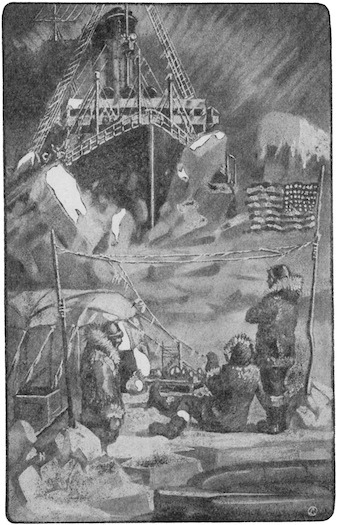

Shoulders squared, head up, young Renaud stood beneath his wireless aerial.

Title: Stand By: The Story of a Boy's Achievement in Radio

Author: Hugh McAlister

Release date: April 25, 2014 [eBook #45490]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Shoulders squared, head up, young Renaud stood beneath his wireless aerial.

| I | The Crystal Wheel |

| II | Strange Experiments |

| III | Hot Wires |

| IV | The Gang Takes a Hand |

| V | Taps |

| VI | Amazing Things |

| VII | Harnessing Lightning Power |

| VIII | Compressed Power |

| IX | Sargon Sound |

| X | A Pencil Line |

| XI | A Mysterious Call |

| XII | The Nardak |

| XIII | Within the Silvery Hull |

| XIV | Danger Ahead |

| XV | Shagun |

| XVI | Quest for Camp |

| XVII | Besieged |

| XVIII | Prospecting |

| XIX | In the Gondola |

| XX | F-O-Y-N |

| XXI | Killers of the Arctic |

| XXII | Hope and Despair |

| XXIII | Fighting Through |

| XXIV | On to Glory |

| XXV | From the Desert of Ice |

There it stood—a great glass wheel, half submerged in the dusty clutter of an old outhouse filled with broken chairs, moth-eaten strips of carpet, and a tangle of ancient harness. Lee Renaud, spider webs draping his black hair and the dust of ages prickling at his nose, persisted in his efforts to clear this strange mechanism of its weight of junk.

At last it was freed, a three-foot circular sheet of glass mounted on a framework of brass and wood. Held against the wheel by slips of wood were pads of some kind of fur, now worn to a few stray hairs and bits of hide. The circle of glass turned on an axis of wood which passed through its center, and attached to this was a series of cogwheels and a handle for cranking the whole affair—at considerable speed, it appeared.

Lee Renaud backed off a bit as he stared at the thing. Glittering in the dim sunlight that filtered into the storage shed, it looked strange, almost sinister.

But then the boy had found everything here at King’s Cove strange and outlandish. King’s Cove! It sounded rather elegant. Instead, it consisted of a handful of shacks that housed a little village of farming and fishing folk, an ignorant people given over to poverty and superstition. King’s Cove had been aristocratic in its past. A fringe of rotting, semi-roofless “big houses” up beyond the cove testified to the long-gone past when a settlement of rich folk had set out great orange orchards and camphor groves in that strip of South Alabama that touches the Gulf of Mexico. All had gone well until the historic freeze of 1868 had ruined the tropic fruits and emptied the purses of the settlers. After that, the population steadily drifted away from King’s Cove. Squatters came in to fish and to scratch the soil for a living.

Of all the old-timers only Gem Renaud remained. He loved the semi-tropic climate, the great oaks swathed in Spanish moss, the bit of sea that indented his land. He preferred remaining in poverty to moving elsewhere and beginning life over again. So he lived on in a white-columned old house that year by year got more leaky and more warped.

Then Gem Renaud had slipped and injured his leg. And Lee Renaud had been sent down by his family to look after his Great-uncle Gem.

Lee’s home was in Shelton, a pleasant and progressive town. Lee’s mother was a widow. Her two older boys were already at work. This vacation, Lee had counted on his first steady job, work at a garage. But because he was not already working and could be spared most easily, the lot had fallen on him to be sent down to King’s Cove.

And here at King’s Cove the boy felt that he had stepped back into the past a hundred years or more—the queer ignorant villagers; no electricity, only candles and little old kerosene lamps; no automobiles, only wagons drawn by lazy, lanky mules or by slow oxen; homemade boats on the bay and bayou; Uncle Gem’s great tumble-down old house where Pompey, the negro that cooked for him, lighted homemade candles in silver candlesticks and served meager meals of corn pone and peas in china that had come from France three-quarters of a century ago.

When Lee went down to the shack of a country store for meal or kerosene, the village loafers looked “offishly” at the tall boy with close-clipped black hair, knickers, and sport cap usually swinging in his hand. Lem Hicks, the storekeeper’s boy, Tony Zita, one of the fishing folk, and other lanky youths, barefooted and in faded overalls, seemed to have no particular interest in life save to lounge on boxes in front of the store and spit tobacco juice into the dust. Sometimes when Lee passed the line of loafers, he caught remarks muttered behind his back—“Stuck-up! Thinks he’s citified, ain’t he!” Once when Lee got home, he found mud spattered on his “store-bought” clothes—and he hadn’t remembered stepping in a puddle either!

Uncle Gem was a queer figure himself. The tall, stooped old man with his sideburns, his chin-whiskers, his long-tailed coat of faded plum color, was a prisoner of his chair now.

As Lee, all dusty and cobwebby, burst in from the storage room, his questions about the strange crystal wheel woke a gleam of excitement in the old man’s eyes.

“The glass wheel—you never saw anything like it before, eh?” Uncle Gem’s long fingers tapped the chair arm. “Gadzooks! That was our old-time 'lightning maker.’ My brothers and I had a tutor, one Master Lloyd, a Welshman, and a very conscientious, thorough little man. He used this mechanism to prove to us boys that electricity, or 'lightning power,’ as he dubbed it, could be tapped by mankind.”

“And did he—could he?”

Great-uncle Gem nodded emphatically.

Lee Renaud’s own black eyes lighted with excitement, too. Electricity! Why, he was so used to it that he had always just taken it for granted—electricity for lights, cars, telephones. And yet here was a man in whose childhood it had been a mere theory, a something to be gingerly toyed with.

But that old wheel must hold power—or rather man’s groping after power.

“Wonder if I could make electricity with it?” Lee was thinking aloud.

“Umph, of course, if there’s enough left of the old mechanism to hitch it up right. I could show you—ouch! Confound that leg!” In his interest in electricity, the old man had forgotten his injury and had tried to put his foot to the floor.

“Wait, wait, Uncle Gem! Pompey and I can carry you, chair and all.”

The darky and Lee finally did achieve getting Mr. Renaud down the steps and out to the dusty, cluttered storehouse. Then Pompey departed for his kitchen, muttering under his breath, “Glad to get away. Pomp don’t mix in with no glass wheel and trying to conjure lightning down out of the sky.”

“Pomp’s not very progressive,” old Gem Renaud smiled wryly. “Lots of other folks around here too that are superstitious about this business of trying to get electricity out of the air with a piece of glass.”

For the rest of that day and for other days to come, the work of renovating the strange old wheel went forward. There was more to be done than one might think for, and so little with which to do the repairing. Propped in his chair, old Gem directed, and Lee, scraping up such crude material as he could in the cast-off junk about the place, tried to carry out his orders.

A brass tube, set in a standard of glass and branching forward so that its two arms nearly touched the crystal plate, had once been set with rows of sharp wires like the teeth of a comb. Most of these were missing now, and Lee spent the better part of one day resetting the empty sockets with metal points patiently hacked from a bit of old barbed wire fencing.

Next, the moth-eaten pads of fur must be replaced.

“Glass and fur,” puzzled Lee. “That’s a strange combination.”

Gem Renaud tugged at his chin-whisker while his mind went searching back into the past. “That book of science, we studied as boys, explains it, if I can just remember. It was something about 'a portion of fair glass well rubbed with silk or fur or leather begets this electrica.’”

“Why, there seem to be all kinds of rubbers or exciters. I reckon though, since fur was used on this contraption at first, fur is what we better use again.” Lee Renaud got up and stretched his legs, then went outside.

He had remembered seeing some squirrel skins tacked to old Pomp’s cabin door. And now he was going forth to do some bargaining.

“Hey, Pompey,” the boy held out his best silk necktie, “how about trading me those skins for this?”

The bright silk was most beguiling. The negro hesitated a moment, then capitulated.

“Yas, sir, I’d sho like to swap. I—I reckon I might’s well trade. You take along them skins, but please, sir, don’t connect me in no way with any glass wheel conjuring you might be using those squirrel pelts for.”

Restraining his laughter, Lee solemnly agreed and soon departed, carrying four good pelts with him. He cut out good-sized pieces of the fur and nailed these on the four blocks of wood that had held the original fur pads. Then he fixed the blocks back in their places on the frame so that the revolving glass would brush between the two pairs of pads, one pair at the top, and one pair at the bottom.

Cogwheels had to be geared up and a new handle made to replace the old one that had rotted. It was dusk of day before Lee Renaud was ready to test out the ancient “lightning maker.” Great-uncle Gem sat erect and eager in his chair. Pompey stood in a far corner, holding a candle for light, rolling his eyes in something of a fright, but sticking by to see after Marse Gem, no matter what happened.

Lee’s heart half smothered him with its excited pounding.

Creak of rusty cogs, whirl of the wheel, fast, faster!

All in a tremble, young Renaud brought his knuckle near to the row of metal points set so close to the revolving disc. His hand was still a space from the metal when with a sharp crackle a spark leaped across.

He had done it! He was making electricity—like those old experimenters! Lee burst into a wild shout.

With a sudden booming detonation, a gunshot roared across the little room, dwarfing every other sound. So close it was that Lee Renaud felt a bullet almost scorch across his face, and heard it thud viciously against a wall. Pomp’s candle clattered to the floor, went out. There came a sound as though Great-uncle Gem had slumped across his chair.

Outside, stealthy footsteps made off into the darkness.

The shot that rang out in the night was echoed by a yell from Lee, who dropped in a huddle beside the glass wheel. For a moment he crouched there, fighting against a wild desire to crawl back under the clutter of rubbish, and hide. What did it all mean? In the dark silence beyond the open window, what manner of fiend was waiting to shoot down innocent people?

But a muttering and moaning and sounds of difficult breathing came to him from other parts of the room. Uncle Gem, old Pomp, both of them might be wounded, dying! He couldn’t crouch here like a craven and leave them to their fate. Lee forced himself to action. He began to crawl across the room to where he knew there were some matches and a candle. Fumbling around in the dark, he at last got the candle lighted, stood up and looked about him.

Pompey, face downwards upon the floor, was moaning loudly, “Lordy, Lordy, the lightning of the air done struck us, like I knowed it would—”

“Lightning nothing! Don’t you know a gunshot when you hear one?” burst from Lee. “If you’re not hurt yourself, come help me quick with Uncle Gem—he looks like he’s dead!”

“Oh, Marse Gem, is you kilt?” Pomp, who had suffered no injury save fright, rolled to his feet and came on the run, his kindly old black face all distorted with grief.

Indeed Gem Renaud did look like one dead. He hung slumped sideways, half fallen out of his chair. His drawn face was ashen, his hands limp and cold.

But, though Lee searched frantically, he could find no sign of gunshot wound or oozing blood. Together he and Pompey laid the long figure out at ease on the floor, sponged the face with a wet handkerchief, and rubbed hands and wrists. At last old Gem Renaud opened his eyelids with a slow, tired movement. Then he motioned Lee to prop him up into sitting position.

“Just fainted—heart not so good! This shooting—must have been that old fool, Johnny Poolak—taking another shot at the glass wheel—”

“Sh-shooting at the wheel?” stammered Lee. “What for?”

“What for? For superstition mostly,” old Gem Renaud’s black eyes snapped angrily, “and some for meanness, too!”

As Great-uncle Gem regained his strength, he told about this Poolak, the half-wit, full of fool religions and imbued with all the superstitions that ignorant people hold to. The rest of the uneducated squatters here in the village were about on this level too. Once, long ago, when Renaud had been experimenting with his crude electrical devices, a cyclone swept the fringes of the town. Immediately the ignorant villagers coupled the crystal wheel with the disaster, and Poolak, bent on destroying the source of evil, took a shot at the “lightning maker.”

“Evidently,” went on Gem Renaud, “old Poolak has noted your work out here and thinks you’re all set to bring on another cyclone and so has taken another shot at the contraption. If you’ll dig out the bullet that’s imbedded in the wall beyond our wheel of glass, I’ll wager that you’ll find it’s a silver bullet. Silver is the only weapon to down witchcraft according to all the old superstitions, you know.”

That night, before he went to bed, Lee slipped down to the old storage room. There, by the light of a candle, he pried with his knife blade into the wall just beyond the crystal wheel. And sure enough, the bullet that he dug out was not made of lead, but of silver. A rough lump that old Poolak must have molded for himself, melting down a hard-earned twenty-five cent piece, most likely! The silver bullet on his palm gave Lee Renaud a queer sensation, a feeling that he had stepped very far back into a past peopled with eerie fears and superstitions.

The next day Lee moved the whole apparatus of the glass wheel into an unused room on the second floor of the dwelling house. It was safer up there. A fellow didn’t have it hanging over his head that a pious old ignoramus was liable to shoot up one’s affairs again with silver bullets.

The wheel, with its wooden base and brass tubes, was heavy, so Lee carried it over piecemeal. This taking it apart and putting it back together again gave young Renaud a much better knowledge of it than he had had heretofore. There was the hollow brass prime conductor, supported on its glass standard and so fixed on its frame that the metal points set on the ends of its curved out-branching arms nearly touched the glass plate. Lee knew that in some way the metal points collected the electricity generated on the glass whirl of the plate and conveyed this electricity to the hollow brass collector. But there was something else he needed to know.

“Uncle Gem,” he questioned, “why is a little chain hung from the fur cushions so as to just dangle down against the floor—what’s it good for?”

“Gadzooks, boy! You can ask more questions in a minute than I can answer in a year.” Great-uncle Gem tugged at his militant chin-whisker. “Wish I could lay hands on Master Lloyd’s old schoolbook on the sciences. It explains lots. Let me see, though, it goes something like this. By the friction of the whirling glass plate against the fur cushions, electricity is developed—the glass plate becomes positively electrified, and the cushions negatively—”

“Positive, negative—positive, negative,” muttered Lee Renaud, shaking his head as if he didn’t quite take it all in.

“Be quiet, sir!” ordered Uncle Gem testily. “Now that I’ve started remembering this blamed thing, I want to finish my say. Without the chains, the cushions are insulated, and the quantity of electricity which they generate is limited, consisting merely of that which the cushions themselves contain. We conquer this by making the cushions communicate with the ground, the great reservoir of electricity. To do this, we merely lay a chain attached to the cushions on the floor or table. After this connection is made, and the wheel is turned again, much more electricity is conveyed to the conductor. Now, young man, do you see?”

“I—I’m much obliged, Uncle Gem. Reckon I took in a little of it.” Lee blinked dazedly and off he went, still muttering under his breath, “Positive, negative—positive, negative.”

That old science book Uncle Gem was always talking about—if he could only find it, he could learn something. For the rest of the day Lee poked around in the dim and dusty attic high up under the eaves of the big house. Now and again he brought down some volume to submit to Uncle Gem’s inspection. But always Gem Renaud shook his head—no, that was not it, not THE BOOK.

Then at last Lee found it, a great calfskin-bound old volume stored away at the bottom of a trunk. Even before he carried it to Uncle Gem, he had a feeling this was the right one. It was so full of strange old illustrations, it was so ponderous—of a truth, it had to be ponderous to live up to its name, “Ye Compleat Knowledge of Philosophy and Sciences.”

Gem Renaud’s hands shook with excitement as he took hold of the ancient tome that had played so large a part in his long gone childhood training.

“Here’s a whole education between two covers. Just listen to the index.” Old Renaud began to read, “Astronomy, Catoptrics, Gyroscope, Distance of Planets, Intensity of Sound, Solar Spectrum—”

“And electricity, there’s plenty about that too, isn’t there?” Lee Renaud couldn’t help but break in.

“Yes, yes,” Gem Renaud agreed with him absently, and went on flipping through the pages. “How natural they all look, the old illustrations, the waterwheel, undershot and overshot, the waterchain, the turbine engine! It seems just yesterday that Master Lloyd, the Welshman, had us boys all down at the creek building these mechanisms out of canes and what-not, building them so as they’d really work, to prove to him that we understood what he was trying to teach us.”

“And did you build electrical things too?”

“Why, yes. Master Lloyd sent all the way back to New York to get the proper materials for us.”

Materials from New York! Lee turned away in disappointment. He had been hoping to experiment some with electricity himself, but what had he out here to work with?

Later in the day Lee picked up the old book again and plunged into its strange, stilted dissertation on electricity. He learned that away back in 1745, von Kleist, a priest in Pomerania, had experimented with a glass jar half full of water, corked, and a long nail driven through the cork to reach down into the water. When the old Pomeranian priest touched this nail head to a frictional machine, he got a “shock” that made him think the jar was full of devils. And that ended experimentation for him. But the next year two Hollanders, professors at Leyden University, carried von Kleist’s experiment forward till they developed the Leyden Jar, a practical method for storing electricity.

To Lee Renaud, stumbling upon all this old knowledge, it seemed that he himself was just discovering electricity. For most of the fifteen years of his life, he had merely accepted electricity as an ordinary, everyday thing. Now the real glory of it smote him, thrilled him, inspired him. He longed desperately to try out these primitive experiments for himself. Here on these pages was given the beginning of man’s knowledge of electricity, the beginning of man’s struggle to harness this mighty power into usefulness.

If only he could “grow up” with this marvelous power, understand it, step by step! A large order, indeed! Especially for a youngster stuck off in the backwoods.

But anyway, Lee Renaud flung young enthusiasm and will power into this strange task he was setting for himself.

Already he had the crystal wheel that could make a spark, that could generate electricity. But unless that electricity could be “stored,” it had no usefulness. So it was up to him to make an electrical condenser. But of what?

Umph, well, those old fellows in the past had gone right ahead and used such things as came to hand—and he was going to do the same thing.

Lee studied the chapter on electricity in “Ye Compleat Knowledge of Philosophy and Sciences” until he could almost say it by heart. Jar of fair glass, brass rod “compleated” with a knob, wooden stopper, sheets of substance tinfoil, chain of brass, three coiled springs—these were the things Lee needed to make the Leyden Jar, which was to be his first forward step in electricity.

Desperately he ransacked the place for “laboratory material” and finally gathered together an old metal door knob, an empty fruit jar, a few links of small chain, some tin cans and bits of wire. It didn’t look very scientific—that pile of junk!

But Lee Renaud set his jaw doggedly, and got down to work. Since he had no “substance tinfoil,” he figured that perhaps pieces of tin from old tin cans might do. So he slit down a can, and cut it nearly all the way off from its bottom. The round bottom he patiently trimmed till it would just slip in through the neck of the jar. By rolling the tin sides smaller, he managed to push the whole affair down into the jar, where the released roll of the tin sprung itself out to fit neatly against the inside surface of the glass. Then the outside had to be “tinned” and Lee kept trying until he found a can that was a good tight fit when the jar was pushed down into it.

And there, he had made a start! Instead of tinfoil, the jar was at least covered in tin in the prescribed manner two-thirds of the way up, inside and outside.

Instead of “ye brass rod” that the old book called for, he used a length of wire which he “compleated” with the old brass door knob. He thrust this wire through a wooden stopper he had whittled to fit the mouth of the jar. He had no metal springs, but decided to make the contact with the bit of chain fastened to the end of the wire. When this was thrust down into the jar, the little chain rested on the tin bottom, which was still in part connected with the tin side lining.

Lee Renaud had worked terrifically hard at his job, but now that he stood back to inspect the finished product, it looked more like junk than ever. It didn’t seem humanly possible that such a thing could be an adjunct to collecting power, to storing the marvel of electricity.

Half-heartedly Lee held the knob of the jar to the metal points set against the crystal “friction maker.” After a few minutes of this, he grasped the jar in his left hand and experimentally approached his right thumb towards the knob.

There came a scream and a rattle of glass and tin as the jar was flung from Lee’s hand to smash into a hundred bits on the floor. The boy leaped high in the air and came down, apparently trying to rub himself in six places at the same time.

Lee’s screech and the crashing clatter of glass and tin brought old Pompey on the run to see what the “devils in the jar” had done now to Marse Lee.

From the next room sounded the pounding of Uncle Gem’s cane as he thumped the floor to summon someone to tell him what was happening.

Lee hurried to his uncle, looking rather sheepish, and rubbing his elbow where the “prickles” still tingled.

“No, sir, not hurt; just got kicked a little,” he reassured the old man. “That thing I made looked mighty innocent, but it had power to it—more’n I thought for.”

Lee Renaud’s first experiment lay smashed all over the floor, but he didn’t care. He could make another Leyden Jar, for he still had the shaped pieces of tin, the knob, and the rest of the necessities. In spite of the smash, he was terrifically thrilled—he had tapped power, real power that time! He had learned something important too: electricity was not anything to be played with. It was as dangerous as it was powerful.

With his next Leyden Jar, Lee went forward more carefully. There was a contrivance of his own that he wanted to try out this time, too.

And a very crude contrivance it was—nothing more than a length of wire and two long slivers of a broken window pane.

The boy gave the wire a twist around the outer tin and left one end free. Then he charged the inner tin negatively at the friction machine, and the outer tin (wire and all) positively, at the positive pole of the mechanism.

Next, oh so carefully, gripping the free end of the wire between the two strips of glass—he didn’t crave any more shocks like that first one—he brought the wire close, and closer up towards the brass knob.

Before he could ever touch wire to knob—Wow! There it came! Snap, crackle, across the air-gap shot a spark an inch long!

Lee’s hands trembled a little as he laid aside his glass pincers. Sure enough, he had done something this time. That was such lively electricity he had gotten penned up in the glass jar that it couldn’t wait for any connecting metallic pathway to be made but had to go leaping across the air-gap.

Power! Power! He was tapping it—and getting a wild excitement out of the job.

It was all true! True! Just like the old book said!

And the musty, ancient volume was full of queer diagrams and elegantly stilted descriptions of other strange experiments. As he turned the pages, Lee Renaud longed to try out more of these things—all of them, if possible.

“Think of it!” Lee muttered admiringly. “That old fellow, Volta, without any friction wheel at all, just piled up some metal and wet cloth and got an electric current! By heck, I want to try that! I want to make a 'Voltaic Pile,’ too!”

The makings of the Voltaic Pile sounded simple enough. Just some discs of iron and copper piled up with circles of wet flannel placed in between. Volta had connected his iron discs and his copper discs with two different wires. Next he touched the ends of the two wires together, and—hecla! He found that electricity began to flow between the copper and the iron.

But when he started out on the hunt for this material, Lee soon ran aground. He got some pieces of iron all right, and as for flannel, a moth-eaten wool shirt in an attic trunk would do for that. But the copper—there seemed to be none anywhere on the whole Renaud place.

Finally old Pompey came to the rescue.

“I don’t know nothing 'bout copper, but you might find it down in Marse Sargent’s junk pile. He’s been dead a long time, but he sho must a throwed away a heap of stuff in his day. Folks been carrying off what-not-and-everything from that junk pile in the gully for years—and there’s still yet junk left there smothered down in the weeds and the bushes.”

Following Pompey’s directions, young Renaud strode along the little woods path that the old darky had pointed out to him. At first he went forward whistling gayly, but after a while the spell of the forest laid its silence upon him. Sometimes the narrow trail wound through the piney woods where a little breeze soughed mournfully in the tree tops and the afternoon sun slanted downwards to cast a weaving of shadows upon the ground. Then again the little path dipped into close glades of live oak where the long gray moss dripped down from the branches, and where the sunshine could scarce penetrate to dapple the shadows. It was eerie out here in the woods, and silent—no, not exactly silent either. Now and then a bird call drifted on the air. And occasionally there came a slight crackle of brush. Now Lee heard it off to the side of him, now directly behind. Was that a stealthy padding, a footstep—was he being followed?

Time and again the boy whirled around quickly, but never could catch sign of any movement whatever, or of any hulking form lurking back in the shadows.

He was being foolish, that was all. He kept telling himself that it was just the soughing of the pine boughs, the ghostly, shaking curtain of the long moss that had gotten on his nerves. Best thing for him to do was to keep his mind on what he had come for, and wind up his business out here in the woods.

It was all as old Pomp had said. Just beyond the scarred snag of the lightning-blasted pine, a flat-hewn log lay across the gulch for a foot-bridge. Then a “tollable piece” on down the gully, where it wound in close behind what had once been a rich man’s house, Lee found a fascinating tangle of cast-offs partly buried in matted vegetation and drift sand. One wheel and the metal skeleton of what once must have been a dashing barouche, debris of broken china and battered kitchen utensils, rusted springs, a splintered table leg—a little of everything reposed here!

As Lee dug into the tangle of junk and vines, there came again the cautious crackle of a twig. Someone was watching him. He was sure of that. But why—what did it mean?

It was after he had started home that the mystery solved itself somewhat for him. Lee was stepping along in the dusk, rather jubilant over having unearthed an old copper pot. Its lack of bottom didn’t matter—all he wanted was copper. And he hoped a bent strip of metal was zinc. Volta had used zinc in another experiment.

Lee strode forward, full of plans of what he was going to try next. Then a tingle of fear knocked plans out of his head as the bushes parted and a hand reached out and grabbed him by the pants leg.

All manner of things flashed through Lee Renaud’s mind. Remembering how loungers at the store had looked their dislike of him, and how Poolak had carried prejudice further and had taken a shot at his friction-wheel experimenting, Lee had full reason to tingle with fear at that clutching hand. Stealthy footsteps had dogged him all up and down these woods, and now he was being dragged off.

The boy stiffened and tightened his grip on the copper pot. He’d put up a fight against whatever was happening to him!

Then as the bushes parted more fully and Lee saw the owner of the clutching hand, he almost dropped the pot in his surprise. A wizen-faced, shock-headed youngster stood before him, one arm uplifted as if to shield his face.

“You—you don’t look so turrible,” said the child. “I bin following you all evening, and you don’t look so harmful. Anyhow, Jimmy Bobb allowed he wanted to set eyes on you, and I come to take you to him—”

“Jimmy Bobb, who’s he? What does he want with me?” queried Lee.

“Jimmy’s my older brother, only he ain’t near so big as me. He had infantile para—para something—”

“Paralysis, was it?” put in Lee.

“Yeah, that’s what a doctor what saw him one time said it was. But Johnny Poolak, him that preaches when the spell gets on him, said it warn’t nothing but tarnation sin what twisted Jimmy all up. I dunno. But Jimmy, he can’t move by himself, just got to sit one place all the time. He heard ’em talking 'bout you. He don’t never see nothing much and he wanted to see you. But promise you won’t conjure up no imps, no nothing and hurt him.”

Lee Renaud felt a wave of pity for the bleak existence of the crippled one, though caution stirred in him too. He didn’t exactly like to mix in with these Cove people. In every meeting with them, he had sensed their antagonism toward him. If he happened to tread on the toes of their ignorance and superstition, why, like as not they’d fill him full of buckshot! He turned back into the path that led toward home.

“Say, you, ain’t you coming?” The child clung to him with desperate, clutching hands. “Jimmy, he’s so powerful lonesome. He said to me, 'Mackey, you go git that there furriner and bring him down here. Folks tell how he’s got store-bought clothes and slicks his hair and looks different an’ all. And I ain’t never seen nothing different in all my life.’ And I promised Jimmy I’d get you. Please, mister, you—you—”

“I—yes.” The child was so insistent that Lee Renaud found himself following down the path. This by-trail twisted in and out through some thickets and suddenly came out before the clean-swept knoll whereon was perched Mackey Bobb’s home.

Lee Renaud may have thought he had seen poor folks before, but now he found himself face to face with real poverty. The dwelling was a square log cabin with a log lean-to on behind. Inside was bareness save for a homemade bedstead spread with a faded old quilt and one chair set by the window opening that had no glass but merely closed with a heavy shutter of wooden slabs. Although it was summer, a fire blazed up the mud-and-wattle chimney. Before it knelt a lanky woman in a faded wrapper and a sunbonnet, frying something in a skillet.

Lee had met these Cove women now and then out on the road, as they carried eggs or chickens to the store to barter for store-bought rations. Always they had on wide aprons and sunbonnets. He hadn’t known they wore these flapping bonnets in the house too.

The woman rose languidly from her supper cooking and came across the room. She looked worn out and old without being old. Her clothing was awkward and her hands were work-roughened, yet she held to a certain dignity.

“Howdy. I’m right thankful to you for coming,” she said. “Jimmy here has been pining for a sight of you. He don’t never get to see much.”

Then Lee saw Jimmy, the prisoner of the old homemade armchair by the window opening. The boy’s limp, twisted legs told why he was a prisoner. The body was undersized, and the face was old with pain, but Jimmy Bobb’s dark blue eyes were eager, interesting eyes.

“You, Mackey,” ordered the woman, “draw out the bench from the shed room. And now, mister,” extending her hand, “lemme rest your hat, and you set and make yourself comfortable.”

When he had first stood on the threshold of this house of poverty, Lee Renaud had thought he was going to be embarrassed with people so different from any he had ever known. But here he found genuine courtesy to set him at ease. More than that, the terrible eagerness in Jimmy Bobb’s eyes turned Lee Renaud’s thoughts entirely away from Lee Renaud. This Jimmy Bobb knew so little, and he wanted to know so much.

“Is it rightly true,” burst from Jimmy before Lee had hardly got settled on the bench, “that you got a whirling glass contraption up at the big house what pulls the lightning right down out of the sky?”

“Well,” Lee tugged at his chin in perplexity. How in Kingdom Come was he, who knew so little about electricity, going to explain it to a fellow who knew even less? “Well,” Lee made another start, “it’s kind of this way. The glass wheel when turned very, very fast between some fur pads, or rubbers, generates a spark of power called electricity. Smart men have proved that this electricity that we generate and the lightning that flashes in the sky are full of the same kind of power. Lightning, you know, shoots through the air in zigzag lines.”

“I know. I’ve watched it often. It goes like this,” and the excited listener made sharp, jerky motions with his hand.

“That’s it. And the electrical discharge from a man-made battery shoots out jagged, too, like the lightning. Lightning strikes the highest pointed objects. Electricity does that too. Lightning sets fire to non-conductors, or rends them in pieces. Lightning destroys animal life when it strikes, and electricity acts just that way—”

“It sounds turrible powerful,” muttered Jimmy Bobb. “What and all you going to do with this here power you are getting out of the air?”

“Nothing in particular,” said Lee ruefully. “I haven’t managed to get any too much of it. But back in the town where I have always lived, there are plenty of folks brainy enough to make electricity do lots of work for them. It makes bright lights and runs telephones and street cars and talking machines—”

“How might a street car look? Tele—telephone, what’s that?”

So the eager questioning went. Lee Renaud found himself leaping conversationally from point to point, drawing word-pictures of a host of everyday conveniences that had seemed so commonplace to him but that seemed almost like magic when recounted to this boy who had never seen anything.

In the midst of all this talk, Sarah Ann Bobb, Jimmy’s mother, still in the flopping sunbonnet, came forward bearing a tin platter set with the usual Cove meal of corn pone and fried hog-meat. “Set and eat,” she said hospitably.

“I—thank you, ma’am, no—” Lee leaped up in confusion. He hadn’t known he was talking so long. Night had dropped down upon him. “Uncle Gem—he’ll be worried—doesn’t know where I am, or what might have happened to me. I—I reckon I better trot along,” Lee stammered, as he reached for his cap that was “resting” where the woman had hung it on a wall peg.

“You, Mackey,” said Sarah Ann Bobb with her kind, crude courtesy, “draw out one of these here pine knots from off the fire so you can light him down the path.”

As Lee said his hasty good-byes, crippled Jimmy Bobb sat in his prison chair like one dazed.

“Street cars, 'lectric lights, talking contraptions!” he muttered to himself. “If,” shutting his eyes tightly, then opening them wide, “if I could only see something myself, oncet, anyway!”

For days after that visit, Jimmy Bobb stuck in Lee’s mind. The cripple boy had so little. If only there were something one could do to give him a little pleasure!

Then a plan came to Lee. He just believed he’d—well, what he believed was so vague that he couldn’t put it into words, but it started him off on a very busy time.

Lee turned back through the pages of the old science book, studying a section here, copying off a diagram there in painstaking pencil lines. In between times he roamed the Renaud place from attic to cellar, from old stable yard to wood lot. And the things he collected—a broken pipestem, a bit of beeswax, some feathers, an old cornstalk, wire, a needle, a few threads raveled from a piece of yellowed silk! A strange assortment for a strong, husky boy to spend his time gathering together! Anybody might have thought he had gone as batty as old Johnny Poolak. Only there was nobody to see. And as for bothering about making himself ridiculous—um! well, Lee Renaud was so intent upon his task that all thought of self had gone out of his head.

Towards the end of the week, Lee tramped over to the Bobb cabin.

“Good evening, everybody! Tomorrow suppose—” in his excitement, Lee twisted his cap round and round in his hands—“suppose old Pomp and I come here and carry Jimmy, chair and all, over to our place. I’ve got something to show him. It would be all right, wouldn’t it?”

“Would it! O-o-oh! Think of going somewhere!” Jimmy Bobb swayed in his chair. His eyes seemed to get three sizes bigger. “I can, can’t I, ma?”

Not being given to over many words, Sarah Ann Bobb merely nodded. But her face was no longer apathetic; some of its tiredness seemed to have gone away.

The next day, though, when Lee and old Pomp parted the bushes on the narrow trail and came out on the bare knoll of the Bobb place, things appeared entirely different. There was a change in atmosphere—due to a group of rough-looking fellows massed close to the cabin door. Some of those tobacco-spitting loafers Lee had had to navigate around every time he went to the country store! Like all the Cove people, these gangling youths were an unkempt, taciturn lot. Even as Lee and Pomp drew nearer, they gave no greeting, but merely drew closer together like a guard before the door.

Lee Renaud could almost feel the down on his spine prickle as his anger rose against them. What was this gang up to? They had gathered here for something! Must have heard that he and Pomp were going to carry Jimmy over to the electrical shop. Full of the Coveite’s ignorances and superstitions, they must have gotten together here to try to interfere with his plans. Well, just let ’em try to stop him—just let ’em! Involuntarily his fists clenched, his jaw tightened. He was going to give Jimmy a good time—as he’d planned! He’d fight ’em all before he’d give up!

Renaud strode forward, with old Pomp edging back a little behind him.

Lem Hicks, who seemed to be leader of the gang, detached himself from his fellows and stepped out into the path.

When the long-armed, hulking Lemuel spoke, what he had to say came nearer knocking the wind out of Lee Renaud than any fist blow might have done.

“We—we allowed we’d carry Jimmy over for you.”

Lee stood like one rooted to the ground. He couldn’t believe he’d heard aright. There must be some trick in it. This rough gang was up to something.

His fists, that had relaxed, tightened up again. Another was stepping out of the group, the one they called Big Sandy. He was a tall fellow, but he grasped a couple of poles taller than himself.

“Done cut some hickory saplings for to slide under Jimmy’s chair for handles, like. Jimmy, he ain’t so big, but I allow he’d be quite a tote for just you two. Us four can do it more better—”

“Sure—fine!” Lee Renaud’s voice surprised himself. He blurted it out almost before he knew it. But there was a something in the eyes of these boys that made him say what he did. It was that same terrible eagerness—like in Jimmy Bobb’s—that hunger after something of interest in their meager lives.

Little dark Tony Zita (one of those lowlife fishing folk, old Pomp had once dubbed him) darted up close to Lee, a new light in the black eyes beneath his tousled black locks. “You gonner let us see it all—what you gonner show to Jimmy? We ain’t never seen no 'lectricity, nor nothing!”

It was a lively procession that went forward down the little woods trail between the log cabin and the warped and leaking elegance of the old Renaud mansion. Jimmy Bobb, almost hysterical with excitement, rode like a king in the wheelless chariot of his old armchair. Lem and Big Sandy, being the strongest in the bunch, handled a pole end on either side where the weight was heaviest. The Zita boy and Joe Burk put a shoulder to the other ends of the poles. Mackey, who went along too, and Lee took their turns at carrying.

Class feeling had been swept away. The antagonism of these secluded backwoods folk for a “city dude what slicked his hair,” the antagonism of an educated fellow toward the narrow, suspicious ignorance of country louts—a new feeling had suddenly taken the place of all this. This group was now just “boys” bound together by an interest.

Up in the littered second-story room that served as Lee’s workshop, young Renaud didn’t need to press very strongly his warning against “folks mixing too much with the dangers of electricity.” The great glass wheel, with its strange gearing of wood and brass and fur, laid its own spell of warning on the boys. The old thing did look queer and outlandish. One almost expected some black-robed wizard to step out of the past and “make magic” on it.

Well, electricity was a sort of magic, it was so wonderful and powerful, thought Lee, only it wasn’t the “black magic” of evil; it was a great power for good.

As Lee cranked the machine into a swift whirl, the other boys stood well back, but looked with all their eyes. Like a showman putting his charges through their stunts, Lee put all his crude, homemade apparatuses through their paces.

“He’s doing it! He’s ketching lightning, like they said!” whispered Tony Zita as sparks leaped and crackled across the metal points set in brass so close to the wheel.

He showed his Leyden Jar “that you stored electricity in just like pouring molasses in a bucket, then shot it out again on a wire what sparks!”

He exhibited his Voltaic Pile, a crude stack of broken bits of iron and pieces of a copper pot and squares of old flannel wet in salt water that, as Lem Hicks admiringly put it, “without no rubbing together of things—without no nothing doing at all except piling up of wet iron and copper—just went ahead and made this here electricity!”

“Gosh A’mighty,” Lem exclaimed, “that’s a smart thing! Wish I could fix up something like it oncet!”

Jimmy Bobb didn’t have so much to say. He just looked, taking it in and storing it away in his eager hungering brain.

Then Lee opened a wall cupboard and brought out his latest treasures—the things he had prepared especially to show Jimmy Bobb what electricity could do. He came back to the group now, bearing the piece of broken pipestem in his hand. It was a clear, yellowish piece of stem, with a pretty sheen to it. Lee handed it to Jimmy, along with a rag of flannel cloth.

“Rub the yellow stuff with the cloth,” he ordered. “Rub hard.”

Jimmy’s legs might be feeble, but his arms were strong. He put in some sharp, vigorous rubs, his face excited but withal mystified. He didn’t know what it was all about, but he was making a try at it.

“Now that’s enough.” As he spoke, Lee scattered some downy feathers on the table. “Reach the yellow piece out, somewhere near the feathers,” he went on, “and see what’ll happen.”

Jimmy stretched out the old piece of pipestem, and the feathers leaped up to it as though they were alive.

“Well, I’ll be blowed!” shouted Jimmy, trying the experiment time and again, and each time having the fluff leap up to cling to the stem. “What is it? What makes it act all alive?”

“Electricity.” Lee Renaud picked up the broken stem. “This thing is amber. I just happened to find it in a junk pile. An old book told me about how people found out long ago that 'delectable amber, rubbed with woolen’ would generate enough electricity to draw to itself light objects.”

“I’ll be blowed! Well, I’ll be blowed!” Jimmy Bobb kept saying to himself, as he tried the amber and feather stunt over and over. “Just think, I can rub up this here lightning-power myself!”

Lee Renaud was not through with his show pieces yet. From the cupboard he brought out the strangest little contraption of all. Upon the center of a stout plank about two feet long, he had erected two small posts of wood. The tiny figure of a man, ingeniously cut out of cornstalk pith, sat in a swing of frail silken thread that hung suspended from the tops of the posts. At one end of the board was an insulated standard of brass. At the other end was a brass standard, uninsulated. Lee carefully arranged this curious apparatus so that the insulated stand was connected with the “prime conductor” of the old glass friction-wheel. Against the other standard was laid a little chain so that the chain end touched the floor, thus making what is known electrically as ground contact.

Now the fun began. Electrified by its connection with the prime conductor, the insulated standard drew the tiny figure in the silken swing up against the brass where the figure took on an electrical charge. Then off swung the little man to discharge his load of electricity against the ground contact post at the other end of the board.

This way, that way swung the tiny figure, an animated little cornstalk man that for all the world looked as if he was enjoying his high riding. Back and forth, back and forth he swung, pulled now by the positive, now by the negative power of that strange thing, electricity. And he continued to swing just as long as electrical power was supplied to him.

Shouts of laughter greeted the antics of Lee’s little man.

“This here electricity’s fun!”

“Better’n a show!”

“We can come again, huh, can’t we?”

Altogether, Lee Renaud had a pleasurable afternoon showing off his treasures. His pride was punctured a bit, though, when, upon leaving, one fellow said, “This here 'lectricity’s a right pretty thing. Pity it ain’t no use for helping folks.”

“What’s this? What’s this?” A rough voice from the doorway startled Lee so that he nearly dropped the glass jar half full of salt water, in which he was just placing a strip of tin and a long stick of charcoal.

The man behind the big voice was a little wizened, gray-headed fellow, with twinkle lines around his eyes that rather belied his gruff manner.

“Well, well, well!” boomed the visitor. Lee thought in amazement that he had never heard such a vast bellow proceed out of such a little man. “Um, yes, you must be Lee, Gem’s nephew. He told me I’d find you up here. I’m Doctor Pendexter from Tilton, old friend of Gem’s. Just now heard about his bum leg and came over to see him. Gem, consarn him, never does write to anybody. Looks like you’re getting ready to generate some sort of power. Used to dabble in electrics myself, I have no time for that nowadays. What’s that you’re up to?”

“I was just following out the Volta experiments as best I could.” Lee touched the jar with its half load of salt water. “Was trying tin and charcoal for electrodes.”

“Um! Go on with it.” Dr. Pendexter drew up a chair close beside Lee’s work table.

At first Lee was embarrassed at having an older head watching over his crude tests. However, as he struggled sturdily on with what he had planned to do, interest in the work claimed his attention till there was no room left for feeling self-conscious.

With a firm twist at each end, Lee proceeded to connect the tops of his two electrodes with a bit of wire. There, he had done it as Volta said. And if Volta were right, there ought to be electricity passing from one of his crude electrodes to the other. He’d test it in his own way. With a quick clip, he cut the wire in the middle, setting the ends apart but very nearly touching. He laid a finger on the gap. A tiny prickling shot through his finger. The thing was working feebly, but working enough to show that the theory was right. Fine—he’d learned another way of making electricity! Then his excitement quickly faded, leaving him looking rather doleful.

“What’s the matter? Didn’t it work? It ought to. I’ve dabbled at that experiment myself. It always works—”

“Yes, sir, it worked. All the old tests I’ve tackled so far have. But just something to play with is as far as I seem to get. I can’t find out how to apply the power, how to make some use out of it.”

Dr. Pendexter’s quick ear caught the note of tragedy in the boy’s voice. To the man came a sudden realization of what a struggle this boy must be having as he strove alone to fathom the almost unfathomable mysteries of electricity. Being a man of action, Pendexter applied a remedy in his own way.

“Consarn it all,” he roared, “don’t look so blasted blue! You’re coming on fine, as far as you’ve gone.” The little Doctor cast a quick eye around the room at the bottles and jars, the Voltaic pile and the crystal wheel with its renovated gear. “The trouble is, you’re going sort of one-sided with nothing but one old book to learn out of,” and he flipped the calfskin cover of “Ye Compleat Knowledge” with his forefinger. “You’ve got to the point where you need something modern to study. What do you know about magnets and magnetism and electromagnets?”

“N-nothing,” stammered Lee Renaud in confusion.

“Umph!” from the Doctor. “Well, you’ve been missing out on one of the biggest things in electricity. The electromagnet, that’s the king pin of ’em all!”

“I’ve seen little magnets, sort of horseshoe-shaped bits of metal that you can pick up a needle or a tack or the like with. Didn’t know magnets had anything to do with electricity!”

“You better be knowing it then!” The Doctor banged the table with an emphatic fist. “The electromagnet is the thing that puts the 'go’ in telegraphy, the telephone, this radio business. Say, I’m going to send you a book about it, a modern one. You study it!” And with that parting command, the wiry, roaring little man was gone.

Staring at the empty chair drawn up close beside his latest experiment in tin and charcoal, Lee Renaud had the feeling that he had only imagined Dr. William Pendexter. The wizened little man with the outlandish voice was queer enough to have been generated out of a jar by one of these old electrical experiments.

A few days later though, Lee had good proof that Pendexter was very real—and a man of his word, too. When Lee made a trip down to the village store for a can of kerosene, Mr. Hicks, who was postmaster as well as storekeeper, shoved a package over the counter to him and said, “Today’s mail day.” (Mail came only three times a week to this little backwash village of King’s Cove, and then never very much of it.) Mr. Hicks thumped the packet importantly, “This here come for you. Must amount to something, 'cording to the passel of stamps they stuck on to it.”

It most certainly did amount to something. When he got off to himself, Lee’s hands trembled so that he could hardly tear the wrappings away. Ah, there it was—a big, fat, red-bound volume, with gold letters, “The Amateur Electrician’s Handbook.”

There was information enough within those red covers to set Lee Renaud off on a brand new set of experiments. From a battery made of a trio of glass jars containing salt water, each jar holding its strips of zinc and copper, and fitted with wiring, he charged a bar of soft iron until it was magnetized—but this would stay magnetized only so long as the current was put to it. Then he electrified a bit of steel—and it became a permanent magnet.

Lee became more ambitious in his experimenting. He was after power, something that would generate real movement. And so he rushed in where a more experienced hand might have been stalled by the lack of material. But Lee Renaud staunchly refused to be stalled, even though his supply of working material was nothing much beyond bits of tin, iron, some barbed wire, old nails, broken glass, and pieces of brass salvaged from old cartridges.

And out of such junk, Lee proposed to make himself an electric motor!

Well, that was the next step for him. If he were going forward, he just had to make a motor.

His first attempt was the simplest of the simple. According to directions and diagrams in the new red book, he took current from his Voltaic Cell and put it in a circuit through a loop of wire which lay in a strongly magnetized field. The push of power in the lines of magnetic force, through changes in the connections, set the loop to revolving. And there it was, his electric motor! Very sketchy, very rudimentary indeed, but it worked in its own crude way.

Later, and after much study, he decided to attempt a real little dynamo. This, by comparison with number one, was to be an elaborate affair, comprising a loop of wire revolving between the poles of a horseshoe-shaped permanent magnet, with two half-cylinders connected to the revolving loop of wire and touched at each half-turn by stationary metal brushes. The metal brushing was to turn the alternating current into a direct current. In the making, Lee ran into all sorts of troubles, mostly due to his poor materials. But he kept on, and at last produced something that sputtered and coughed and was as cranky as a one-eyed mule. But it ran part of the time—enough to teach Lee more about electric motors than all the reading in the world could have done.

A few weeks later, Dr. William Pendexter drove his prim little car out again to see how Gem Renaud’s leg was progressing—which really wasn’t necessary for old Mr. Renaud was coming on finely. He might just as well have admitted that the real reason for driving twenty miles to King’s Cove was to see how Lee and electricity were hitting it off.

The wiry little man roamed all over the Renaud place and roared his approval of Lee’s cranky, balky dynamo. When he was climbing into his car, he called, “Hi there, Lee! I’ve got to go to Tilton and back to bring something I want for Gem. Want to go for the ride?”

To Lee, who for months now had been stuck away down in the backwoods Cove, this trip to town seemed to be bringing him into another world, the progressive world that he had slipped out of for a spell. Drug stores, banks, cars, tall poles for telegraph and telephone wires, electric lights—seeing all these again made his dabblings at Voltaic Cells and the crystal wheel seem truly to belong to a long-gone, primitive period.

Pendexter got out at the railroad station, motioning for Lee to follow. He wrote off a telegram, handing it to the operator. All the while Lee stood like one transfixed, staring in fascination at the telegraph instruments on the dispatcher’s table. Almost without knowing it, the boy was mentally calculating on the coils of wire, the shining brass. Electricity ran that thing; here was power hitched up and working.

Pendexter jerked a thumb in the boy’s direction when he had caught the operator’s eye.

“Plumb batty on electricity!” For once the Pendexter roar was silenced to a mere whisper. “Found him down there in the Cove experimenting all by himself. Consarn it, John Akerly, tell him something about electricity! You know plenty. Got to go by the house for a package—be back.” And the Doctor disappeared.

Akerly reached out a long finger and suddenly clickety-clicked the instrument. “Want to know something about that?” he queried sharply, but with a grin wrinkling up his leathery face.

“I—what—yes, sir!” The click and the voice had startled Lee.

“Know anything about batteries?”

“I made some that worked—sort of. You mean putting two metal strips in an acid solution so as to produce an electric current. Then a lot of jars with this stuff in ’em, and wired up right—you set ’em together and that forms a battery—”

“You’ve got it, kid! With that much in your noodle, I reckon I can pass on to you something about this telegraphing business. To begin with, I’ve got a battery here, with a wire from one pole of it passing through my table and going all the way to Birmingham. Say that this wire came all the way back from Birmingham and connected with the other pole of my battery, what would that make?”

“An electric circuit,” answered Lee. “One that—”

“Yes, one that included the Birmingham station in its circle. Only there isn’t any return wire—”

“Then it isn’t a cir—” Lee began.

“Yes, it is! Think, boy! This old earth of ours is a mighty good electric conductor—”

“Of course!” Lee was crestfallen that he hadn’t thought of that. “I’ve grounded wires myself, and made the circuit.”

“All right then. We’ve got our wire going to Birmingham, grounded at the Birmingham station, and the earth acting as a return for our current. Now we’ll say this circuit is fixed around some instruments on my table, and fixed around the same sort of instruments on the table in Birmingham. Well, when I start tapping my telegraph key—making and breaking the circuit—won’t this current be stopped and started at Birmingham just like it is here? Huh?”

“Yes—an instrument on the same circuit.” Lee cocked his head sidewise in deep thought. “It just naturally would be.”

“Well, son, that’s telegraphy!”

“Telegraphy! Great jumping catfish! Is that all there is to it?”

“Er-r, not exactly,” said Akerly dryly. “There’s the relay, or local battery circuit, the electromagnet sounder, special stuff and duplex work, signals, the code to be learned.” The dispatcher paused a moment in his recital, pulled a battered book out of a drawer, opened it at a page full of queer marks, and added, “Here’s the code.”

Lee bent over the page. “I see,” he said, then added with a wry grin, “or rather I don’t see! How do you hitch all those little signs up so that they mean something on an instrument?”

“All right—it’s like this. I’ll tap the telegraph key for a tenth of a second. That means I’ve let the current flow for a tenth of a second. We call that a 'dot.’ A three-tenths of a second tap makes the 'dash.’ Put 'dot,’ 'dash,’ 'dot’ together in all sorts of combinations, and you’ve got the code. When the fellow at the other end of the line knows the code, he can understand what you’re tapping to him.”

A couple of hours later when Pendexter breezed back into the office, he found the two of them still at it, with the talk switching back and forth about magnetic rotations and cycles and frequency, about multiplying powers and symmetry and resonance.

“Looks like you two sort of speak the same language,” rumbled the Doctor. “Didn’t mean to leave you at it all day but got a patient up there. Had to stop—”

“Why, it’s—it’s late!” Lee looked dazed at the passage of time. “Your work, I didn’t mean to keep you from it—” and the boy leaped up.

“I like to talk about electricity. Come again and we’ll jaw some more.” Lanky, long John Akerly shook hands heartily.

Lee’s mind fairly seethed with the information it had tried to absorb about coils and codes and induction and what-not. Electricity was a language that Dr. William Pendexter spoke too, and the twenty miles back to King’s Cove fairly slid by.

As they drove up to the high sagging porch of the old Renaud place, the little grizzled Doctor started pulling a wooden box out of the back of his car. Lee put a willing shoulder to it, and involuntarily grunted a little. Just a little old box—but gosh, it was heavy!

“Not in here,” roared the Doctor, as Lee started to ease the thing down in his Great-uncle Gem’s room. “Go on upstairs.”

Breathing hard, Lee lugged it on, and following directions, slid it down in a corner of his workshop.

“That’s right! Good place for it. Some junk I’m going to leave with you,” rumbled Pendexter. “Get the lid off.”

The next moment Lee Renaud was on his knees beside the box, touching the contents as though they were gold and diamonds. A code book, some tattered pamphlets full of sketches and diagrams, and these well mixed in with coils of copper wire, screws, an old sounder still bearing its precious electromagnets, some scrap glass and brass. It might all have looked like trash to somebody else, but not to Lee Renaud.

Right here under his hand, experimental stuff such as he had never even hoped to buy! He touched one prize, then another.

“It’s too much! You don’t really mean to leave it?”

“Leaving it! By heck, of course I am. My wife would skin me alive if I brought that box back home to just sit and catch dust and spider webs again. Never fool with it any more, myself,—no time.”

“I—I—how will I ever thank you?” Lee couldn’t keep his hands from straying over the old sounder and the bits of real copper wire.

“Do something with it!” roared Pendexter, backing off testily from any further thanks. “Do something with it, that’s what!”

“Just wonder if’n I’ll ever get it right! Wisht I’d paid more attenshun to teacher that year we had one!” Lem Hicks ran a tragic hand through his sandy hair till it stood out like a bottle brush.

He sat at the table in Lee’s workshop. Before him stood a homemade contraption young Renaud fondly hoped bore enough resemblance to a telegraphic outfit to work. Spread open beside the instrument was the code book, and spread open beside the code book was an old Blue-backed Speller. Lem, with a finger poised above the telegraph key, frantically studied first one book, then the other. It was no use! The excitement of the occasion had driven all the “book larnin’” out of Lem’s head. For days he had been planning on this, the first telegraphic message to be sent in King’s Cove. But the final effort of “putting words into spelling” and then “putting spelling into code” was too much for him. He just had to tap something, though. Lee, waiting at a similar instrument down in the old storage house, which was the end of their telegraph line, was all set to see if the thing really worked. In desperation Lem clickety-clicked at the only piece of the code he could seem to remember—three quick taps, three long taps, then three quick taps again.

And before he had hardly finished, there came a bang of doors downstairs, a gallop of feet on the stairs, and Lee Renaud shot breathless into the room.

“In trouble? What’s the matter?” he yelled. “Short-long-short, three times each, that’s S. O. S., the distress signal of the world. I thought this thing must have blown up or busted or electrocuted somebody.” Lee dropped limply on a bench.

“Naw,” said Lem, flushing shamefacedly. “Every bit of the code 'cept that went clean out of my head. I wanted to get something to you—”

“It got me, all right!” Lee burst out laughing. “But say, man, it worked! We’ve made us something here. That set of taps clicked through to me as clean as anything. When we get some more code in our heads, we can really talk to each other over the wire.”

Lee Renaud’s experimenting with the telegraph set in motion a strange surge for King’s Cove, a surge of educational longings. For the first time in their drab lives, some young Coveites “wisht they had sat under a teacher more.”

In the past these tow-headed youngsters had looked upon the few months of schooling that occasionally came to them as something to be dodged as manfully as possible. Now with the hunger upon them to enter the grand adventure of sending one’s thoughts, clickety-click, far away across a wire, the mistreated reading books and dog-eared spellers were dug out and actually studied. “Great snakes! A fellow railly had to know sump’n if he was goin’ to put his thoughts into spellin’, and then put spellin’ into code,” remarked one lank youth as he lolled in front of the village store, and Tony Zita mournfully allowed it was “more worser than tryin’ to scramble eggs, then tryin’ to unscramble them.”

Great-uncle Gem could hobble around now with his stick. He began taking as lively an interest as the youngsters in Lee’s “tapping machine.” Quite often he would come limping up to sit in the workshop, his black eyes twinkling beneath bushy white brows at the electrical chatter going on around him.

“Just think,” Lee was day-dreaming, “if I had wire enough, I could make my battery send a telegraph signal all the way to Mr. Akerly in Tilton, on to Birmingham, maybe on to my home folks in Shelton—”

“Wait there, wait there! Hold your horses, young man!” Uncle Gem interposed, not wanting this dreamer to dream too big a dream and then have it crash. “Maybe some day you’ll progress enough to send far messages by this wireless we read about, but as long as you’re still talking about telegraph wires, just remember that it would cost some few thousand dollars just to string wires from here to Tilton—”

“A thousand dollars—um, and some more thousands! Gosh, I didn’t know wire cost like that!” Lee’s face fell. “I’d been hoping, anyway, that we could stretch a wire on to Jimmy Bobb’s so he’d be sort of in touch with folks. He’s so—so—”

“From here to the Bobb place is more than half a mile. Half a mile of wire is a considerable bit. Here, give me a pencil; let me do some figuring.” Great-uncle Gem bent his head above a scrap of paper. “There’s the horse lot and the cow pasture—we don’t have any cattle on the place these days. All that was fenced once, four strands high. You might as well take what you can find of it and put it to some use.”

“Hurrah for the famous Renaud-Bobb Telegraph Company!” shouted Lee, leaping up and letting out a whoop like a wild Indian. “Uncle Gem can be president. Who wants to join this mighty organization?”

It seemed that everybody did, or at least all the young crew in King’s Cove. Taking stock in this booming concern consisted merely in contributing all the labor and man-power you had in you.

Stringing up even a half mile of telegraph wire turned out to be a vast task; especially since the wire had to be yanked down from old fences, and some of it was barbed, from which the barbs had to be untwisted. But whenever a Cove youth could be spared from hoeing 'taters and corn or pushing the plow, he rushed off to the Renaud place to work ten times harder. Only this new labor was interesting work—work with a zest to it. One crew logged in the woods for tall, strong cedar poles that were to carry the wires, another crew de-barbed old fencing, still another dug the line of post holes. A great search went on for old bottles to be used as glass insulators.

Then the actual stringing up began to go forward.

“Mind, you boys,” warned Uncle Gem, “don’t let anybody’s clothesline get mixed up in this. We don’t want to stir up any hard feeling round here against our project.”

Which very likely was the reason why the stringing up halted for a time while more old fencing was de-barbed, and why, in the dark of a night, Nanny Borden’s clothes wire miraculously reappeared on its posts.

It was hard for untrained hands to set the posts firm and in a straight line, harder still to string the much-spliced wire taut.

At last, though, the great day came when the Renaud-Bobb Telegraph Line reached from station to station.

The lonely little Bobb cabin suddenly became a center of interest. There was always some youngster happening along who wanted to send a message over the line. Jimmy Bobb’s eager mind picked up the code quickly. His long fingers learned to click the key with real speed. The cripple began to know happiness. For the first time in all his starved, meager years, he was getting in touch with life.

Then one day while Lee Renaud was away from his workshop, a frantic message came clicking over the crude wires.

“That thing’s banging like fury up there!” Uncle Gem waved his stick ceilingwards as Lee dashed into the house.

The boy hesitated a moment. He had come for a bag, and was going out to the old junk heap in the gully. Right now something new was surging in his brain and there might be some metal on that old carriage frame that would help him.

The stuttering of the telegraph clicked on again.

“Just some of the gang wanting to gab,” Lee muttered, turning away.

Then the insistent note of the click caught his ear.

“That’s—that’s S.O.S.!”

Up the stairs he leaped, taking two at a time.

Sharp and loud came the tap-tap-tap, three short, three long, three short! S.O.S.! Save! Save! Save! Again three short, three long—a little crashing thump of the key—then blankness.

“What is it? What is it?” pleaded Lee’s clicking key.

No answer.

“Something’s happened! Can’t get any answer from Jimmy!” he shouted as he left the house on the run. “Send Pomp for help to Ray’s meadow—”

Great-uncle Gem, for all his injured leg, must have put some speed into his search for Pomp. For, as Lee sped down the woods path, he could hear the old darky somewhere behind him hallooing, “Help! Help!” and clanging the dinner bell as he headed across the village towards the open hay fields where everybody was cutting grass while the weather held.

With that racket Pomp would stir up somebody, never a doubt! But Lee wasn’t wasting time waiting on reinforcements. With that last insistent tap-tap call of the telegraph still beating in his ears, he stretched his long legs down the path.

Hurtling through bushes, dodging swishing limbs, he burst panting into the clearing of the Bobb hilltop. Here no human sound greeted him. Instead, the awful crackle of flames filled the air. Whorls of smoke curled up from almost every part of the old shingle roof. As he looked, the smoke whorls began to burst into tongues of flame.

Lee raced to the door and flung himself inside, shouting, “Jimmy, Jimmy, where are you?”

There was no answer.

The heat and smoke were nearly overpowering. Lee dropped to the floor and crawled across the room. Yes, here by the ticker was Jimmy’s chair, and Jimmy in it, slumped in a huddle. Lifting the limp form to his shoulder, Lee staggered back to the door and out into the fresh air.

As he laid Jimmy down in the shelter of the trees on the side off the wind, shouts greeted him. The whole woods seemed alive with people. Pomp and his dinner bell had done their work.

While Lee revived Jimmy Bobb, an impromptu water-line formed. Like magic, buckets and tubs and even gourds of water passed up from the spring under the hill to the flaming hell of the roof. Cove women, not being given to style, wore plenty of clothing. Here and there, a wide apron or a voluminous Balmoral was shed, wetted and wielded as a weapon to beat down the flames. Crews of howling small boys broke pine brush for brooms and swept out any creeping line of flame that caught from sparks and headed for the fence, the slab-sided chicken house, or the cow shed.

Then it was over. The fire was out. Blackened rafters and a pall of smoke told what a fight it had been. The roof was gone, but the cabin walls stood, and the meager homemade furniture was safe.

Sarah Ann Bobb, stirred for once out of her habitual calm, stood near Jimmy, waving her hands and weeping.

One of the Cove men detached himself from the smoke-stained group and went up to her. “Don’t take on so, Miz Bobb,” he consoled awkwardly. “Hit war that old no 'count chimney what must've done it. We aims to build you a new one, and set on another roof. Done plan to start tomorrow, the Lord sparing us!”

“I ain’t crying sorrowful.” Sarah Ann’s knees let her down on the ground. “I’m so happy Jimmy ain’t dead!”

“I’m all right, maw,” Jimmy assured her, “but I bet the telegraph’s all busted.”

“Yep, considerably busted, I suppose.” Lee sounded inordinately cheerful. “But all the real stuff we need is still here, and we’ll be building her over again, good as new, maybe better.”

“Oh,” Jimmy Bobb settled back down, “I’m right thankful you saved hit. Hit sho saved me!”

“Aiming for to go up to Renaud’s?” asked Big Sandy as he fell into step alongside of Lem Hicks.

“Yep! Wanter see how them new fixings up there are going to turn out,” was Lem’s answer.

“You ain’t—you ain’t sorter scared?”

“Scared?” Lem wheeled on Big Sandy, then grinned himself as he saw the teasing grin on the other’s face.

“Honest Injun, though,” went on Big Sandy, “lots of folks round here are scared plumb stiff over this electricity stuff. Old Poolak’s had one of his preaching fits. He’s been spreading the word that it warn’t fire from the chimney what burned Miz Bobb’s roof, but lightning fire what our telegraph conjured down out of the sky. According to his tell, it ain’t Scriptural to be taking electricity out of the air and hitching it on to man’s contrivances. Johnny allows it’s tampering with evil and’s goner bring down fire and brimstone on the whole Cove 'less’n folks take axes to our newfangled fixings—”

“Johnny Poolak better mind his own business and not be mixing in with our wires.” Lem’s chin went out belligerently. “I’m banking turrible strong on this new fixing of Lee’s. It’s so mysterious-like, it don’t seem anyways reasonable. Yet if it works, it’ll be the wonderfullest thing what ever happened down here in the Cove.”

“Well, I’m for it, strong.” Big Sandy flung open the gate to the Renaud yard and went in. Lem followed.

The “new fandangle” that Lee was working on now was an attempt at radio. Telegraphy was wonderful enough. But that took wires, thousands of dollars’ worth to reach any distance at all. With radio, one merely sat at a machine, turned a key and picked up sound that went hurtling through the air with only electrical power to bear it on. It seemed unbelievable—yet man was already doing this unbelievable thing. And Lee Renaud, stuck off in the backwoods, had the temerity to make a try at this same wonder.

Lee was subscribing to a magazine now, “The Radio World.” Hard study and the endless copying of hook-up designs from its pages was the way he was preparing ground for his next experiment. By degrees he had gathered together in his old workshop such materials as he could lay hands on. His collection was crude enough to have gotten a laugh out of a regular “radio ham,” but it was the best he could do under the circumstances.

True enough, little rip-roaring Dr. Pendexter, out of the kindness of his heart, had wanted to buy Lee considerable experimental stuff. But somehow the boy’s pride had rebelled at being under too much obligation to anyone.

“I thank you, but no, sir,” he had stammered, “I can’t let you give me everything. It would be different if I could only earn money some way to pay for it—”

“There is a way!” snorted the Doctor. “Only I didn’t want you fooling away time at it when you could be going forward with electricity. Hell’s bells! You’ve got too much pride!”

The way of money-making that Dr. Pendexter pointed out to Lee was the gathering of wild plants for medicinal purposes. Now and again the boy sent in little packets of such things as bloodroot, wild ginseng, and bay leaves. Quite a lot of herbs brought in only a few dollars, but that money wisely expended brought back some very wonderful things through the mail. One time it was two pairs of ordinary telephone receivers; another time it was a piece of crystal; again it was a little can of shellac and some special wire. In addition, Lee had gathered together an assortment of his own—a piece of curtain pole, some old curtain rings, a piece of mica that had once acted as “back light” in an ancient buggy top, a length of stout oak board, sundry bits of wire and second-hand screws and nails.

Back in his home town of Shelton, Lee had once listened in at someone else’s radio—a sleek affair with all its interior workings neatly housed in a shining wooden case. In those days Lee had never dreamed of aspiring to own a radio, much less aspiring to make one by using an oak board, an old curtain pole and pieces of wire as parts.

Throughout the making, the lanky youths of King’s Cove “drapped in” on Lee whenever they could, to see how the work was progressing.

Now, when Big Sandy and Lem hurried along the shady lane in the dusk, and on up to the workshop, they found Tony and little Mackey and Joe Burk already there ahead of them.

“The aerial’s done up!” shouted Tony Zita. “Done did it yesterday. Had to finish the job by lantern light.”

“I helped!” little Mackey Bobb was fairly bristling with pride. “Us all went up through that funny little door right in the roof of this here house. One end of the wire’s hitched to a pole that’s lashed onto a chimney. T’other end of the wire is rigged to a scantling what’s nailed to the barn.”

“And you’re countin’ on that high-sittin’ wire to pick up music out of the air for you?” asked Big Sandy incredulously.

“Jumping catfish, no!” exploded Lee, who was cutting wrapping paper into long strips. “We’ve got to hitch up a sight of apparatus here in the house, too.”

“Ain’t there something I can do?” Lem Hicks moved over to the bench where Lee was working.