

For I will to the topcastle mysel'.

"Go fetch me down my armour of proof,

For it is gilded with gold so clear;

God be with my brother, John of Barton!

Amongst the Portingalls he did it wear.

But when he had his armour of proof,

And on his body he had it on,

Every man that looked at him,

Said, gun nor arrow he need fear none."

"Come hither, Horsley," says my lord Howard,

"And look your shaft that it go right;

Shoot a good shoot in the time of need,

And for thy shooting thou'st be made a knight."

"I'll do my best," says Horsley then,

"Your honour shall see, before I go;

If I should be hanged at your main-mast,

I have in my ship but arrows two."

But at Sir Andrew he shot then,

He made sure to hit his mark;

Under the spole of his right arm

He smote Sir Andrew quite through the heart.

Yet from the tree he would not start,

But he dinged to it with might and main,

Under the collar then of his jack

He stroke Sir Andrew thorough the brain.

"Fight on, my men," says Si^ Andrew Barton,

"I am hurt, but I am not slain;

I'll lay me down and bleed awhile,

And then I'll rise and fight again.

Fight on, my men," says Sir Andrew Barton,

These English dogs they bite so low;

Fight on for Scotland and St. Andrew,

Till you hear my whistle blow."

But when they could not hear his whistle blow,

Says Harry Hunt, "I'll lay my head

You may board yonder noble ship, my lord,

For I know Sir Andrew he is dead."

With that they boarded this noble ship,

So did they it with might and main;

They found eighteen score Scots alive,

Besides the rest were maimed and slain.

My Lord Howard took a sword in his hand,

And smote off Sir Andrew's head;

The Scots stood by did weep and mourn,

But never a word durst speak or say.

He caused his body to be taken down

And over the hatchboard cast into the sea,

And about his middle three hundred crowns:

"Wheresoever thou lands, it will bury thee."

With his head they sailed into England again,

With right good will, and force and main;

And the day before new year's even

Into Thames mouth they came again.

My Lord Howard wrote to King Henry's grace,

With all the news he could him bring;

"Such a new years gift I have brought to your grace

As never did subject to any king.

"For merchandise and manhood,

The like is not to be found;

The sight of these would do you good,

For you have not the like in your English ground."

But when he heard tell that they were come

Full royally he welcomed them home:

Sir Andrew's ship was the King's new year'sgift;

A braver ship you never saw none.

Now hath our king Saint Andrew's ship,

Beset with pearls and precious stones;

Now hath England two ships of war,

Two ships of war, before but one.

"Who holp to this?" says King Henry,

"That I may reward him for his pain."

"Harry Hunt, and Peter Simon,

William Horsley, and I the same.

"Harry Hunt shall have his whistle and chain,

And all his jewels, whatsoever they be,

And other rich gifts that I will not name,

For his good service he hath done me.

Horsley, right thou'st be a knight,

Lands and livings thou shalt have store;

Howard shall be Earl of Nottingham,

And so was never Howard before.

"Now, Peter Simon, thou art old,

I will maintain thee and thy son;

Thou shalt have five hundred pound all in gold,

For the good service that thou hast done,"

Then King Henry shifted his room;

In came the queen and ladies bright,

Other errands had they none

But to see Sir Andrew Barton, knight.

But when they see his deadly face,

And his eyes were hollow in his head,

"I would give a hundred pound,"says King Henry,

"The man were alive as he is dead.

Yet for the manful part that he hath played,

Both here and beyond the sea,

His men shall have half-a-crown a day

To bring them to my brother, King Jamie."

Lord Thomas and fair Annet

Sate a' day on a hill;

Whan night was come, and sun was set,

They had not talked their fill.

Lord Thomas said a word in jest,

Fair Annet took it ill:

"A' I will never wed a wife

Against my ain friends will."

"Gif ye will never wed a wife,

A wife will ne'er wed ye:"

Sae he is hame to tell his mither.

And knelt upon his knee.

"O rede, O rede, mither," he says,

"A gude rede gie to me:

O sail I tak the nut-brown bride,

And let fair Annet be?"

"The nut-brown bride haes gowd and gear,

Fair Annet she has gat nane;

And the little beauty fair Annet haes,

O it wull soon be gane."

And he has till his brother gane:

"Now, brother, rede ye me;

A', sail I marry the nut-brown bride,

And let fair Annet be?"

"The nut-brown bride has oxen, brother,

The nut-brown bride has kye:

I wad hae ye marry the nut-brown bride,

And cast fair Annet by."

"Her oxen may die i' the house, billie,

And her kye into the byre,

And I sail hae nothing to mysel',

But a fat fadge by the fire."

And he has till his sister gane:

"Now sister, redè ye me;

O sail I marry the nut-brown bride,

And set fair Annet free?"

"I'se rede ye tak fair Annet, Thomas,

And let the brown bride alane;

Lest ye should sigh, and say, Alas,

What is this we brought hame!"

"No, I will tak my mither's counsel,

And marry me out o' hand;

And I will tak the nut-brown bride;

Fair Annet may leave the land."

Up then rose fair Annet's father,

Twa hours or it were day,

And he is gane into the bower

Wherein fair Annet lay.

"Rise up, rise up, fair Annet," he says,

"Put on your silken sheen;

Let us gae to St. Mary's kirk,

And see that rich weddeen."

"My maids, gae to my dressing-room,

And dress to me my hair;

Where-e er ye laid a plait before,

See ye lay ten times mair.

"My maids, gae to my dressing-room,

And dress to me my smock;

The one half is o' the holland fine,

The other o' needle-work."

The horse fair Annet rade upon,

He amblit like the wind;

Wi' siller he was shod before,

Wi' burning gowd behind.

Four and twanty siller bells

Were a' tied till his mane,

And yae tift o' the norland wind,

They tinkled ane by ane.

Four and twanty gay gude knights

Rade by fair Annet's side,

And four and twenty fair ladies,

As gin she had bin a bride.

And whan she cam to Mary's kirk,

She sat on Mary's stean:

The cleading that fair Annet had on

It skinkled in their een.

And whan she cam into the kirk,

She shimmer'd like the sun;

The belt that was about her waist,

Was a' wi' pearls bedone.

She sat her by the nut-brown bride,

And her een they were sae clear,

Lord Thomas he clean forgat the bride,

When fair Annet drew near.

He had a rose into his hand,

He gae it kisses three,

And reaching by the nut-brown bride,

Laid it on fair Annet's knee.

Up than spak the nut-brown bride,

She spak wi' mickle spite;

"And where gat ye that rose-water,

That does mak ye sae white?"

"O I did get the rose-water

Where ye wull ne'er get nane,

For I did get that very rose-water

Into my mithers wame."

The bride she drew a long bodkin

Frae out her gay head-gear,

And strake fair Annet unto the heart,

That word spak never mair.

Lord Thomas he saw fair Annet wax pale,

And marvelit what mote be:

But whan he saw her dear heart's blude,

A' wood-wroth wexed he.

He drew his dagger, that was sae sharp,

That was sae sharp and meet,

And drave it into the nut-brown bride,

That fell dead at his feet.

"Now stay for me, dear Annet," he said,

"Now stay, my dear," he cried;

Then strake the dagger until his heart,

And fell dead by her side.

Lord Thomas was buried without kirk-wa',

Fair Annet within the choir;

And o' the tane there grew a birk,

The other a bonny briar.

And ay they grew, and ay they threw,

As they wad fain be near;

And by this ye may ken right well,

They were twa lovers dear.

Leoffricus the noble earl,

Of Chester, as I read,

Did for the city of Coventry

Many a noble deed;

Great privileges for the town

This nobleman did get,

Of all things did make it so,

That they toll free did sit,

Save only that for horses still

They did some custom pay,

Which was great charges to the town

Full long and many a day.

Wherefore his wife, Godiva fair,

Did of the earl request,

That therefore he would make it free

As well as all the rest.

And when the lady long had sued,

Her purpose to obtain,

At last her noble Lord she took

Within a pleasant vein,

And unto him with smiling cheer

She did forthwith proceed,

Intreating greatly that he would

Perform that godly deed.

"You move me much, fair dame," quoth he;

"Your suit I fain would shun;

But what would you perform and do,

To have the matter done?"

"Why, anything, my lord," quoth she,

"You will with reason crave,

I will perform it with goodwill

If I my wish may have."

"If thou wilt grant one thing," he said,

"Which I shall now require,

So soon as it is finished,

Thou shalt have thy desire."

"Command what you think good, my lord;

I will thereto agree

On that condition, that this town

In all things may be free."

"If thou wilt strip thy clothes off,

And here wilt lay them down,

And at noonday on horseback ride,

Stark naked through the town,

They shall be free for evermore.

If thou wilt not do so,

More liberty than now they have

I never will bestow."

The lady at this strange demand

Was much abashed in mind;

And yet for to fulfil this thing

She ne'er a whit repined.

Wherefore to all the officers

Of all the town she sent,

That they perceiving her good will

Which for their weal was bent,

That on the day that she should ride,

All persons through the town

Should keep their houses and shut their door,

And clap their windows down,

So that no creature, young nor old,

Should in the street be seen

Till she had ridden (all about

Through all the city clean.

And when the day of riding came,

No person did her see,

Saving her Lord, after which time

The town was ever free.

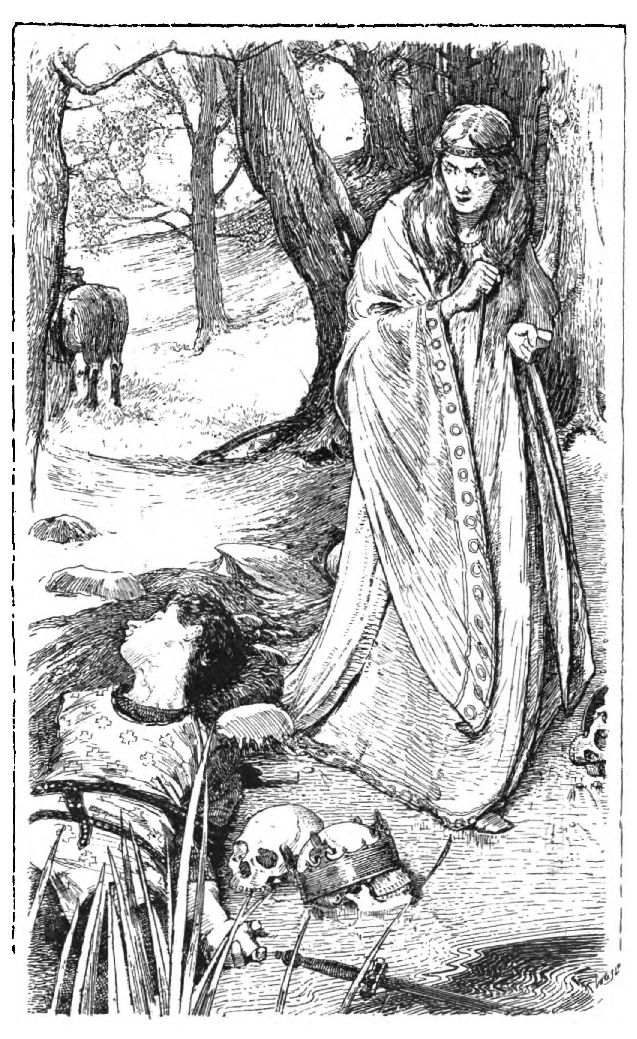

William and Marjorie

Lady Marjorie, Lady Marjorie,

Sat sewing her silken seam,

And by her came a pale, pale ghost,

Wi' mony a sigh and mane.

"Are ye my father, the king?" she says,

"Or are ye my brither John?

Or are ye my true love, sweet William,

From England newly come?"

"I'm not your father, the king," he says,

"No, no, nor your brither John;

But I'm your true love, sweet William,

From England that's newly come."

"Have ye brought me any scarlets sae red,

Or any silks sae fine;

Or have ye brought me any precious things,

That merchants have for sale?"

"I have not brought you any scarlets sae red,

No, no, nor the silks sae fine;

But I have brought you my winding-sheet

O'er many's the rock and hill.

"O Lady Marjorie, Lady Marjorie,

For faith and charitie,

Will ye give to me my faith and troth,

That I gave once to thee?"

"O your faith and troth I'll not give thee,

No, no, that will not I,

Until I get ae kiss of your ruby lips,

And in my arms you come lie."

"My lips they are sae bitter," he says,

"My breath it is sae strang,

If you get ae kiss of my ruby lips,

Your days will not be lang.

"The cocks they are crawing, Marjorie," he says,—

"The cocks they are crawing again;

It's time the dead should part the quick,—

Marjorie, I must be gane."

She followed him high, she followed him low,

Till she came to yon churchyard green;

O there the grave did open up,

And young William he lay down.

"What three things are these, sweet William," she says,

"That stands here at your head?"

"It's three maidens, Marjorie," he says,

"That I promised once to wed."

"What three things are these, sweet William,"she says,

"That stands here at your side?"

"It is three babes, Marjorie," he says,

"That these three maidens had."

"What three things are these, sweet William," she says,

"That stands here at your feet?"

"It is three hell-hounds, Marjorie," he says,

"That's waiting my soul to keep."

She took up her white, white hand,

And she struck him in the breast,

Saying,—"Have there again your faith and troth

And I wish your soul gude rest."

The Gipsy Laddie

The gipsies came to our good lord's gate,

And wow but they sang sweetly;

They sang sae sweet and sae very complete,

That down came the fair lady.

And she came tripping doun the stair,

And a' her maids before her;

As soon as they saw her weel-far'd face,

They coost the glamour o'er her.

"Gae tak frae me this gay mantle,

And bring to me a plaidie;

For if kith and kin and a' had sworn,

I'll follow the gipsy laddie.

"Yestreen I lay in a weel-made bed,

And my good lord beside me;

This night I'll lie in a tennant's barn,

Whatever shall betide me."

"Come to your bed," says Johnie Faa,

"O come to your bed, my deary;

For I vow and I swear by the hilt of my sword,

That your lord shall nae mair come near ye."

"I'll go to bed to my Johnie Faa,

I'll go to bed to my deary;

For I vow and I swear, by what passed yestreen,

That my lord shall nae mair come near me.

"I'll mak a hap to my Johnie Faa,

And I'll mak a hap to my deary;

And he's get a' the coat gaes round,

And my lord shall nae mair come near me."

And when our lord came hame at e'en,

And speir'd for his fair lady,

The tane she cried, and the other replied,

"She's away wi' the gipsy laddie."

"Gae saddle to me the black black steed,

Gae saddle and make him ready;

Before that I either eat or sleep,

I'll gae seek my fair lady."

And we were fifteen weel-made men,

Altho' we were nae bonny;

And we were a' put down for ane,

A fair young wanton lady.

Waly, Waly, but Love be Bonny

O waly, waly up the bank,

And waly, waly down the brae,

And waly, waly yon burn side,

Where I and my love wont to gae.

I lean'd my back unto an aik,

I thought it was a trusty tree;

But first it bow'd, and syne it brak,

Sae my true love did lightly me!

O waly, waly, but love be bonny,

A little time, while it is new -,

But when 'tis auld, it waxeth cauld,

And fades away like morning dew.

O wherefore should I busk my head?

Or wherefore should I kame my hair?

For my true love has me forsook,

And says he'll never love me mair.

Now Arthur-Seat shall be my bed,

The sheets shall ne'er be filed by me:

Saint Anton's well shall be my drink,

Since my true love has forsaken me.

Martinmas wind, when wilt thou blaw,

And shake the green leaves off the tree?

O gentle death, when wilt thou come?

For of my life I am weary.

'Tis not the frost that freezes fell,

Nor blawing snaw's inclemency;

'Tis not sic cauld that makes me cry,

But my love's heart grown cauld to me.

When we came in by Glasgow town,

We were a comely sight to see;

My love was clad in the black velvet,

And I mysel' in cramasie.

But had I wist, before I kiss'd,

That love had been sae ill to win,

I'd lock'd my heart in a case of gold,

And pinn'd it with a silver pin.

Oh, oh, if my young babe were born,

And set upon the nurse's knee,

And I mysel' were dead and gane!

For a maid again I'll never be.

The Bonny Earl of Murray

Ye Highlands, and ye Lawlands,

O where have you been?

They have slain the Earl of Murray,

And they laid him on the green.

"Now wae be to thee, Huntly!

And wherefore did you sae?

I bade you bring him wi' you,

But forbade you him to slay."

He was a braw gallant,

And he rid at the ring;

And the bonny Earl of Murray,

O he might hae been a king.

He was a braw gallant,

And he play'd at the ba;

And the bonny Earl of Murray

Was the flower amang them a.

He was a braw gallant,

And he play'd at the glove;

And the bonny Earl of Murray,

O he was the Queen's love.

O lang will his lady

Look o'er the castle Down,

Ere she see the Earl of Murray

Come sounding thro' the town.

Glasgerion was a king's own son,

And a harper he was good;

He harped in the king's chamber,

Where cup and candle stood,

And so did he in the queens chamber,

Till ladies waxed wood,

And then bespake the king's daughter,

And these words thus said she.=

Said "strike on, strike on, Glasgerion,

Of thy striking do not blin;

There's never a stroke comes over thine harp,

But it glads my heart within."

"Fair might you fall, lady," quoth he,

"Who taught you now to speak?

I have loved you, lady, seven year;

My heart I durst ne'er break."

"But come to my bower, my Glasgerion,

When all men are at rest;

As I am a lady true of my promise,

Thou shalt be a welcome guest."

But home then came Glasgerion,

A glad man, Lord, was he:

And, "come thou hither, Jack, my boy,

Come hither unto me.

"For the king's daughter of Normandy

Her love is granted me;

And before the cock have crowen

At her chamber must I be."

"But come you hither, master," quoth he,

"Lay your head down on this stone;

For I will waken you, master dear,

Afore it be time to gone."

But up then rose that lither lad,

And did on hose and shoon;

A collar he cast upon his neck,

He seemed a gentleman.

And when he came to that lady's chamber,

He tirled upon a pin:

The lady was true of her promise,

Rose up and let him in.

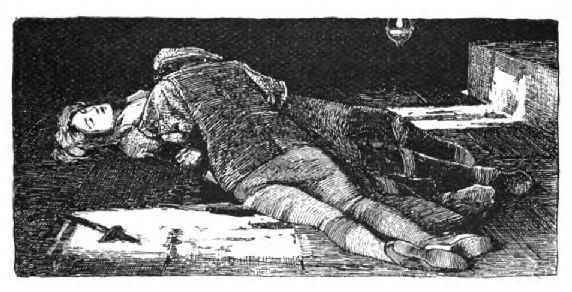

He did not take the lady gay,

To bolster nor to bed:

But down upon her chamber floor,

Full soon he hath her laid.

He did not kiss that lady gay

When he came nor when he youd:

And sore mistrusted that lady gay,

He was of some churlès blood.

But home then came that lither lad,

And did off his hose and shoon;

And cast that collar from about his neck:

He was but a churlès son.

"Awaken," quoth he, "my master dear,

I hold it time to be gone.

"For I have saddled your horse, master,

Well bridled I have your steed,

Have I not served a good breakfast,

When time comes I have need."

But up then rose good Glasgerion,

And did on hose and shoon,

And cast a collar about his neck:

He was a kingés son.

And when he came to that ladys chamber,

He tirled upon a pin -,

The lady was more than true of promise,

Rose up and let him in.

Says "whether have you left with me

Your bracelet or your glove?

Or are you returned back again

To know more of my love?"

Glasgerion swore a full great oath,

By oak, and ash, and thorn;

"Lady, I was never in your chamber,

Sith the time that I was born."

"O then it was your little foot-page,

Falsely hath beguiled me:"

And then she pulled forth a little pen-knife,

That hanged by her knee.

Says, "there shall never no churlès blood

Spring within my body."

But home then went Glasgerion,

A woe man, good [lord] was he.

Says, "come hither thou, Jack my boy,

Come thou hither to me.

"For if I had killed a man to-night,

Jack, I would tell it thee:

But if I have not killed a man to-night,

Jack, thou hast killed three."

And he pulled out his bright brown sword,

And dried it on his sleeve,

And he smote off that lither lads head,

And asked no man no leave.

He set the sword's point til his breast,

The pummel till a stone:

Through that falseness of that lither lad,

These three lives were all gone.

As it fell out on a long summer's day,

Two lovers they sat on a hill;

They sat together that long summer's day,

And could not talk their fill.

"I see no harm by you, Margaret,

Nor you see none by me;

Before to-morrow at eight o'clock

A rich wedding you shall see."

Fair Margaret sat in her bower-window,

Combing her yellow hair;

There she spied sweet William and his bride,

As they were a tiding near.

Then down she laid her ivory comb,

And braided her hair in twain:

She went alive out of her bower,

But ne'er came alive in't again.

When day was gone, and night was come,

And all men fast asleep,

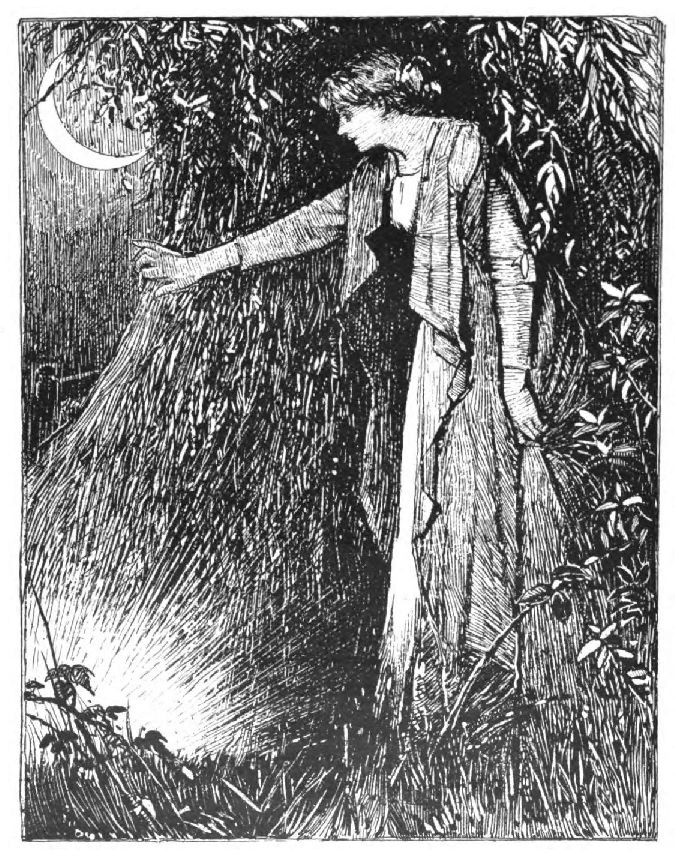

Then came the spirit of fair Margaret,

And stood at William's feet.

"Are you awake, sweet William?" she said,

"Or, sweet William, are you asleep?

God give you joy of your gay bride-bed,

And me of my winding-sheet."

When day was come, and night was gone,

And all men wak'd from sleep,

Sweet William to his lady said,

"My dear, I have cause to weep.

"I dreamt a dream, my dear lady,

Such dreams are never good:

I dreamt my bower was full of red swine,

And my bride-bed full of blood."

"Such dreams, such dreams, my honoured lord,

They never do prove good -,

To dream thy bower was full of swine,

And thy bride-bed full of blood."

He called up his merry men all,

By one, by two, and by three;

Saying, "I'll away to fair Margaret's bower,

By the leave of my lady."

And when he came to fair Margaret's bower,

He knocked at the ring;

And who so ready as her seven brethren,

To let sweet William in.

Then he turned up the covering-sheet;

"Pray let me see the dead;

Methinks she does look pale and wan,

She has lost her cherry red.

"I'll do more for thee, Margaret,

Than any of thy kin:

For I will kiss thy pale wan lips,

Though a smile I cannot win."

With that bespake the seven brethren,

Making most piteous mone,

"You may go kiss your jolly brown bride,

And let our sister alone."

"If I do kiss my jolly brown bride,

I do but what is right;

I ne'er made a vow to yonder poor corpse,

By day, or yet by night.

"Deal on, deal on, my merry men all,

Deal on your cake and your wine:

For whatever is dealt at her funeral to-day,

Shall be dealt to-morrow at mine."

Fair Margaret died to-day, to-day,

Sweet William died the morrow:

Fair Margaret died for pure true love,

Sweet William he died for sorrow.

Margaret was buried in the lower chancel,

And William in the higher:

Out of her breast there sprang a rose,

And out of his a briar.

They grew till they grew unto the church top,

And then they could grow no higher;

And then they tied in a true lover's knot,

Which made all the people admire.

Then came the clerk of the parish,

As you this truth shall hear,

And by misfortune cut them down,

Or they had now been there.

Why does your brand sae drap wi' blood

Edward, Edward?

Why does your brand sae drap wi' blood

And why sae sad gang ye oh?

"Oh I hae killed my hawk sae good,

Mither, mither:

Oh I hae killed my hawk so good,

And I had no mair but he oh."

Your hawk's blood was never sae red,

Edward, Edward;

Your hawk's blood was never sae red,

My dear son I tell thee oh.

"Oh I hae killed my red-roan steed,

Mither, mither:

Oh I hae killed my red roan steed

That erst was sae fair and free oh."

Your steed was auld, and ye hae got mair,

Edward, Edward;

Your steed was auld, and ye hae got mair,

Some other dule ye dree oh.

"Oh I hae killed my father dear,

Mither, mither:

Oh I hae killed my father dear,

Alas! and wae is me oh!"

And whatten penance will ye dree for that,

Edward, Edward?

And whatten penance will ye dree for that?

My dear son, now tell me oh.

"I'll set my feet in yonder boat,

Mither, mither:

I'll set my feet in yonder boat,

And I'll fare over the sea oh."

And what will ye do wi' your towers and your ha',

Edward, Edward?

And what will ye do wi' your towers and your ha',

That were sae fair to see oh?

"I'll let them stand till they down fa',

Mither, mither:

I'll let them stand till they down fa',

For here never mair maun I be oh."

And what will ye leave to your bairns and your wife,

Edward, Edward?

And what will ye leave to your bairns and your wife,

When ye gang over the sea oh?

"The world's room, let them beg through life,

Mither, mither:

The world's room, let them beg through life,

For them never mair will I see oh."

And what will ye leave to your ain mither dear,

Edward, Edward?