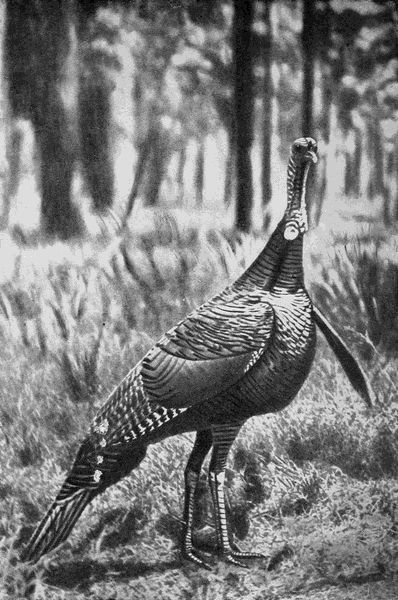

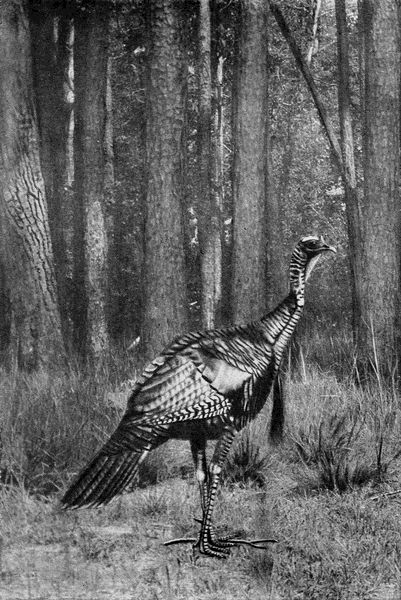

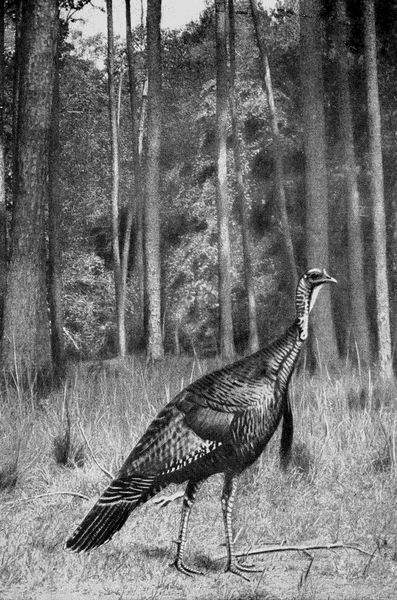

The grandest bird of the American continent

Title: The Wild Turkey and Its Hunting

Author: Edward Avery McIlhenny

Charles L. Jordan

Contributor: Robert W. Shufeldt

Release date: August 9, 2014 [eBook #46542]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charlene Taylor, JoAnn Greenwood, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been repaired.

Several illustration captions mention illustration sizes. Since illustrations had to be resized for electronic publication, those size references are no longer valid.

The grandest bird of the American continent

BY

EDWARD A. McILHENNY

Illustrated from Photographs

GARDEN CITYNEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1914

Copyright, 1912, 1913, 1914, by

The Outdoor World Publishing Company

Copyright, 1914, by

Doubleday, Page & Company

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian

CONTENTS

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | ix | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | My Early Training with the Turkeys | 3 |

| II. | Range, Variation, and Name | 12 |

| III. | The Turkey Prehistoric | 26 |

| IV. | The Turkey Historic | 39 |

| V. | Breast Sponge—Shrewdness | 104 |

| VI. | Social Relations—Nesting—The Young Birds | 111 |

| VII. | Association of Sexes | 119 |

| VIII. | Its Enemies and Food | 134 |

| IX. | Habits of Association and Roosting | 152 |

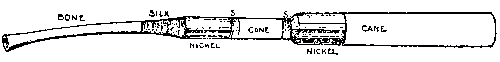

| X. | Guns I Have Used on Turkeys | 163 |

| XI. | Learning Turkey Language—Why Does the Gobbler Gobble | 170 |

| XII. | On Callers and Calling | 181 |

| XIII. | Calling Up the Lovelorn Gobbler | 198 |

| XIV. | The Indifferent Young Gobbler | 213 |

| XV. | Hunting Turkey with a Dog | 218 |

| XVI. | The Secret of Cooking the Turkey | 233 |

| XVII. | Camera Hunting for Turkeys | 238 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Although many eminent naturalists and observers have written of the turkey from the date of its introduction to European civilization to the present time, there has been no very satisfactory history of the intimate life of this bird, nor has there been a satisfactory analysis of either the material from which our fossil turkeys are known, or the many writings concerning the early history of the bird and its introduction to civilization. I have attempted in this work to cover the entire history of this very interesting and vanishing game bird, and believe it will fill a long-felt want of hunters and naturalists for a more detailed description of its life history.

This work was begun by Chas. L. Jordan and would have been completed by him, except for his untimely death in 1909.

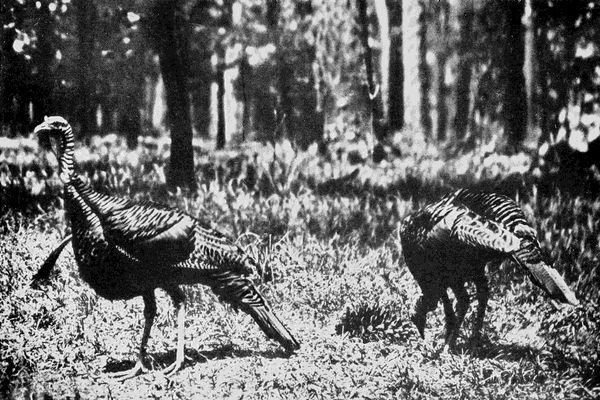

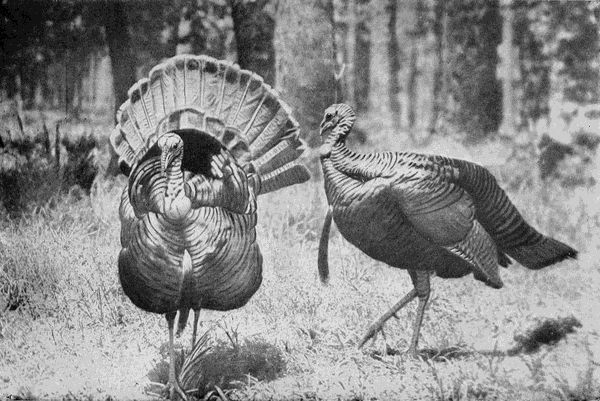

Mr. Jordan for more than sixty years was a[x] careful observer and lover of the wild turkey, and for many years the study of this bird occupied almost his entire time. I feel safe in saying that Mr. Jordan knew more of the ways of the wild turkey in the wilds than any man who ever lived. No more convincing example of his patience and perseverance in his study of the bird can be given than the accompanying photographs, all of which were taken of the wild birds in the big outdoors by Mr. Jordan.

At the time of Mr. Jordan's death he was in his sixty-seventh year and was manager of the Morris game preserve of over 10,000 acres, near Hammond, La. He had been most successful in attracting to this preserve a great abundance of game, and was very active in suppressing poaching and illegal hunting. His activity in this cause brought about his death, as he was shot in the back by a poacher during the afternoon of February 24, 1909, for which Allen Lagrue, his murderer, is now serving a life sentence in the penitentiary.

I had known Mr. Jordan for a number of years before his death and was much interested[xi] in his work with the turkey, as I, for years, had been carrying on similar studies. After Mr. Jordan's death, through the kindness of Mr. John K. Renaud, I secured his notes, manuscript, and photographic plates of the wild turkey, and with these, and my knowledge of the bird, I have attempted to compile a work I think he would have approved.

Mr. Jordan from time to time wrote articles on the wild turkey for sporting magazines, among them Shooting and Fishing, and parts of his articles are brought into the present publication. I have carried out the story of the wild turkey as if told by Mr. Jordan, as his full notes on the bird enable me to do this.

I am indebted to Dr. R. W. Shufeldt for his chapter on the fossil turkey, the introduction of the turkey to civilization, and photographs accompanying his two chapters, written at my request especially for this work.

E. A. M.

THE WILD TURKEY AND ITS HUNTING

My father was a great all-round hunter and pioneer in the state of Alabama, once the paradise of hunters. He was particularly devoted to deer hunting and fox hunting, owning many hounds and horses. He knew the ways and haunts of the forest people and from him my brothers and I got our early training in woodcraft. I was the youngest of three sons, all of whom were sportsmen to the manner born. My brothers and myself were particularly fond of hunting the wild turkey, and were raised and schooled in intimate association with this noble bird; the fondness for this sport has remained with me through life. I therefore may be pardoned when I say that I possess a fair knowledge of their language, their habits, their likes and dislikes.

In the great woods surrounding our home[4] there were numbers of wild turkeys, and I can well remember my brother Frank's skill in calling them. Every spring as the gobbling season approached my brothers and myself would construct various turkey calls and lose no opportunity for practising calling the birds. I can recall, too, when but a mere lad, coming down from my room in the early morning to the open porch, and finding assembled the family and servants, including the little darkies and the dogs, all in a state of great excitement. I hastened to learn the cause of this and was shown with admiration a big gobbler, and as I looked at the noble bird, with its long beard and glossy plumage, lying on the porch, I felt it was a beautiful trophy of the chase.

"Who killed it?" I asked. "Old Massa, he kill 'im," came from the mouths of half a dozen excited little darkies. A few days later my brothers brought in other turkeys. This made me long for the time when I would be old enough to hunt this bird, and these happy incidents inspired me with ambition to acquire proficiency in turkey hunting, and to learn[5] every method so that I might excel in that sport.

As I grew older, but while still a mere lad, I would often steal to the woods in early morning on my way to school, and, hiding myself in some thick bush, sitting with my book in my lap and a rude cane joint or bone of a turkey's wing for a call in my hand, I would watch for the turkeys. When they appeared I would study every movement of the birds, note their call, yelp, cluck, or gobble, and I gradually learned each sound they made had its meaning. I would study closely the ways of the hens and their conduct toward the young and growing broods; I would also note their attention to the old or young gobblers, and the mannerisms of the male birds toward the females. All this time I would be using my call, attempting to imitate every note that the turkeys made, and watching the effect. These were my rudimentary and earliest lessons in turkey lore and lingo, and what I have often called my schooling with the turkeys.

At this age I had not begun the use of a rifle or shotgun on turkeys, although I had killed[6] smaller game, such as squirrels, rabbits, ducks, and quail. I was sixteen years of age when I began to hunt the wild turkeys. I discovered then that although I was able to do good calling I had much more to learn to cope successfully with the wily ways of this bird. It took years of the closest observation and study to acquire the knowledge which later made me a successful turkey hunter, and I have gained this knowledge only after tramping over thousands of miles of wild territory, through swamps and hummocks, over hills and rugged mountain sides, through deep gulches, quagmires, and cane brakes, and spending many hours in fallen treetops, behind logs or other natural cover, not to be observed, but to observe, by day and by night, in rain, wind, and storm. I have hunted the wild turkeys on the great prairies and thickets of Texas, along the open river bottoms of the Brazos, Colorado, Trinity, San Jacinto, Bernardo, as well as the rivers, creeks, hills, and valleys of Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Louisiana. With all modesty, I believe I have killed as many old gobblers with patriarchal beards as[7] any man in the world. I do not wish to say this boastfully, but present it as illustrative of the experience I have had with these birds, and particularly with old gobblers, for I have always found a special delight in outwitting the wary old birds.

I doubt not many veteran turkey hunters have in mind some old gobbler who seemed invincible; some bird that had puzzled them for three or four years without their learning the tricks of the cunning fellow. Perhaps in these pages there may be found some information which will enable even the old hunter to better circumvent the bird. I am aware that there are times when the keenest sportsmen will be outwitted, often when success seems assured.

How well I know this. Many times I have called turkeys to within a few feet of me; so near that I have heard their "put-put." And they would walk away without my getting a shot. Often does this occur to the best turkey hunter, on account of the game approaching from the rear, or other unexpected point, and suddenly without warning fly or run away. No one can[8] avoid this, but the sportsman who understands turkeys can exercise care and judgment and kill his bird, where others unacquainted with the bird fail. I believe I can take any man or boy who possesses a good eye and fair sense, and in one season make a good turkey hunter of him. I know of many nefarious tricks by which turkeys could be easily secured, but I shall not tell of any method of hunting and capturing turkeys but those I consider sportsmanlike. Although an ardent turkey hunter, I have too much respect for this glorious bird to see it killed in any but an honorable way. The turkey's fate is hard enough as it is. The work of destruction goes on from year to year, and the birds are being greatly reduced in numbers in many localities. The extinction of them in some states has already been accomplished, and in others it is only a matter of time; but there are many localities in the South and West, especially in the Gulf-bordering states, where they are still plentiful, and with any sort of protection will remain so. Some of these localities are so situated that they will for generations remain[9] primeval forests, giving ample shelter and food to the turkey.

A novice might think it an easy matter to find turkeys after seeing their tracks along the banks of streams or roads, or in the open field, where they lingered the day before. But these birds are not likely to be in the same place the following day; they will probably be some miles away on a leafy ridge, scratching up the dry leaves and mould in quest of insects and acorns, or in some cornfield gleaning the scattered grain; or perhaps they might be lingering on the banks of some small stream in a dense swamp, gathering snails or small crustacea and water-loving insects.

To be successful in turkey hunting you must learn to rise early in the morning, ere there is a suspicion of daylight. At such a time the air is chilly, perhaps it looks like rain, and on awakening you are likely to yawn, stretch, and look at the time. Unless you possess the ardor of a sportsman it is not pleasant to rise from a comfortable bed at this hour and go forth into the chill morning air that threatens to freeze the[10] marrow in your bones. But it is essential that you rise before light, and if you are a born turkey hunter you will soon forget the discomforts. It has been my custom, when intending to go turkey hunting, never to hesitate a moment, but, on awakening in the morning, bound out of bed at once and dress as soon as possible. It has also been my custom to calculate the distance I am to go, so as to reach the turkey range by the time or a little before day breaks. I have frequently risen at one or two o'clock in the morning and ridden twelve miles or more before daybreak for the chance to kill an old gobbler.

Early morning from the break of day until nine o'clock is the very best time during the whole day to get turkeys; but the half hour after daybreak is really worth all the rest of the day; this is the time when everything chimes with the new-born day; all life is on the move; diurnal tribes awakening from night's repose are coming into action, while nocturnal creatures are seeking their retreats. Hence at this hour there is a conglomeration of animal life and a babel of mingled sounds not heard at any other time of[11] day. This is the time to be in the depths of the forest in quest of the wild turkey, and one should be near their roosting place if possible, quietly listening and watching every sound and motion. If in the autumn or winter you are near such a place, you are likely to hear, as day breaks, the awakening cluck at long intervals; then will follow the long, gentle, quavering call or yelp of the mother hen, arousing her sleeping brood and making known to them that the time has arrived for leaving their roosts. If in the early spring, you will listen for the salutation of the old gobbler.

When America was discovered the wild turkey inhabited the wooded portion of the entire country, from the southern provinces of Canada and southern Maine, south to southern Mexico, and from Arizona, Kansas, and Nebraska, east to the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. As the turkey is not a migratory bird in the sense that migration is usually interpreted, and while the range of the species is one of great extent, as might be expected, owing to the operation of the usual causes, a number of subspecies have resulted. At the present time, ornithologists recognize four of these as occurring within the limits of the United States, as set forth in Chapter IV beyond.

In countries thickly settled, as in the one where I now write, there is a great variety of wild turkeys scattered about in the woods of the[13] small creeks and hills. Many hybrid wild turkeys are killed here every year. The cause of this is: every old gobbler that dares to open its mouth to gobble in the spring is within the hearing of farmers, negroes, and others, and is a marked bird. It is given no rest until it is killed; hence there are few or no wild turkeys to take care of the hens, which then visit the domestic gobbler about the farm-yards. Hence this crossing with the wild one is responsible for a great variety of plumages.

I once saw a flock of hybrids while hunting squirrels in Pelahatchie swamp, Mississippi, as I sat at the root of a tree eating lunch, about one o'clock, with gun across my lap, as I never wish to be caught out of reach of my gun. Suddenly I heard a noise in the leaves, and on looking in that direction I saw a considerable flock of turkeys coming directly toward me in a lively manner, eagerly searching for food. The moment these birds came in sight I saw they had white tips to their tails, but they had the form and action of the wild turkey, and it at once occurred to me that they were a lot of mixed[14] breeds, half wild, half tame, with the freedom of the former. I noticed also among them one that was nearly white and one old gobbler that was a pure wild turkey; but it was too far off to shoot him. Dropping the lunch and grasping the gun was but the work of a second; then the birds came round the end of the log and began scratching under a beech tree for nuts. Seeing two gobblers put their heads together at about forty yards from me, I fired, killing both. The flock flew and ran in all directions. One hen passed within twenty paces of me and I killed it with the second barrel. A closer examination of the dead birds convinced me that there had been a cross between the wild and the tame turkeys. The skin on their necks and heads was as yellow as an orange, or more of a buckskin, buff color, while the caruncles on the neck were tinged with vermilion, giving them a most peculiar appearance; all three of those slain had this peculiar marking, and there was not a shadow of the blue or purple of the wild turkey about their heads, while all other points, save the white-tipped feathers, indicated the wild blood.

Shortly after the foregoing incident, while a party of gentlemen, including my brother, were hunting some five miles below the same creek, they flushed a flock of wild turkeys, scattering them; one of the party killed four of them that evening, two of which (hens) were full-blood wild ones. One of the remaining two, a fine gobbler, had as red a head as any tame gobbler, and the tips of the tail and rump coverts were white. The other bird (a hen) was also a half-breed. There was no buff on their heads and necks, but the purple and blue of the wild blood was apparent.

Early the next morning my brother went to the place where the turkeys were scattered the previous afternoon, and began to call. Very soon he had a reply, and three fine gobblers came running to him, when he killed two, one with each barrel; now these were full-blood wild ones.

I have noted that a number of wild turkeys in the Brazos bottoms are very different in some respects from the turkeys of the piney woods in the eastern section of that state. In Trinity County,[16] Texas, I found the largest breed of wild turkeys I have found anywhere, but in the Brazos bottoms the gobblers which I found there in 1876, in great abundance, were of a smaller stature, but more chunky or bulky. Their gobble was hardly like that of a wild turkey, the sound resembling the gobble of a turkey under a barrel, a hoarse, guttural rumble, quite different in tone from the clear, loud, rolling gobble of his cousin in the Trinity country. The gobblers of the Brazos bottoms were also distinguishable by their peculiar beards. In other varieties of turkeys three inches or less of the upper end of the beard is grayish, while those of the Brazos bottoms were more bunchy and black up to the skin of the breast. There is a variety of turkeys in the San Jacinto region, in the same state, which is quite slender, dark in color, and has a beard quite thin in brush, but long and picturesque. His gobble is shrill. This section is a low plain, generally wet in the spring, partly timbered and partly open prairie. It is a great place for the turkey.

Since the days of Audubon it has been prophesied[17] that the wild turkey would soon become extinct. I am glad to say that the prophecies have not been realized up to the present time, even with the improved implements of destruction and great increase of hunters. There is no game that holds its own so well as the wild turkey. This is particularly true in the southern Gulf States, where are to be found heavily timbered regions, which are suited to the habits of this bird. Here shelter is afforded and an ample food supply is provided the year round. In the states of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, and the Indian Territory the wild turkey is still to be found in reasonable abundance, and if these states will protect them by the right sort of laws, I am of the opinion that the birds will increase rapidly, despite the encroachment of civilization and the war waged upon them by sportsmen. It is not the legitimate methods of destruction that decimate the turkey ranks, as is the case with the quail and grouse, but it is the nefarious tricks the laws in many states permit, namely, trapping and baiting.[18] The latter is by far the most destructive, and is practised by those who kill turkeys for the market, and frequently by those who want to slaughter these birds solely for count. No creature, however prolific, can stand such treatment long. The quail, though shot in great numbers by both sportsmen and market hunters, and annually destroyed legitimately by the thousands, stands it better than the wild turkey, although the latter produces and raises almost as many young at a time as the quail.

There are two reasons for this: one is, the quail are not baited and shot on the ground; the other reason is that every bobwhite in the spring can, and does, use his call, thus bringing to him a mate; but the turkey, if he dares to gobble, no matter if he is the only turkey within a radius of forty miles, has every one who hears him and can procure a gun, after him, and they pursue him relentlessly until he is killed. Among the turkeys the hens raised are greatly in excess of the gobblers. This fact seems to have been provided for by nature in making the male turkey polygamous; but as the male turkey is, during[19] the spring, a very noisy bird, continually gobbling and strutting to attract his harem, and as he is much larger and more conspicuous than the hens, it is only natural that he is in more danger of being killed. Suppose the proportion of gobblers in the beginning of the spring is three to fifteen hens, in a certain stretch of woods. As soon as the mating season begins, these gobblers will make their whereabouts known by their noise; result—the gunners are after them at once, and the chances are ten to one they will all be killed. The hens will then have no mate and no young will be produced; whereas, if but one gobbler were left, each of our supposed fifteen hens would raise an average of ten young each, and we would also have 150 new turkeys in the fall to yield sport and food. It has always been my practice to leave at least one old gobbler in each locality to assist the hens in reproduction. If every hunter would do this the problem of maintaining the turkey supply would be greatly solved.

The greatest of all causes for the decrease of wild turkeys lies in the killing of all the old[20] gobblers in the spring. Some say the yearling gobblers will answer every purpose. I say they will not; they answer no purpose except to grow and make gobblers for the next year. The hens are all right—you need have no anxiety about them; they can take care of themselves; provided you leave them a male bird that gobbles, they will do the rest. Any suitable community can have all the wild turkeys it wants if it will obtain a few specimens and turn them into a small woodland about the beginning of spring, spreading grain of some sort for them daily. The turkeys will stay where the food is abundant and where there is a little brush in which to retire and rest.

Some hunters, or rather some writers, claim that the only time the wild turkey should be hunted is in the autumn and winter, and not in the spring. I have a different idea altogether, and claim that the turkey should not be hunted before November, if then, December being better. By the first of November the young gobbler weighs from seven to nine pounds, the hens from four to seven pounds; in December[21] and January the former weighs twelve pounds and the latter nine pounds. There you are. But suppose you did not hunt in the spring at all. How many old, long-bearded gobblers (the joy and delight above every sort of game on earth to the turkey hunter) would you bag in a year, or a lifetime? Possibly in ten years you would get one, unless by the merest accident, as they are rarely, if ever, found in company with the hens or young gobblers, but go in small bands by themselves, and from their exclusive and retiring nature it is a rare occasion when one is killed except in the gobbling season.

Take away the delight of the gobbling season from the turkey hunter, and the quest of the wild turkey would lose its fascination. In so expressing myself, I do not advise that the gobblers be persecuted and worried all through the gobbling season, from March to June, but believe they could be hunted for a limited time, namely, until the hens begin to lay and the gobblers to lose their fat—say until the first of April. Every old turkey hunter knows where to stop, and does it without limitation of law. Old[22] gobblers are in their best condition until about the first of April, then they begin to lose flesh very rapidly. At this time hunting them should be abandoned altogether.

In my hunting trips after this bird I have covered most of the southern states, and have been interested to note that all the Indians I have met called the turkey "Furkee" or "Firkee"; the tribes I have hunted with include the Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, Seminoles, and the Cherokees, who live east of the Mississippi River, and the Alabams, Conchattas, and Zunis of the west. Whether their name for the bird is a corruption of our turkey, or whether our word is a corruption of their "Furkee," I am not prepared to state. It may be that we get our name direct from the aboriginal Indians. All of the Indian tribes I have hunted with have legends concerning the turkey, and to certain of the Aztec tribes it was an object of worship. An old Zuni chief once told me a curious legend of his people concerning this bird, very similar to the story of the flood. It runs:

Ages ago, before man came to live on the[23] earth, all birds, beasts, and fishes lived in harmony as one family, speaking the same language, and subsisting on sweet herbs and grass that grew in abundance all over the earth. Suddenly one day the sun ceased to shine, the sky became covered with heavy clouds, and rain began to fall. For a long time this continued, and neither the sun, moon, nor stars were seen. After a while the water got so deep that the birds, animals, and fishes had either to swim or fly in the air, as there was no land to stand on. Those that could not swim or fly were carried around on the backs of those that could, and this kept up until almost every living thing was almost starved. Then all the creatures held a meeting, and one from each kind was selected to go to heaven and ask the Great Spirit to send back the sun, moon, and stars and stop the rain. These journeyed a long way and at last found a great ladder running into the sky; they climbed up this ladder and found at the top a trapdoor leading into heaven, and on passing through the door, which was open, they saw the dwelling-place of man, and before the door were a boy[24] and girl playing, and their playthings were the sun, moon, and stars belonging to the earth. As soon as the earth creatures saw the sun, moon, and stars, they rushed for them and, gathering them into a basket, took the children of man and hurried back to earth through the trapdoor. In their hurry to get away from the man whom they saw running after them, the trapdoor was slammed on the tail of the bear, cutting it off. The blood spattered over the lynx and trout, and since that time the bear has had no tail, and the lynx and trout are spotted. The buffalo fell down and hurt his back and has had a hump on it ever since. The sun, moon, and stars having been put back in their places, the rain stopped at once and the waters quickly dried up. On the first appearance of land, the turkey, who had been flying around all the time, lit, although warned not to do so by the other creatures. It at once began to sink in the mud, and its tail stuck to the mud so tight that it could hardly fly up, and when it did get away the end of its tail was covered with mud and is stained mud color to this day. The[25] earth now having become dry and the children of man now lords of the earth, each creature was obliged to keep out of their way, so the fishes took to the waters using their tails to swim away from man, the birds took to their wings, and the animals took to their legs; and by these means the birds, beasts, and fishes have kept out of man's way ever since.

Before dealing with the wild turkeys as they are to-day, it will be well to make a short study of their prehistoric and historic standing; this has been ably done for me by Dr. R. W. Shufeldt of Washington, D. C., who has very kindly written for this work the next two chapters entitled "The Turkey Prehistoric," and "The Turkey Historic."

Probably no genus of birds in the American avifauna has received the amount of attention that has been bestowed upon the turkeys. Ever since the coming to the New World of the very first explorers, who landed in those parts where wild turkeys are to be found, there has been no cessation of verbal narratives, casual notices, and appearance of elegant literature relating to the members of this group. We have not far to seek for the reason for all this, inasmuch as a wild turkey is a very large and unusually handsome bird, commanding the attention of any one who sees it. Its habits, extraordinary behavior, and notes render it still more deserving of consideration; and to all this must be added the fact that wild turkeys are magnificent game birds; the hunting of them peculiarly attractive to the[27] sportsman; while, finally, they are easily domesticated and therefore have a great commercial value everywhere.

The extensive literature on wild and domesticated turkeys is by no means confined to the English language, for we meet with many references to these fowls, together with accounts and descriptions of them, distributed through prints and publications of various kinds, not only in Latin, but in the Scandinavian languages as well as in French, German, Spanish, Italian, and doubtless in others of the Old World. Some of these accounts appeared as long ago as the early part of the sixteenth century, or perhaps even earlier; for it is known that Grijalva discovered Mexico in 1518, and Gomarra and Hernandez, whose writings appeared soon afterward, gave, among their descriptions of the products of that country, not only the wild turkey, but, in the case of the latter writer, referred to the wild as well as to the domesticated form, making the distinction between the two.

In order, however, to render our history of the wild turkeys in America as complete as possible,[28] we must dip into the past many centuries prior to the discovery of the New World by those early navigators. We must go back to the time when it was questionable whether man existed upon this continent at all. In other words, we must examine and describe the material representing our extinct turkeys handed us by the paleontologists, or the fossilized remains of the prehistoric ancestors of the family, of which we have at hand a few fragments of the greatest value. These I shall refer to but briefly for several reasons. In the first place, their technical descriptions have already appeared in several widely known publications, and in the second, what I have here to say about them is in a popular work, and technical descriptions are not altogether in place. Finally, such material as we possess is very meagre in amount indeed, and such parts of it as would in any way interest the general reader can be referred to very briefly.

The fossil remains of a supposed extinct turkey, described by Marsh[1] as Meleagris altus from [29]the Post-pliocene of New Jersey, is, from the literature and notices on the subject, now found to be but a synonym of the Meleagris superba of Cope from the Pleistocene of New Jersey. At the present writing I have before me the type specimen of Meleagris altus of Marsh, for which favor I am indebted to Dr. Charles Schuchert of the Peabody Museum of Yale University. My account of it will be published in another connection later on.

Some years after Professor Marsh had described this material as representing a species to which I have just said he gave the specific name of altus, it would appear that I did not fully concur in the propriety of doing so, as will be seen from a paper I published on the subject[30] about fifteen years ago[2]. This will obviate the necessity of saying anything further in regard to M. superba.

So far as my knowledge carries me, this leaves but two other fossil wild turkeys of this country, both of which have been described by Professor Marsh and generally recognized. These are Meleagris antiqua in 1871, and Meleagris celer in 1872. My comments on both of these species will be found in the American Naturalist for July, 1897, on pages 648, 649.[3]

Plate I

Types: M. antiqua; M. celer. Marsh

Fig. 1. Anconal aspect of the distal extremity of the right humerus of "Meleagris antiquus" of Marsh. Fig. 2. Palmar aspect of the same specimen shown in Fig. 1. Fig. 3. Anterior aspect of the proximal moiety of the left tarso-metatarsus of Meleagris celer of Marsh. Fig. 4. Posterior aspect of the same fragment of bone shown in Fig. 3. Fig. 5. Outer aspect of the same fragment of bone shown in Figs. 3 and 4. All figures natural size. Reproduced from photographs made direct from the specimens by Dr. R. W. Shufeldt.

It will be noted, then, that Meleagris antiqua of Marsh is practically represented by the imperfect distal extremity of a right humerus; and that Meleagris celer of the same paleontologist from the Pleistocene of New Jersey is said to be represented by the bones enumerated in a foregoing footnote. In this connection let it be borne in mind that, while I found fossil specimens of Meleagris g. silvestris in the bone caves of Tennessee, I found no remains of fossil turkeys in Oregon, from whence some classifiers of fossil[32] birds state that M. antiqua came (A. O. U. Check-Listed, 1910, p. 388[4]).

On the 19th of April 1912, I communicated by letter with Dr. George F. Eaton, of the Museum of Yale University, in regard to the fossils described by Marsh of M. antiqua and [33]M. celer, with the view of borrowing them for examination. Dr. Eaton, with great kindness, at once interested himself in the matter, and wrote me (April 20, 1912) that "We have a wise rule forbidding us to lend type material, but I shall be glad to ask Professor Schuchert to make an exception in your favor." In due time Prof. Charles Schuchert, then curator of the Geological Department of the Peabody Museum of Natural History of Yale University, wrote me on the subject (May 2, 1912), and with marked courtesy granted the request made of him by Dr. Eaton, and forwarded me the type specimen of Marsh of M. antiqua and M. celer by registered mail. They were received on the 3rd of May, 1912, and I made negatives of the two specimens on the same day. It affords me pleasure to thank both Professor Schuchert and Dr. Eaton here for the unusual privilege I enjoyed, through their assistance, in the loan of these specimens;[5] also Dr. James E. [34]Benedict, Curator of Exhibits of the U. S. National Museum, and Dr. Charles W. Richmond of the Division of Birds of that institution, for their kindness in permitting me to examine and make notes upon a mounted skeleton of a wild turkey (M. g. silvestris) taken by Prof. S. F. Baird at Carlisle, Penn., many years ago. Mr. Newton P. Scudder, librarian of the National Museum, likewise has my sincere thanks for his kindness in placing before me the many volumes on the history of the turkey I was obliged to consult in connection with the preparation of this chapter.

From what has already been set forth above, it is clear that Marsh's specimen (for he attached but scant importance to the other fragments with it), upon which he based "Meleagris antiquus" was not taken in Oregon, but in Colorado.[6] [35]Both of these fossils I have very critically compared with the corresponding parts of the bones represented in each case in the skeleton of an adult wild turkey (Meleagris g. silvestris) in the collection of mounted bird skeletons in the U. S. National Museum.

Taking everything at my command into consideration as set forth above, as well as the extent of Professor Marsh's knowledge of the osteology of existing birds—not heretofore referred to—I am of the opinion, that in the case of his Meleagris antiqua, the material upon which it is based is altogether too fragmentary to pronounce, with anything like certainty, that it ever belonged to a turkey at all. In the first place, it is a very imperfect fragment (Plate 1, Figs. 1 and 2); in the second, it does not typically present the "characteristic portions" of that end of the humerus in a turkey, as Professor Marsh states it does. Thirdly, the distal end of the humerus is by no means a safe fragment of the skeleton of hardly any bird to judge from.[36] Finally, it is questionable whether the genus Meleagris existed at all, as such, at the time the "Miocene clay deposits of northern Colorado" were deposited.

That this fragment may have belonged to the skeleton of some big gallinaceous fowl the size of an adult existing Meleagris—and long ago extinct—I in no way question; but that it was a true turkey, I very much doubt.

Still more uncertain is the fragment representing Meleagris celer of Marsh. (Plate 1, Figs. 3-5.) The tibia mentioned I have not seen, and of them Professor Marsh states that they only "probably belonged to the same individual" (see antea). As to this proximal moiety of the tarso-metatarsus, it is essentially different from the corresponding part of that bone in Meleagris g. silvestris. In it the hypotarsus is twice grooved, longitudinally; whereas in M. g. silvestris there is but a single median groove. In the latter bird there is a conspicuous osseous ridge extending far down the shaft of the bone, it being continued from the internal, thickened border of the hypotarsus. This ridge is only[37] indicated on the fossil bone, having either been broken off or never existed at all. In any event it is not present in the specimen. The general facies of the fossil is quite different from that part of the tarso-metatarsus in an existing wild turkey, and to me it does not seem to have come from the skeleton of the pelvic limb of a meleagrine fowl at all. It may have belonged to a bird of the galline group, not essentially a turkey; while on the other hand it may have been from the skeleton of some large wader, not necessarily related to either the true herons or storks. Some of the herons, for example, (Ardea) have "the hypotarsus of the tarso-metatarsus three-crested, graduated in size, the outer being the smaller; the tendinal grooves pass between them."[7] As just stated, the hypotarsus of the tarso-metatarsus in Meleagris celer of Marsh is three-crested, and the tendinal grooves pass between them. In M. g. silvestris this process is but two-crested and the median groove passes between them.

The sternum of the turkey, if we have it practically complete, is one of the most characteristic bones of the skeleton; but Professor Marsh had no such material to guide him when he pronounced upon his fossil turkeys. Had I made new species, based on the fragments of fossil long bones of all that I have had for examination, quite a numerous little extinct avifauna would have been created.

"It is often a positive detriment to science, in my opinion, to create new species of fossil birds upon the distal ends of long bones, and surely no assistance whatever to those who honestly endeavor to gain some idea of the avian species that really existed during prehistoric times."[8]

Having disposed of such records as we have of the extinct ancestors of the American turkeys—the so-to-speak meleagrine records—we can now pass to what is, comparatively speaking, the modern history of these famous birds, although some of this history is already several centuries old.

We have seen in the foregoing chapter that all the described fossil species of turkeys have been restricted to the genus Meleagris, and this is likewise the case with the existing species and subspecies. Right here I may say that the word Meleagris is Greek as well as Latin, and means a guinea-fowl. This is due to the fact that when turkeys were first described and written about they were, by several authors of the early times, strangely mixed up with those African forms, and the two were not entirely[40] disentangled for some time, as we shall see further on in this chapter. In modern ornithology, however, the generic name of Meleagris has been transferred from the guinea-fowls to the turkeys. These last, as they are classified in "The A. O. U. Check-List of the American Ornithologists' Union," which is the latest authoritative word upon the subject, stand as follows:

Family Meleagridæ. Turkeys.

Genus Meleagris Linnæus.

Meleagris Linnæus, Syst. Nat., ed. 10, 1, 1758, 156. Type, by subs, desig., Meleagris gallopavo Linnæus (Gray, 1840).

Meleagris gallopavo (Linnæus).

Range.—Eastern and south central United States, west to Arizona and south to the mountains of Oaxaca.

a. [Meleagris gallopavo gallopavo. Extralimital.]

b. Meleagris gallopavo silvestris Vieillot. Wild Turkey [310a].

Meleagris silvestris Vieillot Nouv., Dict. d'Hist. Nat., IX, 1817, 447.

Range.—Eastern United States from Nebraska, Kansas, western Oklahoma, and eastern Texas east to central Pennsylvania, and south to the Gulf coast; formerly north to South Dakota, southern Ontario, and southern Maine.

c. Meleagris gallopavo merriami Nelson. Merriam's Turkey [310].

Meleagris gallopavo merriami Nelson, Auk, XVII, April, 1900, 120.

(47 miles southwest of Winslow, Arizona.)

Range.—Transition and Upper Sonoran zones in the mountains of southern Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, western Texas, northern Sonora, and Chihuahua.

d. Meleagris gallopavo osceola Scott. Florida Turkey [310b].

Meleagris gallopavo osceola Scott, Auk, VII, Oct., 1890, 376. (Tarpon Springs, Florida.)

Range.—Southern Florida.

e. Meleagris gallopavo intermedia Sennett. Rio Grande Turkey [310c].

Meleagris gallopavo intermedia Sennett. Bull. U. S. Geol. & Geog. Surv. Terr., V, No. 3, Nov., 1879, 428. (Lomita, Texas.)

Range.—Middle northern Texas south to northeastern Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas.

The presenting of the above list here does away with giving, in the history of the wild turkeys, any of the very numerous changes that have taken place through the ages which led up to its adoption. The discussion of these changes, as a part of meleagrine history, would make an octavo volume of two hundred pages or more.

It may be said here, however, that the word gallopavo is from the Latin, gallus a cock, and pavo a peafowl, while the meanings of the several[42] words silvestris, merriami, osceola, and intermedia are self-evident and require no definitions.

Audubon, who gives the breeding range of the wild turkey as extending "from Texas to Massachusetts and Vermont" (Vol. V., p. 56), says of them in his long account: "I have ascertained that some of these valuable birds are still to be found in the states of New York, Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine. In the winter of 1832-33, I purchased a few fine males in the city of Boston"; and further, "At the time when I removed to Kentucky, rather more than a fourth of a century ago, turkeys were so abundant that the price of one in the market was not equal to that of a common barn-fowl now. I have seen them offered for the sum of three pence each, the birds weighing from ten to twelve pounds. A first-rate turkey, weighing from twenty-five to thirty pounds avoirdupois, was considered well sold when it brought a quarter of a dollar."[9]

From these remarks we may imagine how plentiful wild turkeys must have been on the [43]North American continent, when Aristotle wrote his work "On Animals," over three hundred years before the birth of Christ, upward of twenty-three centuries ago! A good many changes can take place in the avifauna of a country in that time.

How these big, gallinaceous fowls ever got the name of "turkey" has long been a matter of dispute; and not a few ornithologists and writers of note in the 16th and 17th centuries erroneously conceived that the term had something to do either with the Turks or their country. But this idea has now been entirely abandoned, for it has become quite clear that, during the times mentioned, the turkey was strangely confused with the guinea-fowl, a bird to which the name turkey was originally applied.

Later on, both these birds became more abundant, as more of them were domesticated and reared in captivity, and the fact was gradually realized that they were entirely different species of fowls. During these times, the word turkey was finally applied only to the New World species, and the West African form was thereafter[44] called "Guinea-fowl."[10] After the word turkey was more generally applied to the bird now universally so known, some believe that there was another reason as to how it came about, and this "possibly because of its reputed call-note," says Newton, "to be syllabled turk, turk, turk, whereby it may be almost said to have named itself." (Notes and Queries, ser. 6, III, pp. 23, 369.)[11]

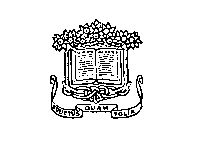

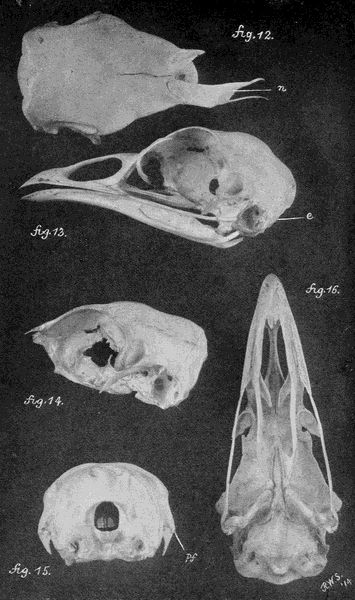

Plate II

Fig. 6. Superior view of the skull of an old male wild turkey; lower jaw removed. No. 9695, Coll. U. S. National Museum. Fig. 7. Lower jaw or mandible of the skull shown in Fig. 6., seen from above. Fig. 8. Superior view of a skull of a wild turkey and probably a female. Lower jaw removed and shown in Fig. 9. No. 19684, Coll. U. S. National Museum. Fig. 9. Lower jaw of the skull shown in Fig. 8. Superior aspect. Fig. 10. Upper view of the skull of a wild Florida turkey (Meleagris g. osceola); lower jaw removed and not figured. Female. No. 18797, Coll. U. S. National Museum. All the figures in this plate are reproductions of photographs of the specimens made natural size by Dr. Shufeldt. Reduced about one-fourth.

So much for the origin of the name turkey; and when one comes to search through the literature devoted to this fowl to ascertain who first described the wild species, the opinion seems to be [45]pretty general that this was done by Oviedo in the thirty-sixth chapter of his "Summario de la Natural Historia de las Indias," which it is stated appeared about the year 1527.

Professor Spencer F. Baird, apparently quoting Martin, says: "Oviedo speaks of the turkey as a kind of peacock abounding in New Spain, which had already in 1526 been transported in a domestic state to the West India Islands and the Spanish Main, where it was kept by the Christian colonists."[12]

In an elegant and comprehensive article on "The Wild Turkey," Bennett states: "Oviedo, whose Natural History of the Indies contains the earliest description extant of the bird, and whose acquaintance with the animal productions of the newly discovered countries was surprisingly extensive. He speaks of it as a kind of Peacock [46]found in New Spain, of which a number had been transported to the islands of the Spanish Main, and domesticated in the houses of the Christian inhabitants. His description is exceedingly accurate, and proves that before the year 1526, when his work was published at Toledo, the turkey was already reduced to a state of Domestication."[13]

Again, in a very elaborate and now thoroughly classical contribution, Pennant states: "The first precise description of these birds is given by Oviedo, who, in 1525, drew up a summary of his greater work, the History of the Indies, for the use of his monarch Charles V.[14] This learned man had visited the West Indies and its islands in person, and paid particular regard to the natural history. It appears from him, that the Turkey was in his days an inhabitant of the greater islands and of the mainland. He speaks [47]of them as Peacocks; for being a new bird to him, he adopts that name from the resemblance he thought they bore to the former. 'But,' says he, 'the neck is bare of feathers, but covered with a skin which they change after their phantasie into diverse colours. They have a horn (in the Spanish Peçon corto) as it were on their front, and hairs on the breast.' (In Purchas, III, 995.) He describes other birds which he also calls Peacocks. They are of the gallinaceous genus, and known by the name of Curassao birds, the male of which is black, the female ferruginous."[15]

Dr. Coues, who has also written an article on the history of the wild turkey, which, by the way, is mainly composed of a lengthy quotation from the above cited article of Bennett's, says: "Linnæus, however, knew perfectly well that the turkey was American. He says distinctly: 'Habitat in America septentrionali,' and quotes as his first reference (after Fn. Soec. 198), the Gallopavo sylvestris novæ angliæ, or New England Wild Turkey of Ray. Brisson distinguished the two perfectly, giving an elaborate description, a copious synonomy, and a good figure of each; and from about this time it may be considered that the history of the two birds, so widely diverse, was finally disentangled, and the proper habitat ascribed to each." (Refers to first describers of the pintado and turkey.)[16]

So much for the earliest describers of the wild [49]turkey, and I shall now pass on to the general history of the bird, and, through presenting what has been collected for us by the best authors on the subject, endeavor to show how, after the wild turkey was found in America by different navigators and explorers, it was brought, from time to time, to several of the countries of the Old World—chiefly Spain and Great Britain—from whence it probably was taken, upon different occasions, into other countries of the continent.

Wild turkeys have always been easy to capture, and we are aware of the fact that they are quite capable of crossing the Atlantic on shipboard in comfort and safety, landing in as good a condition—if properly cared for during the voyage—as when they left America. Josselyn (1672) in his New England Rarities (p. 9) has not a little to say on this point.

As already stated, the literature and bibliography of the turkey is quite sufficient to fill a good many volumes. Nothing of importance, however, has been added to it, gainsaying what we now have as a truthful account of the bird's introduction into Europe. Indeed Buffon (Ois,[50] II, pp. 132-162), Broderip (Zool. Recreat. pp. 120-137), Pennant (Arct. Zool. pp. 291-300), and others, practically cleared up nearly all the points on this part of the turkey's history, making but a few statements that are not wholly reliable and worthy of acceptance. Pennant very properly ignored in his work Barrington's essay (Miscellanies, pp. 127-151) in which the latter attempted to prove that turkeys were known before America was discovered, and that they were shipped over there subsequently to its discovery!

I have already cited above Pennant's article in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (1781), and quoted from it to some extent. It is one of the standard writings on the wild turkey invariably referred to by all authors when writing on the history of that bird. As it is only accessible to the few, and so full of reliable information, I propose to give here, somewhat in full, those paragraphs in it having special reference to the historical side of our subject, and in doing so I retain the spelling and composition of the original production.

"Belon, ('Hist. des Oys.,' 248) the earliest of those writers," says Pennant, "who are of the opinion that these birds were natives of the old world, founds his notion on the description of the Guinea-fowl, the Meleagrides of Strabo, Athenæus, Pliny, and others of the ancients. I rest the refutation on the excellent account given by Athenæus, taken from Clytus Milesius, a disciple of Aristotle, which can suit no other than that fowl. 'They want,' says he, 'natural affection towards their young; their head is naked, and on the top is a hard round body like a peg or nail; from their cheeks hangs a red piece of flesh like a beard. It has no wattles like the common poultry. The feathers are black, spotted with white. They have no spurs; and both sexes are so alike as not to be distinguished by the sight.' Varro (Lib. III. c. 9.) and Pliny (Lib. X. c. 26) take notice of the spotted plumage and the gibbous substance on the head. Athenæus is more minute, and contradicts every character of the Turkey, whose females are remarkable for their natural affection, and differ materially in form from the males, whose heads are destitute[52] of the callous substance, and whose heels (in the males) are armed with spurs."

"Aldrovandus, who died in 1605, draws his arguments from the same source as Belon; I therefore pass him by, and take notice of the greatest of our naturalists Gesner (Av. 481.), who falls into a mistake of another kind, and wishes the Turkey to be thought a native of India. He quotes Ælian for that purpose, who tells us, 'That in India are very large poultry not with combs, but with various coloured crests interwoven like flowers, with broad tails either bending or displayed in a circular form, which they draw along the ground as peacocks do when they do not erect them; and that the feathers are partly of a gold colour, partly blue, and of an emerald colour.' (De Anim. lib. XVI, c. 2.).

"This in all probability was the same bird with the Peacock Pheasant of Mr. Edwards, Le Baron de Tibet of M. Brisson, and the Pavo bicalcaratus of Linnæus. I have seen this bird living. It has a crest, but not so conspicuous as that described by Ælian; but it has not those striking colours in form of eyes, neither does it erect its[53] tail like the Peacock (Edw. II. 67.), but trails it like the Pheasant. The Catreus of Strabo (Lib. XV. p. 1046) seems to be the same bird. He describes it as uncommonly beautiful and spotted, and very like a Peacock. The former author (De Anim. lib. XVII, c. 23.) gives more minute account of this species, and under the same name. He borrows it from Clitarchus, an attendant of Alexander the Great in all his conquests. It is evident from his description that it was of this kind; and it is likewise probable that it was the same with his large Indian poultry before cited. He celebrates it also for its fine note; but allowance must be made for the credulity of Ælian.

"The Catreus, or Peacock Pheasant, is a native of Tibet, and in all probability of the north of India, where Clitarchus might have observed it; for the march of Alexander was through that part which borders on Tibet, and is now known by the name of Penj-ab or five rivers."

"I shall now collect from authors the several parts of the world where Turkies are unknown in the state of nature. Europe has no share in[54] the question; it being generally agreed that they are exotic in respect to that continent."

"Neither are they found in any part of Asia Minor, or the Asiatic Turkey, notwithstanding ignorance of their true origin first caused them to be named from that empire. About Aleppo, capital of Syria, they are only met with, domesticated like other poultry. (Russel, 63). In Armenia they are unknown, as well as in Persia; having been brought from Venice by some Armenian merchants into that empire (Tavernier, 145), where they are still so scarce as to be preserved among other rare fowls in the royal menagery" (Bell's Travels, I. 128).

"Du Halde acquaints us that they are not natives of China; but were introduced there from other countries. He errs from misinformation in saying that they are common in India."

"I will not quote Gemelli Careri, to prove that they are not found in the Philippine Islands, because that gentleman with his pen traveled round the world in his easy chair, during a very long indisposition and confinement, (Sir James[55] Porter's Obs. Turkey, I, 1, 321), in his native country."

"But Dampier bears witness that none are found in Mindanao" (Barbot in Churchill's Coll., V. 29).

"The hot climate of Africa barely suffers these birds to exist in that vast continent, except under the care of mankind. Very few are found in Guinea, except in the hands of the Europeans, the negroes declining to breed any on account of the great heats (Bosman, 229). Prosper Alpinus satisfies us they are not found either in Nubia or in Egypt. He describes the Meleagrides of the ancients, and only proves that the Guinea hens were brought out of Nubia, and sold at a great price at Cairo (Hist. Nat. Ægypti. I, 201); but is totally silent about the turkey of the moderns."

"Let me in this place observe that the Guinea hens have long been imported into Britain. They were cultivated in our farm-yards; for I discover in 1277, in the Grainge of Clifton, in the parish of Ambrosden in Buckinghamshire, among other articles, six Mutilones and six [56]Africanæ fœminæ (Kennett's Parochial Antiq. 287), for this fowl was familiarly known by the names of Afra Avis and Gallina Africana and Numida. It was introduced into Italy from Africa, and from Rome into our country. They were neglected here by reason of their tenderness and difficulty of rearing. We do not find them in the bills of fare of our ancient feasts (neither in that of George Nevil nor among the delicacies mentioned in the Northumberland household book begun in the beginning of the reign of Henry VIII); neither do we find the turkey; which last argument amounts almost to a certainty, that such a hardy and princely bird had not found its way to us. The other likewise was then known by its classical name; for that judicious writer Doctor Caius describes in the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth, the Guinea-fowl, for the benefit of his friend Gesner, under the name of Meleagris, bestowed on it by Aristotle" (CAII Opusc. 13. Hist. An., lib. VI. c. 2).

"Having denied, on the very best authorities, that the Turkey ever existed as a native of the old world, I must now bring my proofs of its being[57] only a native of the new, and of the period in which it first made its appearance in Europe."

"The next who speaks of them as natives of the mainland of the warmer parts of America is Francusco Fernandez, sent there by Philip II, to whom he was physician. This naturalist observed them in Mexico. We find by him that the name of the male was Huexolotl, of the female Cihuatotolin. He gives them the title of Gallus Indicus and Gallo Pavo. The Indians, as well as the Spaniards, domesticated these useful birds. He speaks of the size by comparison, saying that the wild were twice the magnitude of the tame; and that they were shot with arrows or guns (Hist. Av. Nov. Hisp. 27). I cannot learn the time when Fernandez wrote. It must be between the years 1555 and 1598, the period of Philip's reign."

"Pedro de Ciesa mentions Turkies on the Isthmus of Darien (Seventeen Years Travels, 20). Lery, a Portuguese author, asserts that they are found in Brazil, and gives them an Indian name (In De Laet's Descr. des Indes, 491); but since I can discover no traces of them[58] in that diligent and excellent naturalist Marcgrave, who resided long in that country, I must deny my assent. But the former is confirmed by that able and honest navigator Dampier, who saw them frequently, as well wild as tame, in the province of Yucatan (Voyages, Vol II, part II, pp. 65, 85, 114), now reckoned part of the Kingdom of Mexico."

"In North America they were observed by the very first discoverers. When Rene de Landonniere, patronized by Admiral Coligni, attempted to form a settlement near where Charlestown now stands, he met with them on his first landing in 1564, and by his historian has represented them with great fidelity in the fifth plate of the recital of his voyage (Debry): from his time the witnesses to their being natives of the continent are innumerable. They have been seen in flocks of hundreds in all parts from Louisiana even to Canada; but at this time are extremely rare in a wild state, except in the more distant parts, where they are still found in vast abundance."

"It was from Mexico or Yucatan that they[59] were first introduced into Europe; for it is certain that they were imported into England as early as the year 1524, the 15th of Henry VIII. (Baker's Chr. Anderson's Dict., Com. 1, 354. Hackluyt, II, 165, makes their introduction about the year 1532. Barnaby Googe, one of our early writers on Husbandry, says they were not seen here before 1530. He highly commends a Lady Hales of Kent for her excellent management of these fowl, p. 166.)

"We probably received them from Spain, with which we had great intercourse till about that time. They were most successfully cultivated in our Kingdom from that period; insomuch that they grew common in every farm-yard, and became even a dish in our rural feasts by the year 1585; for we may certainly depend on the word of old Tusser in his Account of the Christmas Husbandrie Fare." (Five Hundred Points of good Husbandrie, p. 57.)

"But at this very time they were so rare in France, that we are told, that the very first which was eaten in that Kingdom appeared at the nuptial feast of Charles IX. in 1570 (Anderson's Dict. Com. 1, 410)."[17]

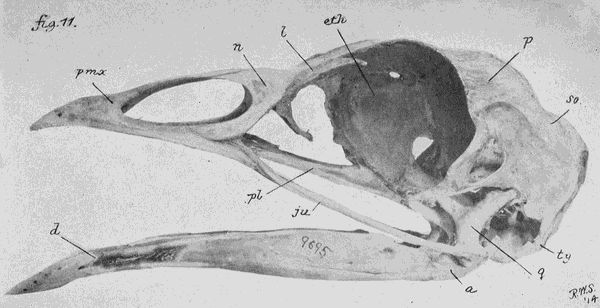

Plate III

Fig. II. Left lateral view of the skull of an old male wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). See Plate II, Fig. 6, No. 9695, Coll. U. S. National Museum. Photo natural size by Dr. Shufeldt. pmx, premaxillary; n, nasal bone; l, lacrymal bone; eth, ethmoid; p, parietal; so, supraoccipital; pl, palatine; ju, jugal; ty, tympanic; q, quadrate; a, angular of lower jaw; d, dentary. There are many more bones in the skull than those indicated, while the latter serve to invite attention to the principal ones as landmarks.

A little later on Bartram in his travels in the South published some notes on the wild turkey [now M. g. osceola] as he found them in Florida during the latter part of the eighteenth century. The original edition of his book, which I have not seen, appeared in 1791. I have, however, examined the edition of 1793, wherein on page 14 he says: "Our turkey of America is a very different species from the Meleagris of Asia [61]and Europe; they are nearly thrice their size and weight. I have seen several that have weighed between twenty and thirty pounds, and some have been killed that have weighed near forty."

And further on in the same work he adds [Florida, p. 81]: "Having rested very well during the night, I was awakened in the morning early by the cheering converse of the wild turkey-cocks (Meleagris occidentalis) saluting each other from the sun-brightened tops of the lofty Cupressus disticha and Magnolia grandiflora. They begin at early dawn and continue till sunrise, from March to the last of April. The high forests ring with the noise, like the crowing of the domestic cock, of these social sentinels; the watchword being caught and repeated, from one to another, for hundreds of miles around, insomuch that the whole country is for an hour or more in a universal shout. A little after sunrise, their crowing gradually ceases, they quit then their high lodging places, and alight on the earth, where, expanding their silver-bordered train, they strut and dance round about[62] the coy female, while the deep forests seem to tremble with their shrill noise."[18]

Another of the early writers (1806), who paid some attention to the history and distribution of the wild turkeys was Barton. I find the following having reference to some of his observations, viz.: "A memoir has been read before the American Philosophical Society in which the author has shown that at least two distinct species of Meleagris, or turkey, are known within the limits of North America. These are the Meleagris gallopavo, or Common Domesticated Turkey, which was wholly unknown in the countries of the Old World before the discovery of America; and the Common Wild Turkey of the United States, to which the author of the memoir has given the name Meleagris Palawa—one of its Indian names.

"The same author has rendered it very probable that this latter species was domesticated by some of the Indian tribes living within the present limits of the United States, before these tribes had been visited by the Europeans. It is certain, however, that the turkey was not domesticated by the generality of the tribes, within the limits just mentioned, until after the Europeans had taken possession of the countries of North America."[19]

Nine or ten years after Barton wrote, De Witt Clinton, who was a candidate for President of the United States in 1812, and a son of James Clinton, was one of the writers of that time on the wild turkey. He pointed out how birds, the turkey included, change their plumage after domestication, and, after giving what he knew of the introduction of the turkey into Spain from America and the West Indies, he adds: "From the Spanish turkey, which was thus spread over [64]Europe, we have obtained our domestic one. The wild turkey has been frequently tamed, and his offspring is of a large size." (p. 126.)[20]

Nearly a quarter of a century after Clinton's article appeared, the anatomy of the wild turkey began to attract some attention. Among the first articles to appear on this part of the subject was one by the late Sir Richard Owen, who, apparently taking the similarity of the vernacular names into account, made anatomical comparisons of the organs of smell in the turkey and the turkey buzzard. Naturally, he found them very different,—quite as different, perhaps, as are the olfactory organs of an owl and an ostrich, which I, for one, would not undertake to make a comparison of for publication, simply for the fact that in both these birds their vernacular name begins with the letter o.[21]

Even twenty years after this paper appeared there were those who still entertained doubts as to the origin of the domesticated turkeys, and believed that they had nothing to do with the [65]wild forms. Among the doubters, no one was more prominent than Le Conte, who published the following as his opinion at the time, stating: "The conviction that these two birds were really distinct species has long existed in my mind. More than fifty years ago, when I first saw a Wild Turkey, I was led to conclude that one never could have been produced from the other." [Bases it on differences of external characters] (p. 179), adding toward the close of his article: "I defy anyone to show a Turkey, even of the first generation, produced from a pair hatched from the eggs of a wild hen," etc. "I repeat, contrary to the assertions of many others, that no one has ever succeeded in domesticating our Wild Turkey," etc. "Thoroughly believe that the tame and wild bird are different species, and the latter not the ancestor of the tame one." (p. 181.)[22]

During the year 1856, the papers Gould published on the wild turkeys attracted considerable attention, and they have been widely quoted since. In one of his first papers on the subject he quotes from Martin the same paragraph which Baird quoted in his article in the Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture (1866 antea), while Baird in his article misquotes Gould by saying that the turkey was introduced into England in 1541; whereas Gould states the introduction took place in 1524.[23]

Before passing to the more recent literature on these birds, and what I will have to say further on about their comparative osteology and their eggs, it will be as well to reproduce here a few more statements made by Bennett, whose work, "The Gardens and Menagerie of the Zoölogical Society Delineated," I have already quoted.[24]

Bennett was also of the opinion that "Daines Barrington was the last writer of any note who denied the American origin of the turkey, and he seems to have been actuated more by a love of paradox than by any conviction of the truth of his theory. Since the publication of his Miscellanies, in 1781, the knowledge that has been obtained of the existence of large flocks of turkeys, perfectly wild, clothed in their natural plumage, and displaying their native habits, spread over a large portion of North America, together with the certainty of their non-existence in a similar state in any other part of the globe, have been admitted on all hands to be decisive of the question." (p. 210).

I have already cited the evidence above to prove that it was Oviedo who first published an accurate description of the wild turkey,—his work being published at Toledo in about the year 1526, at which time the turkey had already[69] become domesticated. In other words, it was the Spaniards who first reduced the bird to a state of domestication, and very soon thereafter it was introduced into England. Spain and England were the great maritime nations of those times, and this fact will amply account for the early introduction of the bird into the latter country. Singularly enough, however, we have no account of any kind whatever through which we can trace the exact time when this took place. As others have suggested, it is just possible that it may have been Cabot, the explorer of the then recently discovered coasts of America, who first transported wild turkeys into England. Baker quotes the popular rhyme in his Chronicle:

that is, about 1524, or the 15th of the reign of Henry VIII.[25]

What was said by the German author Heresbach was translated by a writer on agricultural [70]subjects, Barnaby Googe, who published it in his work. This appeared in the year 1614, and he refers to "those outlandish birds called Ginny-Cocks and Turkey-Cocks," stating that "before the yeare of our Lord 1530 they were not seene with us!"

Further, Bennett points out that "A more positive authority is Hakluyt, who in certain instructions given by him to a friend at Constantinople, bearing date of 1582, mentions, among other valuable things introduced into England from foreign parts, 'Turkey-Cocks and hennes' as having been brought in 'about fifty years past.' We may therefore fairly conclude that they became known in this country about the year 1530."[26]

Guinea-fowls were extremely rare in England throughout the sixteenth century, while tame turkeys became very abundant there, forming by no means an expensive dish at festivals,—the first were obtained from the Levant, while the latter were to be found in poultry yards [71]nearly everywhere. In one of the Constitutions of Archbishop Cranmer it was ordered that of fowls as large as swans, cranes, and turkey-cocks, "there should be but one in a dish."[27]

When in 1555 the serjeants-at-law were created, they provided for their inauguration dinner two turkeys and four turkey chicks at a cost each of only four shillings, swans and cranes being ten, and half a crown each for capons. At this rate, turkeys could not have been so very scarce in those parts.[28] "Indeed they had become so plentiful in 1573," continues Bennett, "that honest Tusser, in his 'Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandrie,'" enumerates them among the usual Christmas fare at a farmer's table, and speaks of them as "ill neighbors" both to "peason" and to hops. (pp. 212, 213.)

"A Frenchman named Pierre Gilles has the credit of having first described the turkey in this quarter of the globe, in his additions to a Latin translation of Ælian, published by him in 1535. His description is so true to nature as to have [72]been almost wholly relied on by every subsequent writer down to Willoughby. He speaks of it as a bird that he has seen; and he had not then been further from his native country than Venice; and states it to have been brought from the New World.

"That turkeys were known in France at this period is further proved by a passage in Champier's 'Treatise de Re Cibaria,' published in 1560, and said to have been written thirty years before. This author also speaks of them as having been brought but a few years back from the newly discovered Indian islands. From this time forward their origin seems to have been entirely forgotten, and for the next two centuries we meet with little else in the writings of ornithologists concerning them than an accumulation of citations from the ancients, which bear no manner of relation to them. In the year 1566 a present of twelve turkeys was thought not unworthy of being offered by the municipality of Amiens to their king, at whose marriage, in 1570, Anderson states in his History of Commerce, but we know not on what authority,[73] they were first eaten in France. Heresbach, as we have seen, asserts that they were introduced into Germany about 1530; and that a sumptuary law made at Venice in 1557, quoted by Zanoni, particularizes the tables at which they were permitted to be served.

"So ungrateful are mankind for the most important benefits that not even a traditionary vestige remains of the men by whom, or the country from whence, this most useful bird was introduced into any European states. Little therefore is gained from its early history beyond the mere proof of the rapidity with which the process of domestication may sometimes be effected." (pp. 213, 214.)

Some ten or more years ago, at a time when I was the natural history editor of Shooting and Fishing, in New York City, I published a number of criticisms and original articles upon turkeys, both the wild and domesticated forms.[29]

About twelve years ago, Mr. Nelson contributed a very valuable article on wild turkeys, portions of which are eminently worthy of the space here required to quote them.[30] He says among other things in this article that "All recent ornithologists have considered the wild turkey of Mexico and the southwestern United States (aside from M. gallopavo intermedia) as the ancestor of the domesticated bird. This idea is certainly erroneous, as is shown by the series of specimens now in the collection of the Biological Survey. When the Spaniards first entered Mexico they landed near the present city of Vera Cruz and made their way thence to the City of Mexico.

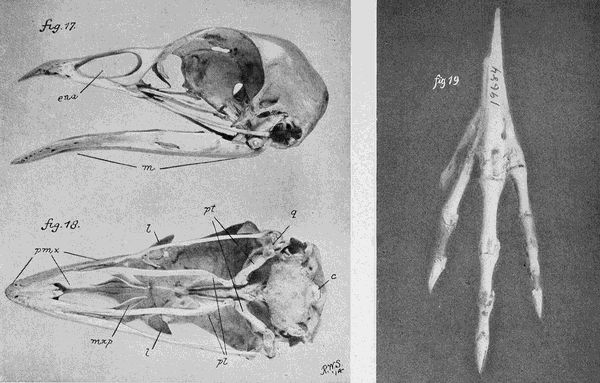

Plate IV

Fig. 12. Superior view of the cranium of a large male tame turkey, with right nasal bone (n) attached in situ. Specimen in Dr. Shufeldt's private collection. Fig. 13. Left lateral view of the skull of a female turkey, probably a wild one. No. 19684, Coll. U. S. National Museum. (See Fig. 8, Pl. II.) e, bony entrance to ear. Compare contour line of cranium with Fig. 14. Fig. 14. Left lateral view of the cranium of a tame turkey; male. Dr. Shufeldt's private collection. Fig. 15. Direct posterior view of the cranium of a tame turkey, probably a female. pf, postfrontal. Specimen in Dr. Shufeldt's collection. Fig. 16. Skull of a wild Florida turkey, seen from below (M. g. osceola). (See Fig. 10, Pl. II.) Bones named in Fig. 18. Photo natural size by Dr. Shufeldt and considerably reduced.

"At this time they found domesticated turkeys among the Indians of that region, and within a few years the birds were introduced into Spain.[31]

"The part of the country occupied by the Spanish during the first few years of the conquest in which wild turkeys occur is the eastern slope of the Cordillera in Vera Cruz, and there is every reason to suppose that this must have been the original home of the birds domesticated by the natives of that region.

"Gould's description of the type of M. mexicana is not sufficiently detailed to determine the exact character of this bird, but fortunately the type was figured in Elliot's "Birds of North America."... In addition Gould's type apparently served for the description of the adult male M. gallopavo in the 'Catalogue of Birds Brit. Mus.' (xxii, p. 387), and an adult female is described in the same volume from Ciudad Ranch Durango.... Thus it will become necessary to treat M. gallopavo and M. mexicana as at least subspecifically distinct. Whatever may be the relationship of M. mexicana to M. gallopavo, the M. g. merriami is easily separable from M. g. mexicana of the Sierra Madre of western Mexico, from Chihuahua to Colima. Birds from northern Chihuahua are intermediate."

In this article Mr. Nelson names M. g. merriami and gives full descriptions of the adult male and female in winter plumage.

What has thus far been presented above on the first discovery of the American wild turkeys, their natural history in the New World, their introduction into Spain, England, France, and elsewhere, is practically all we have on this part of our subject up to date. What I have given is from the very best ornithological and other authorities. Domesticated turkeys are now found in nearly all parts of the world, while in only a very few instances has any record been kept of the different times of their introduction. With the view of accumulating such data, one would have to search the histories of all the countries of all the civilized and semi-civilized peoples of the world, which would be the labor of almost a man's entire lifetime, and in only too many instances his search would be in vain, for the several records of the times of introducing these birds were not made.

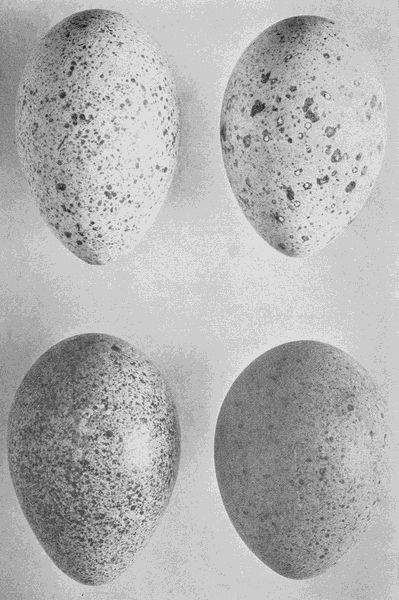

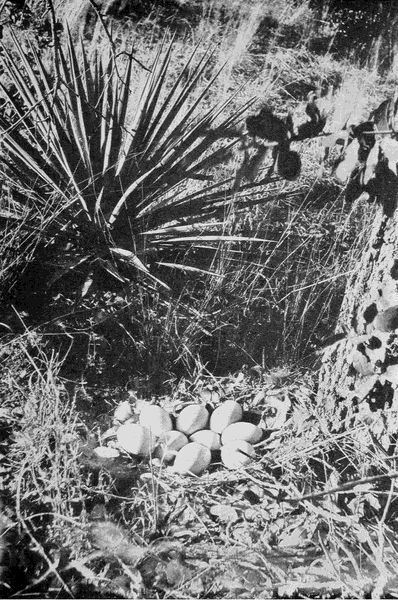

Apart from the description of the wild turkeys, there is still a very large literature devoted to the[77] domesticated forms of turkeys as they occur in this country and abroad, as well as descriptions of their eggs. I have gone over a large part of this literature, but shall be able to use only a small, though nevertheless essential, part of it here. This I shall complete with an account of turkey eggs, which will be presented quite apart from anything to do with their nests, nesting habits, and much else which will be fully treated in other chapters of this book. In some works we meet with the literature of all these subjects together, others have only a part, while still others are confined to one thing, as the eggs.[32] Darwin in his works paid considerable attention to the wild and tame turkeys. He states that "Professor Baird believes (as quoted in Tegetmeier's 'Poultry Book,' 1866, p. 269) that our turkeys are descended from a West Indian species, now extinct. But besides the improbability of a bird having long ago become extinct in these large and luxuriant islands, it appears, as we [78]shall presently see, that the turkey degenerates in India, and this fact indicates that this was not aboriginally an inhabitant of the lowlands of the tropics.

"F. Michaux," he further points out, "suspected in 1802 that the common domestic turkey was not descended from the United States species alone, but was likewise from a southern form, and he went so far as to believe that English and French turkeys differed from having different proportions of the blood of the two parent-forms.[33]