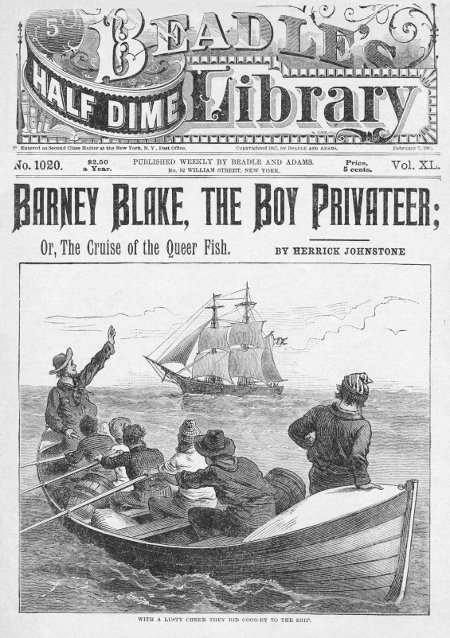

Title: Barney Blake, the Boy Privateer; or, The Cruise of the Queer Fish

Author: Herrick Johnstone

Release date: November 5, 2014 [eBook #47290]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

OR,

THE CRUISE of the QUEER FISH.

BY HERRICK JOHNSTONE.

It was upon a bright morning of the month of May, 1813, as I, a sailor just paid off from my last ship, was wandering along the wharves of Boston, that I was hailed by an old messmate, named Tony Trybrace.

"Ship ahoy!" cried Tony.

"The Barney Blake," I responded. "Out of employment, with compass gone, and nothing to steer by."

"What!" cried Tony, giving me his flipper. "Do you want a ship? A strange wish to go unsatisfied in these times."

"Yes," I hesitatingly rejoined, "but, you see, I've never been in the navy—always sailed in a merchantman—and—"

"Nonsense!" cried Tony. "That kind of blarney won't do for these times. I shipped the other day on as cracky a craft as ever kicked the spray behind her. Come and join us."

"What! on a man-o'-war?"

"Better than that. On a bold privateer! Look out there to windward," said Tony, directing my attention with his pointing hand, "and tell me what you think of her. That's her, the brigantine, with her r'yals half furled."

The vessel indicated to me by my friend did not go back on his off-hand description of her.

"She's a splendid ship!" I exclaimed. "What name does she go by?"

"The Queer Fish," was the reply. "She has six guns—eighteen-pounders—three on each side—with the prettiest thirty-pound brass swivel at her starn, this side of Davy Jones. She starts to-morrow for a year's cruise. Will you go?"

"Yes."

"Spoken like a Yankee tar. Come."

A boat of the privateer was in waiting, and in a few moments we were in it.

Scarcely had we pulled half way before a funny looking old fellow, squint-eyed, red-whiskered, and enormously wide-mouthed, whom they called Old Nick—a Norwegian by birth, was detected by the second mate attempting to take a pull at a green bottle, which he slyly whisked from the inside breast pocket of his pea-jacket. He was rowing at the time, and it required much sleight of hand to disengage one of his hands for the purpose in view. Nevertheless, he succeeded, took a long pull at the bottle, thinking no one saw him, corked it up again, and was about to return it to his pocket, when, at a wink from the second mate, Tony Trybrace, accidentally on purpose, skipped the plunge of his oar and brought it up against the old fellow with such a jostle that overboard flew the bottle, where it bobbed about.

Every one who saw the trick burst into fits of laughter. For a moment Old Nick seemed undetermined what course to pursue. Then nature vindicated her sway. He dropped his oar, rose in his seat, and plunged overboard after the green bottle and its precious contents!

He made straight for the bottle, recovered it, took a long pull at it while he trod water, returned it to his bosom, and made a back track to the yawl.

"You'll git up early in de morgen to rob ein Deitcher of his schnapps," he growled, as he clambered over the gunwale.

So, with many a laugh and jeer at the old fellow's expense, we pulled the balance of the way without further incident, and were soon upon the deck of the Queer Fish Privateer.

I was pleased with her more than ever upon a closer acquaintance. Everything was trim and tidy. Her decks were almost spotless, and nothing could exceed the beauty of her long bright swivel. She was polished up like a looking-glass, and I longed to hear her speak, with an iron pill in her throat.

Tony Trybrace had told nothing but the truth, when he had said that the people of the privateer were the jolliest afloat. They were a comical set from Captain Joker down to Peter Pun, the cabin-boy. Tony was the boatswain, and, as soon as we were aboard, he escorted me down to the cabin, to see the captain and sign the ship's papers.

I shall never forget the impression created upon me by my first introduction to the captain. I thought him the funniest-looking little man I had ever seen. He was a dried-up, weazen-faced, bald-headed little fellow, of fifty or thereabouts, with a red, gin-loving nose, twinkling gray eyes, so small that they were usually almost out of sight, and the expression of his mouth was so intensely humorous, that his lips always seemed to be fighting back a burst of laughter. To add to this, he was every inch a seaman, with the freshness of the ocean breathing from every pore of his wiry frame, and every seam of his weather-beaten face giving evidence of stormy service in sun and clime.

By a great effort, Captain Joker put on a severe expression of countenance as I entered, eyed me with those quick professional eyes of his, and emptied, at a draught, the tumbler of old Santa Cruz which stood at his side on the cabin-table.

Upon Tony's saying that I wished to ship on the Queer Fish, the captain, by a still greater effort, put on a still severer expression, and began to catechize me, while a wink from Tony told me which way the land lay.

"Where do you hail from?" demanded the captain pompously.

"From Salem, sir."

Captain. (With a sly twinkle in his eyes, in spite of himself.) What are the chief staples of Salem?

I. Shoemakers, old maids and sharks' teeth.

Captain. What is your name?

I. Barney Blake, sir.

Captain. Who was your mother?

I. Never had any.

Captain. (With his eyes twinkling more than ever.) Who are you the son of?

I. I'm the son of a sea-cook, was weaned on salt water, reared on sea-biscuit, and am thirsty for prize-money.

"You'll do!" cried the captain, shaking with merriment like a bowl of bonnyclabber, and striking the table with his fat fist. "Boatswain, enter him on the books as Barney Blake, son of a sea-cook; give him a cutlass and two pistols, and make him stand around. Avast, you vagabonds, and look sharp, or I'll be down on you with a cat and spread-eagle!"

The laughter of the captain, as we left him, was anything but in accordance with this monstrous threat.

"Good for you!" whispered Tony, encouragingly, as we ascended the companion-ladder.

He then brought me forward and introduced me to the entire forecastle. His words, upon this occasion, were somewhat characteristic, and here they are:

"Look yer', messmates, this 'ere cove is a perticklar chum o' mine. I've know'd him fer ten year—ran away from school with him, fell in love with the same gal, and cruised with him on the Constitution for three year. All I got ter say is, treat him well, or some o' yer'll git a eye so black yer own mother won't know yer, unless she's a black woman with a sore head: for he's as lively on his pins as a four-year-old cater-mountain, plucky as a Mexican gamecock, and the sweep of his fist is like the flounder of a ground-shark's fluke. Messmates, this 'ere is Barney Blake, Son of a Sea-Cook."

Although I could not consistently indorse this opinion of my abilities, the gusto with which it was received by my future messmates rendered it poor policy to deny it, so I went forward, and a general handshake was the result.

How shall I describe the crew of the Queer Fish? They numbered one hundred and twenty-five men, all told, and were as motley a set as were ever grouped together under hatches.

The majority were American-born, but there were four Hollanders, two Englishmen, six Frenchmen, two Malays, one Norwegian (Old Nick) and half a score of Irishmen. Each one was a character, but to describe each separately, and do him justice, would alone require a thousand pages; so I must be content with sketching the few who most prominently figured in the scenes I am about to narrate.

I have already mentioned Tony Trybrace and Old Nick, as well as the second mate, whose name was Pat Pickle, at least, so-called—a capital fellow as ever spoke through a trumpet, and brave as steel. Next in importance to these worthies was, perhaps, Dicky Drake, the butt of the whole crew. He was a green chap from somewhere down in Pennsylvania—had never been to sea before, except as a cod-fisher—and was the subject of a great number of practical jokes some of which will be duly recorded.

Probably the next worthy to be considered was our cook, a gigantic negro from the Virginia swamps, who went by the name of Snollygoster. I verily believe he was seven feet high, if an inch, and was possessed of the most prodigious strength.

I never saw the celebrated Milo of old. He must have been considerable in his way; but all I have got to say is that I would pit Snollygoster against him any day in the week and have no fear of my money. I have seen him raise a barrel of Santa Cruz and drink from the bunghole as easy as a common mortal would lift a box of cheese, and he was said to have felled an ox by a single blow of his fist. He was as good-humored a fellow as ever lived, and stood any amount of practical joking. The queerest inconsistency in his character was his peaceable disposition. Although no one could accuse him of downright cowardice, he was as timid as a hare and would go a long way out of his way to avoid a fight. But, if this was shown in his intercourse with men, it did not appear, it seems, in any other description of danger. He was the merriest man on board the ship in a tempest, and one of the Malays who had shipped with him in the Indian Ocean, swore that he had no more fear of sharks than of so many flying fish.

There was another queer fellow by the name of Roderick Prinn, who hailed from Southampton. There was nothing very funny about him, either. He had a sad, puritanical aspect, never drank, smoked or even chewed, and had very little to say. The most singular thing was his extraordinary attachment to another of the crew. This was a boy, and a very pretty little fellow to boot, named Willie Warner. They had both shipped at Philadelphia, and there was a thread of mystery between them, which was quite incomprehensible. They would associate together almost entirely, and would frequently converse together in the low tones of a language which no one else could understand. Nevertheless, they did their work well, and, although they were considerably reserved with the rest of the crew, they were generally so kindly and agreeable in what they had to say, that no one could find fault.

Then there was an old salt, just such another as Old Nick, who was full of an innumerable quantity of stories. I don't know what his real name was, but we called him Bluefish, and he liked the name. The amount of yarn that was wound round somewhere inside that old fellow's jaw was somewhat marvelous. He was a regular old spool, and had only to open his mouth to let out the longest and wildest lies on record, this or the other side of the Equator. Many a night, I can tell you, did we sit, gaping, round that old man of the sea, when the gale was blowing through the rigging a boreal tune, and all was snug below, to listen to his wild, weird, and, sometimes, humorous tales. Perhaps the reader will have one or two of them before we get through—who knows?

Well, I must let up on these descriptions, or our story will go a-begging.

I must say a few words about our first mate, and then I shall be all ready for the story, with royals spread, rigging taut, and everything trim to scud before the wind.

There wasn't anything funny about our first mate. He was, on the whole, an ugly, ill-natured dog, and thoroughly hated by every one on the ship, except the captain, who generally stuck to him through thick and thin. He was a Scotchman—one of your low-browed, lantern-jawed, gaunt-boned, mean-livered Scotchmen—a regular Sawney all over, from the top of his red head to the sole of his bunioned feet. He had a voice like a cracked bugle and a heart as hard as the hardest flint on Ben Inverness, with never anything pleasant to say or do. We detested him, and only waited our chance to play a joke upon him.

That will suffice for the men. As for the ship, she was as stanch and pretty a craft as ever plowed the blue waters, was built at Portland, masted at Bangor, and rigged at Boston, with an armament the best that money could procure. She was also a very swift sailer, and we calculated to play hob with John Bull's East Indiamen and whalers before we got through with the cruise.

A brighter morning never flung its golden beams upon the dancing dominion of old Neptune than that bright May morning when the windlass of the Queer Fish creaked with the rising anchor, and the mainsails, topsails and top-gallants fluttered slowly out from her graceful spars. All Boston knew we were going, and a large number of people were out upon the piers to see us start. So we ran up the Stars and Stripes to our peak, and gave a rousing salute with our guns, as we moved majestically down the harbor. We were soon out of it, and "the world was all before us," our path to choose. Taking the line of the southeast, we got all of the gale into our bellying sails, and bowled along gleefully, with a good lookout at the mast-head, to spy a prize, or sing out, if a cruiser hove in sight.

How could the Queer Fish even start to sea without something funny happening? There was one incident which I must not omit mentioning.

We had been overwhelmed with peddlers, bumboat women and fruit-sellers, for some time before our departure. Although they had all been warned to leave the ship in time, one of them, a Polish Jew, allowed his avarice to get the better of him, and remained parleying and auctioneering his trinkets till the anchor was up and we were fairly under way. He then coolly went to the captain, and requested to have a boat to be put ashore, when he was greeted by a sound rating, and an assurance that he couldn't leave the ship short of the Bay of Bengal.

The astonishment of the unfortunate Hebrew can better be imagined than described. At first, he was simply crushed, and, like Shylock, kept a quiet despair. Then, as the land grew beautifully less behind us, terror and rage began to take possession of his soul.

"Mine Gott! mine Gott!" he exclaimed, tearing up and down the deck, and wringing his hands. "V'at vill de vife of mine poosom zay v'en I comes not vonce more to mine house? Oh, Repecca, Repecca, mine peloved vife, varevell, varevell!"

We all enjoyed his misery to our hearts' content, for he was an arrant skinflint, who had swindled three or four of the crew out of their very boots. The captain also enjoyed the sight until we brought up alongside a pilot-boat, on board of which we put the pork-despiser in a summary way, and left him to find his way back to Boston as best he might.

A number of British cruisers were hovering along the coast, and we expected to have some trouble before getting fairly to sea. Nor were we disappointed. We were hardly four hours out before a sail was descried on our starboard quarter and another on our larboard bow. We hoisted the British jack and drove right between them, hoping to escape molestation, as we had little doubt that the sails in view belonged to British men-o'-war. We were correct in this. And, although we escaped the bigger customer to the northward, the other stranger came so close that we were right under her guns. She was a heavily-armed brig, and could have sunk us at a single broadside, but contented herself with questioning us.

"What ship is that?" was bellowed from her quarter deck.

"The brigantine Spitfire," sung our little captain through his trumpet.

"What luck have you had?"

"Have destroyed sixteen smacks off Gloucester and are now in the wake of an Indiaman that got out last night."

"All right."

And the unsuspicious brig drove by us with all sails set.

"We pulled the wool over her eyes, at any rate," mused our little captain, with twinkling eyes, as we continued on our course.

We next fell in with an American vessel, homeward bound, and gave her directions how to escape the blockaders.

"Sail ho!" sung out the lookout, an hour later.

We were immediately in a stew of excitement, thinking that this, at least, must be a prize. But this also proved to be an American, and we were compelled to chew the cud of disappointment.

"Why in blazes ain't you a Britisher?" muttered Tony Trybrace, yawning indignantly, as the true character of the stranger was discovered.

We kept our course, without incident, until the sun went down behind us, and the stars, one by one, began to stud the darkening vault.

Behind us flowed our wake of fire; Tony Trybrace played several tunes on his scrapy violin; and then, as it bade fair to be a peaceful night, we gathered round old Bluefish for a promised yarn.

"Yer see," said old Bluefish, lighting his pipe, "it all happened on board the Big Thunder. She was a splendid East Indiaman, and I was captain onto her."

"Captain? You captain?" exclaimed Snollygoster. "Come now, Massa Bluefish, dat won't do, you know. Dat am de—"

"Hold yer tongue, yer red-mouthed savage, and let me spin my yarn without a break in the thread! Yer see," continued Bluefish, "it all happened on board the Big Thunder. I went to bed feelin' fu'st-rate. It was kinder calm, with a prospect of being more so 'an ever. When I wakes up in the mornin' I was somewhat taken aback at seein' that a new post had sprung up in the cabin durin' the night. It ran straight up through the center of the cabin and was as yaller as a chaw of cavendish, when it's pretty well chawed.

"Well, while I lay there, wondering at the cussed affair, the first lieutenant, he comes roarin' down the companionway, thumpin' at my door like mad:

"'Come in!' I sings out.

"He dropped in, accordin' to orders, lookin' like the very Old Scratch, and inspectin' the new post of the cabin with curious eyes.

"'What's up?' says I.

"'Captain, does yer see this 'ere yaller post?" says he solemnly.

"'I does,' I replies.

"'Captain,' says he, 'this 'ere yaller post takes its root somewhere at the keel and grows up higher than the peak of the mainmast. An' what's more,' says he, 'it all growed up in one night.'

"'Ye'r' talkin' like a ravin', incomprehensible, idiotic fool,' says I.

"'It may seem so,' says the lieutenant, 'but come an' see for yourself.'

"This wasn't no more'n fair. So I gits into my duds, and goes on deck. Thar, sure as yer live, this 'ere yaller post run straight up between the mizzenmast and the tiller, reachin' about forty feet higher than the tallest mast on board. All the crew were standin' round, gaping, and nudging each other, and lookin' kinder skeered, when I begins to take observations from a philosophic point of view."

"From a what?" interrupted Tony Trybrace. "Takin' observations, from a phil—phil—philly—what?"

"Avast, you lubber, and let me spin my yarn! If yer ain't got no edication, is it my fault? If you was brought up outside o' college, am I to blame? Avast, I tell yer.

"Well, as I was a-sayin'. I begins to look at the thing kinder sharp. So I takes a cutlass down from the mast, and begins to cut little chips off the yaller mast. What do yer think came out o' that 'ere yaller mast?"

"Pitch," suggested one.

"Turpentine," said another.

"Old Jamaica," suggested Old Nick.

"Not a bit of it," resumed the narrator. "Nothin' longer, nor shorter, nor hotter, nor reddern'n BLOOD. That 'ere's what came out o' that 'ere yaller mast. Blood, and nothin' else!

"Well, all of 'em were sort o' dumb-foundered when they see'd the blood flowin', and some on 'em was more skeery 'n ever. But I turns to 'em, an' says I:

"'Does yer notice how slow the ship is goin'?'

"And they says:

"'Yes, we does. She isn't makin' much o' any headway, though the breeze are a fair capful.'

"'Well,' says I, 'and doesn't yer know the reason why?'

"'Not a bit on it,' says they.

"'It's because ye'r' towin' a sword-fish under yer keelson,' says I. 'He's pierced the craft in the night, an' this 'ere yaller mast ain't nothin' short of his cussed nose.'

"Well, they were all taken aback at this, yer see, an' now began to crowd up an' examine the thing. It was perfectly round, about two feet through, an' the eend of it was as taperin' an' sharp as a needle. Sure as yer live, it was all true. Well, it was a question what to do with the thing. Most on 'em was in favor of goin' down inter the hold, and cuttin' off the snout, in order to let the thing float; for, as it was, if we should come anywhar whar the water was less'n fifteen fathoms, we should be stranded by the cussed critter afoul of us.

"'Not at all,' says I. 'We don't git a good tough mast for nothin' every day in the week, and I'm in favor of cuttin' clear of the fish on the outside.'

"They were all kinder astonished at this 'ere, but I didn't give 'em breathin'-time, but says again:

"'Now which one on yer'll volunteer to dive under the keel with a handsaw and cut loose from the varmint on the outside?'

"Would yer believe it, not one on 'em wanted to go. So I says:

"'If ye'r' all so pesky skeered, why, I'll go myself. Carpenter, bring me yer handsaw, an' jist sharpen her up while I'm disrobin' my graceful form.'

"So the carpenter brings his handsaw, with a piece of bacon-fat to grease her with, and, when I gits ondressed, overboard I goes with the saw between my teeth. I dove right under the keel in a jiffy, and thar, sure enough, lays the sword-fish, with his nose hard up ag'in' the timbers, and his body danglin' down through the brine about seventy-five feet.

"'What are you goin' ter do?' says he.

"Says who?" broke in Tony.

"Yas, Massa Bluefish, who was it says dat?" demanded Snollygoster, with an incredulous look on his ebony face.

"Why, the sword-fish, yer ignorant lubbers! Doesn't yer know that they talk like lawyers when they git inter a scrape? I knowed a feller what heerd one of 'em sing the Star Spangled Banner fit to kill.

"Well, as I was a-sayin', says he ter me, 'What air you goin' ter do?'

"'Ter saw yer loose from the ship,' I corresponded.

"'All right,' says he," only I'm afeard it'll hurt some.'

"'I shouldn't wonder if it do,' says I; and with that I grabs his nozzle an' begins to saw like sixty.

"The way that poor devil hollered and snorted and flopped was a caution to seafarin' men. The men above water swore it sounded like ninety-three earthquakes piled on to a bu'stin' big volcano, an' I reckon it did. But I kept on sawin' and sawin', till at last the varmint dropped off, while the sea for 'bout ten miles round the ship became perfectly crimson with his blood. He made a big bite at me, but I ducked about like a porpoise, and succeeded in reachin' the deck without a scratch.

"The varmint was bent on vengeance, and made his appearance with his mouth wide open—big enough to have swallered a seventy-four, without so much as a toothache. But we fired a broadside of shrapnel and red-hot shot down his throat, an' he went off, waggin' his tail as if he didn't like it.

"Well, yer see, the blood all ran out of the yaller mast, and left it hard and dry. So I jist had a set of spars and sails rigged on to the thing, an' we arrove into Southampton with four masts."

Bluefish knocked the ashes out of his pipe, from which we judged that his yarn was brought to a close.

"Am dat all true, Massa Bluefish?" asked the innocent giant of a snollygoster.

"Every word on it," was the solemn rejoinder. "It was a thing as occurred in my actual experience."

Singular to relate, some of us had our doubts on this subject.

It was now bedtime for those who were not on duty, and we prepared to turn in.

I was up to seamen's tricks, and examined the stays of my hammock carefully before getting into it. I found them firm, and was about to turn in for a long snooze, when a crash in another corner of the forecastle told me that some one had had the trick played on him, at least.

The dim light of the lantern revealed the state of the case. Dicky Drake's hammock-strings had been all but severed, and he, upon turning in, had come down on the floor with a hard head-bump.

"Who did that? Where is he? Show him to me!" exclaimed the verdant youth, in a rage, plucking out his jack-knife and running through the laughing crew like a wild man.

"It was a mighty mean thing!" Tony Trybrace opined, roaring with laughter.

"Dat's so. I wonder who did it?" Snollygoster asked.

Every one else had some suggestion to make, but the doer of the deed was not found; and Dicky Drake swallowed his fury, reslung his hammock and turned in.

We were all tired and sleepy. I, at least, was soon in the arms of Morpheus, dreaming of the land I had left, and of the bright eyes that would look so long in vain for my return.

Butler. Footman, why art so happy? Art going to be married?

Footman. No, meester.

B. Then thou art married already, and art going to be divorced?

F. No, meester.

B. What then?

F. I've drawn a prize.

—Old Play.

I was awakened about daylight by a tramping on deck, and presently Tony Trybrace's shrill boatswain's whistle pealed out, followed almost immediately by his merry voice with:

"Tumble up! tumble up, you lubbers, if you care for prize-money!"

Every one heard what he said, and every one was on deck in a twinkling.

The morning was just dawning, and, far off, set against the just brightening sky, a sail was visible. I was rather provoked at having been summoned up from my nap, because the vessel was a good five miles off, and, if it was to be a stern chase, a long time would elapse before we could bring her to. Nevertheless, as I was on deck, and as my watch would be on hand in an hour, I thought I might as well stay up and see the thing out.

The men were all stationed, as if for battle, as was the custom of the captain on the slightest provocation. This was certainly the safest and wisest plan, but sailors seldom lose a chance for grumbling. Our little captain himself, however, if he brought the men up to the mark, never failed to toe it himself. There he was now, pacing the poop in his merriest mood. He was always familiar with us, and now he had a smart word for everybody.

"Take a peep through my telescope and tell me what you think of her, Barney."

This was addressed to me, and as there was quite a compliment in the request, I was not slow to comply. I sighted the strange craft well and examined every inch of her as well as the imperfect light would permit.

"Well, well, well," said the captain, impatiently. "What do you make of her?"

"She's a British brig," I replied. "She was built in London. Her name is the Boomerang. Her captain's name is George Willis, and she's very probably loaded with rum and sugar from Jamaica."

The captain was astounded.

"Are you crazy?" he ejaculated.

"I sincerely hope not, captain," was my smiling reply.

"How do you know what you say to be true?"

"Because I made a six months' cruise in that brig, captain, and I know every spar and ratlin of her from the mizzen-peak to the for'ard spankers."

"Well, if that is so, you certainly are the Son of a Sea-Cook all over and a sailor worth promoting," said Captain Joker, laughing as he spoke. "Clap on more sail!" he bawled. "Let out the r'yals to the full! Loosen the jib-sheets! I'll catch the stranger if I have to scrape the sky in doing it."

We sprung into the shrouds, and his orders were promptly executed. The gale, which had been stiff before, also blew stronger, and we bounded from crest to crest like a sea-bird under the influence of the fresh canvas. But when the sun arose we were still three miles from the stranger, who evidently had a suspicion of our character and was cracking on all sail for escape. But we now let out our skysails and came down on her rapidly. Our masts fairly groaned under the added impulse. We actually seemed lifted from billow to billow, rather than to plow through them.

At eight bells we were a mile and a half from the flying ship and fired a shot from our swivel to bring her to. We saw the shot dance off and kick up the spray right under her bows, but she ran up the Union Jack of England and kept on her way. Another shot from our bow-gun had no better effect. We, however, kept on our way, until within a mile, when we let fly again with the swivel, this time striking the vessel in the stern, and sending up a shower of splinters. We thought this would bring her to. But, she was plucky, and seemed determined to show fight. Scarcely had the boom of our Long Tom died away before a column of smoke shot out from the stern of the merchantman, and, before we could fairly make up our minds as to what was going to happen, the end of our bowsprit was knocked off like a pipe-stem, as well as a big splinter gouged out of our mainmast by a thirty-two pound shot.

"She's determined not to be taken alive," said Tony Trybrace.

"We'll see about that!" exclaimed our little captain; "just let me have a shy at her with that bow gun!"

With that he jumped down from his station on the poop, sighted the bow-gun carefully, and, just as we rose majestically on the summit of a huge wave, let her off. The ball danced over the crests with a charming ricochet, and we saw it strike the stranger fair and broad in the mizzenmast, which instantly went by the board, trailing a tangled maze of rigging and canvas into the sea.

"I thought she'd think better of it, after a little while," exclaimed the captain, triumphantly, as we saw the ensign of the stranger lowered in token of surrender, and, at the same time, she hove to. We came on with a rush, and hauled to close under her bows.

"What ship is that?" bawled Captain Joker through his trumpet.

"The brig, Boomerang, of London," was the reply.

"What are you loaded with?"

"Rum and sugar."

"Just stand where you are, and consider yourself a prize. You were right, you Son-of-a-Sea-Cook," added the captain, turning to me. "I'll promote you as soon as I get a chance."

A boat was immediately lowered, placed in command of Pat Pickle, the second mate, and in her a dozen sailors, I among them, pulled for the prize. We boarded her, and she came up to our largest expectations. I here had the satisfaction of renewing my acquaintance with my old skipper, Captain Willis, as well as with some of the crew. They all expressed their regret at seeing me in the character of a privateersman, at which I was not at all put out, but recommended them to merciful treatment, and succeeded in enlisting three of the crew, who were Canadians, for a cruise on the Queer Fish.

There was an Englishman on board the Boomerang, who was a passenger, but as he admitted that he was a consul to the South-American port of Rio de Janeiro, we made a prisoner of him in short order. This worthy will bear a brief description. He was one of the most genuine examples of the John Bull cockney genus it had ever been my fortune to fall in with. Rather short—about five feet and a half, I should judge—he weighed fully two hundred pounds, was dressed in the genuine London plaid trowsers, gaiter shoes and bell-crown hat of the time. His features were red and coarse, and his hair as red as fire. His name was Mr. Adolphus de Courcy. His indignation at learning that he was a prisoner was extreme, but, as the second mate didn't look as if he could bear much bullying, the dignitary reserved his spleen for the captain's ears.

Well, after we had supplied the Queer Fish with all the rum she would be likely to consume in the next six months, we put a prize crew on board the Boomerang, and started her for home, leaving her captain and crew on board. We brought off Mr. Adolphus de Courcy, determining to keep him until we should fall in with some American cruiser to whose safe-keeping we could transfer him. It took several hours to complete all these arrangements, but they were completed at last, and we rowed back to the Queer Fish, leaving the prize crew behind us, and, shortly afterward, the two vessels parted company.

As soon as we were on our own deck once more, Mr. Adolphus de Courcy strode up to our little captain with a majestic air.

"'Ave I the honor to haddress the captain of this piratical craft?" he asked in a most grandiloquent way.

"My name is Captain Joker, and this ship, which I have the honor and good fortune to command, is the Queer Fish, a regular letter-of-marque, commissioned by the United States Government."

"Wery vell, all I 'ave to say is, as 'ow I consider this transaction a wery houtrageous haffair; and I demand hinstant release from your villainous ship."

By this time the Boomerang was a mile or two away, and I saw a merry gleam in the little eyes of Captain Joker, which was premonitory of some fun.

"How can I release you now, sir?" said he, with an air of some concern.

"No matter 'ow, sir, I demand hinstant release from this willainous wessel," exclaimed the cockney, thinking that he had succeeded in browbeating the captain, and that he should now have it all his own way.

"I understand you to mean what you say?" asked the captain.

"Hexactly!" was the lofty reply. "I demand a hinstantaneous deliverance from this wile captivity! I demand it as a peaceable citizen of hold Hingland, whose broad hægis is powerful alike hon the land hand hon the briny deep."

"All right, sir, you shall have your wish: only be careful that you do not change your mind, as it will be of no use. Trybrace!" added Captain Joker, singing out to the boatswain: "have that ar little gig provisioned for two days, put in this little man's luggage, then put him in, and cut him loose. He wants to leave the Queer Fish."

"Ay, ay, sir," sung out Tony, cheery as a cricket; and he immediately set about giving the necessary directions.

"I wish you a good-morning, sir," and, with this Captain Joker bowed courteously to the cockney, and retired to the precincts.

Mr. Adolphus de Courcy appeared at first unable to comprehend what was to be done with him; but, when the truth dawned that he really was to be turned adrift, he seemed perfectly stunned.

"Vill you 'ave the kindness to hexplain this 'ere little harrangement?" he said, going up to Tony, who was busily superintending the outfit of the little boat.

"Ain't got no time, sir. The captain's orders were positive, and he ain't in the habit of repeating them. Clew up that gearing at the bows, you lubbers. And caulk up that 'ere seam in the labbard side. Do you suppose the gentleman wants ter go to Davy Jones's Locker afore he gits well started on his way? Put in the water and the sea-biscuit. Now for the gentleman's luggage. All right! Lower her!"

The arrangements were all completed, and the little craft was lowered from the davits over the stern. She was so small, and her cargo was so great, that she settled down almost to the gunwales, and it was questionable how long she would float after the bulky form of the cockney should have occupied the small amount of room left vacant for him at the stern.

We all preserved a solemn silence. The wretched Englander kept flattering himself that it was a good joke until the final preparations left no room for a doubt.

"All ready, sir," said Tony, touching his hat respectfully. "Will yer Honor be pleased to step inter yer Honor's craft?"

"Ha! ha! a wery good joke hindeed!" exclaimed the cockney, with a forced laugh. "A wery good joke! 'Ave you got out a patent for it? I should like to 'ave it, to hintroduce into hold Hingland."

"It's no joke at all, yer Honor," said Tony, as sober as a judge. "Will yer Honor condescend to make haste? We cain't stand in the middle of the ocean in this way, while there's so much prize-money lyin' about loose."

"My wery good friend," said De Courcy, taking the boatswain affectionately by the hand, "'ave you the serious intention of perwiding a fellow 'uman being with such han houtfit, and consigning him to the mercy of the wast and 'eaving hocean?"

"Them's the orders, sir."

"I then demand to see the captain of this willainous craft hinstantaneously."

"All right, sir. Dicky Drake, jist tell the skipper as how the gentleman wants to bid him good-by."

The message was sent, and Captain Joker made his appearance almost immediately. His face was beaming with cordial farewells as he advanced with outstretched hand toward the dumfounded De Courcy.

"Good-by! good-by, my dear fellow, and a prosperous voyage!" he exclaimed, shaking him warmly by the hand.

"Captain, I vant to know as 'ow—"

"No thanks! no thanks! my dear sir: I make you a present of the boat. There, there, good-by!" and the captain, in the zeal of his farewell, almost thrust the poor fellow over the bulwarks.

"But," persisted the latter, "I vant to know as 'ow—"

"I tell you I will not hear any thanks at all! There, there, farewell!"

The crew now crowded forward, with similar well-wishes, and the unfortunate cockney was fairly hustled over the ship's side into the frail gig, which was almost swamped by his weight.

"There are the oars, sir," sung out the captain. "I hope you will find them easy to your hands. Farewell! Bon voyage! Cut her loose, lads!"

The order was executed at once, and the boat, with its occupant, drifted off. At the same moment we let out our main sheet and continued on our course. We looked back over the stern, and saw the little boat going up and down, in and out of the troughs of the great swells, with its occupant sitting in the stern, looking the very picture of despair.

You needn't suppose that Captain Joker was cruel enough to leave the cockney in this predicament. He merely wanted to learn him a lesson in good manners. And, just as the gig and its occupant were almost cut of sight, we rounded to and bore down for her, tacking against the strong breeze. To show you the captain's kindness of heart, just as we were preparing to round to, a sail was signaled on our starboard bow. Ten chances to one it was another prize, and the temptations to keep on our course were exceedingly strong in us all, especially in the skipper, who was as fond of prize-money as any man I ever saw. Nevertheless, he ordered us to round to and bear up for the gig. The mean old dog of a first mate undertook to argue him into leaving the Englishman to his fate, when he was met with a stern rebuke.

"Mr. Saunders," (that was the name of the first mate) said he, "if you have nothing but such heartless cruelty to urge, I will beg you to defer your suggestions to a more fitting occasion. I am compelled to say, sir, that your heartlessness-not to say avarice—is astonishing, sir, astonishing!"

But the merry captain could not remain long in a bad humor, even with such a flinty-minded old Sawney as Saunders. When we had got pretty close to the gig, the forlorn, disconsolate aspect of Adolphus de Courcy was too much for a mirth loving nature to endure with solemnity, and Joker burst into laughter, as did the entire ship's company, who were all congregated forward, looking over the bows.

At a look from the captain, Tony Trybrace sung out:

"Would your Honor like to come aboard?"

A motion of the Britisher's head signified his assent to the proposition, and, with great difficulty, owing to the roughness of the running sea, we grappled the boat, and hoisted the entire compoodle, bag and baggage, to the deck of the Queer Fish.

The cockney had long ago resigned himself to despair, and when he found himself safe and dry at last, the revulsion was too great, and he burst into tears.

Captain Joker went up and took him by the hand, kindly.

"My dear fellow," said he, "I had no intention of cutting you adrift more than temporarily. It seemed to me that the tone which you assumed to me, on board my ship, was so very extraordinary for a prisoner to address his captor with, that a little lesson of this kind would not be bestowed in vain. Trust me, my dear sir, if I have caused you any pain, you compelled me to do so, and I'm sorry for it. As long as you remain upon my ship, pray consider my cabin your own. I would treat you as a guest rather than as a prisoner. Pray dine with me to-day. And dinner is almost on the table."

This magnanimity almost crushed the poor prisoner. He dried his tears, and said in a much manlier voice than heretofore, as he grasped the hand of his generous foe:

"Captain, you 'ave the goodness to treat me like ha gentleman. This 'ere is returning good for evil vith a wengeance, hand I beg to hacknowledge that I ham halmost crushed by your noble hand belated sentiments."

With that, they went down into the cabin together, and, from the way we heard the corks popping, they must have had a jolly time.

The lesson was not lost upon the cockney. His tone to everybody was thereafter greatly improved. He remained for some time with us, and, though we were frequently amused at his vanity and his antipathy to the letter H, we found him, in the main, a pretty good fellow.

It was on the third morning following the event narrated in our last chapter that we fell in with another—our second prize. She was a noble East Indiaman, a ship that could almost have picked up our saucy little privateer, and carried her at her stern like a yawl, had it not been for the difference of the cannon we carried. But, of course, that made all the difference in the world.

She was loaded with silks, spices and preserved fruits, and was immensely valuable. We had a brisk chase after her, but brought her to in an hour by a shot from our irresistible amidships gun. A large number of passengers were on board, which made a disposal of her somewhat uncomfortable. We had to deplete our ship's company again by putting a prize-crew on board. But we, here again, had some consolation in this, inasmuch as we received several recruits from the crew of the prize.

We had struck a bee-line southward some days before, and were now approaching the equator—the days not growing much cooler in consequence. One day, when we had got becalmed, the whole ship's company (almost) went in bathing, and a thrilling incident was the result.

The captain, always glad to make the men happy, had caused the mainsail to be slung over the side, with either end upheld by the overhanging yards, the belly of the canvas making a long dip in the brine, thus making a delightful shallow for the more timid swimmers to exercise their talents in, while bolder spirits might strike out to any distance they pleased. A great peril was involved in this operation of mid-sea tropical bathing, on account of the sharks, which are always more or less numerous in the wake of a ship.

Well, we all had an excellent time in the water, and were not in a hurry to come out. The captain had got tired of laughing at us, and had gone below for a siesta.

Old Snollygoster, after having got through with his ablutions, was lazily watching us from the rail of the ship. He was probably as able a swimmer as ever lived. He now amused us with sundry suggestions and cautions with regard to sharks, warning us not to go too far from the ship, and solemnly averring that his assistance need not be counted on, in event we were attacked. Several of us had swum to a considerable distance from the vessel, when suddenly some one sung out:

"Sharks! sharks!"

I thought it was a joke at first, but upon turning and casting a look seaward, I, sure enough, discovered several of the ominous black fins cutting water toward us.

I gave the alarm and struck out for the ship, with the strength of forlorn hope, followed by all the rest. To experience the horrible sensations of such a situation is an event which no after events, however stirring, can ever obliterate. It is horrible! horrible! That is all I can say. Every instant you expect to hear the snap of the ravenous jaws in your rear, and the next to feel them on your limbs. I think I never in my life swam so swiftly as upon that occasion. The ship was not distant—only a few rods, but it seemed a league to our excited imaginations. At length, however, with a wild cry of relief, I felt the canvas of the outstretched sail under me, and, clambering quickly up the side, was safe on the bulwarks. My comrades followed right at my heels, and the next moment I had the satisfaction of seeing them safe at my side. All of them? No, not all. A feeble cry behind apprised us that one was less fortunate than the rest. It was Dicky Drake. He had succeeded in almost reaching the sail, and was now all but surrounded by the infernal, swiftly-moving black fins of the monsters, who were actually pushing him about with their muzzles. They evidently thought that they had a sure thing, and might as well have a little sport with their morsel before devouring it. The poor fellow floated on the waves, paralyzed with horror and fright, unable to move hand or foot for his own salvation. It is very probable that this circumstance helped to save his life.

We were all so horrified at the spectacle that we were powerless to render any assistance, even if it were possible.

"Avast there, you lubbers!" said a clear, rough voice behind us.

Upon looking back we saw that it was the giant negro, Snollygoster, who spoke. Unbeknown to us, he had stripped himself, and now stood naked, with a long clasp-knife, open, and between his teeth. With one bound he was in the shallow of the sail below, and, with another, he grasped poor Dicky Drake by the hair of the head and drew him in, and we let down a rope and had the satisfaction of drawing the poor devil, more dead than alive, to the deck.

But the matter did not end here. Right in the midst of the sharks sprung the heroic Snollygoster. He dove out of sight. In an instant the water became suffused with blood.

"By Jove! they've nabbed him!" exclaimed old Bluefish, excitedly.

But they hadn't done anything of the kind. The next instant the woolly head of the negro made its appearance above the surface. It was shark's blood that was dyeing the water. Again the darky disappeared, and the water grew redder and redder, as another of the monsters floated, belly up, with a terrific gash in his paunch. The negro seemed to be as much at home in the sea as the fish themselves. It was a terrific combat, but one of intense interest. In vain would the monsters roll over on their backs and snap at their inexorable foe, or attempt to cut him in two with a sweep of their tremendous flukes. He was away again as quick as he came, attacking them from under the surface. In this he now had an advantage, as the water was so bloody that the fish could not see the blows by which they were being momentarily stricken to death, by the terrible right arm of heroic negro. At length, five of them were floating, dead or dying, on the surface, and the rest of them, with one exception, beat a retreat and did not venture within several rods. But the grand combat was yet to come. The one shark that lingered was by far the biggest of the group. I think he was, without doubt, the largest of the species I have ever seen, and I have seen plenty to choose from. He was thirty-five feet in length, if an inch, and when he opened his jaws the cavity Within was a terrible affair, with its double rows of tusks.

He seemed determined to take upon himself the championship of the whole family and advanced warily upon the negro, who did not flinch for a single instant. At length and as quick as lightning the monster leaped entirely clear of the sea and brought around his tail like the sweep of a scythe. The darky was out of reach just in time. As it was, the ragged edge of the animal's fluke just grazed his temple, drawing the blood. But before the unwieldy monster could recover himself for a renewal of the attack the knife of the negro was buried in his side. The wound was not mortal, but it must have been a painful one, to judge by the way the brute lashed the sea in his fury. It, however, served to render him more wary than before. He now began to swim round and round his foe in the hope of wearying him. But the negro stood bolt upright in the water, treading it with perfect ease, and ever keeping his face to the shark.

At length the latter, losing patience, charged, hoping to tear down Snolly with his snout. But quick as a wink, just as the animal was upon him, the negro disappeared, and the great effusion of blood that instantly followed made us aware that he had received his death-blow from beneath.

I shall never forget the shout with which we greeted the invincible Snollygoster as his woolly head appeared above the blood-dyed waters, while the conquered monster drifted off from the side of the ship, lashing the sea feebly with his tail, but fast expiring. Snolly slowly came out of the water and up the ship's side.

The captain, who had witnessed the last combat, shook him warmly by the hand when he reached the deck, while we all gathered around him with rousing cheers. Little Dicky Drake caught him by the hand and fairly sobbed. I must say that I had a strong impulse to catch the great negro in my arms and hug him for very joy. But Snolly rapidly replaced his clothes, with the simple remark:

"Dis nigga nebber see'd de fish he was afeard of."

You may think that this is quite sufficient for one fish story, but it isn't. We weren't done with the sharks yet. As the blood faded out of the water the school of sharks again clustered about the ship, and the captain determined to afford the men greater sport by catching one, if possible.

"'Ow will you do it?" exclaimed our prisoner. "'Ow will you 'ook one when you 'aven't any worms to bait with?"

"Ha! ha! ha!" laughed the captain. "It's true we haven't any fishing worms, nor grasshoppers, for that matter. But you have been complaining of the mosquitoes all day, my dear sir, and why not use them? However, we might as well try 'em first with a little bacon. So Pickle, just order some one to fetch up the carcass of that pig that died last night."

The bait was duly brought up on deck, much to the astonishment of the Britisher.

In the mean time Tony Trybrace proceeded to rig up the necessary tackle. Upon the end of[Pg 6] a rope about an inch and a half in thickness he fastened a large boat-hook. We then slung the rope through a block and made the latter fast to the jibboom. We thus had a first-rate purchase wherewith to fetch up anything short of a few tons' weight. Having made all ready, we hooked on the bait, and with a dozen stout seamen holding on to the other end, to be ready for any emergency, we lowered her slowly down. The stench of the putrid meat had already set the sharks wild for first bite, but as we wanted to take our choice and capture one of fair size, whenever a little fellow would jump at the bait we would quickly haul up and let his jaws gnash together with nothing between them.

At last, however, one rousing big fellow, who had evidently scented the battle from afar, came rushing up at railroad speed, pushing his voracious way through his smaller fellows. The bait was suspended fully six feet from the surface of the sea, but with a flying leap he took the whole hog at a swallow, and was hooked, of course. His weight drew the line down into the sea with a tremendous splash, almost jerking one or two of us overboard. But the next instant we were ready for him, and began to haul in with a will and a "yo-heave-ho!"

The old fellow didn't like it, but come he must, and, in spite of himself, he began to rise clear of the water. He then endeavored to bite off the rope, but Tony had been too sharp for him there, by twining the line, for three or four feet above the hook, with stout wire, so that the teeth of the monster gritted but harmlessly against the tough rope by which he was held.

Slowly but surely we drew him up until we got him taut up against the tackle-block, when another squad of sailors threw out some grapnels to haul him on deck, tail-foremost. The other men stood by, armed with cutlasses, hatchets and boarding-pikes.

"Now, be ready to pull him in when I give the word," sung out the captain, who was dancing about, the merriest man on the ship. "And be sure you keep out of reach of his flukes, or your mothers will forget you before they see you."

"'Eave 'im hin! 'eave 'im hin!" cried Adolphus de Courcy, who was impatient to try the efficacy of a sword-cane, which he held in his hand.

"Now, lads, haul away!" ordered the captain.

Slowly we brought him in, lowering him by the head as the other squad dragged in the tail. At last the monster was fairly on deck, when, at a signal from the captain, the men at the tail released the grip of their grapnels, while we simultaneously cut the line at his head. You had better believe we sprung out of reach lively, as soon as we had done this. And with reason; for the shark began to flounder at a most terrific rate, and if any one had happened within the reach of his flukes, he would have been a goner.

One laughable incident occurred.

The cockney was either not spry enough in getting out of the way, or he was too intent to get in a shy with his sword-cane; at any rate he caught a side wipe from the flat of one of the flukes, which sent him head over heels into the bow-scuppers.

"W'y, 'ow did that 'appen?" exclaimed the poor fellow, picking himself up, amid a storm of applause. "You see, I just vanted to get von vipe at the willain vith my walliant blade, when down I goes vithout knowing v'ere I vas hit."

It is astonishing how high a shark can leap from the water, but to see one of them bounce up when he has got solid oak beneath him as a purchase, is worth a long voyage. This shark would leap up perpendicularly fully thirty feet in the air, and come down with a crash that would make the vessel tremble to her keel. The blood poured from his mouth from the severe contusions he had received, but he seemed to lose nothing of vitality; until, at length, when we had enjoyed his gymnastics sufficiently, the captain made a sign to commence the assault.

The sailor regards the shark as his natural enemy, and never misses a chance to slay or maim him. So, as soon as the signal was received, we all began to dance about our victim, to get in a blow, which was anything but an easy matter, and, at the same time, avoid the sweep of his flukes, or the snap of his awful jaws.

"First blood!" yelled the cockney, with enthusiasm, as he succeeded in inflicting a slight scratch from which a few drops of blood oozed out.

"Do yer call that blood?" exclaimed old Bluefish contemptuously, as he danced in and fetched the shark a deep gash with his tomahawk, and this time the fountain of life began to flow in earnest.

Then the captain got in a blow, with his cutlass, between the eyes, and almost at the same time I ran my sharp pike clear through the black fin on the shark's back.

The struggles grew sensibly more feeble as the wounds told upon him, until at length the shark lay almost motionless. You may be sure that all hands, even down to Dicky Drake, were as brave as lions when injuries could be inflicted without danger to themselves.

Everybody now rushed, and a general thrusting, slashing and hacking took place until there was nothing left of the shark but a bloody and shapeless mass.

Every one then fell off exhausted, except Adolphus de Courcy, who enjoyed the fun so much that he couldn't be prevailed upon to stop.

"Just let me 'ave von more vipe at the willain!" he exclaimed, stabbing the lifeless mass again and again, until forced at last to desist by the laughter which his ferocity called forth.

Well, the fun was all over, and the next thing to do was to heave the carcass overboard, and to wash the decks, the last of which was performed in a vein somewhat less merry than before. But the captain made quite a holiday of it, gave us plenty of grog, and there was as little grumbling on board the Queer Fish that day as you would be likely to fall in with in a year's voyage.

The greatest holiday at sea is that of crossing the Equator. It is rare fun to the initiated, but to those who have the process in prospect it is a cause of sleepless nights and considerable mental anguish.

The time drew rapidly on for the celebration of this holiday on board the Queer Fish. We were busy making preparations for it, a long time beforehand. Almost every one was in excellent humor. Our cruise had, thus far, been eminently successful. We had captured upward of twelve vessels since our departure from Boston—a period of not more than two months. The prospect was that, if we should bring the cruise to a successful conclusion, we would each and all have something snug laid up at home, with ease and comfort the balance of our lives. So we were in a most excellent frame of mind for the merry-making that drew nigh.

Stop! There were a few exceptions. If any of you had been on the Queer Fish for a day or two prior to the passage of the equinox, you would have noticed, I think, a certain fidgetyness in the manner of both Dicky Drake and Mr. Adolphus de Courcy, in strange contrast to the general cheerfulness of every one else. The latter of these individuals, it is true, would pretend to be exceedingly careless and free-and-easy. He would be heard to hum the scraps of a great many little melodies and to whistle scraps of a great many more, but you would notice, upon close observation, that it was all put on, and that he was in reality faint at heart.

Poor Dicky Drake hadn't the duplicity necessary for any such make-believe as this. He began to look miserable from the very moment that it became known that the equinox was to be passed, and continued to grow worse from day to day, until the despondency of the poor lad was positively pitiful, and I secretly promised myself to exert my influence to render his share of the initiation as light as possible.

There had existed some controversy as to whether Roddy Prinn and his little chum, Willie Warner, were not also "liable." But they had succeeded in proving to the satisfaction of Captain Joker, that they had made the passage from Rio to the Bermudas, and it had eventually been decided that they were exempt.

There were several others of the crew, who were prospective victims. But they were genuine sailors, who really took the thing philosophically. One of them, a little Irishman, by the name of Teddy Tight, swore that he longed for the day to arrive, and that he didn't sleep "aisy" for thinking of the fun in store for him.

The preparations we had been and were making, were somewhat extensive. Everything was prepared beforehand, and we had several rehearsals. Old Nick was to represent Neptune, and, from the description I have given of him, you may judge that he suited the character to a T. Bluefish was chosen for Amphitrite, the wife of the Ruler of the Waves, and, though he had an unladylike habit of hitching up his skirts whenever he wanted to use his jack-knife, it was thought that he would go off very creditably. I was one of the Tritons, whose principal duty, on the occasion, was to assist at the initiation of neophytes, while Tony Trybrace, Roddy Prinn and Willie Warner were among the Nereids, who sung the mystic songs of the ceremony. I can't vouch for the poetic merit of these musical attempts. One of them was:

I cannot say who was the author of these stanzas, but am compelled to admit that I should keep exceedingly dark on the subject, if I were the author.

Another fragment (even worse than that already quoted) ran:

I reckon the author of these must have been an Irishman; at any rate, no one can question him as a poet.

Well, the day at length arrived.

According to rules, the novices were kept in strict confinement, till the performance was ready to commence. The little captain stood looking on, impatiently waiting for the opening ceremonies.

At eight bells, all was ready. Neptune was in his throne, with a beard as blue as the sea, and with a great crown of shells and sea-weed strung round his brows. He had a conch-shell for a breast-pin, and each of his shoes, or, rather, slippers, were surmounted with a large, brilliant-hued bivalve.

Amphitrite sat by his side, with her flowing locks—constructed of oakum—spangled with many varieties of weeds and shells and her long beard (think of a sea queen with a beard!) daintily braided and plaited into grotesque ringlets, while her long, blue paper-muslin robe was intended to have a resemblance to the sea she ruled. The Nereids were grouped around, looking excessively feminine and bewitching (to a sailor), with their long hair, and sea-green garments; while we merry Tritons were rigged in a little more convenient costume, as our work was to be heavy; but, rely on it, we looked hideous enough.

As the ship's bells struck eight, three of us, at a signal from the Ruler of the Waves, dove down below, and appeared, a moment afterward, with Dicky Drake, our first victim.

The poor fellow was almost scared to death. He eyed the various contrivances, which had been prepared for his benefit, and shuddered from his cap to his boots.

"Bring forth the culprit!" roared Father Neptune, in a voice of thunder; and we led the trembling victim before the throne.

"What is his crime?" was the lofty question of the ocean king.

"I ain't done nothin', yer Honor," began Dicky, thinking he might get off by an eloquent appeal. "Yer see, I was brought up in Salem, I was—a place as has furnished a great many sailors for yer Majesty's dominions. It's true I never crossed the line, yer know, but yer see, I almost did it onc't. It all as happened in this 'ere way. Ole Si Jinkins and I, we started out on a mackerel fishin' an' got driv' away down south, almost onto the equator, when a sou'east storm springs up, and sends us back a joe-kiting. Well, as I was about ter say—"

"Peace!" roared Neptune in a voice of thunder.

"Yes, your Majesty, but yer see—"

"Peace!"

"Oh, yes! Wery good! but, as I was about ter say, the—"

"Peace, or I'll kick yer inter Davy Jones's locker!" was the dignified interruption, and Dicky stopped short.

"Lead the prisoner to the plank!" was the final order of Neptune.

Visions of "walking the plank" immediately rose up before the wretched youth, and he began to appeal in heartrending accents.

"But I didn't go an' do nothin', yer know. I was allers exceedingly respectful and perlite. Onc't on a time, I see'd a feller spit inter the sea, an' I remonstrated with indignation, [Pg 7]because I thought yer Honor might be averse to tobacco. Yer see—"

"Silence! Lead him to the plank and shave him!" roared the implacable sea-god, and we led him away.

A great tank of water was situated right in front of the throne, and between the fore and mainmasts of the ship. Over this was drawn a light plank of pine. And the tank, we might as well mention now as any time, was filled with salt water.

Upon this plank we seated our victim, and began to lather him with soft-soap, without paying any regard to his sight. He gave a wild shriek as the suds went into his eyes (but he had had fair warning from me to keep them shut). Then, as my comrade held him fast, I proceeded to scrape his face with the piece of an iron hoop, which I had picked up and somewhat sharpened for the purpose. I laid it on as lightly as I could, but, nevertheless, the performance was so ridiculously painful that the poor fellow yelled again with agony. For the sharp but gritty edge of the saw-like razor would grab the few hairs he had on the chin, and would pull outrageously.

At length the barbering performance was over, and poor Dicky thought that he had got through the whole passage of the equinox.

But, no sooner was he shaved than the plank was suddenly jerked from under him, and down he went into the cold sea-water, where he floundered about fully a dozen seconds before he could scramble out.

He was next submitted to the tumbling apparatus. This was nothing more nor less than the mizzen-royal in the hands of a dozen men or so, two or three grabbing each corner, while the victim was tossed into the middle, where he was flung up and down, now and then letting him down far enough to give him a good bump against the deck. We finished him up with a keel-haul. There are two ways of doing this. The old way consisted in making the victim fast by either ankle, and then flinging him overboard at the bow, dragging him under the keel, with a rope on either side of the ship. But this was never resorted to as pastime; in fact, it was considered the worst of nautical punishments. Victims frequently died under its infliction. If anything of that kind had been tried under the Queer Fish, the sufferer would most certainly have had a hard time of it. For our bottom was completely covered with that small variety of the carbuncle shell-fish, known to seamen as ship-lice, and any one being dragged against them, would have been terribly lacerated.

But, of course, nothing of that kind was to be attempted upon such a merry and good-humored craft as the Queer Fish. Our keel-hauling simply consisted in making the victim fast by the ankles, and shooting him out far behind in the wake of the vessel (always making sure that there were no sharks in the neighborhood), and whisking him back again before he could well know how wet he was.

Poor Dicky Drake had stood everything else like a man, but his soul instinctively revolted from keel-hauling—though, to tell the truth, it was by far the easiest punishment inflicted in our category.

We made fast to his ankles, and swung him over the side, in spite of his entreaties. The ship was going at a spanking pace—a good eight knots an hour—as Dicky touched the water at her foaming wake. We let out lively on the lines, and away he sped, a good fifteen fathoms, from the ship. He squealed like a stuck pig as he hit the water, but we brought him back so quick that his head swam.

We then led him up to the throne of Father Neptune, who stretched his withered hands over his head, blessed him, and proclaimed him a true son of the sea—made so by his last baptism therein. The victim was then permitted to dress himself, was given a rousing glass of grog, and in a few moments felt as merry as a king, quite anxious to laugh at the next victim. They followed, one after another, amid roars of laughter. Most of them were old tars, who took the thing as an excellent joke, and we therefore made little out of them.

At last there were only two victims left. These were Teddy Tight and Mr. Adolphus de Courcy. The latter was reserved as the last, because we expected to have the most fun out of him; end the former was kept as next to last, because we half suspected that his eager anticipation of the fun that was in store for him was all gammon, and merely put on to cloak his terror.

In fact it was the testimony of each of his predecessors in the "ceremonies" that, as his turn came nearer and nearer, Teddy's courage began to sink until, at last, it was at zero. When we led the doughty little Irishman on deck, he was as pale as a ghost, and shook like a leaf.

On being led before the august presence of Father Neptune, however, his native blarney began to overflow, and excuse after excuse began to be poured out in a profusion which would have been limitless, if we had not cut him short.

"Och, yer Honor!" he cried, "w'at has yer Honor got ag'in' sich a poor little spalpeen as meself? Sure, an' hav'n't I sarved yer Honor well, by land and by say? Let me off this time, and I'll sarve ye better than iver. Och, yer Honor, ye must surely remimber me father. He was owld Barney Tight of Killarney. The way he would lick any one who would dare to say onything ag'in' yer Honor's character was a caution to the woorld. An' there was me uncle. Och, an' he was an ixcellent mon, yer Honor. I see'd him onc't knock the top-lights out of a murtherin' spalpeen who was afther injurin' yer Honor's reputation. An' there was my sister—God rest her sowl!—you should 'a' see'd her when she—"

"Silence!" was the gruff reply of the ruler of the waves; and Teddy, though he kicked and squirmed like an ugly worm on a bodkin, was put through the necessary course of sprouts in short order, but with a will.

Then Mr. Adolphus de Courcy was led up amid peals of laughter. He had had the philosophy to strip himself, with the exception of a pair of old pantaloons, and now appeared on deck with an air of offended dignity, which made him ridiculous in his present attire.

"What is yer crime?" was the gruff question of Neptune.

Adolphus eyed the venerable figure of the ruler of the waves with a lofty air of scorn, and did not, at first, deign to reply.

"Yer crime?" bawled the king, seizing his scepter with a menacing gesture.

"May hit please your hill-favored 'Ighness, has I hain't got hanything of that kind habout my person, I hain't hable to produce hany."

"You'r' accused of striving to usurp our throne," exclaimed old Neptune, wrathfully.

"W'ot!" exclaimed the astonished cockney, with his breath almost taken away by the novelty of the charge. "I—I husurp your throne! My dear hold fellow, I vouldn't 'ave it for ha gift."

"Ha! do yer insult us? Executioners, do your duty!" roared the indignant monarch.

"Now, 'old hon, hexecutioners," argued the cockney, remonstrating, "let me warn you not to go han' do hanything so wery rash. Do you 'appen to know 'oo I ham?"

"Yes, you're the grandson of—the Lord Knows Who," said Father Nep.

"Bless me, now, and 'ow did you know that my grandfather was a lord? That's wery astonishing, I declare. Wery well, you see I'm considerably different from halmost all of you fellows, hinhasmuch has I was brought hup a gentleman, hand was born hin dear hold Hingland, the Hempress of the Hocean. Now, certainly, your Hexcellency won't be so unfortunately rash has to hoffend the Hempress of the Hocean by hany hundue hinterference with one of her favorite sons, while hin the pursuit of 'is peaceful havocation."

The Britisher argued this in his most solemn and impressive style, and looked, when he was through, as if he thought the argument to be conclusive. But he roused a new enemy in an unexpected quarter. Scarcely had he finished his harangue, before Amphitrite (née Bluefish) sprung from her throne, with a wild yell, and caught him by the hair.

"Who dares to style any other than me the hempress of the briny deep?" she shrieked in his ear. "Ha! villain, thou art convicted out of thine own mouth. Usurper, thy time's come! Tritons, do your work!"

"But I protest! I demand ha hinstantaneous release has a Hinglishman on the 'igh seas! Captain, I happeal to you! This houtrage to Hinglishmen will be hawfully havenged! I protest—I—"

But he was now on the plank, undergoing the operation of shaving, and his open mouth received the great brush of lather full between his teeth, almost choking him, and completely gagging him for some time to come. Then the plank was whipped from under him, and down he went with an awful splash into the tub, protesting, amid the shouts of laughter, something about his being "a chosen son of hold Hingland."

We tossed him in the sail with the jolliest vehemence, but, when the ropes were being adjusted for the final part of the programme, that of keel-hauling, he begged off piteously.

"Captain, I shall drown, I know I shall," he pleaded, turning with an imploring gesture, to Captain Joker, who was enjoying the thing amazingly. "Captain, I 'ave a natural hantipathy to hanything but 'ot water. A bath hin my present state of perspiration will be the certain death of me, I know hit will. Now, please, captain, for the sake of hour hold and hardent friendship—for the sake—"

But the captain was implacable, and the cockney, though struggling violently, was swung over the taffrail. He was truly in a melting mood. The day was hot enough, as you may judge by the latitude we were in, and the course of sprouts through which we had been rushing our English victim, had made the sweat come from every pore of his skin. The revulsion, therefore, as his body hit the coolness of the rushing ocean stream, must have been very great. As it was, he gave an awful scream, and floundered like a stranded shark. Away he went, far out from the stern in the swift wake of the gliding ship. When we drew him in and landed him safe and sound, once more on deck, he was so overjoyed at his rescue, that he pretended to have liked his bath.

"Do you know, I henjoyed hit himmensely," he exclaimed.

And when he was dressed, with a good, stiff glass of grog in his hold, he really was one of the merriest men on the ship.

Well, that ended the ceremonies, but the holiday was not over by any means. We had an extraordinary dinner, and, after the sun had set and the bright tropic moon had risen, Snollygoster brought out his violin, and we had a glorious dance. Grog was freely distributed, and I am afraid there were a good many heads that felt abnormally large next morning.

In the latter part of the month of July, we succeeded in making a safe entrance into the neutral port of Rio de Janeiro, after having captured several more valuable prizes, and bringing two or three along with us. There was a British man-o'-war, the Atalanta, in this port, when we entered. She could have blown us out of water by one broadside of her great guns, but, nevertheless, she respected the neutrality of the port, and did not dare to molest us.

It may seem strange, from the manner in which Adolphus de Courcy had been treated on board the Queer Fish, that he should regret leaving us. But it is, nevertheless, a fact. When his freedom was given him, he assembled the entire crew around him, thanked them for the jolly time they had afforded him, and shook the captain warmly by the hand. He was really an excellent-hearted fellow, and we gave him three hearty cheers as he went over the ship's side to the boat which was to convey him and his luggage to the British ship before-mentioned. And his sincerity was not of a transient kind; for we afterward learned that he spoke well of us to the officers of the Atalanta.

Going on shore, after a long voyage, is the sailor's paradise. I reckon some of those old streets of Rio were glad enough when we disappeared; for a noisier, wilder, more devil-may-care set of tars never raised a rumpus in a seaport town than did we in Rio. We were allowed to go on shore in squads alternately; and as many of the British sailors were also, more or less, in the town, we had several collisions of a very serious character, though the disturbances were usually speedily quelled by the authorities.

The first disturbance of this kind that I was in happened a few days after we entered the port. A large squad of us—perhaps twenty—had gone on shore, but Tony Trybrace and I had somehow got separated from our companions. We were both of us somewhat in liquor, and had a hankering—a usual one under the circumstances—to have something more to drink. So we entered a queer sort of Spanish gin-shop, and, not understanding the lingo very fluently, proceeded to help ourselves—of course with the intention of paying our way.

In the course of this proceeding, Tony was rudely thrust back from the counter by the proprietor of the place, a wiry Brazilian, and, at the same time, admonished by a torrent of invectives in the unknown lingo.

It is poor policy to treat a drunken man rudely, unless you are a policeman. A sailor, especially, will bear but little handling. Tony staggered back a moment, but, the next, the[Pg 8] Brazilian was lying on the floor from a terrific blow between the eyes. Just at this moment, several English sailors entered the room, and, seeing that we were Americans, of course took the landlord's part. The latter was but little hurt and soon got up, muttering a great string of oaths, the usual consolation of the Spaniard, but, this time, in a much lower voice, and taking care to be out of the reach of Tony's powerful fist.

"Hit's ha hawful mean shame for to see ha poor cuss treated hin that 'ere way," mused one of the Englishmen to his comrades, in a tone so loud that it was evidently meant for our special benefit.

"That's so! Shiver my timbers eff I would stand it eff I was the Spanish cuss," was the elegant rejoinder.

"Whoever don't like it, can take it up whenever he wants," bluntly interposed Tony.

"His that 'ere remark hintended for me?" asked the first speaker.

"Well, it is," said Tony, "and so is this 'ere."

And before I could guess his intention, or move an inch to hinder it, down went the cockney before the same stanch fist of the Yankee sailor. The rest of the Britishers immediately sprung forward to avenge their comrade's fall; and, as I couldn't stand by and see little Tony overpowered, I also went in. There were ten of them, at least, and we were soon on the verge of destruction, when our cries for help reached the ears of friends outside, and in dashed Old Nick and Bluefish, at the head of a dozen or more of our lads, when the way that the Britishers and that entire gin-shop was cleaned out was a caution. Three policemen now dropped in, but we dropped them in as summary a way as the rest of them, and made our escape up the street.

This may be a rude picture, but it is one of truth, and I merely give it as a sample of sailors' life ashore in foreign parts.

But there were other scenes in our Brazilian experience that were much more novel and satisfactory than the foregoing. The town itself—or, rather, city; for it is a large place—is full of interest to the foreigner.

The men are mostly very homely, the women very pretty. The higher classes make a great display in a worldly way. I have seen as elegant "turn-outs" here, as in other parts of the globe. The ladies—some of them—are attired with unparalleled magnificence. You know it is a country of diamonds. The ladies sport a good many of them, but they have another kind of ornament which, perhaps, will be new to most of you. This is a peculiar kind of firefly which the ladies wear in their hair. I have seen them fastened among the black locks of a Brazilian belle at night-time, when the effect was striking in the extreme.

Gambling is very prevalent among the people.