Transcriber's Note.

A list of the changes made can be found at the end of the book.

In the text, the corrections are underlined by a

red dotted line "like this".

Hover the cursor over the underlined text and an explanation of the error should appear.

THE JESUIT RELATIONS

AND

ALLIED DOCUMENTS

Vol. II

The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents

Travels and Explorations

of the Jesuit Missionaries

in New France

1610-1791

THE ORIGINAL FRENCH, LATIN, AND ITALIAN

TEXTS, WITH ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS

AND NOTES; ILLUSTRATED BY

PORTRAITS, MAPS, AND FACSIMILES

EDITED BY

REUBEN GOLD THWAITES

Secretary of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

Vol. II

Acadia: 1612-1614

CLEVELAND: The Burrows Brothers

Company, PUBLISHERS, M DCCCXCVI

Copyright, 1896

by

The Burrows Brothers Co

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Imperial Press, Cleveland

EDITORIAL STAFF

| Editor |

Reuben Gold Thwaites |

| Translator from the French |

John Cutler Covert |

| Assistant Translator from the French |

Mary Sifton Pepper |

| Translators from the Latin |

{ William Frederic Giese |

| |

{ John Dorsey Wolcott |

| Translator from the Italian |

Mary Sifton Pepper |

| Assistant Editor |

Emma Helen Blair |

CONTENTS OF VOL. II

| Preface To Volume II |

1 |

| Documents:— |

| IX. |

Lettre au R. P. Provincial, à Paris. Pierre

Biard; Port Royal, January 31, 1612 |

3 |

| X. |

Missio Canadensis. Epistola ex Porturegali

in Acadia, transmissa ad Praepositvm

Generalem Societatis Jesu.

Pierre Biard; Port Royal, January 31,

1612 |

57 |

| XI. |

Relation Dernière de ce qui s'est Passé au

Voyage du Sieur de Potrincourt. Marc

Lescarbot; Paris, 1612 |

119 |

| XII. |

Relatio Rervm Gestarum in Novo-Francica

Missione, Annis 1613 & 1614 |

193 |

| Bibliographical Data: Volume II |

287 |

| Notes |

291 |

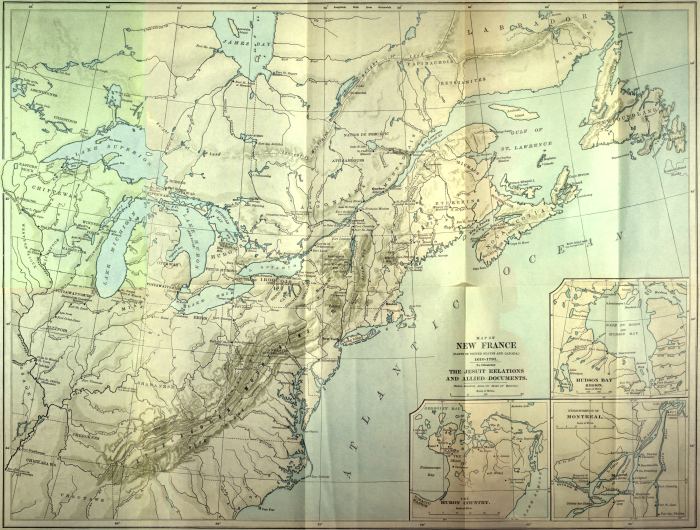

ILLUSTRATIONS TO VOL. II

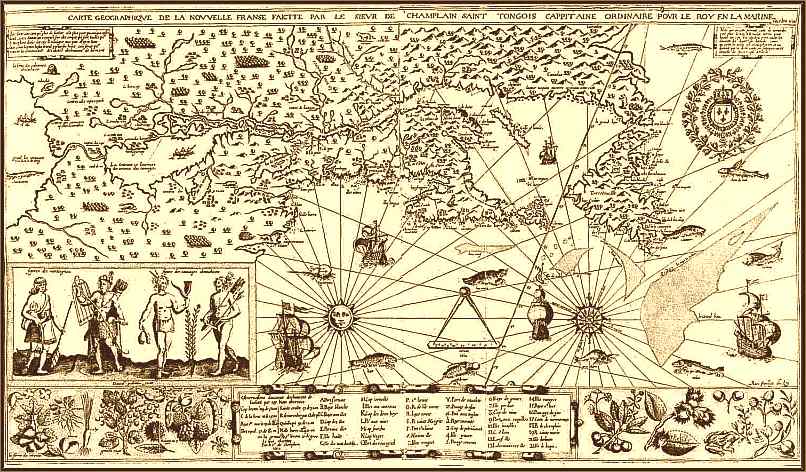

| I.

|

Photographic facsimile of General Map, from Les Voyages du Sieur de Champlain,

(Paris, 1613) |

Facing 56 |

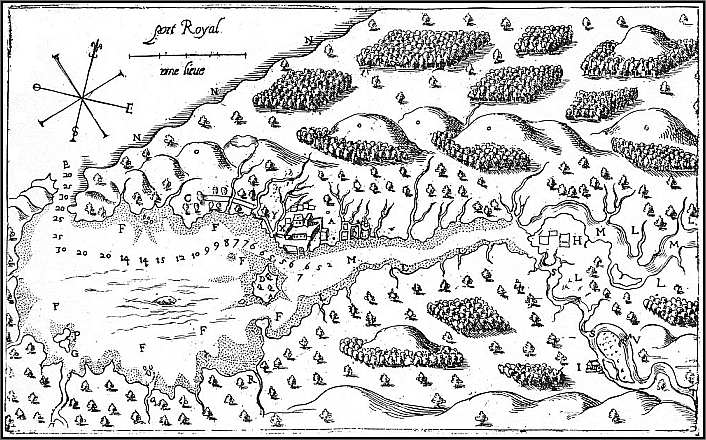

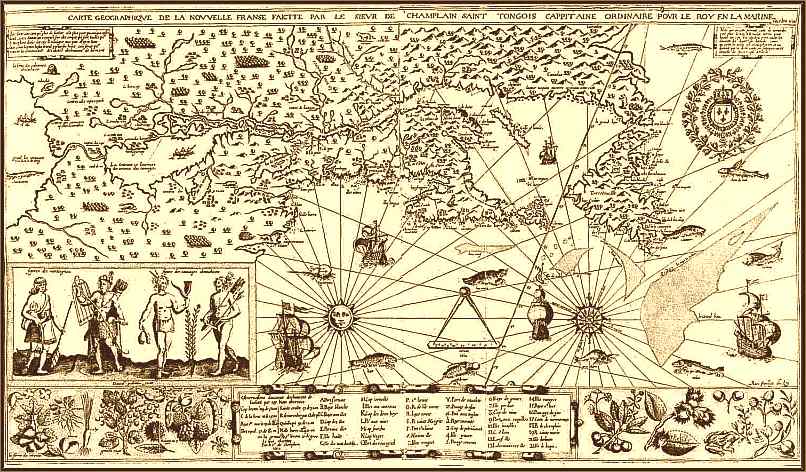

| II. |

Photographic facsimile of Map of Port

Royal, from Ibid |

Facing 118 |

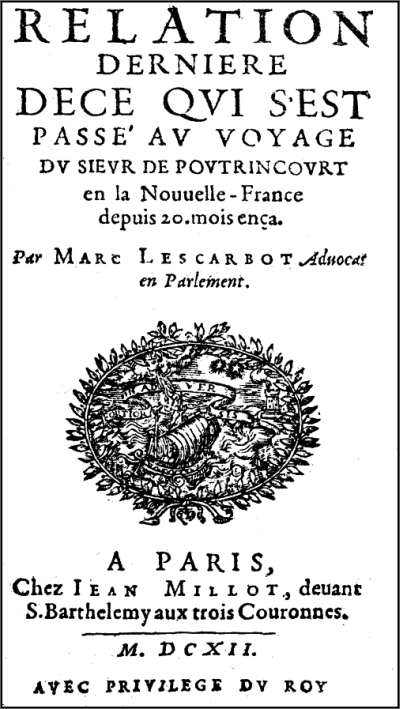

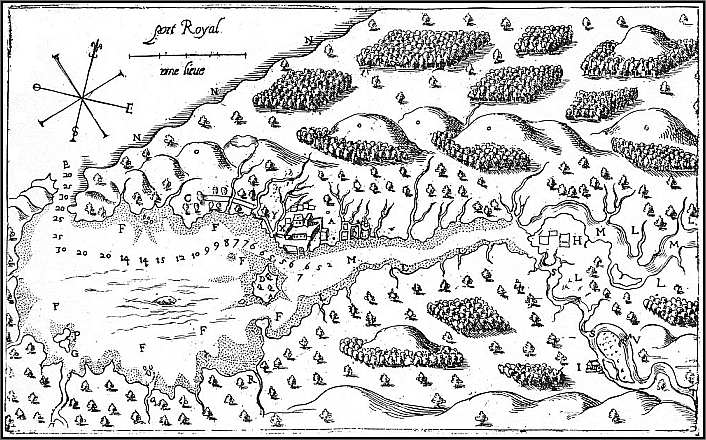

| III. |

Photographic facsimile of title-page, Lescarbot's

Relation Dernière |

122 |

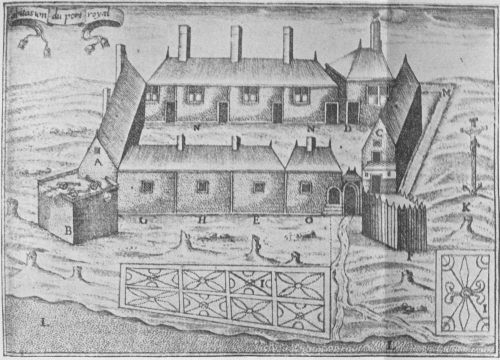

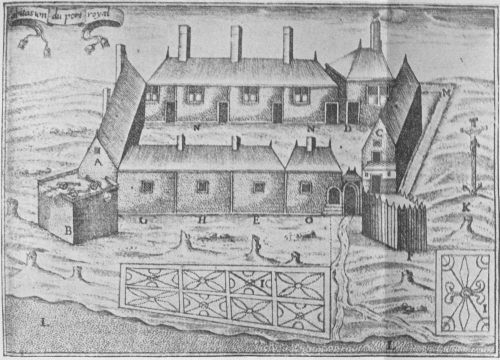

| IV. |

Photographic facsimile of plan of Fort at

Port Royal, from Ibid |

Facing 192 |

PREFACE TO VOL. II

Following is a synopsis of the documents contained

in the present volume:

IX. The indefatigable Biard presents, herein, a

graphic recital of his work among the Acadian savages,

and particularly his journeys into the wilderness.

His report of a trip with a party of Port Royalists to

French trading posts on the St. Croix and St. John

rivers, to an Etchemin town probably on the site of

the present Castine, Me., and to an English fishing

station on the Kennebec, is full of interest.

X. Herein, Biard sends to the general of his order

a full report concerning: (1) New France, its

physical characteristics, and its aborigines; (2) the

circumstances attending the opening of the Jesuit

mission in Acadia; (3) Fléché's work previous to

the coming of the Jesuits; (4) visits to savage tribes

by Massé and himself, with descriptions of conversions

and baptisms, and a statement of the conditions

and prospects of spiritual work among the aborigines.

XI. Lescarbot's Relation Dernière gives an account

of Poutrincourt's voyage to New France, in 1610; of

the conversion and baptism of the savage chief, Membertou,

and others, by the priest, Fléché; of Biencourt's

return to France; and of the experiences of

Poutrincourt at Port Royal. The writer praises Poutrincourt

for his exertions in Canada in behalf of

2

both religion and civilization; and urges that he

should be aided in his colonial enterprise, as a necessary

basis for religious work in this portion of the

New World. He gives a list of the sponsors of the

baptized Indians, who included many of the French

nobility and clergy. The life at Port Royal is pictured

in some detail; its labors and privations are

dwelt upon; and the customs of the natives described.

Lescarbot does not fail, although cautiously, to exhibit

his dislike of the Jesuits, and endeavors to show

that their coming to Port Royal involved delay and

expense to the colonial enterprise, thereby injuring

Poutrincourt. Our author's closing chapter devoutly

catalogues the "Effects of God's Grace in New

France;" he describes how Providence cared for the

colonists in their distress, saved them from shipwreck,

kindly disposed the savages toward them and the

Christian religion, and returned to the Frenchmen

their ship, in time to prevent starvation. The rescue

of Aubry is also mentioned.

XII. The Relatio Rerum Gestarum (1613 & 1614)

opens with a description of New France, its geography,

its climate, its peoples and their customs. The

experience of the Jesuit fathers at Port Royal is related

at length, from their own point of view. A description

is given of the settlement of St. Sauveur,

on Mount Desert Island, and its destruction by the

Virginian, Argall. Then follows an account of the

life of the Jesuit prisoners, in Virginia and England.

The conclusion is reached that, despite these drawbacks,

the Jesuit mission in Canada has made a hopeful

beginning.

R. G. T.

Madison, Wis., September, 1896.

IX

Lettre Du P. Biard

au R. P. Provincial à Paris

Port Royal, Janvier 31, 1612

Source: Reprinted from Carayon's Première Mission des

Jésuites au Canada, pp. 44-76.

4

[44] Lettre du P. Pierre Biard au R. P. Provincial

à Paris.

(Copiée sur l'autographe conservé dans les archives du

Jésus, à Rome.)

Port-Royal, 31 janvier 1612.

Mon Reverend Pere,

Pax Christi.

S'il nous failloit entrer en compte devant

Dieu et Vostre Reverence du geré et negocié par

nous en ceste nouvelle acquisition du Fils de Dieu,

ceste nouvelle France et Chrestienté, depuis nostre

arrivée jusques à ce commencement de nouvel an, je

ne doubte point certes, qu'en la sommation et calcul

final, la perte ne surmontast les profits; le despensé

follement en offençant, le bien et sagement ménagé

en obeyssant, et le receu des talents, graces et tolerances

divines, le mis et employé au royal et amiable

service de nostre grand et autant bening Createur.

Neantmoins, d'autant que (comme je croy) nos ruines

n'édifiroyent personne, et nos rentes n'establiroyent

aucun, il vaudroit mieux que pour le malacquitté,

nous le plorions à part; [45] pour le receu, nous imitions

le metayer d'iniquité loué par Nostre Seigneur

en l'Evangile, sçavoir est que, faisant part à autruy

des biens de nostre Maistre, nous nous en faisions

des amis, et que communiquant à plusieurs ce qui est

d'édification en ces premiers fondemens de Chrestienté,

nous obtenions plusieurs intercesseurs envers

Dieu, et fauteurs de cet œuvre. Mesme que ce

faisant, nous ne defrauderons en rien la debte, ainsy

6

que fit le Censier inique, baillant à plusieurs le bien

de Nostre Maistre avec profit, et peut-estre acquitterons

par ceste œconomie une partie des redevances et

de leur surcroy. Ainsy soit-il.

5

[44] Letter from Father Pierre Biard to the Reverend

Father Provincial, at Paris.

(Copied from the autograph preserved in the archives of

Jesus, at Rome.)

Port Royal, January 31, 1612.

My Reverend Father,

The peace of Christ be with you.

Were we compelled to give an account before

God and Your Reverence of our administration and

our transactions in this newly acquired kingdom of

the Son of God, this new France and new Christendom,

from the time of our arrival up to the beginning

of this new year, I certainly do not doubt that, in the

aggregate and final summing up, the loss would exceed

the profits; the foolish cost of transgression,

the goodness and wisdom of obedience; and the

reception of divine talents, graces, and indulgence

would exceed their outlay and use in the royal and

agreeable service of our great and so benign Creator.

Nevertheless, inasmuch as (I believe) no one would

be edified by our losses, or greatly benefited by our

gains, it is better that we mourn our losses apart;

[45] as to our receipts, we shall be like the unjust

steward commended by Our Lord in the Gospels,

namely, by sharing our Master's goods with others

we shall make them our friends; and in communicating

to many what is edifying in these early foundations

of Christianity, we shall obtain intercessors with

God and supporters of this work. Yet in doing this

we shall in no wise diminish the debt, as did the

7

wicked Steward, giving out Our Master's goods with

profit; but we shall, perhaps, by this prudence acquit

ourselves of a part of the dues and interests.

So be it.

Aujourd'huy, 22 Ianvier, 1612, neuf [huict] mois

sont passez dés notre arrivée en ceste nouvelle

France. Peu aprés nostre arrivée, i'escrivy l'estat

auquel nous avons retrouvé ceste Eglise et Colonie

naissante. Voicy ce qui s'en est ensuivy.

To-day, January 22nd, 1612,

eight1 months have

passed since our arrival in this new France. Soon

after that, I wrote you in regard to the condition in

which we found this infant Church and Colony. Here

is what followed:

Monsieur de Potrincourt s'en allant en France le

mois de Iuin dernier, laissa icy son fils Monsieur de

Biencourt, ieune seigneur de grande vertu et fort

recommandable, avec environ 18 siens domestiques,

et nous deux prestres de la Compagnie. Or la tasche

et travail de nous deux prestres, selon nostre vocation,

a esté, et icy dans la maison et habitation en residant,

et dehors en voyageant. Commençons, comme

l'on dict, de chez nous, de [46] la maison et habitation;

puis nous sortirons dehors.

When Monsieur de Potrincourt went to France

last June he left his son here, Monsieur de Biencourt,

a young man of great integrity and of very estimable

qualities, with about eighteen of his servants and us

two priests of the Society. Now our duties and offices,

in accordance with our calling as priests, have

been performed while residing here at the house and

settlement, and by making journeys abroad. Let us

begin, as they say, at home, that is, at [46] the residence

and settlement; then we shall go outside.

Icy donc nos exercices sont: dire messe tous les

jours, la chanter solemnellement les dimanches et

festes, avec les Vespres, et souvent la procession;

faire prieres publiques matin et soir; exhorter, consoler,

donner les sacremens, ensevelir les morts;

enfin faire les offices de Curé, puisque autres prestres

n'y a en ces quartiers que nous. Et de vray, bon

besoing seroit que fussions meilleurs ouvriers de

Nostre Seigneur; d'autant que gens de marine, tels

que sont quasi nos paroissiens, sont assez d'ordinaire

totalement insensibles au sentiment de leur ame,

n'ayans marque de religion sinon leurs juremens et

reniemens, ny cognoissance de Dieu sinon autant

qu'en apporte la pratique connue de France, offusquée

du libertinage et des objections et bouffonneries

8

mesdisantes des heretiques. D'où l'on peut aussy

veoir, quelle esperance il y a de planter une belle

chrestienté par tels evangelistes. La première chose

que ces pauvres Sauvages apprennent, ce sont les

juremens, parolles sales et injures; et orriés souvent

les Sauvagesses (lesquelles autrement sont fort craintives

et pudiques), mais vous les orriés souvent charger

nos gens de grosses pourries et eshontées opprobres,

en langage françois; non qu'elles en sachent

la signification, ains seulement parce qu'elles voyent

qu'en telles parolles est leur [47] commun rire et ordinaire

passetemps. Et quel moyen de remedier à

cecy en des hommes qui mesprennent (malparlent)

avec (d'autant) plus d'abandon qu'ils mesprisent avec

audace.

Here then are our occupations: to say mass every

day, and to solemnly sing it sundays and holidays,

together with Vespers, and frequently the procession;

to offer public prayers morning and evening;

to exhort, console, administer the sacraments, bury

the dead; in short, to perform the offices of the Curate,

since there are no other priests in these quarters.

And in truth it would be much better if we were

more earnest workers here for Our Lord, since sailors,

who form the greater part of our parishioners

are ordinarily quite deficient in any spiritual feeling,

having no sign of religion except in their oaths

and blasphemies, nor any knowledge of God beyond

the simplest conceptions which they bring with

them from France, clouded with licentiousness and

9

the cavilings and revilings of heretics. Hence it

can be seen what hope there is of establishing a

flourishing christian church by such evangelists.

The first things the poor Savages learn are oaths

and vile and insulting words; and you will often hear

the women Savages (who otherwise are very timid

and modest), hurl vulgar, vile, and shameless epithets

at our people, in the French language; not that

they know the meaning of them, but only because

they see that when such words are used there is

[47] generally a great deal of laughter and amusement.

And what remedy can there be for this evil

in men whose abandonment to evil-speaking (or cursing)

is as great as or greater than their insolence in

showing their contempt?

A ces exercices chrestiens que nous faisons icy à

l'habitation, assistent aucune fois les Sauvages, quand

aucuns y en a dans le port. Ie dis, aucune fois, d'autant

qu'ils n'y sont gueres stylés, non plus les baptisés

que les payens, ne sçachant gueres davantage les uns

que les autres faute d'instruction. Telle fut la cause

pourquoy nous resolusmes dés nostre arrivée de ne

point baptiser aucun adulte, sans que prealablement

il ne fust bien catechisé. Or catechiser ne pouvons-nous

avant que sçavoir le langage.

At these christian services which we conduct here

at the settlement, the Savages are occasionally present,

when some of them happen to be at the port.

I say, occasionally, inasmuch as they are but little

trained in the principles of the faith—those who

have been baptized, no more than the heathen; the

former, from lack of instruction, knowing but little

more than the latter. This was why we resolved, at

the time of our arrival, not to baptize any adults unless

they were previously well catechized. Now in

order to catechize we must first know the language.

De vray, Monsieur de Biancourt, qui entend le sauvage

le mieux de tous ceux qui sont icy, a pris d'un

grand zele, et prend chaque jour beaucoup de peine à

nous servir de truchement. Mais, ne sçay comment,

aussi tost qu'on vient à traitter de Dieu, il se sent le

mesme que Moyse, l'esprit estonné, le gosier tary, et

la langue nouée. La cause en est d'autant que ces

sauvages n'ont point de religion formée, point de magistrature

10

ou police, point d'arts ou libéraux ou mechaniques,

point de commerce ou vie civile; et par

consequent les mots leur défaillent [48] des choses

qu'ils n'ont jamais veues ou apprehendées.

It is true that Monsieur de Biancourt, who understands

the savage tongue better than any one else

here, is filled with earnest zeal, and every day takes a

great deal of trouble to serve as our interpreter.

But, somehow, as soon as we begin to talk about God

he feels as Moses did,—his mind is bewildered, his

throat dry, his tongue tied. The reason for this

is that, as the savages have no definite religion,

11

magistracy or government, liberal or mechanical arts,

commercial or civil life, they have consequently

no words to describe [48] things which they have

never seen or even conceived.

D'avantage, comme rudes et incultes qu'ils sont,

ils ont toutes leurs conceptions attachées aux sens et

à la matiere; rien d'abstraict, interne, spirituel ou

distinct. Bon, fort, rouge, noir, grand, dur, ils le vous

diront en leur patois; bonté, force, rougeur, noircissure,

ils ne scavent que c'est. Et pour toutes les vertus

que vous leur sauriez dire, sagesse, fidelité, justice, misericorde,

recognoissance, pieté, et autres, tout chez eux

tout n'est sinon l'heureux, tendre amour, bon cœur.

Semblablement un loup, un renard, un esquirieu, un

orignac, ils les vous nommeront, et ainsy chaque

espece de celle qu'ils ont, les quelles, hors les chiens,

sont toutes sauvages; mais une beste, un animal, un

corps, une substance, et ainsy les semblables universels

et genres, cela est par trop docte pour eux.

Furthermore, rude and untutored as they are, all

their conceptions are limited to sensible and material

things; there is nothing abstract, internal, spiritual,

or distinct. Good, strong, red, black, large, hard, they

will repeat to you in their jargon; goodness, strength,

redness, blackness—they do not know what they are.

And as to all the virtues you may enumerate to

them, wisdom, fidelity, justice, mercy, gratitude, piety,

and others, these are not found among them at all

except as expressed in the words happy, tender love,

good heart. Likewise they will name to you a wolf, a

fox, a squirrel, a moose, and so on to every kind of

animal they have, all of which are wild, except the

dog; but as to words expressing universal and generic

ideas, such as beast, animal, body, substance, and

the like, these are altogether too learned for them.

Ajoutez à cecy, s'il vous plaist, la grande difficulté

qu'il y a de tirer d'eux les mots mesmes qu'ils ont.

Car, comme ny eux ne sçavent nostre langage, ny

nous le leur, sinon fort peu, touchant le commerce et

vie commune, il nous faut faire mille gesticulations

et chimagrées pour leur exprimer nos conceptions, et

ainsy tirer d'eux quelques noms des choses qui ne se

peuvent monstrer avec [49] le sens. Par exemple,

penser, oublier, se ressouvenir, doubter: pour sçavoir

ces quatre mots, il vous faudra donner beau rire à

nos messieurs au moins toute une aprés-disner, en

faisant le basteleur; et encore, aprés tout cela, vous

trouverez-vous trompé et mocqué de nouveau, ayant

eu, comme l'on dit, le mortier pour un niveau, et le

12

marteau pour la truelle. Enfin nous en sommes là

encore, après plusieurs enquestes et travaux, à disputer

s'ils ont aucune parolle qui corresponde droictement

à ce mot Credo, je croy. Estimez un peu que

c'est du reste du symbole et fondemens chrestiens.

Add to this, if you please, the great difficulty

of obtaining from them even the words that they

have. For, as they neither know our language nor

we theirs, except a very little which pertains to daily

and commercial life, we are compelled to make a

thousand gesticulations and signs to express to them

our ideas, and thus to draw from them the names of

some of the things which cannot be pointed out [49]

to them. For example, to think, to forget, to remember,

to doubt; to know these four words, you will be

obliged to amuse our gentlemen for a whole afternoon

at least by playing the clown; and then, after

all that; you will find yourself deceived, and mocked

anew, having received, as the saying is, the mortar

13

for the level, and the hammer for the trowel. In

short we are still disputing, after a great deal of research

and labor, whether they have any word to

correspond directly to the word Credo, I believe.

Judge for yourself the difficulty surrounding the remainder

of the symbols and fundamental truths of

christianity.

Or tout ce discours de la difficulté du langage, ne

me servira pas seulement pour monstrer en quels

efforts et ahan de langue nous sommes, ains aussy

pour faire veoir à nos Europeans leur felicité mesme

civile: car il est assuré qu'encore mesme

enhanée,[I.]

cette miserable nation demeure touiours en une perpetuelle

enfance de langue et de raison. Ie dis, de

langue et de raison, parce qu'il est évident que là où

la parolle, messagere et despensière de l'esprit et discours,

reste totalement rude, pauvre et confuse, il est

impossible que l'esprit et raison soient beaucoup

polis, abondans et en ordre. Cependant ces pauvres

chetifs et enfants s'estiment [50] plus que tous les

hommes de la terre, et pour rien du monde ne voudroyent

quitter leur enfance et chetiveté. Mais ce

n'est pas de merveille; car, comme j'ay dict, ils sont

enfans.

Now all this talk about the difficulty of the language

will not only serve to show how laborious is our task

in learning it, but also will make our Europeans appreciate

their own blessings, even in civil affairs; for

it is certain that these miserable people, continually

weakened by hardships

[enhanée],[II.]

will always remain

in a perpetual infancy as to language and reason.

I say language and reason, because it is evident

that where words, the messengers and dispensers

of thought and speech, remain totally rude, poor

and confused, it is impossible that the mind and

reason be greatly refined, rich, and disciplined.

However, these poor weaklings and children consider

themselves [50] superior to all other men, and they

would not for the world give up their childishness

and wretchedness. And this is not to be wondered

at, for, as I have said, they are children.

Ne pouvans doncques pour encores baptiser les

adultes, comme nous avons dict, nous restent les enfans,

à qui appartient le royaume des cieux; ainsy

nous les baptisons de la volonté des parens et soubs

la caution des parrains. Et en cette façon, en avons

jà baptisé quatre, Dieu mercy. Les adultes qui sont

en extreme necessité, nous les instruisons autant que

Dieu nous en donne le moyen; et la pratique nous a

faict veoir, que lors Dieu supplée interieurement le

défaut de son outil externe. Ainsy, une vieille

femme dangereusement malade, et une jeune fille,

14

ont esté receues au nombre des enfans de Dieu. La

vieille est encore debout; la fille est allée à Dieu.

Since we cannot yet baptize the adults, as we have

said, there remain for us the children, to whom the

kingdom of heaven belongs; these we baptize with

the consent of their parents and the pledge of the

god-parents. And under these conditions we have

already, thank God, baptized four of them. We instruct

the adults who are in danger of death, as

far as God gives us the means to do so; and experience

has shown us that then God inwardly supplements

the defects of his exterior instruments.

15

Thus, an old woman, dangerously ill, and a young

girl have been added to the number of the children

of God. The woman still lives, the girl has gone to

Heaven.

Je vis cette fille de 8 a 9 ans, toute transie et n'ayant

plus que la peau et les os. Je la demanday à ses

parens pour la baptiser. Ils me respondirent que si

je la voulois, ils me la donnoyent tout à faict. Car

aussy bien, elle et un chien mort, c'estoit tout un.

Ainsy parloyent-ils, d'autant que c'est leur coustume

d'abandonner entierement ceux qu'ils ont une fois

entierement jugés incurables. Nous acceptasmes

l'offre, affin qu'ils vissent la difference du [51] Christianisme

et de leur impieté. Nous fismes conduire

ce pauvre squelette en une cabane de l'habitation, la

secourusmes et nourrismes à nostre possible, et l'ayant

tolerablement instruite, la baptisasmes. Elle fut

appelée Antoynette de Pons, en memoire et recognoissance

de tant de benefices qu'avons receus et

recevons de Madame la Marquise de Guercheville; et

laditte Dame se peut resjouir que jà son nom est au

ciel, car quelques jours aprés son baptesme, cette

ame choysie s'envola en ce lieu de gloire.

I saw this girl, eight or nine years old, all benumbed

and nothing but skin and bone. I asked the

parents to give her to me to baptize. They answered

that if I wished to have her they would give her up

to me entirely. For to them she was no better than

a dead dog. They spoke like this because they are

accustomed to abandon altogether those whom they

have once judged incurable. We accepted the offer,

so that they might see the difference between [51]

Christianity and their ungodliness. We had this

poor skeleton brought into one of the cabins of the

settlement, where we cared for and nourished her as

well as we could, and when she had been fairly well

instructed we baptized her. She was named Antoynette

de Pons, in grateful remembrance of the many

favors we have received and are receiving from Madame

la Marquise de Guercheville, who may rejoice

that already her name is in heaven, for a few days

after baptism this chosen soul flew away to that

glorious place.

Ce luy aussy fut nostre premier né, sur lequel nous

avons pu dire ce que Ioseph prononça sur le sien, que

Dieu nous avoit faict oublier tous nos travaux passés

et la maison de nostre Père. Mais à propos de ce

que les Sauvages abandonnent leurs malades, une

autre occasion de semblablement exercer la charité

chrestienne envers ces délaissés, a eu son issüe plus

joyeuse, et profitable pour détromper ces nations.

Cette occasion fut telle.

This was also our firstborn, for whose sake we

could say, as Joseph did about his, that God had

made us forget all our past hardships and the homes

of our Fathers. But in speaking of the Savages abandoning

their sick, another similar occasion to exercise

charity toward those who are deserted has had a

more happy issue and one more useful in undeceiving

these people. This occasion was as follows:

Le second fils du grand sagamo Membertou, de qui

nous parlerons tantost, appelé Actodin, jà chrestien

et marrié, estoit tombé en une griefve maladie.

16

Monsieur de Potrincourt, s'en allant en France, l'avoit

visité, et, comme il est bon seigneur, l'avoit

invité de se faire porter en l'habitation, pour y estre

medicamenté. Je m'attendois à cela, qu'on [52] le

nous apporteroit; mais on n'en faisoit rien. Ce voyant,

pour ne laisser cette ame en danger, je m'y en

allay de là à quelques jours (car il estoit à 5 lieuës de

l'habitation). Mais je trouvay mon malade en un

bel estat. On estoit sur le poinct de faire tabagie ou

convive solemnel sur son dernier adieu. Trois ou

quatre vastes chaudieres bouilloyent sur le feu. Il

avoit sa belle robe soubs soy (car c'estoit en esté), et

se preparoit à sa harangue funebre. La harangue

devoit finir en l'adieu et comploration commune de

tous. L'adieu et le deuil se clost par l'occision des

chiens à ce que le mourant ait des avants-coureurs en

l'autre monde. L'Occision des chiens est accostée de

la tabagie et de ce qui suyt la tabagie, du chant et

des danses. Après cela, il n'est plus loysible au malade

de manger ou demander aucun secours, ains se

doibt jà tenir pour un des manes ou citoyens de

l'autre vie. Je trouvay donc mon hoste en tel estat.

The second son of the grand sagamore Membertou,

of whom we shall speak by and by, named

17

Actodin, already a christian, and married, fell dangerously

ill. Monsieur de Potrincourt, as he was

about to depart for France, had visited him; and

being a kind-hearted gentleman, had asked him to

let himself be taken to the settlement for treatment.

I was expecting this suggestion [52] to be carried

out; but they did nothing of the kind. When this

became evident, not to leave this soul in danger, I

went there after a few days (for it was five leagues

from the settlement). But I found my patient in a

fine state. They were just about to celebrate tabagie,

or a solemn feast, over his last farewell. Three

or four immense kettles were boiling over the fire.

He had his beautiful robe under him (for it was

summer), and was preparing for his funeral oration.

The oration was to close with the usual adieus and

lamentations of all present. The farewell and the

mourning are finished by the slaughter of dogs, that

the dying man may have forerunners in the other

world. This slaughter is accompanied by the tabagie

and what follows it—namely, the singing and dancing.

After that it is no longer lawful for the sick man

to eat or to ask any help, but he must already consider

himself one of the "manes," or citizens of the other

world. Now it was in this state that I found my host.

I'invectivay contre cette façon de faire, plus de

geste que de langue, car pour la langue, mes interpretes

ne disoyent pas la dixiesme partie de ce que

je voulois. Neantmoins le vieil Membertou, pere du

malade, conceut assés l'affaire, et me promit qu'on

s'arresteroit à tout ce que j'en dirois. Ie luy dis donc

que pour l'adieu et deuil moderé, et encores pour la

tabagie, cela se pourroit tolerer; mais [53] que le

carnage des chiens, et les chants et danses sur un

trespassant, et beaucoup moins l'abandonnement

d'iceluy, ne me playsoyent point; que plus tost, selon

18

qu'ils avoyent promis à Monsieur de Potrincourt, ils

l'envoyassent en l'habitation; qu'à l'ayde de Dieu,

il pourroit bien encore guerir. Ils me donnerent

parolle d'ainsy faire le tout; ce neantmoins, le languissant

ne nous fut apporté que deux jours après.

I denounced this way of doing things, more by

actions than by words; for, as to talking, my interpreters

did not repeat the tenth part of what I

wanted them to say. Nevertheless, old Membertou,

father of the sick man, understood the affair well

enough, and promised me that they would stop just

where I wanted them to. Then I told him that the

farewells and a moderate display of mourning, and

even the tabagie, would be permitted, but [53] that

19

the slaughter of the dogs, and the songs and dances

over a dying person, and what was much worse,

leaving him to die alone, displeased me very much;

that it would be better, according to their promise

to Monsieur de Potrincourt, to have him brought

to the settlement, that, with the help of God, he

might yet recover. They gave me their word that

they would do all that I wished; nevertheless, the

dying man was not brought until two days afterward.

Il prenoit des symptomes si mortels, que souvent

nous n'attendions sinon qu'il nous demeurast entre

les mains. En effet un soir, sa femme et enfans

l'abandonnerent entierement, et s'en allerent cabaner

ailleurs, pensant que c'en estoit vuidé. Si pleut-il à

Dieu tromper heureusement leur desespoir; car, de

là à peu de jours, il fut plein de santé, et l'est encore

aujourd'hui (à Dieu en soit la gloire); ce que M. Hébert,

Parisien et maistre en Pharmacie assés cognu,

qui solicitoit ledit malade, m'a souvent asseuré estre

un vray miracle. De moi, je ne sçay qu'en dire,

d'autant que je ne veux affirmer ny le si ny le non en

ce dont je n'ay évidence. Cela scay-je, que nous

mismes sur le dit languissant un os des precieuses

reliques du glorieux Sainct Laurens, archevesque de

Dublin en Hibernie, que M. de la Place, digne abbé

d'Eu, et Messieurs les Prieurs et Chapitre de laditte

abbaye d'Eu nous donnerent de leur grace pour convoyer

nostre voyage en ces quartiers. Nous [54]

doncques mismes sur le malade de ces sainctes reliques,

faisant vœu pour luy, et depuis il emmeilleura.

His symptoms became so serious that often we expected

nothing less than that he would die on our

hands. In fact, one evening, his wife and children

deserted him entirely and went to settle elsewhere,

thinking it was all over with him. But it pleased

God to prove their despair unfounded; for a few

days afterwards he was in good health and is so to-day

(to God be the glory); which M. Hébert, of

Paris, a well-known master in Pharmacy, who attended

the said patient, often assured me was a

genuine miracle. For my part, I scarcely know what

to say; inasmuch as I do not care either to affirm or

deny a thing of which I have no proof. This I do

know, that we put upon the sufferer a bone taken

from the precious relics of the glorified Saint Lawrence,

archbishop of Dublin in Ireland, which M. de

la Place, the estimable abbé d'Eu, and the Priors and

Canons of the said abbey d'Eu, kindly gave us for

our protection during the voyage to these lands.

So we [54] placed some of these holy relics upon

the sick man, at the same time offering our vows

for him, and then he improved.

Par cet exemple, Membertou, le pere du guery,

comme j'ay dict cy devant, fut fort confirmé en la

foy, et à cette cause sentant le mal dont depuis il est

decedé, voulut aussy tost estre apporté icy; et quoyque

nostre cabane soit tant estroitte que trois personnes

estant dedans, à peine s'y peuvent-elles remuer,

neantmoins si demanda-t-il de grande confiance

20

qu'il avoit en nous, d'estre logé dans l'un de nos

deux licts; ce qu'il fut pour six jours. Mais après,

sa femme, fille et brue estans venues, il cogneut bien

de luy mesme qu'il falloit tramarcher; ce qu'il fit,

s'excusant fort, et nous demandant pardon du continuel

travail qu'il nous avoit donné jour et nuict en

son service. Certes le changement de lieu et traitement

ne lui allegea pas son mal. Par ainsy, le voyant

sur son declin, je le confessay au mieux que je

pus, et luy après (c'est tout leur testament) fit sa

harangue. Or en sa harangue, entre autres choses

il dict sa volonté estre d'avoir sepulture avec ses

femmes et enfants, ez-anciens monumens de sa

maison.

Influenced by this example, Membertou, the

father of the one who had recovered, as I have said

before, was very strongly confirmed in the faith;

21

and because he was then feeling the approach of the

malady from which he has since died, he wished to be

brought here immediately; and although our cabin is

so narrow that when three people are in it they can

scarcely turn around, nevertheless, showing his implicit

confidence in us, he asked to be placed in one

of our two beds, where he remained for six days. But

afterwards his wife, daughter, and daughter-in-law

having come, he himself recognized the necessity of

leaving, and did so with profuse excuses, asking our

pardon for the continual trouble he had given us in

waiting upon him day and night. Certainly the

change of location and treatment did not improve

him any. So then, seeing that his life was drawing

to a close, I confessed him as well as I could; and

after that he delivered his oration (this is their

sole testament). Now, among other things in this

speech, he said that he wished to be buried with his

wife and children, and among the ancient tombs of

his family.

Ie me monstray fort mal content de cecy, craingnant

que les Françoys et Sauvages ne prinssent de

la suspicion qu'il n'estoit mort gueres bon Chrestien.

[55] Mais on m'opposa que telle promesse lui avoit

esté faicte avant qu'il fut baptisé; et qu'autrement

si on l'enterroit en nostre cimetière, ses enfans et

amis ne nous viendroyent jamais plus veoir, puisque

c'est la façon de cette nation d'abhorrer toute memoire

de la mort et des morts.

I manifested great dissatisfaction with this, fearing

that the French and Savages would suspect that he

had not died a good Christian. [55] But I was assured

that this promise had been made before he was

baptized, and that otherwise, if he were buried in our

cemetery, his children and his friends would never

again come to see us, since it is the custom of this nation

to shun all reminders of death and of the dead.

Je disputay contre, et avec moy M. de Biancourt

(car c'est quasi mon unique truchement), neantmoins

en vain; le mourant demeuroit resolu. Le soir assez

tard, nous luy donnasmes l'extreme onction, puisque

autrement il y estoit assez preparé. Voyez l'efficace

du sacrement: le lendemain matin, il mande M. de

Biancourt et moy, et de nouveau il recommence sa

harangue. Par icelle il declaroit avoir de soy mesme

changé de volonté; qu'il entendoit d'estre inhumé

avec nous, commandant à ses enfans de ne point pour

22

cela fuyr le lieu comme infideles, ains d'autant plus

le frequenter comme chrestiens, à celle fin d'y prier

pour son ame et pleurer ses pechez. Il recommanda

aussi la paix avec M. de Potrincourt et son fils; que

de luy, il avait toujours aymé les Françoys, et avoit

souvent empesché plusieurs conspirations contre eux.

De là à peu d'heures il mourut entre mes mains fort

chrestiennement.

I opposed this, and M. de Biancourt, for he is almost

my only interpreter, joined with me, but in

vain; the dying man was obdurate. Rather late that

evening we administered extreme unction to him,

for otherwise he was sufficiently prepared for it.

Behold now the efficacy of the sacrament; the next

23

morning he asks for M. de Biancourt and me, and

again begins his harangue. In this he declares that

he has, of his own free will, changed his mind; that

he intends to be buried with us, commanding his

children not, for that reason, to shun the place like

unbelievers, but to frequent it all the more, like

christians, to pray for his soul and to weep over his

sins. He also recommended peace with M. de Potrincourt

and his son; as for him, he had always

loved the French, and had often prevented conspiracies

against them. A few hours afterward he died

a christian death in my arms.

C'a esté le plus grand, renommé et redouté sauvage

qui ayt esté de memoire d'homme: de riche [56]

taille, et plus hault et membru que n'est l'ordinaire

des autres, barbu comme un françoys, estant ainsy

que quasi pas un des autres n'a du poil au menton;

discret et grave, ressentant bien son homme de commandement.

Dieu luy gravoit en l'ame une apprehension

plus grande du Christianisme, que n'estoit

ce qu'il en avoit pu ouyr, et m'a souvent dict en son

sauvageois. "Apprend vistement nostre langue, car

aussy tost que tu la sçauras et m'auras bien enseingné,

je veux estre prescheur comme toy." Avant mesme

sa conversion, il n'a jamais voulu avoir plus d'une

femme vivante; ce qu'est esmerveillable, d'autant

que les grands sagamos de ce païs entretiennent un

nombreux serail, non plus pour luxure, que pour

ambition, gloire et necessité: pour ambition, à celle

fin d'avoir plusieurs enfans, en quoy gist leur puissance;

pour gloire et necessité, d'autant qu'ils n'ont

autres artisans, agens, serviteurs, pourvoyeurs ou

esclaves que les femmes; elles soustiennent tout le

faix et fatigue de la vie.

This was the greatest, most renowned and most

formidable savage within the memory of man; of

splendid [56] physique, taller and larger-limbed than

is usual among them; bearded like a Frenchman, although

scarcely any of the others have hair upon the

chin; grave and reserved; feeling a proper sense of

dignity for his position as commander. God impressed

upon his soul a greater idea of Christianity

than he has been able to form from hearing about it,

and he has often said to me in his savage tongue:

"Learn our language quickly, for as soon as thou

knowest it and hast taught me well I wish to become

a preacher like thee." Even before his conversion

he never cared to have more than one living wife,

which is wonderful, as the great sagamores of this

country maintain a numerous seraglio, no more

through licentiousness than through ambition, glory

and necessity; for ambition, to the end that they

may have many children, wherein lies their power;

for fame and necessity, since they have no other

artisans, agents, servants, purveyors or slaves than

the women; they bear all the burdens and toil of life.

C'a esté le premier de tous les Sauvages qui en ces

régions aye receu le baptesme et l'extreme-onction,

le premier et le dernier sacrement, et le premier qui,

24

de son mandement et ordonnance, aye été inhumé

chrestiennement. Monsieur de Biancourt honora ses

obsèques, imitant à son possible les [57] honneurs

qu'on rend en France aux grands Capitaines et Seigneurs.

25

He was the first of all the Savages in these parts

to receive baptism and extreme unction, the first and

the last sacraments; and the first one who, by his

own command and decree, has received a christian

burial. Monsieur de Biancourt honored his obsequies,

imitating as far as possible the [57] honors

which are shown to great Captains and Noblemen in

France.

Or, à ce que l'on craigne les jugemens de Dieu,

aussy bien que l'on ayme sa misericorde, je mettray

icy la fin d'un françoys, en laquelle Dieu a monstré

sa justice, aussy bien qu'en celle de Membertou nous

recognoissons sa grâce. Celuy-cy avoit souvent esvadé

le danger d'estre noyé, et tout fraischement le

beau jour de la Pentecoste derniére. Le bénéfice fut

mal recogneu. Pour n'en rien dire de plus, la veille

de S. Pierre et S. Paul, comme le soir on fust entré

en discours des perils de mer, et des vœux qu'on faict

aux Saincts en semblables hazards, ce miserable se

print à s'en rire et moquer impudemment, se gaudissant

de ceux de la compagnie qu'on disoit en telles

rencontre savoir esté religieu. Il eut tost son guerdon.

Le lendemain matin, un coup de vent l'emporta

tout seul dehors de la chaloupe dans les vagues,

et jamais depuis, n'est apparu.

Now, that the judgments of God may be feared as

much as his mercies are loved, I shall here record the

death of a Frenchman, in which God has shown his

justice as much as he has given us evidence of his

mercy, in the death of Membertou. This man had

often escaped drowning, and only recently upon the

blessed day of last Pentecost. He showed but little

gratitude for this favor. Not to make the story too

long, the evening before St. Peter's and St. Paul's

day, as they were discoursing upon the perils of the

sea, and upon the vows made to the Saints in similar

dangers, this wretch began impudently to laugh and

to sneer, jeering at those of the company who were

said to have been religious upon such occasions. He

soon had his reward. The next morning a gust of

wind carried him, and him only, out of the boat into

the waves, and he was never seen again.

Mais laissons l'eau et venons à la rive. Si la terre

de cette nouvelle France avoit aucun sentiment, ainsy

que les Poëtes feignent de leur deesse Tellus, sans

doubte elle eust eu un ressentiment bien nouveau de

liesse cette année; car, Dieu mercy, ayans eu fort

heureuses moissons de ce peu qui avoit esté labouré

du recueilly nous avons faict des hosties, et nous les

avons offertes à Dieu. Ce sont, comme nous [58]

croyons, les premieres hosties qui ayent esté faites du

froment de ce terroir. Notre Seigneur par sa bonté

les aye voulu recevoir en odeur de suavité, et, comme

26

dict le Psalmiste, veuille donner benignité, puisque la

terre luy a rendu son fruict.

But let us leave the water and come on shore. If

the ground of this new France had feeling, as the

Poets pretend their goddess Tellus had, doubtless it

would have experienced an altogether novel sensation

of joy this year, for, thank God, having had

very successful crops from the little that was tilled,

we made from the harvest some hosts [wafers for consecration]

and offered them to God. These are, as we

[58] believe, the first hosts which have been made

27

from the wheat of these lands. May Our Lord, in

his goodness, have consented to receive them as fragrant

offerings and in the words of the Psalmist, may

he give graciously, since the earth has yielded him its

fruits.

C'est assés demeuré à la maison; sortons un peu

dehors, comme nous avons promis de faire, et racontons

ce qui s'est passé par le pays.

We have stayed at home long enough; let us go

abroad a little, as we promised to do, and relate

what has taken place in the country.

J'ay faict deux voyages avec M. de Biancourt, l'un

de quelques douze jours, l'autre d'un mois et demy,

et avons rodé toute la coste dés Port-Royal jusques à

Kinibéqui, ouest-sud ouest. Nous sommes entrez

dans les grandes rivières de S. Iean, de Saincte Croix,

de Pentegoet et du sus-nommé Kinibéqui; avons

visité les Françoys, qui ont hyverné icy cette année

en deux parts, en la rivière S. Iean et en celle de

Saincte-Croix: les Malouins en la riviere S. Iean, et

le capitaine Plastrier à Saincte Croix.

I made two journeys with M. de Biancourt, the one

lasting about twelve days, the other a month and a

half; and we have ranged the entire coast from Port

Royal to Kinibéqui,2

west southwest. We entered

the great rivers St. John, Saincte Croix,

Pentegoët,3

and the above-named Kinibéqui; we visited the

French who have wintered there this year in two

places, at the St. John river and at the river Saincte

Croix; the Malouins at the former place, and captain

Plastrier at the

latter.4

Durant ces voyages, Dieu nous a sauvez de grands

et bien éminents dangers, et souvent; mais quoy que

nous les debvions tousjours retenir en la mémoire

pour n'en estre ingrats, il n'est pas necessaire que

nous les couchions tous sur le papier, de peur d'être

ennuyeux. Ie raconteray seulement ce qu'à mon advis

on orroit plus volontiers.

During these journeys, God often delivered us from

great and very conspicuous dangers; but, although

we ought always to bear them in mind, that we

may not be ungrateful, there is no need of setting

them all down upon paper, lest we become wearisome.

I shall relate only what, in my opinion, will

be the most interesting.

Nous allions voir les Malouins, sçavoir est, le [59]

Sieur du Pont le jeune, et le capitaine Merveilles,

qui, comme nous avons dict, hyvernoyent en la rivière

S. Jean, en une isle appelée Emenenic, avant contremont

le fleuve quelques six lieues. Nous estions

encore à une lieuë et demye de l'isle, qu'il estoit jà

soir et la fin du crepuscule. Ià les estoilles commençoyent

à se monstrer, quand voicy que vers le Nord

soudainement une partie du ciel devint aussy rouge

et sanguine qu'escarlate, et s'estendant peu à peu

en piques et fuseaux, s'en alla droict reposer sur l'habitation

28

des Malouins. La rougeur estoit si esclatante,

que toute la rivière s'en teingnoit et en reluysoit.

Cette apparition dura demy quart d'heure, et

aussy tost après la disparition, en recommença une

autre de mesme forme, cours et consistance.

We went to see the Malouins; namely, [59] Sieur

du Pont, the younger, and captain Merveilles, who, as

we have said, were wintering at St. John river, upon

an island called Emenenic, some six leagues up the

river. We were still one league and a half from the

island when the twilight ended and night came on.

The stars had already begun to appear, when suddenly,

toward the Northward, a part of the heavens became

blood-red: and this light spreading, little by little,

29

in vivid streaks and flashes, moved directly over

the settlement of the Malouins and there stopped.

The red glow was so brilliant that the whole river

was tinged and made luminous by it. This apparition

lasted some eight minutes, and as soon as it disappeared

another came of the same form, direction and

appearance.

Il n'y eut celuy de nous qui ne jugeast tel metheore

prodigieux. Pour nos Sauvages, ils s'escrierent

aussy tost: Gara gara enderquir Gara gara; c'est-à-dire,

nous aurons guerre; tels signales denoncent

guerre. Neantmoins, et nostre abord cette soirée, et

le lendemain matin nostre descente fut fort amiable

et pacifique. Le jour, rien qu'amitié. Mais (malheur!)

le soir venu, tout se vira, ne sçay comment,

le dessus dessous; entre nos gens et ceux de S. Malo,

confusion, brouillis, fureur, tintamarre. Ie ne doubte

point qu'une mauditte bande de furieux et [60] sanguinaires

esprits ne voltigeast toute cette nuit là, attendant

à chaque heure et moment un horrible massacre

de ce peu de Chrestiens qui estions là; mais la

bonté de Dieu les brida, les malheureux. Il n'y eut

aucun sang espandu, et le jour suyvant, cette nocturne

bourrasque finit en un beau et plaisant calme,

les ombrages et fantosmes ténébreux s'estant esvanouis

en serenité lumineuse.

There was not one of us who did not consider this

meteoric display prophetic. As to the Savages, they

immediately cried out, Gara gara enderquir Gara

gara, meaning we shall have war, such signs announce

war. Nevertheless, both our arrival that

evening and our landing the next morning were very

quiet and peaceful. During the day, nothing but

friendliness. But (alas!) when evening came, I

know not how, everything was turned topsy-turvy;

confusion, discord, rage, uproar reigned between our

people and those of St. Malo. I do not doubt that

a cursed band of furious and [60] sanguinary spirits

were hovering about all this night, expecting every

hour and moment a horrible massacre of the few

Christians who were there; but the goodness of God

restrained the poor wretches. There was no bloodshed;

and the next day, this nocturnal storm ended in

a beautiful and delightful calm, the dark shadows and

spectres giving way to a luminous peace.

De vray, la bonté et prudence de M. de Biancourt

parust fort emmy ce fortunal de passions humaines.

Mais aussy je recogneus assés que le feu et les armes

estans une fois entre les mains de gens mal disciplinés,

les maistres ont beaucoup à craindre et à souffrir

de leurs propres. Ie ne sçay s'il y eust aucun qui

fermast l'œil de toute cette nuit. Pour moy je fis

prou de belles propositions et promesses à Nostre

Seigneur, de ne jamais oublier ce sien benefice, s'il

30

plaisoit faire qu'aucun sang ne fust respandu. Ce

qu'il nous donna de son infinie misericorde.

In truth, M. de Biancourt's goodness and prudence

seemed much shaken by this tempest of human passions.

But I also saw, very clearly that if fire and

arms were once put into the hands of badly disciplined

men, the masters have much to fear and suffer

from their own servants. I do not know that there

was one who closed his eyes during that night. For

me, I made many fine propositions and promises to

31

Our Lord, never to forget this, his goodness, if he

were pleased to avert all bloodshed. This he granted

in his infinite mercy.

Il estoit trois heures aprés midy du jour suyvant,

que je n'avois pas eu encores loysir de sentir la faim,

tant j'estois empesché à aller et venir des uns aux

autres. Enfin environ ce temps là, tout fut accoysé,

Dieu mercy.

It was three o'clock in the afternoon of the next

day before I had time to feel hungry, so constantly

had I been obliged to go back and forth from one to

the other. At last, about that time everything was

settled, thank God.

Certes le capitaine Merveilles et ses gens monstrerent

leur piété non vulgaire. Car nonobstant cet

heurt et rencontre si troublant, le deuxiesme jour [61]

d'après, ils se confesserent et communierent avec

grand exemple, et si, à nostre départir, ils me prierent

instamment trestous et par spécial le jeune du Pont,

de les aller veoir et demeurer avec eux à ma commodité.

Ie leur promis d'ainsy le faire, et n'en attends

que les moyens. Car de vray j'ayme ces gens

de bien de tout mon cœur.

Certainly captain Merveilles and his people showed

unusual piety. For notwithstanding this so annoying

encounter and conflict, two days [61] afterwards

they confessed and took communion in a very exemplary

manner; and so, at our departure, they all

begged me very earnestly, and particularly young du

Pont, to come and see them and stay with them as

long as I liked. I promised to do so, and am only

waiting for the opportunity. For in truth I love

these honest people with all my heart.

Mais, départans un peu de pensée d'avec eux,

comme nous fismes lors de presence, continuons

nostre route et voyage. Au retour de cette rivière

Sainct Jean, nostre voyage s'addressoit jusques aux

Armouchiquoys. Deux causes principales esmouvoyent

à cela M. de Biancourt: la premiere, pour

avoir nouvelle des Angloys, et sçavoir si on pourroit

avoir raison d'eux; la seconde affin de troquer du

bled armouchiquoys, pour nous ayder à passer nostre

hyver, et ne point mourir de faim, en cas que nous

ne receussions aucun secours de France.

But dismissing them from our thoughts for the

time being, as we did then from our presence, let us

continue our journey. Upon our return from this

river Saint John, our route turned towards the country

of the Armouchiquoys. Two principal causes led M.

de Biancourt to take this route: first, in order to

have news of the English, and to find out if it would be

possible to obtain satisfaction from them; secondly,

to buy some armouchiquoys corn to help us pass the

winter, and not die of hunger in case we did not receive

help from France.

Pour entendre la première cause, faut sçavoir que

peu auparavant, le capitaine Platrier de Honfleur, cy

devant nommé, voulant aller à Kinibéqui, il fut saisy

prisonnier par deux navires angloys qui estoient en

une isle appelée Emmetenic, à 8 lieües dudit Kinibéqui.

Son relaschement fut moyennant quelques presents

32

(ainsy parle-t-on pour parler doucement) et la

promesse qu'il fit d'obtemperer aux prohibitions à

luy faictes, de point negotier en toute [62] cette coste.

Car les Angloys s'en veulent dire maistres, et sur ce

ils produysoyent des lettres de leur Roy, mais à ce

que nous croyons fausses.

To understand the first cause you must know that,

a little while before, captain Platrier, of Honfleur,

already mentioned, wishing to go to Kinibéqui, was

taken prisoner by two English ships which were at

an island called Emmetenic,85 eight leagues from

33

Kinibéqui. His release was effected by means of

presents (this expresses it mildly), and by his promise

to comply with the interdictions laid upon him not

to trade anywhere upon all [62] this coast. For the

English want to be considered masters of it, and

they produced letters from their King to this effect,

but these we believe to be false.

Or Monsieur de Biancourt ayant ouy tout cecy de

la bouche mesme du capitaine Platrier, il remontra

serieusement à ces gens combien il importoit à luy,

officier de la Couronne et Lieutenant de son pere,

combien aussy à tout bon Françoys, d'aller au rencontre

de cette usurpation des Anglois tant contrariante

aux droits et possessions de sa Majesté. "Car,

disoit-il, il est à tous notoire (pour ne reprendre l'affaire

de plus hault) que le grand Henry, que Dieu

absolve, suyvant les droicts acquis par ses prédecesseurs

et luy, donna à Monsieur des Monts, l'an 1604,

toute cette région depuis le 40e degré d'élévation jusques

au 46. Depuis laquelle donation ledit Seigneur

des Monts, par soy mesme et par Monsieur de Potrincourt,

mon très-honoré pere, son lieutenant, et par

autres, a prins souvent reelle possession de toute la

contrée, et trois et quatre ans avant que jamais les

Angloys ayent habitué, ou que jamais on aye rien

entendu de cette leur vindication." Ceci et plusieurs

autres choses discouroit ledit Sieur de Biancourt encourageant

ses gens.

Now, Monsieur de Biancourt, having heard all this

from the mouth of captain Platrier himself, remonstrated

earnestly with these people, showing how

important it was to him, an officer of the Crown and

his father's Lieutenant, and also how important to

all good Frenchmen, to oppose this usurpation of the

English, so contrary to the rights and possessions of

his Majesty. "For," said he, "it is well known to

all (not to go back any farther in the case) that the

great Henry, may God give him absolution, in accordance

with the rights, acquired by his predecessors

and by himself, gave to Monsieur des Monts, in the

year 1604, all this region from the 40th to the 46th

parallel of latitude. Since this donation, the said

Seigneur des Monts, himself and through Monsieur de

Potrincourt, my very honored father, his lieutenant,

and through others, has frequently taken actual possession

of all the country; and this, three or four

years before the English had ever frequented it, or

before anything had ever been heard of these claims

of theirs." This and several other things were said

by Sieur de Biancourt to encourage his people.

Moy, j'avois deux autres causes qui me poussoyent

au mesme voyage: l'une, pour accompagner [63]

d'ayde spirituel ledict Sieur de Biancourt et ses gens;

l'autre, pour cognoistre et voir la disposition de ces

nations à recevoir le saint evangile. Telles doncques

estoyent les causes de nostre voyage.

As for me, I had two other reasons which impelled

me to take this journey: One, to give [63] spiritual

aid to Sieur de Biancourt and his people; the other,

to observe and to study the disposition of these nations

to receive the holy gospel. Such, then, were

the causes of our journey.

Nous arrivasmes à Kinibequi, 80 lieuës de Port-Royal,

34

le 28 d'octobre, jour de S. Simon et S. Jude,

de la mesme année 1611. Aussy tost nos gens mirent

pied à terre, desireux de veoir le fort des Angloys;

car nous avions appris par les chemins, qu'il n'y

avoit personne. Or, comme de nouveau tout est

beau, ce fust à louër et vanter cette entreprise des

Angloys, et raconter les commodités du lieu; chacun

en disoit ce que plus il prisoit. Mais de là à quelques

jours, on changea bien d'advis; car on vid y avoir

beau moyen de faire un contrefort qui les eust emprisonnés

et privés de la mer et de la riviere; item

que quand bien on les eust laissez là, si n'eussent-ils

point jouy pourtant des commodités de la riviere,

puisqu'elle a plusieurs autres et belles emboucheures

bien distantes de là. Davantage, ce qu'est le pis,

nous ne croyons pas que de là à six lieuës à l'entour

il y ayt un seul arpent de terre bien labourable, le

sol n'estant tout de pierre et roche. Or, d'autant que

le vent nous contrarioit à passer outre, le troisiesme

jour venu, Monsieur de Biancourt [64] tourna l'incident

en conseil et se delibera de recevoir l'ayde du

vent, à refouler contremont la riviere, pour la bien

recognoistre.

35

We arrived at Kinibéqui, eighty leagues from Port

Royal, the 28th of October, the day of St. Simon and

St. Jude, of the same year, 1611. Our people at once

disembarked, wishing to see the English fort, for

we had learned, on the way, that there was no one

there. Now as everything is beautiful at first, this

undertaking of the English had to be praised and extolled,

and the conveniences of the place enumerated,

each one pointing out what he valued the most. But

a few days afterward they changed their views; for

they saw that there was a fine opportunity for making

a counter-fort there, which might have imprisoned

them and cut them off from the sea and river;

moreover, even if they had been left unmolested they

would not have enjoyed the advantages of the river,

since it has several other mouths, and good ones,

some distance from there. Furthermore, what is

worse, we do not believe that, in six leagues of the

surrounding country, there is a single acre of good

tillable land, the soil being nothing but stones and

rocks. Now, inasmuch as the wind forced us to go

on, when the third day came, Monsieur de Biancourt

[64] considered the subject in council and decided to

take advantage of the wind and go on up the river,

in order to thoroughly explore it.

Nous avions advancé jà bien trois lieuës, et le flot

nous manquant nous estions mis à l'anchre au milieu

de la riviere; quand voicy que nous descouvrons six

canots Armouchiquois venir à nous. Ils estoyent

24 personnes dedans, tous gens de combat. Ils firent

mille tentatives et ceremonies avant que nous

aborder. Vous les eussiez parfaictement comparez à

une troupe d'oyseaux, laquelle desire d'entrer en une

cheneviere, mais elle craind l'espouvantail. Cela

nous plaisoit fort, car aussy nos gens avoyent besoin

36

de temps pour s'armer et pavier. Enfin ils vindrent

et revindrent, ils recogneurent, considererent finement

nostre nombre, nos pieces, nos armes, tout; et

la nuict venuë, ils se logerent à l'autre bord du

fleuve, sinon hors la portée, du moins hors la mire

de nos canons.

We had already advanced three good leagues, and

had dropped anchor in the middle of the river waiting

for the tide, when we suddenly discovered six

Armouchiquois canoes coming towards us. There

were twenty-four persons therein, all warriors.

They went through a thousand maneuvers and ceremonies

before accosting us, and might have been

compared to a flock of birds which wanted to go

into a hemp-field but feared the scarecrow. We

37

were very much pleased at this, for our people also

needed to arm themselves and arrange the pavesade.

In short, they continued to come and go; they reconnoitred;

they carefully noted our numbers, our

cannon, our arms, everything; and when night

came they camped upon the other bank of the river,

if not out of reach, at least beyond the aim of our

cannon.

Toute la nuit ce ne fust que haranguer, chanter,

danser; car telle est la vie de toutes ces gens lorsqu'ils

sont en troupe. Or comme nous presumions

probablement que leurs chants et danses estoyent invocations

du diable, pour contrecarrer l'empire de ce

maudict tyran, je fis que nos gens chantassent [65]

quelques hymnes eclesiastiques, comme le Salve,

l'Ave Maris stella et autres. Mais comme ils furent une

fois en train de chanter, les chansons spirituelles leur

manquant, ils se jetterent aux autres qu'ils sçavoyent.

Estant encores à la fin de celles cy, comme c'est le naturel

du François de tout imiter, ils se prindrent à

contrefaire le chant et danse des Armouchiquois, qui

estoyent à la rive, les contrefaisant si bien en tout,

que, pour les escouter, les Armouchiquois se taysoient;

et puis nos gens se taysans, reciproquement

eux recommençoyent. Vrayment il y avoit beau rire:

car vous eussiés dict que c'estoyent deux chœurs qui

s'entendoient fort bien, et à peine eussiés vous pû

distinguer le vray Armouchiquois d'avec le feinct.

All night there was continual haranguing, singing

and dancing, for such is the kind of life all these

people lead when they are together. Now as we

supposed that probably their songs and dances were

invocations to the devil, to oppose the power of this

cursed tyrant, I had our people sing [65] some sacred

hymns, as the Salve, the Ave Maris Stella, and others.

But when they once got into the way of singing, the

spiritual songs being exhausted, they took up others

with which they were familiar. When they came to

the end of these, as the French are natural mimics,

they began to mimic the singing and dancing of the

Armouchiquois who were upon the bank, succeeding

in it so well that the Armouchiquois stopped to listen

to them; and then our people stopped and the others

immediately began again. It was really very comical,

for you would have said that they were two choirs

which had a thorough understanding with each other,

and scarcely could you distinguish the real Armouchiquois

from their imitators.

Le matin venu, nous poursuyvions notre route contremont.

Eux, nous ayans accompagnez, nous dirent

que si nous voulions du piousquemin (c'est leur bled),

que nous debvions avec facilité prendre à droicte, et

non avec grand travail et danger aller contremont;

que prenant à droicte par le bras qui se monstroit, en

peu d'heures, nous arriverions vers le grand sagamo

38

Meteourmite, qui nous fourniroit de tout; qu'ils nous

y serviroient de guides, car aussy bien s'en alloyent

ils le visiter.

In the morning we continued our journey up the

river. The Armouchiquois, who were accompanying

us, told us that if we wanted any piousquemin (corn),

it would be better and easier for us to turn to the

right and not, with great difficulty and risk, to continue

going up the river; that if we turned to the

39

right through the branch which was just at hand, in

a few hours we would reach the great sagamore

Meteourmite, who would furnish us with all we

wanted; that they would act as our guides, since

they themselves were going to visit him.

Il est à presumer, et en avons de grands indices,

qu'ils ne nous donnoyent ce conseil sinon en intention

[66] de nous prendre aux filets, et avoir bon marché

de nous à l'ayde de Meteourmite, lequel ils sçavoient

estre ennemy des Anglois, et le conjecturoient

l'estre de tous estrangers. Mais, Dieu mercy, leurs

embusches se tournerent contre eux.

It is to be supposed, and there were strong indications

of it, that they gave us this advice only with

the intention [66] of ensnaring us, and making

an easy conquest of us by the help of Meteourmite,

whom they knew to be the enemy of the English, and

whom they supposed to be an enemy of all foreigners.

But, thank God, their ambuscade was

turned against themselves.

Cependant nous les creusmes; aussy partie d'eux

s'en alloyent devant nous, partie après, partie aussy

avec nous dedans la barque. Neantmoins Monsieur

de Biancourt se tenoit tousiours sur ses gardes, et souvent

faisoit marcher la chaloupe devant avec la sonde.

Nous n'avions pas faict plus de demy lieue, quand,

venus en un grand lac le sondeur nous crie: "Deux

brasses d'eau, qu'une brasse, qu'une brasse partout."

Aussy tost: Ameine, ameine, lasche l'anchre. Où

sont nos Armouchiquois? où sont-ils? point. Ils

nous avoyent trestous insensiblement quittés. O les

traistres! ô que Dieu nous a bien aydés! Ils nous

avoyent conduicts aux pieges. "Revire, revire."

Nous retournons sur nostre route.

However, we believed them; so a part of them

went ahead of us, part behind, and some in the

barque with us. Nevertheless Monsieur de Biancourt

was always on his guard, and often sent the boat on

ahead with the sounding-lead. We had not gone

more than half a league when, reaching a large lake,

the sounder called out to us: "Two fathoms of

water; only one fathom, only one fathom everywhere,"

and immediately afterward, "Stop! stop!

cast anchor." Where are our Armouchiquois?

Where are they? Not one. They had all silently

disappeared. Oh, the traitors! Oh, how God had

delivered us! They had led us into a trap. "Veer

about, veer about." We retrace our path.

Cependant Meteourmite ayant esté adverty de

nostre venue, nous courroit au devant, et quoyqu'il

nous vist tourner bride, si est-ce qu'il nous poursuyvit.

Bien valut à Monsieur de Biancourt d'etre plus

sage que plusieurs de son esquipage, qui ne crioyent

lors que de tout tuer. Car ils estoyent en grande

cholere et en non moindre crainte; mais la cholere

faisoit plus de bruit.

Meanwhile, Meteourmite having been informed of

our coming, came to meet us, and, although he saw

our prow turned about, yet he followed us. It was

well that Monsieur de Biancourt was wiser than many

of his crew, whose sole cry was to kill them all. For

they were as angry as they were frightened: but

their anger made the most noise.

[67] Monsieur de Biancourt se reprima, et ne faisant

pas autrement mauvaise chere à Meteourmite,

40

apprit de luy qu'il y avoit une route par laquelle on

pourroit passer; qu'à celle fin de ne la pas faillir, il

nous donneroit de ses propres gens dedans nostre

barque; qu'au reste vinssions à sa cabane, il tascheroit

de nous donner contentement. Nous luy crusmes,

et pensasmes nous en repentir; car nous passasmes

des haults et destroicts si perilleux que ne cuidions

quasi jamays en eschapper. D'effect, en deux endroits,

aucuns de nos gens s'escrierent miserablement

que nous estions trestous perdus. Mais, Dieu

mercy, ils crierent trop tost.

[67] Monsieur de Biancourt restrained himself, and

41

not otherwise showing any ill-will toward Meteourmite,

learned from him that there was a route by

which they could pass; that in order not to miss it,

he would let us have some of his own people in our

barque; that, besides, if we would come to his wigwam

he would try to satisfy us. We trusted him,

and thought we might have to repent it; for we traversed

such perilous heights and narrow passes that

we never expected to escape from them. In fact,

in two places some of our men cried out in distress

that we were all lost. But, thank God, they cried

too soon.

Arrivés, Monsieur de Biancourt se mit en armes,

pour en cet arroy aller veoir Meteourmite. Il le

trouva en son hault appareil de majesté sauvagesque,

seul dans une cabane bien nattée le haut et

bas, et quelques quarante puissans jeunes hommes à

l'entour de la cabane, en forme de corps de garde,

chacun son pavois, son arc et flesches à terre au

devant de soy. Ces gens ne sont point niais, nullement,

et qu'on nous en croye.

When we arrived, Monsieur de Biancourt armed

himself, and thus arrayed proceeded to pay a visit to

Meteourmite. He found him in the royal apparel of

savage majesty, alone in a wigwam that was well

matted above and below, and about forty powerful

young men stationed around it like a body-guard,

each one with his shield, his bow and arrows upon

the ground in front of him. These people are by no

means simpletons, and you may believe us when we

say so.

Pour moy, je receus, ce jour là, la plus grande part

des caresses; car, comme j'estois sans armes, les

plus honorables, laissans les soldats, se prindrent à

moy avec mille significations d'amitié. Ils me conduysirent

en la plus grande cabane de toutes; [68]

elle contenoit bien 80 ames. Les places prinses, je

me jettay à genoux, et ayant faict le signe de la

croix, recitay mon Pater, Ave, Credo, et quelques

oraisons; puis, ayant faict pause, mes hostes, comme

s'ils m'eussent bien entendu, m'applaudirent en leur

façon, s'escriant Ho! ho! ho! Ie leur donnay quelques

croix et quelques images, leur en donnant à

apprehender ce que je pouvois. Eux les baysoient

42

fort volontiers, faisoyent le signe de la Croix, et,

chacun pour soy, s'efforçoyent à me presenter ses

enfans, à ce que je les benisse et leur donnasse quelque

chose. Ainsy se passa cette visite, et une autre

que je fis depuis.

As for me, I received that day the greater part of

the welcome; for, as I was unarmed, the most honorable

of them, turning their backs upon the soldiers,

approached me with a thousand demonstrations of

friendship. They led me to the largest wigwam of

all; [68] it contained fully eighty people. When

they had taken their places, I fell upon my knees

and repeated my Pater, Ave, Credo, and some orisons;

then pausing, my hosts, as if they had understood

me perfectly, applauded after their fashion, crying

Ho! ho! ho! I gave them some crosses and pictures,

explaining them as well as I could. They very

43

willingly kissed them, made the sign of the Cross,

and each one in his turn endeavored to present his

children to me, so that I would bless them and give

them something. Thus passed that visit, and another

that I have since made.

Or Meteourmite avoit respondu à Monsieur de

Biancourt, que pour le bled, ils n'en avoyent pas

quantité; mais qu'ils avoyent aucunes peaux, s'il luy

playsoit de troquer.

Now Meteourmite had replied to Monsieur de

Biancourt that as to the corn he did not have much,

but he had some skins, if we were pleased to trade

with him.

Le matin doncques de la troque venu, je m'en allay

en une isle voysine avec un garçon, pour là offrir

l'hostie saincte de nostre reconciliation. Nos gens

de la barque, pour n'estre surprins, soubs couleur de

la troque, s'estoyent armez et barricadez, laissans

place au milieu du tillac pour les Sauvages; mais en

vain, car ils se jetterent tellement en foule et avec si

grande avidité, qu'aussy tost ils remplirent tout le

vaisseau, jà peslemeslés avec les nostres. On se mit

à crier: Retire, retire-toy. Mais [69] à quel profit?

Eux aussy crioyent de leur costé.

Then in the morning when the trade was to take

place I went to a neighboring island with a boy, to

there offer the blessed sacrament for our reconciliation.

Our people in the barque, not to be taken by

surprise under pretext of the trade, were armed and

barricaded, leaving a place in the middle of the deck

for the Savages; but in vain, for they rushed in in

such crowds and with such greediness, that they immediately

filled the whole ship, becoming all mixed

up with our own people. Some one began to cry out,

"Go back, go back." But [69] to what good? On

the other hand, the savages were yelling also.

Ce fut lors que nos gens se penserent estre veritablement

prins, et jà tout n'estoit que clameur et tumulte.