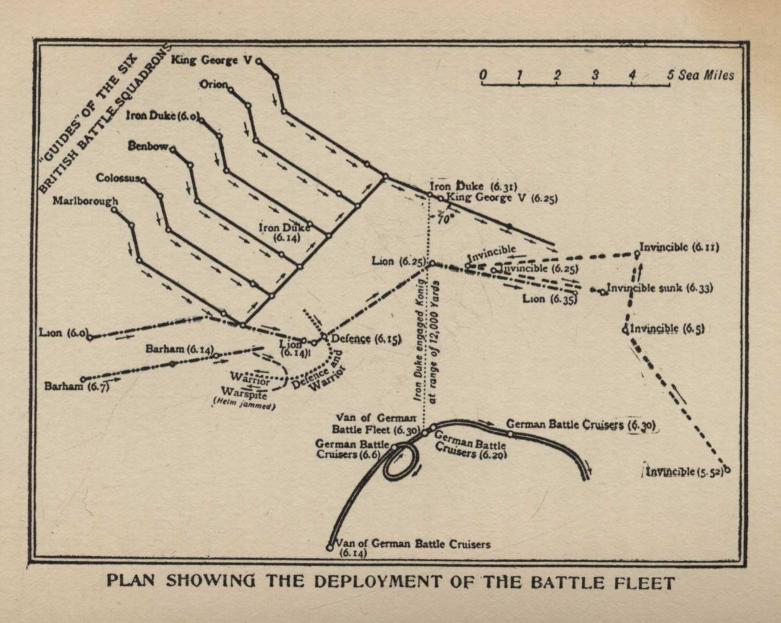

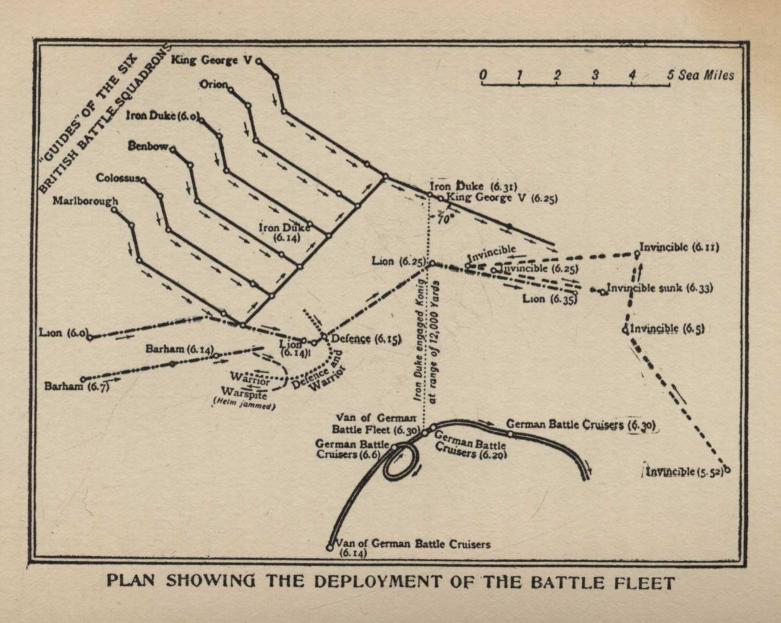

PLAN SHOWING THE DEPLOYMENT OF THE BATTLE FLEET

Title: The Heroic Record of the British Navy: A Short History of the Naval War, 1914-1918

Author: Archibald Hurd

Sir H. H. Bashford

Release date: October 31, 2014 [eBook #47248]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

A Short History of

the Naval War

1914-1918

BY

ARCHIBALD HURD

AND

H. H. BASHFORD

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1919

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF

TRANSLATION INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES,

INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

To the generous help and criticisms of many participants in the events hereafter recorded, and particularly to Admirals Viscount Jellicoe of Scapa Flow and W. S. Sims of the United States Navy; to Vice-Admirals Sir F. Doveton Sturdee and Sir Reginald H. Bacon; and to Lieutenaut-Commander A. D. Turnbull of the United States Navy, the authors desire to express their most grateful acknowledgment.

CONTENTS

Foreword

CHAPTER

I. August 4, 1914

II. The Battle of the Bight

III. Coronel

IV. The Battle of the Falkland Islands

V. Back to the North Sea

VI. The Seamen at Gallipoli

VII. Sub-mariners of England

VIII. The Battle of Jutland

IX. The Dover Patrol

X. The Sealing of Zeebrugge and Ostend

XI. The Coming of the Americans

XII. The Harvest of Sea Power

Index

In the years immediately preceding the Great War, already so hard to reconstruct, it was not uncommonly suggested that the British seafaring instinct had begun to decline. In our professional navy most thinkers had confidence, as in a splendid machine ably manned; but, as regarded the population as a whole, it was feared that modern industrialism was sapping the old sea-love. That this has been disproved we hope to make clear in the following pages—a first attempt, as we believe, to give, in narrative form, a reasonably complete and consecutive history of the naval war. We have indeed gone further, for we have tried to show not only that the spirit of admiralty has survived undiminished, but that we have witnessed such a re-awakening of it, both in Great Britain and America, as has had no parallel since the days of Elizabeth. We have also tried to make clear that, in a thousand embodiments, in men and boys fallen or still living, it has shone with a spiritual even more than any material significance; and that it has again declared itself to be the peculiar expression in world-affairs of the English-speaking races.

Nor was the little apparent interest shown, just before the war, in the navy and the navy's exercises very remarkable. Our attitude, as a people, toward {x} it had always been a curious union of apathy and adventure. We had been sea-worshippers so long that our reverence had often been dulled by much familiarity, and to such an extent, at times, that, only by the supremest efforts, had we, as a nation, escaped catastrophe. But if, on the one hand, we had lost the neophyte's fire, we had perhaps gained a little in tolerance. The seas had not found in us jealous masters. Our harbours and ships had been at the world's disposal. No empire in history had been so leisurely or less designedly built up, as none was to prove, perhaps, to have been so apparently loosely but yet so organically knit—probably because the idea of empire had always meant less to us than the growing idea of admiralty. Nor is that so obscure as it may at first seem, since, in spite of so much outward indifference, the call of the sea, as closer examination will show, was still among the most insistent to which we responded. There was scarcely a cottage, for instance, even in the remotest highlands, in which the picture of a ship did not hang upon the walls, or that had failed to send a son or a brother or a cousin to serve either in the navy or the mercantile marine. Even in the greyest and most smoke-laden of our central industrial cities, wherever there was a pond, the children sailed their little boats upon it; and, once a year, as to some lustral rite, the town-bred inhabitant took his family to the coast.

That these were indications of any racial significance the non-seagoing Briton had seldom, perhaps, realized. That, because of them, his language had become a familiar tongue in the uttermost parts of the {xi} earth; that because of them every would-be world-tyrant, since Philip of Spain, had been frustrated; that because of them the freedom of nations, no less than that of individuals, had slowly become humanity's gospel—this had been as little present to him as to the inhabitant of Turnham Green that he was living in the greatest harbour of the world; and yet that it was so was but a matter of fact, and indeed the natural outcome of our origin. Since Britain had become an island every wave of invaders had necessarily come to it in ships and with experience of the sea. However various may have been their other contributions to the ultimate nation into which they were to be merged, this had been common to them, they had all been seamen, of whatever temperament or complexion; and, while of the earliest inhabitants of what are now the British Islands, no boat-lore can definitely postulated, the discovery of the famous barge in the Carse of Stirling shows that, 3,000 years before Christ, there must have been some knowledge of navigation; while, of the first Celtic immigrants enough must be assumed, at any rate, to have enabled them successfully to cross the Channel.

Of these the Gaelic Celts, landing from Spain upon the coasts of Devon and Cornwall and in Ireland, seem to have been the pioneers, followed by a stronger invasion of Cymric Celts, who landed in Kent and Essex, and afterward drove the Gaels before them into the northern and western fastnesses. Of later Aryans, the first members of the great Teutonic family to land on these shores were, almost certainly, the Belgae, who settled on the south and east coasts; {xii} while the Scillies and Cornwall appear to have been regularly visited by Phoenician traders and Greek merchants from Marseilles—a sea-borne commerce that continued for many years after the first Roman expedition.

This took place under Julius Cæsar, first in B.C. 55, and its ostensible purpose seems to prove the existence of some kind of pre-Roman British fleet—Cæsar's declared object being to punish the Britons for having sent assistance in ships and men to the Veneti, a kindred Celtic tribe, with which he was at war on the mainland. He appears to have encountered no opposition from it, however, for when he set sail from the coast of France, somewhere between the present ports of Calais and Boulogne, his fleet of war-galleys and transports crossed unchallenged, as far as the sea was concerned.

Achieving little more on his first visit than a demonstration of the power of Rome, on his return, a few months later, with 30,000 men, including cavalry, he penetrated deeply inland, although it was not until nearly a century later that Britain became definitely a Roman province; and it was not until the reign of Vespasian at Rome and his deputy Julius Agricola in Britain that Roman vessels for the first time circumnavigated Great Britain and Scotland. The father-in-law of Tacitus, and himself an extremely able and far-sighted administrator, it was by Agricola that the earliest definite foundations of what was to become the British nation may be said to have been laid. Securing the confidence of the islanders, he not only encouraged amongst them the absorption of Roman {xiii} culture, but protected them against any excess of official exploitation; and, although he was presently recalled by the Emperor Domitian, the principles of administration that he had laid down were generally adopted and developed by his successors in office—forming, in many respects, those of that greater empire whose foundations were already being laid.

It would be hard to exaggerate, indeed, the debt of the nations of British origin to the three and a half centuries of Roman rule, during which period the Christian religion was first preached in these islands. And, though it failed, if that had been its design, to create a strong and independent and self-governing colony—so that when the Roman power was finally withdrawn, owing to impending disasters at the core of the Empire, the Islanders became a prey, if not an easy one, to the next Saxon invaders—its legend of equity as between man and man, its perception and methods of development of natural resources, and its patient thoroughness of execution appealed to the minds and survived in the practice of every succeeding race of immigrants.

That together with these qualities and those to be infused with the next current of invasion there was a real love of the sea among this early population has sometimes been doubted; and Ruskin in one of his essays seems definitely to deny this, adducing Chaucer as an argument. In this great poet of a later period, the first representative voice of emerging England, he finds no expression of it and indeed a positive aversion from all that the sea and sea-travel stood for. {xiv} But whether or not that be the case, and though there were undoubtedly periods, notably just before the rise of Alfred, wherein the nation as a whole, if it may so be spoken of, had largely forgotten the importance of sea-power, each of the three great tribes, who had then overrun the land, had depended for their success upon their maritime skill.

Saxons and Jutes and Angles, they had all been coast-dwellers upon the Weser, the Elbe, and the Ems, the sea-banks between them, and the tongue of land dividing the Baltic from the North Sea; and, while a certain number of them had already become settlers in Britain, attracted by its prosperity under Roman rule, the majority had been pirates, with an established reputation as amongst the bravest and fiercest of ocean-adventurers. Bold as they were, however, and disorganized as the Romanized Britons had become, upon the withdrawal of the tutelage of their governors, it was nearly two centuries before Great Britain could be said to have become definitely Anglo-Saxon, and yet another two before the newcomers themselves had established any sort of unity; and already, by that time, fresh bodies of invaders had begun to make their presence felt.

These were the Wikings or Vikings, men of the Scandinavian fiords, racially allied with the original Saxon conquerors, but whose subsequent conversion, both to Christianity and what seemed to them the tamer life of agriculture, they affected to regard with indignation, not unmixed with contempt. Carrying their arms into every known sea, and believed to have been the first discoverers of America, these Vikings {xv} saw in Great Britain, with its increasing fertility, an ideal and convenient theatre of war.

As early as the later years of the eighth century, they were making sporadic raids upon the Northumbrian coast, and, in 832, they sailed up the Thames, ravaged the Isle of Sheppey, and escaped unscathed. A year later, they attacked the coast of Dorset, and, in 834, they joined the Cornish Celts, when they were defeated, however, by Egbert, King of Wessex—the first, in any real sense, King of England.

But this was little more than a local defeat, and almost every succeeding year saw further raids, until, in 855, a squadron actually entrenched in Sheppey and proceeded to spend the whiter there—the first indication in the minds of the Northmen of serious ideas of invasion. From 866 to 870, they made attacks in such force and with such ferocity that, by the beginning of 871, the whole of England, north of the Thames, lay at their mercy; while, several years before this, permanent settlements of Danes had taken place in Ireland, the Shetland Islands, the Hebrides, and the Orkneys.

This was the situation when, at the age of twenty-two, Alfred, afterward to be called the Great, ascended to the throne. Nor could he well have become king at a less propitious moment. For, with the whole of the north and east now firmly in their grasp, the Danes were already pressing upon Wessex. A battle fought almost immediately after his accession to the throne was rather in the nature of a draw than a victory; and, although the enemy withdrew for a time, a few years later found Alfred at bay in the {xvi} marshes of West Somerset, with the Danes overrunning and apparently in secure possession of some of the most fertile parts of his kingdom.

Fortunately for his people, however, Alfred, for all his refinement, his love of culture, and cosmopolitan boyhood, had inherited in full measure the stubborn Saxon refusal to accept either slavery or defeat; and, a few months later, rallying to his standard an army of Hampshire, Wiltshire, and Somersetshire men, he inflicted upon the Danes, at the battle of Ethandun, the severest defeat that they had yet sustained. By the treaty of Wedmore in 878, he secured the integrity of the south and west, recognizing that, in the north and east, the Danish element was not only too strong to be expelled, but was already becoming welded, not wholly to its disadvantage, with the national life. He agreed, therefore, for his own part, to recognize the Danish influence upon the other side of Watling Street, at the same time persuading its representative leaders to forsake their paganism and embrace Christianity.

Against further aggression, however, from abroad, he determined at all costs to protect the Island; and he was the earliest of his line to realize that his country's first defense was the sea that washed its shores. Already, in 875, he had been the victor in Swanage Bay over a small but strong fleet of pirates; and, after the peace of Wedmore, he set himself to the serious construction and effective distribution of a fleet of war. With no lack of raw material, with good craftsmen, and with a maritime population needing nothing but initiative, he built a navy that, in respect of {xvii} personnel no less than in technical equipment, soon outclassed that of the Danes. Distributed round the coast, he had, according to varying accounts, from 120 to 300 warships; and, behind this bulwark, for the next fifteen years, England achieved an almost miraculous degree of progress. In 896, after a considerable struggle, another attempted invasion was crushed, and Alfred's fleet, grown in strength and experience, extinguished the recurrence of piracy that had accompanied it. Merciful in character and tolerant in statesmanship, toward these pirates he showed no clemency, and, when he died in 901, he left a country prosperous and at peace and with its sea-boards inviolate.

To what extent his son and grandson, Edward the Elder and Athelstan, appreciated the full significance of sea-power we do not know; but it is interesting that Athelstan, during whose brilliant reign the Danish portions of England were largely reabsorbed, conferred the dignity of thane-ship upon any merchant who had made three voyages of length in his own trading vessel—thereby fostering, and even perhaps founding, the dynasty of those merchant-adventurers, upon whom in years to come, and on seas then unknown, Britain was to climb to a destiny beyond his imaginings. Nor can the work of Alfred and Athelstan, in these respects, be discounted because of the eclipse that followed in the reign of Ethelred, and that led to the passing of England, predominantly Saxon, under Danish sovereignty for a quarter of a century, and then, after a further period of twenty-four years, under the permanent rule of the Normans.

Tenacious of its rights, impossible to dragoon, there has always been a strain of inertia in the Saxon character—the reflex of that tolerance, perhaps, which has in so many respects been the secret of its influence throughout the world; and it was probably inevitable that there should have been phases in our national growth, and especially in its adolescence, when this should have seemed to be uppermost. To the minority Celt, with his quicker wits, this has often and justly been a subject of annoyance. In it the Normans, conscious in their persons of the latest current of oversea adventure, avid of culture, and contemptuous of ignorance, saw, and at once seized, their opportunity. For men of their enterprise, intellectual subtlety, and disciplined military energy, the prosperous island, with its clannish dissensions and lack of organization, seemed an obvious prey. And if, in the immediate moment, they were largely successful owing to the flank attack upon Harold by his brother Tostig, it was to a lack of vision, curiously Anglo-Saxon, that they were hardly less indebted for their victory.

Gathering for the defense of the realm, both by land and sea, the largest forces that had ever been collected in England, had William and his armies tried to land a month or two earlier they might well have done so in vain. But with August and September came the demands of the harvest, the autumn ploughing, and the neglected farms. As so often before and since in English history, the parochial and individual obscured the national. William had not come. Perhaps he would never come. The discontented soldiery {xix} could not be kept together. The ships of the Fleet, or many of them, had to return for re-fitting, and, when on September 28th, William arrived at Pevensey, three days after Harold had defeated his brother at Stamford Bridge, it was to land unopposed both on shore and at sea. Moreover, there was yet another factor, and one also that was to recur again and again in English history—a failure, fresh from military victory, to appreciate the value of sea-power—that contributed not a little to Harold's defeat. By October 14th, the date of the Battle of Hastings, the English Fleet had again been mobilized, and held the Channel. Between their position in Sussex and their base in France, the Normans' connections had been cut; and, just as in later years it was Nelson's "storm-tossed ships upon which the Grand Army never looked" that stood between Napoleon and the dominion of the world, so might Harold's, had he trusted them more fully, have stood between William of Normandy and the conquest of England.

With William's forces dependent for their supplies upon the rapidly dwindling stores of the surrounding country; with that silent pressure behind him of England's naval power—there would have been time and plenty, had Harold been content to wait, for the English armies to have consolidated themselves in overwhelming strength. But it was not to be. Dazzled by his recent success, and thinking in terms of armies rather than navies, he forced the issue and was defeated, and England passed under Norman power; and yet so incompletely that there are few Englishmen of to-day who, on reading the story of the Battle {xx} of Hastings, do not instinctively associate themselves with the defeated Harold rather than with the conquering William.

Nor is that as remarkable as it might superficially appear, since, within a very few decades of the Battle of Hastings, the same absorptive process that had been so characteristic a reaction of these islands to their previous conquerors was again in full swing. Even the Romans, although in Gaul and Spain they had succeeded in replacing the original dialects with their own stately language, had never succeeded in Latinizing Britain to any appreciable extent; and, while it is true that many Roman contributions remain as permanent features of our laws and customs, their four hundred years' sojourn left a scarcely perceptible impress upon the tongue of the supposedly defeated. Just as in Roman times, too, there was a considerable and real mingling, both in municipal life and in actual marriage, between the original inhabitants and the Roman colonists, so, in Saxon times, we find a similar process always at work in varying degrees, and indeed officially encouraged by several of the most far-sighted of the Anglo-Saxon kings and administrators. A similar absorptive phenomenon became observable in the later relations of Saxon and Dane; and, with the loss of Normandy, in the reign of King John, and the common cause then made between the French-derived barons and the English hitherto so despised by them, the world was to hear in Magna Charta the first authentic word of the England that we know to-day.

Nor was this process, unique though it was, as far {xxi} as recorded history can inform us, altogether inexplicable when the position of Great Britain and its succeeding invaders is considered. To each group of these, in the then world, it was an Ultima Thule. Beyond it, as far as they knew, there was no other—it was the verge of all things. To each its occupation had been an adventure, presumably undertaken by the most daring of the represented race. Each was at bay there to those that followed and of a spirit and fibre that could not easily be obliterated; and, in each, despite the ferocity of the times, was the respect of brave men for each other. Centuries later, on the other side of the Atlantic, similar conditions were to come into being; and it may well be that, in the larger island of America, we are witnessing a similar process on an extended scale.

But America was then in the womb of time, though it is a curious and significant fact that its discovery largely coincided with that great renaissance of the sea-instinct of England, embodied in the persons of the Elizabethan sailors. Up to then, the English national purview had been almost wholly insular and focussed on the Continent. The Anglo-Continental dreams of the Norman and Plantagenet kings had scarcely died; and they had died hard. The loss of Calais, perhaps the culminating factor in bringing about the new vision so soon to dawn, had seemed, at the time, nothing but a disgrace and a disaster, and far from the beginning of a greater epoch.

Yet it was no less than this, and, thence onward, we see the England, that had been on the world's edge, looking toward the New World, and perceiving, {xxii} by right of its position and history, a wider destiny opening overseas. Fighting more stubbornly than ever against every attempt to make it an appanage of Europe, the eyes of England began to turn more and more constantly to those just-discovered realms with their incalculable future. In the imagination of the Celt, the organizing power of the Roman, the tenacity of the Saxon, the daring of the Norman, and in the sea-lore of them all, it seemed that Fate had been slowly forging a new instrument for the new task. It was only the realization of it that was to seek in the composite race that had thus been built up; and it is not too much to say, perhaps, that the loss of Calais was the right-about-turn that brought this about. Not Europe but the West was the new watchword. But the corollary to that was a new conception of the sea. It was no longer the means of defense, insulating Britain from her foes. It was the highway of her full and peculiar national expression. As never before and not often perhaps since, the sense of what admiralty meant flooded through the nation; and though, as in all the enterprises of human society, the motives in this one were no doubt mixed—though the desire for gold and the lust of fighting for fighting's sake were dominant in the minds of many of those sailors—it is equally clear that, for the best and finest of them, the idea of admiralty had a definite spiritual meaning.

As we gather from their letters and records, they had begun to realize in themselves the upholders and missionaries of a nobler life. They were in true succession to the best of those Norman knights, whose {xxiii} spiritual contribution to England they had inherited; and, in admiralty, as they dreamed of it, we may trace the reincarnation, with a fuller and wider outlook, of that older chivalry.

These then were their objects, and the means was the navy, whose first foundations, as we now know it, had already been laid in the reign of Elizabeth's father, Henry VIII. Up to that time, though the Government had possessed the right, in times of war, to employ merchant shipping, there had been no definite navy, permanently established, in the modern sense of the word. In return for certain privileges, merchant ship-owners—and especially, in earlier days, those of the Cinque Ports—were under contract, on demand of the king, to supply a specified number of vessels, manned and equipped for war. It was with fleets so assembled that, in 1212, the English had raided Fécamp and prevented a French invasion; that, two years later, in a similar action under William Longsword, they had again destroyed the French Fleet; and that, in 1334, one of the greatest British naval victories had been won at Sluys over vastly superior numbers. And, though the Cinque Ports had, by this time, already dwindled from their earlier importance, similar arrangements were in force, when Henry VIII came to the throne, with the merchant shippers of Bristol, Plymouth, Newcastle, and many other quickly growing ports.

Under Henry VIII, however, we find coming into being the important Government dockyards of Portsmouth, Deptford, and Woolwich, and every provision made for the regular supply of the timber requisite {xxiv} for their needs. The same reign witnessed the establishment of the Navy Office, out of which our present Admiralty has grown, and the granting of a charter to Trinity House—that corporation of "godly disposed men who, for the actual suppression of evil disposed persons bringing ships to destruction by the shewing forth of false beacons, do bind themselves together in the love of our Lord Christ, in the name of the Master and Fellows of the Trinity Guild, to succour from the dangers of the sea all who are beset upon the coasts of England, to feed them when a-hungered, to bind up their wounds, and to build and light proper beacons for the guidance of mariners." And, although at the time of the Armada, as indeed ever since in moments of maritime urgency, a large bulk of the British Fleet consisted of transformed merchantmen belonging to private owners, the Elizabethan admirals found at their disposal the rudiments, at any rate, of a specialized navy.

How gloriously, and to what purpose, against what was then the greatest Power in the world, they used their inferior instrument, with its improvised auxiliaries, is the birth-story of British admiralty. Pitted not only for life, but, as it was to turn out, for the common freedom of the seas, they showed the world a spectacle of such a victory against odds as it had scarcely beheld since the Homeric ages. On the one hand, it saw an empire, one of the greatest ever known, under the ablest of statesmen and soldiers—an empire including Spain and Portugal, most of the Netherlands, and nearly the whole of Italy; Tunis, Oran, Cape Verde, and the Canary Islands in Africa; {xxv} Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Cuba in America; the mastery of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic; and a yearly revenue ten times that of England—and on the other a little island, of which Wales and Scotland were still largely independent, containing a population less by two million than that of London and its suburbs to-day, and possessing beyond its own coast not a yard of territory overseas.

Such were the odds, and the issue was but one more instance of the inevitable decisiveness of the human factor—a factor that to-day, perhaps, such has been the extravagant growth in the weight and precision of modern weapons, has tended to become once more a little obscured. That history has revealed it again, just as it revealed it for us in the case of the Elizabethans, we hope to show; and, if fortune fought for them, it was not until they had proved themselves superior to it in skill, courage, and equanimity.

"Touching my poor opinion," wrote Sir Francis Drake to Queen Elizabeth on April 15, 1588, how strong your Majesty's Fleet should be to encounter this great force of the enemy, God increase your most excellent Majesty's forces both by sea and land daily; for this I surely think there was never any force so strong as there is now ready or making ready against your Majesty and true religion, but that the Lord of all strength is stronger and will defend the truth of His word, for His own name's sake, unto the which be God all glory given. Thus all humble duty, I continually will pray to the Almighty to bless and give you victory over all His, and your enemies.

"We met with this fleet," wrote Hawkins to Sir {xxvi} Francis Walsyngham on July 31st in the same year, "somewhat to the westward of Plymouth upon Sunday in the morning, being the 21st of July, where we had some small fight with them in the afternoon. By the coming aboard one of the other of the Spaniards, a great ship, a Biscayan, spent her foremast and bowsprit; which was left by the fleet in the sea, and so taken up by Sir Francis Drake the next morning. The same Sunday there was, by a fire chancing by a barrel of powder, a great Biscayan spoiled and abandoned, which my Lord took up and sent away. The Tuesday following, athwart of Portland, we had a sharp and long fight with them, wherein we spent a great part of our powder and shot, so as it was not thought good to deal with them any more till that was relieved. The Thursday following, by the occasion of the scattering of one of the great ships from the fleet, which we hoped to have cut off, there grew a hot fray, wherein some store of powder was spent, and after that, little done till we came near to Calais, where the fleet of Spain anchored, and our fleet by them; and because they should not be in peace there, to refresh their water or to have conference with those of the Duke of Parma's party, my Lord Admiral, with firing of ships, determined to remove them; as he did, and put them to the seas; in which broil the chief galleass spoiled her rudder and so rode ashore near the town of Calais, where she was possessed of our men, but so aground as she could not be brought away. That morning, being Monday, the 29th of July, we followed the Spaniards, and all that day had with them a long and great fight, wherein {xxvii} there was great valour shown generally of our company."

A few days later, Admiral Howard, also writing to Sir Francis Walsyngham, said, "In our last fight with the enemy, before Gravelines, the 29th of July, we sunk three of their ships, and made some go near the shore, leaking so they were not able to live at sea. After that fight, notwithstanding that our powder and shot was well near all spent, we set on a brag countenance and gave them chase, as though we had wanted nothing, until we had cleared our own coast, and some part of Scotland of them."

Such were the Fathers of admiralty as to-day we envisage it; and, dark as some of our naval pages have since been, their tradition has never died, or lacked among us sons to sustain and adorn it in larger issues. There have been times when the country in general and its statesmen in particular have lost or under-valued their sea-vision. In 1667, less than eighty years after the defeat of the Armada, and scarcely ten after the death of Blake, one of the greatest figures in English naval history, to such a pass had our naval administration come that the Dutch were able to sail almost unchallenged up the Medway; to destroy the booms and half-equipped battleships; to capture the Royal Charles as a trophy; for several weeks to blockade London; and, in the end, to compel the English Government to a disadvantageous peace.

Fortunately that was a lesson that England never forgot, and, though there were to follow lapses, not a few, in the struggles that followed against the lust for world-power, first of Louis XVI, and, a hundred {xxviii} later, of Napoleon, the navy of England played a not unworthy and probably a decisive part. In Hawke and Rodney and Hood, and supremely in Nelson, in their unremembered captains and too-often ill-requited men, the spirit of the great Elizabethans lived again and ultimately prevailed, as it was bound to do. Not less for peoples in the comity of nations than for individuals in smaller societies, the highest task is to put at the disposal of human progress their characteristic genius. In military capacity, never the equal of France; behind many other nations in certain of the arts and sciences; lacking the spiritual insight of the East and the buoyant versatility of the West, this maritime adequacy, this gift of admiralty, seems, by virtue of her history, to have been allotted to Britain—and she has always been at her greatest, both for herself and for mankind, when she and her statesmen have realized this most fully.

That among her seamen this conception was as strong as ever, the history of the Great War has abundantly made clear, little as most of them dreamed, on that July morning, to be described in our first chapter, that they were on the verge of an ordeal, in which humanity's fate would lie in their hands as never in history. And yet, had they been gifted with a vision of what was to come, certain doubts might well have been pardoned in them. Colossal as the machinery was, it was largely untried. New methods and engines, with unforeseeable possibilities, were already in embryo or in actual being. The submarine, the airship, the mine—in less than half an hour, a fleet might be at the bottom. Recent {xxix} naval campaigns had shown that, whereas a century before, it had been the exception for a stricken ship to sink, it was now the exception for it to float; and what of the men in a modern naval battle?

For it would have to be remembered that, while on the one hand the terrors of naval warfare had immeasurably increased, the men who had to endure them had become, on the other, the educated products of a more sensitive civilization. Whereas, even in Nelson's time, the majority of British seamen were quite unable to read or write, and were too often, for all their courage, little better than human animals—many had been impressed by slum raids in seaport towns, and disciplined by a brutality now scarcely imaginable—the sailors of to-day, if of the same fibre, were men of a wholly different upbringing. They were the brothers of the shop-attendants, the men in the counting-house, the skilled workmen with their trade unions. They were even better educated than these, with a mellower, deeper, and more humorous philosophy of life. For them the navy was a career, from boyhood to old age, with solid rewards—and not a last resort. How would their new refinement weather the storm?

In the following pages we have tried to answer this, as often as possible, in their own words.

THE HEROIC RECORD OF THE

BRITISH NAVY

Roman, Phoenician, Saxon, Dane,

From these white shores turned not again.

Save to the sea that bore them hence,

For their delight or their defense,

Judgment, persuasion, daring, thrift,

Each to the others lent his gift,

To whom, when all had shared, the sea

Added her own of admiralty.

It was early on the morning of July 20, 1914, that a couple of guests, who had courteously been invited to be present in the gunboat Niger for the King's inspection of the Fleet, made their way through the sleeping streets toward Portsmouth Dockyard. There were to be no manoeuvres this year since, as had already been announced in March, a test mobilization of the Third Fleet was to take their place. This Third Fleet consisted of the older ships of the navy, and depended for a large proportion of its personnel upon the Royal Fleet Reserve—a body of ex-naval seamen and other ratings, brought into being under Lord Goschen, and afterward strengthened and reorganized by the Selborne administration {4} of 1902 onward. To man this fleet had necessitated the calling of about 10,000 seamen and 1,500 marines—all of them volunteers from civil life; and its assemblage at Spithead with the First and Second Fleets had secured, between the Hampshire coast and the Isle of Wight, the greatest exhibition of naval power that the world had then seen.

Since Wednesday, July 10th, the various units and squadrons had been gathering to their appointed stations, in some places eleven lines deep; while, upon the same occasion, and for the first time, there had been a full mobilization of the naval air forces. Less dramatic than the usual manoeuvres, and unaccompanied by any of the splendour that had attended most previous Royal reviews, this test mobilization—this bringing into being of the full fighting power of our naval reserves—was so valuable an exercise that, as Mr. Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, had said in his announcement of it, it was a matter for some surprise that it had never before been undertaken. Nevertheless, as a national spectacle, it had attracted but little public attention, as the blinded windows and empty streets of Southsea and Portsmouth testified.

Grey as steel from vault to horizon but for a single wavering streak of blue, there seemed little prospect in the sky overhead of the fine day that the sailors had foretold; and nothing could have been more sombre than the early morning scene when, without ceremony and almost unnoticed, the Royal Yacht, with the King on board, left her berth in the Dockyard. Picking her course slowly past the Sally Port, {5} so beloved by Marryat, she steamed through the choppy waters to her place at the head of the great fleet; and it was not until she reached Spithead, unsaluted by flag or gun, that the clouds up above began to break, and the sun to shine down on that floating city, now beginning briskly to awake to life.

Long before the little Niger, indeed, was herself out in the Solent, all the long lines were fully astir. Trim picket-boats, scattering spray, were plying up and down with mails and provisions. Cables were rattling till only a single anchor held each of the great ships in her proper position. Flags and semaphores were busy with final instructions. Veils of smoke began to wreathe in the air; and then, at the Admiral's signal, and with no other pageantry than that inherent in its own latent might, the vast assembly, with deliberate precision, began to get under way and out to sea.

Led by the Royal Yacht, the Victoria and Albert, her graceful black hull streaked with gold—preceded, according to custom, by the state vessel of the Elder Brethren of Trinity House—by the time the Iron Duke, at the head of the First Fleet's battleships, came abreast of the Nab Lightship, the Royal Yacht was already at anchor to receive the salutes of the departing navy. For two whole hours the King stood on the bridge, while ship after ship filed before him, each of the larger battleships an embodiment of greater strength than was represented by the whole fleet that had destroyed the Armada, and each of the battle-cruisers capable of a speed and striking-power that, a century before, would have seemed but the {6} wildest of dreams. These were led by the Lion, flying the flag of a then comparatively unknown officer, Sir David Beatty, who, only the evening before, had received the honour of knighthood on board the Royal Yacht.

Following the Lion and her consorts came the light cruisers, and after these the destroyers and submarines, each of the latter submerging and rising to the surface again as she came abreast of the Victoria and Albert, while, to complete the picture, and to foreshadow the enormous development of aerial power in the years immediately to follow, each accompanying aeroplane and seaplane dipped in the air by way of salute.

So the Fleet passed out, great though it was, still only a portion of the total British sea forces, and producing scarcely a ripple upon the national attention, fixed on what seemed to it then a thousand more important matters. Had it been known that, as it then was, no eye would ever behold it again; that, in less than three weeks, stripped at its war stations, the fate of the world would visibly depend upon it—with what other eyes would the whole Empire have watched Spithead on that July morning! But, for the vast mass of Englishmen the world over, the incident passed without notice. Politically, the affairs of Ireland, the readjustment of the House of Lords, and the aspirations of Labour apparently held the field. For the anxious few, to whom the position in Europe seemed already ominously uneasy, it may have been otherwise. But none of them had publicly spoken; and it is now clear, with so sinister a rapidity {7} did the events leading to war follow each other, that the test mobilization designed, not without criticism, to supercede the usual manoeuvres, was coincident with, rather than the outcome of, the hardening of the general diplomatic position.

That was on July 20, 1914, and, upon the political events that ensued, it would be quite impossible, in the present volume, to dwell for more than a moment or two. Very briefly, they succeeded one another as follows. On July 23d, the Austrian memorandum to Serbia, relative to the murder of the Archduke Ferdinand, the heir to the throne, by a Serbian anarchist at Sarajevo on June 28th, was formally submitted. So drastic were the terms of this that its warlike significance was immediately apparent to the whole of Europe: and a reply from Serbia was demanded in forty-eight hours. This was given within the specified time, all the Austrian demands being acceded to, with two exceptions. These were that Austrian representatives should collaborate with Serbia in the suppression of anti-Austrian agitation and also in the judicial proceedings that were demanded against all connected with the Serajevo murder.

The acceptance of these demands would, of course, have been tantamount to an admission by Serbia that she had ceased to be an independent nation. Nevertheless she was ready to refer them to the Hague Tribunal. The Austrian ambassador, however, acting on instructions from his Government, refused to accept anything but an unqualified assent, and left Belgrade on June 25th.

It was clear that, as regarded Serbia at any rate, {8} Austria had determined upon war; but Sir Edward, afterward Viscount, Grey, then in charge of the British Foreign Office, took instant and most strenuous steps to prevent this. He first proposed a conference in London, in which Germany, France, and Italy should participate, to mediate in the issues between the two countries. To this Germany disagreed, stating that discussions were taking place between Austria and Russia, from which she had hopes of a successful issue. So fraught, however, was the whole European atmosphere with dark and immeasurable possibilities, that, in common with every other great Power, Great Britain had been obliged to take certain precautions; and, in the most immediately important of these, the navy was, of course, concerned.

Owing to the illness of his wife, Mr. Winston Churchill had left London for Cromer on the evening of July 24th—Prince Louis of Battenburg, afterward the Marquis of Milford Haven, being, as First Sea Lord, left in charge. About lunch time on Sunday, July 26th, the day after the Austrian Ambassador had left Belgrade, Mr. Churchill telephoned Prince Louis, and, in view of this serious development, told him to take what steps seemed to him advisable, at the same time informing him that he was returning to town that evening instead of on Monday, as he had originally designed.

In ordinary circumstances, the demobilization, following upon the naval exercises, was to have begun on this Monday morning. But Prince Louis, having made himself acquainted with all the telegrams received at the Foreign Office, had an order telegraphed {9} to Admiral Sir George Callaghan, then Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleets at Portland—the newest and most powerful units of which were afterward to form the nucleus of what was to become known as the Grand Fleet—to the effect that no ship was to leave anchorage until further orders, and that all vessels of the Second Fleet were to remain at their home ports near their balance crews. Throughout Monday, July 27th, by telegrams all over Europe to our various representatives, by interviews at home with foreign ambassadors in London, the British Foreign Office, under Sir Edward Grey, ceaselessly worked to avoid the impending collision, or, if that might not be averted, at least to limit its extent.

On Tuesday, July 28th, Austria declared war on Serbia, and, by the next day, was bombarding the Serbian capital. On this day, both Russia and Belgium were mobilizing their armies, Belgium as a precautionary measure of self-defense, and Russia, as regarded her southern armies only, on account of Austria's invasion of Serbia. It was early on Wednesday morning, July 29th, that the German Chancellor, then Herr von Bethmann-Hollweg, suggested to Sir Edward Goschen, our ambassador at Berlin, that if Britain remained neutral in the event of France joining Russia against an Austro-German combination, Germany would guarantee to make no territorial demands of France; would respect the neutrality of Holland; but might be forced to enter Belgium, whose integrity she would preserve, however, after the war. In respect of the French colonies, she would make no promises.

This meant the tearing up, of course, of the treaty, in which we as well as Germany had guaranteed Belgium's inviolability, and was an unmistakable index of the line of action that Germany was prepared to take, should it suit her purpose; and it was on this morning, unreported by the papers, and entirely unknown to the nation, that the First Fleet, under Sir George Callaghan, sailed out of Portland to its war-stations.

Peace was still possible, however, or so Sir Edward Grey hoped; and, while immediately rejecting, as he was in honour bound to do, Germany's proposal with regard to Belgium, he made the new suggestion of a European Council—a Council to which these problems, even at the eleventh hour, might be submitted to avert disaster. This plan was also destined to be fruitless. On July 31st, Germany sent a note to Russia demanding the instant dispersal of her armies, and requesting a favourable answer by eleven o'clock on Saturday, August 1st; and it was on the same day that Sir Edward Grey asked both Germany and France if they would guarantee the integrity of Belgium, always provided that this was not infringed by any other Power. To this France assented at once, but Germany made no reply.

Such was the position on Friday, and, on the Saturday afternoon, August 1st, Germany declared war on Russia, following this up, early on Sunday morning, with the invasion of Luxembourg by part of her advanced armies. This was the day on which the remainder of our naval reservists, including all naval and marine pensioners up to the age of fifty-five, {11} were called to the colours—the plans for their mobilization, reception, and embarkment, in any such event as had now arisen, having been carefully prepared and coördinated with the preliminary steps required of all other Government Departments, and included in the War Book, compiled by the Committee of Imperial Defense, under the presidency of Mr. Asquith, then Prime Minister.

Simultaneously, or rather on the previous Saturday afternoon, an order to mobilize had been received at Dartmouth—the Royal Naval College in which, and in the Britannia before it, so many generations of officers had received their first training. Already, on the preceding Tuesday, the cadets had been summoned to the Quarter Deck, as the big recreation hall was called, and told by the Captain that, in the event of war, they would certainly be mobilized—the six "terms" into which the cadets were divided, being ordered to report in three groups at Chatham, Portsmouth, and Devonport, in this order of departure.

Of the thrill produced by this, anybody who has been a schoolboy of fifteen will have little difficulty in forming an idea; and it may be doubted if any of the boys who heard it—many of them, alas, never to see another birthday—will ever again live through such a moment as when the summons actually came on the following Saturday afternoon. It came with added force, because, since Tuesday, the excitement had naturally died down, while most of the boys, in common with their fathers, and indeed the majority of English men and women, had found it difficult to believe that so huge a convulsion would not in some {12} manner be prevented. By what now seems, too, in retrospect, to have been almost the acme of ironical circumstance, they were due to start their holidays on August 4th, and to these their minds had already begun to turn again.

But the summons came, and with it in each boy, as hardly less in the college itself, the death of an era so instantaneous that it was only a little later that it could be realized. A moment before, and the normal Saturday afternoon life had been swinging along, as for so many years past—on the cricket field, in the swimming baths, in the Devonshire countryside surrounding the college; and the moment after, the cricket field was empty, with the stumps still standing there undrawn, and the lanes and river banks were being everywhere searched for such boys as were not in college. Long before nightfall half the cadets—scarcely more than children—had left the place forever; and it was not until then that the sense of what lay before them fell upon the officers and masters left behind. For a little while this was almost intolerable, and the more so because it would have seemed indecent to them to put it into words. Characteristically enough, perhaps—most of them being products of the same kind of system that had produced the boys—it was finally decided, dusk though it was, and tired as they were, to turn out the beagles.

By the evening of August 3d, therefore, August Bank Holiday, and a day of serene and cloudless beauty, the Admiralty was able to announce that the entire navy had been placed upon a war footing, the mobilization having been completed in all respects by {13} 4 o'clock in the morning. This was the position when, in a House of Commons charged with emotions tenser than any man remembered, Sir Edward Grey rose to explain the situation and the attitude of the Government, for which he desired the country's mandate. Beginning by assuring the House that the Government and himself had worked "with all the earnestness in our power to preserve peace," he went on to deal with the British obligations toward her friends in the Entente—making it clear that the country was not bound, by any secret treaty, to provide armed assistance. That was but a small matter, however, and what had to be determined was our moral position in the circumstances that had arisen.

Dealing first with naval matters, Sir Edward Grey pointed out that, the French Fleet being in the Mediterranean, her northern and western coasts—a tribute to her confidence in ourselves—were left absolutely unprotected; while, in the Mediterranean, should the French Fleet have to be withdrawn for vital purposes elsewhere, we ourselves had not then a fleet strong enough to meet all possible hostile combinations. Under those conditions, and with a German declaration of war upon her probably the question of a few hours, it had obviously been our bounden duty to make our position clear toward France; and this had been done on the previous afternoon. Subject to the support of Parliament, the British Government had promised that, if the German Fleet should come into the Channel, or through the North Sea, to undertake hostile operations against the French coast or shipping, the British Fleet would give to the {14} French all the protection in its power. Just before coming to the House, Sir Edward Grey added, he had learned that, if we would pledge ourselves to neutrality, Germany would be prepared to agree that its fleet should not attack the northern coast of France. But that, as he said, was a far too narrow engagement.

Even more vital, however, was the question of Belgium's integrity, not only to France and ourselves, but to the whole basis upon which the relations of all civilized Powers had come to rest. In connection with this, Sir Edward Grey told the House that a personal telegram had just been received by the King, in which the King of Belgium had made a supreme appeal for the diplomatic intervention of Great Britain. Should Belgium be compelled, Sir Edward Grey pointed out, to compromise her neutrality by allowing the passage of foreign troops, whatever might ultimately happen to her, her independence would have gone. To stand by and see that would, in his opinion—and this was overwhelmingly endorsed both by the House and the country—be "to sacrifice our respect and good sense and reputation before the world."

On the same day, Germany declared war on France, and, on Tuesday, August 4th, Great Britain asked for a definite assurance from Germany that Belgium's refusal to allow the passage of troops through her territory should be respected. An answer was desired before midnight, but the only German reply was to present our ambassador with his passports, and, before the day ended, Great Britain was at war not only for her life but for the life of civilization.

And now, as regarded the navy, there occurred a little incident, not without an element in it of the deepest pathos, but demonstrating, at the outset, that one at least of our great naval traditions shone as brightly as ever. For eight years—longer than any other living admiral—Sir George Callaghan had been afloat in various responsible commands; and, in 1911, he had become Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet. Its efficiency as an instrument was due in no small measure to his personal thoroughness and enthusiasm; and the mingled feelings of pride, confidence, and anxiety, with which he had led it to its war stations, can readily be imagined. At last he was to see in action, under his very eyes, that splendid weapon, for which he had so long been responsible. But it was not to be. Just as in most recent naval campaigns conducted by other countries, it had been considered advisable for the leader in war to have come fresh from staff work at headquarters, so it had been felt in England that the admiral commanding the Fleet in action must be not only a sea-officer of high standing, but one with a more intimate knowledge of the general strategical position than it had been possible for an officer so long afloat to acquire. It was for such reasons that Admiral Sampson had been placed in charge of the American Fleet in the Spanish-American War, and Admiral Togo by the Japanese Government in the Japanese War with Russia, and, for similar considerations, it had been decided to appoint Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, still young as admirals went, to the command of the Grand Fleet.

As a former Director of Ordnance and Torpedoes, and thus familiar with every branch of munitionment; as a former Third Sea Lord in control of ship-building and equipment; and, as Second Sea Lord, responsible not only for personnel but familiar, as Deputy for the First Sea Lord, with all questions of strategy, Admiral Jellicoe, apart from his personal qualities, had had unique opportunities of studying the whole naval problem from every possible standpoint. He had proved himself in addition, during naval manoeuvres, a tactical leader of the highest order; and he was already due, later in the year, to succeed Sir George Callaghan in command of the Home Fleets. It was therefore decided—not without considerable personal reluctance on the part of Admiral Jellicoe himself—that he should at once replace Sir George Callaghan on board the fleet-flagship Iron Duke; and nothing could have been more typical of naval esprit de corps and the subservience of even the most illustrious officer to the interests of the whole service than that this incident took place without a trace of bitterness or the slightest personal jealousy. Even so, five years after Trafalgar, having never been allowed to set foot again on English soil, Collingwood had died in his cabin, content that in his long sea-exile he had served his country; and even so, having carried upon his shoulders perhaps the heaviest individual responsibilities of the war, Jellicoe himself, at the end of 1917, walked quietly out of the Admiralty to hang pictures at home.

Born on December 5, 1859, Sir John Jellicoe was in his fifty-fifth year when he stepped on board the {17} Iron Duke as admiralissimo of the Grand Fleet. The son of a well-known captain in the mercantile marine, who lived long enough, as it is pleasant to remember, to witness his son's success, he was also related ancestrally to that Admiral Patton, who had been Second Sea Lord at the time of Trafalgar; while, in Lady Jellicoe, daughter of the late Sir Charles Cayzer, one of the Directors of the Clan Line of Steamships, he had formed, on his marriage, yet further connections with the sea. After a few years at a private school at Rottingdean, he had entered the Britannia as a cadet in 1872, and, from the first, seems without effort to have made the fullest use of his opportunities.

Passing out of the Britannia, the head of his year, with every possible prize that could be taken, he had qualified—again with three first prizes—as sub-lieutenant in 1878, being appointed a full lieutenant three years later, with three first-class certificates. Two years after this, he had taken part in the Egyptian campaign, obtaining the silver medal for the expedition, and also the Khedive's Bronze Star. Returning to Greenwich for a course in gunnery, he had obtained the £80 prize for gunnery lieutenants, and, soon afterward, had been appointed a Junior Staff Officer at the Excellent School of Gunnery at Portsmouth; and it was here that he had come into contact, and begun a lifelong friendship, with the greatest naval genius of modern times, then plain Captain Fisher, and scarcely known outside the service.

It was while still a lieutenant that, in 1886, he had received the Board of Trade Medal for gallantry {18} in a forlorn attempt—during which he was himself shipwrecked—to save a stranded crew near Gibraltar. Becoming a commander in 1891, he had been appointed to Sir George Tryon's flagship, the ill-fated Victoria, afterward to be sunk during manoeuvres—Commander Jellicoe himself, ill in his cabin at the moment, having the narrowest escape from drowning. Six years later, he had become a captain, joining Sir Edward Seymour's flagship, the Centurion, on the China Station; and it was in China that, three years afterward, he had seen his next active service during the Boxer Rebellion. In this he had been Chief Staff Officer to Sir Edward Seymour, who commanded the Naval Brigade; and, at the Battle of Pietsang, on June 21, 1900, he had been very severely wounded. Happily he had recovered, receiving for his services the Companionship of the Bath, and, four years later, had found himself at the Admiralty as Director of Naval Ordnance—a position that he had held during the revolution produced by the appearance of the first British dreadnought. He had also been largely responsible for the immense improvement in our gunnery, associated with the name of Admiral Sir Percy Scott. In 1907 Captain Jellicoe had been promoted to the rank of Rear-Admiral, being appointed to a command in the Atlantic Fleet a little later in the same year. In 1908 he had become one of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty and Controller of the Navy, and, two years afterward, he had reached the vice-admirals' list and had succeeded to the command of the Atlantic Fleet. In 1911, having already been made a K.C.V.O., he had been {19} honoured with a K.C.B. at the coronation of King George V, and, in 1912, after a short spell of service in command of the Second Battle Squadron of the Home Fleet, he had become Second Sea Lord, the position he was holding on the outbreak of war.

Such were the qualifications of the man in whose hands, on that fateful fourth of August, rested more heavily than in those of any other the destiny of our empire and of mankind. Had they proved inadequate, it is no exaggeration to say that the sun of freedom would have set for both. That they were not so is common knowledge, and the fullest justification of those who had believed in them—chief among whom was that masterful administrator, who had changed the whole aspect of our naval strategy.

Rugged of face, with hosts of detractors, and, at this time, well over seventy years of age; a prey to moods, with some defects of his qualities, and a mind too often intolerant of the weaknesses of others, it was to Lord Fisher of Kilverstone, more than to any single living man, that the navy of August 4th owed its strength. Lacking the hereditary sea-influences so strong in Sir John Jellicoe, and with none of the powerful encouragement that he himself had bestowed upon the younger admiral, Lord Fisher had risen to power by sheer mental ability united with an extraordinary force of character; although full credit must be given to Mr. Balfour who, as Prime Minister in 1902, gave Sir John Fisher, as he then was, the fullest scope for his genius.

These had included changes so radical and far-reaching, in almost every branch of naval {20} administration, that it would be impossible here to recapitulate them; and they are already familiar to most people. Briefly, they had amounted, first, to a drastic redistribution of our whole naval forces, including the partial absorption of the Mediterranean Fleet, hitherto our strongest command, into an enormously powerful force in the home seas always ready for war; the disestablishment of overseas squadrons of no strategical importance; the remorseless scrapping of many old ships that were doing little else than eating up money; and the reduction of distant dockyards that had long ceased to have any potential significance. Hand in hand with all this, a revision of the entire system of naval education had been undertaken; the Royal Fleet Reserve had been strengthened by the inclusion of a number of seamen who had had five or more years' training; and from these were to be drawn the balance crews that, in time of war, were to bring the vessels of the Second Fleet up to their full complement.

It had further become clear, both from the lessons learned in the naval actions between Russia and Japan, and in the strong bid for an overpowering fleet then being made by Germany, that new developments in the matter of design were a problem of the most serious urgency. It had accordingly been decided to replace the very large number of differing vessels, of which the navy then consisted, by a few definite classes, each designed to fulfil in war some clearly thought-out tactical purpose; and, at the same time, in absolute secrecy, the first of the great British dreadnoughts had been laid down.

This had not only compelled an immediate response in every navy throughout the world, but had once more secured for us the margin of vital security that had seriously been encroached upon before these reforms were initiated. That in spite of changes of Government and the natural reluctance of the nation, in view of social necessities, to increase its naval expenditure, Lord Fisher had succeeded in carrying through his programme, was the best evidence of his strength; and men of all parties had become increasingly united in endorsing the general wisdom of his attitude.

So swift, even since then, however, had been the advance in naval construction that, when Sir John Jellicoe stepped on board the Iron Duke, the first of the dreadnoughts was almost obsolete. Itself since outstripped by the ships of the Queen Elizabeth class, when war was declared on August 4th, the Iron Duke, as regarded battleships, was perhaps the flower of the British Navy. In full commission displacing 27,000 tons, and costing more than £2,000,000 to build, she had attained on trial, in spite of her enormous armament, a speed of no less than 22 knots. Each of her large guns, of which she carried ten, so arranged as to be able to fire on each broadside, was capable of hurling a shell from twenty to twenty-five miles, during which it would rise far higher than Mont Blanc; and, besides these, she had a dozen 6-inch guns with which to repel possible destroyer attacks. Her armour at the water-line was twelve inches thick; she was fitted with four submerged torpedo-tubes, and carried on board three thousand tons of fuel {22} and a complement of over a thousand officers and men.

No less powerful, though not so heavily armoured, and capable of a speed when pressed, of about thirty knots an hour, was the Lion, the flagship of the battle-cruisers, of whom Sir David Beatty was in command. She, too, carried ten 13.5-inch guns, with sixteen smaller quick-firing guns, and two submerged torpedo-tubes. Typical of yet another class was the since famous Arethusa flying the pennant of Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt, as he then was—a light armoured cruiser, or, in Mr. Churchill's phrase, "a destroyer of destroyers," displacing a little less than 4,000 tons, but capable of a speed, when pressed, approaching forty knots. Lastly should be mentioned the L class, then the latest of our destroyers, consuming oil fuel only—those antennæ of the Fleet, as fast as an express train, and the very incarnation of vigilance and daring.

Such then was the navy in which on August 3d, speaking in that breathless House of Commons, Sir Edward Grey had said that those responsible for it had the completest confidence. To it had been added, on the outbreak of war, a couple of battleships that had just been completed for Turkey and two destroyer-leaders, built for Chile, that had been purchased from her by arrangement. As the child of the cockle-ships that Alfred had beaten the Danes with, that had won the Battle of Sluys for Edward III; as the offspring of the fleets of Drake or even of Nelson, its least unit would have defied belief. But it was of the same family, legitimately descended, and with the {23} old names scattered amongst its children. Bellerophon, St. George, Téméraire, its history was implicit in its roll call; while the dead animals stood re-invoked upon the prows that bore their legends. Collingwood, Benbow, St. Vincent; Albemarle, Cochrane, Hawke—they were at war for England if only as words. But did they live again in the men that hailed them? Well, the nation believed so, and, in that dark hour, this was the sheet-anchor of its hope. In the words of the King to Sir John Jellicoe, it sent them the full assurance of its confidence that they would "prove once again the true shield of Britain and of her Empire in the hour of trial."

In his speech of August 3d in the House of Commons, Sir Edward Grey told his listeners that we had incurred no obligations to help France either by land or sea. In view not less, however, of the increasing difficulties of our diplomatic relations with Germany than of the spontaneous friendship that had been growing between ourselves and our French neighbours, the question of coöperation with the latter, in certain eventualities, had inevitably arisen and been discussed. It had also been pointed out that unless some conversations were to take place between the naval and military experts of both countries—unless some definite lines were laid down as to the methods by which each country was to help the other—such coöperation, even if desired, would almost certainly be fruitless. At the same time, in a letter written on November 22, 1912, to the French ambassador, Sir Edward Grey had made it clear that these discussions between their respective experts did not commit either Government to a specified course of action "in a contingency which has not yet arisen and may never arise."

When the contingency arose, however, the plans were there; and the mobilization and transport to {25} France of our Expeditionary Force will remain on record as one of the most efficient military operations ever undertaken by any country. Second only to the rapidity and completeness with which the navy took command of the sea, were the speed and secrecy with which those first divisions were conveyed across the Channel. That in mere numbers they seem in retrospect to have been almost ridiculously inadequate is merely a measure of the colossal proportions that the war on land afterward assumed. Small as that army was, however, it was the largest force that we had ever sent oversea as a single undertaking; and it must be borne in mind that, in all probability, it was the most highly trained then in existence, and that its presence in France had both moral and material effects of almost incalculable importance.

Nobody who lived, or was staying, near any of our great southern railway lines during those early days of August will ever forget the emotions roused by that endless series of troop trains, passing with such precision day and night; and of the feelings produced in France by this visible pledge of our friendship there was instant and abundant evidence. Between August 9th and August 23d five Divisions of Infantry and two Cavalry Divisions were safely landed in France; and when it is remembered what a single division consists of some idea may be obtained of what that accomplishment meant.

Apart from the Headquarters' Staff with a personnel of 82, requiring 54 horses, 2 wagons, and 5 motor-cars, it embraced three Infantry Brigades, Headquarters' divisional artillery, three brigades of {26} Field Artillery, one Howitzer Brigade, one heavy battery, a divisional ammunition column, the Headquarters' division of engineers, two Field companies, one Signal company, one Cavalry squadron, one Divisional train, and three Field ambulances—comprising a total personnel of over 18,000 men, 5,500 horses, 870 wagons, 9 motor-cars, and 280 cycles, the number of guns, including machine guns, amounting to 100; and with a base establishment for each division of 1,750 men and 10 horses.

Such was the task performed by the transport officers, every kind of vessel being assembled for the purpose, from the cross-channel packet boat accommodating not more than three hundred at a time to the giant Atlantic liner carrying as many thousands. Chiefly from Southampton, but also from Dover, Folkestone, Newhaven, Avonmouth, and many other ports, that constant stream of men, horses, provisions, and equipment poured ceaselessly for nearly a fortnight, screened by destroyer-escorts, and with aeroplanes and seaplanes keeping watch over them from the sky. Without a single casualty as the result of enemy action, they were mustered and marched into line of the French left flank; and that this great achievement should have been possible within so short a period from the declaration of war is perhaps the completest tribute that could be paid to the consummate skill of our naval dispositions.

Scarcely realized by those splendid battalions, whistling "Tipperary" on the way to Mons, and even now, perhaps, hardly appreciated by the bulk of their countrymen at home, it was the navy and the navy {27} alone that made that glorious epic possible. With their eyes on Europe and the impending clash of the armies; hearing in imagination, under the unsuspected force of the heavy German artillery, the crumpling up of those iron-clad cupolas of the Brialmont forts at Liège—few would have thought twice, perhaps, even if they had known what they were doing, of those tiny submarines E6 and E8 creeping, the first of their kind, into the Bight of Heligoland. Yet but for them and their gallant crews and officers, Lieutenant-Commanders Talbot and Goodhart; but for the presiding destroyers, Lurcher and Firedrake and the submarines of the Eighth Flotilla—the passage of the Expeditionary Force might well have been impossible and the first battle of the Marne fought with another issue.

Within three hours of the first outbreak of the war, E6 and E8 stole out on their perilous errands; and it was upon the information brought back by them from those mined and fortified waters that the later dispositions were made. From August 7th onward, until the Expeditionary Force had been safely landed, the submarines kept their watch. In the lee of islands, at the mouths of channels, in hourly danger of detection and death, day and night, without relief, those cautious periscopes maintained their vigil. Farther to the south, guarding the approaches to the Channel, between the North Goodwins and the Ruytingen, were the two destroyers Lurcher and Firedrake, with the main covering submarine flotilla; while to the northeast of these, the Amethyst and Fearless, each with a flotilla of destroyers, took {28} turns about on patrol duty during the passage of the army.

Nor must it be forgotten, so swift was the subsequent progress both in the range and effectiveness of submarine activity, that this was, at that time, a branch of the service scarcely tried and of unknown possibilities. The submarines used were of a type soon so outclassed as to become almost obsolete, the easiest of prey to net and torpedo, and working at a distance from their bases then unprecedented. Nevertheless, after the Expeditionary Force had been safely transported to France, they were, in the words of Commodore, afterward Vice-Admiral, Roger Keyes, "incessantly employed on the enemy's coast in the Heligoland Bight and elsewhere, and have obtained much valuable information regarding the composition and movement of his patrols. They have occupied his waters and reconnoitred his anchorages, and, while so engaged, have been subjected to skilful and well-executed anti-submarine tactics; hunted for hours at a time by torpedo craft, and attacked by gunfire and torpedoes."

That was written on October 17, 1914, when the action, now about to be described, had already made the Bight of Heligoland a familiar term to most people, but without conveying, perhaps, to more than a very few all that it meant from a strategical standpoint. Between three and four hundred miles from the nearest of our naval bases, and from some of the chief of them more than six hundred miles distant, it was in this small area that there was concentrated practically the whole of Germany's naval forces, the {29} Kiel Canal connecting it with the Baltic, rendering these available in either sea.

Nor would it be easy to imagine, from the point of view of defense, either a bay of littoral with greater natural advantages. Bounded on the east by the low-lying shores of Schleswig-Holstein, with their fringe of protecting islands, and on the south by the deeply indented coast-line between the Dutch frontier and the mouth of the Kiel Canal, each of the four great estuaries, from west to east, of the Ems, the Jade, the Weser, and the Elbe, had been subdivided by sandbanks into a meshwork of channels than which nothing could have been easier to make impregnable. These were further guarded by the continuation of the scimitar curve of the Frisian Islands, beginning opposite Helder in Holland with the Dutch island of Texel, becoming German in the island of Borkum just beyond the Memmert Sands, opposite the mouth of the Ems, and continued, as a natural screen, in the successive islands of Juist, Nordeney, Baltrum, Langeoog, Spiekeroog, and Wangeroog as far as the entrance of Jade Bay, covering the approach to Wilhelmshaven.

Situated on the western lip of this channel, and connected by locks with the Ems and Jade Canal, this was one of the largest of Germany's naval bases and a town of about 35,000 inhabitants. In the next estuary, that of the Weser, and on the eastern coast of it, lay Bremerhaven, another naval base and important dockyard; and, on the same stretch of coast, at the point of the tongue of land between the Weser and the Elbe, lay Cuxhaven, yet a third and {30} immensely powerful naval port. This, with the attendant batteries of Döse, was flanked at sea by the Roter and Knecht sandbanks and the little island of Sharhorn, and was only about forty miles distant from Heligoland, lying in the centre of the Bight and commanding the hole.

Probably, from an offensive standpoint, of less value, under modern conditions, than was generally supposed, the possession of Heligoland, as a fortified outpost, was, if only psychologically, one of Germany's greatest assets. Of rocky formation and rising, at its highest point, to about 200 feet, it was not only a useful observation post but a fortress of the utmost strength. With wide views extending to the mouth of the Elbe and the coast of the neighbouring estuaries, it also protected a roadstead capable of sheltering and concealing a fleet of considerable strength; and, in addition, it possessed a wireless station of the greatest strategical importance.

From an early period, indeed, the peculiar advantages of the island had been obvious to many observers. In the seventeenth century, it had been used as a convenient station by the traders in contraband between France and Hamburg, and, for the same purposes, toward the end of the eighteenth and at the beginning of the nineteenth centuries, by British smugglers. During the Danish blockade of the German ports in the Schleswig-Holstein War of 1848, its advantages had become so manifest to the then British Governor that he made a special report about it to the Colonial Office. "Possessing pilots of all the surrounding coasts and rivers and with its {31} roadstead sufficient for a steam fleet," it would in an emergency, he had pointed out, "amply repay the small cost of its retention in time of peace." Other considerations had supervened, however, and, in 1890, after having been in British possession for more than eighty years, Heligoland had been ceded to Germany, to become, in due course, the keystone of her naval defenses.

Such then was the Bight of Heligoland, commanded at its centre by the rocky island itself; flanked on each side by the sentinel islands of the Frisian and Schleswig coasts; and with its tributary river-mouths each an intricate meshwork of shallow and treacherous sandbanks. Subject to fogs, and responding to its prevalent winds with short steep seas of peculiar violence, it had been mined and protected since the outbreak of war with every means that ingenuity could suggest. As for the island itself, from which all women and civilians, with the exception of five nurses, had been removed, new guns had been mounted there, houses pulled down, and trees felled to assist the gunners; and it is only when this is remembered that some idea becomes possible of all that was involved in those first patrols, and in the affair of outposts, as one officer has described it, afterward to be known as the Battle of the Bight.