Title: Windfalls

Author: A. G. Gardiner

Illustrator: Clive Gardiner

Release date: November 22, 2014 [eBook #47429]

Most recently updated: February 21, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

I think this book belongs to you because, if it can be said to be about anything in particular—which it cannot—it is, in spite of its delusive title, about bees, and as I cannot dedicate it to them, I offer it to those who love them most.

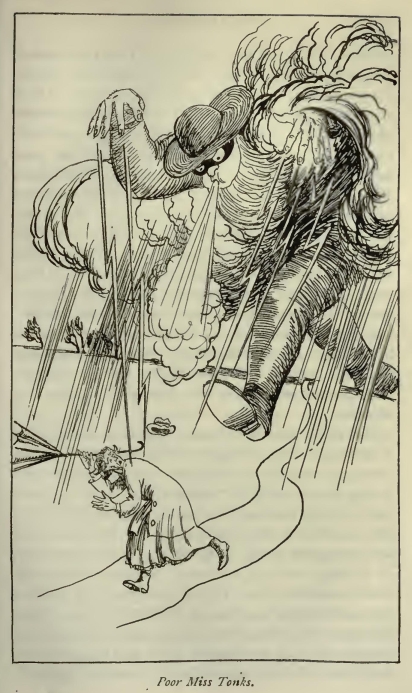

In offering a third basket of windfalls from a modest orchard, it is hoped that the fruit will not be found to have deteriorated. If that is the case, I shall hold myself free to take another look under the trees at my leisure. But I fancy the three baskets will complete the garnering. The old orchard from which the fruit has been so largely gathered is passing from me, and the new orchard to which I go has not yet matured. Perhaps in the course of years it will furnish material for a collection of autumn leaves.

I took a garden fork just now and went out to dig up the artichokes. When Jemima saw me crossing the orchard with a fork he called a committee meeting, or rather a general assembly, and after some joyous discussion it was decided nem. con. that the thing was worth looking into. Forthwith, the whole family of Indian runners lined up in single file, and led by Jemima followed faithfully in my track towards the artichoke bed, with a gabble of merry noises. Jemima was first into the breach. He always is...

But before I proceed it is necessary to explain. You will have observed that I have twice referred to Jemima in the masculine gender. Doubtless, you said, “How careless of the printer. Once might be forgiven; but twice——” Dear madam' (or sir), the printer is on this occasion blameless. It seems incredible, but it's so. The truth is that Jemima was the victim of an accident at the christening ceremony. He was one of a brood who, as they came like little balls of yellow fluff out of the shell, received names of appropriate ambiguity—all except Jemima. There were Lob and Lop, Two Spot and Waddles, Puddle-duck and Why?, Greedy and Baby, and so on. Every name as safe as the bank, equal to all contingencies—except Jemima. What reckless impulse led us to call him Jemima I forget. But regardless of his name, he grew up into a handsome drake—a proud and gaudy fellow, who doesn't care twopence what you call him so long as you call him to the Diet of Worms.

And here he is, surrounded by his household, who, as they gabble, gobble, and crowd in on me so that I have to scare them off in order to drive in the fork. Jemima keeps his eye on the fork as a good batsman keeps his eye on the ball. The flash of a fork appeals to him like the sound of a trumpet to the warhorse. He will lead his battalion through fire and water in pursuit of it. He knows that a fork has some mystical connection with worms, and doubtless regards it as a beneficent deity. The others are content to grub in the new-turned soil, but he, with his larger reasoning power, knows that the fork produces the worms and that the way to get the fattest worms is to hang on to the fork. From the way he watches it I rather fancy he thinks the worms come out of the fork. Look at him now. He cocks his unwinking eye up at the retreating fork, expecting to see large, squirming worms dropping from it, and Greedy nips in under his nose and gobbles a waggling beauty. My excellent friend, I say, addressing Jemima, you know both too much and too little. If you had known a little more you would have had that worm; if you had known a little less you would have had that worm. Let me commend to you the words of the poet:

A little learning is a dangerous thing:

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring.

I've known many people like you, who miss the worm because they know too much but don't know enough. Now Greedy——

But clear off all of you. What ho! there.... The scales!... Here is a bumper root.... Jemima realises that something unusual has happened, assembles the family, and discusses the mystery with great animation. It is this interest in affairs that makes the Indian runners such agreeable companions. You can never be lonely with a family of Indian runners about. Unlike the poor solitary hens who go grubbing about the orchard without an idea in their silly heads, these creatures live in a perpetual gossip. The world is full of such a number of things that they hardly ever leave off talking, and though they all talk together they are so amiable about it that it makes you feel cheerful to hear them.... But here are the scales.... Five pound three ounces.... Now what do you say to that, Jemima? Let us turn to and see if we can beat it.

The idea is taken up with acclamation, and as I resume digging I am enveloped once more by the mob of ducks, Jemima still running dreadful risks in his attachment to the fork. He is a nuisance, but it would be ungracious to complain, for his days are numbered. You don't know it, I said, but you are feasting to-day in order that others may feast tomorrow. You devour the worm, and a larger and more cunning animal will devour you. He cocks up his head and fixes me with that beady eye that gleams with such artless yet searching intelligence.... You are right, Jemima. That, as you observe, is only half the tale. You eat the worm, and the large, cunning animal eats you, but—yes, Jemima, the crude fact has to be faced that the worm takes up the tale again where Man the Mighty leaves off:

His heart is builded

For pride, for potency, infinity,

All heights, all deeps, and all immensities,

Arrased with purple like the house of kings,

To stall the grey-rat, and the carrion-worm

Statelily lodge...

I accept your reminder, Jemima. I remember with humility that I, like you, am only a link in the chain of the Great Mother of Mysteries, who creates to devour and devours to create. I thank you, Jemima. And driving in the fork and turning up the soil I seized a large fat worm. I present you with this, Jemima, I said, as a mark of my esteem...

I have long laboured under a dark suspicion that I am an idle person. It is an entirely private suspicion. If I chance to mention it in conversation, I do not expect to be believed. I announce that I am idle, in fact, to prevent the idea spreading that I am idle. The art of defence is attack. I defend myself by attacking myself, and claim a verdict of not guilty by the candour of my confession of guilt. I disarm you by laying down my arms. “Ah, ah,” I expect you to say. “Ah, ah, you an idle person. Well, that is good.” And if you do not say it I at least give myself the pleasure of believing that you think it.

This is not, I imagine, an uncommon artifice. Most of us say things about ourselves that we should not like to hear other people say about us. We say them in order that they may not be believed. In the same way some people find satisfaction in foretelling the probability of their early decease. They like to have the assurance that that event is as remote as it is undesirable. They enjoy the luxury of anticipating the sorrow it will inflict on others. We all like to feel we shall be missed. We all like to share the pathos of our own obsequies. I remember a nice old gentleman whose favourite topic was “When I am gone.” One day he was telling his young grandson, as the child sat on his knee, what would happen when he was gone, and the young grandson looked up cheerfully and said, “When you are gone, grandfather, shall I be at the funeral?” It was a devastating question, and it was observed that afterwards the old gentleman never discussed his latter end with his formidable grandchild. He made it too painfully literal.

And if, after an assurance from me of my congenital idleness, you were to express regret at so unfortunate an affliction I should feel as sad as the old gentleman. I should feel that you were lacking in tact, and I daresay I should take care not to lay myself open again to such gaucherie. But in these articles I am happily free from this niggling self-deception. I can speak the plain truth about “Alpha of the Plough” without asking for any consideration for his feelings. I do not care how he suffers. And I say with confidence that he is an idle person. I was never more satisfied of the fact than at this moment. For hours he has been engaged in the agreeable task of dodging his duty to The Star.

It began quite early this morning—for you cannot help being about quite early now that the clock has been put forward—or is it back?—for summer-time. He first went up on to the hill behind the cottage, and there at the edge of the beech woods he lay down on the turf, resolved to write an article en plein air, as Corot used to paint his pictures—an article that would simply carry the intoxication of this May morning into Fleet Street, and set that stuffy thoroughfare carolling with larks, and make it green with the green and dappled wonder of the beech woods. But first of all he had to saturate himself with the sunshine. You cannot give out sunshine until you have taken it in. That, said he, is plain to the meanest understanding. So he took it in. He just lay on his back and looked at the clouds sailing serenely in the blue. They were well worth looking at—large, fat, lazy, clouds that drifted along silently and dreamily, like vast bales of wool being wafted from one star to another. He looked at them “long and long” as Walt Whitman used to say. How that loafer of genius, he said, would have loved to lie and look at those woolly clouds.

And before he had thoroughly examined the clouds he became absorbed in another task. There were the sounds to be considered. You could not have a picture of this May morning without the sounds. So he began enumerating the sounds that came up from the valley and the plain on the wings of the west wind. He had no idea what a lot of sounds one could hear if one gave one's mind to the task seriously. There was the thin whisper of the breeze in the grass on which he lay, the breathings of the woodland behind, the dry flutter of dead leaves from a dwarf beech near by, the boom of a bumble-bee that came blustering past, the song of the meadow pipit rising from the fields below, the shout of the cuckoo sailing up the valley, the clatter of magpies on the hillside, the “spink-spink” of the chaffinch, the whirr of a tractor in a distant field, the crowing of a far-off cock, the bark of a sheep dog, the ring of a hammer reverberating from a remote clearing in the beech woods, the voices of children who were gathering violets and bluebells in the wooded hollow on the other side of the hill. All these and many other things he heard, still lying on his back and looking at the heavenly bales of wool. Their dreaminess affected him; their billowy softness invited to slumber....

When he awoke he decided that it was too late to start an article then. Moreover, the best time to write an article was the afternoon, and the best place was the orchard, sitting under a cherry tree, with the blossoms falling at your feet like summer snow, and the bees about you preaching the stern lesson of labour. Yes, he would go to the bees. He would catch something of their fervour, their devotion to duty. They did not lie about on their backs in the sunshine looking at woolly clouds. To them, life was real, life was earnest. They were always “up and doing.” It was true that there were the drones, impostors who make ten times the buzz of the workers, and would have you believe they do all the work because they make most of the noise. But the example of these lazy fellows he would ignore. Under the cherry tree he would labour like the honey bee.

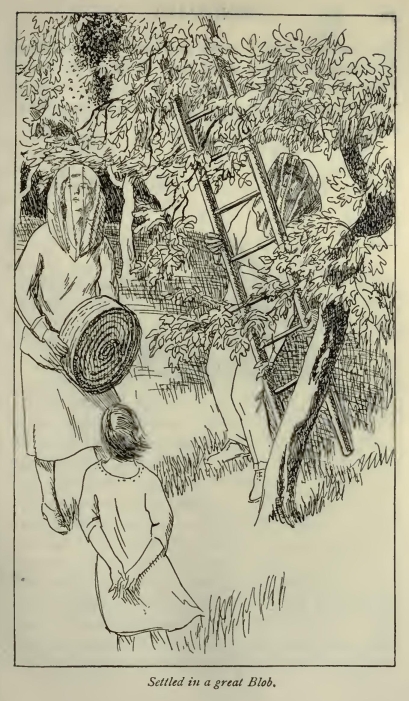

But it happened that as he sat under the cherry tree the expert came out to look at the hives. She was quite capable of looking at the hives alone, but it seemed a civil thing to lend a hand at looking. So he put on a veil and gloves and went and looked. It is astonishing how time flies when you are looking in bee-hives. There are so many things to do and see. You always like to find the queen, for example, to make sure that she is there, and to find one bee in thousands, takes time. It took more time than usual this afternoon, for there had been a tragedy in one of the hives. It was a nucleus hive, made up of brood frames from other hives, and provided with a queen of our best breed. But no queen was visible. The frames were turned over industriously without reward. At last, on the floor of the hive, below the frames, her corpse was found. This deepened the mystery. Had the workers, for some obscure reason, rejected her sovereignty and killed her, or had a rival to the throne appeared and given her her quietus? The search was renewed, and at last the new queen was run to earth in the act of being fed by a couple of her subjects. She had been hatched from a queen cell that had escaped notice when the brood frames were put in and, according to the merciless law of the hive, had slain her senior. All this took time, and before he had finished, the cheerful clatter of tea things in the orchard announced another interruption of his task.

And to cut a long story short, the article he set out to write in praise of the May morning was not written at all. But perhaps this article about how it was not written will serve instead. It has at least one virtue. It exhales a moral as the rose exhales a perfume.

I sat down to write an article this morning, but found I could make no progress. There was grit in the machine somewhere, and the wheels refused to revolve. I was writing with a pen—a new fountain pen that someone had been good enough to send me, in commemoration of an anniversary, my interest in which is now very slight, but of which one or two well-meaning friends are still in the habit of reminding me. It was an excellent pen, broad and free in its paces, and capable of a most satisfying flourish. It was a pen, you would have said, that could have written an article about anything. You had only to fill it with ink and give it its head, and it would gallop away to its journey's end without a pause. That is how I felt about it when I sat down. But instead of galloping, the thing was as obstinate as a mule. I could get no more speed out of it than Stevenson could get out of his donkey in the Cevennes. I tried coaxing and I tried the bastinado, equally without effect on my Modestine.

Then it occurred to me that I was in conflict with a habit. It is my practice to do my writing with a pencil. Days, even weeks, pass without my using a pen for anything more than signing my name. On the other hand there are not many hours of the day when I am without a pencil between thumb and finger. It has become a part of my organism as it were, a mere extension of my hand. There, at the top of my second finger, is a little bump, raised in its service, a monument erected by the friction of a whole forest of pencils that I have worn to the stump. A pencil is to me what his sword was to D'Artagnan, or his umbrella was to the Duke of Cambridge, or his cheroot was to Grant, or whittling a stick was to Jackson or—in short, what any habit is to anybody. Put a pencil in my hand, seat me before a blank writing pad in an empty room, and I am, as they say of the children, as good as gold. I tick on as tranquilly as an eight-day clock. I may be dismissed from the mind, ignored, forgotten. But the magic wand must be a pencil. Here was I sitting with a pen in my hand, and the whole complex of habit was disturbed. I was in an atmosphere of strangeness. The pen kept intruding between me and my thoughts. It was unfamiliar to the touch. It seemed to write a foreign language in which nothing pleased me.

This tyranny of little habits which is familiar to all of us is nowhere better described than in the story which Sir Walter Scott told to Rogers of his school days. “There was,” he said, “a boy in my class at school who stood always at the top, nor could I with all my effort, supplant him. Day came after day and still he kept his place, do what I would; till at length I observed that, when a question was asked him, he always fumbled with his fingers at a particular button in the lower part of his waistcoat. To remove it, therefore, became expedient in my eye, and in an evil moment it was removed with a knife. Great was my anxiety to know the success of my measure, and it succeeded too well. When the boy was again questioned his fingers sought again for the button, but it was not to be found. In his distress he looked down for it—it was to be seen no more than to be felt. He stood confounded, and I took possession of his place; nor did he ever recover it, or ever, I believe, suspect who was the author of his wrong. Often in after-life has the sight of him smote me as I passed by him, and often have I resolved to make him some reparation; but it ended in good resolutions. Though I never renewed my acquaintance with him, I often saw him, for he filled some inferior office in one of the courts of law at Edinburgh. Poor fellow! I believe he is dead, he took early to drinking.”

It was rather a shabby trick of young Scott's, and all one can say in regard to its unhappy consequences is that a boy so delicately balanced and so permanently undermined by a trifle would in any case have come. to grief in this rough world. There is no harm in cultivating habits, so long as they are not injurious habits. Indeed, most of us are little more than bundles of habits neatly done up in coat and trousers. Take away our habits and the residuum would hardly be worth bothering about. We could not get on without them. They simplify the mechanism of life. They enable us to do a multitude of things automatically which, if we had to give fresh and original thought to them each time, would make existence an impossible confusion. The more we can regularise our commonplace activities by habit, the smoother our path and the more leisure we command. To take a simple case. I belong to a club, large but not so large as to necessitate attendants in the cloakroom. You hang up your own hat and coat and take them down when you want them. For a long time it was my practice to hang them anywhere where there was a vacant hook and to take no note of the place. When I sought them I found it absurdly difficult to find them in the midst of so many similar hats and coats. Memory did not help me, for memory refused to burden itself with such trumpery things, and so daily after lunch I might be seen wandering forlornly and vacuously between the rows and rows of clothes in search of my own garments murmuring, “Where did I put my hat?” Then one day a brilliant inspiration seized me. I would always hang my coat and hat on a certain peg, or if that were occupied, on the vacant peg nearest to it. It needed a few days to form the habit, but once formed it worked like a charm. I can find my hat and coat without thinking about finding them. I go to them as unerringly as a bird to its nest, or an arrow to its mark. It is one of the unequivocal triumphs of my life.

But habits should be a stick that we use, not a crutch to lean on. We ought to make them for our convenience or enjoyment and occasionally break them to assert our independence. We ought to be able to employ them, without being discomposed when we cannot employ them. I once saw Mr Balfour so discomposed, like Scott's school rival, by a trivial breach of habit. Dressed, I think, in the uniform of an Elder Brother of Trinity House he was proposing a toast at a dinner at the Mansion House. It is his custom in speaking to hold the lapels of his coat. It is the most comfortable habit in speaking, unless you want to fling your arms about in a rhetorical fashion. It keeps your hands out of mischief and the body in repose. But the uniform Mr Balfour was wearing had no lapels, and when the hands went up in search of them they wandered about pathetically like a couple of children who had lost their parents on Blackpool sands. They fingered the buttons in nervous distraction, clung to each other in a visible access of grief, broke asunder and resumed the search for the lost lapels, travelled behind his back, fumbled with the glasses on the table, sought again for the lapels, did everything but take refuge in the pockets of the trousers. It was a characteristic omission. Mr Balfour is too practised a speaker to come to disaster as the boy in Scott's story did; but his discomfiture was apparent. He struggled manfully through his speech, but all the time it was obvious that he was at a loss what to do with his hands, having no lapels on which to hang them.

I happily had a remedy for my disquietude. I put up my pen, took out a pencil, and, launched once more into the comfortable rut of habit, ticked away peacefully like the eight-day clock. And this is the (I hope) pardonable result.

It is time, I think, that some one said a good word for the wasp. He is no saint, but he is being abused beyond his deserts. He has been unusually prolific this summer, and agitated correspondents have been busy writing to the newspapers to explain how you may fight him and how by holding your breath you may miraculously prevent him stinging you. Now the point about the wasp is that he doesn't want to sting you. He is, in spite of his military uniform and his formidable weapon, not a bad fellow, and if you leave him alone he will leave you alone. He is a nuisance of course. He likes jam and honey; but then I am bound to confess that I like jam and honey too, and I daresay those correspondents who denounce him so bitterly like jam and honey. We shouldn't like to be sent to the scaffold because we like jam and honey. But let him have a reasonable helping from the pot or the plate, and he is as civil as anybody. He has his moral delinquencies no doubt. He is an habitual drunkard. He reels away, in a ludicrously helpless condition from a debauch of honey and he shares man's weakness for beer. In the language of America, he is a “wet.” He cannot resist beer, and having rather a weak head for liquor he gets most disgracefully tight and staggers about quite unable to fly and doubtless declaring that he won't go home till morning. I suspect that his favourite author is Mr Belloc—not because he writes so wisely about the war, nor so waspishly about Puritans, but because he writes so boisterously about beer.

This weakness for beer is one of the causes of his undoing. An empty beer bottle will attract him in hosts, and once inside he never gets out. He is indeed the easiest creature to deal with that flies on wings. He is excessively stupid and unsuspicious. A fly will trust nobody and nothing, and has a vision that takes in the whole circumference of things; but a wasp will walk into any trap, like the country bumpkin that he is, and will never have the sense to walk out the way he went in. And on your plate he simply waits for you to squeeze his thorax. You can descend on him as leisurely as you like. He seems to have no sight for anything above him, and no sense of looking upward.

His intelligence, in spite of the mathematical genius with which he fashions his cells, is contemptible, and Fabre, who kept a colony under glass, tells us that he cannot associate entrance and exit. If his familiar exit is cut off, it does not occur to him that he can go out by the way he always comes in. A very stupid fellow.

If you compare his morals with those of the honey bee, of course, he cuts a poor figure. The bee never goes on the spree. It avoids beer like poison, and keeps decorously outside the house. It doesn't waste its time in riotous living, but goes on ceaselessly working day and night during its six brief weeks of life, laying up honey for the winter and for future generations to enjoy. But the rascally fellow in the yellow stripes just lives for the hour. No thought of the morrow for him, thank you. Let us eat, drink, and be merry, he says, for to-morrow——. He runs through his little fortune of life at top speed, has a roaring time in August, and has vanished from the scene by late September, leaving only the queen behind in some snug retreat to raise a new family of 20,000 or so next summer.

But I repeat that he is inoffensive if you let him alone. Of course, if you hit him he will hit back, and if you attack his nest he will defend it. But he will not go for you unprovoked as a bee sometimes will. Yet he could afford this luxury of unprovoked warfare much better than the bee, for, unlike the bee, he does not die when he stings. I feel competent to speak of the relative dispositions of wasps and bees, for I've been living in the midst of them. There are fifteen hives in the orchard, with an estimated population of a quarter of a million bees and tens of thousands of wasps about the cottage. I find that I am never deliberately attacked by a wasp, but when a bee begins circling around me I flee for shelter. There's nothing else to do. For, unlike the wasp, the bee's hatred is personal. It dislikes you as an individual for some obscure reason, and is always ready to die for the satisfaction of its anger. And it dies very profusely. The expert, who has been taking sections from the hives, showed me her hat just now. It had nineteen stings in it, planted in as neatly as thorns in a bicycle tyre.

It is not only in his liking for beer that the wasp resembles man. Like him, too, he is an omnivorous eater. If you don't pick your pears in the nick of time he will devastate them nearly as completely as the starling devastates the cherry tree. He loves butcher's meat, raw or cooked, and I like to see the workman-like way in which he saws off his little joint, usually fat, and sails away with it for home. But his real virtue, and this is why I say a good word for him, is that he is a clean fellow, and is the enemy of that unclean creature the fly, especially of that supreme abomination, the blow fly. His method in dealing with it is very cunning. I saw him at work on the table at lunch the other day. He got the blow fly down, but did not kill it. With his mandibles he sawed off one of the creature's wings to prevent the possibility of escape, and then with a huge effort lifted it bodily and sailed heavily away. And I confess he carried my enthusiastic approval with him. There goes a whole generation of flies, said I, nipped in the bud.

And let this be said for him also: he has bowels of compassion. He will help a fellow in distress.

Fabre records that he once observed a number of wasps taking food to one that was unable to fly owing to an injury to its wings. This was continued for days, and the attendant wasps were frequently seen to stroke gently the injured wings.

There is, of course, a contra account, especially in the minds of those who keep bees and have seen a host of wasps raiding a weak stock and carrying the hive by storm. I am far from wishing to represent the wasp as an unmitigated blessing. He is not that, and when I see a queen wasp sunning herself in the early spring days I consider it my business to kill her. I am sure that there will be enough without that one. But in preserving the equilibrium of nature the wasp has its uses, and if we wish ill to flies we ought to have a reasonable measure of tolerance for their enemy.

Those, we are told, who have heard the East a-calling “never heed naught else.” Perhaps it is so; but they can never have heard the call of Lakeland at New Year. They can never have scrambled up the screes of the Great Gable on winter days to try a fall with the Arrow Head and the Needle, the Chimney and Kern Knotts Crack; never have seen the mighty Pillar Rock beckoning them from the top of Black Sail Pass, nor the inn lights far down in the valley calling them back from the mountains when night has fallen; never have sat round the inn fire and talked of the jolly perils of the day, or played chess with the landlord—and been beaten—or gone to bed with the refrain of the climbers' chorus still challenging the roar of the wind outside—

Come, let us tie the rope, the rope, the rope,

Come, let us link it round, round, round.

And he that will not climb to-day

Why—leave him on the ground, the ground, the ground.

If you have done these things you will not make much of the call of the temple bells and the palm trees and the spicy garlic smells—least of all at New Year. You will hear instead the call of the Pillar Rock and the chorus from the lonely inn. You will don your oldest clothes and wind the rope around you—singing meanwhile “the rope, the rope,”—and take the night train, and at nine or so next morning you will step out at that gateway of the enchanted land—Keswick. Keswick! Wastdale!... Let us pause on the music of those words.... There are men to whom they open the magic casements at a breath.

And at Keswick you call on George Abraham. It would be absurd to go to Keswick without calling on George Abraham. You might as well go to Wastdale Head without calling on the Pillar Rock. And George tells you that of course he will be over at Wastdale on New Year's Eve and will climb the Pillar Rock or Scafell Pinnacle with you on New Year's Day.

The trap is at the door, you mount, you wave adieus, and are soon jolting down the road that runs by Derwentwater, where every object is an old friend, whom absence only makes more dear. Here is the Bowder Stone and there across the Lake is Causey Pike, peeping over the brow of Cat Bells. (Ah! the summer days on Causey Pike, scrambling and picking wimberries and waking the echoes of Grisedale.)

And there before us are the dark Jaws of Borrowdale and, beyond, the billowy summits of Great Gable and Scafell. And all around are the rocky sentinels of the valley. You know everyone and hail him by his name. Perhaps you jump down at Lodore and scramble up to the Falls. Then on to Rosthwaite and lunch.

And here the last rags of the lower world are shed. Fleet Street is a myth and London a frenzied dream. You are at the portals of the sanctuary and the great peace of the mountains is yours. You sling your rucksack on your back and your rope over your shoulder and set out on the three hours' tramp over Styhead Pass to Wastdale.

It is dark when you reach the inn yard for the way down is long and these December days are short. And on the threshold you are welcomed by the landlord and landlady—heirs of Auld Will Ritson—and in the flagged entrance you see coils of rope and rucksacks and a noble array of climbers' boots—boots that make the heart sing to look upon, boots that have struck music out of many a rocky breast, boots whose missing nails has each a story of its own. You put your own among them, don your slippers, and plunge among your old companions of the rocks with jolly greeting and pass words. What a mingled gathering it is—a master from a school in the West, a jolly lawyer from Lancashire, a young clergyman, a barrister from the Temple, a manufacturer from Nottingham, and so on. But the disguises they wear to the world are cast aside, and the eternal boy that refuses to grow up is revealed in all of them.

Who shall tell of the days and nights that follow?—of the songs that are sung, and the “traverses” that are made round the billiard room and the barn, of the talk of handholds and footholds on this and that famous climb, of the letting in of the New Year, of the early breakfasts and the departures for the mountains, of the nights when, tired and rich with new memories, you all foregather again—save only, perhaps, the jolly lawyer and his fellows who have lost their way back from Scafell, and for whom you are about to send out a search party when they turn up out of the darkness with new material for fireside tales.

Let us take one picture from many. It is New Year's Day—clear and bright, patches of snow on the mountains and a touch of frost in the air. In the hall there is a mob of gay adventurers, tying up ropes, putting on putties, filling rucksacks with provisions, hunting for boots (the boots are all alike, but you recognise them by your missing nails). We separate at the threshold—this group for the Great Gable, that for Scafell, ours, which includes George Abraham, for the Pillar Rock. It is a two and a half hour's tramp thither by Black Sail Pass, and as daylight is short there is no time to waste. We follow the water course up the valley, splash through marshes, faintly veneered with ice, cross the stream where the boulders give a decent foothold, and mount the steep ascent of Black Sail. From the top of the Pass we look down lonely Ennerdale, where, springing from the flank of the Pillar mountain, is the great Rock we have come to challenge. It stands like a tower, gloomy, impregnable, sheer, 600 feet from its northern base to its summit, split on the south side by Jordan Gap that divides the High Man or main rock from Pisgah, the lesser rock.

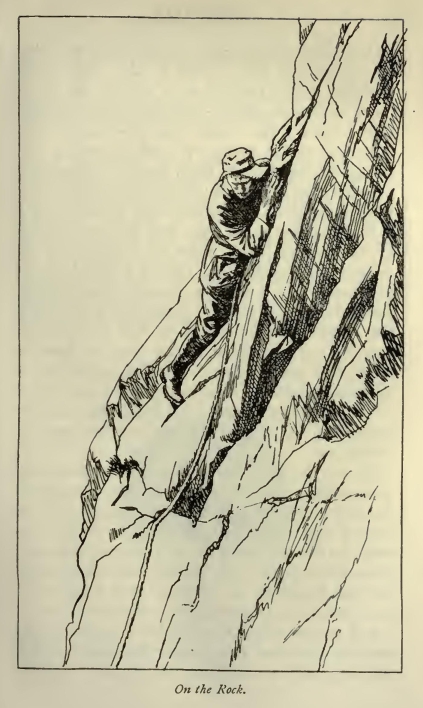

We have been overtaken by another party of three from the inn—one in a white jersey which, for reasons that will appear, I shall always remember. Together we follow the High Level Traverse, the track that leads round the flank of the mountain to the top of Walker's Gully, the grim descent to the valley, loved by the climber for the perils to which it invites him. Here wre lunch and here we separate. We, unambitious (having three passengers in our party of five), are climbing the East face by the Notch and Slab route; the others are ascending by the New West route, one of the more difficult climbs. Our start is here; theirs is from the other side of Jordan Gap. It is not of our climb that I wish to speak, but of theirs. In the old literature of the Rock you will find the Slab and Notch route treated as a difficult feat; but to-day it is held in little esteem.

With five on the rope, however, our progress is slow, and it is two o'clock when we emerge from the chimney, perspiring and triumphant, and stand, first of the year, on the summit of the Pillar Rock, where the wind blows thin and shrill and from whence you look out over half the peaks of Lakeland. We take a second lunch, inscribe our names in the book that lies under the cairn, and then look down the precipice on the West face for signs of our late companions. The sound of their voices comes up from below, but the drop is too sheer to catch a glimpse of their forms. “They're going to be late,” says George Abraham—the discoverer of the New West—and then he indicates the closing stages of the climb and the slab where on another New Year's Day occurred the most thrilling escape from death in the records of the Pillar rock—two men falling, and held on the rope and finally rescued by the third. Of those three, two, Lewis Meryon and the Rev. W. F. Wright, perished the next year on the Grand Paradis. We dismiss the unhappy memory and turn cheerfully to descend by Slingsby's Crack and the Old West route which ends on the slope of the mountain near to the starting point of the New West route.

The day is fading fast, and the moon that is rising in the East sheds no light on this face of the great tower. The voices now are quite distinct, coming to us from the left. We can almost hear the directions and distinguish the speakers. “Can't understand why those lads are cutting it so fine,” says George Abraham, and he hastens our pace down cracks and grooves and over ledges until we reach the screes and safety. And now we look up the great cliff and in the gathering dusk one thing is visible—a figure in a white jersey, with arms extended at full stretch. There it hangs minute by minute as if nailed to the rocks.

The party, then, are only just making the traverse from the chimney to the right, the most difficult manoeuvre of the climb—a manoeuvre in which one, he in the white jersey, has to remain stationary while his fellows pass him. “This is bad,” says George Abraham and he prepares for a possible emergency. “Are you in difficulties? Shall we wait?” he cries. “Yes, wait.” The words rebound from the cliff in the still air like stones. We wait and watch. We can see nothing but the white jersey, still moveless; but every motion of the other climbers and every word they speak echoes down the precipice, as if from a sounding board. You hear the iron-shod feet of the climbers feeling about for footholds on the ringing wall of rock. Once there is a horrible clatter as if both feet are dangling over the abyss and scraping convulsively for a hold. I fancy one or two of us feel a little uncomfortable as we look at each other in silent comment. And all the time the figure in white, now growing dim, is impaled on the face of the darkness, and the voices come down to us in brief, staccato phrases. Above the rock, the moon is sailing into the clear winter sky and the stars are coming out.

At last the figure in white is seen to move and soon a cheery “All right” drops down from above. The difficult operation is over, the scattered rocks are reached and nothing remains but the final slabs, which in the absence of ice offer no great difficulty. Their descent by the easy Jordan route will be quick. We turn to go with the comment that it is perhaps more sensational to watch a climb than to do one.

And then we plunge over the debris behind Pisgah, climb up the Great Doup, where the snow lies crisp and deep, until we reach the friendly fence that has guided many a wanderer in the darkness down to the top of Black Sail Pass. From thence the way is familiar, and two hours later we have rejoined the merry party round the board at the inn.

In a few days it is all over. This one is back in the Temple, that one to his office, a third to his pulpit, another to his mill, and all seem prosaic and ordinary. But they will carry with them a secret music. Say only the word “Wastdale” to them and you shall awake its echoes; then you shall see their faces light up with the emotion of incommunicable things. They are no longer men of the world; they are spirits of the mountains.

Yes,” said the man with the big voice, “I've seen it coming for years. Years.”

“Have you?” said the man with the timid voice. He had taken his seat on the top of the bus beside the big voice and had spoken of the tube strike that had suddenly paralysed the traffic of London.

“Yes, years,” said big voice, crowding as much modesty into the admission as possible. “I'm a long-sighted man. I see things a long way off. Suppose I'm a bit psychic. That's what I'm told. A bit psychic.”

“Ah,” said timid voice, doubtful, I thought, as to the meaning of the word, but firm in admiring acceptance of whatever it meant.

“Yes, I saw it coming for years. Lloyd George—that's the man that up to it before the war with his talk about the dukes and property and things. I said then, 'You see if this don't make trouble.' Why, his speeches got out to Russia and started them there. And now's it's come back. I always said it would. I said we should pay for it.”

“Did you, though?” observed timid voice—not questioningly, but as an assurance that he was listening attentively.

“Yes, the same with the war. I see it coming for years—years, I did. And if they'd taken my advice it' ud have been over in no time. In the first week I said: 'What we've got to do is to build 1000 aeroplanes and train 10,000 pilots and make 2000 torpedo craft.' That's what I said. But was it done?”

“Of course not,” said timid voice.

“I saw it all with my long sight. It's a way I have. I don't know why, but there it is. I'm not much at the platform business—tub-thumping, I call it—but for seeing things far off—well, I'm a bit psychic, you know.”

“Ah,” said timid voice, mournfully, “it's a pity some of those talking fellows are not psychic, too.” He'd got the word firmly now.

“Them psychic!” said big voice, with scorn. “We know what they are. You see that Miss Asquith is marrying a Roumanian prince. Mark my word, he'll turn out to be a German, that's what he'll turn out to be. It's German money all round. Same with these strikes. There's German money behind them.”

“Shouldn't wonder at all,” said timid voice.

“I know,” said big voice. “I've a way of seeing things. The same in the Boer War. I saw that coming for years.”

“Did you, indeed?” said timid voice.

“Yes. I wrote it down, and showed it to some of my friends. There it was in black and white. They said it was wonderful how it all turned out—two years, I said, 250 millions of money, and 20,000 casualties. That's what I said, and that's what it was. I said the Boers would win, and I claim they did win, seeing old Campbell Bannerman gave them all they asked for.”

“You were about right,” assented timid voice.

“And now look at Lloyd George. Why, Wilson is twisting him round his finger—that's what he's doing. Just twisting him round his finger. Wants a League of Nations, says Wilson, and then he starts building a fleet as big as ours.”

“Never did like that man,” said timid voice.

“It's him that has let the Germans escape. That's what the armistice means. They've escaped—and just when we'd got them down.”

“It's a shame,” said timid voice.

“This war ought to have gone on longer,” continued big voice. “My opinion is that the world wanted thinning out. People are too crowded. That's what they are—they're too crowded.”

“I agree there,” said timid voice. “We wanted thinning.”

“I consider we haven't been thinned out half enough yet. It ought to have gone on, and it would have gone on but for Wilson. I should like to know his little game. 'Keep your eye on Wilson,' says John Bull, and that's what I say. Seems to me he's one of the artful sort. I saw a case down at Portsmouth. Secretary of a building society—regular chapel-goer, teetotaller, and all that. One day the building society went smash, and Mr Chapel-goer had got off with the lot.”

“I don't like those goody-goody people,” said timid voice.

“No,” said big voice. “William Shakespeare hit it oh. Wonderful what that man knew. 'All the world's a stage, and all the men and women players,' he said. Strordinary how he knew things.”

“Wonderful,” said timid voice.

“There's never been a man since who knew half what William Shakespeare knew—not one-half.”

“No doubt about it,” said timid voice.

“I consider that William Shakespeare was the most psychic man that ever lived. I don't suppose there was ever such a long-sighted man before or since. He could see through anything. He'd have seen through Wilson and he'd have seen this war didn't stop before the job was done. It's a pity we haven't a William Shakespeare now. Lloyd George and Asquith are not in it with him. They're simply duds beside William Shakespeare. Couldn't hold a candle to him.”

“Seems to me,” said timid voice, “that there's nobody, as you might say, worth anything to-day.”

“Nobody,” said big voice. “We've gone right off. There used to be men. Old Dizzy, he was a man. So was Joseph Chamberlain. He was right about Tariff Reform. I saw it years before he did. Free Trade I said was all right years ago, when we were manufacturing for the world. But it's out of date. I saw it was out of date long before Joseph Chamberlain. It's the result of being long-sighted. I said to my father, 'If we stick to Free Trade this country is done.' That's what I said, and it's true. We are done. Look at these strikes. We stick to things too long. I believe in looking ahead. When I was in America before the war they wouldn't believe I came from England. Wouldn't believe it. 'But the English are so slow,' they said, 'and you—why you want to be getting on in front of us.' That's my way. I look ahead and don't stand still.”

“It's the best way too,” said timid voice. “We want more of it. We're too slow.”

And so on. When I came to the end of my journey I rose so that the light of a lamp shone on the speakers as I passed. They were both well-dressed, ordinary-looking men. If I had passed them in the street I should have said they were intelligent men of the well-to-do business class. I have set down their conversation, which I could not help overhearing, and which was carried on by the big voice in a tone meant for publication, as exactly as I can recall it. There was a good deal more of it, all of the same character. You will laugh at it, or weep over it, according to your humour.

Any careful observer of my habits would know that I am on the eve of an adventure—a holiday, or a bankruptcy, or a fire, or a voluntary liquidation (whatever that may be), or an elopement, or a duel, or a conspiracy, or—in short, of something out of the normal, something romantic or dangerous, pleasurable or painful, interrupting the calm current of my affairs. Being the end of July, he would probably say: That fellow is on the brink of the holiday fever. He has all the symptoms of the epidemic. Observe his negligent, abstracted manner. Notice his slackness about business—how he just comes and looks in and goes out as though he were a visitor paying a call, or a person who had been left a fortune and didn't care twopence what happened. Observe his clothes, how they are burgeoning into unaccustomed gaiety, even levity. Is not his hat set on at just a shade of a sporting angle? Does not his stick twirl with a hint of irresponsible emotions? Is there not the glint of far horizons in his eye? Did you not hear him humming as he came up the stairs? Yes, assuredly the fellow is going for a holiday.

Your suspicions would be confirmed when you found me ransacking my private room and clearing up my desk. The news that I am clearing up my desk has been an annual sensation for years. I remember a colleague of mine once coming in and finding me engaged in that spectacular feat. His face fell with apprehension. His voice faltered. “I hope you are not leaving us,” he said. He, poor fellow, could not think of anything else that could account for so unusual an operation.

For I am one of those people who treat their desks with respect. We do not believe in worrying them about their contents. We do not bully them into disclosing their secrets. We stuff the drawers full of papers and documents, and leave them to mellow and ripen. And when the drawers are full we pile up other papers and documents on either side of us; and the higher the pile gets the more comfortable and cosy we feel. We would not disturb them for worlds. Why should we set our sleeping dogs barking at us when they are willing to go on sleeping if we leave them alone? And consider the show they make. No one coming to see us can fail to be impressed by such piles of documents. They realise how busy we are. They understand that we have no time for idle talk. They see that we have all these papers to dispose of—otherwise, why are they there? They get their business done and go away quickly, and spread the news of what tremendous fellows we are for work.

I am told by one who worked with him, that old Lord Strathcona knew the trick quite well, and used it unblushingly. When a visitor was announced he tumbled his papers about in imposing confusion and was discovered breasting the mighty ocean of his labours, his chin resolutely out of the water. But he was a supreme artist in this form of amiable imposture. On one occasion he was entertained at a great public dinner in a provincial city. In the midst of the proceedings a portly flunkey was observed carrying a huge envelope, with seals and trappings, on a salver. For whom was this momentous document intended? Ah, he has paused behind the grand old man with the wonderful snowy head. It is for him. The company looks on in respectful silence. Even here this astonishing old man cannot escape the cares of office. As he takes the envelope his neighbour at the table looks at the address. It was in Strathcona's own hand-writing!

But we of the rank and file are not dishevelled by artifice, like this great man. It is a natural gift. And do not suppose that our disorder makes us unhappy. We like it. We follow our vocation, as Falstaff says. Some people are born tidy and some are born untidy. We were bom untidy, and if good people, taking pity on us, try to make us tidy we get lost. It was so with George Crabbe. He lived in magnificent disorder, papers and books and letters all over the floor, piled on every chair, surging up to the ceiling. Once, in his absence, his niece tidied up for him. When he came back he found himself like a stranger in a strange land. He did not know his way about in this desolation of tidiness, and he promptly restored the familiar disorder, so that he could find things. It sounds absurd, of course, but we people with a genius for untidiness must always seem absurd to the tidy people. They cannot understand that there is a method in our muddle, an order in our disorder, secret paths through the wilderness known only to our feet, that, in short, we are rather like cats whose perceptions become more acute the darker it gets. It is not true that we never find things. We often find things.

And consider the joy of finding things you don't hope to find. You, sir, sitting at your spotless desk, with your ordered and labelled shelves about you, and your files and your letter-racks, and your card indexes and your cross references, and your this, that, and the other—what do you know of the delights of which I speak? You do not come suddenly and ecstatically upon the thing you seek. You do not know the shock of delighted discovery. You do not shout “Eureka,” and summon your family around you to rejoice in the miracle that has happened. No star swims into your ken out of the void. You cannot be said to find things at all, for you never lose them, and things must be lost before they can be truly found. The father of the Prodigal had to lose his son before he could experience the joy that has become an immortal legend of the world. It is we who lose things, not you, sir, who never find them, who know the Feast of the Fatted Calf.

This is not a plea for untidiness. I am no hot gospeller of disorder. I only seek to make the best, of a bad job, and to show that we untidy fellows are not without a case, have our romantic compensations, moments of giddy exaltation unknown to those who are endowed with the pedestrian and profitable virtue of tidiness. That is all. I would have the pedestrian virtue if I could. In other days, before I had given up hope of reforming myself, and when I used to make good resolutions as piously as my neighbours, I had many a spasm of tidiness. I looked with envy on my friend Higginson, who was a miracle of order, could put his hand on anything he wanted in the dark, kept his documents and his files and records like regiments of soldiers obedient to call, knew what he had written on 4th March 1894, and what he had said on 10th January 1901, and had a desk that simply perspired with tidiness. And in a spirit of emulation I bought a roll-top desk. I believed that tidiness was a purchasable commodity. You went to a furniture dealer and bought a large roll-top desk, and when it came home the genius of order came home with it. The bigger the desk, the more intricate its devices, the larger was the measure of order bestowed on you. My desk was of the first magnitude. It had an inconceivable wealth of drawers and pigeon-holes. It was a desk of many mansions. And I labelled them all, and gave them all separate jobs to perform.

And then I sat back and looked the future boldly in the face. Now, said I, the victory is won. Chaos and old night are banished. Order reigns in Warsaw. I have but to open a drawer and every secret I seek will leap magically to light. My articles will write themselves, for every reference will come to my call, obedient as Ariel to the bidding of Prospero.

“Approach, my Ariel; come,”

I shall say, and from some remote fastness the obedient spirit will appear with—

“All hail, great master; grave sir, hail! I come

To answer thy best pleasure; be 't to fly,

To swim, to dive into the sea, to ride

On the curl'd clouds.”

I shall know where Aunt Jane's letters are, and where my bills are, and my cuttings about this, that, and the other, and my diaries and notebooks, and the time-table and the street guide. I shall never be short of a match or a spare pair of spectacles, or a pencil, or—in short, life will henceforth be an easy amble to old age. For a week it worked like a charm. Then the demon of disorder took possession of the beast. It devoured everything and yielded up nothing. Into its soundless deeps my merchandise sank to oblivion. And I seemed to sink with it. It was not a desk, but a tomb. One day I got a man to take it away to a second-hand shop.

Since then I have given up being tidy. I have realised that the quality of order is not purchasable at furniture shops, is not a quality of external things, but an indwelling spirit, a frame of mind, a habit that perhaps may be acquired but cannot be bought.

I have a smaller desk with fewer drawers, all of them nicely choked up with the litter of the past. Once a year I have a gaol delivery of the incarcerated. The ghosts come out into the daylight, and I face them unflinching and unafraid. They file past, pointing minatory fingers at me as they go into the waste-paper basket. They file past now. But I do not care a dump; for to-morrow I shall seek fresh woods and pastures new. To-morrow the ghosts of that old untidy desk will have no terrors for my emancipated spirit.

We were talking of the distinction between madness and sanity when one of the company said that we were all potential madmen, just as every gambler was a potential suicide, or just as every hero was a potential coward.

“I mean,” he said, “that the difference between the sane and the insane is not that the sane man never has mad thoughts. He has, but he recognises them as mad, and keeps his hand on the rein of action. He thinks them, and dismisses them. It is so with the saint and the sinner. The saint is not exempt from evil thoughts, but he knows they are evil, is master of himself, and puts them away.

“I speak with experience,” he went on, “for the potential madman in me once nearly got the upper hand. I won, but it was a near thing, and if I had gone down in that struggle I should have been branded for all time as a criminal lunatic, and very properly put away in some place of safety. Yet I suppose no one ever suspected me of lunacy.”

“Tell us about it,” we said in chorus.

“It was one evening in New York,” he said. “I had had a very exhausting time, and was no doubt mentally tired. I had taken tea with two friends at the Belmont Hotel, and as we found we were all disengaged that evening we agreed to spend it together at the Hippodrome, where a revue, winding up with a great spectacle that had thrilled New York, was being presented. When we went to the box office we found that we could not get three seats together, so we separated, my friends going to the floor of the house and I to the dress circle.

“If you are familiar with the place you will know its enormous dimensions and the vastness of the stage. When I took my seat next but one to one of the gangways the house was crowded and the performance had begun. It was trivial and ordinary enough, but it kept me amused, and between the acts I went out to see the New Yorkers taking 'soft' drinks in the promenades. I did not join them in that mild indulgence, nor did I speak to anyone.

“After the interval before the concluding spectacle I did not return to my seat until the curtain was up. The transformation hit me like a blow. The huge stage had been converted into a lake, and behind the lake through filmy draperies there was the suggestion of a world in flames. I passed to my seat and sat down. I turned from the blinding glow of the conflagration in front and cast my eye over the sea of faces that filled the great theatre from floor to ceiling. 'Heavens! if there were a fire in this place,' I thought. At that thought the word 'Fire' blazed in my brain like a furnace. 'What if some madman cried Fire?' flashed through my mind, and then 'What if I cried Fire?'

“At that hideous suggestion, the demon word that suffused my brain leapt like a shrieking maniac within me and screamed and fought for utterance. I felt it boiling in my throat, I felt it on my tongue. I felt myself to be two persons engaged in a deadly grapple—a sane person struggling to keep his feet against the mad rush of an insane monster. I clenched my teeth. So long as I kept my teeth tight—tight—tight the raging madman would fling himself at the bars in vain. But could I keep up the struggle till he fell exhausted? I gripped the arms of my seat. I felt beads of perspiration breaking out on my right brow. How singular that in moments of strain the moisture always broke out at that spot. I could notice these things with a curious sense of detachment as if there were a third person within me watching the frenzied conflict. And still that titanic impulse lay on my tongue and hammered madly at my clenched teeth. Should I go out? That would look odd, and be an ignominious surrender. I must fight this folly down honestly and not run away from it. If I had a book I would try to read. If I had a friend beside me I would talk. But both these expedients were denied me. Should I turn to my unknown neighbour and break the spell with an inconsequent remark or a request for his programme? I looked at him out of the tail of my eye. He was a youngish man, in evening dress, and sitting alone as I was. But his eyes were fixed intently on the stage. He was obviously gripped by the spectacle. Had I spoken to him earlier in the evening the course would have been simple; but to break the ice in the midst of this tense silence was impossible. Moreover, I had a programme on my knees and what was there to say?...

“I turned my eyes from the stage. What was going on there I could not tell. It was a blinding blur of Fire that seemed to infuriate the monster within me. I looked round at the house. I looked up at the ceiling and marked its gilded ornaments. I turned and gazed intensely at the occupants of the boxes, trying to turn the current of my mind into speculations about their dress, their faces, their characters. But the tyrant was too strong to be overthrown by such conscious effort. I looked up at the gallery; I looked down at the pit; I tried to busy my thoughts with calculations about the numbers present, the amount of money in the house, the cost of running the establishment—anything. In vain. I leaned back in my seat, my teeth still clenched, my hands still gripping the arms of the chair. How still the house was! How enthralled it seemed!... I was conscious that people about me were noticing my restless inattention. If they knew the truth.... If they could see the raging torment that was battering at my teeth.... Would it never go? How long would this wild impulse burn on my tongue? Was there no distraction that would

Cleanse the stuffed bosom of this perilous stuff

That feeds upon the brain.

“I recalled the reply—

Therein the patient must minister to himself.

“How fantastic it seemed. Here was that cool observer within me quoting poetry over my own delirium without being able to allay it. What a mystery was the brain that could become the theatre of such wild drama. I turned my glance to the orchestra. Ah, what was that they were playing?... Yes, it was a passage from Dvorak's American Symphony. How familiar it was! My mind incontinently leapt to a remote scene, I saw a well-lit room and children round the hearth and a figure at the piano....

“It was as though the madman within me had fallen stone dead. I looked at the stage coolly, and observed that someone was diving into the lake from a trapeze that seemed a hundred feet high. The glare was still behind, but I knew it for a sham glare. What a fool I had been.... But what a hideous time I had had.... And what a close shave.... I took out my handkerchief and drew it across my forehead.”

It was inevitable that the fact that a murder has taken place at a house with the number 13 in a street, the letters of whose name number 13, would not pass unnoticed. If we took the last hundred murders that have been committed, I suppose we should find that as many have taken place at No. 6 or No. 7, or any other number you choose, as at No. 13—that the law of averages is as inexorable here as elsewhere. But this consideration does not prevent the world remarking on the fact when No. 13 has its turn. Not that the world believes there is anything in the superstition. It is quite sure it is a mere childish folly, of course. Few of us would refuse to take a house because its number was 13, or decline an invitation to dinner because there were to be 13 at table. But most of us would be just a shade happier if that desirable residence were numbered 11, and not any the less pleased with the dinner if one of the guests contracted a chill that kept him away. We would not confess this little weakness to each other. We might even refuse to admit it to ourselves, but it is there.

That it exists is evident from many irrefutable signs. There are numerous streets in London, and I daresay in other towns too, in which there is no house numbered 13, and I am told that it is very rare that a bed in a hospital bears that number. The superstition, threadbare though it has worn, is still sufficiently real to enter into the calculations of a discreet landlord in regard to the letting qualities of his house, and into the calculations of a hospital as to the curative properties of a bed. In the latter case general agreement would support the concession to the superstition, idle though that superstition is. Physical recovery is a matter of the mind as well as of the body, and the slightest shadow on the mind may, in a condition of low vitality, retard and even defeat recovery. Florence Nightingale's almost passionate advocacy of flowers in the sick bedroom was based on the necessity of the creation of a certain state of mind in the patient. There are few more curious revelations in that moving record by M. Duhamel of medical experiences during the war, than the case of the man who died of a pimple on his nose. He had been hideously mutilated in battle and was brought into hospital a sheer wreck; but he was slowly patched up and seemed to have been saved when a pimple appeared on his nose. It was nothing in itself, but it was enough to produce a mental state that checked the flickering return of life. It assumed a fantastic importance in the mind of the patient who, having survived the heavy blows of fate, died of something less than a pin prick. It is not difficult to understand that so fragile a hold of life might yield to the sudden discovery that you were lying in No. 13 bed.

I am not sure that I could go into the witness-box and swear that I am wholly immune to these idle superstitions myself. It is true that of all the buses in London, that numbered 13 chances to be the one that I constantly use, and I do not remember, until now, ever to have associated the superstition with it. And certainly I have never had anything but the most civil treatment from it. It is as well behaved a bus, and as free from unpleasant associations as any on the road. I would not change its number if I had the power to do so. But there are other circumstances of which I should find it less easy to clear myself of suspicion under cross examination. I never see a ladder against a house side without feeling that it is advisable to walk round it rather than under it. I say to myself that this is not homage to a foolish superstition, but a duty to my family. One must think of one's family. The fellow at the top of the ladder may drop anything. He may even drop himself. He may have had too much to drink. He may be a victim of epileptic fits, and epileptic fits, as everyone knows, come on at the most unseasonable times and places. It is a mere measure of ordinary safety to walk round the ladder. No man is justified in inviting danger in order to flaunt his superiority to an idle fancy. Moreover, probably that fancy has its roots in the common-sense fact that a man on a ladder does occasionally drop things. No doubt many of our superstitions have these commonplace and sensible origins. I imagine, for example, that the Jewish objection to pork as unclean on religious grounds is only due to the fact that in Eastern climates it is unclean on physical grounds.

All the same, I suspect that when I walk round the ladder I am rather glad that I have such respectable and unassailable reasons for doing so. Even if—conscious of this suspicion and ashamed to admit it to myself—I walk under the ladder I am not quite sure that I have not done so as a kind of negative concession to the superstition. I have challenged it rather than been unconscious of it. There is only one way of dodging the absurd dilemma, and that is to walk through the ladder. This is not easy. In the same way I am sensible of a certain satisfaction when I see the new moon in the open rather than through glass, and over my right shoulder rather than my left. I would not for any consideration arrange these things consciously; but if they happen so I fancy I am better pleased than if they do not. And on these occasions I have even caught my hand—which chanced to be in my pocket at the time—turning over money, a little surreptitiously I thought, but still undeniably turning it. Hands have habits of their own and one can't always be watching them.

But these shadowy reminiscences of antique credulity which we discover in ourselves play no part in the lives of any of us. They belong to a creed outworn. Superstition was disinherited when science revealed the laws of the universe and put man in his place. It was no discredit to be superstitious when all the functions of nature were unexplored, and man seemed the plaything of beneficent or sinister forces that he could neither control nor understand, but which held him in the hollow of their hand. He related everything that happened in nature to his own inexplicable existence, saw his fate in the clouds, his happiness or misery announced in the flight of birds, and referred every phenomenon of life to the soothsayers and oracles. You may read in Thucydides of battles being postponed (and lost) because some omen that had no more relation to the event than the falling of a leaf was against it. When Pompey was afraid that the Romans would elect Cato as prætor he shouted to the Assembly that he heard thunder, and got the whole election postponed, for the Romans would never transact business after it had thundered. Alexander surrounded himself with fortune tellers and took counsel with them as a modern ruler takes counsel with his Ministers. Even so great a man as Cæsar and so modern and enlightened a man as Cicero left their fate to augurs and omens. Sometimes the omens were right and sometimes they were wrong, but whether right or wrong they were equally meaningless. Cicero lost his life by trusting to the wisdom of crows. When he was in flight from Antony and Cæsar Augustus he put to sea and might have escaped. But some crows chanced to circle round his vessel, and he took the circumstance to be unfavourable to his action, returned to shore and was murdered. Even the farmer of ancient Greece consulted the omens and the oracles where the farmer to-day is only careful of his manures.

I should have liked to have seen Cæsar and I should have liked to have heard Cicero, but on the balance I think we who inherit this later day and who can jest at the shadows that were so real to them have the better end of time. It is pleasant to be about when the light is abroad. We do not know much more of the Power that

Turns the handle of this idle show

than our forefathers did, but at least we have escaped the grotesque shadows that enveloped them. We do not look for divine guidance in the entrails of animals or the flight of crows, and the House of Commons does not adjourn at a clap of thunder.

I met a lady the other day who had travelled much and seen much, and who talked with great vivacity about her experiences. But I noticed one peculiarity about her. If I happened to say that I too had been, let us say, to Tangier, her interest in Tangier immediately faded away and she switched the conversation on to, let us say, Cairo, where I had not been, and where therefore she was quite happy. And her enthusiasm about the Honble. Ulick de Tompkins vanished when she found that I had had the honour of meeting that eminent personage. And so with books and curiosities, places and things—she was only interested in them so long as they were her exclusive property. She had the itch of possession, and when she ceased to possess she ceased to enjoy. If she could not have Tangier all to herself she did not want it at all.

And the chief trouble in this perplexing world is that there are so many people afflicted like her with the mania of owning things that really do not need to be owned in order to be enjoyed. Their experiences must be exclusive or they have no pleasure in them. I have heard of a man who countermanded an order for an etching when he found that someone else in the same town had bought a copy. It was not the beauty of the etching that appealed to him: it was the petty and childish notion that he was getting something that no one else had got, and when he found that someone else had got it its value ceased to exist.

The truth, of course, is that such a man could never possess anything in the only sense that matters. For possession is a spiritual and not a material thing. I do not own—to take an example—that wonderful picture by Ghirlandajo of the bottle-nosed old man looking at his grandchild. I have not even a good print of it. But if it hung in my own room I could not have more pleasure out of it than I have experienced for years. It is among the imponderable treasures stored away in the galleries of the mind with memorable sunsets I have seen and noble books I have read, and beautiful actions or faces that I remember. I can enjoy it whenever I like and recall all the tenderness and humanity that the painter saw in the face of that plain old Italian gentleman with the bottle nose as he stood gazing down at the face of his grandson long centuries ago. The pleasure is not diminished by the fact that all may share this spiritual ownership, any more than my pleasure in the sunshine, or the shade of a fine beech, or the smell of a hedge of sweetbrier, or the song of the lark in the meadow is diminished by the thought that it is common to all.

From my window I look on the slope of a fine hill crowned with beech woods. On the other side of the hill there are sylvan hollows of solitude which cannot have changed their appearance since the ancient Britons hunted in these woods two thousand years ago. In the legal sense a certain noble lord is the owner. He lives far off and I doubt whether he has seen these woods once in ten years. But I and the children of the little hamlet know every glade and hollow of these hills and have them for a perpetual playground. We do not own a square foot of them, but we could not have a richer enjoyment of them if we owned every leaf on every tree. For the pleasure of things is not in their possession but in their use.

It was the exclusive spirit of my lady friend that Juvenal satirised long ago in those lines in which he poured ridicule on the people who scurried through the Alps, not in order to enjoy them, but in order to say that they had done something that other people had not done. Even so great a man as Wordsworth was not free from this disease of exclusive possession. De Quincey tells that, standing with him one day looking at the mountains, he (De Quincey) expressed his admiration of the scene, whereupon Wordsworth turned his back on him. He would not permit anyone else to praise his mountains. He was the high priest of nature, and had something of the priestly arrogance. He was the medium of revelation, and anyone who worshipped the mountains in his presence, except through him, was guilty of an impertinence both to him and to nature.

In the ideal world of Plato there was no such thing as exclusive possession. Even wives and children were to be held in common, and Bernard Shaw to-day regards the exclusiveness of the home as the enemy of the free human spirit. I cannot attain to these giddy heights of communism. On this point I am with Aristotle. He assailed Plato's doctrine and pointed out that the State is not a mere individual, but a body composed of dissimilar parts whose unity is to be drawn “ex dissimilium hominum consensu.” I am as sensitive as anyone about my title to my personal possessions. I dislike having my umbrella stolen or my pocket picked, and if I found a burglar on my premises I am sure I shouldn't be able to imitate the romantic example of the good bishop in “Les Misérables.” When I found the other day that some young fruit trees I had left in my orchard for planting had been removed in the night I was sensible of a very commonplace anger. If I had known who my Jean Valjean was I shouldn't have asked him to come and take some more trees. I should have invited him to return what he had removed or submit to consequences that follow in such circumstances.

I cannot conceive a society in which private property will not be a necessary condition of life. I may be wrong. The war has poured human society into the melting pot, and he would be a daring person who ventured to forecast the shape in which it will emerge a generation or two hence. Ideas are in the saddle, and tendencies beyond our control and the range of our speculation are at work shaping our future. If mankind finds that it can live more conveniently and more happily without private property it will do so. In spite of the Decalogue private property is only a human arrangement, and no reasonable observer of the operation of the arrangement will pretend that it executes justice unfailingly in the affairs of men. But because the idea of private property has been permitted to override with its selfishness the common good of humanity, it does not follow that there are not limits within which that idea can function for the general convenience and advantage. The remedy is not in abolishing it altogether, but in subordinating it to the idea of equal justice and community of purpose. It will, reasonably understood, deny me the right to call the coal measures, which were laid with the foundations of the earth, my private property or to lay waste a countryside for deer forests, but it will still leave me a legitimate and sufficient sphere of ownership. And the more true the equation of private and public rights is, the more secure shall I be in those possessions which the common sense and common interest of men ratify as reasonable and desirable. It is the grotesque and iniquitous wrongs associated with a predatory conception of private property which to some minds make the idea of private property itself inconsistent with a just and tolerable social system. When the idea of private property is restricted to limits which command the sanction of the general thought and experience of society, it will be in no danger of attack. I shall be able to leave my fruit trees out in the orchard without any apprehensions as to their safety.

But while I neither desire nor expect to see the abolition of private ownership, I see nothing but evil in the hunger to possess exclusively things, the common use of which does not diminish the fund of enjoyment. I do not care how many people see Tangier: my personal memory of the experience will remain in its integrity. The itch to own things for the mere pride of possession is the disease of petty, vulgar minds. “I do not know how it is,” said a very rich man in my hearing, “but when I am in London I want to be in the country and when I am in the country I want to be in London.” He was not wanting to escape from London or the country, but from himself. He had sold himself to his great possessions and was bankrupt. In the words of a great preacher “his hands were full but his soul was empty, and an empty soul makes an empty world.” There was wisdom as well as wit in that saying of the Yoloffs that “he who was born first has the greatest number of old clothes.” It is not a bad rule for the pilgrimage of this world to travel light and leave the luggage to those who take a pride in its abundance.

I was talking in the smoking-room of a club with a man of somewhat blunt manner when Blossom came up, clapped him on the shoulder, and began:

“Well, I think America is bound to——” “Now, do you mind giving us two minutes?” broke in the other, with harsh emphasis. Blossom, unabashed and unperturbed, moved off to try his opening on another group. Poor Blossom! I had almost said “Dear Blossom.” For he is really an excellent fellow. The only thing that is the matter with Blossom is that he is a bore. He has every virtue except the virtue of being desirable company. You feel that you could love Blossom if he would only keep away. If you heard of his death you would be genuinely grieved and would send a wreath to his grave and a nice letter of condolence to his wife and numerous children.

But it is only absence that makes the heart grow fond of Blossom. When he appears all your affection for him withers. You hope that he will not see you. You shrink to your smallest dimensions. You talk with an air of intense privacy. You keep your face averted. You wonder whether the back of your head is easily distinguishable among so many heads. All in vain. He approacheth with the remorselessness of fate. He putteth his hand upon your shoulder. He remarketh with the air of one that bringeth new new's and good news—“Well, I think that America is bound to——” And then he taketh a chair and thou lookest at the clock and wonderest how soon thou canst decently remember another engagement.