Title: Palmer's Journal of Travels Over the Rocky Mountains, 1845-1846

Author: Joel Palmer

Contributor: Henry Harmon Spalding

Editor: Reuben Gold Thwaites

Release date: September 20, 2014 [eBook #46906]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Matthias Grammel, Greg Bergquist, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries (https://archive.org/details/americana)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Early Western Travels 1748-1846, Volume XXX, by Joel Palmer, Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See https://archive.org/details/earlywesterntrav30thwa |

1748-1846

Volume XXX

Early Western Travels

1748-1846

A Series of Annotated Reprints of some of the best

and rarest contemporary volumes of travel, descriptive

of the Aborigines and Social and

Economic Conditions in the Middle

and Far West, during the Period

of Early American Settlement

Edited with Notes, Introductions, Index, etc., by

Reuben Gold Thwaites, LL.D.

Editor of "The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents," "Original

Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition," "Hennepin's

New Discovery," etc.

Volume XXX

Palmer's Journal of Travels over the Rocky Mountains,

1845-1846

Cleveland, Ohio

The Arthur H. Clark Company

1906

Copyright 1906, by

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Lakeside Press

R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY

CHICAGO

| Preface. The Editor | 9 | ||

|

Journal of Travels over the Rocky Mountains, to the

Mouth of the Columbia River; Made during the

Years 1845 and 1846: containing minute descriptions of

the Valleys of the Willamette, Umpqua, and Clamet; a

general description of Oregon Territory; its inhabitants,

climate, soil, productions, etc., etc.; a list of Necessary

Outfits for Emigrants; and a Table of Distances from

Camp to Camp on the Route. Also; A Letter from the

Rev. H. H. Spalding, resident Missionary, for the last ten

years, among the Nez Percé Tribe of Indians, on the Kooskooskee

River; The Organic Laws of Oregon Territory;

Tables of about 300 words of the Chinook Jargon, and

about 200 Words of the Nez Percé Language; a Description

of Mount Hood; Incidents of Travel, &c., &c. Joel Palmer. |

|||

| Copyright Notice | 24 | ||

| Author's Dedication | 25 | ||

| Publishers' Advertisement | 27 | ||

| Text: Journal, April 16, 1845-July 23, 1846 | 29 | ||

| Necessary Outfits for Emigrants traveling to Oregon | 257 | ||

| Words used in the Chinook Jargon | 264 | ||

| Words used in the Nez Percé Language | 271 | ||

| Table of Distances from Independence, Missouri; and St. Joseph, to Oregon City, in Oregon Territory | 277 | ||

| Appendix: | |||

| Letter of the Rev. H. H. Spalding to Joel Palmer, Oregon Territory, April 7, 1846 | 283 | ||

| Organic Laws of Oregon (with amendments). | 299 | ||

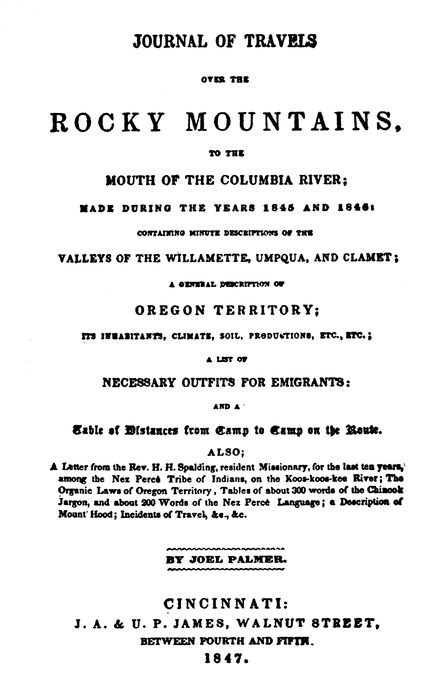

| Facsimile of title-page, Palmer's Journal of Travels. | 23 | ||

In the wake of the pathfinders, fur-traders, Indian scouts, missionaries, scientific visitors, and foreign adventurers came the ultimate figure among early Western travellers, the American pioneer settler, the fore-runner of the forces of occupation and civilization. This concluding volume in our series is, therefore, fitly devoted to the record of an actual home-seeker, and founder of new Western communities.

The significant feature of American history has been the transplanting of bodies of colonists from one frontier to a newer frontier. In respect to the Oregon country, our interest therein is enhanced not only by the great distance and the abundant perils of the way, but also by the political result in securing the territory to the United States, and the growth of a prosperous commonwealth in the Far Northwest corner of our broad domain. In several previous volumes of our series we have witnessed the beginnings of Oregon civilization. Two of our travellers, Franchère and Ross, have graphically detailed the Astoria episode, giving us, not without some literary skill, the skeleton of facts which Irving's masterful pen clothed with living flesh and healthful color; in Townsend's pages we found an enduring picture of the régime of the all-powerful Hudson's Bay Company; De Smet, with faithful, indeed loving, touches has portrayed the vanishing aborigines, whose sad story has yet fully to be told—eventually, when the last [pg. 10] vestige of their race has gone, we shall come to recognize the tale as the sorriest chapter in our annals; Farnham shrewdly narrates the sharp transition to American occupancy; but Palmer tells us of the triumphant progress of the conquering pioneer, and in his pages the destiny of Oregon as an American state is clearly foreshadowed.

"Fifty-four forty, or fight," the belligerent slogan with regard to Oregon, adopted in the presidential campaign of 1844, was after all not so much a notice to the British government that the United States considered the Oregon country her own, beyond recall, as an appeal to the pioneers of the West to secure this vast inheritance by actual occupation. As such it proved a trumpet call to thousands of vigorous American farmers, most of them already possessed of comfortable homes in the growing communities of the Middle West.

"I have an uncle," declared one of the pioneers to Dr. John McLoughlin, Hudson's Bay factor on the Pacific coast, "who is rich enough to buy out your company and all this territory."

"Indeed!" replied the doctor, courteously, "who is he?"

"Uncle Sam," gayly responded the emigrant, with huge enjoyment in his well-worn witticism. It was at the supposed behest of this same "Uncle Sam" that farms were sold, wagons and oxen purchased, outfits prepared, and long caravans of permanent settlers slowly and painfully crossed the vast plains and rugged mountains lying between the comfortable settlements of the "Old Northwest"—the "Middle West" of our [pg. 11] day—and the new land of promise in the Far Northwest of the Pacific Slope.

The emigration of 1845 exceeded all that had gone before. That of 1843, eight hundred strong, had startled the Indians, and surprised the staid officials of the Hudson's Bay Company. That of 1844 had occupied the fertile valleys from Puget Sound on the north to Calapooia on the south. That of 1845 determined that the territory should be the home of Americans; it doubled the population already on the ground, reinforced the compact form of government, and laid broad and deep the foundations of new American commonwealths.

Our author, Joel Palmer, a shrewd, genial farmer from Indiana, was a leader among these emigrants of 1845. Born across the Canada line in 1810, he nevertheless was of New York parentage, and American to the core. In early life his family removed to Indiana, where Joel founded a home at Laurel, in northwest Franklin County. By the suffrages of his neighbors Palmer was sent to the state legislature in 1844, but the following year determined to make a tour to Oregon for personal observation, before deciding to remove his family thither and cast his future lot with its pioneer settlers. Arrived on the Missouri frontier, he found that the usual wagon train had gone in advance. However, he overtook the great body of the emigrants in time to assist in the organization of the caravan on Big Soldier's Creek, in Kansas.

Gathered from all parts of the Middle West, with no attempt at organization nor any pre-arrangement whatsoever, the emigrants, who had not yet forgotten the [pg. 12] frontier traditions of their fathers, proved to be a homogeneous body of about three thousand alert, capable travellers, provided in general with necessities and even comforts for the hardships of the long journey; indeed, after the manner of their Aryan forbears in the great westerly migrations of the past, they were accompanied by herds of cattle, to form the basis of agricultural life in the new land. Each of the several hundred wagons was a travelling house, provided with tents, beds, and cooking utensils; clothing and food were also carried, sufficient not only for the journey out, but for subsistence through the first year, always the crucial stage of agricultural pioneering. The draught cattle were largely oxen, but many of the men rode horses, and others drove them with their cows and bulls.

Aside from the duties of the nightly encampment and morning "catch-up," life upon the migration progressed much as in settled communities. There were instances of courtship, marriage, illness, and death, and not infrequently births, among the migrating families. These, together with the ever-shifting panorama of sky, plains, and mountains, made the incidents of the long and tedious journey. Occasionally there appeared upon the horizon an Indian gazing silently at these invaders of his tribal domain, and at times he came even to the wagon wheels to beg or trade; the mere numbers of the travellers gave him abundant caution not to attempt hostilities. The wagons were so numerous as to render a compact caravan troublesome to manage and disagreeable to travel with. The great cavalcade soon broke into smaller groups, over one of [pg. 13] which, composed of thirty wagons, Palmer was chosen captain.

At Fort Laramie they rested, and feasted the Indians, who, in wonderment and not unnatural consternation, swarmed about them in the guise of beggars. Palmer afterwards harangued the aboriginal visitors, telling them frankly that their entertainers were no traders, they "were going to plough and plant the ground," that their relatives were coming behind them, and these he hoped the red men would treat kindly and allow free passage—a thinly veiled suggestion that the white army of occupation had come to stay and must not be interfered with by the native population, or vengeance would follow.

From Fort Laramie the invaders, for from the standpoint of the Indians such of course were our Western pioneers, followed the usual trail to the newly-established supply depot at Fort Bridger. Thence they went by way of Soda Springs to Fort Hall, where was found awaiting them a delegation from California, seeking, with but slight success, to persuade a portion of the emigrants in that direction. Following Lewis River on its long southern bend, the travellers at last reached Fort Boise, where provisions could be purchased from Hudson's Bay officials, and a final breathing-spell be taken before attempting the most difficult part of the journey—the passage of the Blue and Cascade ranges.

A considerable company of the emigrants, accompanied by the pilot, Stephen H. Meek, left the main party near Fort Hall, to force a new route to the Willamette without following Columbia River. The essay was, however, disastrous. Meek became bewildered, [pg. 14] and was obliged to secrete himself to escape the revenge of the exasperated travellers, who reached the Dalles of the Columbia in an exhausted condition, having lost many of their number through hunger and physical hardships.

Palmer himself continued with the main caravan on the customary route through the Grande Ronde, down the Umatilla and the Columbia, arriving at the Dalles by the closing days of September. Here a new difficulty faced the weary pioneers—there was no wagon road beyond the Dalles; boats to transport the intending colonists were few, and had been pre-empted by the early arrivals, while provisions at the Dalles would soon be exhausted. In this situation Palmer determined to join Samuel K. Barlow and his company in an attempt to cross the Cascades south of Mount Hood, and lead the way overland to the Willamette valley. This proved an arduous task, calling for all the skill and fortitude of experienced pathfinders. In its course, Palmer ascended Mount Hood, which he describes as "a sight more nobly grand" than any he had ever looked upon. At last the valley of the Clackamas was reached, and Oregon City, the little capital of the new territory, was attained, where "we were so filled with gratitude that we had reached the settlements of the white man, and with admiration at the appearance of the large sheet of water rolling over the Falls, that we stopped, and in this moment of happiness recounted our toils, in thought, with more rapidity than tongue can express or pen write." The distance that he had travelled from Independence, Missouri, our author estimates at 1,960 miles.

Passing the winter of 1845-46 in Oregon, Palmer made a careful examination of its resources, and in his book describes the country in much detail. The ensuing spring, after a journey to the Lapwai mission for horses, he started on the return route, arriving at his home in Laurel, Indiana, upon the twenty-third of July.

Palmer's experience, although trying, had been sufficiently satisfactory to justify his intention to make a permanent home in Oregon. In 1847 he took his family thither, the emigration of that year being sometimes known as "Palmer's train," he having been elected captain of the entire caravan, also in recognition of his great utility to the expedition. The new caravan had but just arrived in Oregon—now belonging definitely to the United States—when the Whitman massacre aroused the colonists to punish the Indian participants in order to ensure their own safety. In the organization of the militia force, Joel Palmer was chosen quartermaster and commissary general, whence the title of General, by which he was subsequently known.

He was also made one of two commissioners to attempt to treat with the recalcitrant tribes, and win to neutrality as many as possible. Accompanied by Dr. Robert Newell, a former mountain man, and Perrin Whitman, the murdered man's nephew, as interpreter, Palmer risked his life in the land of the hostiles, and succeeded in alienating many Nez Percés and Wallawalla from the guilty Cayuse. Thus was laid the foundation of that full knowledge of aboriginal character that availed him in his service as United States superintendent of Indians for Oregon.

To this difficult position General Palmer was appointed by President Pierce in 1853, just on the eve of an outbreak in southern Oregon, and his term of office coincided with the period of Indian wars. After pacifying the southern tribes, Palmer inaugurated the reservation system, removing the remnants of the tribes of the Willamette valley and their southward neighbors to a large tract in Polk and Yamhill counties, known as Grande Ronde Reservation. This ended the Indian difficulties in that quarter until the Modoc War, twenty years later.

Palmer found the tribesmen east of the mountains more difficult to subdue. Scarcely had he and Isaac T. Stevens, governor of Washington Territory, made a series of treaties (1855) with the Nez Percés, Cayuse, Wallawalla, and neighboring tribes, when the Yakima War began, and embroiled both territories until 1858. During these difficulties the military authorities complained that Commissioner Palmer was too lenient with former hostiles, and pinned too much faith to their promises. Consequently the Oregon superintendency was merged with that of Washington (1857), and James W. Nesmith appointed to the combined office.

Retiring to his home in Dayton, Yamhill County, which town he had laid out in 1850, General Palmer was soon called upon to serve in the state legislature, being speaker of the house of representatives (1862-63), and state senator (1864-66). During the latter incumbency he declined being a candidate for United States senator, because of his belief that a person already holding a public office of emolument should not during his term be elected to another. In 1870 he was Republican [pg. 17] candidate for governor of the state, but was defeated by a majority of less than seven hundred votes. From this time forward he lived quietly at Dayton, and there passed away upon the ninth of June, 1881. His excellent portrait given in Lyman's History of Oregon (iii, p. 398) is that of an old man; but the face is still strong and kindly, with a high and broad forehead, and gentle yet piercing eyes.

One of Palmer's fellow pioneers said of him, "he was a man of ardent temperament, strong friendships, and full of hope and confidence in his fellow men." Another calls his greatest characteristic his honesty and integrity. Widely known and respected in the entire North-West, his services in the up-building of the new community were of large import.

Not the least of these services was, in our judgment, the publication of his Journal of Travels over the Rocky Mountains, herein reprinted, which was compiled during the winter of 1846-47, and planned as a guide for intending emigrants. The author hoped to have it in readiness for the train of 1847, but the publishers were dilatory and he only received about a dozen copies before starting. The book proved useful enough, however, to require two later editions, one in 1851, another in 1852, and was much used by emigrants of the sixth decade of the past century.

Palmer makes no pretence of literary finish. He gives us a simple narrative of each day's happenings during his own first journey in 1845, taking especial care to indicate the route, each night's camping places, and all possible cut-offs, springs, grassy oases, and whatever else might conduce to the well-being of the [pg. 18] emigrant and his beasts. The great care taken by the author, with this very practical end in view, results in his volume being the most complete description of the Oregon Trail that we now possess. Later, his account of passing around Mount Hood and the initial survey of the Barlow road, produces a marked effect through its simplicity of narrative. His incidents have a quaint individuality, as for instance the reproof from the Cayuse chief for the impiety of card-playing. No better description of the Willamette valley can be found than in these pages, and our author's records of the climate, early prices in Oregon, and the necessities of an emigrant's outfit, complete a graphic picture of pioneering days.

In the annotation of the present volume, we have had valuable suggestions and some material help from Principal William I. Marshall of Chicago, Professor Edmond S. Meany of the University of Washington, Mr. George H. Himes of Portland, Dr. Joseph Schafer of the University of Oregon, and Mr. Edward Huggins, a veteran Hudson's Bay Company official at Fort Nisqually.

With this volume our series of narratives ends, save for the general index reserved for volume xxxi. The Western travels which began in tentative excursions into the Indian country around Pittsburg and Eastern Ohio in 1748, have carried us to the coast of the Pacific. The continent has been spanned. Not without some exhibitions of wanton cruelty on the part of the whites have the aborigines been pushed from their fertile seats and driven to the mountain wall. The American frontier has steadily retreated—at first from the Alleghanies [pg. 19] to the Middle West, thence across the Mississippi, and now at the close of our series it is ascending the Missouri and has sent vanguards to the Farthest Northwest. The ruts of caravan routes have been deeply sunk into the plains and deserts, and wheel marks are visible through the length of several mountain passes. The greater part of the continental interior has been threaded and mapped. The era of railroad building and the engineer is at hand. The long journey to the Western ocean has been ridded of much of its peril, and is less a question of mighty endurance than confronted the pathfinders. When Francis Parkman, the historian of New France, going out upon the first stages of the Oregon Trail in 1847—the year following the date of the present volume—saw emigrant wagons fitted with rocking chairs and cooking stoves, he foresaw the advent of the commonplace upon the plains, and the end of the romance of Early Western Travels.

Throughout the entire task of preparing for the press this series of reprints, the Editor has had the assistance of Louise Phelps Kellogg, Ph. D., a member of his staff in the Wisconsin Historical Library. Others have also rendered editorial aid, duly acknowledged in the several volumes as occasion arose; but from beginning to end, particularly in the matter of annotation, Dr. Kellogg has been his principal research colleague, and he takes great pleasure in asking for her a generous share of whatever credit may accrue from the undertaking. Annie Amelia Nunns, A. B., also of his library staff, has rendered most valuable expert aid, chiefly in proofreading and indexing. The Editor cannot close his [pg. 20] last word to the Reader without gratefully calling attention, as well, to the admirable mechanical and artistic dress with which his friends the Publishers have generously clothed the series, and to bear witness to their kindly suggestions, active assistance, and unwearied patience, during the several years of preparation and publication.

R. G. T.

Madison, Wis., August, 1906.

Palmer's Journal of Travels over the Rocky

Mountains, 1845-1846

Reprint of original edition: Cincinnati, 1847

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1847, by

J. A. & U. P. JAMES,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of Ohio.

TO THE

PIONEERS OF THE WEST,

AND THEIR DESCENDANTS,

THE BONE AND MUSCLE OF THE COMMUNITY,

WHO IMPROVE AND ENRICH THE COUNTRY IN PEACE,

AND PROTECT AND DEFEND IT IN WAR,

THIS WORK

In offering to the public a new work on Oregon, the publishers feel confident that they are performing an acceptable service to all who are desirous of obtaining full and correct information of that extensive and interesting region.

The facts contained in this Journal of Travels over the Rocky Mountains were obtained, by the author, from personal inspection and observation; or derived from intelligent persons, some of whom had resided in the country for ten years previously. It contains, as is believed, much very valuable information never before published, respecting the Oregon Territory.

Mr. Palmer's statements and descriptions are direct and clear, and may be relied on for their accuracy. He observed with the eye of an intelligent farmer the hills and valleys; timbered land and prairies, soil, grass, mill sites, &c.; all of which he has particularly described.

To the man about to emigrate to Oregon just the kind of information needed is given. He is informed what is the best season for setting out; the kinds and quantities of necessary outfits; where they may be purchased to the best advantage, so as to save money, time and useless hauling of provisions, and to promote comfort and prevent suffering on the long journey.

{vi} A particular account of Oregon City is given; the number of houses and inhabitants; the number [pg. 28] and kinds of mechanical trades carried on; and the prices current during the author's stay there.

The objects of natural curiosity on the route—the Solitary Tower—the Chimney Rock—Independence Rock—the Hot Springs—the Devil's Gate—the South Pass—the Soda Springs, and many others—are noticed.

The work is enlivened with anecdotes of mountaineer life—shooting buffalo—hunting bear—taking fish, &c.

Mr. Palmer made the ascent of one of the highest peaks of Mount Hood, almost alone, and with a very scanty supply of provisions. An extraordinary achievement, when the circumstances under which it was accomplished are taken into consideration.

Cincinnati, January, 1847.

Having concluded, from the best information I was able to obtain, that the Oregon Territory offers great inducements to emigrants, I determined to visit it with a view of satisfying myself in regard to it, and of ascertaining by personal observation whether its advantages were sufficient to warrant me in the effort to make it my future home.[1] I started, accordingly, on the morning of the 16th of April, 1845, in company with Mr. Spencer Buckley. We expected to be joined by several young men from Rushville, Ind., but they all abandoned the enterprise, and gave us no other encouragement than their good wishes for our success and safety. I took leave of my family, friends and home, with a truly melancholy heart. I had long looked forward and suffered in imagination the pain of this anticipated separation; but I had not tasted of its realities, and none but those who have parted with a family under similar circumstances, can form any just conception of the depth and power of the emotions which pervaded my breast on that occasion. The undertaking before me was arduous. It might and doubtless would be attended with various and unknown difficulties, privations and dangers. A doubt arose in my mind, whether the advantages, which were expected to result from the trip, would be likely to compensate for the time and expense necessary to accomplish it: but I believed that I was right, hoped for the best, and pressed onward.

We were favoured with a pleasant day and good roads, which tended in some degree to dissipate the gloom which {10} had weighed down my spirits upon leaving home. Our day's travel ended at Blue River, on the banks of which we encamped for the first time on the long and tedious journey before us.[2]

April 17. Arrived at Indianapolis, in the afternoon, where we expected to meet a number of persons, who had expressed a determination to join the party.[3] But here too, as in the case of our Rushville friends, we were doomed to meet disappointment;—not one was found willing to join us in our expedition. After having had our horses well shod, (we traveled in an ordinary wagon drawn by two horses,) and having laid in a supply of medicines, we put up for the night.

April 18. We this day had a sample of what might be called the mishaps of travelers—an encounter with a wild animal, the first which we met in our journey. One of our horses becoming lame, we were obliged to trade him away, and received in exchange one so wild, that it required the greatest vigilance and exertion on our part to prevent him from running away with our whole concern. We reached Mount Meridian after a day's journey of about thirty-four miles, during which we succeeded admirably in taming our wild horse.[4]

April 24. Reached the Mississippi, opposite to St. Louis, having traveled daily, and made the best of our time after leaving Mount Meridian.

April 25. We made a few purchases this morning, consisting chiefly of Indian trinkets, tobacco, powder, lead, &c. and, soon after, resumed our journey upon the road to St. Charles, the seat of justice for St. Charles county.[5] We reached this place at the close of the day, and encamped upon the banks of the Missouri, which appears to be about as wide as the Ohio at Cincinnati, in a fair stage of water; the current is quite strong; the water very thick and muddy. Here, we overtook a company of Germans, from St. Louis, who had started for California. The company consisted of four men, two women and three children; they traveled with a wagon drawn by six mules, and a cart drawn by two,—a very poor means of conveyance for such a long and tedious route. We traveled the same road until we reached Fort Hall.

April 26. At nine o'clock A. M. we crossed the river and traveled twenty-eight miles. The surface of the country is somewhat undulating; the soil, though poorly watered, appears to be good, and produces respectable crops.

April 27. We traveled thirty-one miles. The day was rainy {11} and unpleasant. The country through which we passed is a rolling prairie: some parts of it are very well timbered. On account of the scarcity of springs, the people rely generally upon their supplies of rain water. There we were joined by a clever backwoodsman, by the name of Dodson, who was making the best of his lonely journey to join an emigrating party at Independence; upon his consenting to bear an equal share in our expenses and outfit at that place, we took him in, and traveled together.

April 28. We started this morning at sunrise, and traveled to Lute creek, a distance of six and a half miles.[6] This stream was so much swollen, in consequence of the recent rains, that we were unable to ford it, and were forced to encamp upon its banks, and remain all day. While there, we were greatly annoyed by the wood-tick—an insect resembling, in size and in other respects, the sheep-tick. These insects, with which the bushes and even the ground seemed to be covered, fastened themselves with such tenacity upon our flesh, that when picking them off in the morning, the head would remain sticking fast to the skin, causing in most cases a painful wound.

April 29. We traveled about twenty-six miles, through a gently undulating country: the principal crops consisted of corn, oats, tobacco and some wheat. We passed through Williamsburgh and Fulton. The latter town is the seat of justice for Callaway county.[7]

April 30. We made an advance of about thirty miles through a well timbered country, and passed through Columbia, the seat of justice for Boone county. The town is pleasant and surrounded by a fertile and attractive country. We made our halt and encamped for the night, five miles westward of this town.

May 1. We started this morning at the usual hour, and after a ride of eight miles, reached and re-crossed the Missouri, at Rocheport, and continued our journey until night, passing through Booneville, the county seat of Cooper—a rich and fertile county, making in all a ride of twenty-six miles.[8]

May 2. Passed through the town of Marshall, the seat of justice for Saline county. The town stands upon an elevated prairie, upon which may be found a few groves of shrubby timber. The country upon this [the west] side appeared to be much better supplied with water, than that upon the east side.[9]

May 3. We traveled about twenty-eight miles, over a thinly-settled {12} prairie country. The crops, cultivated generally by negroes, consisted of hemp, corn, oats, and a little wheat and tobacco. The soil appeared to be good, but the scarcity of timber will prove a serious barrier to a complete settlement of the country.

May 4. We traveled twenty-three miles this day, through a better improved and pleasanter part of Missouri, than any we have yet seen. The crops appeared well; there were fine orchards under successful cultivation. The country is well timbered, and there appears nothing to hinder it from becoming the seat of a dense and thriving population.

May 6. Reached Independence at nine o'clock A.M.;[10] and as the main body of emigrants had left a few days previous, we hastily laid in our supplies, and at five o'clock P. M., pushed forward about two miles, and encamped upon the banks of a small creek, in company with four wagons, bound for Oregon. From one of the wagons they drew forth a large jug of whiskey, and before bed-time all the men were completely intoxicated. In the crowd was a mountaineer, who gave us a few lessons in the first chapter of a life among the mountains. At midnight, when all were quiet, I wrapped myself in my blanket, laid down under an oak tree, and began to realize that I was on my journey to Oregon.

May 7. After traveling about fifteen miles we halted and procured an extra set of horse-shoes, and a few additional wagon bows. The main body of the emigrants is twenty-five miles in advance of us: we have now passed out of Missouri, and are traveling in an Indian country—most of which is a rolling prairie.[11]

May 8. We started at seven o'clock, A. M. and traveled about twenty miles. Towards evening we overtook an emigrating company, consisting of thirty-eight wagons, with about one thousand head of loose cattle, all under the direction of a Mr. Brown. We passed this company, expecting to overtake a company of about one hundred wagons, which were but a few miles before us. The night, however, became so dark that we were compelled to encamp upon the prairie. Soon after we had staked our horses, a herd of wild Indian horses came galloping furiously by us, which so alarmed our horses and mules, that they broke loose and ran away after them. Dodson and myself pursued, but were distanced, and after running two or three miles, abandoned the chase as hopeless, and attempted to return to the camp. Owing to the darkness, we {13} were unable to find our camp, until the night had far advanced; and when we finally reached it, it required all my logic, supported by the positive testimony of Buckley, to convince Dodson that we were actually there.

May 9. At daylight, Dodson and I resumed the search for our lost stock. After a fatiguing tramp of several hours, I came upon one of the mules, which being hobbled, had been unable to keep with the herd. Dodson was unsuccessful, and returned to camp before me; during our absence, however, the herd had strolled near the camp, and Buckley had succeeded in taking our two horses. Having taken some refreshments, we started again in search of the lost animals. As I was returning to camp, hopeless, weary and hungry, I saw at a distance Dodson and Buckley mounted upon our two horses, and giving chase to the herd of Indian horses, among which were our two mules. The scene was wild, romantic and exciting. The race was untrammeled [pg. 36] by any of those arbitrary and useless rules with which the "knights of the turf" encumber their races, and was pursued on both sides, for a nobler purpose; it was to decide between the rights of property on the one side, and the rights of liberty on the other. The contest was for a long time doubtful; but the herd finally succeeded in winning the race, and poor Buckley and Dodson were compelled to yield; the former having lost his reputation as a sportsman, and the latter—what grieved him more,—his team; and both had ruined the character of their coursers in suffering them to be beaten. Sad and dispirited, they returned to camp, where, after a short consultation, it was unanimously resolved,—inasmuch as there was no other alternative,—to suffer the mules freely and forever to enjoy the enlarged liberty which they had so nobly won.

The day was nearly spent, but we harnessed up our team and traveled four miles, to the crossing of a creek, where we encamped for the night.

May 10. Re-considered our resolution of last evening, and spent the morning looking for the mules—re-adopted the same resolution, for the same reason, and then resumed our journey.

We advanced about eighteen miles through a very fertile and well watered country, and possessing, along the banks of the water courses, a supply of bur and white oak, ash, elm, and black walnut timber, amply sufficient for all practical purposes. In our travel, we crossed a stream called the Walkarusha, extending back from which, about two miles in width, {14} we discovered a fine bottom covered with heavy bur oak and black walnut timber. After passing through this [pg. 37] bottom, the trail strikes into a level and beautiful prairie, and crossing it—a distance of four miles—rises gradually to the ridge between the Walkarusha and the Caw, or Kansas river.[12] We encamped upon the ridge, in full view of the two streams, which at this place are from six to eight miles apart. The banks of both streams, as far as can be seen, are lined, either way, with excellent timber: the country rises gradually from the streams, for fifteen or twenty miles, with alternate forests and prairies, presenting to the eye a truly splendid scene. I noticed here almost a countless number of mounds, in different directions—some covered with timber, others with long grass. The Caw or Kansas Indians dwell along these streams. Through this part of the route there are two trails, uniting near our camp; the difference in the distance is small.[13]

May 11. We traveled about twenty miles, and passed a company of twenty-eight wagons. The road runs upon the ridge, which after a distance of ten or twelve miles becomes a broad rolling prairie. As night came on, we came up with the company of one hundred wagons which we were in pursuit of: they were encamped upon the banks of a small brook, four miles from the Kansas, into which it empties. We joined this company. At dark the guard was stationed, who becoming tired of their monotonous round of duty, amused themselves by shooting several dogs, and by so doing excited no small tumult in the company, which after some exertion on the part of the more orderly portion was quelled, and tranquility restored.

May 12. We traveled about four miles to Caw or Kansas river. This is a muddy stream, of about two hundred and fifty yards in width. We were obliged to be ferried over it in a flat boat; and so large was our company, and so slowly did the ferrymen carry on the necessary operations, that darkness overtook us before half the wagons had crossed the stream. Fearing molestation from the numerous Indians who were prowling about, we were compelled to keep a strong guard around our camp, and especially around our cattle; and when all the preliminaries had been arranged, we betook ourselves to rest; but our tranquility was soon interrupted by one of the most terrific thunder storms that I ever witnessed. It appeared to me that the very elements had broken loose, and that each was engaging madly in a desperate struggle for the mastery. All was confusion in our camp. The storm had so frightened the cattle, {15} that they were perfectly furious and ungovernable, and rushed through the guard, and dashed forward over the country before us: nothing could be done to secure them, and we were obliged to allow them to have out their race, and endeavor to guard our camp.

May 13. Early this morning we succeeded in finding and taking possession of our cattle, and by noon [pg. 39] all our wagons had crossed the river. Soon after we took up our line of march, and after advancing about three miles, encamped near the banks of Big Soldier creek, for the purpose of organizing the company by an election of officers; the officers then acting having been elected to serve only until the company should reach this place.[14] It was decided, when at Independence, that here there should be a thorough and complete organization. Great interest had been manifested in regard to the matter while upon the road; but now when we had reached the spot and the period for attending to the matter in earnest had arrived, the excitement was intense. The most important officers to be elected were the pilot and captain of the company. There were two candidates for the office of pilot,—one a Mr. Adams, from Independence,—the other a Mr. Meek, from the same place. Mr. Adams had once been as far west as Fort Laramie, had in his possession Gilpin's Notes,[15] had engaged a Spaniard, who had traveled over the whole route, to accompany him, and moreover had been conspicuously instrumental in producing the "Oregon fever." In case the company would elect him pilot, and pay him five hundred dollars, in advance, he would bind himself to pilot them to Fort Vancouver.

Mr. Meek, an old mountaineer, had spent several years as a trader and trapper, among the mountains, and had once been through to Fort Vancouver;[16] he proposed to pilot us through for two hundred and fifty dollars, thirty of which were to be paid in advance, and the balance when we arrived at Fort Vancouver. A motion was then made to postpone the election to the next day. While we were considering the motion, Meek came running into the camp, and informed us that the Indians were driving away our cattle. This intelligence caused the utmost confusion: motions and propositions, candidates and their special friends, were alike disregarded; rifles were grasped, and horses were hastily mounted, and away we all galloped in pursuit. Our two thousand head of cattle were now scattered over the prairie, at a distance of four or five miles from the camp.

{16} About two miles from camp, in full view, up the prairie, was a small Indian village; the greater part of our enraged people, with the hope of hearing from the lost cattle, drove rapidly forward to this place. As they approached the village, the poor Indians were seen running to and fro, in great dismay—their women and children skulking about and hiding themselves,—while the chiefs came forward, greeted our party kindly, and by signs offered to smoke the pipe of peace, and engage with them in trade. On being charged with the theft of our cattle, they firmly asserted their innocence; and such was their conduct, that the majority of the party was convinced they had been wrongfully accused: but one poor fellow, who had just returned to the village, and manifested great alarm upon seeing so many "pale faces," was taken; and failing to prove his innocence, was hurried away to camp and placed under guard. Meanwhile, after the greater part of the company had returned to camp, and the captain had assembled the judges, the prisoner was arraigned at the bar for trial, and the solemn interrogatory, "Are you guilty or not guilty," was propounded to him: but to this, his only answer was—a grunt, the import of which the honorable court not being able clearly to comprehend, his trial was formally commenced and duly carried through. The evidence brought forward against him not being sufficient to sustain the charge, he was fully acquitted; and, when released, "split" for his wigwam in the village. After the excitement had in some degree subsided, and the affair was calmly considered, it was believed by most of us that the false alarm in regard to the Indians had been raised with the design of breaking up or postponing the election. If such was the design, it succeeded admirably.

May 14. Immediately after breakfast, the camp was [pg. 42] assembled, and proceeded to the election of officers and the business of organization. The election resulted in the choice of S. L. Meek, as pilot, and Doctor P. Welch,[17] formerly of Indiana, as captain, with a host of subalterns; such as lieutenants, judges, sergeants, &c.

After these matters had been disposed of, we harnessed up our teams and traveled about five miles, and encamped with Big Soldier creek on our right hand and Caw river on our left.

The next day we were delayed in crossing Big Soldier creek, on account of the steepness of its banks; and advanced only twelve miles through a prairie country. Here {17} sixteen wagons separated from us, and we were joined by fifteen others.

May 17. We traveled eighteen miles over a high, rolling prairie, and encamped on the banks of Little Vermilion creek, in sight of a Caw village. The principal chief resides at this village.[18] Our camp here replenished their stores; and, although these Indians may be a set of beggarly thieves, they conducted themselves honorably in their dealings with us; in view of which we raised for their benefit a contribution of tobacco, powder, lead, &c., and received in return many good wishes for a pleasant and successful journey. After leaving them, we traveled about twelve miles over a fertile prairie. In the evening, after we had encamped and taken our supper, a wedding was attended to with peculiar interest.

May 19. This day our camp did not rise. A growing spirit of dissatisfaction had prevailed since the election; there were a great number of disappointed candidates, who were unwilling to submit to the will of the majority; and to such a degree had a disorderly spirit been manifested, that it was deemed expedient to divide the company. Accordingly, it was mutually agreed upon, to form, from the whole body, three companies; and that, while each company should select its own officers and manage its internal affairs, the pilot, and Capt. Welsh, who had been elected by the whole company, should retain their posts, and travel with the company in advance. It was also arranged, that each company should take its turn in traveling in advance, for a week at a time. A proposition was then made and acceded to, which provided that a collection of funds, with which to pay the pilot, should be made previous to the separation, and placed in the hands of some person to be chosen by the whole, as treasurer, who should give bonds, with approved security, for the fulfilment of his duty.

A treasurer was accordingly chosen, who after giving the necessary bond, collected about one hundred and ninety dollars of the money promised; some refused to pay, and others had no money in their possession. All these and similar matters having been satisfactorily arranged, the separation took place, and the companies proceeded to the election of the necessary officers. The [pg. 44] company to which I had attached myself, consisting of thirty wagons, insisted that I should officiate as their captain, and with some reluctance I consented. We dispensed with many of the offices and formalities which {18} existed in the former company, and after adopting certain regulations respecting the government of the company, and settling other necessary preliminaries, we retired to rest for the night.

May 20. We have this day traveled fifteen miles, through a prairie country, with occasionally a small grove along the streams.

May 22. Yesterday after moving thirteen miles we crossed Big Vermillion, and encamped a mile beyond its west bank; we found a limestone country, quite hilly, indeed almost mountainous. To-day we have crossed Bee, and Big Blue creeks; the latter stream is lined with oak, walnut, and hickory.[19] We encamped two and a half miles west of it. During the night it rained very hard. Our cattle became frightened and all ran away.

May 23. Made to-day but eight miles. Our pilot notified us that this would be our last opportunity to procure timber for axle trees, wagon tongues, &c., and we provided a supply of this important material. Our cattle were all found.

May 25. Early this morning we were passed by Col. Kearney and his party of dragoons, numbering about three hundred. They have with them nineteen wagons drawn by mules, and drive fifty head of cattle and twenty-five head of sheep. They go to the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains.[20] Our travel of to-day and yesterday is thirty-two miles, during which we have crossed several small streams, skirted by trees. The soil looks fertile.

May 26. Overtook Capt. Welsh's company to-day. We passed twelve miles through a rolling prairie region, and encamped on Little Sandy.

May 27. As it was now the turn of our company to travel in advance, we were joined by Capt. Welsh and our pilot. The country is of the same character with that we passed through on yesterday, and is highly adapted to the purpose of settlement, having a good soil, and streams well lined with timber.

May 31. In the afternoon of the 28th we struck the Republican fork of Blue River,[21] along which for fifty miles lay the route we were traveling. Its banks afford oak, ash and hickory, and often open out into wide and fertile bottoms. Here and there we observed cotton wood and willow. The pea vine grows wild, in great abundance on the bottoms. The pea is smaller than our common garden pea and afforded us a {19} pleasant vegetable. We saw also a few wild turkies. To-day we reached a point where a trail turns from this stream, a distance of twenty-five miles, to the Platte or Nebraska river. We kept the left hand route, and some nine or ten miles beyond this trail, we made our last encampment on the Republican Fork.

June 1. We set out at the usual hour and crossed over the country to Platte river; having measured the road with the chain, we ascertained the distance to be eighteen and a half miles, from our encampment of last night. It is all a rolling prairie; and in one spot, we found in pools a little standing water. Some two miles before reaching the Platte bottom the prairie is extremely rough; and as far as the eye can reach up and down that river, it is quite sandy.[22] We encamped near a marshy spot, occasioned by the overflow of the river, opposite an island covered with timber, to which we were obliged to go through the shallows of the river for fuel, as the main land is entirely destitute of trees. Near us the Platte bottom is three and a half miles wide, covered with excellent grass, which our cattle ate greedily, being attracted by a salt like substance which covers the grass and lies sprinkled on the surface of the ground. We observed large herds of antelope in our travel of to-day. In the evening it rained very hard.

June 2. Our week of advance traveling being expired, we resolved to make a short drive, select a suitable spot, and lay by for washing. We accordingly encamped about six miles up Platte river. As I had been elected captain but for two weeks, and my term was now expired, a new election was held, which resulted in the choice of the same person. The captain, Welsh, who was originally elected by all the companies, had been with us one week, and some dissatisfaction was felt, by our company, at the degree of authority he seemed disposed to exercise. We found, too, that it was bad policy to require the several companies to wait for each other;—our supply of provision was considered barely sufficient for the journey, and it behooved us [to] make the best use of our time. At present one of the companies was supposed to be two or three days travel in the rear. We adopted a resolution desiring the several companies to abandon the arrangement that required each to delay for the others; and that each company should have the use of the pilot according to its turn. Our proposition was not, for the present, accepted by the other companies. While we were at our washing encampment one {20} of the companies passed us, the other still remaining in the rear.

June 3. Having traveled about eight miles, we halted at noon, making short drives, to enable the rear company [pg. 48] to join us. We have no tidings of it as yet. We met seventy-five or eighty Pawnee Indians returning from their spring hunt.[23]

June 5. Yesterday we traveled about twelve miles, passing captain Stephens, with his advance company. To-day we traveled about the same distance, suffering Stephens' company to pass us.[24] At noon they were delayed by the breaking of an axletree of one of their wagons, and we again passed them, greatly to their offence. They refused to accede to our terms, and we determined to act on our own responsibility. We therefore dissolved our connection with the other companies, and thenceforward acted independently of them.

June 6. We advanced twenty miles to-day. We find a good road, but an utter absence of ordinary fuel. We are compelled to substitute for it buffalo dung, which burns freely.

June 7. We find in our sixteen miles travel to-day that the grass is very poor in the Platte bottoms, having been devoured by the buffalo herds. These bottoms are from two to four miles in width, and are intersected, at every variety of interval, by paths made by the buffaloes, from the bluffs to the river. These paths are remarkable in their appearance, being about fifteen inches wide, and four inches deep, and worn into the soil as smoothly as they could be cut with a spade.

We formed our encampment on the bank of the river, with three emigrating companies within as many miles of us; two above and one below; one of fifty-two wagons, one of thirteen, and one of forty-three—ours having thirty-seven. We find our cattle growing lame, and most of the company are occupied in attempting to remedy the lameness. The prairie having been burnt, dry, sharp stubs of clotted grass remain, which are very hard, and wear and irritate the feet of the cattle. The foot becomes dry and feverish, and cracks in the opening of the hoof. In this opening the rough blades of grass and dirt collect, and the foot generally festers, and swells very much. Our mode of treating it was, to wash the foot with strong soap suds, scrape or cut away all the diseased flesh, and then pour boiling pitch or tar upon the sore. If applied early this remedy will cure. Should the heel become worn out, apply tar or pitch, and singe with a hot iron. At our encampment to-night we have abundance of wood for fuel.

{21} June 8. We advanced to-day about twelve miles. The bottom near our camp is narrow, but abounds in timber, being covered with ash; it, however, affords poor grazing. So far as we have traveled along the Platte, we find numerous islands in the river, and some of them quite large. In the evening a young man, named Foster,[25] was wounded by the accidental discharge of a gun. The loaded weapon, from which its owner had neglected to remove the cap, was placed at the tail of a wagon; as some one was taking out a tent-cloth, the gun was knocked down, and went off. The ball passed through a spoke of the wagon-wheel, struck the felloe, and glanced. Foster was walking some two rods from the wagon, when the half spent ball struck him in the back, near the spine; and, entering between the skin and the ribs, came out about three inches from where it entered, making merely a flesh wound. A small fragment of the ball had lodged in his arm.

June 9. The morning is rainy. To-day we passed Stephens' company, which passed us on yesterday. Our dissensions are all healed; and they have decided to act upon our plan.

June 10. Yesterday we traveled fifteen miles; to-day the same distance. We find the grazing continues poor. In getting to our encampment, we passed through a large dog town. These singular communities may be seen often, along the banks of the Platte, occupying various areas, from one to five hundred acres. The one in question covered some two hundred or three hundred acres. The prairie-dog is something larger than a common sized gray squirrel, of a dun color; the head resembles that of a bull dog: the tail is about three inches in length. Their food is prairie grass. Like rabbits, they burrow in the ground, throwing out heaps of earth, and often large stones, which remain at the mouth of their holes. The entrance to their burrows is about four inches in diameter, and runs obliquely into the earth about three feet, when the holes ramify in every direction and connect with each other on every side. Some kind of police seems to be observed among them; for at the approach of man, one of the dogs will run to the entrance of a burrow, and, squatting down, utter a shrill bark. At once, [pg. 51] the smaller part of the community will retreat to their holes, while numbers of the larger dogs will squat, like the first, at their doors, and unite in the barking. A near approach drives them all under ground. It is singular, {22} but true, that the little screech-owl and the rattlesnake keep them company in their burrows. I have frequently seen the owls, but not the snake, with them. The mountaineers, however, inform me, that they often catch all three in the same hole. The dog is eaten by the Indians, with quite a relish; and often by the mountaineers. I am not prepared to speak of its qualities as an article of food.

During the night, a mule, belonging to a Mr. Risley,[26] of our company, broke from its tether, and in attempting to secure it, its owner was repeatedly shot at by the guard; but, fortunately, was not hit. He had run from his tent without having been perceived by the guard, and was crawling over the ground, endeavoring to seize the trail rope, which was tied to his mule's neck. The guard mistook him for an Indian, trying to steal horses, and called to him several times; but a high wind blowing he did not hear. The guard leveled and fired, but his gun did not go off. Another guard, standing near, presented his piece and fired; the cap burst, without discharging the load. The first guard, by this time prepared, fired a second time, without effect. By this time the camp was roused, and nearly all seized their fire-arms, when we discovered that the supposed Indian was one of our own party. We regarded it as providential that the man escaped, as the guard was a good shot, and his mark was not more than eighty yards distant. This incident made us somewhat more cautious about leaving the camp, without notifying the guard.

June 11. To-day we traveled ten or twelve miles. Six miles brought us to the lower crossing of Platte river, which is five or six miles above the forks, and where the high ground commences between the two streams. There is a trail which turns over the bluff to the left; we however took the right, and crossed the river.[27] The south fork is at this place about one fourth of a mile wide, and from one to three feet deep, with a sandy bottom, which made the fording so heavy that we were compelled to double teams. The water through the day is warm; but as the nights are cool, it is quite cool enough in the morning. On the west bank of the river was encamped Brown's company, which passed us whilst we were organizing at Caw River. We passed them, and proceeded along the west side of the south fork, and encamped on the river bank. At night our hunters brought in some buffalo meat.

June 13. Yesterday we followed the river about thirteen miles, and encamped on its bank, where the road between the {23} two forks strikes across the ridge toward the North fork. To-day we have followed that route: directly across, the distance does not exceed four miles: but the road runs obliquely between the two streams, and reaches the North fork about nine miles from our last camp. We found quite a hill to descend, as the road runs up the bottom a half mile and then ascends the bluff. Emigrants should keep the bluff sixteen or seventeen miles. We descended a ravine and rested on the bank of the river.

June 15. Yesterday we advanced eight miles, and halted to wash and rest our teams. We have remained all this day in camp. At daylight a herd of buffalo approached near the camp; they were crossing the river, but as soon as they caught the scent, they retreated to the other side. It was a laughable sight to see them running in the water. Some of our men having been out with their guns, returned at noon overloaded with buffalo meat. We then commenced jerking it. This is a process resorted to for want of time or means to cure meat by salting. The meat is sliced thin, and a scaffold prepared, by setting forks in the ground, about three feet high, and laying small poles or sticks crosswise upon them. The meat is laid upon those pieces, and a slow fire built beneath; the heat and smoke completes the process in half a day; and with an occasional sunning the meat will keep for months.

An unoccupied spectator, who could have beheld our camp to-day, would think it a singular spectacle. The hunters returning with the spoil; some erecting scaffolds, and others drying the meat. Of the women, some were washing, some ironing, some baking. At two of the tents the fiddle was employed in uttering its unaccustomed voice among the solitudes of the Platte; at one tent I heard singing; at others the occupants were engaged in reading, some the Bible, others poring over novels. While all this was going on, that nothing [pg. 54] might be wanting to complete the harmony of the scene, a Campbellite preacher, named Foster, was reading a hymn, preparatory to religious worship. The fiddles were silenced, and those who had been occupied with that amusement, betook themselves to cards. Such is but a miniature of the great world we had left behind us, when we crossed the line that separates civilized man from the wilderness. But even here the variety of occupation, the active exercise of body and mind, either in labor or pleasure, the commingling of evil and good, show that the likeness is a true one.

{24} June 17. On our travel of eight miles, yesterday, we found the bluffs quite high, often approaching with their rocky fronts to the water's edge, and now and then a cedar nodding at the top. Our camp, last night, was in a cedar and ash grove, with a high, frowning bluff overhanging us; but a wide bottom, with fine grass around us, and near at hand an excellent spring. To-day five miles over the ridge brought us to Ash Hollow. Here the trail, which follows the east side of the South fork of Platte, from where we crossed it, connects with this trail.[28] The road then turns down Ash Hollow to the river; a quarter of a mile from the latter is a fine spring, and around it wood and grass in abundance. Our road, to-day, has been very sandy. The bluffs are generally rocky, at times presenting perpendicular cliffs of three hundred feet high. We passed two companies, both of which we had before passed; but whilst we were lying by on the North fork, they had traveled up the South fork and descended Ash Hollow.

June 18. We met a company of mountaineers from Fort Laramie, who had started for the settlements early in the season, with flat-boats loaded with buffalo robes, and other articles of Indian traffic. The river became so low, that they were obliged to lay by; part of the company had returned to the fort for teams; others were at the boat landing, while fifteen of the party were footing their way to the States. They were a jolly set of fellows. Four wagons joined us from one of the other divisions, and among them was John Nelson, with his family, formerly of Franklin county, Indiana. We traveled fifteen miles, passing Captain Smith's company.

June 19. Five miles, to-day, brought us to Spring creek; eleven miles further to another creek, the name of which I could not ascertain; there we encamped, opposite the Solitary Tower.[29] This singular natural object is a stupendous pile of sand and clay, so cemented as to resemble stone, but which crumbles away at the slightest touch. I conceive it is about seven miles distant from the mouth of the creek; though it appears to be not more than three. The height of this tower is somewhere between six hundred and eight hundred feet from the level of the river. Viewed from the road, the beholder might easily imagine he was gazing upon [pg. 56] some ancient structure of the old world. A nearer approach dispels the illusion, and it looks, as it is, rough and unseemly. It can be ascended, at its north side, by clambering up the rock; holes having been cut in its face for that purpose. The second, or {25} main bench, can be ascended with greater ease at an opening on the south side, where the water has washed out a crevice large enough to admit the body; so that by pushing against the sides of the crevice one can force himself upward fifteen or twenty feet, which places the adventurer on the slope of the second bench. Passing round the eastern point of the tower, the ascent may be continued up its north face. A stream of water runs along the north-eastern side, some twenty rods distant from the tower; and deep ravines are cut out by the washing of the water from the tower to the creek. Near by stands another pile of materials, similar to that composing the tower, but neither so large nor so high. The bluffs in this vicinity appear to be of the same material. Between this tower and the river stretches out a rolling plain, barren and desolate enough.

June 20. Traveling fourteen miles, we halted in the neighborhood of the Chimney Rock. This is a sharp-pointed rock, of much the same material as the Solitary Tower, standing at the base of the bluff, and four or five miles from the road. It is visible at a distance of thirty miles, and has the unpoetical appearance of a hay-stack, with a pole running far above its top.[30]

June 24. Since the 20th we have traveled about sixty-two miles, and are now at Fort Laramie; making our whole travel from Independence about six hundred and thirty miles. On the 22d we passed over Scott's Bluffs, where we found a good spring, and abundance of wood and grass. A melancholy tradition accounts for the name of this spot. A party who had been trading with the Indians were returning to the States and encountering a band of hostile savages, were robbed of their peltries and food. As they struggled homeward, one of the number, named Scott, fell sick and could not travel. The others remained with him, until the sufferer, despairing of ever beholding his home, prevailed on his companions to abandon him. They left him alone in the wilderness, several miles from this spot. Here human bones were afterwards found; and, supposing he had crawled here and died, the subsequent travelers have given his name to the neighboring bluff.[31]

June 25. Our camp is stationary to-day; part of the emigrants are shoeing their horses and oxen; others are trading at the fort and with the Indians. Flour, sugar, coffee, tea, tobacco, powder and lead, sell readily, at high prices. In the {26} afternoon we gave the Indians a feast, and held a long talk with them. Each family, as they could best spare it, contributed a portion of bread, meat, coffee or sugar, which being cooked, a table was set by spreading buffalo skins upon the ground, and arranging the provisions upon them.

Around this attractive board, the Indian chiefs and their principal men seated themselves, occupying one fourth of the circle; the remainder of the male Indians made out the semi-circle; the rest of the circle was completed by the whites. The squaws and younger Indians formed an outer semicircular row immediately behind their dusky lords and fathers. Two stout young warriors were now designated as waiters, and all the preparations being completed, the Indian chiefs and principal men shook hands, and at a signal the white chief performed the same ceremony, commencing with the principal chief, and saluting him and those of his followers who composed the first division of the circle; the others being considered inferiors, were not thus noticed.

The talk preceded the dinner. A trader acted as interpreter. The chief informed us, that "a long while ago some white chiefs passed up the Missouri, through his country, saying they were the red man's friends, and that as the red man found them, so would he find all the other pale faces. This country belongs to the red man, but his white brethren travels through, shooting the game and scaring it away. Thus the Indian loses all that he depends upon to support his wives and children. The children of the red man cry for food, but there is no food. But on the other hand, the Indian profits by the trade with the white man. He was glad to see us and meet us as friends. It was the custom when the pale faces passed through his country, to make presents to the Indians of powder, lead, &c. His tribe was very numerous, but the most of the people had gone to the mountains to hunt. Before the white man came, the game was tame, and easily caught, with [pg. 59] the bow and arrow. Now the white man has frightened it, and the red man must go to the mountains. The red man needed long guns." This, with much more of the like, made up the talk of the chief, when a reply from our side was expected.

As it devolved on me to play the part of the white chief, I told my red brethren, that we were journeying to the great waters of the west. Our great father owned a large country there, and we were going to settle upon it. For this purpose we brought with us our wives and little ones. We were compelled {27} to pass through the red man's country, but we traveled as friends, and not as enemies. As friends we feasted them, shook them by the hand, and smoked with them the pipe of peace. They must know that we came among them as friends, for we brought with us our wives and children. The red man does not take his squaws into battle: neither does the pale face. But friendly as we felt, we were ready for enemies; and if molested, we should punish the offenders. Some of us expected to return. Our fathers, our brothers and our children were coming behind us, and we hoped the red man would treat them kindly. We did not expect to meet so many of them; we were glad to see them, and to hear that they were the white man's friends. We met peacefully—so let us part. We had set them a feast, and were glad to hold a talk with them; but we were not traders, and had no powder or ball to give them. We were going to plough and to plant the ground, and had nothing more than we needed for ourselves. We told them to eat what was before them, and be satisfied; and that we had nothing more to say.

The two Indian servants began their services by placing a tin cup before each of the guests, always waiting first upon the chiefs; they then distributed the bread and cakes, until each person had as much as it was supposed he would eat; the remainder being delivered to two squaws, who in like manner served the squaws and children. The waiters then distributed the meat and coffee. All was order. No one touched the food before him until all were served, when at a signal from the chief the eating began. Having filled themselves, the Indians retired, taking with them all that they were unable to eat.

This is a branch of the Sioux nation, and those living in this region number near fifteen hundred lodges.[32] They are a healthy, athletic, good-looking set of men, and have according to the Indian code, a respectable sense of honor, but will steal when they can do so without fear of detection. On this occasion, however, we missed nothing but a frying pan, which a squaw slipped under her blanket, and made off with. As it was a trifling loss, we made no complaint to the chief.

Here are two forts. Fort Laramie, situated upon the west side of Laramie's fork, two miles from Platte river, belongs to the North American Fur Company.[33]

The fort is built of adobes. The walls are about two feet thick, and twelve or fourteen feet high, the tops being picketed or spiked. Posts are planted in these walls, and support the timber for the roof. {28} They are then covered with mud. In the centre is an open square, perhaps twenty-five yards each way, along the sides of which are ranged the dwellings, store rooms, smith shop, carpenter's shop, offices, &c., all fronting upon the inner area. There are two principal entrances; one at the north, the other at the south. On the eastern side is an additional wall, connected at its extremities with the first, enclosing ground for stables and carrell. This enclosure has a gateway upon its south side, and a passage into the square of the principal enclosure. At a short distance from the fort is a field of about four acres, in which, by way of experiment, corn is planted; but from its present appearance it will probably prove a failure. Fort John stands about a mile below Fort Laramie, and is built of the same material as the latter, but is not so extensive. Its present occupants are a company from St. Louis.[34]

June 26. This day, leaving Fort Laramie behind us, we advanced along the bank of the river, into the vast region that was still between us and our destination. After moving five miles, we found a good spot for a camp, and as our teams still required rest, we halted and encamped, and determined to repose until Saturday the 28th.

June 28. A drive of ten miles brought us to Big Spring, a creek which bursts out at the base of a hill, and runs down a sandy hollow. The spring is one fourth of a mile below the road. We found the water too warm to be palatable.[35] Five miles beyond the creek the road forks; we took the right hand trail, which is the best of the two, and traversed the Black Hills, as they are called. The season has been so dry that vegetation is literally parched up; of course the grazing is miserable. After proceeding eighteen miles we encamped on Bitter Cottonwood.[36]

June 29. To-day we find the country very rough, though our road is not bad. In the morning some of our cattle were missing, and four of the company started back to hunt for them. At the end of fourteen miles we rested at Horse Shoe creek, a beautiful stream of clear water, lined with trees, and with wide bottoms on each side, covered with excellent grass. At this point our road was about three miles from the river.[37]

July 1. As the men who left the company on the 29th, to look for our lost cattle, were not returned, we remained in {29} camp yesterday. Game seemed abundant along the creek, and our efforts to profit by it were rewarded with three elk and three deer. To-day our cattle hunters still remain behind. We sent back a reinforcement, and hitching up our teams advanced about sixteen miles. Eight miles brought us to the Dalles of Platte, where the river bursts through a mountain spur. Perpendicular cliffs, rising abruptly from the water, five hundred or six hundred feet high, form the left bank of the river. These cliffs present various strata, some resembling flint, others like marble, lime, &c. The most interesting feature of these magnificent masses, is the variety of colors that are presented; yellow, red, black and white, and all the shades between, as they blend and are lost in each other. On the top nods a tuft of scrubby cedars. Upon the south side, a narrow slope between the bluff and river, affords a pass for a footman along the water's edge, while beyond the bluff rises abruptly. Frequently cedar and wild sage is to be seen. I walked up the river a distance of half a mile, when I reached a spot where the rocks had tumbled down, and found something of a slope, by which I could, with the assistance of a long pole, and another person sometimes pushing and then pulling, ascend; we succeeded in clambering up to the top—which proved to be a naked, rough black rock, with here and there a scrubby cedar and wild sage bush. It appeared to be a place of resort for mountain sheep and bears. We followed this ridge south to where it gradually descended to the road. The river in this kanyon is about one hundred and fifty yards wide, and looks deep.[38] At the eastern end of this kanyon comes in a stream which, from appearance, conveys torrents of water at certain seasons of the year. Here, too, is a very good camp. By going up the right hand branch five or six miles, then turning to the right up one of the ridges, and crossing a small branch (which joins the river six or seven miles above the kanyon) and striking the road on the ridge three miles east of the Big Timber creek, a saving might be made of at least ten miles travel. We did not travel this route; but, from the appearance of the country, there would be no difficulty.

July 2. This day we traveled about sixteen miles. The road left the river bottom soon after we started. A trail, however, crosses the bottom for about two miles, and then winds back to the hill. The nearest road is up a small sandy ravine, for two miles, then turn to the right up a ridge, and follow this ridge for eight or ten miles. At the distance of thirteen {30} or fourteen miles, the road which turned to the left near the Big Spring, connects with this. The road then turns down the hill to the right, into a dry branch, which it descends to Big Timber creek, where we encamped.[39]

July 3. This day we traveled about fifteen miles. Six miles brought us to a small branch, where is a good camp. Near this branch there is abundance of marble, variegated with blue and red, but it is full of seams. The hills in this vicinity are of the red shale formation. In the mountain near by is stone coal. The hills were generally covered with grass. The streams are lined with cotton wood, willow and boxalder. The road was very dusty.

July 4. We traveled about fifteen miles to-day, the road generally good, with a few difficult places. Two wagons upset, but little damage was done. We crossed several beautiful streams flowing from the Black hills; they are lined with timber. To-day, as on yesterday, we found abundance of red, yellow and black currants, with some gooseberries, along the streams.

July 5. We this day traveled about twelve miles. Three miles brought us to Deer creek.[40] Here is an excellent camp ground. Some very good bottom land. The banks are lined with timber. Stone coal was found near the road. This would be a suitable place for a fort, as the soil and timber is better than is generally found along the upper Platte. Game in abundance, such as elk, buffalo, deer, antelope and bear. The timber is chiefly cotton wood, but there is pine on the mountains within ten or twelve miles. The road was generally along the river bottom, and much of the way extremely barren. We encamped on the bank of the river.

July 6. In traveling through the sand and hot sun, our wagon tires had become loose; and we had wedged until the tire would no longer remain on the wheels. One or two axletrees and tongues had been broken, and we found it necessary to encamp and repair them. For this purpose all hands were busily employed. We had neither bellows nor anvil, and of course could not cut and weld tire. But as a substitute, we took off the tire, shaved thin hoops and tacked them on the felloes, heated our tire and replaced it. This we found to answer a good purpose.

July 7. This day we traveled about ten miles. In crossing a small ravine, an axletree of one of the wagons was broken. {31} The road is mostly on the river bottom. Much of the country is barren.

July 8. Six miles travel brought us to the crossing of the north fork of the Platte. At 1 o'clock, P. M. all were safely over, and we proceeded up half a mile to a grove of timber and encamped.[41] Near the crossing was encamped Colonel Kearney's regiment of dragoons, on their return from the South Pass. Many of them were sick.

July 9. We traveled about ten miles this day, and encamped at the Mineral Spring. The road leaves the Platte at the crossing, and passes over the Red Buttes.[42] The plains in this region are literally covered with buffalo.

July 10. To-day we traveled about ten miles. The range is very poor, and it has become necessary to divide into small parties, in order to procure forage for our cattle. Out of the company five divisions were formed. In my division we had eleven wagons; and we travel more expeditiously, with but little difficulty in finding grass for our cattle.

July 11. We this day traveled about twelve miles. Soon after starting we passed an excellent spring: it is to the right of the road, in a thicket of willows. One fourth of a mile further the road ascends a hill, winds round and passes several marshy springs. The grass is very good, but is confined to patches. Our camp was on a small branch running into the Sweet Water.